Exhibition dates: 1st February – 30th March 2014

Warning: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander viewers should be aware that the following posting may contain images of deceased persons.

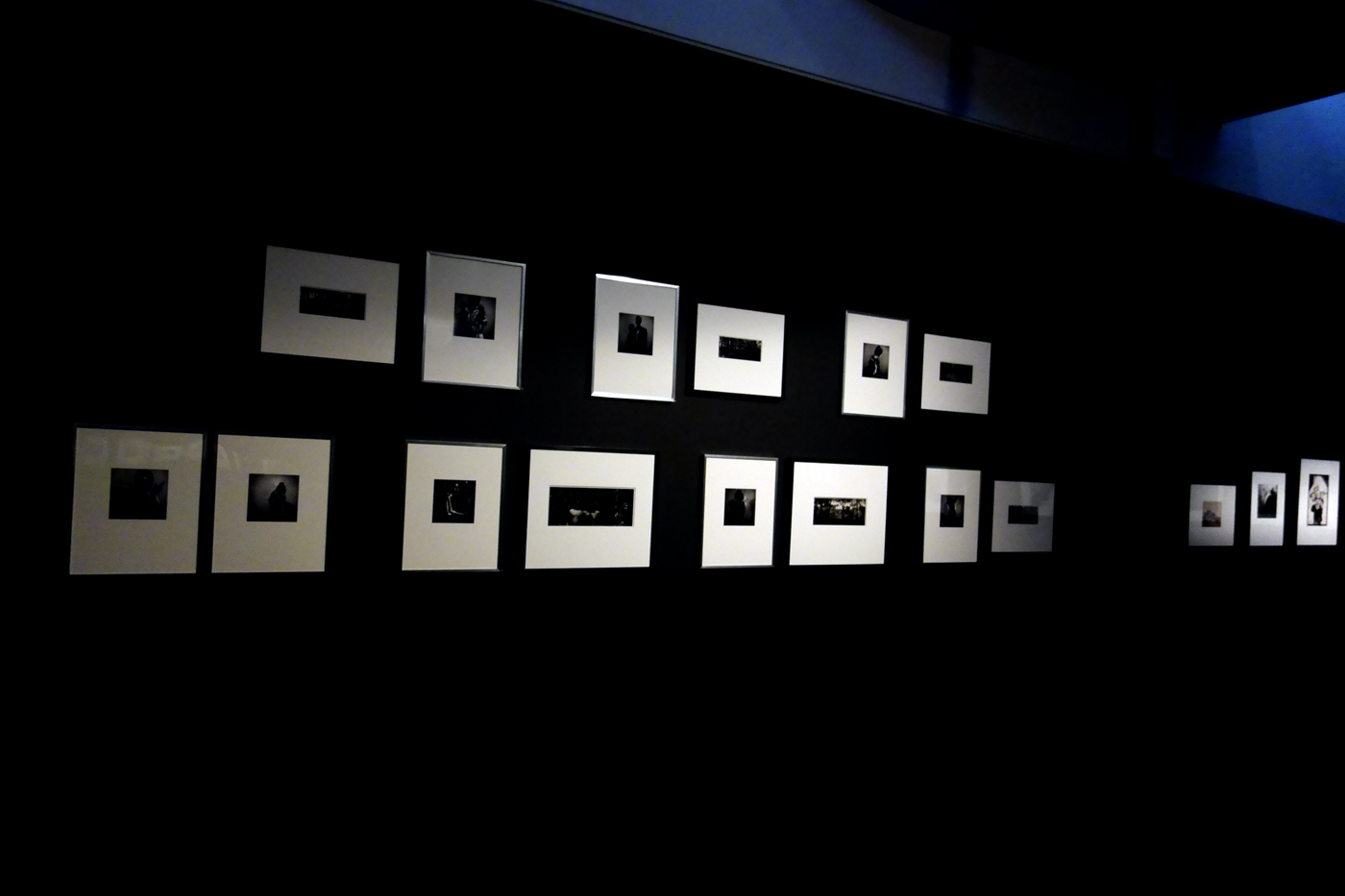

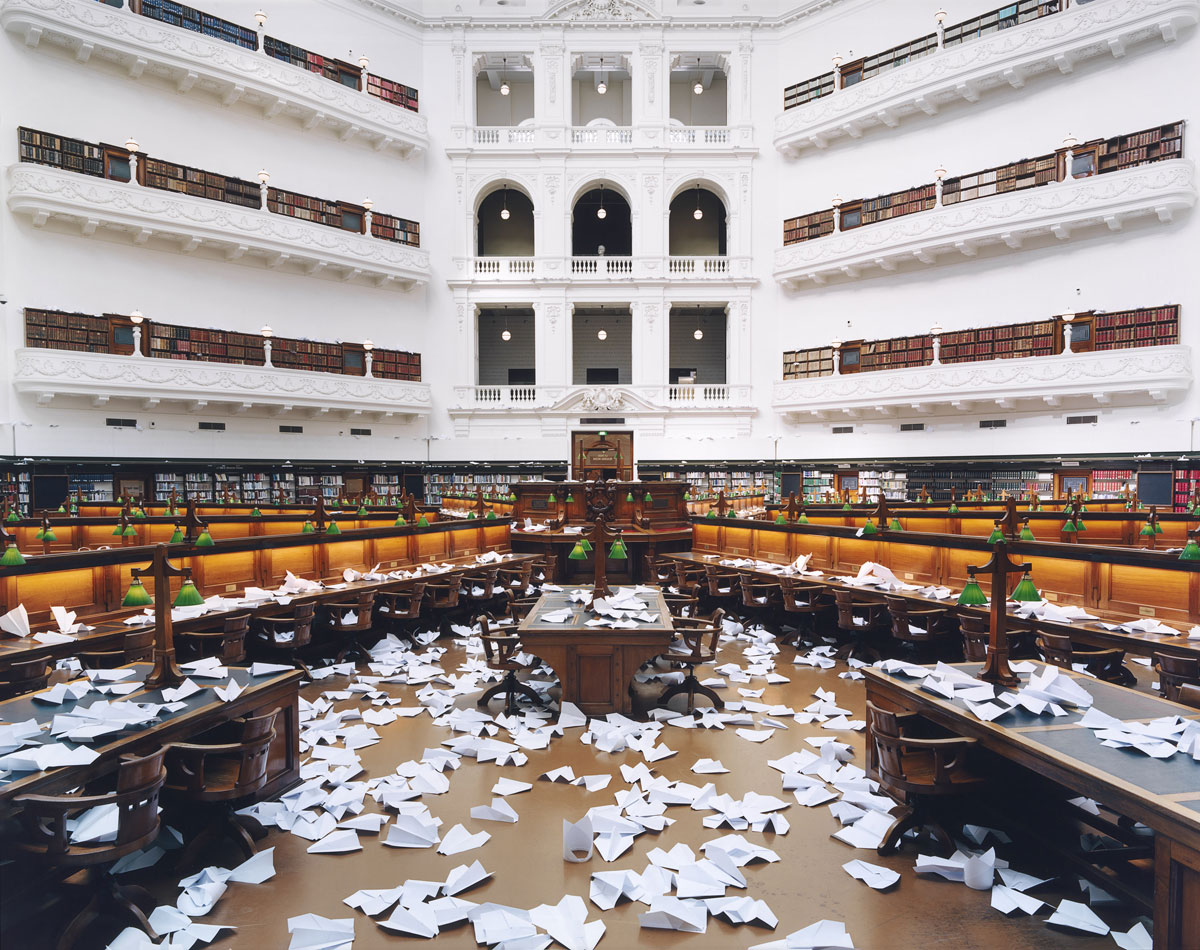

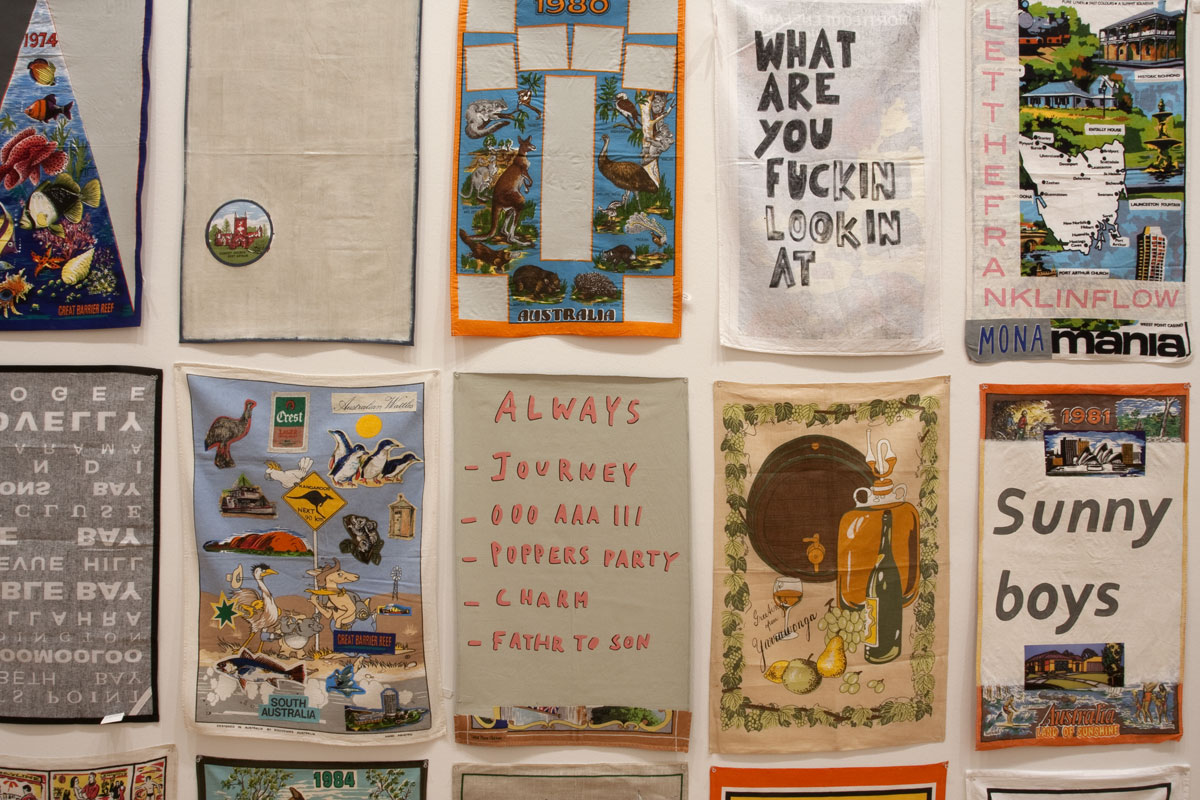

