Exhibition dates: 25th October 2011 – 11th March 2012

![Lyonel Feininger (American, 1871-1956) 'Untitled [Street Scene, Double Exposure, Halle]' 1929-1930 Lyonel Feininger (American, 1871-1956) 'Untitled [Street Scene, Double Exposure, Halle]' 1929-1930](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/street-scene-double-exposure-halle-1929-1930.jpg)

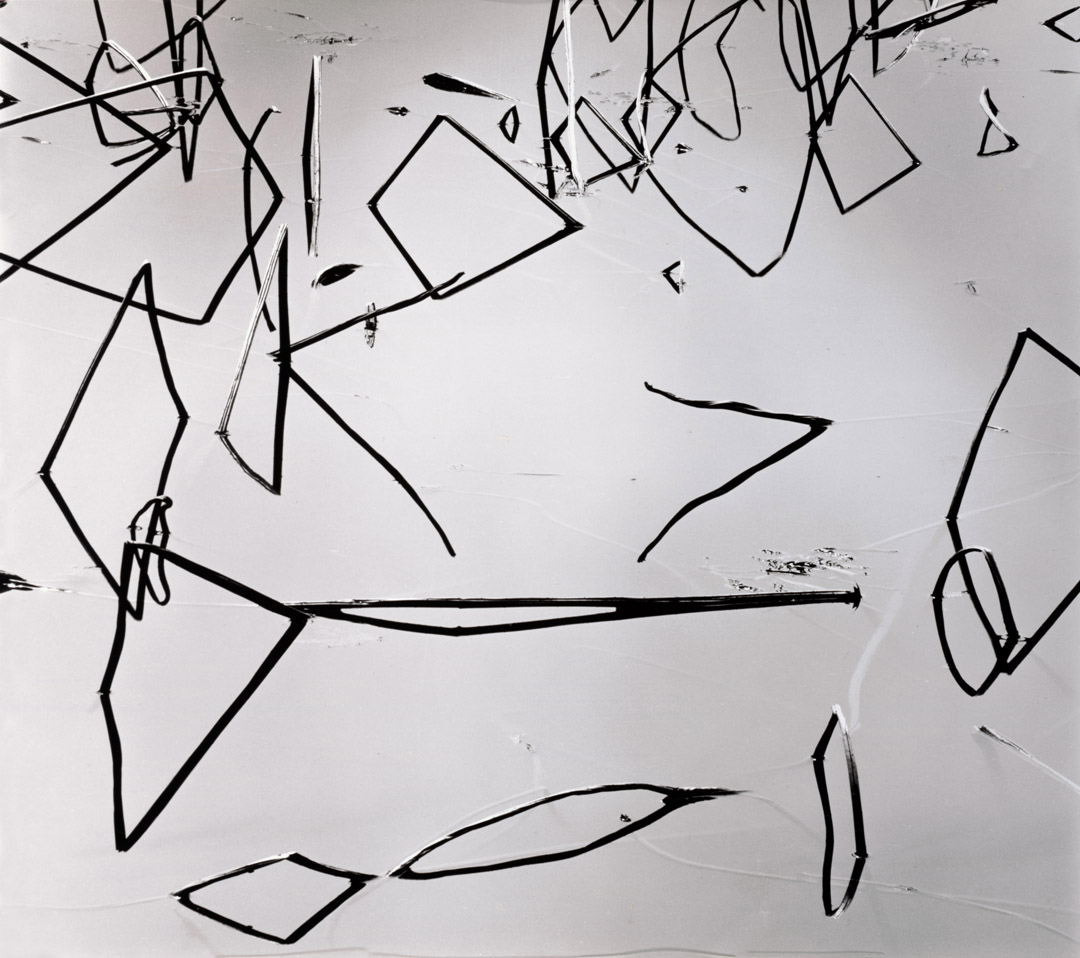

Lyonel Feininger (American, 1871-1956)

Untitled [Street Scene, Double Exposure, Halle]

1929-1930

Gelatin silver print

Image: 17.8 x 23.7cm (7 x 9 5/16 in)

Gift of T. Lux Feininger, Houghton Library, Harvard University

© Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

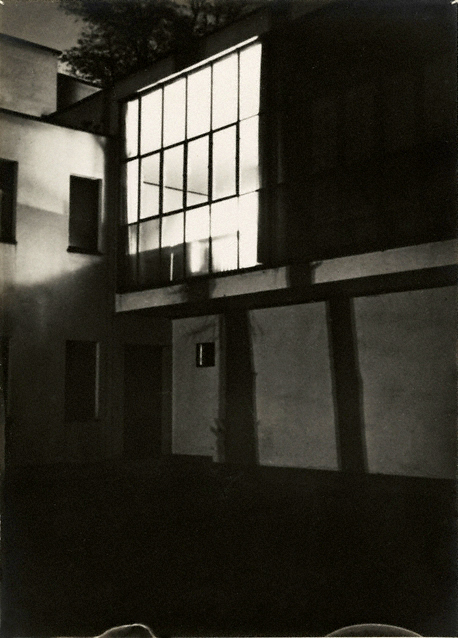

Another photographer whose work was largely unknown to me. His work can be seen to reference Pictorialism, Eugene Atget, Constructivism and Modernism, the latter in the last three photographs of the Bauhaus buildings at night which are just beautiful! The capture of form, light (emanating from windows) and atmosphere is very pleasing.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

P.S. Don’t be confused when looking at the photographs in the posting. Note the difference in the work of Lynonel and his two sons Andreas and Theodore (nicknamed Lux).

Many thankx to the J. Paul Getty Museum for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

![Lucia Moholy (British born Czechoslovakia, 1894-1989) 'Untitled [Southern View of Newly Completed Bauhaus, Dessau]' 1926 Lucia Moholy (British born Czechoslovakia, 1894-1989) 'Untitled [Southern View of Newly Completed Bauhaus, Dessau]' 1926](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/lucia-moholy-southern-view-of-newly-completed-bauhaus.jpg)

Lucia Moholy (British born Czechoslovakia, 1894-1989)

Untitled [Southern View of Newly Completed Bauhaus, Dessau]

1926

Gelatin silver print

Sheet: 5.7 x 8.1cm (2 1/4 x 3 3/16 in)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

![Lyonel Feininger (American, 1871-1956) 'Untitled [Train Station, Dessau]' 1928-1929 Lyonel Feininger (American, 1871-1956) 'Untitled [Train Station, Dessau]' 1928-1929](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/gm_326238ex1.jpg)

Lyonel Feininger (American, 1871-1956)

Untitled [Train Station, Dessau]

1928-1929

Gelatin silver print

Image: 17.7 x 23.7 cm (6 15/16 x 9 5/16 in.)

