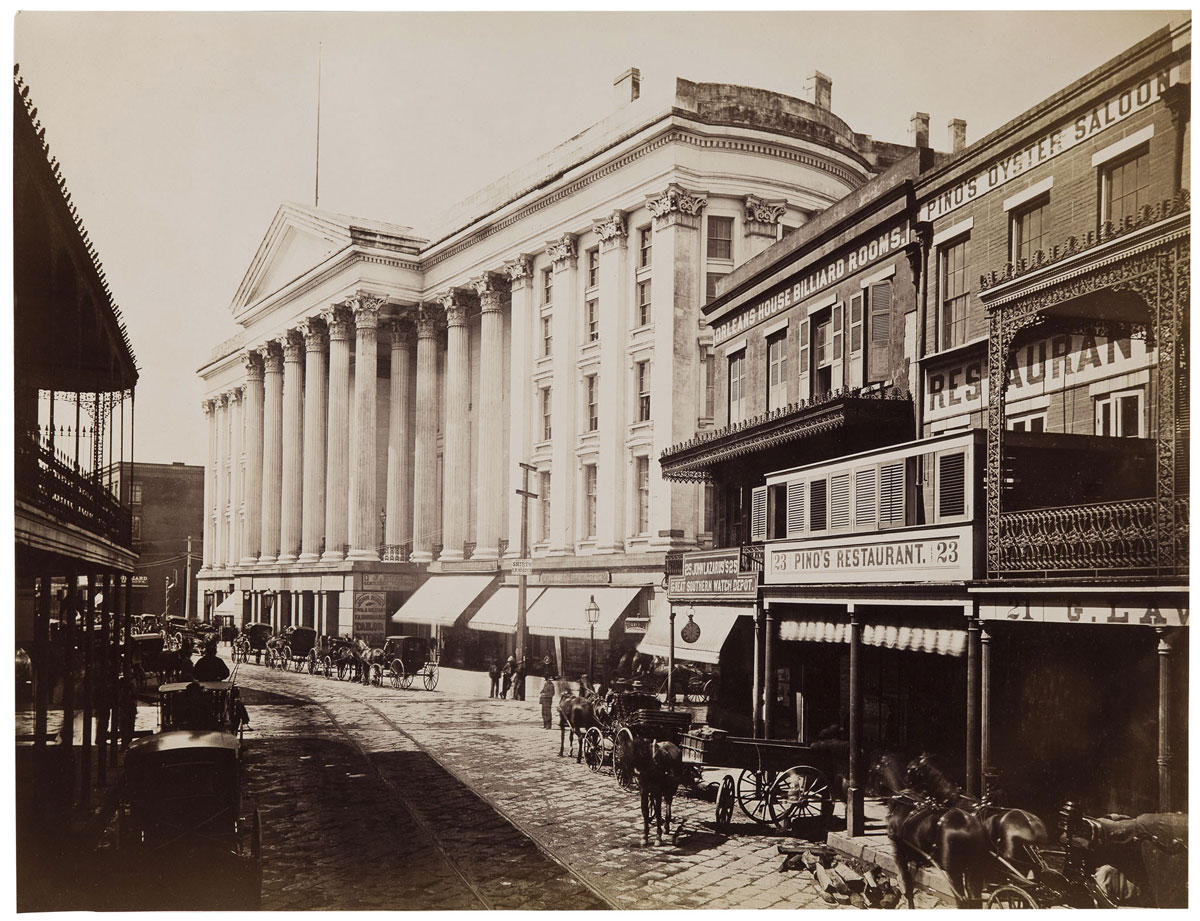

Exhibition dates: 9th November 2013 – 1st June 2014

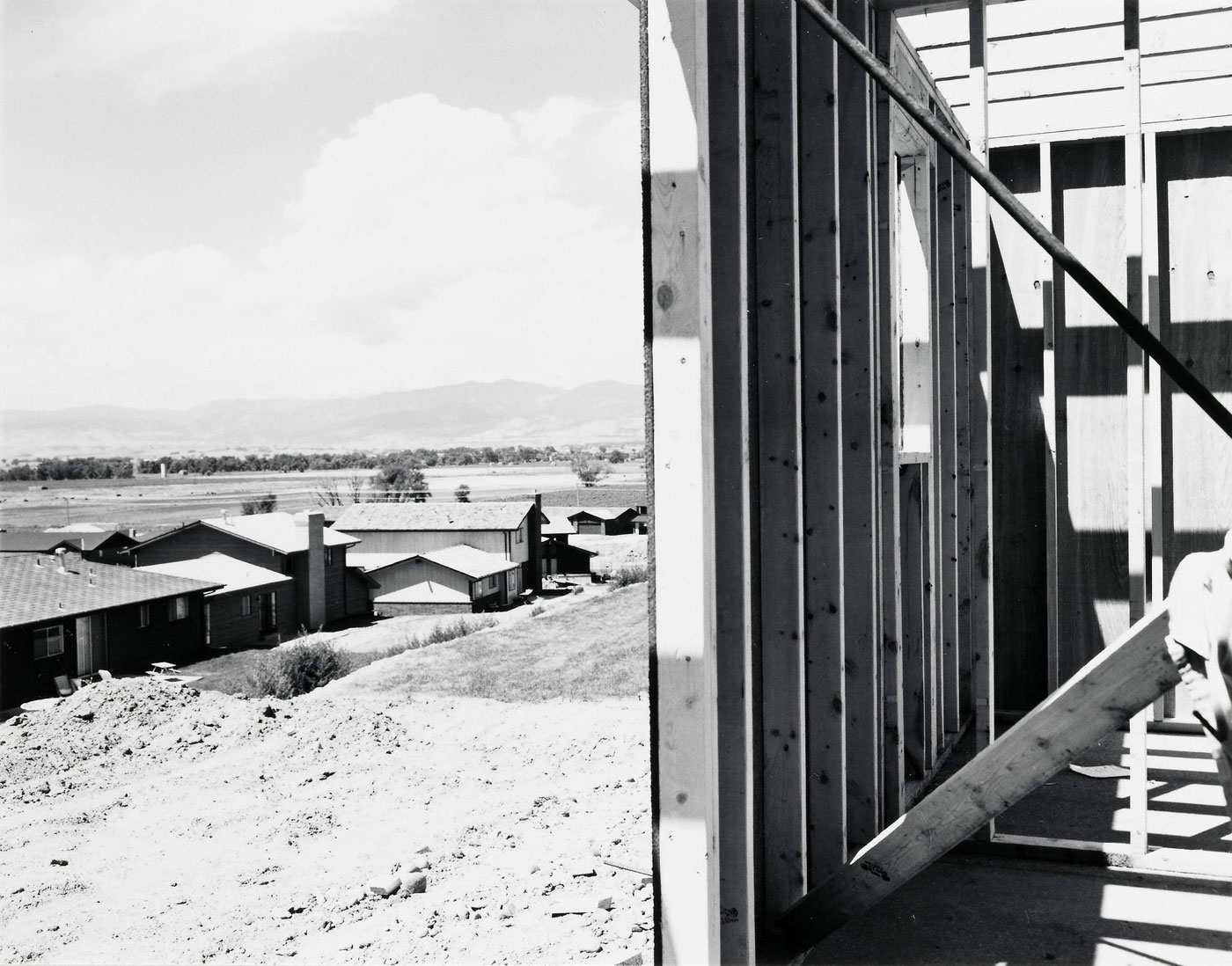

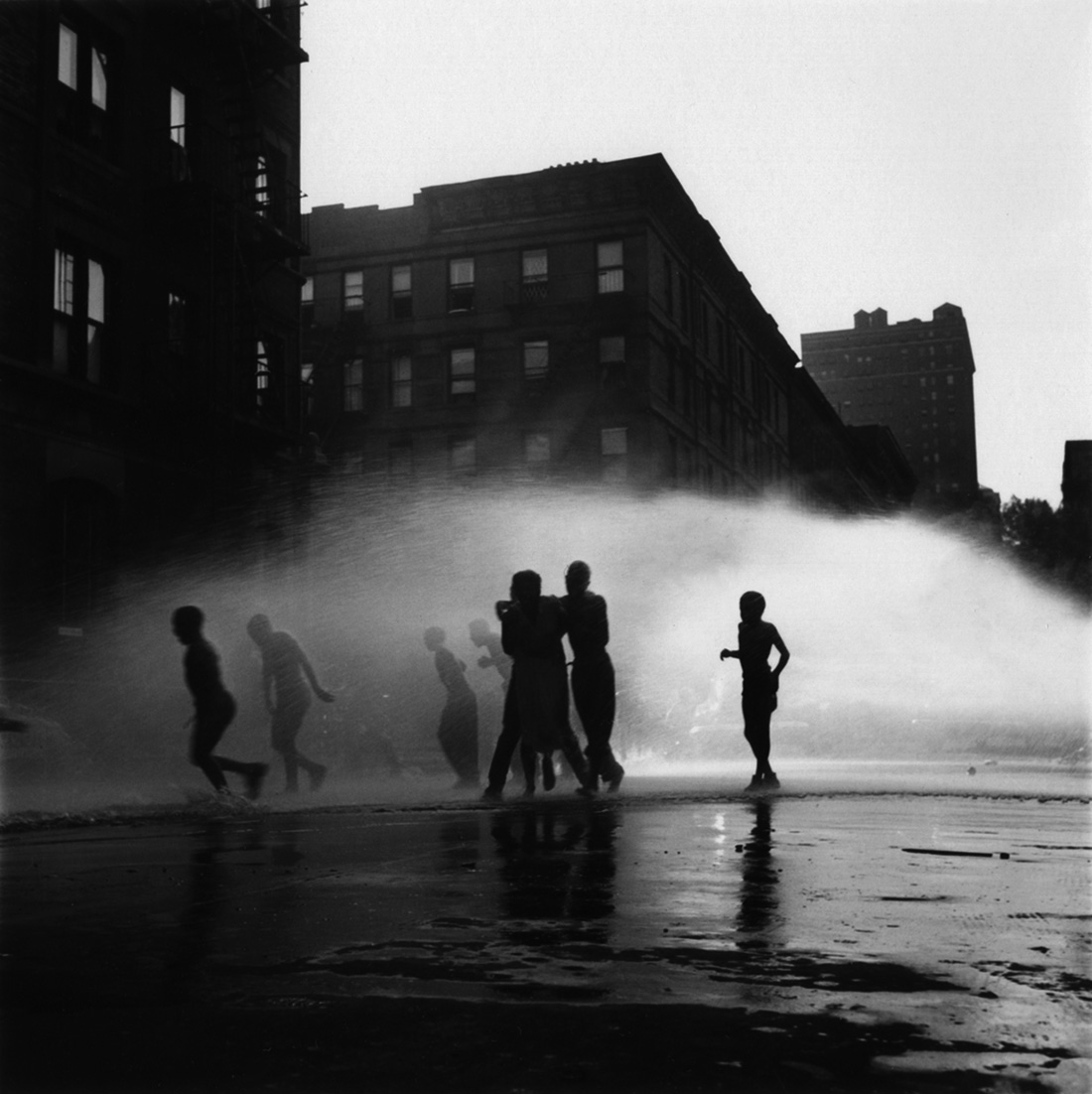

Vivian Maier (American, 1926-2009)

Untitled

1954

© Vivian Maier / Maloof Collection, Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

“Maier doesn’t have a partner to dance with. She sees something well enough, whereas Lee Friedlander expects something. If there is an idea out there in the ether she grabs onto it in a slightly derivative way. Maier states that these things happened with this subject matter but with Arbus, for example, she meets something extra/ordinary and alien – and goes beyond, beyond, beyond.”

Dr Marcus Bunyan May 2014

The next best thing

The photographs of Vivian Maier. Unknown in her lifetime (nanny as secretive photographer), her negatives discovered at an auction after her death – some developed, all scanned, in some cases cropped, the medium format images then printed. The latest “must have” for any self respecting photography collection, be it private or public. But are they really that good?

To be unequivocal about it, they are good – but, in most cases, they are not “great”. Maier is a very good photographer but she will never be a great photographer. This might come as a surprise to the legions of fans on Facebook (and the thousands of ‘Likes’ for each image), those who think that she is the best thing since sliced bread. But let’s look at the evidence – the work itself.

