Exhibition dates: 18th February – 29th May, 2022

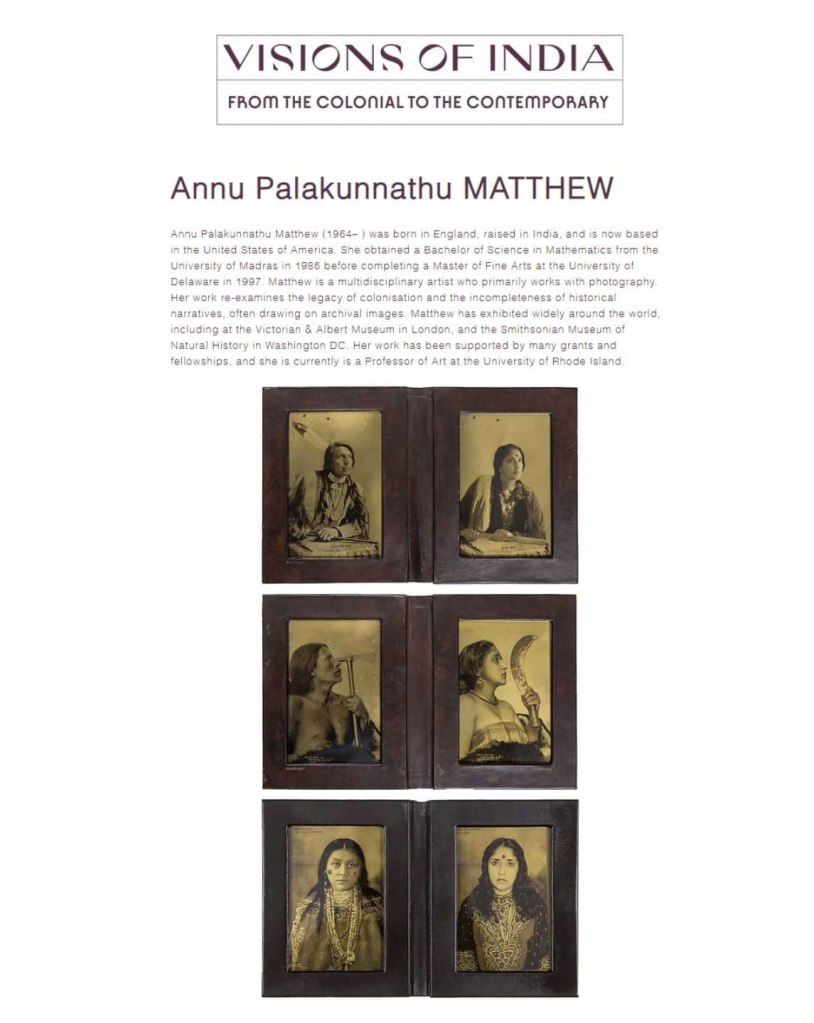

Curator: Elizabeth Siegel, curator of photography and media at the Art Institute of Chicago

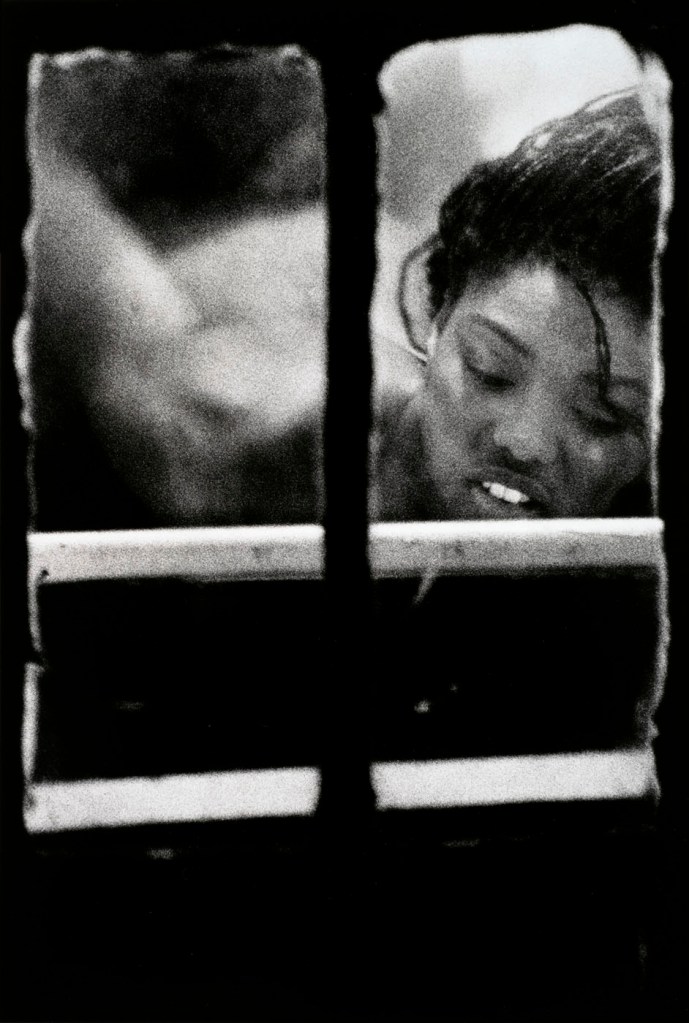

André Kertész (Hungarian, 1894-1985)

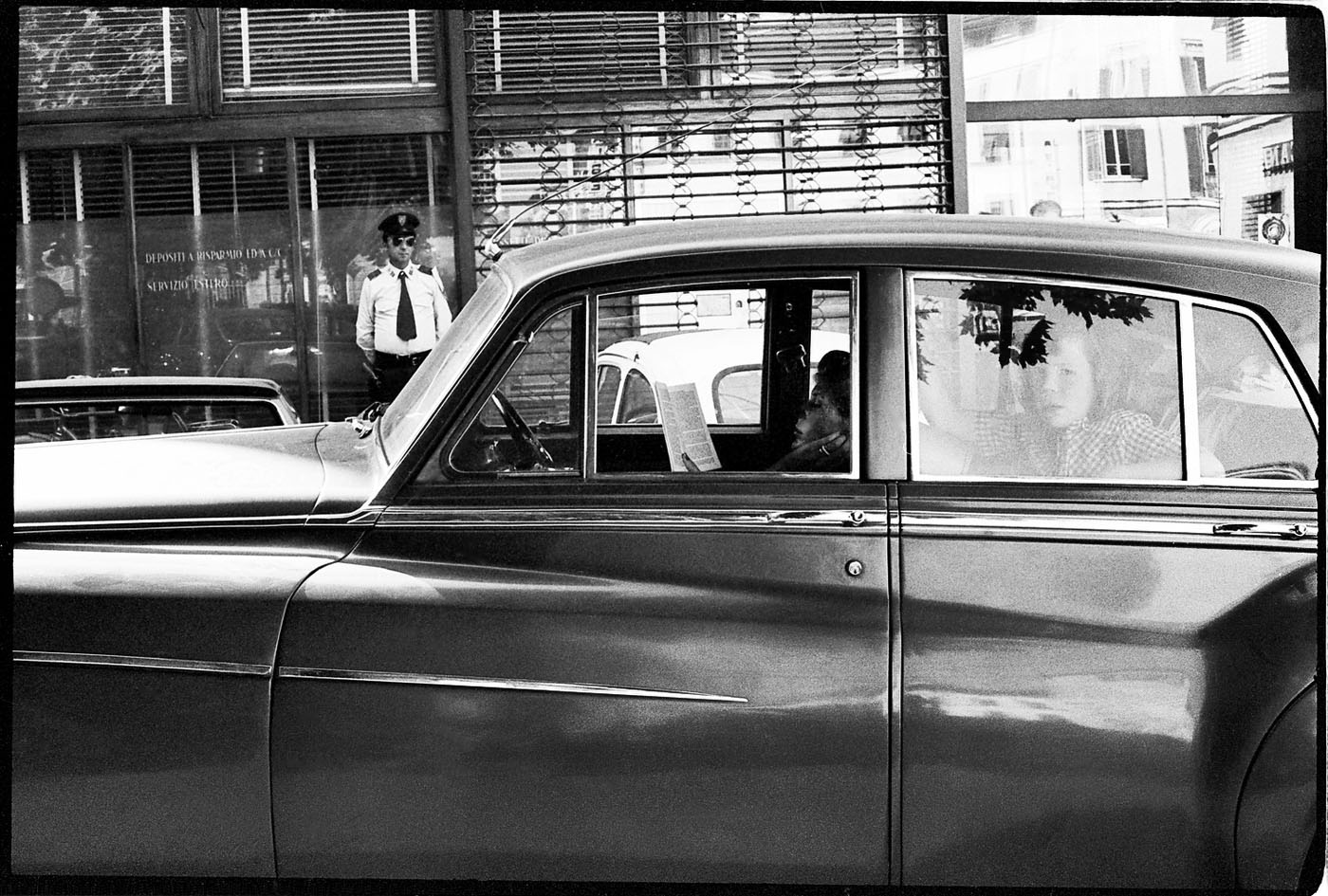

Grands Boulevards

1926

Gelatin silver print on carte postale paper, 1926-1935

Image: 3 1/16 × 45/16″ (7.8 × 10.9cm)

Sheet: 3 5/16 × 5 1/16″ (8.4 × 12.9cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Thomas Walther

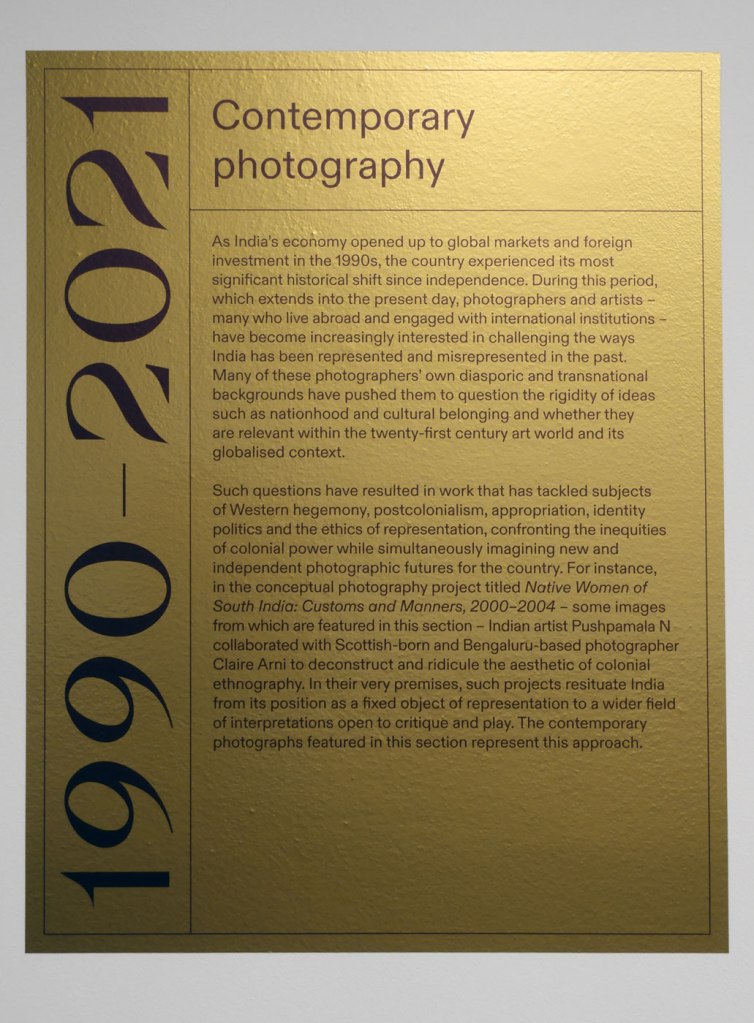

The next two postings focus on the creation and distribution of carte postale – in this posting fine art photographs taken by an artist experimenting with photography at the beginning of his career, intimate images cropped and printed for carte postale (postcard) photographic paper and distributed in very limited numbers to friends and family; and in the next posting social documentary photographs taken by mainly anonymous artists, printed in larger numbers by publishers for public consumption.

Arriving in Paris in 1925 Kertész used to his camera to document his feelings towards his new city, a city that was to become his spiritual home no matter where he lived. I have the same feeling towards Paris. One day I will live there, wander the streets and continue to take photographs of this beloved city. “Kertész used his camera to document his explorations of Paris in his first days there. During long walks, he photographed activity along the Seine, overlooked scenes behind buildings, and the tents at local fairgrounds. With few expectations to satisfy beyond his own ambition, the artist was free to explore and record, refining his eye as he composed his images in the camera and as he reviewed and printed them as cartes postales.”

In this posting there are only four external scenes of Paris including two crisp Modernist photographs of the same homeless man with street posters; an enigmatic image of the Eiffel Tower; and the highlight for me, an atmospheric high angle view of a fairground. Other highlights in the posting include Kertész’s vibrant, expressive Satiric Dancer (1927, below); his modern, simple and unpretentious Fork (1928, below) and Mondrian’s Pipe and Glasses (1926, below) so clearly and crisply observed; and the most famous of all his photographs, the serene and beautiful Chez Mondrian (1926, below) in which Kertész said “Everything was there before me.” It only required his awareness and recognition of the scene to tell the story. My particular favourite is Kertész’s seeming homage to Eugène Atget, Latin Quarter (Étienne Beöthy’s Cousin) (1927, below) … an Atget interior and perspicacious portrait combined.

The key is to see things clearly and intelligently in order to express the story you want to tell with feeling and empathy. As Kertész tells it, to have enough technique to then forget about it. “I believe you should be a perfect technician in order to express yourself as you wish and then you can forget about the technique.” He insightfully observes, “You have beautiful calligraphy, but it’s up to you what you write with it.”

It’s about the story you tell and not (just) about technique and an empty beauty (as with much contemporary photography).

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the High Museum of Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Kertész was an expert printer and a precise technician, even as he strove for spontaneity and naturalism in his imagery and, with the exception of cropping, was apparently averse to manipulations such as experimental darkroom techniques and photomontage.8 He was opinionated on the subject of how his photographs should be made: in 1923, still struggling for recognition, he refused to reprint in bromoil an image he had submitted to a competition, which cost him the silver medal. He later said of the episode, “I have always known that photography can only be photography.”9 In a letter from 1926 Jenö complimented his work, calling it technically impeccable, but Kertész also believed that technical perfection by itself “overshines the boot,” explaining, “You have beautiful calligraphy, but it’s up to you what you write with it.”10 In an interview near the end of his life Kertész said, “Technique is only the minimum in photography. It’s what one must start with. I believe you should be a perfect technician in order to express yourself as you wish and then you can forget about the technique.”11

Nancy Reinhold. “Exhibition in a Pocket: The Cartes Postales of André Kertész,” in Mitra Abbaspour, Lee Ann Daffner, and Maria Morris Hambourg (eds.,). Object: Photo. Modern Photographs: The Thomas Walther Collection 1909-1949. An Online Project of The Museum of Modern Art. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2014.

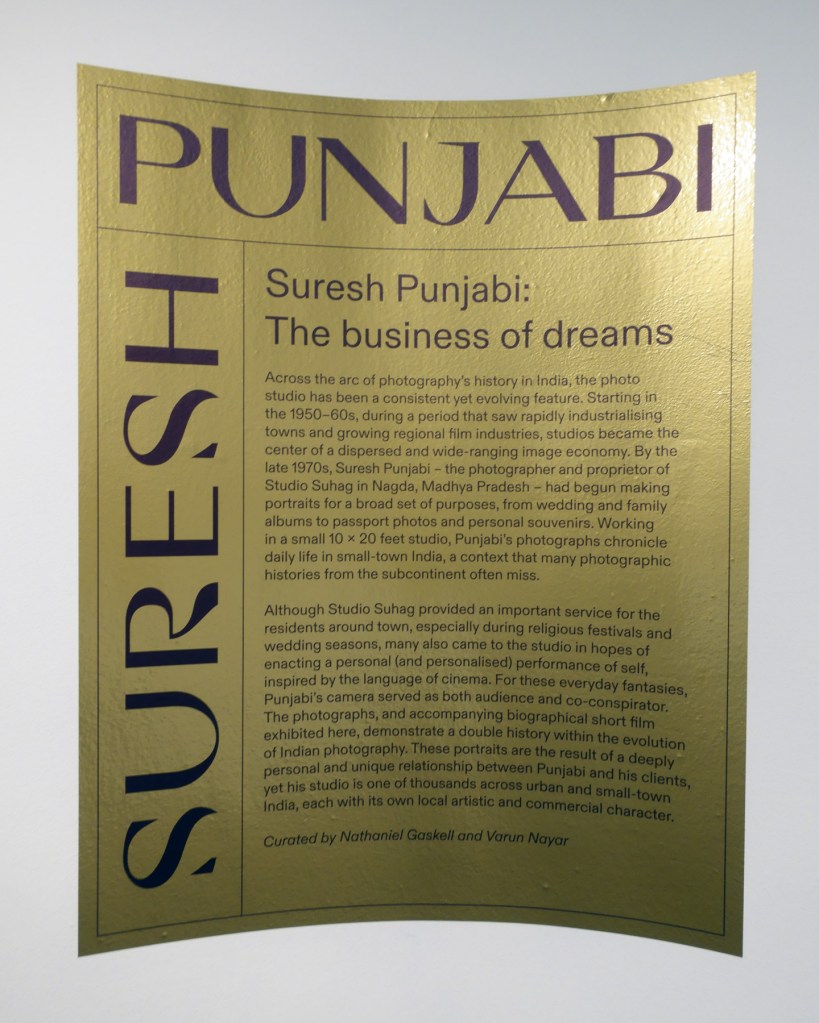

In 1925, photographer André Kertész (American, born Hungary, 1894-1985) arrived in Paris with little more than a camera and meager savings. Over the next three years, the young artist carved out a photographic practice that allowed him to move among the realms of amateur and professional, photojournalist and avant-garde artist, diarist and documentarian. By the end of 1928, he had achieved widespread recognition, emerging as a major figure in modern art photography alongside such figures as Man Ray and Berenice Abbott. During this three-year period, he chose to print most of his photographs on carte postale, or postcard paper. Although this choice may have initially been born of economy and convenience, he turned the popular format toward artistic ends, rigorously composing new images in the darkroom and making a new kind of photographic object.

Postcards from Paris is the first exhibition to bring together Kertész’s rare carte postale prints. These now-iconic works offer new insight into his early, experimental years and reveal the importance of Paris as a vibrant meeting ground for international artists, who drew inspiration from each other to create new, modern ways of seeing and representing the world.

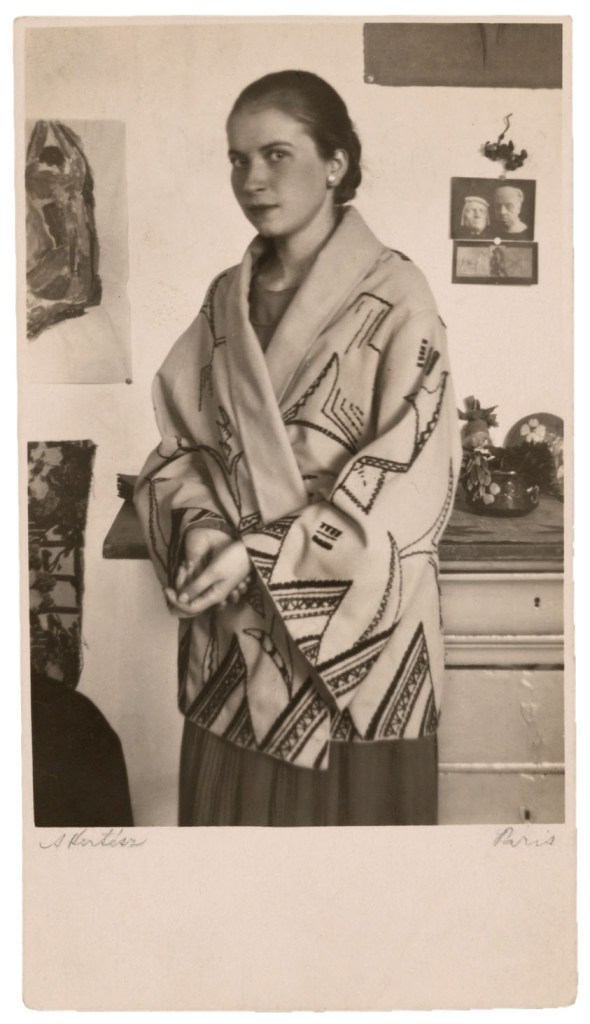

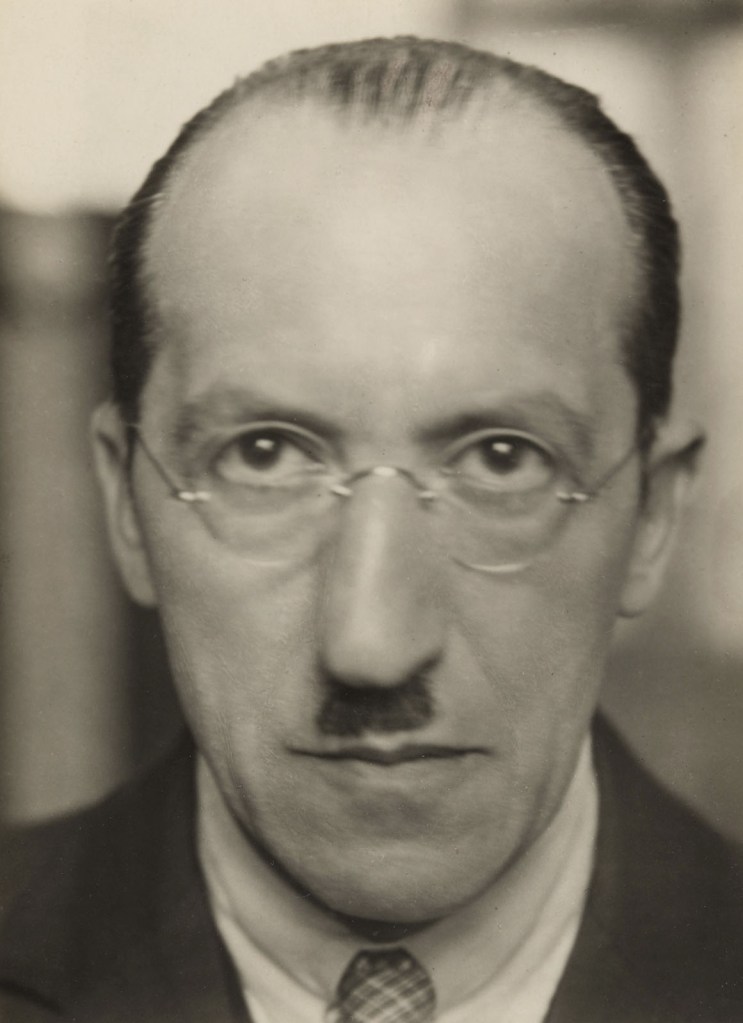

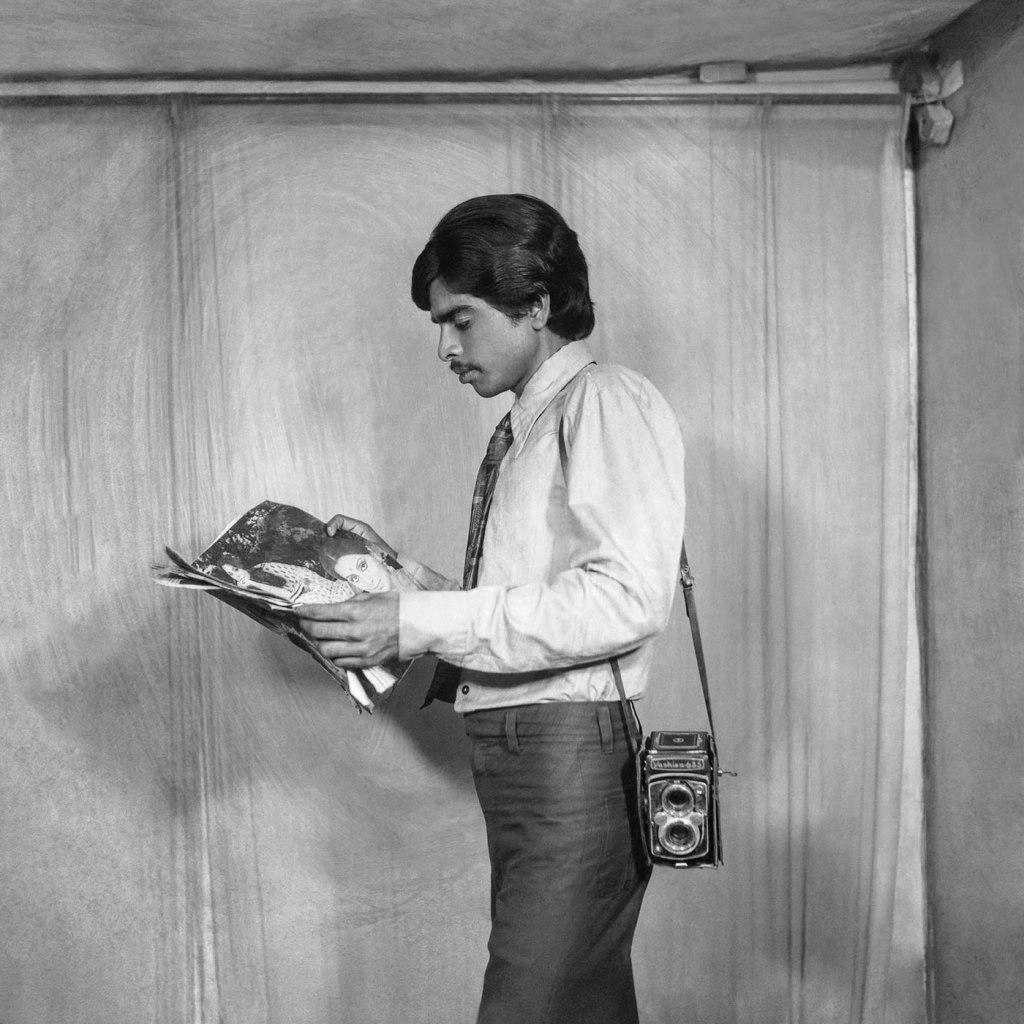

André Kertész (Hungarian, 1894-1985)

