Exhibition dates: Tuesday 22nd July – Saturday 26th July, 2014

Opening: Tuesday 22nd July 6-8pm

Nite Art: Wednesday 23rd July until 11pm

Artists represented: Philip Potter, John Storey, John Englart, Barbara Creed, Ponch Hawkes, Rennie Ellis

Curators: Dr Marcus Bunyan and Nicholas Henderson

Catalogue essay by Professor Dennis Altman (below)

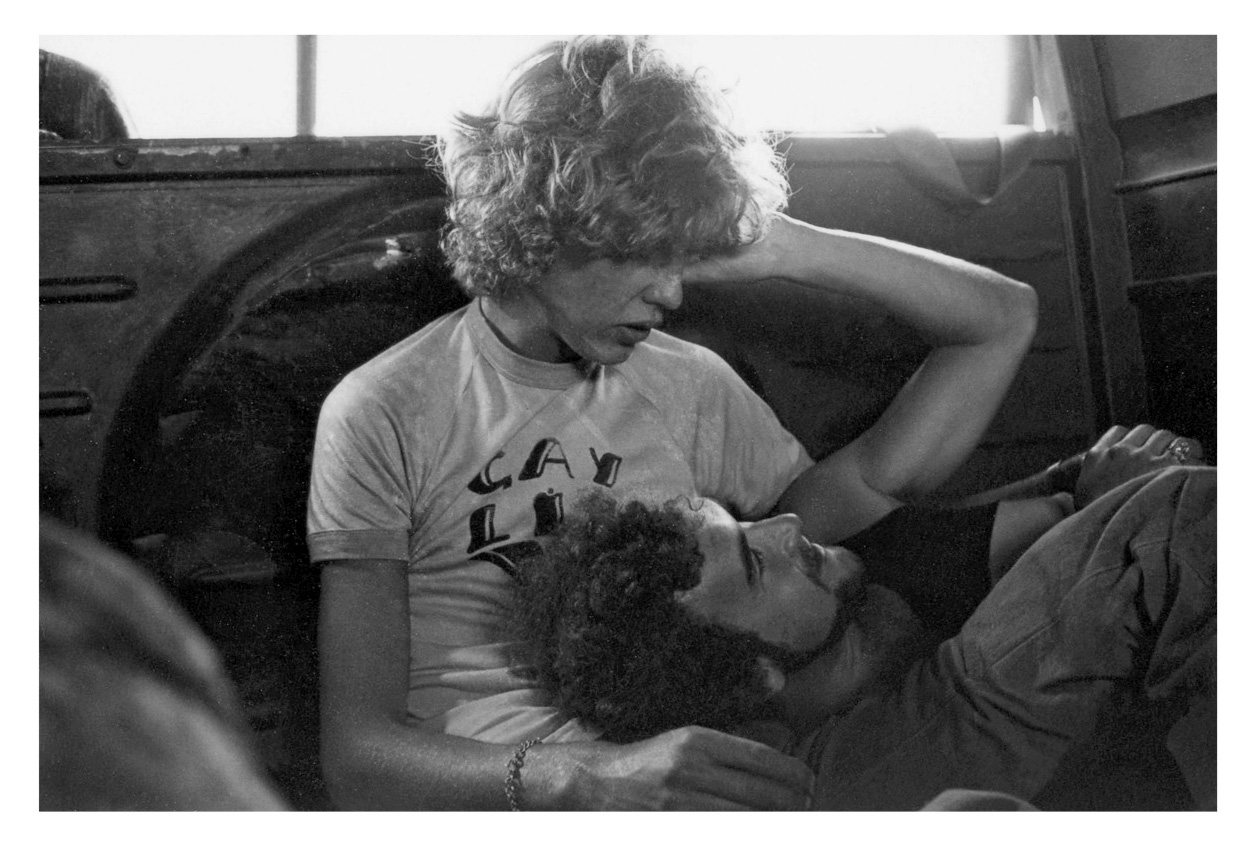

Barbara Creed (Australian, b. 1943)

Julian Desaily and Peter McEwan in the back of a VW Combi van, Melbourne

Melbourne, c. 1971-1973

Digital C type print on Kodak Endura Matte

© Barbara Creed

Five days, that’s all you’ve got! Just five days to see this fabulous exhibition. COME ALONG TO THE OPENING (Tuesday 22nd July 6-8pm) or NITE ART, the following night!

