Exhibition dates: 6th July – 30th October, 2016

Curators: Tanya Barson, Curator, Tate Modern with Hannah Johnston, Assistant Curator, Tate Modern

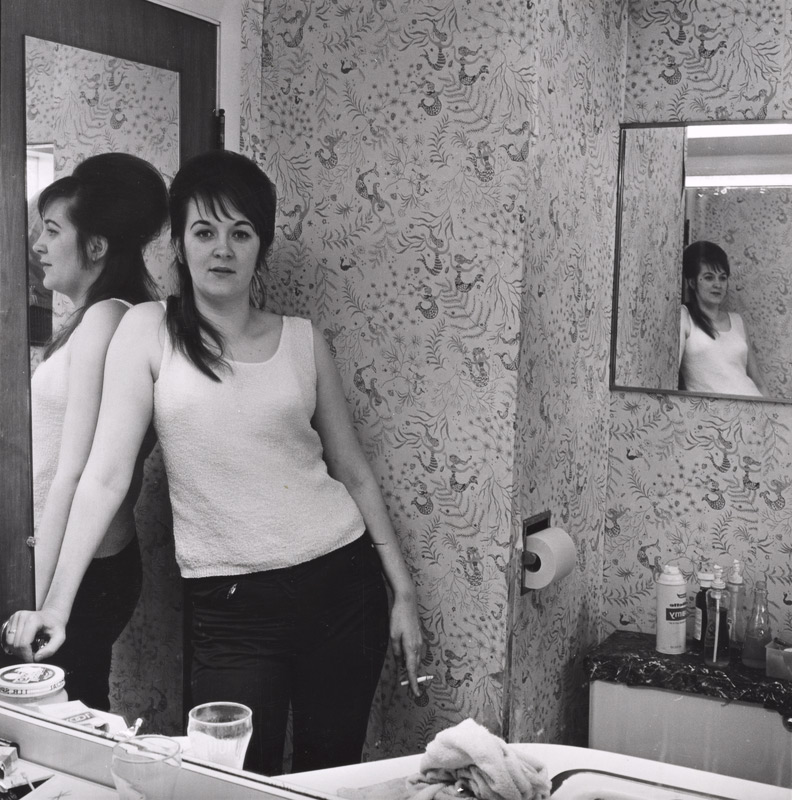

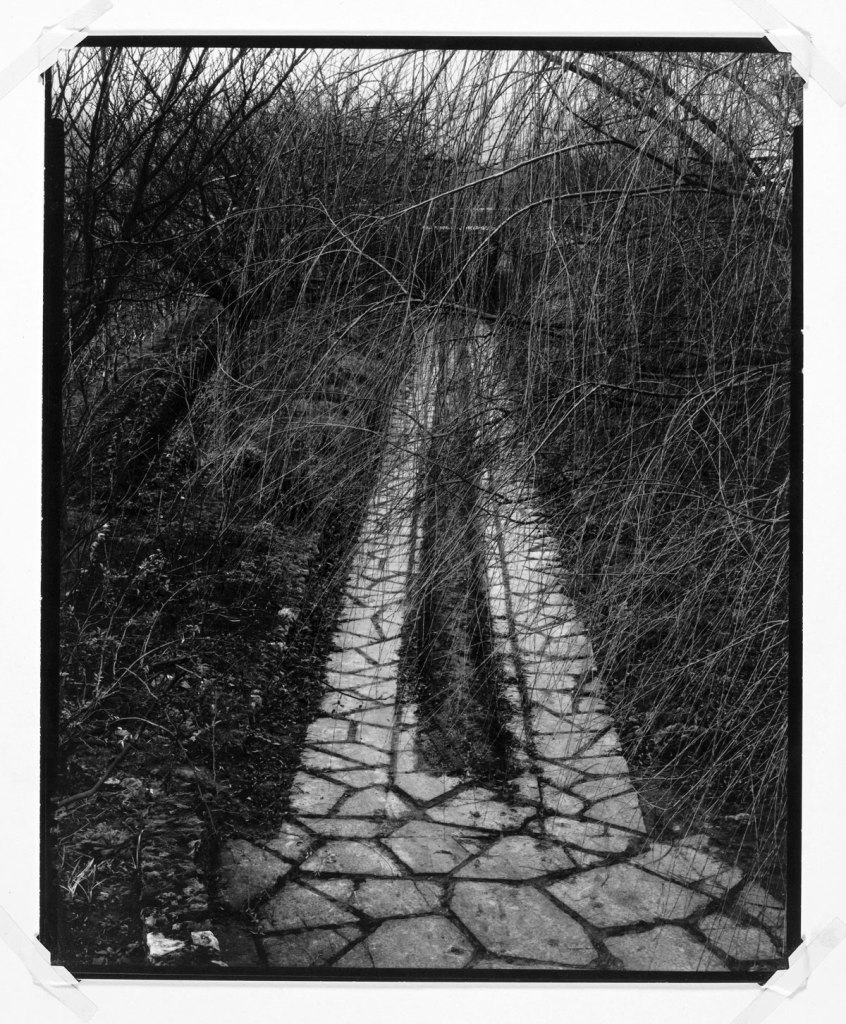

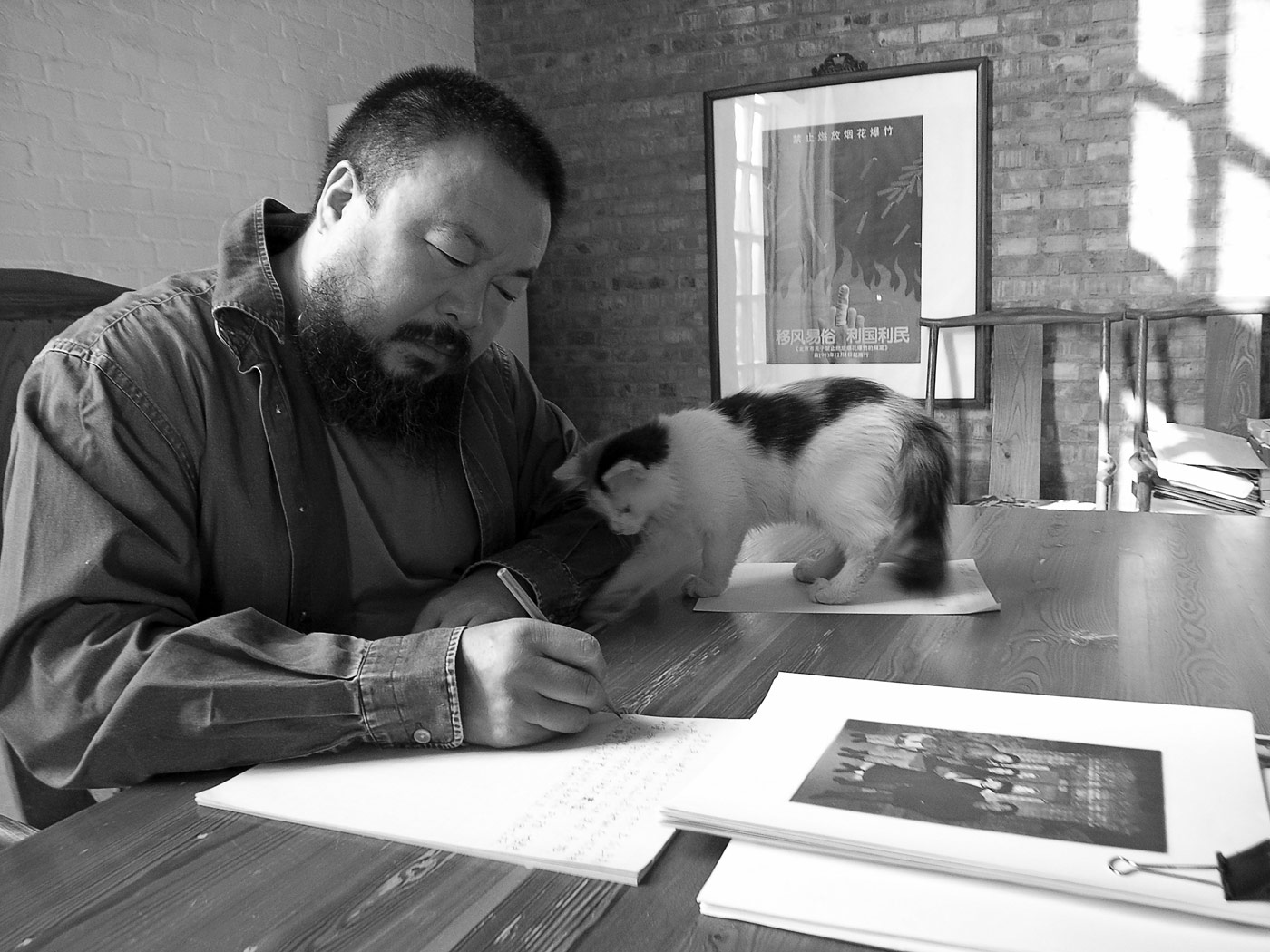

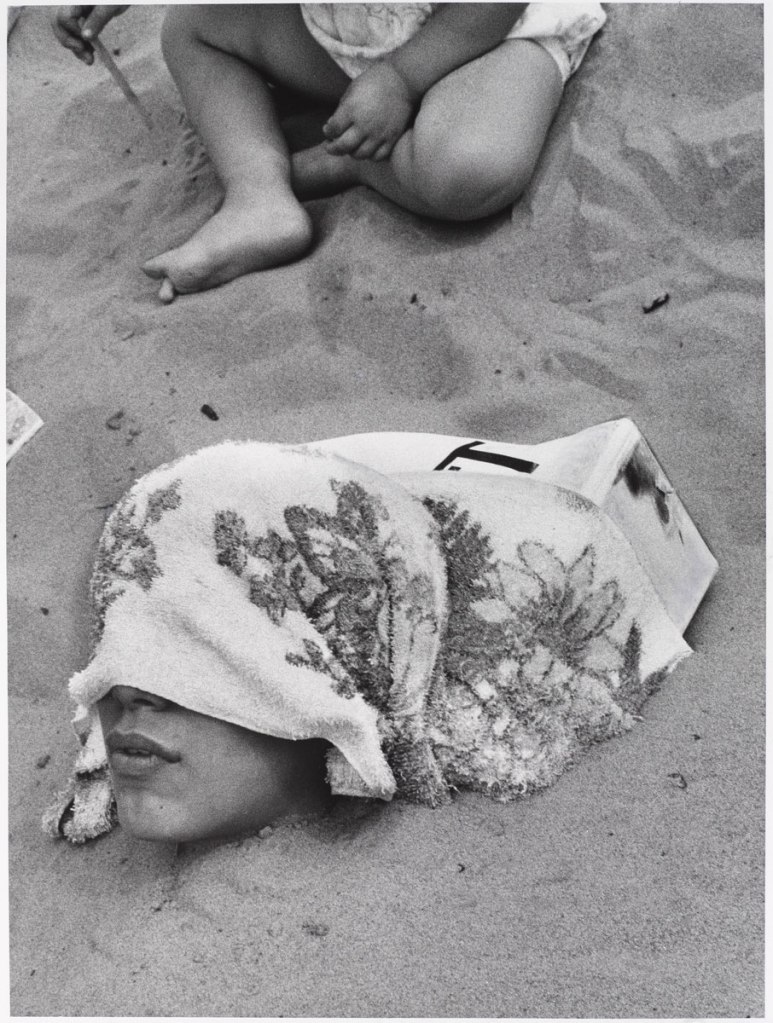

Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946)

Untitled (O’Keeffe with sketchpad and watercolors)

1918

Silver gelatin print

A beautiful world

Briefly I can comment on the influence of photography, calligraphy and Japanese printmaking on the artistic practice of Georgia O’Keeffe.

With their flattened perspective, manipulation of scale, and forms shaped by light, her paintings are a synthesis, a synesthesia of interior and exterior e/motions linked to music and the modern. As Louisa Buck notes, “Texture and painterly qualities were not what was important in the depiction of her smoothed, abstracted forms… Tellingly, she once declared that “art must be a unity of expression so complete that the medium becomes unimportant.””

Important in that unity of expression is the flow of energy in time and space. Throughout a career that spanned many years O’Keeffe never lost that bravura rendition of energy that was present in her early watercolours. The concerns that were present in the first work, developed throughout her career, were still present at the very end in different form. O’Keeffe wasn’t obsessed with the power of the image but rather with insight into the condition of the image, and how it resolved and portrayed the world in its many forms. Texture was not necessary to this clear seeing… of beauty in the intricacy of nature, of Black Place / White Space, and of the faraway – “that memory or dream thing”. Far Away.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to Tate for allowing me to publish the art work in the posting. Please click on the artwork for a larger version of the image.

“When I started painting the pelvis bones I was most interested in the holes in the bones – what I saw through them – particularly the blue from holding them up against the sky… They were the most beautiful thing against the Blue – that Blue that will always be there as it is now after all man’s destruction is finished.”

“Whether you succeed or not is irrelevant, there is no such thing. Making your unknown known is the important thing – and keeping the unknown always beyond you.”

“Someone else’s vision will never be as good as your own vision of yourself. Live and die with it ’cause in the end it’s all you have. Lose it and you lose yourself and everything else. I should have listened to myself.”

Georgia O’Keeffe

“The radical cropping, and the use of fore- and background, but less so of a middle-ground, is clearly influenced by photography – in particular the work of her friend Paul Strand (1890-1976) – but it is disingenuous to suggest that her painting is just like photography, or that photography captures the scenery better (as has been said about some of the works in this exhibition) – since her painterly quality, despite the flatness of the surface, creates a vast sense of space in the composition, reflecting the monumentality of the landscape and a true sense of the expansive horizon. Her landscapes pulsate and, unlike photography, which captures one decisive moment, they are living and breathing. The colours she chooses reflect the atmosphere of the place – particularly the heat of the New Mexico desert – and it is this affinity to a place, this experience of a landscape, that O’Keeffe paints best…

Is it therefore correct that the first major exhibition of O’Keeffe’s work in the UK in 20 years – marking the centenary of her 1916 debut exhibition at 291 – should portray her as half of a co-dependent artistic duo? Of the 221 works in the show, from 71 lenders, only 115 are major O’Keeffes. The rest comprise works by Stieglitz, Strand, Ansel Adams (1902-84), and others – all men – from the sphere in which she was working. What male artist of this calibre would have nearly half the items in his major retrospective made up of works by women who had been working around him? …

Her initial representational painting would be done from life, out in the open air, then she would take the canvas home to her studio and work over it so that it took on an emotional resonance – something she described as: “that memory or dream thing I do that for me comes nearer reality than my objective kind of work”. She painted on canvas with a very fine weave and coated it with a special primer to make the surface extremely smooth, blending one colour into the next, making sure that the brushstrokes were invisible. Her colours remain rich and bright to this day – O’Keeffe was a painter who knew what she was doing on every level.”

Anna McNay, “Georgia O’Keeffe,” on the Studio International website 15 August 2016 [Online] Cited 17/02/2023

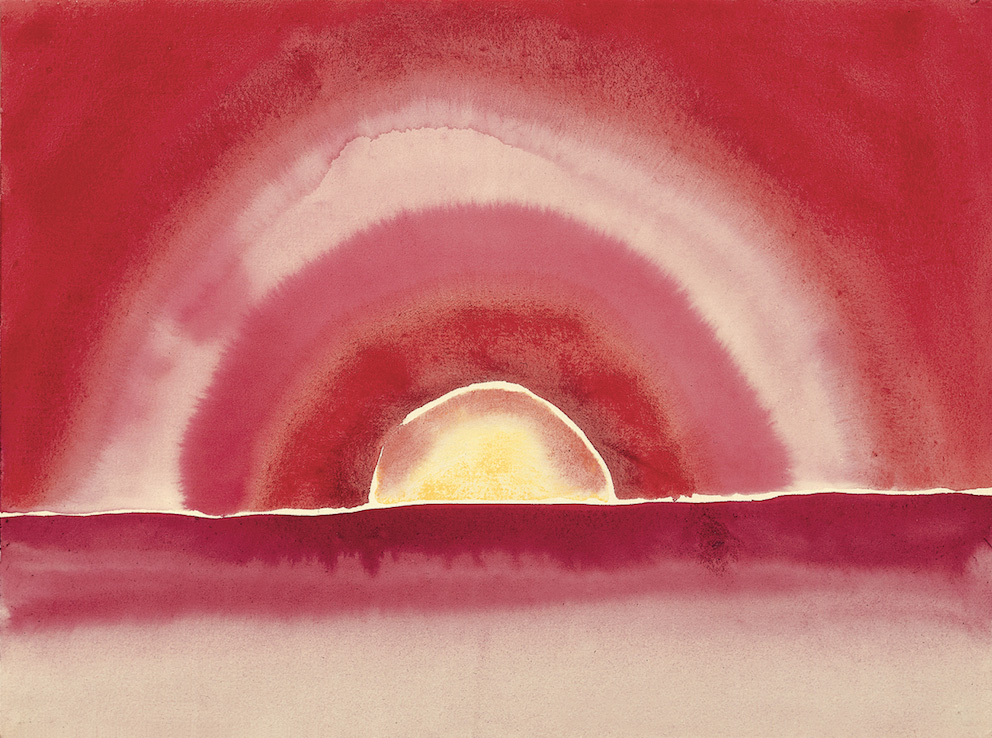

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Sunrise

1916

Watercolour on paper

22.5 x 30.2cm

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/DACS 2016

Courtesy Barney Ebsworth collection

“The Texas country that I know is the plains. It was land like the ocean all the way around. Hardly anybody liked it, but I loved it. The wind blew too hard, the dust flew, and we had heavy dust storms. I’ve come in many times when I’d be the colour of the road. At night you could drive away from the town, right out into space. You didn’t have to drive on the road, and when the sunset was gone, you turned around and went back, lighted by the light of the town.”

Georgia O’Keeffe in the film Georgia O’Keeffe, produced and directed by Perry Miller Adato; a WNET/THIRTEEN production for Women in Art, 1977. Portrait of an Artist, no.1; series distributed by Films, Inc./Home Vision, New York.

