Exhibition dates: 18th April 2012 – 29th April 2013

Josef Albers (German, 1888-1976)

Marli Heimann, Alle während 1 Stunde (Marli Heimann, All During an Hour)

1931

Twelve gelatin silver prints

Overall 11 11/16 x 16 7/16″ (29.7 x 41.8cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of The Josef Albers Foundation, Inc.

© 2012 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Another fascinating exhibition and a bumper posting to boot (pardon the pun!)

A panoply of famous photographers along with a few I had never heard of before (such as Georges Hugnet) are represented in this posting. As the press blurb states, through “key photographic projects, experimental films, and photobooks, The Shaping of New Visions offers a critical reassessment of photography’s role in the avant-garde and neo-avant-garde movements, and in the development of contemporary artistic practices.”

The large exhibition seems to have a finger in every pie, wandering from the birth of the 20th-century modern metropolis, through “New Vision” photography in the 1920s, experimental film, Surrealism, Constructivism and New Objectivity, Dada, Rayographs, photographic avant-gardism, photocollages, photomontages, street photography of the 1960s, colour slide projection performance, through New Topographics, self-published books, and conceptual photography, featuring works that reevaluate the material and contextual definitions of photography. “The final gallery showcases major installations by a younger generation of artists whose works address photography’s role in the construction of contemporary history.”

Without actually going to New York to see the exhibition (I wish!!) – from a distance it does seem a lot of ground to cover within 5 galleries even if there are 250 works. You could say this is a “meta” exhibition, drawing together themes and experiments from different areas of photography with rather a long bow. Have a look at the The Shaping of New Visions exhibition checklist to see the full listing of what’s on show and you be the judge. There are some rare and beautiful images that’s for sure. From the photographs in this posting I would have to say the distorted “eyes” have it…

Dr Marcus Bunyan

.

Many thankx to MoMA for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

László Moholy-Nagy (Hungarian, 1895-1946)

Ein Lichtspiel: schwarz weiss grau (A Lightplay: Black White Gray) (excerpt)

1930

This short film made by László Moholy-Nagy is based on the shadow patterns created by his Light-Space Modulator, an early kinetic sculpture consisting of a variety of curved objects in a carefully choreographed cycle of movements. Created in 1930, the film was originally planned as the sixth and final part of a much longer work depicting the new space-time.

Paul Strand and Charles Sheeler

Manhatta

1921

Film

Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art, New York

© Aperture Foundation Inc., Paul Strand Archive

In 1920 Paul Strand and artist Charles Sheeler collaborated on Manhatta, a short silent film that presents a day in the life of lower Manhattan. Inspired by Walt Whitman’s book Leaves of Grass, the film includes multiple segments that express the character of New York. The sequences display a similar approach to the still photography of both artists. Attracted by the cityscape and its visual design, Strand and Sheeler favored extreme camera angles to capture New York’s dynamic qualities. Although influenced by Romanticism in its view of the urban environment, Manhatta is considered the first American avant-garde film.

Dziga Vertov (Russian, 1896-1954)

Chelovek s kinoapparatom (Man with a Movie Camera)

1929

Film

1 hr 6 mins 49 secs

Excerpt from a camera operators diary

ATTENTION VIEWERS:

This film is an experiment in cinematic communication of real events

Without the help of Intertitles

Without the help of a story

Without the help of theatre

This experimental work aims at creating a truly international language of cinema based on its absolute separation from the language of theatre and literature

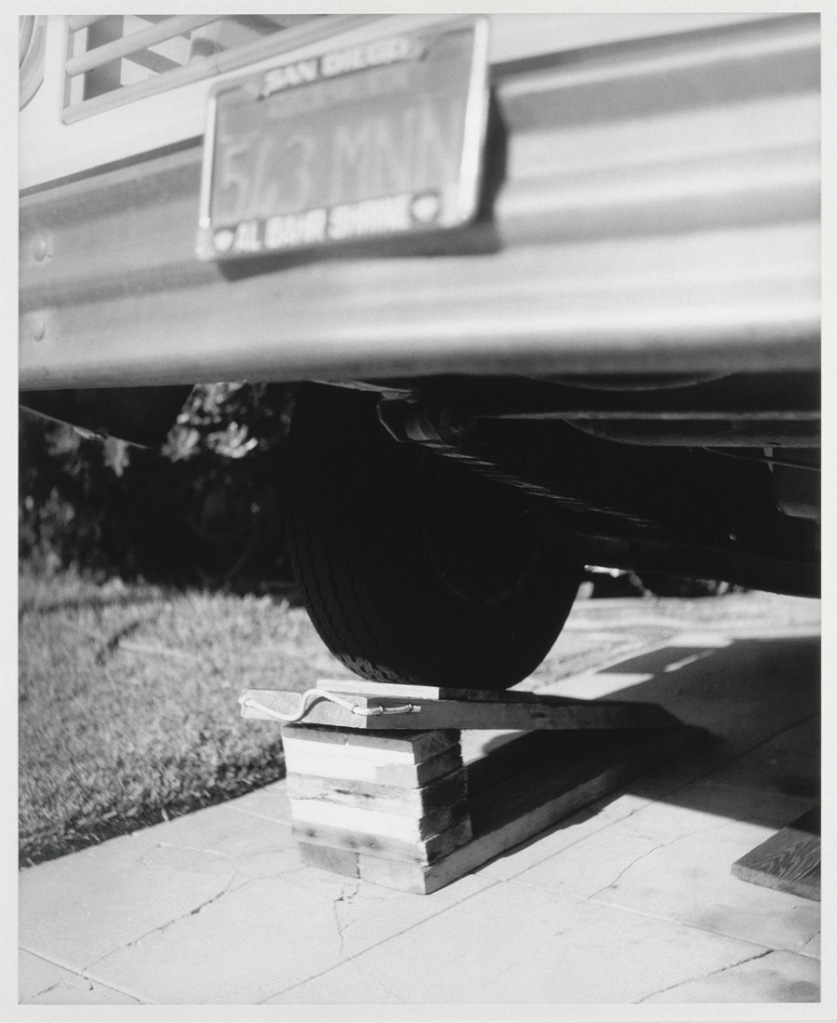

Eleanor Antin (American, b. 1935)

