Exhibition dates: 7th June – 9th September 2018

Curator: Márton Orosz

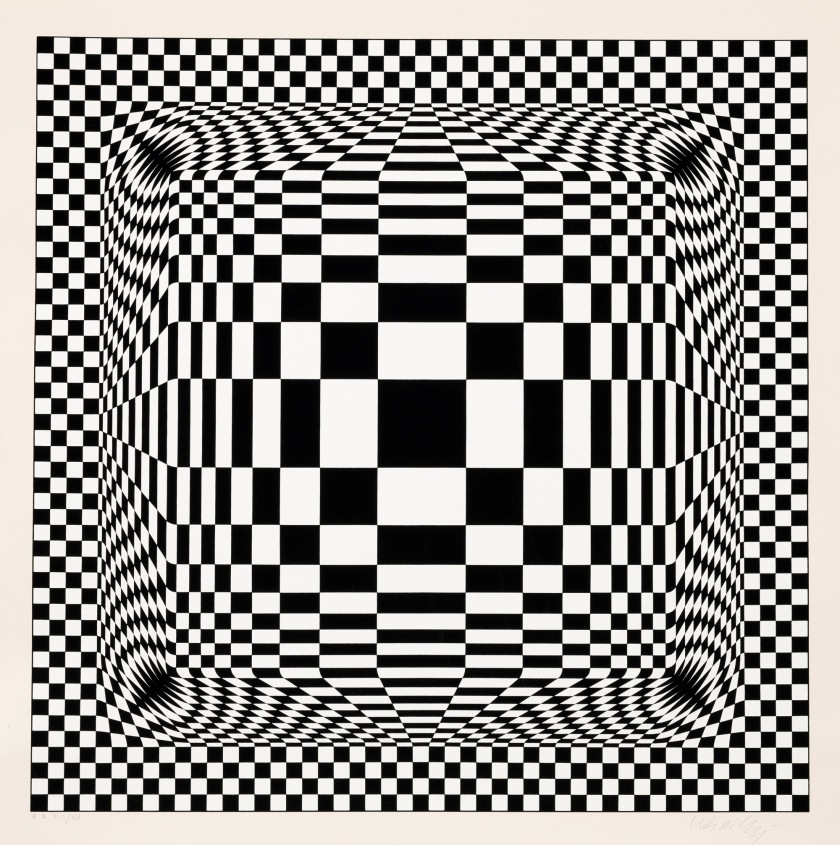

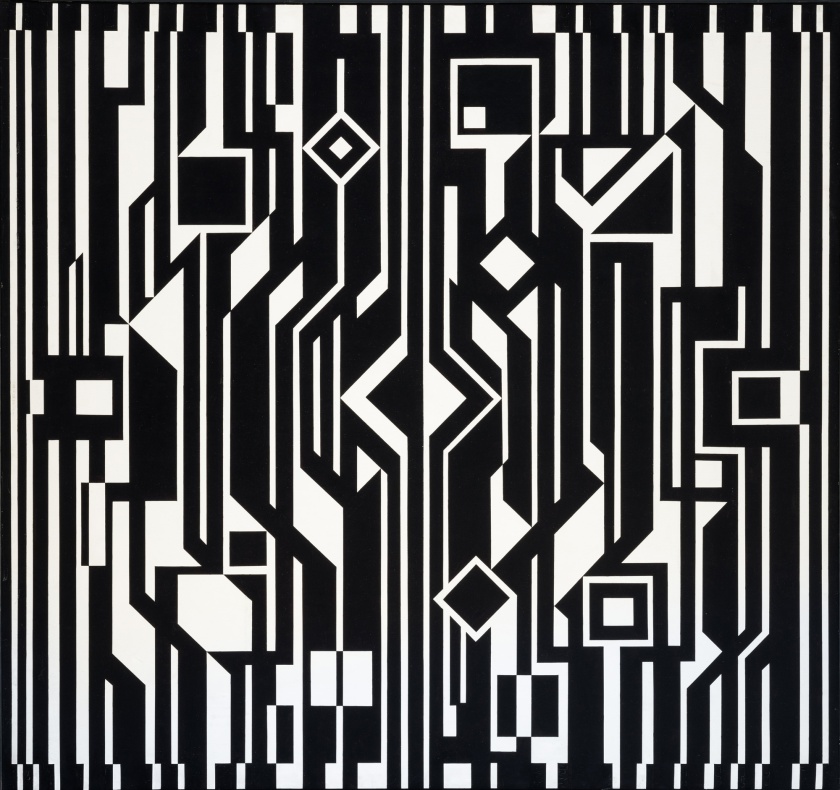

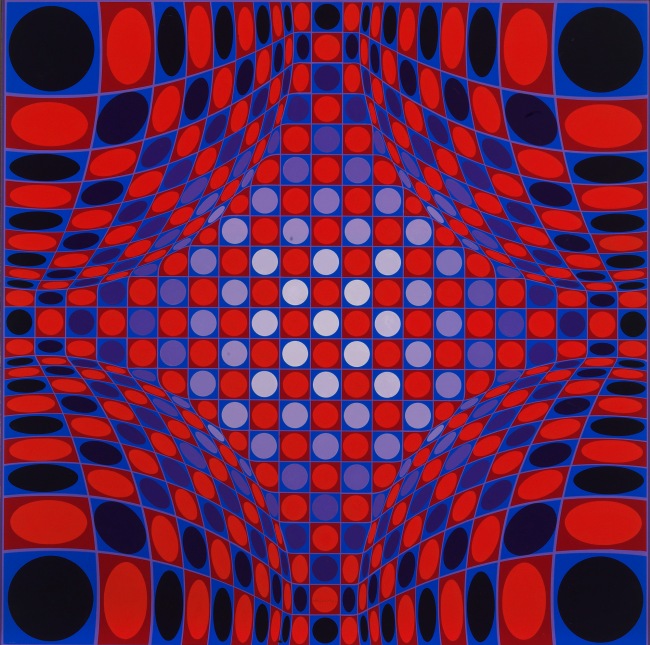

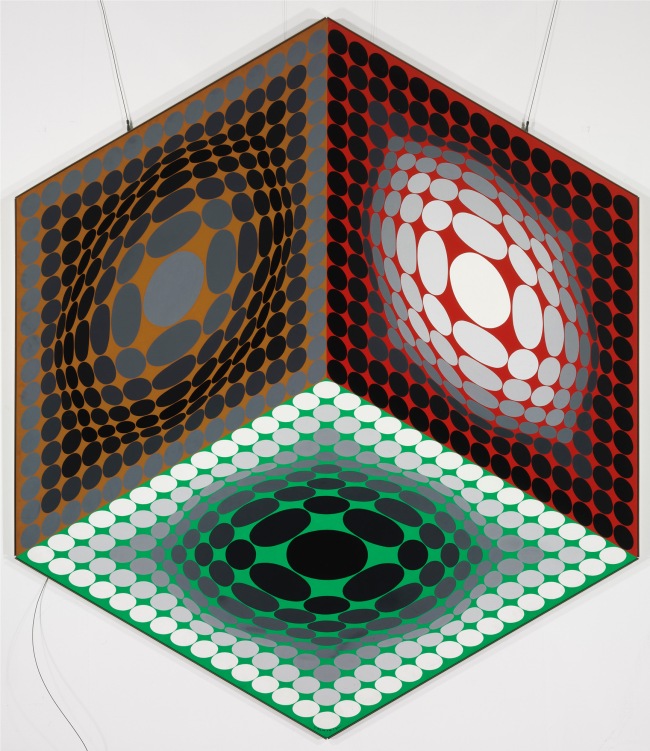

Installation view of the exhibition Victor Vasarely. The Birth of Op Art at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid showing Vasarely’s Feny (1973, below)

Victor Vasarely (Hungarian-French, 1906-1997)

Feny

1973

Acrylic on canvas

180 x 180cm

Colección Carmen ThyssenBornemisza

© Victor Vasarely, VEGAP, Madrid, 2018

(from the Vega Structures section of the exhibition)

Optic geomancer

No comment is really necessary. You just have to look at the spirit and inventiveness of the art. A pioneer of light and colour, a genius of plastic grid and form, is at play here!