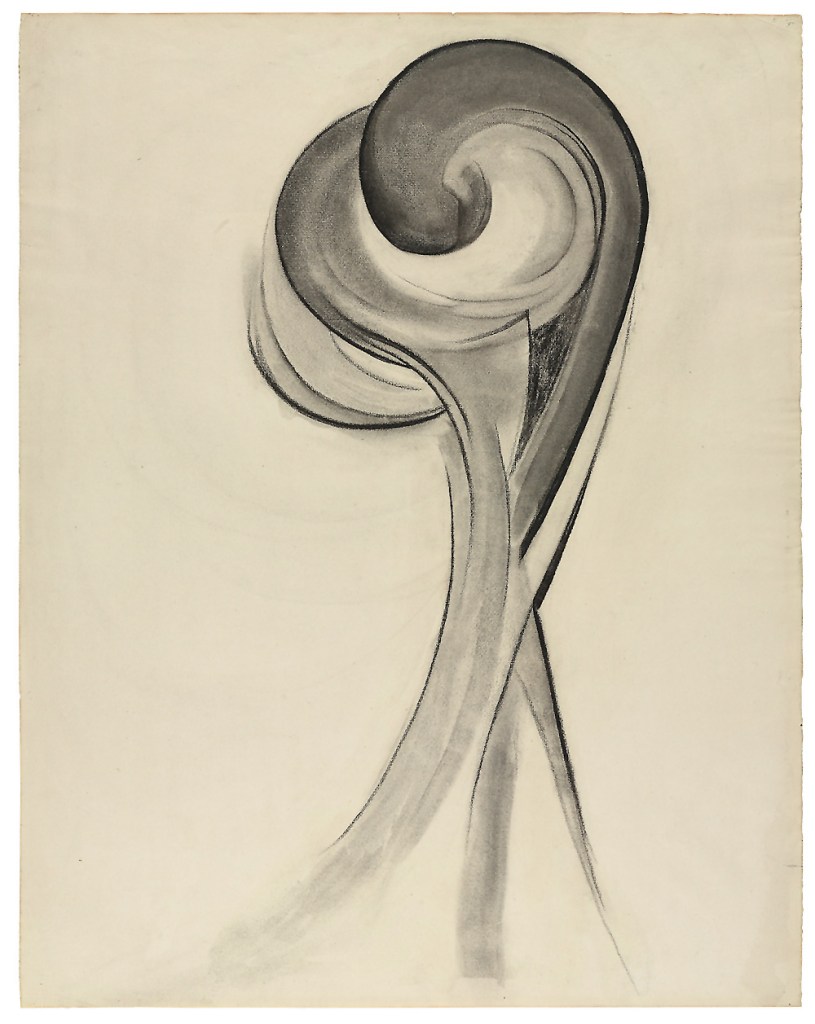

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

No. 12 Special

1916

Charcoal on paper, 61 x 48.3cm

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/DACS 2016

Photo © 2015 Digital image, The Museum of Modern Art, New York/Scala, Florence

“I was busy in the daytime and I made most of these drawings at night. I sat on the floor and worked against the closet door. Eyes can see shapes. It’s as if my mind creates shapes that I don’t know about. I get this shape in my head and sometimes I know what it comes from and sometimes I don’t. And I think with myself that there are a few shapes that I have repeated a number of times during my life and I haven’t known I was repeating them until after I had done it.”

Georgia O’Keeffe in the film Georgia O’Keeffe, produced and directed by Perry Miller Adato; a WNET/THIRTEEN production for Women in Art, 1977. Portrait of an Artist, no.1; series distributed by Films, Inc./Home Vision, New York.

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Untitled (Abstraction/Portrait of Paul Strand)

1917

Watercolour on paper

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Blue I

1916

Watercolour on paper

78.4 x 56.5cm

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/DACS 2016

Photo © 2007 Christie’s Images Limited

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Music – Pink and Blue No 1

1918

Oil on canvas

88.9 x 73.7cm

Collection of Barney A. Ebsworth. Partial and Promised gift to Seattle Art Museum

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/DACS 2016

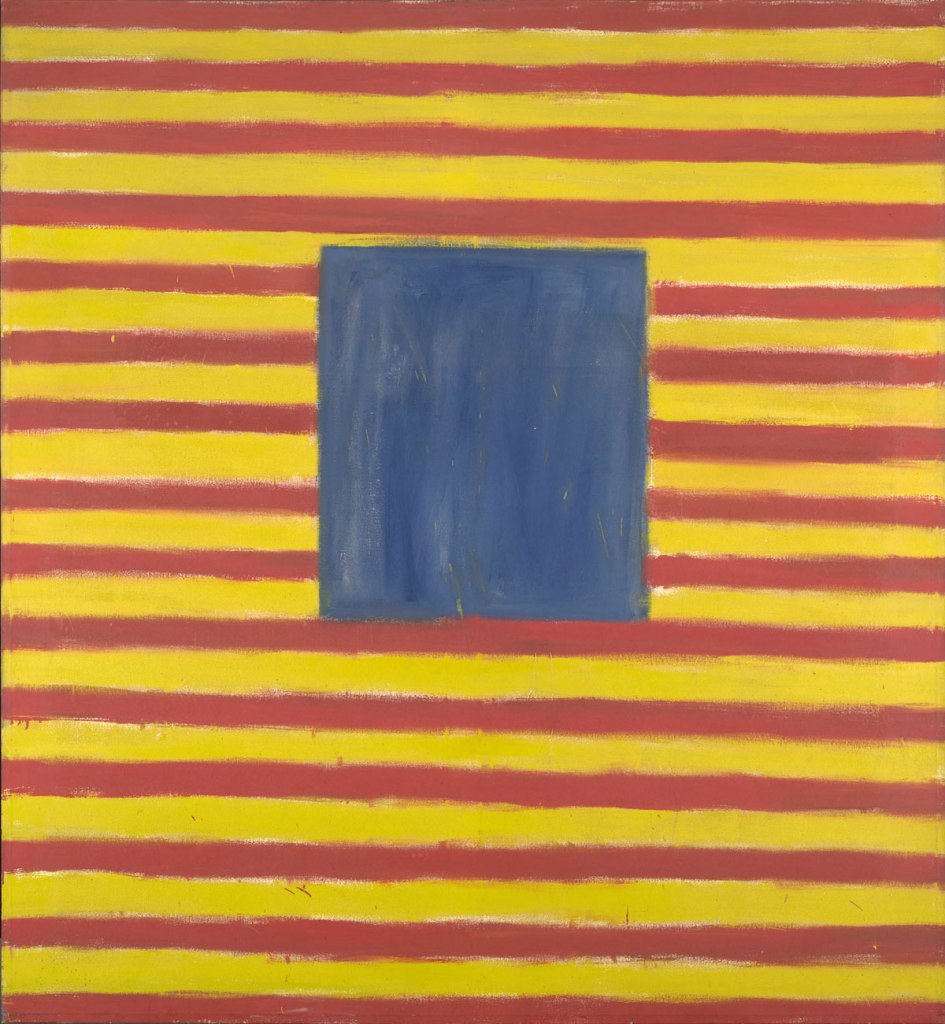

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Blue and Green Music

1921

Oil on canvas

58.4 x 48.3cm

Alfred Stieglitz Collection, gift of Georgia O’Keeffe

The Art Institute of Chicago © The Art Institute of Chicago

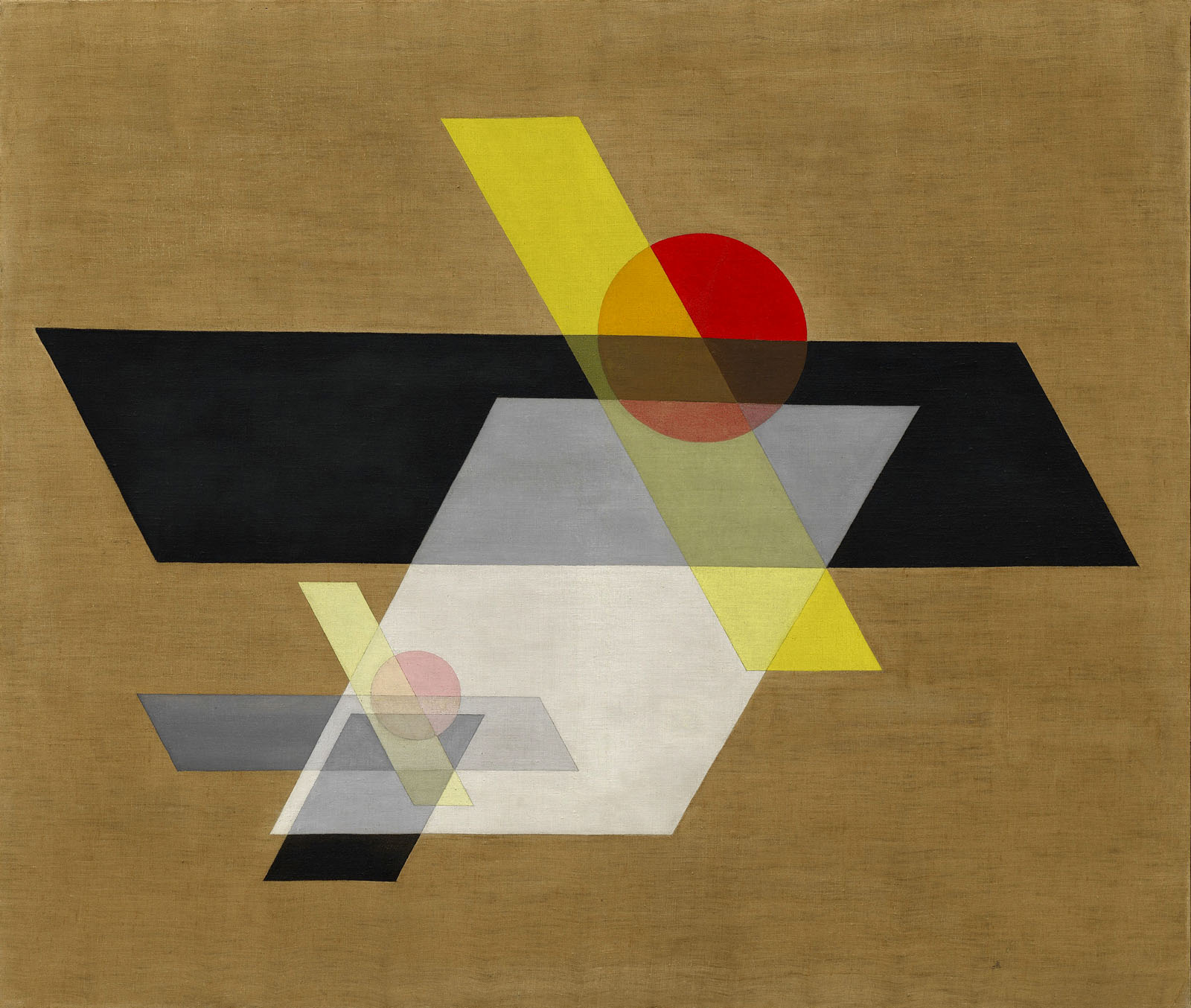

O’Keeffe was inspired by the European modernist movement and Kandinsky’s theories on how visual art can or should be pure patterns of form, colour and line as opposed to representing the material world. Blue and Green Music incorporates these ideas with O’Keeffe’s love of landscapes and the natural world.

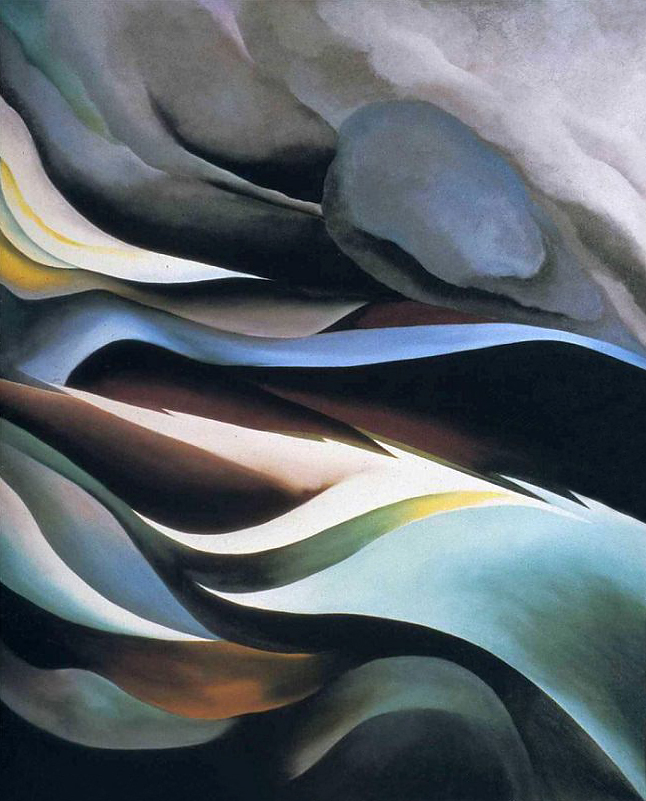

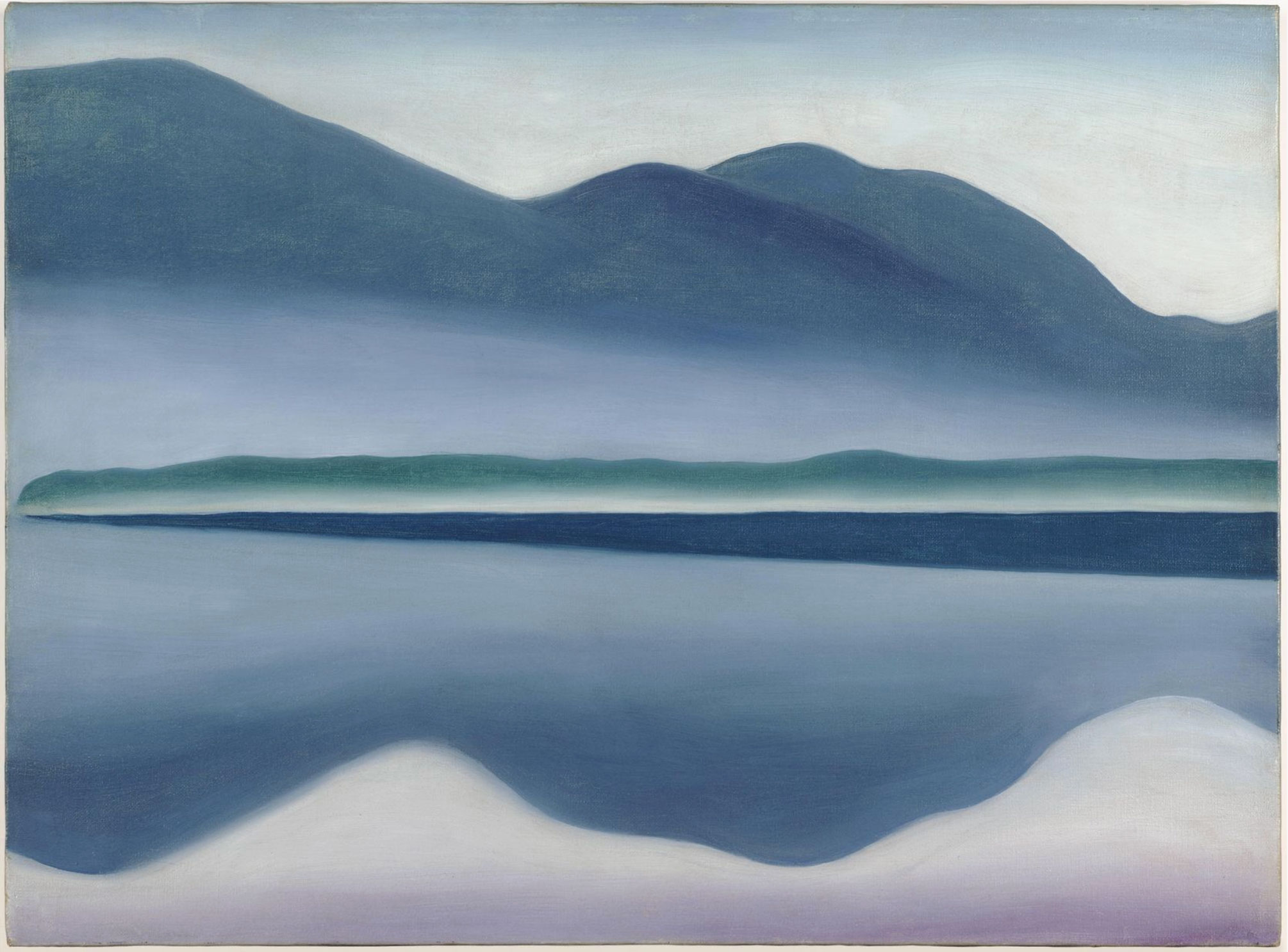

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

From the Lake No. 1

1924

Oil on canvas

91.4 x 76.2cm

Purchased with funds from the Coffin Fine Arts Trust; Nathan Emory Coffin Collection of the Des Moines Art Center

© 2016 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/ DACS, London

Throughout her early work, O’Keeffe was influenced by the European modernist movement and how visual art could be pure patterns of form, colour and line as opposed to representing the material world. From the Lake No.1 clearly demonstrates these ideas, coupled with her enthusiasm for nature and her fascination with bodies of water.

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Autumn Trees – The Maple

1924

Oil on canvas

91.4 x 76.2 cm

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Gift of The Burnett Foundation and Gerald and Kathleen Peters

© 2016 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/ DACS, London

O’Keeffe made many paintings during her regular trips to Lake George, New York, especially of the vibrant colours of the leaves and trees during autumn. Throughout her life she was deeply inspired by nature and was famous for painting natural objects such as flowers, shells and landscapes from areas she lived in throughout her life, or made painting trips to.

