Exhibition dates: 28th January – 29th May 2022

Curator: Thomas Thiel

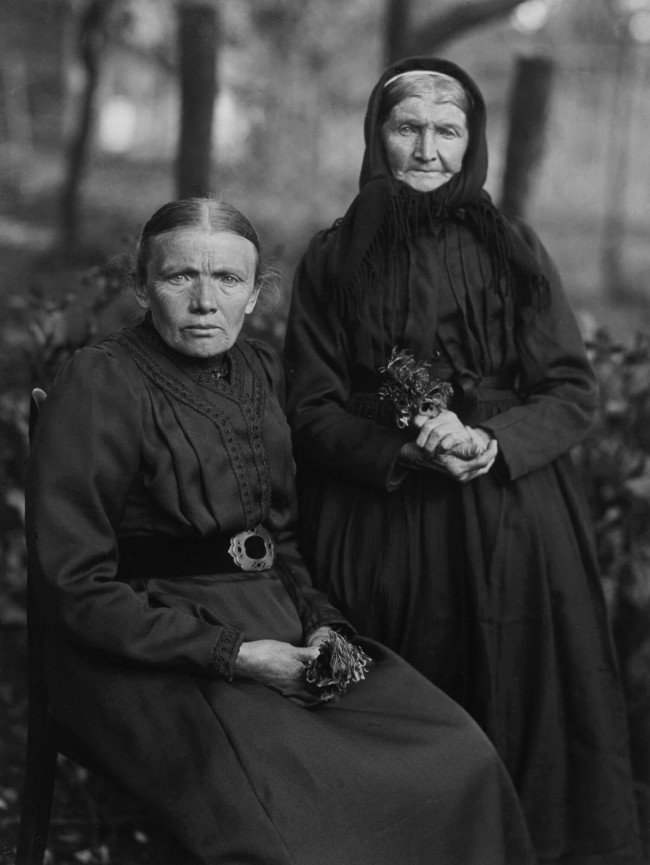

August Sander (German, 1876-1964)

Der erdgebundene Mensch (The earthbound human) / Peasant Woman, Westerwald

1912

Gelatin silver print

Contemporary Collection, MGKSiegen

© Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur, Köln – August Sander Archiv/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2022

I am not sure any of these kinds of exhibition – supposed extrapolations on the work of an earlier famous photographer, in this case contemporary photographers responding in diverse ways to renowned German photographer August Sander (1876-1964), icon of 20th century photography – serve any kind of lasting useful purpose, other than perhaps to acknowledge the alleged and, in most cases, slight influence of the earlier photographer.

While the contemporary work is strong in its own right, too often it seems shoehorned into the concept of the exhibition, artistic positions exhibited in order to revitalise the work of August Sander both directly and indirectly. Sander does not need revitalising… nor do the contemporary artists need the prop of his fame nor his conceptualisation of German identity, family and life to succeed with their projects. Their changed views of life and new influences on the individual are cogent enough – clear, logical, and convincing – not to need a conceptual walking frame.

However, the exhibition does give us the ability to, once more, marvel at the apparent simplicity and directness of Sanders’ portraits and the monumentality of his project “People of the 20th Century”. Frontal, low depth of field, beautiful light, tightly framed photographs which portray individuals as true characters who have undeniable “presence” in the viewers eyes. When thinking about the human condition, nothing in the rest of the exhibition comes close to their insight and intensity…

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Museum für Gegenwartskunst Siegen for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

At second left, August Sander’s Pastry Cook 1928; at fifth left, Coal Delivery Man c. 1915; at seventh left, Handlanger (Bricklayer / Handyman) 1928; and at eighth right, Working-class Mother 1927

At left, Mother and daughter 1912; at third left, August Sander’s Village Band 1913; and at fourth left, Farmer on his Way to Church 1925-1926; and at right, Cretin 1924

After August Sander, Exhibition view, MGKSiegen

Work by August Sander, Portraits of People of the 20th Century, 1912-1932, printed 1961-1963

Contemporary Collection MGKSiegen

© Die Photographische Sammlung / SK Stiftung Kultur, Köln – August Sander Archiv; VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2022

Photo: Philipp Ottendörfer

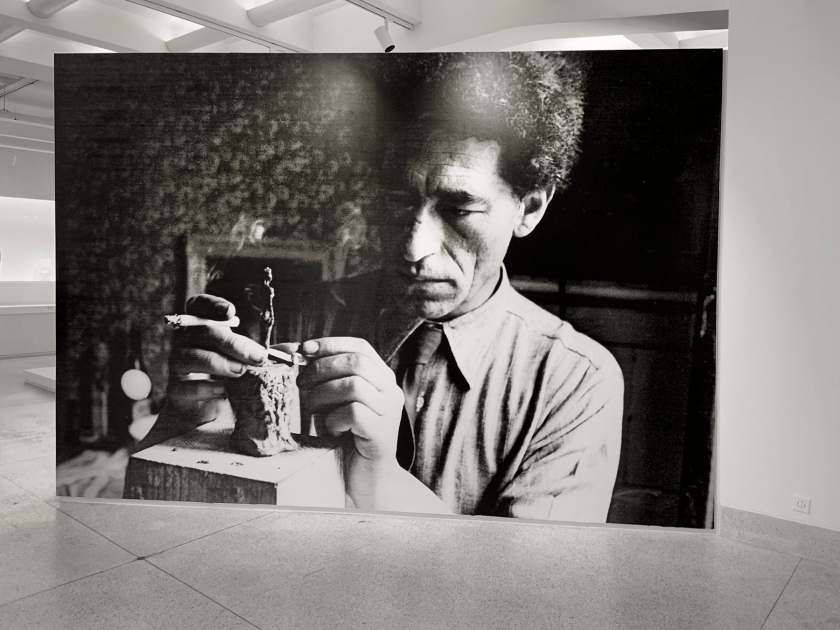

With his collection of portraits, “People of the 20th Century”, August Sander (1876-1964) produced a monumental life’s work that not only made photographic history but went on to influence generations of artists. The photographer, who was born in Herdorf near Siegen, depicted professional groups and social classes for several decades. Altogether he collected more than 600 images in forty-five portfolios, organising them into seven categories: The Farmer, The Skilled Tradesmen, The Woman, Classes and Professions, The Artists, The City (city dwellers), and The Last People, who were found on the fringes of society. A selection was first assembled in the publication “Face of Our Time” (1929). By working on a portrait of society during his time, Sander not only developed archetypal images but also aimed to study the nature of man in relation to his community.