The photographs can seen on the Vivian Maier Official website and I have spent quite a lot of time looking at them. As with any artist, there are some strong images and some not so strong ones but few reach ‘master’ status. The lighting is good, the use of low depth of field, the location and the presence of the people she photographed are all there, as are the influences that you recite in your mind as to the people her photographs remind you of: Lewis Hine, Berenice Abbott, Lisette Model, Diane Arbus, Helen Levitt, Lee Friedlander et al. Somehow through all this she makes the photographs she takes her own for she has a “rare sense of photographic vision” as Edward Petrosky expressed it on my LinkedIn page, but ultimately they don’t really take you anywhere. It’s like she has an addiction to taking photographs (a la Gary Winogrand), but no way of advancing her art to the next level.

Vivien Maier’s photographs stand out because she hasn’t withheld enough within them. What do I mean by that? Let’s look at some examples to explain what I mean…

Included in the postings are two comparisons: Vivian Maier, June 19, 1961, Chicago IL, 1961 / Lee Friedlander, Stony Point, New York, 1966; and Vivian Maier, New York, Nd 1966 / Berenice Abbott, New York at Night, 1932. As with most of Maier’s photography, she relies on intuition when taking a photograph and a bloody good intuition it is too. This intuition usually stands her in good stead and she almost always gets the shot, but there is an underlying lack of structure to her images. Here I am talking as much about psychological structure as physical structure, for both go hand in hand.

