Exhibition dates: 16th October, 2022 – 16th January, 2023

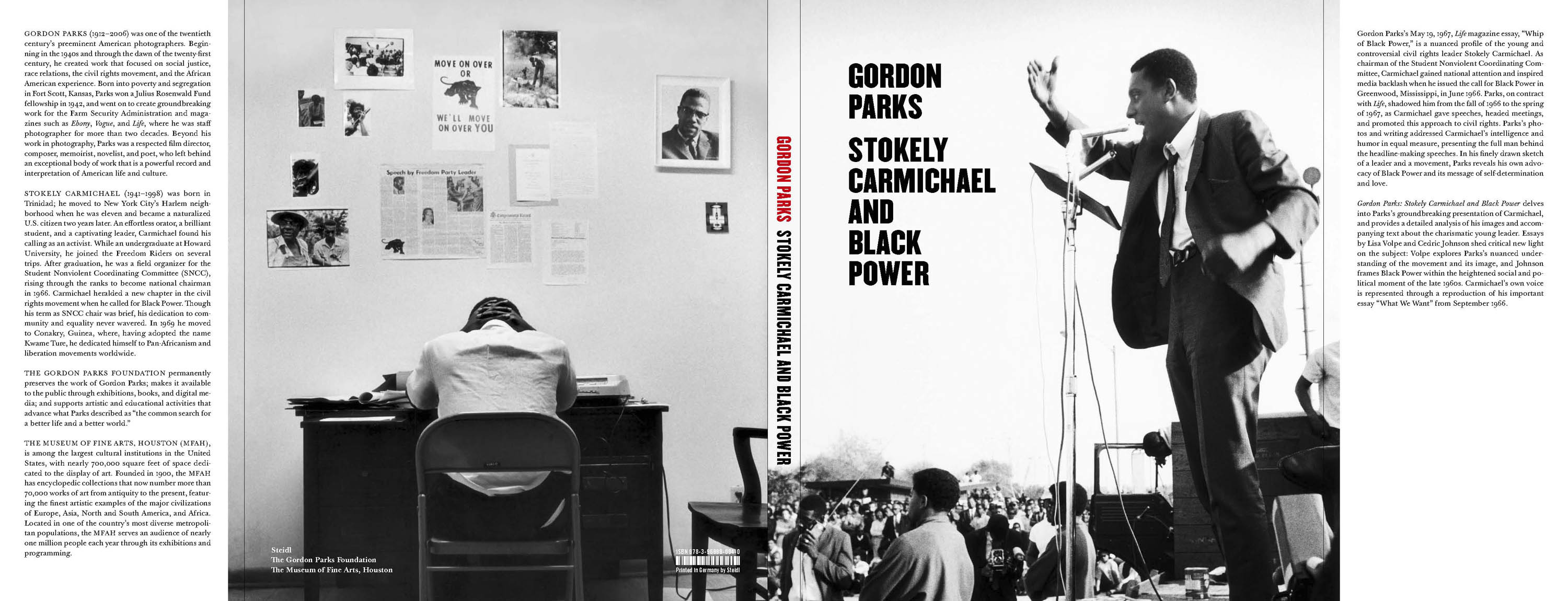

Gordon Parks: Stokely Carmichael and Black Power book cover

Visible Man / Invisible photographer

Only five of Black American Gordon Parks’ photographs of controversial young activist Stokely Carmichael were published in Life magazine in May 1967 in a photo essay with text by Parks titled “Whip of Black Power” out of the 700 photographs that he had actually taken for the assignment. This exhibition dives into these unseen photographs.

“”Whip of Black Power” recounts Parks’s travels with Carmichael from fall 1966 to spring 1967. While the Life essay contained only five photographs, this exhibition presents 53 of Parks’s images from those critical months, a time that coincided with larger social shifts within the civil rights movement and a rising resistance to the Vietnam War. Parks challenged the disparaging view of Carmichael in the mass media, presenting him as a multifaceted and honourable character.”1

“…Parks’s text and photo essay for Life conveyed the nuanced range of Carmichael as a person – not only his anger at America’s deeply rooted racism, but his self-effacing humour, his private moments with family, and his own feelings of dismay that the justice he and the movement sought would not be attained in his lifetime – all part of a “truth,” as Parks described, “the kind that comes through looking and listening.”2

As chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the charismatic Carmichael had “issued the call for Black Power in a speech in Mississippi in June 1966, eliciting national headlines, and media backlash.” “For once, black people are going to use the word they want to use – not just the words whites want to hear. And they will do this no matter how often the press tries to stop the use of the slogan by equating it with racism or separatism.” (Stokely Carmichael) The call for Black Power was consistently misunderstood and misrepresented in the press. “What Carmichael was advocating in his call for Black Power was not revolution but the goal of self-determination: “The goal of black self-determination and black self-identity – Black Power,” Carmichael and Hamilton wrote, “is full participation in the decision-making processes affecting the lives of black people, and recognition of the virtues in themselves as black people.”3

What Parks’ photographs accomplish is to put a human face to Stokely Carmichael the revolutionary firebrand and the culture of black protest, process and progress in which he is embedded, “presenting the complexities and tensions in the ongoing struggle for civil rights and highlighting photography’s capacity to present a powerful statement against hate and fear.”4 Parks’ photographs confront “the inequalities and brutalities of our society” whilst “thrusting forth its images of hope, human fraternity, and individual self-realization.”5 Here, living, a valuable and fruitful life whilst discovering an authentic personal identity, and fighting for personal and collective freedom was the objective.

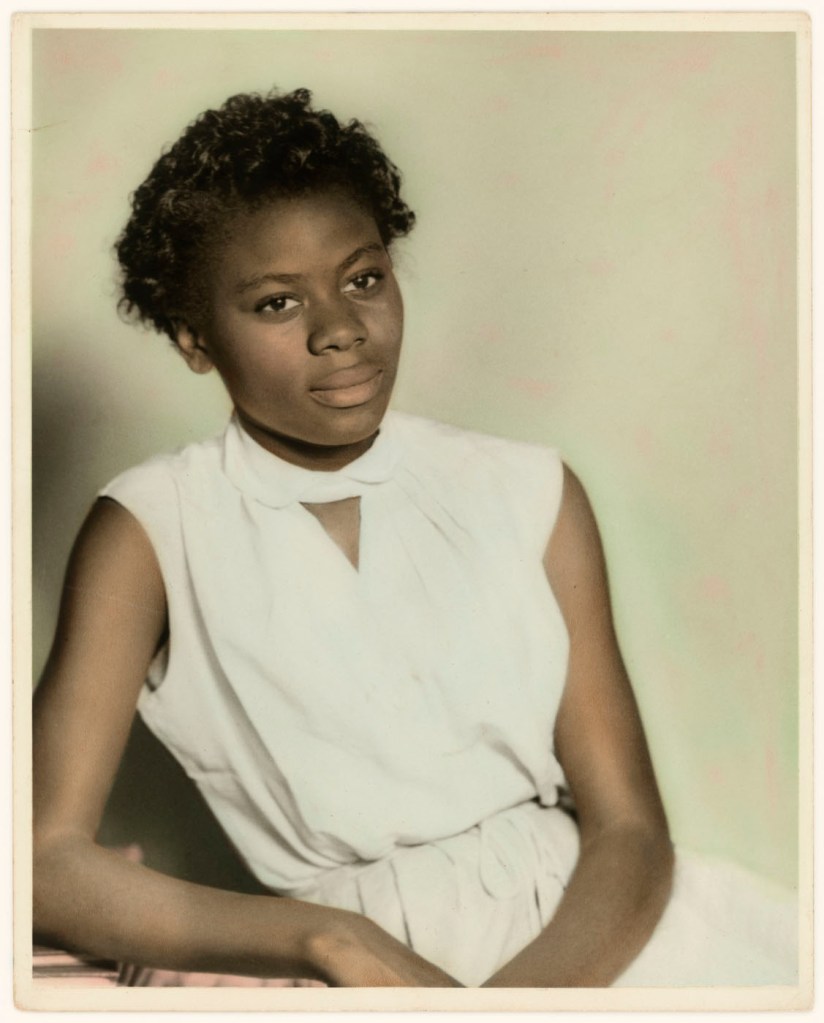

Black people have their own history, traditions and rituals that form a cohesive and complex culture which is the source of a full sense of identity. “As a photographer – through his studies of crime and gang violence to his profiles of black nationalism – Parks illuminated the diversity and richness of black life while also exposing the absurd, systemic injustice that defined the United States. Alongside his photographs, Parks’s writing encourages us to see the complexity of black life, which though demeaned by white racist institutions and behaviors is not reducible to some uniform Black experience. Rather, his own political perspective, which is decidedly more liberal than the black political figures he chose as subjects, is a testament to the diverse strivings, political positions, and discrete prerogatives that have defined black political life during and after Jim Crow.”6

The quest for a viable identity is a universal human challenge which is not dependent on colour, race or religion. As the Black American writer Ralph Ellison observes when quoted in an article by Anne Seidlitz, “black and white culture were inextricably linked, with almost every facet of American life influenced and impacted by the African-American presence – including music, language, dance, folk mythology, clothing styles and sports. Moreover, he [Ellision] felt that the task of the writer is to “tell us about the unity of American experience beyond all considerations of class, of race, of religion.”7

This is what I am hammering on about here: whilst the civil rights movement and the call for Black Power promoted a new politics of black autonomy and militancy which embodied a new politics of black self-assertion and meaningful self-determination, everything is linked together… nothing can be seen other than within a nexus of networked links which inform and affect each other. In this sense Parks’ text and images, together, present a multi-dimensional profile of this charismatic leader, this complex character – as a portrait of his perseverance, gentleness, frustration, despair, joy, anger, laughter, enthusiasm, energy, and passion – sketching the musical and rhythmic character of Stokely Carmichael embedded within the history of interconnected moments, in the contexts of the times, seen through multiple openings in the space / time continuum as the camera lens opens and closes. Parks photographs “put the viewer exactly at the moment of capture letting us be there at the scene.” And they make Stokely Carmichael visible, then and now. At the time the photographer was nearly invisible.

“Now, it’s interesting to note that when I [Lisa Volpe] would share the photos with those men and women captured in them [Parks’ photographs], they all had a very similar reaction. Each one of them remembered the scene. They remembered that meeting, or that lecture, they remembered what was being discussed and how they felt. They really had perfect recall for pretty much everything within the frame … but what was interesting was that they were all shocked to see the photographs. Not a single person I talked to remembered Gordon Parks ever being in the room. Now… when he was on assignment he truly became a fly on the wall in order to get the most truthful images possible. And yes, even speaking to these ladies [in the photograph Sanamu Nyeusi (left) and Hasani Soto (right) of the US Organization at the Watts rally, Will Rogers Park, Los Angeles (1966,below)], they did not even notice Gordon Parks probably three feet in front of them taking their photo.”8

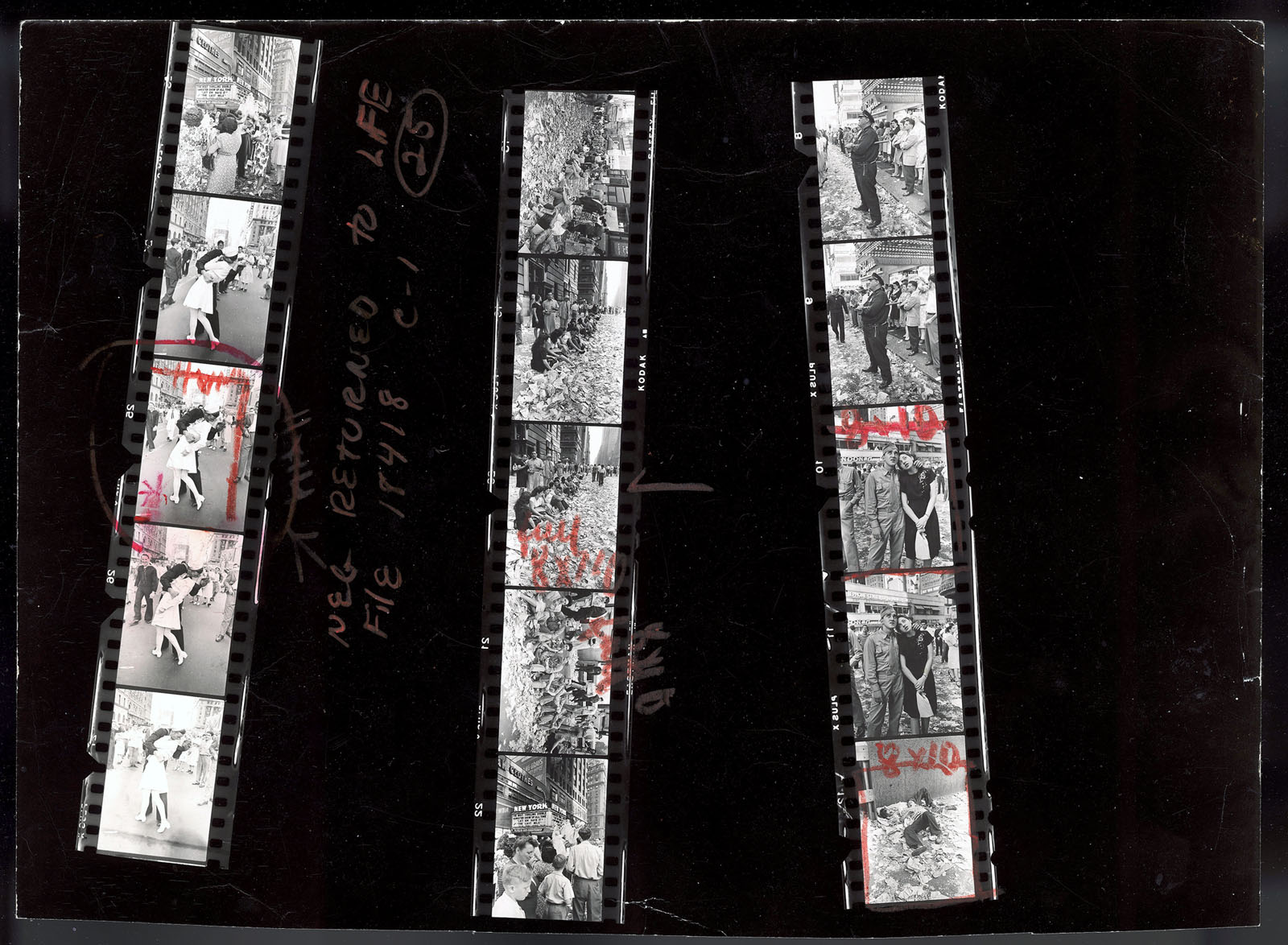

As the recognition of Parks as a photographer has risen over the last 10 years (see the many exhibition postings on Art Blart below), with specialist exhibitions like this that analyse and promote previously hidden aspects and bodies of his work, now at last the invisible photographer stands before us, his portrait of Stokely Carmichael finally revealed in all its subtlety and complexity, intuition and com/passion. In this exhibition for example, all Parks’ negatives on the Life contact sheets were in the wrong order, and / or where from different roll of negatives on the same contact sheet (see video below).9 Through research and the reordering of the negatives we can finally see and feel what images Parks thought were important to the story that he wanted to tell about this man and his crusade (A crusader is a person who works hard or campaigns forcefully for a cause). And through this enunciation of his vision, we the viewer may come to better know what an insightful and compassionate photographer Gordon Parks was… as he now stands before us in the evident presence and generosity of his photographs.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Footnotes

1/ Text from the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston website

2/ Text from the press release from the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

3/ Cedric Johnson. “Luminous Exposures: Gordon Parks, Stokely Carmichael, and the Birth of Black Politics,” in Lisa Volpe. Gordon Parks: Stokely Carmichael and Black Power. Steidl / The Gordon Parks Foundation / The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 2022, p. 28-34

4/ Gordon Parks Introduction wall text

5/ Anne Seidlitz. “Ralph Ellison: An American Journey,” on the PBS American Masters website 19/02/2002 [Online] Cited 30/12/2022

6/ Cedric Johnson, Op cit.,

7/ Anne Seidlitz, Op cit.,

8/ Text from the video of Lisa Volpe, curator of photography, discussing acclaimed photographer Gordon Parks and offering an overview of the exhibition. Lecture | Gordon Parks: Stokely Carmichael and Black Power on the YouTube website 8th January 2023 [Online] Cited 14/01/2022

9/ Ibid.,

Postings about Gordon Parks on Art Blart

1/ Exhibition: ‘Gordon Parks and “The Atmosphere of Crime”‘ at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York, February 2021 ongoing

2/ Photographs: Gordon Parks “The Atmosphere of Crime”, 1957 February 2020

3/ Exhibition: ‘Gordon Parks: The Flávio Story’ at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Getty Center, Los Angeles, July – November 2019

4/ Exhibition: ‘Gordon Parks: Back to Fort Scott’ at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, January – September 2015

5/ Exhibition: ‘Gordon Parks: Segregation Story’ at the High Museum of Art, Atlanta, November 2014 – June 2015

6/ Exhibition: ‘Gordon Parks: The Making of an Argument’ at The New Orleans Museum of Art, September 2013 – January 2014

7/ Exhibition: ‘Gordon Parks: 100 Moments’ at New York State Museum, January – May 2013

8/ Exhibition: ‘Gordon Parks: Centennial’ at Jenkins Johnson Gallery, San Francisco, February – April 2013

9/ Exhibition: ‘Bare Witness: Photographs by Gordon Parks’ at the Phoenix Art Museum, August – November 2011

