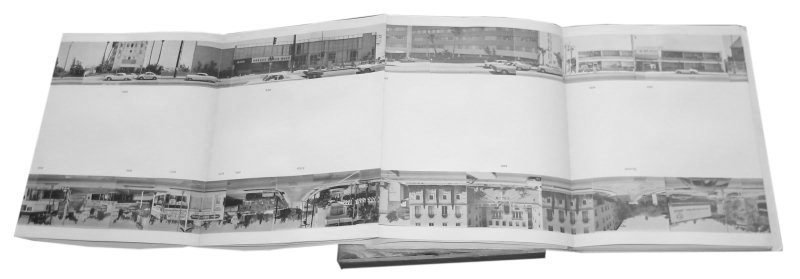

Exhibition dates: 7th April – 19th June 2011

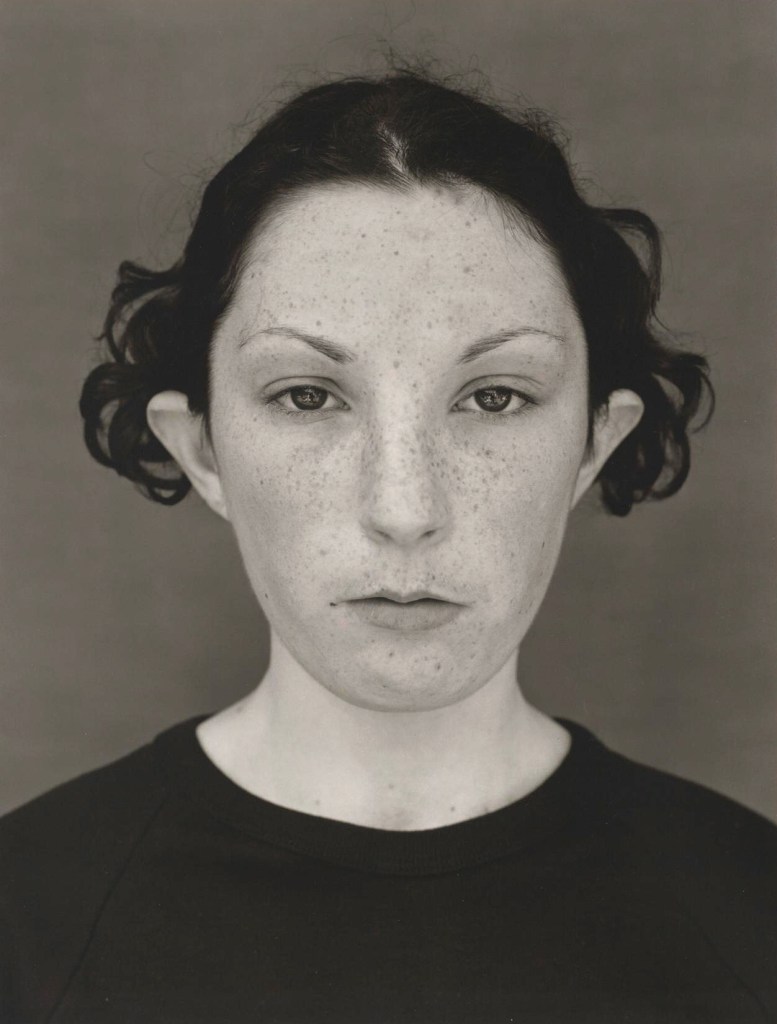

Sue Ford (Australian, 1943-2009)

Self-portrait 1968

1968, printed 2011

From the series Self-portrait with camera (1960-2006)

Selenium toned gelatin silver

22.8 x 24 cm

Courtesy Sue Ford Archive

“Choosing to photograph oneself, one’s life and one’s time exemplified the now well-worn slogan ‘the person is political’. Ford’s self-examination across the decades is unflinching and exacting. As Janine Burke wrote in 1980, her ‘psychological history [is] etched in her face for everyone to see’. Burke concluded that Ford’s self-portraits are ‘as honest as one can ever be about oneself’.”