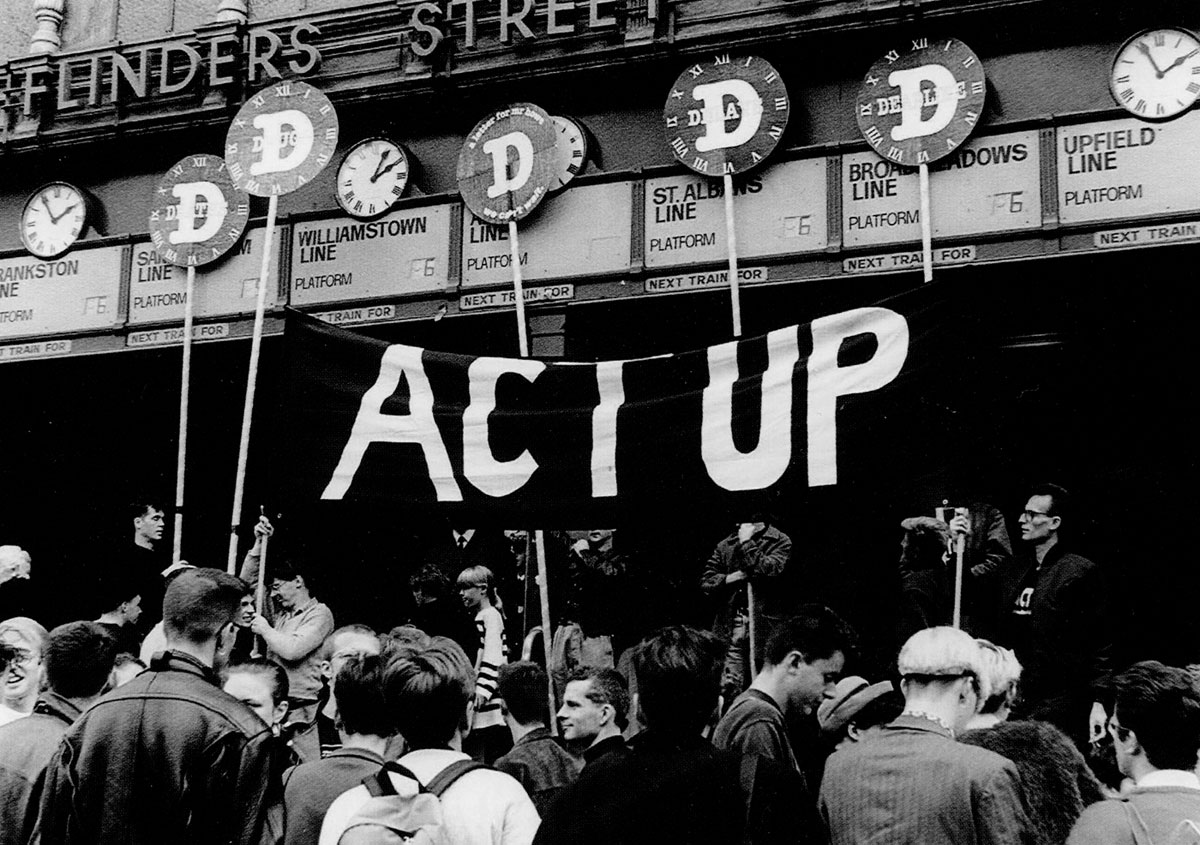

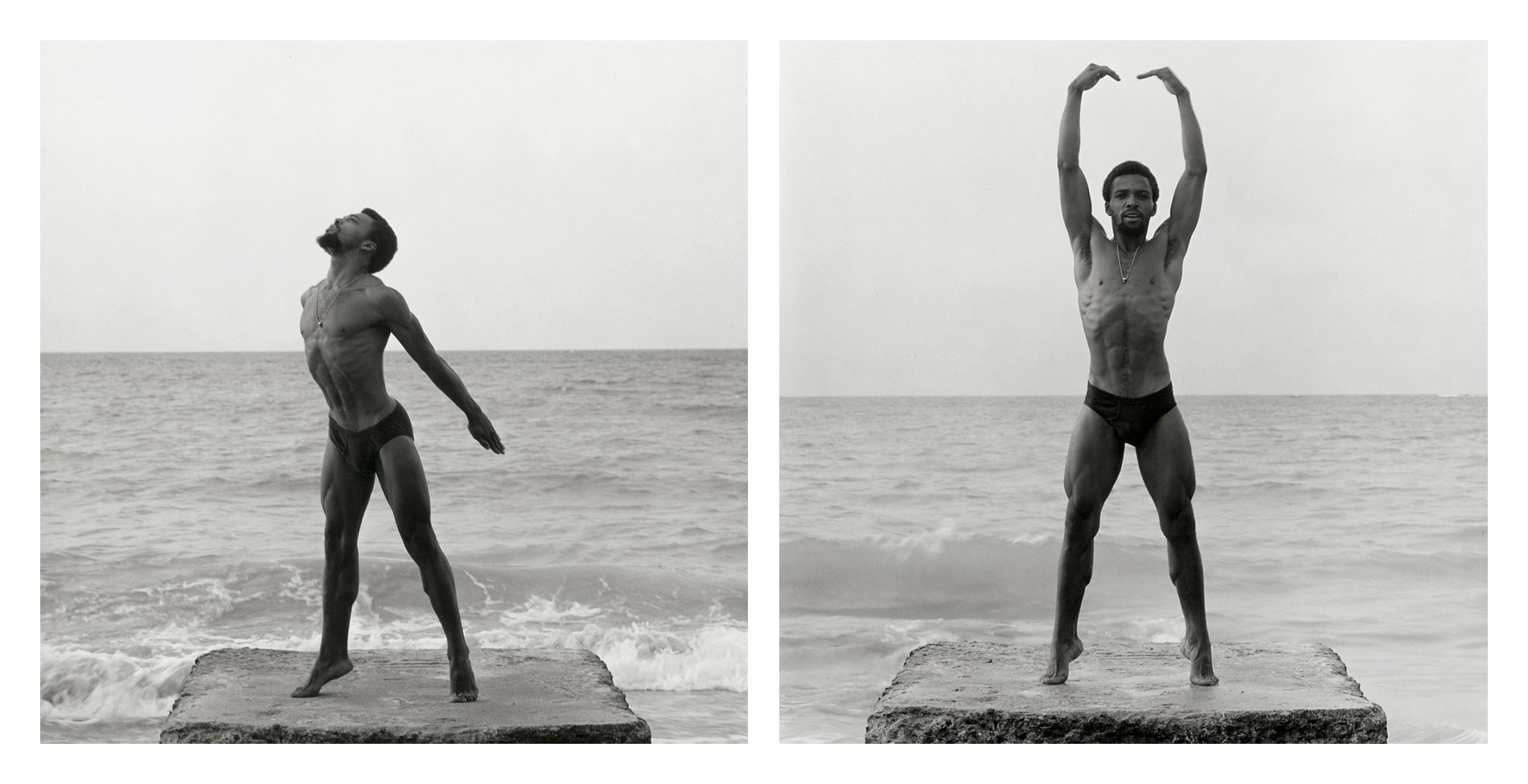

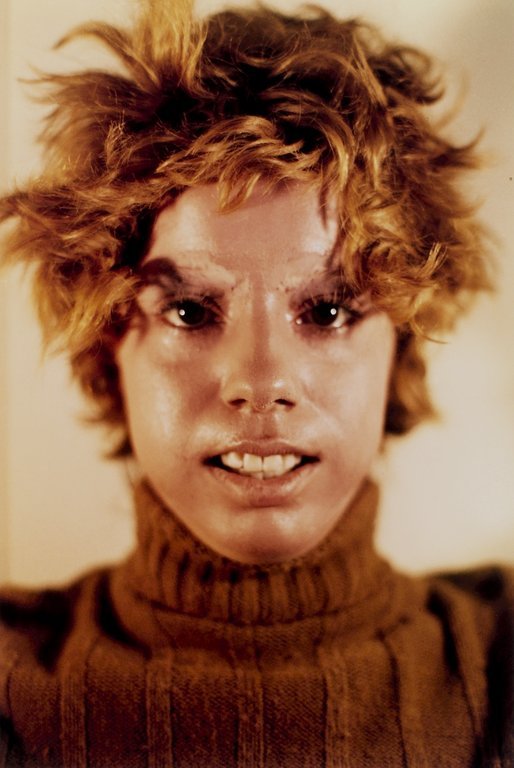

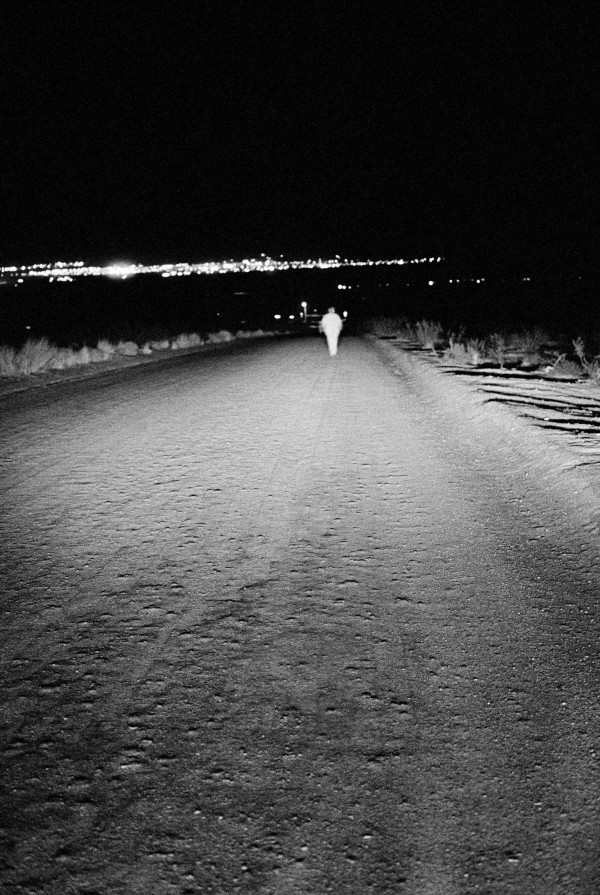

The exhibition Out of the closets, into the streets: gay liberation photography 1971-73 pictures the very beginning of the gay liberation movement in Australia through the work of Philip Potter, John Storey, John Englart, Barbara Creed, Ponch Hawkes and Rennie Ellis. The exhibition examines for the first time images from the period as works of art as much as social documents. The title of the exhibition is a slogan from the period.

As gay people found their voice in the early 1970s artists, often at the very beginning of their careers, were there to capture meetings in lounge rooms, consciousness raising groups and street protests. The liberation movement meant ‘being there’, putting your body on the line. “It was a key feature of the new left that this embodied politics couldn’t stop in the streets: that is, the public arena as conventionally understood. ‘Being there’ politically also applied to households, classrooms, sexual relations, workplaces and the natural environment.”1

Curated by Dr Marcus Bunyan and Nicholas Henderson and with a catalogue essay by Professor Dennis Altman (see below), the show is a stimulating experience for those who want to be inspired by the history and art of the early gay liberation movement in Australia.

The exhibition coincides with AIDS 2014: 20th International AIDS Conference (20-25 July 2014) and Nite Art which occurs on the Wednesday night (23rd July 2014). The exhibition will travel to Sydney to coincide with the 14th Australia’s Homosexual Histories Conference in November at a venue yet to be confirmed.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Connell, Raewyn. “Ours is in colour: the new left of the 1960s,” in Carolyn D’Cruz and Mark Pendleton (eds.,). After Homosexual: The Legacies of Gay Liberation. Perth: UWA Publishing, 2013, p. 43.