Many thankx to the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

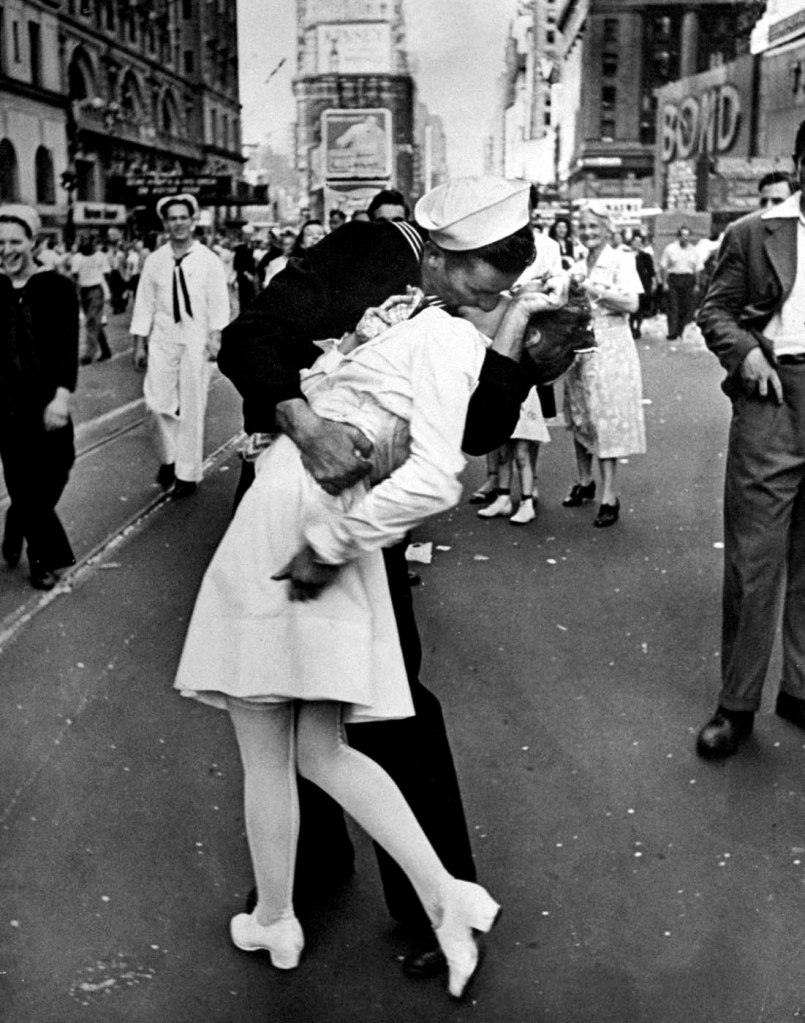

In 1967, Life magazine published photographer Gordon Parks’ groundbreaking images and profile of Stokely Carmichael, the young and controversial civil-rights leader who, as chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, issued the call for Black Power in a speech in Mississippi in June 1966, eliciting national headlines, and media backlash. On the road with Carmichael and the SNCC that fall and into the spring of 1967, Parks took more than 700 photographs as Carmichael addressed Vietnam War protesters outside the U.N. building in New York, with Martin Luther King, Jr.; spoke with supporters in a Los Angeles living room; went door to door in Alabama registering Black citizens to vote; and officiated at his sister’s wedding in the Bronx. In his finely drawn sketch of a charismatic leader and his movement, Parks, then the first Black staff member at Life, reveals his own advocacy of Black Power and its message of self-determination.

Gordon Parks: Stokely Carmichael and Black Power at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston exhibition walk through

Lecture | Gordon Parks: Stokely Carmichael and Black Power

Lisa Volpe, curator of photography, discusses acclaimed photographer Gordon Parks and offers an overview of the exhibition, which captures the civil-rights movement and activist Stokely Carmichael in the 1960s.

Gordon Parks: Stokely Carmichael and Black Power book cover

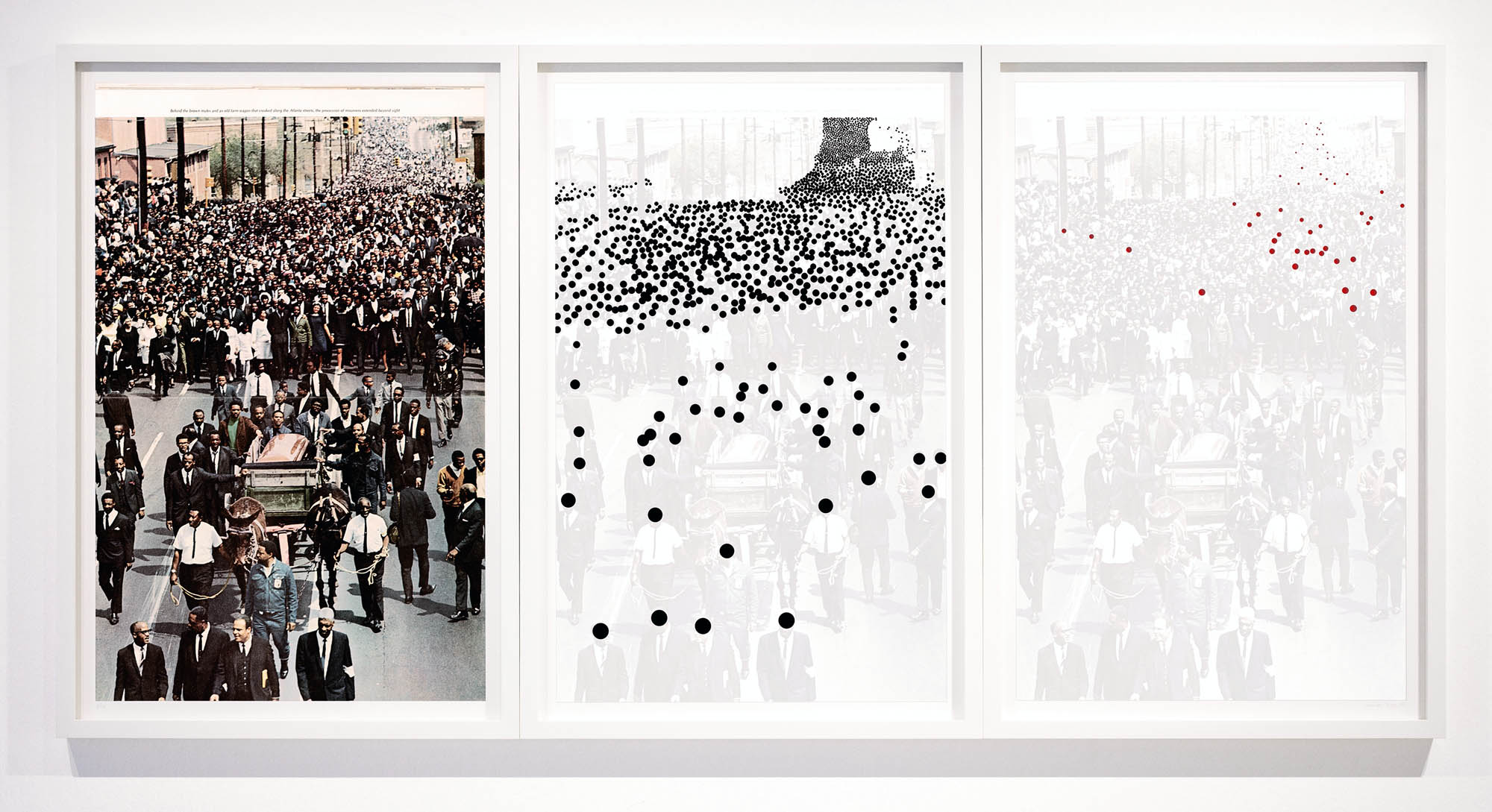

Installation views of the exhibition Gordon Parks: Stokely Carmichael and Black Power at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

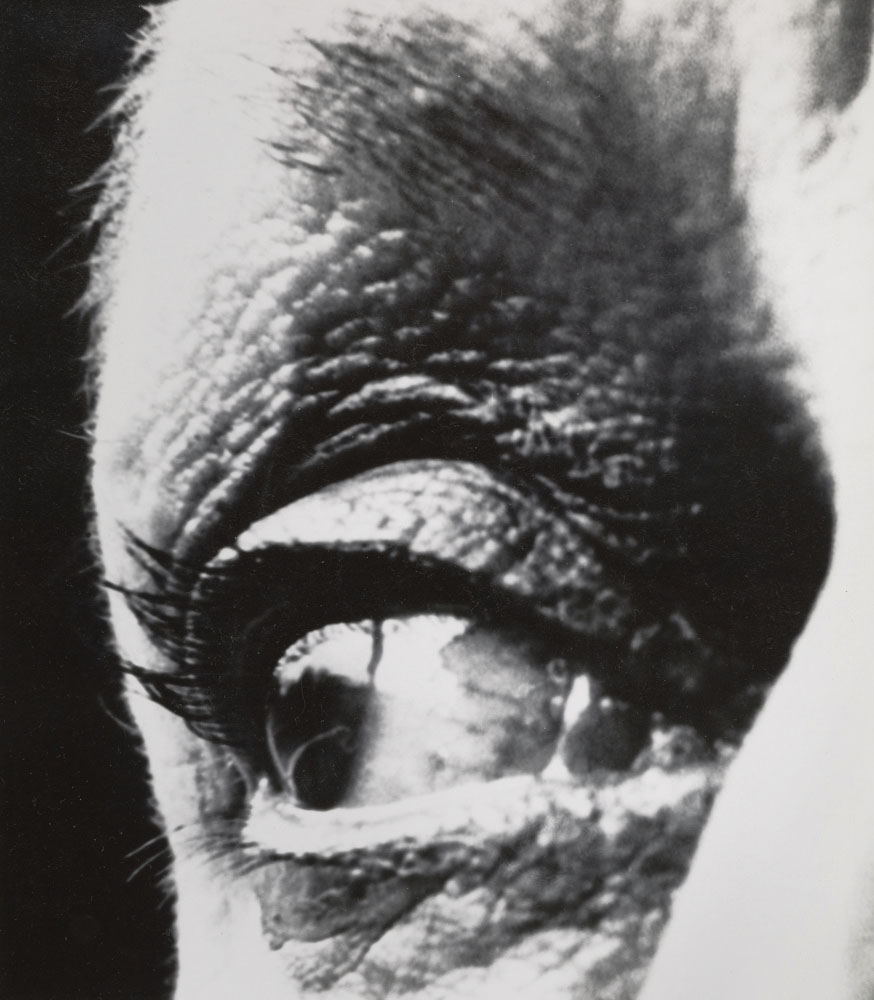

“‘What Their Cry Means to Me’ – A Negro’s Own Evaluation”

Life, May 31, 1963

Text and photographs by Gordon Parks

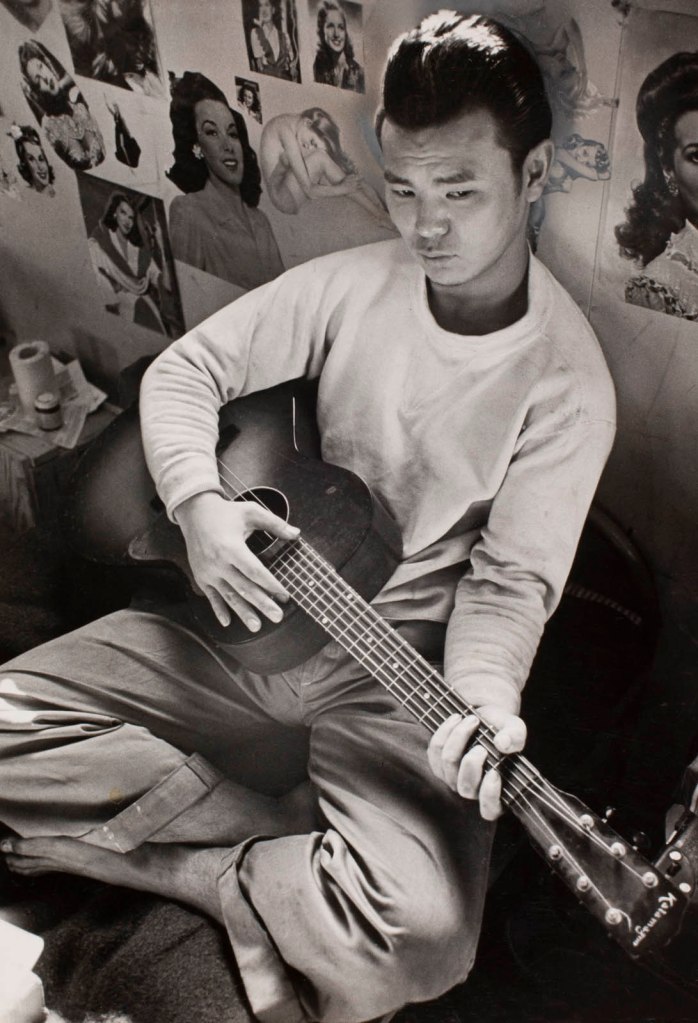

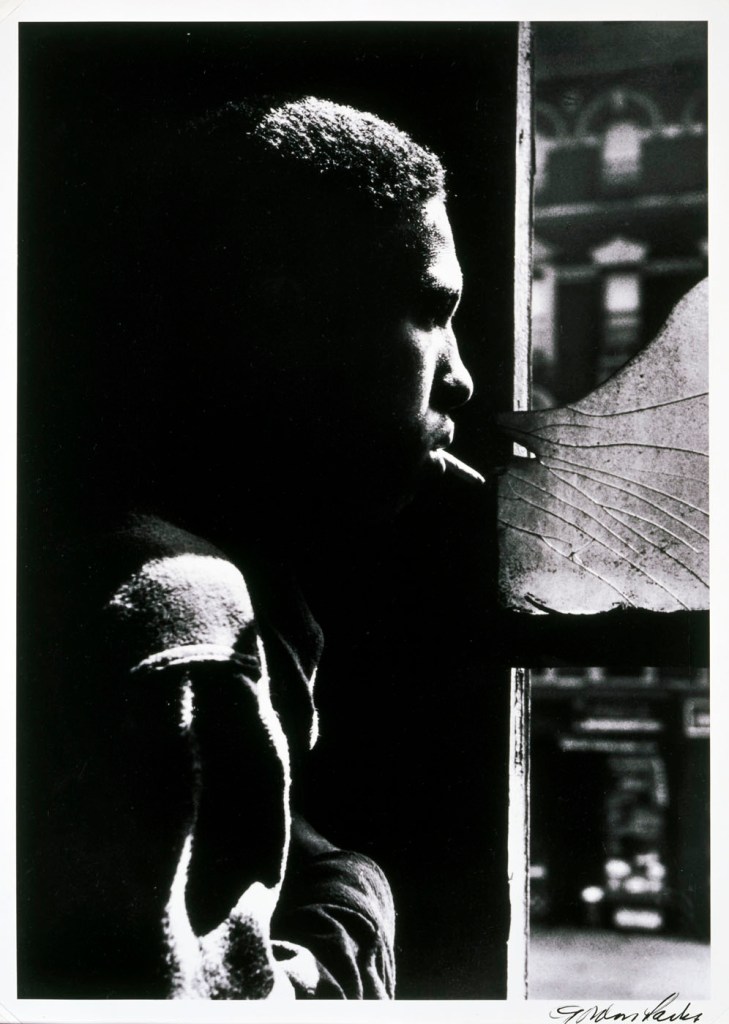

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Untitled, Chicago, Illinois

1963

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of and © The Gordon Parks Foundation

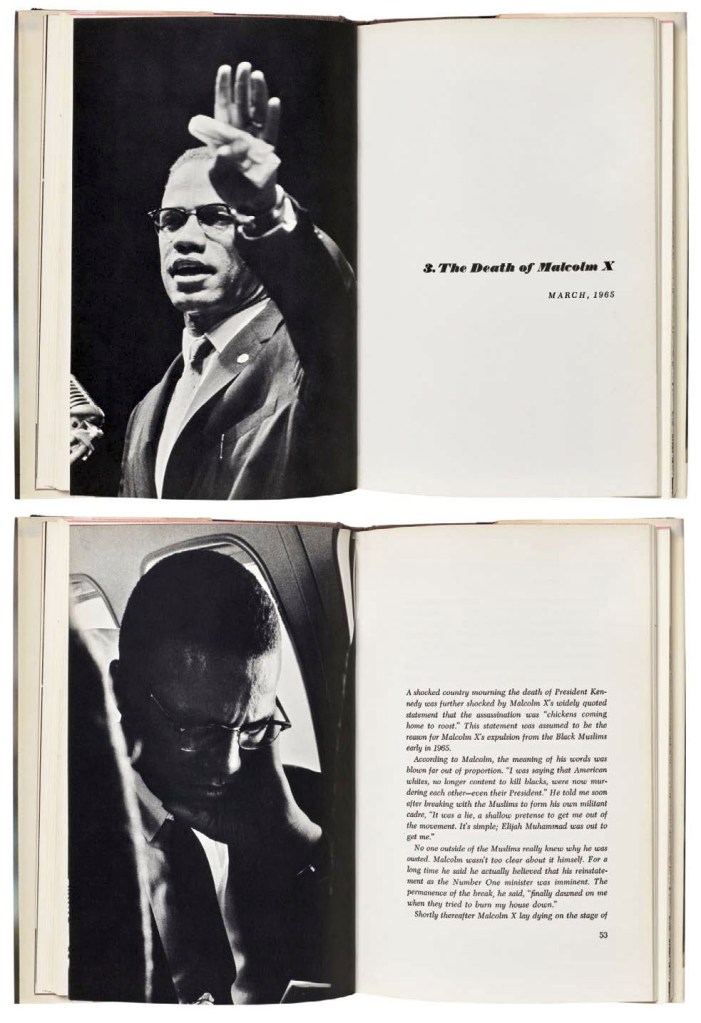

“‘I Was a Zombie Then – Like All Muslims, I Was Hypnotized'”

Life, March 5, 1965

Text by Gordon Parks

Photographs by Ted Russell, Bob Gomel, Henri Dauman, and Greg Harris

Gordon Parks, Born Black, J. B. Lippincott Company, 1971.