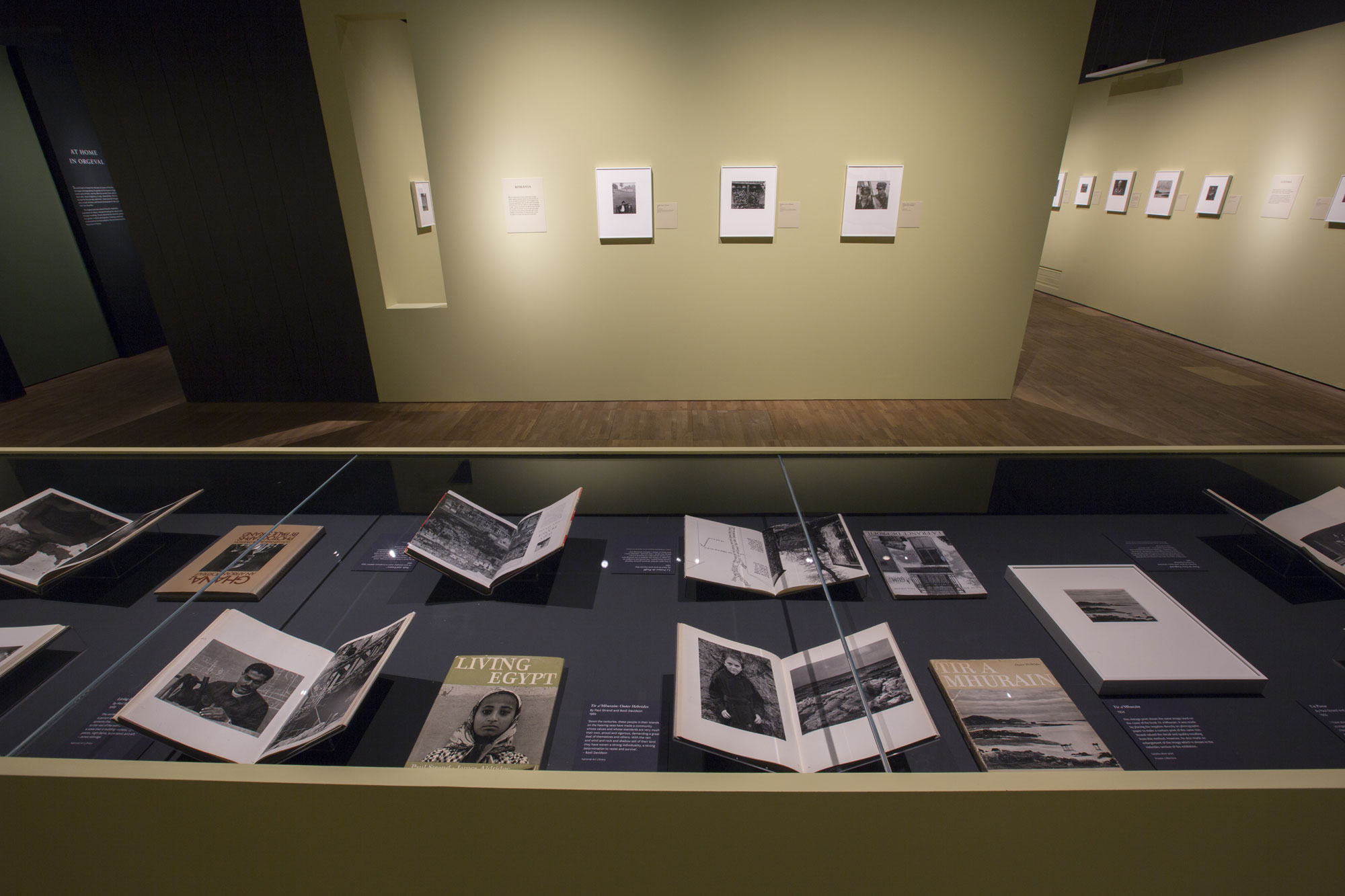

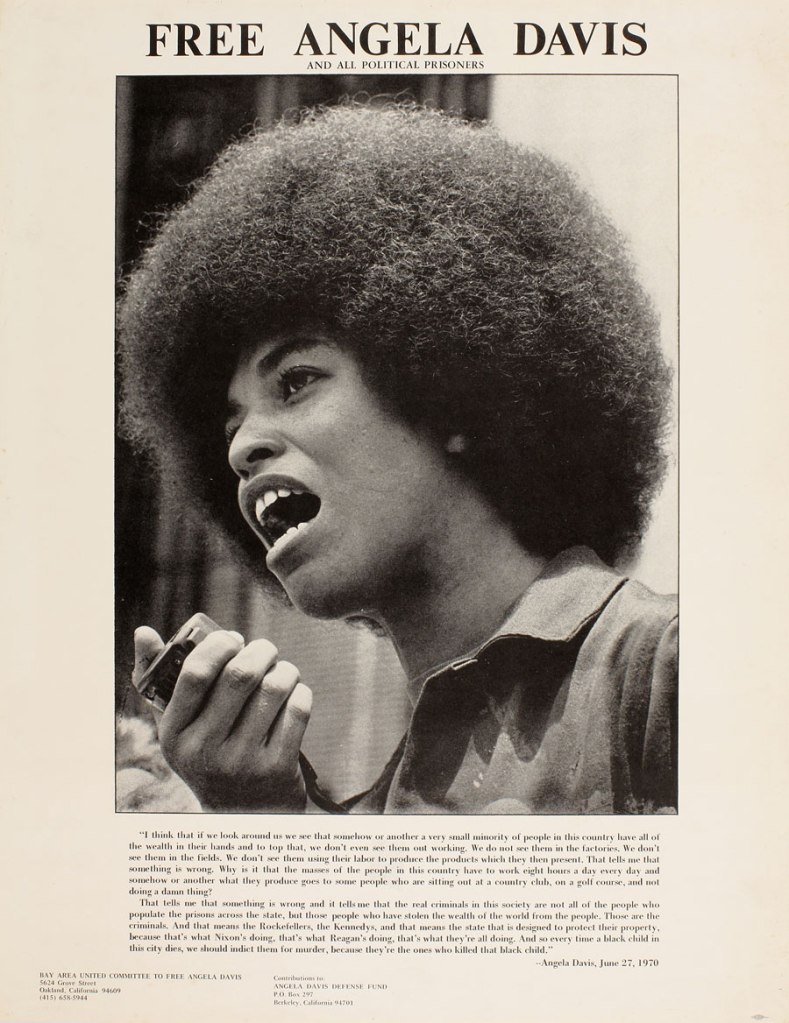

Tate Modern presents the largest retrospective of modernist painter Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986) ever to be shown outside of America. Marking a century since O’Keeffe’s debut in New York in 1916, it is the first UK exhibition of her work for over twenty years. This ambitious and wide-ranging survey reassesses the artist’s place in the canon of twentieth-century art and reveals her profound importance. With no works by O’Keeffe in UK public collections, the exhibition is a once-in-a-generation opportunity for European audiences to view her oeuvre in such depth.

Widely recognised as a founding figure of American modernism, O’Keeffe gained a central position in leading art circles between the 1910s and the 1970s. She was also claimed as an important pioneer by feminist artists of the 1970s. Spanning the six decades in which O’Keeffe was at her most productive and featuring over 100 major works, the exhibition charts the progression of her practice from her early abstract experiments to her late works, aiming to dispel the clichés that persist about the artist and her painting.

Opening with the moment of her first showings at ‘291’ gallery in New York in 1916 and 1917, the exhibition features O’Keeffe’s earliest mature works made while she was working as a teacher in Virginia and Texas. Charcoals such as Special No.9 1915 and Early No. 2 1915 are shown alongside a select group of highly coloured watercolours and oils, such as Sunrise 1916 and Blue and Green Music 1919. These works investigate the relationship of form to landscape, music, colour and composition, and reveal O’Keeffe’s developing understanding of synaesthesia.