Gift of T. Lux Feininger, Houghton Library, Harvard University

© Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

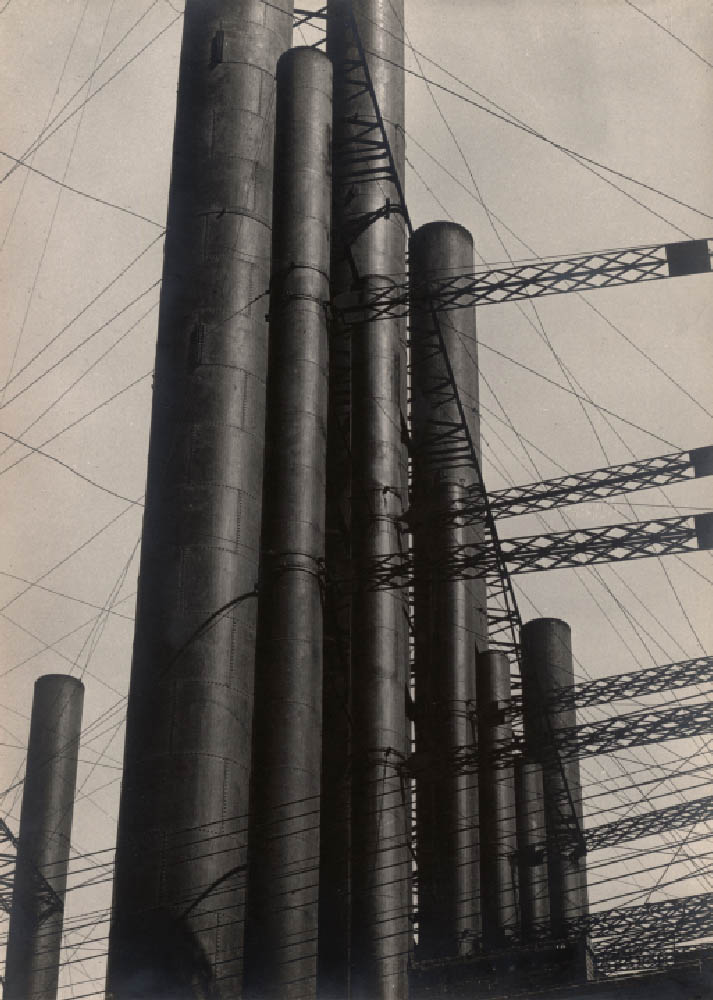

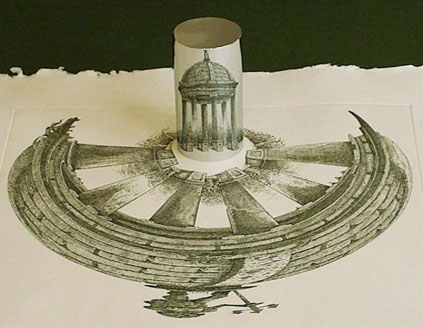

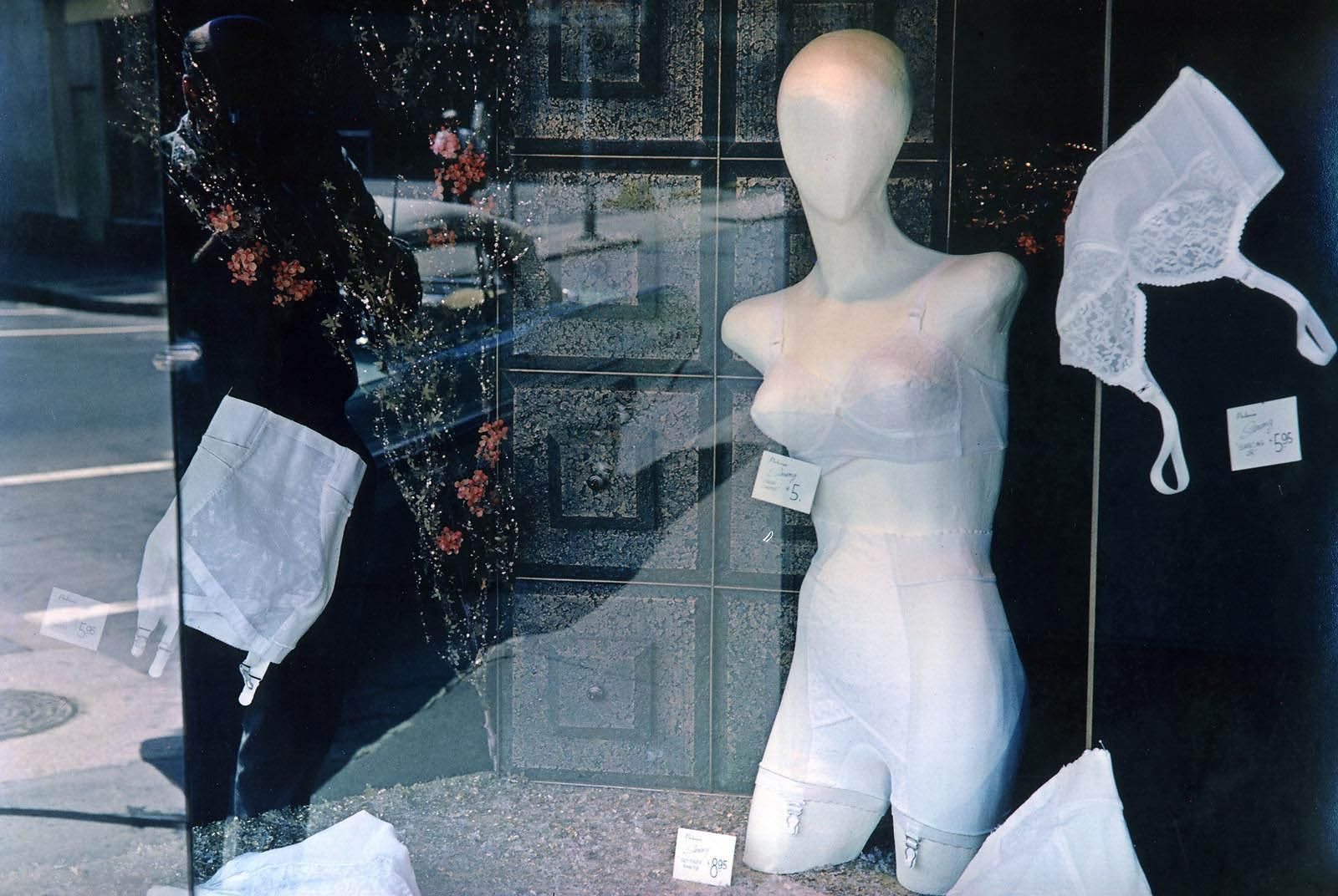

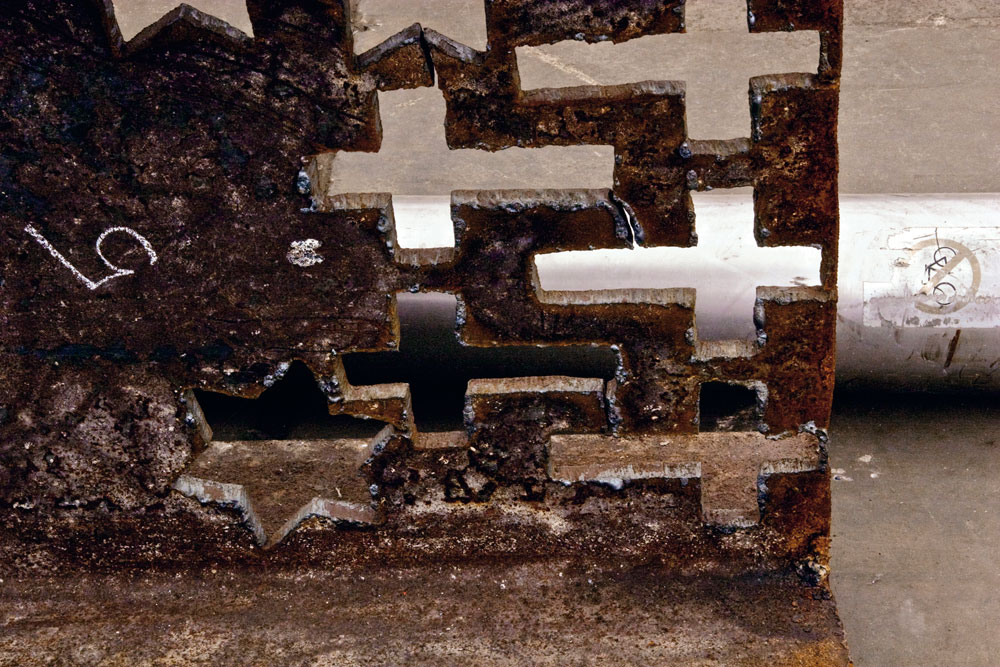

Werner Zimmermann (German, 1906-1975)

In Der Werkstatt [In The Workshop]