Many thankx to all the artists for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

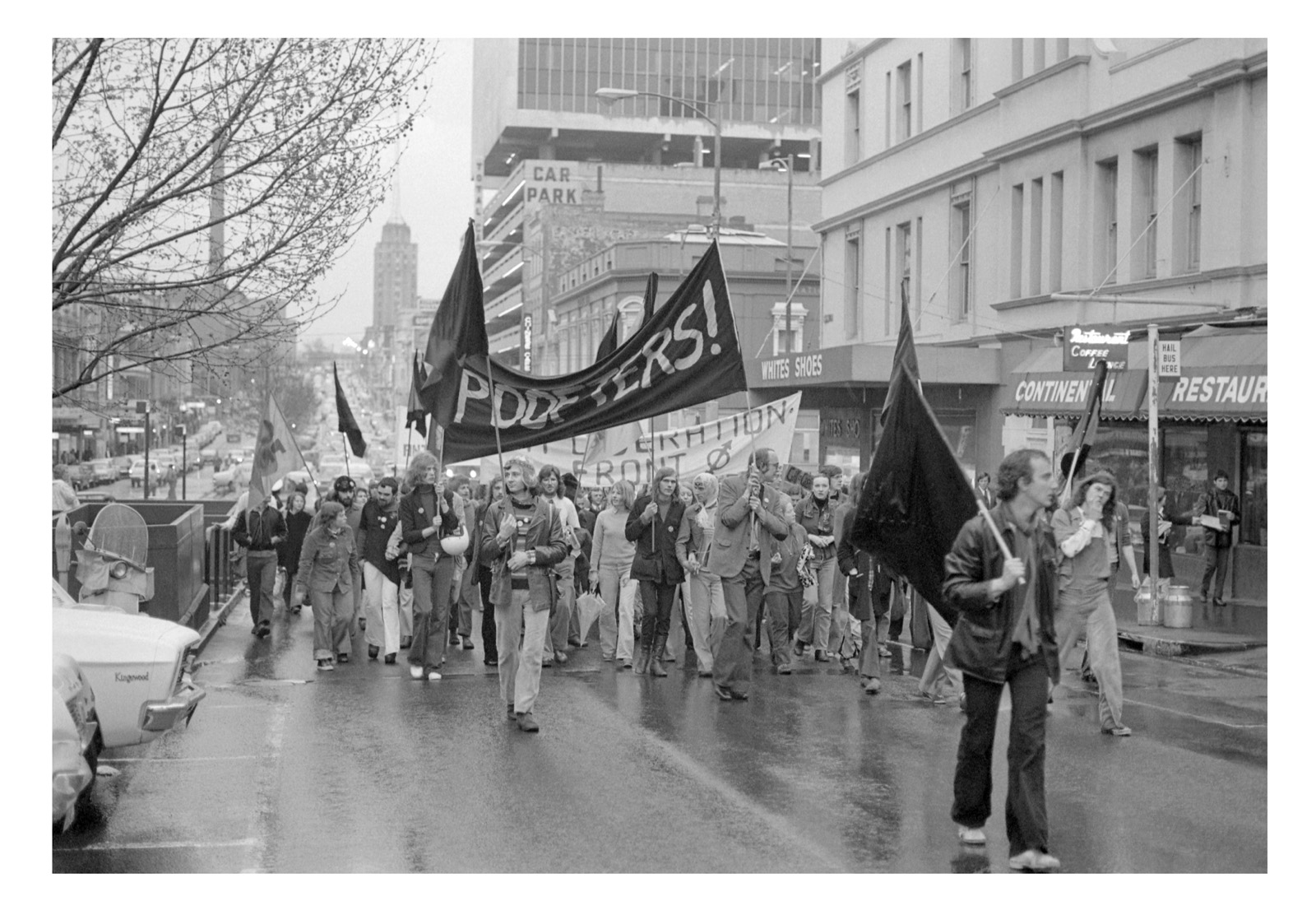

Ponch Hawkes (Australian, b. 1946)

Gay Liberation march, Russell Street, Melbourne

Melbourne, 1973

Digital C type print on Kodak Endura Matte

© Ponch Hawkes

John Englart (Australian, b. 1955)

