Exhibition dates: 7th March – 31st July, 2016

Curators: Jeff L. Rosenheim (Curator in Charge of the Department of Photographs), with Doug Eklund (Curator and a key organiser) and Mia Fineman (Associate Curator), with Beth Saunders (Curatorial Assistant)

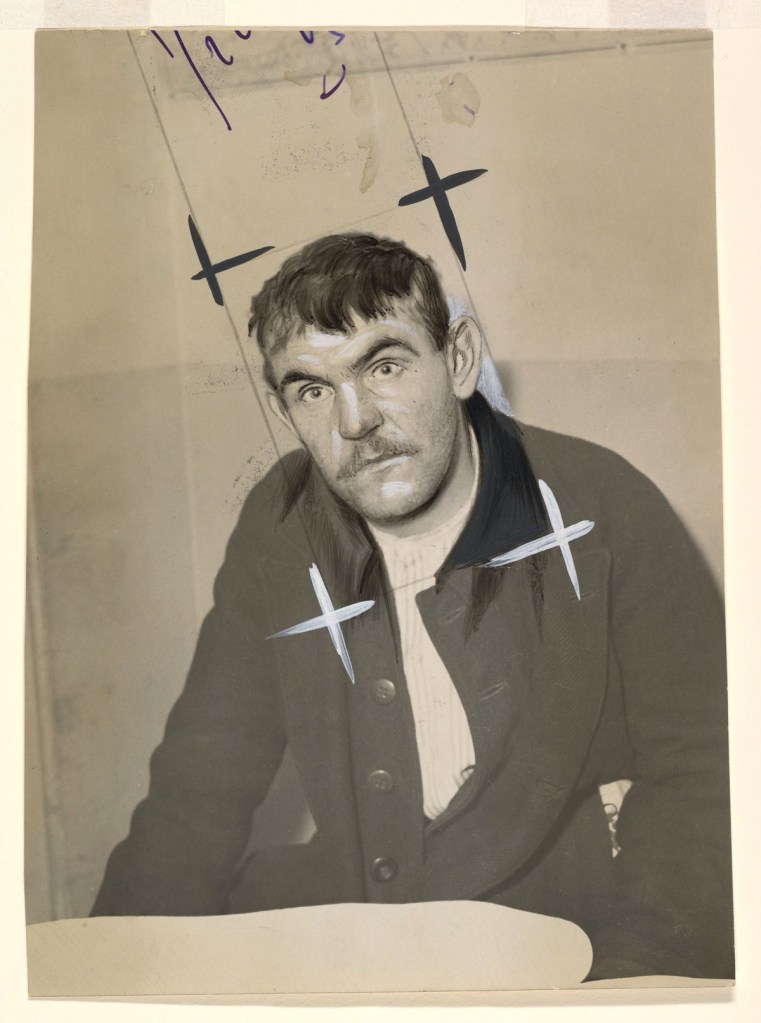

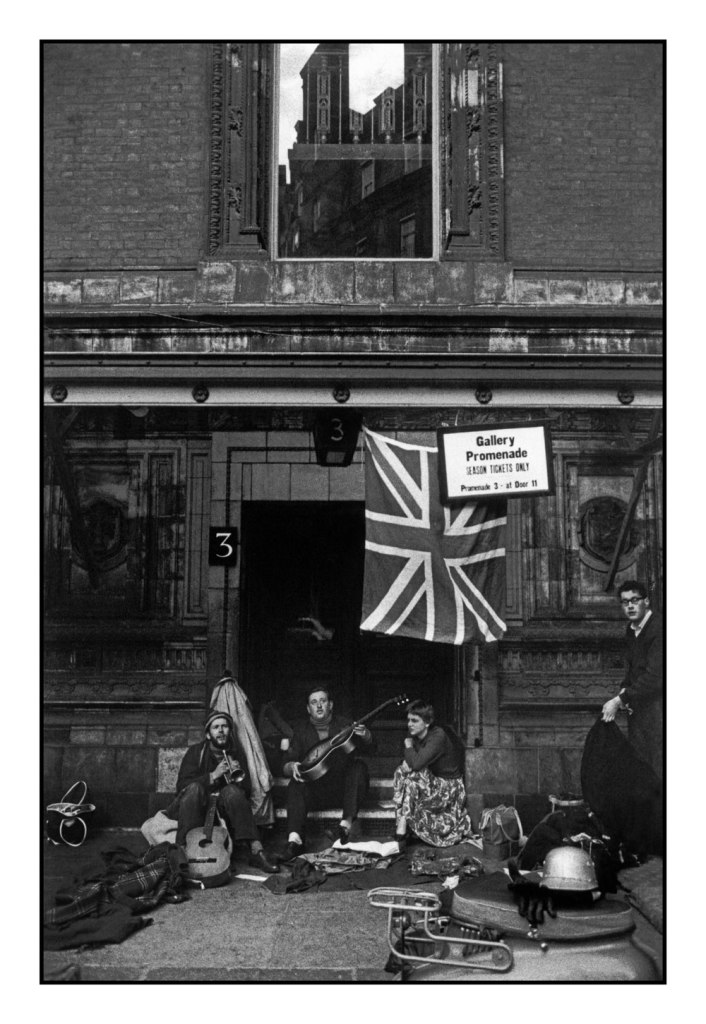

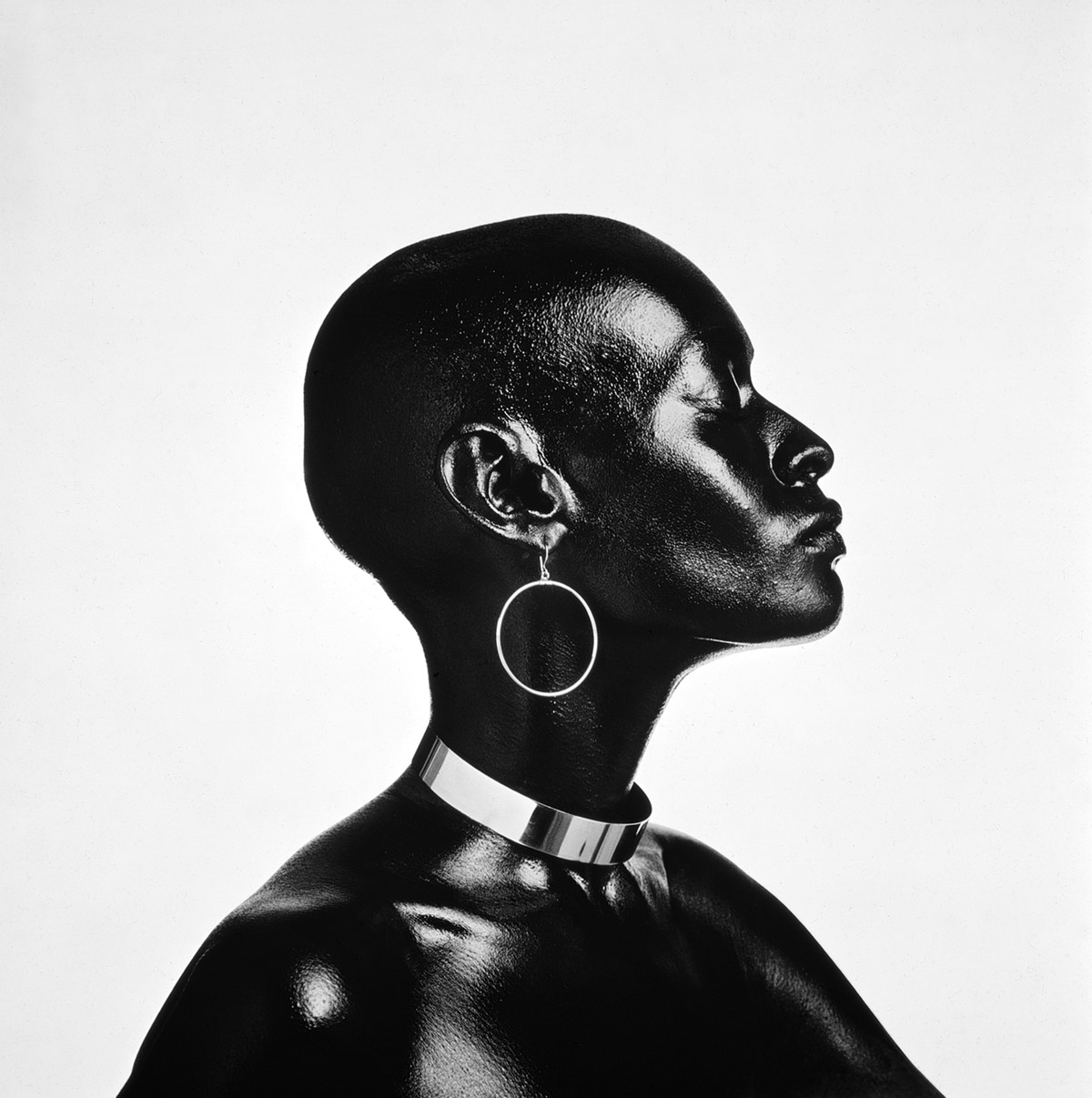

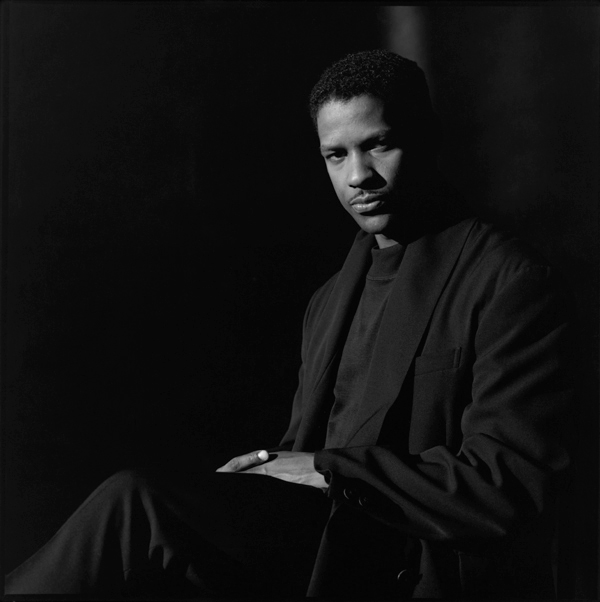

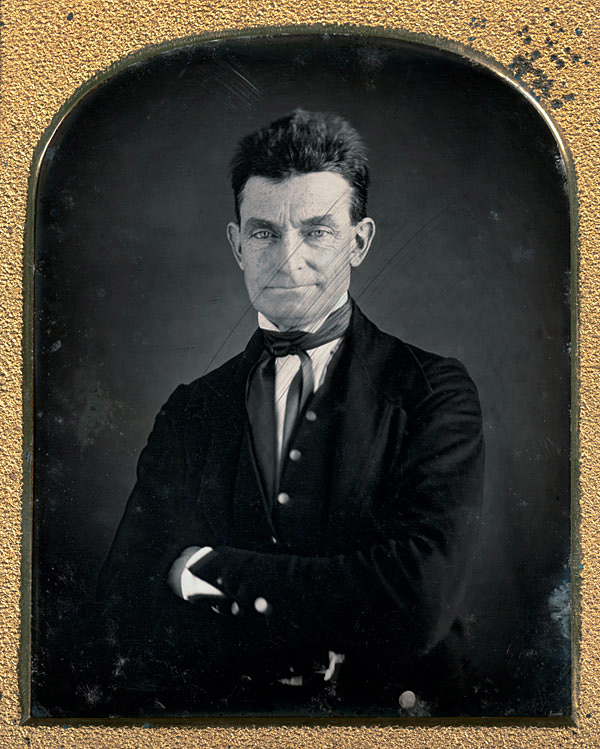

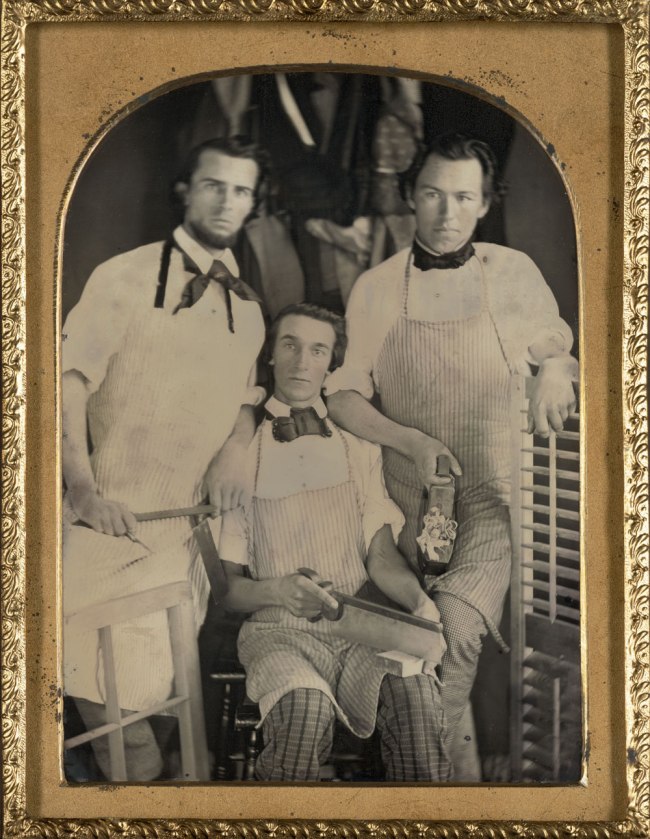

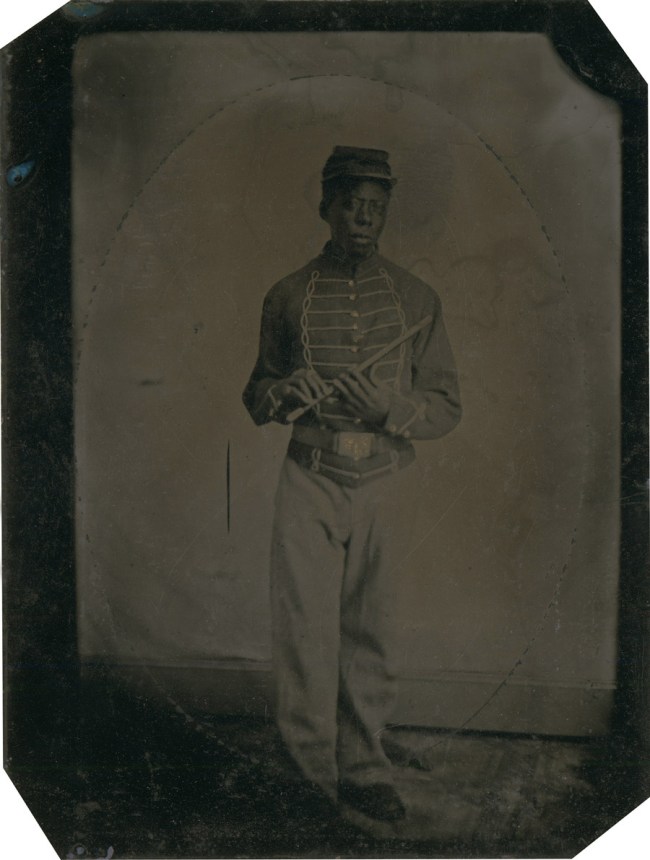

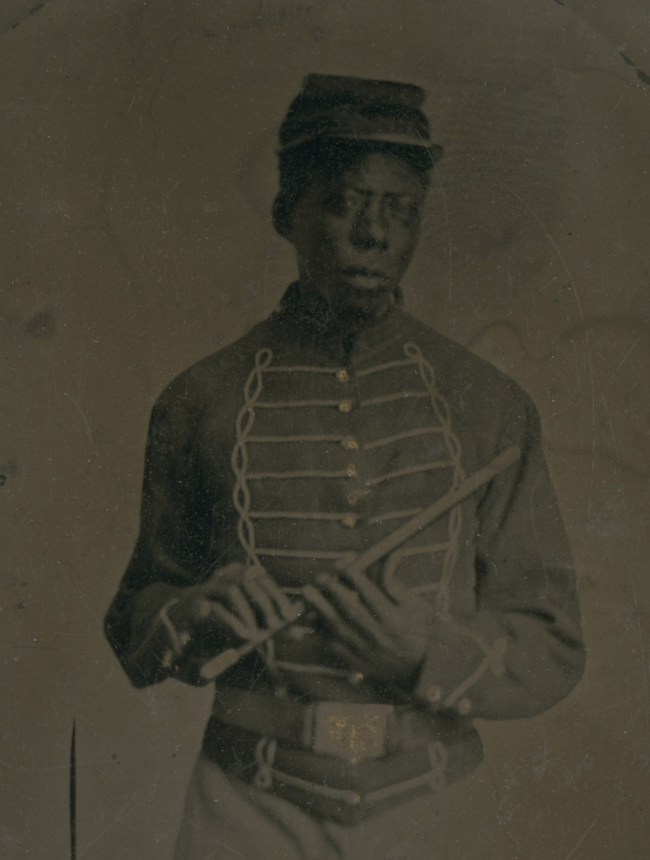

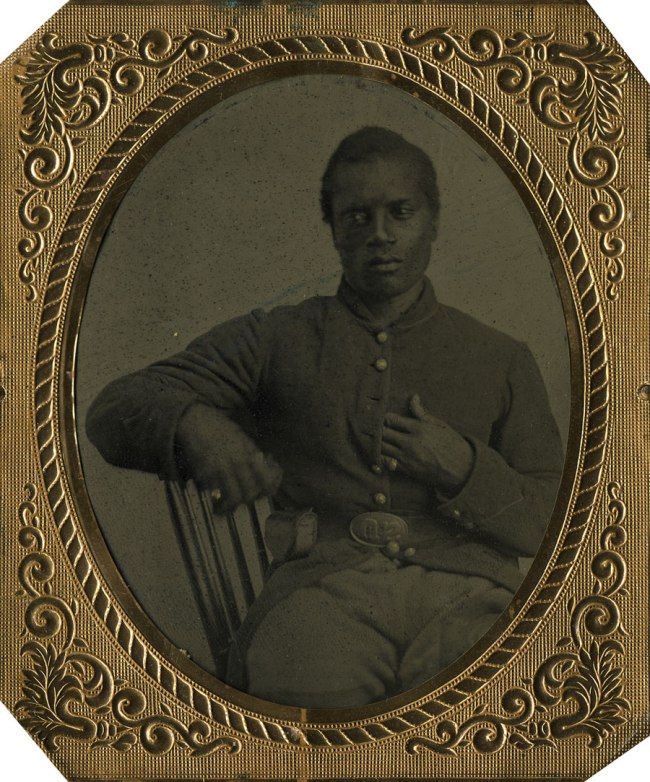

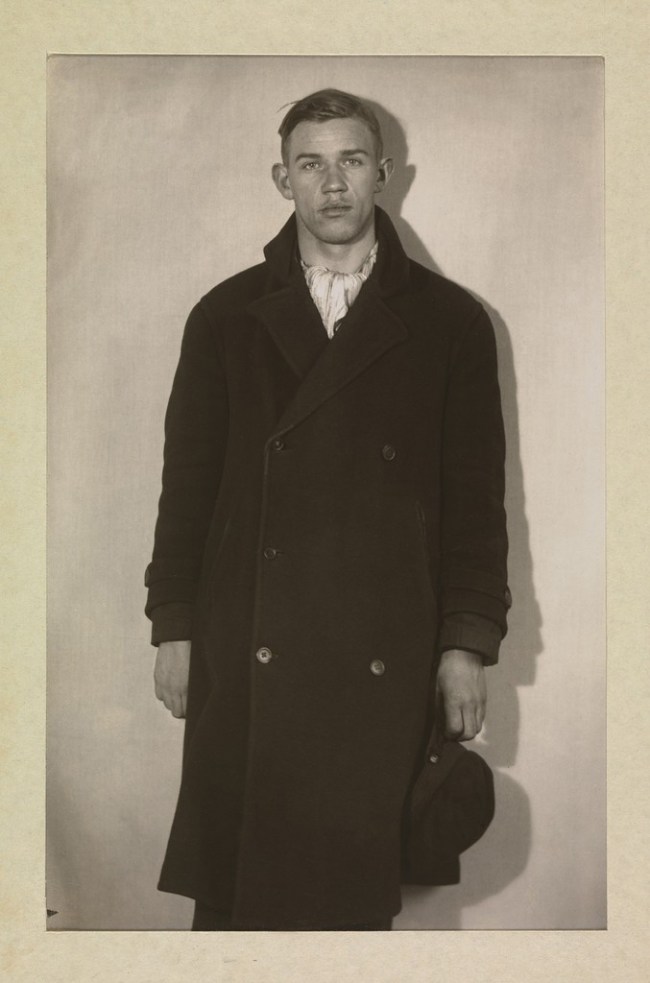

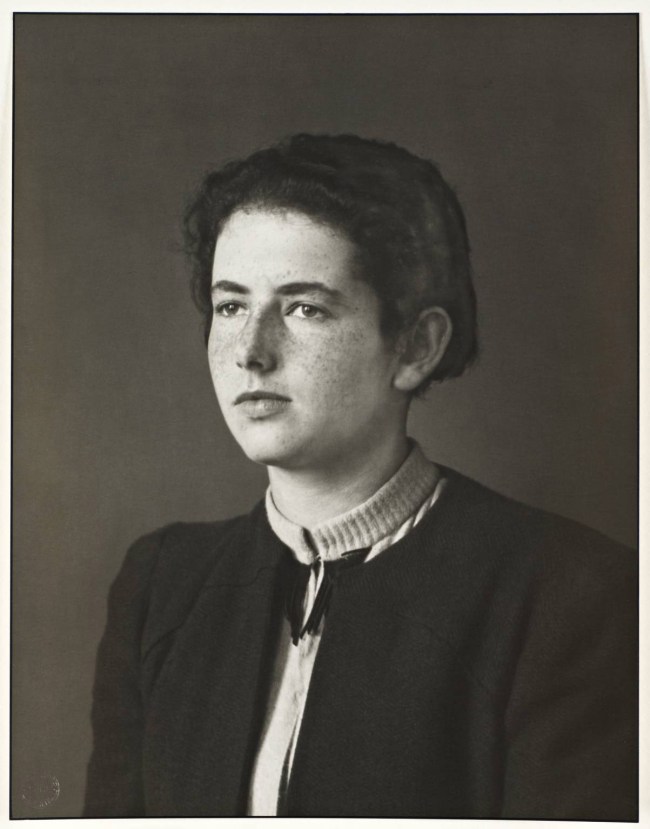

Unknown photographer (American)

[Jeff Briggs, Robert Sims, Otis Hall, and Peter Pamphlet; Full-Length Mugshot from the Chicago Police Department]

1936

Gelatin silver prints

Image: 5 15/16 × 9 1/8 in. (15.1 × 23.1cm)

Sheet: 6 1/8 × 9 5/16 in. (15.6 × 23.6cm)

Twentieth-Century Photography Fund, 2014

One wrong does not a life make

A very large posting on a fascinating subject, for an exhibition that examines “the numerous ways that photography has influenced that favourite human activity, speculating about crimes and the people who commit them.” As the press release notes, “Since the earliest days of the medium, photographs have been used for criminal investigation and evidence gathering, to record crime scenes, to identify suspects and abet their capture, and to report events to the public. This exhibition explores the multifaceted intersections between photography and crime…”

And all this history displayed in just two gallery spaces!

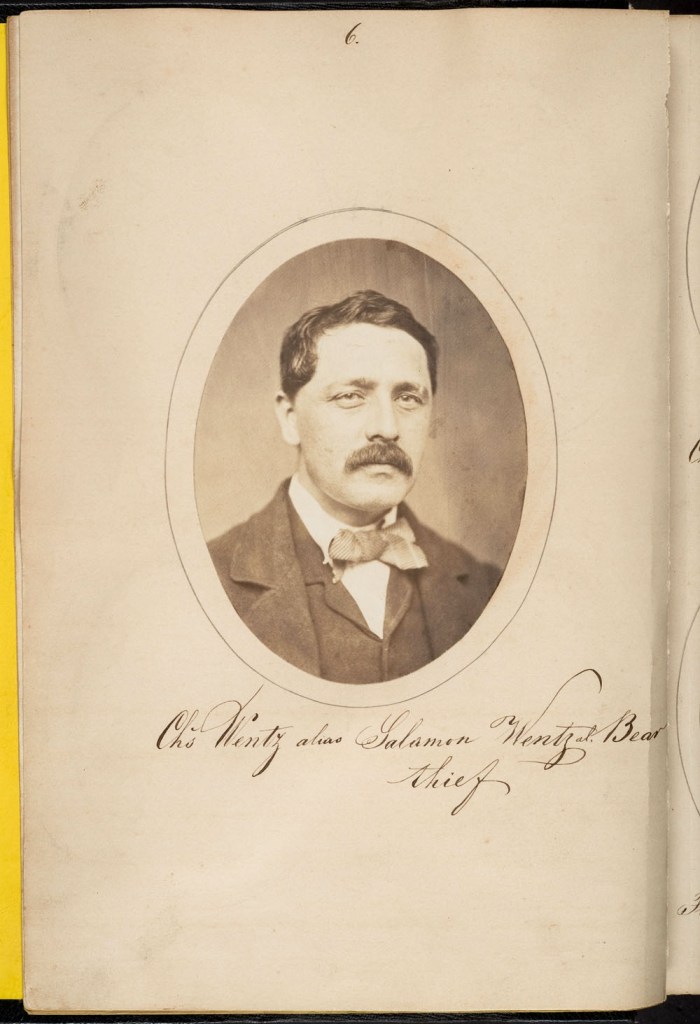

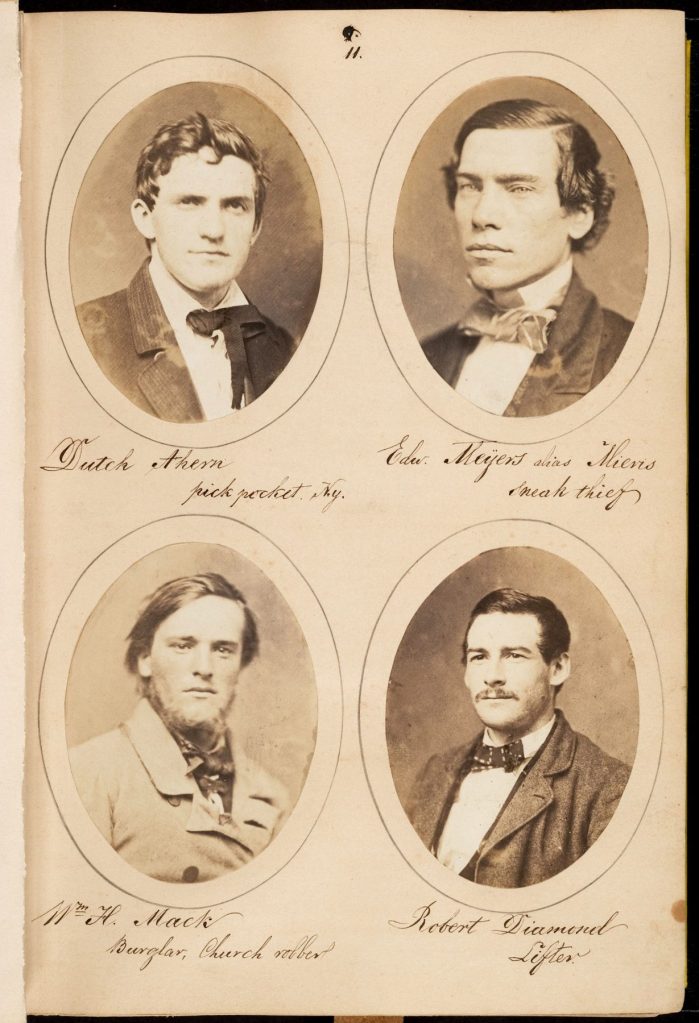

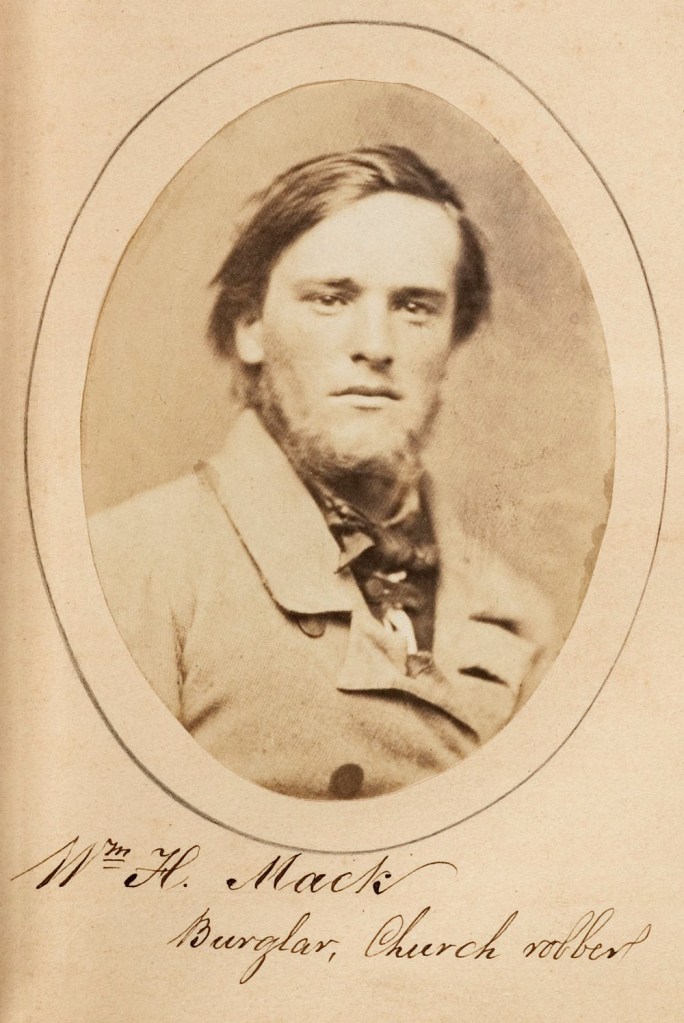

What the press release fails to note is that it is often the people in power (the police, judiciary, and even the photographer) who name and shame those whose likenesses are captured by the camera. In other words, the people in these photographs are already labelled – deviant, lifter, wife poisoner, forger, sneak thief; cracksman, pickpocket, burglar, highwayman; murderer, counterfeiter, abortionist – before their photograph is ever taken. They have already been dressed for the part.

