April 2022

Chicago Photo Co., 389 State Street, Chicago (John B. Wilson, photographer)

Ada Zingara (Harriett O. Shipley, 1861-1937)

early 1900s

Photo-Albumen silver cabinet card

6 1/2 x 4 1/4″

A selection of albumen photographs on cabinet cards and cartes de visite of wonderful human beings. I have added biographical and other information about the photographers and subjects where possible.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

All photographs are used under fair use conditions for the purpose of education and teaching. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Obermüller and Kern, 388 Bowery, N.Y.

Amy Arlington, snake charmer

c. 1880s-1890s

Photo-Albumen silver cabinet card

6 1/2 x 4 1/4″

Charles Eisenmann (American, 1855-1927)

Amy Arlington, snake charmer

c. 1880s-1890s

Photo-Albumen silver cabinet card

6 1/2 x 4 1/4″

About Charles Eisenmann

Charles Eisenmann was an American photographer. His work, which dates from the Victorian-era “Gilded Age” (1870-1890), focused almost exclusively on the “freaks” of the circuses, sideshows, and living museums of New York’s Bowery area. The subject matter was profitable enough to provide a living for both Eisenmann and Frank Wendt, his successor in the business.

Eisenmann was born in Germany in 1850 and emigrated to the United States some time before 1870, settling in New York City. At an early age, Eisenmann established a photography studio in the Bowery. A lower class area that was the hub of popular entertainment, the Bowery was known for its cheap photographic galleries and dime museums. Here Eisenmann discovered his clientele. Dime museums were modelled on P.T. Barnum‘s American Museum on Broadway which exhibited various human “curiosities” as well as many unusual and questionable “scientific” exhibits. Similar in many respects to the circus sideshows, these museums featured human “freaks” who displayed their odd physiognomies and performed before gawking visitors. To help these performers market themselves, Eisenmann and his successor Frank Wendt supplied them with small photographs that they could sell or distribute to publicists. Precisely why Eisenmann was drawn to and focused on this peculiar clientele is not known, though there was evidently money to be made.

Among Eisenmann’s subjects were the famous as well as obscure. They included the “father” of the sideshow, P. T. Barnum, and performers like General Tom Thumb, Jo Jo the Dog-faced Boy, the Wild Men of Borneo, Annie Jones the Bearded Lady, and the Skeleton Man. He also photographed Siamese twins, giants, dwarfs, armless and legless “wonders,” albinos, tattoo artists, and even abnormal animals, such as two-headed cows. While many of these “freaks” were genuine, many were not, having been created out of the imagination and costuming talents of sideshow managers.

Eisenmann’s career in New York began to decline around 1890, and in 1899 he relocated to Plainfield, New Jersey. Wendt joined Eisenmann during this period, at first becoming his business partner, and then son-in-law. Around this same time the warm-toned albumen print process began to disappear, and to be replaced by the cooler silver gelatin process. The change in process did not favour Eisenmann’s techniques. …

The verso of many of Eisenmann’s photographs contained his characteristic tagline, “extra inducements to the theatrical profession,” which reflected the emphasis he placed on his primary clientele.

Anonymous text. “Ronald G. Becker Collection of Charles Eisenmann Photographs,” on the Syracuse University Library website 1998 updated 2016 [Online] Cited 02/04/2022

Charles Eisenmann (American, 1855-1927)

Amy Arlington, snake charmer

c. 1880s-1890s

Photo-Albumen silver cabinet card

6 1/2 x 4 1/4″

Serpent Queens

Snake charming was another speciality that moved from being an almost exclusively male occupation to domination by women. In fact, as snake charming and handling moved into the twentieth century it became almost exclusively a female calling.

Large exotic snakes were exhibited in early museums, and the 1876 and 1893 world fairs imported male snake charmers as part of native villages. During the last two decades of the nineteenth century, when demand for freaks was so high, people, especially partially clad and exotic-looking women, handling or “charming” boas, anacondas, rattlers, cobras, and other serpents became common freak show fare.

