Exhibition dates: 8th February – 2nd November 2014

The Edward Steichen Photography Galleries, third floor

Curators: Organised by Quentin Bajac, The Joel and Anne Ehrenkranz Chief Curator, with Lucy Gallun, Assistant Curator, Department of Photography

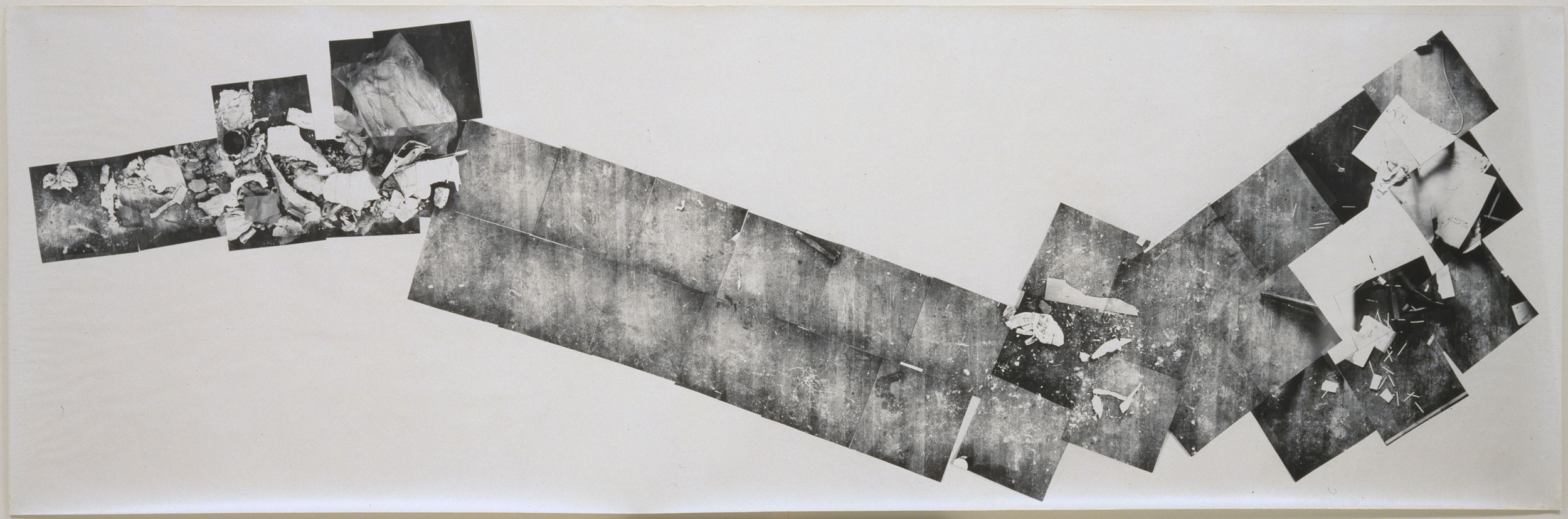

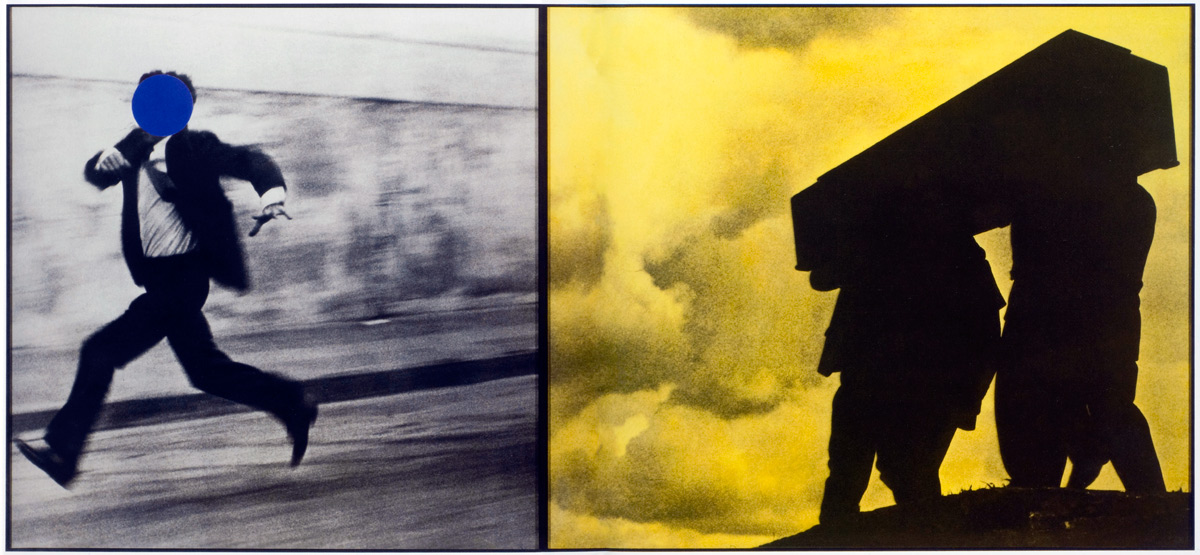

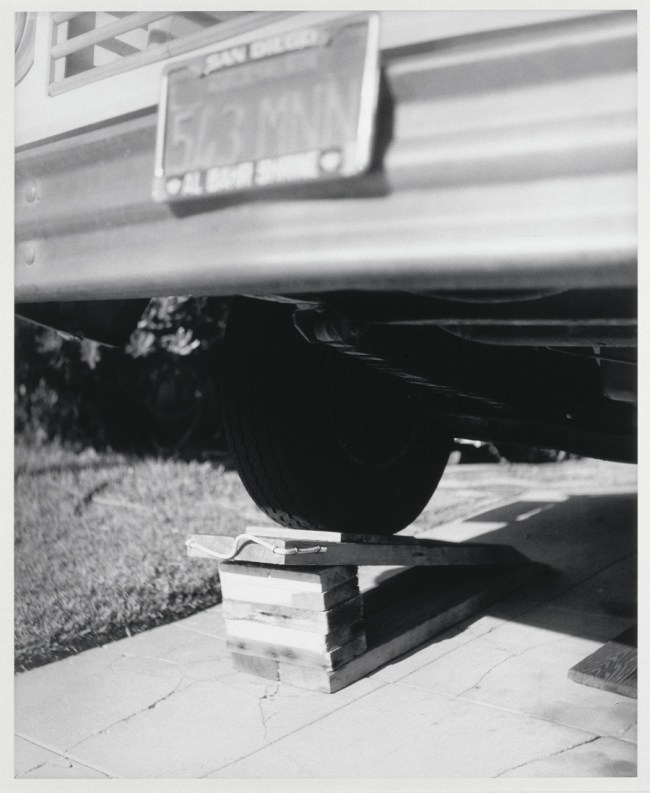

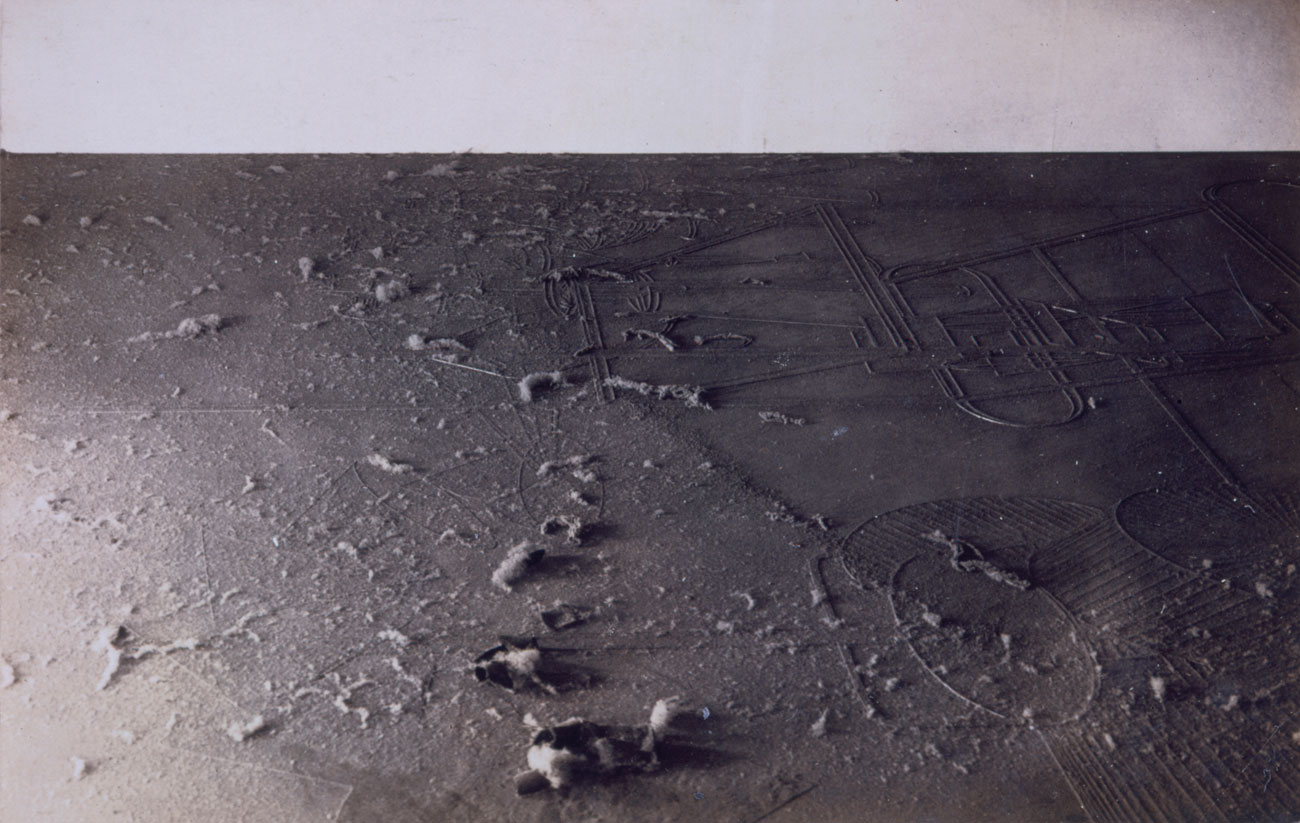

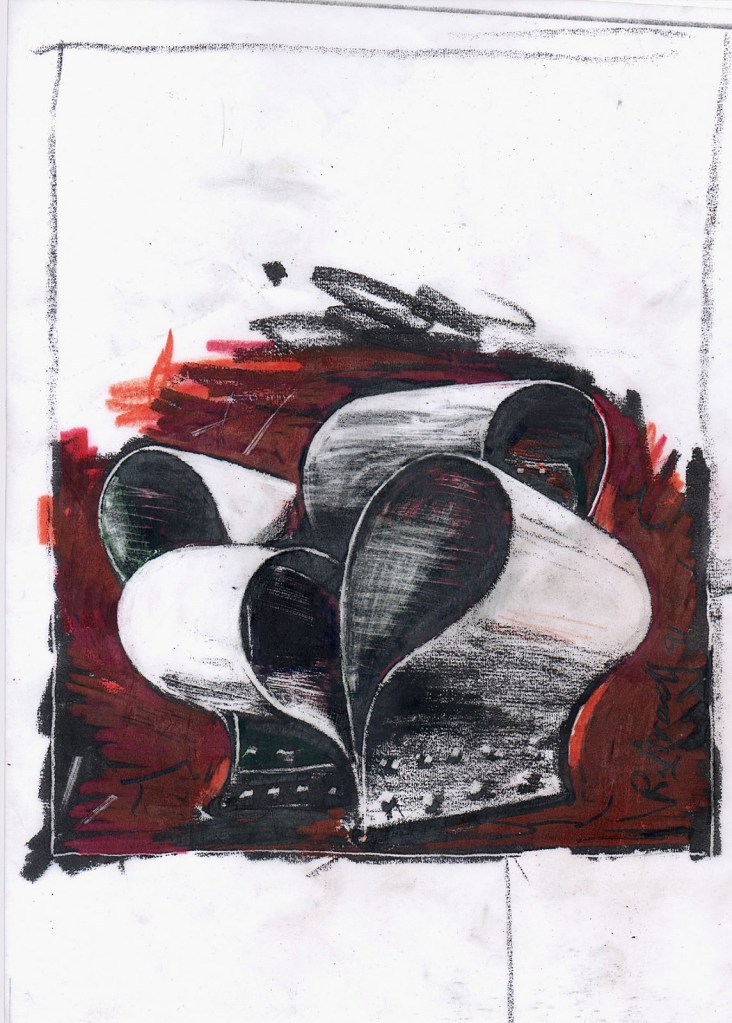

Bruce Nauman (American, b. 1941)