The installation photographs show just how optically magnetic these works are. How they are holistic, singular works which then play magnificently off each other when placed in close proximity. Like the fugues of J.S. Bach these optical illusions create dazzlingly beautiful, intricate and powerful works, an earthly divination of a ‘planetary folklore’.

As my good friend Elizabeth Gertsakis said of the work of Robert Hunter, “he had the mind of abstract divination for a music of the spheres, of any geometry.”

Visit the VR Microsite for a Virtual Reality walk through of the exhibition.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

From 7 June to 9 September 2018, the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza will be presenting a monographic exhibition devoted to Victor Vasarely (Pécs, 1906 – Paris, 1997), the founding father of Op Art. Comprising works from the Vasarely Museum in Budapest, the Victor Vasarely Museum in Pécs, the Fondation Vasarely in Aix-en- Provence and prominent loans from private collections, the exhibition will aim to offer an overall vision of the life and work of this Hungarian painter whose best output was created in France. The exhibition includes works from all the principal phases of Vasarely’s career in order to present a chronological survey of his artistic evolution. Visitors will thus be able to appreciate the key role played by the artist in the development of geometrical post-war abstraction and to learn about the experiments based on his artistic principles and theoretical reflections which he undertook with the aim of bringing art and society closer together.

Victor Vasarely is a towering figure in the history of abstract geometric art. The results of his experiments with spatially ambiguous, optically dynamic structures and their effects on visual perception burst into public consciousness in the mid-1960s under the name of Op Art, launching a short-lived yet extraordinarily popular wave of fashion.

The exhibition is organised in eight chronological sections and an introductory space devoted to Vega Structures, one of the best-known and most emblematic series produced by Vasarely at the height of his career named after the brightest star in the northern hemisphere’s summer night sky.

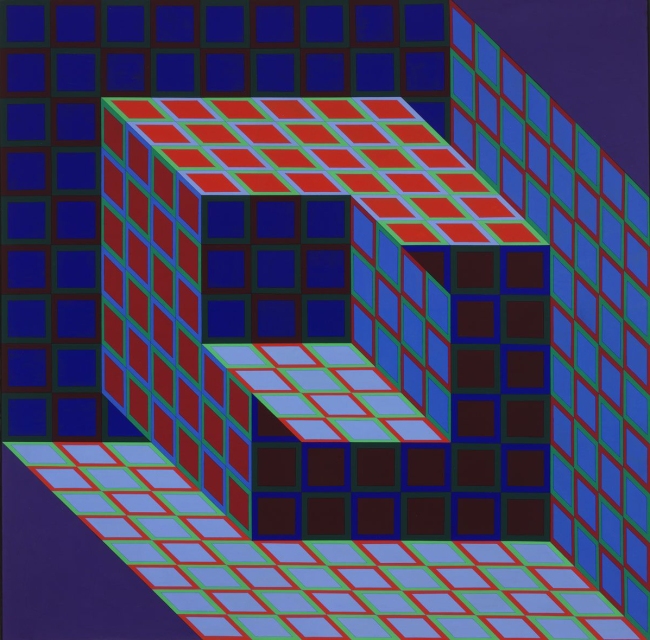

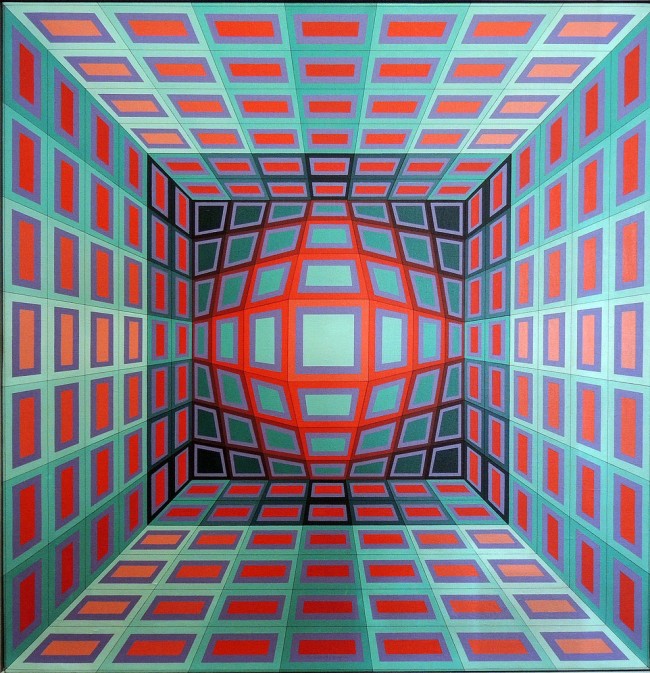

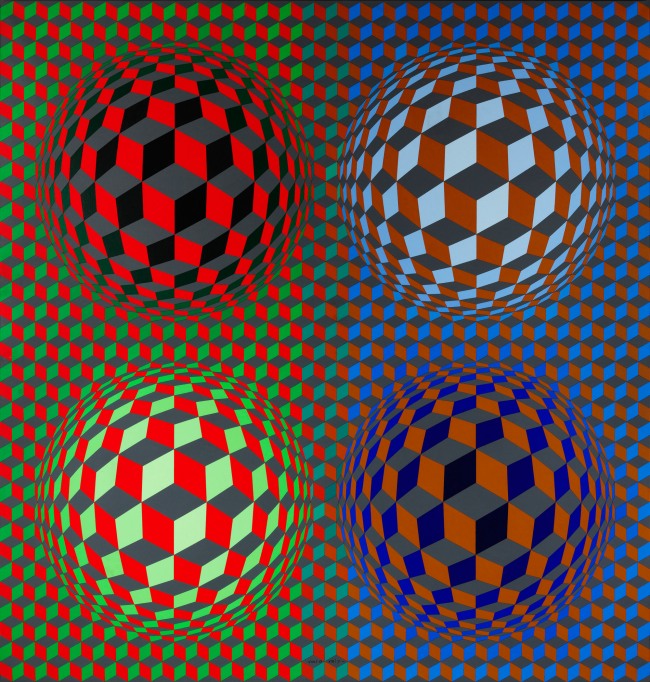

1. Vega Structures

Inspired by contemporary news reports about mysterious signals received from distant galaxies, Vasarely named many of his works after stars and constellations. The Vega pictures rely on convex-concave distortions of a grid-like network, a sophisticated combination of the cube and the sphere, symbolically referring to the two-way motion of the light that emanates from pulsating stars, and to the functioning of condensing galaxies and the expanding universe. The common denominator in these works is Vasarely’s realisation that two dimensions can be expanded into three simply by deforming the basic grid, and that, depending on the degree of enlargement or reduction, the elements in the deformed grid can be transformed into rhombuses or ellipses.