“After August Sander” combines the work of the world-famous yet regionally-based photographer with a contemporary perspective of 13 artists. At the heart of the exhibition is a group of 70 large-format photographs that Sander compiled as late as the early 1960s, also for presentations in the Siegerland. As a gift from Barbara Lambrecht-Schadeberg to mark the MGKSiegen’s 20th birthday, these are now being shown here for the first time. Starting out from this important group of works, the exhibition directs attention towards portraits of people in the 21st century and initiates further examination of images showing contemporary types.

The artistic positions exhibited revitalise the work of August Sander both directly and indirectly. The deliberate leap in time of about 100 years visualises our changed views of life and new influences on the individual. Despite the historical reference, “After August Sander” does not stick exclusively to the medium of photography, but presents video installations and sculptures in a reflection of our times.

With contributions by August Sander, Mohamed Bourouissa, Alice Ifergan-Rey, Jos de Gruyter and Harald Thys, Hans Eijkelboom, Omer Fast, Soham Gupta, Sharon Hayes, Bouchra Khalili, Ilya Lipkin, Sandra Schäfer, Collier Schorr, Tobias Zielony and Artur Zmijewski.

Supported by Kunststiftung NRW

Text from the Museum für Gegenwartskunst Siegen website

Rooms 1 and 2

August Sander (German, 1876-1964)

Bauernpaar – Zucht und Harmonie

1912

Gelatin silver print

Contemporary Collection, MGKSiegen

© Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur, Köln – August Sander Archiv/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2022

August Sander (German, 1876-1964)

Mother and Daughter

1912

Gelatin silver print

Contemporary Collection, MGKSiegen

© Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur, Köln – August Sander Archiv/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2022

August Sander (German, 1876-1964)

Village Band

1913

Gelatin silver print

Contemporary Collection, MGKSiegen

© Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur, Köln – August Sander Archiv/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2022

August Sander (German, 1876-1964)

Jungbauern (Young Farmers)

1914

Gelatin silver print

Contemporary Collection, MGKSiegen

© Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur, Köln – August Sander Archiv/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2022

August Sander (German, 1876-1964)

Coal Delivery Man

c. 1915

Gelatin silver print

Contemporary Collection, MGKSiegen

© Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur, Köln – August Sander Archiv/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2022

August Sander (German, 1876-1964)

Polizeibeamter. Der Wachtmeister (Police Officer)

1925

Gelatin silver print

Contemporary Collection, MGKSiegen

© Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur, Köln – August Sander Archiv/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2022

August Sander (German, 1876-1964)

Der Maler Anton Räderscheidt (Painter Anton Räderscheidt)

1926

Gelatin silver print

Contemporary Collection, MGKSiegen

© Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur, Köln – August Sander Archiv/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2022

August Sander (German, 1876-1964)

Zirkusartistin (Circus performer)

1926-1932

Gelatin silver print

Contemporary Collection, MGKSiegen

© Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur, Köln – August Sander Archiv/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2022

August Sander (German, 1876-1964)

Handlanger (Bricklayer / Handyman)

1928

Gelatin silver print

Contemporary Collection, MGKSiegen

© Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur, Köln – August Sander Archiv/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2022

August Sander (German, 1876-1964)

Pastry Cook

1928

Gelatin silver print

Contemporary Collection, MGKSiegen

© Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur, Köln – August Sander Archiv/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2022

August Sander (German, 1876-1964)

Boxers. Paul Röderstein and Hein Hesse. Köln

c. 1928

Gelatin silver print

Contemporary Collection, MGKSiegen

© Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur, Köln – August Sander Archiv/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2022

August Sander (German, 1876-1964)

The selection of large-format exhibition copies of People of the 20th Century being shown for the first time in the Museum für Gegenwartskunst was compiled from various portfolios by Sander himself in 1961/63. They were intended for presentations in the Siegerland region and printed by his son Gunther Sander under his own supervision. The occasion for this was provided by, amongst others, two exhibitions entitled Antlitz der Zeit (Face of Our Time), shown in Siegen in 1964 and in the fire station close to Herdorf town hall in 1965. Beyond its international significance, for several reasons August Sander’s work also has considerable regional identification value. Sander was born in Herdorf and spent his childhood between Siegerland and the Westerwald. Siegen-based photographers Friedrich Schmeck and Carl Siebel inspired the young Sander to take up photography. Photographs dating from before 1914 were taken in or near his hometown and were subsequently included in the well-known picture atlas. He frequently spent time in the Westerwald and moved his residence to Kuchhausen due to the war in 1942. This exhibition brings a circle to a close in the MGKSiegen. Works by August Sander can now be shown permanently and as part of the collection in Siegen for the first time since the museum’s opening in 2001.

August Sander (German, 1876-1964)

Cretin

1924

Gelatin silver print

Contemporary Collection, MGKSiegen

© Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur, Köln – August Sander Archiv/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2022

August Sander (German, 1876-1964)

Farmer on his Way to Church

1925-1926

Gelatin silver print

Contemporary Collection, MGKSiegen

© Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur, Köln – August Sander Archiv/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2022

August Sander (German, 1876-1964)

Working-class Mother

1927

Gelatin silver print

Contemporary Collection, MGKSiegen

© Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur, Köln – August Sander Archiv/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2022

August Sander (German, 1876-1964)

Putzfrau (Cleaning woman)

1928

Gelatin silver print

Contemporary Collection, MGKSiegen

© Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur, Köln – August Sander Archiv/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2022

August Sander (German, 1876-1964)

The Industrialist

1929

Gelatin silver print

Contemporary Collection, MGKSiegen

© Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur, Köln – August Sander Archiv/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2022

Rooms 3 and 4

After August Sander, Exhibition view, MGKSiegen, Contemporary Collection MGKSiegen showing at left, a work by Sandra Schäfer Kontaminierte Landschaften, (2021); and at right, August Sander’s Bauernpaar – Zucht und Harmonie (1912) from “People of the 20th Century”, 1912-1932

© Die Photographische Sammlung / SK Stiftung Kultur, Köln – August Sander Archiv; © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2022

Photo: Philipp Ottendörfer

Sandra Schäfer (German, b. 1970)

Westerwald: Eine Heimsuchung

2021

Still showing the cover of August Sander – Líchtbíldner folio Der Bauer (The farmer)

