Exhibition dates: 5th October, 2024 – 26th January, 2025

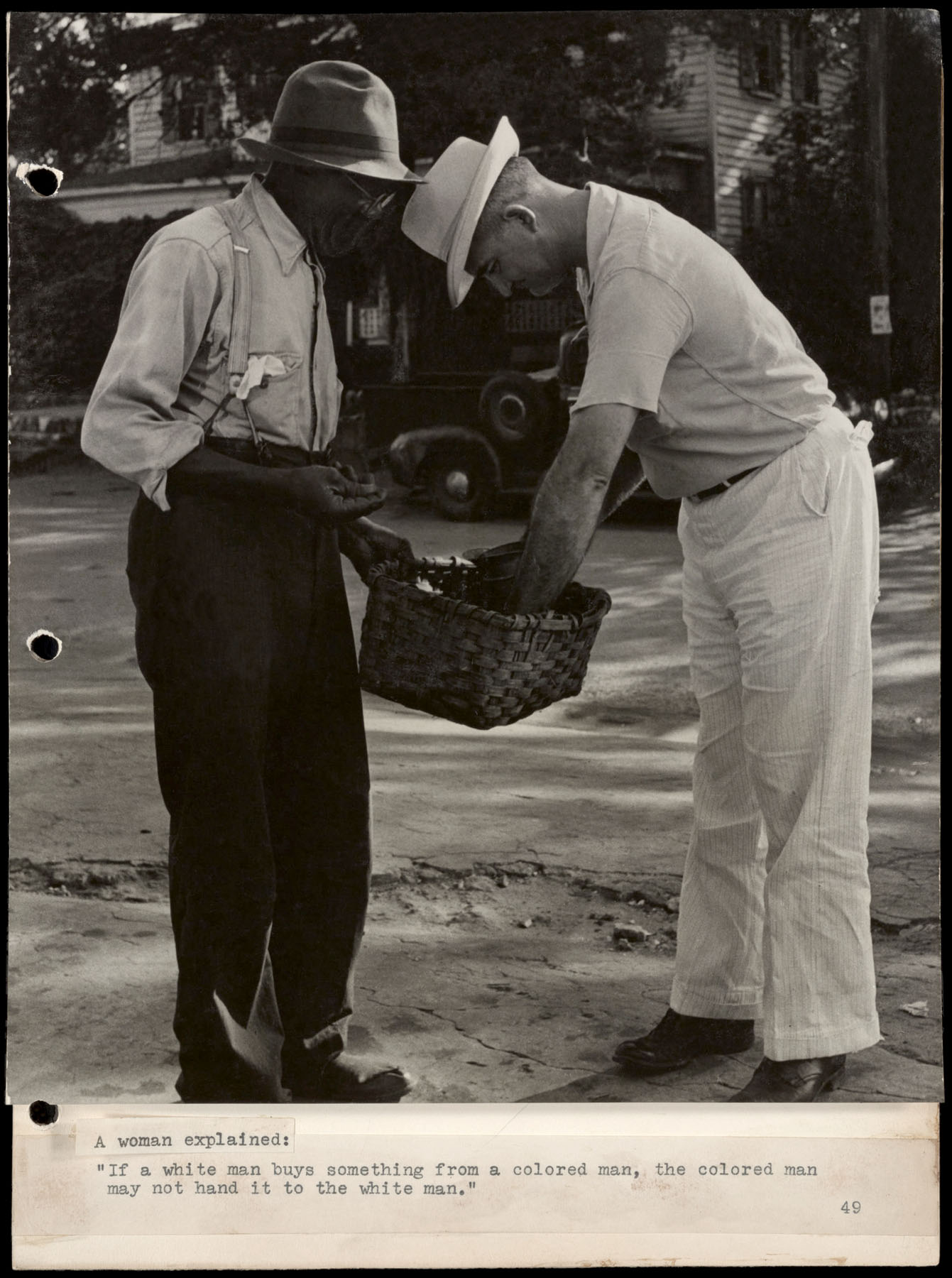

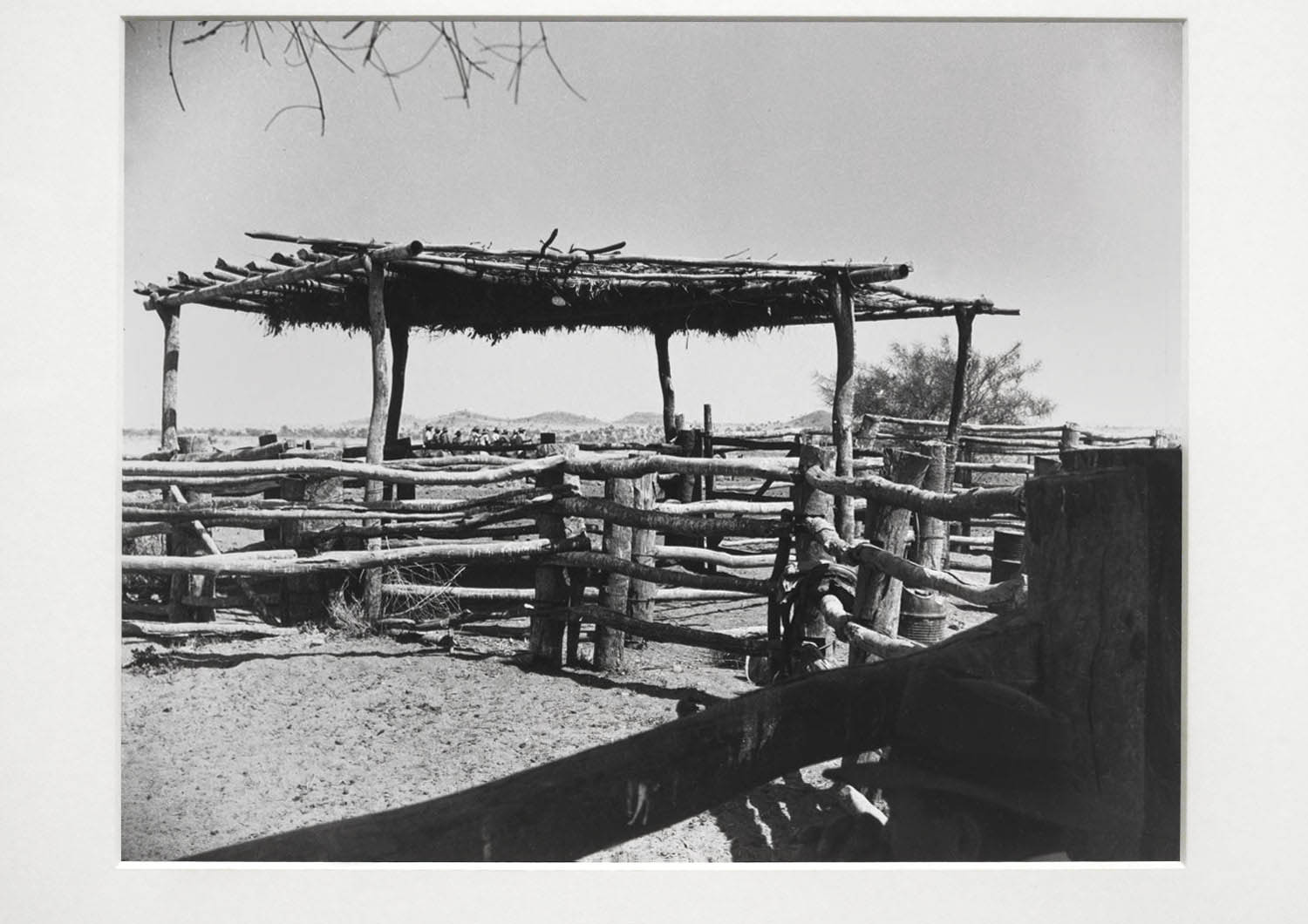

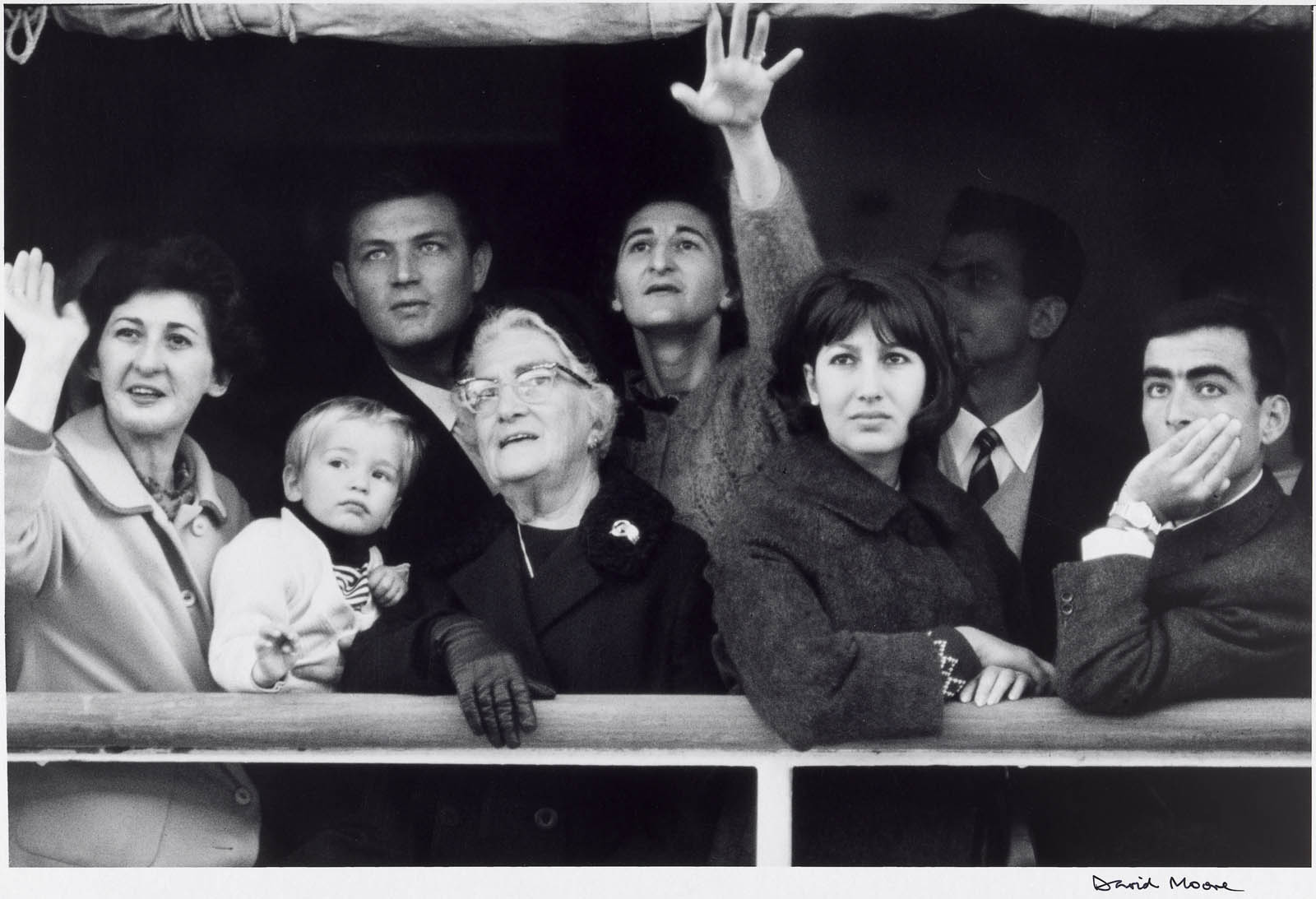

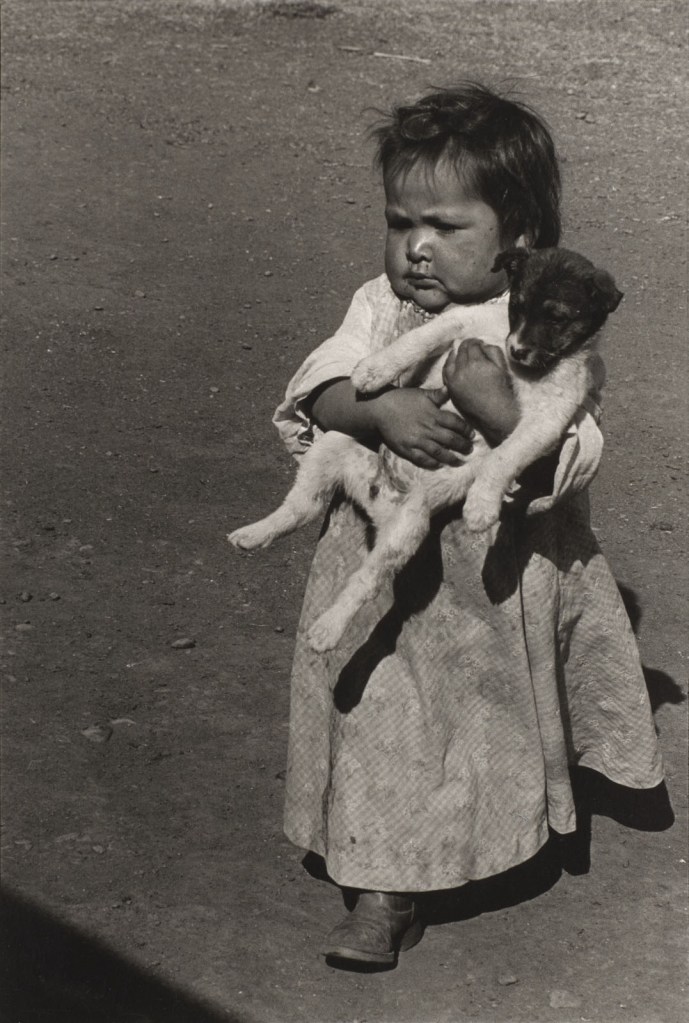

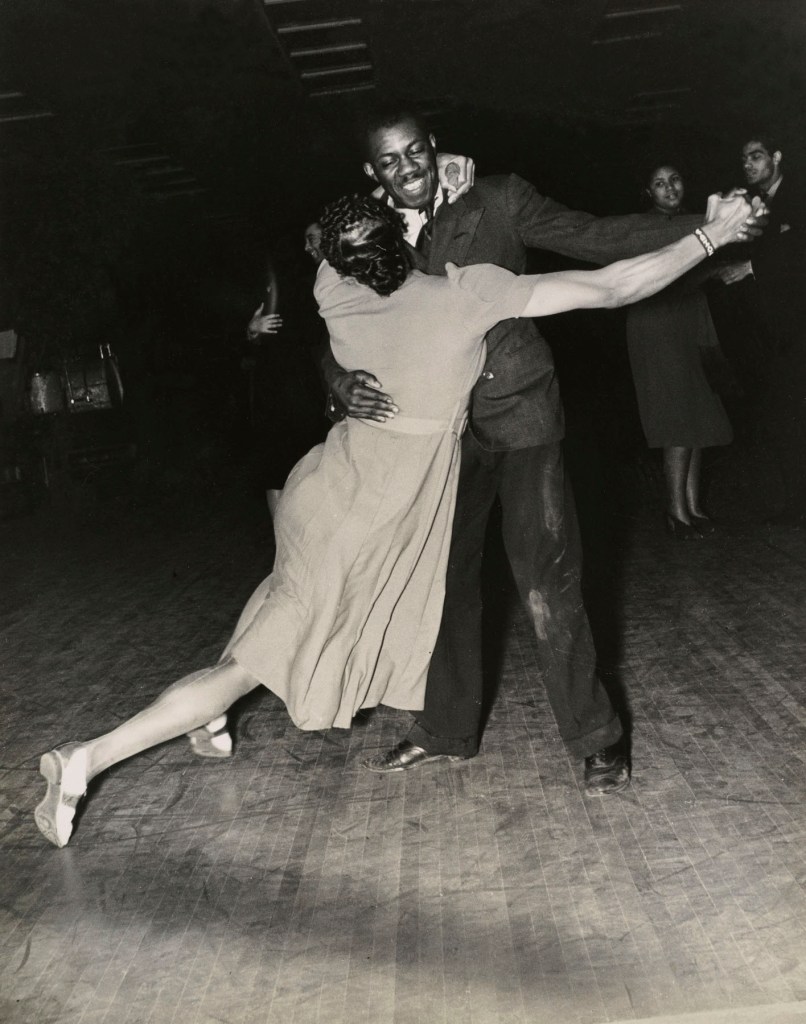

John Vachon (American, 1914-1975)

Untitled photo [possibly related to Farms of Farm Security Administration clients, Guilford and Beaufort Counties, North Carolina, April 1938]

1938

Negative

Please note: photograph not in the exhibition

Contested ground

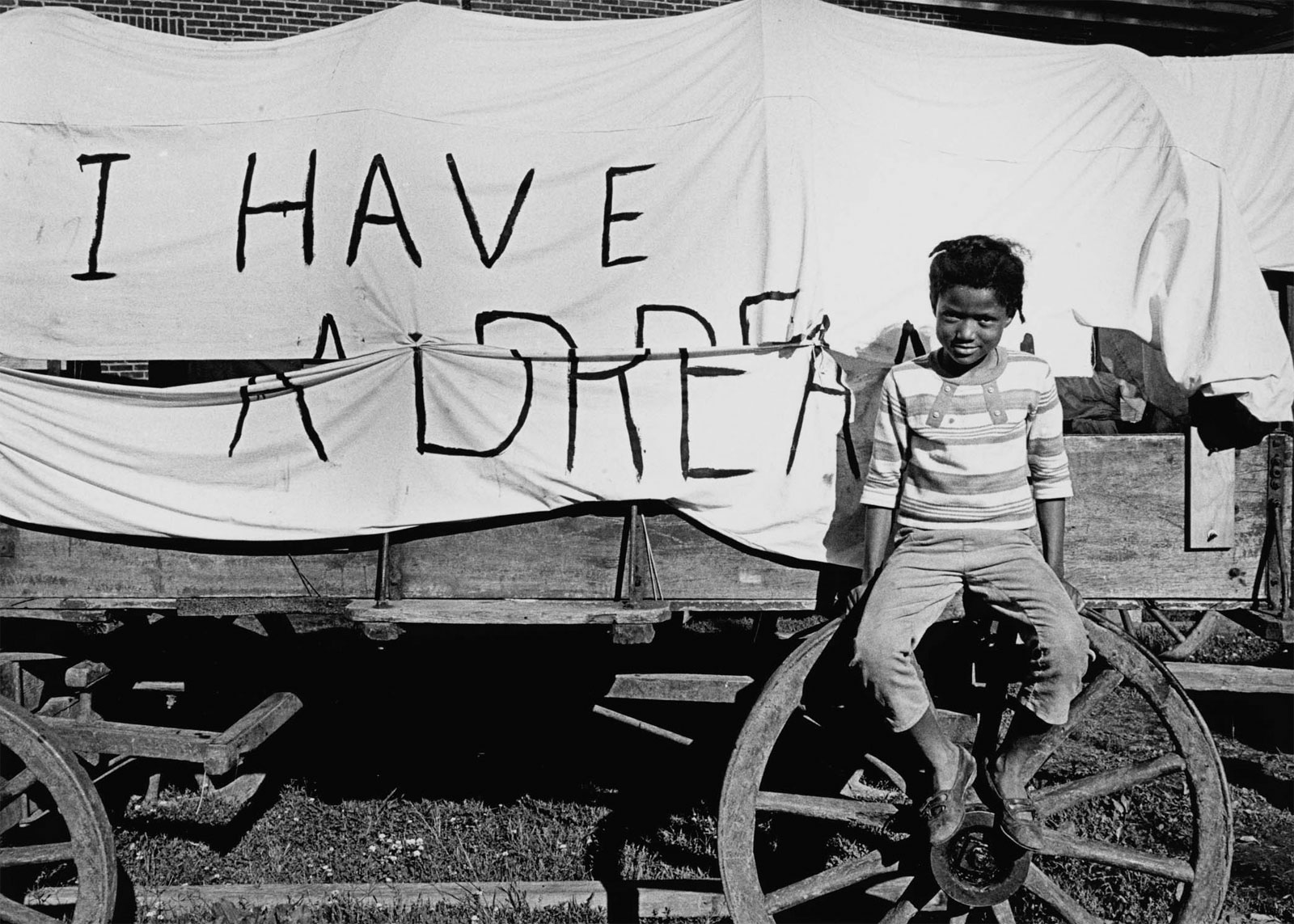

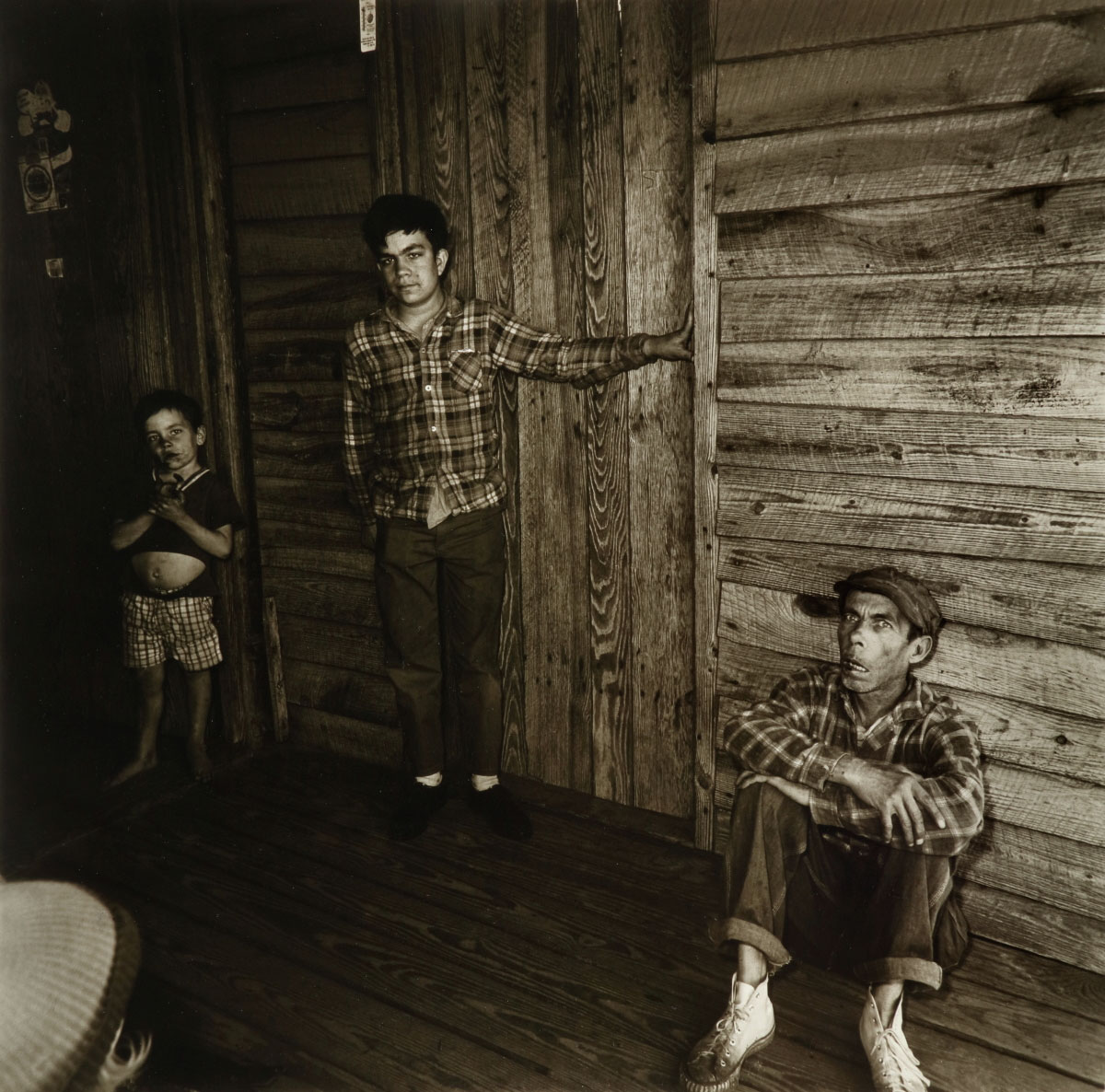

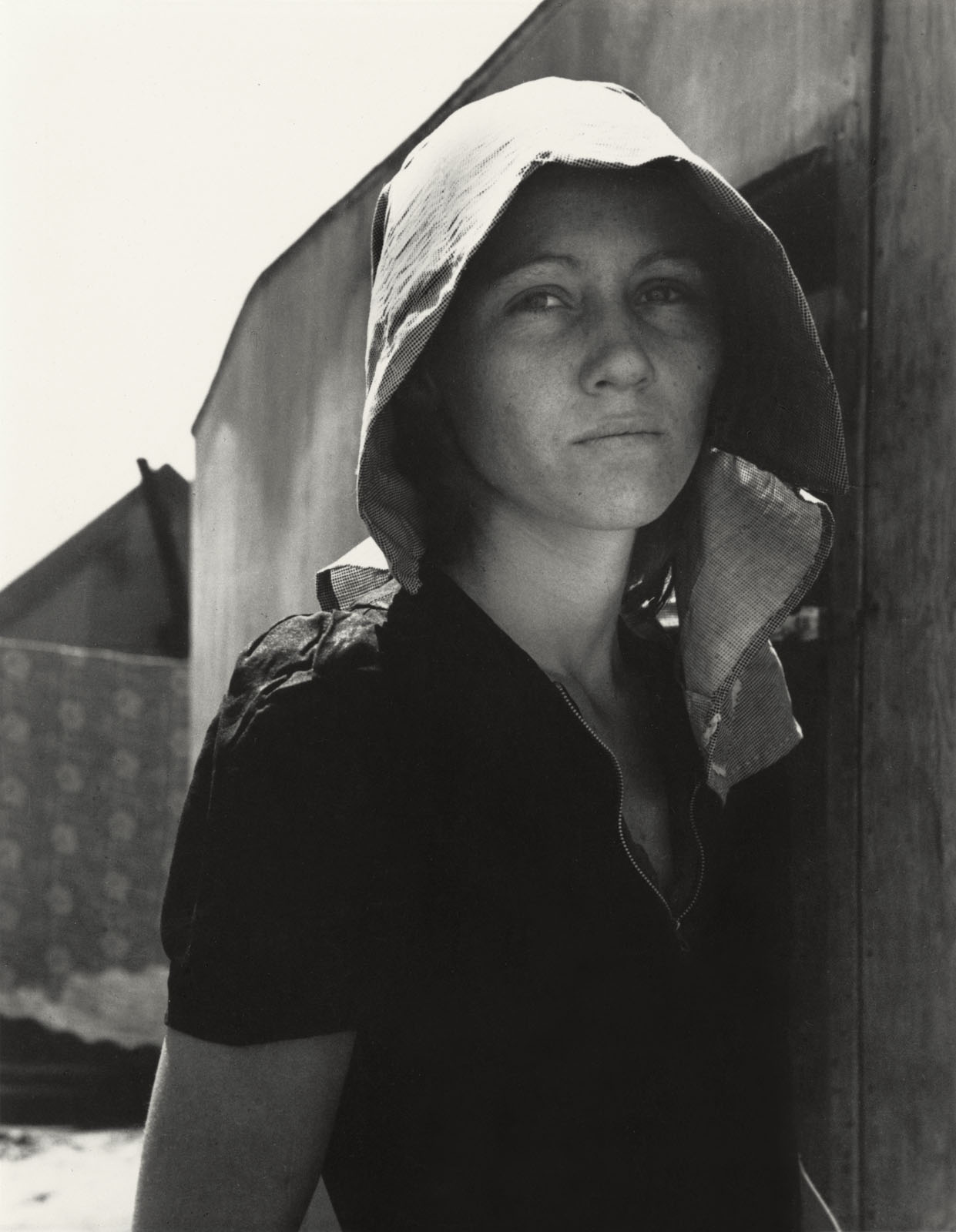

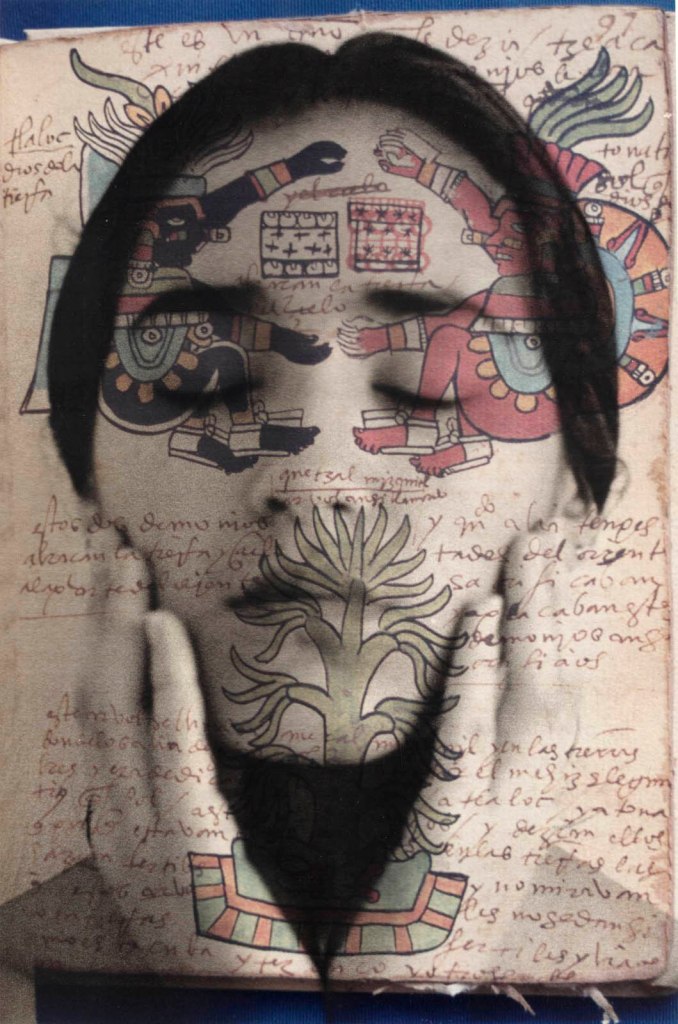

This exhibition traces, through the development of documentary photography, the interweaving strands that make up the fluidity of identity, race and culture that is the American South, addressing through a variety of photographic processes and styles across a large time period the concerns that have engaged human beings in this area for decades and now centuries: freedom, equality, liberty, nation, religion and economic subjugation. As the introductory panel says, “A Long Arc” demonstrates “how Southern photography has shaped American concepts of race, place, and history.”

Gregory Harris, curator of photography at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, observes that, “one of the main themes of the exhibition is how race is articulated and how racial hierarchies and racial stereotypes are reinforced through photographs across the history of photography.” “A Long Arc: Photography and the American South since 1845″ shields viewers from nothing, presenting the South as a chilling microcosm of U.S. culture. The region’s history of violence, disenfranchisement and political strife are not censored in the exhibit.”

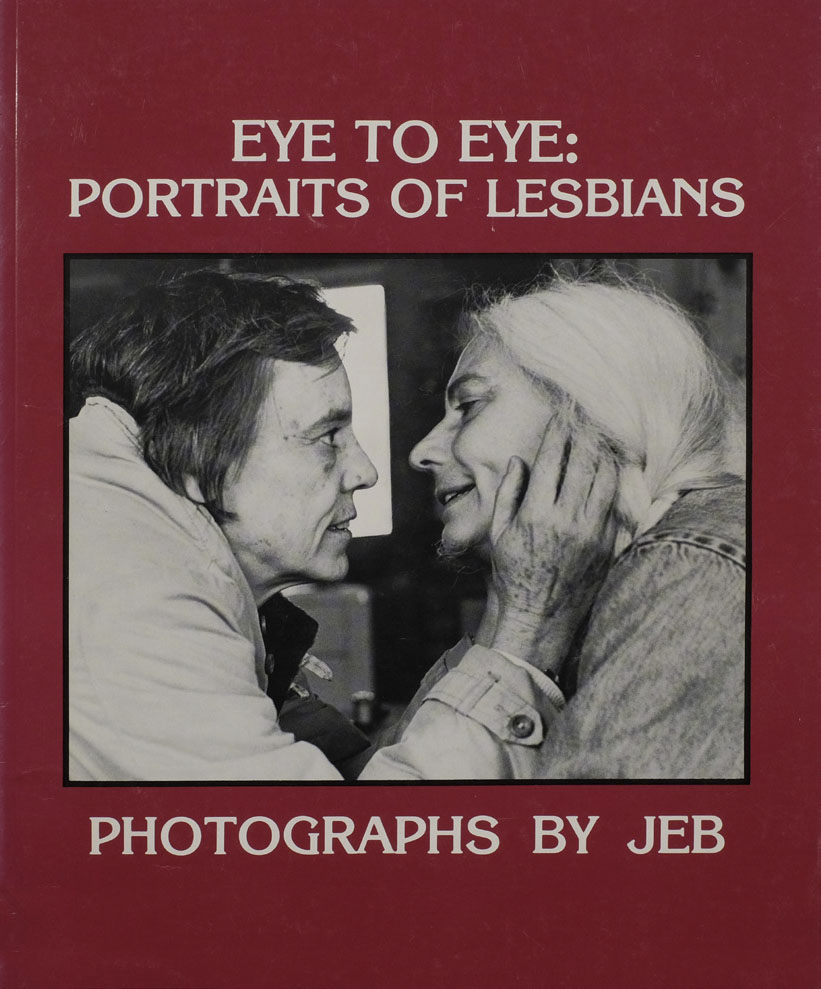

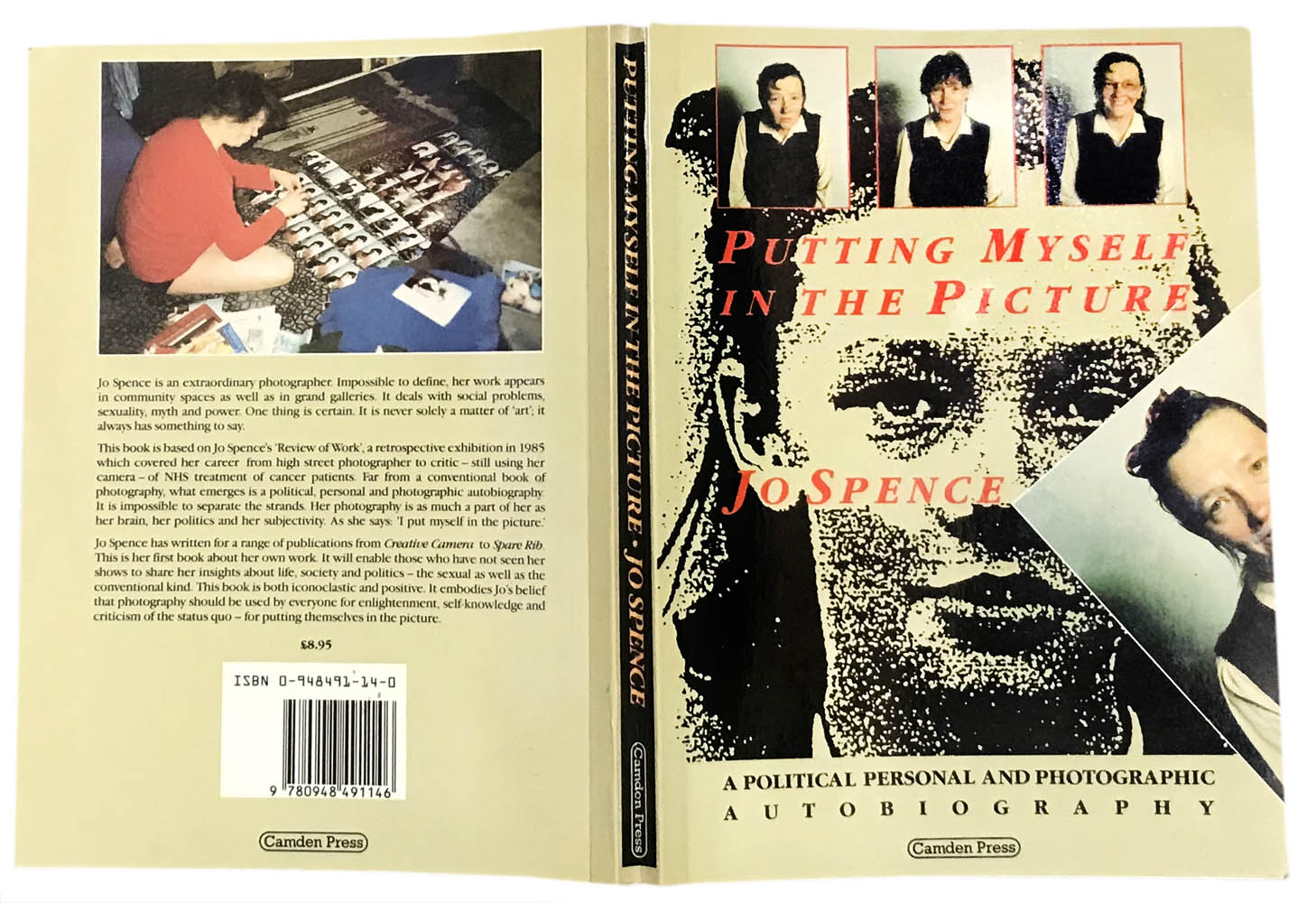

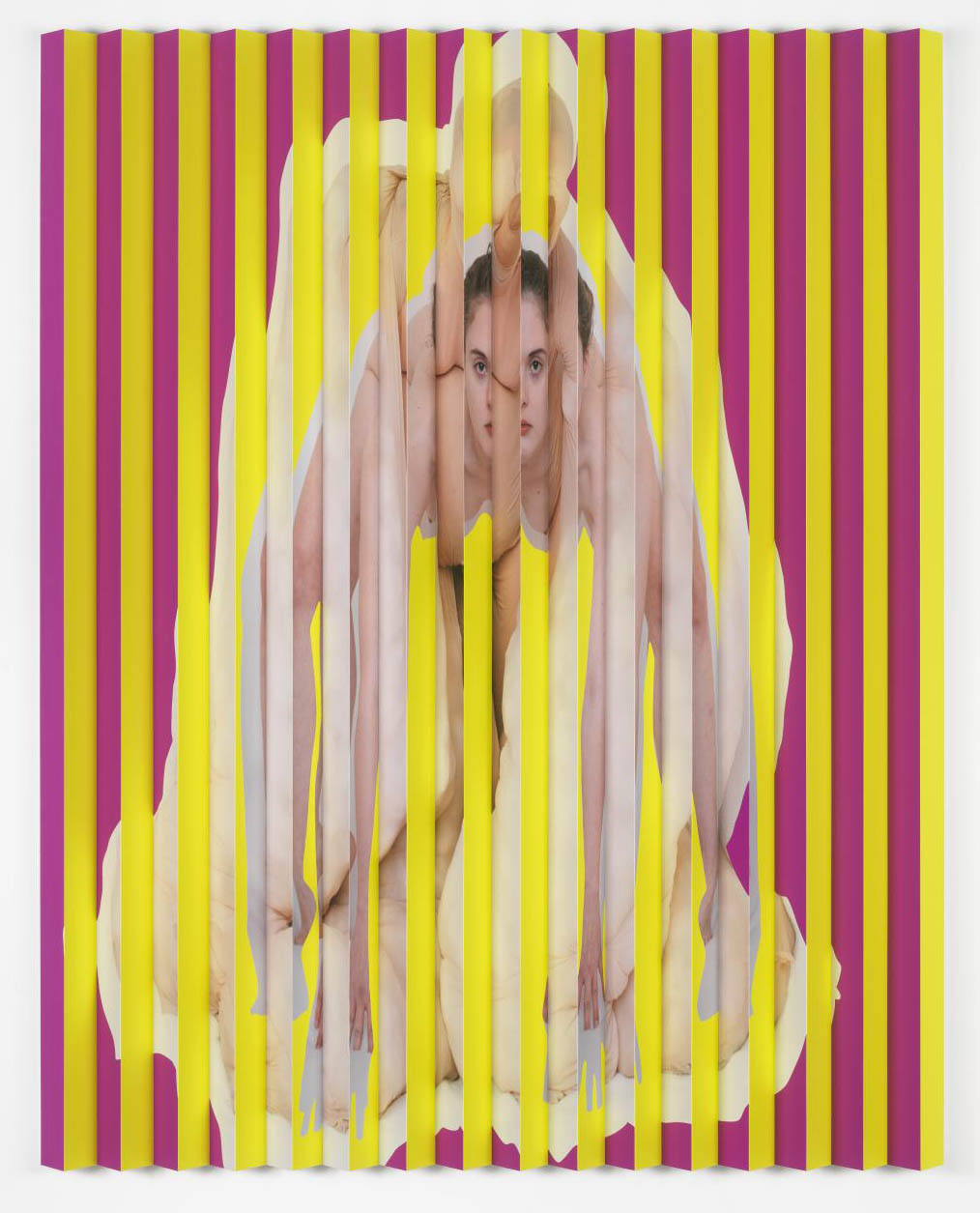

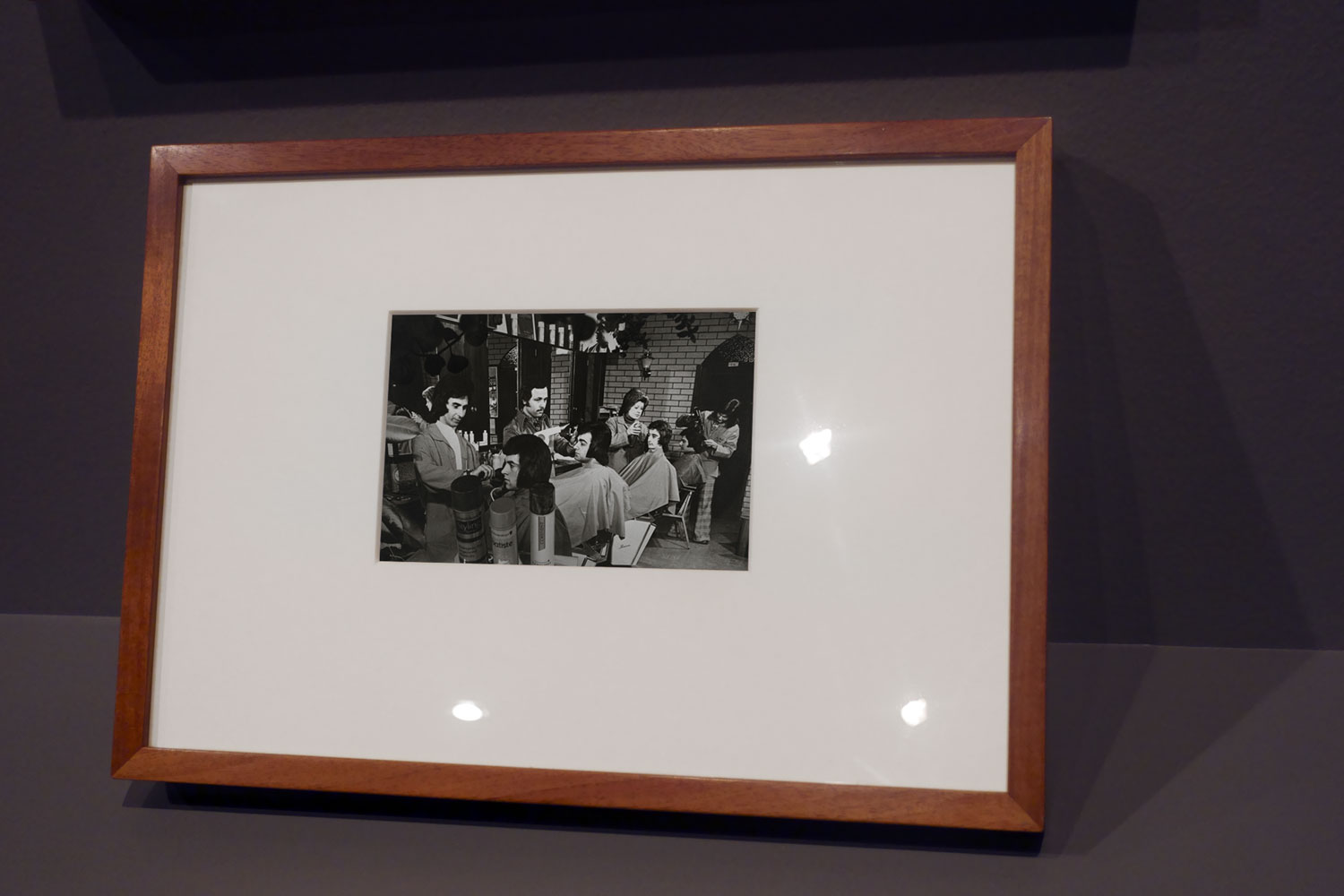

Periods and themes addressed in the exhibition include but are not limited to the Antebellum South, abolition of slavery, American Civil War, Reconstruction era, Jim Crow era, Farm Security Administration, Southern Gothic, Civil Rights Movement and, “in the most modern section, images dive into Southern femininity, the growing acceptance of interracial relationships in the Deep South and the emergence of a thriving LGBTQIA+ culture.”

