Exhibition dates: 16th July – 16th October 2022

A National Gallery Touring Exhibition

Curator: Dr Sarina Noordhuis-Fairfax, Curator of Australian Prints and Drawings at the National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

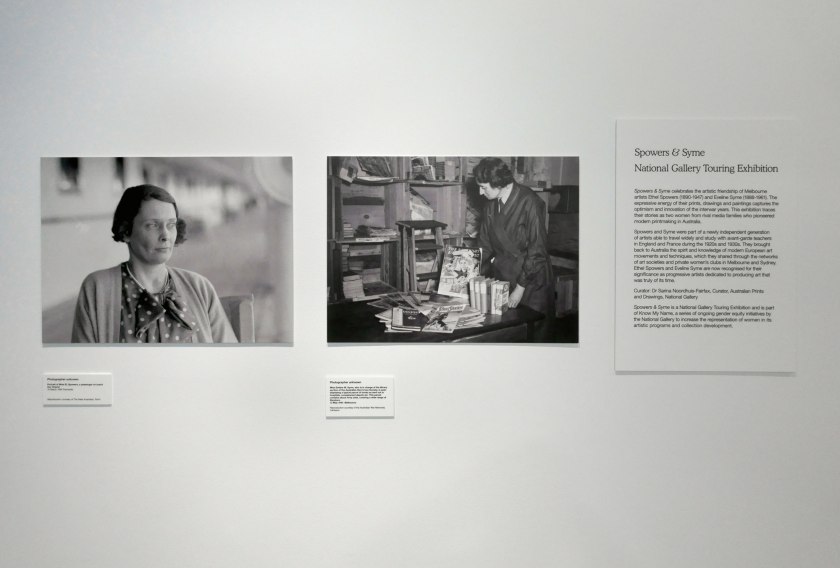

Installation view of the exhibition Spowers & Syme at the Geelong Art Gallery showing photographs of both Ethel Spowers and Eveline Syme (below)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

My friend and I travelled down the highway from Melbourne to Geelong especially to see this National Gallery of Australia touring exhibition – and my god, was it worth the journey!

I have always loved woodcuts and the Art Deco era so it was a great pleasure to see the work of two very talented artists from this period, who were “enthusiastic exponents of modern art in Melbourne during the 1930s and ’40s.” Modern art that would have challenged the conservative (male) art conventions of the day, much as modernist photographs by Max Dupain challenged the ongoing power of Pictorialist photography in 1930s Australia.

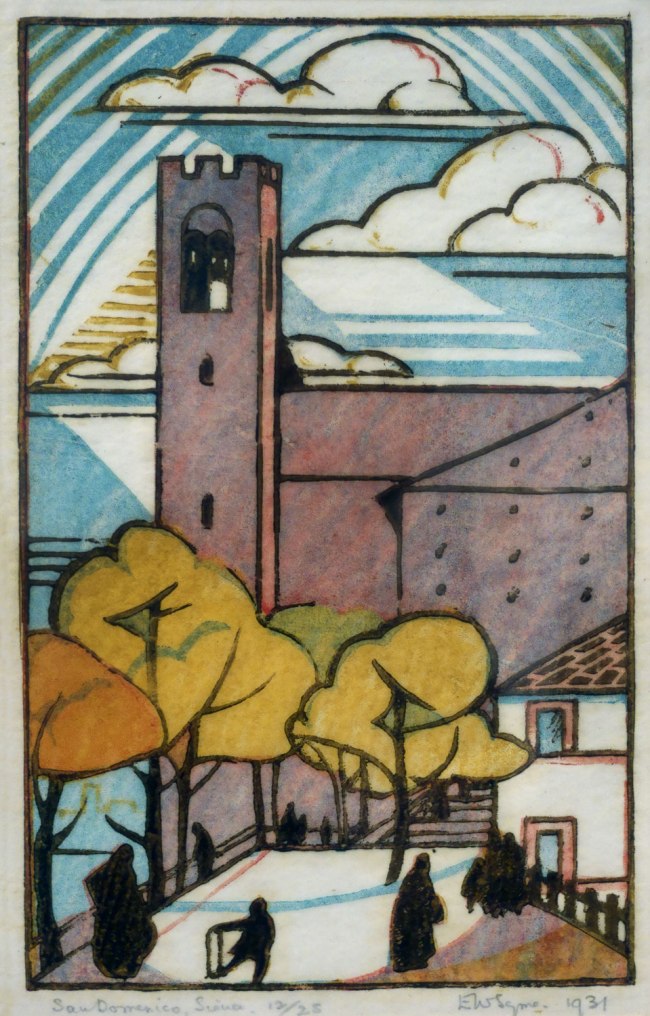

From viewing the exhibition it would seem to me that Eveline Syme has the sparer, more ascetic aesthetic. Her forms are more graphic, her lines more severe, her spaces more “blocky” (if I can use that word – in other words, more positive and negative space), her colour palette more restrained than in the work of Ethel Spowers. But her work possesses its own charm: a wonderful Japanese inspired landscape such as The factory (1933, below), with its mix of modernism and naturalism; silhouetted blue figures full of dynamism, movement in a swirling circular motif in Skating (1929, below); or the flattened perspective and 3 colour palette of Sydney tram line (1936, below) – all offer their own delicious enjoyment of the urban landscape.

But the star of the show is the work of the astonishing Ethel Spowers. Her work is luminous… containing such romanticism, fun, humour, movement, play, intricate design, bold colours, lyrical graphics… and emotion – that I literally went weak at the knees when viewing these stunningly beautiful art works. There is somethings so joyful about Spowers designs that instantly draws you in, that makes you smile, that made me cry! They really touched my heart…

