Exhibition dates: 23rd July, 2016 – 5th March, 2017

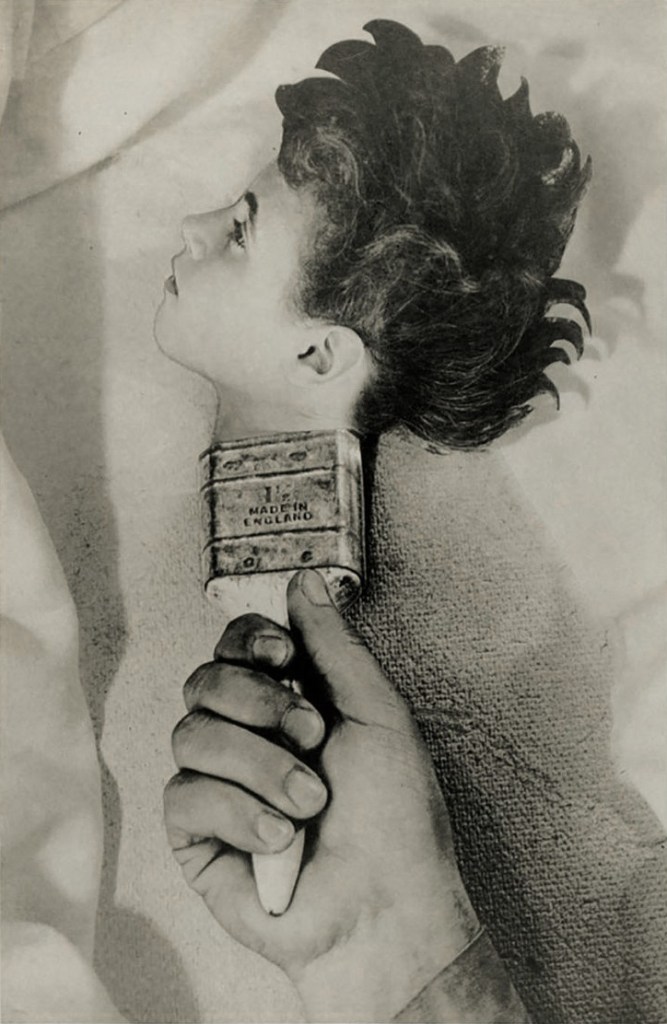

Philippe Halsman (American, 1906-1979)

“Rita Hayworth,” Harper’s Bazaar Studio

1943

© Philippe Halsman Archive

There’s not much to say about this exhibition from afar, except to observe it seems pretty standard fare, with no outstanding revelations or insights into the conditions of the camera’s “becoming” in photographic images or an exploration of the limits of the lens’ seeing. As the Centre for Contemporary Photography notes in their current exhibition, An elegy to apertures, “The camera receives and frames the world through the lens. This aperture is a threshold that demarcates the distinction between the scene and its photographic echo. It is both an entrance and a point of departure.”

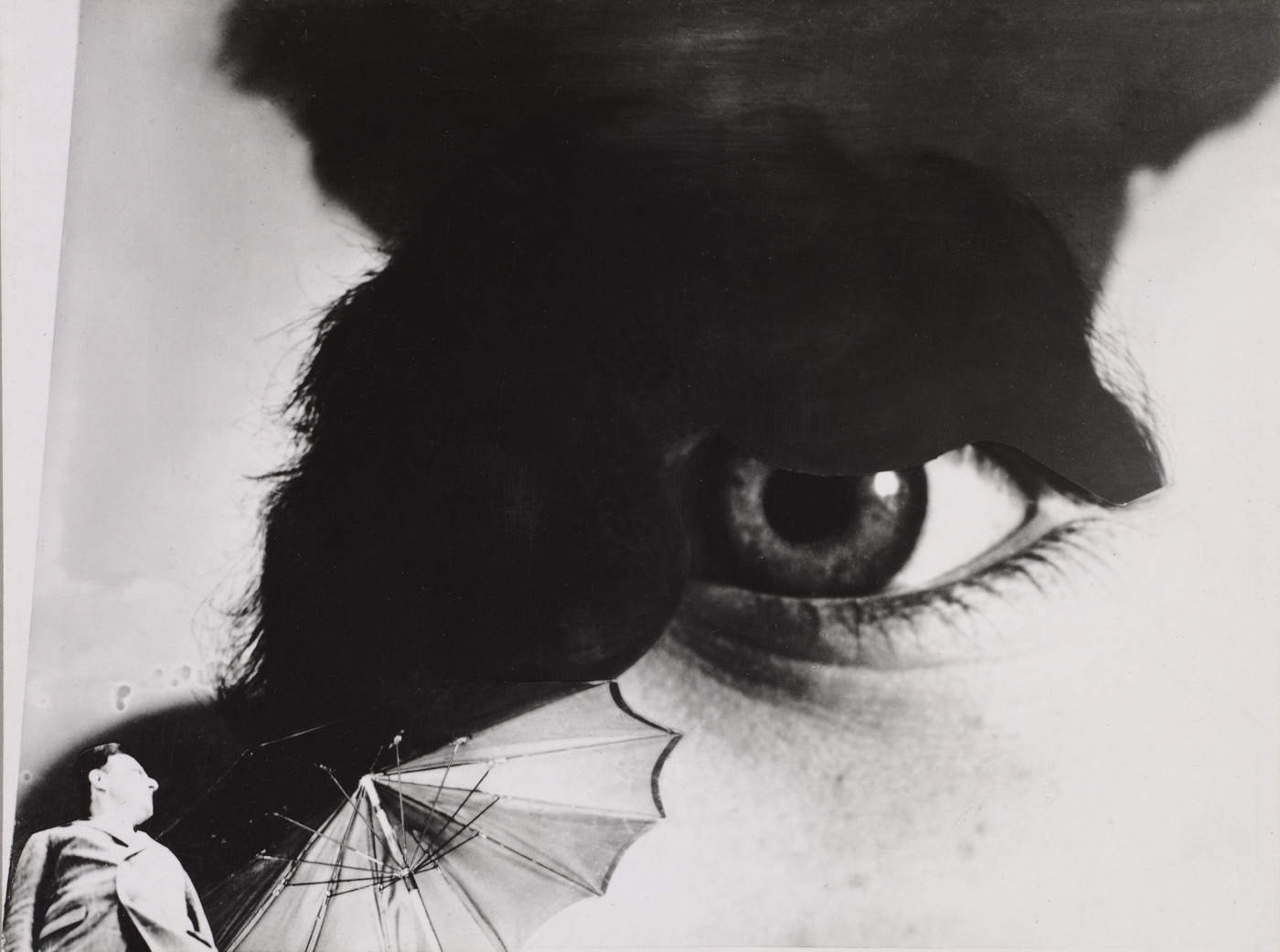

So what happens to this threshold when we fuse the photographer’s eye with the “oculus artificialis” of the camera? When we examine the way apertures, shadows and ghosts haunt photographic images long after the shutter has closed? If, as the text for this exhibition states, “Voyeurism is a recurring motif in photography, as the practice often involves observing and recording others,” what does this voyeurism say about the recording of the self as subject and the camera together – the self actualised, self-reflexive selfie?

An insightful text on the Based on truth (and lies) website (December 17, 2011) observes of a 1925 self-portrait by photographer Germaine Krull (1897-1985) (below):

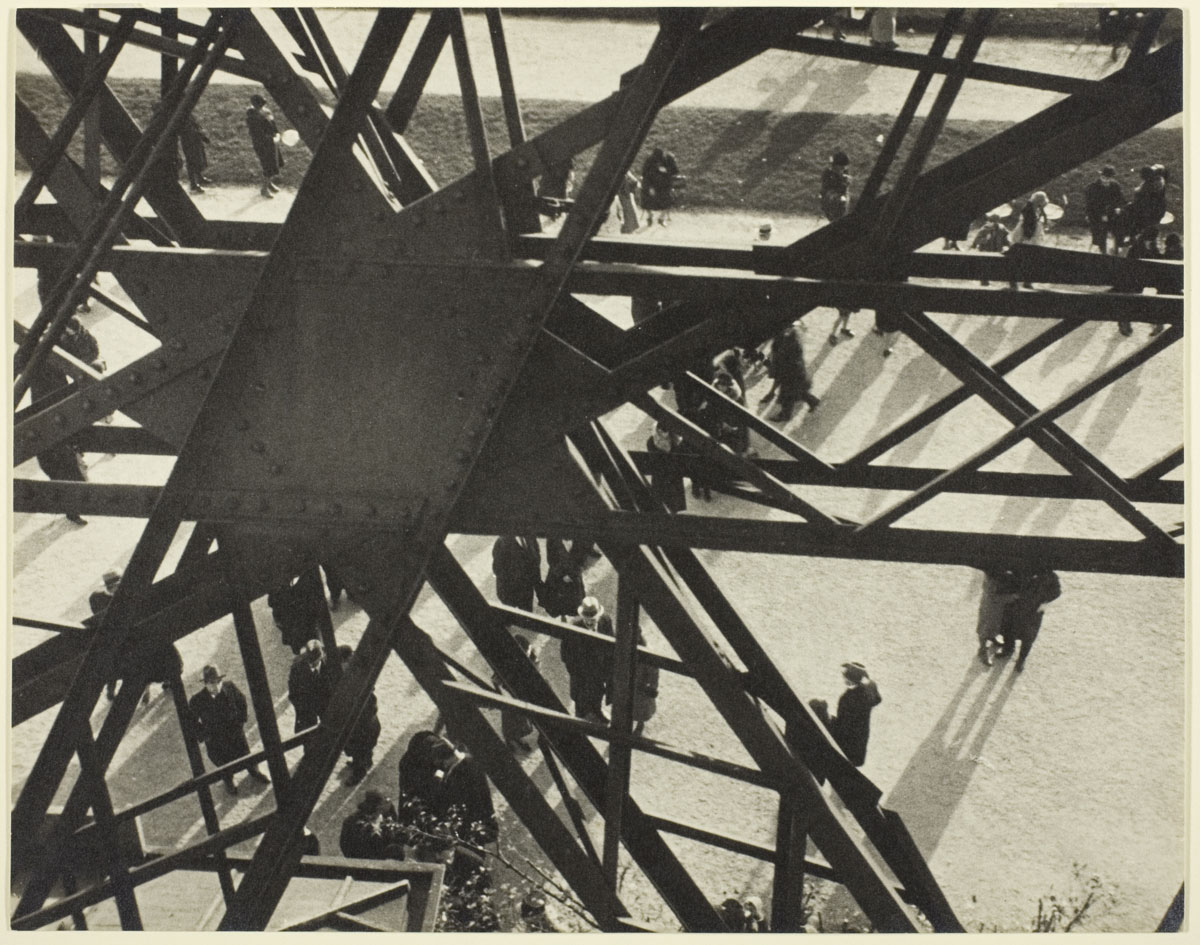

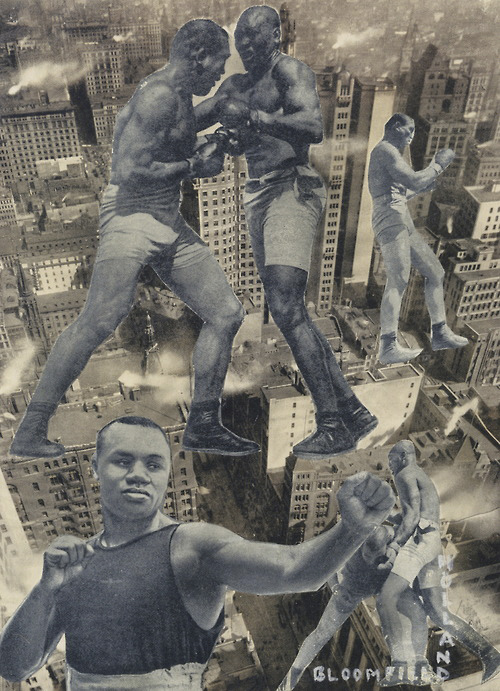

“In 1925, Germaine Krull photographed herself in a mirror with a hand-held camera which half-covered her face. The camera is focused on the foreground of the image, such that the lens and the two hands holding the camera are sharp, while the face behind the camera is blurred. This self-portrait has given rise to many a feminist or professionally critical interpretation, ranging from the female domestication “of the masculinity of technical apparatus” through to the analogy of the camera with a weapon used by the photographer to “reduce the person opposite her […] to an impotent object”. However, if we attempt to interpret the photograph not so much in a figurative sense as in a concrete, phenomenal sense, we arrive at a completely opposite conclusion. By selecting the depth of field in such a way that only the camera and the hands are sharp, Germaine Krull has isolated her act of photographing from her subjectivity and individuality as the photographer. It is the technical apparatus, the camera, which is the focal point of the image and behind which the photographer’s face is blurred beyond recognition. We may assume that this physiognomical retreat behind the camera is less a typical feminine gesture of shyness and reticence than the characteristically ideological approach of a modernist photographer. There is one critical point in Krull’s portrait of herself as a photographer which gives us good reason to make this assumption, namely the fusion of the photographer’s eye with the “oculus artificialis” of the camera. The notion that the camera lens could not only replace the human eye as a means of capturing the world visually but also improve upon its ability to penetrate reality to its invisible depths was paradigmatic of the new, basically positivist photographic aesthetic of the 1920s. It is an aesthetic defined by the Bauhaus theorist László Moholy-Nagy in his manifesto “Painting Photography Film” in 1925 and visualised by countless collages, posters and book covers of the 1920s and 1930s depicting the camera lens as a substitute for the human eye. Germaine Krull’s self-portrait wholly identifies with this new photographic aesthetic, too. Indeed, her influential work “Métal”, a photographic eulogy of modern technology published in 1928, is its embodiment.”1

The highlight for me is that always transcendent image by Judy Dater, Imogen and Twinka at Yosemite (1974, below). I would hope in the exhibition there would be images by Diane Arbus, Edward Weston, Vivian Maier, Man Ray, Rodchenko and others. But you never know.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ sgtr. “Germaine Krull, Selbstporträt mit Ikarette, 1925,” on the Based on truth (and lies) website December 17, 2011 [Online] Cited 01/03/2023

Many thankx to the V&A for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Germaine Krull (German, 1897-1985)

Self-portrait

1925

Gelatin silver print

This photograph is not in the exhibition. It is used under “fair use” conditions for the purposes of education and research.

In the age of the mobile phone, the camera as a stand-alone device is disappearing from sight. Yet generations of photographers have captured the tools of their trade, sometimes inadvertently as reflections or shadows, and sometimes as objects in their own right.

Throughout the history of photography the camera has often made an appearance in its own image, from the glint of Eugène Atget’s camera in a Parisian shop window from the 1900s, to the camera that serves as an eye in Calum Colvin’s 1980s photograph of a painted assemblage of objects.