This is such a complex and contested field to address in one photographic survey exhibition but it seems to me an admirable way to interrogate the ongoing histories and injustices of the American South. As my friend and fellow photographer Colin Vickery observes, “the sheer variety of images gives a richness of viewing experience that I think goes some way towards illustrating life, in all its complexities and contradictions, of the region.” Well said.

“A Long Arc: Photography and the American South since 1845” succeeds in surveying the South in its most complete form: not as a place that is “backward,” but as a place that has forever been the epicenter of contention and change. Documentary photography thrives in the South because the region has always been ground zero of the social disorder reverberating throughout the nation, a place that seems lost in the past. Modern photographers honor the region’s complicated legacy by accenting even the most idyllic, beautiful scenes with a nod to its brutalistic history. The South is not the South without acknowledgment of the bloodshed on its soil…”1

While I am certainly no American scholar, far from it, to me this opposition of utopian and dystopian seems to reflect the infinite duality of the American psyche: the desire for attainment of money and success (any one can become president, anyone can make good) versus the dark underbelly of a brutal history: puritanical, one nation under god, a nation conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal … except that’s never going to happen, forever and ever amen.

Indeed this richly layered and nuanced exhibition seems to be more fully focused on the dystopic rather than any celebration of American South culture per se and here I am particularly thinking of all the achievements in the areas of arts, literature, food, music – for example the energy of gospel, bluegrass and jazz. Yes, there are poetic photographs in the exhibition but there is little sign of joy or happiness in any of the images.

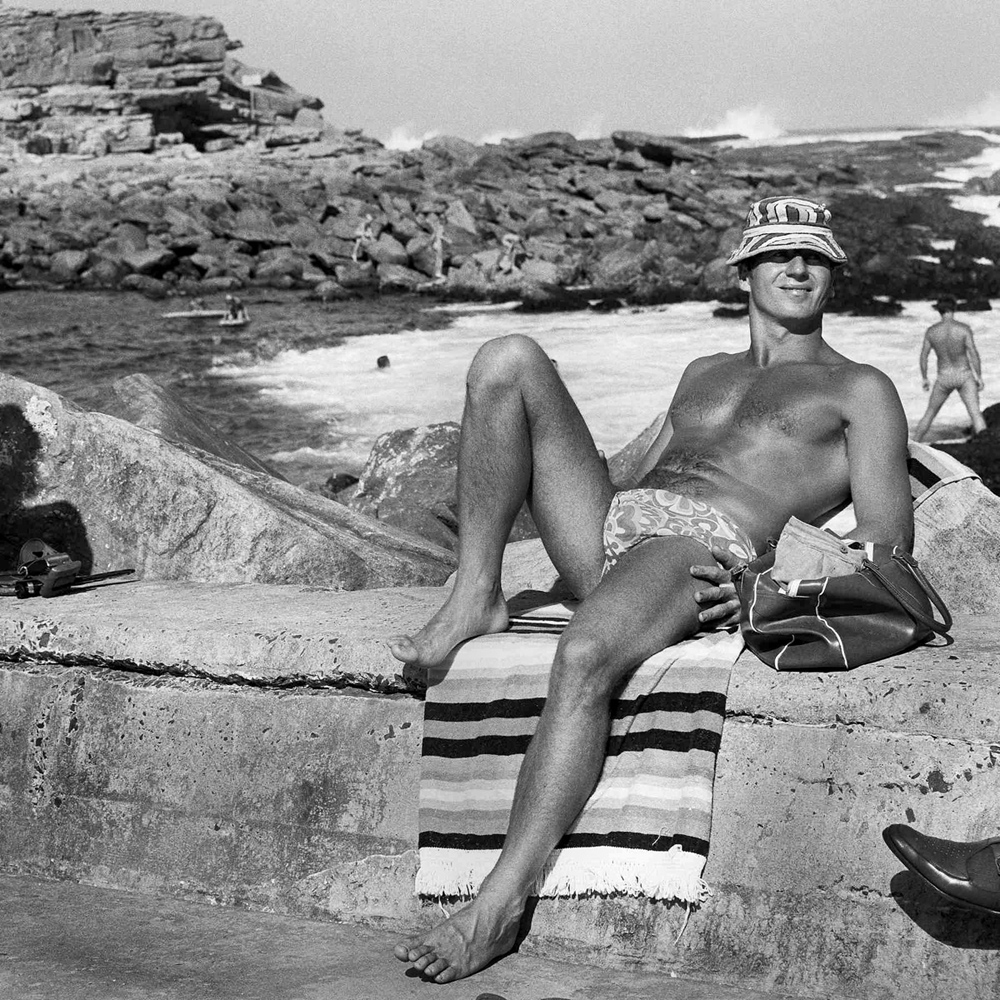

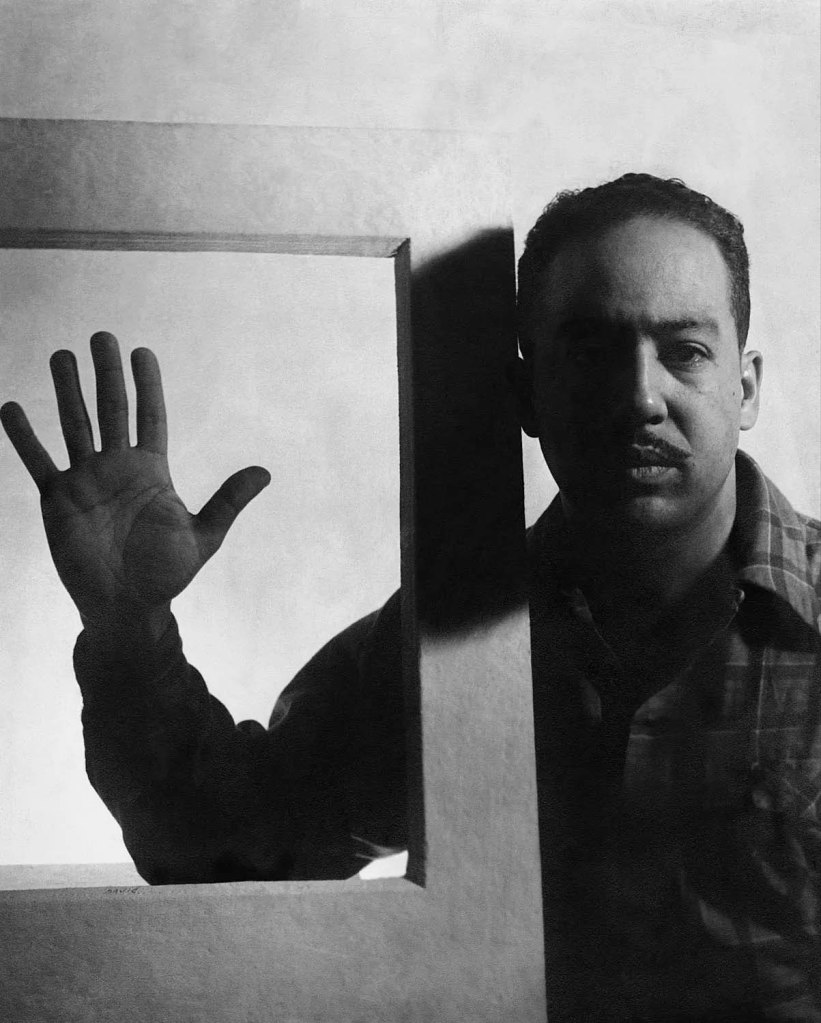

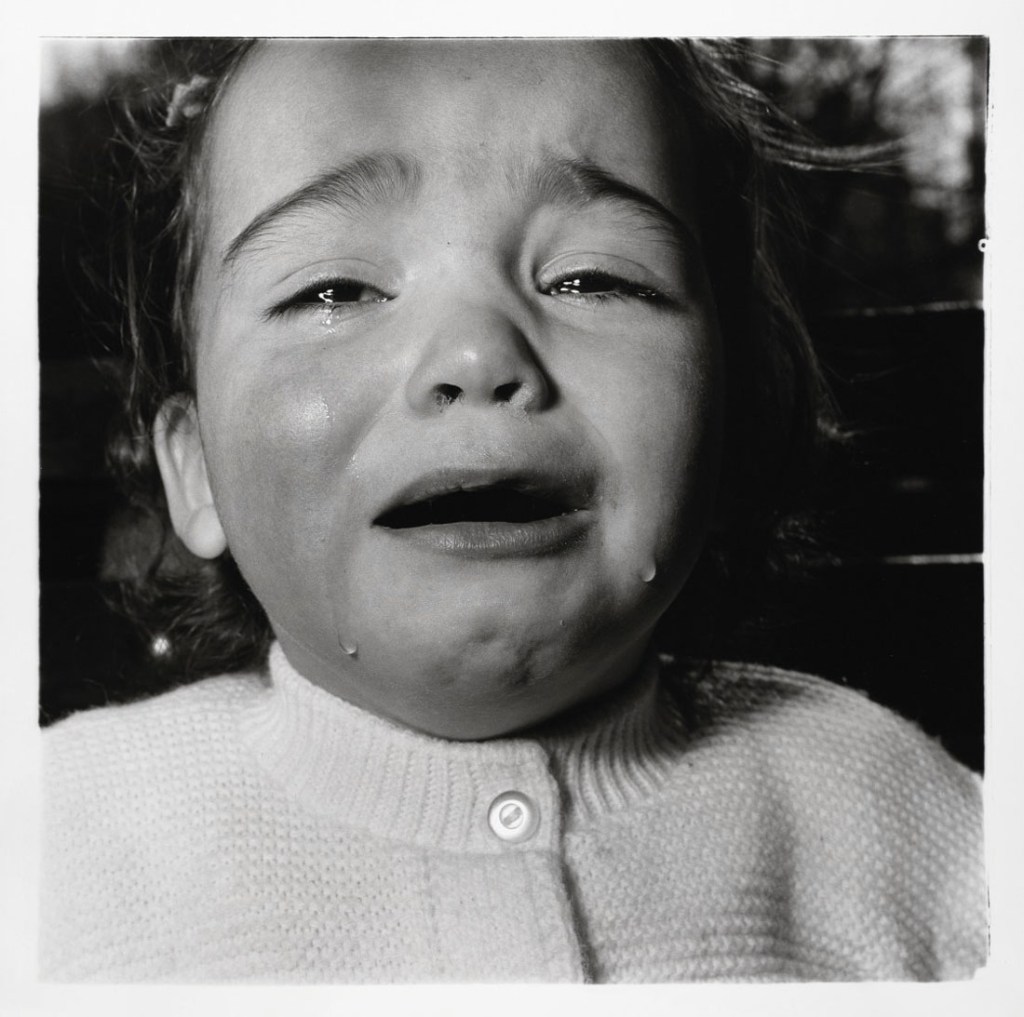

Margaret Renkl observes that, “The most powerful images capture the beauty and the tenderness and the self-possession of people who are living out their lives mostly invisible to the rest of the world,”2 and the stoicism of these lives, but I have struggled to find but a single photograph that evidences the joy of living among the assembled throng in this posting. Which is why I have included that most singular image at the top of the posting (not in the exhibition) by John Vachon of a Black American smiling and laughing. What a joy!

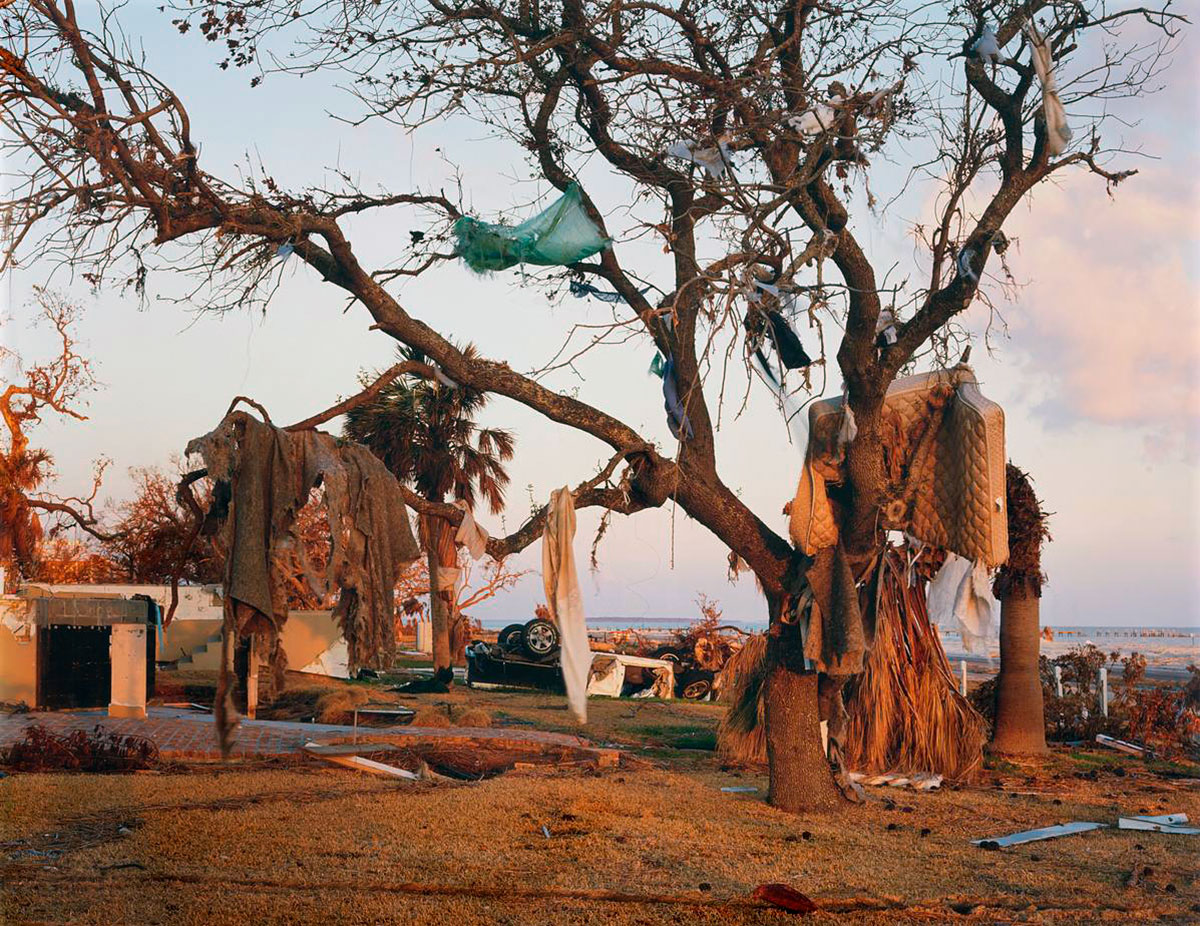

The Southern landscape can be seen as the repository of memory, history, and trauma but it can also be seen as the repository for families, love, kindness, respect and connection between human beings – not always opposition and conflict. And while the photographs in the exhibition “ask us to contemplate the dark, sublimated aspects of American popular culture, including violence, shame, and fear” they also ask us to share our experiences of who we are across time, race and culture. The photographs are memory containers for (still) living people.

By which I mean

Photographs are containers of, fragments of, memories of, histories of, events – remembrances of events – brought from past into present, informing the future, showing only snippets of the stories of both past and present lives. Parallel to the usual thought that photographs are about death, they are also memory containers for (still) living people.

As we look back into these photographs the people in them look forward to us, and live in us here and now. They expect more from us, to fight still against the further rise of intolerance, racism and right wing fascism, and to grasp that the joys and mysteries of life should be open to all.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Sophia Peyser. “New High Museum exhibit captures South at its most macabre,” on The Emory Wheel website Sept 25, 2023 [Online] Cited 23/01/2025

2/ Margaret Renkl. “A Photo Can Tell the Truth About a Lie. Or a Lie About the Truth,” on The New York Times website Sept. 18, 2023 [Online] Cited 20/12/2024

Many thankx to the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

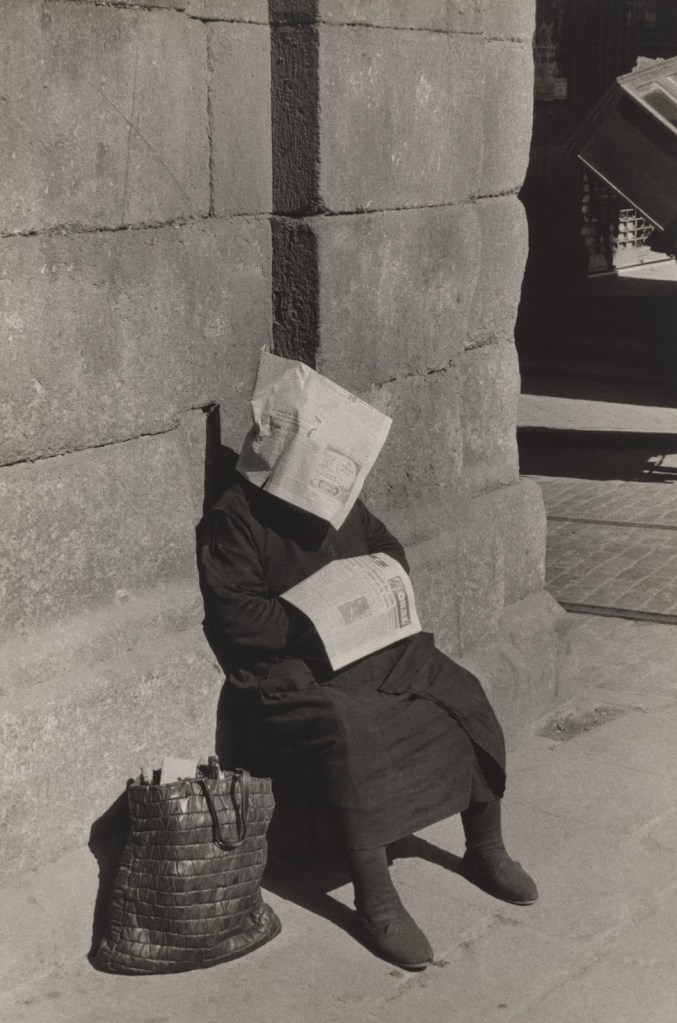

“I have a strong attraction to the American South. People there have a marvellous exterior – wonderful manners, warm friendliness until you touch on things you’re not supposed to touch on. Then you see the hardness beneath the mask of nice manners.”

Elliott Erwitt

“When it comes to the unspeakable facts in the history of America, it’s largely the artists who’ve been willing to show us what others would not.”

“The foundation of this country is built upon speakable tensions – between ideas that we love and hold dear, between liberty, equality, and slavery itself.”

Sarah Lewis

The most powerful images capture the beauty and the tenderness and the self-possession of people who are living out their lives mostly invisible to the rest of the world. Or of the scarred but beautiful landscapes they call home. Or of the ramifications of an unresolved history still unspooling in this history-haunted part of the country. …

The magnificence of a retrospective like this is not just the accounting offered by its historical sweep, but the way it conveys the immense complexity of this region, to inspire a renewed attention to the cruel radiance of what is. Suffering does not always lead to compassion and change, but photographs like these remind us that standing in witness to suffering surely should.

Margaret Renkl. “A Photo Can Tell the Truth About a Lie. Or a Lie About the Truth,” on The New York Times website Sept. 18, 2023 [Online] Cited 20/12/2024

“… no small part of the show’s richness is the allowance it makes for inwardness and mystery. “Southern Gothic,” after all, is no less a part of the region’s cultural baggage than “Lost Cause” or “New South.” Among the most memorable images here, because they’re often the most inscrutable and / or evocative, come from Mann, E.J. Bellocq, Clarence John Laughlin, and Ralph Eugene Meatyard.”

Mark Feeney. “‘A long Arc’ bends toward justice at the Addison Gallery of American Art,” on The Boston Globe website March 7, 2024 [Online] Cited 24/12/2024

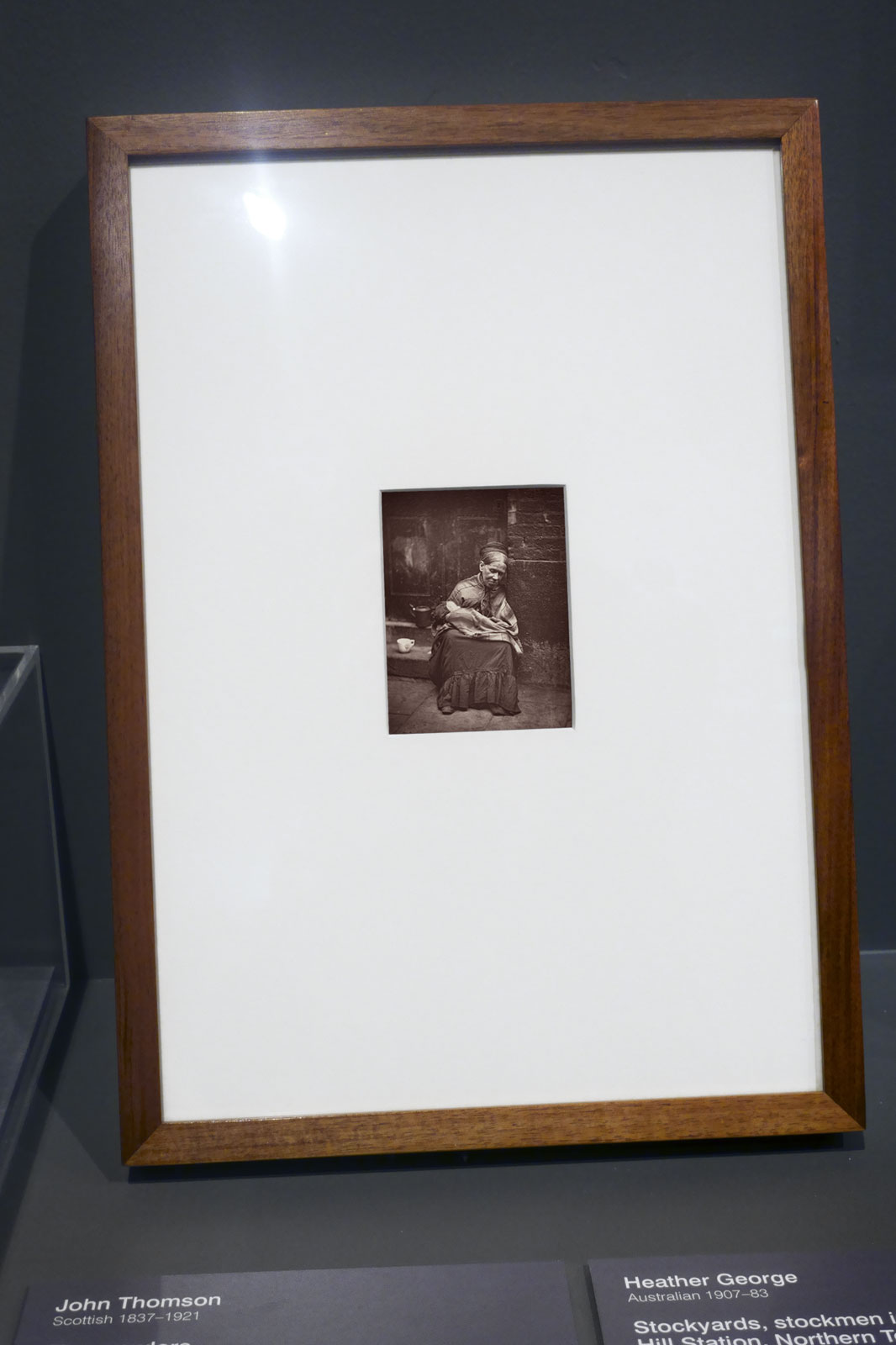

Unidentified photographer

Georgian house, with posed African-American family, Norfolk Harbor, Virginia

Late 1850s

Whole-plate ambrotype

Collection of Michael Mattis and Judith Hochberg

Photo: Steven Paneccasio

Unidentified photographer

Young biracial artilleryman

Undated

Ambrotype

High Museum of Art, Atlanta

Purchase with funds from the Lucinda Weil Bunnen Fund and the Donald and Marilyn Keough Family

The majority of photographs made during the Civil War were inexpensive, small, portable portraits for soldiers on the field and their families at home. As precious keepsakes, these portraits served as testaments to familial bonds, social relations, economic positions, and political ideologies. In carefully orchestrating their dress, accoutrement, and bearing, sitters signaled their allegiances or staged their transformation from citizen to soldier. The opportunity to reinvent themselves before the camera at times even led to a bit of fakery, as soldiers sometimes gussied themselves up with props and uniforms that did not always fit with their military rank.

Text from the Large Print Guide at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

William Abott Pratt (American born England, 1818, active 1844-1856)

View of Main Street, Richmond, Virginia

1847-1851

Half-plate daguerreotype

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

Floyd D. and Anne C. Gottwald Fund

One of a handful of known daguerreotypes of the city of Richmond, this view of Main Street looking east toward Church Hill was probably taken from the window of William Pratt’s first “Virginia Daguerriean Gallery,” in the centre of the city’s printing and publishing industry. The distinctive roof of the Richmond Masonic lodge is visible in the distance, as is the three-story City Hotel just beyond the trees to the east. The hotel served as one of the major auction houses for enslaved individuals, as did the firm Pulliam & Davis across the street.

Text from the Large Print Guide at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

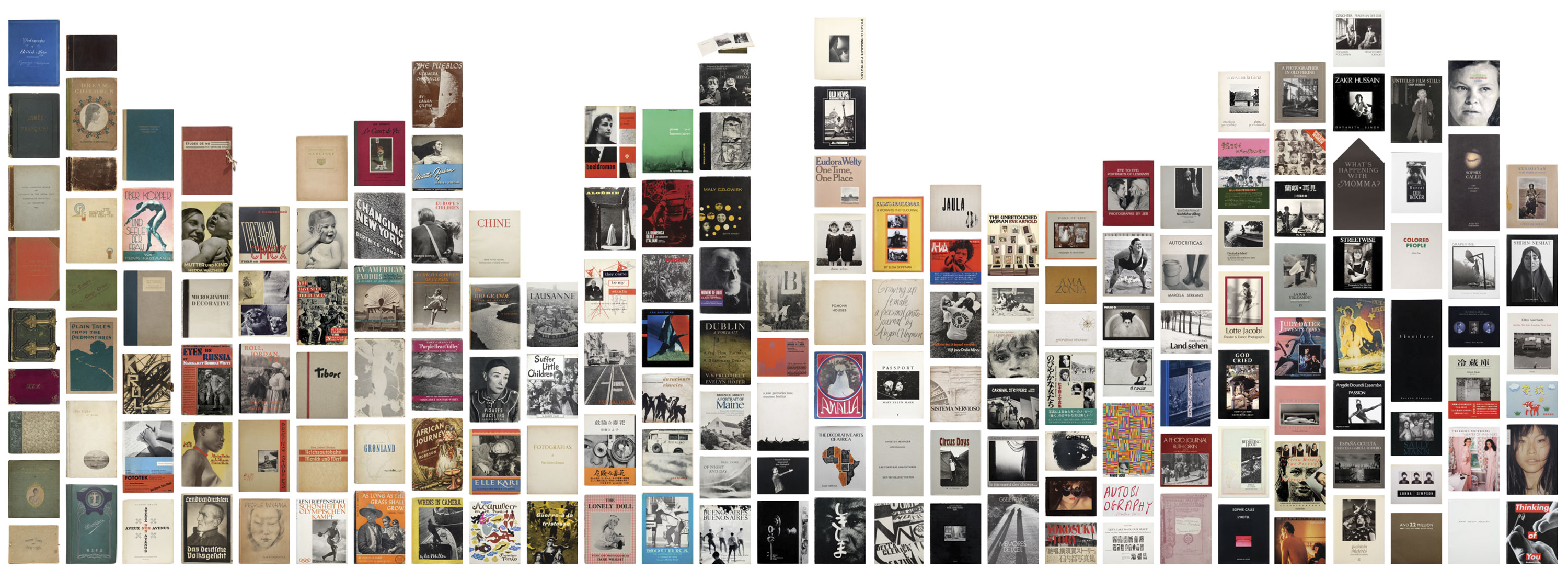

Take an epic journey through the American South from 1845 to today. In A Long Arc: Photography and the American South since 1845, presented at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, encounter the everyday lives and ordinary places captured in evocative photos that contemplate the region’s central role in shaping American history and identity and its critical impact on the development of photography. This is the first major exhibition in more than 25 years to explore the full history of photography in and about the South.

A Long Arc explores the American South’s distinct, evolving, and contradictory character through an examination of photography and how photographers working in the region have reckoned with the South’s fraught history and posed urgent questions about American identity. Organised chronologically, the exhibition traces the South’s shifting identity in more than two hundred photographs made over more than 175 years.

The exhibition’s individual sections delve into the themes of photography before, during, and after the Civil War; documentary photography of the 1930s and ’40s; images of a post-World War II South in economic, racial, and psychic dissonance with the nation; photography as catalyst for change during the civil rights movement; reflective narrative photography of the late 20th century; and contemporary photography examining social, environmental, and economic issues.

A Long Arc presents a richly layered archive that captures the region’s beauty and complexity. Offering a full visual accounting of the South’s role in shaping American history, identity and culture, the exhibition includes photographs by Alexander Gardner, George Barnard, P.H. Polk, Lewis Hine, Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Marion Post Wolcott, Robert Frank, Clarence John Laughlin, Ralph Eugene Meatyard, Bruce Davidson, Danny Lyon, Doris Derby, Ernest Withers, William Eggleston, William Christenberry, Baldwin Lee, Sally Mann, Carrie Mae Weems, Susan Worsham, Carolyn Drake, Sheila Pree-Bright, RaMell Ross, and others.

Text from the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts website

Unidentified photographer

Woman wearing secession sash

c. 1860

Ambrotype

High Museum of Art, Atlanta

Purchase with funds from the Lucinda Weil Bunnen Fund and the Donald and Marilyn Keough Family

In 1860-61, patriotic fervour (both pro- and anti-secession) was at its height, according to the Creative Cockades website. Women, in particular, wore dresses or other garments festooned with cockades, or they might wear a sash, such as this Southern woman. The reality of a bloody war had not yet set in and many thought the coming conflict would be minimal.

In South Carolina, civilian men and women, and even companies of soldiers, wore palmetto emblems during the Civil War, according to Hinman Auctions.

“Southern cockades were generally all blue, all red, or red and white,” according to Creative Cockades. “Once again, center emblems include stars, military buttons and pictures, but additionally Southern products such as palmetto fronds, pine burs, corn or cotton were used.”

Phil Gast. “Tracing ‘A Long Arc’: These 9 Civil War-era photographs in an Atlanta exhibit drive home identity, race and trauma across the South, US,” on The Civil War Picket website Friday, January 12, 2024 [Online] Cited 20/12/2024

Smith & Vannerson (77 Main St., Richmond, Va)

Gilbert Hunt (c. 1780-1863), Virginia freed slave

1861-1863

Salt print on card stock

7 3/8 x 5 1/4 inches print

Public domain

Gilbert Hunt was an African-American blacksmith in Richmond who became known in the city for his aid during two fires: the Richmond Theatre fire in 1811 and the Virginia State Penitentiary fire in 1823. Born enslaved in King William County, Hunt trained as a blacksmith in Richmond and remained there most of the rest of his life. After the Richmond Theatre caught fire on December 26, 1811, he ran to the scene and, with the help of Dr. James D. McCaw, helped to rescue as many as a dozen women. He performed a similar feat of courage on August 8, 1823, during the penitentiary fire. Hunt purchased his freedom and in 1829 immigrated to the West African colony of Liberia, where he stayed only eight months. After returning to Richmond, he resumed blacksmithing and served as an outspoken, sometimes-controversial deacon in the First African Baptist Church. In 1848 he helped form the Union Burial Ground Society. In 1859, a Richmond author published a biography of Hunt, largely in the elderly blacksmith’s own words, but portraying him as impoverished and meek, a depiction at odds with the historical record. Hunt died on April 26, 1863, and a notice in the next day’s Richmond Dispatch described him as “a useful and respected resident of Richmond.” He was buried at Phoenix Burying Ground, later Cedarwood Cemetery, and eventually part of Richmond’s Barton Heights Cemeteries.

Dionna Mann. “Gilbert Hunt (ca. 1780-1863),” in Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Humanities, 07 December 2020

Gilbert Hunt, a skilled blacksmith from Richmond shown here gripping a hammer, understood the power of photography as a tool for self-creation, especially for the formerly enslaved. Hunt, who was lauded for rescuing numerous people from two blazing fires, one in 1811 and one in 1823, ultimately purchased his freedom for $800 in 1829. Over the next three decades, he led a remarkable life, traveling to Liberia to explore the possibilities for Black resettlement with the American Colonization Society before returning to Richmond and serving as an outspoken pastor and blacksmith. This portrait was commissioned by a benevolent society in Richmond who sold prints to raise funds for the elderly Hunt.

Text from the Large Print Guide at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

McPherson & Oliver, Baton Rouge

William D. McPherson (? – October 9, 1867) and J. Oliver (?-?)

Peter or The Scourged Back of “Peter” an escaped slave from Louisiana

April 2, 1863

Albumen silver print (carte de visite)

High Museum of Art, Atlanta

Purchase with funds from the Lucinda Weil Bunnen Fund and the Donald and Marilyn Keough Family

Public domain

“Overseer Artayou Carrier whipped me. I was two months in bed sore from the whipping. My master come after I was whipped; he discharged the overseer. The very words of poor Peter, taken as he sat for his picture.”

Gordon, a runaway slave seen with severe whipping scars in this haunting carte-de-visite portrait, is one of the many African Americans whose lives Sojourner Truth endeavored to better. Perhaps the most famous of all known Civil War-era portraits of slaves, the photograph dates from March or April 1863 and was made in a camp of Union soldiers along the Mississippi River, where the subject took refuge after escaping his bondage on a nearby Mississippi plantation.

On Saturday, July 4, 1863, this portrait and two others of Gordon appeared as wood engravings in a special Independence Day feature in Harper’s Weekly. McPherson & Oliver’s portrait and Gordon’s narrative in the newspaper were extremely popular, and photography studios throughout the North (including Mathew B. Brady’s) duplicated and sold prints of The Scourged Back. Within months, the carte de visite had secured its place as an early example of the wide dissemination of ideologically abolitionist photographs.

Text from The Metropolitan Museum of Art website

The photograph of “Whipped Peter,” who fled a Louisiana plantation after a savage whipping, was among the most widely circulated images of the 19th century. “Peter barely survived the beating that made his back a map,” writes the scholar Imani Perry in an Aperture monograph that accompanies the exhibit, “and then ran to freedom, barefoot and chased by bloodhounds.”

The raised scars in that photograph were undeniable in a way that other accounts of slavery’s brutality, however powerful, had not been. The image tells the truth about slavery “in a way that even Mrs. [Harriet Beecher] Stowe can not approach,” wrote a journalist of the time, “because it tells the story to the eye.”