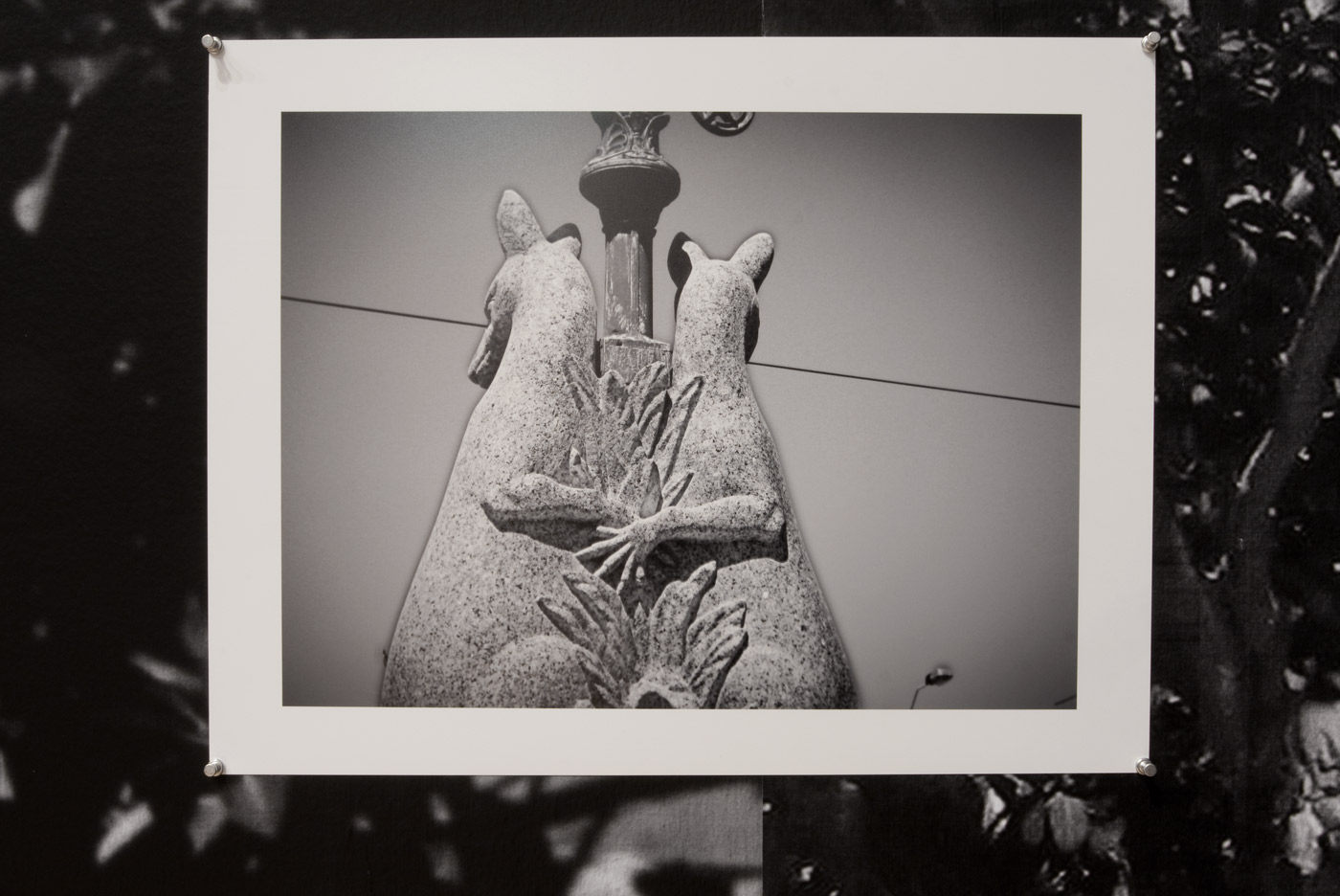

Installation photographs of Wildcards: Bill Henson shuffles the deck at the Monash Gallery of Art

