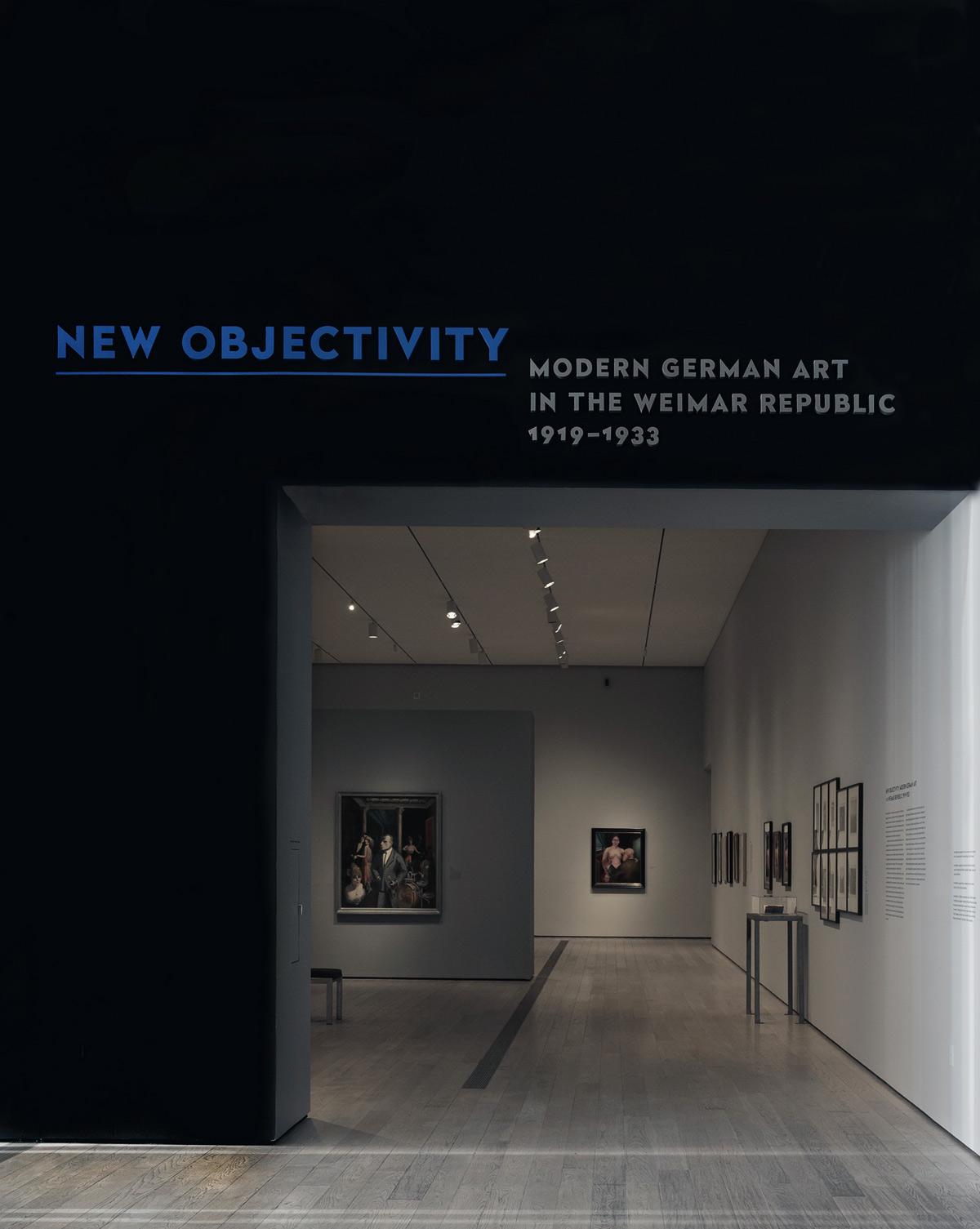

Exhibition dates: 7th October, 2022 – 21st May, 2023

Head Curator: Karolina Kühn

Curators: Juliane Bischoff, Angela Hermann, Sebastian Huber, Anna Straetmans, Ulla-Britta Vollhardt

Wer’e here, we’re queer, we’re not going anywhere.

Despite years of persecution, death and inequality, the presence of queer identity, diversity and creativity remains undimmed.

There are some fabulous, groundbreaking human beings who are “being seen” in this posting. Equally, there are some fabulous art works that illuminate the(ir) human condition.

Let’s celebrate their existence.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Munich Documentation Center for the History of National Socialism for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

About the exhibition

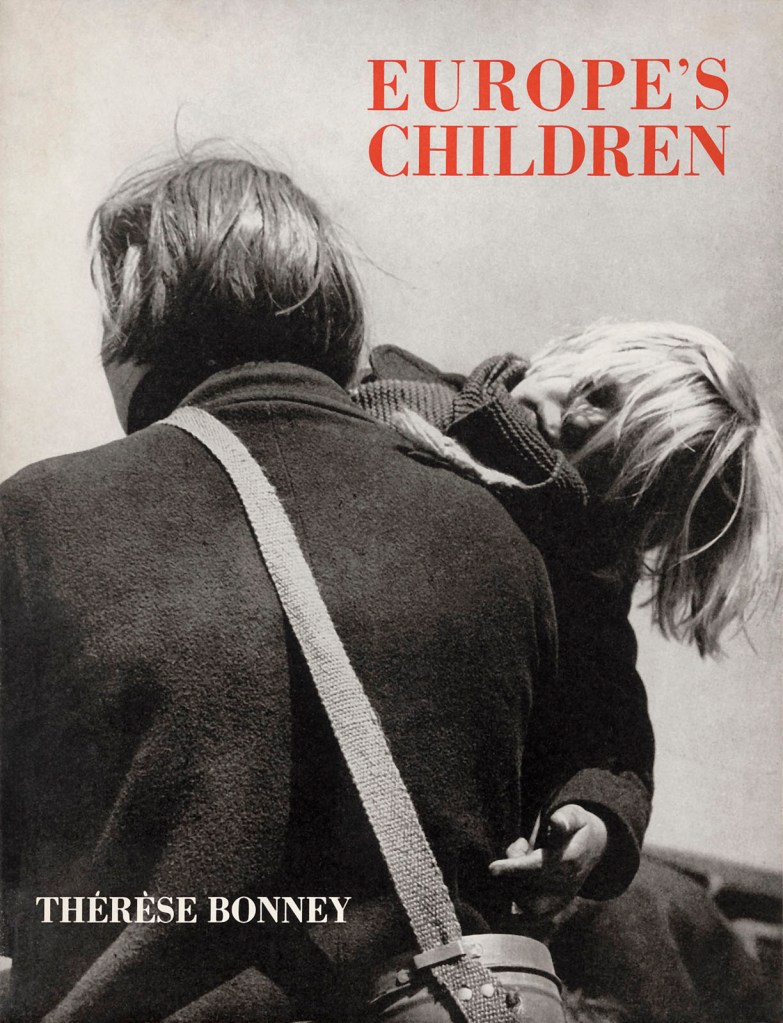

TO BE SEEN is an exhibition devoted to the stories of LGBTQI+ in Germany in the first half of the twentieth century. Through historical testimony and artistic positions from then and now, it traces queer lives and networks, the areas of freedom enjoyed by LGBTQI+, and the persecution they suffered.

The exhibition takes an intimate look at a variety of genders, bodies, and identities. It shows how queer life became ever more visible during the 1920s, giving rise to a more open treatment of role models and of desire. During this period, homosexual, trans, and non-binary people achieved their first successes in their fight for equal rights and social acceptance. They organised, fought for scientific and legal recognition of their gender identity, and carved out their own spaces.

But as recognition and visibility in art and culture, science, politics, and society increased, so did resistance. After the Nazis came to power, the LGBTQI+ subculture was largely destroyed. After 1945, their stories and fates were scarcely archived or remembered.

Text from the Munich Documentation Center for the History of National Socialism website

“When a right is withheld from you, you must fight and not give in; that is a moral duty.”

Joseph Schedel opened the first meeting of the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee of Munich on September 24, 1902

Exterior view of the NS Documentation Center in Munich showing a work in the exhibition TO BE SEEN: Queer Lives 1900-1950 – Maximiliane Baumgartner’s “You look at us – we look at you”: Rubbing against the architecture of the executive gaze (Based on a paper by Anita Augspurg ‘Mißgriffe der Polizei’ / ‘Abuses by the Police’, 1902) 2021

Photo: Connolly Weber Photography/NS-Dokumentationszentrum München

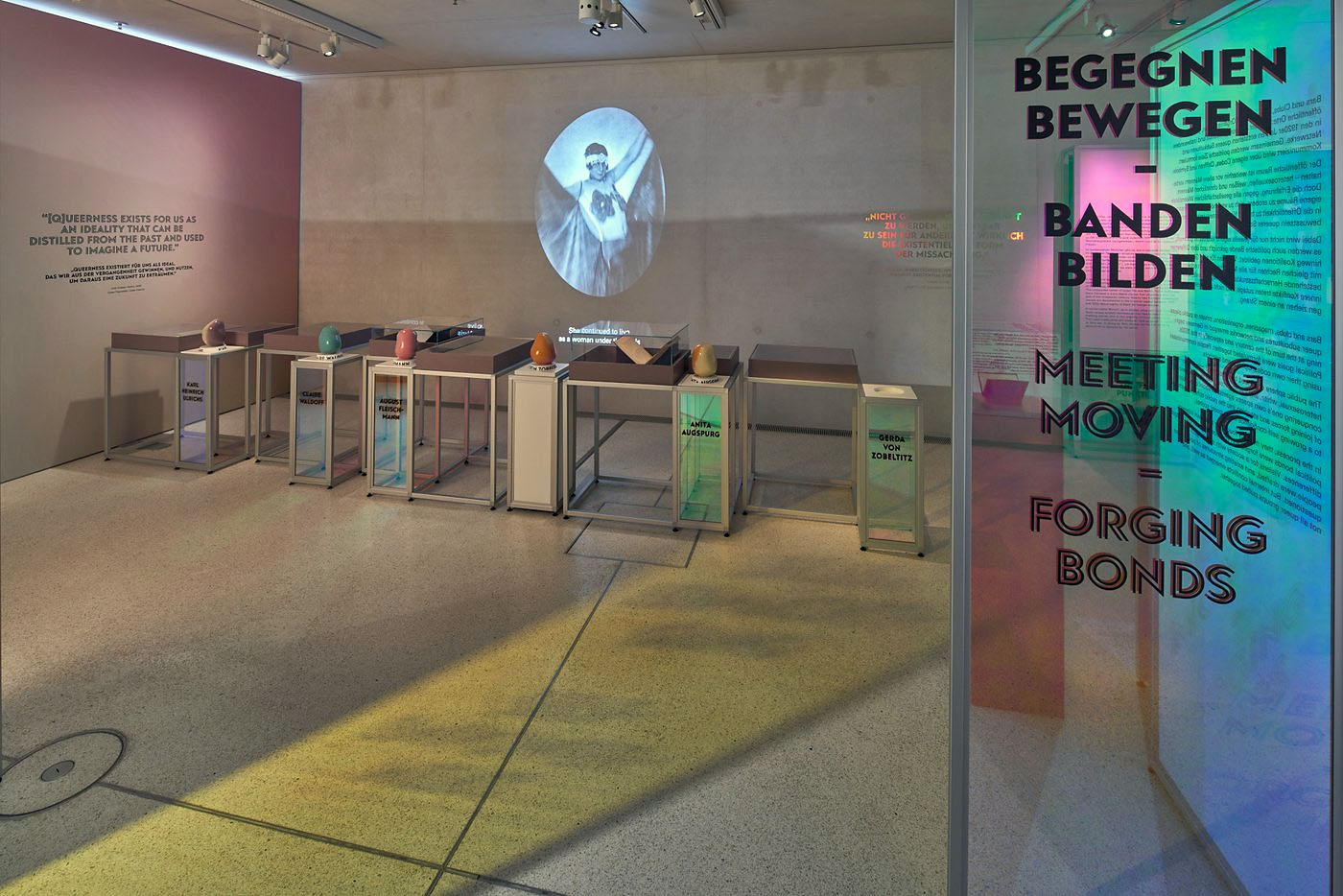

Installation view of the exhibition TO BE SEEN: Queer Lives 1900-1950 at the Munich Documentation Center for the History of National Socialism

Photo: Connolly Weber Photography/NS-Dokumentationszentrum München

TO BE SEEN | Trailer

The exhibition TO BE SEEN: Queer Lives 1900-1950 is dedicated to the stories of LGBTIQ* in Germany in the first half of the 20th century from October 7th, 2022 to May 21st, 2023 at the Munich Documentation Center. With historical testimonies and artistic positions from then to the present, the exhibition traces queer life plans and networks, freedom and persecution.

The exhibition takes an intimate look at diverse genders, bodies and identities. It shows how queer life became more and more visible in the 1920s and how role models and desires were dealt with more openly. Homosexual, trans* and non-binary people achieved their first successes in their fight for equal rights and social acceptance: they organised themselves, fought for scientific and legal recognition of their gender identity and conquered their own spaces.

In addition to recognition and visibility in art and culture, science, politics and society, resistance also increased. After the National Socialists came to power, the LGBTIQ* subculture was largely destroyed. After 1945 their stories and fates were hardly archived or remembered.

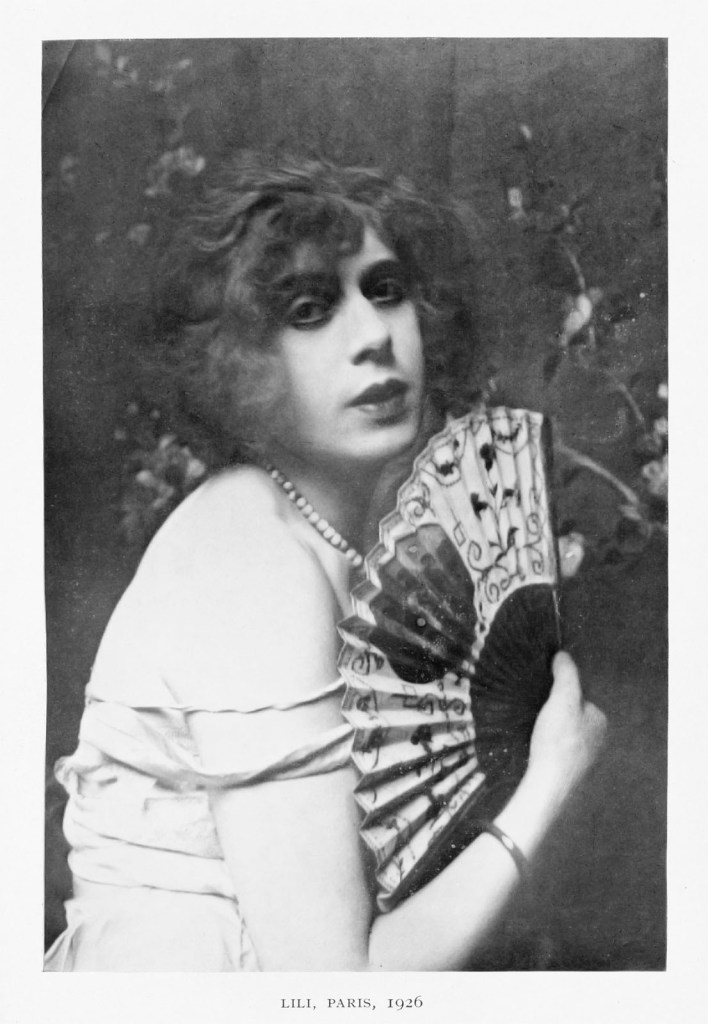

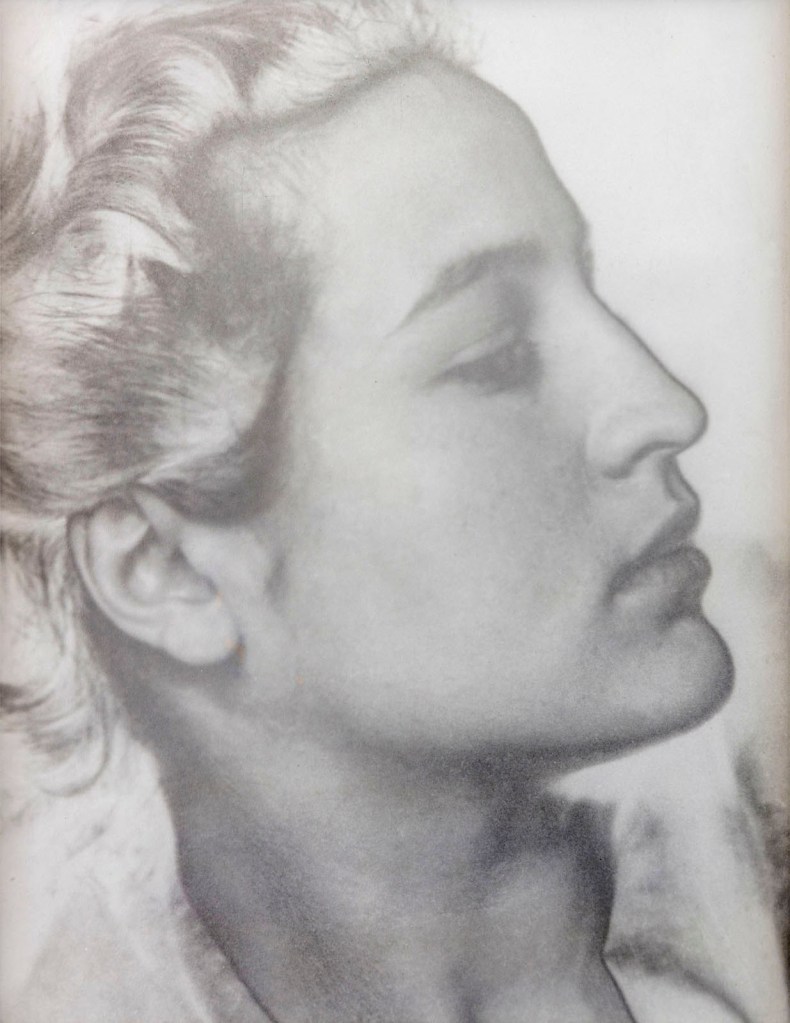

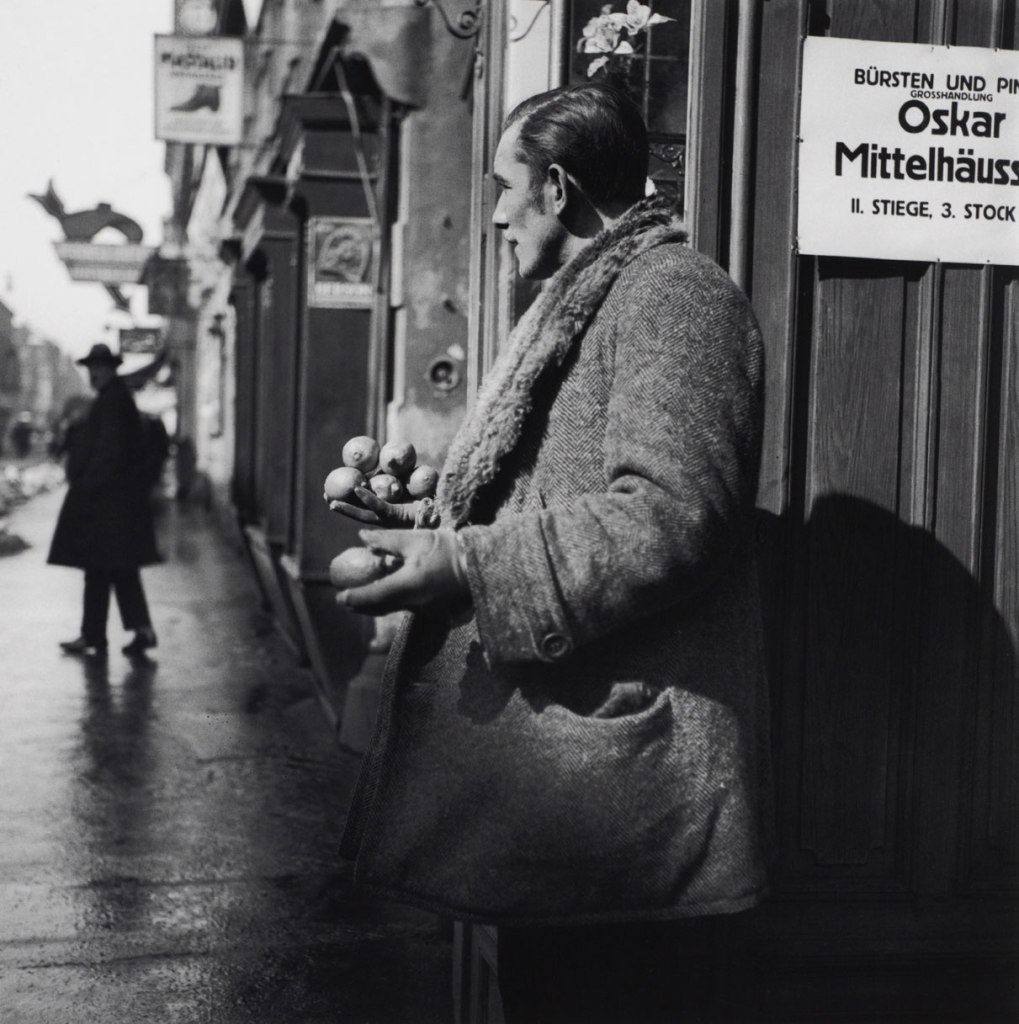

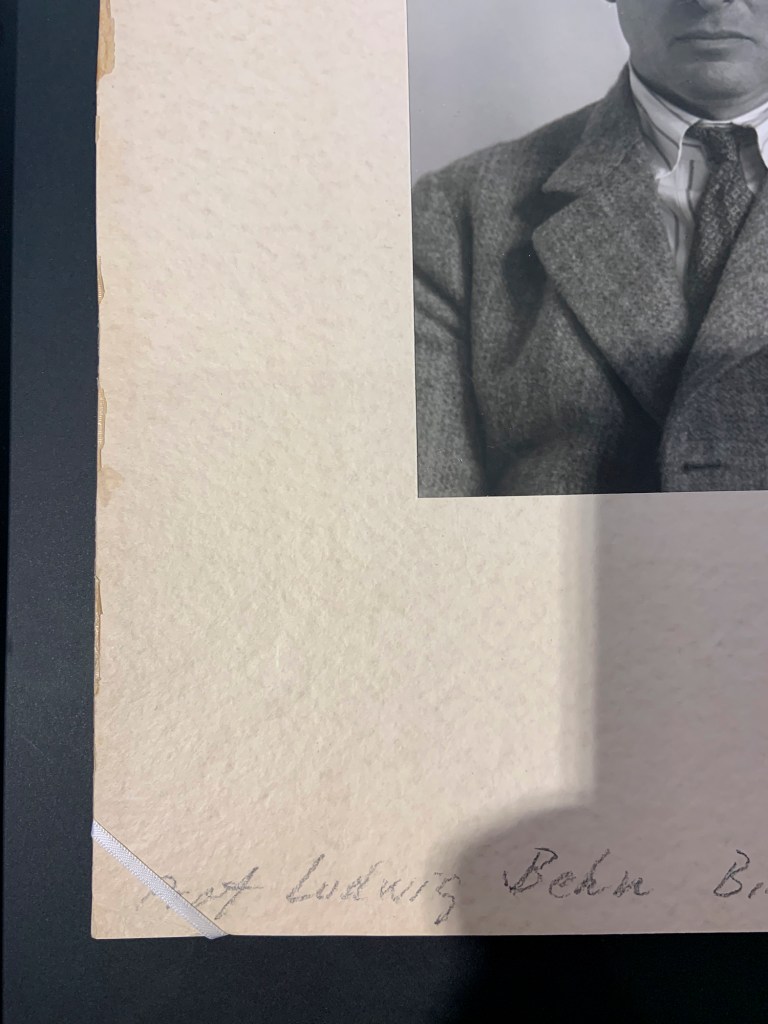

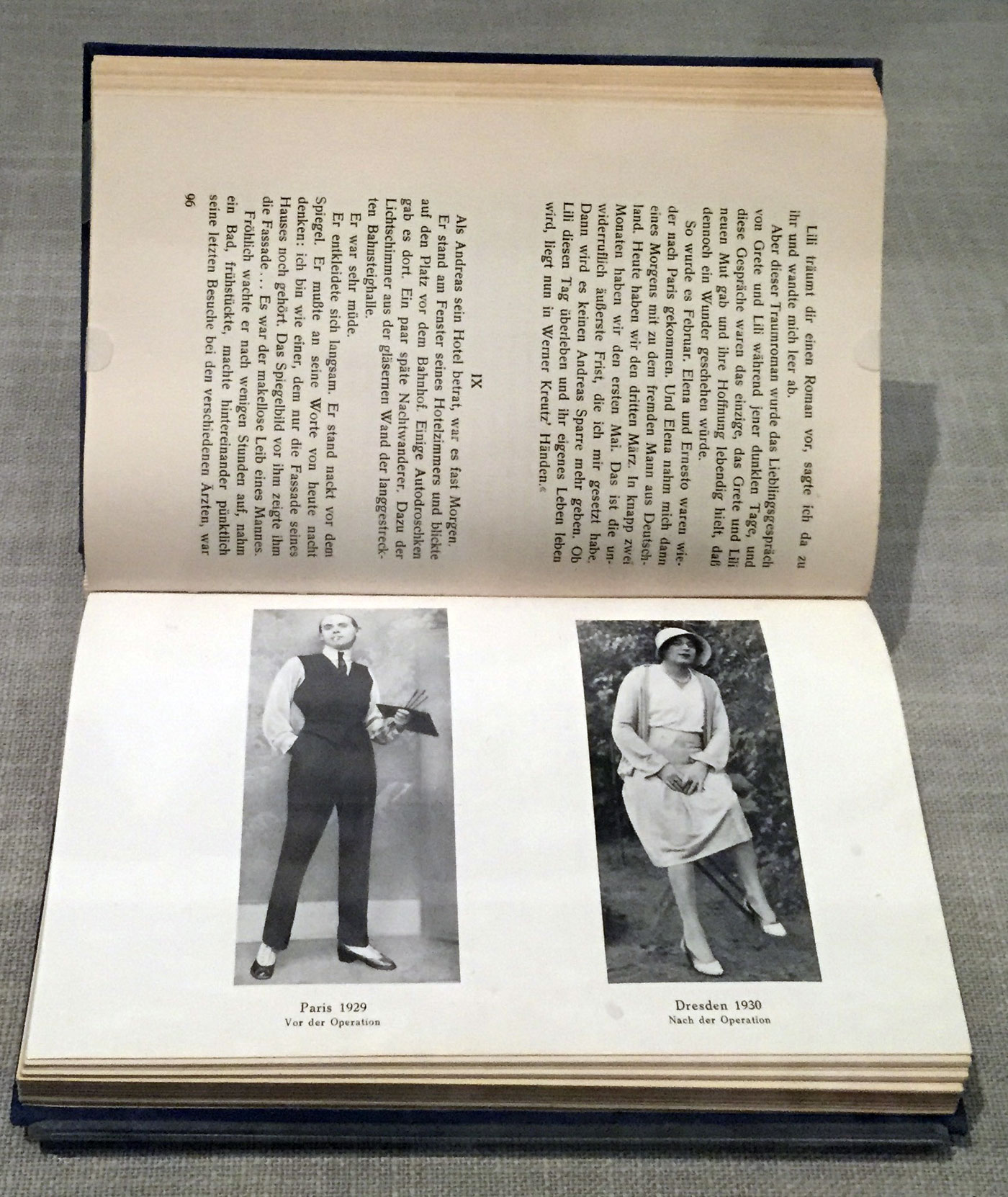

Unknown photographer

Lili, Paris

1926

From N. Hoyer (ed.). Man into Woman. An Authentic Record of a Change of Sex. The true story of the miraculous transformation of the Danish painter Einar Wegener (Andreas Sparre). London: Jarrolds, 1933, 1926, opp. p. 40.

Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Lili Elbe, a transgender woman who underwent sex reassignment surgery in Berlin in the 1930s.

Around 1900, queer people in Germany began gaining more and more visibility in public life – in art, culture, science, and politics. Existing role models for men and women were being questioned. Homosexual women and men as well as trans* and non-binary people achieved initial successes in their struggle for equal rights and acceptance: they organised and fought for scientific and legal recognition of their sexual and gender identity.

They met in public places, founded clubs and associations, and started magazines. New terms were coined to describe their identities and create a sense of belonging. Urning, lesbian, girlfriend, Bubi, homosexual: more than a hundred years ago there were already many expressions for what we call queer today. But as their visibility grew, so did the social and political backlash. The Nazi takeover in 1933 was a defining moment for queer people – their subculture was largely destroyed. In the postwar years, discrimination continued.

Even decades later, LGBTQI+ history is still hardly remembered or preserved in archives. Through historical testimonies and artistic positions from then and now, TO BE SEEN traces queer lives and networks, the spaces of freedom enjoyed by LGBTQI+ people, and the persecution they suffered.

Text from Stories of the exhibition TO BE SEEN: Queer Lives 1900-1950

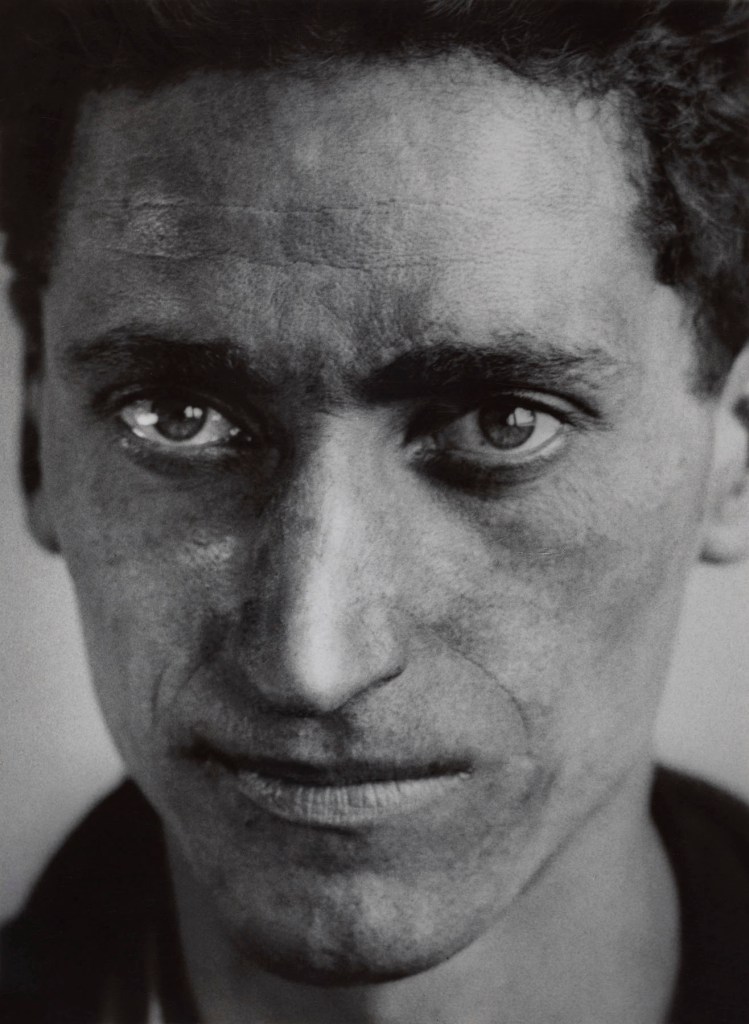

Unknown photographer

Police photo of Liddy Bacroff

1933

Gelatin silver print

© Staatsarchiv Hamburg

Police photo of Liddy Bacroff, taken after an arrest, 1933. Barcoff described themself as a “homosexual transvestite”, lived from sex work, and was convicted several times. In 1943, they was murdered in the Mauthausen concentration camp.

Liddy Bacroff, a transgender woman initially from Ludwigshafen, who moved to Hamburg and lived for the majority of her life publicly presenting herself as a woman. She did not perceive herself to be a man (and, indeed, in papers she left after having been imprisoned, she determined what her name would be while also conspicuously referring to herself as “Liddy Bacroff, Transvestit”). But this was effectively her own form of self-ID. Certainly the authorities didn’t see her as such — her records remain filed under her deadname and identify her as a homosexual man – and, though she’d have been given a Transvestitenschein in Berlin, she wasn’t IN Berlin. Having not visited Hirschfeld and his Institut, it’s a marvel she uses the term “Transvestit”; elsewhere she does refer to herself as a “Mann-Weib” (a “male woman”), and frequently as a girl or a woman. The authorities, again, call her a man or, occasionally, a “Zwitter.” (NB. “Zwitter” means “hermaphrodite” and is here not meant literally but rather as an epithet recorded in the official files – an insult to her.) So the language that is used to describe trans people is inconsistent and, often, absent (depending on the sources). Reading between the lines is necessary, especially in the official records, which view trans women (regardless their lived circumstances or their appearance) only as homosexual men, and charge them as such. And while Hirschfeld was conscientious, the police were… not. This is especially true as the 1930s unfolded and the country Nazified. I wrote a very long thread a while back about “Heinrich Bode”, who was assigned male at birth but frequently presented as a woman. I used that thread to highlight difficulties of definition because Bode denounced their appearance as a woman in court filings and personal testimony, but at the same time also hinted that there was something much deeper than “just” dressing as a woman. But as they were subjected to prosecution by the Nazified judiciary and security state, they were under duress. So, do we assume that Bode was trans, and denied it because of the threat of punishment? Or was their presentation simply playing with the conventions of gender?

Dr. Bodie A. Ashton Historiker, Universität Erfurt. Text from his Twitter account

Unknown photographer

Police photo of Liddy Bacroff

1933

Gelatin silver print

© Staatsarchiv Hamburg

Unknown photographer

Police photo of Liddy Bacroff

1933

Gelatin silver print

© Staatsarchiv Hamburg

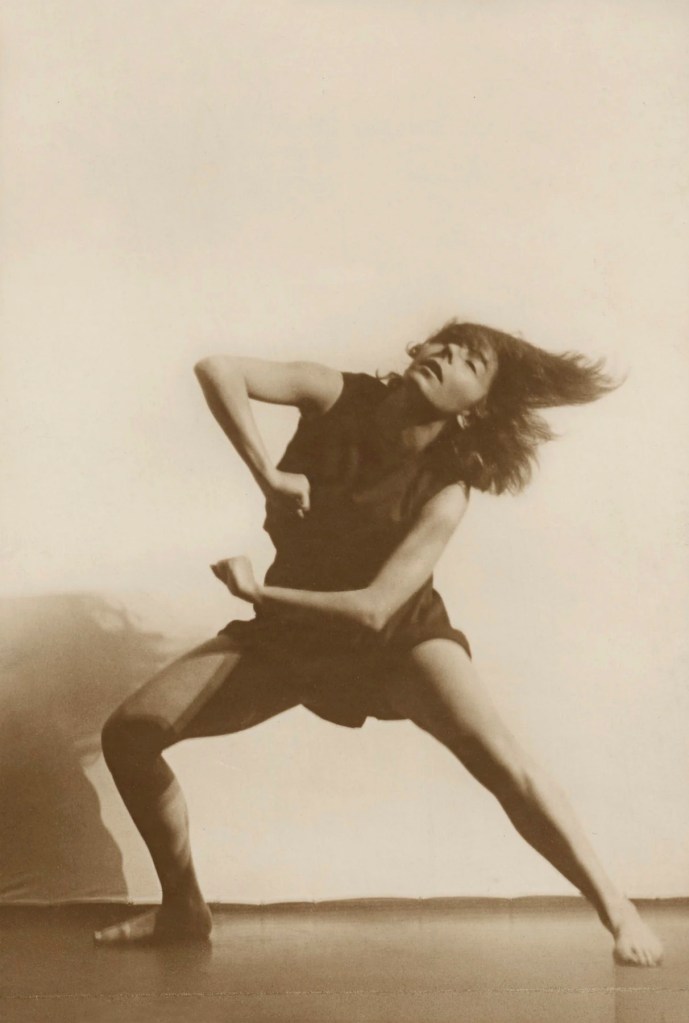

Alexander Sacharoff (Russian, 1886-1963)

Pavane Fantastique

c. 1916/1917

© Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus und Kunstbau München

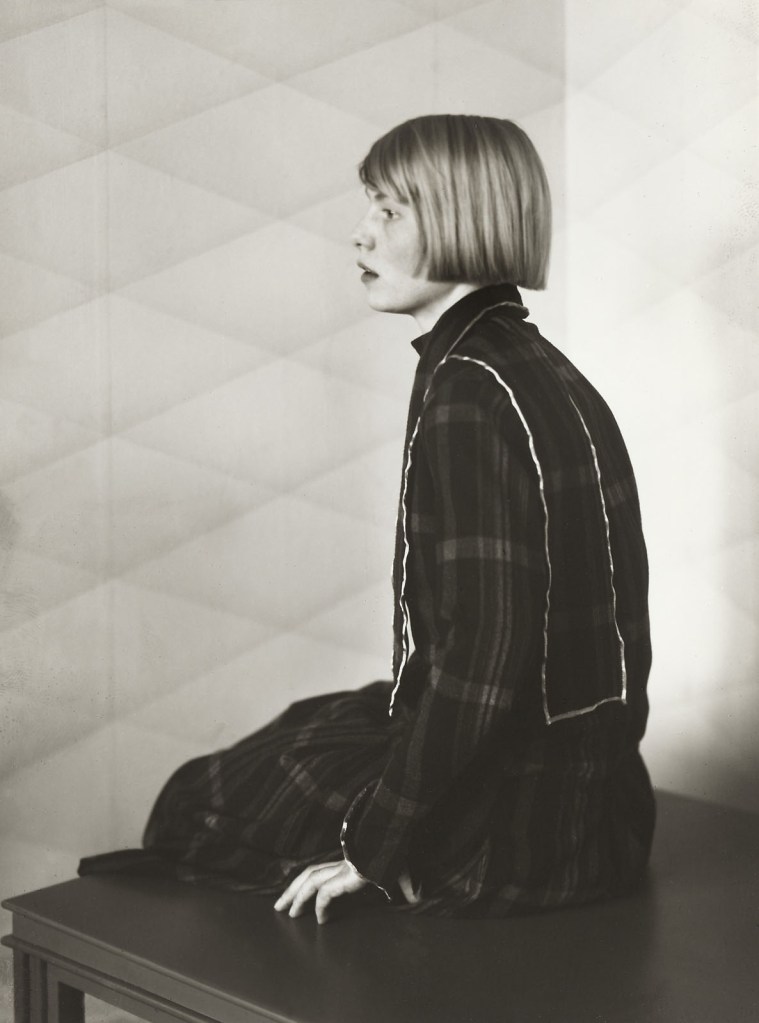

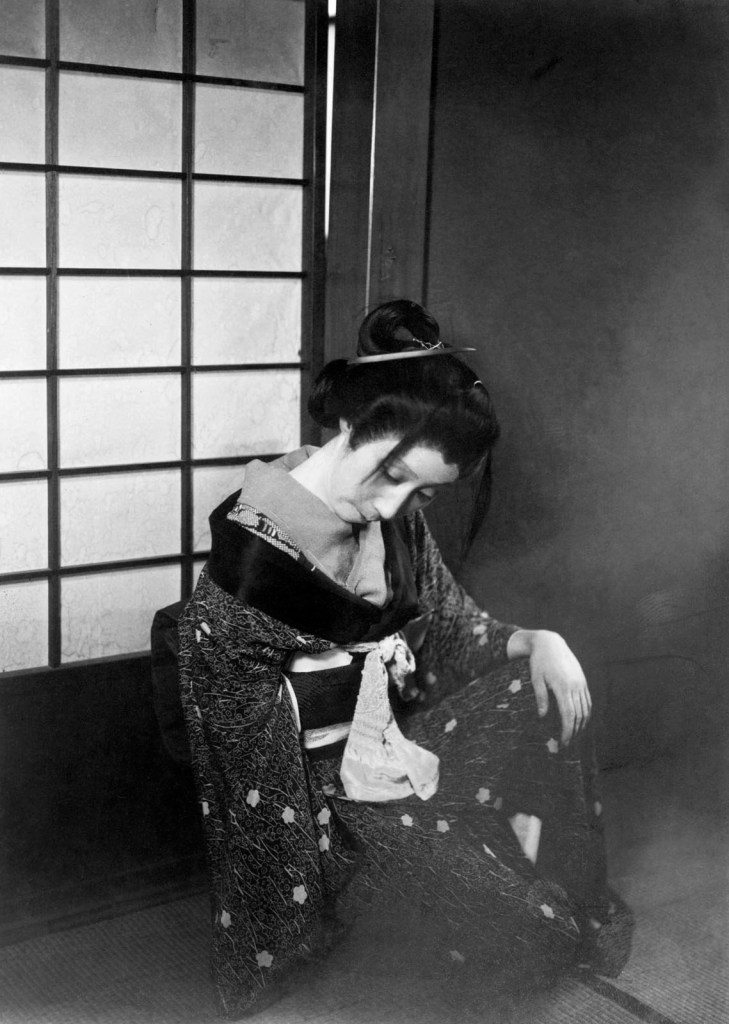

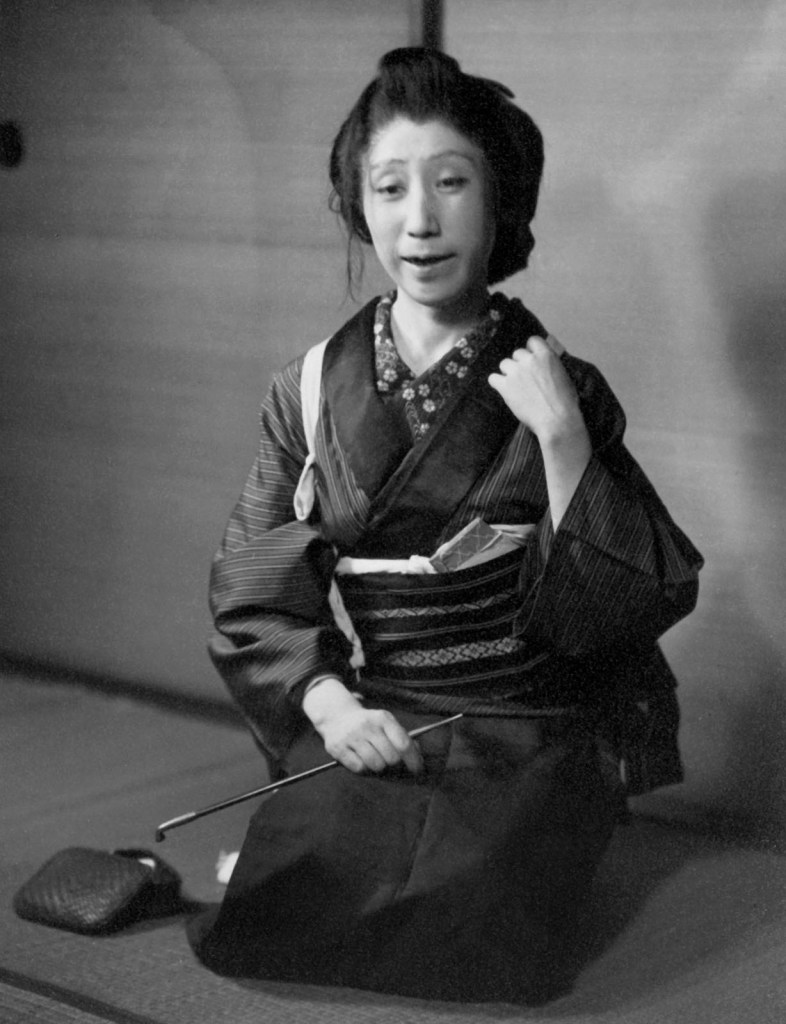

Unknown photographer

Alexander Sacharoff

c. 1914

© Deutsches Theatermuseum München

The androgynous dancer created new body images and developed the swapping of clothes into a stage genre of its own.

