Exhibition dates: 18th September 2015 – 13th March 2016

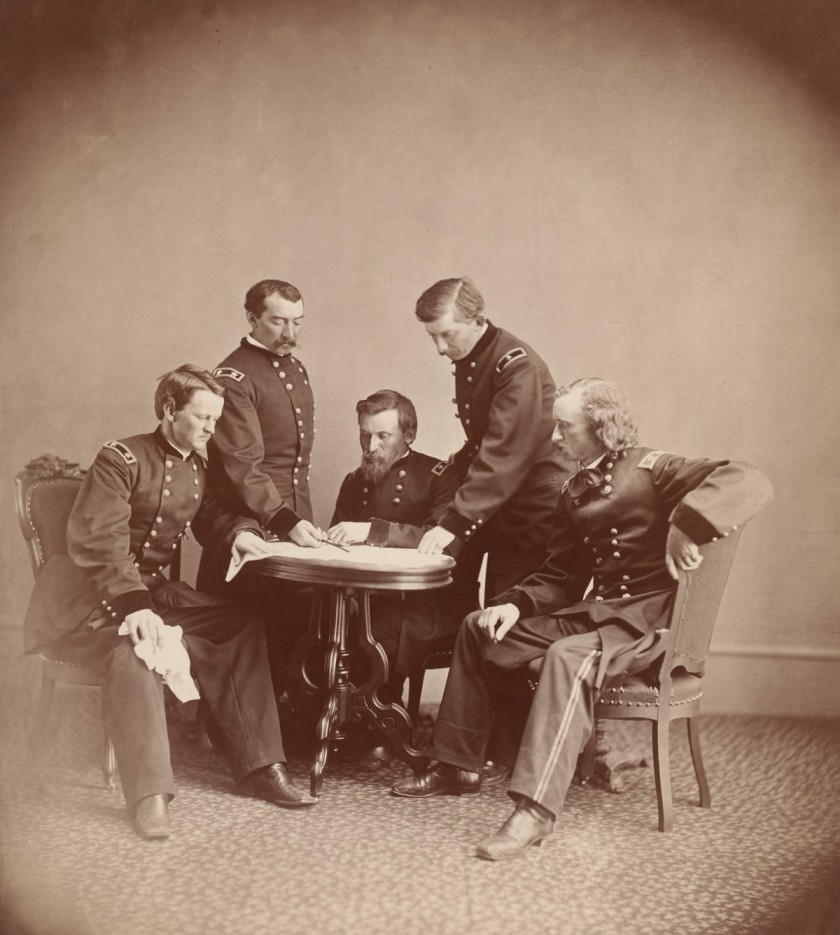

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

Ulysses S. Grant (1822-1885)

c. 1864

Albumen silver print

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

THIS IS THE FIRST OF THREE POSTINGS ABOUT (MAINLY AMERICAN) 19th CENTURY PHOTOGRAPHY.

This monster posting is both fascinating and gruesome by turns. They were certainly dark fields, stained crimson with the blood of men of opposing armies, left bloated and rotting in the hot sun. Can you imagine the smell one or two days later when Alexander Gardner arrived to photograph those very fields.

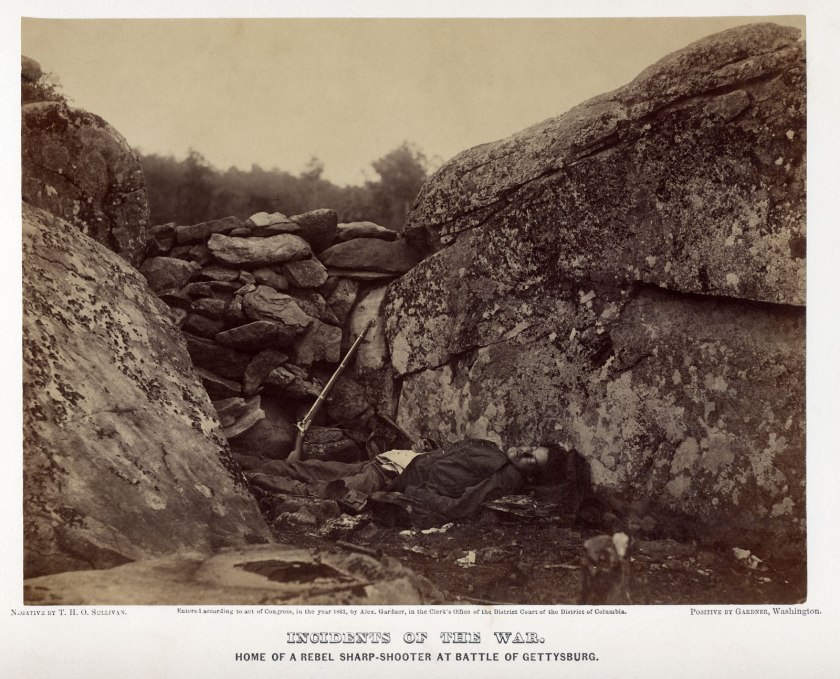

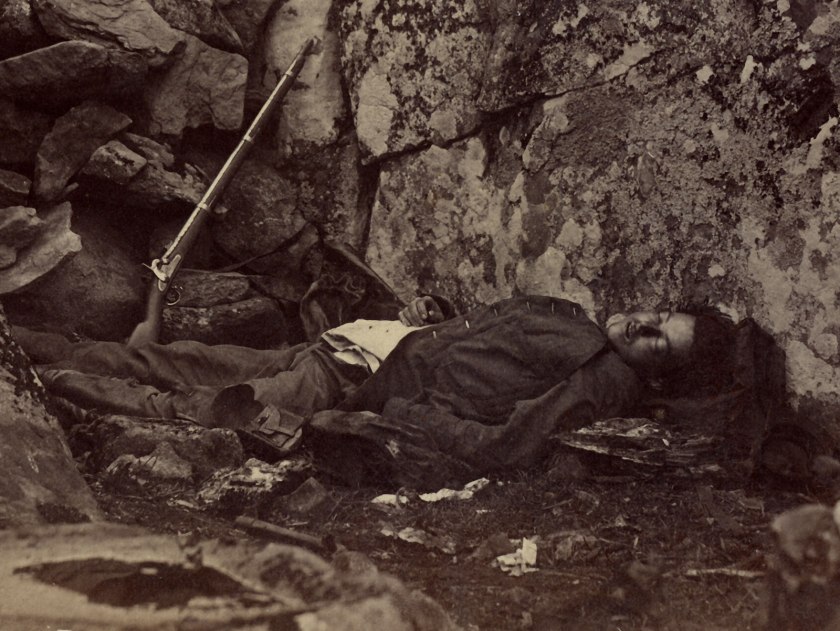

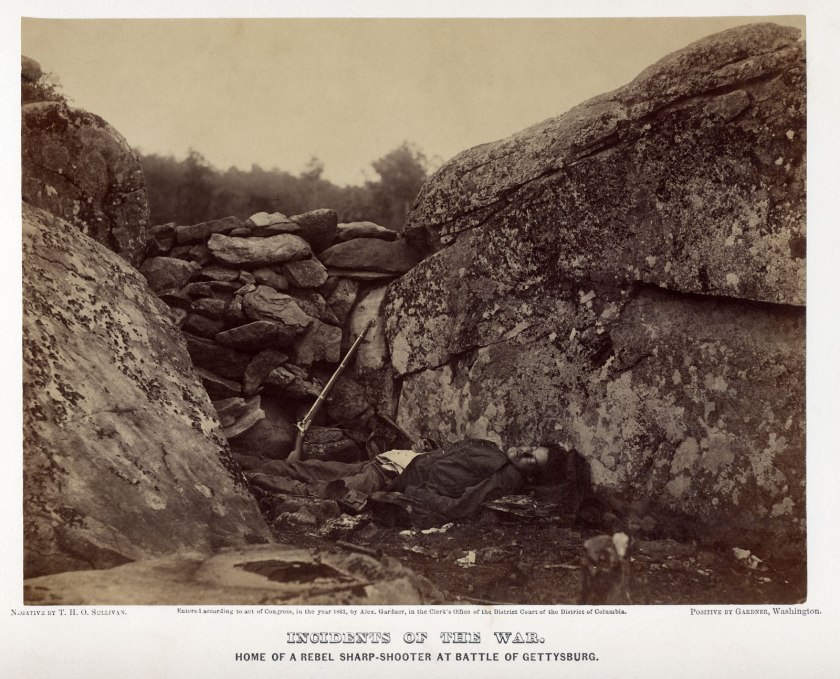

Particularly in the early war years (1861-62).”Gardner has often had his work misattributed to Brady.” Gardner worked for Mathew Brady, running his Washington office and working in the field (as many other operatives did) during the early part of the Civil War. Gardner’s negatives were published under the banner of the studio of Brady. He finished working for Brady in 1862 before setting up his own studio in May 1863 a few blocks from Brady’s Washington studio. This fluidity of authorship continues later in the war when Timothy H. O’Sullivan’s photographs, an assistant to Gardner, appeared under the masthead of Gardner’s studio. Evidence of this can be observed in the image Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter (July 1863, below) where, at least, Sullivan is credited with the negative at bottom left under the image.