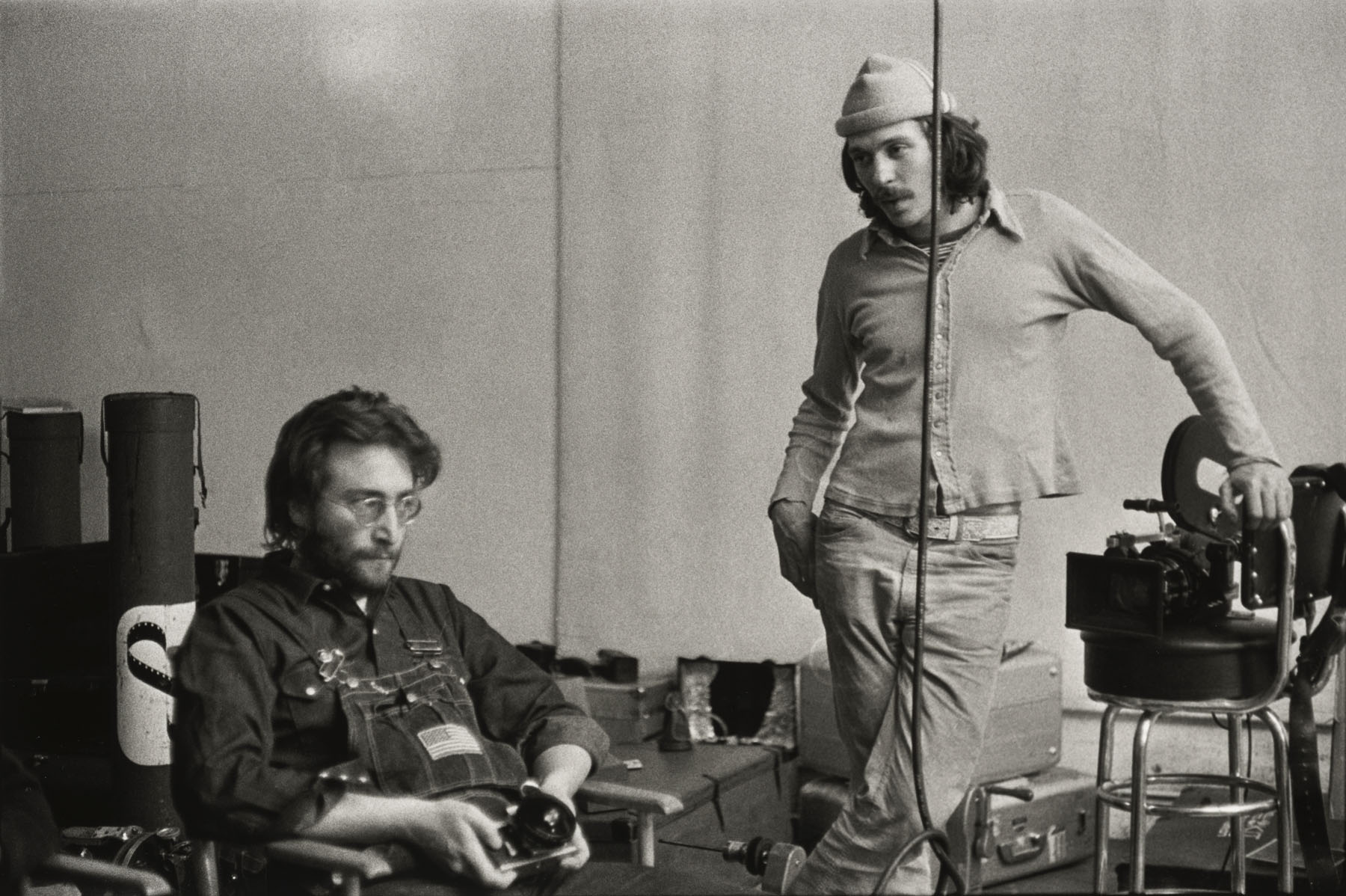

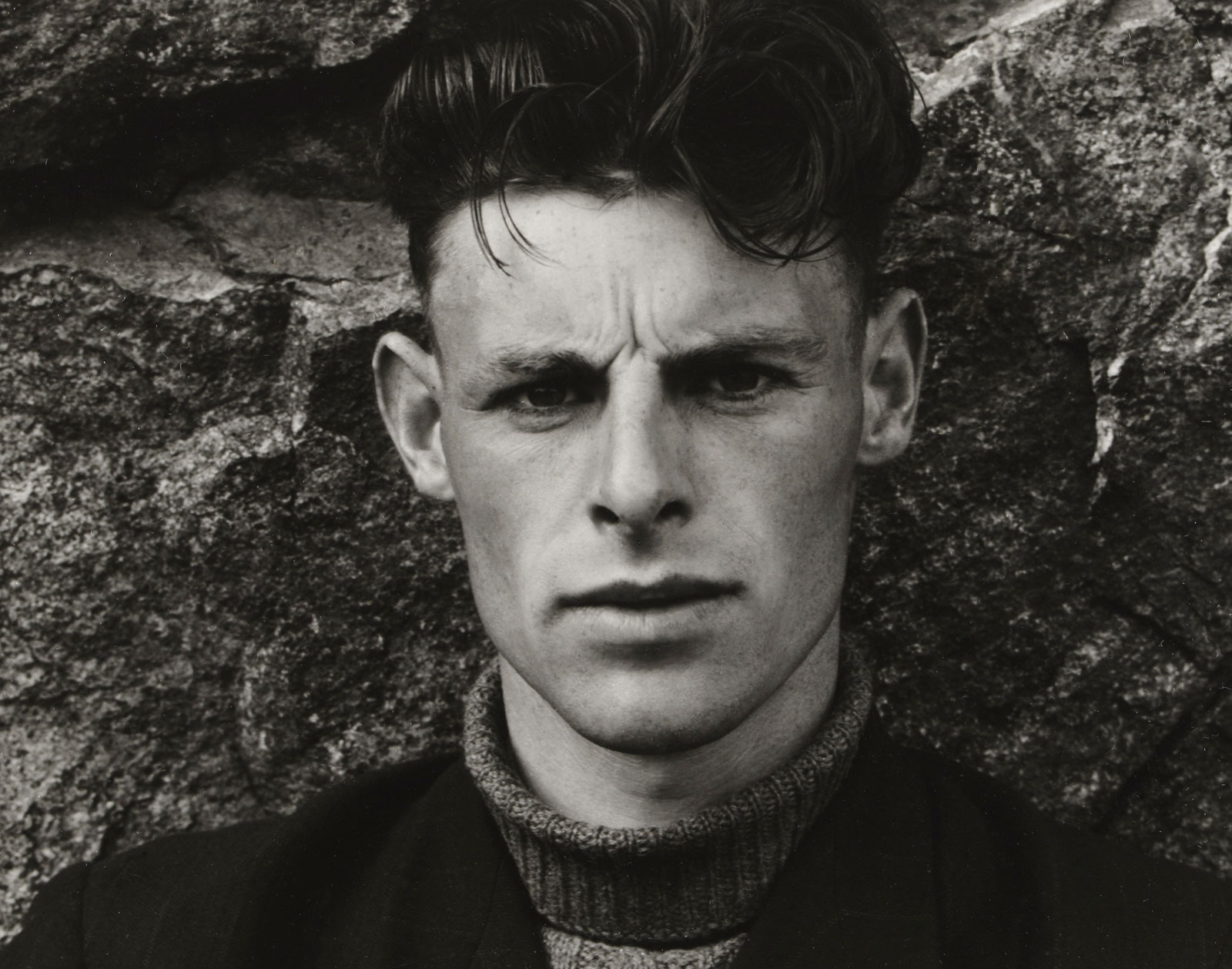

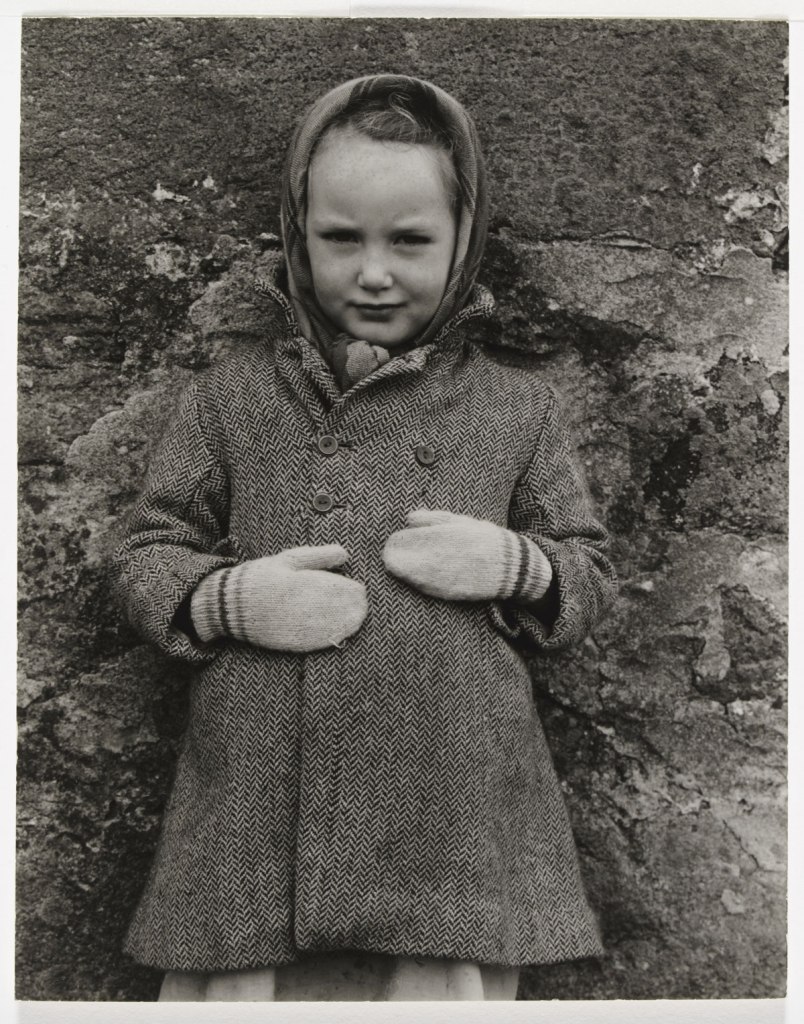

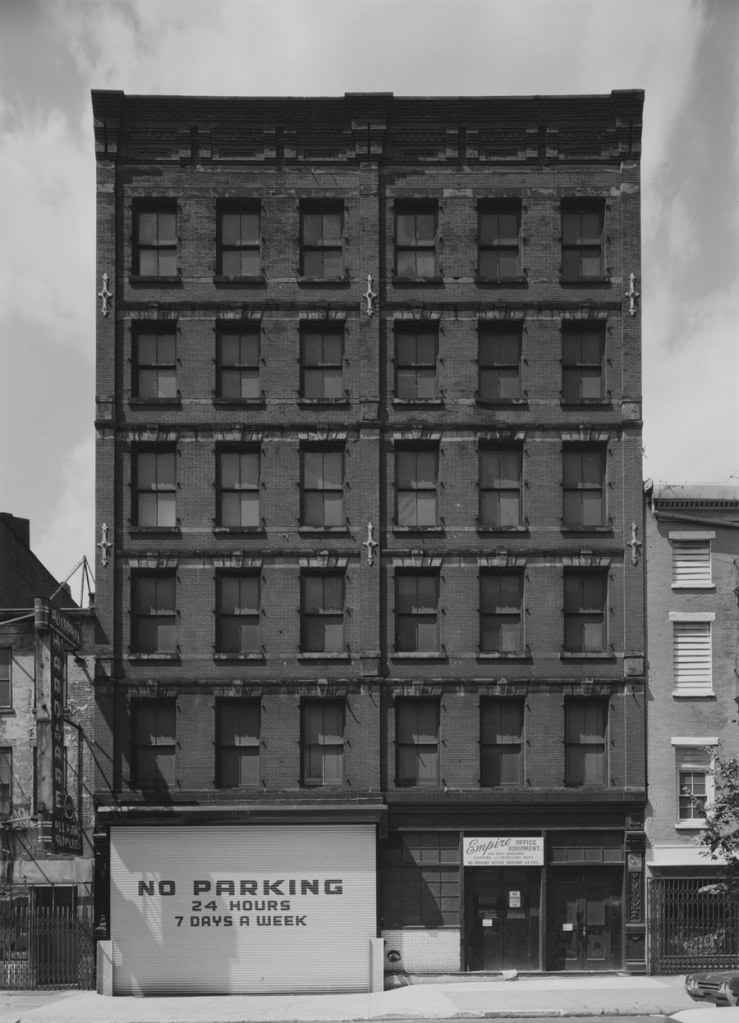

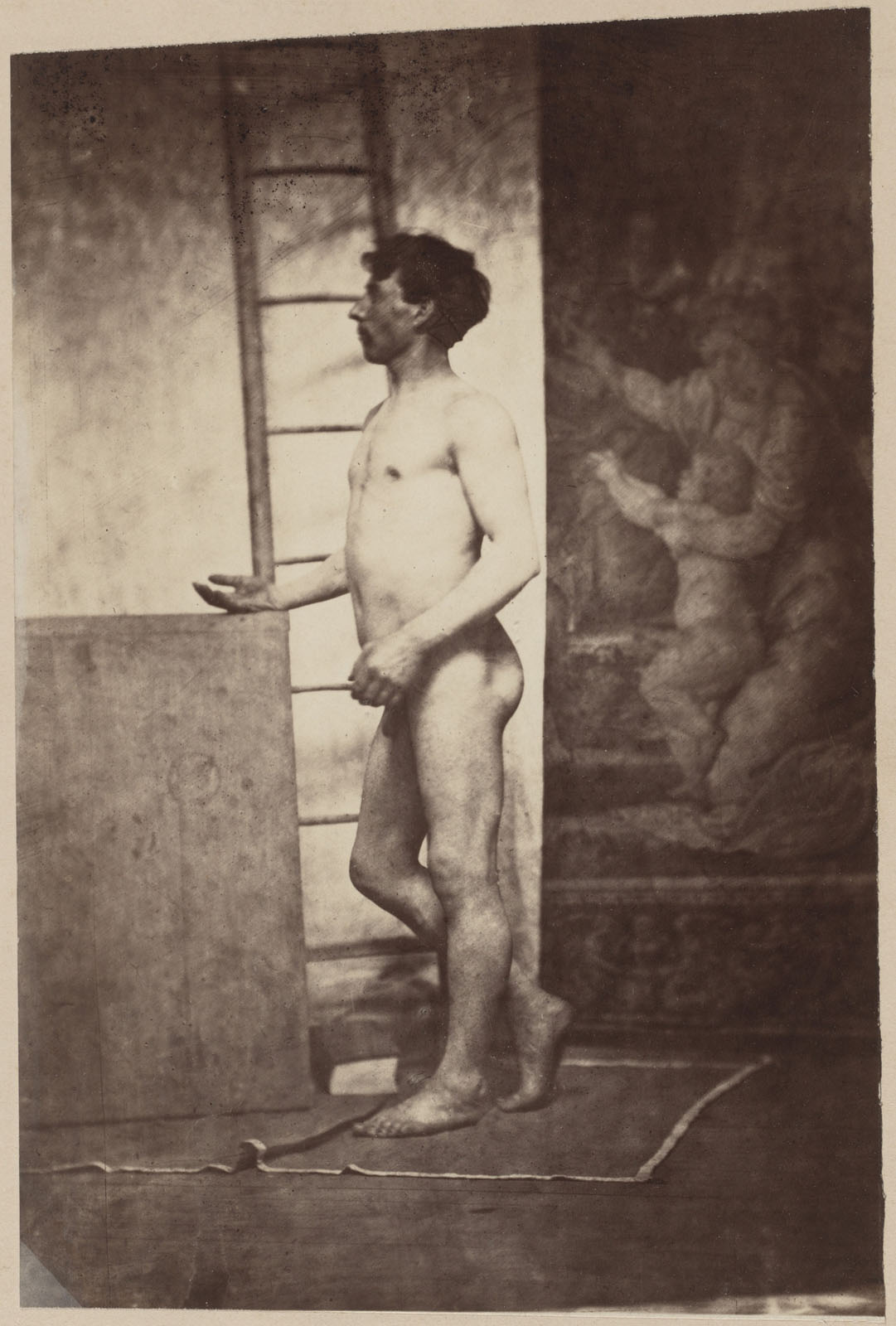

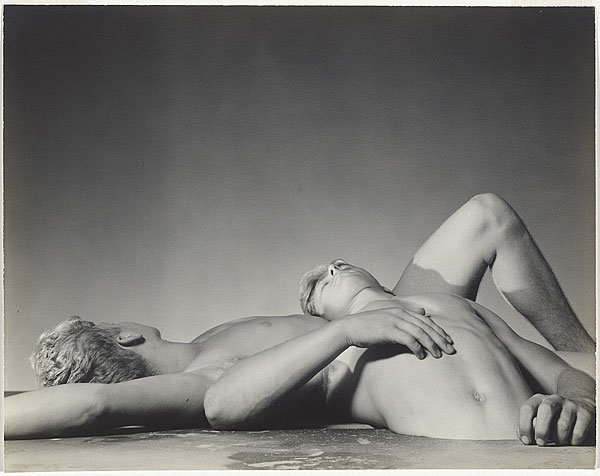

A room in the exhibition considers O’Keeffe’s professional and personal relationship with Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946); photographer, modern art promoter and the artist’s husband. While Stieglitz increased O’Keeffe’s access to the most current developments in avant-garde art, she employed these influences and opportunities to her own objectives. Her keen intellect and resolute character created a fruitful relationship that was, though sometimes conflictive, one of reciprocal influence and exchange. A selection of photography by Stieglitz is shown, including portraits and nudes of O’Keeffe as well as key figures from the avant-garde circle of the time, such as Marsden Hartley (1877-1943) and John Marin (1870-1953).

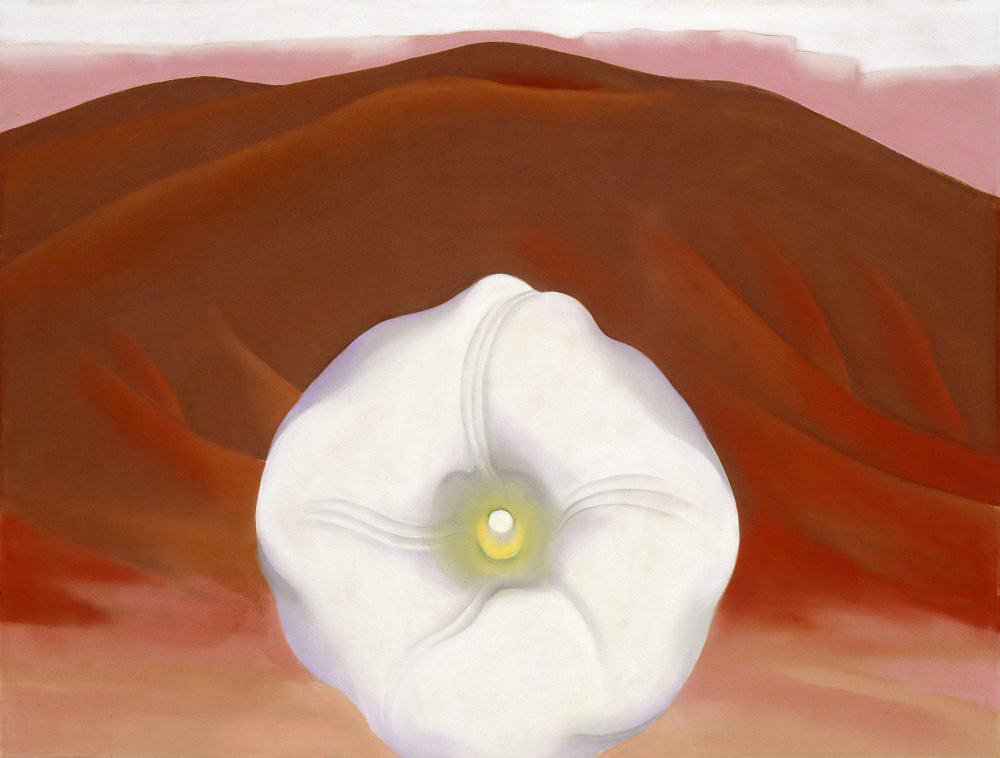

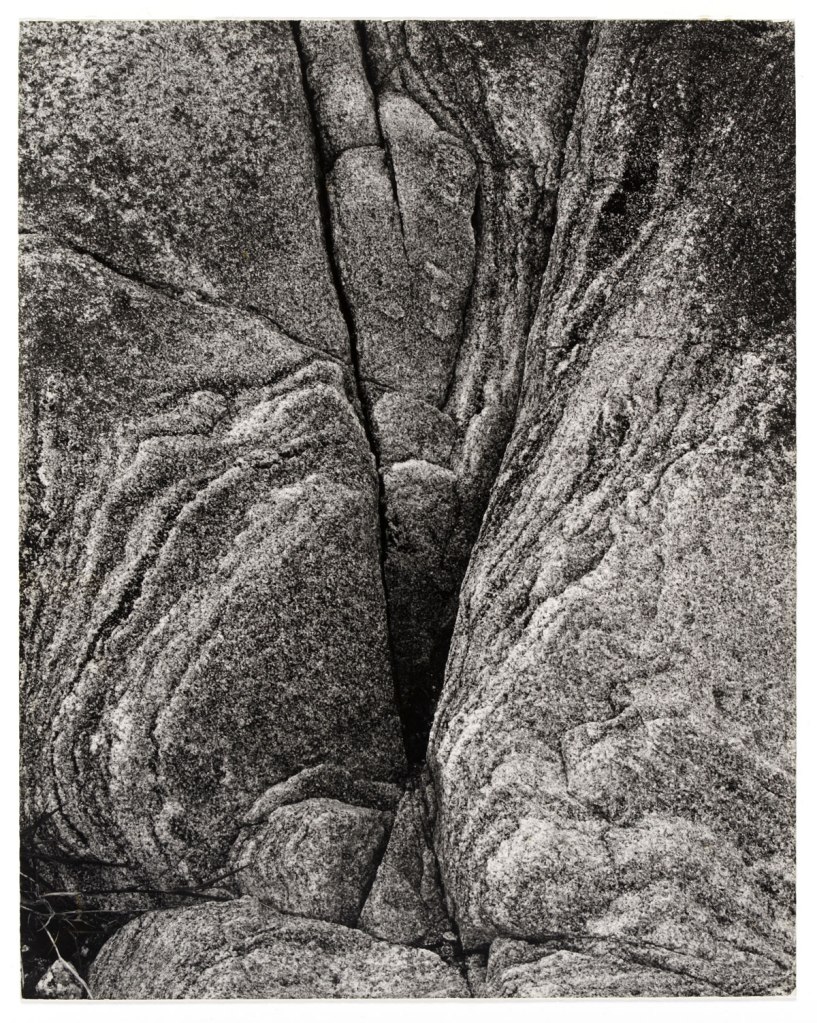

Still life formed an important investigation within O’Keeffe’s work, most notably her representations and abstractions of flowers. The exhibition explores how these works reflect the influence she took from modernist photography, such as the play with distortion in Calla Lily in Tall Glass – No. 2 1923 and close cropping in Oriental Poppies 1927. A highlight is Jimson Weed / White Flower No. 1 1932, one of O’Keeffe’s most iconic flower paintings.

