Exhibition dates: 15th July – 31st October 2022

Curators: The exhibition is curated by artist, author and curator Boaz Levin and Dr. Esther Ruelfs, Head of the Photography and New Media Collection at MK&G.

Artists: Ignacio Acosta, Lisa Barnard, F& D Cartier, Optics Division of the Metabolic Studio (Lauren Bon, Tristan Duke und Richard Nielsen), Susanne Kriemann, Mary Mattingly, Daphné Nan Le Sergent, Lisa Rave, Alison Rossiter, Robert Smithson, Simon Starling, Anaïs Tondeur, James Welling, Noa Yafe, Tobias Zielony

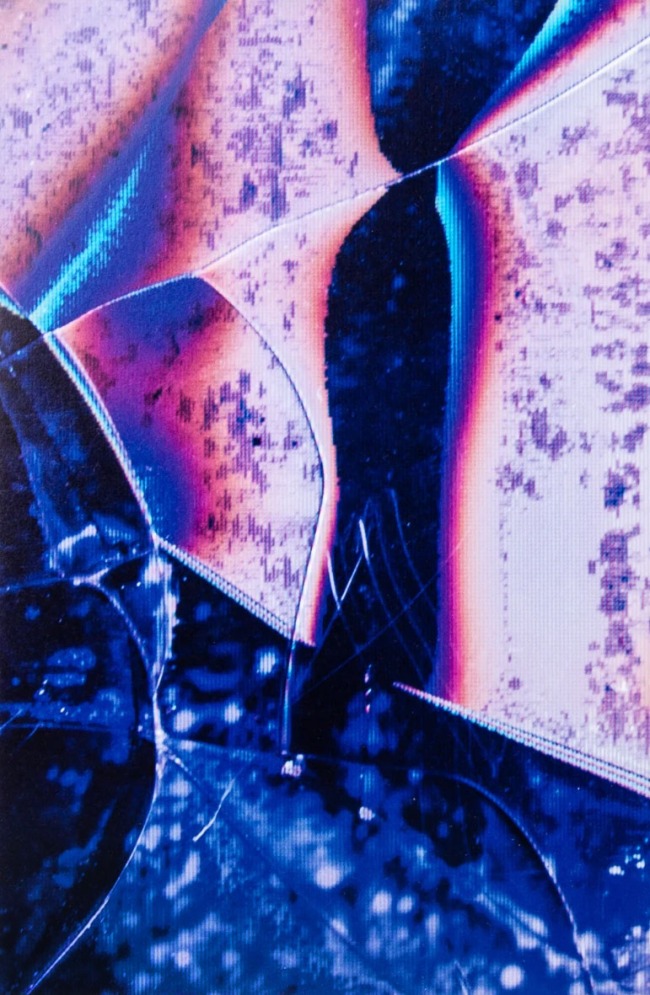

Mary Mattingly (American, b. 1979)

Mineral Seep

2016

C-print

© Mary Mattingly

A worthy subject I had never really thought about. Kudos to the curators for digging into (pardon the pun) and conceptualising the “five chapters following the different materials used for photographic production: Copper for the daguerreotypes, fossil fuels and their derivatives such as coal and bitumen for the printing processes, silver for the widely used silver gelatin prints of the 20th century, Paper as a carrier material, and, today, rare earths and metals for our ever-shrinking cameras and smartphones, and the energy required for the so-called “cloud”.”

Something has to change very quickly because almost everything the human race produces seems to add to the burden of this earth. Consumerism, capitalism, money, power, greed. I despair of the human race saving the earth. We might end up with ‘being’ only to be confronted by ‘nothingness’.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Museum fur Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Installation view of the exhibition Mining Photography. The Ecological Footprint of Image Production at the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg showing at left, work from Anaïs Tondeur’s series Carbon Black

Installation view of the exhibition Mining Photography. The Ecological Footprint of Image Production at the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg showing on the table the work of Ignacio Acosta; and at far right, a contemporary enlargement of G.H. Johnson’s Outdoor view of a large mining operation on the North Fork American River 1852 Daguerreotype enhanced with gold

The exhibition Mining Photography: The Ecological Footprint of Image Production is dedicated to the material history of key resources used for image production, addressing the social and political context of their extraction and waste and its relation to climate change. Using historical photographs and contemporary artistic positions as well as interviews with restorers, geologists, and climate researchers, the exhibition tells the story of photography as one of industrial production, showing the extent to which the medium has been deeply intertwined with human change of the environment. By focusing on the ways by which industrial image production has been materially and ideologically implicated in climate change, rather merely using it to depict its consequences, the exhibition employs a radically new perspective towards this subject.

Ever since its invention, photography has depended on the global extraction and exploitation of so-called natural resources. In the early 19th century, these were salt, fossil fuels such as bitumen and carbon, as well as copper and silver, which were all used for the first images on copper plates and for salt paper prints. By the late 20th century, the photographic industry was one of the most important consumers of silver, responsible, at its peak, for about a quarter of the metal’s global consumption. Today, with the advent of digital photography and the ubiquity of mobile devices, image production is contingent on rare earths and metals such as coltan, cobalt, and europium. Image storage and distribution also consume immense amounts of energy. One scholar recently observed that Americans produce more photographs every two minutes than were made in the entire nineteenth century. Mining Photography: The Ecological Footprint of Image Production is dedicated to the material history of key resources used for image production, addressing the social and political context of their extraction and waste and its relation to climate change. Using historical photographs and contemporary artistic positions as well as interviews with restorers, geologists, and climate researchers, the exhibition tells the story of photography as one of industrial production, showing the extent to which the medium has been deeply intertwined with human change of the environment. By focusing on the ways by which industrial image production has been materially and ideologically implicated in climate change, rather merely using it to depict its consequences, the exhibition employs a radically new perspective towards this subject.

The exhibition is divided into five chapters following the different materials used for photographic production: Copper for the daguerreotypes, fossil fuels and their derivatives such as coal and bitumen for the printing processes, silver for the widely used silver gelatin prints of the 20th century, Paper as a carrier material, and, today, rare earths and metals for our ever-shrinking cameras and smartphones, and the energy required for the so-called “cloud”.

Interviews with conservators, climate scientists, and geologists highlight various aspects of the production process in relation to its ecological footprint. The exhibition thus consists of historical materials used during different image production techniques, historical artefacts, contemporary works, as well as information conveyed by the interviews.

“Mining Photography” traces exemplary individual supply chains, and analyses how photography’s materiality – which remains invisible to naked eye – has changed over the years. For instance, it will ask where the copper and silver used for Hermann Biow’s daguerreotype of the polymath, explorer and mining officer Alexander von Humboldt came from?

The “Copper, Gold, and the Daguerreotype” section looks at the copperplates that were photography’s first image supports in the 1840s and 1850s. The plates were produced on an industrial scale, primarily in Paris, and sold around the world. Copper was refined in Wales, in the area of Swansea, powered by the burgeoning fossil fuel industry. Ores were shipped to England from all over the world and smelted there to be traded worldwide. Photography was dependent on the copper trade, and the rapid proliferation of the medium would have been inconceivable without fossil fuels, colonial expansion, and the exploitative extraction of minerals.

The photographs from the time of the gold rush give a clear indication of the impact of the extractive mining industry, providing a documentary record of both the destruction of the landscape and the self-enactment of the gold miners, who proudly present themselves to the camera as entrepreneurs. Their female counterparts, the “Pit Brow Women” from Wigan represent the invisible labor that accompanies an industrialised product like photography. Specially created for the exhibition, Ignacio Acosta’s Hygieia Watches Over Us links the copper sculpture depicting the personification of health and hygiene with the copper-producing company Aurubis in Hamburg. It is part of the artist’s “Copper Geographies” project (ongoing since 2010), which traces the international trade routes followed by copper originating from his native Chile.

In “Fossil Fuels, Coal, and Bitumen”, we focus on the use of soot or coal as a pigment that is mixed in with photographic dyes, as can be seen, for example, in works by Anaïs Tondeur, Oscar and Theodor Hofmeister, Eduard Arning, and Susanne Kriemann. The motifs that are shown present us with moor landscapes in which coal is mined. An authentic “material unconscious” is laid down here as picture content in the photographs. Another fossil fuel is light-sensitive bitumen, a naturally occurring asphalt that was used in photographic production. For the exhibition, Noa Yafe created a work that shows the Dead Sea landscapes in which this raw material naturally occurs.

“Paper and Its Coating” focuses on the materials cotton, cellulose, gelatin, and celluloid. Europe was the centre of paper production in the 19th century, with cotton or flax rags initially used to make it. In the period around 1860, cotton was planted and harvested in the southern states of the US using slave labor. It was then shipped to Europe, where it was processed into fabrics, which served, in the form of rags, as the basis for most of the paper that was produced. It was not until the 20th century that cellulose derived from wood was first used in paper production. The photographers Alison Rossiter and F&D Cartier explore the different materiality of historical photographic papers in “discovered” images with an abstract poetic quality. Animal products were a vital ingredient used for coating the papers. In the 19th century, it was eggs, followed in the 20th century by gelatin, most of which was obtained from the bones of cows. In their pictures, which centre in different ways on the materials used in photographic coating, Madame d’Ora and James Welling document and reflect upon the brutal reality of industrialised meat production. Another work, especially created for the exhibition by Tobias Zielony and based on research he conducted at the former Agfa Filmfabrik Wolfen, focuses on the aspects of labor and ecology in the photographic industry.