Margaret Renkl. “A Photo Can Tell the Truth About a Lie. Or a Lie About the Truth,” on The New York Times website Sept. 18, 2023 [Online] Cited 20/12/2024

During the Civil War, studio photographers produced and disseminated carte de visite portraits, or small format photographs that could be mass produced, of enslaved and emancipated Black individuals to promote abolitionist causes and reinforce support for the Union Army. Some were meant to shock and spur abolitionist outrage, especially among those who may have only heard accounts of cruelty. This portrait was made in a Union camp in the South where a formerly enslaved man named Peter – often misidentified as Gordon – sought refuge after escaping from a plantation. The image of his horrific whipping scars testified to the violence of slavery and contradicted the narrative that slavery was an economic concern rather than a racist institution. After Harper’s Weekly reproduced the image, photography studios throughout the North duplicated and sold prints to raise funds for abolitionist causes.

Text from the Large Print Guide at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

Mathew B. Brady Studio (American, active 1844-1873)

Slave Pens, Alexandria, VA

1862

Albumen silver print (carte de visite)

High Museeum of Art, Atlanta

Purchase with funds from the Lucinda Weil Bunnen Fund and the Donald and Marilyn Keough Family

Andrew Joseph Russell (American, 1829-1902)

Slave Pen, Alexandria, Virginia

1863

Albumen silver print

High Museum of Art

Purchased with funds Lucinda Weill Bunnen Fund and the Donald and Marilyn Keogh Family

Better known for his later views commissioned by the Union Pacific Railroad, A. J. Russell, a captain in the 141st New York Infantry Volunteers, was one of the few Civil War photographers who was also a soldier. As a photographer-engineer for the U.S. Military Railroad Con struction Corps, Russell’s duty was to make a historical record of both the technical accomplishments of General Herman Haupt’s engineers and the battlefields and camp sites in Virginia. This view of a slave pen in Alexandria guarded, ironically, by Union officers shows Russell at his most insightful; the pen had been converted by the Union Army into a prison for captured Confederate soldiers.

Between 1830 and 1836, at the height of the American cotton market, the District of Columbia, which at that time included Alexandria, Virginia, was considered the seat of the slave trade. The most infamous and successful firm in the capital was Franklin & Armfield, whose slave pen is shown here under a later owner’s name. Three to four hundred slaves were regularly kept on the premises in large, heavily locked cells for sale to Southern plantation owners. According to a note by Alexander Gardner, who published a similar view, “Before the war, a child three years old, would sell in Alexandria, for about fifty dollars, and an able-bodied man at from one thousand to eighteen hundred dollars. A woman would bring from five hundred to fifteen hundred dollars, according to her age and personal attractions.”

Late in the 1830s Franklin and Armfield, already millionaires from the profits they had made, sold out to George Kephart, one of their former agents. Although slavery was outlawed in the District in 1850, it flourished across the Potomac in Alexandria. In 1859, Kephart joined William Birch, J. C. Cook, and C. M. Price and conducted business under the name of Price, Birch & Co. The partnership was dissolved in 1859, but Kephart continued operating his slave pen until Union troops seized the city in the spring of 1861.

Text from The Metropolitan Museum of Art website

Even before photographs of battle fortifications and mass graves and prison camps and cities in ruin brought home in detail the enormous scale and human cost of the Civil War, images of the realities of enslaved people in the South inspired widespread moral outrage and aided the abolitionist movement. Southern politicians had been lying about both the benevolence of enslavers and the “three-fifths” nature of Black humanity since the founding of this country, but the real truth about slavery began to come clear to most people outside the South only when the first photographs of enslaved people emerged.

“Slave pens at Alexandria,” reads the hand-labeled reproduction of a photo by the celebrated Civil War photographer Mathew B. Brady. Think about the cold fact of that label for a moment. The places where enslaved people were imprisoned before being sold weren’t called jails. They were called pens. Built to contain livestock.

Margaret Renkl. “A Photo Can Tell the Truth About a Lie. Or a Lie About the Truth,” on The New York Times website Sept. 18, 2023 [Online] Cited 20/12/2024

At the start of the Civil War, Northerners arriving in Alexandria, Virginia, were shocked to find a site known as the “old slave pen.” Designed by slave traders, these locations housed enslaved individuals as they awaited auction in the District of Columbia or before being transported south. Mathew Brady’s 1862 photograph of the notorious slave trading firm Price Birch & Company (see nearby case) testified to the utter inhumanity of slavery. Made in 1863, Russell’s photograph captured the site when it served a different function, as a holding cell for Confederate prisoners of war.

Text from the Large Print Guide at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

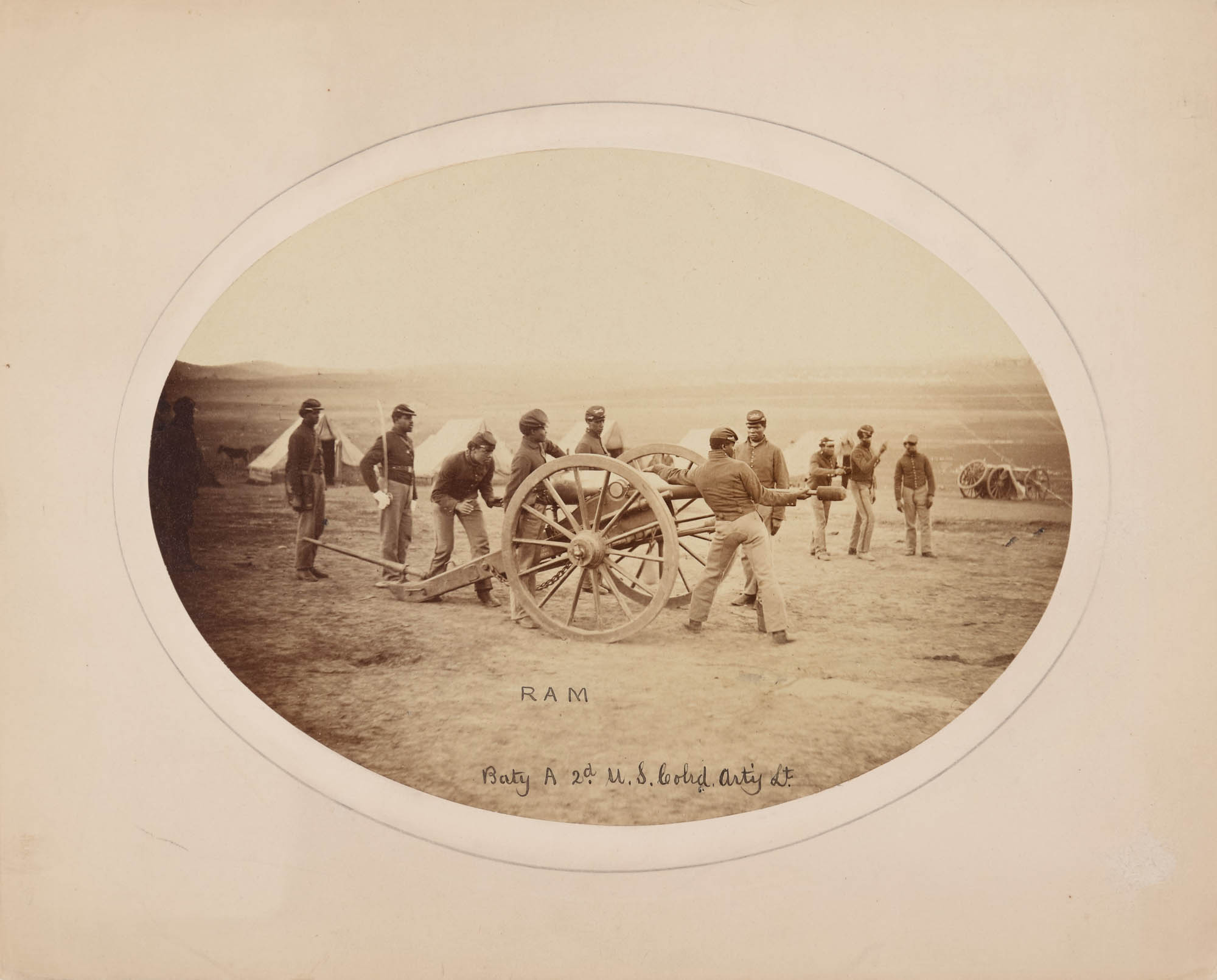

Unidentified photographer

“Ram”, 2nd Regiment, United States Colored Light Artillery, Battery A

c. 1864

Albumen silver print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta

Purchase with funds from the Lucinda Weil Bunnen Fund and the Donald and Marilyn Keough Family

Organised in Nashville in 1864 and dispatched until 1866, Battery A of the 2nd regiment of the US Colored Light Artillery accompanied the infantry and cavalry troops into battle with horse-drawn cannons. More than twenty-five thousand Black artillerymen, many of whom were freedmen from Confederate states, served in the Union Army. Artillerymen, including the cannoneers shown here, were required to handle hundreds of pounds of supplies, such as the gun, its limber, a travelling forge, and caissons to store the ammunition. Though many batteries were relegated to everyday garrison duty, Battery A fought in the Battle of Nashville in December 1864, where these photographs chronicling the loading and firing of the gun may have been taken.

Text from the Large Print Guide at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

George N. Barnard (American, 1819–1902)

Rebel Works in Front of Atlanta, Ga., No. 1

1864

Albumen silver print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta

Gift of Mrs. Everett N. McDonnell

On September 1, 1864, the Confederates abandoned Atlanta, and Barnard headed to the evacuated city with his camera to explore its elaborative defenses. Barnard presents nine views of the destruction of Atlanta – half made during the war, half in 1866. Collectively, the series remains among the most celebrated by any nineteenth-century American photographer. This view is one of the most frequently cited and reproduced of all Barnard’s war photographs. The subject is an abandoned Confederate fort with rows of chevaux-de-frise running through the landscape. As he did in one-third of the photographs in Sherman’s Campaign, Barnard used two negatives to produce the print: one for the landscape, one for the sky. The powerful effect seems to have inspired the set designers of many Civil War motion pictures, from Gone with the Wind (1939) to the present.

Text from The Metropolitan Museum of Art website

George Barnard was one of several photographers who worked for Civil War photographer Mathew Brady before setting out on his own in 1863. Barnard’s best-known works are striking images of General Sherman’s March to the Sea as the Union Army burned nearly everything in its path between Atlanta and Savannah. He published sixty-one albumen plates from this project in 1866 as an album titled Photographic Views of Sherman’s Campaign. More than a documentarian, Barnard wanted his landscapes made in the wake of destruction to convey the emotional complexity that followed the end of the war. He carefully retouched his negatives and often combined two negatives – one exposed for the ground and the other for the sky – to create moody, atmospheric images.

Text from the Large Print Guide at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

A.J. Riddle (American, 1825-1893)

Union Prisoners of War at Camp Sumter, Andersonville Prison, Georgia. View from the main gate of the stockade, August 17

1864

Albumen print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta

Purchase with funds from the Lucinda Weil Bunnen Fund and the Donald and Marilyn Keough Family

Andersonville prison was created in February 1864 and served until April 1865. The site was commanded by Captain Henry Wirz, who was tried and executed after the war for war crimes. The prison was overcrowded to four times its capacity, and had an inadequate water supply, inadequate food, and unsanitary conditions. Of the approximately 45,000 Union prisoners held at Camp Sumter during the war, nearly 13,000 (28%) died. The chief causes of death were scurvy, diarrhoea, and dysentery.

Text from the Wikipedia website

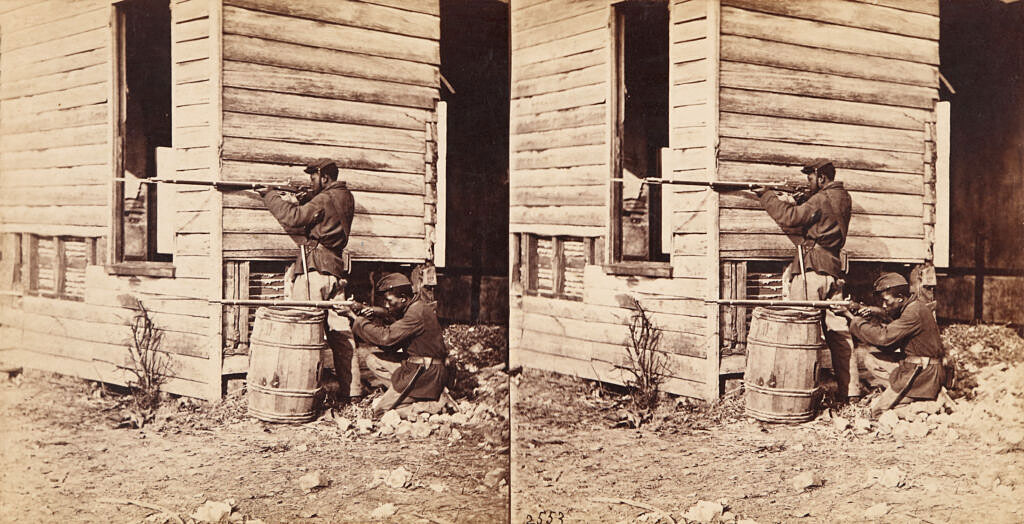

Unidentified photographer

Picket station of colored troops near Dutch Gap Canal, Dutch Gap, Virginia

1864

Albumen silver print (stereocard)

Dimensions

High Museum of Art, Atlanta

Purchase with funds from the Lucinda Weil Bunnen Fund and the Donald and Marilyn Keough Family

A Long Arc presents the diversity, beauty, and complexity of photography made in the American South since the 1840s. It examines how Southern photography has articulated the distinct and evolving character of the South’s people, landscape, and culture and reckoned with its complex history. It shows the role played by Southern photography at key crisis points in the country’s history, including the Civil War, the Great Depression, and the civil rights movement. And it explores the ways that photographers working in the region have both sustained and challenged its prevailing mythologies.

As both region and concept, the South has long held a central place within American culture. Profoundly influential American musical and literary movements emerged here, and many great political and social leaders hail from the region, yet histories of violence, disenfranchisement, and struggle dating back centuries continue to reverberate and shape it. For these reasons, the South is perhaps the most mythologized, romanticised, and stereotyped place in America.

The many contradictions inherent in this country’s history, ideals, and myths are arguably closer to the surface in the South’s unruly landscape and diverse faces than elsewhere in the United States. This makes it ideal terrain for photographers to critically engage with and examine American identity. Through the pictures in this exhibition, the South – so often dismissed as backward or marginalised as a place of alluring eccentricity – emerges as the fulcrum of both American photography and American history.

1845-1865: To Vex the Nation: Antebellum South and the Civil War

Photography arrived in the American South very soon after its introduction in Europe in 1839. By the early 1840s, numerous portrait studios popped up throughout the region, affording people a way to preserve their likenesses. Portrait photography in the antebellum South was most distinctive for how it projected and channelled racial and social identity at a moment of intense debate over slavery. It was not unusual for Southern slaveholders to commission photographs of their children with enslaved members of their

households, a means of reinforcing social hierarchies. Yet, significantly, the medium also offered free Black Americans a means to declare their presence and self-possession in a society that did not regard them as citizens.

With the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, photography emerged as a crucial medium through which Americans witnessed and confronted the horrors of modern warfare and understood the conflict’s significance to themselves and to their country. The mass mobilisation of soldiers coincided with the development of cheaper and faster ways of making pictures, fuelling a vibrant market for Civil War portraits. These precious keepsakes allowed sitters to display their political allegiances and sustain connections between the battlefield and the home front.

While portraiture was the most common form of photography at this time, the demand for photographs of battlefields, military encampments, and sites of conflict grew throughout the course of the war. These pictures circulated widely as both photographs and as newspaper illustrations made from photographs. Images of carnage, ruin, and especially the destruction of Southern cities helped Americans grasp the enormity of loss. They also introduced an enduring photographic trope: the Southern landscape as the repository of memory, history, and trauma.

Organised in Nashville in 1864 and dispatched until 1866, Battery A of the 2nd regiment of the US Colored Light Artillery accompanied the infantry and cavalry troops into battle with horse-drawn cannons. More than twenty-five thousand Black artillerymen, many of whom were freedmen from Confederate states, served in the Union Army. Artillerymen, including the cannoneers shown here, were required to handle hundreds of pounds of supplies, such as the gun, its limber, a traveling forge, and caissons to store the ammunition. Though many batteries were relegated to everyday garrison duty, Battery A fought in the Battle of Nashville in December 1864, where these photographs chronicling the loading and firing of the gun may have been taken.

Text from the Large Print Guide at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

George N. Barnard (American, 1819-1902)

Destruction of Hood’s Ordnance Train

1864

From Photographic Views of Sherman’s Campaign

Albumen silver print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta

Purchase

This dramatic bird’s-eye view documents the aftermath of the destruction of a Confederate military train filled with gunpowder. When abandoning Atlanta, Confederate General John Bell Hood ordered his troops to set the boxcars on fire so that the Union army would never be able to make use of the train. The explosion also completely levelled the nearby mill, leaving evidence of only a few rail wheels and axles.

Text from The Metropolitan Museum of Art website

George N. Barnard (American, 1819-1902)

Ruins in Charleston, S.C.

1865-1866, printed 1866

Albumen silver print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta

Purchase

Before the war, landscape photography in the South was rare and usually indicated the social or economic function of a place. But as the war spread throughout the South, photographers not only documented the military encampments on the battlefields but often rendered the landscape itself as an object of contemplation, reverie, and mourning. In this work, Barnard carefully seated two figures amid the rubble, their gazes casting out onto the ruined city. Posed as observers taking in the scope and spectacle of tragedy, they stand in for the viewers who experienced the war from afar. Photographs like these also served rhetorical purposes by making the immense destruction seem like divine retribution. As Sherman himself wrote, “I doubt any city was ever more terribly punished than Charleston, but as her people had for years been agitating for war and discord, and had finally inaugurated the Civil War, the judgment of the world will be that Charleston deserved the fate that befell her.”

Text from the Large Print Guide at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

George Barnard – widely considered one of the most important documentarians of the Civil War – began working with photography only several decades after its invention. The limitations of this burgeoning technology influenced how, when, and where Barnard shot his images. At the time, it was essentially impossible to capture quick motion, so Barnard primarily documented the effects of the war on landscapes and architecture. His richly detailed images are filled with anecdotal details that help tell the story of the Civil War and Sherman’s massive campaign through the South.

Text from the High Museum of Art website

George N. Barnard (American, 1819-1902)

The “Hell Hole” New Hope Church, Georgia

1861-1866

Albumen silver print from glass negative

Addison Gallery of American Art

The Battle of New Hope Church (May 25-26, 1864) was a clash between the Union Army under Major General William T. Sherman and the Confederate Army of Tennessee led by General Joseph E. Johnston during the Atlanta Campaign of the American Civil War. Sherman broke loose from his railroad supply line in a large-scale sweep in an attempt to force Johnston’s army to retreat from its strong position south of the Etowah River. Sherman hoped that he had outmaneuvered his opponent, but Johnston rapidly shifted his army to the southwest. When the Union XX Corps under Major General Joseph Hooker tried to force its way through the Confederate lines at New Hope Church, its soldiers were stopped with heavy losses.

Text from the Wikipedia website

John Reekie (American, 1829-1885)

A Burial Party, Cold Harbor, Virginia

1865, published 1866

Albumen silver print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta

Purchase with funds from the Lucinda Weil Bunnen Fund and the Donald and Marilyn Keough Family, and the Addison Gallery of American Art

Few of the photographs in the Sketch Book evoke the intense sadness of A Burial Party, Cold Harbor, Virginia, one of the seven photographs Gardner included by the still-obscure field operative John Reekie. It is the only plate in the second volume that shows corpses, here being collected by African American soldiers. Four soldiers with shovels work in the background; in the foreground, a single labourer in a knit cap sits crouched behind a bier that holds the lower right leg of a dead combatant and five skulls – one for each member of the living work crew. Reekie’s atypical low vantage point and tight composition ensure that the foreground soldier’s head is precisely the same size as the bleached white skulls and that the head of one of the workers rests in the sky above the distant tree line. It is a macabre and chilling portrait – literally a study of black and white – that is as memorable as any made during the war.

Text from The Metropolitan Museum of Art website

Isaac H. Bonsall (American, 1833-1909)

Bonsil’s Photo Gallery, Chattanooga, TN

1865

Albumen silver print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta

Purchase with funds from the Lucinda Weil Bunnen Fund and the Donald Marilyn Keough Family

Note the framed photographs at far left on the wooden slat fence advertising the photographer’s work and examples of his carte de visite photographs to the left and right of the entrance. This photograph must have been taken not long after the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln on 15th April 1865 as the president’s image above the door is surrounded by black mourning cloth ~ Marcus

Isaac H. Bonsall was one of many enterprising photographers who took advantage of the public’s growing demand for portraits at the onset of the Civil War. In 1862, the New York Tribune published an observer’s account of the onslaught of travelling portrait studios among the army: “A camp is hardly pitched before one of the omnipresent artists in collodion and amber […] pitches his canvas gallery and unpacks his chemicals.”

Text from the Large Print Guide at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

Isaac H. Bonsall (American, 1833-1909)

Bonsil’s Photo Gallery, Chattanooga, TN (detail)

1865

Albumen silver print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta

Purchase with funds from the Lucinda Weil Bunnen Fund and the Donald Marilyn Keough Family

1865-1930: Less Splendid on the Surface

Between 1865 and 1930, the South experienced the abandonment of the promises of Reconstruction and the violent and legal enforcement of racial segregation. Yet this period also witnessed rebuilding of cities and industries, the founding of new institutions (including a significant number of Black schools), continued cultivation of the land, and the development of creative cultures that spread throughout the nation. Photography bore witness to these developments. Some photographers used the camera to sell an idyllic vision of the South that was at odds with the harsh reality, while others documented injustice and poverty with the goal of calling broader attention to the region’s struggles.

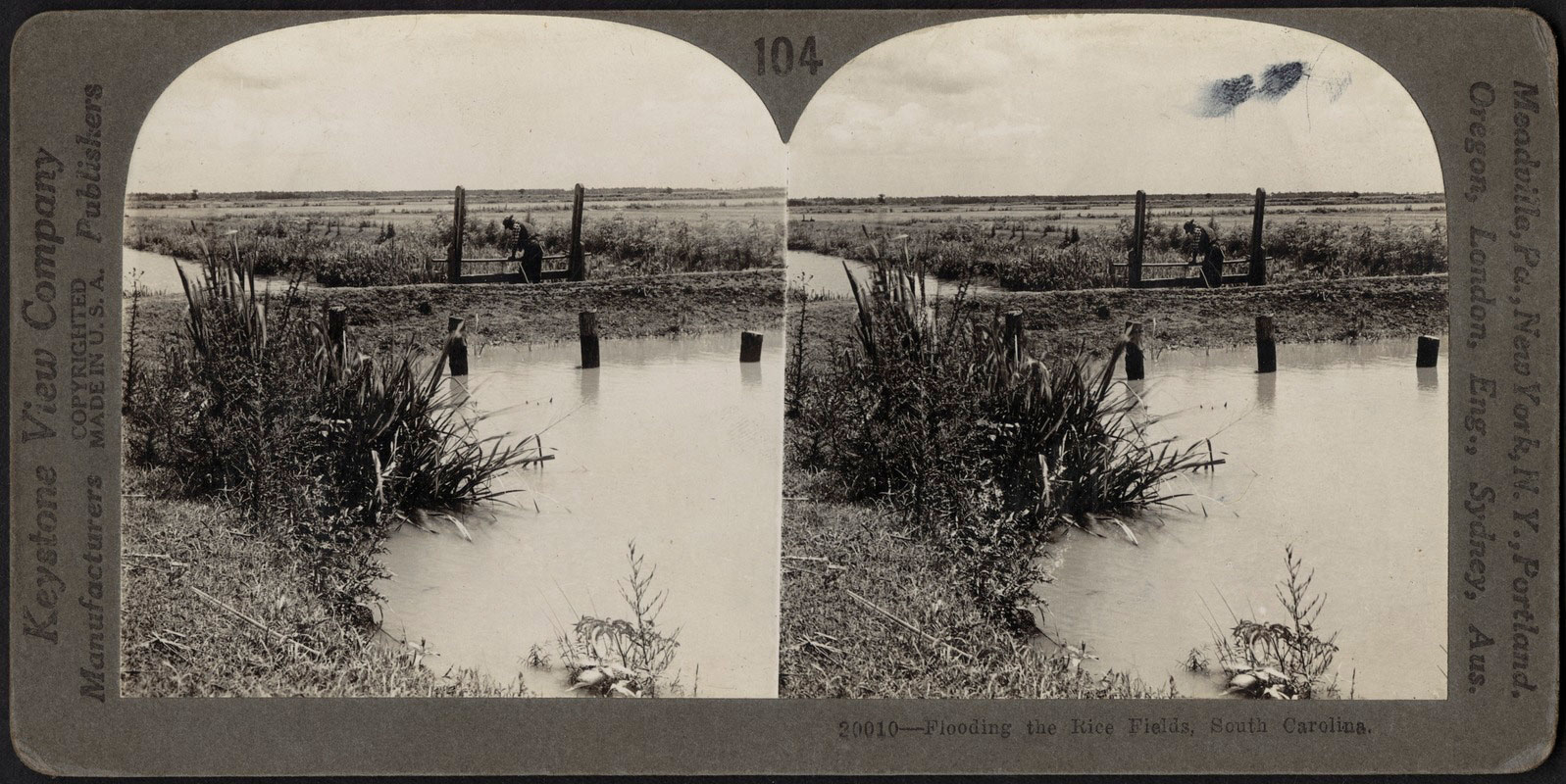

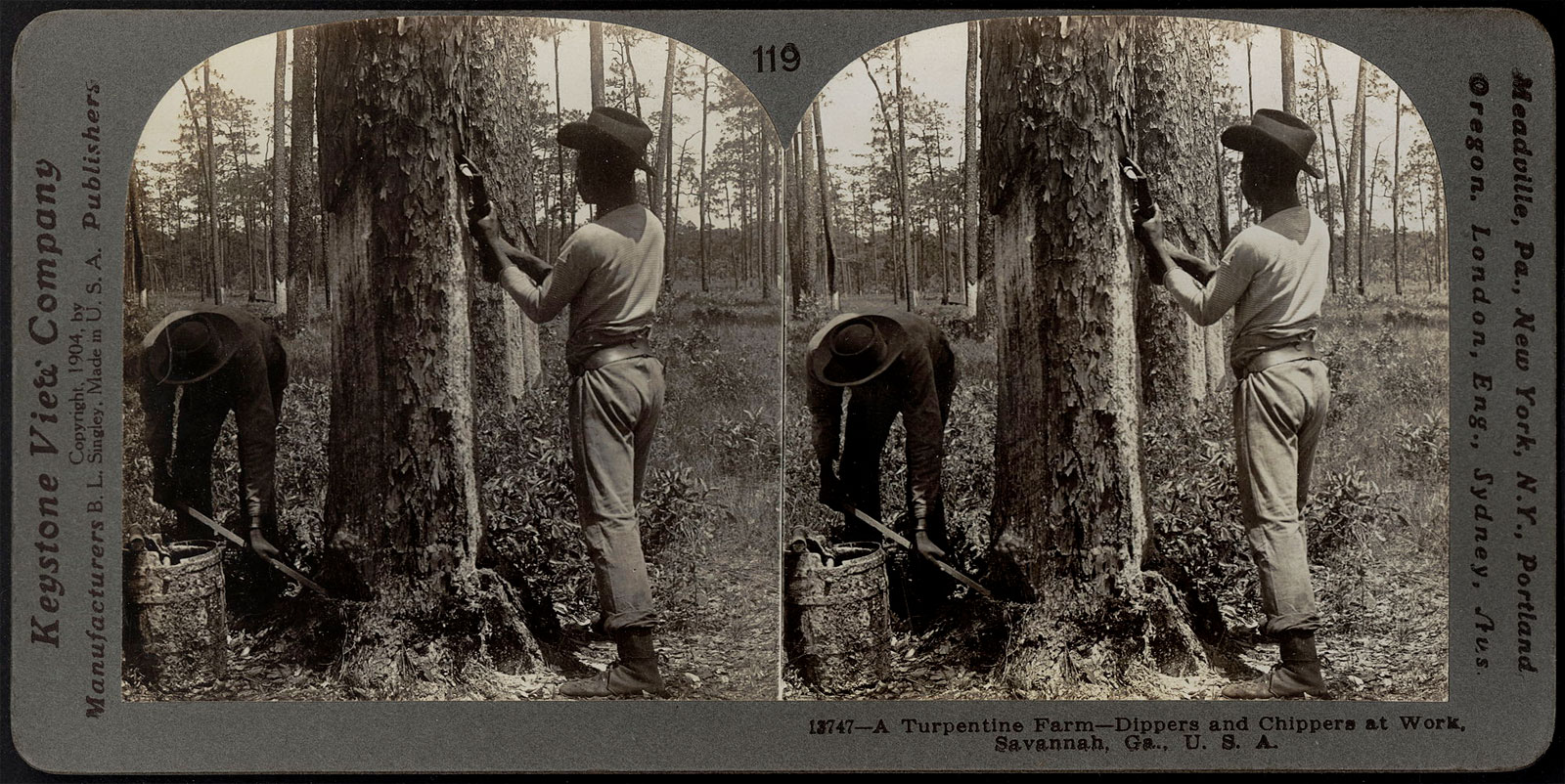

During this period, photography also became an increasingly familiar part of everyday life, accelerated by the rise of “penny picture” photography studios, cheap snapshot cameras, and the proliferation of inexpensive stereographs (a form of 3D photography) that brought the wonders of the world – and the South – into nearly every household. The greater accessibility of photography also opened the profession to a growing number of women and Black makers. Community portraiture in particular flourished, giving ordinary people the opportunity to document their lives and envision themselves as modern citizens. Across the South, studio photographers produced thousands of pictures – of public events, private celebrations, city streets, architectural views, and landscapes – that reveal the texture of everyday life and observe the ways people in the South lived, both together and apart from each other.

Text from the Large Print Guide at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

John Horgan Jr. (American, 1859-1926)

James Richardson’s Plantation, Jackson, MS

1892

Albumen silver print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta

Purchase

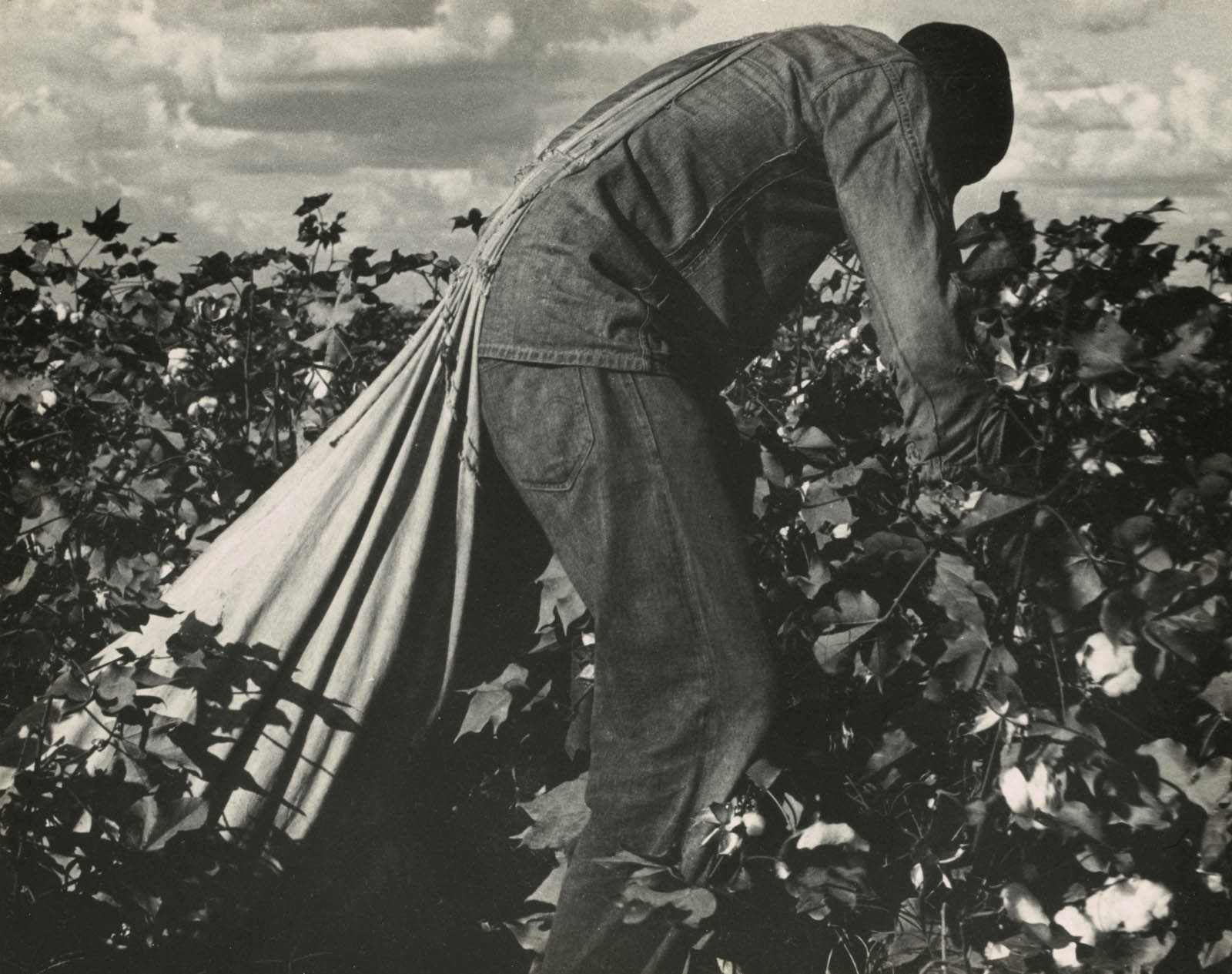

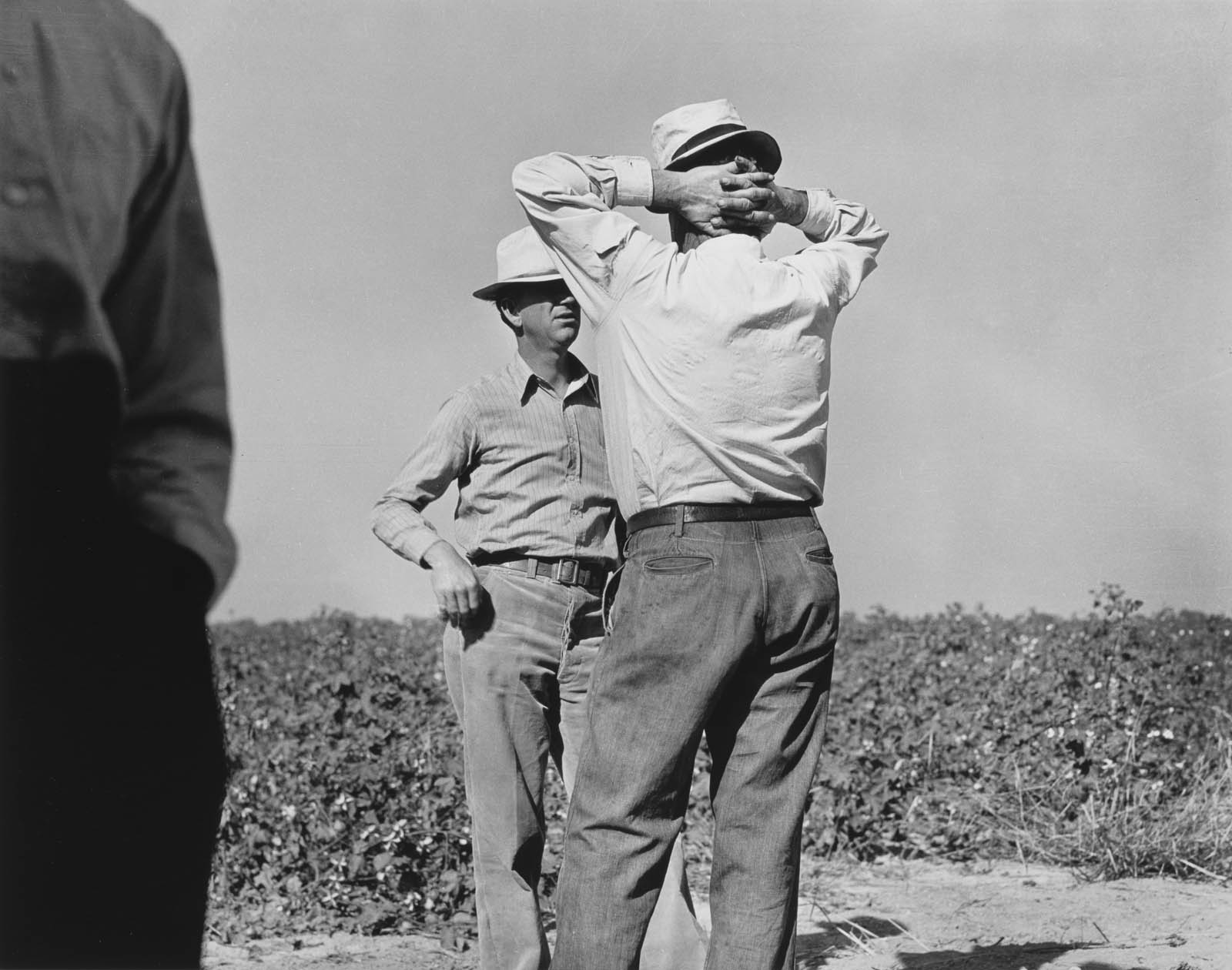

As Alabama’s “first commercial and industrial specialist,” in the 1890s John Horgan Jr. photographed the vast cotton plantations owned by industrial magnate Edmund Richardson, who also founded the lucrative and exploitative practice of convict labour (leasing prisoners from the state for forced, unpaid labour in exchange for supplying housing). Photographing at a plantation owned by Richardson’s son James, Horgan shows Black labourers, including young children, engaged in the backbreaking toil of harvesting and sorting cotton. Though made almost thirty years after the abolition of slavery, Horgan’s views of antebellum-style labour were a form of propaganda that minimised the conditions of extreme poverty and inequality that shaped African American life in the South.

Text from the Large Print Guide at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

William Henry Jackson (American, 1843-1942)

Florida. Tomaka River. The King’s Ferry

1898

Chromolithograph

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

Gift of an Anonymous Donor

William Henry Jackson (American, 1843-1942)

St. Charles Street, New Orleans

1900

Chromolithograph

High Museum of Art, Atlanta

Gift of Joshua Mann Pailet in memory of Charlotte Mann Pailet (1924-1999)

The painter, explorer, and survey photographer William Henry Jackson is best known for his images of the American West, many of which he produced as part of the United States Geological Survey. In 1897, Jackson became a director of the Detroit Publishing Company in a venture to publish colour lithographic prints from black-and-white negatives by himself and other photographers. These views were taken across the United States, including the American South, and were widely disseminated as prints and postcards.

Text from the Large Print Guide at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

William Henry Jackson (American, 1843-1942)

Cotton on the Levee

1900

Chromolithograph

High Museum of Art, Atlanta

Gift of Joshua Mann Pailet in memory of Charlotte Mann Pailet (1924-1999)

The first major exhibition of Southern photography in more than 25 years, A Long Arc: Photography and the American South since 1845, will be on display at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond from Oct. 5, 2024, to Jan. 26, 2025.

A Long Arc comprises more than 175 years of photography from a broad swath of the American South – from Maryland to Florida to Arkansas to Texas and places in between. Visitors to the expansive exhibition will encounter everyday lives and ordinary places captured in evocative photos that contemplate the region’s central role in shaping American history and identity. The exhibition also examines the South’s critical impact on the development of photography.