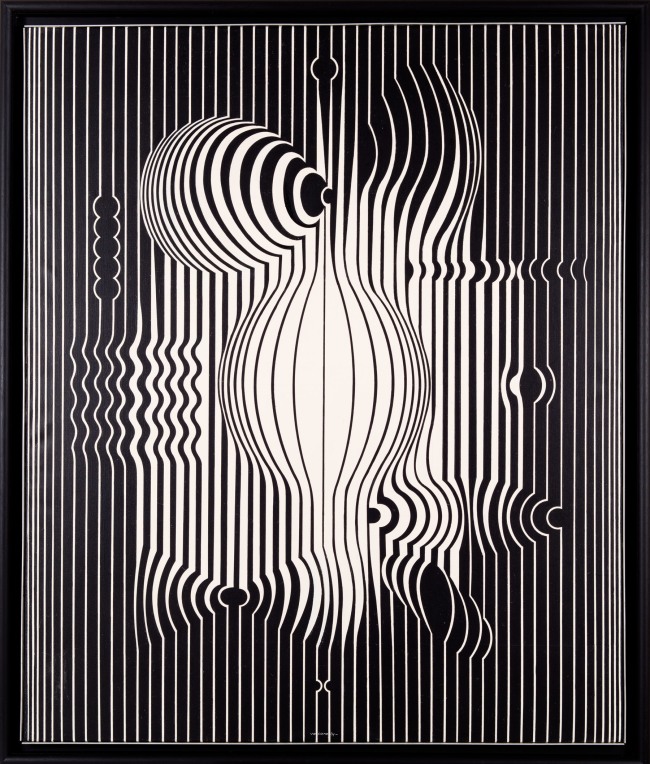

Installation view of the exhibition Victor Vasarely. The Birth of Op Art at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

Victor Vasarely (Hungarian-French, 1906-1997)

Nora-Dell

1974-1979

Silkscreen on paper

87 x 78cm

Vasarely Múzeum, Budapest

© Victor Vasarely, VEGAP, Madrid, 2018

Victor Vasarely (Hungarian-French, 1906-1997)

Manipur–negativo (Negative Manipur)

1971

Acrylic on canvas

156 x 130cm

Colección privada. Cortesía

Fondation Vasarely

© Victor Vasarely, VEGAP, Madrid, 2018

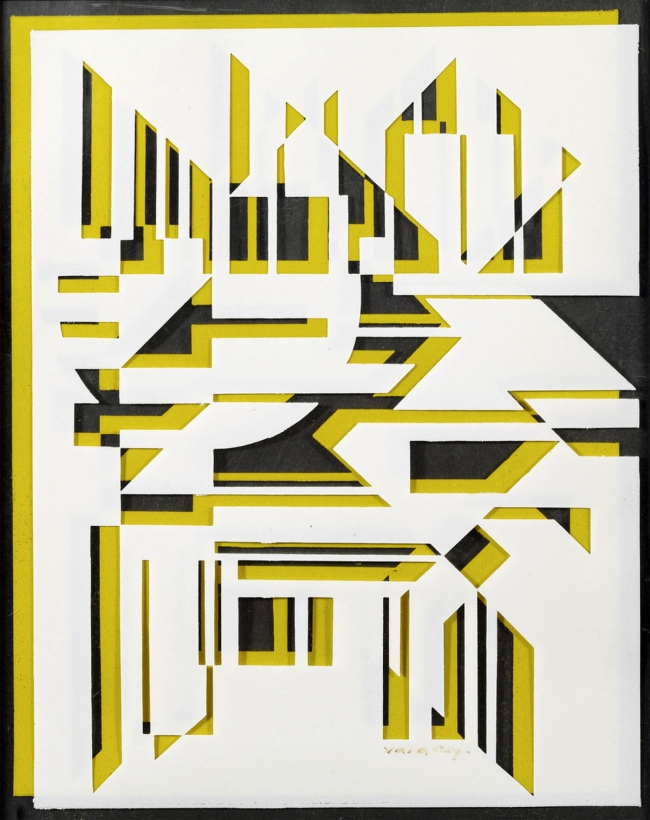

2. Graphic Period

Blessed with exceptional drawing ability, Vasarely studied the basics of graphic design at Műhely (Workshop) from 1929 to 1930. The private school in Budapest was run by Sándor Bortnyik, a painter and graphic designer who had connections with the Bauhaus in Weimar. Through Bortnyik, Vasarely began to take an interest in the formal problems of the kind of art in which composition is based on geometric principles, and as such he adopted Piet Mondrian, Theo van Doesburg, El Lissitzky, Kazimir Malevich and László Moholy-Nagy as his spiritual masters. In the first period of the artist’s career, which lasted until 1939, the imagery had not yet broken away from the primary visual world, that is, it was not entirely abstract, but the paradoxical optical effects produced by his networks of lines and crosses already bore hints of the illusionistic spatiality to come.

Installation view of the exhibition Victor Vasarely. The Birth of Op Art at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid showing the works Man in motion. Study of Motion (The Man) 1943 (left) and Material Study-Wood 1939 (right)

Victor Vasarely (Hungarian-French, 1906-1997)

Hombre en movimiento – Estudio del movimiento (El hombre)

Man in motion. Study of Motion (The Man)