Self-Portrait

July 1927

Gelatin silver print on carte postale paper

Estate of André Kertész, courtesy of Stephen Bulger Gallery, Toronto

Kertész sent this print to his brother Jenő with the inscription, “To my younger brother, Bandi.” (“Bandi” was André’s family nickname.) Although the photographer frequently mailed his carte postale prints to family and friends, he sent them in envelopes rather than affixing a stamp to the back and posting them directly in the manner the manufacturers intended. Moreover, rather than signing them on the back, as one would a postcard, he almost always signed them on the front, like a finished work of art. The paper’s utilitarian format nonetheless may have inspired him to circulate his pictures through the mail and use them to communicate with his family.

A Portrait of the Artist

With this self-portrait, André Kertész declared himself a cosmopolitan artist. He appears surrounded by objects that refer to both his birthplace of Hungary and his new home in Paris.

Kertész printed this image on postcard paper and sent it home to his family. Rather than writing on the back of the card and adding postage, he mailed it safely in an envelope as proof that he was surviving and even thriving in his new city and still resolved to become a photographer.

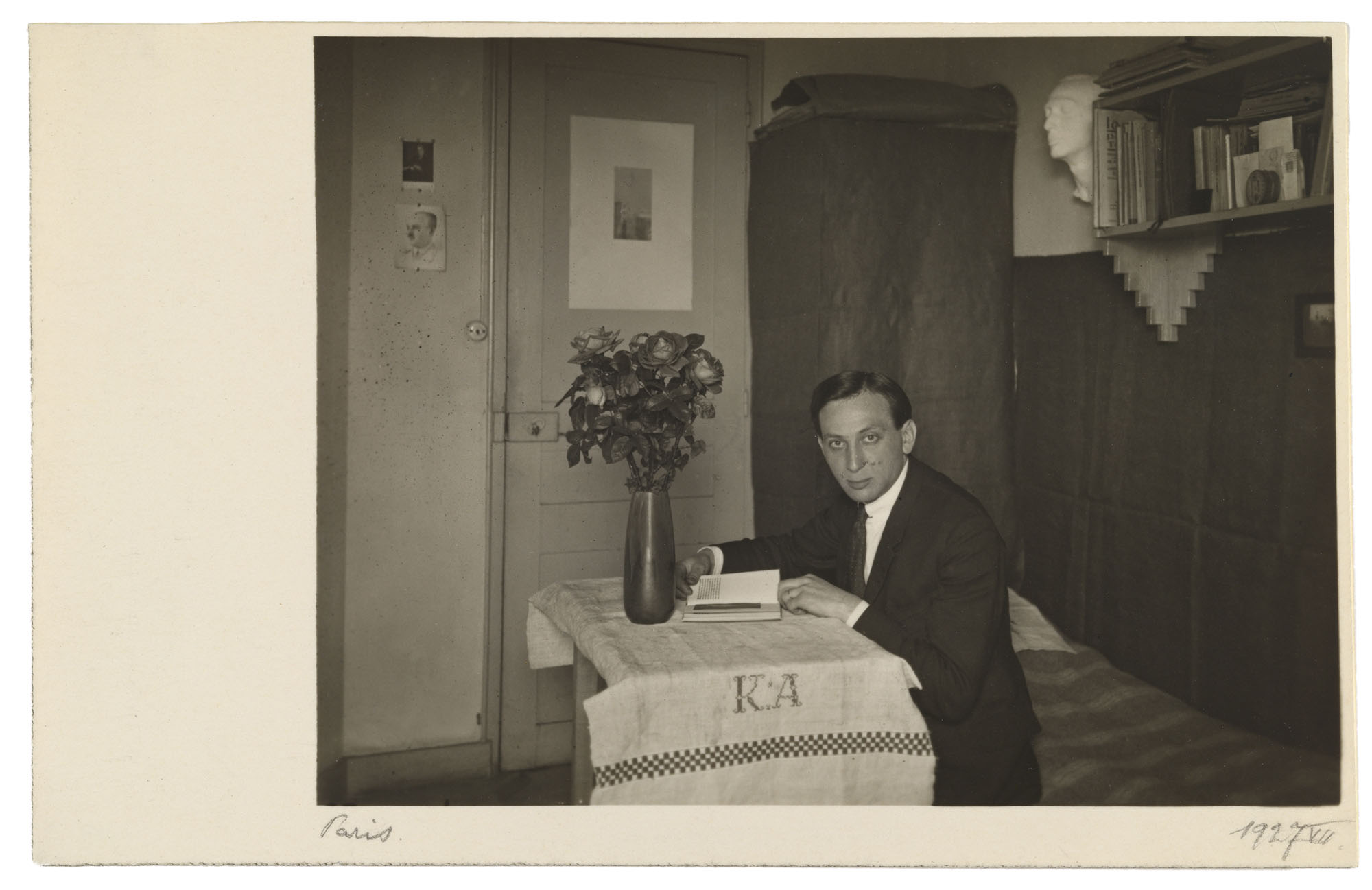

From Immigrant to Insider

Kertész arrived in Paris in fall 1925 with little other than his cameras and some savings. His first years were filled with experimentation as he learned from a community of other expatriate artists. Kertész hung a portrait of his mother on the door to his small apartment [see below]. Made at a professional studio in Budapest, it was printed on carte postale paper, the same kind he used to make his self-portrait and most of his work in Paris.

A Memento of Home

Kertész arranged himself at a table covered by a cloth from Hungary embroidered by his mother with the initials K.A., for Kertész Andor, his name before he adopted the French “André.”

Kertész’s apartment also featured a life mask, a plaster cast of his own face, which he kept as he moved from Hungary to Paris and later to New York. It appears as an alter ego – a strategy of doubling that he used often in his photographs.

Kertész presented himself as cultured and educated, with an overflowing bookshelf behind him and an open book before him on the table. Although he spoke three languages, Kertész later said, “My English is bad. My French is bad. Photography is my only language.”

Hanging prominently above the artist’s head is his take on an iconic Parisian landmark, the Eiffel Tower [see below]. One of the earliest photographs he made in Paris, this image – enlarged for the wall – symbolises his new home.

Romer Erzs Studio (Hungarian) Budapest

Kertesz’s Mother

Before 1925

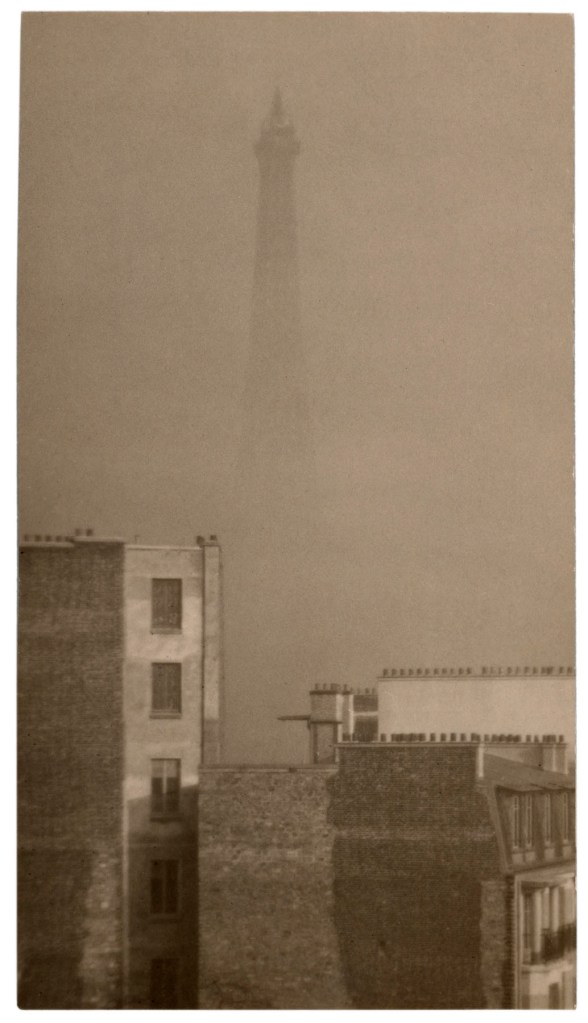

André Kertész (Hungarian, 1894-1985)

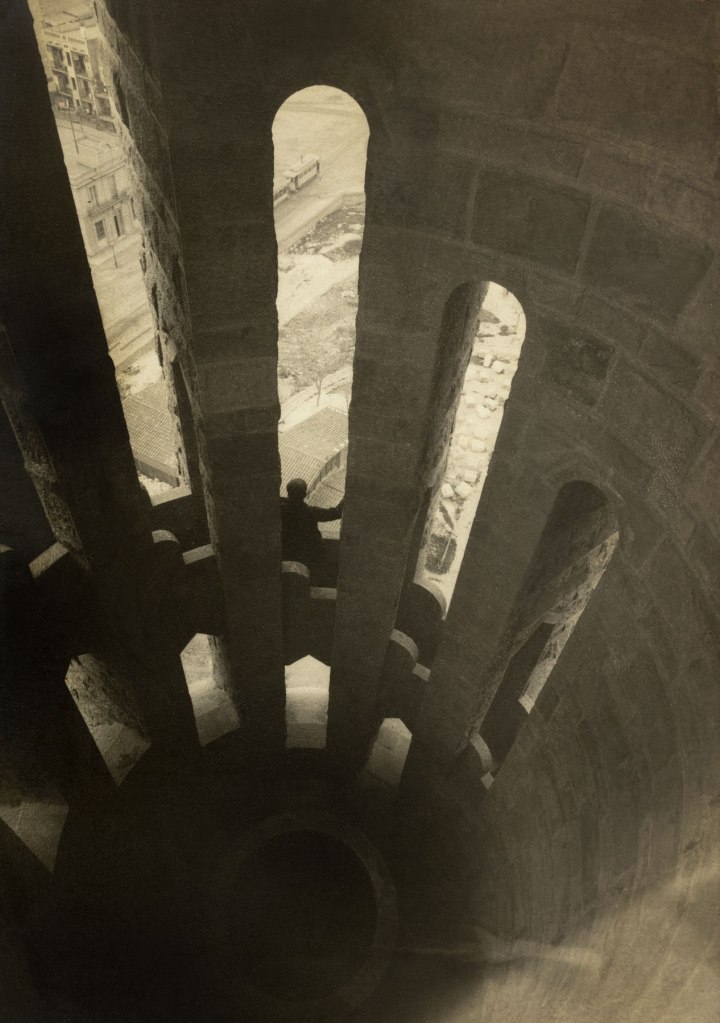

Eiffel Tower

1925

Gelatin silver print on carte postale paper

Family Holdings of Nicholas and Susan Pritzker

Among Kertész’s earliest Parisian photographs is this view of the Eiffel Tower [see on the wall behind the artist in his Self-Portrait 1927, above]. Taken from a window in the apartment of a Hungarian architect, the moody image is less a typical tourist snapshot than a specific vision of the landmark captured from the perspective of a local. In a self-portrait, an enlarged version of this work can be seen hanging prominently on the wall of the photographer’s apartment – a decorating choice emblematic, perhaps, of his immersion in his adopted city. Kertész used his camera to document his explorations of Paris in his first days there. During long walks, he photographed activity along the Seine, overlooked scenes behind buildings, and the tents at local fairgrounds. With few expectations to satisfy beyond his own ambition, the artist was free to explore and record, refining his eye as he composed his images in the camera and as he reviewed and printed them as cartes postales. He maintained decades after he left the city, “Paris became my home and it still is. Paris accepted me as an artist just as it accepted any artist, painter, or sculptor. I was understood there.”

