Exhibition dates: 29th October – 29th November 2014

Polixeni Papapetrou (Australian, 1960-2018)

The Day Dreamer

2014

Pigment print

100 x 150cm

“Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible.”

Paul Klee. Creative Credo [Schöpferische Konfession] 1920

When “facing” adversity, it is a measure of a person’s character how they hold themselves, what face they show to the world, and how their art represents them in that world. So it is with Polixeni Papapetrou. The courage of this artist, her consistency of vision and insightful commentary on life even while life itself is in the balance, are inspiring to all those that know her.

Papapetrou has always created her own language, integrating the temporal dissemination of the historical “case” into a two-dimensional space of simultaneity and tabulation (the various archetypes and ancient characters), into an outline against a ground of Cartesian coordinates.1 In her construction, in her observation and under her act of surveillance, Papapetrou moves towards a well-made description of the states of the body in the tables and classification of the psychological landscape. Her tableaux (the French tableau signifies painting and scene (as in tableau vivant), but also table (as in a table used to organise data)) are a classification and tabulation that is an exact “portrait” of “the” illness, the lost psyche of the title. Her images lay out, in a very visible way, the double makeover: of the outer and inner landscape.

These narratives are above all self-portraits. The idea that image, archetype and artist might somehow be one and the same is a potent idea in Papapetrou’s work. What is “rendered” visible in her art is her own spirit, for these visionary works are nothing less than concise, intimate, focused self-portraits. They speak through the mask of the commedia dell’ arte of a face half turned to the world, half immersed in imaginary worlds. The double skin (as though human soul, the psyche, is erupting from within, forcing a face-off) and triple skin (evidenced in the lack of depth of field of the landscape tableaux) propose an opening up, a revealing of self in which the anatomy (anatemnein: to tear, to open a body, to dissect) of the living is revealed. The images become an autopsy on the living and the dead: “a series of images, that would crystallize and memorize for everyone the whole time of an inquiry and, beyond that, the time of a history.”2

Papapetrou’s images become the “true retina” of seeing, close to a scientific description of a character placed on a two dimensional background (notice how the stylised clouds in The Antiquarian, 2014 match the fur hat trim). In the sense of evidence, the artist’s archetypes proffer a Type that is balanced on the edge of longing, poetry, desire and death, one that the objectivity of photography seeks to fix and stabilise. These images serve the fantasy of a memory: of a masked archetype in a made over landscape captured “exact and sincere” by the apparatus of the camera. A faithful memory of a tableau in which Type is condensed into a unique image: the visage fixed to the regime of representation,3 the universal become singular. This Type is named through the incorporated Text, the Legend: I am Day Dreamer, Immigrant, Merchant, Poet, Storyteller.

But even as these photographs seek to fix the Type, “even as the object of knowledge is photographically detained for observation, fixed to objectivity,”4 the paradox is that this kind of knowledge slips away from itself, because photography is always an uncertain technique, unstable and chaotic, as ever the psyche. In the cutting-up of bodies, cutting-up on stage, a staging aimed at knowledge – the facticity of the masked, obscured, erupting face; the corporeal surface of the body, landscape, photograph – the image makes visible something of the movements of the soul. In these heterotopic images, sites that relate to more stable sites, “but in such a way as to suspect, neutralise, or invert the set of relations that they happen to designate, mirror or reflect,”5 Papapetrou’s psyche, “creates the chain of tradition which passes a happening on from generation to generation.”6 In her commedia dell’ arte, an improvised comedy of craft, of artisans (a worker in a skilled trade), the artist fashions the raw material of experience in a unique way.7 We, the audience, intuitively recognise the type of person being represented in the story, through their half masks, their clothing and context and through the skilful dissemination of collective memory and experience.

