Exhibition dates: 24th May – 5th October 2014

Frank Stella (American, 1936-2024)

Double Scramble

1978

Oil on canvas

174.9 x 350.5cm

Collection of Preston H. Haskell, Class of 1960

© 2014 The Franz Kline Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / photo Douglas J. Eng

Frank Stella was an American artist best known for his use of geometric patterns and shapes in creating both paintings and sculptures. Arguably one of the most influential living American artists, Stella’s works utilise the formal properties of shape, colour, and composition to explore non-literary narratives… “Abstraction didn’t have to be limited to a kind of rectilinear geometry or even a simple curve geometry. It could have a geometry that had a narrative impact. In other words, you could tell a story with the shapes,” he explained. “It wouldn’t be a literal story, but the shapes and the interaction of the shapes and colours would give you a narrative sense. You could have a sense of an abstract piece flowing along and being part of an action or activity.”

Text from the Artnet website

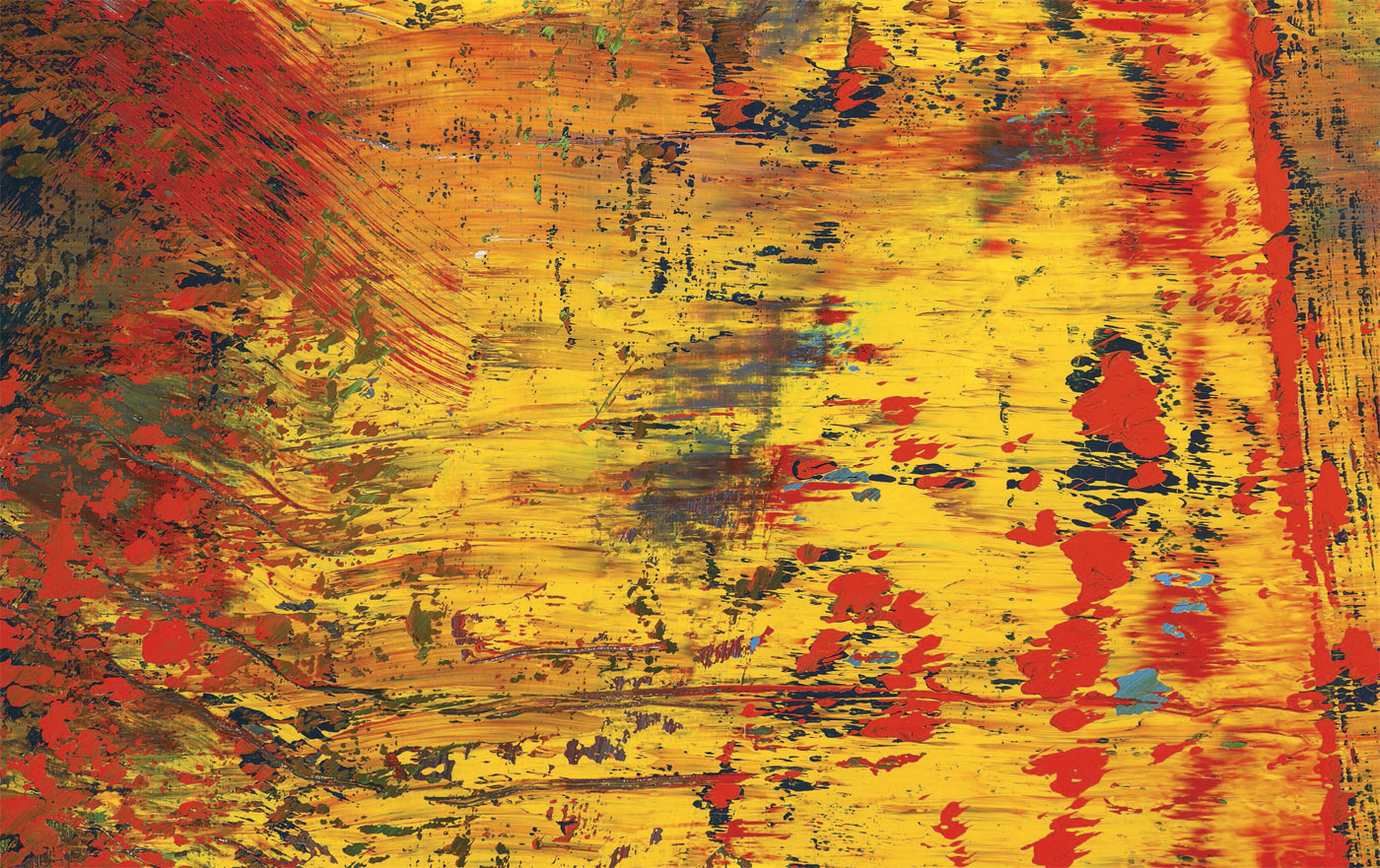

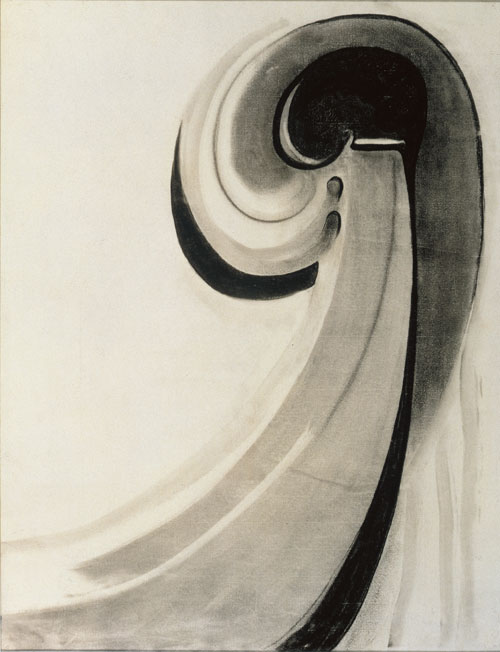

Think about the big 4 colours: Red Green Blue Yellow – and then there are the browns, the purples, magenta, cyan etc etc… Then have a look at the Gerhard Richter (Abstract Painting (613-3), 1986 below) in that light. A great colourist – but very reliant on the big four. Now compare him to Helen Frankenthaler (Belfry, 1979 below) – with this artist it’s a sort of a green, a sort of a red. And she used that palette in her watercolours as well.

They are both certainly aware of the presence of something else. I don’t know if Helen Frankenthaler would say that, and Gerhard Richter certainly wouldn’t, but there is an energy that is not human in the work of both of these artists. My benchmark in photography has always been the first Paul Caponigro exhibition which was called “In the presence of …” : hardly the vibrancy or the zeitgeist of Frankenthaler and Richter, but he had it right in front of his camera.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Princeton University Art Museum for allowing me to publish the art work in the posting. Please click on the art work for a larger version of the image.