Gay Pride Week poster, outside the Town Hall Hotel, Sydney Town Hall

Sydney, 1973

Digital C type print on Kodak Endura Matte

© John Englart

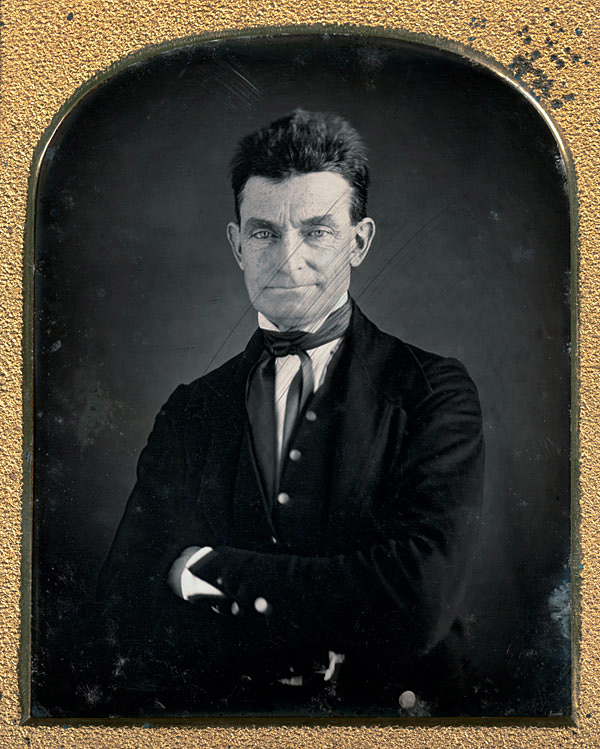

Out of the closets, onto the streets

Professor Dennis Altman

This exhibition chronicles a very specific time in several Australian cities, the period when lesbians and gay men first started demonstrating publicly in a demand to be accorded the basic rights of recognition and citizenship. Forty years ago to be homosexual was almost invariably to lead a double life; the great achievement of gay liberation was that a generation – although only a tiny proportion of us were ever Gay Liberationists – discovered that was no longer necessary.

The Archives have collected an extraordinary range of materials illustrating the richness of earlier lesbian and gay life in Australia, but this does not deny the reality that most people regarded homosexuality as an illness, a perversion, or a sin, and one for which people should be either punished or cured. It is revealing to read the first avowedly gay Australian novel, Neville Jackson’s No End to the Way [published in 1965 – in Britain – and under a pseudonym] to be reminded of how much has changed in the past half century.

Gay Liberation had both local and imported roots; the Stonewall riots in New York City, which sparked off a new phase of radical gay politics – when ‘gay’ was a term understood to embrace women, men and possibly transgender – took place in June 1969. They were barely noticed at the time in Australia, where a few people in the civil liberties world, most of them not homosexual, had started discussing the need to repeal anti-sodomy laws.

Small law reform and lesbian groups had already existed, but the real foundation of an Australian gay movement came in September 1970 when Christabel Pol and John Ware announced publicly the formation of CAMP, an acronym that stood for the Campaign Against Moral Persecution but also picked up on the most used Australian term for ‘homosexual’. Within two years there were both CAMP branches in most Australian capital cities, as well as small gay liberation groups that organised most of the demonstrations illustrated in this exhibition.

The differences between gay liberation and CAMP were in practice small, but those of us in Gay Liberation prided ourselves on our radical critique, and our commitment to radical social change. CAMP, with its rather daggy social events and its stress on law reform – at a time in history when homosexual conduct between men was illegal across the country – seemed to us too bourgeois, though ironically it was CAMP which organised the first open gay political protest in Australia [immediately identified by the balloons in the Exhibition photos].

It is now a cliché to say “the sixties” came to Australia in the early 1970s, but a number of forces came together in the few years between the federal election of 1969, when Gough Whitlam positioned the Labor Party as a serious contender for power, and 1972, the “It’s Time” election, when the ALP took office for the first time in 23 years. We cannot understand how a gay movement developed in Australia without understanding the larger social and cultural changes of the time, which saw fundamental shifts in the nature of Australian society and politics.

The decision of the Menzies government in 1965 to commit Australian troops to the long, and ultimately futile war in Vietnam, led to the emergence of a large anti-war movement, capable of mobilising several hundred thousand people to demonstrate by the end of the decade. Already under the last few years of Liberal government the traditional White Australia Policy was beginning to crumble, as it became increasingly indefensible, and awareness of the brutal realities of dispossession and discrimination against indigenous Australians was developing. Perhaps most significant for a movement based on sexuality, the second wave feminist movement, already active in the United States and Britain, began challenging the deeply entrenched sexist structures of society.