© Sandra Schäfer/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

After August Sander, Exhibition view, MGKSiegen

Work by Sandra Schäfer, Kontaminierte Landschaften, 2021, Courtesy the artist

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

Photo: Philipp Ottendörfer

Sandra Schäfer (German, b. 1970)

Sandra Schäfer’s artistic practice is concerned with the development of urban and geopolitical space and its history. Her works are often based on long-term research that involves a re-presentation of images, documents, and narratives. In her video installation Westerwald: Eine Heimsuchung (2021), Schäfer – starting out from August Sander’s series of Westerwald farmers and rural labourers – deals with the transformation of the rural region in which she grew up, and by which she has been strongly influenced. Her great-great-great- aunt Katharina Horn, born Schäfer, and her husband Adam Horn, were also the famous farming couple that Sander photographed as early as 1912. The artist juxtaposes August Sander’s perspective with her own, contemporary view in the form of a double projection and two photographs. Schäfer shows how the landscape depicted and its agricultural use have changed over the course of time. She talks to relatives and farmers, as well as to photographic curators about Sander, his photos and the situation in the village of Kuchhausen. She is also interested in the value and varying attributions that the images have experienced in the art world and in private memories. The artist questions existing pictorial orders and narratives with her work, and so ventures her own personal search for home.

Sandra Schäfer (German, b. 1970)

Westerwald: Eine Heimsuchung (installation view not at Museum für Gegenwartskunst Siegen)

2021

© Sandra Schäfer/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

Sandra Schäfer (German, b. 1970)

Westerwald: Eine Heimsuchung

2021

Still

© Sandra Schäfer/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

Room 5

After August Sander, Exhibition view, MGKSiegen

Work by Hans Eijkelboom, Photo Notes, 1994-2022, Courtesy the artist

© Die Photographische Sammlung / SK Stiftung Kultur, Köln – August Sander Archiv; VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2022

Photo: Philipp Ottendörfer

Hans Eijkelboom (Dutch, b. 1949)

Photo Note October 21, 2006 (Camouflage)

2006

Courtesy the artist

Hans Eijkelboom (Dutch, b. 1949)

Photo Note October 21, 2006 (Camouflage) (detail)

2006

Courtesy the artist

Hans Eijkelboom (Dutch, b. 1949)

As early as 1981, Hans Eijkelboom realised an “Ode to August Sander” by asking and categorising citizens of Arnhem, where he lived at the time, on the basis of their distinguishing features and developing the results into a multi-part series of street photographs. Since the early 1990s, the artist has been taking photographs in the business districts of large cities around the world. Unnoticed, he analyses the pedestrians passing by and focuses on them according to formal criteria of their external appearance. Eijkelboom’s gaze – with a thoroughly benevolent sense of humour – falls on the people’s clothing. Fashion statements and similarities in behaviour interest him in formal terms, as uniform codes. He arranges his snapshot-like Photo Notes into groups according to the motif and date of the shot, and then presents them in wall-sized tableaus. Arranged in this way, the exclusively colour portraits direct the viewer’s attention towards the human need to distinguish oneself by means of external features and so underline one’s own identity. In Eijkelboom’s photographs, this striving for individuality is exposed as an illusion due to global trends and milieu-related codes.

Hans Eijkelboom (Dutch, b. 1949)

Photo Note October 23, 2015 (Hoed)

2015

Courtesy the artist

Hans Eijkelboom (Dutch, b. 1949)

Photo Note October 23, 2015 (Hoed) (detail)

2015

Courtesy the artist

Room 6

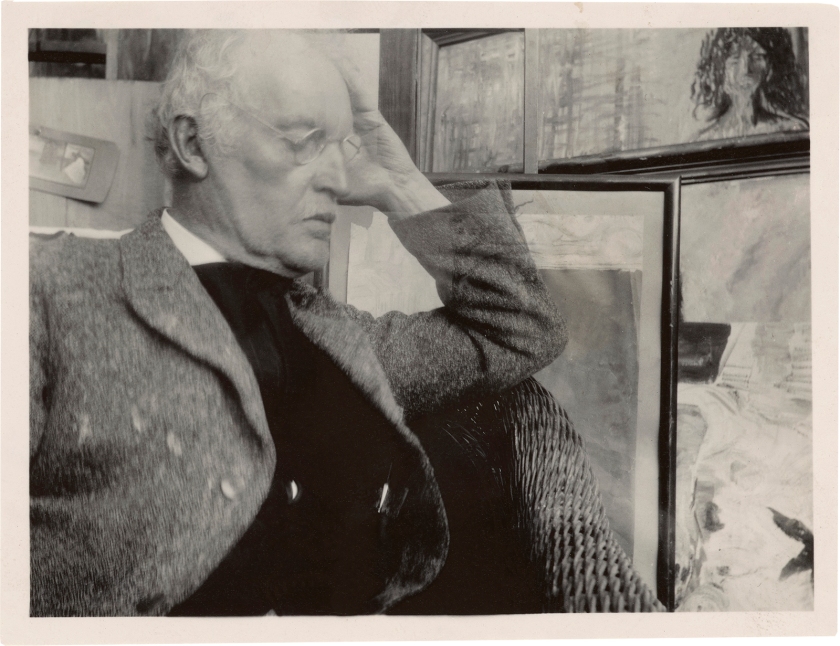

Omer Fast (Israeli, b. 1972)

August

2016

Still

Courtesy the artist

Photo: Stephan Ciupek/Filmgalerie 451

Omer Fast (Israeli, b. 1972)

In his films, Omer Fast frequently tells stories of trauma, war and relationships. His working method enables him to question current and historical events as well as the conventions of the cinematic narrator. The short film August (2016), shot in 3D, revolves around the life and work of August Sander, painting a fictional picture of his last days in the early 1960s. The cinematic flashbacks are oriented on biographical facts. In surreal dream sequences, Sander is haunted by memories: recalling his son Erich, who died as a victim of political persecution in a Nazi prison in 1944, as well as iconic motifs such as the Young Farmers or Workers hauling bricks. The film August shows both the visionary artist and the powerless man, scarred by personal loss and entangled in the political circumstances. Omer Fast deconstructs and at the same time contextualises the artist and man August Sander on the basis of his attitudes in an extremely difficult time politically, the late phase of the Weimar Republic and the transition to National Socialist Germany.