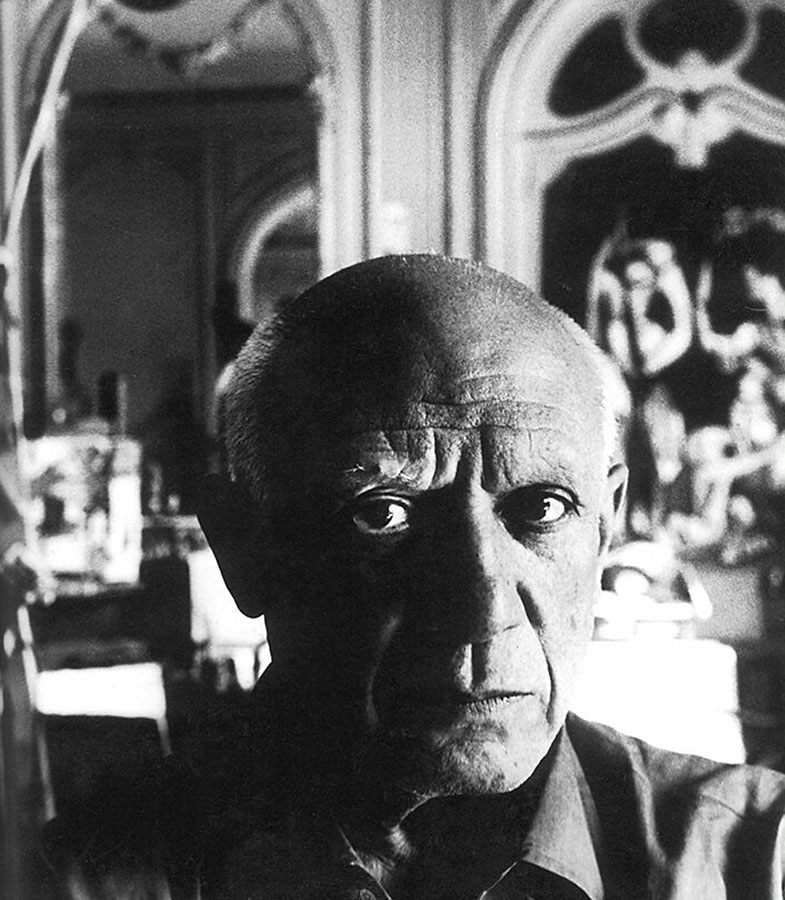

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Muhammad Ali

1966

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of and © The Gordon Parks Foundation

The MFAH exhibition centres on Gordon Parks’s five iconic images of controversial young activist Stokely Carmichael, published in Life magazine in May 1967. Organised with the Gordon Parks Foundation, the show presents dozens more photographs from Parks’s series that have never before been published or exhibited

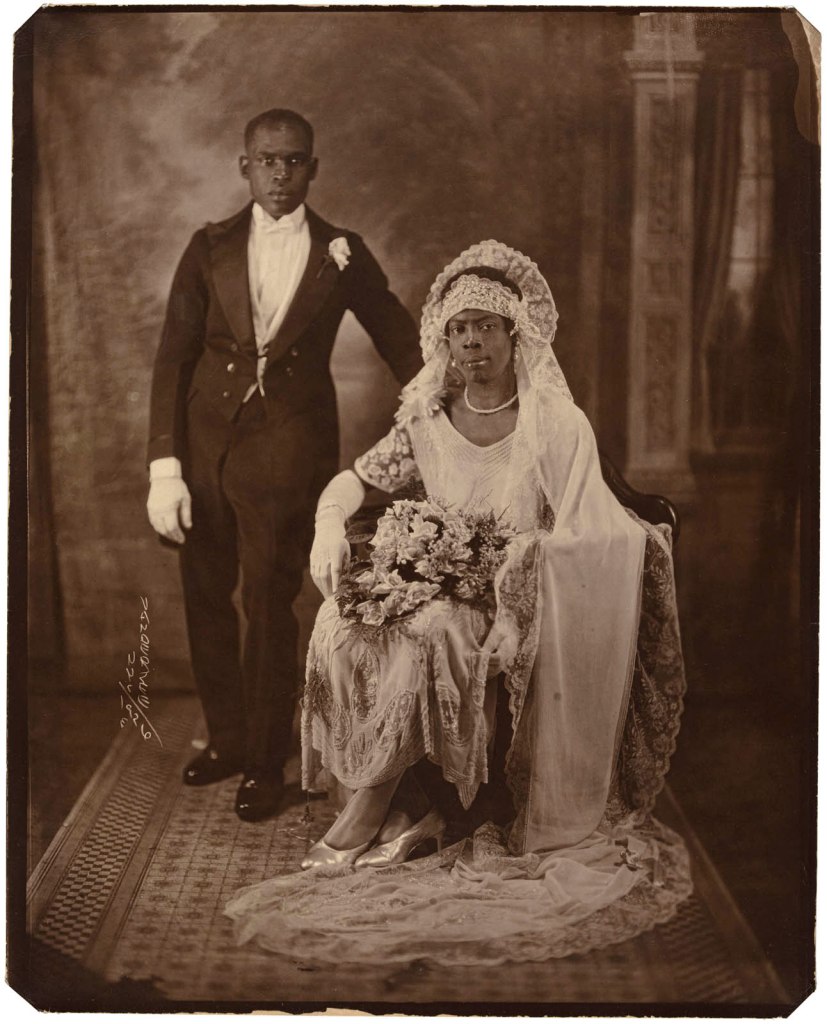

Fifty-five years ago today, Life magazine published photographer Gordon Parks’s groundbreaking images and profile of Stokely Carmichael, the young and controversial civil-rights leader who, as chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, issued the call for Black Power in a speech in Mississippi in June 1966, eliciting national headlines, and media backlash. On the road with Carmichael and the SNCC that fall and into the spring of 1967, Parks took more than 700 photographs as Carmichael addressed Vietnam War protesters outside the U.N. building in New York, with Martin Luther King, Jr.; spoke with supporters in a Los Angeles living room; went door to door in Alabama registering Black citizens to vote; and officiated at his sister’s wedding in the Bronx. In Parks’s finely drawn sketch of a charismatic leader and his movement, Parks, the first Black staff member at Life, reveals his own advocacy of Black Power and its message of self-determination.

On view only at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (October 16, 2022, to January 16, 2023), the exhibition Gordon Parks: Stokely Carmichael and Black Power will present the five images from Parks’s 1967 Life article, in the context of nearly 50 additional photographs and contact sheets that have never before been published or exhibited, as well as footage of Carmichael’s speeches and interviews.

“Extending the Museum’s commitment to photography from the civil-rights era, and following our presentation of the exhibition Soul of a Nation in 2020, which included Gordon Parks’s famous 1942 American Gothic, I am very pleased that we are able to present Parks’s landmark project for Life magazine, in collaboration with the Gordon Parks Foundation,” commented Gary Tinterow, Director and Margaret Alkek Williams Chair of the MFAH. “Parks is well known as one of America’s most important 20th-century photographers; this exhibition will further illuminate his accomplishments as a writer and journalist, as well.”

Commented Lisa Volpe, exhibition curator and MFAH curator of photography, “Gordon Parks’s portrayal of Stokely Carmichael illustrates Parks’s unmatched talent in producing illuminating and sensitive profiles. Through dynamic photographs and a personal text, he sketches both his subject and the complexities and tensions inherent in the ongoing struggle for civil rights. It is as relevant to our current moment as it was to Life‘s readers in 1967. I am grateful to the Gordon Parks Foundation for the opportunity to present these never-before-seen works and to celebrate Parks’s legacy.”

Exhibition Background

Parks met Stokely Carmichael (later, Kwame Ture) in September 1966, as Carmichael’s rallying cry for “Black Power” was grabbing national attention. Parks was a prominent contributor to Life magazine, photographing and writing essays that chronicled, with his characteristic humanity, Benedictine monks and Black Muslims; a Harlem family and a teenage gang member. Carmichael, then 25 and a recent graduate with a philosophy degree from Howard University, was consistently in the news, whether publishing his own writing in the New York Review of Books or being profiled in Esquire and Look magazines.

As chair of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Carmichael was the figure most identified with the call for Black Power, and was routinely depicted as a representative of anger and separatism. But Parks’s text and photo essay for Life, “Whip of Black Power,” conveyed the nuanced range of Carmichael as a person – not only his anger at America’s deeply rooted racism, but his self-effacing humour, his private moments with family, and his own feelings of dismay that the justice he and the movement sought would not be attained in his lifetime – all part of a “truth,” as Parks described, “the kind that comes through looking and listening.”

Exhibition Organisation and Catalogue

This exhibition is organised by the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, in collaboration with the Gordon Parks Foundation.

The accompanying catalogue, Gordon Parks: Stokely Carmichael and Black Power, published by Steidl, explores Parks’s groundbreaking presentation of Carmichael, and provides detailed analysis of Parks’s images and accompanying text. The book is the latest instalment in a series that highlights Parks’s bodies of work throughout his career, published by the Gordon Parks Foundation and Steidl. Essays by Lisa Volpe, MFAH associate curator of photography, and Cedric Johnson, professor of African American studies and political science at the University of Illinois at Chicago, shed critical new light on the subject: Volpe explores Parks’s nuanced understanding of the movement and its image, and Johnson frames Black Power within the heightened social and political moment of the late 1960s. Carmichael’s September 1966 essay in the New York Review of Books, “What We Want,” is reproduced in the book.

Gordon Parks

Parks (1912-2006) was one of the 20th century’s preeminent American photographers. Beginning in the 1940s and through the early 2000s, he created work that focused on social justice, race relations, the civil-rights movement, and the African American experience. Born into poverty and segregation in Fort Scott, Kansas, Parks won a Julius Rosenwald Fund fellowship in 1942, and went on to create groundbreaking work for the Farm Security Administration and magazines such as Ebony, Vogue, and Life, where he was staff photographer for more than two decades. Beyond his work in photography, Parks was a respected film director, composer, memoirist, novelist, and poet.

Stokely Carmichael

Carmichael (1941-1998) was born in Trinidad; he moved to New York City’s Harlem neighbourhood when he was 11 and became a naturalised U.S. citizen two years later. An effortless orator, a brilliant student, and a captivating leader, Carmichael found his calling as an activist. While an undergraduate at Howard University, he joined the Freedom Riders on several trips. After graduation, he was a field organiser for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and became national chairman in 1966. Carmichael heralded a new chapter in the civil-rights movement when he called for Black Power. In 1969 he moved to Conakry, Guinea, where, having adopted the name Kwame Ture, he dedicated his work to Pan-Africanism and liberation movements worldwide.

The Gordon Parks Foundation

The Foundation permanently preserves the work of Gordon Parks; makes it available to the public through exhibitions, books, and digital media; and supports artistic and educational activities that advance what Parks described as “the common search for a better life and a better world.”

Press release from the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Gordon Parks Interprets Ralph Ellison’s “Invisible Man” | UNIQLO ARTSPEAKS

A prelude to the Civil Rights movement. Naeem Douglas, a content producer on the Creative Team (at MoMA), finds contemporary resonance in a selection of photographs – including 1952’s “Emerging Man, Harlem, New York” – that Gordon Parks created to celebrate Ralph Ellison’s “Invisible Man.”

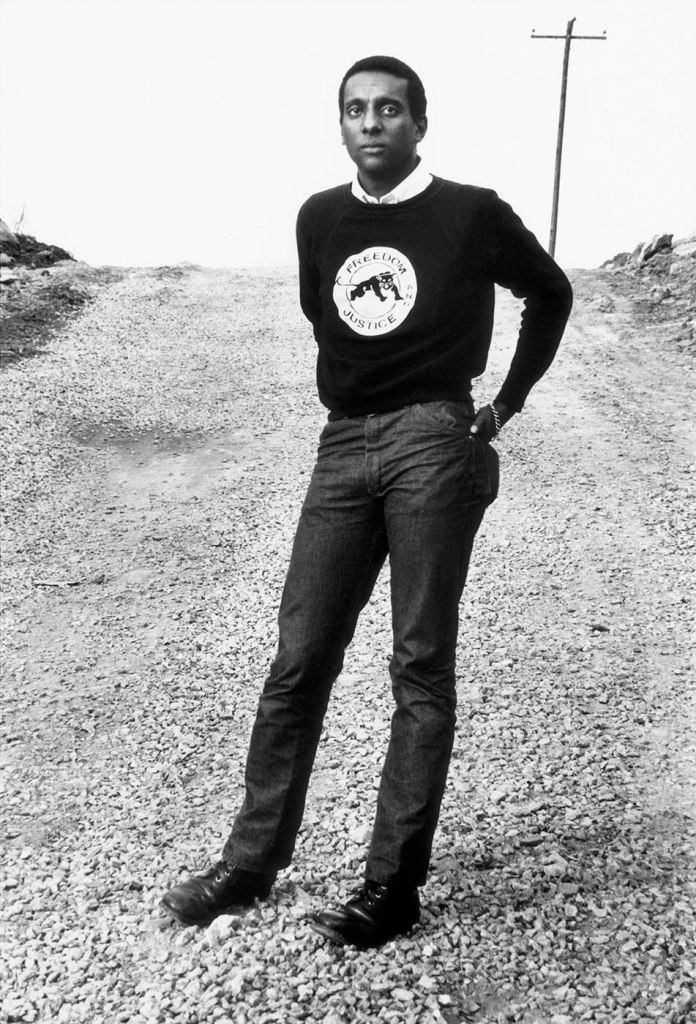

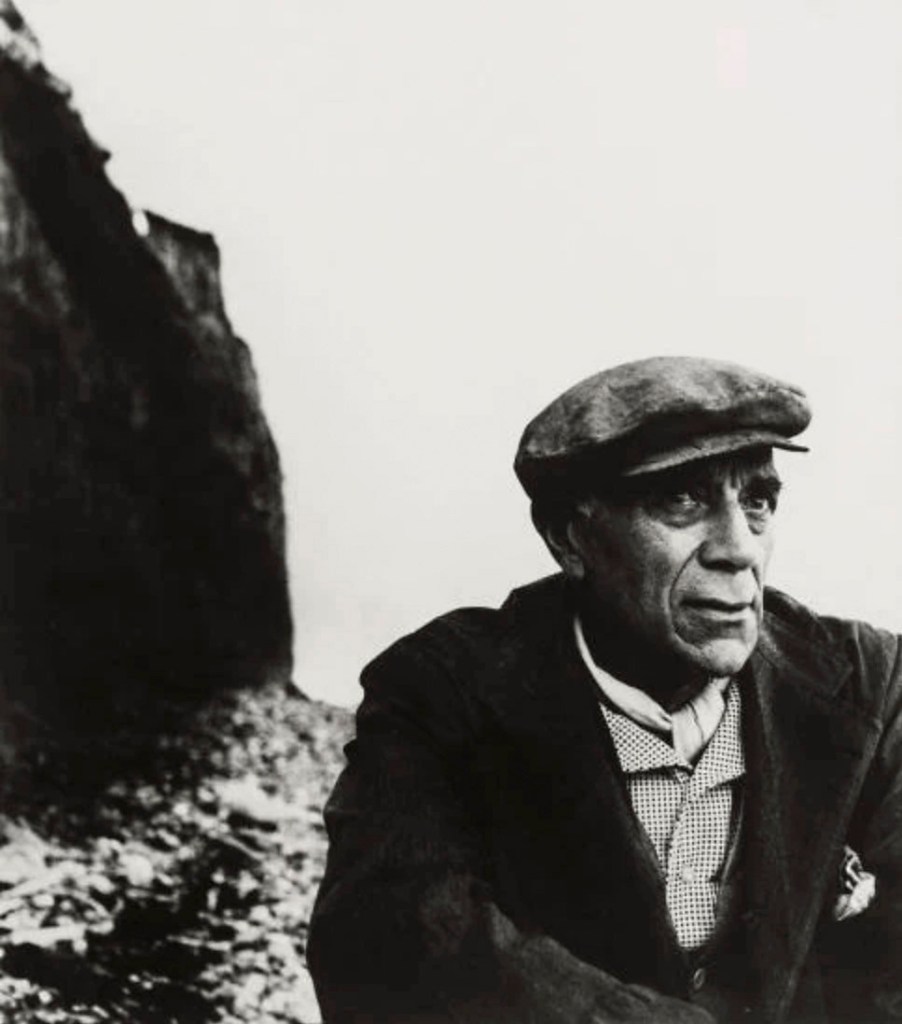

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Stokely Carmichael, Lowndes County, Alabama

1966, printed 2022

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of and © The Gordon Parks Foundation

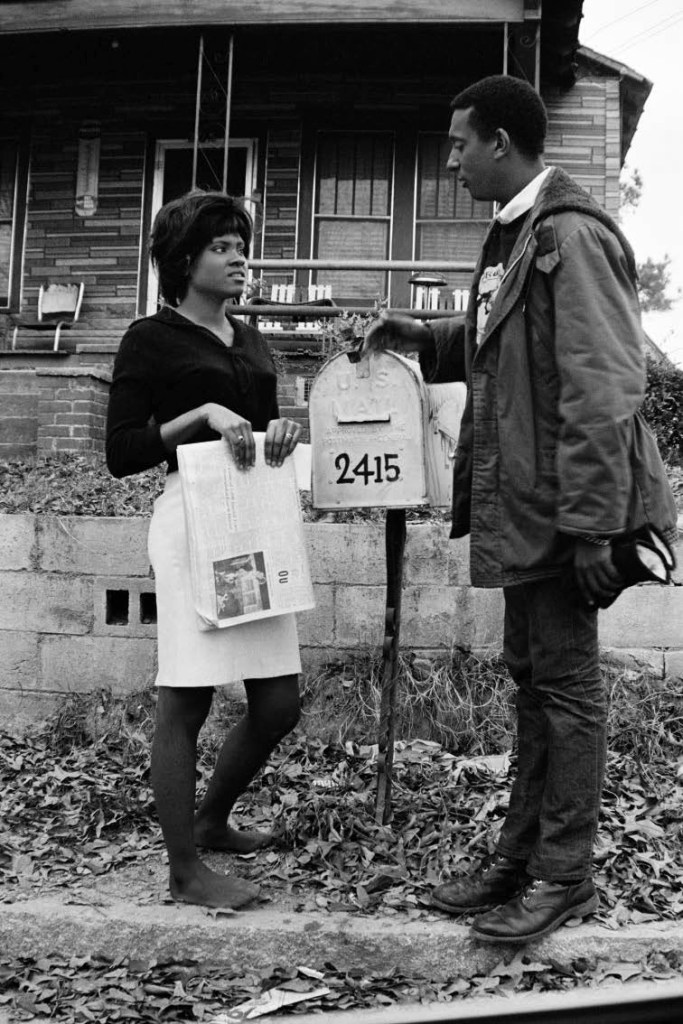

Carmichael on the road in Lowndes County, Alabama, 1966

In defiance of the governing party’s symbol – a white rooster with the phrase “White supremacy for the right” above it – Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO) chose a black panther as its symbol, an animal that becomes ferocious when cornered.

