January 2018

Publisher: Daylight Books

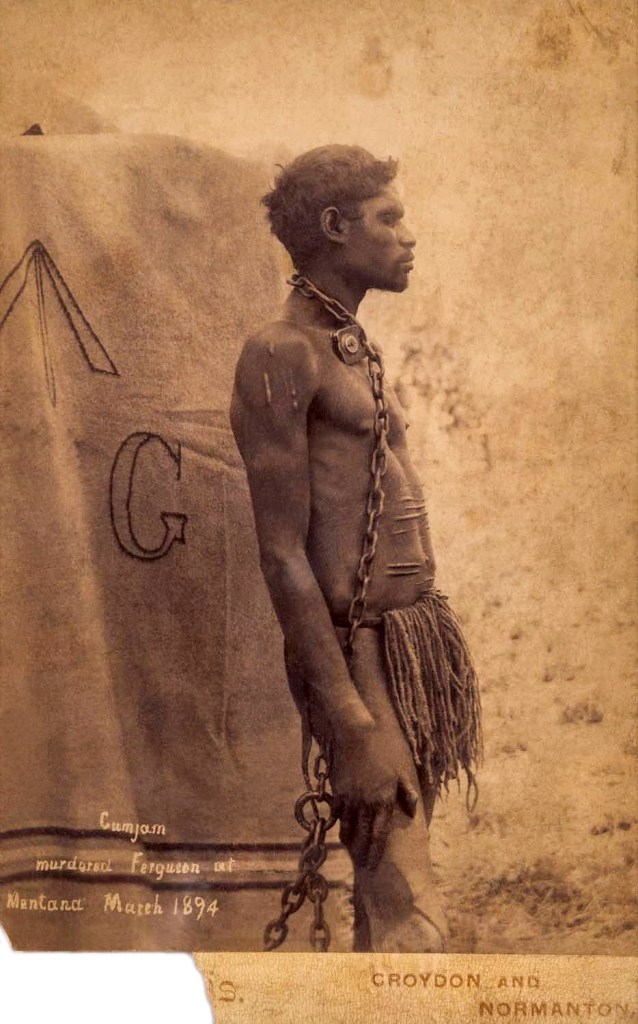

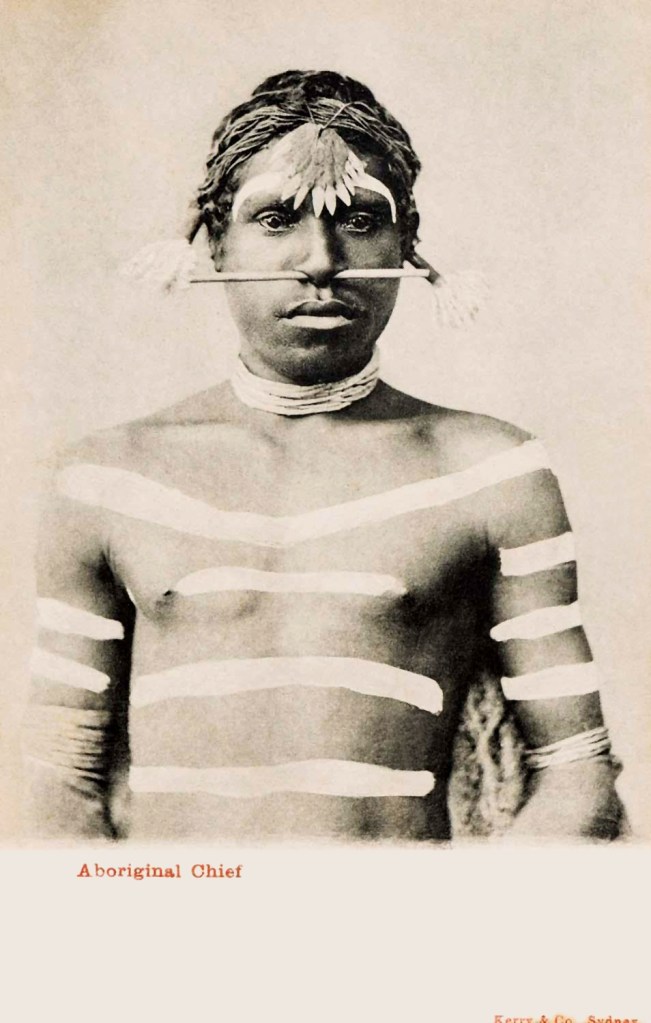

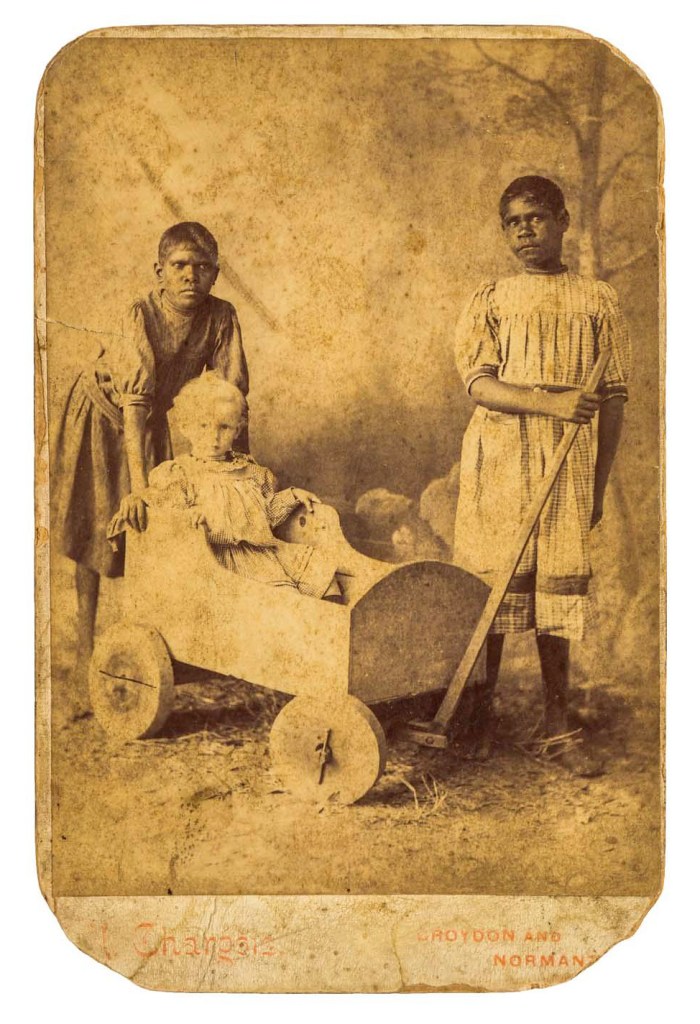

Warning: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers should be aware that the posting on this book contains images and names of people who may have since passed away.

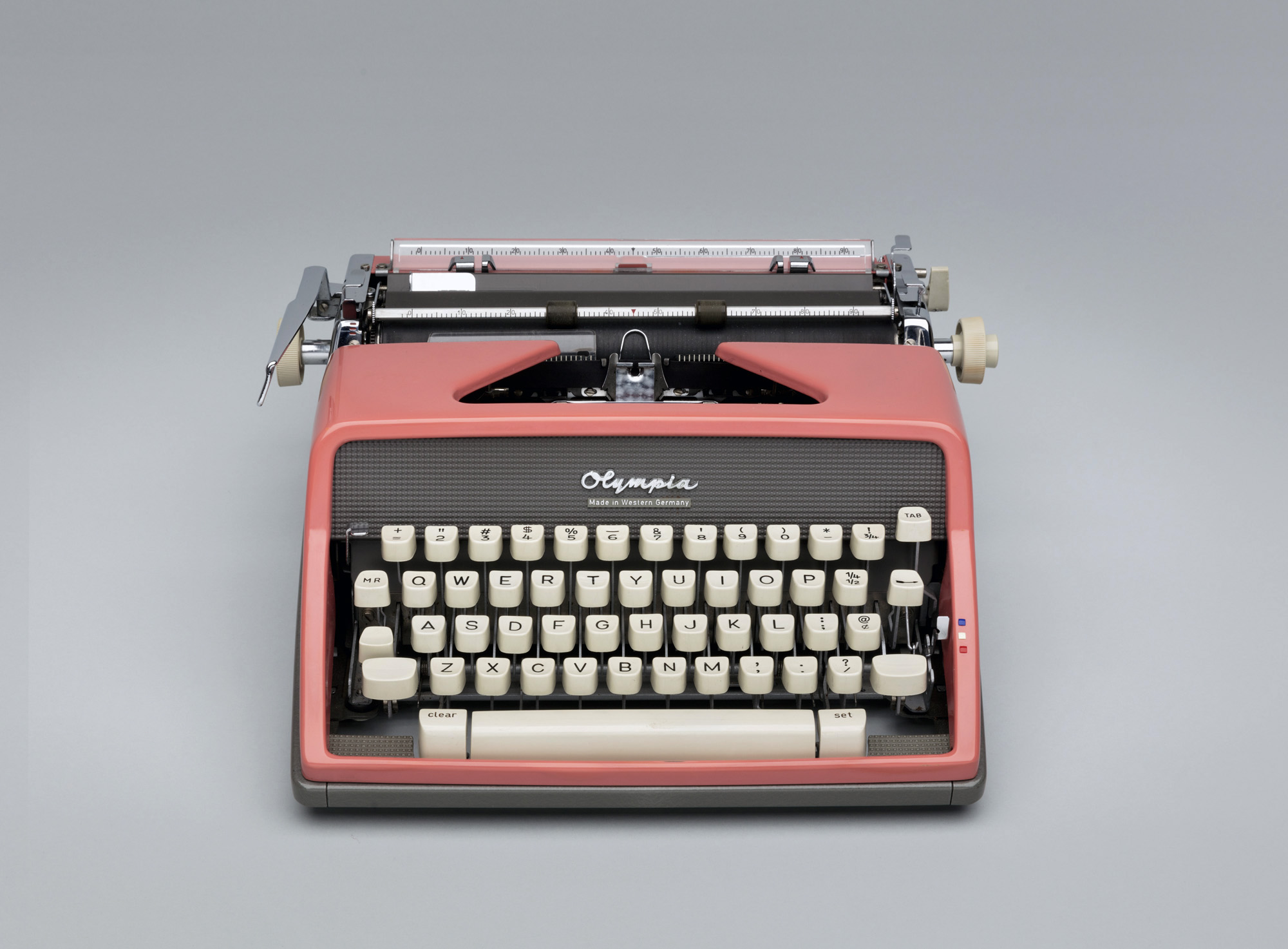

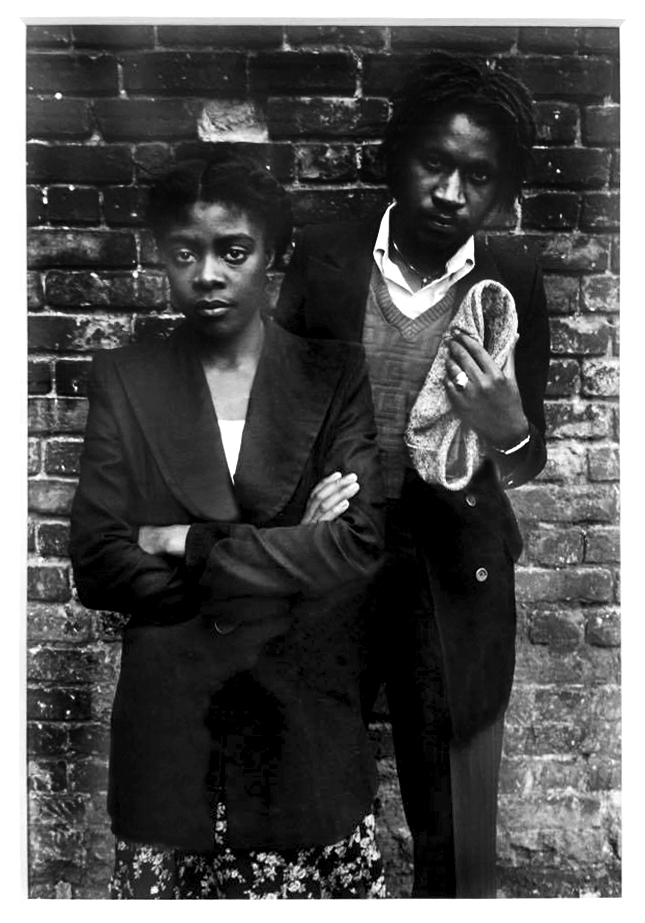

Judith Crispin (Australian / Bpangerang, b. 1970)

Sonya Napaljarri Cook Painting

Warnayaka Arts Centre, Lajamanu Community NT, December 2015

Judith Crispin (Australian / Bpangerang, b. 1970)

Tabra Nakamarra’s Puppy

Lajamanu Community NT, June 2015

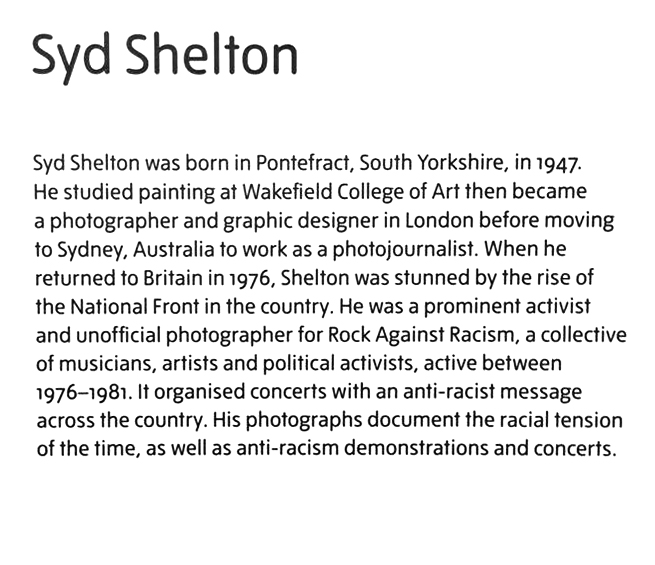

Truth and consequence in red dirt country

Australia has a long tradition of social documentary photography, dating back to the late nineteenth century. From Fred Kruger’s photographs of the Aboriginal community at Coranderrk in the 1870-80s through, variously but not exclusively:

Frank Hurley‘s photographs of the First World War, Antarctic exploration, Aboriginal communities and Australian industry

F. Oswald Barnett and his photographs of the slums of Melbourne in the 1930s

Charles P. Mountford (1890-1976) was an ethnographer and photographer, working from the 1930s-1960s who “showed a keen interest in and respect for Aboriginal culture, a fact that is evident in his archive. Although peppered with the vernacular and attitudes of the times, Mountford’s writing, and more tellingly his photographs, are indicative of his belief that Aboriginal life was richer and more complex than most white Australians conceded.” (State Library of South Australia)

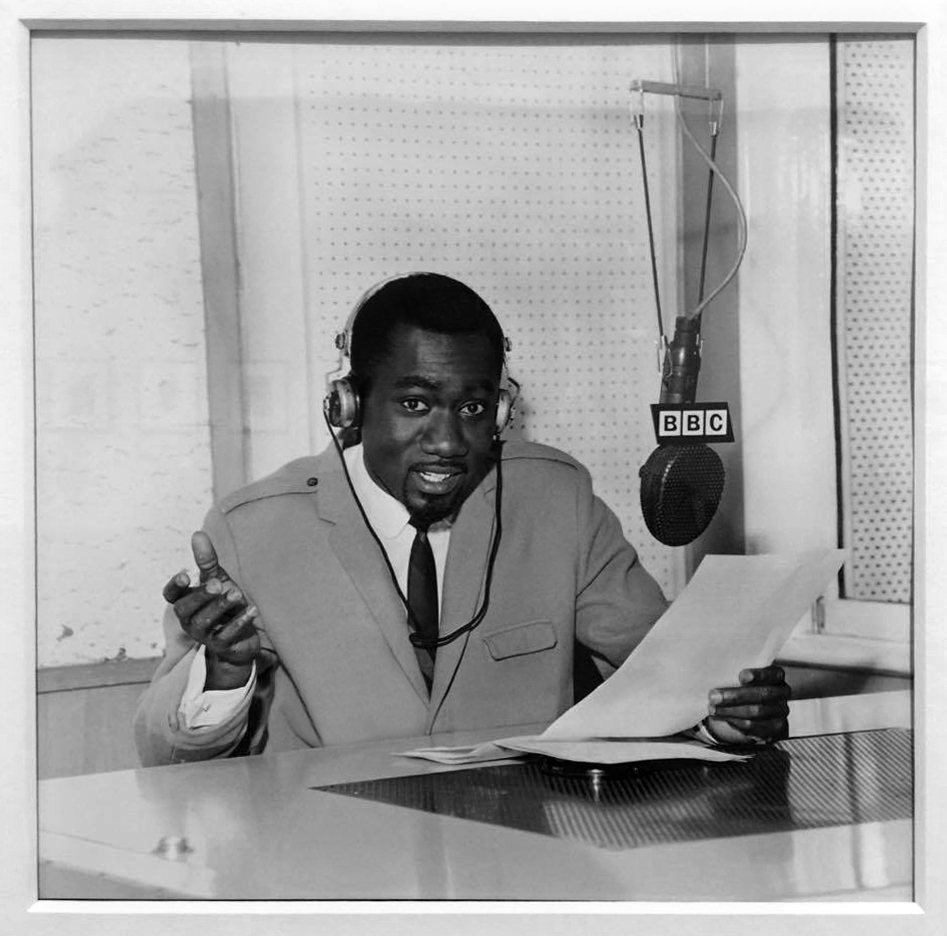

Mervyn Bishop (born 1945), followed in 1974, an Australian news and documentary photographer whose work combines journalistic and art photography. Joining The Sydney Morning Herald as a cadet in 1962 or 1963, he was the first Aboriginal Australian to work on a metropolitan daily newspaper and one of the first Aboriginal Australians to become a professional photographer. Focusing on Indigenous self-determination, Bishop’s work “covered the major developments in Aboriginal communities throughout Australia, including the historical moment in 1975 when the (then) Prime Minister, Gough Whitlam, poured a handful of earth back into the hand of Vincent Lingiari, Gurindji elder and traditional land owner. This image – representing the Australian government’s recognition of Aboriginal land rights – became an icon of the land rights movement and Australian photography.” (Art Gallery of New South Wales)

See more of Mervyn Bishop’s photographs

Harold Cazneaux and Max Dupain‘s photographs of Australian life from the 1920-1980s

Jim Fitzpatrick and his Drouin series from WW2

Rennie Ellis‘ photographs of celebrity and Melbourne life

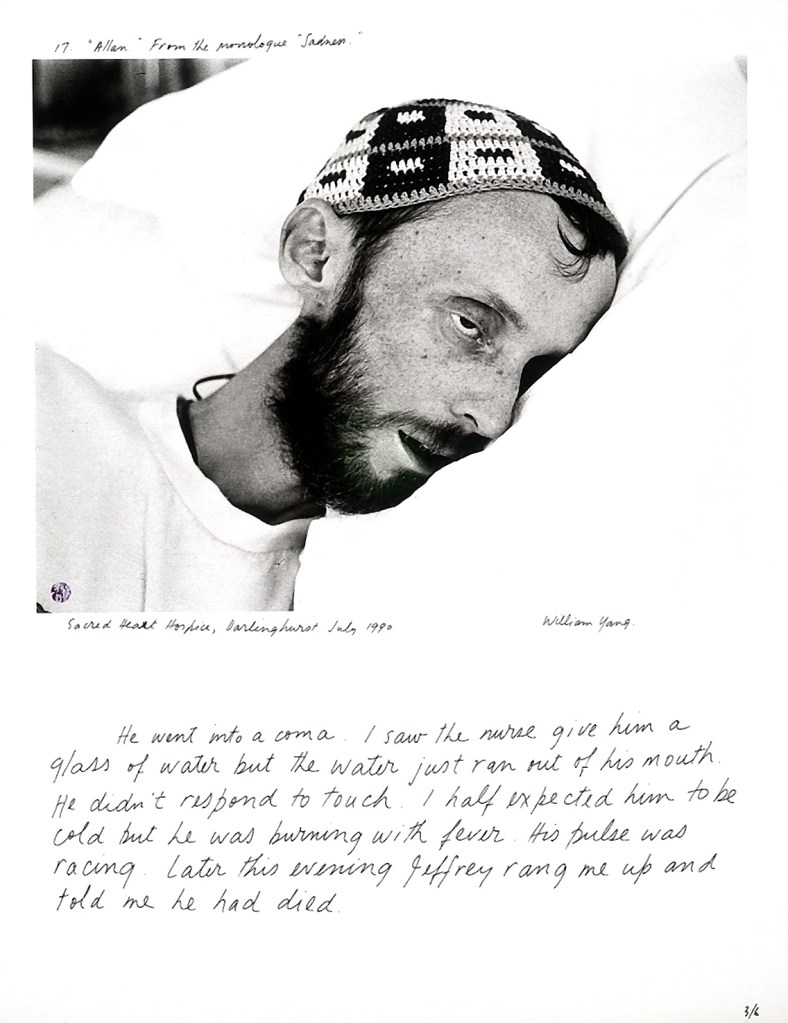

William Yang‘s photographs exploring issues of cultural and sexual identity

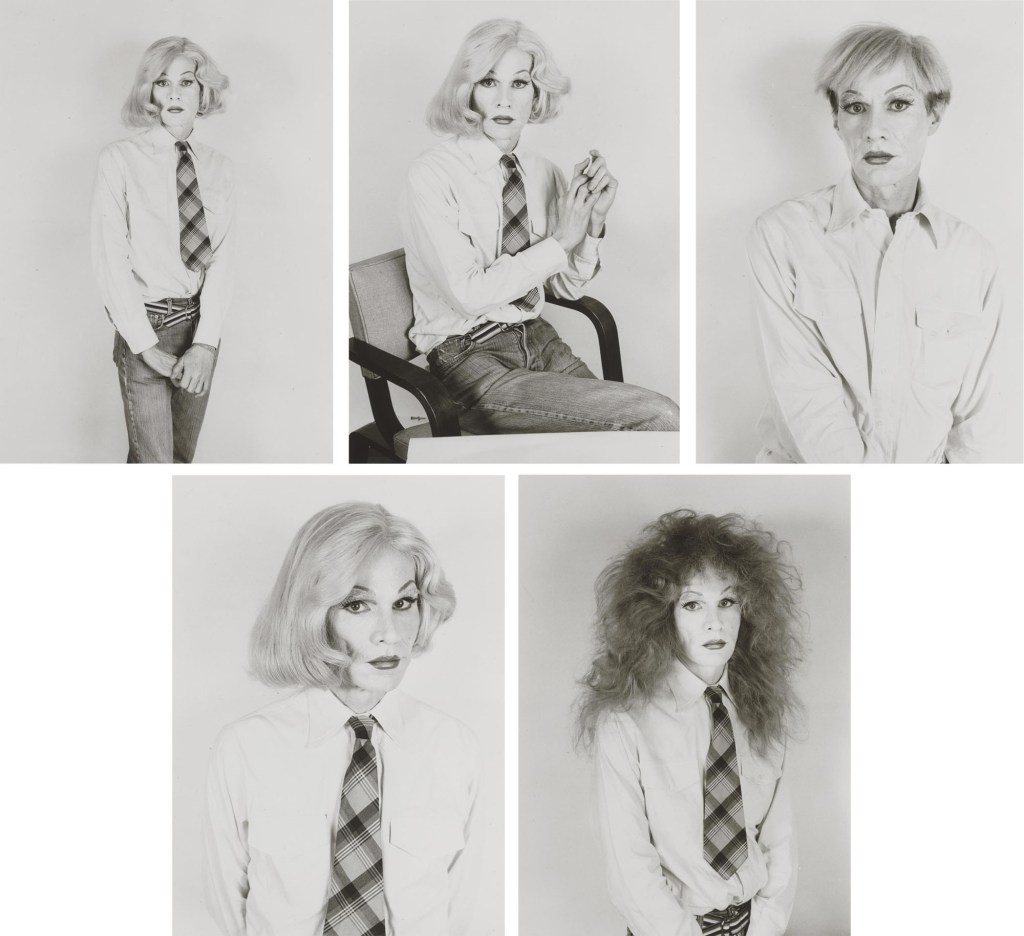

Female photographers of the 1960s-90s, such as Micky Allan, Sue Ford and Carol Jerrems who all crossed over into art photography

Robert McFarlane (1960s onwards) who specialises in social issues

John F. Williams who photographed Sydney in the 1970s

Jeff Carter who photographed all around Australia from the 1950s onwards

Ian North and Gerrit Fokkema who photographed Canberra in the 1980s

Joyce Evans (1980s onwards) who took important portraits of a diverse cross-section of Australian intelligentsia and personalities and documented Australian country towns and events for the National Library of Australia

Glenn Sloggett who photographed Australian suburbia with a startling mix of warmth and melancholy from the 1990s onwards

More recently, the war photographs of °SOUTH members such as Tim Page, Stephen Dupont, David Dare Parker, Jack Picone and Michael Coyne

Trent Parke who is the only Australian member of the Magnum Photo Agency, whose work moves beyond the strictly documentary to sit between fiction and reality, offering an emotional and psychological portrait of family life and Australia that is poetic and often darkly humorous

And Juno Gemes Indigenous social documentary photography, who documents the changing social landscape of Australia

Unlike America, where social documentary photographers are well known, hardly a name from the above list (save perhaps Max Dupain and possibly Frank Hurley) would be recognised by a wider Australian public and there is little evidence or acknowledgement of their work in Australia. I believe that this is because social documentary photography has never been heavily promoted in this country and that this type of photography is a slice of many people’s work without becoming the driving force behind their oeuvre.

As my friend and curator Nick Henderson observes, “Perhaps the lack of visibility is in part due to many of the social documentary photographers undertaking work for the various state libraries, who regularly commission work documenting place – sometimes external, but also staff photographers – whose work is then not exhibited: many of the institutional galleries haven’t devoted much time to displaying and promoting that work.” While there may have been social documentary photographers in each country town and embedded within federal and state institutions, their work never seems to reach the audience it deserves.

