Exhibition dates: both 21st September 2012 – 6th January 2013

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Migratory Cotton Picker

Eloy, Arizona, 1940

Gelatin silver print

© Library of Congress

Courtesy of Howard Greenberg Collection

This is a meta-post where I have brought together photographs from the second exhibition Freaks, The Monstrous Parade: Photographs from Enrico Praloran Collection and all the good quality images of Todd Browning’s cult film Freaks (1932) that were available online, since the museum only provided me with three media images (the first three) on a fascinating subject. By reflection, the photographs from Freaks have a strange correlation to the photographs that appear in the Howard Greenberg, Collection.

There is an interesting discussion by Amanda Ann Klein on her blog (see link below) about her students reaction to the film that she taught as part of her Trash Cinema class. She observes that, “Freaks preaches acceptance and… the belief that we are all “God’s children.” And yet, the film was intended to “out horror” Frankenstein through its fantastic display of disabled bodies…” but that her students did not see it as an exploitation film, in fact they approved of the revenge taken by the freaks on Cleopatra and Hercules at the end of the film, even though this seemed to replicate the very imagery Browning denounced earlier in the film. Klein insightfully notes that “it did prove to be an interesting example of how a film’s reception can change dramatically over time.”

The content of a work of art is never fixed by the author as the context and meaning of the work is never fixed by the viewer. As David Smail notes the truth changes according to, among other things, developments in our values and understandings. There can be many truths depending on our line-of-sight and point-of-view but a subjective non-final truth has to be actively struggled for:

“Where objective knowing is passive, subjective knowing is active – rather than giving allegiance to a set of methodological rules which are designed to deliver up truth through some kind of automatic process [in this case the image], the subjective knower takes a personal risk in entering into the meaning of the phenomena to be known … Those who have some time for the validity of subjective experience but intellectual qualms about any kind of ‘truth’ which is not ‘objective’, are apt to solve their problem by appealing to some kind of relativity. For example, it might be felt that we all have our own versions of the truth about which we must tolerantly agree to differ. While in some ways this kind of approach represents an advance on the brute domination of ‘objective truth’, it in fact undercuts and betrays the reality of the world given to our subjectivity. Subjective truth has to be actively struggled for: we need the courage to differ until we can agree. Though the truth is not just a matter of personal perspective, neither is it fixed and certain, objectively ‘out there’ and independent of human knowing. ‘The truth’ changes according to, among other things, developments and alterations in our values and understandings … the ‘non-finality’ of truth is not to be confused with a simple relativity of ‘truths’.”

Smail, David. Illusion and Reality: The Meaning of Anxiety. London: J.M. Dent & Sons, 1984, pp.152-153.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Musée de l’Elysée, Lausanne for allowing me to publish some of the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

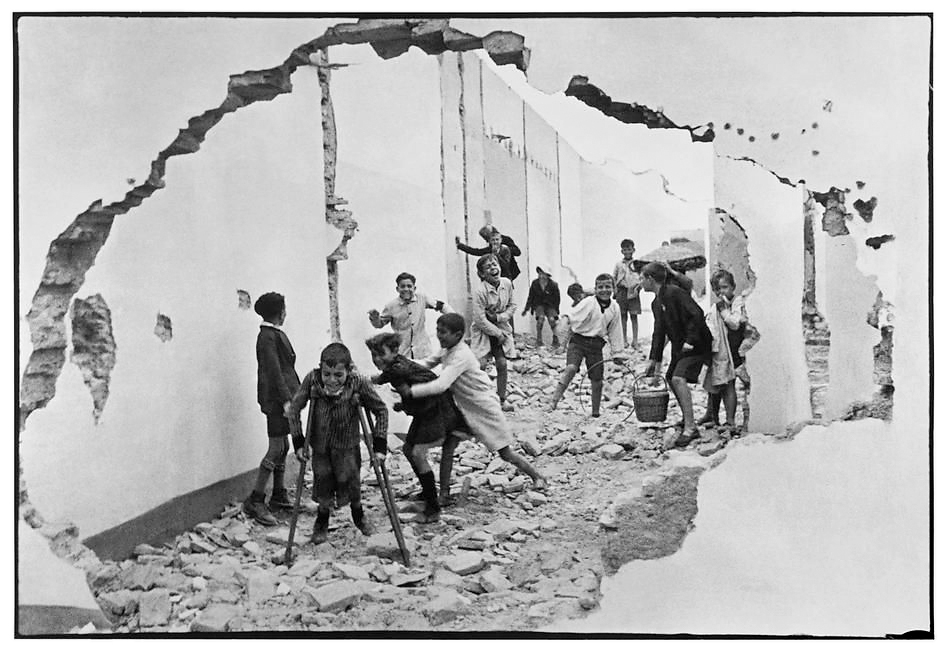

Henri Cartier-Bresson (French, 1908-2004)

Madrid

1933

Gelatin silver print

© Henri Cartier-Bresson/Magnum Photos

Courtesy of Fondation HCB and Howard Greenberg Collection

Henri Cartier-Bresson (French, 1908-2004)

Seville

1933

Gelatin silver print

© Henri Cartier-Bresson/Magnum Photos

Courtesy of Fondation HCB and Howard Greenberg Collection

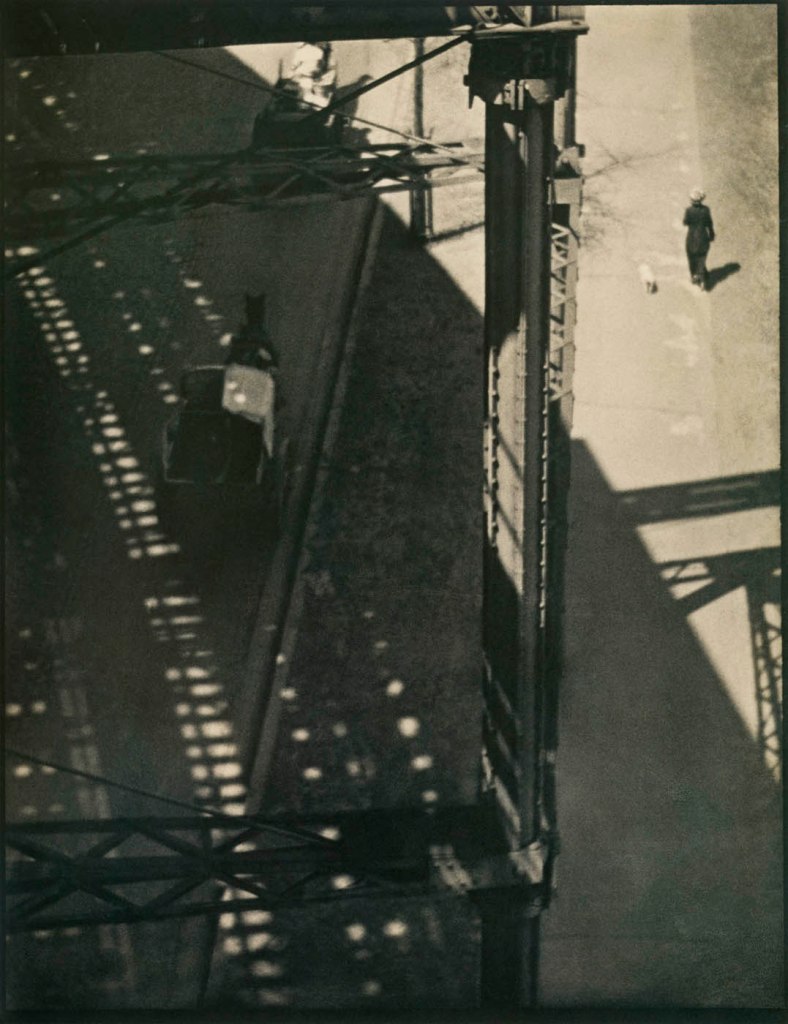

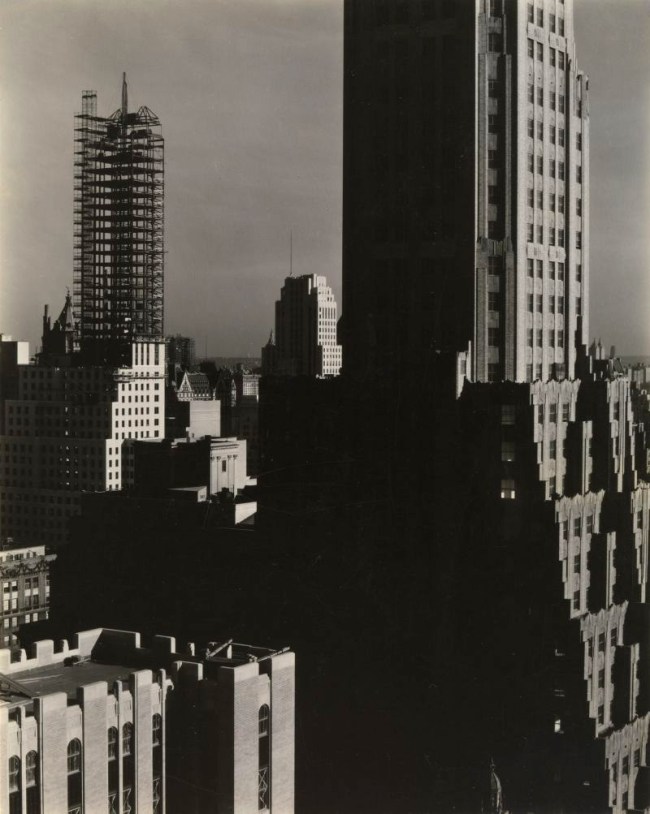

Berenice Abbott (American, 1898-1991)

