Exhibition dates: 8th April – 2nd May, 2009

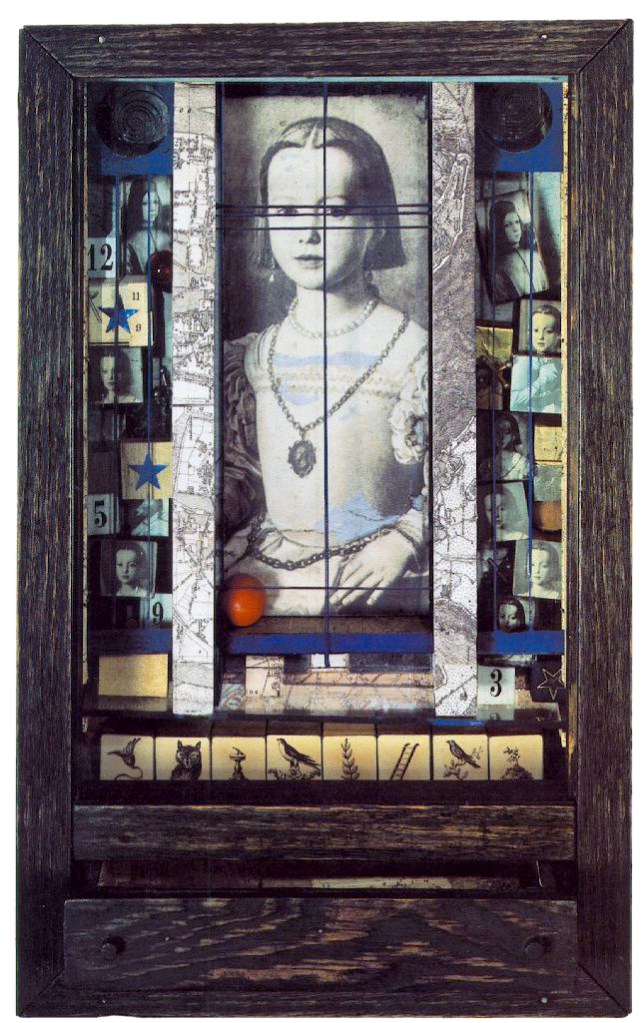

Mark Strizic (Australian, 1908-2012)

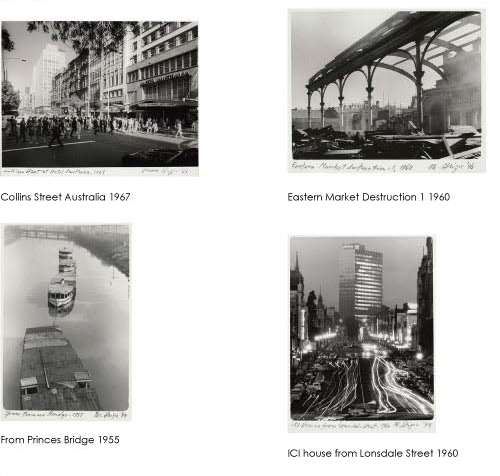

Eastern Market Destruction – 1

1960, printed 1996

Silver gelatin photograph

19 x 22.5cm

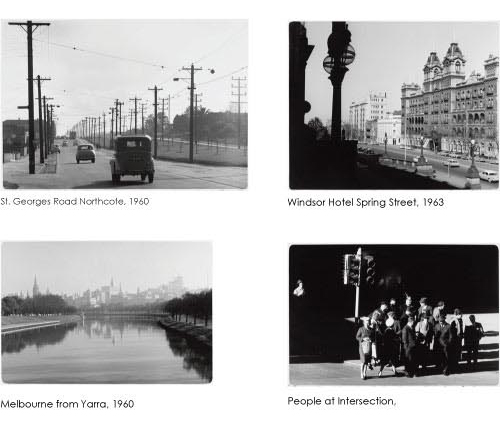

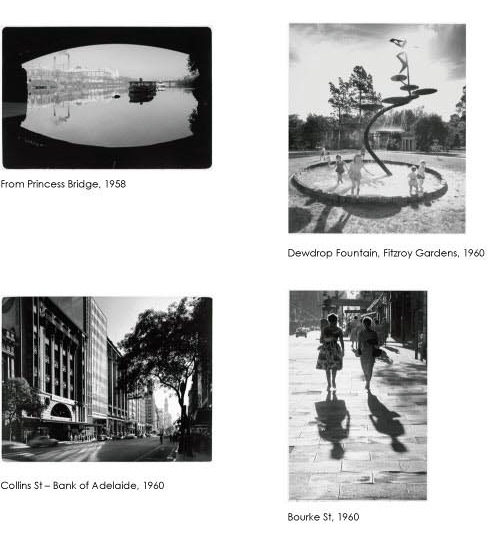

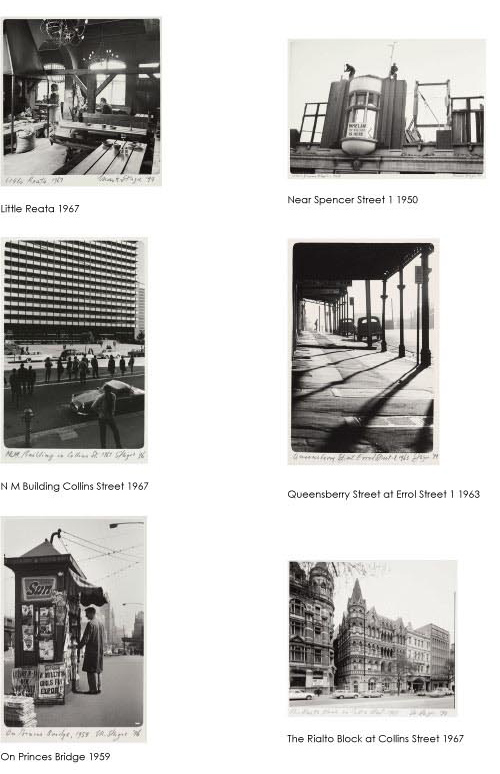

Social Fact and Urban Vision

This is an exhibition by the veteran Australian photographer Mark Strizic that plays like the coda at the end of a piece of music, the pensive full stop at the end of a well read book. There are some stunning highlight photographs among the 139 black and white silver gelatin prints on display, some good photographs and some fairly mundane images and prints. With some judicious editing of the photographs (perhaps by a third), the exhibition could have had a stronger artistic aesthetic and carried the voice of the photographer with greater projection. As it is the exhibition will be popular drawing in the crowds because of the photographs subject matter and their appeal to both an individual and collective nostalgia.