Helen Ennis. Faces are Maps: Sue Ford and Portraiture.1

“The search for the self is a journey into a mental labyrinth that takes random courses and ultimately ends at impasses. The memory fragments recovered along the way cannot provide us with a basis for interpreting the overall meaning of the journey. The meanings that we derive from our memories are only partial truths, and their value is ephemeral. For Foucault, the psyche is not an archive but only a mirror. To search the psyche for the truth about ourselves is a futile task because the psyche can only reflect the images we have conjured up to describe ourselves. Looking into the psyche, therefore, is like looking into the mirror image of a mirror. One sees oneself reflected in an image of infinite regress. Our gaze is led not toward the substance of our beginnings but rather into the meaninglessness of previously discarded images of the self.”

Patrick Hutton. Foucault, Freud,

and the Technologies of the Self.2

This is a solid exhibition of the work of beloved Australian photographer Sue Ford, essential looking for anyone wanting to have an overview of Australian photography.

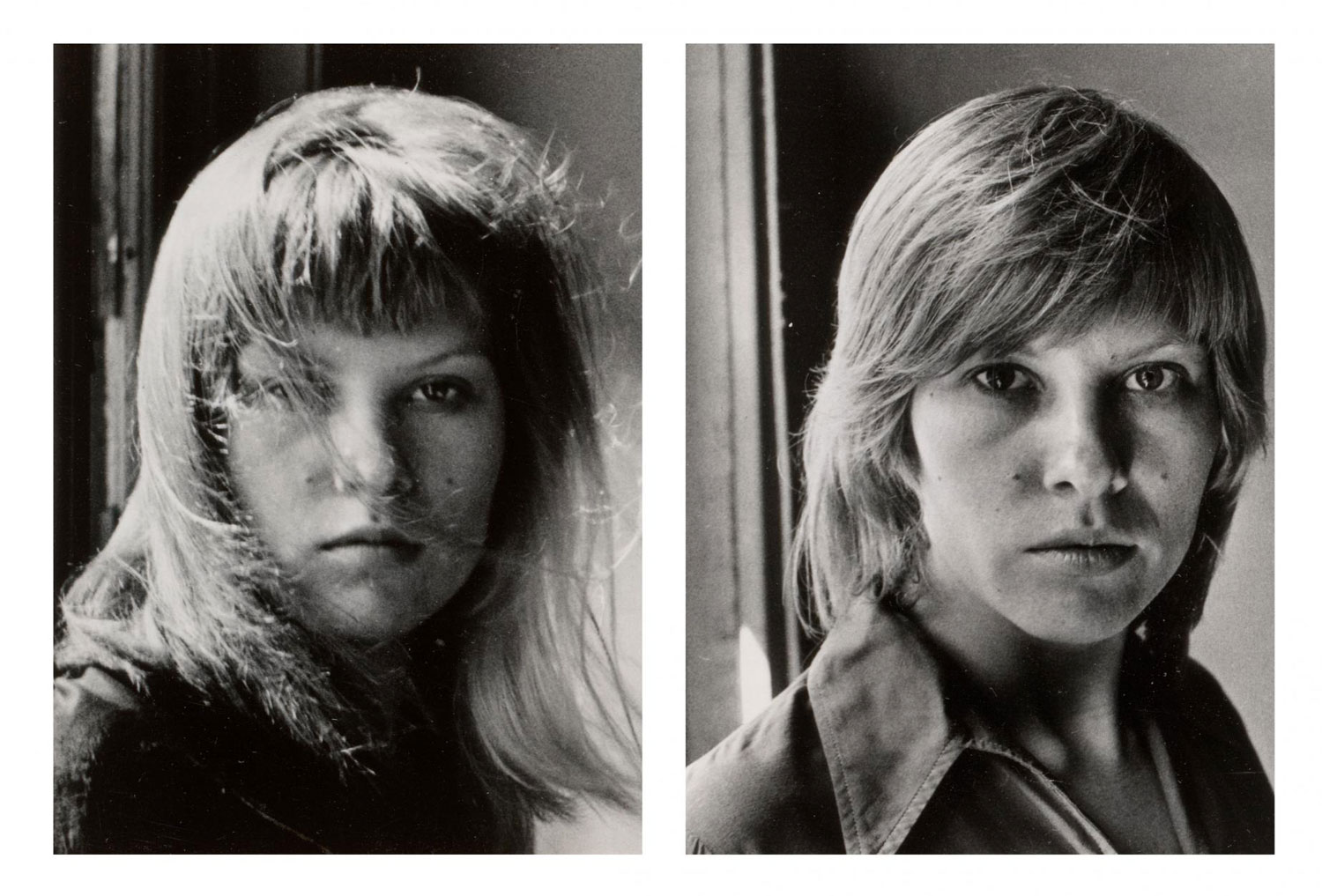

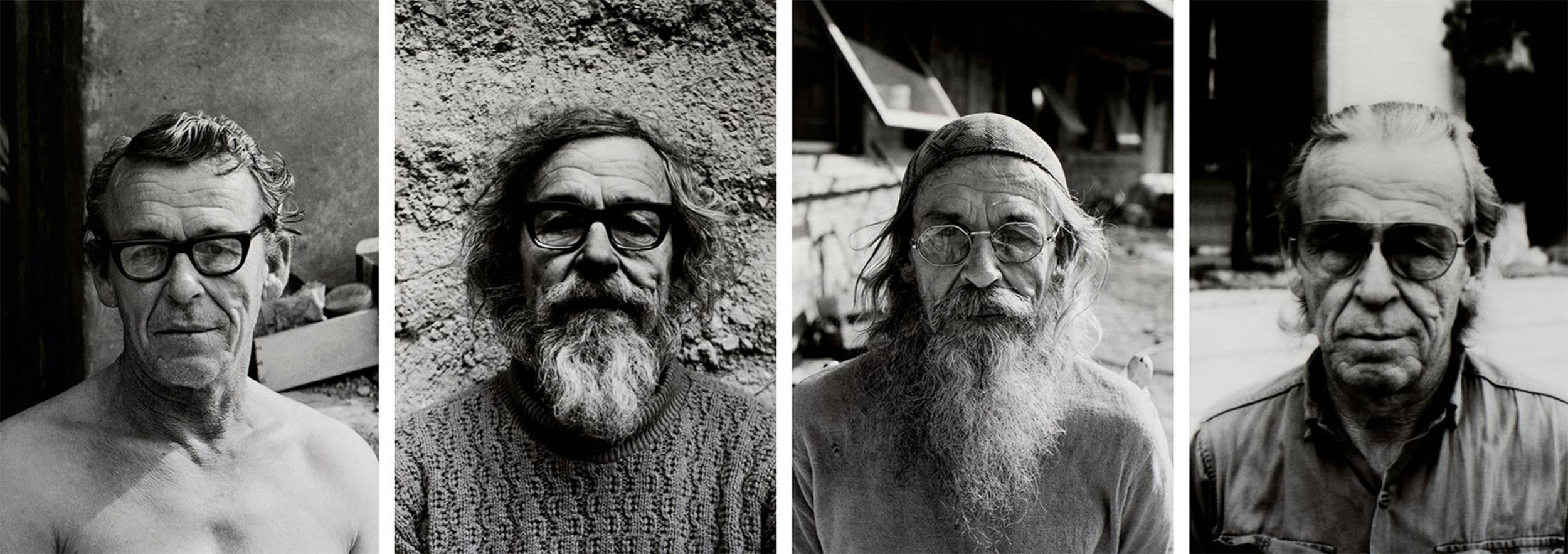

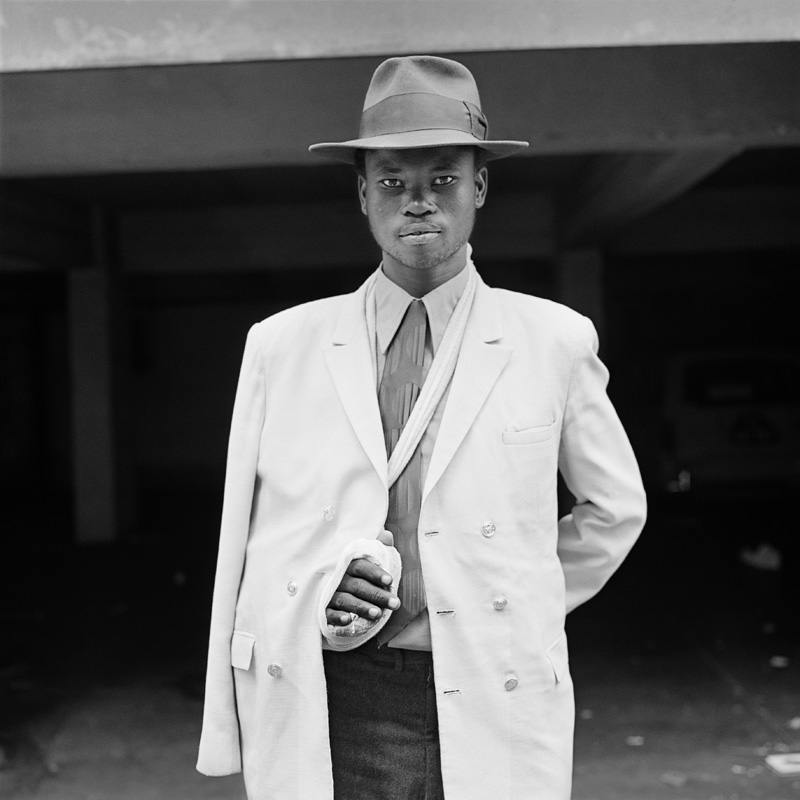