Greyhound Bus Terminal, 33rd and 34th Streets between Seventh and Eighth Avenues, Manhattan

1936

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of Howard Greenberg Collection

Ruth Orkin (American, 1921-1985)

American Girl in Italy

1951

Gelatin silver print

© Ruth Orkin

Courtesy of Howard Greenberg Collection

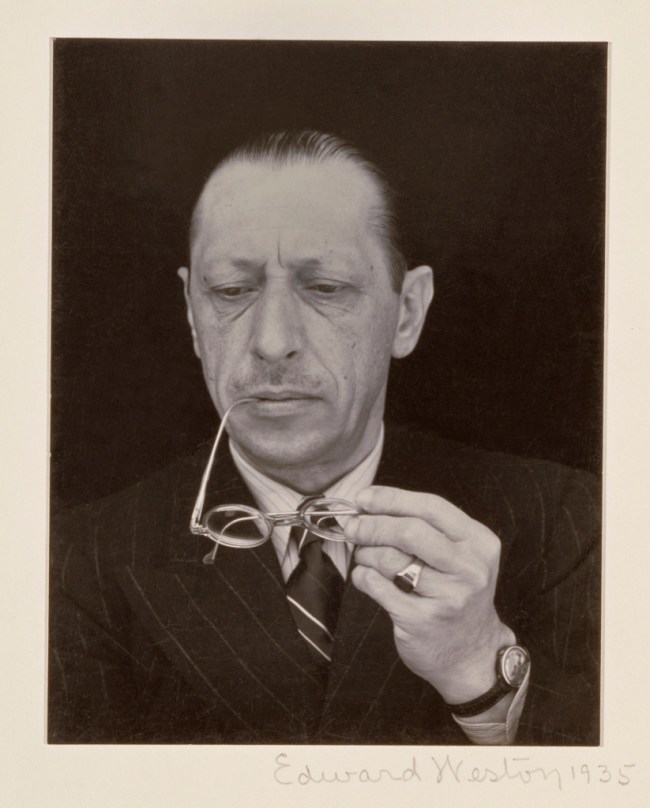

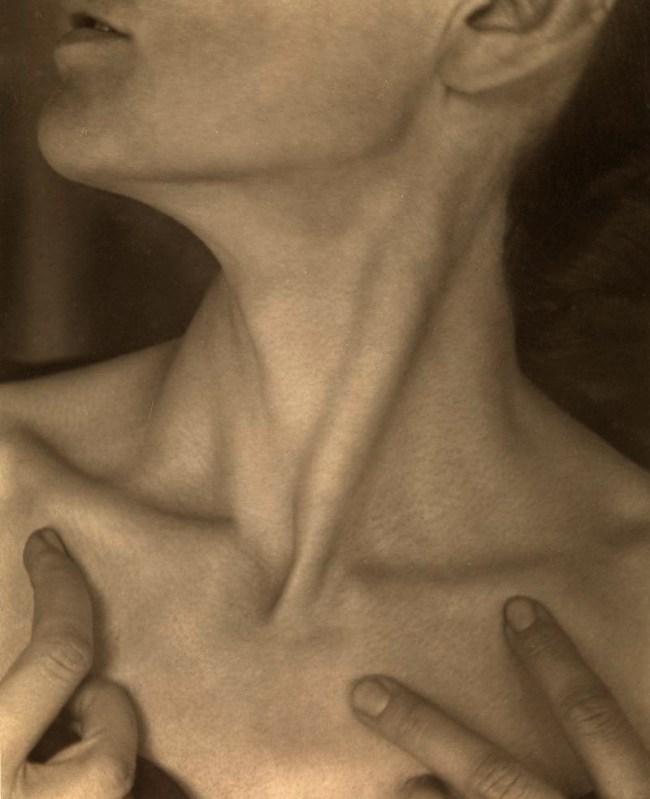

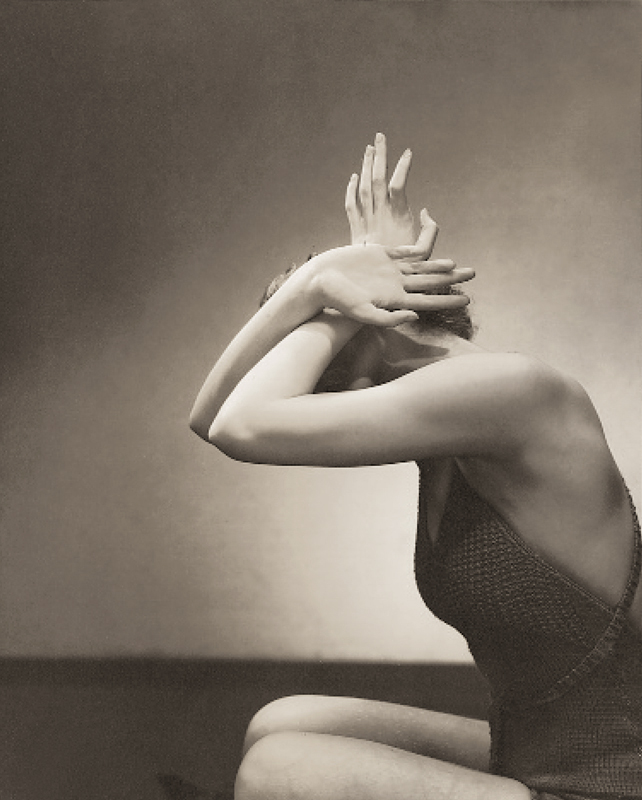

Edward Weston (American, 1886–1958)