Installation view of the exhibition TO BE SEEN: Queer Lives 1900-1950 at the Munich Documentation Center for the History of National Socialism

Photo: Connolly Weber Photography/NS-Dokumentationszentrum München

Queer

“Queer” originally referred to anything that did not fit into the usual categories. In English the word queer (meaning strange, other, suspicious), was used earlier as a derogative term for homosexuals. Since the 1990s, however, the term has been adopted by many non heterosexual and non-binary people as a positive self-designation. Within the exhibition, queer is used as a catch-all term for a variety of sexual and gender identities and practices that deviate from heterosexual ideas. The term primarily, but not only, refers to LGBTQI+ – in other words lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and intersexual persons. Furthermore, “queering” can be understood as a practice of combating various forms of discrimination and exclusion. Applied to gender, sexuality, and identity issues, it means casting a critical gaze at the worldview that regards a heterosexual relationship between two persons as the social norm. The rigid binary division of gender into man and woman and the associated role models are thrown into question. In the exhibition, historical self-designations are used where they can be traced through sources.

Self empowerment

In the German Empire, politics, the economy, and society were dominated by men. The gender order, which was maintained over centuries by state and church, was strictly divided into two parts: men and women were assigned clear roles within which they must operate. People who did not conform to these role models and lived gender and sexual identities outside the normative order were ostracised. They were considered immoral, criminal, or ill. According to Paragraph 175 of the Imperial Criminal Code of 1871, sexual acts between men were forbidden and punishable by imprisonment. In Austria, sex between women was also punishable.

But there were individuals who rebelled against the prevailing gender order and fought for a more open society. They opposed the outlawing of homosexuality and transsexuality, advocated a change in criminal law, and assertively engaged in the recognition of their identities. New alliances and self-images emerged. Many of these pioneers paid a high price for their rebellion: they lost their jobs, their families, and their friendships, and were socially isolated.

Text from Stories of the exhibition TO BE SEEN: Queer Lives 1900-1950

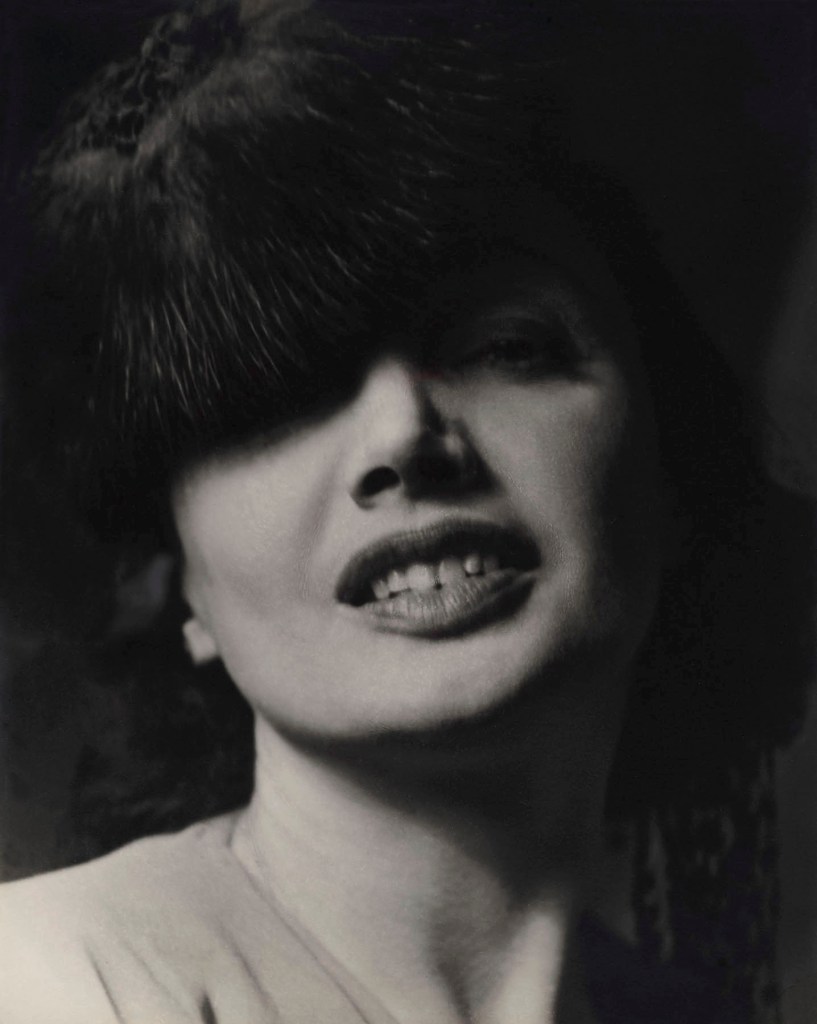

Emil Orlík (European born Prague, 1870-1932)

Claire Waldoff

c. 1930

© bpk | Stiftung Deutsches Historisches Museum

In TO BE SEEN #QueerLives we present individuals and movements who rebelled against the gender order that prevailed around 1900 and advocated a more open society. In their fight for equal rights and acceptance, they showed solidarity with each other, organised themselves in clubs, founded magazines, coined new terms and met in bars and clubs.

One of them was the chansonnière and cabaret artist Claire Waldoff (1884-1957). Born as Clara Wortmann in Gelsenkirchen, she is a central figure in the Berlin cultural scene of the 1920s. Her songs are known throughout Germany. She lives openly with her partner Olga (Olly) von Roeder and shapes the city’s lesbian scene.

Emil Orlik (21 July 1870 – 28 September 1932) was a painter, etcher and lithographer. He was born in Prague, which was at that time part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and lived and worked in Prague, Austria and Germany.

Emil Orlik was born the son of a tailor on July 21, 1870, in Prague, then the capital of a province within the Austro-Hungarian empire. He first studied art at the private art school of Heinrich Knirr, where one of his fellow pupils was Paul Klee. Other friends at this time included Franz Kafka, Max Brod, and Rainer Maria Rilke.

Starting in 1891, Orlik studied at the Munich Academy under Wilhelm Lindenschmit. He later learned engraving from Johann Leonhard Raab and proceeded to experiment with various printmaking processes, including woodcut, which he and his friend, Bernard Pankok, experimented with in 1896.

Orlik left the Academy in 1893. He performed his military service for a year before returning to Prague in 1894. He relocated to Munich in 1896, where he worked for the magazine Jugend (Youth). He spent most of 1898 travelling through Europe, visiting the Netherlands, Great Britain, Belgium, and Paris.

Emil Orlik’s prints and techniques went through extensive changes as he traveled internationally, learning new methods wherever he went. Known for his portraits of a wide variety of well-known individuals including Josephine Baker, Albert Einstein, and Marc Chagall, Orlik was an artistic chameleon, never sticking to one genre or style but studying many. His prints catalog his travels, creating a kind of pictorial diary of the years 1892 to 1900 in particular. Many of his works, often produced in color, appeared in the European periodical PAN, along with the work of Toulouse-Lautrec, Kathe Kollwitz, and Max Klinger.

Japanese art and culture fascinated Orlik. He was aware of the impact Japanese art was having on European art and decided to visit Japan. In 1900, he traveled to Japan and spent a year studying Japanese woodblock cutting and printing. His studies of the Japanese culture led him to the art of Utamaro and Hiroshige. Orlik studied the language before his departure and within four months of his arrival he was proficient enough in Japanese to converse with the artisans whose work he admired and under whom he studied.

Orlik never limited himself to popular subject matter. He studied any scene that inspired him, major events or everyday life. He produced fourteen lithographs of the trial of Arthur Schnitzler and his fellow actors; reenactment of the banned play, “Aus dem Reigin,” for which Orlik was a defence witness. After the trial, Orlik began working for the theatre as a designer of costumes, stage sets, and posters.

He kept all his early woodblocks and, in 1920, he published his celebrated portfolio Kleine Holzschnitte (Small woodcuts) in an edition of 100, which also contained the text of his descriptions of each of the prints. The portfolio contained thirty-four woodcuts, eighteen of which were printed in colours. The complete portfolio is now very rarely found. It included such delightful items as Aus London and the superb colour woodcut Schneiderwerkstatt bei Orlik in Prag (the Orlik tailoring workshop in Prague), which depicts his father and colleague’s busy sewing.

Orlik was also commissioned to design colour posters for the Best-Litovsk Peace Conference at which Russia and Germany ended their conflict. He produced seventy-two lithographs, including a number portraits of Leon Trotsky. Around this time he also began to study photography, and by the mid-1920s was photographing celebrities such as Marlene Dietrich and Albert Eintstein.

Emil Orlik died of a heart attack on September 28, 1932. His brother Hugo was willed the estate, and with it the numerous works of art Orlik had collected throughout the years. Hugo Orlik and his family perished in WWII at the hands of the Nazis, and the only survivor was an aunt who regained what little was left of Emil’s effects. To this day Orlik’s work is still exhibited throughout the world.

Anonymous. “Emil Orlik Biography” on The Annex Galleries website Nd [Online] Cited 17/04/2023

Installation views of the exhibition TO BE SEEN: Queer Lives 1900-1950 at the Munich Documentation Center for the History of National Socialism

Photo: Connolly Weber Photography/NS-Dokumentationszentrum München

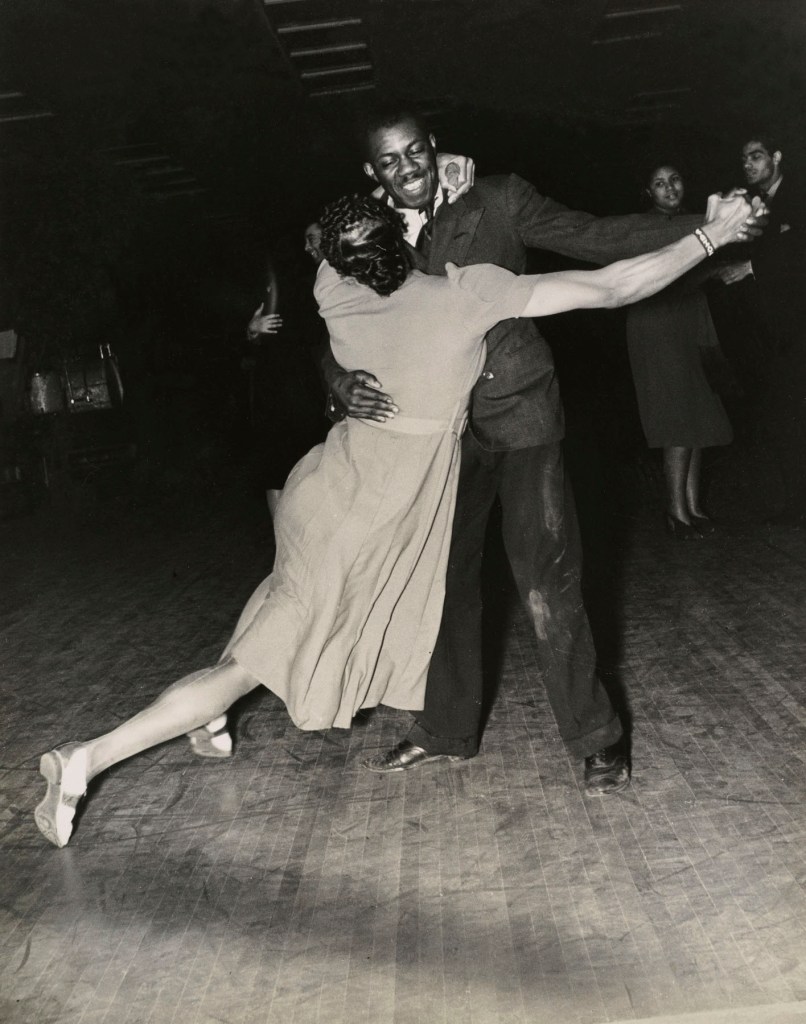

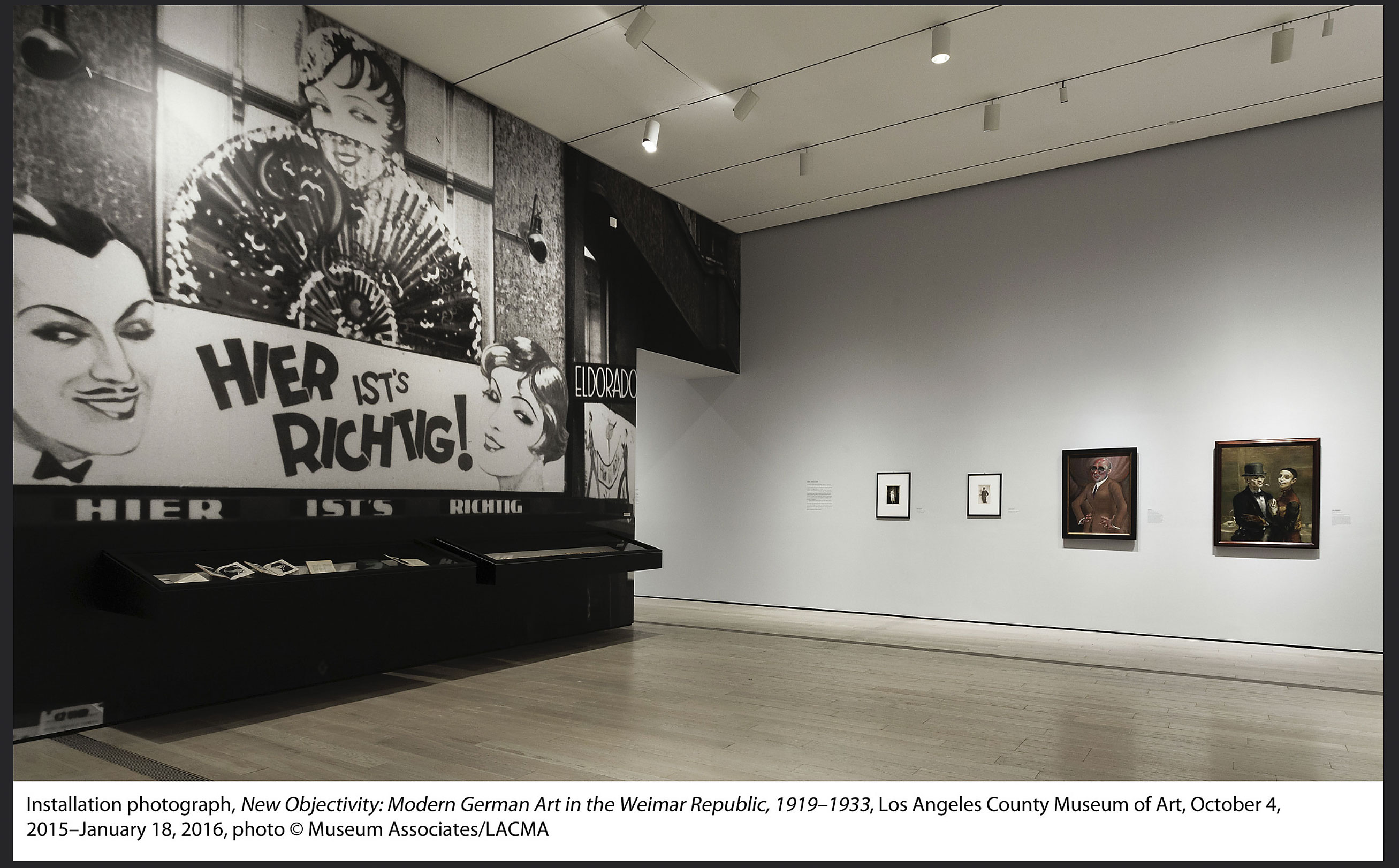

Unknown photographer

Trans* people in the Eldorado in Berlin

1926

© bpk / Kunstbibliothek, SMB

Meeting, moving – forging bonds

Bars and clubs, magazines, organisations, private or public places: queer subcultures and networks emerged in Germany beginning at the turn of the century and especially in the 1920s. Political goals were formulated together. People communicated using their own codes, ciphers, and symbols.

The public sphere continued to be reserved primarily for men – heterosexual, white, and Christian men. But the experience of conquering one’s own spaces against all social opposition, of joining forces and stepping into the public sphere together, led to a growing self-confidence in the queer scenes. In the process, they not only fought for their own interests; political bonds were forged and coalitions formed that bridged differences.

Visions for a society with equal rights for all people were drafted, and existing structures of power were questioned. But internal conflicts emerged as well, and not all queer groups pulled together.

§ 175 des Reichsstrafgesetzbuchs

Trancript: “Paragraph 175: Perverse fornication committed between persons of the male sex or by persons with animals is punishable by imprisonment; loss of civil rights may also be imposed.”

According to Paragraph 175 of the Imperial Criminal Code, sexual intercourse between men was punishable. This provision originated in the Prussian Criminal Code and was introduced throughout Germany with the founding of the German Empire in 1871. Prior to this, homosexuality was exempt from punishment in some German states, such as Bavaria, Württemberg, and Baden, following the example of France. The paragraph was controversial from the beginning: ecclesiastical conservatives and extreme right-wing parties demanded it be made more severe; liberals, social democrats, and communists called for its abolition.

Organisations and the conquest of public space

At the end of the nineteenth century, gay men joined forces to fight against persecution based on Paragraph 175. They founded clubs and associations and sought supporters to achieve their vision of a more open society. Berlin became the hub of this movement and developed into a leading centre of attraction for queer people. It was in Berlin that, in 1897, the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee was founded, which aimed to achieve legal and social equality for homosexual and trans* people.

Some activists from the women’s movements joined this struggle, especially when the extension of Paragraph 175 to encompass women was debated in 1909. Their goal was far-reaching sexual and social reform: a woman’s right to sexual self-determination, abortion, extramarital relations, and independence from her husband. Some leading women’s rights activists lived with another woman, but only few openly identified as lesbian.

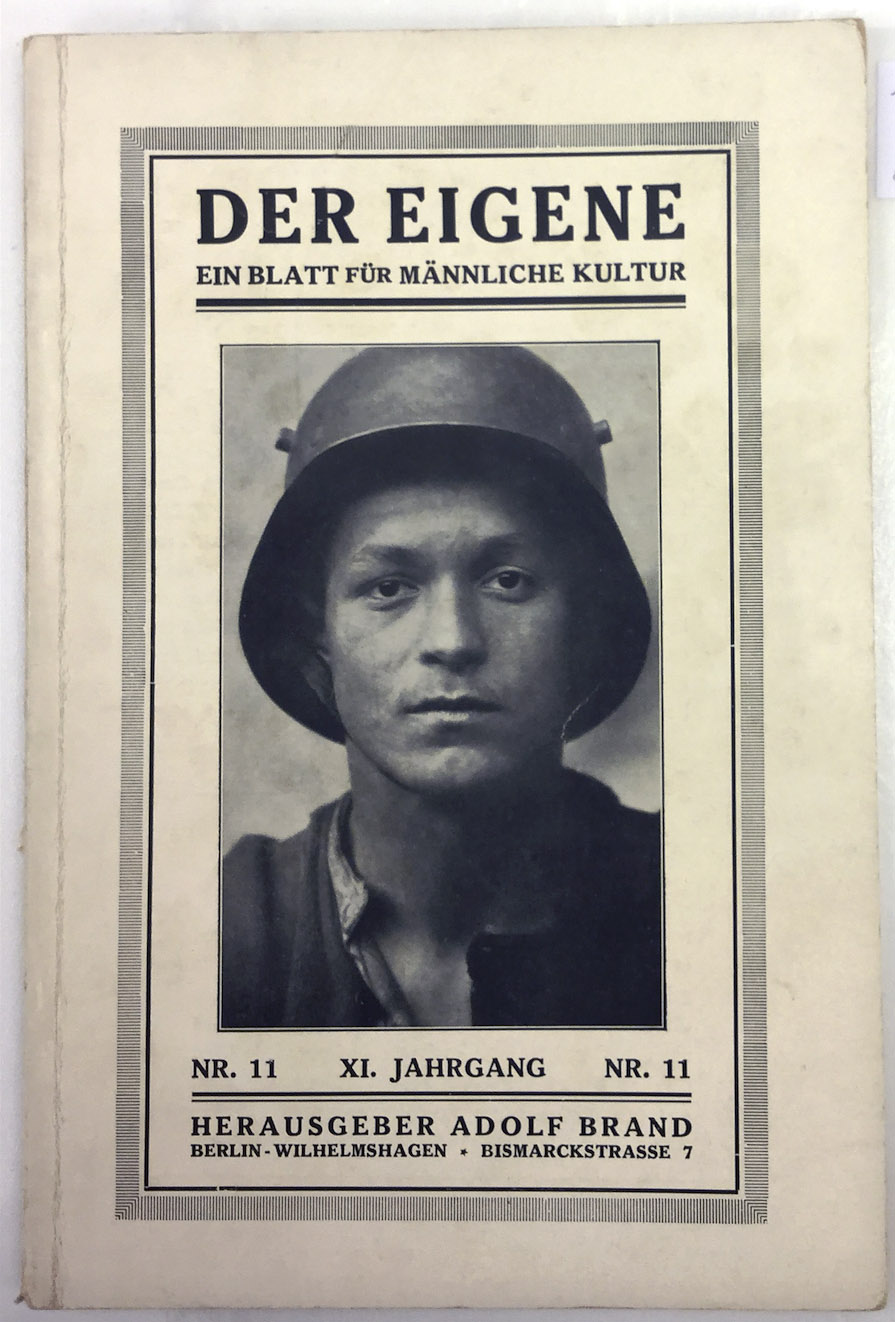

Queer subcultures flourished in the Weimar Republic. A diverse landscape of organisations emerged that represented the interests of gays, lesbians, and trans* persons. However, the struggle against Paragraph 175 was not always synonymous with advocacy for an open society. Among gay activists there were also those who paid homage to a homoerotic male cult. They excluded – in addition to women – all those who did not conform to their heroic, in some cases also racist ideas of masculinity.

Text from Stories of the exhibition TO BE SEEN: Queer Lives 1900-1950

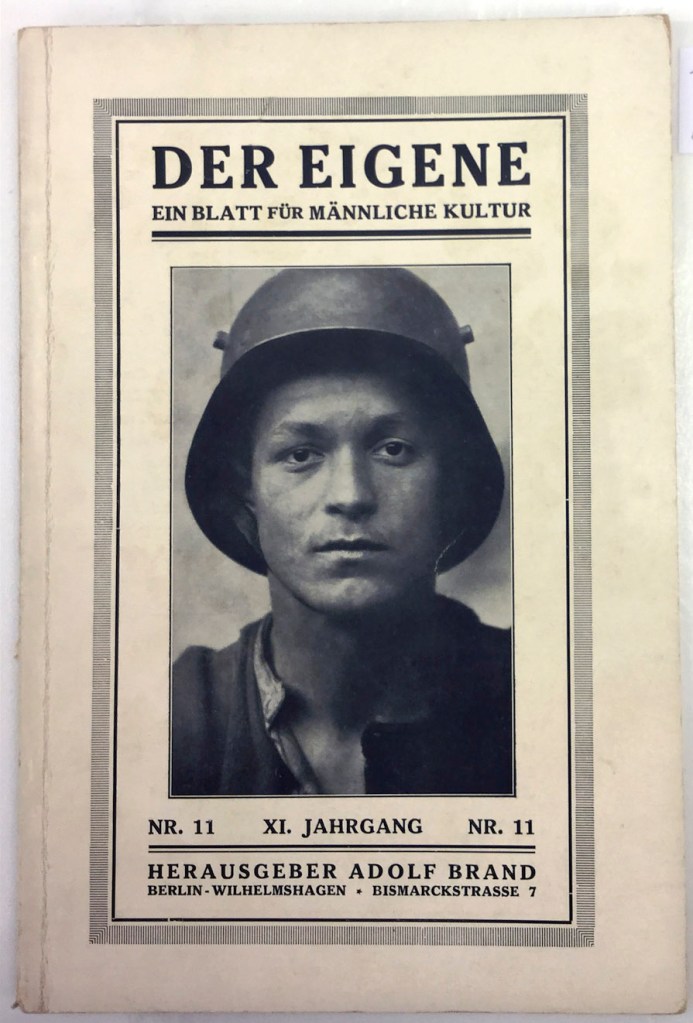

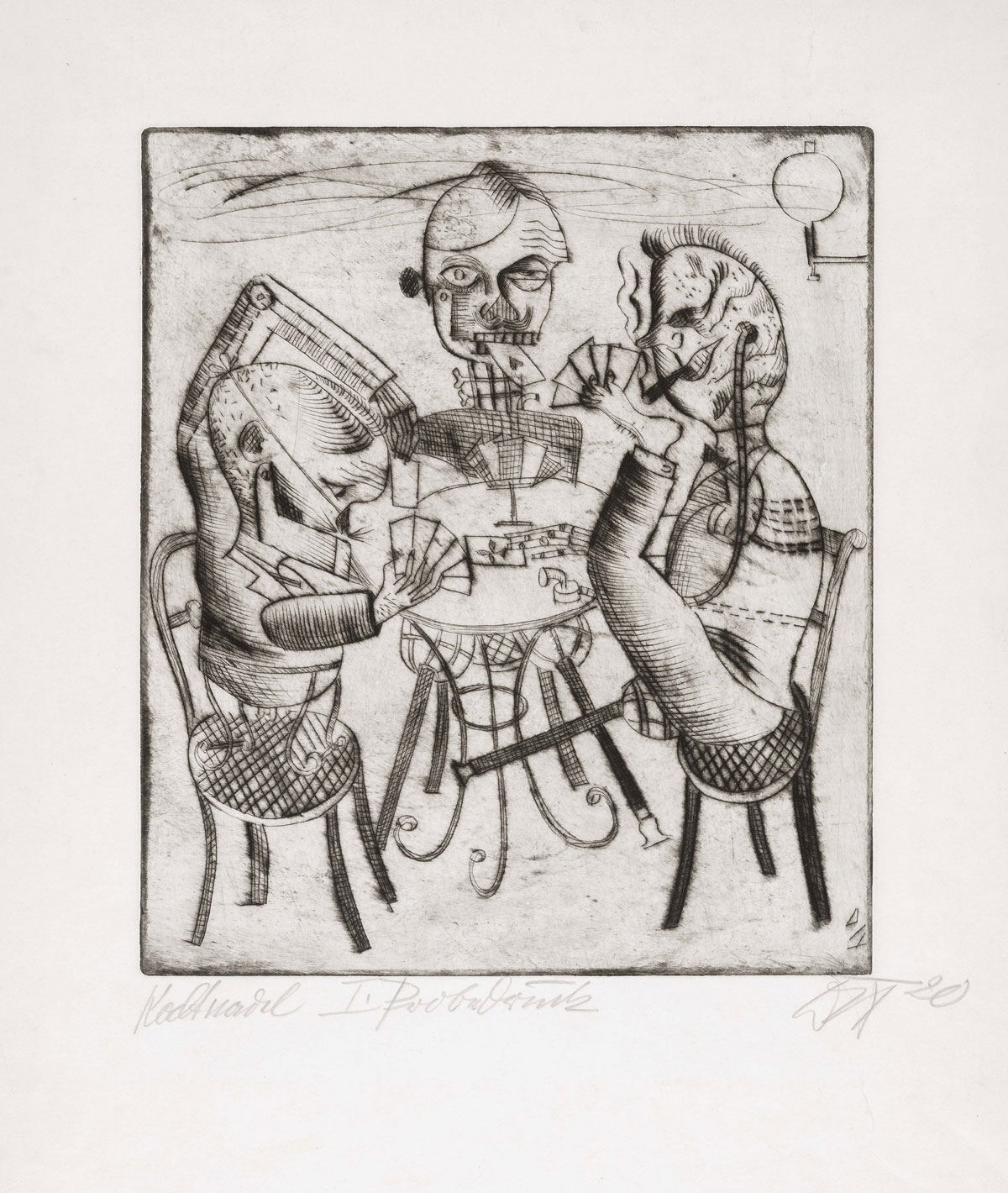

Adolf Brand (publisher)

Der Eigene (The Unique)

1926

Founded in 1896 by Adolf Brand, “Der Eigene” was the longest-running homosexual journal. With its literary-artistic contributions it evoked the image of heroic masculinity.

Struggle against Paragraph 175: the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee

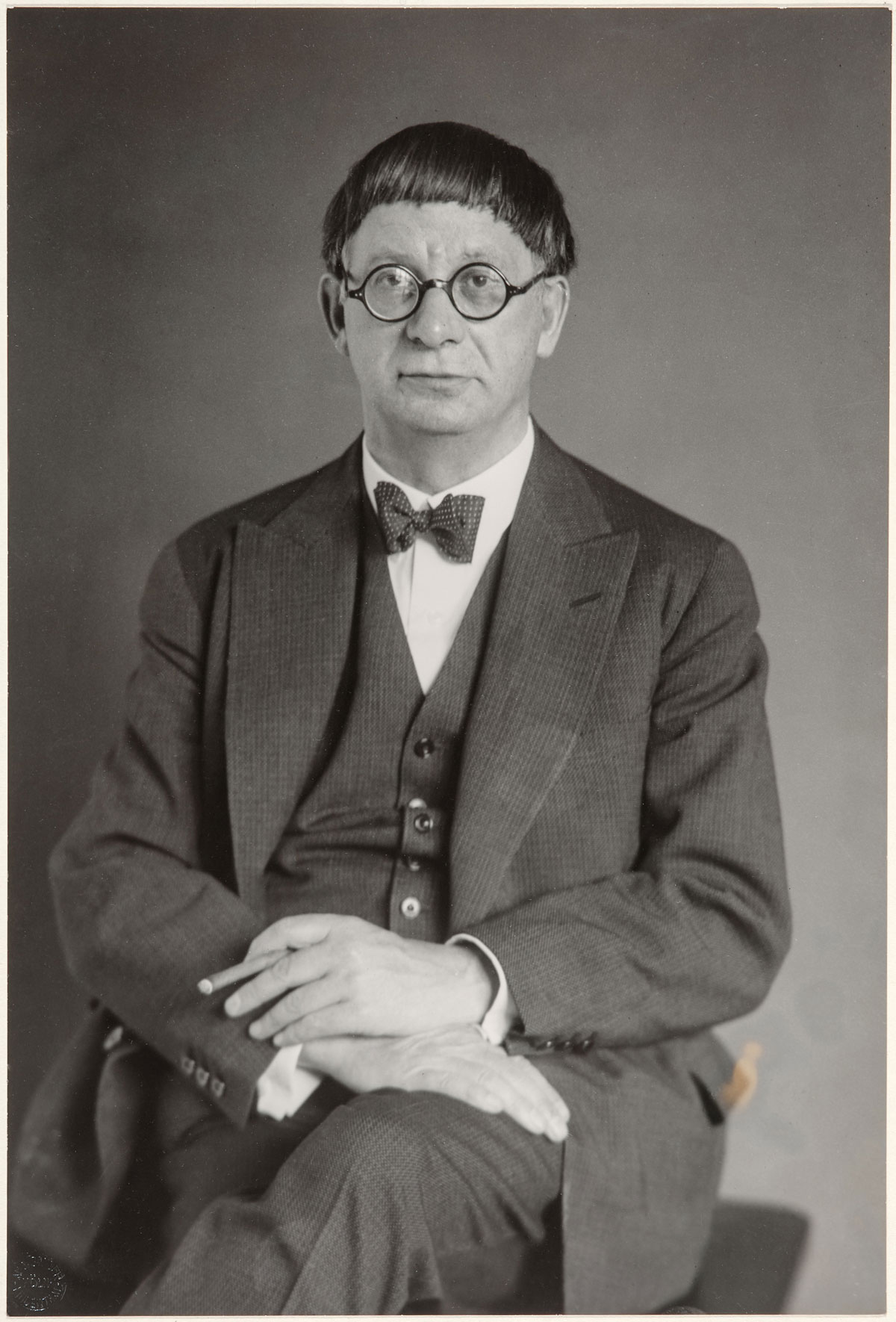

The physician Magnus Hirschfeld (1868-1935) came from a liberal Jewish family and began actively campaigning for the abolition of Paragraph 175 at the end of the nineteenth century. His actions were motivated by the persecution to which gay men were subjected. As a sexual reformer and founder of the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee, he fought against the prevailing rigid sexual morality and contributed significantly to the visibility of queer people.

Magnus Hirschfeld utilised modern means in his educational activities. The silent film drama was shot in 1919 with his active participation. It is considered the first film to deal openly with Anders als die Andern (Different from the Others) the subject of homosexuality. Heavily attacked by conservative and right-wing extremists, and by some with anti-Semitic motives, the film was used as an opportunity to curtail the artistic freedom introduced after the 1918 revolution. After being screened publicly for a full year, the film was banned by censors in 1920 and almost all copies were destroyed.

“Anders als die Andern” is about a homosexual musician who is subject to blackmail. When he no longer knows what to do and files charges, not only is the blackmailer convicted, but he himself is also sentenced – for violating Paragraph 175. He is shattered by the verdict and takes his own life.

Text from Stories of the exhibition TO BE SEEN: Queer Lives 1900-1950

Excerpt from Different from the Others | © UCLA Film & Television Archive

Excerpts from Different From the Others (Anders als die Andern) (Germany, 1919), which was preserved by UCLA Film & Television Archive as part of the Outfest UCLA Legacy Project. Funding provided by The Andrew J. Kuehn Jr. Foundation and the members of Outfest.

Synopsis

The concert violinist Paul Koerner takes a student under his wing, much to the worry of the boy’s parents. Koerner is meanwhile being blackmailed by a former lover, since in Germany any homosexual relations at that time were punishable under the law, codified in Article 175, which was not removed from the books until the 1960s. The German film, Different From the Others is, as far as we know, the first fiction feature film to address a specifically gay audience. Fortunately, even though more than 90% of all German silent films have disappeared, this film exists today in at least half its original length. When the film was first shown in 1919, gay and lesbian audiences must have been amazed that a mainstream fiction feature film would portray their situation as a fact of nature, rather than a perversion. Today, this film celebrates the brief opening of that door, before it slammed shut for another 50 years.

The film was produced and directed by Richard Oswald, at that time one of Germany’s most prolific independents, who made films cheaply and premiered them in a Berlin cinema he owned, where his wife would often handle the office box. Oswald had earned a fortune in 1917 / 1918 with a number of “educational” feature films about sexually transmitted diseases, which were approved by the censorship authorities, simply because syphilis was rampant in the trenches. Oswald would continue to produce controversial films, like his acknowledged masterpiece, The Captain from Koepenick (1931) based on Carl Zuckmayer’s anti-authoritarian play. The Nazis never forgave Oswald for Anders als die Andern or Koepenick, forcing Oswald into exile and eventually to Hollywood, where he directed several films and televisions shows. Although long under appreciated in Germany, recent critical reappraisals have valued his in-your-face aesthetic and modern subject matter.

Only a severely truncated version of the film has survived, with Ukrainian titles, as Gosfilmofond in Russia. It was restored previously to a semblance of the original 1919 release by the Munich Film Museum. The UCLA restoration is based on that Munich reconstruction, with some changes and additions made.

Credits

Richard-Oswald-Produktion. Screenwriters: Magnus Hirschfeld and Richard Oswald. Cinematographer: Max Fassbender. With: Conrad Veidt, Leo Connard, Ilse von Tasso-Lind, Alexandra Willegh, Ernst Pittschau, Fritz Schulz.

Different From Others: A Legacy Preserved (2012)

Featurette about the restoration of German silent film Different From Others (1919). Produced for the Outfest Legacy Project and the UCLA Film & Television Archive.

On October 6 the exhibition TO BE SEEN: Queer lives 1900-1950 opens at the Munich Documentation Center for the History of National Socialism. TO BE SEEN is devoted to the stories of LGBTQI+ in Germany in the first half of the 20th century. Through historical testimony and artistic positions from then and now, it traces queer lives and networks, the areas of freedom enjoyed by LGBTQI+, and the persecution they suffered.

The exhibition takes an intimate look at a variety of genders, bodies, and identities. It shows how queer life became ever more visible during the 1920s, giving rise to a more open treatment of role models and of desire. During this period, homosexual, trans, and non-binary people achieved their first successes in their fight for equal rights and social acceptance. They organised, fought for scientific and legal recognition of their gender identity, and carved out their own spaces.

But as recognition and visibility in art and culture, science, politics, and society increased, so did resistance. After the Nazis came to power, the LGBTQI+ subculture was largely destroyed. After 1945, their stories and fates were scarcely archived or remembered.

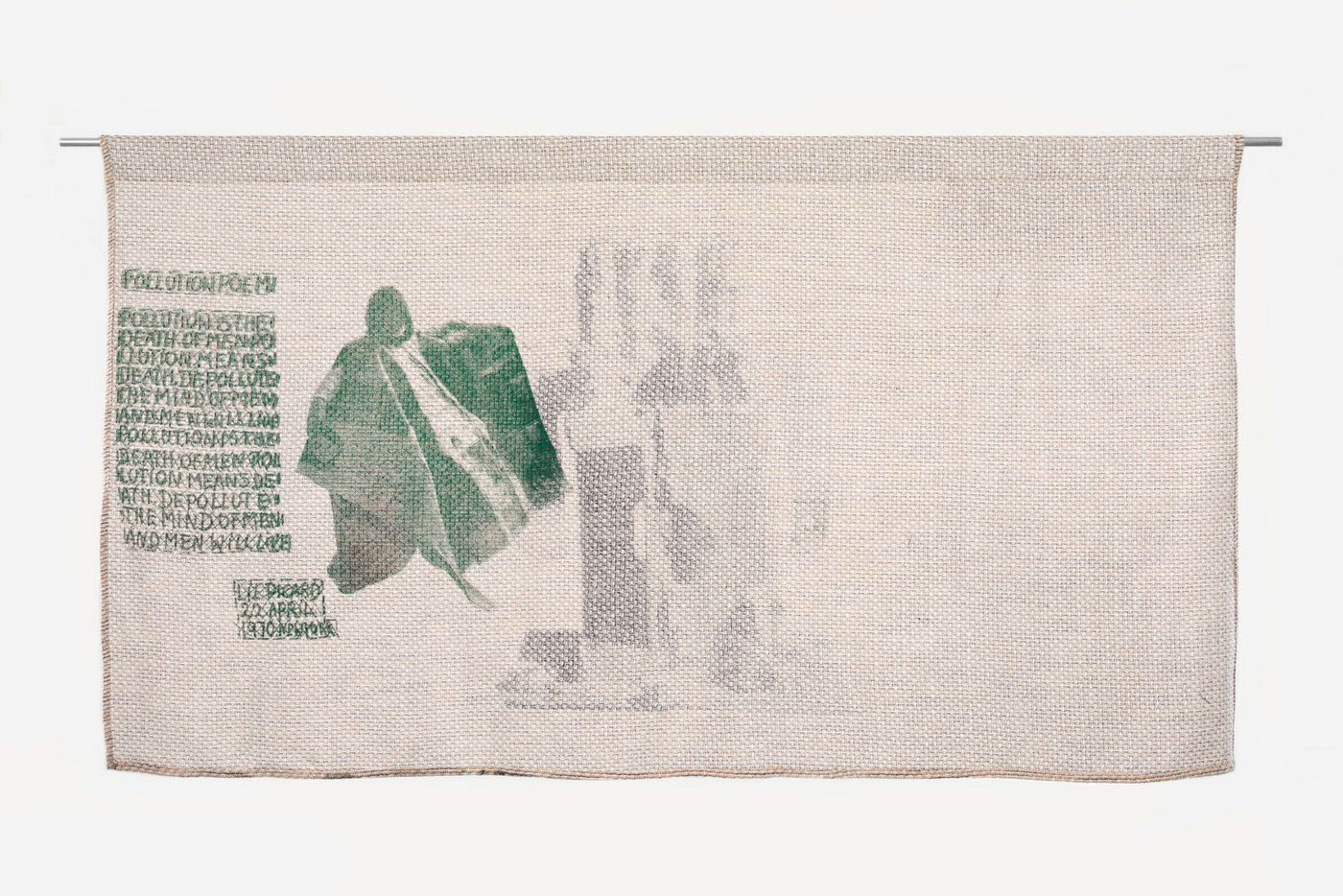

Participating artists

Katharina Aigner, Maximiliane Baumgartner, Pauline Boudry & Renate Lorenz, Claude Cahun, Zackary Drucker & Marval Rex, Nicholas Grafia, Philipp Gufler, Richard Grune, Lena Rosa Händle, Hannah Höch, Paul Hoecker, Nina Jirsíková, Germaine Krull, Elisar von Kupffer, Zoltán Lesi & Ricardo Portilho, Herbert List, Heinz Loew, Jeanne Mammen, Michaela Melián, Henrik Olesen, Emil Orlik, Max Peiffer Watenphul, Jonathan Penca, Lil Picard, Karol Radziszewski, Alexander Sacharoff, Gertrude Sandmann, Christian Schad, Renée Sintenis, Mikołaj Sobczak, Wolfgang Tillmans and others.

TO BE SEEN will be accompanied by an extensive program of events and outreach on topics such as the persecution of LGBTQI+ persons under National Socialism, the queer history of Munich, intersectionality and drag, as well as queer identity in literature and film. All information and updates can be found at nsdoku.de/tobeseen.

The accompanying publication features a collection of texts and artworks from the exhibition as well as essays by key voices that shed light on past and present queer lives from an academic and social perspective. The book in German and English will be published in December 2022 by Hirmer Verlag. It features contributions by, among others, Gürsoy Doğtaş, Michaela Dudley, Sander L. Gilman, Dagmar Herzog, Ulrike Klöppel, Ben Miller, Cara Schweitzer, Sebastien Tremblay.

TO BE SEEN: Queer lives 1900-1950 takes place under the patronage of Claudia Roth, Minister of State for Culture and Media. The exhibition was funded by the German Federal Cultural Foundation and the German Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media.

Director: Mirjam Zadoff

Head Curator: Karolina Kühn

Curators: Juliane Bischoff, Angela Hermann, Sebastian Huber, Anna Straetmans, Ulla-Britta Vollhardt

Project Management: Karolina Kühn, Anna Straetmans, Sebastian Huber

Press release from the Munich Documentation Center for the History of National Socialism

Film still from The Mystery of Gender

Austria 1933

© Filmarchiv Austria

In April 1933, the film “The Mystery of the Gender” ran in Viennese cinemas for about two weeks before it was banned. The film is a mixture of romance and medical educational film, including close-ups of the women’s genitals. Among the protagonists are – without mentioning their names – Toni Ebel, Charlotte Charlaque and Dora Richter. You can find an excerpt of the film in our storytelling http://www.tobeseen.nsdoku.de

Toni Ebel converted to Judaism in early 1933, but reversed the conversion as the pressure of persecution increased. After 1945 she was recognised in the GDR as a victim of fascism. Ebel was able to start a new life as a painter.

Charlotte Charlaque and Toni Ebel remained in correspondence after their forced separation in 1942. In 1946 Charlaque told her friend about her loneliness, her arrival as a refugee in New York and the difficulties in getting her female name recognised.

Dora Richter became known as one of the first trans* women to undergo gender reassignment surgery. Since it was difficult for trans* people to find work, she took a job as a housemaid at the Institute for Sexology, which was looted by National Socialist groups in 1933. Nothing is known of Richter’s fate after 1933.