Examining Strizic’s photographs we note a traditional structure to the picture plane. Unlike the photographs of Eugene Atget who photographed Paris in the early 20th century there is little sublime spatial representation in Strizics photographs, that different angle of alignment that Atget achieved with the positioning of his camera. Further, we observe that unlike an immigrant to another country at around the same time, Robert Frank and America, the photographs follow traditional format: none of the revolutionary experimentation in handheld, grainy images of jukeboxes, cut up people or images of flags appear in this work. We can also say that unlike Helen Levitt’s early black and white images of New York from around the same period there is little ‘joie de vivre’, little engagement with the actual nitty gritty stuff of living in Strizic’s work. The quote below articulates what Strizic’s photographs both address and dismiss:

“To walk in the city is to experience the disjuncture of partial vision/partial consciousness. The narrativity of this walking is belied by a simultaneity we know and yet cannot experience. As we turn a corner, our object disappears around the next corner. The sides of the street conspire against us; each attention suppresses a field of possibilities. The discourse of the city is a syncretic discourse, political in its untranslatability. Hence the language of the state elides. Unable to speak all the city’s languages, unable to speak all at once, the state’s language become monumental, the silence of headquarters, the silence of the bank. In this transcendent and anonymous silence is the miming of corporate relations. Between the night workers and the day workers lies the interface of light; in the rotating shift, the disembodiment of lived time. The walkers of the city travel at different speeds, their steps like handwriting of a personal mobility. In the milling of the crowd is the choking of class relations, the interruption of speed, and the machine. Hence the barbarism of police on horses, the sudden terror of the risen animal.”1

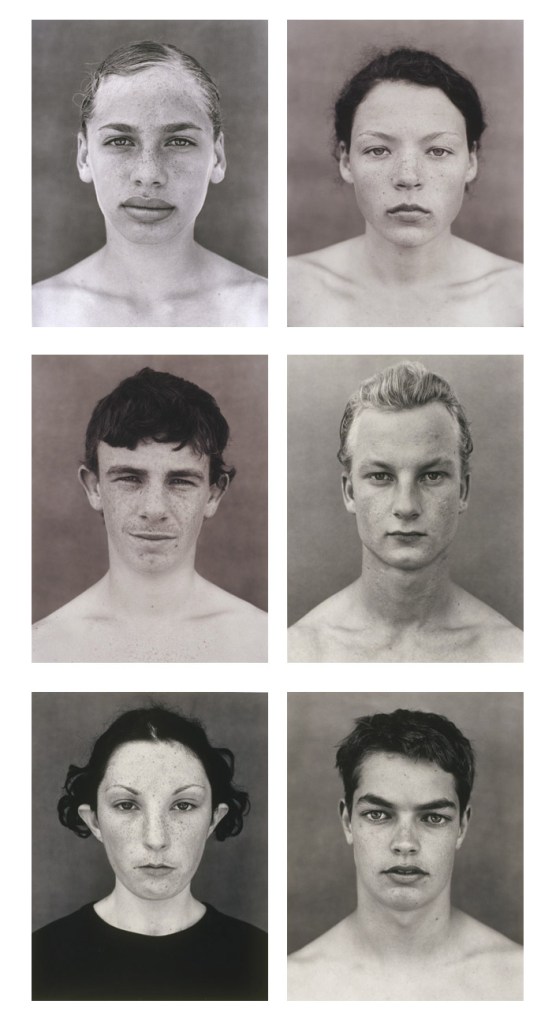

We observe in the photographs an emphasis on surfaces, on a supreme understanding of light and shade coupled with a certain distance and emotional remoteness from the frenetic hubbub of city life. Empty streets and isolated people fall into shadow and their is little evidence of ‘play’ in the photographs. This is observation not interaction or integration as an immigrant observing Melbourne life. There is no up front presence of disembodied people as in Robert Franks photographs in The Americans. Here the alienation that pervades the photographs is the alienation of the photographer from the people as much as it is the alienation of the people from themselves. People are shot in silhouette against the sun or shop windows or peering in at unobtainable goods; desolate streets and working class suburbs all express the isolation of city life but at a structured distance from them.

When Strizic’s photographs are good they are very good. His understanding of light is magnificent: light reflects off water, hazes and shimmers off city buildings. The mixing of shadows and sun and his use of the technique of ‘contre jour’ (shooting into the sun) the one thing Strizic does against traditional conventions works to good effect in some of the best photographs. His 1968 night time long exposure photograph of the old Gas and Fuel Building is rewarding for the black bulk of the end of the building looming over Flinders Street and the striations of car headlamps. The photograph Flinders Lane (1967, below) shows a delicate use of depth of field where the foreground of cars and person are out of focus, the light bouncing off the edges of the woman, the focus of the image in the far distance. The photograph McPhersons Building (1958, below) is one of my personal favourites in the exhibition and is a stunning photograph for the atmosphere the photographer has captured.

