Exhibition dates: 4th October, 2014 – 18th January, 2015

Curators: Ann Temkin, The Marie-Josée and Henry Kravis Chief Curator of Painting and Sculpture, and Paulina Pobocha, Assistant Curator, Department of Painting and Sculpture

Many thankx to MoMA for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

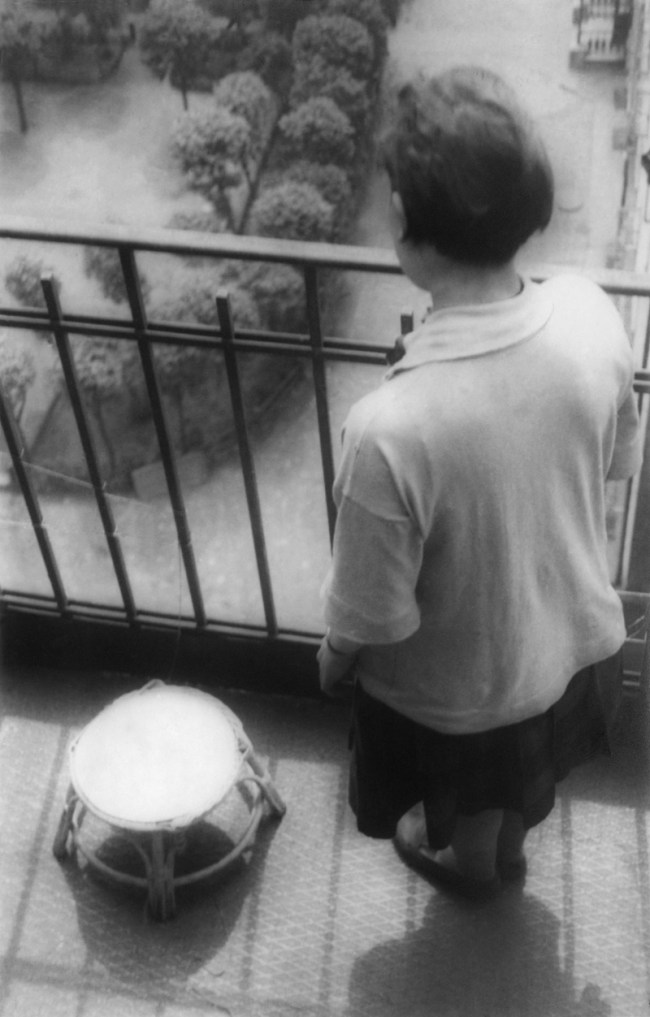

Robert Gober (American, b. 1954)

X Playpen

1987

Wood and enamel paint

27 x 37 x 37″ (68.6 x 94 x 94cm)

Batsheva and Ronald Ostrow

Image credit: D. James Dee, courtesy the artist and Paula Cooper Gallery

© 2014 Robert Gober

“Begun in 1984, the sink series appeared during the darkest period of the AIDS epidemic. Gober, who is gay, responded to the tragedy with poetic indirection: the sinks’ cold air of clinical hygiene. The Times critic John Russell nailed the artistic effect: “Minimal forms with maximum content.” The fact that the content must be intuited by the viewer, who is free to regard the sinks as just cleverly manufactured found objects, typifies Gober’s circumspection. His works are enigmatic but not coy, morally driven but not aggrieved. They radiate a quality that is as rare in life as it is in art: character. …

The heart is an excitable physical organ that registers sensations of fight or flight and of love or aversion: the first and last unimpeachable witness to what can’t help but matter, for good and for ill, in every life.”

Peter Schjeldahl. “Found Meanings: A Robert Gober Retrospective,” October 6, 2014 in ‘The Art World’ October 13, 2014 Issue on ‘The New Yorker’ website [Online] Cited 09/07/2021. Used under fair use conditions for the purposes of education and research

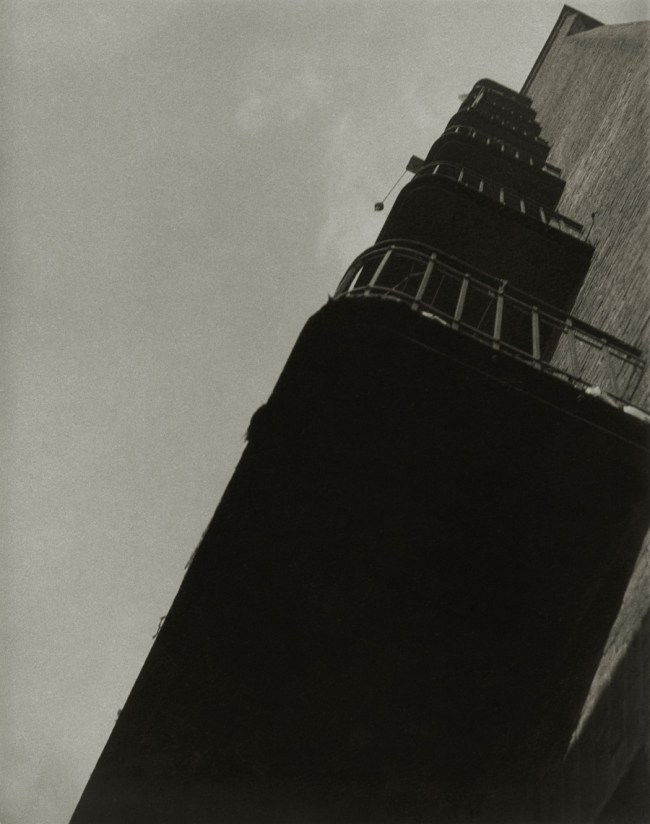

Robert Gober (American, b. 1954)

The Ascending Sink

1985

Plaster, wood, steel, wire lath, and semi-gloss enamel paint

Two components, each: 30 x 33 x 27″ (76.2 x 83.8 x 68.6cm); floor to top: 92″ (233.7cm)

Installed in the artist’s studio on Mulberry Street in Little Italy, Manhattan

Collection of Thea Westreich Wagner and Ethan Wagner, New York

Promised gift to the Whitney Museum of American Art

Image credit: John Kramer, courtesy the artist

© 2014 Robert Gober

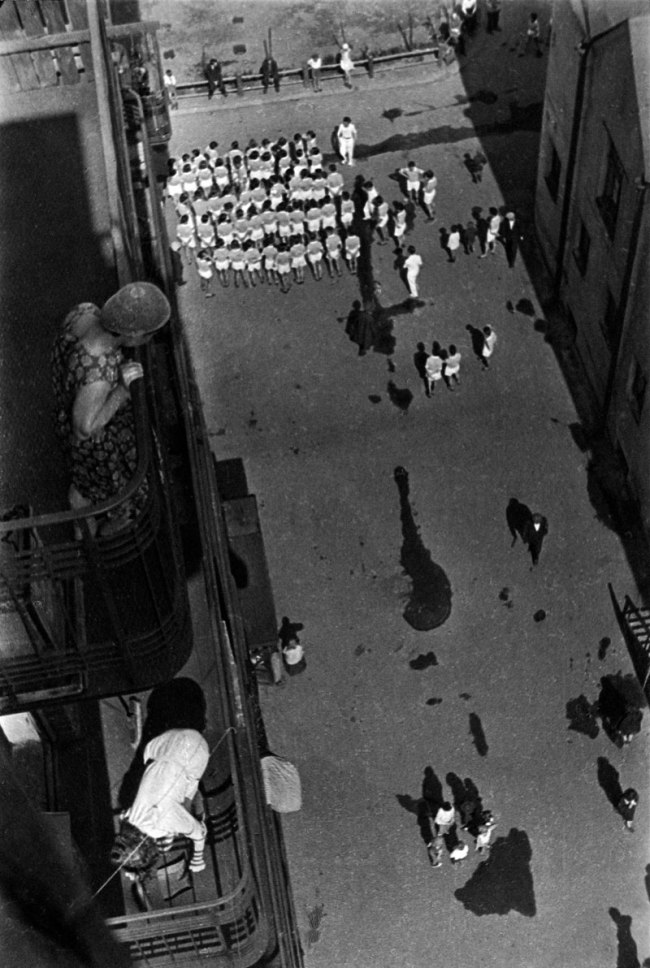

Robert Gober (American, b. 1954)

Untitled

1984

Plaster, wood, wire lath, aluminium, watercolour, semi-gloss enamel paint

28 x 33 x 22 1/2″ (71.1 x 83.8 x 57.2cm)

Rubell Family Collection

Courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery

© 2014 Robert Gober

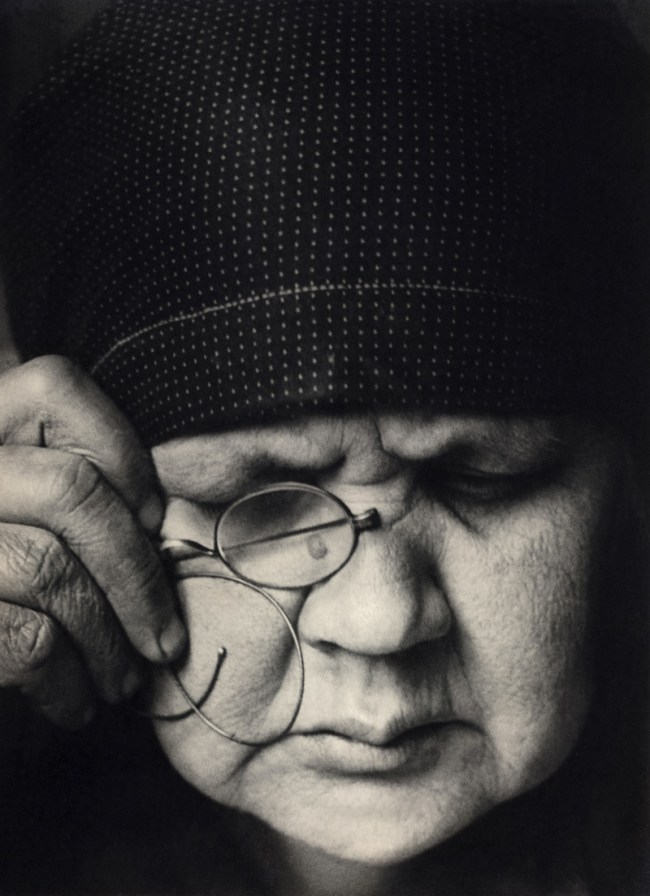

Robert Gober (American, b. 1954)

Two Partially Buried Sinks

1986-1987

Cast iron and enamel paint

Right: 39 x 25 1/2 x 2 1/2″ (99.1 x 64.8 x 6.4cm)

Left: 39 x 24 1/2 x 2 3/4″ (99.1 x 62.2 x 7cm)

Private collection

Image credit: Andrew Moore, courtesy the artist

© 2014 Robert Gober

Robert Gober (American, b. 1954)

Untitled Closet

1989

Wood, plaster, enamel paint

84 x 52 x 28″ (213.4 x 132.1 x 71.1cm)

Private collection

Courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery

© 2014 Robert Gober

Robert Gober (American, b. 1954)

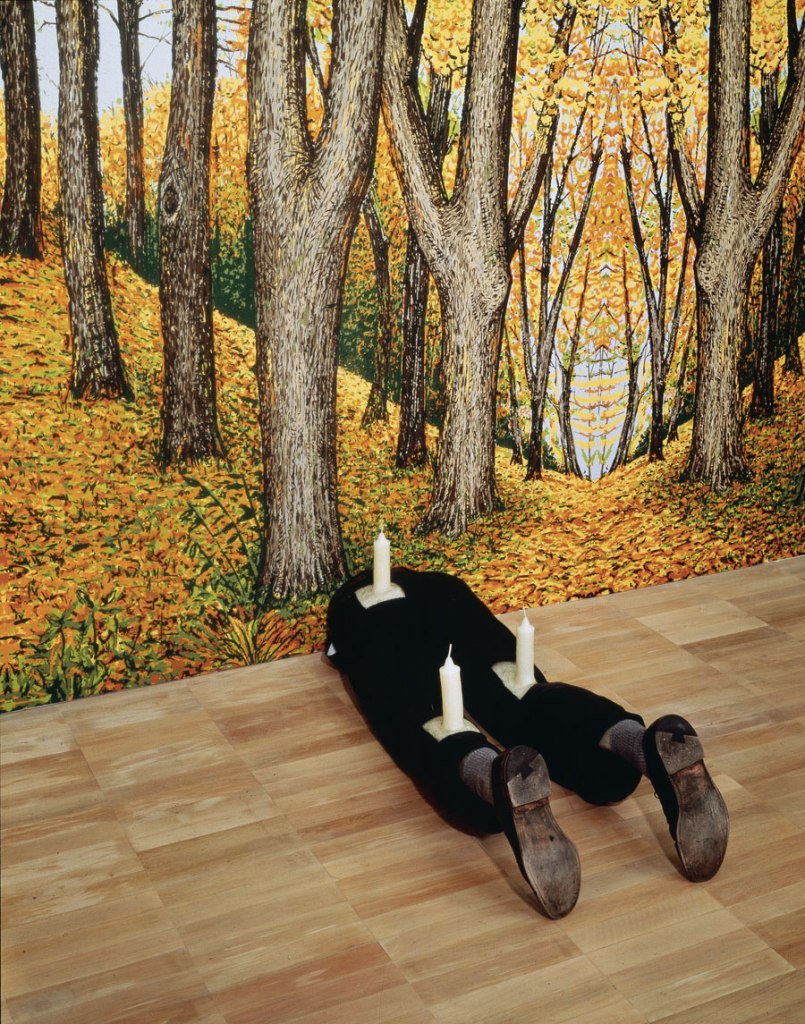

Untitled

1991

Wood, beeswax, human hair, fabric, paint, shoes

9 x 16 1/2 x 45″ (22.9 x 41.9 x 114.3cm)