To quote myself, this at least reduces charges of plagiarism: “Anyone over fifty in Australia has lived through extraordinary changes in how we imagine the basic rules of sex and gender. We remember the first time we saw women bank tellers, heard a woman’s voice announce that she was our pilot for a flight, watched the first woman read the news on television. Women are now a majority of the paid workforce; in 1966 they made up twenty-nine per cent. When I was growing up in Hobart it was vaguely shocking to hear of an unmarried heterosexual couple living together and women in hats and gloves rode in the back of the trams (now long since disappeared). As I look back, it seems to me that some of the unmarried female teachers at my school were almost certainly lesbians, although even they would have been shocked had the word been uttered.”

In Australia Germaine Greer’s book The Female Eunuch became a major best seller, and Germaine appeared [together with Liz Fell, Gillian Leahy and myself] at the initial Gay Liberation forum at Sydney University in early 1972; looking back it is ironic that a woman who has been somewhat ambivalent in her attitudes to homosexuality was part of the public establishment of the gay movement.

But the early demonstrations illustrated in this exhibition did often include sympathetic “straights” – a term that seems to have disappeared from the language – for whom gay liberation was part of a wider set of cultural issues. It is essential to recognise that while political demonstrations may seem to assert certain claims they play widely different roles for those who participate. For some of us a public protest is a form of “coming out”; indeed many people had never been public about their sexuality before they attended their first demonstration. For others a demonstration is primarily a place to find solidarity, friendship, and, if lucky, sex.

For the gay movement more than any other just to declare oneself as gay was to take an enormous step, a step that some found remarkably easy while others had to wait until late in life to discover that actually almost everyone knew anyway. I remember the now dead Sydney playwright, Nick Enright, who was one of the first people to be open about his homosexuality, and was so without any sense of difficulty; at the same time there are still people who go to great lengths to hide their sexuality even while acknowledging they would face little risk of discrimination were they not to do so

Maybe there is a parallel for people who now declare their lost Aboriginal heritage, unsure how they will be regarded but aware that this is crucial to their sense of self. Every generation has its own version of coming out stories, this exhibition hones in on that time in our national history when everything seemed in flux, and gay liberation seemed a small part of creating a brave new world in which old hierarchies and restraints would disappear.