Nahui Olin

1923

Platinum print

Courtesy of Howard Greenberg Collection

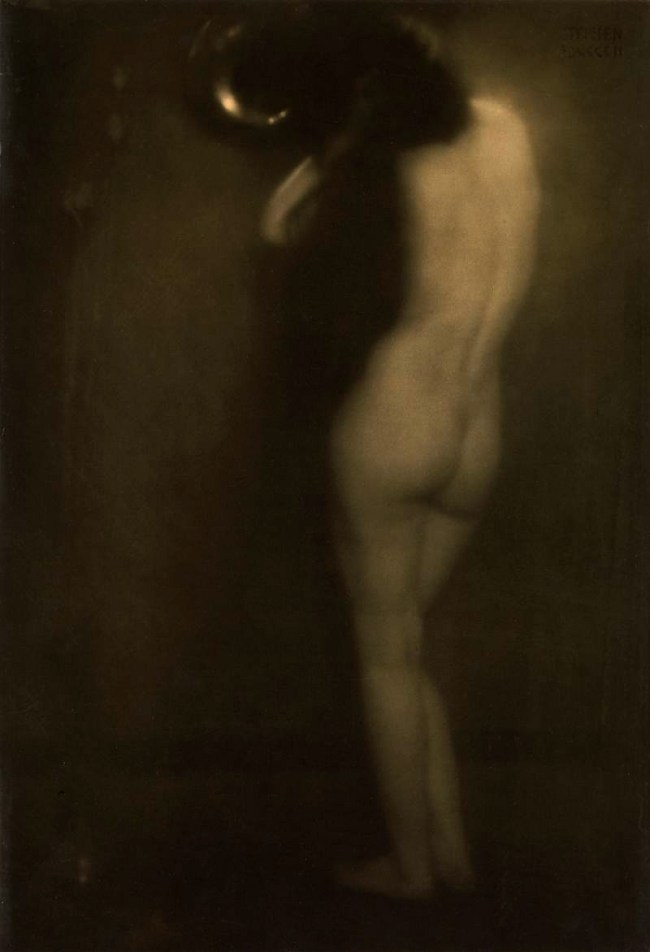

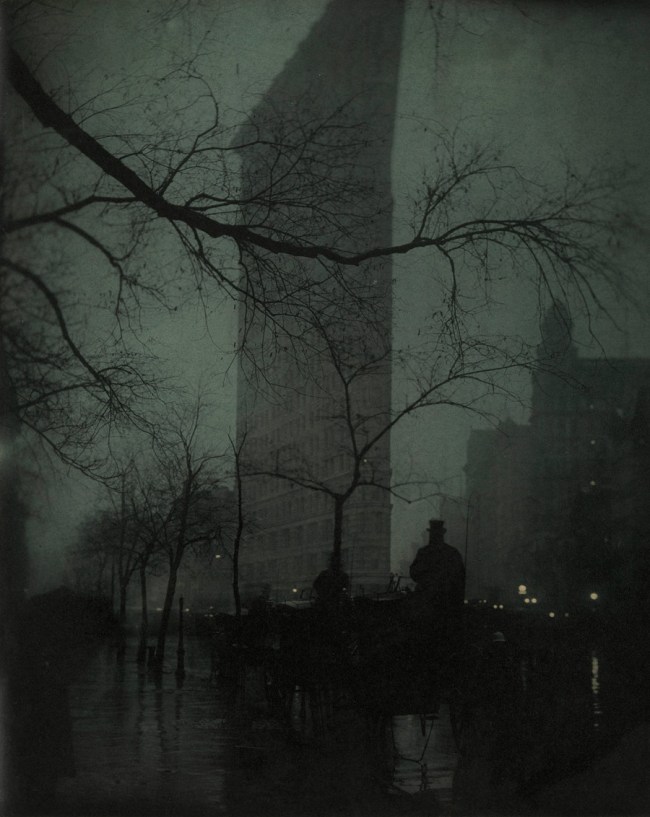

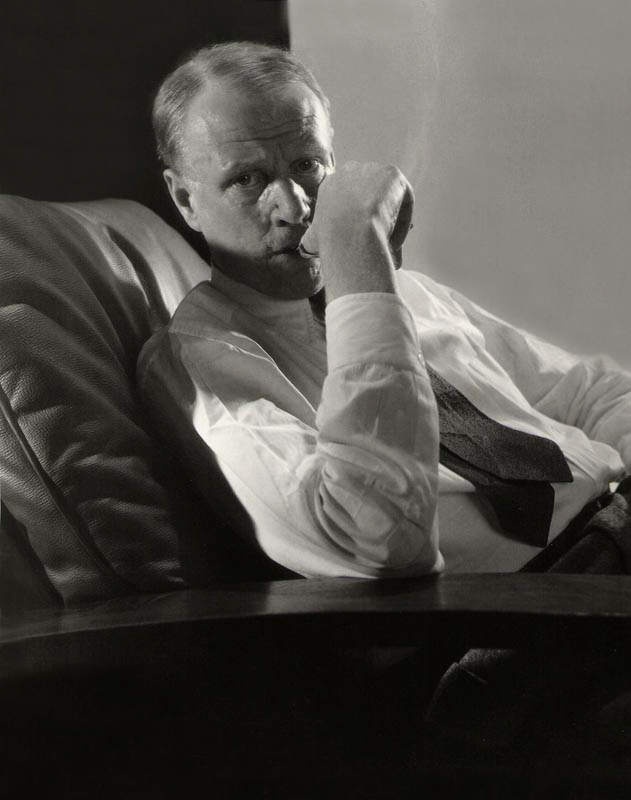

Edward Steichen (American born Luxembourg, 1879–1973)

Gloria Swanson

1924

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of Howard Greenberg Collection

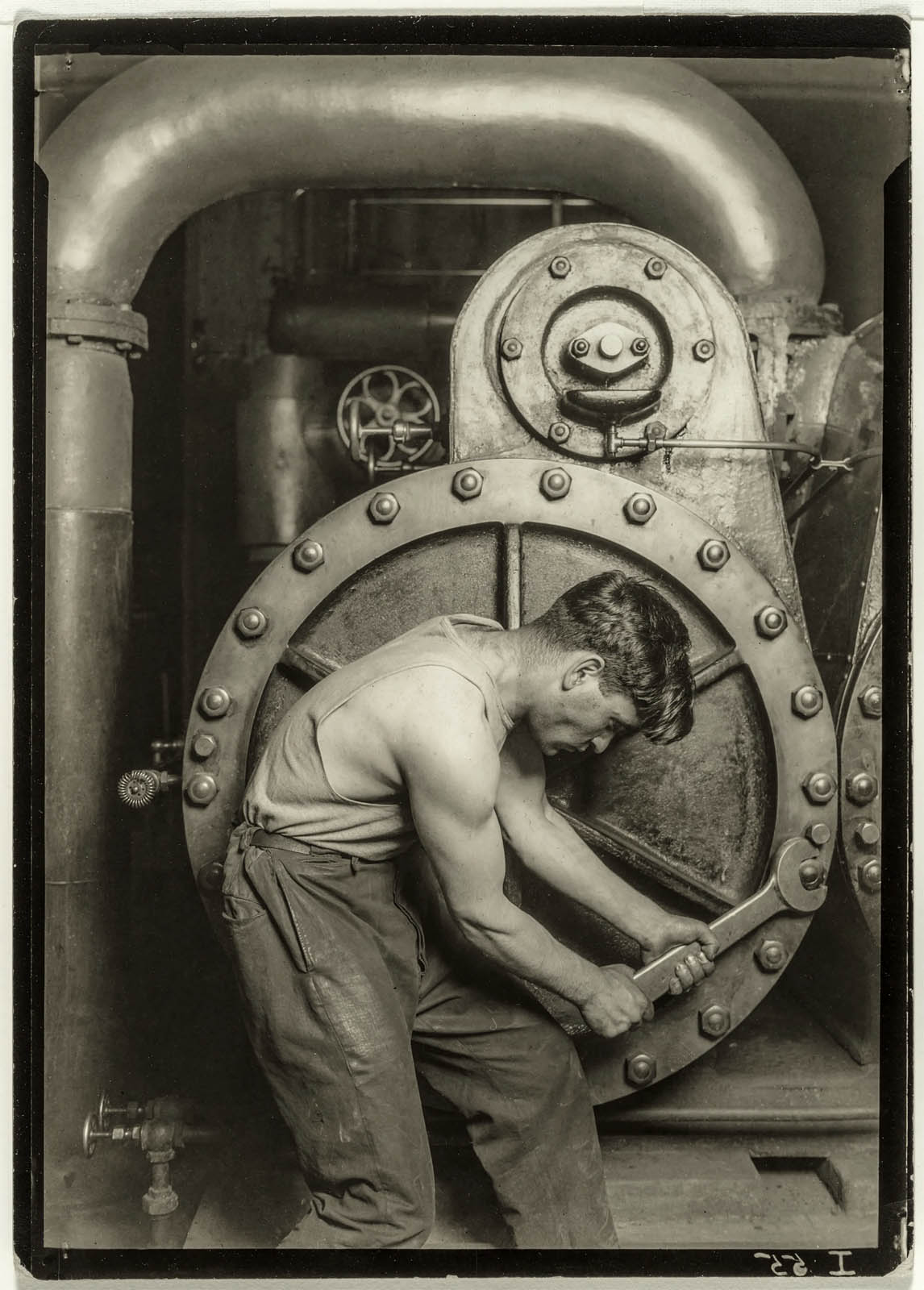

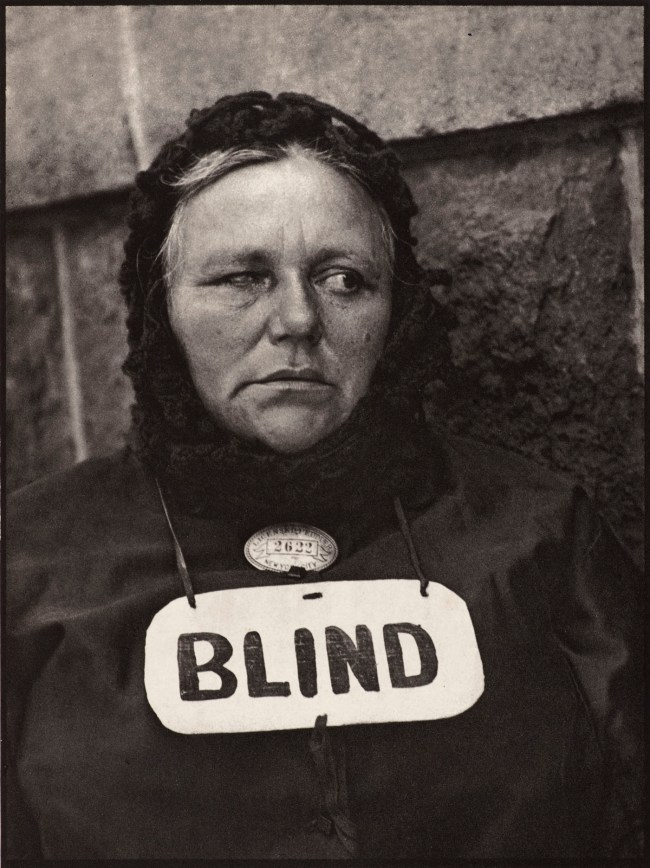

Lewis W. Hine (American, 1874–1940)

Powerhouse Mechanic

1924

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of Howard Greenberg Collection

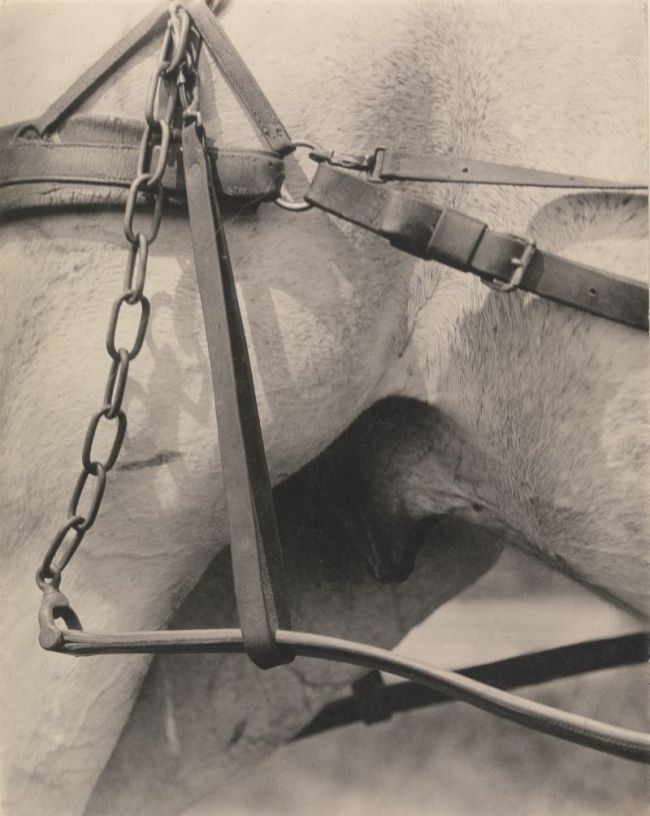

André Kertész (American born in Hungary, 1894-1985)