Carmichael proudly wore his Black Panther sweatshirt when he was working in Lowndes County. Taken from a low angle, Parks’s portrait presents Carmichael as a heroic figure, fighting for the rights emblazoned on his shirt: freedom and justice.

Label text from the exhibition

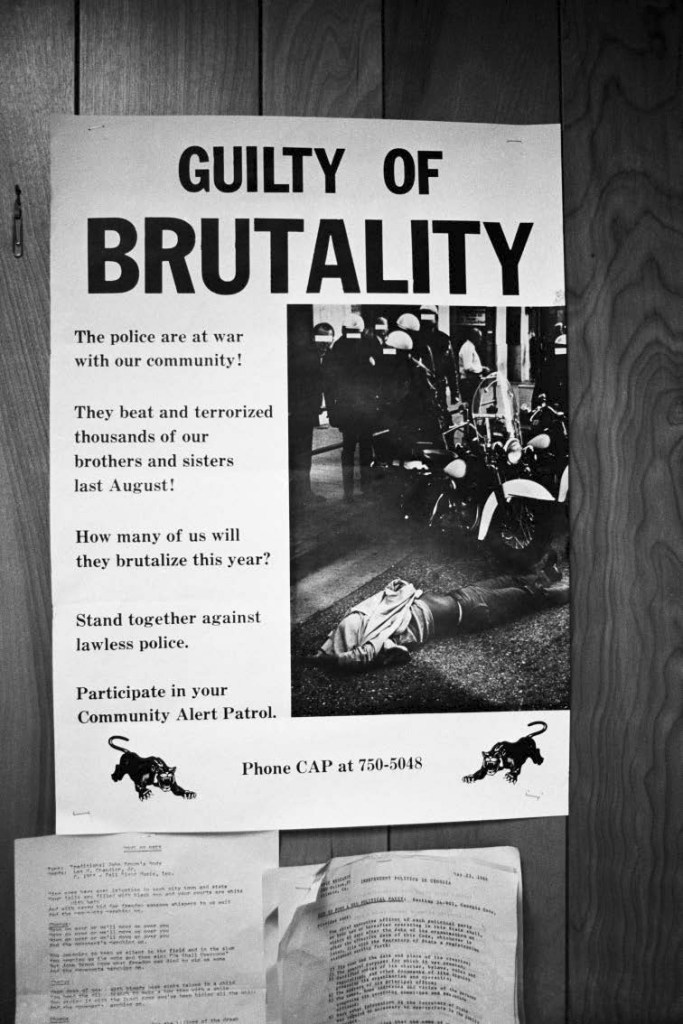

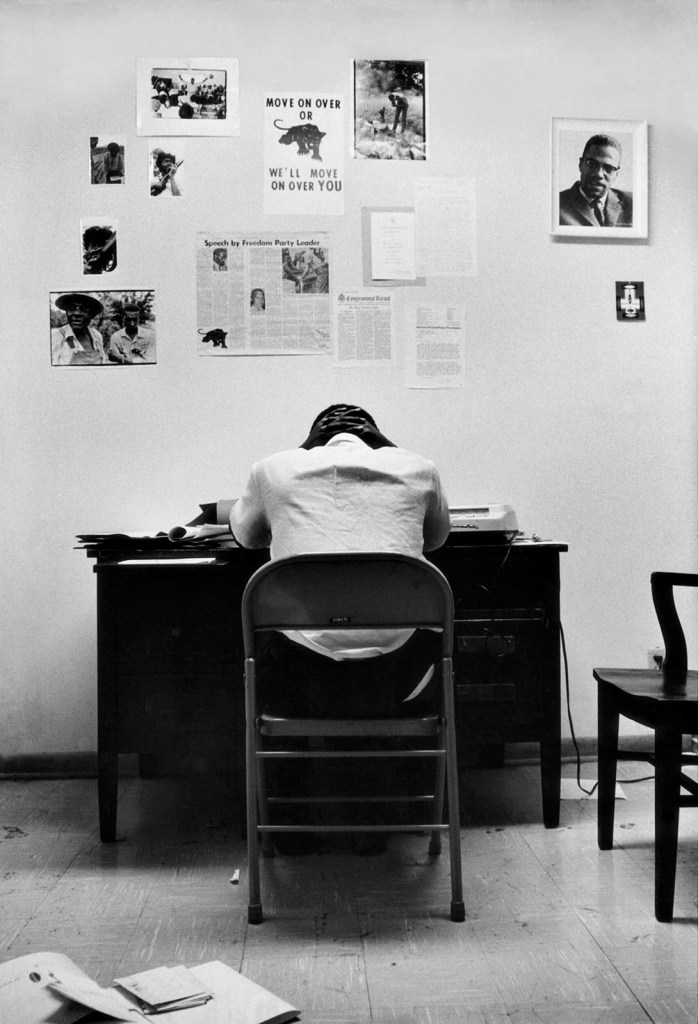

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Watts Community Alert Patrol flyer at SNCC’s Atlanta headquarters

1966

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of and © The Gordon Parks Foundation

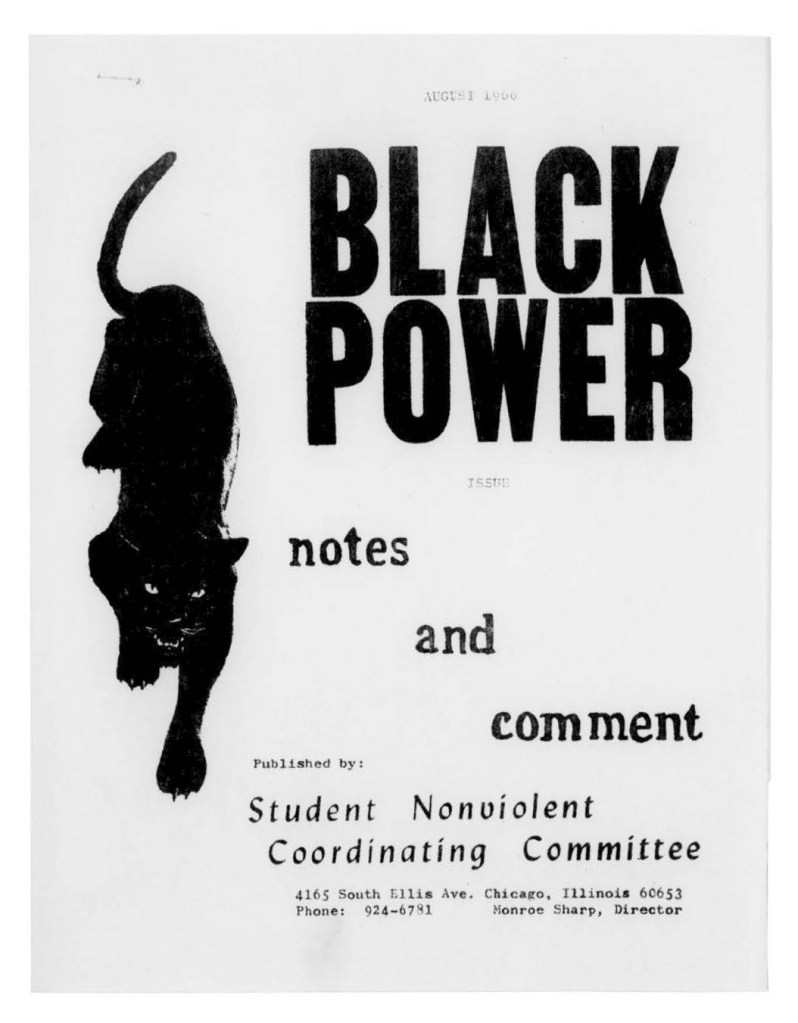

Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee pamphlet

1966

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Untitled, Atlanta, Georgia

1966, printed 2022

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of and © The Gordon Parks Foundation

Carmichael at his desk at SNCC’s Atlanta headquarters, 1966

In his profile of Carmichael, Parks aimed to combat the mass media’s one-sided depictions of the civil rights leader by capturing his complex character and emotions. At SNCC headquarters in Atlanta, Georgia, Parks documented Carmichael in a moment of weary frustration. A portrait of Malcolm X, photographs of Lowndes County residents, and SNCC pamphlets hang above the modest desk. Carefully composed, Parks’s photo guides viewers to a more holistic understanding of Carmichael. The view of the slumped leader with images above him also recalls scenes of religious pilgrims at an altar, deep in thought and prayer.

Label text from the exhibition

Gordon Parks Introduction wall text

In fall 1966 the American photographer and writer Gordon Parks (1912-2006) was contracted by Life magazine to profile 25-year-old Stokely Carmichael, one of the most maligned and misunderstood men in America.

Carmichael, the newly elected chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced “snick”), issued the first public call for Black Power on June 16, 1966, in Greenwood, Mississippi. This robust vision for a Black, self-determined future combined Black unity for social and political advancement, the breaking of psychological barriers to self-love, and self-defence when necessary. Yet, media organisations dissected and defined Black Power for white audiences with various levels of prejudice and fear, and Carmichael was cast as a figure of racial violence – a distortion of his character and his message.

“Whip of Black Power,” recounts Parks’s travels with Carmichael from fall 1966 to spring 1967. While the Life essay contained only five photographs, this exhibition presents 53 of Parks’s images from those critical months, a time that coincided with larger social shifts within the civil rights movement and a rising resistance to the Vietnam War. Parks challenged the disparaging view of Carmichael in the mass media, presenting him as a multifaceted and honourable character.

Produced more than 40 years ago, Gordon Parks’s revealing profile on Stokely Carmichael is as relevant to our current moment as it was in 1967, presenting the complexities and tensions in the ongoing struggle for civil rights and highlighting photography’s capacity to present a powerful statement against hate and fear.

Unless otherwise noted, all works are by Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006) and are courtesy of The Gordon Parks Foundation.

Text from the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Carmichael (bottom) speaking to SNCC members and staff of ‘The Movement’, including Terry Cannon (top right, wearing glasses) and Bobbi Ricca (top right), San Francisco

1966, printed 2022

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of and © The Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Carmichael speaking to SNCC members and staff of ‘The Movement’, San Francisco

1966, printed 2022

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of and © The Gordon Parks Foundation

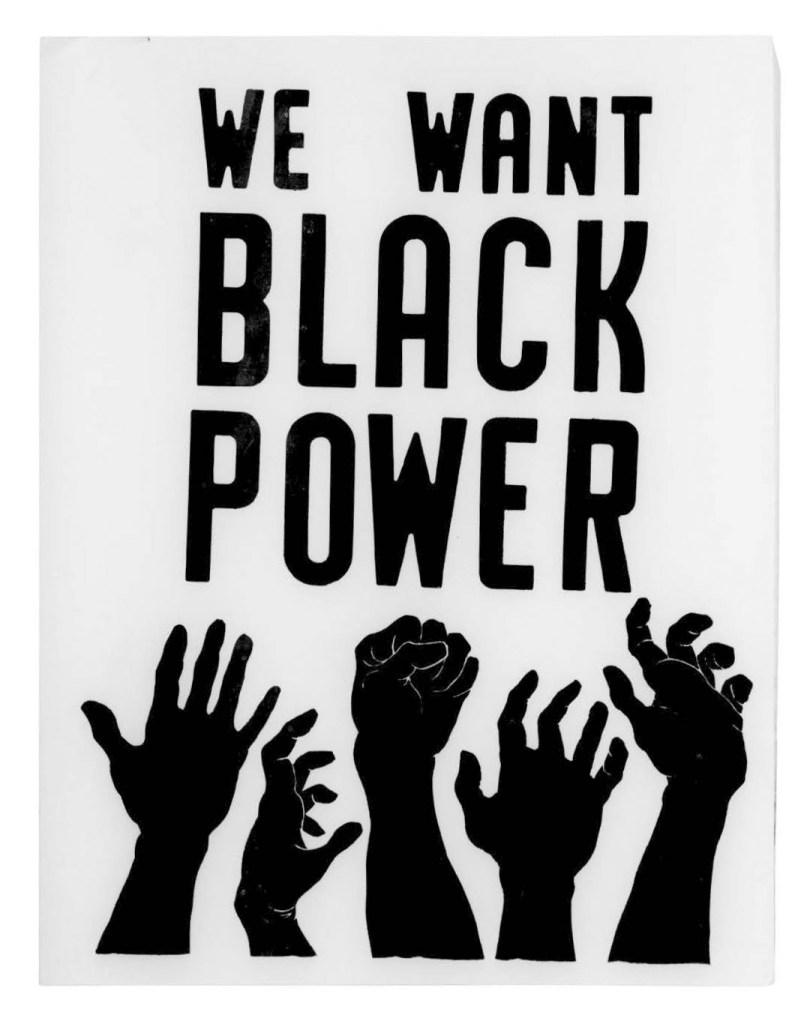

Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee poster

1966

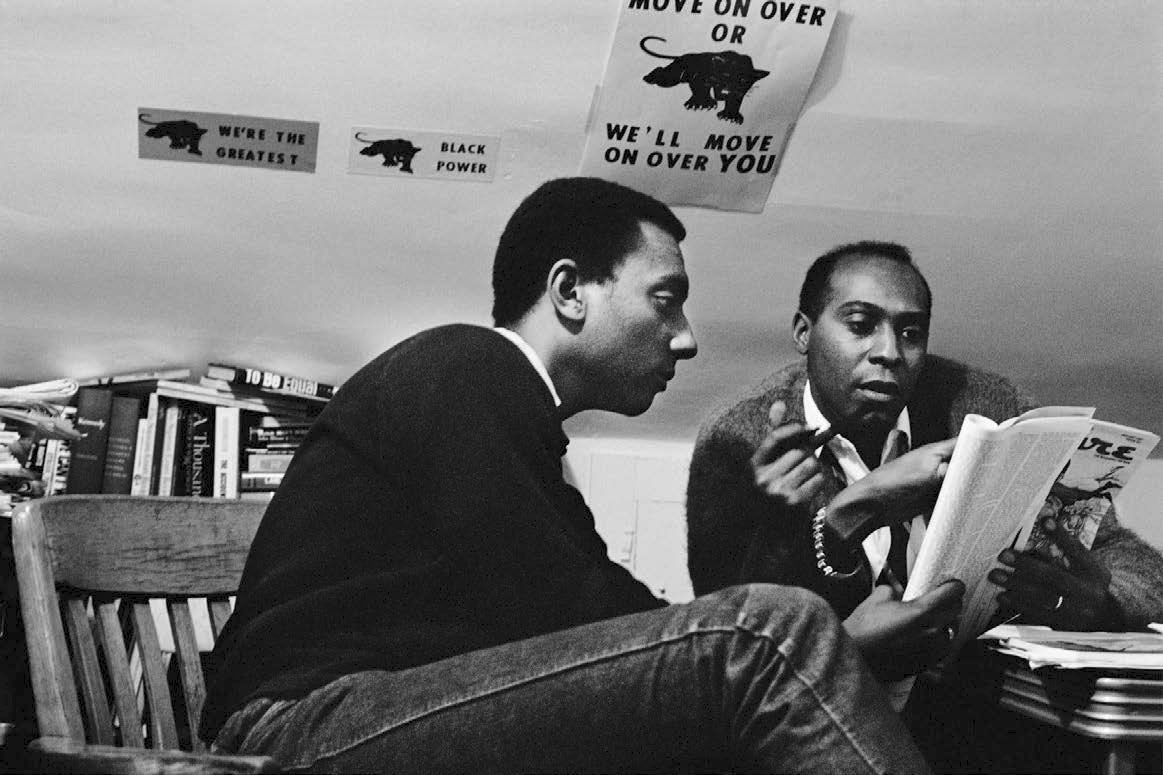

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Carmichael with Charles V. Hamilton reading a profile of Stokely in the January 1, 1967, issue of Esquire, Oxford, Pennsylvania

1966, printed 2022

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of and © The Gordon Parks Foundation

“We were in the home of [Carmichael’s] friend and adviser Charles V. Hamilton, chairman of the political science department, located near Oxford, PA,” Parks noted in his Life essay. Parks captured Carmichael and Hamilton writing and editing portions of the book, Black Power: The Politics of Liberation in America, published in October 1967. The text was one of many attempts to clarify the meaning of Black Power for a larger audience. Parks’s images from one writing session show the authors alternating between moments of intense concentration and overwhelming joy.