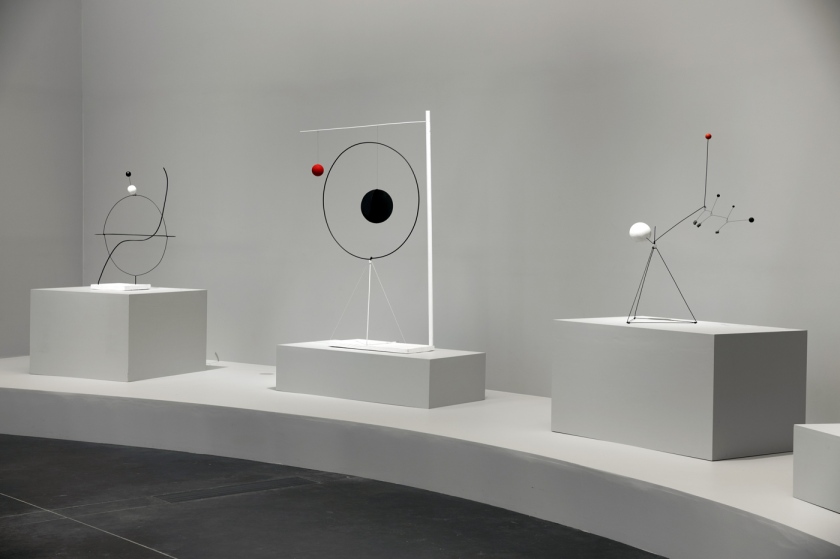

Josef Albers (German, 1888-1976)

Study for Homage to the Square

1964

Oil on paper

30.8 x 33.3cm

Collection of Preston H. Haskell, Class of 1960

© 2014 The Franz Kline Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / photo Douglas J. Eng

Study for Homage to the Square reveals a great deal about the series that has done more than any other to establish Josef Albers’s reputation in the United States. More than one thousand Homages to the Square exist, some paintings, others prints. Launched in 1950, the series forecasts many of the key concerns of the 1960s, including seriality and repetition. In its predilection for regular shapes and methodical compositions, as well as spatial and chromatic illusionism, Homage to the Square also lays the foundation for that decade’s romance with geometric abstraction. Importantly, Homages to the Square are rooted in interwar Constructivism. Albers spent more than ten years at the Bauhaus, from 1920 to 1933, experimenting with glass, typography, furniture design, photography, printmaking, and painting. There he was weaned on the insights of artists like Piet Mondrian and fellow teachers Laslo Moholy-Nagy and Walter Gropius. Albers also played an important role in transmitting European modernism to a younger generation of American artists, first at Black Mountain College, where he taught between 1933 and 1949, and then at Yale, where he was an instructor from 1950 to 1958.1

Each work in the Homage to the Square series conforms to one of four formats, all based on nested squares. What distinguishes one format from another is the mathematical ratio governing the intervals between the squares.2 Within this standardised program, however, Albers extracts incredible variety. The squares are rendered in a range of hues that vary in their degree of brightness and saturation, creating “optical reversals” that cause some squares to project and others to recede. Albers once described the Homage to the Square series as a stage on which colour might “act.”3 While individual works experiment with different “colour climates,” the cycle in its entirety explores the “relational” character of colour.4 Colour, Albers believed, is one of the most mutable, contingent, even deceptive phenomena in the world: any one colour is invariably affected by the colours around it, altering its identity and manipulating perception in the process.5 What we see is never what we see in the Homage to the Square cycle. The paint handling in Study is much looser than in other works from the series, whose smooth, fastidious surfaces are free of what Albers called “hand-writing,” by which he meant texture, impasto, and visual incident.6 However, the very informality of this smaller piece underscores an often overlooked feature of the series as a whole: the gentle, imprecise edges separating one square from another. In finessing the boundaries between shapes, Albers also finessed the boundaries between colours, investing his works with maximum visual intensity.

Kelly Baum

1/ Richard Anuszkiewicz studied with Albers at Yale between 1953 and 1955.

2/ See Werner Spies, Josef Albers (New York: Abrams, 1970), pp. 48-50.

3/ See Sewell Sillman, Josef Albers: Paintings, Prints, Projects (New York: Clarke and Way / Associates in Fine Arts, 1956), p. 36.

4/ See Spies, Josef Albers, 44. In 1963, Albers published the important Interaction of Color.

5/ In this respect, Albers sought to exploit the “discrepancy” between “physical fact” and “psychic effect.” See Hal Foster, “The Bauhaus Idea in America,” in Albers and Moholy-Nagy: From the Bauhaus to the New World, ed. Achim Borchardt-Hume (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2006), p. 99.

6/ Kynaston L. McShine, Josef Albers: Homage to the Square (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1964), n.p. In the same publication, Albers describes his painting technique, which involved applying paint directly from the tube with a palette knife in one thin, even coat to create a “homogenous” “paint film.”

Robert Motherwell (American, 1915-1991)

Untitled (red)

1972

Acrylic on canvas

182.6 x 137.3cm

Collection of Preston H. Haskell, Class of 1960

© 2014 The Franz Kline Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / photo Douglas J. Eng

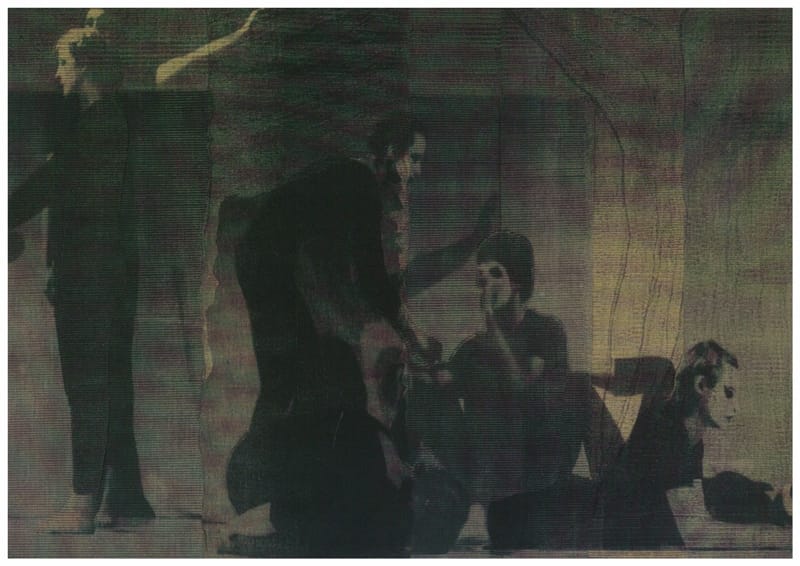

Willem de Kooning (Dutch-American, 1904-1997)

