Exhibition dates: 5th November, 2008 – 1st February, 2009

Lyndell Brown (Australian, b. 1961) and Charles Green (Australian, b. 1953)

Afghan traders with soldiers, market, Tarin Kowt base, Uruzgan province, Afghanistan

2007-2008

From The approaching storm series 2007-2009

Digital colour inkjet photograph

155 × 107.5cm

Despite one brilliant photograph and some interesting small painted canvases this exhibition is a disappointment. No use beating around the figurative bush in the landscape so to speak, talking plainly will suffice. Firstly, let’s examine the photographs. Thirteen large format colour photographs are presented in the exhibition out of an archive of “thousands of photographs Brown and Green created on tour”1 from which the paintings are derived.

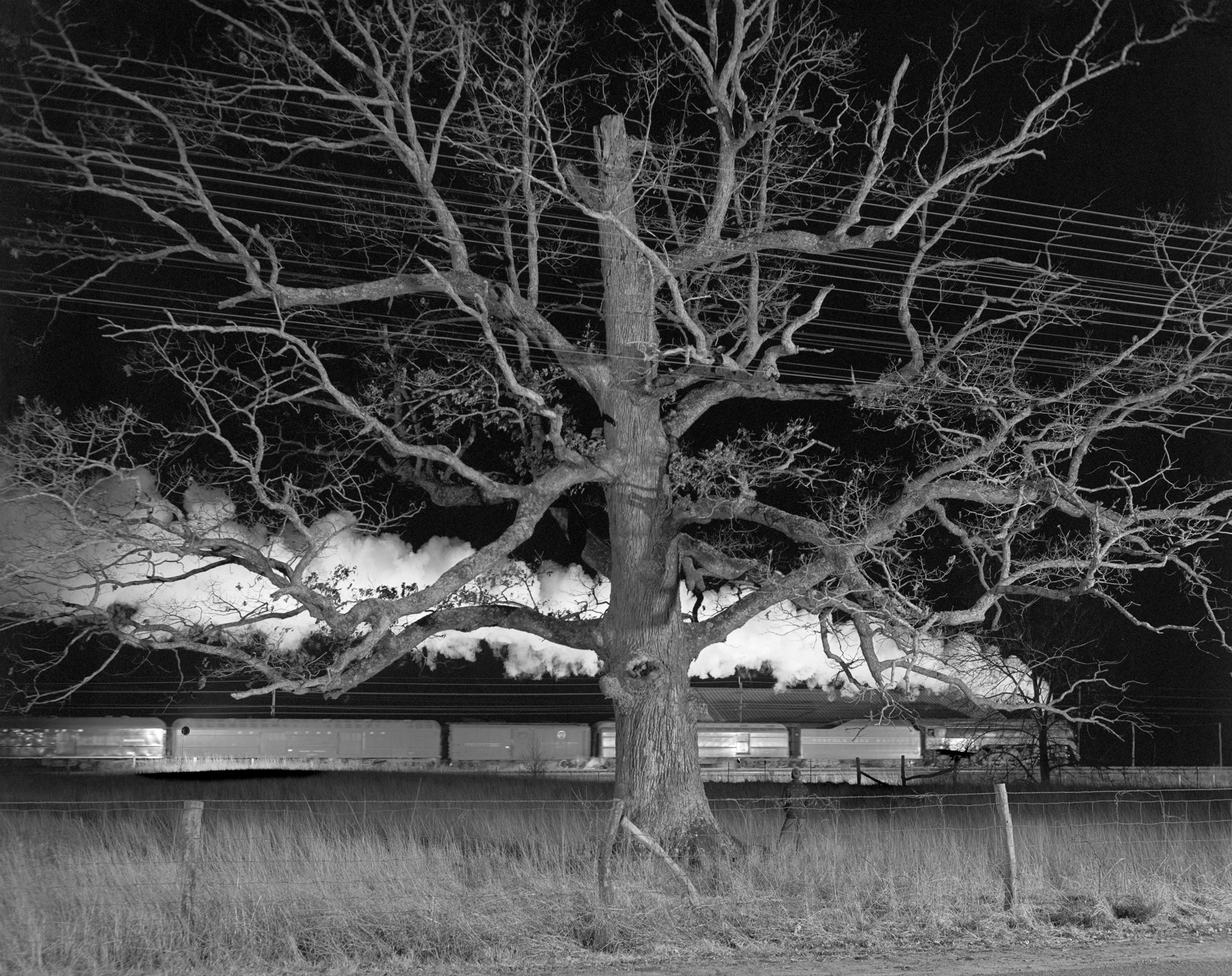

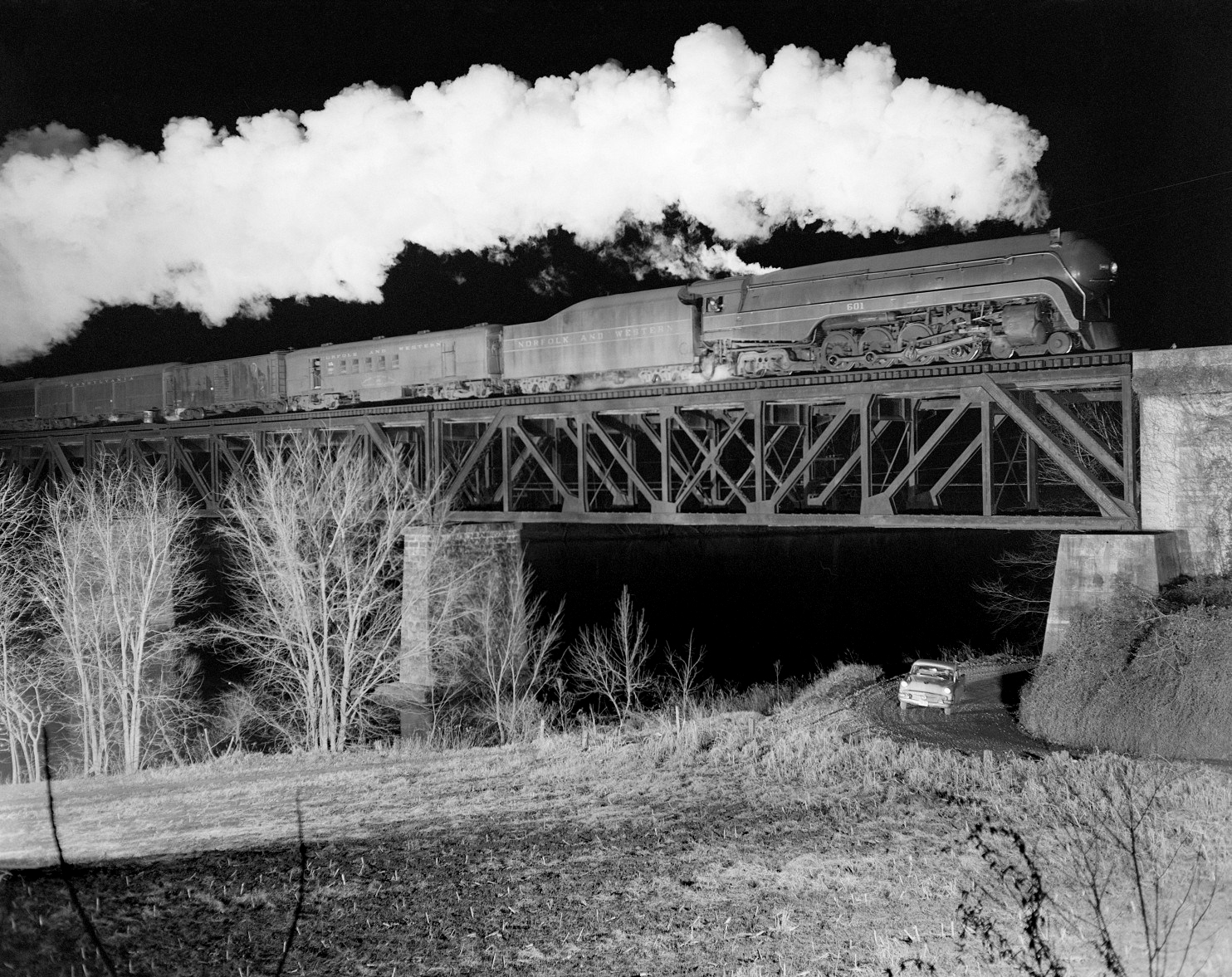

Most of the photographs are inconsequential and need not have been taken. Relying on the usual trope of painters who take photographs they are shot at night, dusk or dawn when the shadows are long, the colours lush supposedly adding ‘mystique’ to the scene being portrayed. In some cases they are more like paintings than the paintings themselves. Perhaps this was the artist’s plan, the reverse marriage of photography and painting where one becomes the other, but this does little to advance photography as art. There is nothing new or interesting here: sure, some of the photographs are beautiful in the formal representation of a vast and fractured landscape but the pre-visualisation is weak: bland responses to the machines, industry, people and places of the conflict. Go look at the Andreas Gursky photographs at the National Gallery of Victoria to see world-class photography taking reality to the limit, head on.

Too often in these thirteen images the same image is repeated with variants – three images of the an aircraft having it’s propeller changed show a lack of ideas or artefacts to photograph – presented out of the thousands taken seems incongruous. The fact that only one photograph is reproduced in the catalogue is also instructive.