Label text from the exhibition

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Watts Community Alert Patrol providing transportation for the Watts rally, Los Angeles

1966, printed 2022

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of and © The Gordon Parks Foundation

The Community Alert Patrol (CAP) was formed in the aftermath of the 1965 Watts Uprising. Ron Wilkins, whose car is pictured in the background, noted, “CAP volunteers constituted the first community organisation in the U.S. whose members put their lives on the line to police the police in an effort to end law enforcement’s campaign of terror against Black people.” Fearing police interference, CAP members drove Stokely Carmichael and Gordon Parks to the Watts rally in 1966.

Label text from the exhibition

Gordon Parks Section Panels

Lowndes County, Alabama, and Atlanta, Georgia

Although 80 percent of Lowndes County was Black, by 1965, not one Black resident was registered to vote. That year, Carmichael created the Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO), a political party formed of Black residents with candidates and an agenda drawn from the community. Carmichael was certain, “If we can break Lowndes County, the rest of Alabama will fall into line.” The young leader set a dizzying schedule throughout the end of 1966 and start of 1967, travelling between Lowndes and SNCC events across the nation. Gordon Parks documented his efforts along the way, revealing Carmichael’s adaptability and charisma.

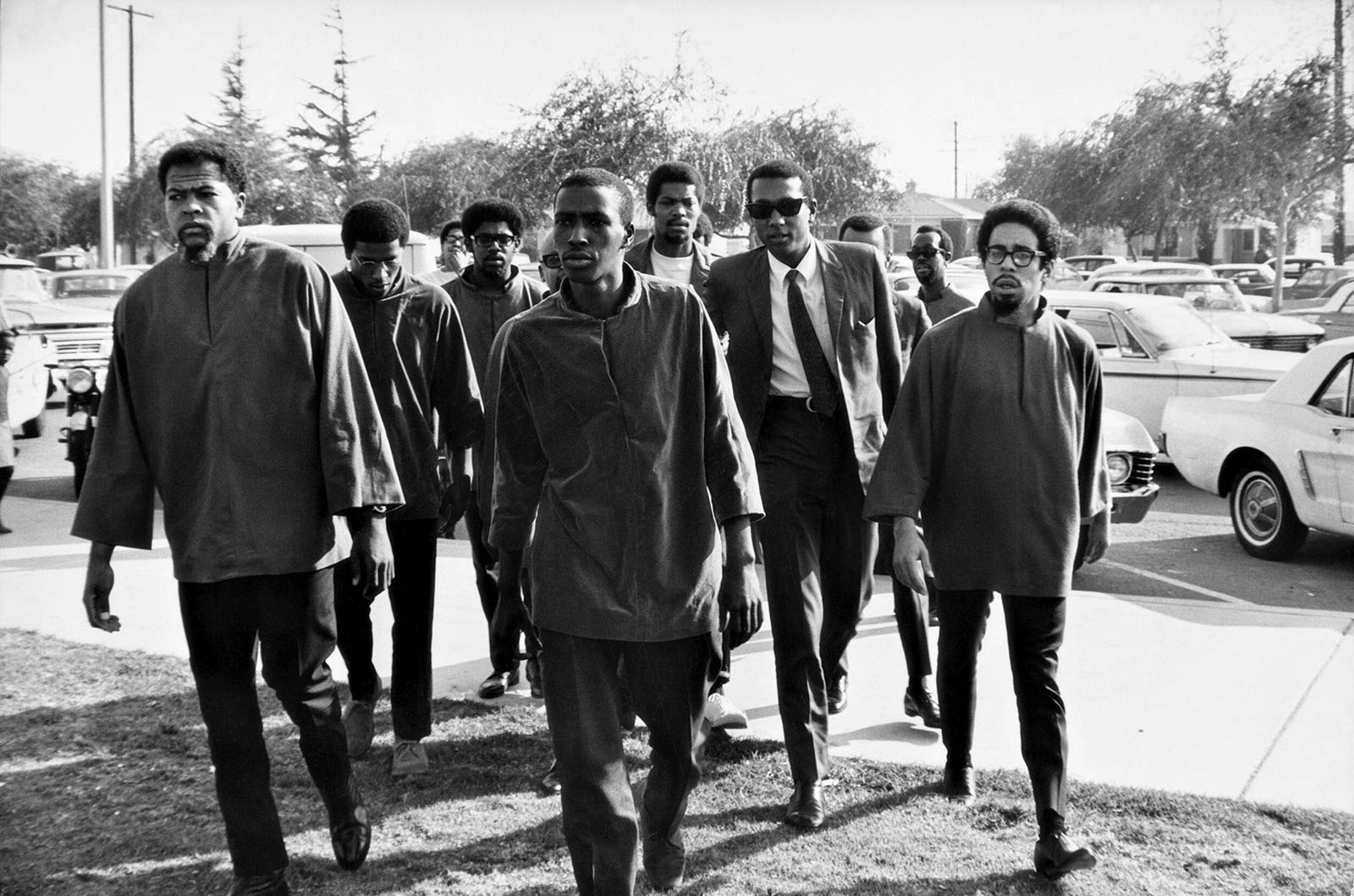

Watts, California

The Watts Uprising took place in August 1965 in a Black neighbourhood of South Central Los Angeles. It began with the arrest of a local man, Marquette Frye, by a highway patrol officer and ended with 4,000 arrests, 1,000 injuries, and 34 deaths. Carmichael spoke to thousands of residents one year later at the Watts rally. In a speech that resonates today, Carmichael declared, “We have to have community alert patrols, not to patrol our neighbourhoods, but to patrol the policeman.” Gordon Parks recorded the jubilant reactions of the community in words and pictures and opened his Life photo-essay by describing the energetic scene.

Across the Country

At a press conference following his election as chairman in May 1966, Carmichael found the white press members vehemently opposed to SNCC’s call for Black Power. He recalled, “[It was] as though they were stuck in 1960 with the student sit-ins and we were speaking in unknown tongues… [They] missed that the new direction was simply a necessary response to current political realities.” To clarify the position, Carmichael wrote persuasive articles, oversaw hundreds of press releases, agreed to dozens of interviews, and spoke across the country. Despite these efforts, Black Power was consistently misunderstood and misrepresented in the press. Carmichael noted the only fair assessment was Gordon Parks’s Life photo-essay.

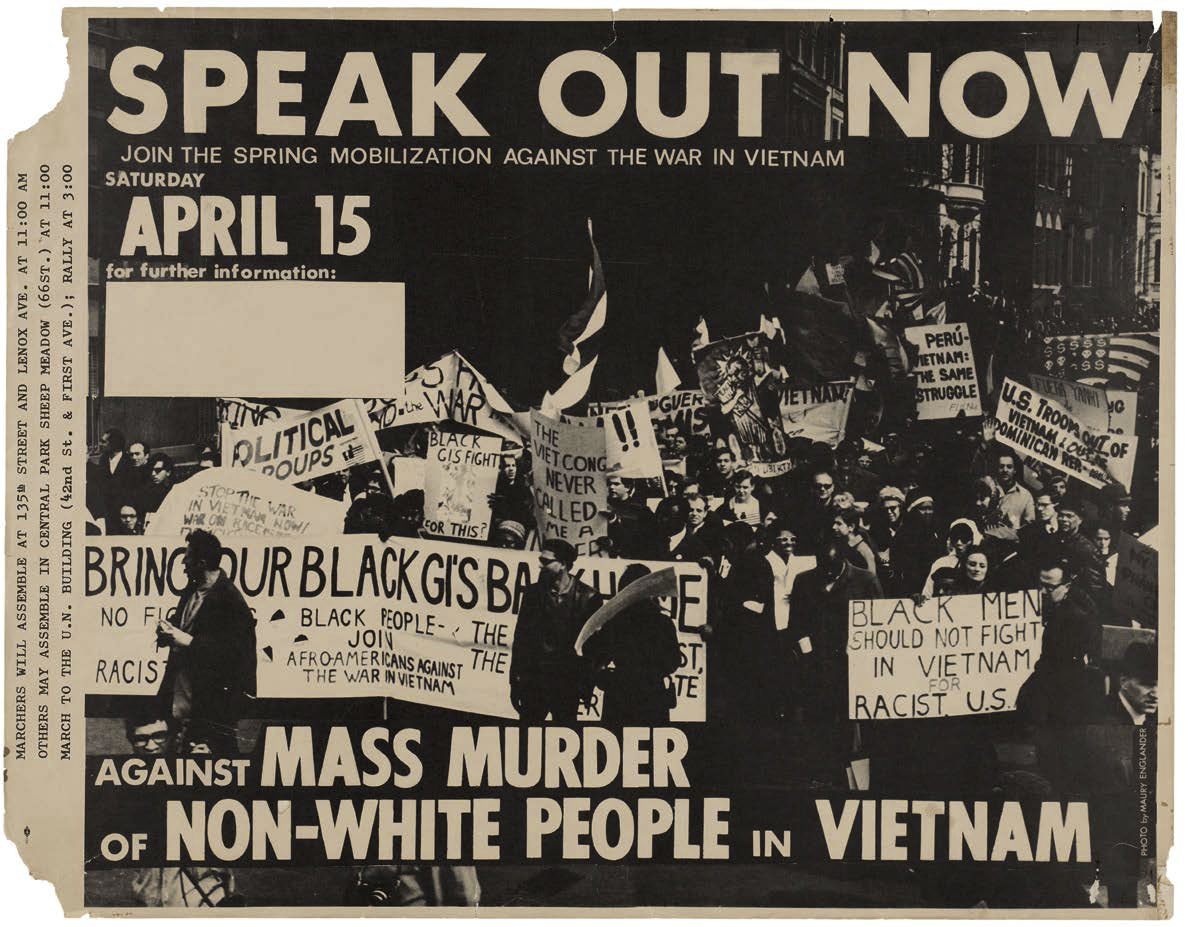

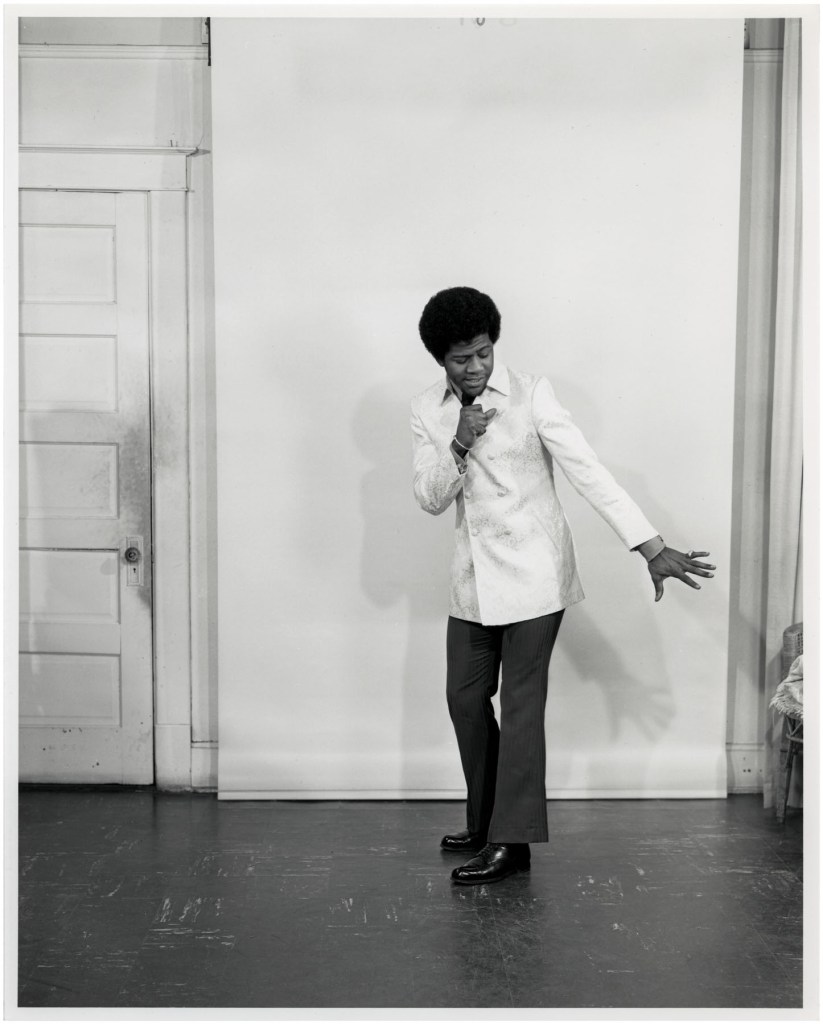

New York, New York

On April 15, 1967, outside the United Nations headquarters, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Harry Belafonte, Dr. Benjamin Spock, Stokely Carmichael, and others addressed a massive crowd at the Spring Mobilization against the War in Vietnam. Carmichael’s rousing speech at the anti–Vietnam War demonstration inspired Parks to write, “[Carmichael] was on fire, spitting his heat into the crowd.” Parks’s photographs from the event similarly depict Carmichael as a fiery figure, leaning toward his audience, his gaze direct and burning, his open coat thrashing the air like licking flames.

Houston, Texas

Just days after Gordon Parks’s photo-essay “Whip of Black Power” was printed in Life magazine, Stokely Carmichael visited Houston. He delivered speeches at the University of Houston (UH) and at Texas Southern University (TSU). “We will define ourselves as we see fit. We will use the term that will gather momentum for our movement,” Carmichael said, addressing public critiques of Black Power. The speeches were part of a SNCC nationwide campus tour. Yet, Carmichael’s appearance in Houston was auspiciously timed. Spring 1967 was a time of heightened social unrest in the city, and local universities were hubs of civil rights activism.

Text from the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

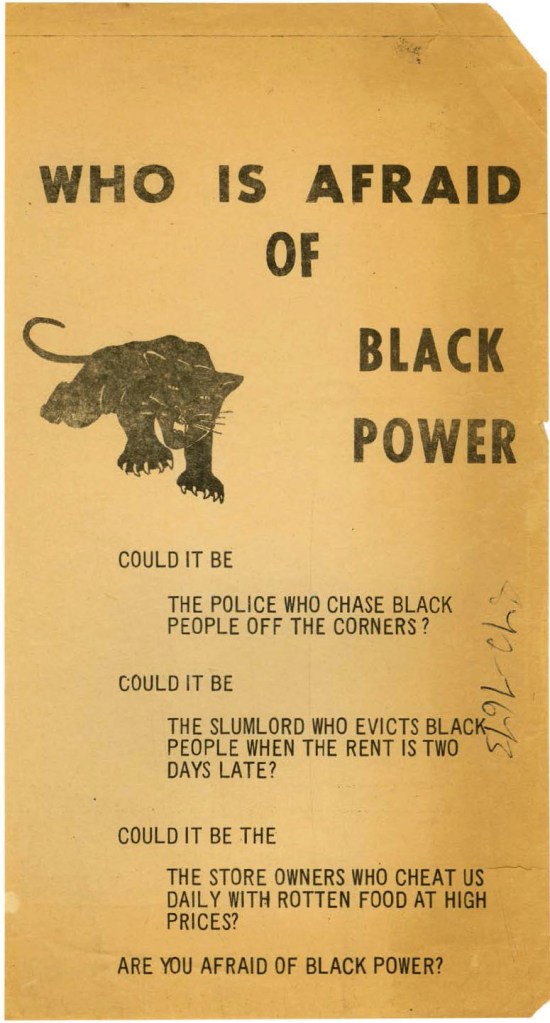

Black Panther Party pamphlet

1966

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Untitled, Watts, California

1967, printed 2022

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of and © The Gordon Parks Foundation

Members of the US Organization, including James Doss-Tayari (left), Tommy Jaquette-Mfikiri (behind Carmichael), and Ken Seaton-Msemaji (right), walking with Carmichael to the Watts rally, Los Angeles, 1966.

Parks had little control over the final pictures and captions chosen by Life‘s editors. However, his role as both a writer and photographer allowed him more influence than most. With knowledge gained through experience, Parks carefully crafted a statement in words and pictures that was less vulnerable to the editing process. The largest of only five images published in Life, this photo was like many others in the press at the time, presenting Carmichael as cocky and determined. Yet, the vast majority of Parks’s other images captured him in tender and humanising moments, bringing out the full character of this public figure.