Untitled (Woman)

1965

Oil on paper

73.7 x 58.4cm

Collection of Preston H. Haskell, Class of 1960

© 2014 The Willem de Kooning Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / photo Douglas J. Eng

Willem de Kooning (Dutch-American, 1904-1997)

Untitled (Woman) (detail)

1965

Oil on paper

73.7 x 58.4cm

Collection of Preston H. Haskell, Class of 1960

© 2014 The Willem de Kooning Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / photo Douglas J. Eng

Woman II and Untitled (Woman) attest to de Kooning’s pursuit of fluidity and irresolution. Over the course of the 1960s, he altered his materials so as to facilitate his protracted editing process and increase the speed, vitality, and fluency of his brushwork – smooth supports reduced drag while safflower oil and kerosene slowed the drying time of his paints. As de Kooning said in 1960, “I was never interested … [in] how to make a good,” as in a perfect, finished “painting.” “I didn’t want to pin it down at all.”

Helen Frankenthaler (American, 1928-2011)

February’s Turn

1979

Oil on canvas

Collection of Preston H. Haskell, Class of 1960

© 2014 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / photo Douglas J. Eng

Helen Frankenthaler (American, 1928-2011)

Belfry

1979

Acrylic on canvas

208.4 x 219.7cm

Collection of Preston H. Haskell Class of 1960

© 2014 The Franz Kline Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / photo Douglas J. Eng

An intriguing paradox lies at the heart of Helen Frankenthaler’s work. In 1952 the artist started to create paintings that were gestural in appearance but not in fact. Thanks to a novel technique called staining, in which paint is poured onto canvas, Frankenthaler made marks that mimicked the sweeping strokes of Abstract Expressionism but indexed neither her hand nor her distinctive personality. Insofar as she minimised the role of will, choice, and subjectivity, Frankenthaler heralded a paradigm shift in postwar painting, breaking with Abstract Expressionism and planting a wedge between gesture and hand, art and artist. Frankenthaler’s technique, which evolved over time to include implements as unconventional as rags, mops, basters, sponges, squeegees, and windshield wipers,1 also has bearing on the equally paradoxical space of her paintings. In one respect, Frankenthaler strove to acknowledge, through the very act of painting, the feature that distinguishes painting from every other medium – flatness.2 This she did by thinning her paint and applying it to unprimed canvas, allowing the paint to penetrate the fabric. What results is not only a flat surface that reiterates the flat support on which it resides but also an image that is identified exactly with its ground. At the same time,

Frankenthaler’s work generates undoubtedly atmospheric effects. As the artist said in 1971, “Pictures are flat and part of the nuance and often the beauty or the drama that makes a work, or gives it life … is that it presents such an ambiguous situation of an undeniably flat surface, but on it and within it an intense play and drama of space, movements, light, illusion, [and] different perspectives.”3 Belfry and February’s Turn, both from the midpoint of Frankenthaler’s career, rely on just such an ambiguous sensation of space and depth. In their case, however, this ambiguity is exacerbated by the intrusion of marks that contradict the illusion of “aerated” flatness.4 Take the anomalous, almost gratuitous brushstroke in the centre right of Belfry, for instance, or the beige clump and the area of black impasto in February’s Turn, all of which lie obstinately on the surface of otherwise dyed canvases.

These marks very clearly qualify as painterly touches. As such, they introduce a degree of materiality to Frankenthaler’s mostly disembodied paintings and recall traditional Abstract Expressionism. Belfry and February’s Turn likewise exemplify a theme that concerned Frankenthaler from the very beginning of her career: landscape. Although abstract, these paintings evoke, through format, palette, and composition, the environments in which the artist lived and traveled, including the waterfront property she bought in Connecticut in 1978 and the arid, sunburned deserts of Arizona, which she visited in 1976 and 1977.

Kelly Baum

1/ Susan Cross, “The Emergence of a Painter,” After Mountains and Sea: Frankenthaler 1956-1959 (New York: Guggenheim Museum, 1998), p. 41.

2/ See, for instance, Clement Greenberg’s, “Modernist Painting [1960-65],” in Art in Theory, 1900-1990: An Anthology of Changing Ideas, ed. Charles Harrison and Paul Wood (Oxford, UK: Blackwell, 1993), pp. 754-60.

3/ Cindy Nemser, “Interview with Helen Frankenthaler,” Arts Magazine 46 (November 1971), p. 54.

4/ John Elderfield, Frankenthaler (New York: Abrams, 1989), 66, 255. See also E. A. Carmean, “On Five Paintings by Helen Frankenthaler,” Art International 22, No. 4 (1978): pp. 28-32; and Karen Wilkin, Frankenthaler: The Darker Palette (Savannah, GA: Savannah College of Art and Design), 1998.

Paul Caponigro (American, b. 1932)

Monument Valley, Utah

1970

From Portfolio II

Gelatin silver print

Paul Caponigro (American, b. 1932)

Rock Wall, Connecticut

1959

Gelatin silver print

Gerhard Richter (German, b. 1932)

Abstract Painting (613-3)

1986

Oil on canvas

260.7 x 203cm

Collection of Preston H. Haskell, Class of 1960

© 2014 The Franz Kline Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / photo Douglas J. Eng

Few artists have tackled the subject of painting with more self-consciousness, with greater sensitivity to the history, dilemmas, and possibilities of the medium, than Gerhard Richter. For the last five decades, Richter has explored the very nature of painting with and in paint, making his an especially reflexive enterprise. In many ways, contradiction defines his prolific body of work, as does diversity, whether of mode, style, technique, or content. A student of two very different art academies, one in Dresden and the other in Düsseldorf, where he trained with Joseph Beuys, Richter was weaned on Eastern European Social Realism as well as Western Pop and Fluxus. His earliest mature canvases, from the early 1960s, consist of blurry renditions of mostly ready-made photographs representing subjects both banal and chilling, from automobiles and Nazi officials to military aircraft and aerial cityscapes. By 1966, Richter had begun to experiment with abstraction. To this day, he still alternates between objective and nonobjective painting.