Text from the Munich Documentation Center for the History of National Socialism Instagram page

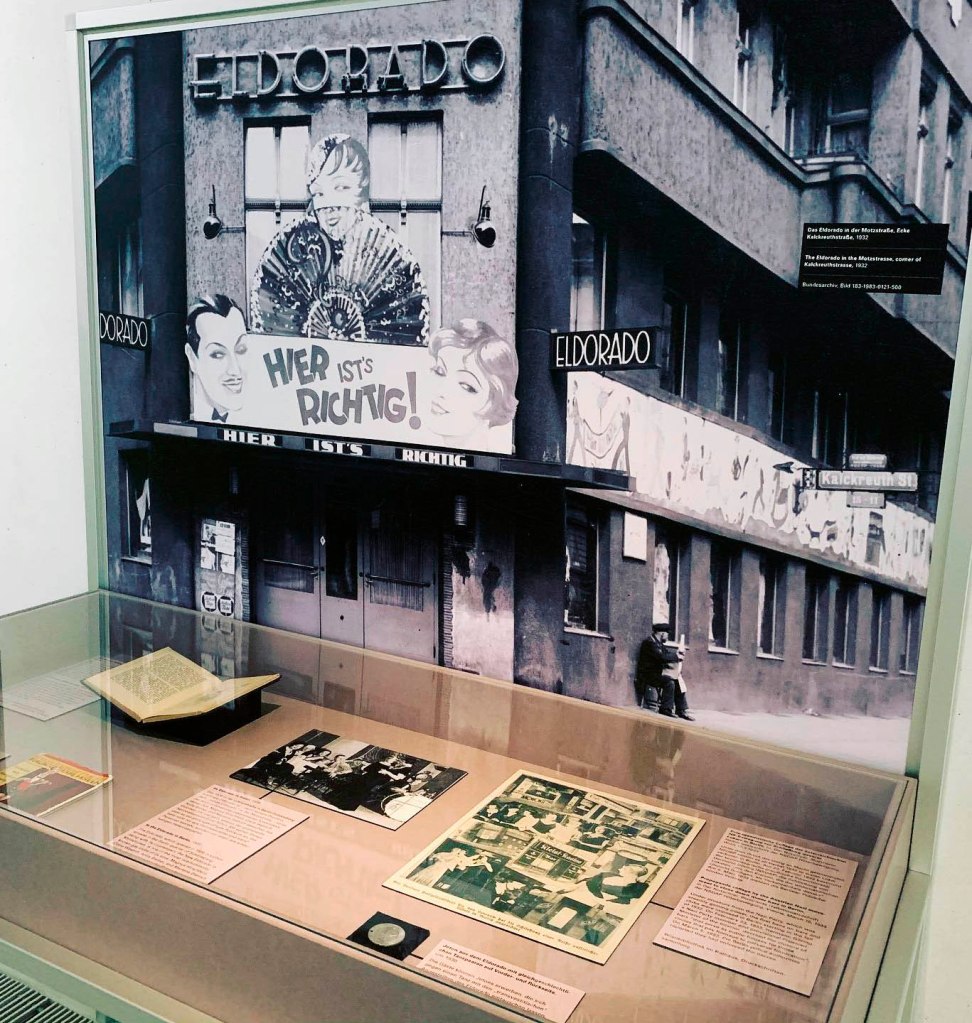

Installation view of the exhibition TO BE SEEN: Queer Lives 1900-1950 at the Munich Documentation Center for the History of National Socialism showing at rear, an enlargement of an image by an unknown photographer of the Eldorado in the Motzstrasse (1932, below); and at left centre in the display cabinet, an image by an unknown photographer Trans* people in the Eldorado in Berlin (1926, above)

Photo: Connolly Weber Photography/NS-Dokumentationszentrum München

The Eldorado on Lutherstraße was one of the city’s infamous cabaret bars.

The Eldorado was the name of multiple nightclubs and performance venues in Berlin before the Nazi Era and World War II. The name of the cabaret Eldorado has become an integral part of the popular iconography of what has come to be seen as the culture of the period in German history often referred to as the “Weimar Republic”. …

Eldorado was a gay cabaret in that along with gay, lesbian, bisexual, trans* patrons, a heterosexual-identifying audience (artists, authors, celebrities, tourists) would have been present as well. “Cross-dressing” was tolerated on the premises, though for the most part legally prohibited and / or sharply regulated in public (and to an extent in private) at the time. This exception to everyday life attracted not only male patrons who wished to dress in the “clothing of the opposite sex”, and their admirers, but also to no small extent women who wished to do the same, and their admirers. Wealthy lookers-on were encouraged to come and drink and watch as so-called “Zechenmacher” (tab payers). The practice was particularly common in so-called “Lesbian bars” or at so-called “Lesbian balls” in the neighbourhood at the time and up the 1960s in places like the Nationalhof at nearby Bülowstraße 37. As women’s incomes were on average much lower than men’s then as now, male spectators with money to spend were explicitly welcome, and it was not uncommon that there were sex-workers present to offer their services. Eldorado also included what have come to be called drag shows as a regular part of the cabaret performances.

Text from the Wikipedia website

The Eldorado, which opened in 1926 on Lutherstrasse in Berlin-Schoeneberg, was – along with its counterpart, the “new Eldorado” on Motzstrasse – one of the internationally most well-known trendy bars of its time. Magnus Hirschfeld, Claire Waldoff, Anita Berber and Marlene Dietrich often and happily visited the Eldorado, as did the prominent National Socialist Ernst Röhm. With its shows, it attracted a wealthy audience, which soon consisted not only of homosexuals and trans* people, but above all of onlookers heterosexuals. Guests could purchase tokens that could be exchanged for a dance with the Eldorado’s “transvestite” staff.

Token from the Eldorado with same-sex dancing couples on the front and back

c. 1930

© Gay Museum, Berlin

Dance monocle in original bag

© dhmberlin

A popular accessory for lesbian women in the 1920s was the “dance monocle”

Short hair, ties, tails, and top hats were other identifying marks within part of the lesbian scene – and soon to be common among modern heterosexual women as well. The “New Woman” of the 1920s broke away from traditional gender images and appropriated new things and spaces that had previously been occupied by men.

In the Berlin scene, but also in other cities, numerous gay and lesbian clubs that rented premises, called for social activities, but also explicitly pursued political and emancipatory goals. One of the largest “women’s clubs” was the Violetta Ladies’ Club, founded in Berlin in 1926.

The founder of the women’s club Violetta was the lesbian activist Lotte Hahm (1890-1967), who also wrote for “The Girlfriend”. Together with her Jewish partner Käthe Fleischmann (1899-1967) she ran the lesbian bar Monokel-Diele in Berlin. After 1933, both initially tried to maintain lesbian networks and meeting places under cover names. Fleischmann, persecuted as a Jew, survived the Nazi era in various hiding places.

Text from the Munich Documentation Center for the History of National Socialism Instagram page

Invitations to monocle parties of the Violetta women’s club in Berlin and the women’s association “Geselligkeit” in Chemnitz

In Garçonne 1931/1939

© forummuenchenev

Unknown photographer

The Eldorado in the Motzstrasse, corner of Kalckreuthstrasse

1932

© nsdoku

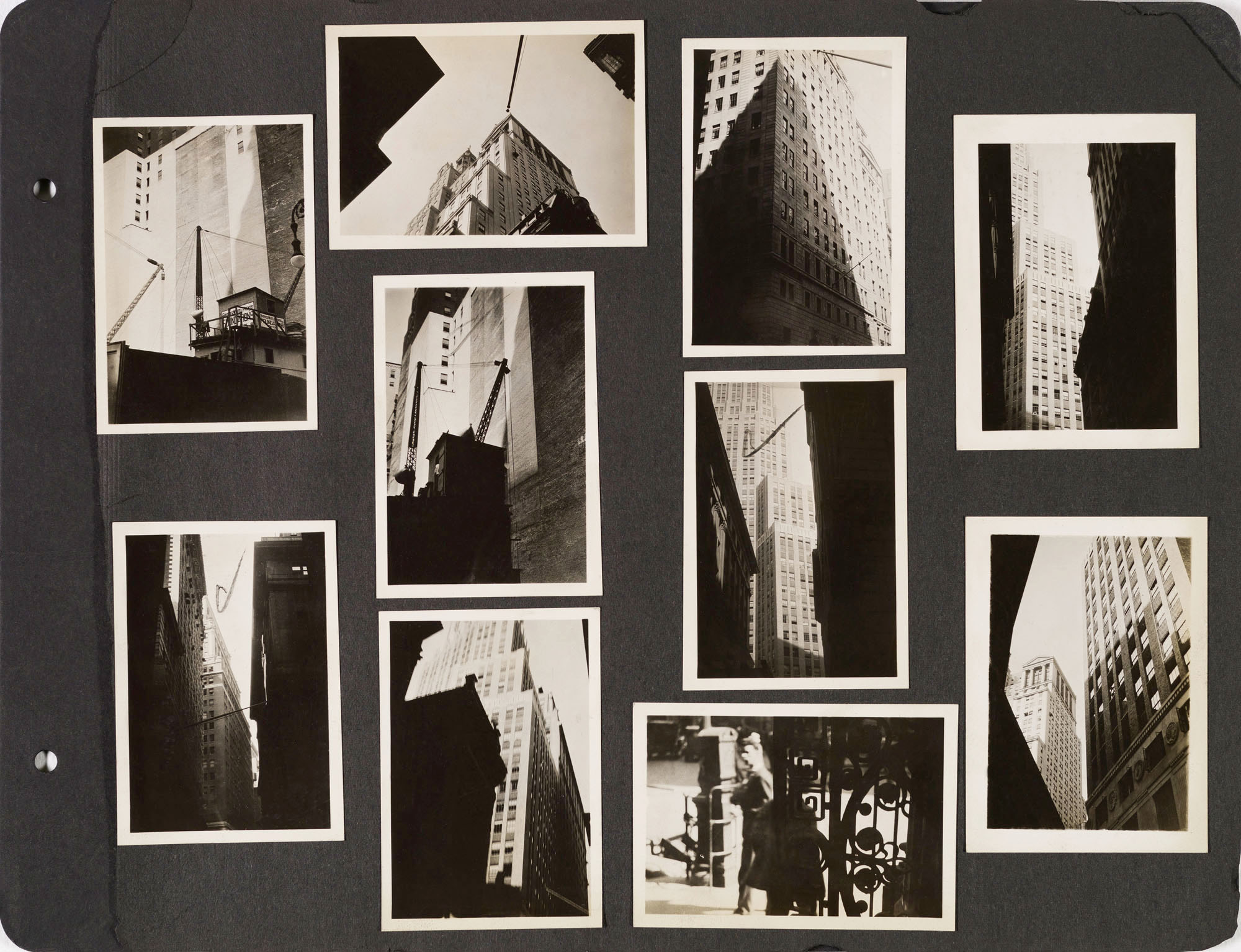

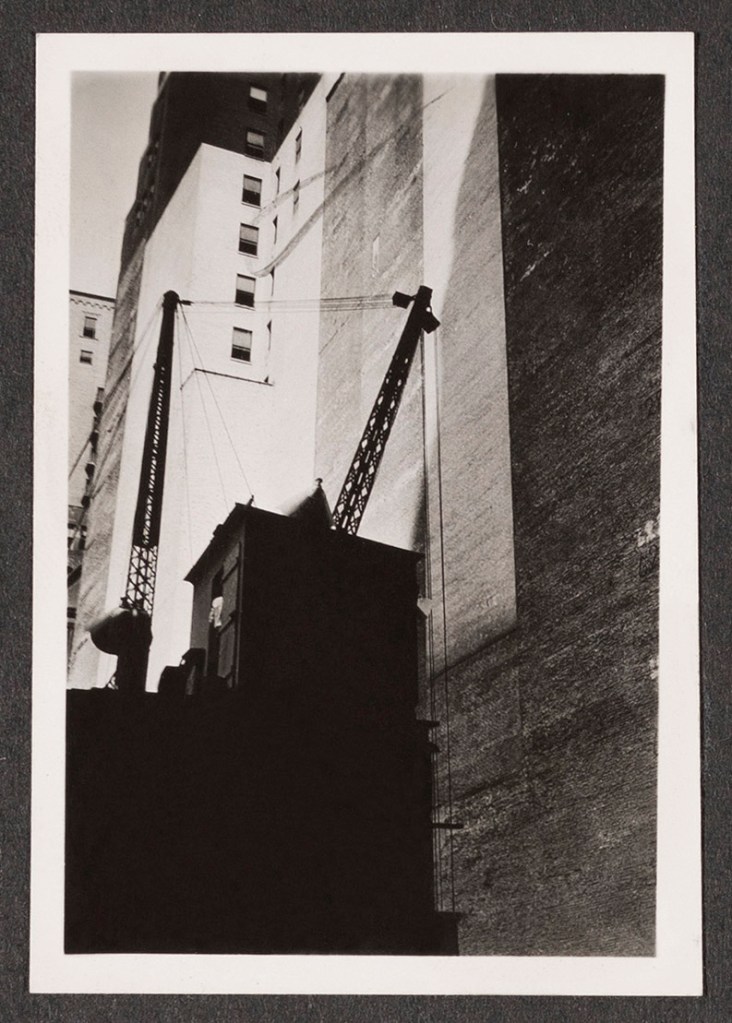

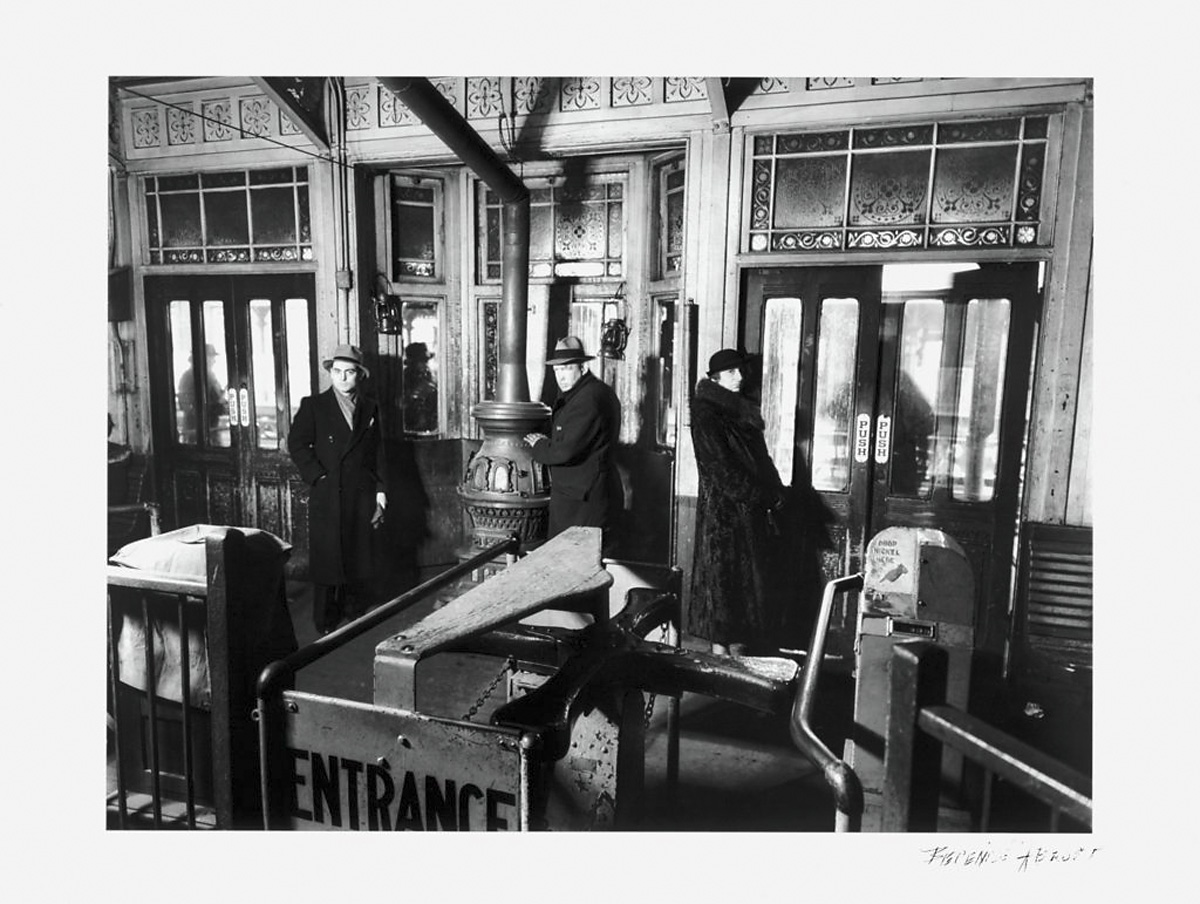

Meeting places

A lively scene for homosexuals and trans* persons emerged in Germany during the 1920s. Especially in major cities, a number of clubhouses, bars, and clubs functioned as meeting places. The undisputed centre of queer life was Berlin. Police authorities there followed a more liberal course than elsewhere after the end of the nineteenth century. Nearly two hundred subcultural venues are documented in the imperial capital between 1919 and 1933, about eighty of them for lesbian women.

In conservative Munich, as in smaller cities and rural areas, fewer venues existed. Homosexual men had to resort to informal meeting places, due to the ongoing criminal persecution. They used public parks and toilets as “pick-up spots” to socialise or have sex. In doing so, they always ran the risk of being denounced or stopped by the police.

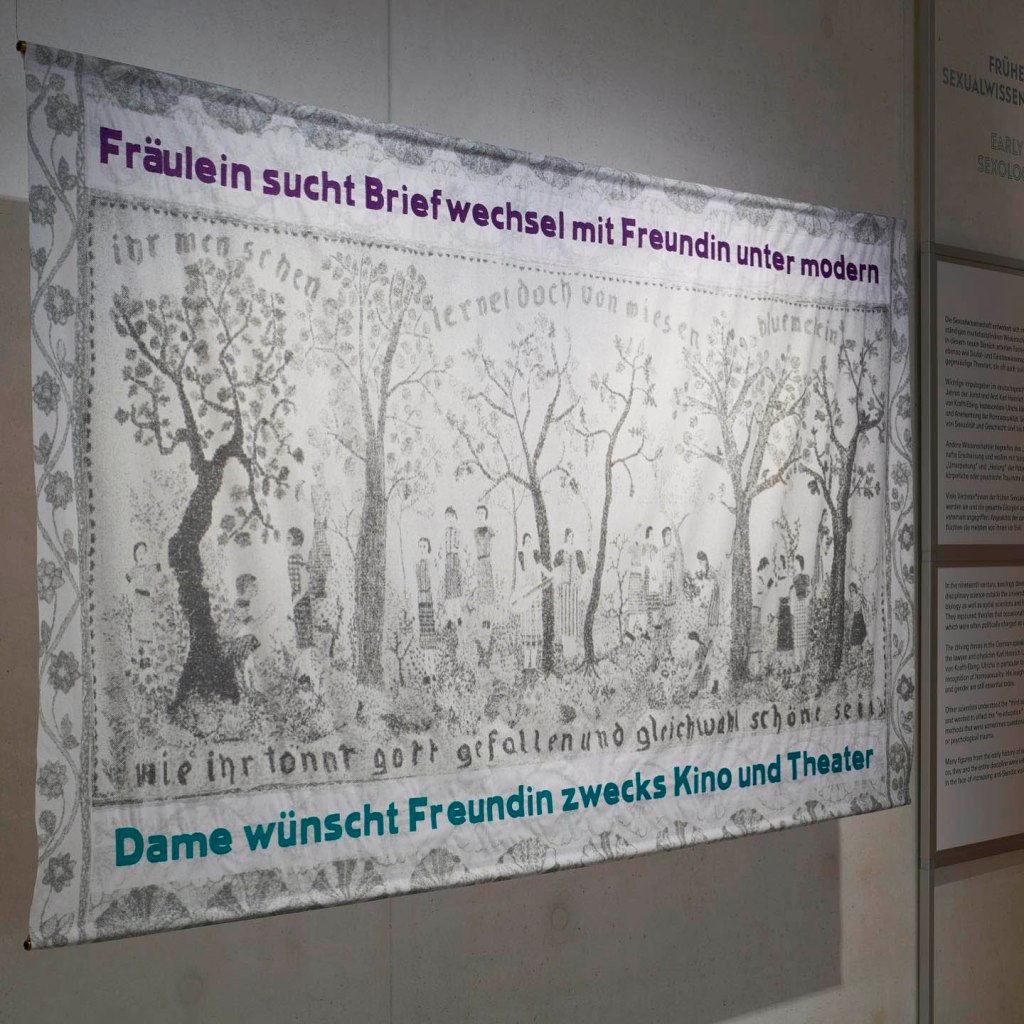

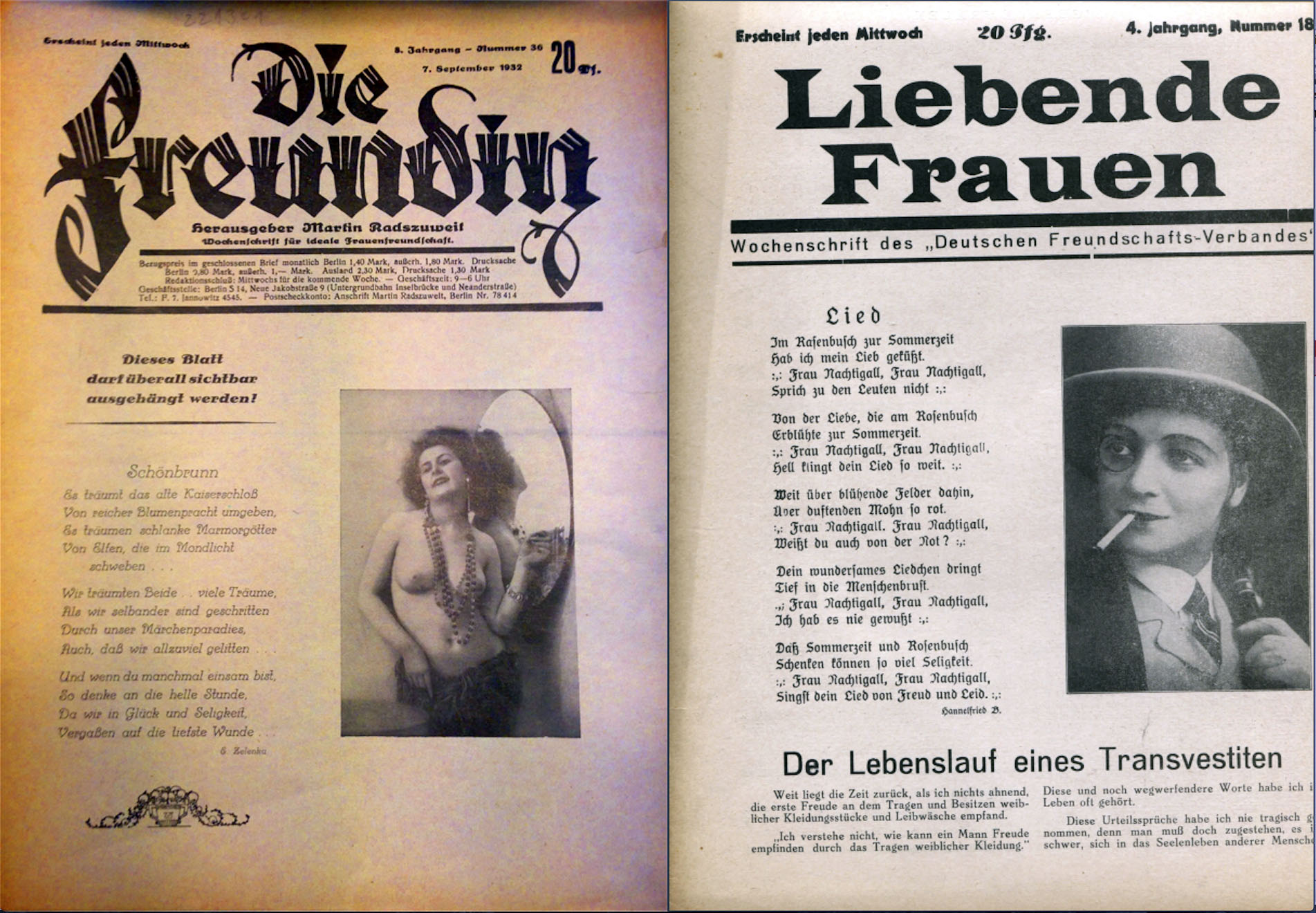

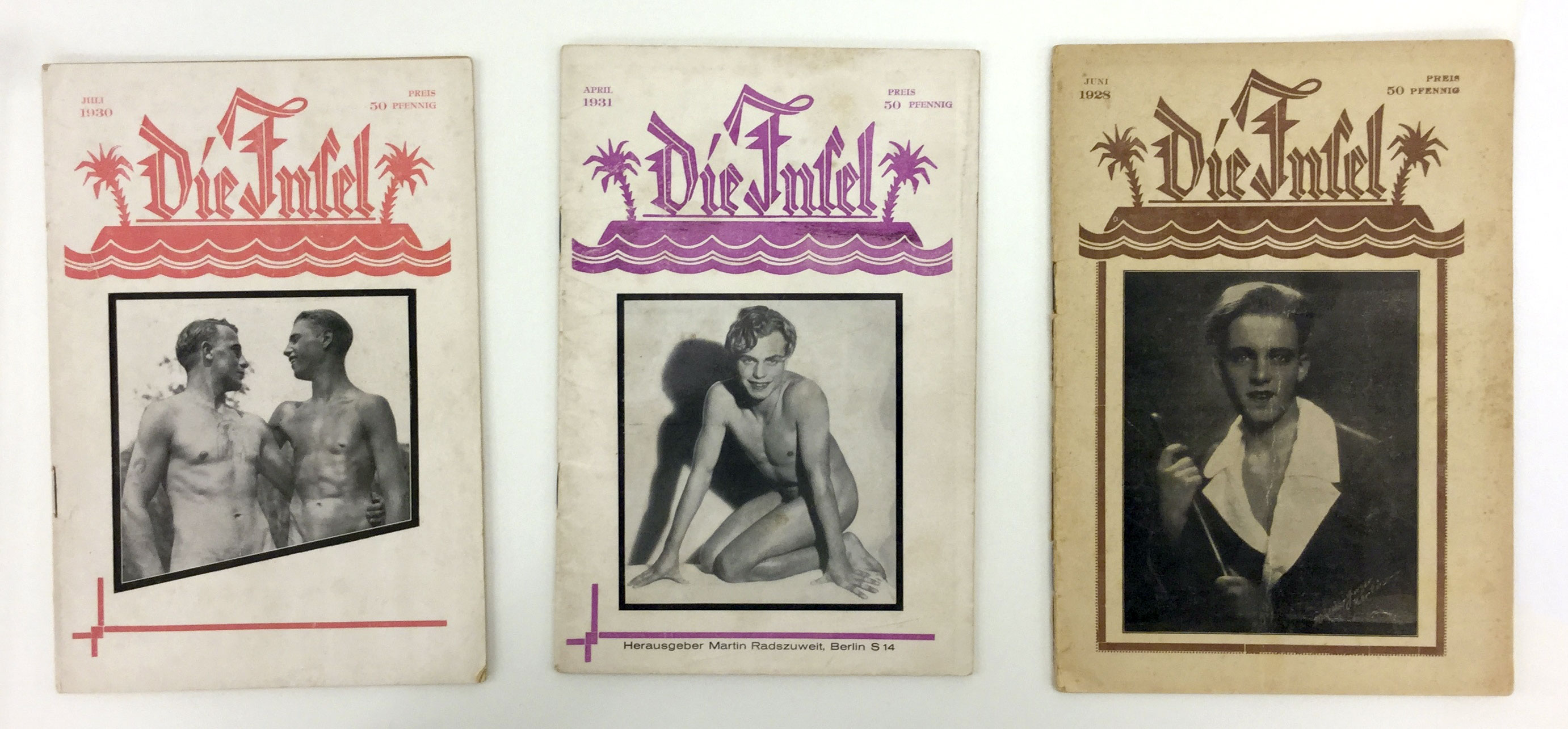

Magazines and informal networks

Magazines were an important means of communication for queer subcultures. They listed relevant clubs and bars, bookstores, and associations, and served as contact exchanges. These references and opportunities were essential particularly for queer people in rural areas, where there were no functioning networks. However, the publishers had to reckon with the banning of their print products at any time. It was not uncommon for entire print runs or volumes to be labeled as “trash texts” and confiscated.

In order to avoid police persecution and social exclusion, the scene employed its own linguistic codes. Camouflage terms such as “friend”, “girlfriend”, “ideal friendship”, “friendly exchange of ideas”, or “ideal-minded” were used to refer to lesbian and gay connections. Lonely hearts ads in relevant magazines were often the only way to find like-minded people, especially in smaller towns and in the countryside.

Text from Stories of the exhibition TO BE SEEN: Queer Lives 1900-1950

Installation view of the exhibition TO BE SEEN: Queer Lives 1900-1950 at the Munich Documentation Center for the History of National Socialism showing historical magazines

In TO BE SEEN you can leaf through historical magazines. They were an important means of communication for queer subcultures.

Magazines such as “Die Freundsblatt”, “DasFreundschaftsblatt” or “Frauenliebe” referred to relevant pubs, bookstores and associations and served as contact exchanges. Especially for queer people in rural areas, where there were no functioning networks, these tips and opportunities were essential. However, the publishers had to expect their printed products to be banned at any time. It is not uncommon for entire editions or volumes to be marked as “trash and dirty writing” and confiscated.

“The Girlfriend” (subtitle “The Ideal Friendship Journal”, later “Weekly Journal for Ideal Female Friendship”) was a magazine for lesbian women from 1924 to 1933 in Berlin during the Weimar Republic. It is considered the first lesbian magazine and was first published monthly, then every two weeks, and later even weekly.

The editor was Friedrich Radzuweit (1876-1932), chairman of the Federation for Human Rights. The content focuses on information on lesbian life and meeting places for lesbians, political topics, short stories, serialised novels and classifieds. Although “The Girlfriend” was primarily aimed at a lesbian readership, there are also numerous articles that deal with topics such as ‘transvestism’ or transgender. It was discontinued a few weeks after the National Socialists seized power in January 1933: the last issue appeared on March 15, 1933, a week before the Enabling Act was passed.

Covers from Die Freundin (The Girlfriend), September 1932, and Liebende Frauen (Women in Love), 1929

Cover of “Die Freundin” (The Girlfriend)

26. December 1927

© Forum Queeres Archiv München

Unknown photographer

Magnus Hirschfeld

c. 1900

© Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz

Unknown photographer

“Zwischenstufenwand” (sexual transitions wall)

c. 1925-1930

Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz

The “Zwischenstufenwand” (sexual transitions wall) in the Institute for Sexology illustrated Hirschfeld’s theory that all people have male and female qualities in them.

The famous picture wall, illustrating Hirschfeld’s sex and gender theories. It was first exhibited in Leipzig (1922) on occasion of the German Natural Scientists’ and Physicians’ centenary and then in Vienna (1930) at the World League for Sexual Reform’s congress. The picture wall (2×1 m by 4×5 m) always had a prominent place in the Institute and was used to explain sexual theories to visitors.

Installation view of the exhibition TO BE SEEN: Queer Lives 1900-1950 at the Munich Documentation Center for the History of National Socialism

Knowledge, diagnosis, control

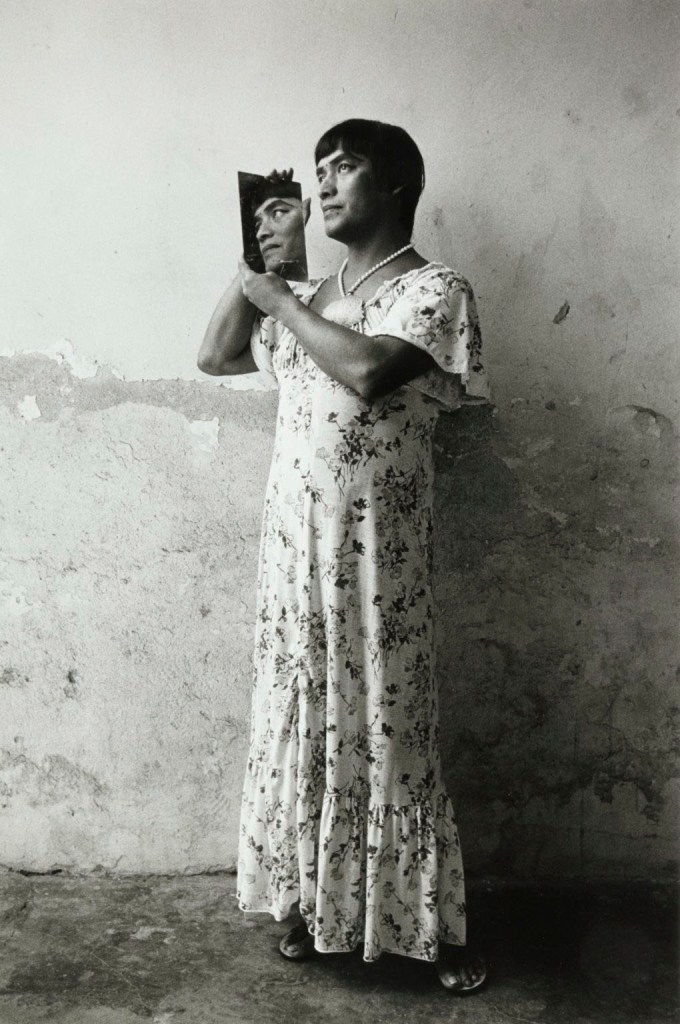

Scientific interest in sexuality and gender was expanding around the turn of the century. The amount of sexological research and number of publications increased. Most writings described homosexuality or trans* identities as “pathological” conditions. This assumption has since been scientifically refuted. At the same time, groundbreaking theories emerged, for example Magnus Hirschfeld’s model of “sexual intermediates.” In it, the sexologist anticipated the later realisation that numerous other gender identities besides man and woman exist.

Yet, then as now, knowledge also meant power and control. People were examined, described, classified, and judged as patients. Some sexologists incorporated ideas in their research that drew on biologism and eugenics. These were spread throughout society and later played a central role for the Nazis: their conception of so-called “racial hygiene” distinguished between “valuable” and “unworthy” life.

The driving forces in the German-speaking world from the 1860s on were the lawyer and physician Karl Heinrich Ulrichs and the physician Richard von Krafft-Ebing. Ulrichs in particular fought for the decriminalisation and recognition of homosexuality. His insights into the diversity of sexuality and gender are still essential today. Other scientists understood the “third sex” as a pathological phenomenon and wanted to effect the “re-education” and “healing” of their patients with methods that were sometimes questionable. The result was often physical or psychological trauma.

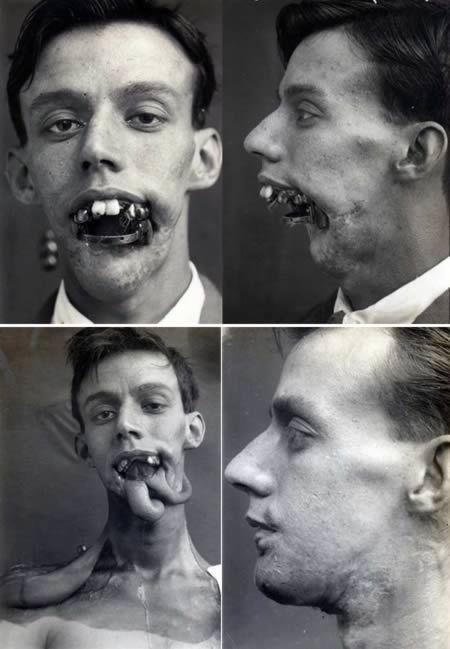

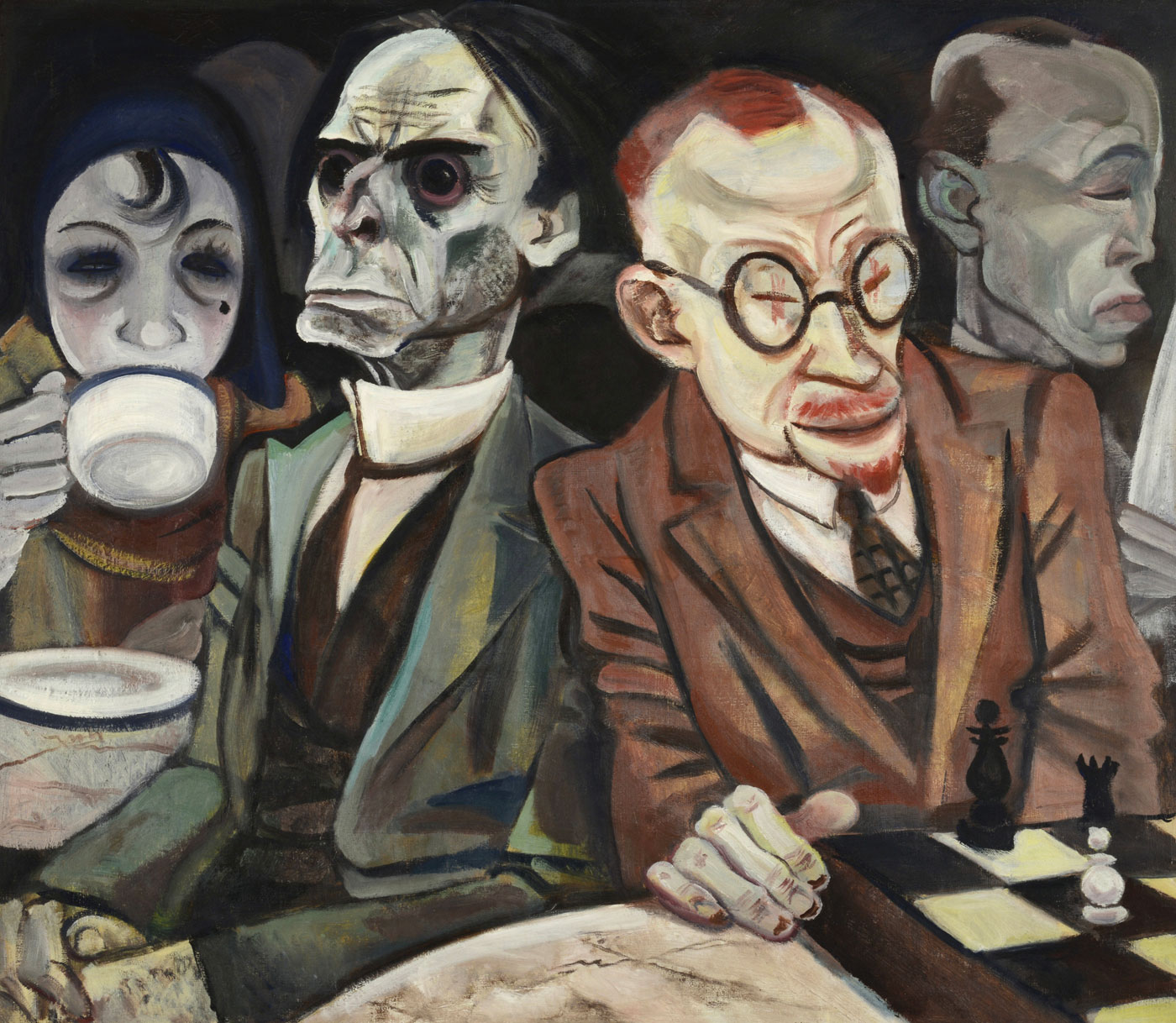

The Institute for Sexology and its patients

Magnus Hirschfeld was the best-known representative of sexology in the German-speaking world. He combined a pursuit for emancipation and a scientific perspective, was a champion of decriminalisation and a physician at the same time. His Institute for Sexology, founded in Berlin in 1919, became the centre of the liberal-leftist sexual reform movement of the Weimar Republic. In addition to research and medical consulting, the institute operated a library, an archive, and a museum. Unlike conservative sexologists, Hirschfeld and his staff worked towards the self-acceptance of homosexuals and trans* persons.

This “adaptation therapy” or “milieu therapy” aimed to help people adapt to the queer milieu that suited them, instead of repressing their identity. Many important people from the gay community, such as Lili Elbe, were treated here. Homosexual writers such as André Gide and Christopher Isherwood visited the institute. People who today would be considered intersex were also counselled. From the beginning, the Nazis were disturbed by liberal sexology, Hirschfeld, and his institute. Many of the institute’s employees were, like Hirschfeld himself, Jewish. In 1933, Nazi students and SA members demolished the institute; Hirschfeld was on a world tour at the time and remained in exile in France.

The institute grew to become a refuge for “transvestites”. This is how people who we understand today as trans* persons were called at the time. Some of them lived in the institute and earned their living there. They were particularly dependent on it. Despite the institute’s great merits, the relationship between doctors and “patients” was not unproblematic from today’s point of view.

By mediating between queer people and state power, Hirschfeld and his colleagues were able to protect their patients and fight for more rights and freedom for them. But in order to do so, they cooperated with the police and the courts, thus providing the state institutions with access and control. Then as now, intersex and trans* people were rarely perceived as experts on themselves, making them dependent on the recognition bestowed by medicine and the justice system. This was accompanied by a scientific and state-regulatory view of their bodies that pushed them into the role of patients, externally controlled subjects, instead of granting them autonomy over their bodies as well as their own voice.

Text from Stories of the exhibition TO BE SEEN: Queer Lives 1900-1950

Hirschfeld’s medical practices are controversial today

However, Magnus Hirschfeld also referred those male homosexuals who, based on his biological research, assumed that homosexuality could also be treated, to other doctors. They castrated the patients and implanted heterosexual testicles in them.

Not only Magnus Hirschfeld’s medical practices, but also his scientific approach is controversial today. His absolute belief in biology leaned towards social Darwinism and eugenics. He founded a “Medical Society for Sexology and Eugenics”. He thus promoted “sexual selection” in order to improve the “mental fitness of the offspring”. He was thus at the same time far away and entirely in line with the National Socialists.

The National Socialists saw Hirschfeld as a security risk, a threat to the population growth of the “Aryan race” and not only in him. Tens of thousands of gay men are sentenced to prison, jail, and concentration camps, the gay civil rights movement is crushed, gay hangouts are closed, magazines are banned, and then, on May 6, 1933, the Institute for Sex Research is looted and its library burned.

Gabi Schlag and Benno Wenz. “Magnus Hirschfeld – pioneer of sex research,” on the SWR website 29.7.2021 [Online] Cited 12/04/2023

Unknown photographer

First Congress for Sexual Reform on a Sexological Basis

1921

From Magnus Hirschfeld, Sexology, vol. 4, plates

© Forum Queeres Archiv München

Session of the “International Conference for Sex Reform on a Sexological Basis”, organised by Hirschfeld 1921 in Berlin at the Langenbeck-Virchow-Haus. (Hirschfeld, leaning forward, is seated just beneath the lectern.) This was the first sexological congress held anywhere, and it laid the groundwork for the Copenhagen congress of 1928.

Willy Römer (German, 1887-1979)

Transvestites in Front of the Institute of Sexology

1921

Gelatin silver print

© bpk / Kunstbibliothek, SMB, Photothek Willy Römer

Titled “Transvestites in Front of the Institute of Sexology” this photograph was taken on the occasion of the First International Congress for Sexual Reform on the Basis of Sexology in Berlin, 1921.

Willy Römer (December 31 , 1887 in Berlin – October 26, 1979 in West Berlin ) was a press photographer. His picture agency was one of the ten most important of the Weimar period. The pictures mainly illustrate life in Berlin from 1905 to 1935. It is thanks to a rare stroke of luck that his extensive picture archive survived the Second World War almost unscathed.

“Transvestite Certificate” for Gerd Katter

1928

© Archiv der Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft

Starting in 1900, “Transvestite Certificates” were issued by a doctor, that officially certified that a person was known to be “wearing men’s clothing” or “wearing women’s clothing”.

In TO BE SEEN #QueerLives we also show Gerd Katter’s “Transvestite License”. From 1900, “transvestite certificates” were issued in some cities. It is a medically certified official confirmation that a person is known as “wearing men’s clothing” or “wearing women’s clothing”. The authorities refrain from making an arrest if you show them during checks. However, those affected are thus registered with the police and can be monitored more easily.