Chez Mondrian

1926

Gelatin silver print on carte postale

The Howard Greenberg Collection

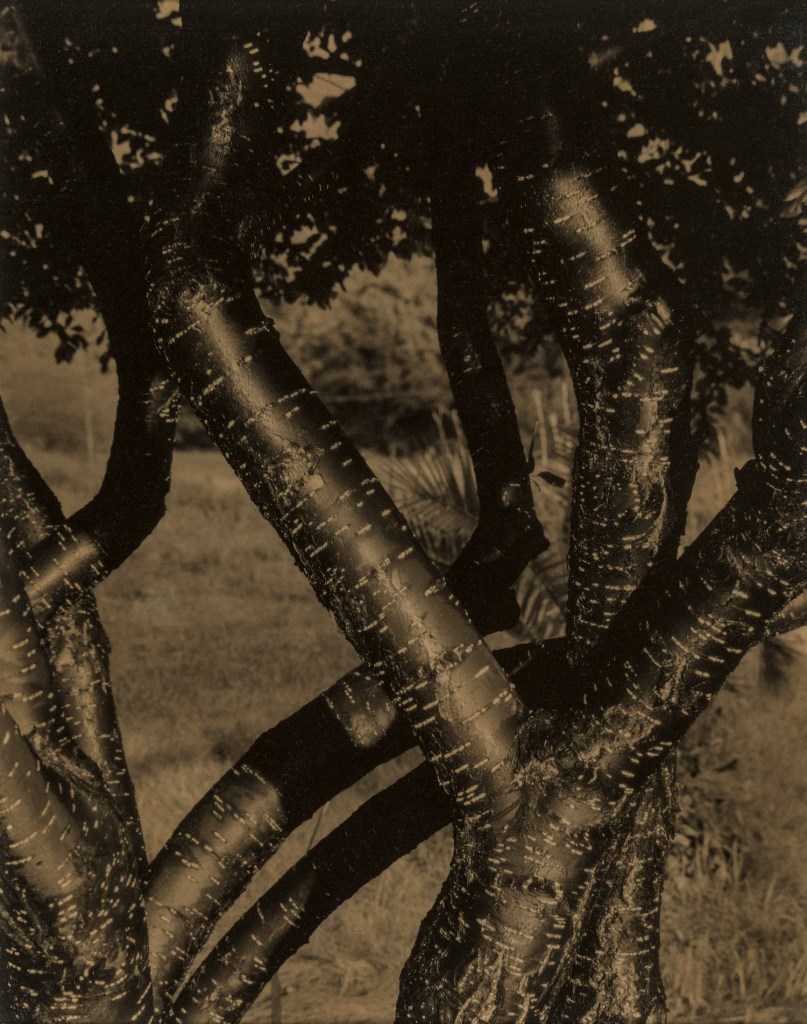

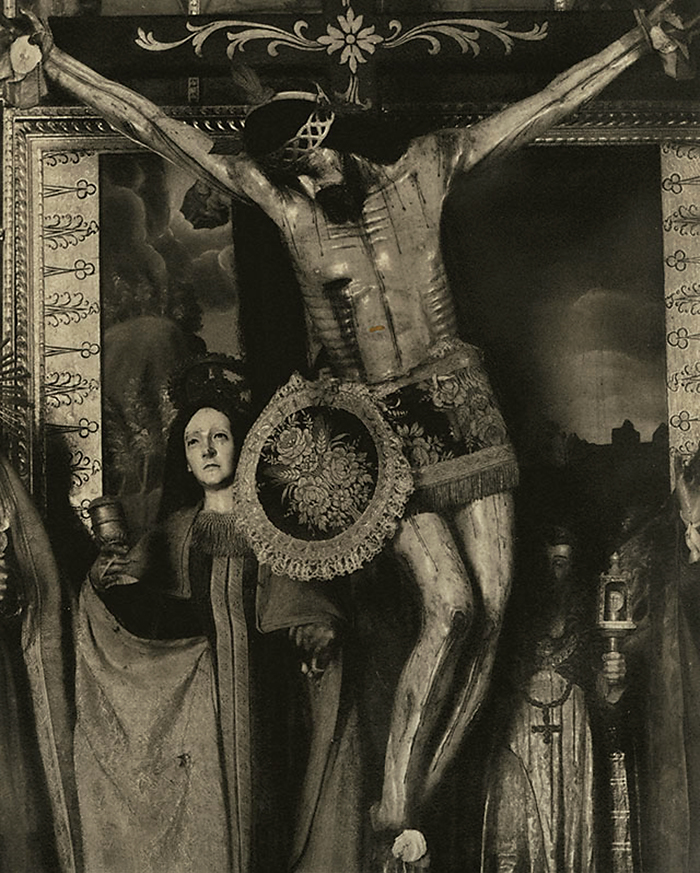

Manuel Alvarez Bravo (Mexican, 1902–2002)

The Daughter of the Dancers

1933

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of Howard Greenberg Collection

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Negro Church, South Carolina