About 1929

Gelatin silver print

7.9 × 11cm (3 1/8 × 4 5/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

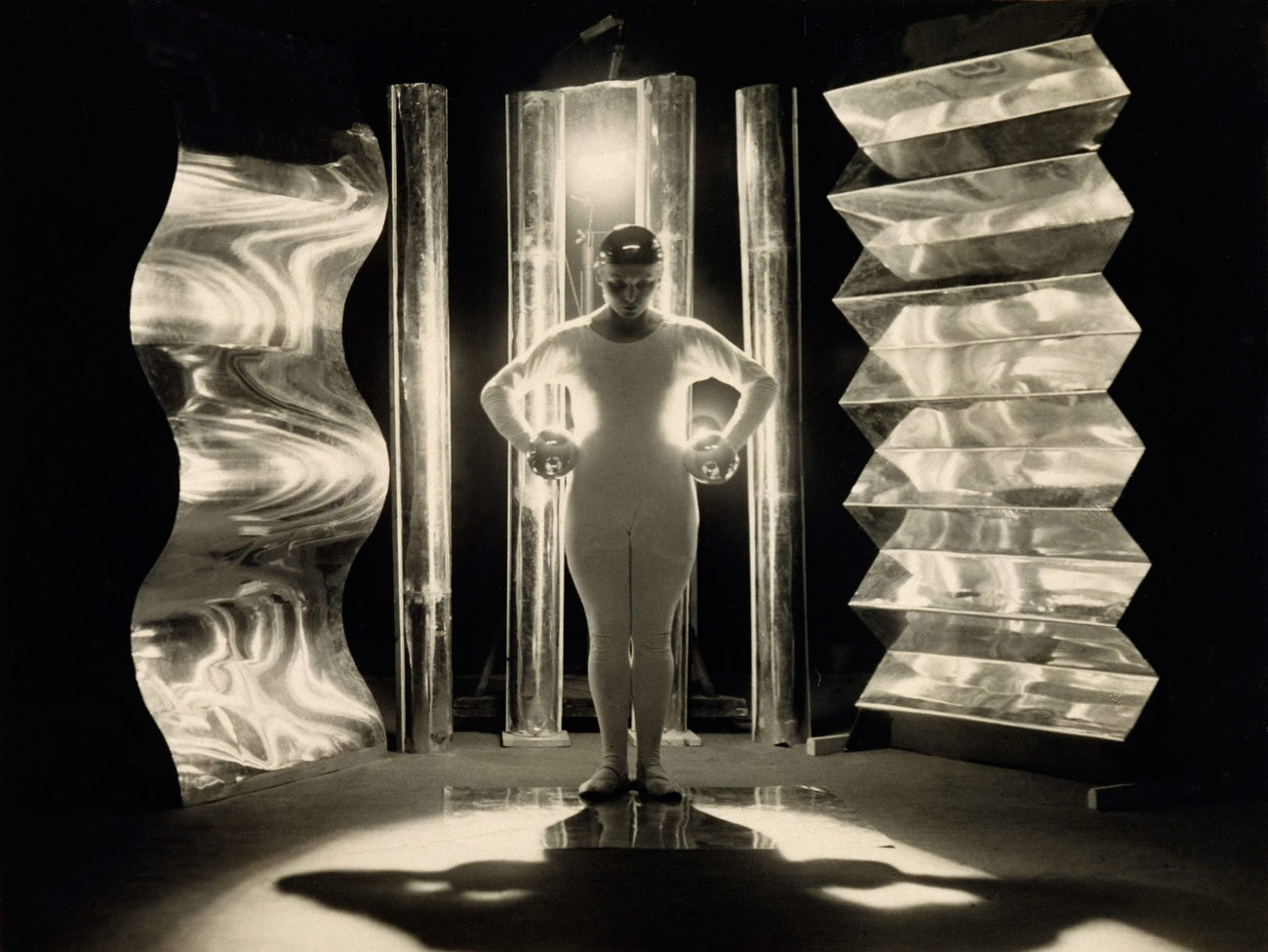

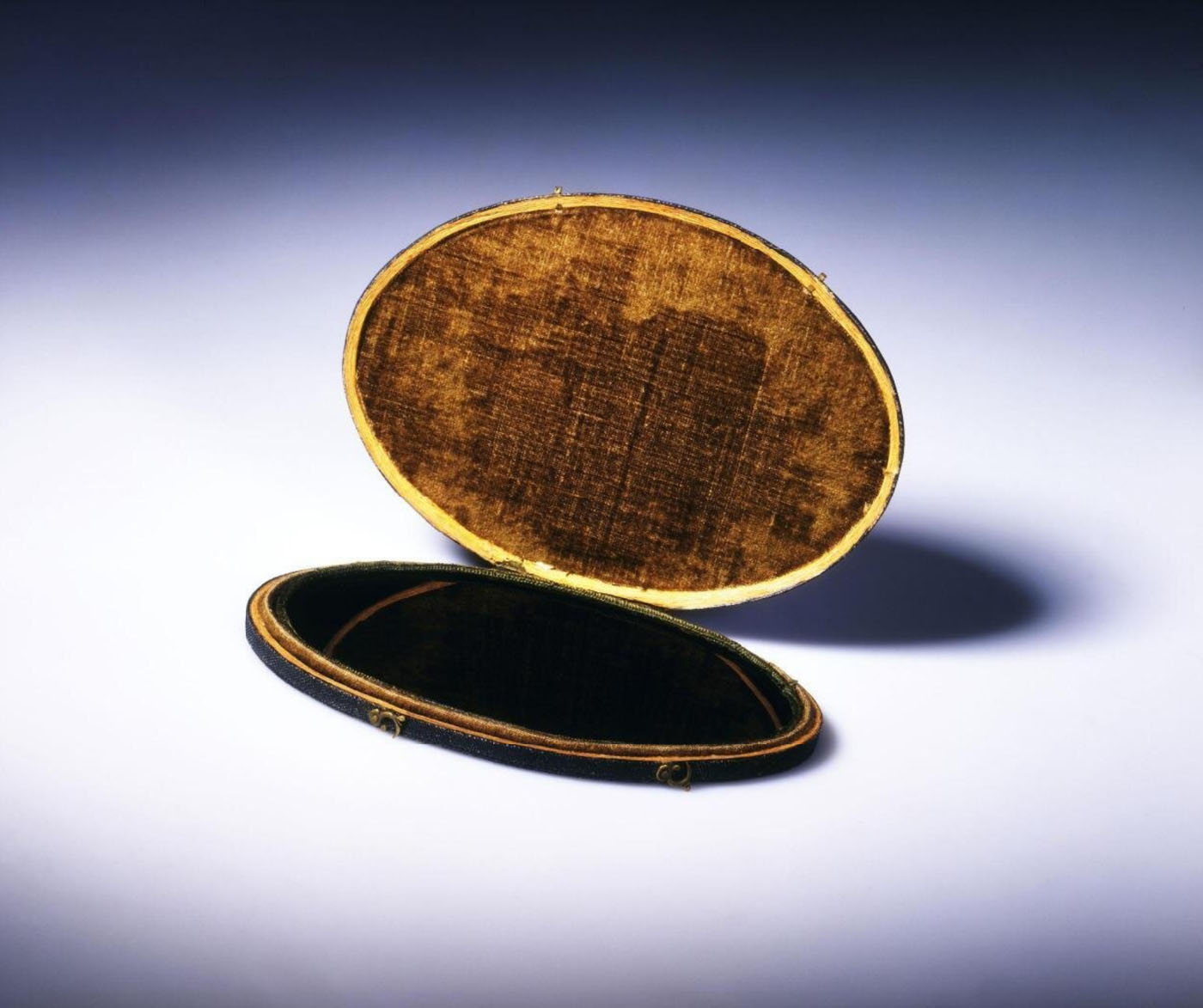

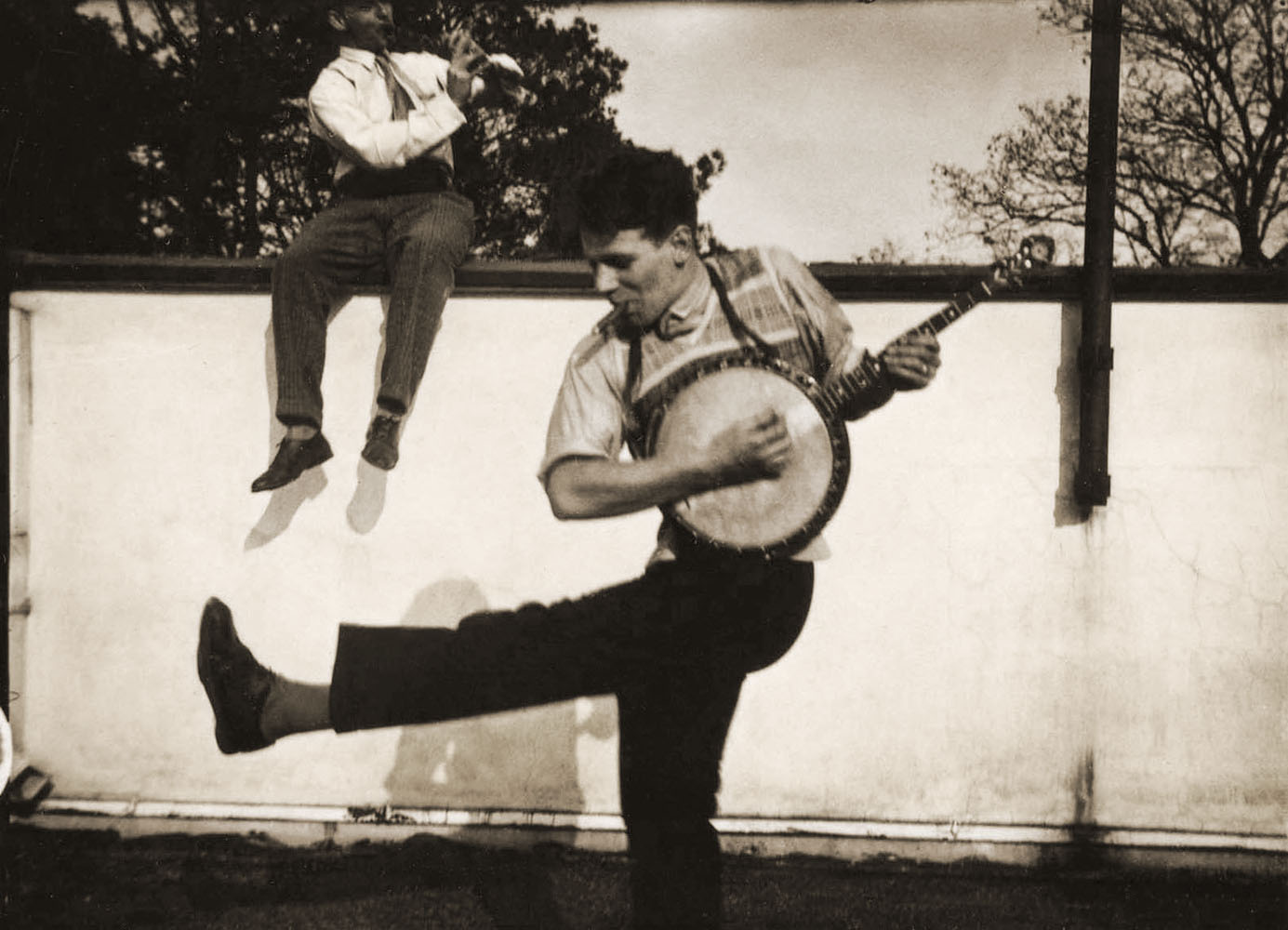

T. Lux Feininger (American born Germany, 1910-2011)

Metalltanz

1929

Gelatin silver print

Image: 10.8 x 14.4cm (4 1/4 x 5 5/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© Estate of T. Lux Feininger

Widely recognised as a painter, printmaker, and draftsman who taught at the Bauhaus, Lyonel Feininger (American, 1871-1956) turned to photography later in his career as a tool for visual exploration. Drawn mostly from the collections at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Lyonel Feininger: Photographs, 1928-1939 at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Getty Center, October 25, 2011 – March 11, 2012, presents for the first time Feininger’s unknown body of photographic work. The exhibition is accompanied by a selection of photographs by other Bauhaus masters and students from the Getty Museum’s permanent collection. The Getty is the first U.S. venue to present the exhibition, which will have been on view at the Kupferstichkabinett, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin from February 26 – May 15, 2011 and the Staatliche Graphische Sammlung, Pinakothek der Moderne in Munich from June 2 – July 17, 2011. Following the Getty installation, the exhibition will be shown at the Harvard Art Museums from March 30 – June 2, 2012. At the Getty, the exhibition will run concurrently with Narrative Interventions in Photography.

“We are delighted to be the first U.S. venue to present this important exhibition organised by the Harvard Art Museums / Busch-Reisinger Museum,” says Virginia Heckert, curator of photographs at the J. Paul Getty Museum and curator of the Getty’s installation. “The presentation at the Getty provides a unique opportunity to consider Lyonel Feininger’s achievement in photography, juxtaposed with experimental works in photography at the Bauhaus from our collection.”

Lyonel Feininger Photographs

When Lyonel Feininger (1871-1956) took up the camera in 1928, the American painter was among the most prominent artists in Germany and had been on the faculty of the Bauhaus school of art, architecture, and design since it was established by Walter Gropius in 1919. For the next decade, he used the camera to explore transparency, reflection, night imagery, and the effects of light and shadow. Despite his early skepticism about this “mechanical” medium, Feininger was inspired by the enthusiasm of his sons Andreas and Theodore (nicknamed Lux), who had installed a darkroom in the basement of their house, as well as by the innovative work of fellow Bauhaus master, László Moholy-Nagy.

Although Lyonel Feininger would eventually explore many of the experimental techniques promoted by Moholy-Nagy and practiced by others at the school, he remained isolated and out of step with the rest of the Bauhaus. Working alone and often at night, he created expressive, introspective, otherworldly images that have little in common with the playful student photography more typically associated with the school. Using a Voigtländer Bergheil camera (on display in the exhibition), frequently with a tripod, he photographed the neighbourhood around the Bauhaus campus and masters’ houses, and the Dessau railway station, occasionally reversing the tonalities to create negative images.