“The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts is excited to present A Long Arc: Photography and the American South since 1845, an astounding exhibition of powerful images of our shared Southern – and American – history by many of this country’s foremost photographers,” said the museum’s Director and CEO Alex Nyerges. “The exhibition also includes a number of captivating images of Richmond and the Commonwealth from the museum’s ever-growing collection of photographs.”

A Long Arc is organised by the High Museum of Art (Atlanta, Georgia) and co- curated by Gregory Harris, the Donald and Marilyn Keough Family curator of photography at the High Museum of Art, and Dr. Sarah Kennel, the Aaron Siskind curator of photography and director of the Raysor Center for Works on Paper at VMFA.

“A Long Arc reckons with the region’s fraught history, American identity and culture at large, asking us to consider the history of American photography with the South as its focal point,” said Dr. Kennel. “The exhibition examines the ways that photographers from the 19th century to the present have articulated the distinct and evolving character of the South’s people, landscape and culture.”

More than 180 works of historical and contemporary photography are featured in A Long Arc, which includes many from VMFA’s permanent collection.

Organised chronologically, A Long Arc opens with an exploration of the years from 1845 to 1865, where visitors will encounter compelling photographs made before and during the American Civil War. Photographers of this time, including Alexander Gardner and George Barnard, transformed the practice of the medium and established visual codes for articulating national identity and expressing collective trauma. Following the war, photographs made from 1865 to 1930 reveal the South’s incomplete project of Reconstruction, including new industries, a rise of community- based photography studios, the erection of white supremacist monuments and scenes conveying social division.

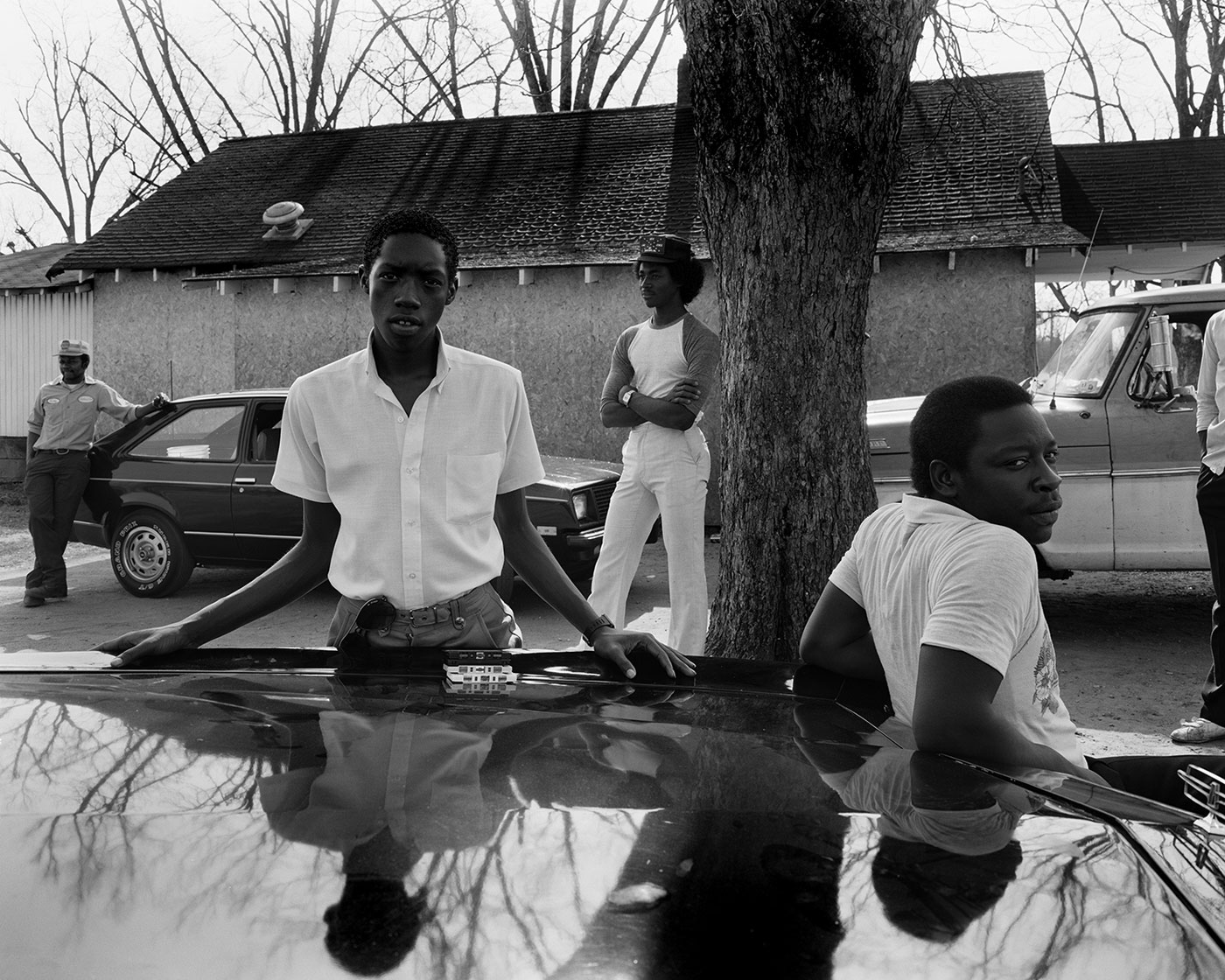

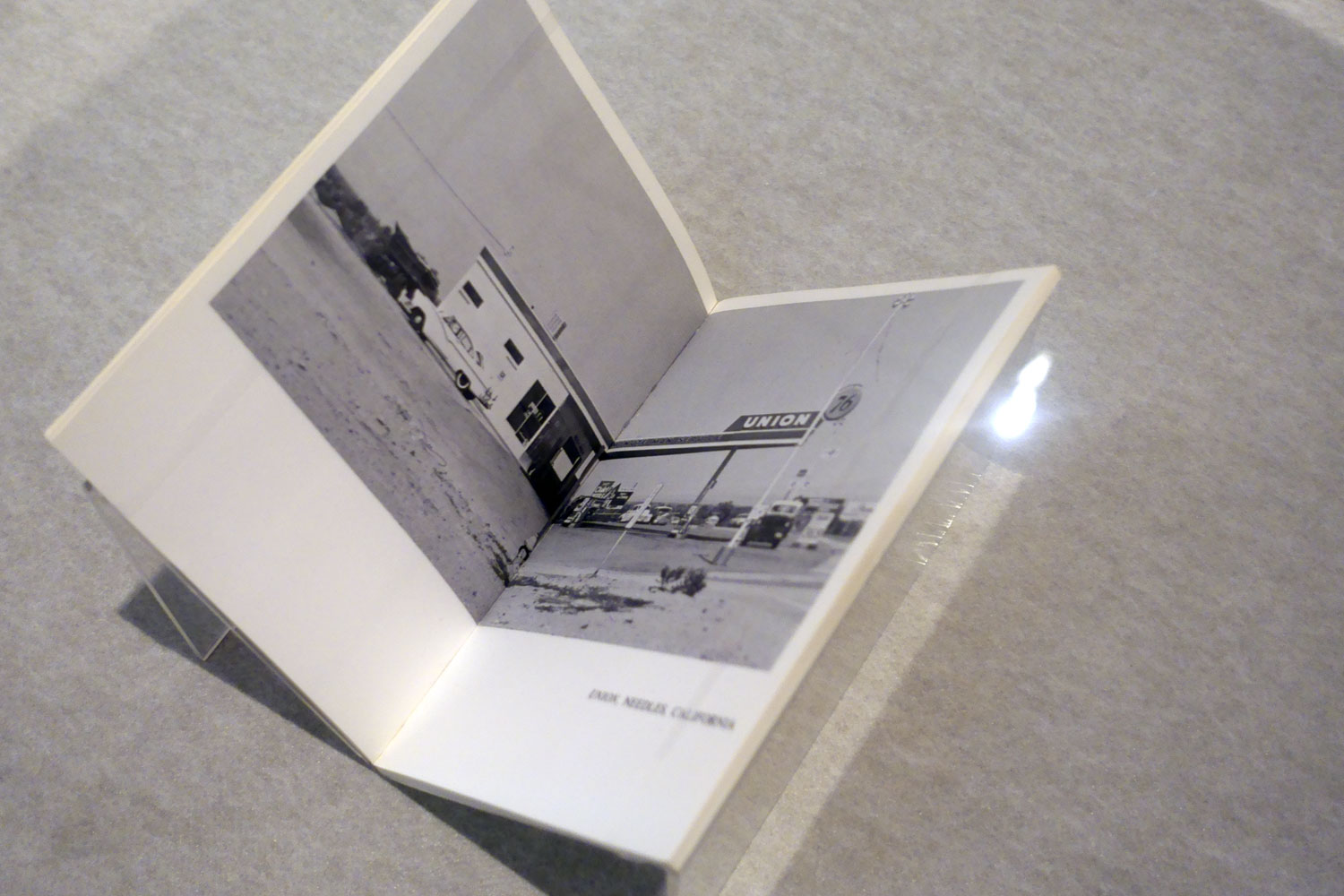

With the emergence of documentary photography in the 1930s, photographs made in the South raised national consciousness around social and racial inequities. During this time, Farm Security Administration photographers working in the region, including Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange and Marion Post Wolcott, defined a kind of documentary approach that dominated American photography for decades and recast a Southern vernacular into a new kind of national style.

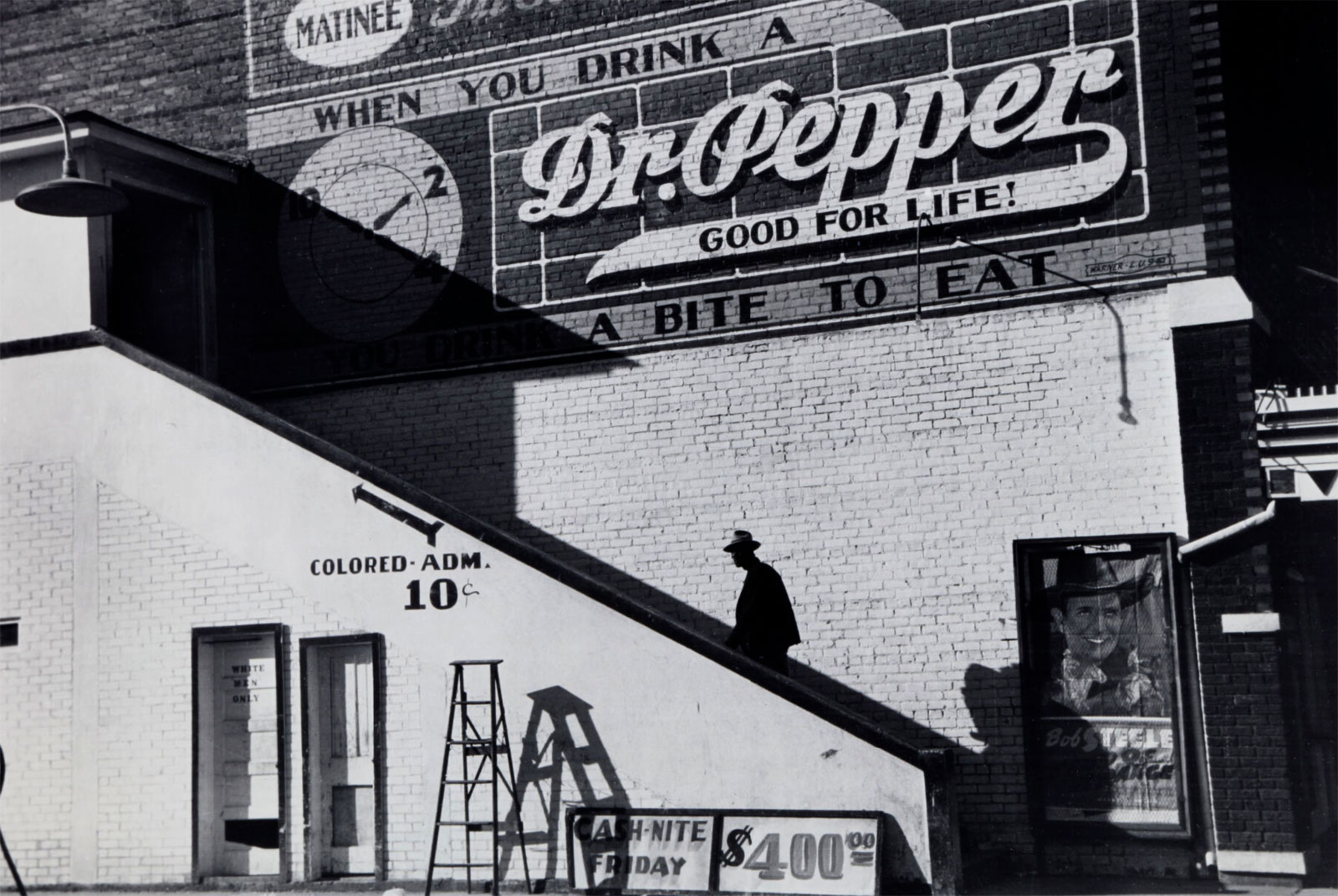

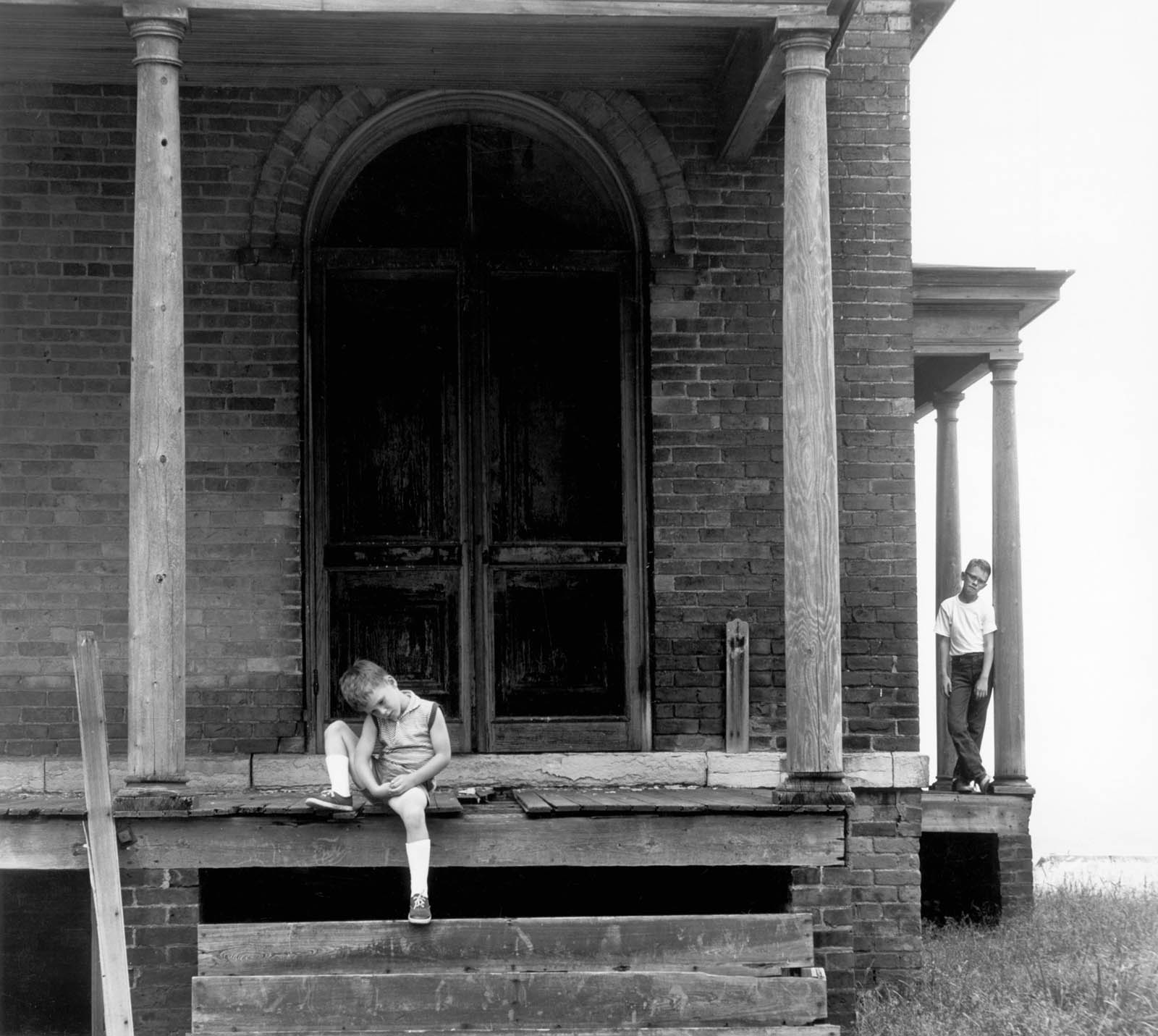

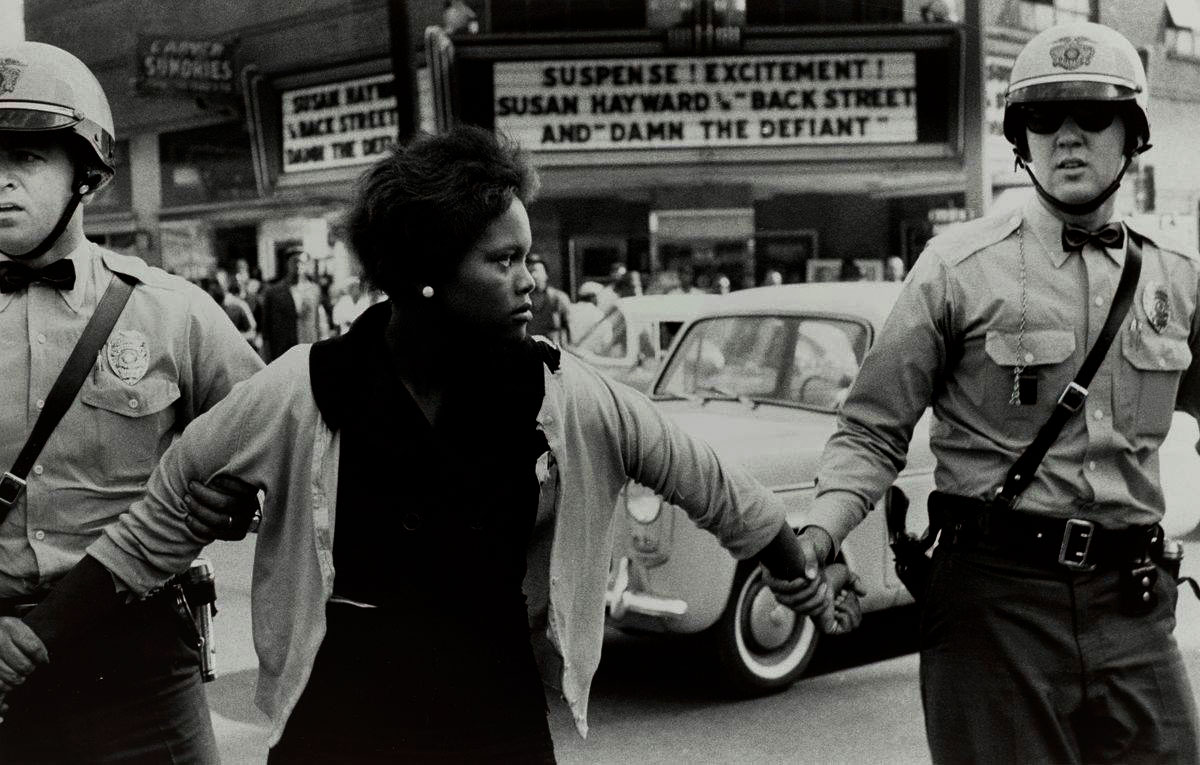

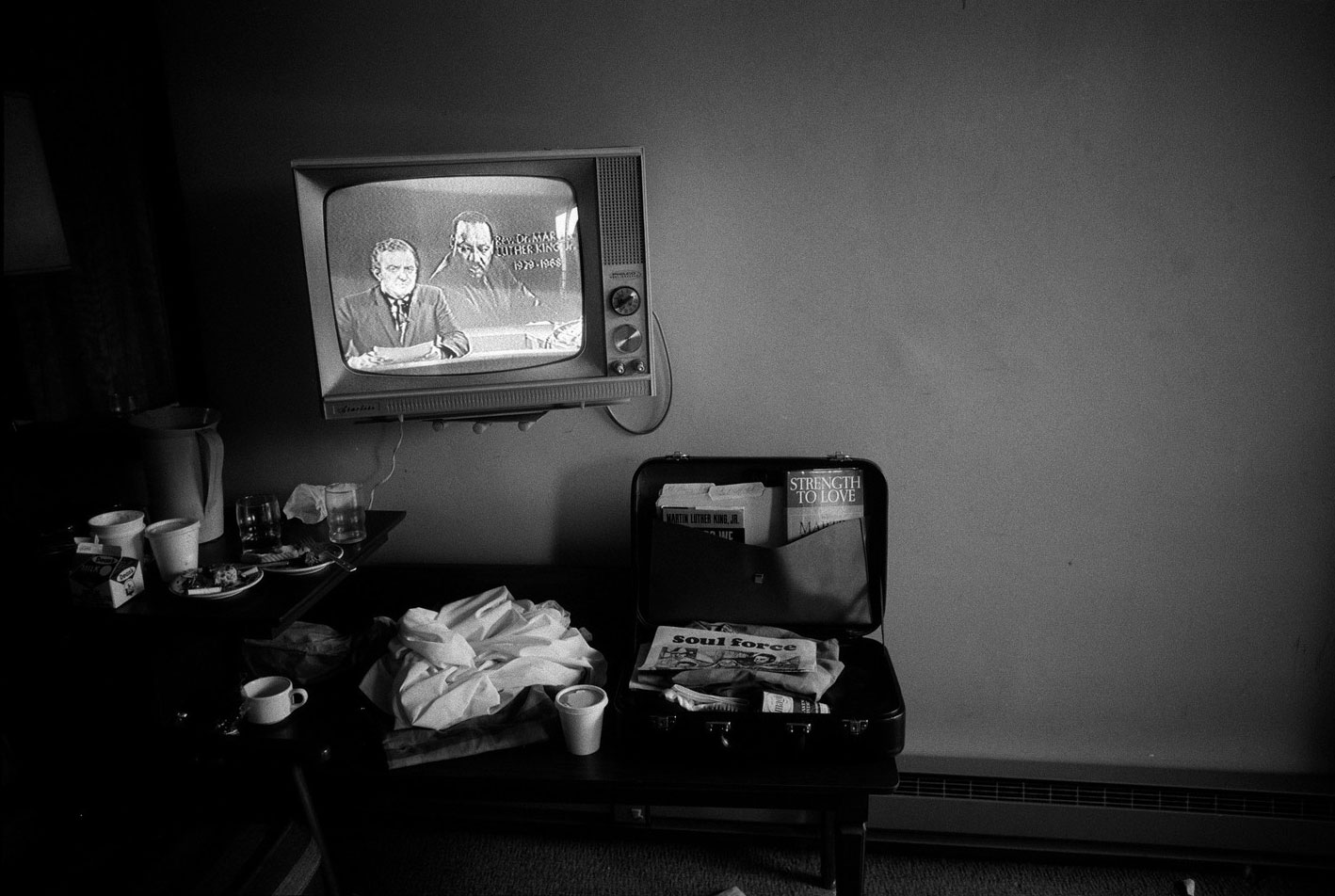

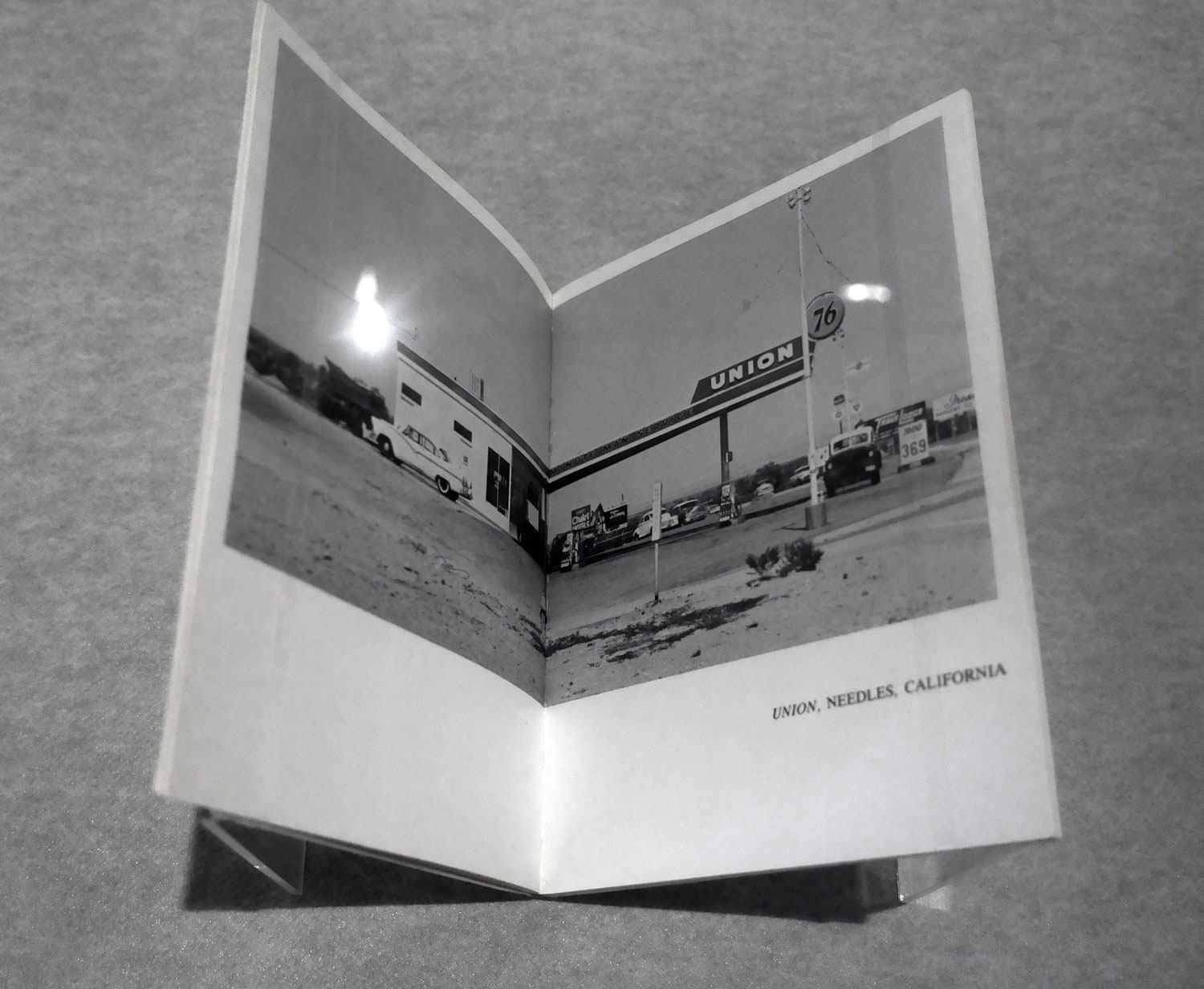

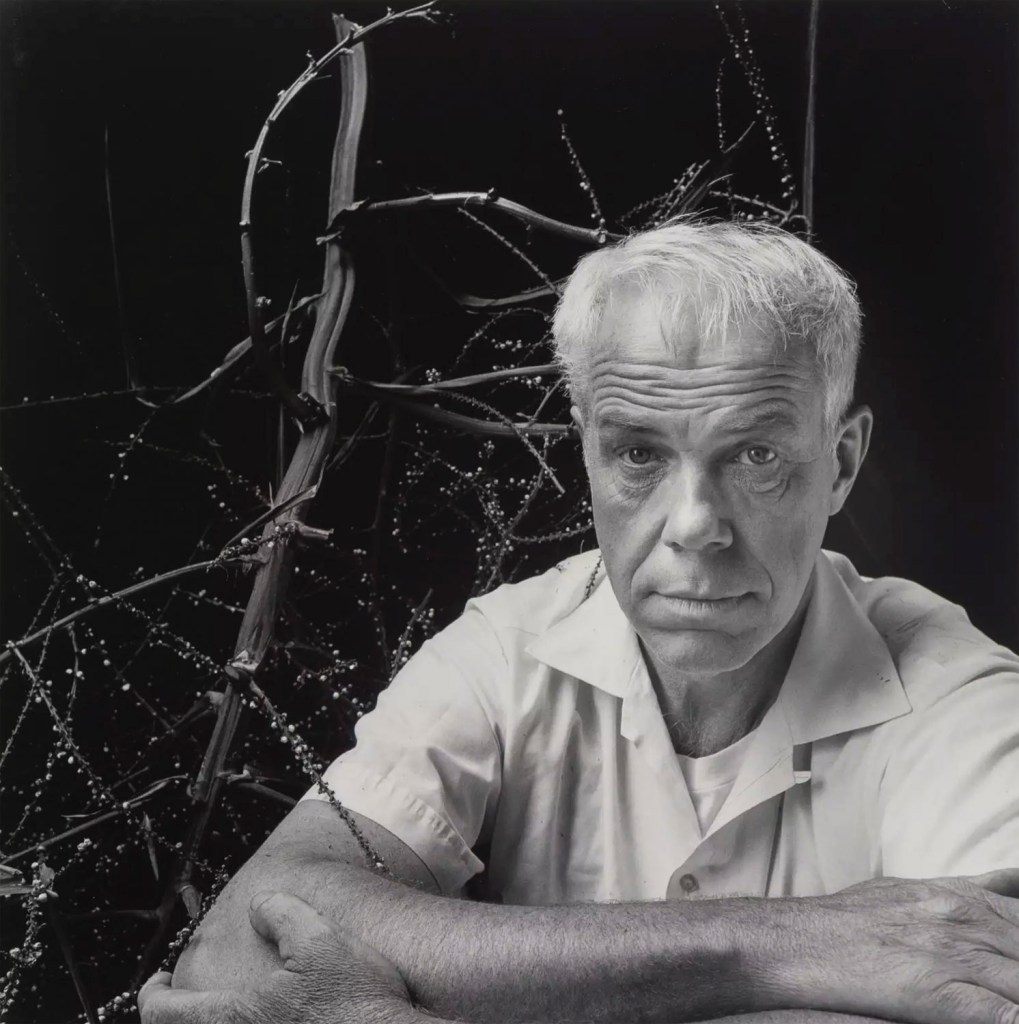

During the 25 years following World War II, from 1945 to 1970, photography in the South was characterised by an incongruence between America’s optimistic image of itself and the enduring shadow of Jim Crow-era segregation. Artists like Robert Frank, Clarence John Laughlin and Ralph Eugene Meatyard made jarring and unsettling photographs that revealed economic, racial and psychic dissonance at odds with conventional images of American prosperity, while photographs of the civil rights movements by Bruce Davidson, Danny Lyon, Doris Derby and James Karales galvanised and shocked the nation with raw depictions of violence and the struggle for justice.

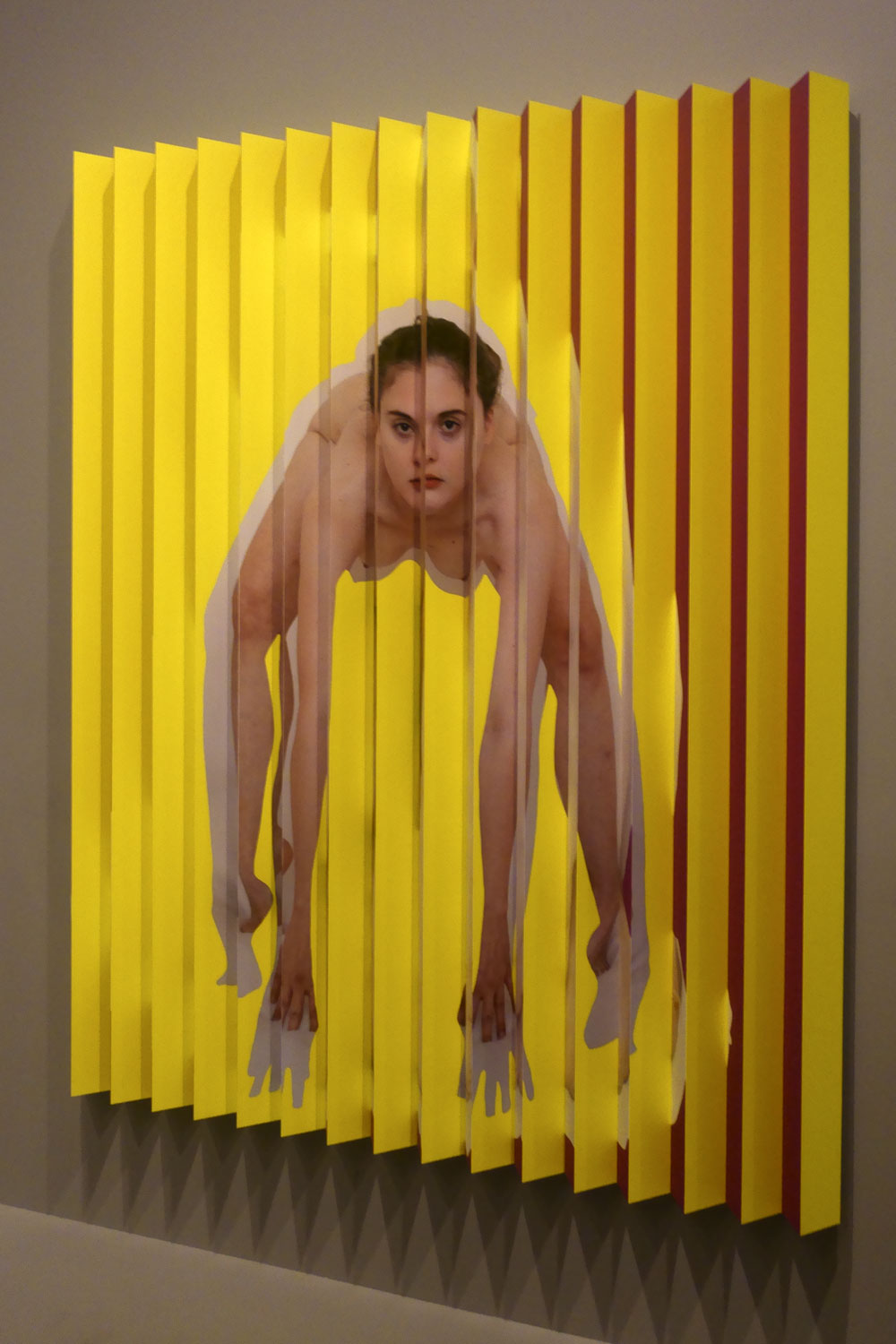

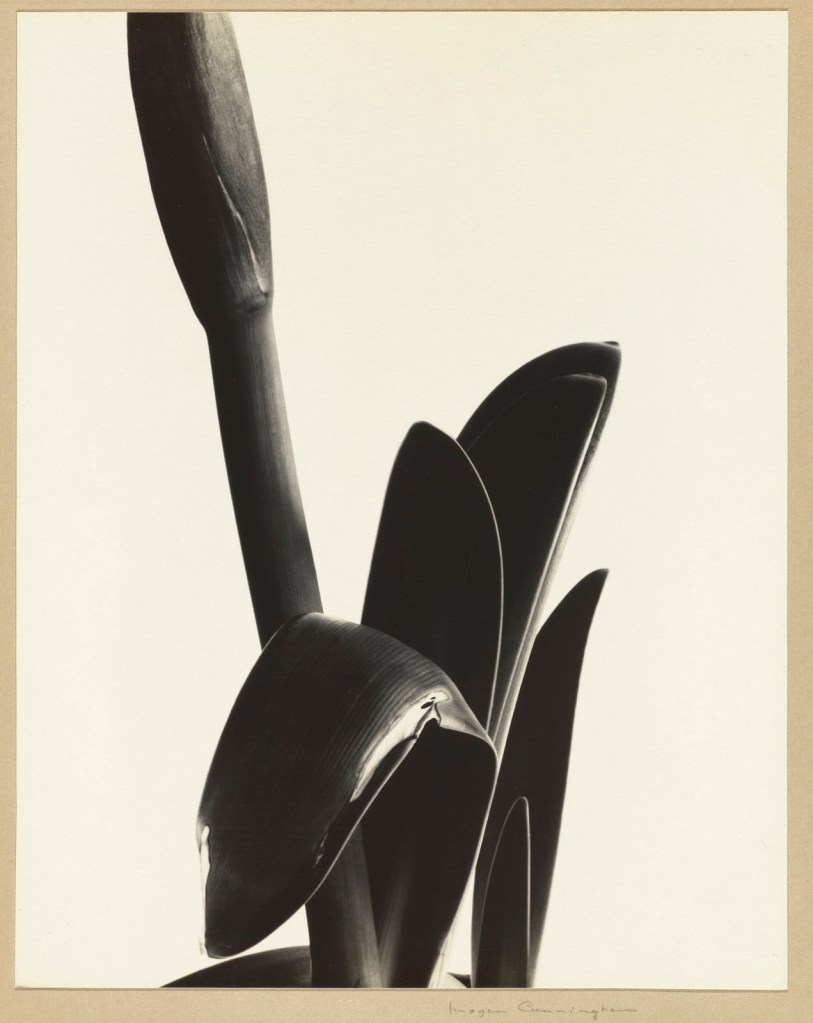

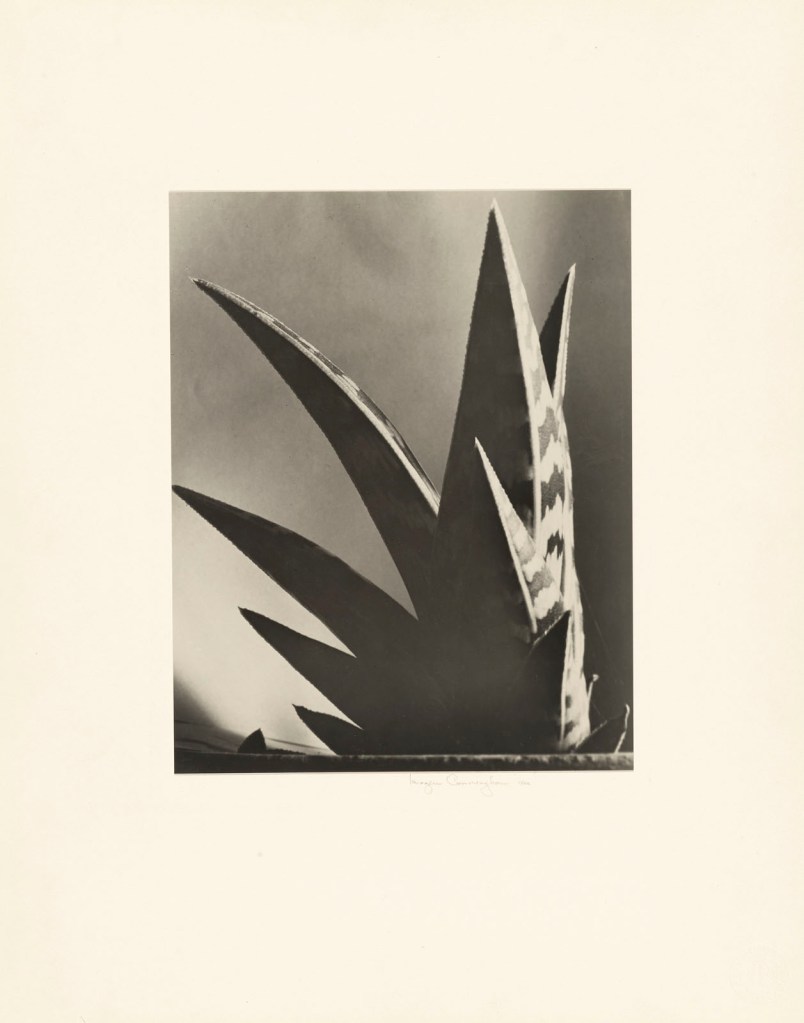

Photography in the South exhibits a sense of reflection, return and renewal in the three decades following the tumult of the 1960s, as artists like Sally Mann, William Eggleston and William Christenberry created narrative, self-reflexive bodies of work that simultaneously sustained and interrogated the South’s brutal histories and enduring cultural mythologies.