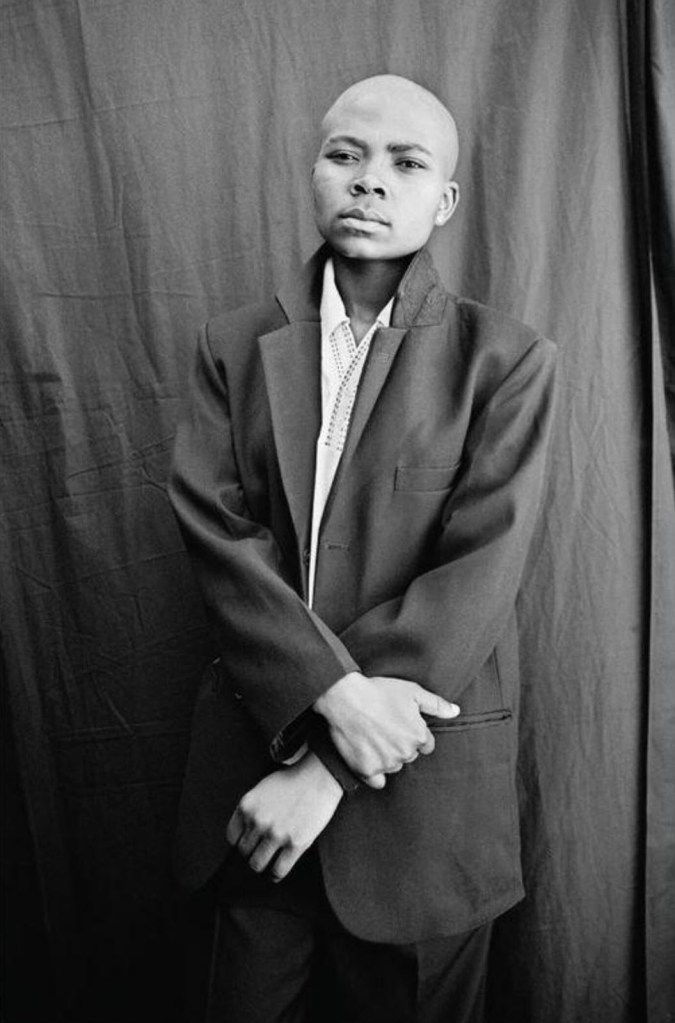

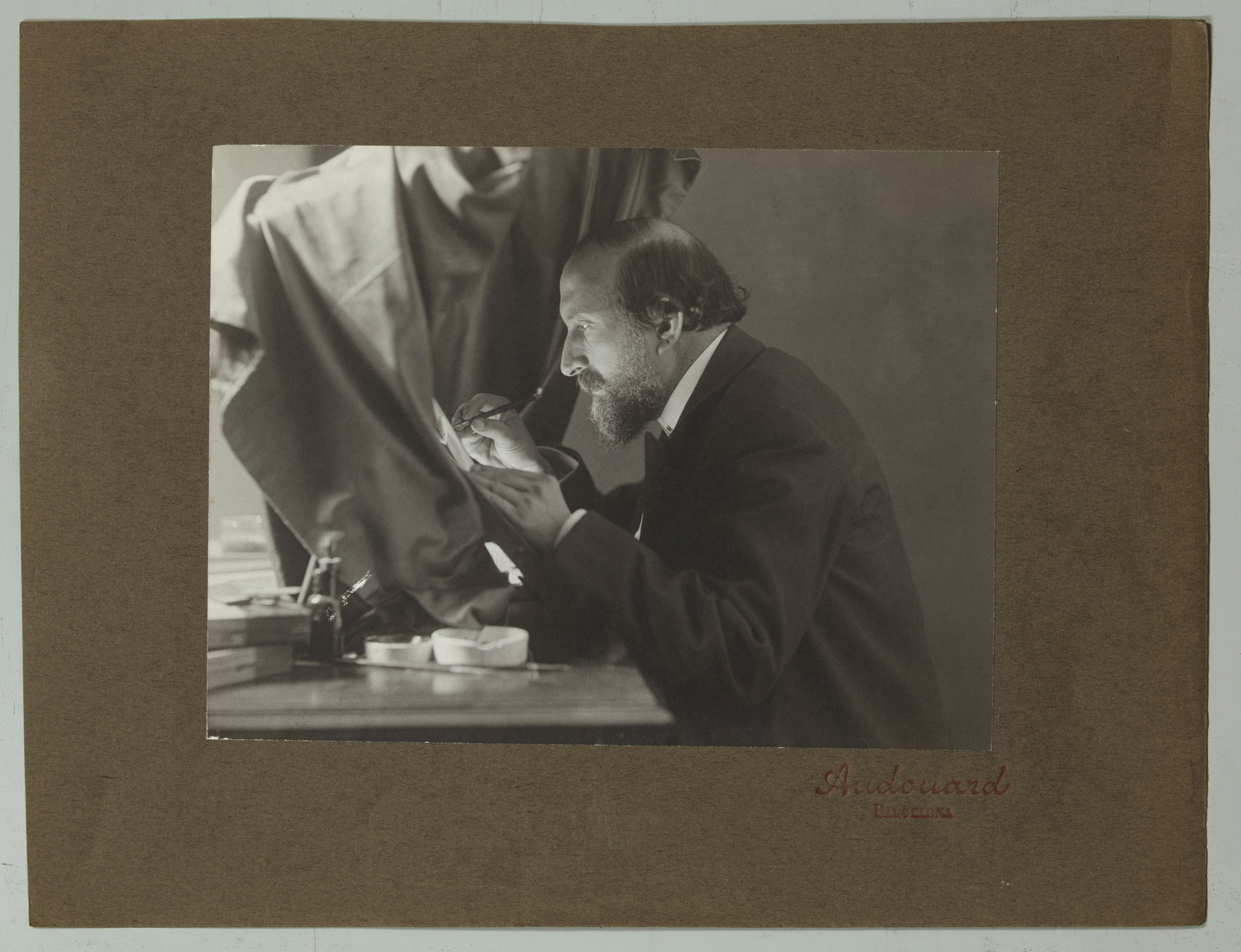

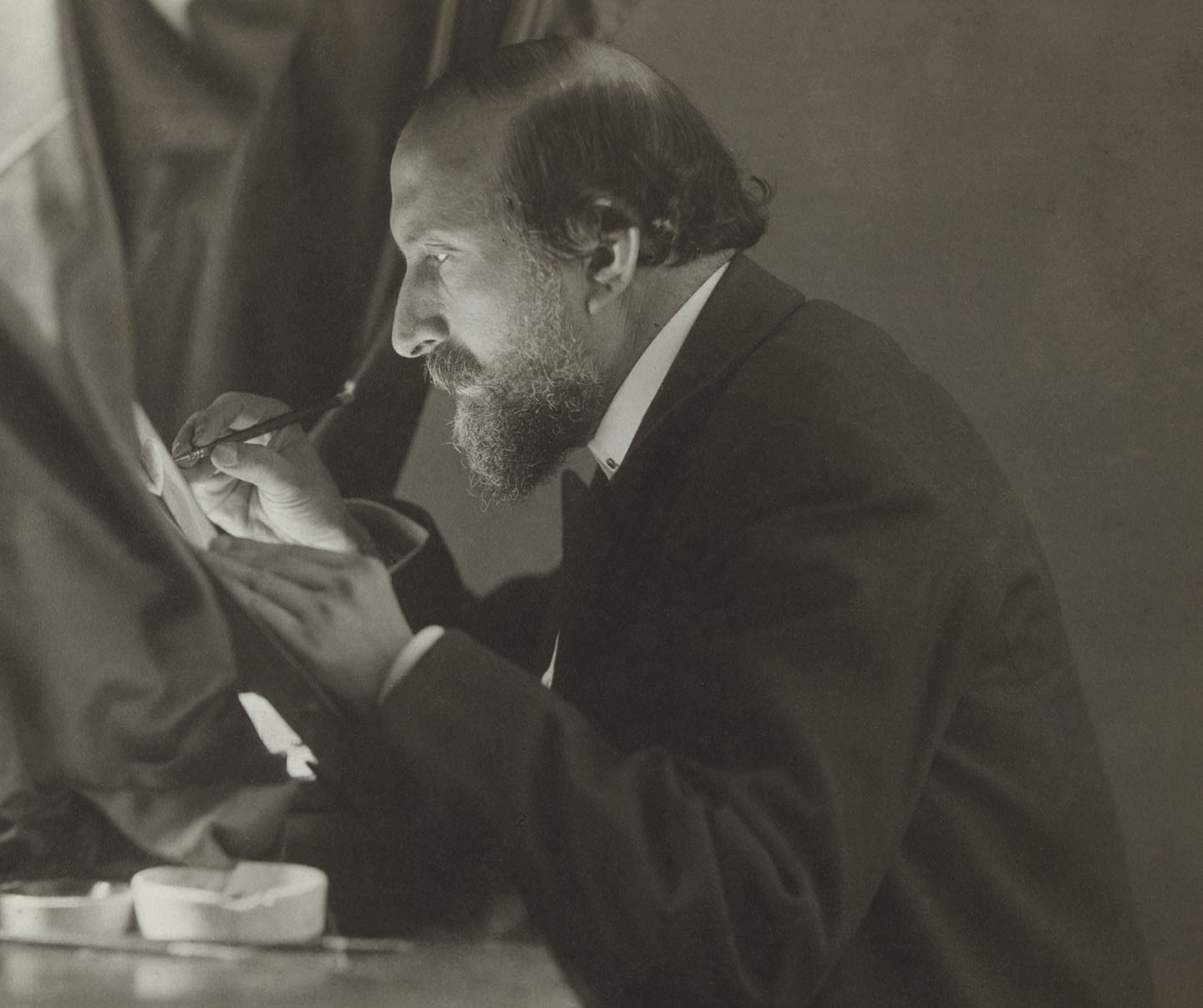

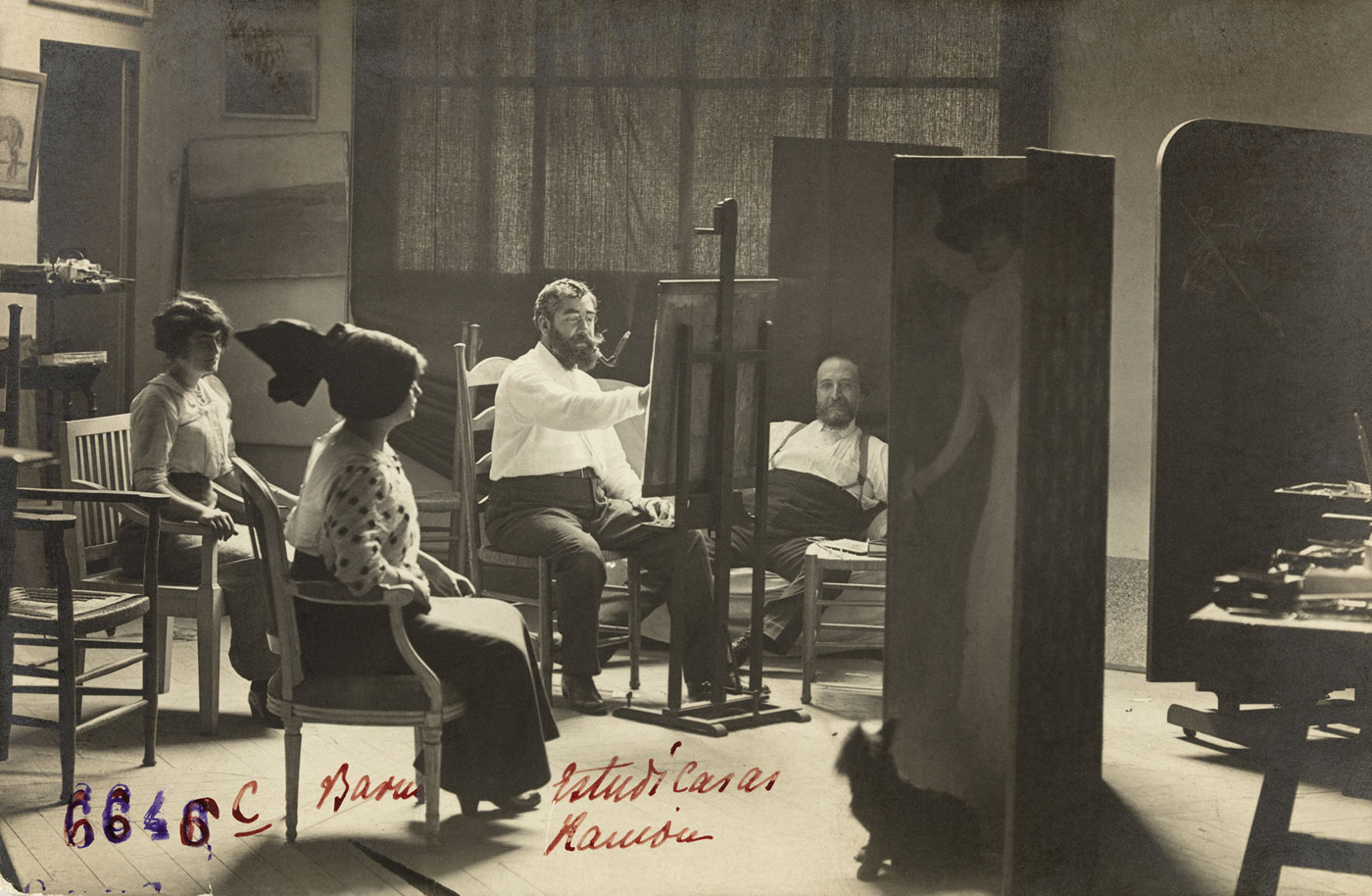

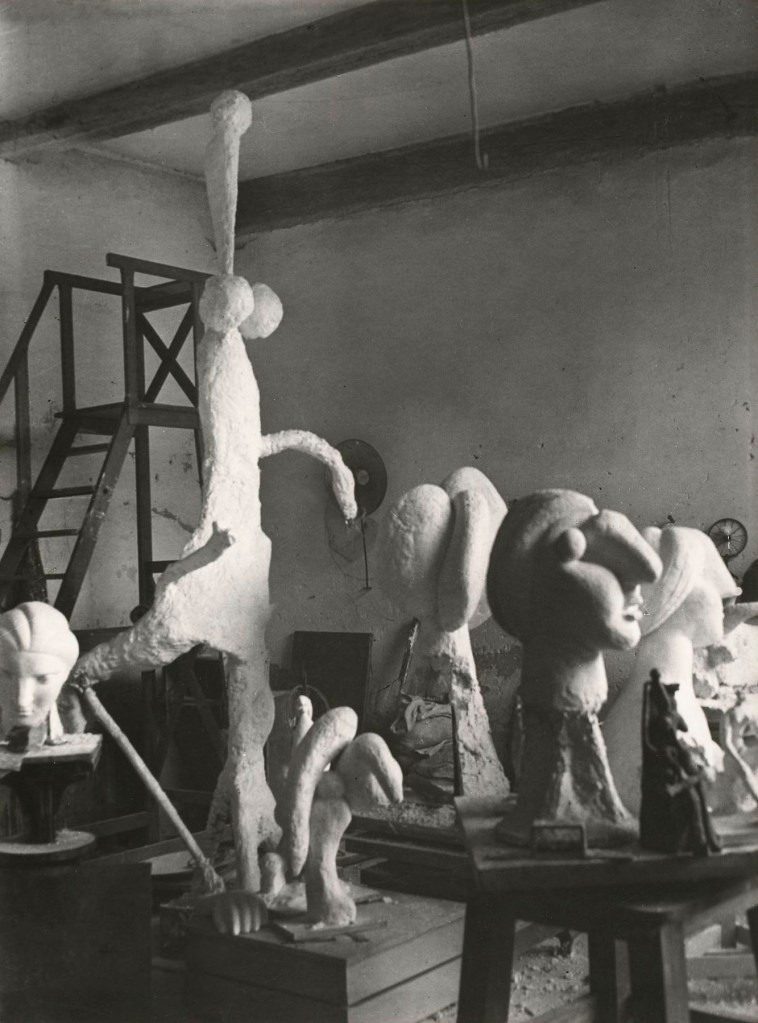

André Kertész (Hungarian, 1894-1985)

József Csáky

1926

Gelatin silver print on carte postale paper

Image: 10.9 × 7.2cm

Card: 12.9 × 7.5cm

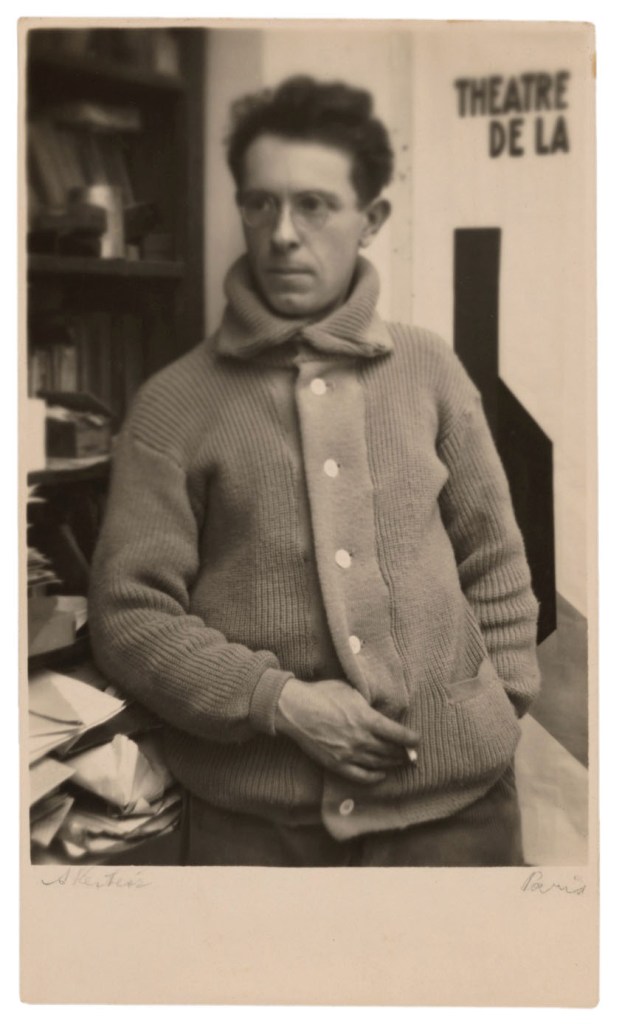

Joseph Csaky (also written Josef Csàky, Csáky József, József Csáky and Joseph Alexandre Czaky) (18 March 1888 – 1 May 1971) was a Hungarian avant-garde artist, sculptor, and graphic artist, best known for his early participation in the Cubist movement as a sculptor. Csaky was one of the first sculptors in Paris to apply the principles of pictorial Cubism to his art. A pioneer of modern sculpture, Csaky is among the most important sculptors of the early 20th century. He was an active member of the Section d’Or group between 1911 and 1914, and closely associated with Crystal Cubism, Purism, De Stijl, Abstract art, and Art Deco throughout the 1920s and 1930s.

Csaky fought alongside French soldiers during World War I and in 1922 became a naturalised French citizen. He was a founding member of l’Union des Artistes modernes (UAM) in 1929. During World War II, Csaky joined forces with the French underground movement (la Résistance) in Valençay. In the late 1920s, he collaborated with some other artists in designing furniture and other decorative pieces, including elements of the Studio House of the fashion designer Jacques Doucet.

After 1928, Csaky moved away from Cubism into a more figurative or representational style for nearly thirty years. He exhibited internationally across Europe, but some of his pioneering artistic innovation was forgotten. His work today is primarily held by French and Hungarian institutions, as well as museums, galleries and private collections both in France and abroad. …

Legacy

Joseph Csaky contributed substantially to the development of modern sculpture, both as a pioneer in applying Cubism to sculpture, and as a leading figure in nonrepresentational art of the 1920s.

After fighting alongside the French underground movement against the Nazis during World War II, Csaky faced many difficulties: health issues, family problems and a lack of work-related commissions. Unlike many of his friends, whose names became widely known, Csaky was appreciated by fewer people (but they notably included art collectors, art historians and museum curators).

“Today, however,” writes Edith Balas, “in a postmodernist atmosphere, those aspects of his art that made Csáky unacceptable to the more advanced modernists are readily accepted as valid and interesting. The time has come to give Csáky his rightful place in the ranks of the avant-garde, based on an analysis of his artistic innovations and accomplishments.”

Text and more information on the artist can be found on his Wikipedia entry

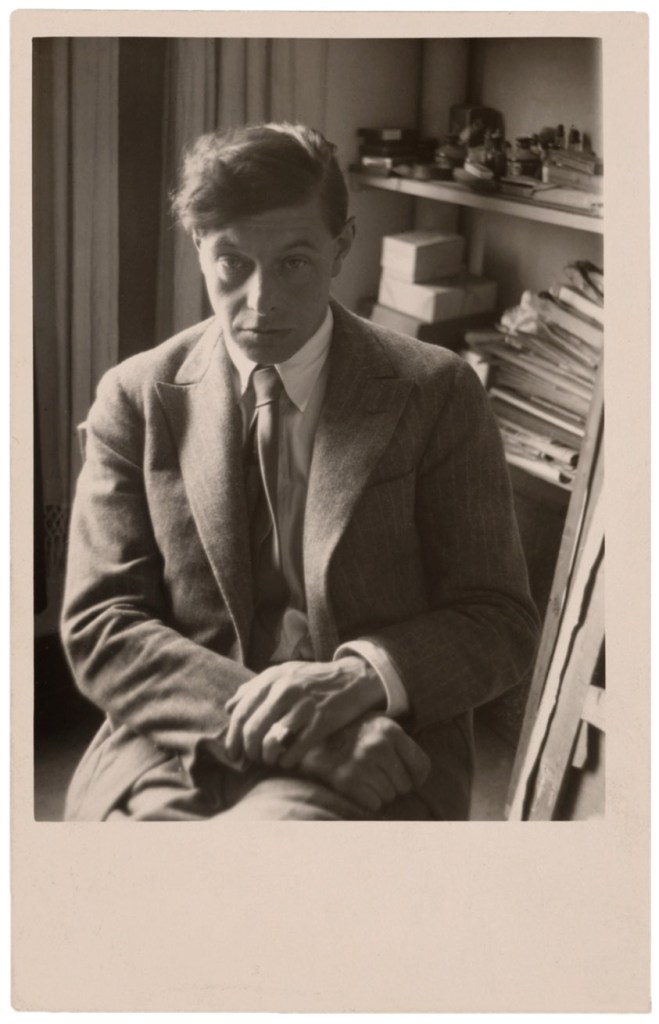

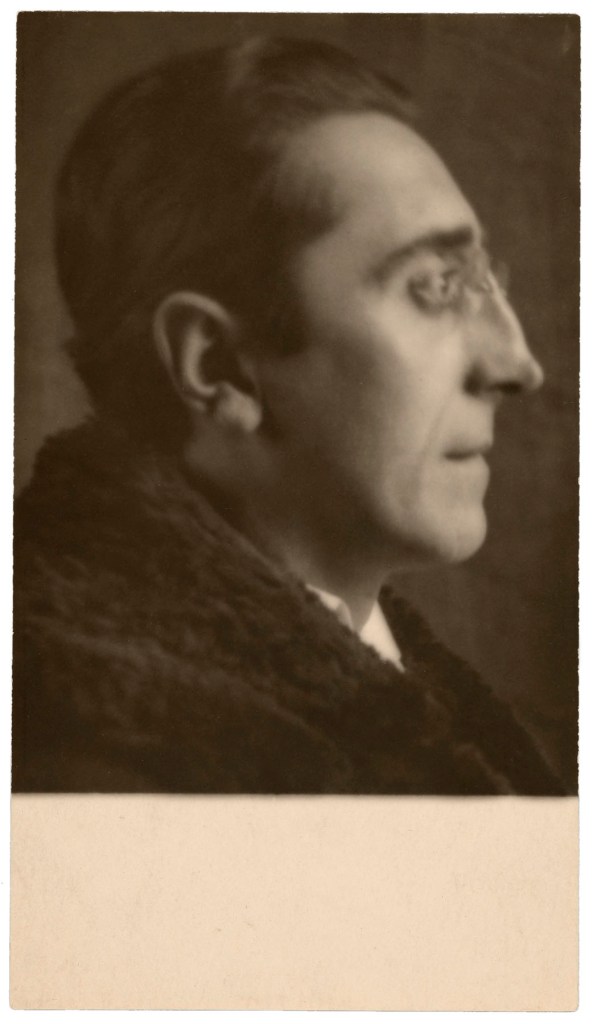

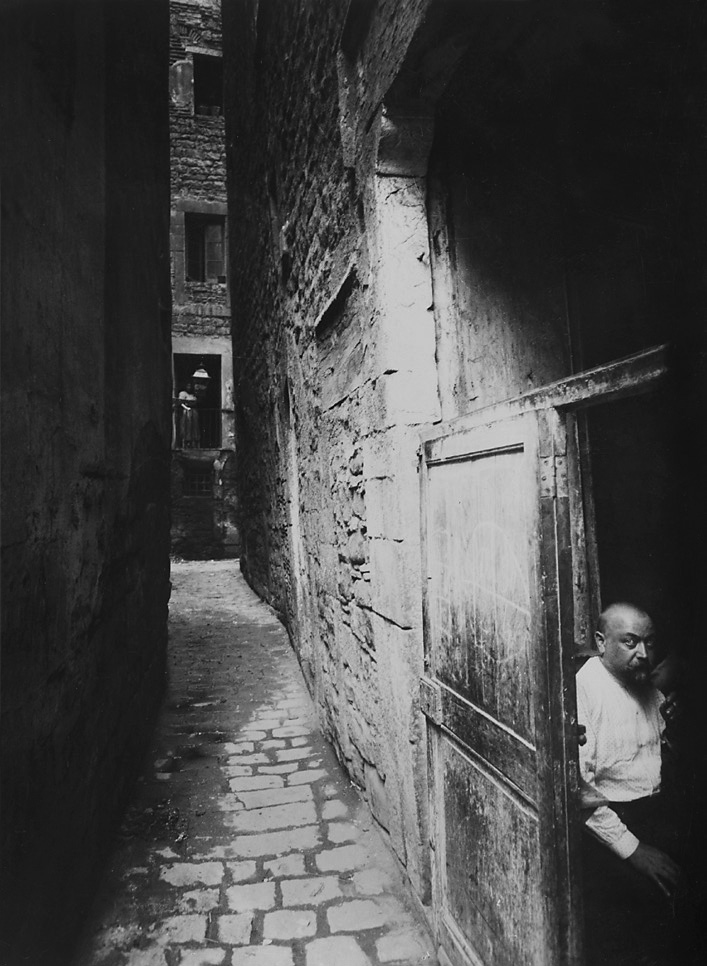

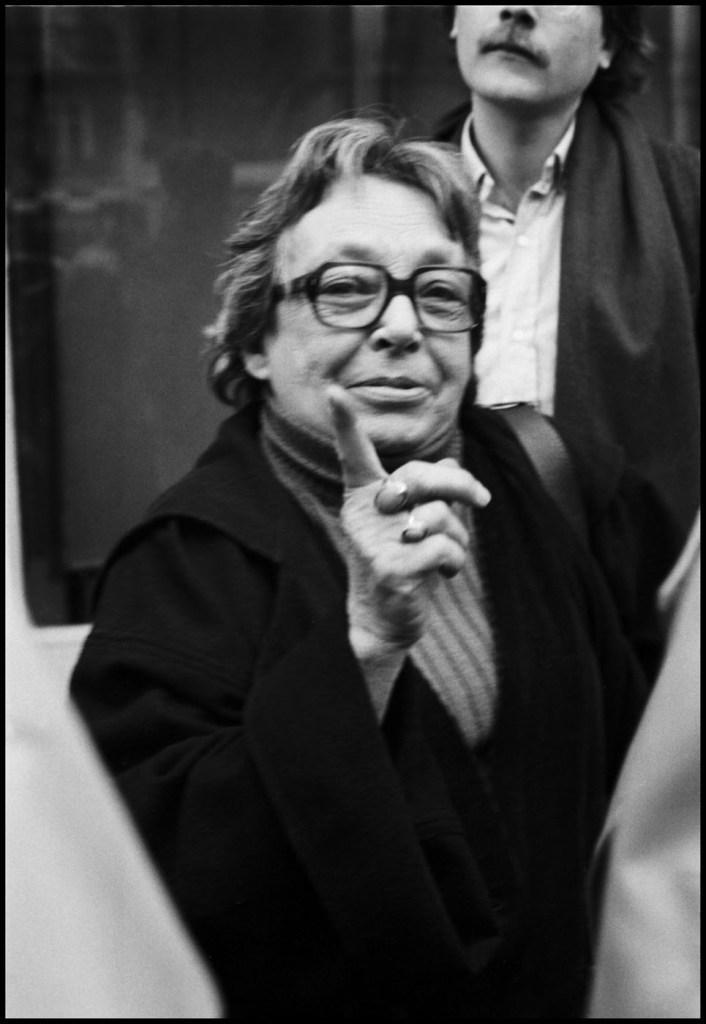

André Kertész (Hungarian, 1894-1985)

Pierre Mac Orlan

1927

Gelatin silver print on carte postale paper

Unmarked recto; inscribed verso, on paper, along left edge, sideways, in graphite: “6” [one arrow extending from the left and the right side, running along the left edge]”; verso, upper centre, sideways, in graphite: “Pierre McOxlan / 1927.”; verso, lower centre, sideways, in graphite: “142”; printed verso, along right edge, sideways, in black ink: “CARTE POSTALE / Correspondance Adresse”

Image: 10.8 × 7.8cm

Card: 11.1 × 18.1cm

Pierre Mac Orlan, sometimes written MacOrlan (born Pierre Dumarchey, February 26, 1882 – June 27, 1970), was a French novelist and songwriter. His novel Quai des Brumes was the source for Marcel Carné’s 1938 film of the same name, starring Jean Gabin. He was also a prolific writer of chansons, many of which were recorded and popularized by French singers such as Juliette Gréco, Monique Morelli, Catherine Sauvage, and Germaine Montero.