New Pictures: Omer Fast, Appendix exhibition video

This “New Pictures” exhibition [at the Minneapolis Institute of Art 2018] features two films by the Berlin-based Israeli artist Omer Fast (b. 1972), along with more than 20 portraits by the German photographer August Sander (1876-1964) from his series People of the Twentieth Century, selected from Mia’s and Minneapolis-based collections. Through reflections of Sander’s portraits, including Young Farmers (1914) and Bricklayer (1928), Fast’s latest film, August (2016), portrays Sander at the end of his life, tracing the photographer’s career during the transition from the Weimar Republic to Nazi Germany. Fast’s para-fictional (i.e., blending facts and fiction) film subverts the boundary between collective history and personal memory, questioning photography’s ability to tell the truth.

Text from the YouTube website

Omer Fast (Israeli, b. 1972)

August

2016

Still

Courtesy the artist

Photo: Stephan Ciupek/Filmgalerie 451

Room 7

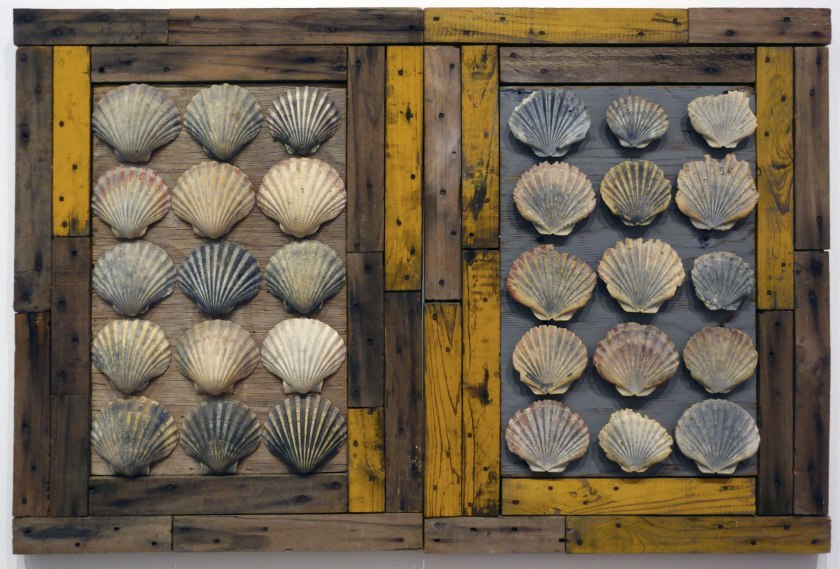

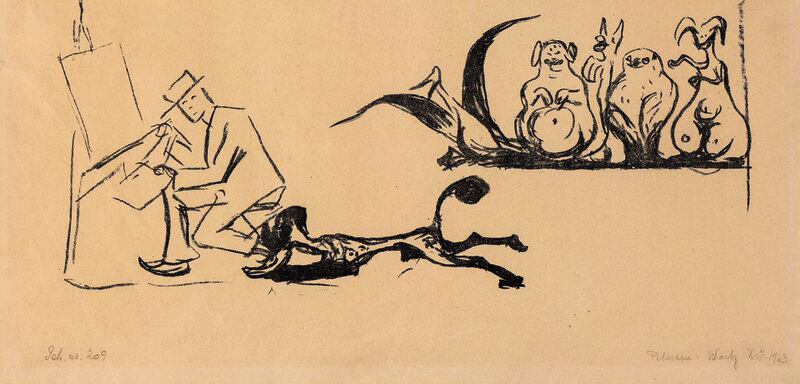

Jos de Gruyter (Belgium, b. 1965) and Harald Thys (Belgium, b. 1966)

Mondo Cane (The Town Crier)

2019

Courtesy the artists and Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin

Photo: Nick Ash

Jos de Gruyter (Beligian, b. 1965) and Harald Thys (Belgian, b. 1966)

Jos de Gruyter’s and Harald Thys’ works are devoted to the absurdity of the everyday. Their interest in the psychological state of societies leads them to create portraits of human existence both tragic and comical. The figures assembled here were part of the exhibition Mondo Cane (eng. Dog World) produced for the Belgian Pavilion at the 58th Venice Biennale in 2019. The presentation was conceived as a kind of folkloristic museum examining the human condition and its grotesque diversity. In the shape of partly mechanised, life-sized dolls, it gathered together simple artisans as well as madmen and outcasts. The doll heads were modelled on fictional characters as well as real people. Scattered throughout the exhibition rooms in Siegen we find a ventriloquist, a town crier, a Stasi spy and a French denunciator from the World War II era. As protagonists, they occupy the museum for the duration of the exhibition and interact with the other works. As representatives, the humorous and sinister characters refer to popular stereotypes as well as to historical attitudes and relationships within Europe.

Jos de Gruyter’s and Harald Thys’ work Mondo Cane (2019) at Biennale Arte 2019 – Belgium