This verdict is further reinforced when images, such as those by Weggee, appear in newspapers and, using Walker Evans phrase, the “Ladies and gentlemen of the jury” confirm what has been fed to them. As noted in the text in the posting about the photographs of Samuel G. Szabó, “Would the serious young man in the overcoat and silk top hat appear roguish without the caption “John McNauth alias Keely alias little hucks / Pick Pocket” below his portrait?” I think not (which is what the viewer does when confronted with the veracity of the photograph and the text supplied by those in a position of power)…

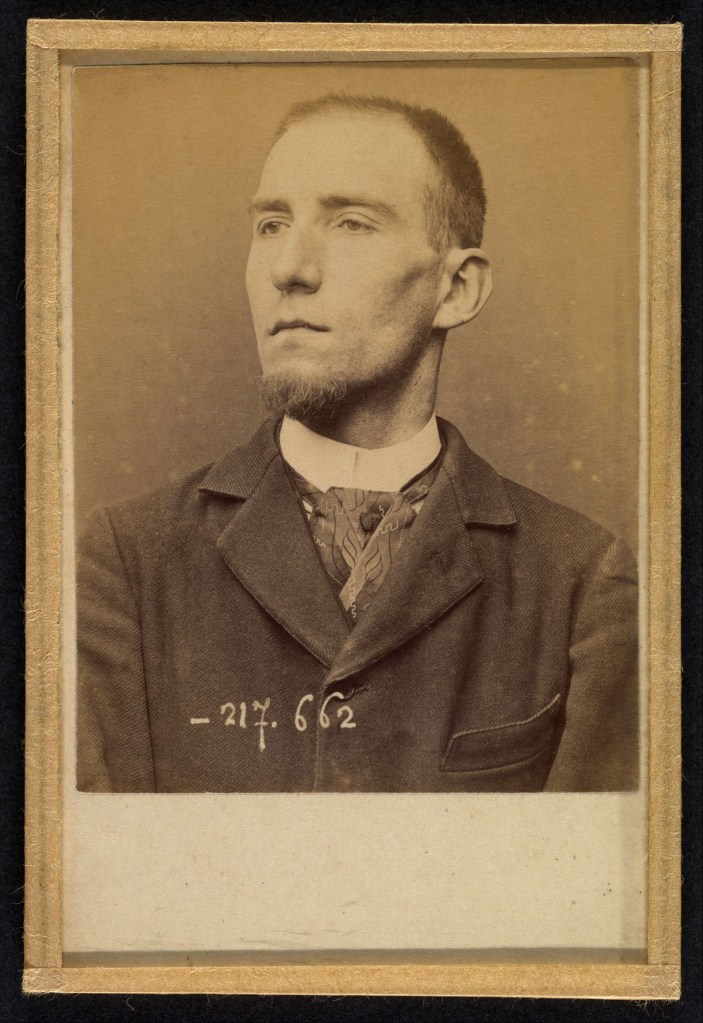

What strikes me about the “mugshot” photographs of Samuel G. Szabó and Alphonse Bertillon is the ordinariness of the people he captured – tailor, printer, accountant, photographer, seamstress – and how they have forever been labelled “anarchists”. Nothing is known of the rest of their lives and a search on the internet reveals nothing about them, except those people indelibly printed onto the fabric of history: Ravachol, murderer and anarchist who was bent on improving the conditions of the poor (no name or age under his photograph); and Félix Fénéon – head and eyes directed away from the camera whereas most others stare straight into the camera (upon direction) – all haughty superiority, as though the process of being photographed as an “anarchist” was beneath the witty critique (no name or age under his photograph as well). Only by this is it recorded that they are morally suspicious and this is done at the behest of the authorities. Whatever else they did in their life counts as if for nothing.

What also strikes me about the “en situ” photographs of the habitats of the murdered victims and the places where they were found, is again the mundanity of the interiors and places of execution. In the photographs that document the Assassination of Monsieur V. Lecomte, 74 Rue des Martyrs, 1902 we note the ephemera of human existence – the photographs standing on three-tiered wooden shelves, the open box on the table, the body on the floor – photographed from both directions, once with the camera pointing towards the windows, the other from 180 degrees, with the camera pointing into the room. And then we notice the mantlepiece photographed from another direction, with the open box on the table. And the bound and gagged man on the floor is still on the floor out of frame. And then another place of murder, that of the ending of a life, marked out in Bertillon’s photograph “Place where the corpse was found” by two pieces of wood laying on the ground and two pieces of wood propped at 45 degrees against the wall. As though this is all that is left of the existence of Mademoiselle Mercier along a street (Rue de l’Yvette) that still exists in Paris to this day … a photograph of pieces of wood and an empty space. Pace HEAD by Weggee.

It’s all about the stories, or the lack of them, that these photographs tell/sell. Weggee’s photographs of a sixteen-year old child killer, Frank Pape, are brutal in their exposure of this adolescent man. The way the horizontal negative has been cropped over and over again, to gain best effect, best value for the tabloid dollar, gives an idea of the pejorative pronunciation of guilt upon this individual before trial. What happened to Frank Pape? I’ve been digging, trying to find out… but nothing. Did he live, was he executed? What led him to that point and what happened to the rest of his life? This is the great unknown after the click of the shutter, the key in the lock, the silence of history. Here I am not advocating for the celebrity of the criminal, as in Richard Avedon’s photographs of the murderer Dick Hickock, but an acknowledgement that one wrong does not a life make.

But then again, for the victim, in shootings like that of Sen. Robert F. Kennedy – the pain of the photograph and the look in his eyes says it all. Here he is a victim, twice over (the victim of the assassin and the camera), and is to remain a victim for eternity, as long as people look at this photograph. This is such a sad and painful photograph. I remember the day it happened. I was ten years old at the time, and it’s one of those events that you will always remember the rest of you life, where you were, who you were with – like the moon landings or 9/11. I was in a car outside a small shop and the news came on the radio. Robert F. Kennedy had been shot – first aural, then visual on the black and white tv that night, then textual in the newspapers and then visual again with this photograph. The pain of the loss of those heady days of hope lessen not.

Today we live in a police state where surveillance and recognition are everything, where those in power seek to control and regulate ever more the freedom of the people, and the people are lost to anonymity and time.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Word count: 1,046

Many thankx to the Metropolitan Museum of Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“Crime Stories: Photography and Foul Play,” an exhibit currently on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, proposes to examine the numerous ways that photography has influenced that favorite human activity, speculating about crimes and the people who commit them. This would be an ambitious undertaking for a ten-room show; this one is limited to only two. The result is something of a hodgepodge, hemmed in by a vague set of constraints. The bulk of the photos were taken in the United States between the mid-nineteenth and mid-twentieth centuries, none after the seventies, and all are in black and white, as if to emphasize their historical remove from our own filtered times. But the aesthetic and ethical questions the exhibit raises – about the American attraction to criminal glamour, and our queasy, not always critical fascination with looking at violence – are the right ones to ask during the current vogue for “true crime,” that funny phrase we use for stories told in public about terrible things others suffer privately.

Alexandra Schwartz. “The Long Collusion of Photography and Crime,” on The New Yorker website April 9, 2016 [Online] Cited 03/10/2021

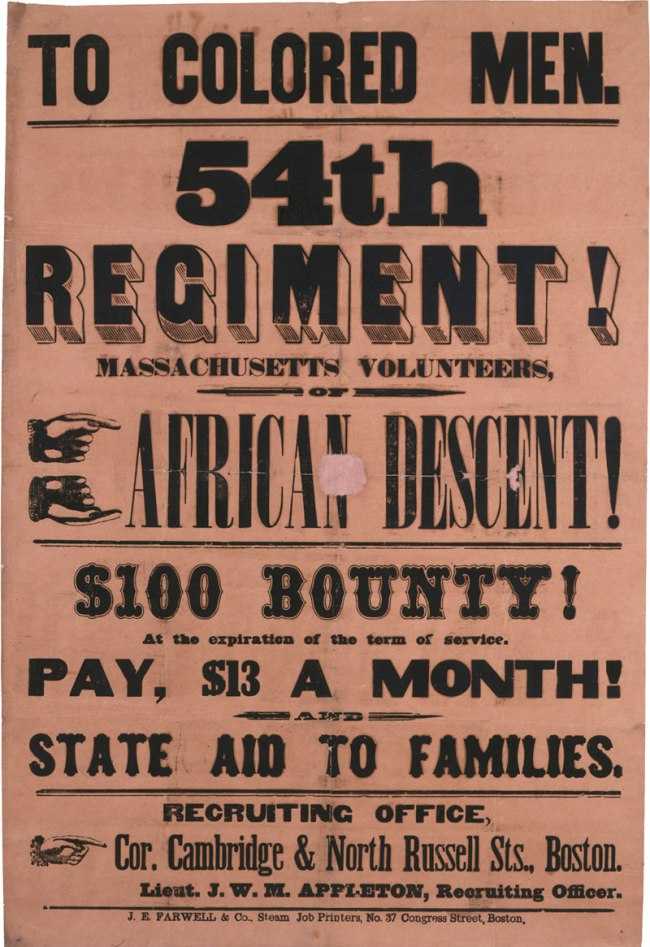

Since the earliest days of the medium, photographs have been used for criminal investigation and evidence gathering, to record crime scenes, to identify suspects and abet their capture, and to report events to the public. This exhibition explores the multifaceted intersections between photography and crime, from 19th-century “rogues’ galleries” to work by contemporary artists inspired by criminal transgression. The installation will feature some 70 works, drawn entirely from The Met collection, ranging from the 1850s to the present.

Among the highlights of the installation is Alexander Gardner’s documentation of the events following the assassination of President Lincoln, as well as rare forensic photographs by Alphonse Bertillon, the French criminologist who created the system of criminal identification that gave rise to the modern mug shot. Also on display is a vivid selection of vintage news photographs related to cases both obscure and notorious, such as a study of John Dillinger’s feet in a Chicago morgue in 1934; Jack Ruby shooting Lee Harvey Oswald in 1963; and Patty Hearst captured by bank surveillance cameras in 1974. In addition to exploring photography’s evidentiary uses, the exhibition will feature work by artists who have drawn inspiration from the criminal underworld, including Richard Avedon, Larry Clark, Walker Evans, John Gutmann, Andy Warhol, and Weegee.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

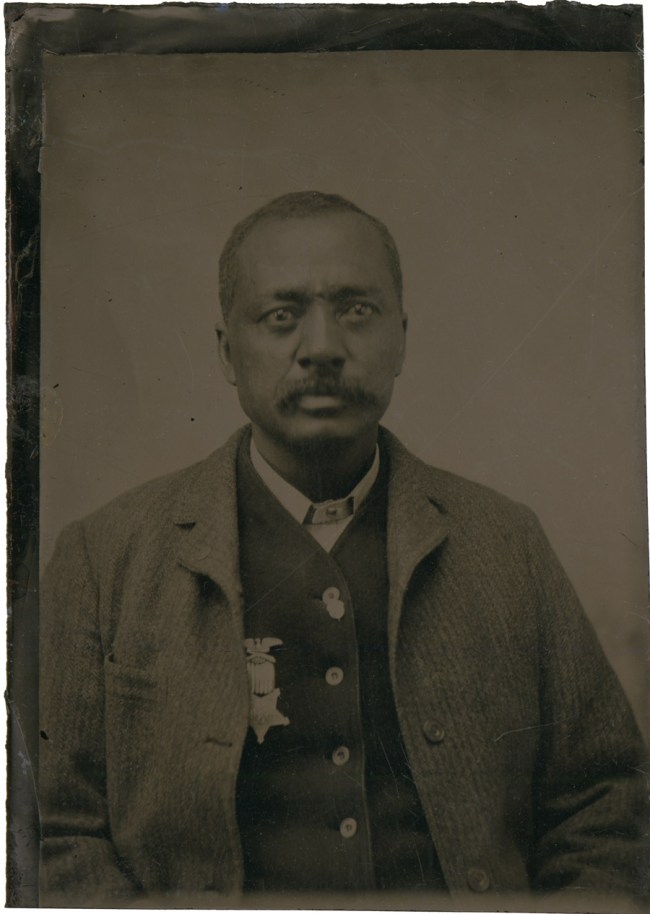

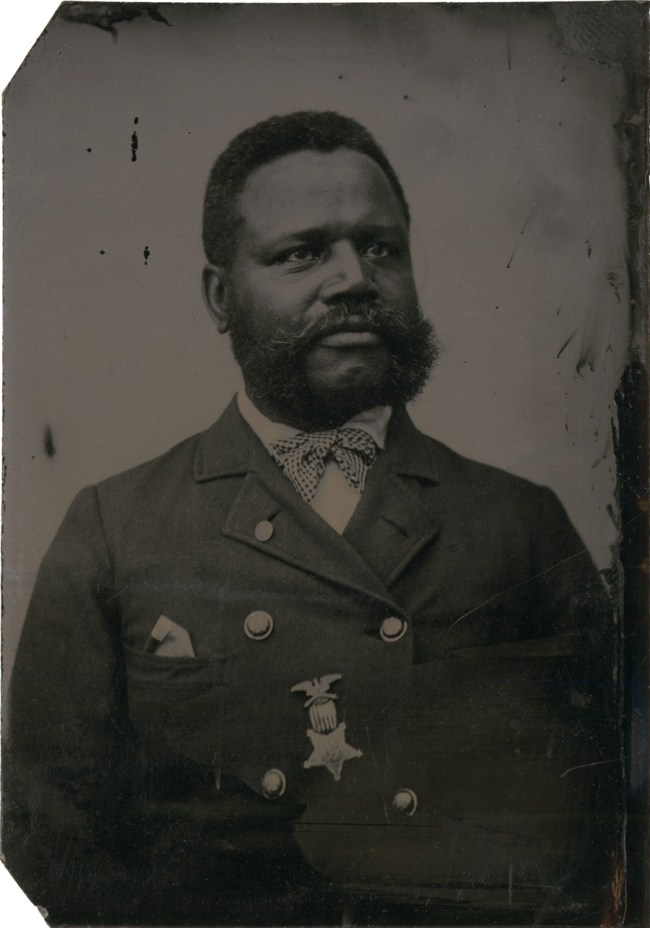

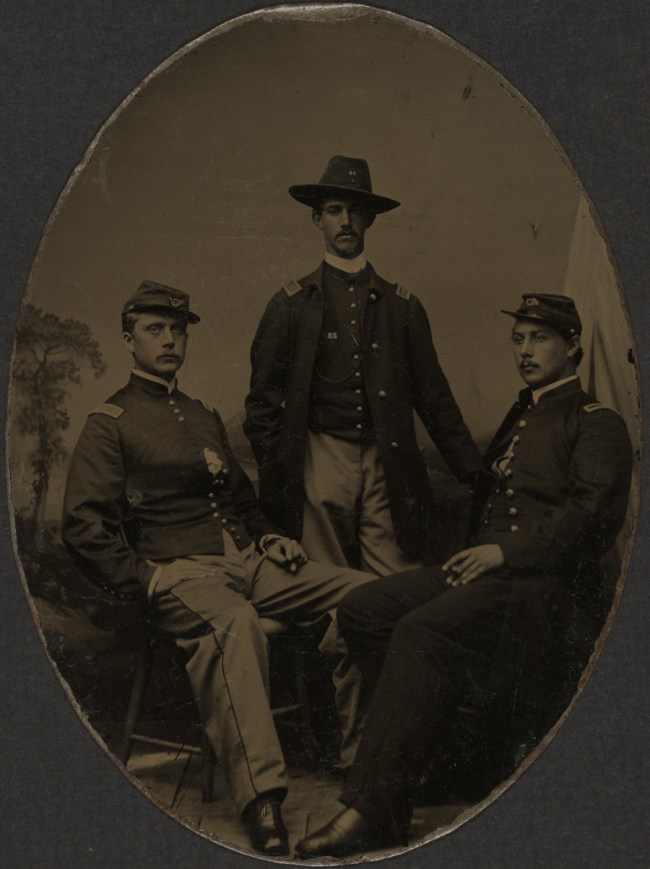

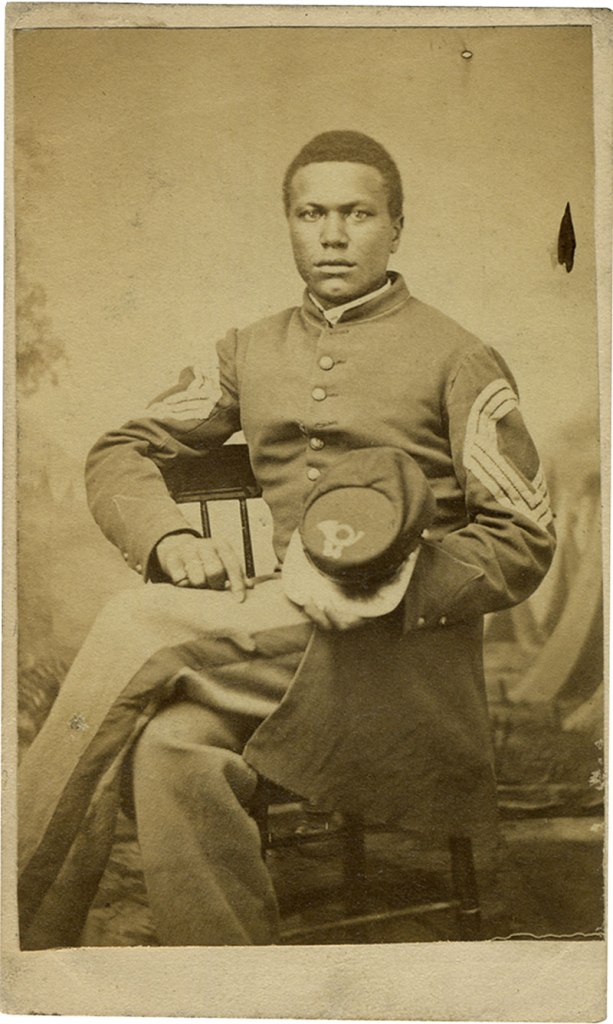

Unknown photographer (American)

[John Dillinger’s Feet, Chicago Morgue]

1934

Gelatin silver print

4 11/16 x 7 13/16 in. (11.9 x 19.8cm)

Purchase, The Marks Family Foundation Gift, 2001

© Bettmann / CORBIS

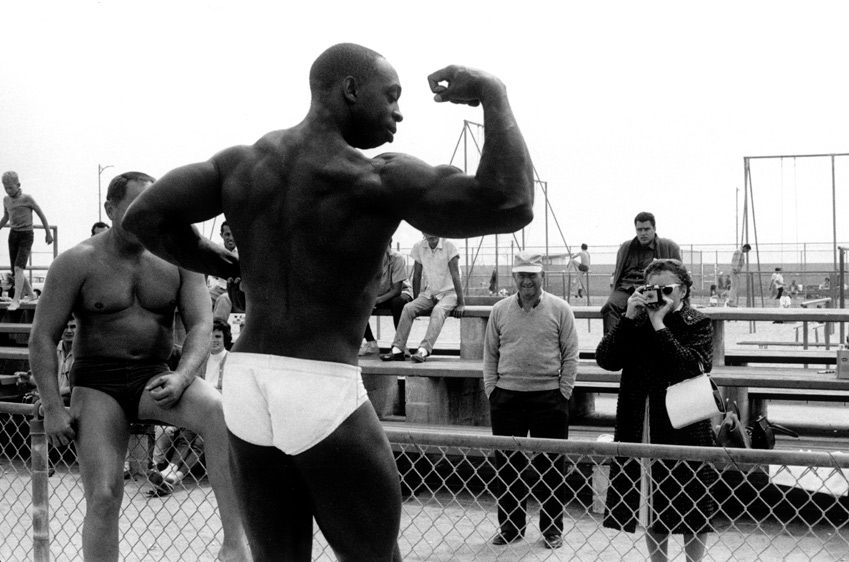

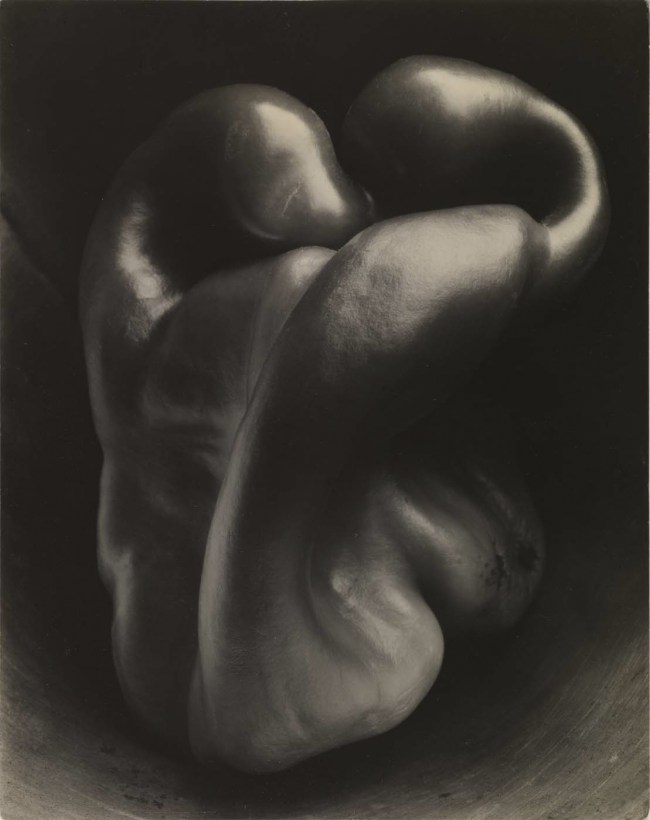

This press photo of John Dillinger, the celebrity gangster from Chicago shot down at age 31, morbidly embodies the twentieth-century’s obsession with fame and hunger for physical contact with media personae. As the Depression era’s most successful bank robber, Dillinger had become a folk hero for his brash, cocky manner and disregard for authority. This unflinching view of Dillinger laid out on a slab in the Chicago morgue not only bares the facts but ironically recalls Mantegna’s The Lamentation Over the Dead Christ (c. 1490).

John Dillinger & “Baby Face” Nelson Hunted by FBI

Unknown photographer (American)

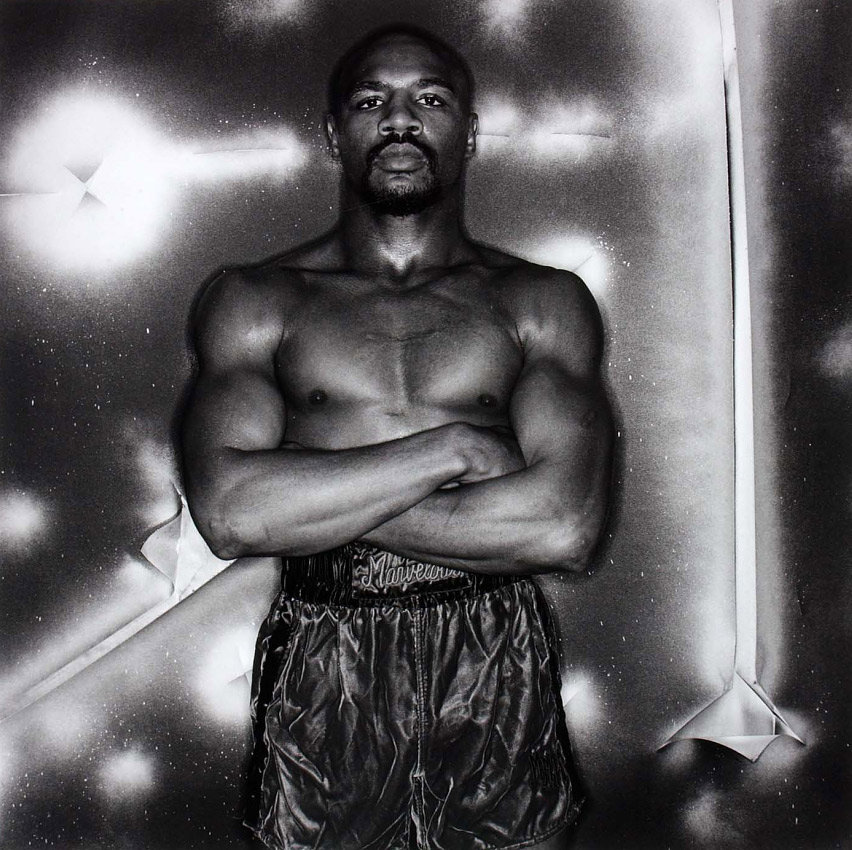

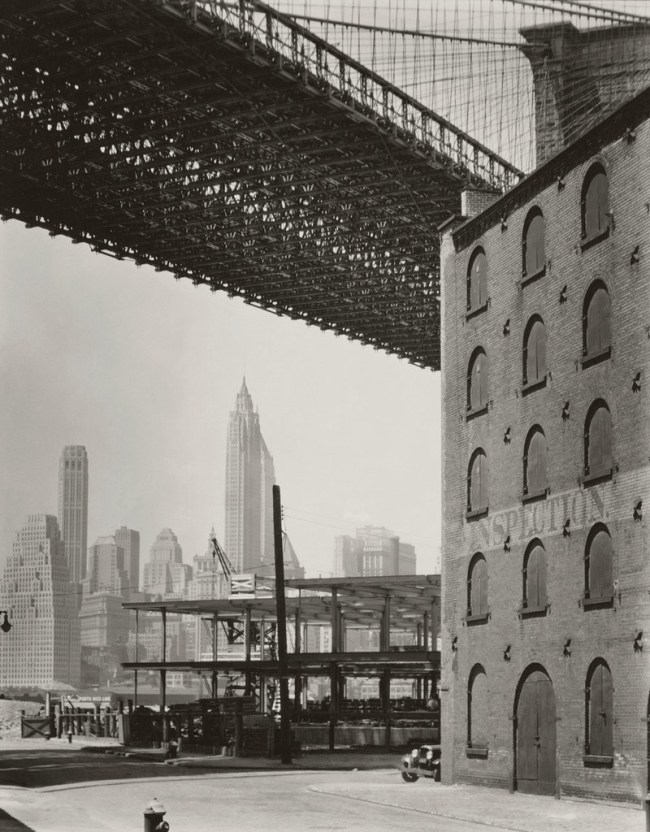

[Jeff Briggs, Robert Sims, Otis Hall, and Peter Pamphlet; Full-Length Mugshot from the Chicago Police Department]

1936

Gelatin silver prints

Image: 5 15/16 × 9 1/8 in. (15.1 × 23.1cm)

Sheet: 6 1/8 × 9 5/16 in. (15.6 × 23.6cm)