1936

Gelatin silver print

© Library of Congress

Courtesy of Howard Greenberg Collection

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California

1936

Gelatin silver print

© Library of Congress

Courtesy of Howard Greenberg Collection

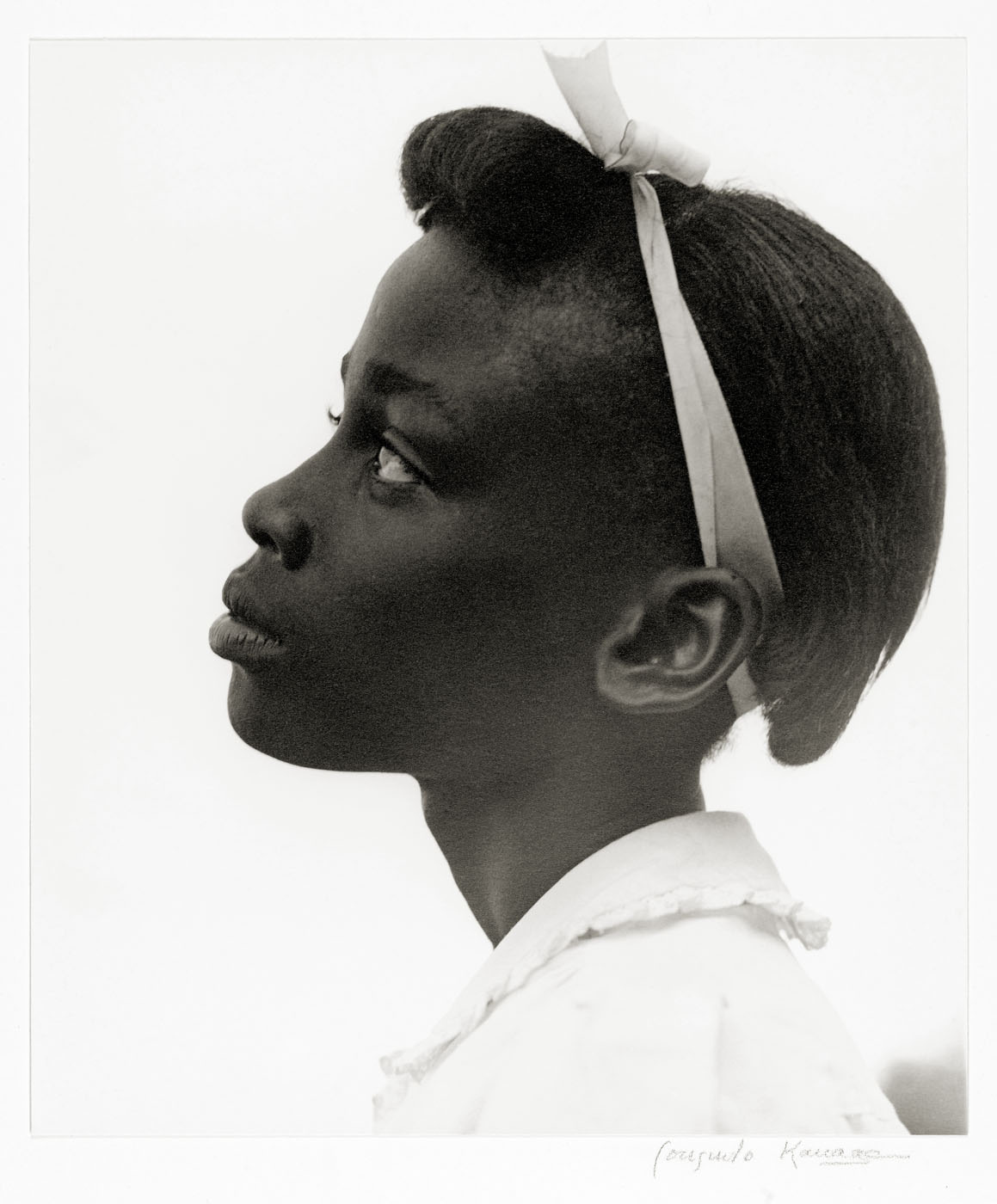

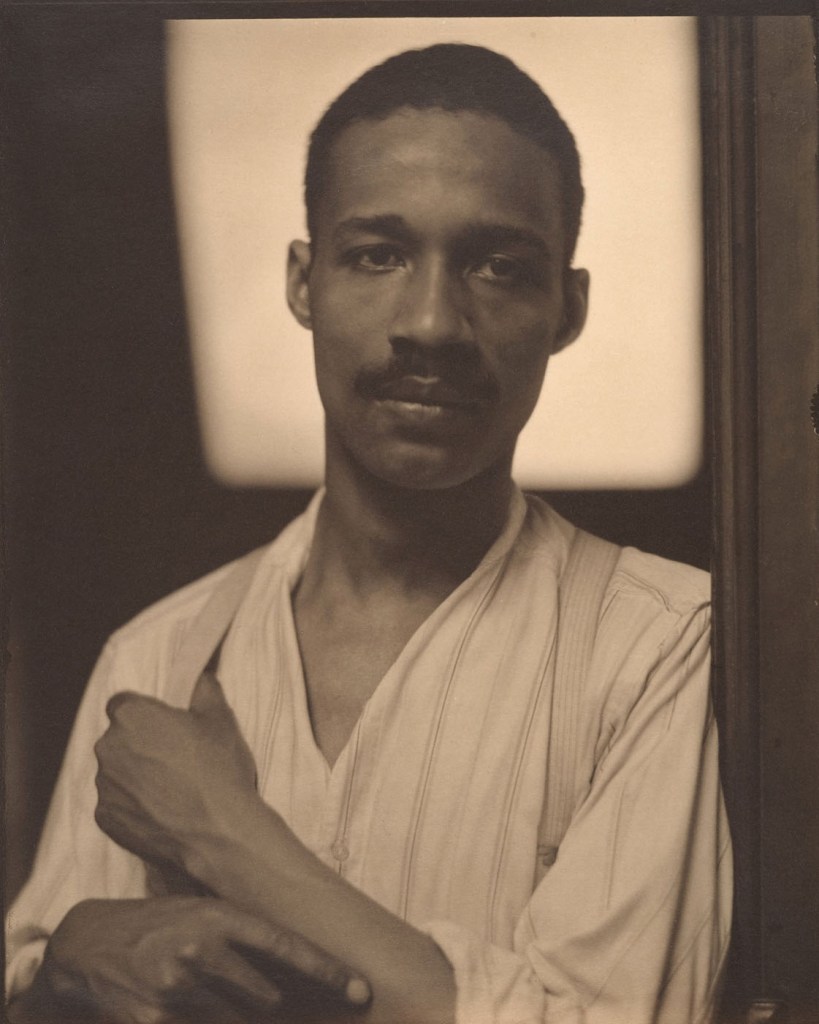

Consuelo Kanaga (American, 1894-1978)

Young Girl in Profile

1948

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of Howard Greenberg Collection

Leon Levinstein (American, 1910-1988)

Fifth Avenue

c. 1959

© Howard Greenberg Gallery

Courtesy of Howard Greenberg Collection

The Musée de l’Elysée presents different approaches to collecting photography by means of these original exhibitions.