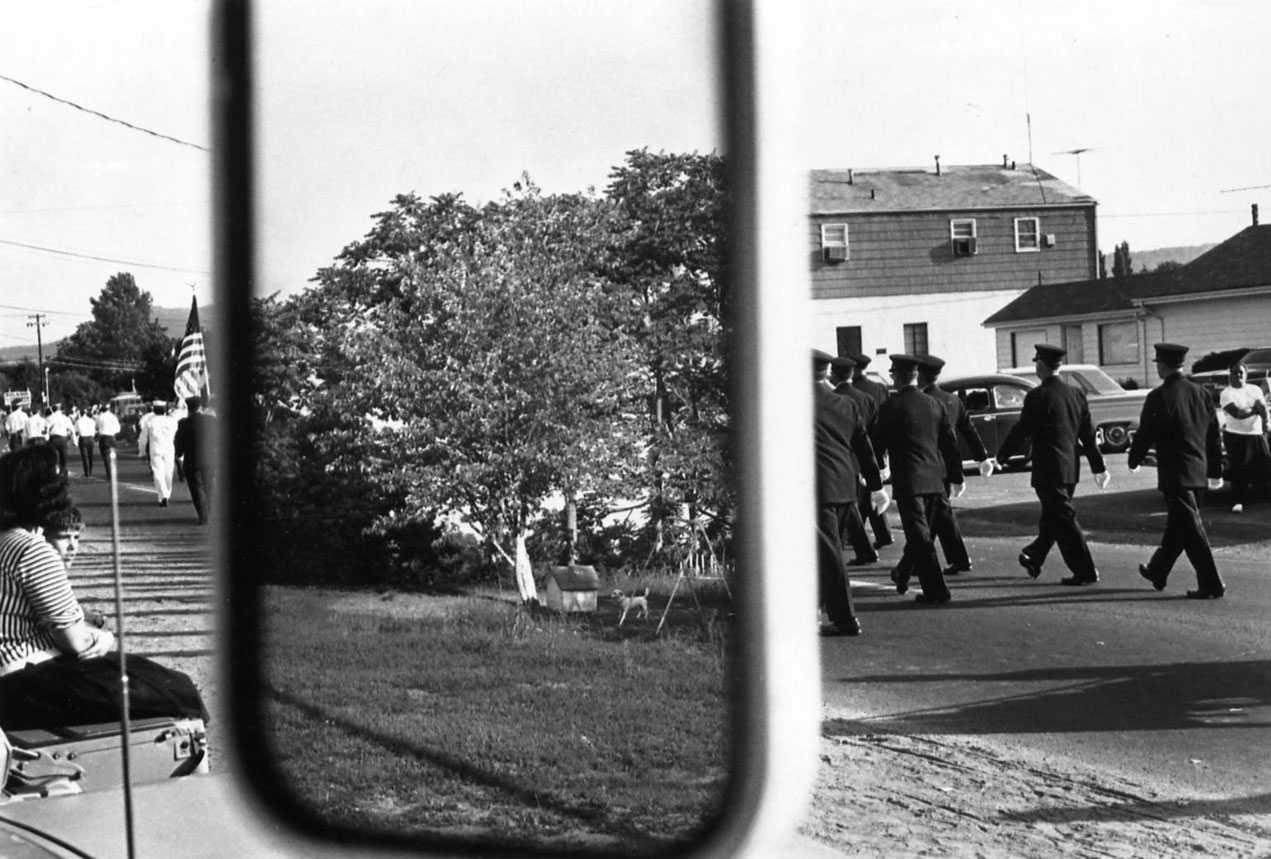

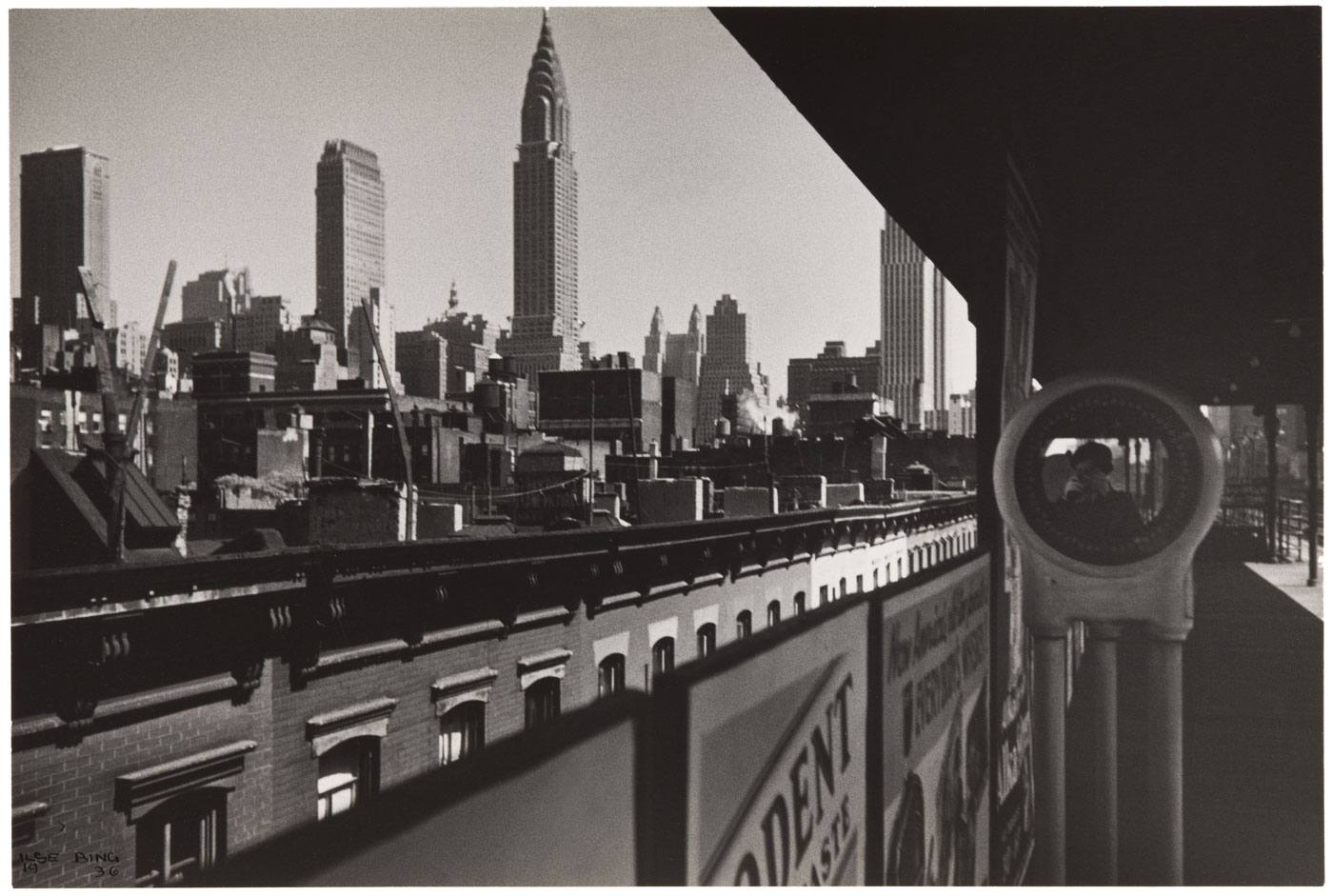

If we compare the Maier with the Friedlander we can say that, if we look at the windows in the Friedlander, every one is a masterpiece! From the mother and son at left with the white-coated marchers, to the central window with the miniature house, dog and tree, to the dark-suited marchers at right. Everything feels compelling, intricate weavings of a narrative that the viewer has to try and make sense of. Each part of the Friedlander image is absolutely necessary for that picture… whereas there are so many things in the Vivien Maier that belong in other pictures ie. a good picture but a lot that doesn’t belong in that picture. Things that should have been held back, by making another image somewhere else. Her narrative is confusing and thus the eye is also confused.

A similar scenario can be observed when comparing the photographs of New York at night by Abbott and Maier. Abbott’s photograph is a tight, orchestrated and muscular rendition of the city which seethes with energy and form. Maier’s interpretation fades off into nothingness, the main arterials of the city leading the eye up to the horizon line and then [nothing]. It is a pleasant but wishy-washy photograph, with all the energy of the city draining away in the mind and in the eye.

One of Maier’s photographs that most resonates with me is September 1953, New York, NY (1953, below). This IS a masterpiece. There is a conciseness of vision here, reminiscent of Weston’s Nude of 1938 with its link to the anamorphic structure of his photographs of peppers. There is nothing auxiliary to the purpose of the photograph, yet there is that indefinable something that takes it out of itself. The dirt of the clothes, under the fingers, the ring on the hand, the shape that no human should be in and its descent onto the pavement, the despair of that descent captured in the angle of the camera looking down on the victim. The photograph has empathy, promotes understanding and empathy in the viewer. Most of us have been there. Other photographs that approach a higher perspective are Maier’s self-portraits, in which there is a conscious exploration of her reflection in/of the world: a slightly dour, serious figure reflected back from the world into the lens of the camera – a refracted identity, the phenomenon of self as light passing obliquely through the interface between one medium and another, between living, the camera and memory.

But too often Maier’s photographs are just so… obvious. Did she wait long enough for the composition to reveal itself to her more, god what’s the word, more ambiguously. Maier doesn’t have a partner to dance with. She sees something well enough, whereas Lee Friedlander expects something. If there is an idea out there in the ether she grabs onto it in a slightly derivative way. Maier states that these things happened with this subject matter but with Arbus, for example, she meets something extra/ordinary and alien – and goes beyond, beyond, beyond.

What we can say is that Maier’s vision is very good, her intuition excellent, but there is, critically, not that indefinable something that takes her images from good to great. This is the key thing – everything is usually thrown at the image, she withholds nothing, and this invariably stops them taking that step to the next level. This is a mighty difficult step for any artist to take, let alone one taking photographs in the shadows. Personally I don’t believe that these images are a “photographic revelation” in the spirit of Minor White. What is a revelation is how eagerly they have been embraced around the world as great images without people really looking deeply at the work; how masterfully they have been promoted through films, books, websites and exhibitions; how Maier’s privacy has been expunged in the quest for dollars; and how we know very little about her vision for the negatives as there are no extant prints of the work.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Château de Tours for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Edward Weston (American, 1886-1958)

Nude

1936

Gelatin silver print

Vivian Maier (American, 1926-2009)

September 1953, New York, NY

1953

© Vivian Maier / Maloof Collection, Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