A Long Arc concludes with a wide-ranging and provocative selection of photographs made in the past two decades. Artists like Richard Misrach, Lucas Foglia, Gillian Laub, An-My Lê, Sheila Pree-Bright, RaMell Ross and Jose Ibarra Rizo explore Southern history and American identity in the 21st century as forged by legacies of slavery and white supremacy, marked by economic inequality and environmental catastrophe and transformed by immigration, technology, urbanisation, globalisation and shifting ethnic, cultural, racial and sexual identities.

A complex and layered archive of the region, A Long Arc captures how the South has occupied an uneasy place in the history of American photography while simultaneously exemplifying regional exceptionalism and the crucible from which American identity has been forged over the past two centuries.

Press release from the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

James Van Der Zee (American, 1886-1983)

Whittier Preparatory School, Phoebus, Va.

1907

Gelatin silver print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta

Purchase

© James Van Der Zee Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

This is an early photograph by the self taught photographer James Van Der Zee when he was only 21 years old, made in Phoebus, Virginia where he had moved with his wife Kate L. Brown. He returned to Harlem in 1916 and became a leading figure in the Harlem Renaissance, his portrait of black New York people and culture becoming the most comprehensive artistic photographs of the period.

In the years following the Civil War, numerous schools were founded throughout the South to educate the emancipated Black population. Literacy, which was strictly forbidden by plantation overseers, became a beacon of hope and accomplishment for Black Americans. This dedication to education was so strong among freed peoples that the literacy gap between white and Black communities in the American South closed within a generation. The Whittier Preparatory School in Phoebus, Virginia, was distinguished among its peer institutions for its expanded curriculum, including classes up to ninth grade that encompassed art and music education and dedicated science facilities.

Text from the Large Print Guide at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

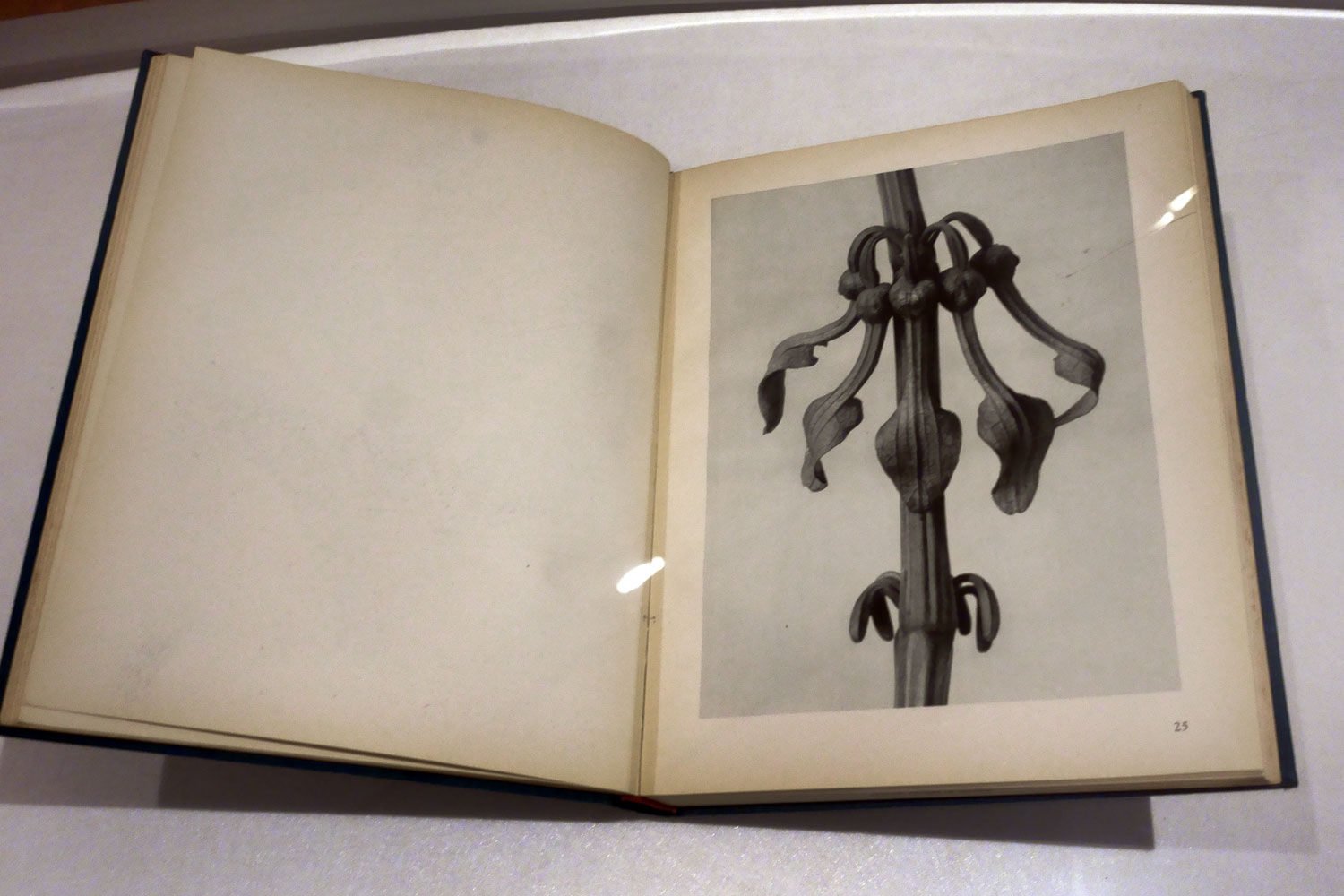

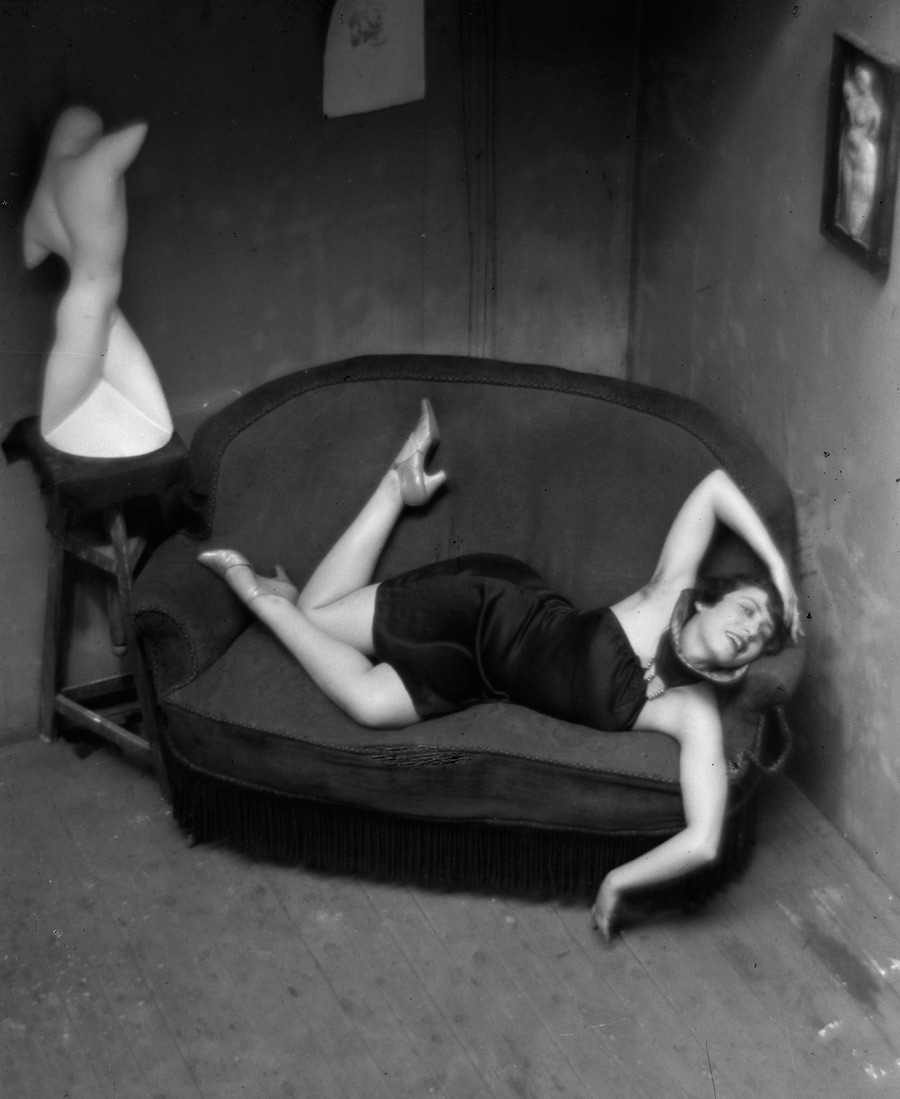

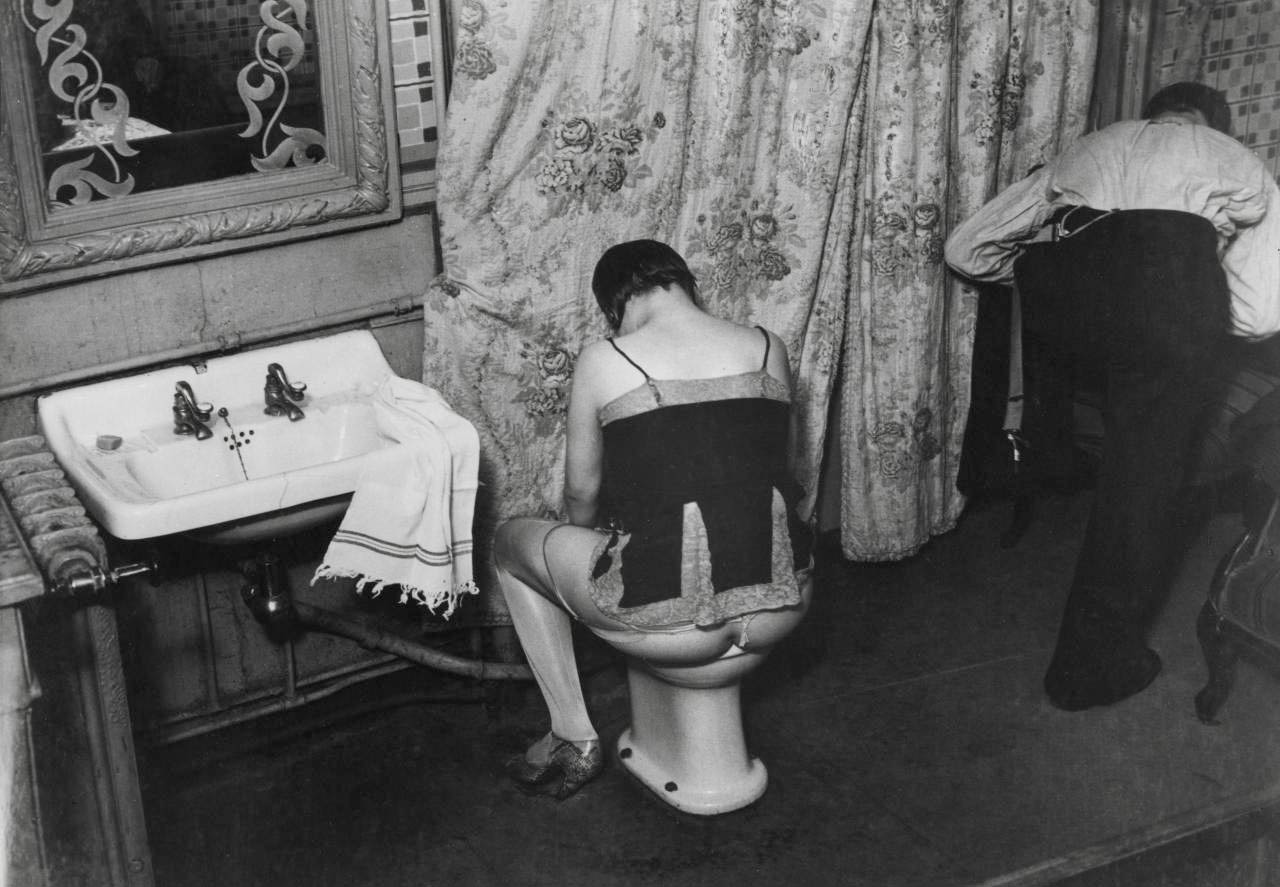

Ernest Joseph Bellocq (American, 1873-1949)

Storyville prostitute / Storyville Portrait, New Orleans

c. 1912, printed 1966

Gelatin silver print

Addison Gallery of American Art, Phillips Academy, Andover, Massachusetts

Museum purchase

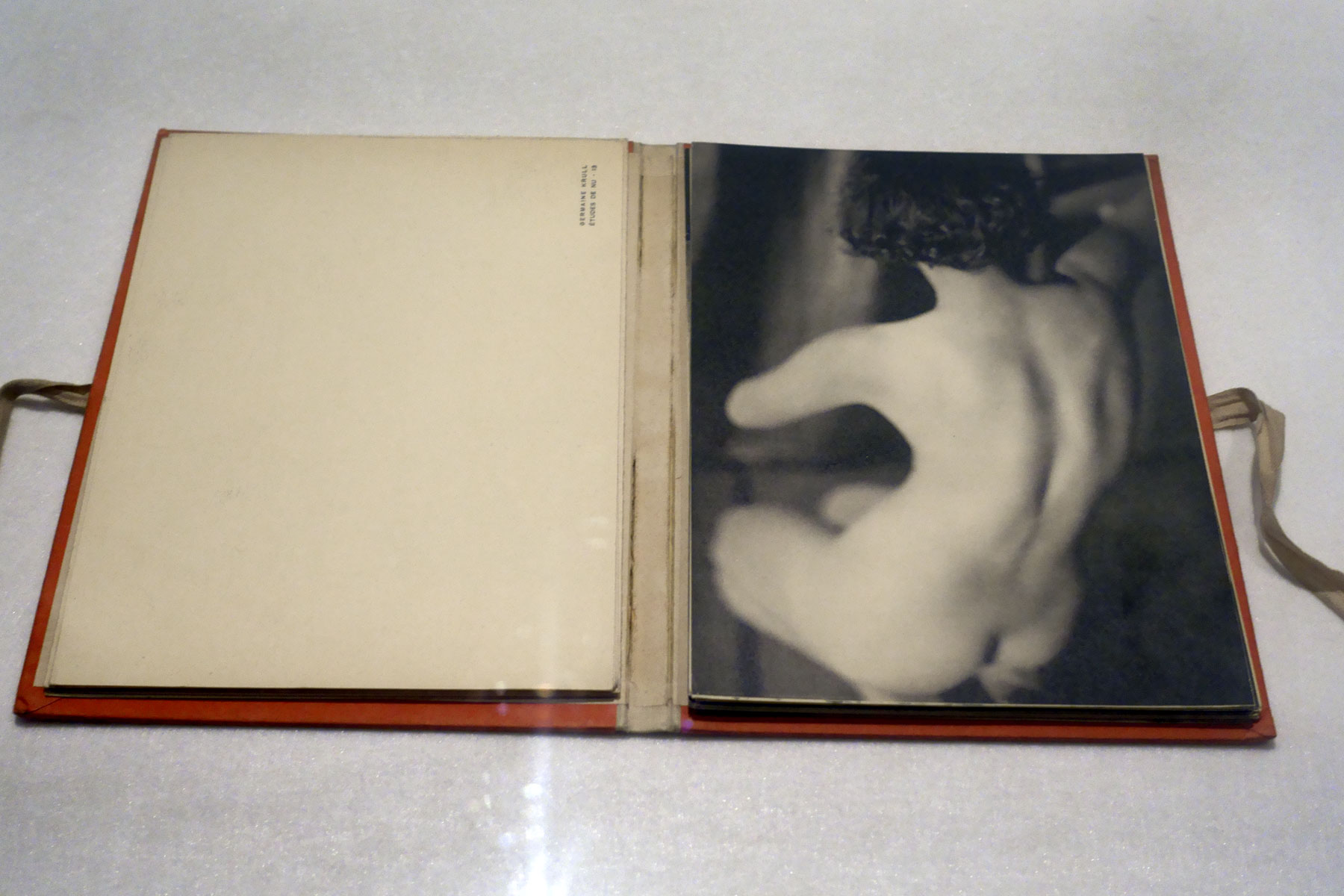

Storyville was born on January 1, 1898, and its bordellos, saloons and jazz would flourish for 25 years, giving New Orleans its reputation for celebratory living. Storyville has been almost completely demolished, and there is strangely little visual evidence it ever existed – except for Ernest J. Bellocq’s other wordly photographs of Storyville’s prostitutes. Hidden away for decades, Bellocq’s enigmatic images from what appeared to be his secret life would inspire poets, novelists and filmmakers. But the fame he gained would be posthumous. …

E. J. Bellocq wasn’t just photographing ships and machines. What he kept mostly to himself was his countless trips to Storyville, where he made portraits of prostitutes at their homes or places of work with his 8-by-10-inch view camera. Some of the women are photographed dressed in Sunday clothes, leaning against walls or lying across an ironing board, playing with a small dog. Others are completely or partially nude, reclining on sofas or lounges, or seated in chairs.

The images are remarkable for their modest settings and informality. Bellocq managed to capture many of Storyville’s sex workers in their own dwellings, simply being themselves in front of his camera – not as sexualised pinups for postcards. If his images of ships and landmark buildings were not noteworthy, the pictures he took in Storyville are instantly recognisable today as Bellocq portraits – time capsules of humanity, even innocence, amid the shabby red-light settings of New Orleans. Somehow, perhaps as one of society’s outcasts himself, Bellocq gained the trust of his subjects, who seem completely at ease before his camera. …

In 1958, 89 glass negatives were discovered in a chest, and nine years later the American photographer Lee Friedlander acquired the collection, much of which had been damaged because of poor storage. None of Bellocq’s prints were found with the negatives, but Friedlander made his own prints from them, taking great care to capture the character of Bellocq’s work. It is believed that Bellocq may have purposely scratched the negatives of some of the nudes, perhaps to protect the identity of his subjects.

Gilbert King. “The Portrait of Sensitivity: A Photographer in Storyville, New Orleans’ Forgotten Burlesque Quarter,” on the Smithsonian Magazine website March 28, 2012 [Online] Cited 20/12/2024

From 1898 to about 1923, New Orleans’s legally protected red-light district, known as Storyville, flourished with saloons, jazz clubs, gambling halls, and brothels. The prostitutes of these establishments were the favourite subjects of E. J. Bellocq, a photographer from a wealthy family of creole origins who was better known at the time for his industrial pictures of ships and machinery for local companies. His personal photographs of the women of Storyville do not glamorise or eroticise their subjects but instead show them in their private quarters, often at ease in varying states of dress. Although Bellocq destroyed many of his negatives before his death, in the mid-1960s the photographer Lee Friedlander discovered a cache of Storyville glass plates, made prints from them, and showed them at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1970, launching the once-obscure Bellocq into newfound, posthumous fame.

Text from the Large Print Guide at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

Unidentified photographer

Keystone View Company (American, 1892-1972)

Mining Phosphate and Loading Cars Near Columbia, Tennessee

c. 1898

Albumen silver print (stereocard)

Addison Gallery of American Art

Unidentified photographer

Keystone View Company (American, 1892-1972)

Flooding the Rice Fields, South Carolina

c. 1904

Albumen silver print (stereocard)

Addison Gallery of American Art

Unidentified photographer

Keystone View Company (American, 1892-1972)

A Turpentine Farm – Dippers and Chippers at Work, Savannah, Georgia

1904

Albumen silver print (stereocard)

Addison Gallery of American Art

Unidentified photographer

Keystone View Company (American, 1892-1972)

Alligator Joe’s Battle with a Wounded Gator, Palm Beach, Florida

1904

Albumen silver print (stereocard)

Addison Gallery of American Art

Unidentified photographer

Keystone View Company (American, 1892-1972)

Hoeing Rice, South Carolina

1904

Albumen silver print (stereocard)

Addison Gallery of American Art

Lewis Hine (American, 1874-1940)

A Young Oyster Fisher, Apalachicola, Florida

1909

Gelatin silver print

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

Museum Arts purchase fund

Lewis Hine (American, 1874-1940)

A little spinner in a Georgia Cotton Mill

1909

Gelatin silver print

Addison Gallery of American Art

As a member of the National Child Labor Committee, Lewis Hine was an activist who deployed photography as an instrument of social reform. At the turn of the 1900s, there were two million children in the labor force, and Hine traveled to mines, textile mills, and factories to document their dismal working conditions. In order to gain access to these sites, he often posed as a salesman, insurance agent, or other profession. His photographs of children working in textile mills in Georgia appeared in pamphlets and posters throughout the country, contributing to a shift in public perception that ultimately led to child labor laws, many of which are still in effect today.

Text from the Large Print Guide at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

Lewis Hine (American, 1874-1940)

Cherokee Hosiery Mill, Rome, Georgia

1913

Gelatin silver print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta

Gift of Murray H. Bring

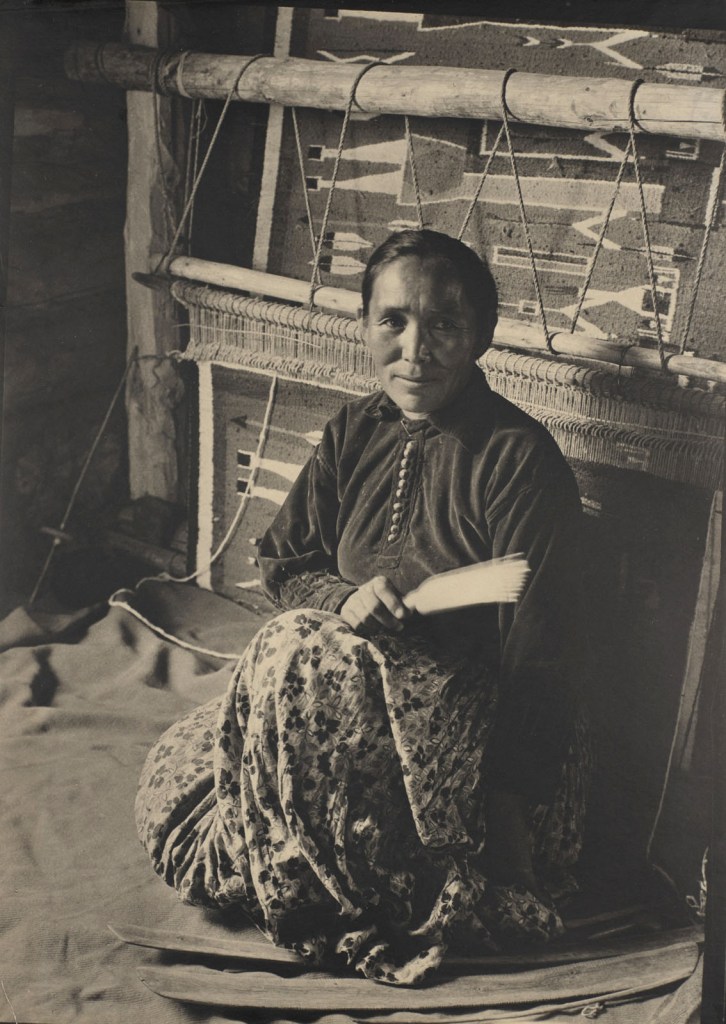

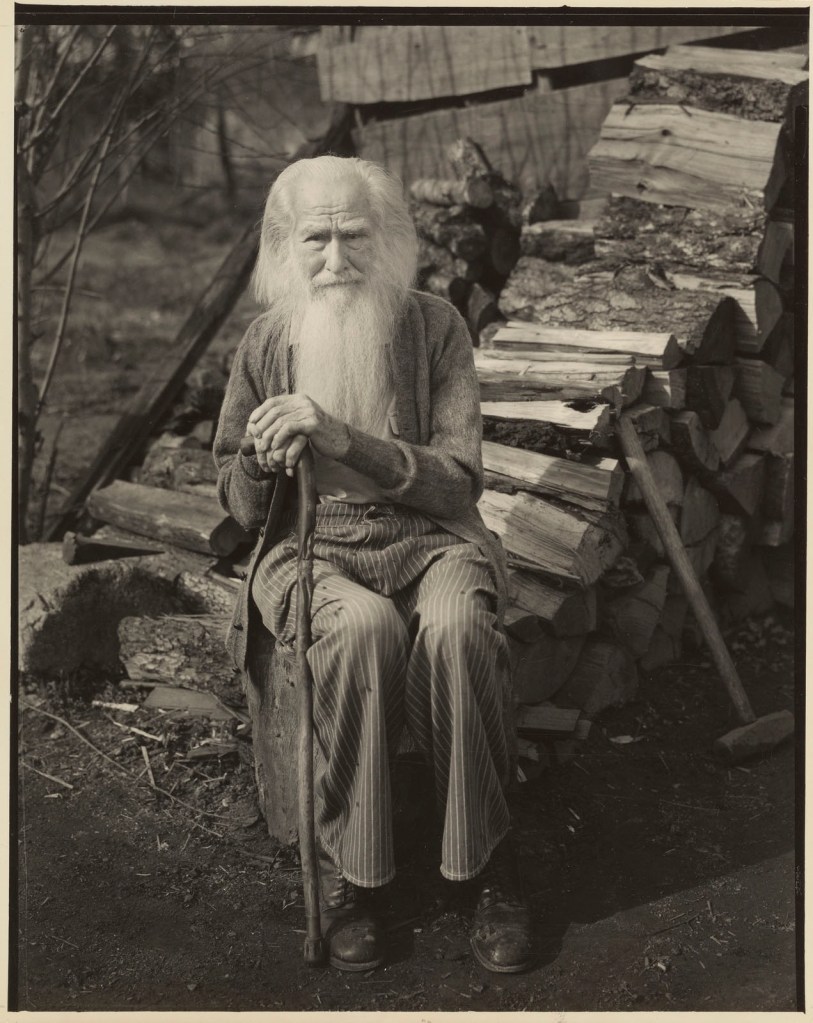

Doris Ulmann (American, 1884-1934)

Laborers, Kingdom Come School House

c. 1931

Platinum print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta

Purchase

Doris Ulmann was an American photographer, best known for her portraits of the people of Appalachia, particularly craftsmen and musicians, made between 1928 and 1934.

Prentice Herman Polk (American, 1898-1984)

The Boss

c. 1932

Gelatin silver print

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, VA

Kathleen Boone Samuels Memorial Fund

P. H. Polk worked as the official photographer for Alabama’s Tuskegee Institute, a private, historically Black land grant university that was founded in 1881. For more than forty-five years, Polk documented the school’s activities and its illustrious faculty and staff. He made photographs that challenged stereotypical images of Black life in the South by chronicling scientific, industrial, and academic advancements by Black innovators and capturing portraits of nearby residents. At a time when most popular images portrayed Black Southerners as subservient, Polk showed the aptly named “boss” standing self-assured, in full control of her image and addressing the camera confidently.

Text from the Large Print Guide at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

Louise Dahl-Wolfe (American, 1895-1989)

Black Man In Bijou Theatre, Nashville, Tennessee

1932, printed later

Gelatin silver print

Addison Gallery of American Art

The Bijou Theatre became the Nashville flagship of the Bijou Amusement Company, one of the first African American theatre chains in the south.

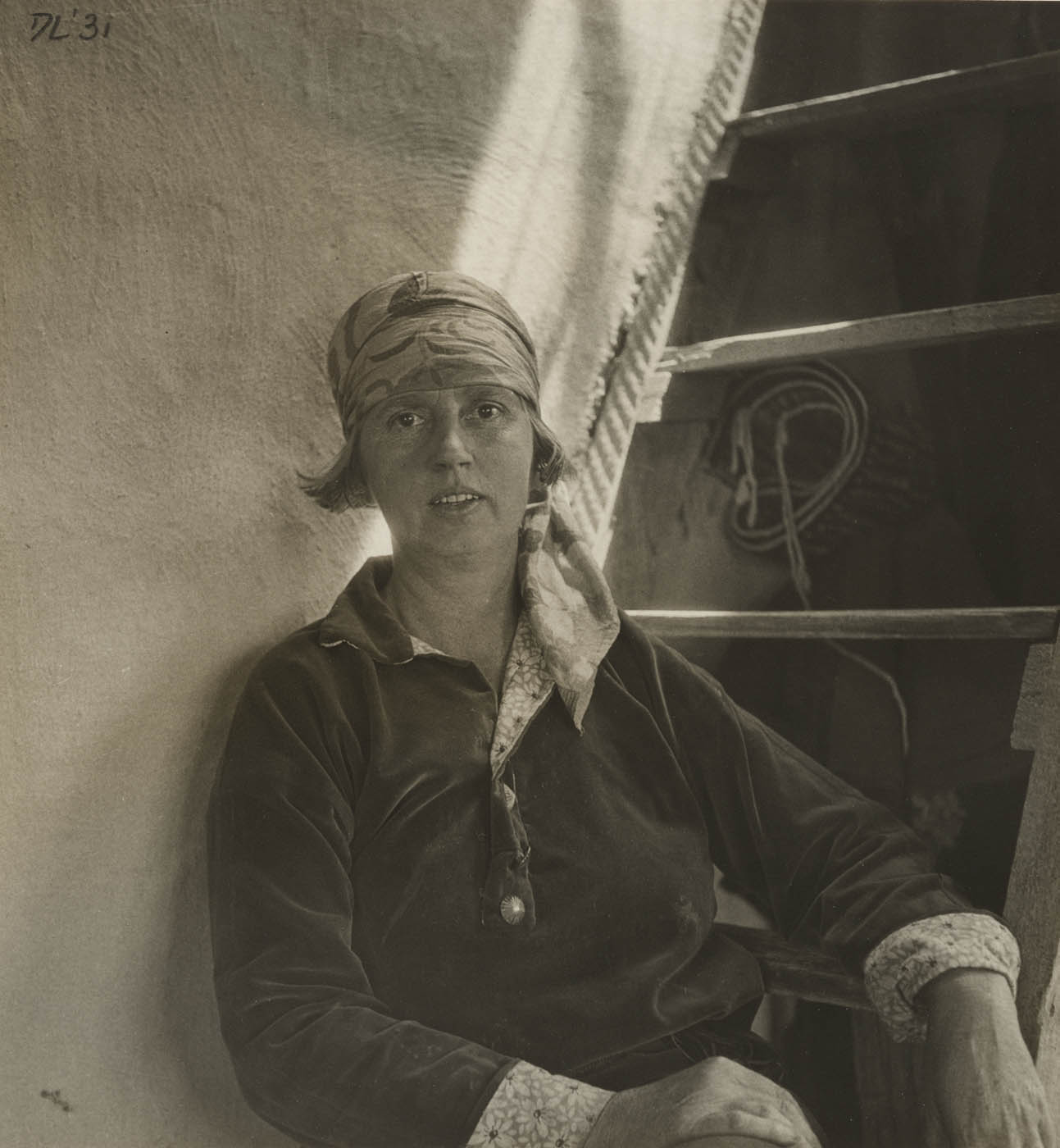

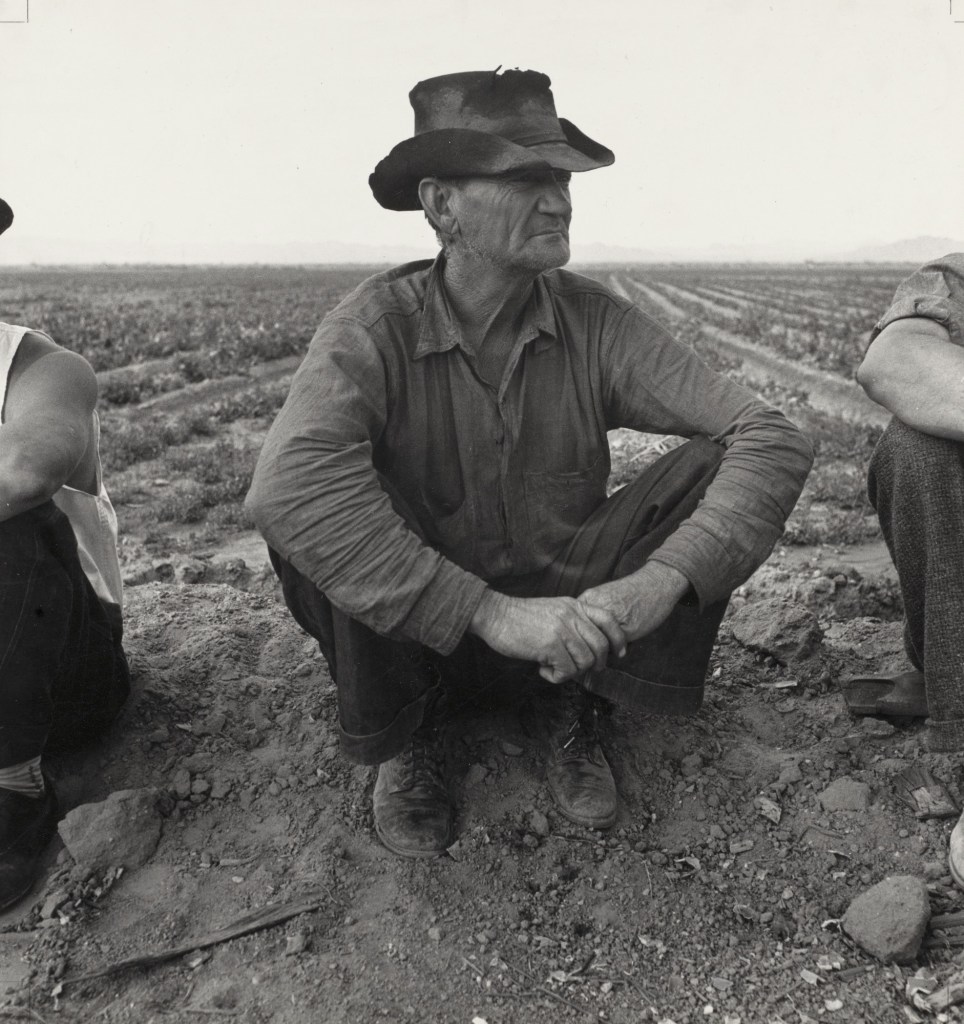

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Three Generations of Texans (Now Drought Refugees)

c. 1935

Gelatin silver print

Addison Gallery of American Art

The artwork captures a poignant and compelling scene of three men representing different generations, standing together, likely under difficult circumstances as suggested by the title referencing them as “drought refugees.” The expressions, attire, and the stark composition tell a visual story of resilience and hardship, which is characteristic of Dorothea Lange’s work. The photograph’s detail and the subjects’ piercing gazes evoke a sense of solemn dignity despite their apparent adversities, reflecting the social realism movement’s focus on the lives of everyday people affected by social and economic issues.

Text from the Artchive website

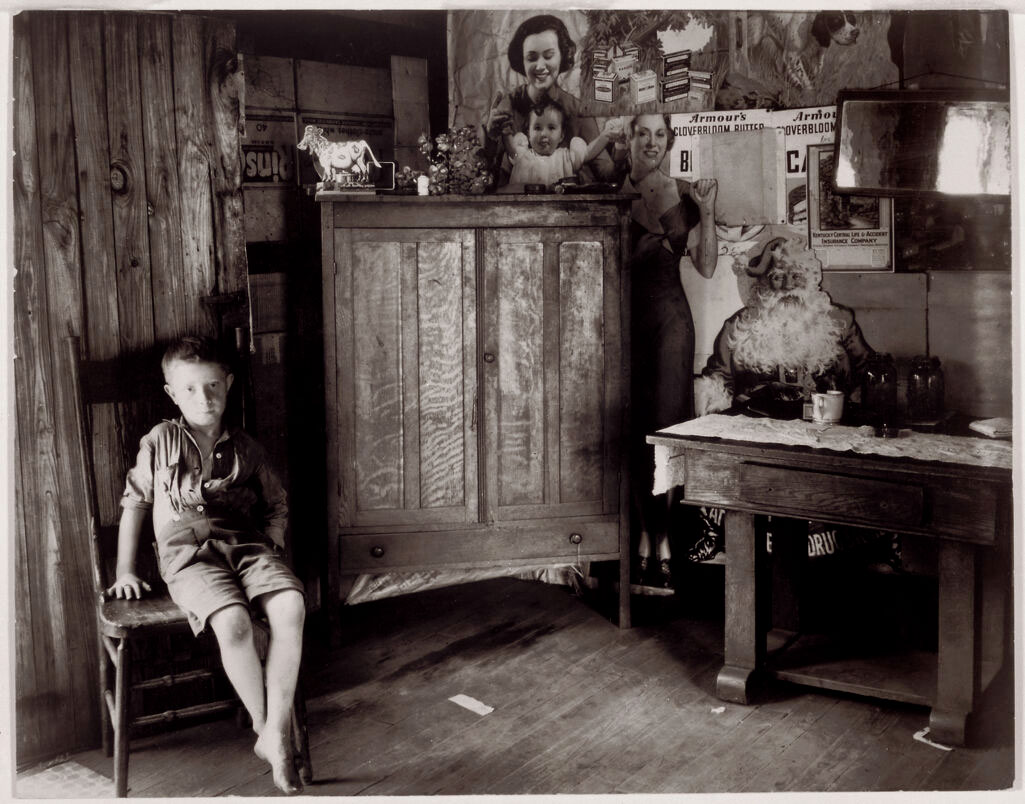

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

House in New Orleans

c. 1935

Gelatin silver print

Addison Gallery of American Art

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

West Virginia Living Room

1935

Gelatin silver print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta

Purchase with funds from the Atlanta Foundation

Evans made this photograph during the first year of the photography division of the Resettlement Administration (later renamed the Farm Security Administration). The mission of this newly formed government agency was to document the hardships of the Great Depression and the positive effects of New Deal policies. The furnishings of this coal miner’s home are spare and worn; the walls are decorated with commercial advertisements that reflect a prosperity this family was not likely to experience. But this photograph transcends its immediate mission as government propaganda. Rather than a condescending look at poverty, “West Virginia Living Room” captures the dignity of the family. The barefoot boy sitting awkwardly in the chair looks straight into the camera and challenges the viewer. His direct stare shows no shame and asks for no pity.

Text from the High Museum of Art website

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Atlanta, Georgia

1936

Gelatin silver print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta

Purchase with funds from the Atlanta Foundation

© Estate of the artist

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Allie Mae Burroughs, Hale County, Alabama

1936

Gelatin silver print

Addison Gallery of American Art, Phillips Academy, Andover, Massachusetts

Gift of Norman Selby (PA 1970) and Melissa G. Vail

On assignment for Fortune, Walker Evans collaborated with writer James Agee in Hale County, Alabama, for three weeks, recording the lives of three families of white tenant farmers. The photographs offer a raw, direct perspective on a sharecropper’s life yet also diminish the depth and nuance of their subjects. In the original title, Evans referred to Allie Mae Burroughs as a sharecropper’s wife, anonymising her and negating her role in the farm’s operations. Yet through the photograph, her face has become one of the defining images of the Great Depression. The story never ran in Fortune, whose wealthy readers wanted no reminder of the impoverished conditions of rural America, but it was published in 1941 as the book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men and remains one the most influential works of photography and literary nonfiction.