Twentieth-Century Photography Fund, 2014

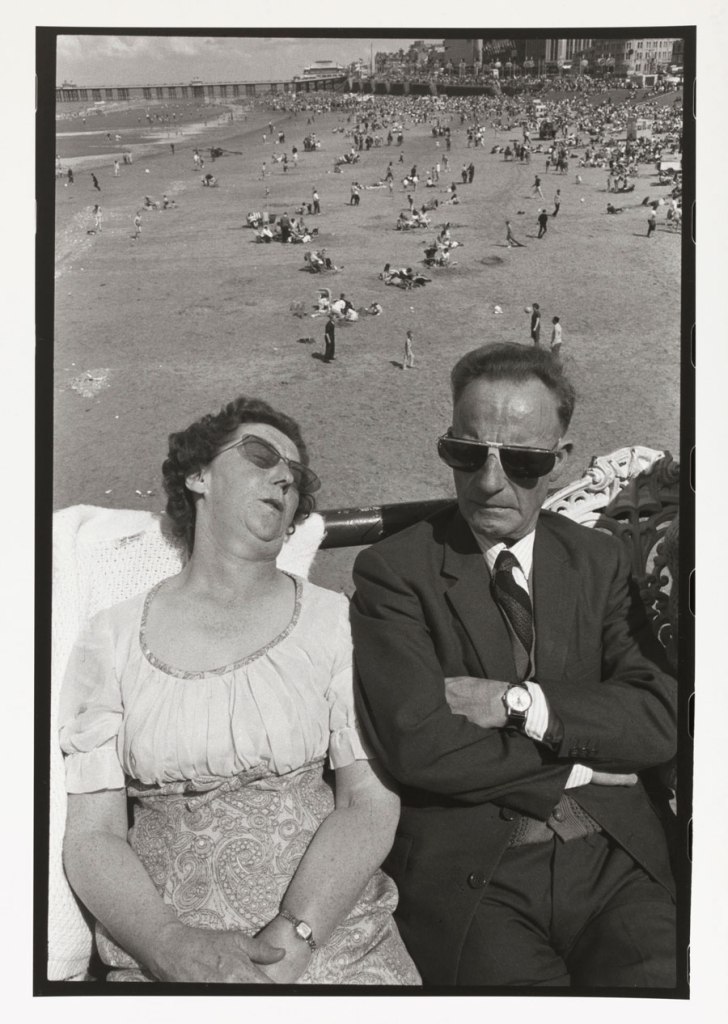

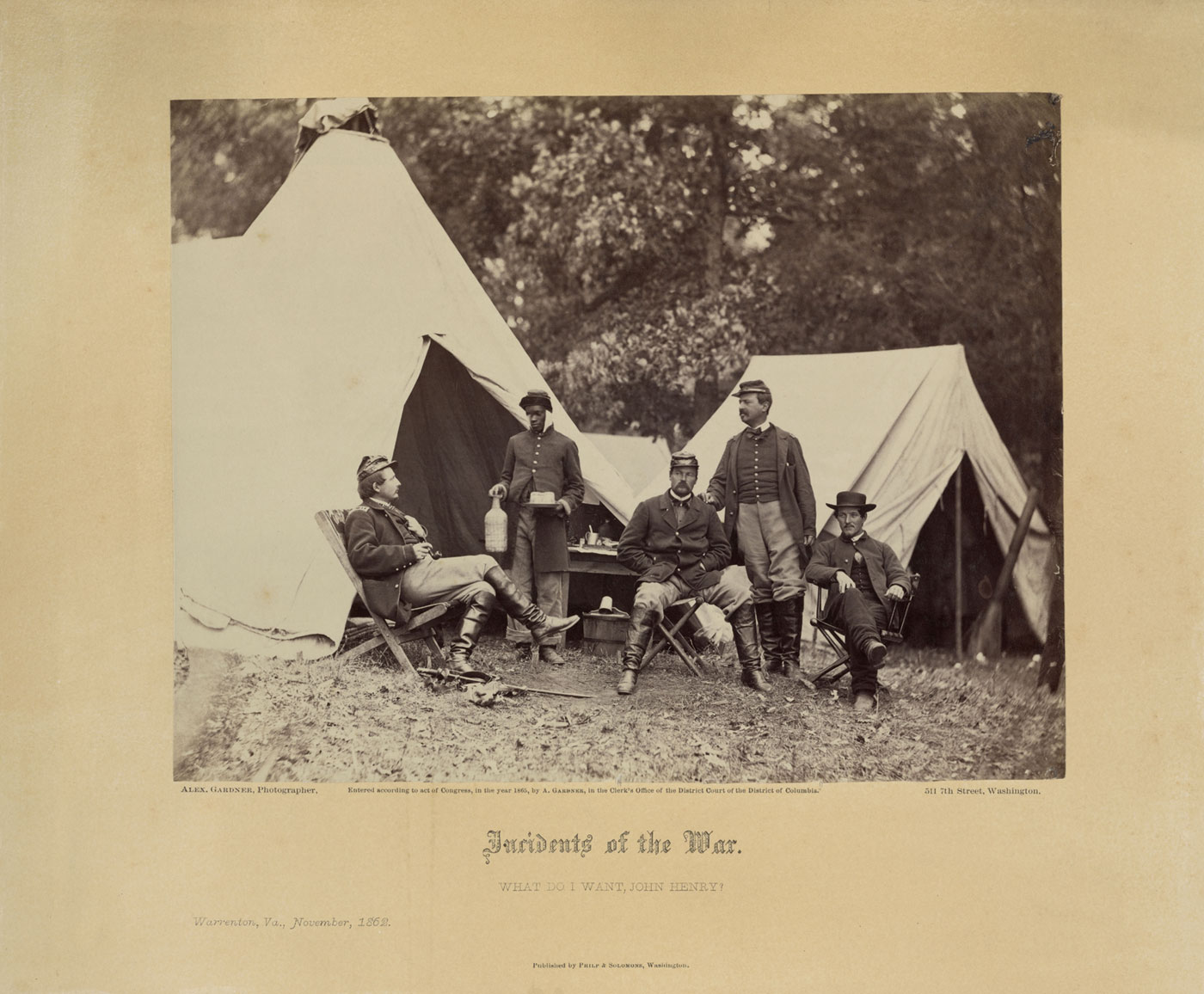

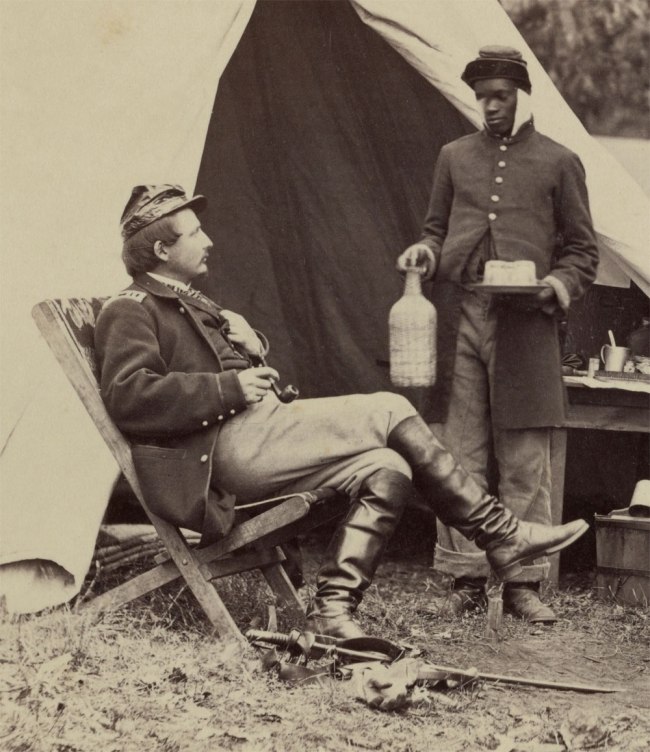

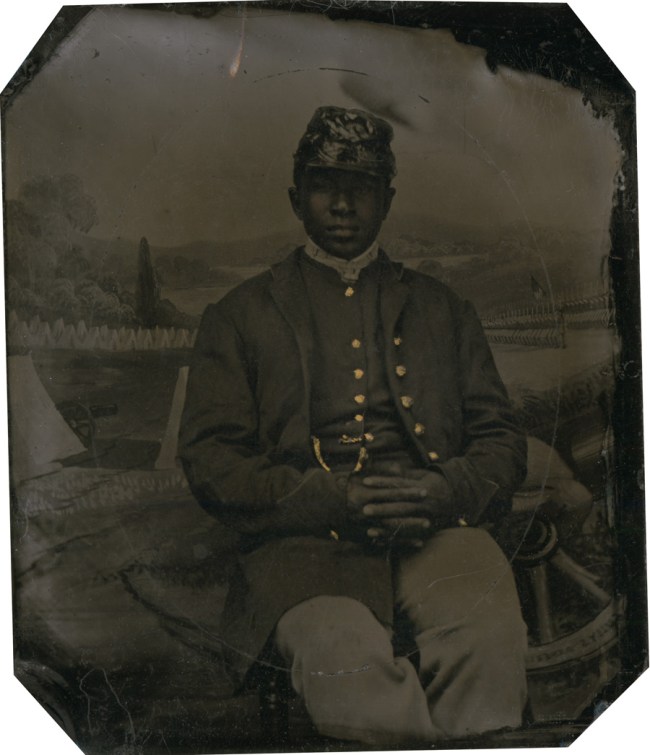

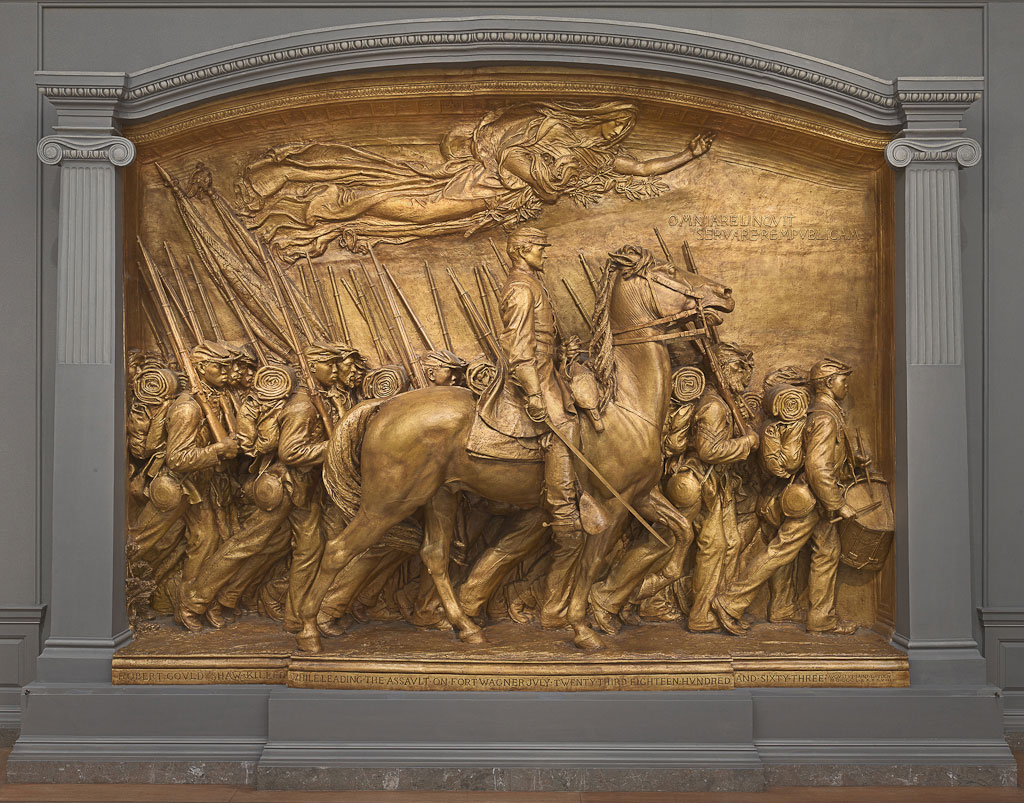

The Chicago Police Department likely made these discarded file photographs when arrested suspects entered the precinct for booking. Each is accompanied by a typewritten caption recording the subjects’ names, vital statistics, and, in some cases, the crimes for which they were arrested (carrying concealed weapons, assault and robbery at gunpoint). With their subjects lined up theatrically against a dark velvet curtain, the images vividly evoke an era and milieu familiar to fans of film noir and hard-boiled detective fiction of the 1930s and 1940s.

A similar defiant dignity is evident in two booking photographs taken by the Chicago Police Department, part of a series made between 1936 and 1946. In the first, four black men in suits line up in front of what seems to be a theatre curtain. In the second, they strike the same pose, now in longer coats and with hats, as if auditioning for different parts in the same play. One of the men smiles affably, a flash of personality in a process meant to cloak it. The others look out evenly, returning the camera’s gaze and reminding whoever is behind the shutter that they, too, have the power to see.

Walker Evans (American, St. Louis, Missouri 1903 – 1975 New Haven, Connecticut)

[Subway Passengers, New York City]

1938

Gelatin silver print

12.2 x 15.0cm (4 13/16 x 5 15/16 in.)

Gift of Arnold H. Crane, 1971

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

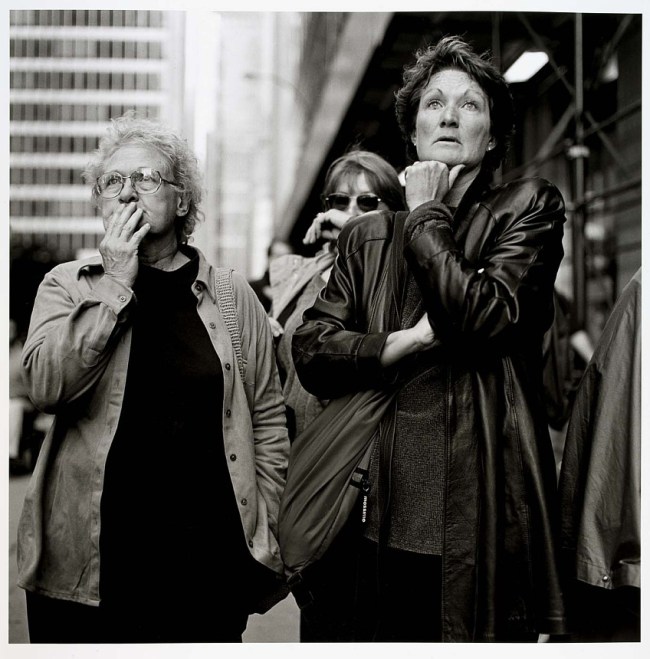

“Ladies and gentlemen of the jury,” Evans called his unwitting subjects. In this example, a smirking, vaguely menacing young man is engrossed in his copy of the Daily News. PAL TELLS HOW GUNGIRL KILLS, reads the headline. An obese woman, obviously not an acquaintance, sits miserably beside him.

During the winter months between 1938 and 1941, Evans strapped a camera to his midsection, cloaked it with his overcoat, and snaked a cable release down his suit sleeve to photograph New York City subway passengers unawares. In his book of these unposed portraits, Many Are Called (1966), the artist referred to his quarry as “the ladies and gentlemen of the jury.” What he was after stylistically, though, was more in keeping with the criminal mug shot: frontal and without emotional inflection. In this photograph, the tabloid headline “PAL TELLS HOW GUNGIRL KILLED” across the newspaper nods to Evans’s interest in vernacular source material.

Inspired by the incisive realism of Honoré Daumier’s Third-Class Carriage, Walker Evans sought to avoid the vanity, sentimentality, and artifice of conventional studio portraiture. The subway series, he later said, was “my idea of what a portrait ought to be: anonymous and documentary and a straightforward picture of mankind.”

Walker Evans’ candid photos of 1930s subway passengers are early conceptual art | Art, Explained

“I think it is one of the first conceptual art projects that I’m aware of.”

Art, Explained invites 100 curators from across the Museum to talk about 100 works of art that changed the way they see the world.

Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American born Ukraine (Austria), Złoczów (Zolochiv) 1899 – 1968 New York)

A Bunch of Cops

1940s

Gelatin silver print

Gift of Bruce A. Kirstein, in memory of Marc S. Kirstein, 1978

© Weegee / International Center of Photography

In Cold Blood – Trailer

IN COLD BLOOD dramatises actual events and people in a realistic, technically well-crafted fashion, based upon Truman Capote’s novel. The movie is a faithful docudrama about the real-life mass murder of the Clutter family, which took place in Holcomb, Kansas on November 15, 1959 by two psychopathic killers. © 1967, renewed 1995 Pax Enterprises, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

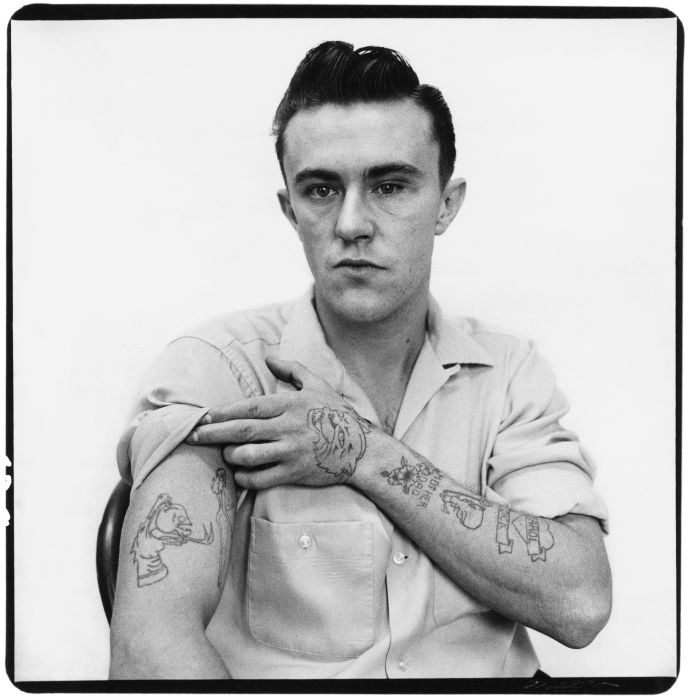

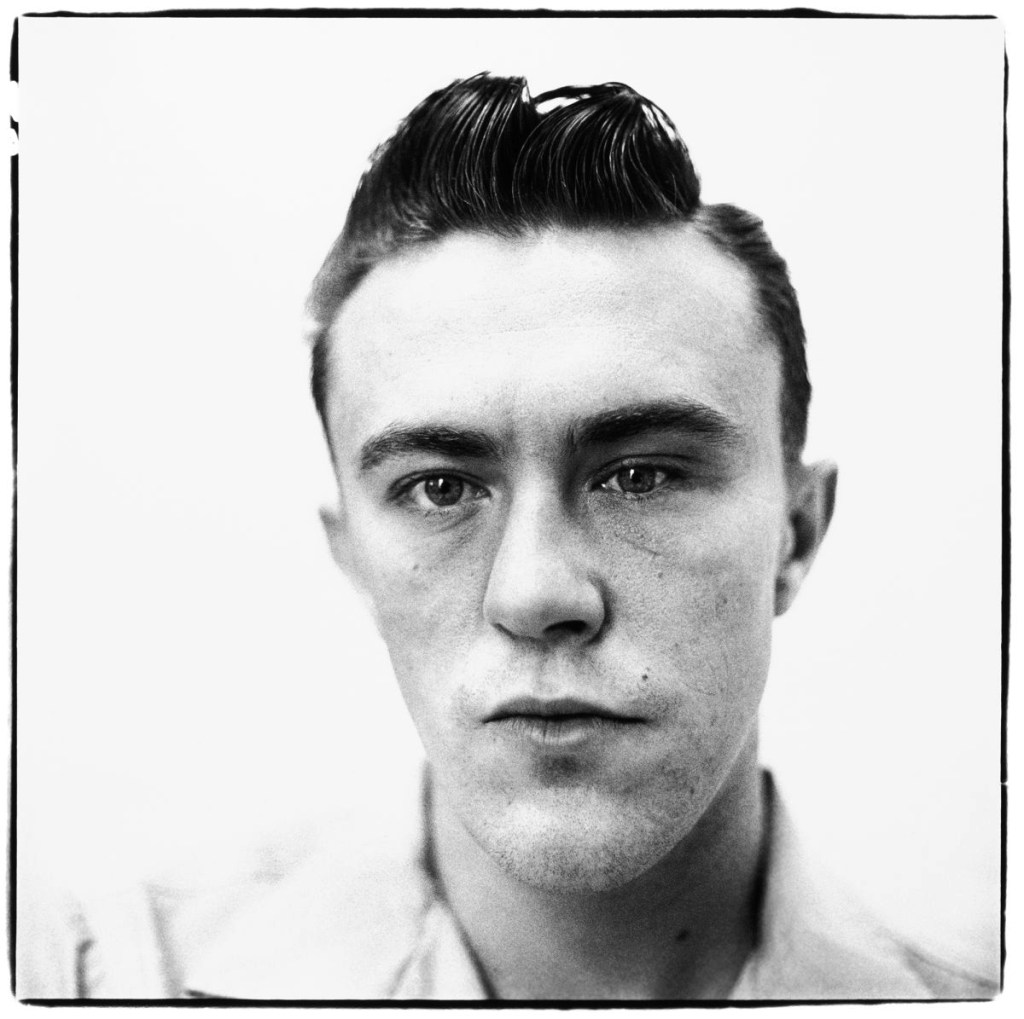

Richard Avedon (American, New York 1923 – 2004 San Antonio, Texas)

Dick Hickock, Murderer, Garden City, Kansas

April 1960

Gelatin silver print

Image: 50.8 x 50.8cm (20 x 20 in.)

Frame: 59.7 x 59.7cm (23 1/2 x 23 1/2 in.)

Gift of the artist, 2002

© Richard Avedon

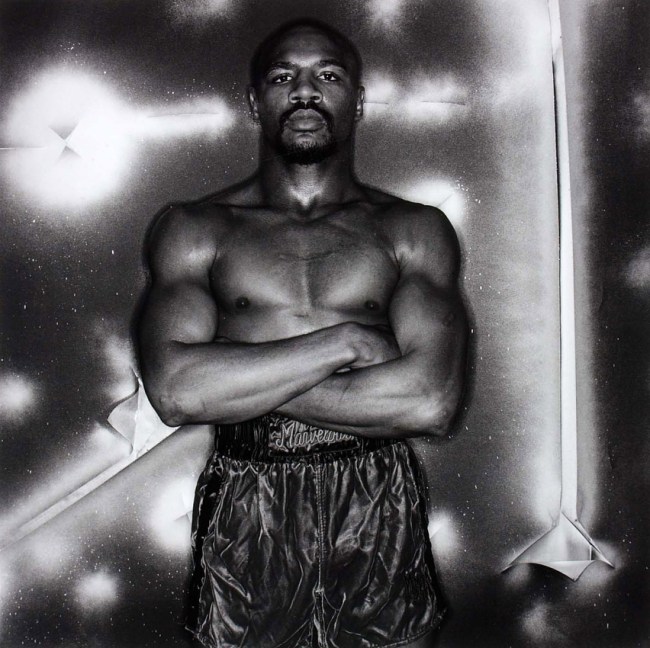

In April 1960 Avedon traveled to Garden City, Kansas, to photograph the individuals connected with the savage murder of the four-member Clutter family in their remote farmhouse. He came at the request of his friend Truman Capote, who was there gathering material for his groundbreaking true-crime novel In Cold Blood (1966). Working with a handheld Rolleiflex camera, Avedon made this striking photograph of one of the killers, Richard “Dick” Hickcock, while he was in jail awaiting trial. The mug shot-like portrait captures Hickock’s sullen, lopsided face with mesmerising clarity, as if searching for physiognomic clues to his criminal pathology.

“One of the show’s most striking pictures is a Richard Avedon portrait of Dick Hickock, one of the two murderers immortalized in Truman Capote’s true-crime touchstone “In Cold Blood.” Hickock and Perry Smith, both ex-convicts out on parole, had set out to rob the home of Herbert Clutter, a farmer in Holcomb, Kansas; when they didn’t find the safe they’d been looking for, they killed Clutter, his wife, and his two children. Looking at Hickock’s mug shot, Capote writes, the wife of the case’s investigator is reminded “of a bobcat she’d once seen caught in a trap, and of how, though she’d wanted to release it, the cat’s eyes, radiant with pain and hatred, had drained her of pity and filled her with terror.” Here, Hickock gets the soft-focus celebrity treatment, the line between notoriety and fame as blurred as ever. Hickock, according to Capote, had always been self-conscious about his long, lopsided face. His nose juts out at a Picasso angle, and while his right eye meets Avedon’s lens straight on, his smaller left one seems to look inward. The result is a double portrait, part persona, part awkward, vulnerable self, both haunted by Capote’s own verbal portrait of Hickock’s victims, the Clutter family, at their funeral: “The head of each was completely encased in cotton, a swollen cocoon twice the size of an ordinary blown-up balloon, and the cotton, because it had been sprayed with a glossy substance, twinkled like Christmas-tree snow.”

Alexandra Schwartz. “The Long Collusion of Photography and Crime,” on The New Yorker website April 9 2016 [Online] Cited 15/07/2016

Richard Avedon (American, New York 1923 – 2004 San Antonio, Texas)

Dick Hickock, Murderer, Garden City, Kansas

April 1960

Gelatin silver print

Image: 50.8 x 50.8cm (20 x 20 in.)

Frame: 59.7 x 59.7cm (23 1/2 x 23 1/2 in.)

Gift of the artist, 2002

© Richard Avedon

“Richard Avedon is represented by his 1960 portrait of Dick Hickock, the Kansas murderer who was one of the subjects of Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood. In his typical style, Avedon presents a large-scale investigation of Hickock’s face: the black greased pompadour combed just so, the slightly fleshy nose, the disturbingly engaging eyes, all of it ever so slightly skewed by the impression of Hickock’s inscrutable lopsided grievance. (Hickock had suffered a brain injury in an automobile accident when he was nineteen.) As with Gardner’s 1865 portrait of Lewis Powell (who was also executed by hanging for his crime), you sense how seriously Hickock takes being photographed, his wish to give something of himself, to influence, if not control, the emanations of his image and how he is being portrayed.”

Michael Greenberg. “Caught in the Act,” on The New York Review of Books website, April 7, 2016 [Online] Cited 22/06/2016

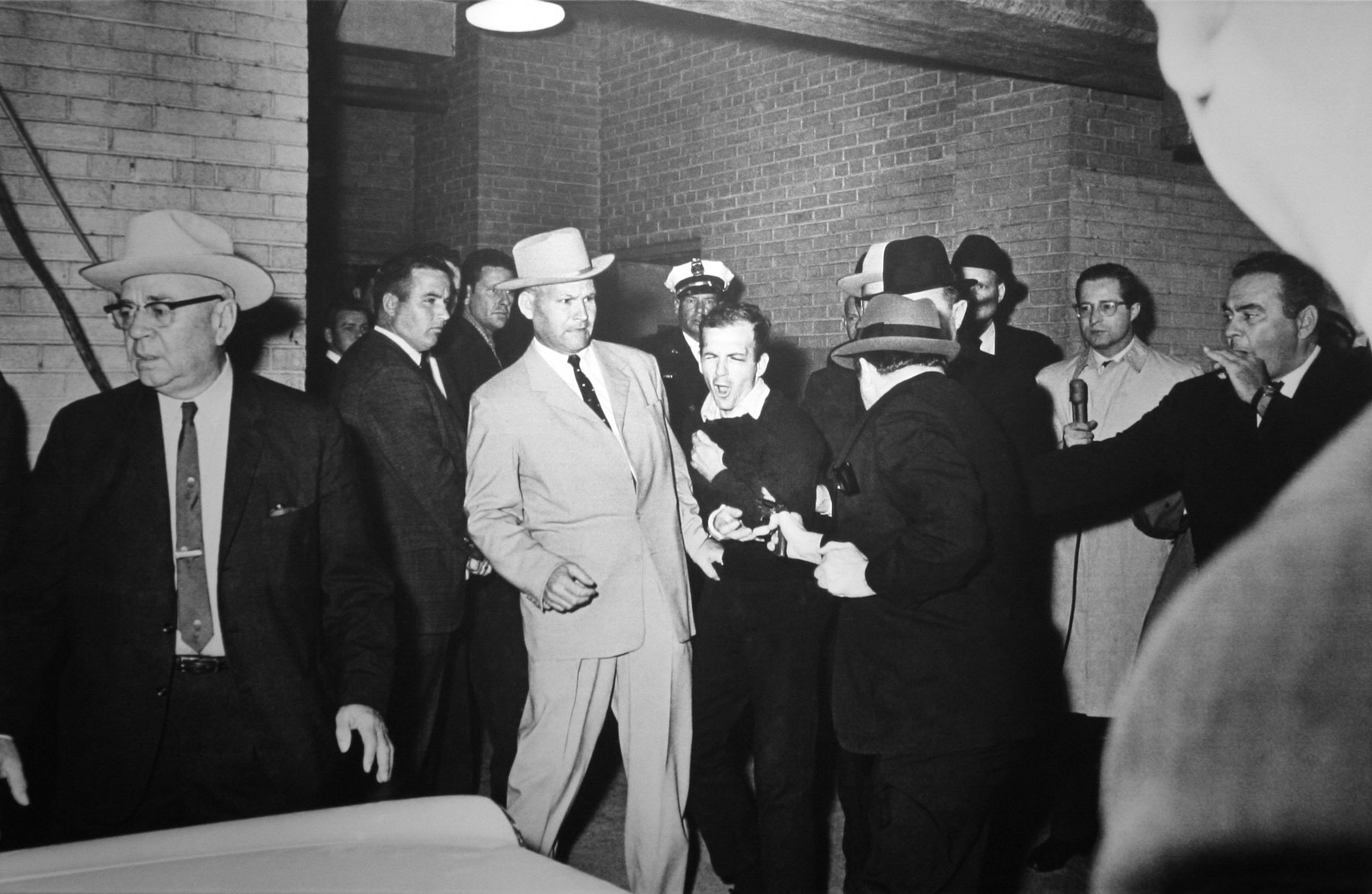

Robert H. Jackson (American, born 1934)

FATAL BULLET HITS OSWALD. Jack Ruby fires bullet point blank into the body of Lee Harvey Oswald at Dallas Police Station. Oswald grimaces in agony

November 24, 1963

Gelatin silver print

Image: 16.8 x 19.5 cm (6 5/8 x 7 11/16 in.)