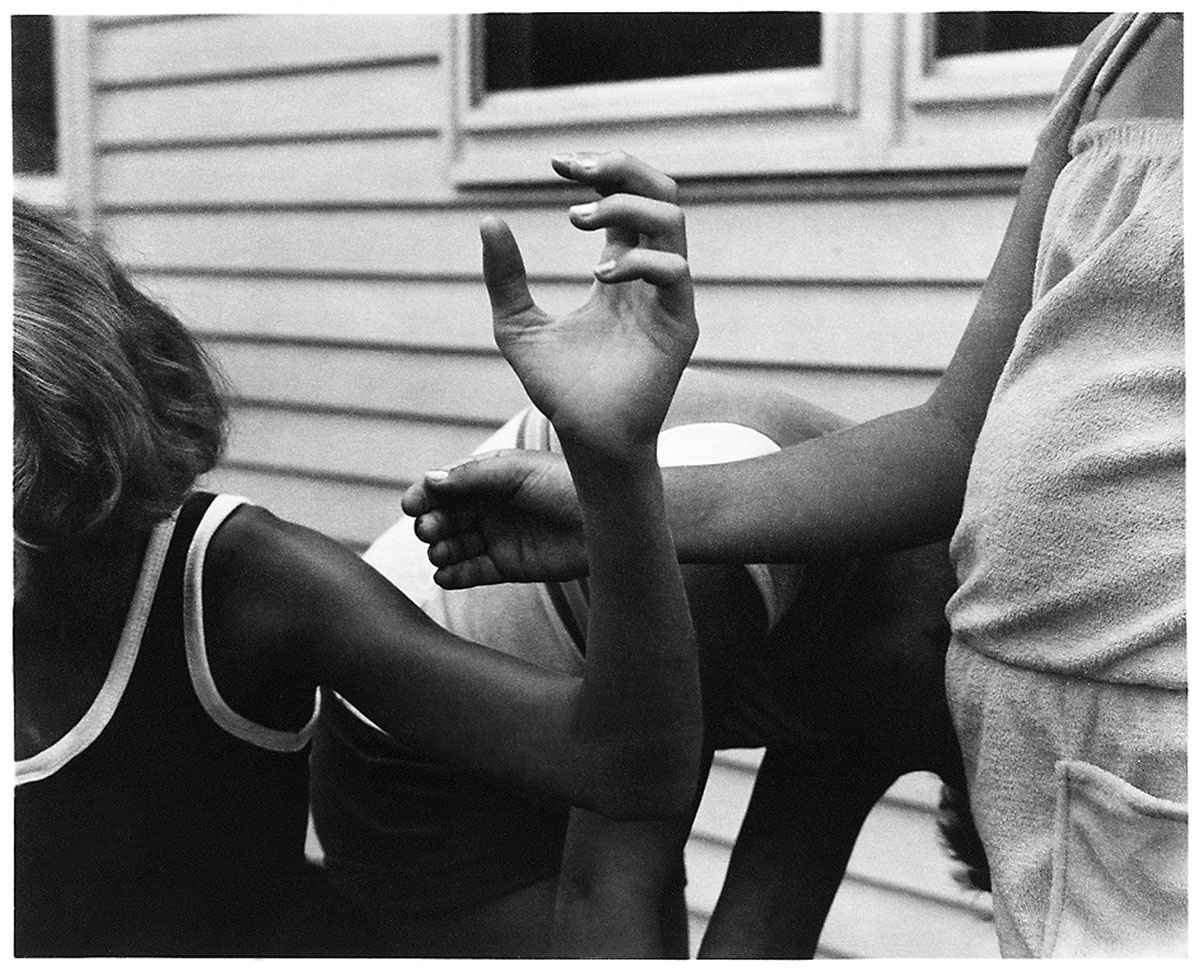

Vivian Maier (American, 1926-2009)

June 19, 1961, Chicago IL

1961

© Vivian Maier / Maloof Collection, Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

Lee Friedlander (American, b. 1934)

Stony Point, New York, 1966

1966

Silver gelatin photograph

Vivian Maier (American, 1926-2009)

New York

Nd

© Vivian Maier / Maloof Collection, Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

Berenice Abbott (American, 1898-1991)

New York at Night

1932

Gelatin silver print

12 7/8 x 10 9/16″ (32.7 x 26.9cm)