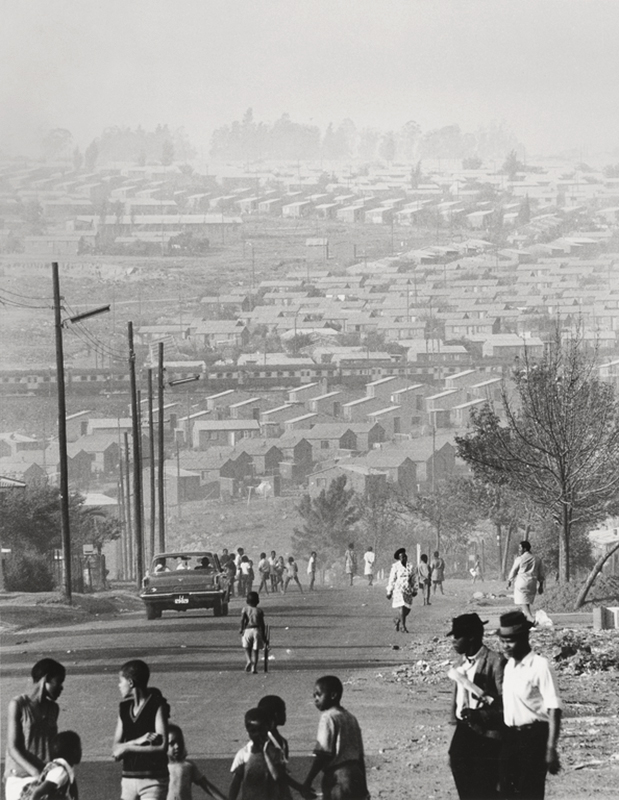

The beautifully hung exhibition flows like music, interweaving up and down, the photographs framed in thin, black wood frames. It features examples of Ford’s black and white fashion and street photography; a selection of work from the famous black and white Time series (being bought for their collection by the Art Gallery of New South Wales) – small, snapshot size double portraits, the first portraits taken during the 1960’s, the second around 1974, formalist portraits in which the sitter is closely cropped around head and shoulders with the photographer using the camera as objectively as possible, the double portrait used to display changes in identity over time; a selection of Photographs of Women – modern prints from the Sue Ford archive that are wonderfully composed photographs with deep blacks that portray strong, independent, vulnerable, joyous women (see last four photographs below); and the most interesting work in the exhibition, the posthumous new series Self-portrait with camera (1960-2006) that evidence, through a 47 part investigation using colour prints from Polaroids, silver gelatin prints printed by the artist, prints made from original negatives and prints from scanned images where there was no negative available, a self-portrait of the artist in the process of ageing (see the two photographs above and below this review).

One of my favourite photographs in the exhibition was Margaret with Emma, Redcliffs, Queensland, 1971. The black and white photograph features a grandmother with her granddaughter, close to each other, both wearing floral dresses of different pattern, both staring intently out of the image at what is possibly a television with a weatherboard backdrop. A dark form hovers at the upper left of the photograph adding a disturbing note to the image but it is the look on the grandmother’s face – a look of shock, enthralment, blankness with eyes wide, that is matched by the intensity on the granddaughter’s face as she stares intently – that transcends the distance between photograph and viewer, between grandmother and granddaughter across time and space. The process of looking and ageing captured by the ‘time machine’, the camera, in one single image. The viewer understands this photograph for we all experience the evidence of our bodies, our mortality. We relate intimately to how the photograph reanimates in the present this moment from the past, the momenti mori of the photograph, the little death becoming our future death.