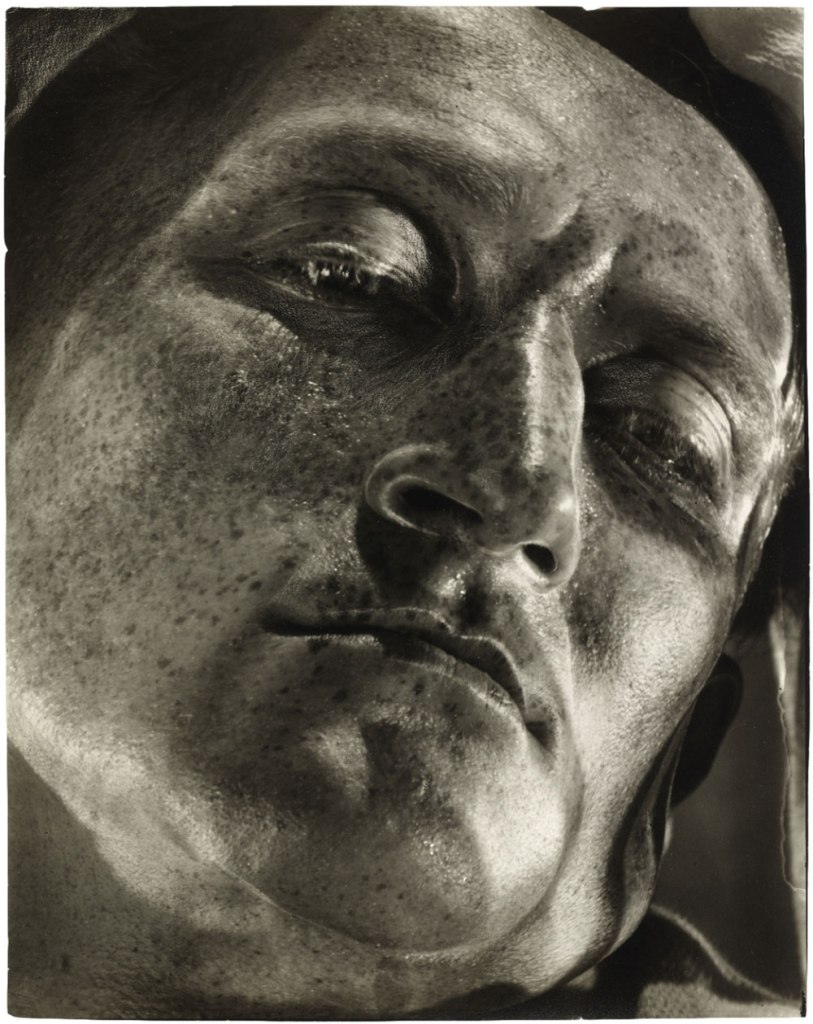

Many images of cameras exploit the instrument’s anthropomorphic qualities. Held up to the face, as in Richard Sadler’s portrait of Weegee, it becomes a mask, the lens a mechanical eye. It conceals the photographer’s features yet reinforces his or her identity. Set on a tripod, it can take on human form, appearing like a body supported by legs, and can stand in for the photographer.

Photographs that include cameras often draw attention to the inherent voyeurism of the medium by turning the instrument towards the viewer. Such images confront the viewer’s gaze, returning it with the cool, mechanical look of the lens. The viewer cannot help but be aware not only of seeing, but of being seen.

Anonymous text. “The camera as star,” on the V&A website Nd [Online] Cited 24/11/2021

Lady Clementina Hawarden (Viscountess, British 1822-1865)

Clementina Maude, 5 Princes Gardens; Photographic Study

c. 1862-1863

Albumen print; Sepia photograph mounted on green card

21.6 x 23.2cm

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Lady Clementina Hawarden, a noted amateur photographer of the 1860s, frequently photographed her children. Here, her second-eldest daughter Clementina Maude poses next to a mirror, in which a bulky camera is reflected. The camera seems to stand in for the photographer, making this a mother-daughter portrait of sorts.

This photograph gives a good idea of Lady Hawarden’s studio and the way she used it. It was situated on the second floor of her house at 5 Princes Gardens in the South Kensington area of London. Here her daughter Clementina poses beside a mirror. A movable screen has been placed behind it, across the opening into the next room. A side table at the left balances a desk at the right. The figure of the young girl is partially balanced and echoed by the camera reflected in the mirror and the embroidery resting on the table beside it.

Hawarden appears to have worked with seven different cameras. The one seen in the mirror is the largest. Possibly there is a slight suggestion of a hand in the act of removing and/or replacing the lens cap to begin and end the exposure.

Anonymous. “Clementina Maude, 5 Princes Gardens,” on the V&A website Nd [Online] Cited 01/03/2023

Lady Clementina Hawarden (Viscountess, British 1822-1865)

Clementina Maude, 5 Princes Gardens; Photographic Study (detail)

c. 1862-1863

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

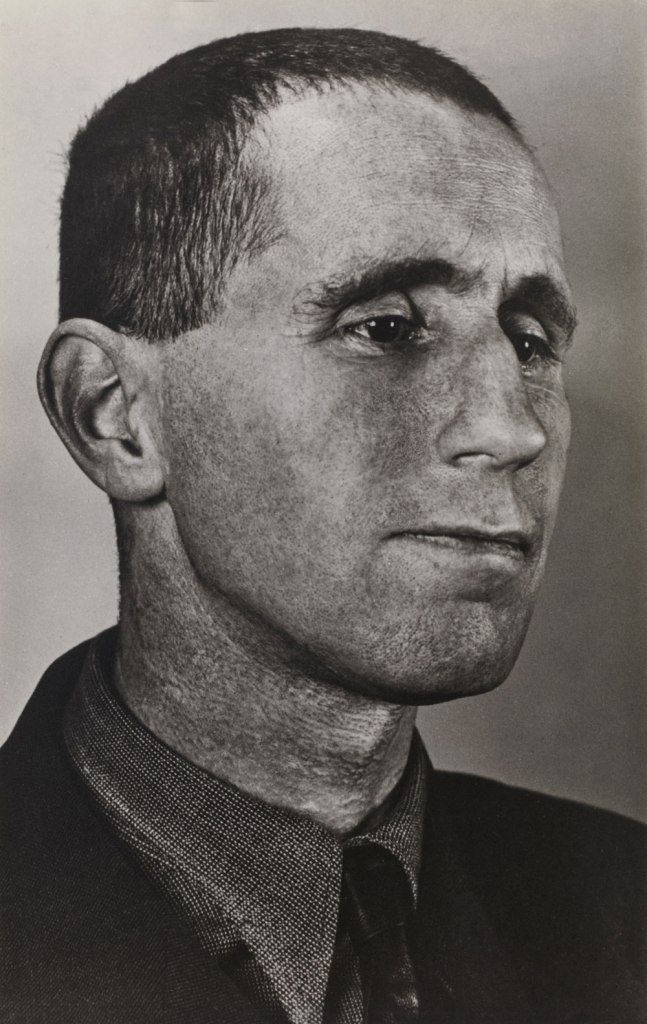

Laelia Goehr (British born Russia, 1908-2002)

Bill Brandt with his Kodak Wide-Angle Camera

1945

© Alexander Goehr

Laelia Goehr (1908-2002), learned photography from Bill Brandt, who poses for this portrait with his newly-acquired Wide-Angle Kodak. This model was originally used by police to photograph crime scenes – the lens provides 110 degrees angle of view, equating approximately to a 14/15mm lens on a 35mm camera. Brandt experimented with it to produce his series Perspectives on Nudes, the same year as this portrait was taken. Brandt’s camera, which was made of mahogany and brass with removable bellows, was sold by Christie’s in 1997 for £3450.

Anonymous. “The camera as star: produced as part of The Camera Exposed,“ on the V&A website Nd [Online] Cited 01/03/2023

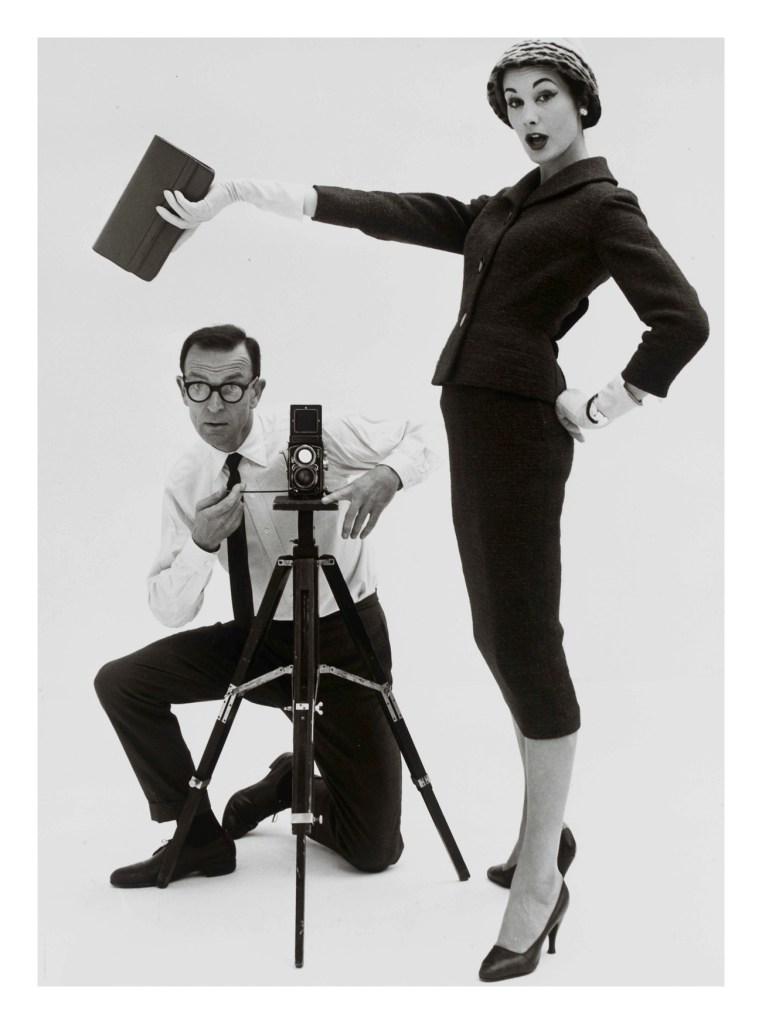

John French (English, 1907-1966)

John French and Daphne Abrams in a tailored suit

1957, printed October 2009; print made by Jerry Jack

Gelatin silver print

27.8 x 38cm

Published in the TV Times, 1957

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

French often left the actual release of the shutter to his assistants. On this occasion however, he inserted himself into the picture, kneeling behind a tripod-mounted Rolleiflex with the shutter release cable in his hand. His crouched, slightly rumpled presence gives a sense of behind-the scenes studio work and contrasts playfully with the polished elegance of the model beside him.

Richard Avedon (American, 1923-2004)

Suzy Parker, dress by Nina Ricci, Champs-Elysée, Paris

1962

© Richard Avedon Foundation

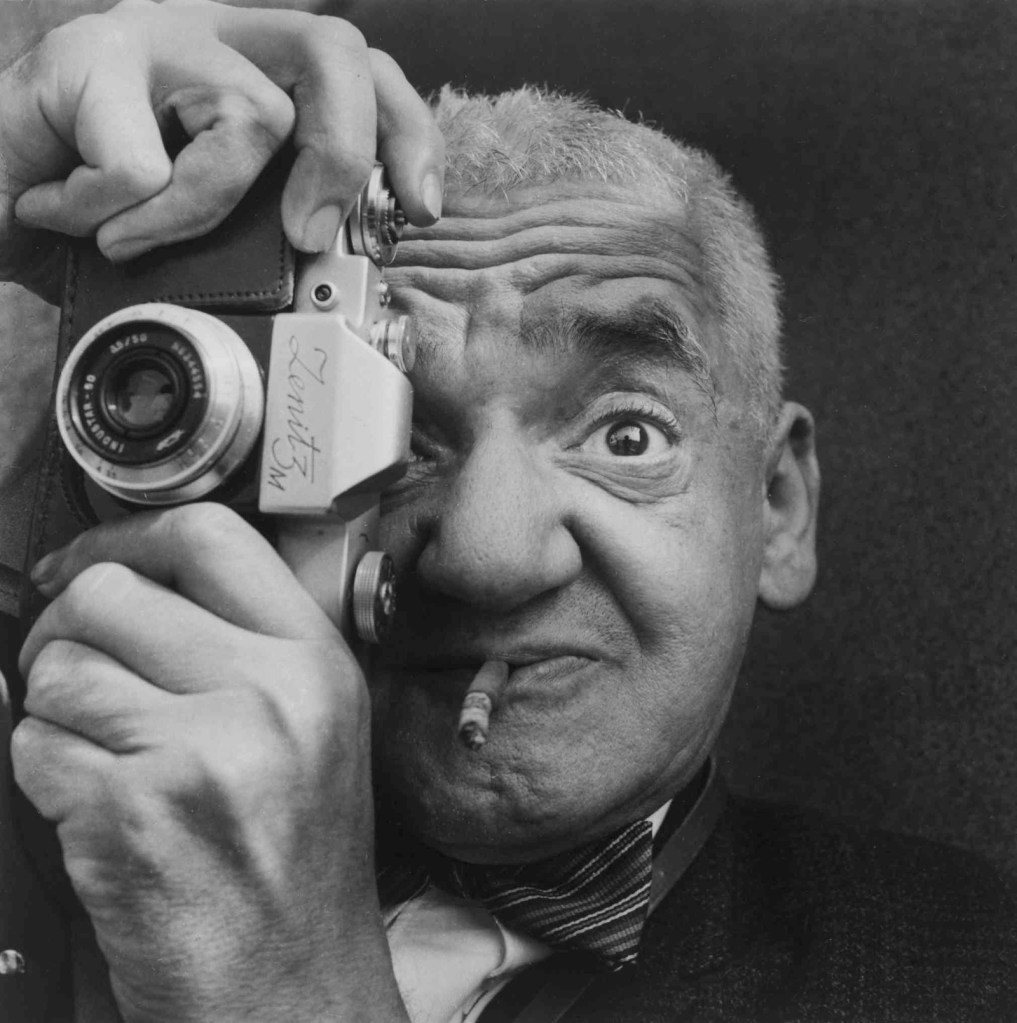

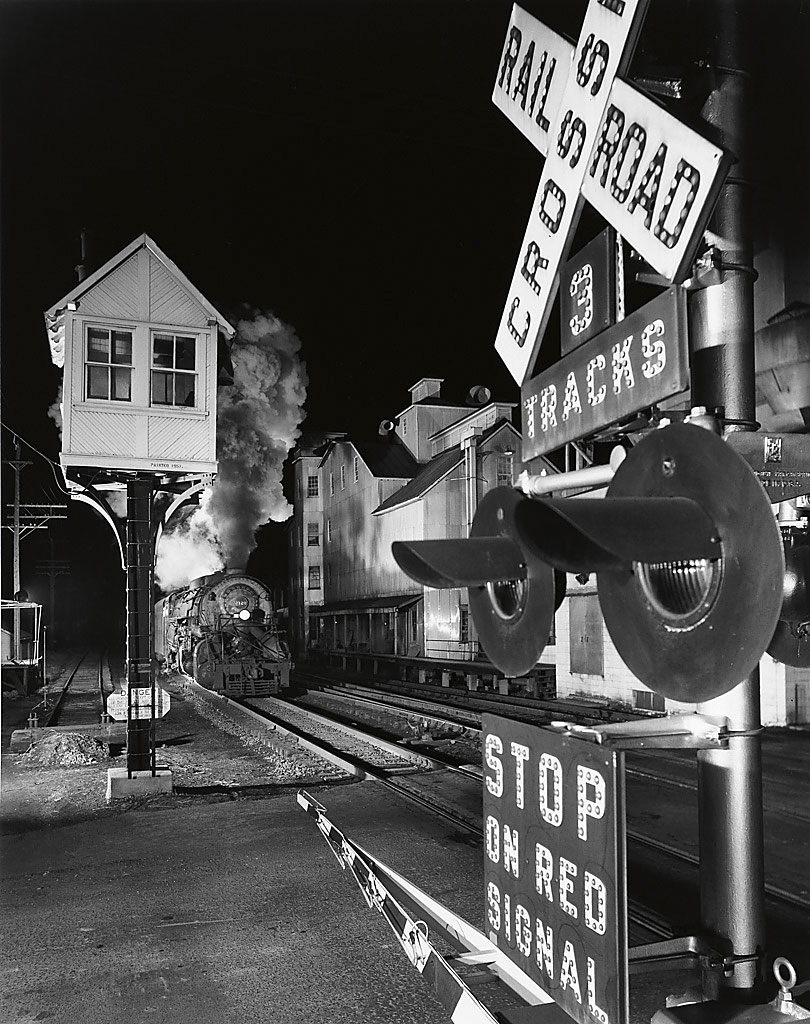

Richard Sadler (British, 1927-2020)

“Weegee the Famous”

1963

© Richard Sadler FRPS

Coventry-based portrait photographer Richard Sadler (b. 1927) photographed the self-proclaimed ‘Weegee the Famous’ in 1963. Weegee was a New York press photographer who gained his nickname – a phonetic spelling of Ouija, the fortune-telling board game – for his reputation for arriving at crime scenes before the police. His fame was international by the time this portrait was taken. Weegee’s visit to Coventry coincided with ‘Russian Camera Week’ at the city’s Owen Owen department store. The camera Weegee holds up to his eye here is the Zenit 3M, a newly-introduced Russian model made by the Krasnogorsk Mechanic Factory between 1962 and 1970.