Collection the artist

Image credit: Andrew Moore, courtesy the artist

© 2014 Robert Gober

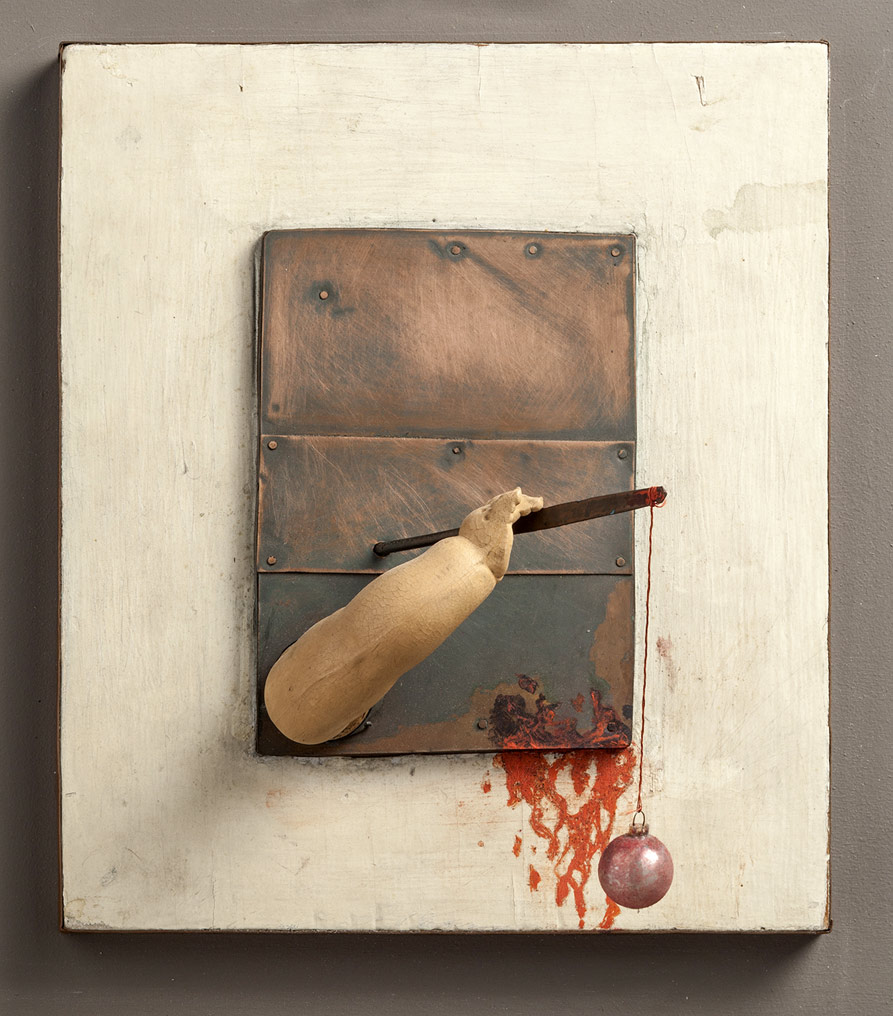

Robert Gober (American, b. 1954)

Untitled

1994-1995

Wood, beeswax, brick, plaster, plastic, leather, iron, charcoal, cotton socks, electric light and motor

47 3/8 × 47 × 34″ (120.3 × 119.4 × 86.4cm)

Emanuel Hoffmann Foundation, on permanent loan to the Öffentliche Kunstsammlung Basel

Image credit: D. James Dee, courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery

© 2014 Robert Gober

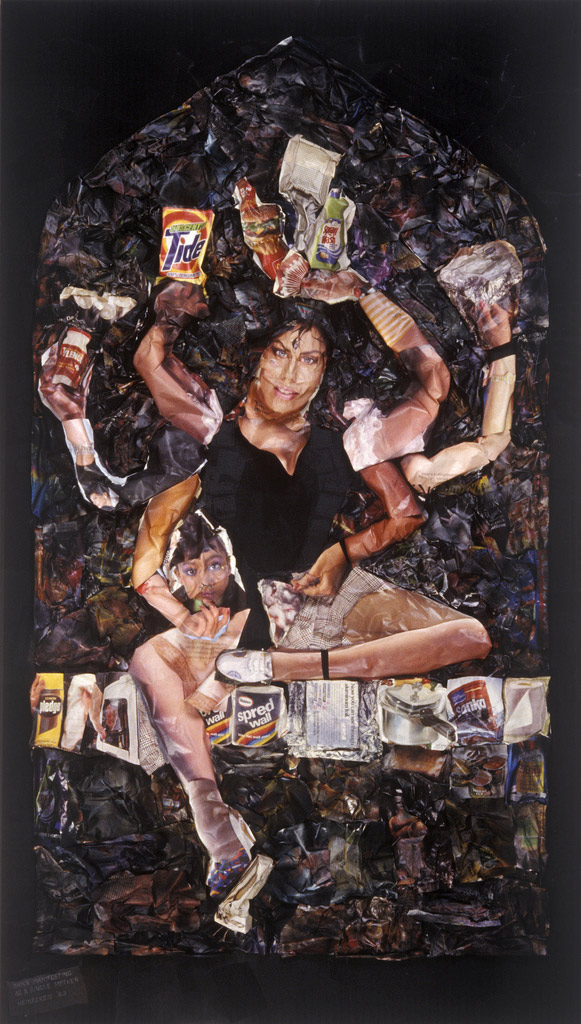

Chronicling a 40-year career, Robert Gober: The Heart Is Not a Metaphor is the first large-scale survey of Robert Gober’s (American, b. 1954) work to take place in the United States. The exhibition is on view from October 4, 2014 to January 18, 2015, and features approximately 130 works across several mediums, including individual sculptures, immersive sculptural environments, and a distinctive selection of drawings and prints. Robert Gober: The Heart Is Not a Metaphor is organised by Ann Temkin, The Marie-Josée and Henry Kravis Chief Curator, and Paulina Pobocha, Assistant Curator, Department of Painting and Sculpture, MoMA, working in close collaboration with the artist.

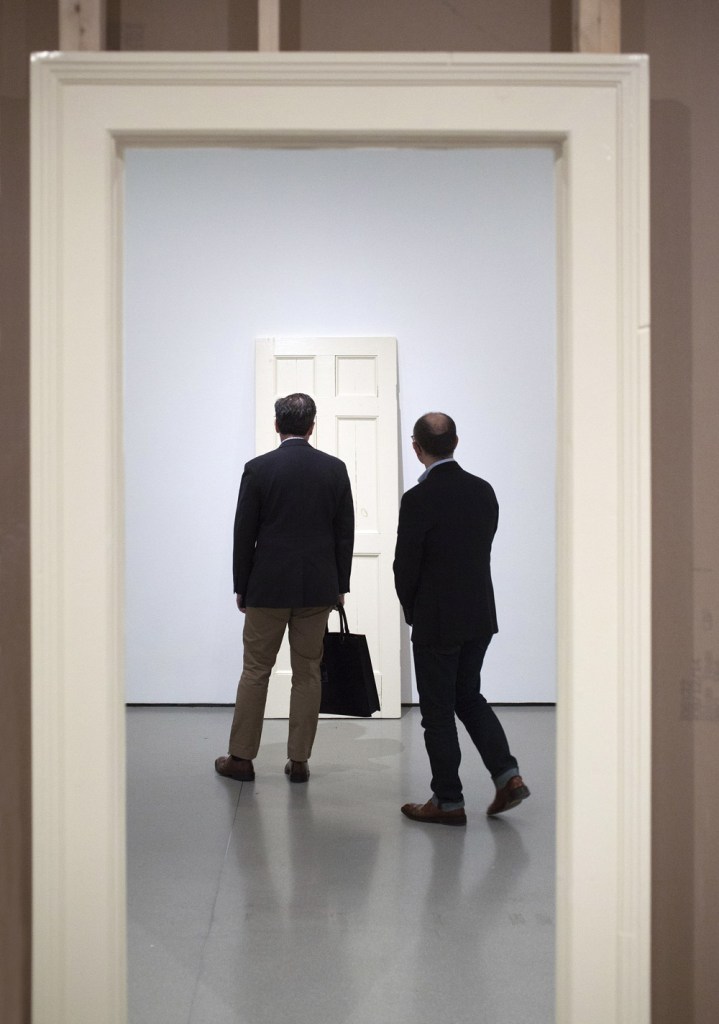

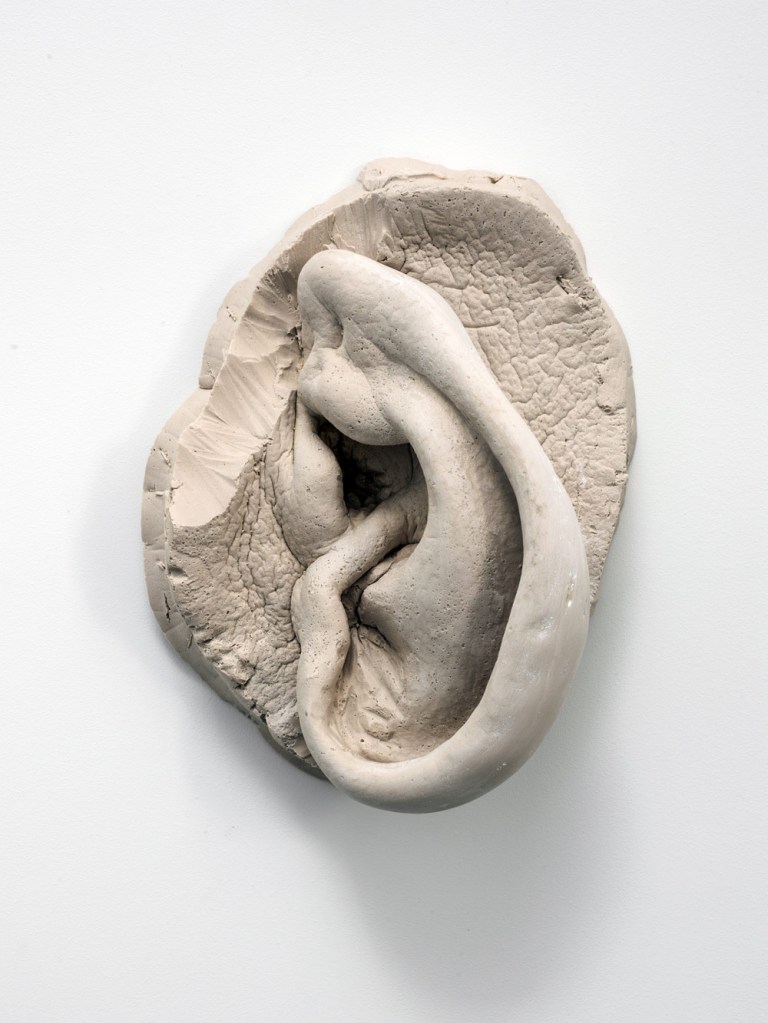

Early on, Gober’s sculptures declared themselves an indispensable part of the landscape of late-twentieth century art; since then they have continued to evolve while remaining tightly bound to the principles outlined by the artist almost four decades ago. Gober places narrative at the centre of his endeavour, embedding themes of sexuality, religion, and politics into work drawn from everyday life. Spare in its use of images and motifs while protean in its capacity to generate meaning, Gober’s work is an art of contradictions: intimate yet assertive, straightforward yet enigmatic. Taking imagery familiar to anyone – doors, sinks, legs – Gober dislocates, alters, and estranges what we think we know. Although a first glance might suggest otherwise, all of Gober’s objects are entirely handmade, by the artist and by collaborators with the necessary expertise.