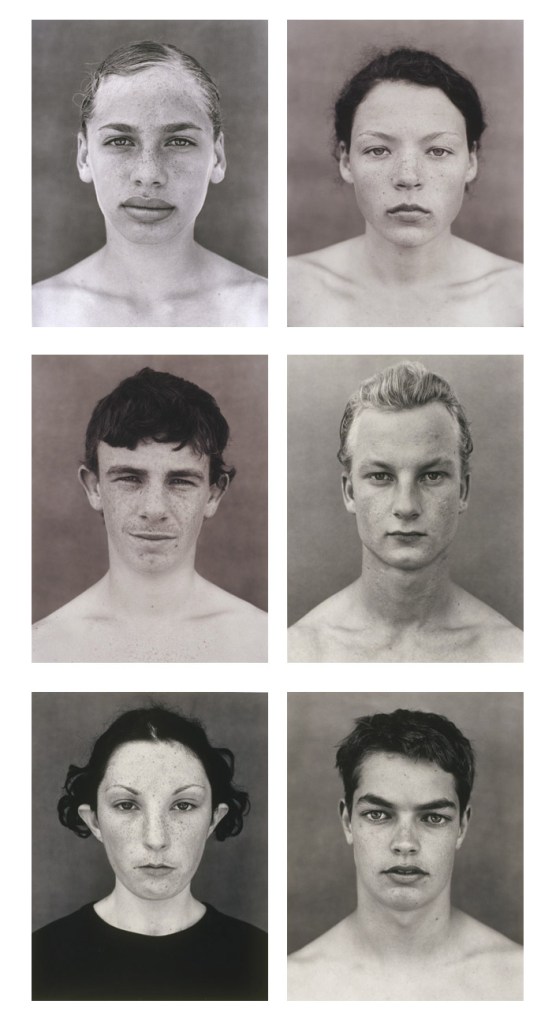

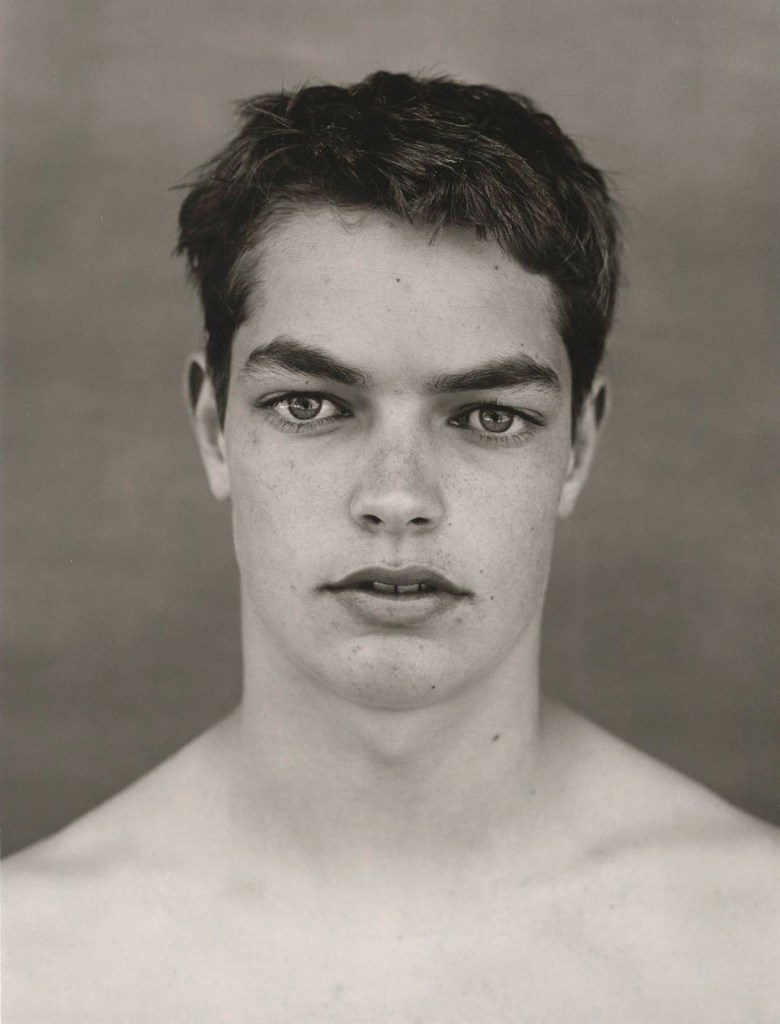

This notion is particularly poignant in the series Self-portrait with camera (1960-2006), a work that Sue Ford was actively engaged with before her death. Smaller colour prints from negatives and Polaroids are here interspersed with black and white photographs up to about 8″ x 10″ in size: the series contains 12 chromogenic photographs, 7 silver gelatin photographs, 6 dye fusion photographs and 22 selenium-toned photographs (printed 2011). In dark, contrasty prints the artist has photographed herself looking down into the camera shooting into a mirror, looking directly into the mirror with camera, with the camera on a timer, with the camera in/visible, being shot by other people with the camera pointed directly at her, with the camera perpendicular to the artist shot by someone else, with Ford behind a movie camera, with multiple refractions in mirrors. Sometimes Ford even becomes the camera (as in the 1986 self-portrait below: I am the camera, the camera is me).

Ford becomes the “one who looks” knowingly at herself, sometimes the author of that observation, sometimes oblivious to it (until later when she has collected these images). As Burke and Ennis note, these photographs of self-examination across the decades are as honest as one can ever be about oneself. This a deeply political but also deeply psychoanalytical investigation: not to “take care of yourself” as a form of knowing as in Greco-Roman antiquity but “knowing yourself” as the fundamental principle of understanding yourself: a procedure of objectification and subjection in which the photograph ‘marks’ our status and the passage of time, that makes us who we are – photographs as vital techniques in the constitution of the self as subject.3