The groundwork for pieces like Abstract Painting (613-3) was laid in the early 1970s, when Richter began a series of nonrepresentational paintings based on photographic enlargements of brushstrokes.1 Because they depict, in a highly illusionistic manner, reproductions of otherwise abstract marks, such paintings confuse the handmade and the technological, the original and the copy. Richter continued to duplicate brushstrokes until 1980, when he started to make actual abstract paintings, albeit in unconventional ways.2 Abstract Painting (613-3) exemplifies the technique for which Richter is recognised today, one in which editing, subtraction, and cancellation play crucial roles.3 Here as elsewhere, the artist fleshed out a preliminary composition with ordinary brushes. As it was drying, he covered the hard edge of a squeegee with paint and dragged it across the surface of the canvas, an action that blended some layers but removed others, thereby revealing what was previously concealed.4 The resulting works are tapestries of abrasions and palimpsests, heterogeneous fields of visual incident. Discontinuity is particularly evident in Abstract Painting (613-3), due to variations in the directionality of paint, the combination of cool and warm hues, and the presence of a vertical seam near the middle of the canvas. To the extent that it cedes some control to chance and introduces the spectre of mechanicity, Richter’s process “muffles singular signs of personal expression”5 and trades existential drama for moderation, unlike the gestural, virtuosic canvases his paintings superficially resemble. As with many of his abstractions after 1980, Abstract Painting (613-3)’s palette is bright and sumptuous in appearance but not necessarily in tone.6 For Richter, colour does not signify “happiness,” he once said, but instead a “tense” or “artificial” “cheeriness” associated with “gritted teeth.”7

Kelly Baum

1/ See Robert Storr, Gerhard Richter: Forty Years of Painting (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2002), 53, pp. 68-69.

2/ These new abstractions coincided with a revival of Expressionism, called Neo-Expressionism, in the United States and Europe, a tradition from which Richter felt alienated and to which his works stand in pointed contrast. See “MoMA Interview with Robert Storr, 2002,” in Gerhard Richter: Writings, 1961-2007, ed. Dietmar Elger and Hans Ulrich Obrist (New York: D.A.P., 2009), p. 428.

3/ See ibid., pp. 71–74.

4/ Richter’s squeegees are essentially long pieces of rectangular plastic, often as wide as his canvases, to which handles are attached. While abrading a surface with the squeegee, Richter will sometimes use a brush or a knife to further blend and scrape. See Gerhard Richter Painting, directed by Corinna Belz (Berlin: Zero One Film, 2011), dvd.

5/ Hal Foster, “Semblance According to Gerhard Richter,” Raritan 22 (Winter 2003): 160. See also Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, Gerhard Richter: Abstract Paintings 2009 (Cologne: Walther Kônig, 2009), 89, 95. Richter does not always agree with this reading of his work. See “Interview with Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, 1986,” in Gerhard Richter: Writings, p. 180.

6/ The stringent quality of this and other abstractions by Richter is due as much to his predilection for bright, sharply contrasting colours as it is to his avoidance of earth tones.

7/ See “Interview with Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, 2004,” p. 489.

Gerhard Richter (German, b. 1932)

Abstract Painting (613-3) (detail)

1986

Oil on canvas

260.7 x 203cm

Collection of Preston H. Haskell, Class of 1960

© 2014 The Franz Kline Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / photo Douglas J. Eng

Extract from MARK, MAKER, METHOD by Kelly Baum

The paintings in Rothko to Richter narrate a history of postwar art whose greatest points of tension and most important moments of breakthrough revolve around facture, from the Latin facere, meaning “to make.”3 Together they demonstrate a fundamental fact: when painting’s prerogatives change, so too do its procedures. Focusing on select works from the Haskell Collection, this essay explores the nature of marks and mark-making in abstract painting after World War II. In the case of the artists seen here, mark-making was an activity of incredible consequence. The success or failure of any one painting might rest on something as elementary as the choice between oil paint and acrylic paint or a brush and a palette knife. It might depend on the difference between staining and smearing, between choppy strokes and fluid swipes, or between painting dry-on-dry and wet-on-wet.

With this in mind, my essay examines how and what marks signify within a single artist’s work as well as in postwar painting as a whole. How do shifts in the way marks are made signal broader shifts in artistic practice? What are the different, often competing logics of mark-making at any given moment? How do marks reflect or, alternately, disavow the impact of mass media, technology, and photomechanical reproduction in the mid- to late twentieth century? Such an investigation is premised on a particular understanding of the word “mark.” First and foremost, “mark” is a product as well as a process – more specifically, it is an end that cannot be separated from its means. Marks are also structural – as well as vocal – components of any given painting. Not only do they reveal a great deal about a painting’s meaning, they also shape that meaning, give it form and substance, for the viewer. For the purposes of this essay, then, I consider the mechanics of mark-making to be socially, physically, symbolically, and historically important.

Marks are the constituent feature, the backbone, of painting. A painting may be comprised of hundreds, if not thousands, of marks. In most cases, these marks are made in paint, on a support, by the hands of an artist. Even when those hands wield an implement – a brush or palette knife, for example – a physical connection still obtains between artist and mark.4 (What are implements like these, after all, but prostheses that extend the hand’s reach and capability?) Many of the artists in Rothko to Richter exploit this very character of the mark. In their paintings, a direct, transparent relationship exists between mark and method, a one-to-one correspondence between every stroke of paint and every movement of the artist’s hand. Here mark and method are tautological: the former records the latter. However, not every artist in Rothko to Richter subscribes to this approach. Several developed techniques designed to depersonalise the act of mark-making, to literally divorce the mark from the artist’s hand. Some even went so far as to erase the traces their tools left behind, effacing marks as soon as they were created. Instead of flaunting the process by which their paintings were produced, these artists dissimulated.

Dominating the Haskell Collection are Abstract Expressionist painters and their counterparts in Europe, including Appel, de Kooning, Goldberg, Kline, Riopelle, Rothko, and Tworkov.5 To varying degrees, these artists prized immediacy, virtuosity, and expression. Autographic gestures play a key role in their paintings.6 Such marks constitute a kind of painterly handwriting that indexes the artist’s distinct will, personality, and psychological state – his or her very self.

Etymologically, “gesture” derives from the Medieval Latin gestura, meaning “to carry.” In its original form, gesture denoted bearing – that is, the manner in which human beings deport themselves physically. It was also affiliated with rhetoric: in the past, gesture delineated a set of “bodily movements, attitudes, expression of countenance” intended to “giv[e] effect to oratory.”7 Gesture was a supplement to speech, a kind of accent or embellishment, in other words. All such connotations are relevant to the Expressionist canvases in the Haskell Collection: for artists like Goldberg and Kline, gestures were overtures, forms of communication that served to address viewers directly and invite them to participate in a subjective exchange. Gesturing involved gesticulating in the sense we understand that word today. In Appel’s Dans la Tempête (1960) or de Kooning’s Woman II (1961), for instance, the artist’s hand, wrist, and arm – sometimes his entire body – are marshalled so as to externalise otherwise private impulses, instincts, and passions. The affective power of such gestures was in direct proportion to their muscularity, fluidity, and dynamism, traits enthusiastically embraced by American and European Expressionists, who equated intensity of spirit with intensity of brushwork.