Text from the Wikipedia website

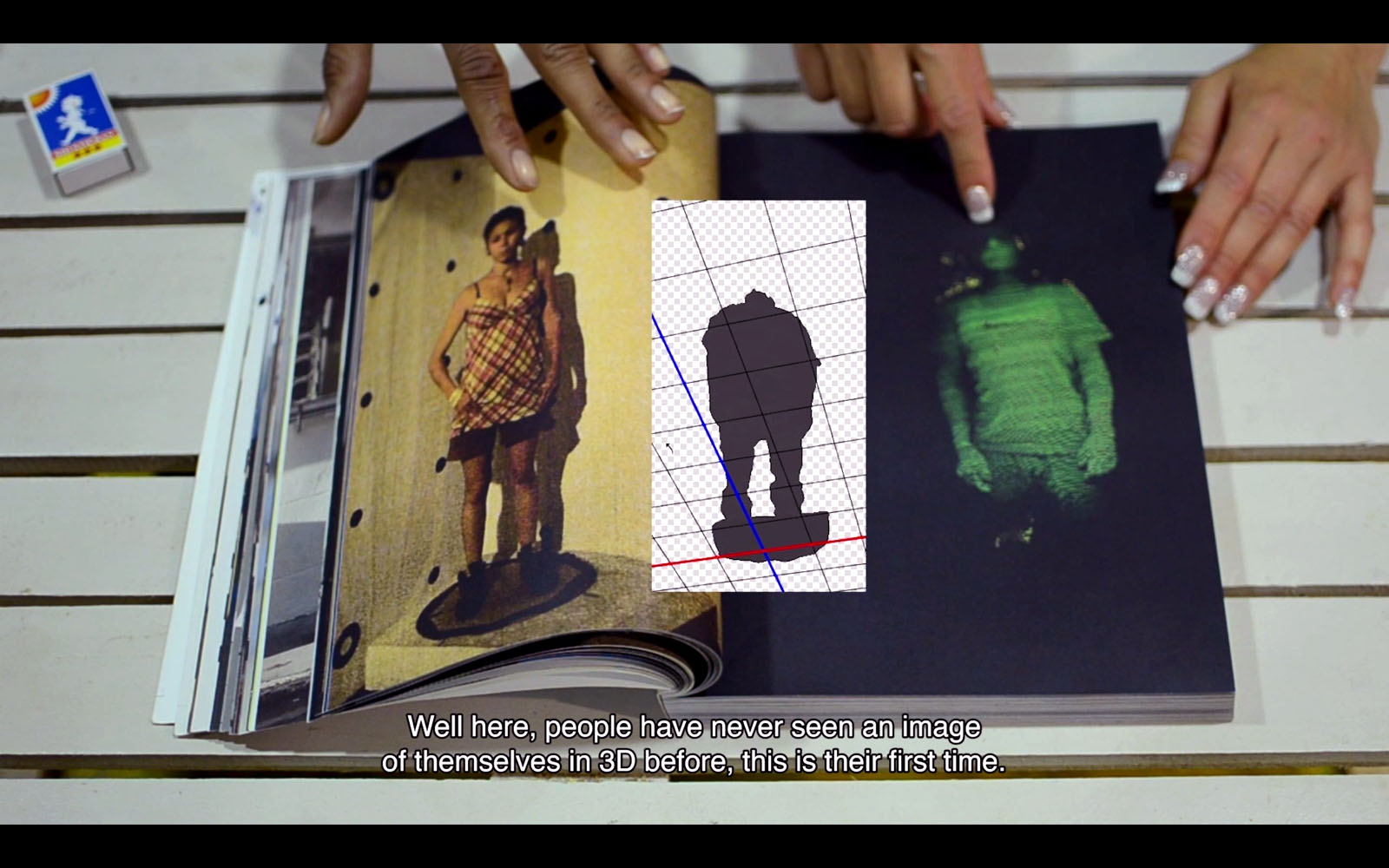

In 1925, photographer André Kertész (American, born Hungary, 1894-1985) arrived in Paris with little more than a camera and meager savings. Over the next three years, the young artist carved out a photographic practice that allowed him to move among the realms of amateur and professional, photojournalist and avant-garde artist, diarist and documentarian. This spring, the High Museum of Art will present “André Kertész: Postcards from Paris” (Feb. 18-May 29, 2022), the first exhibition to focus exclusively on his rare cartes postales, precise prints on inexpensive yet lush postcard paper.

Organised by the Art Institute of Chicago, “Postcards from Paris” brings together more than 100 of these prints from collections across Europe and North America and offers insight into Kertész’s early experimental years, during which he produced some of his now-iconic images and charted a new path for modern photography. The exhibition will also reveal the importance of Paris as a vibrant meeting ground for international artists, who drew inspiration from each other to create fresh ways of seeing and representing the world.

“We are delighted for the opportunity to share these rare prints by one of the most intriguing and groundbreaking photographers of the 20th century,” said Rand Suffolk, the High’s Nancy and Holcombe T. Green, Jr., director.

“Kertész was one of the most consequential photographers of the 20th century, and this exhibition focuses on his most innovative and prolific period,” said Gregory Harris, the High’s Donald and Marilyn Keough Family curator of photography. “He was a pioneer who mastered intimate portraiture, dynamic street photography and precise interior studies, moving effortlessly between his personal and commercial work. These distinctive carte postale prints are some of the finest examples of his iconic early photographs.”

Kertész moved to Paris due to the limited opportunities in his native Hungary, and by the end of 1928, he was contributing regularly to magazines and exhibiting his work internationally alongside well-known artists such as Man Ray and Berenice Abbott. The three years between his arrival in Paris and his emergence as a major figure in modern art photography marked a period of dedicated experimentation and exploration for Kertész. During that time, he produced most of his prints on carte postale paper, turning this popular format toward artistic ends, rigorously composing images in the darkroom and making a new kind of photographic object. “Postcards from Paris” pays careful attention to the works as both images and objects, emphasising their experimental composition and daringly cropped formats.

The exhibition includes vintage prints of images that would come to define Kertész’s career, including “Chez Mondrian” (1926), an exquisitely composed scene of Piet Mondrian’s studio emphasising the painter’s restrained geometry; “Satiric Dancer” (1927), uniting photography with dance and sculpture by fellow Hungarians in Paris; and “Fork” (1928), declaring that photography could transform even the humblest of objects into art.

“Postcards from Paris” is curated by Elizabeth Siegel, curator of photography and media at the Art Institute of Chicago. The exhibition will be presented in the Lucinda Weil Bunnen Photography Galleries on the Lower Level of the High’s Wieland Pavilion.

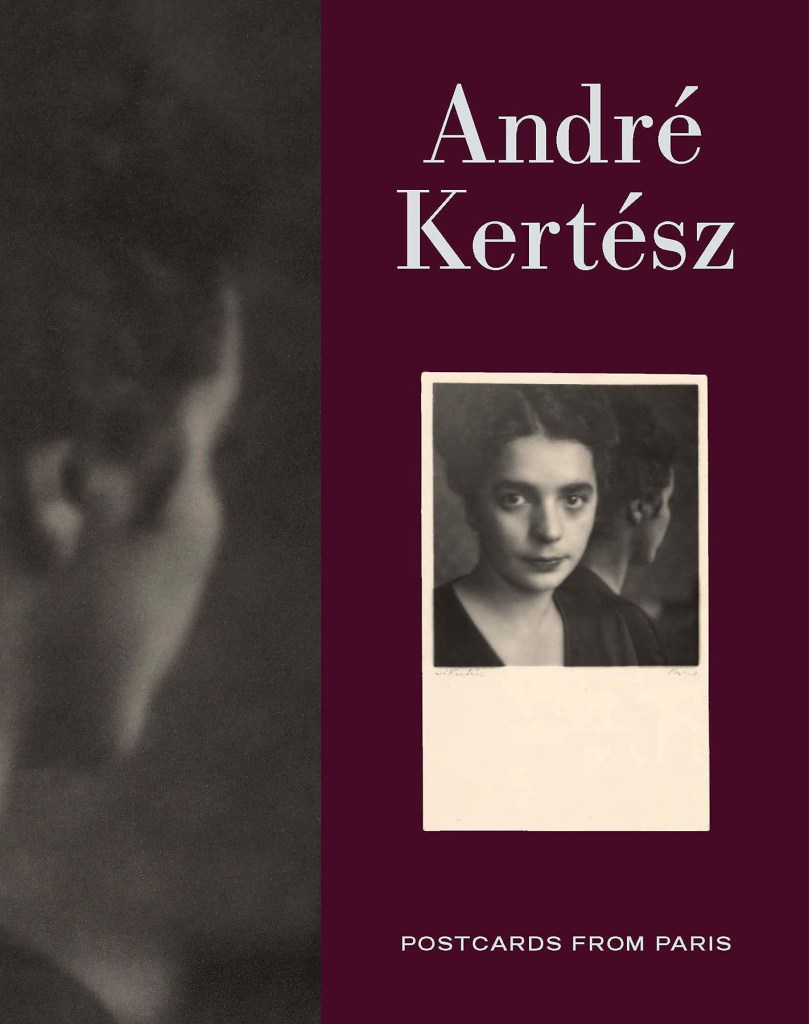

Exhibition Catalogue

The exhibition catalogue unites all of André Kertész’s known carte postale prints, including portraits, views of Paris, careful studio scenes and exquisitely simple still lifes. Essays shed new light on the artist’s most acclaimed images; themes of materiality, exile and communication; his illustrious and bohemian social circle; and the changing identity of art photography. The book’s design reflects the spirit of 1920s Paris while underscoring the modernity of the catalogue’s more than 250 illustrated works. It was selected as Photography Catalogue of the Year for Aperture’s 2021 PhotoBook Awards Shortlist.

“André Kertész: Postcards from Paris” is organised by the Art Institute of Chicago.

Press release from the High Museum of Art

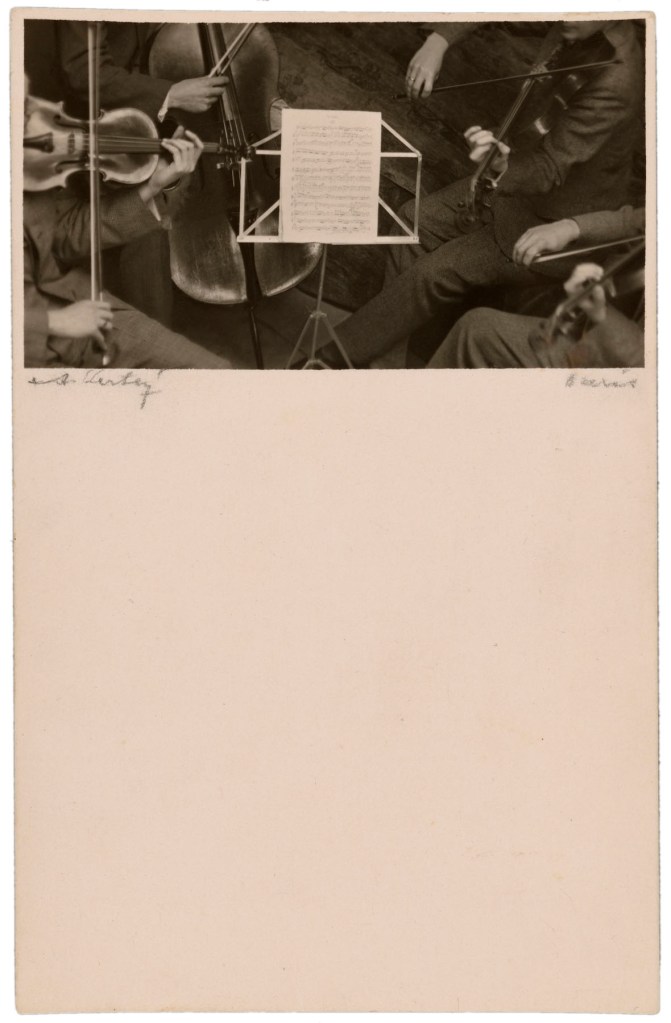

André Kertész (Hungarian, 1894-1985)

Quartet

1926

Gelatin silver print on carte postale paper

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Nicholas and Susan Pritzker

Kertész often radically revised the images he captured with the camera. He produced all of his cartes postales as contact prints by placing the negative in contact with the postcard paper during exposure instead of using an enlarger. He made this photograph of Feri Roth’s string quartet by masking the negative (blocking out certain sections with tape) before printing to highlight just a small section of a publicity picture the group had commissioned. By cropping out the players’ heads to concentrate on their angled bows and the lines of the music stand, Kertész abstracted the idea of a quartet to hands, instruments, and a white rectangle of sheet music. He left a dramatic ratio of the postcard paper blank to emphasise the image’s unusual placement at the top of the support. He then trimmed the card to custom proportions, as he did with nearly all his cartes postales, underlining the interplay between image and paper as an indispensable component of the artwork. Kertész saw these bold interventions as a way to distinguish his art from his budding commercial career: the whole image was for them, he later said in an interview; the cropped print was for him.

A Close Look at André Kertész’s Quartet

André Kertész’s image of the Feri Roth string quartet is tiny, but it packs a wallop.

Four musicians gather to play, with four sets of hands holding their bows at different angles. Kertész (American, born Hungary, 1894-1985) zooms in to concentrate on the lines of the bows and the music stand, resulting in a dynamic composition that abstracts the idea of a quartet to hands, instruments, and a white rectangle of sheet music.

Printed on intimately scaled carte postale (postcard) paper, this print could have been held in the hand, sent home to his family in Hungary, or passed along to a widening circle of international artist friends at the café tables Kertész frequented in 1920s Paris. In its subject and in its form, Quartet represents a key moment in the photographer’s career as he carved out a new, modern photographic practice in his adopted city.

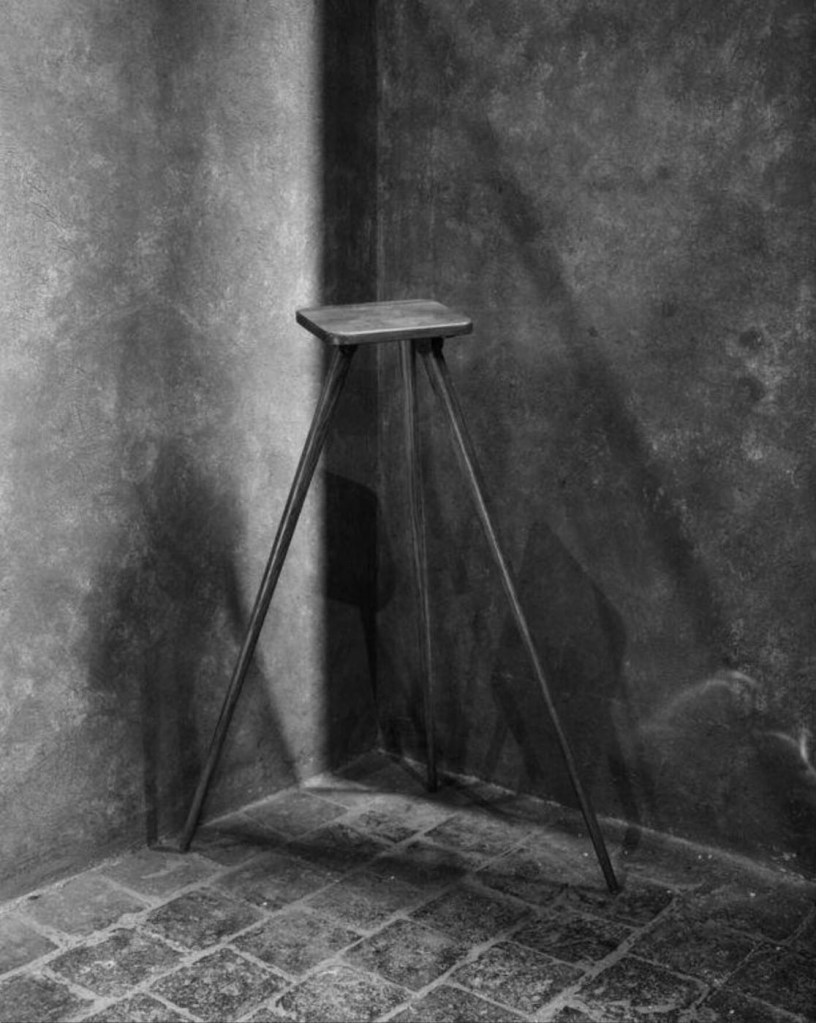

The photograph began as a commission for his friend Feri Roth, a Hungarian musician whose renowned string quartet toured in Europe throughout the 1920s and was in need of publicity photographs. Kertész stood on a chair or stool to get an elevated position (a favourite technique) and made a wide picture that showed the complete scene.

The camera Kertész typically used produced negatives about the same size as the carte postale paper, which allowed for easy contact printing – meaning he placed the negative in direct contact with the postcard paper during exposure instead of using an enlarger. For this image, however, Kertész employed a larger camera, which allowed him to make some dramatic changes in the darkroom as he made his contact print: he cropped out all of the players’ heads and tilted the image slightly to orient it around the geometrical forms of the music stand. The photographer saw these interventions in the negative as a way to distinguish his art from his budding commercial career – the whole image was for them, he later said in an interview; the cropped print was for him.

Kertész’s approach in this print was typical of his work in his early years in Paris. He often made creative revisions in the darkroom, where he could produce a more refined composition by cropping out selected portions of the image. As was his habit with nearly all his carte postale prints, he precisely trimmed the card to custom proportions and carefully signed it on the front. Here, however, Kertész took an even more dramatic step in the print: he left most of the expanse of the postcard paper as empty white space, further emphasising the image’s cropping and its unusual placement at the top of the card. All of these actions elevated these humble materials of mass culture and underlined the interplay between image and paper as an indispensable component of the artwork.

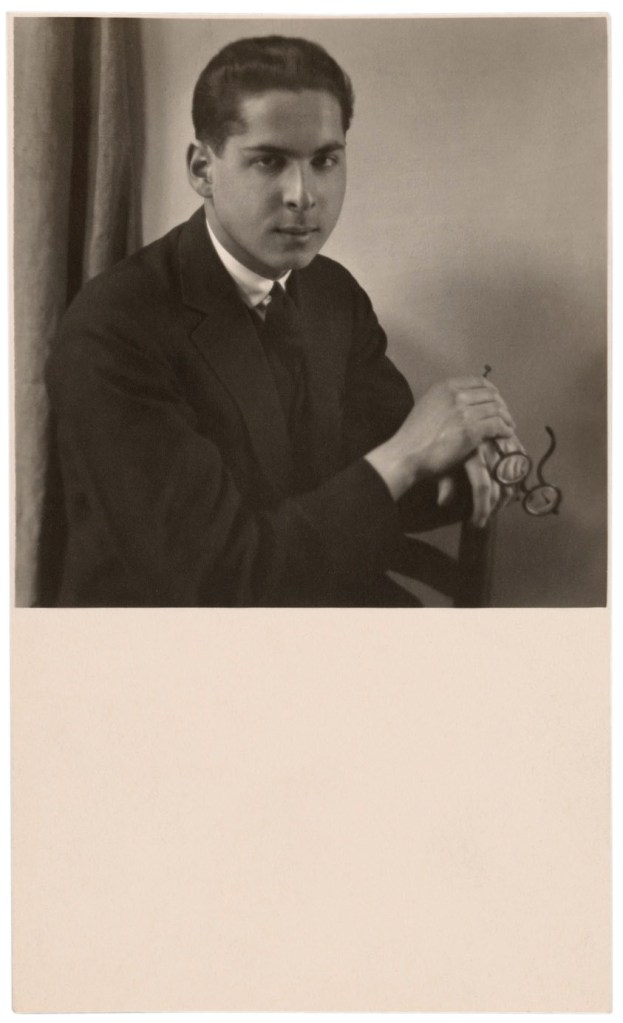

Kertész also adapted this method of making a new composition out of an older one to his camera technique. Take, for example, his portrait of his friend Paul Arma (Imre Weisshaus), a Hungarian composer and pianist. Kertész first made a more traditional seated portrait showing the upper half of the musician’s body, his hands against the chair back holding his distinctive glasses. In another picture from the same sitting, he zoomed in on that gesture in an abstracted portrayal. Here, selected elements stand in for the whole subject, distilling Arma’s persona down to his instrument-playing hands and his particular vision.

Beyond demonstrating Kertész’s experimental approach, Quartet also tracks his expanding network, as he began connecting first to Hungarian – and soon to international – artists, musicians, dancers, and writers. He had built a community of creatives in his native Budapest, and in Paris he linked up with a group of Hungarian expatriates that included painter Lajos Tihanyi, sculptors Joseph (József) Csáky and Étienne (István) Beöthy, experimental puppeteer Géza Blattner, and dancer Magda Förstner, among others – all of whom he made carte postale portaits of. As his French improved and his circle widened, Kertész got to know and came to photograph French writer Pierre Mac Orlan, the poets Tristan Tzara (French-Romanian) and Paul Dermée (Belgian), Swedish painter Gundvor Berg, Spanish ceramicist Josep Llorens Artigas, Russian painter and gallery owner Evsa Model, and especially the Dutch painter Piet Mondrian, whose spare painting and studio left a deep impression on the photographer.

Quartet is one of over one hundred rare carte postale prints brought together for the first time in the exhibition André Kertész: Postcards from Paris. This exhibition takes a focused look at a three-year period in the artist’s career – his first years in Paris – when he explored new compositions and techniques and printed most of his work in the intimate carte postale format. As a reminder of Kertész’s daring experimentalism in photography, the importance of understanding his works as objects as much as images, and proof of his widening network and expansive artistic influences, this small photograph has a big impact.

~ Elizabeth Siegel, curator, Photography and Media

Elizabeth Siegel, “A Close Look at André Kertész’s Quartet,” on the Art Institute of Chicago website October 26, 2021 [Online] Cited 17/03/2022

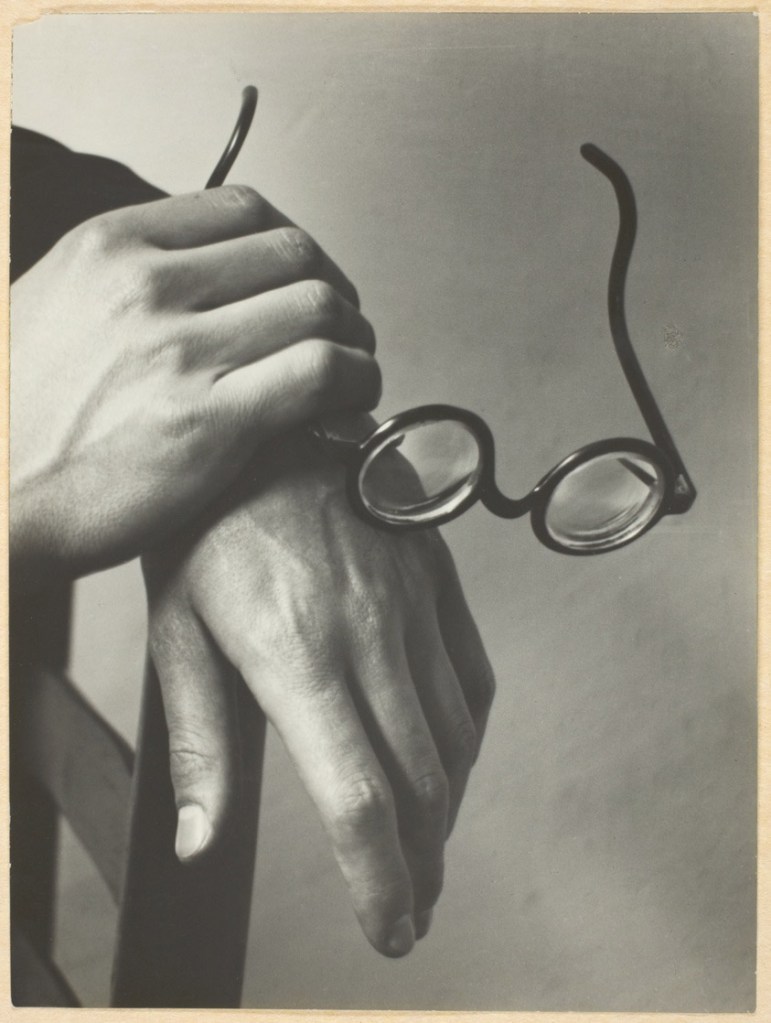

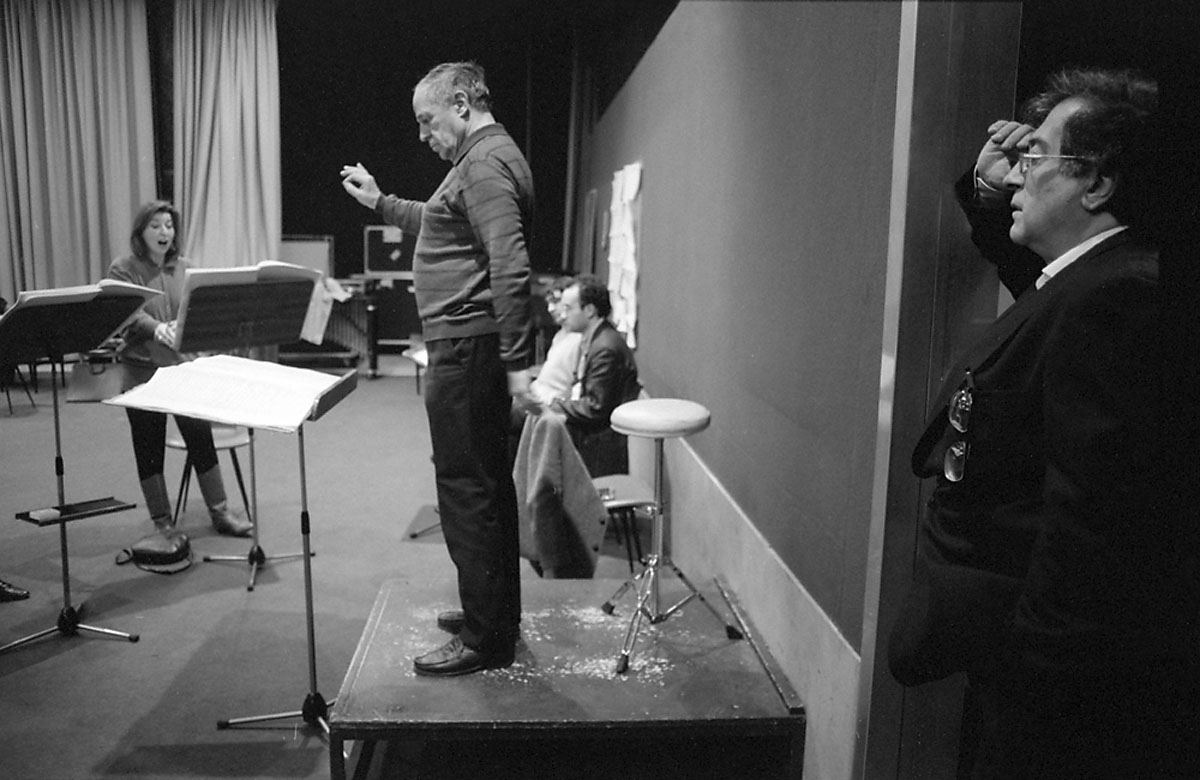

André Kertész (Hungarian, 1894-1985)

Paul Arma

1928

Gelatin silver print on carte postale paper

Image: 7.9 × 7.9cm

Card: 13.5 × 8.1cm

Paul Arma (Hungarian: Arma Pál, aka Amrusz Pál; né Weisshaus Imre; 22 November 1905, in Budapest – 28 November 1987, in Paris) was a Hungarian-French pianist, composer, and ethnomusicologist.