Sheet: 20.5 x 20.1 cm (8 1/16 x 7 15/16 in.)

Twentieth-Century Photography Fund, 2011

Before today’s fast-paced twenty-four hour news cycle, an eager American public followed the development of criminal investigations through the grey tones of press photographs. News outlets used a wire service to send images via in-house or portable transmitters, converting black-and-white tones into electrical pulses that were instantaneously received and printed using the same technology. Mundane courtroom proceedings, such as arraignments and evidence display, became newsworthy through the immediacy of reportage. Every small detail was devoured by a public impatient for news about notorious bank robbers and murderers – some of whom, like John Dillinger, were elevated to the status of folk heroes. In other instances, such as the assassinations of Robert F. Kennedy and Lee Harvey Oswald, newspapers and television brought the drama and intensity of firsthand observation into people’s homes.

Boris Yaro (American, 1938-2020)

LOS ANGELES. KENNEDY MOMENTS AFTER SHOOTING. Sen. Robert F. Kennedy Lies Gravely Wounded on the floor at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles shortly after midnight today, moments after he was shot during a celebration of his victory in yesterday’s California primary election

June 5, 1968

Gelatin silver print

17.2 x 21.1cm (6 3/4 x 8 5/16 in.)

Twentieth-Century Photography Fund, 2010

June 5, 1968: “Presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy lies on the floor at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles moments after he was shot in the head. He had just finished his victory speech upon winning the California primary. Times photographer Boris Yaro was standing 3 feet from Kennedy when the shooting began. “The gunman started firing at point-blank range. Sen. Kennedy didn’t have a chance,” Yaro recounted in a June 6, 1968, story for The Times. The Democratic senator, 42, was alive for more than 24 hours and was declared dead on the morning of June 6. The shooter was later identified as Sirhan B. Sirhan, who was found guilty of Kennedy’s assassination on April 17, 1969. His motives remain a mystery and controversy to this day.”

1964 Pulitzer Prize, Photography, Robert Jackson, Dallas Times Herald November 22, 1963

Andy Warhol (American, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 1928 – 1987 New York)

Electric Chair

1971

Printer: Silkprint Kettner, Zurich

Publisher: Bruno Bischofberger

Portfolio of ten screenprints

35 1/2 x 48 inches (90.2 x 121.9cm)

Gift of Robert Meltzer, 1972

Assassination of Monsieur V. Lecomte, 74 Rue des Martyrs, 1902 (and detail)

Assassination of Monsieur V. Lecomte, 74 Rue des Martyrs, 1902 (and detail)

Assassination of Monsieur V. Lecomte, 74 Rue des Martyrs, 1902 (and detail)

Assassination of Monsieur V. Lecomte, 74 Rue des Martyrs, 1902 (and detail)

Murder of Madame Veuve Bol, Projection on a Vertical Plane (and detail)

1st November 1902. Assassination of Mademoiselle Mercier, Rue de l’Yvette á Bouvry la Reine. Photograph of the corpse.

Place where the corpse was found (and detail)

House of the victim (and detail)

Attributed to Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914)

[Album of Paris Crime Scenes]

1901-1908

Gelatin silver prints

Overall: 24.3 x 31cm (9 9/16 x 12 3/16in.)

Page: 23 x 29cm (9 1/16 x 11 7/16 in.)

Gilman Collection, Purchase, The Howard Gilman Foundation Gift, 2001

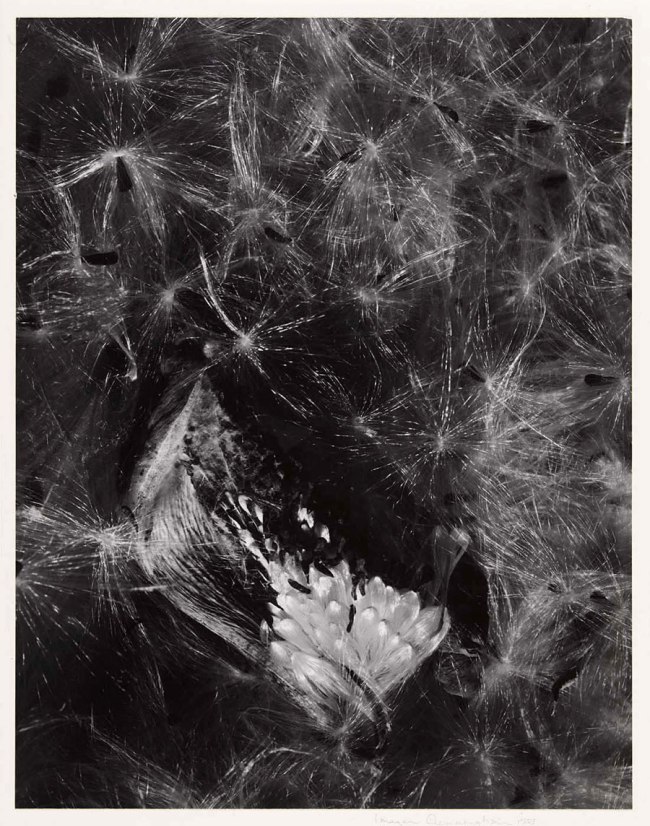

Alphonse Bertillon, the chief of criminal identification for the Paris police department, developed the mug shot format and other photographic procedures used by police to register criminals. Although the images in this extraordinary album of forensic photographs were made by or under the direction of Bertillon, it was probably assembled by a private investigator or secretary who worked at the Paris prefecture. Photographs of the pale bodies of murder victims are assembled with views of the rooms where the murders took place, close-ups of objects that served as clues, and mug shots of criminals and suspects. Made as part of an archive rather than as art, these postmortem portraits, recorded in the deadpan style of a police report, nonetheless retain an unsettling potency.

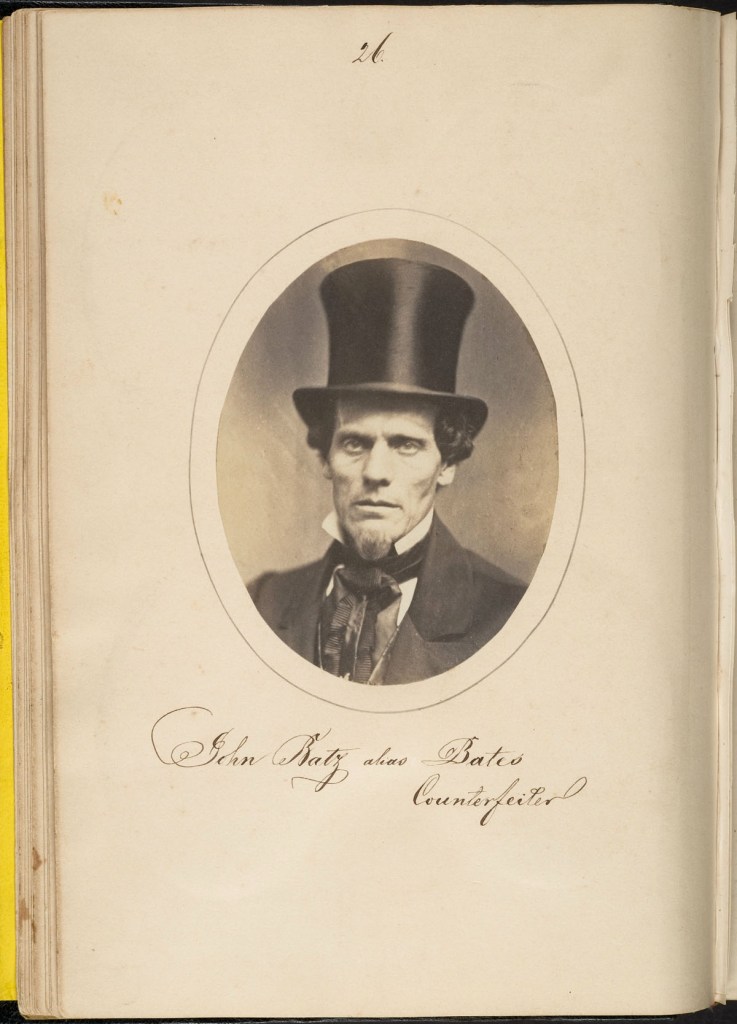

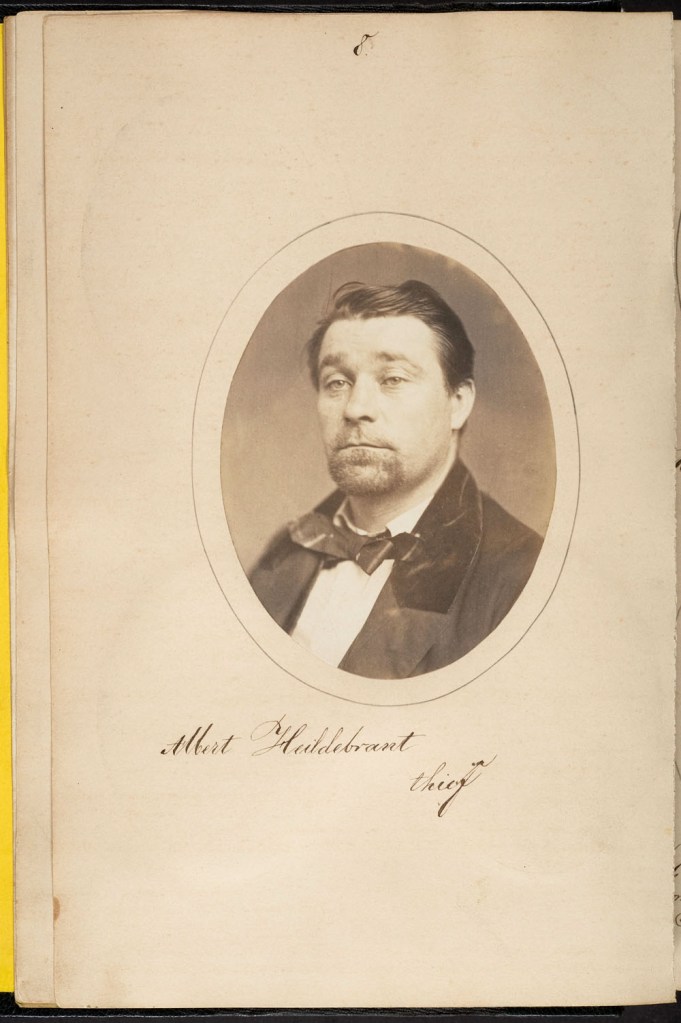

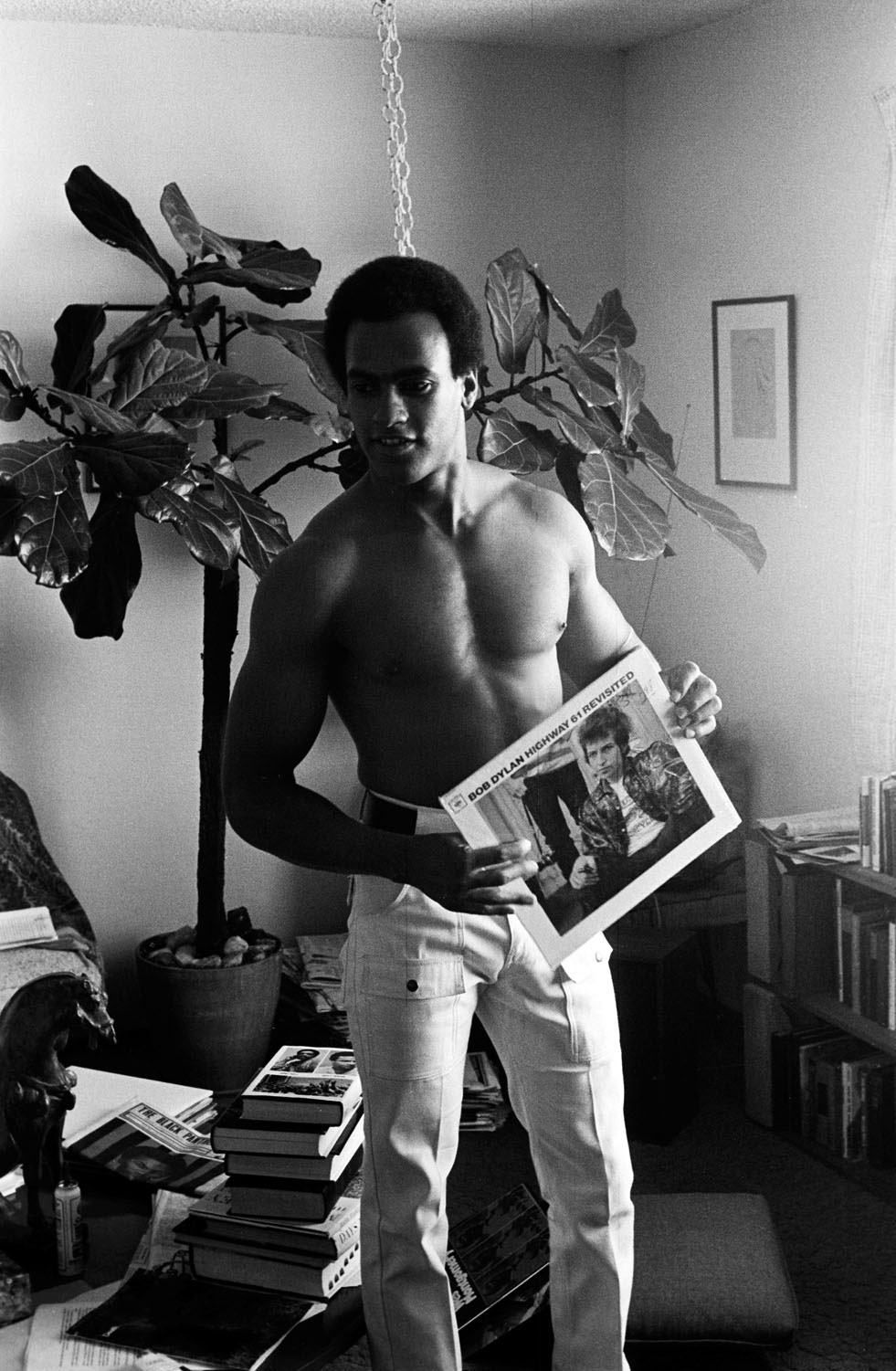

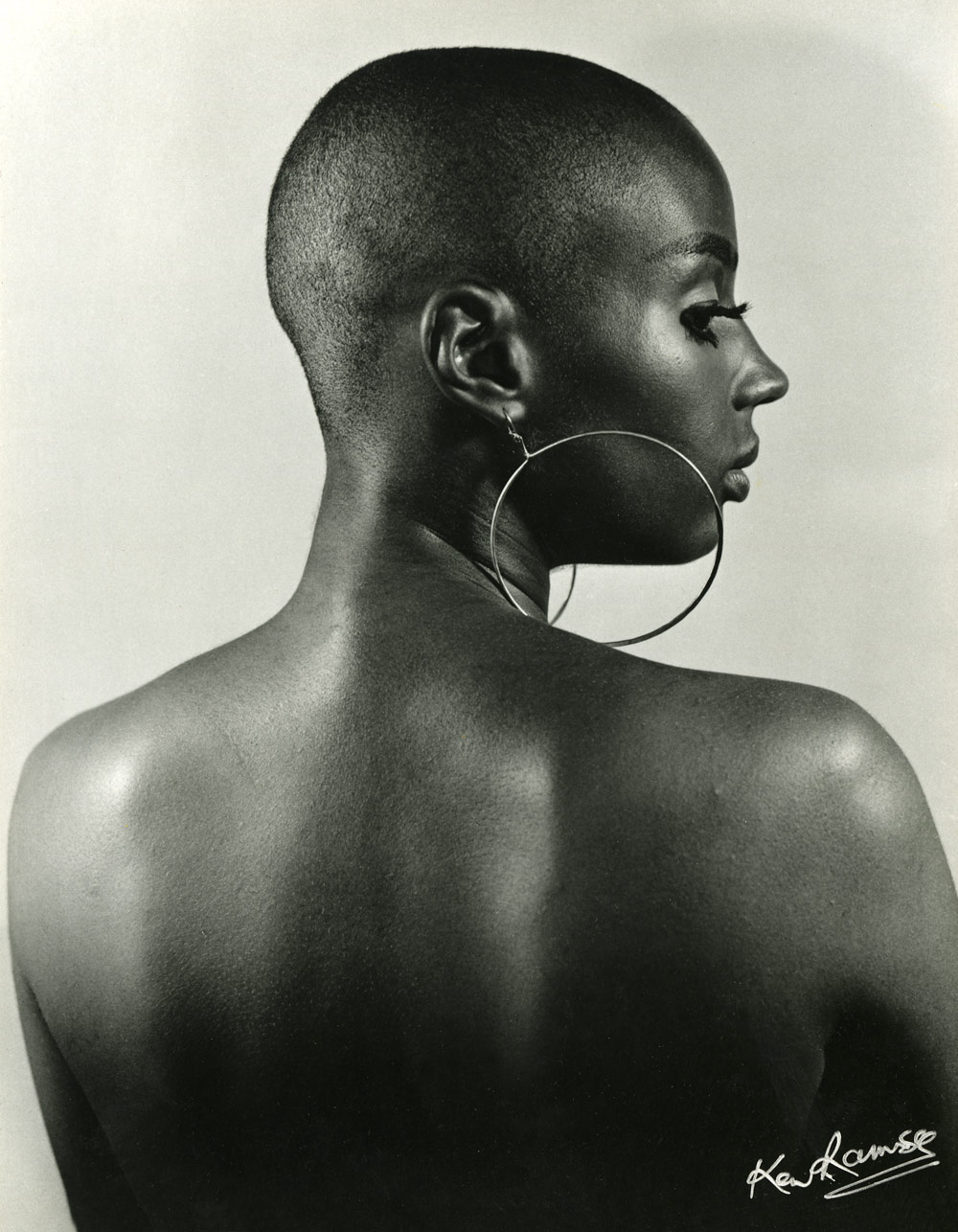

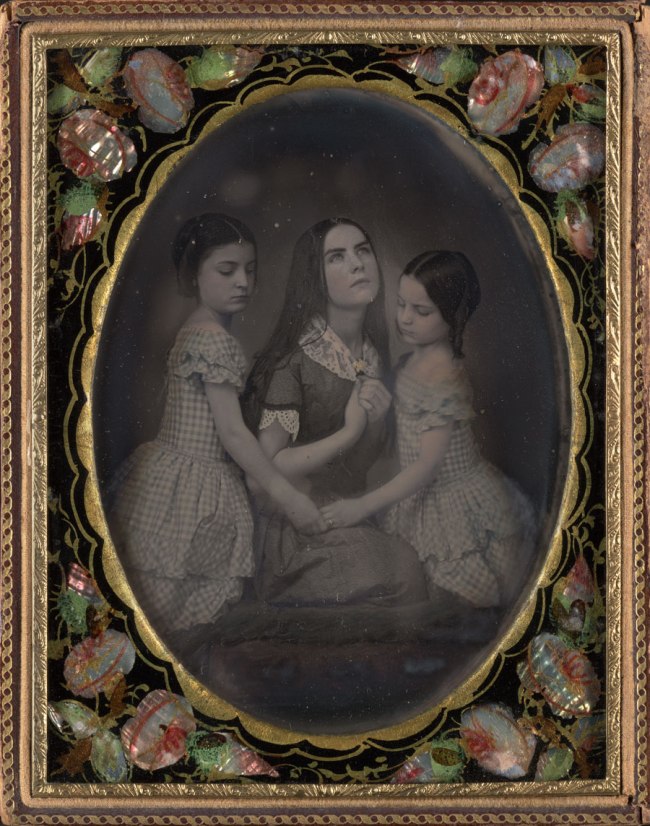

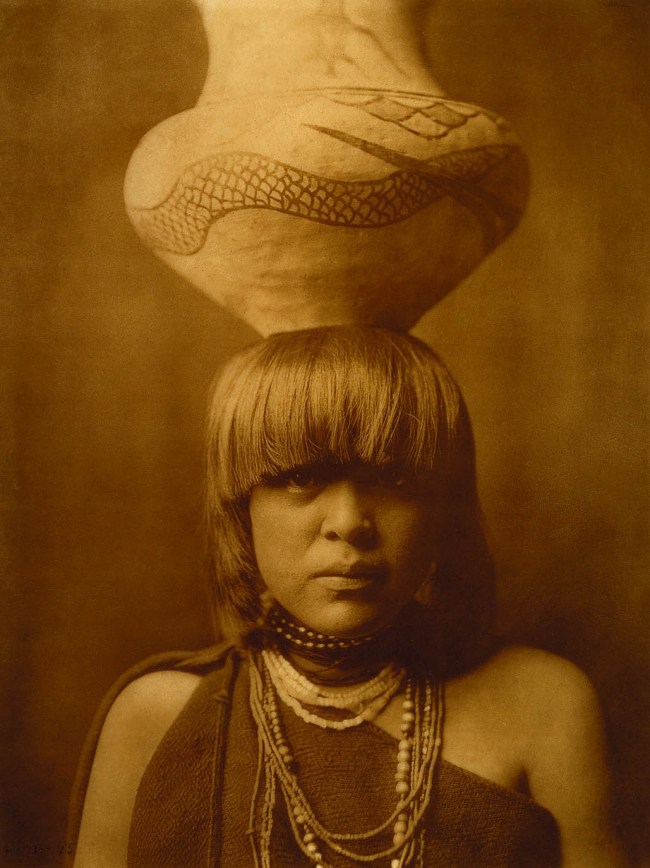

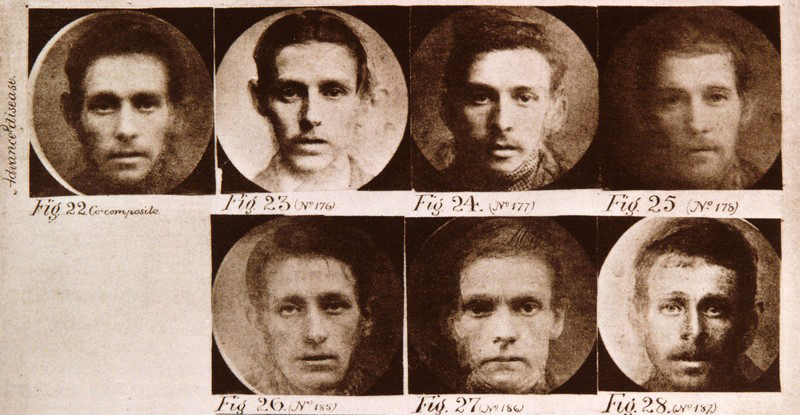

Samuel G. Szabó (Hungarian, active America c. 1854-1861)

Rogues, a Study of Characters

c. 1860

Salted paper prints from glass negatives

From 8.8 x 6.6cm (3 7/16 x 2 5/8 in.) to 11.5 x 8.8cm (4 1/2 x 3 7/16 in.)

Gilman Collection, Purchase, Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee Gift, 2005

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Lifter, wife poisoner, forger, sneak thief; cracksman, pickpocket, burglar, highwayman; murderer, counterfeiter, abortionist – each found a place in this gallery of rogues. Photography was first put to service for the identification and apprehension of criminals in the late 1850s. In New York, for example, 450 photographs of known criminals could be viewed by the public in a real rogues’ gallery at police headquarters, the portraits arranged by category, such as “Leading pickpockets, who work one, two, or three together, and are mostly English.”

Little is known of Samuel G. Szabó, his methods or his intentions. He appears to have left his native Hungary in the early or mid-1850s by necessity, but the reason for his exile remains a mystery.

In the United States Szabó moved frequently. Between May 1857 and his return to Europe in July 1861 he traveled to New Orleans, Cincinnati, Chicago, Saint Louis, Philadelphia, and New York, settling for a brief period in Baltimore, where he was listed in the city directory as a daguerreotypist. His whereabouts when he made this album are unknown. One may speculate that Szabó made these portraits while working for, or with the cooperation of, the police, and some of the 218 prints in the album appear to be copy prints made from other photographic portraits.

But this is more than a collection of mug shots; it is a study of characters by a “photogr[aphic] artist,” as Szabó signed the title page of this album. Just as Mathew Brady believed that portraits of America’s great men and women held clues to the nobility of their character and could serve as moral and political exemplars to those who contemplated them, others attempted to discern in photographs such as Szabó’s physical characteristics of the criminal psyche. Yet, as in Hugh Diamond’s portraits of the insane (no. 30), the reading of individual portraits is not always self-evident. Would the serious young man in the overcoat and silk top hat appear roguish without the caption “John McNauth alias Keely alias little hucks / Pick Pocket” below his portrait?

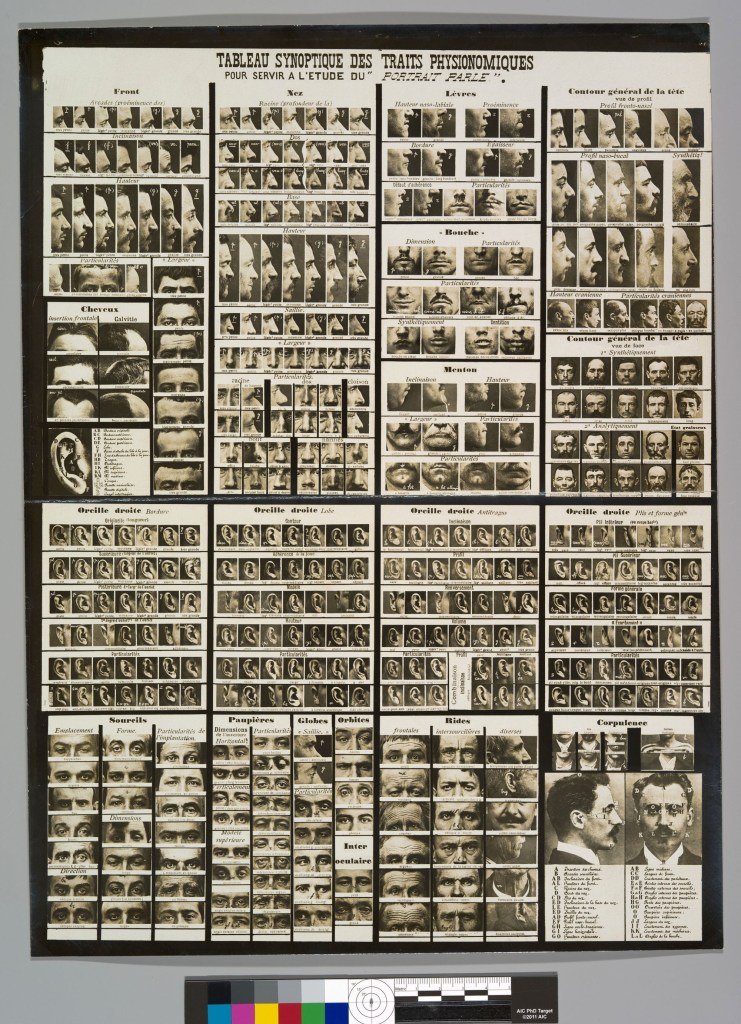

Eyebrows, eyelids, globes, orbits, wrinkles

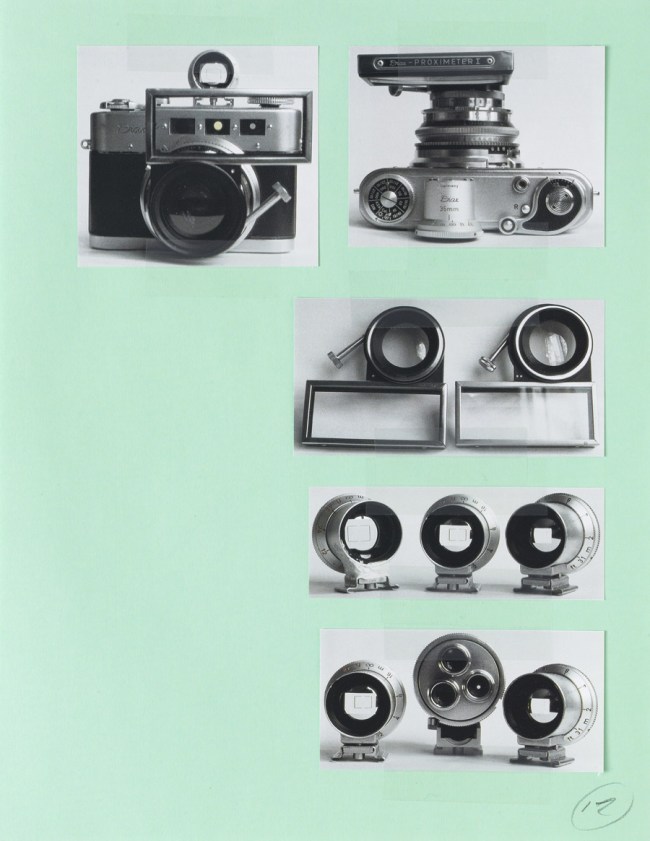

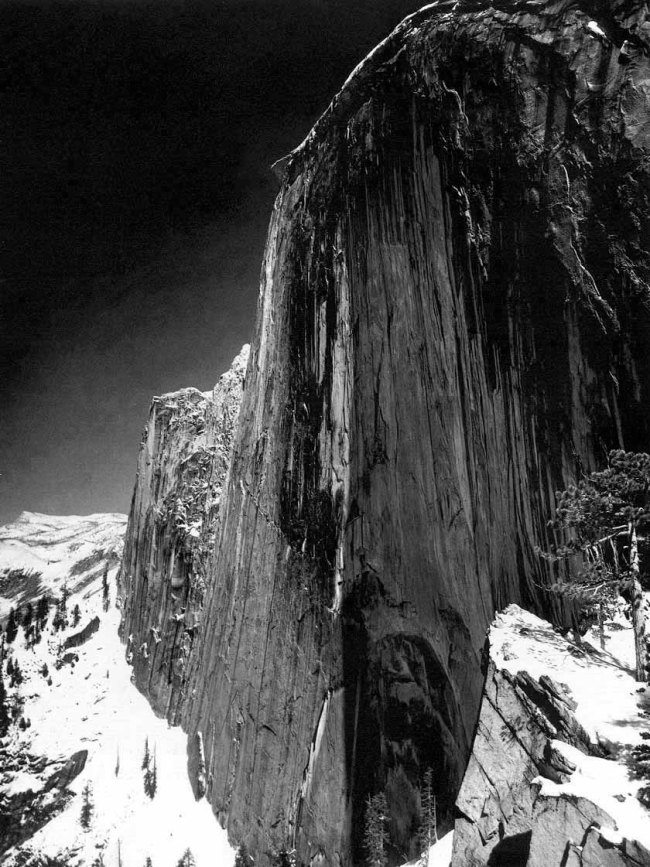

Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914)

Tableau synoptic des traits physionomiques: pour servir a l’étude du “portrait parlé” (and details)

c. 1909

Gelatin silver print

39.4 x 29.5cm (15 1/2 x 11 5/8 in.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Twentieth-Century Photography Fund, 2009

Nineteenth-century police headquarters were host to disorganised “rogues’ galleries” swollen with photographic portraits of criminals, which turned even the simplest of searches into a Sisyphean labor. As a response, police clerk Alphonse Bertillon introduced a rigorous system of classification, or signalment, to help organise archives, a process that included not only quantitative anthropometric measurements of the head, body, and extremities but also qualitative descriptions of the face. Photography’s potential for exactitude made it a crucial tool for Bertillon’s system, and his portrait parlé – the basis for today’s mugshot – posited a powerful analogy between a photographic likeness and the ink fingerprint.