After a while the use of the ‘contre jour’ technique becomes tiresome. Other photographs simply document a city in transition. These photographs appeal both to an individual nostalgia (‘I used to work in that building’; ‘My grandmother used to live in that street’) and a collective nostalgia where people experience things collectively, “in the sense that [collective] nostalgia occurs when we are with others who shared the event(s) being recalled, and also in the sense that one’s nostalgia is often for the collective – the characteristics and activities of a group or institution in which the individual was a participant.”2

Collective nostalgia refers to that condition in which the symbolic objects are of a highly public, widely shared and familiar character, i.e. those symbolic resources from the past which can under proper conditions trigger off wave upon wave of nostalgic feeling in millions of persons at the same time3 and in this exhibition it is the photographs of a city in transition that trigger this nostalgia, a city now lost to the mists of time. Through these photographs we remember what Melbourne was like at this time collectively.

As Harper has observed

“Nostalgia combines bitterness and sweetness, the lost and the found, the far and near, the new and the familiar, absence and presence. The past which is over and gone, from which we have been or are being removed, by some magic becomes present again for a short while. But its realness seems even more familiar, because renewed, than it ever was, more enchanting and more lovely …”4

Does this collective nostalgia make the photographs good? This is a pertinent question.

Today, nostalgia has become a cultural phenomenon one centred on a longing for home (home is where you are happy to be!) in a collective sense and promoted through commercialisation and the realisation that nostalgia sells. The use of the value seeking word ‘rare’ in the exhibition title is instructive in this regard. Only about 25% of the photographs in this exhibition are “vintage” prints, in other words photographs printed within 3 years of the negative being taken. All other photographs have been printed within the last 15 years. Some are ‘Unique state’ gelatin photographs while others are not. What does this mean. Are they are unique state only in this size? What about the common or garden silver gelatin prints in the show? What does the status word “rare” imply for them?

I remember seeing an exhibition of the photographs of Henri Cartier-Bresson in Scotland about ten years ago. Three rooms had large prints of his work. One room just had vintage prints. The contrast was astounding. The room full of vintage prints had an intensity of vision, of his vision at the time he took the photographs evidenced in small jewel like photographs that the three other rooms photographs simply did not possess – through scale, printing and aesthetics. The same question, without any need for an answer, can be posed here. Only the word ‘rare’ demands that answer for the modern prints are just what they are and nothing more.

In conclusion this is a strong show by Strizic that could have been edited and focused in a more rewarding way. Strizic is one of Australia’s best photographers for understanding the significance of place. His use of light is superb but there always seems to be an emotional distance to his photographs. An element of collective nostalgia adds to their documentary appeal but the best photographs do not just record, they challenge and transcend the subject matter taking the work to an altogether different plane of existence.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Stewart, Susan. On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection. Durham: Duke University Press, 1993, p. 2. Prologue

2/ Wilson, Janelle. “”Remember when …” a consideration of the concept of nostalgia,” in et Cetera. Concord: Fall 1999. Vol. 56, Iss. 3; pg. 296, 9 pgs

3/ Davis, F. Yearning For Yesterday: A Sociology of Nostalgia. New York: The Free Press, 1979, p. 222

4/ Harper, R. Nostalgia: An Existential Exploration of Longing and Fulfilment in the Modern Age. The Press of Western Reserve University, 1966, p. 120 quoted in Wilson, Janelle. “”Remember when …” a consideration of the concept of nostalgia,” in et Cetera. Concord: Fall 1999. Vol. 56, Iss. 3; pg. 296, 9 pgs

Many thankx to Gallery 101 for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on some of the photographs for a larger version of the image.