Arma studied under Béla Bartók from 1920 to 1924 at the Franz Liszt Academy of Music, after which time he toured Europe and America giving concerts and piano recitals. Béla Bartók influenced Arma in his love for folksong and collection. He left Hungary in 1930, eventually settling in Paris in 1933, where he became the piano soloist with Radio Paris. His music is generally characterised by modernist tendencies, although his varied output includes folk song arrangements, film music, popular and patriotic songs, in addition to solo, chamber, orchestral and electronic music.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Paul Arma is a crucial figure in the history of French Resistance music, both because of the songs he composed and because of his tireless efforts to preserve the enormous body of music created during the war. Arma saw the songs of the Resistance not simply as sources of hope and acts of wartime courage, but also as important artifacts to be saved as symbols of France’s national spirit. Born in 1905 as Imre Weisshaus, the Hungarian pianist, conductor, and composer Paul Arma studied with Bartok at the Academy of Franz-Liszt in Budapest. He worked as a conductor of orchestras and choirs in Berlin and Lepizig until 1933, before being arrested by the SS in Leipzig for spying against the Germans and for his connections with the intellectual and artistic avant-garde. Though deemed not enough of a threat to be imprisoned, Arma was subject to a mock execution by the SS prior to being released. He subsequently fled to Paris, where he worked until 1939 as a pianist for Radio-Paris and wrote songs supporting the Republican Spanish for the International Brigades such as ‘Madrid’ and ‘No pasaran’ (Do not pass). After the arrival of the Nazis, Arma composed ‘Les chants du silence’ (Songs of silence) on texts of Vercors, Eluard, Romain Rolland and Paul Claudel among others, writing: ‘During a period when, in France, freedom had to take place in prescribed silence … I sang silence in order to blackmail life.’ During the war, Arma secretly collected over 1,800 French songs, transcribing the melodies together with his wife. After the war, he sent out an appeal on radio and in national newspapers in France, Spain, Hungary, Italy, the Ukraine, Armenia and Bulgaria, seeking additional songs for his collection. The response was enormous: listeners sent in over 1,300 songs. From October to December 1945, Arma broadcast a number of these songs on the radio as part of a series entitled La Résistance qui chante (Resistance singing). …

From 1954-1984 Arma conducted research into electromagnetic music, as well as making 81 sculptures out of wood and metal on the theme of music, called Musiques sculptées (sculpted music). In the 1980s he became a French national, was awarded the S.A.C.E.M. Enesco prize, and was made a Knight of the National Order of the Legion of Honour, an Officer of the National Order of Arts and Letters, and an Officer of the National Order of Merit. He died in 1987 and his wife donated his music collection to the Musée Régionale de la Résistance et de la Déportation de Thionville (Regional Museum of the Resistance and Deportation at Thionville).

Daisy Fancourt. “Paul Arma,” on the Music and the Holocaust website Nd [Online] Cited 11/04/2021

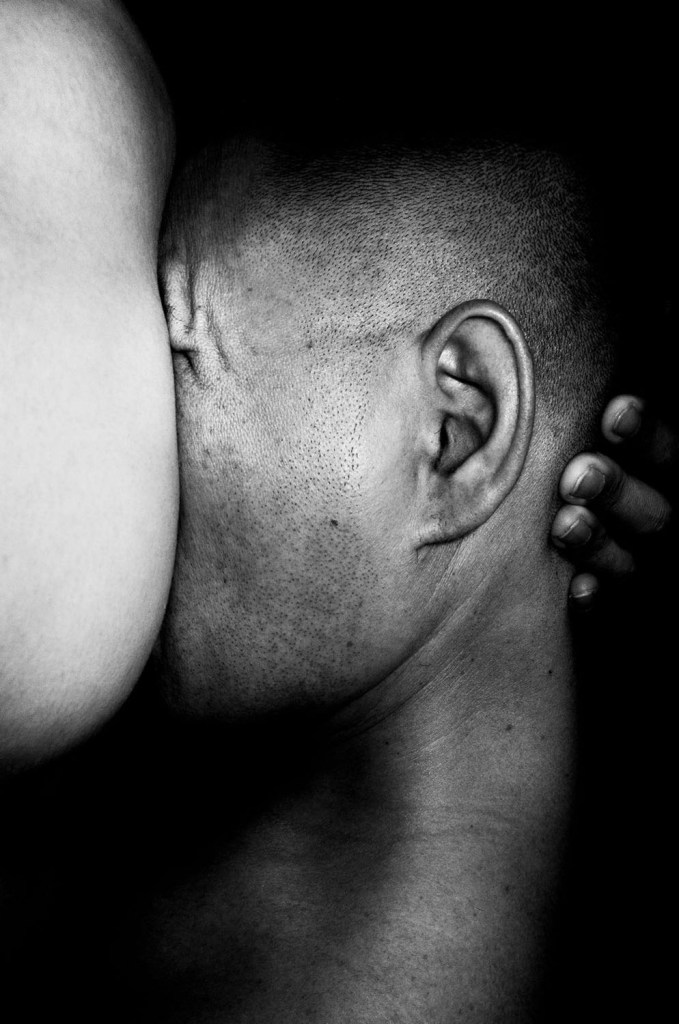

André Kertész (Hungarian, 1894-1985)

Paul Arma’s Hands, Paris

1928

Gelatin silver print on carte postale paper

Image: 24 × 18 cm

Mount: 36.8 × 27.3cm

Art Institute of Chicago

Julien Levy Collection, Special Photography Acquisition Fund

André Kertész (Hungarian, 1894-1985)

Lajos Tihanyi

1926

Gelatin silver print on carte postale paper

Image: 10.9 × 7.9cm

Card: 11.2 × 8.1cm

Lajos Tihanyi (29 October 1885 – 11 June 1938) was a Hungarian painter and lithographer who achieved international renown working outside his country, primarily in Paris, France. After emigrating in 1919, he never returned to Hungary, even on a visit.

Born in Budapest, as a young man, Tihanyi was part of the “Neoimpressionists” or “Neos”, and later the influential avant-garde group of painters called The Eight (A Nyolcak), founded in 1909 in Hungary. They were experimenting with styles of Post-Impressionism and rejected the naturalism of the Nagybánya artists’ colony. Their work is considered highly influential in establishing modernism in Hungary to 1918, when the First World War and revolution overtook the country.

After the fall of the Hungarian Democratic Republic in 1919, Tihanyi left and lived briefly in Vienna. He moved on to Berlin for a few years, where he connected with many Hungarian émigré writers and artists, such as Gyorgy Bölöni and the future Brassaï. By 1924 Tihanyi and numerous other artists moved to Paris, where he stayed for the remainder of his life.

In Paris, Tihanyi gradually shifted to more abstract styles in his work. His paintings and lithographs are held by the Hungarian National Gallery, Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, and the Brooklyn Museum of Art in New York City, among other institutions, and by private collectors. With the centenary of The Eight’s first exhibition, Tihanyi has been featured in five exhibitions since 2004, including ones held in 2010 and 2012 in Hungary and Austria, and another in 2012 devoted to a solo retrospective of his work.

Text and more information on the artist can be found on his Wikipedia entry

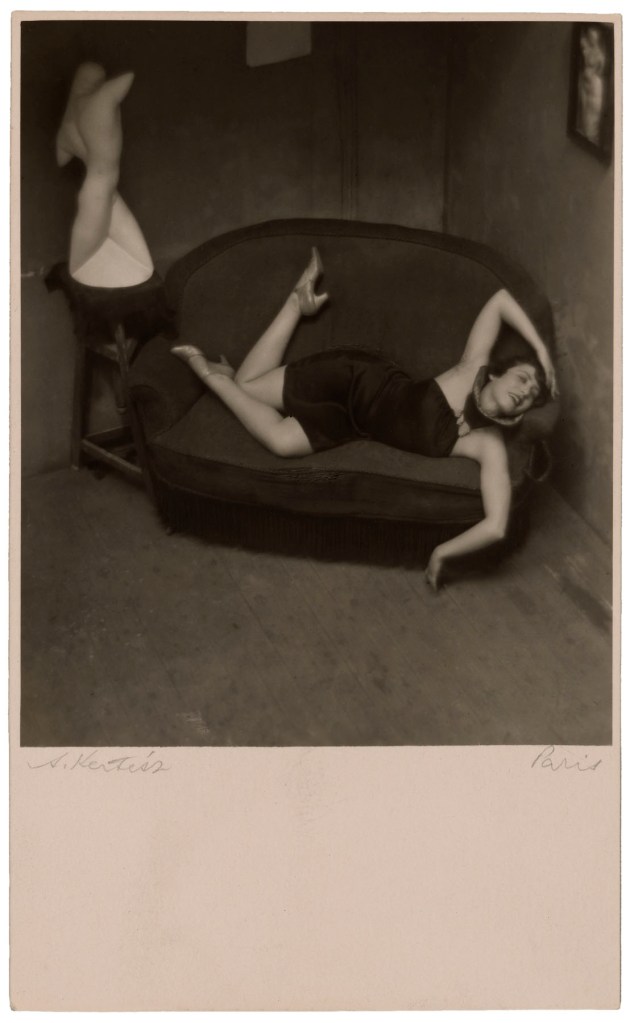

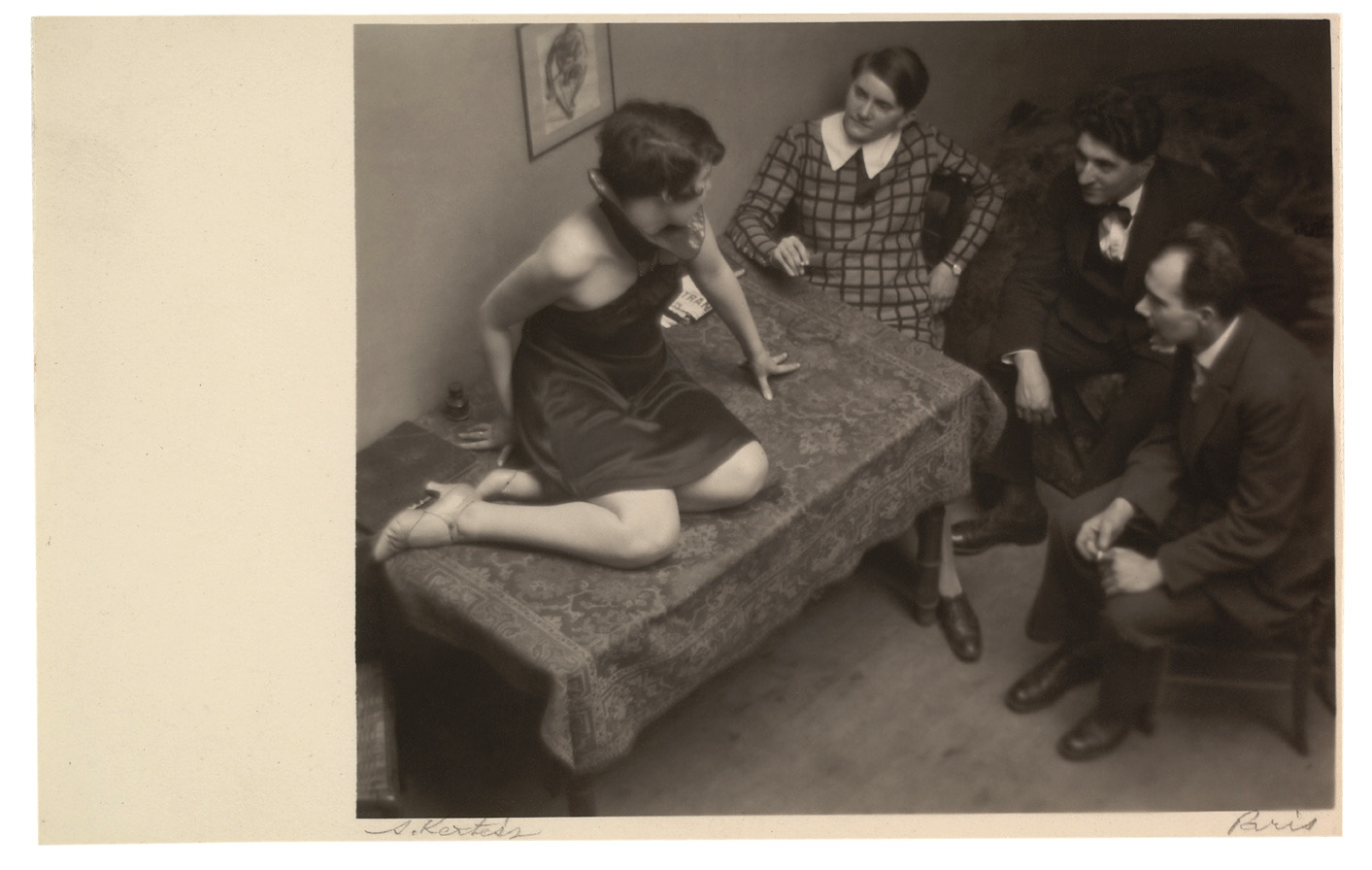

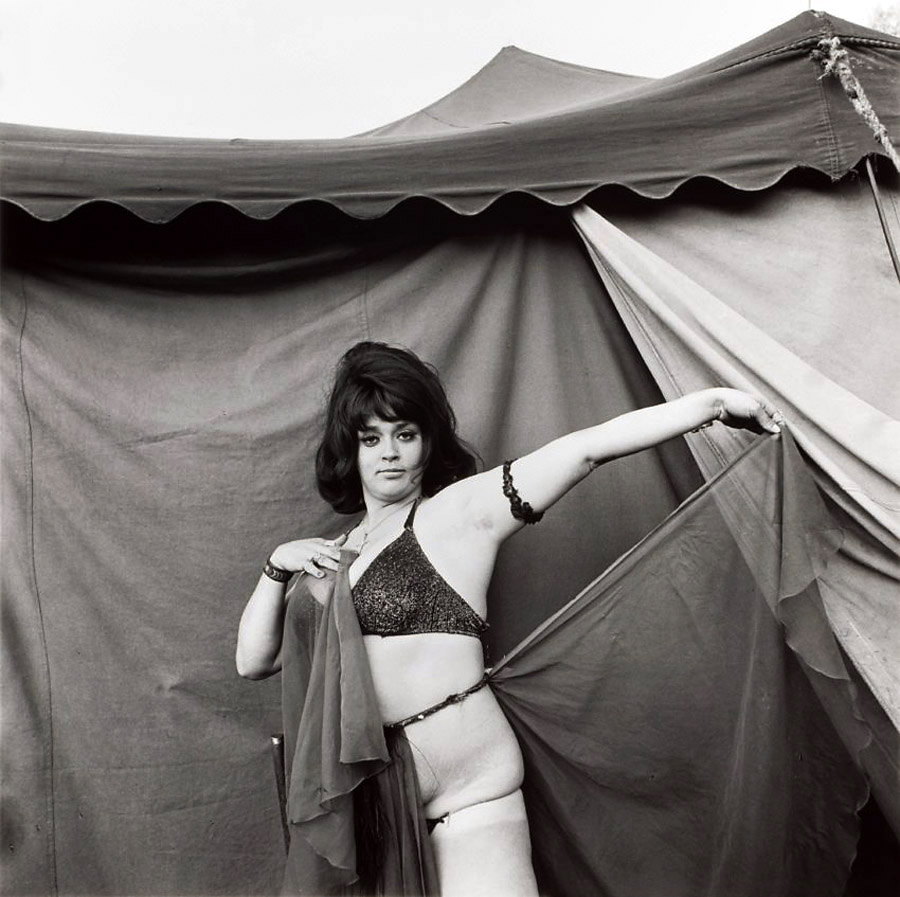

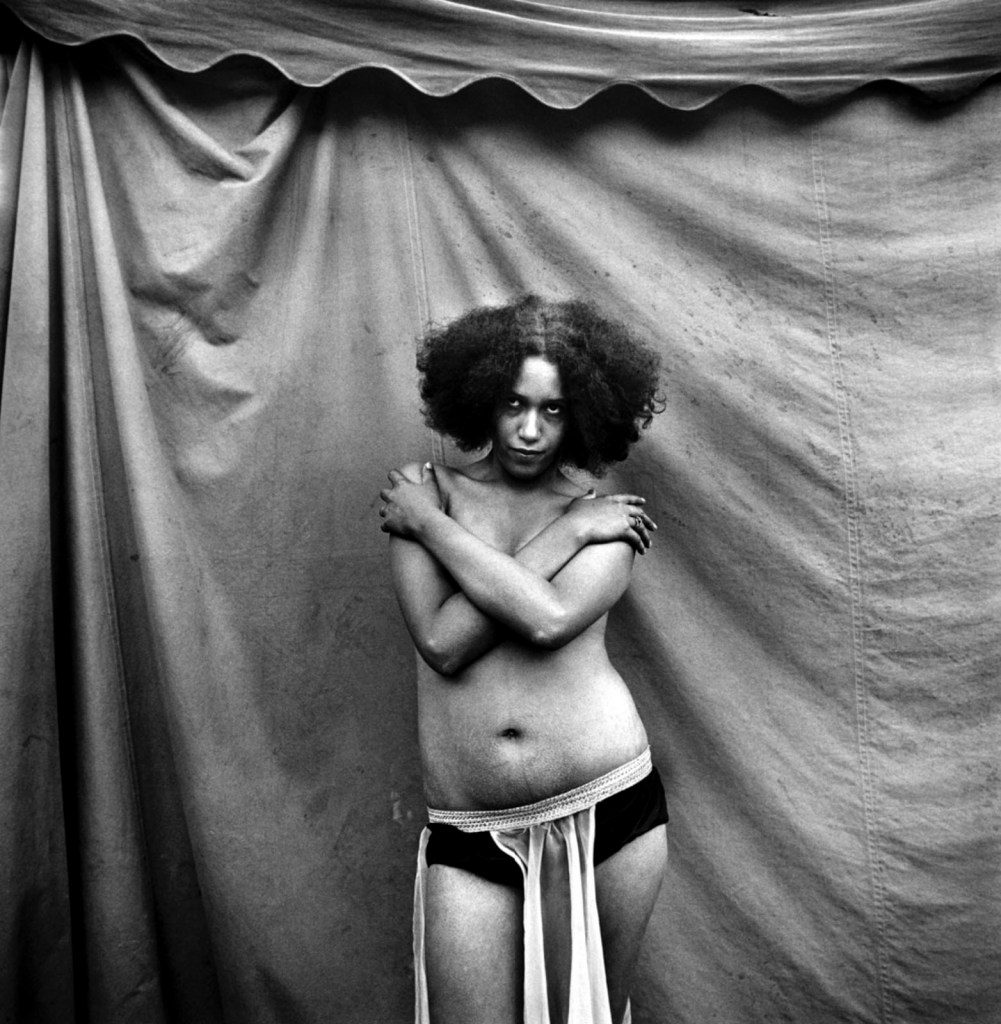

André Kertész (Hungarian, 1894-1985)