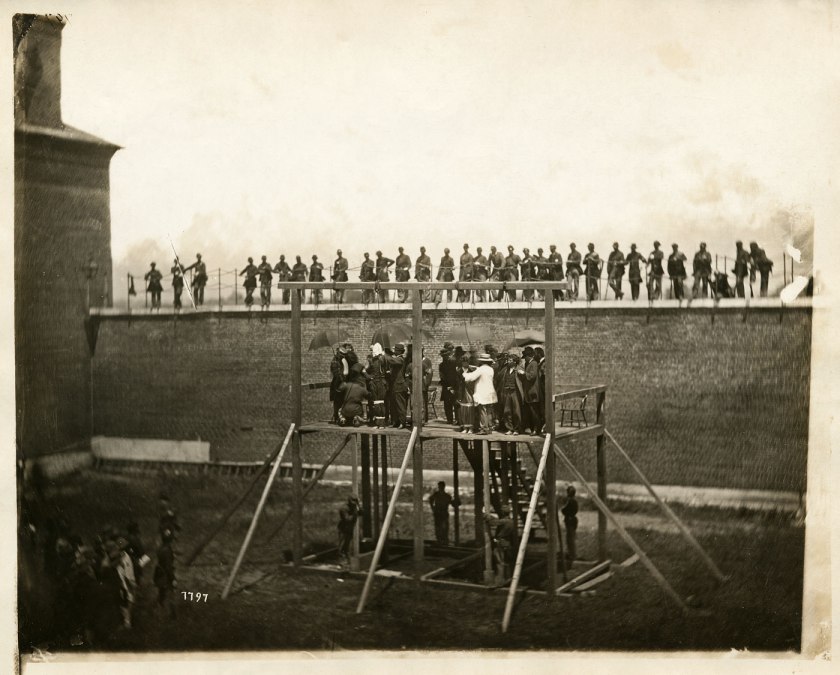

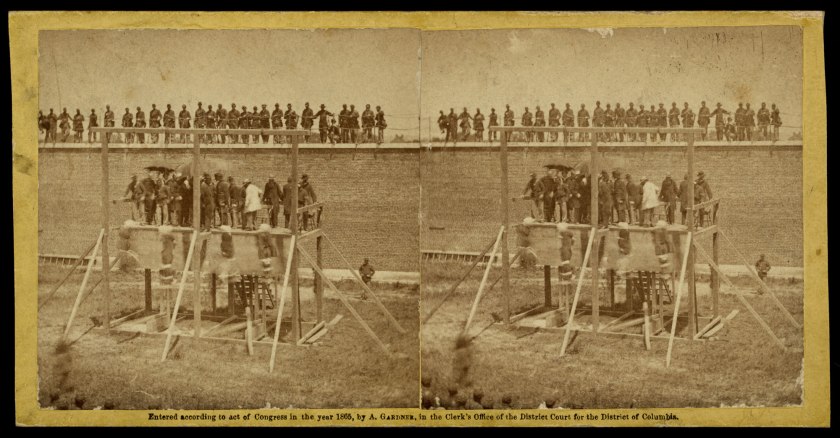

Gardner changed the face of photography. He endowed it with an immediacy and energy that it had previously been lacking. His photographs of the battlefield brought the action “presently” into the lounge rooms of the well-heeled and, by engravings taken from the photographs, into newspapers of the time. His series of photographs of the hanging of the conspirators convicted of Abraham Lincoln’s assassination are “considered one of the first examples of photojournalism ever recorded.” But he wasn’t above rearranging the scene to his liking, as in the moving of the body in Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter (July 1863, below) to make a more advantageous “view” … much like Roger Fenton’s moving of the cannonballs in his epic photograph The Valley of the Shadow of Death (1855). Today this would be frowned upon, but in the era these photographs were taken it seemed the most “natural” thing to do, to make a better photograph, and nothing was thought of it.

The exhibition text states, “But his arrangement of the corpse reflects how difficult it was for Gardner and his contemporaries to process the reality of mass casualties in which the dead became anonymous. Caught at a transitional moment, Gardner did not trust the images his camera captured. That this photographic construction would be more marketable to a public still steeped in Victorian sentimentality only adds to Gardner’s malfeasance.” Malfeasance is a strong word. Malfeasance is defined as an affirmative act, “the performance by a public official of an act that is legally unjustified, harmful, or contrary to law; wrongdoing (used especially of an act in violation of a public trust).” (Dictionary.com) The exhibition text also states that “His actions are unforgivable from both a moral and artistic point of view,” and are a blot on Gardner’s career.

I don’t agree. Of course Gardner trusted the images that his camera captured, he was a photographer! This is a ludicrous statement… it is just that, arriving days after the battle, he wanted compositions that created news and views that were memorable. His affirmative action was not illegal or contrary to the law. Although morally it could be seen as a violation of public trust he was reporting the depravities of war within the first 25 years of the beginning of photography, and he was trying to get across to the general public the lonely desperation of death. In that era, at the very beginning of photographic reportage, who was to tell him it was wrong or illegal? We view these actions through retrospective eyes knowing that this kind of re-arrangement would not be tolerated today (but it is, in the digital manipulation of images!) and the condemnation of today is just a hollow statement. Photography has ALWAYS re-presented reality – through the hand of the author, through the eyes of the viewer.

Other interesting things to note in the posting are:

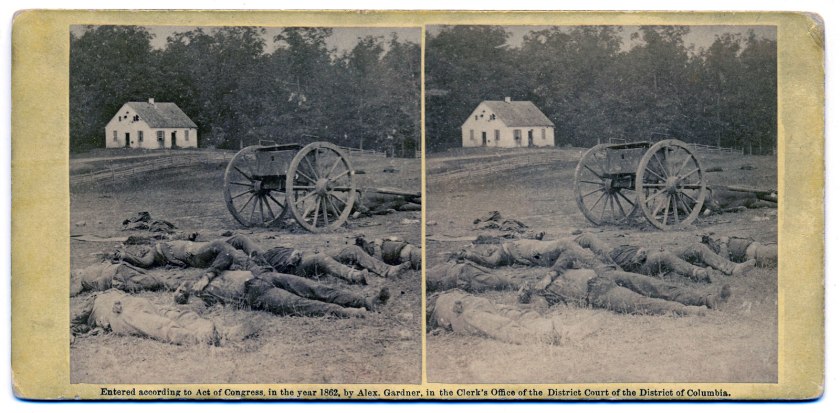

~ the mechanical overlaying of colour in the stereograph View on Battle Field of Antietam, Burial party at work (1862, below) where the colour is applied subtly in the left hand photograph while in the right hand image, the colour almost obliterates the figures

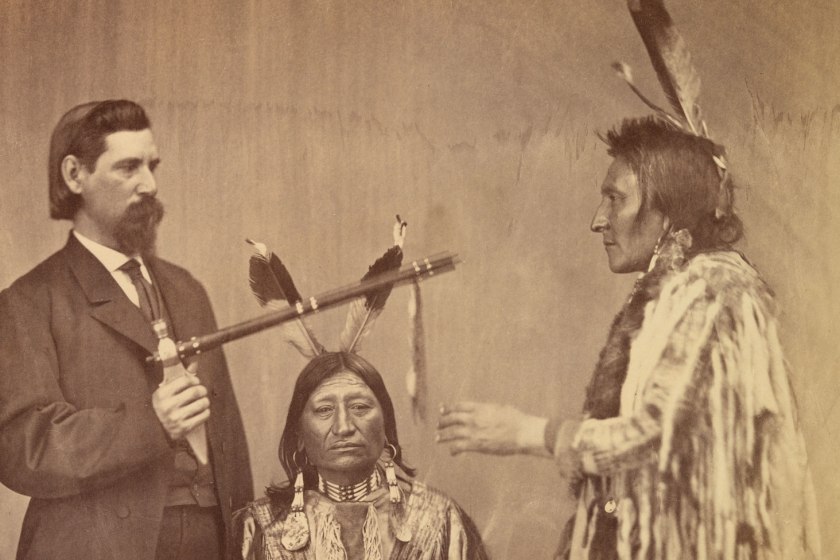

~ the attitude of the participants in Indian Peace Commissioners in council with the Northern Cheyenne and Northern Arapaho, Fort Laramie, Dakota Territory (1868, below). The military and civilian representatives of the government sit at right on boxes, four of them staring directly into the camera aware they are being photographed for prosperity (General William T. Sherman does not, looking pensive with his hands clasped) while on the left, the Native American Indian representatives sit on the ground wrapped in blankets with the backs of two interpreters towards the camera. They do not make eye contact with the camera except for one man, who has turned his head towards the camera and gives it a defiant stare (perhaps I am imagining, but I think not)

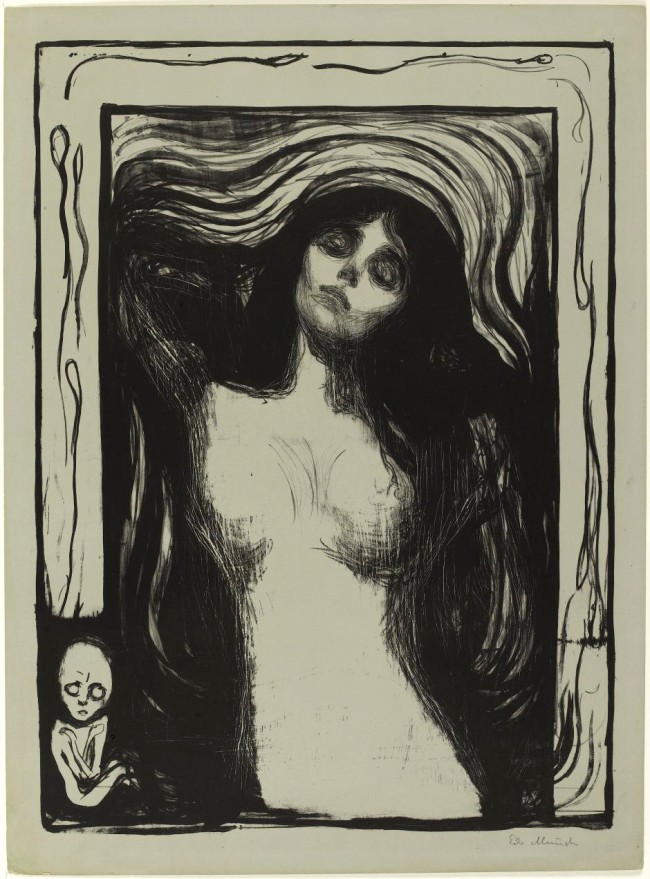

The strongest photographs in this posting, other than the masterpiece Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter are not the empirical scenes of the battlefield but two portraits: Ulysses S. Grant (1864, below) and the war weary “cracked plate” image of Abraham Lincoln (1865, below). Both are memorable not just for the low depth of field or the “capture” of remarkable leaders of men during war but for something essentially interior to themselves – their contemplation of self. With Grant you can feel the steely determination (this in the second last year of the war) and, yet, comprehend his statement,

“Though I have been trained as a soldier, and participated in many battles, there never was a time when, in my opinion, some way could not be found to prevent the drawing of the sword”

in this image. What must be done has to be done, but by God I wish it wasn’t so. The eyes have it.

With the Lincoln portrait – of which Gardner only pulled one print from the plate before he destroyed it, making this the rarest of images – the charismatic leader is shown with craggy, war weariness. The contextless space around the body is larger than is normal at this time, allowing us to focus on the “thing itself” … and then we have that prophetic crack. “During this sitting, Gardner created this portrait by accident,” says the text from the exhibition. How do you create a portrait like this by accident? With the length of the exposure, Lincoln would have had to remain immobile for seconds… not something that you do by accident. No, both Gardner and Lincoln knew that a portrait was being taken. This is previsualisation (depth of field, space around and above the body) at its finest. That the plate was accidentally cracked and then discarded in no way makes this portrait an accident. If this is a portrait of, “Lincoln between life and death, between his role as a historical actor and the mystical figure that he would become with his assassination,” it is also the face of a man that you could almost reach out and touch!

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the National Portrait Gallery, Washington for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Gardner has often had his work misattributed to Brady, and despite his considerable output, historians have tended to give Gardner less than full recognition for his documentation of the Civil War. Lincoln dismissed McClellan from command of the Army of the Potomac in November 1862, and Gardner’s role as chief army photographer diminished. About this time, Gardner ended his working relationship with Brady, probably in part because of Brady’s practice of attributing his employees’ work as “Photographed by Brady”. That winter, Gardner followed General Ambrose Burnside, photographing the Battle of Fredericksburg. Next, he followed General Joseph Hooker. In May 1863, Gardner and his brother James opened their own studio in Washington, D.C, hiring many of Brady’s former staff. Gardner photographed the Battle of Gettysburg (July 1863) and the Siege of Petersburg (June 1864-April 1865) during this time.