Label text from the exhibition

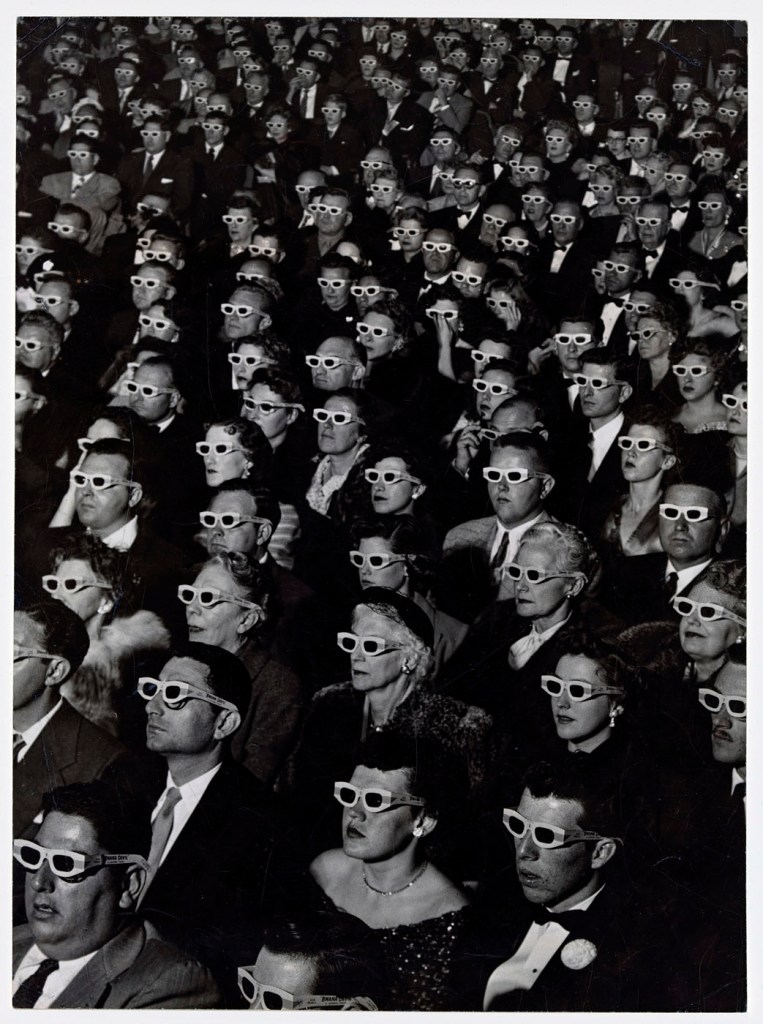

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Crowd at the Watts rally, Will Rogers Park, Los Angeles

1966, printed 2022

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of and © The Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Untitled, Los Angeles, California

1966, printed 2022

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of and © The Gordon Parks Foundation

Carmichael addresses the Watts crowd from a truck bed, Los Angeles 1966

In the essay, Parks quotes Carmichael, “Black Power means black people coming together to form a political force either electing representatives or forcing their representatives to speak their needs. It’s an economic and physical bloc that can exercise its strength in the black community instead of letting the job go to the Democratic or Republican parties or a white-controlled black man set up as a puppet to represent black people. Black Power doesn’t mean anti-white, violence, separatism, or any other racist things the press says it means. It’s saying. ‘Look, buddy, we’re not laying a vote on you unless you lay so many schools, hospitals, playground and jobs on us.'”

Label text from the exhibition

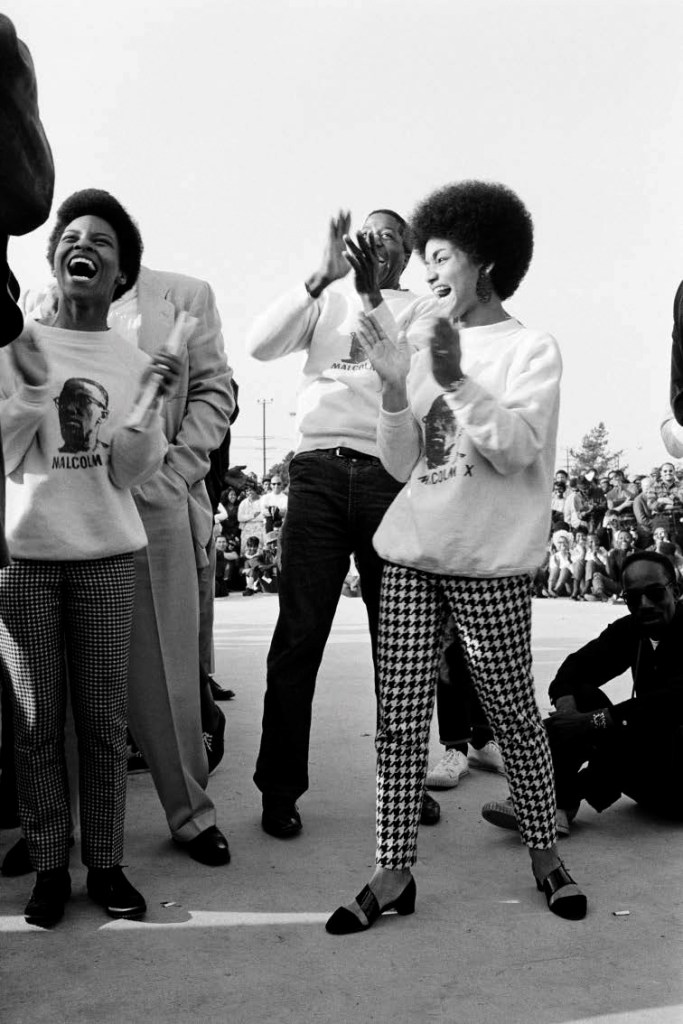

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Sanamu Nyeusi (left) and Hasani Soto (right) of the US Organization at the Watts rally, Will Rogers Park, Los Angeles

1966, printed 2022

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of and © The Gordon Parks Foundation

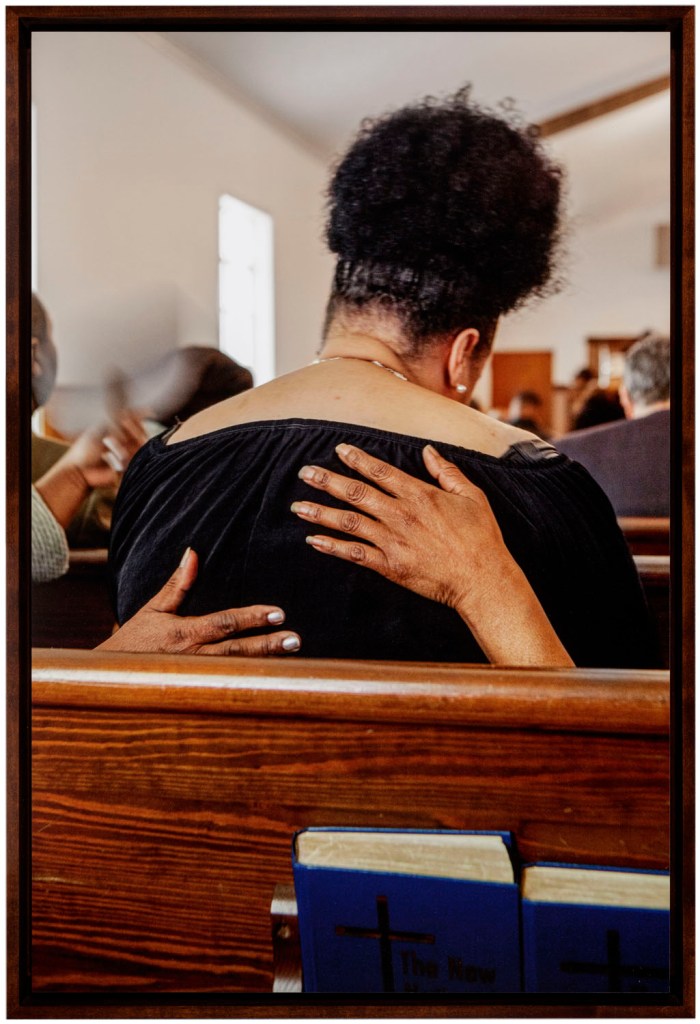

Members of civil rights organisations across Southern California came together to present a panel of speakers at the Watts rally in November 1966, culminating in a keynote speech from Stokely Carmichael. Parks was struck by the intensity of those gathered and chose to focus on the energy of the crowd both in his Life essay and in his numerous photographs from the day. In this photograph, members of the cultural nationalist organisation “Us” react to Carmichael’s fiery speech. Their yellow sweatshirts bearing the image of Malcolm X were a reminder to unite in brotherhood.

Label text from the exhibition

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Carmichael leaving the Watts rally in a Community Alert Patrol car, Los Angeles

1966, printed 2022

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of and © The Gordon Parks Foundation

Parks wrote in his essay, “On the way out [of the Watts rally], groups of boys and girls rushed the car. Stokely waved at them. … ‘People think I’m militant. Wait until those kids grow up! There are young cats around here that make me look like a dove of peace.'”

Label text from the exhibition

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Carmichael continuing the campaign for voter registration in Lowndes County, Alabama

1966, printed 2022

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of and © The Gordon Parks Foundation

Parks shadowed Carmichael as he went door to door to register voters in Lowndes County, marveling at the young activist’s ability to “adjust to any environment,” and noting how Carmichael changed his manner of dress and speech to put his audience at ease. While Carmichael’s tireless efforts recommended him for the role of chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), he always felt more suited for community organising. He revealed to Parks that he was “anxious to return” to field work and resigned from leadership in May 1967, just days before Parks’s photo-essay was published in Life.

Label text from the exhibition

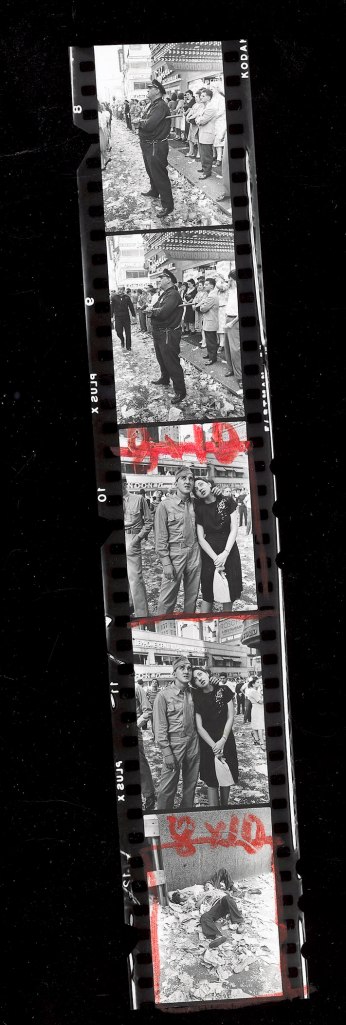

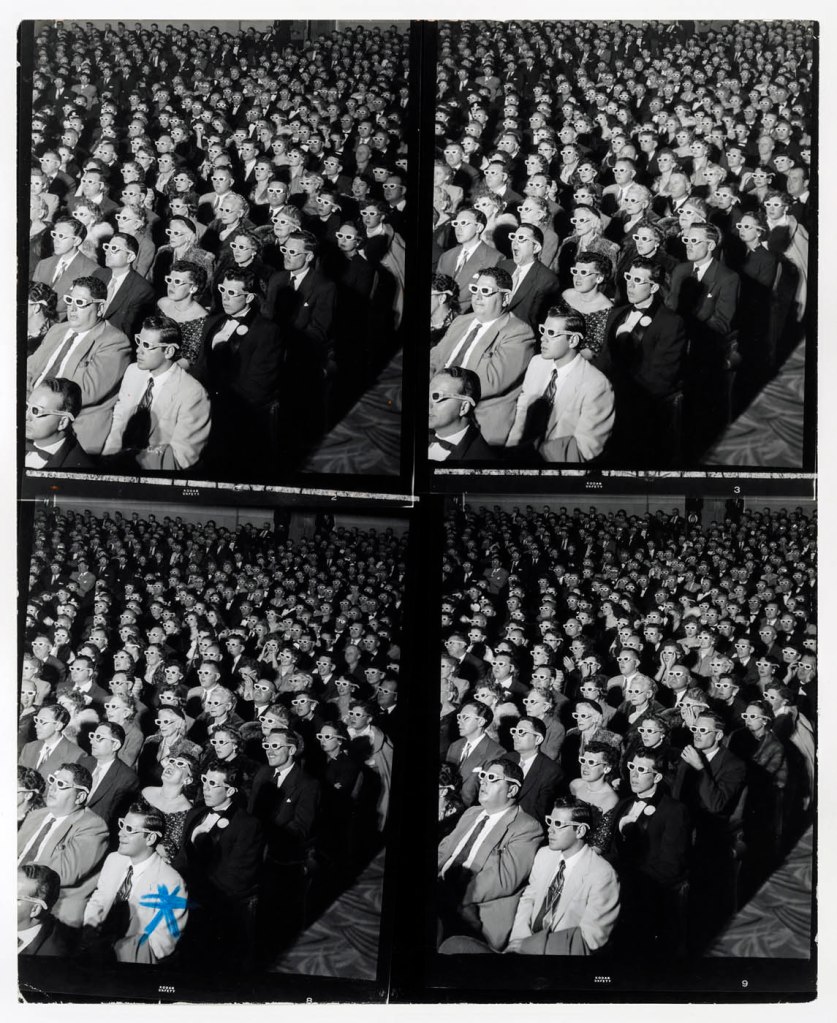

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Contact sheet of Carmichael in Lowndes County, Alabama

1966, printed 2022

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of and © The Gordon Parks Foundation

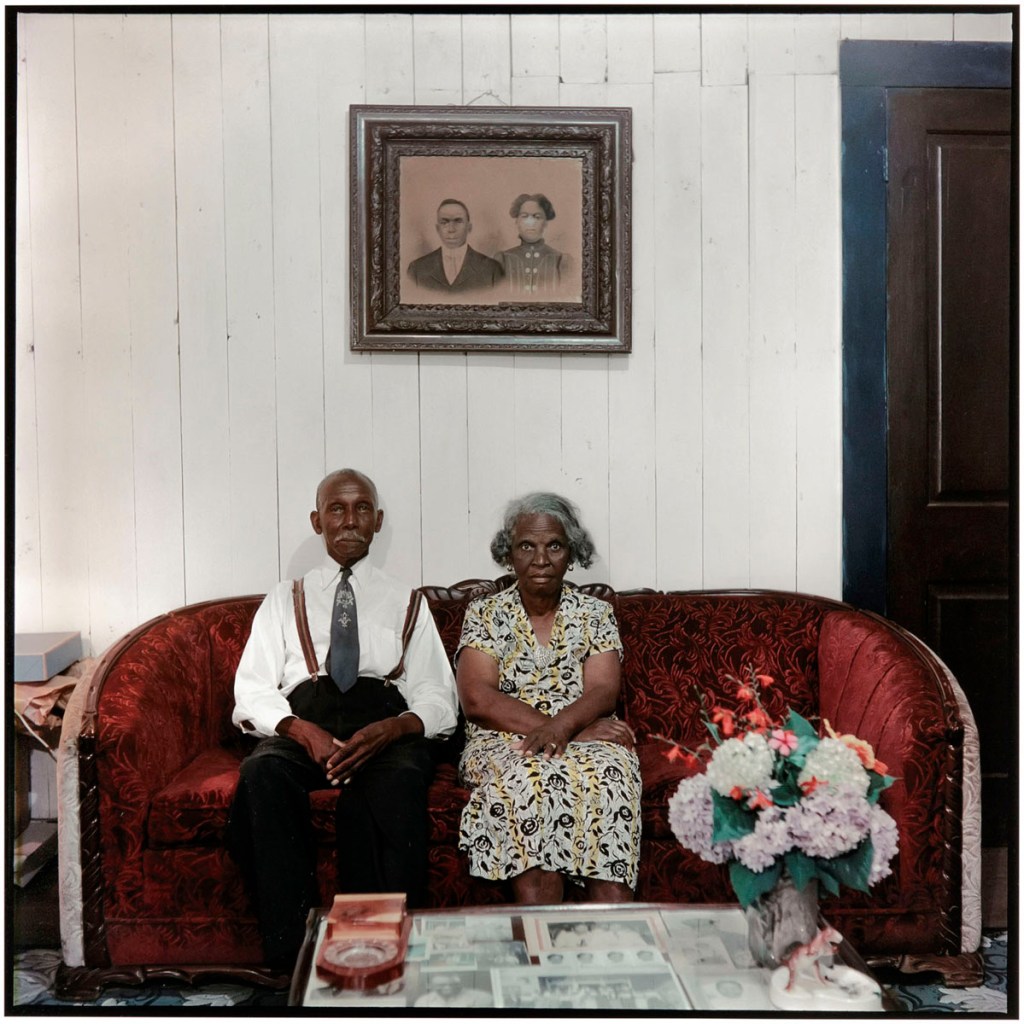

This contact sheet shows nine of Gordon Parks’s photographs of Stokely Carmichael walking at daybreak through Lowndes County. Each image bears a striking resemblance to the opening photograph of the 1948 Life photo-essay “Country Doctor,” by W. Eugene Smith. In that famous image, Dr. Ernest Ceriani walks through a field at dawn to reach a sick patient. Here, Parks harnessed the temperamental skies, rural setting, and lone figure to intentionally echo Smith’s image. By doing so, Parks cast Carmichael, like the Country Doctor, as a selfless local hero, working for the benefit of others.