100 Boots

1971-1973

Photographed by Philip Steinmetz

Halftone reproductions on 51 cards

4 1/2 x 7 in. each

Courtesy Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York

© Eleanor Antin

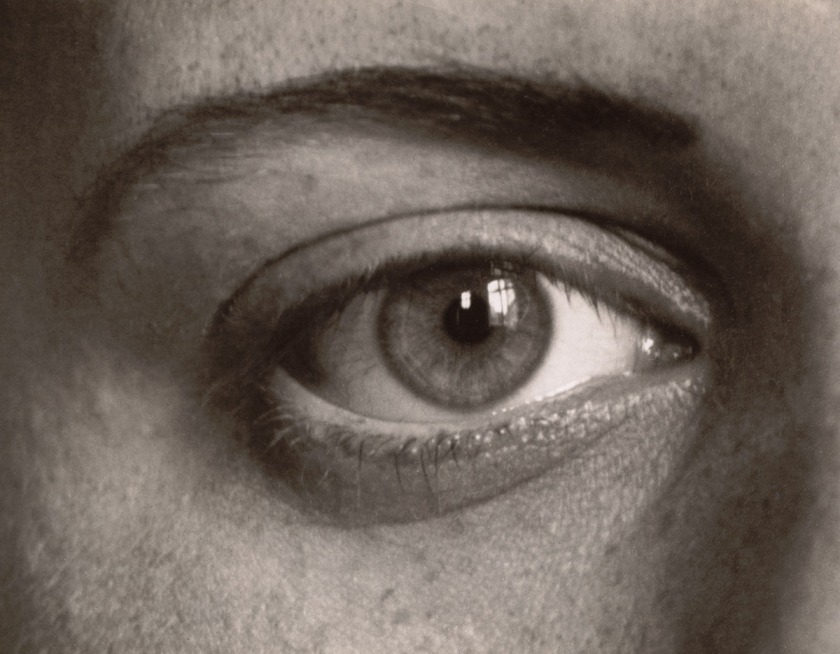

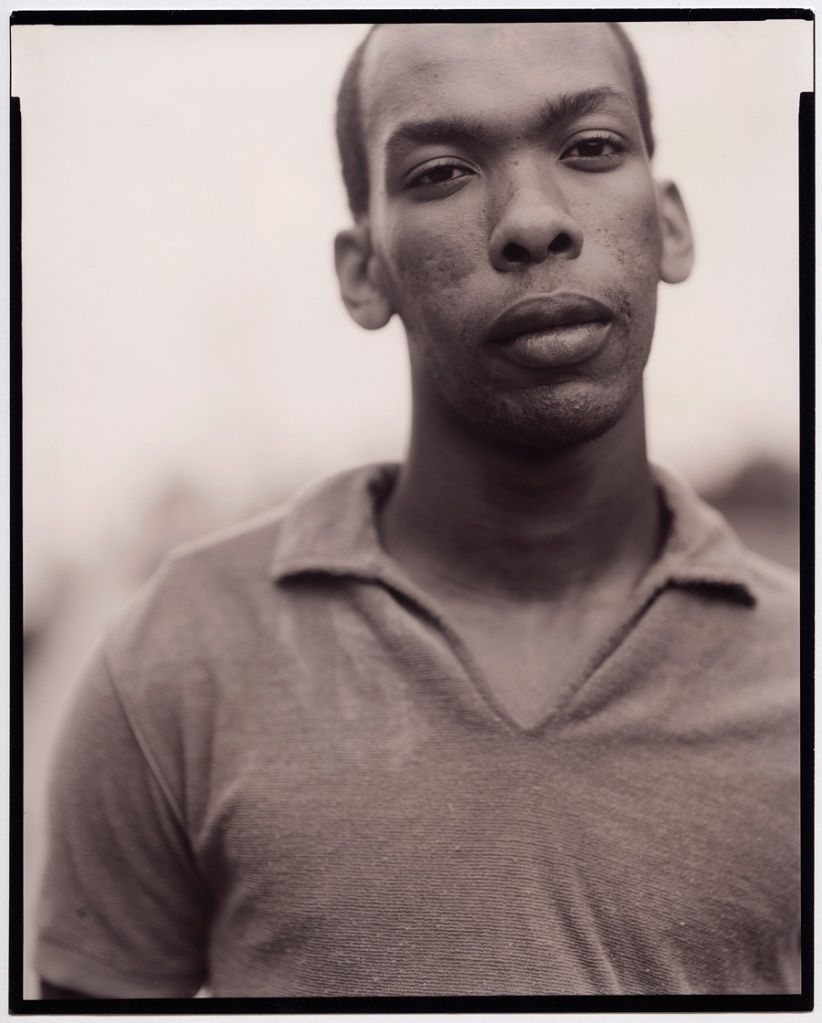

August Sander (German, 1876-1964)

Das rechte Auge meiner Tochter Sigrid (The Right Eye of My Daughter Sigrid)

1928

Gelatin silver print

7 1/16 x 9″ (17.9 x 22.9cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of the photographer

© 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

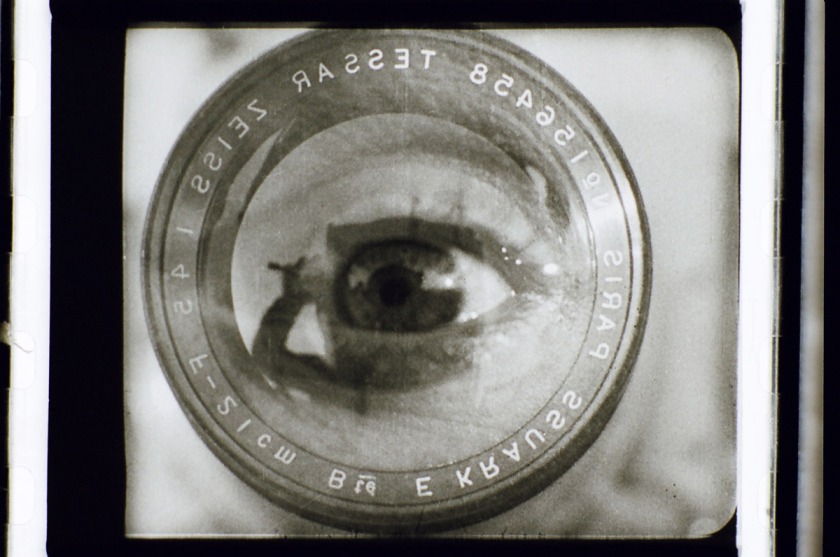

Dziga Vertov (Russian, 1896-1954)