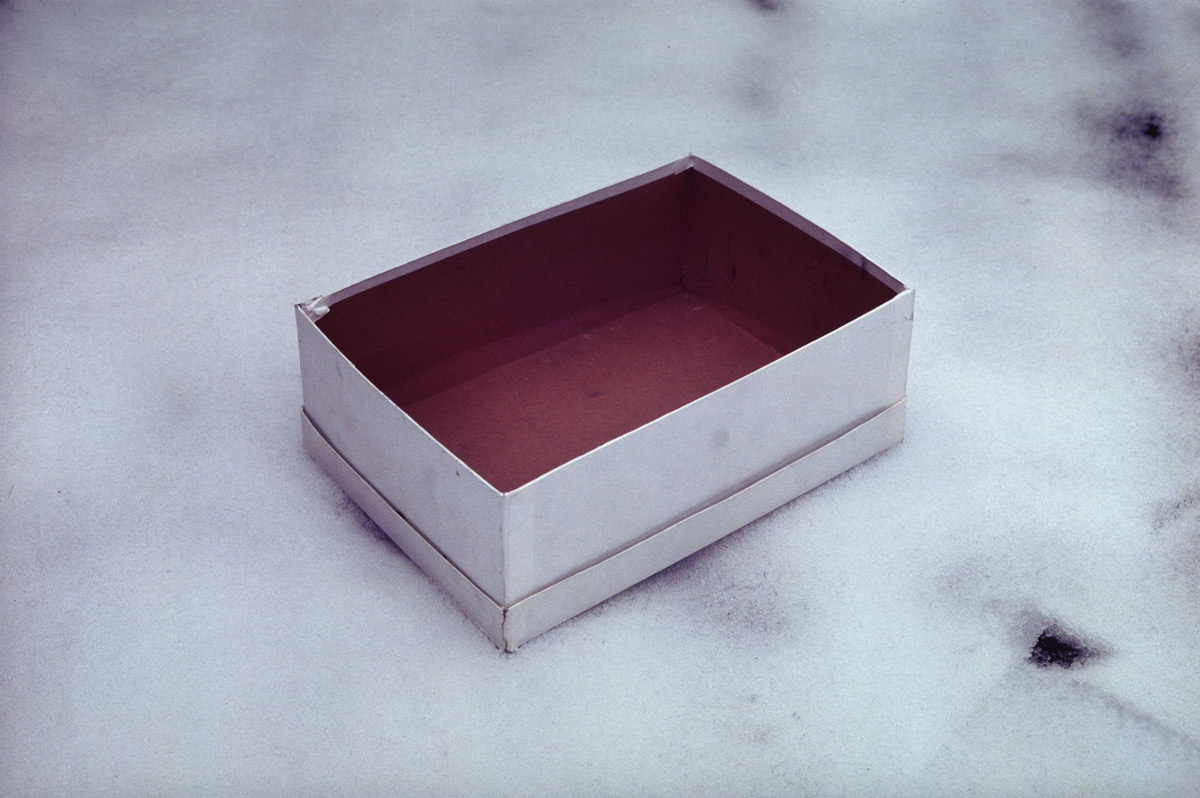

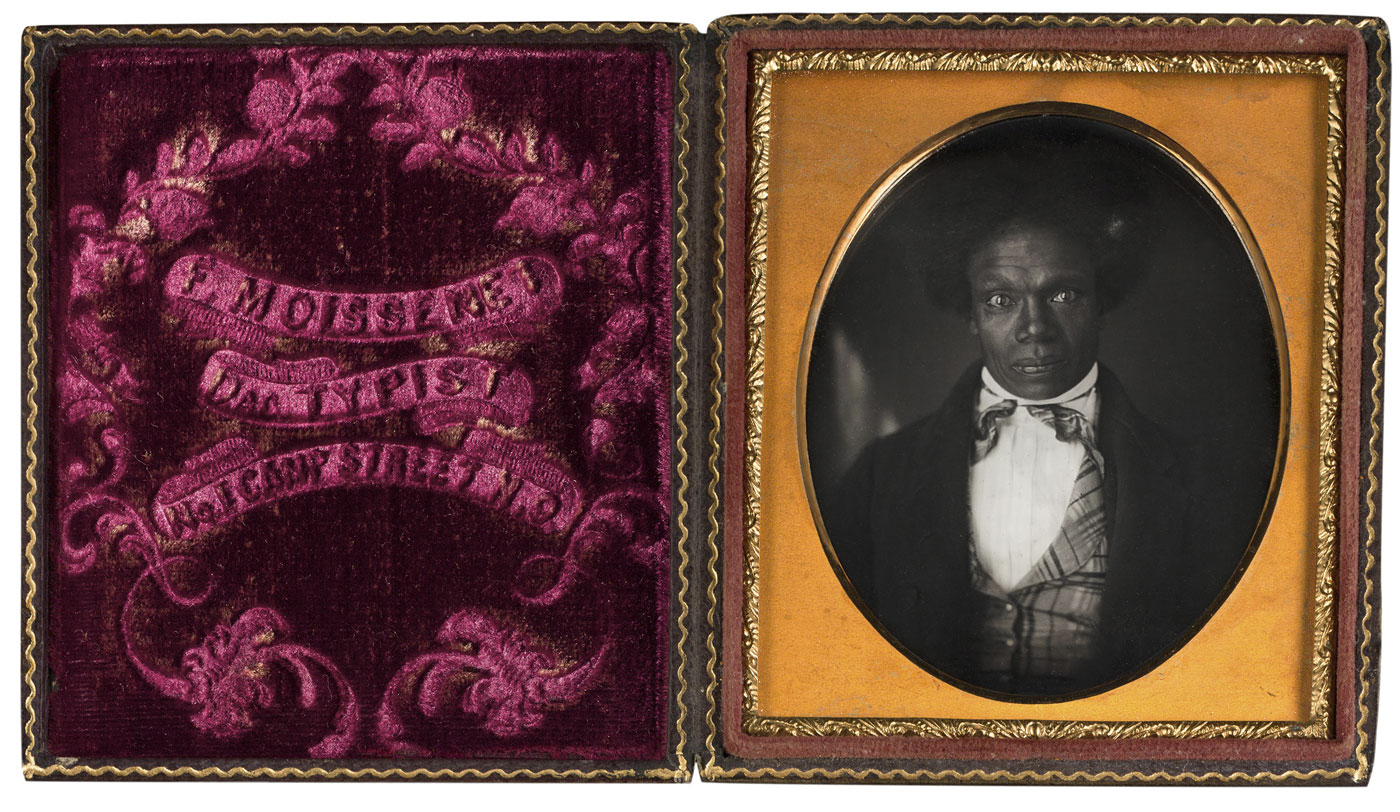

Vivian Maier (American, 1926-2009)

New York, NY, 18 Octobre 1953

1953

© Vivian Maier / Maloof Collection, Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

Vivian Maier (American, 1926-2009)

New York, NY

c. 1953

© Vivian Maier / Maloof Collection, Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

Vivian Maier (American, 1926-2009)

St East nº108, New York , NY, September 28, 1959

1959

© Vivian Maier / Maloof Collection, Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