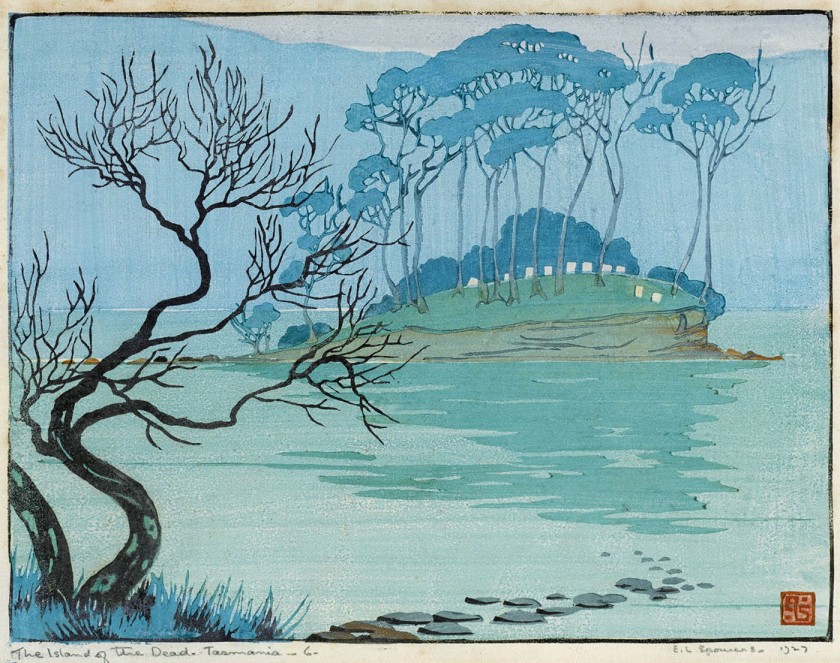

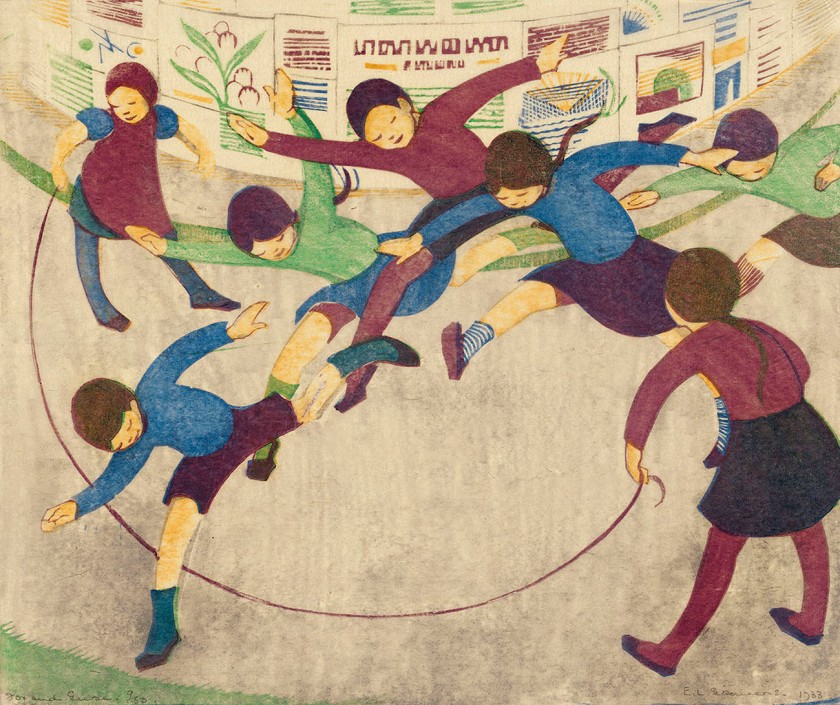

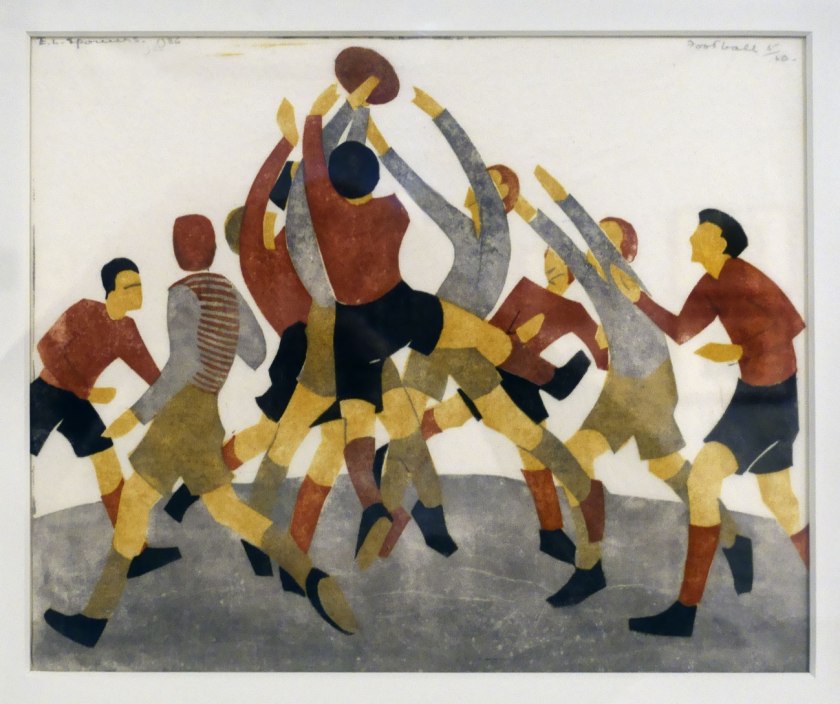

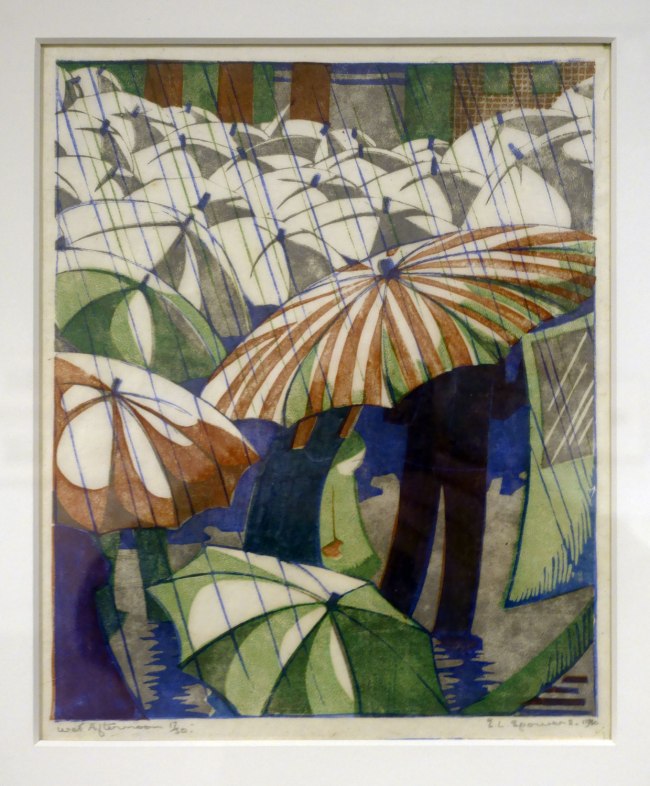

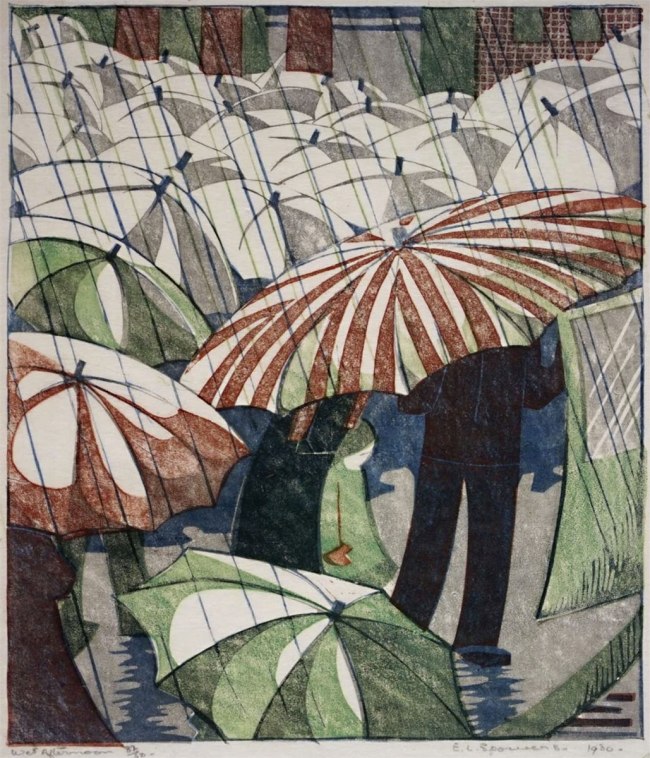

Even now writing about them, they seem to me like stills from a dream, scenes out of a fairy tale: the pattern of the white gulls obscuring the plough; the rays of sunlight striking the ground behind The lonely farm; the mysterious stillness of The island of the dead; the arching leap over the rope in Fox and geese; the pyramid construction of Football; the delicacy of movement and line in Swings; and the butterfly-like canopies in Wet afternoon. I could go on and on about the joy these works brought me when looking at them, their vivaciousness, their intense, effervescent spirit. If you get a chance before the exhibition closes next weekend in Geelong please go to see them.

As you may have gathered I am totally in love with the work of Ethel Spowers. Thank you, thank you to the artist for making them, and thank you to the energy of the cosmos for allowing me to see them in person!

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to Geelong Art Gallery for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image. All installation images © Marcus Bunyan, Geelong Art Gallery and the National Gallery of Australia.

“Is it too great a truism to repeat that the best art is always the child of its own age?”

Eveline Syme

Celebrating the artistic friendship of Melbourne artists Ethel Spowers and Eveline Syme, the National Gallery Touring Exhibition Spowers and Syme will present the changing face of interwar Australia through the perspective of two pioneering modern women artists.

The exhibition offers rare insight into the unlikely collaboration between the daughters of rival media families. Studying together in Paris and later with avant-garde printmaker Claude Flight in London, Ethel Spowers and Eveline Syme returned to the conservative art world of Australia – where they became enthusiastic exponents of modern art in Melbourne during the 1930s and ’40s.

Much-loved for their innovative approach to lino and woodcut techniques, Spowers and Syme showcases their dynamic approach through prints and drawings whose rhythmic patterns reflect the fast pace of the modern world through everyday observations of childhood themes, overseas travel and urban life.

Text from the Geelong Gallery website

Installation views of the exhibition Spowers & Syme at the Geelong Art Gallery

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Photographer unknown

Portrait of Miss EL Spowers, a passenger on board the ‘Orama’ (installation view)

19 March 1935

Fremantle

Reproduction courtesy of The West Australian, Perth

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Photographer unknown

Miss Eveline W. Syme, who is in charge of the library section of the Australian Red Cross Society, is seen displaying a typical parcel of books as sent out to hospitals, convalescent depots etc. This parcel contains about forty units, covering a wide range of literature (installation view)

13 May 1943

Melbourne

Reproduction courtesy of the Australian War Memorial, Canberra

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Ethel Spowers (Australian, 1890-1947)

The gust of wind (installation view)

1931

Melbourne

Linocut, printed in colour inks, from four blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1976

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Ethel Spowers (Australian, 1890-1947)

The gust of wind

1931

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1976

Ethel Spowers (Australian, 1890-1947)

Special edition (installation view)

1936

Melbourne

Linocut, printed in colour inks, from four blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1976

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Raised in Toorak society, Ethel Spowers was the second daughter of William Spewers, an Aotearoa New Zealand-born journalist and proprietor of The Argus and The Australasian newspapers. The Spowers family lived at Toorak House in St Georges Road. Eveline Syme was the first-born daughter of company director and pastoralist Joseph Syme, who was a partner in competing newspaper The Age until 1891. The Syme family lived at Rotherfield (now Sherwood Hall) in St Kilda. Eveline moved to Toorak in around 1927.

Wall text

Ethel Spowers (Australian, 1890-1947)

Special edition

1936

Melbourne

Linocut, printed in colour inks, from four blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1976

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

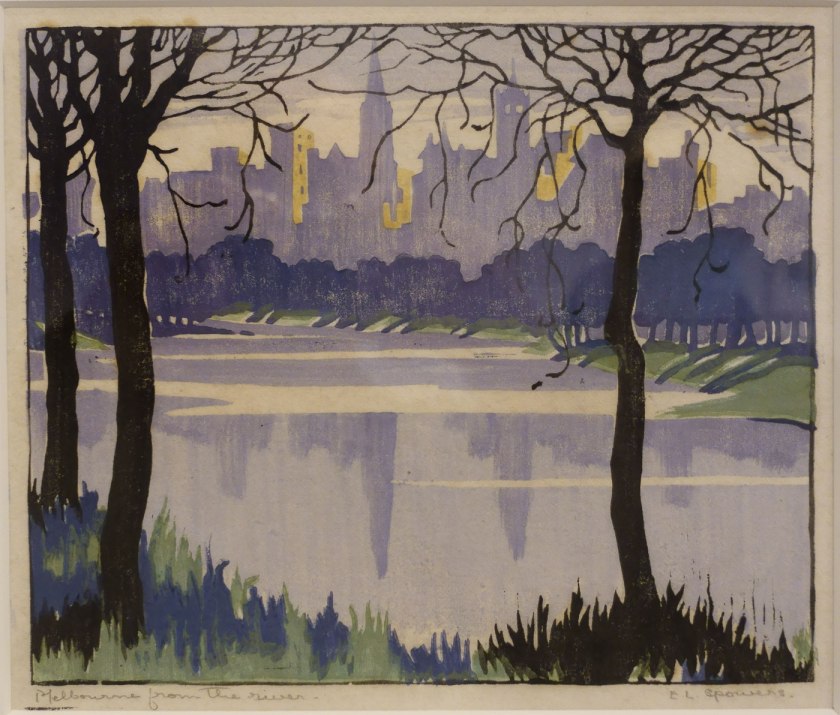

Ethel Spowers (Australian, 1890-1947)

Melbourne from the river (installation view)

c. 1924

Melbourne

Woodcut, printed in colour inks in the Japanese manner, from five blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1976

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

A sense of place is important to all of us. For Spowers and Syme, Melbourne (Naarm) was their home and held a special place in their hearts. In the 1920s, Melbourne was an important city. Lively and busy, it was also very accessible to the river and beautiful landmarks. The Yarra River (Birrarung) winding gently through the city and the industrial landscape at Yallourn were worthy subjects to focus on. Spowers’ earlier work Melbourne from the river c 1924 (below) was created looking at the river and is framed by spindly trees.