Snake charmers – or serpent enchantresses, as they were also called – were, like tattooed persons and Circassians, easy to come by. Although there were tricks to make large snakes lethargic and poisonous snakes benign, some acts contained a distinct elements of danger. For the most part, however, snake charming involved little skill and, aside from the ability to master repulsion and fear, few personal qualifications. There was a seemingly unending supply of charmers – more charmers than snakes by far. Indeed, the cost and supply of snakes was a bigger factor in controlling the number of acts than the number of applicants. While charmers became commonplace and never demanded the high salaries of featured attractions, there was always a place for them on the platform. Audiences continued to squirm in delighted disgust year after year, and, as with human art galleries, innovation provided a continuous element of novelty. After Circassians became commonplace, there were Circassian snake-charmers. In search of novelty, one man wrestled pythons in a five-hundred-gallon tank. Although the types and number of snakes the charmer worked with provided some variety as well, the most important element of the exhibit was the presentation.

There were snake charmers and serpent queens who claimed to be from the East, having learned their skill through apprenticeship to mystics. Others claimed to be born with serpent power. Even though a few who practiced the art probably were from India and other far-off places, most were homegrown Americans…

Whether a domestic exotic or an import, one’s story and stage presence were important elements of success. The difference between a fill-in and an attraction was ingenuity and flair. But most snake charmers were minor attractions, and we know very little about the women around whom the snakes wrapped themselves. A few, however, like Amy Arlington who as with Barnum and Bailey in the 1890s, left many photo portraits of themselves entwined by serpents. Some “true life” booklets are preserved, and, although less elaborate and sophisticated than those of featured stars, they do provide a glimpse of their presentation – a presentation in the high exotic mode.

Robert Bogdan. Freak Show: Presenting Human Oddities for Amusement and Profit. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1988, pp. 256-258

Charles Eisenmann (American, 1855-1927), New York

Charles B. Tripp “Armless Wonder” (33 years old)

1888

Photo-Albumen silver cabinet card

6 1/2 x 4 1/4″

Albumen print on original studio mount features the armless Tripp drinking tea with his feet. Notice the date “1888” near Tripp’s right foot.

Charles B. Tripp (Canadian-American, 1855-1930) was an artist and sideshow performer known as the “Armless Wonder”.

A native of Woodstock, Ontario, Tripp was born without arms but learned to use his legs and feet to perform everyday tasks. He was a skilled carpenter and calligrapher and started supporting his mother and sister when he was a teenager. In 1872, Tripp visited P. T. Barnum in New York City and was quickly hired to work for Barnum’s Great Traveling World’s Fair. He worked for Barnum (and later James Anthony Bailey) for twenty-three years, then toured for the Ringling brothers for twelve years.

On stage, Tripp cultivated a gentlemanly persona and exhibited his skills in carpentry and penmanship. He also cut paper, took photographs, shaved, and painted portraits. For extra income, he signed promotional pictures of himself with his feet. Tripp often appeared in photographs with Eli Bowen, a “legless wonder” from Ohio. In the photographs, the two rode a tandem bicycle, with Tripp pedalling and Bowen steering.

By the 1910s, Tripp was no longer drawing large crowds for the major circuses, so he joined the traveling carnival circuit. He was accompanied by his wife, Mae, who sold tickets for midway attractions. Tripp died of pneumonia (or asthma) in Salisbury, North Carolina, where he had been wintering for several years. He was buried in Olney, Illinois.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Charles Eisenmann

Charles Eisenmann (October 5, 1855 – December 8, 1927) was a famous New York photographer during the late 1880s who worked in the Bowery district.

Eisenmann’s photography was sold in the form of Cabinet cards, popular in this era, available to the middle class. Eisenmann also supplied Duke Tobacco Company with cheesecake photography to stuff in their tobacco cans. The book Victorian Cartes-de-Visite credits Eisenmann with being the most prolific and well known photographer when it comes to Cabinet cards.