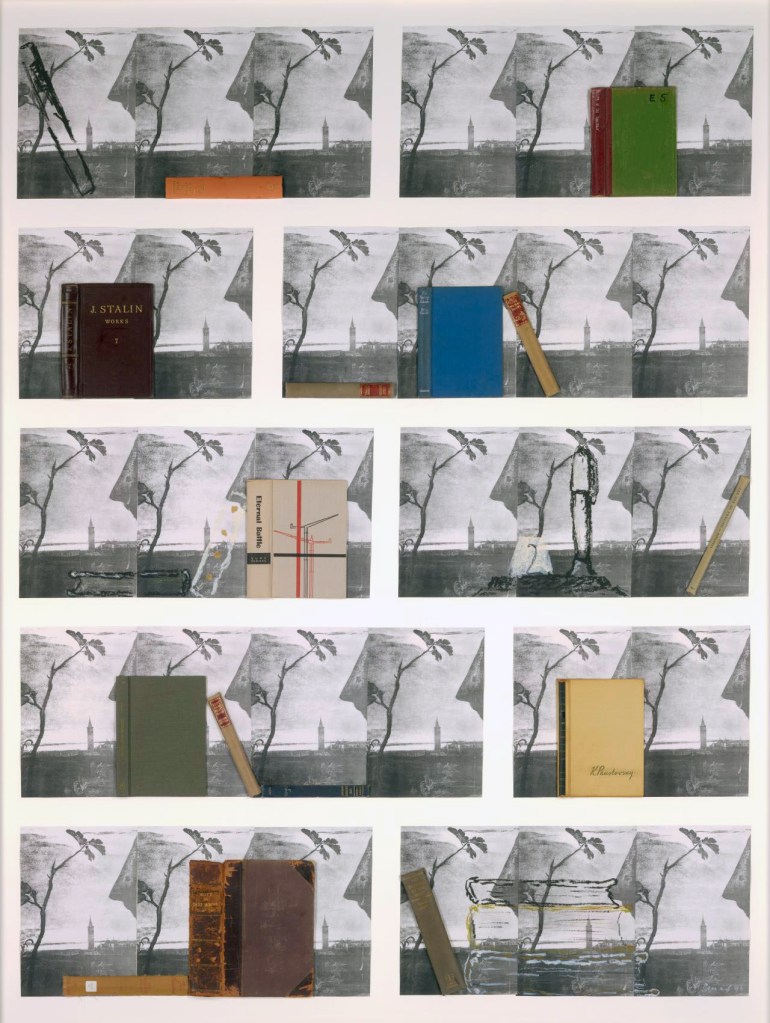

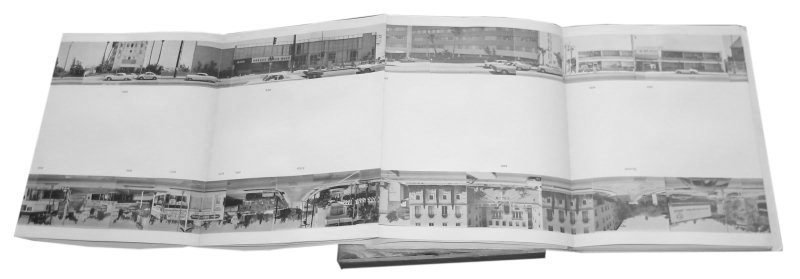

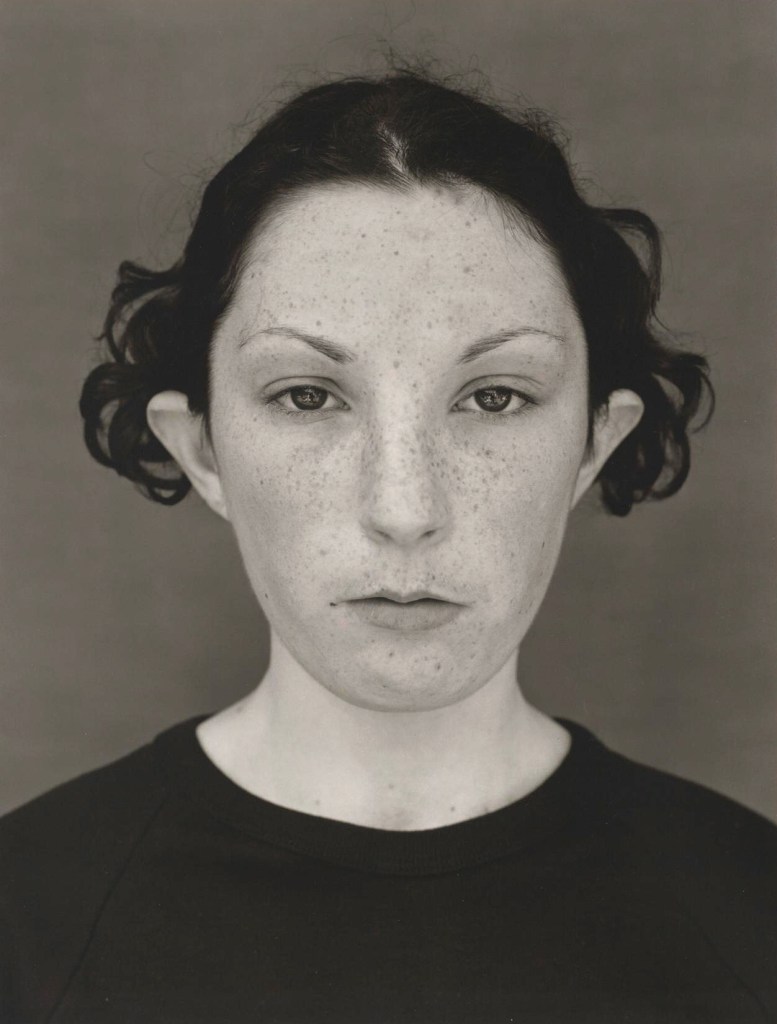

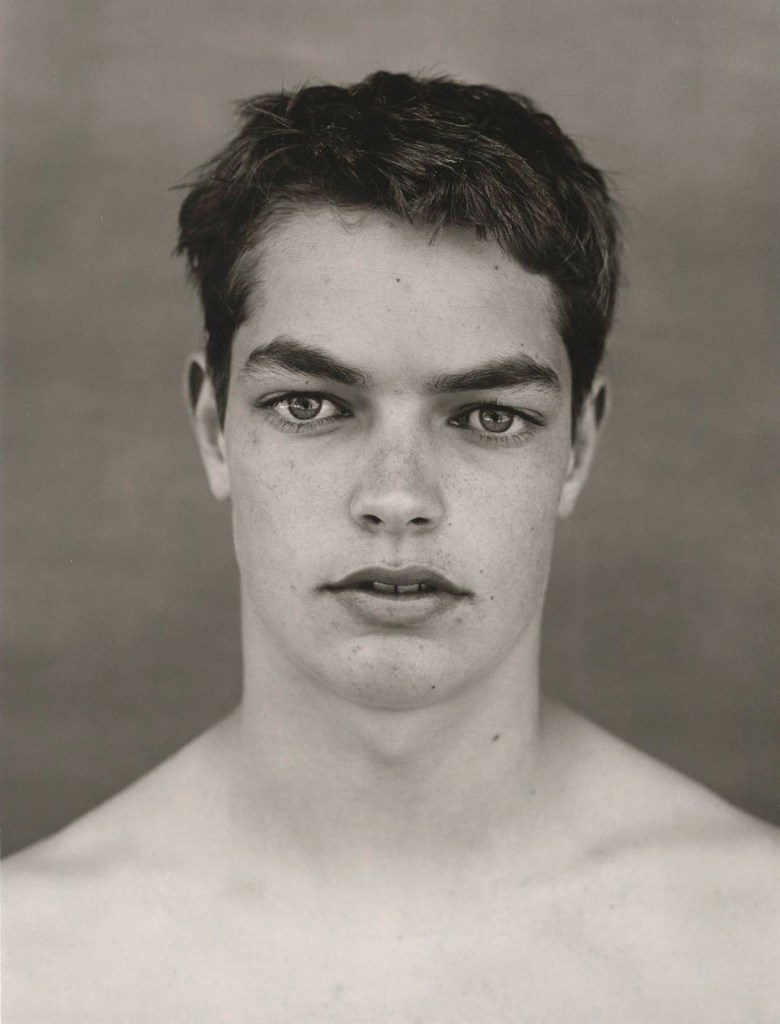

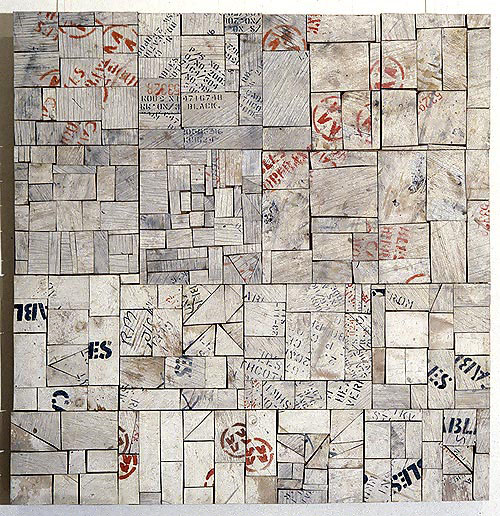

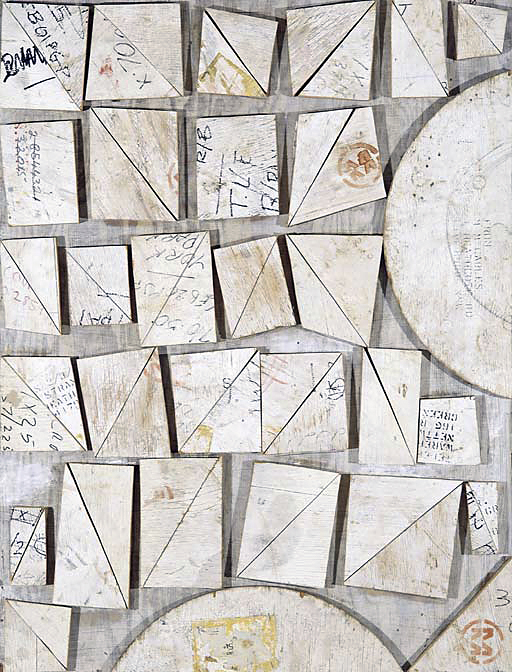

Installation views of the exhibition Mark Strizic: Melbourne – A City in Transition exhibition at Gallery 101, Melbourne

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

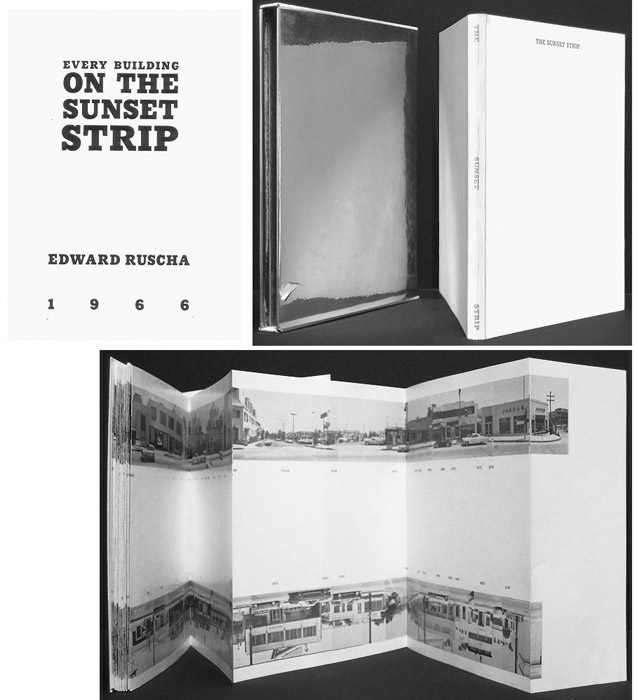

Mark Strizic, one of Australia’s eminent photographic artists presents us with nostalgic views of Melbourne and the changing face of the city in rare silver gelatin photographs. The exhibition, Melbourne – A City in Transition will be held at Gallery 101 from 8th April – 2nd May. There will be an evening artist reception on Thursday 9th April to celebrate the opening of the exhibition. Strizic’s oeuvre represents a collection of iconic images of architecture and of life – a record of the changing face of a migrating society of new prosperity, youth and popular culture – taken with a sympathetic eye for humanistic detail.

The exhibition will coincide with the announcement of the forthcoming publication, Mark Strizic, Melbourne: Marvellous to Modern, published by Thames & Hudson in association with the State Library of Victoria. In 2007, the State Library of Victoria acquired Mark Strizic’s entire archive of approximately 5000 negatives, colour transparencies and slides. In addition, the Library holds a fine collection of Strizic photographs, including examples of all types of photographic print, from gelatin silver to digital, produced by the photographer during his long career.

Press release from Gallery 101

“‘Melbourne – A City in Transition’ is a collection of iconic images of Melbourne city life taken with a sympathetic eye for humanist detail. Strizic accurately depicts the joys and hardships experienced in everyday life with a fresh and living memory. He successfully captures the vicarious essence of suburban life. His portrait of Melbourne includes the city, harbour and river banks – streets and trams, pavements, arcades and lanes, stations and bridges, billboards and facades and public sculpture. We see people going about their daily activities – commuting, shopping at leisure, trading, embracing, conversing, reading the newspaper and visiting the beach. Other works record the demolition and construction of building sites and the changing face of Melbourne, both in society and the urban landscape.”

Text from the exhibition flyer

“In these eloquent studies of light and shadow, Strizic finds beauty in the commonplace – Melbourne’s desolate lanes, street paving, derelict ferries – adopting interesting camera angles, viewpoints and cropping. Through his images, this visual humanist teaches us to observe, to see our surroundings, perhaps with the intention of stimulating us to a higher level of civilisation.”