Lyonel Feininger: Photographs, 1928-1939 also includes the artist’s photographs from his travels in 1929-1931 to Halle, Paris, and Brittany, where he investigated architectural form and urban decay in photographs and works in other media. In Halle, while working on a painting commission for the city, Feininger recorded architectural sites in works such as Halle Market with the Church of St. Mary and the Red Tower (1929-1930), and experimented with multiple exposures in photographs such as Untitled (Street Scene, Double Exposure, Halle) (1929-1930), a hallucinatory image that merges two views of pedestrians and moving vehicles.

Since 1892 Feininger had spent parts of the summer on the Baltic coast, where the sea and dunes, along with the harbours, rustic farmhouses, and medieval towns, became some of his most powerful sources of inspiration. During the summers Feininger also took time off from painting, focusing instead on producing sketches outdoors or making charcoal drawings and watercolours on the veranda of the house he rented. Included in the exhibition are photographs Feininger created in Deep an der Rega (in present-day Poland) between 1929 and 1935 which record the unique character of the locale, the people, and the artistic and leisure activities he pursued.

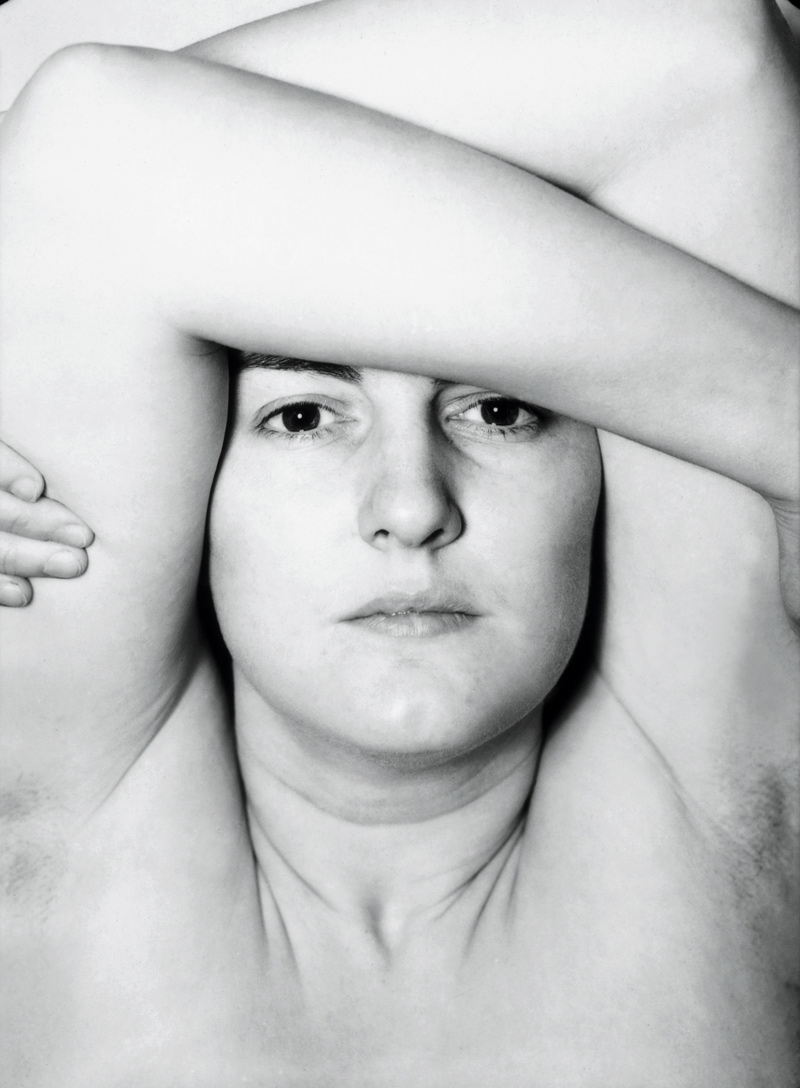

In the months after the Nazis closed the Bauhaus, and prior to Feininger’s departure from Dessau in March 1933, he made a series of unsettling photographs featuring mannequins in shop windows such as Drunk with Beauty (1932). Feininger’s images emphasise not only the eerily lifelike and strangely seductive quality of the mannequins, but also the disorienting, dreamlike effect created by reflections on the glass.

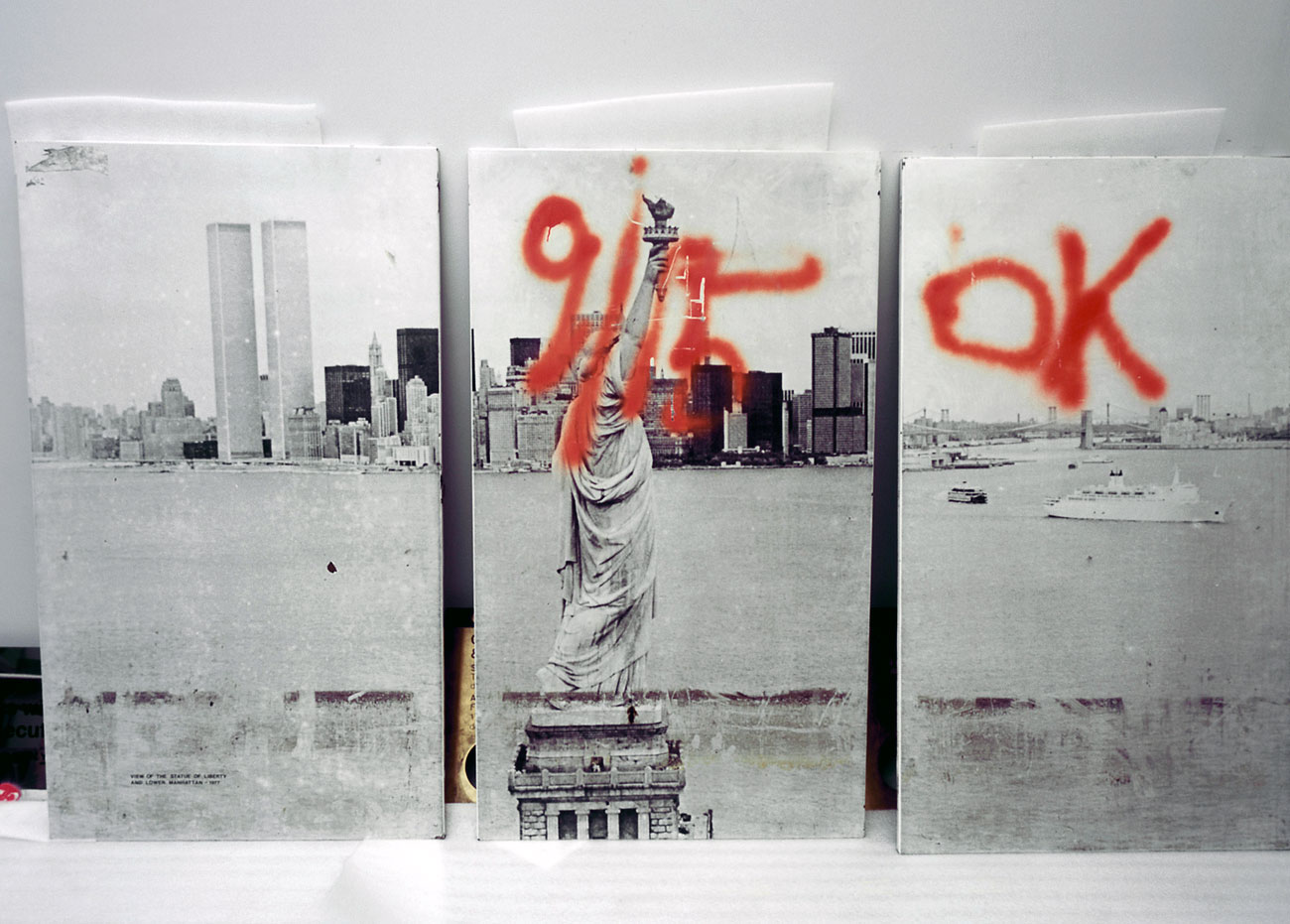

In 1937 Feininger permanently settled in New York City after a nearly 50-year absence, and photography served as an important means of reacquainting himself with the city in which he had lived until the age of sixteen. The off-kilter bird’s eye view he made from his eleventh-floor apartment of the Second Avenue elevated train tracks, Untitled (Second Avenue El from Window of 235 East 22nd Street, New York) (1939), is a dizzying photograph of an American subject in the style of European avant-garde photography, and mirrors the artist’s own precarious and disorienting position between two worlds, and between past and present.