His work was the subject of a 1979 monograph, Monsters of the Gilded Age, focusing on his work on human oddities from the Barnum and Bailey circus, with a notable widely circulated picture of Jojo the Dog-faced Boy. Although a number of his photographs were of obvious fakes (called “gaffed freaks”), many others were genuinely anomalous, including the giant Routh Goshen, the four-legged girl Myrtle Corbin, and the Siamese twins Chang and Eng and Millie and Christine. …

Humbugs

In his book, Secrets of the Sideshows, Joe Nickell points out that Eisenmann used a number of notable humbugs or gaffs. These included his “Circassian beauties”, women with teased, large hairdos who were said to have escaped from Turkish harems. The models were locals from the Bronx with hair made frizzy and wild by washing in beer, who earned money for posing. …

Victorian society and circus freaks

In the late 1880s, A new phenomenon appeared with Victorian society’s fascination and sympathy for people who appeared to have genetic abnormalities. There was much publicity, for example, over Princess Alexandra’s attention to Joseph Merrick, the “Elephant Man.”

Eisenmann saw the golden opportunity in this fascination, and photographed circus people dressed as Victorian society, and conversely Victorian society with circus props. In New York city circus people were quite well received, as evidenced by the proliferation of dime museums and the PT Barnum circus located in New York.

One of Eisenmann’s subjects, Charles Stratton (Major Tom Thumb) was quite well known, and his wedding was quite the affair. “The couple’s elaborate wedding took place in Grace Episcopal Church in New York City. The Astors and the Vanderbilts were said to have attended as Barnum sold tickets for $75.”

Other prestigious clients included Mark Twain, and Annie Oakley. In some ways Eisenmann can be considered a kind of Annie Leibovitz of the Victorian Bowery district. His career suffered a downturn with the introduction of Gelatin silver process photography which made photographs more inexpensive and available for mass consumption. Also, Vaudeville overtook circuses in popularity at this time as well. In 1898 Eisenmann closed his studio and was succeeded by Frank Wendt. Frank was a sort of intern of his. For a few years, he sold photographic equipment and took conventional portraits in Plainfield, New Jersey but by 1907 he had disappeared from the public record, some believing he went to Germany. This was the second time he went off the radar, the first time being when his first wife died. At that time he was believed to have gone to Asia.

Eventually, in the early 1900s, he resurfaced as the head of the photography department for DuPont taking pictures of employees. He died in 1927.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Charles Eisenmann (American, 1855-1927), New York

Miss Delina Rossa (age 28)

c. 1880s

Photo-Albumen silver cartes de visite

4 1/4 x 2 1/2″

Rossa is presumed from Paris, as one photo of her is marked “born in Paris” but nothing much else is known about her.

Unknown photographer (American)

Mademoiselle Zana, The only Bearded Russian Lady, 20 years of age

c. 1880s

Photo-Albumen silver cartes de visite

4 1/4 x 2 1/2″

Unknown photographer (American)

“Bearded Girl and her Mother”