Text from the National Gallery of Australia website

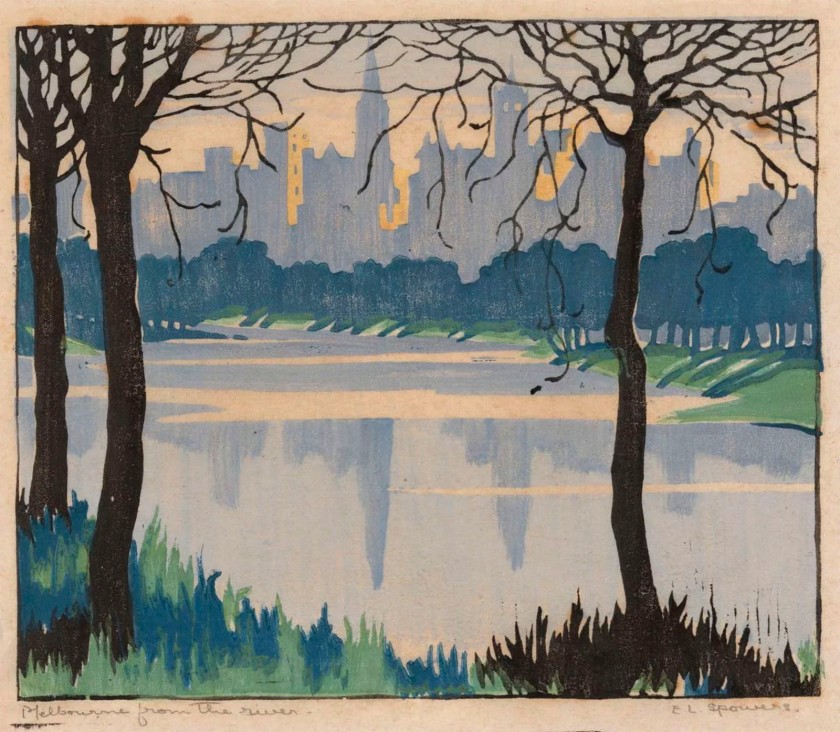

Ethel Spowers (Australian, 1890-1947)

Melbourne from the river (installation view)

c. 1924

Melbourne

Woodcut, printed in colour inks in the Japanese manner, from five blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1976

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Ethel Spowers (Australian, 1890-1947)

Melbourne from the river

c. 1924

Melbourne

Woodcut, printed in colour inks in the Japanese manner, from five blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1976

Eveline Syme (Australian, 1888-1961)

Banks of the Yarra (installation view)

1935

Melbourne

Linocut, printed in colour inks, from three blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Eveline Syme (Australian, 1888-1961)

Banks of the Yarra

1935

Melbourne

Linocut, printed in colour inks, from three blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

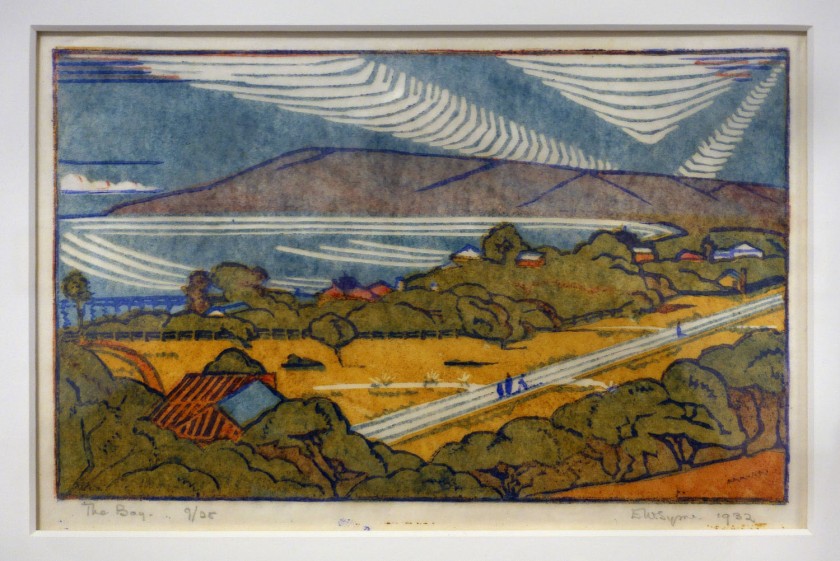

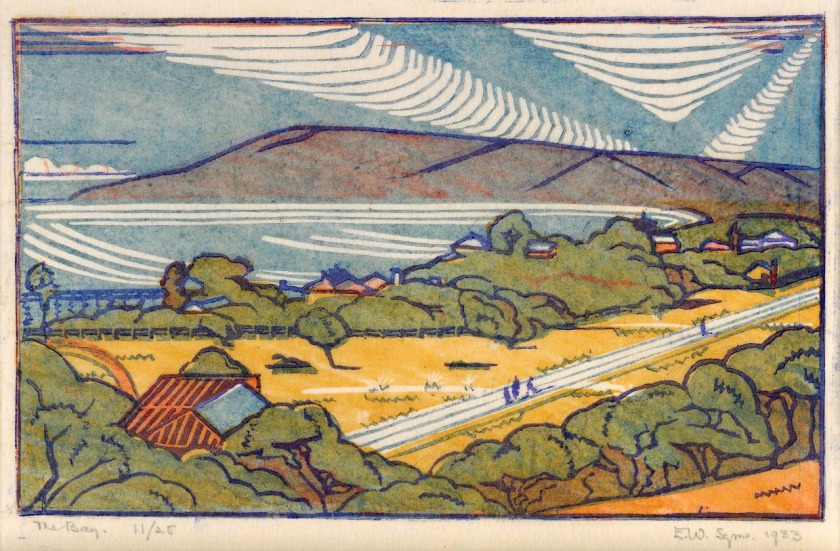

Eveline Syme (Australian, 1888-1961)

The bay (installation views)

1932

Melbourne

Linocut, printed in colour inks, from four blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1977

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Eveline Syme (Australian, 1888-1961)

The bay

1932

Melbourne

Linocut, printed in colour inks, from four blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1977

Geelong Gallery is delighted to present National Gallery of Australia Touring Exhibition, Spowers & Syme opening on Saturday 16 July 2022.

Celebrating the artistic friendship of Melbourne artists Ethel Spowers and Eveline Syme, the Know My Name touring exhibition presents the changing

face of interwar Australia through the perspective of two pioneering women artists.

The National Gallery’s Curator of Australian Prints and Drawings, Dr Sarina Noordhuis-Fairfax hopes that Geelong and Victorian audiences will add the

names Spowers and Syme to their knowledge of ground-breaking women artists from the era including Margaret Preston, Thea Proctor, Dorrit Black and Grace Cossington Smith.

‘Spowers and Syme are often overlooked in Australian art history, yet during the 1930s they were recognised by peers as being among the most progressive artists working in Melbourne.’

‘Exhibiting in Australia and England, they championed key ideas from European modernism such as contemporary art reflecting the pace and vitality of life,’ said Noordhuis-Fairfax.

Much-loved for their dynamic approach to lino and woodcut prints, Spowers & Syme offers rare insights into the creative alliance between the daughters of rival media families from Melbourne-based newspapers The Argus and The Age. After studying art together in Paris and London, Spowers and Syme returned to the conservative art world of Australia where they became enthusiastic exponents of modern art during the 1930s and 1940s.

Geelong Galley Director & CEO, Jason Smith says ‘We look forward to sharing the important works of Spowers and Syme and exploring their contributions further through a number of public and education programs. Spowers & Syme will be further contextualised by modernist works by women artists in our Geelong permanent collection including a major survey of printmaker, Barbara Brash.

Press release from the Geelong Art Gallery

Ethel Spowers (Australian, 1890-1947)

Balloons

c. 1920

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Gift of Chris Montgomery 1993

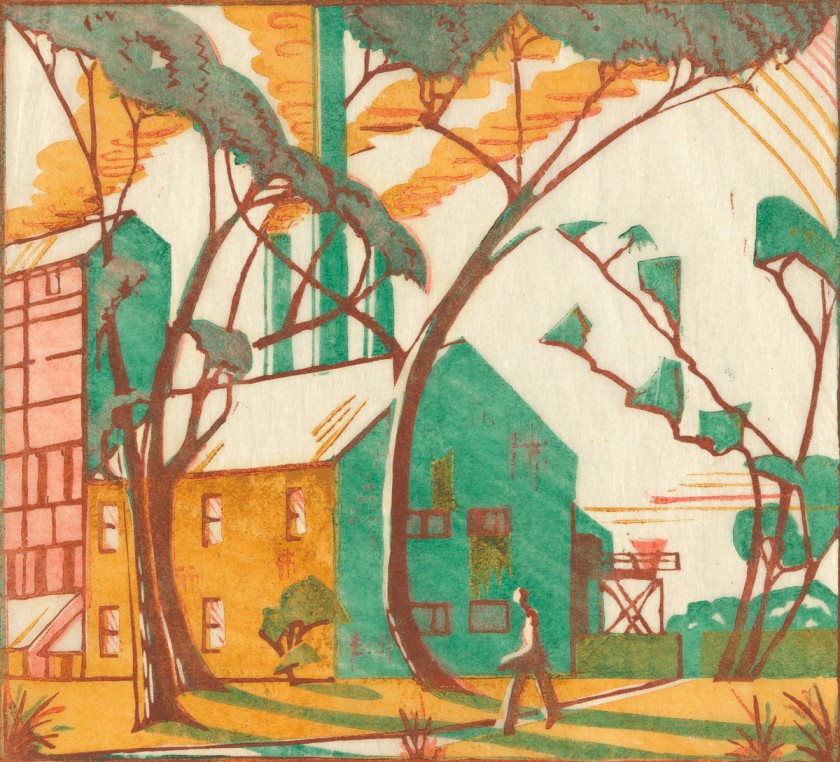

Eveline Syme (Australian, 1888-1961)