Satiric Dancer

1927

Gelatin silver print on carte postale paper

Family Holdings of Nicholas and Susan Pritzker

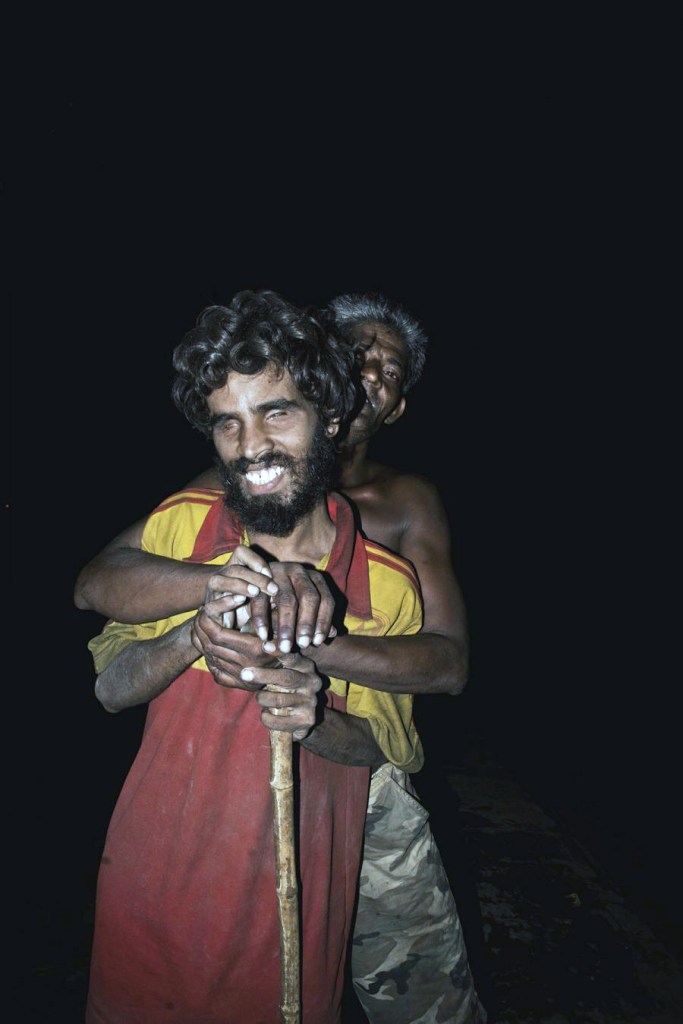

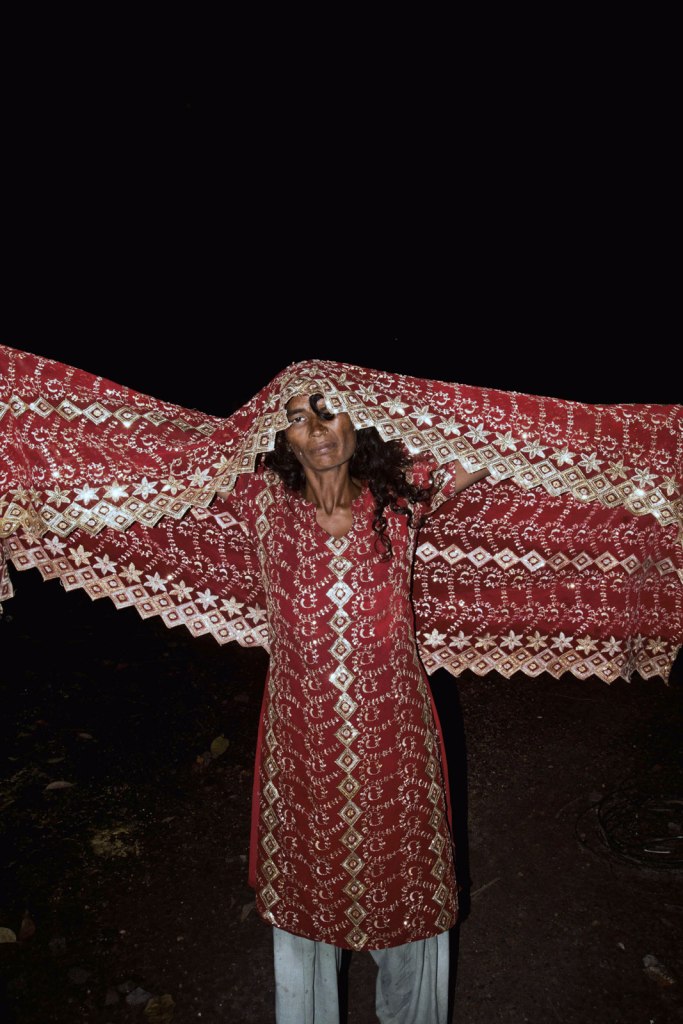

“Do something with the spirit of the studio corner,” Kertész told his subject before he took this picture. He captured Hungarian dancer Magda Förstner in sculptor Etienne Beöthy’s studio, her contorted pose playfully mimicking the angular form of the work next to the sofa, Beöthy’s Direct Action. “She just made a movement. I took only two photographs. No need to shoot a hundred rolls like people do today. People in motion are wonderful to photograph. It means catching the right moment – the moment when something changes into something else.” Although Satiric Dancer, as it eventually came to be known, was not published or exhibited much during Kertész’s Paris years, it later became one of the artist’s most recognised images. Linking dance, sculpture, and photography, it evokes the ethos of sexual freedom and experimental self-expression that some women embraced in the 1920s as they shed patriarchal constraints, an ethos in which Kertész was steeped during his early years in Paris. It also reflects Förstner’s creative ends: she upends the traditional relationship between male artist and female model, such that Beöthy’s sculpture serves as inspiration for her own artistry.

Etienne Beöthy (Hungarian, 1897-1961)

István (Etienne) Beöthy (1897 – 27 November 1961) was a Hungarian sculptor and architect who mainly lived and worked in France.

After the First World War, in which he served, Beöthy began to study architecture in Budapest. There he was in contact with the avant-garde poet and painter Lajos Kassák, who familiarized him with the tenets of constructivism and suprematism. His earliest work as an architectural draftsman, from 1919, displayed constructivist tendencies. In that same year he would write the manifesto “Section d’Or” (The Golden Section), which did not appear in Paris until 1939.

From 1920 to 1924, Beöthy studied under János Vaszary at the Hungarian University of Fine Arts. He travelled on a grant to Vienna, from where he undertook other travels to western Europe, until in 1925 he settled in Paris. Beöthy found a place in the Parisian art scene and took part in the exhibit of the Salon des Indépendants. In 1927 he married Anna Steiner, and in 1928 he had his first one-man show in the Galerie Sacre-Printemps.

In 1931, Beöthy co-founded the group Abstraction-Creation with sculptor Georges Vantongerloo and painter Auguste Herbin, and was its vice-president for a time. From 1931 to 1939, he had an exclusive contract with Leonce Rosenberg’s Galerie de l’Effort Moderne, and in 1938 he organised an exhibit in Budapest, which was the first exposure of his nonfigurative art to the public in Hungary. Like Herbin, he later explored parallels to other forms of self-expression, particularly music. His sculptures after this point develop along the lines of harmonies, which interact with each other like musical notes.

During World War II Beöthy designed fliers for the French Resistance. In 1946, he became a founding member of the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles, and the Galerie Maeght in Paris showed a retrospective of his work. In 1951, he became a founding member of another group, “Espace”, and founded the journal “Formes et Vie”, with Fernand Léger and Le Corbusier. For a short time between 1952 and 1953, he gave lectures on colour and proportion to architecture classes at the École des Beaux-Arts, and in his subsequent years he worked together with architects and was otherwise part of the planning for the expansion of Le Havre.

Beöthy died in Paris on 27 November 1961.

Text from the Wikipedia website

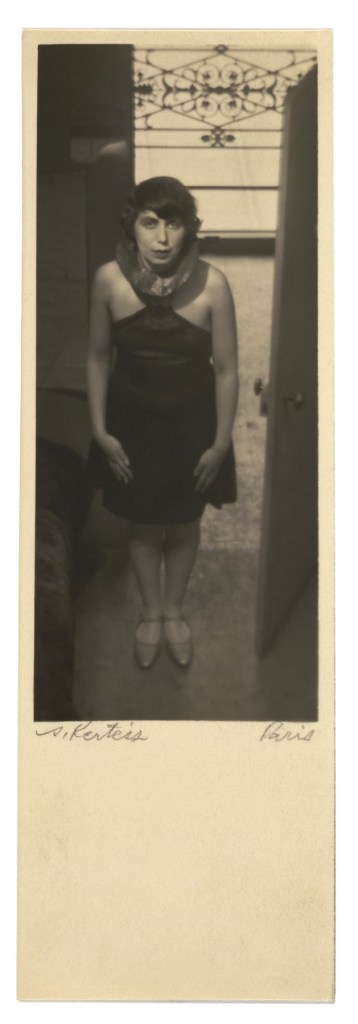

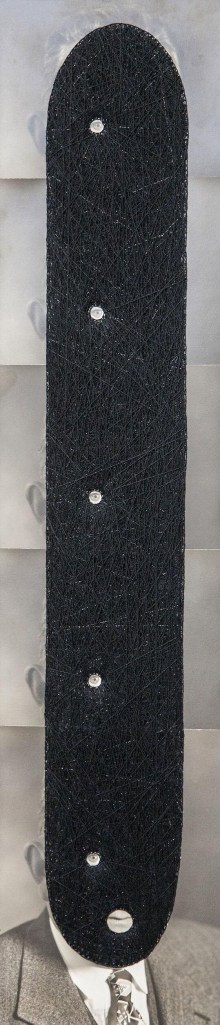

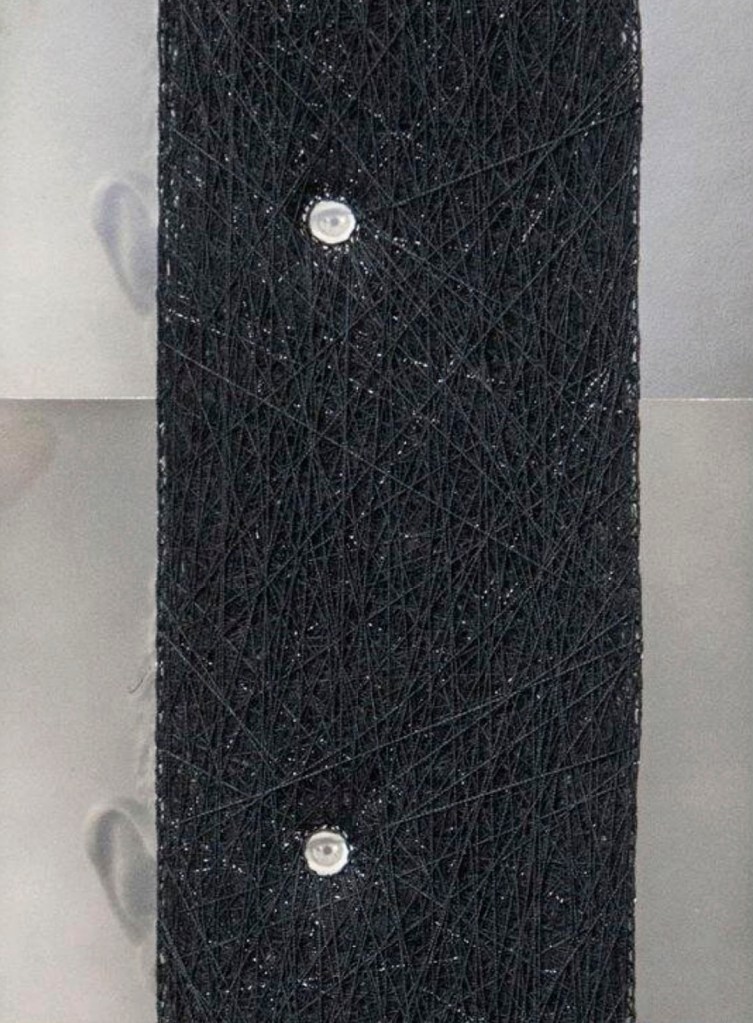

André Kertész (Hungarian, 1894-1985)

Magda Förstner (Standing in the doorway of Etienne Béothy’s studio)

1926

Gelatin silver print on carte postale paper, c. 1929

Image: 3 9/16 × 1 1/2″ (9.1 × 3.8cm)

Sheet: 5 1/8 × 1 11/16″ (13 × 4.3cm)

Mount: 14 1/2 × 10 11/16″ (36.8 × 27.2 cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Thomas Walther

In the year he met Piet Mondrian (1872-1944), André Kertész became acquainted with an aspiring [Hungarian] actress and cabaret singer named Magda Förstner (dates unknown). She was also his model for the celebrated Satiric Dancer.

Text from the Getty Museum website

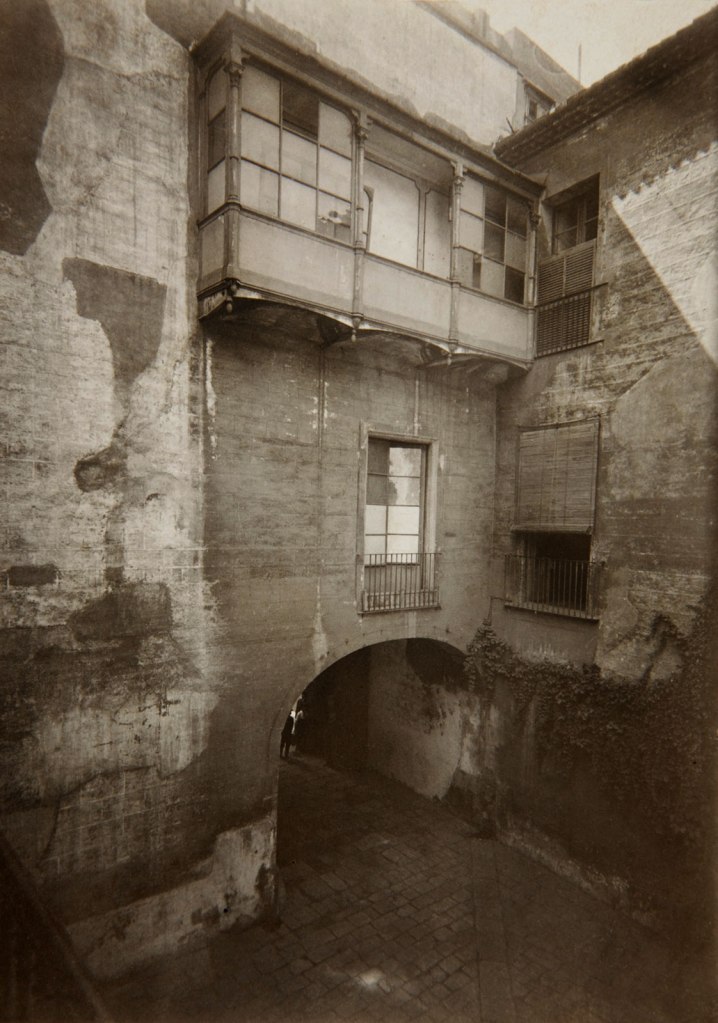

André Kertész (Hungarian, 1894-1985)

Latin Quarter (Étienne Beöthy’s Cousin)

1927

Gelatin silver print on carte postale paper

Image: 3 7/8 × 3 1/16″ (9.8 × 7.8 cm)

Sheet: 4 15/16 × 3 3/16″ (12.6 × 8.1 cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Thomas Walther Collection. Grace M. Mayer Fund

André Kertész (Hungarian, 1894-1985)

Fork

1928

Gelatin silver print on carte postale paper

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, purchased 1978

On the edge of a dinner plate, Kertész posed an ordinary fork. Its shadow traces a faithful double across the tabletop and bends into slanted stripes along the plate’s lip. Clean and modern, simple and unpretentious, this photograph asserted that art could be made with the humblest objects so long as they were carefully observed. Fork, as it came to be known, was an instant icon, featured in numerous international exhibitions and publications almost immediately after its making. One review of an exhibition in which it appeared read, “Among the still lives, one must above all admire a fork by André Kertész – yes, simply a fork – which is almost moving in its purity and its tones. It is perhaps the only image that gave me the impression of a true work of art.” Fork may have been the last image Kertész printed in the carte postale format. In 1928 he acquired a smaller, lightweight 35mm Leica camera, which gave him increased mobility and spontaneity but produced negatives too small for contact printing. He began photographing regularly for Parisian magazines, allowing them to crop and sequence works according to their own preferences. And his work was included in more international exhibitions, for which larger prints were more desirable. Nevertheless, he must have appreciated seeing Fork at carte postale scale, since he printed it at this size on different papers around the same time.

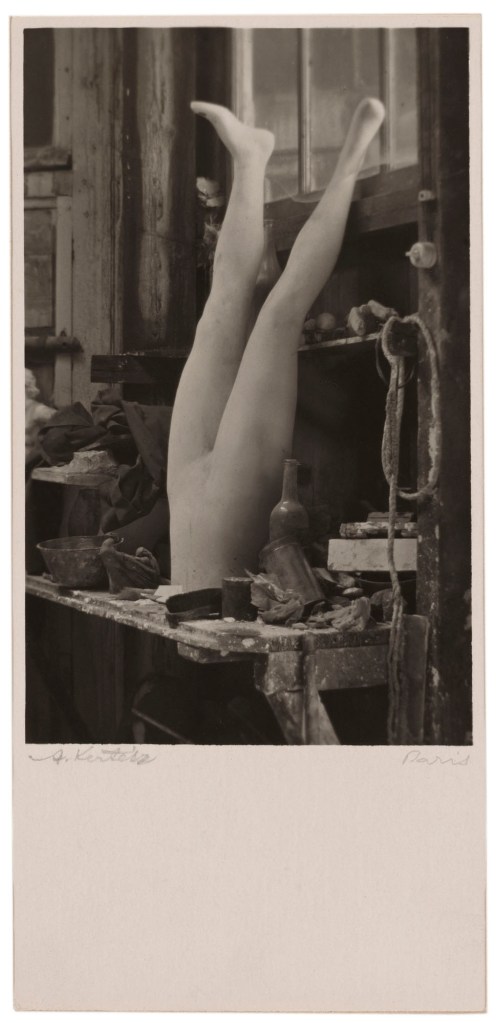

André Kertész (Hungarian, 1894-1985)

Legs

1925

Gelatin silver print on carte postale paper

Family Holdings of Nicholas and Susan Pritzker

On the back of this print, which he mailed home to Hungary, Kertész wrote, “Interesting coincidence. They claim it as being surrealistic, if it suits people better.” He recognised that the erotically suggestive image of overturned mannequin legs in a sculptor’s studio would have appealed to artists like photographer Man Ray, with whom he was becoming associated in exhibitions and criticism. But Kertész never embraced a fantastical approach to his work, maintaining firmly, “I am not a Surrealist. I am absolutely a realist.”

André Kertész (Hungarian, 1894-1985)

Gundvor Berg in Her Studio

1926

Gelatin silver print on carte postale paper

Image: 10.9 × 7.2cm

Card: 13.6 × 7.6cm

Andre Kertész: Postcards from Paris; Edited by Elizabeth Siegel; With essays by Sarah Kennel, Sylvie Penichon, and Elizabeth Siegel. Distributed for the Art Institute of Chicago

André Kertész (Hungarian, 1894-1985)

Jean Sliwinsky, Herwarth Walden, and Friends at Au Sacre du Printemps, Paris

1927

Gelatin silver print on carte postale paper

The J. Paul Getty Museum

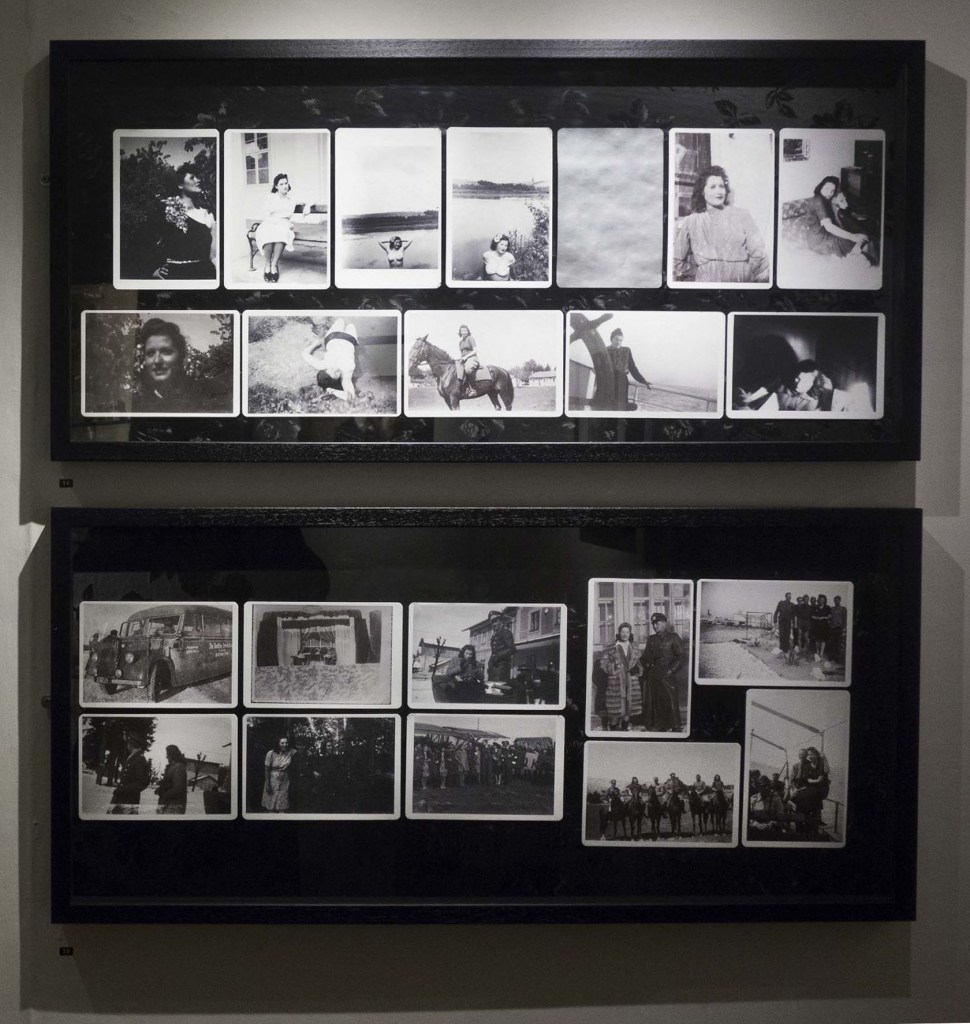

At the Exhibition

Kertész took this photograph at his first major exhibition, held only a year and a half after he arrived in Paris. The 30 photographs showcased the fruits of an extraordinarily productive period. The works on the wall in the background of this photograph focused on still lifes and scenes of Paris.

This group of Kertész friends includes the gallery’s owner, Jan Sliwinsky [seated centre in the photograph]. Sliwinsky, who was a composer and pianist, was instrumental in connecting expatriate artists, musicians, and writers.

Included in the exhibition was a print of Chez Mondrian [bottom row second from right in the above photo; and below], which later became one of Kertész’s most well known images. Made in painter Piet Mondrian’s meticulously arranged studio, it is a study in contrasts: rectangles against curves, smooth surfaces against rough, and light against shadow.

Kertész made more carte postale prints of this image than of any other from the period, evidence, perhaps, of how much he esteemed it at the time of its making.

The works on view reflect Kertész’s engagement with the Parisian avant-garde and his widening circle of international artist friends.

André Kertész (Hungarian, 1894-1985)

Chez Mondrian

1926

Gelatin silver print on carte postale paper

10.8 × 7.9 cm (image/paper); 37.2 × 27.4 cm (mount)

The Art Institute of Chicago, Julien Levy Collection, gift of Jean and Julien Levy

Kertész’s encounter with Dutch painter Piet Mondrian marked a turning point in the photographer’s early Paris years. The geometry and balance of Mondrian’s painting – which extended to his rigorously controlled studio space – had a lasting effect on Kertész’s work. He captured the painter and his living space several times, culminating in this image showing the door of Mondrian’s studio opening onto a common stairway. Kertész later recalled the moment he took the picture: “I could see how the inside and the outside contrasted and yet balanced each other, aided by the natural light and shadows… Everything was there before me.” Kertész made at least eight prints of Chez Mondrian in the carte postale format, more than of any other image, an indication of how much the artist appreciated it at the time of its making. The photograph eventually became one of his most famous and enduring works. Kertész trimmed and mounted the version here in the style he favoured for exhibition.