Gerd Katter (1910-1995) came to the Institute for Sexology at the age of 16 – at that time still with a female birth name. Barred from having his breasts amputated because of his youth, Katter tries to operate on himself, which requires an emergency amputation. Katter is one of many people who receive concrete, albeit unconventional, help at the institute. So he is prescribed to visit bars where “transvestites” meet. According to the adaptation therapy pursued at the institute, those seeking advice should be brought into contact with like-minded people. This is how they should learn to accept themselves.

Magnus Hirschfeld repeatedly invited Gerd Katter to the institute to show his guests a medical case study – a practice of displaying people and their bodies that was common at the time, but which is problematic from today’s medical-ethical point of view. Gerd Katter later completed an apprenticeship as a carpenter and lived in the GDR.

Text from the Munich Documentation Center for the History of National Socialism Instagram page

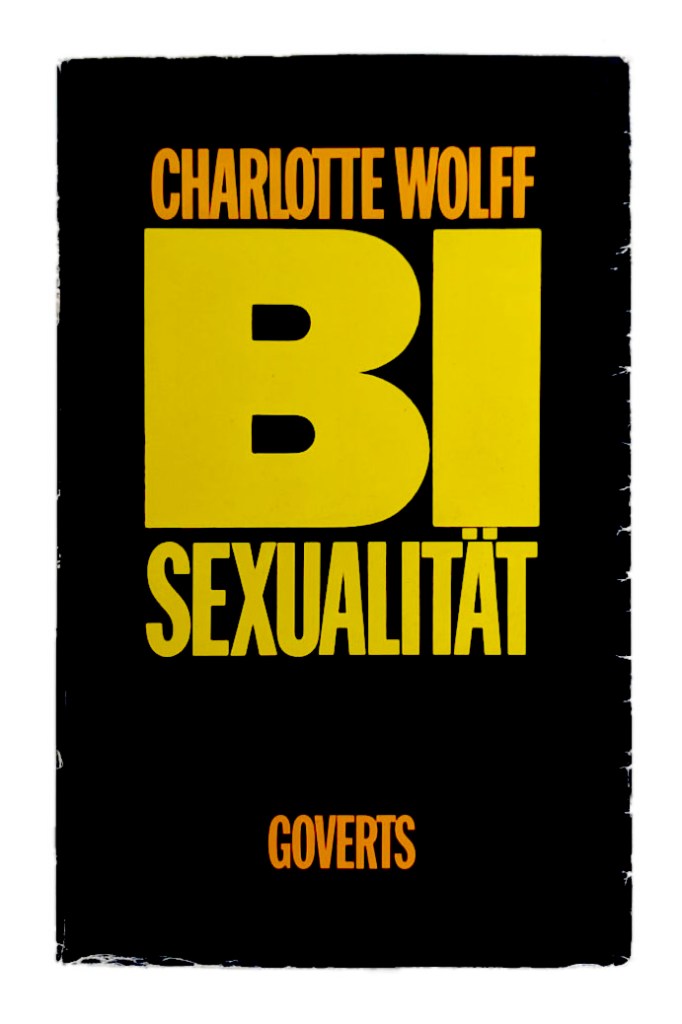

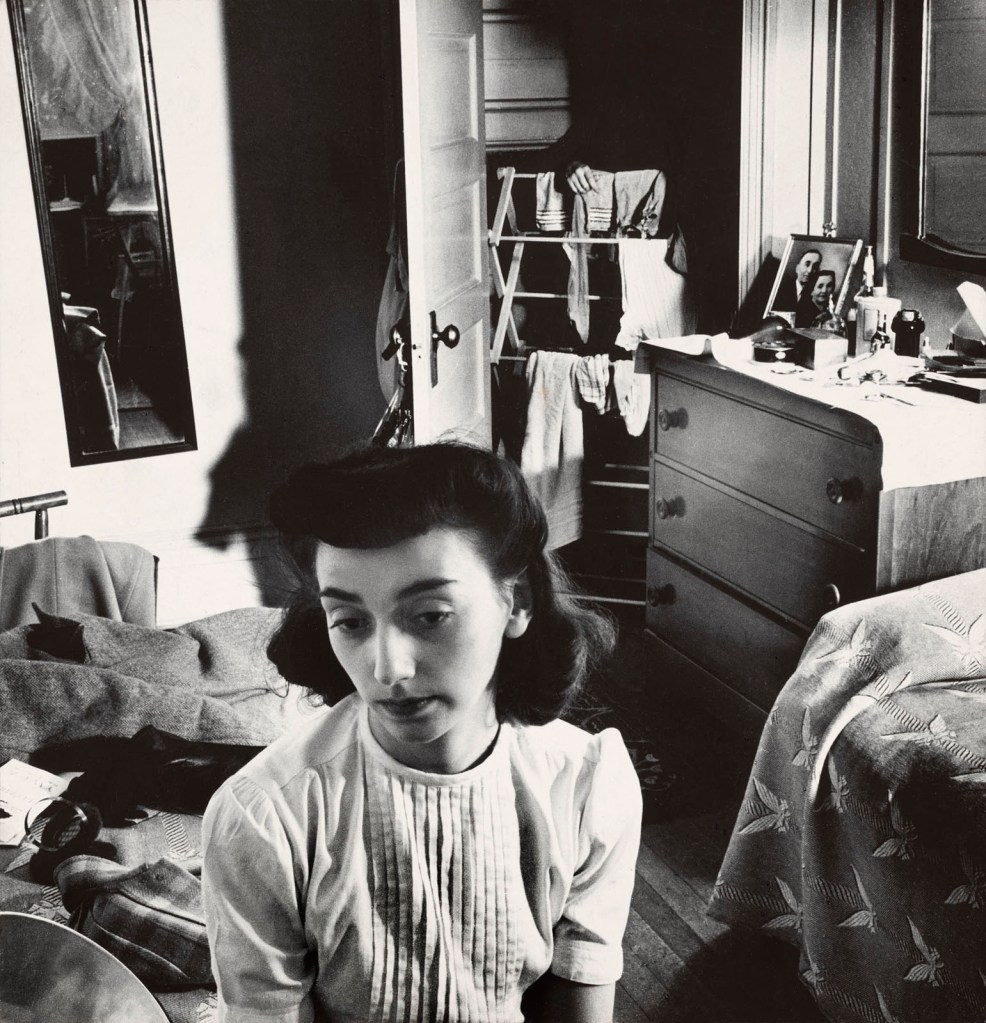

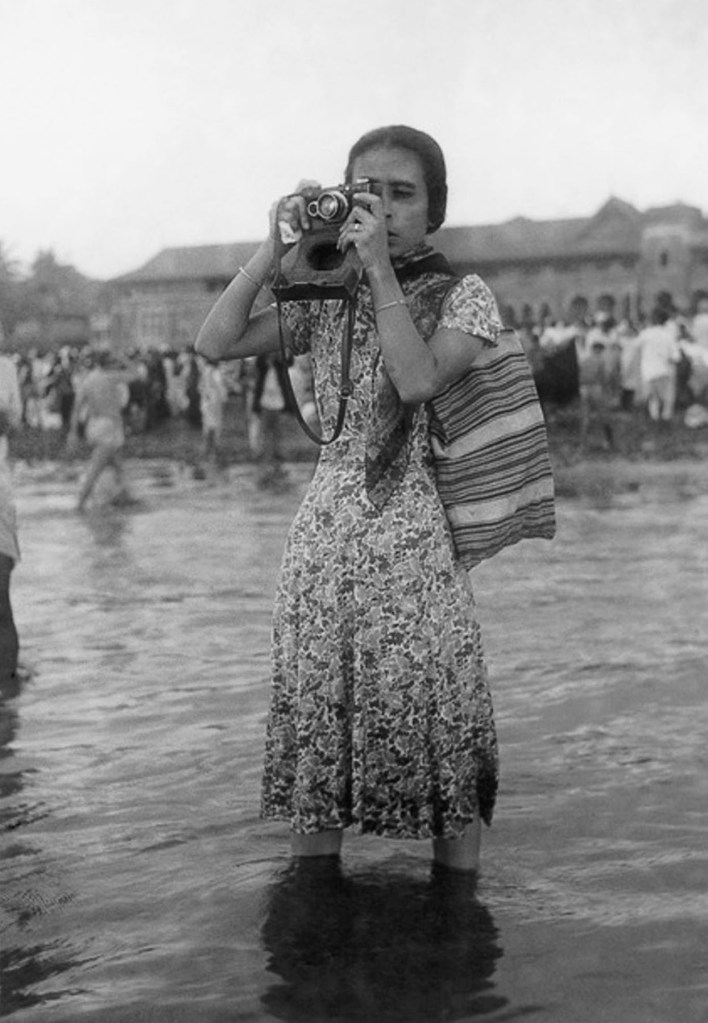

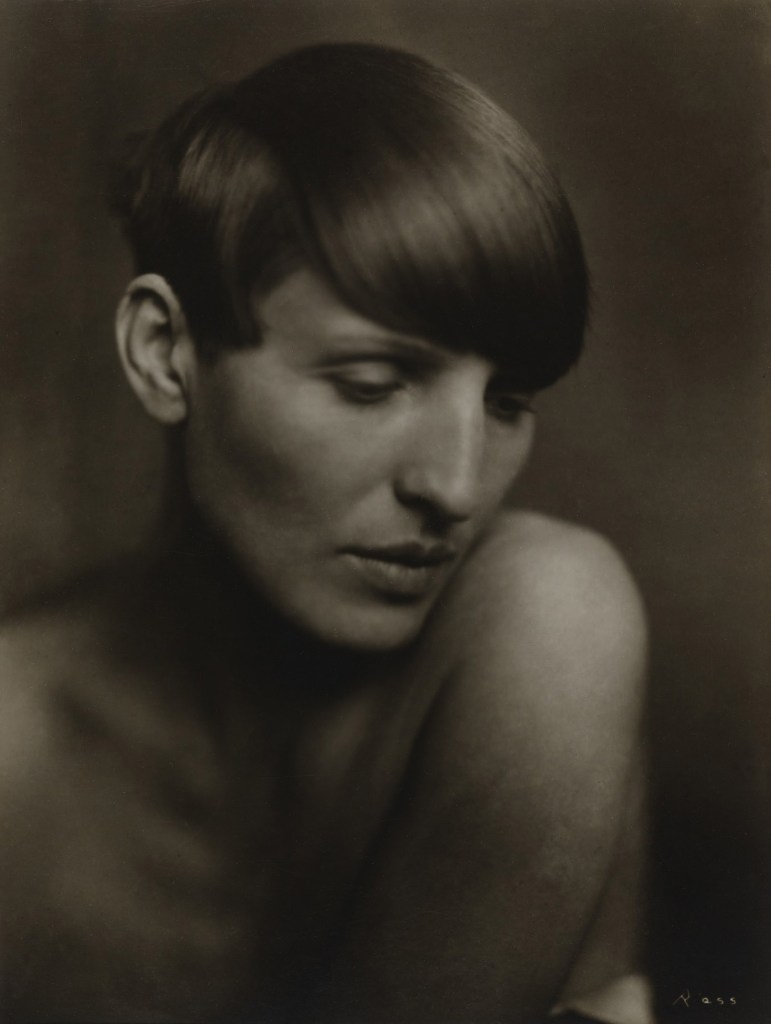

Charlotte Wolff (German-British, 1897-1986)

Bisexuality

German edition from 1981

© NS-Dokumentationszentrum München

Charlotte Wolff – Sexology in Exile

Female homosexuality and bisexuality received little attention in the male-dominated field of sexology. An exception was the research of Charlotte Wolff (1897-1986). The physician situated precisely these topics at the centre of her work. After 1933, left-wing, Jewish, and openly lesbian women in Germany were increasingly targeted by the Nazis. Being Jewish, she emigrated to Paris in 1933, and to London in 1936. Her research on lesbian sexuality and bisexuality earned her international recognition beginning in the 1960s.

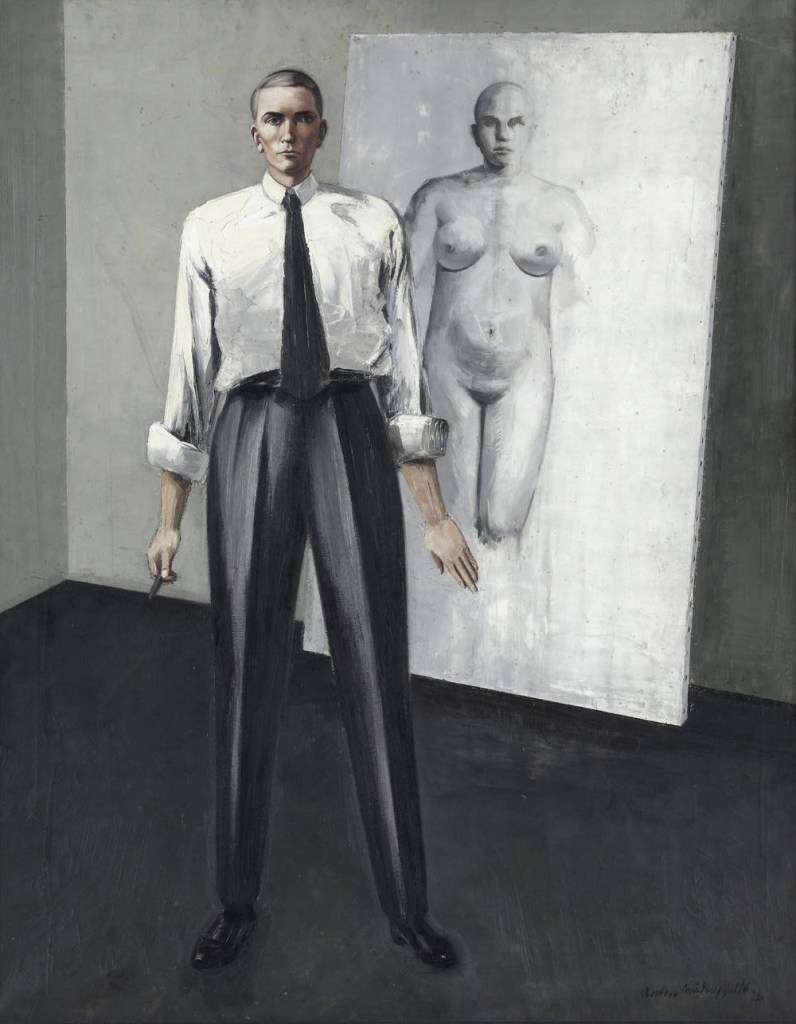

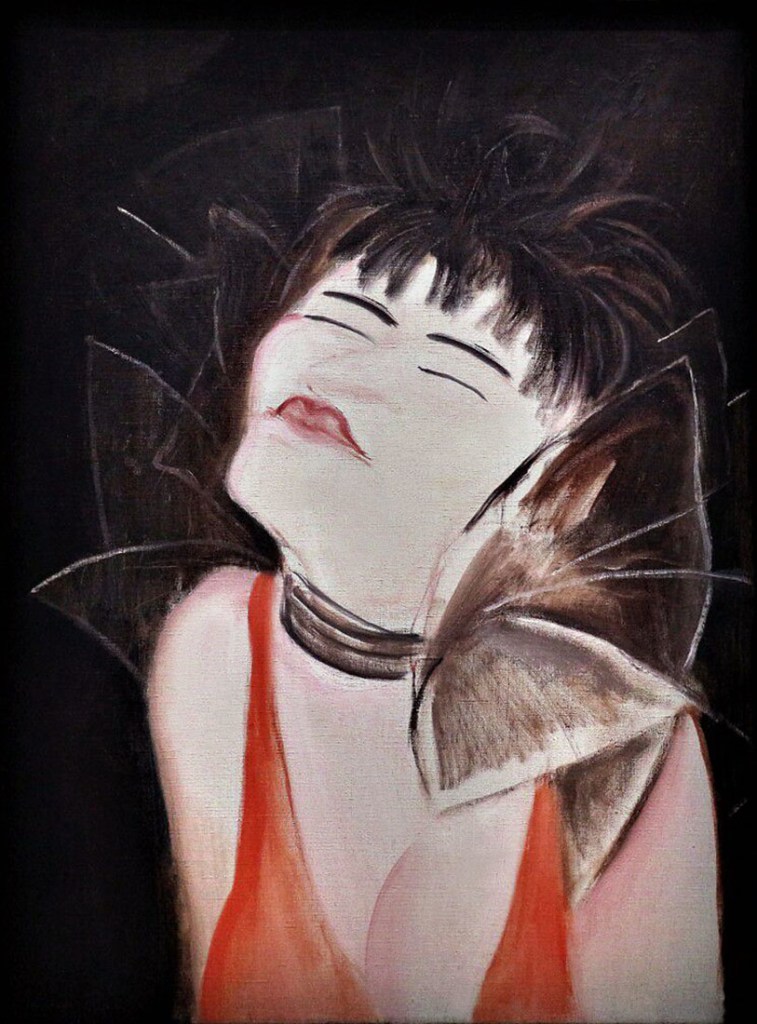

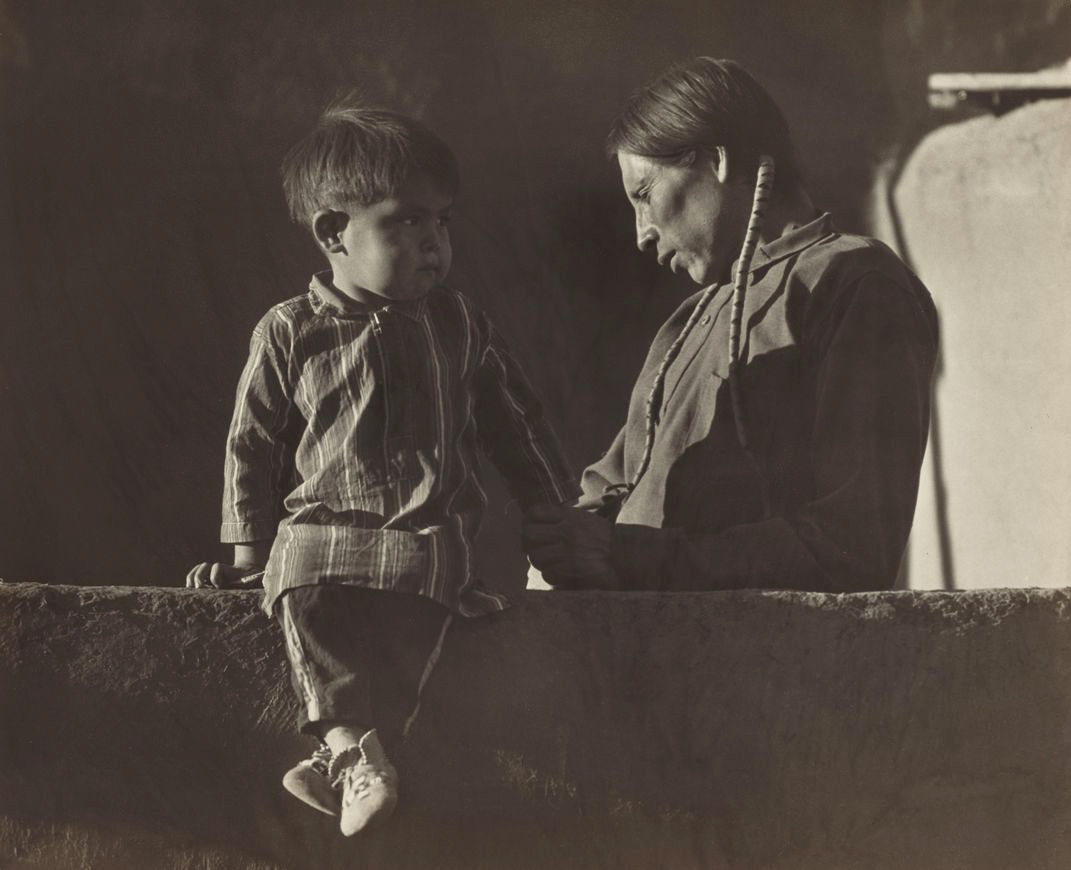

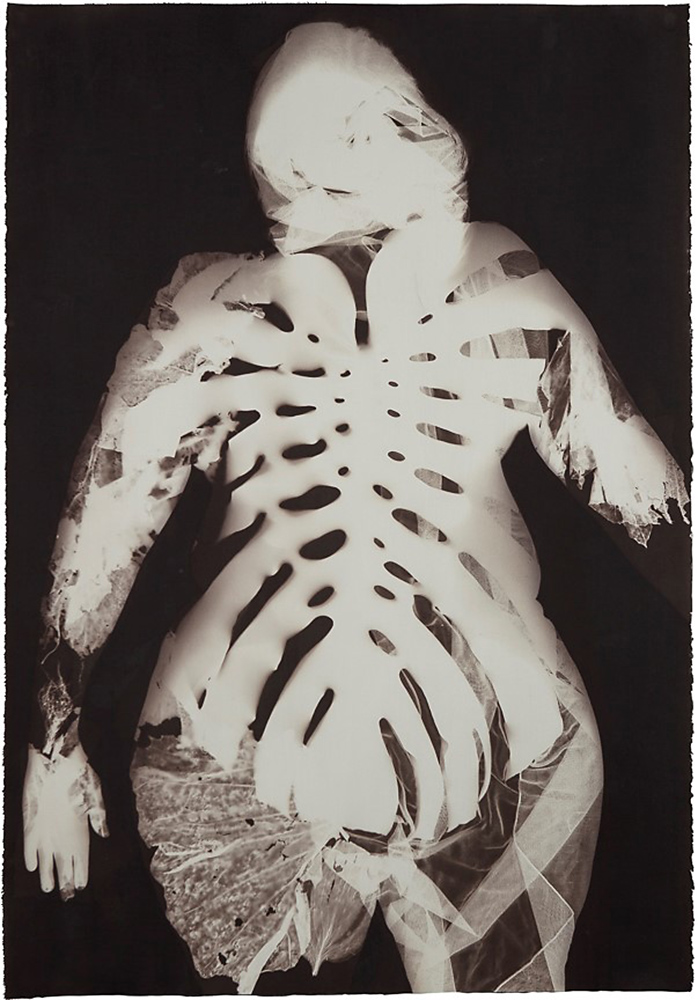

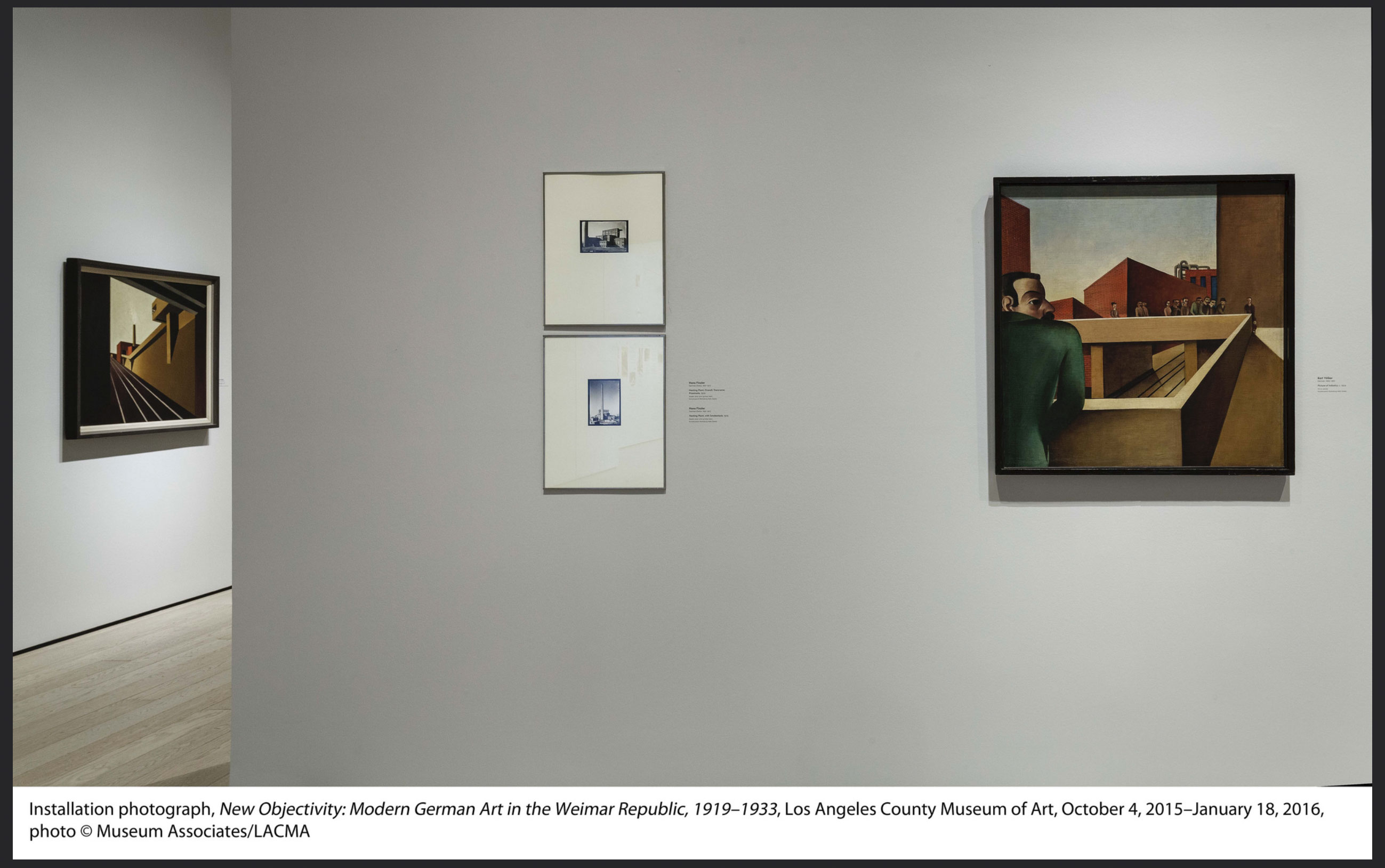

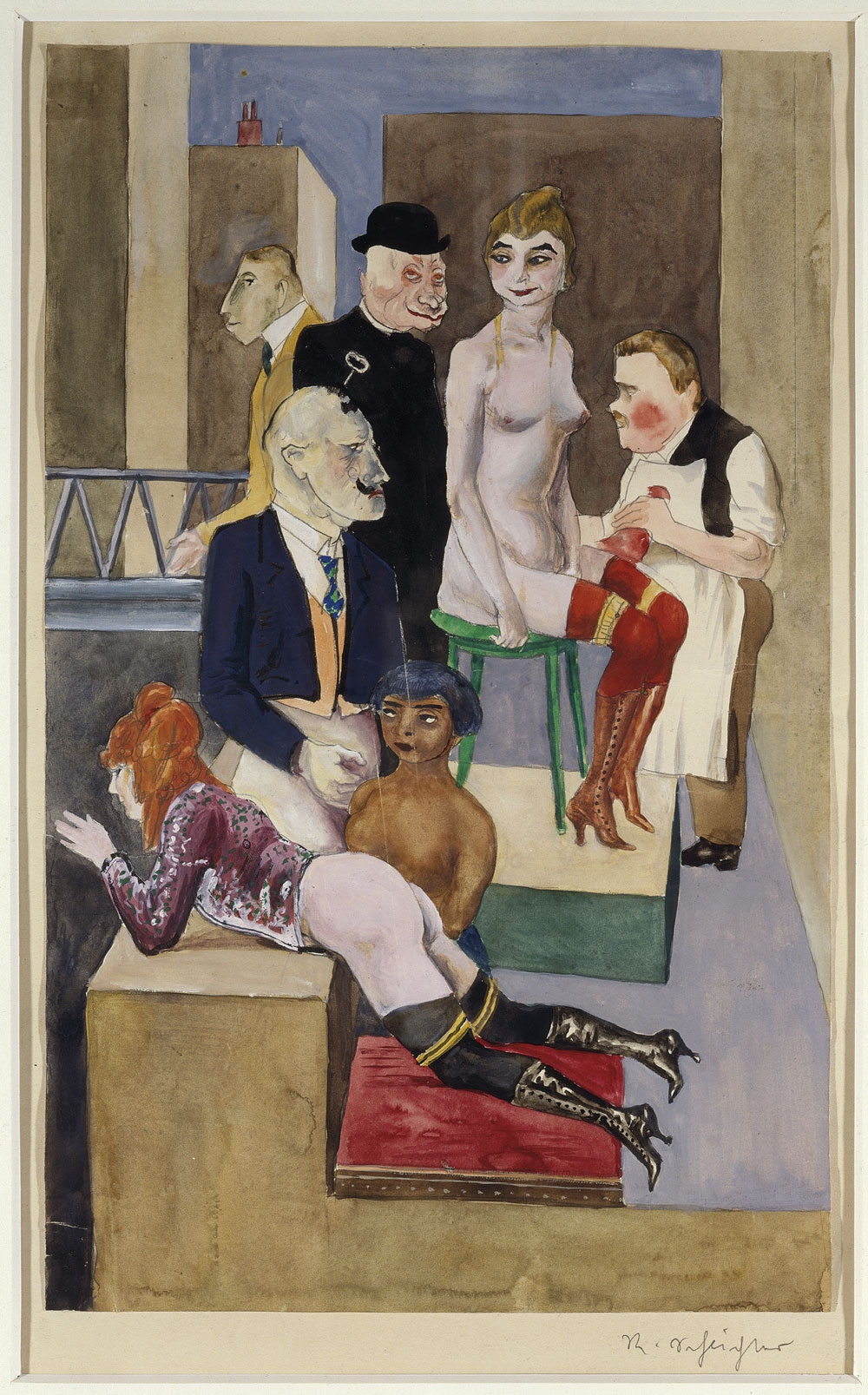

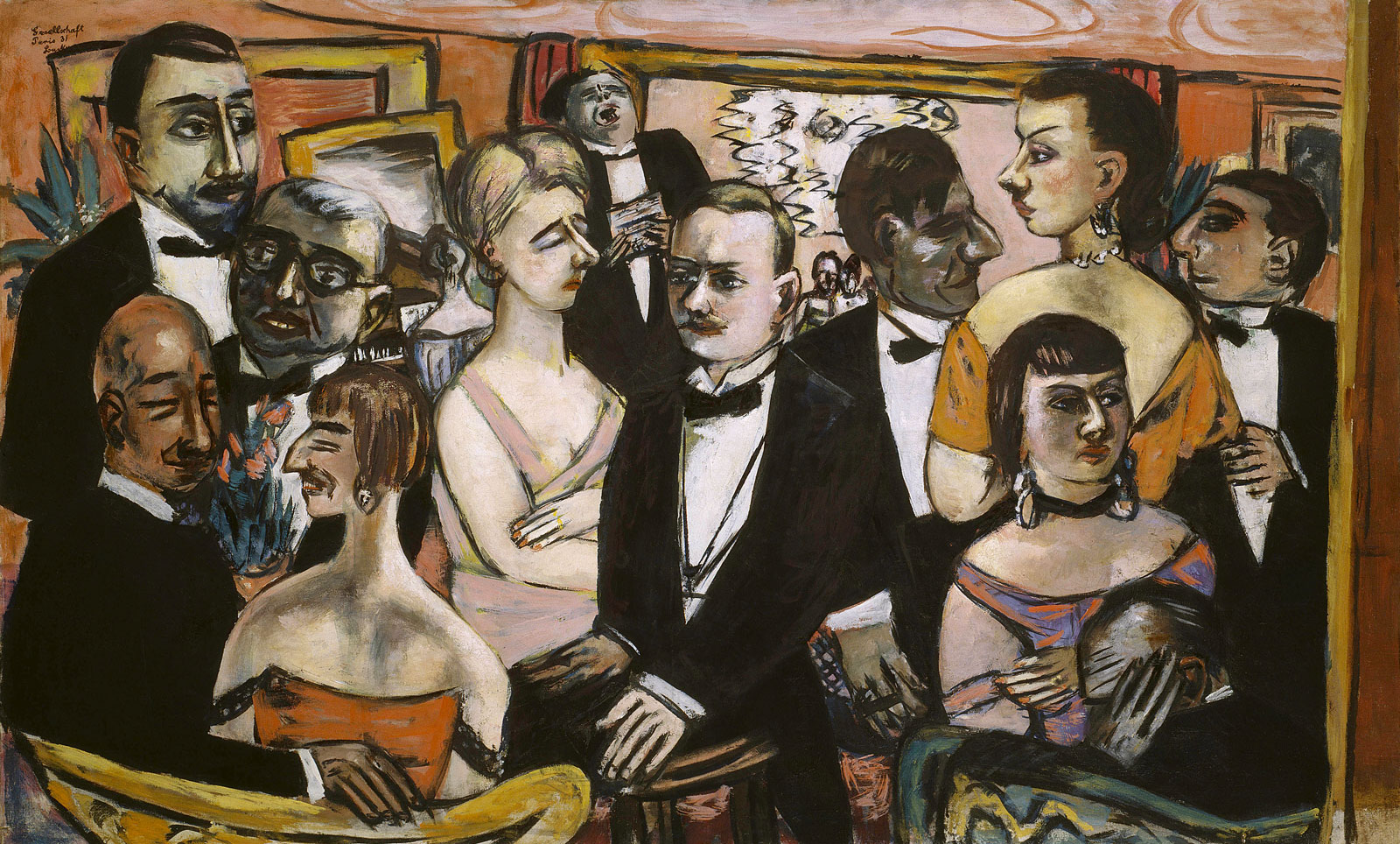

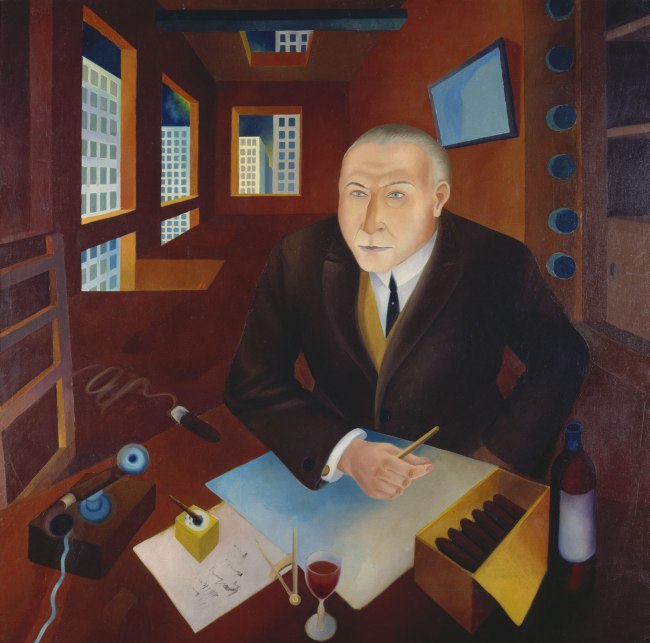

Feeling Bodies, Seeing Images

At the same time as the advancements in sexology, new notions of the body, gender, and intimacy were finding expression in art and culture. Literature, theatre, film, and the visual arts offered an opportunity to question gender stereotypes and to create new roles and body images. These served as the basis for imagining freer ways of living and to lay the foundation for what we perceive today as queer aesthetics.

While Article 142 of the Weimar Constitution promised extensive artistic freedom, censorship was simultaneously introduced for the new medium of film. Munich in particular had numerous bans on film and theatre performances deemed offensive.

Text from Stories of the exhibition TO BE SEEN: Queer Lives 1900-1950

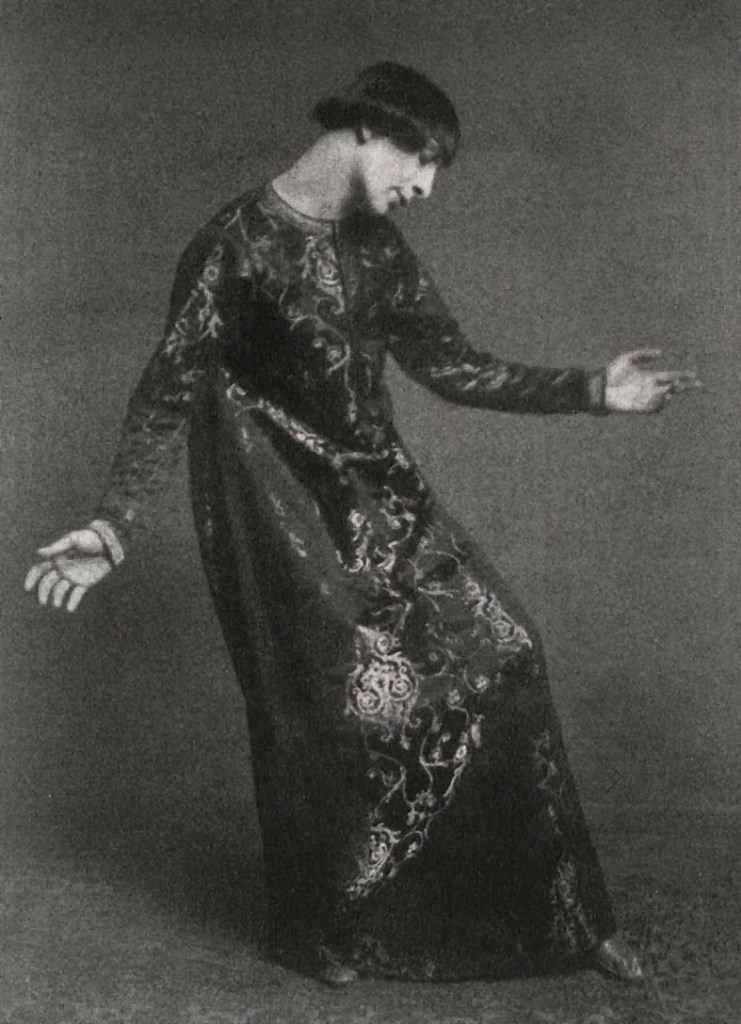

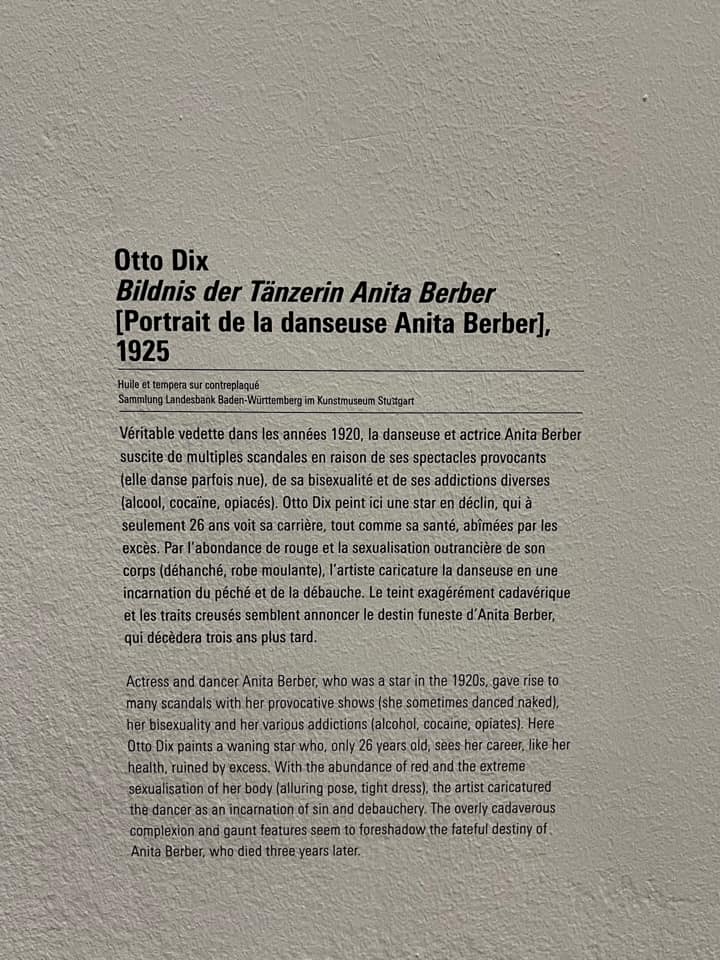

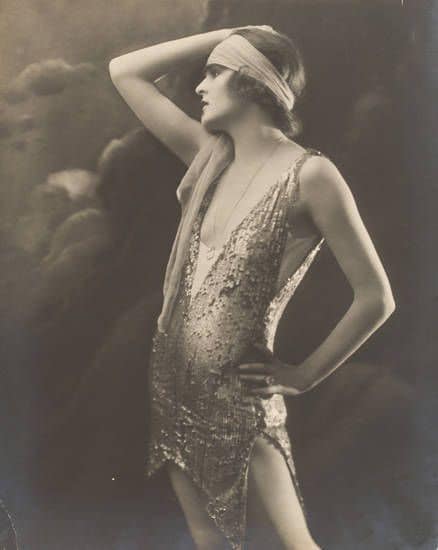

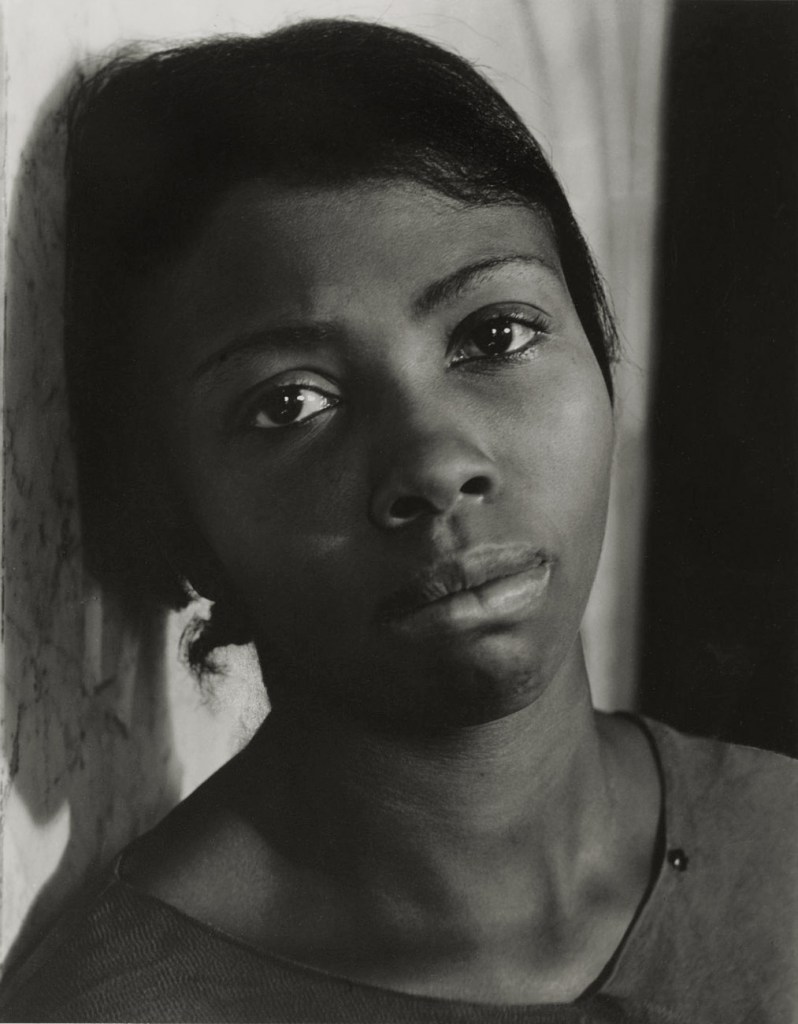

Unknown photographer

Anita Berber

c. 1925

© Stiftung Stadtmuseum Berlin – Archive German State Opera

The bisexual dancer Anita Berber (1899-1928) confronted audiences with homoeroticism, nudity, and drug use, addressing issues that were taboo in the public eye.