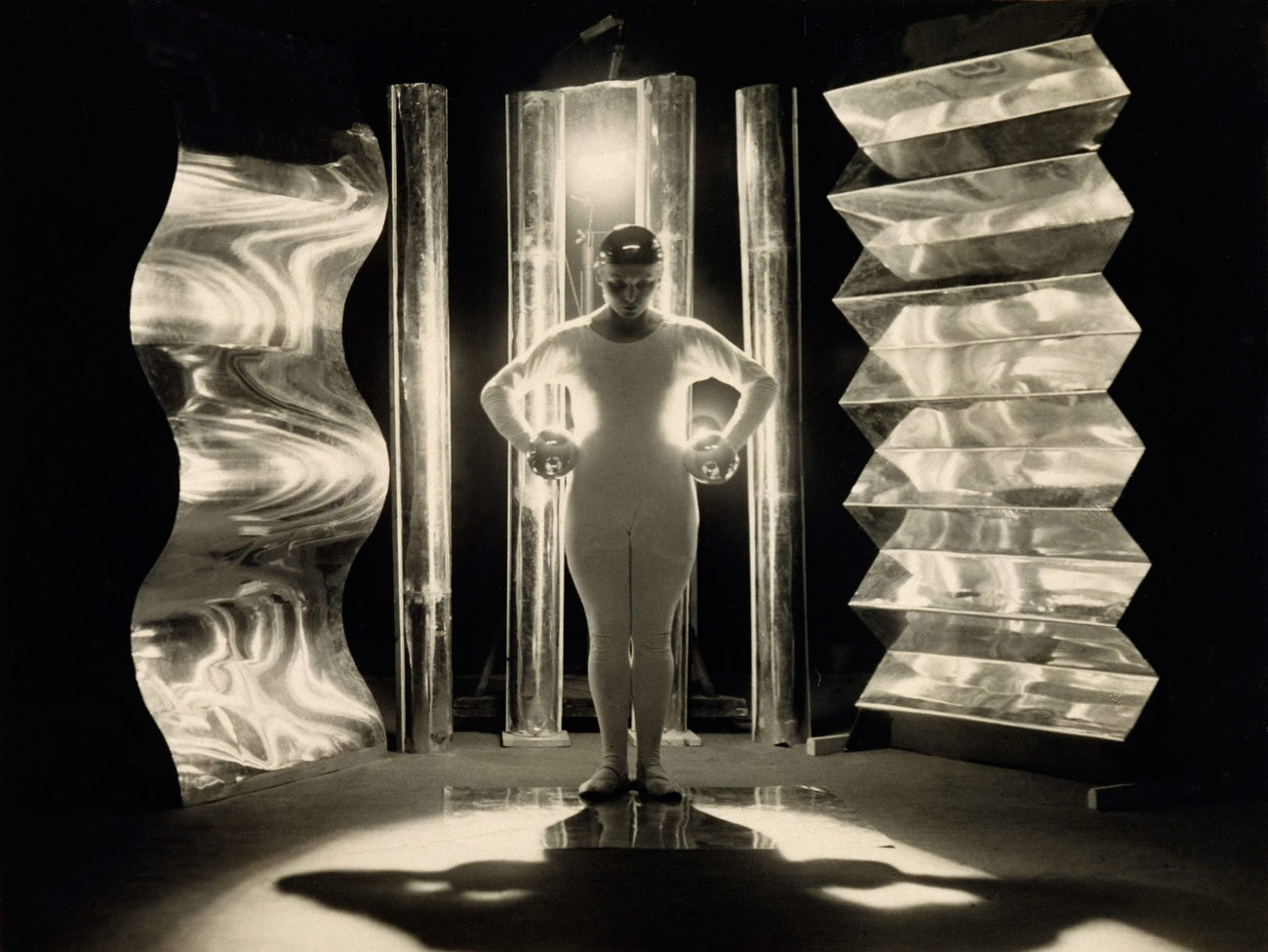

The Bauhaus

Walter Gropius, director of the Bauhaus from 1919 to 1928, changed the face of art education with his philosophy of integrating art, craft, and technology with everyday life at the Bauhaus. When Gropius’s newly designed building in Dessau was completed in December 1926, its innovative structure did more than house the various components of the school; it became an integral aspect of life at the Bauhaus and a stage for its myriad activities, from studies and leisurely pursuits to theatrical performances. From the beginning, the camera recorded the architecture as the most convincing statement of Gropius’ philosophy as well as the fervour with which the students embraced it. The photographs in this complementary section of the exhibition also examine the various ways photography played a role at the Bauhaus, even before it became part of the curriculum.

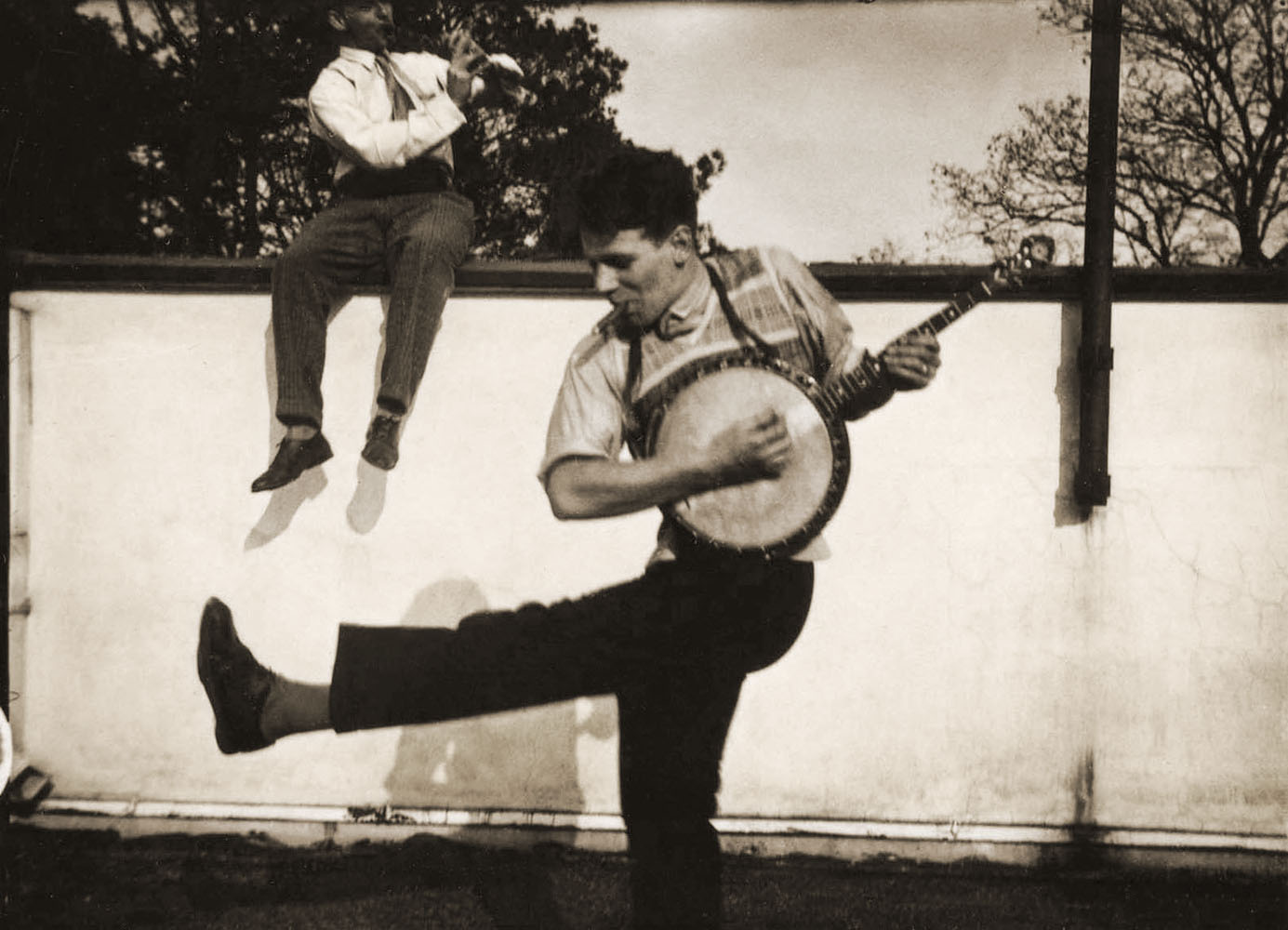

In addition to the collaborative environment encouraged in workshops, students found opportunities to bond during their leisure time, whether in a band that played improvisational music or on excursions to nearby beaches, parks, and country fairs. One of the most active recorders of life at the Bauhaus was Lyonel Feininger’s youngest son, T. Lux, who was also a member of the jazz band.