The earliest works in the exhibition date from the mid-to-late 1970s when Gober was largely working in two dimensions. A painting of the house he grew up in Connecticut hangs at the entrance to the galleries. The first room of the exhibition offers an introduction to Gober’s career, as told through five works: a sculpture of a paint can, a man’s leg, and a closet, as well as a drawing and a small print.

Between 1983 and 1986, Gober created more than 50 sculptures of sinks and scores of related drawings. Based on real sinks, including one in the artist’s childhood home, Gober built them from wood, plaster, and wire lath, and finished them with multiple coats of paint to mimic the appearance of enamel. But, crucially, they lack faucets and plumbing. The sinks’ appearance coincided with the early years of the AIDS epidemic, and their uselessness spoke to the impossibility of cleansing oneself. The sculptures on view in the second gallery of the exhibition were featured in Gober’s first show of sinks, held at the Daniel Weinberg Gallery, Los Angeles, in 1985.

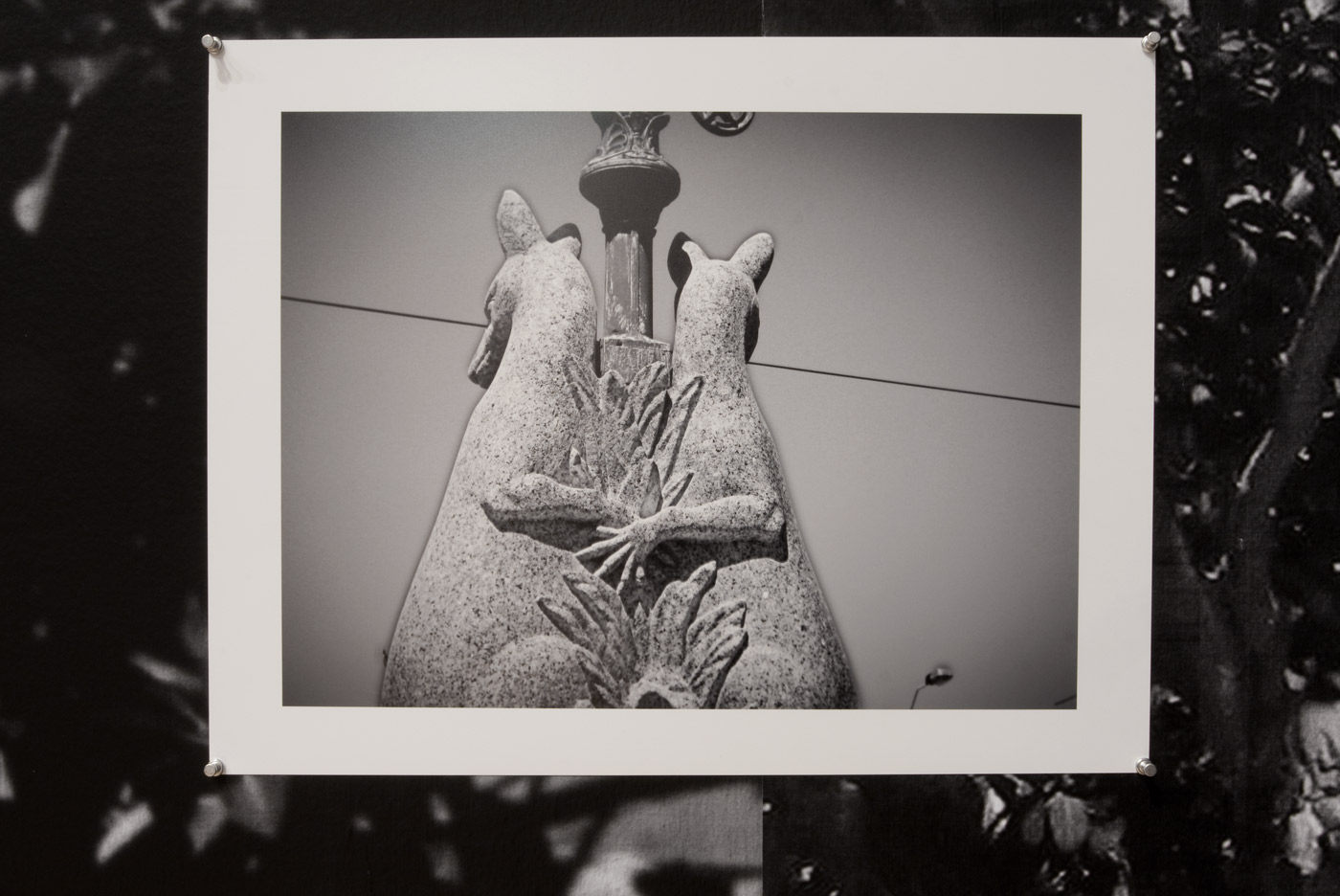

Gober’s early and straightforward sink sculptures gave way in 1985 to a group of distorted sinks whose bodies are variably stretched, bent, multiplied, and divided. The evolution of form registers in the works’ titles: self-evident descriptions become increasingly expressive (eg. The Sink Inside of Me). By the mid-1980s, the artist’s preoccupation with domestic objects expanded to include sculptures of furniture such as beds and playpens, as well as an armchair, on view in the third gallery. Between 1986 and 1987, Gober created Two-Partially Buried Sinks, among the last sink sculptures of the decade. This work is positioned outside the walls of the Museum on a scaffold, and can be viewed through the gallery’s window.

In 1989 at the Paula Cooper Gallery, Gober exhibited his first room-sized installations. Each is framed by wallpapers: a pattern pairing a sleeping white man and a lynched black man in one, and line drawings of male and female genitalia in the other, both of which are on view in the following galleries. These backdrops powerfully inflect the sculptures contained within: a freestanding bridal gown and hand-painted plaster cat litter bags in the first room and a bag of donuts with cast-pewter drains inset into the walls in the second. With characteristic concision, Gober sets off a complex swirl of questions about the unease surrounding issues to everyday life in America.

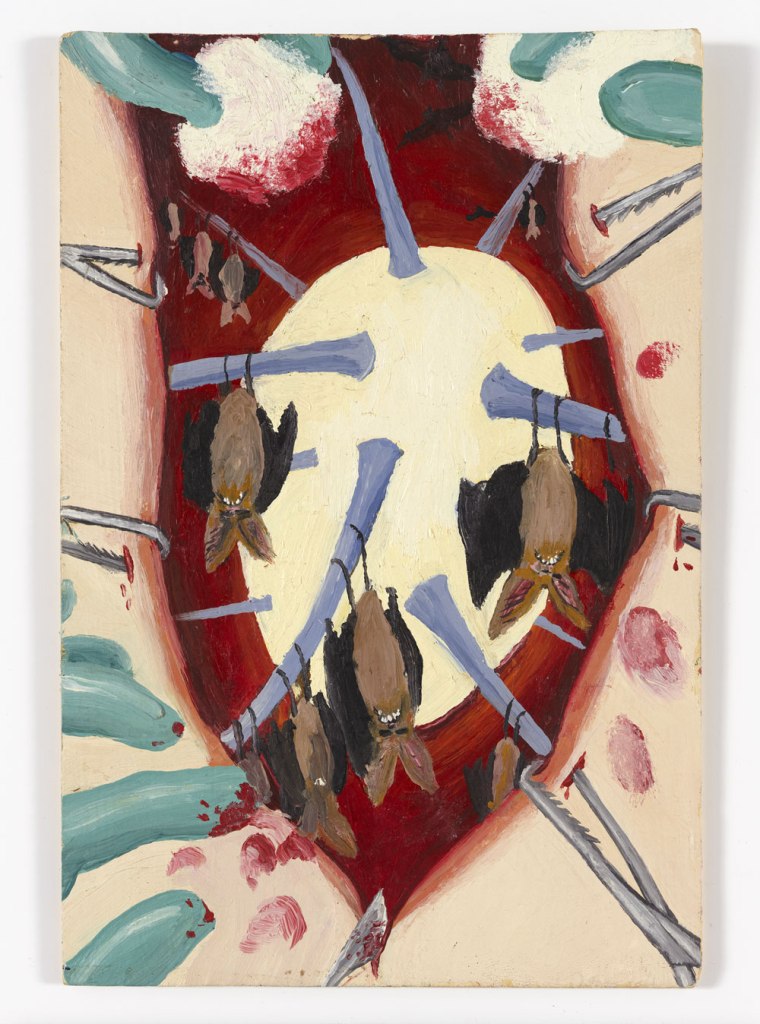

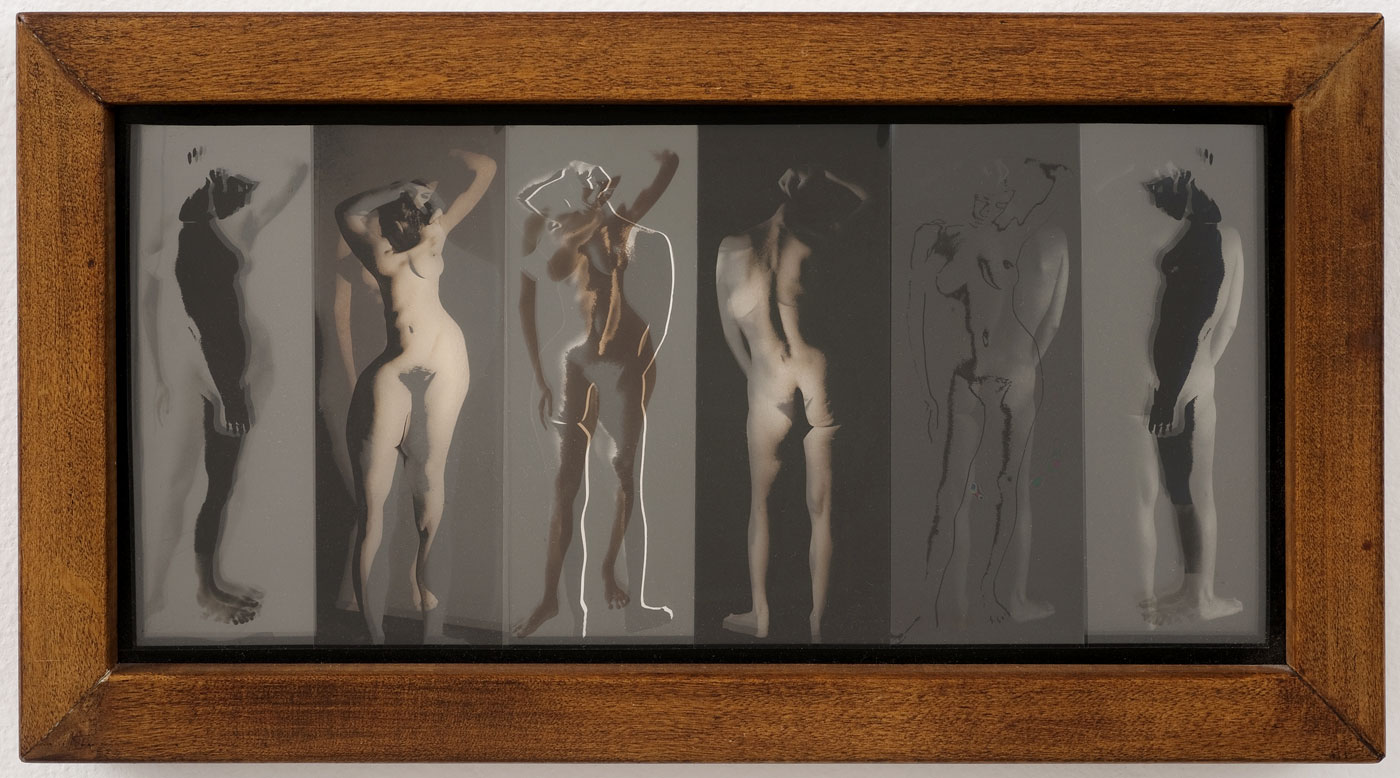

Gober made Slides of a Changing Painting between 1982 and 1983. During this year, he painted on a small Masonite board and photographed the imagery as it changed over time. Eventually, he had accumulated more than 1,000 slides, which he edited down and organised into a slide projection that he showed in 1984. After the exhibition, Gober put the slides away. When he revisited the project around 1990, he realised that he had unknowingly employed many of the same images in his subsequent sculptures. Slides of a Changing Painting has continued to be generative; it provides a nearly complete index of Gober’s visual themes and vocabulary. The work is on view in a gallery centrally located within the exhibition.