c. 1880s

Photo-Albumen silver cartes de visite

4 1/4 x 2 1/2″

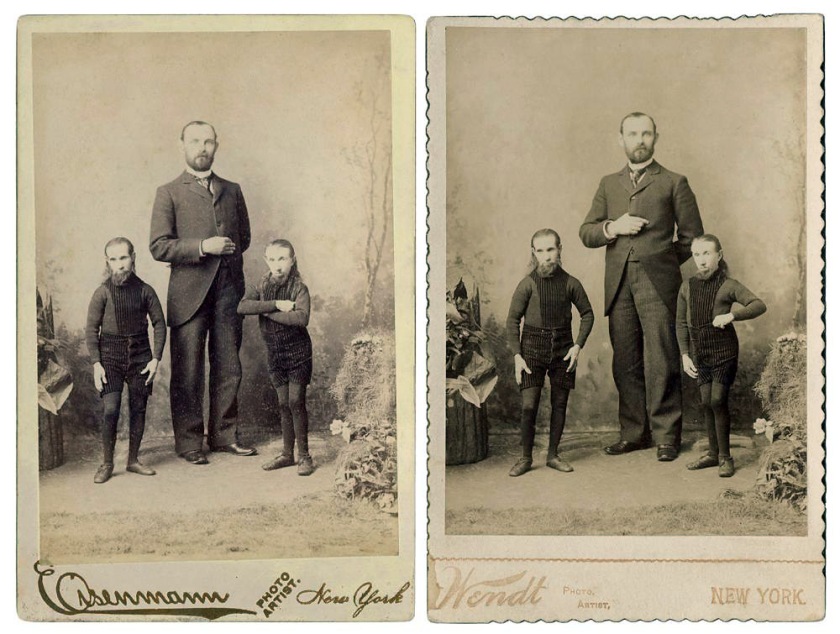

Charles Eisenmann (American, 1855-1927), New York

Frank Wendt (American, 1858-1930), New York

Waino and Plutano “The Wild Men of Borneo” (60-70 years old)

c. 1880s

Photo-Albumen silver cabinet cards

Image: 5 1/2 x 3 7/8 in. (14 x 9.8cm)

Mount: 6 1/2 x 4 1/4 in. (16.5 x 10.8cm)

Wild Men of Borneo

The Wild Men of Borneo, Waino and Plutanor, were a pair of exceptionally strong dwarf brothers who were most famously associated with P. T. Barnum and his freak show exhibitions.

Life

Waino and Plutanor were actually Hiram W. and Barney Davis, two mentally disabled brothers from Pleasant Township, Knox County, Ohio farm, born in 1825 in England and 1827 in Ohio respectively. The 1850 census for them suggests they were born slightly later in 1829 and 1831. Their parents were David Harrison Davis and Catherine Blydenburgh. After their father’s death in 1842, their mother remarried to William Porter. They were each 40 inches tall (100cm) and weighed about 45 pounds (20kg), yet could perform feats of great strength such as lifting heavy weights and wrestling with audience members on stage. Discovered and subsequently promoted by a traveling showman known as Doctor Warner in 1852, Hiram and Barney were given new names, Waino and Plutanor, and a sensational back story – they were said to be from the island of Borneo, where they had been captured after a great struggle with armed sailors. They initially had modest success, but at least one newspaper believed them to be dwarves from the United States. The two soon went on to be exhibited at state fairs across the United States. At the time of the 1860 census they were living in Somerville, Massachusetts in the household of Henry Harvey, a showman. At some point in the next few years management of the pair was transferred to a relative of Doctor Warner, Hanford A. Warner.

In 1874 they were valued at $50,000. In January 1877 they were performing at the New American Museum located in Manhattan. In June 1880 at the time of the federal census, they were touring with William C. Coup’s circus and were enumerated under their assumed identities. By 1882 Waino and Plutanor became involved with P. T. Barnum and his traveling exhibitions. With Barnum’s fabled promotional skill, the careers of the Wild Men of Borneo took off and over the course of the next 25 years, the pair earned approximately $200,000, which was an enormous sum in that era, equivalent to $6,000,000 today. Their exhibitions primarily consisted of performing acts of great strength, such as lifting adult audience members and wrestling with both audience members and each other. They were said to be able to lift up to 300 pounds (140 kg) each. In November 1887 they were performing at Eugene Robinson’s Dime Museum and Theatre. In the 1890s Hanford’s son Ernest took over the management duties of the Davis brothers due to the elder Hanford becoming blind.