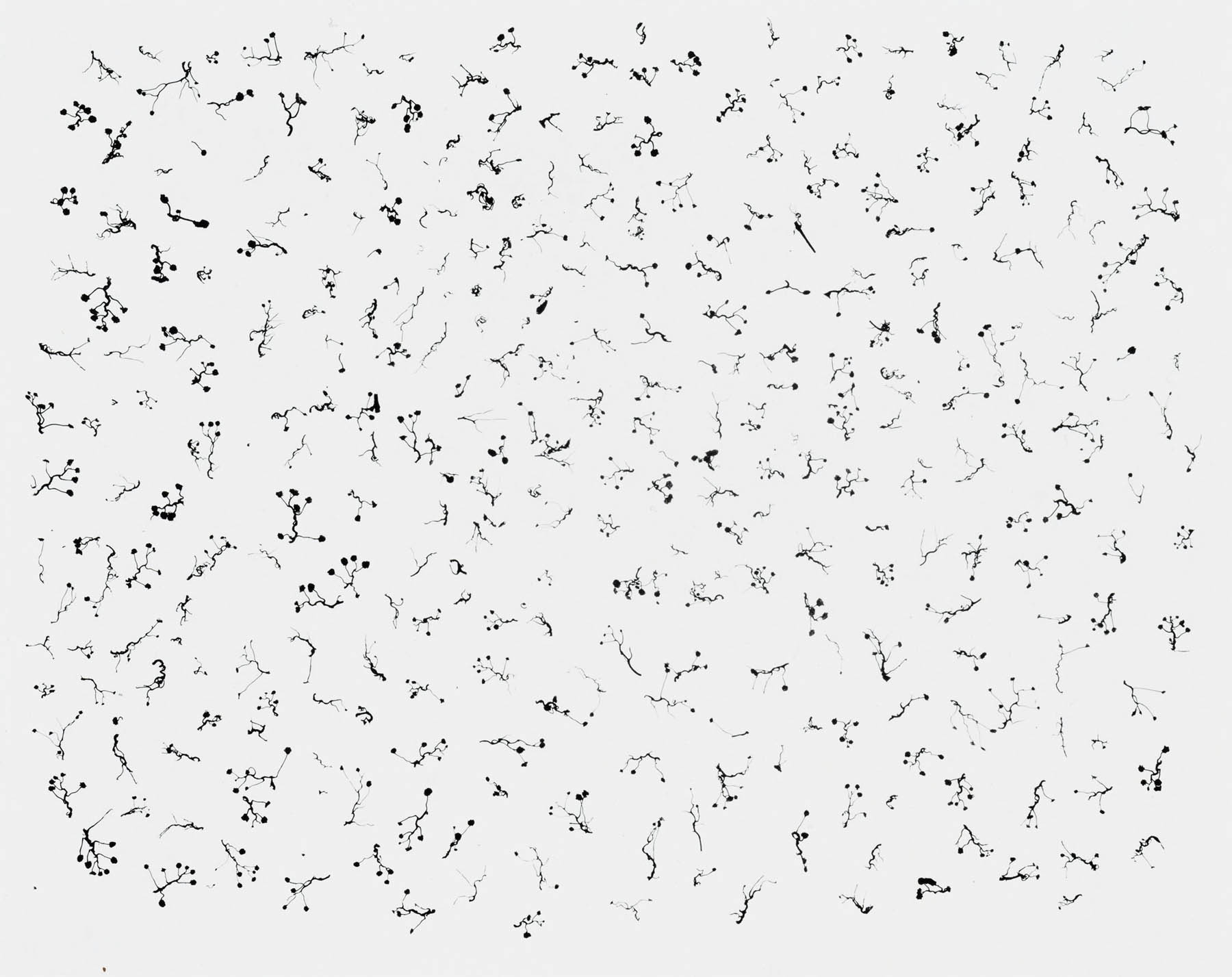

Masters and students alike at the Bauhaus took up the camera as a tool with which to record not only the architecture and daily life of the Bauhaus, but also one another. Although photography was not part of the original curriculum, it found active advocates in the figures of László Moholy-Nagy and his wife Lucia Moholy. With his innovative approach and her technical expertise, the Moholy-Nagys provided inspiration for others to use the camera as a means of both documentation and creative expression. The resulting photographs, which included techniques such as camera-less photographs (photograms), multiple exposures, photomontage and collages (“photo-plastics”), and the combination of text and image (“typo-photo”), contributed to Neues Sehen, or the “new vision,” that characterised photography in Germany between the two world wars.

It was not until 1929 that photography was added to the Bauhaus curriculum by Hannes Meyer, the new director following Gropius’s departure. A part of the advertising department, the newly established workshop was led by Walter Peterhans, who included technical exercises as well as assignments in the genres of portraiture, still life, advertisement, and photojournalism in the three-year course of study.”

Press release from the J.Paul Getty Museum website

![Lyonel Feininger (American, 1871-1956) 'Untitled [Night View of Trees and Street Lamp, Burgkühnauer Allee, Dessau]' 1928 Lyonel Feininger (American, 1871-1956) 'Untitled [Night View of Trees and Street Lamp, Burgkühnauer Allee, Dessau]' 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/night-view-of-trees-and-streetlamp-burgkc3bchnauer-allee-dessau-1928.jpg)

Lyonel Feininger (American, 1871-1956)

Untitled [Night View of Trees and Street Lamp, Burgkühnauer Allee, Dessau]

1928

Gelatin silver print

Image: 17.7 x 23.7cm (6 15/16 x 9 5/16 in)

Gift of T. Lux Feininger, Houghton Library, Harvard University

© Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Andreas Feininger (American, 1906-1999)

Stockholm (Shell sign at night)

1935

Gelatin silver print

17.4 x 24.2cm

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of the Estate of Gertrud E. Feininger

© Estate of Gertrud E. Feininger

Lyonel Feininger (American, 1871-1956)

Drunk with Beauty

1932

Gelatin silver print

Image: 17.9 x 23.9cm (7 1/16 x 9 7/16 in)

Gift of T. Lux Feininger, Houghton Library, Harvard University

© Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Lyonel Feininger (American, 1871-1956)

Bauhaus

March 22, 1929

Gelatin silver print

Image: 17.8 x 23.9cm (7 x 9 7/16 in)

Harvard Art Museums/Busch-Reisinger Museum, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Lyonel Feininger

© Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

T. Lux Feininger (American born Germany, 1910-2011)

Untitled (Georg Hartmann and Werner Siedhoff with Other Students)

1929

Gelatin silver print

© Estate of T. Lux Feininger

Lyonel Feininger and Photography

Lyonel Feininger took up the camera at the age of 58 in fall 1928. Despite his early skepticism about this “mechanical” medium, the painter was inspired by the enthusiasm of his sons Andreas and Theodore (nicknamed Lux), as well as by the innovative work of László Moholy-Nagy, a fellow master at the Bauhaus in Dessau, Germany.

Photography remained a private endeavour for Feininger. He never exhibited his prints, publishing just a handful during his lifetime and sharing them only with family and a few friends.

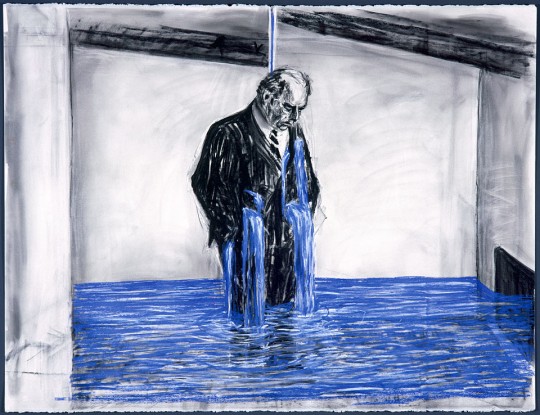

Bauhaus Experiments in Photography

Although Feininger explored many of the experimental photographic techniques being practiced at the Bauhaus, he remained isolated and out of step with the rest of the school. Working alone and often at night, he created expressive, introspective, otherworldly images that have little in common with the playful student photography more typically associated with the school.

Using a Voigtländer Bergheil camera (on display in the exhibition), frequently with a tripod, he photographed the neighbourhood around the masters’ houses, the Bauhaus campus, and the Dessau railway station, experimenting with night imagery, reversed tonalities, and severe weather conditions.

Halle, 1929-1931

In 1929 Feininger created numerous photographic sketches to prepare for a series of paintings he was commissioned to make of the city of Halle, Germany.

A photograph of Halle included in the exhibition, Untitled (Bölbergasse, Halle), was the basis for one of these paintings, which is now lost. It was perhaps the most inventive and photographic of the Halle series, transforming a view of an unremarkable street into a dramatic, almost abstract composition through tight framing and an unusual perspective. The painting is visible in a 1931 photograph of the artist’s studio also included in the exhibition

Feininger also made many photographs of his Halle studio and the paintings he produced there. While many are purely documentary, others are sophisticated compositions that explore formal relationships between a particular painting and the space in which it was created, such as the one shown at right.

Feininger would never again use photography so extensively in connection with his paintings as he did in conjunction with the Halle series.

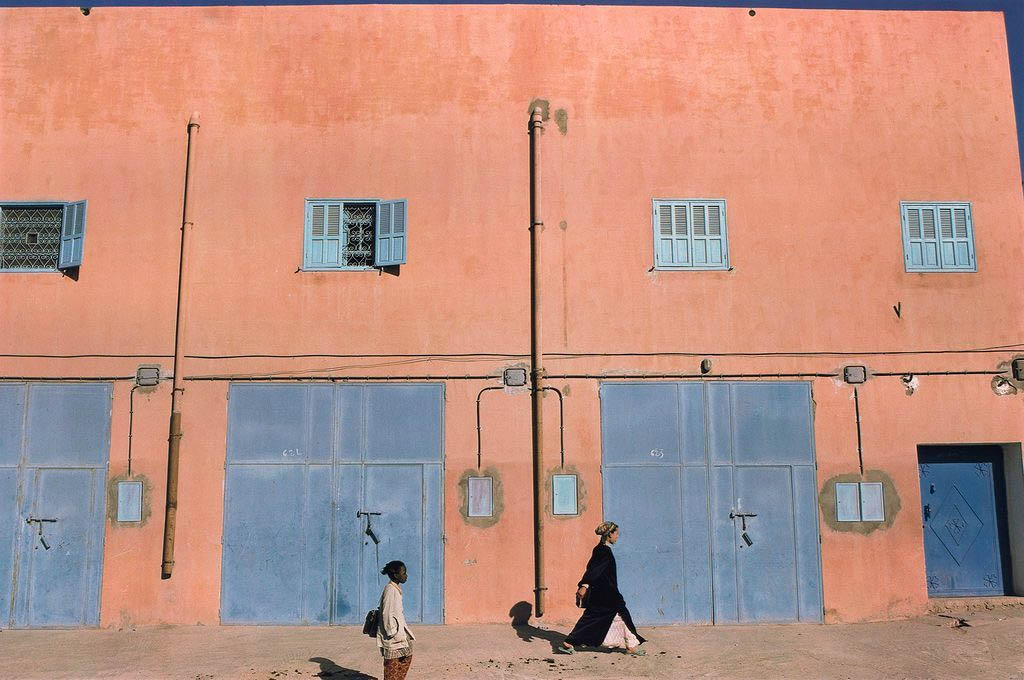

France, 1931

After completing his painting commission in Halle, Feininger spent several weeks in June and July of 1931 in France. In Paris and in the village of Bourron, he created images with his Voigtländer Bergheil camera as well as with his newly acquired Leica (also on display in the exhibition), in which he used 35 mm film for the first time. He also sketched and photographed Brittany on a bicycle tour with his son Lux, capturing views of the architecture and seaside.

In Paris, primed by his recent experience of photographing historic buildings in the streets of Halle, Feininger was drawn to architectural views and urban scenes. On returning from a day trip, he wrote to his wife Julia: “I wandered on foot through the city, flâné! Armed with both cameras, I made photographs… From ‘Boul-Miche’ I crisscrossed through the Quartier Mouffetard… through all possible old narrow and fabulous lanes and I hope that I snapped some very, very good things. Luckily the ‘Leica’ functioned flawlessly” (June 16, 1931, Feininger Papers, Houghton Library).

The Baltic Coast, 1929-1935

Beginning in 1892 Lyonel Feininger spent parts of his summers on the Baltic coast, where the sea and dunes, along with the harbours, rustic farmhouses, and medieval towns, became some of his most powerful sources of inspiration.

Every summer between 1929 and 1935, he used the camera to document family trips to Deep an der Rega (in present-day Poland), where the beach became a playground for his three athletic sons, Andreas, Laurence, and Lux. Feininger looked forward to his time in Deep and the restorative, transformative effect it always had on him.