Composite Photo of Two Messes on the Studio Floor

1967

Gelatin silver print

40 1/2″ x 10′ 3″ (102.9 x 312.4cm)

Gift of Philip Johnson

Museum of Modern Art Collection

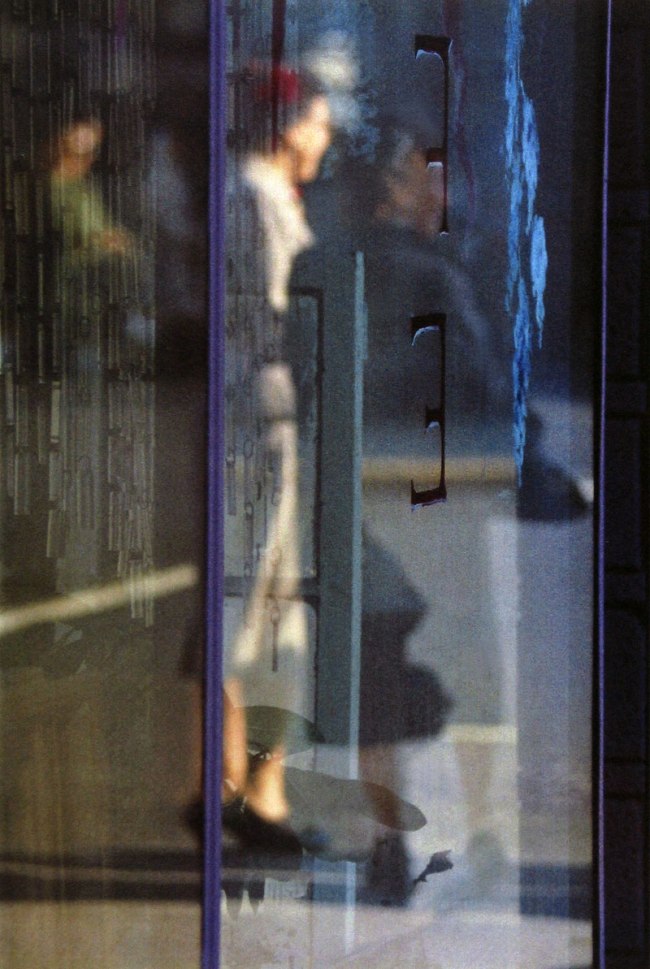

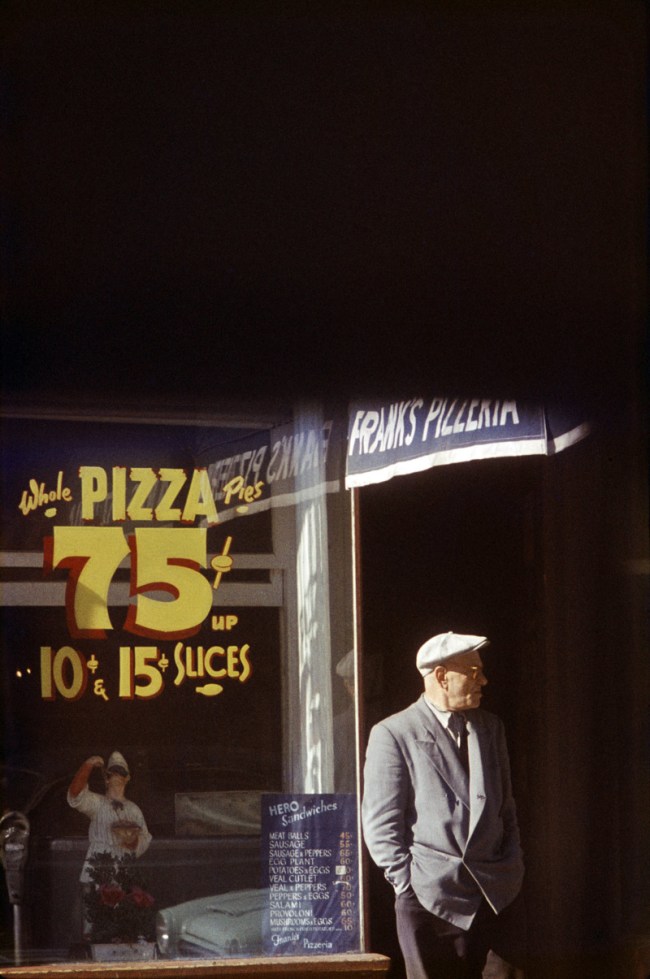

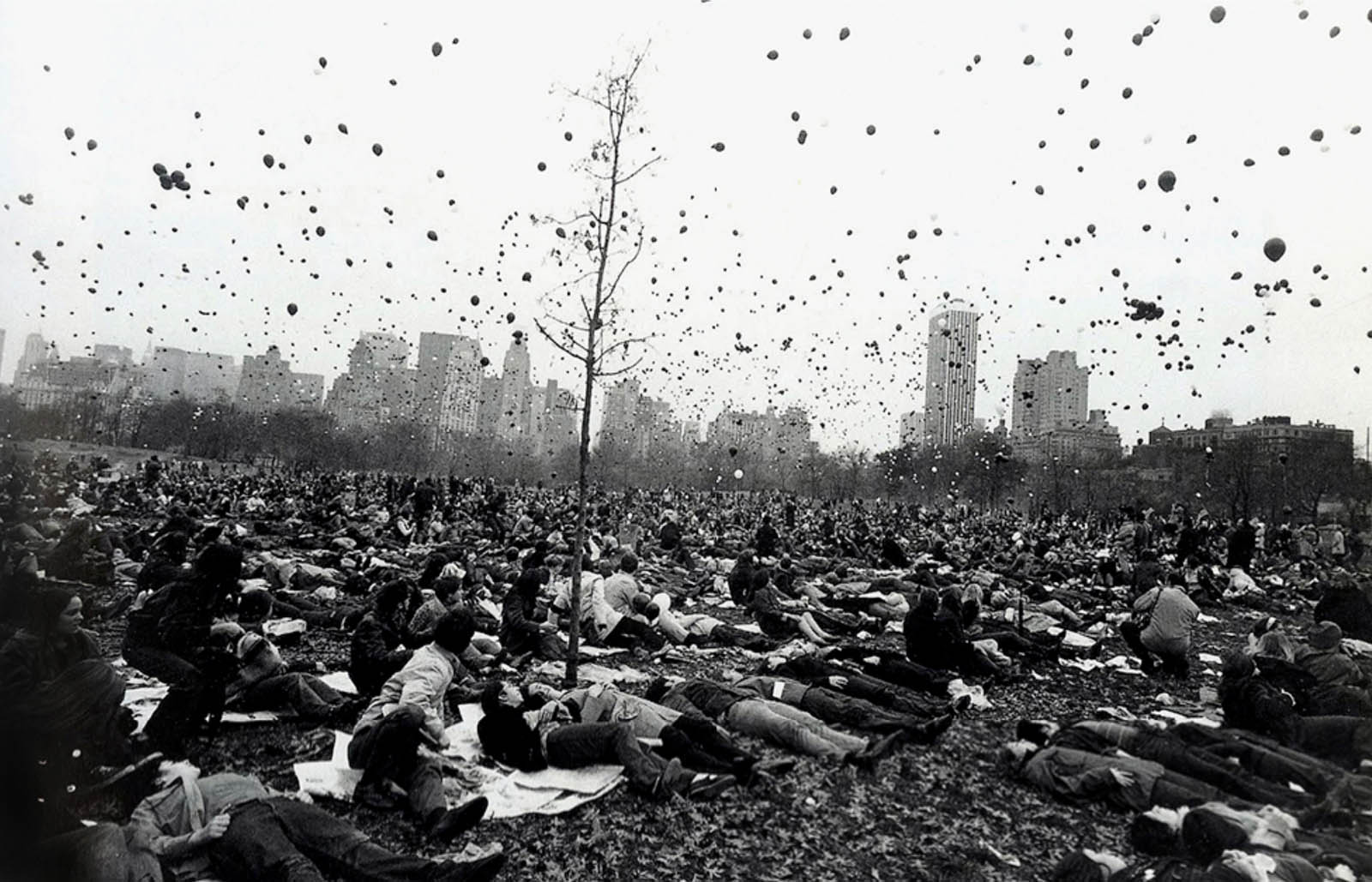

A bumper two part posting on this fascinating, multi-dimensional subject: photographic practices in the studio, which may be a stage, a laboratory, or a playground. The exhibition occupies all MoMA’s six photography galleries, each gallery with its own sub theme, namely, Surveying the Studio, The Studio as Stage, The Studio as Set, A Neutral Space, Virtual Spaces and The Studio, from Laboratory to Playground.

The review of this exhibition “When a Form Is Given Its Room to Play” by Roberta Smith on the New York Times website (6th February 2014) damns with faint praise. The show is a “fabulous yet irritating survey” which “dazzles but often seems slow and repetitive.” Smith then goes on to list the usual suspects: “And so we get professional portraitists, commercial photographers, lovers of still life, darkroom experimenters, artists documenting performances and a few generations of postmodernists, dead and alive, known and not so, exploring the ways and means of the medium. This adds up to plenty to see: around 180 images from the 1850s to the present by some 90 photographers and artists. The usual suspects here range from Julia Margaret Cameron to Thomas Ruff, with Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, Lucas Samaras, John Divola and Barbara Kasten in between.” There are a few less familiar and postmodern artists thrown in for good measure, but all is “dominated by black-and-white images in an age when colour reigns.” The reviewer then rightly notes the paucity of “postmodern photography of the 1980s, much of it made by women, that did a lot to reorient contemporary photo artists to the studio. It is a little startling for an exhibition that includes so many younger artists dealing with the artifice of the photograph (Ms. Belin, for example) to represent the Pictures Generation artists with only Cindy Sherman, James Casebere and (in collaboration with Allan McCollum) Laurie Simmons” before finishing on a positive note (I think!), noting that the curators “had aimed for a satisfying viewing experience, which, these days, is something to be grateful for.”