After August Sander, Exhibition view, MGKSiegen

Work by Jos de Gruyter and Harald Thys, Madame Legrand, 2019

Courtesy the artists and Galerie Micheline Szwajcer

Photo: Philipp Ottendörfer

Room 8

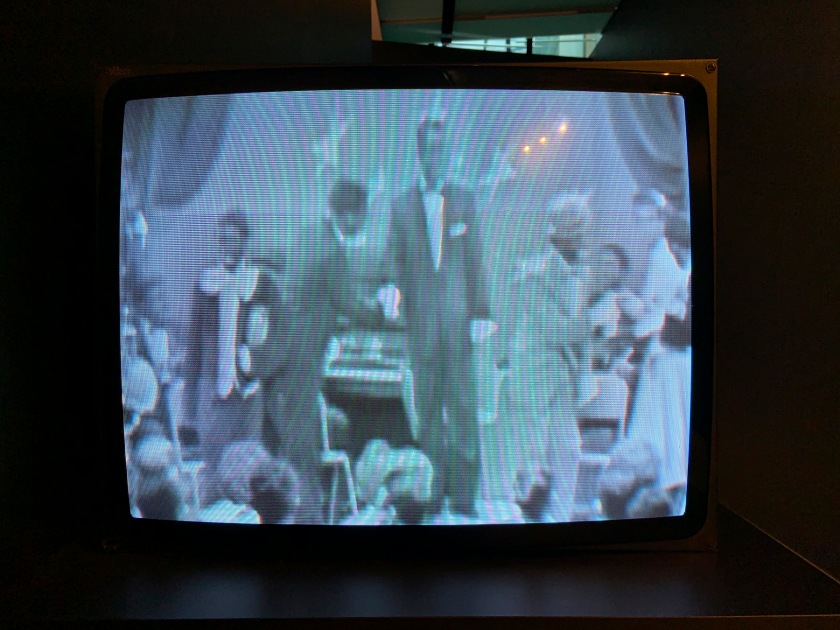

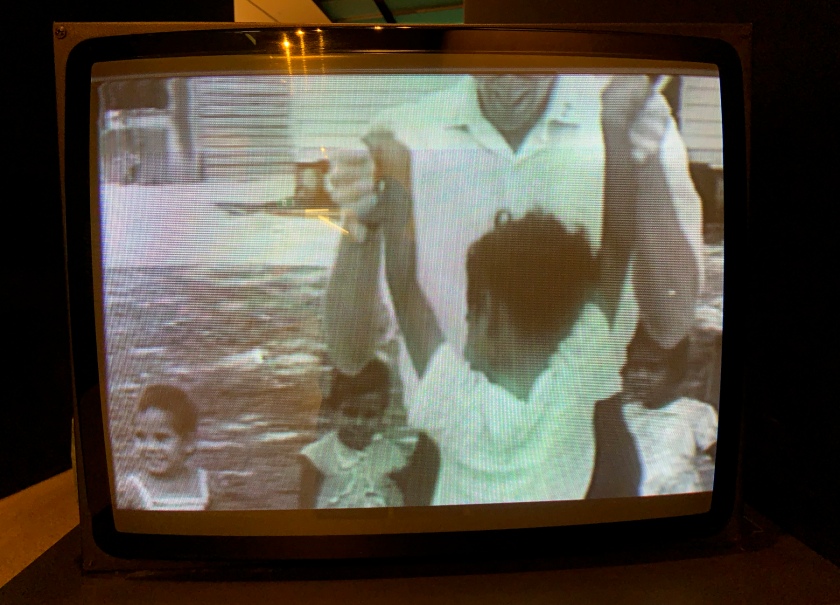

Sharon Hayes (American, b. 1970)

Ricerche: one

2019

Still

Courtesy the artist and Tanya Leighton, Berlin

Sharon Hayes (American, b. 1970)

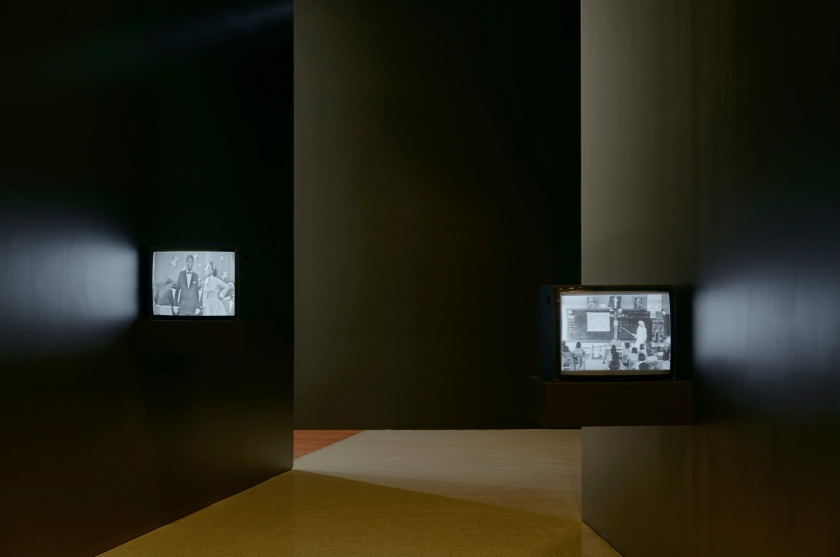

Sharon Hayes’ videos, performances and installations address the complex processes of shaping public opinion on politics, history, identity and language. Her film series Ricerche (engl. Research) began in 2013 and now consists of five parts. Her starting point was the documentary film Love Meetings (1964, ital. Comizi d’amore) by Pier Paolo Pasolini, who travelled through Italy to ask people of different ages and social backgrounds explicit questions about love, sexuality, and morality. Hayes follows the structure of the film and the conceptual idea of interviewing people outdoors and in groups. The video diptych Ricerche: one (2019) portrays two age groups: 5-8 year olds and young adults. All the participants in the video, shot in Provincetown (Massachusetts, USA), are children of queer parents. Depending on their age, they give fragmented or detailed insights into their complex family structures. The artist mirrors social understanding of gender dominated by the norm, sexuality and family constellations. She shows how present conditions shape national, religious and ethnic identities.

Biennale Arte 2013 – Sharon Hayes

After August Sander, Exhibition view, MGKSiegen

Work by Sharon Hayes, Ricerche: one, 2019, Courtesy the artist and Tanya Leighton, Berlin