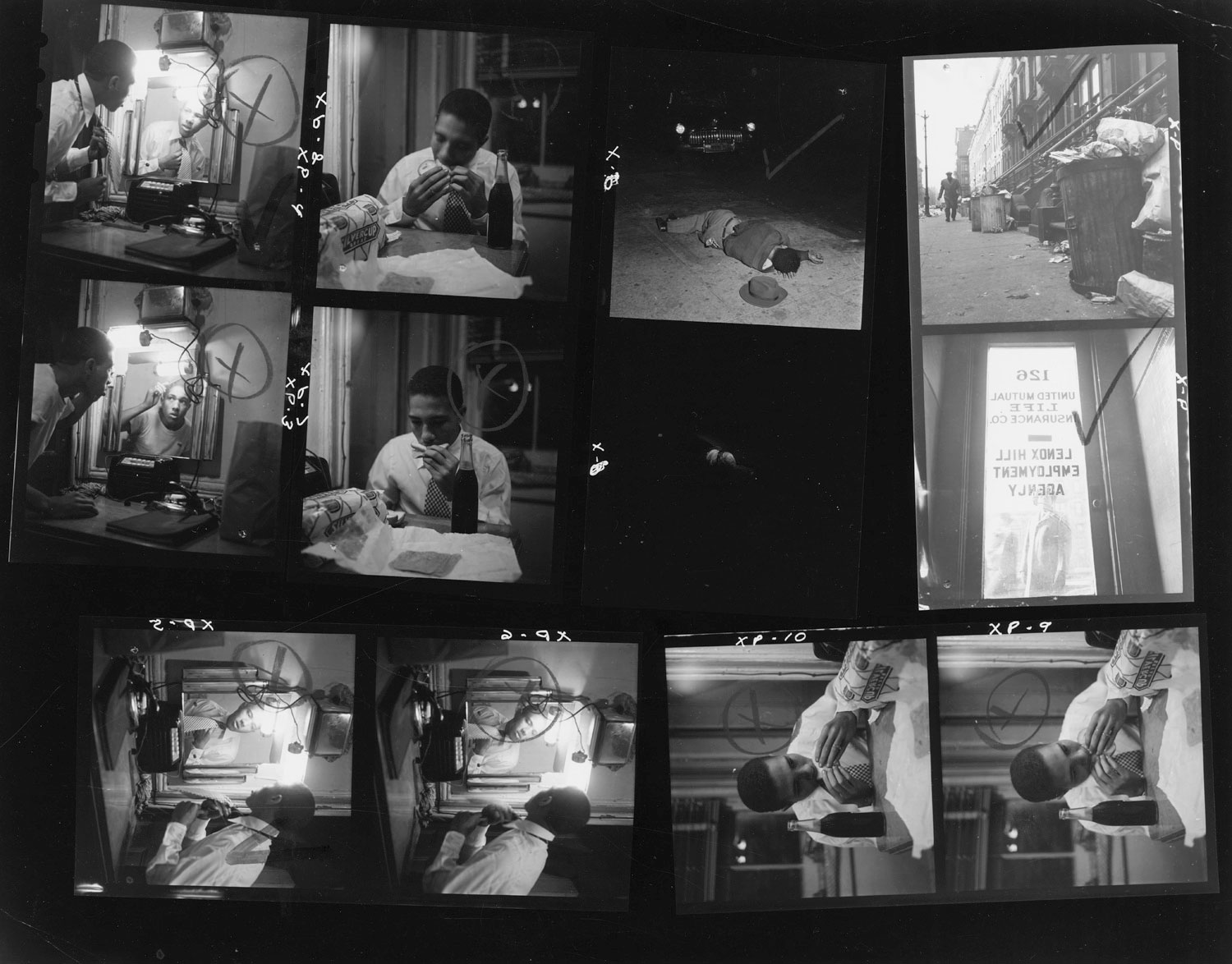

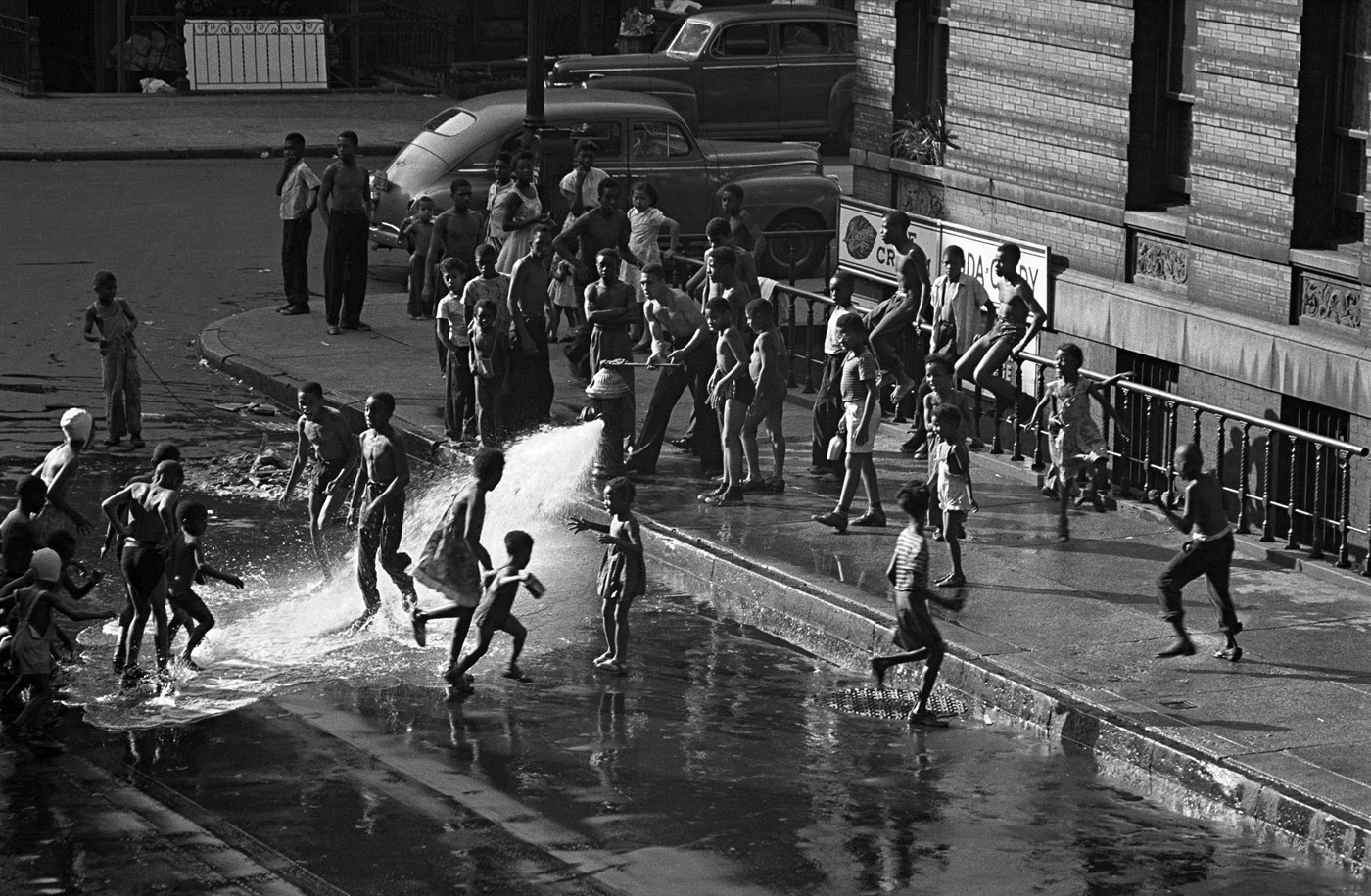

Vivian Maier (American, 1926-2009)

New York, NY

1954

© Vivian Maier / Maloof Collection, Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

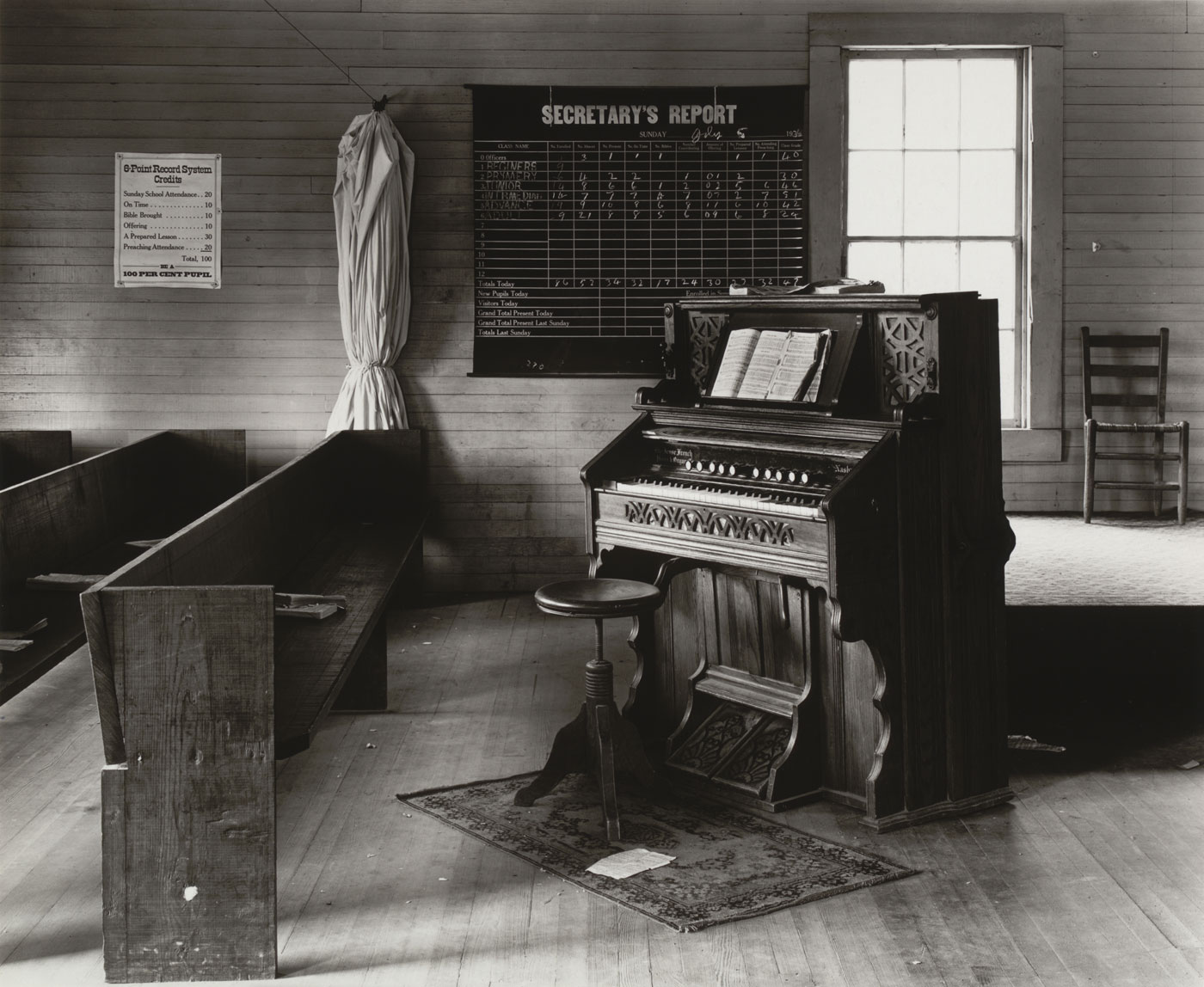

Vivian Maier was the archetypal self-taught photographer with a keen sense of observation and an eye for composition. She was born in New York in 1926, but spent part of her childhood in France before returning to New York in 1951 when she started taking photos. In 1956, she moved to Chicago, where she lived until her death in 2009.

Her talent is comparable with that of the major figures of American street photography such as Lisette Model, Helen Levitt, Diane Arbus and Garry Winogrand. The exhibition presented at the Château de Tours by the Jeu de Paume, in partnership with the Municipality of Tours and diChroma photography, is the largest ever exhibition in France devoted to Vivian Maier. It includes 120 black and white and colour gelatin silver prints from the original slides and negatives, as well as extracts from Super 8 films she made in the 60s and 70s. This project, which is sourced from John Maloof’s collection, with the valuable assistance of Howard Greenberg Gallery in New York, reveals a poetic vision that is imbued with humanity.

John Maloof discovered Vivian Maier’s astonishing photos completely by chance in 2007 at an auction in Chicago. At the time, this young collector was looking for historical documentation about a specific neighbourhood of the city and he bought a sizeable lot of prints, negatives and slides (of which a major part had not even been developed) as well as some Super 8 films by an unknown and enigmatic photographer, Vivian Maier. By all accounts, Vivian Maier was a discreet person and somewhat of a loner. She took more than 120,000 photos over a period of thirty years and only showed this consequential body of work to a mere handful of people during her lifetime.