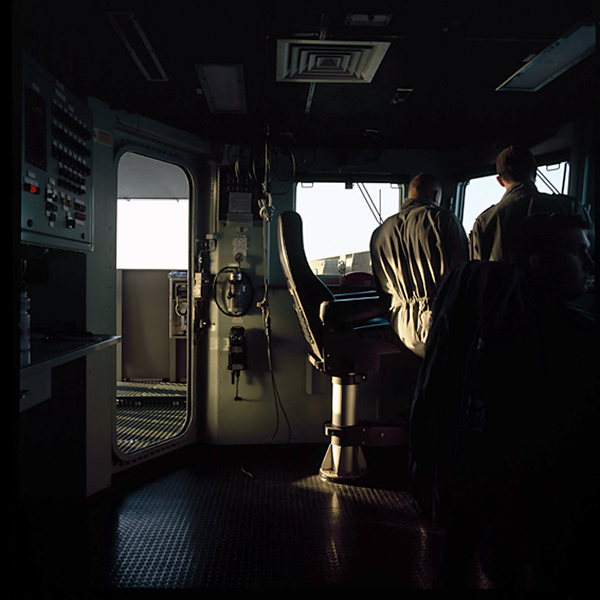

Some images are just unsuccessful. For example the photograph Dusk, ship’s bridge with two sailors, northern Gulf is of a formulaic geometry that neither holds the viewers attention nor gives a deeper insight into their lives aboard ship and begs the question why was the photograph taken in the first place? The dark space has little physical or metaphysical illumination and seems purely to be an exercise in formalism. The photograph Dusk, ships’ bridge with sailor, northern Gulf is more successful in the use of light and shade as they play across the form of a sailor, his head resting pensively in his hand, red life vests adding a splash of colour to the bottom right of the photograph.

The brilliant photograph of the group is View from Chinook, Helmand province, Afghanistan. This really is a monstrous photograph. With the large black mass of the helicopter in the foreground of the image containing little detail, the eye is drawn upwards to the windscreen through which a mountain range rises, with spines like the back of a Stegosaurus. To the right a road, guarded by a desolate looking pillbox and yellow barrier, meanders into the distance. Dead flies on the windscreen look like small bullet holes until you realise what they are. This is the image that finally evidences a disquieting beauty present in the vast and ancient landscape.

Turning to the paintings we can say that some of the small 31cm x 31cm paintings work well. From an ‘original’ photograph the artist selects and crops a final image that they work up into a highly detailed oil painting. Distilled (as the artist’s like to put it) from the ‘original’ photographs, the paintings become a “merging of a contemporary sense of composition – borrowed from photography, film and video – with the textures and processes of traditional oil painting.”2

“These works were developed by the artists to be something akin to “Hitchcockian clues” which create the sense of looking out at a scene but being distanced from the action. To some degree the entire suite of small pictures participate in developing this intrigue, by showing an array of ambiguous scenes in which direct action is never present, or is obscured by limited perspectives … The artists noted that the war zones they witnessed were low in action but high in tension”3

To an extent this tension builds in some of the small paintings: the small size lends an intimate, intense quality and forces the viewer to engage with highly detailed renditions of textures of clothing, material, skin and hair and the distorted scale of the ships and aeroplanes portrayed. In these intense visions the painting seems less like a photograph and more like a new way of seeing. However, this occurs only occasionally within the group of small paintings.

If we think of a photograph in the traditional sense as a portrayal of reality, then a distillation of that photograph (the removal of impurities from, an increase in the concentration of) must mean that these paintings are a double truth, a concentrated essence of the ‘original’ photograph that changes that essence into something new. Unfortunately most of these small canvases show limited viewpoints of distilled landscapes that do not lead to ambiguous enigmas, but to the screen of the camera overlaid by a skein of paint, a patina of posing.

This feeling is only amplified in the three large ‘History’ paintings. The three paintings seem static, lifeless, over fussy and lacking insight into the condition of the ‘machine’ that they are attempting to portray. It’s a bit like the ‘Emperors New Clothes’, the lack of substance in the paintings overlaid with the semantics of History painting (“a traditional genre that focused on mythological, biblical, historical and military subjects”) used to confirm their existence and supposed insight into the doubled, framed reality. As Robert Nelson noted in his review of 2008 art in Melbourne in The Age newspaper it would seem that painting is sliding into terminal decline. These paintings only seem to confirm that view.

Here was a golden opportunity to try something fresh in terms of war as conflict – both in photography and painting – to frame the discourse in an eloquent, innovative manner. Most of this work is not interesting because it does not seem to be showing, or being discursive about anything beyond a personal whim. Because an artist can talk about some things, doesn’t mean that he can make comments about other things that have any value. Although the artist was looking to portray landscapes of globalisation and entropy, there are more interesting ways of doing this, rather than the nature of the transcription used here.