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2022

Photo: Philipp Ottendörfer

Room 9

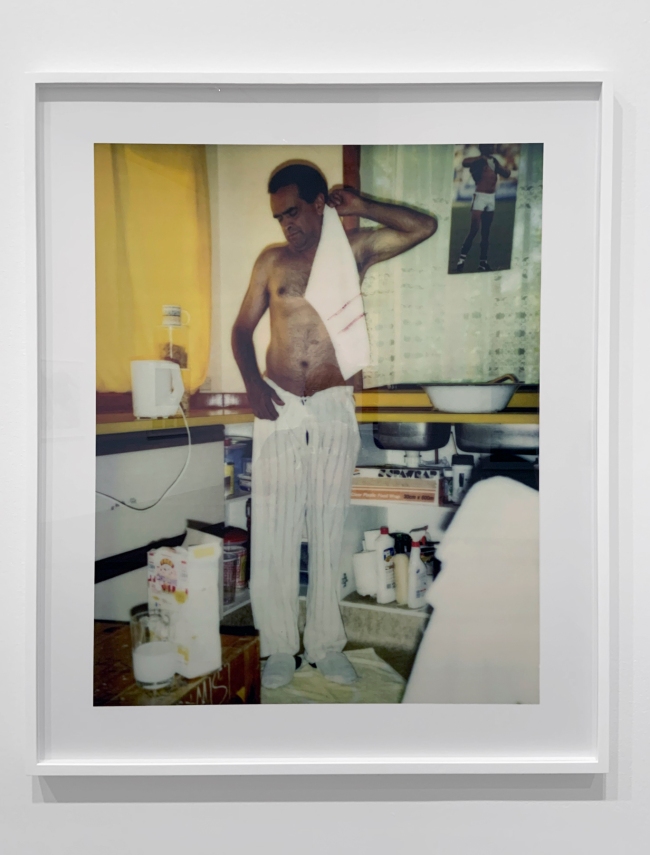

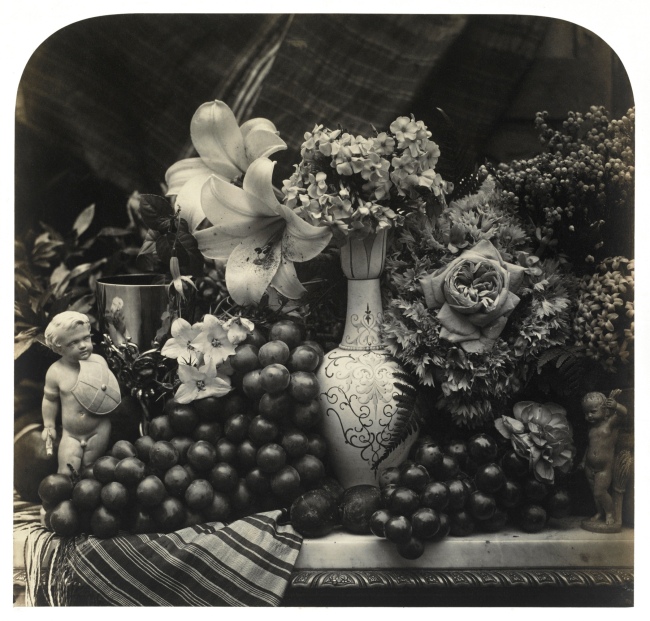

Mohamed Bourouissa and Alice Ifergan-Rey

Je vous raconte comment Mohamed Bourouissa a changé des chômeurs en sculpture dans un camion à Marseille

I tell you how Mohamed Bourouissa changed unemployed people into sculpture in a truck in Marseille

2019

Still

© Mohamed Bourouissa /VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022 and Alice Ifergan-Rey

L’Utopie d’August Sander, Mohamed Bourouissa, Alice Ïfergan-Rey

After August Sander, Exhibition view, MGKSiegen

Work by Collier Schorr, Castle, 1994, Collier as Horst, 2021, Swimming Pool Eyes, 1996, A Possible Mutation, 1994, After Cindy Sherman, 1994

© the artist, Courtesy Stuart Shave/ Modern Art, London and 303 Gallery, New York

Photo: Philipp Ottendörfer

Collier Schorr (American, b. 1963)

Swimming Pool Eyes

1996

Black and white photograph

Courtesy the artist and Modern Art, London and 303 Gallery, New York

Collier Schorr (American, b. 1963)

A Possible Mutation

1994

C-print

Courtesy the artist and Modern Art, London and 303 Gallery, New York

Collier Schorr (American, b. 1963)

Collier Schorr’s portraits can be positioned in the border area between documentation, staging and fiction. Her photographs explore the relationship between nationality, gender, and identity. For over 20 years, Schorr travelled to southern Germany every summer to visit the small town of Schwäbisch Gmünd. Her portraits of the town’s inhabitants taken against an authentic local backdrop reflect a fascination with a culture that was initially foreign to her. Collier Schorr places androgynous-looking teenagers in the German landscape, which she sees as pastoral. They are mostly male adolescents from her close environment, photographed in the garden, in front of and on trees, or in the forest. One of the main characters is Horst, and she adds a later self-portrait to this group: Collier as Horst (2021), wearing men’s underpants and gripping her crotch. These stagings, which dissolve gender boundaries by means of clothing, makeup and props, also include portraits of uniformed soldiers as pictorial subjects. In Matti at Attention (Durlangen) (2001), which shows a young man as a soldier in a forest clearing, the landscape takes on a symbolic charge and becomes a speculative space of remembrance. Aware of Sander’s photographic approach and the gaps in his reception, Schorr sets out to find her own Face of our Time that incorporates her Jewish origins and personal ideas of Germany.

After Horst

“I had these ideas about modern West Germany. It was silent. It was empty. The figures were small, or they were art students lined up in front of coloured squares of paper. Whatever I saw in the work of Andreas Gursky and Thomas Struth and Thomas Ruff was somewhat perfect, organised, static, airless. And frozen in time that looked like the 70’s. West Germany itself, a word I might see on a watch face or an Olympic memorial to the Israeli wrestlers killed by Palestinians in Munich. Somehow, I was there and not there. Dead, memorialised, alive and dead again.

I went to Germany in 1989. And again, for 20 summers. During the third summer I started taking photographs. I was convinced the German landscape held some truth other than the one I had seen in the large-scale imports I saw at 303 Gallery and Marian Goodman Gallery. Schwäbisch Gmünd was soft and pastoral. And the local boys seemed soft and pastoral. I would have never made photos in New York. Nan Goldin, Jack Pierson and Larry Clark already made them. But in Germany, I could take a figure of my imagination and place them in the landscape memorialised by the Düsseldorf School. And I could as they say now – queer the space. So I shot my girlfriend’s nephew Horst and a fusion of myself and him, of a young girl and of a young boy of a woman who looked like a boy. I wanted to make him suffer for his luxury… as if he knew he had this luxury which I can never know. Ultimately, it’s a simple proposition. An image of queerness in an open airfield, rather than a club or a closet or a tenement New York apartment or West Side street corner. One image is called After Cindy Sherman because of how I wished I could use myself to talk about myself. But to do that I would have to find my image bearable and I did not. I saw Germany as a very romantic place and I attacked it and was seduced by it every year. I took the one category in August Sander’s work that the Düsseldorf kids didn’t touch: the Nazi’s. I thought to myself, wow, they really left those soldiers out. Don’t they realise that’s the guts and the ghosts worth tearing apart? I began to enjoy the fact that my story about Germany, my Antlitz Der Zeit, was completely ignored. Too romantic, too gay but not authored by a gay male, too Jewish but not Jewish enough, too personal.

Now I look at Horst and I think about my own body naked on the cover of Frieze magazine and dancing in a ballet I’m making. And posing with Jordan Wolfson in Fantastic Man. The same face the same hair. Over 30 years difference. Suddenly acceptable. Perhaps because the queer figure has more presence agency representation. I still find Horst, with his Levis’s and sweat socks, the tropes of Christopher Street and his teenage girl make up somewhat radical. Because he looks like a living paper doll. Dressed and pasted into a landscape to disrupt the pristine crisis of a German photograph, transmounted, with a wide white border, expansive and somewhat toeing the line.”