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

1/ stygian gloom

2/large grouping of 14 works by Wesley Stacey

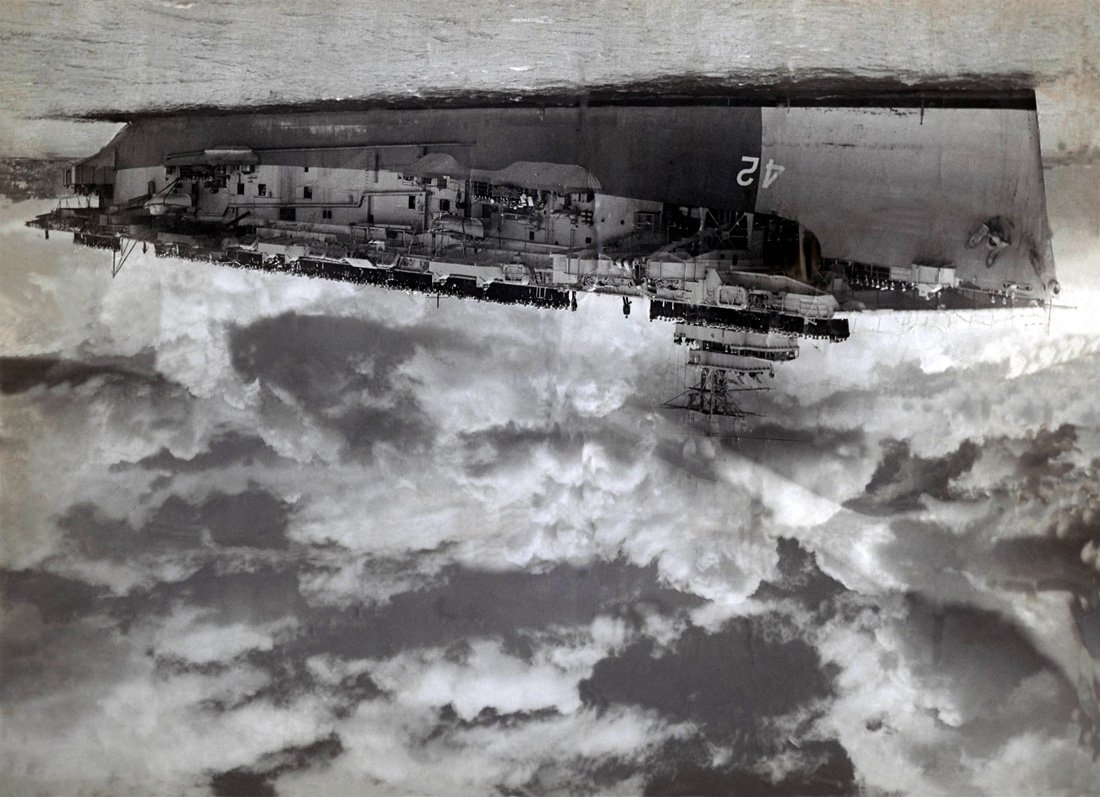

Unknown photographer

Untitled

c. 1900

Cyanotype print

Monash Gallery of Art, City of Monash Collection

Acquired 2012

vapid [vap-id]

adjective

lacking or having lost life, sharpness, or flavourOrigin:

1650-60; Latin vapidus; akin to va·por [vey-per]

noun

a visible exhalation, as fog, mist, steam, smoke diffused through or suspended in the air; particles of drugs that can be inhaled as a therapeutic agent

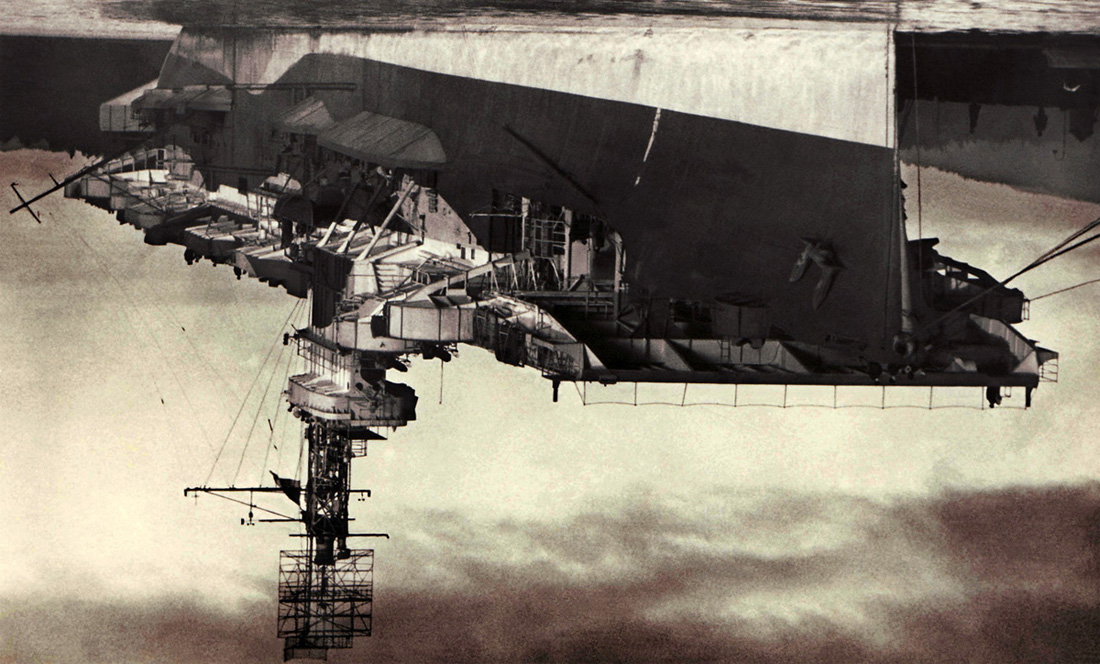

This is an unexceptional exhibition, one that lacks jouissance in the sense of a transgressive kind of enjoyment, an investigation of the subject that gives pleasure in taking you to unexpected places. At times I felt like a somnambulist walking around this exhibition of photographs from the Monash Gallery of Art collection curated by Bill Henson, pitched into stygian darkness and listening to somewhat monotonous music. It was a not too invidious an exercise but it left me with a VAPID feeling, as though I had inhaled some soporific drug: the motion of the journey apparently not confined by a story, but in reality that story is Henson’s mainly black and white self-portrait. The photographs on the wall, while solid enough, seemed to lack sparkle. There were a couple of knockout prints (such as David Moore’s Himalaya at dusk, Sydney, 1950 below; the Untitled cyanotype c. 1900, above; and Mark Hinderaker’s delicate portrait of Fiona Hall, 1984 below) and some real bombs (the large Norman Lindsay photographs, modern reproductions printed many times their original size were particularly nauseous). And one has to ask: were the images chosen for how they were balanced on the wall or were they chosen for content?