The factory (installation view)

1933

Melbourne

Linocut, printed in colour inks, from four blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1979

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Eveline Syme (Australian, 1888-1961)

The factory

1933

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1979

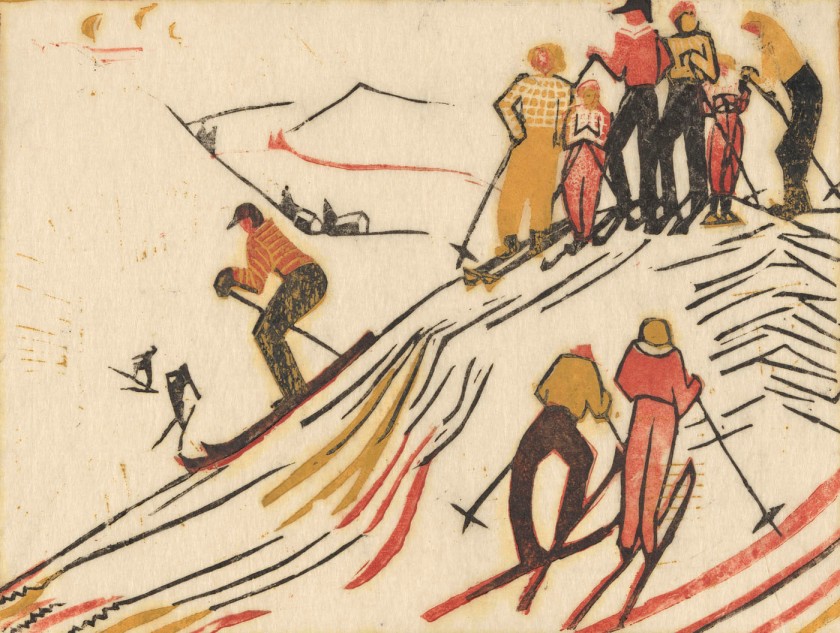

Eveline Syme (Australian, 1888-1961)

Beginners’ class

1956

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1992

Ethel Spowers (Australian, 1890-1947)

Drawing for the linocut ‘School is out’ (installation view)

1936

Melbourne

Drawing in pen and black ink over pencil

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Gift of Chris Montgomery 1993

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

At the end of 1936 Spowers held her sixth and final solo exhibition. It was a survey of old favourites and new works, spanning a decade of imagination and experimentation. Among the twenty prints and six watercolours shown at Grosvenor Galleries in Sydney were five fresh linocuts: Kites, Football, School is out, Children’s hoops and Special edition. These works were a return to her most treasured themes: children and family.

Wall text

Ethel Spowers (Australian, 1890-1947)

School is out

1936

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1976

Ethel Spowers and Eveline Syme captured the joy and dynamism of movement in sport and play. Through colour, pattern and intersecting lines we see the speed and energy of children skipping, running, reaching to catch a ball and the pace of skaters circling the rink in the icy coldness. Who could forget the wonderful feeling of swinging as high as possible, looking down at the world?

Spowers’ images of children playing are reminiscent of her own childhood and have a whimsical charm about them. They capture the sense of wonder and curiosity seen in young children.

Linoleum (lino) was a floor covering that was invented in 1860. Imaginative artists discovered how effective it was for creating prints. With the right tools, it was easy to carve an image into it and make prints using coloured inks on the exposed surface.

Anonymous text. “Play and Games – Spowers & Syme: Primary School Learning Resource,” on the National Gallery of Australia website Nd [Online] Cited 29/08/2022

Ethel Spowers (Australian, 1890-1947)

The bamboo blind

1926

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1976

Ethel Louise Spowers (1890-1947), painter and printmaker, was born on 11 July 1890 at South Yarra, Melbourne, second of six children of William George Lucas Spowers, a newspaper proprietor from New Zealand, and his London-born wife Annie Christina, née Westgarth. Allan Spowers was her only brother. She was educated at the Church of England Girls’ Grammar School, Melbourne, and was a prefect in 1908. Wealthy and cultured, her family owned a mansion in St Georges Road, Toorak. Ethel continued to live there as an adult and maintained a studio above the stables.

After briefly attending art school in Paris, Miss Spowers undertook (1911-1917) the full course in drawing and painting at Melbourne’s National Gallery schools. Her first solo exhibition, held in 1920 at the Decoration Galleries in the city, showed fairy-tale drawings influenced by the work of Ida Outhwaite. In 1921-1924 Spowers worked and studied abroad, at the Regent Street Polytechnic, London, and the Académie Ranson, Paris. She exhibited (1921) with fellow Australian artist Mary Reynolds at the Macrae Gallery, London. Two further solo shows (1925 and 1927) at the New Gallery, Melbourne, confirmed her reputation as an illustrator of fairy tales, though by then she was also producing woodcuts and linocuts inspired by Japanese art and covering a broader range of subjects.

A dramatic change in Spowers’ style occurred in 1929 when she studied under Claude Flight (the leading exponent of the modernist linocut) at the Grosvenor School of Modern Art, London. Her close friend Eveline Syme joined her there. Following further classes in 1931, during which Spowers absorbed modernist ideas of rhythmic design and composition from the principal Iain Macnab, she published an account of the Grosvenor School in the Recorder (Melbourne, 1932). In the 1930s her linocuts attracted critical attention for their bold, simplified forms, rhythmic sense of movement, distinctive use of colour and humorous observation of everyday life, particularly the world of children. They were regularly shown at the Redfern Gallery, London. The British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum purchased a number of her linocuts.

Stimulated by Flight’s proselytising zeal for the medium, Spowers organised in 1930 an exhibition of linocuts by Australian artists, among them Syme and Dorrit Black, at Everyman’s Library and Bookshop, Melbourne. A founding member (1932-1938) of George Bell‘s Contemporary Group, Spowers defended the modernist movement against its detractors. In an article in the Australasian on 26 April 1930 she called on ‘all lovers of art to be tolerant to new ideas, and not to condemn without understanding’.

Frances Derham remembered Spowers as being ‘tall, slender and graceful’, with ‘a small head, dark hair and grey eyes’. A rare photograph of Spowers, published in the Bulletin (3 September 1925), revealed her fashionable appearance and reflective character. In the late 1930s she stopped practising as an artist due to ill health, but continued her voluntary work at the Children’s Hospital. She died of cancer on 5 May 1947 in East Melbourne and was buried with Anglican rites in Fawkner cemetery. Although she had destroyed many of her paintings in a bonfire, a memorial exhibition of her watercolours, line-drawings, wood-engravings and colour linocuts was held at George’s Gallery, Melbourne, in 1948. Her prints are held by the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, State galleries in Melbourne and Sydney, and the Ballarat Fine Art Gallery, Victoria.

Stephen Coppel. “Spowers, Ethel Louise (1890-1947),” in the Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 16 , 2002, online in 2006 [Online] Cited 26/08/2022

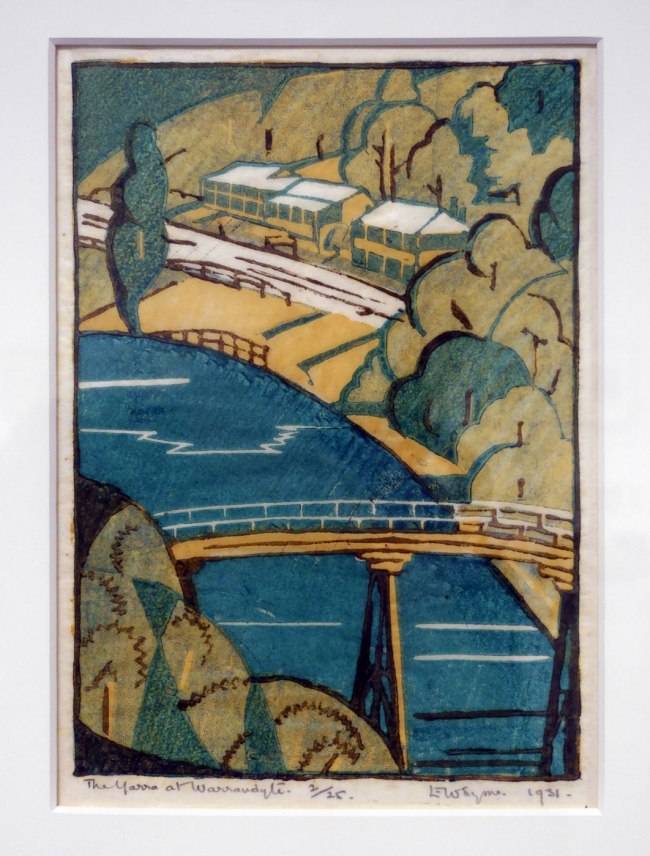

Eveline Syme (Australian, 1888-1961)

The Yarra at Warrandyte (installation views)

1931

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1977

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Eveline Syme (Australian, 1888-1961)

The Yarra at Warrandyte

1931

Melbourne

Linocut, printed in colour inks, from four blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1977

Eveline Winifred Syme (1888-1961), painter and printmaker, was born on 26 October 1888 at Thames Ditton, Surrey, England, daughter of Joseph Cowen Syme, newspaper proprietor, and his wife Laura, née Blair. Ebenezer Syme was her grandfather. Eveline was raised in the family mansion at St Kilda, Melbourne. After leaving the Church of England Girls’ Grammar School, Melbourne, she voyaged to England and studied classics in 1907-1910 at Newnham College, Cambridge (B.A., M.A., 1930). Because the University of Cambridge did not then award degrees to women, she applied to the University of Melbourne for accreditation, but was only granted admission to third-year classics. She chose instead to complete a diploma of education (1914).