A few years later Weegee made a comparable self-portrait in which the camera (this time a recent Nikon model) obscures his right eye.

Anonymous. “The camera as star: produced as part of The Camera Exposed,“ on the V&A website Nd [Online] Cited 01/03/2023

Photographer unknown

Camera on black cloth

Date unknown

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The camera pictured here is a Super Ikonta C 521/2 camera, produced by the German company Zeiss Ikon from about 1936 to 1960. It has been carefully lit and arranged on a velvet cloth as if it were a still-life subject, by an unknown photographer.

Anonymous. “The camera as star: produced as part of The Camera Exposed,“ on the V&A website Nd [Online] Cited 01/03/2023

Tim Walker (British, b. 1970)

Lily Cole with Giant Camera

2004

© Tim Walker

British fashion photographer Tim Walker (born 1970) has collaborated with the art director and set designer Simon Costin for over a decade, and Costin’s oversized props feature in many of Walker’s sparkling, magical scenes. Costin based the giant camera on Walker’s 35mm Pentax K1000. Walker found inspiration for this shoot in a 1924 fashion illustration by Vogue artist Benito. Benito depicted girls reading a magazine from which the models appear to be coming alive.

Anonymous. “The camera as star: produced as part of The Camera Exposed,“ on the V&A website Nd [Online] Cited 01/03/2023

Every photograph in this display features at least one camera. From formal portraits to casual snapshots, still-lifes to collages, they appear as reflections or shadows, and sometimes as objects in their own right. This summer the V&A displays of over 120 photographs that explore the camera as subject. People are taking more photographs today than ever before, but as they increasingly rely on smartphones, the traditional device is disappearing from sight.

The Camera Exposed showcases works by over 57 known artists as well as many unidentified amateur photographers. From formal portraits to casual snapshots, and from still-lifes to cityscapes, each work features at least one camera. Portraits of photographers such as Bill Brandt, Paul Strand and Weegee, posed with their cameras, are on display alongside self-portraits by Eve Arnold, Lee Friedlander and André Kertész, in which the camera appears as a reflection or a shadow. Other works depict cameras without their operators. In the earliest photograph included in the display, from 1853, Charles Thurston Thompson captures himself and his camera reflected in a Venetian mirror. The most recent works are a pair of 2014 photomontages by Simon Moretti, created by placing fragments of images on a scanner.

The display showcases several new acquisitions, including a recent gift of nine 20th-century photographs. Amongst these are a Christmas card by portrait photographer Philippe Halsman, an image of photojournalist W. Eugene Smith testing cameras and a self-portrait in the mirror by the French photojournalist Pierre Jahan. On display also is a recently donated collection of 50 20th-century snapshots of people holding cameras or in the act of taking photographs. These anonymous photographs attest to the broad social appeal of the camera.

Many of the photographs in the display highlight the anthropomorphic qualities of the camera. Held up to the face like a mask, as in Richard Sadler’s Weegee the Famous, the lens becomes an artificial eye. In Lady Hawarden’s portrait of her daughter, a mirror reflection of the camera on a tripod takes on a human form, a body supported by legs.

Cameras in photographs can also emphasise the inherent voyeurism of the medium. Judy Dater explores this theme in her well-known image of the fully clothed photographer Imogen Cunningham posed as if about to snap nude model Twinka Thiebaud. In other photographs on display, the camera confronts the viewer with its mechanical gaze, drawing attention to the experience not only of seeing, but of being seen.

Press release from the V&A

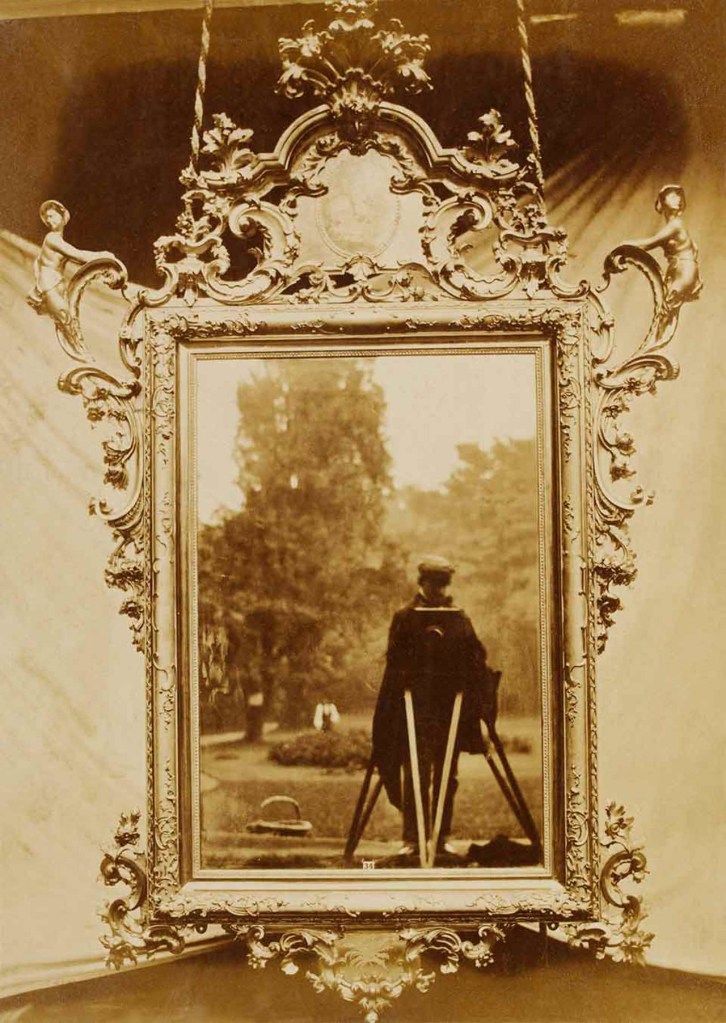

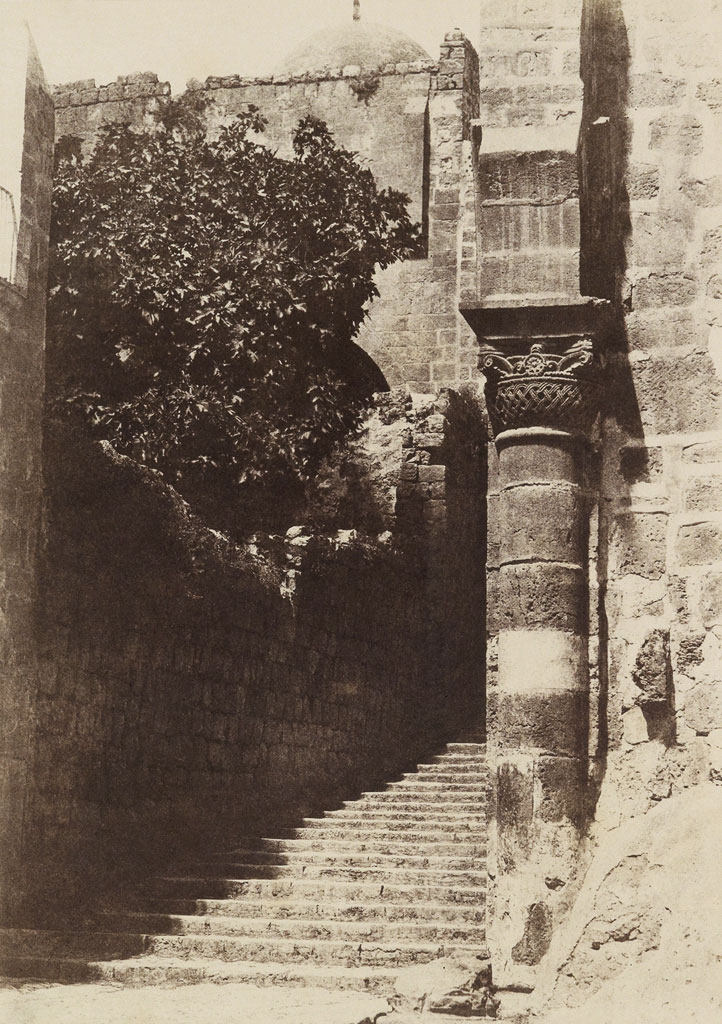

Charles Thurston Thompson (British, 1816-1868)

Venetian mirror circa 1700

1853

Albumen print from wet collodion-on-glass negative

22.8 x 16.3cm

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

As early as 1853, Charles Thurston Thompson (1816-1868), the first official photographer to the South Kensington Museum (as the V&A was then called), recorded his reflection, along with that of his camera, in the glass of an ornate Venetian mirror. Loan objects such as the mirror were photographed so that photographic copies could be sold to designers, craftsmen and students, and also filed in the Museum’s library for study. By recording not only the frame’s intricate carvings but also his reflection and that of his box form camera and tripod, Thompson showed the very process by which he made the image. It gives us a vivid glimpse of a photographer at work outdoors in the early days of the Museum and the profession of Museum Photography.

Anonymous. “The camera as star: produced as part of The Camera Exposed,“ on the V&A website Nd [Online] Cited 01/03/2023

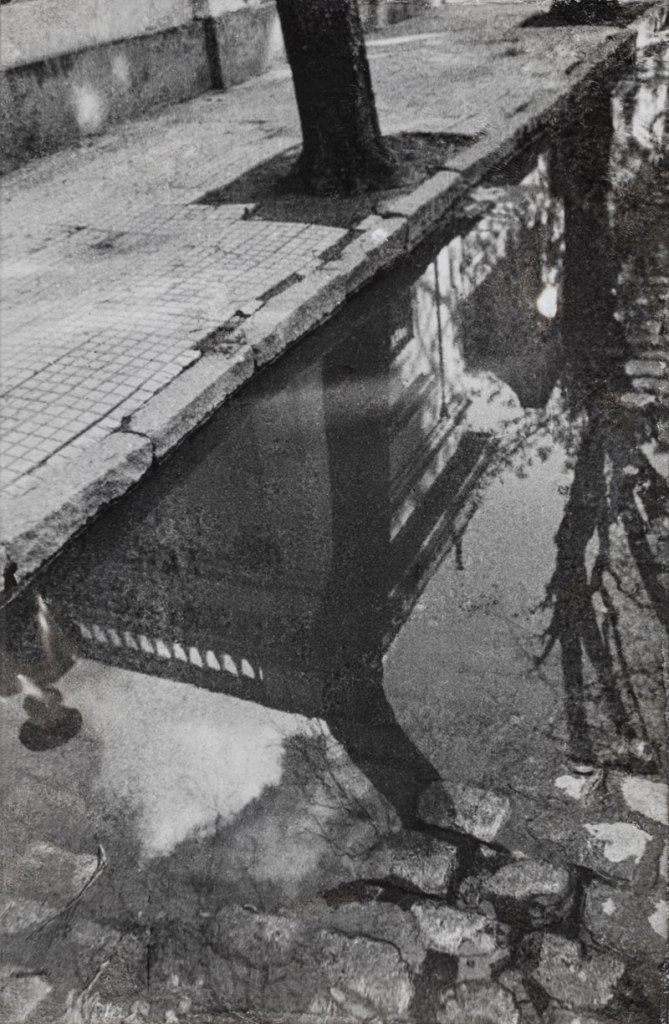

Eugène Atget (French, 1857-1927)

Shopfront, Quai Bourbon, Paris, France

c. 1900

Albumen print from gelatin dry plate negative

21 x 17.5cm

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The reflection of Eugène Atget’s (1857-1927) camera is an appealing detail in this photographic record of Parisian architecture from the turn of the century. Atget’s photographs had a primarily documentary role – this image was purchased by the V&A in 1903 as an illustration of Parisian ironwork. Yet it carries a strangeness which has fascinated 20th-century photographers. His photographs acquired artistic status in the mid-1920s when they were ‘discovered’ by artists associated with Surrealism.

Anonymous. “The camera as star: produced as part of The Camera Exposed,“ on the V&A website Nd [Online] Cited 01/03/2023

This photograph is an albumen print, contact printed by Atget from a 24 x 18 glass negative. The dark shapes of two clips which held the negative in place on the right edge of the image are visible. This image was one of many photographs bought by the V&A directly from Atget, in this case, in 1903. This photograph would have been bought as simply an illustration of ironwork in Paris.

The albumen process was almost never used by the early 1900s, so the image can be dated to the 19th century. The use of this developing process also supports the non-art status intended for the photograph. There is, however, an ambiguity in the reading of this image and most strongly in the reflection in the door of the street and Atget with his camera. This is one of a number of Atget images where it is possible to see why his photographs have fascinated 20th-century photographers; it carries, whether intended or not, a strangeness which invests the image with potential meaning beyond its primarily documentary role.

Anonymous. “Shopfront, Quai Bourbon, Paris, France,” on the V&A website Nd [Online] Cited 01/03/2023

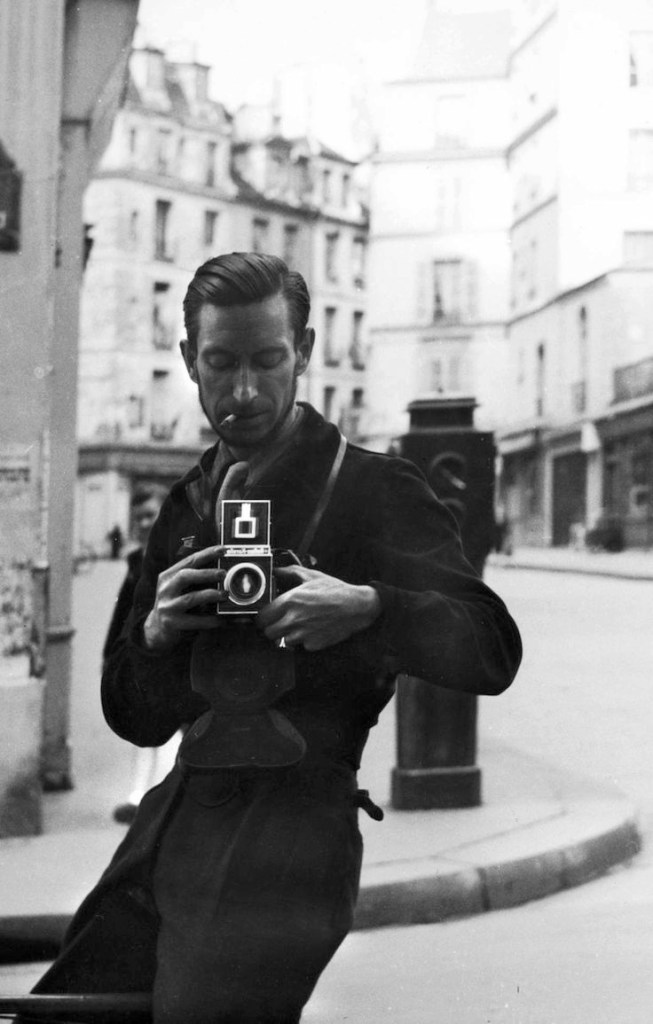

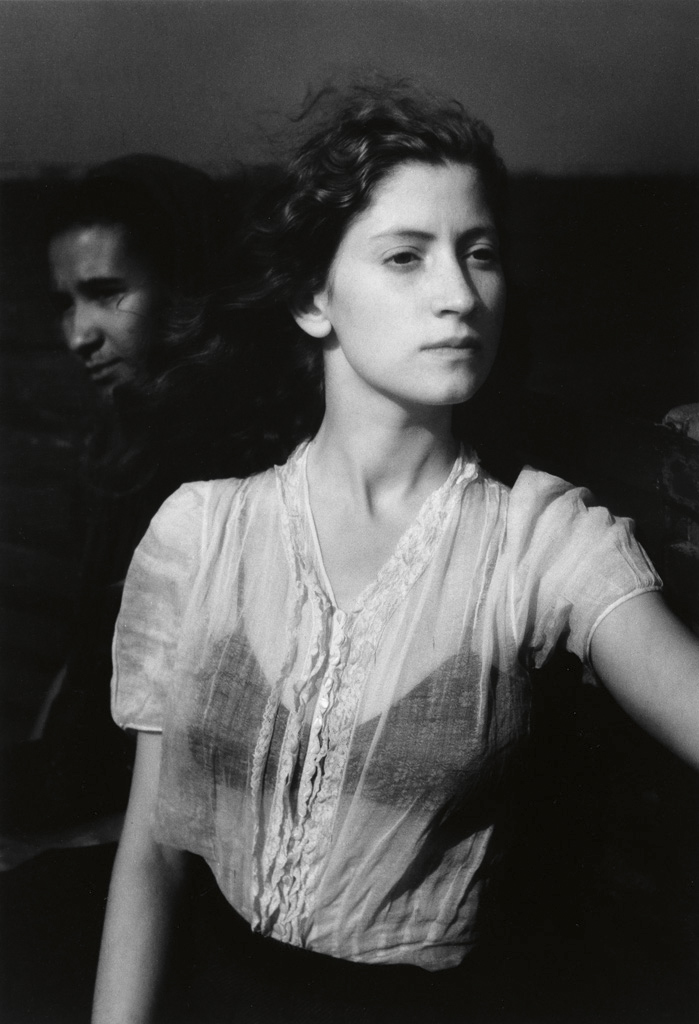

Pierre Jahan (French, 1909-2003)