As art historian Meyer Schapiro astutely argued in 1957, the new emphasis on gesture among abstract painters of the postwar generation precipitated concomitant changes in technique. “The consciousness of the personal and spontaneous” in painting, Schapiro wrote, “stimulates the artist to invent devices of handling, processing, surfacing, which confer to the utmost degree the aspect of the freely made. Hence the great importance of the mark, the stroke, the brush, the drip, the quality of the substance of paint itself, and the surface of the canvas as a texture and field of operation.”8 This holds true of Appel’s Dans la Tempête (1960), de Kooning’s Untitled (Woman) (1965), Goldberg’s The Keep (1958), and Kline’s Untitled (1960), among other works, whose richly impastoed surfaces and bold, impetuous brushwork register not only heightened emotion but also the presence of the artist.

If Schapiro championed these paintings as enthusiastically as he did, it was because they represented, in his view, the “last hand-made personal objects within our culture.”9 Insofar as Rothko’s and de Kooning’s canvases preserved increasingly obsolete methods of fabrication, privileging manual over industrial forms of production, they “affirmed the individual in opposition to the contrary qualities of the ordinary experience of working and doing.”10 For Schapiro, the importance of painters like Goldberg and Tworkov lay precisely in their efforts to humanise art at a moment when the subject was under assault from the dehumanising forces of science, technology, and mass media. In his view, Abstract Expressionism represented the last bastion of freedom and individuality in an increasingly homogenous, mechanised world, a bulwark against the intrusion of standardisation into every walk of life.

However, by the late 1950s, when Schapiro made this claim, a sea change was already well under way in the world of art. Even then, a younger generation of artists, represented by Rauschenberg and Stella, was beginning to embrace at the level of technique the very shifts in society and subjectivity that Schapiro and the Abstract Expressionists decried. As the 1950s gave way to the 1960s, increasing numbers of artists would cease to identify either physically or emotionally with their canvases. Simultaneously, they began to align painting with fabrication, deriving insight from the fields of design and engineering. Gradually, the taste for “the machine-made, the impersonal, and reproducible,” likewise “an air of coolness and mechanical control,” would infiltrate art, heralding a break with Abstract Expressionism.11

3/ Sometimes reduced to “texture,” facture designates the way a work of art has been made and the manner in which its material components have been manipulated.

4/ As much as possible, I have tried to avoid falling into the all-too-common trap of fetishising the painted mark. Although much can be learned about a painting by deciphering the marks that comprise it, the mark is often conflated with something more problematic, the artist’s touch, a supposed symbol of singularity and authenticity that is inextricably related to the work’s exchange value and its status as a commodity on the market.

5/ For more information on Expressionism in Europe, see Serge Guilbaut, “Disdain for the Stain: Abstract Expressionism and Tachisme,” in Abstract Expressionism: The International Context, ed. Joan Marter (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2007).

6/ As Michael Leja argues, this was a historically, culturally, and ideologically specific self that invested great importance in “irrationality” and reflected new knowledge about the human mind, psyche, and condition. See his Reframing Abstract Expressionism: Subjectivity and Painting in the 1940s (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1993), pp. 2-9, pp. 36-41. See also Ann Eden Gibson, Abstract Expressionism: Other Politics (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1997).

7/ Oxford English Dictionary Online, s.v. “Gesture,” http://www.oed.com/search?searchType=dictionary&q=gesture&_searchBtn=Search.

8/ Meyer Schapiro, “Recent Abstract Painting (1957),” in Modern Art: 19th and 20th Centuries (New York: George Braziller, 1978), p. 218.

9/ Ibid., p. 217.

10/ Ibid., p. 218.

11/ Ibid., p. 219. As Schapiro notes, if science and engineering were “distasteful” to the Abstract Expressionists, it was due largely to the role they played in World War II and the Holocaust.

Franz Kline (American, 1910-1962)

Untitled

1960

Brush and oil on canvas

47 x 45.1cm

Collection of Preston H. Haskell, Class of 1960

© 2014 The Franz Kline Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / photo Douglas J. Eng

Hans Hofmann (American born Germany, 1880-1966)

Composition #3

1952

Oil on canvas

76.8 x 61.3cm

Collection of Preston H. Haskell, Class of 1960

© 2014 Estate of Hans Hofmann / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / photo Douglas J. Eng

Hans Hofmann (American born Germany, 1880-1966)

Midday

1956

Oil on canvas

46.4 x 35.9cm

Collection of Preston H. Haskell, Class of 1960

© 2014 Estate of Hans Hofmann / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / photo Douglas J. Eng

Hans Hofmann is generally associated with the New York School, but he actually belongs to an earlier generation of artists based in Europe. Indeed, Hofmann witnessed firsthand the invention of abstraction while living in Paris from 1904 to 1914. Between 1933 and 1958, he would impart the lessons of Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso as well as those of Wassily Kandinsky and Piet Mondrian to the students who attended his art schools in New York and Provincetown, Massachusetts.1 Later in life, after the works in the Haskell Collection were made, Hofmann helped broker the transition from Abstract Expressionism to Minimalism, a movement that shared his more recent predilection for restraint, objectivity, and pictorial problem-solving.2

Hofmann was never wedded to any one approach to painting. Indeed, “diversity” was in many respects his signature style. Before the late 1940s, he produced paintings of abstracted interiors, still lifes, landscapes, and figure studies, all of which bear the imprint of Cubism and Fauvism. By 1950, however, his paintings were reliably abstract: no, or almost no, recognisable content remained. Characterised by radiant luminosity, brilliant colour contrasts, and tactile surfaces, Composition #3 and Midday were created just a few years before the artist closed his two schools, a moment that coincided with his critical recognition as a painter. Colour serves a structural role in both paintings, generating form and defining space. In Composition #3, paint is added and subtracted, sometimes ferociously, with implements ranging from fingertips and spatulas to thick brushes and sharp paintbrush handles, all of which register clearly on the canvas. Clement Greenberg could have been describing this work when he wrote, “Klee and Soutine were perhaps the first to address the picture surface consciously as a responsive rather than inert object, and painting itself as an affair of prodding and pushing, scoring and marking, rather than of simply inscribing or covering. Hofmann has taken this approach further, and made it do even more.”3 For its part, Midday exemplifies Hofmann’s distinctive brand of “grandiose Pointillism,” a manner adopted around 1954.4 Covered in a dense crust of paint, the work is made of staccato brush marks that extend from edge to edge, resulting in an atomised, decomposed surface whose impasto projects into space.5 Midday’s resemblance to a mosaic is more than coincidental: in 1950 and 1956, Hofmann received commissions to create monumental mosaics for public spaces.