The precious metal silver forms the basis of the photographic image, which still relies on it today. Of all the raw materials dealt with in the exhibition, silver is absolutely key to the global photographic industry, which, at least for now, is at present its largest consumer. It is here that we get the clearest indication of the sheer quantity of material that is required. The works of Daphné Nan Le Sergent, Simon Starling, and Metabolic Studio’s Optics Division allude to the connections between silver mining’s colonial background, the extraction of the raw material, and the process of refining it. Sergent also shows how the metals’ market value has been a the influence of the market value of metals, a driving force behind photographic technical innovations, which it has made that has made them more lucrative. Rather than being brilliant individual success stories, inventions are only possible and fruitful at a particular time and under particular conditions: witness the work of Hercule Florence, whose parallel development of a photographic process in South America remained unknown.

Lastly, “The Weight of the Cloud: Rare Earths, Metals, Energy, and Waste” looks at the resources that are needed to produce, display, and store digital images. Mining rare earths requires considerable amounts of energy: together with the “conflict minerals”, they are built into our smartphones and data storage devices used in the distribution of images. The rare earths ultimately end up in the burgeoning mountains of e-waste in the Global South, which are constantly growing to keep pace with our hunger for new devices. Lisa Barnard’s research-based work The Canary and the Hammer looks at the aspect of recycling with a focus on the precious metal gold. Mary Mattingly tracks cobalt’s complex and often opaque supply chains, mapping their course and constantly updating her rendering of them in response to market events. Lisa Rave’s video essay centres on the rare-earth metal europium. The app developed by Christoph Knoth and Konrad Renner together with their students at the University of Fine Arts Hamburg (HFBK) allows visitors to look at their phones in terms of their durability and recyclability, enabling them to probe into their own energy consumption.

Historical Material and Loans

The exhibition shows historical works by Eduard Christian Arning, Hermann Biow and Oscar and Theodor Hofmeister, Jürgen Friedrich Mahrt and Hermann Reichling. Together with historical photographic material from the Agfa Fotohistorama Leverkusen, photographic material from the Eastman Kodak Archive, Rochester, the FOMU Antwerpen and mineral samples collected by Alexander von Humboldt from the collection of the Museum für Naturkunde, Berlin, they represent the wealth of photographic products and processes whose raw materials the exhibition focuses on.

The exhibition is curated by artist, author and curator Boaz Levin and Dr. Esther Ruelfs, Head of the Photography and New Media Collection at MK&G.

Catalogue

The exhibition will be accompanied by a publication (German/English) with contributions by Siobhan Angus, Nadia Bozak, Boaz Levin, Brett Neilson, Esther Ruelfs, Christoph Ribbat, Karen Soli, 174 pages, Spector Verlag, Leipzig

Press release from the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg

Tobias Zielony (German, b. 1973)

Dunkelraum (Darkroom)

2022

Slide installation

© Tobias Zielony

Ever since its invention, photography has depended on the global extraction and exploitation of so called natural resources. In the early 19th century, these were salt, fossil fuels such as bitumen and carbon, and copper and silver, which were all used for the first images on copper plates and for salt paper prints. By the late 20th century, the photographic industry was one of the most important consumers of silver, responsible, at its peak, for over half of the metal’s global consumption. Today, with the advent of digital photography and the ubiquity of mobile devices, image production is contingent on rare earths and metals such as coltan, cobalt, and europium. The storage and distribution of images also generate immense amounts of CO2.

The exhibition is dedicated to the material history of the key resources used for photography. It traces the social and political context of their extraction and disposal and how this relates to climate change. Using historical photographs and contemporary artistic positions as well as interviews with a chemist, an activist, a restorer, a mineralogist, and a biologist, the exhibition tells the story of photography as one of industrial production, showing the extent to which the medium is implicated in climate change.

Copper and the Daguerreotype

In 1802, Alexander von Humboldt collected mineral samples containing copper and silver on his research trip through South and Central America. A good forty years later, the use of such materials made it possible for Humboldt to be photographed. Silver-coated copper plates were the first image supports to enjoy widespread usage in photography. The silver layer of these daguerreotypes, made light sensitive by iodine, was applied to a base of copper, which resulted in plates that were both more robust and less expensive. In 1839, when the daguerreotype was invented, such silver-coated copper sheets, produced using the so-called Sheffield Plate technique, were an inexpensive material employed for a whole range of silver household items, from trays to candlesticks. In Paris alone, the production of daguerreotypes required 100 tons of copper a year, producing in 1851 almost a million whole plates. Photography thus benefited decisively from the upswing in copper processing.

Beginning in the early 18th century in Swansea, Wales, coal was used to smelt copper ore on an industrial scale far away from the site where it was found. By the 1840s, ores from Cuba, Mexico, Colombia, Chile, Peru, Australia, and New Zealand were being processed in Swansea smelting works, which now produced more than a third of the copper that was traded worldwide – not without consequences for people and the environment. A look at Swansea reveals that photography’s global success would have been inconceivable without the use of fossil fuels, colonial expansion, and the world-wide extraction of metal deposits.

Hermann Biow and Alexander von Humboldt

Photographic pioneer Hermann Biow’s clear, unfussy visual language quickly made him a sought-after portraitist in prominent circles. In 1850, his Deutsche Zeitgenossen (German Contemporaries) portfolio was published with copperplate engravings from his photographs of artists, scientists, and politicians. In 1847, Biow had also photographed the famous naturalist Alexander von Humboldt in Berlin for the project. Humboldt, whose goal it was to depict the entire physical world in one work, was employed as a mining official for the Prussian authorities before setting out in 1799 on his first major research trip through South, Central, and North America. He brought back from there samples of the metals that would be the key elements in Biow’s daguerreotypes half a century later. The silver- and copper-bearing minerals that he collected give a sense of how these raw materials occur in nature and how, after the complex processing steps, their materiality is ultimately concealed by the finished photograph. Humboldt also recorded the way these precious metals circulated between the continents – a requirement for the industrial-scale production of daguerreotype plates – in a map in his Geographical and Physical Atlas of the Kingdom of New Spain, published in 1811. There is still some dispute, however, as to whether Humboldt was the first to warn of the dangers of anthropogenic climate change when, in 1843, he raised the question in his publication Central-Asien of the extent to which humans were influencing the climate “by felling the forests, altering the arrangement of bodies of water, and developing large masses of steam and gas at the epicenters of industry.”

Hermann Biow (b. 1804 in Breslau, d. 1850 in Dresden) was a portrait painter and lithographer and an important pioneer of photography in Germany. His documentation of the devastation of Hamburg after the fire of 1842 was the first photo reportage in history. The natural scientist Alexander von Humboldt (b. 1769 in Berlin, d. 1859 in Berlin) was an early fan of photography and saw it as “one of the most delightful and wondrous discoveries” of his time, even if he never operated a camera himself.

Daguerreotypes of the Californian Gold Rush

When, in 1848, it became known that gold had been discovered in the bed of the American River, people headed west to California in their hundreds of thousands to seek their fortune, together with traders, merchants, and photographers. Every gold prospector was also a potential customer wanting to send home a photo after a successful dig. The gold rush led to a boom in early photography and became the first event in US history to be comprehensively documented in photographs. Many daguerreotypists travelled straight to the mines as itinerant photographers. They portrayed gold diggers in threadbare clothing with tools and weapons, thereby presenting the Californian adventurers as the antithesis of the sophisticated denizens of the big cities. At the same time, they recorded the ongoing evolution of the techniques used in gold prospecting. The prospectors started out manually washing the precious metal from the river sediment using pans. But in the 1850s companies began extracting gold on an industrial scale. Watercourses were diverted so that gold could be retrieved from the drained riverbeds; “hydraulic” mining applied high pressure jets of water to detach gold-bearing sediments from hillsides and cliffs; and explosives and heavy equipment were used to dig veins of gold from underground. The gold rush daguerreotypes are thus the first documentation too of environmentally destructive mining practices. Here, it is easy to miss the fact that the images also record the mining of a material that was necessary for their own production: gold chloride had been in constant use as a fixative for daguerreotypes since 1841. Mercury represents another link between mining and photography. While photographers’ use of it as a developing agent jeopardised their own health primarily, its accessory role in gold washing caused the contamination of entire rivers in the area around the mines.