The pejorative connotations of decadence as a moral failing or degenerate or degenerative state have often played into the pathologisation and criminalisation of specific bodies and practices. This is especially the case when these bodies and practices come to be seen as a threat to the health and integrity of a nation. Some of the most interesting examples can be found in Berlin at the dawn of the Weimar Republic, when the city itself was subject to charges of miasmic contagion. ‘Even the alkaline air around the Prussian capital (Berliner Luft)’, writes performance scholar Mel Gordon in characteristically hyperbolic style, ‘was said to contain a toxic ether that attacked the central nervous system, stimulating long suppressed passions as it animated all the external tics of sexual perversity’.[1]

Dance was regarded as a vector of transmission in spreading this toxic ether. Social dancing (Tanztaumel) swept Berlin in the year following the armistice, offering writers and cultural commentators a rich repository of tropes and metaphors for describing a social, economic and political situation that appeared to be spinning out of control. …

For dance and theater scholar Karl Toepfer, Berber’s aestheticization of her addictions to a plethora of narcotics presented ‘an almost satiric critique of the pretensions to a healthy, modern identity’.[11] Sickness formed the basis of a carefully stage-managed persona in the public eye that was to manifest in equally carefully choreographed routines. For instance, in one of the better-known dances from the Tänze des Lasters series, Kokain (Cocaine, 1922), Berber stages an embattled, spasmodic body torn between a will to live and the delirious effects of a narcotic. One reviewer described the dance as ‘a product of decay’ and a ‘style of degeneracy’,[12] suggesting that her embodiment of Berlin’s ‘toxic ether’ landed with her audiences (ether was also one of Berber’s drugs of choice, particularly once mixed with chloroform and white rose petals). That this piece was set to Camille Saint-Saëns’s Danse macabre (1874) makes it tempting to position it as the epitome of Berlin’s own ‘dance of death’ in which death and sexuality perform a pas de deux across Berber’s performing body – a body that was to succumb to tuberculosis aged only twenty-nine.

Berber’s dances have been read as ‘jejune’ and derivative;[13] however, this does a disservice to what Susan Laikin Funkenstein describes as ‘a more profound understanding of her contributions’ to modern dance history that were ahead of their time.[14] Although Funkenstein is looking to put some distance between Berber’s perception as a ‘depraved vamp’ and her innovativeness as a dancer, I argue that these are mutually enriching considerations in the development of her decadent choreographies. Berber’s ‘sickness’ as an addict, her perceived corruption as a sexual libertine, and (later) her physical sickness after contracting tuberculosis were not adjacent to her work as a dancer. She danced as she lived – which is to say, decadently – just as her bohemian aestheticism makes it difficult to distinguish where her choreographies begin and end.

Dr Adam Alston. “Dancing decadence: Anita Berber,” on the Staging Decadence website 24 January 2023 [Online] Cited 11/04/2023

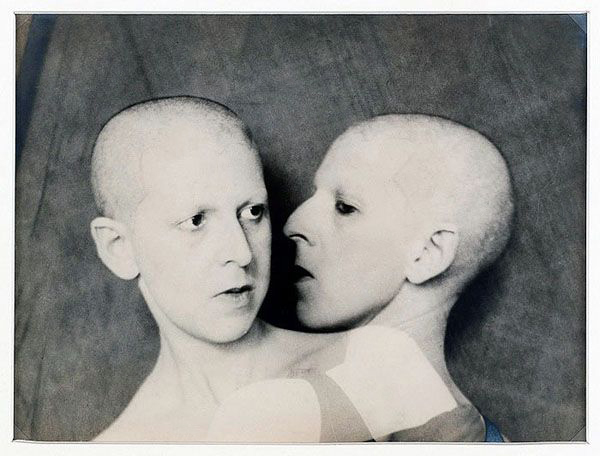

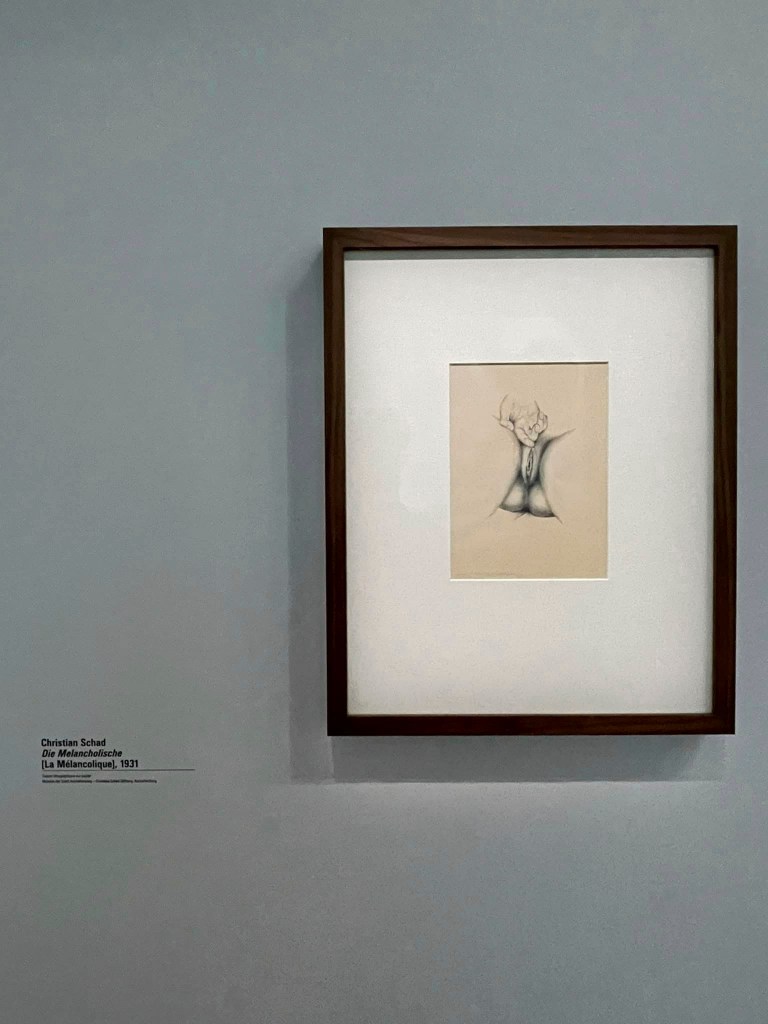

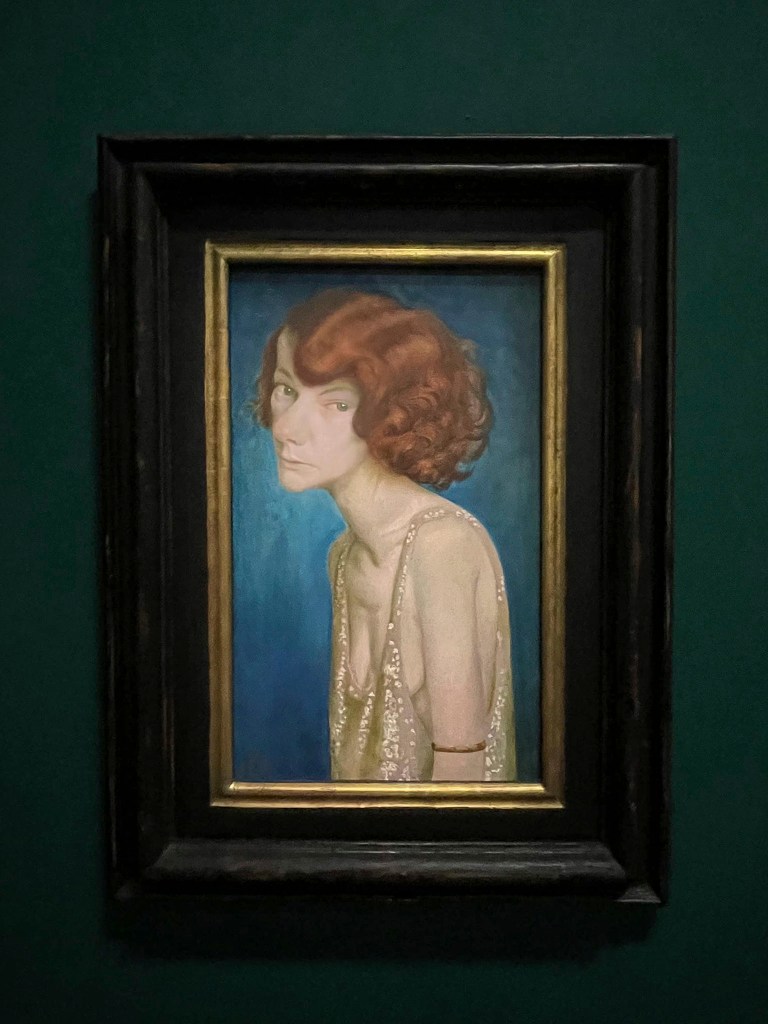

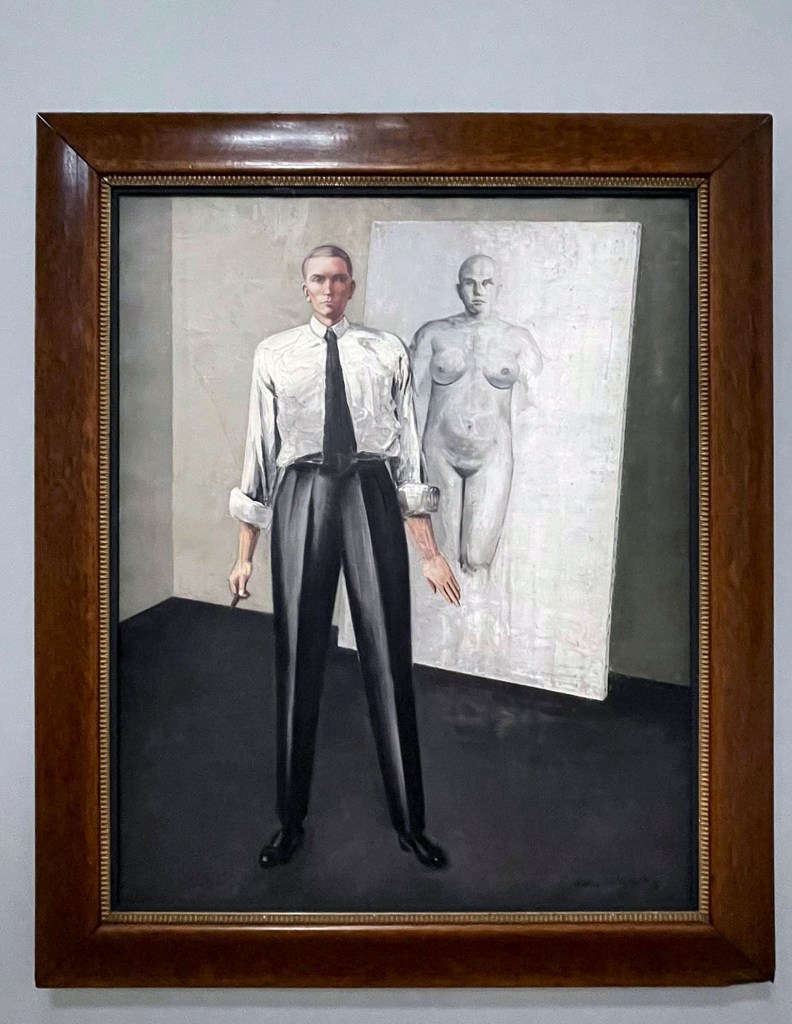

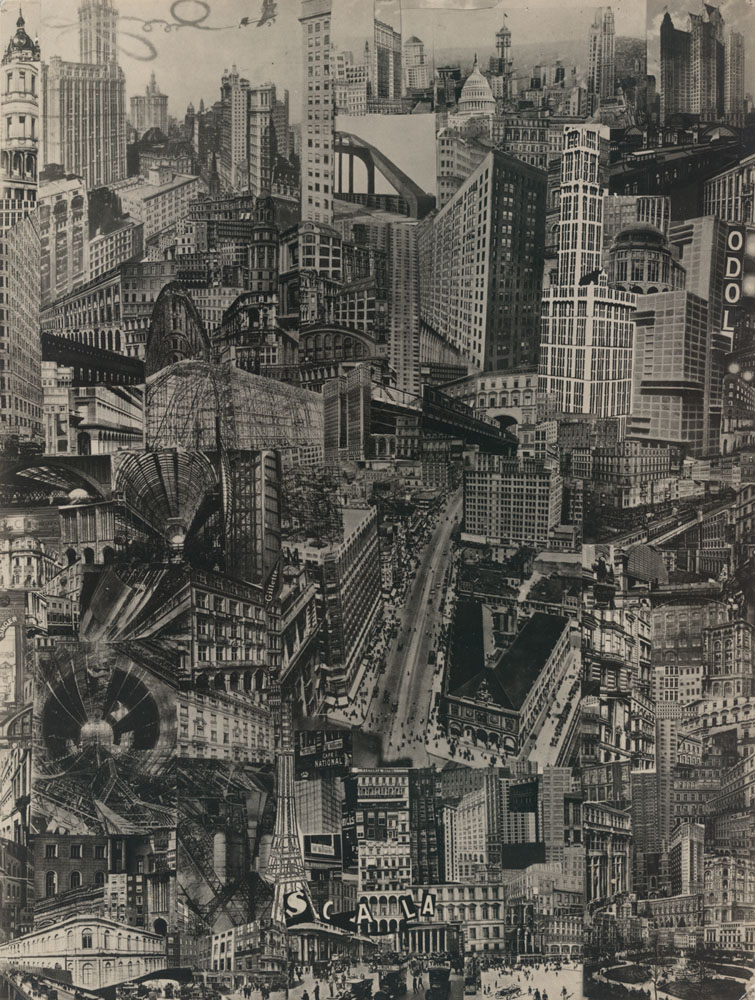

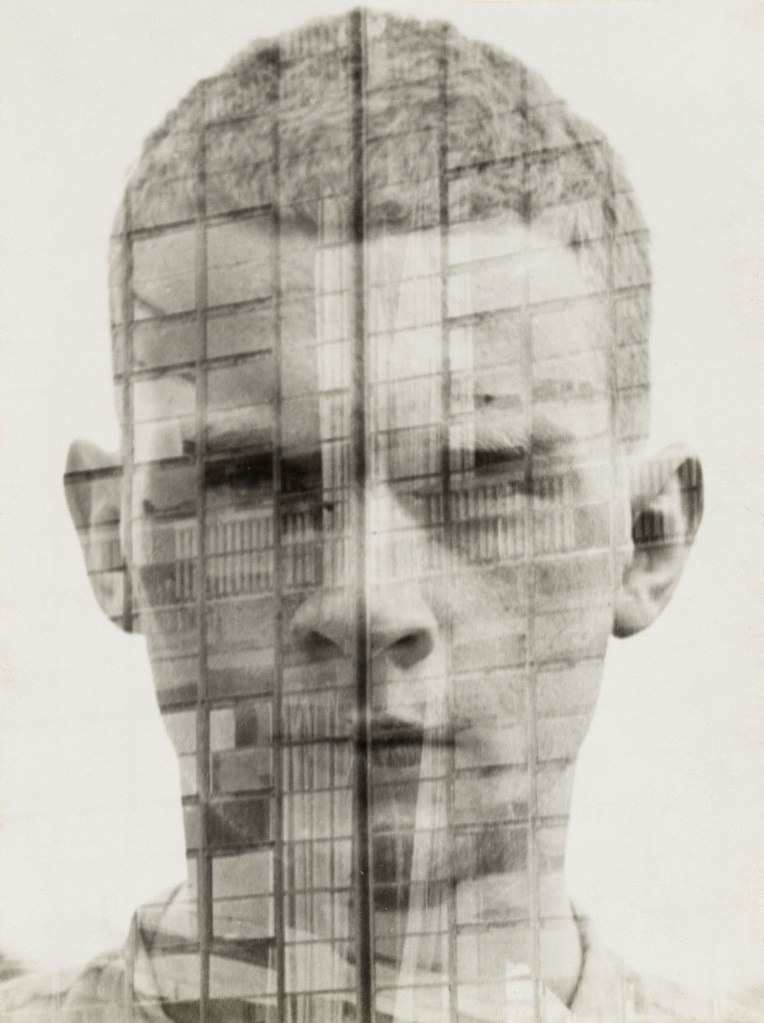

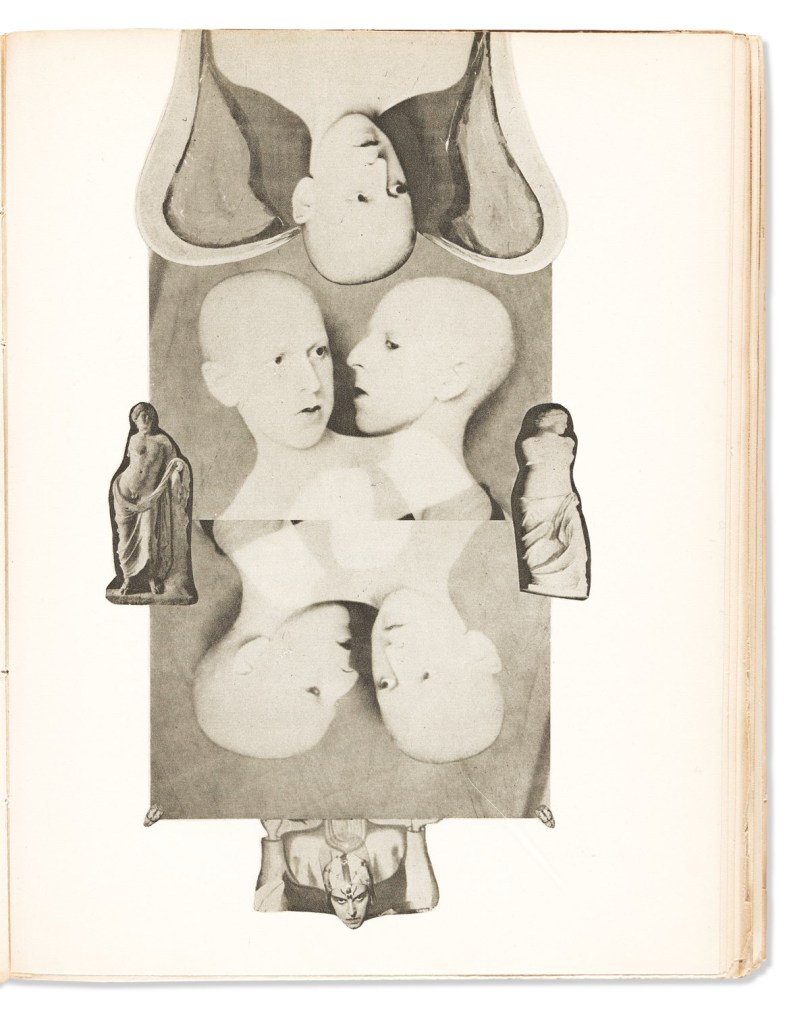

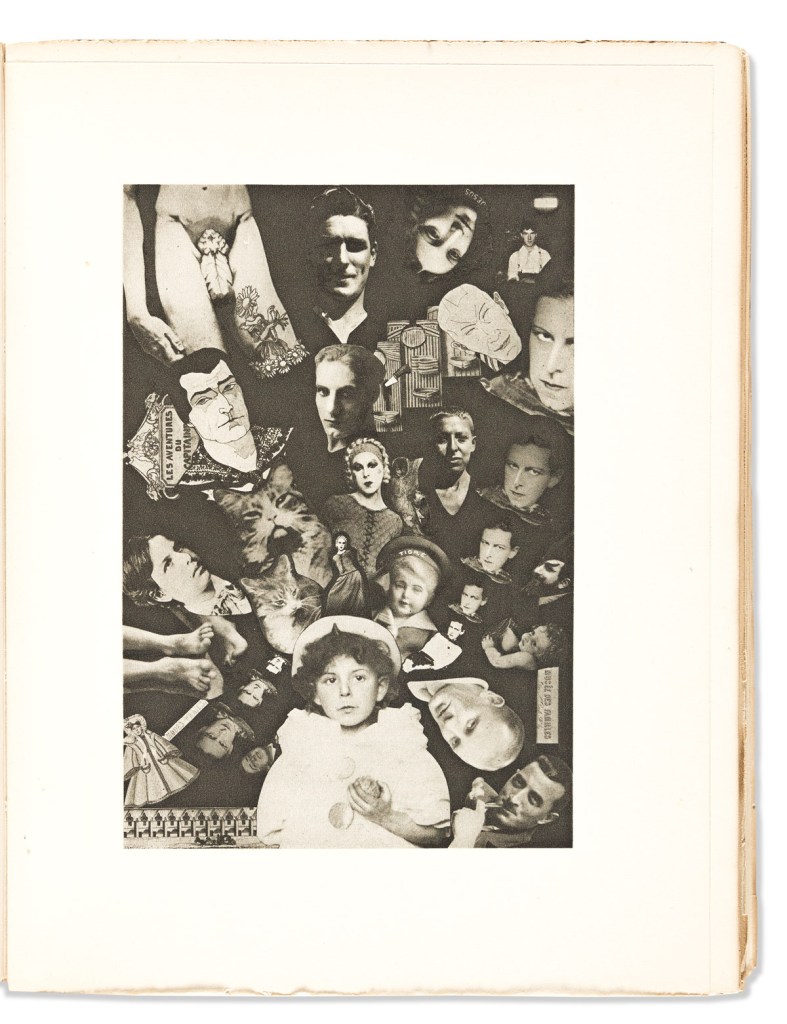

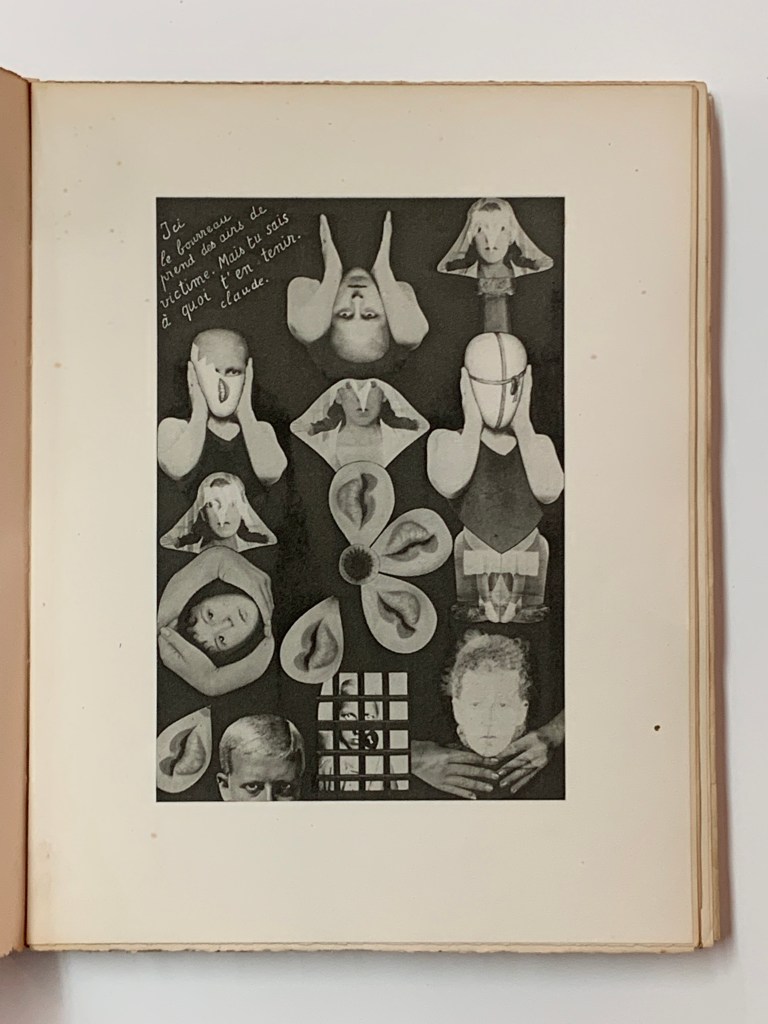

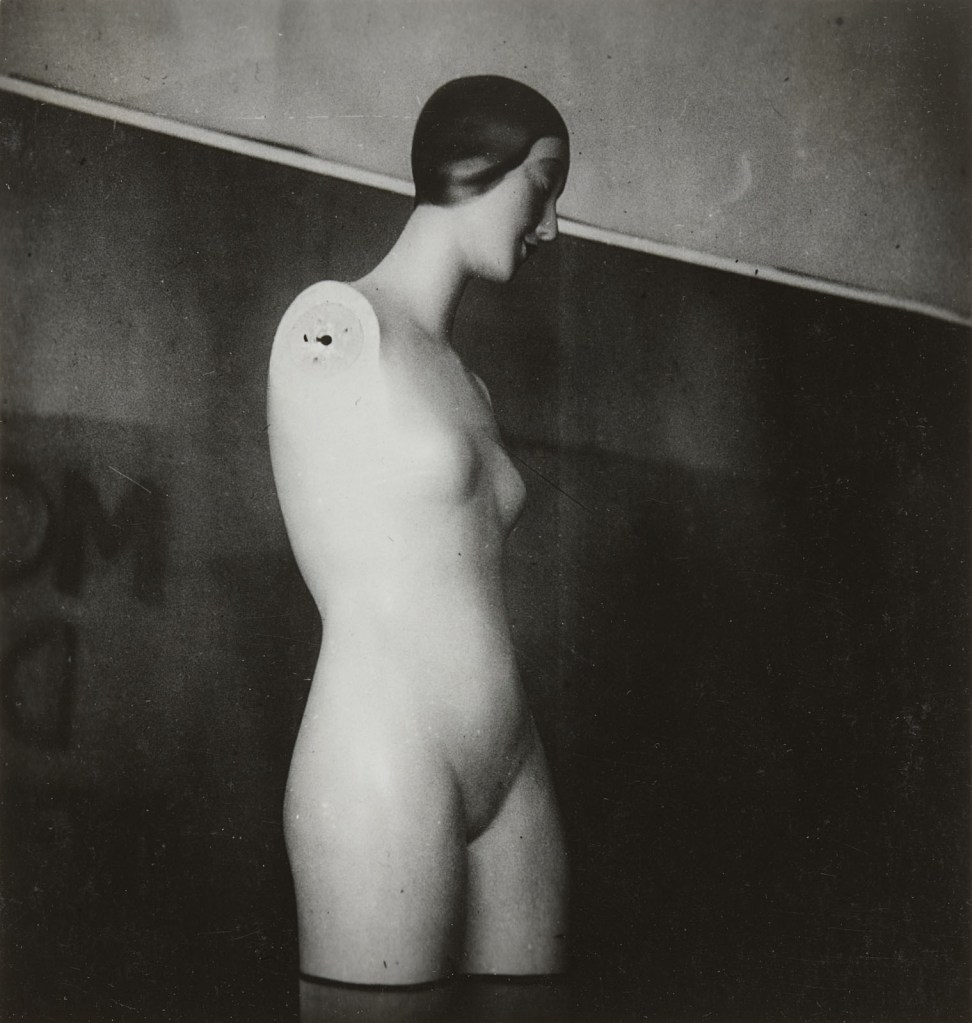

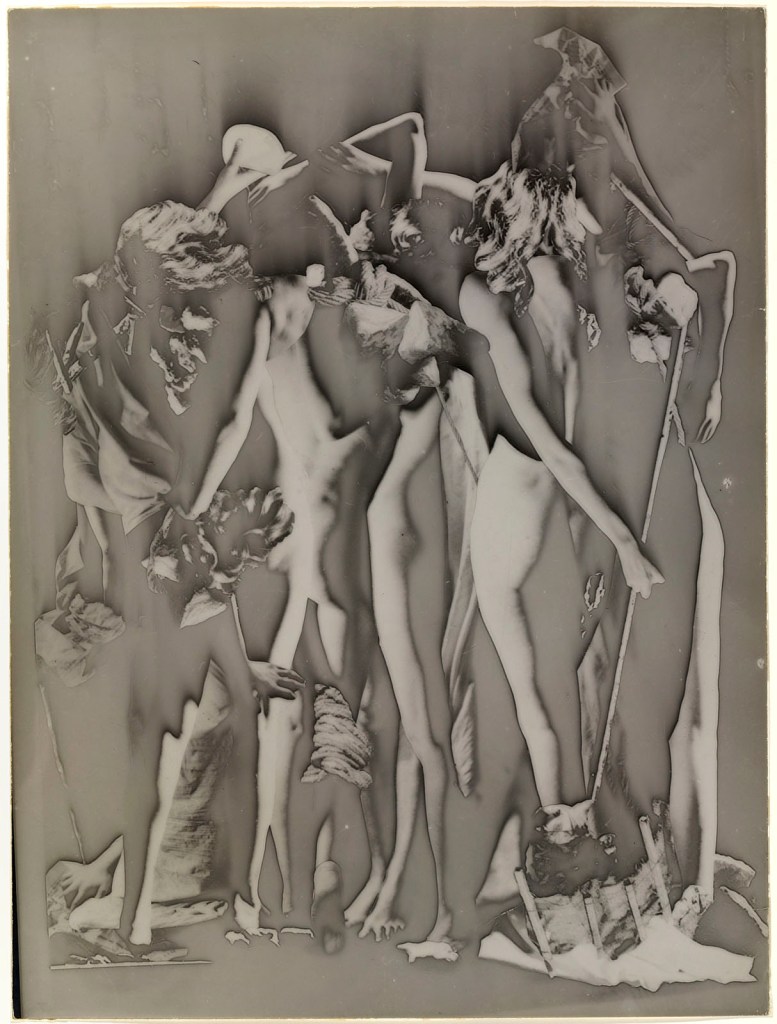

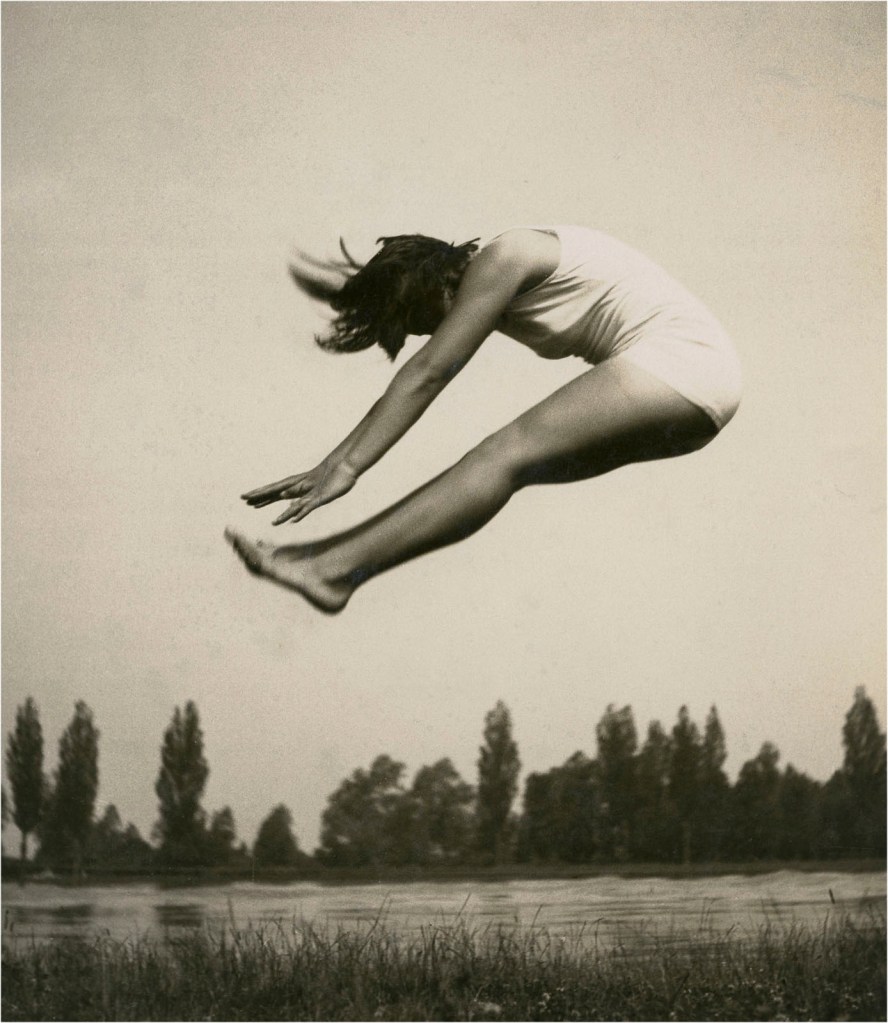

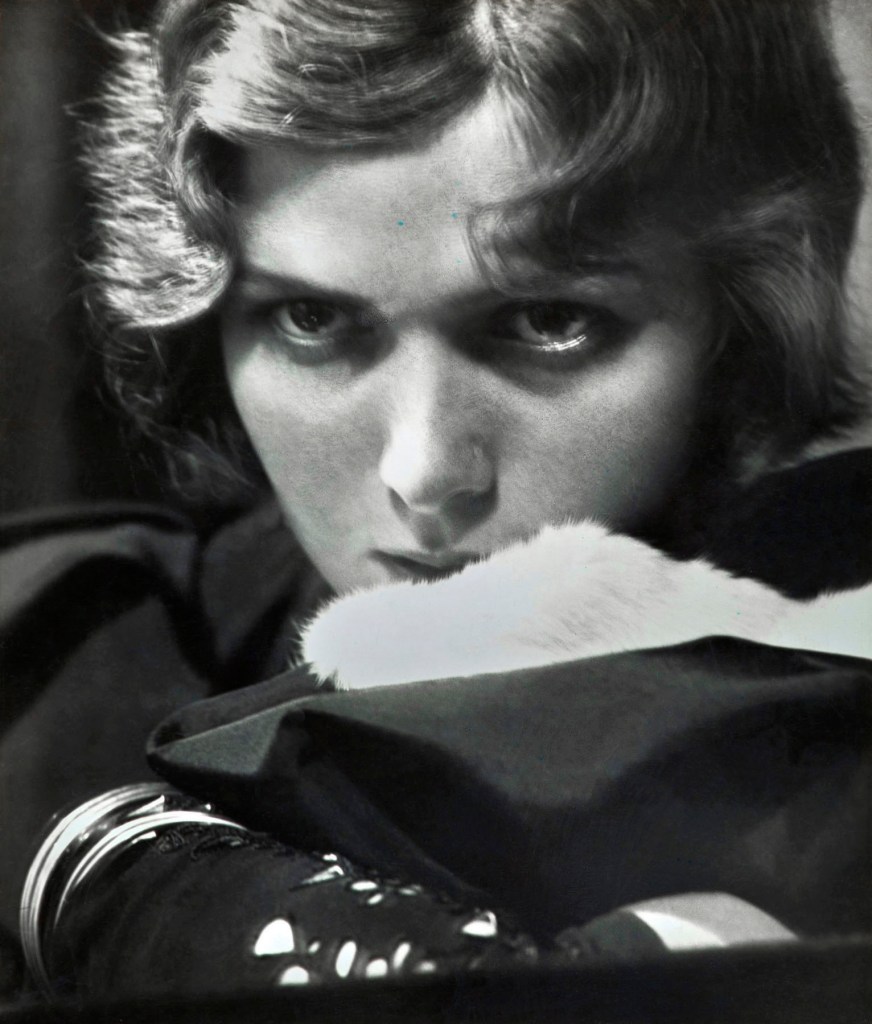

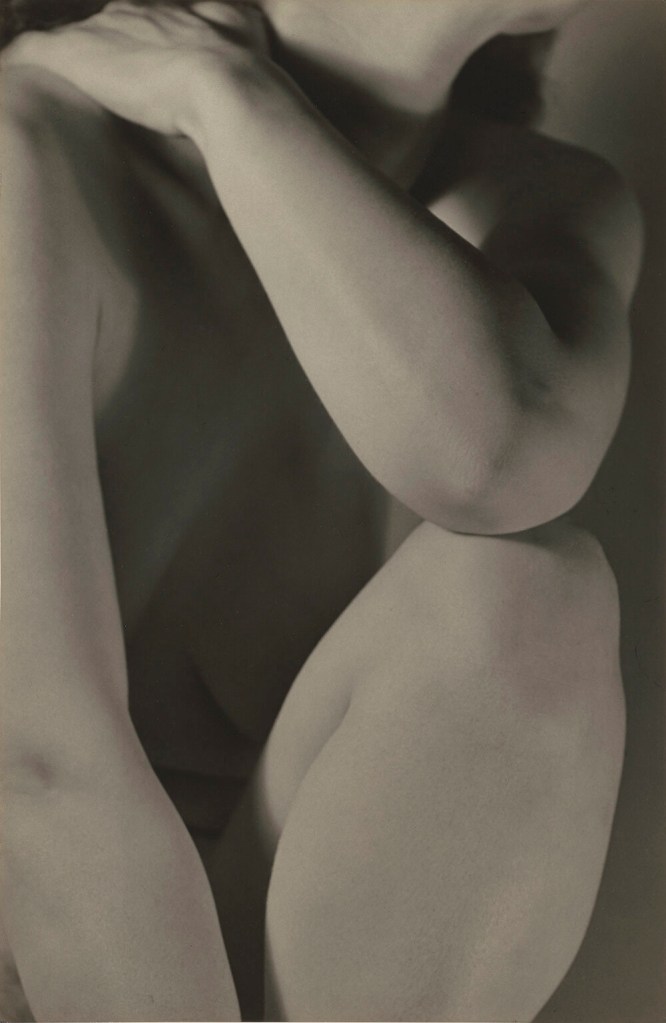

New images of the body

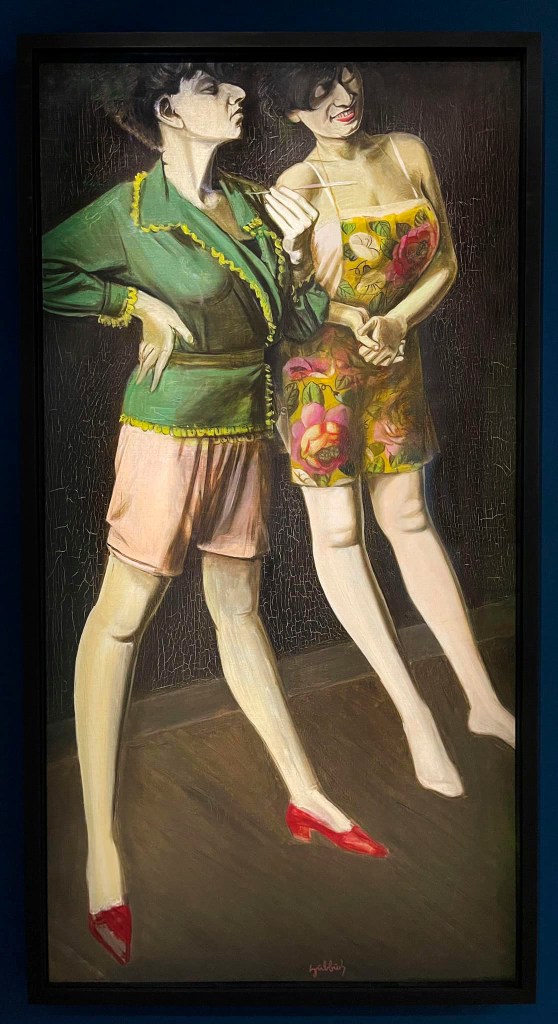

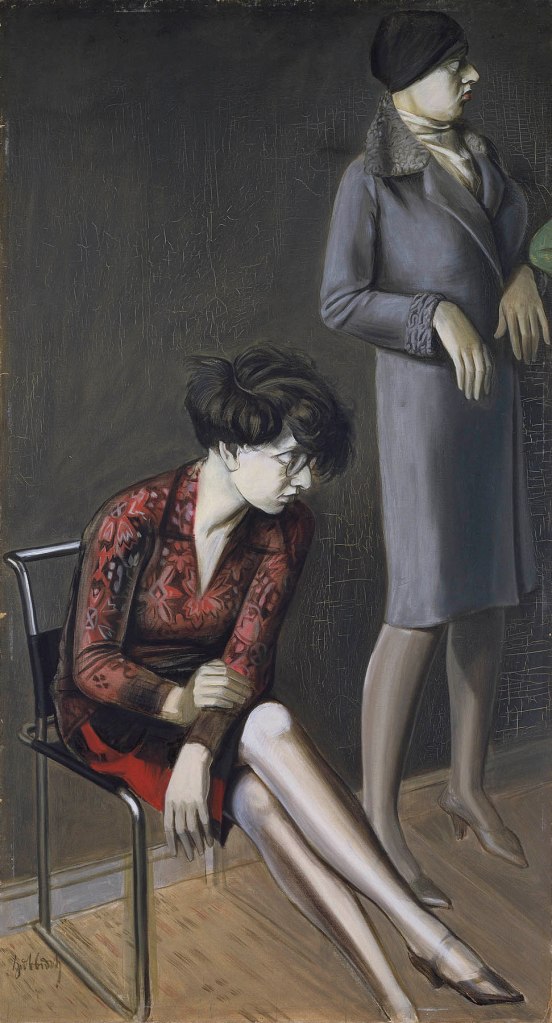

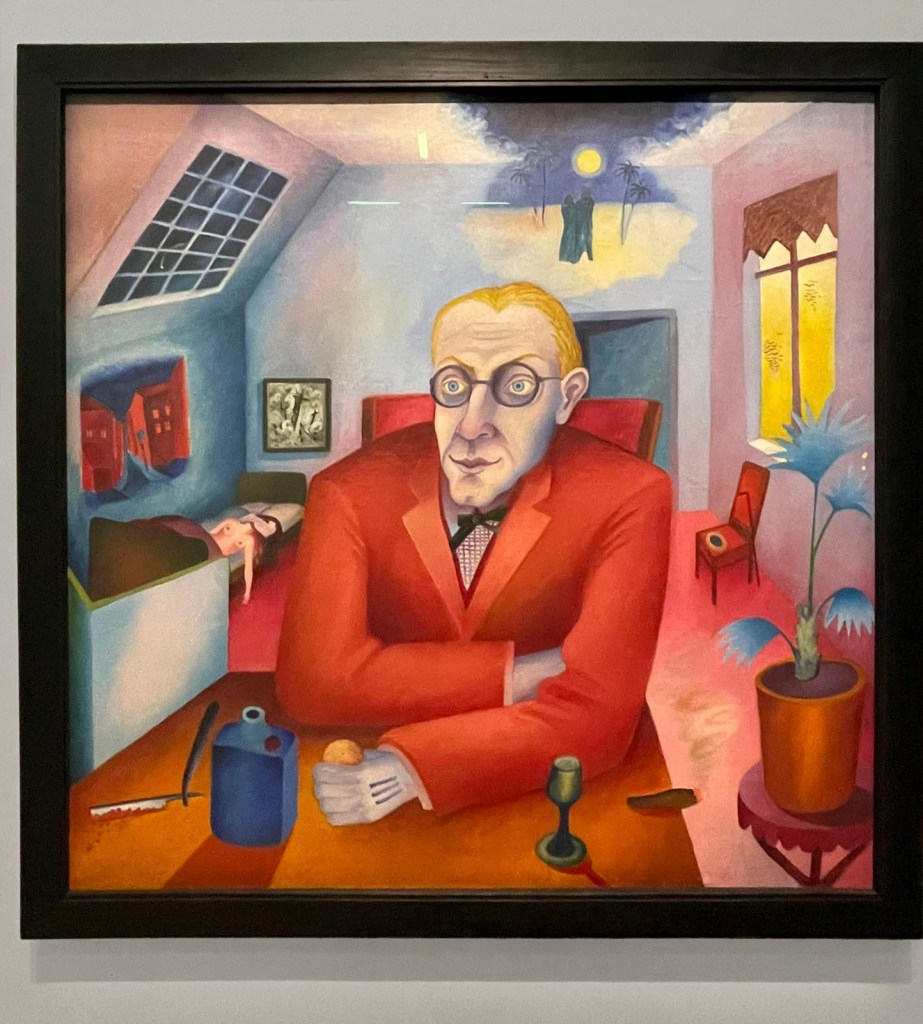

In the first half of the twentieth century, artists experimented with new representations of the human body. They conceived of a wide spectrum of possible identities and sexualities situated outside the dominant categories. Artists subverted binary notions of gender, whether through ambiguities, gender-neutral codes, or playing with androgynous body images.