Kelly Baum

1/ On the ways in which Hofmann divests the tradition of abstraction embodied by Mondrian and Kandinsky of its social and utopian aspirations, see Sam Hunter, “Introduction,” in Hans Hofmann, ed. James Yohe (New York: Rizzoli, 2002), pp. 15-16.

2/ Like many of his contemporaries in Europe and the United States, Hofmann often linked the creation of art to spirituality, on the one hand, and to the artist’s personal temperament, on the other. However, these priorities were far less pronounced in his work than in that of artists such as Mondrian and Rothko. Hofmann’s concern was more for the mechanics – the grammar – of art. Ibid., p. 16, 20.

3/ “Hans Hofmann [1958],” in Art and Culture: Critical Essays (Boston: Beacon Press, 1961), p. 195.

4/ Hunter, “Introduction,” p. 29.

5/ On the art historical importance of Hoffmann’s “fat” surfaces, which contribute to the perception of his pictures as “objects,” see Clement Greenberg, Hofmann (Paris: G. Fall, 1961), p. 32, 34.

Hans Hofmann (American born Germany, 1880-1966)

Midday (detail)

1956

Oil on canvas

46.4 x 35.9cm

Collection of Preston H. Haskell, Class of 1960

© 2014 Estate of Hans Hofmann / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / photo Douglas J. Eng

IN THE WAKE OF ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM by Hal Foster

This selection from the Haskell Collection focuses on Abstract Expressionism and its aftermath and, as such, provides an occasion to reflect on the fate of these two terms, abstraction and expression, in the advanced painting of this period. I want to do so briefly here, one term at a time.

In Western painting at least since Rembrandt, we look for expression, first and foremost, in brushwork, especially brushwork that exceeds the task of representation, brushwork that appears as gesture. Gesture in excess of representation tends to be read as the mark of the artist, not only of his distinctive touch but of that touch at a particular moment. We thus take gesture to be singular, original, authentic, in a word, individual – an indication, perhaps, of the very subjectivity of the artist at that instant in time. Now, what happens to this set of associations when we jump two hundred and fifty years, from Rembrandt to Van Gogh (to stay on a Dutch axis), and then move fifty years further, from Van Gogh to Willem de Kooning (who is represented in the Haskell Collection by two oil studies for his great Woman paintings)? In what ways do these associations, these conventions (for that is what they are), come under pressure?

Pitched in this way, the question is too general; so consider the works in the Haskell Collection produced by 1960 or so by Karel Appel, Michael Goldberg, Hans Hofmann, Franz Kline, Jean-Paul Riopelle, and Jack Tworkov. Can we agree that, in each case, the artist appears to believe in his gesture as defined above, that is, as a bearer of a uniquely subjective touch? All of these pieces, even when not large, conceive the picture as an “arena” for “action” (per the famous account of Abstract Expressionism given by the critic Harold Rosenberg in 1952).1 At the same time, this action is always qualified by calculation: note, for example, how Hofmann minds the edges of his canvases; and this gesture is sometimes wilful: note, for instance, how Goldberg seems a little forced in his painterly attack.

Once reiterated, a gesture, whether within one painting or from one painting to another, becomes a performance (not simply an action) as well as a sign (not simply an expression), and in this way it becomes divided from the very presence that it appeared to register in the first place. Jackson Pollock struggled with this conundrum – it was one factor that led to his partial return to figuration as early as 1951 – and we can sense this struggle in some of the works in the Haskell Collection, too (I see it in the Riopelle, among others). This problem of the reiteration of gesture is compounded by the greater difficulty of the repetition of style, that is, the repetition of the set of conventions that is Expressionism. For if de Kooning, Pollock, and friends worked in the wake of German Expressionism, so their followers laboured in the aftermath of Abstract Expressionism; thus they were belated Expressionists, in effect, twice over. As gesture came under existential pressure and Expressionism under art historical pressure, they could not help but see that the former might not be as singular, nor the latter as original, as they had once thought.2

Note what occurs after 1960, in part in response to this predicament, in the Color Field painting of Helen Frankenthaler, Paul Jenkins, and Morris Louis: gesture becomes muted, and the paint is loosened from the brush. Letting paint flow is what Frankenthaler learned from the drip paintings of Pollock, and what Louis and others learned from Frankenthaler (they exploited the new fluidity of acrylics here). And yet, however liberated, this paint speaks less of the expressive presence of the painter than of the material conditions of the painting – the fact that acrylic paint runs, mixes, responds to gravity, and stains the canvas (if it is not gessoed) in such a way that its weave becomes apparent and its flatness is foregrounded. “Flatness and the delimitation of flatness”: according to the critic Clement Greenberg, these are, respectively, the essential attribute of painting in general and the distinctive capability of abstract painting in particular.3 In this respect, see how Louis, in the 1962 painting in the Haskell Collection, lets his long bands of paint develop in a way that declares not only the vertical hang of the painting but also its flat surface; here the physical characteristics of paint, colour, and canvas are the sole subjects. Indeed, the painting seems to be produced as though by gravity alone, as though it were almost automatic; in comparison with Abstract Expressionism, the expressivity of the artist is here suppressed.

Such is the lesson that Frank Stella took from Louis in paintings like Double Scramble (1978) – a late example of work initiated in the mid-1960s. The critic Michael Fried termed such compositions “deductive structures” because they seemed to derive strictly from the rectangle of the support and the width of the stretcher, that is, they were deduced from the given structure of the painting alone.4 Here we are even further from the expressivity of Abstract Expressionism than we were with Louis: the composition seems to draw itself. Expressivity appears to return in the abstractions of Gerhard Richter, who is also represented in the Haskell Collection, yet the victory is a Pyrrhic one: like his canvases, his gestures are so numerous and so reiterative that they seem to cancel one another out and so to nullify as much as to register any expressive self.