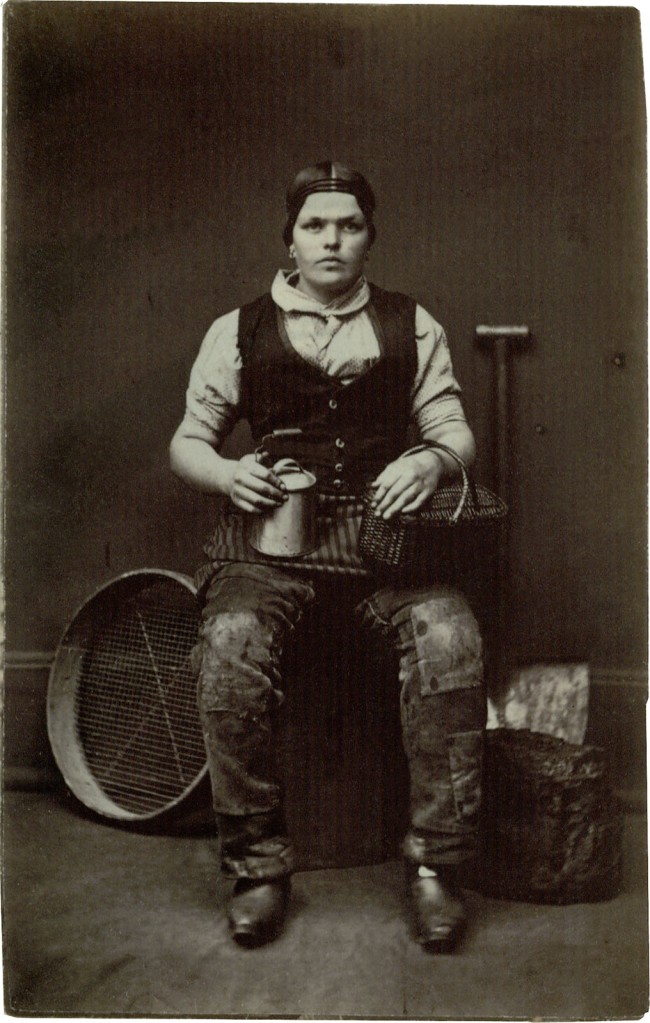

Cartes de visite of pit brow women

The photographs show the women who, from the early 17th century on, worked unseen in Britain’s coal mines, first below ground, and later, following the passage of the Mines and Collieries Act (1842), carrying out the lower-paid jobs on the surface. As mine workers, they moved lumps of coal with shovels and carts and separated them from the gangue using large sieve pans. Their work was a major economic contributor to Britain’s industrial success. Coal was a key element underpinning many production sectors, and it was crucial for the processing of copper, which was used in manufacturing daguerreotype plates. The British poet Arthur J. Munby collected photographs of working-class women, which catered to his interest in sociology. He bought photographs of women workers distributed as cartes de visite and also had studio photographs taken that depicted the women in their work clothes and pit gear. Unlike the Californian prospectors, who presented themselves in daguerreotypes as gold rush entrepreneurs and adventurers, the women seen in these images had little in common with the classical notions of the Victorian era. The view they showed of women in dirty work clothes (including trousers) turned the pictures into collectible motifs. We see the women sitting with legs apart and hands on hips – self-reliant poses with strong male connotations – photographed in a studio setting, where the furnishings were at odds with their class affinities.

Ignacio Acosta

Created for the exhibition, Ignacio Acosta’s multimedia installation centres on forty photographs arranged in a four-row grid structure. They combine three motifs linked together in a visually associative network, straddling copper production and water consumption. In the topmost rank, we see a smokestack belonging to the Hamburg copper producer Aurubis AG rising aloft, paralleled by the sculpture of Hygieia, which is mounted on a fountain with her back turned on Hamburg’s city hall, looking towards the Chamber of Commerce. Acosta makes a connection between the resource-intensive and, above all, water intensive industry – a major source of pollution for the Elbe River – and the politically charged sculpture commemorating the dreadful cholera epidemic of 1892, which was caused by contaminated water. In the rows below, close-up views of the fountain are interlaced with stained rubber suits worn by Aurubis AG’s workers to protect themselves from sulfuric acid. Visual and material analogies arise, linking the copper parts of the bronze sculpture, which have been oxidised to a green patina, with the tokens of “dirty” work in the copper plant – a thematic examination of the relationships between industry, politics, and society in terms of water and resource consumption. Acosta delves deeper into these themes in a video interview with Klaus Baumgardt from the Hamburg-based environmental protection initiative “Save the Elbe.” This new installation thus expands on his work Copper Geographies, an investigation into the global mobility of mined copper that he began in 2010.

Text from the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg

John Cooper (British)

Woman miner

1860s

Carte de visite Trinity College Library, Cambridge

Installation view of the exhibition Mining Photography. The Ecological Footprint of Image Production at the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg showing the work of Ignacio Acosta

Ignacio Acosta (Chilean, b. 1971)

Computer Aid

2015

© Ignacio Acosta

Ignacio Acosta (Chilean, b. 1971)

Hygieia Watches Over Us (detail)

2022

Installation comprising 40 pigment prints and video

© Ignacio Acosta

Coal and Bitumen: Fossil Fuels and Moorland

The majority of photographic processes popular around 1900, such as pigment printing, rubber printing, and heliogravure, did not require silver. In pigment or carbon printing, charcoal powder or lampblack, which consists of nearly pure carbon, replaces the silver grains. The heliogravure technique uses plates coated with bitumen and pigments, which lend the images their colour. This section of the exhibition deals with different perceptions of the landscapes in which the raw materials were found and extracted: peat bogs and moors in northern Germany, bitumen in the area around the Dead Sea in Jordan.

The pictures produced by Reichling and Mahrt – natural scientist and farmer, respectively – document the transformation of the moors and the shift from peasant labour to turf cutting and industrialised peat extraction. At the turn of the 20th century, when the work of draining, reclaiming, and burning the moorland began on a large scale, the landscape, which had been transformed by human intervention, was also consciously aestheticised and presented as an artistic ideal.

The raw materials used to produce these images originated in the moors too. The coal dust used as a pigment is created from dead trees, enriched with solar energy, that over the course of millennia have been pressed first into peat and then into coal. The photographs by Louis Vignes, and Charles Nègre’s prints of these images, depict the landscape of the Dead Sea, an area where bitumen, a form of petroleum, occurs naturally. Nègre used this material to coat the plates for their production of Vignes’s photos. This knowledge makes evident the connection between the motif, the landscape from which the raw material is extracted, and bitumen. Although invisible at first, this material relation inscribes in the image a kind of second, unconscious history.

Theodor and Oscar Hofmeister

The Hofmeister brothers present the moorlands around Hamburg as an area imbued with longing. The white blooms of the cottongrass accentuate the charming, painterly qualities of the idealised landscape, which is rendered in vertical format in the style of Japanese woodblock prints. The Hofmeisters do not show the furrowed ground, marked by the incipient signs of systematic peat extraction, or the geometrical lines of the drainage ditches. Instead, our eye is drawn in by a walkway projecting into the picture at an angle. The technique of multicolour gum bichromate printing, which came into vogue in the 1890s, uses pigments to render the photographic masters as prints that are made more durable by the admixture of soot.

Theodor Hofmeister (b. 1868 in Hamburg, d. 1943 in Hamburg) and Oscar Hofmeister (b. 1871 in Hamburg, d. 1937 in Ichenhausen) were amateur photographers alongside their professional work (as businessman and legal clerk, respectively). Exponents of the Pictorialist approach, they began exhibiting their work internationally in 1895. They specialised in multicolour gum bichromate printing.

Jürgen Friedrich Mahrt and Hermann Reichling

Moorlands contain the organic commodity peat. Once it has been drained, dug, and dried, it can be burned as a source of energy. This usage has a long history and was of great importance until the emergence of the coal industry. As naturalists, Jürgen Friedrich Mahrt and Hermann Reichling recorded how peat cutting infringed on nature and documented the massive impact it had. While Mahrt’s hand-coloured photographs are illustrative of the arduous manual labor involved, Reichling’s work gives a palpable sense of the industrial scale of this undertaking. He often seeks out compositions that set up a contrast between the supposedly pristine moor – which represents such an important habitat – and the drastic impact of human agency. In this way, he clearly shows how the natural vegetation is inscribed with an industrial grid of furrows, which gives structure to the photographs’ pictorial space as a graphical raster. It becomes evident here how nature is turned into a commodity, how with every cut that is dug, whether with a spade or an excavator, sods of peat are removed from the earth as a monetisable product. The shots showing the edges of the peat in cross section – as documented by both photographers – also allude to the temporal dimension of the resource: in the right conditions, it takes a thousand years to produce 1 meter of peat from organic material. However, the climate is being damaged not only by the commercial exploitation of the moorlands but also by the process of draining them, which releases huge amounts of CO2.

Jürgen Friedrich Mahrt (b. 1881 in Elsdorf, d. 1940 in Rendsburg) was a farmer and Hermann Reichling (b. 1890 in Heiligenstadt, d. 1948 in Münster) a biologist. As self-taught photographers, they made a record of their cultural and natural surroundings. In the 1920s, Mahrt founded a private museum in Elsdorf in which he exhibited natural history dioramas and photographs. Reichling was director of Münster’s museum of natural history, Provinzialmuseum für Naturkunde, from 1921 to 1948.

Eduard Arning

If you look closely at Eduard Arning’s large-format gum bichromate print of an iron and steel works, it has a leathery look that resembles skin. The print’s surface structure contains the pigments that give it its murkily indistinct visual effect. This is produced in large part by a blue-black colour produced when larger amounts of soot were mixed into the pigments. The surface of the paper, which has been treated with pigments and a binding agent, is exposed: these areas become fixed, while less exposed parts are rinsed away and remain lighter. In this case, the result is a nocturnal view of an iron and steel works, whose chimneys spout fire and belch smoke. The leaping flames and brightly lit windows were added after the fact by Arning and convey a Romantic idea of industrial production at the turn of the 20th century. To the right of the picture, a shadowy heap of ore looms large in the foreground, while on the left a somewhat brighter swath leads the eye into the depths of the picture and the glowing entrance to the factory. Towering next to it is the monumental chimney from which soot rises – a symbol of industrial progress. This returns in material form as blue-black pigment, extending right to the frontmost plane of the picture and giving the dark pile of ore its shape.