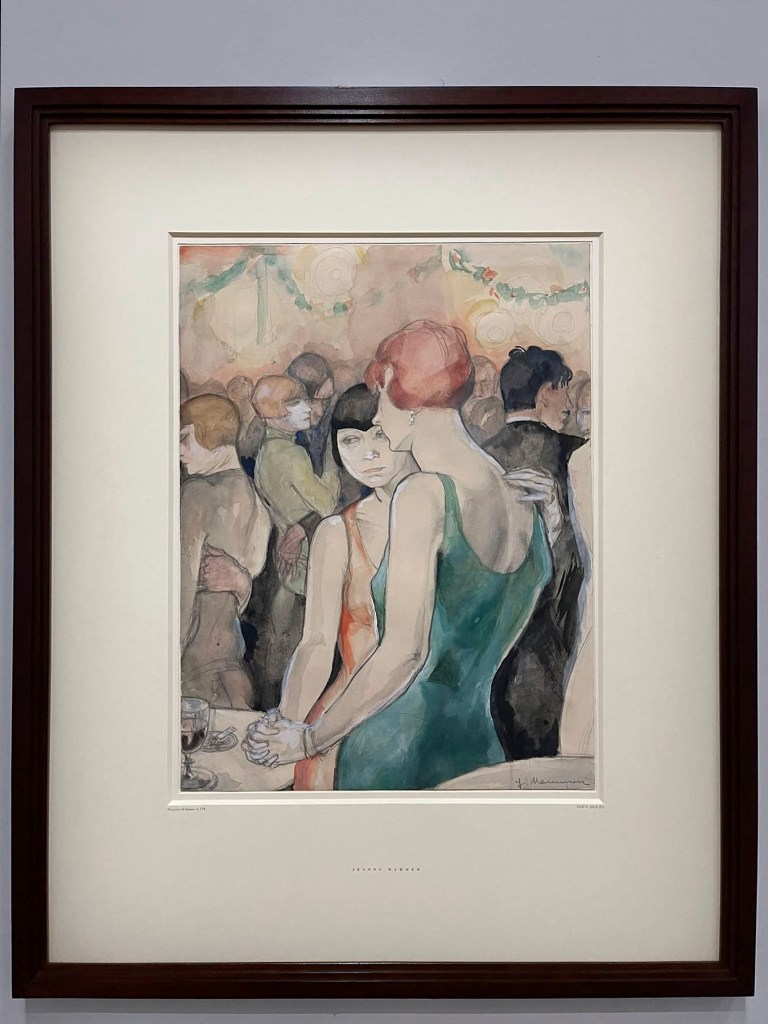

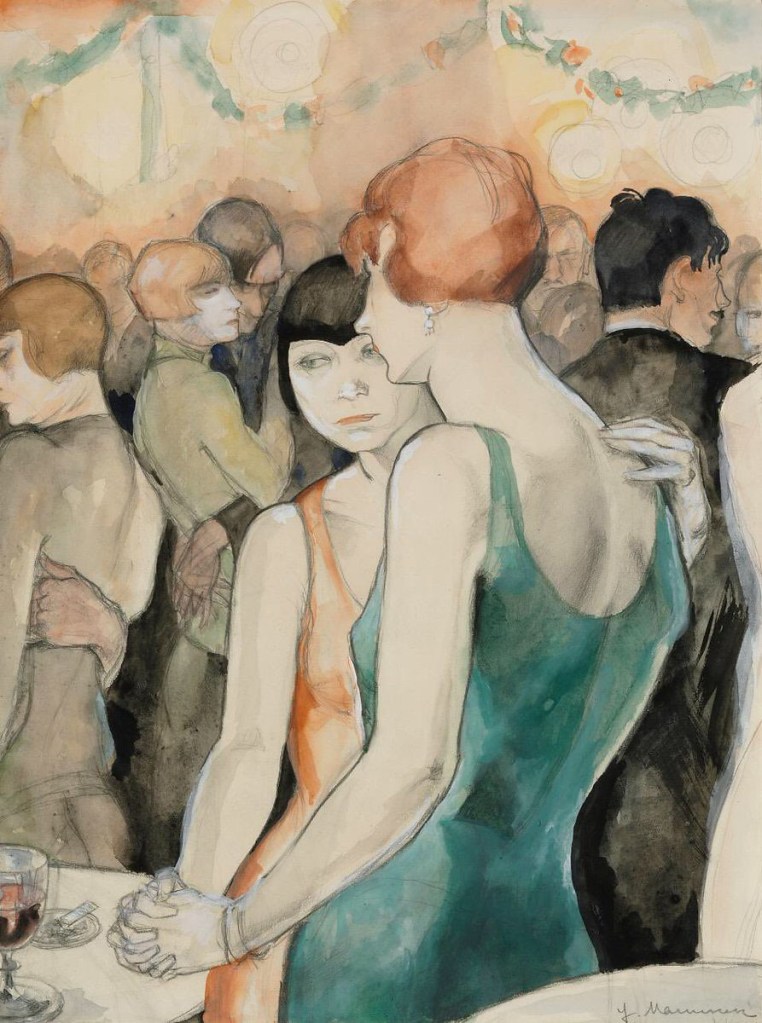

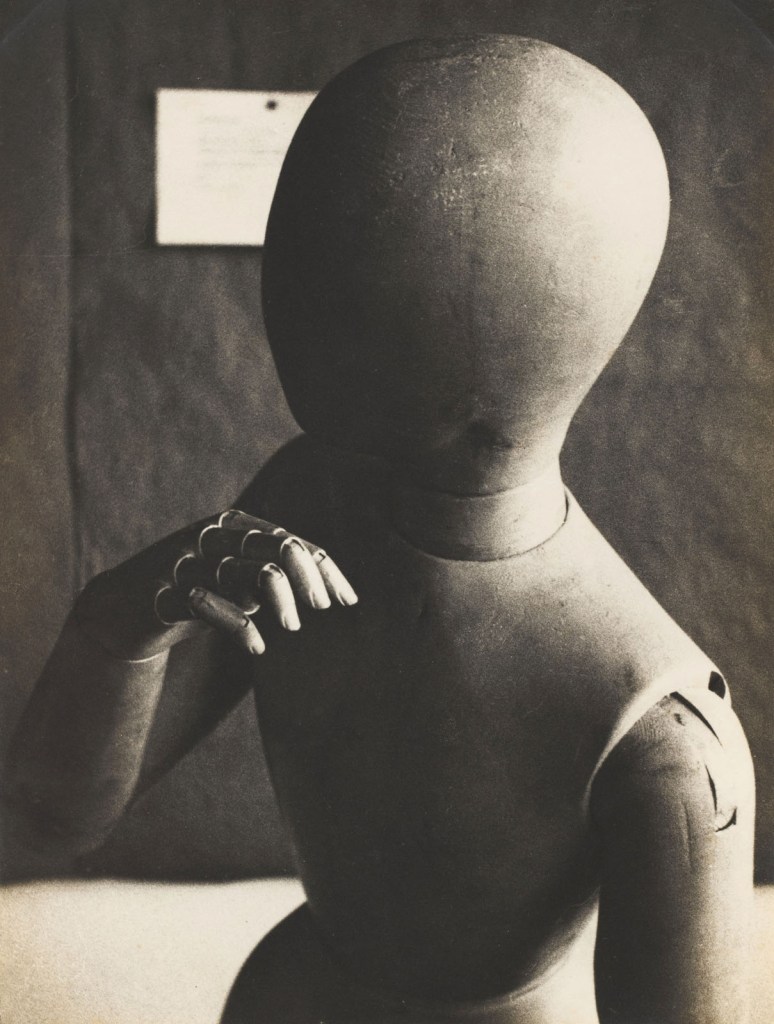

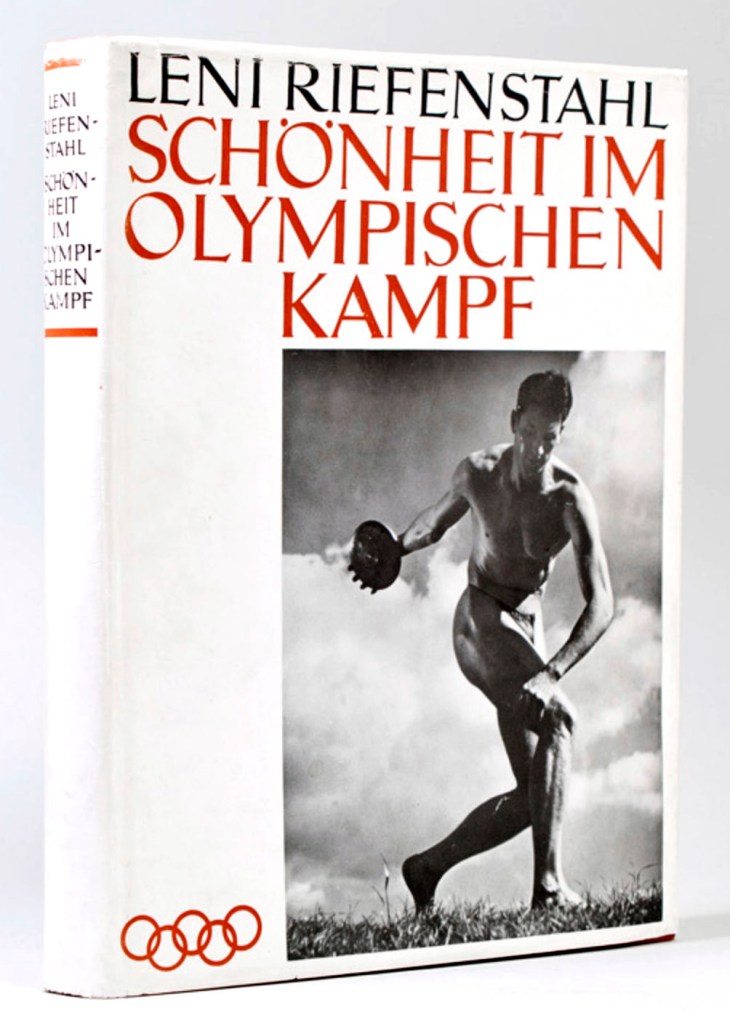

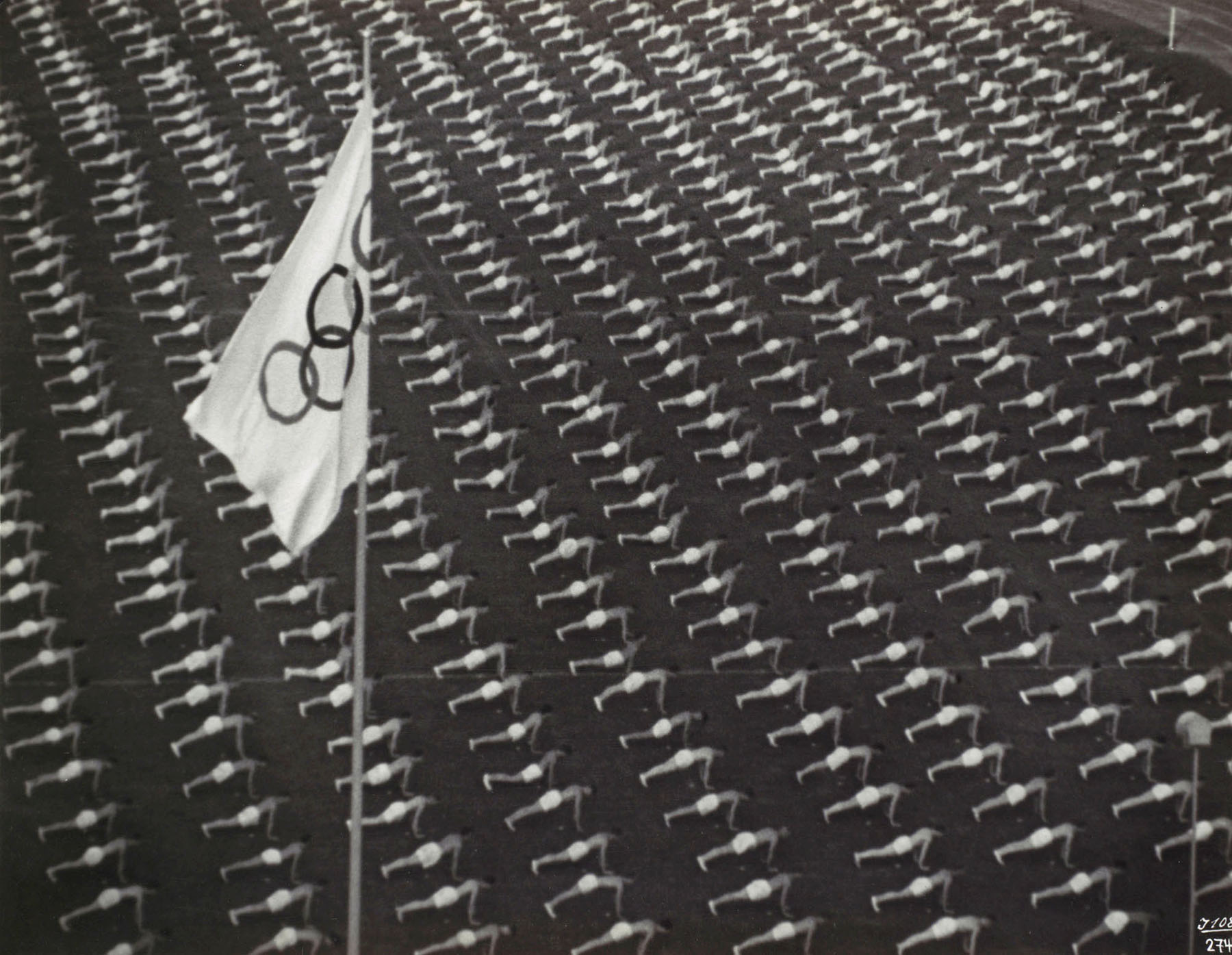

In 1933, the Nazis put an end to this diversity. Avant-garde works by artists such as Hannah Höch or Jeanne Mammen were denounced as “degenerate” and confiscated, banned, or destroyed. The regime instead honoured artists such as Arno Breker, Leni Riefenstahl, and Josef Thorak, who immortalised traditional gender images in monumental depictions. Such images supported the Nazi regime’s racial ideals, and endured well into the postwar period.

Text from Stories of the exhibition TO BE SEEN: Queer Lives 1900-1950

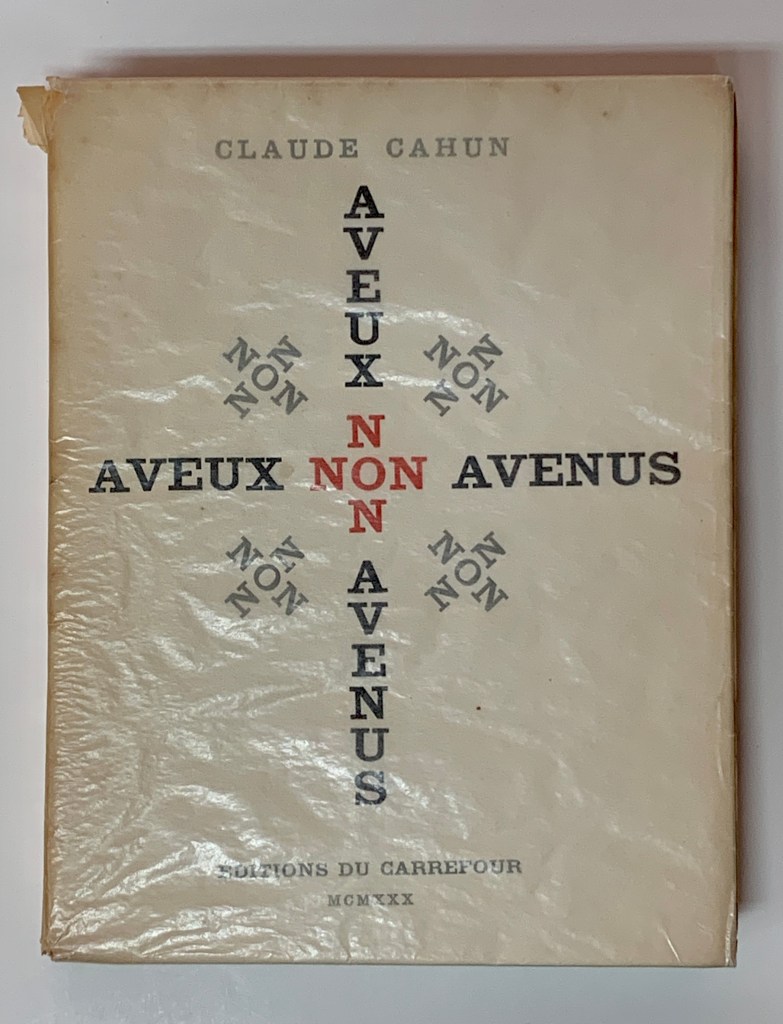

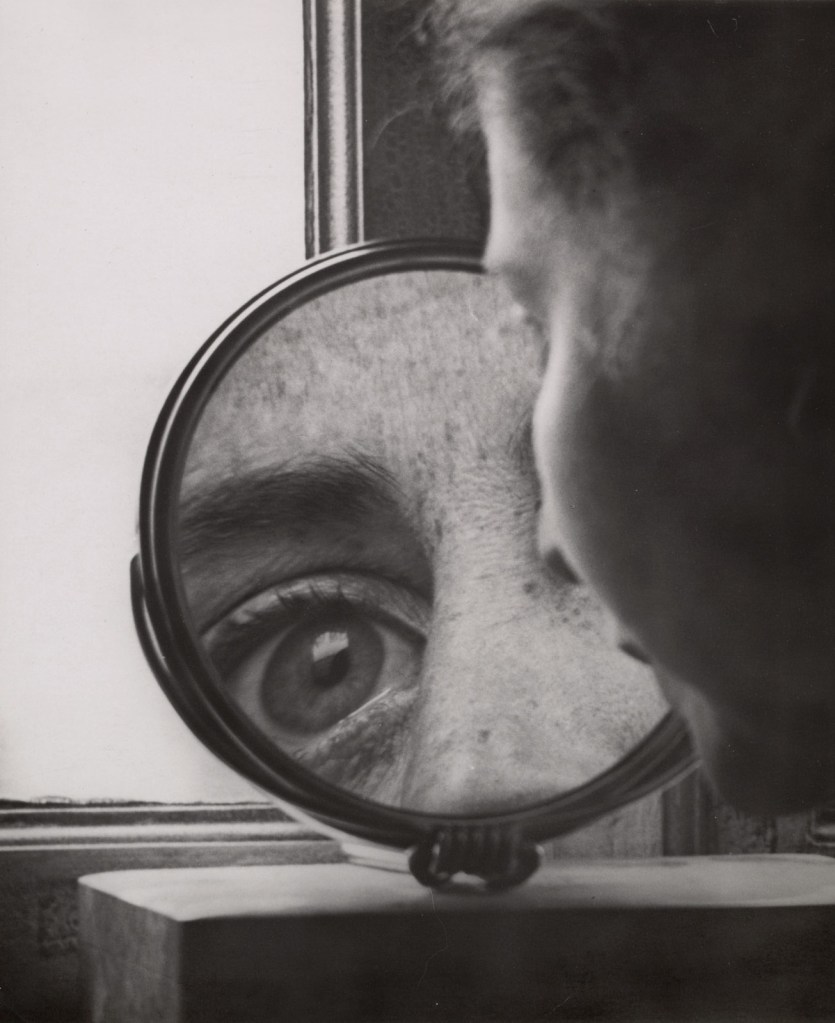

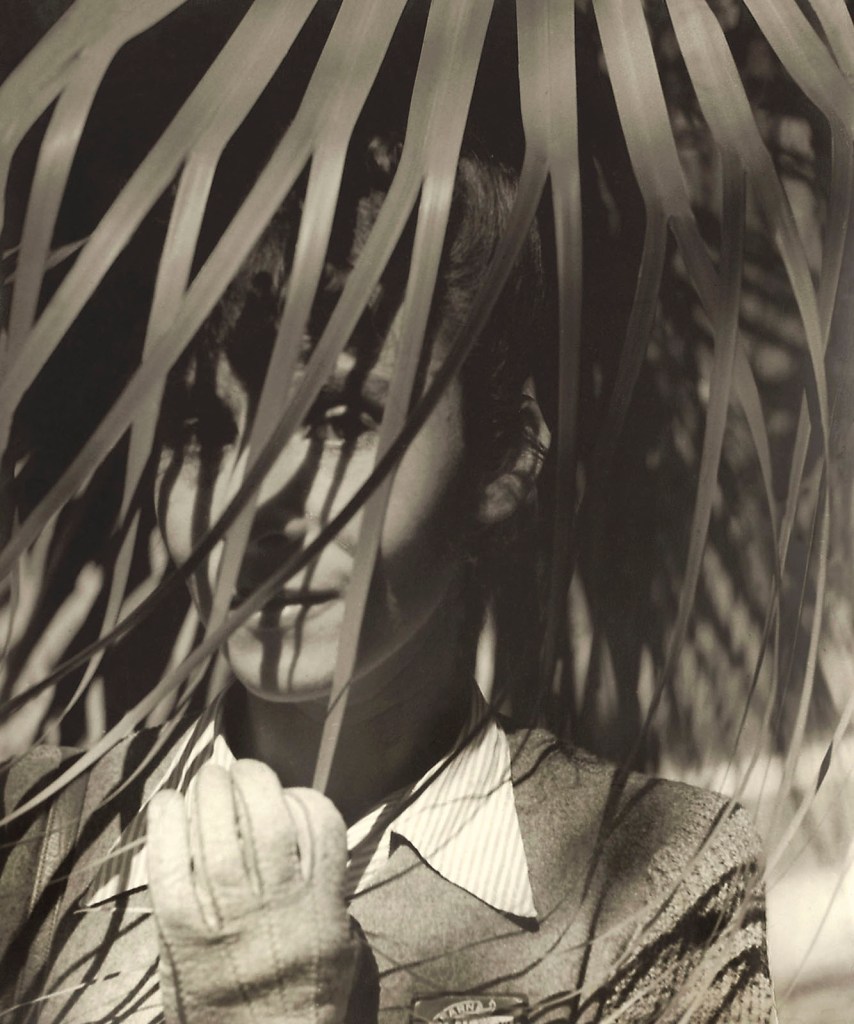

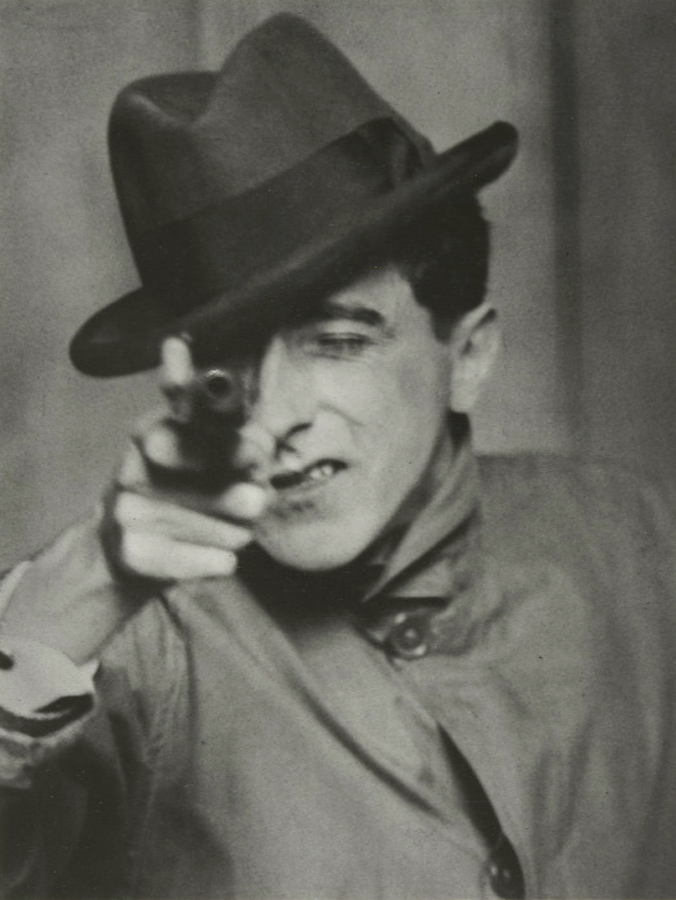

Claude Cahun (French, 1894-1954)

Que me veux-tu?

1929

Gelatin silver print

Paris Musees, musée d’Art moderne

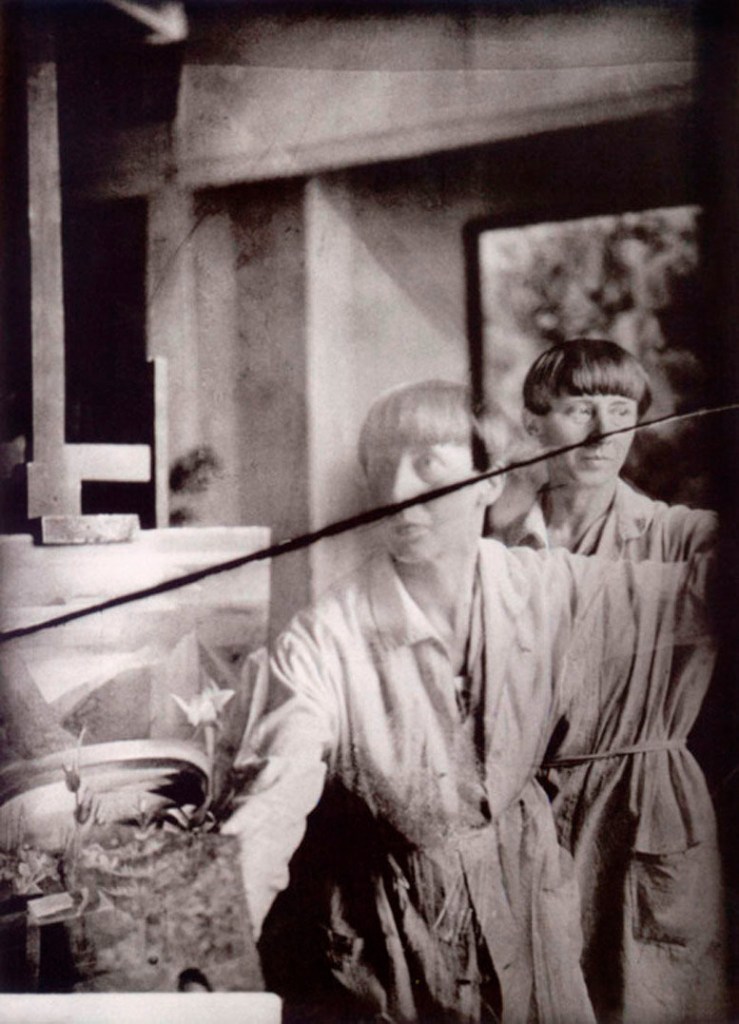

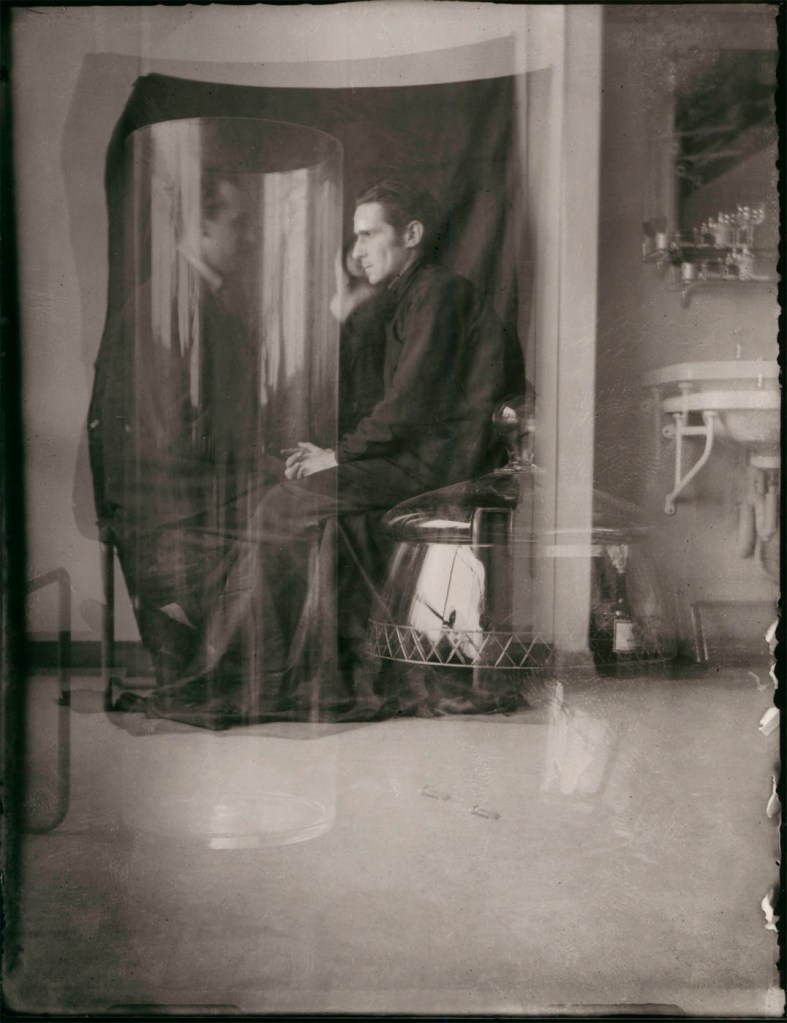

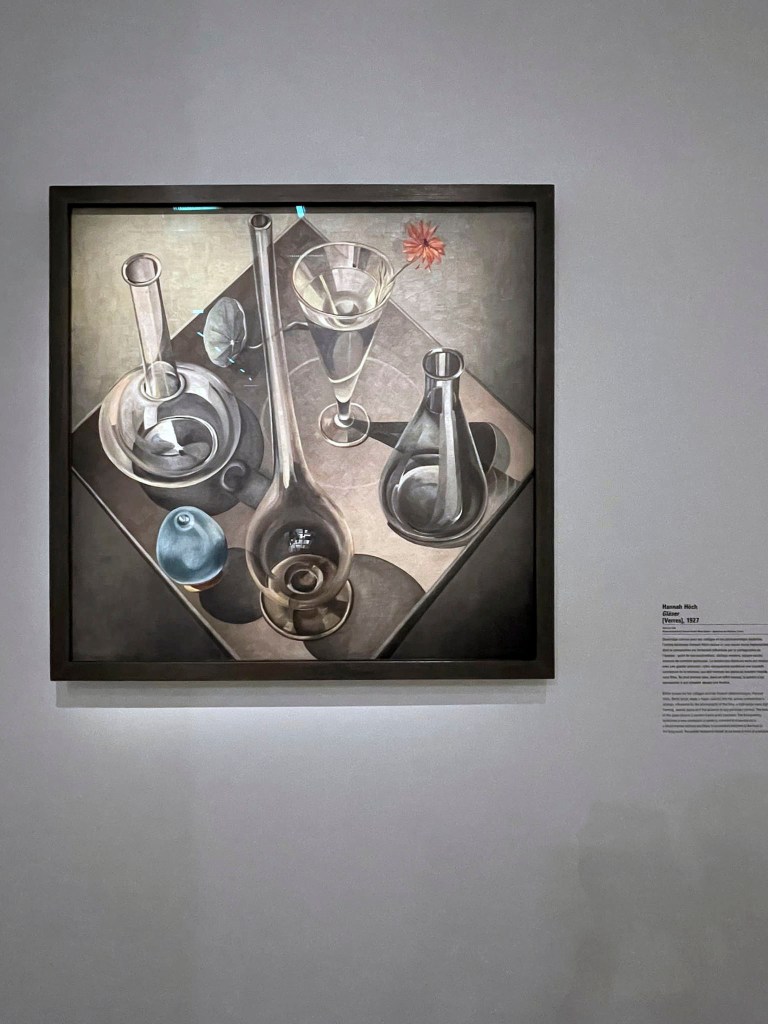

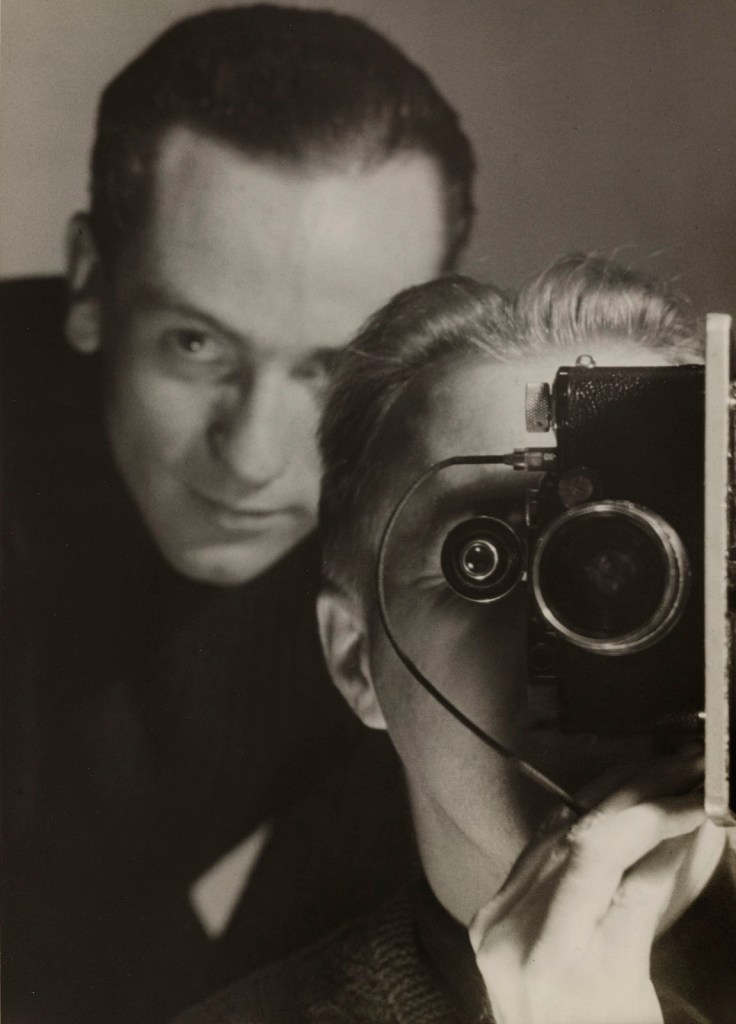

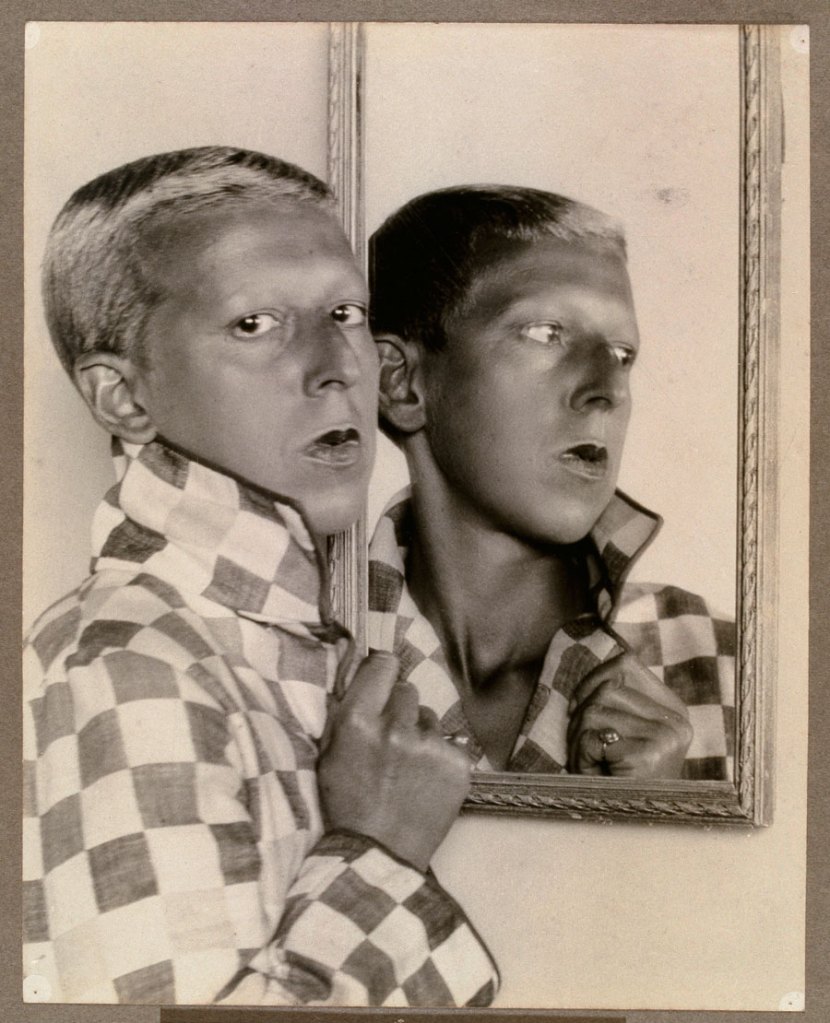

Hannah Höch (German, 1889-1978)

Untitled (Hannah Höch at her easel, The Hague; self-portrait (double exposure) with the painting Symbolic Landscape III)

1930

Gelatin silver print

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

Hannah Höch worked with clichés and role models in her art and was a significant influence on the Dada movement.

Hannah Höch (German: [hœç]; 1 November 1889 – 31 May 1978) was a German Dada artist. She is best known for her work of the Weimar period, when she was one of the originators of photomontage. Photomontage, or fotomontage, is a type of collage in which the pasted items are actual photographs, or photographic reproductions pulled from the press and other widely produced media.

Höch’s work was intended to dismantle the fable and dichotomy that existed in the concept of the “New Woman”: an energetic, professional, and androgynous woman, who is ready to take her place as man’s equal. Her interest in the topic was in how the dichotomy was structured, as well as in who structures social roles.

Other key themes in Höch’s works were androgyny, political discourse, and shifting gender roles. These themes all interacted to create a feminist discourse surrounding Höch’s works, which encouraged the liberation and agency of women during the Weimar Republic (1919-1933) and continuing through to today.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Installation view of the exhibition TO BE SEEN: Queer Lives 1900-1950 at the Munich Documentation Center for the History of National Socialism

Photo: Connolly Weber Photography/NS-Dokumentationszentrum München

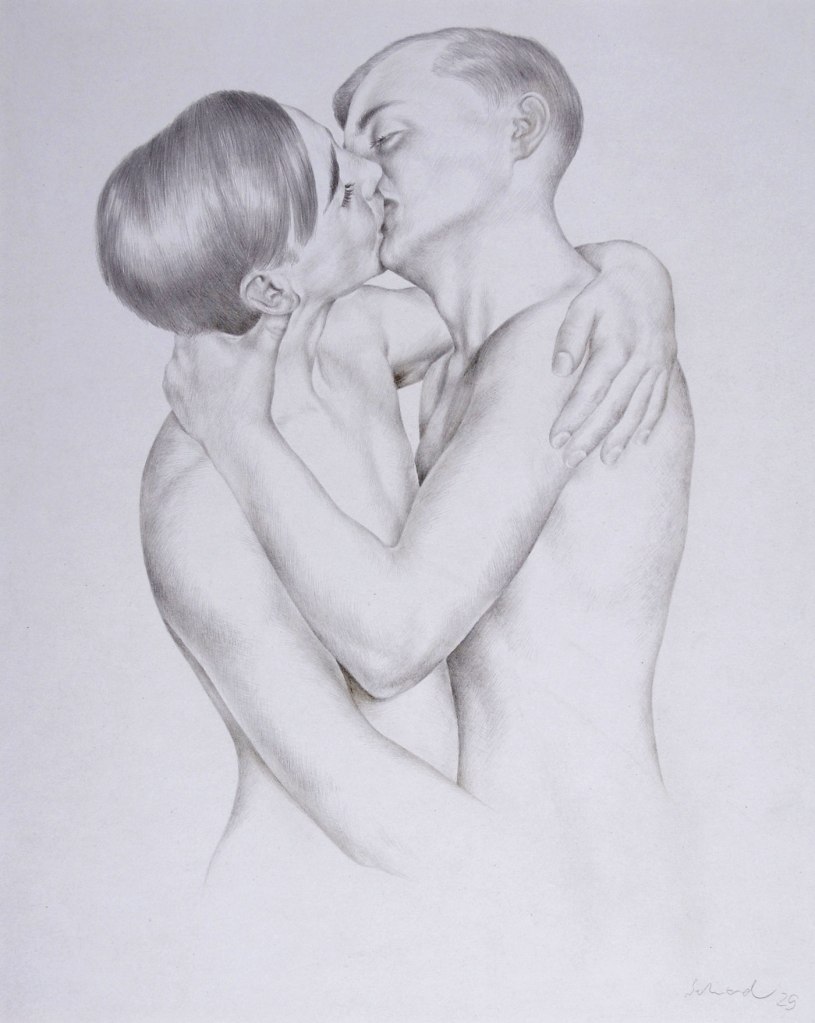

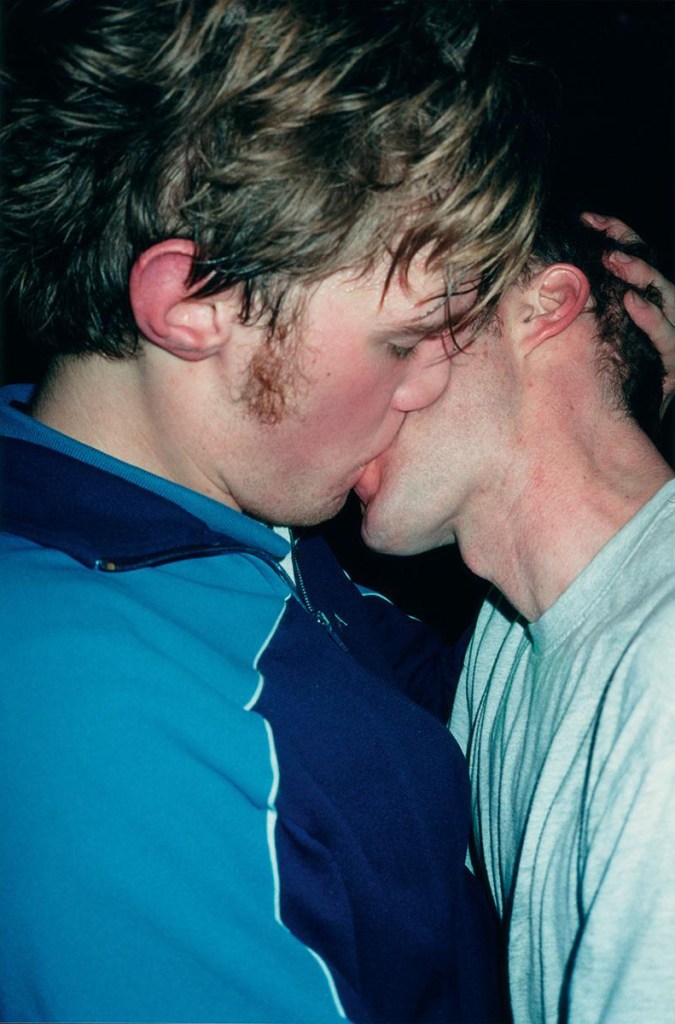

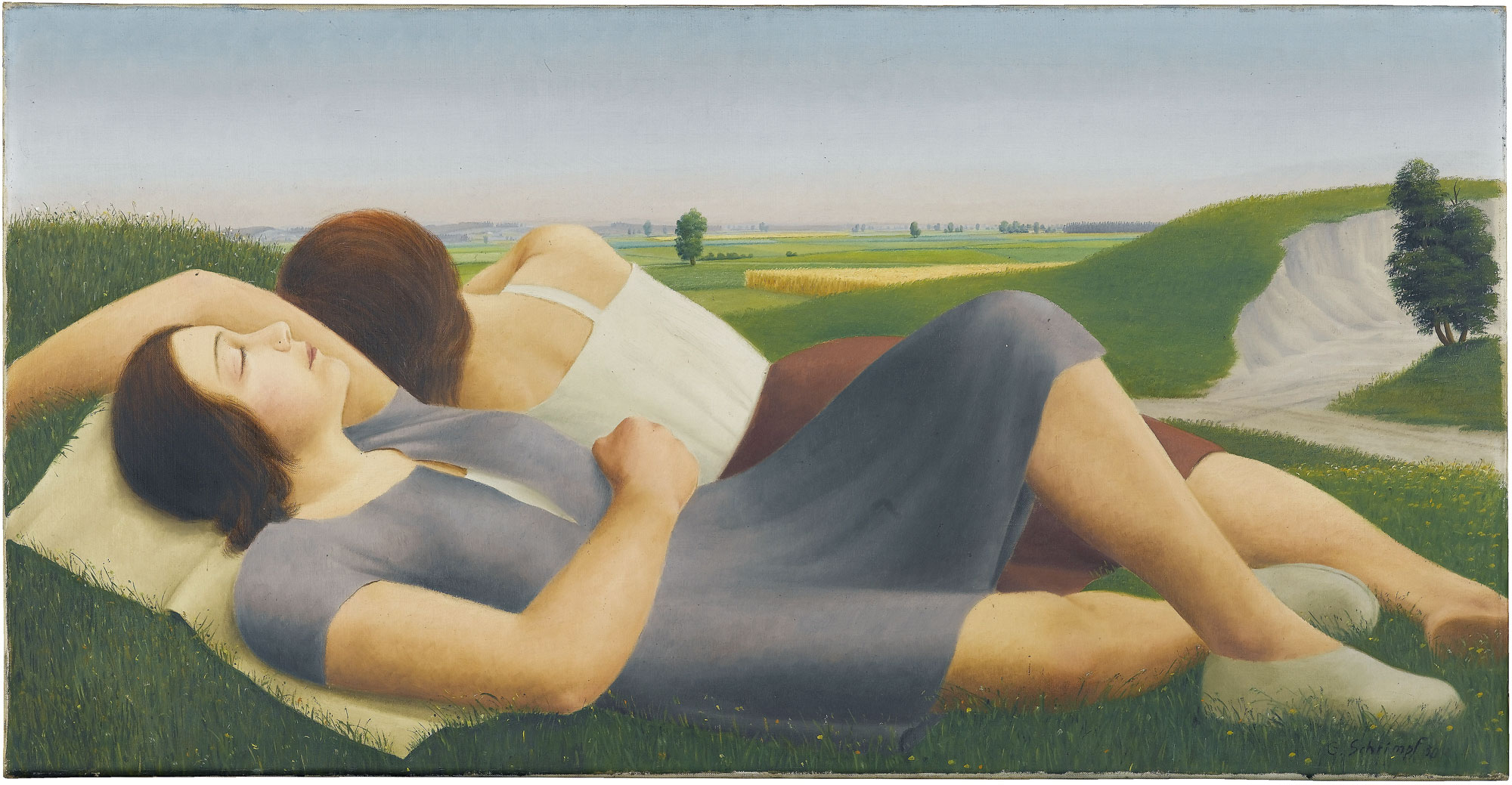

Lovers

The works gathered here show homosexual couples and their intimate relationship with each other. At a time when gay and lesbian love could almost solely take place in secret, capturing queer intimacy within art became a political statement. The images represent an act of self-assertion within a discriminatory environment. They propose utopias and alternative realities that make togetherness possible – partly with recourse to antiquity, partly with a visionary view of future forms of loving and being.