In 1903 the brothers were withdrawn from exhibitions by the Warner family. Hiram died in Waltham, Massachusetts on March 16, 1905. Barney stopped working after his brother’s death. Their former manager Hanford Warner died in 1910. Barney died on May 31, 1912 at Waltham, Massachusetts at the Warner family home. The two are buried together in Mount Vernon, Ohio, under a gravestone marked “Little Men.” Newspapers from the time report them being buried in Waltham, Massachusetts. It is unknown when their bodies were moved to Ohio.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Morris Yogg (American, active c. 1885 to 1935, d. 1939), Newark, NJ

Sharpshooter Wyoming Jack

c. 1890s

Photo-Albumen silver cabinet card

6 3/4 x 4 1/4″

The long-haired sharpshooter posing with a revolver at his waist and three rifles at his side.

Stated on the verso of Yogg’s cards: “If you have beauty, come, we’ll take it; if you have none, come, we’ll make it.” Where Yogg was challenged by lack of beauty, he used accessories in an effort to enhance the sitter’s appearance. The photographer was at 162 Springfield Ave. between 1885-1914.

Charles Stacy (American) Corner 9th St. & 5th Ave. Brooklyn

Col. W. F. Cody “Buffalo Bill”

c. 1900s

Photo-Albumen silver cabinet card

6 1/2 x 4 1/4″

Charles Eisenmann (American, 1855-1927), New York

Ettie Rogers

c. 1880s-1890s

Photo-Albumen silver cartes de visite

4 1/4 x 2 1/2″

Unknown photographer (American)

Ettie Rogers

c. 1880s-1890s

Photo-Albumen silver cartes de visite

4 1/4 x 2 1/2″

Ettie Rogers was an albino woman who featured in many traveling shows, notably P. T. Barnum’s travelling museums.

Unknown photographer (American)

Ettie Rogers

c. 1880s-1890s

Photo-Albumen silver cartes de visite

4 1/4 x 2 1/2″

Abraham Bogardus (American, 1822-1908), New York

Chang Yu Sing “The Chinese Giant”

c. 1880s

Photo-Albumen silver cabinet card

5 7/8 in. x 4 in. (150 mm x 101 mm)

Card imprinted with Chang’s height and weight, advertising that he is now appearing with Barnum, Bailey & Hutchinson

Abraham Bogardus

Abraham Bogardus (November 29, 1822 – March 22, 1908) was an American daguerreotypist and photographer who made some 200,000 daguerreotypes during his career. …

Wanting to retire in 1884, Bogardus advertised in the Philadelphia Photographer: “Wishing to retire from the photographic business, I now offer my well-known establishment for sale, after thirty-eight years’ continuous existence in this city. The reputation of the gallery is too well known to require one word of comment. The stock of registered negatives is very valuable, containing a large line of regular customers, and also very many of our prominent men, Presidents, Senators, etc., and for which orders are constantly received. They include Blaine and Logan. Entire apparatus first-class; Dallmeyer lens, etc. For further information, address Abraham Bogardus & Co., 872 Broadway cor. 18th St., New York.”

Text from the Wikipedia website

Bogardus thought extensive retouching of images a kind of representational violence. In national venues he spoke in favour of minimal intervention on the negative – “I retouch but very little, just enough to smooth down the rough parts of the picture, and remove the freckles or spots, or anything we want removed, and soften down the heavy lights.” For Bogardus, altering some defect of a sitter’s appearance for the better violated the verisimilitude of the photographic resemblance, that very thing that made the image true and valuable. This modesty stood at odds with the aesthetic of Sarony, and particularly Mora, who wished to push celebrity images in the direction of the ideal. For this reason, Bogardus enjoyed a particularly high regard among prominent male sitters. He was the only photographer that Cornelius Vanderbilt allowed to sell his image. Politicians, churchmen, plutocrats, and soldiers reckoned him the reliable artist who could fix their characters on paper.

Bogardus had a second talent that rivalled his skill with a camera. He was an excellent writer, with a familiar plain style, and an orderly way of presenting complex subjects. For much of the 1880s he edited an eight-page monthly entitled The Camera, cherished as a fund of wit and common sense. He contributed frequently to the pages of the photographic journals. He retired from active business in 1887, and spent the remainder of his life restoring daguerreotypes, insuring that the first popular vehicle of “light writing” remained in pristine condition for posterity to experience.