Anaïs Tondeur

Anaïs Tondeur’s work Carbon Black sees her delving into soot particles, which were an essential component used in photographic methods at the turn of the 20th century. A product of industrial combustion processes, consisting almost exclusively of carbon, soot is carried by wind and air currents and does not usually fall to the ground until it is hundreds of kilometres from the site of emission. The black particles of carbon absorb the sun’s rays, warming the atmosphere and thus contributing to the melting of the ice caps. Soot enters the human body through the lungs as a fine dust measuring less than 2.5 micrometers – breathed into the alveoli, it is transported into the bloodstream and finds its way into the internal organs. Working together with two climate researchers, the artist set out on a fifteen-day expedition traversing the UK. Using airflow analyses, the team determined the trajectory of soot particles, a trail that led from Fair Isle in Scotland to the port of Folkestone in the south of England. At each stop on their journey, they took photographs of the horizon using a helmet camera, measured the concentration of particulate matter, and recovered soot particles from the air. Inserted into printer cartridges as pigment, these particles were then used to produce a landscape photograph whose colour characteristics are specific to the site where the picture was taken. The severity of the air pollution is thus given expression in the dramatic grey and black tones of the cloud constellations depicted.

Anaïs Tondeur (b. 1985 in France) studied at Central Saint Martins and at the Royal College of Arts in London. Her research-based work explores the dynamic realm connecting the natural sciences, anthropology, and mythic narratives.

Susanne Kriemann

The artist works with heliogravure, a manual printing technique that is now no longer used in practice: the copper plate is dusted with asphalt powder and printed using a highly pigmented paint mixed with soot. In 2017, Susanne Kriemann began accompanying scientists from the University of Jena on their research trips to investigate the renaturation of the uranium mining area formerly operated by SDAG Wismut in the Ore Mountains (Erzgebirge). Uranium ore, a highly radioactive substance, was mined there between 1949 and 1990. Today, its soil is severely contaminated with heavy metals. Kriemann uses photography for her artistic research on the project – her logging of contaminated plants stretches the medium to the very limits of what it can depict, as the radiation measured by the researchers cannot be seen in the photograph. Notwithstanding, Kriemann has devised a method that allows her to inscribe the radioactivity in the image: she harvests individual plants that she has previously photographed and processes them to produce different-coloured pigments, which she mixes with soot and uses to print her heliogravures. This technique allows her to include the plants directly in the work she creates. In this way, the radioactivity becomes a physical element in her images.

Susanne Kriemann (b. 1972 in Erlangen) studied at the Stuttgart State Academy of Art and Design (ABK Stuttgart) and the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Her research-based work is concerned with the technical requirements and historical conditions of photographic production.

Robert Smithson

In his 1969 work Asphalt Rundown, Robert Smithson abandoned the gallery space completely to realise his first outdoor earthwork. In a stone quarry south of Rome, he had a truckload of hot, liquid asphalt tipped down an eroding slope. In choosing the quarry, he opted for a landscape that bore the marks of human intervention, the first link in a variety of industrial supply chains. Smithson’s Asphalt Lump from 1968 had already demonstrated his interest in industrial composites and nature as shaped by humanity: it was at this point that he was invited by the Konrad Fischer Galerie to conduct research on the slag heaps in the Ruhr, together with the photographer couple Bernd and Hilla Becher. In the work in Rome, the inky black mass covers the barren earth in next to no time, causing the ground to disappear beneath it as it pushes its way down the slope like a natural river, cooling and congealing.

Smithson conceived the sculpture as a symbol of frozen time. In his view, time does not simply pass – rather, it is deposited in an ongoing process like layers of sediment in the soil. As a language construct, Asphalt Rundown links into the idea of photographic images as frozen moments. On the material level, meanwhile, Smithson’s use of asphalt also alludes to Nicéphore Niépce’s heliographic experiments, where the hardening of asphalt on a tin plate under the action of light was used to record fleeting images and was thus a means to freeze time. The natural asphalt used by Niépce can be found as bitumen judaicum in the area around the Dead Sea, where the visual scenery bears a striking resemblance to Smithson’s artificially created volcanic landscape.

Robert Smithson (b. 1938 in Passaic, New Jersey, d. 1973 in Texas) gained a reputation as an early exponent of land art. He applied his conceptual approaches to a study of the relationships between humans and nature, drawing parallels between industrial and geological processes.

Honoré d’Albert de Luynes, Louis Vignes, Charles Nègre

The atlas Voyage d’exploration à la mer Morte is a documentary account of the 1864 scientific, archaeological, and artistic expedition to the Dead Sea basin and the interior of Jordan. Financed by Honoré d’Albert, duc de Luynes, an archaeologist, scientist, and art connoisseur, the expedition was accompanied by, among others, the geologist Louis Lartet and the photographer Louis Vignes. D’Albert subsequently commissioned Charles Nègre – who was one of France’s best-known photographers and had developed a photomechanical reproduction process – to translate Vignes’s photographs into an official report on the expedition using photogravure plates. The publication that came out of this process can still be termed a handmade book. Nègre was not merely an accomplished technician, he also had the eye of an art photographer and created intermediate tonalities and shadows for Vignes’s images, which turned out to have too much contrast. His prints, which are rich in detail and the play of light and shadow, were on occasion composed of several negatives, and, in some cases, the clouds were superimposed. The atlas shows, among other things, the sites where the natural deposits of bitumen were found: this was the basis, in turn, for the gravure printing process that Nègre refined.

Honoré Théodoric Paul Joseph d’Albert de Luynes (b. 1802 in Paris, d. 1867 in Rome) was a numismatist, archaeologist, collector, scholar, and art lover. Born into an aristocratic family, he was endowed with a considerable fortune and financed the research trip to Jordan, in which he also took part. Louis Vignes (b. 1831 in Bordeaux, d. 1896 in Paris) was an admiral in the French navy and an amateur photographer. Charles Nègre (b. 1820 in Grasse, d. 1880 in Grasse) was a painter and photographer as well as a technician and inventor of his own photogravure method.

Noa Yafe

At first glance, we see a two-dimensional image, and it is only when we get closer to what is apparently a photograph mounted in the exhibition space that we register the three-dimensional sculpture let into the wall surface, which opens up like a diorama into the space behind it. Noa Yafe’s sculptures are based on photographs: these are used as templates. It is often scientific images that capture her imagination. The artist deals with the verity of photography and the moment of illusion; at the same time, by turning photographs into objects, she also addresses materiality in an age in which images have become immaterial. The master for the work she made for the exhibition is the black-and-white photograph Vue Prise au dessus de Mar Saba (View over Mar Saba) of the Jordanian hillscape around the Dead Sea. The picture was taken by Louis Vignes and reproduced by Charles Nègre using the photogravure technique: it appeared in the atlas Voyage d’exploration à la mer Morte (Expedition to the Dead Sea, 1868-1874). The artist uses real materials for the “photograph” she constructs.

Noa Yafe (b. 1978 in Israel) studied at the HaMidrasha School of Art at Beit Berl College and at the School of Visual Arts in New York City. She works in the medium of photography and sculpture.

Text from the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg

Jürgen Friedrich Mahrt (German, 1882-1940)

Making baked peat on Hartshoper Moor

c. 1930

Gelatine silver paper, hand coloured

Collection Mahrt/Storm, Rendsburg/Berlin

Installation view of the exhibition Mining Photography. The Ecological Footprint of Image Production at the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg showing the work of Robert Smithson

Robert Smithson (American, 1938-1973)

Asphalt Rundown

1969

Documentary photograph

© Holt/Smithson Foundation VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

When the Bechers’ friend Robert Smithson poured oceans of glue down a hillside, or bulldozed dirt onto a shed until its roof cracked, he was mimicking the moves of heroic construction, not aiming to build anything.

Blake Gopnik. “Photography’s Delightful Obsessives,” on The New York Times website July 28, 2022 [Online] Cited 20/10/2022

Installation view of the exhibition Mining Photography. The Ecological Footprint of Image Production at the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg showing work from Anaïs Tondeur’s series Carbon Black

Anaïs Tondeur (French, b. 1985)

North Sea, 27.05.2017, Carbon Black Level (PM2.5): 13,8 µg/m

2017-2018

From the series Carbon Black

15 Carbon ink prints photographs, carbon black particles, cartography

100 x 150cm

Despite the absence of industries, the inhabitants of the isle of Fair suffer from suffocation. As Anaïs Tondeur reached the island she sent her geographic coordinates to climate modellers Rita van Dingenen and Jean-Philippe Putaud (JRC, European Commission) who retraced the itinerary of the particulate matters meeting her. By means of atmospheric backward trajectory models and the analyses of anthropogenic emission of air pollutants, they could define the site of emission of the particles. This abstract trajectory line lead the artist to an expedition of 837 miles by foot, ferry, fishing boat and car unravelling the journey of the anthropic meteors.

She crystallised each day in a photograph of the sky as well as filtering black carbon particles she encountered through breathing masks. The particles were later extracted by scientist J.P Putaud and turned into ink. In point of fact, black carbon is a collateral form of soot, used for centuries as the primary component of Indian ink. The photographs are thus printed with some ink composed from the particles captured in the sky where they were shot.