Akin to a cheat-sheet for police clerks, this composite photograph illustrates how the mugshot could yield a series of classifications, dividing the male criminal’s face into discrete units of information. Such points of identification include the precise differentiation between left ear and right, the angle of inclination of the chin, and the pattern of the folds on the brow. Although intended merely as a filing aide, this image of the human face in all its striations of repetition and difference renders surveillance as a terrifying manifestation of the modern sublime.

“Bertillon’s other major legacy in the field of forensics was his invention of the mug shot. In the mid-nineteenth century, criminal photography focussed on identifying types of offenders; the exhibit’s earliest images are from an album of “rogues,” taken around 1860 in the United States by the photographer Samuel G. Szabó, who sought to distinguish the physiognomy of a counterfeiter from that of a “sneak thief,” a burglar, and a pickpocket. (Whatever revealing differences Szabó may have discerned, his subjects all look mad as hell to be stuck in his perp pictures.) Bertillon countered this hypothetical typology with empirical method, taking “anthropometric” measurements – determining the length of a convict’s middle finger, for example – as well as making elaborate verbal descriptions of a subject’s physical aspect, covering everything from his wrinkles to his eyelids, and two standardised photographs of his face, one from the front, one in profile.”

Alexandra Schwartz. “The Long Collusion of Photography and Crime,” on The New Yorker website April 9 2016 [Online] Cited 15/07/2016

Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914)

Véret. 0ctave-Jean. 19 ans, né à Paris XXe. Photographe. Anarchiste. 2/3/94

1894

Albumen silver print from glass negative

10.5 x 7 x 0.5cm (4 1/8 x 2 3/4 x 3/16 in.)

Gilman Collection, Museum Purchase, 2005

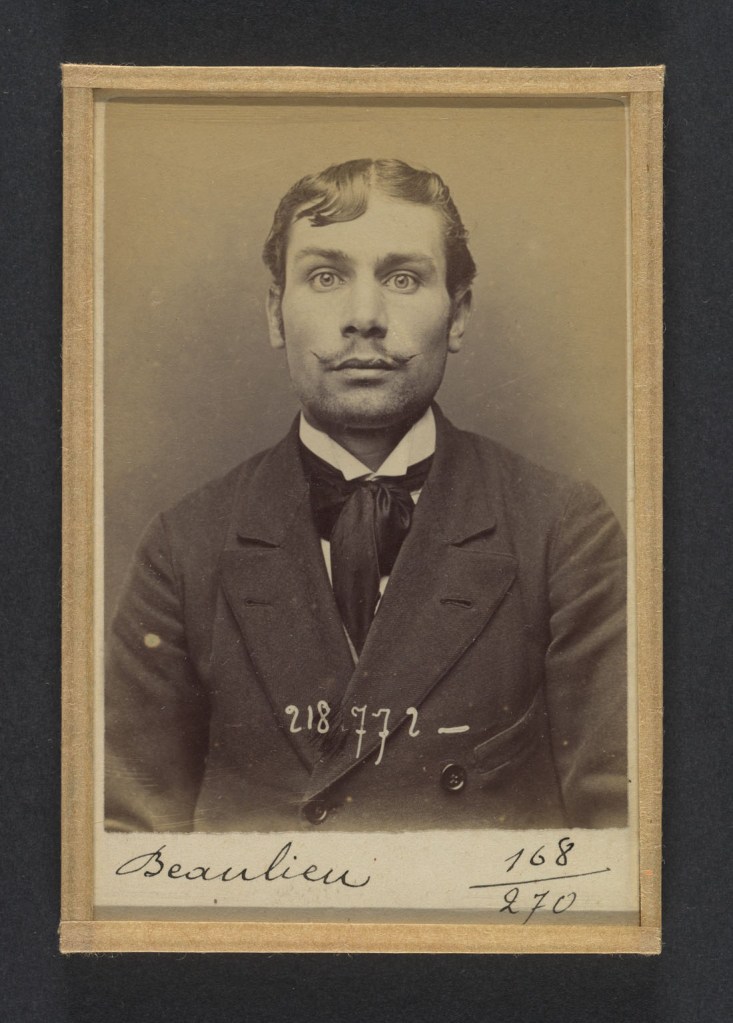

Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914)

Beaulieu. Henri, Félix, Camille. 23 ans, né le 30/11/70 à Paris Ve. Comptable. Anarchiste. 23/5/94

1894

Albumen silver print from glass negative

10.5 x 7 x 0.5cm (4 1/8 x 2 3/4 x 3/16 in.)

Gilman Collection, Museum Purchase, 2005

Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914)

Soubrier. Annette (femme Chericotti). 28 ans, né Paris Ille. Coutiére. Anarchiste. 25/3/94

1894

Albumen silver print from glass negative

10.5 x 7 x 0.5cm (4 1/8 x 2 3/4 x 3/16 in.)

Gilman Collection, Museum Purchase, 2005

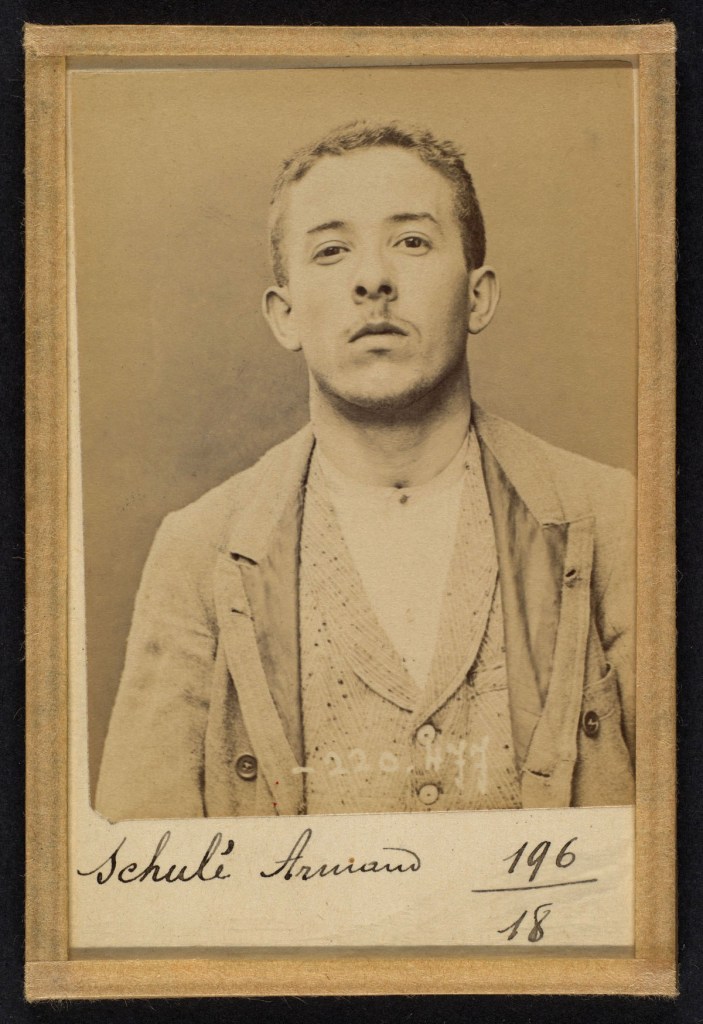

Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914)

Schulé. Armand. 21 ans, né le 28/2/73 Choisy-le-Roi. Comptable. Anarchiste. 2/7/94

1894

Albumen silver print from glass negative

10.5 x 7 x 0.5cm (4 1/8 x 2 3/4 x 3/16 in.)

Gilman Collection, Museum Purchase, 2005

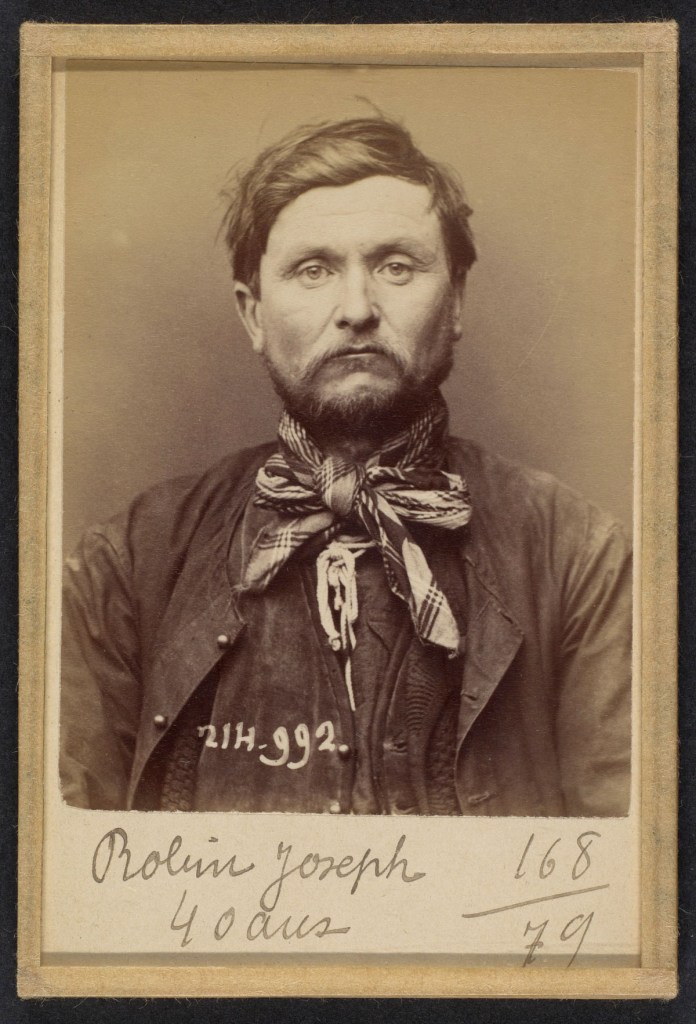

Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914)

Roobin. Joseph. 40 ans, né Bourgneuf (Loire-Inférieure). Terrassier. Anarchiste. 2/3/94

1894

Albumen silver print from glass negative

10.5 x 7 x 0.5cm (4 1/8 x 2 3/4 x 3/16 in.)

Gilman Collection, Museum Purchase, 2005

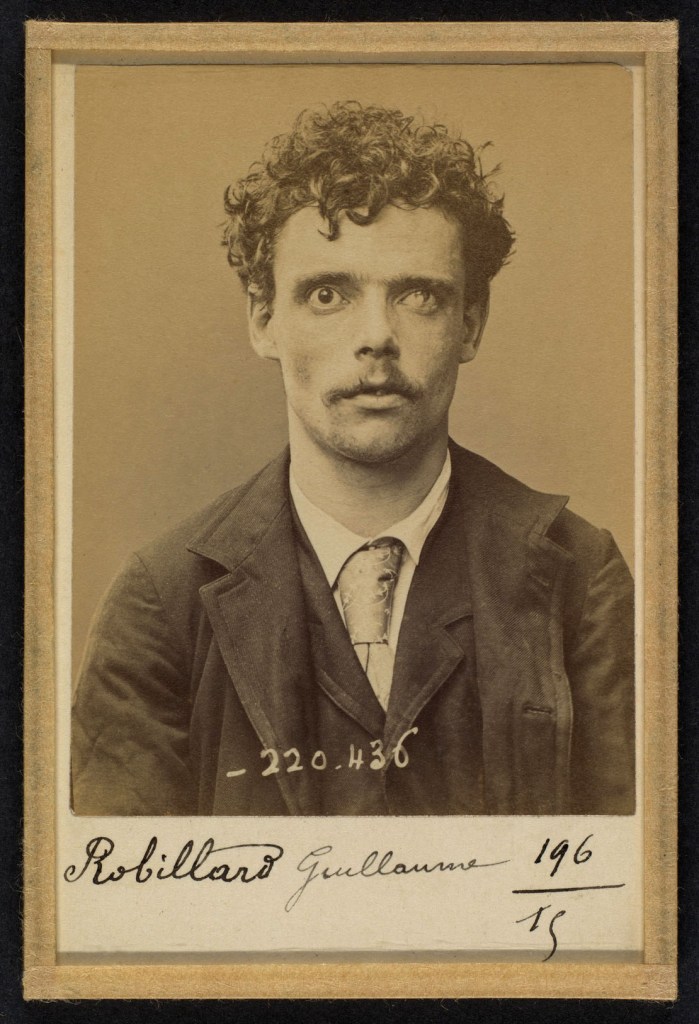

Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914)

Robillard. Guillaume, Joseph. 24 ans, né le 17/11/68 Vaucresson. Fondeur en cuivre. Anarchiste. 2/7/94

1894

Albumen silver print from glass negative

10.5 x 7 x 0.5cm (4 1/8 x 2 3/4 x 3/16 in.)

Gilman Collection, Museum Purchase, 2005

Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914)

Ravachol. François Claudius Kœnigstein. 33 ans, né St-Chamond (Loire). Condamné le 27/4/92

1892

Albumen silver print from glass negative

10.5 x 7 x 0.5 cm (4 1/8 x 2 3/4 x 3/16 in.)

Gilman Collection, Museum Purchase, 2005

Condemned 27/04/1892

François Claudius Koenigstein, known as Ravachol (1859-1892), was a French anarchist. He was born on 14 October 1859, at Saint-Chamond, Loire and died guillotined on 11 July 1892, at Montbrison.

François Koenigstein was born in Saint-Chamond, Loire as the eldest child of a Dutch father (Jean Adam Koenigstein) and a French mother (Marie Ravachol). As an adult, he adopted his mother’s maiden name as his surname, following years of struggle after his father abandoned the family when François was only 8 years old. From that time on he had to support his mother, sister, and brother; he also looked after his nephew. He eventually found work as a dyer’s assistant, a job which he later lost. He was very poor throughout his life. For additional income he played accordion at society balls on Sundays at Saint-Étienne.

Ravachol became politically active. He joined the anarchists as well as groups organising to improve working conditions. Labor unrest resulted in fierce reprisals by police. On 1 May 1891, at Fourmies, a workers demonstration took place for the eight-hour day; confrontations with the police followed. The Police opened fire on the crowd, resulting in nine deaths amongst the demonstrators. The same day, at Clichy, serious incidents erupted in a procession in which anarchists were taking part. Three men were arrested and taken to the commissariat of police. There they were interrogated (and brutalised with beatings, resulting in injuries). A trial (the Clichy Affair) ensued, in which two of the three anarchists were sentenced to prison terms (despite their abuse in jail.

In addition to these events, authorities kept up repression of the communards, which had continued from the time of the insurrection of the Paris Commune of 1871. Ravachol was aroused to take action in 1892 against members of the judiciary. He placed bombs in the living quarters of the Advocate General, Léon Bulot (executive of the Public Ministry), and Edmond Benoît, the councillor who had presided over the Assises Court during the Clichy Affair.

An informant told of his actions, and Ravachol was arrested on 30 March 1892 for his bombings at the Restaurant Véry. The day before the trial, anarchists bombed the restaurant where the informant worked. Ravachol was tried at the Assises Court of Seine on 26 April. He was convicted and condemned to prison for life. On 23 June, Ravachol was condemned to death in a second trial at the Assises Court of Loire for three murders. His participation in two of them is disputed (he confessed only to the murder of the hermit of Montbrison, claiming it was due to his own poverty). On 11 July 1892, Ravachol was publicly guillotined.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Cover page of “Le Petit Journal” illustrating the arrest of French anarchist and assassin Ravachol (1859-1892)

Bibliothèque nationale de France

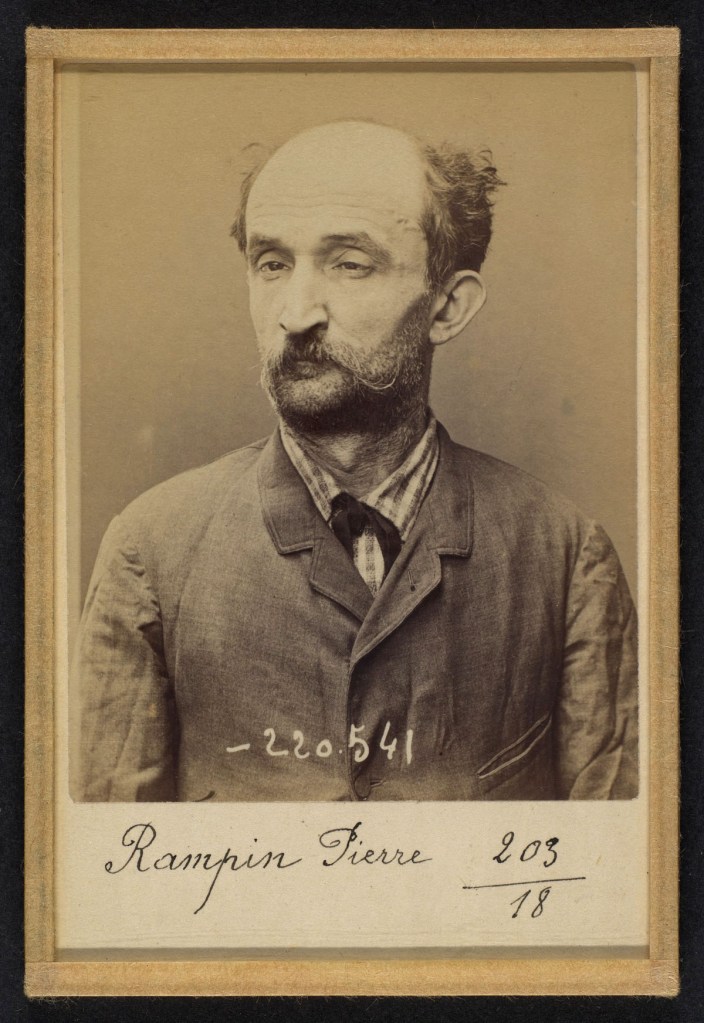

Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914)

Rampin. Pierre. 3/7/94

1894

Albumen silver print from glass negative

10.5 x 7 x 0.5cm (4 1/8 x 2 3/4 x 3/16 in.)

Gilman Collection, Museum Purchase, 2005

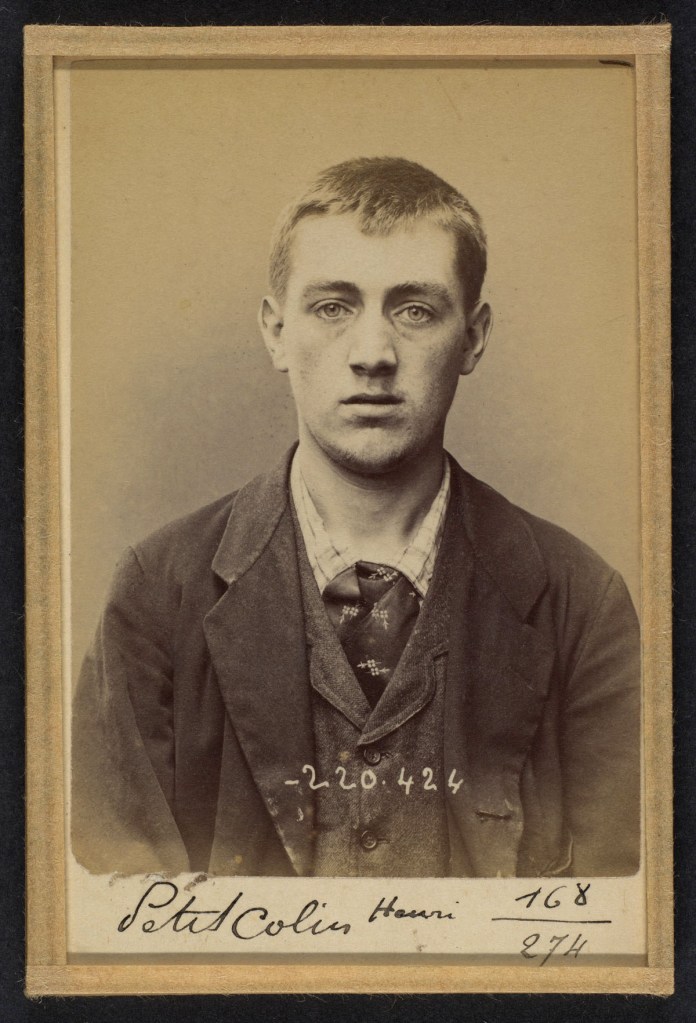

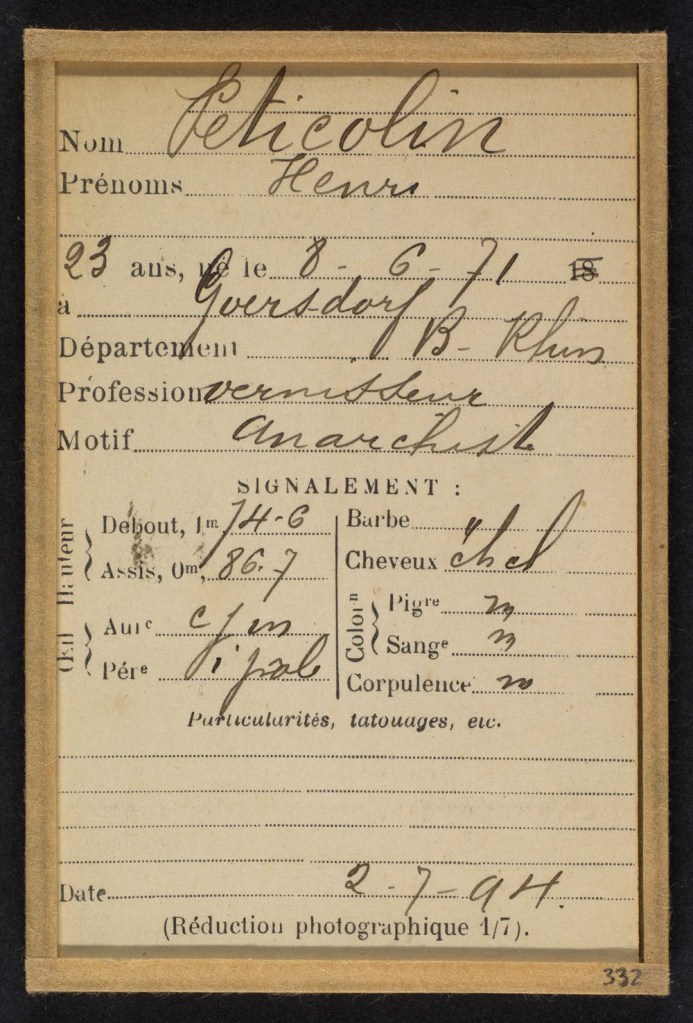

Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914)

Peticolin. Henri. 23 ans, né le 8/6/71 Goersdorf (Bas-Rhin). Vernisseur. Anarchiste. 2/7/94

1894

Albumen silver print from glass negative

10.5 x 7 x 0.5cm (4 1/8 x 2 3/4 x 3/16 in.)

Gilman Collection, Museum Purchase, 2005

Varnisher. Anarchist.

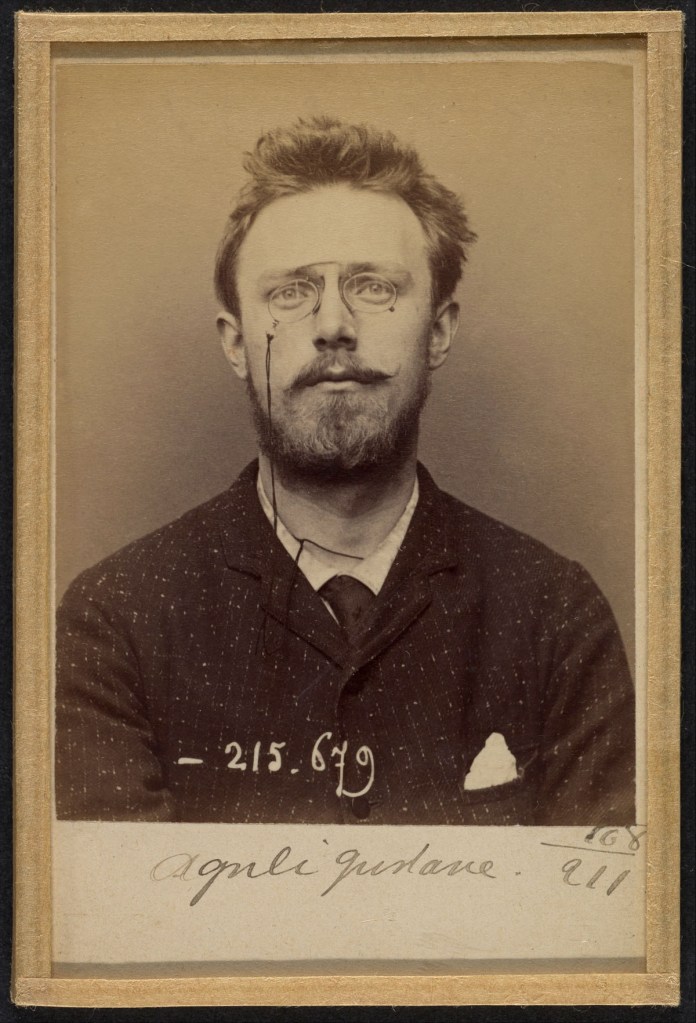

Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914)

Olguéni Gustave. 24 ans, né à Sala (Suède) le 24-5-69. Artiste-peintre. Anarchiste. 14-3-94

1894

Albumen silver print from glass negative

10.5 x 7 x 0.5cm (4 1/8 x 2 3/4 x 3/16 in.)