Syme’s artistic career was enhanced by her close friendship with Ethel Spowers. She studied painting at art schools in Paris in the early 1920s, notably under Maurice Denis and André Lhote, and held a solo exhibition, mainly of watercolours, at Queen’s Hall, Melbourne, in 1925. Her one-woman shows, at the Athenaeum Gallery (1928) and Everyman’s Library and Bookshop (1931), included linocuts and wood-engravings. While many of her watercolours and prints drew on her travels through England, Provence, France, and Tuscany, Italy, she also responded to the Australian landscape, particularly the countryside around Melbourne and Sydney, and at Port Arthur, Tasmania. Syme’s chance discovery of Claude Flight’s textbook, Lino-Cuts (London, 1927), inspired her to enrol (with Spowers) in his classes at the Grosvenor School of Modern Art, London, in January 1929. In keeping with Flight’s modernist conception of the linocut, she began to produce prints incorporating bold colour and rhythmic design.

Returning to Melbourne in 1929 with an exhibition of contemporary wood-engravings from the Redfern Gallery, London, Syme became a cautious advocate of modern art. She published a perceptive account of Flight and his teaching in the Recorder (1929) and spoke on the radio about wood-engraving; she also wrote a pioneering essay on women artists in Victoria from 1857, which was published in the Centenary Gift Book (1934), edited by Frances Fraser and Nettie Palmer. Syme was a founding member (1932-1938) of George Bell‘s Contemporary Group. She regularly exhibited with the Melbourne Society of Women Painters and Sculptors and with the Independent Group of Artists. Her linocuts, perhaps her most significant achievement, owed much to her collaboration with Spowers.

During the mid-1930s Syme was prominent in moves to establish a women’s residential college at the University of Melbourne. In 1936, as vice-president of the appeal committee, she donated the proceeds of her print retrospective (held at the gallery of the Arts and Crafts Society of Victoria) to the building fund. A foundation member (1936-1961) of the council of University Women’s College, she served as its president (1940-1947) and as a member of its finance committee. She was appointed to the first council of the National Gallery Society of Victoria in 1947 and sat on its executive-committee in 1948-1953. In addition, she was a member (1919) and president (1950-1951) of the Lyceum Club.

A tall, elegant and reserved woman, Syme had a ‘crisp, quick voice’ and a ‘rather abrupt manner’. She died on 6 June 1961 at Richmond and was buried with Presbyterian forms in Brighton cemetery. In her will she left her books and £5000 to University Women’s College. Edith Alsop’s portrait (1932) of Syme is held by University College. Syme’s work is represented in the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, State galleries in Melbourne, Sydney and Adelaide, and the Ballarat Fine Art Gallery, Victoria.

Stephen Coppel. “Syme, Eveline Winifred (1888-1961),” in the Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 16 , 2002, online in 2006 [Online] Cited 26/08/2022

Installation view of the exhibition Spowers & Syme at the Geelong Art Gallery showing at top left, Spowers The timber crane (1926, below); at top right, Spowers The plough (1928, below); at bottom left, Spowers The works, Yallourn (1933, below); and at bottom right, Spowers The lonely farm (1933, below)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Ethel Spowers (Australian, 1890-1947)

The timber crane (installation view)

1926

Melbourne

Linocut, printed in colour inks in the Japanese manner, from five blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1976

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

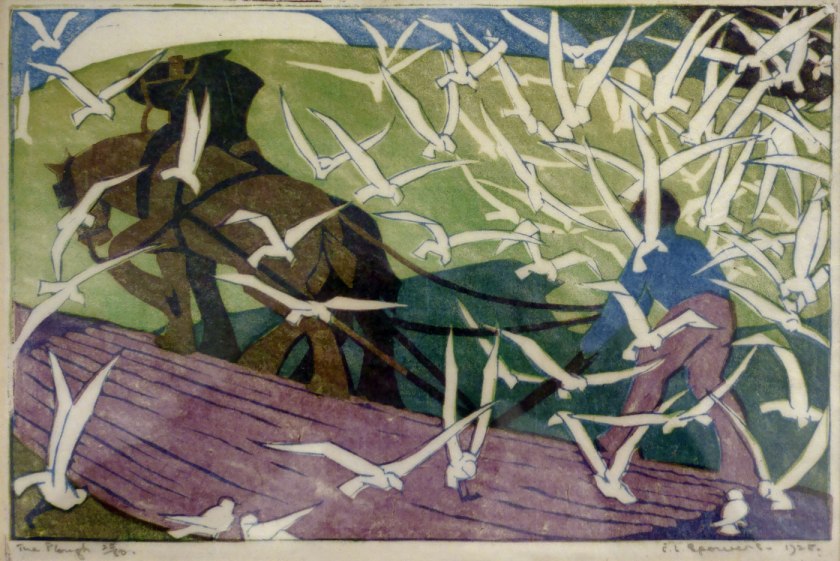

Ethel Spowers (Australian, 1890-1947)

The plough (installation view)

1928

London

Linocut, printed in colour inks, from three blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1978

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Ethel Spowers (Australian, 1890-1947)

The plough

1928

London

Linocut, printed in colour inks, from three blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1978

Ethel Spowers (Australian, 1890-1947)

The works, Yallourn

1933

Linocut

15.7 x 34.8cm (printed image)

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1976

Eveline Syme (Australian, 1888-1961)

Bulla Bridge

1934

Wood engraving

10.1 x 14.7cm (printed image)

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1977

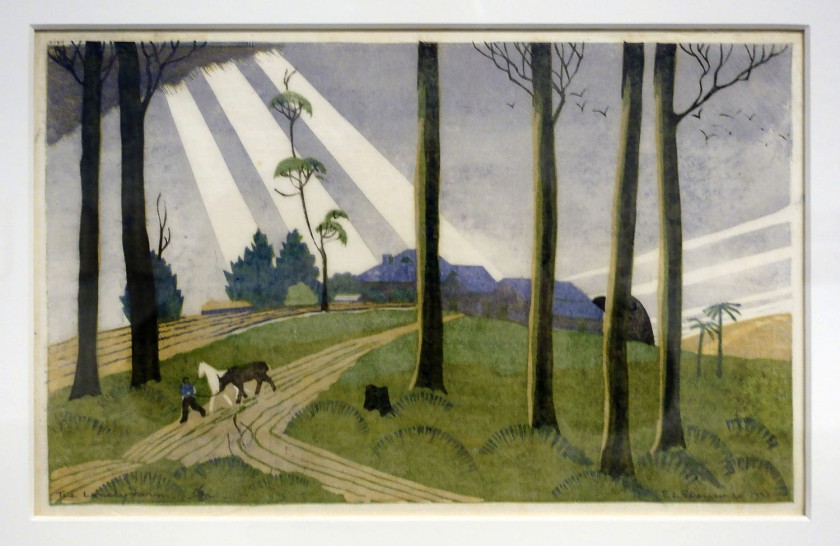

Ethel Spowers (Australian, 1890-1947)

The lonely farm (installation views)

1933

Melbourne

Linocut, printed in colour inks, from five blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1976

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Ethel Spowers (Australian, 1890-1947)

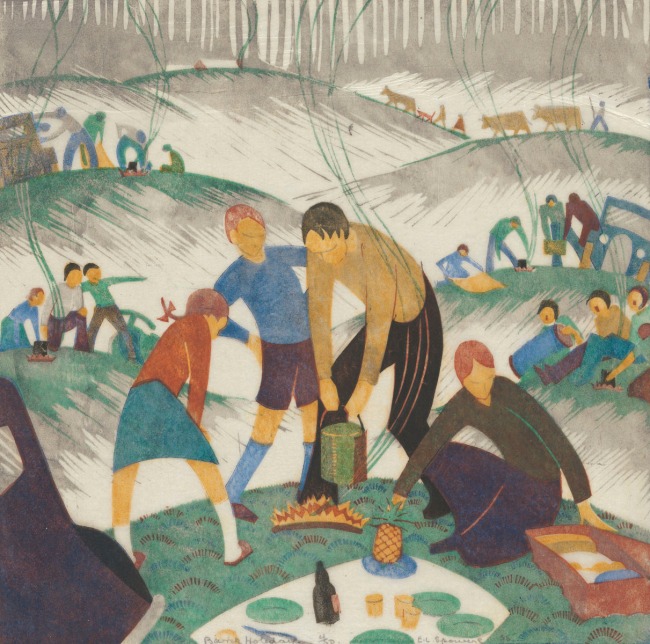

Harvest (installation view)

1932

Melbourne

Linocut, printed in colour inks, from five blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1976

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

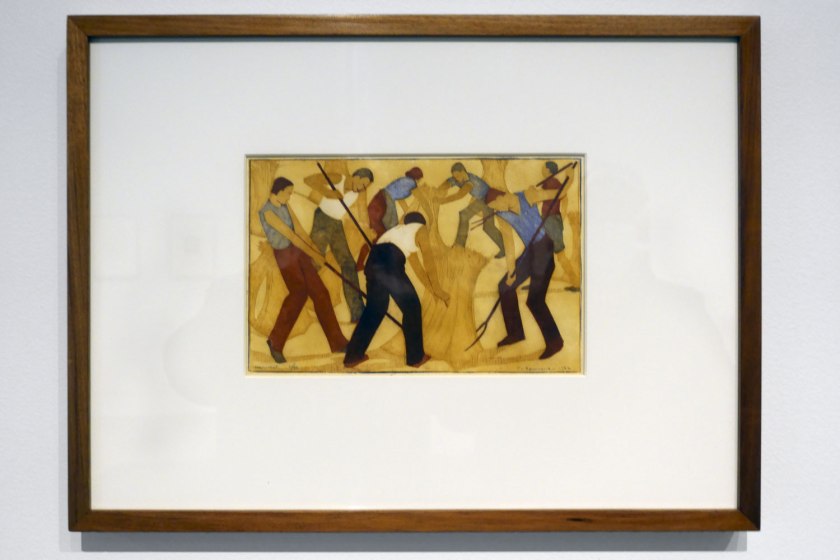

Ethel Spowers (Australian, 1890-1947)