Text from the Anaïs Tondeur website [Online] Cited 16/10/2022

Anaïs Tondeur (French, b. 1985)

Edinburg, 30.05.2017, Carbon Black Level (PM2.5): 8,18 µg/m³

2017-2018

From the series Carbon Black

15 Carbon ink prints photographs, carbon black particles, cartography

100 x 150cm

Installation view of the exhibition Mining Photography. The Ecological Footprint of Image Production at the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg showing at left in the bottom photograph, heliogravures by Susanne Kriemann

Susanne Kriemann (German, b. 1972)

Bitterkraut aus: Falsche Kamille, Wilde Möhre, Bitterkraut (Zyklus 2)

Bitterweed from: false chamomile, wild carrot, bitterweed (Cycle 2)

2017

Photogravure with ox-tongue pigment, 0.6 g soot on paper

80 x 60cm

© Susanne Kriemann

Paper and Its Coating: Cotton, Pulp, Gelatin, and Celluloid

The development of photography as a mass product, first made possible using paper as a material substrate, came at a cost. For most of the 19th century, photographic paper consisted primarily of rag made of cotton and flax. European manufacturers dominated the markets for textiles and paper throughout the century, but much of the raw material they used was sourced from the United States, which became cotton’s leading cultivator through its utilisation of slave labour and, after the Civil War, of share croppers and tenant farmers.

The cultivation of cotton was closely intertwined with the often-violent emergence of capitalism, precipitating the drainage of wetlands – whose ecosystems play a crucial role in carbon storage – and thus accelerating climate change. This cotton was then exported to Europe, where it was spun into clothes, which, when worn out, were collected by ragpickers – predominantly working-class children and women – and sold back to European paper mills, where women prepared them for pulping, removing buttons and bleaching them white using newly discovered toxic chlorine compounds.

The ever-increasing demand eventually led producers to seek an alternative to cotton. Perfected in Germany, wood pulping in entails the boiling of wood in sulfuric acid so as to separate it into individual cellulose fibres. The photo-paper industry’s use of animal-derived substances, such as albumin and gelatin, relied on industrialised farming and slaughter houses. A single photographic paper producer in Dresden used six million eggs a year for albumen coating, and as late as 1999 Kodak was still processing over thirty million kilos of cow skeletons every year.

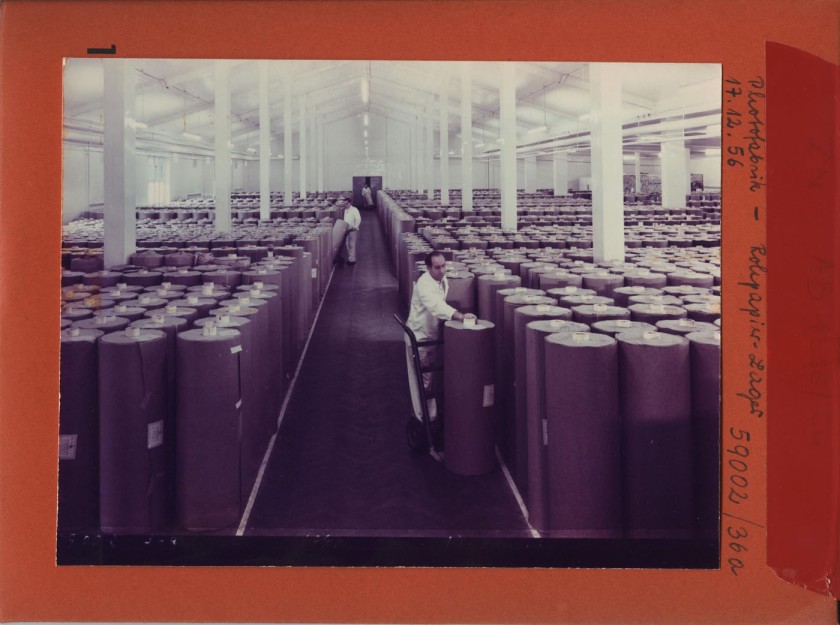

Gevaert Photographic Paper

The 1964 merger of the German corporation Agfa AG and the Belgian company Gevaert Photo-Producten NV led to the creation of the Agfa- Gevaert Group. These two enterprises, each with a long tradition, combined to form one of the world’s leading producers of photographic goods, whose line extended from cameras to X-ray film. If we take, for example, black-and-white gelatin silver paper – one of Agfa-Gevaert’s core products and a staple of the photographic industry in general – it is still manufactured according to the same principles today. The paper substrate is coated with a layer of barium sulfate (also known as baryte), which covers the paper fibres and ensures that the emulsion of gelatin and light-sensitive silver halide grains applied at the end adheres to the base. The pictures from the Agfa archive offer an insight into this process. Although the layers were always built up in the same way, there was considerable variety in the photographic paper that was produced. The possible surfaces might be white or cream coloured, glossy or matte, smooth or textured and were available in up to six variants to allow the motif to be rendered with different degrees of contrast, from extra soft to ultra hard. Systematic research into photographic papers and their material properties did not start until a few years ago. One such example is the documentation of Gevaert papers by the FOMU Photo Museum in Antwerp, which should provide a better understanding of these products and facilitate their processing in both artistic and technical terms. A study of the packaging reveals that successful product lines were offered over a period of decades, even if their outer form changed with the times in line with contemporary tastes.

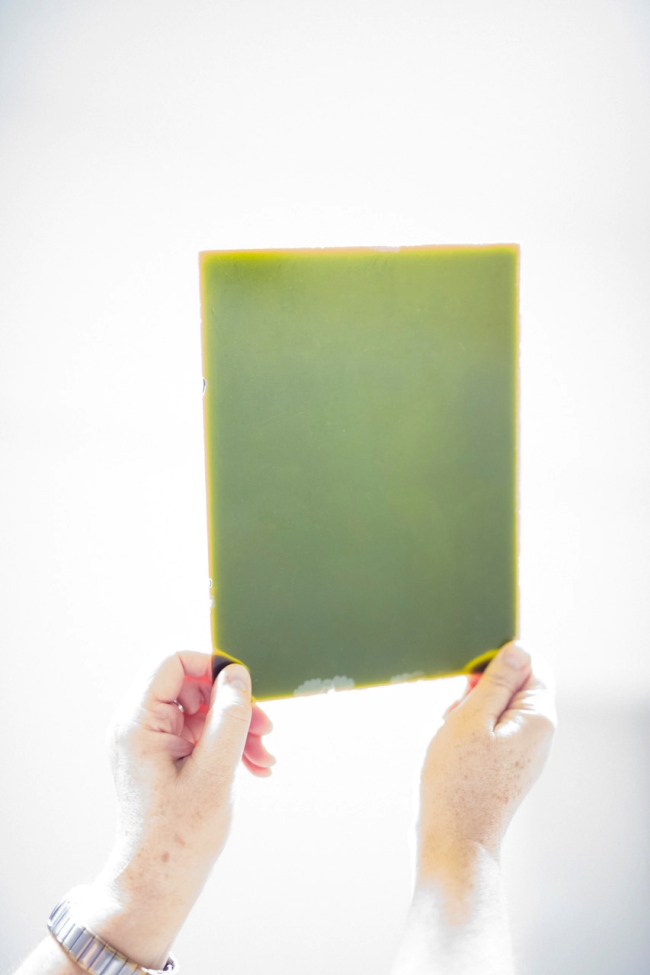

Alison Rossiter

Alison Rossiter’s photographic work is created without a camera or a lens, using expired photographic paper. Since 2007, the artist has collected approximately fifteen hundred packages of old photographic paper, starting from the late 19th century and representing every decade of the 20th. Rossiter mines what she describes as a “cross section of the history of photographic print materials” for their latent images – created by the effect on the paper over time of oxidation, light leaks, pollutants, or physical damage and then developed by the artist in the darkroom to reveal “found photograms.” At times, the artist marks the surface intentionally by pouring or pooling photographic developer directly onto the paper, or else limiting its contact with it, deftly combining chance and skill. The results are abstract images, fields of texture, spilled marks, and monochromes, in a subtle array of blacks, greys, and whites reminiscent of mid-century modernist painting. Each work’s title contains three facts: the manufacturer and type of paper, its expiration date as stated on its package, and the date that Rossiter processed the material. As indicated by its title, a work consisting of six prints included in the exhibition was produced using Gevaert Gevaluxe Velours paper, but their exact expiration date is unknown. First produced by Gevaert in 1933, Gevaluxe Velours was advertised by the company as the “most beautiful paper ever made” and is considered to this day to have been one the best commercially available papers due to its matte surface and intensely deep black shadows. A second work comprises of two images printed using an unnamed photographic paper produced by The Haloid Company, Rochester, for the US military. The abstract geometrical compositions’ material provenance reveals their connection to what could be called the military-photo-industrial-complex, but also hints at the origins of digital technologies within the photographic industries: in 1961 Haloid changed its name to Xerox Corporation, and would go on to invent some of the key technologies in personal computing.

F & D Cartier, Wait and See – The Never Taken Images

In 1998, F & D Cartier began investigating the materiality of photographic paper in a work group entitled Wait and See. For them, the work is an exploration of the rudiments of the medium and a way of engaging with the flood of photographic images produced in the digital age. In their installations, the artists use expired photographic papers dating from the years 1890 to 2000, which have lost some of their sensitivity but still respond to light. Their exposure in the exhibition space triggers an ongoing process of slow change as their appearance constantly alters. Without any recourse to a camera or photochemistry, the duo thus brings to life images that were never taken and examines their potential. At the same time, their radically simplified experiment, designed to record light and time, connects back to the early days of the medium, when developing photographic paper was still unusual and daylight exposure was the principal means of blackening the silver salts. The surprising colours produced by the undeveloped gelatin silver emulsions reveal another invisible aspect of analog photography: in this way, F & D Cartier’s experiment conveys a profound sense of the complexity of a material that was ubiquitous in the 20th century.