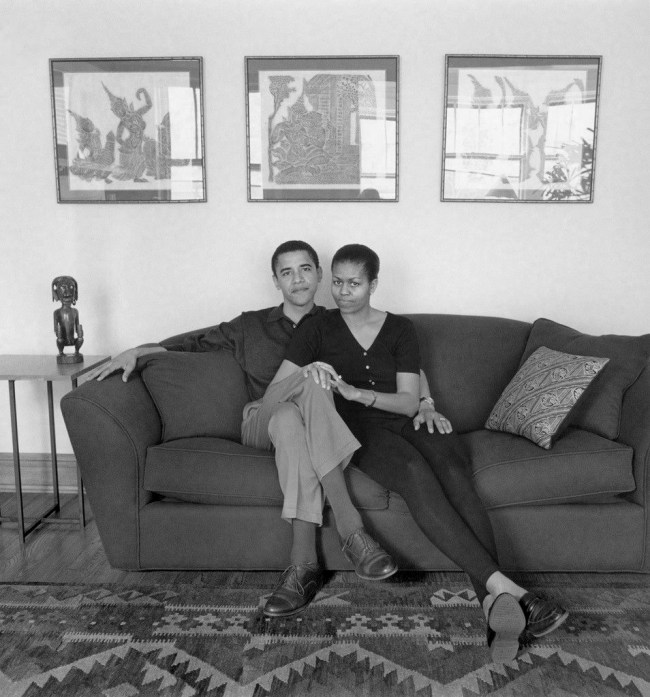

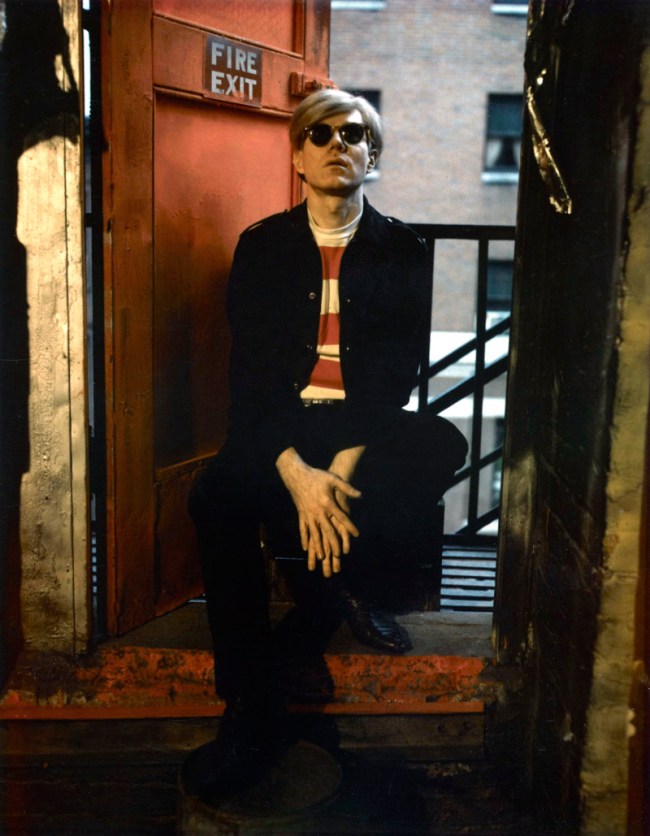

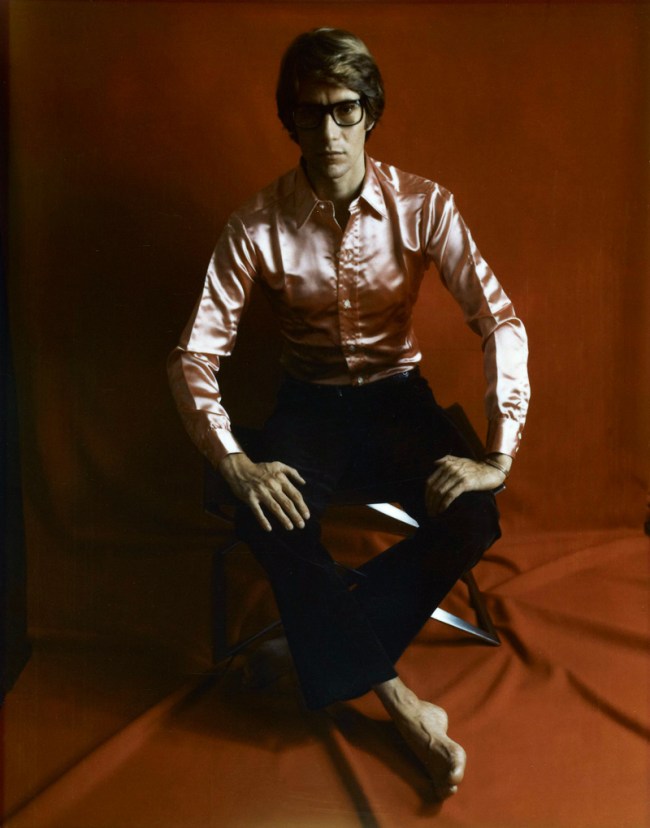

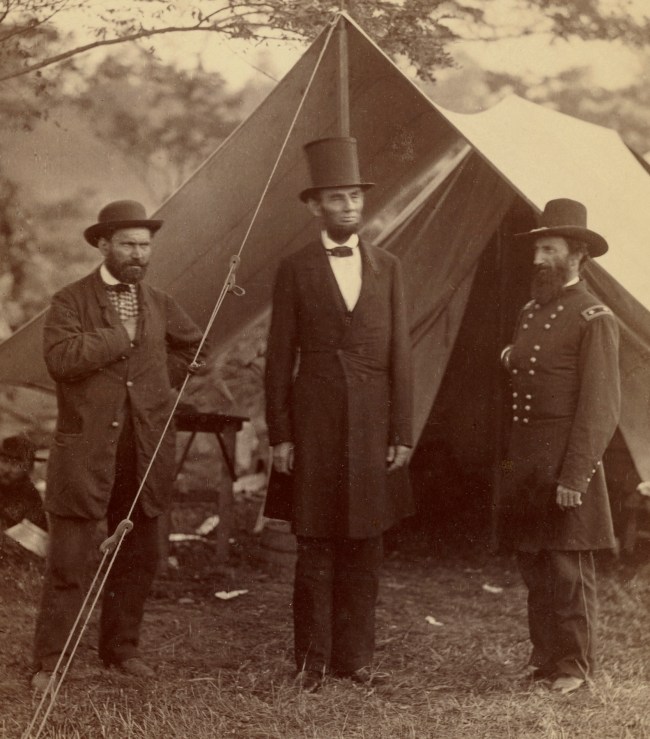

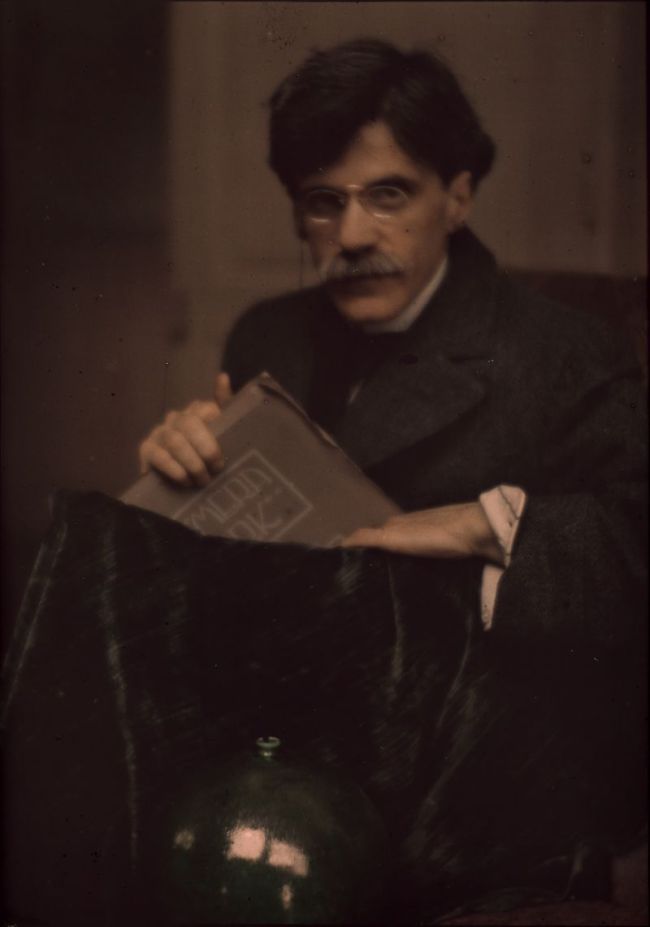

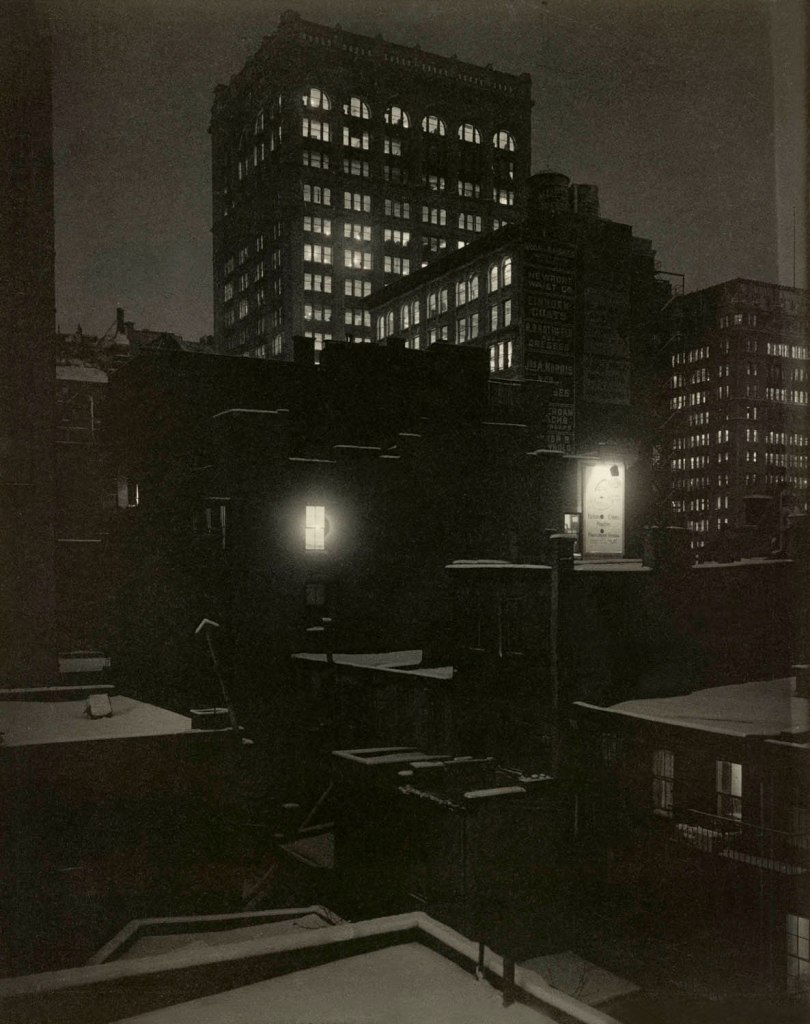

Howard Greenberg, Collection

Howard Greenberg has been a gallery owner for over thirty years and is considered today one of the pillars of the New York photography scene. While his position as a dealer is well established, little was known of his passion for collecting, presently revealed to the public for the first time. The primary reason to explain why it took so long to discover this collection is because building such a collection demands time. Only in time can the maturity of a collection be measured; the time necessary to smooth trends, confirm the rarity of a print, and in the end, validate the pertinence of a vision. In an era of immediacy, when new collectors exhibit unachieved projects or create their own foundation, great original collections are rare. Howard Greenberg’s is certainly one of the few still to be discovered.

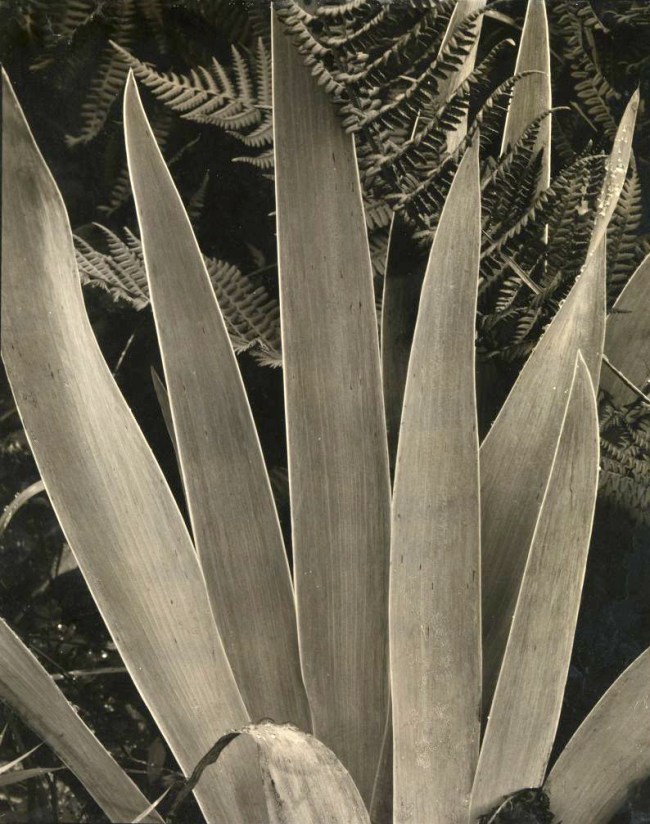

The quality of a collection does not rely on the sole accumulation of master pieces but can best be assessed through a dialectical movement: a collection is the collector’s oeuvre, a set of images operating a transformation in the perception not only of the photographs, but also of photography. This renewed perception is two-fold in the Greenberg collection; through the surprising combination of two approaches, the experimental practice of photography that questions the medium as such, bringing it to the limits of abstraction on one hand, and on the other, a documentary practice, carried out through its recording function of the real. This apparently irreconcilable duality takes on a particular signification in the Greenberg collection, an investigation of the possibilities offered by photography, a quest for photography itself, questioning what it is.

Howard Greenberg and his collection have largely contributed to the writing of a chapter of history. While contributing to the recognition of long neglected figures of the New York post-war photography scene, filling a gap, as gallery owner, Howard Greenberg, the collector, ensured the preservation of a coherent body by building over that period a unique collection of major photographs.