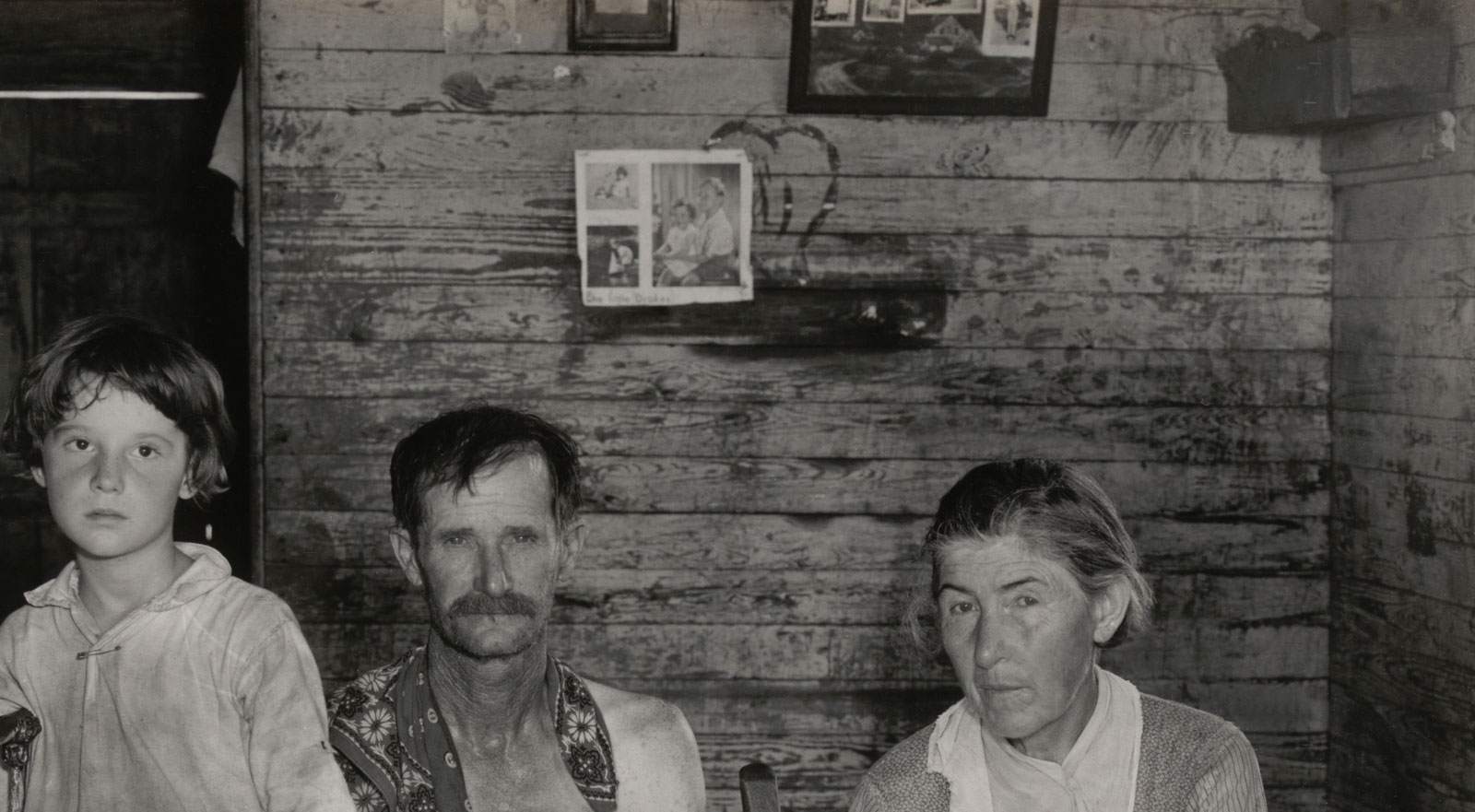

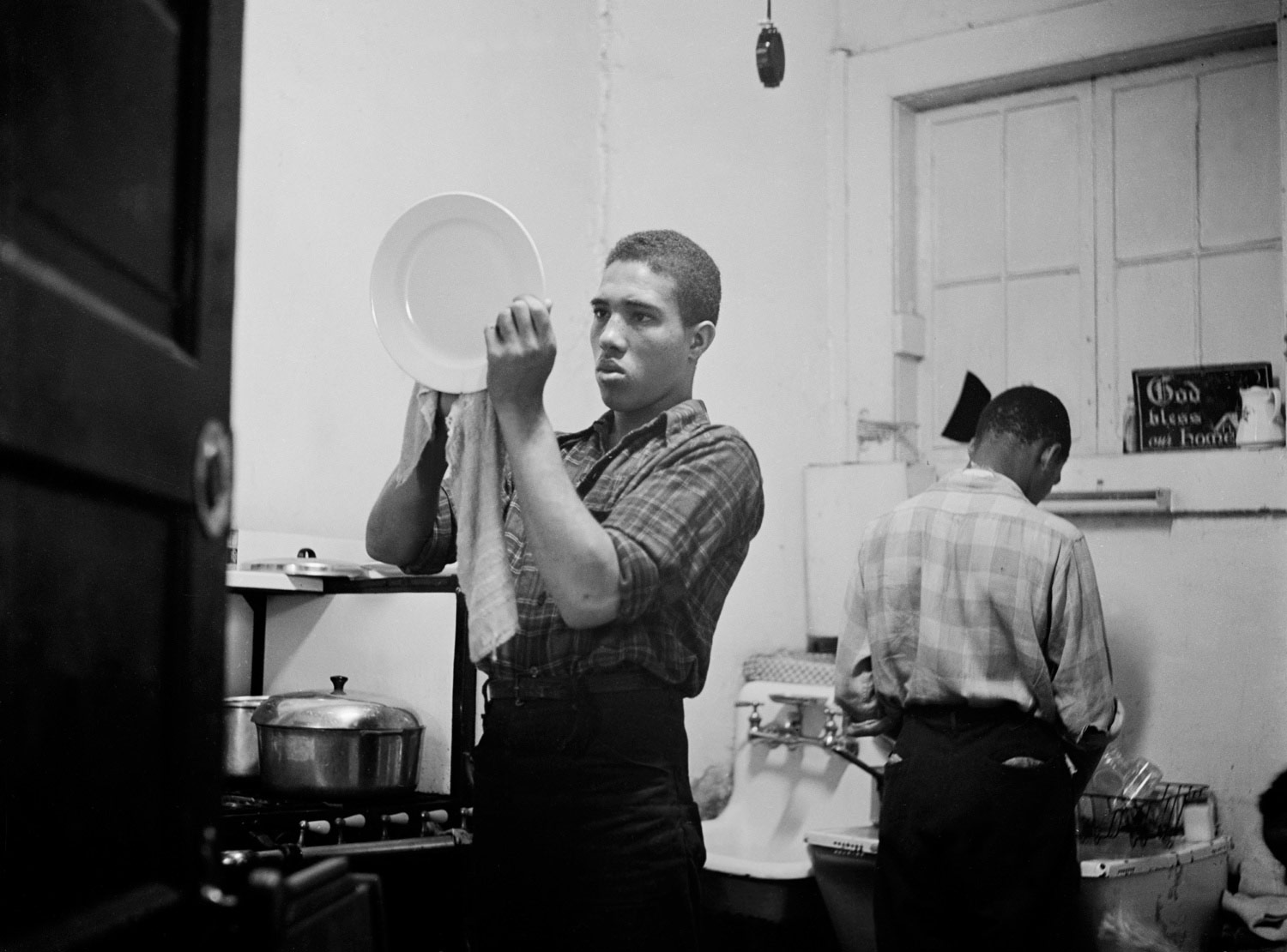

Vivian Maier earned her living as a governess, but all her free time and every day off was spent walking through the streets of New York, then later Chicago, with a camera slung around her neck (first of all box or folding cameras, later a Leica) taking photos. The children she looked after describe her as a cultivated and open-minded woman, generous but not very warm. Her images on the other hand bear witness to her curiosity for everyday life and the attention she paid to those passers – by who caught her eye: facial features, bearing, outfits and fashion accessories for the well-to-do and the telltale signs of poverty for those who were less fortunate.