And that is the true

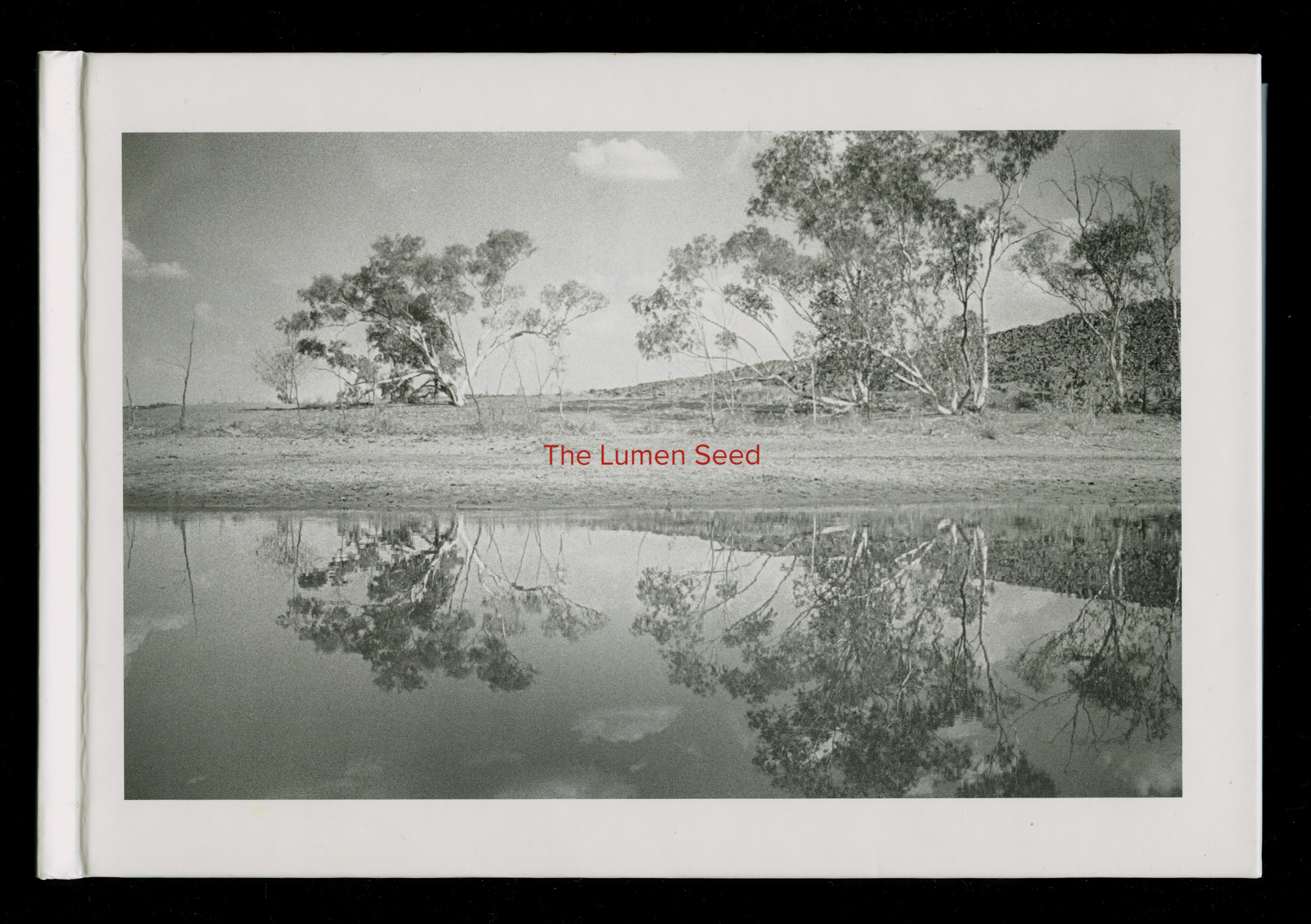

Into this amorphous arena comes a brilliant book Sydney based poet, photographer and composer Judith Crispin titled The Lumen Seed (Daylight Books 2016), a book of that addresses the stories of the Warlpiri people of Lajamanu through conversation, poetry, drawings and photographs, a book that should be compulsory reading for all Australians.

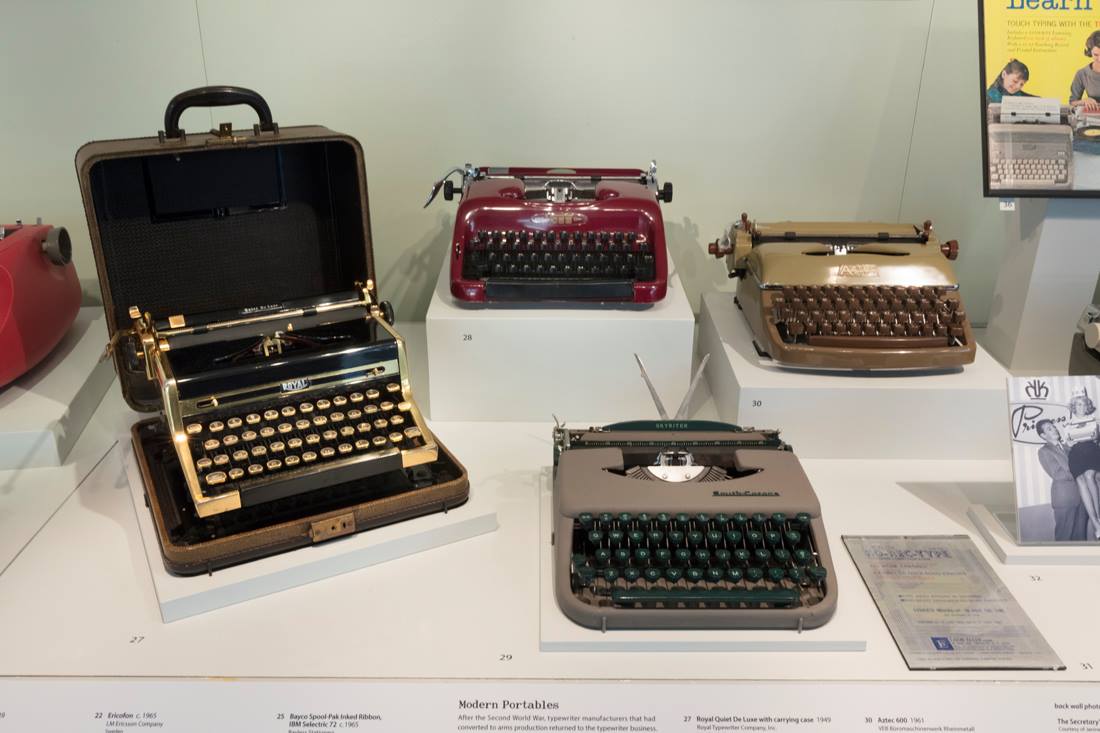

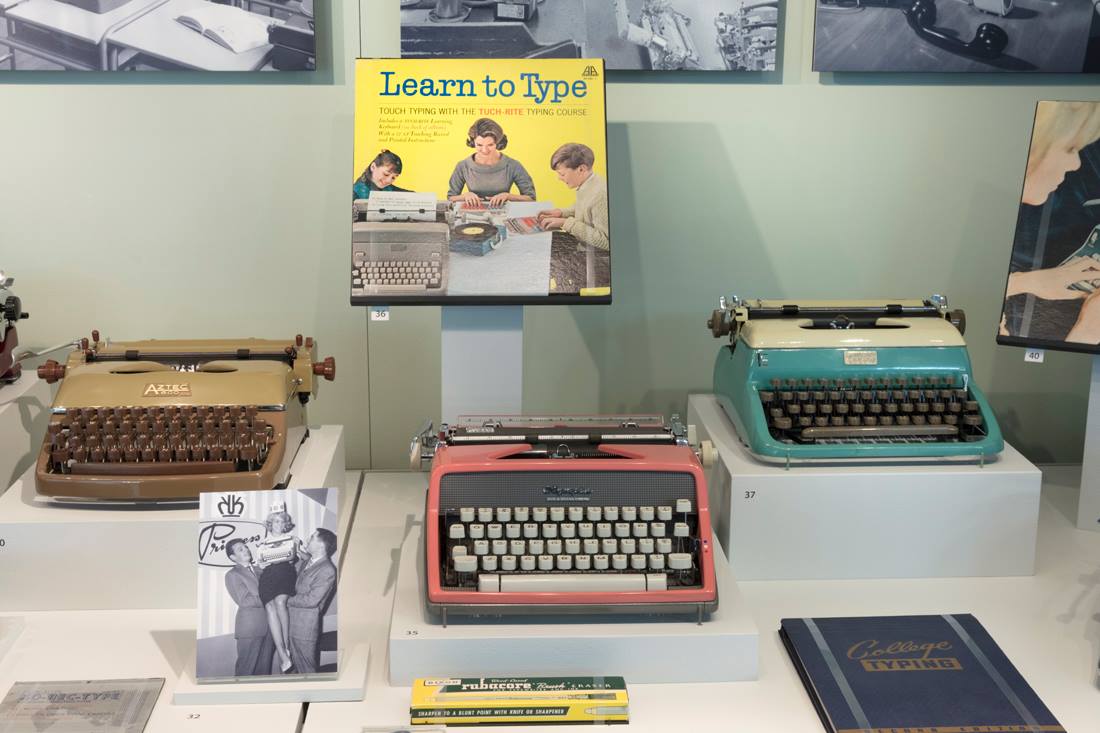

This smallish book (in size, 23.5cm wide by 15cm high) of 120 pages has good strong boards, excellent typography, nicely weighted paper and feels solid in the hand. The book is well printed, although some of the highlights of the photographs have gone missing in action. The layout of the images and text is engaging, challenging the reader to comprehend, contemplate and consider what is being shown and spoken to them. Use of negative space, as can be seen in the example pages below, is excellent. The reader does not feel overwhelmed by comatose verbiage, but empowered when listening to the stories, proposed: “This book is about magic. Not the magic of Kabbalists, Theosophists, or conjurers, not Crowley’s magick with a k, not the magic of the New Age or Western religion – but magic that describes the world hidden inside this world, a world seen only by Aboriginal elders and the dying.” (Judith Crispin, Introduction, p. 12)

As Crispin states, this book is not a book of photojournalism and is the most subjective it can be, the photographs growing out of her love for this community. The multi-dimensional photo essay, for that is what it is in more traditional terms, represents some of the views and customs of the Warlpiri people and for Crispin, her journey started in the centre of Australia’s Anglophile government, Canberra, and ended at Wolfe Creek Crater, birthplace of the rainbow snakes, the Warnayarra, which underpin all Australian Aboriginal cultures. The peoples of this ancient culture speak to the earth, they tend it and understand it; they believe in the deep magic of the landscape, and strengthen the land through gardening and the trees through song. They speak to the spirits of the waterholes and have a deep respect for the spirit of the animals that inhabit the land. “The deep love that Warlpiri people have for the landscape, its mountains and waterholes, is almost incomprehensible for white people.” (Juno Gemes, Foreword, p. 9)

I’m British and I have been here in Australia since 1986 and I have never understood the non-relationship Australia has with its Indigenous people. Growing up on a farm for the first twelve years of my life in England gives me some understanding of a life lived well on the land. We were working class poor, my mother having to boil water on a stove so us kids could have a bath in a copper on the kitchen room floor; and we lived on what we could shoot from the land – pigeons, pheasants, rabbits and hares – and we were acutely aware of the providence and blessings of nature for our sustenance. A totally different connection to land than an Aboriginal one, but a connection none the less, as I found out when I visited the old farm on a recent visit to the UK in August. Walking up the cart path where I had played as a kid brought all the magic rushing back… the flowers, the forest, the trees, the animals and the earth.

Therefore, when I read of the white man’s abuse of the traditional lands of the Aboriginal people I am appalled. If you read the extract from Five Threnodies for Maralinga printed below, you begin to understand the pain and anguish of these people, killed by the atomic cloud of over 7 major tests and 700 minor trials involving plutonium, uranium, and beryllium at the Maralinga site which occurred between 1956 and 1963, part of the Woomera Prohibited Area in South Australia and about 800 kilometres north-west of Adelaide. “In 1948, Warlpiri people were forcibly relocated almost 600 kilometers from their spiritual homeland to Hooker Creek, now Lajamanu, in Gurindji country. Old people, afraid to live among Gurindji ancestors and spirits, tried to walk back to Yuendumu but were rounded up and returned.” (p. 45)

This beautiful, powerful and deeply personal book tells some of their stories. It saddens me beyond belief that these wonderful people have been estranged and displaced from their traditional lands; decimated, killed, and abused; have been exposed to nuclear radiation, poverty, and untold harm and deprivation, both physical and mental. That they endure is a testament to their courage and culture. Juno Gemes observes that, “Crispin’s images are filled with compassion and tenderness. This is not an easy work… The Lumen Seed is a tough and powerful work in photographs, narrative texts, drawings, and poems it sings stories off the Warlpiri at Lajamuna at five minutes to midnight.” (p. 9)

The book needs to be tough to tell the true. But through poetry, love and light a new cosmology emerges that brings hope for a better future. Truth and consequence in red dirt country.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to Myrtille Beauvert, Daylight Books and the artist for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

The Lumen Seed by Judith Crispin (Daylight Books), a cultural dialogue that is taking place before a backdrop of offences against the Australian continent, as well as a history of systematic discrimination against Indigenous peoples on the part of the country’s white population.

“Yeah, it make me real sad and cry for my country. Because God bin put me there, God put my people there. Why someone could move us, because of his power, because of his idea? Cutting off God’s power, God’s idea here. God’s word, God’s light… and that is the true. Cut off like this electric wire, if you cut him off, like that.”

Jerry Jangala, senior Warlpiri elder and Law man from Lajamanu in the Tanami Desert

“The Lumen Seed is a tough and powerful work. In photographs, narrative texts, drawings, and poems it sings stories of the Warlpiri at Lajamanu at five minutes to midnight. Who will hear, who will see, who will act?

Judith Crispin’s experience echoes mine 40 years earlier, although I could not always get back to the same teachers. We belong to a long photographic tradition. It is the tradition of Tina Modotti and Josef Koudelka – a generation of documentary photographers who believe fervently that if you show people what is actually happening in the world, they will understand and be moved to demand change. Activist social documentary photography has always been defined by this passionate subjective belief in democracy and action.”