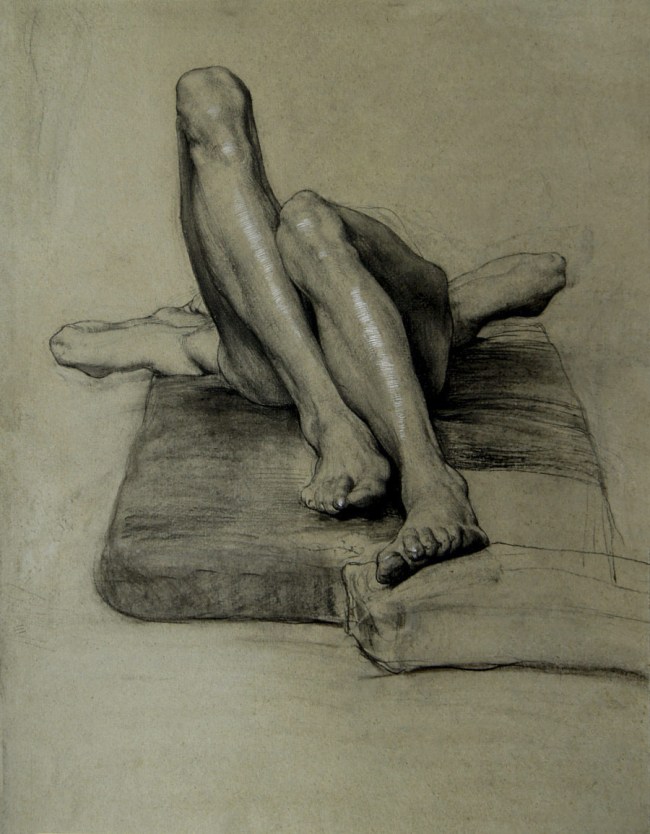

The human figure was absent from Gober’s sculptural repertoire until 1989, when he made his first sculpture of a man’s leg, a breakthrough that ushered in many related works. Single legs wearing trousers and shoes and truncated at mid-shin were followed by pairs of legs that Gober left whole to the waist. He showed these surreal sculptures in a 1991 exhibition in Paris, recreated in the following gallery. Three pairs of legs, augmented by candles, drains, and a musical score, are positioned around the perimeter of a room wallpapered with a kaleidoscopic landscape of a beech forest in autumn. In the centre of the gallery sits a human-sized cigar composed of tobacco sheafs purchased from a Pennsylvania supplier. To learn how to preserve this organic material as it aged, Gober consulted an expert at the American Museum of Natural History. Seeking out specialists’ advice on complicated projects is a hallmark of the artist’s craft based practice.