Chelovek s kinoapparatom (Man with a Movie Camera) (still)

1929

35mm film

65 min ( black and white, silent)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Department of Film

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Rayograph

1922

Gelatin silver print (photogram)

9 3/8 x 11 3/4″ (23.9 x 29.9cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of James Thrall Soby

© 2012 Man Ray Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

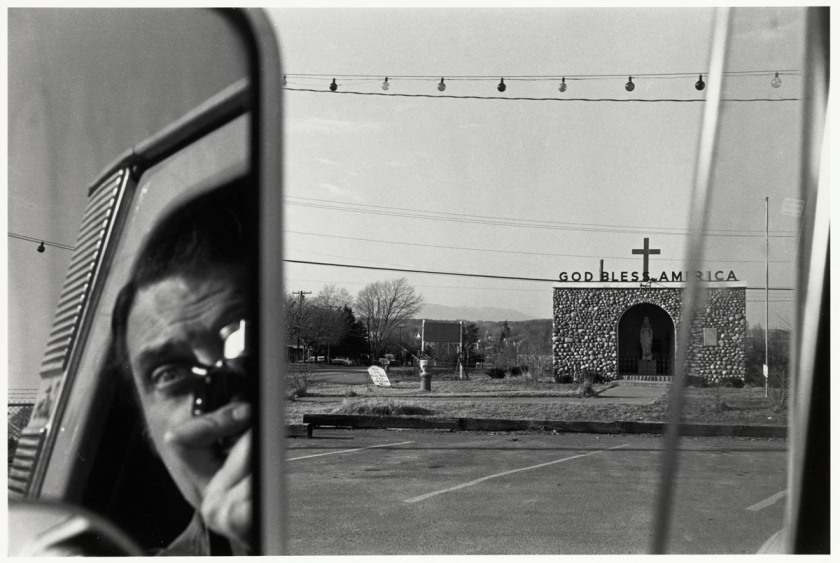

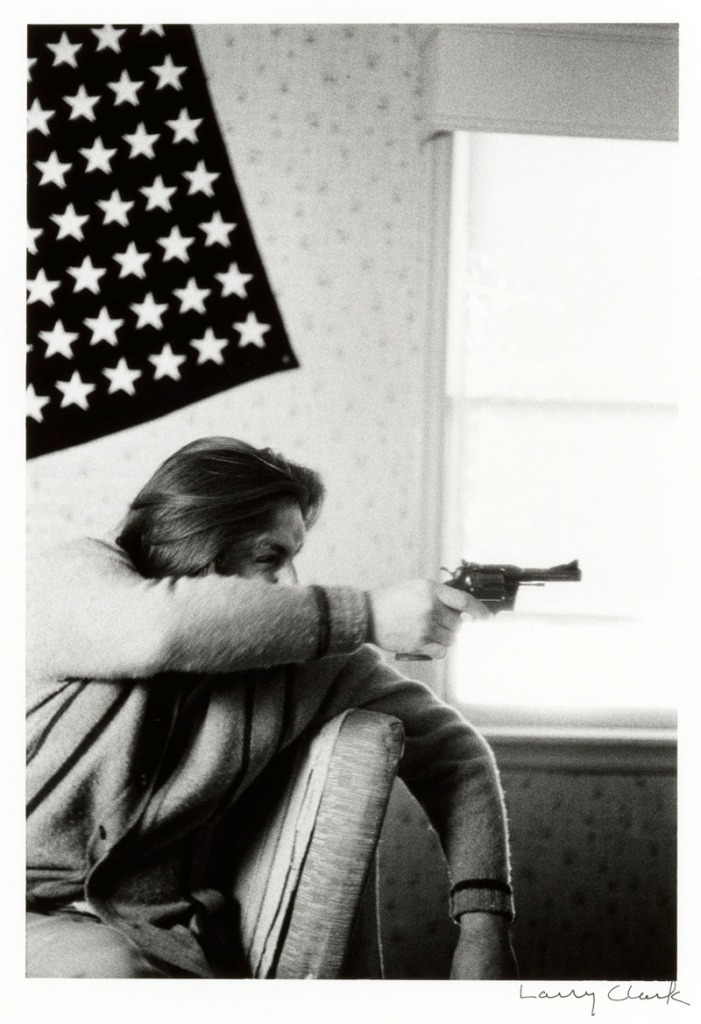

William Klein (American, b. 1928)

Gun, Gun, Gun, New York

1955

Gelatin silver print

10 1/4 x 13 5/8″ (26 x 34.6 cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Arthur and Marilyn Penn

Georges Hugnet (French, 1906-1974)

Untitled [Surrealist beach collage]

c. 1935

Collage of photogravure, lithograph, chromolithograph and gelatin silver prints on gelatin silver print

11 7/8 x 9 7/16″ (30.2 x 24cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Timothy Baum in memory of Harry H. Lunn, Jr.