Autoportrait à Velo (‘Self-portrait on bike’)

June 1944

Gelatin silver print

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Here, Jahan seems to have paused while cycling through the streets of Paris to snap himself in a mirror. His dangling cigarette and precarious perch on the bicycle suggest spontaneity, but the design of his camera demanded a deliberate approach. A Reflex-Korelle, manufactured in Dresden, it usually required the operator to hold it at waist level and look down into the viewfinder.

Pierre Jahan (French, 1909-2003)

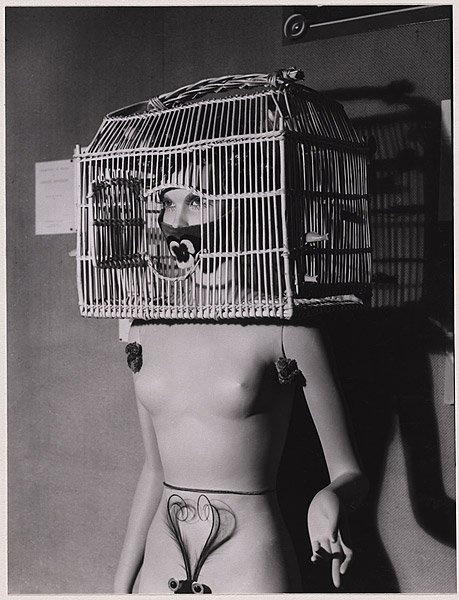

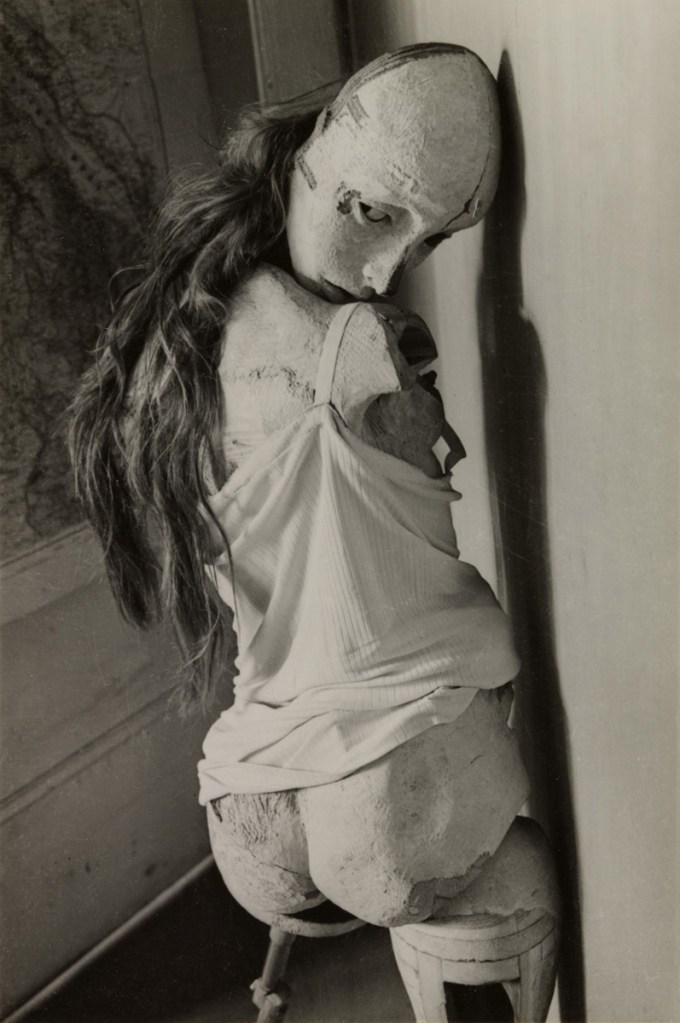

Pierre Jahan (9 September 1909 – 21 February 2003) was a French photographer who often worked in a Surrealist style.

Born in Amboise and introduced to photography by his family at a very early age, Jahan received his first professional commission when he moved to Paris in 1933, through a meeting with ad-man Raymond Gid. In 1936 he joined the Rectangle group of photographers. This group, founded by Emmanuel Sougez, among others, encouraged him in his career as a photographer.

During the Occupation, he worked for the magazine Images de France, making portraits of celebrity figures such as Colette, and he produced large series of pictures such as “La mort et les statues,” published in 1946 with a text by Jean Cocteau. They also co-published a book in which Cocteau’s poem “Plain Chant” is illustrated by photographed nudes (1947).

A passionate experimenter with a strong interest in Surrealism, Jahan produced many collages and photomontages, which he used freely for the many advertising commissions that came his way after the end of World War II.

A committed activist for photographers’ rights, he helped to found the French federation of art photographers (FAPC), of which he became vice-chairman. In 1949 he joined the professional photographers’ association Le Groupe des XV alongside Robert Doisneau, Willy Ronis, and others, to lobby for the conservation of France’s photographic heritage. He took part in their exhibitions and in those held by the Salon National de la Photographie.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Unknown photographer

Vernacular photograph

c. 1940s

Gelatin silver print

71mm x 98mm

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Vernacular portrait photograph of a woman in front of a fence, using a camera held at chest height. Photographer unknown, c. 1940s. Gelatin silver print, from the collection of Peter Cohen, given as part of a group of 50 photographs featuring cameras.

Elsbeth Juda (British born Germany, 1911-2014)

Mediterranean Fortnight

1953

© Siobhan Davies

Elsbeth Juda (British born Germany, 1911-2014)

Elsbeth Juda (1911-2014) was a British fashion photographer who worked for more than 20 years as photographer and editor on The Ambassador magazine. This image was shot at an archaeological site in Cyprus for a story on British fashion abroad. The model appears to pose for a local tintype photographer with a homemade looking camera. Tintype, also called ferrotype, was an early photographic process which produced an underexposed negative using a thin metal plate. Tintype photography was around 100 years old when Juda took this shot.

Anonymous. “The camera as star: produced as part of The Camera Exposed,“ on the V&A website Nd [Online] Cited 01/03/2023

Elsbeth Ruth Juda (née Goldstein) and known professionally as Jay (2 May 1911 – 5 July 2014), was a British photographer most notable for her pioneering fashion photographs and work as associate editor and photographer for The Ambassador magazine between 1940 and 1965.

The Ambassador

Hans and Elsbeth Juda originally opened a London satellite office for the Dutch trade magazine International Textiles. After 1940, however, when Amsterdam came under control of the Germany army, the magazine proved too difficult to continue. In March 1946 the Judas changed the name of the publication to The Ambassador and changed its focus to British industry, trade and exports. The magazine was influential from its inception and encouraged by the British Government, who helped by ensuring a continual supply of paper during the war. Indeed, The Ambassador, The British Export Magazine became the voice of British manufacturing for export when the nation’s trade was struggling to emerge after 1945. It was published monthly in four languages (English, German, French and Portuguese), had subscribers in over ninety countries, and a circulation of 23,000 copies.

Juda’s husband, Hans, coined the official motto “Export or Die” for The Ambassador. Later, as the magazine became an essential marketing and press journal for a Britain desperate to reestablish itself as a global exporter in the post-war era, the phrase would become a mantra for the national manufacturing industry. Throughout their work during the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s, Juda and her husband became two of the United Kingdom’s greatest champions for export, constantly promoting every facet of British manufacturing, culture and the arts and, in the process, coming into close contact with a host of distinguished artists, writers, designers and photographers. The critic Robert Melville described Ambassador as “the most daring and enterprising trade journal ever conceived… no other magazine… has so consistently and brilliantly demonstrated the relevance of works of art to the problems of industrial design.”

Juda’s shoots for The Ambassador combined elements of fashion, modernism and trade. Her series of photos of the famed British model Barbara Goalen modelling Scottish textiles among the heavy machinery of working textile factory are especially representative of her unique visual aesthetics. Together they built a considerable art collection from the many artists that they came in contact with at The Ambassador. It is a much wider circle of friends, however, which would allow Jay to capture every facet of a reemerging post-war Britain through the lens of her camera. The magazine was bought by Thomson Publications in 1961 and continued to be published until 1972.

Text from the Wikipedia website

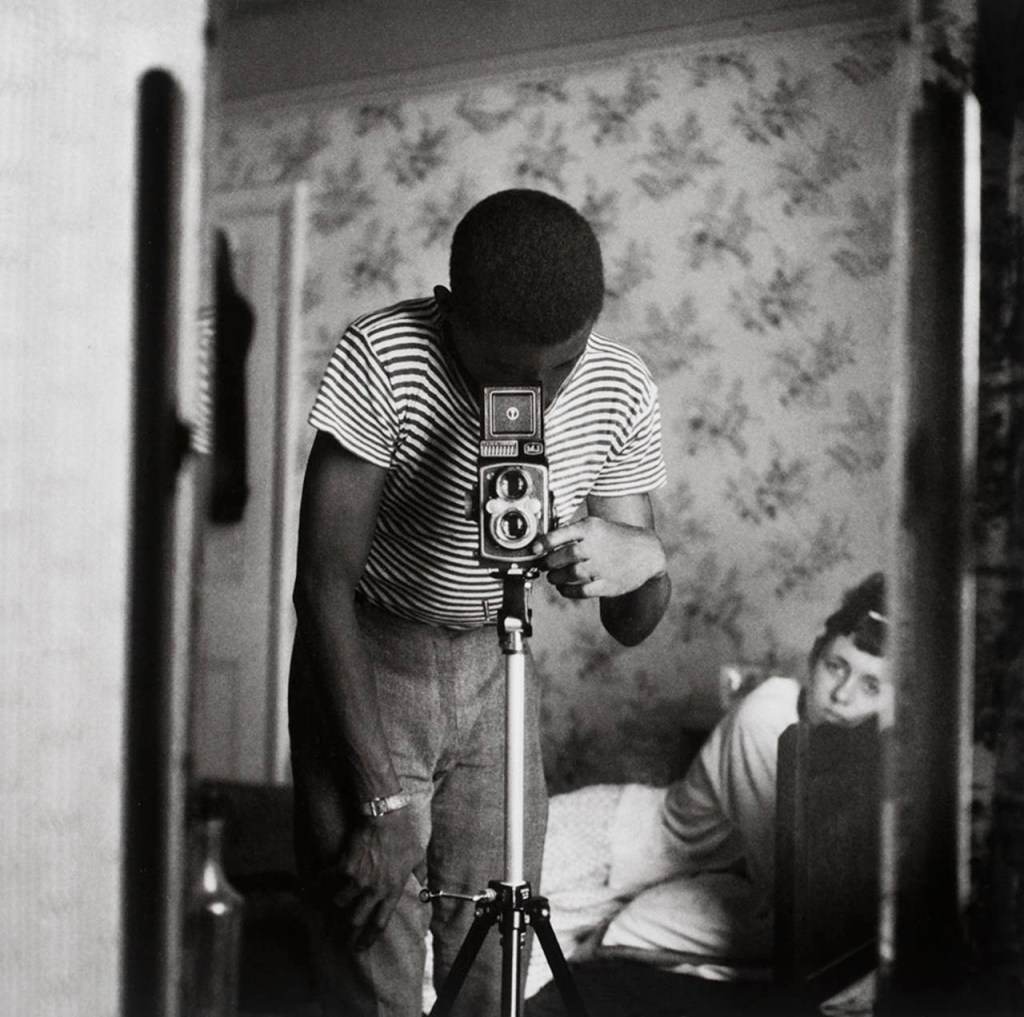

Armet Francis (British born Jamaica, b. 1945)

Self-portrait in Mirror

1964

© Armet Francis

Armet Francis was born in Jamaica in 1945 and moved to London at the age of ten. His photographic career began in his mid-teens when he worked as an assistant for a West End photographic studio. His early photographs show him experimenting with the camera as a technical device and a tool for self-representation. The camera in this self-portrait is a Yashica-Mat LM twin lens reflex, an all-mechanical model introduced in 1958, with an inbuilt light meter. It records his identity as a professional photographer, while the surrounding scene offers an intimate glimpse into his personal life.

Anonymous. “The camera as star: produced as part of The Camera Exposed,“ on the V&A website Nd [Online] Cited 01/03/2023

Armet Francis is a Jamaican-born photographer and publisher who has lived in London since the 1950s. He has been documenting and chronicling the lives of people of the African diaspora for more than 40 years and his assignments have included work for The Times Magazine, The Sunday Times Supplement, BBC and Channel 4.

He has exhibited worldwide and his work is in collections including those of the Victoria & Albert Museum and the Museum of London. One of his best known photographs is 1964’s “Self Portrait in Mirror”.