Shop Windows, 1932-1933

From September 1932, when the National Socialist majority of the Dessau city council voted to close the Bauhaus, through March 1933, when he and his family left for Berlin, Feininger made a series of unsettling photographs that feature mannequins in shop windows. Feininger’s images emphasise not only the eerily lifelike and strangely seductive quality of the mannequins but also the disorienting, dreamlike effect created by reflections on the glass.

In the work shown here, the reflection seems to transport the languid central figure – “drunk with beauty” and oblivious to the camera – beyond the confines of the glass.

Germany to America, 1933 to 1939

Feininger came under increasing scrutiny by the National Socialists, who had stepped up their campaign against the avant-garde after rising to power in January 1933. He produced few paintings during this oppressive period, but continued to photograph regularly in spite of having little access to darkroom facilities. In 1937 he and his wife moved to the United States, renting an apartment in Manhattan – marking his permanent return to New York after an absence of nearly 50 years.

In the years that followed, photography remained an important part of Feininger’s life, though few prints exist from his time in America.

Text from the J. Paul Getty Museum website

T. Lux Feininger (American born Germany, 1910-2011)

Untitled (Bauhaus Band)

About 1928

Gelatin silver print

3 1/4 x 4 1/2 in.

The J. Paul Getty Museum

© Estate of T. Lux Feininger

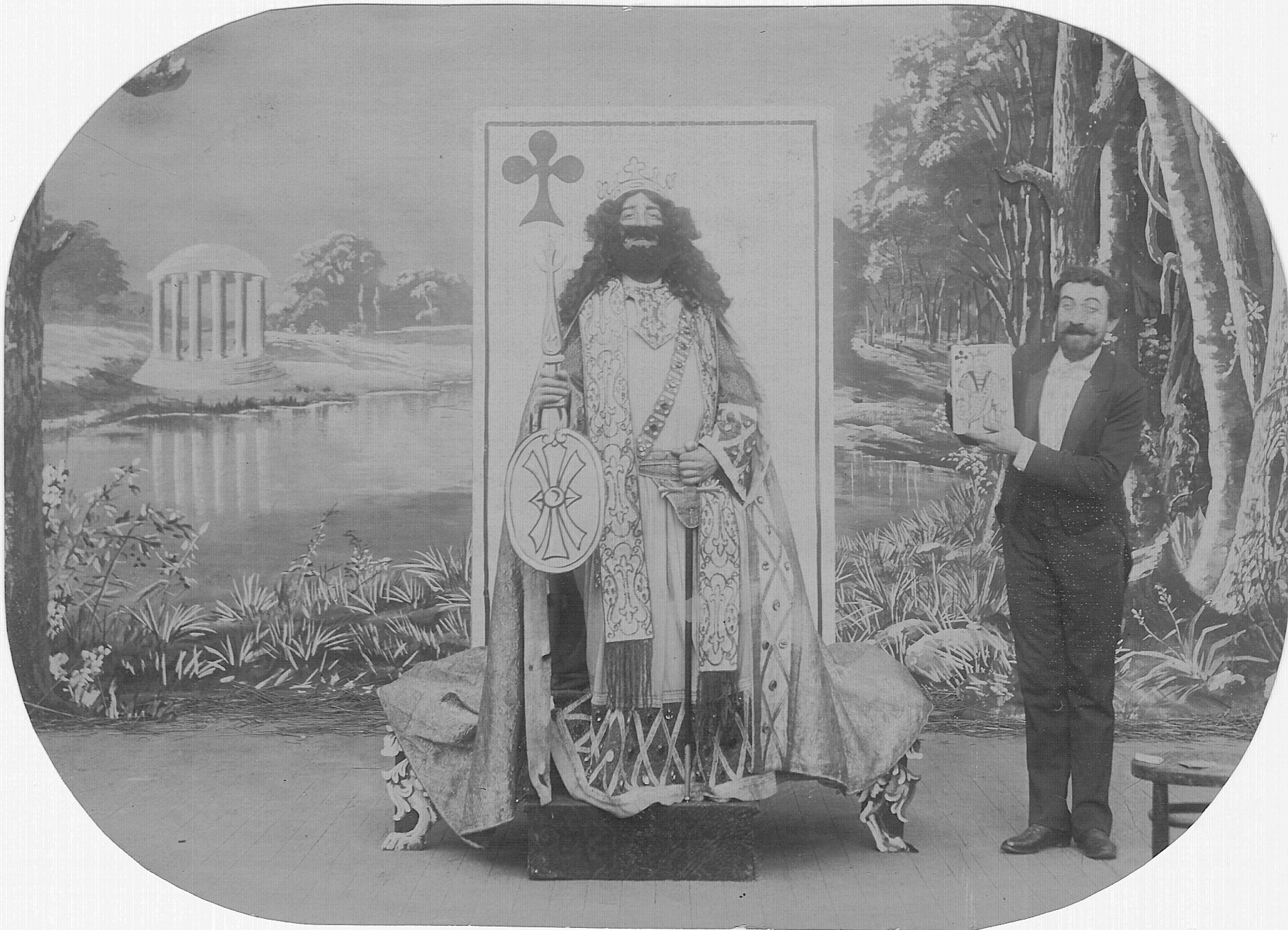

Photography at the Bauhaus

The exhibition Lyonel Feininger: Photographs, 1928-1939 features a complementary selection of over 90 photographs from the Getty Museum’s permanent collection made at the Bauhaus.

The Bauhaus was founded in 1919 in Weimar, Germany, by the architect Walter Gropius. Students entered specialised workshops after completing a preliminary course that introduced them to materials, form, space, colour, and composition. Lyonel Feininger was one of the first masters appointed by Gropius.

The school moved to Dessau in 1925 and to Berlin in 1932, closing under pressure from the National Socialists in 1933.

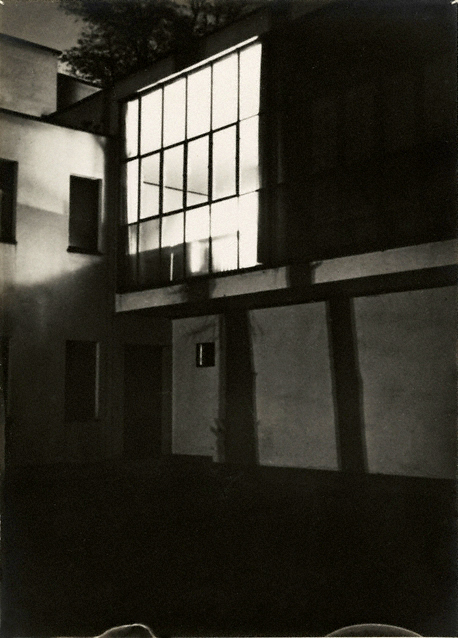

The Bauhaus Building as Stage

Walter Gropius’s building in Dessau became an integral aspect of life at the Bauhaus. The camera recorded the architecture as the most convincing statement of Gropius’s philosophy of uniting art, design, and technology with everyday life, and captured the fervor with which the students embraced this philosophy.

Tight framing, dramatic use of light and shadow, and unusual angles from above and below underscored the dynamism generated by the program. The campus’s architecture was often incorporated into rehearsals and performances by the school’s theater workshop.

Masters and Students

Bauhaus masters and students alike took up the camera as a tool for documentation and creative expression.

Photography served as a medium to record student life at the Bauhaus. In addition to the collaborative environment encouraged in classes and workshops, students found opportunities to bond during their leisure time, whether in a band that played improvisational music, in excursions to nearby beaches, parks, and fairs, or at Saturday-night costume parties.

One of the most active recorders of life at the Bauhaus was Lyonel Feininger’s youngest son Theodore, nicknamed Lux, a student who also became a member of the jazz band.

László Moholy-Nagy

At the Bauhaus, photography found active advocates in the figures of László Moholy-Nagy and his wife Lucia Moholy. Hired in 1923 to head the metal workshop and teach the preliminary course, Moholy-Nagy promoted photography as a form of visual literacy and encouraged experimental techniques of what he called a “new vision,” which included dramatic camera angles, multiple exposures, negative printing, collage and photomontage (fotoplastik), the combination of text and image (typofoto), and cameraless photography (the photogram, made by placing objects on photosensitised paper).

Moholy-Nagy did not differentiate between commercial assignments and personally motivated projects; he used the same strategies in both sectors of his practice.