1943

Tempera on plywood

117 x 132cm

Vasarely Múzeum, Budapest

© Victor Vasarely, VEGAP, Madrid, 2018

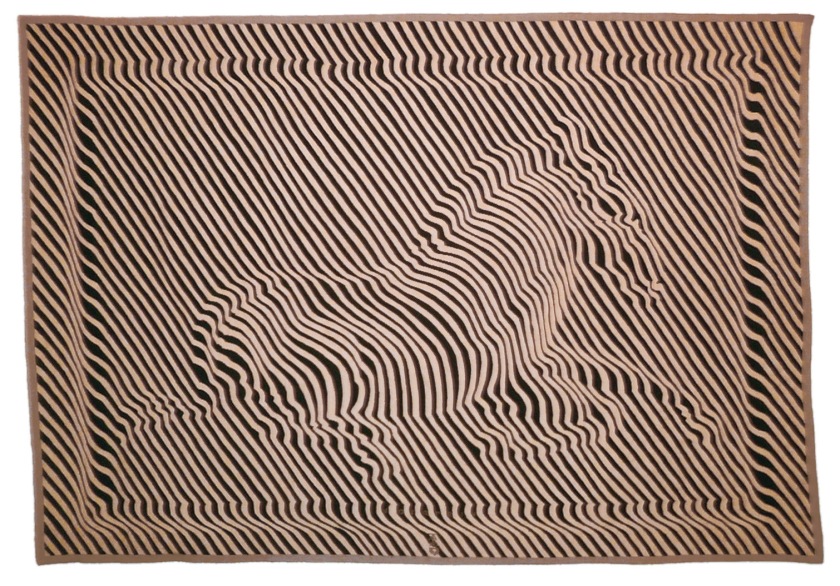

3. Pre-Kinetic Studies and Naissances

In 1951, the Galerie Denise René in Paris held an exhibition titled Formes et couleurs murales (Mural Forms and Colours). It was at this time that the Hungarian-French artist first considered representing the spatial problems of his pictures on a more monumental scale. At this exhibition, Vasarely used photographic methods to blow up his earlier pen-and-ink drawings, which he then arranged in series covering entire walls. These compositions were later rechristened Naissances (Births). The new name came about when the artist swept the photographic negatives of the drawings over one another, and disquieting, randomly arranged patterns emerged. In is Oeuvres profondes cinétiques (deep kinetic works), first exhibited in 1955, which Vasarely created following the same method of image-making, structuring them out of superimposed sheets of glass, acrylic or transparent foil, the sense of spatiality was combined with actual three-dimensional depth. Exploiting the physical laws of refraction and reflection, he produced spatial collages in a constant state of flux generated by the interference of two abstract patterns projected over each other, which were brought alive as the viewer changed position.

Victor Vasarely (Hungarian-French, 1906-1997)

Cébras – Estudio precinético (Zebras. Prekinetic Study)

1939

Tempera, pencil, colour and white chalk on paper

62 x 57cm

Vasarely Múzeum, Budapest

© Victor Vasarely, VEGAP, Madrid, 2018

Victor Vasarely (Hungarian-French, 1906-1997)

Zebra

1938-1960

Wooden wool tapestry

150 x 214cm

Victor Vasarely Múzeum, Pécs

© Victor Vasarely, VEGAP, Madrid, 2018

Victor Vasarely (Hungarian-French, 1906-1997)

Sophia-III

1952

Oil on canvas

132 x 200cm

Victor Vasarely Múzeum, Pécs

© Victor Vasarely, VEGAP, Madrid, 2018

Victor Vasarely (Hungarian-French, 1906-1997)

Naissances (del album “Hommage à J.S Bach”, suplemento 3)

Naissances (From the album Hommage à J.S. Bach, Supplement No.3)

1954-1960

Multiple. Silkscreen on glass

56 x 49.5 x 7.5cm

Vasarely Múzeum, Budapest

© Victor Vasarely, VEGAP, Madrid, 2018

4. Belle-Isle / Crystal / Denfert

In 1947, while spending the summer on Belle Île, an island off the coast of Brittany, he discovered the internal geometry of nature. He took irregularly shaped glass tiles and pebbles polished by the ocean waves and stylised their abstract forms into ellipses. In 1948, he produced delicate pen-and-ink drawings that conjured up the strange meandering patterns of the hairline cracks that pervaded the ceramic tiles covering the Paris metro station named Denfert-Rochereau. From his sketches, which reveal a vivid imagination, he created evocative paintings composed with well unified colours. Those same years also saw the beginning of his Crystal period, which was inspired by the strict geometric structure of the stone houses in Gordes, a medieval town built on a cliff in the South of France. Vasarely strove to transpose reality into the two-dimensional plane with the help of the axonometric approach.

Installation view of the exhibition Victor Vasarely. The Birth of Op Art at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid showing from left, the works Lan 2, 1953; Amir (Rima) 1953; and Vessant, 1952

Victor Vasarely (Hungarian-French, 1906-1997)

Vessant (Versant)

1952

Oil on plywood

150 x 190cm

Vasarely Múzeum, Budapest

© Victor Vasarely, VEGAP, Madrid, 2018

Victor Vasarely (Hungarian-French, 1906-1997)

Amir (Rima)