Françoise Cartier (b. 1952 in Tavannes) studied sculpture at École des Arts Appliqués in Bern; Daniel Cartier (b. 1950 in Biel/Bienne) studied photography at Zurich University of the Arts (ZHdK). Their experiments with photographic materials, which they embarked on together in 1995, have been devoted to themes relating to remembering, forgetting, and the passing of time.

James Welling

Throughout his career, James Welling has reflected on photography’s history and nature by examining the medium’s materiality through the lens of its most common components. Used as a binding layer for gelatin silver prints, gelatin’s prevalence in photographic images normally remains invisible to the naked eye. In this series, produced in 1984, Welling chose to portray the substance in a style reminiscent of product photography. Infused with black ink and then cooled, the sculpted chunks of gelatin were placed against a seamless white background, creating semi-abstract compositions with the appearance of shining coal or black glass. Welling’s work highlights photography’s artifice: reflecting on the way it is consciously and explicitly staged, its choice of subject, and its referential indeterminacy. This is accentuated by the fact that it is difficult at first to tell what exactly it is we are looking at. In his work, Welling often creates a delay between the moment an image is seen and the time viewers understand what it depicts. Here, what the image is of is exactly what it is made of: as if by sleight of hand, Welling reveals image and substrate to be one and the same, reflecting on all that is normally left out of the frame or taken for granted – or all that is hidden by it – when we normally think of what photography is, and what it does to the world.

James Welling (b. 1951, Connecticut, US) studied at Carnegie Mellon University and the University of Pittsburgh and later at the California Institute of the Arts in Valencia. Throughout his career, Welling has experimented with different photographic media, exploring the tensions within and between representation and abstraction and challenging the medium’s conventions.

Madame d’Ora

Between 1949 and 1953, Madame d’Ora produced an unsparing photographic study of two Parisian slaughterhouses, which she would go on to describe as her “great final work.” Built during the 19th century under Napoleonic decree and in keeping with Baron Haussmann’s vision, slaughterhouses such as the Abattoir Ivry Les Halles and Abattoir de Vaugirard signalled the emergence in France of industrialised meat production governed by capitalist imperatives. It was in such abattoirs that the repetitive, procedural, and rationalised mode of the factory was first introduced into the realm of animal slaughter, a practice that was later perfected in the US with the introduction of the assembly line. Enabled by such developments, the exponential growth of the cattle industry during the 19th century contributed to the dramatic acceleration in carbon emissions that began in those years. To this day, cattle are considered the number one agricultural source of greenhouse gases worldwide (responsible for about 14 percent of total human-induced emissions). Madame d’Ora’s images seem to dissect her subjects, portraying them with a sense of tactility and precision and, at times, of the absurd. In some images, skin is stretched across the picture plane, resulting in near abstraction, while, in others, pools of blood and rows of clipped and flayed corpses fill the frame to capacity, creating a mood of excess and serialised death. Evoking a mixture of detachment and brutality, distance and cruelty, reminiscent of the horrors of the 20th century, the series has often been read as an implicit response to the Holocaust, during which many of d’Ora’s family members, including her sister Anna, were killed. By documenting the unpleasant reality behind industrial meat production, an essential component in many everyday commodities – including the gelatin-silver paper used for these prints – d’Ora sheds light on a dark and often ignored aspect of modernity.

Madame d’Ora (née Dora Philippine Kallmus, b. 1881 in Vienna, d. 1963 in Frohnleiten, Austria) was an Austrian Jewish photographer and one of the most acclaimed portraitists of fin-de-siècle Vienna. After the war, d’Ora was commissioned to produce a series representing refugees and displaced persons by the United Nations. It was at that time too that she started working on her slaughterhouse series.

Tobias Zielony

For Blackbox Wolfen, Tobias Zielony has created a fictional archive of the AGFA-ORWO film factory in Wolfen, combining still images and interviews with former employees who worked in the factory’s darkrooms. Predominantly women, the workers had to perform their tasks in near pitch darkness, in extreme cold or heat, exposed to various toxic chemicals. For the GDR, filmstock represented a valuable commodity that could be traded with the Soviet Union in exchange for silver, oil, and gas. ORWO also supplied cinematographic material to other socialist countries, as well as non-socialist economies such as Egypt and Brazil. One of the biggest export markets for ORWO film was India, which needed stock for its burgeoning movie industry and provided sun-bleached cow bones, used for high-quality film gelatin, in exchange. Today, only a single small company exists in Wolfen, primarily producing a highly specialised black-and-white archival film. Used by the German Federal Archive, the film is said to survive for up to a thousand years once exposed if it is stored in dark and cold environments, such as Germany’s National archive, which is located deep underground in the decommissioned silver mine of

Tobias Zielony (b. 1973 in Wuppertal, Germany) studied photography at the University of Wales, Newport, and later at the Academy of Fine Arts (HGB) Leipzig. He is known for his photographic and filmic depictions of youth and subcultures, which employ a critical approach to documentary photography.

Text from the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg

Madame d’Ora (Dora Kallmus) (Austrian, 1881-1963)

Severed cows legs in a Parisian abattoir

c. 1953-1954

Gelatin silver print

Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg

Madame d’Ora (Dora Kallmus) (Austrian, 1881-1963)

Severed calf’s head in a Parisian slaughterhouse

c. 1953-1954

Gelatin silver print

31.7 × 24.5cm

Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg

Unknown photographer

Raw paper storage, Agfa AG, Leverkusen

1956

C-print, mounted on cardboard

Agfa Collection, Museum Ludwig, Cologne

© Museum Ludwig

James Welling (American, b. 1951)

Gelatin Photograph 45

1984

Inkjet print

50.8 × 40.6cm

F&D Cartier

Wait and See

1998 – today

Exposure tests, untreated gelatin silver photographic papers from Leonar, Illingworth & Co., Hans Mahn & Co., Wephota

©F&D Cartier

Tobias Zielony (German, b. 1973)

Dunkelraum (Darkroom)

2022

Slide installation

© Tobias Zielony

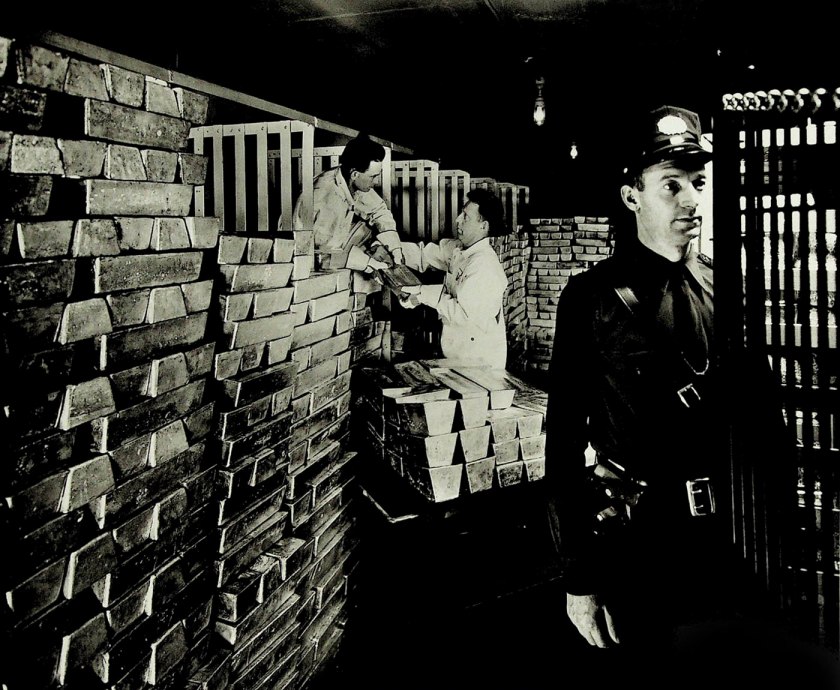

Silver

Since the advent of the medium, silver has been the basis of the photographic image and the most important raw material used in the photochemical industry. In the popular gelatin silver process, it is embedded in the gelatin layer of the photographic paper, and the light-sensitive material then registers the image. The final image consists of small particles of metallic silver that turn black when exposed to light, while the unexposed silver halide crystals are washed away.

It was only the automation of production and commercial film development services that enabled photography to become a veritable mass medium. The growing number of amateur photographers caused the industry’s silver consumption to explode. Photography remained the largest consumer of silver worldwide, even after 1979, when a massive rise in the price of silver led to the development of smaller photographic formats such as 110 film as well as research into digital photography. Photography is interwoven with global trade, the extraction of raw materials, and colonialism. The exploitation of Cerro Rico (“Rich Mountain”) in the Potosí region of Bolivia started back in the 15th century, and until the mid-20th century most silver was sourced in North and South America.

The production of film and photographic paper and its development has always been accompanied by significant environmental pollution, through both its high levels of water consumption and the contamination of waste water with alkalis, acids, and traces of silver. The impact of such pollution is to this day clearly visible in the areas around Eastman Kodak’s headquarters in Rochester (USA) and the ORW Ofactories in Bitterfeld-Wolfen.