Juno Gemes, Introduction to The Lumen Seed, 2016

Judith Crispin. The Lumen Seed book cover

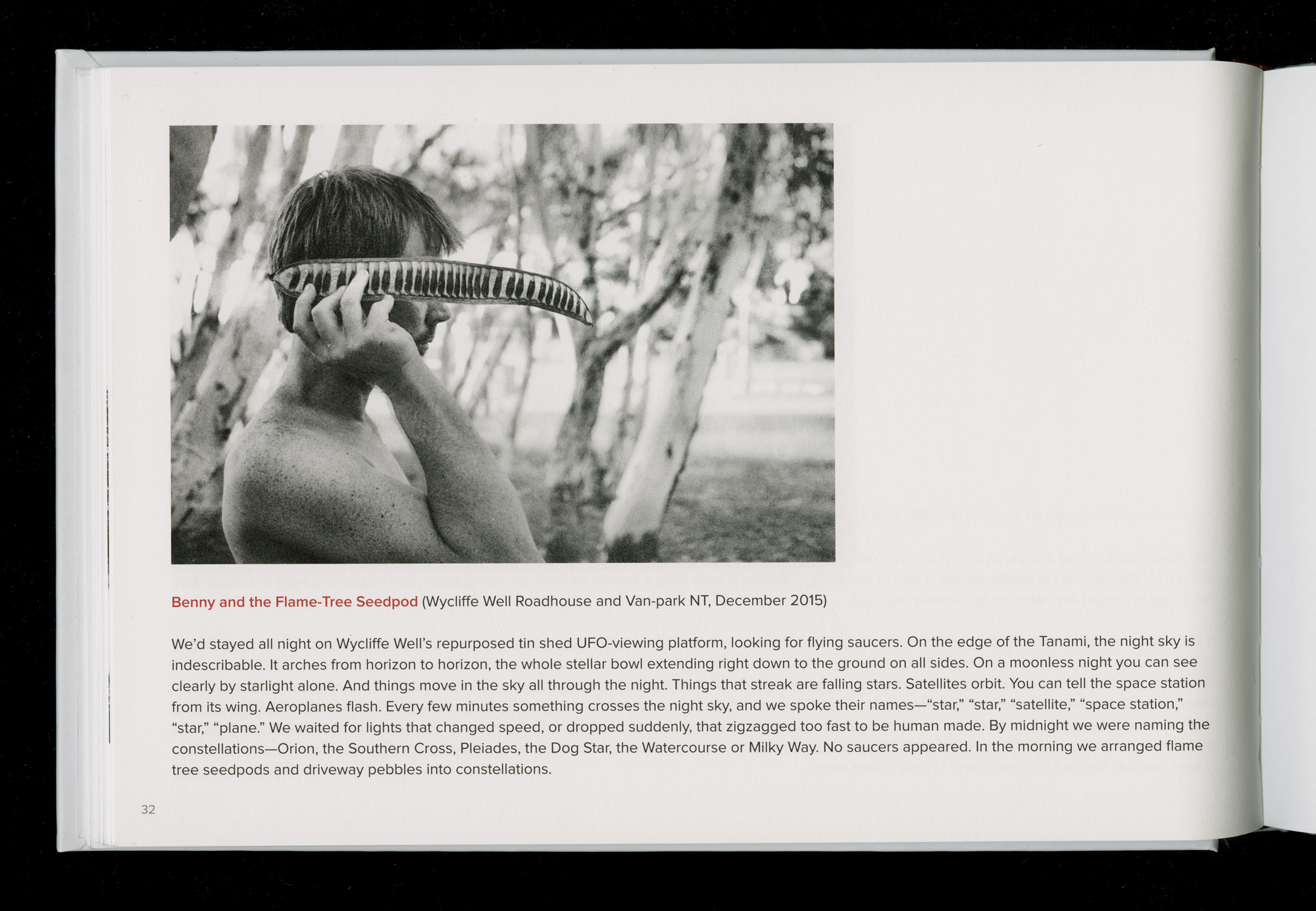

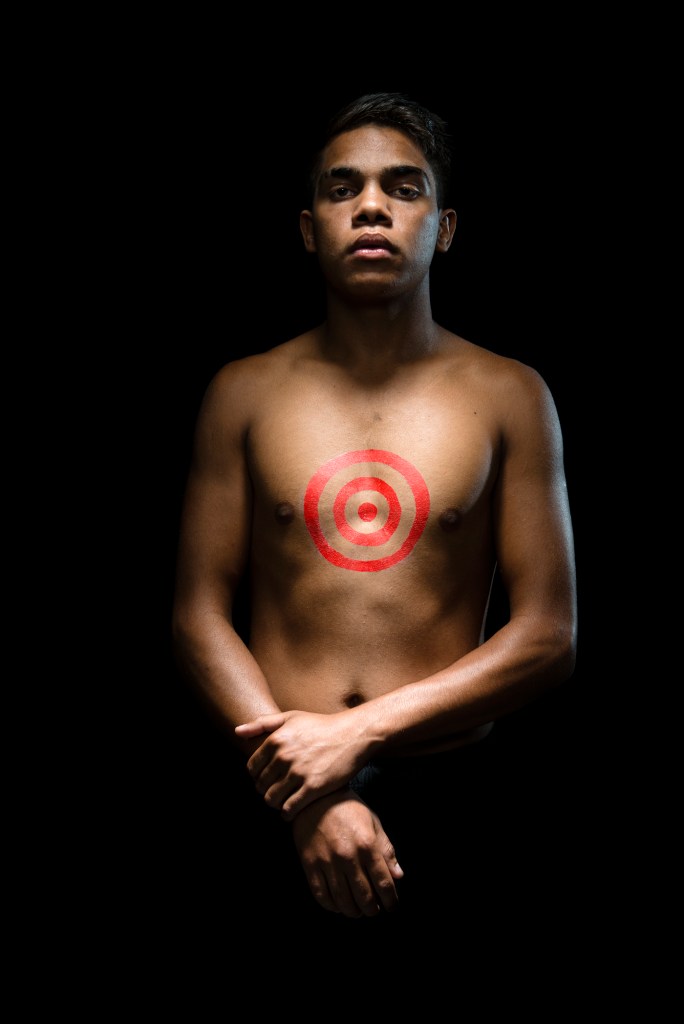

Judith Crispin. The Lumen Seed p. 29

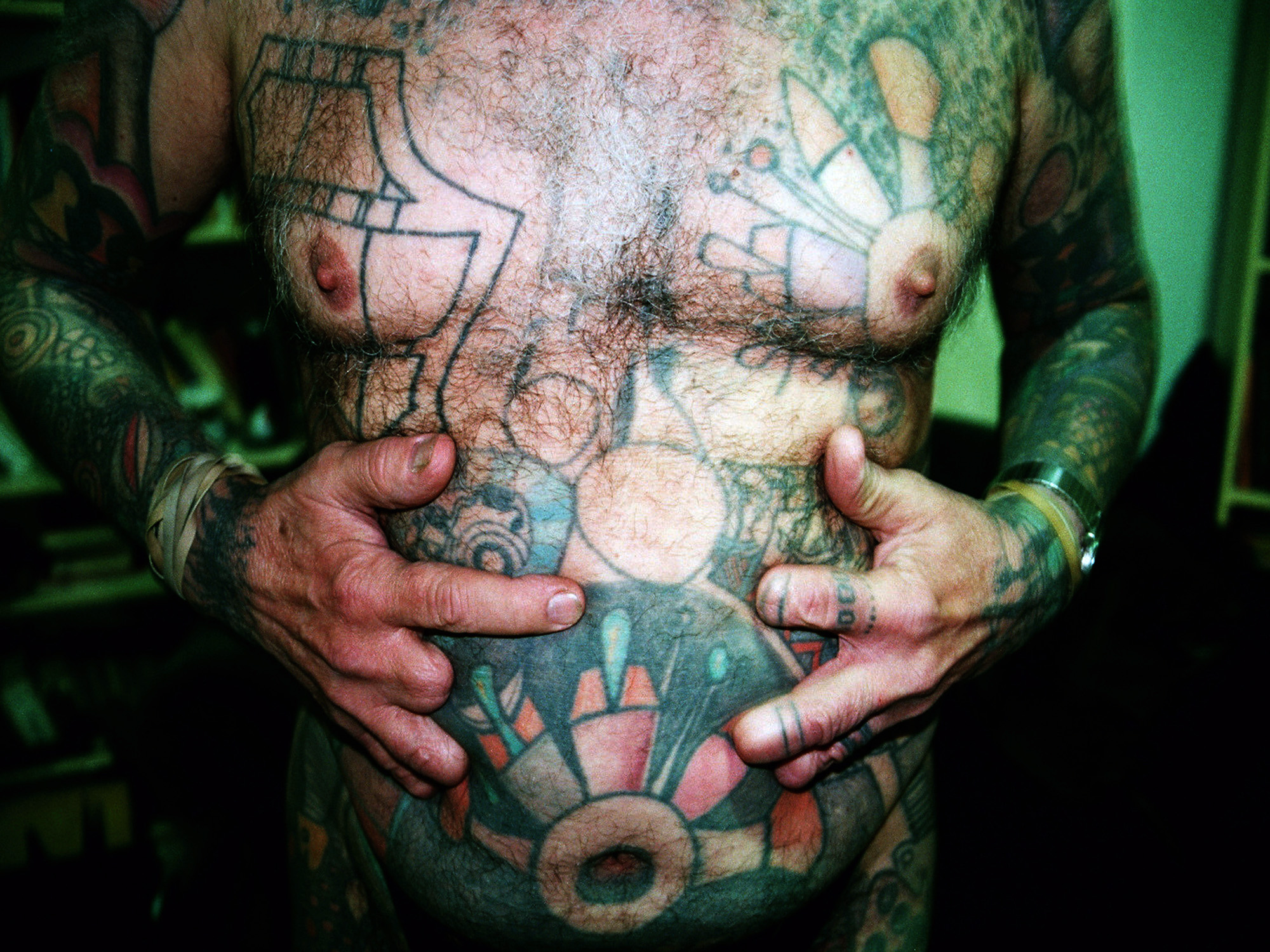

Judith Crispin. The Lumen Seed p. 32

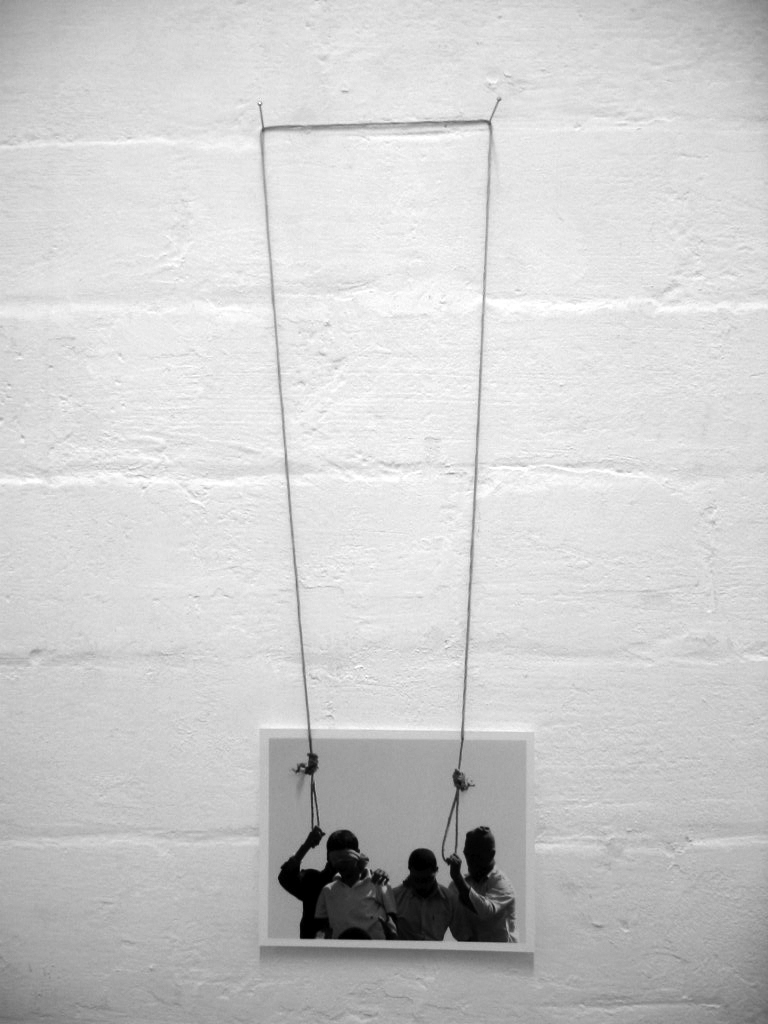

Judith Crispin. The Lumen Seed p. 46

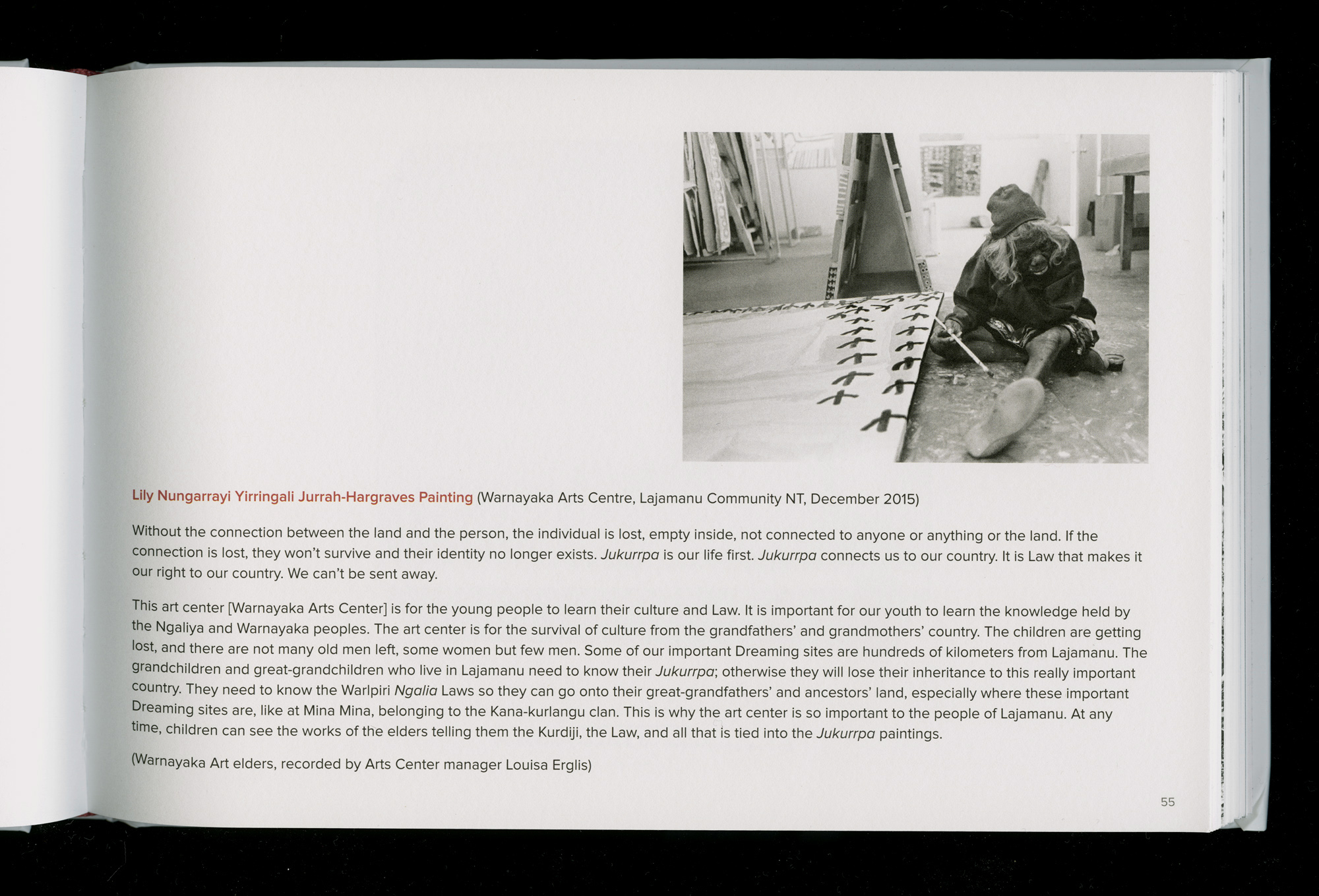

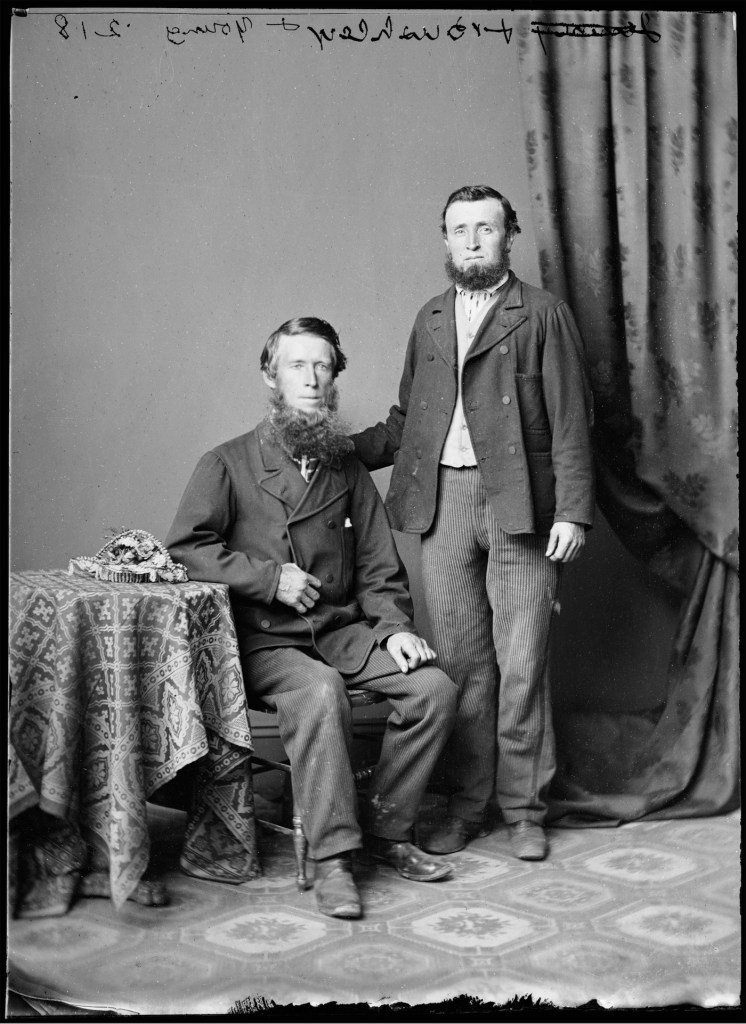

Judith Crispin. The Lumen Seed p. 55

Judith Crispin. The Lumen Seed p. 74

Foreword: Five Minutes to Midnight

There is nothing like twilight in red dirt country – the soft crackling of fire warming your billycan as the Seven Sisters begin their dance across the night sky. Or the camaraderie around a campfire as people speak in their indigenous languages – the women making jokes about the day’s goings-on or about mistakes made in the intricate protocols of a Law you are learning, day by day. Everything that lives has meaning here. Upholding knowledge is a lifelong obligation for First Nation Custodians – not only in the present but into the future. How can we Australians know this land or our place in it, if not through relationship with our hosts, the Aboriginal people?

When inviting me to write this foreword, Judith Crispin explained her choice, saying, “You are uniquely positioned, as Australia’s premier and longest-serving photographer who has worked collaboratively with Aboriginal people in communities around the country making their culture and struggle for justice visible.” Truly, in both a professional and a practical way, I know the difficulties and the deep satisfactions of working in community. I understand the privileges of learning about the Law, the reciprocity of gratitude, and the obligation to stay true to the received teaching over a lifetime.

As a photographer of long experience, with friendships in Aboriginal communities, I know how everything depends on one’s openness to experience, on the give and take inside relationships that informs how one sees and feels. Photographers in this tradition work in slow time. You learn to move with the people, move within the rhythm of their days, within their country, their wind and sky. What is learned through these relationships can change how one sees forever. By invitation, we become messengers from the frontier of interpersonal experience, conveying urgent messages from our teachers and hosts.

Into this collaborative tradition of relational interpersonal documentary photography – which began with the work of committed photographers in Australia during the 1970s – now steps Judith Crispin with her important book about magic, knowledge, and history. She relates teachings of the Law men who adopted her, who gave her the skin name Nangala, a name that defines her relationship to everyone in the community. In this way, she is being “growed up,” learning how to see the universe according to Warlpiri Law.

“There is a particularly miraculous vision of the world that comes only with the diagnosis of serious illness. … Something is different now – because I know there is a secret world nested inside this one. I’ve seen it.”

The Lumen Seed opens onto an apocalyptic scene. A hardwood mulga tree, reaching for the sky, holds a placard: “The Lord’s Return is Near.” In Coober Pedy, a curved handmade house rendered in warm mid-tones is edged with the sign “Welcome to Nowhere.” Dusty desert roadscapes unfold into the giant sacred stones of Karlu Karlu. An emu wanders nonchalantly into a gas station. We’re in Emu Dreaming Country now, meeting Crispin’s traveling friends.

A UFO mural at the gas station resonates later in the book with stories of Wolfe Creek Crater, where the meteorite landed. In the Jukurrpa we are told two rainbow snakes created that country, way back at the beginning. UFOs “zipping around the trees” form part of our desert lore. Funky and surreal, these images are imbued with humour. The images that follow lead us onward into a country of visual narratives – foretelling beginnings and endings. Intuitions manifest unpredictably. We enter a thousand kilometres of “bull dust and bone-jarring track, into the Tanami Desert,” which is as nothing compared with the howling grief of Crispin’s first poem…

Foreword extract by Juno Gemes, Hawkesbury River, April 11, 2016, pp. 6-7.

Introduction

In late 2015 I was diagnosed with cancer. Before then, I’d not understood how five words could change everything. “I’m sorry, Judith,” my doctor told me, “it’s cancer.” It’s a cliché that you only learn to value life when death is walking beside you, but it was absolutely true for me. I remember driving over Clyde Mountain to bring the word cancer to my parents’ home. Every tree on the range seemed invested with vital force. Every leaf was vibrant, iridescent. Gray mountain gums, in headlights, seemed to manifest ancient intelligence – bearing witness to the fleeting existence of human beings. The threat of death reminds you how precious people are – your oldest friends, children, lovers, parents – you wonder how you’ll bear to leave them. There is a particularly miraculous vision of the world that comes only with the diagnosis of serious illness.

The interval between diagnosis and surgery is an eternity. The surgeon showed me a chart – “If the cancer falls into this range,” he said, “you’ll live; this range and you’ll die.” I felt like Schrödinger’s cat, neither living nor dying. People who see their own death live in two worlds, one mundane and one miraculous. Later, when the cancer had been removed and my death sentence lifted, I watched that other world diminish day by day. No matter how I clung to that miraculous vision, it faded – just as the certain knowledge of my death faded. But something remained. Something is different now – because I know there is a secret world nested inside this one. I’ve seen it. …

The earliest photographs in this book were taken in 2013, when I still believed the Warlpiri needed my help – to promote literacy and health, to outline positive pathways toward reconciliation, and so on. The later photographs were taken in December 2015, when I knew, without a shadow of doubt, that I was the drowning woman and the Warlpiri were the lifeboat. Lajamanu’s elders, especially Wanta Jampijinpa, Henry Jackamarra, and Jerry Jangala, were kind to me. They gave me a skin name1 and showed me how to be a “policewoman” for Jdbrille Waterhole. They seemed genuinely delighted by my interest in Warlpiri cosmology, which they illustrated with stories and drawings – some of which are reproduced in this book. The older women took me “hunting” for wattle seed and bush potato. They told me stories of covenants entered into with ancient star-beings and showed me places along the Tanami Track where min-min lights had chased travellers. Fairy tales and mysteries take on new importance when your life feels precarious.