Harvest

1932

Melbourne

Linocut, printed in colour inks, from five blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1976

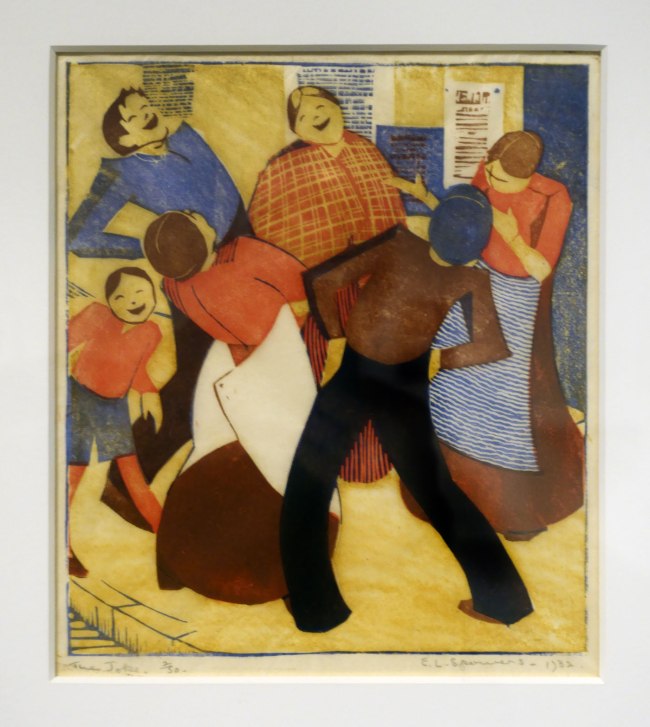

Ethel Spowers (Australian, 1890-1947)

The joke (installation views)

1932

Melbourne

Linocut, printed in colour inks, from four blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1976

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Ethel Spowers (Australian, 1890-1947)

The joke

1932

Melbourne

Linocut, printed in colour inks, from four blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1976

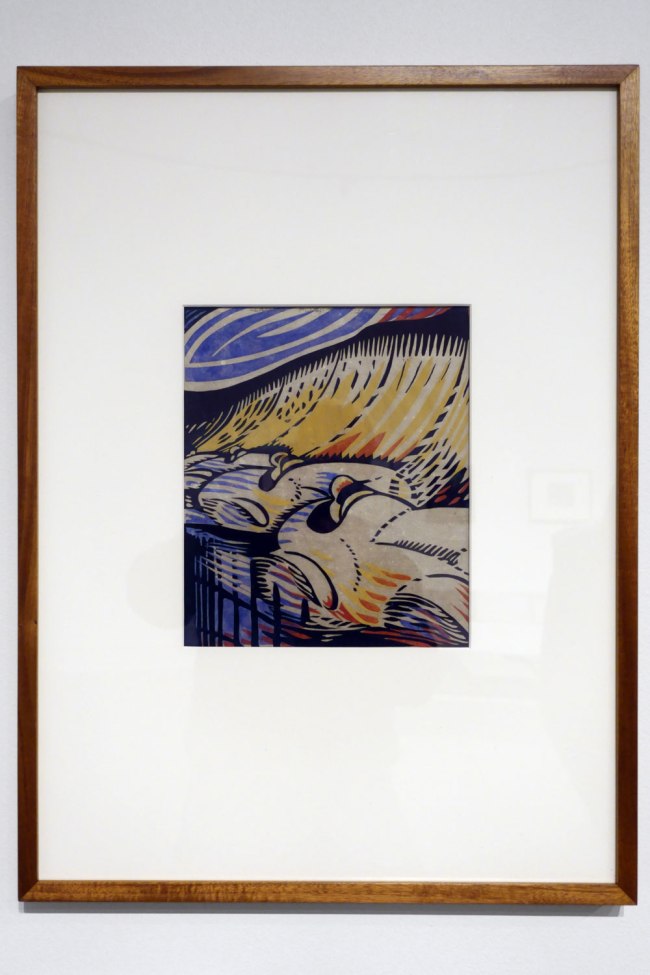

Ethel Spowers (Australian, 1890-1947)

The island of the dead (installation view)

1927

Melbourne

Linocut, printed in colour inks in the Japanese manner, from seven blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1995

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

In January 1927 Spowers and Syme holidayed in Iutruwita / Tasmania. After they visited the penal settlement at Port Arthur, Spowers produced this view of the nearby cemetery of Point Puer. Following this trip, Syme made a monochrome wood-engraving, The ruins, Port Arthur c. 1927

Wall text

Ethel Spowers (Australian, 1890-1947)

The island of the dead

1927

Melbourne

Linocut, printed in colour inks in the Japanese manner, from seven blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1995

Eveline Syme (Australian, 1888-1961)

Skating (installation view)

1929

London

Linocut, printed in colour inks, from two blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1979

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

When Syme joined Spowers at the Grosvenor School of Modern Art in January 1929 she made the two-block linocut Skating, which summarises Claude Flight’s teachings on how a composition ‘builds into a geometrical pattern of opposing rhythms’. Her design is simplified, using the repetition of intersecting lines and curves to suggest action. Although the skaters are frozen mid-turn, the print is filled with light and movement, with Syme’s humorous suggestion of novice efforts captured in awkwardly angled arms and legs.

Wall text

Eveline Syme (Australian, 1888-1961)

Skating

1929

London

Linocut, printed in colour inks, from two blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1979

Ethel Spowers (Australian, 1890-1947)

Fox and geese (installation view)

1933

Melbourne

Linocut, printed in colour inks, from five blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1978

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Ethel Spowers (Australian, 1890-1947)

Fox and geese

1933

Melbourne

Linocut, printed in colour inks, from five blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1978

Ethel Spowers (Australian, 1890-1947)

Football (installation view)

1936

Melbourne

Linocut, printed in colour inks, from four blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1982

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Ethel Spowers (Australian, 1890-1947)

Tug of war (installation view)

1933

Melbourne

Linocut, printed in colour inks, from four blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1976

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Ethel Spowers (Australian, 1890-1947)

Tug of war

1933

Melbourne

Linocut, printed in colour inks, from four blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1976

Ethel Spowers and Eveline Syme were lifelong friends who inspired and encouraged each another in their artistic pursuits. They were pioneers in printmaking and modern art and their careers reflected the changing circumstances of women after World War 1. Spowers and Syme were among a core group of progressive Australian artists who travelled widely and studied with avant-garde artists. They were at the forefront of Modernism in Australia.

Both women grew up in Melbourne in very comfortable circumstances. Their fathers ran rival newspapers, so their families had many common interests. Spowers’ father was involved with The Argus and The Australasian, while Syme’s father helped run The Age. Both families were dedicated to many causes and generous in their efforts to help others. They also supported war efforts and the Red Cross.

Spowers was the second child of six siblings and her home life was filled with rich and varied creative experiences. Her family lived in a large home in inner Melbourne called Toorak House, a graceful mansion with large gardens to play in and explore. Syme was also one of six siblings and lived nearby in a large house in St Kilda called Rotherfield.

Spowers and Syme studied and travelled together in Australia and overseas. Both were inspired by the artist Claude Flight who taught them at the Grosvenor School in London. He encouraged his students to capture the joy of movement through colour and rhythmic line and the new method of colour linocut printing. Spowers and Syme became strong supporters of being brave as artists, prepared to experiment and promote new ways of doing and seeing.

Throughout their lives the two friends advocated for important causes. Spowers’ focus was always on the welfare of children through her involvement in kindergarten education and volunteering at the local children’s hospital. Syme was particularly dedicated to the advancement of women’s university education.

Anonymous text. “About the Artists – Spowers & Syme: Primary School Learning Resource,” on the National Gallery of Australia website Nd [Online] Cited 29/09/2022

Eveline Syme (Australian, 1888-1961)

San Domenico, Siena (installation view)

1931

Melbourne

Linocut, printed in colour inks, from four blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1977

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

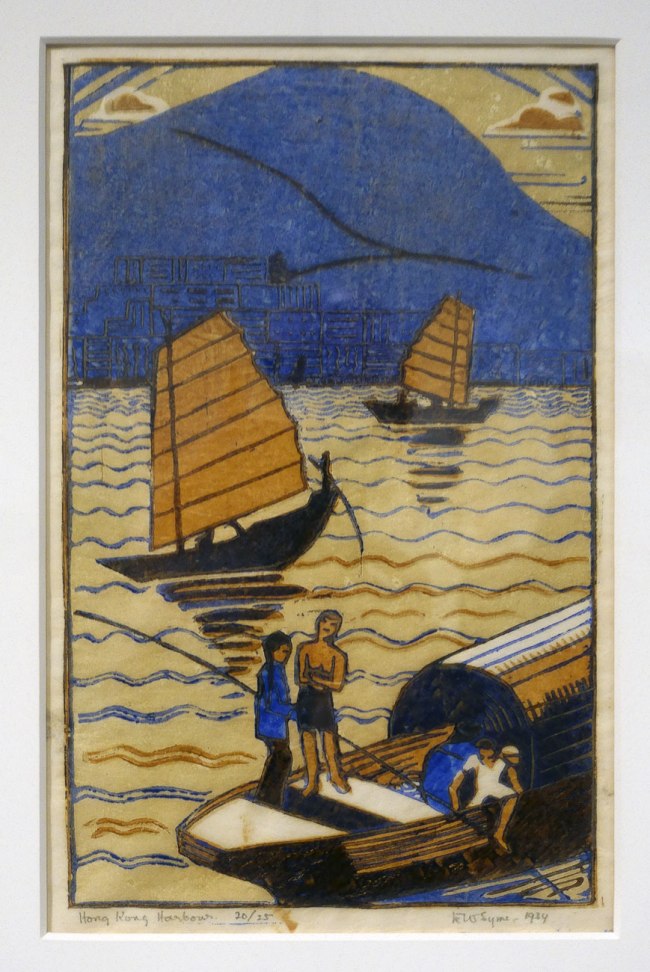

An inveterate traveller, Syme produced drawings and watercolours of landscape views from her trips around Victoria, her voyages to England via Colombo, and her travels through Europe, Japan, Hong Kong and the United States of America. In addition to exhibiting her watercolours, Syme often used these compositions as the basis for subsequent prints and oil paintings.