Henson states that there was no concept or agenda when picking the 88 photographs for this exhibition, simply his INTENSITY of feeling and intuition, his intuitive response to the images when he first saw them – to allow “their aesthetics to determine their presence… our whole bodies to experience these photographs – objects as pictures as photographs.”1 Henson responded as much as possible to the thing which then becomes an iconography (which appeals to his eye) as he asks himself, why is one brush stroke compelling, and not another? The viewer can then go on a journey in which MEANING comes from FEELING, and SENSATIONS are the primary stuff of life.

One of Henson’s preoccupations, “is an interest in the photograph as an object, in the physical presence of the print or whatever kind of technology is being used to make it.”2 He would like us to acknowledge the presence and aura (Walter Benjamin) of the photograph as we stand in front of it, responding with our whole bodies to the experience, not just our eyes. He wants us to have an intensity of feeling towards these works, responding to their presence and how he has hung the works in the exhibition. “There are no themes but rather images that appeal to the eye and, indeed, the whole body. Because photographs are first and foremost objects, their size, shape grouping and texture are as important as the images they’re recording.”3

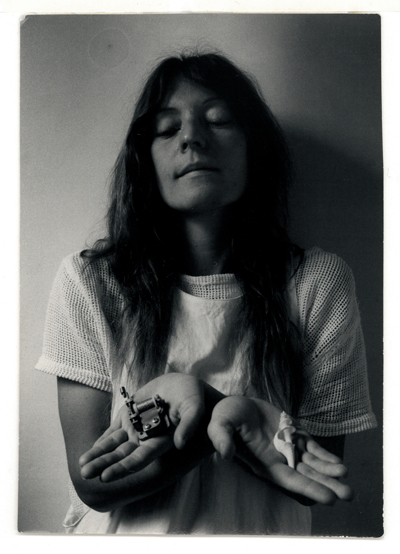

Henson insists that there was no preconceived conceptual framework for picking these particular photographs but this is being disingenuous. Henson was invited to select images from the MGA collection with the specific idea of holding an exhibition, so this is the conceptual jumping off point; he then selected the images intuitively only to then group and arrange then intuitively/conceptually – by thinking long and hard about how these images would be grouped and hung on the wall of the gallery. I would like to believe that Henson was thinking about MUSIC when he hung this exhibition, not photography. Listen to Henson talk about the pairing of Leonie Reisberg’s Portrait of Peggy Silinski, Tasmania (c. 1976, below) and Beverley Veasey’s Study of a Calf, Bos taurus (2006, below) in this video, and you will get the idea about how he perceives these photographs relate to each other, how they transcend time and space.