André Kertész (Hungarian, 1894-1985)

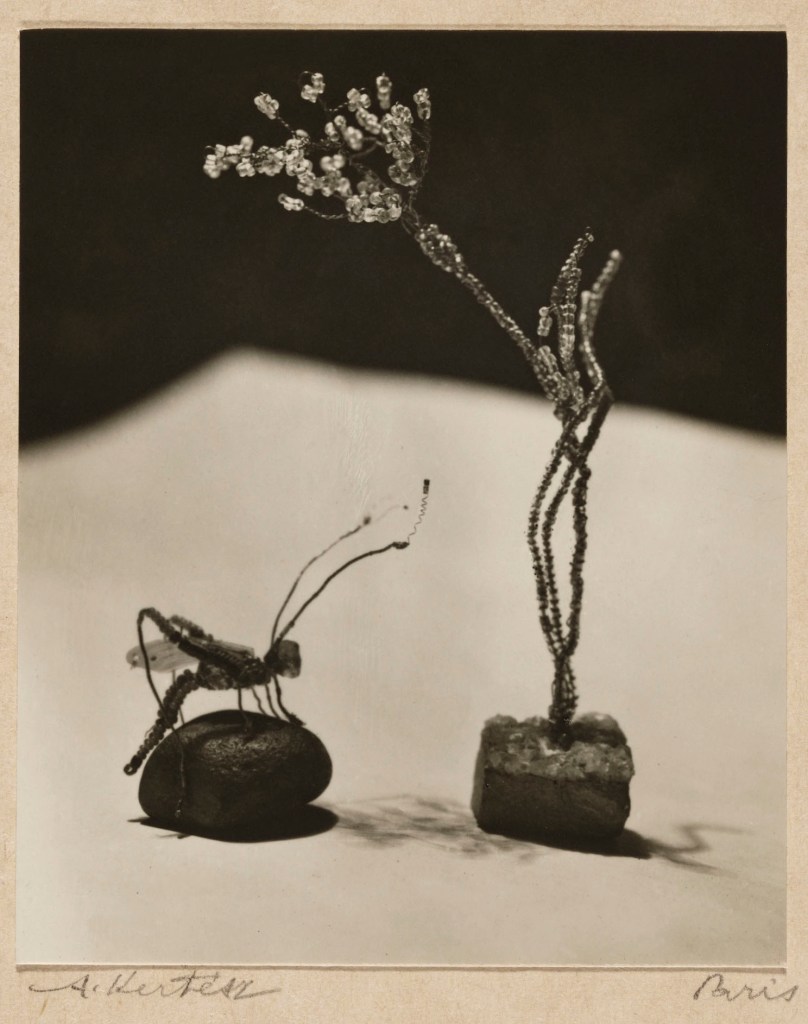

Sculptures

1927

Gelatin silver print on carte postale paper

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, gift of Patricia Corkin Kennedy and John Kennedy in honour of Jane Corkin

This photograph captures a tabletop sculpture by the German handcraft artist Hilda Daus. It can be seen third from left in the middle row of the Au Sacre du Printemps photograph.

André Kertész (Hungarian, 1894-1985)

Hilda Daus

1927

Gelatin silver print on carte postale paper

Jane Corkin, Toronto

Hilda Daus was a German handcraft artist; Kertész also made a carte postale print of her delicate tabletop sculptures. He included the image here in his first exhibition in Paris, in 1927 at the gallery Au Sacre du Printemps, where Daus also exhibited.

André Kertész (Hungarian, 1894-1985)

Paul Dermée

1927

Gelatin silver print on carte postale paper

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Nicholas and Susan Pritzker

Belgian poet Paul Dermée was one of the founders of L’Esprit Nouveau, an avant-garde art journal that had ceased publication some years before but which he helped revive for one more issue in 1927. The issue, which debuted one month after Kertész’s exhibition at the gallery Au Sacre du Printemps, placed his photographs among works by an international group of artists active in Paris and elsewhere in Europe. Dermée also penned a poem in honour of the exhibition, which was featured on the invitation.

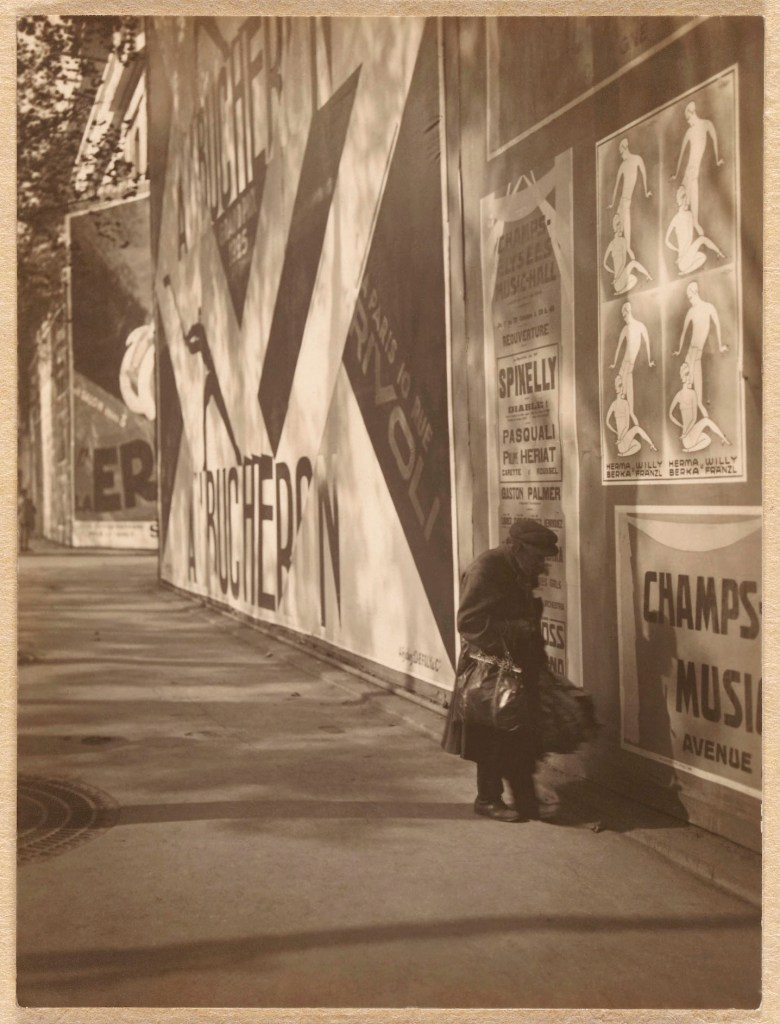

André Kertész (Hungarian, 1894-1985)

Wall of Posters

1926

Gelatin silver print on carte postale paper

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund, The Manfred Heiting Collection

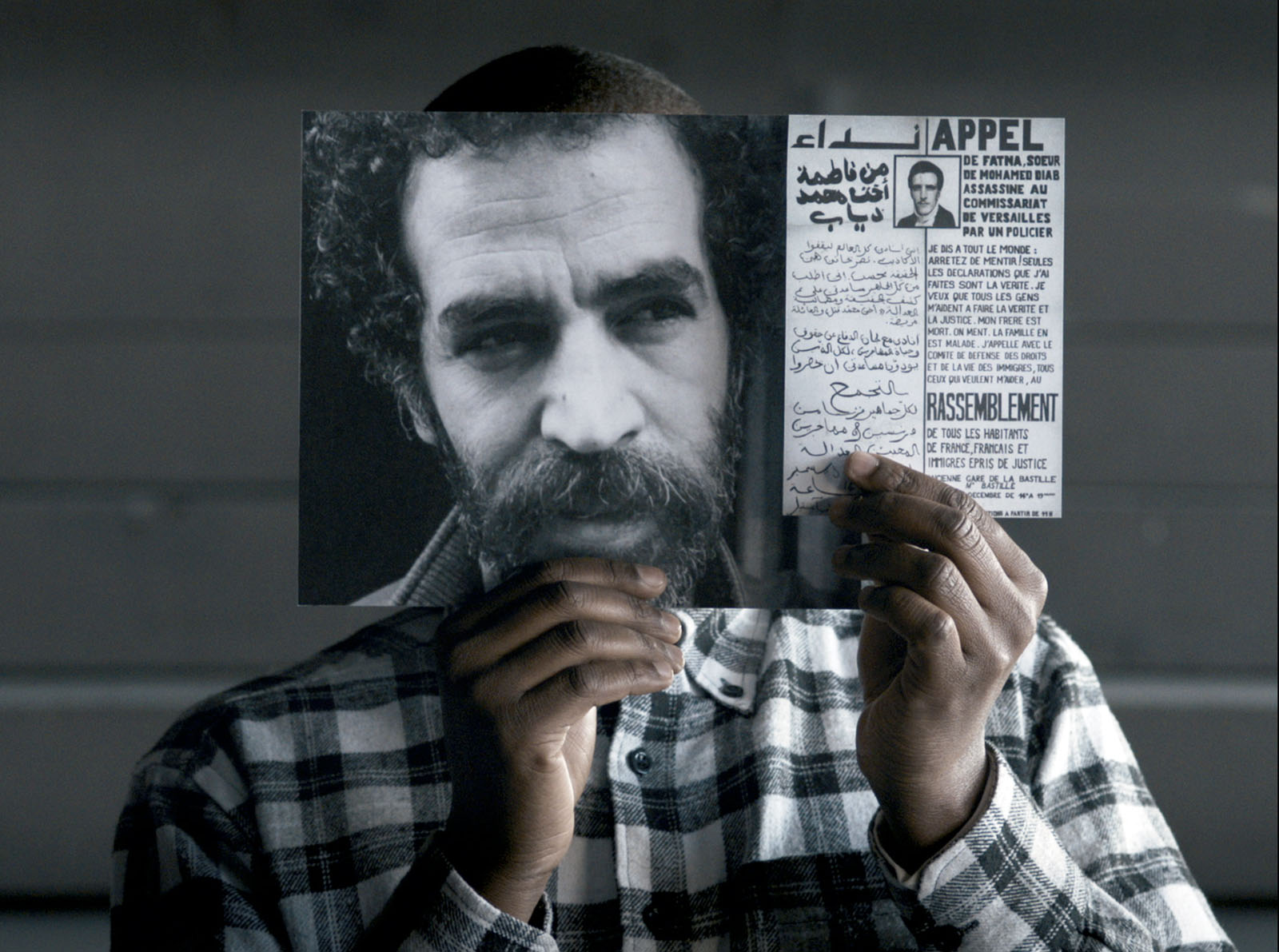

The exhibition also included Kertész’s scenes of Paris streets, made in a diaristic fashion on exploratory walks through his new city. This photograph [fifth from the left on the bottom row of the Au Sacre du Printemps photograph] demonstrates the artist’s new interest in the geometry of typography as well as his sympathy for the city’s clochards, or vagrants.

André Kertész (Hungarian, 1894-1985)

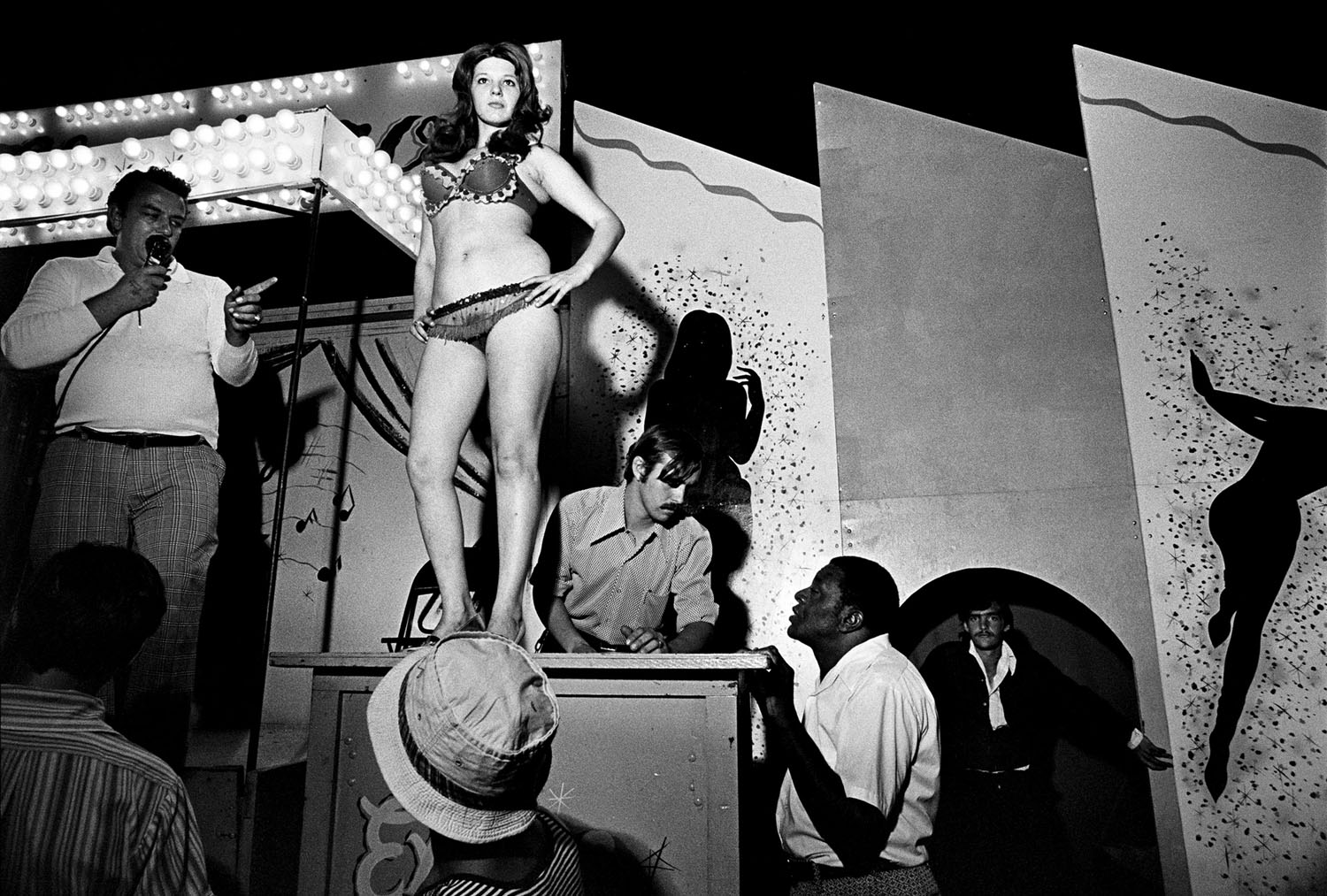

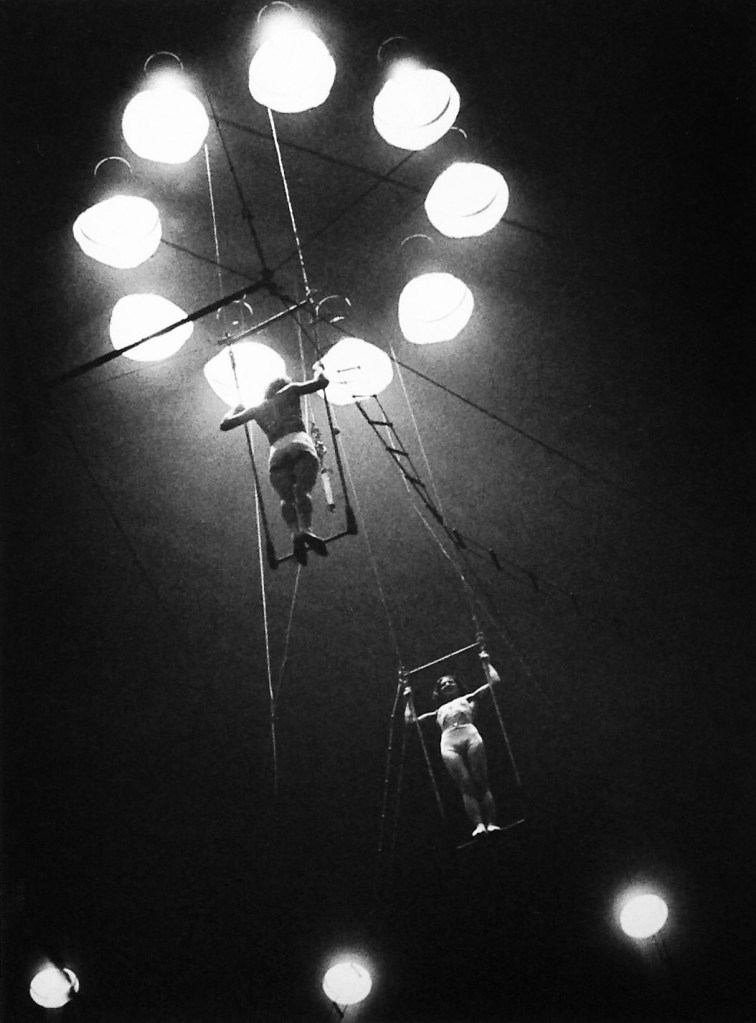

Fairground, Quai de l’Hôtel de Ville

1926

Gelatin silver print on carte postale paper

Private collection, courtesy of Corkin Gallery, Toronto

Fairgrounds were particularly appealing to the photographer. Visitors could also have carte postale prints made of themselves playing games or posed in whimsical scenes. In this image [see third from left on the bottom row of the Au Sacre du Printemps photograph], Kertész capitalised on an elevated view, something he often explored in his portraits of artists in their studios.

Kertész’s exhibition shared the space with the abstract paintings of Ida Thal, another Hungarian artist. As the photographer absorbed formal lessons from avant-garde painters, sculptors, and designers, his work became more carefully composed.

Kertész’s exhibition drew praise from critics. The Chicago Tribune, reviewing the show, called him “one of the few talented photographers who recognise that their medium possesses the necessary qualifications for being an independent art.”

Unless otherwise noted, all works are by André Kertész (American, born Hungary, 1894-1985) and are gelatin silver prints on carte postale paper.

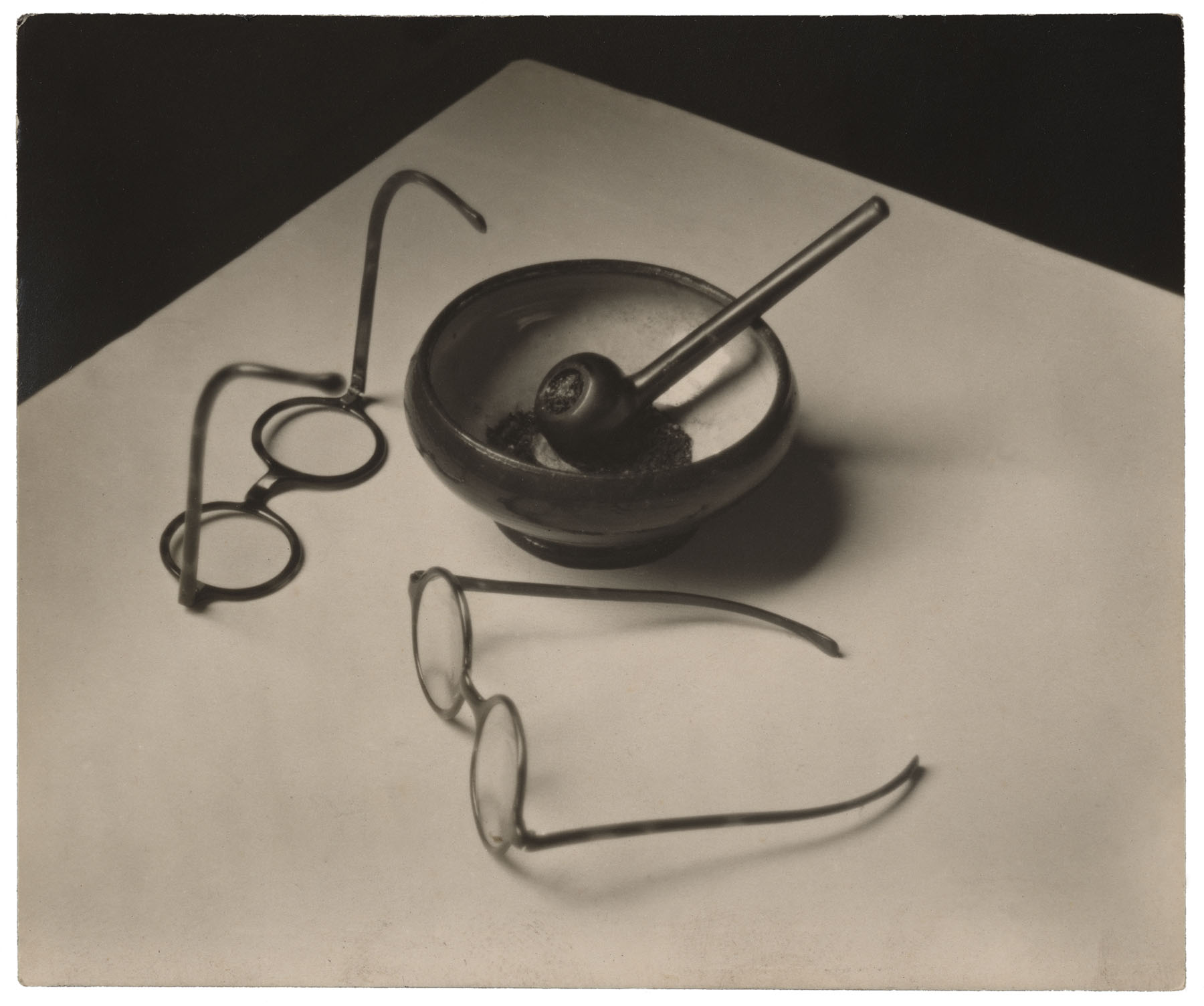

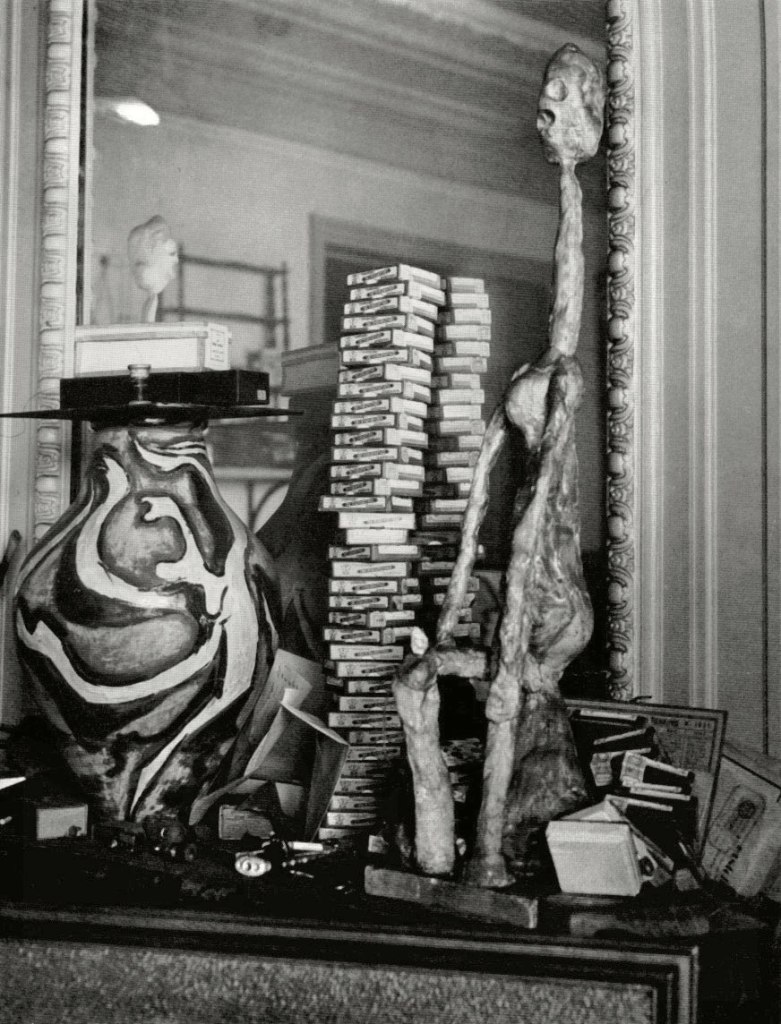

André Kertész (Hungarian, 1894-1985)

Mondrian’s Pipe and Glasses

1926

Gelatin silver print on carte postale paper

Family Holdings of Nicholas and Susan Pritzker

With this photograph [second from left in the bottom row of the Au Sacre du Printemps photograph], Kertész perfected his technique of making a portrait in the absence of the sitter, evoking the Dutch painter Piet Mondrian with only his glasses, pipe, and ashtray. Whereas his images of Mondrian’s studio emphasised the straight lines and right angles of the space, here Kertész highlighted circular elements that allude to human shapes amid a rectilinear environment.