The mirror is frequently used in these photographs to portray the self. While it is true that these are strong, intimate, unflinching and exacting images, in the use of the mirror the im(pose)tures of life are singled / doubled / tripled – a reflection of the psyche that lead to discarded images of the self that are of little use in understanding the substance of our beginnings … or the overall interpretation of the journey. What they do offer is cumulative evidence of a deep, personal conviction into the inquiry: who am I?

Rembrandt famously painted, drew and etched himself hundreds of times in the process of ageing; Ford has likewise done the same. If, as Victor Burgin observes, “An identity implies not only a location but a duration, a history,”4 then the nature of photography (including Ford’s self-reflexive project), concerned as it is with space and time, becomes the mirror in a search for identity. Photography as a mirror on the world constantly repeats moments of illumination in a re/vision of eternal recurrence, a performance that is a hybrid site: both a homogenous (the same “I”) and heterogenous (a different “I”) site of self-representation, different every time we look. To that end I would like you to look at the self-portrait from 1976 (below). The artist is completely absent, her silhouette, her dark shadow swallowed whole by the blank photographic plate on the left hand side of the image as though Ford, the camera and an image of infinite regress have become one, eternally engulfed by space-time but open to re/view at any time.

Whether looking down, looking toward or looking inward these fantastic photographs show a strong, independent women with a vital mind, an élan vital, a critical self-organisation and an understanding of the morphogenesis of things that will engage us for years to come. Essential looking.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Burke, Janine. Self-portrait/self-image 1980-1981. Melbourne: Australian Directors’ Council, 1981. p. 4 quoted in Ennis, Helen. “Faces are Maps: Sue Ford and Portraiture,” in Lakin, Shaune (ed.,). Sue Ford: Self-portrait with camera (1960-2006). Melbourne: Monash Gallery of Art, 2011, np.