Gilman Collection, Museum Purchase, 2005

Olguéni Gustave. 24 years old, born in Sala (Sweden) on 24-5-69. Painter. Anarchist. 14-3-94

Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914)

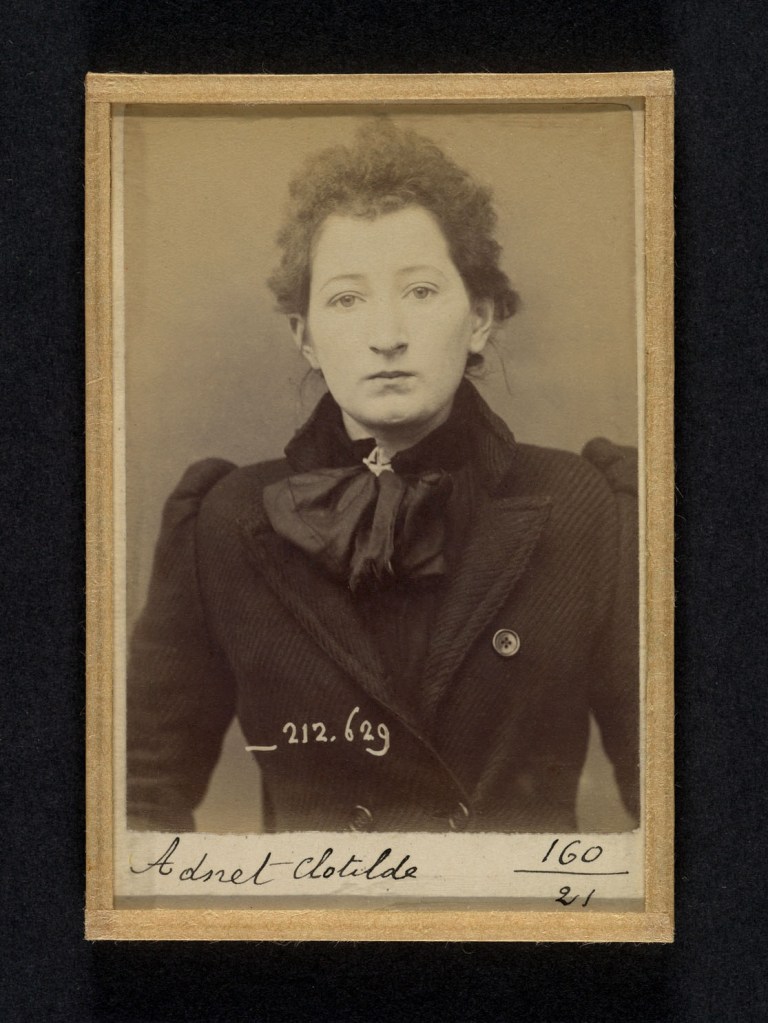

Adnet. Clotilde. 19 ans, née en décembre 74 à Argentant (Orne). Brodeuse. Anarchiste. Fichée le 7/1/94

1894

Albumen silver print from glass negative

10.5 x 7 x 0.5cm (4 1/8 x 2 3/4 x 3/16 in.)

Gilman Collection, Museum Purchase, 2005

Embroiderer. Anarchist.

Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914)

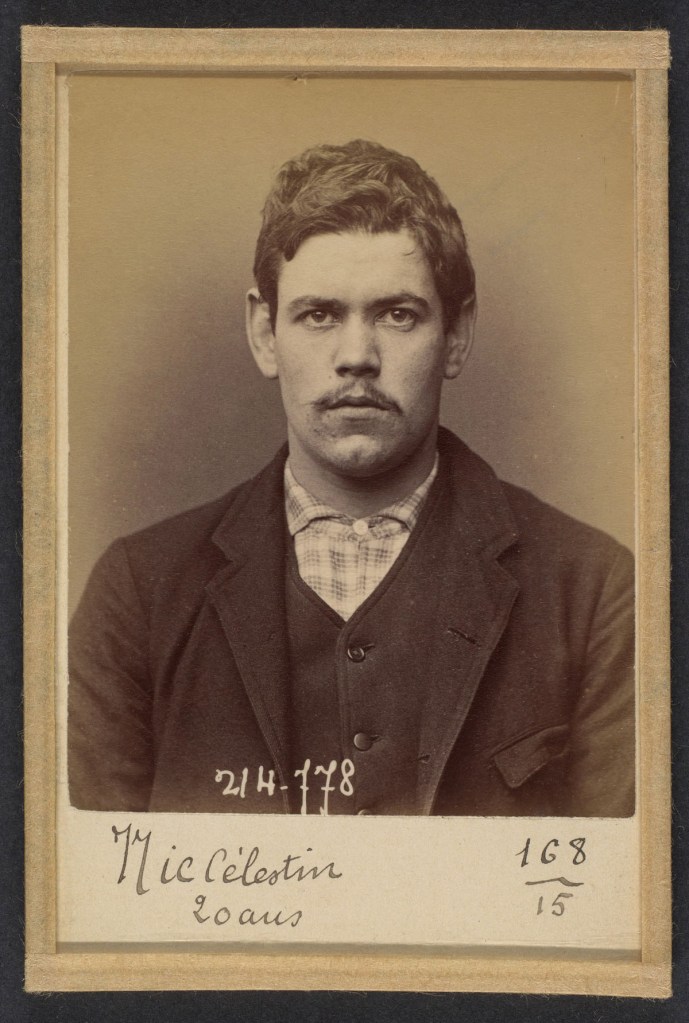

Nic. Celestin. 20 ans, né Conflans-St-Honorine (Seine & Oise). Emballeur. 26/2/94

1894

Albumen silver print from glass negative

10.5 x 7 x 0.5cm (4 1/8 x 2 3/4 x 3/16 in.)

Gilman Collection, Museum Purchase, 2005

Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914)

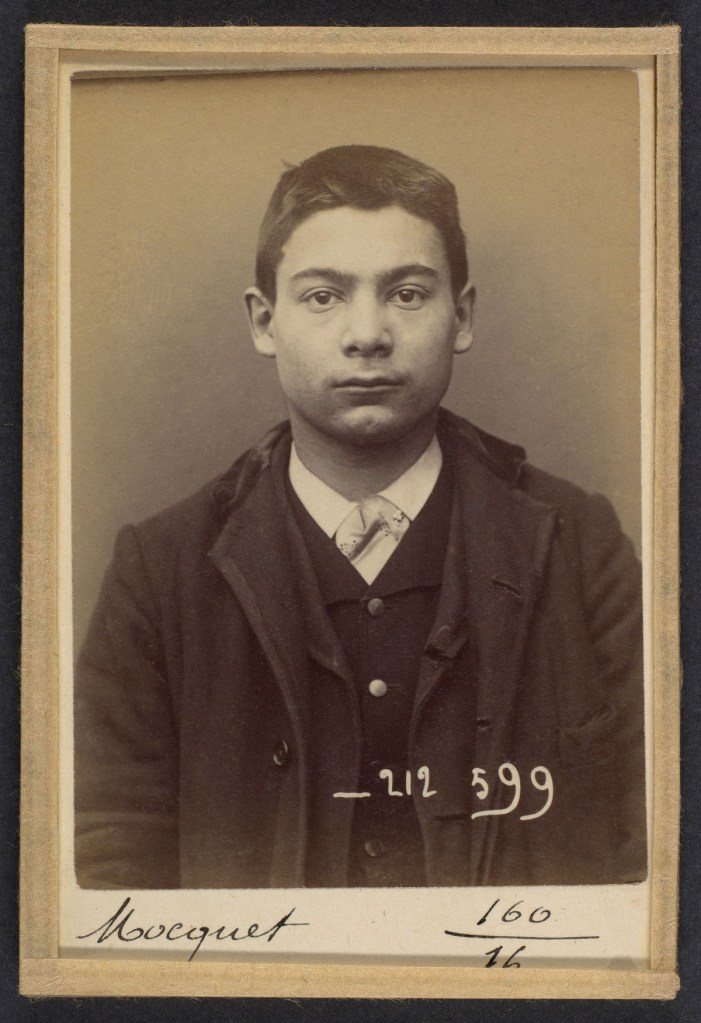

Mocquet. Georges, Gustave. 17 ans, né le 17/5/76 Paris IXe. Tapissier. Anarchiste. 6/1/94

1894

Albumen silver print from glass negative

10.5 x 7 x 0.5cm (4 1/8 x 2 3/4 x 3/16 in.)

Gilman Collection, Museum Purchase, 2005

Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914)

Feneon. Felix. Clerk of the Galerie Berheim Jeune

1894-1895

Albumen silver print from glass negative

10.5 x 7 x 0.5cm (4 1/8 x 2 3/4 x 3/16 in.)

Gilman Collection, Museum Purchase, 2005

Félix Fénéon (22 June 1861, Turin, Italy – 29 February 1944, Châtenay-Malabry) was a Parisian anarchist and art critic during the late 19th century. He coined the term “Neo-Impressionism” in 1886 to identify a group of artists led by Georges Seurat, and ardently promoted them.

Felix Fénéon was a prominent literary stylist, art critic, and anarchist born in Turin, Italy in 1861. He was later raised in Burgundy, presumably because his father was a travelling salesman. After placing first in the competitive exams for jobs, Fénéon moved to Paris to work for the War Office where he achieved the rank of chief clerk. During his time in the war office he edited many works, including those of Rimbaud and Lautréamont, as well as helped to advance the fledgling pointillist movement under Georges Seurat. He was also a regular at Mallarmé’s salons on Tuesday evenings as well as active in anarchist circles.

Fénéon, ironically, worked 13 years at the War Office while remaining heavily active in supporting anarchist circles and movements. In March 1892 French police talked about Fénéon as an ‘active Anarchist’, and they had him shadowed. In 1894 Fénéon was arrested on suspicion of conspiracy because of an anarchist bombing of the Foyot restaurant, a popular haunt of politicians. He was also suspected of connection with the assassination of the French President, Sadi Carnot, by an Italian anarchist. He and twenty-nine others were arrested under charges of conspiracy in what became known as the “Trial of Thirty”. Fénéon was acquitted with many of the original thirty. However, the trial was a high point in publicity for Fénéon, normally behind the scenes, as he championed his wit to the amusement of the jury. Of the courtroom scene, Julian Barnes writes, “When the presiding judge put it to him that he had been spotted talking to a known anarchist behind a gas lamp, he replied coolly: Can you tell me, Monsieur le Président, which side of a gas lamp is its behind?”

After the trial, Fénéon became even more elusive. In 1890, the Neo-Impressionist Paul Signac asked to produce a portrait of the lauded critic. Fénéon refused several times before agreeing, on the condition that Signac produced a full face effigy. Signac naturally refused, painting instead a famous profile of Fénéon with his characteristic goatee, a picture that largely became a symbol of the movement, spawning many variations. Fénéon, though displeased, hung the picture on his wall until Signac’s death 45 years later. Aside from Novels in Three Lines that first appeared as clippings in the Parisian Le Matins in 1906 and later as a collection, only because his mistress Camille Pateel had collected them in an album, Fénéon published only a 43-page monograph in Les Impressionists (1886). When asked to produce Les Nouvelles en Trois Lignes as a collection, Fénéon famously replied with an angry “I aspire only to silence”. As Luc Sante points out, Fénéon, one might say, is invisibly famous, having affected so much without being recognisable to many.

Text from the Wikipedia website

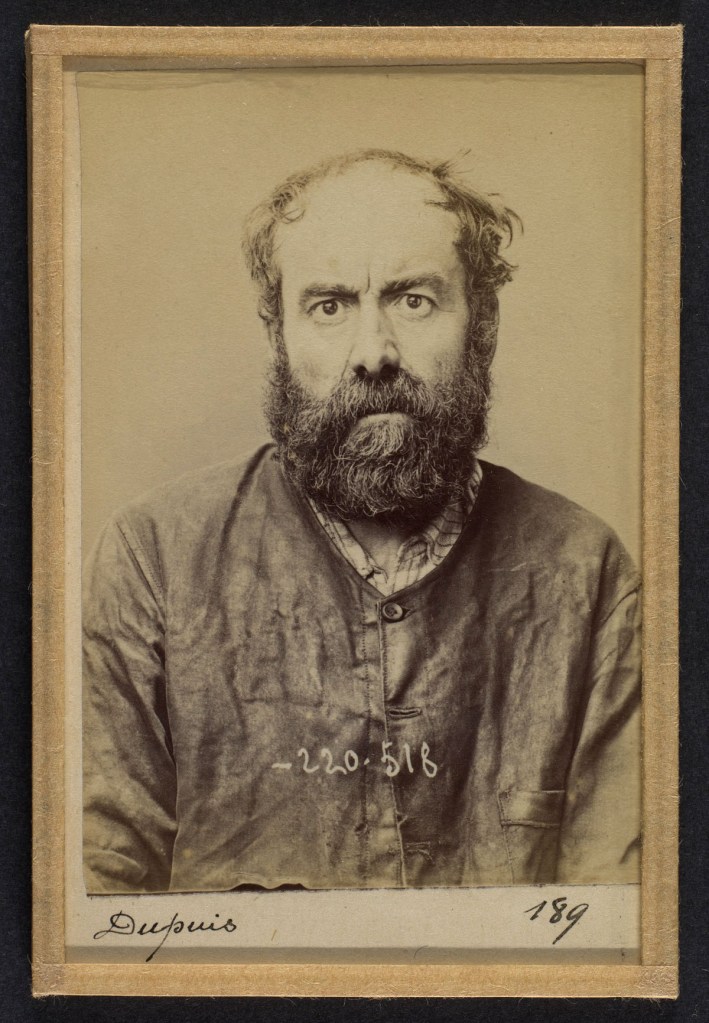

Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914)

Dupuis. Augustin. 53 ans, né le 24/6/41 Dourdan (Seine & Oise). Charron, forgeron. Anarchiste. 3/7/94

1894

Albumen silver print from glass negative

10.5 x 7 x 0.5cm (4 1/8 x 2 3/4 x 3/16 in.)

Gilman Collection, Museum Purchase, 2005

Wheelwright, blacksmith. Anarchist.

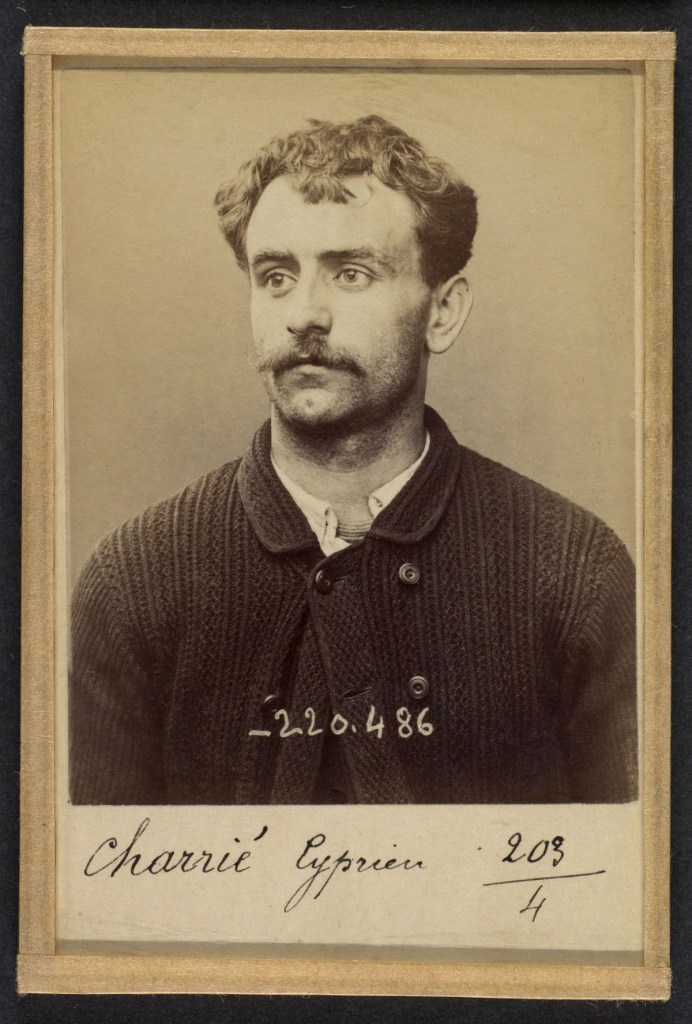

Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914)

Charrié. Cyprien. 26 ans, né le 7/10/67 Paris XVIlle. Imprimeur. Anarchiste 2/7/94

1894

Albumen silver print from glass negative

10.5 x 7 x 0.5cm (4 1/8 x 2 3/4 x 3/16 in.)

Gilman Collection, Museum Purchase, 2005

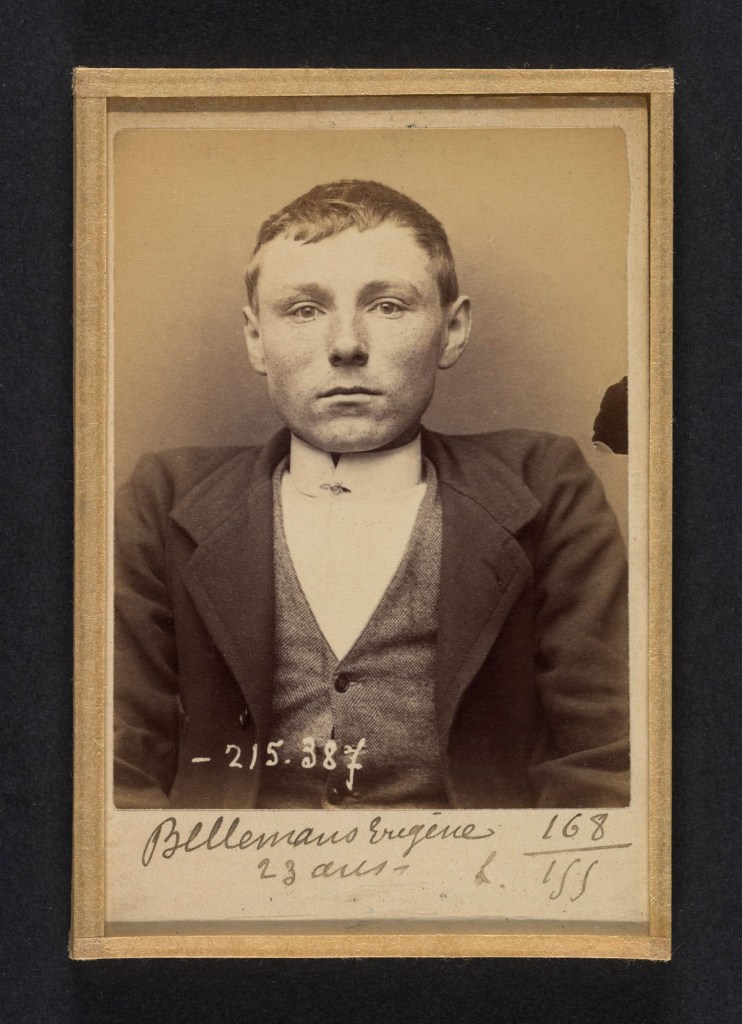

Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914)

Bellemans. Eugène (ou Michel). 23 ans, né à Gand (Belgique). Tailleur d’habits. Anarchiste. 9/3/94

1894

Albumen silver print from glass negative

10.5 x 7 x 0.5cm (4 1/8 x 2 3/4 x 3/16 in.)

Gilman Collection, Museum Purchase, 2005

Born into a distinguished family of scientists and statisticians, Bertillon began his career as a clerk in the Identification Bureau of the Paris Prefecture of Police in 1879. Tasked with maintaining reliable police records of offenders, he developed the first modern system of criminal identification. The system, which became known as Bertillonage, had three components: anthropometric measurement, precise verbal description of the prisoner’s physical characteristics, and standardised photographs of the face.

In the early 1890s Paris was subject to a wave of bombings and assassination attempts carried out by anarchist proponents of “propaganda of the deed.” One of Bertillon’s greatest successes came in March 1892, when his system of criminal identification led to the arrest of an anarchist bomber and career criminal who went by the name Ravachol. The publicity surrounding the case earned Bertillon the Legion of Honor and encouraged police departments around the world to adopt his anthropometric system.

![Unknown photographer (American) '[Broadside for the Capture of John Wilkes Booth, John Surratt, and David Herold]' 1865 Unknown photographer (American) '[Broadside for the Capture of John Wilkes Booth, John Surratt, and David Herold]' 1865](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/dp274835-murder-web.jpg?w=544)

Unknown photographer (American)

[Broadside for the Capture of John Wilkes Booth, John Surratt, and David Herold]

Artist: Alexander Gardner (American, Glasgow, Scotland 1821 – 1882 Washington, D.C.)

Photography Studio: Silsbee, Case & Company (American, active Boston)

Photography Studio: Unknown

April 20, 1865

Ink on paper with three albumen silver prints from glass negatives

Sheet: 60.5 x 31.3cm (23 13/16 x 12 5/16 in.)

Each photograph: 8.6 x 5.4cm (3 3/8 x 2 1/8 in.)

Gilman Collection, Purchase, The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 2005

On the night of April 14, 1865, just five days after Lee’s surrender to Grant at Appomattox, John Wilkes Booth shot Lincoln at the Ford Theatre in Washington, D.C. Within twenty-four hours, Secret Service director Colonel Lafayette Baker had already acquired photographs of Booth and two of his accomplices. Booth’s photograph was secured by a standard police search of the actor’s room at the National Hotel; a photograph of John Surratt, a suspect in the plot to kill Secretary of State William Seward, was obtained from his mother, Mary (soon to be indicted as a fellow conspirator), and David Herold’s photograph was found in a search of his mother’s carte-de-visite album. The three photographs were taken to Alexander Gardner’s studio for immediate reproduction. This bill was issued on April 20, the first such broadside in America illustrated with photographs tipped onto the sheet.

The descriptions of the alleged conspirators combined with their photographic portraits proved invaluable to the militia. Six days after the poster was released Booth and Herold were recognised by a division of the 16th New York Cavalry. The commanding officer, Lieutenant Edward Doherty, demanded their unconditional surrender when he cornered the two men in a barn near Port Royal, Virginia. Herold complied; Booth refused. Two Secret Service detectives accompanying the cavalry, then set fire to the barn. Booth was shot as he attempted to escape; he died three hours later. After a military trial Herold was hanged on July 7 at the Old Arsenal Prison in Washington, D.C.

Surratt escaped to England via Canada, eventually settling in Rome. Two years later a former schoolmate from Maryland recognised Surratt, then a member of the Papal Guard, and he was returned to Washington to stand trial. In September 1868 the charges against him were nol-prossed after the trial ended in a hung jury. Surratt retired to Maryland, worked as a clerk, and lived until 1916.

![Alexander Gardner (American, Glasgow, Scotland 1821 - 1882 Washington, D.C.) 'Lewis Powell [alias Lewis Payne]' April 27, 186 Alexander Gardner (American, Glasgow, Scotland 1821 - 1882 Washington, D.C.) 'Lewis Powell [alias Lewis Payne]' April 27, 1865](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/lewis-powell-web.jpg?w=811)

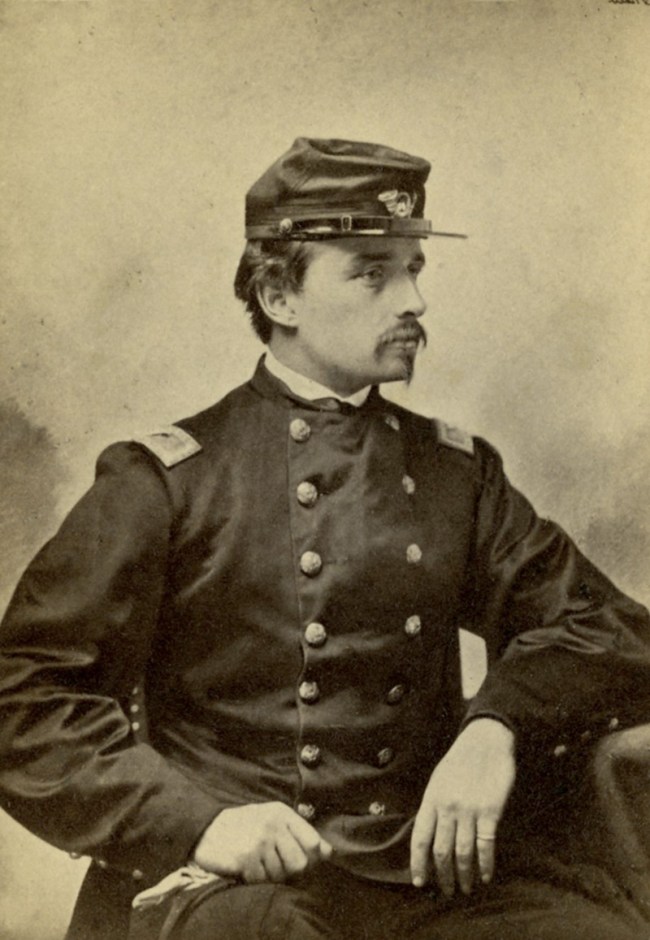

Alexander Gardner (American, Glasgow, Scotland 1821 – 1882 Washington, D.C.)

Lewis Powell [alias Lewis Payne]

April 27, 1865

Albumen silver print from glass negative

22.4 × 17.4cm (8 13/16 × 6 7/8 in.)

Gilman Collection, Purchase, The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 2005

Alexander Gardner’s 1865 portrait of Lewis Powell, a conspirator with John Wilkes Booth. At roughly the same time that John Wilkes Booth shot President Lincoln, Lewis Paine attempted unsuccessfully to murder Secretary of State William Seward. The son of a Baptist minister from Alabama, Paine (alias Wood, alias Hall, alias Powell) was one of at least five conspirators who planned with Booth the simultaneous assassinations of Lincoln, Vice President Andrew Johnson, and Seward. A tall, powerful man, Paine broke into the secretary’s house, struck his son Frederick with the butt of his jammed pistol, brutally stabbed the bedridden politician, and then escaped after stabbing Seward’s other son, Augustus.

Four days later, Paine was caught in a sophisticated police dragnet and arrested at the H Street boarding house of fellow conspirator Mary Surratt. Detained aboard two iron-clad monitors docked together on the Potomac, Paine and seven other presumed conspirators were photographed by Alexander Gardner on April 27. Gardner made full-length, profile, and full-face portraits of each of the men, presaging the pictorial formula later adopted by law-enforcement photographers. Of the ten known photographs of Paine, six show him against a canvas awning on the monitor’s deck, the others against the dented gun turret. In this portrait, Paine, towering more than a head above the deck officer, appears menacingly free of handcuffs. He was twenty years old.

Alexander Gardner (American, Glasgow, Scotland 1821 – 1882 Washington, D.C.)

Execution of the Conspirators

July 7, 1865

Albumen silver print from glass negative

16.8 x 24.2cm (6 5/8 x 9 1/2 in.)

Gilman Collection, Purchase, The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 2005

Alexander Gardner’s intimate involvement in the events following President Lincoln’s assassination would have challenged even the most experienced twentieth-century photojournalist. In just short of four months, Gardner documented in hundreds of portraits and views one of the most complex national news stories in American history. The U.S. Secret Service provided Gardner unlimited access to individuals and places unavailable to any other photographer. Free to retain all but one of his negatives-a portrait of Booth’s corpse-Gardner attempted to sell carte-de-visite and large-format prints of the whole picture story. America, still wounded from the four-year war, was less than interested.

The photographs of the execution of Mary Surratt, Lewis Paine, David Herold, and George Atzerodt on July 7, 1865, were, however, highly sought after by early collectors of Civil War ephemera beginning in the 1880s. This photograph shows the final preparations on the scaffolding in the yard of the Old Arsenal Prison. The day was extremely hot and a parasol shades Mary Surratt, seated at the far left of the stage. (She would become the first woman in America to be hanged.) Two soldiers stationed beneath the stage grasp the narrow beams that hold up the gallows trapdoors. The soldier on the left would later admit he had just vomited, from heat and tension. Only one noose is visible, slightly to the left of Surratt; the other three nooses moved during the exposure and are registered by the camera only as faint blurs. Members of the clergy crowd the stage and provide final counsel to the conspirators. A private audience of invited guests stands at the lower left. Minutes after Gardner’s exposure, the conspirators were tied and blindfolded and the order was given to knock out the support beams.