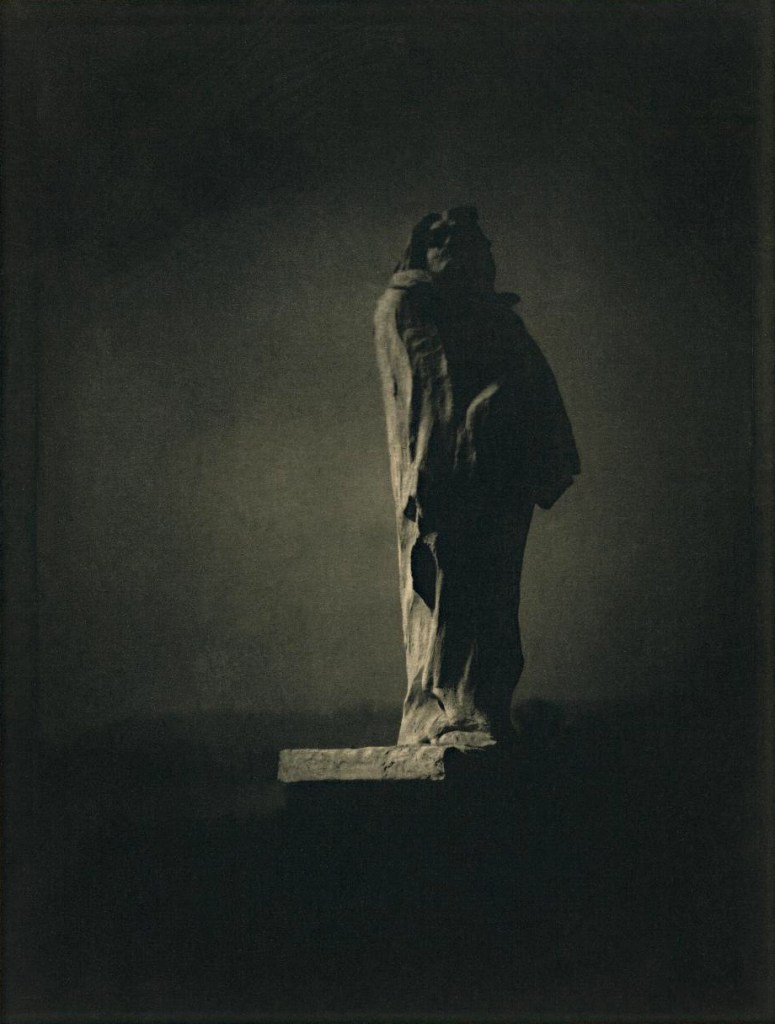

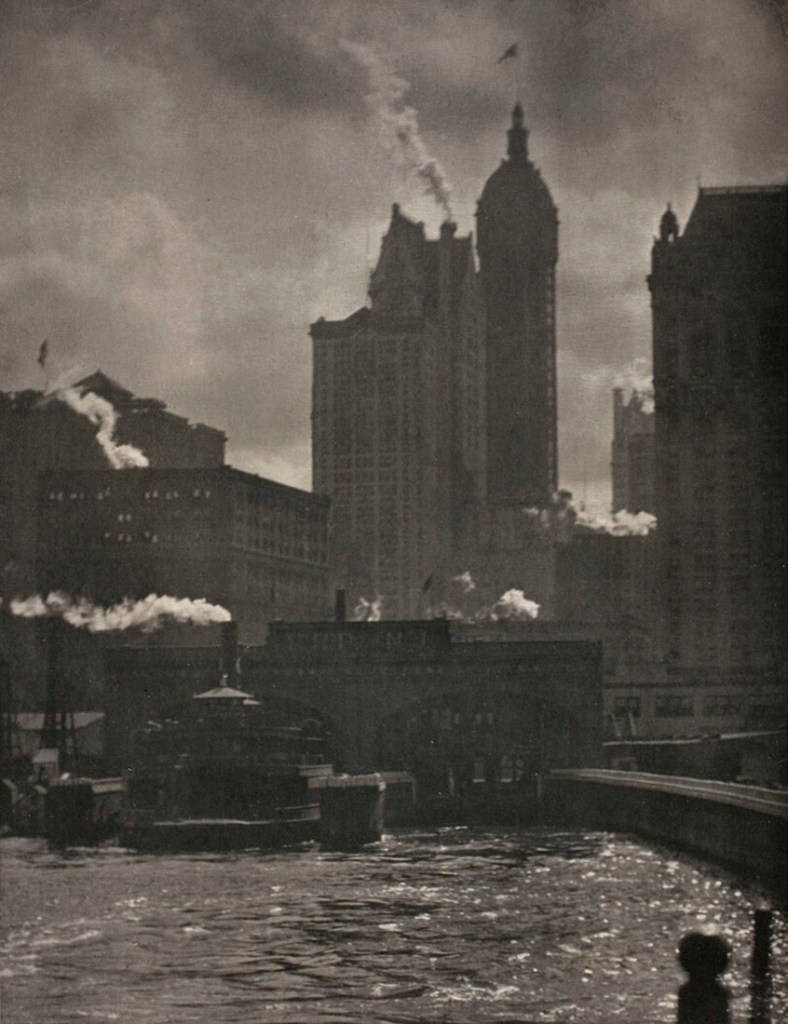

This collection of over 500 photographs was patiently built over the last thirty years and stands out for the high quality of its prints. A set of some 120 works are exhibited for the first time at the Musée de l’Elysée, revealing different aspects of Howard Greenberg’s interests, from the modernist aesthetics of the 20s and 30s, with works by Edward Steichen, Edward Weston or the Czech School, to contemporary photographers such as Minor White, Harry Callahan and Robert Frank. Humanist photography is particularly well represented, including among others, Lewis Hine and Henri Cartier-Bresson. An important section is dedicated to the Farm Security Administration’s photographers, such as Walker Evans or Dorothea Lange, witnesses to the Great Depression years of the 30s. Above all, the collection demonstrates the great influence of New York in the history of 20th century photography with the images of Berenice Abbott, Weegee, Leon Levinstein or Lee Friedlander conveying its architecture and urban lifestyle. Commending its work and prominent position, and wishing to make his private collection available to a large audience, Howard Greenberg selected the Musée de l’Elysée to host his collection.

The Musée de l’Elysée and the Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson jointly produce this exhibition which, after Lausanne, will subsequently be presented in Paris.

Press release from the Musée de l’Elysée website

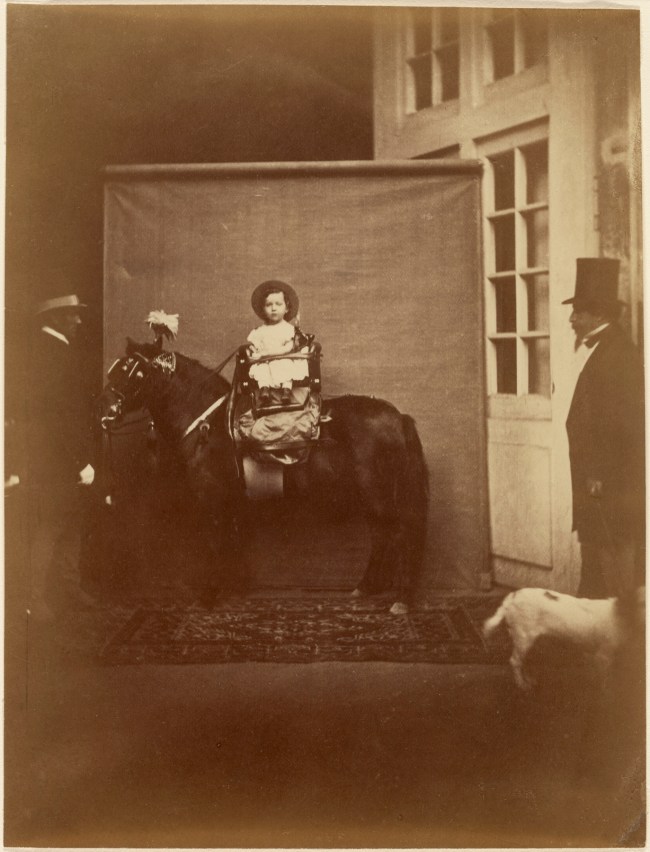

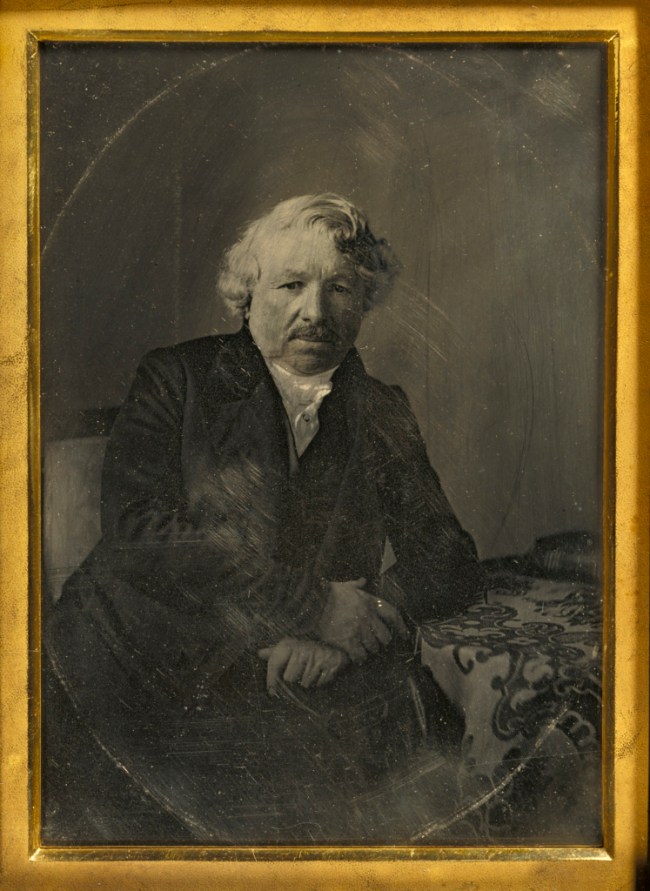

Freaks, The Monstrous Parade: Photographs from Enrico Praloran Collection

American director Tod Browning (1880-1962) has a particular attraction for the uncanny. Freaks, his cult movie shot in 1932, is inspired by a short story written by Clarence Aaron “Tod” Robbins. Set in a circus, the performers are disabled actors. The movie caused a scandal when it was released and Freaks was soon censored, reedited, shortened, sometimes removed from theatres, and in cases banned in some countries. Not until the 60s, when it was presented at the Cannes Festival, was the movie acclaimed to the point of becoming a reference for artists such as Diane Arbus or David Lynch.