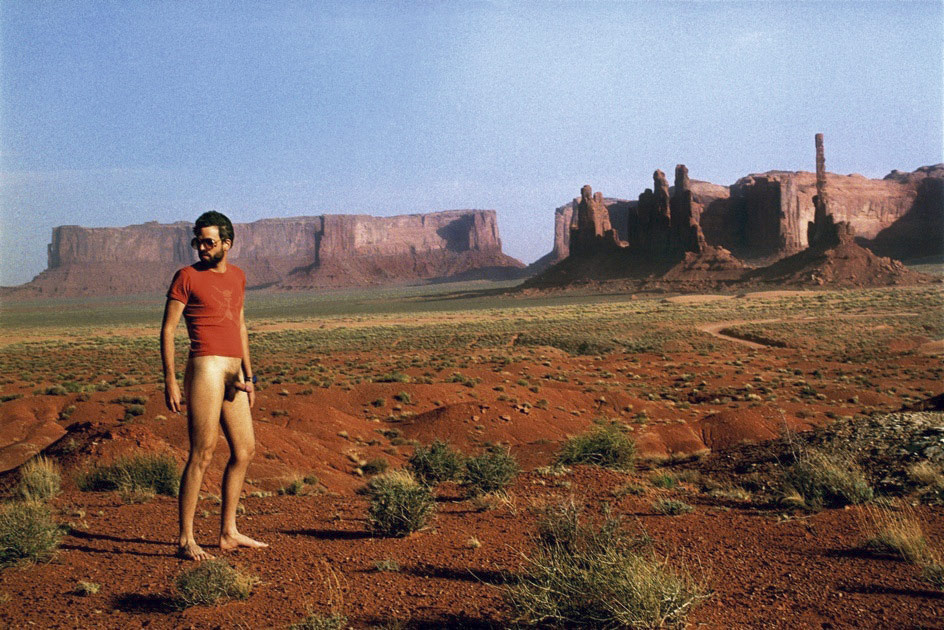

This is one of the key elements of the exhibition: how Henson pushes and pulls at time and space itself through the placing of images of different eras together. The other two key elements are how the music rises and falls through the shape of the photographs themselves; and how the figures within the images are pulled towards or pushed away from you. With regard to the rise and fall, Henson manipulates the viewer through the embodiedness of both horizontal and vertical photographs, reminding me of a Japanese artist using a calligraphy brush (see the second installation image above, where the photographs move from the vertical to the square and then onto panoramic landscape). In relation to the content of the images, there seems to be a preoccupation (a story, a theme?) running through the exhibition with the body being consumed by the landscape or the body being isolated from the landscape but with the threat of being consumed by it. Evidence of this can be seen in Wesley Stacey’s Willie near Mallacoota (1979, below) where the body almost melts into the landscape and David Moore’s Newcastle steelworks (1963, below) where the kids on the bicycles are trying to escape the encroaching doom that hovers behind them.

One of the key images in the exhibition for me also reinforces this theme – a tiny Untitled Cyanotype (c. 1900, above) in which two Victorian children are perched on a bank near a stream with the bush beyond – but there are too many of this ilk to mention here: either the figures are pulled towards the front of the frame or pushed back into the encroaching danger, as though Henson is interrogating, evidencing un / occupied space. Overall, there is an element of control and lyrical balance in how he has grouped and hung these works together, the dark hue of the gallery walls allowing the photographs to exist as objects for themselves. Henson puts things next to each other in sequences and series to, allegedly, promote UNEXPECTED conversations and connections through a series of GESTURES.

As Henson notes,

“Maybe it’s the fact that the photographs have the ability to suggest some other thing and that’s what draws you in – that’s that feeling, the thing that slips away from thought. These are really the same things that apply to our meetings with any work of art, whether it’s a piece of music or a sculpture or anything else. There’s something compelling, there’s something there that sort of animates your speculative capacity, causes you to wonder. Other times, or most of the time, that’s not the case. Certainly most of the time that’s not the case with photography.”4

.

For me, there was little WONDER in this exhibition, something that you would go ‘oh, wow’ at, some way of looking at the world that is interesting and insightful and fractures the plaisir of cultural enjoyment and identity. While the photographs may have been chosen intuitively and then hung intuitively/conceptually, I simply got very little FEELING, no ICE/FIRE (as Minor White would say) – no frisson between his pairings, groupings and arrangements. It was all so predictable, so ho-hum. Everything I expected Henson to do… he did!

There were few unexpected gestures, no startling insight into the human and photographic condition. If as he says, “Everything comes to you through your whole body, not just through your eyes and ears,”5 and that photographs are first and foremost objects, their size, shape, grouping and texture as important as the images they’re recording THEN I wanted to be moved, I wanted to feel, to be immersed in a sensate world not a visible exhalation (of thought?), a vapor that this exhibition is. Henson might have painted an open-ended self-portrait but this does not make for a very engaging experience for the viewer. In this case, the sharing of a story has not meant the sharing of an emotion.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Interview with Bill Henson by Toby Fehily posted 01 Feb 2014 on the Art Guide Australia website [Online] Cited 18/02/2014. No longer available online

2/ Ibid.,

3/ Fiona Gruber. “Review of Wildcards, Bill Henson Shuffles the Deck” on the Guardian website, Wednesday 12 February 2014 [Online] Cited 16/03/2014

4/ Fehily op. cit.,

5/ Fehily op. cit.,

Many thankx to the Monash Gallery of Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

MGA Collection: Bill Henson on Leonie Reisberg and Beverley Veasey

Bill Henson talks about the photographs of Leonie Reisberg and Beverley Veasey from the MGA Collection in WILDCARDS: BILL HENSON SHUFFLES THE DECK, Monash Gallery of Art, 1 February to 30 March 2014.

John Eaton (born United Kingdom 1881; arrived Australia 1889; died 1967)

Sheep in clearing

c. 1920s

Gelatin silver print

15.6 x 23.8cm

Monash Gallery of Art, City of Monash Collection

Donated by Janice Hinderaker through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program 2003

Fred Kruger (born Germany 1831; arrived Australia 1860; died 1888)

Queen Mary and King Billy outside their mia mia

c. 1880

Albumen print

13.4 x 20.8cm

Monash Gallery of Art, City of Monash Collection acquired 2012

David Moore (Australia 1927-2003)

Himalaya at dusk, Sydney

1950

Gelatin silver print, printed 2005

24.5 x 34.25cm

Monash Gallery of Art, City of Monash Collection donated by the Estate of David Moore 2006

Courtesy of the Estate of David Moore (Sydney)

Wesley Stacey (Australia, b. 1941)

Willie near Mallacoota

1979

From the series Koorie set

Gelatin silver print

Monash Gallery of Art, City of Monash Collection

Donated through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program by Christine Godden 2011

Published under fair use for the purpose of art criticism

David Moore (Australia, 1927-2003)

Newcastle steelworks

1963

Gelatin silver print

Monash Gallery of Art, City of Monash Collection

Acquired 1981

Published under fair use for the purpose of art criticism

One of those preoccupations is an interest in the photograph as an object, in the physical presence of the print or whatever kind of technology is being used to make it. Part of the reason for that is that photography, more than any other medium, suffers from a mistake or misunderstanding people have when they’ve seen a reproduction in a magazine or online: they think they’re seeing the original. A certain amount of photography is made with its ultimate intention being to be seen in a magazine or online, but most photography, historically, ended up in its final form as a print – a cyanotype, or a tin type or a daguerreotype or whatever it might be.”