Wall text

Eveline Syme (Australian, 1888-1961)

Hong Kong harbour (installation views)

1934

Melbourne

Linocut, printed in colour inks, from four blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1976

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Ethel Spowers (Australian, 1890-1947)

Swings (installation view)

1932

Melbourne

Linocut, printed in colour inks, from four blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1976

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Ethel Spowers (Australian, 1890-1947)

Swings

1932

Melbourne

Linocut, printed in colour inks, from four blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1976

Eveline Syme (Australian, 1888-1961)

Sydney tram line (installation views)

1936

Melbourne

Linocut, printed in colour inks, from three blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1979

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Powers and Syme were associated with numerous art and social group, which established intersecting circles of connection and opportunity in Melbourne and Sydney. During the 1930s they both exhibited in Sydney with other progressive artists at Dorrit Black’s Modern Art Centre and with the Contemporary Group co-founded by Thea Proctor. This print is based on an earlier watercolour by Syme, drawn after staying with Spowers’ sister at Double Bay in 1932.

Wall text

Eveline Syme (Australian, 1888-1961)

Sydney tram line

1936

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1979

© Estate of Eveline Syme

Ethel Spowers (Australian, 1890-1947)

Still life (installation view)

1925

Melbourne

Wood-engraving, printed in black ink, from one block

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1981

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Ethel Spowers (Australian, 1890-1947)

The noisy parrot (installation view)

1926

Melbourne

Woodcut, printed in colour inks in the Japanese manner, from five blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 2015

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Ethel Spowers (Australian, 1890-1947)

The noisy parrot

1926

Melbourne

Woodcut, printed in colour inks in the Japanese manner, from five blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 2015

Ethel Spowers (Australian, 1890-1947)

Wet afternoon (installation view)

1930

Melbourne

Linocut, printed in colour inks, from four blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1983

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

In July 1930 Claude Flight included this print in British lino-cuts, the second annual exhibition held at the Redfern Gallery in London. Impressions were acquired by the Victoria & Albert museum and the British Museum. Wet afternoon was exhibited again in September at the annual exhibition of the Arts and Crafts Society of Victoria at Melbourne Town Hall and in the first exhibition of linocuts in Australia held in December at Everyman’s Lending Library in the centre of avant-garde Melbourne.

Wall text

Ethel Spowers (Australian, 1890-1947)

Wet afternoon

1930

Melbourne

Linocut, printed in colour inks, from four blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1983

Prints, pigments & poison

The vibrant works by Ethel Spowers and Eveline Syme, printed on smooth Japanese gampi papers from 1927 to 1950, demanded special consideration during conservation preparation from the Spowers & Syme exhibition. Andrea Wise, Senior Conservator, Paper, explains the process and details the green pigment with the toxic backstory. …

The typical palette in Spowers & Syme works feature carbon black, yellow and brown ochres, ultramarine, cobalt and cerulean blues, emerald green and two organic lake pigments – alizarin crimson and a distinct lilac. Lake pigments are made by attaching a dye to a base material such as alumina, making a dyestuff into a workable particulate pigment. This process can also extend more expensive dyestuffs, making them cheaper to use. Bound with oil to create printer’s inks, this limited palette was then overprinted to achieve a wider range of colours.

Emerald green commonly recurs throughout the works. A highly toxic vivid green, invented in the 19th century, it was still commercially available until the early 1960s. Many historical pigments are toxic, based on arsenic, mercury and lead.

Today we are increasingly aware of the health and safety issues related to work of art, but this was not always the case. Emerald green belongs to a group of copper acetoarsenate pigments that were extensively used for many household goods including furniture and wallpapers. A similar pigment, Scheele’s green, was used on the wallpaper in Napoleon’s apartments on St Helena and has been suggested as the cause of his death. Large amounts of arsenic (100 times that of a living person) were found on Napoleon’s hair and scalp after he had died. While poisoning theories still abound, it has been confirmed through other medical cases from the period that arsenic dust and fumes would be circulated in damp Victorian rooms sealed tight against the drafts that were thought to promote ill health.

Anonymous text. “Prints, pigments & poison,” on the National Gallery of Australia website Nov 18, 2021 [Online] Cited 30/08/2022

Ethel Spowers (Australian, 1890-1947)

Children’s Hoops

1935

Melbourne

Linocut, printed in colour inks, from five blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Ethel Spowers (Australian, 1890-1947)

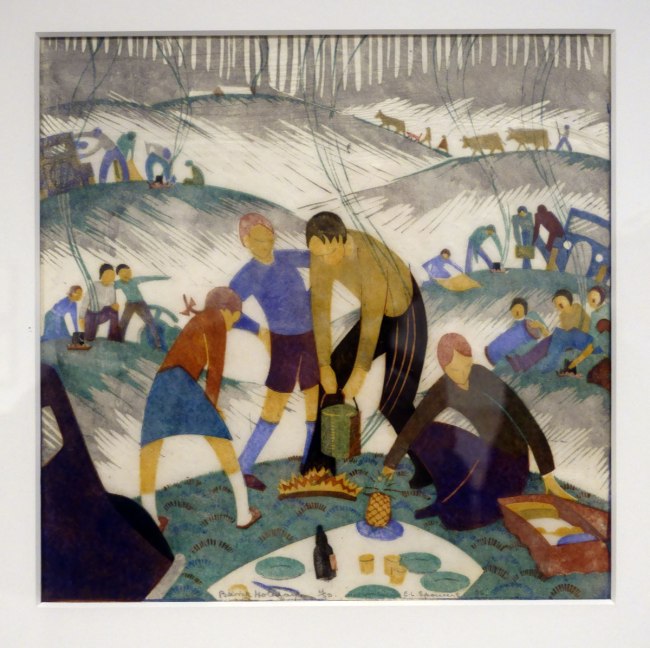

Bank holiday (installation view)

1935

Melbourne

Linocut, printed in colour inks, from six blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1976

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Ethel Spowers (Australian, 1890-1947)

Bank holiday

1935

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1976

Ethel Spowers (Australian, 1890-1947)

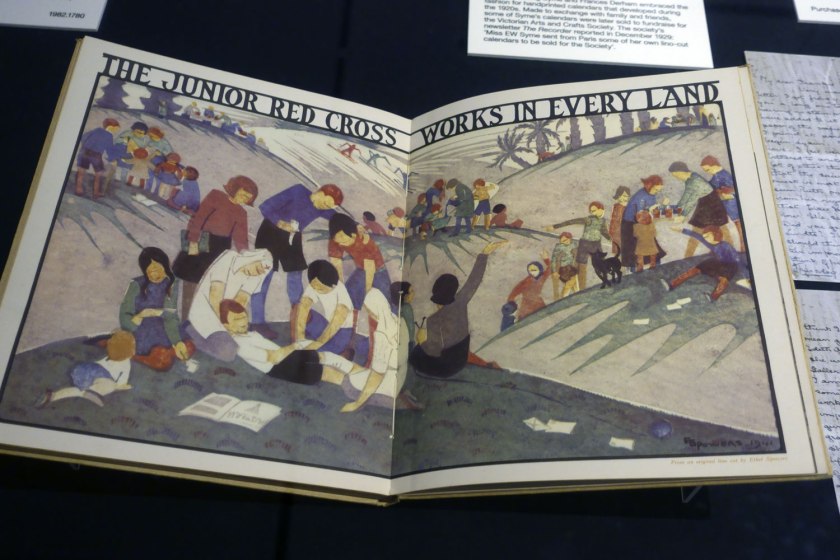

The Junior Red Cross works in every land (installation view)

Linocut, printed in colour, from six blocks

Reproduced in Joan and Daryl Lindsay

The story of the Red Cross Melbourne, 1941

National Gallery of Australia Research Library

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Powers made one final linocut print around 1941 for inclusion in a published history of the Australian Red Cross Society compiled by Joan and Daryl Lindsay. The Spowers family had a long philanthropic connection with this cause, and Eveline Syme became the first chairperson of the Red Cross Society Picture Library. Reproduced as a lithographic illustration, the long narrow composition is based on the picnicking families in Spowers’ earlier linocut Bank holiday 1935 (see above).

Wall text

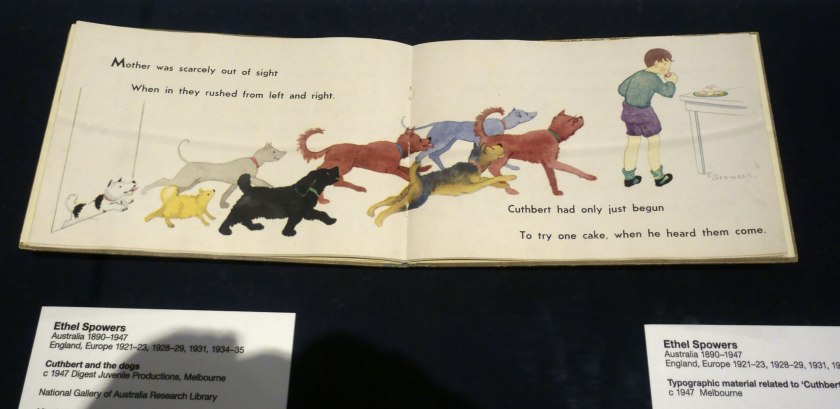

Ethel Spowers (Australian, 1890-1947)

Cuthbert and the dogs (installation view)

c. 1947

Digest Juvenile Productions, Melbourne

National Gallery of Australia Research Library

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

After being diagnosed with breast cancer in the mid-1930s, Spowers stopped printmaking and began a series of short stories for children. During the last decade of her life, she wrote and illustrated at least seven books. Their charm drew on stories the Spowers siblings wrote together as children, yet these were cautionary tales in which youthful characters were often reformed by the results of their actions. Of these, only Cuthbert and the dogs was published.