In 1866, Gardner published a two-volume work, Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the Civil War. Each volume contained 50 hand-mounted original prints. The book did not sell well. Not all photographs were Gardner’s; he credited the negative producer and the positive print printer. As the employer, Gardner owned the work produced, as with any modern-day studio. The sketchbook contained work by Timothy H. O’Sullivan, James F. Gibson, John Reekie, William Pywell, James Gardner (his brother), John Wood, George N. Barnard, David Knox and David Woodbury, among others. Among his photographs of Abraham Lincoln were some considered to be the last to be taken of the President, four days before his assassination, although later this claim was found to be incorrect, while the pictures were actually taken in February 1865, the last one being on the 5th of February. Gardner would photograph Lincoln on a total of seven occasions while Lincoln was alive. He also documented Lincoln’s funeral, and photographed the conspirators involved (with John Wilkes Booth) in Lincoln’s assassination. Gardner was the only photographer allowed at their execution by hanging, photographs of which would later be translated into woodcuts for publication in Harper’s Weekly.

Text from the Wikipedia website

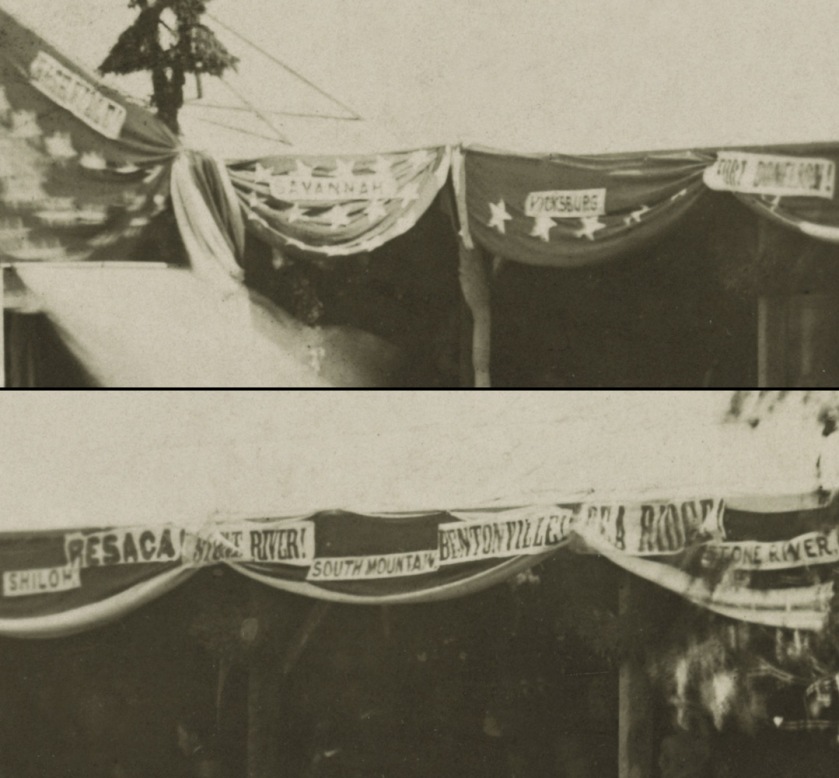

Installation views of the exhibition Dark Fields of the Republic: Alexander Gardner Photographs, 1859-1872 at the National Portrait Gallery, Washington

Dark Fields of the Republic: Alexander Gardner Photographs, 1859-1872

His photographs have “a terrible distinctness.” So wrote the New York Times about the work of trailblazing photographer Alexander Gardner (1821-1882). In a career spanning the critical years of the nineteenth century, Gardner created images that documented the crisis of the Union, the Civil War, the United States’ expansion into the western territories, and the beginnings of the Indian Wars.

As one of a pioneering generation of American photographers, Gardner helped revolutionise photography, both in his mastery of techniques and by recognising that the camera’s eye could be fluid and mobile. In addition to creating portraits of leaders and generals – he was Abraham Lincoln’s favourite photographer – Gardner followed the Union army, taking indelible images of battlefields and military campaigning. His battlefield photographs – including those of the newly dead – created a public sensation, contributing to the change under way in American culture from romanticism to realism, a realism that was the hallmark of his work.

At war’s end, Gardner went west. Fascinated, like many artists, by American Indians, he took a series of stunning images of the western tribes, setting set these figures in their native grounds: these photographs are the pictorial evocation of the seemingly limitless western land and sky. He also took images of the Indians in Washington, D.C., where they traveled to negotiate preservation of their way of life. Gardner’s portraits of Native Americans are dignified likenesses of a resistant people fighting for their way of life.

In their documentary clarity and startling precision, Alexander Gardner’s photographs – taken in the studio, on battlefields, and in the western territories – are a summons back into a darkly turbulent and heroic period in American history.”

Text from the exhibition website

Installation views of the exhibition Dark Fields of the Republic: Alexander Gardner Photographs, 1859-1872 at the National Portrait Gallery, Washington with, in the bottom photograph, two people looking at a photograph of Lieutenant General Grant.

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

Ulysses S. Grant (detail)

c. 1864

Albumen silver print

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

There is a story that when Ulysses S. Grant traveled east in 1864 to take command of all the Union armies, the desk clerk at Washington’s Willard Hotel did not recognise him and assigned him to a mean, nondescript room. (When Grant identified himself, he was upgraded to a suite.) The anecdote points out that likenesses were not yet widely distributed, even after the advent of photography. It was possible for famous people to remain unidentified. But fame meant that one had one’s photograph taken, as Grant did in this image Gardner took after the western general arrived in Washington. Grant was coming off a string of successes in the West, including the successful siege of Vicksburg, which made him the inevitable choice for overall command. In Grant, Lincoln finally found a general who would consistently engage the enemy’s forces. Indicative of Grant’s stature, Lincoln bestowed on him the rare title of lieutenant general, a rank previously held only by George Washington.

Text from the exhibition website

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

Abraham Lincoln

1861

Albumen silver print

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

Abraham Lincoln (detail)

1863

Albumen silver print

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

This portrait of Abraham Lincoln was taken on February 24, 1861, just before his inauguration on March 4. It has been conjectured that Lincoln is hiding his right hand in his lap because it was swollen from shaking so many hands during his travel from Illinois to Washington. This is also the first studio image depicting Lincoln with a full beard, which he had famously grown between the election and inauguration, purportedly at the behest of a little girl who wrote him from New York that it would improve his appearance. Lincoln was early to recognise the power of the relatively new medium of photography to mould and shape a public persona. He credited a photograph by Mathew Brady, taken when he came to New York City to present himself to Republican Party power brokers, as helping to confirm his suitability for the presidency by showing him well-dressed and dignified. Interestingly, the Brady photograph shows Lincoln standing; in this portrait he is seated, as if ready to begin work as president.

Text from the exhibition website

Installation view of the exhibition Dark Fields of the Republic: Alexander Gardner Photographs, 1859-1872 at the National Portrait Gallery, Washington showing the “Imperial” glass-plate negative of President Abraham Lincoln from his August 9, 1863, sitting at Gardner’s Washington studio, with a print from the negative on the wall behind

This exhibition provides the rare opportunity to display the means by which a photographic image was produced on paper: the glass-plate negative that was the “film” of early photography. Because of their fragility, surviving glass-plate negatives of this size (the so-called “imperial”) are rare: this is one of two of Lincoln that have survived and dates from his August 9, 1863, sitting at Gardner’s Washington studio. The process Gardner used was relatively new to America and consisted of hand-coating a glass plate with collodion – a syrupy mixture of guncotton dissolved in alcohol and ether to which bromide and iodine salts had been added. The difficulty for the photographer was that the glass plate had to be coated with collodion, sensitised in a bath of silver nitrate, and exposed in the camera immediately, while the emulsion was still damp. Gardner was acknowledged as a master in evenly coating the plate, which resulted in prints of exceptional clarity.

Text from the exhibition website

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

Abraham Lincoln

1865

Albumen silver print

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

The “cracked-plate” image of Abraham Lincoln, taken by Alexander Gardner on February 5, 1865, is one of the most important and evocative photographs in American history. In preparing for his second inaugural, Lincoln had a series of photographs taken at Gardner’s studio. During this sitting, Gardner created this portrait by accident: at some point, possibly when the glass-plate negative was heated to receive a coat of varnish, a crack appeared in the upper half of the plate. Gardner pulled a single print and then discarded the plate, so only one such portrait exists.

The portrait represents a radical departure from Gardner’s usual crisp empiricism. The shallow depth of field created when Gardner moved his camera in for a close-up yielded a photograph whose focus is confined to the plane of Lincoln’s cheeks, while the remainder of the image appears diffused and even out of focus. Lincoln is careworn and tired, his face grooved by the emotional shocks of war. Yet his face also bears a small smile, perhaps as he contemplates the successful conclusion of hostilities and the restoration of the Union. This is Lincoln between life and death, between his role as a historical actor and the mystical figure that he would become with his assassination. Although Lincoln looked forward to his second term, we know, as he could not, that he will soon be assassinated. This image inextricably links history and myth, creating one of the most powerful American portraits.

Text from the exhibition website

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

Abraham Lincoln (detail)

1865

Albumen silver print

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Smithsonian’s First Major Retrospective of Alexander Gardner’s Photographs at the National Portrait Gallery

Exhibition Will Highlight Gardner’s Civil War Photographs, Including His One-of-a-Kind Image of President Lincoln

Considered America’s first modern photographer, just as the Civil War is considered the first modern war, Alexander Gardner created dramatic and vivid photographs of battlefields and played a crucial role in the transformation of American culture by injecting a sobering note of realism to American photography.

“Gardner’s photographs showed how the new medium and art form could develop to meet the challenges of modern society,” said Kim Sajet, director of the Portrait Gallery. “These are a record of the sacrifice and loss that occurred in the great national struggle over the Union. Our photograph of Lincoln by him, known as the ‘cracked-plate,’ is the museum’s ‘Mona Lisa.'” [see above]

The first section of the exhibition will highlight Gardner’s Civil War photographs, and his role as President Abraham Lincoln’s preferred photographer. Gardner photographed the president many times, recording the impact of the war on his face. Among these images is the “cracked-plate” portrait, a photograph that is arguably the most iconic image of Lincoln. In addition, the exhibition will encompass Gardner’s portraits of other prominent statesmen and generals, as well as private citizens.

Also in the exhibition are Gardner’s landscapes of the American West and portraits of American Indians. These document the course of American expansion as postwar settlers moved westward, challenged by geography and Indian tribes resistant to losing their ancestral homelands. Gardner’s landscapes are evocative studies of almost limitless horizons, giving a sense of the emptiness of western space. These are contrasted with his detailed portraits of Indian chiefs and tribal delegations.

Curated by David C. Ward, Portrait Gallery senior historian, and guest curator Heather Shannon, former photo archivist at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian, with research assistance from Sarah Campbell, this exhibition will feature more than 140 objects, including photographs, prints and books. The exhibition will be the finale of the Portrait Gallery’s seven-part series commemorating the 150th anniversary of the Civil War.