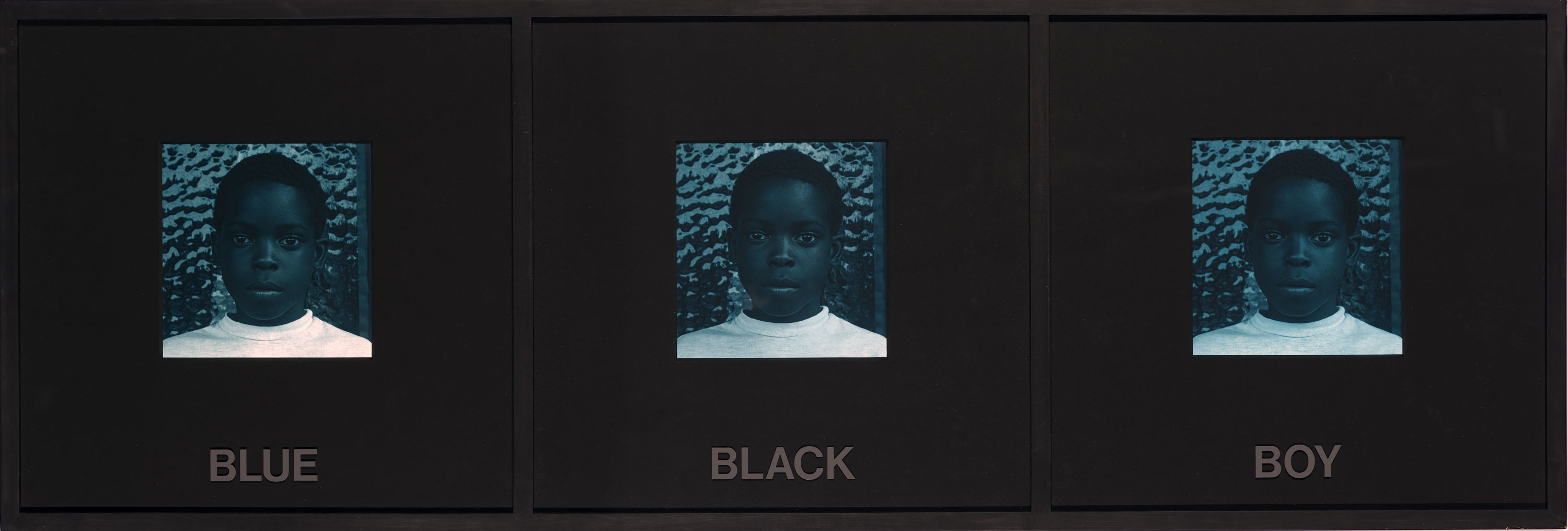

While some photos are obviously furtively taken snapshots, others bear witness to a real encounter between the photographer and her models, who are photographed face-on and from close up. Her photos of homeless people and people living on the fringe of society demonstrate the depth of her empathy as she painted a somewhat disturbing portrait of an America whose economic boom was leaving many by the wayside.

Vivian Maier remained totally unknown until her death in April 2009. She had been taken in by the Gensburgs, for whom she had worked for almost seventeen years, and many of her possessions as well as her entire photographic output had been placed in storage. It was seized and sold in 2007 to settle unpaid bills.

Her biography has now been reconstructed, at least in part, thanks to a wealth of research and interviews carried out by John Maloof and Jeffrey Goldstein after the death of Vivian Maier. Jeffrey Goldstein is another collector who purchased a large part of her work. According to official documents, Vivian Maier was of Austro-Hungarian and French origin and her various trips to Europe, in particular to France (in the Alpine valley of Champsaur where she spent part of her childhood) have been clearly identified and documented. However, the circumstances that led her to take an interest in photography and her life as an artist remain veiled in mystery.

Photography seemed to be much more than a passion: her photographic activity was the result of a deeply felt need, almost an obsession. Each time she changed employers and had to move house, all her boxes and boxes of films (that she hadn’t had developed for want of money), as well as her archives comprising books and press cuttings about various stories in the news, came along too.

Vivian Maier’s body of work highlights those seemingly insignificant details that she came across during her long walks through the city streets: odd gestures, strange figures and graphic arrangements of figures in space. She also produced a series of captivating self-portraits from her reflection in mirrors and shop windows.

Press release from the Château de Tours

Vivian Maier (American, 1926-2009)

Self-portrait

Nd

© Vivian Maier / Maloof Collection, Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

Vivian Maier (American, 1926-2009)

Chicago

Nd

© Vivian Maier / Maloof Collection, Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

Vivian Maier (American, 1926-2009)

Florida, 9 January 1957

1957

© Vivian Maier / Maloof Collection, Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

Vivian Maier (American, 1926-2009)

Untitled

1954

© Vivian Maier / Maloof Collection, Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

Vivian Maier (American, 1926-2009)

Chicago, IL, January, 1956

1956

© Vivian Maier/Maloof Collection, Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

Vivian Maier (American, 1926-2009)

Chicago, August 22, 1956

1956

© Vivian Maier/Maloof Collection, Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

Château de Tours

25 Avenue André Malraux

37000 Tours

Opening hours:

Tuesday to Friday: 2pm – 6pm

Saturday and Sunday: 3pm – 6pm

![Eugène Atget (French, Libourne 1857-1927 Paris) 'Untitled [Atget's Work Room with Contact Printing Frames]' c. 1910 Eugène Atget (French, Libourne 1857-1927 Paris) 'Untitled [Atget's Work Room with Contact Printing Frames]' c. 1910](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/atgets-work-room-web1.jpg?w=650&h=783)

![Eugène Atget (French, Libourne 1857–1927 Paris) 'Untitled [Atget's Work Room with Contact Printing Frames]' c. 1910 (detail) Eugène Atget (French, Libourne 1857–1927 Paris) 'Untitled [Atget's Work Room with Contact Printing Frames]' c. 1910 (detail)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/atget-workroom-detail-web.jpg)

![Marie-Charles-Isidore Choiselat (French, 1815-1858) Stanislas Ratel (French, 1824-1904) 'Untitled [The Pavillon de Flore and the Tuileries Gardens]' 1849 Marie-Charles-Isidore Choiselat (French, 1815-1858) Stanislas Ratel (French, 1824-1904) 'Untitled [The Pavillon de Flore and the Tuileries Gardens]' 1849](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/the-pavillon-de-flore-web.jpg)

![Edward J. Steichen (American born Luxembourg, Bivange 1879 - 1973 West Redding, Connecticut) 'Untitled [Brancusi's Studio]' c. 1920 Edward J. Steichen (American born Luxembourg, Bivange 1879 - 1973 West Redding, Connecticut) 'Untitled [Brancusi's Studio]' c. 1920](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/edward_steichen_brancusis_studio_1920-web.jpg?w=650&h=816)

![Lewis Hine (American, 1874-1940) '[Mechanic and Steam Pump]' c. 1930 Lewis Hine (American, 1874-1940) '[Mechanic and Steam Pump]' c. 1930](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/79-84-hine-web.jpg?w=650&h=892)

![Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[Air vents, New York]' 1945 Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[Air vents, New York]' 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/air-vents-web.jpg?w=650&h=502)

![Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[42nd Street at First Avenue, New York]' c. 1945 Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[42nd Street at First Avenue, New York]' c. 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/42nd-street-at-first-avenue-web.jpg?w=650&h=512)

![Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[Oceano Dunes, California]' 1934 Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[Oceano Dunes, California]' 1934](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/oceano-dunes-california-web.jpg?w=650&h=509)

![Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[Stoop with broom, arrow, and pushcart, New York]' 1944 Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[Stoop with broom, arrow, and pushcart, New York]' 1944](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/stoop-with-broom-web.jpg?w=650&h=495)

![Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[Airshafts, New York]' c. 1945 Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[Airshafts, New York]' c. 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/airshafts-web.jpg)

![Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[Courtyard, New York]' c. 1945 Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[Courtyard, New York]' c. 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/courtyard-web.jpg)

![Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[House, Ewing Street, Staten Island, New York]' c. 1945 Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[House, Ewing Street, Staten Island, New York]' c. 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/house-ewing-street-web.jpg?w=547&h=677)

![Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[Sutton Place, New York]' c. 1945 Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[Sutton Place, New York]' c. 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/sutton-place-web.jpg)

![Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[Skylight and fences, Midtown, New York]' c. 1945 Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[Skylight and fences, Midtown, New York]' c. 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/skylight-and-fences-web.jpg?w=547&h=677)

![Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[Wrought iron fence, New York]' c. 1945 Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[Wrought iron fence, New York]' c. 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/wrought-iron-fence-web.jpg?w=563&h=700)

![Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[Church door, Bowery, New York]' c. 1945 Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[Church door, Bowery, New York]' c. 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/church-door-web.jpg)

![Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[Pillars and tree, New York]' 1944 Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[Pillars and tree, New York]' 1944](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/pillars-and-tree-web.jpg)

![Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[St. Francis Grocery & Fruit, New York]' c. 1945 Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[St. Francis Grocery & Fruit, New York]' c. 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/st-francis-grocery-and-fruit-web.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.