Emma Matthews. Mark Strizic, Melbourne: Marvellous to Modern. Thames & Hudson in association with the State Library of Victoria, September, 2009.

“This magnificent collection of photographs arose from the creativity of a young photographer and his adoption of his new home town, Melbourne. His pictures were taken at a time when the Victorian elegance of the city once known as ‘Marvellous Melbourne’ was being punctuated by a wave of development and the modern architectural movement. Today Mark Strizic is renowned as a photographer. In the 1950s he was a young science student from Europe playing with the possibilities of the camera. As he gained work as a professional his commercial success was accompanied by the instincts and eye of an artist. His solid technicality was accompanied by the whimsy and wit that made him the ‘poet of the fleeting movement’. The versatility of his work shows us many aspects of Melbourne – its magnificent architectural heritage, its intimate and vibrant laneways, its grand arcades counter-posed against the sudden spaces of the wrecker, the brash intrusion of the glass and concrete skyscrapers, the poignancy of poverty in the rundown inner suburbs. We see the people, on grand occasions such as the 1954 Royal Visit, or just caught in their own world of travelling, shopping, resting, walking, working.”

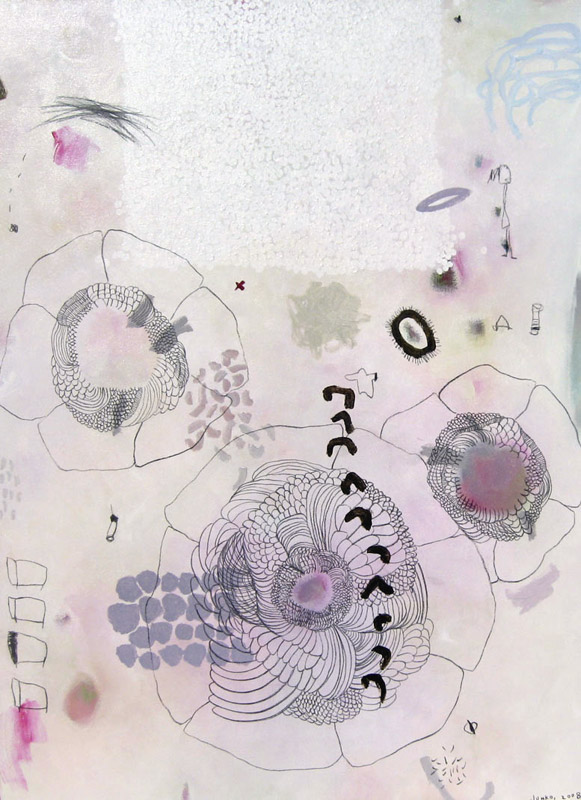

Mark Strizic, Melbourne: Marvellous to Modern book cover

Mark Strizic (Australian, 1908-2012)

From Princes Bridge

1958, printed 2006

Silver gelatin photograph

58 x 39cm

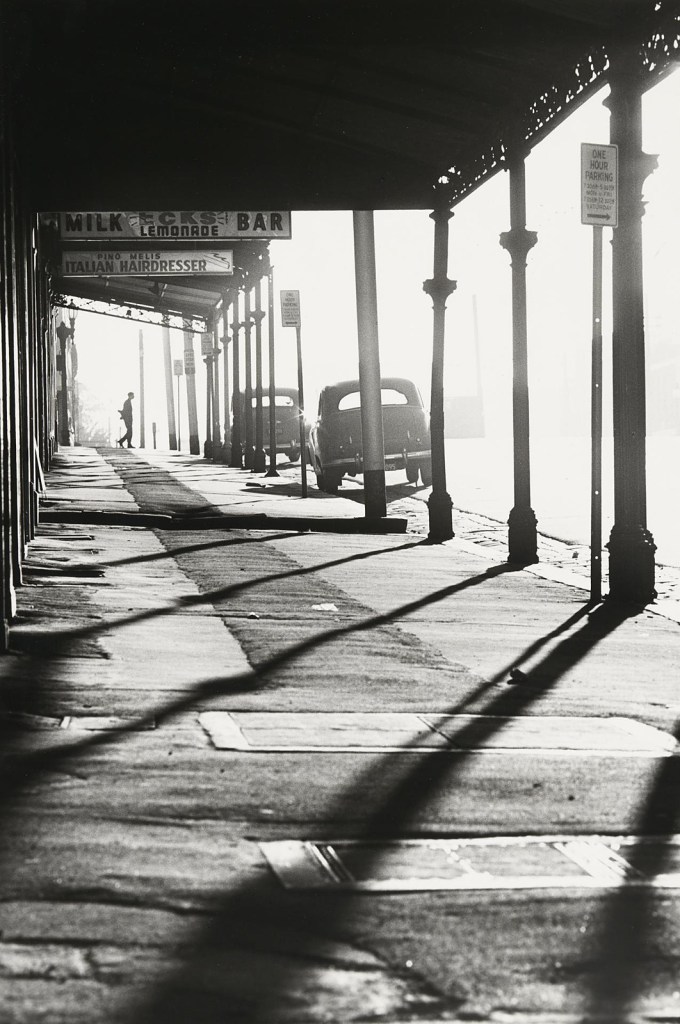

Mark Strizic (Australian, 1908-2012)

Near Spencer Street – 1

1950

Silver gelatin photograph

27.5 x 38.5cm

Mark Strizic (Australian, 1908-2012)

At St. Pauls (St Paul’s Cathedral steps)

1954, printed 1999

Silver gelatin photograph

17.8 × 24.5cm

Mark Strizic (Australian, 1908-2012)

St Paul’s Cathedral steps

1954, printed 1999

Silver gelatin photograph

17.8 × 24.5cm

Mark Strizic (Australian, 1908-2012)

Collins Street at Russell Street

1957, printed 1997

Unique silver gelatin photograph

39 x 56cm

Mark Strizic (Australian, 1908-2012)

St Georges Road, Northcote at Summer Av.