Collier Schorr. “After Horst,” on the Modern Art website March 2021 [Online] Cited 02/04/2022

Collier Schorr (American, b. 1963)

After Cindy Sherman

1994

C-print

Courtesy the artist and Modern Art, London and 303 Gallery, New York

Collier Schorr (American, b. 1963)

Wes Portrait

2009-2018

Black and white photograph

Courtesy the artist and Modern Art, London and 303 Gallery, New York

Room 10

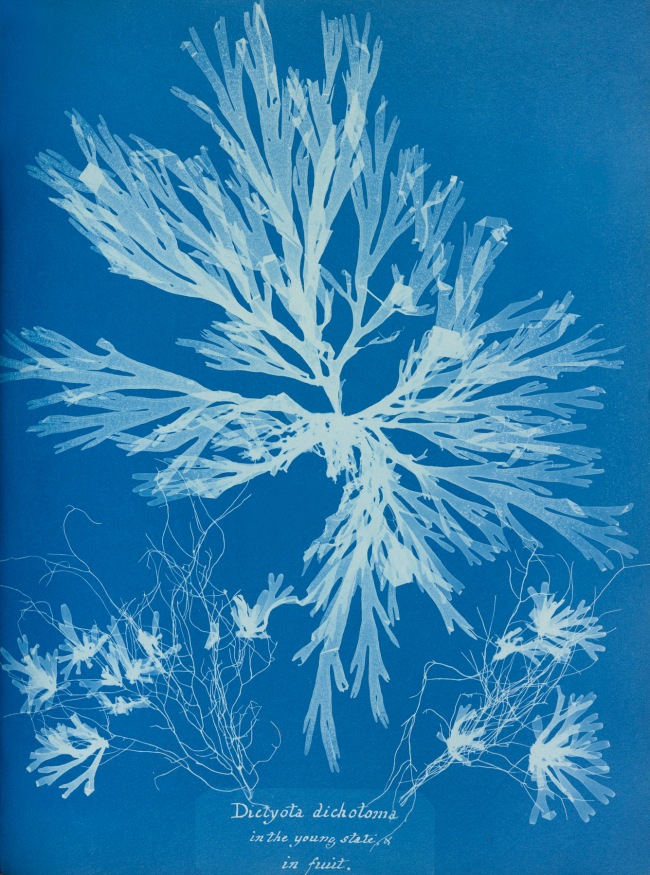

Bouchra Khalili (Moroccan-French, b. 1975)

The Tempest Society

2017

Still

Courtesy mor charpentier, Paris

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

Bouchra Khalili (Moroccan-French, b. 1975)

In her films, photographs, installations and publications, Bouchra Khalili examines the effects of colonial history on migration and political self-image. She provides a voice for social minorities, repeatedly formulating the links between individual actions and collective history. For the video work The Tempest Society (2017), which was shown for the first time at documenta 14, a group of Athenians come together on the stage of a former factory to talk about Europe and their own homeland. It is a portrait of three people from different social backgrounds who joined together to form a theatre group called The Tempest Society. The title is homage to Al Assifa (arab: The Tempest), a project by North African workers and French students who founded an ensemble in Paris in the 1970s to address issues such as racism and social inequality. The individuals in Khalili’s The Tempest Society also address similar problems in contemporary society: Ghani, Katerina and Malek talk about their experiences as people living in Europe and share their stories with each other. At the same time, it is about sharing a collective space – both on stage and in life, and about how the European continent may provide a home.

Bouchra Khalili. The Tempest Society / Twenty-Two Hours 24. August – 21. Oktober 2018

After August Sander, Exhibition view, MGKSiegen

Work by Bouchra Khalili, The Tempest Society, 2017, Courtesy the artist

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

Photo: Philipp Ottendörfer

Room 11

Artur Żmijewski (Polish, b. 1966)

Dieter, Patricia, Ursula

2007

Still

Courtesy the artist, Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Zürich, and Foksal Gallery Foundation, Warschau

Artur Żmijewski (Polish, b. 1966)

Artur Żmijewski is known for his works investigating historical as well as current social orders – often in a radical way, employing mechanisms of power and oppression. The human body is an essential means of expression in his provocative works, which are mainly interviews, documentaries or experimental settings. The trilogies Dieter, Patricia, Ursula (2007) and Katarzyna, Barbara, Zofia (2012) belong to a ten-part series, for which Żmijewski observed people in Germany, Italy, Mexico and Poland with his camera – each for over 24 hours, as they carried out a simple but often physically strenuous activity. In this case, he accompanies an excavator driver, a snack vendor, a tram driver and three cleaners in their everyday lives – from the moment they get up in the morning until they go to bed. From the footage, Żmijewski created a 15-minute portrait of each person, following the artist’s narrative structure alone, and simply showing what happens without any commentary. Routine and moments of repetition are common to all the portraits. Apparently individual, they are also representative of a group within society. The artist therefore functions, on the one hand, as a sociological catalyst of snapshots; on the other hand, the medium of documentary filming operates as an objective instance.

After August Sander, Exhibition view, MGKSiegen

From left, work by Tobias Zielony, Selection of: Curfew, 2001, Ha Neu, 2003, Quartier Nord, 2003, Big Sexyland, 2006, The Cast, 2007, Trona – Armpit of America, 2008, Manitoba, 2009-2011, Jenny Jenny, 2013, Golden, 2018, Courtesy the artist and KOW, Berlin; and at right, Artur Żmijewski’s Dieter, Patricia, Ursula, 2007 (still), © the artist, Courtesy Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Zürich and Foksal Gallery Foundation, Warschau