Label text from the exhibition

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Untitled

1966, printed 2022

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of and © The Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Untitled, Bronx, New York

1967

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of and © The Gordon Parks Foundation

Mary Charles Carmichael serving her children Lynette and Stokely at Lynette’s wedding dinner in the Bronx, 1966

Weddings were a frequent subject in Life‘s photographs. Parks knowingly exposed several rolls of film at Carmichael’s sister’s wedding in December 1966. The variety, amount, and quality of the images would have encouraged the editors to add one of the photos to the final printed essay. Parks knew that showing Carmichael as part of this conservative tradition would contradict the popular impression of him as an anarchist and outsider.

Label text from the exhibition

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Carmichael speaking at a private home, Los Angeles

1966, printed 2022

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of and © The Gordon Parks Foundation

In “Whip of Black Power,” Parks wrote, “In the four months that I traveled with him I marvelled at his ability to adjust to any environment. Dressed in overalls, he tramped the backlands of Lowndes County, Alabama, urging Negroes, in a Southern-honey drawl, to register and vote. The next week, wearing a tight dark suit and Italian boots, he was in Harlem lining up ‘cats’ for the cause… A fortnight later, jumping from campuses to intellectual salons, where he was equally damned and lionised, he spoke with eloquence and ease about his cause, quoting Sartre, Camus and Thoreau.”

Label text from the exhibition

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Carmichael at a SNCC gathering, Los Angeles

1966, printed 2022

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of and © The Gordon Parks Foundation

Luminous Exposures: Gordon Parks, Stokely Carmichael, and the Birth of Black Politics

Cedric Johnson

Gordon Parks’s 1967 Life magazine article on Stokely Carmichael, “Whip of Black Power,” still radiates more than a half century since its publication. It is an invaluable artifact of black political life during the sixties, but so much more. In images and words, Parks depicted the warmth and generous spirit of Carmichael, the youthful civil rights activist morphing into celebrity. In hindsight, the essay also effectively captures Carmichael in political twilight, at the height of his political relevance. Parks’s essay portends the triumphs and new social contradictions set in motion by Black Power militancy. Within a few years of Parks’s Life article, Carmichael would go into exile, taking up residence in the Guinean capital of Conakry, and rather than stoking revolution on American soil, the Black Power slogan he popularized would produce broad, unprecedented black political and economic integration into American society.

Stokely Standiford Churchill Carmichael was born on June 29, 1941, in Port of Spain, Trinidad. His early years were spent among a large extended family on the island, and at age eleven he joined his parents in New York City. Carmichael’s father, Adolphus, was a master carpenter who also worked as a taxi driver and at various odd jobs. Carmichael often said his father died of hard work, suffering a heart attack in his forties. Carmichael’s mother, Mabel, a native of Montserrat, supported the family through domestic work and as a passenger ship stewardess. She remained a dominant influence for Carmichael. “This little dynamo of a woman,” he wrote, “was the stable moral presence, the fixed center around which the domestic life of this migrant African family revolved. … We children quickly learned to see her as tireless, omnipresent, and all-seeing, the ever vigilant enforcer of order and family standards, whose displeasure was to be avoided at all costs.”1 Carmichael was, for a time, the sole black member of the Morris Park Dukes, a youth gang in the mostly Jewish and Italian Tremont section of the Bronx, and he was also among the most promising students admitted to the prestigious Bronx High School of Science. Acclaimed science fiction writer and fellow Bronx Science alumnus Samuel R. Delany, who met Carmichael in freshman gym class, recalled him as someone who “had always been quick with banter and repartee with the gym teacher, who’d alternated between enjoying it and being frustrated by it.”2 When the two students once spent detention together, Carmichael held court with the teacher assigned to supervise them and managed to soften him up to the point of laughter. Carmichael’s capacity to win people over with humor and charisma would serve him well when he dove deeper into political life in his twenties.

As a boy in Trinidad, Carmichael had expressed a precocious interest in politics, and his friendship with Gene Dennis, Jr., a classmate at Bronx Science and a red-diaper baby [a child of parents who were members of the United States Communist Party (CPUSA) or were close to the party or sympathetic to its aims], further politicized the young Carmichael, introducing him to the world of the New York left and acquaintances such as socialist and civil rights strategist Bayard Rustin [American, 1912-1987, an African American leader in social movements for civil rights, socialism, nonviolence, and gay rights]. Although he was initially skeptical and at times dismissive of desegregation protests, Carmichael was eventually drawn to the gathering southern movement, and after he witnessed the heroism of lunch counter protesters in 1960, as he described it, “something happened to me. Suddenly I was burning.”3 The next year, while a freshman at Howard University, he traveled as a Freedom Rider to Mississippi, where he was arrested and detained at the notorious Parchman Farm prison for forty-nine days [Mississippi State Penitentiary (MSP), also known as Parchman Farm, is a maximum-security prison farm located in unincorporated Sunflower County, Mississippi, in the Mississippi Delta region]. During his time at Howard, Carmichael spent three summers working for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced “snick”), organizing voter registration drives, and in 1966, after graduating, he became chairman of the organization. Concurrent with his new leadership position, Carmichael’s political development tracked the transition from the southern campaigns against Jim Crow to the increasingly militant protests of late-sixties urban rebellions and anti-Vietnam mobilizations.

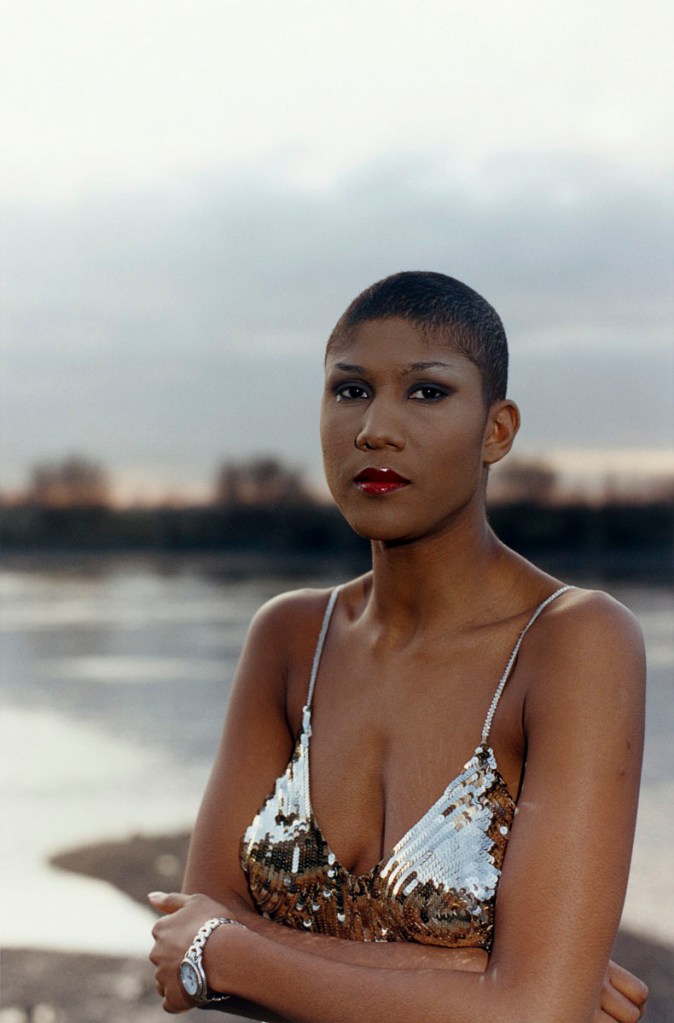

In “Whip of Black Power,” Parks summed up Carmichael’s charismatic manner and the new politics of black autonomy and militancy: “Cool, outwardly imperturbable, Stokely gives the impression he would stroll through Dixie in broad daylight using the Confederate flag for a handkerchief.”4 Parks’s images present Carmichael in all his glory. Youthful, confident, hip, and exuberant, Carmichael embodied a new politics of black self-assertion. His words were sharp, witty, and playful, yet deadly serious in their indictment of American racism and imperialism. But Parks also sensed naivete and disingenuous motives in the new black militancy, later writing that many younger activists seemed “obsessed with a hunger for danger.”5

The Origins of Black Power

By the time Parks’s photo essay was published in Life, Carmichael was widely seen as the progenitor of Black Power. The slogan had emerged from the ranks of SNCC activists, propelled in part by longer-standing, simmering tensions over strategy and tactics, interracialism, and the promise of liberal democracy, which sharpened as the movement produced historic victories in the form of national civil rights legislation. Even in the aftermath of historic reform, white vigilante retaliation against the southern movement tested the resolve of SNCC cadre, with some increasingly embracing black political autonomy and armed self-defense, in stark contrast to the interracialist and nonviolent commitments of the organization’s founding.

After the March 1965 murder of Viola Liuzzo, a white NAACP member who had traveled from Michigan to join the Selma-to-Montgomery marches, SNCC activists began organizing in Lowndes County, Alabama. At the time, the county was 86 percent black but had no black registered voters, reflecting the pervasive disfranchisement through the cotton counties of the Black Belt on the eve of the Voting Rights Act. Carmichael and other SNCC activists formed the Lowndes County Freedom Organization to register voters and elect the area’s first black political candidates. Members adopted the image of a pouncing black panther as the organization’s logo.6 One of the more striking pictures in Parks’s 1967 article is of Carmichael staring plaintively on a gravel road in Lowndes, smartly dressed, his hands in his back pockets, his sweatshirt emblazoned with the panther symbol.

Carmichael came to head SNCC through a contentious process. In early 1966, John Lewis, a soft-spoken Alabama native, was reelected as chairman, but at the end of a late-night meeting and after many staff members had gone home, Lewis’s election was overturned by the remaining attendees, and Carmichael was installed. As historian Clayborne Carson and others have noted, Carmichael made a choice in the ensuing months between, on one hand, continuing the grounded political work SNCC had conducted in places like Lowndes, and on the other, “becoming preoccupied with rhetorical appeals for the unification of black people on the basis of separatist ideals.”7 This development would be tragic for SNCC, which, along with the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), proceeded to expel white members. Carmichael and some SNCC members embraced more militant posturing and drifted further away from the local organizing campaigns that had won real victories for black southerners, and what resulted was the precipitous decline and political irrelevance of the organization.

Some SNCC members used the slogan “Black Power for Black People” during the Alabama voting rights campaigns of 1965. In Harlem, leaders including Congressman Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., and tenant organizer Jesse Gray had also used the phrase “Black Power,” as had Richard Wright, who published a travelogue of his time in newly independent Ghana with that title.8 It was SNCC activist Willie Ricks, however, who began using the phrase in speeches throughout the South, often asking from the podium, “What do you want?” to audiences, who shouted back, “Black Power!”

The slogan reached national consciousness amid the 1966 Meredith March Against Fear. In June 1966, James Meredith, who had integrated the University of Mississippi, set out on a lone march from Memphis, Tennessee, to Jackson, Mississippi, through the staunchly segregationist Delta counties. He was shot in ambush on the second day of his journey and had to be hospitalized. Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, as well as the younger, more militant CORE and SNCC, decided to continue the march on Meredith’s behalf. During an overnight stop in Greenwood, Mississippi, Carmichael used the chant Ricks had developed, sparking excitement from the crowd, consternation from the civil rights establishment, and hysteria from the white press. In the wake of the Meredith March, Black Power militancy reoriented black political life, igniting public debate, new mobilizations and local campaigns, and heightened scrutiny of the established leadership, strategies, and goals that had defined the postwar civil rights movement.

The demand for Black Power, intended to build real power for the most dispossessed working-class denizens of black southern towns and northern ghettos, had many unintended consequences. Black poverty would be cut in half in the years after major civil rights reforms, and the ranks of the black middle class would expand greatly through antipoverty measures, access to higher education, and public employment, but real, meaningful self-determination for those trapped at the bottom of the nation’s socioeconomic ladder would remain elusive.

Seeing Black Political Life with Gordon Parks

Representation of the growing Black Power movement in the popular press was key to both its successes and its failures. Although Parks was among several photographers whose images of the movement throughout its evolution influenced its perception, his position as a black photographer working for a publication targeted at a predominantly white audience placed him in a unique position. He was among America’s greatest twentieth-century intellectuals, a designation denied to him by the yoke of Jim Crow that dominated that century. As a photographer – through his studies of crime and gang violence to his profiles of black nationalism – Parks illuminated the diversity and richness of black life while also exposing the absurd, systemic injustice that defined the United States. Alongside his photographs, Parks’s writing encourages us to see the complexity of black life, which though demeaned by white racist institutions and behaviors is not reducible to some uniform Black experience. Rather, his own political perspective, which is decidedly more liberal than the black political figures he chose as subjects, is a testament to the diverse strivings, political positions, and discrete prerogatives that have defined black political life during and after Jim Crow. His voice, especially in the context of his work on black nationalism, adds a critical-sympathetic view of this political alternative to the postwar civil rights movement.

In his writings on black nationalism – ranging from his 1963 Life article on the Nation of Islam, “‘What Their Cry Means to Me,'” to his 1967 essay on Carmichael – we find Parks, like many black people at the time, cautious, curious, and not always in full agreement, but certainly inspired by the example of these black nationalist figures and movements. As Parks said of Malcolm X in the wake of his murder, “He was brilliant, ambitious and honest. And he was fearless. He said what most of us black folk were afraid to say publicly.”9 In many ways, Parks’s politics were undoubtedly closer to those of the vast majority of black people living through the end of Jim Crow. His commitment to work for a mainstream magazine was criticized by his black peers, at a time when many were touting black cultural autonomy and the formation of separate institutions. His choice to use the Life magazine platform reflected the liberal democratic spirit of the civil rights movement and prefigured the unprecedented integration of black actors, writers, musicians, and producers into the culture industry in the closing decades of the twentieth century.

Parks’s work remains sympathetic to black nationalism, however, in as much as he provides an antidote to the slander, fear mongering, and “black domination” narratives that defined mainstream press coverage, such as The Hate That Hate Produced, the 1959 CBS documentary co-produced by Mike Wallace and black journalist Louis Lomax. Parks’s photographs and essays during the sixties reflect the optimism and surging sense of political efficacy coursing through black life at the time, as well as lurking social and political contradictions.

In his exchanges with Carmichael, we find Parks reflective and at times skeptical. In an especially poignant, self-effacing conclusion to his 1967 “Whip of Black Power” article, Parks momentarily compares Carmichael’s position on the Vietnam War to that of his own son, David, who was serving as an Army tank gunner. Carmichael had expressed the increasingly popular view in black communities that Vietnam was not their war. “Our stake will come from the struggle against white supremacy here at home,” Carmichael said. “I’d rather die fighting here tomorrow than live 20 years fighting over there. Why should I go help the white man kill other dark people while he’s still killing us here at home?”10 Parks’s son David had been awarded the Purple Heart medal for bravery in combat, but in the face of Carmichael’s sharp criticism, Parks now “wondered which boy was giving himself to a better cause.”11 “There was no immediate answer,” he concluded. “But in the face of death, which was so possible for both of them, I think Stokely would surely be more certain of why he was about to die.”12

The Meaning of Black Power

The same year “Whip of Black Power” was published, Carmichael and political scientist Charles V. Hamilton published Black Power: The Politics of Liberation in America, an attempt to operationalize the political slogan. They rejected reactionary claims that Black Power meant “racism in reverse” and “black supremacy.” Although Carmichael’s public rhetoric constantly evoked a coming revolution, the actual definition of Black Power he and Hamilton provided was something tamer, the pursuit of black empowerment in the mold of urban ethnic politics. “The goal of black self-determination and black self-identity – Black Power,” Carmichael and Hamilton wrote, “is full participation in the decision-making processes affecting the lives of black people, and recognition of the virtues in themselves as black people.” Black Power, they continue, meant that “in Lowndes County, Alabama, a black sheriff can end police brutality. A black tax assessor and tax collector and county board of revenue can lay, collect, and channel tax monies for the building of better roads and schools serving black people.”13

National legislation and demographic changes made the pursuit of this black ethnic politics touted by Carmichael and Hamilton possible in various locales from northern urban centers to the majority-black rural counties of the southern Black Belt. The Black Power slogan emerged from the internal debates over strategy and organizing approaches within SNCC as members sought to empower black southerners who had endured a long winter of disfranchisement and dispossession. The national popularity of Black Power, however, was propelled by the political possibilities created by the victories of the Second Reconstruction, the restoration of black suffrage rights and passage of anti-discrimination and antipoverty legislation under the Johnson administration. In terms of urban investments, the 1964 Economic Opportunity Act and, later, the Model Cities program channeled federal grants to local jurisdictions, and these policy initiatives had the longer-term effect of cultivating and empowering a post-segregation generation of black urban political leadership.14 In addition, the demography of many American cities was changing rapidly due to suburbanization, and as whites vacated old-ethnic enclaves in the urban core, many cities became majority or near-majority black.

Black Power as employed by Carmichael and Hamilton advanced two political myths that remain prevalent and dangerous into our own times – that interracial coalitions are ineffective and doomed to failure, and that black unity is a necessary part of black political life. Both notions are predicated on the false assumption that political interests are synonymous with racial affinity. Surely, practical black solidarity was central to the local boycotts, lunch counter sit-ins, and other demonstrations that would defeat Jim Crow, but the political triumphs of the postwar civil rights movement were always interracial in composition, with Americans of diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds and classes contributing to the movement as donors, volunteers, legal counsel, activists, trainers, participants, lobbyists, legislators, and supporters. And both of those anti-interracialist notions run counter to the basic majoritarian premise of liberal democratic society, where broad coalitions and mass pressure have been fundamental to whatever real social justice has ever been accomplished in the United States.