“It is very good to copy what one sees: it is much better to draw what you can’t see any more but in your memory. It is a transformation in which imagination and memory work together. You only reproduce what struck you, that is to say, the necessary. That way your memory and your fantasy are freed from the tyranny of nature.”4

No thinking but the putting away of intellect and the reliance on memory and imagination, memory and fantasy to ‘distil’ the essence. This is what needed to happen both in the photographs and paintings – leaving posturing aside (perhaps an ‘unofficial war artist’ would have had more success!) to uncover the transformation of landscape that the theatre of this environment richly deserves.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Footnotes

1/ Heywood, Warwick. Framing Conflict: Iraq and Afghanistan exhibition catalogue. Canberra: Australian War Memorial, 2008, p. 6

2/ Heywood, Warwick. Framing Conflict: Iraq and Afghanistan exhibition catalogue. Canberra: Australian War Memorial, 2008, p. 6

3/ Heywood, Warwick. Framing Conflict: Iraq and Afghanistan exhibition catalogue. Canberra: Australian War Memorial, 2008, p. 11

4/ Degas, Edgar quoted in Halligan, Marion. “Between the brushstrokes,” in A2 section, The Saturday Age newspaper, January 17th 2008, p. 18

Many thankx to The Ian Potter Museum of Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Lyndell Brown (Australian, b. 1961) and Charles Green (Australian, b. 1953)

Afghan National Army perimeter post with chair, Tarin Kowt base, Uruzgan province, Afghanistan

2007-2008

From The approaching storm series 2007-2009

Digital colour inkjet photograph

111.5 × 151.5cm

Lyndell Brown (Australian, b. 1961) and Charles Green (Australian, b. 1953)

Dusk, ship’s bridge with two sailors, northern Gulf

2007-2008

Digital colour inkjet photograph

Lyndell Brown (Australian, b. 1961) and Charles Green (Australian, b. 1953)

Late afternoon, flight line, military installation, Middle East

2007

Oil on linen

Lyndell Brown (Australian, b. 1961) and Charles Green (Australian, b. 1953)

Market, Camp Holland, Tarin Kowt, Uruzgan province, Afghanistan

2007

Oil on linen

Lyndell Brown (Australian, b. 1961) and Charles Green (Australian, b. 1953)

View from Chinook, Helmand province, Afghanistan

2007-2008

From The approaching storm series 2007-2009

Digital colour inkjet photograph

111.5 × 151.5cm

Lyndell Brown (Australian, b. 1961) and Charles Green (Australian, b. 1953)

View from Chinook, Helmand province, Afghanistan

2007

Oil on linen

Lyndell Brown (Australian, b. 1961) and Charles Green (Australian, b. 1953)

Trolley, propeller change, on flightline at night, military installation, Gulf

2007-2008

From The approaching storm series 2007-2009

Digital colour inkjet photograph

87.0 × 87.4cm

Lyndell Brown (Australian, b. 1961) and Charles Green (Australian, b. 1953)

History painting: market, Tarin Kowt, Uruzgan province, Afghanistan

2007

Oil on linen

Lyndell Brown and Charles Green

Installation view of photographs from the exhibition Framing Conflict at The Ian Potter Museum of Art, The University of Melbourne

2009

Lyndell Brown (Australian, b. 1961) and Charles Green (Australian, b. 1953)

Installation view of paintings from the exhibition Framing Conflict at The Ian Potter Museum of Art, The University of Melbourne

2009

The Ian Potter Museum of Art

The University of Melbourne,

Corner Swanston Street and Masson Road

Parkville, Victoria 3010

Opening hours:

Tuesday – Saturday 11am – 5pm

![Addison Scurlock (American, 1883-1964) 'Charles Drew with the first mobile blood collecting unit [Charles Drew and Red Cross Medical Team]' February 1941 Addison Scurlock (American, 1883-1964) 'Charles Drew with the first mobile blood collecting unit [Charles Drew and Red Cross Medical Team]' February 1941](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/01/scurlock-red-cross-web.jpg)

![Carleton Watkins (American, 1829-1916) '[Section Grizzly Giant, Mariposa Grove]' 1861 Carleton Watkins (American, 1829-1916) '[Section Grizzly Giant, Mariposa Grove]' 1861](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/01/watkins-section-grizzly-giant.jpg)

![Carleton Watkins (American, 1829-1916) '[Sugarloaf Islands at Fisherman's Bay, Farallon Islands]' About 1869 Carleton Watkins (American, 1829-1916) '[Sugarloaf Islands at Fisherman's Bay, Farallon Islands]' About 1869](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/01/watkins-sugarloaf-islands-at-fishermans-bay-farallon-islands.jpg)

![Carleton Watkins (American, 1829-1916) '[Thompson's Seedless Grapes]' 1880 Carleton Watkins (American, 1829-1916) '[Thompson's Seedless Grapes]' 1880](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/01/watkins-thompsons-seedless-grapes.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.