1953

Oil on plywood

140 x 180cm

Vasarely Múzeum, Budapest

© Victor Vasarely, VEGAP, Madrid, 2018

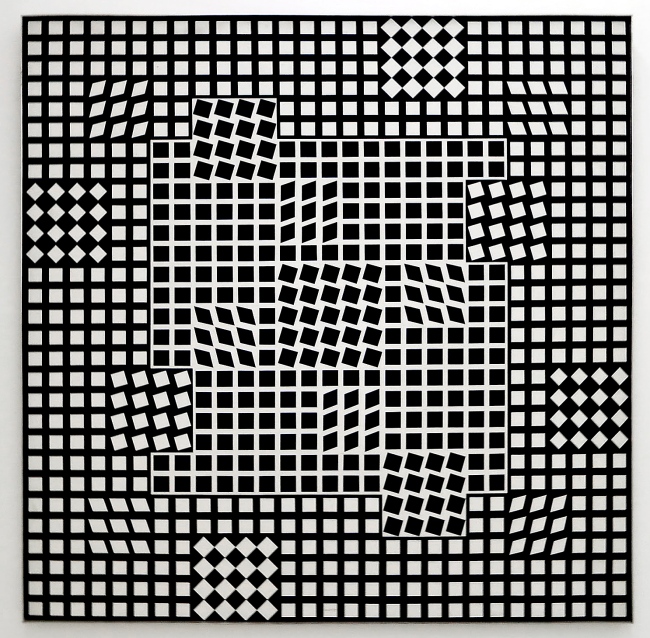

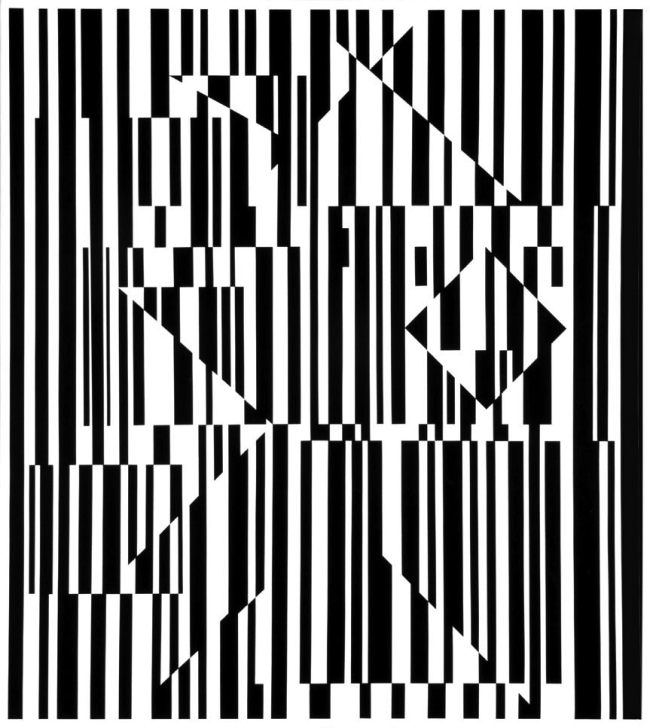

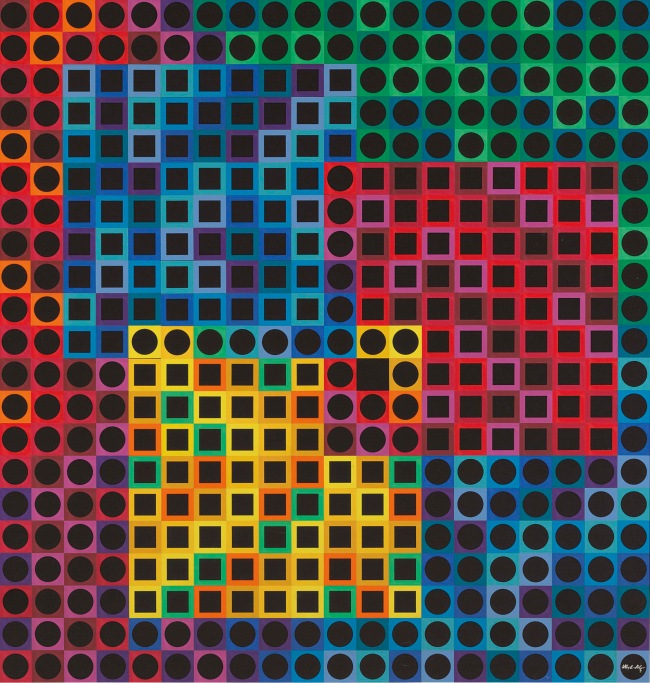

5. Black and White Period (Kineticism)

Inspired by Kazimir Malevich’s Suprematist composition, Black and White (1915), which embodies the harmony of spirituality and is widely interpreted as the ‘end point’ of painting, Vasarely conceived of the picture titled Homage to Malevich. Its basic component, a square rotated about its axis so that it appears as a rhombus, became the starting point of his ‘kinetic’ works.

Victor Vasarely (Hungarian-French, 1906-1997)

Tlinko-F

1956-1962

Oil on canvas

145 x 145cm

Vasarely Múzeum, Budapest

© Victor Vasarely, VEGAP, Madrid, 2018

Victor Vasarely (Hungarian-French, 1906-1997)

Gixeh

1955-1962

Oil on canvas

170 x 160cm

Museo de Bellas Artes, Budapest

© Victor Vasarely, VEGAP, Madrid, 2018

Installation view of the exhibition Victor Vasarely. The Birth of Op Art at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid showing from left, the works Doupla, 1970-1975; Kotzka, 1973-1976 and Gixeh, 1955-1962

Installation view of the exhibition Victor Vasarely. The Birth of Op Art at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid showing from left, the works Nethe, 1964; Noorum, 1960-1977 and Tlinko-F, 1956-1962

Installation view of the exhibition Victor Vasarely. The Birth of Op Art at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid showing from left, the works Afa III, 1957-1973 Nethe, 1964; Noorum, 1960-1977

Victor Vasarely (Hungarian-French, 1906-1997)

Noorum

1960-1977

Acrylic on canvas

112 x 84cm

Vasarely Múzeum, Budapest

© Victor Vasarely, VEGAP, Madrid, 2018

Installation view of the exhibition Victor Vasarely. The Birth of Op Art at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid showing from left, the works Taymir II, 1956 and Afa III, 1957-1973

Victor Vasarely (Hungarian-French, 1906-1997)

Taymir II

1956

Acrylic on canvas

135 x 120cm

Victor Vasarely Múzeum, Pécs

© Victor Vasarely, VEGAP, Madrid, 2018

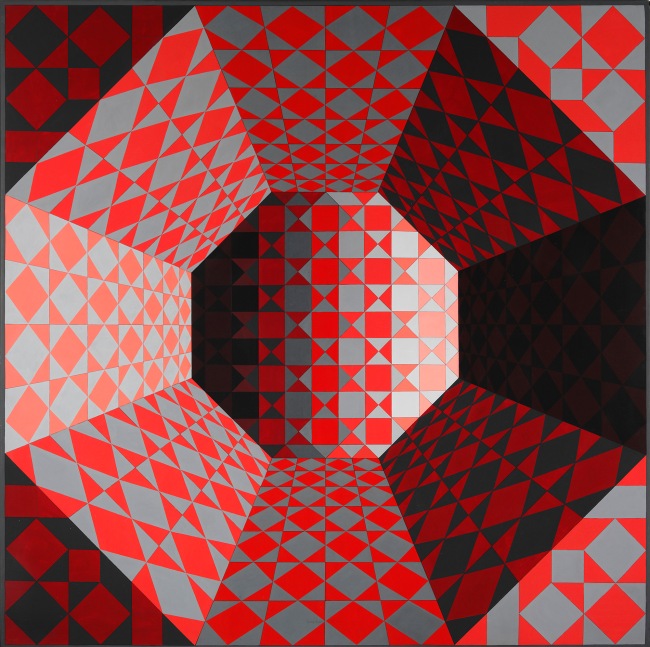

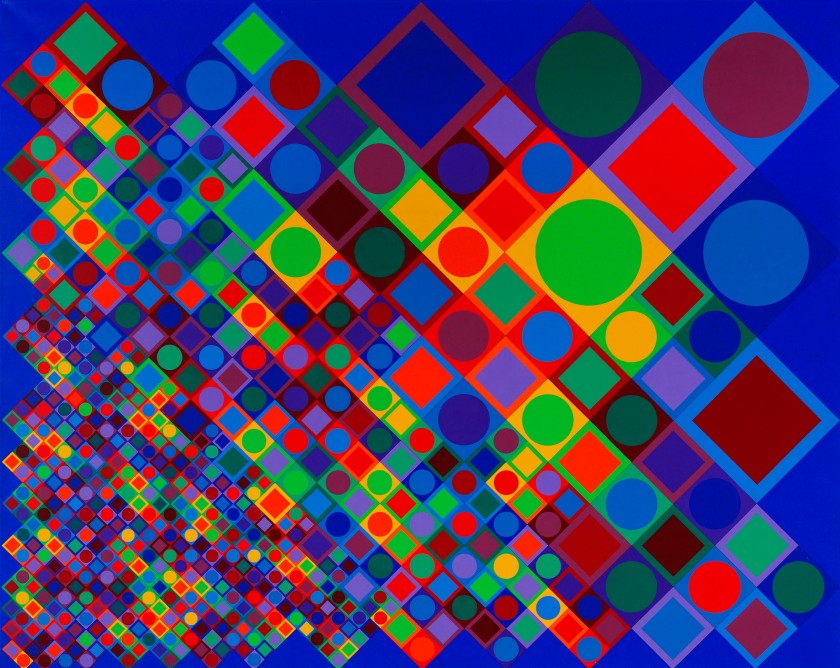

6. Universal systems built from a plastic alphabet

Vasarely presented the results of his analytical research into the Plastic Unit at an exhibition held in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris in 1963. His formula for this was built on the structural interplay of form and colour. He regarded colour-forms as the cells or molecules out of which the universe was made. ‘The form-color unit […] is to plasticity what the particle-wave is to nature’, he declared. In pictures based on the mutual association between forms and colours, he claimed to perceive a ‘grammar’ of visual language, with which a set of basic forms making up a composition could be arranged into a system similar to musical notation.