Press release from the National Portrait Gallery

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

Samuel Wilkeson (1817-1889)

c. 1859

Salted paper print

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Museum purchase from the Charles Isaacs Collection made possible in part by the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment

On July 1, 1863, at the Battle of Gettysburg, nineteen-year-old Lieutenant Bayard Wilkeson and his men attempted to slow the Confederate forces. A shell mangled the lieutenant’s right knee as his unit, Battery G of the Fourth U.S. Artillery, drew the attention of Confederate cannons. After amputating his leg with a pocket knife and being carried to an almshouse, Wilkeson ordered his men to return to battle. A few days later, his father, Samuel Wilkeson, a journalist, wrote home to say he had found Bayard dead “from neglect and bleeding.” On the front page of the July 6 New York Times, Samuel wrote a moving, influential, and widely circulated account of the battle. Bayard’s story and his father’s grief became symbolic of the North’s suffering, sacrifice, and righteousness. The article concludes, “oh, you dead, who at Gettysburg have baptised with your blood the second birth of Freedom in America, how you are to be envied!”

Text from the exhibition website

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

Samuel Wilkeson (1817-1889)

c. 1859

Salted paper print

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Museum purchase from the Charles Isaacs Collection made possible in part by the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

Samuel Wilkeson (1817-1889) (detail)

c. 1859

Salted paper print

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Museum purchase from the Charles Isaacs Collection made possible in part by the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

Self-Portrait

c. 1861

Albumen silver print

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

In this self-portrait taken at Mathew Brady’s Washington studio, Alexander Gardner presents himself wearing the garb of a mountain man or trapper, sporting buckskins and a fur hat; Gardner’s trademark full, ungroomed beard only adds to the frontiersman image. Gardner holds a bow and arrow while standing on Indian rugs. The image captures America’s enduring fascination with the West and adopting the garb of Native peoples. It also shows Gardner, a man about whom we know little, in disguise, hiding himself in a fictional frontier persona. Although he is acting a role, Gardner, whose family had bought land in Iowa in the antebellum period, was genuinely interested in the western lands and the fate of the Indians. In the 1860s he began his project of photographing the western tribal delegations when they came to Washington. After the Civil War he went west to photograph Indians on their native grounds.

Text from the exhibition website

James Gardner (American born Scotland, c. 1832 – ?)

Alexander Gardner

1863

Albumen silver print

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Larry J. West

James Gardner (American born Scotland, c. 1832 – ?)

Alexander Gardner (detail)

1863

Albumen silver print

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Larry J. West

Not as flamboyantly costumed as in his first self-portrait, this image of Alexander Gardner shows him as a workingman, which was his family’s heritage back in Scotland. Gardner’s proficiency as a photographer was based in part on his manual dexterity; he was a master at coating the glass-plate negatives with collodion, which formed the plate’s light-sensitive emulsion. By the beginnings of 1863 James Gardner was working with his brother in Washington.

Text from the exhibition website

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

Rose Greenhow (c. 1854-?)

Rose O’Neal Greenhow (c. 1815-1864)

1862

Albumen silver print

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

One of the Confederacy’s most successful female spies, Rose O’Neal Greenhow was a prominent Washington widow and a staunch southern sympathiser. The Confederacy recruited her as a spy after war erupted in 1861. Most notably, Greenhow is credited with passing along intelligence prior to the First Battle of Manassas, insuring a southern victory. Soon after, her covert activities were uncovered and she was placed under house arrest. Gardner took this photograph after “Rebel Rose” and her daughter, Little Rose, were transferred to the Old Capitol Prison in 1862. Greenhow served five months before being exiled to the South. She then traveled to Europe to promote the Confederate cause. Returning in September 1864, Greenhow drowned attempting to run the federal blockade of Wilmington, N.C. The Confederacy buried her with military honours.

Text from the exhibition website

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

View on Battle Field of Antietam, Burial party at work

1862

Coloured Stereograph (Albumen silver print on stereo card)

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

View on Battle Field of Antietam, Burial party at work (detail)

1862

Coloured Stereograph (Albumen silver print on stereo card)

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

View on Battle Field of Antietam, Burial party at work (details of left and right photographs)

1862

Coloured Stereograph (Albumen silver print on stereo card)

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

Antietam Bridge, Maryland

1862

Albumen silver print

Photograph by Alexander Gardner, from Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the War

Records of the War Department General and Special Staffs, Record Group 165, National Archives Still Picture Branch, College Park, Maryland

Antietam Bridge (not to be confused with the more famous Burnside Bridge located to the south, which was the site of a confused Union attack during the Battle of Antietam’s third phase) spanned Antietam Creek, roughly in the middle of the battlefield. Before the battle, some Union troops used it to move toward the Confederate lines arrayed just outside the village of Sharpsburg. The bridge was not brought into play during the battle since George McClellan, fearful of overcommitting his troops, kept a large reserve near his headquarters at the Pry House, a reserve that would have used the bridge in its attack if it had been sent against Robert E. Lee’s lines. Unlike Burnside Bridge, the original stone Antietam Bridge, with its three arches, has not survived and has been replaced by a modern span.

Text from the exhibition website

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

Scouts and Guides to the Army of the Potomac, Berlin, MD, October, 1862

October 1862

Albumen silver print

Photograph by Alexander Gardner, from Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the War

Records of the War Department General and Special Staffs, Record Group 165, National Archives Still Picture Branch, College Park, Maryland

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

Scouts and Guides to the Army of the Potomac, Berlin, MD, October, 1862

October 1862

Albumen silver print

Photograph by Alexander Gardner, from Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the War

Records of the War Department General and Special Staffs, Record Group 165, National Archives Still Picture Branch, College Park, Maryland

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

Scouts and Guides to the Army of the Potomac, Berlin, MD, October, 1862 (detail)

October 1862

Albumen silver print

Photograph by Alexander Gardner, from Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the War

Records of the War Department General and Special Staffs, Record Group 165, National Archives Still Picture Branch, College Park, Maryland

Gardner documented specialised units in the Union army, as with the Telegraphic Corps, and here with the so-called “Scouts and Guides,” who were part of the intelligence service that Allan Pinkerton ran for the Army of the Potomac. Gardner took this group portrait when he returned to the area around Antietam; Berlin (now Brunswick), Maryland, is on the Potomac, just downstream from Harpers Ferry. In his Sketchbook Gardner wrote about the hardship and dangers faced by men who frequently acted as spies and could be executed if caught: “Their faces are indexes of the character required for such hazardous work.” Gardner’s statement exemplifies how connections are drawn between appearance and personality; a photograph was seen as particularly informative psychologically.

Text from the exhibition website

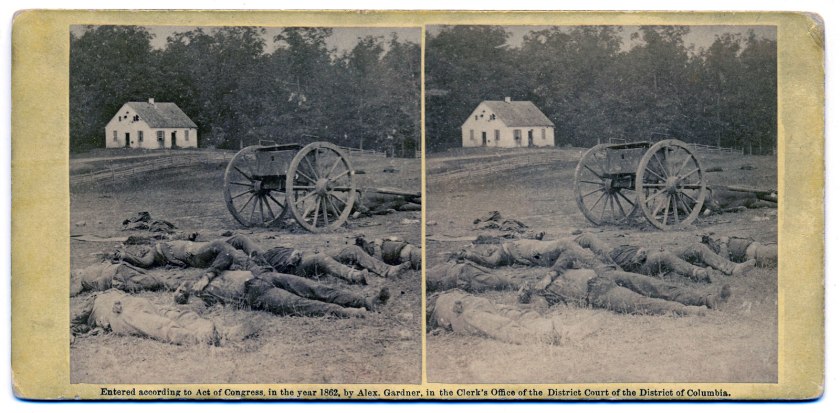

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

Completely Silenced: Dead Confederate Artillerymen, as they lay around their battery after the Battle of Antietam

1862

Stereograph (Albumen silver print on stereo card)

Collection of Bob Zeller

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

Completely Silenced: Dead Confederate Artillerymen, as they lay around their battery after the Battle of Antietam (detail)

1862

Stereograph (Albumen silver print on stereo card)

Collection of Bob Zeller

The Battle of Antietam (Maryland) occurred on September 17, 1862, and it is still America’s bloodiest day, with more than 25,000 combined casualties (killed and wounded) on both sides. Despite a nearly three-to-one numerical advantage, the Union forces were unable to score a decisive victory. The heavy casualties did force Robert E. Lee to withdraw, however, ending his first invasion of the North. Gardner probably arrived at the battlefield on September 18. He took this image of dead Confederates near the Dunker Church, a focal point of the Union attack, which began shortly after 7.00 am the day before.

Text from the exhibition website

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

Gathered Together for Burial after the Battle of Antietam (View in Ditch on the Right Wing after the Battle of Antietam)

1862

Stereograph (Albumen silver print on stereo card)

Collection of Bob Zeller

This photograph, probably taken on September 19, graphically exposes the savagery of the fighting that occurred at the “Sunken Road” during the second, midday phase of the Union assault on Lee’s defensive line. A worn-down cart path provided perfect cover for Confederate troops, who initially blunted the Union attack, inflicting tremendous casualties. However, once the northerners had flanked the road, southern troops were trapped and exposed to a withering fire that choked the road with their corpses; hereinafter, the “Sunken Road” was known as “Bloody Lane.”

Text from the exhibition website

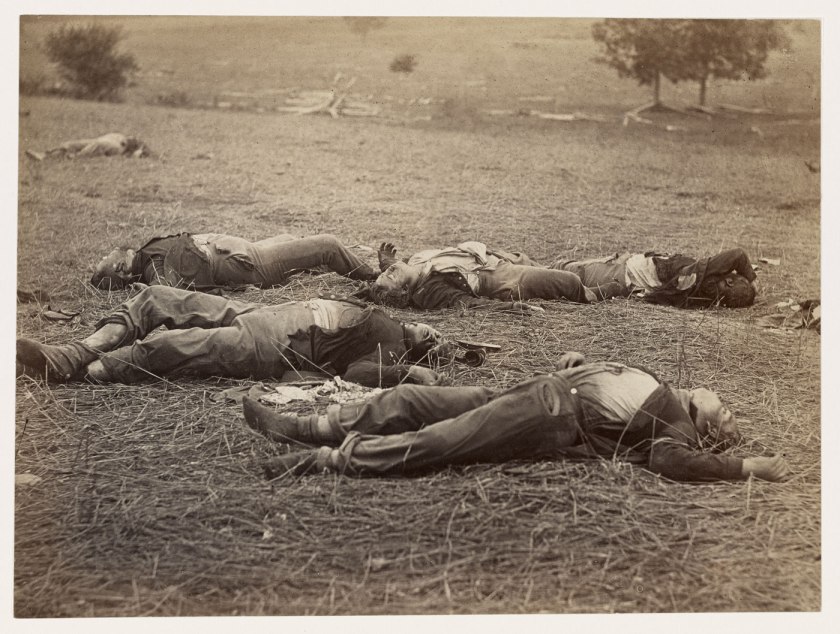

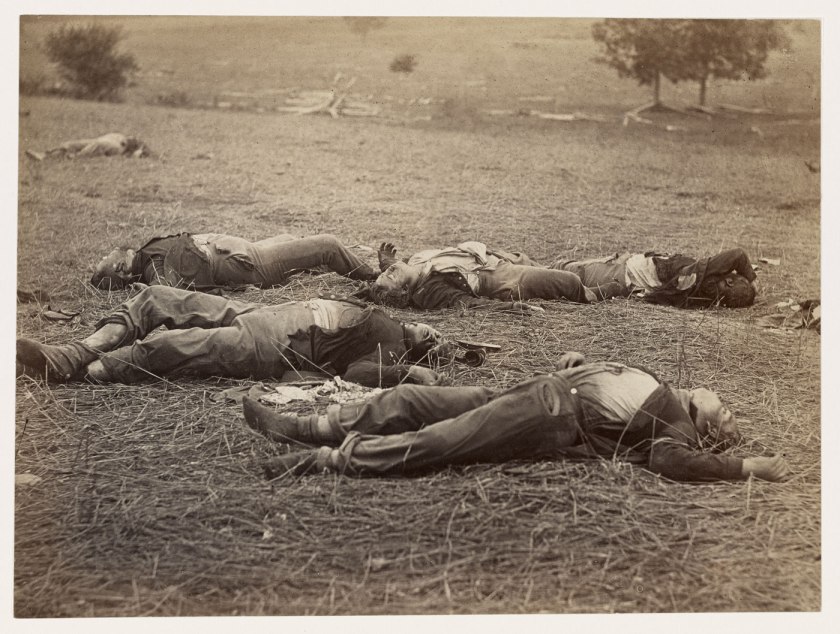

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882) and Timothy O’Sullivan (American, 1840-1882)