SOMETHING TO BE GRATEFUL FOR… OH, TO BE SO LUCKY IN AUSTRALIA!

Just to have the opportunity to view an exhibition of this quality, depth and breadth of concept would be an amazing thing. Even a third of the number of photographs (say 60 works) that address this subject at any one of the major institutions around Australia would be fantastic but, of that, there is not a hope in hell.

Think Marcus, think… when was the last major exhibition, I mean LARGE exhibition, at a public institution in Australia that actually addressed specific ISSUES and CONCEPTS in photography (such as this), not just putting on monocular exhibitions about an artists work or exhibitions about a regions photographs? Ah, well… you know, I can’t really remember. Perhaps the American Dreams exhibition at Bendigo Art Gallery, but that was a GENERAL exhibition about 20th century photography with no strong investigative conceptual theme and it was imported from George Eastman House.

Here in Australia, all we can do is look from afar, purchase the catalogue and wonder wistfully what the exhibition actually looks like and what we are missing out on. MoMA sent me just 10 images media images. I have spent hours scouring the Internet for other images to fill the void of knowledge and vision (and then cleaning those sometimes degraded images), so that those of us not privileged enough to be able to visit New York may gain a more comprehensive understanding of what this exhibition, and this multi-faceted dimension of photography, is all about. It’s a pity that our venerable institutions and the photography curators in them seem to have had a paucity of ideas when it comes to expounding interesting critiques of the medium over the last twenty years or so. What a missed opportunity.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to MoMA for allowing me to publish six of the photographs in the posting. The rest of the images were sourced from the Internet. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Installation view of the exhibition A World of Its Own: Photographic Practices in the Studio at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York

Surveying the Studio

Uta Barth (American, b. 1958)

Sundial (07.13)

2007

Chromogenic colour prints

each 30 x 28 1/4″ (76.2 x 71.8cm)

The Photography Council Fund

Museum of Modern Art Collection

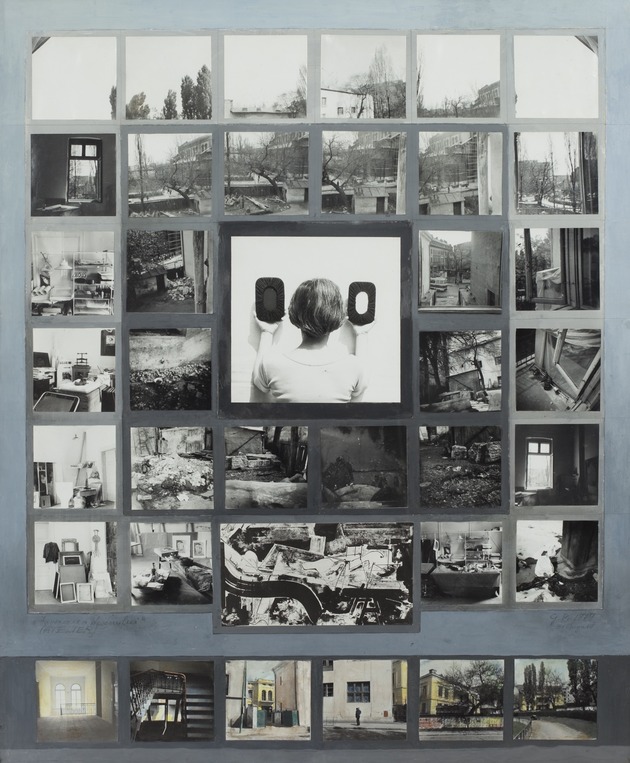

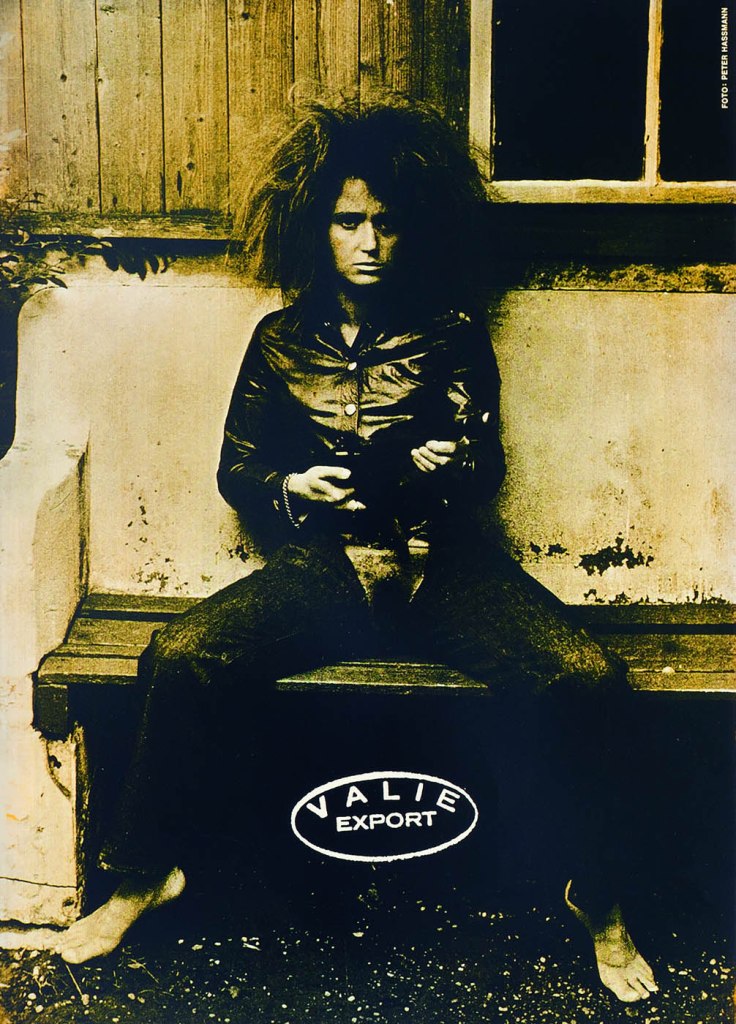

Geta Brâtescu (Romanian, 1926-2018)

The Studio. Invocation of the Drawing (L’Atelier. Invocarea desenului)

1979

Gelatin silver prints with tempera on paper

33 1/16 x 27 9/16″ (84 x 70cm)

Modern Women’s Fund

Museum of Modern Art Collection

Geta Brătescu was a Romanian visual artist with works in drawing, collage, photography, performance, illustration and film. In 2008, Brătescu received an honorary doctorate from the Bucharest National University of Arts for “her outstanding contributions to the development of contemporary Romanian art”. Brătescu was artistic director of literature and art magazine Secolul 21. A major retrospective of her work was held at the National Museum of Art of Romania in December 1999. In 2015 Brătescu’s first UK solo exhibition was held at the Tate Liverpool. In 2017, she was selected to represent Romania at the 57th Venice Biennale.

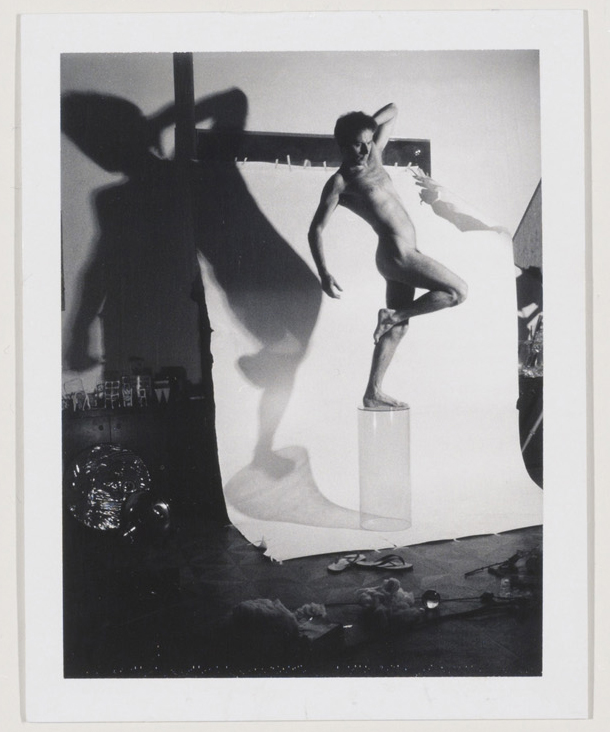

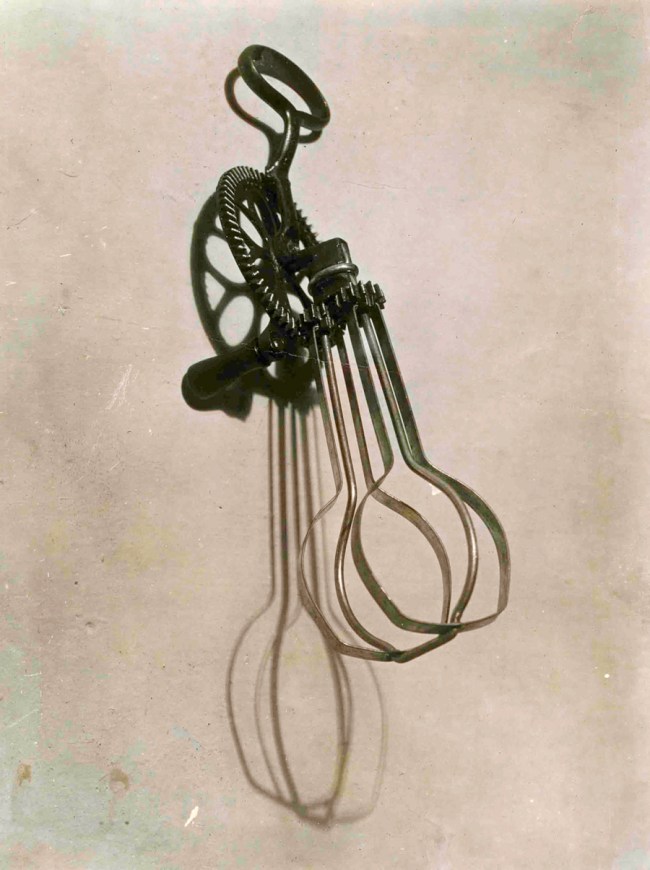

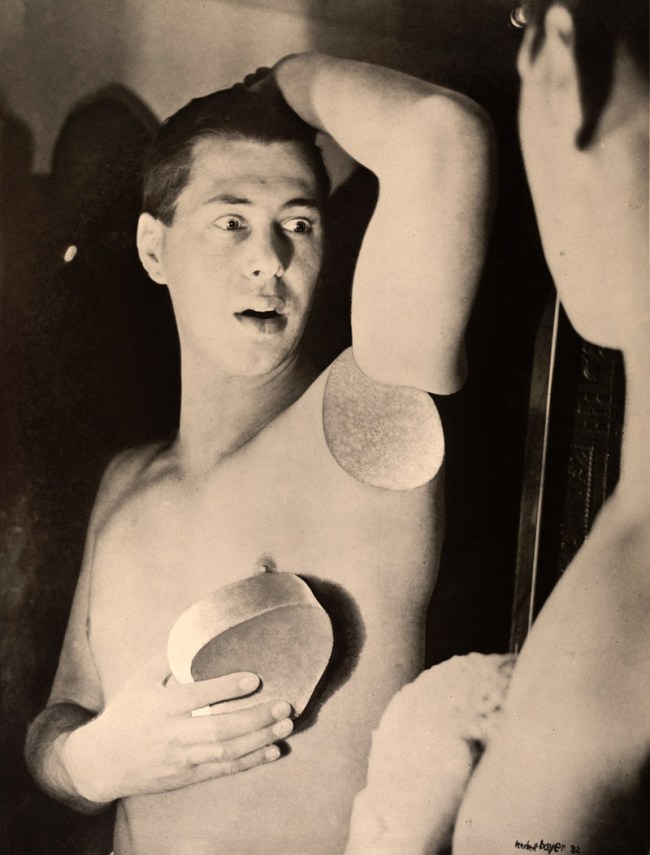

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Laboratory of the Future

1935

Gelatin silver print

9 1/16 x 7″ (23.1 x 17.8cm)