Lajamanu in 2016 is a meeting of two universes. Elders check their Facebook status on iPhones while explaining, in matter-of-fact tones, about a landscape that will hold you or kill you, depending on your scent – where spirit snakes live in the waterways and the dead walk side by side with the living. In Lajamanu I lost my fear of dying, and more importantly, I lost my fear of living. This is a book about magic. Not the magic of Kabbalists, Theosophists, or conjurers, not Crowley’s magick with a k, nor the magic of the New Age or Western religion – but magic that describes the world hidden inside this world, a world seen only by Aboriginal elders and the dying.

This is not a book of photojournalism and makes no attempt to be objective. Quite the contrary, in fact, I wanted this book to be as subjective as possible. These photographs, especially the portraits, have grown out of my love for this community – the poetry of these often physically fragile people, whose unshakable belief in the deep magic of the landscape gives them a strength rarely evident in the city. Warlpiri culture is gentle; it leaves no tracks on the earth. The history of Aboriginal Australia is largely a record of gardening – “cleaning up country” with firestick farming and ceremonies to strengthen trees through song. When Warlpiri people move through the landscape, they introduce themselves. They apologise to that country for breaking twigs. They ask permission to take water from the creeks. If humanity ever transcends its selfish and murderous nature, it will be because of people like the Warlpiri.

Introduction extract by Judith Crispin pp. 11-13.

You shall not trap me in this fish-trap of yours in which you trap the dead,

because I know it, and I know its name,

I know the name in which it came into being.

(Coffin Texts)

Judith Crispin (Australian / Bpangerang, b. 1970)

The Lord’s Return is Near

Coober Pedy SA, November 2014

The Stuart Highway is a bisecting line in a thousand kilometres of nothing. The sheer scale of the landscape is overwhelming. I’d driven for two days with only Leonard Cohen and David Bowie for company, and had never felt more isolated. I don’t know why I stopped, leaving the Land Rover idling in the middle of the highway, and walked over to the tree. Perhaps its tallness startled me – its length so exposed above the desert floor. I wanted to lay my palm against its bark. At first I didn’t notice the sign nailed high on its trunk: “The Lord’s Return is Near.”

This stretch of highway lies south of the rocket range at Woomera. There are oceans of blood on this land. The Woomera immigration detention centre continued a legacy of suffering that began years earlier, in the 1950s, when Maralinga’s radioactive clouds blew over Woomera, a military township, and killed all the children.

Between 1952 and 1963, British forces dropped nine nuclear weapons and nine thermonuclear weapons between Woomera and the Western Australian border, within contamination distance of urban centres. The Menzies-led Australian government of that time was wholly complicit and lied about the known dangers of nuclear tests. Between these bombings, Britain conducted continuous “minor trials,” which, according to the Royal Commission into British Nuclear Tests in Australia, additionally detonated 99.35 kg of beryllium, 23.979 kg of plutonium, and 7968.88 kg of depleted uranium. By contrast, Little Boy, dropped on Hiroshima in 1945 by the United States, contained only 64 kg of uranium-235, and Fat Man, dropped on Nagasaki in 1945 by the United States, contained only 6.4 kg of plutonium. Anyone who wishes to immediately lose faith in the human race should read the short transcript of the Royal Commission, which is freely available online. (pp. 16-18)

Judith Crispin (Australian / Bpangerang, b. 1970)

Welcome to Nowhere

Coober Pedy SA, November 2014

I arrived in Coober Pedy the same week that dust storms tore the roof off the pub. This dugout, borrowed from friends in Alice Springs, was built from a disused shaft. I slept near the door separating their home from the remaining length of shaft, extending far into the rock. Strange sounds echoed behind that door – sounds of wind, or dogs howling. The door was nailed closed. When I first visited Coober Pedy, it was the farthest into the desert that I had ever ventured. Beyond it stretched the expanse of the Great Victoria Desert, Simpson Desert, Strzelecki Desert, Pedirka Desert, Tirari Desert, and Sturt Stony Desert. I was at the start of a journey that would follow Stuart Highway into nothingness and emerge in the huge Tanami Desert of the Northern Territory and Western Australia. Leaving the dugout, I stopped to photograph the words painted on its roof: “Welcome to Nowhere.” (pp. 22-23)

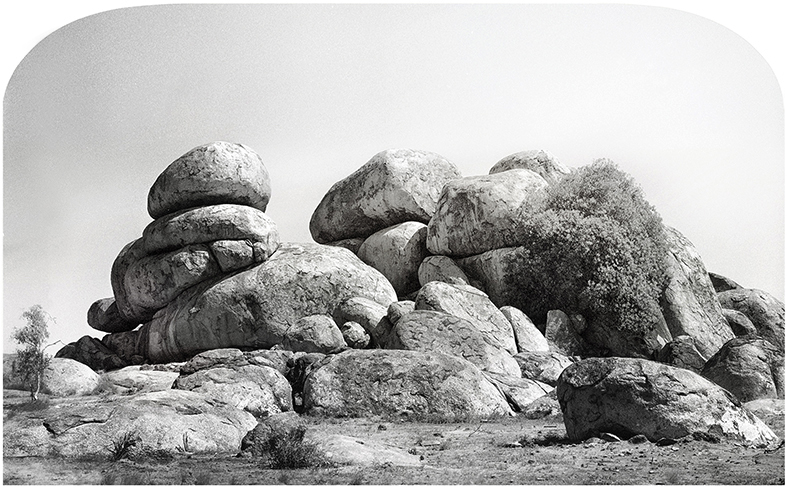

Judith Crispin (Australian / Bpangerang, b. 1970)

Karlu Karlu I

Near Ayleparrarntenhe NT, November 2014

Karlu Karlu, nicknamed “The Devil’s Marbles” by white people, was long considered too spiritually dangerous for anyone but Warumungu elders conducting ceremony. Between these giant stones, on a 48-degree day, the radiant heat is almost unimaginable. Near the skeleton of a burned office chair, I found patches of black glass. A Warumungu friend explained that the heat has, in recent years, become so intense at Karlu Karlu that the air itself ignites, fusing desert sand to glass. In Australia’s deserts the evidence of climate change is irrefutable. (p. 24)

Judith Crispin (Australian / Bpangerang, b. 1970)

Eemie at the UFO Roadhouse

Wycliffe Well Roadhouse and Van-park NT, December 2015

UFO enthusiast Arc Vanderzalm moved to the desert in 2004 to establish a UFO-themed van park. In the van park’s early years, Arc rescued an abandoned emu chick and raised him by hand. He named him Eemie. Travellers stopping for fuel at Wycliffe Well roadhouse are sometimes surprised by an adult emu staring in at them through the window. While a guest of the van park, I once startled Eemie by walking into the ladies’ shower block. He peered out at me through the shower curtain with an air of embarrassment, as though I’d intruded at a delicate moment. Later, as I drove toward Tennant Creek, I spotted Eemie chasing a farm dog down the highway, legs akimbo. (p. 29)

Judith Crispin (Australian / Bpangerang, b. 1970)

Sexy John

Alice Springs NT, November 2014

Sexy John was rescued as a small calf after his mother was culled as part of a government program to reduce feral camels. He was raised by artists in a collective on the outskirts of Alice Springs and befriended a wild blond-haired boy. More than 160 thousand camels were culled between 2009 and 2013, approximately one-fifth of the camel population of the central deserts. (p. 35)

Extract from Five Threnodies for Maralinga

V

At Woomera,

seventy-five identical graves

remember babies lost to the predation

of atomic clouds.