2/ Hutton, Patrick. “Foucault, Freud, and the Technologies of the Self,” in Martin, Luther and Gutman, Huck and Hutton, Patrick (eds.,). Technologies of the Self: A Seminar with Michel Foucault. London: Tavistock Publications, 1988, p. 139

3/ Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish, quoted in Gutman, Huck. “Rousseau’s Confessions: A Technology of the Self,” in Martin, Luther and Gutman, Huck and Hutton, Patrick (eds.,). Technologies of the Self: A Seminar with Michel Foucault. London: Tavistock Publications, 1988, p. 99

4/ Burgin, Victor. In/Different Spaces: Place and Memory in Visual Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995, p. 36

Many thankx to Mark Hislop for his help and the Monash Gallery of Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Sue Ford (Australian, 1943-2009)

Self-portrait 1986

1986

From the series Self-portrait with camera (1960-2006)

Gelatin silver print, printed 2011

8.4 x 6.5cm

Courtesy Sue Ford Archive

Sue Ford (Australian, 1943-2009)

Self-portrait 1976

1976, printed 2011

From the series Self-portrait with camera (1960-2006)

Selenium toned gelatin silver print

24 x 18cm

Courtesy Sue Ford Archive

Sue Ford (Australian, 1943-2009)

Self-portrait 1974

1974, printed 2011

From the series Self-portrait with camera (1960-2006)

Selenium toned gelatin silver print

19.9 x 18cm

Courtesy Sue Ford Archive

On 16 April 2011, the first major exhibition of the work of the late Sue Ford for two decades will open at Monash Gallery of Art.

Sue Ford (1943-2010) was one of Australia’s most important photographers and filmmakers. Ford studied photography at RMIT and in 1974 was the first Australian photographer to be given a solo exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria.

Ford passed away in 2009. Before her death, she was working with Monash Gallery of Art on an exhibition of her work which would feature her final major project Self-portrait with camera (1960-2006). This series of 47 photographs has never been shown before, and presents a compelling self-portrait of an artist. It underscores the central role the camera played in Ford’s life. Self-portrait with camera will be shown alongside a survey of Ford’s black-and-white photographs from the 1960s and 70s and examples of her most iconic work, Time series (1960s-1970s).

The exhibition describes a period when photography was charged with political and personal meaning. As photographic historian and contributor to the publication accompanying the exhibition Helen Ennis states: “Ford’s approach to art making has always been straightforward … She does not cultivate a mysterious artistic persona [since] … her art practice is purposeful; it is the outcome of her view of art as a political activity that is democratic, liberating and relevant to contemporary society.”

As MGA Director and curator of the exhibition Shaune Lakin states: “This exhibition provides a great opportunity for Australian audiences to reassess the work of this important photographer, whose work was always at once political, beautiful and elegiac. In an era when the photograph has become a highly disposable thing, it is important to acknowledge its role as an agent of change and memory.”