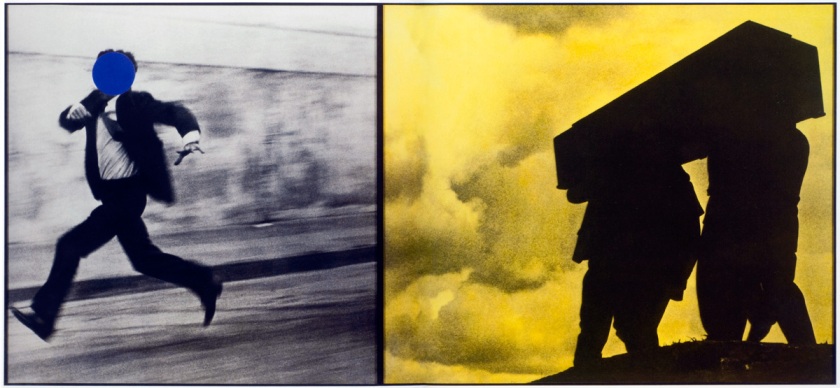

Martha Rosler (American, b. 1943)

Red Stripe Kitchen

1967-1972

From the series Bringing the War Home: House Beautiful

Pigmented inkjet print, printed 2011

23 3/4 x 18 1/8″ (60.3 x 46cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Purchase and The Modern Women’s Fund

