November 2023

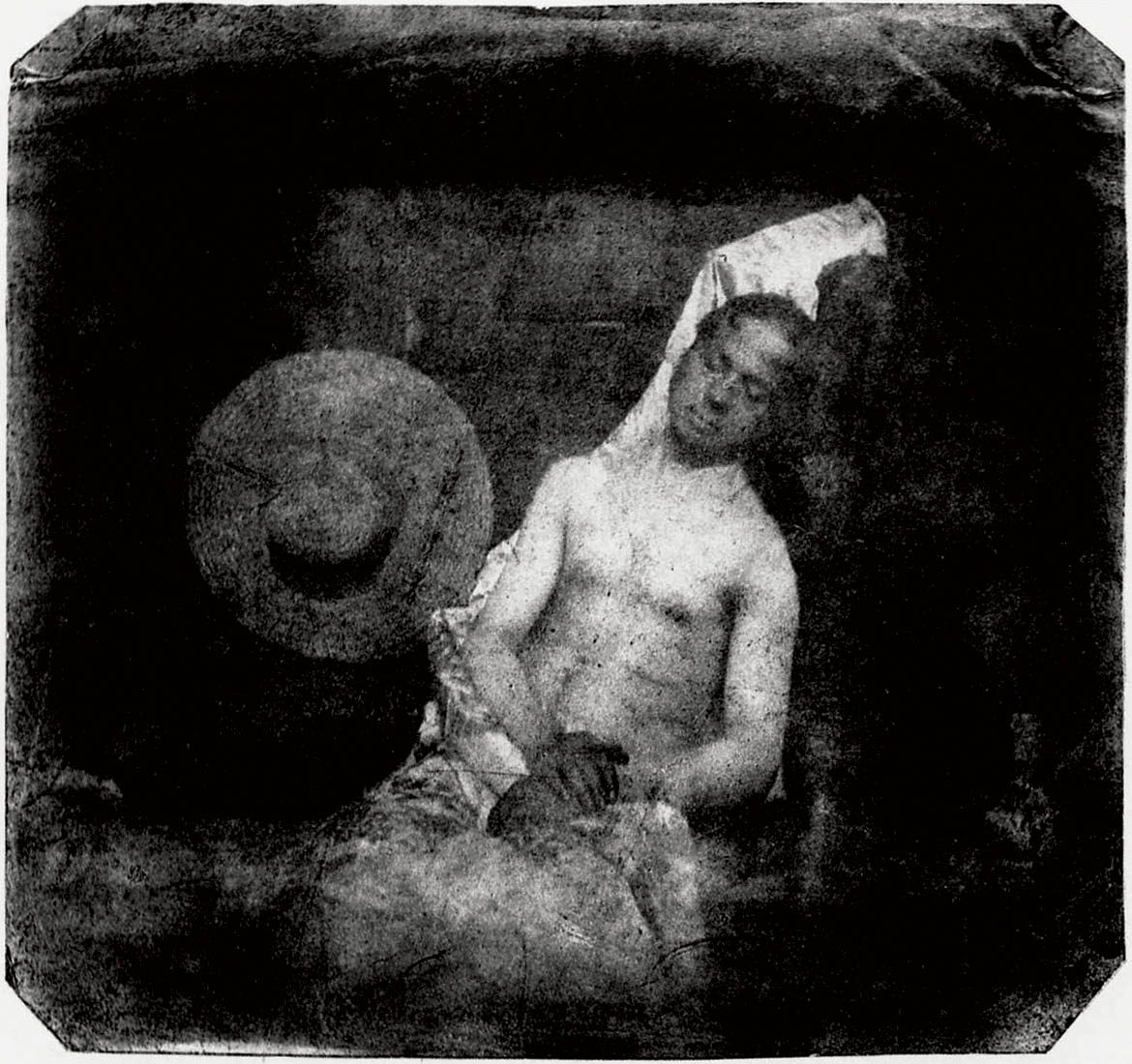

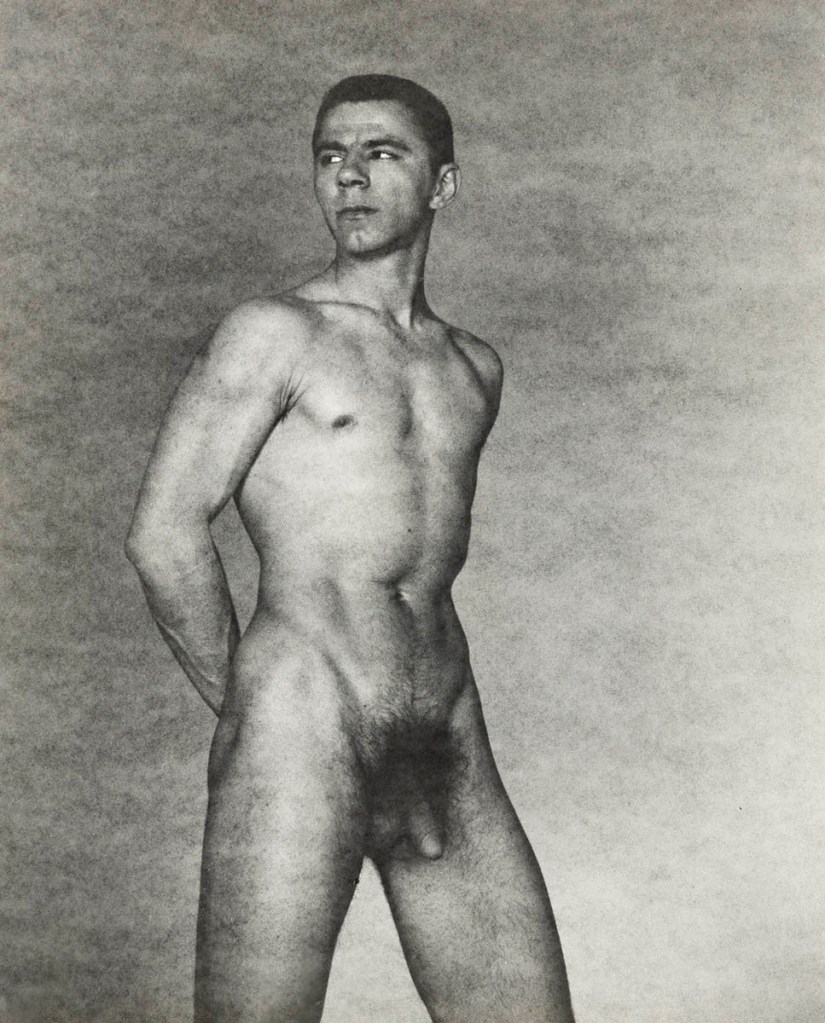

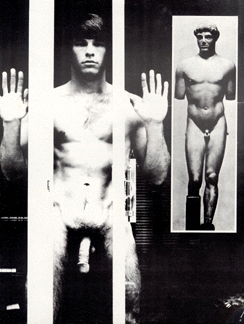

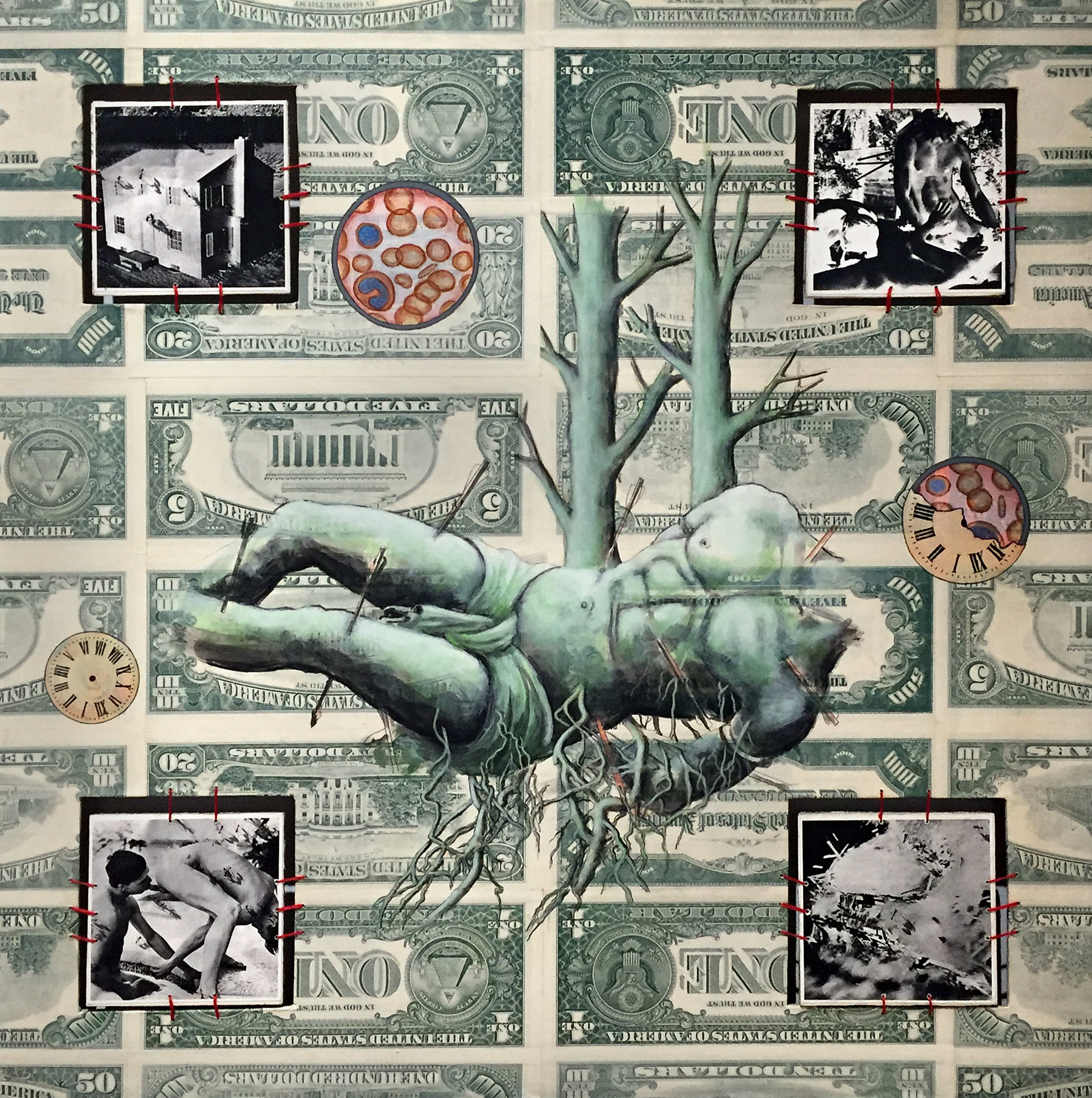

Marcus Bunyan (Australian born England, b. 1958)

“My Body (But I Do Not Own It) – Not the Governments Nor the Churches.” Self portrait as gay skinhead

1992

Silver gelatin photograph

The title of this photograph is taken from graffiti seen in Newtown, Sydney, Australia, where my scarification was done. In the image you can see that I have just had tribal scarification (cutting causing scarring) to my arm the previous night. I suggest body modifications such as tattooing, branding or scarring confronts the keeper of the body with a journey of exploration into the Self, a continuing ‘rite of passage’ through life. It is my body but I am just the keeper of it for a short period of time and I experience my body through touch, intimacy and an understanding of its interactions with my-Self and others. The title also reveals an ironic challenge to the dominant notions of traditional heterosexual skinhead identity: gay men have appropriated the skinhead image subverting it’s social identity construction because of their sexuality whilst still desiring the fantasy because of its masculinity. While this fantasy may reinforce the lust for the power of patriarchy through the use of a hyper-masculine image, the image of two gay skins walking down the street arm in arm challenges and subverts the ‘normal’ ideology and social identity of the skinhead image as racist, fascist and heterosexual.

Since the demise of my old website, my PhD research Pressing the Flesh: Sex, Body Image and the Gay Male (RMIT University, Melbourne, 2001) has no longer been available online.

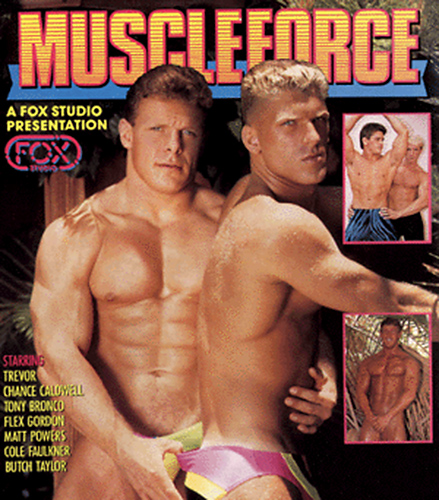

I have now republished the fourth of twelve chapters, “Re-Pressentation”, so that it is available to read. More chapters will be added as I get time. I hope the text is of some interest. Other chapters include Historical Pressings (examines the history of photographic images of the male body) and Bench Press (investigates the development of gym culture, its ‘masculinity’, ‘lifestyle’, and the images used to represent it); and In Press (investigates the photographic representation of the muscular male body in the (sometimes gay) media and gay male pornography. In the title of the chapter I use the word ‘press’ to infer a link to the media.

Dr Marcus Bunyan November 2023

“Re-Pressentation” chapter from Marcus Bunyan’s PhD research ‘Pressing the Flesh: Sex, Body Image and the Gay Male’, RMIT University, Melbourne, 2001

Through plain language English (not academic speak) the text of this chapter investigates alternative ways of imag(in)ing the male body and the issues surrounding the re-pressentation of different body images for gay men. The title is a play on the word representation, an alternative way of re-pressing and re-pressenting the body in different non-stereotypical forms.

Keywords

male body, representation of the male body, male body image, gay men, alternative male body image, body image and self-esteem, masculinity, body images facades and fantasies, imaging the gay male body, gay male body

Sections

1/ The power of masculinity

2/ Body image and self-esteem

3/ High and low self-esteem

4/ Sex and self-esteem

5/ Love and respect

6/ Increasing self-esteem and happiness

7/ Body images, facades and fantasies

8/ Getting older

9/ Imaging the gay male body

10/ Re-Pressing, responsibility and respect

11/ Re-imag(in)ing the male body

12/ Conclusion

Word count: 12,048

The power of masculinity

“Awareness of the Cult of Masculinity‘s power and pull helps to loosen its grip on us. Awareness allows us to look at masculinity as something in large part that is constructed within our culture … But we must stop allowing masculinity to define who we are: We must reject the use of terms like “straight-acting” in describing ourselves and others, prevailing those among us whom we deem as more “masculine,” and thus more “straight.” We must understand that what was considered our preferred “sexual type” was in all likelihood actually formed soon after we entered the gay ghettos and saw what the Cult of Masculinity deemed as “hot.” We can each remember a time when we liked older men or thinner men or heavier men or men whose bodies didn’t fit so rigidly to the standard, men whose bodies weren’t the first or only thing we noticed.”

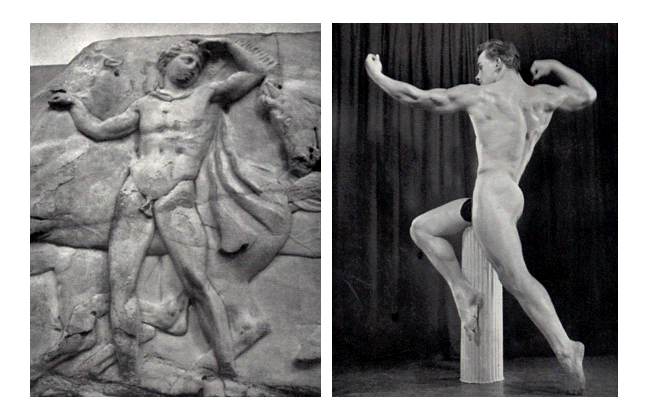

Michelangelo Signorile.1

To be made aware of the power of masculinity allows us the possibility of challenging that power. If we have the will and determination to do so! As we have seen in the In Press chapter it is still all too easy for the dominant hegemonic group within a subculture or society to impose and identify what a ‘valuable’ body should look like. This is achieved mainly through physical and pictorial appearance. As Michelangelo Signorile says in the above quotation, what gay men find desirable today is probably a behaviour that was formed soon after they entered the gay ghetto and saw what was termed a “hot” body. My research suggests that body-type desirability in gay men may be learned from an exposure to the images and bodies of men at a relatively early age.

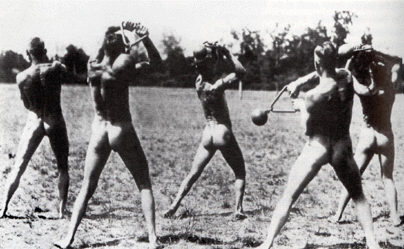

These images may be found in at the beach, playing sports, reading magazines and looking at TV and pornography to name but a few. In some cases I found that the desirability for a particular type of body was altered after the gay man came out and was exposed to the imagery and body idealism present within the gay community, causing a narrowing in the range of body-types that person found desirable. This narrowing of desirability may cause anxiety and insecurity amongst gay men as they seek a partner who ‘fits’ their ideal body-type and try to match this ‘ideal’ themselves. They may feel inferior about their own body, causing a dis-ease within themselves and in their relations with others. Body image may then affect levels of self-esteem.

I suggest that the ‘Cult of Masculinity’ doesn’t necessarily attract young gay men after they first come out. Personally I believe that it is only after a period of experimentation (perhaps with androgyny, ‘campness’ or being a twink for for example, that may last some years) that gay men then start looking more closely at the development of their bodies. After the first flush of being ‘out’ and going to the clubs is over they start to want to attract a different type of man, a more masculine man, and feel they have to have the body to do so. I think gay men can then become complicit in their addiction to and desire of, the ‘ideal’ gay male hyper-masculine body. This addiction is not so much learnt in childhood but observed and stored in adolescence and the early days of being on the scene until it later finds full expression as gay men grow up.

With the emergence of the gay man onto the ‘scene’ he is exposed to the intense rituals of male body worship which are focused on one particular type of body. The images and rituals of body beautification are presented to gay men who, as free agents, are responsible for their developing addiction. As I noted in the In Press chapter, we cannot blame our addictions solely on the media or consumerism for, in reality, these images are an expression of our identity and our desires. In an interview with counsellor Barry Taylor2 I asked how he thought gay identity was formed:

BT: Perceptions are important – your perception of what you think it is to be gay is based on stereotypes – drag, dirty men in park, Commercial Road, Mardi Gras, TV, paedophilia, etc., … There is a wide range of stereotypes to draw from/engage with.

MAB: Before you ‘come out’ you don’t have ‘the look’. Gay people take on board the images of the gay community very quickly after ‘coming out’. Are there social pressures to conform to this style?

BT: Your desire to belong to the group is strong. What you have given up to come and belong to the group (eg. family, security, love) is great.

Is there something about natural beauty that leads people to it. What is it that appeals to us? The nature of the appeal of beauty.

MAB: Does it just have to be the facade though. I am interested in the inner self. How do people relate to this image. How do you get across to gay people a positive, alternative self image that says self is enough?

BT: That’s a maturity thing. When you are young and come out onto the scene you take on the image of the gay body. It happens in a short space of time. And so about 22, I start asking more questions – What’s my inner self. I see an uptake of people that come to counselling between 22-26 because there must be more to life than parties. Vulnerability – lots of depression at this time. In the gay community we can put off this 22-26 period indefinitely and continue partying (exterior image) which leads to alcohol and substance abuse and no inner development under the facade.

Gay men are attracted to identity images and styles that are seen as perpetually powerful, successful identity images within the gay community. One such style is known as the ‘Party Boy’, which is based on social affluence, looks and body image appearance, a style which is, as Damien Ridge notes below, highly restrictive. Not all gay men have the physical attributes, money, time and social contacts to attain this style, and the relentless pursuit of it can leave undeveloped the inner Self because of substance abuse, partying and the need to focus constant attention on the facade. I examine the issue of building identity & self-esteem based on appearance & body image on the following page.

“Styles such as the ‘Party Boy’, promoted on the scene and in the gay media, are highly restrictive. As with women exposed to ‘supermodels’ promoted by the fashion industry, few men have the social resources, appearances and body type to fully emulate the ‘Party Boy’. In an environment that prioritises style, this inadequacy readily taps into informants’ insecurities. The inability to fit in with dominant gay middle-class styles works to isolate and alienate young men regardless of class or ethnicity. Informants report they need to constantly work on their styles, such as their weight and physiques, to gain and maintain access to valued social networks, sex, and relationships.”3

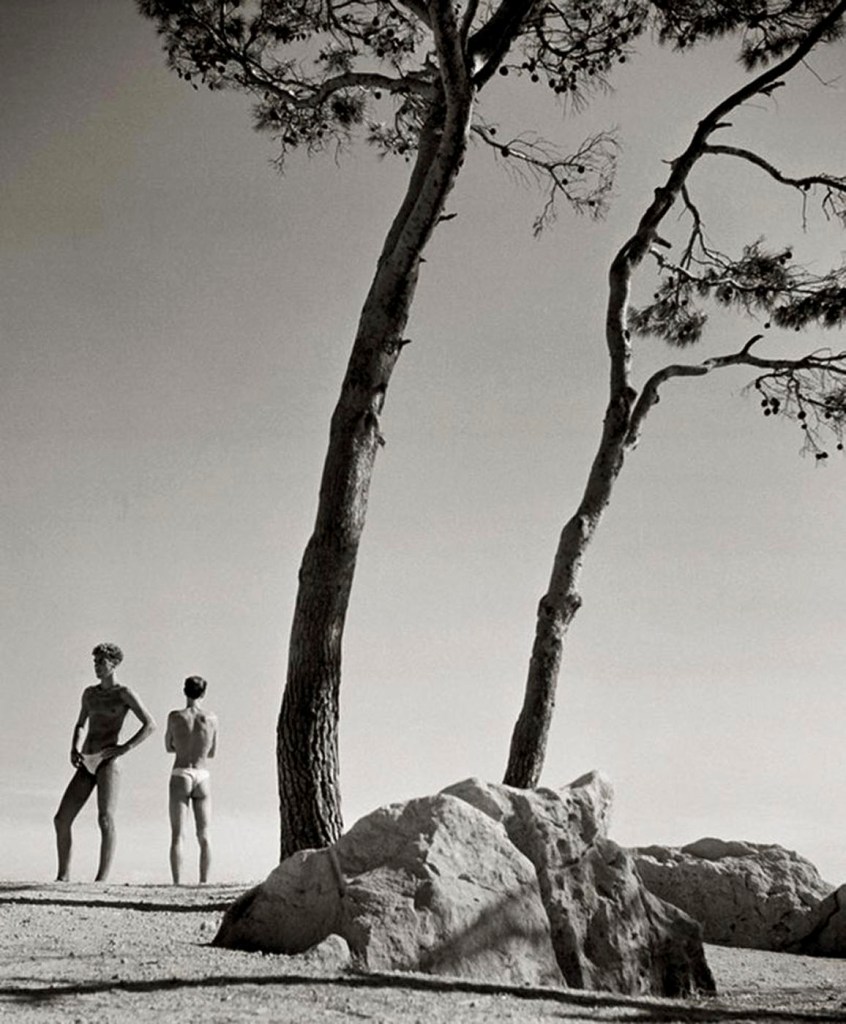

Marcus Bunyan (Australian born England, b. 1958)

I Do Dick, Glenn, Darlinghurst, Sydney

1992

Silver gelatin photograph

The title is taken from the graffiti seen at the right of Glenn

Body image and self-esteem

“Appearance is not a very stable or permanent basis for self-esteem. Not everyone agrees about who is attractive, so even the best-looking are bound to receive mixed reviews. Furthermore, no matter how attractive people are, there will always be times when they do not feel attractive – when suffering from a cold or when they get old. We can always find flaws in ourselves. Objective observers may tell us we are cute and adorable, but we are likely to mutter, “Sure, except for my nose.” Finally, no matter how good-looking a person is, there will always be others who seem better looking. Many of the best looking people compare themselves with someone better-looking, someone younger, and conclude they are not good enough.”

Elaine Hatfield and Susan Sprecher4

May I suggest that self-esteem is an evaluation, either positively or negatively, of self worth. It is based on global (or overall) self-esteem and local self- esteem (such as body image) – conditions that positively or negatively affect each other. Self-esteem is formed by reflected appraisal (what you think other people think of you) and social comparison (comparing yourself with others) and is improved by achieving things within different spheres of your life. Positive self-esteem can lead to a condition of happiness with all aspects of the self. It is the ability to value and love yourself not in an ego way (look at me I’m beautiful, I’m gorgeous) but in a way that accepts all faults and grievances and values them as part of an overall identity.

Lou Benson thinks that self-esteem, “Is a quiet confidence in one’s own worth regardless of any shortcomings or deficiencies. Fromm describes it as the ability to love oneself, not by falsifying a version of the self, but by acceptance of what one really is.”5

Erich Fromm says that self-esteem is essential if we are to love ourselves as well as others. He continues, “The affirmation of one’s own life, happiness, growth, freedom, is rooted in one’s capacity to love, ie., in care, respect, responsibility, and knowledge. If an individual is able to love productively he loves himself too; if he can only love others he cannot love at all.”6

Here Fromm is arguing for a love of the self that is not narcissistic, but based on a true ‘care’ for the self. I think that many gay men suffer from an inability to truly love themselves in this sense. They seek completion of their self in an image of themselves (narcissism) and in the image of others (voyeurism). This is where body image impacts on levels of self-esteem. Researchers such as Leonard Wankel7 have found that body image is related to self-esteem. Crockett and Peterson8 have also found that in adolescence physical attractiveness is one of the key domains that affect a person’s judgement of their self-esteem. My research also suggests that how a gay man feels about his own and his partner’s body image can be a factor in the decision to have sex without a condom. Gay men place greater emphasis on physical attractiveness than heterosexual men and it continues to be a priority throughout their lives.

Appearance is vital in the association between self-esteem and body image (because it is present in every visible social interaction, including sexual relations, that takes place between human beings), but as Elaine Hatfield and Susan Sprecher have noted in the quotation above, appearance is not a very permanent or stable basis for self-esteem. Still, it would seem that many gay men seek higher self-esteem by altering their appearance, believing it (higher SE) can be attained by changing their bodies. This is like building a house on sand – eventually the house is washed away as the foundations are built on unstable ground; we all get older and loose our looks and there is always someone that is better looking than ourselves.

Through behaviours formed in the crucible of the gay beauty ritual some gay men come to believe that the only way to raise their self-esteem is to pump their bodies at the gym in order to be able to compete against other gay men. But having a good body image does not necessarily mean that you will also have good self-esteem.

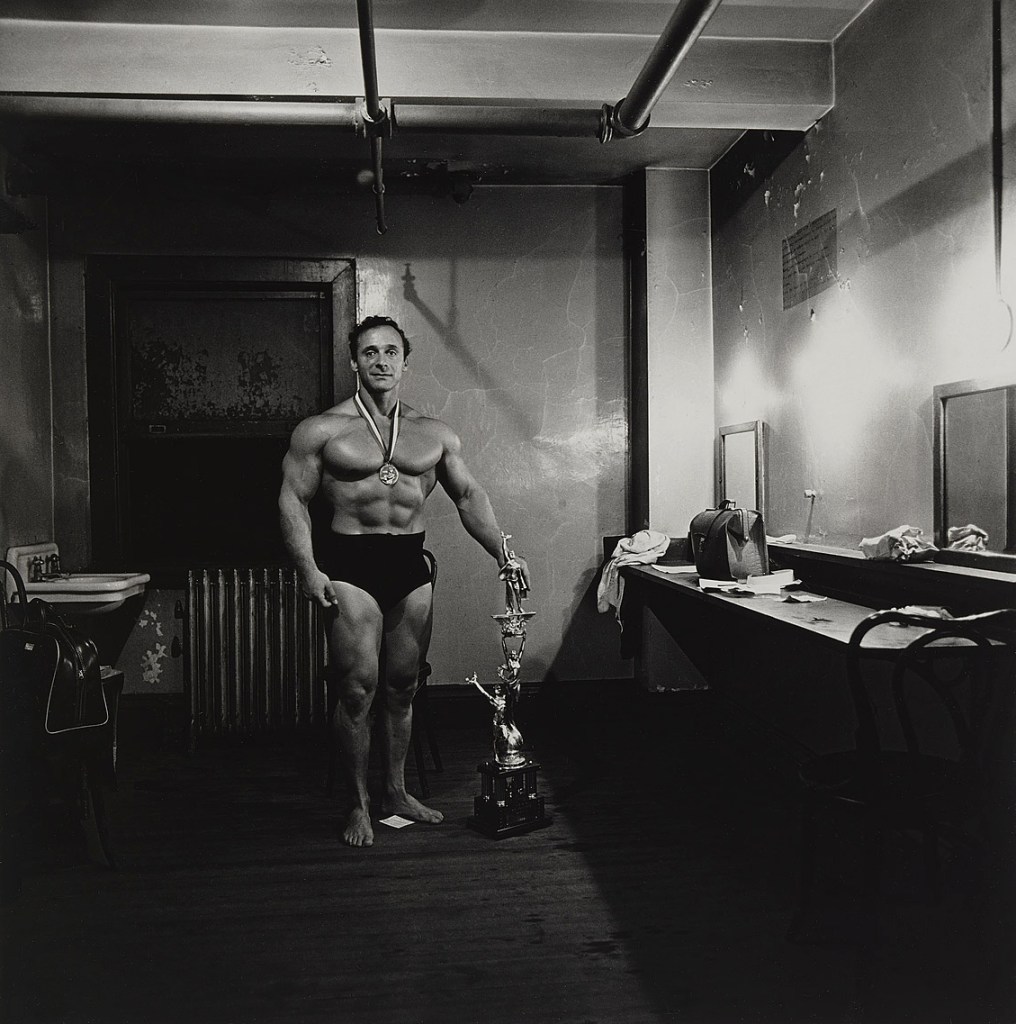

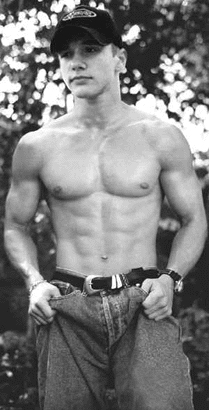

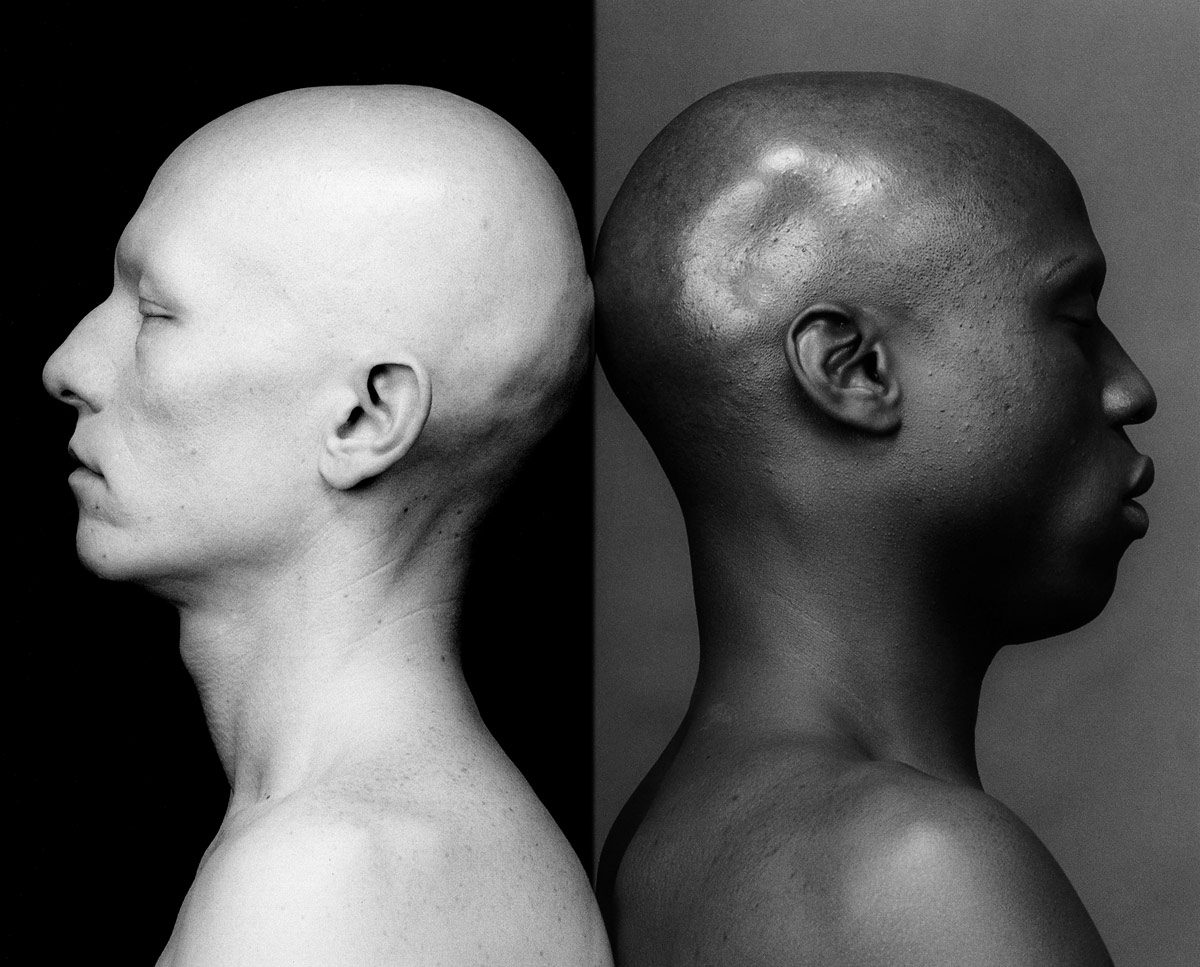

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Glenn, Darlinghurst, Sydney

1992

Silver gelatin photograph

High and low self-esteem

According to Hatfield and Sprecher, “People with low self-esteem are often afraid they will be rejected. They fear stepping out of line and being different. They seek social approval. Shy teenagers, unsure of themselves, find it very difficult to date a person who friends find unappealing. High self-esteem individuals, on the other hand, are not so desperate for social approval. They can afford to date someone much less attractive than they are.”9

Fundamentally I believe that these observations are flawed.

I agree that people with low self esteem are often afraid of rejection. But do they seek social approval? Perhaps not. For example, if an unattractive person was given the chance of having sex with his body image ideal only by having sex without a condom he would not be seeking social approval for his actions. His actions would be contrary to societies moral and ethical taboo against unsafe sex. On the other hand high self-esteem individuals are equally if not more desperate for social approval so that they can keep their self-esteem high. They usually date someone who is as beautiful and as built, tanned, and toned as they are! Its like looking in a mirror – they see a reflection of their own perfection in their partner and they have to show this possession off to other people to reinforce their high self-esteem; if they fear loosing him they could have sex without a condom to try to keep him.

From the evidence of my research data I suggest that people with different levels of self-esteem are equally likely to have sex without a condom.

People with low self-esteem might have unsafe sex because they think that they won’t get the man they desire otherwise. People with high self-esteem could have unsafe sex because they feel invincible and that their stunning partner couldn’t possibly be infected with the HIV / AIDS virus. People with a built body image but low self-esteem might seek validation of themselves and their body through the adoration of another and then fuck this other person unsafely. There are so many different contexts and no hard and fast rules.

Having a great body does not necessarily mean we feel good about ourselves as appearance is not everything; overall self-esteem is based on a whole heap of other factors, as well as body image, that affect our lives. Conversely, if we feel good about our overall self this can help us feel good about our body and I think that an acceptance of Self does not come through appearance alone, but is possible only through the integration of all parts of the Self into a balanced holistic whole. Of course, self-esteem, body image and sex without a condom are very complex issues and I realise that body image is not the only criteria in assessing the likelihood of unsafe sexual practices taking place.

Sex and self-esteem

“The myth of the ‘Cult of Masculinity’ … is that validation and self- worth are achieved through physical adoration. The cult encourages single gay men to believe they can achieve self-worth through sex, and it encourages men in relationships to believe that they can boost self-esteem by having sex outside the relationship.”

Michelangelo Signorile10

Much like money, photographs of muscular male bodies have ‘value’ without the owner of the body ever being present. This is because society knows the semiotic language in which they (the bodies and the photographs) speak and what their social value and power is. The same thing could be said for muscular bodies in real life; even though you can see and desire the bodies in question and you know their social value and the power of their image you can’t touch unless given permission. And usually permission is given only to those that match up to the same ‘ideals’ so that sex then becomes a validation of Self, of the person’s own existence. As Michelangelo Signorile has said (in the quotation above), this encourages gay men to believe they can increase their self worth through sex (trophy collecting), especially by having sex with someone who comes close to the ‘ideal’ either inside or outside of a relationship.

Having sex with someone is exciting and fun but it is not an understanding of the whole person. Personally I have used sex with gay men as a form of handshake, getting to know what they were like, an introduction as to whether we were compatible sexually yes, but also whether we got along on a social and intellectual level. That I could get along with him, that I wanted him around, that we liked doing things together and that we wanted to help each other along the way. Sex for me has always been used as a tool in this manner – to make friendships and relationships with other gay men. To have great sex, to have some fun but also to find out what makes them tick.

I believe that there are many gay men that use sex to increase their self worth but I also suggest that quite a few gay men use sex in the way I do, as a way of getting to know other men.11 They are looking for something or someone. Not just an addiction to pleasure, an increasing of self worth through sex but a search for a deeper connection. But paradoxically gay men seem scared of this connection, fearful of the exposure and revealing of Self to others that this intimacy brings. For gay men who are supposed to be more sensitive to the feminine side of their masculinity, I find that many gay men are afraid of touching, holding and intimacy.

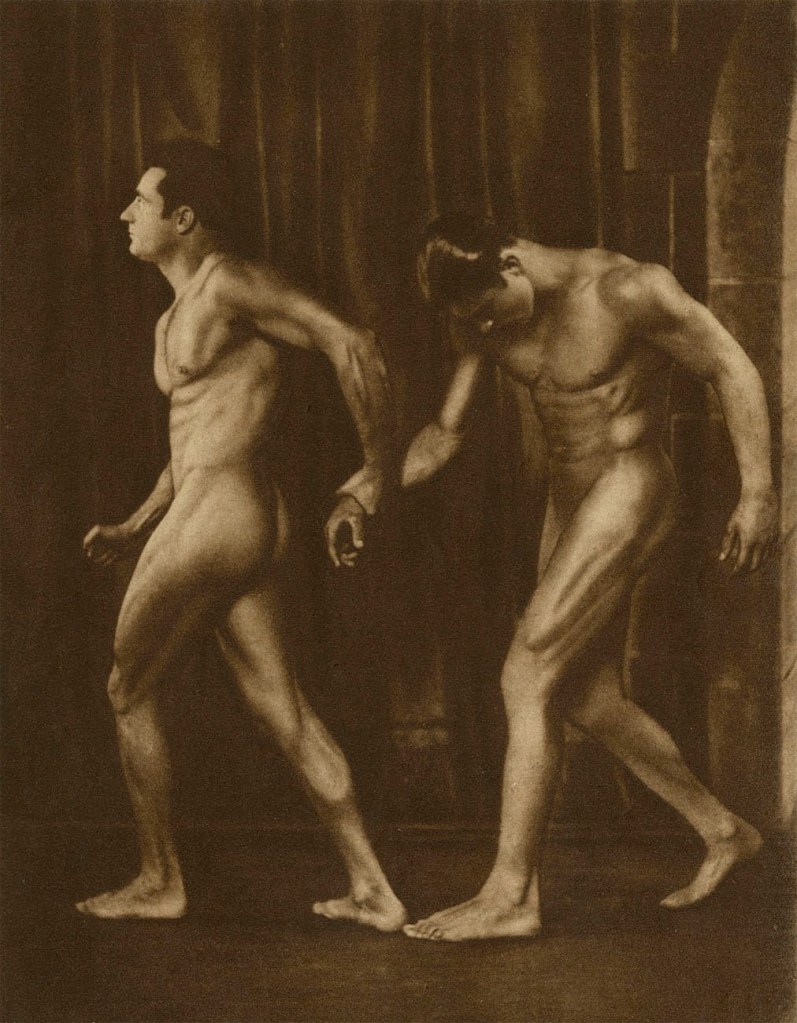

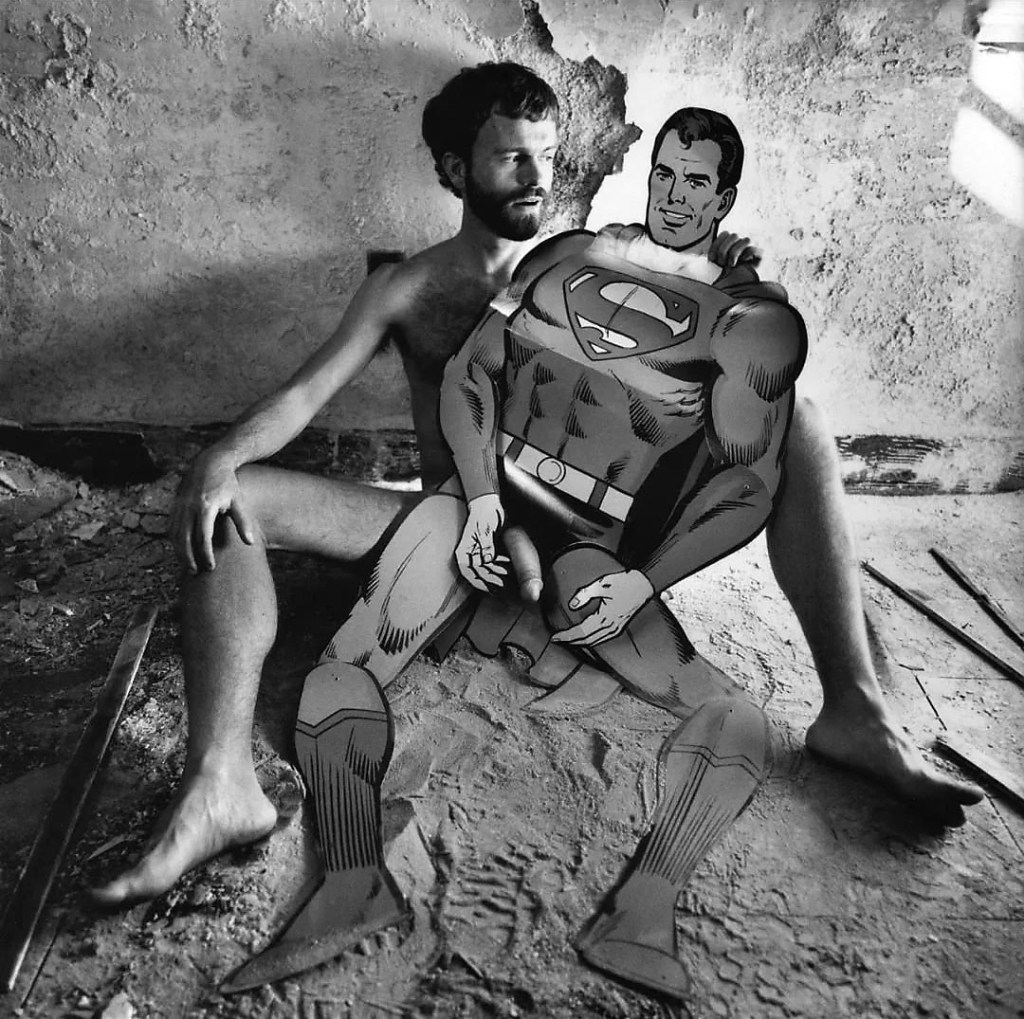

(The hero in our society is usually ‘masculine’, with a well defined and muscular body such as Tarzan or Superman, the Man of Steel. Heterosexual iconography portrays him as powerful, masterly, and virile. Gay men have adopted this stereotype in opposition to the effeminate ‘camp’ pansy stereotype still present today. I suggest that gay men adopt this ‘masculine’ stereotype in order to be seen as ‘real’ men. In adopting this symbolic facade, the mask like iconography may create a paradox between the desire for, and fear of, intimacy and closeness. This fear may form a taboo against intimacy and closeness and the troubling revelations that these conditions can bring.)

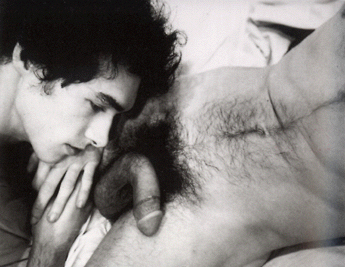

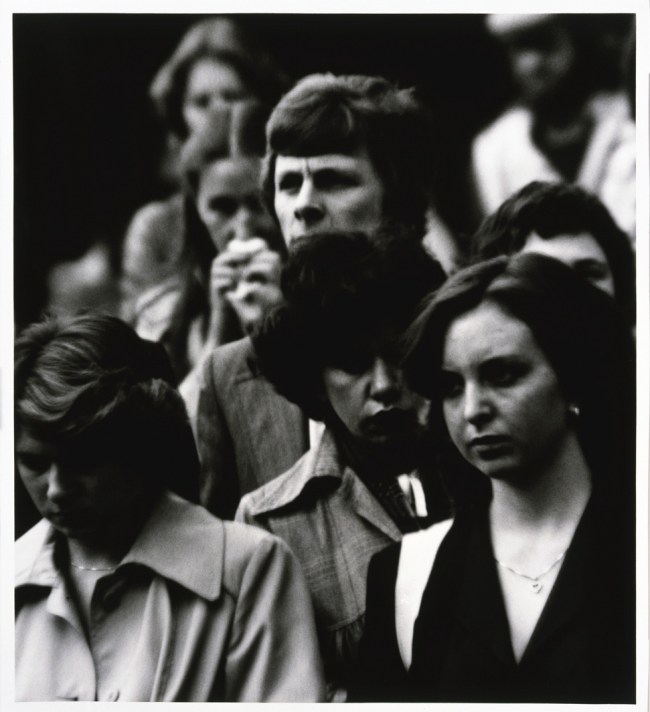

Marcus Bunyan (Australian born England, b. 1958)

Fred and Andrew Smoking a Joint in Paris

1992

Silver gelatin photograph

Love and respect

“One of the most essential factors in the respect for others concerns their uniqueness and individuality. Love in this sense becomes the recognition and affirmation of the uniqueness of the other. It is not the loss of the self or the subservience of one’s self to another, but the recognition of the many individual qualities that make up the particular individual and the acceptance of their existence. The lover even respects those qualities of the other with which he is not always in accord.”

Lou Benson13

According to Lou Benson love is a respect for the uniqueness and individuality of your partner even if you don’t agree with him on some issues. I believe he is right. It is not the loss of the Self in an-other nor the completion of the Self in an-other (your partner is one’s ‘other half’ as though you are completing your- self in another), it is love through an understanding of the true representation of Self and other and the development of a happiness within and through that journey. But one doesn’t have to be in love to put this understanding into practice. In everyday life the relationships and interactions that we form can be informed by our respect for others, whatever they look like, whoever they are. We are ‘aware‘ of our situation, of our own and other’s ego projections, and this awareness can help us in the acceptance of ourselves and others. Through exploration and respect for the Self we can make our lives happier.

Increasing self-esteem and happiness

Good self-esteem involves the acceptance of all facets of our identity. It is the integration of all strands of our personality into a unified whole. If we visualise, are aware of what we do at any given time; if we are aware of the process of, say, the creativity of cooking a meal, we enjoy the experience as much as the outcome. It is not just the final product but the journey itself that gives us satisfaction. This process is called ‘self-actualization’,14 and I think it can help us to attain higher self-esteem. We fulfil our potential both in the journey and in the outcome and this can make us happier. Instead of pinning after something we cannot have, we accept what we have to work with and get on with it! We enjoy the experience instead of whingeing about it all the time.

“Another important area in which self-actualizing people differ from others is in their non-judgemental acceptance of themselves. Maslow says that they seem to have a lack of overriding guilt and crippling shame and also to be free of the anxieties that usually accompany these feelings. They can accept their own human nature in the stoic style, with all its shortcomings, with all its discrepancies from the ideal image without feeling real concern (Maslow 1970). Such feeling of comfort and acceptance with the self are extremely important in terms of laying down a tone that underlies a person’s whole existence.” (My bold).

~ Lou Benson15

I feel that the above quotation is very important for gay men who have been persecuted, may feel guilt and shame at being homosexual, hate their bodies, and who may have given up the security and love of family and friends to ‘come out’ as a gay man. They hopefully learn to accept their own human nature with all its discrepancies from the ‘ideal’ image. This acceptance of Self helps to improve overall self-esteem and provides the basis for a state of happiness within the Self. Interest in change should be encouraged. Instead of sitting in the middle of a comfort zone we can put some faith in ourselves and our ability to challenge cultural and personal stereotypes.

Marcus Bunyan (Australian born England, b. 1958)

Jeff standing on his Chrysler, Studley Park, Melbourne, Victoria, 1992

1992

Silver gelatin photograph

Body images, facades and fantasies

“There are these guys, hot guys with, I mean, the really chiselled bodies, who I used to look at in awe, who wouldn’t give me the time of day,” recalls David … “I didn’t exist to them. I wasn’t a person. I’d try to strike up a conversation at the bar, and they’d just turn away, in a mean way – treated me like shit. Now, here it is four years later, and I’m all built up, got my forty-two-inch chest and my big biceps, and now these guys are all over me – they can’t get enough of me. And, well, I have to say it does make me feel powerful. I’ve conquered them. That is a feeling of power.”

Michelangelo Signorile16

Has David really conquered them or has he been defeated by the very ‘disciplinary system’ (the power of the muscular body) that was excluding him in the first place? If you can’t beat ’em, join ’em so to speak. That feeling of power that he now feels he has; does he now ignore other people who used to look like he did; does he treat them the same way he was treated; does he treat them like shit as well?

I don’t think that David has conquered them at all.

I suggest he has just capitulated and joined the dominant body image ideology within gay society. Is this power giving him a false sense of self-esteem? Possibly. For in the end he is relying on his body, one part of himself which with wither and age anyway, to uphold his self-esteem. Without the body he was always wanting to belong. Now he has the body he belongs to what?

Perhaps he belongs to a powerful hierarchical ‘disciplinary system’ that controls the desires of other gay men through the symbolic image of the muscular mesomorphic body image. I asked Barry Taylor17 about body image, the fantasy of the ‘ideal’, self-esteem and learning to accept the self:

BT: Because of metabolism, some people will never have the body beautiful and this ALMOST BECOMES A GRIEF to them. THE CRUCIAL POINT THEN BECOMES HOW CAN I BE SATISFIED IN MY-SELF? Then it becomes who am I, and about my self-acceptance.

MAB: How do you change images of the male body to broaden their appeal?

BT: Its difficult. You are dealing with fantasy and the erotic, transcending the mundane of everyday life…

MAB: And so this body beautiful image becomes the fantasy?

BT: Yes, it is the fantasy.

MAB: How can you change that image to become different fantasies not just one?

BT: This would be a long term process of cultural change. One way would be to present images that are normative but are also sexy … Another way would be a broader cultural change in which we are encouraging a greater sense of self-awareness and depth, [NOT self-reflexivity] so that people can be more accepting of those kind of differences – that we feel good about those kind of different relationships. I can construct and feel sexy in bigness, hairy legs, being thin … The last thing would be to build resilience in our lives and this happens by experiencing success and achievement in our lives (and this builds self-esteem).

How do I measure success and achievement?

If I measure success and achievement by getting the body beautiful …

MAB: And belonging to the ‘A team’ …

BT: … then I am going to be constantly disappointed. But if I say this is Barry Taylor and I am happy with who I am, I am happy in my work or whatever, I’m not only successful, but I also have MEANING and am CONTENTED with that.

MAB: I think it is very good to challenge the self, challenge the path you are taking in life, but also for that path to have meaning and for you to be contented in what you are doing.

BT: To be comfortable in going through that process. The other thing is that people around you affirm that path, and affirm and celebrate what we do. Once you find a group of like-minded people that are affirming and nurturing of me, then growth often occurs.

MAB: For the older gay man who hasn’t developed that inner sense of self, and the body sags and its all gone, how do they cope?

BT: Vulnerable thing. The new priest, as it were, is the therapist. Not only because people have problems to deal with, but because they are on a spiritual journey.

The construction, social reproduction and representation of meaning in image identity is critical.

Indeed, Barry Taylor sees the last part of ‘coming out’ as an integration of sexuality into the identity of the whole self. This process may not take place until the gay men is well into his thirties, when they are on a spiritual journey. Unfortunately, as Barry Taylor comments later in the interview (see below), many gay men put off this journey by constantly immersing themselves in the ‘Party Boy’ image and living behind a facade.

In an age when I believe there is a shifting down of the time frame of the development of not just homosexual men but all human beings, I suggest it is important that we do not hide behind facades and have the courage to face adversity and encourage our diversity. We can help maintain high self-esteem by promoting the positive side of our identities and abilities without hiding behind masks.

We must not be afraid to fantasise about bodies that are different from the stereotype. I like scars, broken noses, bow legs and slim boys! I find these things very, very sexy but some people are amazed that I do. They think it strange, but attractiveness rather than ‘beauty’ depends upon a deeper understanding in the eye of the beholder; someone may be considered a great beauty in a ‘collective’ sense but I believe attractiveness is of a more personal, individual consideration.

For example, I don’t think that work alone would make many gay men fancy a ‘weary’, world worn face and many would find such a face unattractive. But many gay men still have fantasies about ‘straight-acting’ men such as plumbers and labourers! To be told through social stereotyping that something is beautiful is not the same as making up our own mind that we find a person attractive.

Lakoff and Scherr have pointed out,

“We must learn to separate our judgements about beauty from our learned expectations, that is, our social stereotypes. We must close the gap between what we really find beautiful, and what we think we find beautiful because we have been told to think that way … We must learn, somehow, to accept a wider range of physical attributes as potentially ‘beautiful’.”18 (My bold).

We form our self-esteem partially through the appraisal of those around us. If we can encourage gay men to appreciate a wider range of body-types as fantasies, then perhaps more gay men would not feel the need to conform to the dominant ideal of the muscular mesomorphic body and this could lead to higher levels of self-esteem in gay men who do not ‘fit’ this ideal.

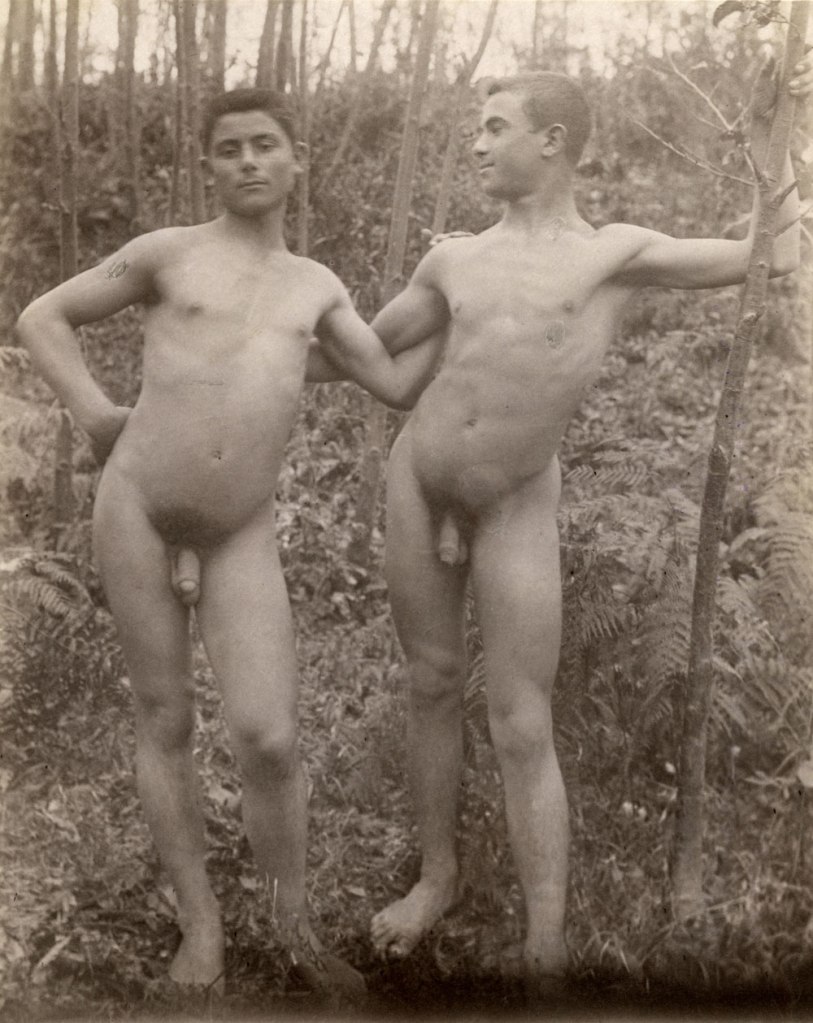

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Fred and Andrew, Sherbrooke Forest

1992

Gelatin silver print

Getting older

As gay men get older (from their mid-twenties onwards) they may perhaps begin to contemplate the rituals of life in a more understanding and accepting way (although the ageism evidenced in online gay cruising sites is particularly evident). Their seems to be a general expansion of the body-types that gay men find desirable at this time. Perhaps this expansion is due to several factors:

1. Sexual attractions may change and become more diverse the older we get.

2. As we get older (into our thirties), we may become less fussy in our choice of sexual partners due to the availability of sex with prospective partners that ‘fit’ our ideal body-types.

3. We may become more aware of every-body having something to offer and that what is presented is just an image – that we must get past the image / facade to look inside.

Extracts from research project interviews

Can you tell me what was your ideal body type:

a) When you were first attracted to men 14-17: About the same body shape as himself – tall, slender, petite.

b) When you had your first sexual experiences with men. 17-20: It changed into a bit more muscular. Anthony had moved to the city by this time and he had just started going to gay clubs, around the age of 17-18. Saw his first gay porn around the age of 20. Anthony was looking at older guys with bigger, more developed bodies. Anthony wanted a body like that himself because he was very thin.

c) Now 32: Like stocky guys now, depends on what sexual experience he is after. So the body influences the sexual experience. He has a greater appreciation of different body-types now. Range of desire is broader. Still smooth: 0-10% hairy chest only.

Interview with Anthony, Australian, 32, 5’10”, 69kg. Melbourne. 23/09/1998.

Can you tell me what was your ideal body type:

a) When you were first attracted to men: A proper man or what he defined then as a proper man. Straight acting, slightly butch type. This was before coming out. About 16 saw Tv experience on Channel 4 – homosexual virtual sex , voyeurism, rubbing of naked bodies and simulated fucking. They were gym fit, stereotypical gay bodies. First idea of a gay body was this kind of body. His idea of the ideal body type was formed quite early on before coming out.

b) When you had your first sexual experiences with men: Basically the same.

c) Now 23: It has changed now. He doesn’t look at stereotypes as much now and looks at the individual person instead. He tends to notice them more if they have shaved heads. Is this just another stereotype though? Its personal taste and depends on who the individual is – what chemistry is happening. More confident about his body now after starting going to the gym. Promised himself to get a “better” body – brings other rewards – more attention, more looks from people, gives him more self-esteem. Works on different areas – is quite aware of mental, spiritual areas and feels body is just part of an overall package.

Phil feels that if he wanted sex any time he could go out and get it (the sauna or sex venue) and this would not be based so much on body image. Does not use his body to go out and get sex. He has lower self-esteem in regards to positioning his body in an order of desirability – he feels that there are more people higher up the body chain with better bodies than him. How does that make him feel? He shuts himself off to this when cruising. On the street it does not matter as he has higher self-esteem there.

Interview with Phil, English, 23, about 5’10”, 73kg, robotics technician, middle class. Melbourne. 13/09/1997.

MB: Interesting that in situations of cruising and the street that levels of body image self-esteem change – possibly because in one situation Phil reveals his body image, has less control and is more vulnerable to the judging gaze of others. In the other he is clothed and the revealing of his body can be escaped from. The element of an ‘order of desirability’ is much more pronounced in an unclothed cruising environment.

Can you tell me what was your ideal body type:

a) When you were first attracted to men 13-19: Large and ripply. Because he is small he was attracted to the security of larger men. Particularly muscles, smooth people. Pre-anything in gay mags – going down beach seeing other men.

b) When you had your first sexual experiences with men 19-20: Difficult to attract men – sheltered because he liked that muscular stereotype and could not have it. So he was on his own, so when he was approached he tried to make friends instead of solely looking at the body. That worked OK.

c) Now 23: It has changed a lot – he now likes all manner of shapes and sizes. Growing up and accepting other people for who and what they are. Now he is much happier in his self and this helps!

Interview with Marcus, Australian, 23, 5’4″, 65kg, worker – storeman/packer, waiter, middle-class. Lives country Victoria area. 28/09/1997.

Can you tell me what was your ideal body type:

a) When you were first attracted to men: Definitely muscular Adonis look – bulging everything, smooth. Formed that through a natural liking for this kind of body – influenced by seeing these images in news media and TV programmes such as OUT (gay and lesbian programme on SBS) and gay magazines. Bombarded by this image.

b) When you had your first sexual experiences with men (came out at 18): Very much the same.

c) Now 22: Hairy men are quite attractive now – explains this through experiencing them. Attraction with hairier men because they were more masculine. Still muscular – an appreciation of the image. He has become more perceptive towards peoples individuality in body-image composition. Very rarely do people fit into the media image ideal that they sell us. It is not important that they do – is it important for them?

Interview with Michael, Australian, 22, 5’10”, 83kg, clerk, working-middle class. Melbourne. 05/10/1997.

Can you tell me what was your ideal body type:

a) When you were first attracted to men 12-26: Usually the blond hair, blue eyes and slim muscular thing – good legs, good arse. Not attracted to body hair. Never attracted to really tall men – went for the balanced, proportionate look in respect to height.

b) When you had your first sexual experiences with men 26-30: Gavin’s first sexual experience was 2 men in a car in a car park in St. Kilda. The blue-eyed blond was supplemented when he started to look at gay porn videos – hairy chests, the Mediterranean look, interested in the construction worker, working men (‘straight-acting’ fantasy). The images in the porn videos and mags influenced the bodies he liked. Even started to look at family albums and noticed how handsome relatives were in their earlier years.

c) Now 34: Gavin’s idea of “gorgeous” is really wide – but whether he goes further depends upon their personality, intelligence, sensitivity, honesty, punctuality, inner soul stuff. Guys who exercise their inner spirituality in some way. He finds it difficult to relate to people who spend lots of time at the gym and on the facades. His appreciation of different body-types has increased a lot – in combination with inner work.

Interview with Gavin, Australian, 34, 6′, 70kg, middle-class. Melbourne. 03/11/1997.

For some gay men this expansion is a very positive growth experience. Other gay men do not undertake it at all, forever mired in the never ending circuit of drugs, body, lifestyle and party scene until well into their mid-thirties to early forties.

Barry Taylor had important things to say about this age group:

BT: The next big group is 35 onwards – who by now may have developed a major alcohol and drug problem.

In their 40’s, they desire the body beautiful and try to buy young boys, go to the sauna and can’t pick up. They suicide because of loneliness – because the gay community doesn’t provide any other model for them (other than the body beautiful). No place for them to meet and be part of.

MAB: I always wanted a big body. I have struggled with that for years. Now, at 39, how does the gay community support men in mid-life? In the last 6 months acceptance is starting to come that I am no longer young in body, but still young at heart!

BT: This happens because you start to synthesise yourself. This is the last stage of coming out, I believe. This is Barry Taylor who works in the area of suicide, who likes classical music, has a sense of the spiritual self and is also gay. So the area of sexuality is only one part of who I am. I am not reliant on going to gay places all the time. If I’m still in the PRIDE stage, so long as your young and fit into the image, on and on it goes. BUT – if a relationship fails, you loose your job, or have some insight of who you really are, that’s when suicide can happen. They crack or they do something about it.

MAB: Is this mid-life crisis happening younger these days?

BT: Yes, I’m seeing some suicidal people at 14-15 who have had enough of life, are wearied out. At 22-26 people are looking for more choices. The first group used to be in their 20’s but are now in their teens.

MAB: Ages have not compacted but have shifted down.

BT: Yes, people are finding a void and are looking for a spiritual self earlier.In the past it has been mainstream religion but now they are searching for something different in the void of boredom – because mainstream religion has not been a factor in their lives.

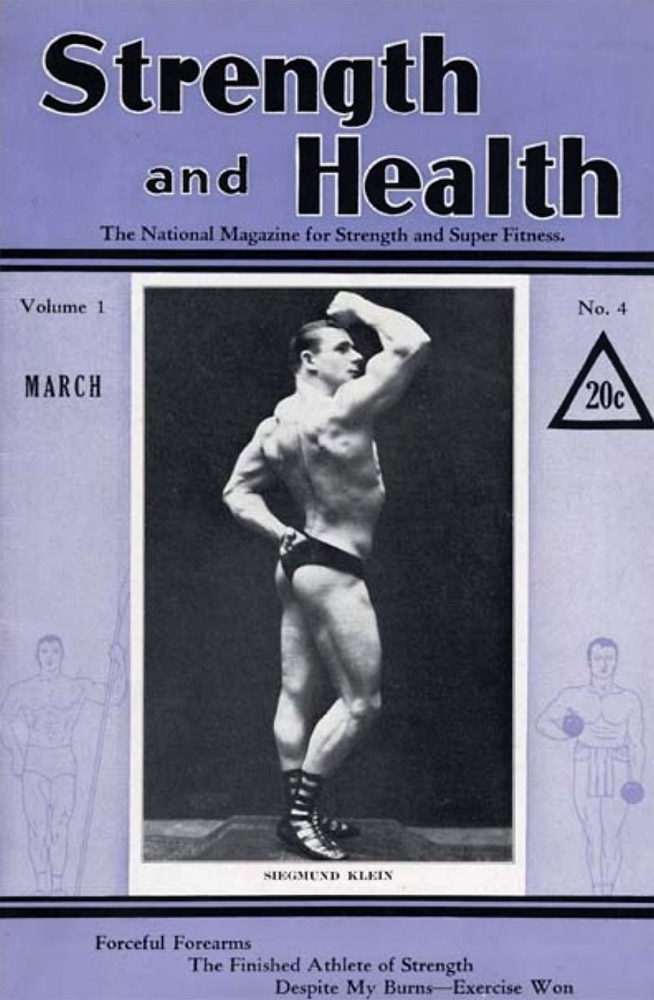

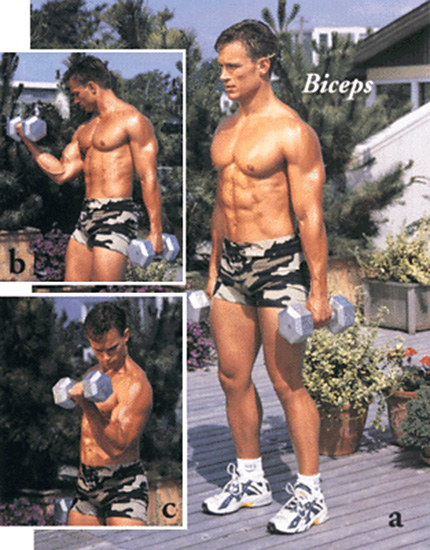

MAB: The adverts that appear in Blue, XY, Large magazines – they perpetuate the myth of the beautiful body.

BT: Yes, that’s right. Gay life is like school or adolescence. If you are invited to a group party, they have the power, they are popular, the select ‘in’ crowd.”

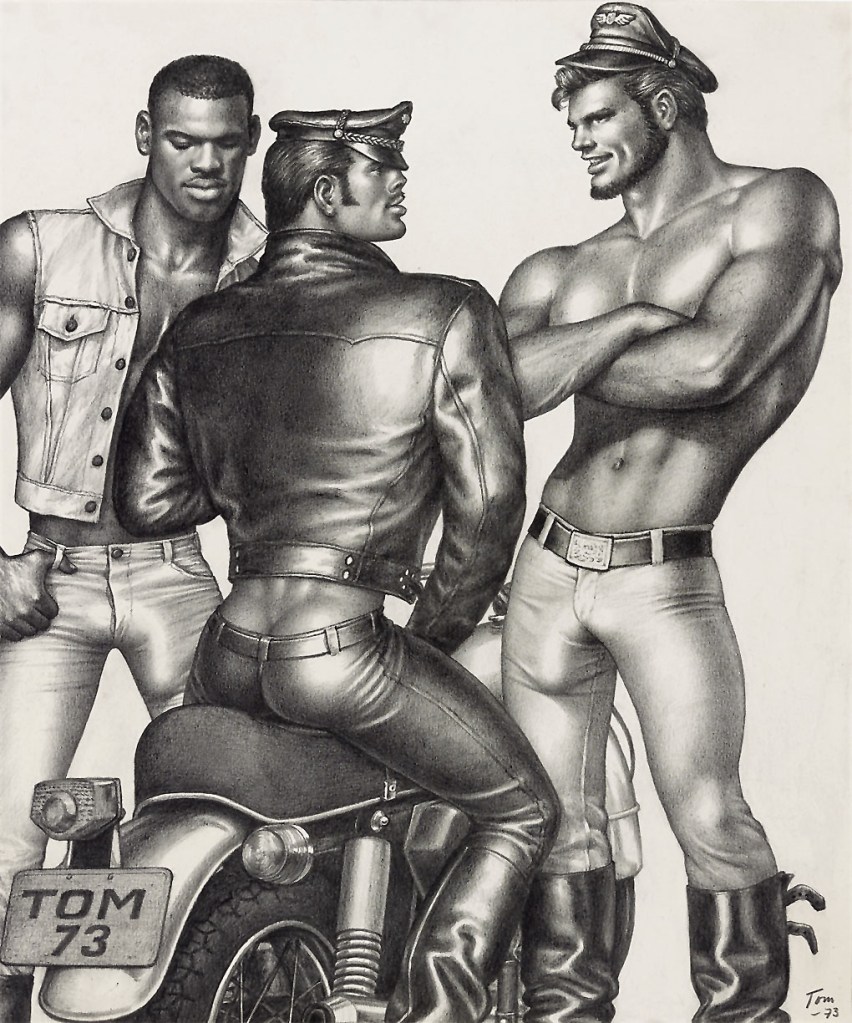

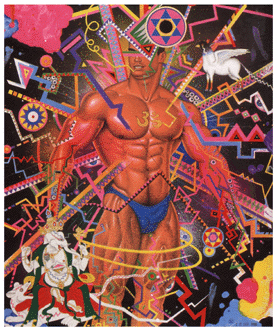

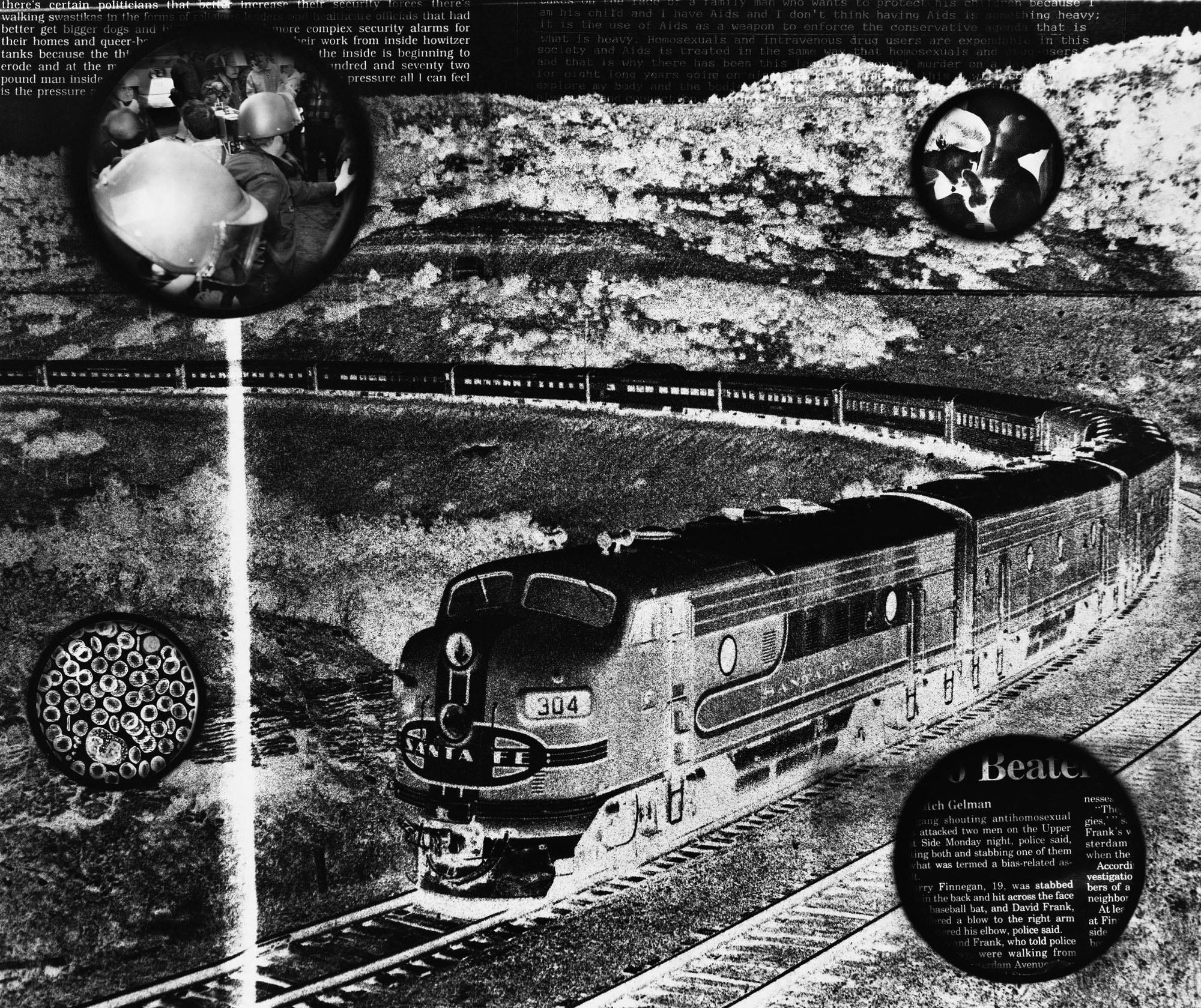

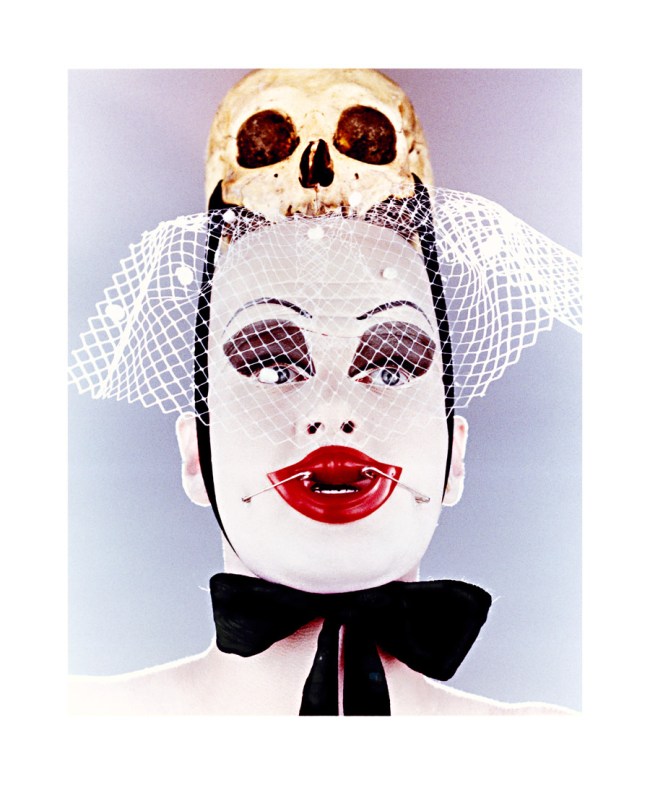

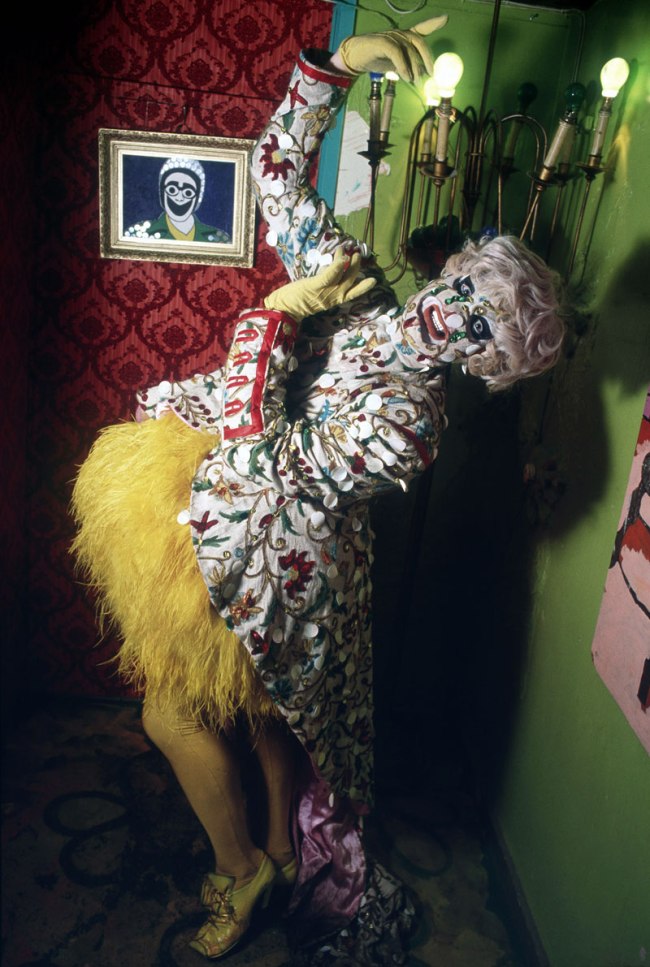

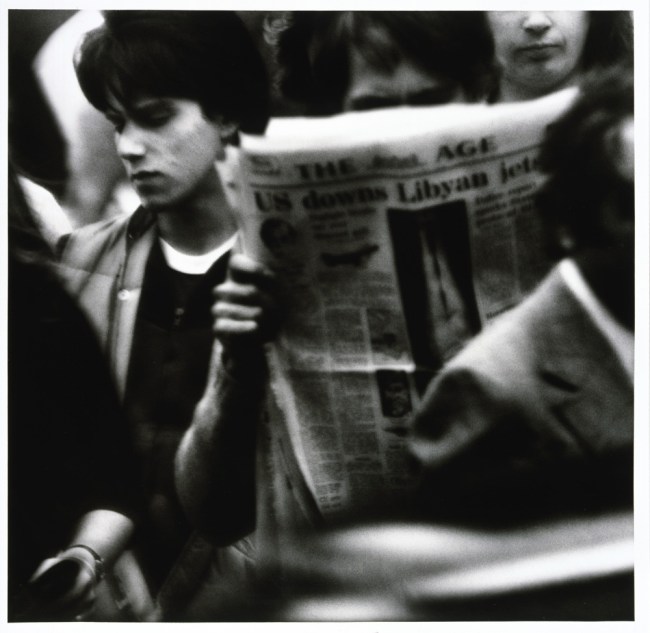

Jez Smith (Australian)

Antigay

Nd

in Blue Magazine. Sydney: Studio Magazines, April 1997, p. 23.

“There’s a new gay sentiment sweeping the globe and it’s perpetrators are homos themselves. They don’t object to what we are – just what we’ve become.”

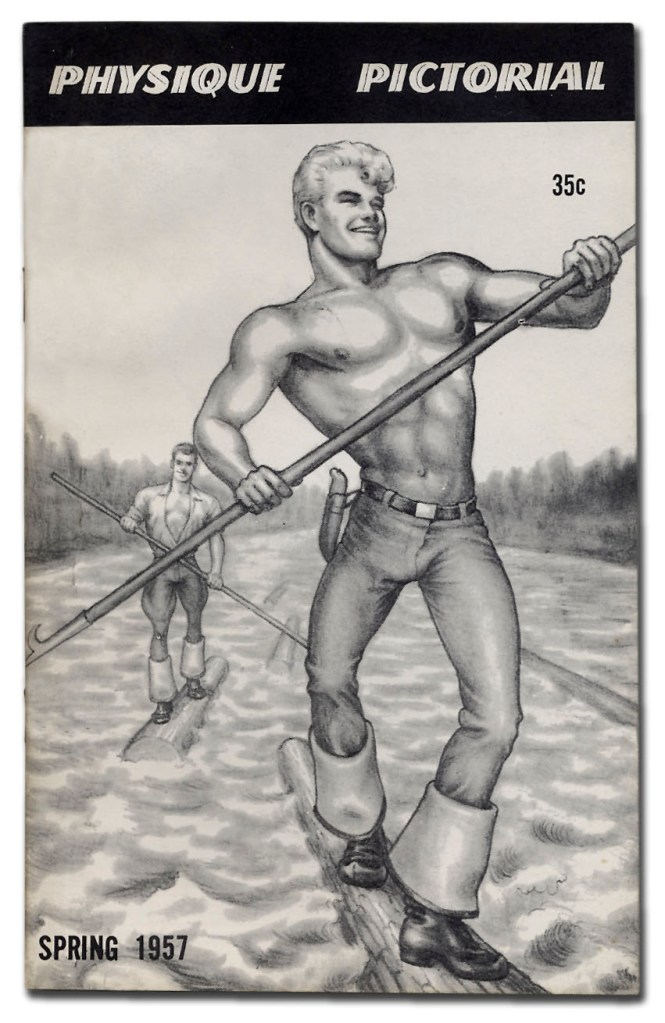

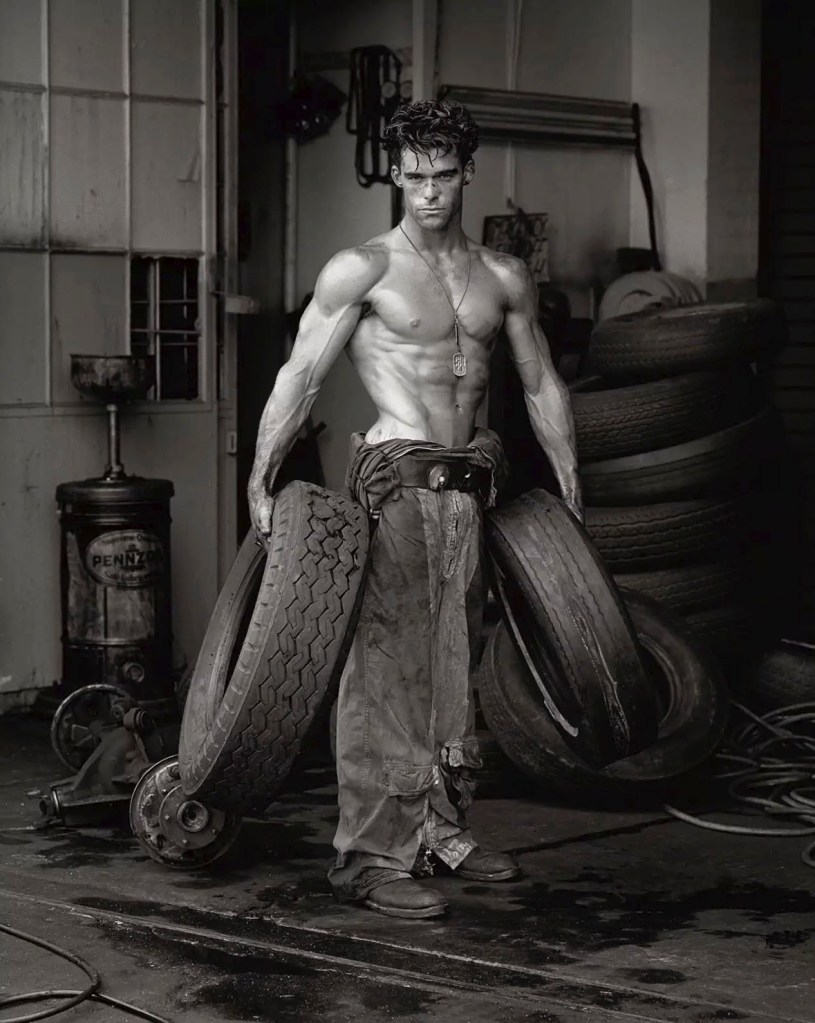

Imaging the gay male body

“The gay scene is a market and both sellers and buyers have become used to the coinage of appeal and neither can change it without losing out. The way the compulsive cruisers present themselves is geared to the way the buyers choose: looking no further than skin deep, ignoring what might or what might not be underneath … The majority of gays are placing their cosmetic selves, not their real selves, on the line.”

R. Houston19

An article in April 1997 Blue Magazine titled “McQueer” examined the impact of the commercialisation of ‘gay’. In a short but interesting article David Taylor looked at a book called ‘Anti-Gay’ edited by Mark Simpson, first published in 1996. This book, through essays by social commentators from different parts of the world, examines the development of a backlash against the attitudes and ideologies of the commercial gay scene.

In the article The Divine David observes that, “Anti-gay is a reaction by the people to their dissatisfaction with a lot of the imagery used in the gay media that centres around total body obsession, and the idea that being gay is some sort of lifestyle that has to be pandered to (and is quite expensive). Being gay has become a commercial thing which doesn’t seem to have anything to do with civil rights or people feeling comfortable with their sexuality. ‘Gay’ has resulted in something which is quite soulless.”

Paul Burston also explains that, “When I say I’m anti-gay, it doesn’t mean that I hate all of the things that the gay scene is. What I’m saying is that I hate a lot of the mindset that comes attached to that – it’s the herding instinct I hate. And there is no reason why people should feel they can’t still take part in the scene, so long as they think for themselves.”

Here is the crux of the argument. To think for oneself. To be aware.

Because it is not enough to blame the media or the ‘scene’, it is important to think for oneself and be aware of the pressures, addictions and imagery that interacting with the commercial gay scene may involve. As an alternative to the commercial gay scene quite a few alternative clubs like Kooky and Home in Sydney and Queer & Alternative in Melbourne have sprung up over the last 5 years to cater for gay people disillusioned with the usual scene pubs and clubs.

‘Blue’ choose to illustrate the “McQueer” article with the image above by Jez Smith. While interesting the image is difficult to read. The body, in it’s deconstruction, becomes dehumanised and has virtually no identity at all. The image seems to be saying that by being anti-gay your body is not worthy of being a fantasy for other gay men. Compare this with other images appearing in the same and later issues of ‘Blue’ with the interchangeability and replaceability of the muscular, smooth, white Adonis that usually grace the pages of the magazine.

As informative social comment the article pays lip service to alternative points of view, to alternative discursive structures and images within society that do not have space to express themselves, but is just a token gesture on the part of the publisher whose magazine constantly reinforces underlying social values and stereotypes in regards to male body image representations.

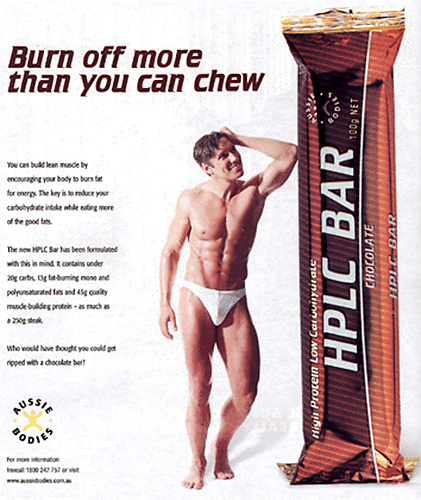

A different approach has been taken by the Body Shop. The first issue of it’s magazine Full Voice20 looks at the body and self-esteem. Of course, the Body Shop promotes it’s own philosophy and ‘natural’ product within this magazine – it’s a commercial money making enterprise otherwise they wouldn’t be in business – but the magazine does not pull any punches. Below is an image from the magazine; it shows how a ‘natural’ looking Barbie model would appear and comments on how many women really do look like supermodels.

Anonymous photographer

Untitled

1997

Body Shop advertisement in Roddick, Anita (ed.,). Full Voice Issue One. Australia: Adidem Pty. Ltd., 1997

The magazine asks what self-esteem is? It replies:

“SELF RESPECT

SELF AUTHORITY

DIGNITY

PRIDE

AWARENESS

CALMNESS

THE PURSUIT OF DREAMS

A SENSE OF ACHIEVEMENT

A TWINKLE IN THE EYE

THE LIVING OF LIFE”

The magazine contains articles for women on such issues as ‘ideal’ body image versus ‘real’ body image, 10 social symptoms of high and low self-esteem, fat versus thin, how to create a beauty advert called “Want to Know a Secret?” (which is a real laugh), and what is beauty? It concludes with these lines:

“Somewhere in time, society lost the plot. We decided how a person looked was more important that who that person was. When that time was, no-one knows. But we can remember the time we started to put it right.”

The Body Shop should be applauded for their effort. We must acknowledge, though, that people will be attracted to other people through an appearance that engages with their sexual fantasies. This only becomes a problem when sexual attraction through physical appearance turns to discrimination against other people who don’t match their ‘ideal’ look. In an important observation, Greg Blanchford has noted of the sexual objectification of gay men occurring in casual encounters that,

“People in these situations will not be attracted to someone unless they are attracted by some external feature that fulfils some sexual fantasy. It follows that there must be an emphasis on surface or cosmetic characteristics. And because the criteria of selection can be highly specific, one is, in turn, concerned to present an image of oneself that will attract others. Therefore appearance, dress, manner and body build are very important.”21

Of course these elements are important but unfortunately, in our society, not everyone can have a fabulous body build, appearance or dress and the way we treat attractive as opposed to unattractive people is not always equal and fair. Our reaction to the individual shapes the way that their self-esteem may develop and may affect their relationship with the world. If you keep telling an unattractive person that they are unattractive they will eventually begin to believe this themselves. This is called a ‘self-fulfilling prophecy‘. The individual becomes a victim of our discrimination and eventually perpetuates this damaging discrimination upon themselves.

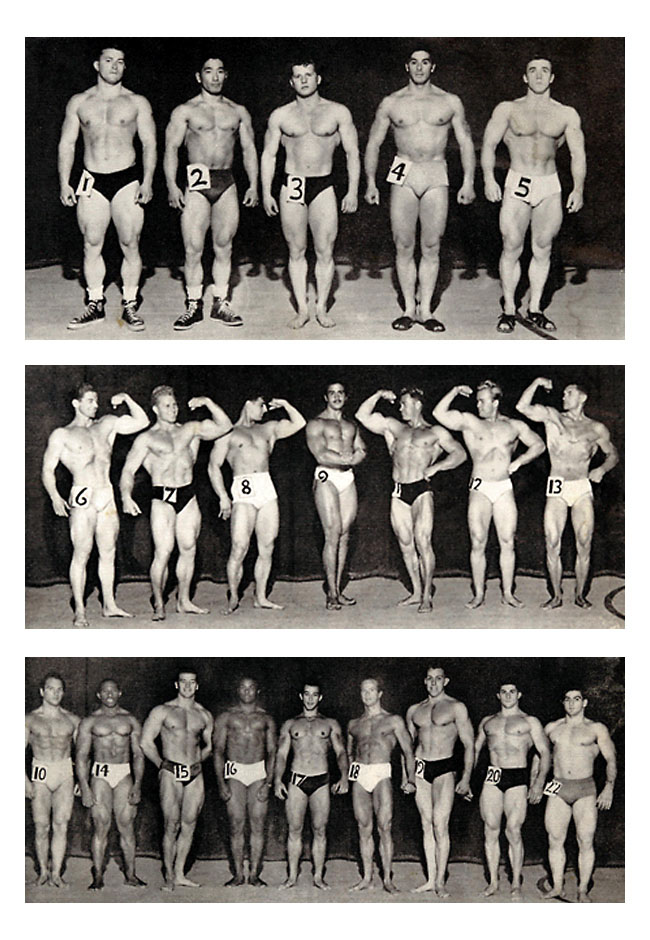

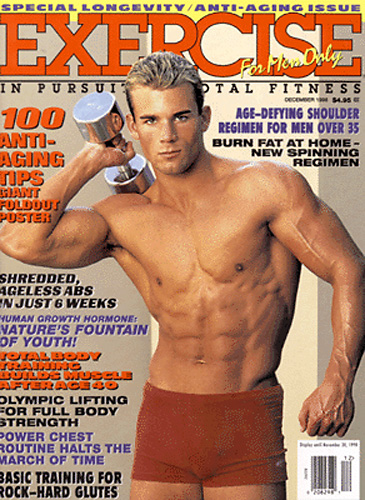

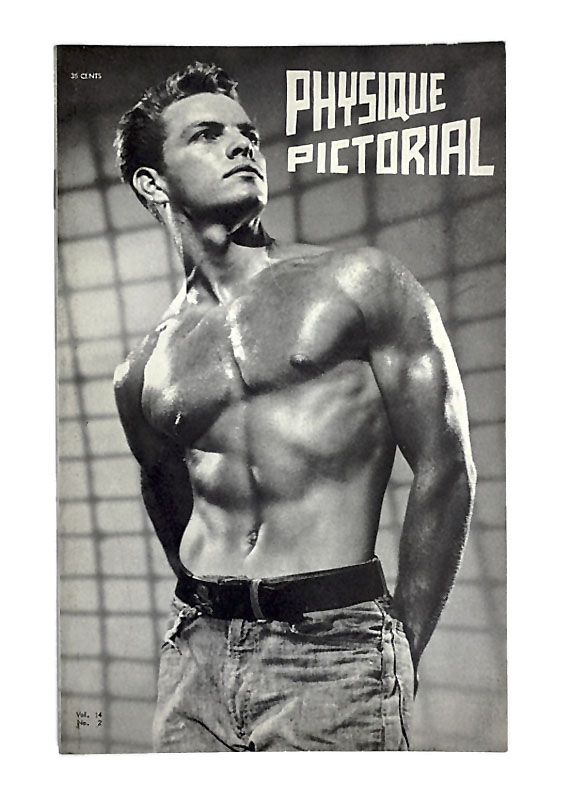

XY Magazine, a publication aimed principally at gay youth, ran a Body Issue in April 1997. Under the title “Perfect Bound,” William Mann talked to social commentators Michelangelo Signorile, Michael Bronski and Victor D’Lugin amongst others. In a thought provoking article Mann asks,

“How many gay kids are … struggling through identity issues like being skinny, or socially awkward or whatever? What does the image of the pumped-up pretty white boy – plastered all over our magazines, our advertising, our literature, and our erotica – say to the non-white or skinny gay kid, looking to find a place in a community that seems to have no place for people who look like him?”22

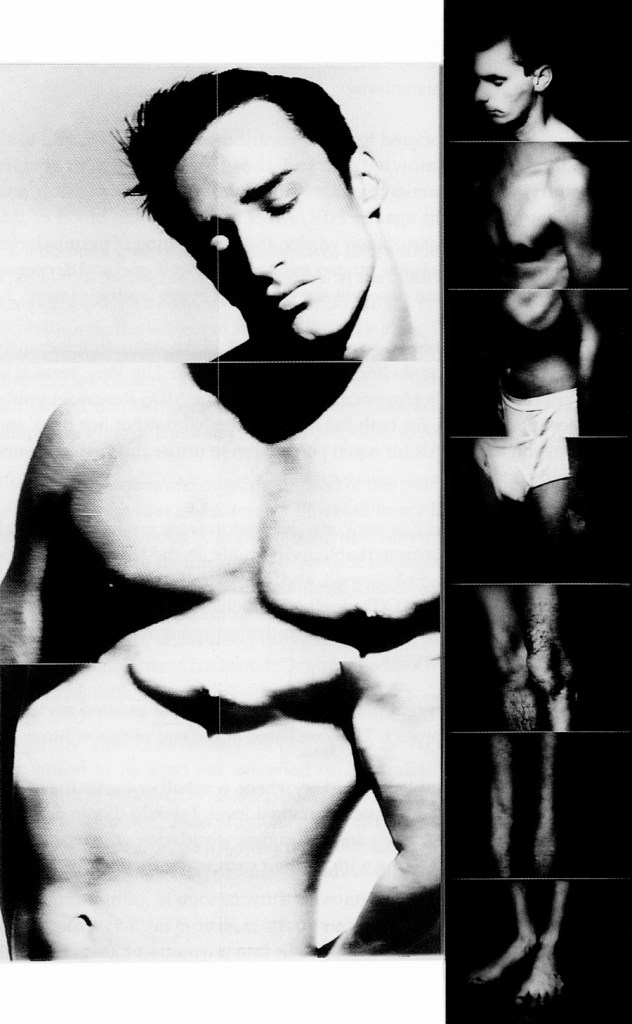

Anonymous photographers

Untitled

Nd

Pages from back issues featured in XY Magazine No. 7. California: XY Publishing. April/May 1997

What indeed – what does it say to them? Does the image make them feel inadequate? Does it alienate them not just from themselves but also from the gay community, a community to which they aspire to belong?

Here, I am not saying you can’t find muscular bodies desirable as long as you understand the possible consequences for other gay men who do not possess such a body. As Michael Bronski notes in the same article, “The minute someone points out something where we should be more culturally sensitive, there’s this cry of political correctness. People see it as an attack on them, a loss for them. But nobody’s saying you can’t find Marky Mark and his kind attractive.”

Indeed nobody is, including myself. I am the first to admire a good, muscular body and always wanted one myself. But I am aware of the problems and alienation from self that such a desire can cause. Under the heading NO PECS, NO SEX Mann goes on to say that this kind of body is not always available for sex and the more that we find this kind of body attractive the less sex we will have. “And when we do [have sex], its always the same, and we miss many kinds of pleasure.” Mann asks Michael Bronski about this point and, talking about the body of the buffed, white, muscular male he replies, “The image is so clean and ultimately non-threatening that it doesn’t allow for us to explore our sexuality, to see what the limits of our fantasies might be.”

Michelangelo Signorile observes that,

“Looking out at the hordes of shirtless, pumped-up men, each virtually indistinguishable from the next, it dawned on me just how much pressure is put on young gay men as they enter the gay community – more than ever before. It’s true that there have always been paradigms in the gay world, but it seemed in the past there were more choices, more leeway about what was considered a gay stud. Today only one very precise body type is acceptable – one that very few gay men have or can achieve. …

We need to empower people who don’t feel attractive. I’m not saying that for vast numbers of people the club and party scene is not fun, is not great. But those who don’t fit in need to see other images. Lots of people don’t see themselves in what they see of gay culture. The range of what’s attractive needs to be expanded, not because it’s a good thing we should do, but because the range really is broader.””23

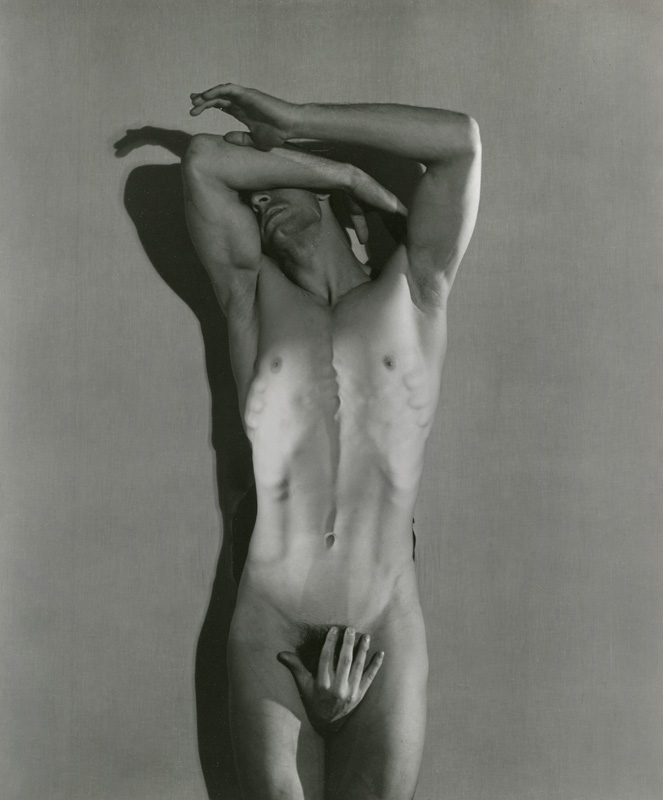

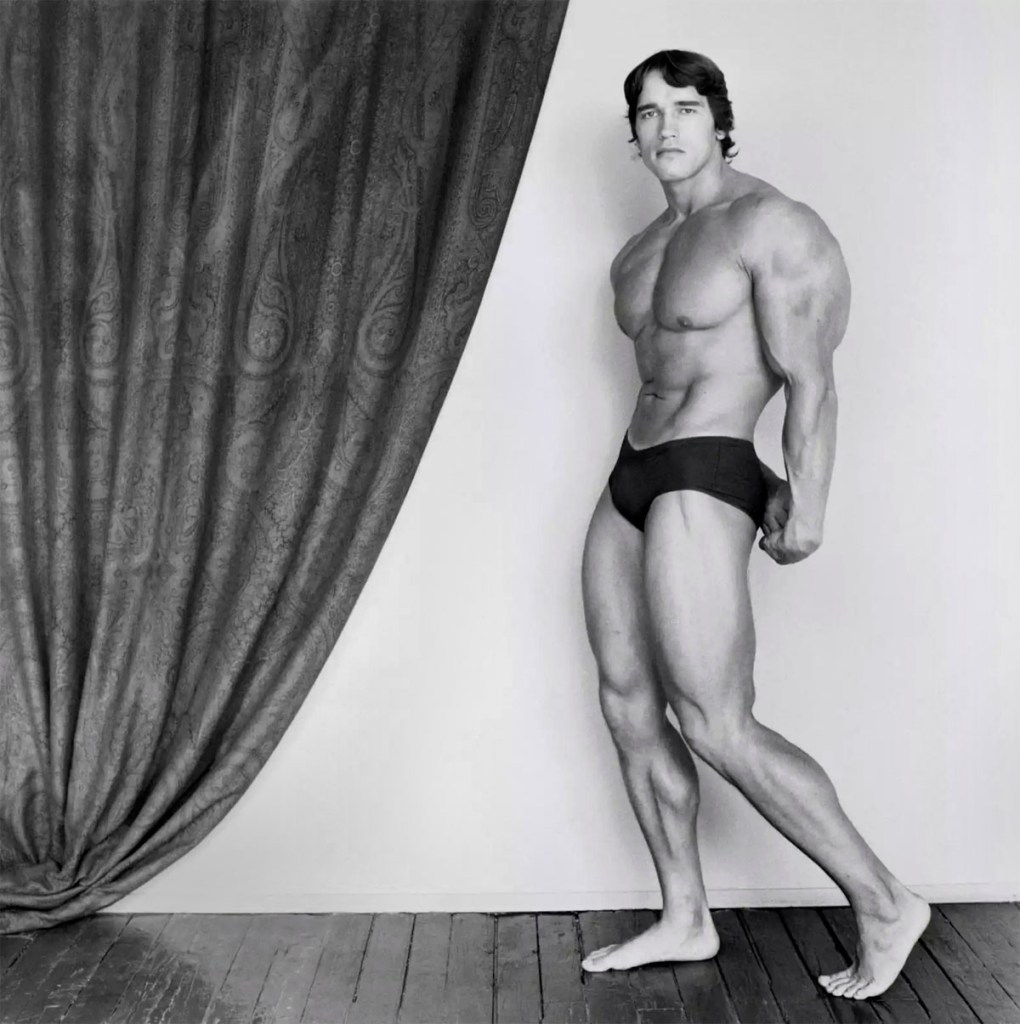

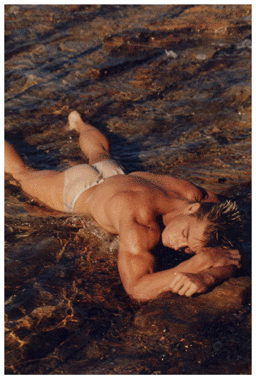

Anonymous photographer

Marky Mark

Nd

in XY Magazine No.7. April/May 1997, p. 27

“Marky Mark on 60 foot high Calvin Klein advertising board: icon of beauty, or body fascism?”

Finally, the conclusions reached by the article are that:

1. We should try and empower people who don’t feel attractive.

2. We should offer different images to people who feel they don’t fit in.

3. We should broaden the range of what can be seen as attractive.

4. We have limited our own sexual freedom by this hierarchy of beauty.

Then we look at the images that run in the same issue of XY Magazine, a magazine which is marketed and primarily sells to young gay men.

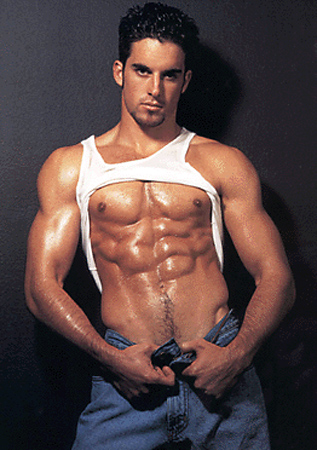

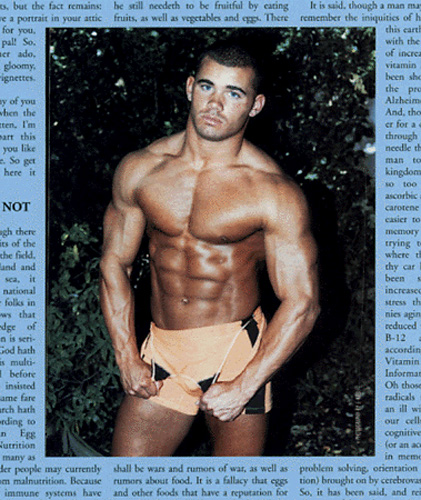

Advertisements for back issues include images that illustrate articles such as ‘Confessions of a Jock-Lover’, or ‘Palm Springs DOA: I Survived the White Party’, (see above images) which feature stunning, rippled torsos. The White Party is a Circuit party in America held to raise money for HIV / AIDS research where there are lots of gorgeous built men all running around having sex and taking drugs – the contrast between the built body and the AIDS body full of sad irony. Then there is the fashion shoot titled ‘Straight acting’. Yes, the models are from different ethnic backgrounds (no racial discrimination here!), but they are all smooth and built (see image below).

These photographs and many more like them feature in the monthly issues of XY magazine, a mag aimed at gay youth. I believe it is constructive that such issues are being debated but, as with the ‘Blue’ article, it is just a token offering that does very little to change omnipresent omnipotent social ideals.

Bradford Noble

Untitled

Nd

Images from ‘Straight Acting’ Clothes feature, XY Magazine No. 7. California: XY Publishing. April/May 1997, pp. 45-49.

Spiros Politis

Untitled

Nd

in Todd, Matthew. “In the Eye of the Beholder,” in Mattera, Adam (ed.,). Attitude Vol. 1 No. 66. London: Northern and Shell PLC, October 1999, pp. 56-57.

Left to right: Phil 49, engineer; Andy 21, student; Jon 21, student; Josh 25, escort; Jody 21, aerobics instructor.

Another article that attempts to address issues of beauty, body image and self-esteem in gay men appeared in the October 1999 issue of the London based Attitude magazine. Titled “In the Eye of the Beholder,” journalist Matthew Todd asks rather inane questions about the representation of bodies and the ‘scene’ of four ‘ordinary’ and one ‘perfect’ gay men (see image above). It is interesting to observe that these ‘ordinary’ gay men, while noting that gay magazines “ram it down your throat that ‘You should look like this!'” (Andy) offer no possible alternatives that they think would work to break the dominance of the visual stereotype of the muscular mesomorphic body image.

Although articles such as this do raise awareness of some of the issues concerned with self-esteem and body image, they also confirm the authority of visual ‘fantasy’ images that allows magazines (such as Attitude) to justify the continued publication of white, smooth, muscular ‘Party Boys’ as the epitome of what a gay man should look like by confirming that this image is what the consumer wants to see. This observation is confirmed by presenting a selection of the male body images that appear in articles, not advertisements, in the same issue of Attitude magazine.

Escapism and fantasy (linked to anti-authority and the feminine) are thus grounded in the authority and fixity of the sign of the muscular mesomorphic body image through desire for and “attraction to good looks,” through the watching of the objective eye, and through a nostalgia for the paradise of the perfect body. The authority and meaning of this sign is upheld “through the interpretative acts of members of a sign community,” particularly when the meaning and power of the sign is reinforced and dominant within the gay community. This can be contrasted with a partially seeing objective eye which offers an appreciation of ‘truth’ (subjective, objective, fluid and non-final) through imperfection, diversity, and an acknowledgement of difference. I correlate this non-finality with the quotation by Wendy Chapkis that I use as a summation at the end of the Re-Pressentation chapter.

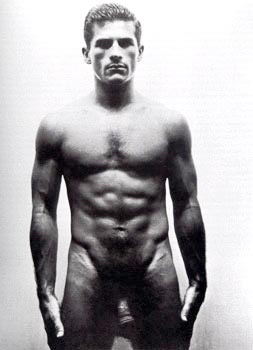

Axel Hoedt

Eric Travis

Nd

in Todd, Matthew. “”Naked,” in Mattera, Adam (ed.,). Attitude Vol. 1 No. 66. London: Northern and Shell PLC, October 1999, p. 38.

Axel Hoedt

Will Mellor

Nd

in Todd, Matthew. “”Naked,” in Mattera, Adam (ed.,). Attitude Vol. 1 No. 66. London: Northern and Shell PLC, October 1999, p. 48.

David Zanes

Ryan Elliot

Nd

in Todd, Matthew. “”Naked,” in Mattera, Adam (ed.,). Attitude Vol. 1 No. 66. London: Northern and Shell PLC, October 1999, p. 50.

Neil MacKenzie

Luke Goss

Nd

in Todd, Matthew. “”Naked,” in Mattera, Adam (ed.,). Attitude Vol. 1 No. 66. London: Northern and Shell PLC, October 1999, p. 54.

Stephan Ziehan

Sam Fragiacomo

Nd

in Clark, Adrian and Day, Luke. “Essentials: Grooming,” in Mattera, Adam (ed.,). Attitude Vol. 1 No. 66. London: Northern and Shell PLC, October 1999, p. 104.

I love how all the penises are covered up with towels or cushions and I note that traditional symbols of masculinity are also well represented – the cigar and the boxing gloves for example. Eric Tavis also happens to be a wrestler as well as a model. Also, notice how all bodies are smooth, white, muscular and look like they could have been pressed from the same mould.

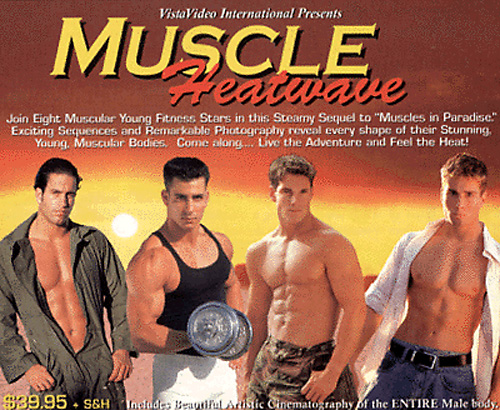

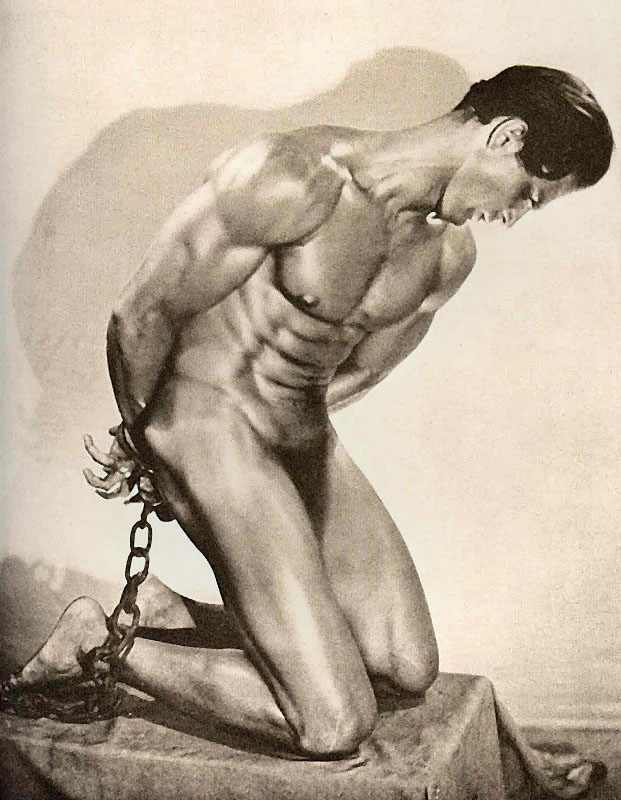

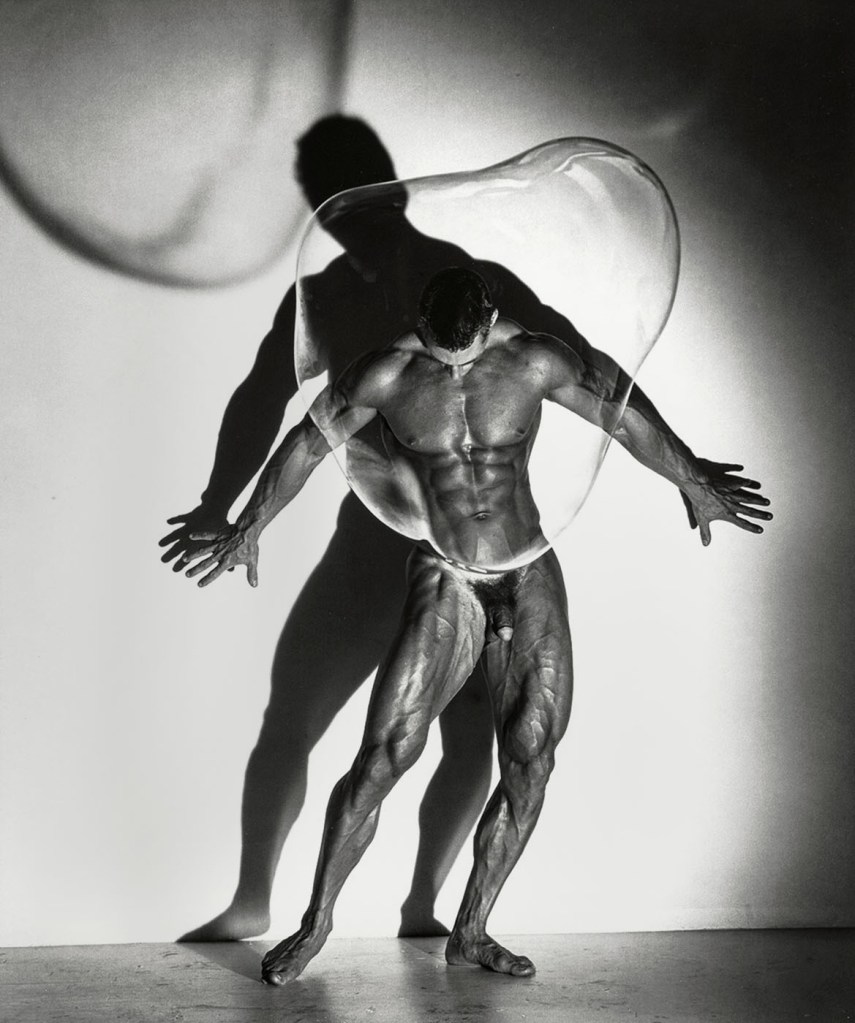

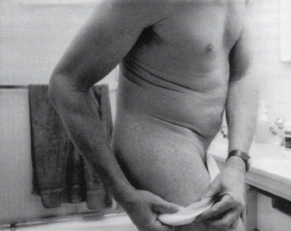

For gay men in contemporary society the maintenance of a healthy social body has become a moral concern, for supposedly anybody can make their frame-work a ‘work of art’ and attain that longed for paradise of the ‘perfect’ body, the body as a sign of virility and traditional masculinity. You only have to exercise and build that lean, hard look, have your tummy tucked or face reconstructed, take those steroids to make your body into a sculpture …

Your body could be a work of art if only you would let it …

Anonymous photographer

Make your body a work of art

‘Body Sculpture’ brochure

1998

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Andy in the flat, Punt Road, South Yarra

1991-1992

Gelatin silver print

Re-Pressing, responsibility and respect

Bodies and images of the body signify their meaning through representation. How can we re-press the representation of the male body so that we can offer alternative images to gay men that will act as fantasies for them? According to John Tagg25 we must demonstrate that the meaning of already dominant images within a society can be negated and rendered incoherent. Tagg says there are 2 ways of doing this:

1. “We must search for other signifying conventions, other orders of meaning already present in the culture (through conflict of classes, ideologies and forms of control) that are denied a semiotic space to express themselves.” (Semiotics is the study of signs)

2. “We must abandon the above search for other forms of meaning in bodies and body images and adopt images that refuse any meaning at all – bodies and images of them cannot be read or possessed and therefore may come to mean nothing. In other words the image does not signify anything, much like the early non-sexual androgynous ‘figure’ of the gay liberation movement. The figure had no ascertainable gender, even though the body was still actively sexual.”

Personally I think that the second option would be very difficult to achieve on a broad social level.

Body images are understood through ‘conditions of understanding’, in other words how their meaning is understood is through a collective knowledge of the history of context, place and the language that those images speak in. Images are the main source of sensual stimulation in contemporary society and their language is learnt from an early age.

To culturally deny this language would be a very difficult thing to achieve. The first option has a greater possibility of success: that we can open up spaces for images that have previously been denied the room to speak for themselves. This is especially true in regard to the dominance of images of the muscular mesomorph within gay society. We must try and propose different body image types as fantasies for gay men and give them the space within the community to express themselves!

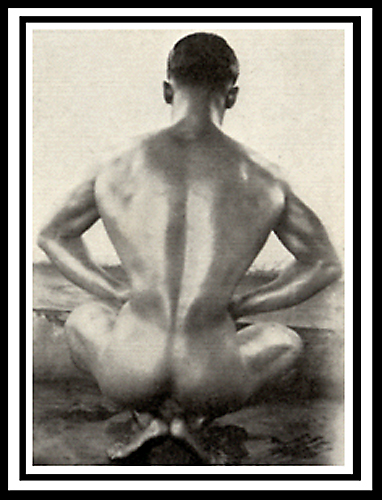

The image below is a good example of allowing other orders of meaning already present within images in our culture to speak for themselves. The photograph below is another form of re-pressentation of the male body image that usually finds no representative space within the context of gay media. These kind of images do offer themselves as alternative fantasy images for gay men but are often denied the space to express themselves and therefore reach a larger audience of gay men. Here I am, accept me for who I am.

Anonymous photographer

Untitled

1998

Image from a personal gay web page

An understanding of re-pressentation is the responsibility of every gay man. It is an ability to be able to respond (which is what responsibility means) to his own needs and the needs of others in a voluntary, altruistic and non-discriminatory way. It implies a care and concern for others as well as for the self. This is a hope, a dream if you like, but a good dream all the same. I suggest that, above all, responsibility for the acceptance of difference in others requires an understanding and respect towards yourself.

As Erich Fromm has said more eloquently than I can ever say,

“Respect is not fear and awe, it denotes, in accordance with the root of the word (respicere = to look at), the ability to see a person as he is, to be aware of his unique individuality. Respect means the concern that the other person should grow and unfold as he is. Respect, thus, implies the absence of exploitation … It is clear respect is possible only if I have achieved independence; if I can stand and walk without needing crutches, without having to dominate and exploit anyone else. Respect exists only on the basis of freedom … To respect a person is not possible without knowing him; care and responsibility would be blind if they were not guided by knowledge. Knowledge would be empty if it were not motivated by concern. There are many layers of knowledge; the knowledge which is an aspect of love is one which does not stay at the periphery, but penetrates to the core. It is possible only when I can transcend the concern for myself and see the other person in his own terms.”26 (My bold)

I think this is a fantastic way to view our relationship with the world.

Respect, responsibility, care, and concern are key words in this positive relationship with ourselves and with others, which I believe will increase self-esteem by surrounding both with good energy. I realise that this may be very difficult to put into practice all of the time but if we could try then I believe the world can become a healthier, more balanced place.

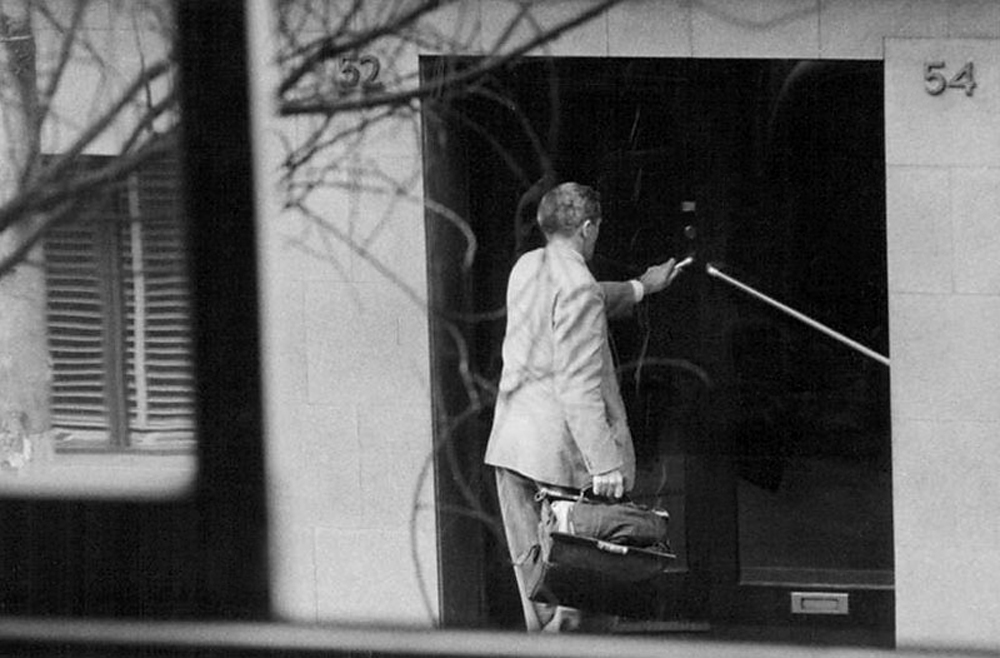

Marcus Bunyan. ‘Self-portrait in Punk Jacket’ 1991-1992 from the series ‘Self-portraits and nudes’ 1991-1992

Marcus Bunyan. ‘Self-portrait in Punk Jacket’ 1991-1992 from the series ‘Self-portraits and nudes’ 1991-1992

Marcus Bunyan (Australian born England, b. 1958)

Self-portrait in Punk Jacket

1991-1992

From the series Self-portraits and nudes 1991-1992

Gelatin silver print

Re-imag(in)ing the male body

“Modern man is alienated from himself, from his fellow men, and from nature. He has been transformed into a commodity, experiences his life forces as an investment which must bring him the maximum profit obtainable under existing market conditions. Human relations are essentially those of alienated automatons, each basing his security on staying close to the herd, and not being different in thought, feeling or action. While everybody tries to be as close as possible to the rest, everybody remains utterly alone, pervaded by the deep sense of insecurity, anxiety and guilt which always results when human separateness cannot be overcome …” (My bold)

Erich Fromm27

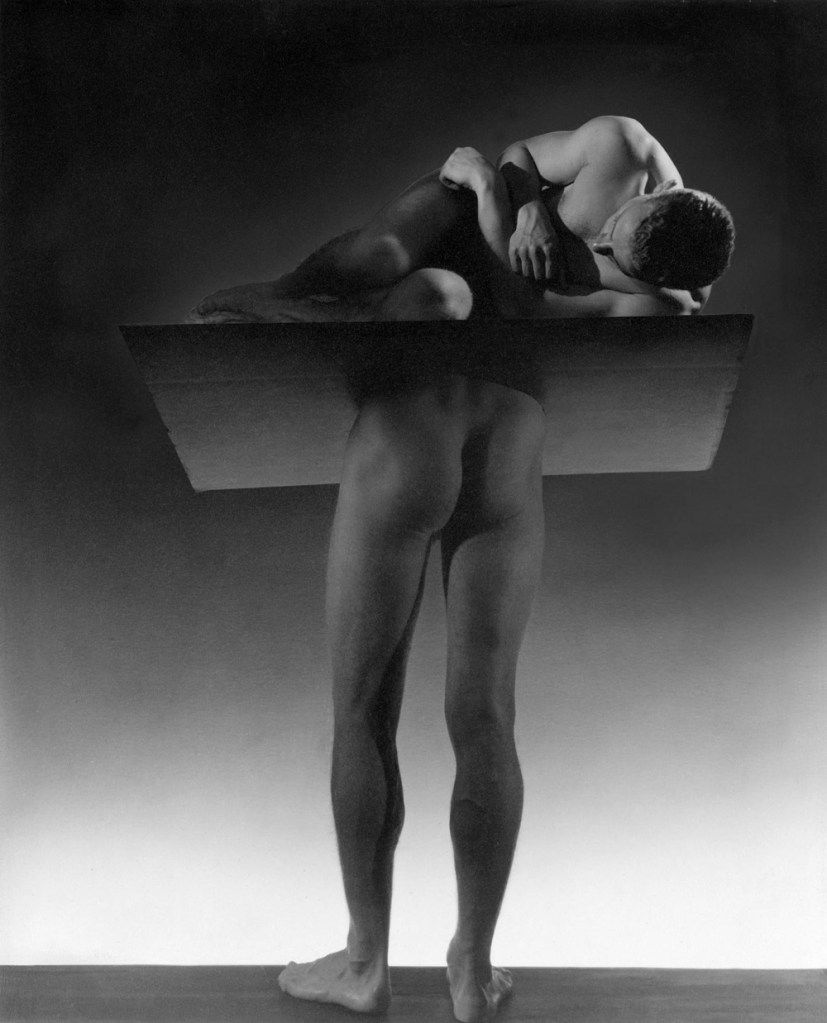

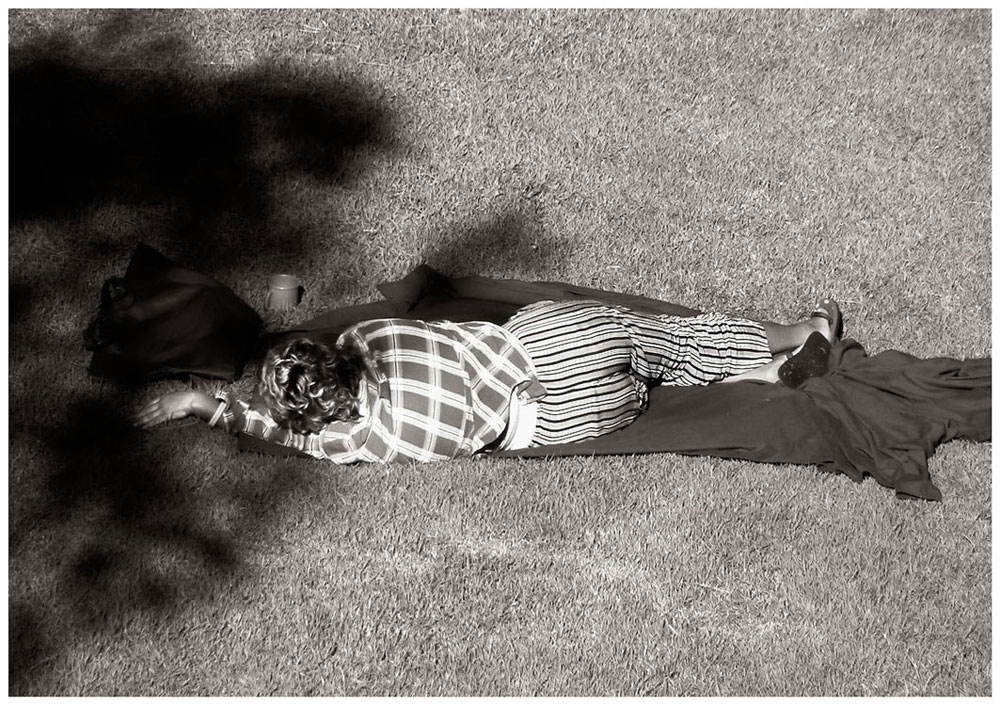

Marcus Bunyan (Australian born England, b. 1958)

Untitled

1995

From the series Sleep/Wound

Gelatin silver print

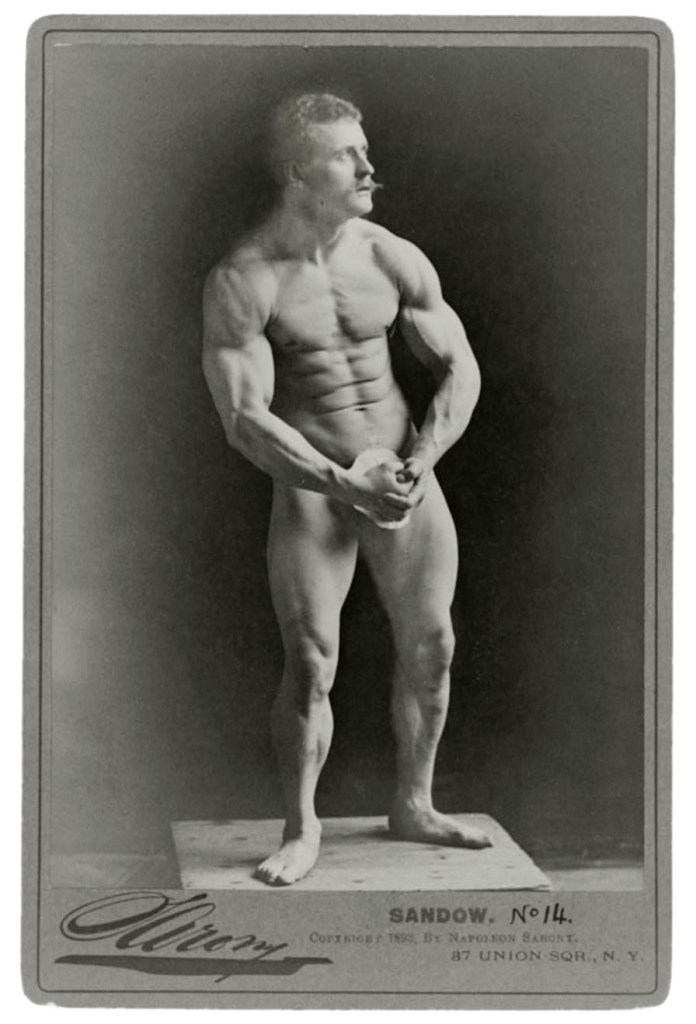

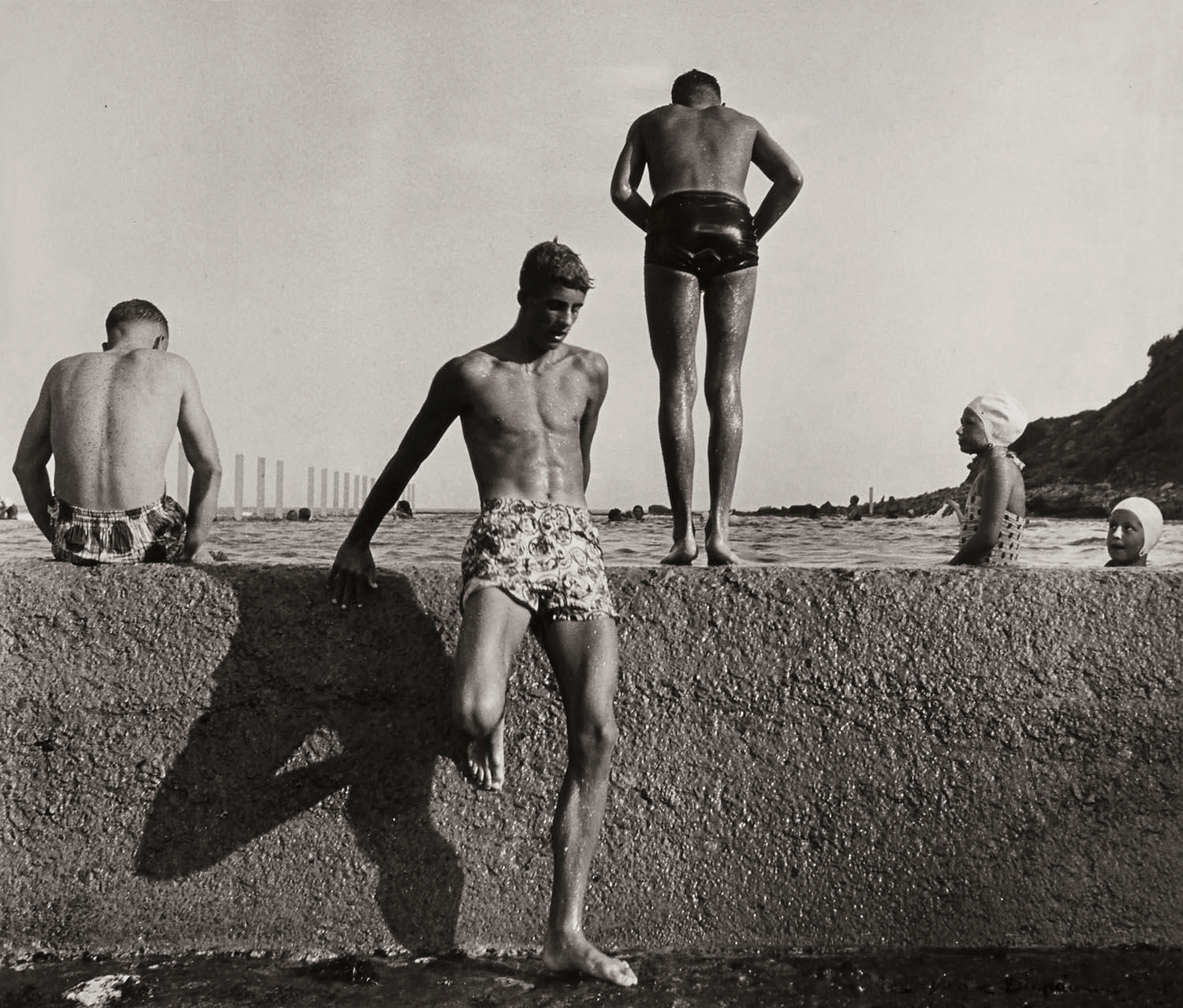

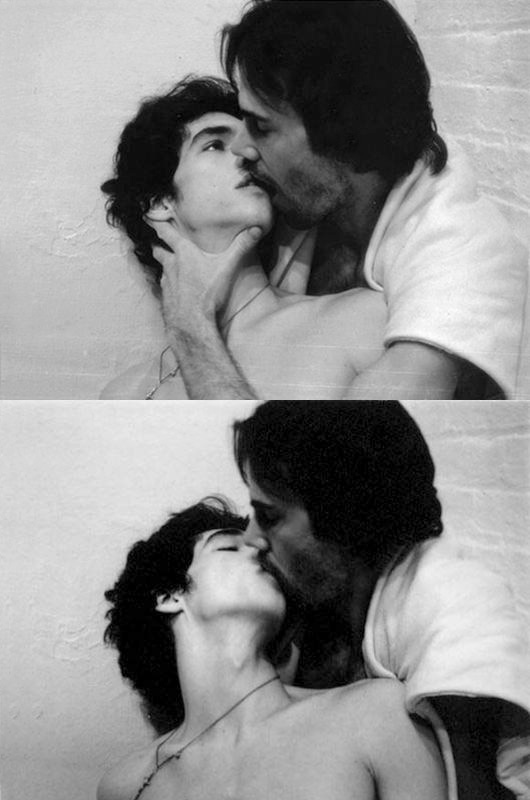

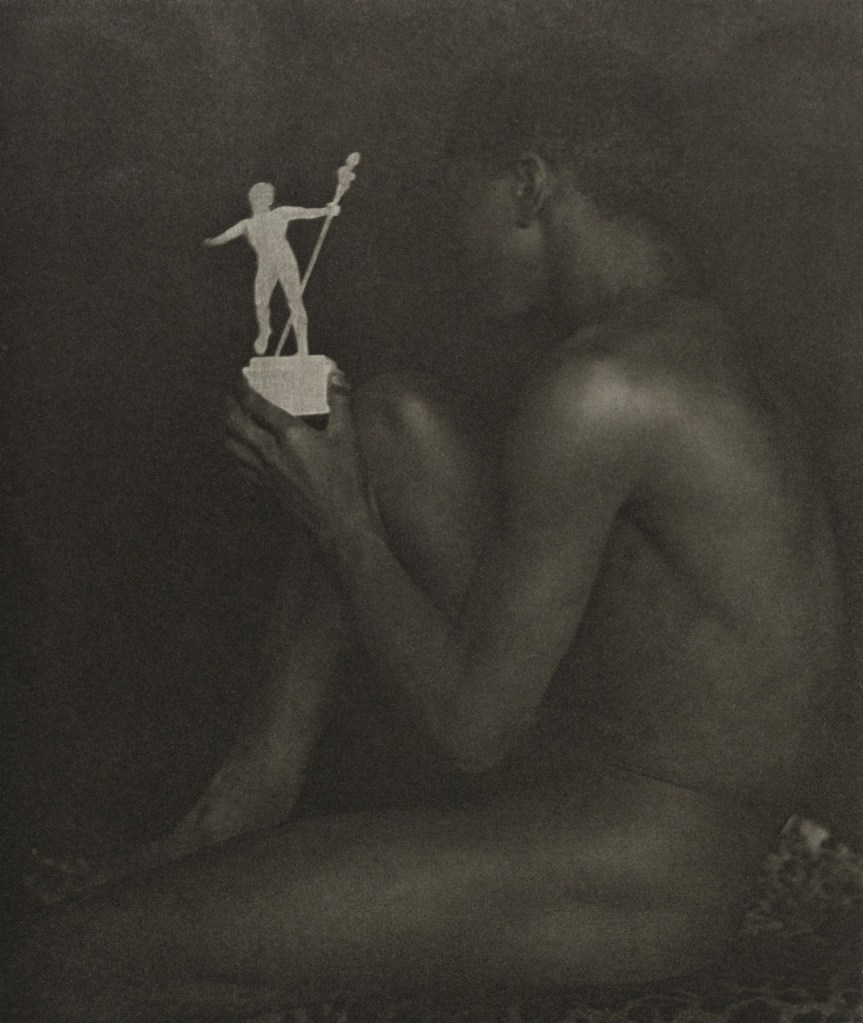

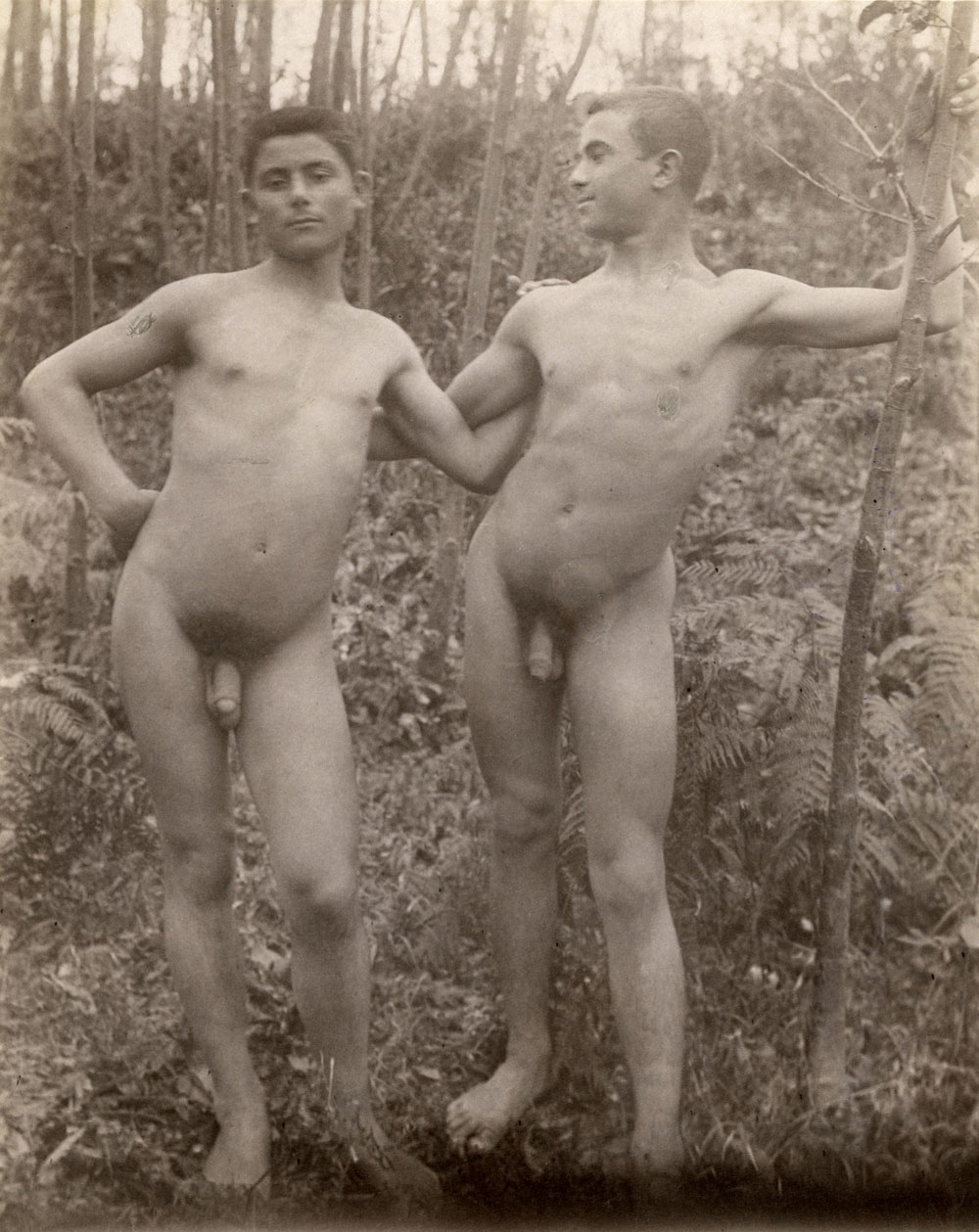

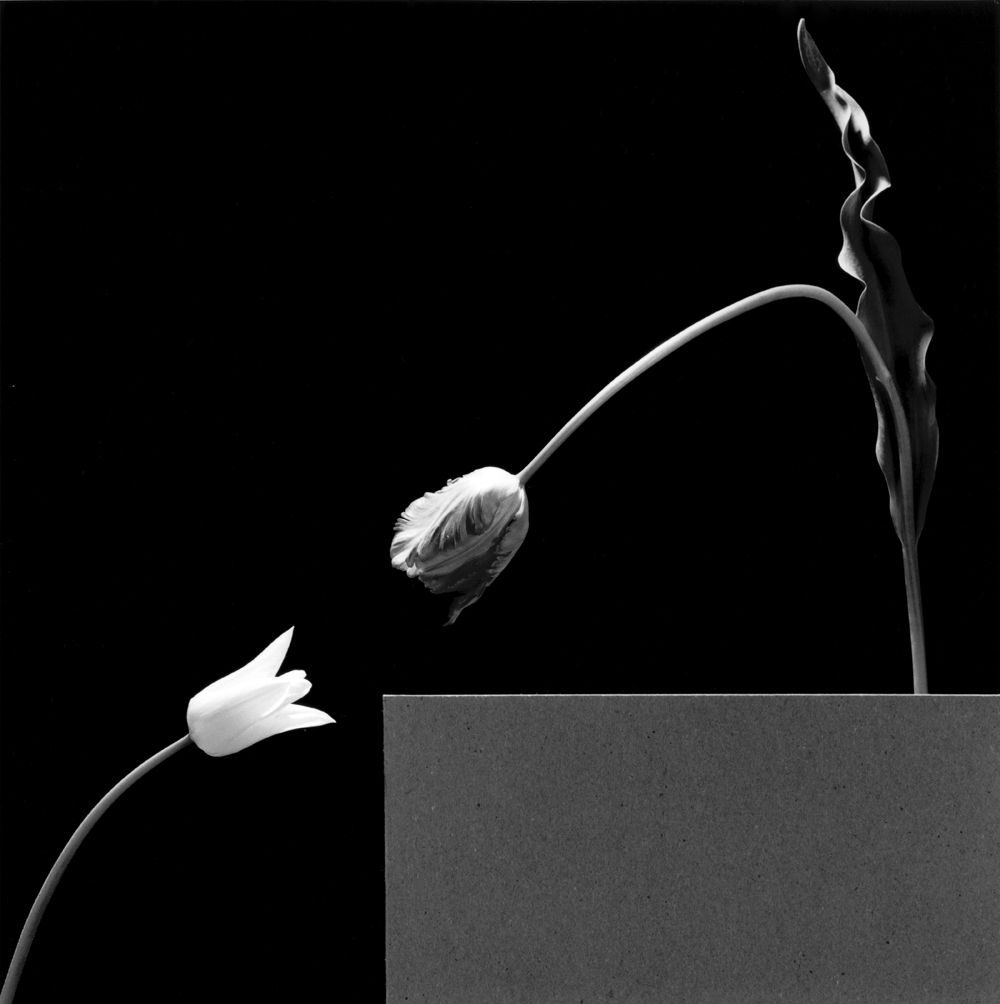

In the series of photographs I try to explore the gay male body not from the usual viewpoint of desire but from the viewpoint of intimacy, touch, affection and love. The infrared images are the positions of sleep of myself and my partner. If people find them erotic then that is their reading of the photographs. They are not meant to be. They explore an area of imagery of the male body which I think has been totally overlooked – male2male intimacy. An early example of this intimacy is a photograph by Minor White (below). Few have really developed this theme further. This is an imagery not as reliant on the posing, hard bodied, clench fisted, body as phallus orientated iconography so prevalent in contemporary male society. It is an example of imagery that has yet to find a semiotic space to express itself.

We seek to belong to a society that values coherence and conformity whilst promoting ‘individuality’. Staying close to the herd; not being different in thought, feeling or action; assuming masks; the replaceability and interchangeability of bodies. These are all conditions of this supposed ‘individuality’ in contemporary society, a society that is really afraid of any expression of difference and diversity. The gay community, long priding itself on valuing diversity, is equally guilty of this charge. Gay becomes a ‘performativity’,28 a repetition of rituals which does result in a loss of individuality, the subsuming of the individual into the ‘team’.

“The idea of being one’s self is often expressed as “doing one’s own thing.” We can say that one is being himself when he is doing (or thinking) what he really wants to do (or think). When, however, one is acting in a way that is intended to appeal to others or to a code of behaviour that does not come naturally to him, he is not “doing his own thing” at all. He is, in fact, “doing someone else’s thing.”29

A gay man may not really be ‘doing his own thing’ as he would like to think, but ‘doing someone else’s thing’, doing what every-body else is doing. This conformity is enforced by gay men themselves. Not society but individual will, the will to be part of the ‘team’; to seamlessly belong. Erich Fromm has said this is union by conformity. “In contemporary capitalistic society the meaning of equality has been transformed. By equality one refers to the equality of automatons; of men who have lost their individuality. Equality today means ‘sameness’, rather than ‘oneness’.”30

Of course, we are all convinced that we follow our own desires but in the gay community we see how these desires can be shaped to fit in with a standardised ‘ideal’ in regards to male body image, in order to become ‘the same’. I believe that gay men must try to negate and transcend the power inherently embodied in stereotypical representations of male body images. Says Chris Schilling,

“If our embodied experiences negate dominant conceptions of gender roles, for example, there is the basis for the creation or support of alternative views about men and women … It is important to note that not all bodies are changed in accordance with dominant images of masculinity and femininity, and there is much individuals can do to develop their bodies in different directions.”30 (My italics)

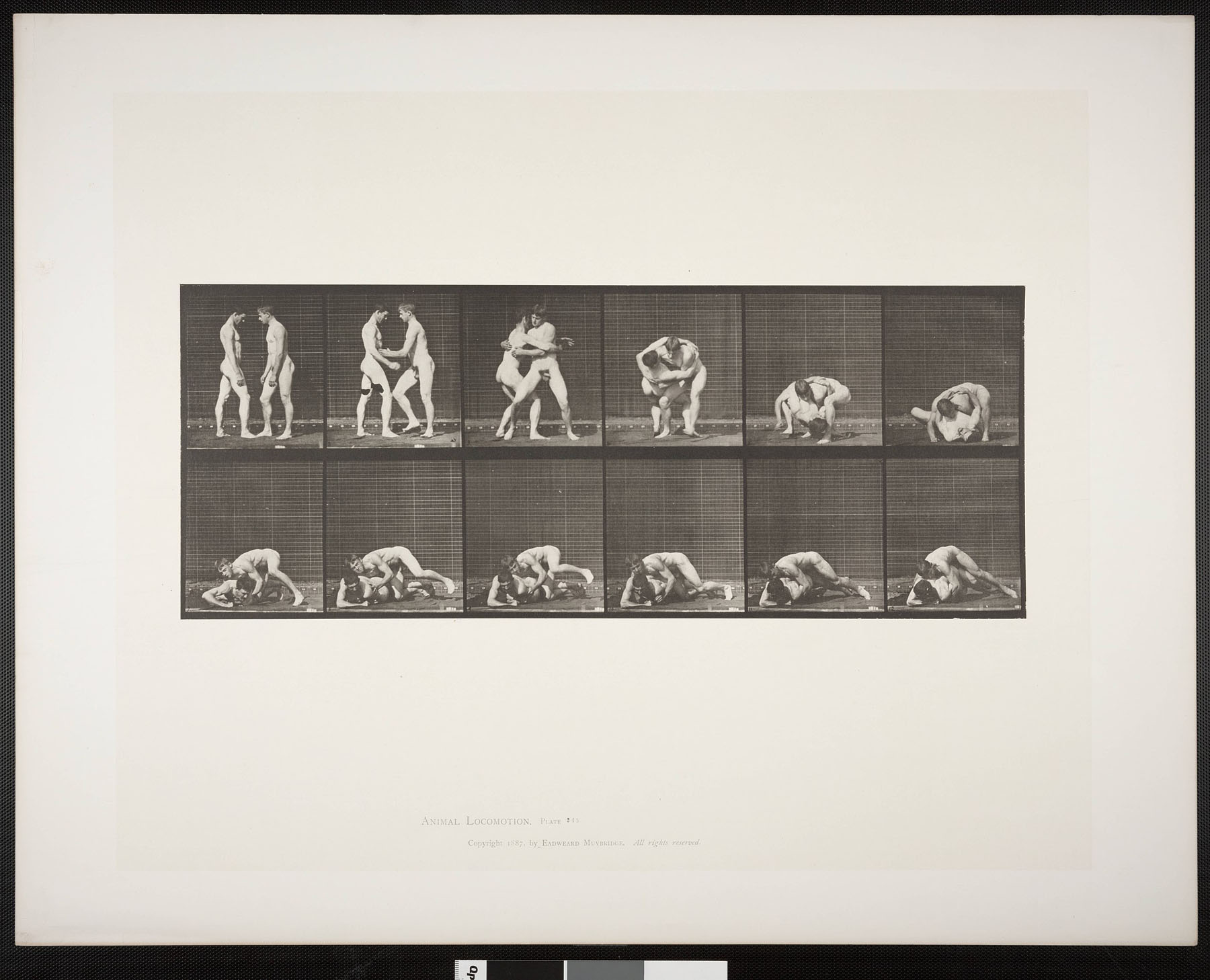

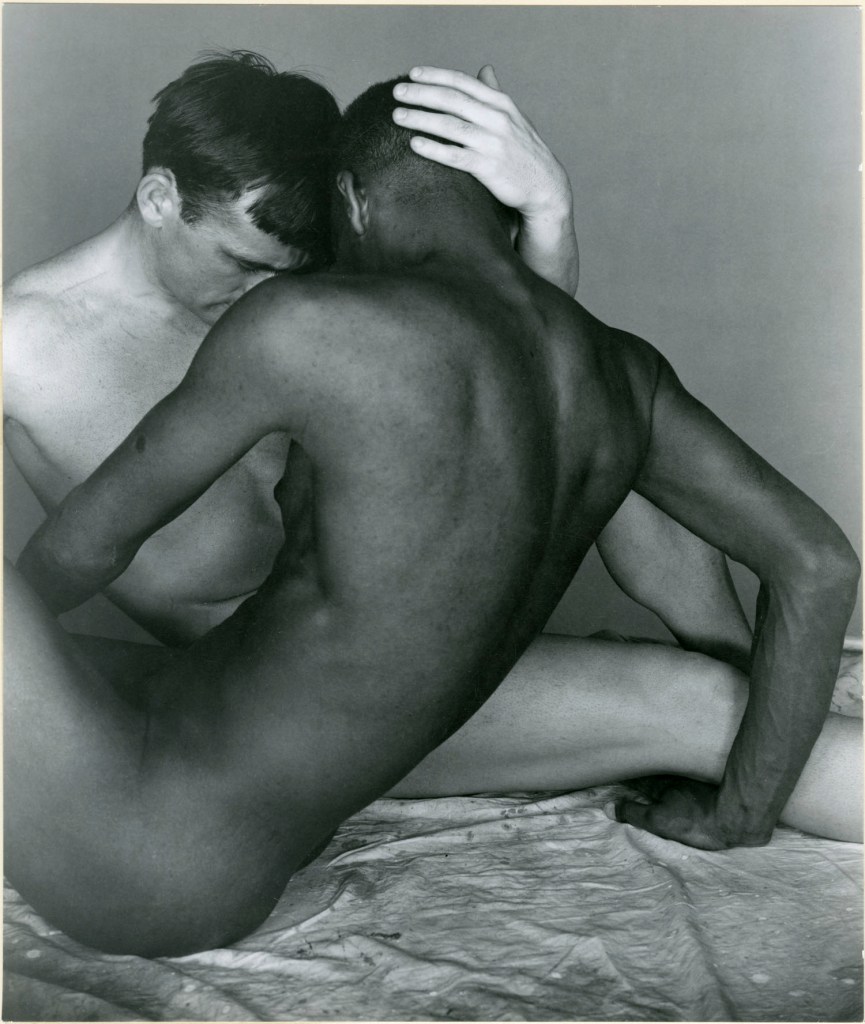

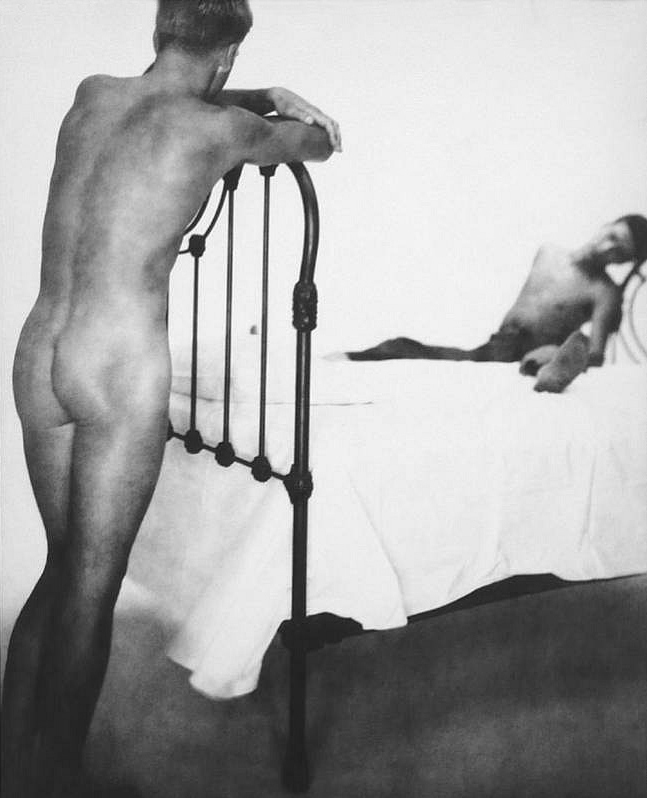

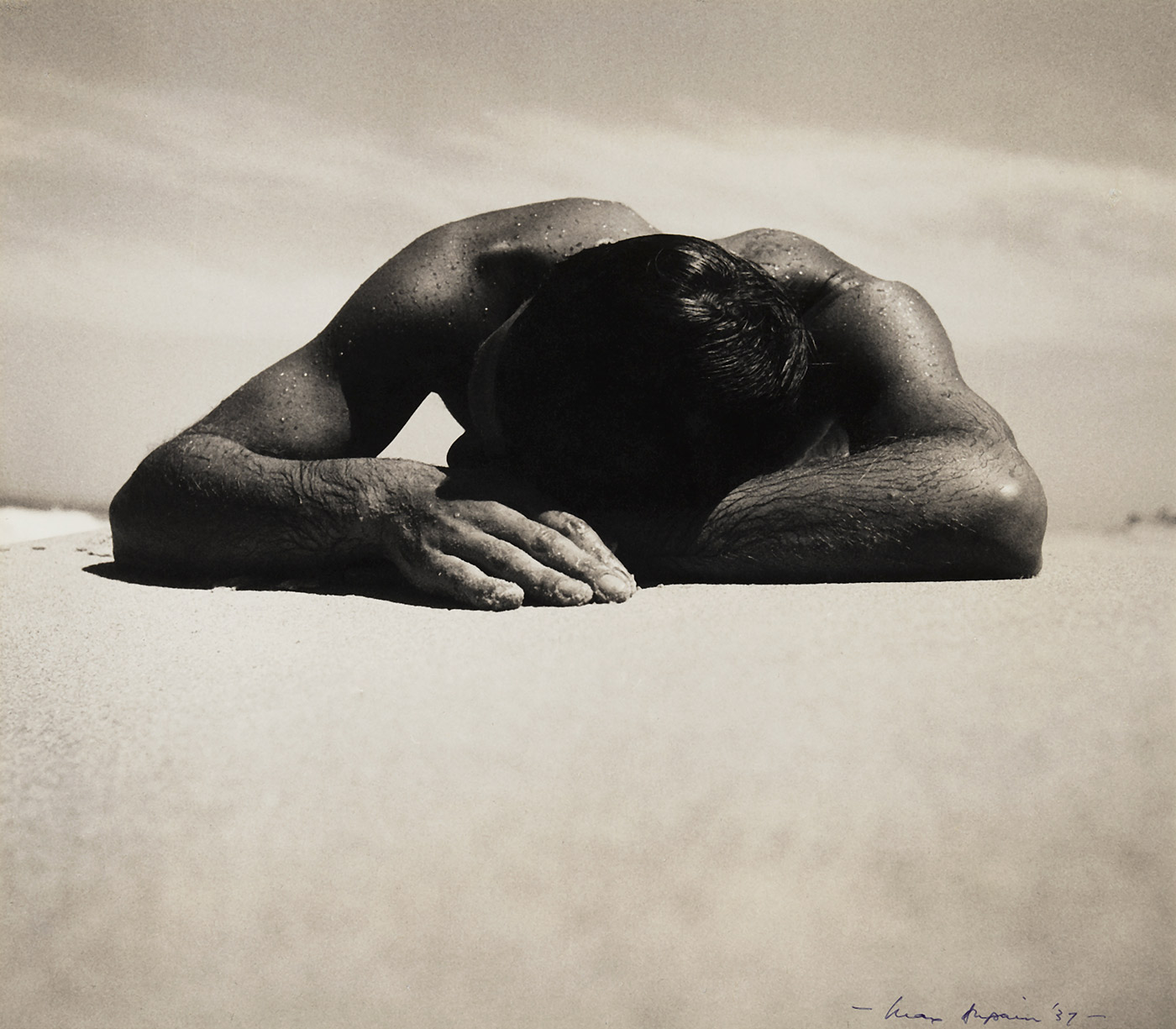

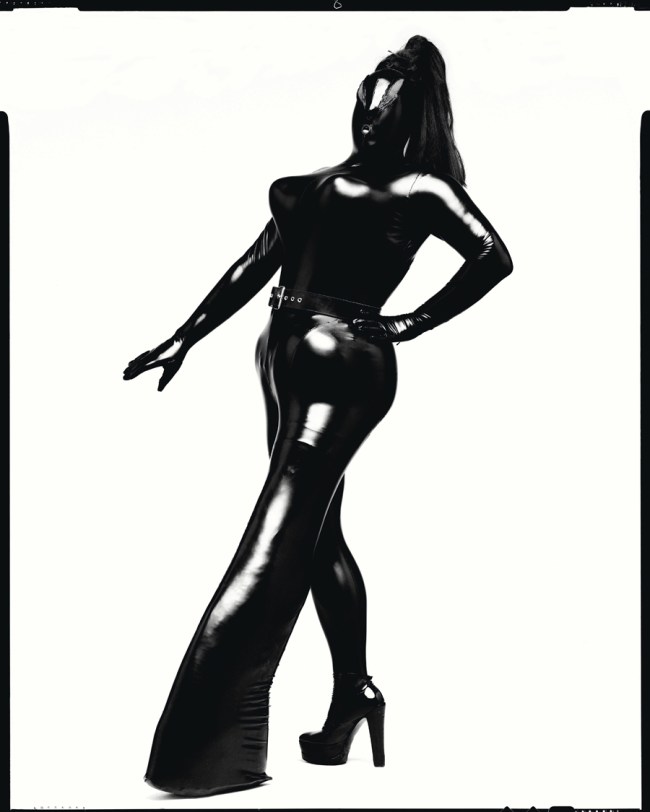

Minor White (American, 1908-1976)

Ernest Stones and Robert Bright (San Francisco)

1949

Gelatin silver print

in Bunnell, Peter. Minor White: The Eye That Shapes. Bulfinch Press, 1989, Figure 32

Negative No. 2342I. ‘Ernest Stones and Robert Bright’. 1949. 6″ x 6″ contact print (?)

One of my favourite Minor White photographs. Same men as above but lighter skin tones. Richness – tonality in shirts is amazing. Much more contrast than the reproduction, Plate 32 in Bunnell, Peter. Minor White: The Eye That Shapes. Boston: Bulfinch Press/Princeton University, 1989. Much more clarity than the reproduction, Plate 62 in Ellenzweig, Allen. The Homoerotic Photograph. New York: Columbia University Press, 1992, p. 111.

The presence of the hand on the shoulder is incredible. Such an intimate image between two men!

Bunyan, Marcus. “Research notes on photographs from the Minor White Archive,” Princeton University, New Jersey, 06/08/1999.

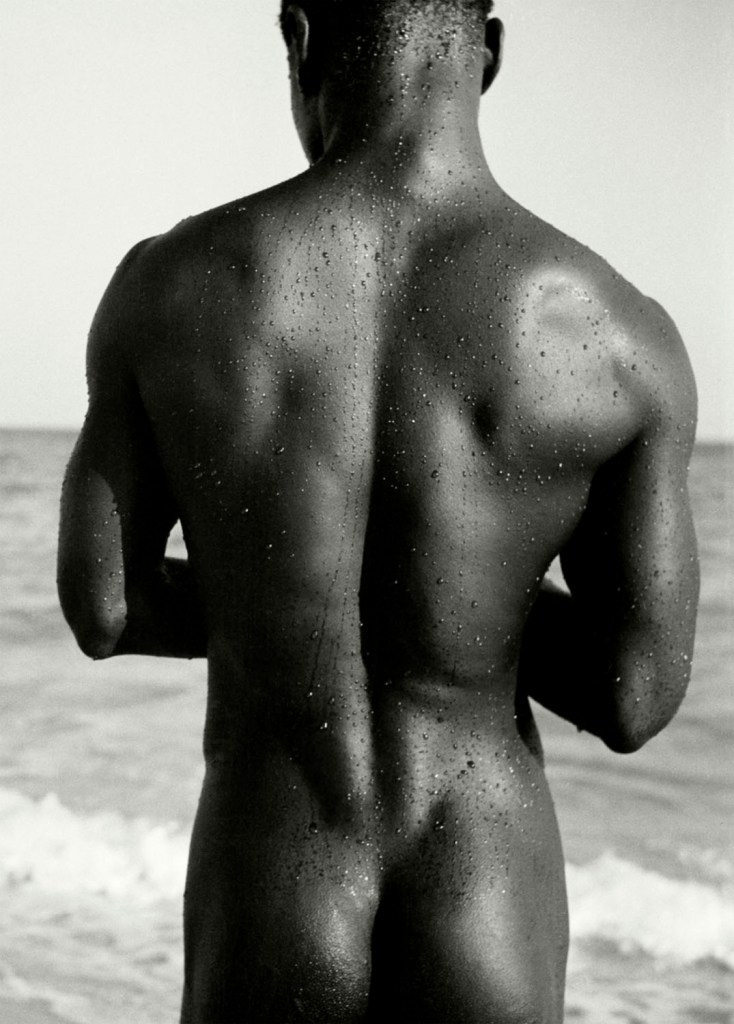

Marcus Bunyan (Australian born England, b. 1958)

Untitled

1995

From the series Sleep/Wound

Gelatin silver print

Through our lived experience, our history of body, it’s context and it’s language, it is possible to support and encourage alternative ways that gay men can look at their own and other men’s bodies. As Michelangelo Signorile said it is possible to remember a time when we liked different types of bodies; we can promote an acceptance of different fantasies in regards to gender role representation that help support alternative views of masculinity, that help create a multiplicity of desires, because we have all previously desired different types of bodies.

As Naomi Wolf in her seminal book The Beauty Myth notes, “The shape and weight and texture and feel of bodies is crucial to pleasure but the appealing body will not be identical … The world of attraction grows blander and colder as everyone, first women and soon men, begin to look alike.”31

As gay men our personal experience of the feel of male bodies is crucial to an acceptance of difference. In the fluctuation of body image and identity boundaries through the interaction of bodies in sex, gay men may begin to explore the possibility of new forms of pleasure. But it would seem to me that gay men, instead of inventing new pleasures, constantly repeat and reiterate an old limiting pleasure, the desire for stereotypical muscular body image ideals. In the desire for intimacy, connection and possession of a man that has the signifier of the ‘ideal’ muscular mesomorphic body image, gay men may have multiple intimate sexual encounters that do not reinvent pleasure but repeatedly seek to confirm existing ‘ideals’ of social reproduction. This is not a multiplicity of pleasures expressed through a desire for different forms, but the expression of a singular, monocular pleasure that validates the social worth of one body-type.

The multiplicity of casual sexual encounters might open a gay man up to new experiences but these experiences are based on a desire for the fixed form of a solid, stable, secure, traditional masculine body. This is not a dissolution of boundaries to reinvent new pleasures but the reinforcement of traditional patriarchal masculine stereotypes that promotes discrimination against gay men who do not possess this kind of body. In revealing themselves in intimate casual sexual encounters by having unsafe sex with a muscular body image ‘ideal’ gay men may be exploring the diversity and difference of man sex in liberating but possibly dangerous ways, ways born out of desperation and desire to possess the body image ‘ideal’ that may be evidenced through a nihilistic lack of care, concern and responsibility for the inner Self and a lack of respect for others.

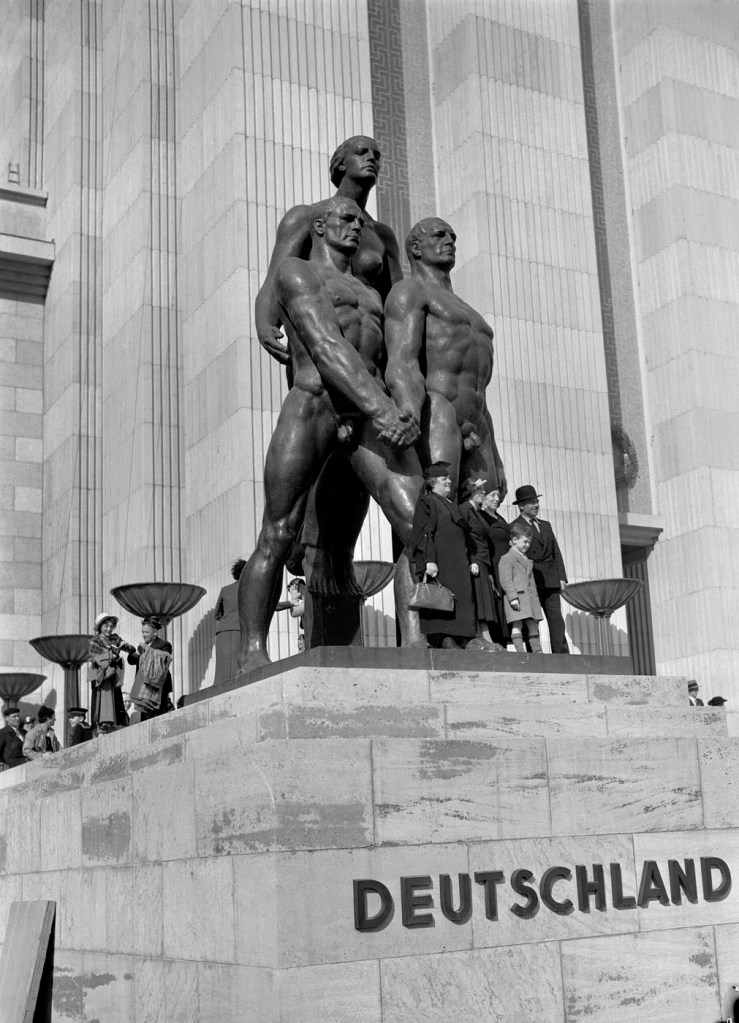

Expanding on a quotation by Kenneth Dutton I observe that: “The feminist struggle to overcome stereotypical images and open-up to women a range of options as to the roles they may wish to play, free of the male-imposed constraints of traditional socio-sexual expectation, is yet to find its masculine counterpart”31 in the body images of the male within the gay community.

Overcoming stereotypical images means first overcoming the hype of the hyper-masculine body. Strength in itself is not power but this type of muscular body is increasingly seen as powerful within the gay community. For some gay men a desire for the power of patriarchy is evidenced in their desire for these ‘ripped’ bodies with their ‘shredded’ muscle (both, ironically, terms of disembodiment and therefore dehumanisation) as proof that they are ‘real’ masculine men. The supposed irony present in gay male sex and sexuality, of one man fucking another man to disrupt the ‘norms’ of hegemonic masculinity has, I believe, disappeared in a reaffirmation of traditional forms of masculine identity.

The power of beauty is no longer the power of the effete, the weak, the hidden, but the power of the muscularly visible. Judgements made by gay men on other gay men depend to a significant degree on the representation of this power through the possession of the form of the muscular body, the desire for it’s hardness and strength dictated by the collective desire of a gay male sexual orientation. Gay men must be made more aware that this collective desire is based on traditional forms of hegemonic masculinity replete with the discriminations that this identity construction entails. Learning from past histories and experiences we must try to stop such conditions being repeated so that discrimination does not exist in future identities.

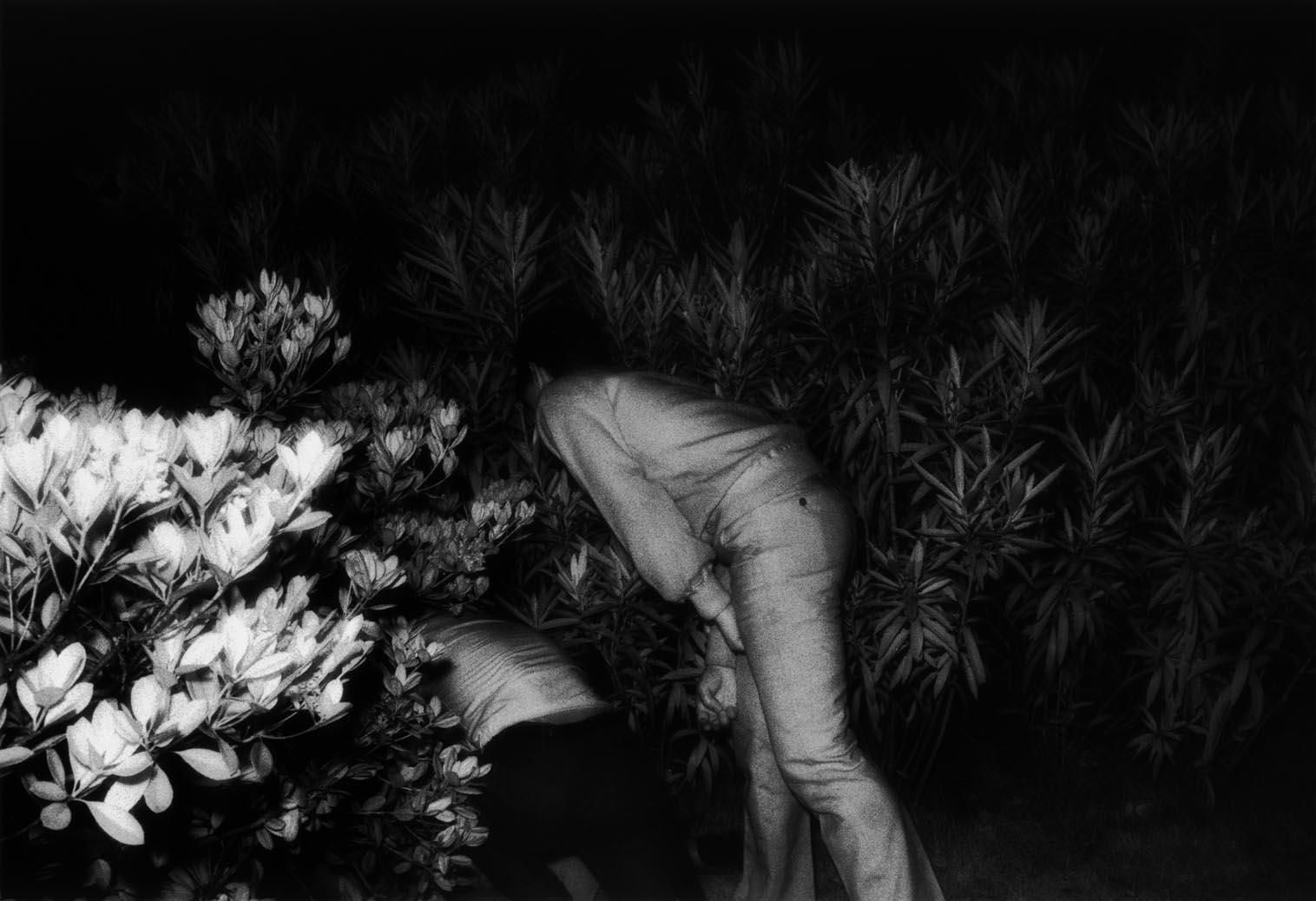

Marcus Bunyan (Australian born England, b. 1958)

Untitled

1995

From the series Sleep/Wound

Gelatin silver print

We must work to expand the underlying societal attitude of what is seen as the desirable ‘look’ of the gay male body in order to open up different body-types as fantasies for gay men. It is gay men’s (re)actions in regards to bodies of all types that is important. We must encourage a personal self-acceptance that increases self-esteem through achievement. This may include going to the gym to develop your body but this activity should be undertaken with an awareness of all the issues involved in such a quest. As Michael East comments,

“At the end of the day, we as men have to do what the women have had to do to cope with body image pressure for the last 50 years: ie., accept ourselves as we are. Ultimately, no matter how big our muscles are, how cool an exterior we can project, or how mental, agile or superior we pretend we are, we too are human, and must set our own bench marks, and not use others. At the end of the day, it comes down to how you feel about your body. No matter what size or shape you’re in, if you are cool about it – that is of primary importance.”33 (My italics and bold).

He goes on to suggest several strategies that help promote an acceptance of body image:

1/ “Make a deal with yourself that you are going to stop giving yourself a hard time about it. With a clear head and less subjective approach to the situation you’ll be better equipped to take stock of what the real issues are, and these could have nothing to do with your body at all.

2/ Clear out the junk – negative thoughts about yourself, the world, what you’re doing with your life [basically self-actualization]. This also includes associates that subtly or otherwise give you a hard time about your body shape/size.

3/ If your house or private space is furnished with nothing but multitudes of images of semi naked men with great bods, why not take them down for a while to give yourself a more neutral space to take stock?

4/ Focus on other aspects of yourself. Unless you’ve convinced yourself that you are a complete loser, list all the good things that you have done with your life, an all the good things about you that people compliment you on.” [Increasing self-esteem through achievement]

I think that the last point is vitally important. Body image is part of an overall self-esteem package and feeling better about yourself overall will help you feel better about your body. Conversely, feeling better about your body by getting in shape, going to the gym for the right reasons, can help improve your overall self-esteem. Self-esteem is built through the acceptance and achievement of an integrated identity, valuing all parts of the self. Its no good going to the gym and getting a great body if you haven’t sorted out other issues in your life because you’ll still think that you look like crap anyway! Then you’ll want bigger muscles and an even better body thinking this will improve your self-esteem and be the solution to your problems34 ….

Conclusion

I will conclude this chapter with an eloquent quotation by Wendy Chapkis and a few comments from myself. I believe that this quotation is a fitting summation to this chapter and perhaps to the whole research project. It most closely expresses and reflects – through the spiritually succinct words of someone I admire – ideas and thoughts on the subject matter that have evolved as this research project has developed to fruition.

“The politics of appearance inextricably bound up with the structures of social, political and economic inequality … Fighting pressure to conform, attempting to hold one’s own against the commercial and cultural images of the acceptable is a crucial first act of resistance. The attempt to pass and blend in actually hides us from those we most resemble. We end up robbing each other of authentic reflections of ourselves. Instead, imperfectly visible behind a fashion of conformity, we fear to meet each others’ eyes … Real diversity can only become a source of strength if we learn to acknowledge it rather than disguise it. Only then can we recognize each other as different and therefore exciting, imperfect and as such enough.”35 (My italics)

Our difference and diversity is our strength as gay people.

We must not crush our difference through discrimination.

We must not hide our diversity behind masks.

We must resist commercial and cultural images of the acceptable.

Yes we are imperfect and what an exciting perfection it is!

Dr Marcus Bunyan 2001

Footnotes

1/ Signorile, Michelangelo. Life Outside: The Signorile Report on Gay Men: Sex, Drugs, Muscles, and the Passages of Life. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1997, pp. 298-299.

2/ Interview with Taylor, Barry. Melbourne. 01/07/1997. Manager of the Victorian State Youth Suicide Prevention Programme 1996 and now working with gay people on mental health issues.

3/ Ridge, Damien. “Queer Connections: Community, ‘the Scene’ and an Epidemic,” in Journal of Contemporary Ethnography June 1996, pp. 15-16.

4/ Hatfield, Elaine and Sprecher, Susan. Mirror, Mirror: The Importance of Looks in Everyday Life. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1986, p. 313.

5/ Benson, Lou. Images, Heroes and Self-Perceptions. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1974, p. 30.

6/ Fromm, Erich. The Art of Loving. London: Allen and Unwin, 1957, quoted in Benson, Lou. Images, Heroes and Self-Perceptions. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1974, p. 30.

7/ “… body attractiveness is so highly valued that it has the single most important impact on many individuals feelings of physical self-worth. Physical self-worth affects self-esteem.”

Wankel, Leonard. “Self-Esteem and Body Image: The Research File: information for professionals from the Canadian Fitness and Lifestyle Research Institute,” in Canadian Medical Association Journal 153 (5). September 1st, 1995, p. 607.

See also Berscheid, E., Hatfield (Walster), E. and Bohrnstedt, G. “The Happy American Body: A Survey Report,” in Psychology Today 7. 1973, pp. 119-131.