The plastic alphabet

The plastic alphabet is a kind of programmed language with an infinite number of form and colour variations. The basic unit of the alphabet is a coloured square containing smaller basic shapes like squares, triangles, circles and rectangles. Vasarely used these patterns and primary colours plus endless colour permutations as the duplicating and changing elements in his works. In each unit there was a number which determined its colour, tone, form and place in the whole.

Vasarely saw that his plastic alphabet, by enabling serial production, could open the way to countless applications. It could be used as the basis for planning houses and whole environments for cities: it offered countless permutations of form and colour, and the size of the basic unit could be changed or enlarged as required.

Installation view of the exhibition Victor Vasarely. The Birth of Op Art at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid showing from centre to right, the works Villog, 1979; Zila, 1981 and Pavo II, 1979

Victor Vasarely (Hungarian-French, 1906-1997)

Pavo II

1979

Acrylic on plywood

60 x 60cm

Vasarely Múzeum, Budapest

© Victor Vasarely, VEGAP, Madrid, 2018

Installation view of the exhibition Victor Vasarely. The Birth of Op Art at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid showing from left to right in the bottom image, the works Vonal-Fegn, 1968-1971; Helios, 1964 (multiple) and Villog, 1979

Installation view of the exhibition Victor Vasarely. The Birth of Op Art at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid showing from left in the bottom image, Doupla, 1970-1975; Kotzka, 1973-1976 and Vonal-Fegn, 1968-1971

Installation view of the exhibition Victor Vasarely. The Birth of Op Art at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid showing from left, Bi-Octans, 1979; Doupla, 1970-1975; Kotzka, 1973-1976; Vonal-Fegn, 1968-1971 and Helios, 1964 (multiple)

Victor Vasarely (Hungarian-French, 1906-1997)

Vonal-Fegn

1968-1971

Tapestry, cotton and wool

252 x 255cm

Victor Vasarely Múzeum, Pécs

© Victor Vasarely, VEGAP, Madrid, 2018

Victor Vasarely (Hungarian-French, 1906-1997)

Kotzka

1973-1976

Acrylic on canvas

130 x 130cm

Vasarely Múzeum, Budapest

© Victor Vasarely, VEGAP, Madrid, 2018

Victor Vasarely (Hungarian-French, 1906-1997)

Doupla

1970-1975

Acrylic on canvas

210 x 114cm

Vasarely Múzeum, Budapest

© Victor Vasarely, VEGAP, Madrid, 2018

Installation view of the exhibition Victor Vasarely. The Birth of Op Art at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid showing from left Dirac, 1978 and Bi-Octans, 1979

Victor Vasarely (Hungarian-French, 1906-1997)

Bi-Octans

1979

Acrylic on canvas

180 x 180cm

Vasarely Múzeum, Budapest

© Victor Vasarely, VEGAP, Madrid, 2018

7. Algorithms and Permutations

Vasarely first discussed the necessity for his works to be duplicated and disseminated widely in 1953. Then, in his Yellow Manifesto of 1955 he outlined his ideas on the possibilities of re-creation, multiplication and expansion. He believed that a basic set of corpuscular elements, by virtue of their multiplicability and permutability, could be transformed using a pre-selected algorithm into a virtually infinite number of different compositions. The programmations that would record the picture-composition process onto graph paper assumed that the colours, shades and forms making up each image could be notated numerically, and even fed into an electronic brain to be retrieved at any time. Although Vasarely himself had never worked with computers, his principles led logically to the possibility of creating images with such technology. As conceived by the artist, in future, employing codes of colour and form that were objectively defined using alphanumerical data, his compositions could be recreated at anytime, anywhere in the world, by anybody at all.

Victor Vasarely (Hungarian-French, 1906-1997)

Stri-Per

1973-1974

Acrylic on canvas

76 x 76cm

Vasarely Múzeum, Budapest

© Victor Vasarely, VEGAP, Madrid, 2018

Installation view of the exhibition Victor Vasarely. The Birth of Op Art at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid showing from left Kekub, 1976-1978; Black Orion, 1970; Marsan-2, 1964-1974 and Eroed-Pre, 1978

Victor Vasarely (Hungarian-French, 1906-1997)

Eroed-Pre

1978

Acrylic on cardboard

52 x 52cm

Vasarely Múzeum, Budapest

© Victor Vasarely, VEGAP, Madrid, 2018

Victor Vasarely (Hungarian-French, 1906-1997)

Marsan-2

1964-1974

Acrylic on canvas

202 x 253cm

Vasarely Múzeum, Budapest

© Victor Vasarely, VEGAP, Madrid, 2018

Victor Vasarely (Hungarian-French, 1906-1997)

Orion noir (de la serie “Kanta”)

Black Orion (From the “Kanta” series)

1970

Polystyrene

100 x 105cm

Vasarely Múzeum, Budapest

© Victor Vasarely, VEGAP, Madrid, 2018

Victor Vasarely (Hungarian-French, 1906-1997)

Zint-MC

1960-1976

Acrylic on canvas

179 x 153cm

Vasarely Múzeum, Budapest

© Victor Vasarely, VEGAP, Madrid, 2018

Installation view of the exhibition Victor Vasarely. The Birth of Op Art at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid showing in the bottom image from left Yllus, 1978; V.P. 102, 1979; Trybox, 1979 and Toro, 1973-1974

Victor Vasarely (Hungarian-French, 1906-1997)

Yllus

1978

Acrylic on canvas

87 x 87cm

Vasarely Múzeum, Budapest

© Victor Vasarely, VEGAP, Madrid, 2018

Victor Vasarely (Hungarian-French, 1906-1997)

Trybox

1979

Acrylic on canvas

192 x 218cm

Vasarely Múzeum, Budapest

© Victor Vasarely, VEGAP, Madrid, 2018

Victor Vasarely (Hungarian-French, 1906-1997)

Toro (Bull)

1973-1974

Acrylic on canvas

175 x 175cm

Vasarely Múzeum, Budapest

© Victor Vasarely, VEGAP, Madrid, 2018

Victor Vasarely (Hungarian-French, 1906-1997)

Stri-Oet

Acrylic on canvas

211 x 191cm

Vasarely Múzeum, Budapest

© Victor Vasarely, VEGAP, Madrid, 2018

Installation view of the exhibition Victor Vasarely. The Birth of Op Art at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid showing in the bottom image from left Stri-Oet, 1979; Cheiyt-Stri-F, 1975; Peer-Rouge, 1977; Woo, 1972-1975; Kekub, 1976-1978 and Black Orion, 1970

8. Planetary Folklore

In the early 1960s, Vasarely put forward a proposal for the use of a universal visual language formulated in accordance with the principle of the Plastic Unit, which he called ‘planetary folklore’. He believed that regularly arranged and numbered, homogeneous colours and constant forms, of the kind that could be manufactured industrially, could have meaning attached to them. His intention was for the opportunity of aesthetic pleasure to become part of the everyday environment. As Vasarely argued, artworks not only belonged in museums and galleries, but were also needed in every single segment of urban life. His concept, which built on the ideas of Le Corbusier and Fernand Léger, and which proclaimed a synthesis of the different fields of the arts, was for the building blocks of the cities of the future to consist of mass-produced, monumental ‘plastic’ works that could be extended to any desired size, which would provide limitless possibilities of variation. The first of his architectural integrations was implemented in Venezuela in 1954, on the campus of the Central University of Caracas; this was followed by monumental ‘plastic’ installations on buildings in Bonn, Essen, Paris and Grenoble.