Photo: Philipp Ottendörfer

Room 12

After August Sander, Exhibition view, MGKSiegen

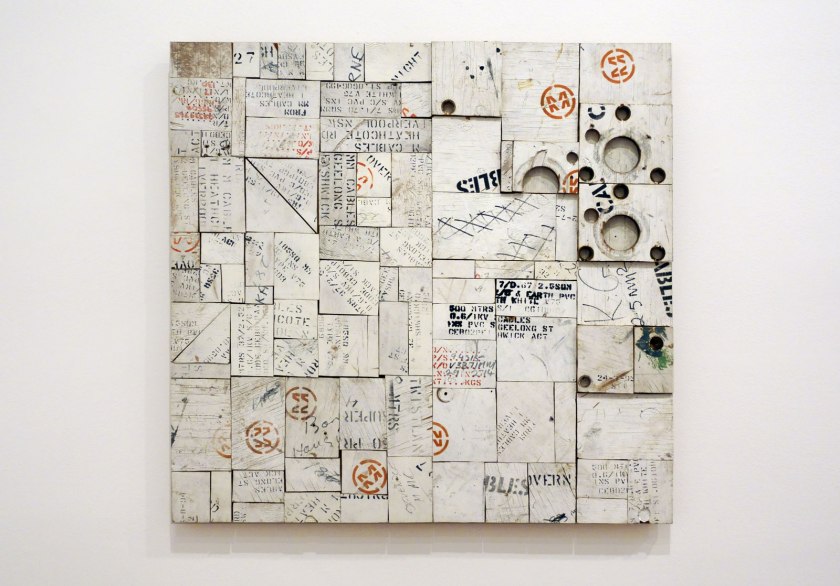

Work by Ilya Lipkin, Untitled, 2019, Courtesy the artist and Lars Friedrich, Berlin

Photo: Philipp Ottendörfer

Ilya Lipkin (Latvian, b. 1982)

Untitled

2019

Courtesy the artist and Lars Friedrich, Berlin

Ilya Lipkin (Latvian, b. 1982)

In his work, Ilya Lipkin breaks with the conventions of applied and artistic photography, moving playfully between fashion and art, studio and street photography. His work is characterised by a self-reflective approach incorporating contemporary trends and styles. The series Untitled (2019) assembles a number of photographs of young women, all taken in public places in various cities around the world, including on Alexanderplatz in Berlin. Photographed with a fast-focus digital camera in burst mode, the images have been retouched and edited according to the usual standards of fashion photography. In some cases, the background was removed and replaced with bright red or neutral white. This immediacy reveals a generation of girls and young women who are extremely conscious of their own image, but also influenced visually by the clichéd image conventions of social media channels. Quite intuitively, they seem to deny us any insight into their inner selves. By means of clothing, style and technology, they express their desire to please in a global society rather than in specific subcultures.

Ilya Lipkin (Latvian, b. 1982)

Untitled

2019

Courtesy the artist and Lars Friedrich, Berlin

Ilya Lipkin (Latvian, b. 1982)

Untitled

2019

Courtesy the artist and Lars Friedrich, Berlin

After August Sander, Exhibition view, MGKSiegen

Work by Tobias Zielony, Selection of: Curfew, 2001, Ha Neu, 2003, Quartier Nord, 2003, Big Sexyland, 2006, The Cast, 2007, Trona – Armpit of America, 2008, Manitoba, 2009-2011, Jenny Jenny, 2013, Golden, 2018, Courtesy the artist and KOW, Berlin

Photo: Philipp Ottendörfer

Tobias Zielony (Germany, b. 1973)

Jay

2007

Courtesy the Artist and KOW, Berlin

Tobias Zielony (Germany, b. 1973)

Skandalous

2007

Courtesy the Artist and KOW, Berlin

Tobias Zielony (Germany, b. 1973)

In his photographs and videos, Tobias Zielony directs artistic attention towards youth subcultures and marginalised groups in society. His image cycles, developed over a long period of time and drawing on various means of pictorial reportage, are always characterised by a special intimacy and direct proximity. Social, media and subcultural changes provide the thematic framework for these photographs. In his work, Zielony has dealt frequently with the significance of origins, fashion, and the representation of identity. For this exhibition and with a view to August Sander’s portfolio work, he has now assembled a first selection of portraits from the last twenty years. On view are single, double, and group portraits ranging from the early series Curfew (2001), depicting youths in Bristol, to a more recent series, Golden, featuring Riga’s queer underground scene. The presentation highlights strategies of portraiture, masking as well as the increased intermingling of social and visual codes in global, mediatised cultural development. Zielony’s fascination with the people photographed reveals a fundamental human interest in the Other in the sense of experiencing foreignness and vibrancy apart from traditional social categories.

Tobias Zielony (Germany, b. 1973)

Two boys

2008

Courtesy the Artist and KOW, Berlin

Tobias Zielony (Germany, b. 1973)

From the series Golden

2018

Courtesy the Artist and KOW, Berlin

Room 13

After August Sander, Exhibition view, MGKSiegen

Work by Soham Gupta, Untitled, from the series Angst (2013-2017), Courtesy the artist

Photo: Philipp Ottendörfer

Soham Gupta (Indian, b. 1988)

Untitled

From the series Angst (2013-2017)

Collection Museum Folkwang Essen

Courtesy the artist

Soham Gupta (Indian, b. 1988)

As early as 10 years ago, Soham Gupta began photographing people he encountered in the darkness by Howrah Bridge in the Indian megacity, Calcutta. The bridge connects the two Indian cities of Calcutta and Howrah across the Hugli River. Nearby is Howrah Railway Station, one of the largest railway stations in India. His photographs in colour and black and white capture people across all age groups, who seem to belong to the lower class. The living spaces captured in the photographs leave no doubt about their poverty and their status as social outsiders, abandoned and cast out. While these snapshots – glaring flash images set against dark backdrops – have a certain fleeting character and convey the impression of spontaneous shots, they are in fact the partly staged results of a development in the relationship between the photographer and the respective sitter. These people – individuals, couples or small groups – look towards the camera, towards the artist or their bodies are angled in his direction. Sometimes, they assume poses that seem grotesque. The series Fear poses the question of the photographer’s ambivalent role between the apparent objectivity of documentary photography and the importance of a subjective perspective. In essence, Gupta’s photographs focus on the human condition and search for a connection with marginalised groups in a society.

Soham Gupta (Indian, b. 1988)

Untitled

From the series Angst (2013-2017)

Collection Museum Folkwang Essen

Courtesy the artist

Soham Gupta (Indian, b. 1988)

Untitled

From the series Angst (2013-2017)

Collection Museum Folkwang Essen

Courtesy the artist

Soham Gupta (Indian, b. 1988)

Untitled

From the series Angst (2013-2017)

Collection Museum Folkwang Essen

Courtesy the artist

Museum für Gegenwartskunst Siegen

Unteres Schloss 1

57072 Siegen

Phone: 0271 405 77 10

Opening hours:

Monday Closed

Tuesday 11am – 6pm

Wednesday 11am – 6pm

Thursday 11am – 8pm

Friday 11am – 6pm

Saturday 11am – 6pm

Sunday 11am – 6pm

You must be logged in to post a comment.