Press release from the Monash Gallery of Art

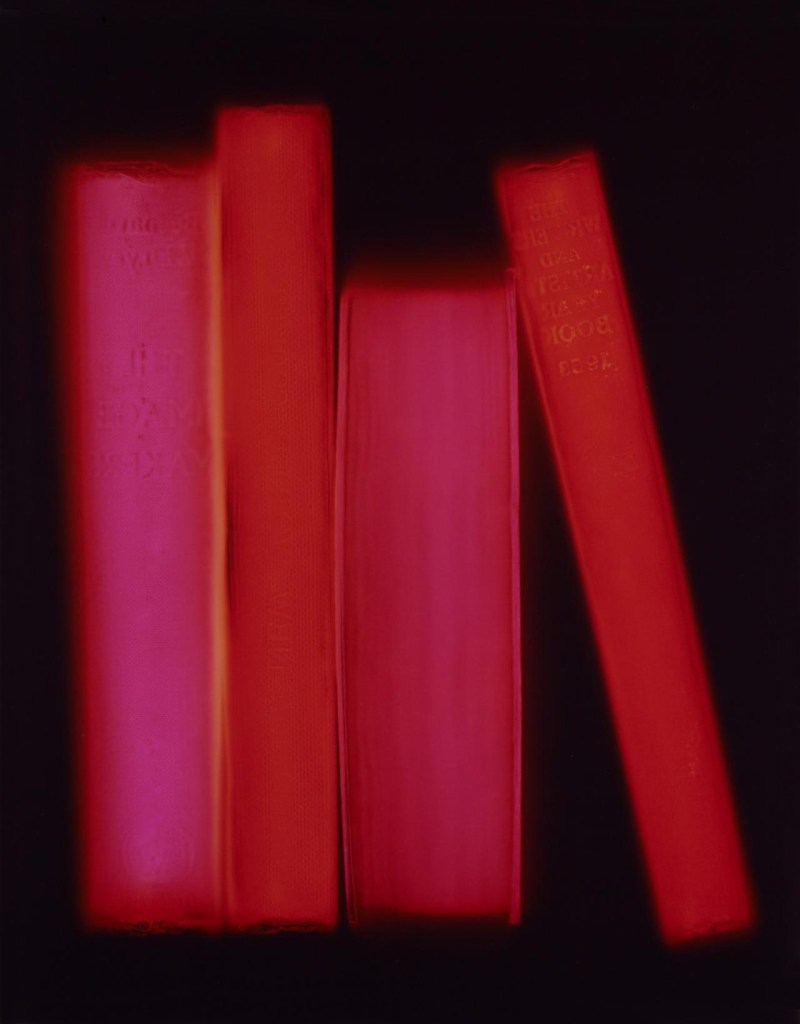

Sue Ford (Australian, 1943-2009)

Helen, 1962; Helen, 1974

1974

From the series Time series

Gelatin silver prints

11.0 x 8.0cm; 11.5 x 8.3cm

Museum of Australian Photography, City of Monash Collection

Acquired with assistance from the Robert Salzer Foundation and the Friends of MGA Inc 2020

Sue Ford (1943-2009) was one of Australia’s most important twentieth-century photographers, and Time series is her most iconic body of work, widely recognised as a key moment in the history of Australian photography. First exhibited at the NGV and Brummels Gallery of Photography in 1974, the series highlights Ford’s interest in the camera’s ability to record the effects of time and history. To create this series, Ford made portraits of her friends and acquaintances during the early to mid-1960s then rephotographed the sitters around a decade later, showing the second portraits beside the first. In some cases Ford later added third and fourth portraits to create Time series II, which she made for exhibition at the 1982 Sydney Biennale. Ford described the camera as a ‘time machine’ and the works in these series bracket periods in the lives of her subjects. With a tender pathos, they evoke the inevitability of time’s passing along with the processes of human ageing and constant change.

Text from the Museum of Australian Photography website 2021

Sue Ford (Australian, 1943-2009)

Annette 1962; Annette 1974

1974

From the Time series

Gelatin silver prints

11.1 x 20.1cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased with the assistance of the Visual Arts Board and the KODAK (Australasia) Pty Ltd Fund, 1974

Sue Ford (Australian, 1943-2009)

Jim, 1964; Jim, 1969; Jim, 1974; Jim, 1979

1982

From the series Time series

Gelatin silver prints

11.0 x 7.6cm (each)

Museum of Australian Photography, City of Monash Collection

donated by the Sue Ford Archive 2020

Sue Ford (Australian, 1943-2009)

Lynne and Carol

1962, printed 2011

Selenium toned gelatin silver print

38.0 x 38.0cm

Courtesy Sue Ford Archive

Sue Ford (Australian, 1943-2009)

Carol, Little Collins St studio

1962, printed 2011

Selenium toned gelatin silver print

37.9 x 38.1cm

Courtesy Sue Ford Archive

Sue Ford (Australian, 1943-2009)

St Kilda

1963, printed 2011

Selenium toned gelatin silver print

38.0 x 38.0cm

Courtesy Sue Ford Archive

![Sue Ford (1943-2009) 'Untitled [Bliss at Yellow House, King's Cross, Sydney]' c. 1972–1973 Sue Ford (1943-2009) 'Untitled [Bliss at Yellow House, King's Cross, Sydney]' c. 1972–1973](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/008.jpg)

Sue Ford (Australian, 1943-2009)

Untitled [Bliss at Yellow House, King’s Cross, Sydney]

c. 1972-3, printed 2011

Selenium toned gelatin silver print

47.9 x 34.2cm

Courtesy Sue Ford Archive

Monash Gallery of Art

860 Ferntree Gully Road, Wheelers Hill

Victoria 3150 Australia

phone: + 61 3 8544 0500

Opening hours:

Tue – Fri 10am – 5pm

Sat – Sun 10pm – 4pm

Mon/public holidays closed

You must be logged in to post a comment.