Through her storytelling Papapetrou moves towards a social and spiritual transformation, one that unhinges the lost psyche. Her landscape narratives are a narrative of a recognisable, challenging, unstable non-linear art, an art practice that embraces “the speculative mystery of ancient roles… They’re all souls with divided emotions, torn between dream and reality, who like us, converge on the collective stage that is the world.” They are archetype as self-portrait: portraits of a searching, erupting, questioning soul, brave and courageous in a time of peril. And the work is for the children (of the world), for without art and family, extinction.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Footnotes

1/ Adapted from Didi-Huberman, Georges. Invention of Hysteria: Charcot and the Photographic Iconography of the Salpetriere (trans. Alisa Hartz). Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2003, p. 24-25. I am indebted to the ideas of Georges Didi-Huberman for his analysis of the ‘facies’ and the experiments of Jean-Martin Charcot on hysteria at the Hôpital Salpêtrière in Paris in the 1880s.

2/ Ibid., p. 48

3/ Ibid., p. 49

4/ Ibid., p. 59

5/ Foucault, Michel. “Of Other Spaces,” in Diacritics Spring 1986, p. 24 quoted in Fisher, Jean. “Witness for the Prosecution: The Writings of Coco Fusco,” in Fusco, Coco. The Bodies That Were Not Ours. London: Routledge, 2001, pp. 226-227

6/ Fisher, Ibid., p. 227-228

7/ “One can go on and ask oneself whether the relationship of the storyteller to his material, human life, is not in itself a craftsman’s relationship, whether it is not his very task to fashion the raw material of experience, his own and that of others, in a solid, useful, and unique way.”

Benjamin, Walter. Illuminations (trans. by Harry Zohn; edited by Hannah Arendt). New York: Schocken Books, 1968 (2007), p. 108

Many thankx to Polixeni Papapetrou and Stills Gallery for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image. All images copyright of the artist.

“For her, history indicates a view of culture that is more congruent with mortality, with the biological swell of great things arising and perishing, brilliant and melancholy, august and yet brittle. Without judgement, she reorients history as phenomenology: it contains a bracing dimension of loss which is congruent with that fatal sentiment lodged in our unconscious, that our very being – our psyche – is ultimately lost…

Lost Psyche is always about lost cultural innocence, where culture gets too smart and ends by messing with an earlier equilibrium. Papapetrou identifies these moments not to promote gloom but to recognise all the parallels that make for redemption. Parts of the psyche are undoubtedly lost; but Papapetrou proposes and proves that they can still be poetically contacted.”

Robert Nelson 2014

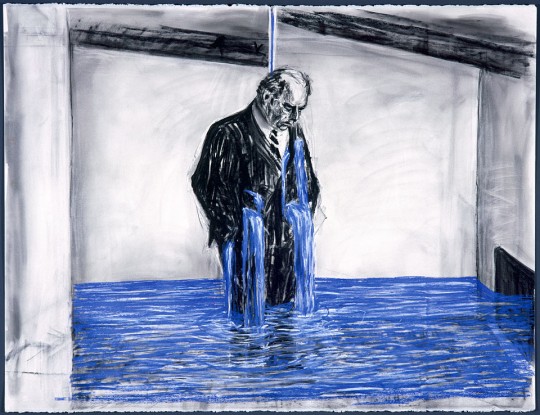

Polixeni Papapetrou (Australian, 1960-2018)

The Immigrant

2014

Pigment print

100 x 150cm

Polixeni Papapetrou (Australian, 1960-2018)

The Merchant

2014

Pigment print

100 x 150cm

Polixeni Papapetrou (Australian, 1960-2018)

The Orientalist

2014

Pigment print

100 x 150cm

Polixeni Papapetrou (Australian, 1960-2018)

The Poet

2014

Pigment print

100 x 150cm

Polixeni Papapetrou (Australian, 1960-2018)

The Storyteller

2014

Pigment print

100 x 150cm

In Lost Psyche, Polixeni Papapetrou portrays emblematic figures that have come to the end of their tradition, their rationale, their place in the world. These intriguing and charismatic characters – the poet, the tourist, the immigrant, among others – bring to life antique Victorian paper masks. Yet, despite being cast beyond our immediate reality, their costumes harking back to earlier times, their settings to fantastical places, these archetypal figures live on in the cultural imagination.