The Musée de l’Elysée presents a selection of some fifty vintage black and white silver prints, gathered by Enrico Praloran, a collector based in Zurich. This unique set is the opportunity for an encounter with the movie’s strange protagonists, Johny Eck, the Half Boy, Daisy and Violet Hilton, the Siamese sisters, Martha Morris, the “Armless Marvel”, or the Bearded Lady and the Human Skeleton. They all are artists for real, coming from the Barnum Circus.

The plot is transcribed in images through stills from the movie’s major scenes, completed by set or shooting photographs, taking us behind the scenes, including on the footsteps of Tod Browning himself.

Press release from the Musée de l’Elysée website

Tod Browning (director)

Freaks (Cleopatra followed by the freaks)

1932

Still photograph

1932

Courtesy of Praloran Collection, Zurich

Tod Browning (director)

Freaks (Johnny Eck)

1932

Still photograph

Courtesy of Praloran Collection, Zurich

Tod Browning (director)

Freaks

1932

Still photograph

Courtesy of Praloran Collection, Zurich

Freaks centres on an enchanting performer, Cleopatra, who entices a “midget,” named Hans, into falling in love with her. They were called midgets then, now they are referred to as little people. The “midget” is in fact engaged to another woman who is incidentally, also a “midget,” named Freida. Cleopatra was at first only trying to fool around with Hans and get money from him occasionally. She soon realised that Hans had inherited quite a large amount of money. She devises a plan to marry Hans and later poison him to inherit the money. Arguably, the most famous scene in Freaks is Hans and Cleo’s wedding reception. The “freaks” reluctantly decide to accept her despite her “normality” and chant the notoriously disturbing yet hilarious quote, “We accept you, one of us! Gooble Gobble!” Afterwards, Hans then becomes very ill by Cleo’s hand. He soon figures out her plan and the freaks become offended. They knew she could not be one of them. The film ends with a horrific and disturbing chase in the rain where the “freaks” follow her slowly and Cleo screams for her life. Her and her lover, the “muscle man,” are caught and not killed, but worse. They become freaks themselves. They are mutilated, castrated, and deformed until they are the subject of a freak show. They became one of the “freaks” they hated so much…

One of the most gut-wrenching things about this films is the fact that every “freak” in the film was a real person with the same deformity their characters had. This gives the story a profound sense of reality, making the betrayal of Hans by Cleo all the more tragic. The film was extremely controversial when released and hated by audiences. The scenes where Cleo and the muscle man were mutilated had to be cut from the film in order to be shown in theatres. That footage has since been lost. In a viewing of the film, a sudden jump takes place after the freaks catch Cleo. The audience feels cheated. We have waited so long to see Cleo get her punishment. Part of that dissatisfaction adds to the mystique of this bizarre trip. The film was forgotten about until the mid 1970s where it was rediscovered as a counterculture cult film. A counterculture film runs counter to the the norm of society. Freaks is a great example of fame by taboos and controversy. It explores themes of humanity that are still relatively unexplored today.

Text from the Cult Films and Cultural Significance website December 6, 2011 [Online] Cited 14/09/2020

Freaks is a tale of love and vengeance in a traveling circus…

In her essay “Intolerable Ambiguity: Freaks as/at the Limit,” Elizabeth Grosz attempts to unpack our fascination with freak shows. She concludes that the individuals most frequently showcased in these spectacles, including Siamese twins, hermaphrodites, “pinheads” (microcephalics), midgets, and bearded ladies “imperil the very definitions we rely on to classify humans, identities and sexes – our most fundamental categories of self-definition and boundaries dividing self from otherness” (57). In other words, while we comfort ourselves by breaking down the world into neat binary oppositions, such as Male/Female, Self/Other, Human/Animal, Child/Adult, “freaks” blur the boundaries between these reassuring oppositions. She concludes, “The freak confirms the viewer as bounded, belonging to a ‘proper’ social category. The viewer’s horror lies in the recognition that this monstrous being is at the heart of his or her identity, for it is all that must be ejected or abjected from self-image to make the bounded, category-obeying self possible” (65). We need the freak to confirm our own static, bounded identities. And yet, I think there is a certain terror that we may not be as bounded as we think. If the hermaphrodite can transcend traditional gender categories, then perhaps our own genders are more fluid. For many that is a truly horrifying thought.

For example, in one of the film’s earliest scenes we witness the “pinheads” Schlitze, Elvira and Jenny Lee dancing and playing in the forest. From a distance they look like innocent, happy children. But as the camera approaches, it is clear that they are neither children, nor are they quite adults either. Thus it is the ambiguity here, rather than the disability itself, which is momentarily disturbing…

Grosz also mentions that “Any discussion of freaks brings back into focus a topic that has had a largely underground existence in contemporary cultural and intellectual life, partly because it is considered below the refined sensibilities of ‘good taste’ and ‘personal politeness’ in a civilised and politically correct milieu” (55).

Amanda Ann Klein. “Teaching Todd Browning’s FREAKS,” on the Judgemental Observer blog, September 13, 2009 update September 1, 2014 [Online] Cited 14/09/2020

~ Grosz, Elizabeth. “Intolerable Ambiguity: Freaks as/at the Limit,” in Rosemarie Garland Thomson (ed.). Freakery: Cultural Spectacles of the Extraordinary Body. New York: New York University Press, 1996, pp. 55-68

~ Hawkins, Joan. “‘One of Us’: Tod Browning’s Freaks,” in Rosemarie Garland Thomson (ed.). Freakery: Cultural Spectacles of the Extraordinary Body. New York: New York University Press, 1996, pp. 265-276

~ Norden, Martin F. The Cinema of Isolation: A History of Physical Disability in the Movies. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1994

Tod Browning (director)

Freaks (Cleopatra and freaks)

1932

Still photograph

Tod Browning (director)

Publicity photo for Freaks, featuring much of the cast with director, Tod Browning

1932

Still photograph

Tod Browning (director)

Freaks (with Siamese Twins Daisy and Violet Hilton)

1932

Still photograph

Tod Browning (director)

Freaks

1932

Still photograph

Tod Browning (director)

Freaks (shooting the wedding banquet)

1932

Still photograph

Tod Browning (director)

Freaks (with Cleopatra and Hans at the wedding banquet)

1932

Still photograph

Tod Browning (director)

Freaks (Olga Baclanova as Cleopatra after her transformation into chicken woman)

1932

Still photograph

Theatrical poster for Freaks

1932

God’s Children

In this scene from Freaks (1932, Tod Browning), we meet several of the film’s characters.

The Freaks Revenge

In this scene from Freaks (1932, Tod Browning), the freaks take their revenge on Hercules and Cleopatra.

The Musée de l’Elysée

18, avenue de l’Elysée

CH – 1014 Lausanne

Phone: + 41 21 316 99 11

Opening hours:

Wednesday – Monday 10am – 6pm

Closed Tuesdays

![Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946) '[Self-Portrait]' Negative 1907; print 1930 Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946) '[Self-Portrait]' Negative 1907; print 1930](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/stieglitz-self-portrait-1907.jpg?w=650&h=872)

![Sarah Choate Sears (American, 1858-1935) '[Julia Ward Howe]' about 1890 Sarah Choate Sears (American, 1858-1935) '[Julia Ward Howe]' about 1890](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/sears-julia-ward-howe.jpg?w=650&h=825)

![Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) '[Sarah Bernhardt as the Empress Theodora in Sardou's "Theodora"]' Negative 1884; print and mount about 1889 Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) '[Sarah Bernhardt as the Empress Theodora in Sardou's "Theodora"]' Negative 1884; print and mount about 1889](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/nadar-sarah-bernhardt.jpg?w=650&h=994)

![Charles DeForest Fredricks (American, 1823-1894) '[Mlle Pepita]' 1863 Charles DeForest Fredricks (American, 1823-1894) '[Mlle Pepita]' 1863](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/fredricks-mlle-pepita.jpg?w=650&h=1046)

![André Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri (French, 1819-1889) '[Rosa Bonheur]' 1861-1864 André Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri (French, 1819-1889) '[Rosa Bonheur]' 1861-1864](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/disdecc81ri-rosa-bonheur.jpg?w=650&h=1062)

![John Robert Parsons (British, about 1826-1909) '[Portrait of Jane Morris (Mrs. William Morris)]' Negative July 1865; print after 1900 John Robert Parsons (British, about 1826-1909) '[Portrait of Jane Morris (Mrs. William Morris)]' Negative July 1865; print after 1900](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/parsons-portrait-of-jane-morris.jpg?w=650&h=779)

![Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'George Sand (Amandine-Aurore-Lucile Dupin), Writer' c. 1865 Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'George Sand (Amandine-Aurore-Lucile Dupin), Writer' c. 1865](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/realideal5-web.jpg?w=650&h=854)

![Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'Alexander Dumas [père] (1802-1870) / Alexandre Dumas' 1855 Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'Alexander Dumas [père] (1802-1870) / Alexandre Dumas' 1855](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/nadar_alexander_dumas.jpg?w=650&h=803)

You must be logged in to post a comment.