Victor Vasarely (Hungarian-French, 1906-1997)

Ferde

1966-1974

Collage on cardboard

78 x 77cm

Vasarely Múzeum, Budapest

© Victor Vasarely, VEGAP, Madrid, 2018

Installation view of (l-r):

Victor Vasarely (Hungarian-French, 1906-1997)

Estudio BR 14, serie “Pignons” Muros ciegos, Integraciones monumentales, Viviendas colectivas, Edificios grandes

Study BR 14. ‘Pignons’ Series: Blind Walls, Monumental Interations, Collective Dwellings, Large Buildings

1970

Mixed: Collage on board

75.8 x 81.8cm

Fondation Vasarely, Aix-en- Provence

© Victor Vasarely, VEGAP, Madrid, 2018

Victor Vasarely (Hungarian-French, 1906-1997)

Estudio BR 3, serie “Pignons” Muros ciegos, Integraciones monumentales, Viviendas colectivas, Edificios grandes

Study BR 3. ‘Pignons’ Series: Blind Walls, Monumental Interations, Collective Dwellings, Large Buildings

1970

Mixed: Collage on board

75.8 x 81.8cm

Fondation Vasarely, Aix-en- Provence

© Victor Vasarely, VEGAP, Madrid, 2018

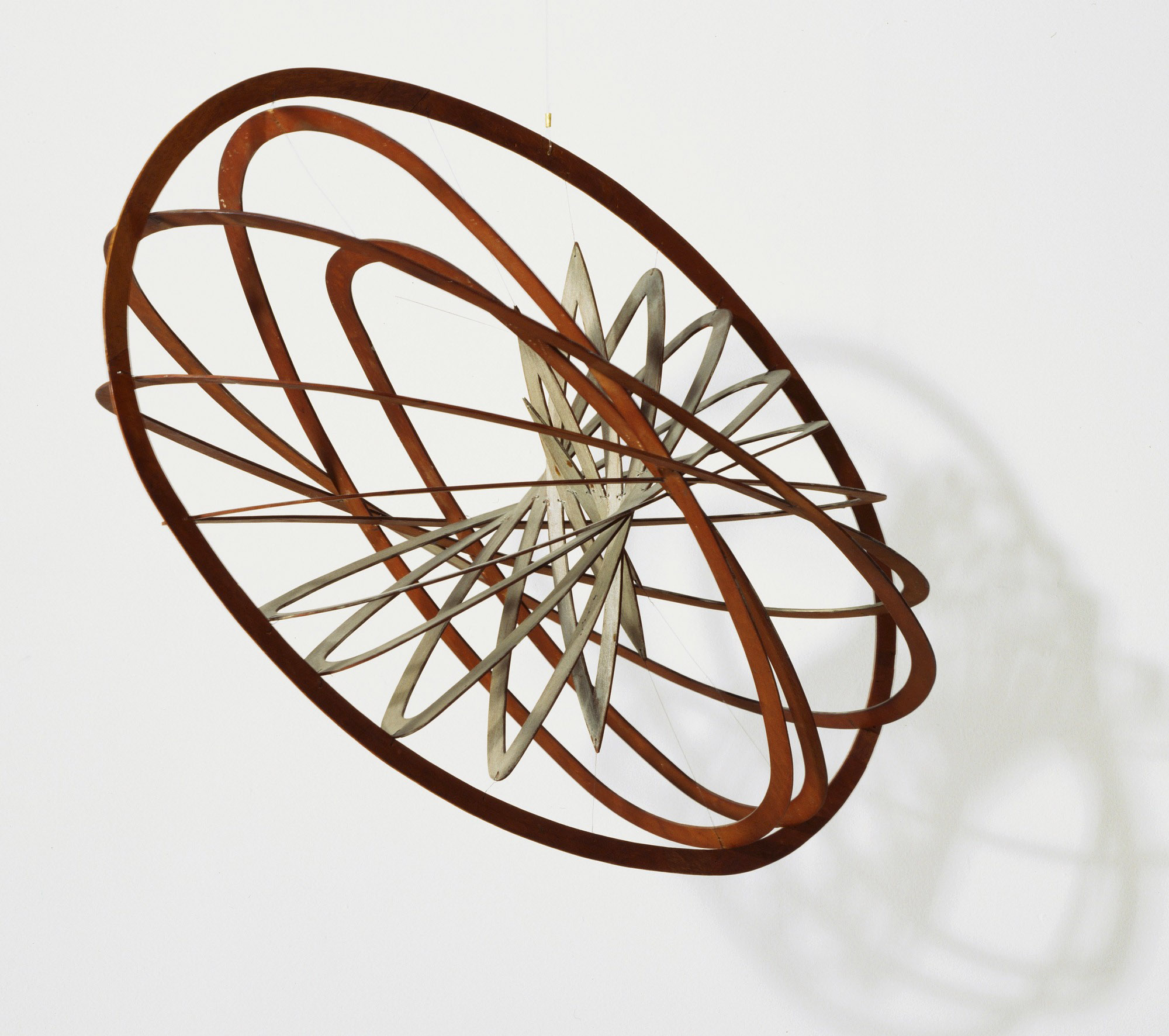

9. Multiples

An important part of Vasarely’s art philosophy was his conscious refusal to discriminate between an individual work and its duplicate. He was convinced that an artwork came alive again when multiplied, and that the multiple was the most democratic form of art. His aim was to topple the elitist concept of owning unique and unrepeatable works by replacing it with the notion of making pictures for mass distribution. The artist experimented with the most diverse assortment of materials and techniques, from the most modern to the most ancient. Weaving workshops in Aubusson, following traditions dating back centuries, produced tapestries from his designs. Vasarely was also especially fond of the serigraph. His individually signed and numbered screen prints were commercially available on the art market, as were the multiple objects composed of individually handcoloured or industrially reproduced sheets mounted on wooden or metal backing materials.

Victor Vasarely (Hungarian-French, 1906-1997)

Kroa-MC

1969

44 x 44 x 50cm

Multiple. Metal, silk screen on metal

Vasarely Múzeum, Budapest

© Victor Vasarely, VEGAP, Madrid, 2018

Victor Vasarely (Hungarian-French, 1906-1997)

Tridim- HH

1972

Multiple. Acrylic on board

30 x 24 x 6cm

Vasarely Múzeum, Budapest

© Victor Vasarely, VEGAP, Madrid, 2018

Victor Vasarely (Hungarian-French, 1906-1997)

Beryl-Positive

1967

Multiple, acrylic on plywood

36 x 36 x 4.5cm

Vasarely Múzeum, Budapest

© Victor Vasarely, VEGAP, Madrid, 2018

Victor Vasarely (Hungarian-French, 1906-1997)

Ajedrez (Chess Set)

1980

Plexiglass on acrylic board

70 x 70 x 15cm

Vasarely Múzeum, Budapest

© Victor Vasarely, VEGAP, Madrid, 2018

Vasarely and the ‘Op Art’ phenomenon

Márton Orosz

‘…here comes Op Art!’