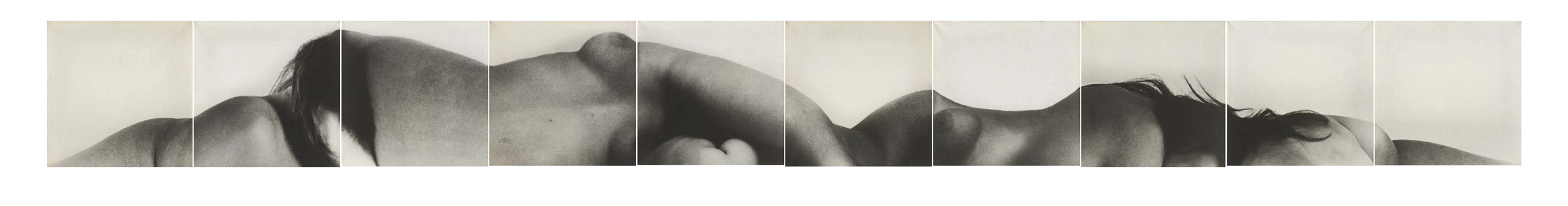

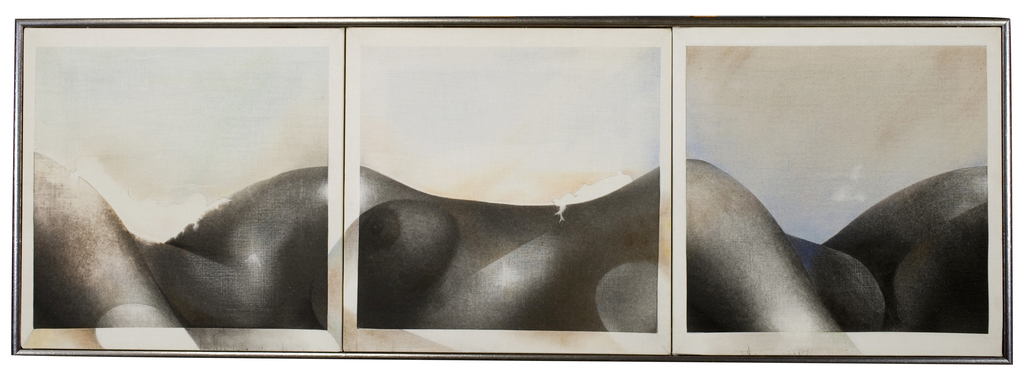

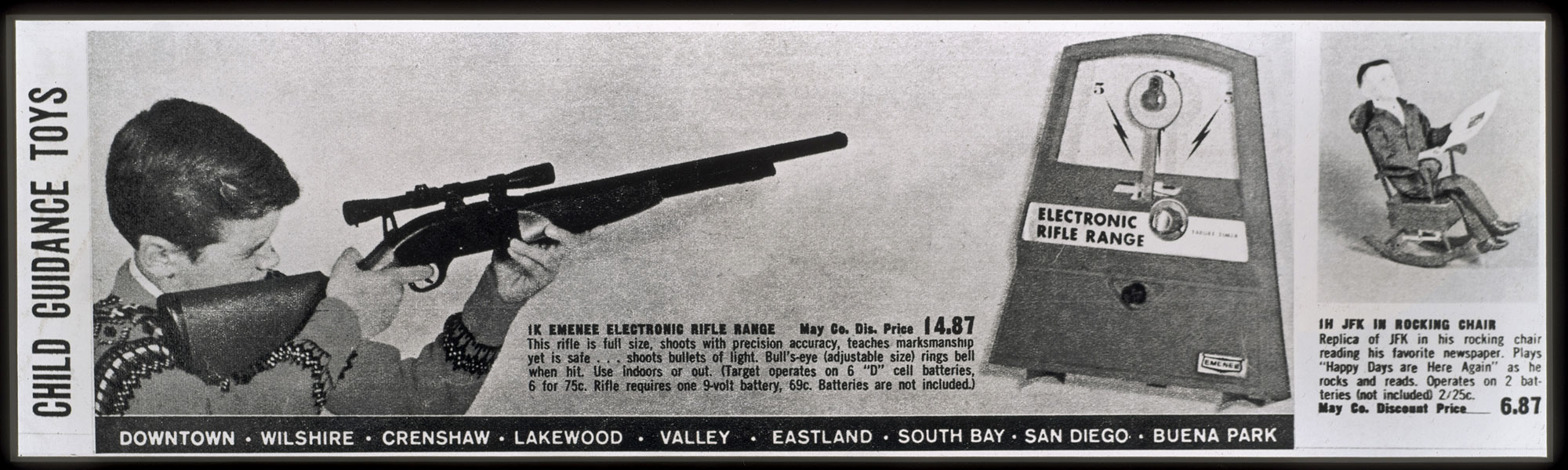

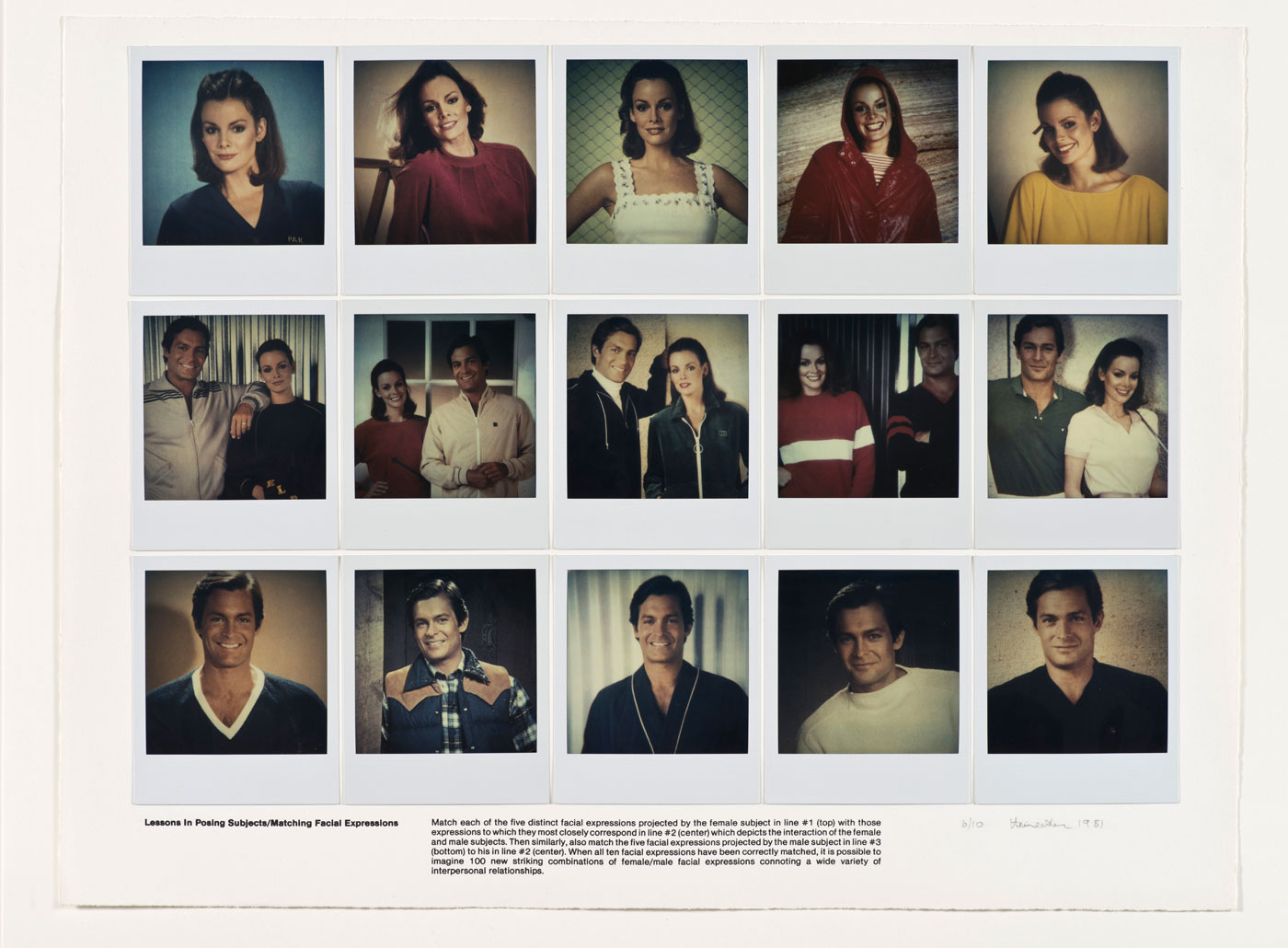

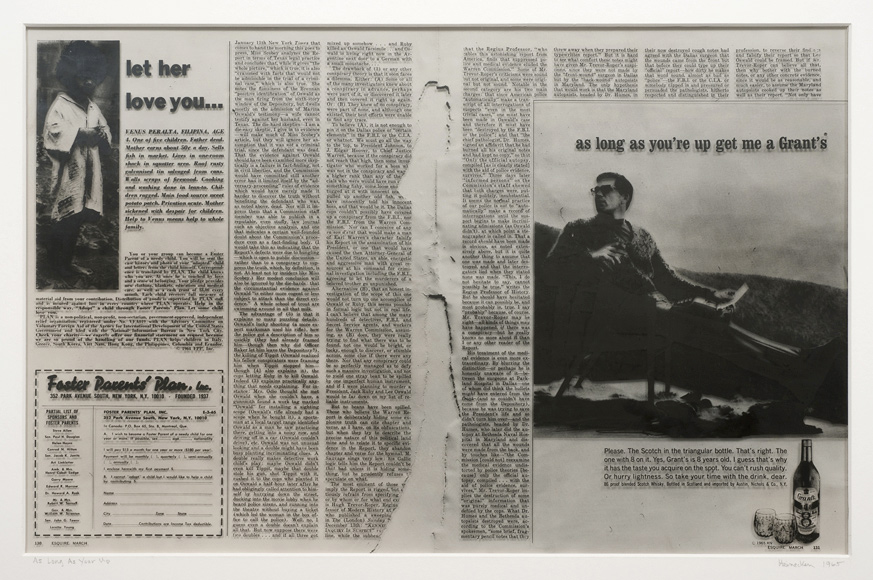

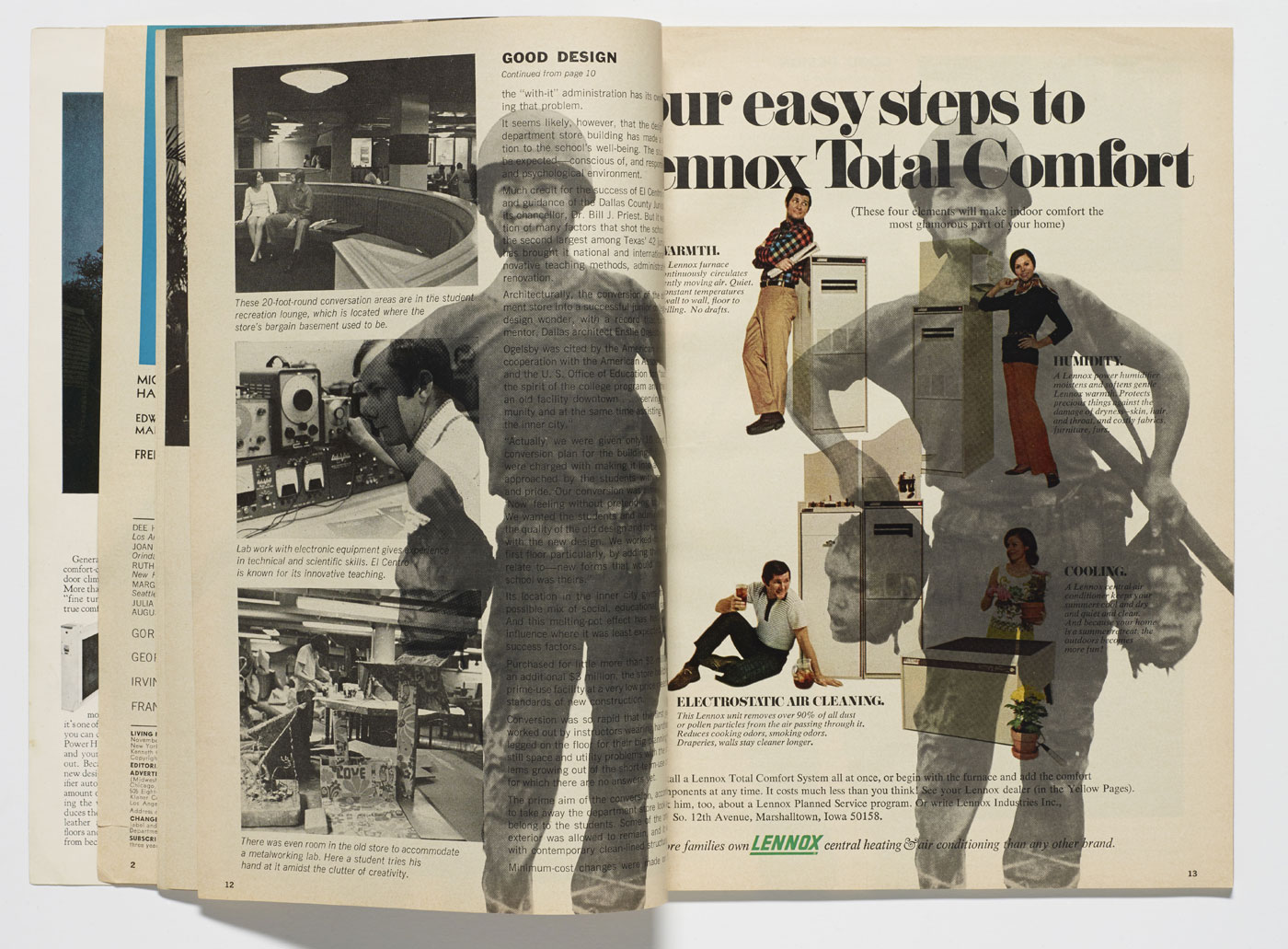

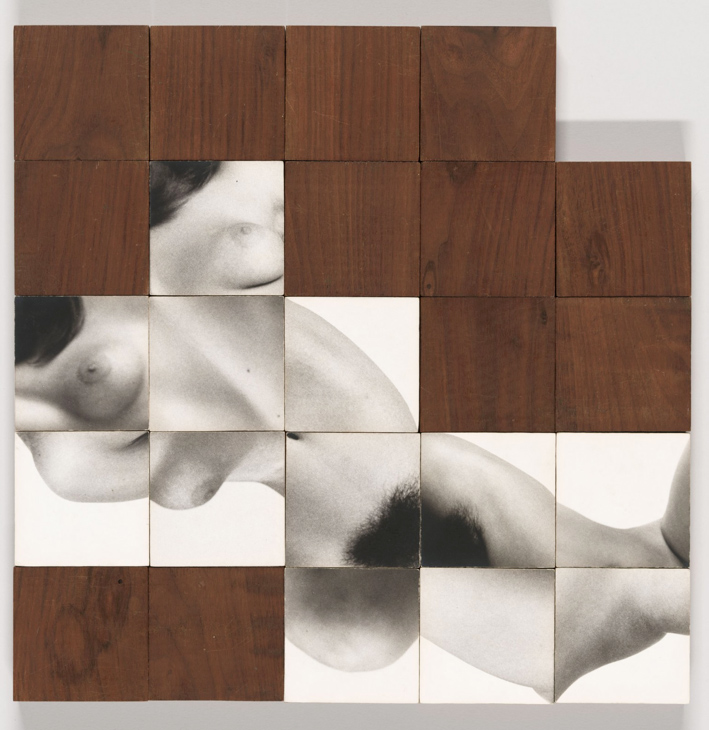

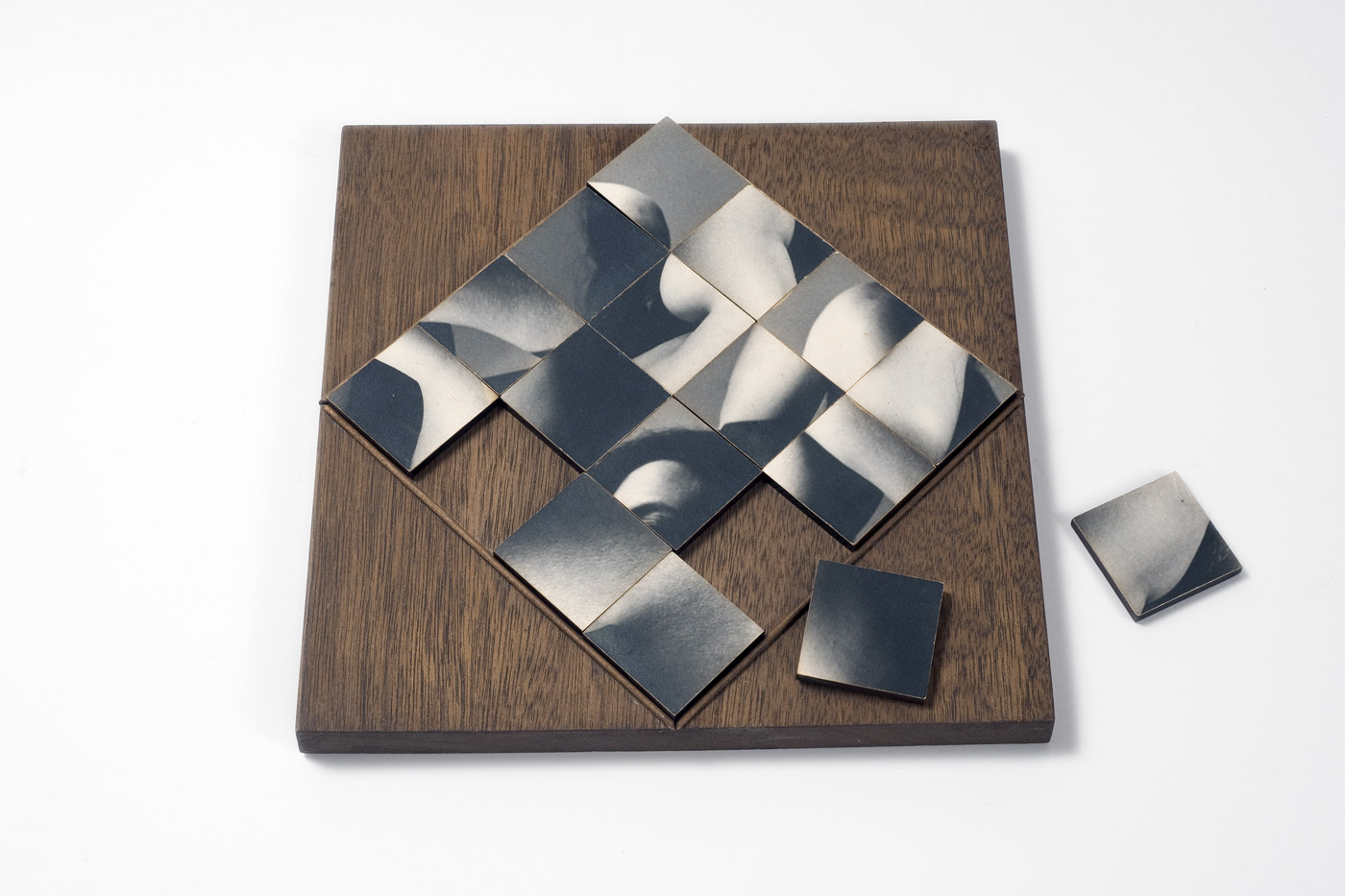

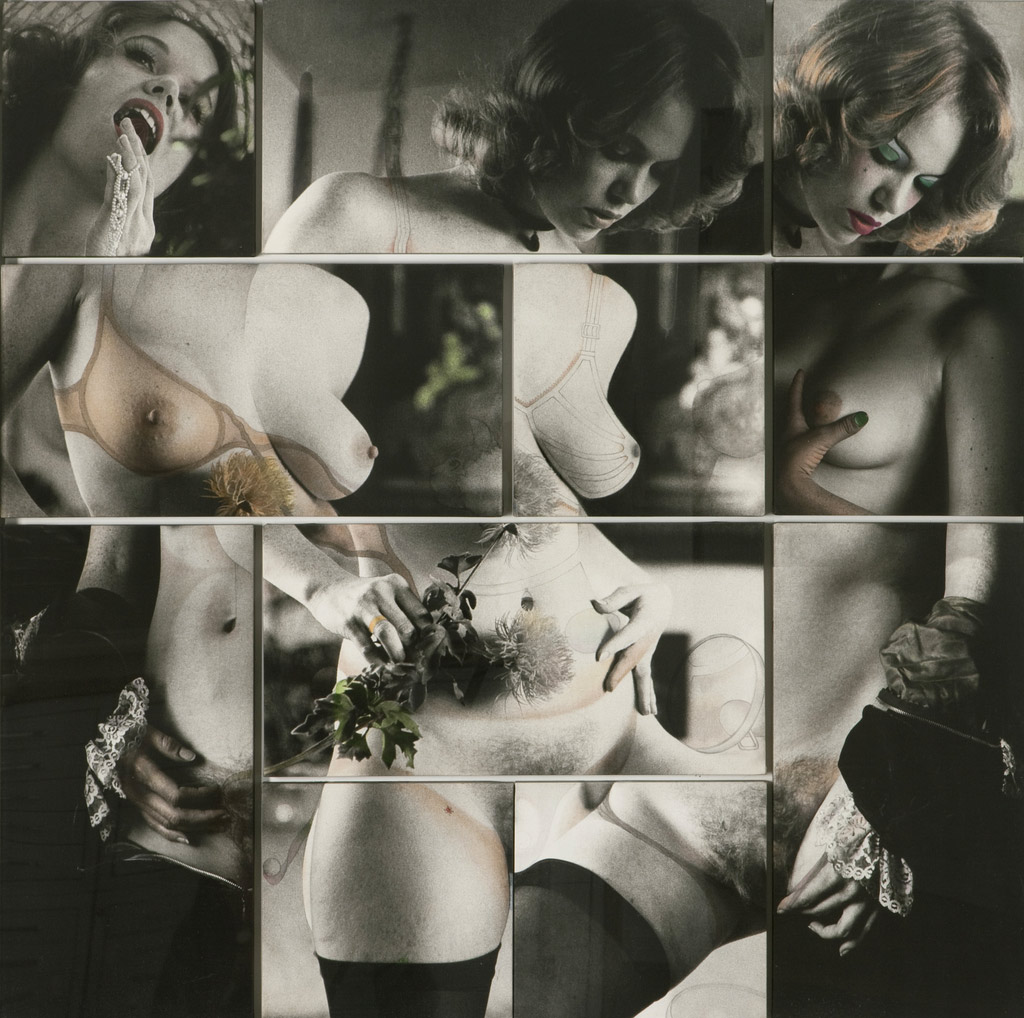

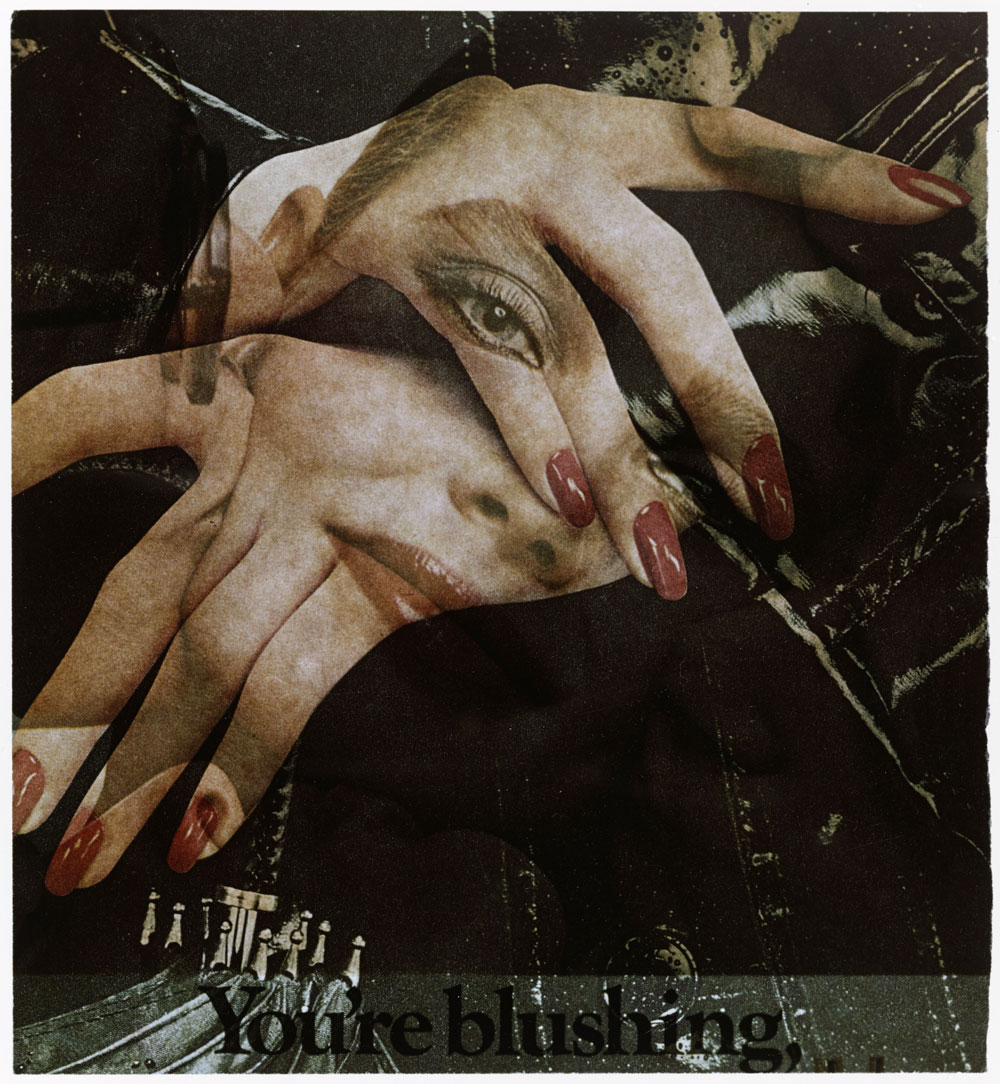

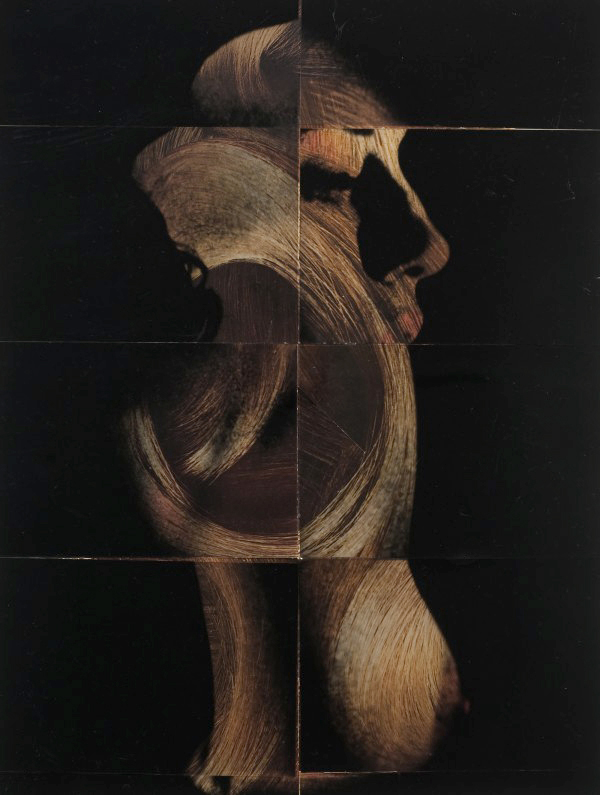

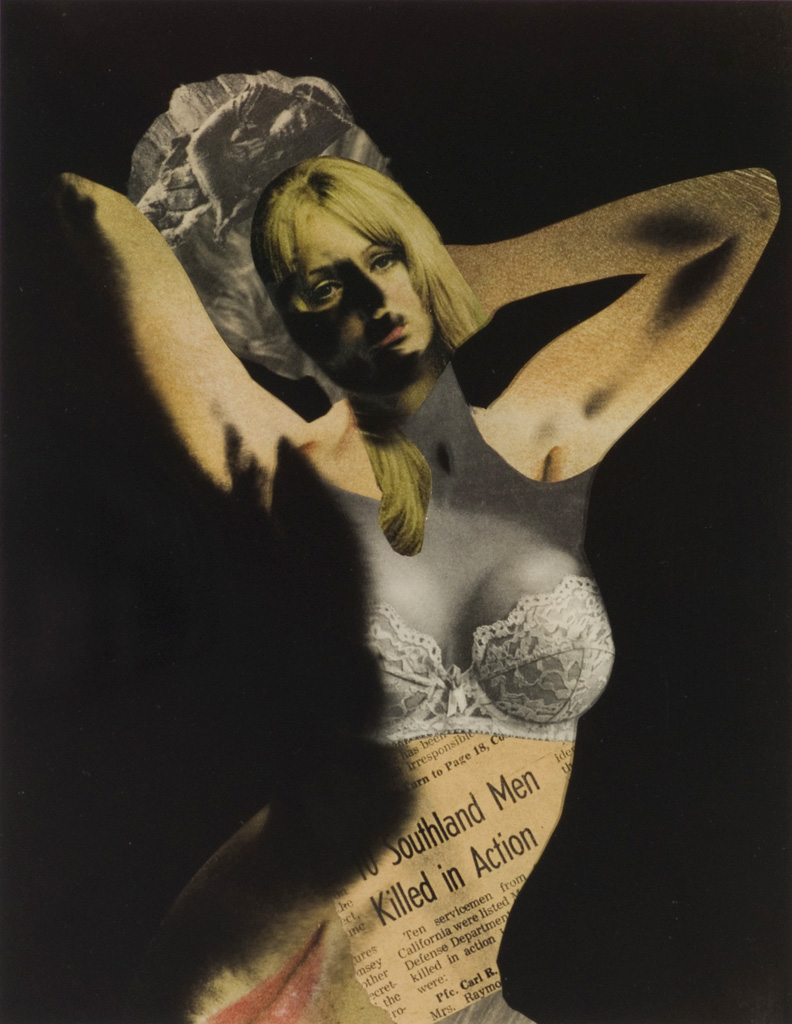

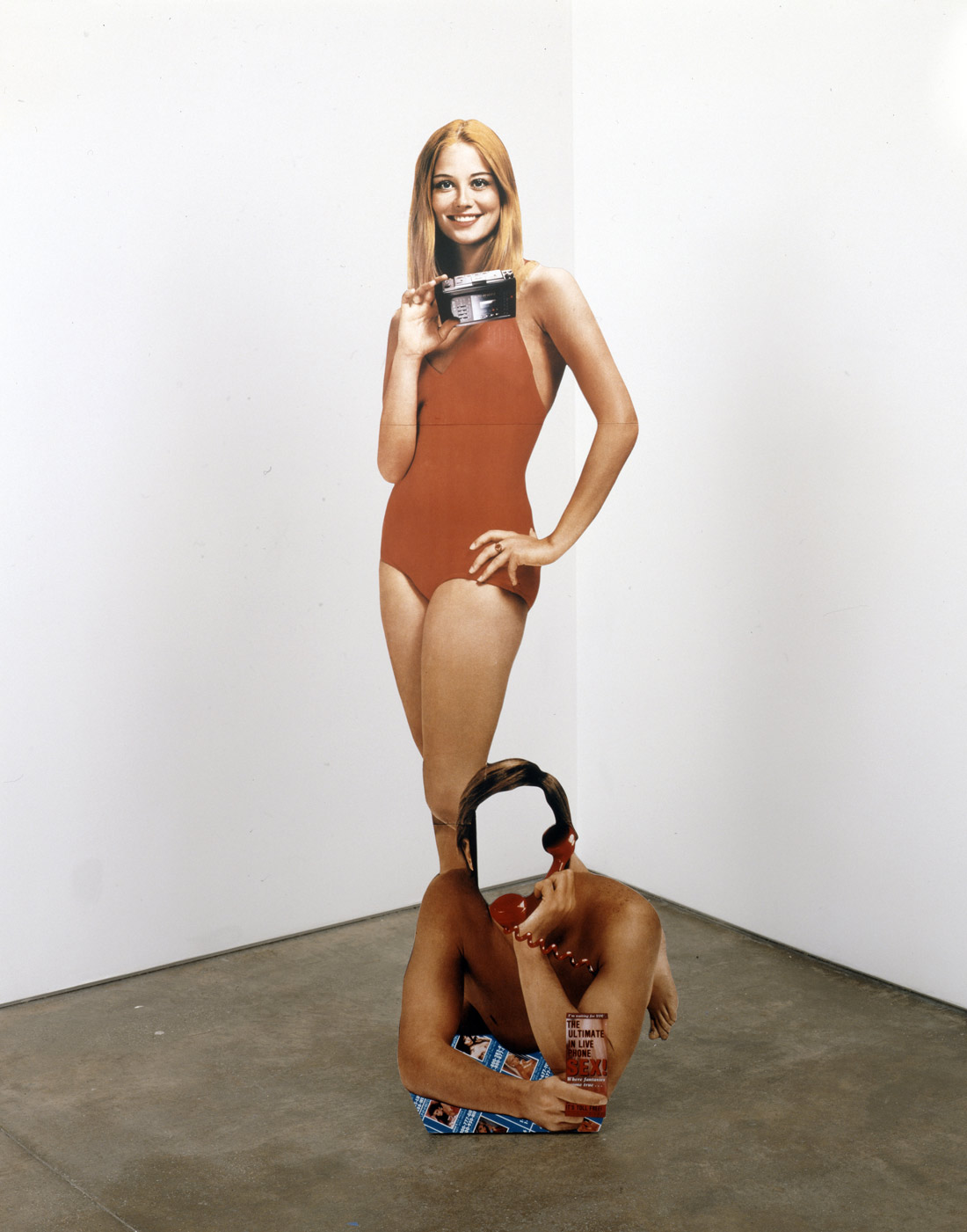

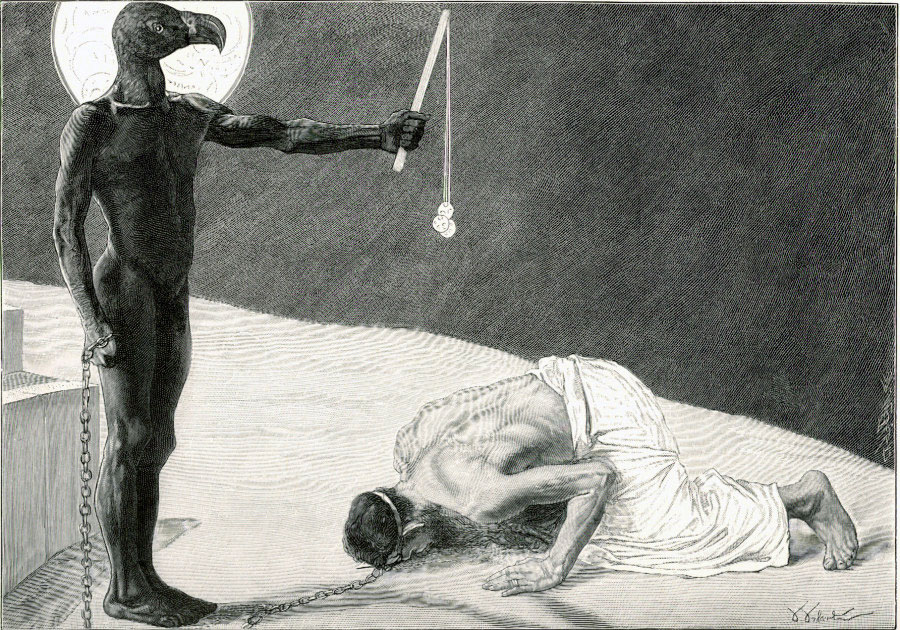

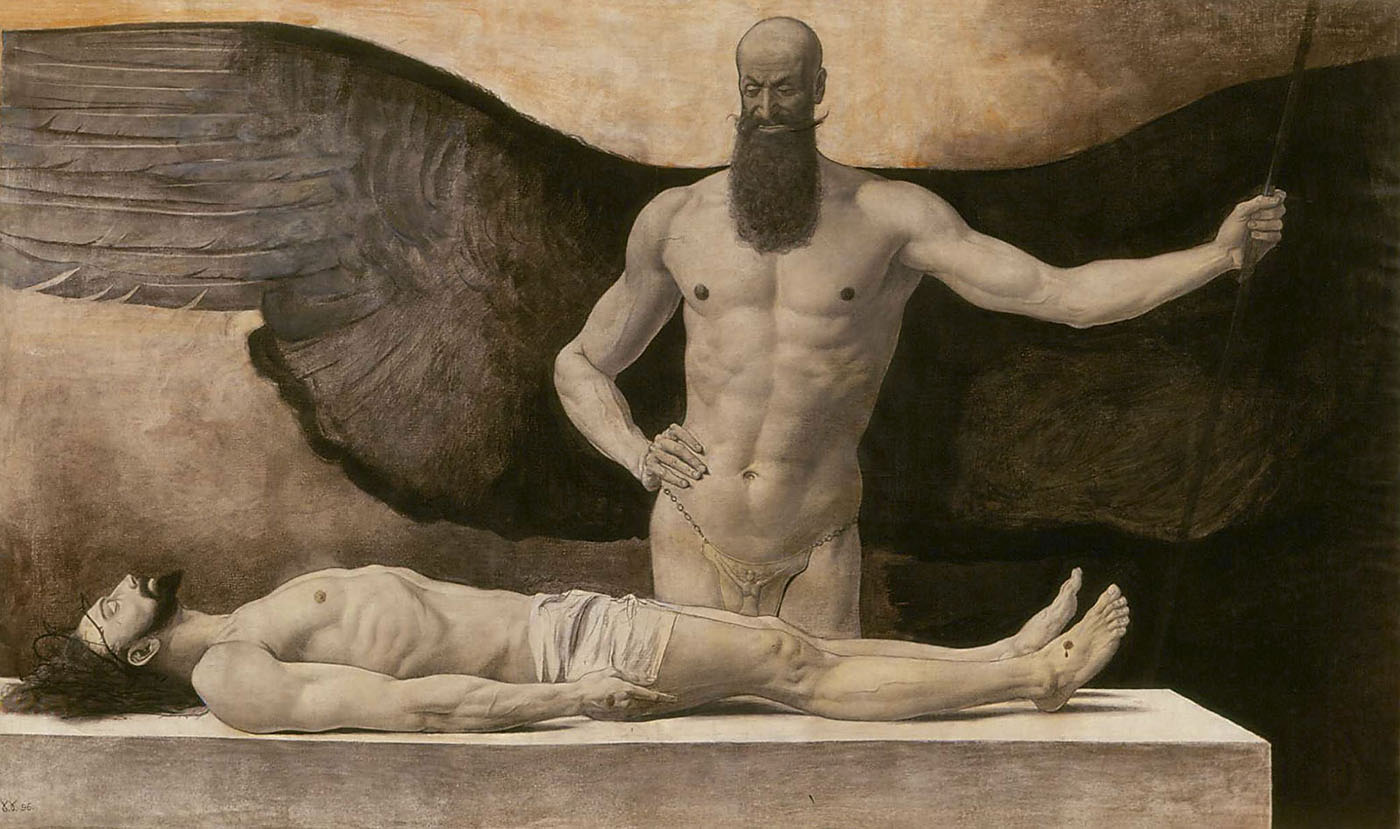