Text from Stories of the exhibition TO BE SEEN: Queer Lives 1900-1950

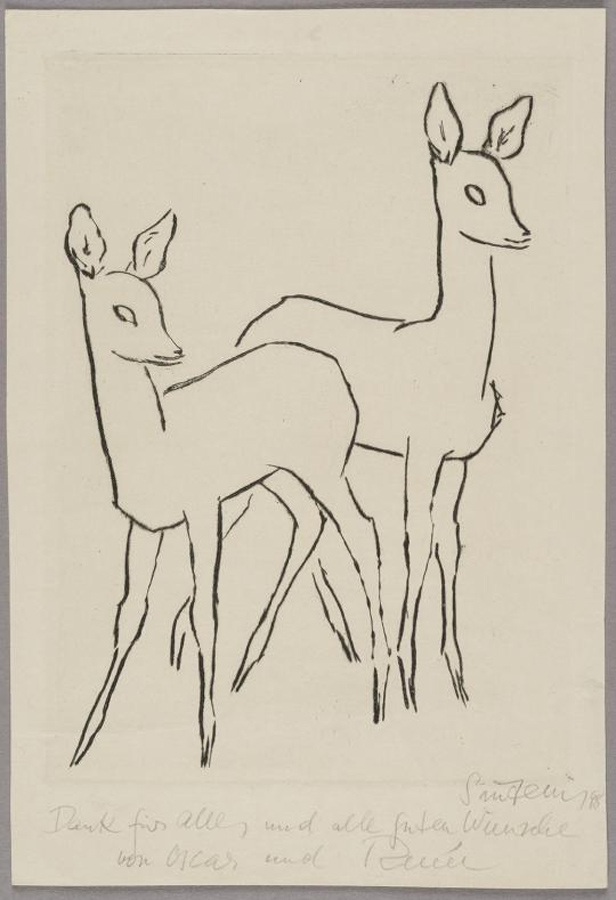

Gertrude Sandmann (German, 1893-1981)

Rosa Nachthemd und schwarzer Pyjama (Pink nightgown and black pyjamas)

1928

© Anja Elisabeth Witte/Berlinische Galerie

Gertrude Sandmann (16 November 1893 – 6 January 1981) was a German artist and Holocaust survivor. Born into a wealthy German-Jewish family, Sandmann studied at the Verein der Berliner Künstlerinnen and had private tutelage from Käthe Kollwitz. In 1935 she was banned from practicing her profession due to the Nuremberg Laws. Given a deportation order in 1942, she ignored it, faked her own suicide, and hid with friends in Berlin until the end of the war. She lived in an apartment in Berlin-Schöneberg until the end of her life. She was a lesbian and, after the war, worked to improve the rights and visibility of LGBT people. Much of her oeuvre is held by the Potsdam Museum.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Gertrude Sandmann (1893-1981), who trained in Berlin and Munich, took private lessons from Käthe Kollwitz in the 1920s. She and the older artist remained lifelong friends. Unlike Kollwitz, however, Sandmann was less focused on social critique. A committed feminist, women were her favourite theme, as they were for her colleague Jeanne Mammen, who was about the same age.

Installation view of the exhibition TO BE SEEN: Queer Lives 1900-1950 at the Munich Documentation Center for the History of National Socialism showing at centre, Dora Kallmus’ photograph The trapeze artist Barbette (Nd, below)

Photo: Connolly Weber Photography/NS-Dokumentationszentrum München

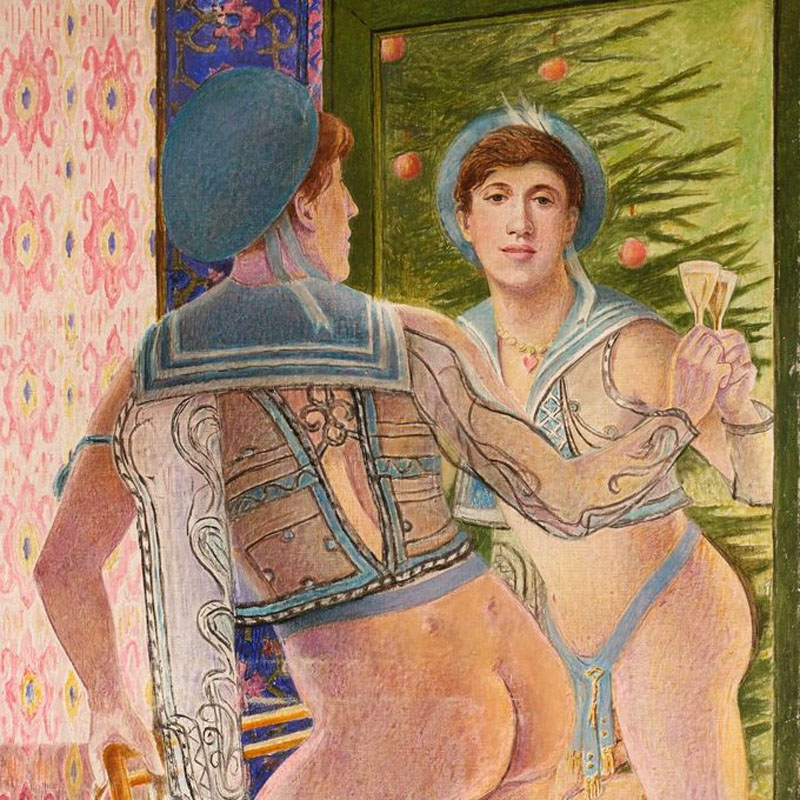

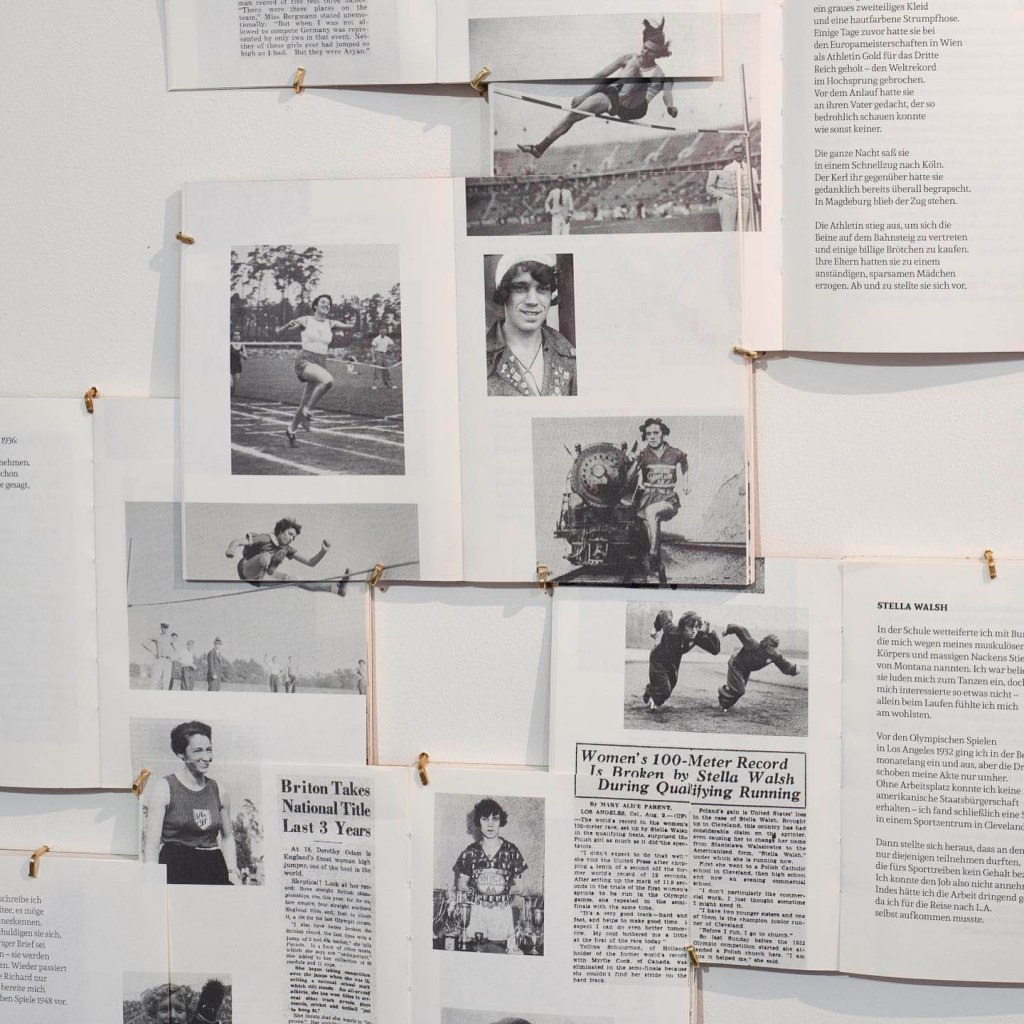

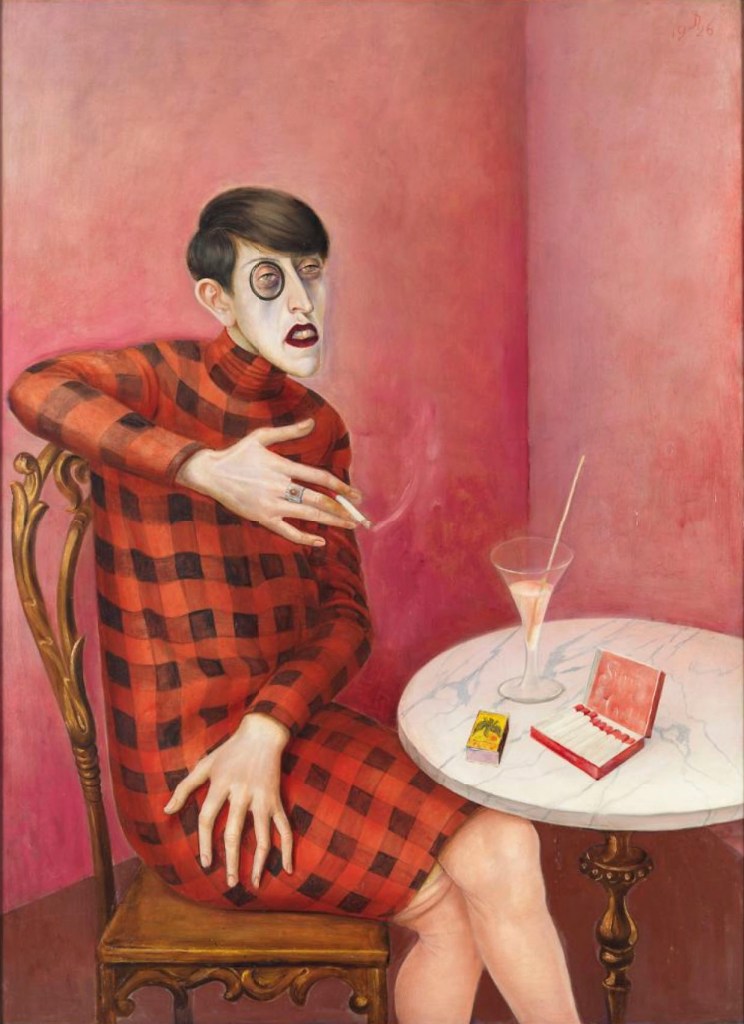

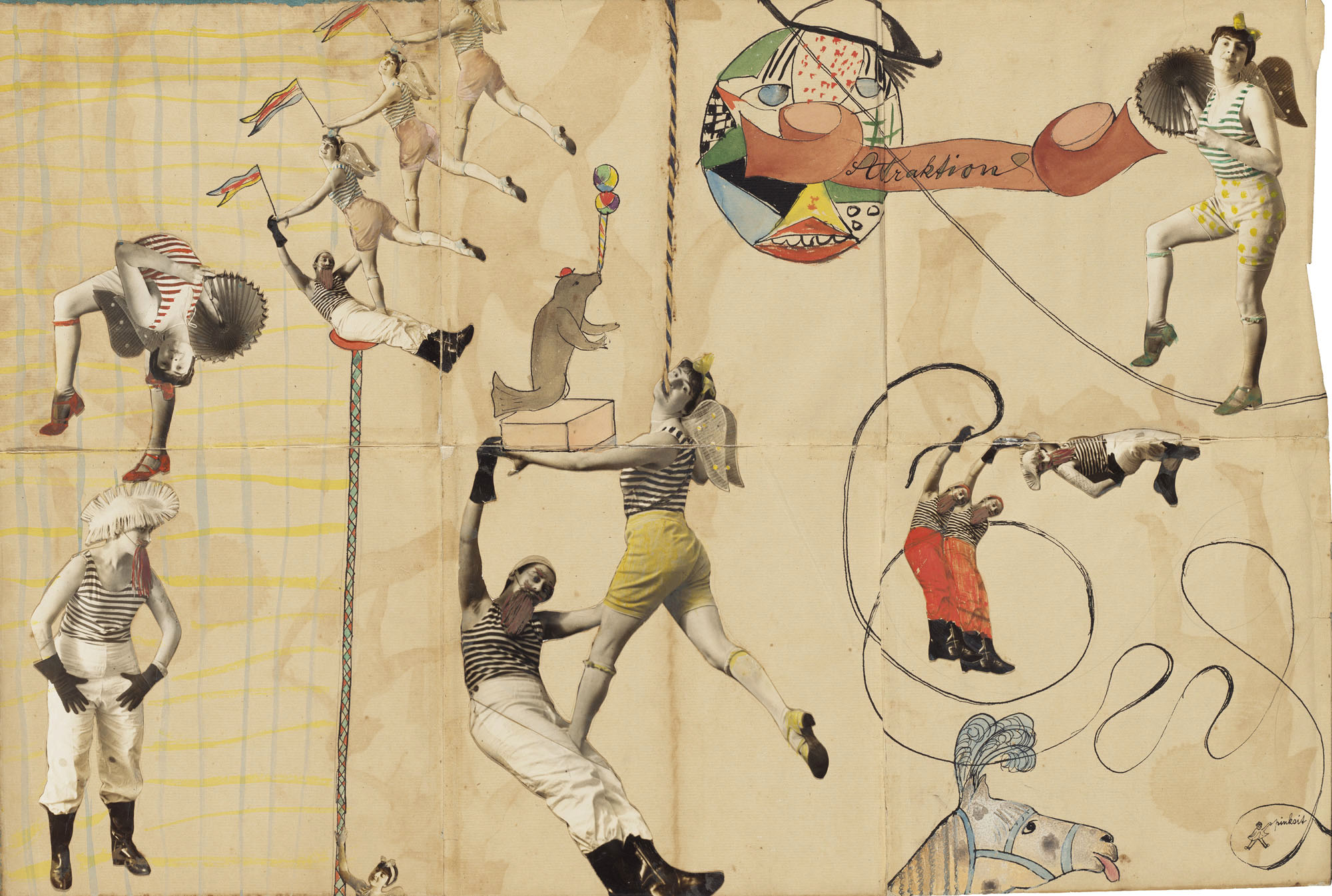

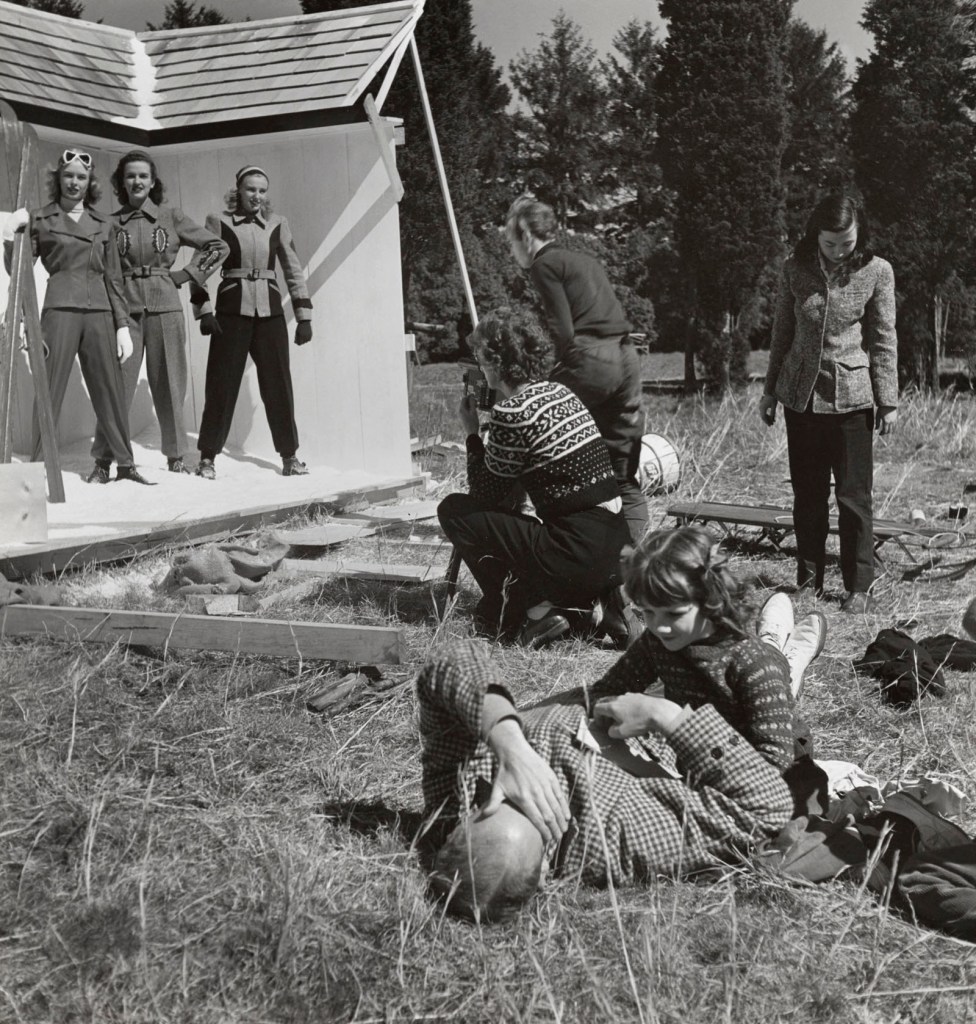

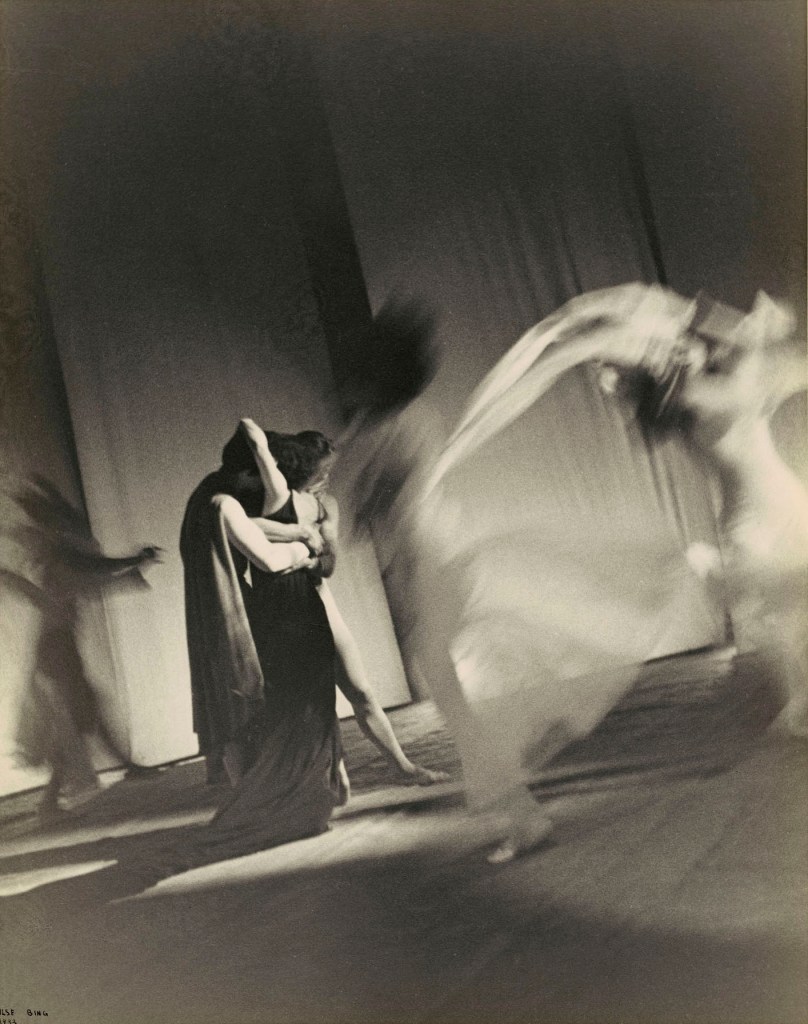

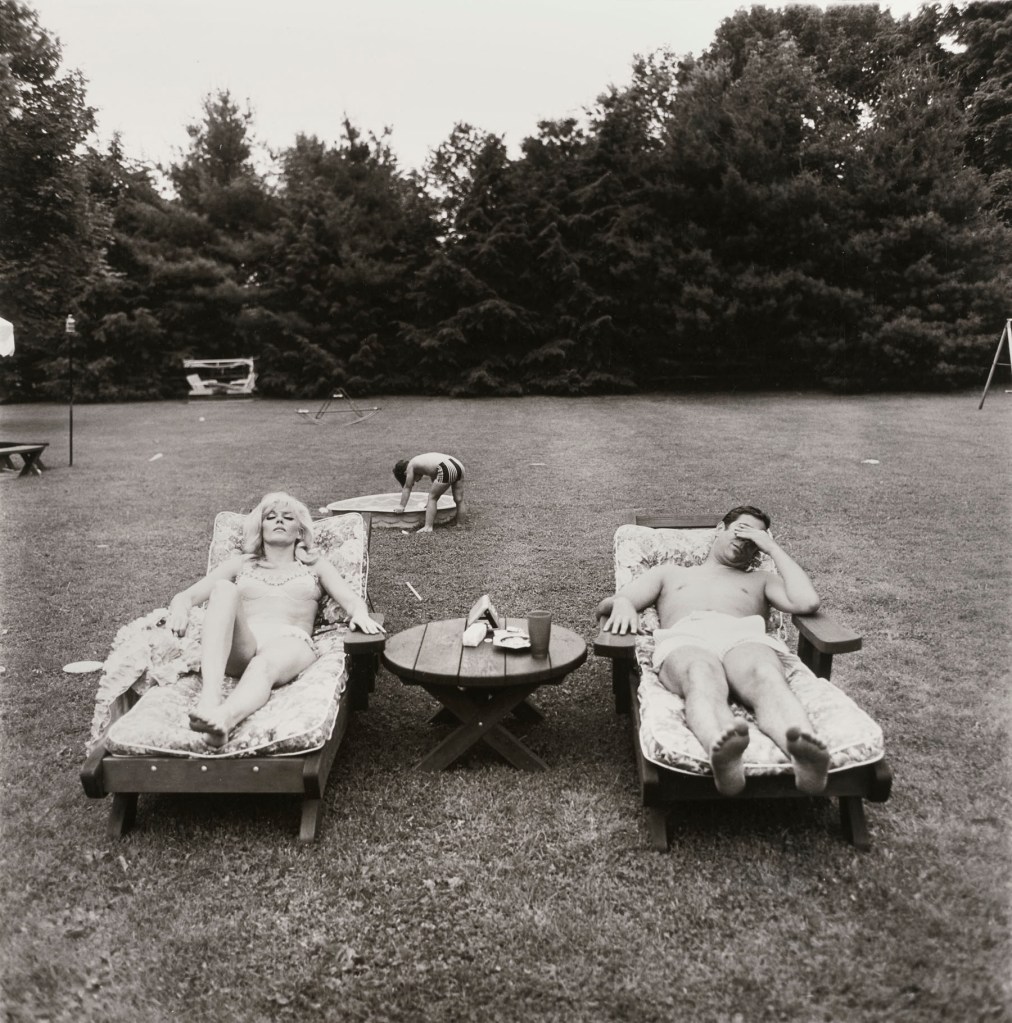

The stage as site of utopias

In the Weimar Republic, vaudevilles, theatres, and nightclubs emerged in many major cities, on whose stages a freer treatment of sexuality and gender identities was allowed. Stage celebrities became role models for alternative gender roles, with drag performances developing into a genre in its own right.

The 1920s, often referred to as “golden” years, were by no means characterised by prosperity for most citizens, even though more and more people gained access to entertainment culture. War trauma and economic hardship stimulated the need to escape the worries of everyday life.

For many people, the bars and clubs of this period were places where they came into contact with alternative gender images and homosexuality, as well as where social debates were sparked.

Text from Stories of the exhibition TO BE SEEN: Queer Lives 1900-1950

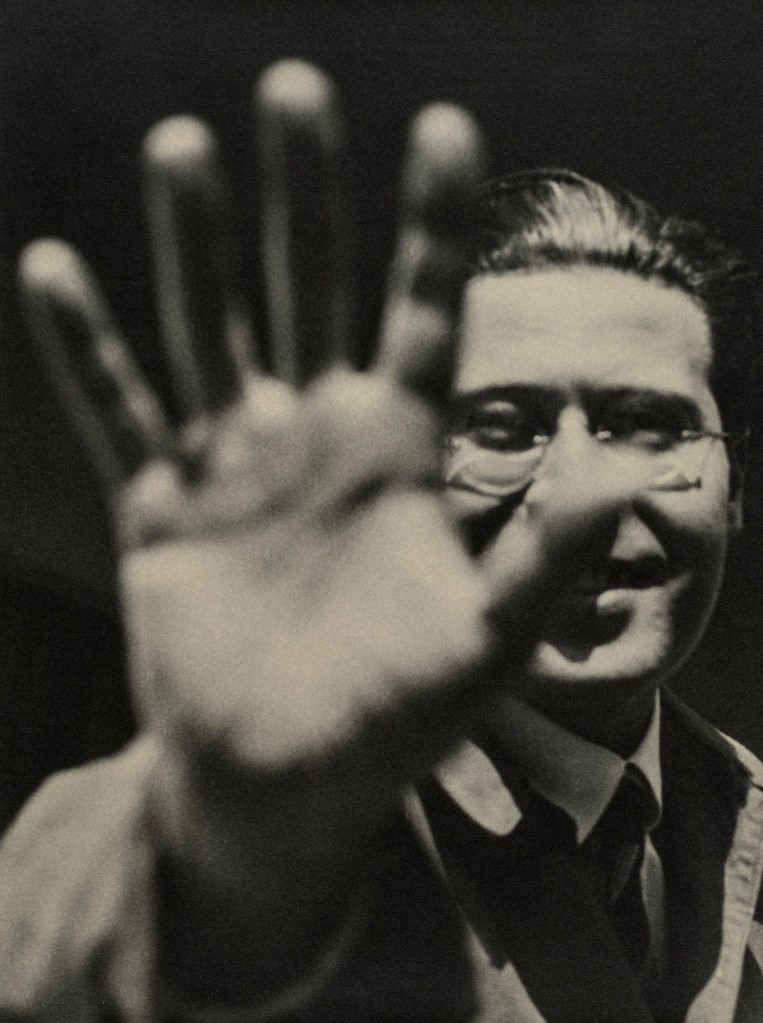

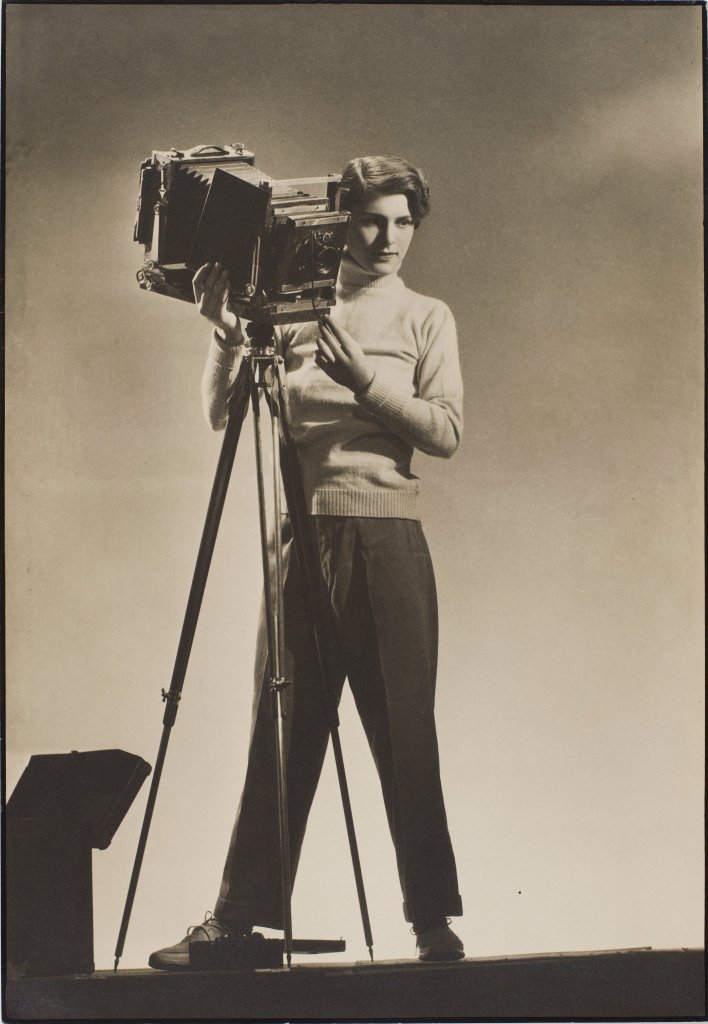

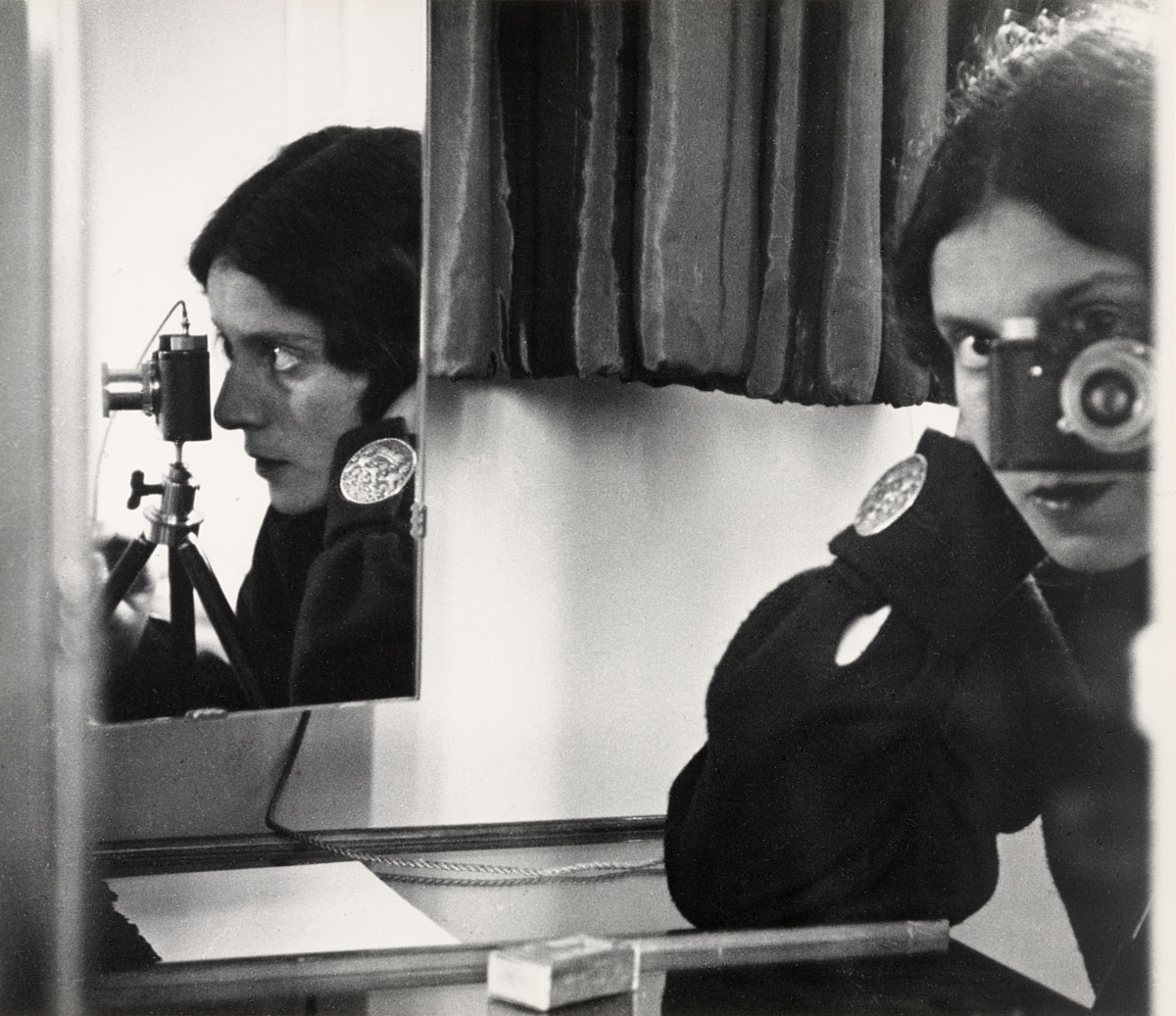

Dora Kallmus (Atelier d’Ora) (Austrian, 1881-1963)

The vaudeville and trapeze artist Barbette

Nd

© Estate of Madame d’Ora, MK&G ~ Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg

The trapeze artist Barbette (real name Vander Clyde, 1899-1973) celebrated great success in Europe from the mid-1920s. Barbette performed, among other things, in the Berlin Varieté Wintergarten. The sensational productions of the “female impersonators” became increasingly known to a mass audience – and thus also helped the male and female impersonators of the Berlin scene to gain acceptance.

Dora Philippine Kallmus (20 March 1881 – 28 October 1963), also known as Madame D’Ora or Madame d’Ora, was an Austrian fashion and portrait photographer.

Early life

Dora Philippine Kallmus was born in Vienna, Austria, in 1881 to a Jewish family. Her father was a lawyer. Her sister, Anna, was born in 1878 and deported in 1941 during the Holocaust. Although her mother, Malvine (née Sonnenberg), died when she was young, her family remained an important source of emotional and financial support throughout her career.

She and her sister, Anna, were both “well-educated,” spoke English and French, and played the piano. They had also traveled throughout Europe.

She became interested in the photography field while assisting the son of the painter Hans Makart, and in 1905 she was the first woman to be admitted to theory courses at the Graphische Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt (Graphic Training Institute). That same year she became a member of the Association of Austrian photographers. At that time she was also the first woman allowed to study theory at the Graphischen Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt, which in 1908 granted women access to other courses in photography.

Career

In 1907, she established her own studio with Arthur Benda in Vienna called the Atelier d’Ora or Madame D’Ora-Benda. The name was based on the pseudonym “Madame d’Ora”, which she used professionally. D’ora and Benda operated a summer studio from 1921 to 1926 in Karlsbad, Germany, and opened another gallery in Paris in 1925. The Karlsbad gallery allowed D’Ora to cater to the “international elite vacationers.” These same clients later convinced her to open her Paris studio.

Between 1917 and 1927, D’Ora’s studio “produced” photographs for Ludwig Zwieback & Bruder, a Viennese department store. She was represented by Schostal Photo Agency (Agentur Schostal) and it was her intervention that saved the agency’s owner after his arrest by the Nazis, enabling him to flee to Paris from Vienna.

Her subjects included Josephine Baker, Coco Chanel, Tamara de Lempicka, Alban Berg, Maurice Chevalier, Colette, and other dancers, actors, painters, and writers.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Dora Kallmus (Austrian, 1881-1963)

The vaudeville and trapeze artist Barbette (detail)

Nd

© Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg

Unknown photographer

Dance study of Alexander Sakharoff

1912

Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration: illustr. Monatshefte für moderne Malerei, Plastik, Architektur, Wohnungskunst u. künstlerisches Frauen-Arbeiten – 30.1912

Installation view of the exhibition TO BE SEEN: Queer Lives 1900-1950 at the Munich Documentation Center for the History of National Socialism

Photo: Connolly Weber Photography/NS-Dokumentationszentrum München

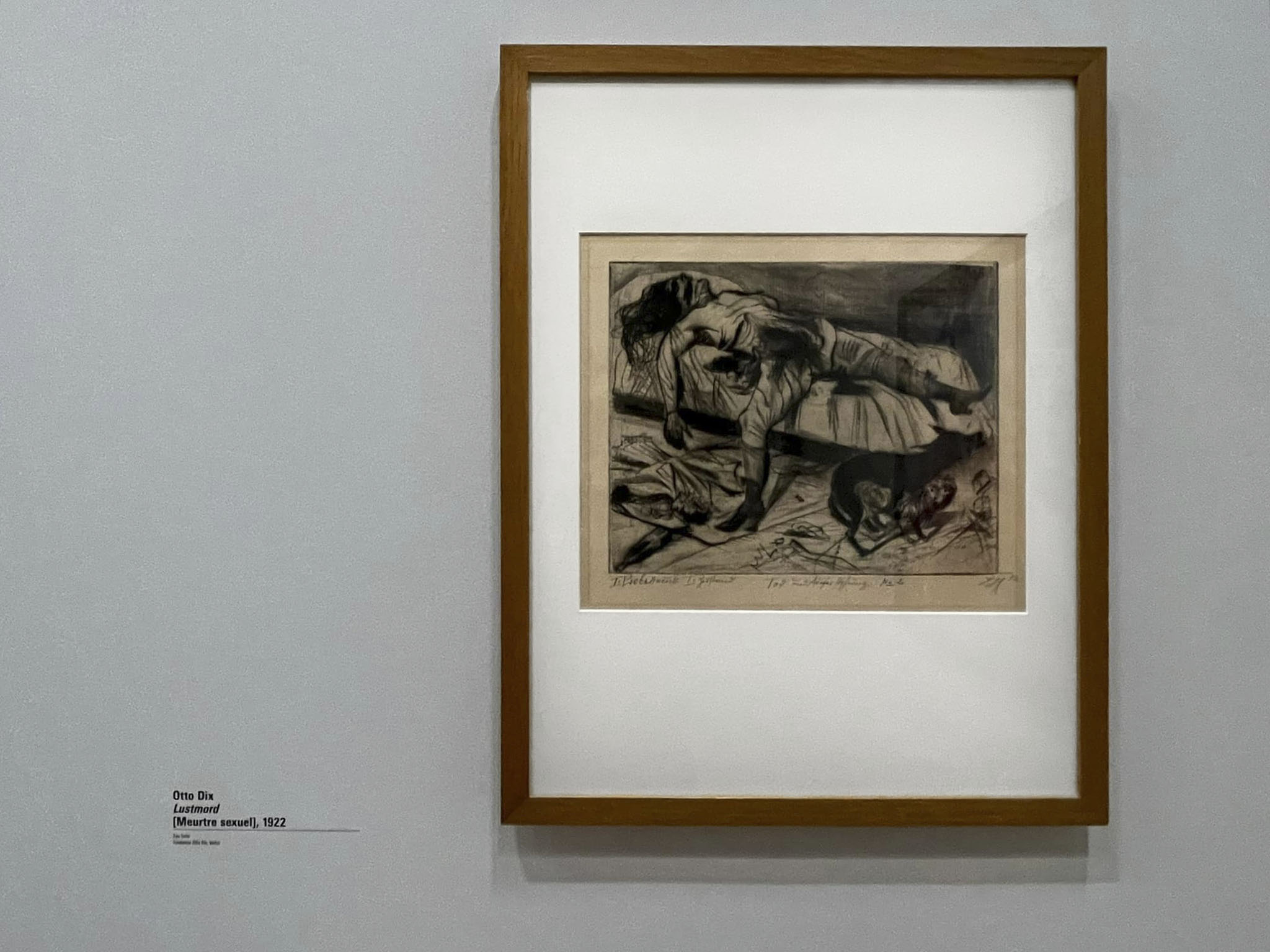

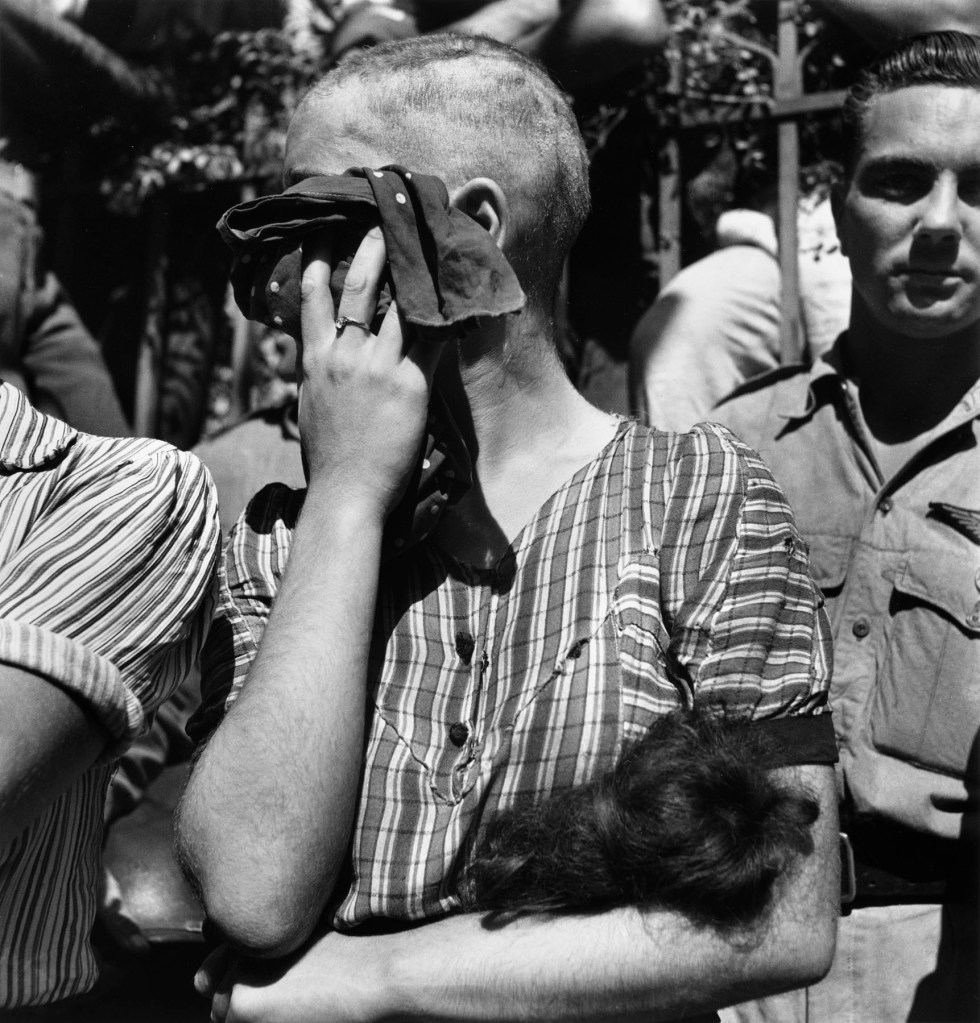

Life under dictatorship

After the Nazis took power in 1933, every form of queer life was threatened and continued to exist only in private spaces or secret locations. Hopes for a tacit tolerance of homosexuality by the Nazis were finally dashed after the murder of Ernst Röhm, chief of- staff of the SA (Storm Troopers). The period of open persecution had begun.