André Kertész (Hungarian, 1894-1985)

Mondrian’s Studio

1926

Gelatin silver print on carte postale paper

4 3/16 × 2 5/8″ (10.7 × 6.6cm)

Thomas Walther Collection. Grace M. Mayer Fund

© 2022 Estate of André Kertész

André Kertész (Hungarian, 1894-1985)

Mondrian

1926

Gelatin silver print on carte postale paper

4 5/16 × 3 1/8″ (10.9 × 7.9cm)

Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Thomas Walther

© 2022 Estate of André Kertész

André Kertész (Hungarian, 1894-1985)

Géza Blattner

1925

Gelatin silver print on carte postale paper

3 1/16 × 3 1/4″ (7.7 × 8.2cm)

Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Thomas Walther

© 2022 Estate of André Kertész

Géza Blattner (Hungarian, 1893-1967)

Hungarian puppeteer, painter/stage designer and director who worked mostly in France. Géza Blattner studied painting in Munich (Germany) with the Hungarian painter Simon Hollósy. He became involved with puppetry during World War I by collaborating on productions of the Budapest City Theatre. To the great dismay of his parents he then dedicated himself fully to puppetry and completed his training with Richard Teschner in Vienna and Paul Brann in Munich.

In Budapest, in 1919, he held his first “secessionist” puppet show for adults entitled Wajang játékok (Wayang Plays), (see Wayang) using flat figures animated by strings to present works by famous Hungarian authors such as Dezső Kosztolányi and Béla Balázs. Between 1919 and 1925, he attempted to recreate fairground shows with Antal Németh (1903-1967), who later became a famous Hungarian theatre personality and an influential advocate of puppetry. Blattner also experimented with new lever-operated puppets (also called keyboard puppets) which he later improved upon after he immigrated to France in 1925.

Géza Blattner settled in Paris where he established the Arc-en-ciel (Rainbow) Puppet Theatre. Artists from all over gathered around him: Constantin Detre, Sándor Toth, Marie Vassilieff … Others joined them later: Paul Jeanne, Frédéric O’Brady, Sigismund Walleshausen. The first important public show was in Paris at the 2nd UNIMA Congress in 1929. Up until 1934, Blattner performed experimental, “grotesque” or aesthetic pantomime productions with his puppets, and then later added classic mysteries and a variety of dramatic works.

Géza Blattner was one of the first to break with the traditional style of dialogue and naturalism to create a visual theatre that introduced new values in puppetry performance. He exerted a strong influence in Europe, especially in France and Hungary.

Géza Balogh. “Géza Blattner,” on the World Encyclopaedia of Puppetry Arts website (translated Anne Nguyen) 2013 [Online] Cited 11/04/2022

André Kertész (Hungarian, 1894-1985)

Magda, Mme Beöthy, M. Beöthy, and Unknown Guest, Paris

1926-1929

Gelatin silver print on carte postale paper

Image: 3 1/8 × 3 7/8″ (7.9 × 9.8cm)

Sheet: 3 5/16 × 5 3/16″ (8.4 × 13.2cm)

© 2022 Estate of André Kertész

The postcards are beautifully executed and finished works. Mondrian’s Studio (1926; MoMA 1722.2001) is one of several prints made from a single negative, as Kertész refined this now-famous image by cropping it. Most of the prints, such as Magda, Mme Beöthy, M. Beöthy, and Unknown Guest, Paris (1926-1929, above), have been expertly retouched or etched with a sharp tool in order to remove technical flaws in the image, such the dust spots that inevitably occur during printing (fig. 13). Kertész also retouched his negatives to reduce what might be considered flaws in the appearance of his subjects, such as, in Mondrian (fig. 15), the lines around the artist’s mouth (fig. 16). Other prints show slightly more invasive interventions, where various design elements have been reinforced with an unidentified medium that has been so skilfully applied with a brush that it is difficult to see even under magnification (fig. 14). Such subtle alterations have been used by photographers since the invention of the medium.

Nancy Reinhold. “Exhibition in a Pocket: The Cartes Postales of André Kertész,” in Mitra Abbaspour, Lee Ann Daffner, and Maria Morris Hambourg (eds.,). Object: Photo. Modern Photographs: The Thomas Walther Collection 1909-1949. An Online Project of The Museum of Modern Art. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2014.

André Kertész – Postcards from Paris book cover

The High Museum of Art

1280 Peachtree St NE

Atlanta, GA

30309

Opening hours:

Tuesday – Saturday 10am – 5pm

Sunday 12 – 5pm

Monday closed

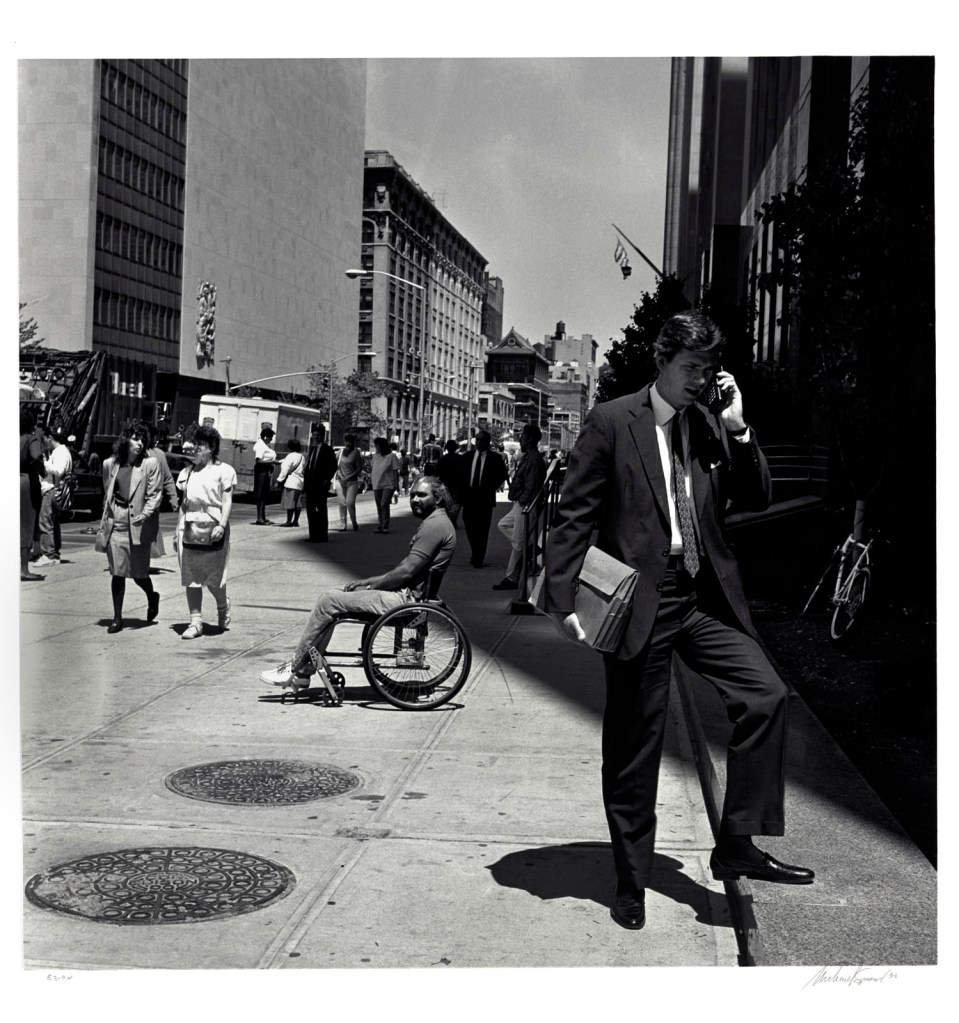

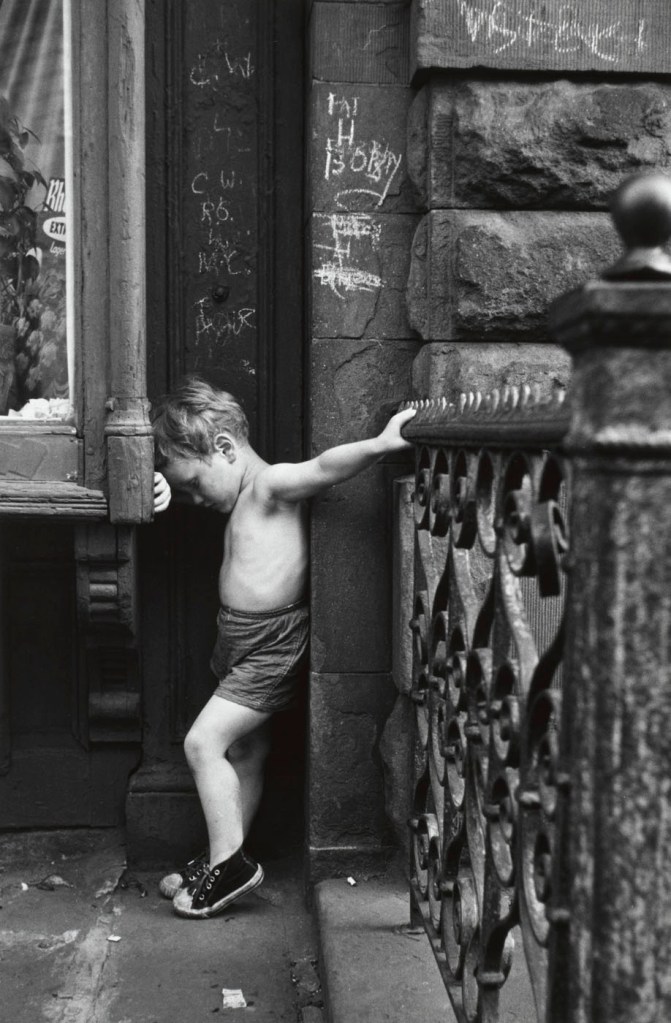

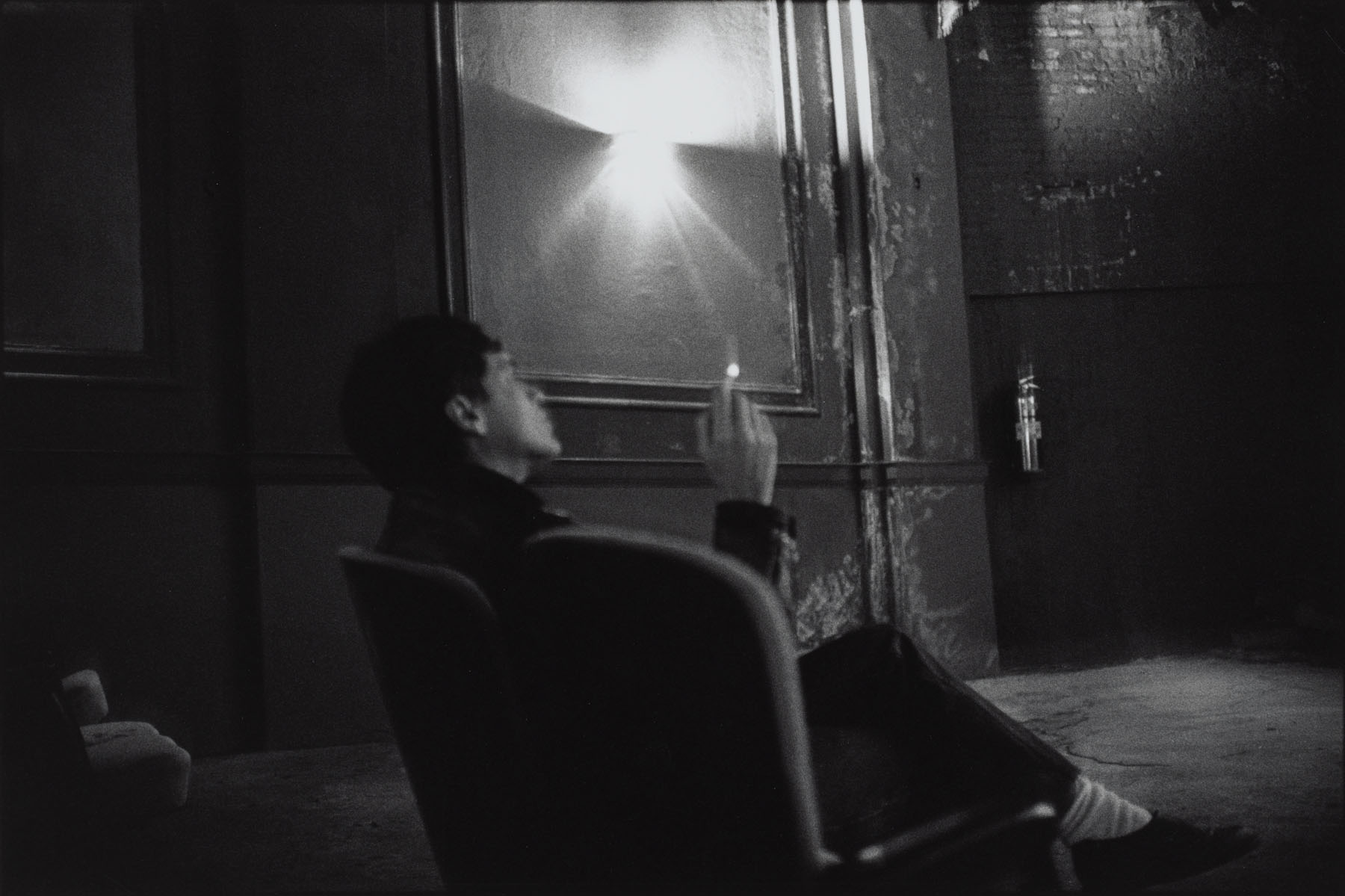

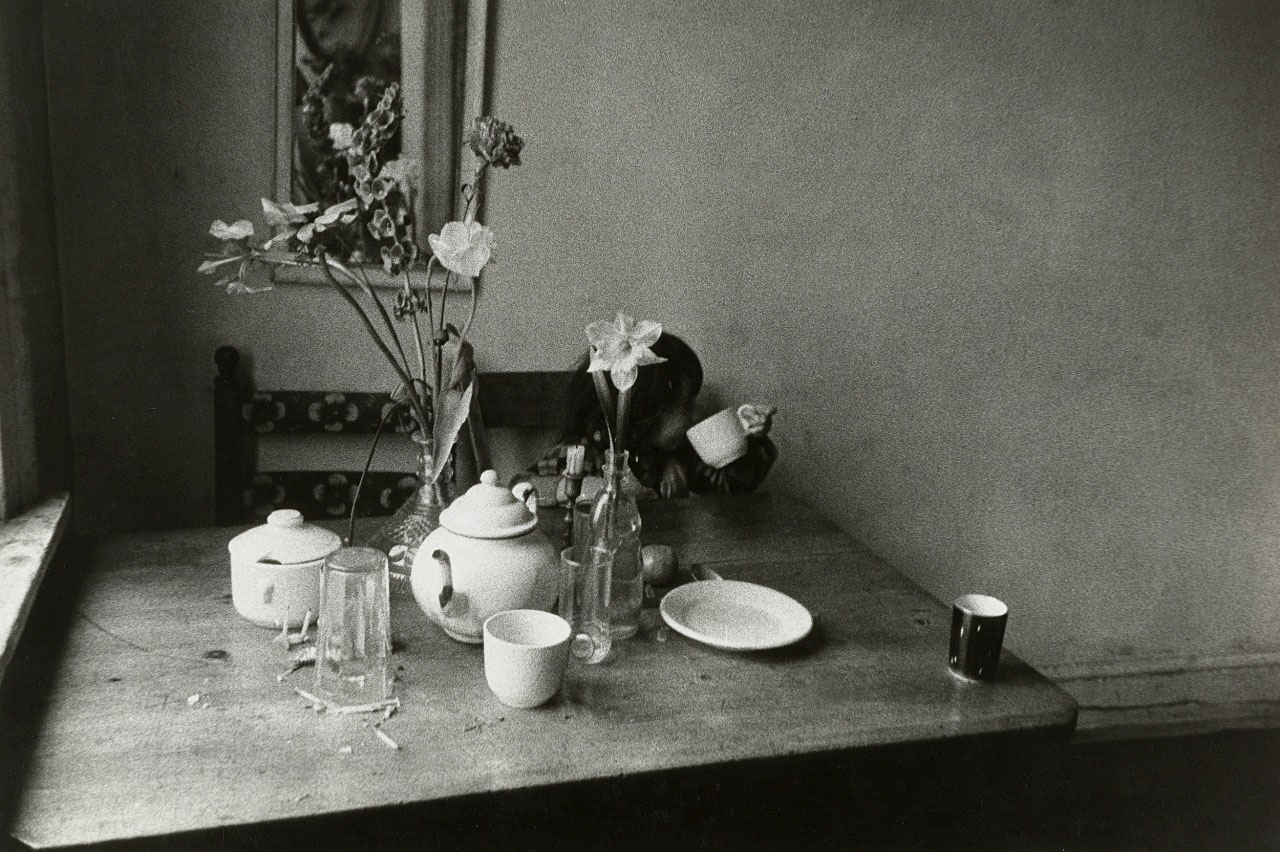

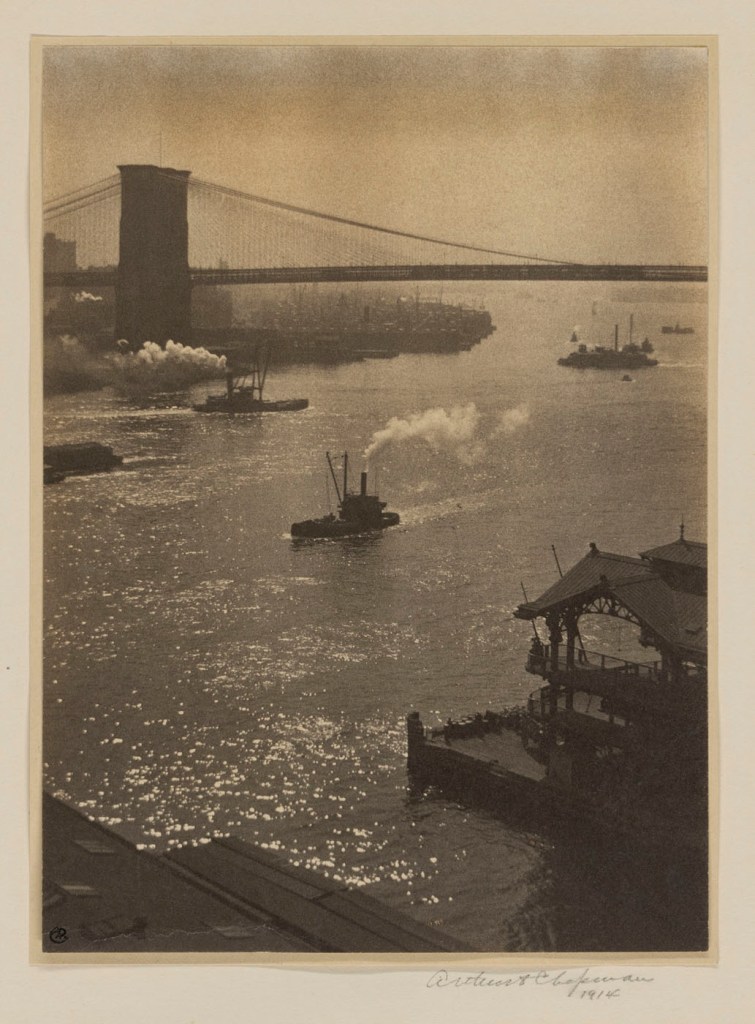

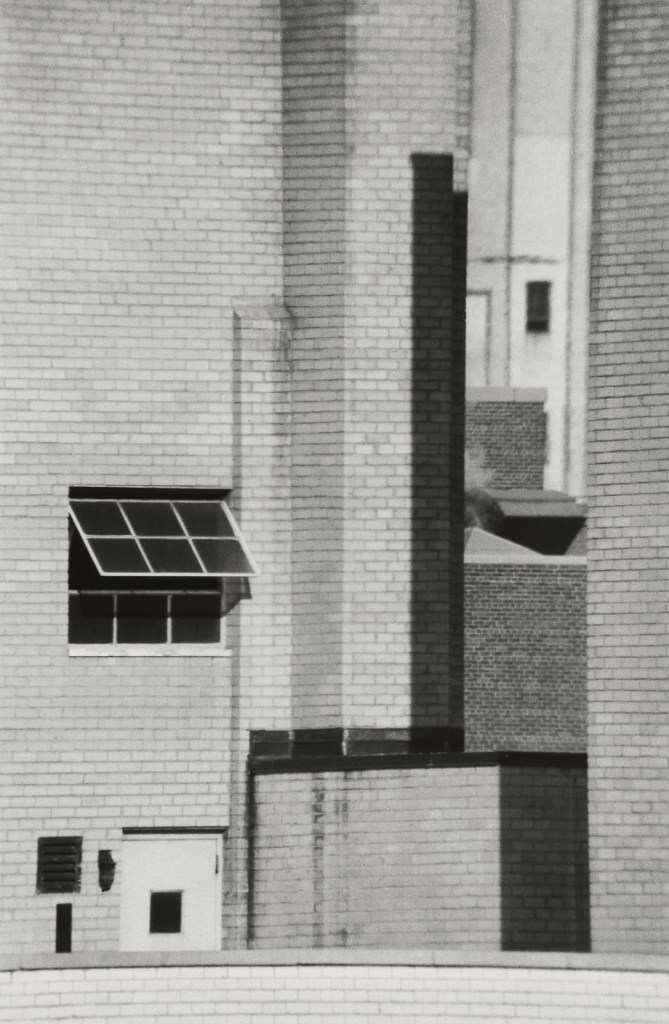

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Celebrating the City: Recent Acquisitions from the Joy of Giving Something' at the Museum of the City of New York showing at right, Mitch Epstein's 'Untitled [New York #3]' 1995 Installation view of the exhibition 'Celebrating the City: Recent Acquisitions from the Joy of Giving Something' at the Museum of the City of New York showing at right, Mitch Epstein's 'Untitled [New York #3]' 1995](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/blf-2022-mcny-celebratingthecity-119.jpg?w=650)

You must be logged in to post a comment.