The works on view in the following gallery were made by artists Anni Albers, Robert Beck, Cady Noland, and Joan Semmel; photographs by Nancy Shaver hang in the adjoining space. Gober brought these objects together for the first time in an exhibition he organised at the Matthew Marks Gallery, New York in 1999. Gober has been curating exhibitions since the mid-1980s, most recently focusing on monographic presentations of the works by American artists Charles Burchfield and Forrest Bess. The contemporary artists included in this gallery share with Gober daring approaches to the representation of sexuality, violence, and American culture.

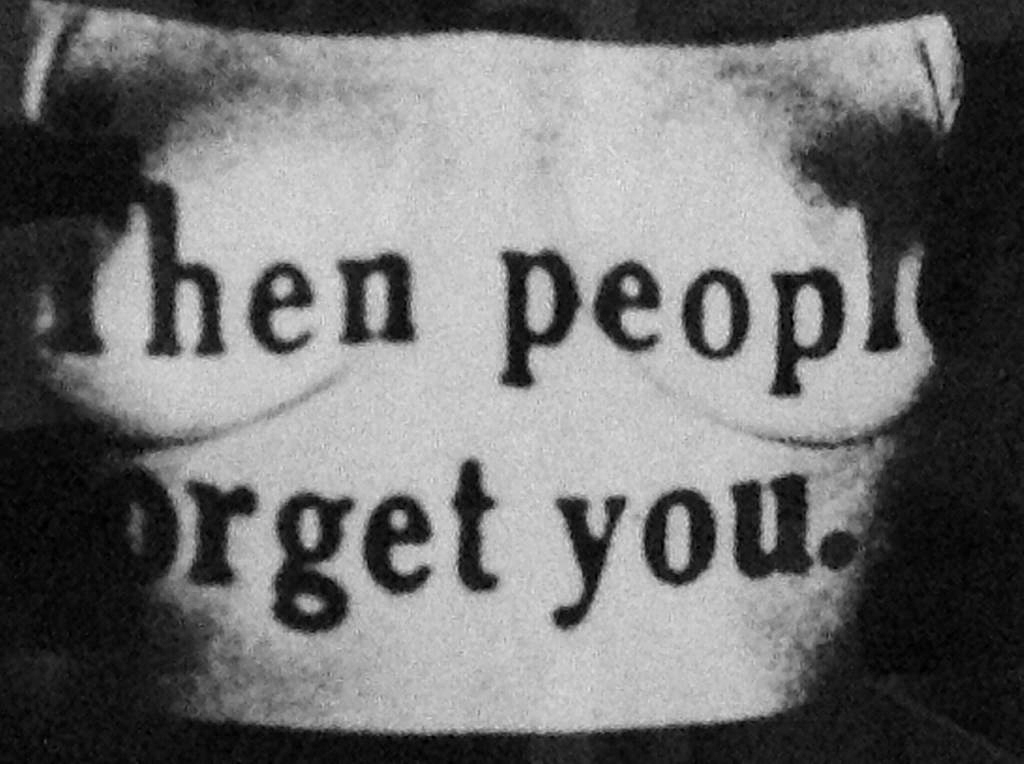

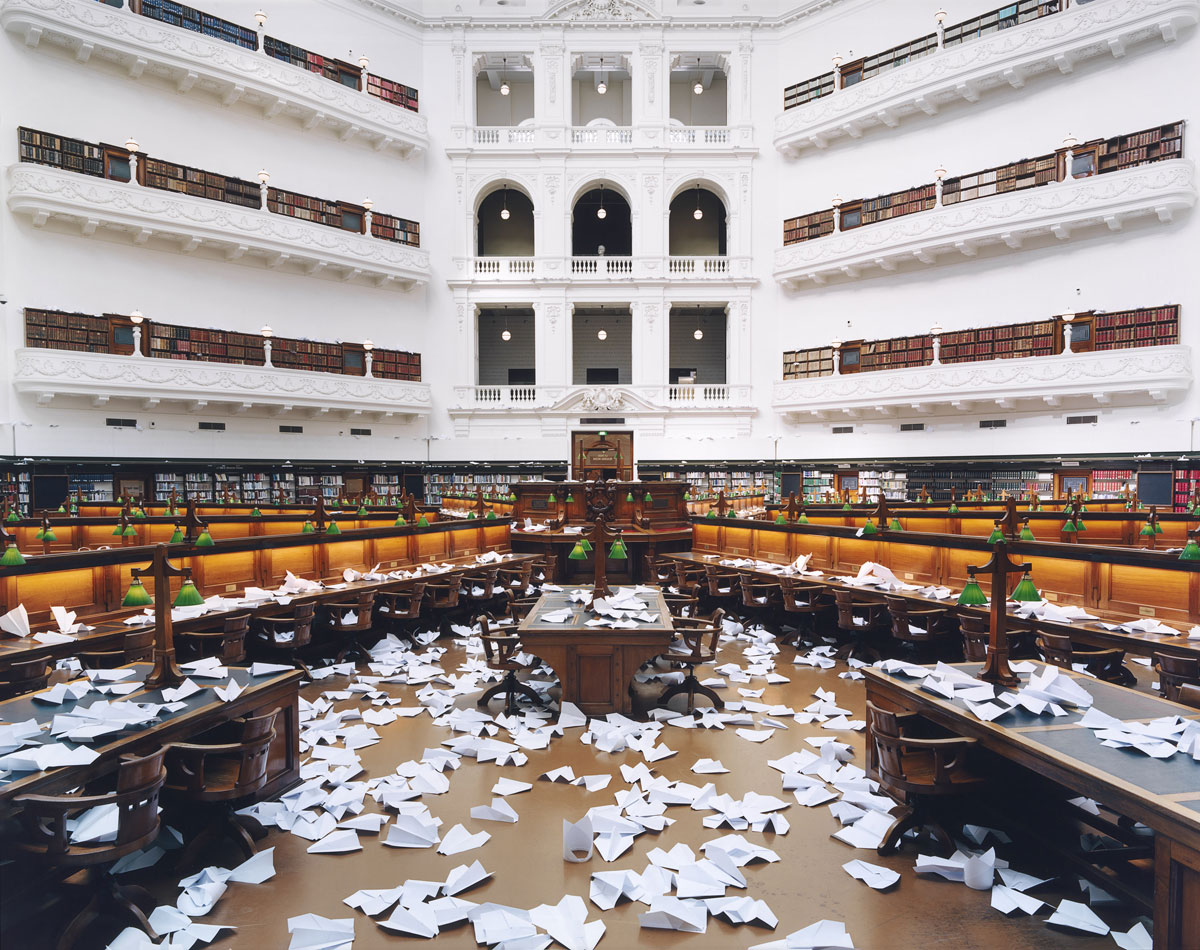

The immersive installation Gober conceived for a 1992 exhibition at the Dia Center for the Arts, New York is on view nearby. All three rooms of that original presentation are reconstructed: an antechamber, a central gallery, and a dark cul-de-sac. The main space features a hand-painted mural, executed in a paint-by-number method by scenic painters, depicting a forest inspired by the landscape of Long Island’s North Fork. Barred prison windows, through which a blue sky is visible, interrupt the verdant panorama. Placed throughout the gallery are hand-painted plaster sculptures of boxes of rat bait and bundles of newspapers – actually photolithographic facsimiles of newspapers featuring real and invented content. After a six-year absence from Gober’s work, sinks reappeared in the installation at Dia, water now running freely from their faucets.