1958, printed 1998

Silver gelatin photograph

Mark Strizic (Australian, 1908-2012)

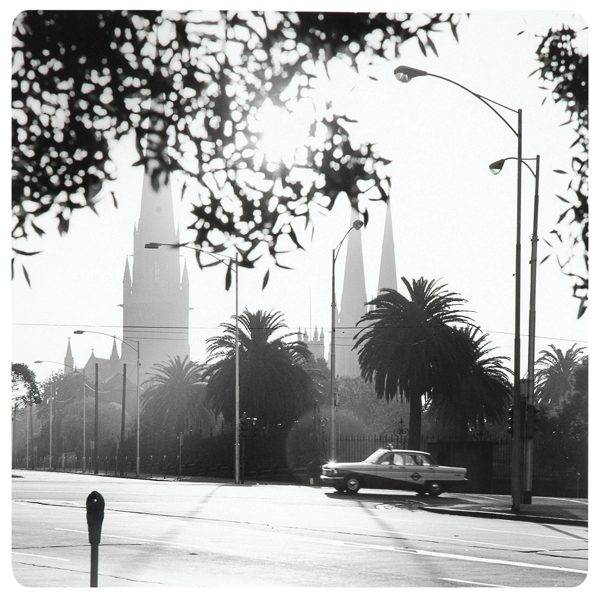

St. Patrick’s Cathedral

January 1967, printed 1998

Unique silver gelatin photograph

27 x 41cm

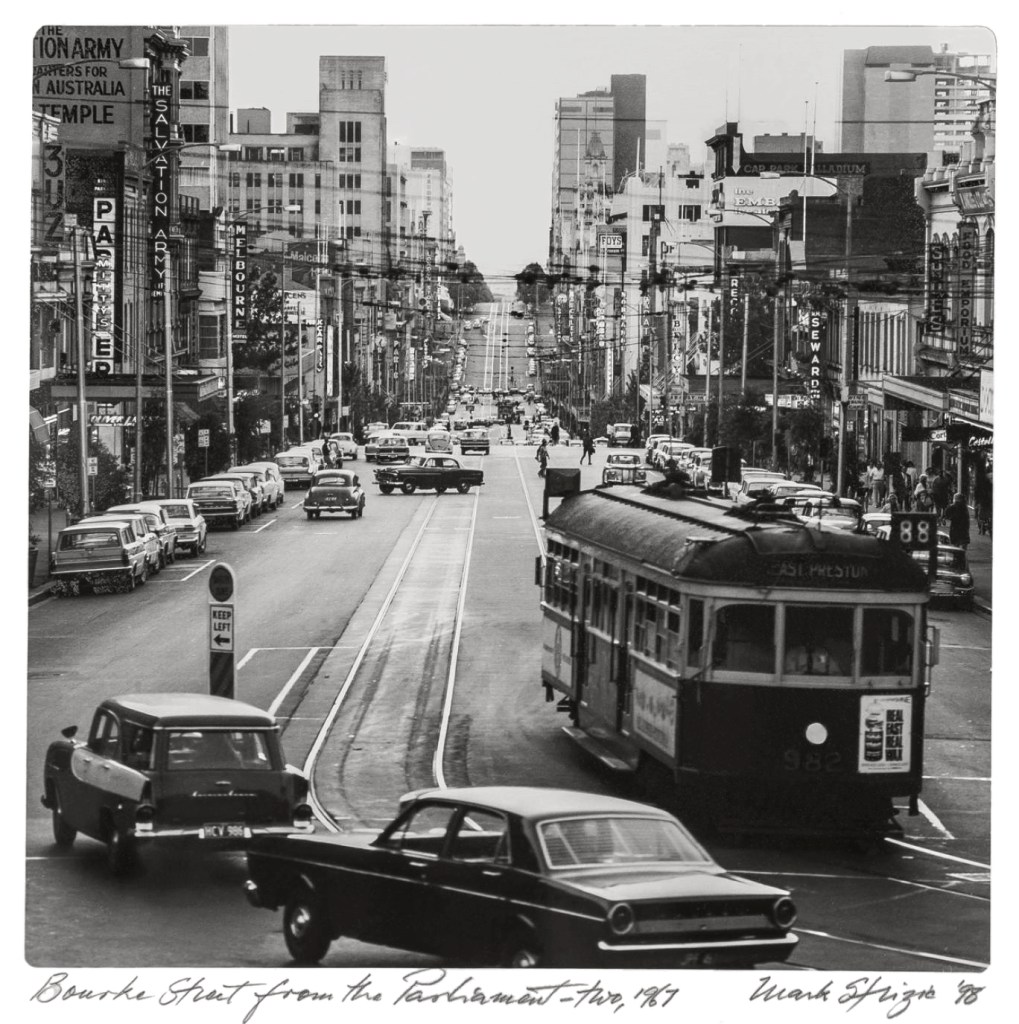

Mark Strizic (Australian, 1908-2012)

Bourke Street from the Parliament – 2

1967, printed 1998

Silver gelatin photograph

38 x 27cm

Mark Strizic (Australian, 1908-2012)

Russell Street Pawn Shop

1958

Silver gelatin photograph

Mark Strizic (Australian, 1908-2012)