Read a fuller biography on the Wikipedia website

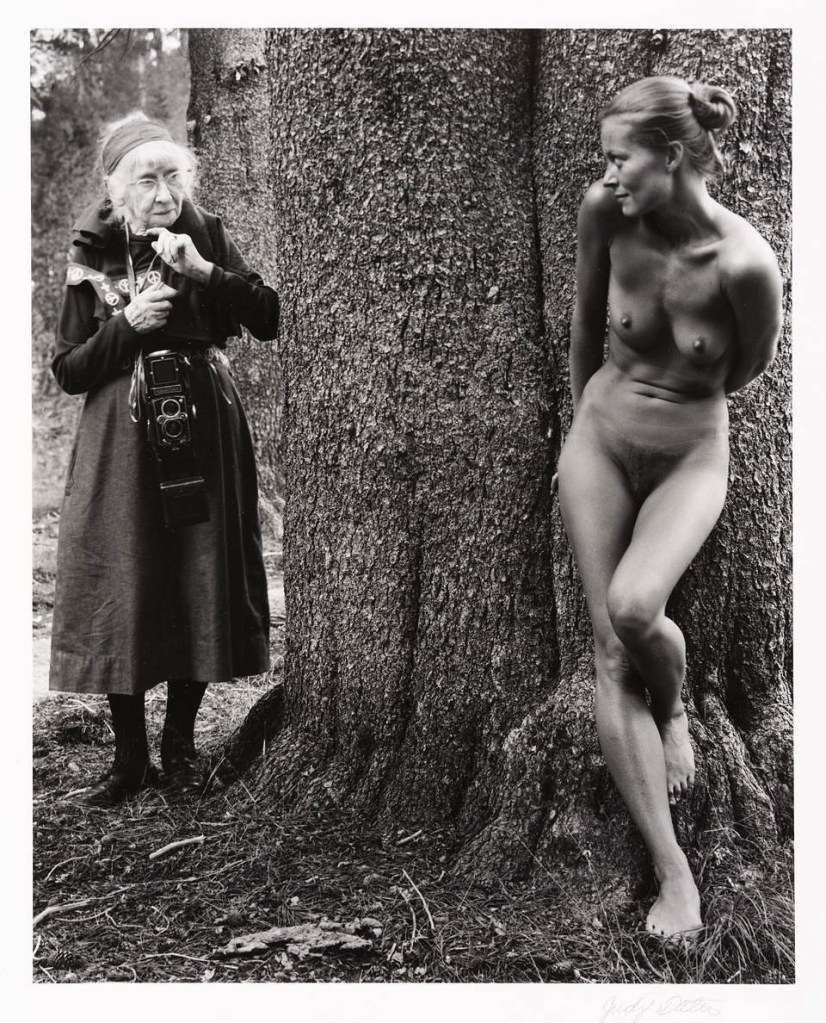

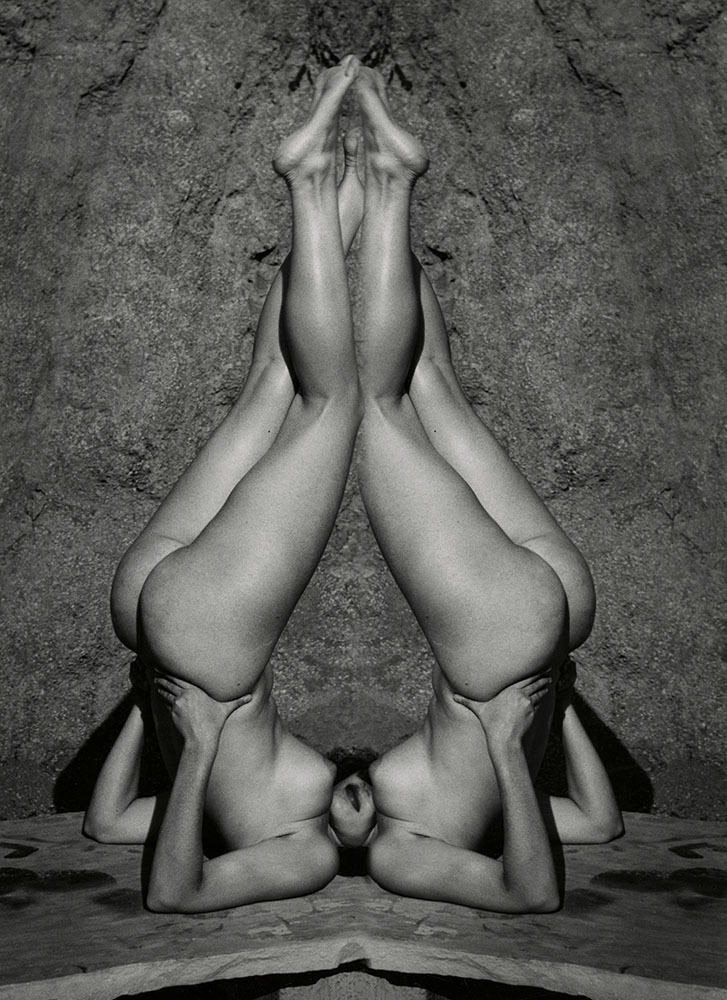

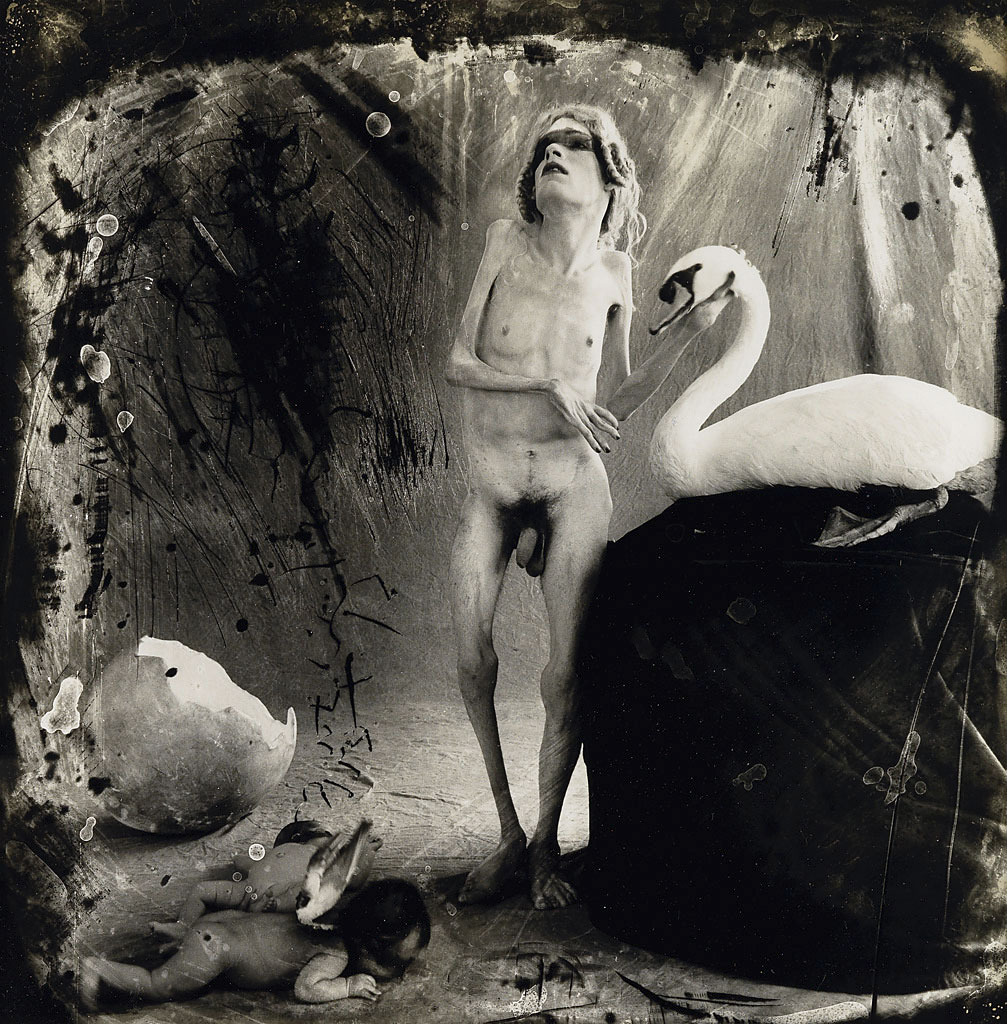

Judy Dater (American, b. 1941)

Imogen and Twinka at Yosemite

1974

© Judy Dater

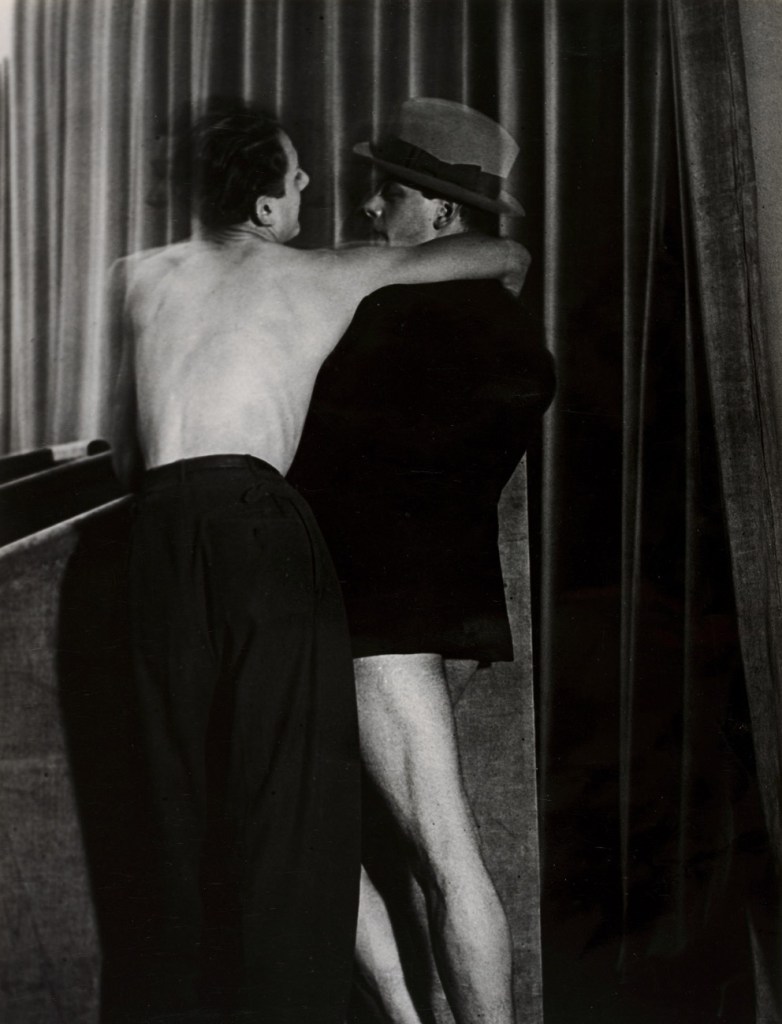

Cameras in photographs can also emphasise the inherent voyeurism of the medium. Judy Dater explores this theme in her well-known image of the fully clothed photographer Imogen Cunningham posed as if about to snap nude model Twinka Thiebaud.

Dater met Imogen Cunningham, a prominent American photographer, in 1964. Cunningham acted as a mentor to Dater, and the two became close friends. This image is from Dater’s larger series addressing the theme of voyeurism, in particular the idea of someone clothed watching someone nude. Voyeurism is a recurring motif in photography, as the practice often involves observing and recording others.

Judy Dater (American, b. 1941)

Judith Rose Dater (née Lichtenfeld; June 21, 1941) is an American photographer and feminist. She is perhaps best known for her 1974 photograph, Imogen and Twinka at Yosemite, featuring an elderly Imogen Cunningham, one of America’s first woman photographers, encountering a nymph in the woods of Yosemite. The nymph is the model Twinka Thiebaud. The photo was published in Life magazine in its 1976 issue about the first 200 years of American women. Her photographs, such as her Self-Portraiture sequence, were also exhibited in the Getty Museum. …

Photography

Judy Dater uses photography as an instrument for challenging traditional conceptions of the female body. Her early work paralleled the emergence of the feminist movement and her work became strongly associated with it. At a time when female frontal nudity was considered risqué Dater pushed the boundaries by taking pictures of the naked female body. However, she did so in a way which did not objectify her subject which was in many cases, herself. Dater began taking photographs in the 1960s and she is still taking photographs today. Mark Johnstone, an Idaho resident whom Dater photographed in the early 80’s remarked that “During this time, she never got swayed by or indulged in trends, but moved with her own vision. She’s one of the few successful women in the art world, especially photography, who never depended on ongoing academic support to fuel and expand her artistic exploration.”

While her subject and message remained relatively constant throughout her career, Dater experimented with a variety of compositions as her career developed. Her photographs, and in particular, her portraits (which she specialises in) are taken in both black and white, and in colour. She has taken portraits in the Southwestern desert and also posed as female stereotypes in a more obvious display of activism. Her 1982 portrait “Ms. Clingfree” demonstrated the latter as Dater posed with an assortment of cleaning supplies.

She was influenced by the vital cultural intersection of photography and feminism, and the second wave of feminism which started in the 1960s and lasted up till the 1980s. In the 1980s, much has changed and the country as a whole became more conservative in areas of political life. The gains of the women’s movement began to slow, and many feminists became discouraged with the continuation of sexist attitudes and behaviour. Through her powerful photography and personal sense of style, Dater was able to surpass these conservative values and was able to effectively convey her views to her audience.

One of her famous photograph sequences taken in the 1980s, known as the Self-Portraiture sequence, exploited themes such as identity, feminism, and the human connection with nature. She effectively conveyed these themes and delivered, through her photography, the stories of women’s lives, relationships, and personal emotions. For example, in her photograph titled, My Hands, Death Valley, Dater presents the theme of feminism through the placement of the artist’s hands on the car’s glass window; her hands are crinkled, which is a sign of ageing. The theme of personal identity is explored in connection with the theme of feminism. The background is of the hazy Death Valley, the grounds are dry, her hands are weathered, and she’s trying to force open a car window. The theme of human’s connection with nature is exploited by taking the photograph in a natural landscape setting, and putting herself out there.

Read a fuller biography on the Wikipedia website

Victoria and Albert Museum

Cromwell Road

London

SW7 2RL

Phone: +44 (0)20 7942 2000

Opening hours:

Daily 10 – 17.45

Friday 10 – 22

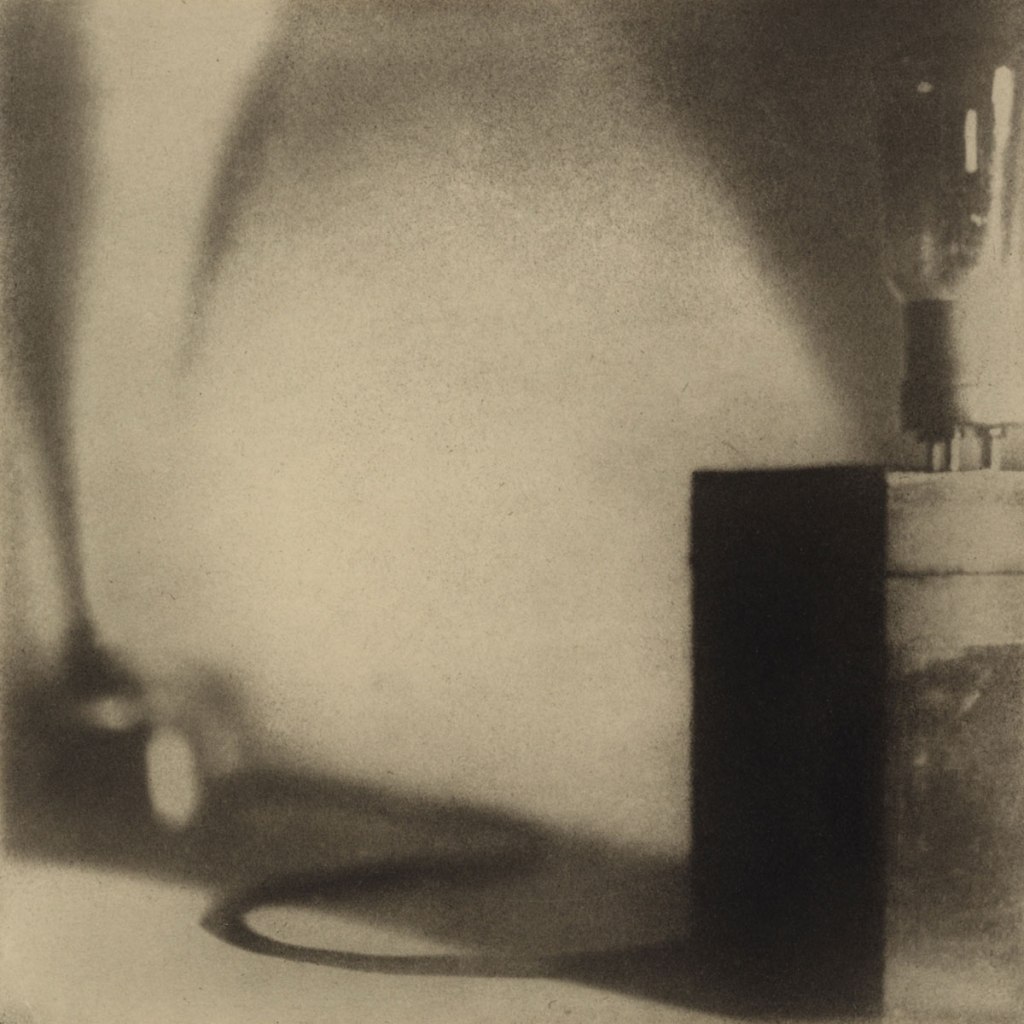

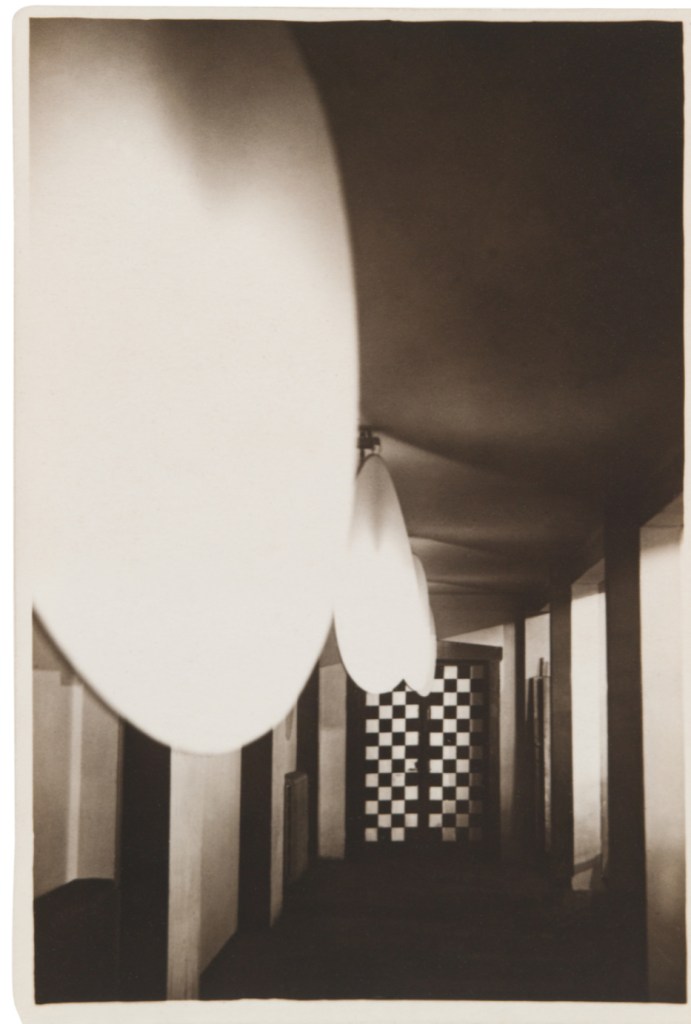

![Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Dimanche après-midi à l'île Kolín' [Sunday afternoon at Kolín island] c. 1922–1926 Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Dimanche après-midi à l'île Kolín' [Sunday afternoon at Kolín island] c. 1922–1926](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/sudek-dimanche-aprc3a8s-midi-c3a0-l_c3aele-kolc3adn-vers-1922e280931926-web1.jpg?w=898)

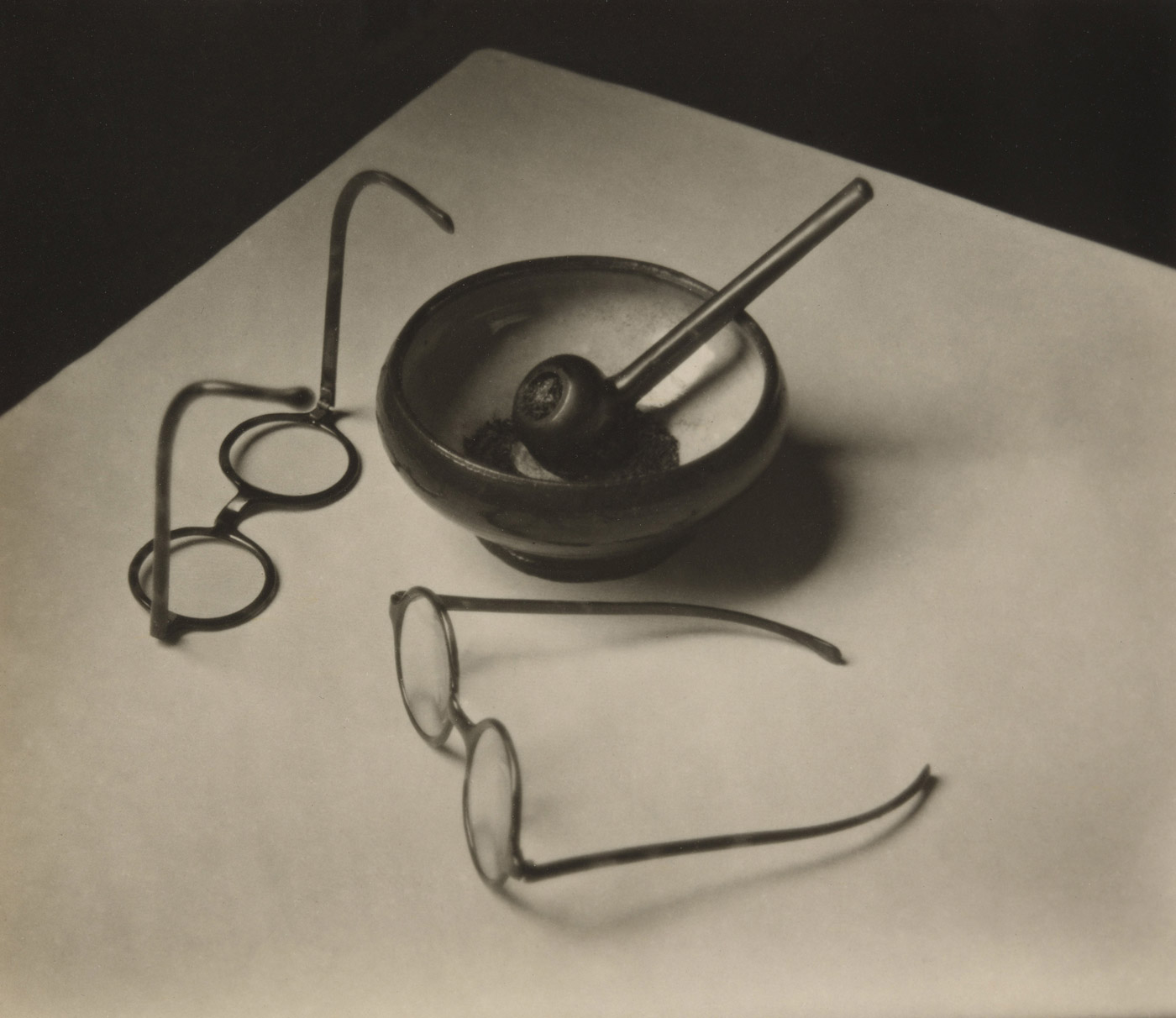

![Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Portrait de mon ami Funke' [Portrait of my friend Funke] 1924 Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Portrait de mon ami Funke' [Portrait of my friend Funke] 1924](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/sudek-portrait-de-mon-ami-funke-1924-web1.jpg?w=798)

![Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'La Fenêtre de mon atelier' [The window of my studio] c. 1940-1948 Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'La Fenêtre de mon atelier' [The window of my studio] c. 1940-1948](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/sudek-la-fenc3aatre-de-mon-atelier-vers-1940e280931948-web1.jpg?w=708)

![Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'La Fenêtre de mon atelier' [The window of my studio] c. 1940–1954 Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'La Fenêtre de mon atelier' [The window of my studio] c. 1940–1954](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/josef-sudek-la-fenc3aatre-de-mon-atelier-vers-1940e280931954-web1.jpg?w=769)

![Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'La Fenêtre de mon atelier' [The window of my studio] c. 1940-1950 Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'La Fenêtre de mon atelier' [The window of my studio] c. 1940-1950](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/josef-sudek-la-fenc3aatre-de-mon-atelier-vers-1940e280931950-web1.jpg?w=838)

![Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Quatre saisons: l'été' [Four seasons: summer] c. 1940-1954 Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Quatre saisons: l'été' [Four seasons: summer] c. 1940-1954](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/josef-sudek-quatre-saisons-l_c3a9tc3a9-vers-1940e280931954-web1.jpg?w=738)

![Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'La Dernière Rose' [The Last Rose] 1956 Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'La Dernière Rose' [The Last Rose] 1956](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/sudek-la-dernic3a8re-rose-1956-web1.jpg?w=838)

![Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Le Jardin Royal' [The Royal Garden] c. 1940-1946 Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Le Jardin Royal' [The Royal Garden] c. 1940-1946](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/sudek-le-jardin-royal-vers-1940e280931946-web1.jpg?w=750)

![Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Prague pendant la nuit' [Prague at night] 1950 Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Prague pendant la nuit' [Prague at night] 1950](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/sudek-prague-pendant-la-nuit-1950-web1.jpg)

![Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Prague pendant la nuit' [Prague at night] c. 1950-1959 Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Prague pendant la nuit' [Prague at night] c. 1950-1959](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/sudek-prague-pendant-la-nuit-vers-1950e280931959-web1.jpg)

![Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Prague pendant la nuit' [Prague at night] c. 1950-1959 Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Prague pendant la nuit' [Prague at night] c. 1950-1959](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/josef-sudek-prague-pendant-la-nuit-vers-1950e280931959-web1.jpg)

![Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Le Jardin de Rothmayer' [The Rothmayer Garden] 1954-1959 Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Le Jardin de Rothmayer' [The Rothmayer Garden] 1954-1959](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/sudek-le-jardin-de-rothmayer-1954e280931959-web1.jpg)

![Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Dans le jardin' [In the garden] 1954-1959 Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Dans le jardin' [In the garden] 1954-1959](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/sudek-dans-le-jardin-1954e280931959-web1.jpg)

![Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Labyrinthe sur ma table' [Labyrinth on my table] 1967 Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Labyrinthe sur ma table' [Labyrinth on my table] 1967](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/sudek-labyrinthe-sur-ma-table-1967-web1.jpg?w=826)

![Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Labyrinthe de verre' [Glass Maze] around 1968-1972 Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Labyrinthe de verre' [Glass Maze] around 1968-1972](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/sudek-labyrinthe-de-verre-vers-1968e280931972-web1.jpg?w=808)

![Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Sans titre (Nature morte sur le rebord de la fenêtre)' [Untitled (Still life on the windowsill)] 1951 Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Sans titre (Nature morte sur le rebord de la fenêtre)' [Untitled (Still life on the windowsill)] 1951](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/josef-sudek-sans-titre-nature-morte-sur-le-rebord-de-la-fenc3aatre-1951-web1.jpg?w=836)

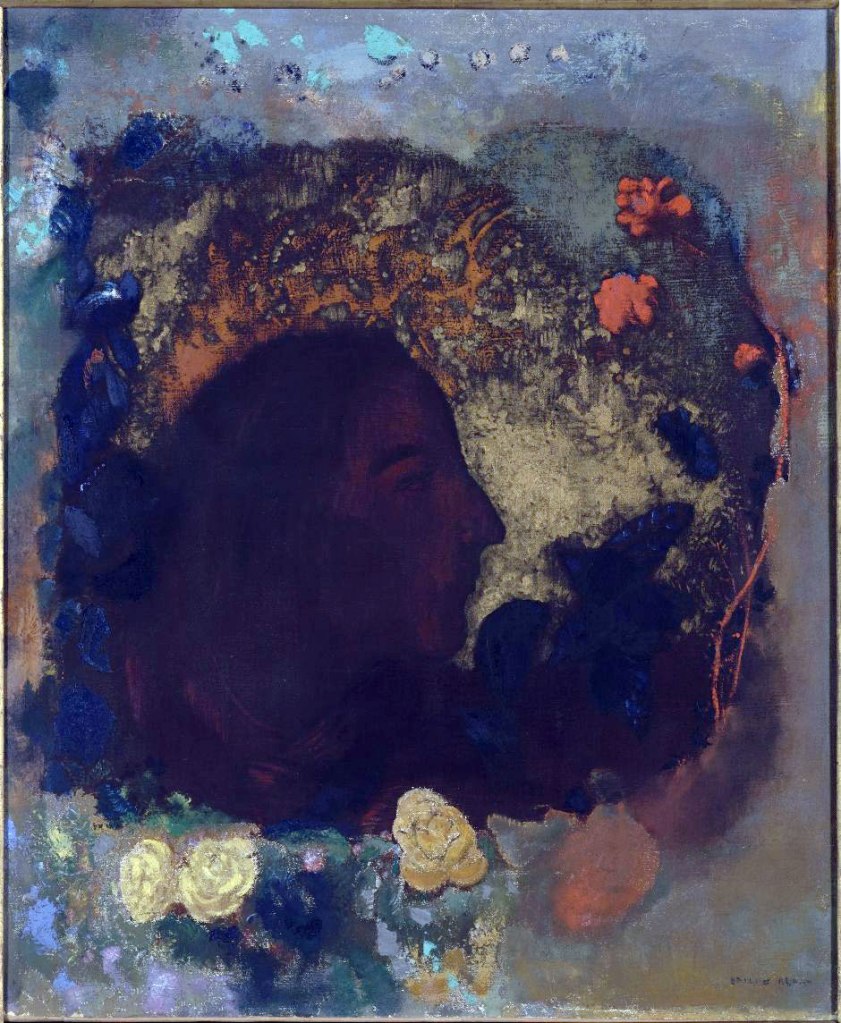

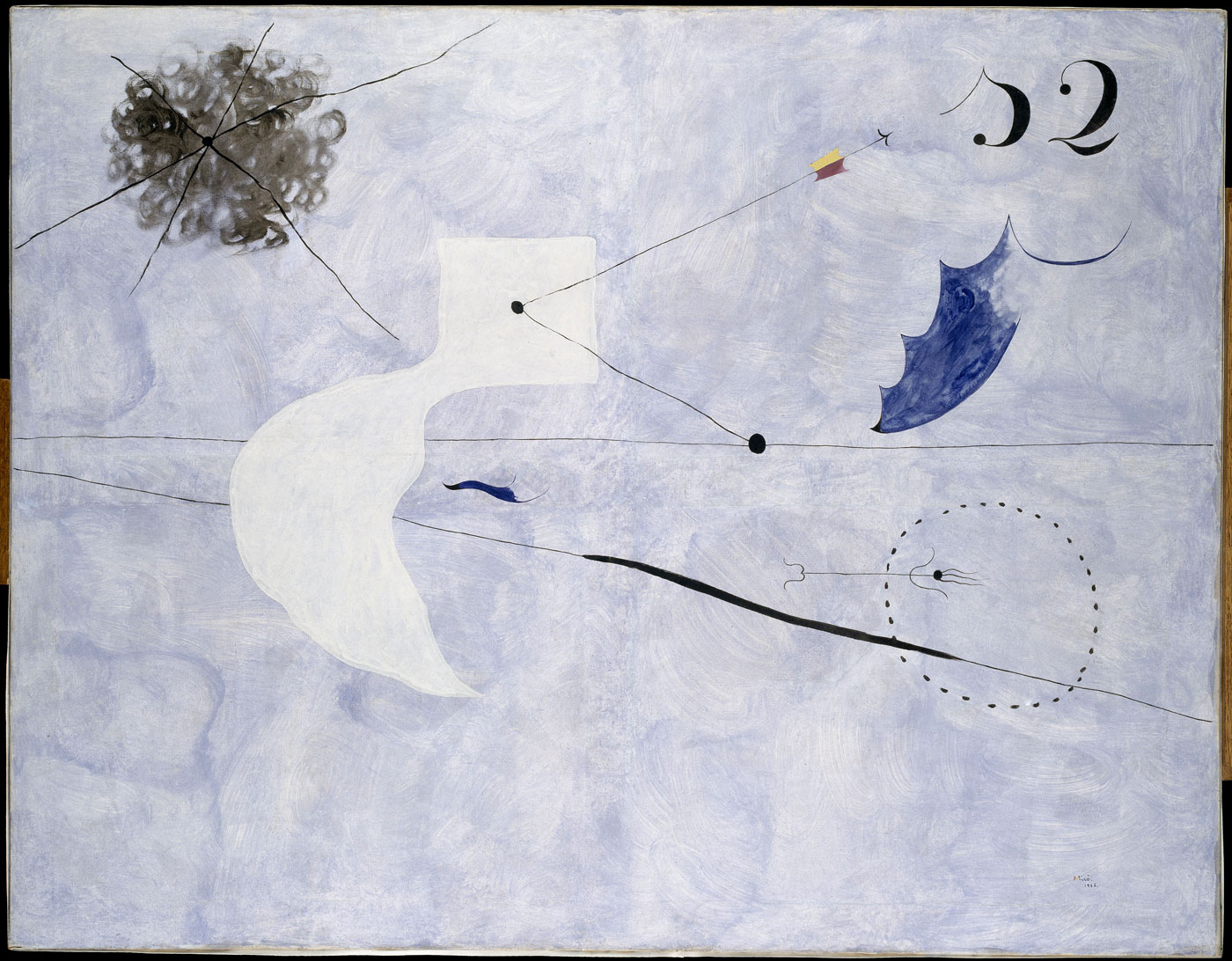

![Joan Miró (Spanish, 1893-1983) 'Tête de Paysan Catalan' [Head of a Catalan Peasant] 1925 from the Collections of Roland Penrose, Edward James, Gabrielle Keiller and Ulla and Heiner Pietzsch' at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, June- Sept, 2016 Joan Miró (Spanish, 1893-1983) 'Tête de Paysan Catalan' [Head of a Catalan Peasant] 1925 from the exhibition 'Surreal Encounters: Collecting the Marvellous: Works from the Collections of Roland Penrose, Edward James, Gabrielle Keiller and Ulla and Heiner Pietzsch' at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, June- Sept, 2016](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/joan-mirc3b3-tc3aate-de-paysan-catalan-web.jpg?w=795)