Their epitaphs are brief-

Michael Clarke Jones

died 24 August 1952,

aged eight and a half hours.

No one has been here for a long time.

Weeds struggle.

A military vehicle passes,

heading east toward the rocket range.

In the west, Woomera township

is a grid of air force housing.

Land Cruisers fill neat driveways,

lawns are trimmed,

blinds closed.

And no one ever steps out for milk,

no one walks a dog.

I photograph each headstone,

stooping sometimes to straighten a plastic posy,

a tilted ceramic bear.

Wind presses a faded greeting card

to the metal fence.

A matchbox car beside a small boy’s grave

is blue.

There are nineteen stones without toys or flowers,

for stillborns named only “baby”-

Baby Spencer,

Baby Dowling,

Baby Stone.

Don’t look at me

Baby Gower

Baby Roads

from a soldier’s gunny bag

with your eyes too white, too open

like the eyes of poisoned fish

tumbling

in the Pilbara’s poisoned surf.

Judith Crispin (Australian / Bpangerang, b. 1970)

Warlpiri Family

Lajamanu Community NT, December 2015

In 1948, Warlpiri people were forcibly relocated almost 600 kilometers from their spiritual homeland to Hooker Creek, now Lajamanu, in Gurindji country. Old people, afraid to live among Gurindji ancestors and spirits, tried to walk back to Yuendumu but were rounded up and returned. In the 1970s, Gurindji people held a series of unique ceremonies to hand over the area and its Wampana and Spectacled Hare Wallaby Dreaming stories to the residents of Lajamanu. While this gesture brought some relief to Warlpiri people, who viewed their involuntary occupation of Gurindji land as a breach of traditional Law, they continue to struggle with their relationship to the country. (p. 45)

Judith Crispin (Australian / Bpangerang, b. 1970)

Four Kurdu-kurdu [Kids] with Trampoline

Lajamanu Community NT, December 2015

Country [Gurindji country], hills… well, I put country first… hills, tree, don’t like you – even that water – and that is true. If you drink water from that, or if you not talking to that country because you don’t know, you got no songs with that area… and in the night, or during the day too, you got no language for to try to talk to that country.

When God bin put you there, in your country, that’s it. You got a right to live on there. You can get sick alright, but not too much. Yuwayi [yes], you know God? He say, “Yeah you get sick but you’ll be alright,” you know? “I’m with you there,” that God talking. And same thing for our ceremony too. You’re right to use your ceremony. You’re right to sing your own Dreaming song and talking to your country … and tell it true – real true.

Jerry Jangala (pp. 50-51)

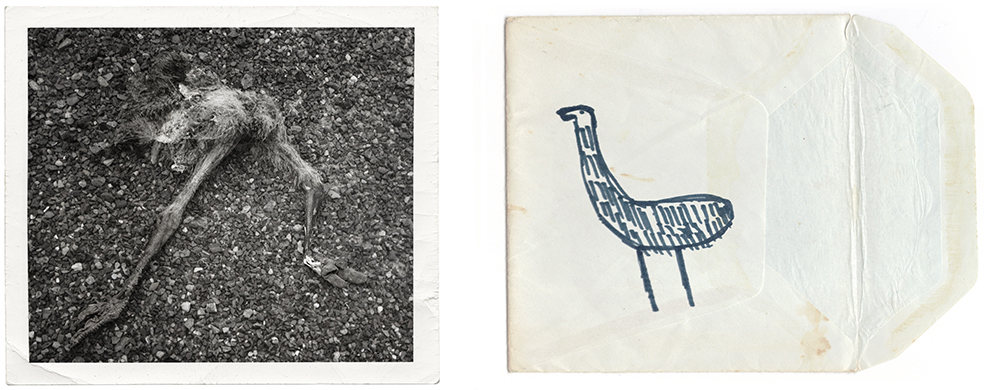

Judith Crispin (Australian / Bpangerang, b. 1970)

Emu Roadkill and Portrait by Shemaiah Matthews

Lajamanu Community NT, December 2015

Judith Crispin (Australian / Bpangerang, b. 1970)

Lily Nungarrayi Yirringali Jurrah-Hargraves Painting

Warnayaka Arts Centre, Lajamanu Community NT, December 2015

Without the connection between the land and the person, the individual is lost, empty inside, not connected to anyone or anything or the land. If the connection is lost, they won’t survive and their identity no longer exists. Jukurrpa is our life first. Jukurrpa connects us to our country. It is Law that makes it our right to our country. We can’t be sent away.

This art center [Warnayaka Arts Center] is for the young people to learn their culture and Law. It is important for our youth to learn the knowledge held by the Ngaliya and Warnayaka peoples. The art center is for the survival of culture from the grandfathers’ and grandmothers’ country. The children are getting lost, and there are not many old men left, some women but few men. Some of our important Dreaming sites are hundreds of kilometers from Lajamanu. The grandchildren and great-grandchildren who live in Lajamanu need to know their Jukurrpa; otherwise they will lose their inheritance to this really important country. They need to know the Warlpiri Ngalia Laws so they can go onto their great-grandfathers’ and ancestors’ land, especially where these important Dreaming sites are, like at Mina Mina, belonging to the Kana-kurlangu clan. This is why the art center is so important to the people of Lajamanu. At any time, children can see the works of the elders telling them the Kurdiji, the Law, and all that is tied into the Jukurrpa paintings.

Warnayaka Art elders, recorded by Arts Center manager Louisa Erglis (p. 55)

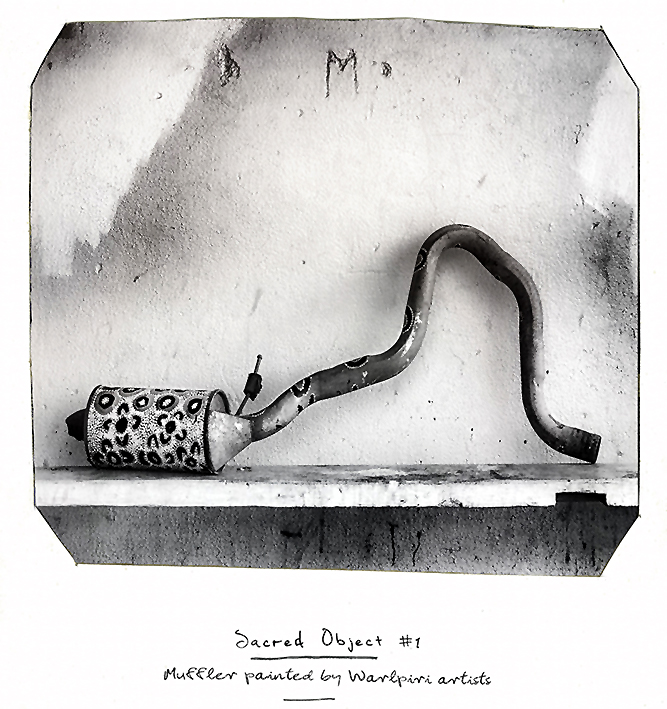

Judith Crispin (Australian / Bpangerang, b. 1970)

Sacred Object #1

Nd

Muffler painted by Warlpiri artists

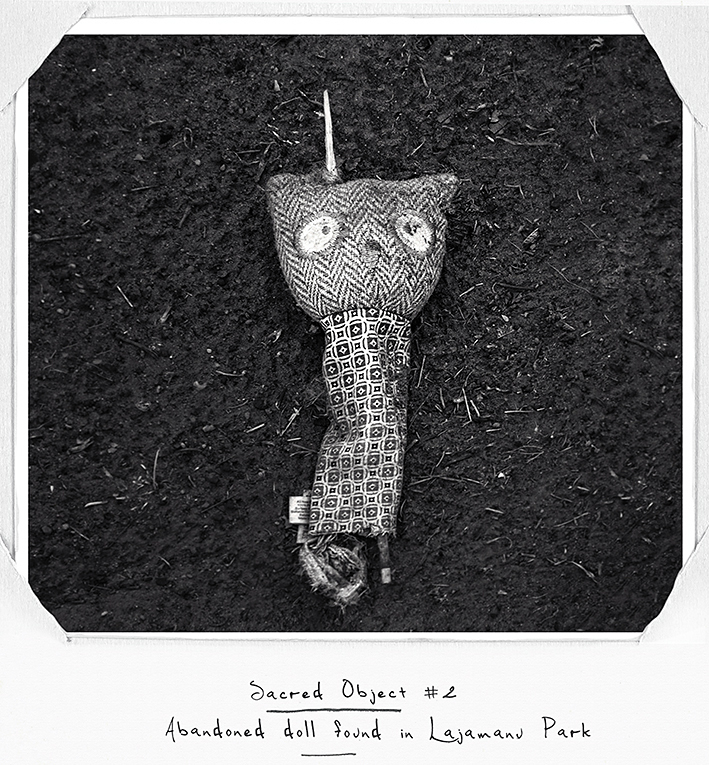

Judith Crispin (Australian / Bpangerang, b. 1970)

Sacred Object #2

Nd

Abandoned doll found in Lajamanu Park

Judith Crispin (Australian / Bpangerang, b. 1970)

Beth Nungarrayi at Jdbrille Waterhole

Jdbrille Waterhole, Tanami Desert NT, June 2015

This area here, no river. It’s the same deal in this country, and so – what do you call it? Soak? [A soakage, or soak, also called a native well, is a source of water in the Australian desert.] You know … I’m trying to get that word there. Soak, yeah, you take all right down to find that water, that water make. Sometimes no water, like this time when it’s dry. Look for the water tree. That’s what my father, my grandpa, my great-grandpa, grandmother, they all look for that water tree. Rock holes down. That’s in our country. We can say it today in a Kardiya way, you know? We can say “Lajamanu is my country.” But that not true. It’s not true … yuwayi, Nangala. My country is back there … my area is back there.

Jerry Jangala (pp. 68-69)

Judith Crispin (Australian / Bpangerang, b. 1970)

Wirntali-Jarra [Friends]

near Emu waterhole, Tanami Desert NT, December 2015

Henry Jackamarra and Jerry Jangala have known each other since they were small children. More than a decade his senior, Henry treats Jerry like a little brother – still lecturing him on what he eats and wears, although both men are now respected elders. (p. 72)

Judith Crispin (Australian / Bpangerang, b. 1970)

Jerry Jangala Oversees Kangaroo Ceremony

Tanami Desert Outpost NT, November 2014

The animal is honoured by sprinkling handfuls of dirt over its fur before it is prepared for cooking in the traditional way. Jerry explains that in the old days the punishment for getting this ceremony wrong was death. In modern times, the penalty for making mistakes in this ceremony is exile. Wanta Jampijinpa, Jerry’s son, reassured me that exile did not necessarily mean death in the Tanami desert. A person could earn his or her place back in the community by accomplishing a special task. The exile must find the way to catch a wedge-tailed eagle and bring its soft underbelly feathers back to Lajamanu as proof. Wanta explained to me how such a seemingly impossible task could be accomplished, but I do not have permission to reproduce that here. (p. 78)

Judith Crispin (Australian / Bpangerang, b. 1970)

Henry Jackamarra Cook, Last Kangaroo Dancer

Lajamanu Community NT, December 2015

Light Trails of Henry Jackamarra Cook

Law is a gray kangaroo dancing

the thin landscape of Henry Cook into being,

somewhere in the Tanami,

where knucklebone winds scrape bare rock

and Henry stands marsupial

in firelight’s weird.

In Lajamanu, tin houses edge the street.

No one is outside,

no one.

In the arts center, old ladies paint seed-dreaming.

Breeze lifts the hem of a curtain,

then stillness.

It is still.

Henry doesn’t paint anymore. He sits alone,

watching ceremony from the 1970s.

Everyone in the videos is dead now, except him.

And the dead are in the desert,

faceless as the desert is,

and as remote.

Ten years ago it seemed nothing to walk

three days to his sacred country,

granite country,

where great salt lakes exhale their thirst

over spinifex and sand,

the rattling sun.

But arthritis and cataracts have caged him.

Inside the arts center,

the lights are switched off.

We drag chairs across a concrete porch

to watch the Tanami darken, shelf clouds

seal the crater at Wolfe Creek.

Rain wakens on his tongue

the angular syllables of displacement.

And home is the desert breathing over itself by night,

erasing tracks of all who walk there –

night’s emu rising savage in the Milky Way,

and eyes, eyes in the granite mines.

One day, he tells me, I’ll walk out

to my country and never come back.

At town’s edge, a kangaroo left by poachers.

Red dust thickens its pelt, as the red dust lies thick

on Henry’s Ray-Bans, stiffening his white hair to wires.

I photograph him disemboweling the buck,

its intestines knotted to ritual marks –

Henry and his flayed brother, backlit

against chained ridges,

and the last sun rearing.