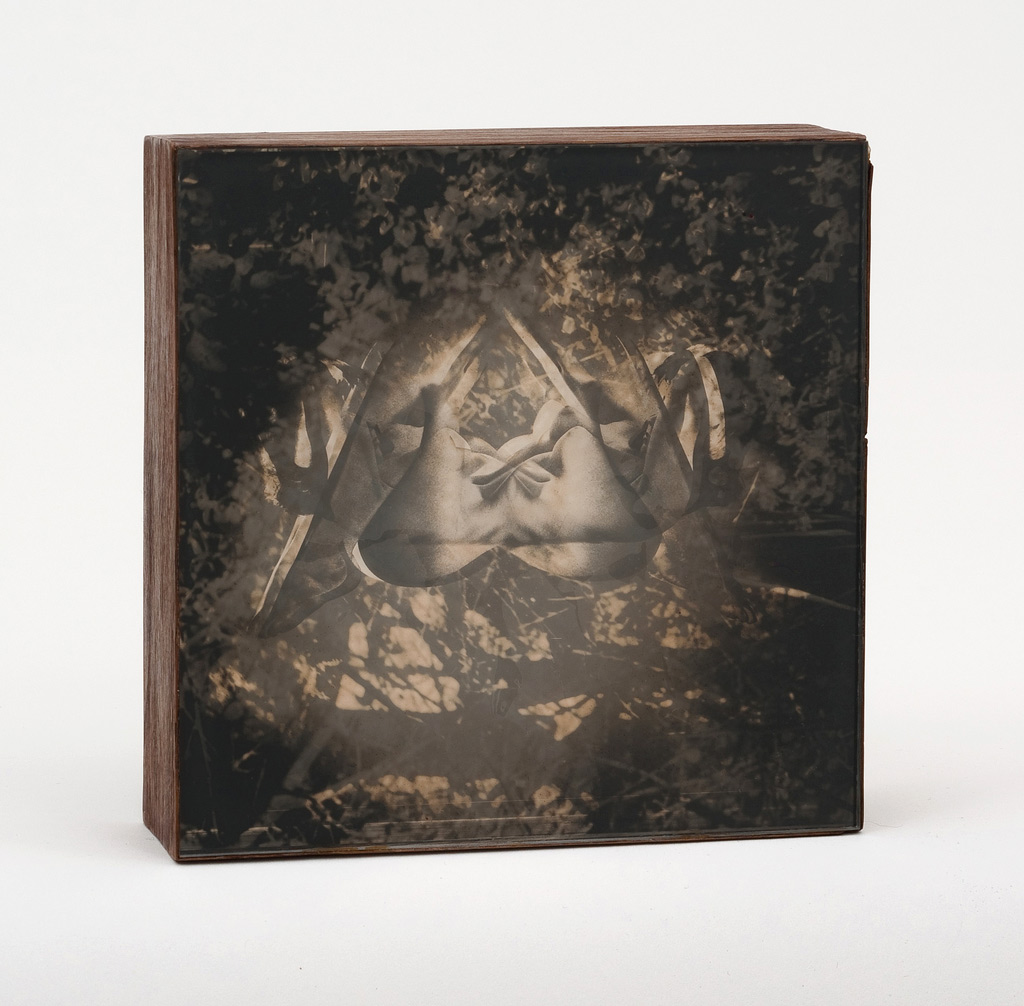

Following the introduction of mens’ legs into his sculptural vocabulary, Gober cast the leg of a young boy and used that mould as the basis for several subsequent works, including a fireplace where legs take the place of firewood, a vision invoking childhood nightmares and uncensored fairy tales. Also on view is a sculpture of a suitcase that occupies space below ground as well as above. Its lid opens to reveal a sewer grate and a brick shaft that leads to a subterranean tidal pool complete with seaweed, mussel shells, and starfish. Visible through the depths of the water, amid the marine life, are the legs of a man and baby, one holding the other in a manner suggestive of baptism. While primarily a sculptor, Gober has worked across a range of media throughout his career including drawing and printmaking. Drawings sit the closest to his work in three dimensions; most of his sculptures and installations are preceded by preparatory drawings. A selection of Gober’s works on paper is also on view in this gallery.

The final installation included in the exhibition was made in response to the attacks of September 11, 2001, and results from Gober’s desire to create a space of refuge and reflection. The overall structure evokes the interior of a church: a central aisle separating rows of pews leads to an altar-like area flanked by two chapels. From the nipples of a headless Christ, regenerative “living water” flows into a large hole jackhammered into the floor. In the pastel drawings hanging on the side walls, the power of human embrace confronts the harrowing news contained within the photo-lithographed pages of the September 12, 2001, issue of The New York Times. In this installation, the overt references to Catholicism explore the vitality of such symbolism in the wake of contemporary tragedy.

Over the past decade, Gober’s sculptures have become increasingly complex, both technically and iconographically. The artist sometimes uses casts of existing sculptures and combines them to create hybrid objects, as in the conjunction of a chest, a stool, and a twisted network of children’s legs. Elsewhere, Gober pushes recognisable imagery into unpredictable terrain: a sink’s backsplash morphs into gnarled planks of wood interwoven with casts of fragmented arms. New motifs, such as a surrealistically melting rifle, also have entered the artist’s visual universe. The strangeness of these new sculptures is presaged by Prayers Are Answered (1980-1981), an early work loosely based on a Catholic church on 7th Street and Avenue B in the East Village. Rather than the traditional religious scenes to be found in paintings lining the walls, Gober has furnished the church with murals depicting the harshness of daily life in the city.

The exhibition’s final gallery presents works made as early as 1979 and as recently as this past spring. Images of domestic objects and architecture and themes of childhood and the body reverberates across the decades. The dollhouse placed on the floor is one of several that Gober designed and built during his first years in New York City, as one way of earning a living. The sculpture and installations that would follow may be considered life-size realisations of the imaginative potential contained within these small structures.

Published in conjunction with the exhibition and prepared in close collaboration with the artist, Robert Gober: The Heart Is Not a Metaphor traces the development of his work, highlighting themes and motifs to which he has returned throughout the decades. The book features an essay by Hilton Als – a text both wide-ranging and personal – and an in-depth narrative of Gober’s life. The rich selection of images illustrates every phase of the artist’s career, and includes previously unpublished photographs from his own archive. Hardcover. 6.5″w x 9.75″h; 272 pages; 169 illustrations. ISBN: 978-0-87070-946-3. $45.

Ann Temkin

The Marie-Josée and Henry Kravis Chief Curator of Painting and Sculpture

The Museum of Modern Art

Ms. Temkin assumed the role of Chief Curator of Painting and Sculpture in 2008, after joining The Museum of Modern Art in 2003 as Curator. During her tenure, Ms. Temkin has worked extensively with her colleagues on reimagining the Painting and Sculpture collection galleries at the Museum. Along with Robert Gober: The Heart Is Not A Metaphor, her exhibitions at MoMA include Ileana Sonnabend: Ambassador for the New (2013); Abstract Expressionist New York (2010); Gabriel Orozco (2009); and Color Chart: Reinventing Color, 1950 to Today (2008). Prior to MoMA, Ms. Temkin was the curator of modern and contemporary art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art from 1990 to 2003, where she organised such exhibitions as Barnett Newman (2002), Constantin Brancusi (1995), and Thinking is Form: The Drawings of Joseph Beuys (1994).

Paulina Pobocha

Assistant Curator, Department of Painting and Sculpture

The Museum of Modern Art

Ms. Pobocha is an assistant curator in the Department of Painting and Sculpture at The Museum of Modern Art. She joined the Museum in 2008 and has worked on the exhibitions Gabriel Orozco (2009) and Abstract Expressionist New York (2010). In 2013 she co-organised Claes Oldenburg: The Street and The Store. She has also worked extensively with the Museum’s collection. Prior to MoMA, Ms. Pobocha was a Joan Tisch Fellow at the Whitney Museum of American Art, where she lectured on a broad range of subjects in contemporary and modern art. In 2011, she was appointed Critic at the Yale University School of Art.

Press release from the MoMA website

Robert Gober (American, b. 1954)

X Pipe Playpen

2013-14

Wood and bronze

26 1/8 x 55 x 55″ (66.4 x 139.7 x 139.7cm)

Collection the artist

Robert Gober (American, b. 1954)

Untitled (installation view)

1989-1996

Silk satin, muslin, linen, tulle, welded steel, hand-printed silkscreen on paper, cast hydrostone plaster, vinyl acrylic paint, ink, and graphite

Dimensions variable, approximately 800 square feet installed

The Art Institute of Chicago, restricted gift of Stefan T. Edlis and H. Gael Neeson Foundation; through prior gifts of Mr. and Mrs. Joel Starrels and Fowler McCormick

© 2014 Robert Gober

Robert Gober (American, b. 1954)

Bag of Donuts

1989

paper, dough and rhoplex (12 donuts)

© 2014 Robert Gober

Robert Gober (American, b. 1954)

Untitled Leg

1989-1990

Beeswax, cotton, wood, leather, human hair

11 3/8 x 7 3/4 x 20″ (28.9 x 19.7 x 50.8 cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of the Dannheisser Foundation

© 2014 Robert Gober

Robert Gober (American, b. 1954)

Cigar (installation view)

1991

Wood, paint, paper, tobacco

15 3/4 x 15 3/4 x 70 7/8″ (40 x 40 x 180cm)

The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Purchased with funds provided by the Collectors Committee in honour of Marcia Simon Weisman

© 2014 Robert Gober

Robert Gober (American, b. 1954)

Forest

1991

Hand-printed silkscreen on paper

180″ x 124″ (457.2 x 315cm)

Courtesy the artist

© 2014 Robert Gober

Robert Gober (American, b. 1954)

Untitled

1991

Wood, beeswax, leather, fabric, and human hair

13 1/4 x 16 1/2 x 46 1/8″ (33.6 x 41.9 x 117.2cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Werner and Elaine Dannheisser

Background: Forest, 1991

Hand-painted silkscreen on paper

Image credit: K. Ignatiadis, courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery

© 2014 Robert Gober

Robert Gober (American, b. 1954)

Untitled (installation view)

1992

Paper, twine, metal, light bulbs, cast plaster with casein and silkscreen ink, stainless steel, painted cast bronze and water, plywood, forged iron, plaster, latex paint and lights, photolithography on archival (Mohawk Superfine) paper, twine, hand-painted forest mural

511 3/4 × 363 3/16 × 177 3/16″ (1300 × 922.5 × 450.1cm)

Glenstone

© 2014 Robert Gober

Robert Gober (American, b. 1954)

Untitled

1992

Paper, twine, metal, light bulbs, cast plaster with casein and silkscreen ink, stainless steel, painted cast bronze and water, plywood, forged iron, plaster, latex paint and lights, photolithography on archival (Mohawk Superfine) paper, twine, hand-painted forest mural

511 3/4 × 363 3/16 × 177 3/16″ (1300 × 922.5 × 450.1cm)

Glenstone

Image credit: Russell Kaye, courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery

© 2014 Robert Gober

Robert Gober (American, b. 1954)

Untitled

2003-2005

Courtesy MoMA and Matthew Marks Gallery

Image credit: Russel Kaye

© 2014 Robert Gober

Robert Gober (American, b. 1954)

Untitled (detail)

2003-2005

© 2014 Robert Gober

Robert Gober (American, b. 1954)

Untitled

1980-1981

Oil on wood panel

8 x 5 3/4″ (20.3 x 14.6cm)

Collection the artist

Image credit: Ron Amstutz, courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery

© 2014 Robert Gober

Robert Gober (American, b. 1954)

Slip Covered Armchair

1986-1987

Plaster, wood, linen, and fabric paint

31 1/2 x 30 1/2 x 29″ (80 x 77.5 x 73.7cm)

Collection the artist

Image credit: D. James Dee, courtesy the artist

© 2014 Robert Gober

Robert Gober (American, b. 1954)

Untitled Door and Door Frame (installation view)

1987-1988

Wood, enamel paint

Door: 84 x 34 x 1 1/2″ (213.4 x 86.4 x 3.8cm)

Doorframe: 90 x 43 x 5 1/2″ (228.6 x 109.2 x 14cm)

Collection Walker Art Center, Minneapolis. Gift of the John and Mary Pappajohn Art Foundation, 2004

© 2014 Robert Gober

Installation views of Robert Gober: The Heart Is Not a Metaphor, The Museum of Modern Art, October 4, 2014 – January 18, 2015

All works by Robert Gober © 2014 Robert Gober © 2014 The Museum of Modern Art

Photos: Jonathan Muzikar

Robert Gober (American, b. 1954)

Untitled

2005-2006

Aluminium-leaf, oil and enamel paint on cast lead crystal

4 3/4″ high × 4 1/4″ diameter (12.1 × 10.8cm)

Collection the artist

Image credit: Bill Orcutt, courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery

© 2014 Robert Gober

Robert Gober (American, b. 1954)

Untitled

2008

Cast gypsum polymer

14 1/2 x 10 3/4 x 6″ (36.8 x 27.3 x 15.2cm)

Edition of 4, with 1 AP

Collection the artist

Image credit: Fredrik Nilsen, courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery

© 2014 Robert Gober

Robert Gober (American, b. 1954)

Leg with Anchor

2008

Forged iron and steel, beeswax, cotton, leather, and human hair

28 × 18 × 20″ (71.1 × 45.7 × 50.8cm)

Glenstone

Image credit: Bill Orcutt, courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery

© 2014 Robert Gober

The Museum of Modern Art

11 West 53 Street

New York, NY 10019

Phone: (212) 708-9400

Opening hours:

10.30 am – 5.30 pm

Open seven days a week

![Giacomo Balla (Italian, 1871-1958) 'The Hand of the Violinist (The Rhythms of the Bow)' (La mano del violinista [I ritmi dell’archetto]) 1912 Giacomo Balla (Italian, 1871-1958) 'The Hand of the Violinist (The Rhythms of the Bow)' (La mano del violinista [I ritmi dell’archetto]) 1912](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/01_balla_handoftheviolinist-web.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.