The recovery of silver from photographic waste was first developed for economic reasons during the 19th century but was only established as standard practice in photographic production in the 1960s. Today such recycling processes are important – and not just with regard to a single finite raw material.

Simon Starling

In his sculptural work, Starling zooms in on the materiality of the photograph, using an electron microscope to single out two silver particles in the emulsion of a historical photo and then rendering them, with the help of a computer program, at a magnification of 1:1,000,000. This rendering is converted into a stainless-steel three-dimensional sculpture that is larger than a person, its seemingly fluid polished surface creating a virtual effect. Starling has described the photograph as a “deposit of matter”, an image produced by an agglomeration of silver particles. His rendering has its origins in the materiality and documentary function of a stereo-photograph showing Chinese migrant workers who had been brought to Massachusetts in 1870 to break a strike in a shoe factory. Made in China because of lower production costs, the sculptures reverse the trajectory in this story of labour migration. The Nanjing Particles can also be regarded, therefore, as a work about the development of systems of global production. Starling treats photographs as material objects that need to be produced and preserved. In the process, photographs activate memory and knowledge, at times revealing stories that have been suppressed.

Simon Starling (b. 1967 in Epsom) studied art and photography at various institutions, including the Glasgow School of Art. He works in the area of conceptual art. Starling’s work draws on models of sustainability and wasteful extravagance to focus on the historical trajectories of exploitation.

Optics Division of the Metabolic Studio (Lauren Bon, Tristan Duke, and Richard Nielsen)

The dry expanse of Owens Lake in the California desert is not only the subject of the work by the artists’ collective, it also supplies the material for it. Liminal Prints Buried in Owens Lake shows two large format photographs buried in the mud of the lake, where they are being “developed.” These images are on show in the exhibition along with the utensils used for the purpose. The silver nugget on display is the silver from two years of photographic work – including the exposures from the AgH2O series – that has been recovered from the fixer by a process of electrolysis.

The group of works originated with the artists’ attempt to produce their own photographic materials. The members of Metabolic Studio collected silver from the disused Cerro Gordo mine, harvested halide salts from the bottom of the lake, and processed gelatin from cattle from the region. The darkroom was replaced by the nighttime darkness, and the chemicals by brine from the lakebed, which contains large quantities of sodium thiosulfate, a fixing agent employed since the invention of photography. This rarely occurring element is produced by the microorganisms present there – archaea – which metabolise sulfur. The lakebed develops the images and fixes them at the same time.

To create the photographs in the AgH2O series, the collective used its “Liminal Camera,” a shipping container that has been converted into a large-format camera. The container symbolises the global trade in silver and water and the overexploitation of these resources: the silver from the Owens Valley was mostly used by Eastman Kodak to produce film (the company also supplied Hollywood), while, from 1913 on, the water slaked the increasing thirst of Los Angeles’s expanding metropolis. By 1924, the lake was all but dry. The landscape in the photographs is itself a quotation: we are familiar with the steppe valley from Hollywood westerns and Ansel Adams’s landscape images.

Lauren Bon (b. 1962 in New Haven), Tristan Duke (b. 1981 in Campaign), and Richard Nielsen (b. 1966 in Vancouver) started Optics Division of the Metabolic Studio in 2010: the artists’ collective examines the relationship between Los Angeles and Owens Valley as part of an ongoing process.

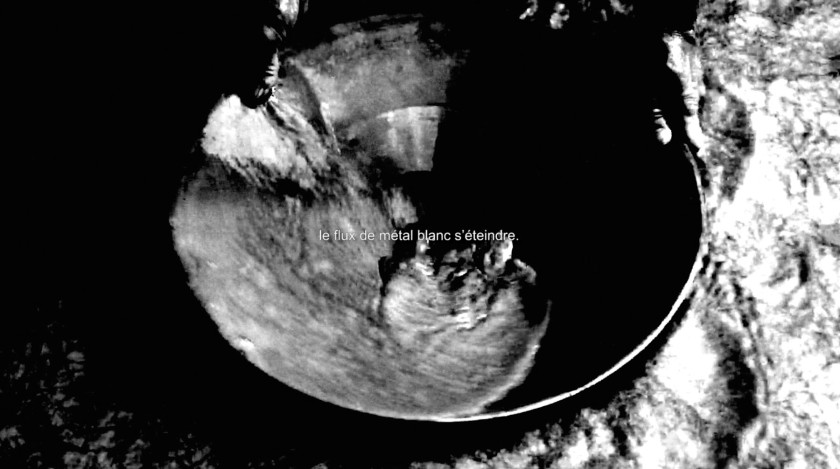

Daphné Nan Le Sergent

The film L’image extractive (The Extractive Image) intercuts macro photography of a silver surface with black-and-white landscape shots showing silver and gold mining in the Americas. This takes us on a journey to Mexico’s mining regions. The video essay weaves together fact and fiction. It tells the story of how photography was invented: the artist does not begin her account in 1839 but rather starts with the discovery and mining of silver in South America. The film tells of the legendary El Dorado and recounts an alternative story of the medium’s invention set in Brazil, where photographic pioneer Hercule Florence secretly discovered a gold-based process at the same time as French inventors Daguerre and Arago made their own discoveries. This is followed by images of die stamping, of silver’s stock price, and of miners. On the soundtrack, the artist speaks of the photographic industry’s late 19th-century boom, which she associates with the introduction of the gold standard around 1870 and the devaluation of silver. She recalls how the vertiginous rise in the price of silver led to the invention of digital photography in 1985. She also suggests a link between the P. G. Morgan company’s interests in silver speculation and its promotional work in the field of art photography. Her narrative arc ranges from the gold rush to data mining. She uses haunting music to underscore the repetitive loop of images showing gold and silver prospecting and the landscape being scoured in search of gold nuggets. The textual layer of the film uses a staccato verse sequence to tell a hypothetical and speculative story, drawing on a plethora of historical facts from Le Sergent’s artistic research.

Daphné Le Sergent (b. 1975 in Seoul) grew up in Paris. Her work deals with geopolitical issues and the way they inscribe themselves in the bodies of individuals.

Text from the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg

Unknown photographer

Silver bars in the Kodak vault

1945

Gelatine silver paper

Kodak Historical Collection #003, Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation, University of Rochester

Used with permission from Eastman Kodak Company

Optics Division of the Metabolic Studio (Lauren Bon, Tristan Duke und Richard Nielsen)

Lake Bed Developing Process

2013

© Optics Division of the Metabolic Studio

On moonless nights on the Owens Valley dry lakebed, to the soundtrack of KPPG Live on the radio, Lauren Bon and Optics Division’s Rich Nielsen and Tristan Duke use the valley as their photographic darkroom. They take light-sensitive photographic paper and bury it for the night in the concentrated salt brine. The lakebed’s bio- and geo-chemistry works on the paper with unconventional developing and fixing properties, yielding unique renderings of and by the lakebed. These unique photographs are developed and fixed by the chemicals in the lakebed, creating warm, earthy, and metallic tones.

Optics Division of the Metabolic Studio (Lauren Bon, Tristan Duke und Richard Nielsen)

Owens Lake Panorama 1

Nd

Silver gelatin print processed in Owens Dry Lakebed

© Optics Division of the Metabolic Studio

Daphné Nan Le Sergent (South Korean, b. 1975)

L’image extractive (The extractive image) (film still)

2021

Video, b/w and colour, sound, 20′

© Daphné Nan Le Sergent

Simon Starling (English, b. 1967)

The Nanjing Particles

2008

Forged stainless steel

200 x 420 x 150cm and 200 x 450 x 170cm

Courtesy of the artist and Casey Kaplan, New York

The Weight of the Cloud: Rare Earths, Metals, Energy, and Waste

Digital photography’s materiality is even less visible than its analog predecessor. In 2021, it was estimated that over ninety percent of all images were taken using phones, with more than a trillion images produced that year alone. Most digital images are archived digitally or shared using “social media” platforms, which have developed in parallel with the rise of smart phones and their cameras and are fuelled by their visual content. User data, stored on the so-called cloud, is “mined” by tech companies for targeted advertising. Yet it’s not only data that is mined. The cloud – though advertised as ephemeral and virtual – is heavy with metals and waste. Digital photography relies on a vast material network: from the mining of metals and rare earths used for electronic circuitry to elaborate supply chains operating on a global scale, data storage facilities with ever-growing carbon emissions, and, ultimately, vast amounts of electronic waste. Fifty-four million tons of e-waste were generated in 2019 alone, with Northern Europe being responsible for the highest per capita waste globally. Most of it is exported to lower-income countries, causing environmental damage and increasing health risks. A single smart phone can require up to 75 elements for its production (out of the 118 elements in the periodic table), many of which – such as gold, tin, cobalt, coltan, and tungsten – are considered “conflict minerals,” whose trade involves forced labour and finances armed militias. Even small quantities of metal necessitate large amounts of mining: it has been estimated that 34 kilograms of ore would have to be mined to produce the metals that make up a single 129-gram iPhone.