Internationally celebrated for an oeuvre that has consistently tested the boundaries of performance and photography, reality and fantasy, childhood and adulthood, Lost Psyche marks a significant return for Papapetrou. Having extensively explored the Australian landscape as a stage for her photographic fictions, and working in response to the natural and historical dramas of our country, this series takes us back into her studio and the expansive scope of imaginary worlds.

Expressive, luscious and knowingly naïve, the painted backdrops bring to mind the simple seduction of children’s storybooks. At the same time, they reference the painting heavyweights and photographic forerunners that are celebrated within art history. Papapetrou’s image The Duchess, for instance, echoes Goya’s commanding oil painting of the Duchess of Alba (1797). Yet, in this newly imagined version, the ‘role’ of Duchess is playfully acted not endured, and like the melodrama of theatre, the dark sky and downcast actor are softened to become illustrative and symbolic – a scene in a universal story. So too, The Orientalist evokes Felix Beato’s 19th Century photographic forays in Japan, recalling his hand-colouring techniques and depictions of social ‘types’.

Consciously foregrounding this ever-present potential for art to present stereotyped representations, Papapetrou reminds us how these social roles and ‘masks’ play out within our souls and psyche’s just as they do on the cultural stage. As a metaphor for the loss of childhood, a time in which we openly switch between characters, identities and roles, this work evokes the persistence of that imagination, as it lives on within the adult world.

In Lost Psyche, the speculative mystery of ancient roles enjoys a fantastical and touching afterlife. In the contemporary world we may also entertain the inner poet, the storyteller, the clown, the connoisseur, the courtesan, the day dreamer or the dispossessed. They’re all souls with divided emotions, torn between dream and reality, who like us, converge on the collective stage that is the world.

Polixeni Papapetrou is an internationally acclaimed artist. Her works feature in significant curated exhibitions, including recently the 13th Dong Gang International Photo Festival, Korea, the TarraWarra Biennale, VIC, Remain in Light, Museum of Contemporary Art, and Melbourne Now, National Gallery of Victoria. She exhibits worldwide, including in Paris, New York, Tokyo, Seoul, Athens and Berlin. Recent solo exhibitions include Under My Skin, Northern Centre for Contemporary Art, 2014, Between Worlds in Fotogràfica Bogotá, 2013, and A Performative Paradox, Centre for Contemporary Photography, 2013. Her work is held in numerous institutional collections, including the National Gallery of Australia, National Gallery of Victoria, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Monash Gallery of Art, Artbank, Fotomuseo, Colombia, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Florida, USA.

Press release from Stills Gallery

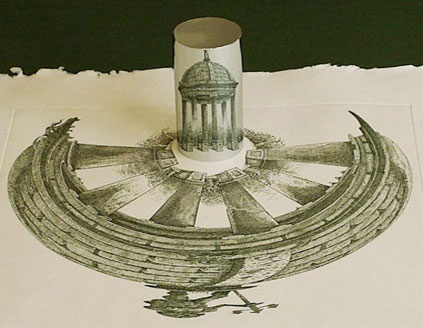

Polixeni Papapetrou (Australian, 1960-2018)

The Antiquarian

2014

Pigment print

150 x 100cm

Polixeni Papapetrou (Australian, 1960-2018)

The Duchess

2014

Pigment print

150 x 100cm

Polixeni Papapetrou (Australian, 1960-2018)

The Summer Clown

2014

Pigment print

150 x 100cm

Polixeni Papapetrou (Australian, 1960-2018)

The Troubadour

2014

Pigment print

150 x 100cm

Stills Gallery

This gallery has now closed.

You must be logged in to post a comment.