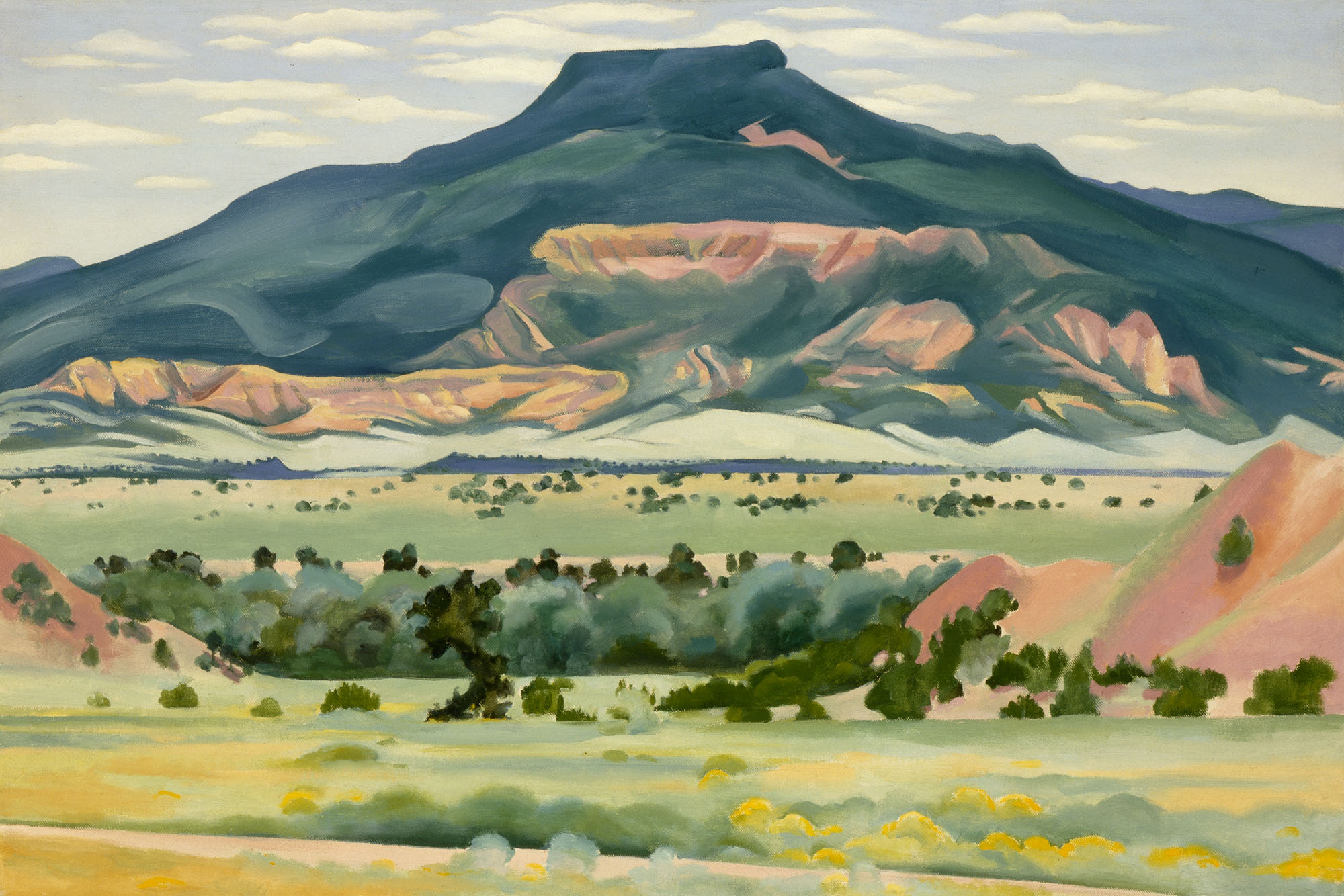

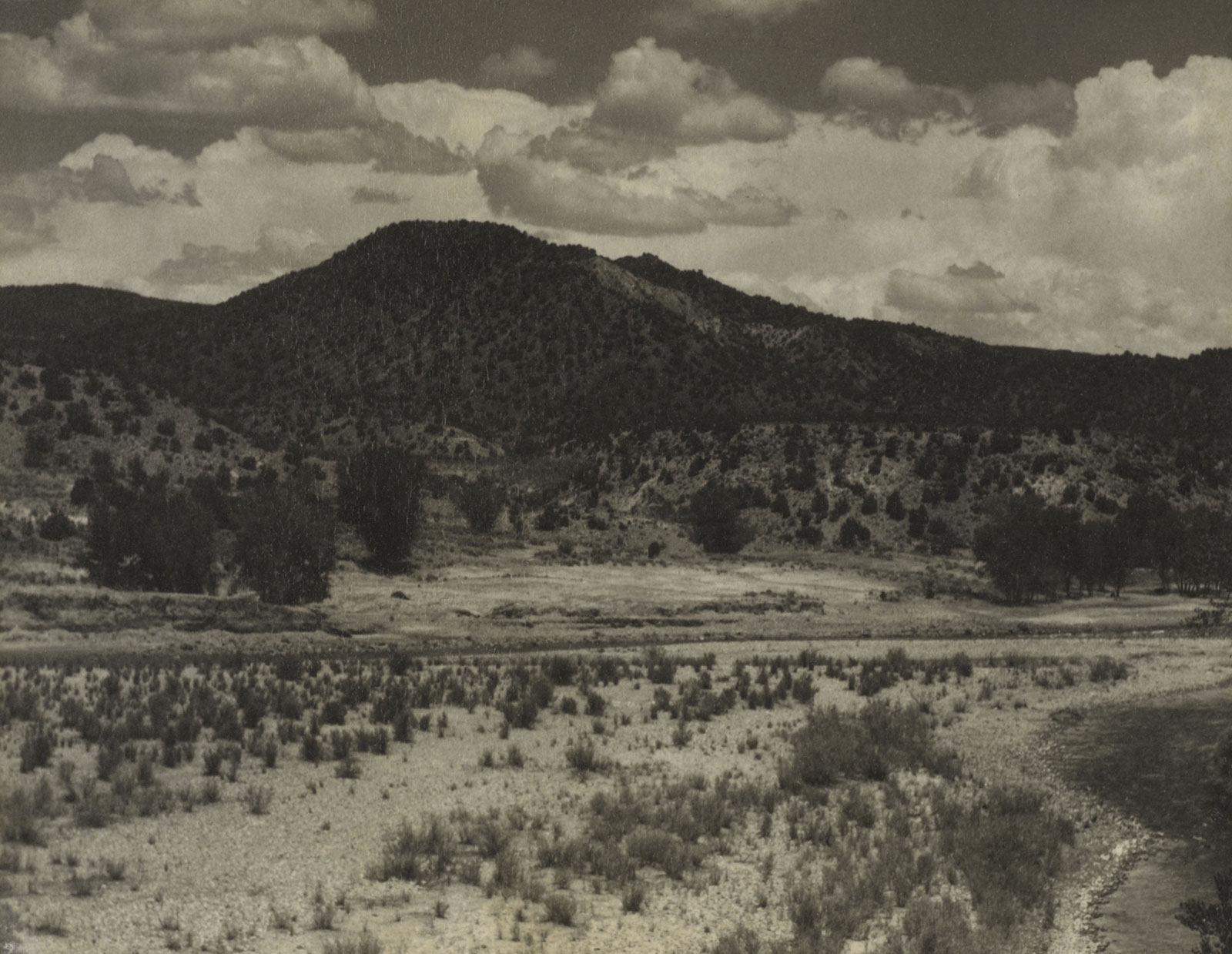

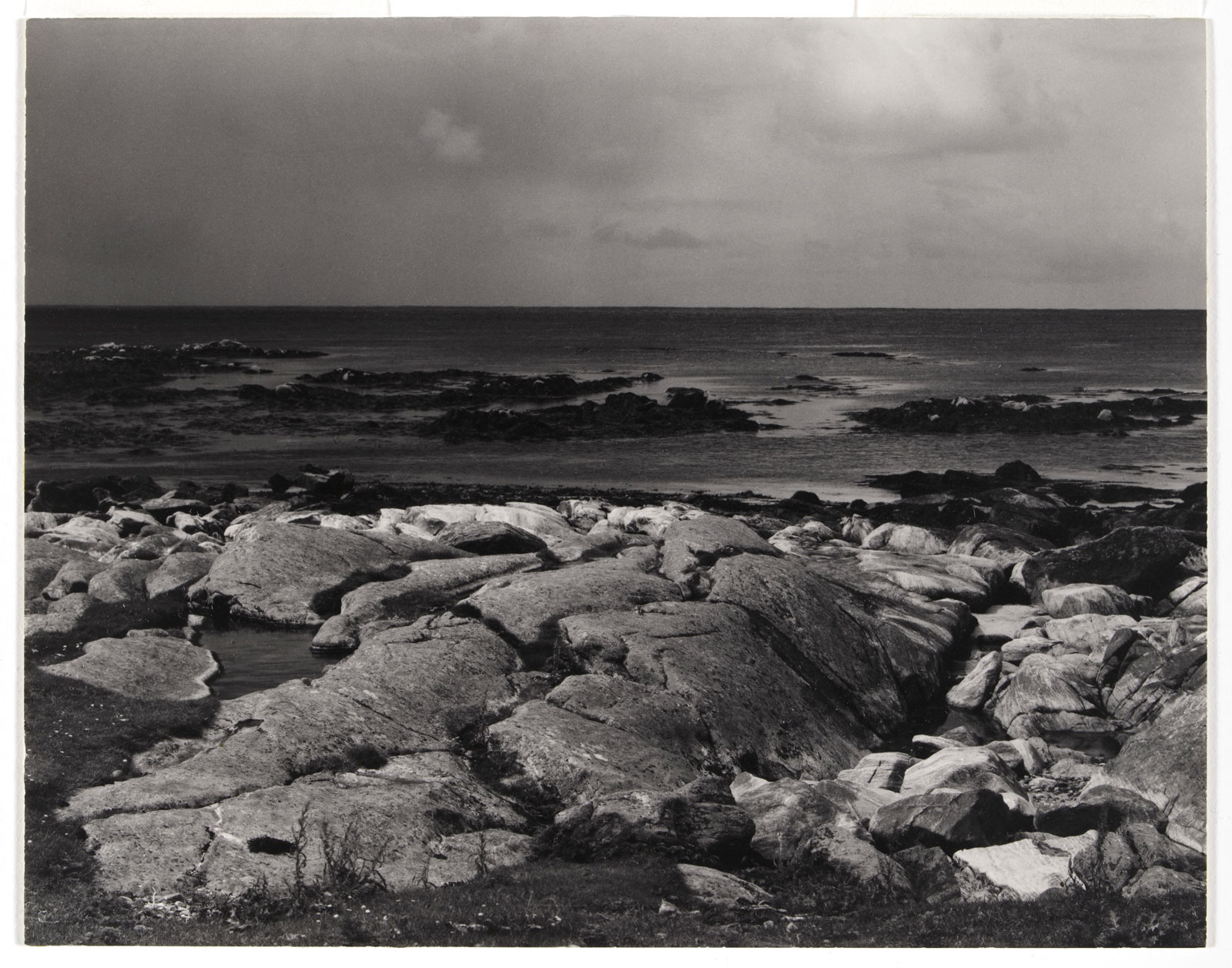

O’Keeffe’s most persistent source of inspiration however was nature and the landscape; she painted both figurative works and abstractions drawn from landscape subjects. Black Mesa Landscape, New Mexico / Out of Black Marie’s II 1930 and Red and Yellow Cliffs 1940 chart O’Keeffe’s progressive immersion in New Mexico’s distinctive geography, while works such as Taos Pueblo 1929/34 indicate her complex response to the area and its layered cultures. Stylised paintings of the location she called the ‘Black Place’ are at the heart of the exhibition.

Georgia O’Keeffe is curated by Tanya Barson, Curator, Tate Modern with Hannah Johnston, Assistant Curator, Tate Modern. The exhibition is organised by Tate Modern in collaboration with Bank Austria Kunstforum, Vienna and the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto. It is accompanied by a catalogue from Tate Publishing and a programme of talks and events in the gallery.

Press release from Tate Modern

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

New York Street with Moon

1925

Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza (Madrid, Spain)

© 2016 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/DACS, London

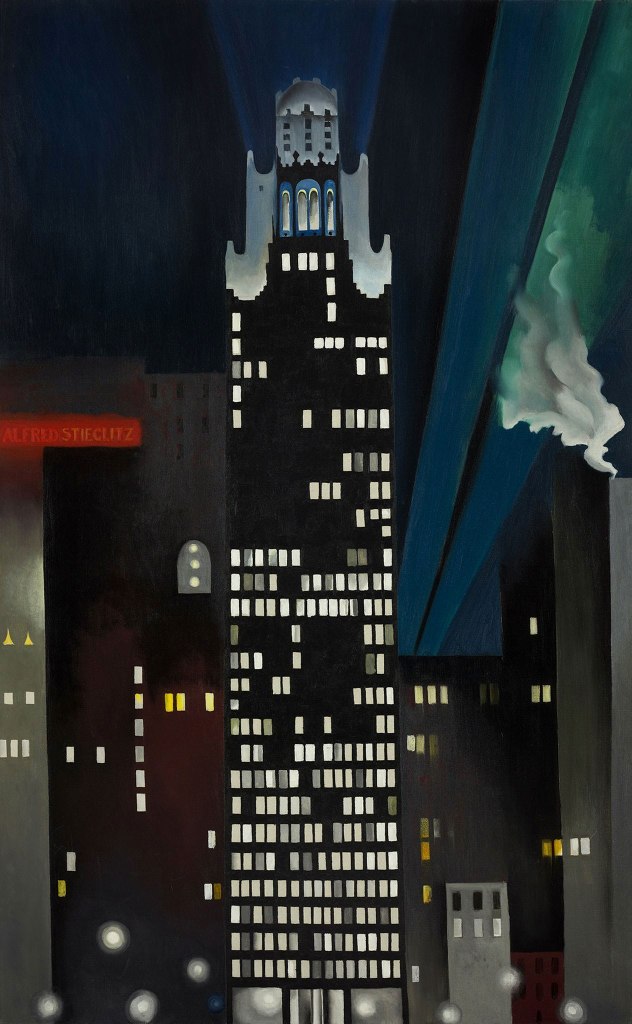

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Radiator Building – Night, New York

1927

Oil on canvas

121.9 x 76.2cm

Alfred Stieglitz Collection, Co-owned by Fisk University, Nashville, Tennessee, and Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas

© 2016 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/ DACS, London Photo: by Edward C. Robison III

While living in New York in the 1920s and 1930s O’Keefe made many paintings of the city inspired by the architecture and lifestyle. In Radiator Building – Night, New York O’Keeffe displays her keen eye for composition and uses colour sparingly, but expertly, to convey the atmosphere of the city at night.

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

East River from the 30th Story of the Shelton Hotel

1928

Oil on canvas

76.2 x 122.2cm

Courtesy of the New Britain Museum of American Art Stephen B. Lawrence Fund

© 2016 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/ DACS, London

O’Keeffe lived in New York during the 1920s and 30s and made many paintings of the city despite being told to ‘leave New York to the men’. She lived in The Shelton Hotel in Manhattan, for 11 years and this piece is a beautiful example of the studies she created of the city from above in her 30th floor apartment.

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Lake George

1922

Oil on canvas

16 1/4 in. x 22 in.

Collection SFMOMA

Gift of Charlotte Mack

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Grey Lines with Black, Blue and Yellow

c. 1923

Oil on canvas

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (Houston, USA)

© 2016 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/DACS, London

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Red Canna

1924

Oil on canvas

© 2016 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/DACS, London

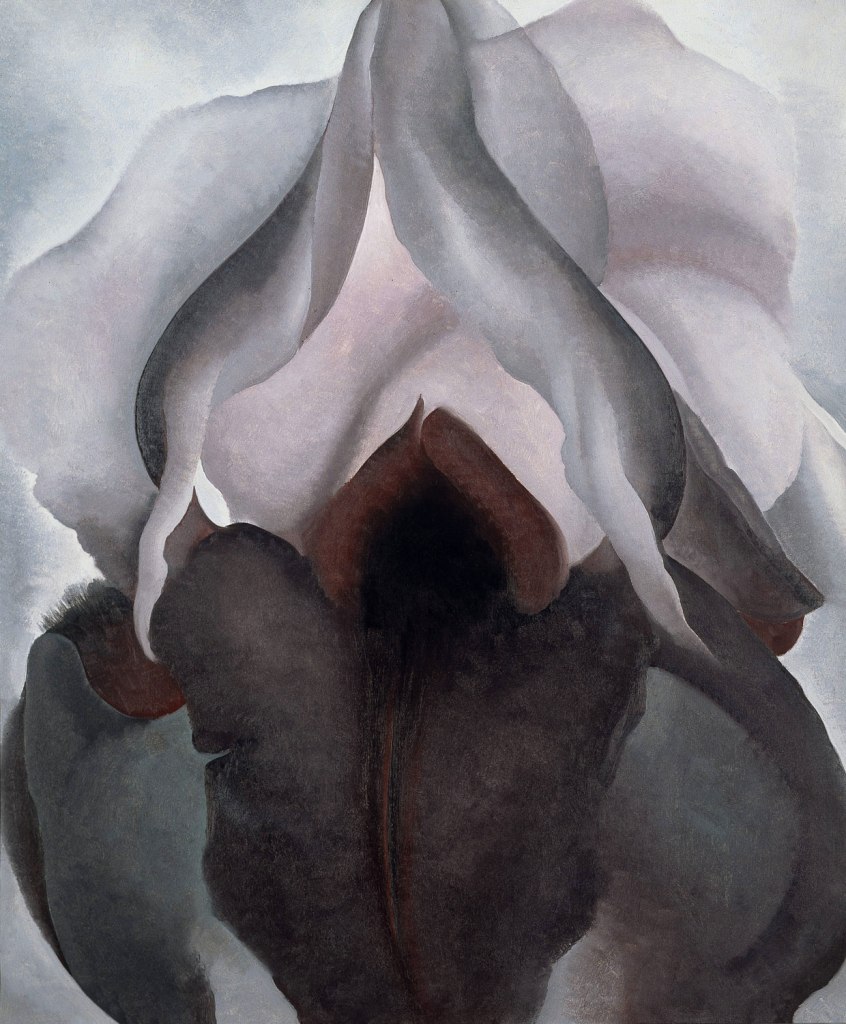

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Black Iris

1926

Oil on canvas

91.4 x 75.9cm

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1969

Photo: Malcom Varon ? 2015

Image copyright The Metropolitan Museum of Art/ Art Resource/ Scala, Florence

O’Keeffe’s large close-up paintings of flowers were intended to ‘make even busy New Yorkers take time to see what I see of flowers’ who often didn’t take the time to engage with nature as she did. This detail of a black iris uses a subtle colour pallet to explore the intricacies of the flower petals and their contrasting tones.

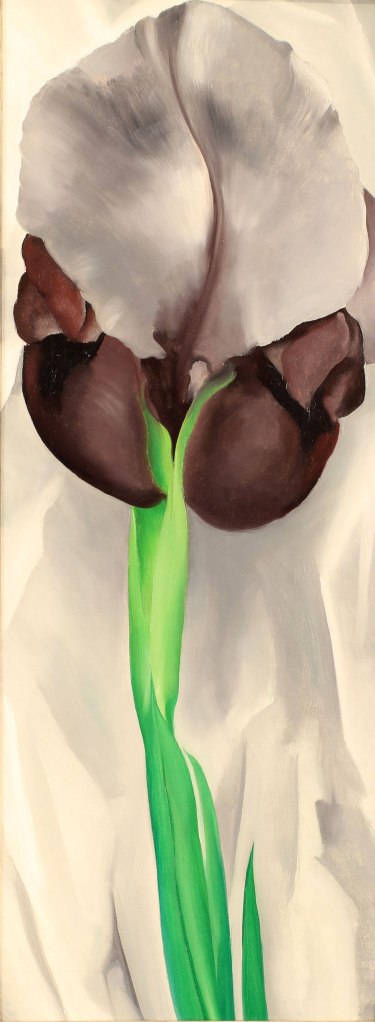

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Dark Iris No. 1

1927

Oil on canvas

© 2016 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/DACS, London

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Abstraction White Rose

1927

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum (Santa Fe, USA)

© 2016 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/DACS, London

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Abstraction Blue

1927

Oil on canvas

102.1 x 76cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Acquired through the Helen Acheson Bequest, 1979 ?

2015 Digital image, The Museum of Modern Art, New York / Scala, Florence

O’Keeffe experimented with abstraction in her early work, saying ‘it is only by selection, by elimination, by emphasis, that we get at the real meaning of things’. Her love of nature is evident in Abstraction Blue, which hints at flower petals, clouds, the sky and the streams, rivers and seashores she enjoyed making studies of.

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Shell No. 2

1928

Oil on board

23.5 x 18.4cm

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Gift of The Burnett Foundation, 1997

© 2016 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/ DACS, London

O’Keeffe was fascinated with nature, and collected natural objects such as flowers, bones, shells and leaves to use as subjects in her paintings. Shell No.2 is unusual in the way O’Keeffe has arranged a collection of objects related to the sea, as her paintings typically show objects in isolation to their natural environment.

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Two Calla Lilies on Pink

1928

Oil on canvas

101.6 x 76.2cm

Philadelphia Museum of Art; Bequest of Georgia O’Keeffe for the Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1987

© Philadelphia Museum of Art

O’Keeffe was constantly inspired by nature and hoped that her paintings of enlarged flowers would draw the attention of busy New Yorkers and encourage them to appreciate the beauty in intricacy of nature that might otherwise pass them by. This piece depicts a close up of two lilies, a regularly repeated subject that earned O’Keeffe the nickname ‘The Lady of the Lily’, first coined by caricaturist Miguel Covarrubias in the New Yorker.

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Grey, Blue & Black – Pink Circle

1929

Oil on canvas

91.4 x 122cm

Dallas Museum of Art, gift of The Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation

Originally painted in 1929, Grey Blue & Black – Pink Circle demonstrates O’Keeffe’s interest in the European modernist movement that concentrated on the idea that visual art could or should be purely patterns of form, colour and line. Using vivid colour palettes inspired by nature, she often abstracted natural objects such as flowers, trees and shells.

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

White Iris

1930

Oil on canvas

40 x 30 in.