![Francis Picabia (French, 1879-1953) 'Fille née sans mère' [Girl Born without a Mother] c. 1916-1917 from the Collections of Roland Penrose, Edward James, Gabrielle Keiller and Ulla and Heiner Pietzsch' at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, June- Sept, 2016 Francis Picabia (French, 1879-1953) 'Fille née sans mère' [Girl Born without a Mother] c. 1916-1917 from the Collections of Roland Penrose, Edward James, Gabrielle Keiller and Ulla and Heiner Pietzsch' at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, June- Sept, 2016](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/francis-picabia-fille-nc3a9e-sans-mc3a8re-web.jpg)

![Max Ernst (German, 1891-1976) 'La Joie de vivre' [The Joy of Life] 1936 Max Ernst (German, 1891-1976) 'La Joie de vivre' [The Joy of Life] 1936](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/max-ernst-la-joie-de-vivre-1936-web.jpg)

![Dorothea Tanning (American, 1910-2012) 'Eine Kleine Nachtmusik' [A Little Night Music] 1943 Dorothea Tanning (American, 1910-2012) 'Eine Kleine Nachtmusik' [A Little Night Music] 1943](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/dorothea-tanning-eine-kleine-nachtmusik-1943-web.jpg)

![Salvador Dalí (Spanish, 1904-1989) 'Couple aux têtes pleines de nuages' [Couple with their Heads Full of Clouds] 1936 Salvador Dalí (Spanish, 1904-1989) 'Couple aux têtes pleines de nuages' [Couple with their Heads Full of Clouds] 1936](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/salvador-dalc3ad-couple-aux-tc3aates-pleines-de-nuages-web.jpg)

![Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881-1973) 'Tête' [Head] 1913 Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881-1973) 'Tête' [Head] 1913](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/tc3aate-head-1913-by-pablo-picasso-web.jpg?w=763)

![Max Ernst (German, 1891-1976) 'Jeune homme intrigué par le vol d’une mouche non-euclidienne' [Young Man Intrigued by the Flight of a Non-Euclidean Fly] 1942–1947 Max Ernst (German, 1891-1976) 'Jeune homme intrigué par le vol d’une mouche non-euclidienne' [Young Man Intrigued by the Flight of a Non-Euclidean Fly] 1942–1947](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/32_ernst-max_jeune-homme-intriguc3a9-1942-47-web.jpg?w=817)

![Max Ernst (German, 1891-1976) 'Une semaine de bonté' [A Week of Kindness] 1934 Max Ernst (German, 1891-1976) 'Une semaine de bonté' [A Week of Kindness] 1934](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/ernst-une-semaine-de-bontc3a9-web.jpg?w=761)

![Max Ernst (German, 1891-1976) 'Une semaine de bonté' [A Week of Kindness] 1934 Max Ernst (German, 1891-1976) 'Une semaine de bonté' [A Week of Kindness] 1934](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/ernst-une-semaine-de-bontc3a9-web2.jpg?w=755)

![Alberto Giacometti (Italian, 1901-1966) 'Objet désagréable, à jeter' [Disagreeable Object, to be Thrown away] 1931 Alberto Giacometti (Italian, 1901-1966) 'Objet désagréable, à jeter' [Disagreeable Object, to be Thrown away] 1931](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/alberto-giacometti-objet-dc3a9sagrc3a9able-web.jpg)

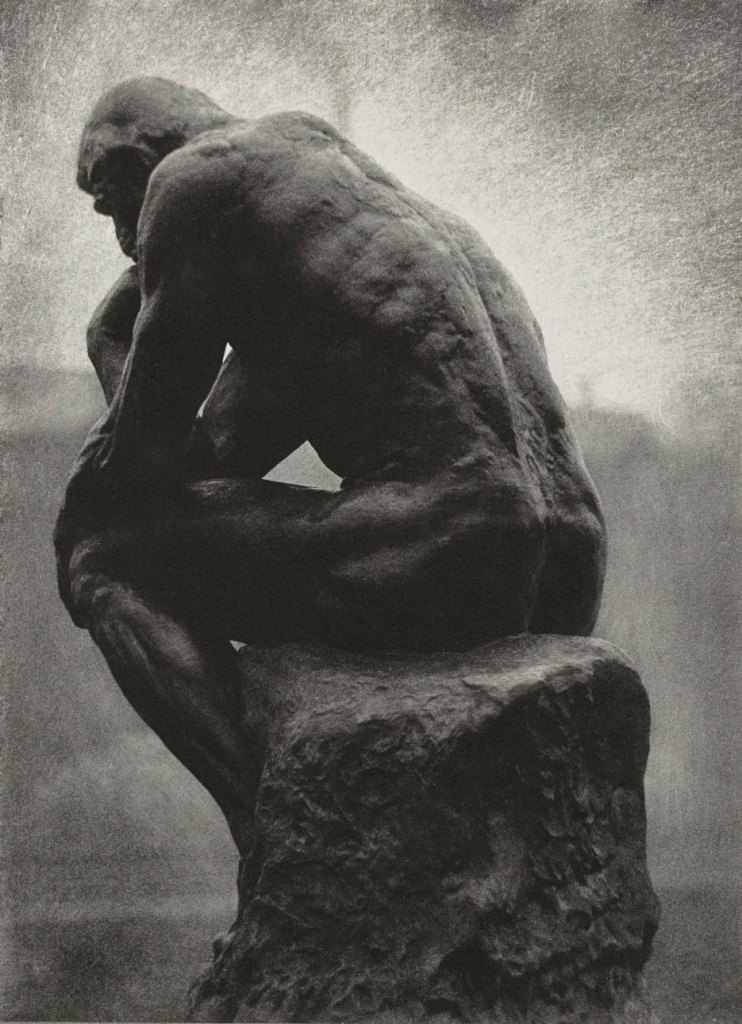

![Auguste Rodin (French, 1840-1917) 'Le Penseur [The Thinker]' 1903 Auguste Rodin (French, 1840-1917) 'Le Penseur [The Thinker]' 1903](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/rodin-le-penseur-web.jpg?w=768)

![Vassily Kandinsky (Russian, 1866-1944) 'Bild mit rotem Fleck [Tableau à la tache rouge / Image with red spot]' 25 February 1914 Vassily Kandinsky (Russian, 1866-1944) 'Bild mit rotem Fleck [Tableau à la tache rouge / Image with red spot]' 25 February 1914](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/kandinsky-bild-mit-rotem-fleck-web.jpg?w=1000)

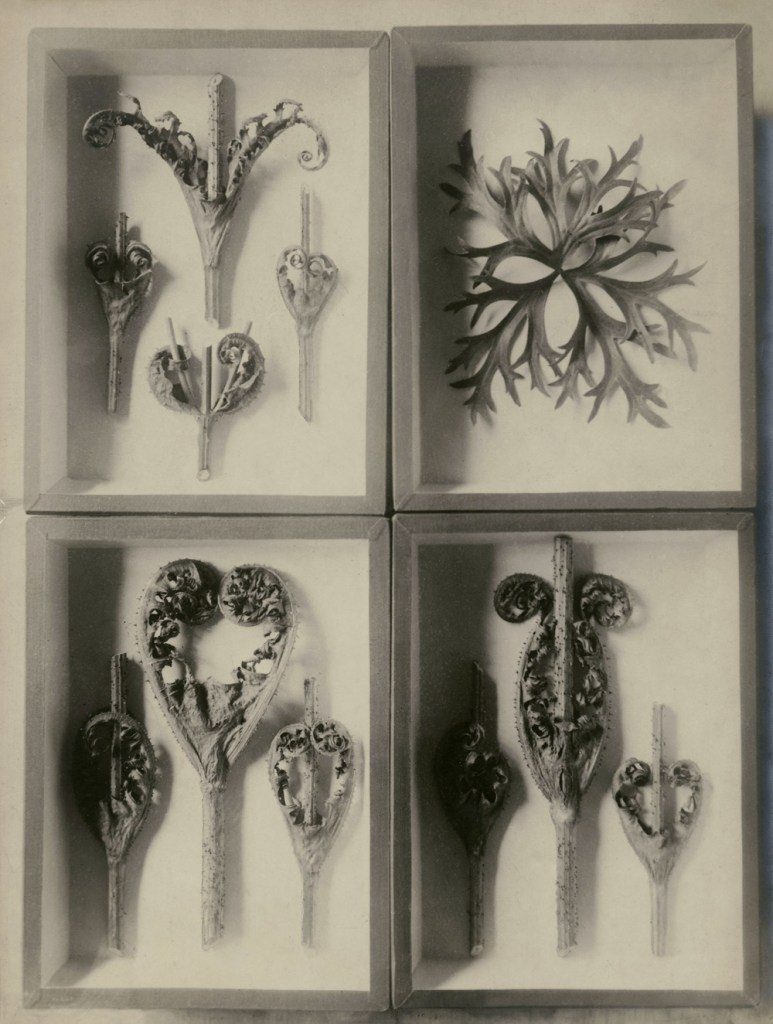

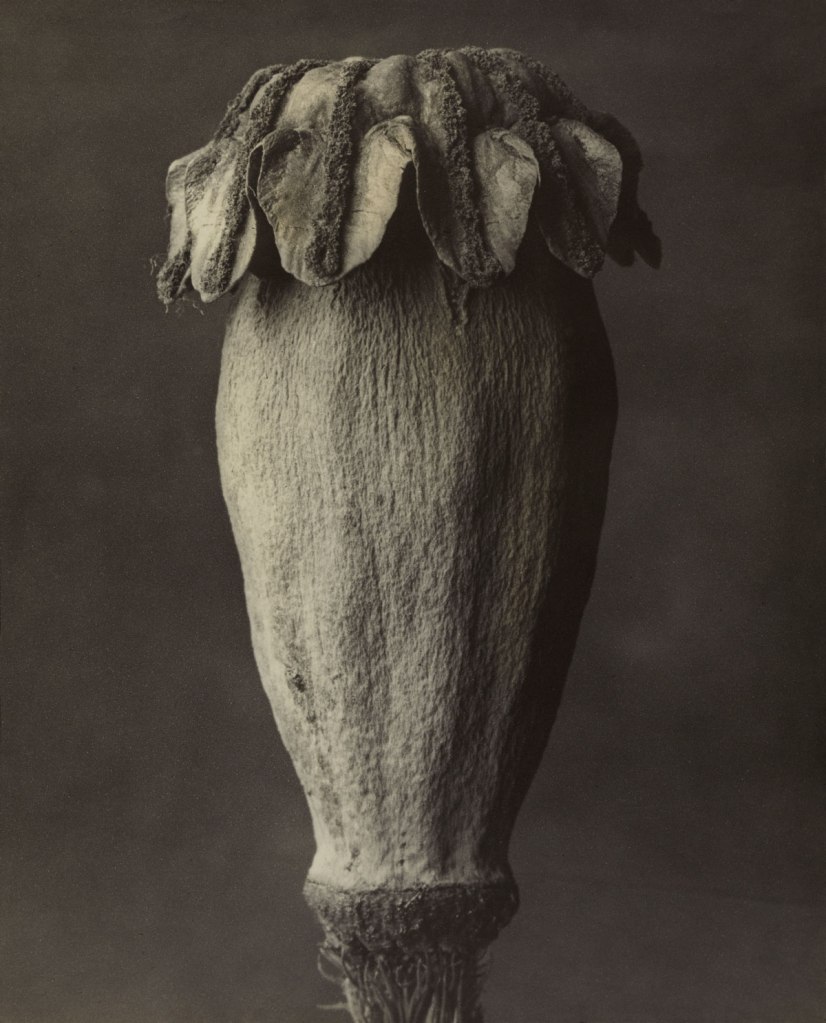

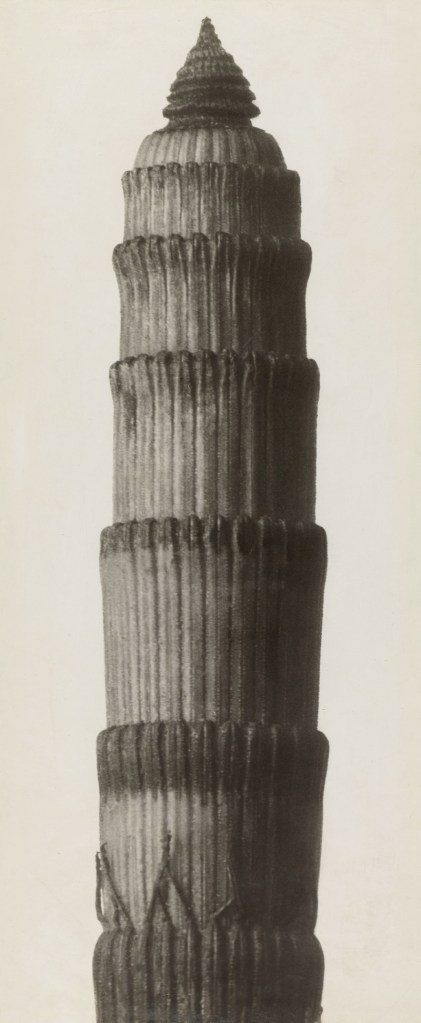

![Karl Blossfeldt (German, 1865-1932) 'Acanthus mollis' (Acanthus mollis [Akanthus, Bärenklau. Deckblätter, die Blüten sind entfernt, in 4facher Vergrößerung]) 1898-1928 Karl Blossfeldt (German, 1865-1932) 'Acanthus mollis' (Acanthus mollis [Akanthus, Bärenklau. Deckblätter, die Blüten sind entfernt, in 4facher Vergrößerung]) 1898-1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/karl-blossfeldt-german-1865e280931932-acanthus-mollis-web.jpg?w=825)