Interview with Bill Henson by Toby Fehily posted 01 Feb 2014 on the Art Guide Australia website [Online] Cited 18/02/2014. Used under fair use for the purpose of art criticism. No longer available online.

Leonie Reisberg (Australia, b. 1955)

Portrait of Peggy Silinski, Tasmania

c. 1976

Gelatin silver print

Monash Gallery of Art, City of Monash Collection

Donated by Janice Hinderaker through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program 2003

Beverley Veasey (Australia, b. 1968)

Study of a Calf, Bos taurus

2006

Chromogenic print

Monash Gallery of Art, City of Monash Collection

Acquired 2006

I think when you look through any collection, you’re often struck by the kind of pointlessness and banality of photography. It doesn’t matter which museum in the world you look at. It’s like, “is there any need for this thing to exist at all?”. It probably comes back to the capacity of the object, the image to suggest things, the suggestive potential rather than the prescriptive, which is a given in photography of course, the evidential authority of the medium preceding any individual reading we have of particular pictures. Maybe it’s the fact that the photographs have the ability to suggest some other thing and that’s what draws you in – that’s that feeling, the thing that slips away from thought. These are really the same things that apply to our meetings with any work of art, whether it’s a piece of music or a sculpture or anything else. There’s something compelling, there’s something there that sort of animates your speculative capacity, causes you to wonder. Other times, or most of the time, that’s not the case. Certainly most of the time that’s not the case with photography.

Interview with Bill Henson by Toby Fehily posted 01 Feb 2014 on the Art Guide Australia website [Online] Cited 18/02/2014. Used under fair use for the purpose of art criticism. No longer available online.

Axel Poigant (born United Kingdom 1906; arrived Australia 1926; died 1986)

Jack and his family on the Canning Stock Route

1942

Gelatin silver print, printed 1986

Monash Gallery of Art, City of Monash Collection

Acquired 1991

Tim Johson (Australia, b. 1947)

Light performances

1971-1972

Gelatin silver print

Monash Gallery of Art, City of Monash Collection

Acquired 2011

Cherine Fahd (Australia, b. 1974)