While Carmichael would leave the United States for West Africa and become the leading spokesperson for the All-African People’s Revolutionary Party after the death of its founder, deposed Ghanaian president Kwame Nkrumah, many of his SNCC comrades would enter institutional politics in the United States. John Lewis would go on to become a long-serving congressman from Georgia, Eleanor Holmes Norton was the District of Columbia’s nonvoting delegate in Congress, and Marion Barry would win multiple terms as a city councilman and as Washington, D.C.’s first elected black mayor. Other SNCC veterans would play important roles as campaign organizers and politicos, with many former SNCC members migrating to the nation’s capital in the seventies. In contrast, Carmichael for the rest of his life would remain a political outsider and an evangelist for anticapitalist revolution and Pan-African unity, even after many of the Third World left regimes that inspired such politics had long collapsed into dictatorship, civil war, and underdevelopment.

Waiting for Revolution

Parks’s 1967 photographs and text convey the impressive stamina of Carmichael and his movement comrades, and equally, the tremendous physical and psychological toll of their work. “In the four months that I traveled with him,” Parks recalled of Carmichael, “I marveled at his ability to adjust to any environment.”15 Carmichael was chameleon-like, shifting in ways to effectively connect and communicate with his audience: “Dressed in bib overalls, he tramped the backlands of Lowndes County, Alabama, urging Negroes, in a Southern-honey drawl, to register and vote. The next week, wearing a tight dark suit and Italian boots, he was in Harlem lining up ‘cats’ for the cause, using the language they dig most – hip and very cool. A fortnight later, jumping from campuses to intellectual salons, where he was equally damned and lionized, he spoke with eloquence and ease about his cause, quoting Sartre, Camus and Thoreau.”16

The Life magazine article depicts Carmichael in a moment when he is moving quickly from grounded political organizing within a powerful social movement to becoming an enduring symbol of black radicalism, though sadly lacking any real constituency. Mass media played a powerful role in amplifying, influencing, and, in part, undoing the black movements of the fifties and sixties. In the wake of Emmett Till’s murder in Money, Mississippi, in 1955, black journalists were crucial in building opposition to Jim Crow after the teen’s mother, Mamie Till, decided to hold an open-casket funeral so everyone could see what racist vigilantes had done to her son. Throughout the southern campaigns, television broadcasts and the images of well-dressed black marchers being bludgeoned by white police and attacked with dogs and firehoses helped shift public sentiment against the perpetuation of Jim Crow. And yet the same media coverage bore negative consequences, contributing to processes of leadership certification that proved divisive, antidemocratic, and careerist, by too often elevating more telegenic personalities, breeding internal tensions, and shifting priorities away from the grounded politics that had been so central to the movement’s successes.17 Parks clearly sought to cast a different light on Carmichael against the popular white anxieties conjured by the Black Power slogan.

The broader machinery of publicity, however, took its toll on Carmichael and the internal lives of movement organizations, heightening rivalries and fueling overinflated rhetoric and posturing that ran counter to building effective political power – the goal of any movement worthy of the name. Parks’s article captures some of these sharpening tensions within the nascent Black Power movement, when he discusses the friction between the US Organization and other black political formations in Los Angeles over providing security for Carmichael during his visit. The FBI and local police would aggravate existing cleavages within and between black groups like US and the Black Panther Party, instigating and inflaming conflicts that would ultimately destroy lives, optimism, and political momentum.

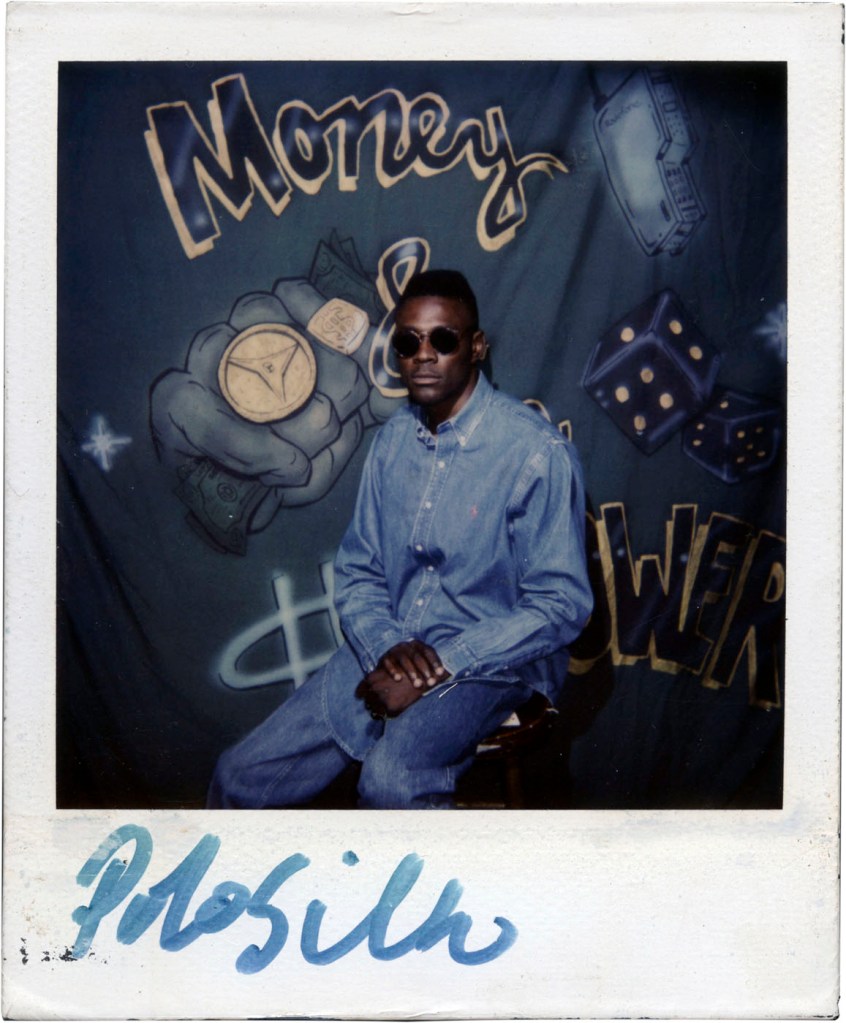

Carmichael spent the decades after the sixties touring the world and lecturing at universities and in community centers, unwavering in his commitment to revolutionary Pan-Africanism [a worldwide movement that aims to encourage and strengthen bonds of solidarity between all Indigenous and diaspora peoples of African ancestry]. I had a chance to meet him briefly during one of those stateside tours, in the fall of 1989, when I was a first-year student at Southern University-Baton Rouge, at the time the largest historically black college in the United States. Carmichael delivered an afternoon talk in Stewart Hall, which then housed the Junior Division, essentially a community college within the university that repaired the damage wrought by poorly funded public schools whence many of our students hailed. His Afro and goatee were graying, but his wide grin, quick wit, and gregarious manner recalled the youthful activist, his slim mod suit now replaced with a brocade dashiki. Since his exile, he had taken the name Kwame Ture, an homage to the anti-colonial revolutionaries Kwame Nkrumah and Sékou Touré. The room was only about half full, but that didn’t dissipate Carmichael’s energy. We matched his enthusiasm, laughing and shouting at various turns. Carmichael was in vogue again for our cohort, the sons and daughters of the civil rights generation now suffering the waning years of the Reagan-Bush administration. We were living through a prolonged period of urban implosion, the social chaos of the crack cocaine crisis, rising gun violence, and the ramped-up policing and imprisonment of black men – what we would later come to know as mass incarceration. We were drawn to the rhetorical style of Carmichael, Malcolm X, and the Panthers and the criticisms they leveled against white supremacy and the goal of racial integration still promoted by the old civil rights vanguard. Carmichael’s criticisms of capitalism resonated with us in a town where the smokestacks of petrochemical refineries dominated the skyline, their stench filling the North Baton Rouge air day and night. After the talk, I stood around with a handful of other students engaging Carmichael. He seemed to take all our questions, however errant they might have been, with seriousness. He didn’t appear bored or impatient, and he tarried with us for some time.

In his memoir Dreams from My Father, Barack Obama characterized Carmichael in disparaging terms after a similar collegiate encounter with him – “his eyes glowed inward as he spoke, the eyes of a madman or a saint.”18 As he ascended to national leadership, Obama often disassociated from black radicalism and socialist politics. Recall how he publicly rejected his one time pastor, the Reverend Jeremiah Wright, the man who officiated at his wedding, once that association became a political liability on the campaign trail. It is not surprising that Carmichael’s damning criticism of American hypocrisy and empire rattled the young Obama. For those of us confined to underfunded and failing urban school districts and equally maligned black colleges, and angered by the bipartisan decimation of the welfare state, Carmichael’s words were like manna, affirming our sense that we were not failures, but that the society itself had failed to live up to its most basic promises.

Carmichael was neither madman nor saint. Since 1969 he was something more tragic – a revolutionary without a revolution. His decades-long exile estranged him from the very political constituencies responsible for his fame, and the world itself had changed dramatically in the same period. The defeat and collapse of socialist and progressive- left postcolonial regimes across Africa, Latin America, the Caribbean, and Asia, the end of the Cold War, and limited but very real cultural and political changes hewn by the Second Reconstruction in the United States rendered his calls for revolutionary Pan-Africanism simultaneously alluring, overly nostalgic, and tragically out of step with the world we lived in. His criticisms still echoed loudly in the lecture hall but did not offer black laboring classes grappling with day-to-day existence under austerity and resurgent capitalist class power any legitimate, workable political alternative. What was needed then and now wasn’t so much the correct ideological line, a favorite diversion of the American left for decades, but rather a politics that returned to the beginning, to places like Lowndes County, where Carmichael once went house to house, patiently conversing with black sharecroppers about their needs and hopes, gaining their trust, and, in careful and protracted collaboration, building effective popular power.

Carmichael’s longtime friend Michael Thelwell, a SNCC veteran and novelist, provides a touching elegy, reminding us how even as his body was ravaged by cancer, Carmichael’s spirit burned ever brighter. In the waning days of his illness, after he had returned to Guinea for the last time, Carmichael was met with a steady stream of visitors, “humble folk and dignitaries alike,” Thelwell recalled.19 One such group included Mozambican amputees who had traveled to Conakry, prompting Thelwell to ask: What motive “could have brought simple farmers and old soldiers so great a distance?” They were, he came to understand, propelled by a deep sense of gratitude. When Carmichael learned of the horrible consequences of war and land mines wrought on these men and their communities, he appealed to the Cuban embassy, which responded with a supply of prosthetics.

Carmichael stands alongside King, Rustin, Liuzzo, Ella Baker, James Forman, Fannie Lou Hamer, Rosa Parks, E. D. Nixon, and a broad pantheon of activists, martyrs, and forgotten figures who defeated Jim Crow and ushered unprecedented black political progress. Parks’s images and impressions of Carmichael should remind us of his historical significance, his limitations, virtues, and sacrifices, and the decisive role that mass political pressure has played in making concrete progressive advances in American society. And what role popular social movements must play again if we want to build on this progress and effectively abolish the myriad injustices in our midst.

Cedric Johnson. “Luminous Exposures: Gordon Parks, Stokely Carmichael, and the Birth of Black Politics,” in Volpe, Lisa. Gordon Parks: Stokely Carmichael and Black Power. Steidl / The Gordon Parks Foundation / The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 2022, p. 28-34

Footnotes

1/ Stokely Carmichael with Ekwueme Michael Thelwell, Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture) (New York: Scribner, 2005), 49.

2/ Samuel R. Delany, The Motion of Light in Water: Sex and Science Fiction Writing in the East Village (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2004), 85.

3/ Gordon Parks, “Whip of Black Power,” Life, May 19, 1967, 80.

4/ Parks, “Whip of Black Power,” 78.

5/ Gordon Parks, Voices in the Mirror: An Autobiography (New York: Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, 1990), 238.

6/ Hasan Kwame Jeffries, Bloody Lowndes: Civil Rights and Black Power in Alabama’s Black Belt (New York: New York University, 2009).

7/ Clayborne Carson, In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s (Cambridge, MA, and London: Harvard University Press, 1981), 206.

8/ Richard Wright, Black Power: A Record of Reactions in a Land of Pathos (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1954).

9/ Gordon Parks, “‘I Was a Zombie Then – Like All Muslims, I Was Hypnotized,'” Life, March 5, 1965, 30.

10/ Parks, “Whip of Black Power,” 82.

11/ Parks, “Whip of Black Power,” 82.

12/ Parks, “Whip of Black Power,” 82.

13/ Stokely Carmichael and Charles V. Hamilton, Black Power: The Politics of Black Liberation in America (New York: Vintage Books, 1992 [1967]), 47.

14/ Kent B. Germany, New Orleans After the Promises: Poverty, Citizenship and the Search for the Great Society (Atlanta: University of Georgia, 2007); Adolph Reed, Jr., Stirrings in the Jug: Black Politics in the Post-segregation Era (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999).

15/ Parks, “Whip of Black Power,” 78.

16/ Parks, “Whip of Black Power,” 78.

17/ Todd Gitlin, The Whole World Is Watching: Mass Media in the Making and Unmaking of the New Left (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980).

18/ Barack Obama, Dreams from My Father: A Story of Race and Inheritance (New York: Crown, 2004), 140.

19/ Carmichael with Thelwell, Ready for Revolution, 783.

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Carmichael before an appearance on KTTV, Los Angeles

1966, printed 2022

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of and © The Gordon Parks Foundation

National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam poster with photograph by Maury Englander

1967

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Martin Luther King, Jr., at Spring Mobilization to End the War in Vietnam, New York City

1967, printed 2022

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of and © The Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Carmichael speaking at Spring Mobilization to End the War in Vietnam, New York City

1967, printed 2022

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of and © The Gordon Parks Foundation

“Whip of Black Power,” Life Magazine

Photographs and Text by Gordon Parks

Introduction by Life Editors, May 19, 1967

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

1001 Bissonnet Street

Houston, TX 77005

Opening hours:

Wednesday 11am – 5pm

Thursday 11am – 9pm

Friday 11am – 6pm

Saturday 11am – 6pm

Sunday 12.30pm – 6pm

Closed Monday and Tuesday, except Monday holidays

Closed Thanksgiving Day and Christmas Day

![Life Magazine (1883-1972) '[Harlem Gang Leader opening spread]' 1948 Life Magazine (1883-1972) '[Harlem Gang Leader opening spread]' 1948](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/15_p.-96_97-harlem-gang-leader-opening-spread.jpg)

![Unidentified photographer (American). 'Untitled [Two Men in Work Clothes, Wearing Hats, One Standing, One Seated]' c. 1880 from the exhibition 'Called to the Camera: Black American Studio Photographers' at the New Orleans Museum of Art (NOMA), Sept 2022 - Jan 2023 Unidentified photographer (American). 'Untitled [Two Men in Work Clothes, Wearing Hats, One Standing, One Seated]' c. 1880 from the exhibition 'Called to the Camera: Black American Studio Photographers' at the New Orleans Museum of Art (NOMA), Sept 2022 - Jan 2023](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/83-60-4.jpg?w=903)

![Morgan and Marvin Smith (American, 1910-1993)(American, 1910-2003) 'Untitled [Marvin and Morgan Smith and Sarah Lou Harris Carter]' 1940 Morgan and Marvin Smith (American, 1910-1993)(American, 1910-2003) 'Untitled [Marvin and Morgan Smith and Sarah Lou Harris Carter]' 1940](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/sp-2022-59-11.jpg?w=1024)

![Hooks Brothers Studio (Robert and Henry Hooks) 'Untitled [Man in Dollar Bill Suit with Congregation]' c. 1940 Hooks Brothers Studio (Robert and Henry Hooks) 'Untitled [Man in Dollar Bill Suit with Congregation]' c. 1940](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/sp-2022-63-20.jpg)

![Hooks Brothers Studio (Robert and Henry Hooks) 'Untitled [Students looking at photographs]' c. 1950 Hooks Brothers Studio (Robert and Henry Hooks) 'Untitled [Students looking at photographs]' c. 1950](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/sp-2022-63-26.jpg)

![Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968) 'Aufsicht (yellow)' (View from Above [yellow]) 1999 Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968) 'Aufsicht (yellow)' (View from Above [yellow]) 1999](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/tillmans-aufsicht-yellow.jpg?w=700)

![Marie Høeg (Norwegian, 1866-1949) 'Untitled [Marie Høeg and her brother in the studio]' c. 1895-1903 Marie Høeg (Norwegian, 1866-1949) 'Untitled [Marie Høeg and her brother in the studio]' c. 1895-1903](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/image-10_berghoeg-c.-1895-1903.jpg?w=657)

![Claude Cahun (French, 1894-1954) 'Untitled [Self portrait in profile, sitting cross legged]' 1920 Claude Cahun (French, 1894-1954) 'Untitled [Self portrait in profile, sitting cross legged]' 1920](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/claude-cahun-self-portrait-in-profile-sitting-cross-legged-1920.jpg?w=797)

![Anonymous photographer (France). 'Untitled [Two Black actors (Charles Gregory and Jack Brown), one in drag, dance together on stage]' c. 1903 Anonymous photographer (France). 'Untitled [Two Black actors (Charles Gregory and Jack Brown), one in drag, dance together on stage]' c. 1903](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/image-7_untitled-two-black-actors....jpg?w=673)

![Frances Hodgkins (New Zealand, 1869-1947) 'Friends (Double Portrait)' [Hannah Ritchie and Jane Saunders] 1922-1923 Frances Hodgkins (New Zealand, 1869-1947) 'Friends (Double Portrait)' [Hannah Ritchie and Jane Saunders] 1922-1923](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/image-13_frances-hodgkins-friends-double-portrait.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.