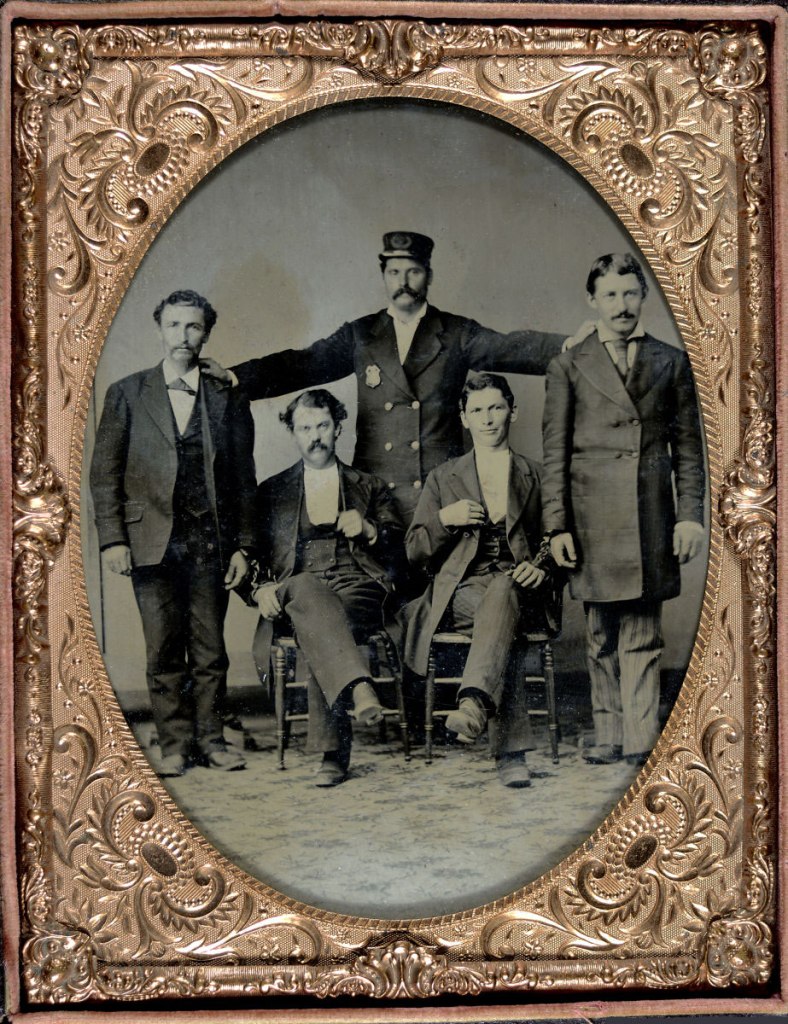

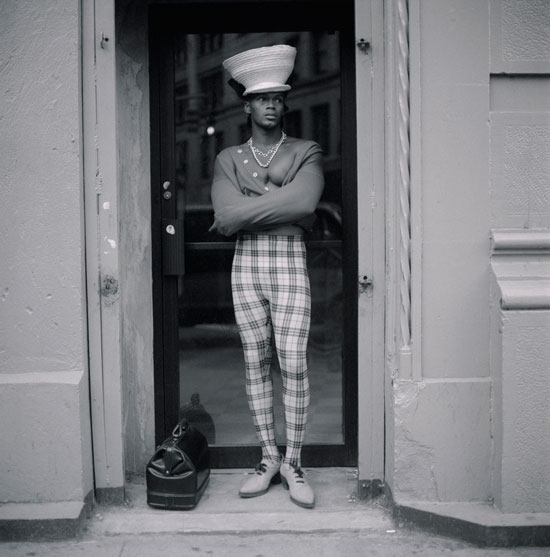

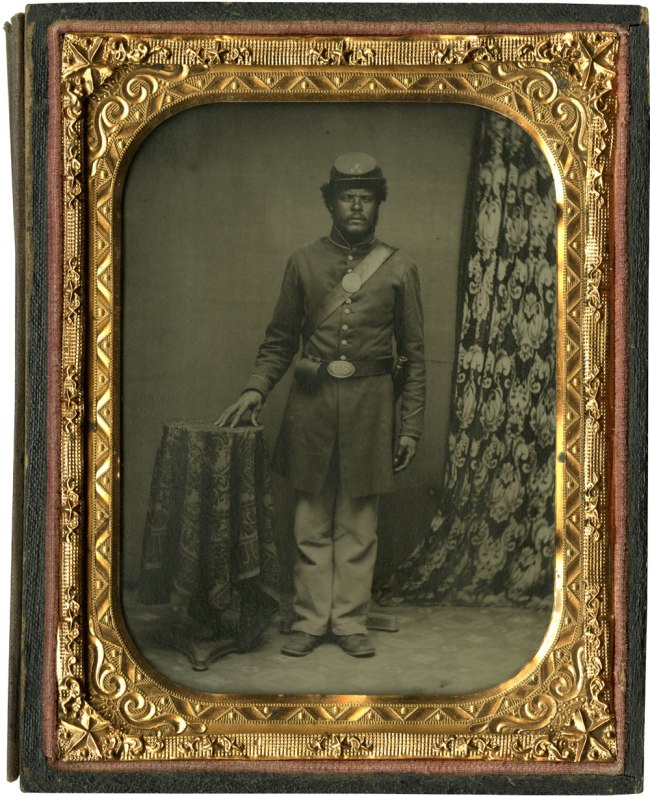

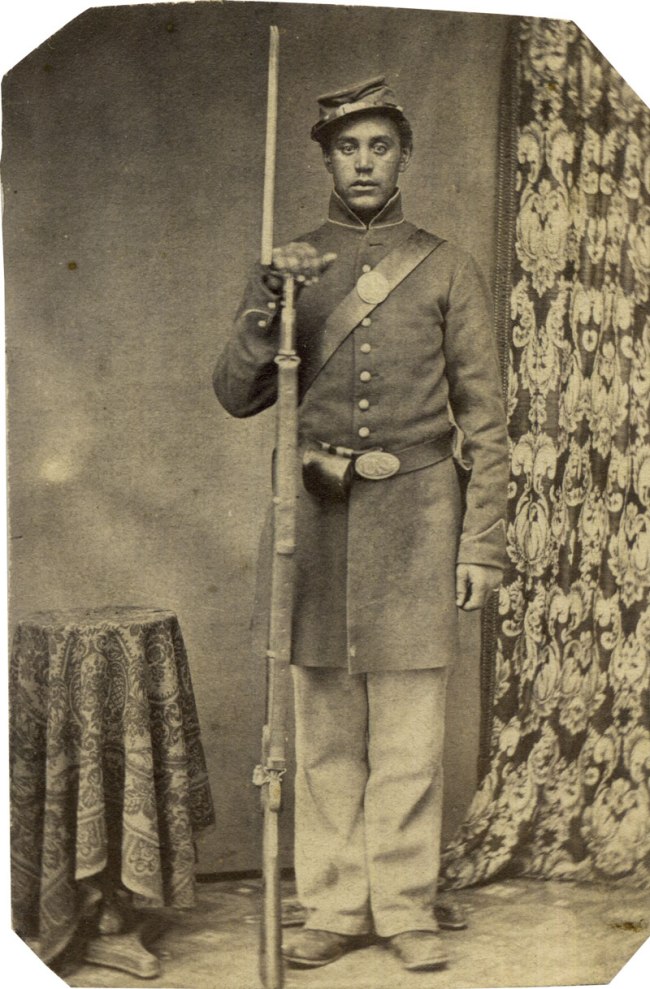

Unknown photographer (American)

Policeman Posing with Four “Collared” Thugs

c. 1875

Tintype

Image: 4 5/8 × 3 9/16 in. (11.7 × 9cm), visible

Plate: 5 7/16 × 4 1/16 in. (13.8 × 10.3cm), approx.

Gift of Stanley B. Burns, MD and The Burns Archive, in honour of Elizabeth A. Burns, 2016

This rare narrative tintype of a policeman posing with four criminals handcuffed to one another may be viewed as an occupational portrait of sorts. The officer’s police cap and gleaming badge indicate his profession, while his pose and central placement emphasise his authority.

![Unknown photographer (American). '[Five Members of the Wild Bunch]' c. 1892 Unknown photographer (American). '[Five Members of the Wild Bunch]' c. 1892](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/the-wild-bunch-web.jpg?w=745)

Unknown photographer (American)

[Five Members of the Wild Bunch]

c. 1892

Tintype

Image: 8.4 x 6.2cm (3 5/16 x 2 7/16 in.)

Gilman Collection, Gift of The Howard Gilman Foundation, 2005

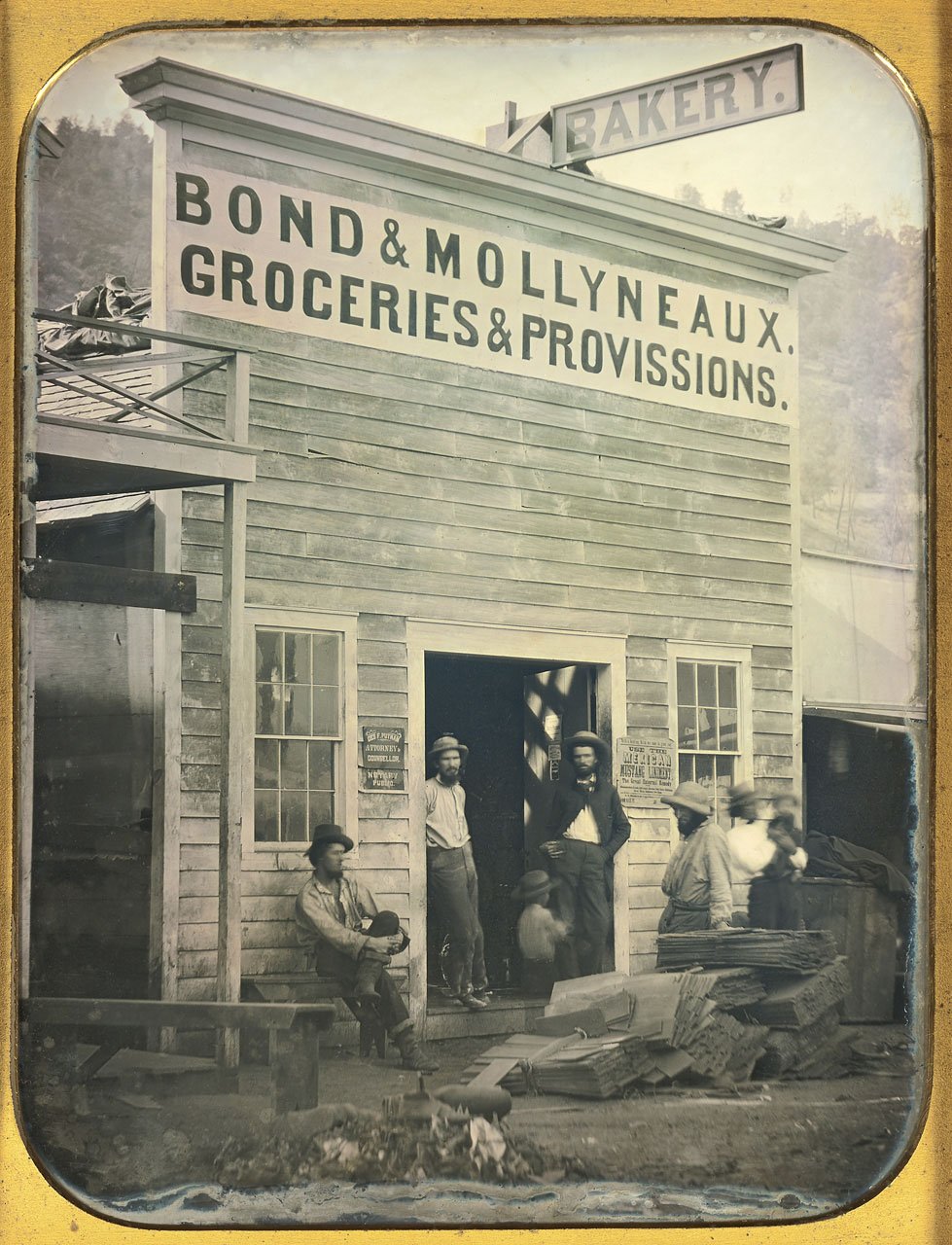

The Wild Bunch was the largest and most notorious band of outlaws in the American West. Led by two gunmen better known by their aliases, Butch Cassidy (Robert LeRoy Parker) and Kid Curry (Harvey Logan), the Wild Bunch was an informal trust of thieves and rustlers that preyed upon stagecoaches, small banks, and especially railroads from the late 1880s to the first decade of the twentieth century.

This crudely constructed tintype portrait of five members of the gang dressed in bowler hats and city clothes shows, clockwise, from the top left, Kid Curry, Bill McCarty, Bill (Tod) Carver, Ben Kilpatrick, and Tom O’Day. Without their six shooters and cowboy hats the outlaws appear quite civilised and could easily be mistaken for the sheriffs and Pinkerton agents who pursued them in a “Wild West” already much tamed by the probable date of this photograph. Gone was the open range – instead, homesteads and farms dotted the landscape and barbed-wire fences frustrated the cattleman’s drive to market. Gone too was the anonymity associated with distance, as the camera and the telegraph conspired to identify criminals. Bank and train robbery were still lucrative, but the outlaw’s chances for escape gradually shifted in favour of the sheriff’s chances for arrest and conviction.

By 1903 the Wild Bunch had disbanded. A few members of the gang followed Butch Cassidy to South America, while the majority remained in the West, trying to avoid capture. McCarty was shot dead in 1893, in a street in Delta, Colorado, after a bank robbery; Carver died in prison; Kilpatrick was killed during a train robbery in 1912; Tom O’Day was captured by a Casper, Wyoming, sheriff in 1903; and Kid Curry died either by his own hand in Parachute, Colorado, in 1904, or, as legend has it, lived until he was killed by a wild mule in South America in 1909. The photograph comes from the collection of Camillus S. Fly, a pioneer photographer in Tombstone, Arizona, in the 1880s and sheriff of Cochise County in the 1890s.

![Tom Howard (American, 1894-1961) '[Electrocution of Ruth Snyder, Sing Sing Prison, Ossining, New York]' 1928 Tom Howard (American, 1894-1961) '[Electrocution of Ruth Snyder, Sing Sing Prison, Ossining, New York]' 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/electrocution-of-ruth-snyder-web.jpg?w=822)

Tom Howard (American, 1894-1961)

[Electrocution of Ruth Snyder, Sing Sing Prison, Ossining, New York]

1928

Gelatin silver print

24 x 19.3cm (9 7/16 x 7 5/8 in.)

Twentieth-Century Photography Fund, 2008

© The New York Daily News Archive / Getty Images

In spite of the universal ban on cameras in American death chambers, news editors have long recognised the public’s hunger for eyewitness images of high-profile executions. In January 1928 Tom Howard made tabloid history when he photographed, using a miniature camera strapped to his ankle, the electrocution of the convicted murderer Ruth Snyder at Sing Sing prison in Ossining, New York. The sensational picture ran under banner headlines on the front page of the New York Daily News two days in a row.

“In 1925, Snyder, a housewife from Queens Village, Queens, New York City, began an affair with Henry Judd Gray, a married corset salesman. She then began to plan the murder of her husband, enlisting the help of her new lover, though he appeared to be very reluctant. Her distaste for her husband apparently began when he insisted on hanging a picture of his late fiancée, Jessie Guishard, on the wall of their first home, and named his boat after her. Guishard, whom Albert described to Ruth as “the finest woman I have ever met”, had been dead for 10 years.

Ruth Snyder first persuaded her husband to purchase insurance, with the assistance of an insurance agent (who was subsequently fired and sent to prison for forgery) “signed” a $48,000 life insurance policy that paid extra (“double indemnity”) if an unexpected act of violence killed the victim. According to Henry Judd Gray, Ruth had made at least seven attempts to kill her husband, all of which he survived. On March 20, 1927, the couple garrotted Albert Snyder and stuffed his nose full of chloroform-soaked rags, then staged his death as part of a burglary. Detectives at the scene noted that the burglar left little evidence of breaking into the house; moreover, that the behaviour of Mrs. Snyder was inconsistent with her story of a terrorised wife witnessing her husband being killed.

Then the police found the property Ruth claimed had been stolen. It was still in the house, but hidden. A breakthrough came when a detective found a paper with the letters “J.G.” on it (it was a memento Albert Snyder had kept from former love Jessie Guishard), and asked Ruth about it. A flustered Ruth’s mind immediately turned to her lover, whose initials were also “J.G.,” and she asked the detective what Gray had to do with this. It was the first time Gray had been mentioned, and the police were instantly suspicious. Gray was found upstate, in Syracuse. He claimed he had been there all night, but eventually it turned out a friend of his had created an alibi, setting up Gray’s room at a hotel. Gray proved far more forthcoming than Ruth about his actions. He was caught and returned to Jamaica, Queens and charged along with Ruth Snyder. Dorothy Parker told Oscar Levant that Gray tried to escape the police by taking a taxi from Long Island to Manhattan, New York, which Levant noted was “quite a long trip.” According to Parker, in order “not to attract attention, he gave the driver a ten-cent tip.” …

Snyder became the first woman executed in Sing Sing since 1899. She went to the electric chair only moments before her former lover. Her execution (by “State Electrician” Robert G. Elliott) was caught on film, by a photograph of her as the electricity was running through her body, with the aid of a miniature plate camera custom-strapped to the ankle of Tom Howard, a Chicago Tribune photographer working in cooperation with the Tribune-owned New York Daily News. Howard’s camera was owned for a while by inventor Miller Reese Hutchison, then later became part of the collections of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.”

Text from the Wikipedia website

Unknown photographer (French)

Publisher: Le Petit Parisien (French, active 1876–1944)

Marius Bourotte

1929

Gelatin silver print with applied colour

11.6 x 16.2cm (4 9/16 x 6 3/8 in.)

Purchase, The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 1996

These photographs of thieves and assassins were heavily retouched with ink and gouache to facilitate their reproduction in illustrated newspapers and magazines. Although they were not conceived as typological studies, the cropping and retouching deliberately intensified their sinister aspect, producing caricatures of criminality that satisfied the sensationalism of the picture press.

![Unknown photographer (American) '[Automobile Murder Scene]' c. 1935 Unknown photographer (American) '[Automobile Murder Scene]' c. 1935](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/automobile-murder-scene-circa-1935-web.jpg?w=816)

Unknown photographer (American)

[Automobile Murder Scene]

c. 1935

Gelatin silver print

24.3 x 20.1cm (9 9/16 x 7 15/16 in.)

Twentieth-Century Photography Fund, 2008

This picture is a master class in the aesthetics of the crime photograph. As the writer Luc Sante has noted, photography stops time, while crime photography shows the stopped time of an individual life cut short. The anonymous cameraman (whose shadow can be seen in the image) may have worked for the police but was more likely a newspaper photographer. His editors must have considered this an absolute bull’s-eye combination of titillation, voyeurism, and fig-leaf moralising that lets readers have their cake and eat it too. Most importantly, the stopped time of the crime photograph imparts a heightened significance to all the details within the frame, which could either be clues or random accident.

Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American born Ukraine (Austria), Złoczów (Zolochiv) 1899 – 1968 New York)

Human Head Cake Box Murder

c. 1940

Gelatin silver print

33.6 x 26.9cm (13 1/4 x 10 9/16 in.)

Ford Motor Company Collection, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell, 1987

© Weegee / International Center of Photography

It is hard to decide which of the several mysteries contained in this macabre photograph is the most bizarre: the murder to which the title alludes, the headless bodies standing flat-footedly around a bodyless head, the “scriptboy” who enters at upper left, how the police photographer can be both rooted to the spot and levitating above it, why he wears his hat as he works, or where Weegee is standing.

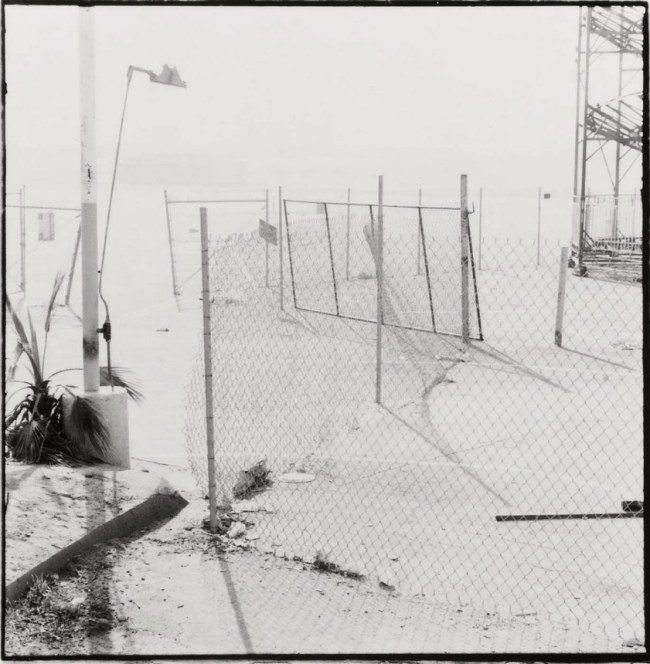

John Gutmann (American born Germany, Breslau 1905 – 1998 San Francisco)

“X Marks the Spot Where Ralph Will Die”

1938

Gelatin silver print

23.4 x 17.8cm (9 3/16 x 7 in.)

Ford Motor Company Collection, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell, 1987

© 1998 Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents

Trained as a painter, Gutmann fled Germany for America in 1933. In need of money, the artist began photographing across the country as a foreign correspondent for the tremendously popular picture magazines of his homeland, which had an insatiable appetite for all things American. What began as an assignment in exile – travelling from New York, Chicago, and Detroit to New Orleans and San Francisco – became a remarkable lifelong career in a new medium and country.

One of the earliest and most inventive practitioners of street photography, Gutmann was one of the great poets and chroniclers of a particularly American kind of city life – the endless supply of characters and spontaneous dramas set against a backdrop of skyscrapers, signs, and graffiti.

Weegee Tells How

Arthur Fellig, better known as Weegee, was a New York city freelance news photographer from the 1930s to the 1950s. Here he talks about his career and gives advice to those wanting to become news photographers.

![Weegee (American, born Ukraine (Austria), Złoczów (Zolochiv) 1899 - 1968 New York) '[Outline of a Murder Victim]' 1942 Weegee (American, born Ukraine (Austria), Złoczów (Zolochiv) 1899 - 1968 New York) '[Outline of a Murder Victim]' 1942](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/weegee-outline-web.jpg)

Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American born Ukraine (Austria), Złoczów (Zolochiv) 1899 – 1968 New York)

[Outline of a Murder Victim]

1942

Gelatin silver print

33.9 x 27.4cm (13 3/6 x 10 13/16 in.)

Gift of Bruce A. Kirstein, in memory of Marc S. Kirstein, 1978

© Weegee / International Center of Photography

Working as a freelance press photographer in New York City during the mid-1930s and 1940s, Weegee achieved notoriety through sensational photographs of a crime-ridden metropolis. Although his nickname derived from an earlier job as a “squeegee boy” drying photographic prints in a professional darkroom, through brazen self-styling he designated himself a human Ouija board, who always seemed to know where the next big scoop would be. In fact, he lived across the street from police headquarters and used a department-issued radio. Here, Weegee distills the genre of the crime scene photograph into a minimalist trace: the camera’s flashbulb illuminates a hastily drawn chalk outline bearing the stark label “HEAD.”

Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American born Ukraine (Austria), Złoczów (Zolochiv) 1899 – 1968 New York)

Man Escorting Frank Pape, Arrested for Strangling Boy to Death, New York. November 10, 1944

1944

Gelatin silver print

9 1⁄2 × 7 9/16″ (24.1 × 19.2cm)

International Center of Photography. Bequest of Wilma Wilcox

© 2014 Weegee/ International Center of Photography/Getty Images

PHOTOGRAPH NOT IN EXHIBITION.

Taken prior to the famous image by Weggee below.

The first of these 8 by 10s (above), although not without its pleasures (the sad ambivalence registered on Pape’s face; the awkward delicacy with which he toys with his cap; the encroaching elbow at right announcing the crowdedness of the photographic field here), is utterly banal. It is “photojournalism” as generally understood, an ostensibly uncomplicated document relating the newsworthy event, its composition dictated only by the informational concern of Pape’s bittersweet apprehension in the wake of the false accusation of the victim’s older brother.

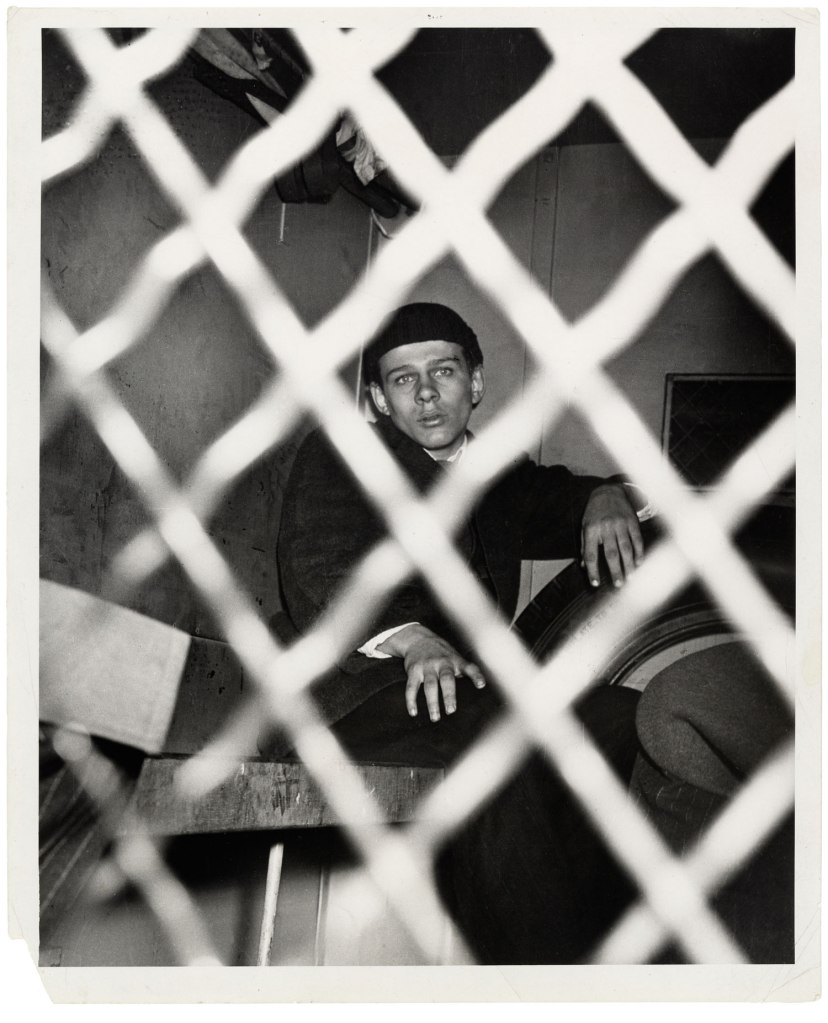

Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American born Ukraine (Austria), Złoczów (Zolochiv) 1899 – 1968 New York)

Frank Pape, Arrested for Homicide

1944

Gelatin silver print

33.6 x 26.4cm (13 1/4 x 10 3/8 in.)

Anonymous Gift, 2005

“For Weegee… a photographic print was usually nothing more than a by-product. Weegee’s prints served as the matrices from which halftone and gravure printing plates were made (by others) for reproduction in magazines, books, and newspapers. Weegee intended these mass-produced multiples, and not the photographic prints themselves, to be the final forms of his imagery… He did not expect or intend his work to be experienced in the form of photographic prints.”

A. D. Coleman, “Weegee as Printmaker: An Anomaly in the Marketplace,” in Tarnished Silver: After the Photo Boom. New York: Midmarch, 1996, p. 28. (Emphasis added.) quoted in Jason E. Hill.

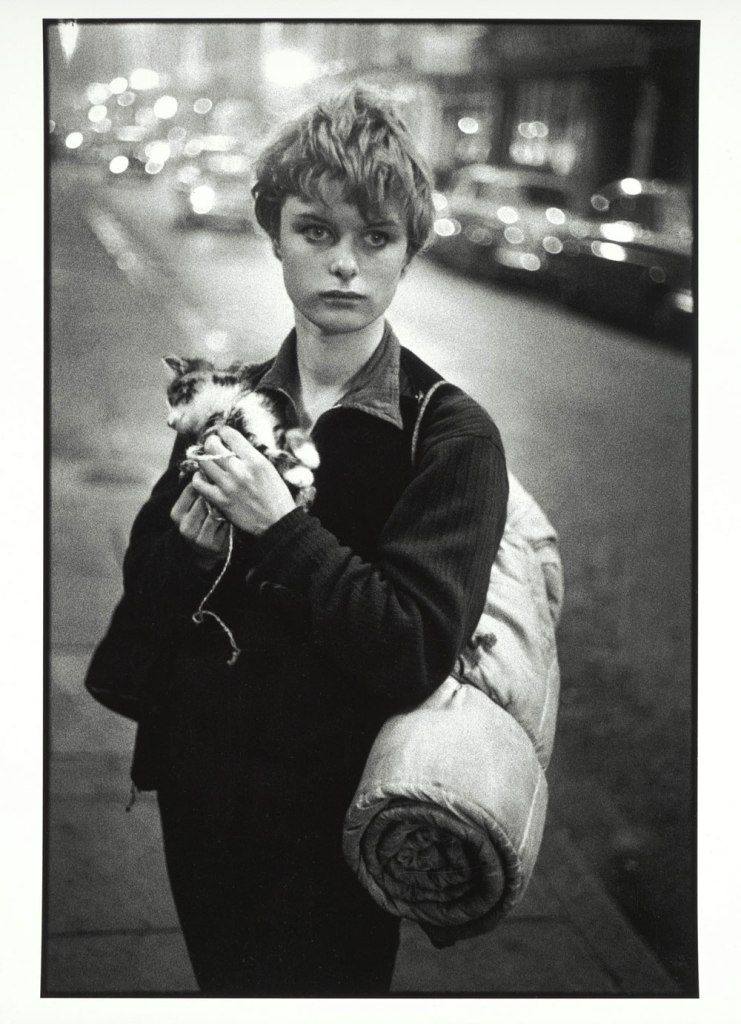

The subject of this photograph, a sixteen-year-old boy, confessed to tying up and strangling four-year-old William Drach in the Bronx on October 29, 1944, allegedly mimicking what he had seen in a movie. Here, Weegee adapts the traditional tropes of portraiture, in which the sitter’s hands and facial features are of the utmost importance, to present a caged criminal still armed with his weapons. Exploiting the cramped quarters of the police van, Weegee frames the boy’s placid face within the crisscross of the chain-linked fence. The boy’s hands – the presumed tools of his crime – are eerily dismembered from his body.