Like expression, abstraction also comes under pressure during the period surveyed by the Haskell Collection. Although presented in transcendental terms by pioneers of abstract painting such as Wassily Kandinsky in the 1910s, it was largely drained of this metaphysics by the 1960s, to the point where Stella could describe his work in the most positivist of terms: “What you see is what you see.”5 At the same time, abstraction was still endowed with great consequence for art history in general. In 1936, when the curator Alfred H. Barr Jr. presented his famous diagram of “Cubism and Abstract Art” for his show of that title at the new Museum of Modern Art in New York, abstraction served as the through-line of twentieth-century art, one that Greenberg made not only coherent but also ineluctable through his narrative of the progressive self-refinement of “modernist painting.” This story provided continuity as well as goal to twentieth-century art: “I cannot insist enough,” Greenberg wrote in “Modernist Painting” (1961), “that Modernism has never meant, and does not mean now, anything like a break with the past.”6

However, this story soon hit a large bump in the road. As abstract painting focused evermore on its own materiality, its status as an object became impossible to avoid; clearly the next step, it seemed to some avant-gardists, was to dispense with paintings altogether and to produce objects instead. Greenberg already glimpsed this heretical possibility with Stella, and this is why he never included Stella in his canon. Even if Fried still regarded Stella as the exemplar of “modernist painting,” for others, such as his close friend Carl Andre, Stella was on the other side, their side, the side of the Minimalist object as defined by the artist-critic Donald Judd. At this point, then, a “deductive structure” by Stella could be read – was read – as pure painting by some and as specific object by others.

This ambiguous status of abstract painting – as both transcendental force and mere thing, as both full and null – was already glimpsed in its first years. For example, for Kazimir Malevich, the monochrome, in its ideality, pointed to a world beyond this one; for his compatriot Aleksandr Rodchenko, however, the monochrome, in its materiality, underscored that this world was the only one we have. (At times these poles switched their charge: for some artists, transcendental abstraction suggested an emptying out of painting, a sort of Zen nullity of its own, while for others, mundane abstraction suggested a thingly presence, a fullness of its own, but the ambiguous status remained constant.) The paradox of abstraction as both full and null returns in the period surveyed by the Haskell Collection: the canvases by Robert Motherwell, Mark Rothko, and others clearly hold to the metaphysical power of abstract painting, whereas the paintings by Richter, Stella, and others manifestly do not.

Abstract painting was challenged by more than its own objecthood; it also faced an external threat, one that was even more grave. This problem runs back to its early days too, for abstraction emerged, circa 1912-1913, along with two other avant-garde inventions, the collage and the readymade, which brought the mass-media image and the mass-produced object into the frame of high art. For many artists and critics, abstract painting was all the more important for the stout resistance it offered to these troublesome incursions (this is certainly what Greenberg believed), yet it could not fend off such mediation forever, and in the 1950s and 1960s it mostly gave up.7 De Kooning, for example, used bits of collage in his Woman series, and Robert Rauschenberg, who is also represented in the Haskell Collection, added massive amounts of mediated images to his paintings.8 By the time of Richter, such mediation is fully folded into painting: almost from the start of his career, he has moved back and forth between abstract paintings and figurative ones based on photographs (both appropriated and his own); moreover, as suggested above, his abstract paintings appear mediated in their own ways. And this always-already mediated condition is the very point of departure of the spectacular paintings by Jack Goldstein in the Haskell Collection: however abstract they appear, they are worked up entirely from appropriated images. At this point the categories of abstraction and expression are transformed beyond recognition.9

1/ Harold Rosenberg, “The American Action Painters,” Art News 51 (December 1952).

2/ As represented in the Haskell Collection, some artists, such as Sam Francis and Joan Mitchell, carried on as if these problems didn’t matter much.

3/ Clement Greenberg, “After Abstract Expressionism,” Art International 25 (October 1962), p. 30.

4/ Michael Fried, Three American Painters: Kenneth Noland, Jules Olitski, Frank Stella (Cambridge, MA: Fogg Art Museum, 1965).

5/ Frank Stella, quoted in Bruce Glaser, “Questions to Stella and Judd,” Art News 65 (September 1966), p. 59.

6/ Clement Greenberg, “Modernist Painting,” Arts Yearbook 4 (1961), p. 108.

7/ It is not clear how opposed abstraction was to these other forms in the first place. For example, a monochrome or a grid painting is already a kind of readymade, and as soon as paint comes from an industrial tube, it is a sort of readymade too.

8/ De Kooning was rarely fully abstract; Greenberg comments on his “homeless representation” in “After Abstract Expressionism,” p. 25.

9/ These complications continue in the current work of Wade Guyton, Amy Sillman, Christopher Wool, and many others; indeed, they are largely what sustain advanced painting in the present.

Karel Appel (Dutch, 1921-2006)

Dans la Tempête

1960

Oil on canvas

88.9 x 115.9cm

Collection of Preston H. Haskell, Class of 1960

© 2014 Estate of Hans Hofmann / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / photo Douglas J. Eng

Karel Appel (Dutch, 1921-2006)

Dans la Tempête (detail)

1960

Oil on canvas

88.9 x 115.9 cm

Collection of Preston H. Haskell, Class of 1960

© 2014 Estate of Hans Hofmann / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / photo Douglas J. Eng

“We live always in a tremendous chaos,” Karel Appel stated to an interviewer in 1986, “and who can make the chaos positive anymore? Only the artist.”1 Registering, but also redeeming, social, political, and psychic conflict was an ethical imperative for Appel, who came of age as an artist in the 1940s. Appel witnessed firsthand the brutalisation of human beings by war, prejudice, deprivation, and occupation, and he sought to visualise these experiences through art. His canvases are ravaged, quite literally, by brushes, palette knives, and fingers. Choked by thick layers of impasto, their surfaces are as agitated as the animals and figures the paintings depict. Form, colour, content, and technique all serve as corollaries to the period of profound turmoil in which Appel worked. Importantly, the artist’s approach to historical trauma was dialectical. The devastation of pre- and postwar Europe, he believed, was a tabula rasa making possible the rebirth of both art and human beings.2

Appel was a founding member of Cobra (1948-1951), a group of Expressionist painters from Amsterdam, Brussels, and Copenhagen. Appel shared with other Cobra artists an appreciation for the art of the untutored, including children and the mentally ill, whose supposed alienation from Western, classical tradition granted them privileged access to the wellsprings of creativity: fantasy, passion, and instinct.3 Believing that society had been betrayed by logic and science, Appel turned to the irrational for inspiration. His predilection for the primal aligned him with Jean Dubuffet and Art Brut, an association formalised by his appearance in French critic Michel Tapié’s 1952 exhibition Un Art autre. Dans la Tempête was painted in 1960, three years after Appel relocated temporarily to New York, where he socialised with Abstract Expressionists such as Willem de Kooning and Franz Kline. Upon arriving in Manhattan, Appel was struck not only by the spontaneous, improvisatory spirit of jazz but also by the city’s “unfinished quality.”4 He subsequently sought to translate this contingency into paintings like Dans la Tempête. Trapped in a state of arrested development, this work also demonstrates Appel’s longstanding fascination with the “creaturely,” that is, with the reduction of humans to the condition of animals.5 Here as elsewhere, the artist elides the one and the other, manufacturing from their cross-pollination a grotesque bestiary of mutants whose anatomical deformations evoke distress. Much as Appel blends pigment by painting wet-on-wet, so too does he blur the boundaries between things and the grounds they inhabit: permeability trumps both spatial and physical integrity, as seen in Dans la Tempête, where a yellow zoomorphic shape at the left and a barely legible demi-human at the right thrash amongst swirls of paint.6

Kelly Baum

1/ Sam Hunter, “Karel Appel in the Spirit of Our Time,” Arts Magazine 62 (January 1988), p. 60.