Field Where General Reynolds Fell, Gettysburg, July, 1863

July 1863

Albumen silver print

Photograph by Timothy O’Sullivan, from Alexander Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the War. Records of the War Department General and Special Staffs, Record Group 165, National Archives Still Picture Branch, College Park, Maryland

General John Reynolds (1820-1863) of Pennsylvania was the highest-ranking casualty at Gettysburg. One of the Union’s best generals, Reynolds had been considered a potential replacement for George McClellan. On July 1, commanding the left wing of the Union forces, Reynolds moved his infantry forward to blunt the Confederate advance, bringing on a wholesale engagement of the two armies; his decisiveness bought time for the Union to consolidate its forces at Gettysburg. He was killed leading a charge by the Second Wisconsin just west of the town. Despite its title, it is unlikely that Gardner’s photograph depicted this spot since he did not photograph any of the sites from Gettysburg’s first day. Instead, documentary evidence indicates that it was probably taken near Rose Farm, south of the battlefield. Initially Gardner published the photograph without reference to Reynolds. That was added later when Gardner realised he had missed an opportunity and sought to capitalise on Reynolds’s heroism.

Text from the exhibition website

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

Incidents of the War: Unfit for Service at the Battle of Gettysburg

July 1863

Albumen silver print

Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, VA

Gift of David L. Hack and Museum purchase, with funds from Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., by exchange

After the success of his series “The Dead of Antietam,” which he had made while working for Mathew Brady, Gardner paid special attention in his Gettysburg photography to concentrate on the casualties, both human and animal. He got to the battlefield quickly, probably by July 7, as the process of burying the dead was just under way. In addition to the more than 7,000 soldiers killed, it has been estimated that more than 1,500 artillery horses died during the battle. Disposal of the horses complicated the task of clearing the land; while attempts were made to deal respectfully with human remains, the horses were collected into piles and burned. Gardner’s title for this picture may be taken as ironically low-key: the graphic image needed no rhetorical embellishments.

Text from the exhibition website

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

Panorama of Camp Winfield Scott, Yorktown, Virginia

1863

Albumen silver prints from glass negatives

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Gilman Collection, Museum Purchase, 2005

Image copyright: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Gardner and his family immigrated to the United States in 1856. Finding that many friends and family members at the cooperative he had helped to form were dead or dying of tuberculosis, he stayed in New York. He initiated contact with Brady and came to work for him that year, continuing until 1862. At first, Gardner specialised in making large photographic prints, called Imperial photographs, but as Brady’s eyesight began to fail, Gardner took on increasing responsibilities. In 1858, Brady put him in charge of his Washington, D.C. gallery. (Wikipedia)

“Before leaving home, he had seen and admired photographs by Mathew Brady, who was already famous and prosperous as a portraitist of American presidents and statesmen. It was Brady that likely paid Gardner’s passage to New York and soon after arriving, he went to visit the famous photographer’s studio and decided to stay.

Gardner was so successful there that Brady sent him to manage his Washington, D.C., studio, and soon after that, he was photographing Abraham Lincoln as the owner of his own studio [May 1863], and about to produce his historic images of the nation’s struggle. But there was more – after Appomattox, unknown to most of those who have praised his groundbreaking photographs of the war, he went on to record the westward march of the railroads and the Native American tribes scattering around them.

When the Civil War began, Mathew Brady sent more than 20 assistants into the field to follow the Union army. All of their work, including that of Gardner and the talented Timothy O’Sullivan, was issued with the credit line of the Brady studio. Thus the public assumed that Brady himself had lugged the fragile wagonload of equipment into the field, focused the big boxy camera and captured the images. Indeed, sometimes he had. But beginning with the battle of Antietam in September 1862, Gardner determined to take a step beyond his boss and his colleagues.

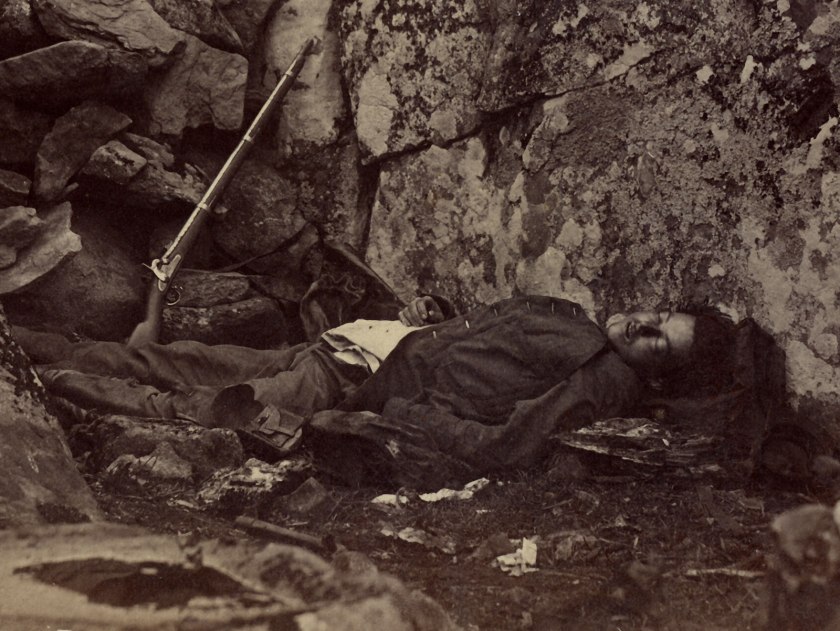

It pictured a dead Confederate soldier in a rocky den [see above], with his weapon propped nearby. Photographic historian William Frassanito has compared it to other images and believes that Gardner moved that body to a more dramatic hiding place to make the famous photo. Taking such license would blend with the dramatic way his album mused over the fallen soldier: “Was he delirious with agony, or did death come slowly to his relief, while memories of home grew dearer as the field of carnage faded before him? What visions, of loved ones far away, may have hovered above his stony pillow?”

Significantly, as illustrated by that image and description, Gardner’s book spoke of himself as “the artist.” Not the photographer, journalist or artisan, but the artist, who is by definition the creator, the designer, the composer of a work. But of course rearranging reality is not necessary to tell a gripping story, as he showed conspicuously after the Lincoln assassination. First he made finely focused portraits that caught the character of many of the surviving conspirators (much earlier in 1863, he had done the slain assassin, the actor John Wilkes Booth). Then, on the day of execution, he pictured the four – Mary Surrat, David Herold, Lewis Powell and George Atzerodt – standing as if posing on the scaffold, while their hoods and ropes were adjusted. Then their four bodies are seen dangling below while spectators look on from the high wall of the Washington Arsenal – as fitting a last scene as any artist might imagine.

After all Gardner had seen and accomplished, the rest of his career was bound to be anticlimax, but he was only 43 years old, and soon took on new challenges. In Washington, he photographed Native American chieftains and their families when they came to sign treaties that would give the government control over most of their ancient lands. Then he headed west.

In 1867, Gardner was appointed chief photographer for the eastern division of the Union Pacific Railway, a road later called the Kansas Pacific. Starting from St. Louis, he traveled with surveyors across Kansas, Colorado, New Mexico and Arizona and on to California. In their long, laborious trek, he and his crew documented far landscapes, trails, rivers, tribes, villages and forts that had never been photographed before. At Fort Laramie in Wyoming, he pictured the far-reaching treaty negotiations between the government and the Oglala, Miniconjou, Brulé, Yanktonai, and Arapaho Indians. This entire historic series was published in 1869 in a portfolio called Across the Continent on the Kansas Pacific Railroad (Route of the 35th Parallel).

Those rare pictures and the whole expanse of Gardner’s career are now on display at the National Portrait Gallery in a show entitled Dark Fields of the Republic: Alexander Gardner Photographs, 1859-1872. Among the dozens of images included are not only his war pictures and those of the nation’s westward expansion, but the famous “cracked-plate” image that was among the last photographs of a war-weary Abraham Lincoln. With this show, which will run into next March, the gallery is recognising a body of photography – of this unique art – unmatched in the nation’s history.”

Ernest B. Furgurson. “Alexander Gardner Saw Himself as an Artist, Crafting the Image of War in All Its Brutality,” on the Smithsonian.com website October 8, 2015 [Online] Cited 27/02/2016.

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

Gardner’s Gallery

c. 1863-1865

Albumen silver print

DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University, Dallas, Texas

The nation’s capital was a centre for photography during the war, and Alexander Gardner set up his new studio in May 1863 at Seventh and D Streets, just a few blocks from that of his former employer, Mathew Brady. Gardner split with Brady after the success of his Antietam photographs. The signage gives a full range of Gardner’s services, showing how he catered to the market for photographic images; the main sign reads “News of the War.”

Text from the exhibition website

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

Walt Whitman and Party

c. 1863

Albumen silver print

The Western Reserve Historical Society, Cleveland, Ohio

“This picture comes from a time when materials worked for each other. If pictures from these times were enlarged we would find their sharpness to be disappointing … but as this concept was not imagined, it shouldn’t be considered. The lens, the paper, the chemistry, the contact process all worked together. It is a superb image. If it were possible to make images like this, it is no wonder that highly talented people wanted to be photographers. And with talent, there were some with this level of sensitivity.

Note how the enlargement shows us some details that were not easily visible, but the tonality of the original has not carried over. Look at how the tonality of the curved branch combines with the figure of Whitman in the original, but it has crumbled in the enlargement … it is probably not possible to scan the original and keep the tonality without spending a squillion. Anyhow, it is a moment that has not been lost. It is almost too big a step of faith to believe that this much of the “air” of the original scene could be preserved.”