Victor Vasarely, 18 April 1964

When the major exhibition titled The Responsive Eye opened at the New York Museum of Modern Art in 1965, it made Optical Art famous almost overnight. The limelight was stolen by two Europeans: Josef Albers, who continued the legacy of the Bauhaus in his art, and Victor Vasarely. Both men were represented at the show with six works each. But whereas Albers, oft neglected by the critics, was turned into the black sheep of the movement by contemporary art history writing, for Vasarely, who was just reaching the peak of his career, the show served as a launch pad to fame.(…)

The scientific definition of Op Art came soon afterwards, with the first attempt made in 1967 by the German art historian, Max Imdahl. Imdahl interpreted the art of Victor Vasarely as deriving from the Orphism of Robert Delaunay, which ascribed meaning to colour, the Neo-Plasticism of Piet Mondrian, which rested on the symmetry of two-dimensional structures, and the Mechano-Faktura of Henryk Berlewi, which borrowed its aesthetic principles from the schematism of mechanical production. Vasarely, meanwhile, preferred to call his own invention Kineticism, and he was fully justified in doing so, because if we accept the contents of his art philosophical writings, published in chronological order under the title of Notes brutes, then the artist was the first person to consistently use this name for the movement. He coined the phrase ‘kinetic art’ in 1953, basing the term on the description of the movement of gases written by Nicolas Sadi Carnot, the nineteenth-century French engineer who developed thermodynamics. In the light of Vasarely’s consistency of thought, his wide-ranging knowledge and his enthusiasm for science, it would have been the logical outcome of his principles to classify his works under a style or movement of his own construction. Kineticism, however, was regarded by Vasarely as something more than a simple art movement. He not only referred to it in a formal sense, but also accorded it ethical, economic, social and philosophical functions. He believed it to be of greater significance than Cubism, and he was convinced the Kineticism offered, for the first time since the Renaissance, a synthesis of ‘the two creative expressions of man: the arts and the sciences’. The simultaneous representation of movement, space and time had already found expression in Constructivist art in the 1920s, but Vasarely’s Op Art was fundamentally different, in that it aimed to generate a spatial effect through the use of a two-dimensional surface by creating the illusion of motion in macro-time, whereby the image formed on the retina underwent virtual manipulation. Consequently, the name Op Art can be given to any artwork ‘that shifts during the spectator’s act of perception’. (…).

‘Optical’ paintings

(…) Vibrant surfaces created from patterns of geometric figures arranged according to a particular algorithm can be found among the mosaics of Antiquity. The first stage in the history of the autonomisation of retina-based art, however, came at the end of the nineteenth century with Pointillist painting, which relied on the scientific theory of the optical combination of colours, and with the so-called Divisionists, who strove to separate optical effects using an analytical method. Georges Seurat’s ‘optical painting’, however, remained firmly attached to the real spectacle. Primary shapes became a means of generating illusions with the arrival of non-objective, abstract art styles, especially Cubism. Optical games derived from periodic series of geometric elements were incorporated into the repertoire of applied photography in the second half of the 1920s. During his studies in Budapest, Vasarely may have come across such depictions, even in the printed press, such as the photograph of the Hollywood actress, Alice White, in a room of mirrors decorated with abstract patterns.

Yet optical illusion was not enough to bring about Op Art, which also needed the dynamism of kinetics. It became inseparable from the concept of the fourth dimension of motion-time, which tipped the static work out of its fixed position by involving the viewer and turning the eye into the active organ of sight. In this sense, Vasarely’s optical kineticism also posed the question of the dematerialisation of the artwork, for in his works, the actual spectacle is not present on the canvas at rest in front of us, but comes about through interacting with the work and is generated on the retina. Vasarely was never concerned with the type of mechanical movement that brought about the works of Jean Tinguely or Marcel Duchamp. The Hungarian artist’s planar kineticism was in this respect far more closely connected to visual research than to the approach of works that emphasise their industrial nature. (…)

Op Art as Algorithm

(…) When it came to the aesthetic and market values of artworks that existed in multiple copies, opinion was split even among the artists participating in the exhibition. In terms of form, the experiments into perception conducted by Vasarely and Bridget Riley, for example, had much in common, and yet their views on the democratisation and interdisciplinarity of art differed sharply. Unlike Riley, who always insisted on her paintings being one of a kind, Vasarely’s programme of art targeted a re-evaluation of the aesthetic of reproduced, duplicated objects. It was in this regard that Vasarely came closest to Pop Art and to its iconic exponent, Andy Warhol. In spite of this, Vasarely was not in thrall to Pop Art. He spoke appreciatively of its achievements, but he considered it to be a movement outside the realm of painting, a parody or caricature of its own times. Pop Art, meanwhile, suffered greatly from the fact that Op Art ultimately proved far more popular. ‘I am “pop” in the sense that I would like to be popular’, Vasarely wittily replied when one journalist pressed him on his personal position in Op Art, shortly after it had found fame as a fashion phenomenon. A few years later, at a reception held in the Galerie Spiegel in Cologne in September 1971, where a work by Vasarely hung on the wall beside Tom Wesselmann’s Great American Nude, an iconic piece from the rival movement, the Hungarian-born artist was asked his opinion of Pop Art. He could not refrain from commenting that the essence of Pop was exaggeration. He then cast a malicious glance at Wesselmann’s painting before declaring, ‘Art is not about painting gigantic pictures for billionaires’. When it was subsequently suggested that his democratic views were not compatible with the high prices commanded by his works, he replied, ‘The critics compare me to hippies who loathe money but who want to get around by hitchhiking. And at such times it is of no concern to them that they are travelling with the help of General Motors, Shell and other billionaire companies’.

There was, however, a whole group of Pop-Art fans who would never have dreamed of denigrating Kineticism. Warhol, for instance, began to follow Vasarely’s career after seeing his works at the opening of The Responsive Eye. He was present at the artist’s exhibition held in 1965 in the Pace Gallery in New York, and his admiration endured until 1984, when he attended Vasarely’s birthday party, arranged by Yoko Ono. It was probably on this occasion that Warhol was given a handkerchief signed by Vasarely, decorated with a pre-kinetic zebra composition, which the American artist preserved among his relics up until his death. We would find few artists in the twentieth century who achieved more in rethinking the aesthetic of the multiplied artwork than Vasarely and Warhol, so there is a striking contradiction in the fact that the only work by Vasarely in Warhol’s collection was a monochromatic oil painting, titled Onix 107 (1966), which actually represented the counterpoint to the paradigm expressing the latent artistic opportunities in duplication (including the entire spectrum of vibrant and saturated colours). (…)

Extract from the catalogue

Victor Vasarely (Hungarian-French, 1906-1997)

Transparence-XIII

1952

Kinetic object, silkscreen on plastic foils mounted on plywood

40 x 33cm

Vasarely Múzeum, Budapest

© Victor Vasarely, VEGAP, Madrid, 2018

(from the Belle-Isle / Crystal / Denfert section of the exhibition)

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza

Paseo del Prado 8, 28014 Madrid, Spain

Phone: 91 791 13 70

Opening hours:

Tuesday to Sunday: 10.00 – 19.00

You must be logged in to post a comment.