Law is an old man dancing

the gray kangaroo into being,

sewing him back into the desert’s body,

into his own body, ochre and growl,

a hunting boomerang beaten on the ground.

Night erases this landscape –

slow trees, sand,

the saltbush has gone.

Just Henry’s heels rising and falling

along a wind-scored track,

utterances of a language which belongs to him

and to which he belongs.

Tomorrow, the Catfish Waterhole

will stretch his white hair out elastic,

as telephone wires vanishing into the Tanami.

Mud returns to him,

the cool slow memories of country

before the missions, before diabetes and grog

shrank his ancestors down so small

he holds them in a single cupped hand

like fireflies, tiny comets

crossing in the black.

Tomorrow he’ll thread gumleaves

through the hole in his nose,

and say, photo me like this Nangala

I am a beautiful man.

Judith Crispin (pp. 81-83)

Judith Crispin (Australian / Bpangerang, b. 1970)

Lily Nungarrayi Yirringali

Tanami Desert NT, November 2014

I was told Lily, when she was young, was in love with a Karadji man but couldn’t be with him because she didn’t want to leave her community. Her arms reveal the parallel ritual marks of someone on a “sacred path.” Now, despite caring relationships with her family, friends, and fourteen adopted dogs, somehow Lily is always alone. When, together with Molly and Rosie, Lily took me to see Catfish Waterhole, she explained that we were going to see her “mother.” I carried Lily, too frail to descend the bank, to the edge of the water. There she turned water over her palms, the traditional way of greeting the waterhole and avoiding surprising any Warnayarra who might be there. The deep love that Warlpiri people have for the landscape, its mountains and waterholes, is almost incomprehensible for white people. Here Lily sings quietly to Catfish Waterhole – not for any ceremonial or traditional reason, I’m told, but just because it makes the waterhole feel loved. (p. 95)

Judith Crispin (Australian / Bpangerang, b. 1970)

Molly’s Flame-Tree Seed-pods

Tanami Desert NT, November 2014

Judith Crispin (Australian / Bpangerang, b. 1970)

Molly Napurrula Sifts Wattleseed

Tanami Desert NT, November 2014

Warlpiri people still supplement their diet with bush food. Ground wattleseed is mixed with oil and baked into a kind of flat bread. The older ladies took me out “hunting” for wattleseed and kurrajong seedpods. In a township with only one shop, where a head of broccoli costs more than a takeaway meal for a family, it is vitally important to supplement the community’s diet with “bush food.” White Australians have almost no idea of the variety of native fruits and vegetables that grow in the apparent desert – bush potatoes, bush tomatoes, bush bananas, honey ants, land crabs, wattleseeds, etc., can be gathered throughout the Tanami. (p. 104)

Buy Judith Crispin’s The Lumen Seed on the Daylight Books website

![Judith Crispin (Australian / Bpangerang, b. 1970) 'Four Kurdu-kurdu [Kids] with Trampoline' 2015 Judith Crispin (Australian / Bpangerang, b. 1970) 'Four Kurdu-kurdu [Kids] with Trampoline' 2015](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/four-kurdu-kurdu-kids-with-trampoline-web.jpg)

![Judith Crispin (Australian / Bpangerang, b. 1970) 'Wirntali-Jarra [Friends]' 2015 Judith Crispin (Australian / Bpangerang, b. 1970) 'Wirntali-Jarra [Friends]' 2015](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/wirntali-jarra-friends-web.jpg)

![Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966) 'Brasilianischer Melonenbaum von unten gesehen [Brazilian melon tree seen from below]' 1923 Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966) 'Brasilianischer Melonenbaum von unten gesehen [Brazilian melon tree seen from below]' 1923](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/renger-patzsch-brasilianischer-melonenbaum.jpg?w=787)

![Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966) 'Krabbenfischerin [Shrimp fisherwoman]' 1927 Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966) 'Krabbenfischerin [Shrimp fisherwoman]' 1927](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/renger-patzsch-krabbenfischerin.jpg?w=755)

![Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966) 'Ritzel and Zahnräder, Lindener Eisen-und Stahlwerke [Sprockets and gears, Lindener Eisen-und Stahlwerke factory]' 1927 Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966) 'Ritzel and Zahnräder, Lindener Eisen-und Stahlwerke [Sprockets and gears, Lindener Eisen-und Stahlwerke factory]' 1927](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/renger-patzsch-ritzel-und-zahnracc88der.jpg)

![Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966) 'Bügeleisen für Schuhfabrikation, Faguswerk Alfeld [Shoemakers' irons, Fagus factory, Alfeld]' 1928 Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966) 'Bügeleisen für Schuhfabrikation, Faguswerk Alfeld [Shoemakers' irons, Fagus factory, Alfeld]' 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/renger-patzsch-bugeleisen-fur-schuhfabrikation.jpg?w=761)

![Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966) 'Gebirgsforst im Winter (Fichtenwald im Winter)' [Mountain forest in winter (spruce forest in winter)] 1926 Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966) 'Gebirgsforst im Winter (Fichtenwald im Winter)' [Mountain forest in winter (spruce forest in winter)] 1926](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/renger-patzsch-gebirgsforst-im-winter.jpg?w=761)

![Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966) 'Natterkopf [Head of an adder]' 1925 Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966) 'Natterkopf [Head of an adder]' 1925](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/renger-patzsch-natterkopf.jpg)

![Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966) 'Hände [Hands]' 1926-1927 Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966) 'Hände [Hands]' 1926-1927](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/renger-patzsch-hacc88nde.jpg?w=778)

![Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966) 'Landstraße bei Essen [Country road near Essen]' 1929 Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966) 'Landstraße bei Essen [Country road near Essen]' 1929](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/renger-patzsch-landstrac39fe-bei-essen.jpg)

![Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966) 'Landschaft bei Essen und Zeche "Rosenblumendelle" [Landscape near Essen with the Rosenblumendelle colliery]' 1928 Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966) 'Landschaft bei Essen und Zeche "Rosenblumendelle" [Landscape near Essen with the Rosenblumendelle colliery]' 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/renger-patzsch-landschaft.jpg)

![Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966) 'Zeche "Victoria Mathias" in Essen [Colliery "Victoria Mathias" in Essen]' 1929 Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966) 'Zeche "Victoria Mathias" in Essen [Colliery "Victoria Mathias" in Essen]' 1929](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/renger-patzsch-zeche-victoria-mathias.jpg?w=761)

![Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966) 'Kauper, Hochofenwerk Herrenwyk, Lübeck [Cowper, blast furnace Herrenwyk, Lübeck]' 1927 Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966) 'Kauper, Hochofenwerk Herrenwyk, Lübeck [Cowper, blast furnace Herrenwyk, Lübeck]' 1927](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/renger-patzsch-kauper.jpg?w=799)

![Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966) 'Ein Knotenpunkt der Fachwerkbrücke Duisburg-Hochfeld [A node from the latticework bridge in Duisburg-Hochfeld]' 1928 Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966) 'Ein Knotenpunkt der Fachwerkbrücke Duisburg-Hochfeld [A node from the latticework bridge in Duisburg-Hochfeld]' 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/albert-renger-patzsch-ein-knotenpunkt-der-fachwerkbrucc88cke-duisburg-hochfeld-1928-web.jpg?w=754)

![Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966) 'Zeche "Heinrich-Robert", Turmförderung, Pelkum bei Hamm [Headframe at the Heinrich-Robert colliery in Pelkum, near Hamm]' 1951 Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966) 'Zeche "Heinrich-Robert", Turmförderung, Pelkum bei Hamm [Headframe at the Heinrich-Robert colliery in Pelkum, near Hamm]' 1951](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/renger-patzsch-zeche-heinrich-robert.jpg?w=749)

![Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966) 'Zeche "Graf Moltke", Gelsenkirchen-Gladbeck [Graf Moltke colliery, in the Gladbeck district of Gelsenkirchen]' 1952-1953 Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966) 'Zeche "Graf Moltke", Gelsenkirchen-Gladbeck [Graf Moltke colliery, in the Gladbeck district of Gelsenkirchen]' 1952-1953](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/renger-patzsch-zeche-graf-moltke.jpg?w=745)

![Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966) 'Zeche "Katharina", Schacht Ernst Tengelmann, Essen-Kray [Katharina colliery, Ernst Tengelmann well, in the Kray district of Essen]' 1955-1956 Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966) 'Zeche "Katharina", Schacht Ernst Tengelmann, Essen-Kray [Katharina colliery, Ernst Tengelmann well, in the Kray district of Essen]' 1955-1956](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/renger-patzsch-zeche-katharina.jpg?w=752)

![Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966) 'Jenaer Glas (Zylindrische Gläser) [Jena glass (cylinders)]' 1934 Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966) 'Jenaer Glas (Zylindrische Gläser) [Jena glass (cylinders)]' 1934](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/renger-patzsch-jenaer-glas.jpg?w=750)

![Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966) 'Buchenwald [Beech forest]' 1936 Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966) 'Buchenwald [Beech forest]' 1936](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/renger-patzsch-buchenwald.jpg?w=769)

![Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966) 'Das Bäumchen [The little tree]' 1928 Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966) 'Das Bäumchen [The little tree]' 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/renger-patzsch-das-bacc88umchen.jpg?w=749)

![Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966) 'Mechanismus der Faltung [Fold mechanism]' 1962 Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966) 'Mechanismus der Faltung [Fold mechanism]' 1962](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/renger-patzsch-mechanismus-der-faltung.jpg?w=543)

![Unknown photographer. 'Untitled [Aboriginal ceremony]' c. 1892 Unknown photographer. 'Untitled [Aboriginal ceremony]' c. 1892](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/a-collection-of-five-photographs-nicholas-caire-and-unknown-photographers-king-billy-maloga-aboriginal-native-group-aboriginals-lake-tyers-aborignal-ceremony-d-web.jpg)

![J. W. Lindt. 'Untitled [Two men in rural Victoria]' c. 1880s J. W. Lindt. 'Untitled [Two men in rural Victoria]' c. 1880s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/a-collection-of-18-photographs-depicting-rural-scenes-in-victoria-circa-1880s-men-web.jpg?w=730)

![Unknown photographer. 'Untitled [Australian Aborigines in chains]' Nd Unknown photographer. 'Untitled [Australian Aborigines in chains]' Nd](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/australian-aborigines-c-web.jpg)

![Unknown photographer. 'Untitled [Aboriginal man smoking a pipe]' Nd Unknown photographer. 'Untitled [Aboriginal man smoking a pipe]' Nd](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/artist-unknown-aboriginal-man-smoking-a-pipe-web.jpg?w=627)

![Unknown photographer. 'Untitled [Aboriginal making fire]' Nd Unknown photographer. 'Untitled [Aboriginal making fire]' Nd](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/anonymous-photographer-aboriginal-making-fire-nd-web.jpg?w=637)

![Anonymous photographer. 'Untitled [Aboriginal with spear]' Nd Anonymous photographer. 'Untitled [Aboriginal with spear]' Nd](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/anonymous-photographer-aboriginal-with-spear-nd-web.jpg?w=699)

![Anonymous photographer. 'Untitled [Aboriginal with scars]' Nd Anonymous photographer. 'Untitled [Aboriginal with scars]' Nd](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/anonymous-photographer-aboriginal-with-scars-nd-web.jpg?w=752)

![Anonymous photographer. 'Untitled [Aboriginal group]' Nd Anonymous photographer. 'Untitled [Aboriginal group]' Nd](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/anonymous-photographer-aboriginal-group-nd-web.jpg)

![Anonymous photographer. 'Untitled [Aboriginal family group]' Nd Anonymous photographer. 'Untitled [Aboriginal family group]' Nd](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/anonymous-photographer-aboriginal-family-group-nd-web.jpg?w=781)

![Hermann and Marianne Aubel (authors) Karl Robert Langewiesche (publisher) 'Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time]' 1928 Hermann and Marianne Aubel (authors) Karl Robert Langewiesche (publisher) 'Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time]' 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/book-cover-web.jpg?w=757)

![Elvira (Munich) 'Isadora Duncan' from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 1 Published 1928 Elvira (Munich) 'Isadora Duncan' from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 1 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/isadora-duncan-p1-web11.jpg?w=680)

![Rudolf Jobst (Austrian, 1872-1952) 'Schwestern Wiesenthal [Wiesenthal sisters]' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 4 Published 1928 Rudolf Jobst (Austrian, 1872-1952) 'Schwestern Wiesenthal [Wiesenthal sisters]' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 4 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/schwestern-wiesenthal-p4-web2.jpg?w=1024)

![Hugo Erfurth (German, 1874-1948) 'Schwestern Wiesenthal [Wiesenthal sisters]' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 5 Published 1928 Hugo Erfurth (German, 1874-1948) 'Schwestern Wiesenthal [Wiesenthal sisters]' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 5 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/schwestern-wiesenthal-p5-web2.jpg?w=1024)

![Hugo Erfurth (German, 1874-1948) 'Grete Wiesenthal' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 6 Published 1928 Hugo Erfurth (German, 1874-1948) 'Grete Wiesenthal' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 6 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/grete-wiesenthal-p6-web2.jpg?w=712)

![Rudolf Jobst (Vienna) 'Else Wiesenthal' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 7 Published 1928 Rudolf Jobst (Vienna) 'Else Wiesenthal' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 7 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/else-wiesenthal-p7-web2.jpg?w=739)

![Hanns Holdt (German, 1887-1944) 'Sent M'Ahesa' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 10 Published 1928 Hanns Holdt (German, 1887-1944) 'Sent M'Ahesa' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 10 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/sent-m-ahesa-p10-web1.jpg?w=770)

![Franz Löwy (Austrian, 1883-1949) 'Sent M'Ahesa' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 11 Published 1928 Franz Löwy (Austrian, 1883-1949) 'Sent M'Ahesa' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 11 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/sent-m-ahesa-p11-web1.jpg?w=686)

![Hugo Erfurth (German, 1874-1948) 'Sent M'Ahesa' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 12 Published 1928 Hugo Erfurth (German, 1874-1948) 'Sent M'Ahesa' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 12 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/sent-m-ahesa-p12-web1.jpg?w=739)