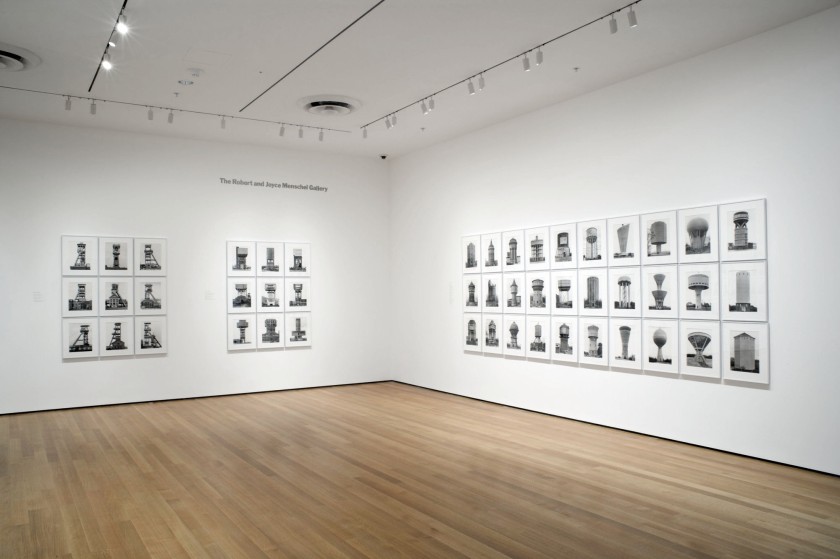

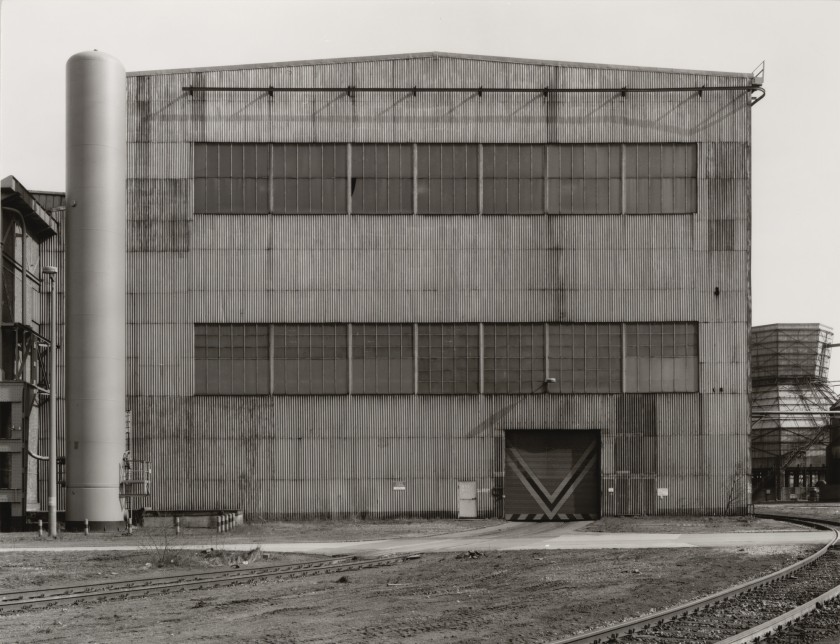

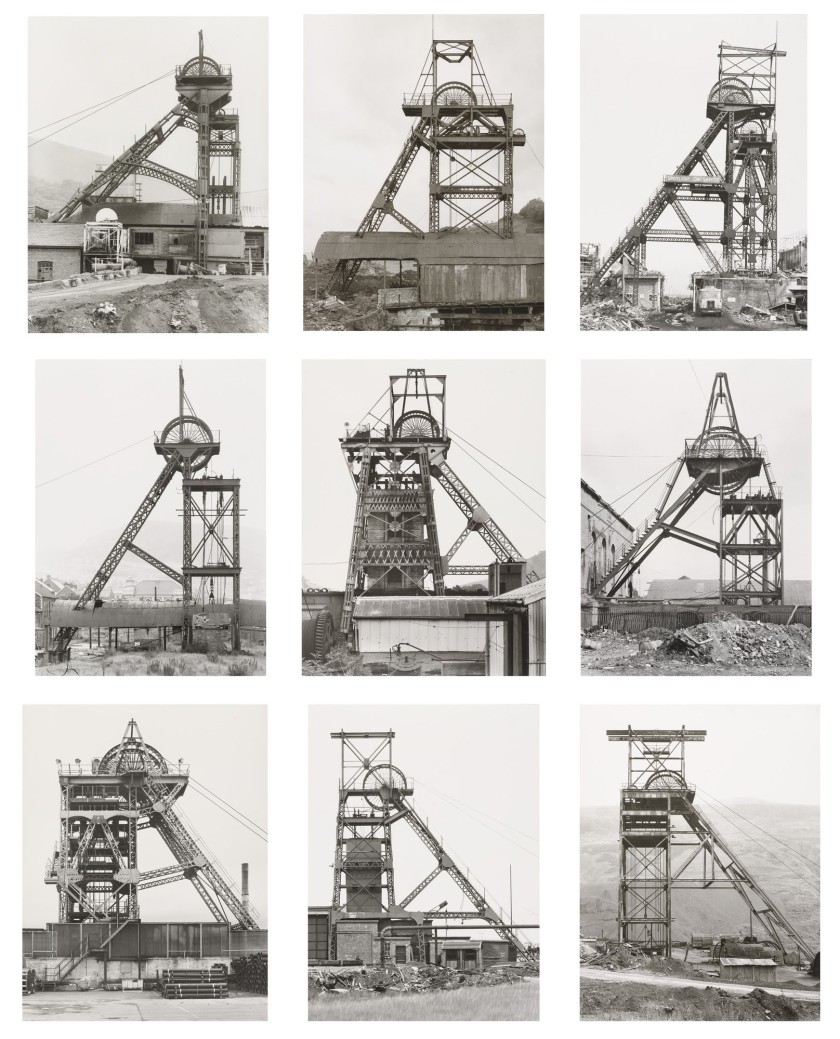

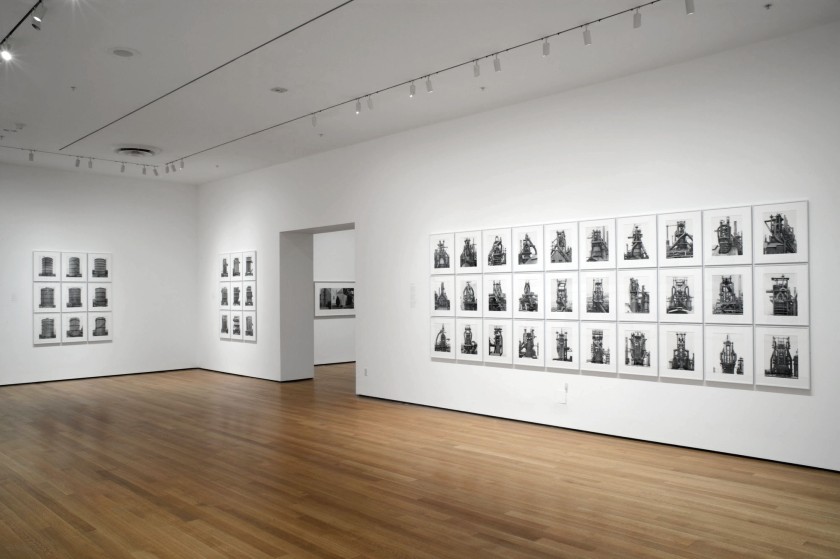

The Museum of Modern Art draws from its collection to present the exhibition The Shaping of New Visions: Photography, Film, Photobook on view from April 18, 2012, to April 29, 2013. Filling the third-floor Edward Steichen Photography Galleries, this installation presents more than 250 works by approximately 90 artists, with a focus on new acquisitions and groundbreaking projects by Man Ray, László Moholy-Nagy, Aleksandr Rodchenko, Germaine Krull, Dziga Vertov, Gerhard Rühm, Helen Levitt, Robert Frank, Daido Moriyama, Robert Heinecken, Edward Ruscha, Martha Rosler, Bernd and Hilla Becher, Philip-Lorca diCorcia, Paul Graham, and The Atlas Group / Walid Raad. The exhibition is organised by Roxana Marcoci, Curator, Department of Photography, The Museum of Modern Art.

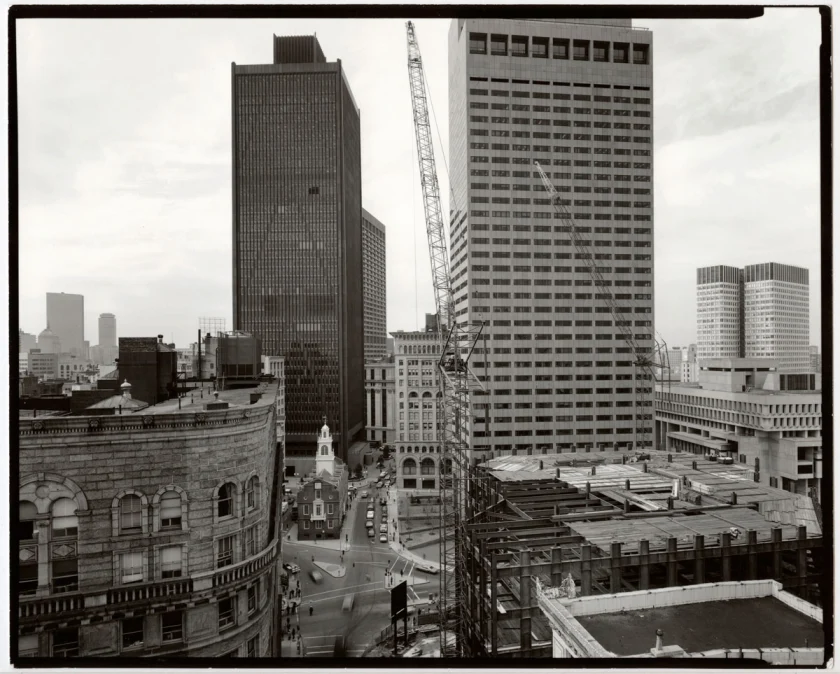

Punctuated by key photographic projects, experimental films, and photobooks, The Shaping of New Visions offers a critical reassessment of photography’s role in the avant-garde and neo-avant-garde movements, and in the development of contemporary artistic practices. The shaping of what came to be known as “new vision” photography in the 1920s bore the obvious influence of “lens-based” and “time-based” works. The first gallery begins with photographs capturing the birth of the 20th-century modern metropolis by Berenice Abbott, Edward Steichen, and Alfred Stieglitz, presented next to the avant-garde film Manhatta (1921), a collaboration between Paul Strand and Charles Sheeler.

The 1920s were a period of landmark constructions and scientific discoveries all related to light – from Thomas Edison’s development of incandescent light to Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity and light speed. Man Ray began experimenting with photograms (pictures made by exposing objects placed on photosensitive paper to light) – which he renamed “rayographs” after himself – in which light was both the subject and medium of his work. This exhibition presents Man Ray’s most exquisite rayographs, alongside his first short experimental film, Le Retour à la raison (Return to Reason, 1923), in which he extended the technique to moving images.