Like most of the successful New York celebrity photographers, Bogardus hired a chief camera operator and a good chemist as a head of his print processing department. In the 1880s these assistants, Charles Sherman and A. Joseph McHugh, were granted a credit line on prints, and in 1889 took over the running of the portrait aspect of the business. This partnership ceased in 1895.

Anonymous. “Abraham Bogardus,” on the Broadway Photographs website Nd [Online] Cited 04/03/2022

Abraham Bogardus (American, 1822-1908), New York

Chang Yu Sing “The Chinese Giant”

c. 1880s

Photo-Albumen silver cabinet card

5 7/8 in. x 4 in. (150 mm x 101 mm)

Chang Woo Gow (Chang Yu Sing) (1841-1893), ‘The Chinese Giant’

Born in the Canton Province, China, Gow grew to the height of 7 feet and 8.75 inches (235.5cm) tall. Well-travelled, he was a man of exceptional intelligence, speaking at least 10 languages. Believed to be the tallest man in the world, he earned money through appearances billed as ‘The Chinese Giant’, becoming a popular tourist attraction. In Australia he met his second wife Catherine who bore him two sons, Edwin (born in Beijing) and Ernest (born in Paris). After appearing in Barnum and Bailey’s ‘Greatest Show on Earth’ he tired of 30 years of travelling the world as a marvel and retired. To cure his suspected tuberculosis, the family settled in Bournemouth (1890), establishing an Oriental-bazaar and tea-room business at their home. He became a popular local ‘attraction’ in Bournemouth when he and his wife took walks in the evenings, now known as ‘The Gentle Giant’ he was always kind and friendly, but he sought a quiet life. Heartbroken at the death of his wife, he died 4 months later. Still mourning the loss of his wife, on his deathbed he requested a quiet funeral. His funeral was therefore kept a secret to prevent hundreds of onlookers from attending. He was buried in an unmarked grave alongside his wife in a coffin said to be eight and a half feet long.

Anonymous. “Chang Woo Gow (Chang Yu Sing) (1841-1893),” on the National Portrait Gallery website Nd [Online] Cited 04/03/2022

Abraham Bogardus (American, 1822-1908), New York

Chang Yu Sing “The Chinese Giant”

c. 1880s

Photo-Albumen silver cabinet cards

5 7/8 in. x 4 in. (150 mm x 101 mm) (each)

Jacob J. Ginther (American, b. 1859), Buffalo, NY

Gustavo Arcaris Knife-Thrower

c. 1890

Photo-Albumen silver cabinet card

6 1/2 x 4 1/4″

Jacob J. Ginther, born 1859 in NY, and was working into the early 1930’s in Buffalo, is said to have started his Buffalo photography business in 1884.

Sepia-toned albumen print on original studio mount of a knife (and other weapons) thrower, Arcaris, and his female assistant with her body outlined in knives against a board.

Gustavo Arcaris, Father of Modern Knife Throwing

Gustavo Arcaris, better known as “The Great Arcaris”, was discovered by P. T. Barnum in Italy in the late 1880s. Barnum brought him to the US to act as a show man for the Barnum circus. The woman who performed as his assistant was Gustavo’s sister Kate.

Gustavo Arcaris and his wife were born in Italy. He came from Naples and in 1887 he emigrated with his wife Mary to America, first living in Illinois and then settled in Detroit, Michigan. In 1897 he and his wife were naturalised. According to the 1920 census he was living with his wife Mary and their four children in Detroit. The couple is listed with their three sons, Salvatore, Louis, and George, and one daughter, Virginia – who was still with the circus.

Unknown photographer (American)

Nettie Littell

c. 1885

Photo-Albumen silver cabinet card

6 1/2 x 4 1/4″

Early albumen print of Littell, with pencil inscription on verso reading “Capt. Nettie Littell Champion Long Distant (sic) Rider of America”. Littell was a Colorado long distance rider and shooter.