Block Arcade

1967, printed February 2008

Unique silver gelatin photograph

53.5 x 37cm

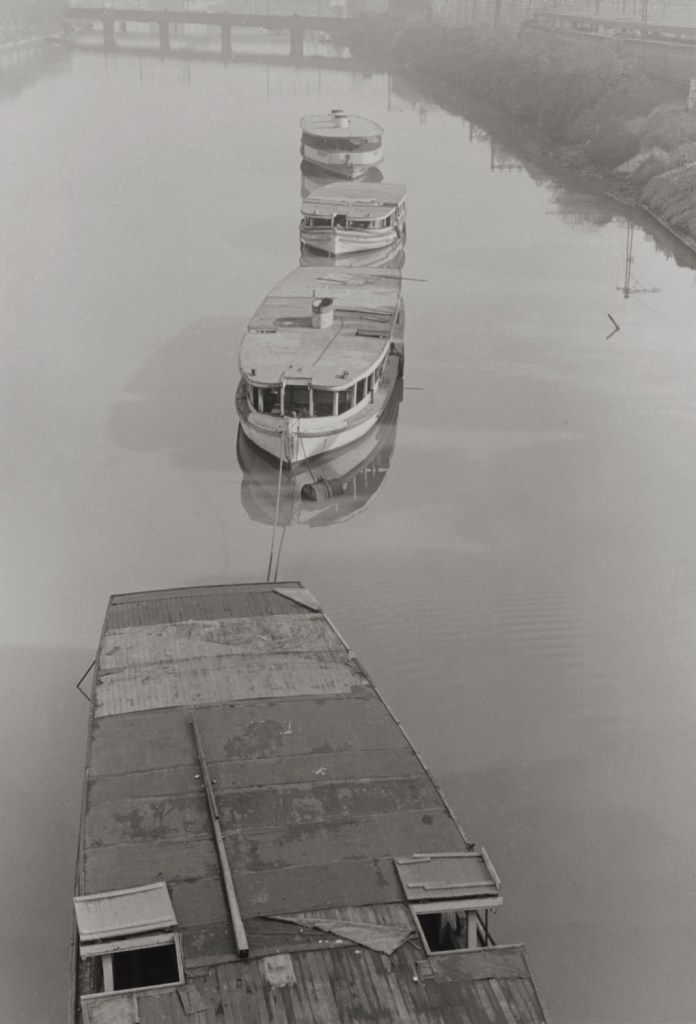

Mark Strizic (Australian, 1908-2012)

From Princes Bridge (Winter moorings from Princes Bridge)

1955, printed 2006

Silver gelatin photograph

58 x 39cm

Mark Strizic (Australian, 1908-2012)

Flinders Lane

1967, printed 1998

Unique silver gelatin photograph

41 x 41cm

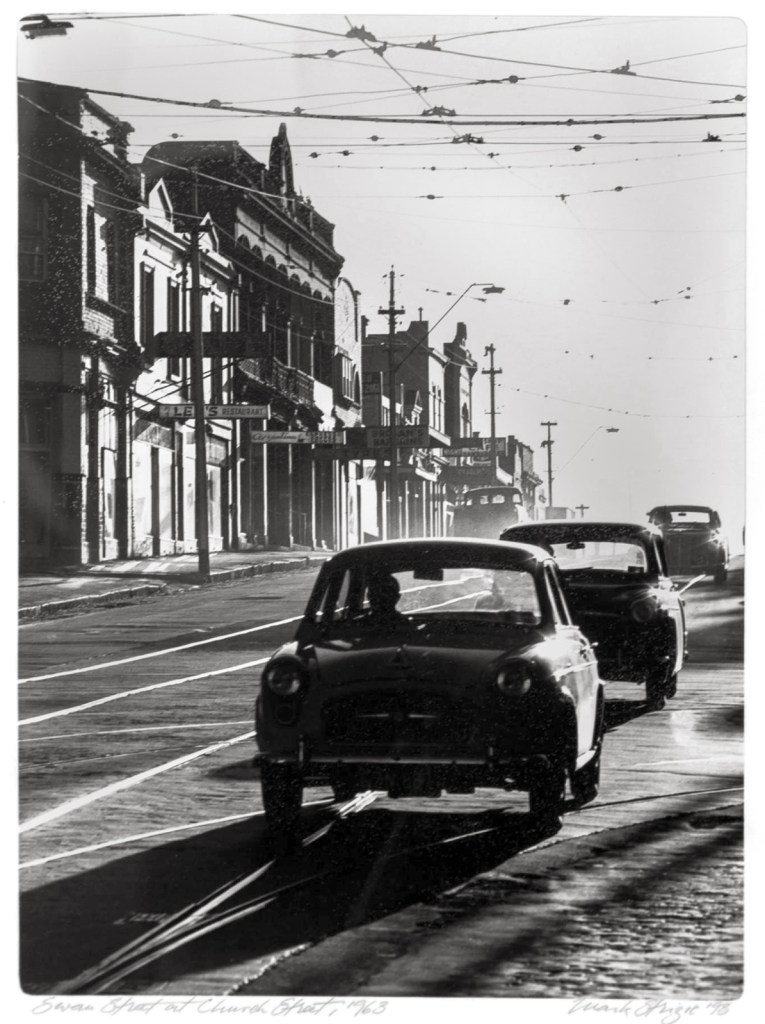

Mark Strizic (Australian, 1908-2012)

Swan Street, Richmond, at Church Street

1963

Silver gelatin photograph

Mark Strizic (Australian, 1908-2012)

Queensberry Street at Errol Street, North Melbourne

1963

Silver gelatin photograph

Mark Strizic (Australian, 1908-2012)

Swan Street at Church Street

1963, printed 1998

Silver gelatin photograph

Mark Strizic (Australian, 1908-2012)

Coates Building

1960, printed 1961

Vintage silver gelatin photograph

23.5 x 15cm

Mark Strizic (Australian, 1908-2012)

Macphersons Building – 1

1958

Silver gelatin photograph

Mark Strizic (Australian, 1908-2012)

On Princes Bridge

1959, printed 1996

Silver gelatin photograph

17 x 24cm

Gallery 101

This gallery is now closed.

You must be logged in to post a comment.