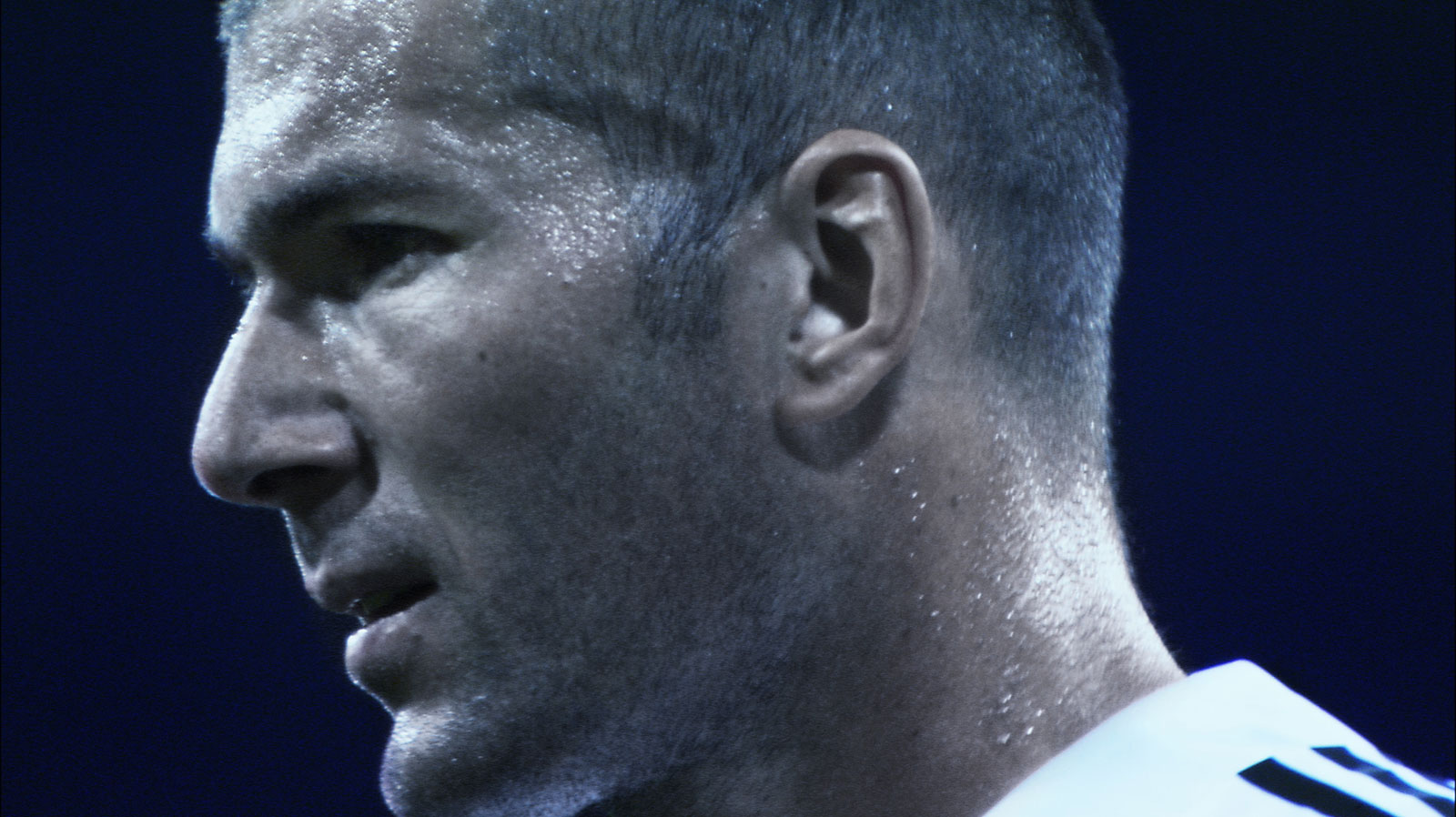

Looking back at the photos creates a certain nostalgia – we all look so young, so sure that we were changing the world, though in reality most of us were putting on a brave front. The oddest thing is that in some ways we did change the world. Forty years ago we looked at the police as threatening, symbolised in the photograph from Melbourne Gay Pride 1973 where the policeman is clearly telling people to move on. Today openly lesbian and gay cops march with us in the streets, and the very idea that homosexuality could be criminalised, as it still is in many parts of the world, has largely disappeared from historical memory. Indeed to many people attending this exhibition that may be the first time they confront the reality that being gay in Australia in the early 1970s was to live in a world of silence, evasion and fear.

Professor Dennis Altman

July 2014

© Dennis Altman

Reproduced with permission

Anonymous photographer

I am a Lesbian, Gay Pride Week

Adelaide, 1973

Digital C type print on Kodak Endura Matte

© Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives

Anonymous photographer

Man in black hat and red shirt, Gay Pride Week

Adelaide, 1973

Digital C type print on Kodak Endura Matte

© Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives

Sponsored by

For photographic services in Australia, Art Blart highly recommends CPL Digital (03) 8376 8376 cpldigital.com.au |

Dr Marcus Bunyan and the best photography archive sponsor this event artblart.com |

The Archives actively collects and preserves lesbian and gay material from across Australia queerarchives.org.au/ |

Supported by

Rennie Ellis is an award winning photographer and writer (03) 9525 3862 www.rennieellis.com.au |

AIDS 2014: 20th International AIDS Conference

20 July – 25 July 2014

Melbourne, Australia

Edmund Pearce Gallery

This gallery has now closed.

![Ana Mendieta (Cuban-American, 1948-1985) 'Itiba Cahubaba (Esculturas Rupestres)' [Old Mother Blood (Rupestrian Sculptures)] 1982 Ana Mendieta (Cuban-American, 1948-1985) 'Itiba Cahubaba (Esculturas Rupestres)' [Old Mother Blood (Rupestrian Sculptures)] 1982](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/ana-mendieta_itiba-cuhababa-web.jpg?w=650&h=878)

You must be logged in to post a comment.