Text from the Large Print Guide at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

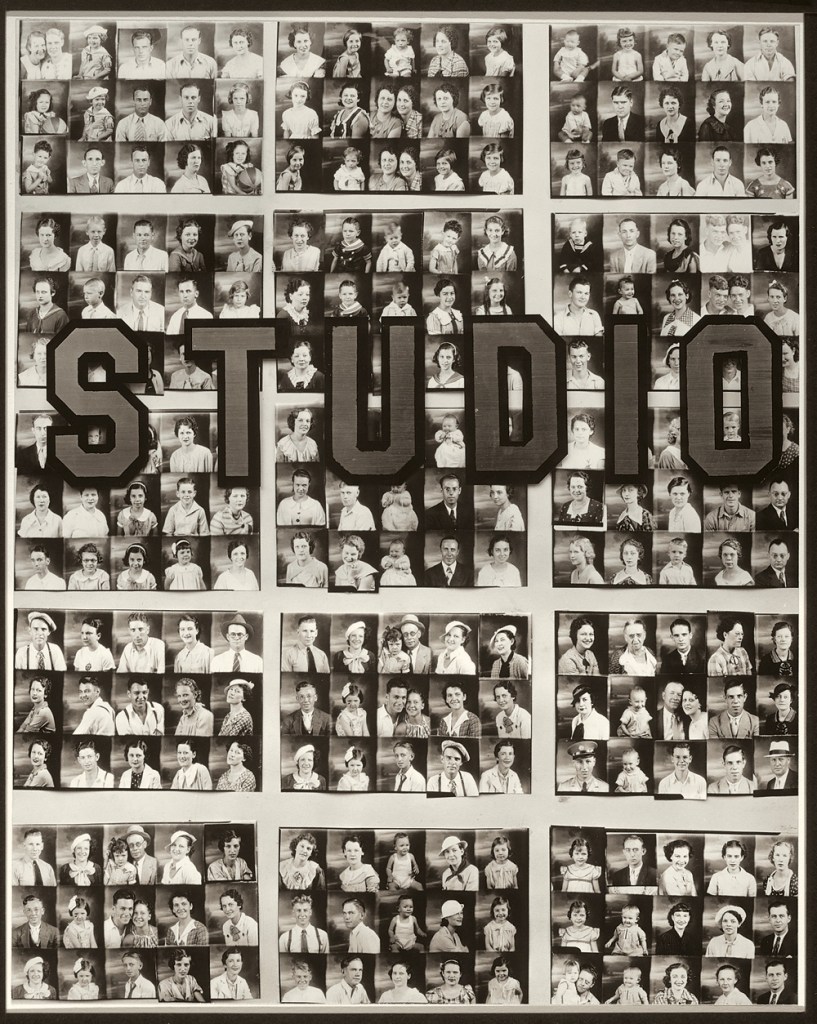

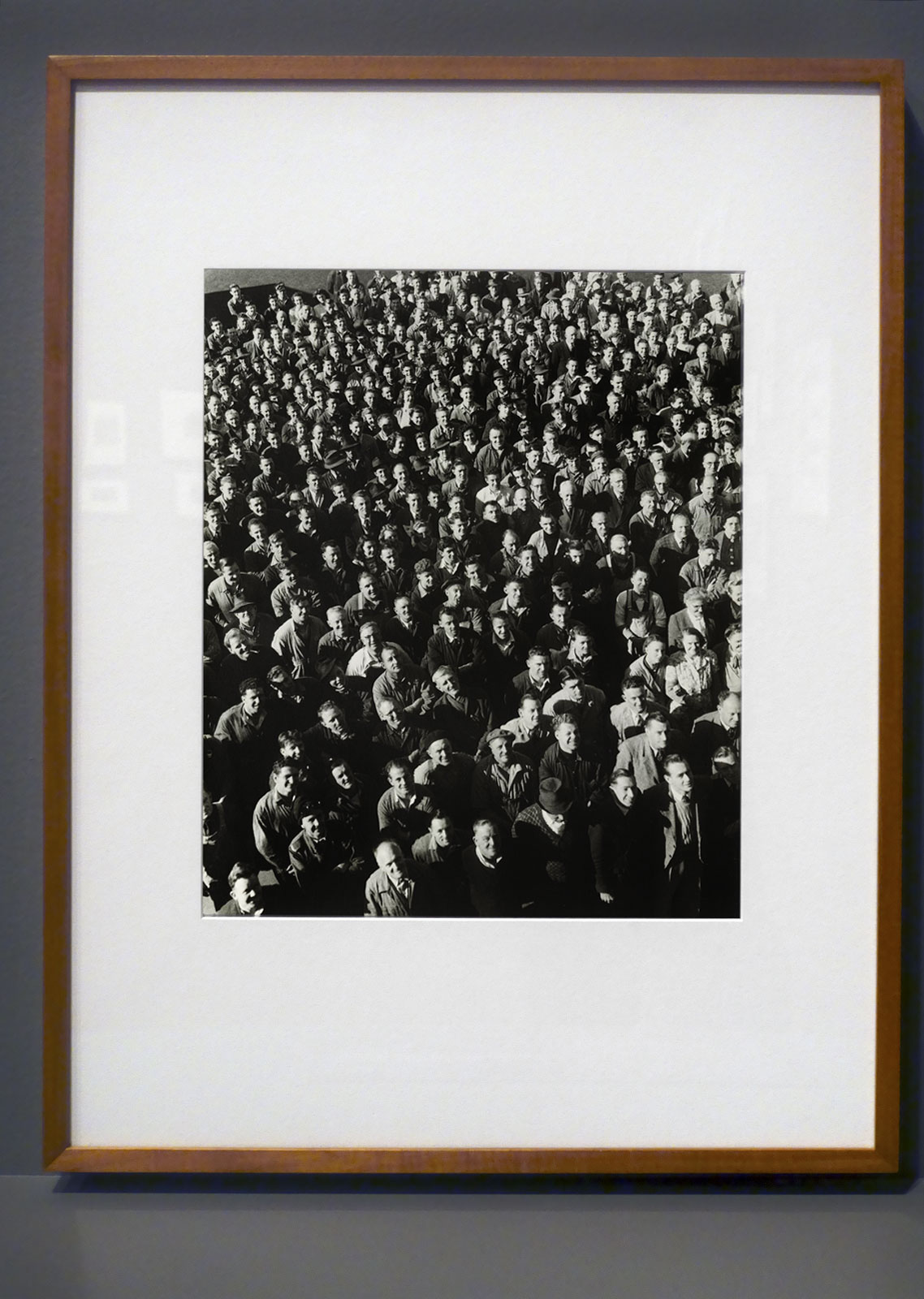

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Penny Picture Display, Savannah

1936

Gelatin silver print

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

Sherritt Art Purchase Fund

Walker Evans was enthralled by the traditional and folk cultures of the South. He developed a direct, often flat manner of photographing that echoed the spareness of the signage and architecture he encountered throughout the region. In his photograph of a portrait photographer’s studio window, he plays on the consonance between the flatness of the window, the plane of his camera, and the resulting photographic print. In photographing the anonymous photographer’s advertisement, he not only condenses time, labor, individuality, and generations but also flattens history. When he made this image, forty percent of Savannah’s population was Black, a fact belied by the over two hundred white faces that make up the image.

Text from the Large Print Guide at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

Arthur Rothstein (American, 1915-1985)

Weighing Cotton, Texas

1936

Gelatin silver print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta

Gift of Howard Greenberg

Plantation owner’s daughter checks weight of cotton.

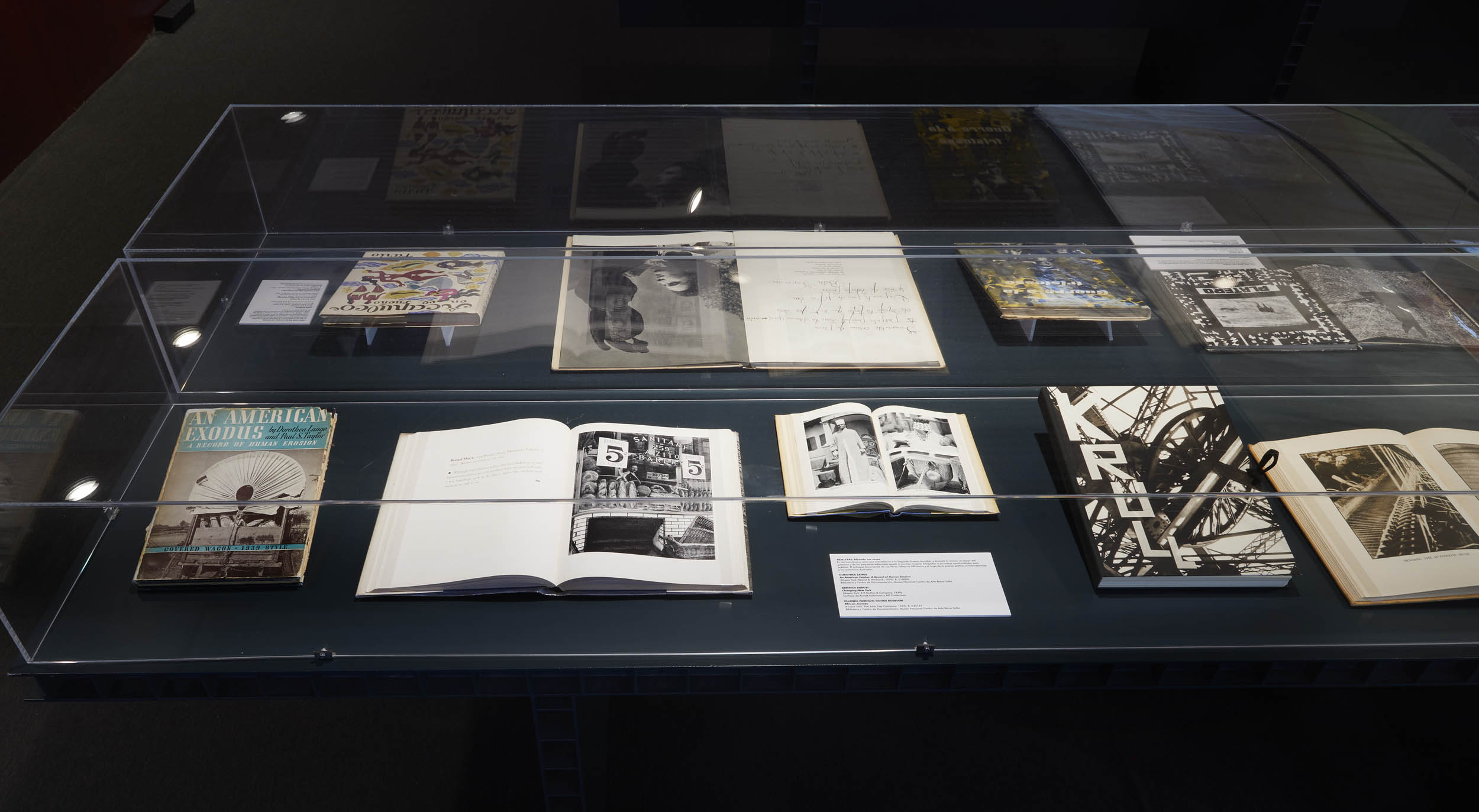

1930-1945: The Cruel Radiance: A New Documentary Tradition

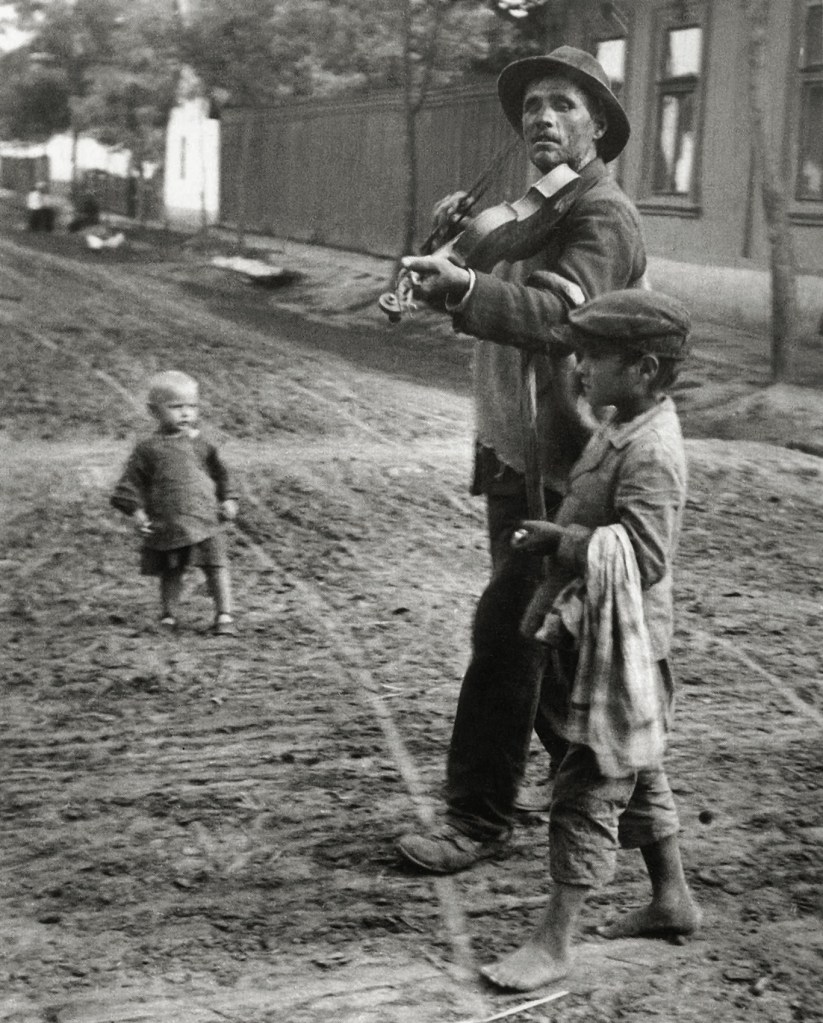

The impact of the Great Depression on the American South – a region that was already poorer than the rest of the nation – was devastating. In addition to economic havoc, many of the other problems convulsing the country – poverty, racism, and the erosion of rural cultures – appeared in their most concentrated and vivid forms in the South. Photographers responded to these crises with indelible images of hardship and injustice that they hoped would spur reform and modernize the region. In this way, the Great Depression changed the course of American photography by cementing the concept and practice of documentary photography as a tool for social reform.

Most of these documentary photographs were produced under the auspices of the federal government as part of a New Deal effort to provide relief to rural areas. From 1935-1942, some two dozen photographers were hired by the government to capture images of rural poverty in order to raise both public sympathy and congressional support for resettlement and other forms of aid. Although there was not a single native Southerner among them, together this group of photographers produced around sixteen thousand photographs of the region and profoundly changed how the nation saw the South, and by extension, itself. Widely reproduced in newspaper articles, magazines, exhibitions, and photo books, these documentary projects brought the South into national focus and debate.

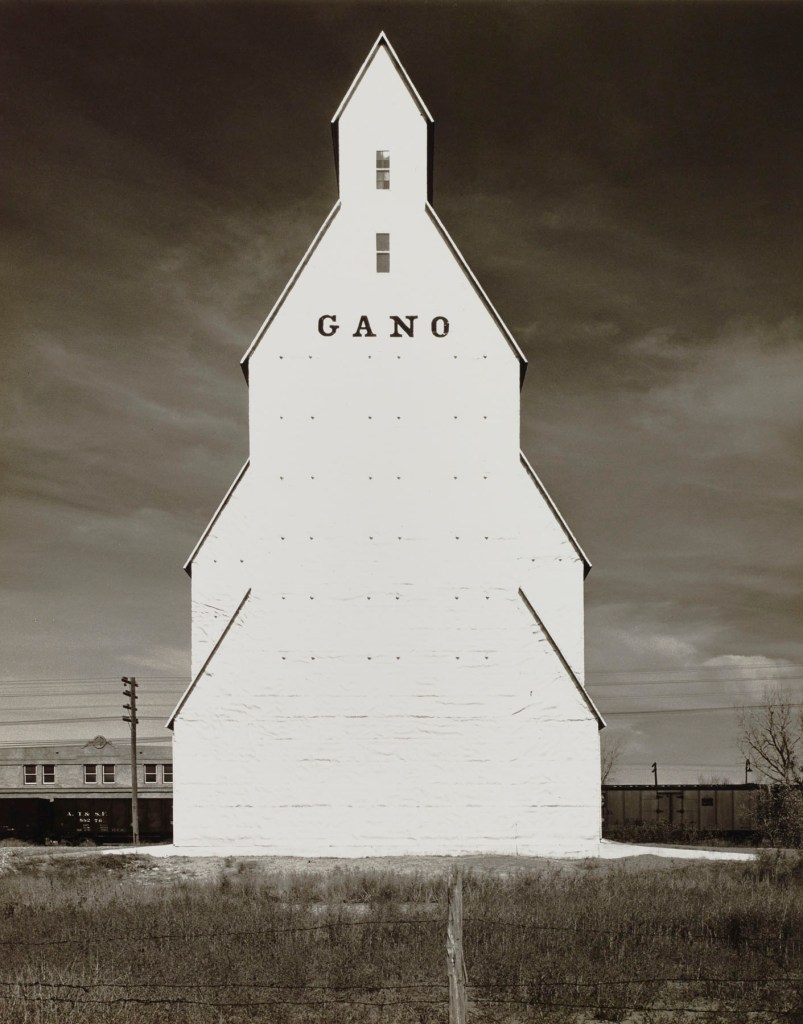

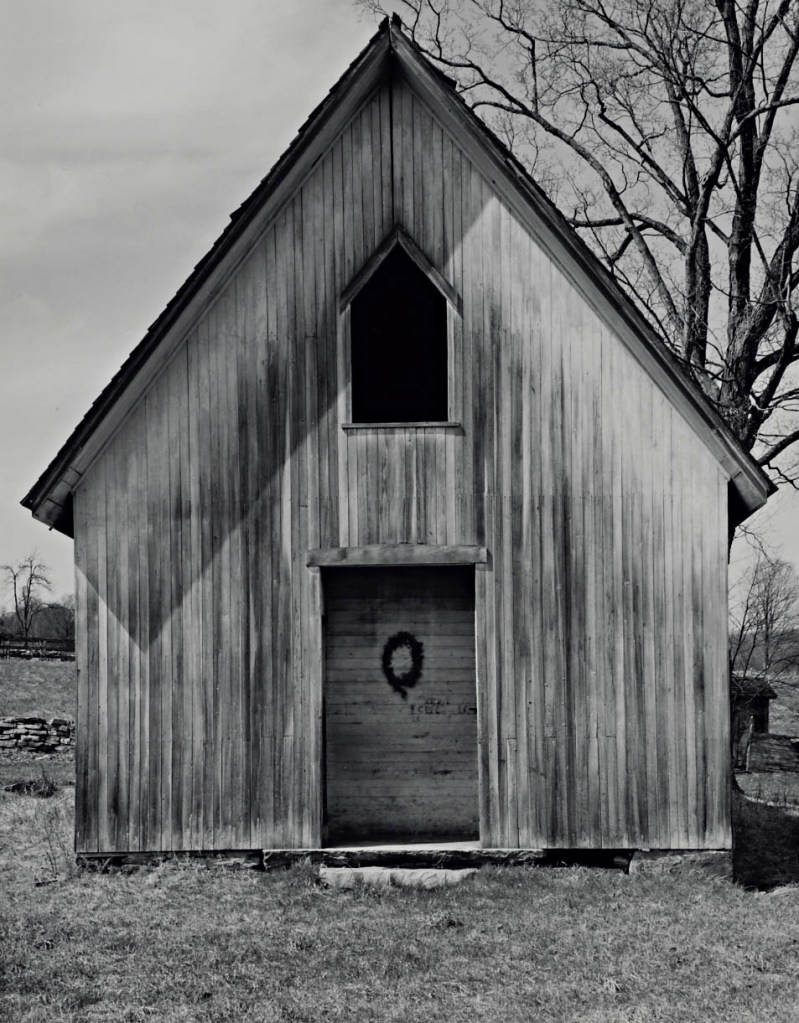

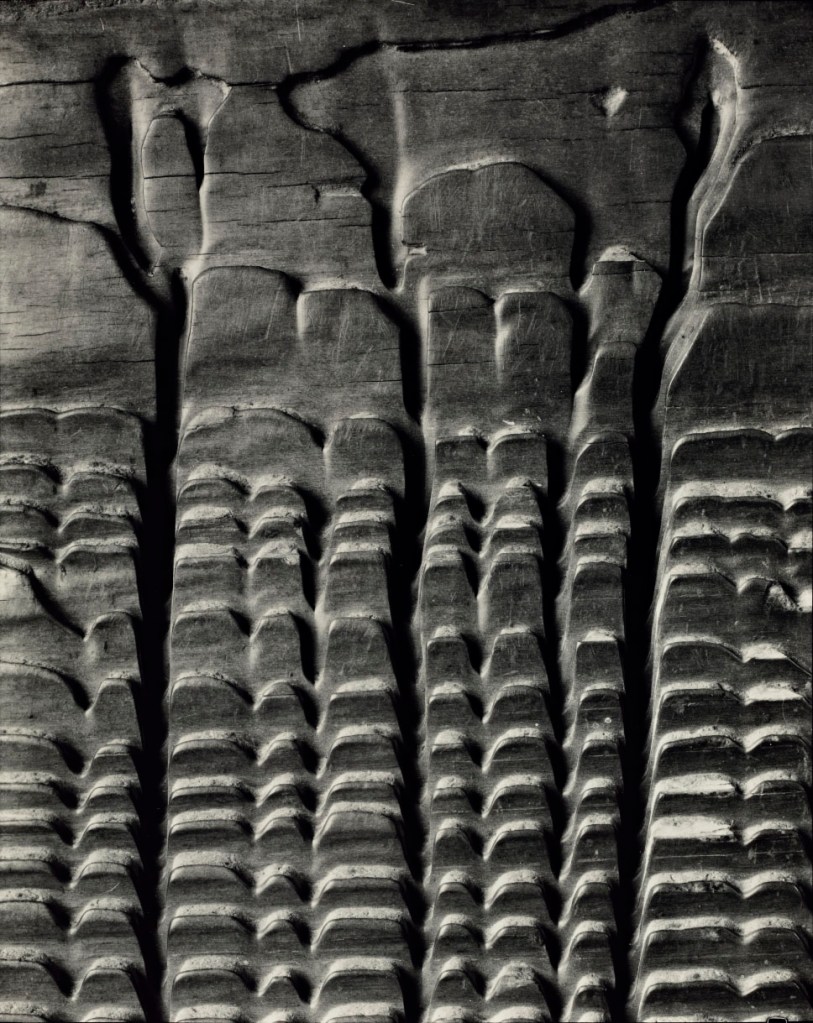

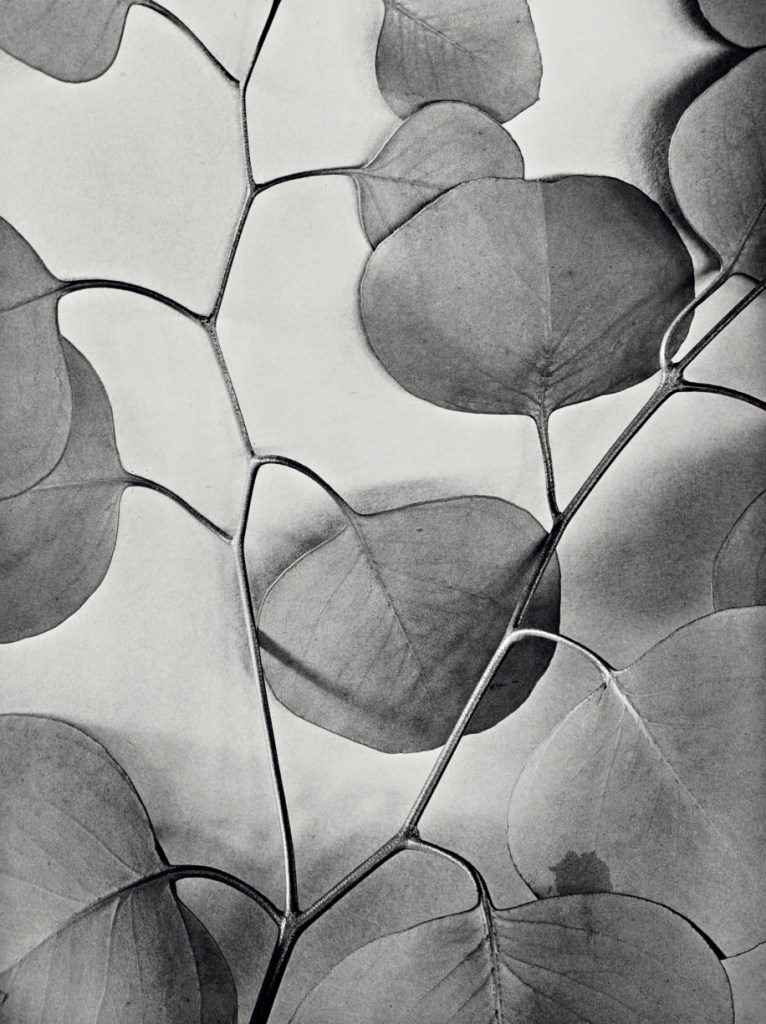

Not all of the photographers who flocked to the South during this time sought to document its stricken conditions. The region’s seeming resistance to progress also seduced photographers who saw vestiges of agrarian life that nurtured distinctive folkways and vernacular architecture – that is to say, buildings based on regional or local traditions. To them, this South – so different from the rapidly changing urban centres in the Northeast and Midwest – resembled a cultural eddy, an alluring place cut off from the flow of time where one could photograph the beautiful remnants of a largely imagined past.

Text from the Large Print Guide at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

Margaret Bourke White (American, 1904-1971)

Louisville Flood Victims

1937, printed later

Gelatin silver print

Addison Gallery of American Art

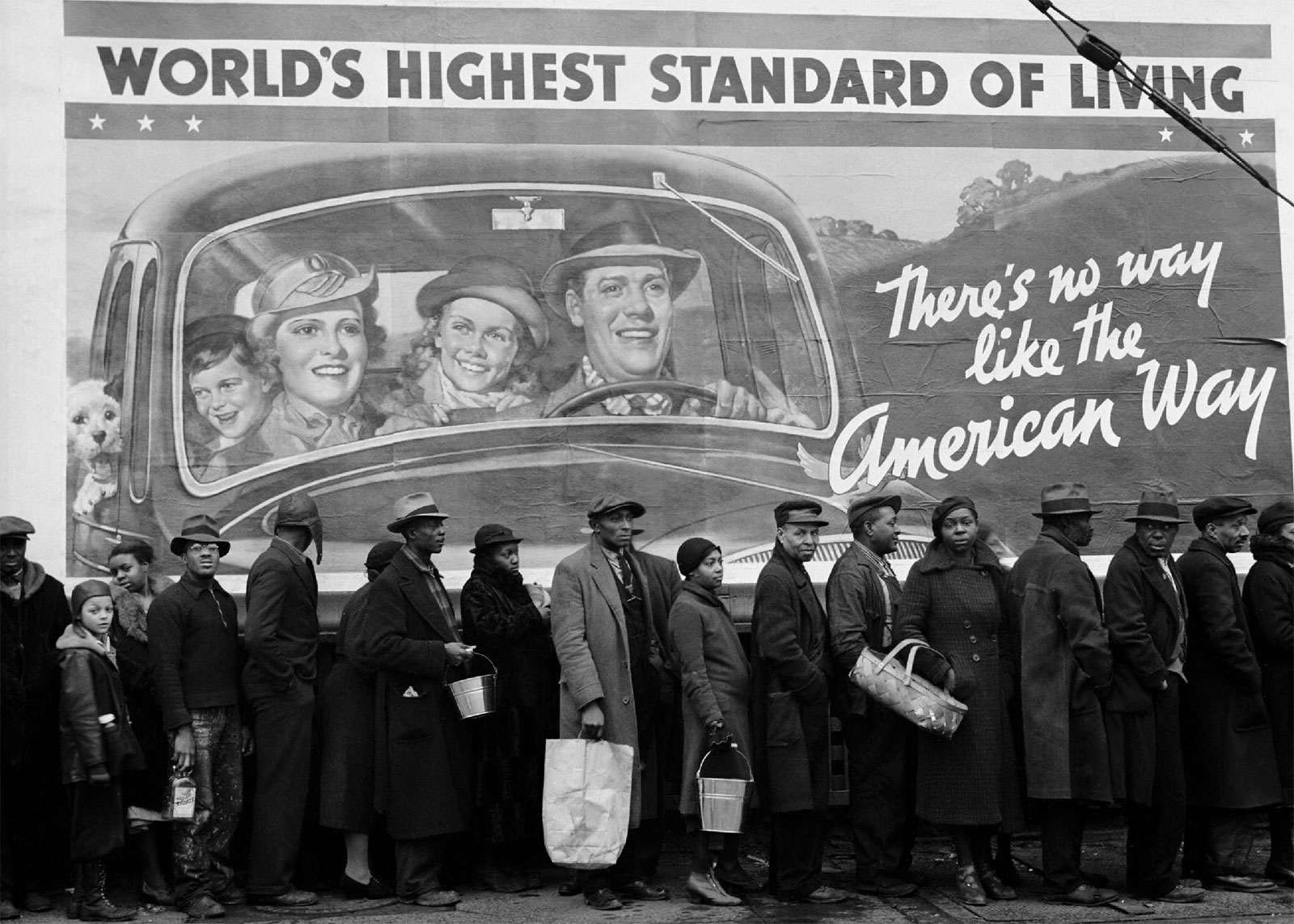

In January 1937, the swollen banks of the Ohio River flooded Louisville, Kentucky, and its surrounding areas. With one hour’s notice, photojournalist Margaret Bourke-White caught the next plane to Louisville. She photographed the city from makeshift rafts, recording one of the largest natural disasters in American history for Life magazine, where she was a staff photographer. The Louisville Flood shows African-Americans lined up outside a flood relief agency. In striking contrast to their grim faces, the billboard for the National Association of Manufacturers above them depicts a smiling white family of four riding in a car, under a banner reading “World’s Highest Standard of Living. There’s no way like the American Way.” As a powerful depiction of the gap between the propagandist representation of American life and the economic hardship faced by minorities and the poor, Bourke-White’s image has had a long afterlife in the history of photography.

Text from the Whitney Museum of American Art website

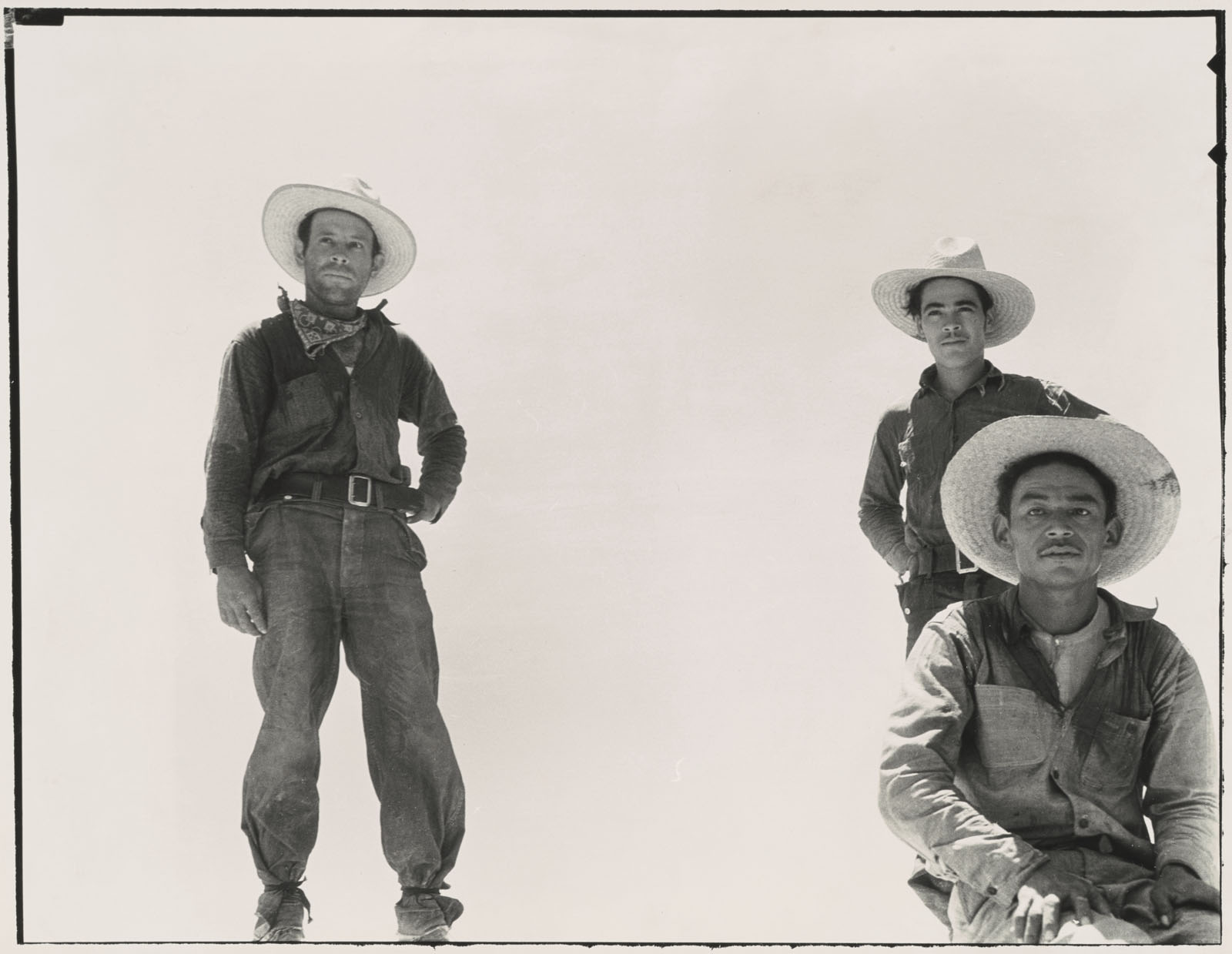

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Displaced Tenant Farmers, Goodlett, Hardeman County, Texas

July 1937

Gelatin silver print

Collection of Michael Mattis and Judith Hochberg

“All displaced tenant farmers, the oldest 33. None able to vote because of Texas poll tax. They support an average of four persons each on $22.80 a month.” ~

Six Tenant Farmers Without Farms exemplifies the best of Lange’s Depression-era photographs from the deep South. The dignity of her subjects – young farmers who had lost their livelihood when tractors replaced horse-and-plow tilling of the land – is immortalised by Lange, who portrays them with clear compassion but no sentimentality.