Gift of James Johnson Sweeney

Museum of Modern Art Collection

Charles Sheeler (American, 1883-1965)

Cactus and Photographer’s Lamp, New York

1931

Gelatin silver print

9 1/2 x 6 5/8″ (23.5 x 16.6cm)

Gift of Samuel M. Kootz

Museum of Modern Art Collection

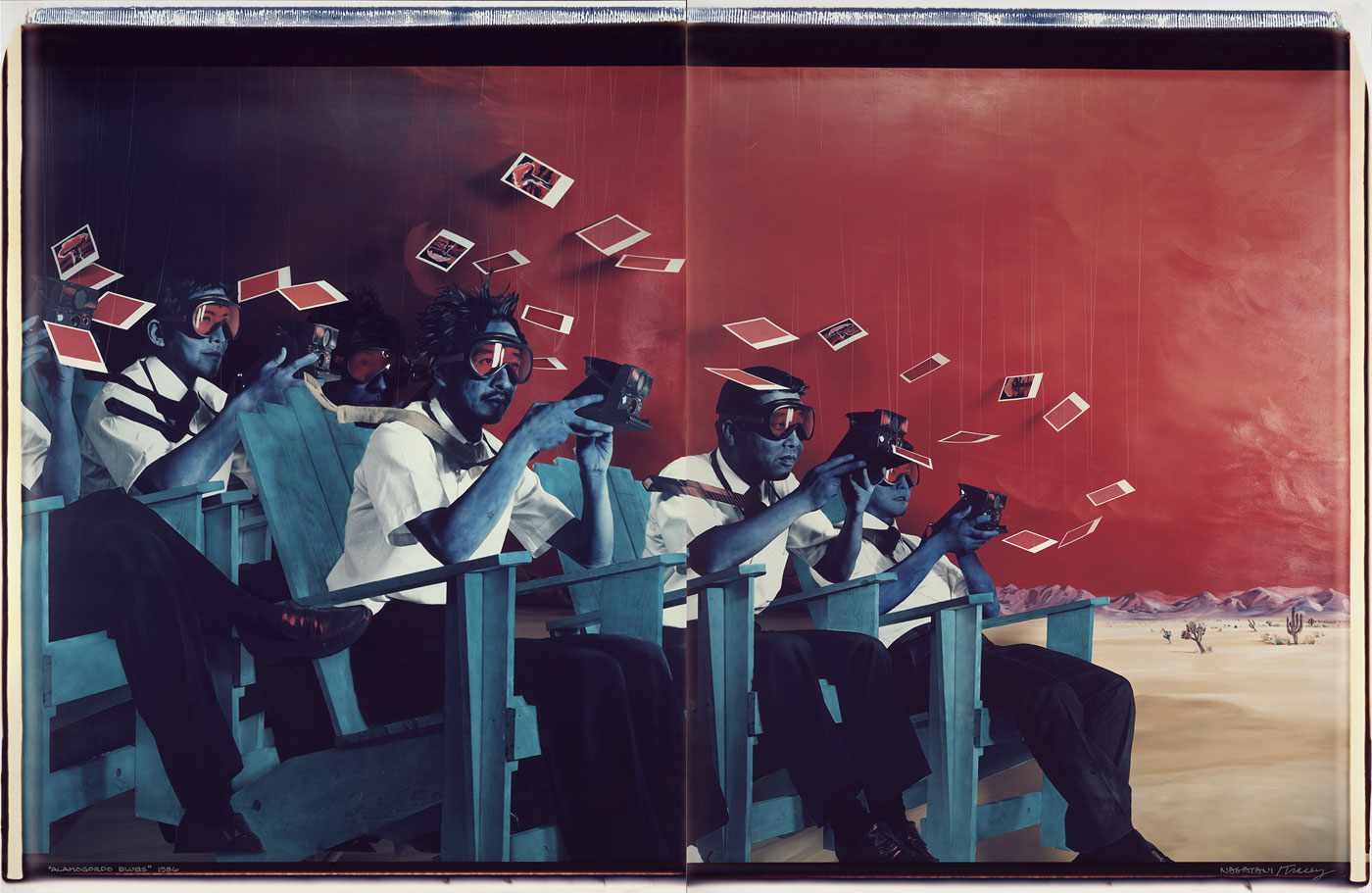

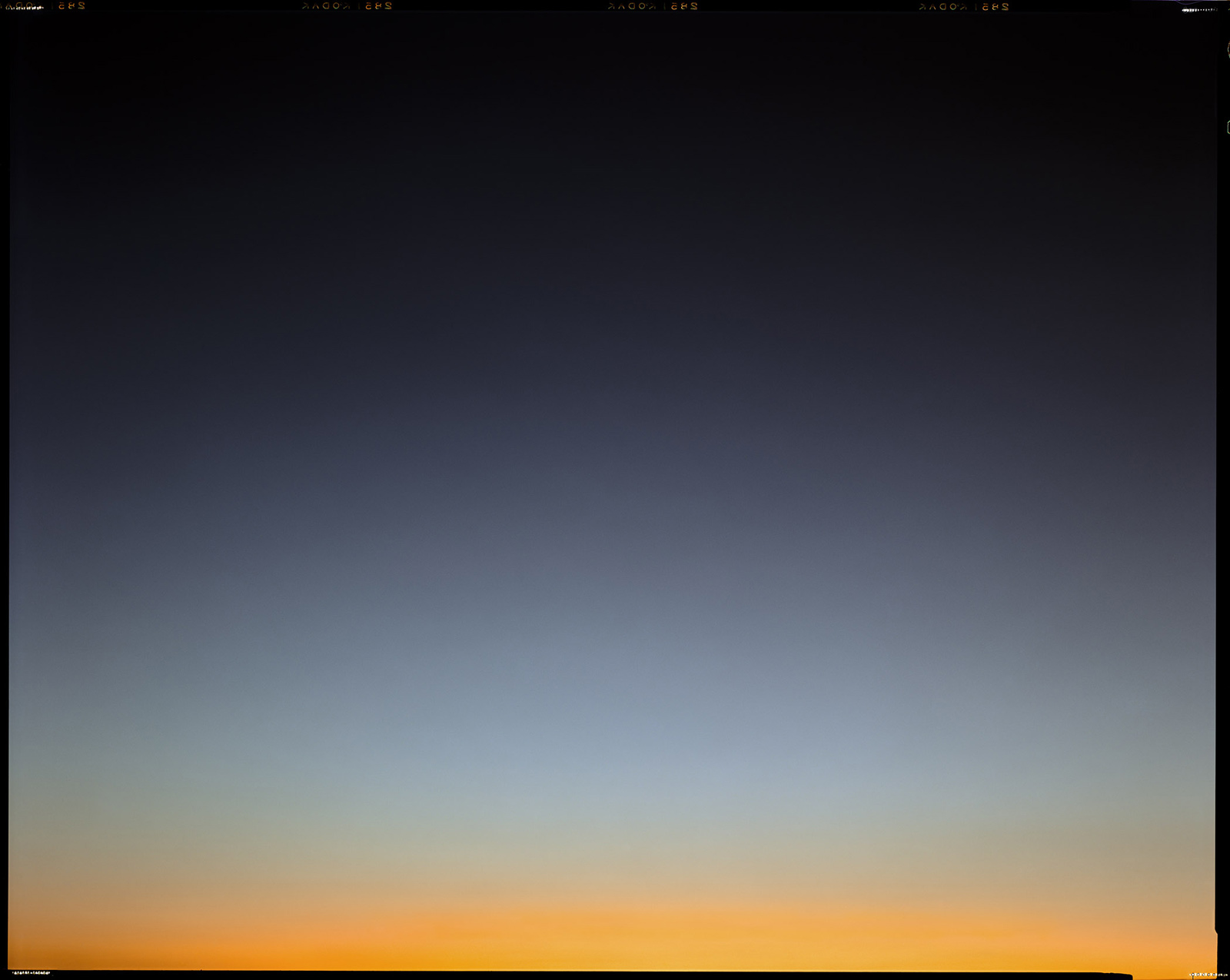

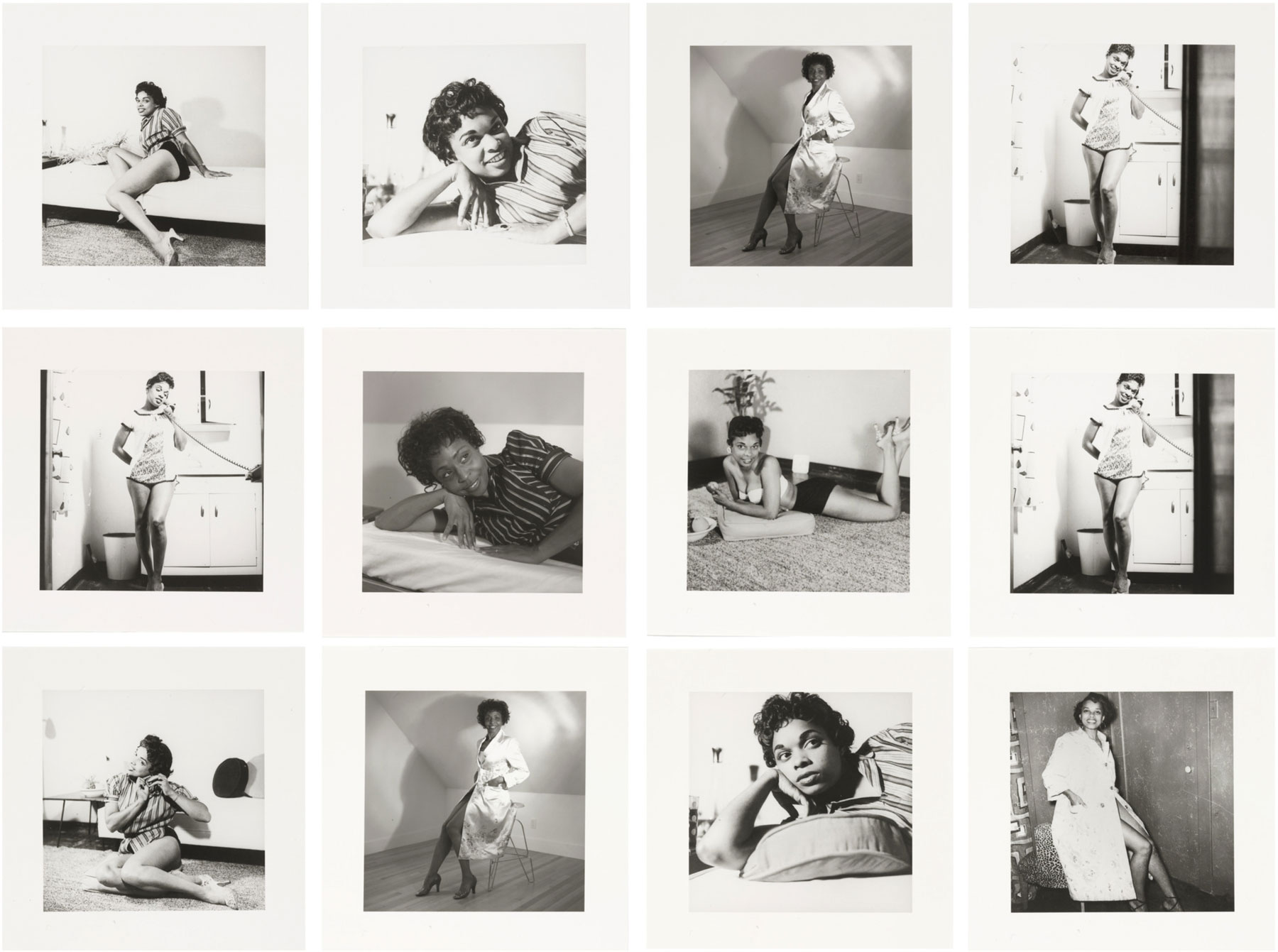

Bringing together photographs, films, videos, and works in other mediums, A World of Its Own: Photographic Practices in the Studio examines the ways in which photographers and artists using photography have worked and experimented within the four walls of the studio space, from photography’s inception to today. Featuring both new acquisitions and works from the Museum’s collection that have not been on view in recent years, A World of Its Own includes approximately 180 works, by approximately 90 artists, such as Berenice Abbott, Uta Barth, Zeke Berman, Karl Blossfeldt, Constantin Brancusi, Geta Brătescu, Harry Callahan, Robert Frank, Jan Groover, Barbara Kasten, Man Ray, Bruce Nauman, Paul Outerbridge, Irving Penn, Adrian Piper, Edward Steichen, William Wegman, and Edward Weston.

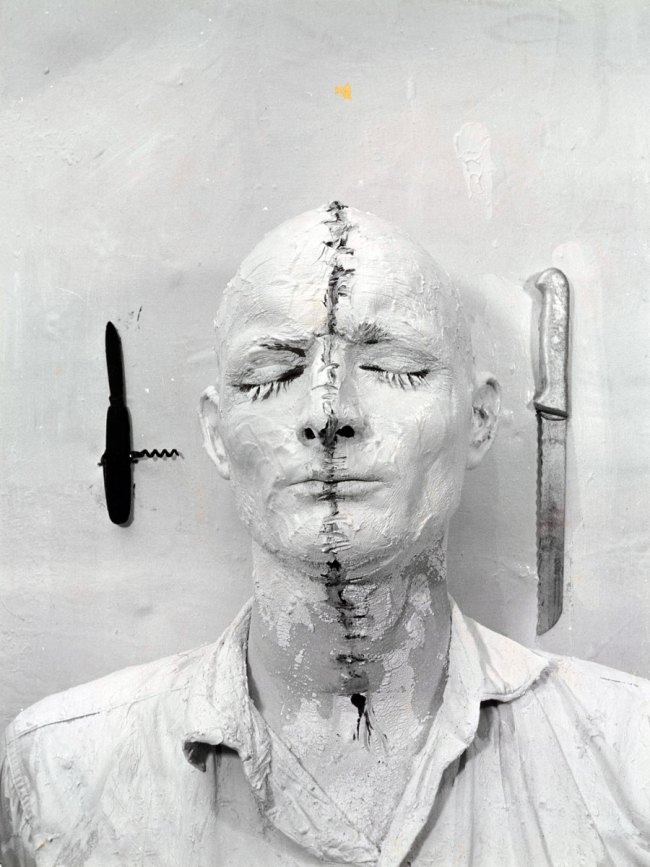

The exhibition considers the various roles played by the photographer’s studio as an autonomous space; depending on the time period, context, and the individual motivations (commercial, artistic, scientific) and sensibilities of the photographer, the studio may be a stage, a laboratory, or a playground. Organised thematically, the display unfolds in multiple chapters. Throughout the 20th century, artists have explored their studio spaces using photography, from the use of composed theatrical tableaux (in photographs by Julia Margaret Cameron or Cindy Sherman) to neutral, blank backdrops (Richard Avedon, Robert Mapplethorpe); from the construction of architectural sets within the studio space (Francis Bruguière, Thomas Demand) to chemical procedures conducted within the darkroom (Walead Beshty, Christian Marclay); and from precise recordings of time and motion (Eadweard Muybridge, Dr. Harold E. Edgerton) to amateurish or playful experimentation (Roman Signer, Peter Fischli / David Weiss). A World of Its Own offers another history of photography, a photography created within the walls of the studio, and yet as groundbreaking and inventive as its seemingly more extroverted counterpart, street photography.”

Text from the MoMA website

The exhibition is divided into 6 themes each with its own gallery space:

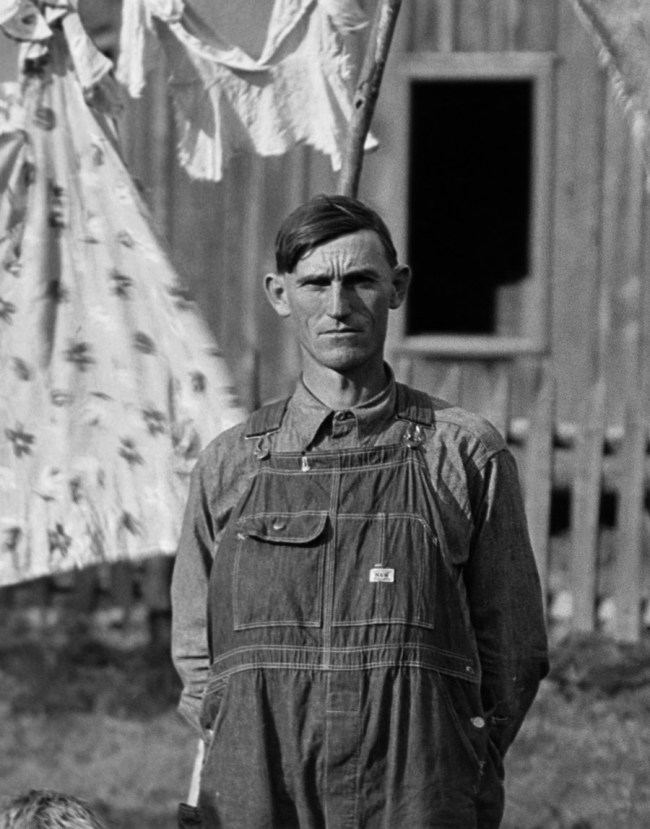

1/ Surveying the Studio

2/ The Studio as Stage

3/ The Studio as Set

4/ A Neutral Space

5/ Virtual Spaces

6/ The Studio, from Laboratory to Playground

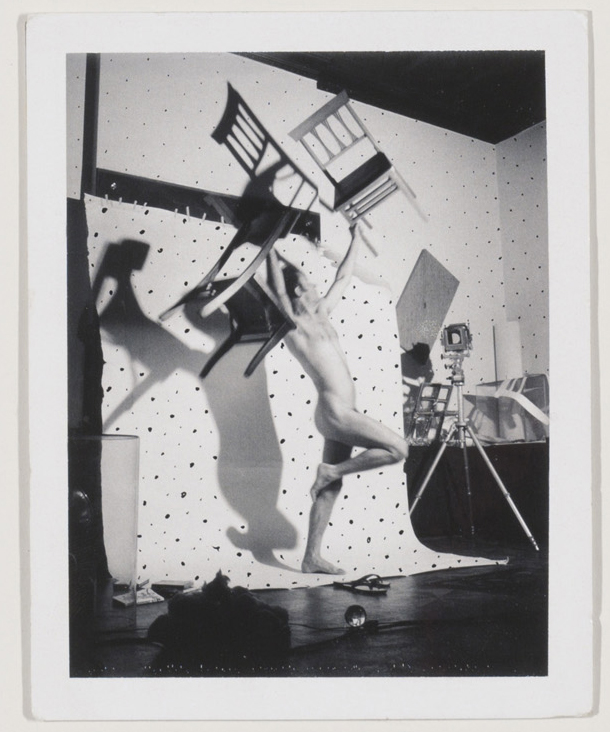

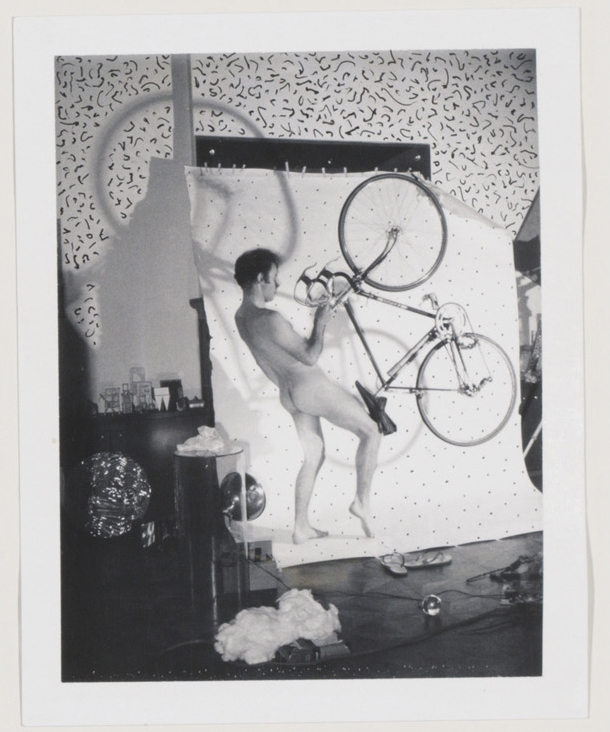

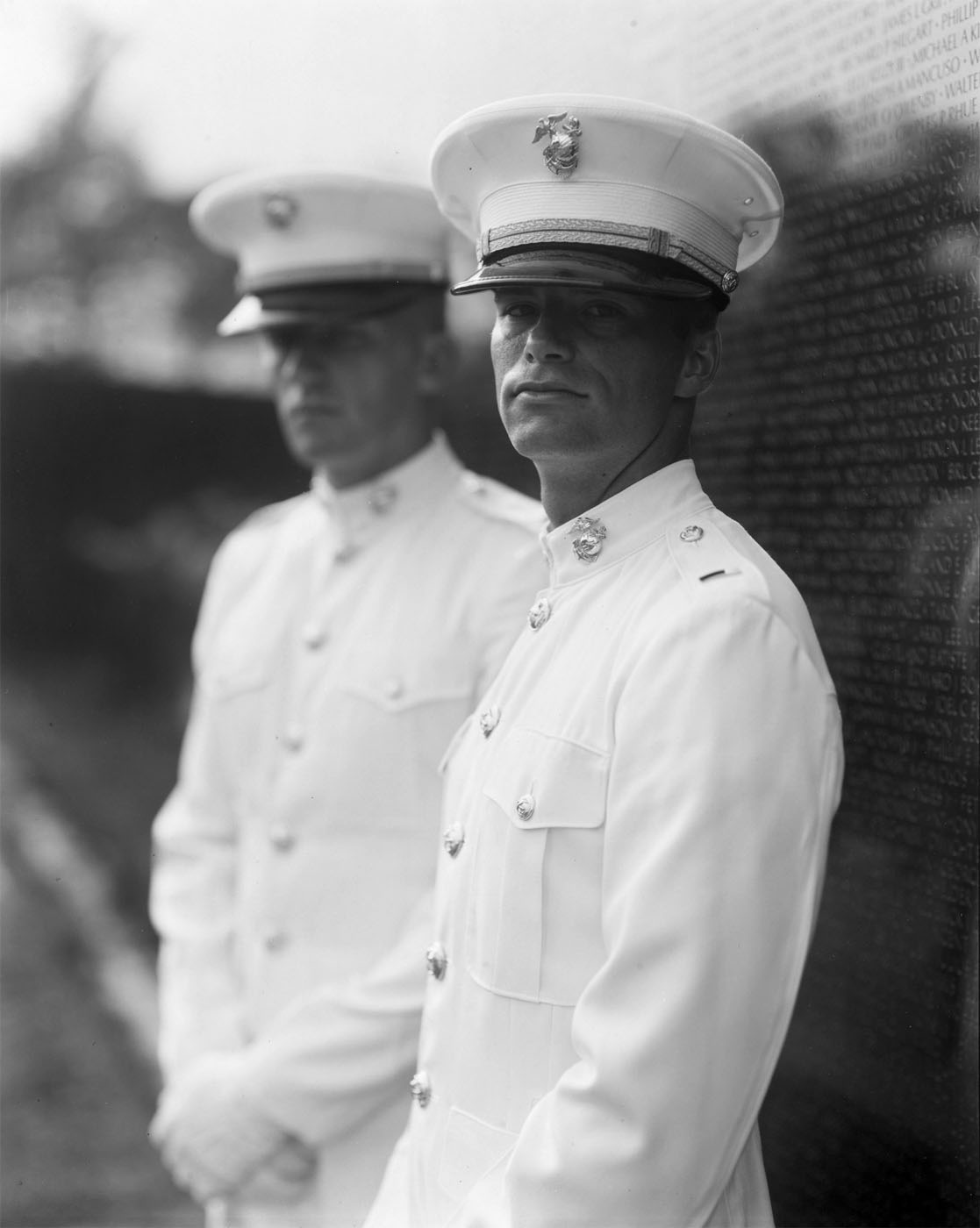

The Studio as Stage

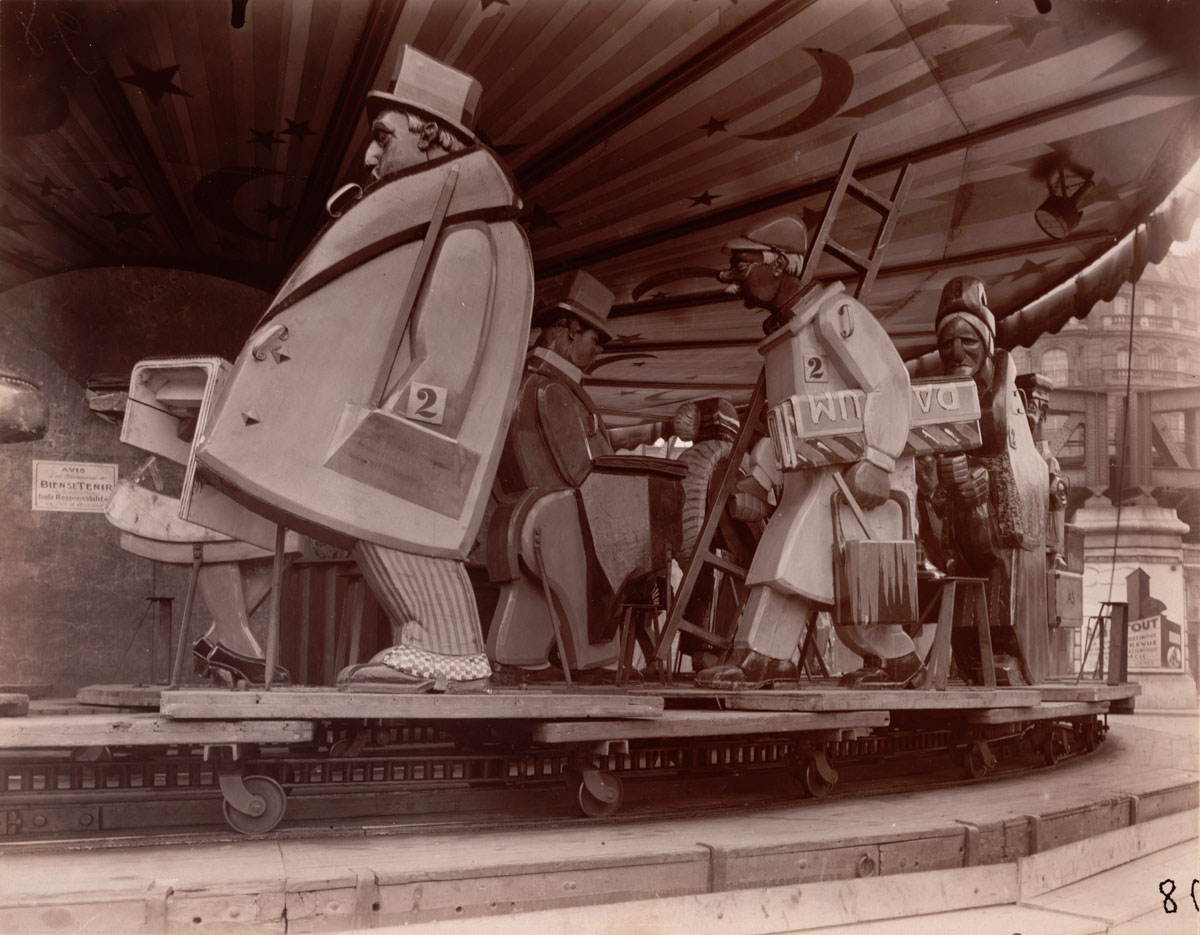

Unidentified photographer (French?)

Untitled

c. 1855

Albumen silver print from a wet-collodion glass negative

9 3/16 × 6 1/8″ (23.4 × 15.5cm)

Gift of Paul F. Walter

Museum of Modern Art Collection

Cecil Beaton (British, 1904-1980)

Edith Sitwell

1927

Gelatin silver print

11 1/2 × 9 5/8″ (29.3 × 24.5 cm)

Gift of Paul F. Walter

Museum of Modern Art Collection

© 2022 Estate of Cecil Beaton

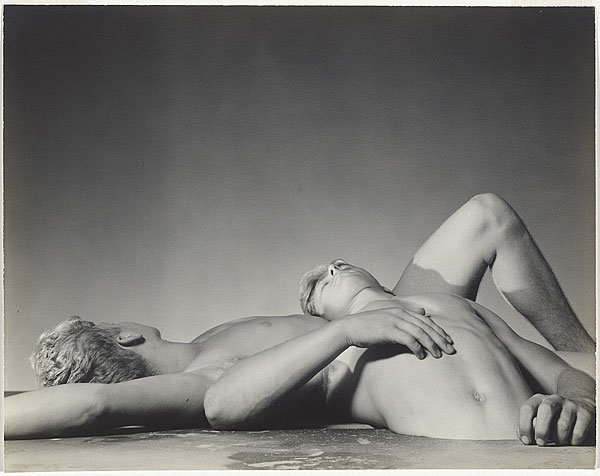

George Platt Lynes (American, 1907-1955)

Untitled

1941

Gelatin silver print

7 5/8 x 9 5/8″ (19.2 x 24.4cm)

Anonymous gift

Museum of Modern Art Collection

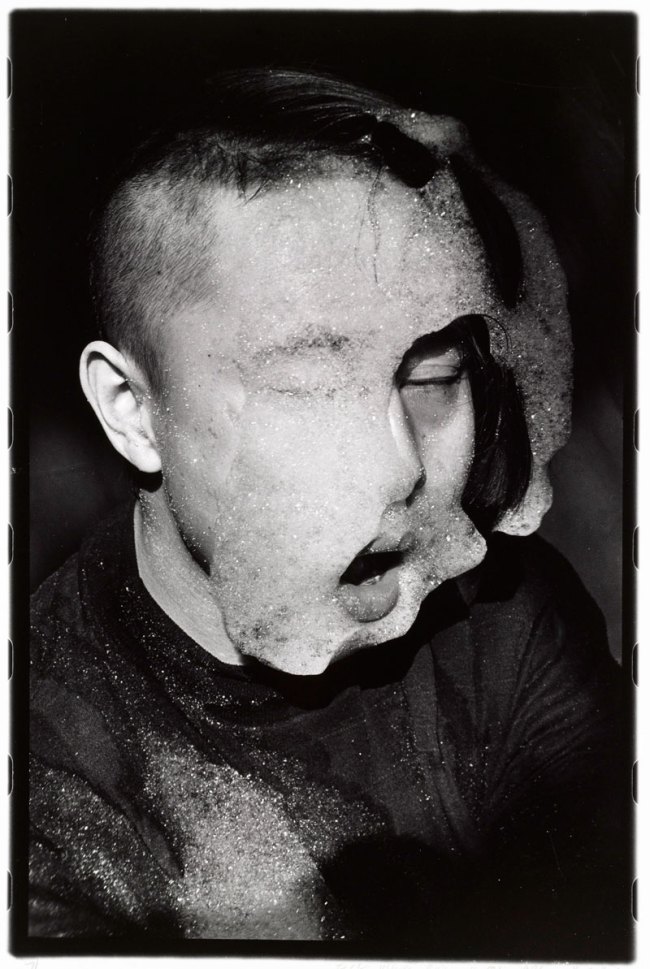

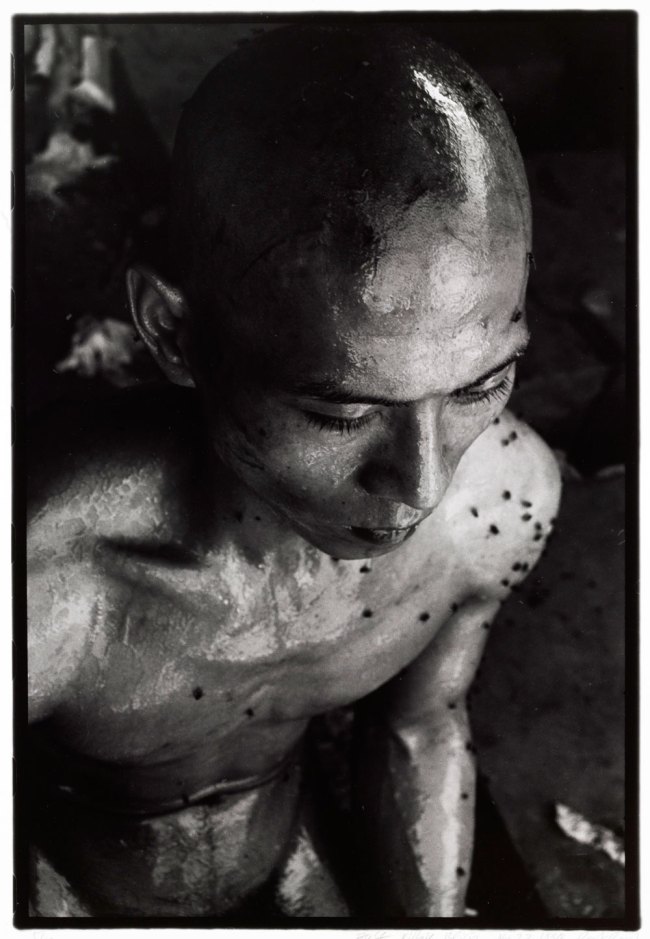

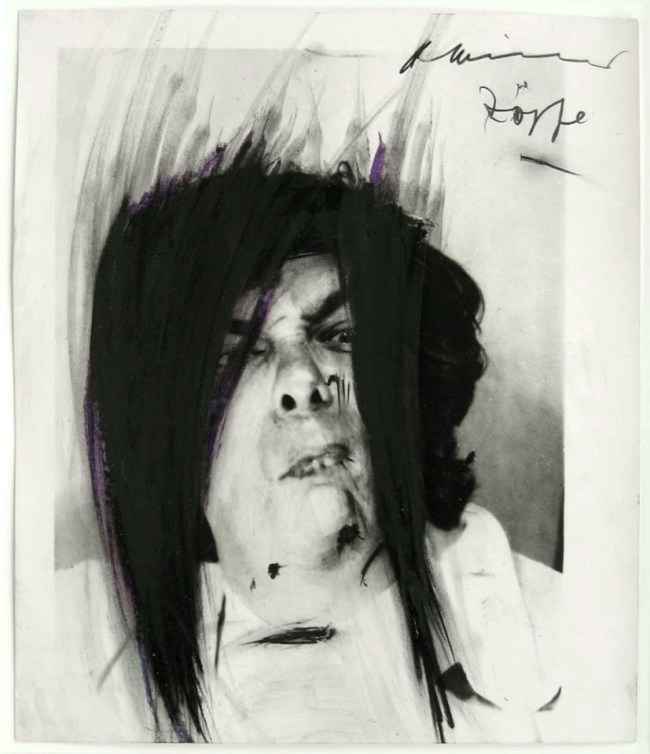

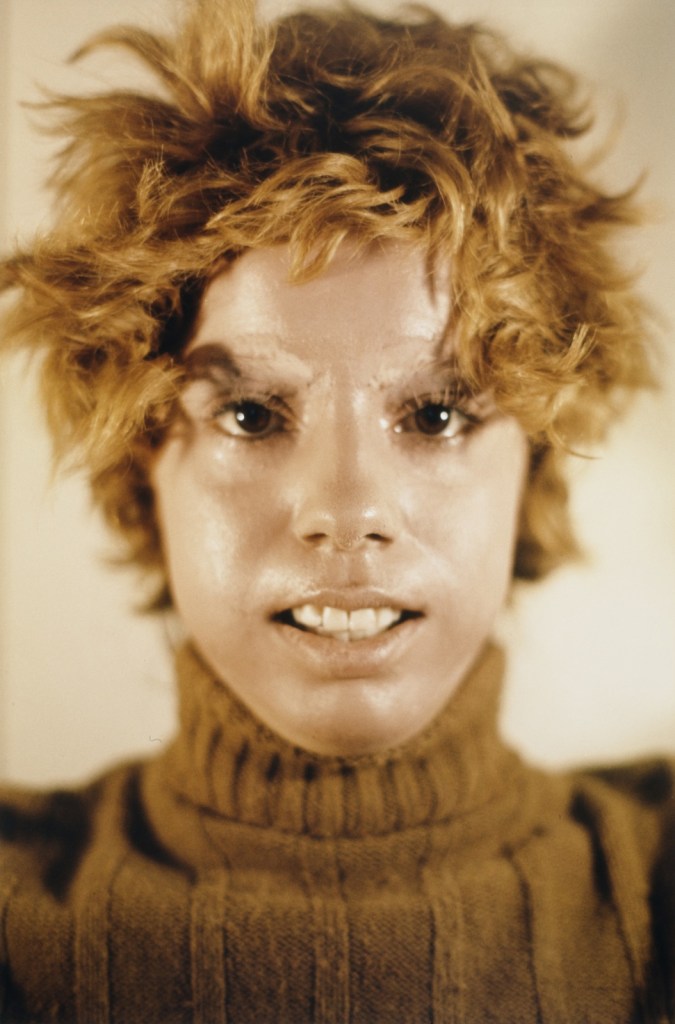

Lucas Samaras (American born Greece, 1936-2024)

Auto Polaroid

1969-1971

Eighteen black-and-white instant prints (Polapan), with hand-applied ink

Each 3 3/4 x 2 15/16″ (9.5 x 7.4cm)

Overall 14 5/8 x 24″ (37.2 x 61cm)

Gift of Robert and Gayle Greenhill

Museum of Modern Art Collection

Working in the digital realm long before it was associated with fine art, Samaras pioneered radical new modes of image making throughout his storied career, pushing and redefining the boundaries of portraiture and self-portraiture over the course of seven decades. Centering on the body and the psyche, Samaras’s autobiographical work across photography, painting, installation, assemblage, drawing, textile, and sculpture often meditates on the malleable, shapeshifting nature of selfhood. “I like remaking myself in photography,” the artist once said. …

In the late 1960s, Samaras began working with a Polaroid 360 camera, creating his iconic Auto Polaroids by altering hundreds of images, mostly self-portraits, with applications of ink by his own hand. In 1973, using a Polaroid SX-70, he took this collagist approach further by manipulating the wet emulsion of the film with a stylus or his fingertip before the chemicals set. The resulting distortions in his Photo-Transformations series took on abstract, otherworldly effects, which he would continue exploring amid the rise of other image making technologies in the following decades.

Anonymous. “Remembering Lucas Samaras,” on the Pace Gallery website Mar 7, 2024 [Online] Cited 06/06/2024

Lucas Samaras (American, 1936-2024)

Auto Polaroid (details)

1969-1971

Eighteen black-and-white instant prints (Polapan), with hand-applied ink

Each 3 3/4 x 2 15/16″ (9.5 x 7.4cm)

Overall 14 5/8 x 24″ (37.2 x 61cm)

Gift of Robert and Gayle Greenhill

Museum of Modern Art Collection

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

Madonna with Children

1864

Albumen silver print

10 1/2 x 8 5/8″ (26.7 x 21.9cm)

Gift of Shirley C. Burden

Museum of Modern Art Collection

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

Untitled (Mary Ryan?)

c. 1867

Albumen silver print

13 3/16 x 11″ (33.5 x 27.9cm)

Gift of Shirley C. Burden

Museum of Modern Art Collection

Nadar (Gaspard-Félix Tournachon) (French, 1820-1910)

Adrien Tournachon (French, 1825-1903)

Pierrot Surprised

1854-1855

Albumen silver print

11 1/4 x 8 3/16″ (28.6 x 20.8cm)

Suzanne Winsberg Collection. Gift of Suzanne Winsberg

Museum of Modern Art Collection

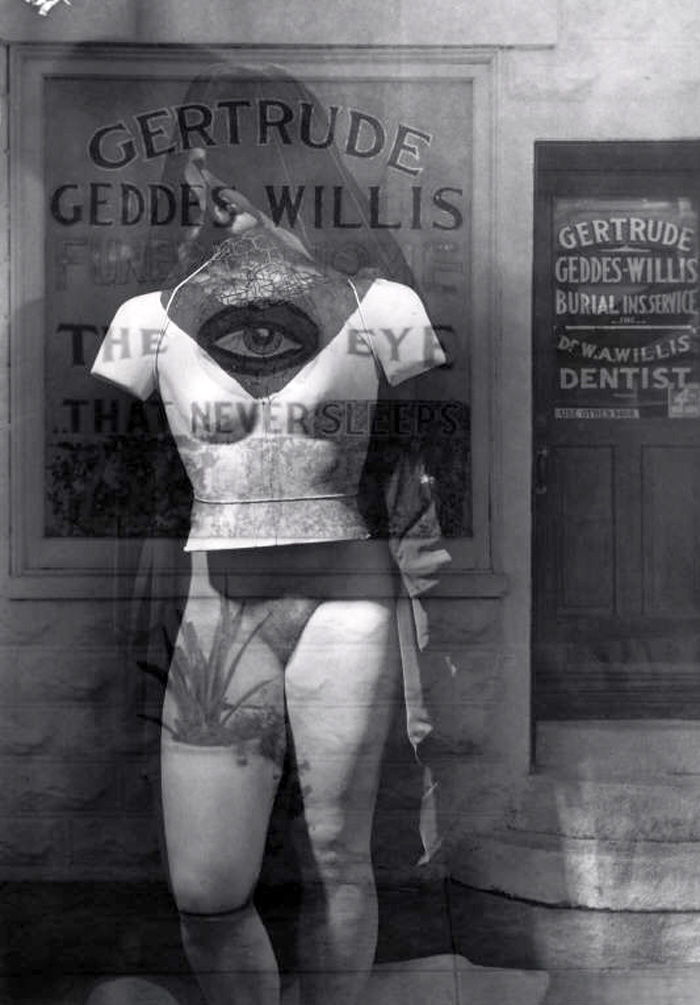

Maurice Tabard (French, 1897-1984)

Untitled

1929

Gelatin silver print

6 9/16 x 6 1/2″ (16.7 x 16.5cm)

Gift of Robert Shapazian

Museum of Modern Art Collection

Edward Steichen (American born Luxembourg, 1879-1973)

Anna May Wong

1930

Gelatin silver print

16 9/16 x 13 7/16″ (42.1 x 34.1cm)

Gift of the artist

Museum of Modern Art Collection

“Taking people away from their natural circumstances and putting them into the studio in front of a camera did not simply isolate them, it transformed them. Sometimes the change was subtle; sometimes it was great enough to be almost shocking. But always there was transformation.”

~ Irving Penn 1974

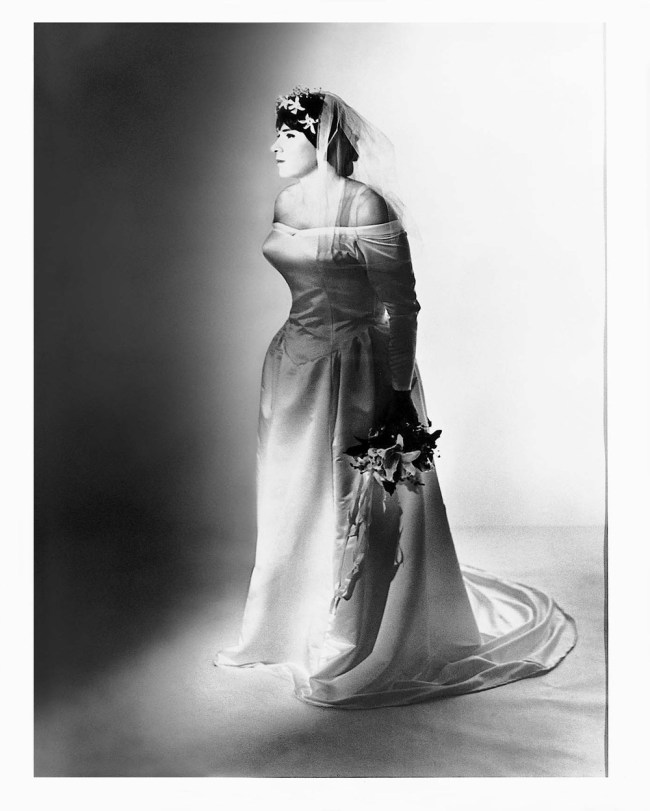

Cindy Sherman (American, b. 1954)

Untitled #131

1983

Chromogenic colour print

35 x 16 1/2″ (89 x 41.9cm)

Joel and Anne Ehrenkranz Fund

Museum of Modern Art Collection

The Studio as Set

Barbara Kasten (American, b. 1936)

Construct I-F

1979

Colour instant print (Polaroid Polacolor)

9 1/2 x 7 1/2″ (24.0 x 19.0cm)

Acquired through the generosity of Wendy Larsen

Museum of Modern Art Collection

Barbara Kasten (American, b. 1936)

Construct NYC 17

1984

Silver dye bleach print

29 3/8 x 37 1/16″ (74.7 x 94.1cm)

Gift of Foster Goldstrom

Museum of Modern Art Collection

James Casebere (American, b. 1953)

Subdivision with Spotlight

1982

Gelatin silver print

14 13/16 x 18 15/16″ (37.6 x 48.1cm)

Purchase

Museum of Modern Art Collection

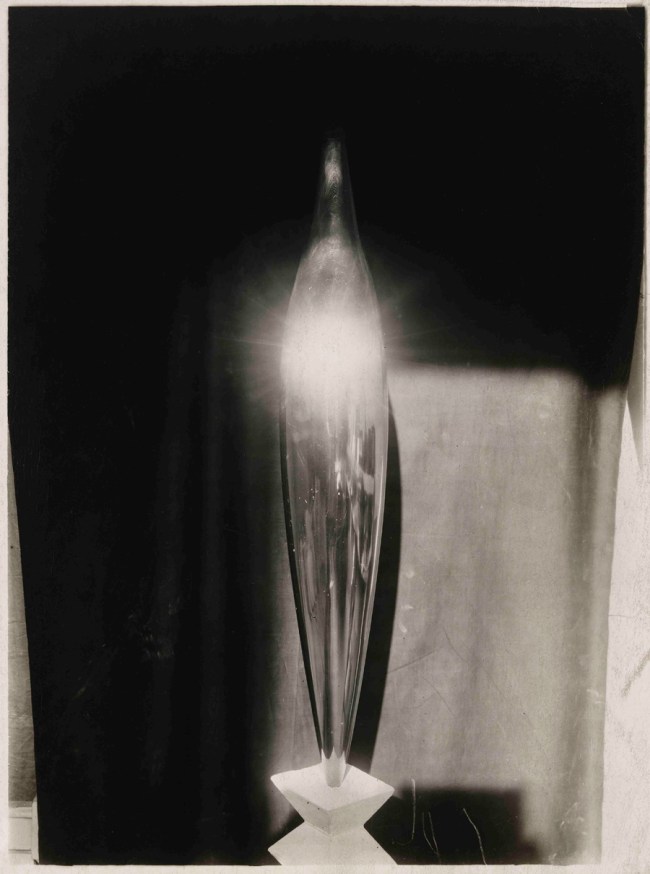

Francis Bruguière (American, 1879-1945)

Light Abstraction

c. 1925

Gelatin silver print

9 15/16 x 7 15/16″ (25.2 x 20.2cm)

Gift of Arnold Newman

Museum of Modern Art Collection

Francis Joseph Bruguière (15 October 1879 – 8 May 1945) was an American photographer.

Francis Bruguière was born in San Francisco, California, to Emile Antoine Bruguière (1849-1900) and Josephine Frederikke (Sather) Bruguière (1845-1915). He was the youngest of four sons born into a wealthy banking family and was privately educated. His brothers were painter and physician Peder Sather Bruguière (1874-1967), Emile Antoine Bruguiere Jr. (1877-1935), and Louis Sather Bruguière (1882-1954), who married wealthy heiress Margaret Post Van Alen. He was also a grandson of banker Peder Sather. His mother died in the 1915 sinking of the British ocean liner SS Arabic by a German submarine.

In 1905, having studied painting in Europe, Bruguière became acquainted with photographer and modern art promoter Alfred Stieglitz (who accepted him as a Fellow of the Photo-secession), and set up a studio in San Francisco, recording in a Pictorialist style images of the city after the earthquake and fire; some of them were reproduced in a book called San Francisco in 1918. He co-curated the photographic exhibition at the 1915 Panama-California Exposition in San Diego, and nine of his photographs were included in The Evanescent City (1916) by George Sterling.

In 1918, following the decline of the family fortune, he moved to New York City where he made his living by photographing for Vanity Fair, Vogue, and Harper’s Bazaar. Soon he was appointed the official photographer of the New York Theatre Guild. In this role he photographed the British stage actress Rosalinde Fuller, who was debuting in What’s in a Name? (1920), and she partnered him for the rest of his life.

Throughout his life, Bruguière experimented with multiple-exposure, solarization (years ahead of Man Ray), original processes, abstracts, photograms, and the response of commercially available film to light of various wavelengths. Until his one-man show at the Art Centre of New York in 1927, he showed this work only to friends. In the mid-1920s, he planned to make a film called The Way, depicting stages in a man’s life, to be played by Sebastian Droste with Rosalinde doing all the female parts. To obtain funding, Bruguière took photographs of projected scenes, but Droste died before filming started; so we are left with only the still pictures.

In 1927 they moved to London, where Bruguière co-created the first British abstract film, Light Rhythms, with Oswell Blakeston. Long thought to have been lost, it has now been recovered. During World War II, he returned to painting.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Jaromír Funke (Czech, 1896-1945)

Composition

c. 1925

Gelatin silver print

9 1/4 × 11 9/16″ (23.4 × 29.3cm)

Acquired through the generosity of Blanchette Hooker Rockefeller

Museum of Modern Art Collection

© 2022 Miloslava Rupešová

Jaromír Funke (1 August 1896 – 22 March 1945) was a leading Czech photographer during the 1920s and 1930s.

Funke was recognised for his “photographic games” using mirrors, lights, and insignificant objects, such as plates, bottles, or glasses, to create unique works. In his still life imagery he created abstracts of forms and shadows reminiscent of photograms. His work was regarded as logical, original and expressive in nature. A typical feature of Funke’s work would be the “dynamic diagonal.”

Text from the Wikipedia website

Paul Outerbridge (American, 1896-1958)

Images de Deauville

1936

Tri-colour carbro print

15 3/4 x 12 1/4″ (40 x 31.1cm)

Gift of Mrs. Ralph Seward Allen

Museum of Modern Art Collection

Shozo Kitadai, Kiyoji Otsuji

Untitled from the portfolio APN (Asahi Picture News)

1953-1954

Gelatin silver print, printed 2003

7 1/2 × 5 9/16″ (19 × 14.2cm)

Gift of Shigeru Yokota

Museum of Modern Art Collection

© 2022 Seiko Otsuji

Irving Penn (American, 1917-2009)

Three Steel Blocks, New York

1980

Platinum/palladium print

13 1/4 × 20 11/16″ (33.6 × 52.5cm)

Acquired through the generosity of Lily Auchincloss

Museum of Modern Art Collection

© The Irving Penn Foundation

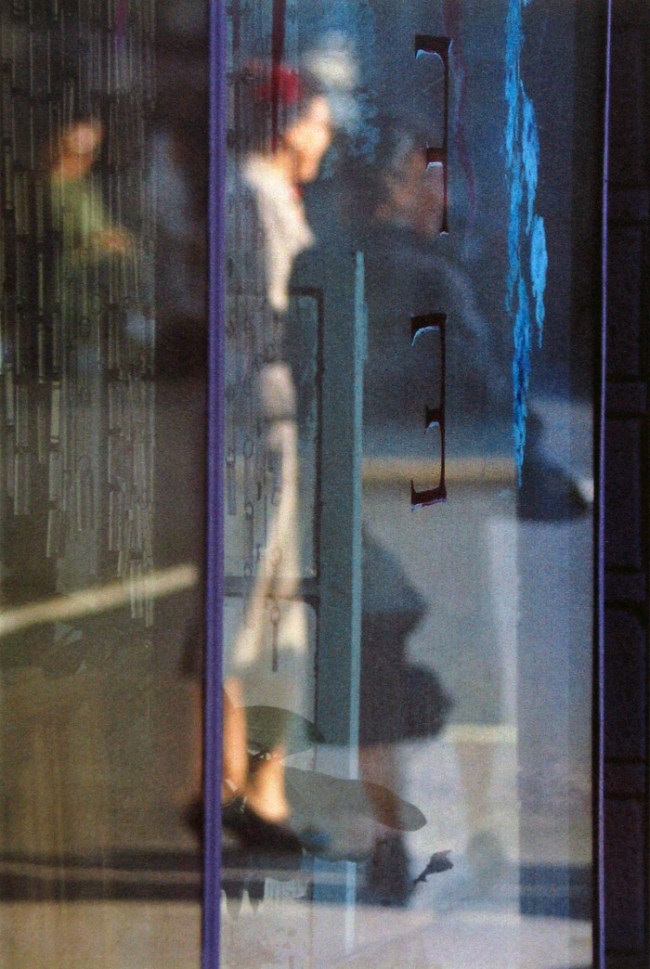

Elad Lassry (Israeli, b. 1977)

Nailpolish

2009

Chromogenic colour print

14 1/2 x 11 1/2″ (36.8 x 29.2cm)

Fund for the Twenty-First Century

Museum of Modern Art Collection

The Museum of Modern Art

11 West 53 Street

New York, NY 10019

Phone: (212) 708-9400

Opening hours:

10.30am – 5.30pm

Open seven days a week

You must be logged in to post a comment.