Frank Wendt (American, 1858-1930), Bowery N.Y.

Mille Mojur, Sword Walker

c. 1890s

Photo-Albumen silver cabinet card

6 1/2 x 4 1/4″

Other than Charles Eisenmann, Frank Wendt was the most well-known freak and dime museum photographer of the 19th century. Wendt was Charles Eisenmann’s protege, successor and son-in-law, taking over his father-in-law’s business in 1875 at 229 Bowery in New York City.

Anonymous text. “Frank Wendt, photographer,” on the Show History website Nd [Online] Cited 04/03/2022

Mille Mojur posing by a ladder made of swords. Signed faintly in pencil on the verso, likely by the performer herself.

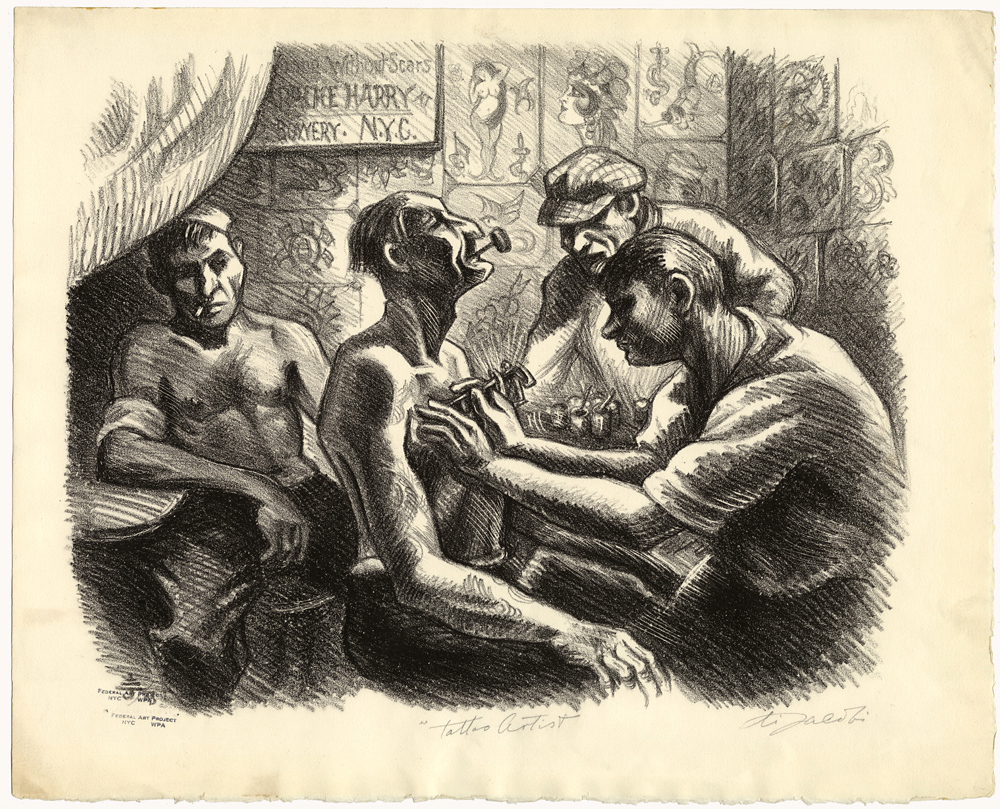

![Unknown photographer. 'Untitled [Millie Hull tattooing in her studio]' Nd Unknown photographer. 'Untitled [Millie Hull tattooing in her studio]' Nd](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/millie-hull-web.jpg)

![Unknown photographer. 'Untitled [Charlie Wagner tattooing in his studio]' Nd Unknown photographer. 'Untitled [Charlie Wagner tattooing in his studio]' Nd](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/charlie-wagner-web.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.