During the first major Nazi raids against homosexuals on October 20, 1934, 145 men were arrested in Munich alone. Paragraph 175 of the penal code was made more severe in June 1935: any act between men bearing sexual suggestion was now punishable.

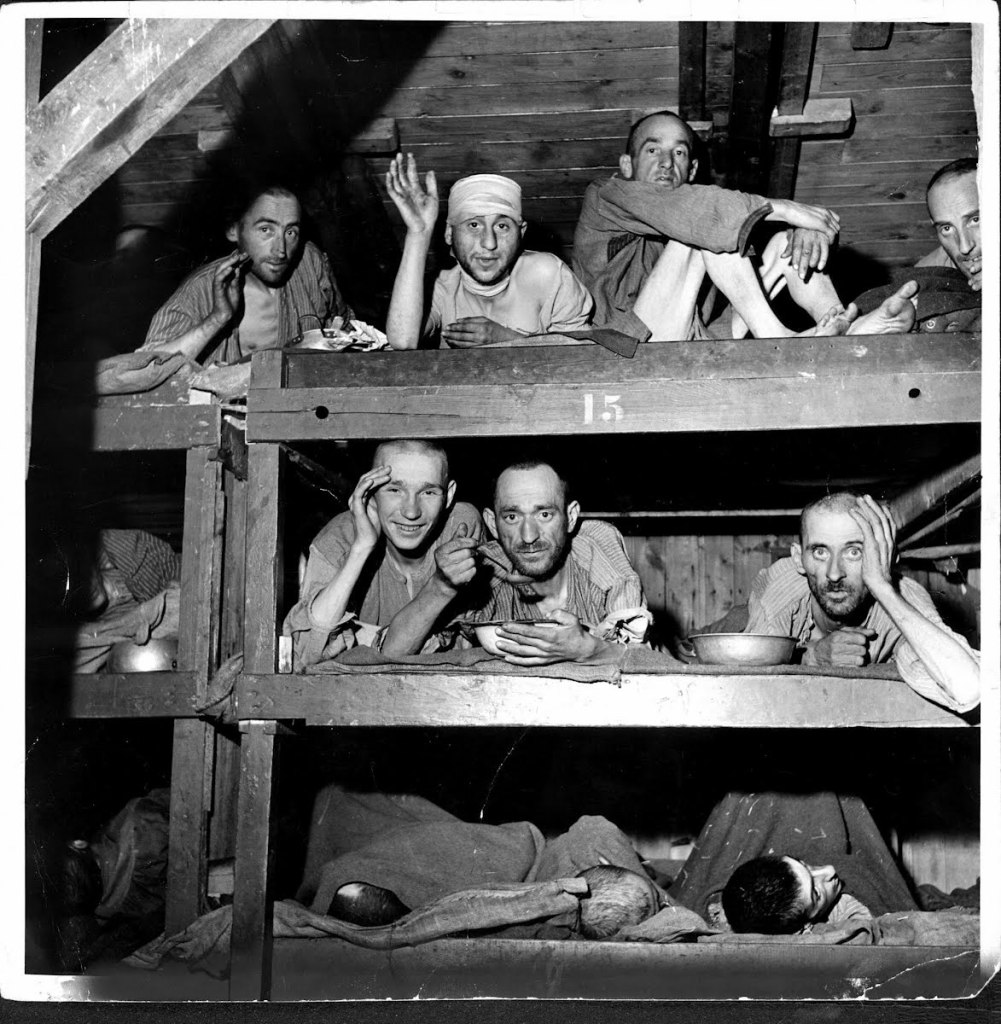

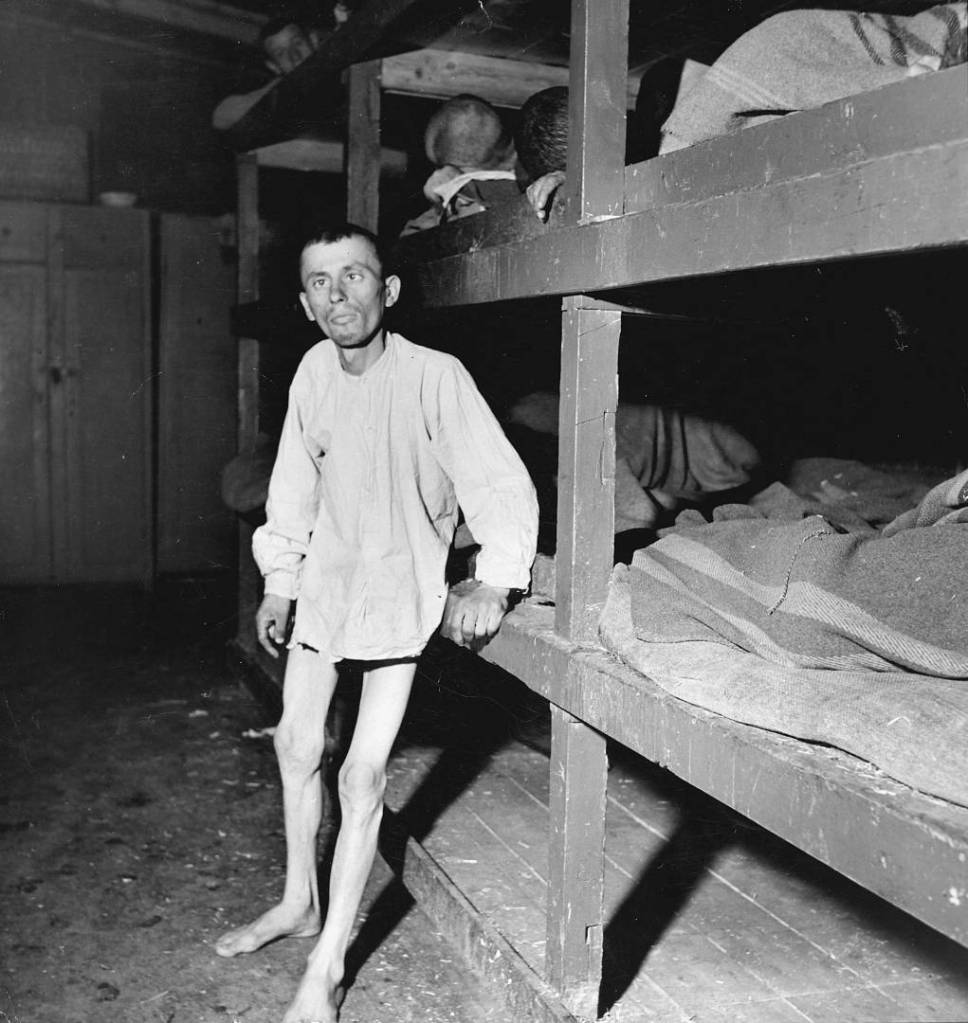

About 57,000 homosexual men were sentenced to prison, and between 6,000 and 10,000 of them were deported to concentration camps, of whom at least half were murdered.

Female homosexuality was not prosecuted in the dictatorship, but was socially ostracised. If lesbian women and persons who did not conform to their gender were denounced, they were threatened with police investigations, house searches, and interrogations. If political opposition, social deviance, or racial persecution additionally occurred, they faced repression or even internment in a concentration camp.

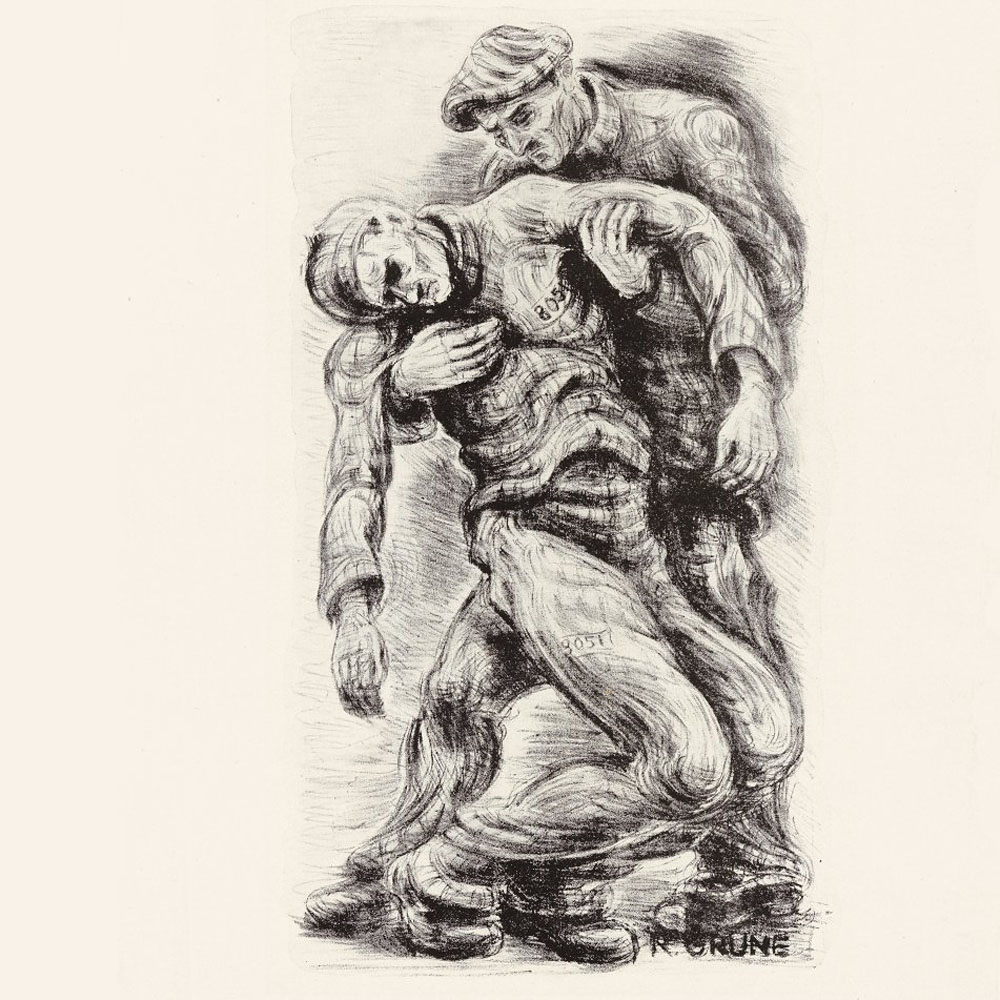

The graphic artist Richard Grune (1903-1983) was imprisoned almost continuously from 1934 to 1945 because of his homosexuality. After his liberation from the concentration camp, he processed what he had experienced through art.

Text from Stories of the exhibition TO BE SEEN: Queer Lives 1900-1950

Richard Grune (German, 1903-1983)

Solidarity: Prisoner Supports His Exhausted Comrade

1945-1947

Lithograph

© Wien Museum

“Solidarity,” a lithograph of one prisoner supporting another, by German artist Richard Grune, who spent eight years in Nazi concentration camps after being convicted for homosexuality.

Trained as an artist and graphic designer, 29-year-old Richard Grune moved to Berlin the same month that the police began forcing these establishments to shut down. Although prominent nightclubs like the Eldorado faced closure, members of these communities still found ways to continue gathering more privately. For example, Grune hosted two parties for friends in his studio in fall 1934. He was denounced afterward – along with dozens of others – by a private citizen who often passed information to police. Grune was then arrested for alleged violations of Paragraph 175, the statute of the German criminal code that criminalised sexual relations between men. He was imprisoned for several months before being convicted and sentenced to a year in prison.

After serving his sentence, Grune was arrested again by the Gestapo and held indefinitely in what was misleadingly referred to as “protective custody” (“Schutzhaft”) – an experience shared by many convicted of violating Paragraph 175 under the Nazi regime.5 Grune spent the next decade in concentration camps, including Sachsenhausen and Flossenbürg. He escaped from Flossenbürg in April 1945 as American forces approached and camp authorities evacuated the prisoners.

Grune created the featured lithograph6 – “Solidarity: Prisoner Supports His Exhausted Comrade” – in 1945 as part of a series of images inspired by his experiences as a prisoner in the Nazi camp system. These lithographs were reproduced in two published portfolios in 1947.7 Grune’s artwork reflects many of his own experiences, but it does not reference his persecution as a gay man in any specific way. Instead, his lithographs seem to suggest the idea of shared suffering among all concentration camp prisoners. Because sexual relations between men remained criminalised for decades in Germany after the end of World War II, many people convicted under Paragraph 175 chose to conceal the details of their past persecution under the Nazi regime.8

After the war, Grune chose to portray himself as a political prisoner of Nazism, but he was not able to obtain official recognition or compensation for his suffering. Although his lithographs are among the most important artistic representations of concentration camp experiences created immediately after the war, Grune could not support himself as an artist. He did occasionally find design and illustration work, but he made his living by working as a bricklayer. Grune died in obscurity in Kiel, Germany in 1983.

Anonymous. “Lithograph by Richard Grune,” on the Holocaust Sources in Context website Nd [Online] Cited 10/04/2023

“This is how the Führer cleaned up!”

Front page of the extra issue of the Völkischer Beobachter, June 30, 1934, Berlin edition

Public domain

Homosexuality in Nazi organisations and in the military

The proscription of homosexuality was used by various sides in the political struggle. In 1931 / 1932, the Social Democrats utilised Ernst Röhm’s homosexuality to harm the Nazi Party. The Röhm case served the notion of “gay Nazis” gathering together in male associations, a phenomenon that did exist. Beginning in the mid-1930s, the Nazi regime increasingly cracked down on homosexual activity in the army, police, and Nazi associations. Intimacy between men was now punished particularly severely in party organisations and the police. Nazi propaganda labeled homosexual men as “enemies of the state” to legitimise this persecution. Nevertheless, clandestine homosexual encounters continued to occur.

Adapting to survive

After the dismantling of gay and lesbian subcultures across the entire state and the harshening of criminal law, homosexual contact took place almost exclusively in private spaces. Fear of denunciation and persecution drove most homosexuals to hide their sexuality and conform.

This also applied to lesbian women and trans* persons, who were not prosecuted per se. They could remain unhampered as long as they did not attract attention. Marriages of convenience were one of many survival strategies. Certain prominent artists were tolerated by the Nazi regime despite their widely known homosexuality. The regime, which needed these stars for its propaganda, held off on persecution, and demanded that they conform in their way of living.

Persecution and imprisonment

The Nazi regime’s treatment of homosexuals and trans* persons was not uniform. Initially, most of the men convicted under Paragraph 175 were released after serving their prison sentences. Especially since 1940 many were transferred to concentration camps. Lesbian women and trans* persons were sometimes charged with other crimes, such as prostitution or indecent behaviour. Others were persecuted for political, social, or racist reasons.

The Nazi regime’s treatment of homosexuals and trans* persons was not uniform. Initially, most of the men convicted under Paragraph 175 were released after serving their prison sentences. Especially since 1940 many were transferred to concentration camps. Lesbian women and trans* persons were sometimes charged with other crimes, such as prostitution or indecent behaviour. Others were persecuted for political, social, or racist reasons.

Text from Stories of the exhibition TO BE SEEN: Queer Lives 1900-1950

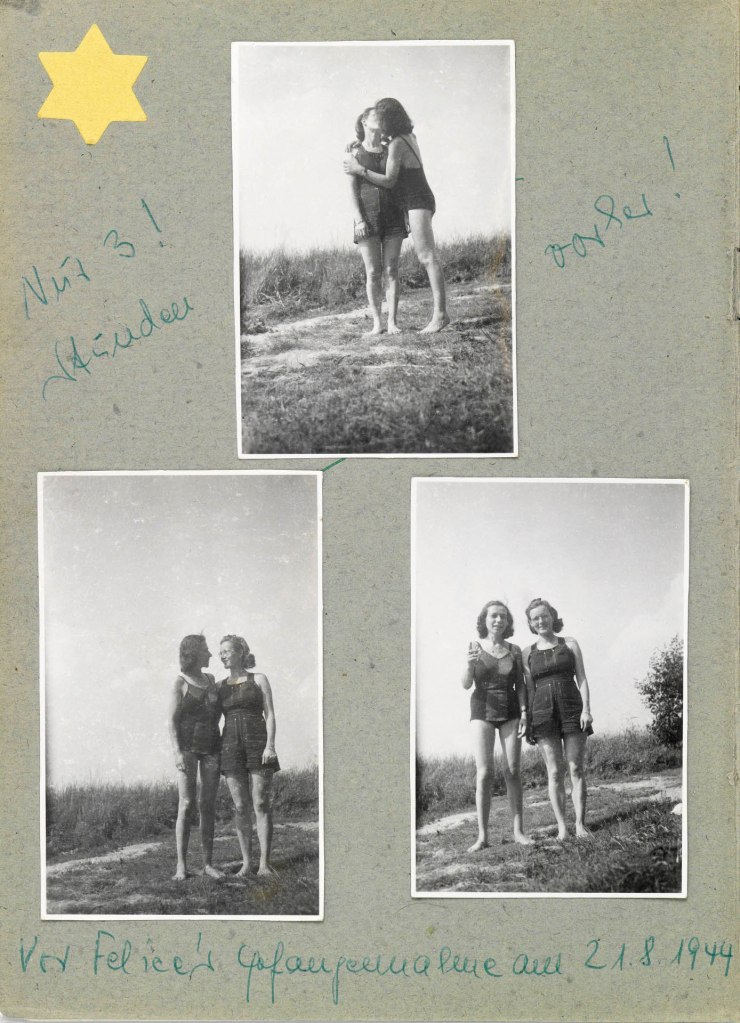

Unknown photographer

Photographs from Elisabeth (Lilly) Wust’s diary entry on the deportation of her Jewish partner Felice Schragenheim to the Theresienstadt concentration camp

August 21, 1944

© Jewish Museum Berlin

Part of the diary entry by Elisabeth (Lilly) Wust on the deportation of her Jewish partner Felice Schragenheim to the Theresienstadt concentration camp, August 21, 1944

Elisabeth (Lilly) Wust (1913-2006) and Felice Schragenheim (1922-1945) met in Berlin in 1942, shortly after Schragenheim went into hiding as a Jew. They moved in together a little later and promised to marry in June 1944. On August 21, 1944, Felice Schragenheim was discovered and taken to a Berlin collection point for Jews. Lilly Wust visited her there several times before the deportation to the Theresienstadt ghetto. In the hope of being able to help her beloved, Lilly Wust travelled to Theresienstadt herself in the fall of 1944.

Felice was deported to Auschwitz a little later. She died in early 1945, probably in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. Lilly Wust searched for her for years.

The love story of Lily Wust and Felice Schragenheim gained notoriety in the 1990s through the book “Aimée & Jaguar” and the feature film of the same name. However, there is another version of the story: Elenai Predski-Kramer, a former girlfriend of Felice Schragenheim, tells her perspective on the love story after the book was published and expresses the suspicion that Lilly Wust herself might have betrayed Felice Schragenheim. However, there is no evidence for this.

Text from the Munich Documentation Center for the History of National Socialism Instagram page

Unknown photographer

Photograph from Elisabeth (Lilly) Wust’s diary entry on the deportation of her Jewish partner Felice Schragenheim to the Theresienstadt concentration camp (detail)

August 21, 1944

© Jewish Museum Berlin

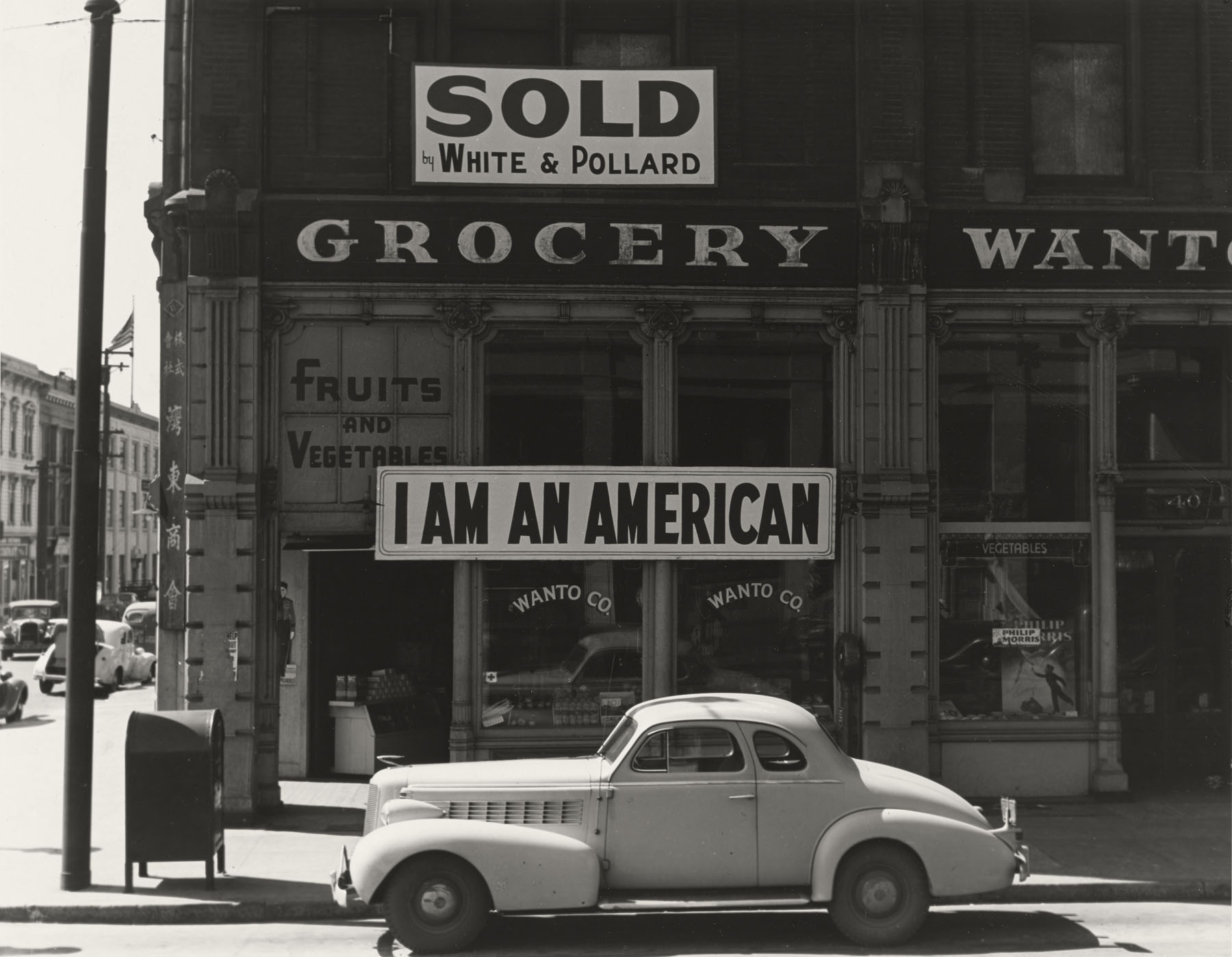

Exile and resistance

Only a few homosexual and trans* people succeeded in escaping Nazi persecution through emigration. This option was usually only open to the wealthy or those who had international contacts and could find work abroad thanks to their education and language skills. Leaving Nazi Germany was made more difficult by the measures against capital transfer, which were tightened in 1934. The “Reich Flight Tax” reduced assets by 25 percent upon departure, the export of foreign currency was prohibited, and the transfer of bank or securities assets was made almost impossible.

Individual homosexual or transgender people decided to actively resist the Nazi regime, also in the territories occupied by Germany. They documented the crimes of the Nazi regime, called for resistance, carried out sabotage, committed attacks, or fought as partisans or members of foreign troops against Hitler’s Germany.

Text from Stories of the exhibition TO BE SEEN: Queer Lives 1900-1950

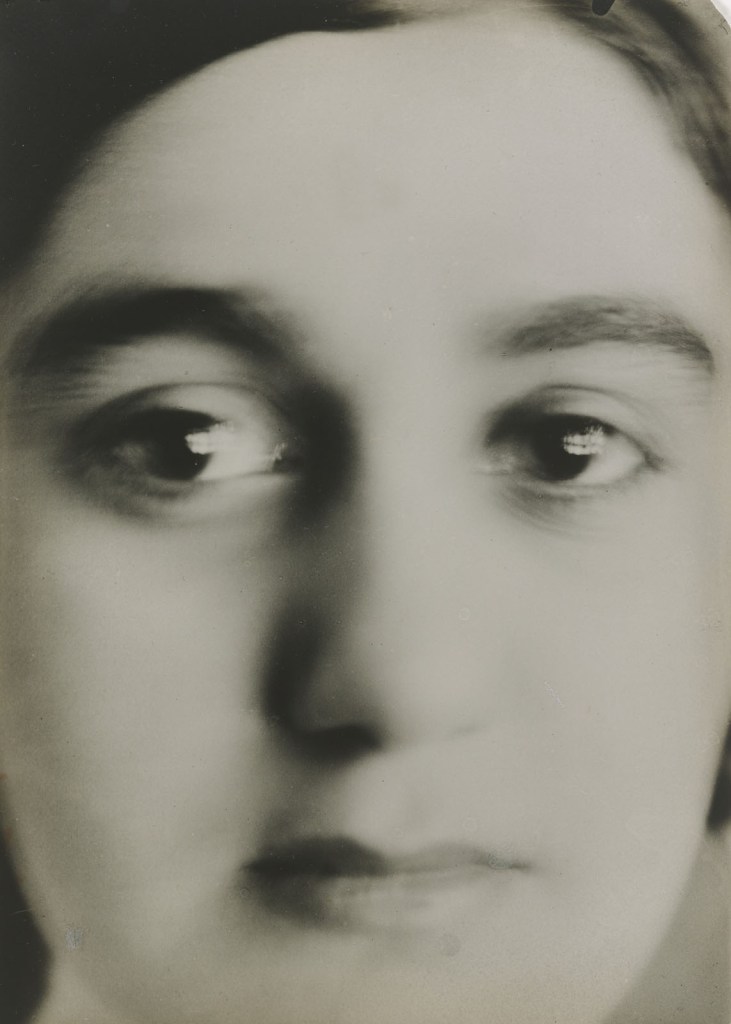

Claude Cahun (French, 1894-1954)

Self Portrait (with Nazi badge between her teeth)

1945

Gelatin silver print

© Jersey Heritage Collection

Jewish-French author and photographer Claude Cahun (French, 1894-1954) and her partner Marcel Moore (French, 1892-1972) put up resistance against the Nazi regime.

After four years of subversive activity, the pair were arrested by the Germans in 1944. Initially, the Nazi authorities couldn’t believe that the women carried it out by themselves. “They believed that there must be somebody else involved, there must be a man involved,” says Downie.

While waiting to be questioned, Cahun and Moore attempted suicide. They both took pills – barbiturates – which put them into a coma. Once they were well enough, they were sentenced to death for undermining the German forces. But the Bailiff of Jersey and the French Consul pleaded on their behalf – by that time, the Normandy landings had happened and Saint-Malo (the main connecting port) had been liberated, so they could no longer be deported to camps in Europe – and their sentence was commuted.

Although their lives had been saved, Moore and Cahun were not pleased. “They wanted to be martyrs for their cause,” says Downie. “To them, that would’ve been the realisation of their life of resistance, to be a martyr for freedom.”

At 3.40pm on May 9, 1945, the swastika was lowered from Fort Regent, a 19th-century fortification in St Helier, and the Union Jack was hoisted, signalling the official end of the occupation. Then the celebrations began. Cahun joined the crowds in Royal Square cheering, flag-waving, and holding a sailor aloft. Despite ill health from their time in prison, they kept on creating work after the war. In the same month, a photograph shows them gripping a Nazi eagle badge brazenly between their teeth, a silk scarf tied around their head, their hands dug into their coat pockets, their eyes staring defiantly at the camera.

Jessie Williams. “Claude Cahun: Jersey’s queer, anti-Nazi freedom fighter,” on the Huck website 14th May, 2020 [Online] Cited 17/04/2023

After 1945

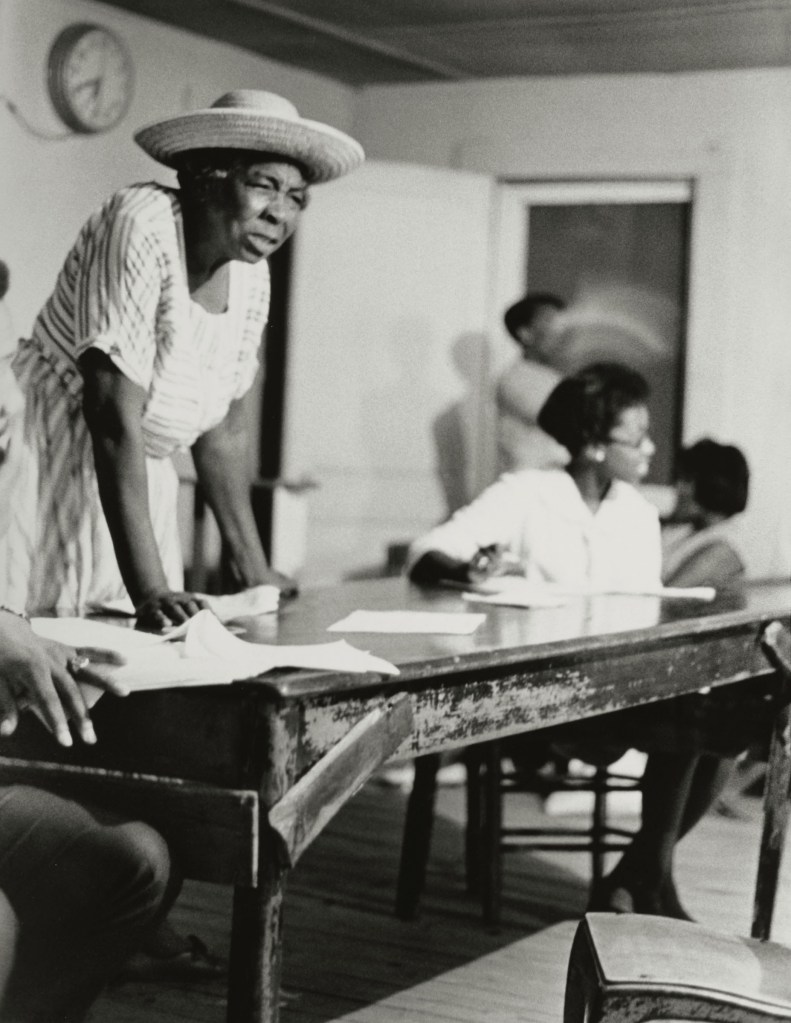

Queer history was hardly remembered or archived after 1945. To this day, we know only some of the pioneers of the queer emancipation movement. We know even less about the life of those who were persecuted, driven into exile, murdered – or simply remained invisible.

After the end of the war, queer people continued to be marginalised. Gay men in particular continued to suffer in large numbers under Paragraph 175, many of whom did not go free but were transferred from concentration camps directly to prisons.

The ongoing discrimination by state and society changed only slowly. In 1969, Paragraph 175 was reformed and criminal law liberalised. Beginning in the 1970s, new social movements emerged, including a homosexual emancipation movement. Various groups reclaimed the “pink triangle” as a symbol to stand up for the rights of queer people.

Lesbian and feminist groups also gained popularity during the 1970s. Although lesbian sexuality was not directly persecuted by the state, many suffered from the misogynistic legal situation. The legal preferential treatment of men made it difficult to live out lesbian relationships, due to discrimination in labor and marriage laws.

The emergence of HIV in the 1980s affected many gay men and trans* people: thousands became infected, developed AIDS, and died. The state did not help, but instead relied on stigmatising measures and an aggressive rhetoric of exclusion, especially in Bavaria. For those affected, this recalled the previous period of open persecution.

Thanks to the efforts of activists, the health, political, and social situation of LGBTQI+ persons has improved since the 1990s. Today, queer people in Germany can celebrate some achievements and are also represented in politics. However, much remains to be done for LGBTQI+ equality. In many places around the world the situation is increasingly deteriorating. Trans* people in particular continue to face great discrimination.

Therefore, the commitment to queer self-determination is not over, but more relevant than ever. Because in the end, it not only ensures the preservation of LGBTIQ* human rights, but creates a more just society for all.

Text from Stories of the exhibition TO BE SEEN: Queer Lives 1900-1950

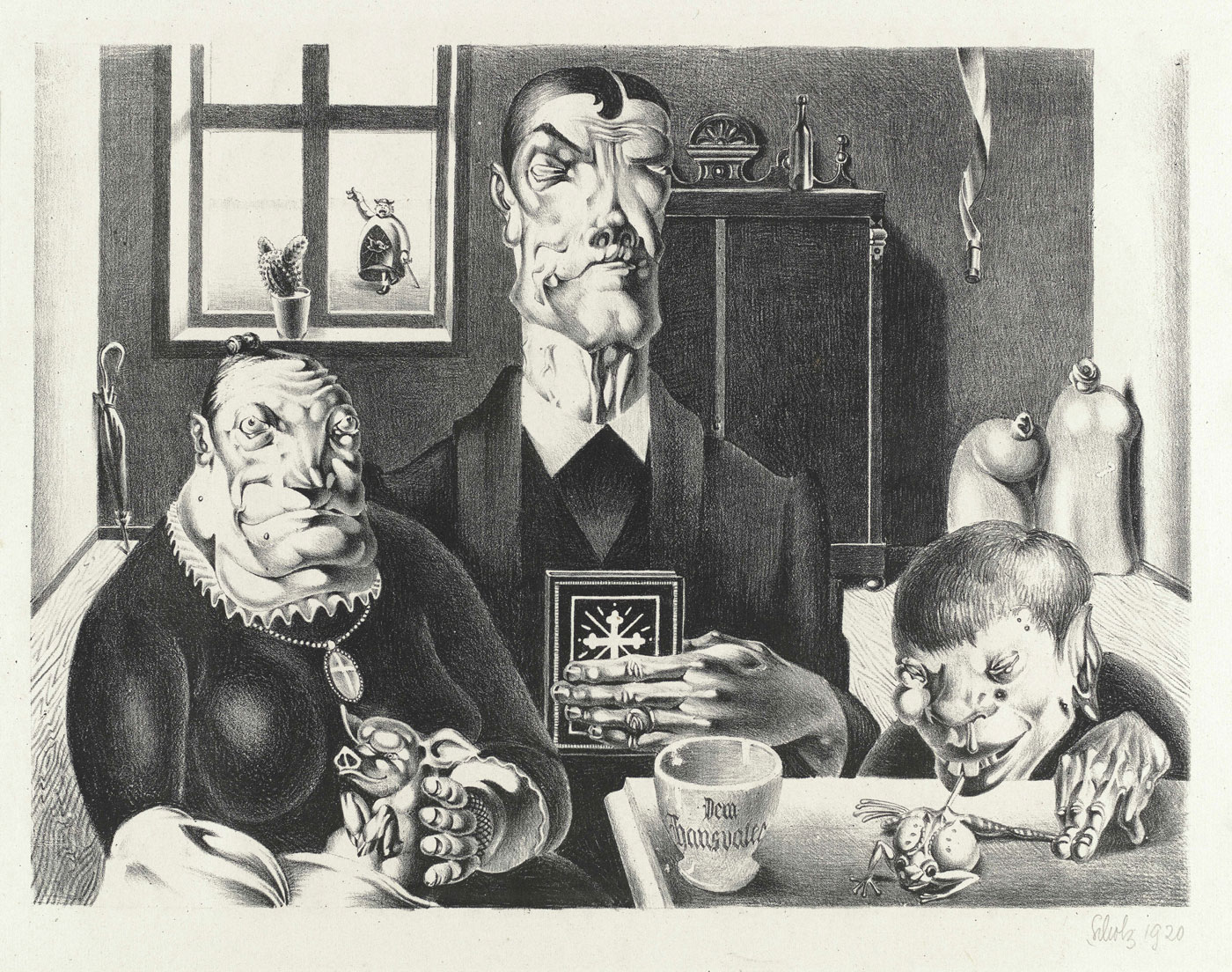

Paul Hoecker (German, 1854-1910)

Installation view of the exhibition TO BE SEEN: Queer Lives 1900-1950 at the Munich Documentation Center for the History of National Socialism showing in the bottom image at left on the wall, Paul Hoecker’s painting Head of a youth / Portrait of a boy (1901); and at right on the wall, Paul Hoecker’s painting Pierrot (Nd)

Photo: Connolly Weber Photography/NS-Dokumentationszentrum München

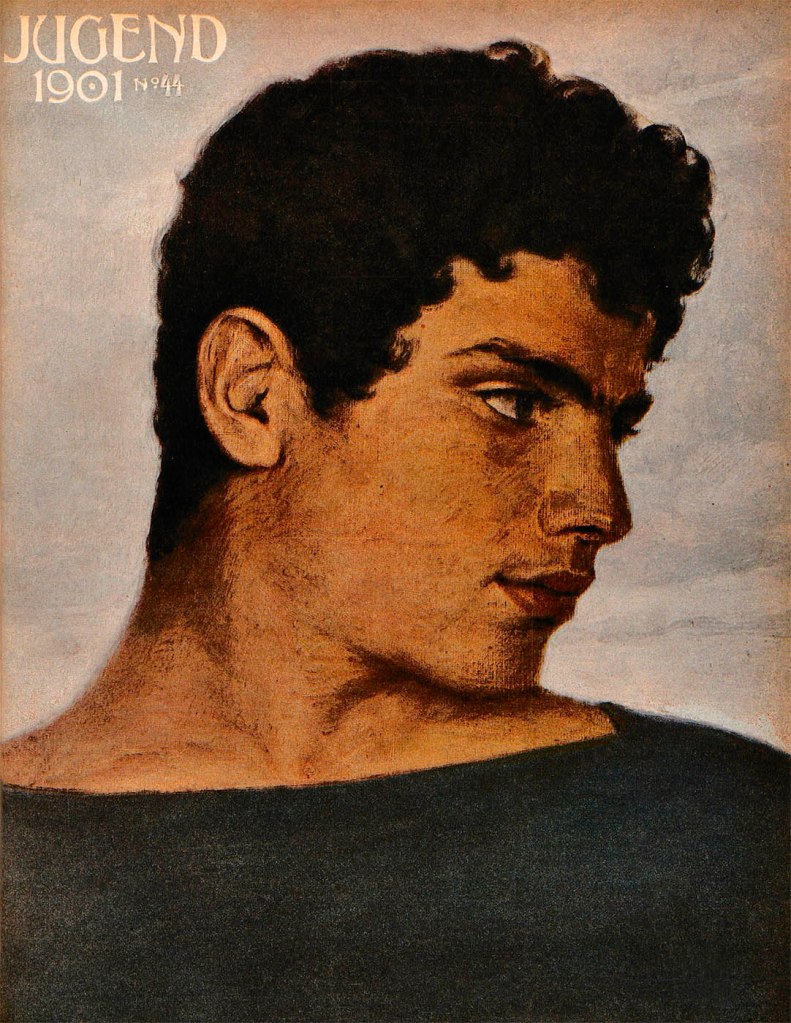

Paul Hoecker (German, 1854-1910)

Young Man’s Head

Cover of Jugend magazine, volume 44, 1901

Public domain

A chapter of TO BE SEEN #QueerLives is dedicated to the artist Paul Hoecker (1854-1910). It was created in collaboration with @forummuenchenev, which researches Hoecker’s story to honor and commemorate his life and work.

Paul Hoecker shaped the Munich art scene in the late 19th century. After his homosexuality became known, the artist was excluded and fell into oblivion. As a professor at the Munich Academy of Fine Arts, Hoecker had a great deal of influence during his lifetime: almost all the painters in the artist group “Die Scholle” and many illustrators for the magazines “Simplicissimus” and “Die Jugend” were among his students. The co-founder of the Munich Secession also received great recognition for his artistic work.

Hoecker privately exchanged views with the sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld about the fact that he has “contrasexual tendencies”, i.e. is gay. When a sex worker was recognised in the model of his acclaimed work “Ave Maria”, he was involuntarily outed. Paul Hoecker forestalled a scandal by resigning from his professorship. In this way he was able to avoid having to take a public position on his sexuality. He withdrew first to Italy and later to his home in Silesia, Oberlangenau.

Text from the Munich Documentation Center for the History of National Socialism Instagram page

Paul Hoecker (11 August 1854, Oberlangenau – 13 January 1910, Munich) was a German painter of the Munich School and founding member of the Munich Secession…

The Munich Academy

In 1891, at the young age of 36, he was appointed to the Munich Academy, where he replaced Friedrich August von Kaulbach, who had resigned suddenly. He was the first teacher at the academy to take his students on field trips, which often lasted two weeks. He was also one of the first “modern” teachers there, exposing his students to impressionism and the latest developments from the Barbizon School. His studio was often referred to as the “Geniekasten” (Genius Box).

Due to the pervasive influence of Franz von Lenbach, very little exhibition space was available for any art that was considered modern. In 1892, shortly after being appointed a professor, this problem motivated Hoecker to become one of the founding members of the Munich Secession, acting as its secretary. The Secession ultimately inspired similar movements in Berlin and other cities.

Scandal