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Bruce C. Gottwald

© 2016 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/DACS, London

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Oriental Poppies

1927

The Collection of the Frederick R. Weisman Art Museum at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis

© 2016 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/DACS, London

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Jimson Weed/White Flower No. 1

1932

Oil paint on canvas

48 x 40 inches

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Arkansas, USA

Photography by Edward C. Robison III

© 2016 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/DACS, London

Introduction

Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986) is widely recognised as a foundational figure within the history of modernism in the United States, and during her lifetime became an American icon. Her career spanned more than seven decades and this exhibition encompasses her most productive years, from the 1910s to the 1960s. It aims to dispel the clichés that persist about O’Keeffe’s painting, emphasising instead the pioneering nature and breadth of her career.

O’Keeffe was born in Sun Prairie, Wisconsin, the daughter of Irish and Dutch-Hungarian immigrants, and died in Santa Fe, New Mexico, at the age of 98. She decided to be an artist before she was 12 years old. She was the most prominent female artist in the avant-garde circle around the photographer and gallerist Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946), later O’Keeffe’s husband. The first showing of her work was at Stieglitz’s New York gallery ‘291’ in 1916, now 100 years ago. Tate Modern’s exhibition therefore marks a century of O’Keeffe

The early years and ‘291’

“I have things in my head that are not like what anyone has taught me – shapes and ideas so near to me … I decided to start anew – to strip away what I had been taught… I began with charcoal and paper and decided not to use any other colour until it was impossible to do what I wanted to do in black and white.”

O’Keeffe’s earliest mature works were abstractions in charcoal, made while she was working as an art teacher in Virginia and Texas. These drawings, made on a comparatively large scale, were exhibited by Alfred Stieglitz at ‘291’ (evoked by this room) in O’Keeffe’s debut in 1916 and in her first solo exhibition in 1917. O’Keeffe had sent her drawings to Anita Pollitzer, a friend from her student days, who first showed them to Stieglitz. He exclaimed: ‘finally a woman on paper’.

This early period also reveals O’Keeffe to be a gifted colourist, skilled in watercolour. Strikingly vivid paintings of the mountain landscapes of Virginia and plains of Texas demonstrate her skilful handling of colour. Her early oil paintings also took their inspiration from the landscape and show an interest in synaesthesia, the stimulation of one sense by another, for example translating sounds such as cattle lowing into abstract forms

Abstraction and the senses

“I paint because colour is a significant language to me.”

After moving from Texas to New York in 1918, O’Keeffe turned with greater assurance to abstraction and to oil paint as a medium. Focusing on paintings from 1918 until 1930, this room shows the importance of abstraction in O’Keeffe’s work and how she took inspiration from sensory stimulation. Here, her paintings investigate the relationship of form to music, colour and composition, showing her understanding of synaesthesia and chromothesia, or as she said ‘the idea that music could be translated into something for the eye’. We also see her early flower-abstractions.

The critical response emphasised O’Keeffe’s identity as a woman artist and attributed essential feminine qualities to her work, often hinting heavily at erotic content. Stieglitz was a major source for such attitudes and supported them by introducing psychoanalytic interpretations of her paintings. Frustrated with this limited view, O’Keeffe began to transform her style and this room includes several less widely-known hard-edged or cubist-inspired abstractions.

“When people read erotic symbols into my paintings, they’re really talking about their own affairs.

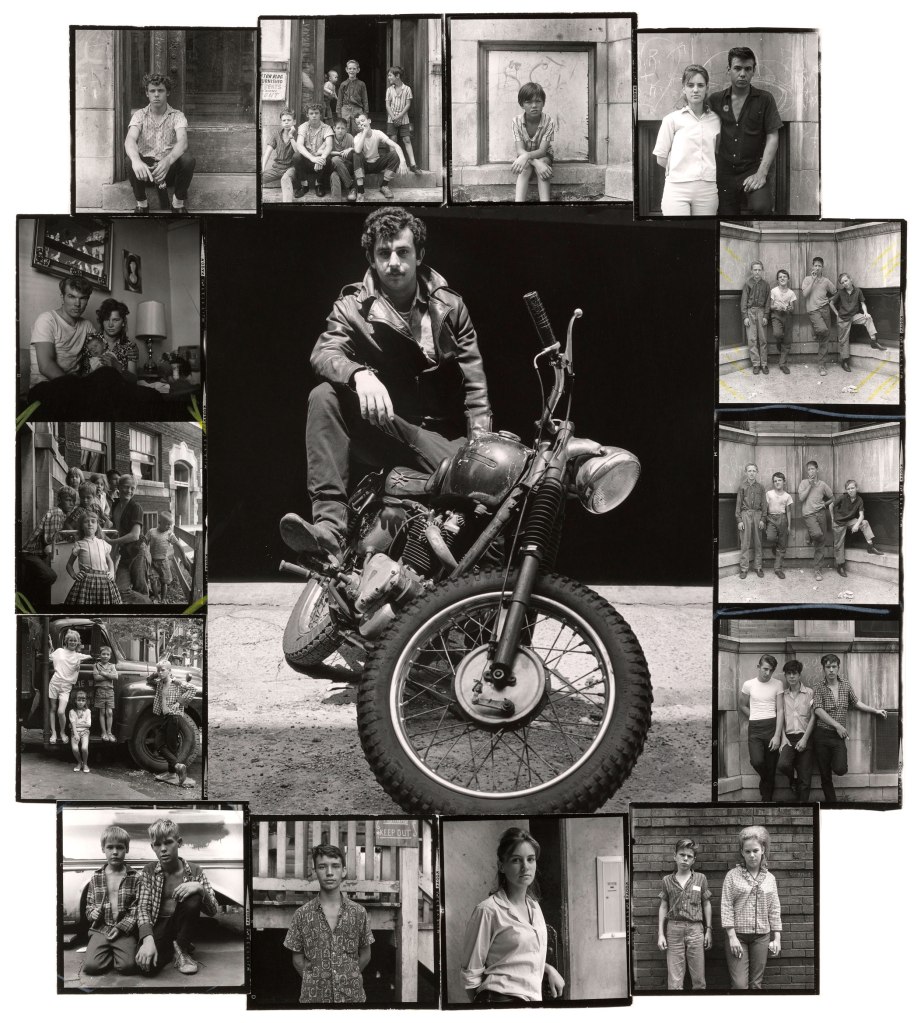

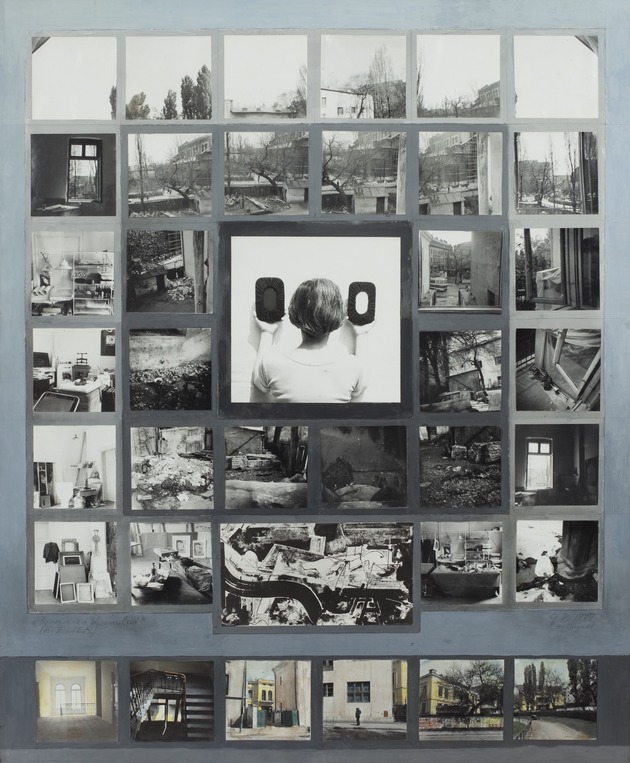

O’Keeffe, Stieglitz and their circle

“I have been much photographed… I am at present prejudiced in favour of photography.”

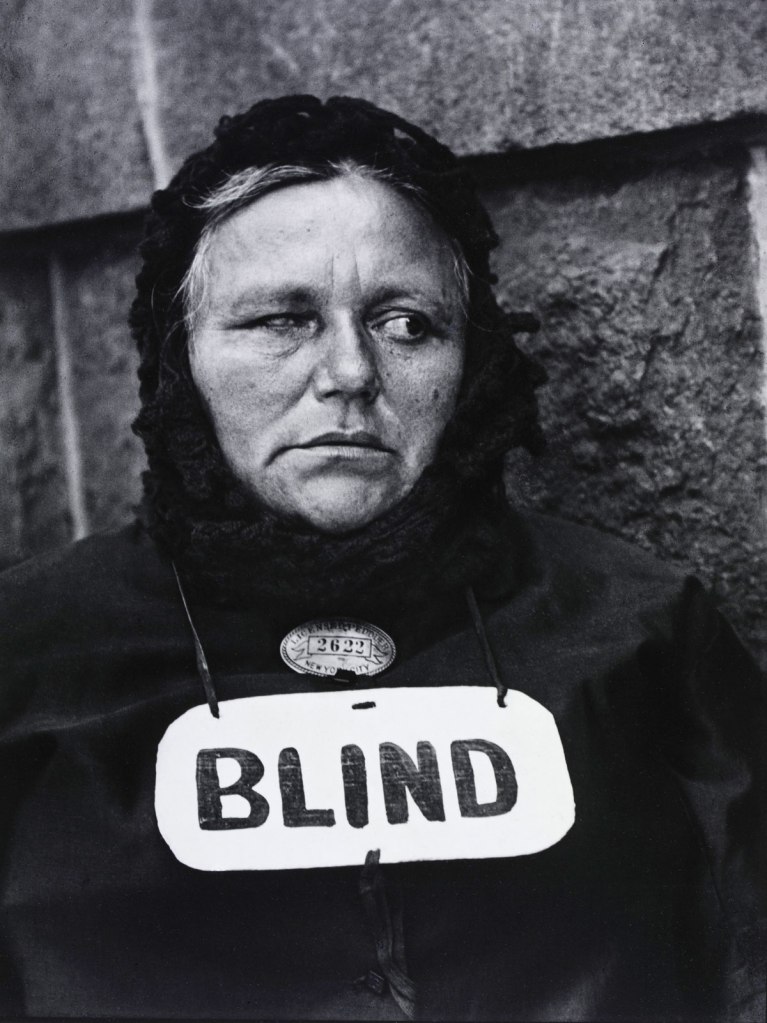

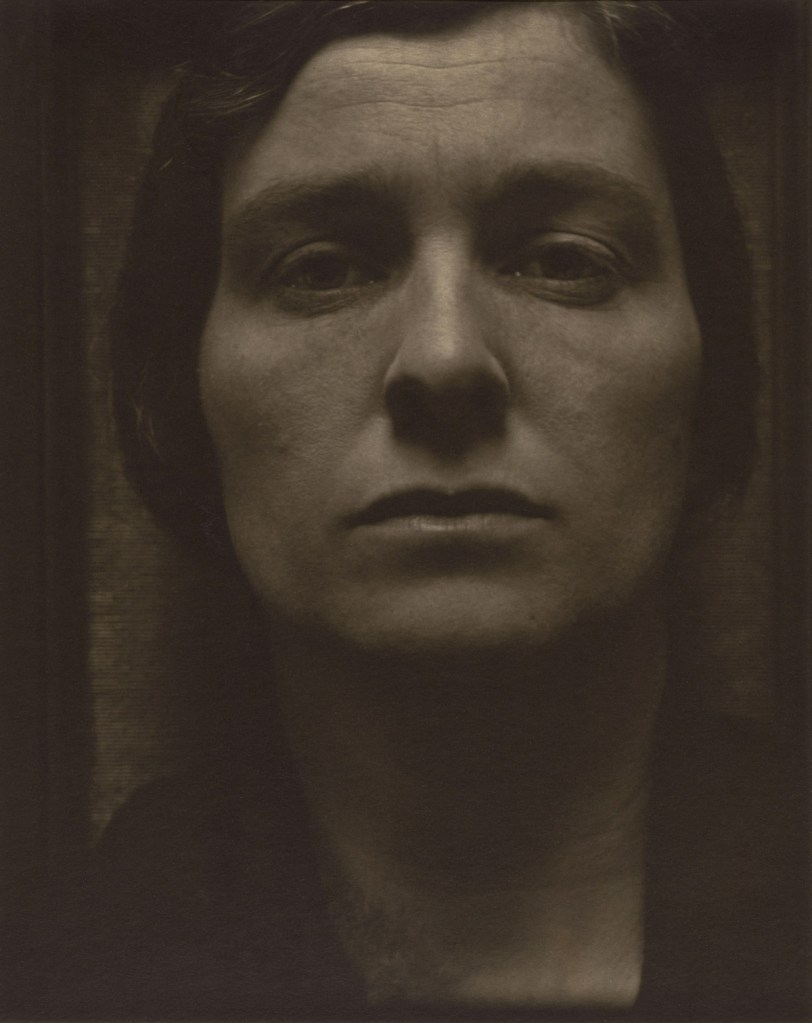

This room takes a closer look at O’Keeffe’s creative and personal partnership with Alfred Stieglitz and the circle of artists, writers and cultural figures that congregated around him and the couple. Many of their personal acquaintances are pictured in Stieglitz’s photographs, figures who impacted on their professional and private lives. This was the generation of the ‘Progressive Era’, men and women who came of age in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century and who embodied an optimistic cultural nationalism, wanting to create a modern America.

Two major series of Stieglitz’s work are displayed here: his extended portrait of O’Keeffe, in which we can see her as both muse and collaborator, and his sky photographs titled Equivalents, several of which were also made as portraits of Georgia, linking the two series. Their personal and aesthetic exchange is continued in the painting A Celebration 1924, an image of clouds made by O’Keeffe the year they married. Other works by O’Keeffe can also be considered indirect portraits of Stieglitz.

New York cityscapes

When O’Keeffe first expressed an intention to paint New York, she said, ‘Of course, I was told it was an impossible idea – even the men hadn’t done too well with it’. She made her first painting of the city in 1925, continuing with the same subject for the rest of the decade. O’Keeffe’s paintings show views from street level, the tall buildings providing an urban parallel to her early depictions of canyons in Texas and later in New Mexico. O’Keeffe and Stieglitz lived on the 30th floor of a skyscraper, and she delighted in the vantage point it afforded of the city beneath.

“I know it is unusual for an artist to want to work way up near the roof of a big hotel, in the heart of a roaring city, but I think that’s just what the artist of today needs for stimulus… Today the city is something bigger, grander, more complex than ever before in history.”

O’Keeffe stopped painting New York not long after the Wall Street Crash of 1929, the year she made her first prolonged visit to New Mexico. With the onset of the Great Depression, the city’s utopian spirit vanished, and it no longer held her attention.

Lake George

“I wish you could see the place here – there is something so perfect about the mountains and the lake and the trees – sometimes I want to tear it all to pieces – it seems so perfect – but it is really lovely.”

The rural Northeast, through Lake George in upstate New York, as well as coastal Maine and Canada, contrasts both with New York City and, later, O’Keeffe’s travels to the Southwest. Lake George in particular, where the Stieglitz family had a summer home, enabled O’Keeffe to continue her investigation of abstraction from nature. O’Keeffe first visited Lake George as a student in 1908, but during her three-decade relationship with Stieglitz, she spent summer and autumn there. ‘Here I feel smothered with green’, she remarked, revealing her ambivalence towards the location. Nevertheless, the years she spent summering there were some of the most prolific of her career.

Lake George and the Northeast suggested a different palette to O’Keeffe. Her works made there range from soft blue and green to the red and purple of maple trees and the warm red of apples and autumn leaves. Like the images of New York, there are correlations between her works and Stieglitz’s photography – key motifs include the lake itself, trees, turbulent clouds, barns and still lifes of apples or leaves.

Flowers and still lifes

“Nobody sees a flower – really – it is so small – we haven’t time – and to see takes time… So I said to myself – I’ll paint what I see – what the flower is to me, but I’ll paint it big and they will be surprised into taking time to look at it – I will make even busy New Yorkers take time to see what I see of flowers… Well – I made you take time to look … and when you took time … you hung all your own associations with flowers on my flower and you write about my flower as if I think and see what you think and see of the flower – and I don’t.”

O’Keeffe is renowned for her flower paintings, which she made from the 1920s until the 1950s. At first her work tended towards imaginative, semi-abstract compositions inspired by flowers, or showing the entire form of the flower, as in her delicate calla lilies of the 1920s. They progressed to works with a greater photographic realism, focusing in close-up on the blooms themselves. This move to realism was partly motivated by her aim to dispel the sexual or bodily interpretations of her work made by critics, and O’Keeffe lamented that this view continued.