Alicia

2003

From the series A woman runs

Gelatin silver print

Monash Gallery of Art, City of Monash Collection

Donated through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program 2011

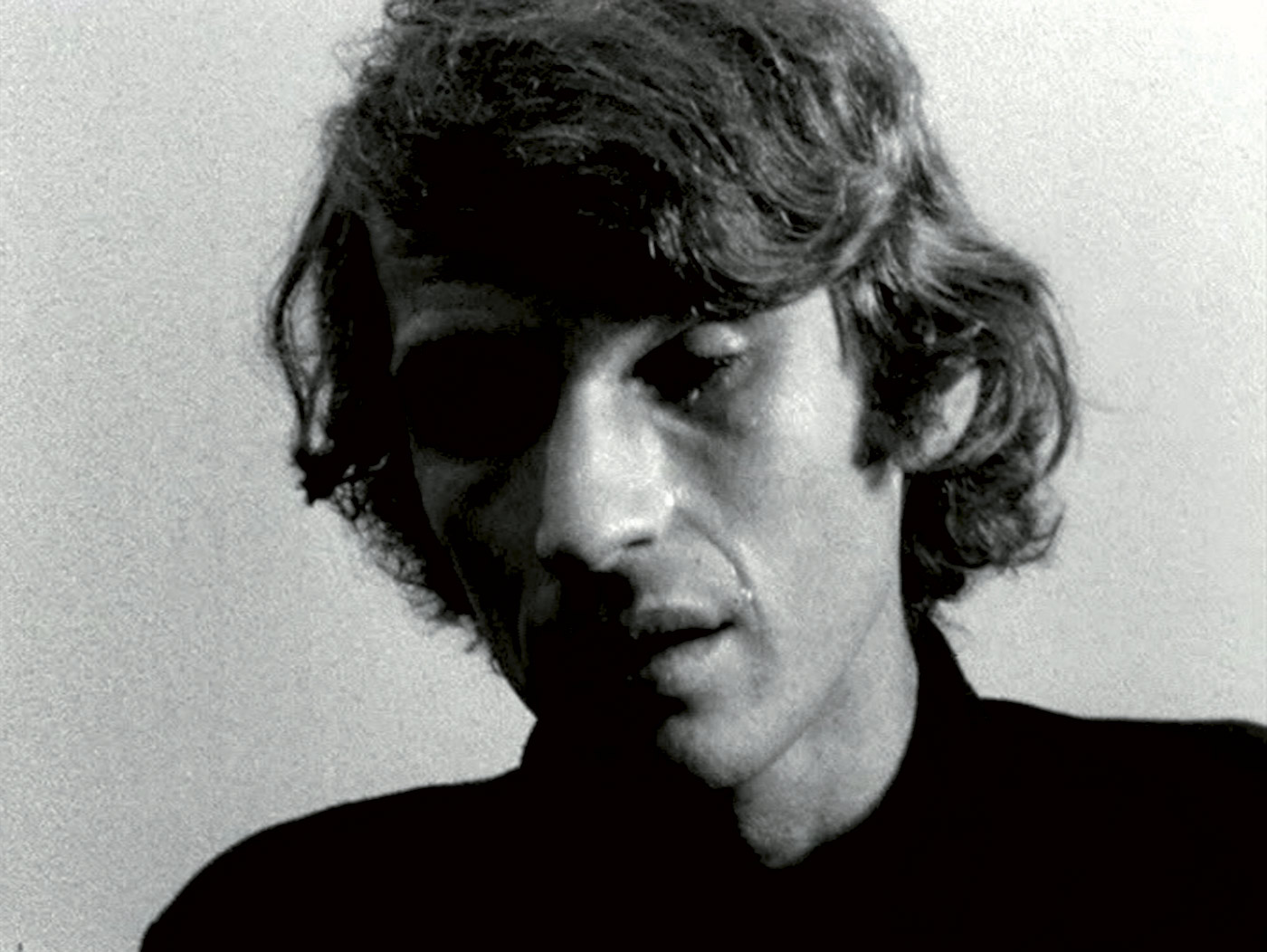

Wesley Stacey (Australia, b. 1941)

Untitled

1973

From the series Friends

Gelatin silver print

Monash Gallery of Art, City of Monash Collection

Donated by Bill Bowness 2013

That was one of the things that interested me and continues to interest me about photography: how these things inhabit the world as objects. And indeed we read them not just with our eyes but with how our whole bodies read and encounter and negotiate these objects, which happen to be photographs. And that’s very much a thing that interests me in the way that I work. I feel sometimes that I only happen to make photographs myself and that it’s a means to an end… So there’s a sense in which I’m interested in these objects that happen to be photographs and the way that they inhabit the same space that our bodies inhabit. Everything comes to you through your whole body, not just through your eyes and ears – it’s a vast amount of information. Watching something get bigger as you draw closer to it, not just matters of proximity, but texture or the way objects sit in a space when they’re lit a certain way – all of this is very interesting to me, always has been.”

Interview with Bill Henson by Toby Fehily posted 01 Feb 2014 on the Art Guide Australia website [Online] Cited 18/02/2014. Used under fair use for the purpose of art criticism. No longer available online.

Mark Hinderaker (born United States of America 1946; arrived Australia 1970; died 2004)

Fiona Hall

1984

Gelatin silver print

Monash Gallery of Art, City of Monash Collection

Donated by Janice Hinderaker through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program 2003

Lionel Lindsay (Australia 1874-1961)

Norman Lindsay and Rose Soady, Bond Street studio

c. 1909

Gelatin silver print, printed 2000

Monash Gallery of Art, City of Monash Collection

Donated by Katherine Littlewood 2000

Mark Strizic (born Germany 1928; arrived Australia 1950; died 2012)

BHP steel mill, Port Kembla, 1959

1959

Gelatin silver print, printed 1999

Monash Gallery of Art, City of Monash Collection

Donated by the Bowness Family through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program 2008

Monash Gallery of Art

860 Ferntree Gully Road, Wheelers Hill

Victoria 3150 Australia

Phone: + 61 3 8544 0500

Opening hours:

Tue – Fri: 10am – 5pm

Sat – Sun: 10pm – 4pm

Mon/public holidays: closed

![Barbara Creed (Australian, b. 1943) 'Untitled [Gay Liberation Front banner]' Melbourne, 1973 Barbara Creed (Australian, b. 1943) 'Stills from a Super 8mm film of a Women’s Liberation march' Melbourne, 1973](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/barbara-creed-gay-liberation-front-1973.jpg)

![Barbara Creed (Australian, b. 1943) 'Untitled [Gay Lib Woman]' Melbourne, 1973 Barbara Creed (Australian, b. 1943) 'Stills from a Super 8mm film of a Women’s Liberation march' Melbourne, 1973](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/barbara-creed-gay-lib-woman-1973.jpg)

![Claudia Terstappen (Australian born Germany, b. 1959) 'Namandi spirit [Queensland, Australia]' 2002 Claudia Terstappen (Australian born Germany, b. 1959) 'Namandi spirit [Queensland, Australia]' 2002](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/tersappen_namandi_spirit_web.jpg?w=650&h=650)

![Claudia Terstappen (Australian born Germany, b. 1959) 'Full moon [France]' 1997 Claudia Terstappen (Australian born Germany, b. 1959) 'Full moon [France]' 1997](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/terstappen_fullmoon_france_web.jpg?w=650&h=650)

![Claudia Terstappen (Australian born Germany, b. 1959) 'Mountain [Brazil]' 1991 Claudia Terstappen (Australian born Germany, b. 1959) 'Mountain [Brazil]' 1991](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/terstappen_mountain_brazil_web.jpg?w=650&h=650)

![Claudia Terstappen (Australian born Germany, b. 1959) 'Mountain [Las Palmas, Spain]' 1992 Claudia Terstappen (Australian born Germany, b. 1959) 'Mountain [Las Palmas, Spain]' 1992](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/terstappen_portugal_web.jpg?w=650&h=650)

You must be logged in to post a comment.