Dr Marcus Bunyan, March 2016

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

Walt Whitman and Party (detail)

c. 1863

Albumen silver print

The Western Reserve Historical Society, Cleveland, Ohio

Walt Whitman (1819-1892) came to Washington from New York City in search of his brother George, who had been wounded on December 13, 1862, at the Battle of Fredericksburg. Whitman found his brother, whose wound was not serious, and decided to stay in Washington. Whitman had been in a funk in New York: Leaves of Grass was not selling, and he was finding it difficult to write or revise his poetry. In Washington, Whitman assumed the role of a hospital visitor, comforting wounded soldiers, bringing them small treats, and, most important, writing their letters. He observed Abraham Lincoln, whom he idolised, from afar. And he began a relationship with Peter Doyle, a former Confederate soldier, whom he met on a streetcar and lived with for eight years. The other people in this photograph cannot be identified. The leaves on the trees would indicate that it was taken in late spring or summer of 1863.

Text from the exhibition website

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter

July 1863

Albumen silver print

Collection of Ron Perisho

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter

July 1863

Albumen silver print

Collection of Ron Perisho

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter (detail)

July 1863

Albumen silver print

Collection of Ron Perisho

Gardner’s manipulation of this Confederate casualty to create a narrative vignette about the soldier’s fate indicates how unstable the line was between fiction and truth in the creation of photographs. Gardner’s intrusion shows that he thought he had to improve his images so that they would function as a sentimental narrative that could be more easily read by his audience. His actions are unforgivable from both a moral and artistic point of view. But his arrangement of the corpse reflects how difficult it was for Gardner and his contemporaries to process the reality of mass casualties in which the dead became anonymous. Caught at a transitional moment, Gardner did not trust the images his camera captured. That this photographic construction would be more marketable to a public still steeped in Victorian sentimentality only adds to Gardner’s malfeasance.

In his Sketchbook Gardner created an elaborate story around his photographs of a dead Confederate “sharpshooter” who apparently had fallen during fighting at the Devil’s Den. Gardner claimed that he took photographs when he returned to the battlefield in the fall of 1863 and “discovered” the corpse, along with the rifle propped against the stone wall, still undisturbed where the soldier had fallen. The story isn’t credible: four months after the battle, the body would have long since decayed, and souvenir hunters would have picked up the rifle. The truth, untangled by photographic historian William Frassanito, is a blot on Gardner’s career: Gardner and his assistants moved a dead soldier [below] from a nearby line of bodies being readied for burial. Shortly after the battle they posed it amid the boulders, including the carefully positioned rifle. The soldier was a regular infantryman, not a sharpshooter or sniper.

Text from the exhibition website

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

A Sharpshooter’s Last Sleep, Gettysburg, July 1863

1863

Albumen silver print

National Archives, Washington, D.C.

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

Ruins of the Arsenal, Richmond, Virginia, April 1863

1865

Albumen silver print

Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick, Maine, Museum Purchase, Lloyd O. and Marjorie Strong Coulter Fund

Ironically, destruction of the major Confederate armoury occurred not from a Union assault but by an accidental fire that started in Richmond after the government began to evacuate the city on April 1, 1865, leaving it vulnerable. Chaos and confusion reigned as panicked residents faced the prospect of being occupied by the invading northerners; looting and destruction of property occurred as well. In the breakdown of order, fires broke out and quickly spread, destroying as many as fifty city blocks, until Union soldiers acting as firefighters extinguished them in part. Among the major buildings destroyed were the Tredegar Iron Works and the Arsenal. The Arsenal had been built earlier in the century but had fallen into disuse. It was made operative again when the war broke out; among the weapons it housed were those taken from the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry in 1861.

Text from the exhibition website

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

Abraham Lincoln delivering his second inaugural address as President of the United States, Washington, D.C.

March 4, 1865

Albumen silver print

Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

Abraham Lincoln delivering his second inaugural address as President of the United States, Washington, D.C. (detail)

March 4, 1865

Albumen silver print

Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress

Abraham Lincoln’s major speeches as president – at both inaugurals and at Gettysburg – focused on large themes, in particular human nature and God’s will, as well as the character of the nation. The hard politics of formulating and implementing the details of, for instance, emancipation, civil rights, and reconstruction, were kept offstage in the day-to-day process of governing. So at his second inaugural on March 4, 1865, Lincoln delivered a moral homily on how neither side, North or South, could know God’s will for mankind, and that the war had unintended consequences. Both parties now had to accept living with those consequences, namely the end of slavery and the beginning of civil equality for African Americans, Lincoln hinted. He ended with his majestic call to move on from war to civic peace: “With malice toward none, with charity for all,” let us “bind up the nation’s wounds” to “achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace.” Flush with victory, many in the North were puzzled or displeased by the president’s conciliatory words.

Text from the exhibition website

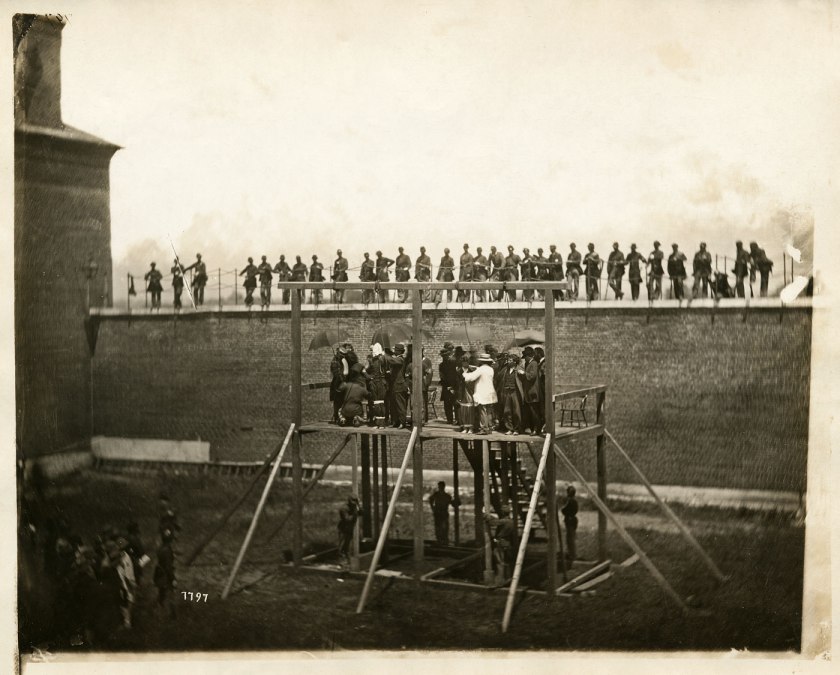

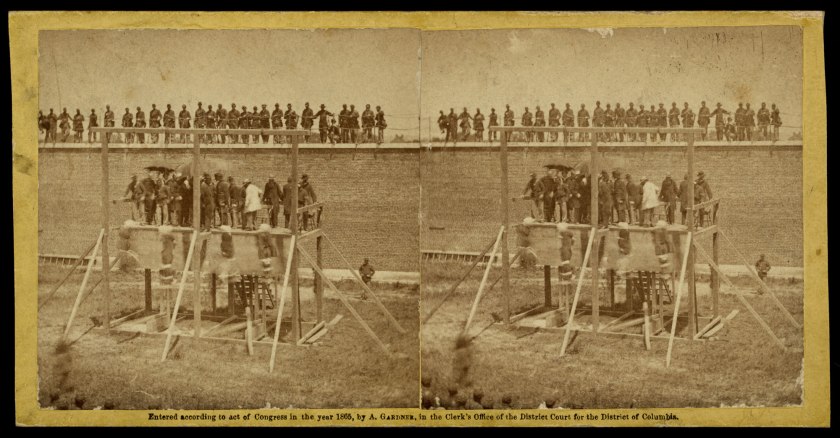

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

Adjusting the Ropes

July 7, 1865

Albumen silver print

Indiana Historical Society (P0409)

Daniel R. Weinberg Lincoln Conspirators Collection

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

Adjusting the Ropes (detail)

July 7, 1865

Albumen silver print

Indiana Historical Society (P0409)

Daniel R. Weinberg Lincoln Conspirators Collection

Of the eight Booth conspirators tried for their role in the assassination plot, four were sentenced to death: Mary Surratt, David Herold, Lewis Powell, and George Atzerodt. While the men had been major participants in the plot (even if Herold and Atzerodt had failed at their assignments), Mary Surratt sentence was more controversial, as it was argued that her boardinghouse was simply where the conspirators had met; that her son John was part of the conspiracy did not help her cause. The jury was also uneasy about the federal government executing a woman for the first time. Convicted and sentenced on June 30, the conspirators were executed on July 7 at Washington’s Old Arsenal Prison, out of public view. In a macabre display of chivalry, a man holding an umbrella shielded Mary Surratt from the sun before the traps were sprung.

Gardner was the only photographer allowed to document the executions, a recognition of his prominence as a documentarian. His camera position on the wall of the prison allowed him a panoramic view.

Text from the exhibition website

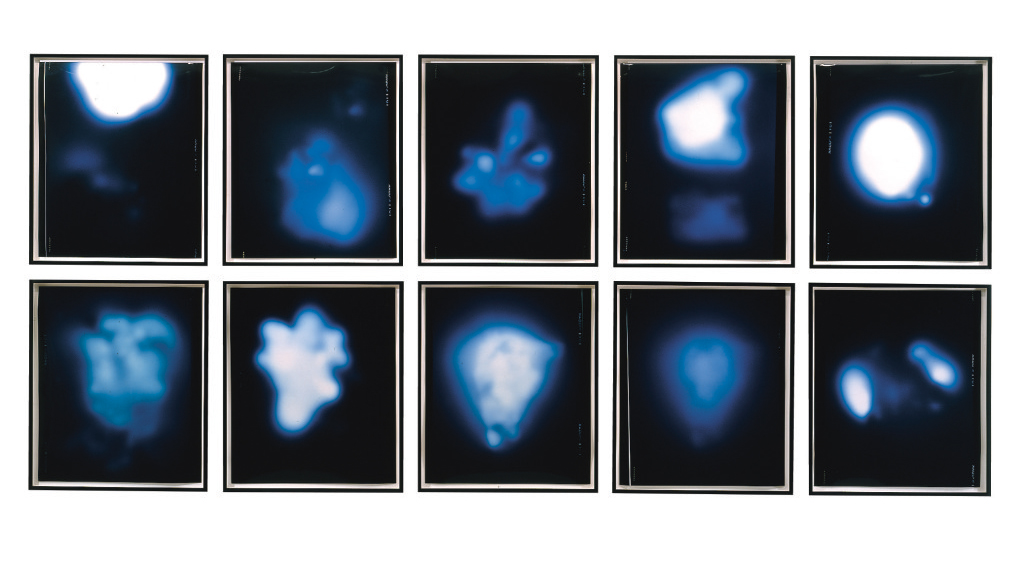

The date was July 7, 1865. Alexander Gardner and his assistant Timothy O’Sullivan took a series of ten photographs using both a large format camera with collodion glass-plate negatives and a stereo camera (used to make 3D stereoscope pictures). This series of photographs are considered one of the first examples of photojournalism ever recorded.

Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, David Herold and Georg Atzerodt. The four conspirators are now standing (Mrs. Surratt is supported by two soldiers) and is being bound. A hood has already been placed over Lewis Powell’s head by Lafayette Baker’s detective John H. Roberts. The nooses are being fitted around the necks of David Herold and George Atzerodt.