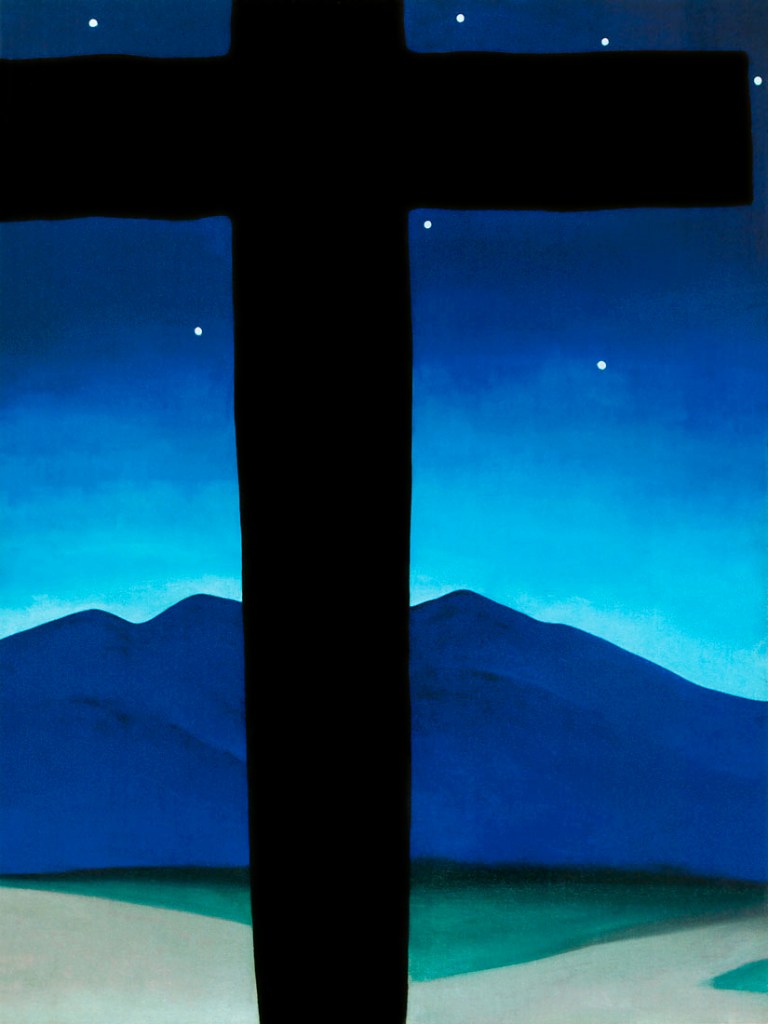

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Black Cross with Stars and Blue

1929

Oil on canvas

101.6 x 76.2cm

Private Collection

© 2016 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/ DACS, London

Black Cross with Stars and Blue demonstrates O’Keeffe’s passion for the New Mexico landscape with her talent for creating strong compositions and using a limited colour palette effectively. This early painting of New Mexico echoes her city paintings of the era, using the cross as a towering foreground for the even more monumental mountains behind.

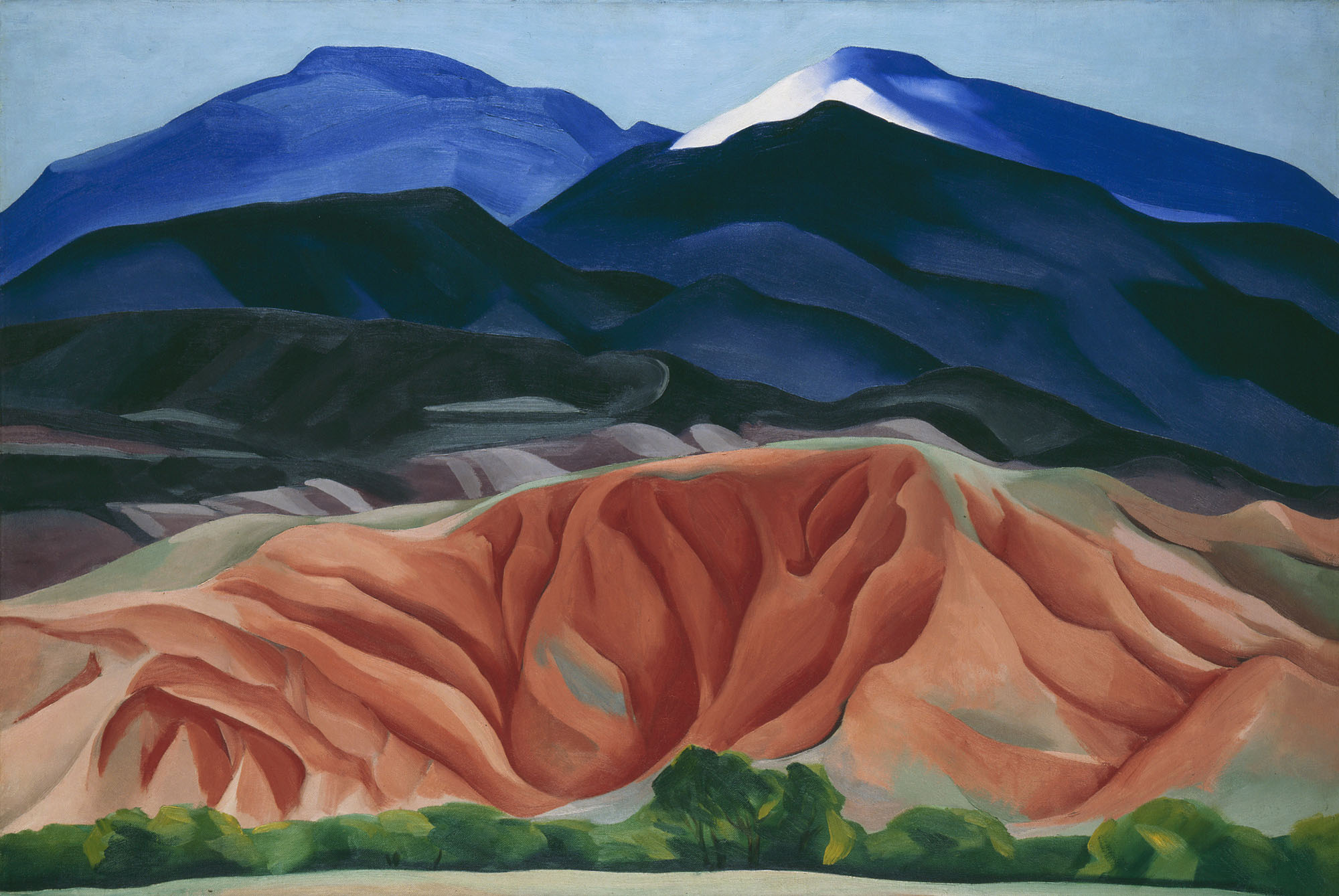

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Black Mesa Landscape, New Mexico / Out Back of Marie’s II

1930

Oil on canvas mounted on board

24 1/4 x 36 1/4 in. (61.6 x 92.1cm)

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. Gift of The Burnett Foundation

© 2016 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/DACS, London

This is one of O’Keeffe’s earliest paintings of the New Mexico landscape after she first visited the area in the summer of 1929. It’s a beautiful example of her early style of painting, with a focus on colour and contour, simplifying and refining the dessert terrain that truly inspired her.

“When I got to New Mexico, that was mine. As soon as I saw it, that was my country. I’d never seen anything like it before, but it fitted to me exactly. It’s something that’s in the air, it’s just different. The sky is different, the stars are different, the wind is different.”

Georgia O’Keeffe in the film Georgia O’Keeffe, produced and directed by Perry Miller Adato; a WNET/THIRTEEN production for Women in Art, 1977. Portrait of an Artist, no.1; series distributed by Films, Inc./Home Vision, New York.

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Rust Red Hills

1930

Oil on canvas

40.6 x 76.2cm

Sloan Fund Purchase Brauer Musuem of Art

Valpariaso University

© 2016 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/ DACS, London

Having made the first of many trips to New Mexico the previous year, O’Keeffe was constantly inspired by the distinctive red hills of the area, and made it her permanent home in later life. In Rust Red Hills, O’Keeffe uses a range of rich colours, exploring the natural form of the local landscape and the variation of colour within the rock formations.

Sangre de Cristo Mountains in Taos County, New Mexico, with Arroyo Hondo in the front

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Horse’s Skull with Pink Rose

1931

Oil on canvas

101.6 x 76.2cm

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Gift of the Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation 1994

Photo: © 2015. Digital image Museum Associates/ LACMA/ Art Resource NY/ Scala, Florence

The arid desert terrain of New Mexico, where O’Keeffe spent many months in her Ghost Ranch house, was littered with animal bones which she often collected and painted. She frequently positioned these bones alongside flowers in her pieces to express how she felt about the desert she enjoyed so much.

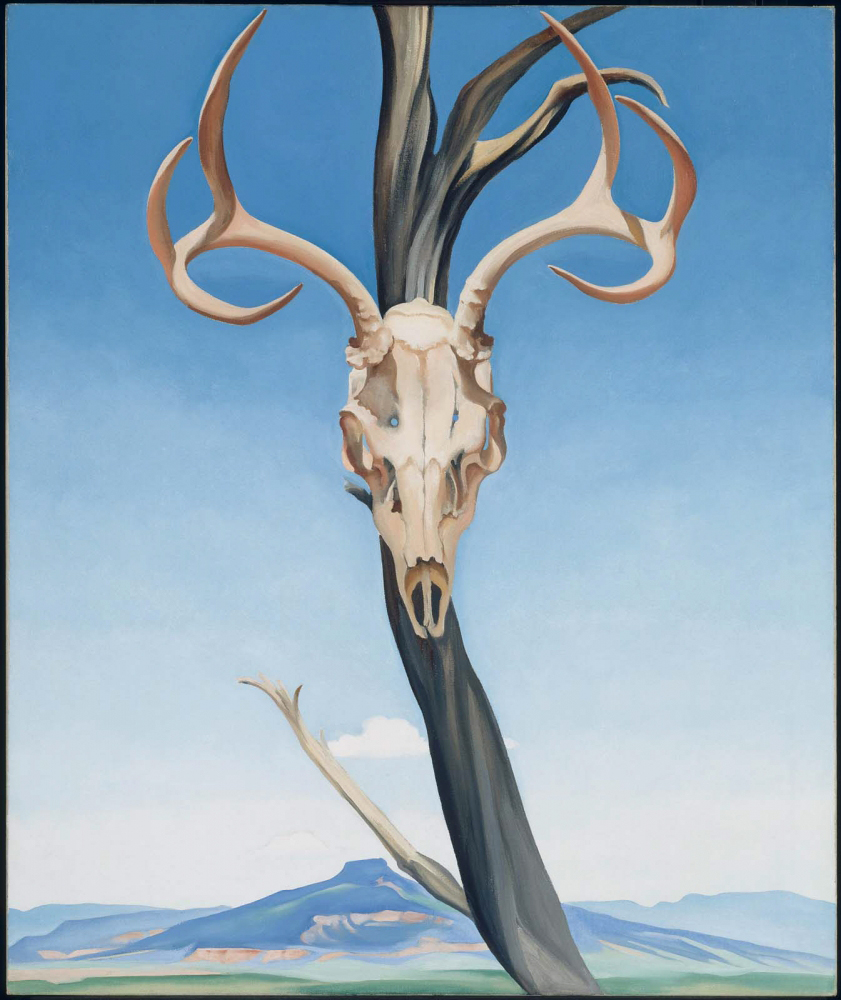

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Deer’s Skull with Pedernal

1936

Oil on canvas

91.44 x 76.52cm

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Gift of the William H. Lane Foundation

© 2016 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/ DACS, London

Photo: © 2016 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The mountain Pedernal was visible from the front door of O’Keeffe’s Ghost Ranch house in New Mexico and is present in a vast amount of her paintings of the New Mexico landscape. O’Keeffe felt a deep connection with the area and described the flat top mountain as ‘my private mountain. It belongs to me’. She picked up animal skulls from the desert terrain and often used them as subjects for her paintings, which became some of her most iconic works.

“The first year I was out here I began picking up bones because there were no flowers. I wanted to take something home, something to work on… When it was time to go home I felt as if I hadn’t even started on the country and I wondered what I could take home that I could continue what I felt about the country and I couldn’t think of anything to take home but a barrel of bones. So when I got home with my barrel of bones to Lake George I stayed up there quite a while that fall and painted them. That’s where I painted my first skulls, from this barrel of bones.”

Georgia O’Keeffe in the film Georgia O’Keeffe, produced and directed by Perry Miller Adato; a WNET/THIRTEEN production for Women in Art, 1977. Portrait of an Artist, no.1; series distributed by Films, Inc./Home Vision, New York.

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

From the Faraway, Nearby

1937

Oil in canvas

Photograph: Georgia O’Keeffe/The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource/Scala, Florence

New Mexico: Taos and Alcalde

“When I got to New Mexico that was mine. As soon as I saw it that was my country. I’d never seen anything like it before, but it fitted to me exactly. It’s something that’s in the air – it’s different. The sky is different, the wind is different. I shouldn’t say too much about it because other people may be interested and I don’t want them interested.”

In 1929 O’Keeffe made her first prolonged visit to New Mexico in the Southwestern United States, a dry and arid high altitude desert region. Initially she was invited to stay with the socialite, art patron and writer Mabel Dodge Luhan in her house in Taos, a town already home to an established artistic community.

Over the next few years, O’Keeffe made repeated visits to New Mexico. Here she had found a landscape that was a contrast to the East coast but whose rural and expansive qualities felt familiar. O’Keeffe explored the specifics of the region, the adobe or earth-built architecture, the crosses, as well as views of the wide mesas or flat mountain plateaus, revealing its cultural complexity – the layering of Native American and Spanish colonial influences on the landscape

From the faraway, nearby: Skull Paintings

“When I found the beautiful white bones on the desert I picked them up and took them home… I have used these things to say what is to me the wideness and wonder of the world as I live in it.”

O’Keeffe began painting animal bones, principally skulls, around 1931, but had collected them since 1929. As she explained, “that first summer I spent in New Mexico I was a little surprised that there were so few flowers. There was no rain so the flowers didn’t come. Bones were easy to find so I began collecting bones.” Wanting to take something back with her she decided “the best thing I could do was to take with me a barrel of bones.”

Writers and painters at this time were searching for a specifically American iconography, or in O’Keeffe’s words ‘the Great American Thing’. In O’Keeffe’s paintings the bones, particularly when juxtaposed with the desert landscape of the Southwest, summarise the essence of America which she felt was not in New York but was the country west of the Hudson River, which symbolised what she called ‘the Faraway’

Ghost Ranch

“I wish you could see what I see out the windows – the earth pink and yellow cliffs to the north – the full pale moon about to go down in an early morning lavender sky behind a very long beautiful tree-covered mesa to the west – pink and purple hills in front and the scrubby fine dull green cedars – and a feeling of much space – It is a very beautiful world.”

O’Keeffe first discovered Ghost Ranch in 1934 – a ‘dude ranch’ for wealthy tourists to gain an experience of the ‘wild west’. Though O’Keeffe wanted nothing to do with the ranch’s patrons she stayed in an adobe house on the property from 1937, purchasing the house in 1940, her first home in New Mexico. During the later 1930s and 1940s O’Keeffe deepened her exploration of the distinctive landscape of the Southwest – the intense reds and pinks of the earth and cliffs, the desiccated trees, the Chama River and the Cerro Pedernal (‘flint hill’), which is the Spanish name for the flat-topped mesa viewed in the distance from Ghost Ranch. ‘It’s my private mountain. It belongs to me’, she said, half-jokingly. ‘God told me if I painted it enough, I could have it’.

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Pedernal with Red Hills (Red Hills with the Pedernal)

1936

Oil on canvas

50.8 x 76.2cm

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Gift of The Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation, 2006

© 2016 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/ DACS, London

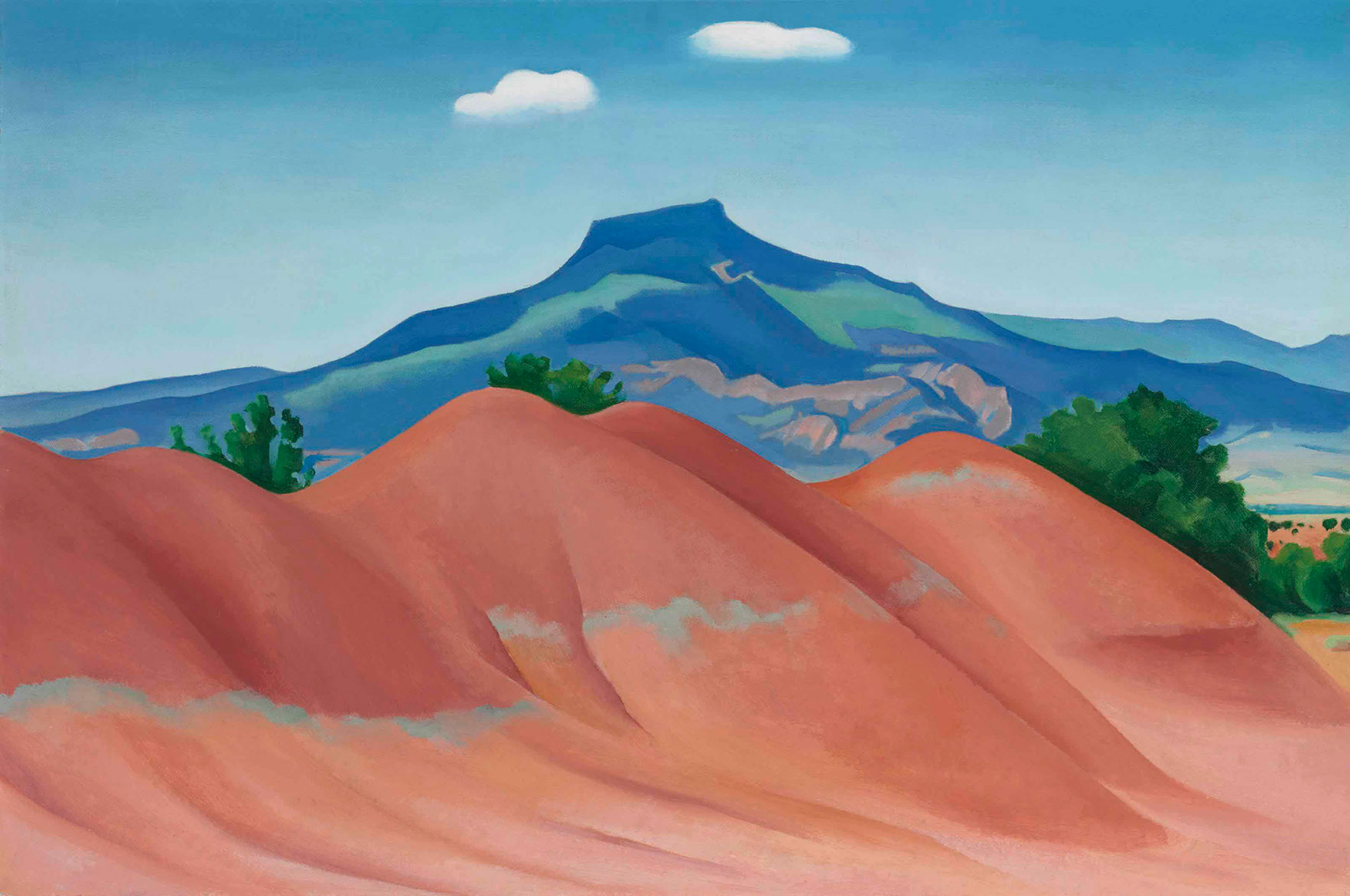

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Red Hills and White Flower

1937

Pastel on paper covered board

19 3/8 x 25 5/8 in.