Text from the Sotheby’s website

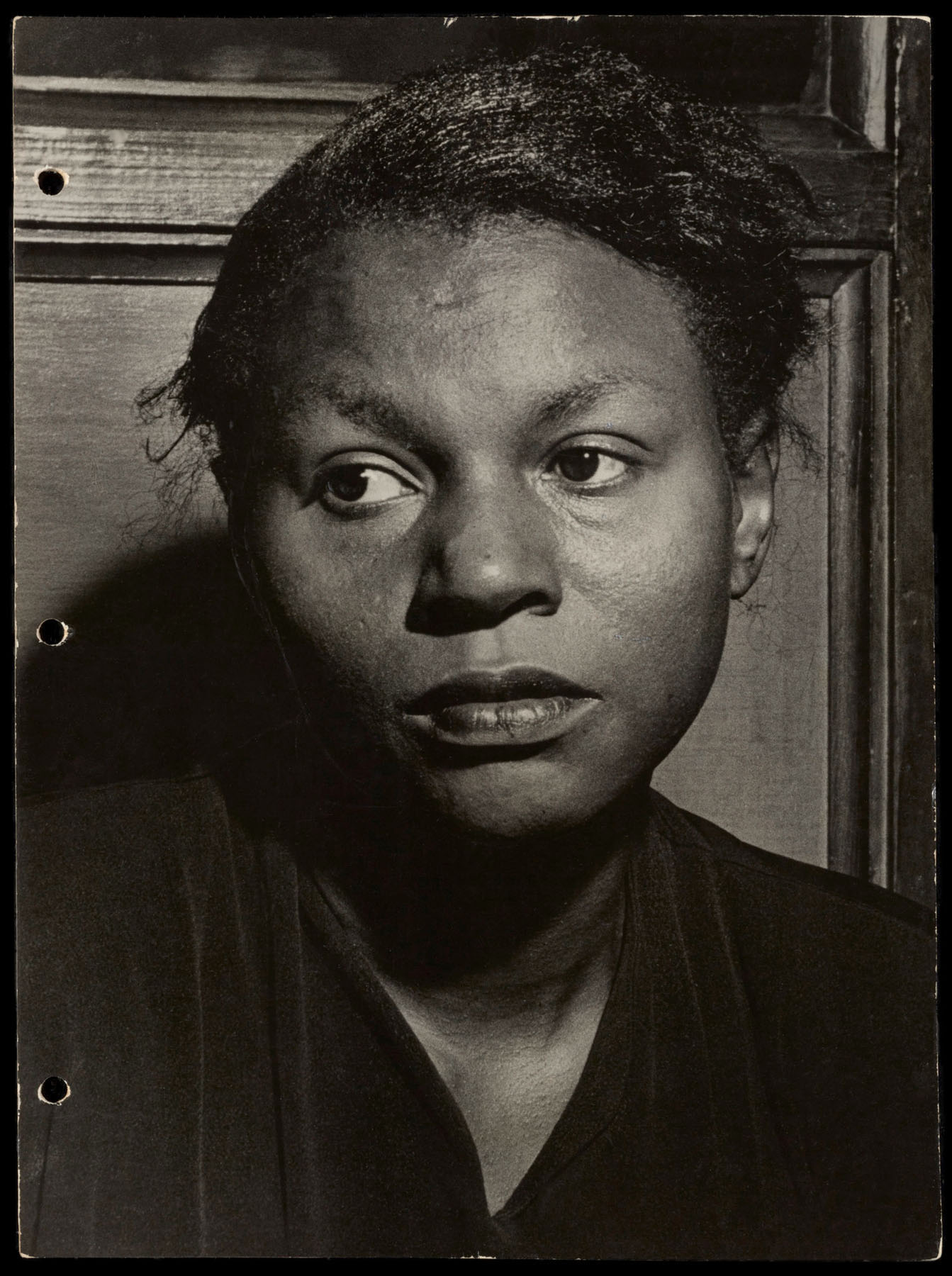

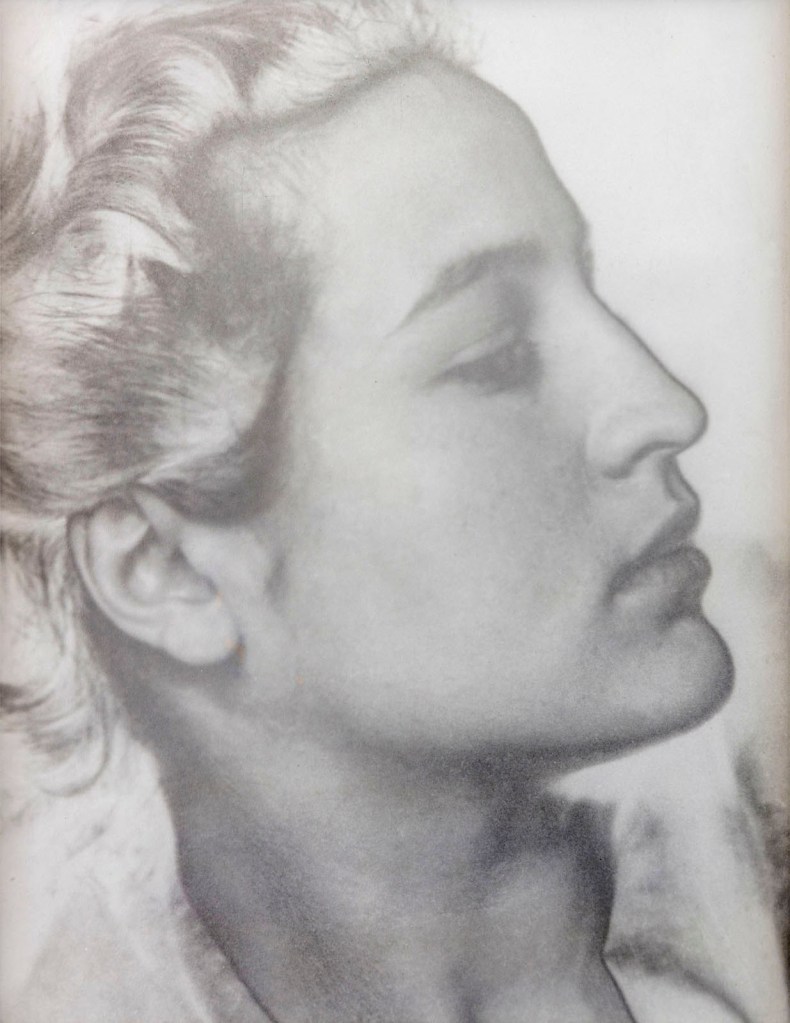

Prentice Herman Polk (American, 1898-1984)

Mildred Hanson Baker

1937

Gelatin silver print

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

John C. and Florence S. Goddin, by exchange

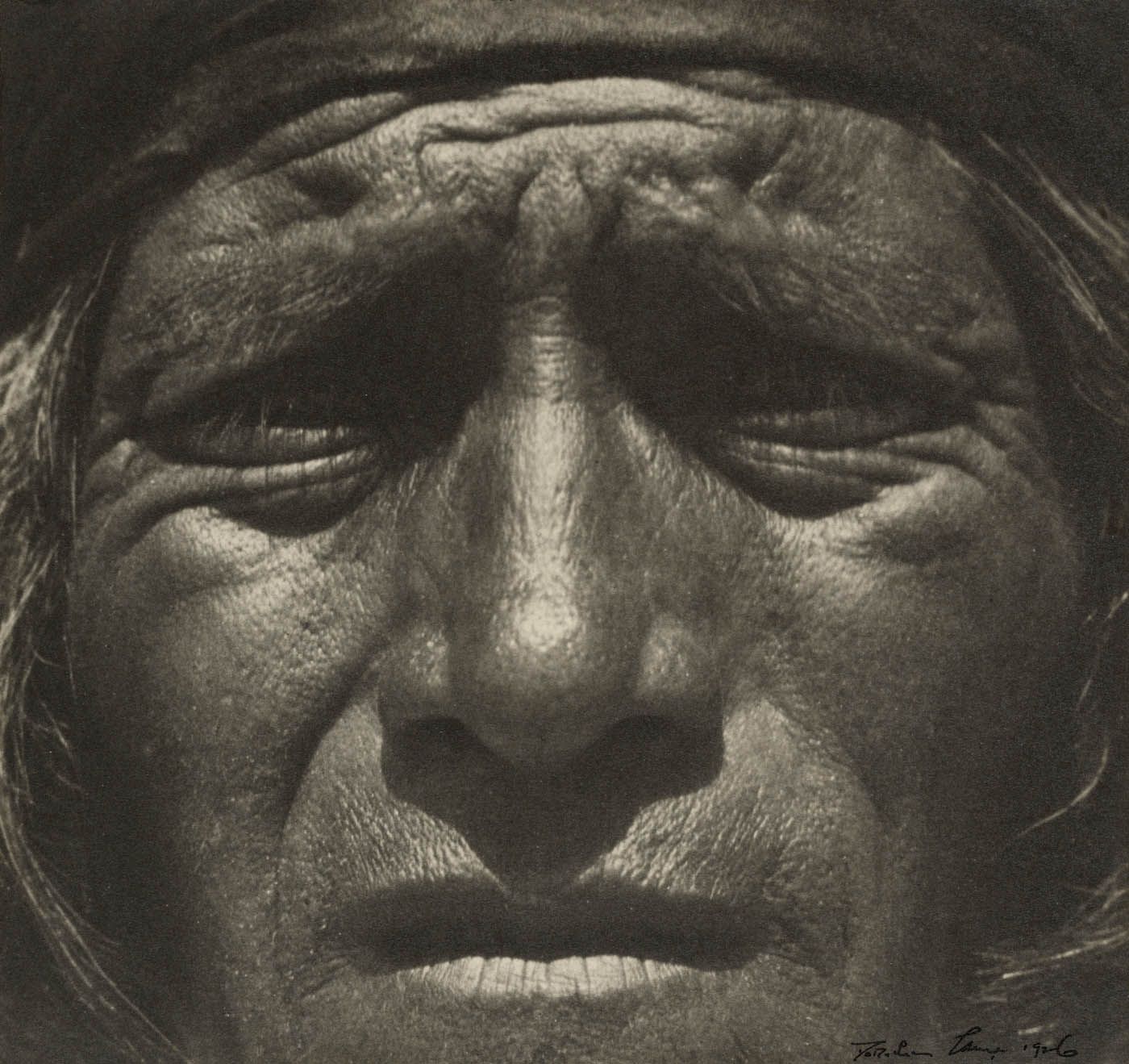

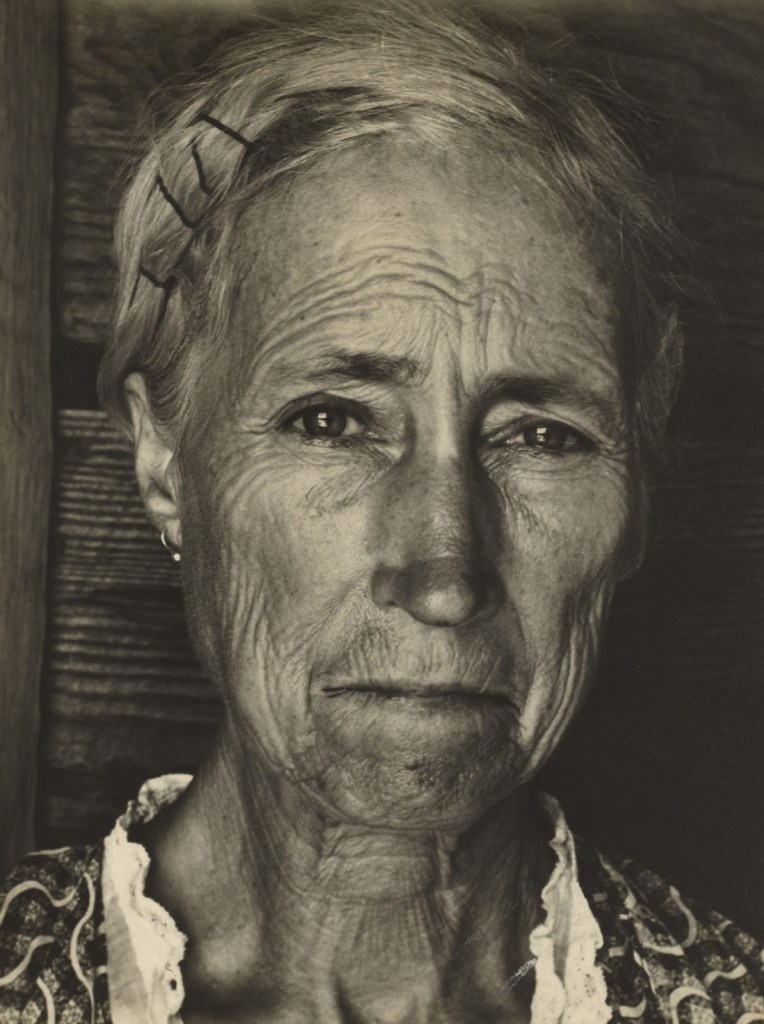

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Formerly Enslaved Woman, Alabama

1938

Gelatin silver print

National Gallery of Art

Dorothea Lange’s Depression-era portrait of a woman who had been born enslaved offers a poignant and understated meditation on the legacy of slavery. Lange’s empathic approach to portraiture was distinct for its ability to express the lasting effects of trauma, poverty, and prejudice in the lives of formerly enslaved people and their descendants. Her photographs demonstrate how the deprivation of the Jim Crow era was compounded by the aftermath of World War I and the Great Depression, making life in the South increasingly turbulent for Black Americans.

Text from the Large Print Guide at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

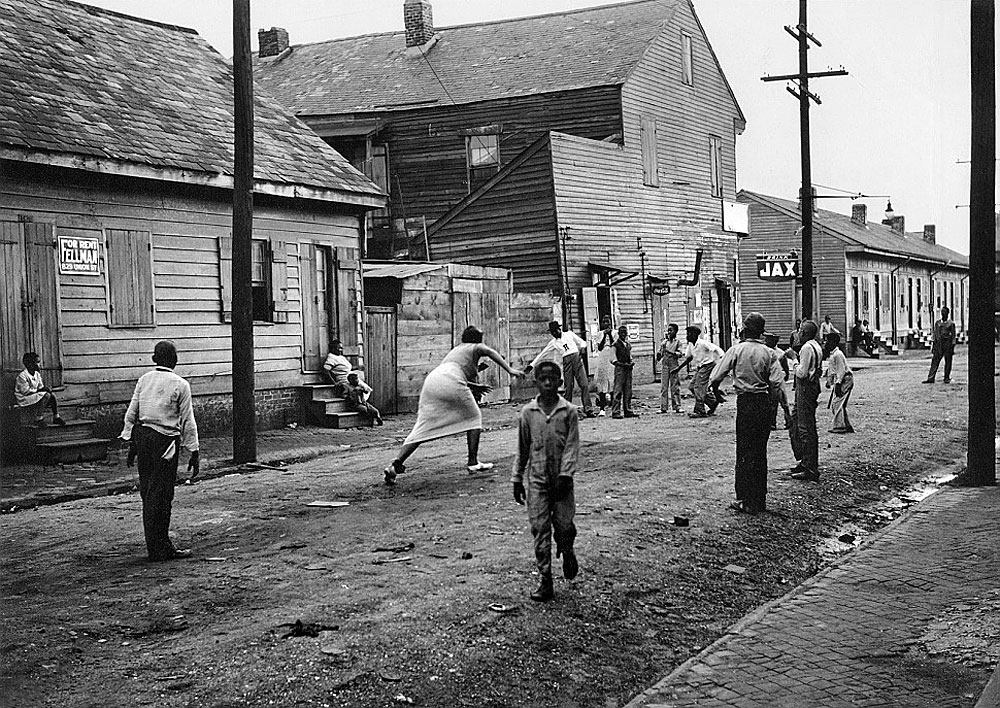

Peter Sekaer (Danish, 1901-1950)

Irish Channel, Future Site of St. Thomas Housing Project, New Orleans

c. 1938

Gelatin silver print

Addison Gallery of American Art

Museum purchase

St. Thomas Development was a notorious housing project in New Orleans, Louisiana. The project lay south of the Central City in the lower Garden District area. As defined by the City Planning Commission, its boundaries were Constance, St. Mary, Magazine Street and Felicity Streets to the north; the Mississippi River to the south; and 1st, St. Thomas, and Chippewa Streets, plus Jackson Avenue to the west. In the 1980s and 1990s, St. Thomas was one of the city’s most dangerous and impoverished housing developments. It made national headlines in 1992 after the deadly shooting of Eric Boyd.

Text from the Wikipedia website

It is interesting to compare photographs by Walker Evans and his assistant Peter Sekelear, whose pictures reflect similar interests with different eyes. Both photographers turned their attention to the vernacular, bringing a sense of place into focus. Many of the photographers exhibiting in A Long Arc were neither southern nor poor. This calls into question the contribution that 1930’s depictions of southern poverty had on stereotyping, imploring viewers to feel sorry for the destitute rather than questioning the systems that kept their communities impoverished.

Suzanne Révy and Elin Spring. “A Long Arc,” on the What Will You Remember website March 20, 2024 [Online] Cited 19/12/2024

Russell Lee (American, 1903-1986)

Louisiana

1939

Gelatin silver print

Addison Gallery of American Art

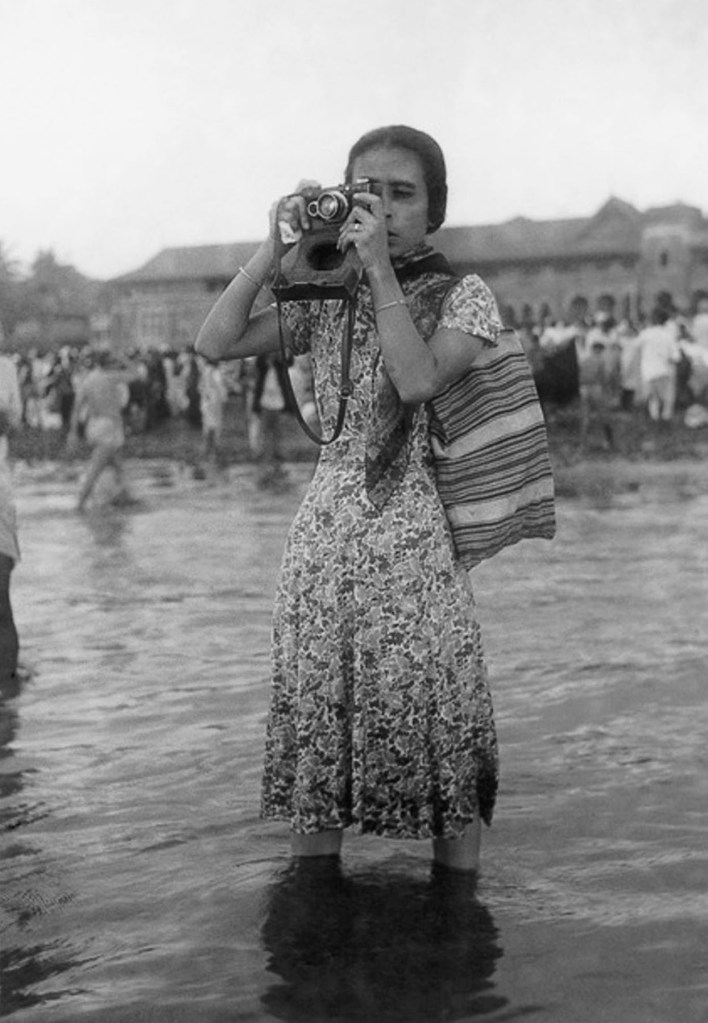

Marion Post Wolcott (American, 1910-1990)

Black Man Using “Colored” Entrance to Movie Theatre, Belzoni, Mississippi

1939, printed later

Gelatin silver print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta

Gift of Ann and Ben Johnson

Marion Post Wolcott (American, 1910-1990)

Waiting to be Paid for Picking Cotton, Inside Plantation Store, Marcella

1939

Gelatin silver print

Collection of Michael Mattis and Judith Hochberg

Mike Disfarmer (American, 1884–1959)

Wallace Sloane, Elliot Smith and Brother Homer

c. 1940

Gelatin silver print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta

Purchase with funds from Jane and Clay Jackson

Mike Disfarmer operated the only professional photography studio in Heber Springs, Arkansas, between the 1930s and ’50s. His spare and at times severe portraits offer a plainspoken vision of rural, predominantly white America during and after the Great Depression. For most of his sitters, being photographed was an unusual occurrence, and a visit to the studio marked a milestone. People often posed for Disfarmer in groups, as in his portrait of three young men casually draping their arms around each others’ shoulders, reinforcing their sense of familiarity and friendship, perhaps on their last night together before one of them heads off for military service.

Text from the Large Print Guide at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

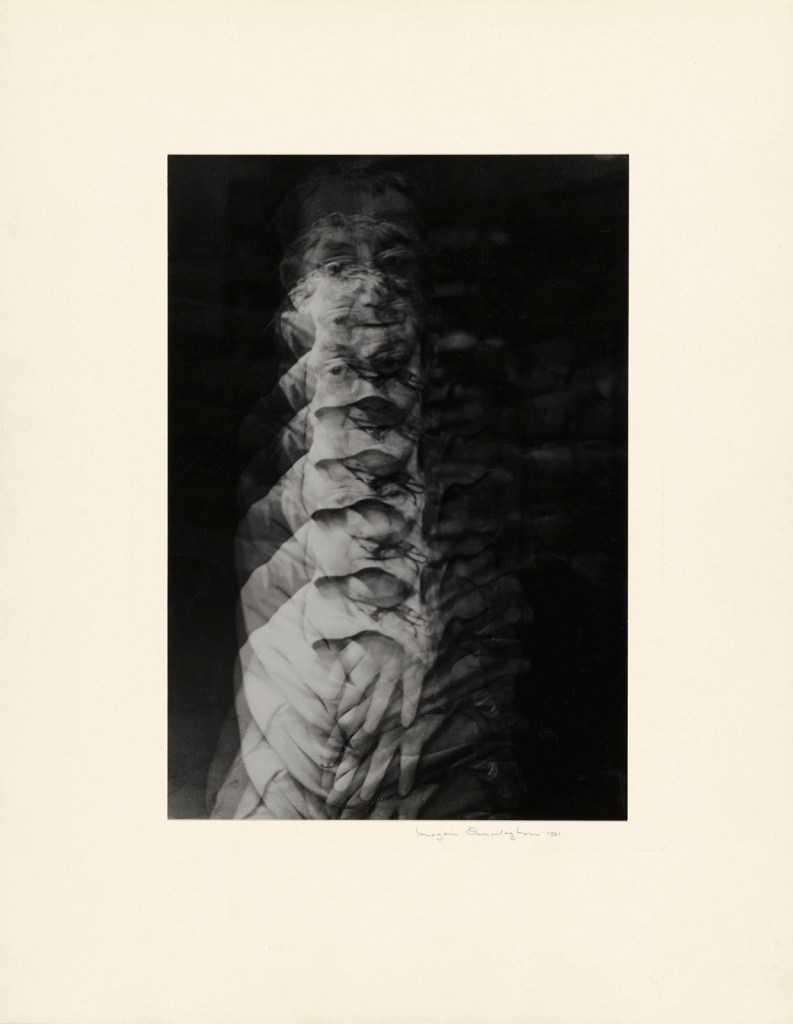

Clarence John Laughlin (American, 1905-1985)

Time Phantasm, Number Six

1941

Gelatin silver print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta

Gift of Joshua Mann Pailet in honor of his mother, Charlotte Mann Pailet; her family members Josef, Jiri and Alma Beran Mann, all of whom perished in the Holocaust; and Sir Nicholas Winton, the British hero who orchestrated Charlotte’s escape with 669 Czechoslovakian children in 1939