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

The Drop

July 7, 1865

Albumen silver print

Stereograph (Albumen silver print on stereo card)

Library of Congress

On July 7, 1865, at 1.15 pm., a procession led by General Hartranft escorted the four condemned prisoners through the courtyard and up the steps to the gallows. Each had their ankles and wrists bound by manacles. Mary Surratt led the way, wearing a black bombazine dress, black bonnet, and black veil. More than 1,000 people – including government officials, members of the U.S. armed forces, friends and family of the accused, official witnesses, and reporters – watched. General Hancock limited attendance to those who had a ticket, and only those who had a good reason to be present were given a ticket. (Most of those present were military officers and soldiers, as fewer than 200 tickets had been printed.) Alexander Gardner, who had photographed the body of Booth and taken portraits of several of the male conspirators while they were imprisoned aboard naval ships, photographed the execution for the government. Hartranft read the order for their execution. Surratt, either weak from her illness or swooning in fear (perhaps both), had to be supported by two soldiers and her priests. The condemned were seated in chairs, Surratt almost collapsing into hers. She was seated to the right of the others, the traditional “seat of honor” in an execution. White cloth was used to bind their arms were bound to their sides, and their ankles and thighs together. The cloths around Surratt’s legs were tied around her dress below the knees. Each person was ministered to by a member of the clergy. From the scaffold, Powell said, “Mrs. Surratt is innocent. She doesn’t deserve to die with the rest of us”. Fathers Jacob and Wiget prayed over Mary Surratt, and held a crucifix to her lips. About 16 minutes elapsed from the time the prisoners entered the courtyard until they were ready for execution.

A white bag was placed over the head of each prisoner after the noose was put in place. Surratt’s bonnet was removed, and the noose put around her neck by a Secret Service officer. She complained that the bindings about her arms hurt, and the officer preparing said, “Well, it won’t hurt long.” Finally, the prisoners were asked to stand and move forward a few feet to the nooses. The chairs were removed. Mary Surratt’s last words, spoken to a guard as he moved her forward to the drop, were “Please don’t let me fall.” Surratt and the others stood on the drop for about 10 seconds, and then Captain Rath clapped his hands. Four soldiers of Company F of the 14th Veteran Reserves knocked out the supports holding the drops in place, and the condemned fell. Surratt, who had moved forward enough to barely step onto the drop, lurched forward and slid partway down the drop – her body snapping tight at the end of the rope, swinging back and forth. Surratt’s death appeared to be the easiest. Atzerodt’s stomach heaved once and his legs quivered, and then he was still. Herold and Powell struggled for nearly five minutes, strangling to death.

Each body was inspected by a physician to ensure that death had occurred. The bodies of the executed were allowed to hang for about 30 minutes. The bodies began to be cut down at 1.53 pm. A corporal raced to the top of the gallows and cut down Atzerodt’s body, which fell to the ground with a thud. He was reprimanded, and the other bodies cut down more gently. Herold’s body was next, followed by Powell’s. Surratt’s body was cut down at 1.58 pm. As Surratt’s body was cut loose, her head fell forward. A soldier joked, “She makes a good bow” and was rebuked by an officer for his poor use of humour.

Upon examination, the military surgeons determined that no one’s neck had been broken by the fall, as intended. The manacles and cloth bindings were removed (but not the white execution masks), and the bodies were placed into the pine coffins. The name of each person was written on a piece of paper by acting Assistant Adjutant R. A. Watts, and inserted in a glass vial (which was placed into the coffin). The coffins were buried against the prison wall in shallow graves, just a few feet from the gallows.

“Mary Surratt” text from the Wikipedia website

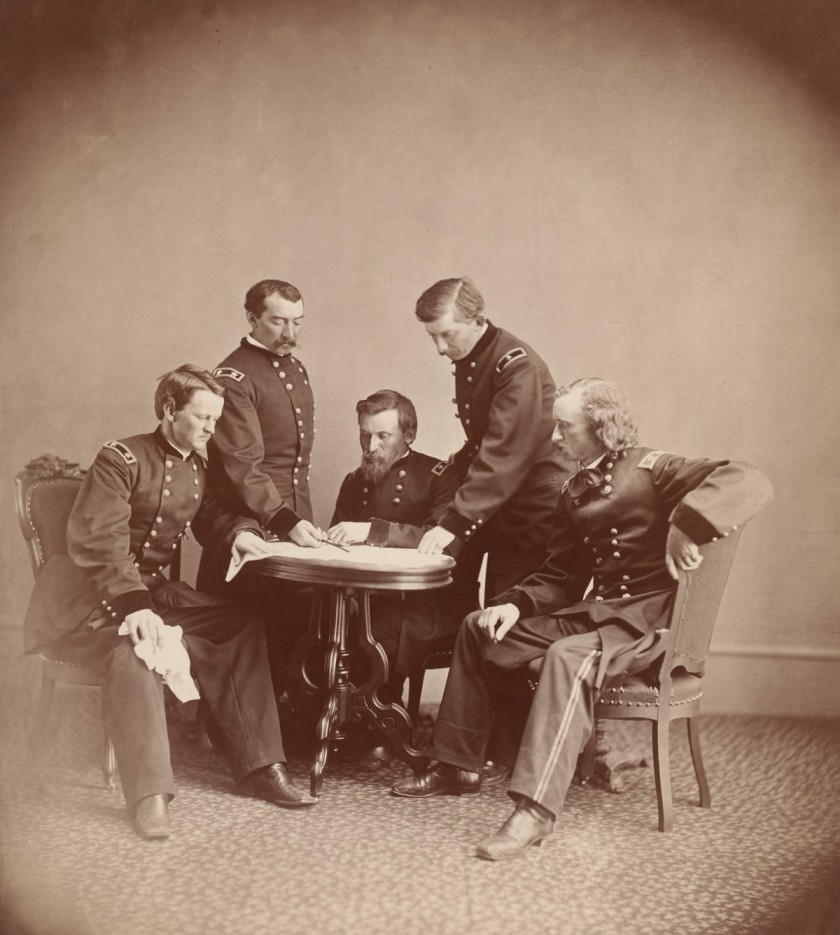

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

General Sheridan and His Staff

c. 1865

Albumen silver print

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Another in Alexander Gardner’s valedictory series of the major Union commanders in each theatre of the war, this photograph groups four of the figures from the 1864 campaign in the Shenandoah Valley under the command of Philip Sheridan (1831-1888). Sheridan is standing to the left; at the table are cavalry officer Wesley Merritt (1834-1910); George Crook (1830-1890), who had an independent force in western Virginia before joining Sheridan’s army; Sheridan’s chief of staff, James W. Forsyth (1835-1906); and perhaps America’s most famous cavalryman, George A. Custer (1839-1876).

This photograph brings together the men who would be major figures in the settlement of the Great Plains and the Indian Wars – none more emblematic than Custer. As such, it provides the bridge between the first half of Gardner’s career during the Civil War and the images of western land and people on which he focused during the rest of his photographic career. One war had ended; another was beginning.

Text from the exhibition website

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

General Sheridan and His Staff

c. 1865

Albumen silver print

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

General Sheridan and His Staff (detail)

c. 1865

Albumen silver print

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

” … Gardner was born in Paisley in 1821 and trained as a jeweller before moving into the world of newspapers. An idealist and socialist, he formed the left-leaning newspaper the Glasgow Sentinel in 1851. His keen interest in photography led to him emigrating across the pond in the hope of furthering his career. He was headhunted by [Matthew] Brady and at the outbreak of the war was well-positioned in Washington.

He was recruited as a staff photographer by General George B. McClellan, commander of the Army of the Potomac, and made history on 19 September 1862 when he took the first photographs of casualties on the battlefield at Antietam. In 1863, Gardner split from Brady and formed his own gallery in Washington with his brother James [May 1863]. In July of that year, he photographed the aftermath of the Battle of Gettysburg, developing images in his travelling darkroom.

Author Keith Steiner said: ‘Gardner was essentially a photojournalist. He had to process and develop the photographs on the move and in the middle of a battlefield which was not easy. He was highly regarded and Walt Whitman once said that he ‘saw beyond his camera’… ‘He was an artist, in some ways a scientist and a publisher. He was the complete package.’

Gardner was also the official photographer to President Abraham Lincoln. He captured him seven times, including before his inauguration in March 1861 and in February 1865, just weeks before he was assassinated. The war-time leader personally visited Gardner to have his photograph taken every year instead of the Scotsman visiting the White House.

Keith said: ‘Most of the photographs you see of Lincoln were taken by Gardner and chart how he aged physically. He was pictured in 1861 then a few years later and it is like a different man. In February 1865, he is a broken man and has aged about 20 years through the stress of the civil war. It is an incredibly revealing photograph’.”

Anonymous. “How Abraham Lincoln’s Scottish photographer became the first man to capture the horrors of the Civil War but was robbed of the credit… until now,” on the Daily Mail Australia website 25 January 2014 [Online] Cited 27/02/2016.

The West, 1867-1872

After the war, Alexander Gardner photographed events and people associated with one of the most abiding preoccupations of the nineteenth century: westward expansion. From 1867 to 1872 he made portraits of American Indian leaders who traveled to Washington to negotiate preservation of their traditional lands and lifeways, even as white Americans flooded the frontier. In 1867, Gardner became the first photographer to document a transcontinental project, making views of the Kansas Pacific Railroad’s construction activities, bustling frontier towns and settlements, Army forts, Indian villages, and magnificent empty landscapes.

The federal government then hired Gardner to photograph the spring 1868 treaty negotiations between the Indian Peace Commission and leaders of the Crow, Northern Cheyenne, Northern Arapaho, and Lakota in the Dakota Territory. The Fort Laramie Treaty established reservations on the northern Plains, marking a watershed moment in the relationship between Native peoples and the government. Gardner’s images are the only photographs of treaty negotiations ever commissioned by the U.S. government.

Text from the exhibition website

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

“Westward the Course of Empire Takes its Way.” Laying track, 300 miles west of Missouri River, 19th October, 1867

1867

Albumen silver print

William T. Sherman Collection of Alexander Gardner Photographs, National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution (P10134)

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

“Westward the Course of Empire Takes its Way.” Laying track, 300 miles west of Missouri River, 19th October, 1867 (detail)

1867

Albumen silver print

William T. Sherman Collection of Alexander Gardner Photographs, National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution (P10134)

Alexander Gardner quoted from the final stanza of a 1726 poem by Bishop George Berkeley for the title of this photograph. The Anglo-Irish philosopher had originally offered his verse as a lamentation on the decline of British influence in North America, but after the Civil War, as the United States turned with determination to its expansionist agenda, Americans found particular resonance in Berkeley’s line, “Westward the course of empire takes its way.” Constructing a transcontinental railroad was central to the achievement of these ambitions. Although the company survived into the 1870s, the Kansas Pacific Railroad was unable to rally federal support for a transcontinental route along the southerly thirty-fifth and thirty-second parallels. On May 10, 1869, at Promontory Point in the Utah Territory, the “Golden Spike” ceremony joined the more northern tracks of the Union Pacific Railroad with those of the Central Pacific Railroad, marking the completion of the first railroads to link the East and West coasts of the United States.