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Gift of the Burnett Foundation © 1987, Private Collection

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Red and Yellow Cliffs

1940

Oil on canvas

61 x 91.4cm

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Alfred Stieglitz Collection, Bequest of Georgia O’Keeffe, 1986

Photo: © 2015. Image copyright The Metropolitan Museum of Art/ Art Resource/ Scala, Florence

The distinctive landscape of the New Mexico desert was a constant source of inspiration for O’Keeffe, from her first visit to the area in 1929. She discovered Ghost Ranch in 1934 where she made many painting trips and purchased a house there in 1940. O’Keeffe’s paintings of New Mexico terrain and the natural objects she found there became some of her best known works.

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

My Backyard

1937

Oil on canvas

© 2016 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/ DACS, London

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

My Front Yard, Summer

1941

Oil on canvas

50.8 x 76.2cm

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Gift of The Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation, 2006

© 2016 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/ DACS, London

O’Keeffe was deeply inspired by the New Mexico landscape that she visited on painting trips from 1929 onwards. She bought a house at Ghost Ranch 1940 before moving there permanently in 1949 and never tired of the desert landscape that she made countless studies of. ‘It’s my private mountain. It belongs to me’, she said, half-jokingly ‘God told me if I painted it enough, I could have it’

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Red Hills and Bones

1941

Oil on canvas

75.6 x 101.6cm

Philadelphia Museum of Art: The Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949

© Philadelphia Museum of Art

The arid desert landscape of New Mexico, where O’Keeffe had a house at Ghost Ranch, was a constant inspiration for her paintings. Red Hills and Bones depicts the distinctive red hills of the local area, exaggerating their colours in contrast to the white animal bones, which in turn mirror the ridges of the landscape in the background.

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Black Place III

1944

Oil on canvas

36 x 40 in.

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum (Santa Fe, USA)

© 2016 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/DACS, London

“The Black Place is about one hundred and fifty miles from Ghost Ranch and as you come to it over a hill, it looks like a mile of elephants – grey hills all about the same size with almost white sand at their feet. When you get into the hills you find that all the surfaces are evenly crackled so walking and climbing are easy…

I don’t remember what I painted on my first trip over there. I have gone so many times. I always went prepared to camp. There was a fine little spot quite far off the road with thick old cedar trees with handsome trunks – not very tall but making good spots of shade…

Such a beautiful, untouched lonely-feeling place – part of what I call the Far Away.”

Georgia O’Keeffe in Georgia O’Keeffe (A Studio Book), published by Viking Press, New York, 1976

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Black Place Green

1949

Oil on canvas

94.6 x 117.5 cm

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/DACS 2016, collection of Jane Lombard

The black place and the white place

“I must have seen the Black Place first driving past on a trip into the Navajo country and, having seen it, I had to go back to paint – even in the heat of mid-summer. It became one of my favourite places to work … as you come to it over a hill, it looks like a mile of elephants – grey hills all about the same size.”

Two very specific locations recur frequently in O’Keeffe’s work. Their repetition allowed her to explore the various conditions of landscape through changing light and seasons, and its representation through degrees of abstraction. In one location, the ‘White Place’ – a site of grey-white cliffs in the Chama River valley – she explored the differing variations of light on the white limestone cliffs and contrasted this with vivid blue sky. In the more distant ‘Black Place’ – which is 150 miles west of Ghost Ranch – she progressively abstracted from observed, perceptual reality towards more intensely-coloured, non-naturalistic compositions, painted from memory.

In the ‘White Place’ and ‘Black Place’ paintings O’Keeffe also became more clearly engaged with seriality, obsessively returning to the same motif and working through it in its different permutations.

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

In the Patio No IV

1948

Illustration: 2016 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/ DACS, London

“Those little squares in the door paintings are tiles in front of the door; they’re really there, so you see the painting is not abstract. It’s quite realistic. I’m always trying to paint that door – I never quite get it… It’s a curse – the way I feel I must continually go on with that door. Once I had the idea of making the door larger and the picture smaller, but then the wall, the whole surface of that wonderful wall, would have been lost.”

Georgia O’Keeffe in Katherine Kuh, The Artist’s Voice: Talks with Seventeen Artists, published by Harper & Row, New York, 1961; quoted in Georgia O’Keeffe and Her Houses, 2012.

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Pelvis Series, Red with Yellow

1945

Oil on canvas

91.8 x 122.2cm

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. Extended loan, private collection

© 2016 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/ DACS, London

During her long stays in her Ghost Ranch house in New Mexico, O’Keeffe picked up bones from the desert floor and began to paint them. This piece is part of a series of paintings she made to show the sky as seen through the various holes in a pelvis bone she found.

“When I started painting the pelvis bones I was most interested in the holes in the bones – what I saw through them – particularly the blue from holding them up against the sky… They were the most beautiful thing against the Blue – that Blue that will always be there as it is now after all man’s destruction is finished.”

~ Georgia O’Keeffe

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Pelvis Series

1947

Oil on canvas

101.6 x 121.9cm

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/DACS 2016, courtesy Eykyn Maclean

The series: Abiquiú Patios, pelvis bones and cottonwood trees

“When I started painting the pelvis bones I was most interested in the holes in the bones – what I saw through them – particularly the blue from holding them up in the sun against the sky… They were most beautiful against the Blue – that Blue that will always be there as it is now after all man’s destruction is finished.”

Working in series became an increasingly evident approach for O’Keeffe in the 1940s and 1950s. She developed three series simultaneously during this period, each one exploring a path towards abstraction, in parallel to developments in abstract painting in New York. They were also made against the backdrop of the Second World War (referred to in the quotation above), and of Stieglitz’s death in 1946. At the same time O’Keeffe’s work was becoming increasingly prominent, with major solo exhibitions at The Art Institute of Chicago and the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

O’Keeffe continued her investigation of bones, using pelvis bones rather than skulls, held up against the sky, or viewing a distant landscape through an aperture in the bone. Another motif was the patio of O’Keeffe’s house at Abiquiú, her second New Mexico home, with its distinctive door presented in varying degrees of naturalism and abstraction. Lastly the series of cottonwood trees reveals a more painterly approach to the serialised motif.

Photograph of the Chama River, New Mexico, taken by Georgia O’Keeffe

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/DACS 2016

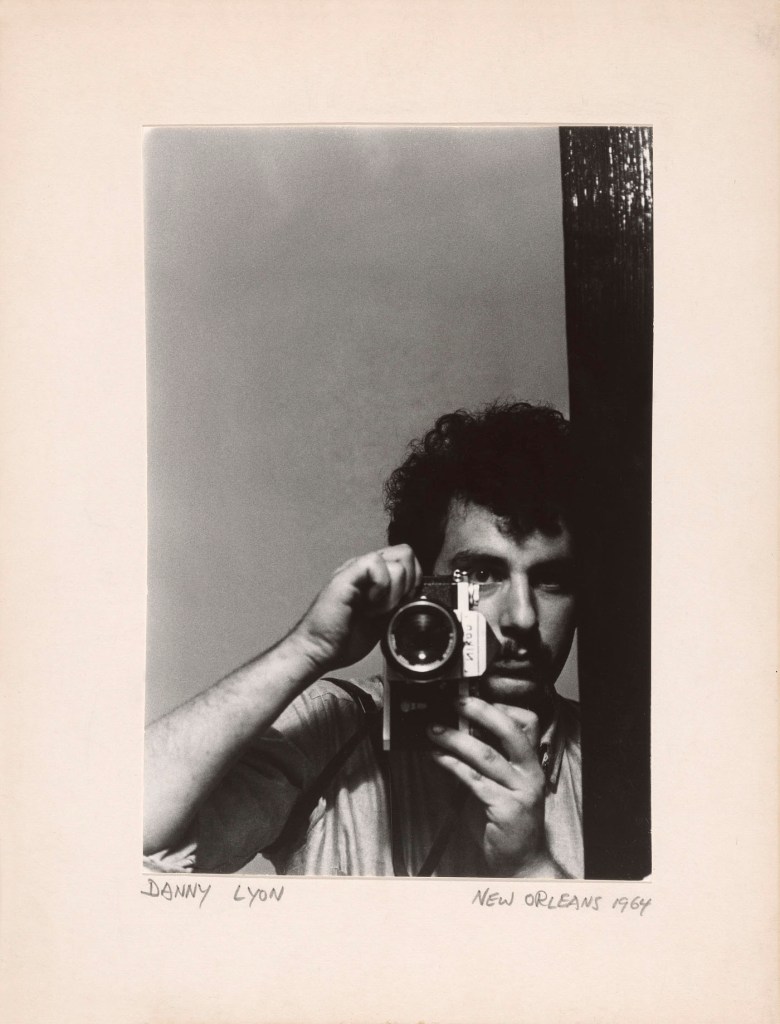

Tony Vaccaro (American, 1922-2022)

Georgia O’Keeffe, Taos Pueblo, New Mexico 1960

1960

Gelatin silver print on paper

16.7 x 23.5cm

Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, VA; photo courtesy Michael A. Vaccaro Studios

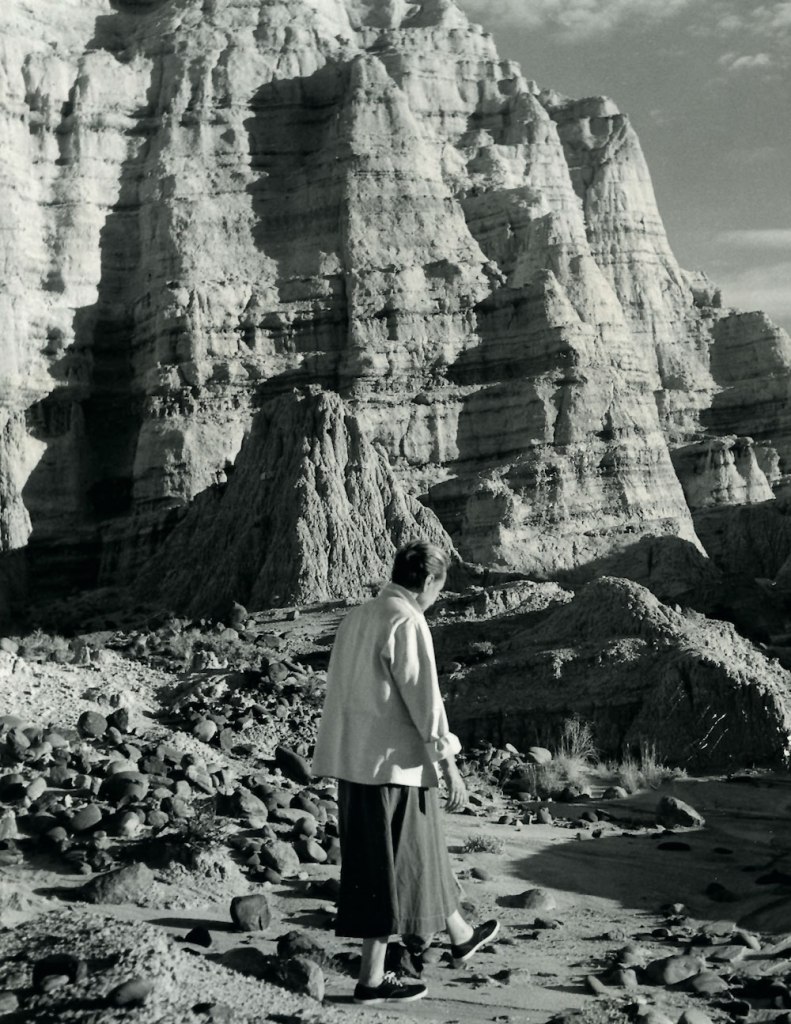

Todd Webb (American, 1905-2000)

Georgia O’Keeffe walking at the White Place, New Mexico, 1957

1957

© Estate of Todd Webb, Portland, Maine, USA

The Southwest

“Where I was born and where and how I have lived is unimportant. It is what I have done with where I have been that should be of interest.”

O’Keeffe’s engagement with the Southwest was deep and enduring. This room includes drawings and sketches that reveal aspects of her working method as she immersed herself within the landscape or worked back in one of her two houses and their respective studios. It also includes photographs of O’Keeffe taken by Stieglitz in New York State, but with attributes that place her in the Southwest such as Native American blankets and her car – a sign of her independence. Other photographs are by her close friend Ansel Adams who shared her fascination with the Southwest, its landscape and cultures.

From her arrival in New Mexico and spanning the 1930s and 1940s, O’Keeffe also made a number of paintings of Native American ‘kachinas’ – figures of spirit beings carved in wood or modelled in clay and painted. These works make clear O’Keeffe’s awareness of the indigenous Native American cultures of the region and show her fascination with their ritual life. Painting the objects was for her a way of painting the country

Late abstracts and skyscapes

“One day when I was flying back to New Mexico, the sky below was a most beautiful solid white. It looked so secure that I thought I could walk right out on it to the horizon if the door opened. It was so wonderful I couldn’t wait to be home to paint it.”

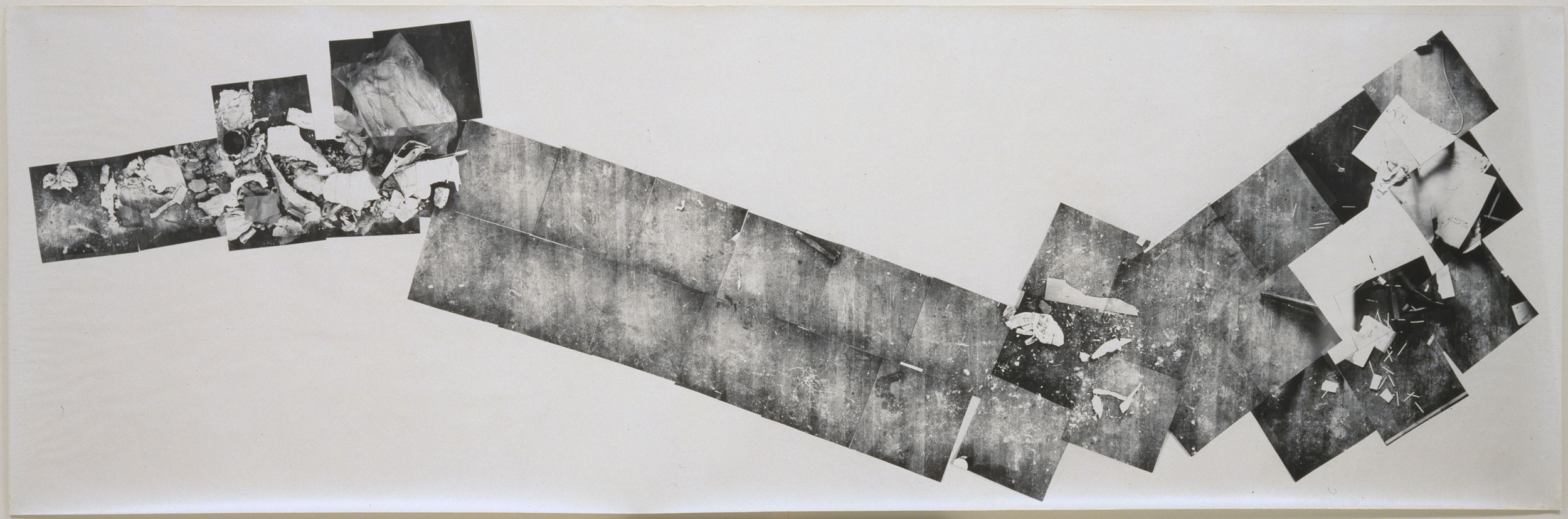

This final room shows O’Keeffe’s late paintings of the 1950s and 1960s, focusing on two series that are inspired by aeroplane journeys she took in her later years. One series of the late 1950s takes its cue primarily from aerial views of rivers, which O’Keeffe transformed to create lyrical abstractions that hark back to her earliest works in oil, watercolour and charcoal from the 1910s. A second series of stylised near-abstractions represents the view from a plane over the clouds. Both reveal her awareness of contemporary abstract painting, particularly colour field painting, then dominating American art. O’Keeffe’s works were always rooted in a direct experience of the landscape and her emotional connection to it, and continued to be so until the end of her career.

“It is breathtaking as one rises up over the world one has been living in… It is very handsome way off into the level distance … like some marvellous rug patterns of maybe “Abstract Paintings”.”

Text from the Tate Modern website

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

From the River – Pale

1959

Oil on canvas

Photograph: 2016 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/ DACS, London

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Winter Road I

1963

Oil on canvas

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/DACS 2016

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Sky Above Clouds IV

1965

Oil on canvas

243.8 x 731.5cm

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/DACS 2016, courtesy Art Institute of Chicago

Tate Modern

Bankside

London SE1 9TG

United Kingdom

Opening hours:

Daily 10.00 – 18.00

![Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946) 'Untitled [O'Keeffe with sketchpad and watercolors]' 1918 from the exhibition 'Georgia O'Keeffe' at Tate Modern, London, July - Oct, 2016 Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946) 'Untitled [O'Keeffe with sketchpad and watercolors]' 1918 from the exhibition 'Georgia O'Keeffe' at Tate Modern, London, July - Oct, 2016](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/georgia_okeeffe_by_stieglitz_1918-web.jpg)

![Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987) 'Silver Liz [Ferus Type]' 1963 Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987) 'Silver Liz [Ferus Type]' 1963](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/exhi032777-web.jpg?w=1021)

![Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987) 'Screen Test: Edie Sedgwick [ST308]' 1965 Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987) 'Screen Test: Edie Sedgwick [ST308]' 1965](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/exhi037605-web.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.