Lisa Rave

Structured like a nautilus shell, with layers of narrative gradually unfolding and echoing each other in the process, Lisa Rave’s Europium makes visible connections between Papua New Guinea’s colonial past and the planned excavation of the rare earth element Europium from the Bismarck Sea. Using a combination of historical found footage, interviews, and performative sequences, the essay film revolves around the rare earth Europium, whose fluorescent qualities are used to validate European banknotes and to ensure the brilliance of colours on flat-screen surfaces. Pointing to the human and ecological violence inherent in the extraction of so-called resources and their transformation into monetary value, Rave directs her anthropological gaze back toward our own society, exposing the ghosts of the past as they appear in the technologies and screens that surround us.

Lisa Rave (b. 1979, London) is a Berlin-based artist and filmmaker. Rave studied experimental film at the University of Arts Berlin and photography at Bard College, New York. In her work, Rave connects the histories of colonial domination with current forms of extraction and ecological violence.

Mary Mattingly

Combining chalk-drawn maps of global supply chains, satellite imagery, staged photographs of sculptural assemblages, and documentary images, Mary Mattingly’s series Cobalt – a selection of which is shown in the exhibition – is an attempt to comprehend a system of immense scale, scope, and complexity that remains hidden in plain sight. Over 60 percent of the world cobalt extraction, the “blood diamond of batteries,” takes place in the Democratic Republic of Congo in dangerously precarious conditions. The extracted metal, mined predominantly as a by-product of copper or nickel, is purchased by Chinese manufacturers, who process and then retail it to clients in the consumer market. Cobalt is then used in our phone’s sensor components and lithium-ion batteries of all kinds (from laptops to vacuum cleaners to electric cars). Capable of withstanding extreme heat, the mineral is also used in weapons and alloyed steel and has been classified as a “strategic mineral” by the US, in an attempt to encourage its local mining and production. In Mattingly’s work, we can see different stages in cobalt’s life cycle: mineral seepage visible in an exposed cliff face; a recently opened mine in Michigan, whose manmade structures protrude from the natural landscape; an ore transportation station. Weaving them all together is an elaborate map, tracing its supply chain across its different stages. Mattingly’s work seeks to address the ways in which we are inevitably entangled in the violent and extractive logic of neoliberalism and its ecological toll. Through her attentive mapping, we see how even forms of critical representation are dialectically bound to a mode of production wrought by ecological devastation and radical inequality. It is only by recognising these conditions, Mattingly suggests, that we can begin to work toward changing them.

Mary Mattingly (b. 1979, Connecticut) studied at Parsons School of Design, New York, and the Pacific Northwest College of Art in Portland, Oregon. Mattingly creates photographs, sculptures, and large-scale public art projects that address climate change, thereby tracing connections between the social and economic forces behind the current political ecology impacting our environment.

Lisa Barnard

In the “The Fox and the Rooster” section of her extensive project The Canary and the Hammer, Lisa Barnard uses documentary photography to examine the economy of waste surrounding the precious metal gold. One of the most expensive materials on earth, gold is used in making our smartphones, cameras, and televisions, turning worn-out devices into a precious commodity. However, e-waste contains not only precious substances but also some that are extremely poisonous – metals such as lead, mercury, and cadmium, which are highly toxic for both humans and the environment. China, which is responsible for 10 million tons of toxic substances every year, is one of the world’s largest sources of e-waste as well as its biggest importer. In her research, the artist looks at China’s trade in illegal e-waste, in which gold is extracted from old devices using aqua regia, a highly explosive mixture of hydrochloric acid and nitric acid, whose name is derived from its ability to dissolve the precious metals gold and platinum. An illustration of this reaction can be found in alchemist Basilius Valentinus’s treatise “The Twelve Keys,” which was published in 1599. The work contains a woodcut showing a rooster (symbolising gold) eating a fox, which in turn is eating a rooster. The gold is dissolved not by the acid itself but rather by the products it creates when it reacts with the precious metal. Barnard’s choice of title thus makes reference to the potential dangers involved in recovering gold as well as to the mysterious aura that still surrounds it, even in the recycling loop that is a feature of the modern tech economy.

Lisa Barnard (b. 1967) studied photography at the University of Brighton and critical theory at the University of South Wales. Her documentary practice is concerned with current debates about materiality and global capitalism.

Mari Lebanidze, Cleo Miao, Leon Schweer, Marco Wesche with the mentoring of Prof. Christoph Knoth and Prof. Konrad Renner of the University of Fine Arts (HFBK) Hamburg – Digital Graphics class

Using the same sort of facial recognition technologies employed by tech companies to mine behavioural data for speculative value, Terraformed Self tracks exhibition visitors’ behaviour. Having identified people using their smartphone, the interactive installation informs visitors about their own contribution to the ecological footprint of digital image production using a playful game-like animation. How many selfies have been taken in front of this screen? How much carbon dioxide are they responsible for? What is the equivalent of a minute of scrolling on Instagram? While the work seems to invite visitors to take the obligatory exhibition selfie in front of the large, mirrored structure, it offers a sobering reflection on how our daily smartphone habits are implicated in a planetary system of resource extraction. The work is accompanied by an Instagram face filter – using the platform to reflect on its own footprint.

Digital Graphics class. Against the backdrop of omnipresent digital forms that mingle with artefacts from the past, the class, led by Prof. Christoph Knoth and Prof. Konrad Renner of the University of Fine Arts (HFBK) Hamburg, explores the integrity of modern technologies and conceives visual models in the context of culture and digital possibilities.

Text from the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg

Installation view of the exhibition Mining Photography. The Ecological Footprint of Image Production at the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg showing the work of Mary Mattingly

Mary Mattingly (American, b. 1979)

Eagle Mine

2016

© Mary Mattingly

Mary Mattingly (American, b. 1979)

Ore Transport Station

2016

© Mary Mattingly

Lisa Barnard (British, b. 1967)

Broken mobile phone screen, Shenzhen, China

2018

© Lisa Barnard

Events in the history of capitalism, ecology, and photography

With excerpts from the time line compiled by Lukas Egger and Nils Güttler for the exhibition “Nach uns die Sintflut (After Us, the flood)” at Kunst Haus Wien

1492 Columbus arrives in the Americas, setting in motion a process described as the “Columbian exchange”: the movement of diseases, ideas, food, crops, and populations between the New World and the Old World brought about by European colonisation.

1556 Dere Metallica (On the Nature of Metals) by Georgius Agricola (Georg Bauer), is published. Illustrated with over 270 woodcuts, the treatise quickly became the authoritative text of its day on mining and helped popularise technical knowledge in the field.

1717 The German polymath Johann Heinrich Schulze (1687-1744) is the first to demonstrate the photosensitivity of silver salts.

1776 James Watt’s steam engine, originally invented and perfected to be used in mines, is introduced. Signalling the advent of the first industrial revolution, steam power allows for previously labour-intensive forms of production to become mechanised, especially in the textile industry. Coal is now an increasingly important energy source.

1800 While traveling in Venezuela, Alexander von Humboldt is one of the first scientists to describe the harmful effects of Human-induced climate change and its relation to colonialism, observing the adverse effects of the deforestation brought about by Europeans on the local soil quality and the moisture levels in the atmosphere.

1807 Claude and Nicéphore Niépce obtain a patent for the Pyréolophore (from Greek: pyr = fire, aeolos = the keeper of wind, and phore = carrier) one of the earliest internal combustion engines, fuelled by coal mixed with resin.

1827 Joseph Nicéphore Niépce produces the first Heliograph (Greek for “writing with sun”), by dissolving light-sensitive “bitumen of Judea,” a semi-solid form of petroleum, in oil of lavender, and applying a thin coating over a polished pewter plate.

1838 The first steam-powered crossing of the Atlantic ocean.

1839 Louis Daguerre presents the Daguerreotype before the French Académie des Sciences.

1840 William Henry Fox Talbot submits his first patent for an internal combustion engine titled “Obtaining Motive Power”. By 1852, he had registered four additional engine patents.

1844-1846 Wiliam Henry Fox Talbot publishes “The Pencil of Nature”, widely considered to be the first commercially published photo-illustrated book.

1846 Nitrocellulose (also known as “gun cotton”) is patented. It is used as an explosive in mines, as well as for the production of early – infamously flammable – cellulose film. It led to the invention of thermoplastic.

1851 A staggering 893,000 daguerreotype plates are produced in Paris alone in only one year. Converted to the standard portrait size of a quarter or eighth plates, 3-8 million portrait images could betaken.

1859 British glaciologist John Tyndall begins a series of laboratory experiments to demonstrate the significance of atmosphere gasses – including CO2 – for global warming.

1862 Writing for the US magazine Atlantic Monthly, Oliver Wendell Holmes estimates the annual consumption of precious metals for photography at ten tons of silver and half a ton of gold.

1870 Start of the Second Industrial Revolution, the electrification of production processes and of spheres of private life begins. Crude oil becomes increasingly important as a fuel for powering combustion engines.

1872 The correspondent of the English journal The Year-Book of Photography describes various methods of silver recovery from the developer fluids of photochemistry – for example, by reducing silver nitrate with the help of charcoal or by burning the papers and dissolving the ash with nitric acid and water.

1877 Founding of the Moorversuchsstation (Moor Experiment Station) in Bremen, the first NGO to campaign against moor burning. The first provisions pertaining to air pollution control are issued in a number of countries.

1888 The Eastman Kodak Company introduces the Kodak No.1 camera model, marking the beginning of the industrial processing of photographs in the laboratory. Advertised with the slogan “You press the button – we do the rest!,” the new camera and the company’s service relieved photographers of the chemical processing of their photos, introducing photography to a popular audience.