2/ Hal Foster, “Creaturely, Cobra,” October 141 (Summer 2013), p. 7.

3/ See Karel Appel, Psychopathological Notebook: Drawings and Gouaches, 1948-1950 (Bern: Gachnang and Springer, 1999).

4/ Hunter, “Karel Appel,” p. 62.

5/ Foster, “Creaturely, Cobra,” pp. 6-8.

6/ Appel described his work from 1955 to 1960 as “nightscapes” that merge “paysage” and “visage.” Helena Kontova and Giancarlo Politi, “Karel Appel,” Flash Art, no. 134 (May 1987), p. 53.

Jack Tworkov (American, 1900-1982)

Bond

1960

Oil on canvas

154.9 x 91.4cm

Collection of Preston H. Haskell, Class of 1960

© 2014 Estate of Hans Hofmann / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / photo Douglas J. Eng

Jack Tworkov (American, 1900-1982)

Bond (detail)

1960

Oil on canvas

154.9 x 91.4cm

Collection of Preston H. Haskell, Class of 1960

© 2014 Estate of Hans Hofmann / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / photo Douglas J. Eng

Jean Dubuffet (French, 1901-1985)

Mire G119

1983

Acrylic on paper

135.7 x 99.5cm

Collection of Preston H. Haskell, Class of 1960

© 2014 Estate of Hans Hofmann / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / photo Douglas J. Eng

Modularity, seriality, and repetition – three of his main concerns here – ground us firmly in modernity, in the realm of synthetics and industrial production. Importantly, the title of the series, Mires, has both televisual and physiological connotations: it is French for “test pattern” (a signal used to calibrate television sets), but it also means “sight” as well as “aim,” as in “the sense of focusing sight on a point in an unlimited continuum.” Instead of the visionary, then, the Mires address vision itself. As the artist once wrote, the Mires “represent the spectacles that are offered to our eyes,” by which he meant the myriad optical enticements that bombard viewers in the form of signs, displays, and advertisements. Following from this, we might say that Dubuffet sought in works like Mire G119 to fashion an artistic equivalent for the “mobile,” “dynamic,” “impulsive,” and wholly mediated character of vision in the late twentieth century.

Kelly Baum

Richard Diebenkorn (American, 1922-1993)

Untitled (Ocean Park)

1983

Acrylic, gouache, crayon, and pasted paper on paper

96.2 x 63.5cm

Collection of Preston H. Haskell, Class of 1960

© 2014 Estate of Hans Hofmann / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / photo Douglas J. Eng

Paul Jenkins (American, 1923-2012)

Phenomena Spanish Cape

1975

Acrylic on canvas

86.7 x 86.7cm

Collection of Preston H. Haskell, Class of 1960

© 2014 Estate of Hans Hofmann / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / photo Douglas J. Eng

Although his paintings seem to share a great deal with those of Morris Louis and Helen Frankenthaler, Paul Jenkins never counted himself a member of the Color Field school – or indeed, of any school at all. Jenkins moved to New York in 1948, during the heyday of Abstract Expressionism, but relocated to Paris just five years later, joining an artistic community that included Joan Mitchell, Jean-Paul Riopelle, Michel Tapiés, and Wols. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Jenkins absorbed a dizzying array of writing on matters ranging from art and magic to psychoanalysis and Zen Buddhism.1 From this heady brew, he developed a distinctly mystical art that sought to make the invisible visible. The role of the artist, Jenkins believed, was to serve as a conduit, or “medium,” through which memories, emotions, and experiences passed directly onto canvas.2

In 1959-60, Jenkins’s work took a dramatic turn: after visiting a small port on the northeast coast of Spain, near the Cap de Creus, he began to prioritise fluidity as both a style and a concept, a decision that led him to experiment with water-based acrylic. Method played a crucial role in creating the effect of flux that Jenkins sought. In Phenomena Spanish Cape paint is poured directly onto the canvas from a can or watering pot, allowing for continuous, uninterrupted shapes to emerge.3 The downward flow of paint was hastened by gravity but controlled by the artist, who tilted the support right and left, up and down, to encourage the medium in one direction or another. Jenkins used water to mute or lighten tones and ivory knives, which left no discernible trace on the canvas, to spread the paint as it pooled.4 The result is a paradox: a painting born of the artist but from which all evidence of his hand – his labor – has been effaced. Phenomena Spanish Cape suggests expansion, radiation, and suspension. Evoking eddies, clouds, and tides, the sheets of colour seem to swell and drift like the natural events whose appearances they distill.5 We might also recognise in the work’s composition – with its veils of colour that project out from a dominant red mass into areas of white-primed canvas – an aerial view of a peninsula, perhaps the Spanish cape referenced in the title. In all of Jenkins’s paintings after 1960, the title of the work is prefaced by the word “phenomena,” meaning an event of spiritual and subjective import, a snapshot of “ever-changing reality” objectified on canvas.6

Kelly Baum

1/ For more on Jenkins’s spiritual and intellectual background, see Albert Elsen, Paul Jenkins (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1973), pp. 20-21, p. 35, 46, 67.

2/ Ibid., p. 19.

3/ Ibid., p. 56. Jenkins first experimented with pouring paint in 1953-54.

4/ For more on the artist’s technique and materials, which he honed, quite literally, to a science, see ibid., pp. 65-76.

5/ On the role of nature in his work, see Jean Cassou, Jenkins (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1963), pp. 13-14.

6/ Ibid., p. 6.

Mark Rothko (American, 1903-1970)

Untitled

1968

Oil on paper laid down on canvas

Collection of Preston H. Haskell, Class of 1960

© 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / photo Douglas J. Eng

Mark Rothko (American, 1903-1970)

Untitled (detail)

1968

Oil on paper laid down on canvas

Collection of Preston H. Haskell, Class of 1960

© 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / photo Douglas J. Eng

Princeton University Art Museum

McCormick Hall, Princeton, NJ

Phone: (609) 258-3788

The Museum is located on the Princeton University campus, a short walk from Nassau Street in downtown Princeton. Once on campus, simply follow the lamppost Museum banners.

Opening hours:

The main Museum building is closed for construction of our new Museum, designed by architect Sir David Adjaye and anticipated to open in late 2024.

You must be logged in to post a comment.