In 1925, two years after he joined the faculty of the Bauhaus school in Weimar Germany, László Moholy-Nagy published his influential book Malerei, Fotografie, Film (Painting, Photography, Film) – part of a series that he coedited with Bauhaus director Walter Gropius – in which he asserted that photography and cinema are heralding a “culture of light” that has overtaken the most innovative aspects of painting. Moholy-Nagy extolled photography and, by extension, film as the quintessential medium of the future. Moholy-Nagy’s interest in the movement of objects and light through space led him to construct Light-Space Modulator, the subject of his only abstract film, Ein Lichtspiel: schwarz weiss grau (A Lightplay: Black White Gray, 1930), which is presented in the exhibition next to his own photographs and those of Florence Henri.

The rise of photographic avant-gardism from the 1920s to the 1940s is traced in the second gallery primarily through the work of European artists. A section on Constructivism and New Objectivity features works by Paul Citroën, Raoul Hausmann, Florence Henri, Germaine Krull, El Lissitzky, Albert Renger-Patzsch, and August Sander. A special focus on Aleksandr Rodchenko underscores his engagement with the illustrated press through collaborations with Vladimir Mayakovsky and Sergei Tretyakov on the covers and layouts of Novyi LEF, the Soviet avant-garde journal of the “Left Front of the Arts,” which popularised the idea of “factography,” or the manufacture of innovative aesthetic facts through photomechanical processes. Alongside Rodchenko, film director Dziga Vertov redefined the medium of still and motion-picture photography with the concept of kino-glaz (cine-eye), according to which the perfectible lens of the camera led to the creation of a novel perception of the world. The exhibition features the final clip of Vertov’s 1929 experimental film Chelovek s kinoapparatom (Man with a Movie Camera), in which the eye is superimposed on the camera lens to form an indivisible apparatus fit to view, process, and convey reality, all at once. This gallery also features a selection of Dada and Surrealist works, including rarely seen photographs, photocollages, and photomontages by Hans Bellmer, Claude Cahun, George Hugnet, André Kertész, Jan Lukas, and Grete Stern, alongside such avant-garde publications as Documents and Littérature.

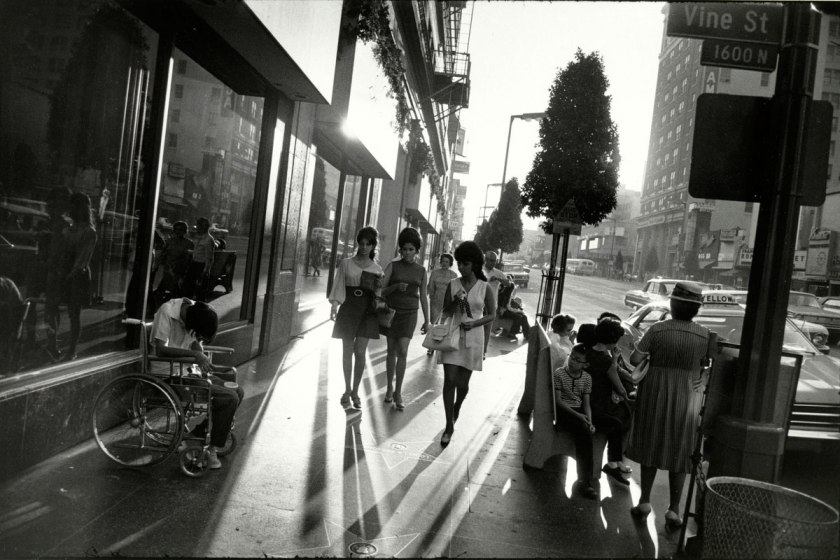

The third gallery features artists exploring the social world of the postwar period. On view for the first time is a group of erotic and political typo-collages by Gerhard Rühm, a founder of the Wiener Gruppe (1959-1960), an informal group of Vienna-based writers and artists who engaged in radical visual dialogues between pictures and texts. The rebels of street photography – Robert Frank, William Klein, Daido Moriyama, and Garry Winogrand – are represented with a selection of works that refute the then prevailing rules of photography, offering instead elliptical, off-kilter styles that are as personal and controversial as are their unsparing views of postwar society. A highlight of this section is the pioneering slide show Projects: Helen Levitt in Color (1971-1974). Capturing the lively beat, humour, and drama of New York’s street theatre, Levitt’s slide projection is shown for the first time at MoMA since its original presentation at the Museum in 1974.