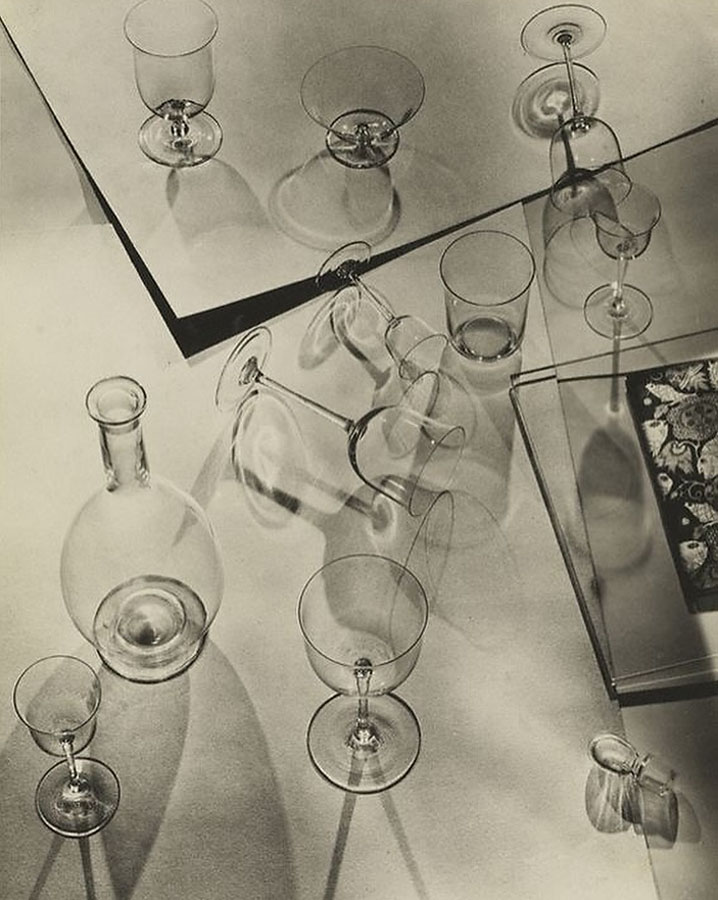

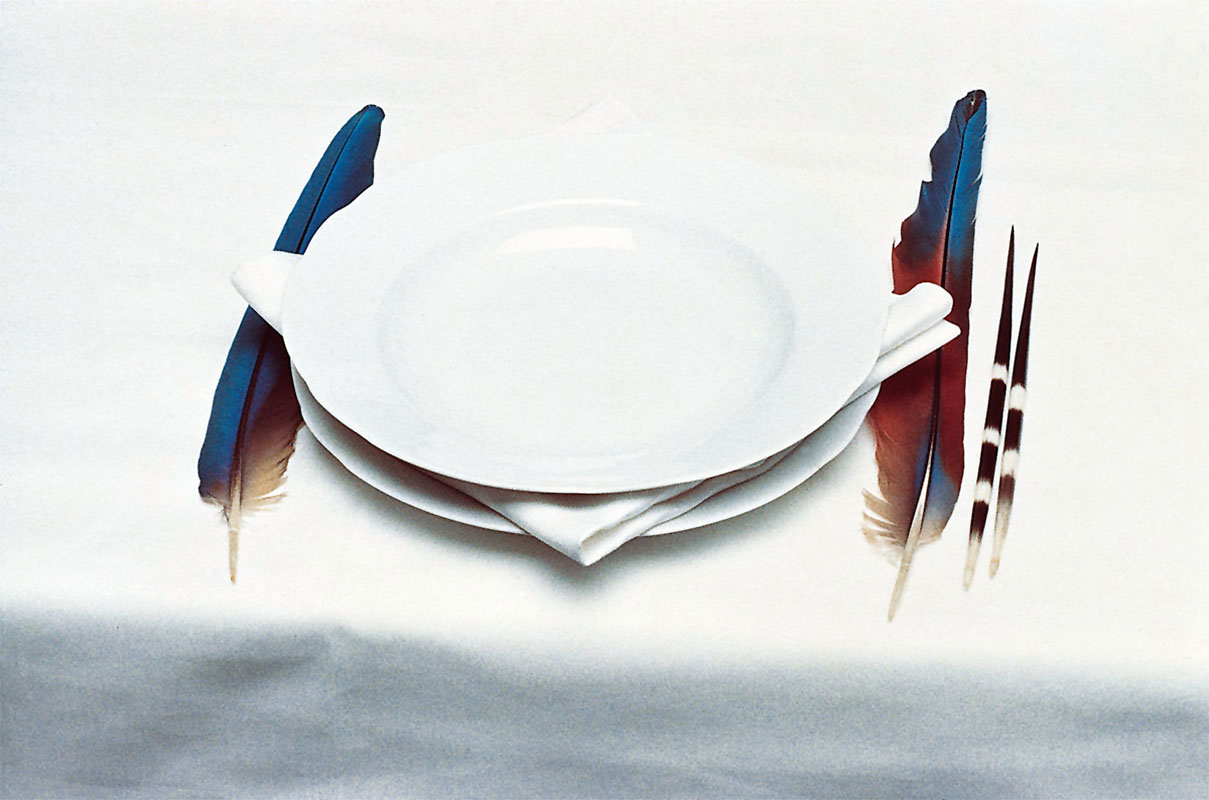

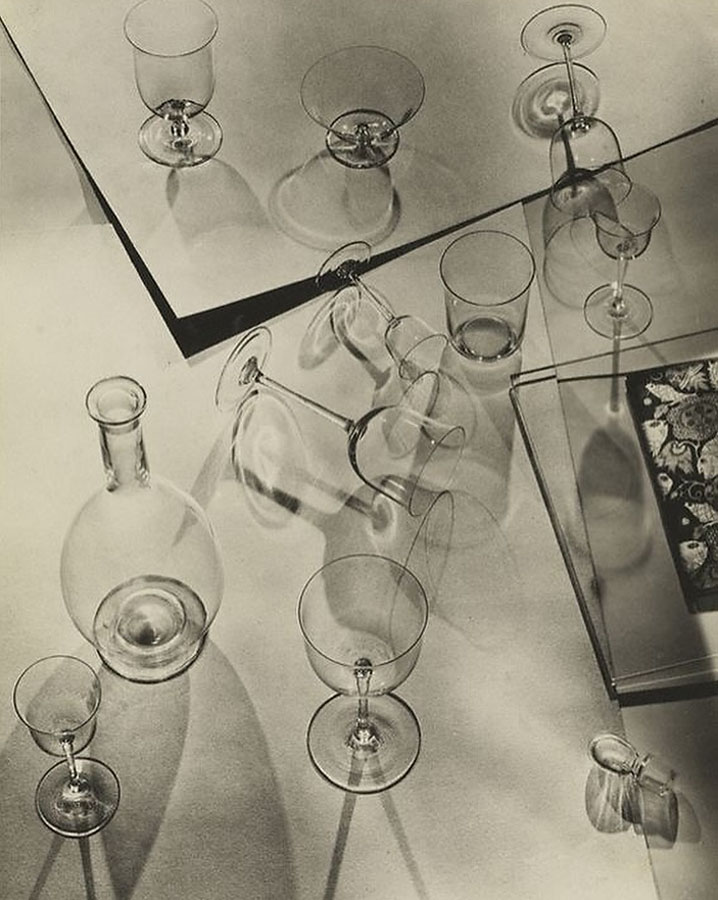

Walter Peterhans

A photography workshop was established at the Bauhaus in 1929, led by Walter Peterhans, a professional photographer and the son of the director of camera lens manufacturer Zeiss Ikon A.G. The three-year course of study included technical exercises as well as assignments in portraiture, still life, advertisement, and photojournalism.

In his own work, Peterhans created haunting still lifes and portraits that are at once straightforward and evocative. Titles such as Portrait of the Beloved, Good Friday Magic, and Dead Hare lend surrealistic overtones to the meticulous arrangements of richly textured, disparate objects that he photographed from above, resulting in ambiguous spatial relationships.

Text from the J. Paul Getty Museum website

Walter Peterhans (German, 1897-1960)

Untitled (Composition with Nine Glasses and a Decanter)

1929-1933

Gelatin silver print

© Estate Walter Peterhans, Museum Folkwang, Essen

Lyonel Feininger (American, 1871-1956)

Bauhaus

March 26, 1929

Gelatin silver print

Image: 17.9 x 14.3cm (7 1/16 x 5 5/8 in)

Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

© Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Lyonel Feininger (American, 1871-1956)

“Moholy’s Studio Window” around 10 p.m.

1928

Gelatin silver print

Image: 17.8 x 12.8 cm (7 x 5 1/16 in.)

Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

© Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Lyonel Feininger (American, 1871-1956)

On the Lookout, Deep an der Rega

1932

Gelatin silver print

Image: 17.7 x 12.7cm (6 15/16 x 5 in)

Gift of T. Lux Feininger, Houghton Library, Harvard University

© Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

![Irene Bayer-Hecht (American, 1898-1991) 'Untitled [Students on the Shore of the Elbe River, near Dessau]' 1925 Irene Bayer-Hecht (American, 1898-1991) 'Untitled [Students on the Shore of the Elbe River, near Dessau]' 1925](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/irene-bayer-bauhacc88usler-am-strand-der-elbe-bei-dessau-web.jpg?w=650&h=903)

Irene Bayer-Hecht (American, 1898-1991)

Untitled [Students on the Shore of the Elbe River, near Dessau (Georg Muche, Hinnerk Scheper, Herbert Bayer, Unknown, Unknown, Marcel Breuer, László Moholy Nagy, Unknown, Xanti Schawinsky)]

1925

Gelatin silver print

Image: 7.5 x 5.4cm (2 15/16 x 2 1/8 in)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

The J. Paul Getty Museum

1200 Getty Center Drive

Los Angeles, California 90049

Opening hours:

Daily 10am – 5pm

The J. Paul Getty Museum website

LIKE ART BLART ON FACEBOOK

Back to top

![Lyonel Feininger (American, 1871-1956) 'Untitled [Street Scene, Double Exposure, Halle]' 1929-1930 Lyonel Feininger (American, 1871-1956) 'Untitled [Street Scene, Double Exposure, Halle]' 1929-1930](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/street-scene-double-exposure-halle-1929-1930.jpg)

![Lucia Moholy (British born Czechoslovakia, 1894-1989) 'Untitled [Southern View of Newly Completed Bauhaus, Dessau]' 1926 Lucia Moholy (British born Czechoslovakia, 1894-1989) 'Untitled [Southern View of Newly Completed Bauhaus, Dessau]' 1926](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/lucia-moholy-southern-view-of-newly-completed-bauhaus.jpg)

![Lyonel Feininger (American, 1871-1956) 'Untitled [Train Station, Dessau]' 1928-1929 Lyonel Feininger (American, 1871-1956) 'Untitled [Train Station, Dessau]' 1928-1929](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/gm_326238ex1.jpg)

![Lyonel Feininger (American, 1871-1956) 'Untitled [Night View of Trees and Street Lamp, Burgkühnauer Allee, Dessau]' 1928 Lyonel Feininger (American, 1871-1956) 'Untitled [Night View of Trees and Street Lamp, Burgkühnauer Allee, Dessau]' 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/night-view-of-trees-and-streetlamp-burgkc3bchnauer-allee-dessau-1928.jpg)

![Irene Bayer-Hecht (American, 1898-1991) 'Untitled [Students on the Shore of the Elbe River, near Dessau]' 1925 Irene Bayer-Hecht (American, 1898-1991) 'Untitled [Students on the Shore of the Elbe River, near Dessau]' 1925](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/irene-bayer-bauhacc88usler-am-strand-der-elbe-bei-dessau-web.jpg?w=650&h=903)

You must be logged in to post a comment.