“On November 9, 1944, the American photographer Weegee made three exposures of Frank Pape, moments after the sixteen year old was arraigned on homicide charges for the accidental strangling death of a four-year-old neighbor and as he was escorted into a police wagon outside the Manhattan Police Headquarters, on Centre Market Place, en route to the 161st Street courthouse in the Bronx.1 Of these, the third expo- sure, which pictures the young Pape through the luminously articulated mesh of that police wagon’s grated rear window and is the basis for Frank Pape, Arrested for Homicide, November 10, 1944 in the Thomas Walther Collection, now stands among the photographer’s best-known and most widely collected and reproduced works.”

1/ On October 29, 1944, four-year-old Billy Drach was found by his father and eight-year-old brother, Bobby, bound and gagged in the basement of the apartment building where the family lived. Initially Bobby confessed that he had tied Billy up while playing “commando,” and the police ruled the death accidental. The Drach family, however, pressed for further investigation, which ultimately led to the confession of Pape, who lived nearby. Pape said that he had wanted to mimic a scene from a movie he had just seen, had found Billy drawing with chalk on the street, and had asked him, “Want to play tie-up?” As the tabloid story that accompanied the publication of Weegee’s photograph recounts (see fig. 9), Pape claimed he panicked when Billy began to struggle, and he left the younger boy bound with rope in the basement, with a handkerchief in his mouth and a burlap sack over his head. See “Neighbor Boy Admits Tying Bobby Drach,” PM, November 10, 1944, p. 15.

For more on the creation and dissemination of this print, see Jason E. Hill, “In the Police Wagon, in the Press, and in The Museum of Modern Art (A Note on Weegee’s Frank Pape, Arrested for Homicide, November 10, 1944)”

The original negative was horizontal and was cropped in various proportions, photographs taken from the above article by Jason E. Hill:

Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American born Ukraine (Austria), Złoczów (Zolochiv) 1899 – 1968 New York)

Frank Pape, Arrested for Strangling Boy to Death, New York

1944

Photographic negative (digitally scanned and inverted)

4 x 5″ (10.2 x 12.7cm)

International Center of Photography

© 2014 Weegee/International Center of Photography/Getty Images

PHOTOGRAPH NOT IN EXHIBITION

This print, made by Sid Kaplan in 1983, shows the entire view of Weegee’s original negative for the third exposure he took of Frank Pape in November 1944. Coloured frames indicate the cropping of prints, now in various collections, derived from the negative: Sid Kaplan’s portfolio of Weegee’s prints, International Center of Photography, New York (red); Frank Pape, Arrested for Homicide, J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles (blue); Sixteen-Year-Old Boy Who Strangled a Four-Year-Old Child to Death, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (dark green); Frank Pape, Arrested for Homicide, November 10, 1944, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. (brown); Frank Pape, Arrested for Homicide, November 10, 1944, The Museum of Modern Art, New York (orange); Frank Pape, Arrested for Strangling Boy to Death, New York, International Center of Photography (yellow); the image as it was first published in PM (white); the image as it appeared in Weegee’s 1945 book, Naked City (light green).

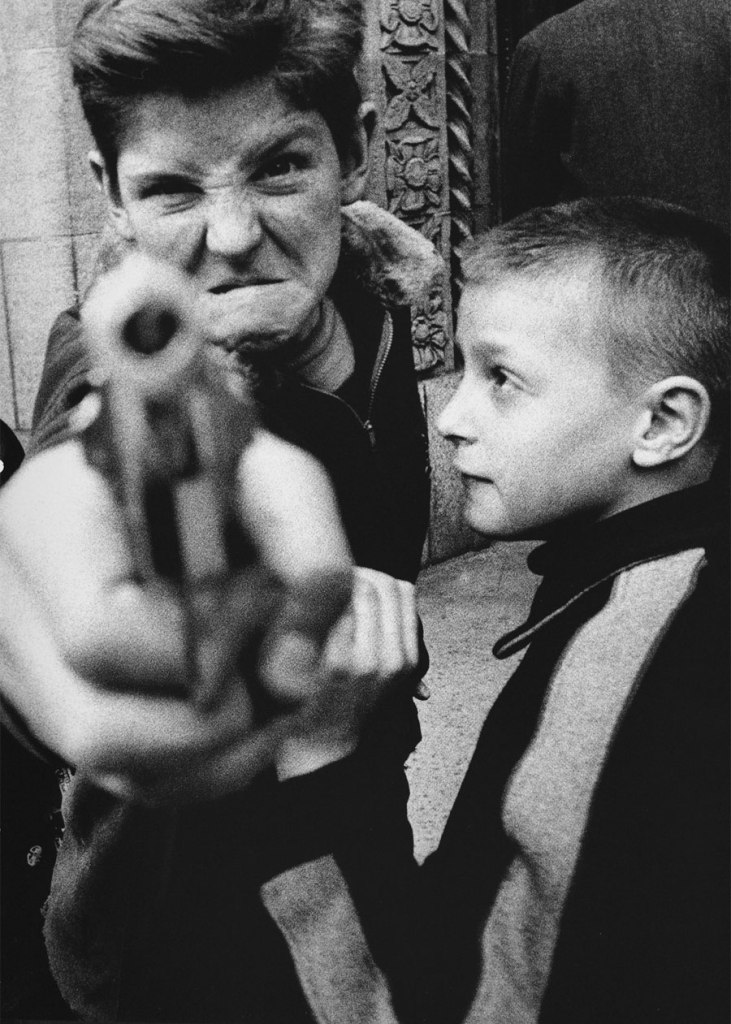

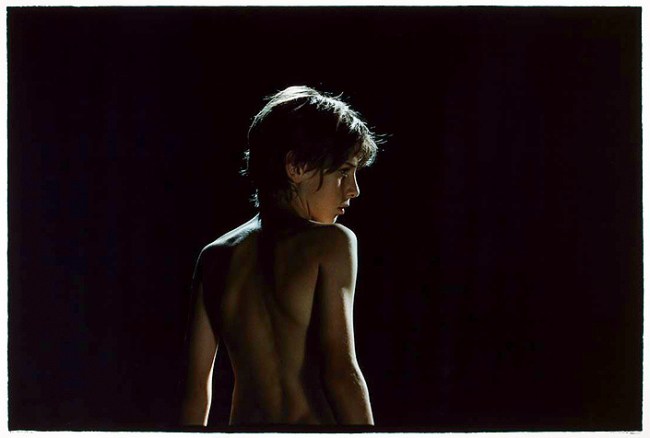

William Klein (American, 1928-2022)

Gun 1, New York

1954, printed 1986

Gelatin silver print

45.4 x 33.3cm (17 7/8 x 13 1/8 in.)

Gift of the artist, in honor of his mother, Mrs. Helen Klein, 1987

Upon his return home in the late 1940s after eight years abroad in the army, Klein found his native New York City familiar but strange. Commissioned by Vogue to create a photographic book about the city, Klein recorded its vibrancy and grittiness, producing an uncompromising portrait that the magazine ultimately rejected. He subsequently took his photographs to Paris and published them under the title Life is Good & Good for You in New York. For this photograph, Klein asked two boys on Upper Broadway to pose. One pointed a gun at the camera, his face erupting with rage, mimicking the stereotypical poses of criminals in our image-saturated society.

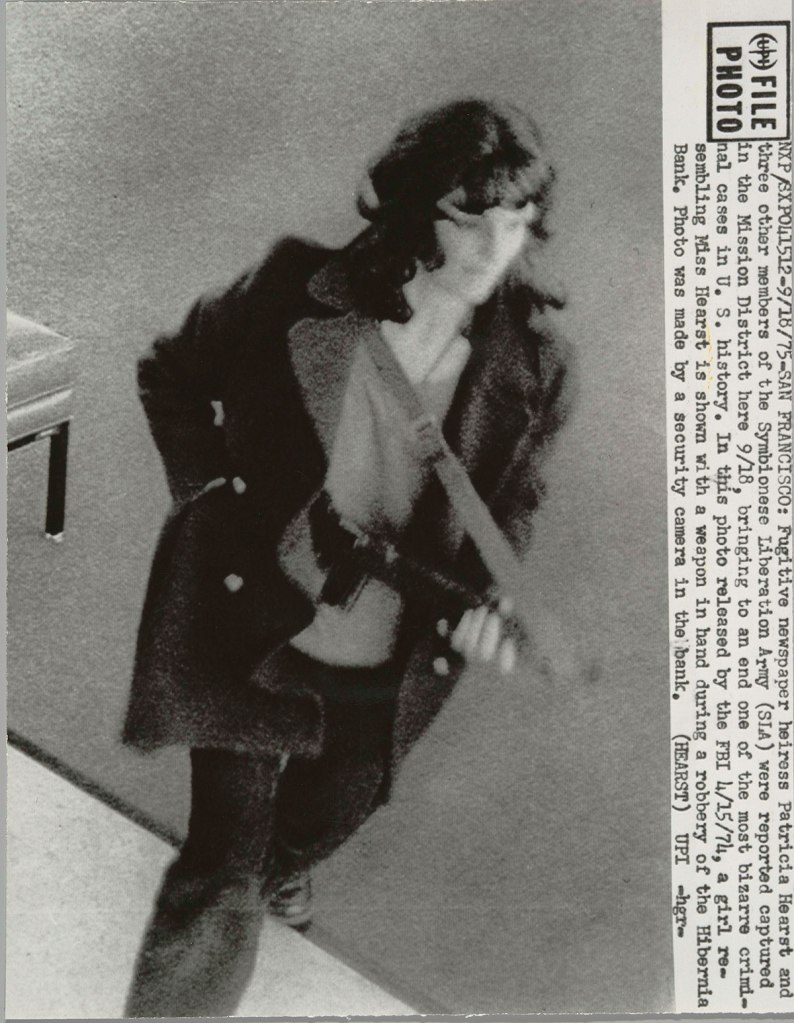

United Press International (American)

Person in Photograph: Patricia Hearst (American, b. 1954)

SAN FRANCISCO. Fugitive newspaper heiress Patricia Hearst and three other members of the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA) were reported captured in the Mission District here 9/18, bringing to an end one of the most bizarre criminal cases in U.S. History. In this photo released by the FBI 4/15/74, a girl resembling Miss Hearst is shown with a weapon in hand during a robbery of the Hibernia Bank

1974

Gelatin silver print

22.4 x 17.5cm (8 13/16 x 6 7/8 in.)

Gift of Alan L. Paris, 2011

The newspaper heiress Patricia Hearst in a 1974 shot from a bank surveillance camera.

The kidnapping of newspaper heiress Patty Hearst by the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA) was one of the most sensational news stories of the twentieth century. As part of its mission to dismantle the U.S. government and its capitalist values, the SLA abducted Hearst, an act that catapulted the terrorist group onto an international stage. A few months later, the SLA released tapes of Hearst declaring that she had joined their crusade, and within weeks she was photographed participating in a San Francisco bank robbery. The bank’s surveillance camera captured the photographs, vividly demonstrating the power of the medium to render a dramatic image of an event, even without a person behind the lens.

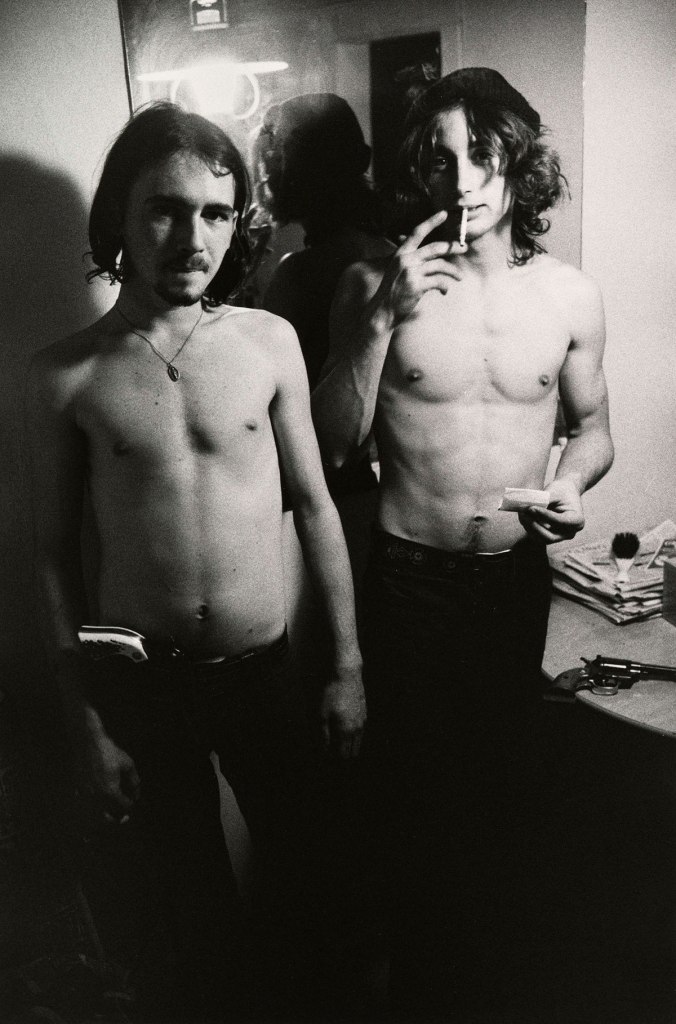

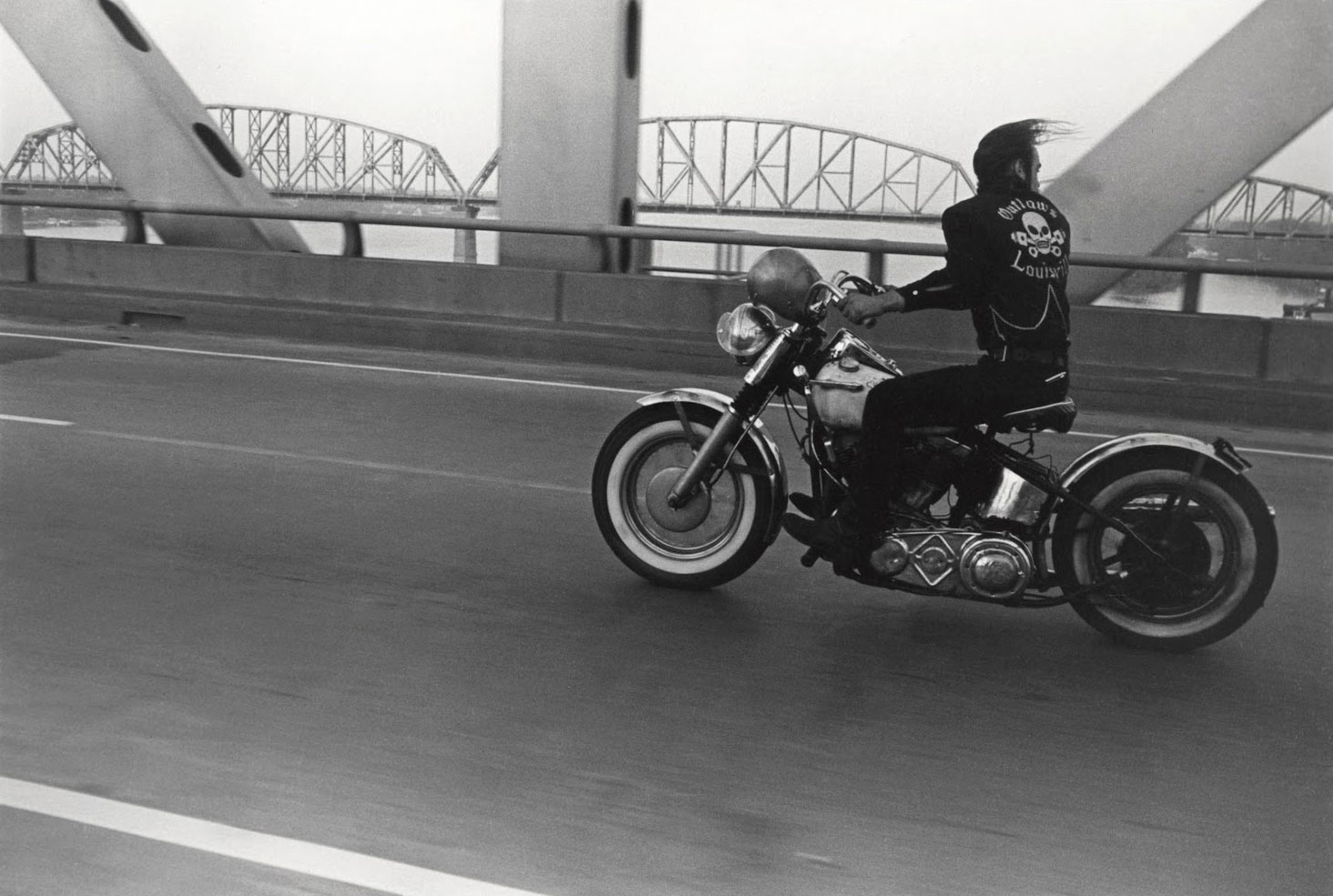

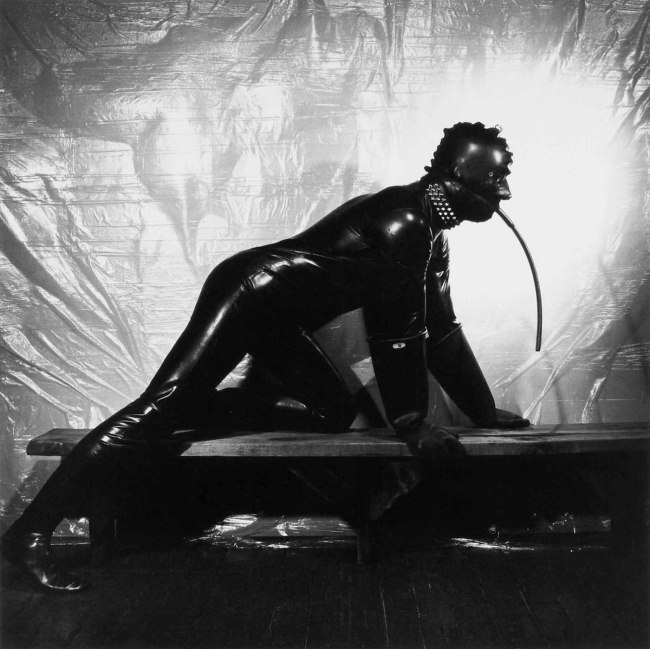

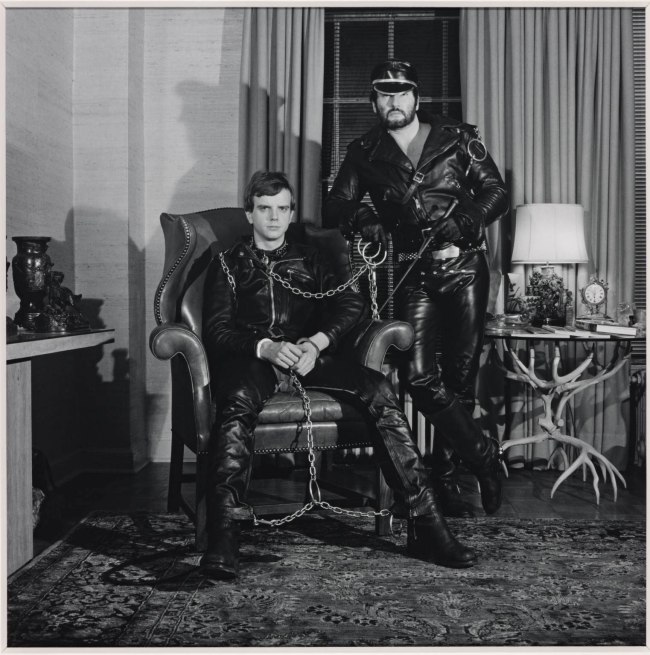

Larry Clark (American, b. 1943)

Armed Robbers, Oklahoma City

1975, printed 1981

Gelatin silver print

30.5 x 20.2cm (12 x 7 15/16 in.)

Purchase, The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 1994

© Larry Clark

A child of Eisenhower’s strait laced and conformist 1950s America, Clark saw the camera as a way to “turn back the years” and photograph a younger crowd doing the kinds of things he either did or wanted to have done when he himself was a teenager – shooting drugs, shacking up with prostitutes, and committing all manner of crimes. Because of the nature of who and what he was photographing, almost all of Clark’s work from this period would become memorial in nature. This double portrait makes manifest the dangerous allure that is often attached to portrayals of criminality.

![United Press International (American) '[Bank Robber Aiming at Security Camera, Cleveland, Ohio]' March 8, 1975 United Press International (American) '[Bank Robber Aiming at Security Camera, Cleveland, Ohio]' March 8, 1975](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/cleveland-1975-web1.jpg?w=745)

United Press International (American)

[Bank Robber Aiming at Security Camera, Cleveland, Ohio]

March 8, 1975

Gelatin silver print

Image: 6 7/8 × 4 13/16 in. (17.4 × 12.2cm)

Sheet: 7 1/2 × 5 7/8 in. (19.1 × 15cm)

Twentieth-Century Photography Fund, 2015

This startling photograph captures a robber firing his pistol at a bank camera to prevent it from recording his identity. Although he and his accomplices absconded with $11,600 in the heist, the gunman was too slow for the ever-watchful eye of the security camera, which caught his face right before the shot rang out, enabling authorities to identify their suspect.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

1000 Fifth Avenue at 82nd Street

New York, New York 10028-0198

Phone: 212-535-7710

Opening hours:

Sunday – Tuesday and Thursday: 10am – 5pm

Friday and Saturday: 10am – 9pm

Closed Wednesday

![Unknown photographer (American) '[Jeff Briggs, Robert Sims, Otis Hall, and Peter Pamphlet; Full-Length Mugshot from the Chicago Police Department]' 1936 from the exhibition 'Crime Stories: Photography and Foul Play' at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, March - July, 2016 Unknown photographer (American) '[Jeff Briggs, Robert Sims, Otis Hall, and Peter Pamphlet; Full-Length Mugshot from the Chicago Police Department]' 1936 from the exhibition 'Crime Stories: Photography and Foul Play' at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, March - July, 2016](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/mug-shot1-web.jpg)

![Unknown photographer (American) '[John Dillinger's Feet, Chicago Morgue]' 1934 from the exhibition 'Crime Stories: Photography and Foul Play' at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, March - July, 2016 Unknown photographer (American) '[John Dillinger's Feet, Chicago Morgue]' 1934 from the exhibition 'Crime Stories: Photography and Foul Play' at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, March - July, 2016](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/john-dillingers-body-web.jpg)

![Unknown photographer (American) '[Jeff Briggs, Robert Sims, Otis Hall, and Peter Pamphlet; Full-Length Mugshot from the Chicago Police Department]' 1936 Unknown photographer (American) '[Jeff Briggs, Robert Sims, Otis Hall, and Peter Pamphlet; Full-Length Mugshot from the Chicago Police Department]' 1936](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/mug-shot2-web.jpg)

![Walker Evans (American, St. Louis, Missouri 1903–1975 New Haven, Connecticut) '[Subway Passengers, New York City]' 1938 Walker Evans (American, St. Louis, Missouri 1903–1975 New Haven, Connecticut) '[Subway Passengers, New York City]' 1938](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/walker-evans-subway-passengers-new-york-city-web.jpg)

![Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914) '[Album of Paris Crime Scenes]' 1901-1908 Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914) '[Album of Paris Crime Scenes]' 1901-1908](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/bertillon-a-web.jpg)

![Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914) '[Album of Paris Crime Scenes]' 1901-1908 (detail) Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914) '[Album of Paris Crime Scenes]' 1901-1908 (detail)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/bertillon-a-detail.jpg)

![Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914) '[Album of Paris Crime Scenes]' 1901-1908 Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914) '[Album of Paris Crime Scenes]' 1901-1908](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/bertillon-b-web.jpg)

![Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914) '[Album of Paris Crime Scenes]' 1901-1908 (detail) Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914) '[Album of Paris Crime Scenes]' 1901-1908 (detail)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/bertillon-b-detail.jpg)

![Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914) '[Album of Paris Crime Scenes]' 1901-1908 Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914) '[Album of Paris Crime Scenes]' 1901-1908](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/bertillon-c-web.jpg)

![Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914) '[Album of Paris Crime Scenes]' 1901-1908 (detail) Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914) '[Album of Paris Crime Scenes]' 1901-1908 (detail)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/bertillon-c-detail.jpg)

![Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914) '[Album of Paris Crime Scenes]' 1901-1908 Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914) '[Album of Paris Crime Scenes]' 1901-1908](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/bertillon-d-web.jpg)

![Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914) '[Album of Paris Crime Scenes]' 1901-1908 (detail) Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914) '[Album of Paris Crime Scenes]' 1901-1908 (detail)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/bertillon-d-detail.jpg)

![Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914) '[Album of Paris Crime Scenes]' 1901-1908 Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914) '[Album of Paris Crime Scenes]' 1901-1908](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/bertillon-h-web.jpg)

![Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914) '[Album of Paris Crime Scenes]' 1901-1908 (detail) Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914) '[Album of Paris Crime Scenes]' 1901-1908 (detail)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/bertillon-h-detail.jpg)

![Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914) '[Album of Paris Crime Scenes]' 1901-1908 Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914) '[Album of Paris Crime Scenes]' 1901-1908](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/bertillon-e-web.jpg)

![Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914) '[Album of Paris Crime Scenes]' 1901-1908 (detail) Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914) '[Album of Paris Crime Scenes]' 1901-1908 (detail)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/bertillon-e-detail.jpg)

![Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914) '[Album of Paris Crime Scenes]' 1901-1908 Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914) '[Album of Paris Crime Scenes]' 1901-1908](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/bertillon-f-web.jpg)

![Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914) '[Album of Paris Crime Scenes]' 1901-1908 (detail) Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914) '[Album of Paris Crime Scenes]' 1901-1908 (detail)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/bertillon-f-detail.jpg)

![Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914) '[Album of Paris Crime Scenes]' 1901-1908 Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914) '[Album of Paris Crime Scenes]' 1901-1908](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/bertillon-g-web.jpg)

![Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914) '[Album of Paris Crime Scenes]' 1901-1908 (detail) Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914) '[Album of Paris Crime Scenes]' 1901-1908 (detail)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/bertillon-g-detail.jpg)

![Unknown photographer '[The Pattillo Brothers (Benjamin, George, James, and John), Company K, "Henry Volunteers," Twenty-second Regiment, Georgia Volunteer Infantry]' 1861-1863 Unknown photographer '[The Pattillo Brothers (Benjamin, George, James, and John), Company K, "Henry Volunteers," Twenty-second Regiment, Georgia Volunteer Infantry]' 1861-1863](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/patillo-brothers-close-up-web.jpg)

![Unknown photographer '[The Pattillo Brothers (Benjamin, George, James, and John), Company K, "Henry Volunteers," Twenty-second Regiment, Georgia Volunteer Infantry]' (detail) 1861-1863 Unknown photographer '[The Pattillo Brothers (Benjamin, George, James, and John), Company K, "Henry Volunteers," Twenty-second Regiment, Georgia Volunteer Infantry]' (detail) 1861-1863](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/patillo-brothers-close-up-detail.jpg)

![Unknown maker. '[Civil War Portrait Lockets]' 1860s Unknown maker. '[Civil War Portrait Lockets]' 1860s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/dp273827-lockets-web.jpg)

![Unknown maker. '[Civil War Portrait Lockets]' (detail) 1860s (detail) Unknown maker. '[Civil War Portrait Lockets]' (detail) 1860s (detail)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/dp273827-lockets-detail.jpg?w=650)

![Alexander Gardner (American, Glasgow, Scotland 1821 - 1882 Washington, D.C.) '[President Abraham Lincoln, Major General John A. McClernand (right), and E. J. Allen (Allan Pinkerton, left), Chief of the Secret Service of the United States, at Secret Service Department, Headquarters Army of the Potomac, near Antietam, Maryland]' October 4, 1862 Alexander Gardner (American, Glasgow, Scotland 1821 - 1882 Washington, D.C.) '[President Abraham Lincoln, Major General John A. McClernand (right), and E. J. Allen (Allan Pinkerton, left), Chief of the Secret Service of the United States, at Secret Service Department, Headquarters Army of the Potomac, near Antietam, Maryland]' October 4, 1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/dp248329-abraham-lincoln-web.jpg?w=650)

![Alexander Gardner (American, Glasgow, Scotland 1821 - 1882 Washington, D.C.) '[President Abraham Lincoln, Major General John A. McClernand (right), and E. J. Allen (Allan Pinkerton, left), Chief of the Secret Service of the United States, at Secret Service Department, Headquarters Army of the Potomac, near Antietam, Maryland]' October 4, 1862 (detail) Alexander Gardner (American, Glasgow, Scotland 1821 - 1882 Washington, D.C.) '[President Abraham Lincoln, Major General John A. McClernand (right), and E. J. Allen (Allan Pinkerton, left), Chief of the Secret Service of the United States, at Secret Service Department, Headquarters Army of the Potomac, near Antietam, Maryland]' October 4, 1862 (detail)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/dp248329-abraham-lincoln-detail.jpg)