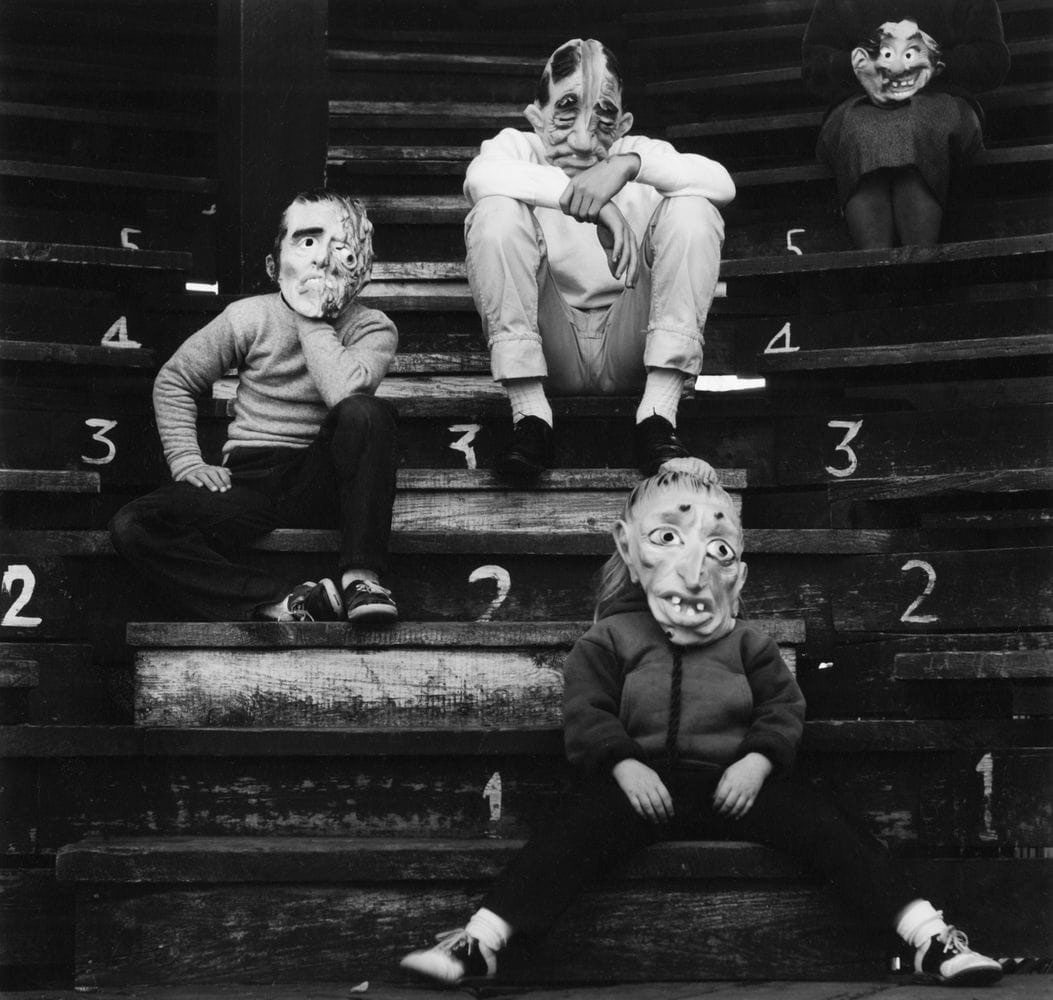

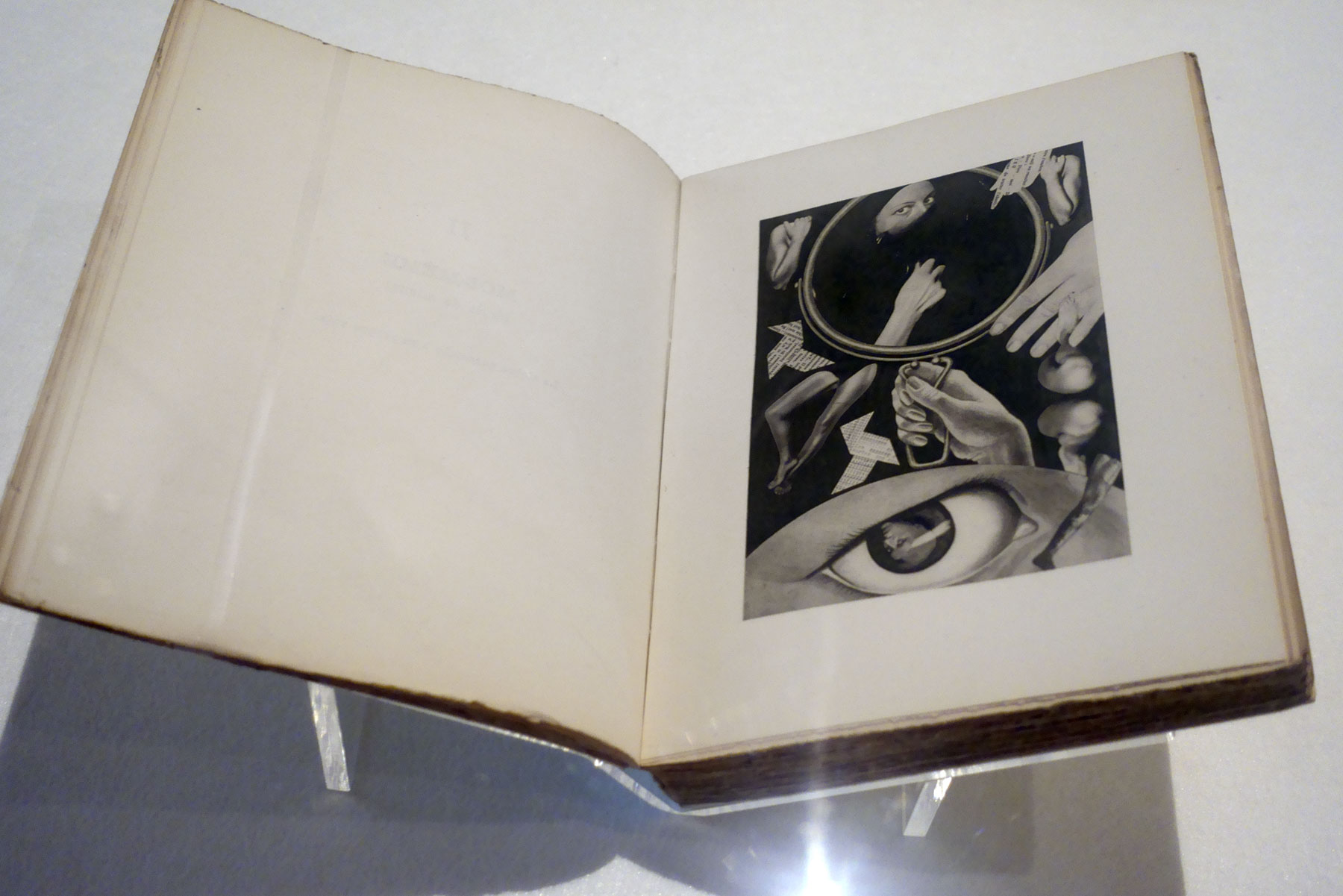

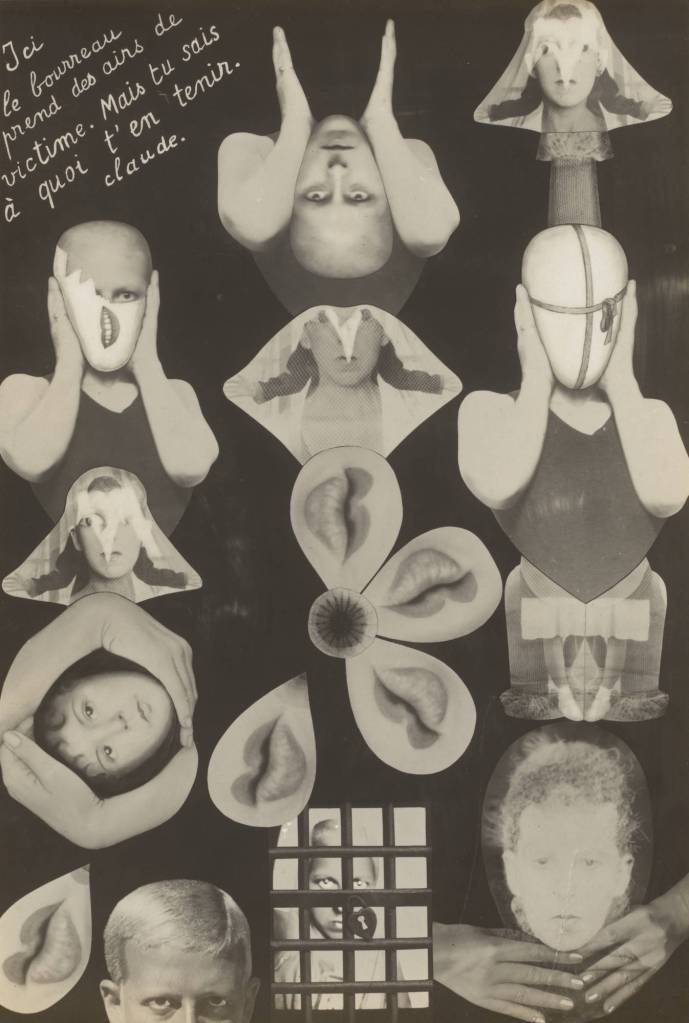

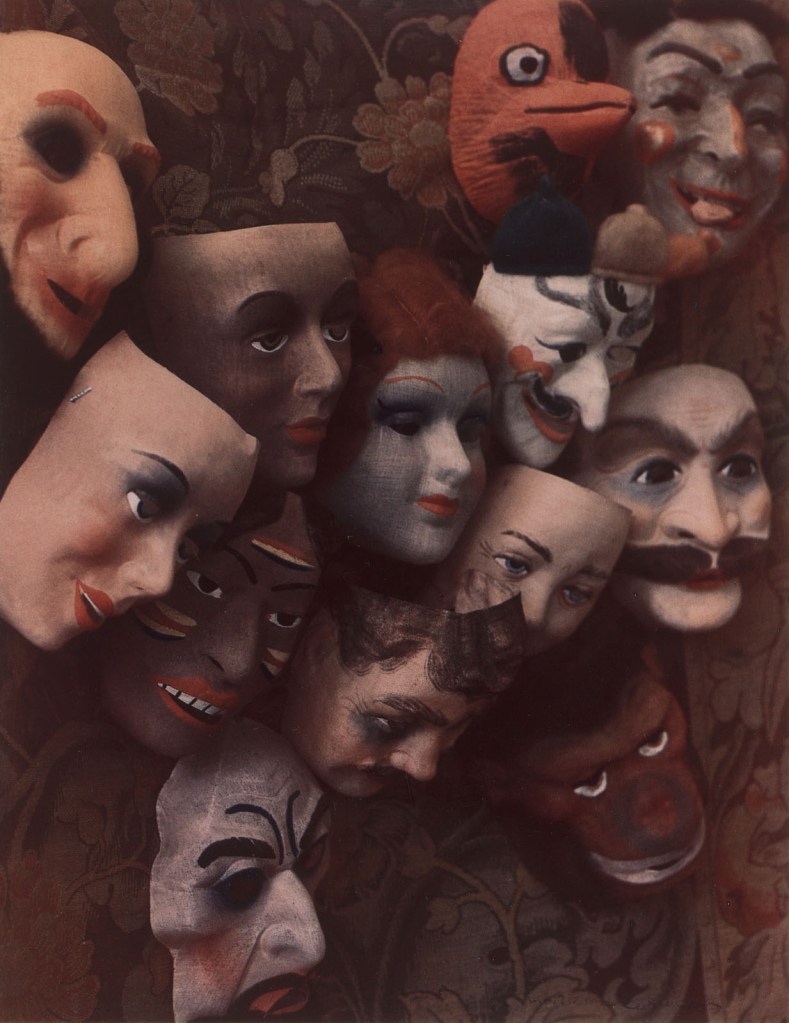

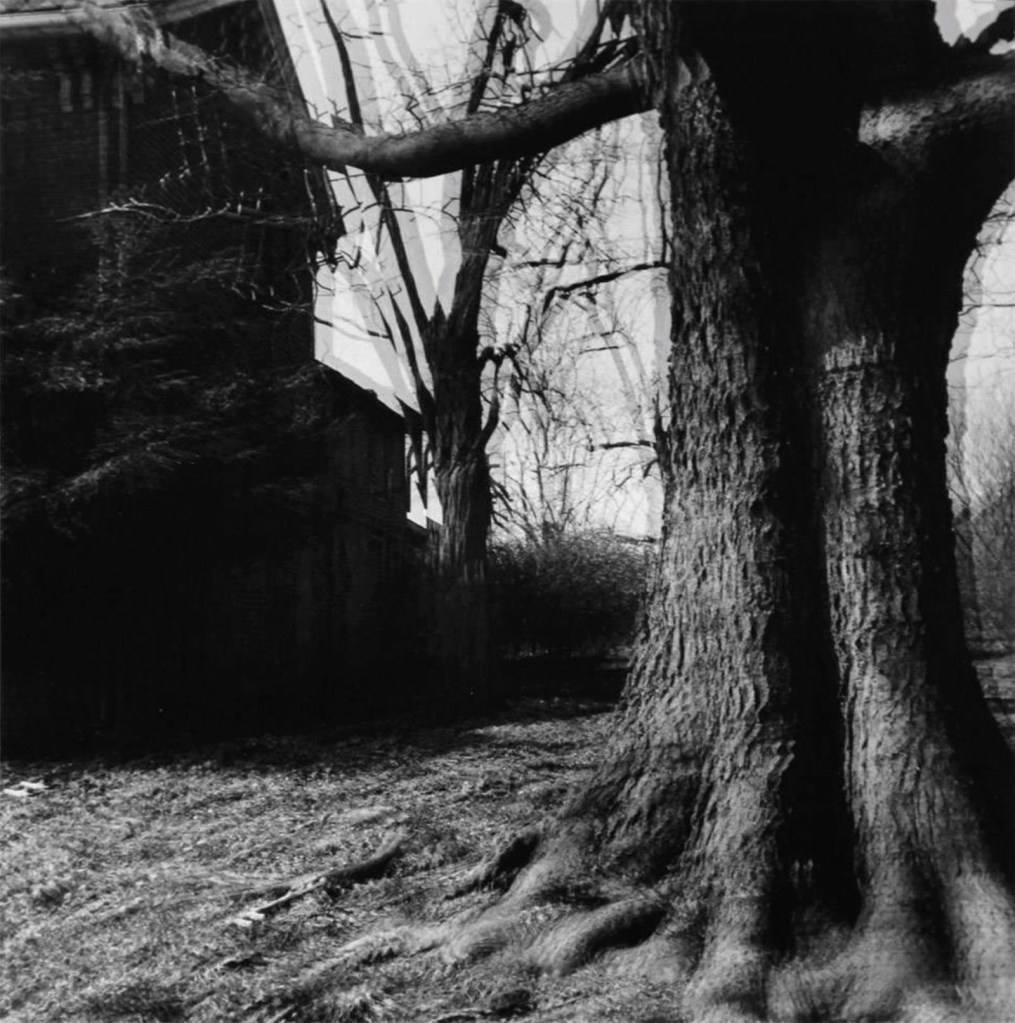

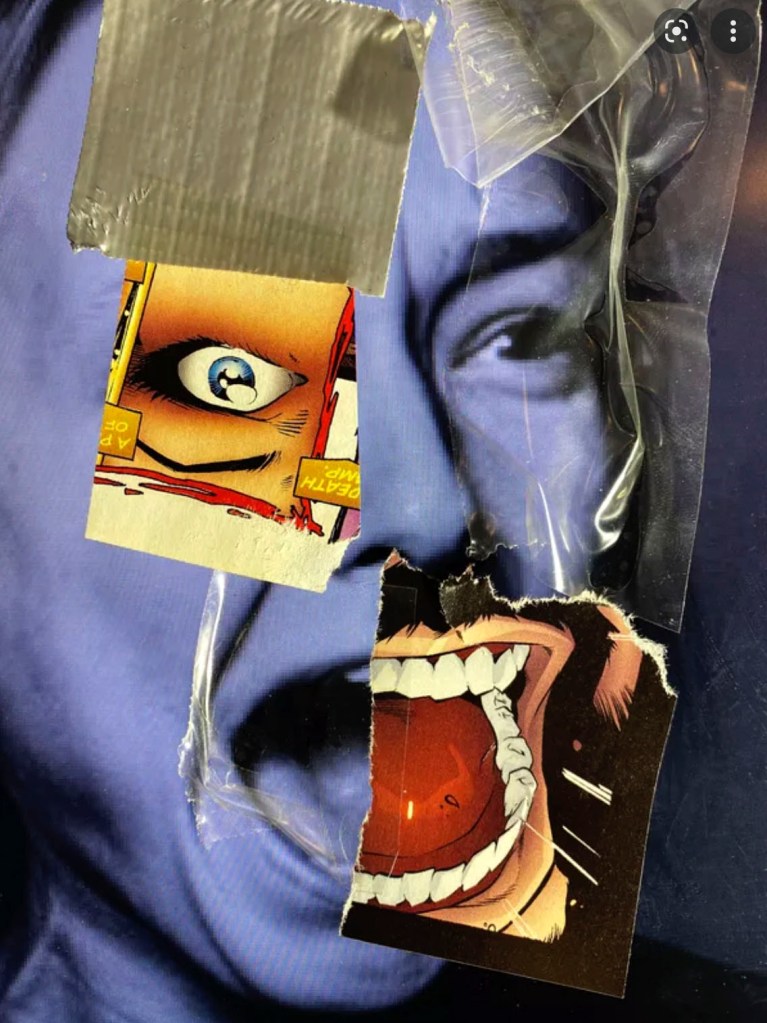

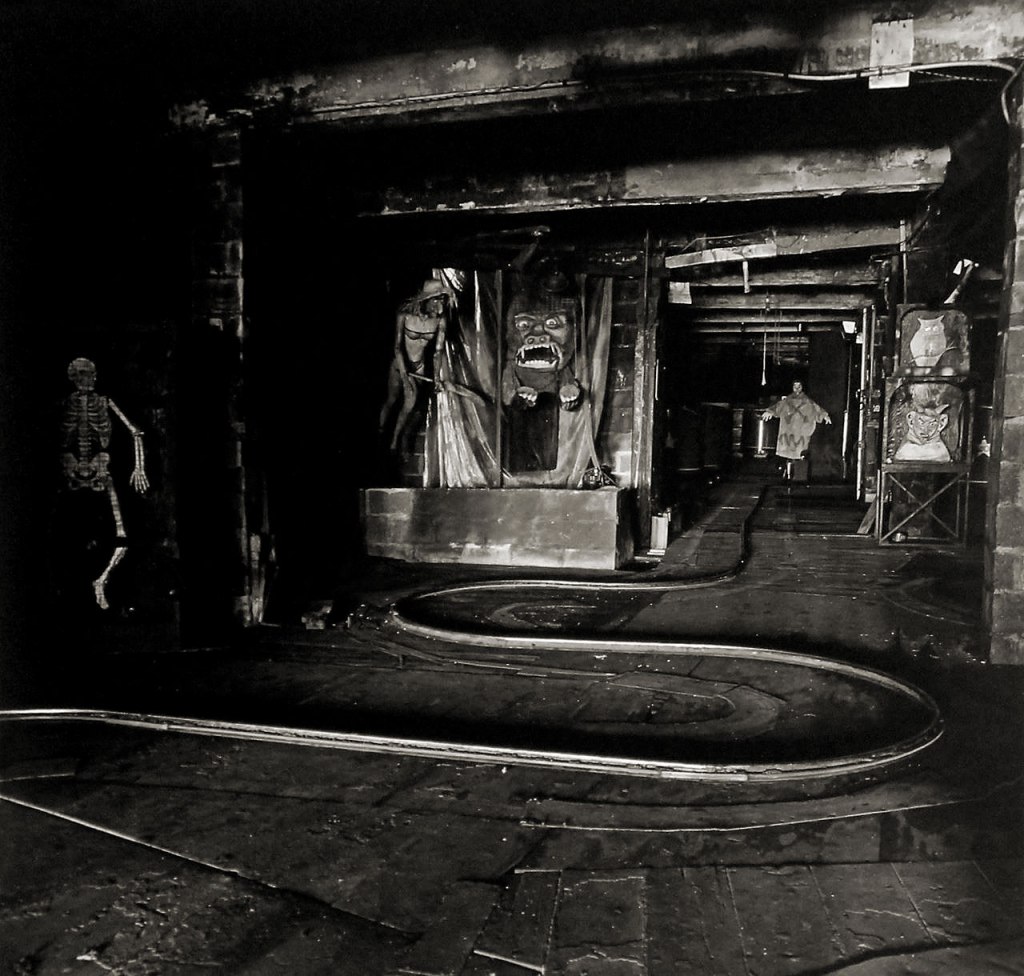

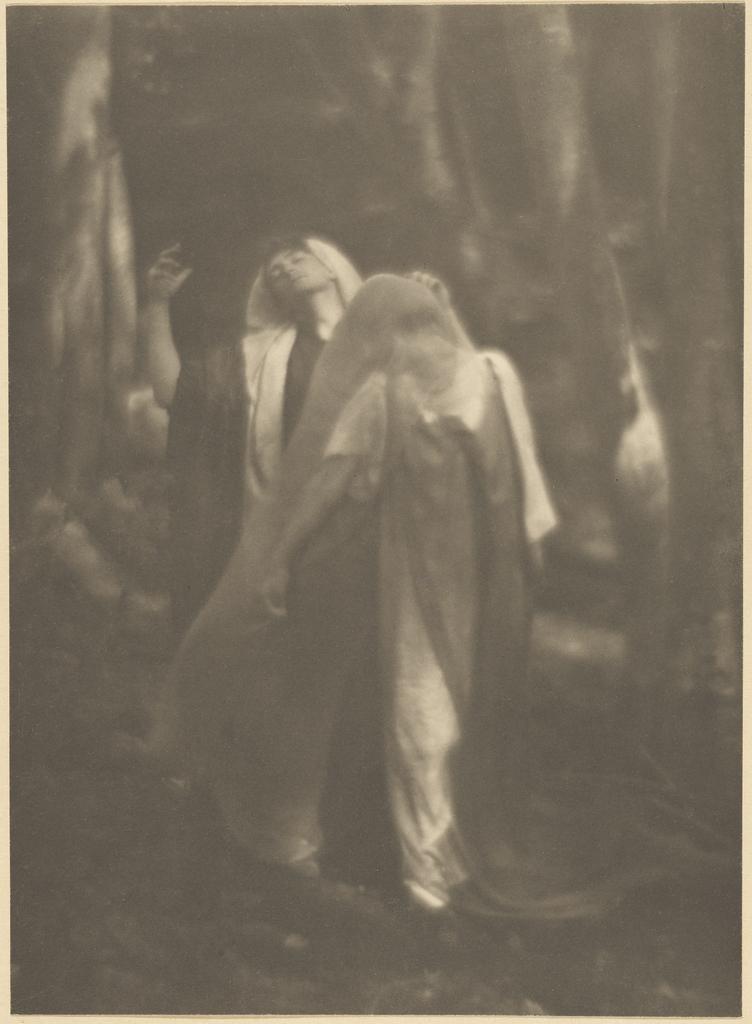

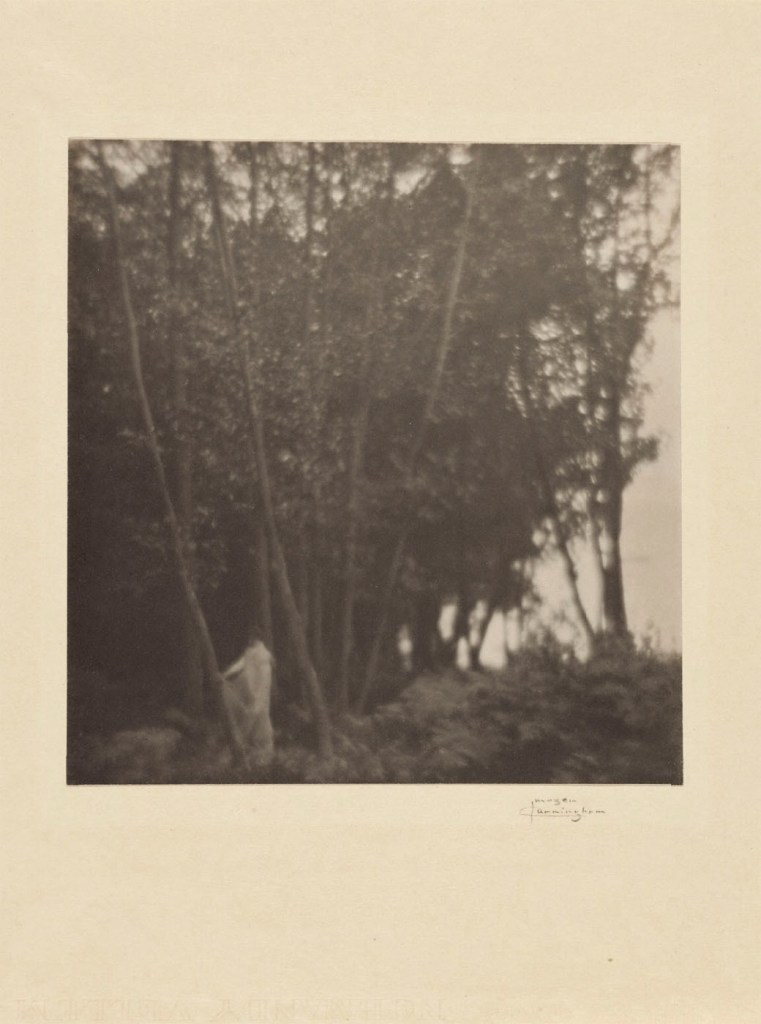

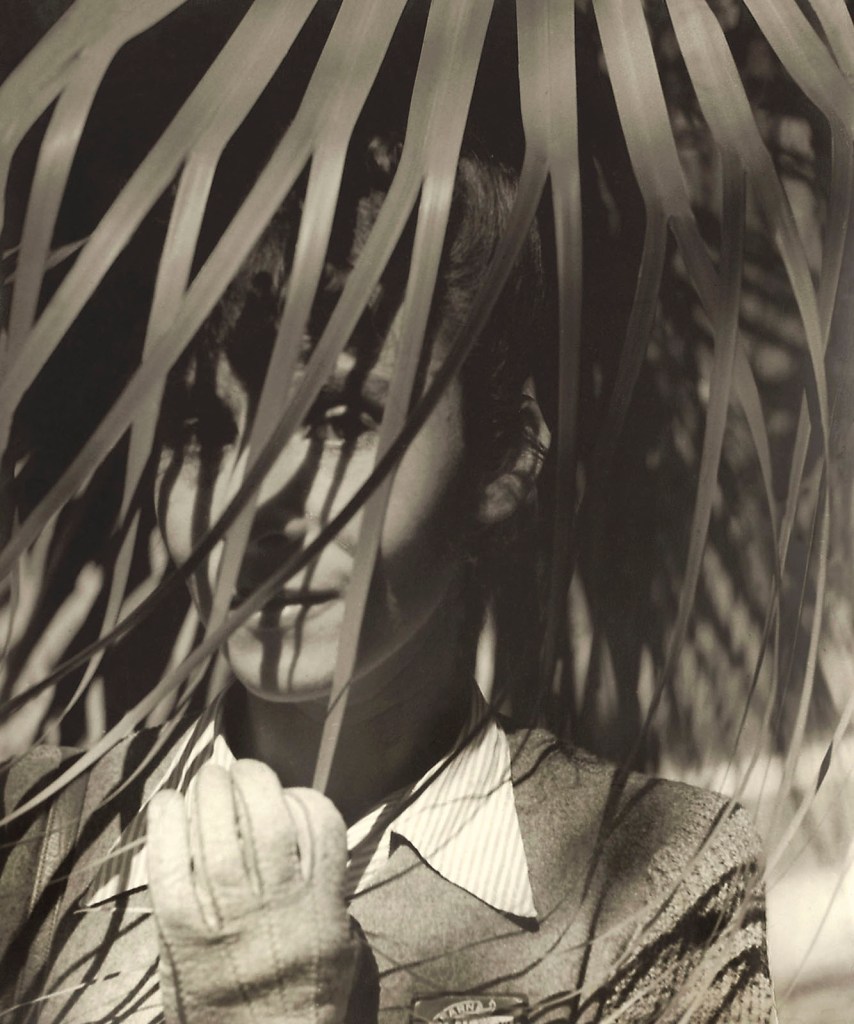

A strong southern penchant for the surreal can be observed in images like those by Clarence John Laughlin, Ralph Eugene Meatyard and Emmet Gowin. Laughlin photographed a decaying antebellum structure alongside Edward Weston in 1941. His soft focus and presence of a ghostly figure in a window create a mysterious mood in contrast to the sharp reality of Weston’s image. And his use of a mask and slight camera shake in “The Masks Grow to Us” transforms a beautiful face into an hypnagogic visage.

Twenty years later, Meatyard photographed his sons in similarly abandoned structures and fields in the countryside surrounding Louisville, Kentucky. Also known for employing masks, Meatyard creates a dreamlike reverence for vanishing rural life in some of the best quality prints of his that we have ever seen. Emmet Gowin’s balmy composition of his multi-generational family splayed around their backyard with two watermelons is, like so many images of the south, both prosaic and magical.

Suzanne Révy and Elin Spring. “A Long Arc,” on the What Will You Remember website March 20, 2024 [Online] Cited 19/12/2024

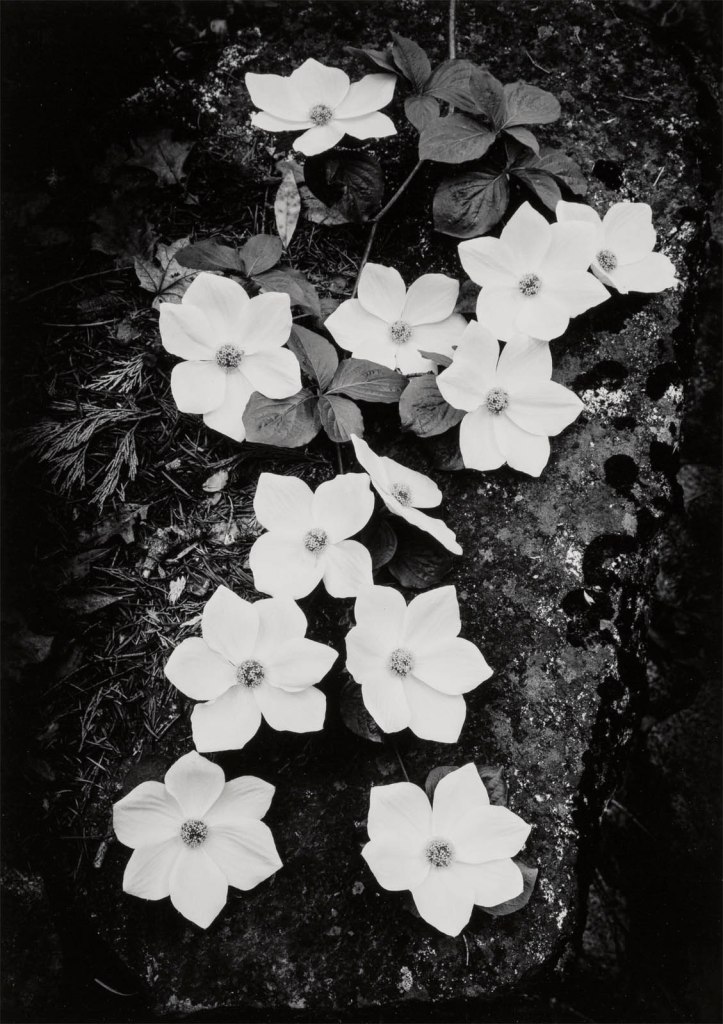

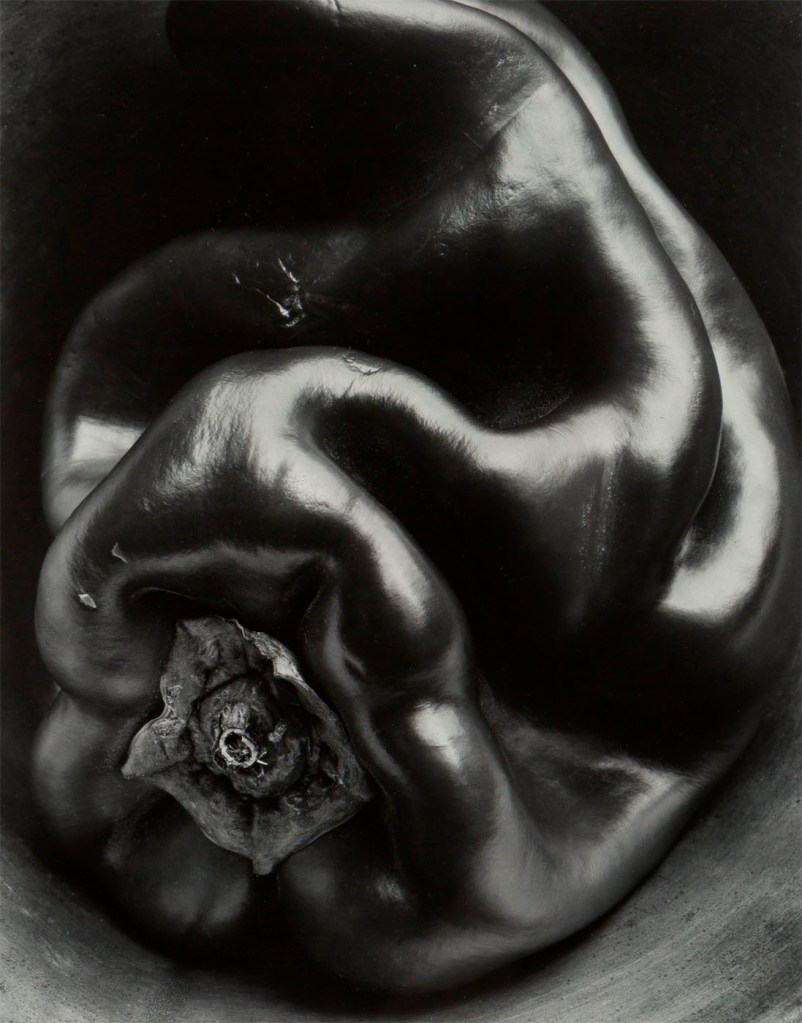

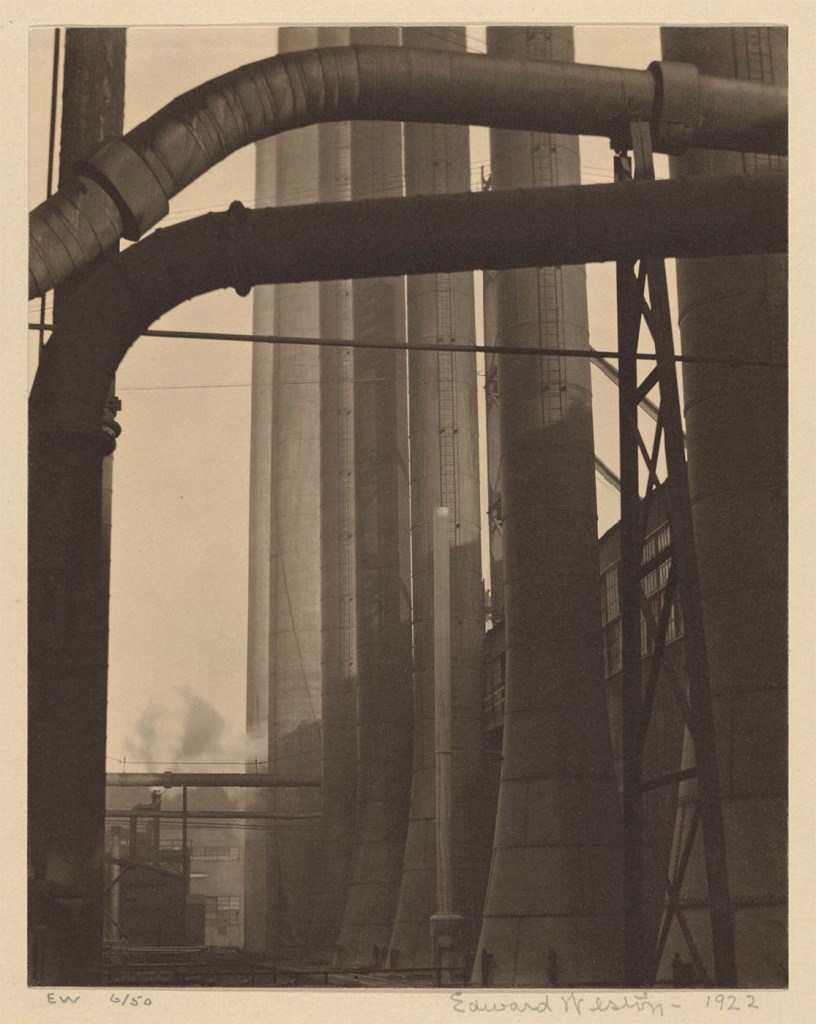

Edward Weston (American, 1886-1958)

Woodland Plantation

1941

Gelatin silver print

New Orleans Museum of Art

In 1941, Clarence John Laughlin and Edward Weston photographed alongside one another for a few days as Weston traveled the South making photographs to illustrate a new edition of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. Both photographers produced images of the same location but in notably different ways. Weston, who is known for his mastery of sharp focus and a rich tonal range, created a precise and balanced view of the scene. Meanwhile, Laughlin, who was dubbed the “Father of American Surrealism” for his atmospheric depictions of decaying antebellum architecture, spun a more ambiguous and haunting tale. He even posed Weston’s collaborator and wife, Charis Wilson, as a ghostly apparition on the second floor.

Text from the Large Print Guide at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

Clarence John Laughlin (American, 1905-1985)

The Masks Grow to Us

1947

Gelatin silver print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta

Purchase with funds from Robert Yellowlees

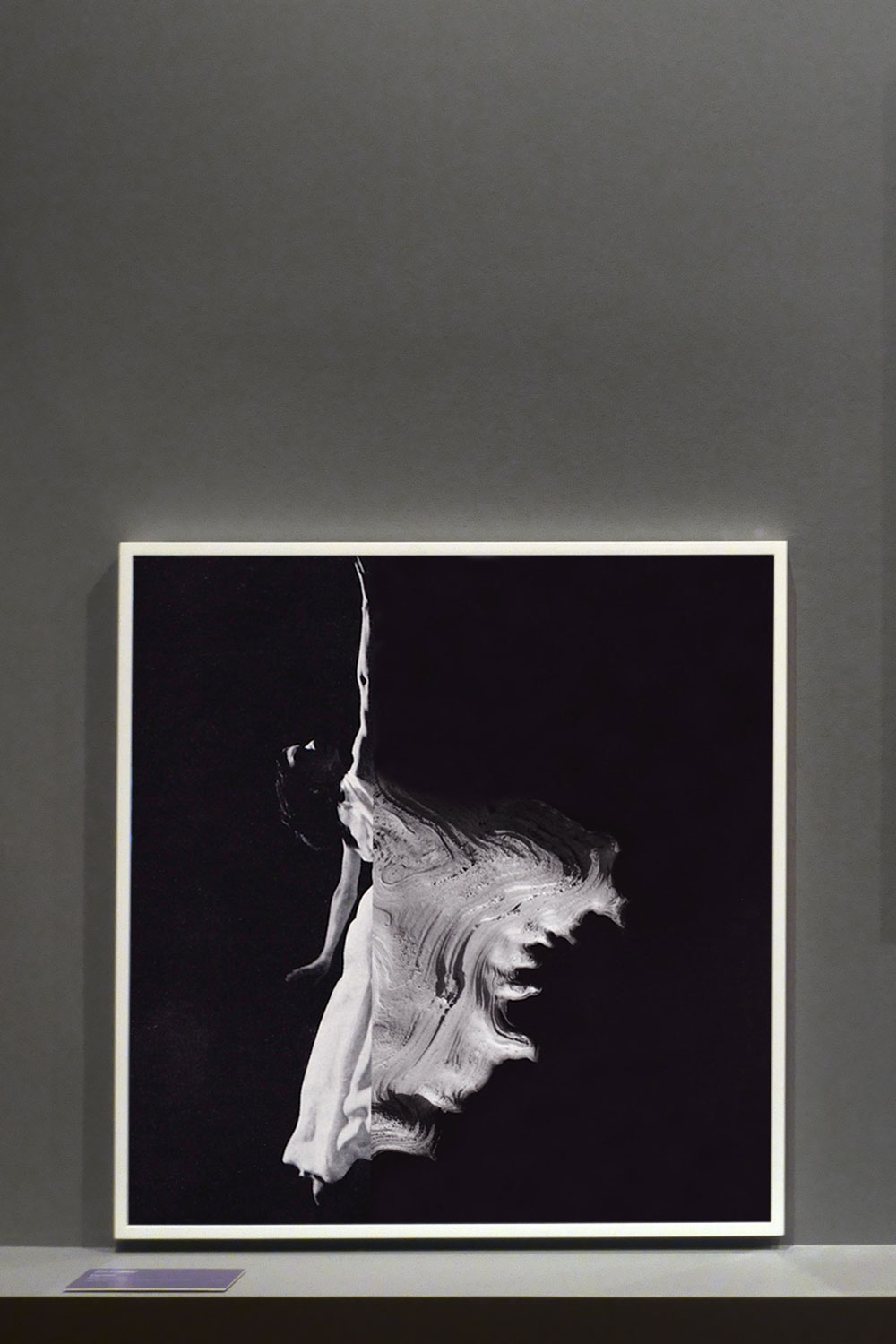

1945-1970: History as Myth, Progress as Peril

Following World War II, two competing visions shaped popular views of the South: one based on the country’s image of itself as optimistic and prosperous and the other grounded in the continued poverty, racial violence, and segregation that marked the region. Photographers grappled with the dissonance between conventional images of American affluence and progress in popular culture and mass media and the reality of life for many in the South by making a startling mix of images, from powerful examples of photojournalism to more subjective pictures that explored psychological and emotional states.

As the first Black staff photographer for LIFE, in 1956 Gordon Parks shocked Americans with lush, colourful pictures made in Mobile, Alabama, that powerfully revealed the ugliness and psychological anguish of segregation. Other photojournalists traveling to the American South – including Elliot Erwitt and Henri Cartier-Bresson – homed in on the contradictions between Southern gentility and the reality of race relations. While these photographers continued to employ the documentary style that had taken shape in the 1930s, with its crisp focus, straightforward compositions, and faith in the possibilities of objectivity, others, like Robert Frank, broke from this tradition to make raw, searing, and idiosyncratic pictures that grasped something elemental about American culture.

Other photographers – especially those who knew the South intimately – turned inward. Some, like Virginia native Emmet Gowin, chose to photograph their families and loved ones, seeking sustenance in what was closest at hand. Others, like the Kentucky optician-turned photographer Ralph Eugene Meatyard, embraced a dreamlike surrealism to create pictures suffused with social and psychological tension, capturing the alienation produced within such a divided society.

Text from the Large Print Guide at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

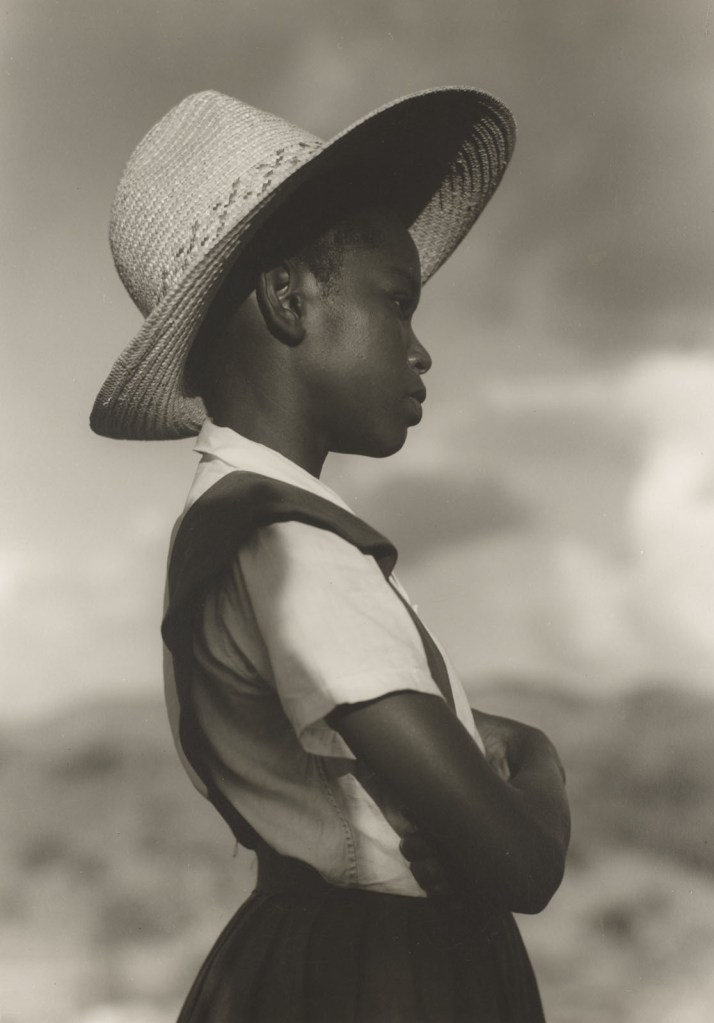

Consuelo Kanaga (American, 1894-1978)

Young Girl, Tennessee

1948

Gelatin silver print

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

Adolph D. and Wilkins C. Williams Fund

In the late 1940s, many photographers traversed the country with the support of fellowships and grants to capture the spirit of postwar America. Consuelo Kanaga traveled throughout the South, concentrating her lens on communities of color. Rather than dwelling on hardships or poverty, she presents her subjects with dignity, often framed in spare compositions that focus on the emotions conveyed in their facial expressions. Emblematic of this approach, her photograph of this contemplative girl silhouetted against a light sky while gazing upward echoes classical portraiture.

Text from the Large Print Guide at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

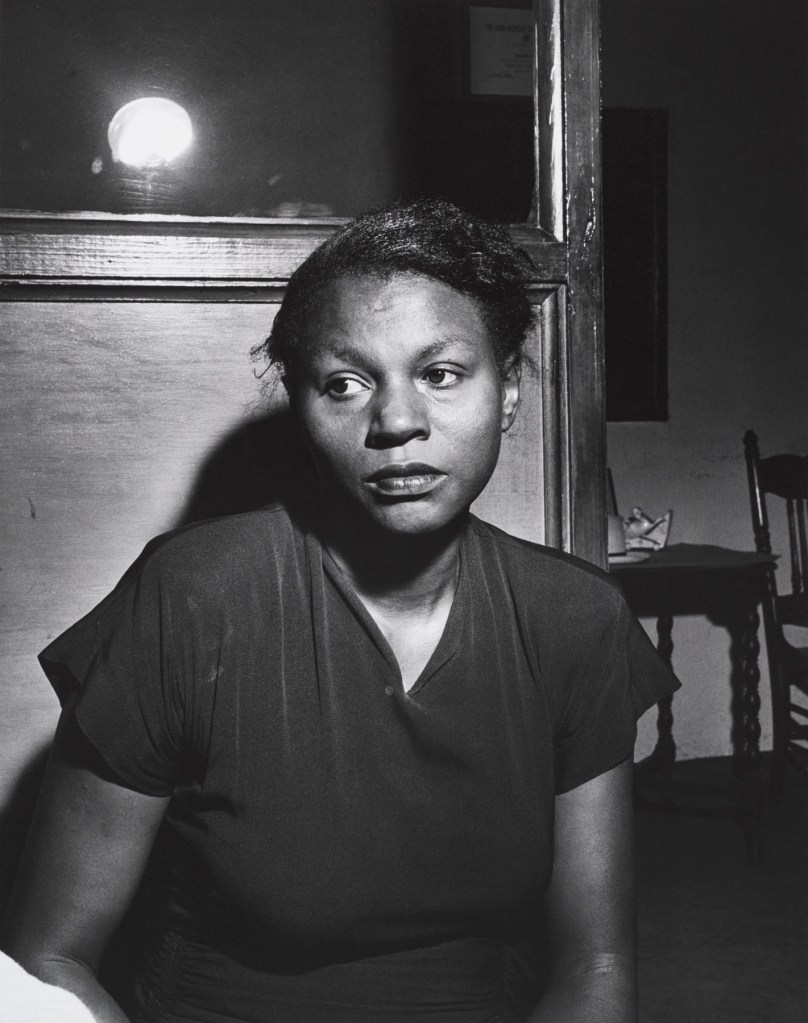

Marion Palfi (American born Germany, 1907-1978)

Josie Hill, Wife of a Lynch Victim, Irwinton, Georgia

1949

Gelatin silver print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta

Gift of Ben Bivins

Born in Germany, Marion Palfi worked as a freelance photographer and portraitist in Berlin before emigrating to the United States in 1936. Shocked at the racial and economic inequalities she encountered, she devoted her photographic career to documenting various communities to expose the virulent effects of racism and poverty. In 1949, she made this portrait of Josie Hill, widow of Caleb Hill, the victim of the first reported lynching of that year. A father of three, the twenty-eight year old Hill had been arrested for allegedly stabbing a man. After the sheriff left the jail’s front door open and the keys to the cell on his desk, Hill was pulled from jail in the middle of the night and shot to death. Two white men were charged with the crime, but the all-white grand jury did not indict them.

Text from the Large Print Guide at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

Leonard Freed (American, 1929-2006)

North Carolina (segregation fountain)

1950

Gelatin silver print

Addison Gallery of American Art

W. Eugene Smith (American, 1918-1978)

Maude at Stove

1951

Gelatin silver print

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

Floyd D. and Anne C. Gottwald Fund

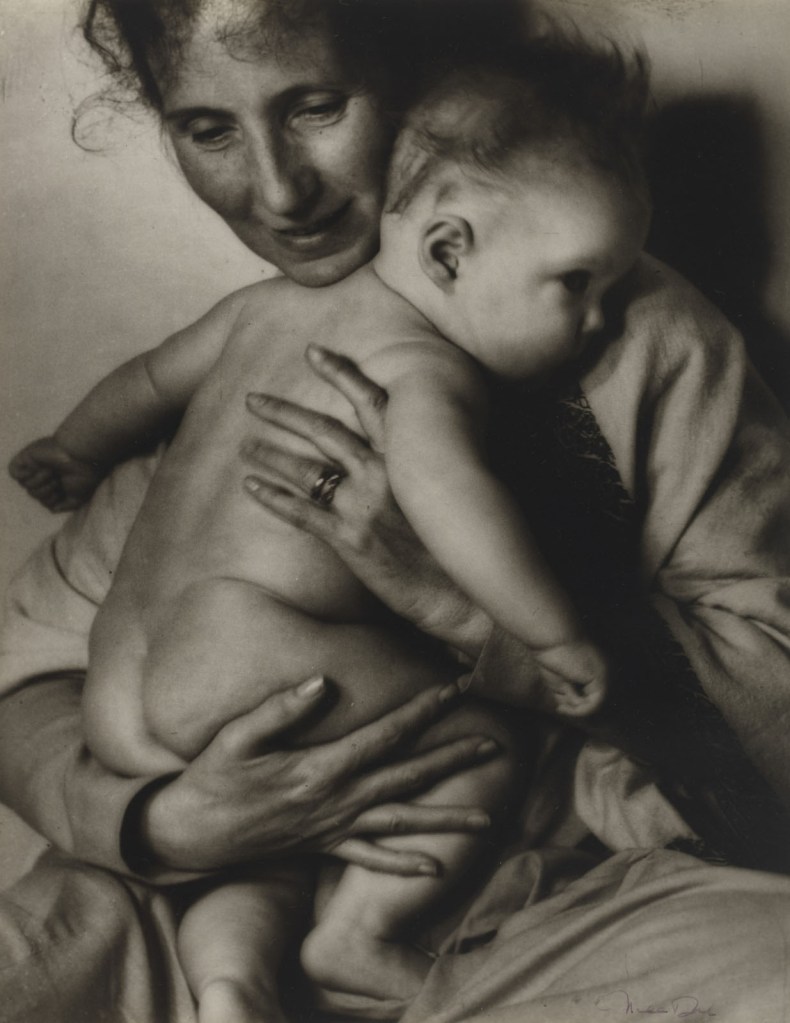

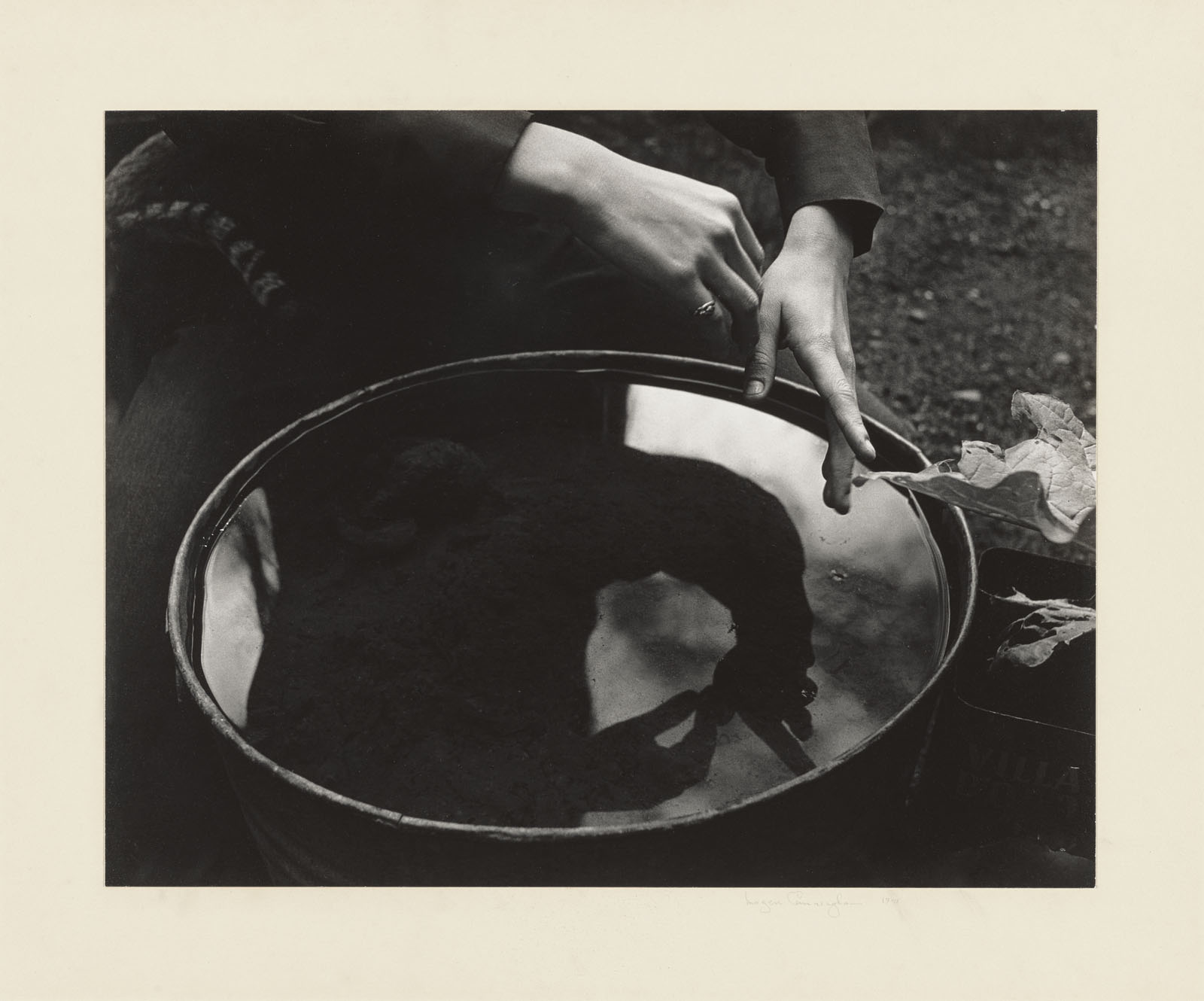

In December 1951, LIFE published W. Eugene Smith’s photo essay on Maude Callen, a nurse and midwife who worked in rural South Carolina. Smith’s powerful photographs illuminated Callen’s extraordinary efforts to serve her patients, who were among the poorest and most neglected in the country. As detailed in the magazine, “Callen drives 36,000 miles within the county each year, is reimbursed for part of this by the state, and must buy her own cars, which last 18 months. Her workday is often sixteen hours and she earns $225 a month.” After the article was published, readers sent donations totalling more than $27,000, allowing Callen to build a clinic and train others to become healthcare workers.

Text from the Large Print Guide at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

Robert Frank (Swiss-American, 1924-2019)

Trolley, New Orleans

1955

Gelatin silver print

Addison Gallery of American Art, Phillips Academy, Andover, Massachusetts

Museum purchase

In 1955 and 1956, Switzerland-born photographer Robert Frank travelled across the United States with the support of a Guggenheim Fellowship. With an incisive, unsparing eye, he sought to understand and decode the brutal beauty of his adopted home. Raw, violent, tender, and edgy, his photographs of an America plagued by racial division, economic disparity, consumerism, and wilful ignorance shocked viewers for how they savagely undercut the country’s postwar view of itself as prosperous, peaceful, and progressive. In the South, Frank was keenly attuned to the persistence of segregation. His photograph of a New Orleans trolley, white people up front and Black people behind, succinctly captures the ruthlessness and anguish of racial stratification.

Text from the Large Print Guide at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

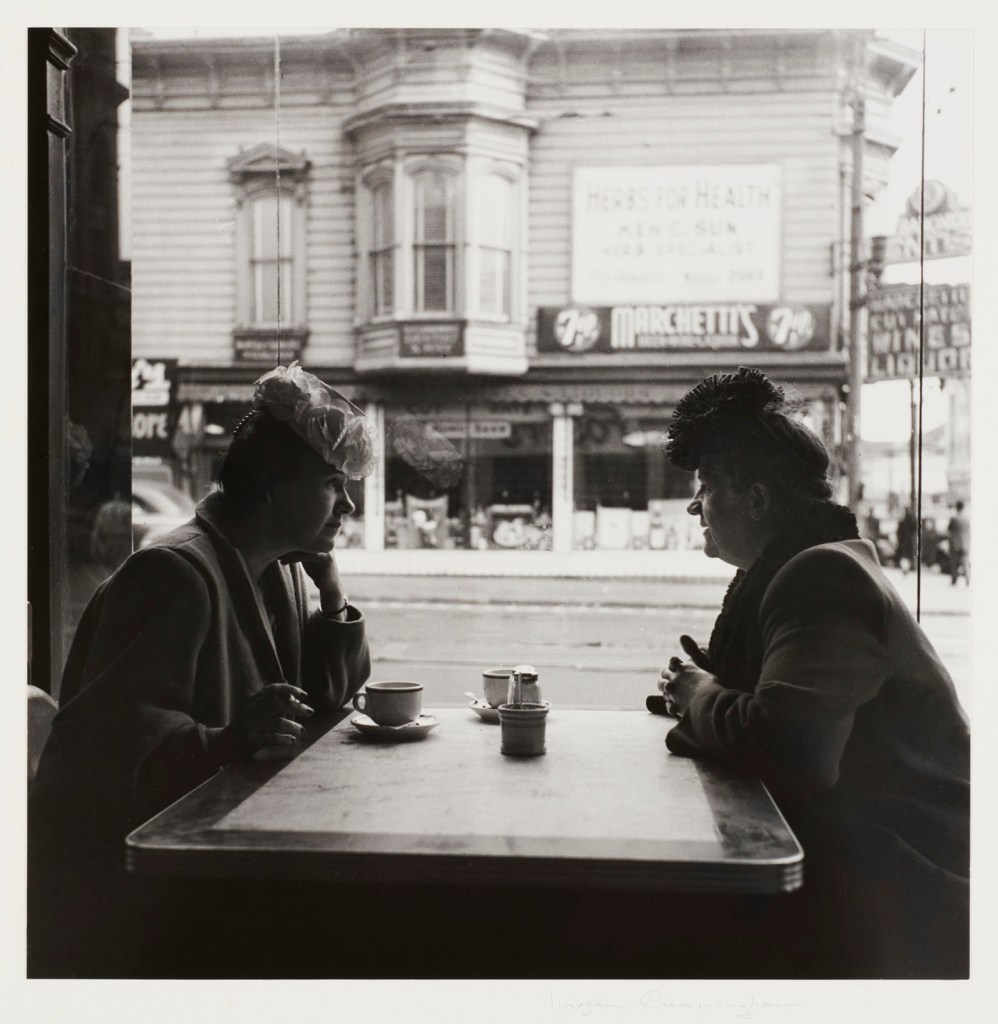

Robert Frank (Swiss-American, 1924-2019)

Café, Beaufort, South Carolina

1955

Gelatin silver print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta

Robert Frank (Swiss-American, 1924-2019)

Charleston, South Carolina

1955-1956

Gelatin silver print

Addison Gallery of American Art, Phillips Academy, Andover, Massachusetts

Museum purchase

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Outside Looking In, Mobile, Alabama

1956

Inkjet print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta

Gift of The Gordon Parks Foundation

Courtesy of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation