December 2022

Monty Fresco (English, 1936-2013)

Boy Brings Home Christmas Tree, Spitalfields Market, London

1946

Gelatin silver print

Season’s Greetings from Art Blart

Thank you to all Art Blart readers for their support in 2022!

Marcus

Installation view of Wolfgang Tillmans: To look without fear, on view at The Museum of Modern Art, New York from September 12, 2022 – January 1, 2023 Photo: Emile Askey

There are so many exhibitions that finish before mid-January 2023 that I am going to post at odd times over the festive season and New Year so that I can fit them all in.

Another exhibition by this superb artist, this time his first museum survey in New York. ‘The decisive logic of his practice is a visual democracy, best summarised by his phrase “If one thing matters, everything matters.”‘

This relationship to the world, of living and loving in the world, of being an aware social and political artist, reminds me of a wonderful quote by that magical Irish poet Thomas Heaney:

“The watergaw, the faint rainbow glimmering in chittering light, provides a sort of epiphany, and MacDiarmid connects the shimmer and weakness and possible revelation in the light behind the drizzle with the indecipherable look he received from his father on his deathbed … Each expression, each cadence, each rhyme is as surely and reliably in place as a stone on a hillside.” ~ Seamus Heaney1

Each of Tillmans’ individual images offer the possibility of an epiphany … collectively, they propose a sure and reliable nonhierarchical nexus of relationships that is revelatory.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Heaney, Seamus. The Redress of Poetry. London: Faber and Faber, 1995, pp. 107-108.

Many thankx to the Museum of Modern Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Download the Wolfgang Tillmans exhibition brochure (2.4Mb pdf)

Installation view of Wolfgang Tillmans: To look without fear, on view at The Museum of Modern Art, New York from September 12, 2022 – January 1, 2023 shwoing at left, Tillmans Victoria Park (2007, below)

Photo: Emile Askey

The Museum of Modern Art will present Wolfgang Tillmans: To look without fear, the artist’s first museum survey in New York, from September 12, 2022 through January 1, 2023, in the Steven and Alexandra Cohen Center for Special Exhibitions. Unique groupings of approximately 350 of Tillmans’s photographs, videos, and multimedia installations will be displayed according to a loose chronology throughout the Museum’s sixth floor. Informed by new scholarship and eight years of dialogue with the artist, the exhibition will highlight how Tillmans’s profoundly inventive, philosophical, and creative approach is both informed by and designed to highlight the social and political causes for which he has been an advocate throughout his career.

From the outset of his career, Wolfgang Tillmans (b. 1968, Germany) has revolutionised the prevailing conventions of photographic presentation, making connections between his pictures in response to a given context and activating the space of the exhibition by hanging photographs in a corner, above a doorframe, on a free-standing column, or next to a fire extinguisher. In developing his own language for these overall installations, Tillmans’s practice verges into a sculptural dimension. The decisive logic of his practice is a visual democracy, best summarised by his phrase “If one thing matters, everything matters.”

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Victoria Park

2007

Image courtesy of the artist, David Zwirner, New York / Hong Kong, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin / Cologne, Maureen Paley, London

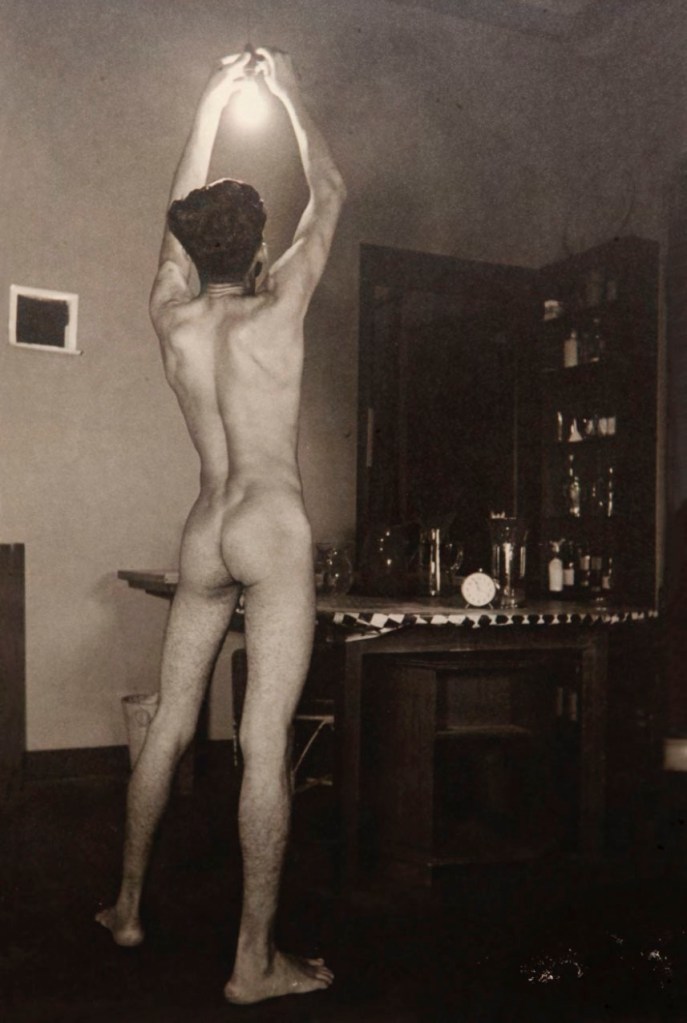

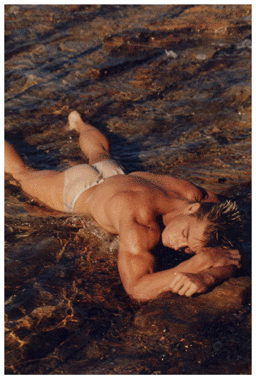

Installation view of Wolfgang Tillmans: To look without fear, on view at The Museum of Modern Art, New York from September 12, 2022 – January 1, 2023 showing at top left, Tillmans Lacanau (self) (1986, below)

Photo: Emile Askey

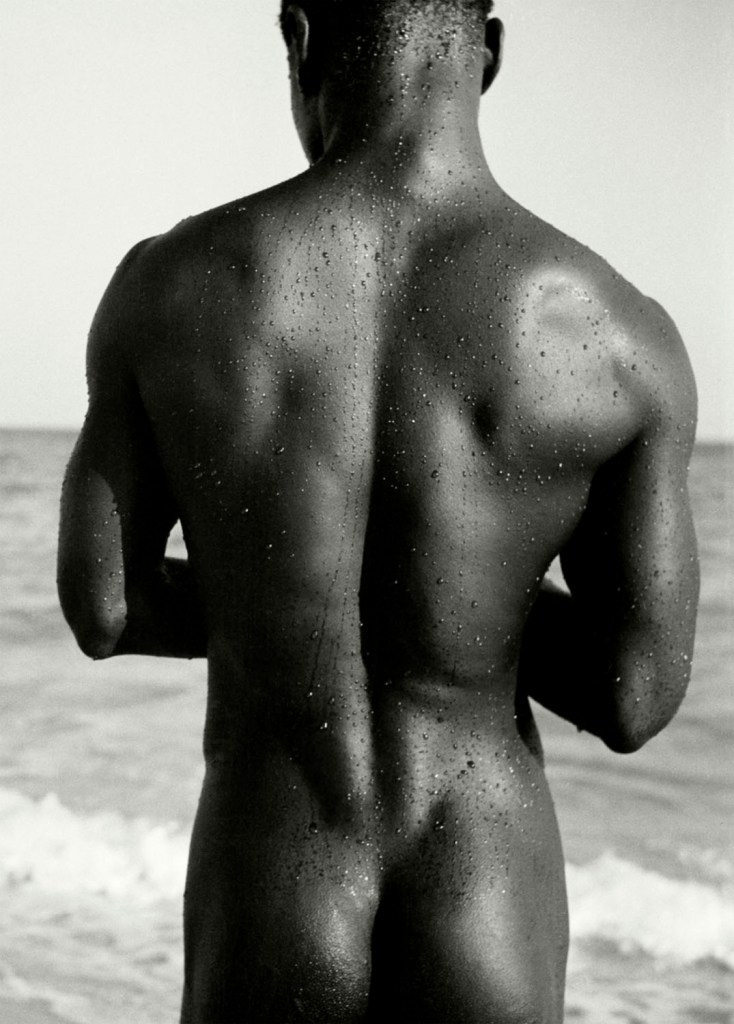

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Lacanau (self)

1986

Image courtesy of the artist, David Zwirner, New York / Hong Kong, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin / Cologne, Maureen Paley, London

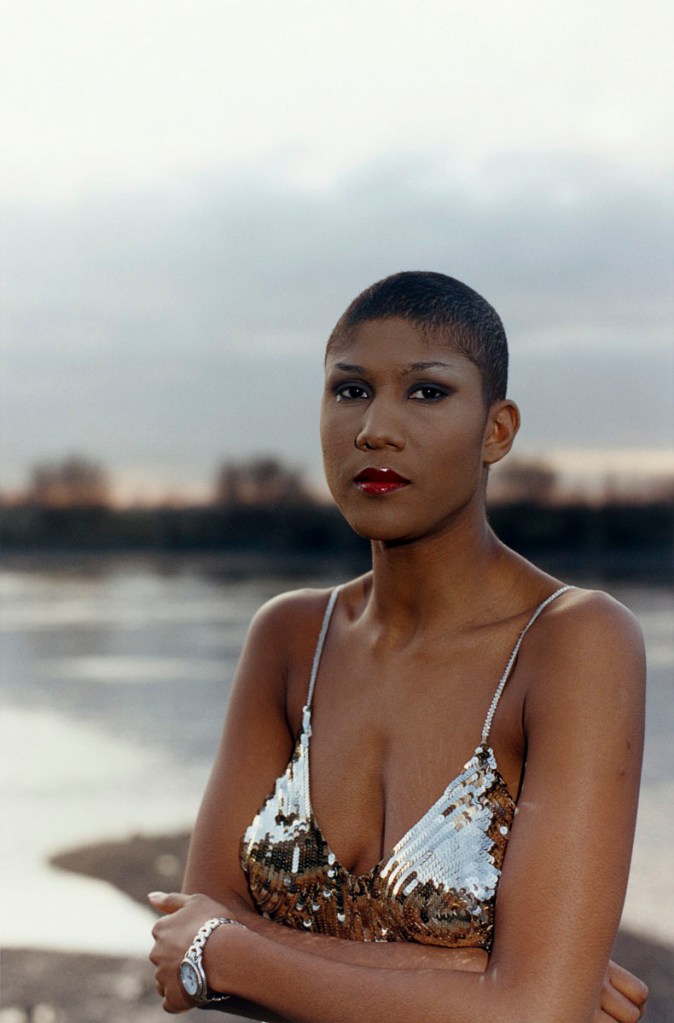

Installation views of Wolfgang Tillmans: To look without fear, on view at The Museum of Modern Art, New York from September 12, 2022 – January 1, 2023 showing in the bottom image at right, Smokin’ Jo (1995, below)

Photo: Emile Askey

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Smokin’ Jo

1995

Image courtesy of the artist, David Zwirner, New York / Hong Kong, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin / Cologne, Maureen Paley, London

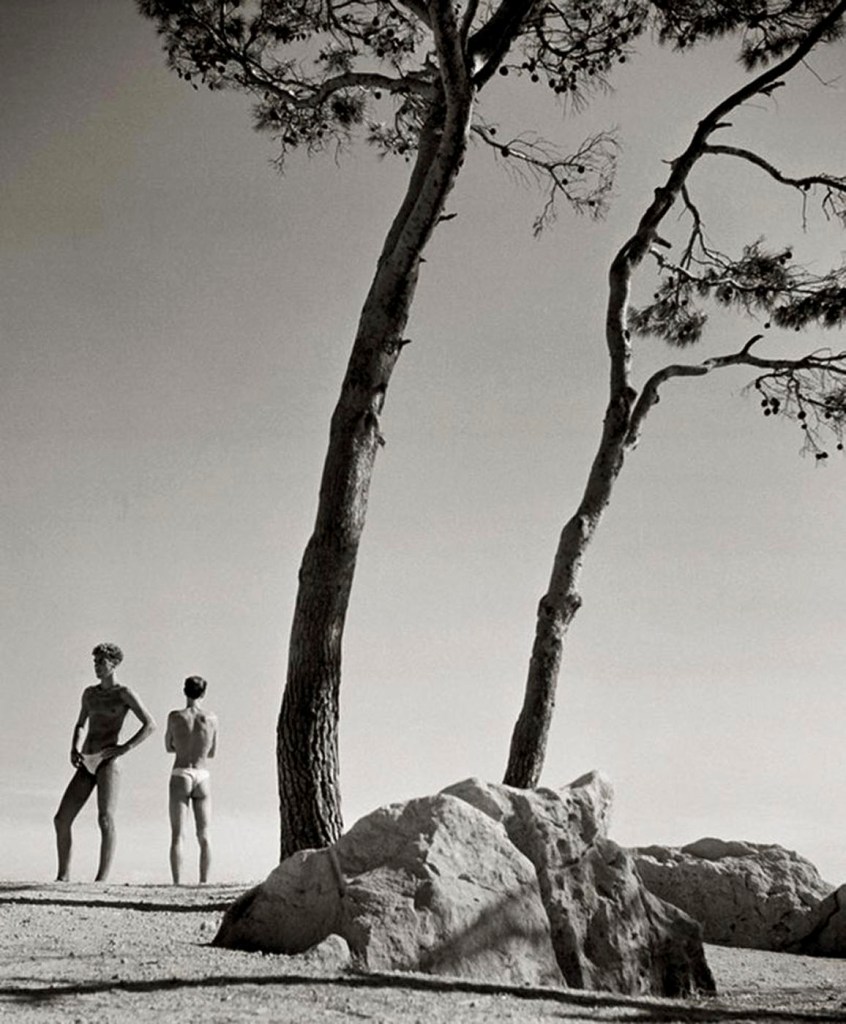

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Arkadia I

1996

Installation views of Wolfgang Tillmans: To look without fear, on view at The Museum of Modern Art, New York from September 12, 2022 – January 1, 2023 showing at top right in the top image, Arkadia I (1996, above); and at right in the bottom image, Tillmans work Concorde Grid (1997), a series of 56 colour photographs of equal dimensions

Photos: Emile Askey

A series of fifty-six colour photographs of equal dimensions arranged in a grid four rows high and fourteen columns wide. The series was created in an edition of ten plus one artist’s proof. Tate’s copy is number four. The photographs were taken as part of a commission for the Chisenhale Gallery, London on the occasion of I Didn’t Inhale, Tillmans’ solo exhibition there in 1997. An artist’s book consisting of sixty-two Concorde images was produced to accompany the exhibition. It was published by Walther König, Cologne. Fifty-four of the images in the photographic edition are reproduced in the book. The photographs were taken at a number of sites in and around London, including close to the perimeter fence at Heathrow airport. Several photographs of the airplane landing and taking off from the airport were taken looking through the security fence, which is included in the image as a blurred outline. In another sequence, the jet is viewed taking off dramatically over an expanse of brilliant green grass, suggesting that the artist may have pushed his camera lens between the gaps in the fence so as not to include it in the frame. Further photographs were taken from such vantage points as suburban railway tracks, roads close to the airport, a yard containing parked trucks and an open common. The airplane is depicted in varying scales viewed from a wide variety of angles. At times it resembles a bird, at others (when it flies directly above the camera at close range) an air-borne sting-ray. In several images it is barely visible in the haze of distance and the afterburn of its engines. Tillmans’ project has the flavour of a birdwatcher’s obsessive tracking and recording. He has written:

“Concorde is perhaps the last example of a techno-utopian invention from the sixties still to be operating and fully functioning today. Its futuristic shape, speed and ear-numbing thunder grabs people’s imagination today as much as it did when it first took off in 1969. It’s an environmental nightmare conceived in 1962 when technology and progress was the answer to everything and the sky was no longer a limit … For the chosen few, flying Concorde is apparently a glamorous but cramped and slightly boring routine whilst to watch it in the air, landing or taking-off is a strange and free spectacle, a super modern anachronism and an image of the desire to overcome time and distance through technology.”

(Quoted on the inner sleeve of Concorde)

Elizabeth Manchester. “Concorde Grid,” on the Tate website January 2003 [Online] Cited November 2022

Installation views of Wolfgang Tillmans: To look without fear, on view at The Museum of Modern Art, New York from September 12, 2022 – January 1, 2023 showing in the top image at left Tillmans work Aufsicht (yellow) (1999, below); and at right in the bottom image, Icestorm (2001, below)

Photos: Emile Askey

![Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968) 'Aufsicht (yellow)' (View from Above [yellow]) 1999 Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968) 'Aufsicht (yellow)' (View from Above [yellow]) 1999](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/tillmans-aufsicht-yellow.jpg?w=700)

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Aufsicht (yellow) (View from Above [yellow])

1999

Image courtesy of the artist, David Zwirner, New York/Hong Kong, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne, Maureen Paley, London

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Icestorm

2001

Image courtesy of the artist, David Zwirner, New York / Hong Kong, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin / Cologne, Maureen Paley, London

Installation views of Wolfgang Tillmans: To look without fear, on view at The Museum of Modern Art, New York from September 12, 2022 – January 1, 2023

Photos: Emile Askey

“The viewer… should enter my work through their own eyes, and their own lives,” the photographer Wolfgang Tillmans has said. An incisive observer and a creator of dazzling pictures, Tillmans has experimented for over three decades with what it means to engage the world through photography. Presenting the full breadth and depth of the artist’s career, Wolfgang Tillmans: To look without fear invites us to experience the artist’s vision of what it feels like to live today.

From ecstatic images of nightlife to abstract images made without a camera, sensitive portraits to architectural slide projections, documents of social movements to windowsill still lifes, astronomical phenomena to intimate nudes, Tillmans has explored seemingly every imaginable genre of photography, continually experimenting with how to make new pictures. He considers the role of the artist to be that of “an amplifier” of social and political causes, and his approach is animated by a concern with the possibilities of forging connections and the idea of togetherness.

Tillmans has rejected the prevailing conventions of photographic presentation, continuously developing connections between his pictures and the social space of the exhibition. In his installations, unframed prints are taped to the walls or clipped and hung from pins, and framed photographs appear alongside magazine pages. Constellations of images are grouped on walls and tabletops as photocopies, colour or black-and-white photographs, and video projections, exemplifying the artist’s idea of visual democracy in action. “I see my installations as a reflection of the way I see, the way I perceive or want to perceive my environment,” Tillmans has said. “They’re also always a world that I want to live in.”

Following its presentation at MoMA, the exhibition will travel to the Art Gallery of Ontario and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Organised by Roxana Marcoci, The David Dechman Senior Curator, with Caitlin Ryan, Curatorial Assistant, and Phil Taylor, former Curatorial Assistant, Department of Photography.

Text from the MoMA website

Installation views of Wolfgang Tillmans: To look without fear, on view at The Museum of Modern Art, New York from September 12, 2022 – January 1, 2023 showing at third left in the second image, Venus, transit (2004, below); and at right in the bottom image, Tillmans Freischwimmer 230 (Free Swimmer 230) (2012, below)

Photos: Emile Askey

Installation view of Wolfgang Tillmans: To look without fear, on view at The Museum of Modern Art, New York from September 12, 2022 – January 1, 2023 showing at left, Freischwimmer 230 (Free Swimmer 230) (2012, below)

Photo: Emile Askey

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Venus transit

2004

Image courtesy of the artist, David Zwirner, New York / Hong Kong, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin / Cologne, Maureen Paley, London

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Freischwimmer 230 (Free Swimmer 230)

2012

Image courtesy of the artist, David Zwirner, New York / Hong Kong, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin / Cologne, Maureen Paley, London

The Museum of Modern Art will present Wolfgang Tillmans: To look without fear, the artist’s first museum survey in New York, from September 12, 2022, through January 1, 2023, in the Steven and Alexandra Cohen Center for Special Exhibitions. Unique groupings of approximately 350 of Tillmans’s photographs, videos, and multimedia installations will be displayed according to a loose chronology throughout the Museum’s entire sixth floor. Shaped by new scholarship and eight years of dialogue with the artist, the exhibition will highlight how Tillmans’s profoundly inventive, philosophical, and creative approach is both informed by and designed to highlight the poetic possibilities and social and political causes for which he has been an advocate throughout his career. Wolfgang Tillmans: To look without fear is organised by Roxana Marcoci, The David Dechman Senior Curator of Photography, with Caitlin Ryan, Curatorial Assistant, and Phil Taylor, former Curatorial Assistant, Department of Photography.

Wolfgang Tillmans (b. 1968, Germany) has explored seemingly every genre of photography imaginable, continually experimenting with how to make pictures meaningful. Since the beginning of his career, Tillmans has revolutionised the prevailing conventions of photographic presentation, making connections between his pictures in response to a given context and activating the space of the exhibition. Spanning the artist’s production from the 1980s to the present, this survey will present iconic photographs alongside his rarely seen significant bodies of work, foregrounding the ways in which Tillmans’s concern with social themes, lived experiences, and the idea of togetherness are inextricable from this ongoing investigation of the medium.

“Social themes form a rich vein throughout his practice,” said Roxana Marcoci. “They motivate Tillmans’s exploration of the questions of how to see and how to communicate seeing.” His approach to art making emphasises the ideas of human connections, with his work reflecting a deep care for his subjects. Tillmans has pictured survival and loss amid the AIDS crisis, mined the media’s aestheticisation of military forces, given voice to LGBTQ+ communities around the world, and tracked the diffusion of globalism. To look without fear will present several different bodies of work and will reflect Tillmans’s distinct strategies of display. In his installations, unframed prints are taped to the walls or hung with clips, and framed photographs appear alongside magazine pages. Constellations of images – colour and black-and-white photographs and photocopies – grouped on walls and tabletops alongside video projections and sonic installations exemplify the artist’s idea of visual democracy in action. “I see my installations as a reflection of the way I see, the way I perceive or want to perceive my environment,” Tillmans has said.

The works that will be installed at the entrance to the exhibition exemplify Tillmans’s engagement with new forms of technology, which is traceable to his childhood passion for astronomy. It was through his early trials with the telescope, and later with the photocopier and video camera, that he ultimately arrived at his photographic practice. Victoria Park (2007), depicting two friends lounging in a park in East London, reflects his long-standing engagement with the laser photocopier, which he first happened upon as a teenager in a local print shop in 1986. Often enlarging images up to 400 percent, Tillmans aspired to expand the limits of photographic materials and techniques, an ambition that aligned with his near-contemporaneous experiments with electronic music. In the 2017 video untitled (leg), a single bare leg rotates slowly in rhythm, recalling 19th-century pre-cinematic motion studies, while its vertical aspect ratio evokes a 21st century-format: the smartphone screen.

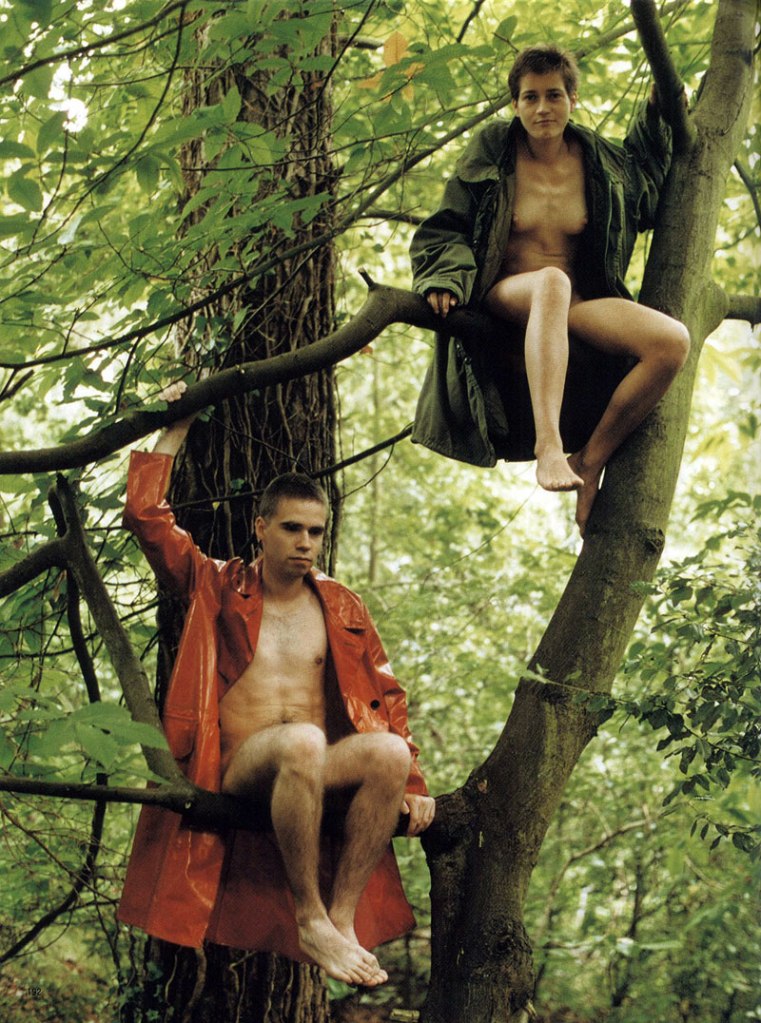

In the exhibition’s first gallery, Tillmans’s early photocopies will be installed alongside images that brought him to prominence as a chronicler of youth subculture and nightlife, including Lutz & Alex sitting in the tree (1992) and Chemistry Squares (1992), which were both published in the British alternative magazine i-D in the early 1990s. The persistent presence of magazines in his exhibitions is indicative of how Tillmans harnesses the capacity of his pictures to amplify ideas when they are distributed across media platforms.

The second gallery will include early photographs that foreground Tillmans’s abiding interest in music and performance. His portrait, made for Interview magazine in 1995, of the legendary DJ Joanne Joseph – better known by her stage name, Smokin’ Jo – will be installed near wall of speakers (1992), made on a trip to Kingston, Jamaica, where Tillmans photographed the local ragga music scene. This photograph captures an outdoor festival’s precariously stacked sound system, depicting the structure as both a sculptural object and a means of experimentation capable of producing thunderous bass sounds.

The following gallery will include works that speak to Tillmans’s subversion of traditional art-historical subjects and genres. In the photographs he calls Faltenwurf (German for “drapery”), clothes hang drying on radiators, are crumpled into balls, or lie in heaps, alluding to drawn and painted studies of fabric. Beginning in the late 1990s, Tillmans became increasingly invested in the possibilities afforded by darkroom abstraction, experimenting with new techniques, such as applying coloured tints and using flashlights to manipulate a negative while it developed. In his monumental I don’t want to get over you (2000), a title inspired by the lyrics of a song by the Magnetic Fields, gestural green streaks and dark, thread-like lines fuse with the image of a vast, barren-looking, otherworldly landscape.

Tillmans’s video work – an under-recognised facet of his practice – brings together movement, electronic music, ambient sound, technology, and quotidian imagery. The fourth gallery will feature two such video works. Lights (Body) (2000-2002) focuses on the flashing lights in a busy nightclub, revealing the specks of dust rising off the ravers’ clothes and skin, accompanied by the hypnotic dance beat of Air’s “Don’t Be Light (The Hacker Remix).” Peas (2003), a three-minute study of a pot of boiling peas in close-up, shot in Tillmans’s former East London studio, depicts the mutual rhythm of the vegetables over audible sounds from a Pentecostal church across the street.

A fifth gallery is dedicated to Soldiers: The Nineties (1999), an installation of enlarged newspaper photographs exploring the geopolitical implications of visual culture. Throughout the 1990s, as Cold War tensions eased, the front pages of newspapers often featured images of soldiers engaged in acts of leisure, such as smoking, casually sitting, or playing chess, as thousands of military personnel were deployed to conflict-ridden nations to participate in peacekeeping missions sponsored by the United Nations. Tillmans was intrigued by the erotic undertones of these photographs of anonymous, occasionally bare-chested servicemen, informed by his previous attention to the ways that queer and techno subcultures had adopted camouflage and utility wear.

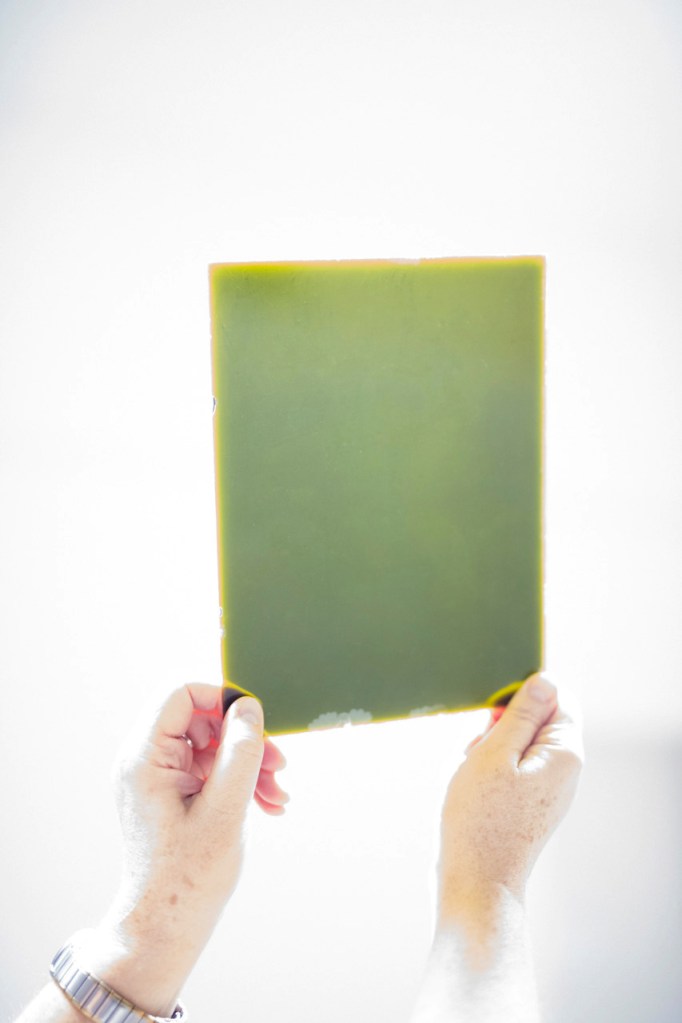

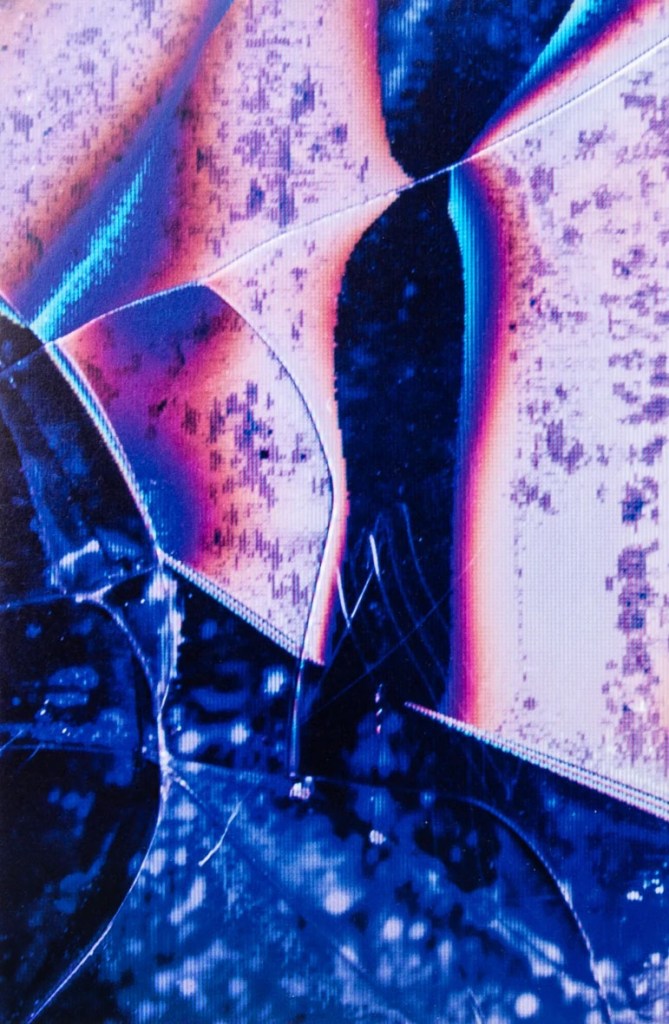

Gallery six will explore Tillmans’s work at the threshold of abstraction and representation, as well as his deep interest in the materiality of photographic paper. Tillmans first created a body of work called paper drops after he acquired an industrial-sized printer in 2001 and began experimenting with the optical effects of gravity, which allowed the paper to freely bend and curl. “For me, the photo has always been an object,” Tillmans has said. The manipulated colour fields of the Lighter (ongoing since 2005) works expand upon this dynamic. Made without a camera, the photographic paper is either folded in the darkroom or exposed to evoke the effects of folding, and then framed in plexiglass. The Silvers (ongoing since 1992) are also cameraless works made by feeding photographic paper through a developer that Tillmans has purposely not cleaned, allowing interferences of dirt and traces of silver salts be visible.

The centre space of the exhibition will include an iteration of Tillmans’s Truth Study Center, a type of structure first presented by Tillmans in 2005, in which unpretentious wooden tabletops serve as the display architecture for a mix of his own photographs, clippings, and printouts of newspaper and magazine articles. Tillmans introduced this tactic to question notions of absolutism – whether it be the Bush Administration’s claims of weapons of mass destruction to justify the war in Iraq, or religious dogma in any form – while also acknowledging the universal human desire to search for truth. Half of the tables in this room contain material from the early 2000s installations while the other half has been composed specifically for the MoMA exhibition using recent material.

Between 2008 and 2012, Tillmans embarked on a major new project that coincided with his adoption of the digital camera. Comprising portraiture, still life, landscape, street photography, and architectural studies, Neue Welt (“New World”) observes the flows of finance, commodities, and people around the world. Alongside these works, gallery seven will feature documents of social movements that bring to the fore the ethics of care at the heart of Tillmans’s practice. One such exemplary work is a 2014 photograph of dancing figures at one of St. Petersburg’s few gay clubs, the Blue Oyster Bar, taken a year after Vladimir Putin signed a bill outlawing the dissemination of “propaganda for non-traditional sexual relations.” Another notable example is Black Lives Matter protest, Union Square, b (2014), depicting an outstretched hand at a Black Lives Matter protest in the wake of widely publicised police killings of African Americans.

A highlight of To look without fear will be the first US museum presentation of an audiovisual listening room for Tillmans’s first full-length album, Moon in Earthlight (2021), a quintessential example of his unique style of “audio photography” As a musician and documentarian of music, Tillmans has long engaged with music, its cultural significance, and the shared experience of listening – from images of raves, clubs, and dance parties to videos of the artist himself dancing. Produced primarily during the pandemic, the 53-minute album incorporates spoken word, ambient field recordings, and pulsating electronic beats, emphasising the performative nature of music and its status as a preeminent force that brings people together.

This comprehensive exhibition will conclude with recent and never-before-seen portraits, landscape, and astrophotography, alongside older works. The platform just outside the sixth-floor exhibition space will feature Tillmans monumental collaboration with German sculptor Isa Genzken, Science Fiction / Hier und jetzt zufrieden sein (2001), a dizzying environment comprised of two irregularly gridded mirrored structures by Genzken and wake, the largest photograph Tillmans has ever made, depicting the aftermath of a party bidding farewell to his London studio. The installation’s title is partially drawn from the German phrase meaning “happy in the here and now,” evoking a contemplative mindfulness as visitors depart the exhibition.

Press release from MoMA

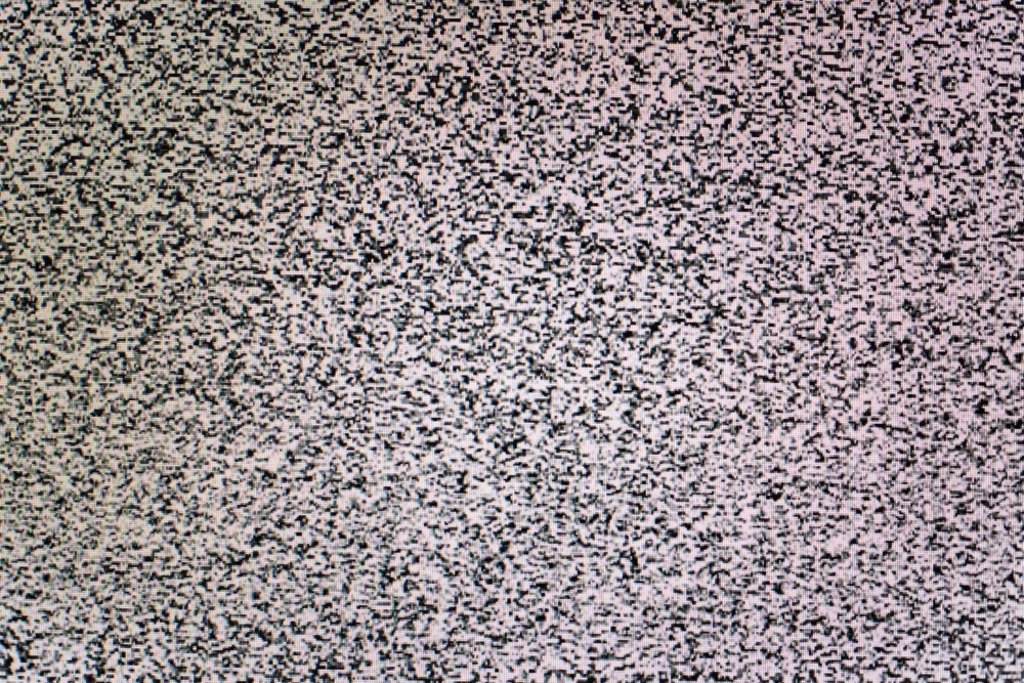

Installation view of Wolfgang Tillmans: To look without fear, on view at The Museum of Modern Art, New York from September 12, 2022 – January 1, 2023 showing at second right, The Spectrum Dagger (2016, below); and at right, Sendeschluss / End of Broadcast I (2014, below)

Photo: Emile Askey

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

The Spectrum Dagger

2016

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Sendeschluss / End of Broadcast I

2014

Installation views of Wolfgang Tillmans: To look without fear, on view at The Museum of Modern Art, New York from September 12, 2022 – January 1, 2023 showing in the bottom image at second left, Tillmans Lutz & Alex sitting in the trees (1992, below)

Photos: Emile Askey

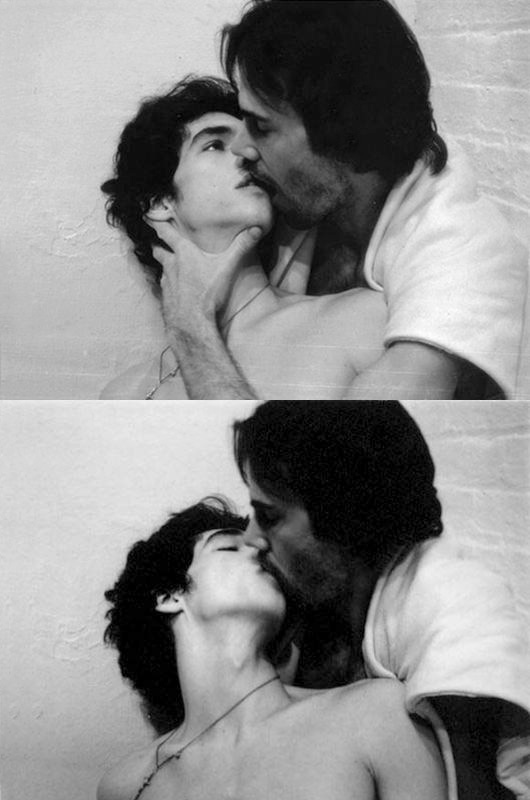

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Lutz & Alex sitting in the trees

1992

Image courtesy of the artist, David Zwirner, New York / Hong Kong, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin / Cologne, Maureen Paley, London

Roxana Marcoci

Sep 8, 2022

The potential of the “wandering image” – the migrant, incessantly decentralized image, which moves and performs across communication platforms – has been critical to Wolfgang Tillmans since the beginning of his artistic practice.1 The unfettered circulation of images plays an important role in his embrace of mobility, diversity, and the variety and mutability of sexual identity in the world. By transmitting, sharing, and setting images free, by multiplying their lives, he proposes a fully democratized experience of art.

Such a notion of photography’s potential role is not entirely new. As early as the mid-1930s, writer and politician André Malraux praised the medium’s capacity to encompass the globe (a forecast of the digital age). For Malraux, furthermore, photography offered a way to understand the human condition, enabled cross-cultural analysis, and democratized the experience of art by freeing original objects from their contexts and relocating them “closer” to the viewer. In his 1947 book Le musée imaginaire, he advocated for a pancultural “museum without walls,” postulating that art history has in fact become “the history of that which can be photographed.”2 His thesis, forward-thinking as it was, has been challenged recently by scholars who note that Malraux (a player in France’s political sphere in the 1950s and ’60s) indiscriminately brought together works of art from all periods and regions, ruthlessly deracinating them from their history and heritage and repurposing them in service to the ideological interests of colonialism.3

In his practice, Tillmans offers an alternative, even inverse proposition: he links the wandering image to a politics of equality and historical consciousness. The photograph’s reproducibility, its ubiquity across media, counters the aura attributed to the original – and to the ideals of uniqueness and specificity. Photography actualizes art’s potential itinerancy and multiplicity. Indeed, Tillmans’s work raises a number of questions: Might the mediated image at times be more impactful or enduring than a direct experience of the work? Might it be equally significant, even if different? How to see and how to communicate seeing are at the crux of photography’s capacity to articulate the world in relational terms – decentered, nonhierarchical, open to differences. Making connections between images seen for the first time or images looked at again in new configurations or across a spectrum of platforms as if for the first time – all this constitutes the evolving knowledge of the visible.

Tillmans has distributed his photographs and ideas across the pages of magazines and books, postcards and newspaper inserts, music videos and records, posters, billboards, nightclubs, architectural contexts, and the theatrical stage. “His various tactics of distribution,” critic Johanna Burton notes, “enable various permeations, recognizing that there are multiple kinds of cultural repositories, all with different logics and dimensions.”4 Yet each context also invests Tillmans’s peripatetic images with additional meanings. And – paradoxically, but perhaps inevitably – the artist brings light to these meanings through his attentive engagement with the singular image within each singular installation.

The most often used of his platforms is the gallery installation, but even in a familiar space such as this his unorthodox display strategies defamiliarize viewing habits. Sidestepping museological conventions of material, scale, and subject matter, he organizes his installations in relational montages inspired by the aesthetics of cinema and magazine layouts, eschewing a uniformly linear display logic. He activates the images’ latent effects through nonverbal yet resonant associations. Large inkjet prints, attached to the wall with binder clips, bowing slightly along the edges, are juxtaposed with postcard-sized images, photocopies, magazine pages, and glossy chromogenic prints fastened with Scotch Magic Tape. Tillmans organizes each part of the wall almost as though it were a page layout and makes full use of the architecture of the room, hanging photographs in a corner, above a doorframe in the vicinity of the exit sign, on a freestanding column, next to a fire extinguisher. There are also table-based configurations, and crumpled or folded monochrome pictures whose sculptural volumes are encased in acrylic frames. The decisive logic of his practice is the visual democracy he brings to each installation, best summarized by his phrase “If one thing matters, everything matters.”5

Entangled with humanist ideas, Tillmans’s value system revolves around some central questions: What can pictures make visible? What can one know at all? Who deserves attention? How can one connect with other people? How might we foster solidarity? In what do art’s political potential and its ethical worth reside? As he notes: “For me art was the area where I could oppose. Express difference.”6 This desire to observe the world with intention is matched by an empirical openness to nontraditional formats and alternative venues. Operating on the basic premise that all motifs and platforms are worth investigating, Tillmans subjects his own photographic vision to perpetual recontextualization.

This openness to a range of forms and spaces can be seen in his very earliest efforts. In February 1988 Tillmans had his first show, at Café Gnosa in Hamburg. There he presented Approaches (1987-1988), a group of photocopied triptychs made with a Canon laser photocopier, which he utilized like a stationary camera. His exercises with enlarging xerographic images up to 400 percent demonstrate his aspiration to expand the limits of materials and techniques used in making works, and are in a sense aligned with his near contemporaneous experiments with mechanically produced electronic music.

In September 1988 a second exhibition of Tillmans’s work took place, at the Fabrik Fotoforum in Hamburg, where he showed a new selection of Approaches: a sequence of progressive enlargements of vacation shots and newspaper images, together with photographs of video stills of closeup self-portraits he had made with a portable VHS camera. This body of work was featured again, later in the same year, at the Stadtteilbücherei RemscheidLennep.

Tillmans’s intensive observation and engagement with technology can be traced back to his childhood passion for astronomy. His earliest photographs (from 1978, when he was 10 years old) were of celestial bodies, captured by holding his father’s camera up to the eyepiece of his first telescope. Through these incipient trials with the telescope, and later the photocopier and video camera, he ultimately settled on photography. His route there took him through diverse modes of expression, from writing song lyrics to making clothes to painting and drawing to scientific studies and explorations.

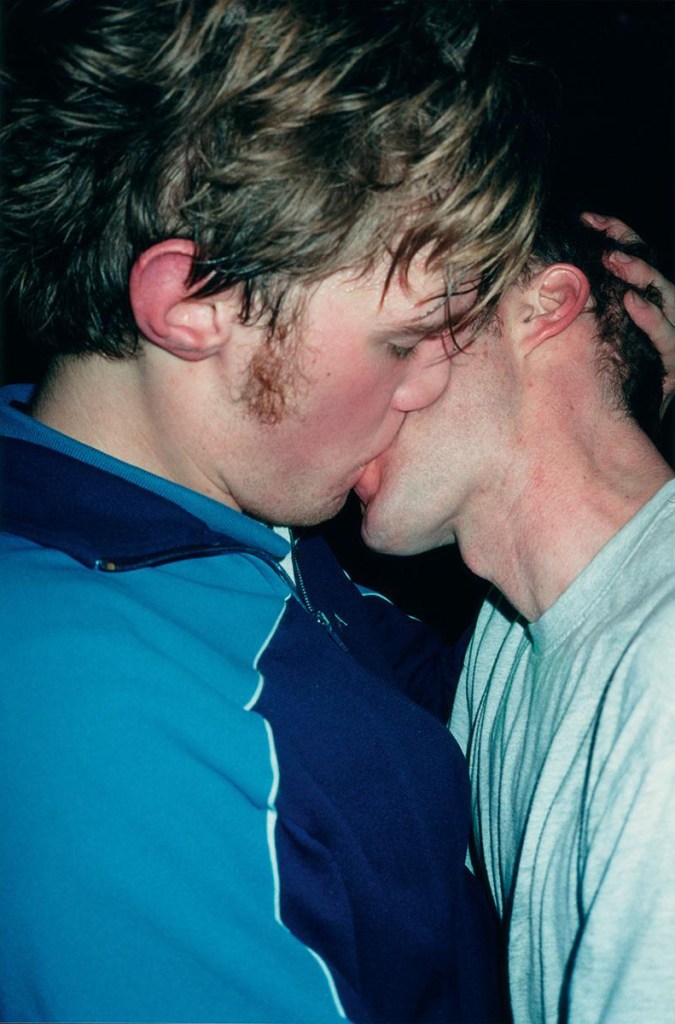

In November 1992 Tillmans presented a large picture printed on fabric, Lutz & Alex sitting in the trees, at Maureen Paley’s Interim Art stand at the UnFair in Cologne, an event organized by young galleries in a disused factory an alternative to the city’s official art fair. In the same month, Lutz & Alex was published as part of an eight-page photo spread titled “like brother like sister” in i-D – a British magazine covering anti–high fashion, music, and youth culture – to which he had recently started contributing.7 Two months later, in early 1993, he had his first gallery exhibition, at Daniel Buchholz’s two spaces in Cologne. In the back of an antique bookshop run by Buchholz and his father, Tillmans mounted a completely nonhierarchical installation, interspersing handprinted chromogenic prints, magazine pages, and laser photocopies. Large-scale inkjet prints mounted on fabric were appended directly to the walls in Buchholz’s second space. In the bookshop itself he showed photocopies pegged on clotheslines among the antiquarian prints that were already hanging. The exhibition also included a display case holding four magazines from different countries, all featuring the same photograph by Tillmans, of two men kissing at a EuroPride rally in London, each printed with a slightly different tonality. In the shop window he stuck a grid of techno club pictures from 1991, made in Ghent, London, and Frankfurt, which had been published that year in i-D.

The wide ambit of Tillmans’s installations was thus established in his first exhibitions. As artist and curator Julie Ault observes: “Taken together the installations reflect the artist’s parallel tracks of interest in the singular self-sufficient image and in relationships between images and production types.”8 They also highlight Tillmans’s wide-eyed interest in image networks and the potentials of spatial dynamics. A pioneer of the photographic exhibition itself as spatial medium, he created the conditions with which to communicate his ideas about social and political realities while intensifying visitors’ viewing and sensory experiences.9

As we consider the many platforms, media, and display strategies Tillmans has engaged to articulate his work, the larger principles of his worldview become clear. His relationship to reality is, he points out, always “above all, more ethical than technical, or purely aesthetic.”10

Wolfgang Tillmans: To look without fear, organized by Roxana Marcoci, The David Dechman Senior Curator, with Caitlin Ryan, Curatorial Assistant, and Phil Taylor, former Curatorial Assistant, Department of Photography, is on view September 12, 2022 – January 1, 2023.

1/ The phrase “wandering image” is Tillmans’s own. See Wolfgang Tillmans, interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist, The Conversation Series, no. 6 (Cologne: Walther König, 2007), p. 76. See WT Reader, p. 138.

2/ André Malraux, Le musée imaginaire (1947); in English as Museum without Walls (London: Zwemmer, 1949). This was the first volume of a three-part compendium, La psychologie de l’art (The Psychology of Art), which Malraux subsequently expanded and reissued in a single book as Les voix du silence (The Voices of Silence, 1951).

3/ Scholar Hannah Feldman critiques Malraux’s “amnesiac aesthetics,” noting that his cultural policies before and during the time he served as France’s first Minister of Cultural Affairs (1959-1969), under President Charles de Gaulle, coincided with the country’s colonial wars first in Indochina and then in Algeria. See Feldman, From a Nation Torn: Decolonizing Art and Representation in France, 1945-1962 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014), p. 11.

4/ Johanna Burton, “Pictures in the Present Tense,” in Wolfgang Tillmans (London: Phaidon, exp. ed. 2014), p. 190. See also Mark Godfrey, “Worldview,” in Wolfgang Tillmans, ed. Chris Dercon and Helen Sainsbury with Wolfgang Tillmans (London: Tate Publishing, 2017).

5/ This was the title of Tillmans’s retrospective exhibition at Tate Britain (June 6 – September 4, 2003).

6/ Wolfgang Tillmans, interview with Shirley Read, “Oral History of British Photography,” British Library Sound & Moving Image Catalogue (Recording 4, May 4, 2015, 00:17:16, digital file name: 021AC0459X0220XX0004MO.mp3).

7/ Wolfgang Tillmans, “like brother like sister,” i-D, no. 110 (November 1992), pp. 80-87.

8/ Julie Ault, “The Subject Is Exhibition (2008): Installations as Possibility in the Practice of Wolfgang Tillmans,” in Wolfgang Tillmans: Lighter, ed. Daniel Birnbaum, Julie Ault, and Joachim Jäger (Ostfildern, Germany: Hatje Cantz, 2008), p. 15.

9/ In the 1920s and 1930s groundwork was laid for experimentation with spaces and media technologies in exhibition installations. Notable among these efforts: El Lissitzky’s psychoperceptual Demonstrationsräume (Demonstration Spaces), which marked the emergence of exhibition theory and the exhibition as a medium; Friedrich Kiesler’s exploratory Raumbühne (Space Stage, 1924), by which he proposed dispensing with the old proscenium frame of classical theaters and cinema houses and merging auditorium and stage into an interactive arena; Herbert Bayer’s 1935 spatial scheme for extending the viewing experience – a post-Bauhaus diagram consisting of rings of image panels installed at 360 degrees around the viewer to enhance sensorial agency; and László Moholy-Nagy and Lucia Moholy’s synthesis of typography, photography, sound recording, and film into a generative intermedia experience, in “ProduktionReproduktion,” De Stijl 5, no. 7 (July 1922), pp. 97-101.

10/ Wolfgang Tillmans, interview with Beatrix Ruf, “New World/Life Is Astronomical,” in Tillmans, Neue Welt (Cologne: Taschen, 2012), n.p. See WT Reader, p. 188.

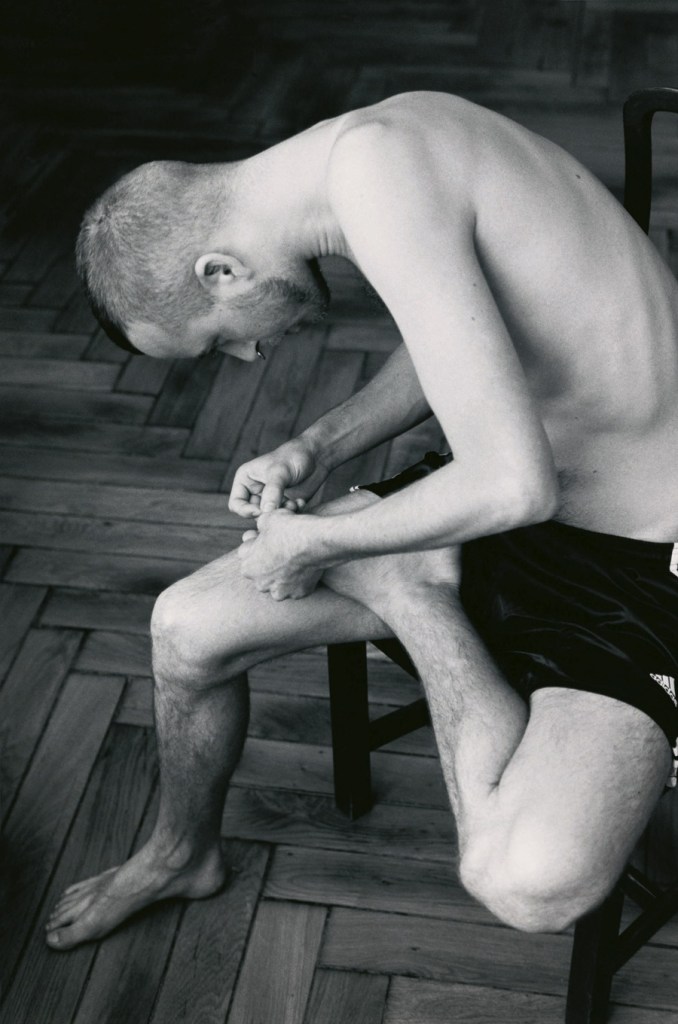

Installation view of Wolfgang Tillmans: To look without fear, on view at The Museum of Modern Art, New York from September 12, 2022 – January 1, 2023 showing at second left top, Tillmans The Cock (kiss) (2002, below); and at centre, Anders pulling splinter from his foot (2004, below)

Photo: Emile Askey

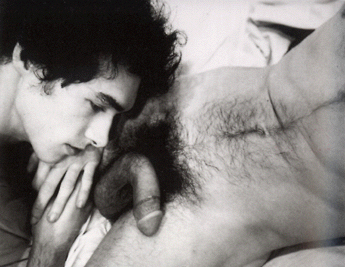

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

The Cock (kiss)

2002

Image courtesy of the artist, David Zwirner, New York / Hong Kong, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin / Cologne, Maureen Paley, London

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Anders pulling splinter from his foot

2004

Installation view of Wolfgang Tillmans: To look without fear, on view at The Museum of Modern Art, New York from September 12, 2022 – January 1, 2023

Photo: Emile Askey

Installation views of Wolfgang Tillmans: To look without fear, on view at The Museum of Modern Art, New York from September 12, 2022 – January 1, 2023 showing in the top image at centre, The Blue Oyster Bar, Saint Petersburg (2014, below); in the bottom image at top right inner, NICE HERE but ever been to KRYGYZSTAN free Gender Expression WORLDWIDE (2006, below); and at right, The Spectrum Dagger (2016, above)

Photos: Emile Askey

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

The Blue Oyster Bar, Saint Petersburg

2014

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

NICE HERE but ever been to KRYGYZSTAN free Gender Expression WORLDWIDE

2006

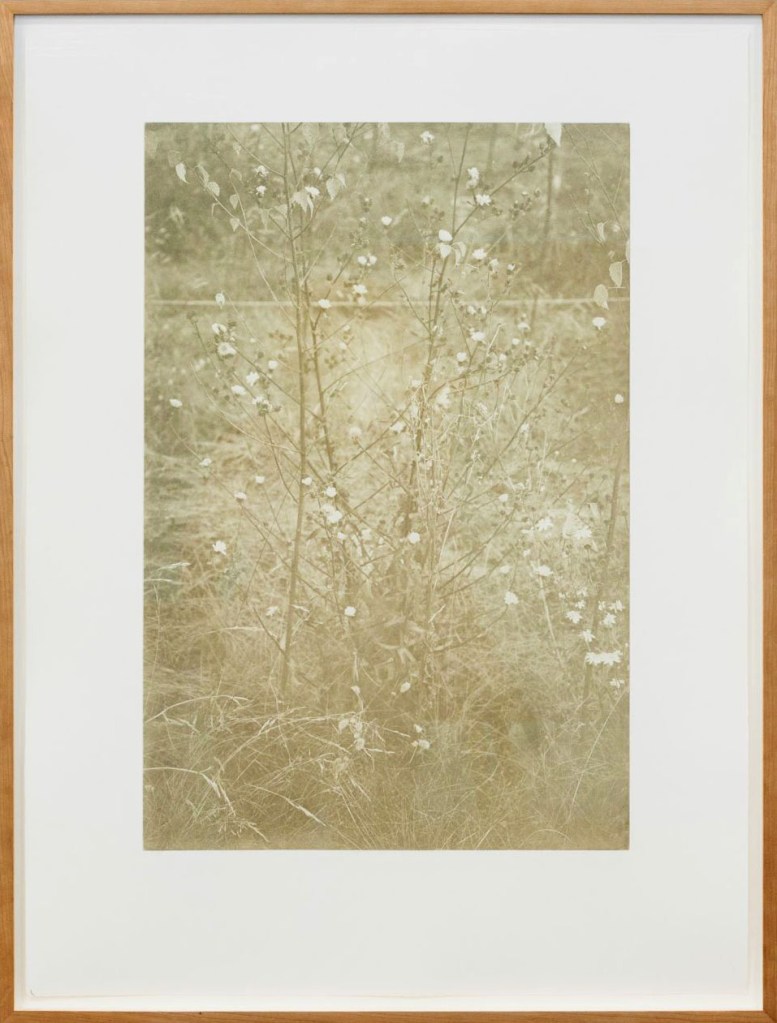

Installation views of Wolfgang Tillmans: To look without fear, on view at The Museum of Modern Art, New York from September 12, 2022 – January 1, 2023 showing in the bottom image at third left, Tukan (2010, below); and at right, Headlight (f) (2012, below); and at right, Weed (2014, below)

Photos: Emile Askey

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Tukan (Toucan)

2010

Image courtesy of the artist, David Zwirner, New York / Hong Kong, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin / Cologne, Maureen Paley, London

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Headlight (f)

2012

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Weed

2014

Aimee Lin

Jan 11, 2022

Edited by Roxana Marcoci and Phil Taylor, the just-released Wolfgang Tillmans: A Reader (2021) is the first publication to present the artist’s contributions as a thinker and writer in a systematic manner, illuminating the breadth of his engagement with audiences across diverse platforms. The interview excerpt below is included in the reader.

Aimee Lin: In the catalogue [DZHK Book 2018] for your Hong Kong exhibition [at David Zwirner] you have reproduced an email conversation with a printing company you contacted in response to a spam email. How did that dialogue start?

Wolfgang Tillmans: It was just by chance. The email caught my eye because it was so unsophisticated and innocent. I thought that, rather than malicious phishers, these might be real people. So I wrote back, and their response was quite touching. They explained they were young and sending out random emails to find customers for their printing business. We think of it as spam, but it is no different from a leaflet through the letter-box. They really were trying to find clients, but I naturally assumed that it was some terrible virus or phishing scam.

Aimee Lin: Why did you want to include this in the catalogue? It’s a very beautiful story, very funny, even flirty.

Wolfgang Tillmans: I see this catalogue as an artist’s book. I like to explore different materialities in books, different ways of thinking. It’s not just a representation of images, it’s a book of poetry. When I was laying out the book, I thought of it as writing. I can’t tell you the story in words, but I feel it in the sequence of pictures. The book is about language, but not necessarily a verbal or literary language. Text is included in my recent pictures, including the works exhibited in this show. And I considered this exchange with the printer “Klaus” as a kind of concrete poetry.

Aimee Lin: The conversation reminded me of Manuel Puig’s 1976 novel Kiss of the Spider Woman. It’s about two inmates, a political prisoner and a thief, and in each chapter one of the guys tells the story of a film they’ve seen.

Wolfgang Tillmans: I never understood myself as speaking only through photography. I feel like I can say almost everything I want to with photography, and I still haven’t gotten tired of it, but on the other hand it is only one medium. More and more, I realize that language is something I care about and have developed as a medium in the shape of interviews and lectures. The lectures are like eighty-minute performances, with language, pictures, and silence. This performative element moved into video and finally back into music. Music is a lot about words being spoken and sung.

Aimee Lin: The exhibition at David Zwirner’s Hong Kong space will include images of Shenzhen, Macau, and Hong Kong, all of which are political and geographical borders inside China. I’m curious about why you chose to photograph those places.

Wolfgang Tillmans: The Macau picture is from 1993, which is the first time I was in Macau and the last time I was in Hong Kong, so there’s been twenty-five years between my two visits. Back then I wanted to see the border with China. I’m interested in understanding the difference across a border when the earth – the ground, the matter – is the same. I never took borders for granted, and I don’t necessarily want to tear them down, but I do want to understand them in their material reality. To feel them. Clothes also interest me, this thin layer of fabric that conceals plain human bodies that are pretty much the same. The putting on of clothes changes so much. A uniform creates authority and distance, which is in a way ridiculous, because it’s just a piece of fabric, it’s nothing. A pair of ripped jeans is seen by a parent as something that should be thrown away, and by a teenager as the most beloved piece of clothing.

Aimee Lin: Clothes are an artificial border against your natural body.

Wolfgang Tillmans: Yes. I acknowledge that there are borders between people, languages, and races. But I think that by looking at them, touching them, smelling them, feeling them, you can also see them for what they are. Strangely, that’s the visible medium of photography. It’s not a scientific way of looking deeper, but it does put me into situations where I can explore those limits, whether that’s being at a border or looking through an extremely large telescope. I spent a weekend in Chile at an observatory, looking at the border of the visible.

Aimee Lin: The far end of the universe.

Wolfgang Tillmans: Astronomy is located at the limit. Can I see something there? Is that a detail or is it just noise in the camera sensor? By going to the limits, to the borders, I find comfort in being in-between. I always felt held in-between the infinite smallness of subatomic space and the infinite largeness of the cosmos. It gives me comfort to feel infinity.

Aimee Lin: How does that experience, that feeling, relate to your high-resolution digital photographs, which are printed at a very large scale? Those images are so massive, contain so much detailed visual information, that they are overwhelming.

Wolfgang Tillmans: I wasn’t originally interested in super-sharp, large-format film, because I wanted my photographs to describe how it feels to look through my eyes. For that, 100 ASA [ISO] 35mm film is close enough to how I feel things look. But since 1995 I have also shown very large photographs, the largest of which is called wake (2001), recently shown at the Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin. Those pictures were made with 35mm negatives, but in 2009 I started to work with a high-resolution digital camera. Suddenly I found myself with an instrument in my hand that was as powerful as a large-format camera. It took me three years to learn how to speak with this new language. By 2012, the whole world had become high-definition. Being able to zoom in on a huge print, and still see detail after detail, is how the world feels now, through my eyes. I’m grateful that I was able to make that development from film to high-resolution digital photography, because it opened up a new language in the history of art. One of the pictures, included in the Hong Kong exhibition, showing the texture of wood and an onion [Sections (2017)], is of such shocking clarity that you find yourself facing an idea of infinity. These pictures contain more information than you can ever remember. Only these large-format prints are able to display the full range of detail, color, and scale, and so digital has actually made the objects almost more unique. The object can only be experienced in the full depth of its presence and its material reality in that room at that time.

Aimee Lin: This material reality is only accessible through the picture. The eyes can’t process so much information in one go.

Wolfgang Tillmans: I find that miraculous. There’s something deeply philosophical in having to learn to let go of information. It’s an analogy for the information age, and the challenge of valuing things at the same time as being prepared to let them go. To understand everything as the same, and yet to decide that some things are more valuable than others. I choose to value certain things, and at the same time to understand that everything is materially equal, if we accept that things are infinite. That’s a strange opposition.

The full article was originally published as “Wolfgang Tillmans: On the Limits of Seeing in a High-Definition World,” by Aimee Lin. ArtReview Asia, Spring 2018, 64-65. Courtesy Aimee Lin and ArtReview Asia.

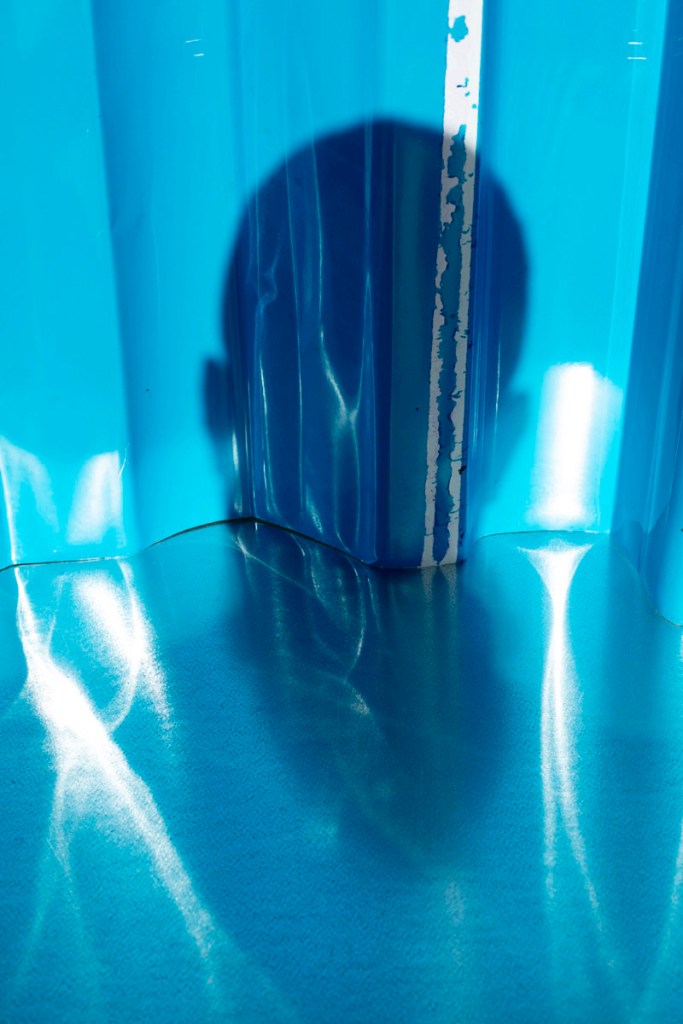

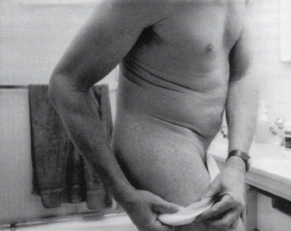

Installation views of Wolfgang Tillmans: To look without fear, on view at The Museum of Modern Art, New York from September 12, 2022 – January 1, 2023 showing at centre, Frank, in the shower (2015, below); and at second right, blue self–portrait shadow (2020, below)

Photos: Emile Askey

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Frank, in the shower

2015

Image courtesy of the artist, David Zwirner, New York / Hong Kong, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin / Cologne, Maureen Paley, London

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

blue self–portrait shadow

2020

Image courtesy of the artist, David Zwirner, New York / Hong Kong, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin / Cologne, Maureen Paley, London

Installation views of Wolfgang Tillmans: To look without fear, on view at The Museum of Modern Art, New York from September 12, 2022 – January 1, 2023 showing at second right, blue self–portrait shadow (2020, above); and at right, Concrete Column III (2021, below)

Photos: Emile Askey

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Concrete Column III

2021

Image courtesy of the artist, David Zwirner, New York / Hong Kong, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin / Cologne, Maureen Paley, London

Page spreads from “like brother like sister”

i-D, no. 110 (November 1992)

layout designed by Tillmans

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

still life, New York

2001

Image courtesy of the artist, David Zwirner, New York / Hong Kong, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin / Cologne, Maureen Paley, London

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

wake

2001

Image courtesy of the artist, David Zwirner, New York / Hong Kong, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin / Cologne, Maureen Paley, London

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Installation view, Panorama Bar, Berghain, Berlin

2004

Image courtesy of the artist, David Zwirner, New York/Hong Kong, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne, Maureen Paley, London

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

August self portrait

2005

Image courtesy of the artist, David Zwirner, New York / Hong Kong, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin / Cologne, Maureen Paley, London

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Faltenwurf (skylight)

2009

Image courtesy of the artist, David Zwirner, New York / Hong Kong, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin / Cologne, Maureen Paley, London

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Lighter, white convex I

2009

Chromogenic print in acrylic hood

25 1/4 x 21 1/16 x 2 3/8″ (64.2 x 54.2 x 6cm)

Image courtesy of the artist, David Zwirner, New York / Hong Kong, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin / Cologne, Maureen Paley, London

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

in flight astro ii

2010

© Wolfgang Tillmans, and courtesy the artist; David Zwirner, New York and Hong Kong; Galerie Buchholz, Berlin and Cologne; Maureen Paley, London

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

sensor flaws and dead pixels, ESO

2012

© Wolfgang Tillmans, and courtesy the artist; David Zwirner, New York and Hong Kong; Galerie Buchholz, Berlin and Cologne; Maureen Paley, London

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Silver 152

2013

Chromogenic print

21 5/16 × 25 1/4″ (54.2 × 64.2cm)

Image courtesy of the artist, David Zwirner, New York / Hong Kong, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin / Cologne, Maureen Paley, London

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Playing cards, Hong Kong

2018

© Wolfgang Tillmans, and courtesy the artist; David Zwirner, New York and Hong Kong; Galerie Buchholz, Berlin and Cologne; Maureen Paley, London

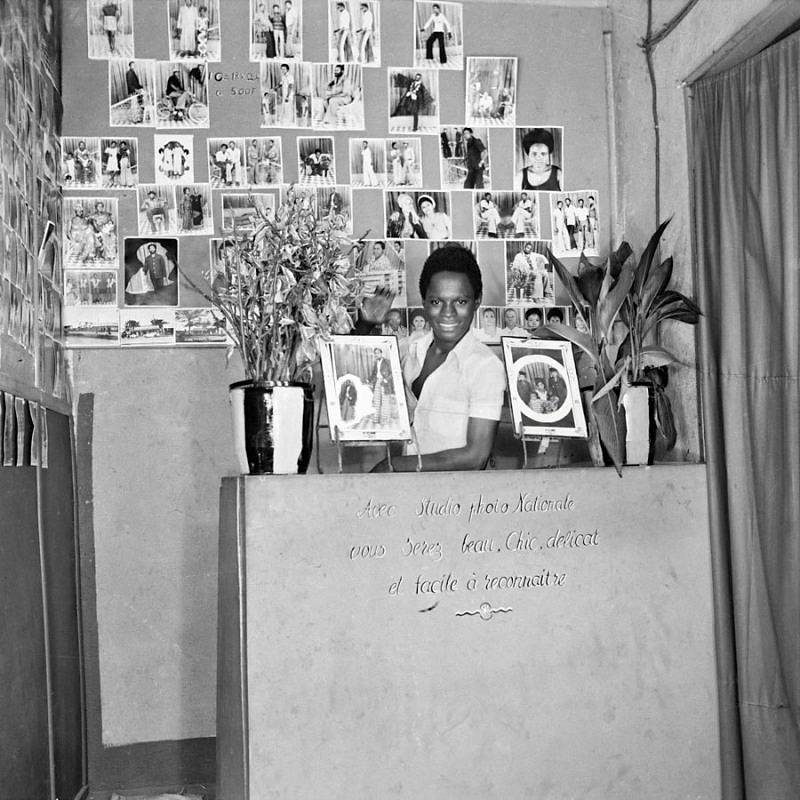

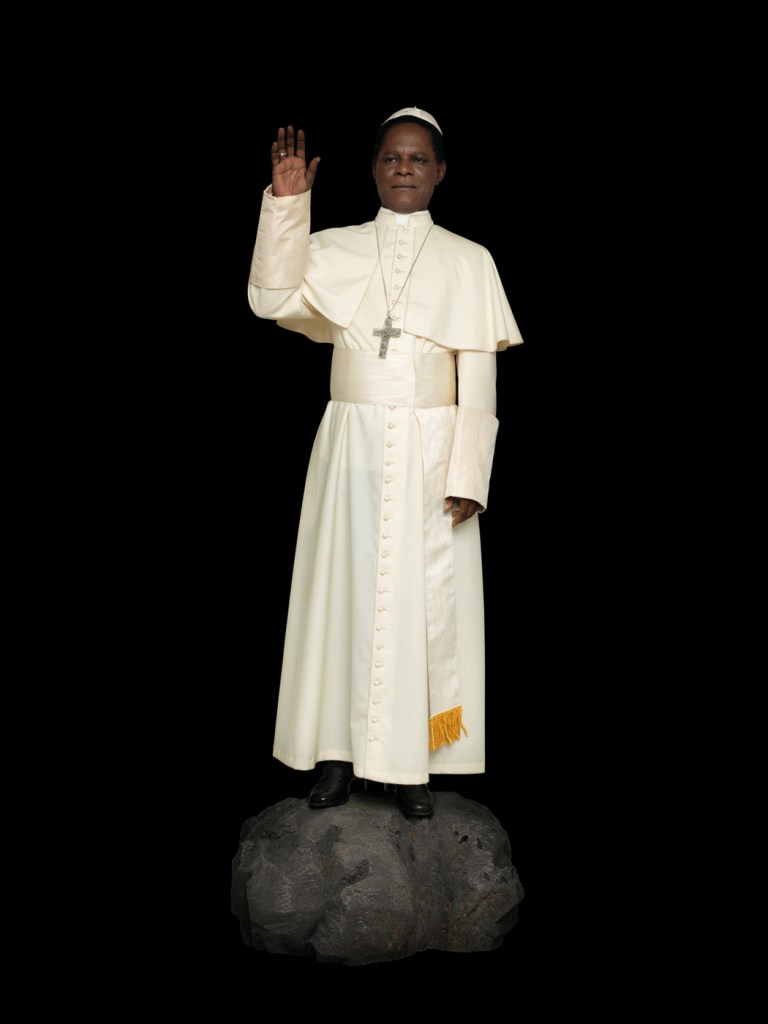

Wolfgang Tillmans: Fragile

Installation view, Contemporary Art Gallery, Yaoundé, Cameroon, 2019

Image courtesy of the artist, David Zwirner, New York / Hong Kong, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin / Cologne, Maureen Paley, London

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Lüneburg (self)

2020

Image courtesy of the artist, David Zwirner, New York / Hong Kong, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin / Cologne, Maureen Paley, London

The Museum of Modern Art

11 West 53 Street

New York, NY 10019

Phone: (212) 708-9400

Opening hours:

10.30am – 5.30pm

Open seven days a week

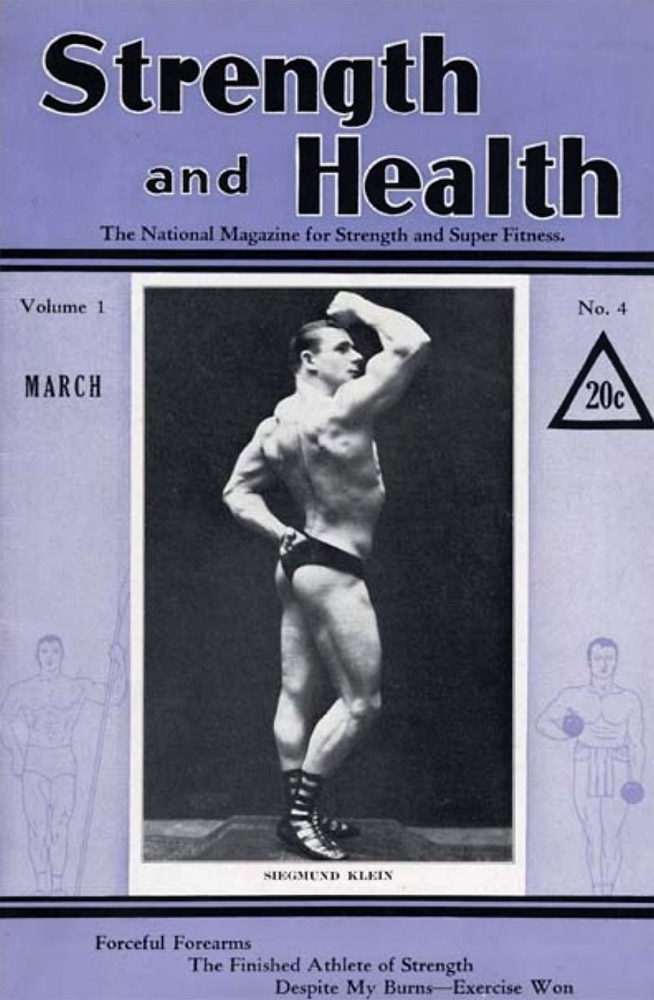

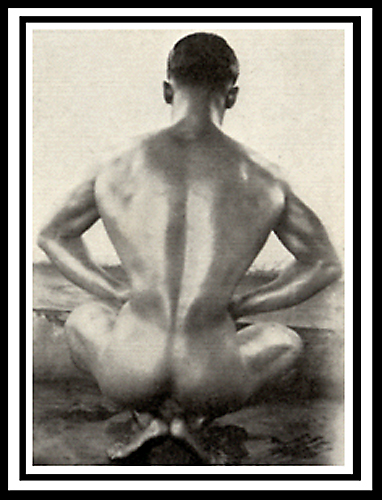

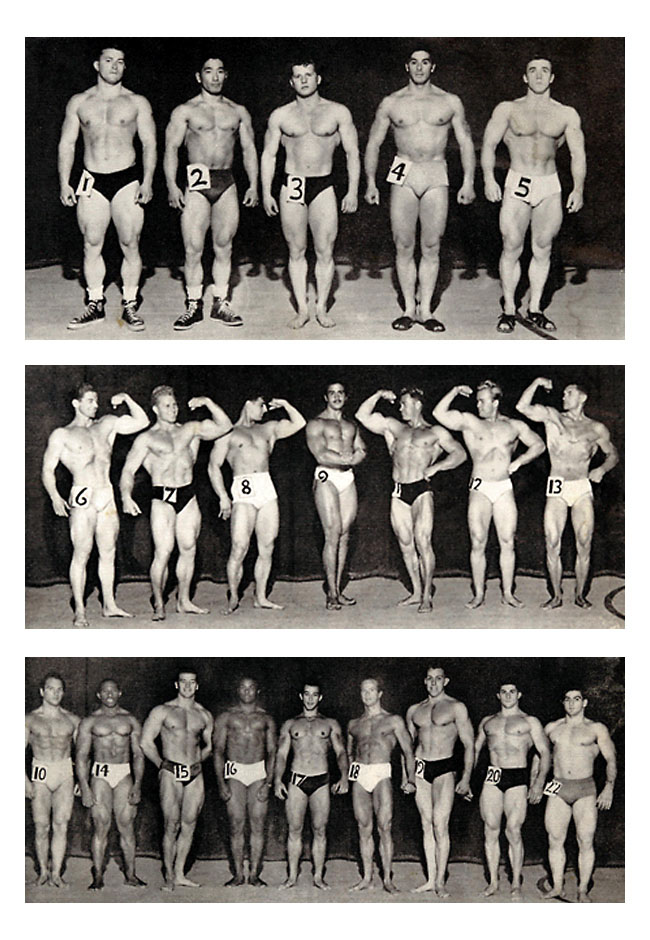

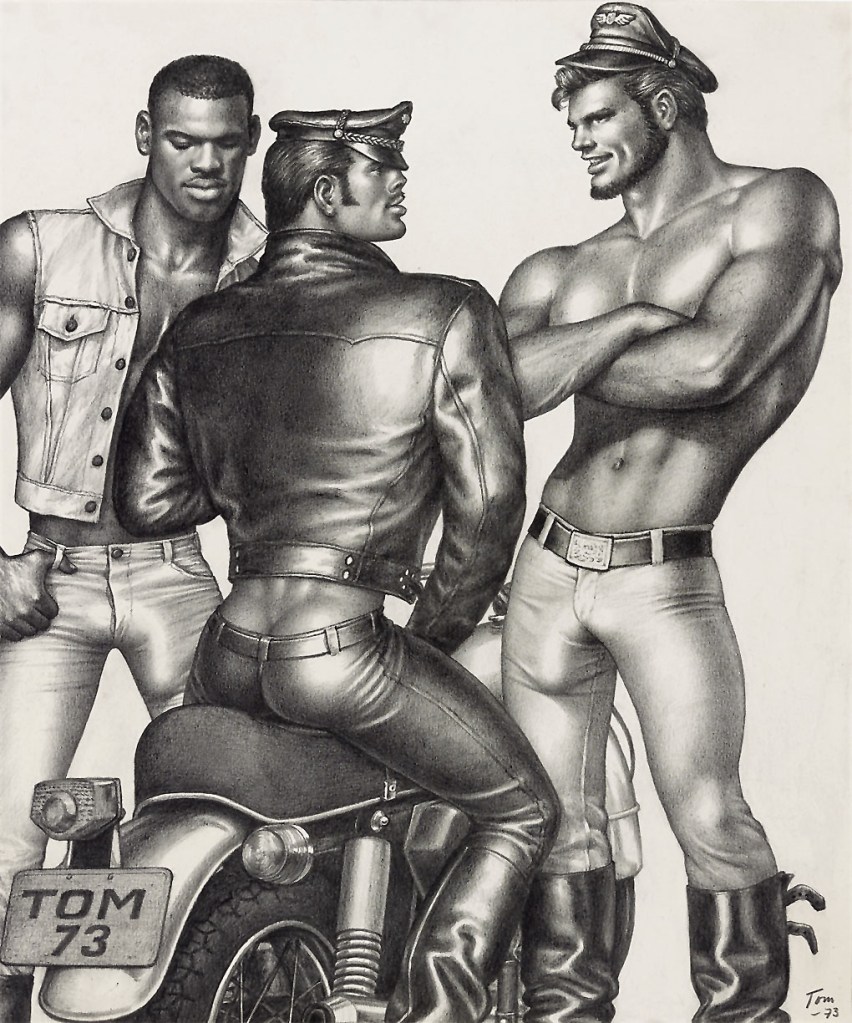

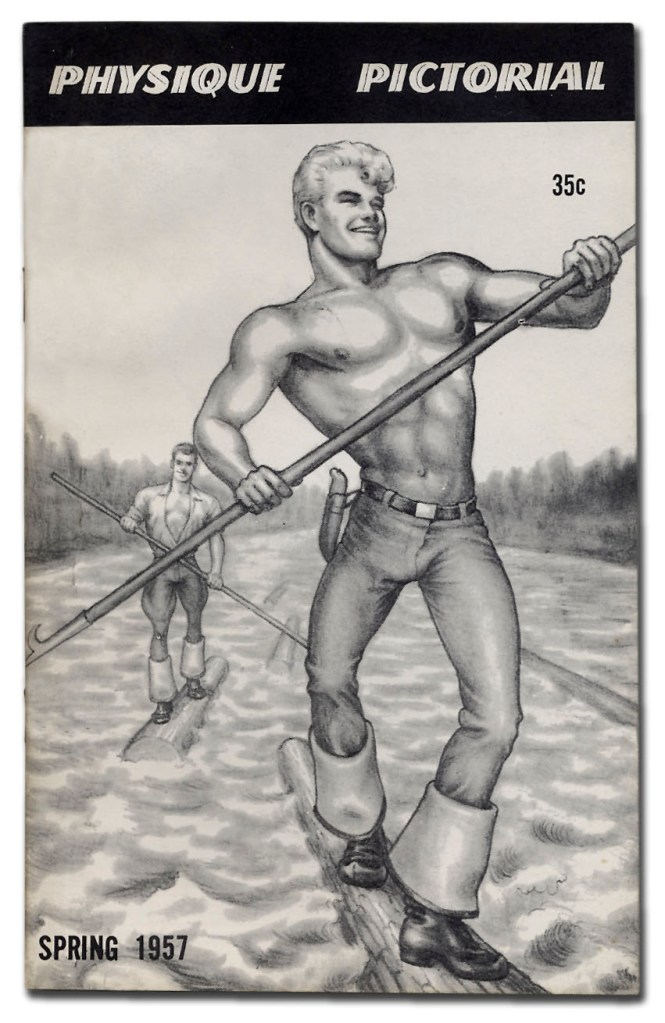

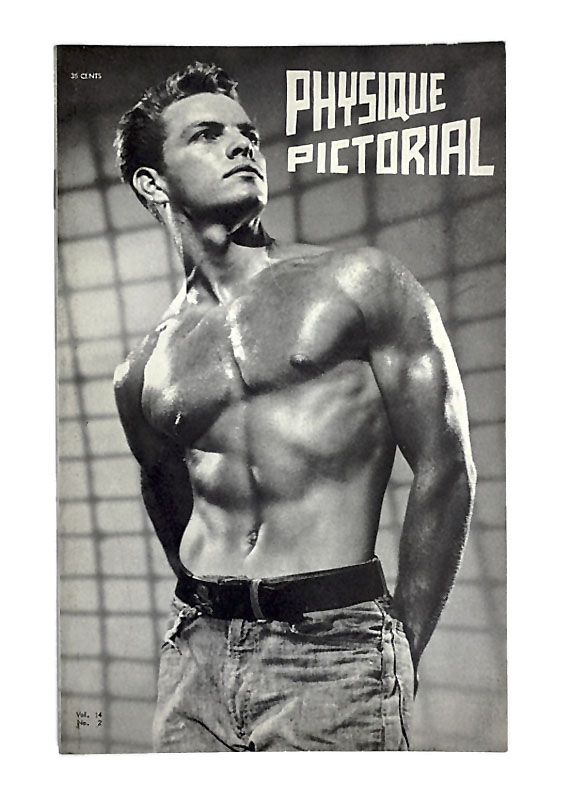

Curators: Jonathan D. Katz, Curator and Johnny Willis, Associate Curator

Please note: This exhibition contains sexually explicit content. For mature audiences only.

Roberto Montenegro (Mexican, 1885-1968)

Retrato de un anticuario o Retrato de Chucho Reyes y autorretrato

Portrait of an antiquarian or Portrait of Chucho Reyes and self-portrait

1926

Oil on canvas

40.4 x 40.4 in (unframed)

41.7 x 41.6 x 1.6 in (framed)

Colección Pérez Simón, Mexico

© Arturo Piera

Short and sweet…

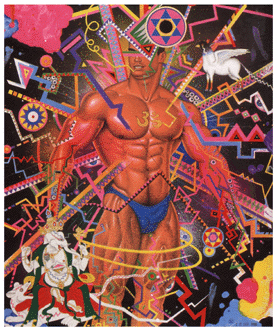

I believe that any artist that lives at the edge of desire, of creativity, of individuality, exploration and feeling – in seeing the world from different points of view – pushes the boundaries of what the conservative mass of humanity finds acceptable.

Defying the taboo is only possible because the taboo exists in the first place. The taboo against sensuality, eroticism and pleasure can only be broken by approaching those ecstatic and liminal spaces that lead to other states of consciousness, by being attentive to the dropping away of awareness so that we avoid the frequency of common intensities, instead illuminating spaces and languages where new cultural symbols and meanings can emerge. This is what artists and people of difference do: we approach the ‘Thing Itself’. We live on the edge of ecstasy, oblivion and revelation.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

PS. I have added bibliographic information to the posting where possible.

Many thankx to Wrightwood 659 for allowing me to publish the art work in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

The First Homosexuals: Global Depictions of a New Identity, 1869-1930 takes as its starting point the year 1869, when the word “homosexual” was first coined in Europe, inaugurating the idea of same-sex desire as the basis for a new identity category. On view will be more than 100 paintings, drawings, prints, photographs, and film clips – drawn from public and private collections around the globe and including a number of national treasures which have never before been allowed to travel outside their countries. This groundbreaking exhibition offers the first multi-medium survey of the very first self-consciously queer art, exploring what the “first homosexuals” understood themselves to be, how dominant culture, in turn, understood them, and how the codes of representation they employed offer us previously unknown glimpses into the social and cultural meanings of same-sex desire.

The First Homosexuals is being organised in two parts, due to COVID-related delays, with part one opening on October 1 with approximately 100 works, and on view only at Wrightwood 659. Three years from now, in 2025, 250 masterworks will be gathered at Wrightwood 659 for part two of The First Homosexuals in an exhibition which will travel internationally and be accompanied by a comprehensive catalogue.

The exhibition is being developed by a team of 23 international scholars led by art historian Jonathan D. Katz, Professor of Practice in the History of Art and Gender, Sexuality and Women’s Studies at the University of Pennsylvania, with associate curator Johnny Willis.

Alice Austen (American, 1866-1952)

Trude & I Masked, Short Skirts

1891

Print, 4 x 5 in

Historic Richmond Town

Elizabeth Alice Austen (March 17, 1866 – June 9, 1952) was an American photographer working in Staten Island.

One of America’s first female photographers to work outside of the studio, Austen often transported up to 50 pounds of photographic equipment on her bicycle to capture her world. Her photographs represent street and private life through the lens of a lesbian woman whose life spanned from 1866 to 1952. Austen was a rebel who broke away from the constraints of her Victorian environment and forged an independent life that broke boundaries of acceptable female behaviour and social rules. …

Alice Austen’s life and relationships with other women are crucial to an understanding of her work. Until very recently many interpretations of Austen’s work overlooked her intimate relationships. What is especially significant about Austen’s photographs is that they provide rare documentation of intimate relationships between Victorian women. Her non-traditional lifestyle and that of her friends, although intended for private viewing, is the subject of some of her most critically acclaimed photographs. Austen would spend 53 years in a devoted loving relationship with Gertrude Tate, 30 years of which were spent living together in her home which is now the site of the Alice Austen House Museum and a nationally designated site of LGBTQ history.

Austen’s wealth was lost in the stock market crash of 1929 and she and Tate were evicted from their beloved home in 1945. Tate and Austen were finally separated by family rejection of their relationship and poverty. Austen was moved to the Staten Island Farm Colony where Tate would visit her weekly. In 1951 Austen’s photographs were rediscovered by historian Oliver Jensen and money was raised by the publication of her photographs to place Austen in private nursing home care. On June 9, 1952 Austen passed away. The final wishes of Austen and Tate to be buried together were denied by their families.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Violet Oakley (American, 1874-1961)

Edith Emerson Lecturing

c. 1935

Oil on canvas

35 x 45 in.

Woodmere Art Museum, Philadelphia, PA: gift of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, 2012

Courtesy of Woodmere Art Museum

Violet Oakley (June 10, 1874 – February 25, 1961) was an American artist. She was the first American woman to receive a public mural commission. During the first quarter of the twentieth century, she was renowned as a pathbreaker in mural decoration, a field that had been exclusively practiced by men. Oakley excelled at murals and stained glass designs that addressed themes from history and literature in Renaissance-revival styles.

Edith Emerson (American, 1888-1981)

Portrait of Violet Oakley

Date unknown

Oil on canvas

25 x 30 in.

Woodmere Art Museum, Philadelphia, PA: gift of Jane and Noble Hall, 1998

Courtesy of Woodmere Art Museum

Edith Emerson (July 27, 1888 – November 21, 1981) was an American painter, muralist, illustrator, writer, and curator. She was the life partner of acclaimed muralist Violet Oakley and served as the vice-president, president, and curator of the Woodmere Art Museum in the Chestnut Hill neighbourhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, from 1940 to 1978. …

[Oakley’s] life partner, Edith Emerson, was a painter and, at one time, a student of Oakley’s. In 1916, Emerson moved into Oakley’s Mount Airy home, Cogslea, where Oakley had formed a communal household with three other women artists, calling themselves the Red Rose Girls. Emerson and Oakley’s relationship endured until Oakley’s death and Emerson subsequently established a foundation to memorialise Oakley’s life and legacy. The foundation dissolved in 1988 and the assets donated to the Smithsonian Museum.

Following Violet Oakley’s death in 1961, Emerson created the Violet Oakley Memorial Foundation to keep her teacher and companion’s memory and ideals alive. The foundation also sought to house and preserve the contents of Oakley’s studio, which was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1977 as the Violet Oakley Studio. Emerson served as the foundation’s president, as well as curator and general caretaker of the studio. The studio was opened to the public as a kind of museum, and Emerson organised various activities there, including concerts, exhibitions, poetry readings, and lectures on American art and illustration. Following Emerson’s death, the foundation dispersed the contents, sold the house, and disbanded.

In 1979, Emerson was instrumental in mounting an Oakley revival as an exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Owe Zerge (Swedish, 1894-1984)

Model Act

1919

Oil on canvas

53.1 x 19.7 in.

Private Collection

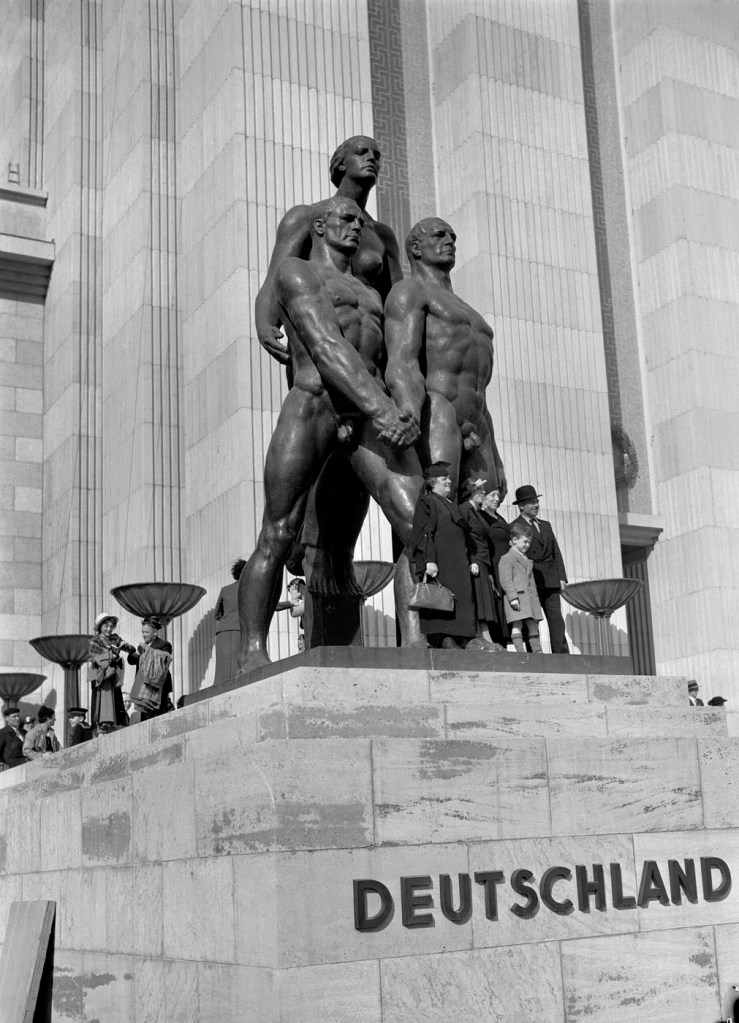

Role of Art in the Modern Construction of Same-Sex Desire Explored for First Time in Groundbreaking Two-Part Exhibition at Wrightwood 659 in Chicago

The First Homosexuals: Global Depictions of a New Identity, 1869-1930, begins in the year 1869, when the word “homosexual” was coined in Europe, inaugurating the idea of same-sex desire as the basis for a new identity category. With more than 100 paintings, drawings, prints, photographs, and film clips – drawn from public and private collections around the globe and including works which have never before been allowed to travel outside their countries – this large-scale international exhibition offers the first multi-media survey of some of the founding works of queer art. The First Homosexuals explores what the earliest homosexuals understood themselves to be, how dominant culture understood them, and how the codes of representation they employed offer previously unknown glimpses into the social and cultural meanings of same-sex desire.

The First Homosexuals is organised in two parts, due to Covid-related delays, with Part I on view only at Wrightwood 659 in Chicago from October 1 through December 17, 2022. Three years from now, in 2025, 250 masterworks will be gathered at Wrightwood 659 for Part II, in a major exhibition that will travel internationally, accompanied by a comprehensive catalogue.

Already three years in the making, the exhibition is being developed by a team of 23 international scholars, led by art historian Jonathan D. Katz, Professor of Practice in the History of Art and Gender, Sexuality and Women’s Studies at the University of Pennsylvania, with associate curator Johnny Willis.

The First Homosexuals rewrites conventional art history, in part by deepening the reading of works of art by familiar artists – whether it be Henry Fuseli, Thomas Eakins, or George Bellows – and in part by lifting the cover off works that previously have not been widely understood as declarations of same-sex attachment. The exhibition also introduces American museum goers to a number of artists who are little known in the United States but revered in their own countries, including Gerda Wegener (Denmark); Eugéne Jansson (Sweden); and Frances Hodgkins (New Zealand).

The First Homosexuals explores the cohesion of a new global identity at a liminal moment, one that art can tell uniquely well. While the written archive of the period must necessarily use accepted words to describe ideas, art is notably free of such consensus, allowing for the emergence of more idiosyncratic, contested, and exploratory forms.

“The First Homosexuals is an international project of an incredible scale. It perfectly fulfils our mission of presenting novel, socially engaged exhibitions,” says Chirag G. Badlani, Executive Director of Alphawood Foundation Chicago, which is presenting The First Homosexuals through Alphawood Exhibitions. “We are thrilled that the community can experience an important exhibition like this at Wrightwood 659 – given the content, it otherwise might not be seen.” He added, “We are particularly proud to show a collection of early Russian queer works borrowed from the Odesa Fine Arts Museum in Ukraine, amidst the ongoing war, helping to safeguard these important pieces of queer history from potential damage or destruction.”

Dr. Katz, notes, “The First Homosexuals demonstrates that as the language used to name same-sex desire narrowed into a simple binary of homosexual / heterosexual, art went the opposite direction, giving form to a range of sexualities and genders that can best be described as queer. Art became the place where the simplistic sexual binary could be nuanced and particularised, evoking emotions and responses that language couldn’t yet express.”

Dr. Katz continues, “The reality is that current-day conceptions about homosexuality are only roughly as old as the oldest living Americans. Our goal in this exhibition is to read queer desire as it manifested itself in this not-so-long-ago past, while being alert to the very different forms it took globally.”

Part I of The First Homosexuals is installed in nine sections, occupying the entire second floor of the Tadao Ando-designed galleries of Wrightwood 659. The first section, entitled Before Homosexuality, features 19th-century works that suggest how unself-consciously same-sex eroticism was portrayed before the coinage of the word homosexual. A highlight is a print depicting a sexual act between two men by Hokusai, the ukiyo-e master of Japan’s Edo period. Hokusai’s image would have been entirely uncontroversial in its day.

Among the works installed in Couples, the second section, is a leisurely boating scene by the French painter Louise Abbéma, showing herself in masculinate garb with her lover, the celebrated actress Sarah Bernhardt. Two other paintings represent reverse homages, wherein the American artist Edith Emerson paints her lover Violet Oakley and Oakley returns the favour by producing an oil study of Emerson. Also on view in this section is an illustration by Oakley that ran in the December 1903 issue of the popular The Century Magazine, depicting heaven as populated entirely by lithe young women in flowing gold and white robes.

Especially notable in Between Genders is a seductive reclining nude, a painting of one of the first modern transgender women: Gerda Wegener’s Reclining Nude (Lili Elbe), 1929. Nearby, the Russian artist Konstantin Somov’s delicate Portrait of Cécile de Volanges, 1917, appears to portray an 18th-century aristocratic beauty; however, the face is the artist’s own.

Between Genders abounds with photographs documenting the social experiments of the time, including a postcard of the French chanteuse Josephine Baker in male evening attire; the Norwegian Marie Høeg dressed as a man in a variety of carte de visite poses, the calling cards of their day; the French surrealist Claude Cahun in a meditative position with a shaved head looking neither male nor female; and, from across the Atlantic, c. 1890s sepia-toned photographs of an African American man, perhaps once enslaved, performing female drag on the vaudeville stage. A film segment featuring Loïe Fuller performing her legendary Serpentine Dance, 1905, contrasts with another film clip by the Frères Lumière of a male dancer performing the same dance and dressed like Fuller in flowing, billowing robes.

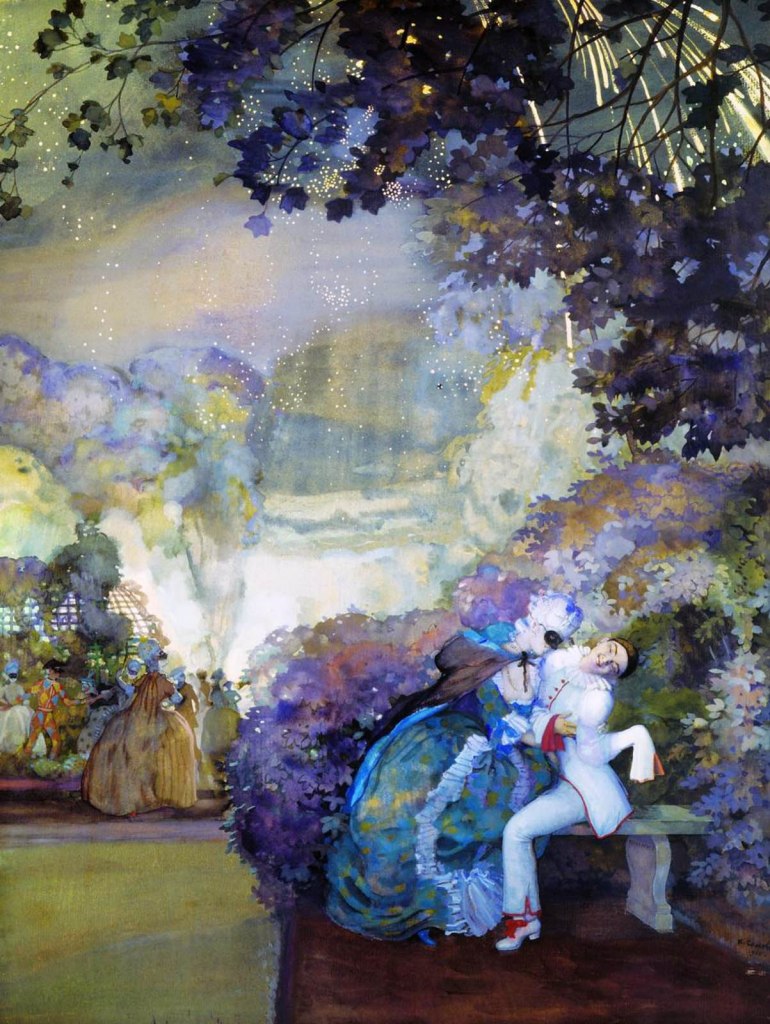

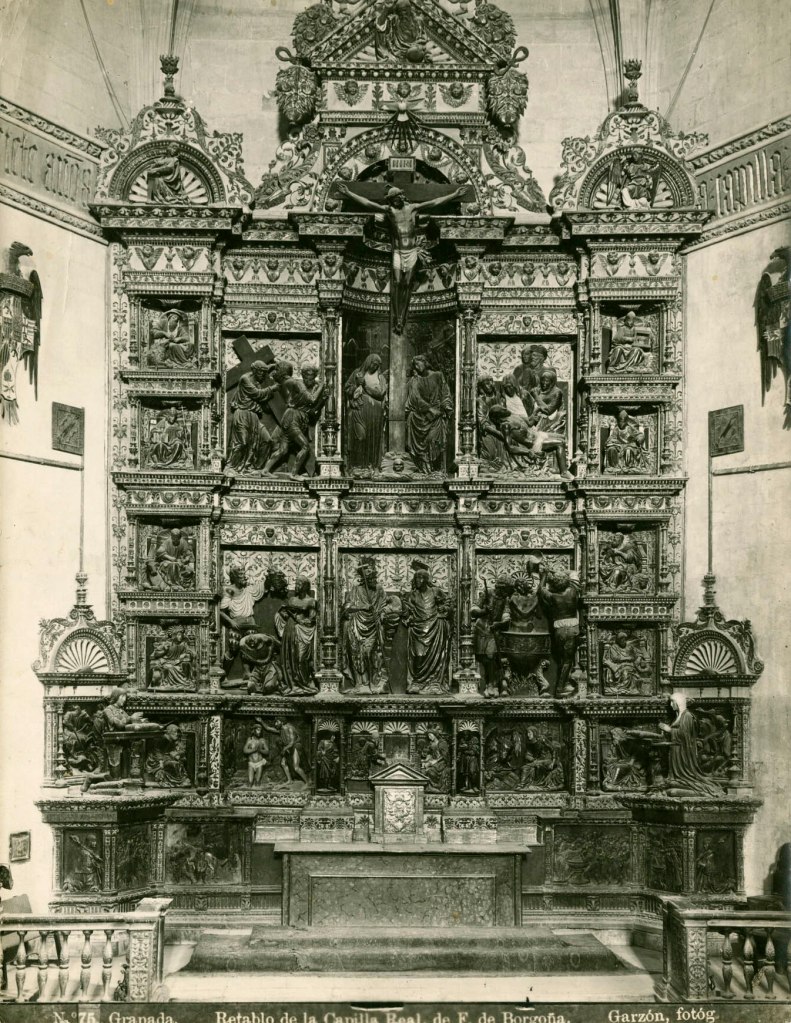

In the section Pose is a famous portrait by the Mexican artist Roberto Montenegro of his friend, the antique and antiquities dealer Chucho Reyes. The limp wrist, the tilted chin, and the amused smile are legible tropes of queer codes even today. As well as picturing Reyes ensconced proudly among his treasures, including an oval miniature of a woman, Montenegro included in the foreground a silver ball reflecting his own visage, thus bringing himself into the picture.

A contrasting note is hit nearby where a recording of “Ma” Rainey’s blues song, “Prove It On Me,” will be played and a vintage advertisement for the vinyl record displayed. Rainey had been arrested for participating in a lesbian sex orgy, a notorious event that she shrewdly parlayed into the #1 best-selling record within the African American community in 1928.

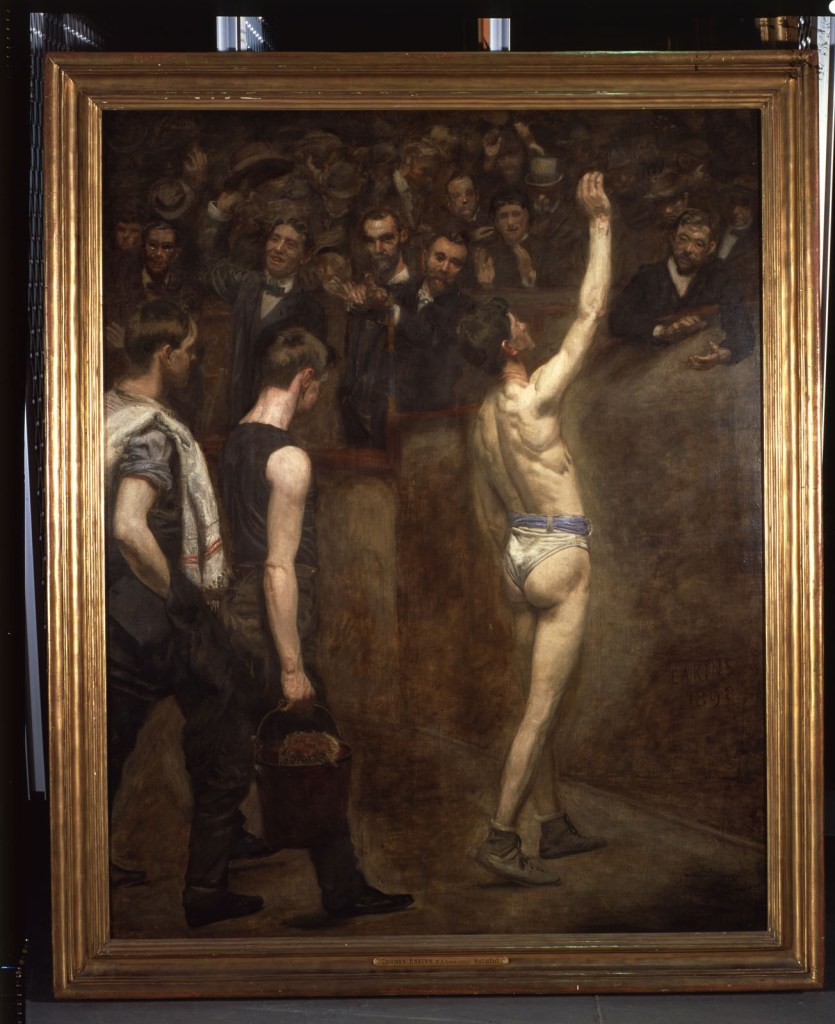

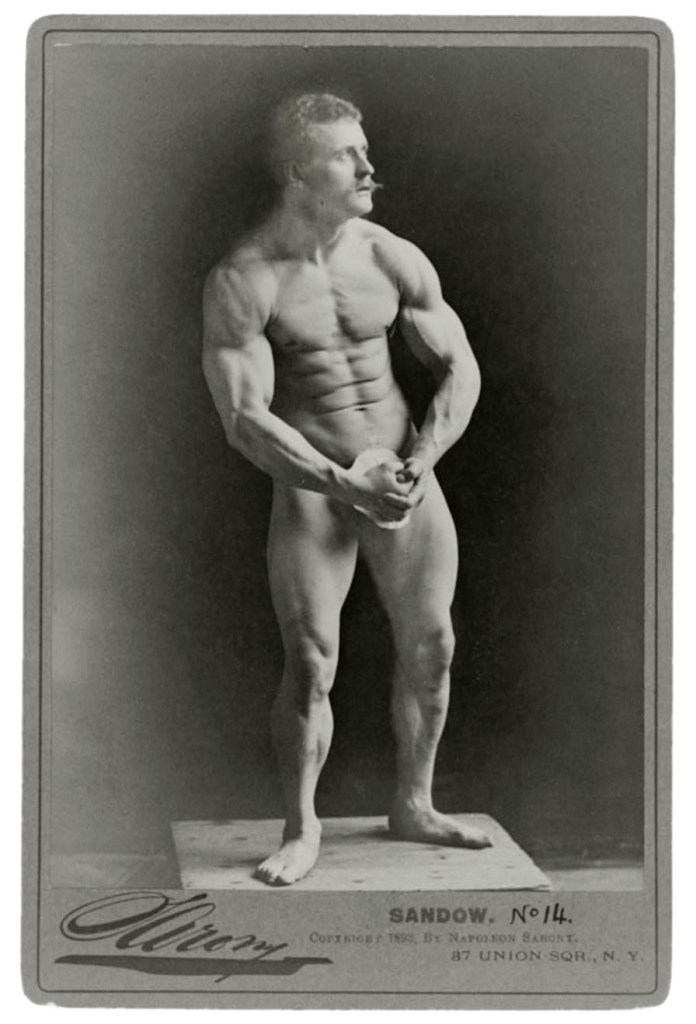

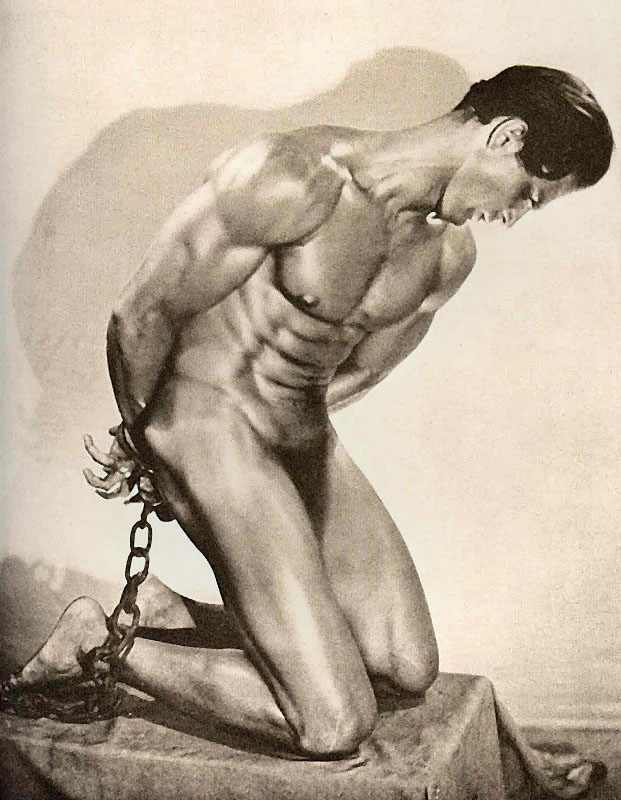

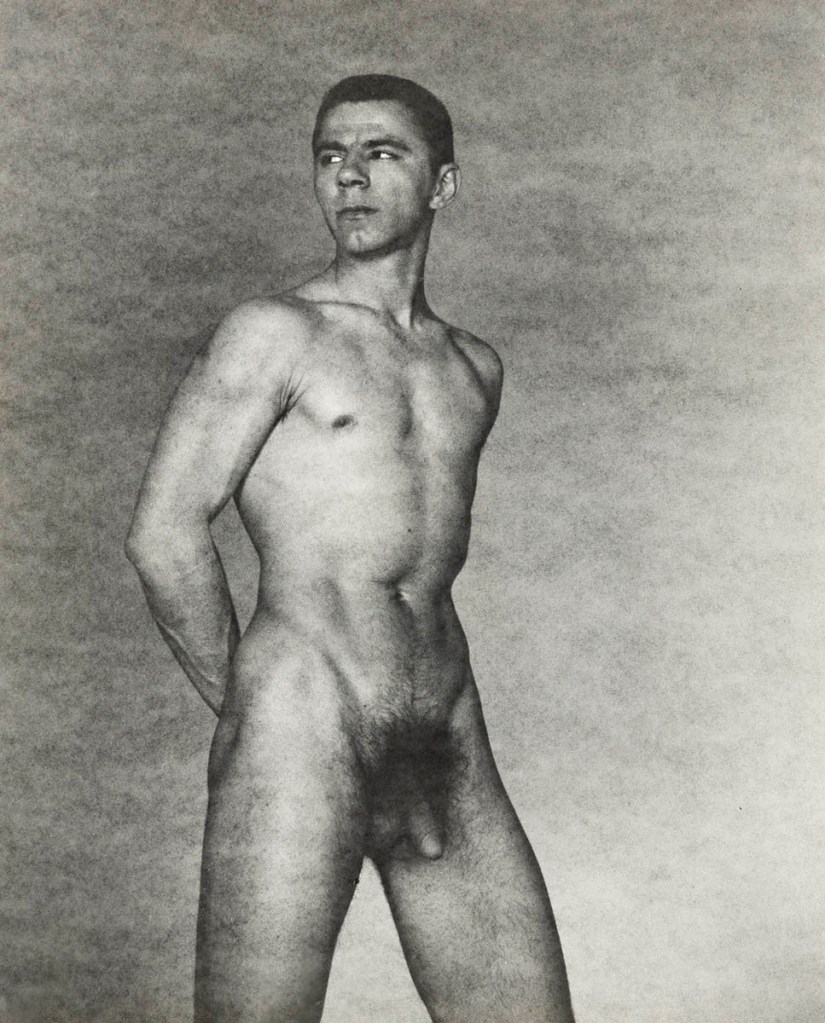

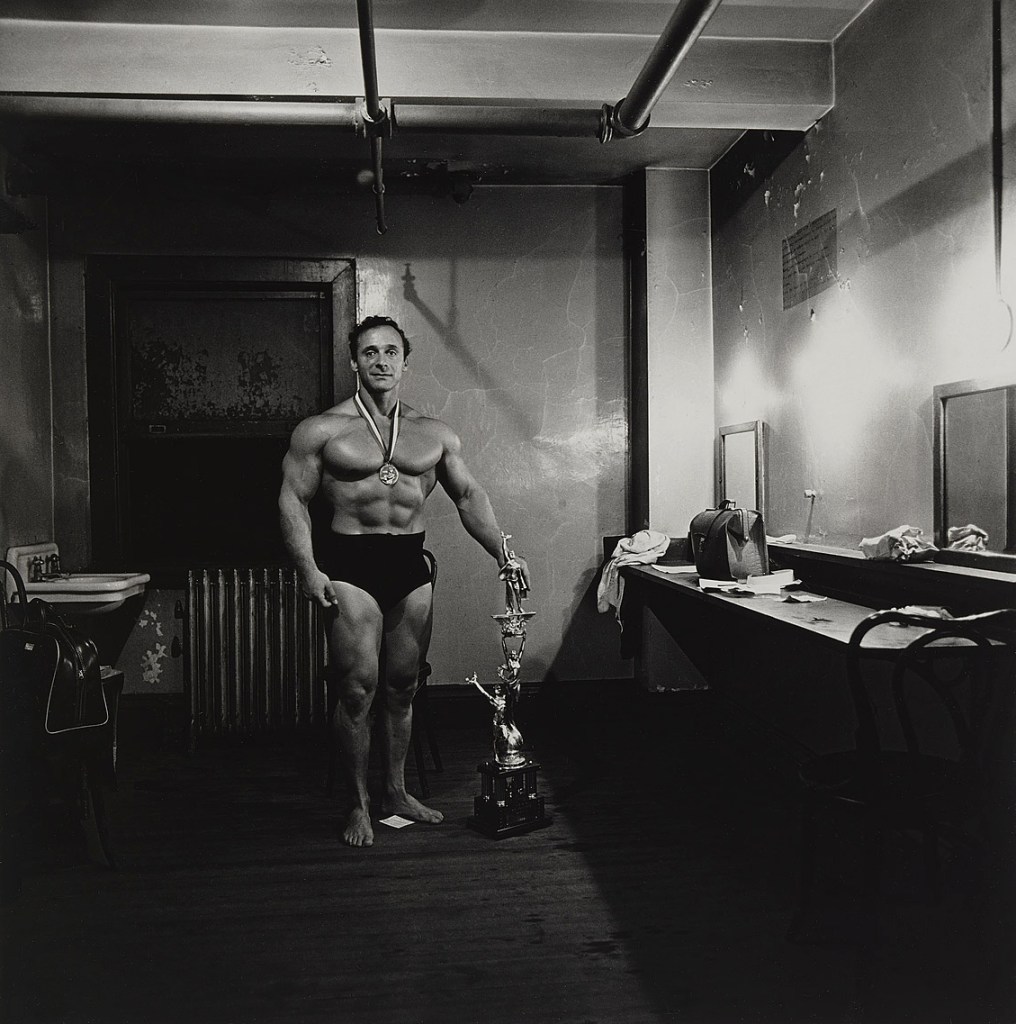

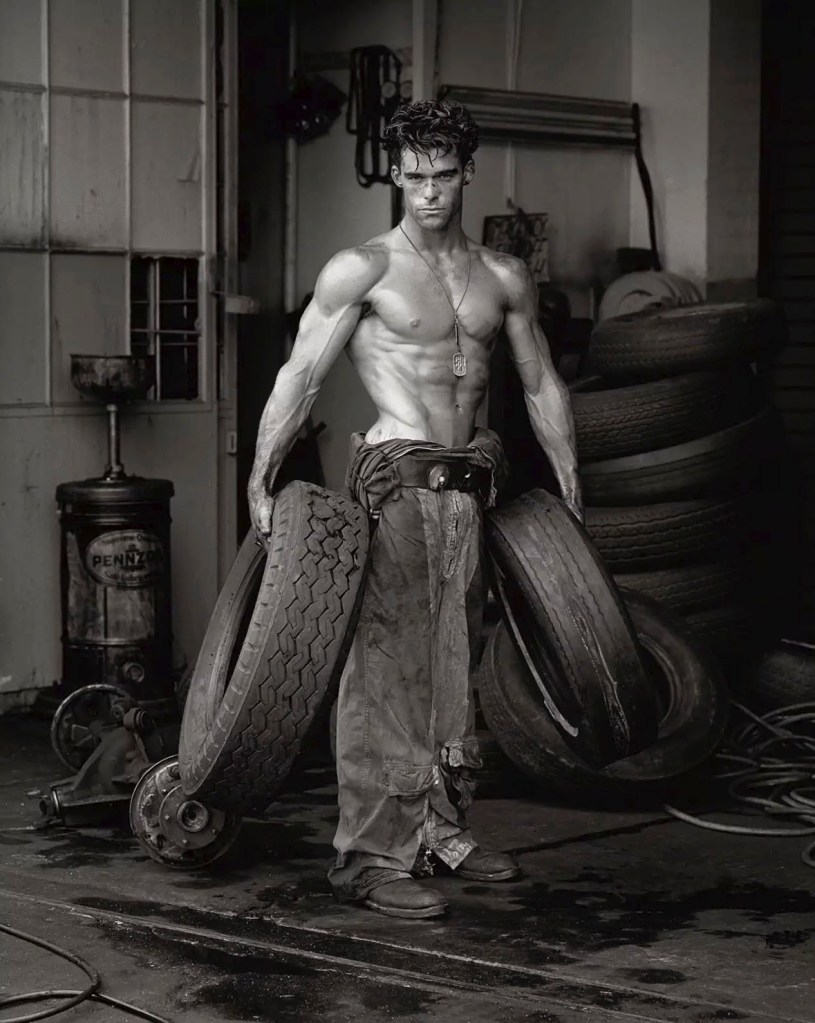

Dr. Katz anchors the exhibition section called Archetypes around an acknowledged masterpiece of American painting, Thomas Eakins’s Salutat,1898. The painting is shown in The First Homosexuals as an example of a scene engineered to focus attention on an erotic part of the young male body. Dr. Katz observes that the crowd appears to be not so much cheering a boxing victory as absorbing a perfect specimen of male beauty.

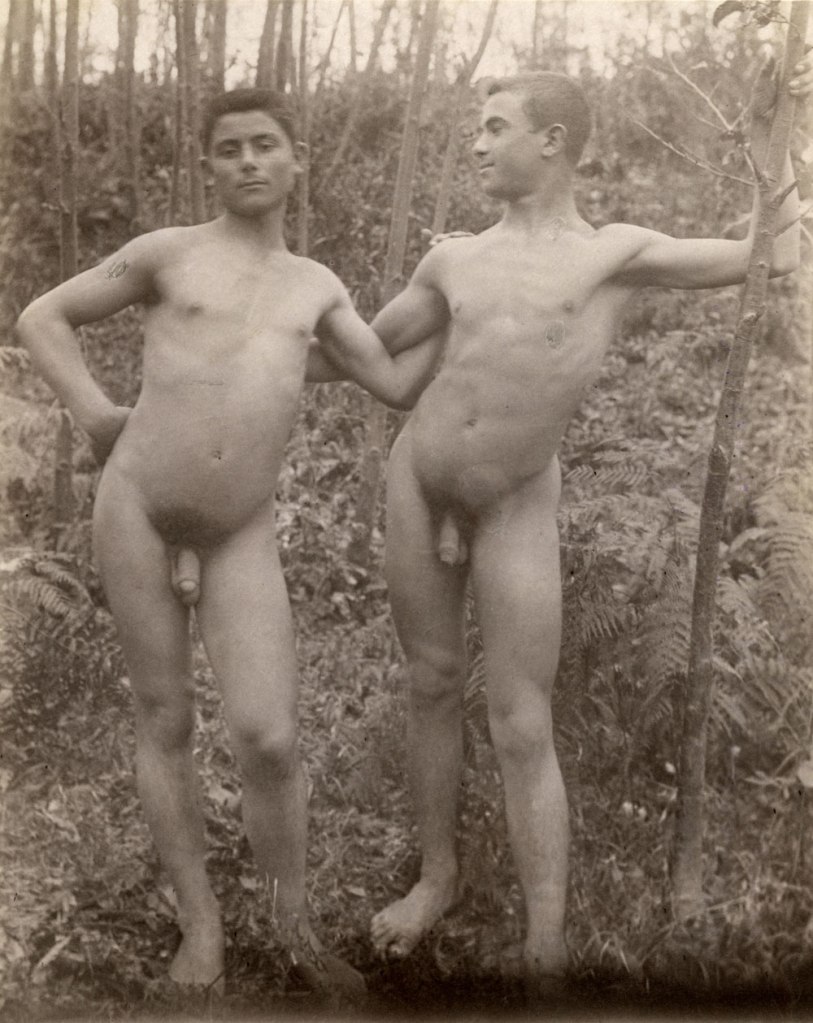

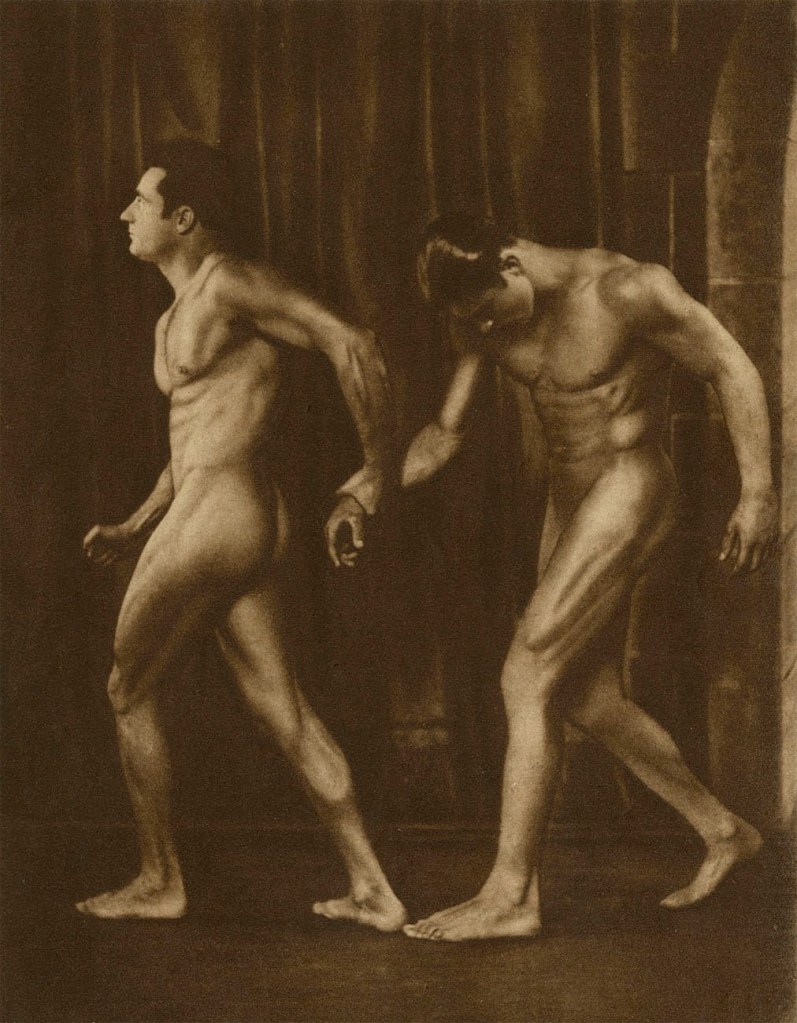

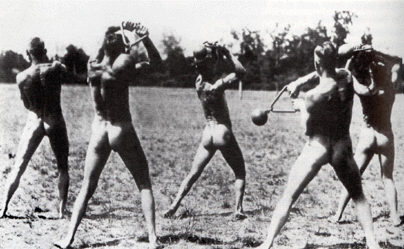

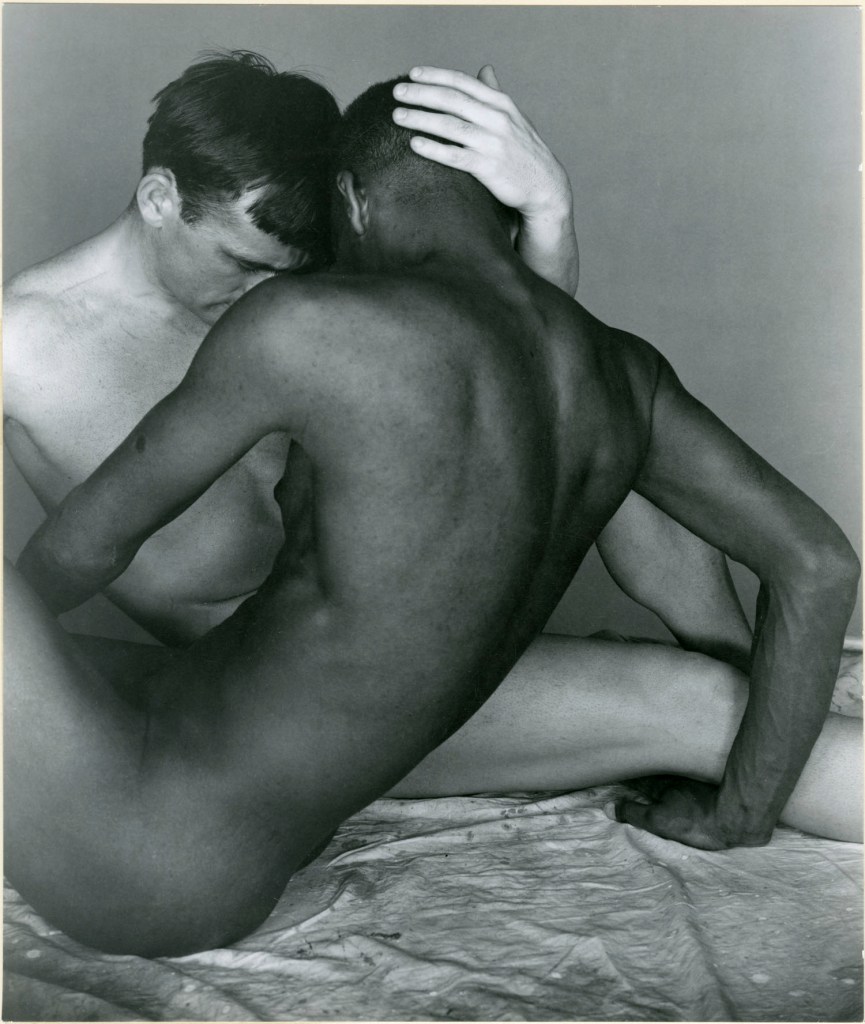

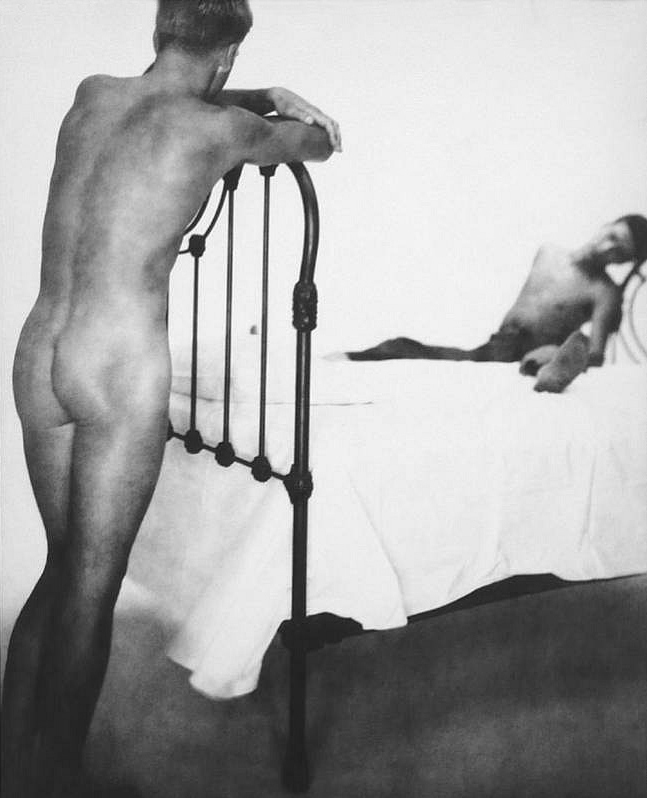

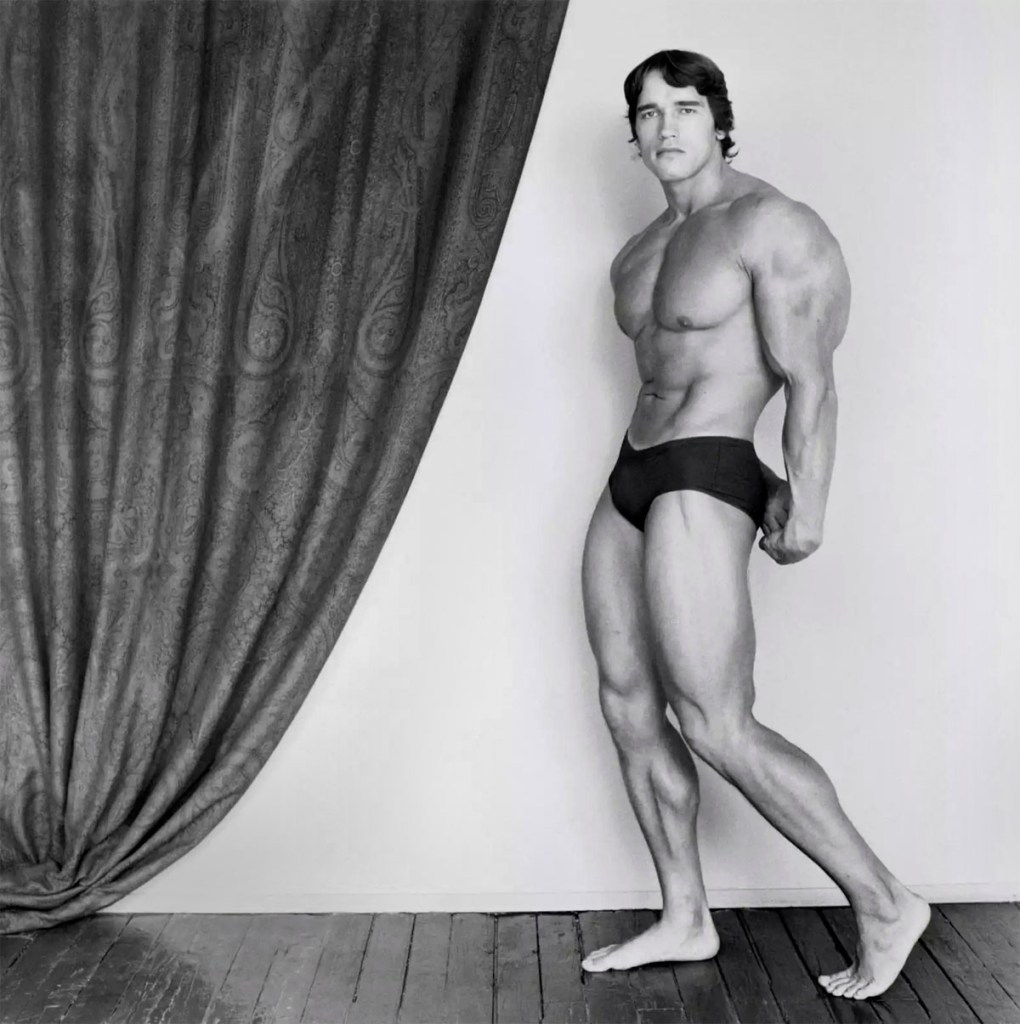

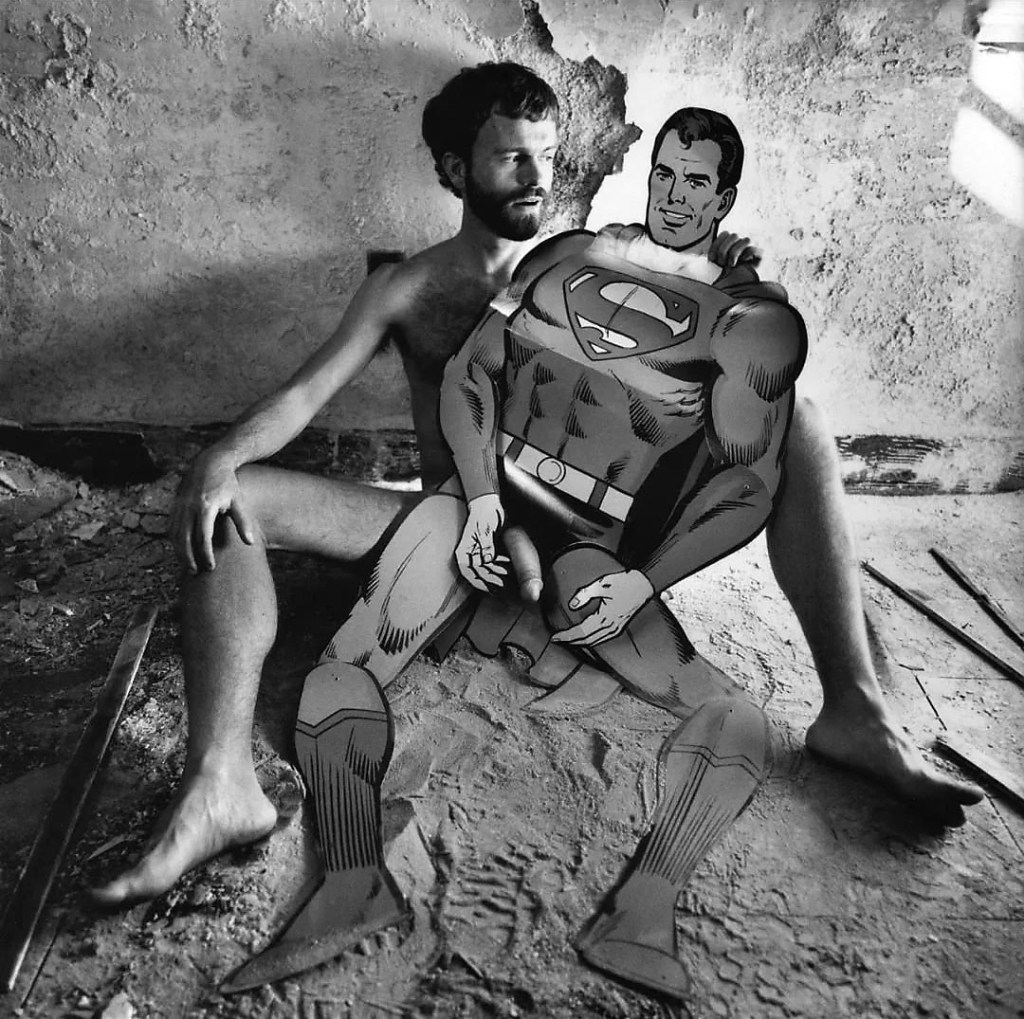

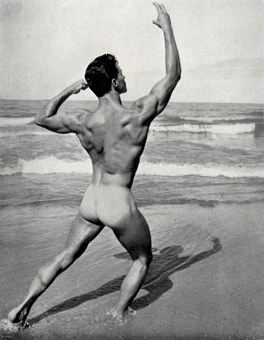

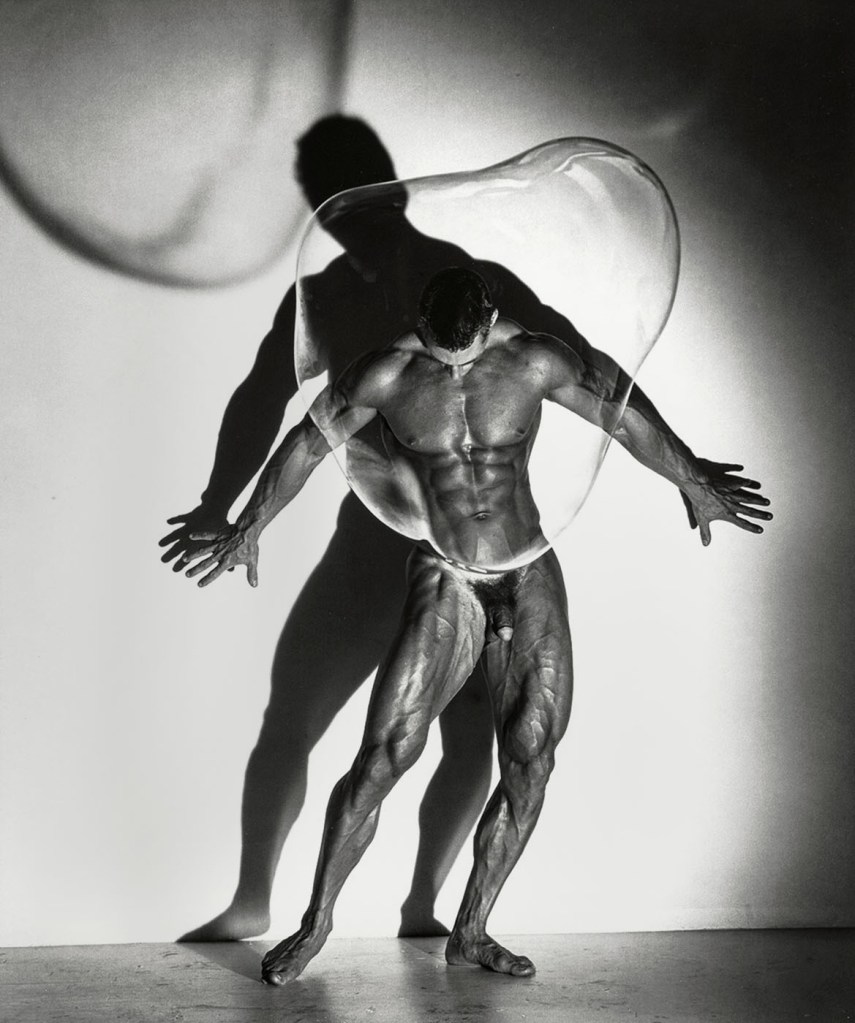

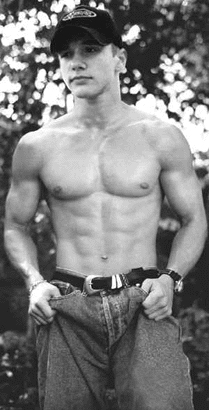

Throughout this section, the viewer can track the ideal of male beauty evolving beyond the 19th-century ephebic (youthful male beauty idealised in ancient times) to a more masculinised ideal of perfection. A defining work here is a study by Swedish artist Eugène Jansson for his most famous painting, The Naval Bath House, 1907. The custom of young men swimming nude in all-male settings was universal in the West – as seen elsewhere in The First Homosexuals. In this drawing, Jansson carefully employs Cezanne-like strokes to work out seven different poses for as many young men.

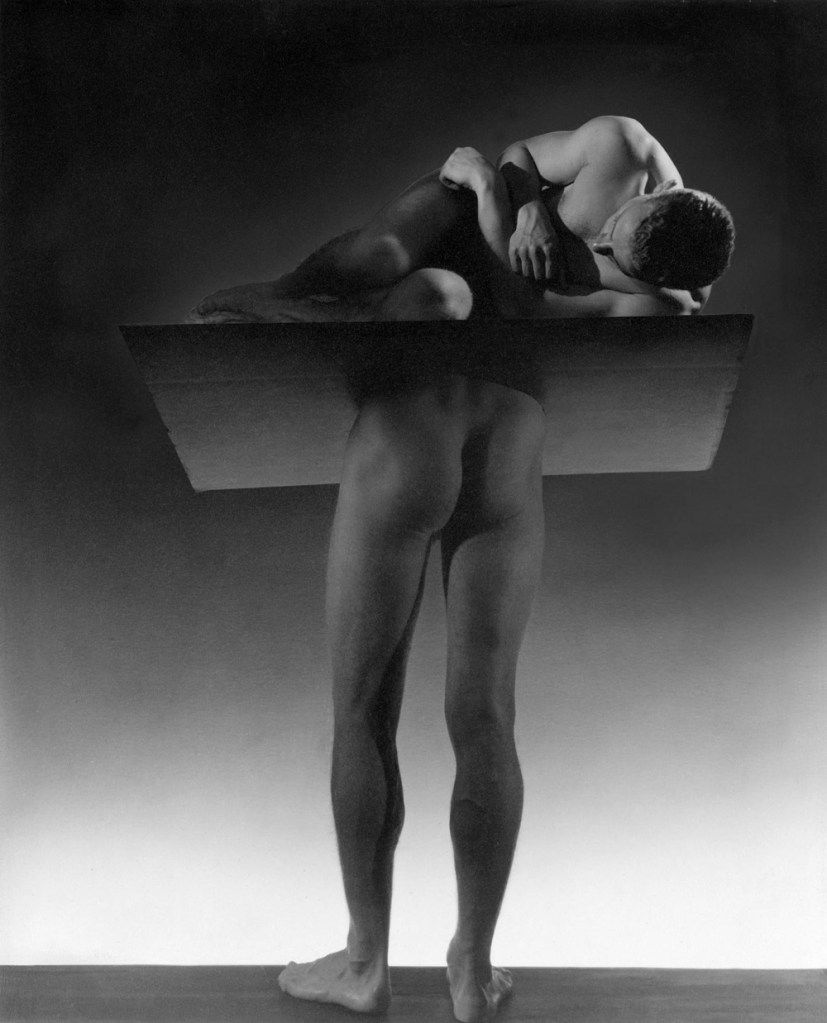

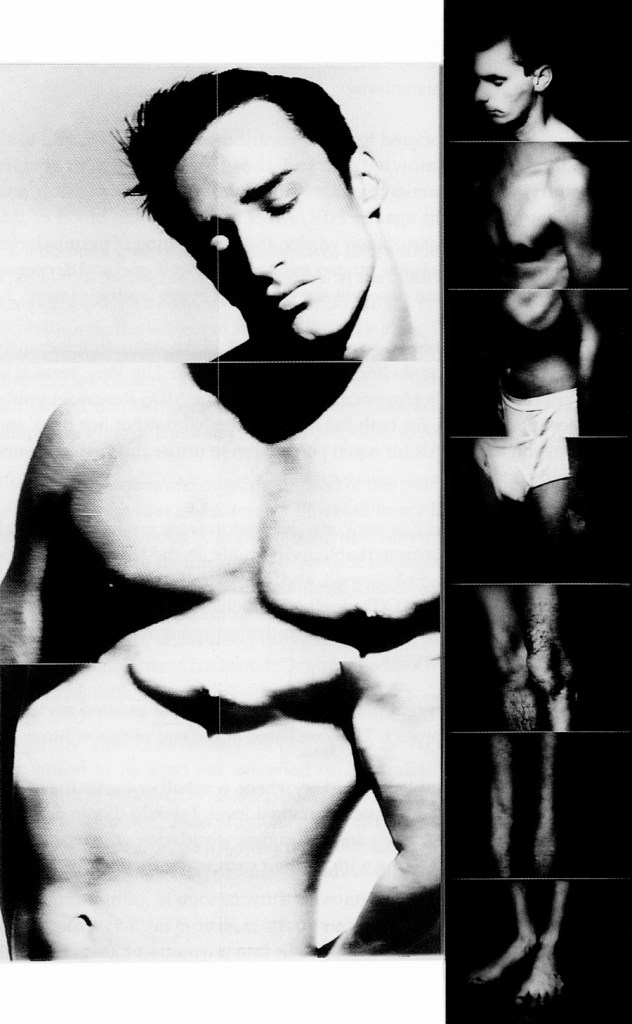

The section entitled Desire brings together works of art that are stylistically varied, according to the visual language of the artist’s national culture and training, but alike in depicting same-gender sex or magnifying parts of the body for erotic effect. These include erotica from China, Japan, Iran, and India and a pair of seemingly sedate figure drawings by the French artist Jane Poupelet focusing on the rear view of female models, so as to eroticise women in a way that works to exclude the heterosexual male gaze.

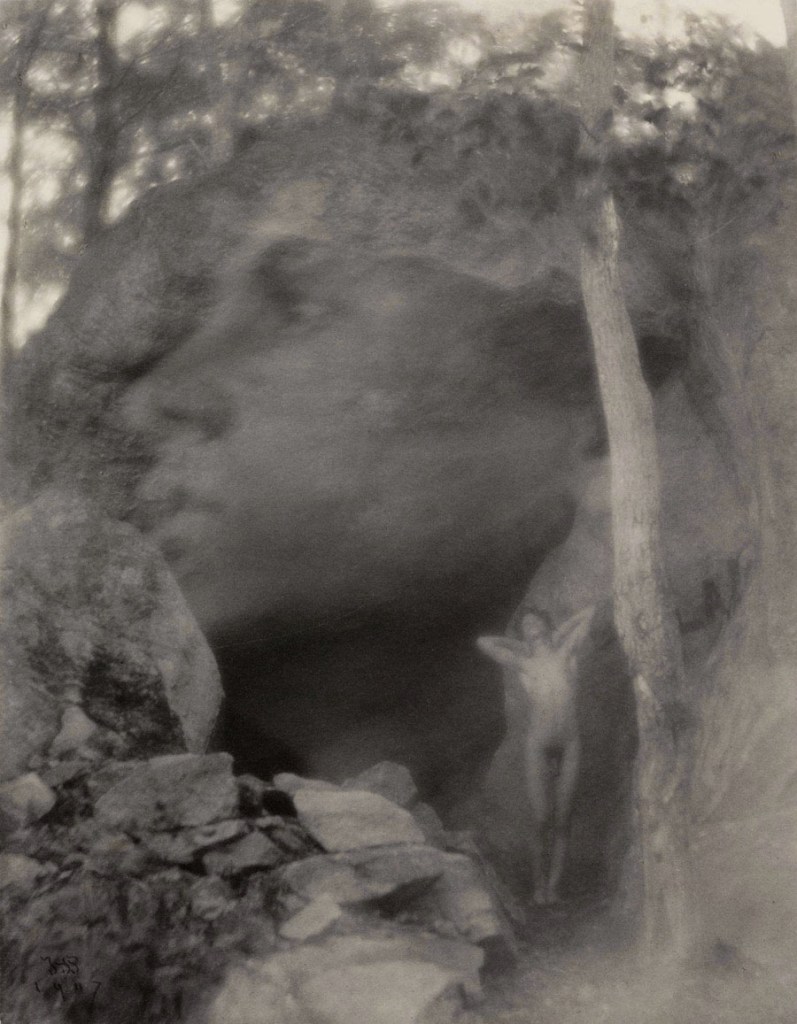

In the section entitled Colonizing, the art on view reflects a number of dynamics, including the Euro-centric definition of early homosexuality, which often clashed with more indigenous forms, and the Western presumption that the East was decadent. European interlopers employed the latter to excuse otherwise forbidden sexual alliances as well as to justify political domination. Here are works as disparate as the Sri Lankan painter David Paynter’s modernist oil, L’après midi, 1935; F. Holland Day’s haunting double exposure photograph, The Vision, (Orpheus Scene), 1907; and a propaganda piece dropped by Japanese nationals into Russian territory to demoralise Russian troops during the Russo-Japanese War.

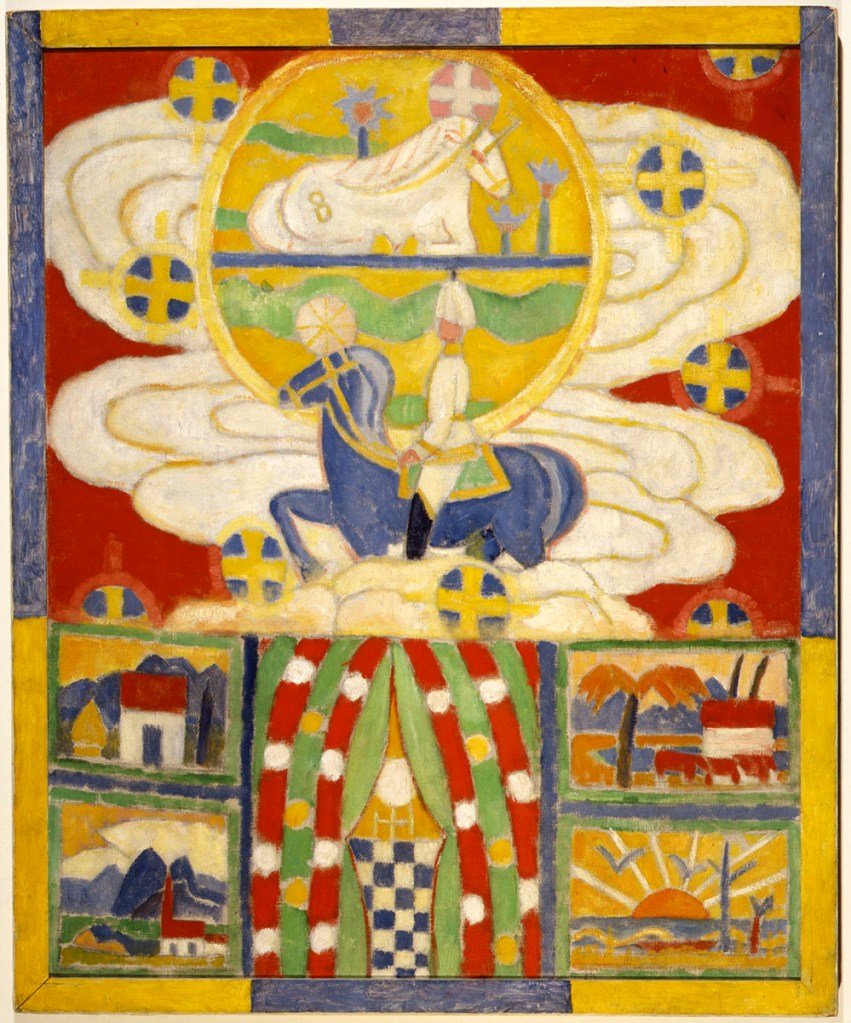

Following, in the section Public and Private, comes Charles Demuth’s ‘morning after’ scene of three young men in pyjamas and underwear in a stylish domestic interior; lesbian genre scenes set in Eastern Europe; and Marsden Hartley’s Berlin Ante War, 1914, a painting charting life, death, faith, sunrise, and sunset in symbolic forms and colours.

The centrepiece of the final thematic section, Past and Future, is a little-known masterpiece by the Finnish artist, Magnus Enckell, an impressionist-styled painting that reverses the classical myth of Leda and the swan, illustrating a nude man strangling the rapacious figure of Zeus in the form of a swan. Other works here evidence what is likely the earliest use of the rainbow as a symbol of same-sex love; photographs by Wilhelm von Gloeden that combine classical ruins and Sicilian youth; and the desire to acknowledge same-sex precedents in ancient history, as in the colour lithograph, Hadrian and Antinous, 1906, by Paul Avril (Édouard-Henri Avril).

The First Homosexuals documents The Elisarion, a temple to the arts built by the same-sex cultist and visionary Elisar von Kupffer in 1926 in Minusio, a tiny principality in Switzerland. Paintings of scenes illustrating same-sex desire once covered the walls of von Kupffer’s Sanctuarium. A cache of these were discovered recently in a municipal warehouse in Minusio by Dr. Katz and his team. This fall, the paintings will be seen for the first time in documentary photographs. In 2025, the actual large-scale paintings will be exhibited for the first time outside Switzerland in Part II of The First Homosexuals: Depictions of a New Identity, 1869-1930.

Press release from Wrightwood 659

![Marie Høeg (Norwegian, 1866-1949) 'Untitled [Marie Høeg and her brother in the studio]' c. 1895-1903 Marie Høeg (Norwegian, 1866-1949) 'Untitled [Marie Høeg and her brother in the studio]' c. 1895-1903](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/image-10_berghoeg-c.-1895-1903.jpg?w=657)

Berg & Høeg (Horten)

Bolette Berg (Norwegian, 1872-1944)

Marie Høeg (Norwegian, 1866-1949)

Untitled [Marie Høeg and her brother in the studio]

c. 1895-1903

Print, 2.4 x 3.1 in

Owner: Preus Museum Collection, Norway

Berg & Høeg (Horten)

Bolette Berg (Norwegian, 1872-1944)

Marie Høeg (Norwegian, 1866-1949)

Marie Høeg dressed as a man

1895-1903

Owner: Preus Museum Collection, Norway

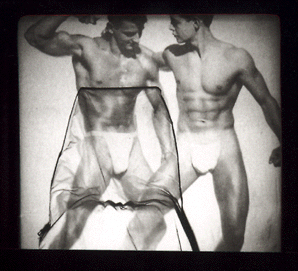

Eugène Jansson (Swedish, 1862-1915)

Bath house study

Nd

Black chalk on paper

33 1/2 x 39 inches

Eugène Fredrik Jansson (18 March 1862, Stockholm – 15 June 1915, Skara) was a Swedish painter known for his night-time land- and cityscapes dominated by shades of blue. Towards the end of his life, from about 1904, he mainly painted male nudes. The earlier of these phases has caused him to sometimes be referred to as blåmålaren, “the blue-painter”. …

After 1904, when he had already achieved success with his Stockholm views, Jansson confessed to a friend that he felt absolutely exhausted and had no more wish to continue with what he had done until then. He stopped participating in exhibitions for several years and went over to figure painting. To combat the health issues he had suffered from since childhood, he became a diligent swimmer and winter bather, often visiting the navy bathhouse, where he found the new subjects for his paintings. He painted groups of sunbathing sailors, and young muscular nude men lifting weights or doing other physical exercises.

Art historians and critics have long avoided the issue of any possible homoerotic tendencies in this later phase of his art, but later studies (see Brummer 1999) have established that Jansson was in all probability homosexual and appears to have had a relationship with at least one of his models. His brother, Adrian Jansson, who was himself homosexual and survived Eugène by many years, burnt all his letters and many other papers, possibly to avoid scandal (homosexuality was illegal in Sweden until 1944).

Text from the Wikipedia website

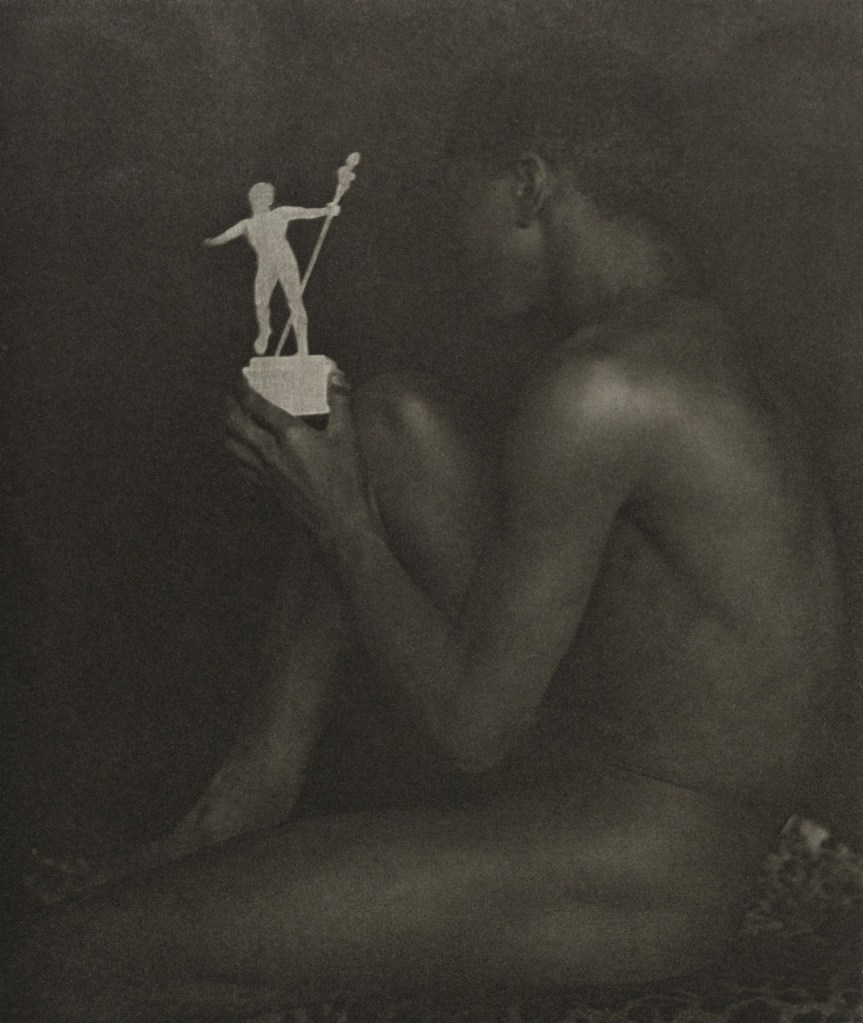

F. Holland Day (American, 1864-1933)

The Vision (Orpheus Scene)

1907

Platinum print

Florence Carlyle (Canadian, 1864-1923)

The Guest, Venice

1913

Oil on canvas

28.9 x 15 in

Woodstock Art Gallery, Woodstock, Ontario, gift of Lenora McCartney

Photo Credit: John Tamblyn

Florence Carlyle (1864-1923) was a Canadian painter born in Ontario. Carlyle studied painting in Paris beginning in 1890, where she exhibited work at Paris Salons while gaining recognition in Canada and the United States – achievements unusual for women of her time. After Carlyle returned to Canada in 1896, she continued to exhibit widely and contributed artworks to major exhibitions and museum collections. Influenced by the French Barbizon School, Impressionism, and the work of fellow female painters, Carlyle was known for intimate, domestic scenes of middle-class women’s lives.

In 1911, Carlyle traveled to Italy and England, where she met Judith Hastings, who would become her lifelong companion and model. In 1913, Carlyle and Hastings settled in Yew Tree Cottage in East Sussex. The Guest, Venice shows Hastings and Carlyle in conversation at sunset in a scene dominated by warm reds and yellows. The women’s poses and gestures seem to reflect each other – Hastings, seated, invitingly pulls on a long necklace while Carlyle leans comfortably on a windowsill, their complimentary poses suggesting an intimate relationship. The Threshold depicts Hastings as a bride. In place of a groom, Hastings stands across from an empty chair and a vase of flowers, this absence perhaps a subtle allusion to her relationship with Carlyle.

The First Homosexuals: Global Depictions of a New Identity, 1869-1930 is the first exhibition to display Carlyle’s artwork in the context of same-sex desire and relationships.

On view: Self Portrait, c. 1901, Oil on canvas; The Threshold, 1913, Oil on canvas; The Guest, Venice, 1913, Oil on canvas.

Florence Carlyle (Canadian, 1864-1923)

The Threshold

1913

Oil on canvas

117 x 96.5cm

![Claude Cahun (French, 1894-1954) 'Untitled [Self portrait in profile, sitting cross legged]' 1920 Claude Cahun (French, 1894-1954) 'Untitled [Self portrait in profile, sitting cross legged]' 1920](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/claude-cahun-self-portrait-in-profile-sitting-cross-legged-1920.jpg?w=797)

Claude Cahun (French, 1894-1954)

Untitled [Self portrait in profile, sitting cross legged]

1920

Gelatin silver print

Claude Cahun (1894-1954) was a French photographer and writer known for works created in collaboration with their artistic and life partner Marcel Moore (1892-1972), an illustrator for magazines and avant-garde dance and theatre productions. Both artists adopted androgynous names in the 1910s and lived together in Paris by the early 1920s. In Paris, Cahun made theatrical and surrealist self-portraits, often dressing in masculine clothing with a shaved head or short-cropped hair and in elaborate costume, makeup, or masks.

Although Cahun considered themself a surrealist, and their images and writings presaged the 1924 Surrealist Manifesto, they were not aways readily accepted by Surrealist circles who celebrated images of women but rejected female artists. Despite this, many surrealists held Cahun in high regard, including Andre Breton, who recognised Cahun as, “one of the most curious spirits of our time.” Cahun’s 1930 surrealist autobiographical text Aveux non avenus combines non-linear stories and ideas with photomontages and self-portraits. In this text, Cahun also draws connections between their gender-fluid self-portraiture and identity, declaring that “neuter is the only gender that invariably suits me.”

On view: Illustration for Vues et Visions, 1919, Exhibition print; Untitled [Self portrait in profile, sitting cross legged], 1920, Exhibition print.

![Anonymous photographer (France). 'Untitled [Two Black actors (Charles Gregory and Jack Brown), one in drag, dance together on stage]' c. 1903 Anonymous photographer (France). 'Untitled [Two Black actors (Charles Gregory and Jack Brown), one in drag, dance together on stage]' c. 1903](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/image-7_untitled-two-black-actors....jpg?w=673)

Anonymous photographer (France)

Untitled [Two Black actors (Charles Gregory and Jack Brown), one in drag, dance together on stage]

c. 1903

Print, 5.5 x 3.5 in

Wellcome Collection

Charles Gregory and Jack Brown were American performing artists credited with introducing the wildly popular Cake-Walk dance to Paris in 1902. The Cake-Walk, which often featured gaudy and ostentatious costumes worn by both men and women, began as a parody of the European “Grand March” performed by Black enslaved people on antebellum Southern plantations. Although the dance was originally performed by and for Black communities, the Cake-Walk became popular with white slaveholders as well, who incorporated the dance into minstrel shows where it would be performed in blackface.

In the late 19th century, the Cake Walk took off as a dance craze, in the United States and Europe. Around the same time, the dance was also adopted by the underground Black queer community. William Dorsey Swann, the first self-proclaimed “queen of drag”, held the first drag balls in Washington, D.C., which featured Cake-Walk dances performed by men in women’s clothing. Drag balls went on to become a mainstay of Black queer and trans expression, becoming popular during the Harlem Renaissance and later in Chicago, Detroit, New Orleans, Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, and San Francisco. This film of Jack Brown and Charles Gregory is the first extant drag film, produced by those famed early innovators in cinema, the Lumière Brothers.

On view: Unknown artist, Le cake-walk. Dansé au Nouveau Cirque. Les nègres [Two black actors, Charles Gregory and Jack Brown, one in drag, dancing the Cake-Walk in Paris], 1903, Exhibition print; Untitled [Two black actors (Charles Gregory and Jack Brown), one in drag, dance together on stage], c. 1903, Exhibition print; Auguste and Louis Lumière, Nègres, [I], c. 1902-1903, Digital reproduction of film.

Gerda Wegener (Danish, 1885-1940)

Venus and Amor

Nd

Oil on canvas

81 by 116cm (31 3/4 by 45 3/4in.)

Gerda Wegener (Danish, 1885-1940)

Reclining Nude (Lili Elbe)

1929

Watercolour on paper