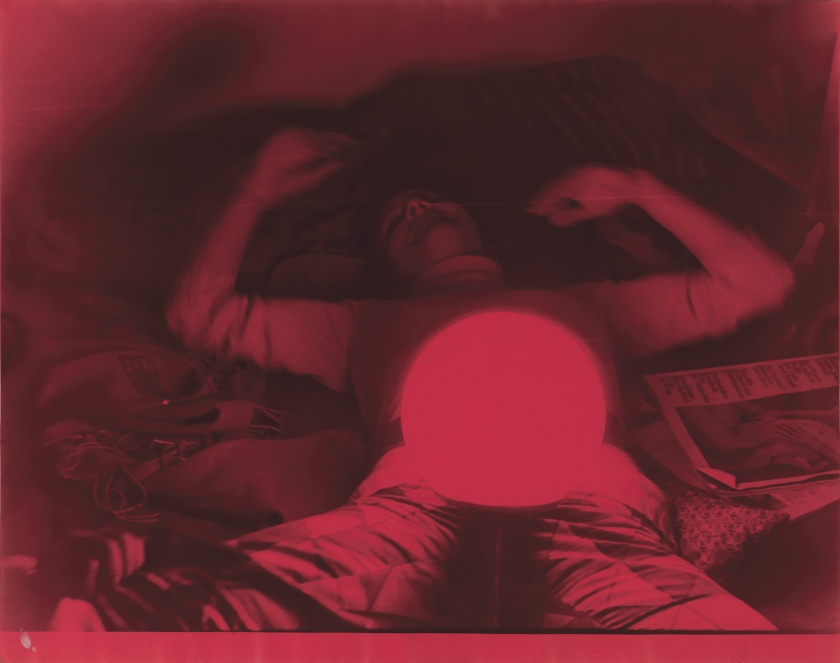

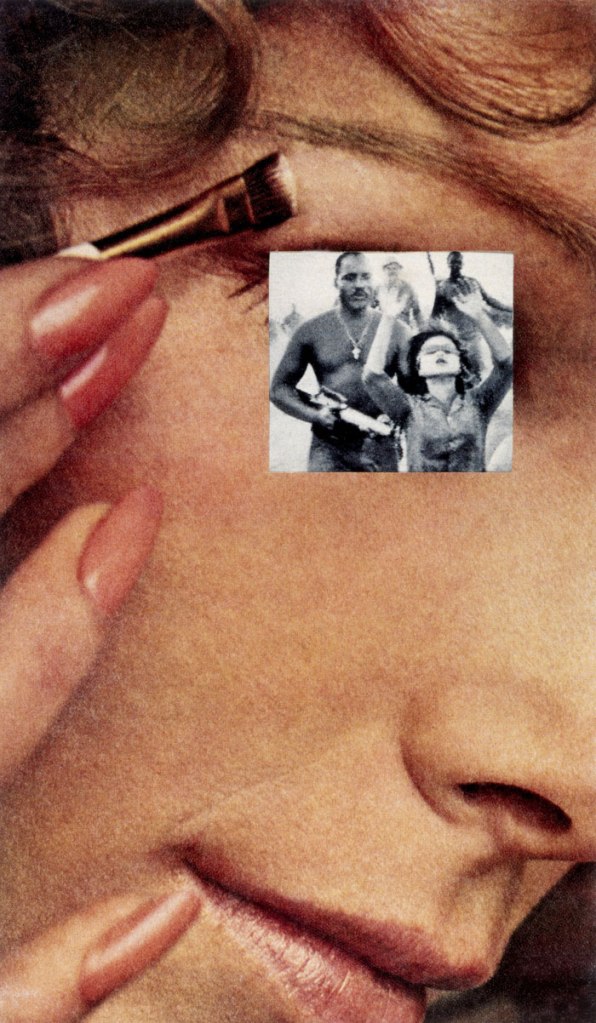

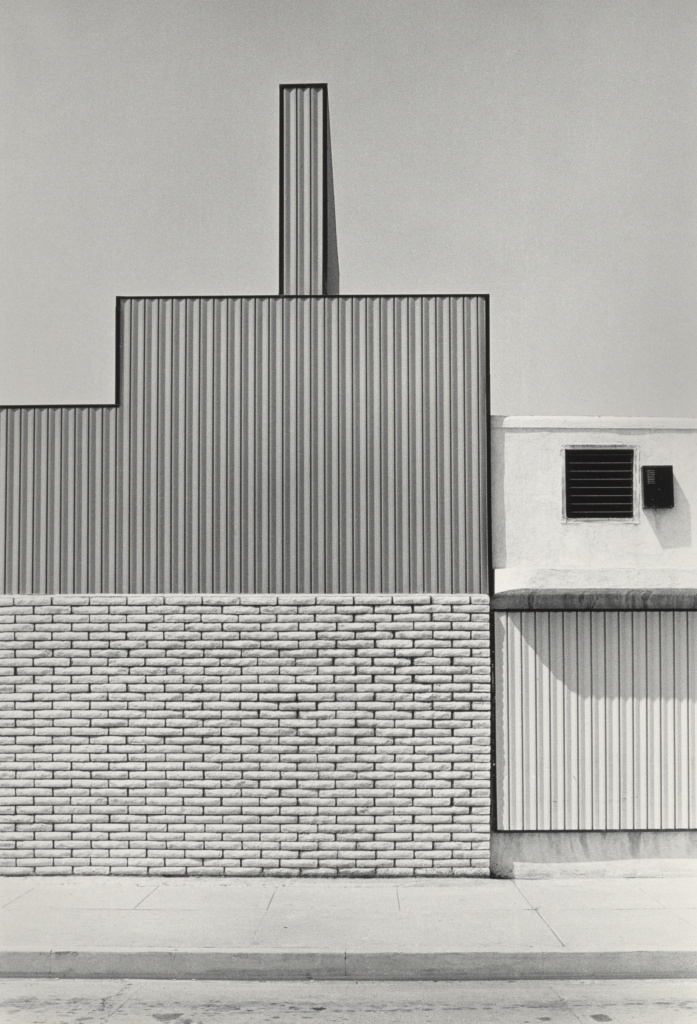

Photography’s tradition in the postwar period continues in the fourth gallery, which is divided into two sections. One section features “new topographic” works by Robert Adams, Bernd and Hilla Becher, Stephen Shore, and Joel Sternfeld, along with a selection of Edward Ruscha’s self-published books, in which the use of photography as mapmaking signals a conceptual thrust. This section introduces notable works from the 1970s by artists who embraced photography not just as a way of describing experience, but as a conceptual tool. Examples include Eleanor Antin’s 100 Boots (1971-1973), Mel Bochner’s Misunderstandings (A theory of photography) (1970), VALIE EXPORT’s Einkreisung (Encirclement) (1976), On Kawara’s I Got Up… (1977), and Gordon Matta-Clark’s Splitting (1974), all works that reevaluate the material and contextual definitions of photography. The other section features two major and highly experimental recent acquisitions: Martha Rosler’s political magnum opus Bringing the War Home (1967-72), developed in the context of her anti-war and feminist activism, for which the artist spliced together images of domestic bliss clipped from the pages of House Beautiful with grim pictures of the war in Vietnam taken from Life magazine; and Sigmar Polke’s early 1970s experiments with multiple exposures, reversed tonal values, and under-and-over exposures, which underscore the artist’s idea that “a negative is never finished.” The unmistakably cinematic turn that photography takes in the 1980s and early 1990s is represented with a selection of innovative works ranging from Robert Heinecken’s Recto/Verso (1988) to Philip-Lorca diCorcia’s breakthrough Hustler series (1990-92).