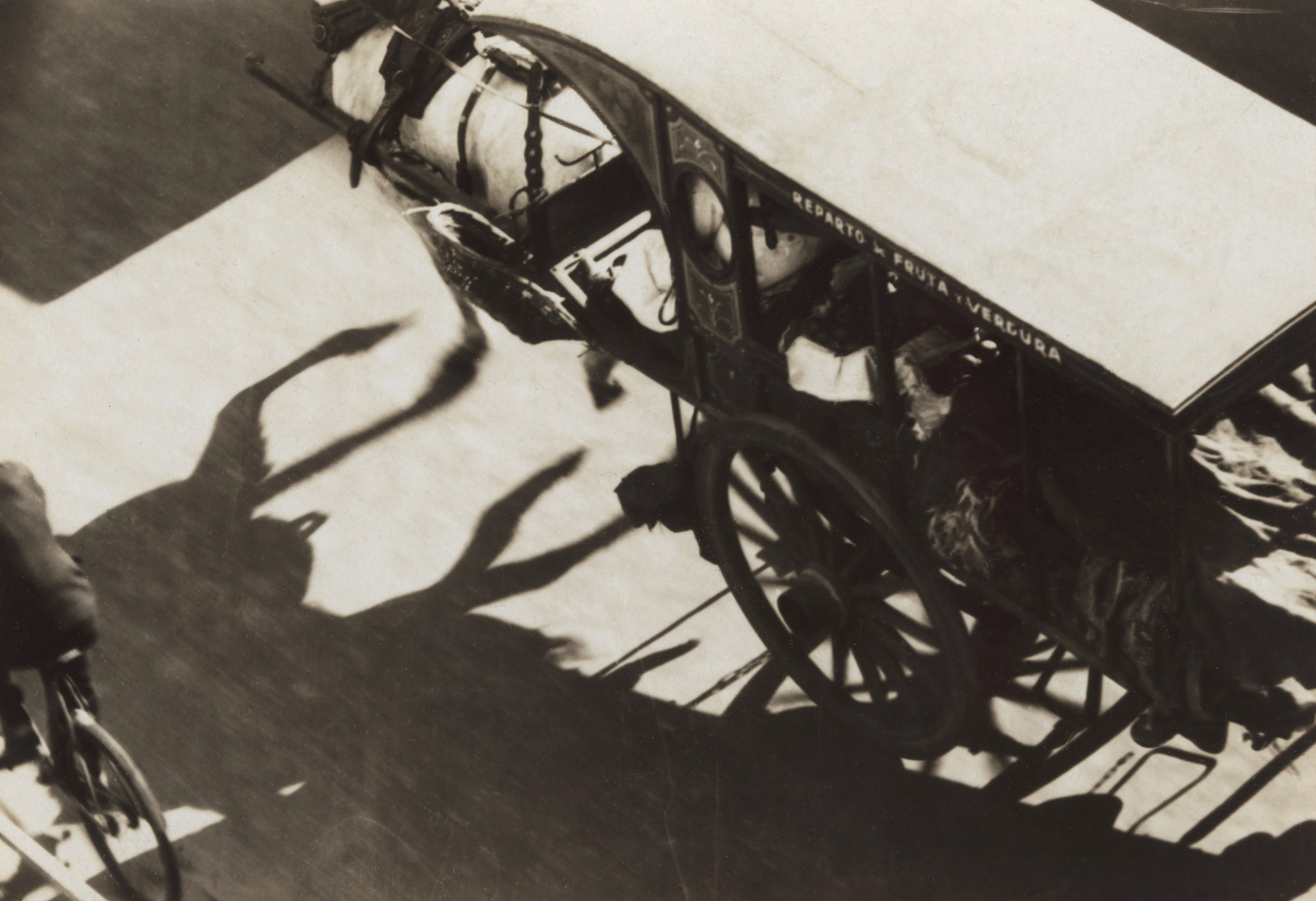

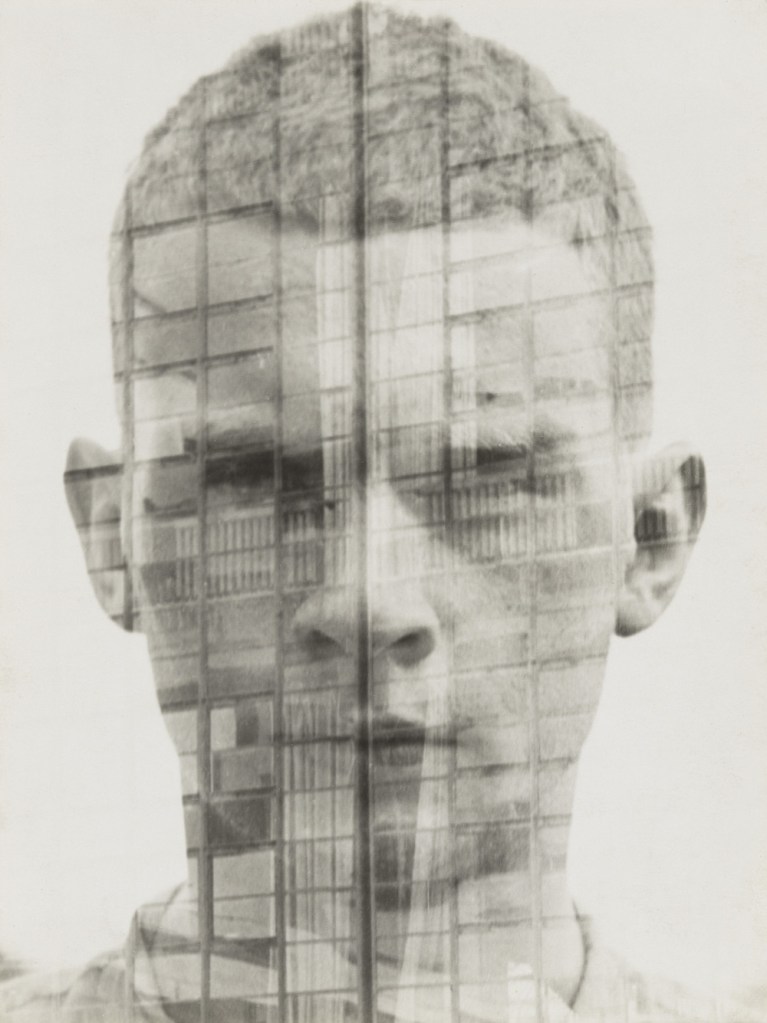

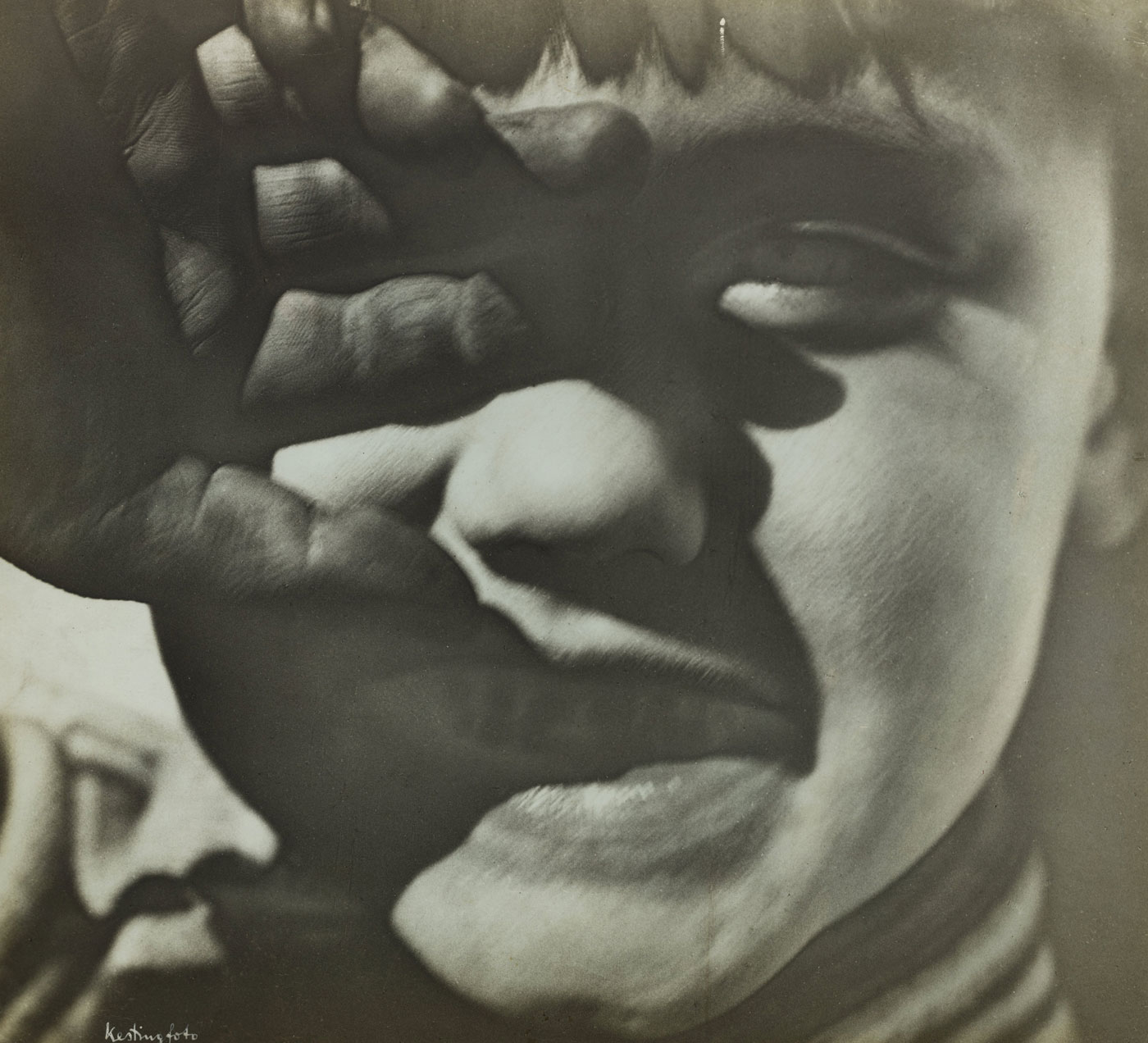

![Iwao Yamawaki (Japanese, 1898-1987) 'Lunch (12-2 p.m.)' (Mittagessen [12-2 Uhr]) 1931 Iwao Yamawaki (Japanese, 1898-1987) 'Lunch (12-2 p.m.)' (Mittagessen [12-2 Uhr]) 1931](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/iwao-yamawaki-japanese-1898e280931987-lunch-12e280932-p-m-web.jpg?w=725)

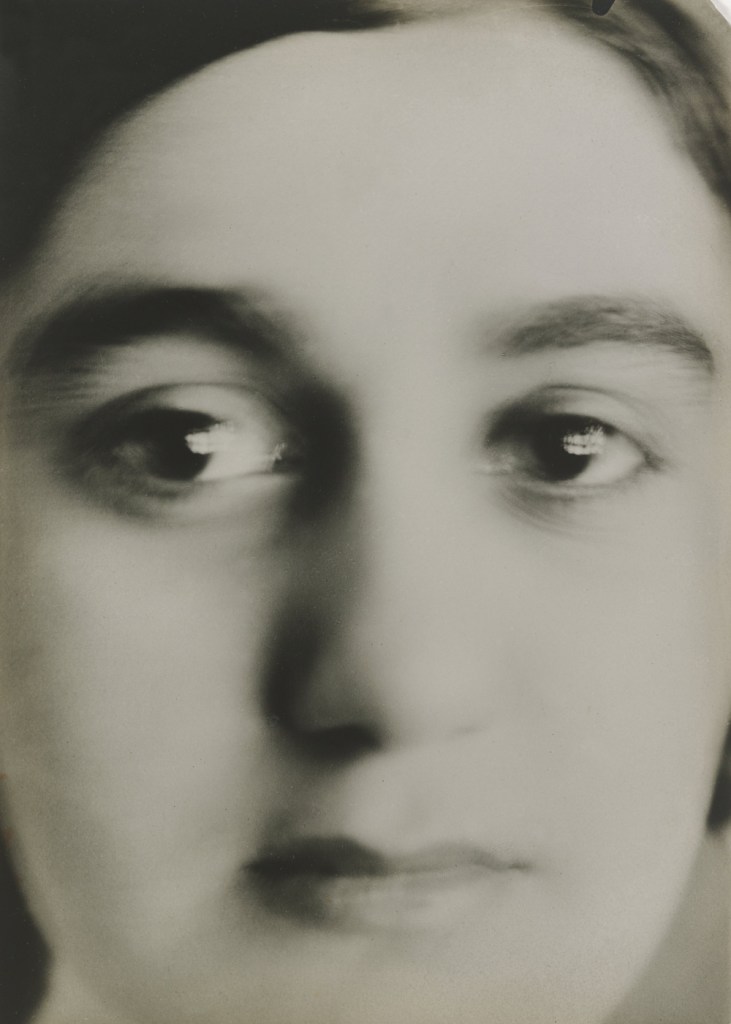

![Max Burchartz (German, 1887-1961) 'Lotte (Eye)' (Lotte [Auge]) 1928 Max Burchartz (German, 1887-1961) 'Lotte (Eye)' (Lotte [Auge]) 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/max-burchartz-lotte-eye-1928-web.jpg)

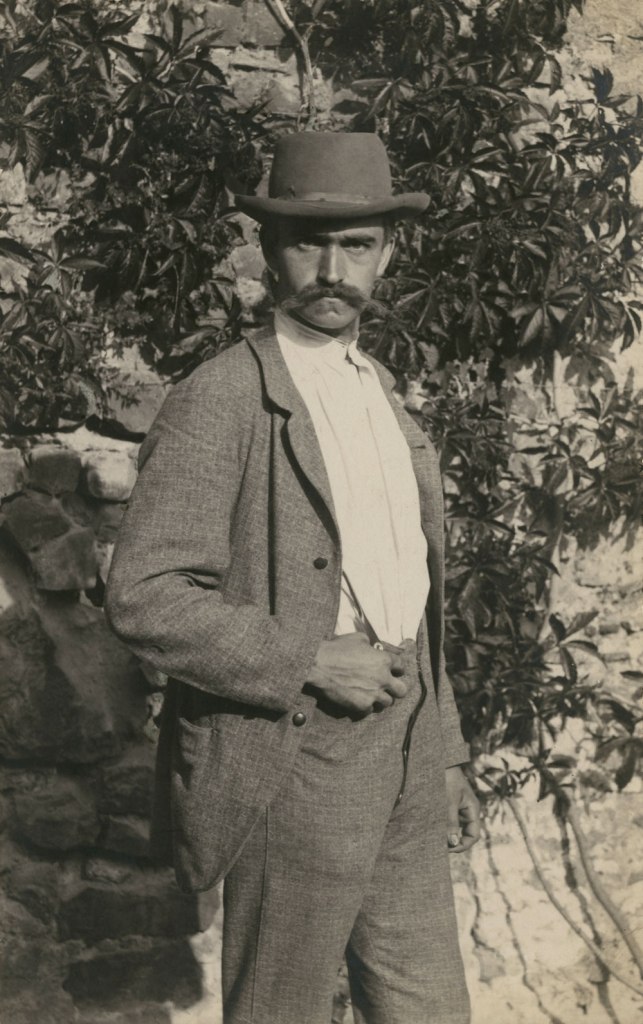

![Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz (Polish, 1885-1939) 'Self-Portrait, Zakopane [Broken Glass]' 1910 Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz (Polish, 1885-1939) 'Self-Portrait, Zakopane [Broken Glass]' 1910](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/witkiewicz_self-portrait-zakopane-web.jpg?w=728)

You must be logged in to post a comment.