Wall text

Grosvenor School of Modern Art

This progressive private school was established in 1925 by Scottish wood-engraver Iain Macnab at 33 Warwick Square in Pimlico. Formerly the London studio and house of Scottish portraitist James Rannie Swinton, the ground-floor interior was repurposed into studios for tuition in drawing, painting and composition, with the basement set up for lithography, etching and block printing. With no entrance examinations or fixed terms, students could attend classes at any time by purchasing a book of fifteen tickets, with each ticket permitting entry to a two-hour session.

Merchant hand-selected a small team of similarly anti-academic staff, including Claude Flight. For five years Flight taught weekly afternoon classes on colour linocuts. He emphasised that art must capture the vitality of the machine age and taught his students a new way of seeing that analysed the activities of urban life and condensed these into dynamic compositions bursting with rhythm and energy.

Frank Weitzel (New Zealand, 1905 – England 1932)

Slum street (installation view)

c. 1929

Sydney

Linocut, printed in black ink, from one block

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1993

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

The son of German immigrants, Weitzel has a volatile upbringing in Aotearoa New Zealand where his father interned as an enemy alien. At the age of 16, Wentzel emigrated with his mother to the united States of America, where he studied sculpture in California. After travels through Europe, he relocated to Sydney in 1928 were he produced a series of linocuts in response to the city and was invited by Dorrit Black to exhibit with the Group of Seven. Black arranged for Wentzel to meet Claude Flight in London in 1930; Flight included his prints in the annual linocut exhibitions at Redfern Gallery in 1930 and 1931.

Wall text

Frank Weitzel was known mainly as a sculptor but in his studio over Grubb’s butcher shop at Circular Quay, he worked in the tradition of the artist-craftsman, producing linocut batik shawls and wall-hangings, lamp shades, book-ends etc. He also played violin in the Conservatorium Orchestra and designed a modern room (with Henry Pynor) at the Burdekin House Exhibition in 1929. In 1931, looking for work in London he sought out David Garnett, a publisher and member of the Bloomsbury Group of artist-craftsman. While Garnett was not interested in Weitzel’s drawings for publication, he became an admirer of his sculpture and invited Weitzel to care-take his property ‘Hilton Hall’ and commissioned him to do heads of children. Weitzel came to be praised also by Jacob Epstein, Roger Fry, Paul Nash and Duncan Grant. Garnett describes Weitzel in his autobiography as “small, thin, with frizzy hair which stood piled up on his head, blue-eyed, with a beaky nose. I guessed he was not eating enough… He was proletarian, rather helpless, very eager about art and also about communism”. At around this time Weitzel wrote to Colin Simpson back in Australia, “Now I am working on a show of my own which is being arranged for me by some terrific money bags”. The exhibition was never held. Weitzel contracted tetanus apparently from minerals which got under his finger nails while digging for clay for his sculptures. He died on the 22 February 1932 at the age of 26. A posthumous exhibition was organised by Dorrit Black at the Modern Art Centre, 56 Margaret Street, Sydney, on the 7 June 1933- opened by another supporter of modernism, the artist John D. Moore. The works had been brought back to Sydney by Weitzel’s sister Mary, who had travelled to England to collect them. This small show (41 works) included illustrations to a poem by Weitzel, poster designs for the Empire Marketing Board, Underground Railways, Shell Motor Spirit, Barclay’s Lager and the Predential Insurance Company, as well as sculpture, drawings and linocuts which had been exhibited with Grosvenor School artists in London.

Anonymous text. “Frank Weitzel (1905-1932),” on the Christie’s website Nd [Online] Cited 28/08/2022

Lill Tschudi (Swiss, 1911-2004)

Fixing the wires (installation view)

1932

London

Linocut, printed in colour inks, from two blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Gift of the artist 1990

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

In December 1929, at the age of 18, Tschudi enrolled at the Grosvenor School of Modern Art where she studied under Claude Flight for six months. She also studied in Paris with progressive teachers including André Lhote. Flight was a lifelong supporter of Tschudi and using Fixing the wires as an empale in his 1934 textbook on linocut techniques nothing that ‘the most important point to consider … is the arrangement whereby each colour block is considered as a space-filling whole, as well as part of the final composition made up of the superimposition of all the colour harmonies’.

Wall text

Lill Tschudi (Swiss, 1911-2004)

Fixing the wires

1932

London

Linocut, printed in colour inks, from two blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Gift of the artist 1990

Claude Flight (English, 1881-1955)

Brooklands (installation view)

c. 1929

London

Linocut, printed in colour inks, from four blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1978

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

At the Grosvenor School of Modern Art in London, Claude Flight taught his students the art of the modern colour linocut. He emphasised the importance of composition, building his images of urban life out of simplified form and pattern. Flight’s own practice drew on an exciting mix of avant-garde ideas: from the abstraction of British Vorticism to the dynamism of Italian Futurism to the bold geometric energy of Art Deco and the Arts and Crafts Movement’s emphasis on the handmade.

Wall text

Claude Flight (English, 1881-1955)

Brooklands

c. 1929

London

Linocut, printed in colour inks, from four blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1978

Sybil Andrews (English-Canadian, 1898-1992)

Speedway (installation view)

1934

London

Linocut, printed in colour inks, from four blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1978

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Andrews first studied art by correspondence while working as a welder at an airbase in bristol during the First World War. After meeting her mentor Cyril Power in Bury St Edmonds, they moved to London to study art before Andrews joined the Grosvenor School of Modern Art as a school secretary. Like Flight, Andrews and Power believed that art should reflect the spirit of the time. Andrews showed her work in joint exhibitions with Power at Redfern Gallery, and often explored the them of manual about. She left London in 1938 and emigrated to Canada with her husband Walter Morgan in 1947, where she eventually established a practice as artist and teacher.

Wall text

Sybil Andrews (English-Canadian, 1898-1992)

Speedway

1934

London

Linocut, printed in colour inks, from four blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1978

Cyril E Power (English, 1872-1951)

Skaters (installation view)

c. 1932

London

Linocut, printed in colour inks, from three blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1978

Sybil Andrews (English-Canadian, 1898-1992)

The winch (installation view)

1930

London

Linocut, printed in colour inks, from three blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1978

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Sybil Andrews (English-Canadian, 1898-1992)

The winch (installation view)

1930

London

Linocut, printed in colour inks, from three blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1978

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Sybil Andrews (English-Canadian, 1898-1992)

The winch

1930

London

Linocut, printed in colour inks, from three blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Purchased 1978

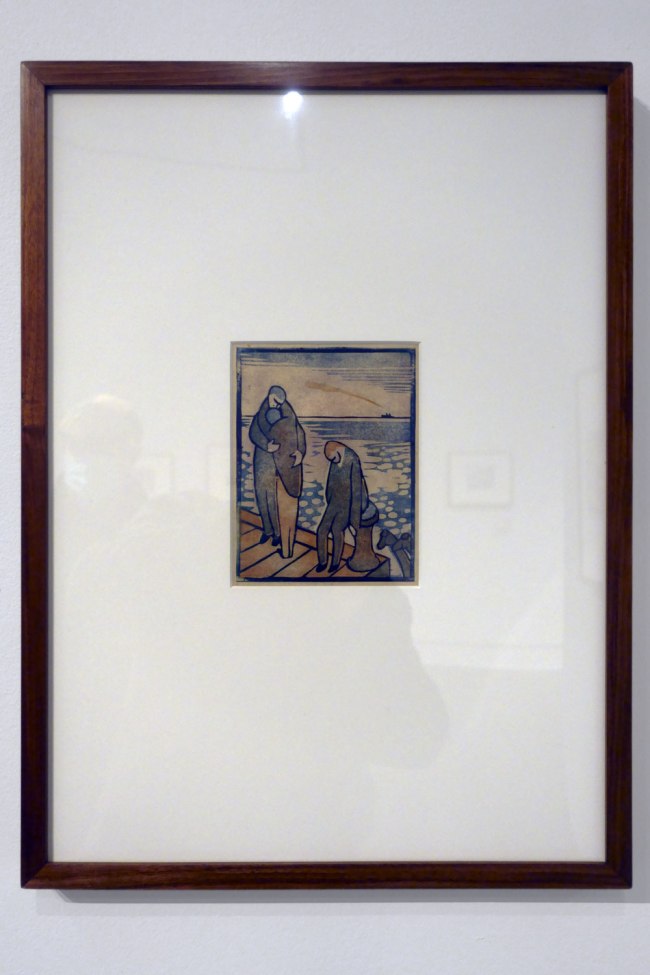

George Bell (Australian, 1876-1966)

The departure (installation view)

1931

Melbourne

Linocut, printed in colour inks, from three blocks

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

Gift of Mrs B Niven 1988

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Geelong Art Gallery

Little Malop Street

Geelong, Victoria

Australia 3220

Phone: +61 3 5229 3645

Opening hours:

Daily 10am – 5pm

![Giacomo Balla. 'The Hand of the Violinist (The Rhythms of the Bow)' (La mano del violinista [I ritmi dell’archetto]) 1912](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/01_balla_handoftheviolinist-web.jpg?w=840)

You must be logged in to post a comment.