The final gallery showcases major installations by a younger generation of artists whose works address photography’s role in the construction of contemporary history. Tapping into forms of archival reconstitution, The Atlas Group / Walid Raad is represented with My Neck Is Thinner Than a Hair: Engines (1996-2004), an installation of 100 pictures of car-bomb blasts in Beirut during the Lebanese civil war (1975-1990) that provokes questions about the factual nature of existing records, the traces of war, and the symptoms of trauma. A selection from Harrell Fletcher’s The American War (2005) brings together bootlegged photojournalistic pictures of the U.S. military involvement in Southeast Asia, throwing into sharp focus photography’s role as a documentary and propagandistic medium in the shaping of historical memory. Jules Spinatsch’s Panorama: World Economic Forum, Davos (2003), made of thousands of still images and three surveillance video works, chronicles the preparations for the 2003 World Economic Forum, when the entire Davos valley was temporarily transformed into a high security zone. A selection of Paul Graham’s photographs from his major photobook project a shimmer of possibility (2007), consisting of filmic haikus about everyday life in today’s America, concludes the exhibition.

Press release from the MoMA website

On Kawara (Japanese, 1932-2014)

I Got Up At…

1974-1975

(Ninety postcards with printed rubber stamps)

The semi autobiographical I Got Up At… by On Kawara is a series of postcards sent to John Baldessari. Each card was sent from his location that morning detailing the time he got up. The time marked on each card varies drastically from day to day, the time stamped on each card is the time he left his bed as opposed to actually waking up. Kawara’s work often acts to document his existence in time, giving a material form to which is formally immaterial. The series has been repeated frequently sending the cards to a variety of friends and colleagues.

Philip-Lorca diCorcia (American, b. 1951)

Marilyn; 28 Years Old; Las Vegas, Nevada; $30

1990-1992

Chromogenic colour print

24 x 35 15/16″ (61 x 91.4cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

E.T. Harmax Foundation Fund

© 2012 Philip-Lorca diCorcia, courtesy David Zwirner, New York

Helen Levitt (American, 1913-2009)

Projects: Helen Levitt in Color (detail)

1971-1974

40 colour slides shown in continuous projection

Originally presented at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, September 26-October 20, 1974

Atlas Group, Walid Raad

My Neck is Thinner Than a Hair: Engines (detail)

1996-2004

100 pigmented inkjet prints

9 7/16 x 13 3/8″ (24 x 34cm) each

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Fund for the Twenty-First Century

Daido Moriyama (Japanese, b. 1938)

Entertainer on Stage, Shimizu

1967

Gelatin silver print

18 7/8 x 28″ (48.0 x 71.2cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of the photographer

© 2012 Daido Moriyama

VALIE EXPORT (Austrian, b. 1940)

Einkreisung (Encirclement)

1976

From the series Körperkonfigurationen (Body Configurations)

Gelatin silver print with red ink

14 x 23 7/16″ (35.5 x 59.6cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Carl Jacobs Fund

© 2012 VALIE EXPORT / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VBK, Austria

Grete Stern (German-Argentinian, 1904-1999)

No. 1 from the series Sueños (Dreams)

1949

Gelatin silver print

10 1/2 x 9″ (26.6 x 22.9cm)

Latin American and Caribbean Fund through gift of Marie-Josée and Henry R. Kravis in honor of Adriana Cisneros de Griffin

© 2012 Horacio Coppola

Sigmar Polke (German, 1941-2010)

Untitled (Mariette Althaus)

c. 1975

Gelatin silver print (red toned)

9 1/4 x 11 13/16″ (23.5 x 30cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Acquired through the generosity of Edgar Wachenheim III and Ronald S. Lauder

© 2012 Estate of Sigmar Polke / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, Germany

Martha Rosler (American, b. 1943)

Hands Up / Makeup

1967-1972

From the series Bringing the War Home: House Beautiful

Pigmented inkjet print, printed 2011

23 3/4 x 13 15/16″ (60.4 x 35.4cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Purchase and The Modern Women’s Fund

© 2012 Martha Rosler

Robert Heinecken (American, 1931-2006)

Recto/Verso #2

1988

Silver dye bleach print

8 5/8 x 7 7/8″ (21.9 x 20cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Mr. and Mrs. Clark Winter Fund

© 2012 The Robert Heinecken Trust

Berenice Abbott (American, 1898-1991)

Portrait of the Artist as a Young Woman

Negative c. 1930/Distortion c. 1950

Gelatin silver print

12 3/4 x 10 1/8″ (32.6 x 25.7cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Frances Keech Fund in honor of Monroe Wheeler

© 2012 Berenice Abbott/Commerce Graphics

Raoul Hausmann (Austrian, 1886-1971)

Untitled

February 1931

Gelatin silver print

5 3/8 x 4 7/16″ (13.6 x 11.2cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection Gift of Thomas Walther

© 2012 Raoul Hausmann / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Claude Cahun (French, 1894-1954)

Untitled

c. 1928

Gelatin silver print

4 9/16 x 3 1/2″ (10 x 7.6cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Purchase and anonymous promised gift

© 2012 Estate of Claude Cahun

Aleksandr Rodchenko (Russian, 1891-1956)

Sovetskoe foto (Soviet Photo) No. 10

October 1927

Letterpress

10 3/8 x 7 1/4″ (26.3 x 18.4cm)

Publisher: Ogonek, Moscow

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of the Judith Rothschild Foundation

The Museum of Modern Art

11 West 53 Street

New York, NY 10019

Phone: (212) 708-9400

Opening hours:

10.30am – 5.30pm

Open seven days a week

![Georges Hugnet (French, 1906-1974) 'Untitled [Surrealist beach collage]' c. 1935 Georges Hugnet (French, 1906-1974) 'Untitled [Surrealist beach collage]' c. 1935](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/georges-hugnet-untitled-surrealist-beach-collage.jpg?w=806&h=1024)

You must be logged in to post a comment.