Text from the exhibition website

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

Bridge over the Laramie River near its Junction with the North Platte River, Fort Laramie, Dakota Territory

1868

Albumen silver print

William T. Sherman Collection of Alexander Gardner Photographs, National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution (P10128)

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

Indian Peace Commissioners in council with the Northern Cheyenne and Northern Arapaho, Fort Laramie, Dakota Territory

1868

Albumen silver print

National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution; William T. Sherman Collection of Alexander Gardner Photographs (P15390)

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

Indian Peace Commissioners in council with the Northern Cheyenne and Northern Arapaho, Fort Laramie, Dakota Territory (details)

1868

Albumen silver print

National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution; William T. Sherman Collection of Alexander Gardner Photographs (P15390)

Left to right: Colonel Samuel F. Tappan (1831-1913), General William S. Harney (1800-1889), General William T. Sherman (1820-1891), General John B. Sanborn (1826-1904), General Christopher C. Augur (1821-1898), General Alfred H. Terry (1827-1890), and Commission Secretary Ashton S. H. White (life dates unknown)

In the summer of 1867, when Congress convened the Indian Peace Commission, popular opinion in the eastern United States supported a diplomatic resolution to the so-called “Indian problem” on both the northern and southern Plains. (The negotiations on the southern Plains were not photographed.) Consisting of civilians and army generals, the commission managed to secure treaties with the region’s “hostile” tribes and convened its final meeting on October 7, 1868. By then, public sentiment had taken an aggressive turn and demanded increased military intervention in Indian matters. Overruling their more diplomatically minded colleagues, the commission’s military members – led by General William T. Sherman – used the shift in the political landscape to advantage. As a body, the commission resolved that the government “should cease to recognise the Indian tribes as ‘domestic dependent nations.'” Treaty-making, or diplomacy, was at an end, and in the coming years, military conflict characterised U.S.-Indian relations on the Plains.

Text from the exhibition website

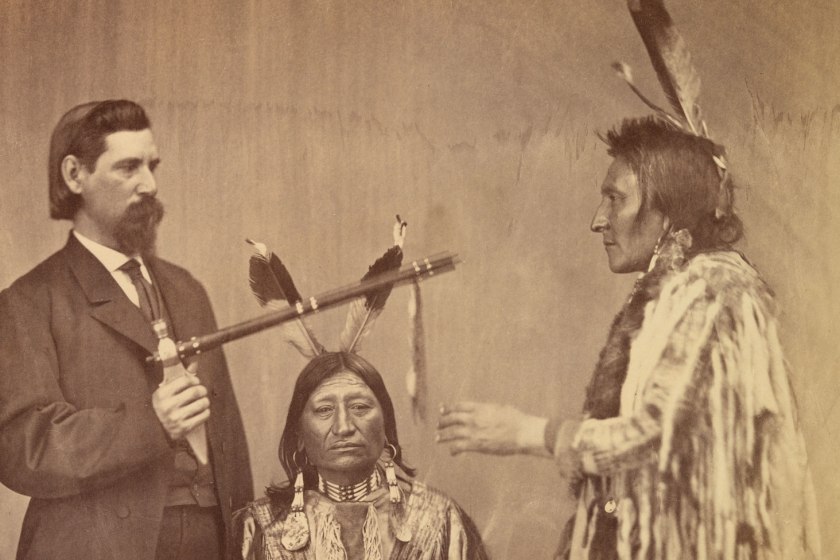

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

Lakota delegates Medicine Bull, Iron Nation, and Yellow Hawk with their Agent-Interpreter, Washington, D.C.

1867

Albumen silver print

William T. Sherman Collection of Alexander Gardner Photographs, National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution (P10139)

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

Lakota delegates Medicine Bull, Iron Nation, and Yellow Hawk with their Agent-Interpreter, Washington, D.C. (detail)

1867

Albumen silver print

William T. Sherman Collection of Alexander Gardner Photographs, National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution (P10139)

Left to right: Medicine Bull (life dates unknown), unidentified interpreter, Iron Nation (1815-1894), and Yellow Hawk (life dates unknown)

Alexander Gardner made three portraits of each American Indian pictured here: a group portrait and two separate portraits of each delegate, one in his Native and one in his Western attire. (A suit was often among the gifts given to Native delegates to the capital.) It is unknown how Medicine Bull (Sicangu Lakota), Iron Nation (Sicangu Lakota), and Yellow Hawk (Itazipacola Lakota) were dressed when they arrived to sit for their portraits, but Gardner’s apparent desire to make two individual portraits of each in many ways anticipates the popular “before and after” photographs of Native people that circulated in the following decades. The photographs were made to document the supposed salutary benefits of the sitter’s exposure to American civilisation.

Text from the exhibition website

The Lakȟóta people (pronounced [laˈkˣota]; also known as Teton, Thítȟuŋwaŋ (“prairie dwellers”), and Teton Sioux (from Nadouessioux – ‘snake’ or ‘enemy’) are an indigenous people of the Great Plains of North America. They are part of a confederation of seven related Sioux tribes, the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ or seven council fires, and speak Lakota, one of the three major dialects of the Sioux language. The Lakota are the westernmost of the three Siouan language groups, occupying lands in both North and South Dakota. The seven bands or “sub-tribes” of the Lakota are:

Sičháŋǧu (Brulé, Burned Thighs)

Oglála (“They Scatter Their Own”)

Itázipčho (Sans Arc, Without Bows)

Húŋkpapȟa (“End Village”, Camps at the End of the Camp Circle)

Mnikȟówožu (“Plant beside the Stream”, Planters by the Water)

Sihásapa (“Black Feet”)

Oóhenuŋpa (Two Kettles)

Notable Lakota persons include Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake (Sitting Bull) from the Húnkpapȟa band; Touch the Clouds from the Miniconjou band; and, Tȟašúŋke Witkó (Crazy Horse), Maȟpíya Lúta (Red Cloud), Heȟáka Sápa (Black Elk), Siŋté Glešká (Spotted Tail), and Billy Mills from the Oglala band.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

Ihanktonwan Nakota delegates Long Foot and Little Bird, Washington, D.C.

1867

Albumen silver print National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution; William T. Sherman Collection of Alexander Gardner Photographs (P10149)

Alexander Gardner (American, 1821-1882)

Ihanktonwan Nakota delegates Long Foot and Little Bird, Washington, D.C. (detail)

1867

Albumen silver print National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution; William T. Sherman Collection of Alexander Gardner Photographs (P10149)

In a letter dated February 20, 1867, Smithsonian Institution Secretary Joseph Henry pressed Commissioner of Indian Affairs Lewis V. Bogy to fund a comprehensive effort to photograph Native delegates to Washington. Henry envisioned a kind of archive, a “trustworthy collection of likenesses of the principal tribes of the United States,” urgently adding that with the passing of “the Indian” only a few years remained to undertake such a project. Bogy apparently passed on the project, but the Smithsonian found an alternative collaborator in Englishman William Blackmore. (Blackmore posed before Alexander Gardner’s camera with Oglala Lakota leader Red Cloud. The portrait of the two men is on display nearby.) Blackmore commissioned local Washington photographers like Gardner to make portraits of visiting delegates such as the Ihanktonwan Nakota delegates Long Foot (life dates unknown) and Little Bird (life dates unknown), pictured here. Blackmore made his photographs available to the Smithsonian; they represent the institution’s very first photograph collection and are now housed in the National Anthropological Archives.

Text from the exhibition website

Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery

8th and F Sts NW

Washington, DC 20001

Opening hours:

11.30am – 7.00pm daily

Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery website

LIKE ART BLART ON FACEBOOK

Back to top

![Auguste Rodin (French, 1840-1917) 'Le Penseur [The Thinker]' 1903 Auguste Rodin (French, 1840-1917) 'Le Penseur [The Thinker]' 1903](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2016/03/rodin-le-penseur-web.jpg?w=650&h=867)

![Vassily Kandinsky (Russian, 1866-1944) 'Bild mit rotem Fleck [Tableau à la tache rouge / Image with red spot]' 25 February 1914 Vassily Kandinsky (Russian, 1866-1944) 'Bild mit rotem Fleck [Tableau à la tache rouge / Image with red spot]' 25 February 1914](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2016/03/kandinsky-bild-mit-rotem-fleck-web.jpg?w=650&h=651)

![James Maguire (American, 1816-1851) '[Portrait of Zachary Taylor]' 1847 James Maguire (American, 1816-1851) '[Portrait of Zachary Taylor]' 1847](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2016/02/gm_06991301-web.jpg?w=650&h=749)

![James P. Weston (American, active South America about 1849 and New York 1851-1852 and 1855-1857) '[Portrait of an Asian Man in Top Hat]' c. 1856 James P. Weston (American, active South America about 1849 and New York 1851-1852 and 1855-1857) '[Portrait of an Asian Man in Top Hat]' c. 1856](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2016/02/gm_05595301-web.jpg?w=650&h=841)

![Unknown maker (American) '[Portrait of an Unidentified Daguerreotypist Displaying a Selection of Daguerreotypes] / Daguerreotypist (?) Displaying Thirteen Daguerreotypes' 1845 Unknown maker (American) '[Portrait of an Unidentified Daguerreotypist Displaying a Selection of Daguerreotypes] / Daguerreotypist (?) Displaying Thirteen Daguerreotypes' 1845](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2016/02/gm_06329401-web.jpg?w=650&h=737)

![Unknown maker (American) '[Chinese Woman with a Mandolin]' 1860 Unknown maker (American) '[Chinese Woman with a Mandolin]' 1860](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2016/02/gm_05620001-web.jpg?w=650&h=838)

![Unknown maker (American) '[Chinese Woman with a Mandolin]' 1860 (detail) Unknown maker (American) '[Chinese Woman with a Mandolin]' 1860 (detail)](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2016/02/gm_05620001-detail.jpg?w=650&h=839)

![Mathew B. Brady. 'Untitled [Spectators massing for the Grand Review of the Armies, 23-24 May 1865, at the side of the crepe-draped U.S. Capitol, flag at half mast following the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln]' 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/matthew-brady-captured-spectators-massing-web.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner. "Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand]," from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 Alexander Gardner. "Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand]," from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-b.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner. "Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand]," from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 Alexander Gardner. "Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand]," from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-b-whole.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner. "Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand]," from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 (detail) Alexander Gardner. "Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand]," from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 (detail)](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-b-detail.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner. "Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand and mounted cavalry]," in the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 Alexander Gardner. "Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand and mounted cavalry]," in the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-c-web.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner. "Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand and mounted cavalry]," in the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 Alexander Gardner. "Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand and mounted cavalry]," in the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-c-whole.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner. "Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand and mounted cavalry]," in the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 (detail) Alexander Gardner. "Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand and mounted cavalry]," in the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 (detail)](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-c-detail.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-d-web.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-d-whole.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 (detail) Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 (detail)](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-d-detail.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-e-web.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-e-whole.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 (detail) Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 (detail)](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-f-detail.jpg?w=650&h=464)

![Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-f-web.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-f-whole.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Gand Review, Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Gand Review, Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-g-web.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Gand Review, Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Gand Review, Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-g-whole.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Gand Review, Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Gand Review, Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-h-web.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Gand Review, Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Gand Review, Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-h-whole.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Gand Review, Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Gand Review, Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-i-web.jpg?w=840)