![d'Ora (Arthur Benda) (Vienna) 'Sent M'Ahesa' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 13 Published 1928 d'Ora (Arthur Benda) (Vienna) 'Sent M'Ahesa' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 13 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/sent-m-ahesa-p13-web1.jpg?w=456)

![Hugo Erfurth (German, 1874-1948) 'Sent M'Ahesa' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 14 Published 1928 Hugo Erfurth (German, 1874-1948) 'Sent M'Ahesa' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 14 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/sent-m-ahesa-p14-web1.jpg?w=785)

![Hanns Holdt (Munich) 'Sent M'Ahesa' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 15 Published 1928 Hanns Holdt (Munich) 'Sent M'Ahesa' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 15 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/sent-m-ahesa-p15-web1.jpg)

![Hanns Holdt (German, 1887-1944) 'Sent M'Ahesa' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 16 Published 1928 Hanns Holdt (German, 1887-1944) 'Sent M'Ahesa' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 16 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/sent-m-ahesa-p16-web1.jpg?w=701)

![Franz Löwy (Austrian, 1883-1949) 'Sent M'Ahesa' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 17 Published 1928 Franz Löwy (Austrian, 1883-1949) 'Sent M'Ahesa' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 17 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/sent-m-ahesa-p17-web1.jpg?w=656)

![Hanns Holdt (German, 1887-1944) 'Sent M'Ahesa' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 18 Published 1928 Hanns Holdt (German, 1887-1944) 'Sent M'Ahesa' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 18 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/sent-m-ahesa-p18-web1.jpg?w=708)

![Minya Diez-Dührkoop (German, 1873-1929) 'Clotilde von Derp-Sacharoff' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 19 Published 1928 Minya Diez-Dührkoop (German, 1873-1929) 'Clotilde von Derp-Sacharoff' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 19 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/clotilde-von-derp-sacharoff-p19-web1.jpg?w=760)

![Hugo Erfurth (German, 1874-1948) 'Clotilde von Derp-Sacharoff' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 20 Published 1928 Hugo Erfurth (German, 1874-1948) 'Clotilde von Derp-Sacharoff' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 20 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/clotilde-von-derp-sacharoff-p20-web1.jpg?w=769)

![Hugo Erfurth (German, 1874-1948) Clotilde von Derp-Sacharoff c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 21 Published 1928 Hugo Erfurth (German, 1874-1948) Clotilde von Derp-Sacharoff c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 21 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/clotilde-von-derp-sacharoff-p21-web1.jpg?w=691)

![Hugo Erfurth (German, 1874-1948) 'Clotilde von Derp-Sacharoff' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 23 Published 1928 Hugo Erfurth (German, 1874-1948) 'Clotilde von Derp-Sacharoff' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 23 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/clotilde-von-derp-sacharoff-p23-web2.jpg?w=710)

![Hugo Erfurth (German, 1874-1948) 'Clotilde von Derp-Sacharoff' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 26 Published 1928 Hugo Erfurth (German, 1874-1948) 'Clotilde von Derp-Sacharoff' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 26 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/clotilde-von-derp-sacharoff-p26-web2.jpg?w=710)

![Atelier Veritas (Munich) (Stephanie Held-Ludwig) (German born Schaulen, Russia now Lithuania, 1871-1943) 'Clotilde von Derp-Sacharoff' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 27 Published 1928 Atelier Veritas (Munich) (Stephanie Held-Ludwig) (German born Schaulen, Russia now Lithuania, 1871-1943) 'Clotilde von Derp-Sacharoff' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 27 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/clotilde-von-derp-sacharoff-p27-web1.jpg?w=659)

!['Nijinski' From the works "The Russian Theater", Amalthea-Verlag, Vienna c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 28 Published 1928 'Nijinski' From the works "The Russian Theater", Amalthea-Verlag, Vienna c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 28 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/nijinski-p28-web1.jpg?w=709)

!['Nijinski' Portrait cards Verlag Leiser, Berlin - Wilmersdorf c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 29 Published 1928 'Nijinski' Portrait cards Verlag Leiser, Berlin - Wilmersdorf c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 29 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/nijinski-p29-web2.jpg?w=714)

![E. O. Hoppé (British, 1878-1972) 'Nijinski' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 30 Published 1928 E. O. Hoppé (British, 1878-1972) 'Nijinski' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 30 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/nijinski-p30-web2.jpg?w=590)

!['Nijinski' From the works "The Russian Theater", Amalthea-Verlag, Vienna c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 31 Published 1928 'Nijinski' From the works "The Russian Theater", Amalthea-Verlag, Vienna c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 31 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/nijinski-p31-web2.jpg?w=710)

!['Nijinski' Portrait cards Verlag Leiser, Berlin - Wilmersdorf c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 32 Published 1928 'Nijinski' Portrait cards Verlag Leiser, Berlin - Wilmersdorf c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 32 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/nijinski-p32-web1.jpg?w=686)

!['Nijinski' From the works "The Russian Theater", Amalthea-Verlag, Vienna c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 33 Published 1928 'Nijinski' From the works "The Russian Theater", Amalthea-Verlag, Vienna c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 33 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/nijinski-p33-web1.jpg?w=800)

!['Nijinski' From the works "The Russian Theater", Amalthea-Verlag, Vienna c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 35 Published 1928 'Nijinski' From the works "The Russian Theater", Amalthea-Verlag, Vienna c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 35 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/nijinski-p35-web2.jpg)

![d'Ora (Arthur Benda) (Vienna) 'Anna Pavlova' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 36 Published 1928 d'Ora (Arthur Benda) (Vienna) 'Anna Pavlova' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 36 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/anna-pavlova-p-36-web1.jpg?w=767)

![Hänse Herrmann (German, 1864-1932) 'Anna Pavlova' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 37 Published 1928 Hänse Herrmann (German, 1864-1932) 'Anna Pavlova' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 37 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/anna-pavlova-p-37-web1.jpg?w=737)

![Hänse Herrmann (German, 1864-1932) 'Anna Pavlova' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 38 Published 1928 Hänse Herrmann (German, 1864-1932) 'Anna Pavlova' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 38 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/anna-pavlova-p-38-web1.jpg?w=780)

![Hänse Herrmann (German, 1864-1932) 'Anna Pavlova' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 39 Published 1928 Hänse Herrmann (German, 1864-1932) 'Anna Pavlova' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 39 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/anna-pavlova-p-39-web1.jpg?w=750)

![Hänse Herrmann (German, 1864-1932) 'Anna Pavlova' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 40 Published 1928 Hänse Herrmann (German, 1864-1932) 'Anna Pavlova' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 40 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/anna-pavlova-p-40-web3.jpg?w=728)

![Hänse Herrmann (German, 1864-1932) 'Anna Pavlova' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 41 Published 1928 Hänse Herrmann (German, 1864-1932) 'Anna Pavlova' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 41 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/anna-pavlova-p-41-web3.jpg?w=801)

![Hänse Herrmann (German, 1864-1932) 'Anna Pavlova' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 42 Published 1928 Hänse Herrmann (German, 1864-1932) 'Anna Pavlova' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 42 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/anna-pavlova-p-42-web1.jpg?w=689)

![Hänse Herrmann (German, 1864-1932) 'Anna Pavlova' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 43 Published 1928 Hänse Herrmann (German, 1864-1932) 'Anna Pavlova' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 43 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/anna-pavlova-p-43-web2.jpg?w=793)

![Ernst Schneider (German, 1881-1959) 'Anna Pavlova' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 44 Published 1928 Ernst Schneider (German, 1881-1959) 'Anna Pavlova' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 44 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/anna-pavlova-p-44-web1.jpg?w=687)

![E. O. Hoppé (British, 1878-1972) 'Anna Pavlova' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 45 Published 1928 E. O. Hoppé (British, 1878-1972) 'Anna Pavlova' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 45 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/anna-pavlova-p-45-web1.jpg?w=730)

![Walter Mittelholzer (Swiss, 1894-1937) 'Wilde Schlussszene des Opfertanzes [Wild final scene of the sacrificial dance]' 1926-1927 Walter Mittelholzer (Swiss, 1894-1937) 'Wilde Schlussszene des Opfertanzes [Wild final scene of the sacrificial dance]' 1926-1927](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/lbs_mh02-03-0084-a-web.jpg)

![Walter Mittelholzer (Swiss, 1894-1937) 'Fremdenverkehr vor der Sphinx [Tourism in front of the Sphinx]' 1929 Walter Mittelholzer (Swiss, 1894-1937) 'Fremdenverkehr vor der Sphinx [Tourism in front of the Sphinx]' 1929](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/lbs_mh02-07-0161-web.jpg)

![Walter Mittelholzer (Swiss, 1894-1937) 'Itu-Mann vom Südosten Abessiniens [Itu man from southeastern Abyssinia]' c. 1934 Walter Mittelholzer (Swiss, 1894-1937) 'Itu-Mann vom Südosten Abessiniens [Itu man from southeastern Abyssinia]' c. 1934](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/lbs_mh02-22-0756-web.jpg?w=971)

![Walter Mittelholzer (Swiss, 1894-1937) 'Dankali-Mädchen [Dankali girl]' c. 1934 Walter Mittelholzer (Swiss, 1894-1937) 'Dankali-Mädchen [Dankali girl]' c. 1934](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/lbs_mh02-22-0775-web.jpg?w=969)

![Walter Mittelholzer (Swiss, 1894-1937) 'Flugplatz in Addis Abeba [Airfield in Addis Ababa]' c. 1934 Walter Mittelholzer (Swiss, 1894-1937) 'Flugplatz in Addis Abeba [Airfield in Addis Ababa]' c. 1934](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/lbs_mh02-22-0778-web.jpg?w=966)

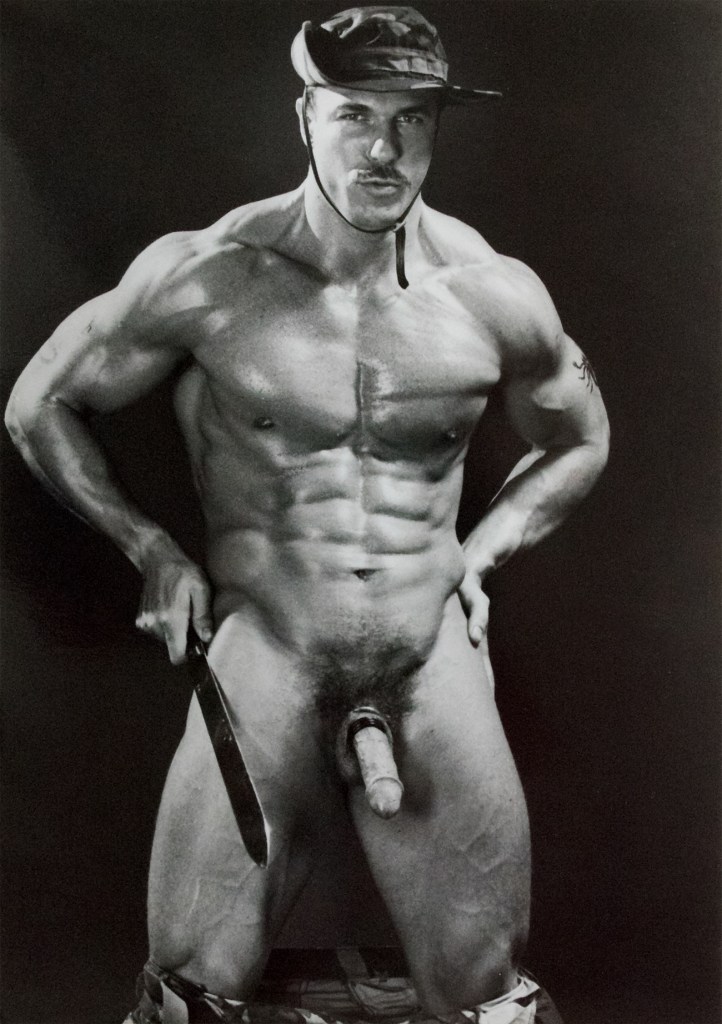

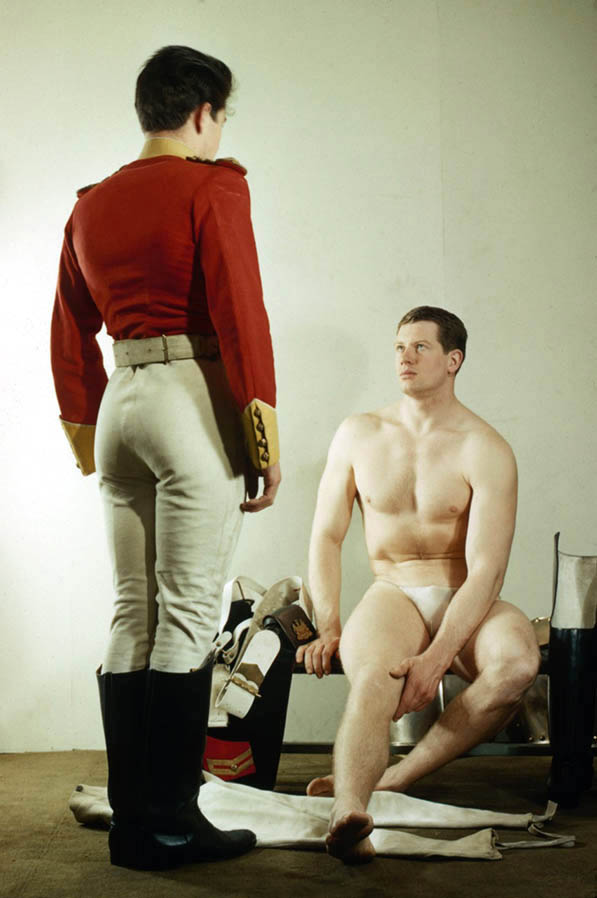

![Peter Elfes (Australia, b. 1961) 'Brenton [Heath-Kerr] as Tom of Finland' 1992 Peter Elfes (Australia, b. 1961) 'Brenton [Heath-Kerr] as Tom of Finland' 1992](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/elfes-brenton-heath-kerr-web.jpg?w=686)

![Unknown photographer. 'Untitled [Auschwitz victim]' N Unknown photographer. 'Untitled [Auschwitz victim]' Nd](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/unknown-photographer-untitled-auschwitz-victim-nd-web.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.