Exhibition dates: 5th November 2023 – 31st March 2024

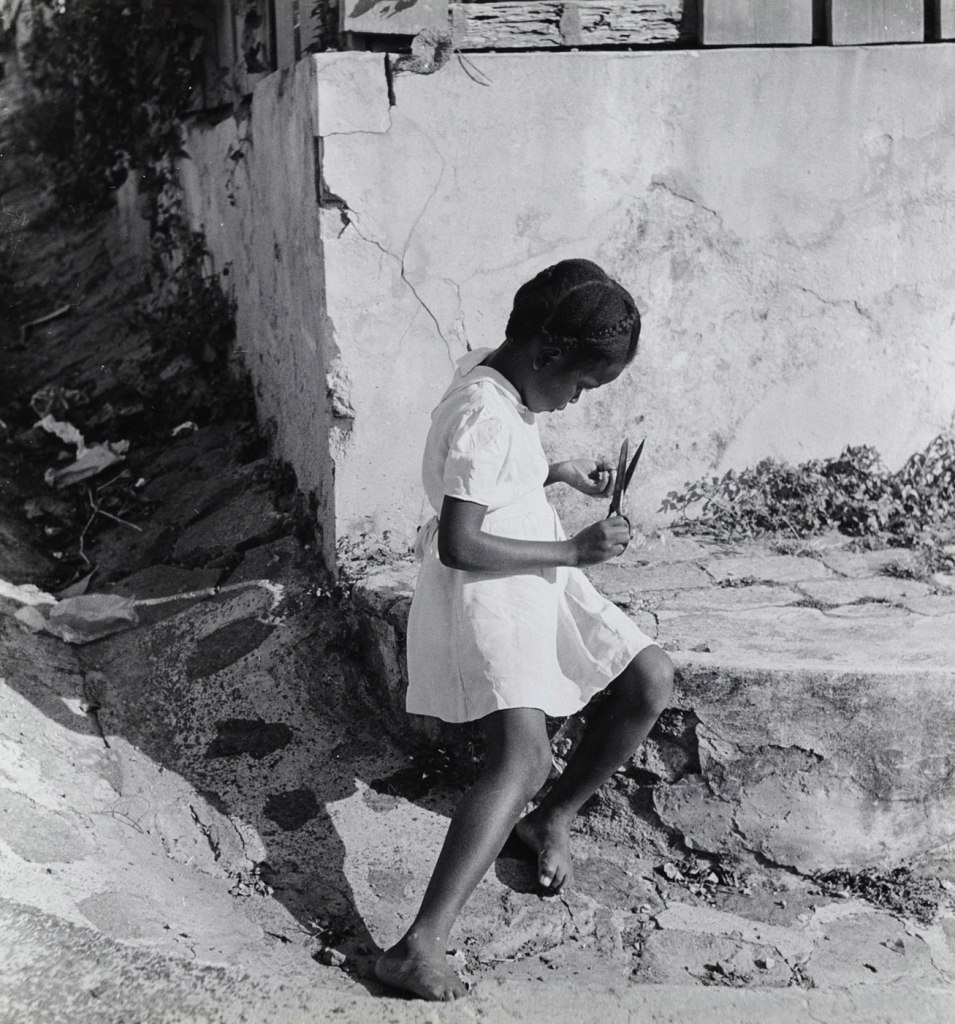

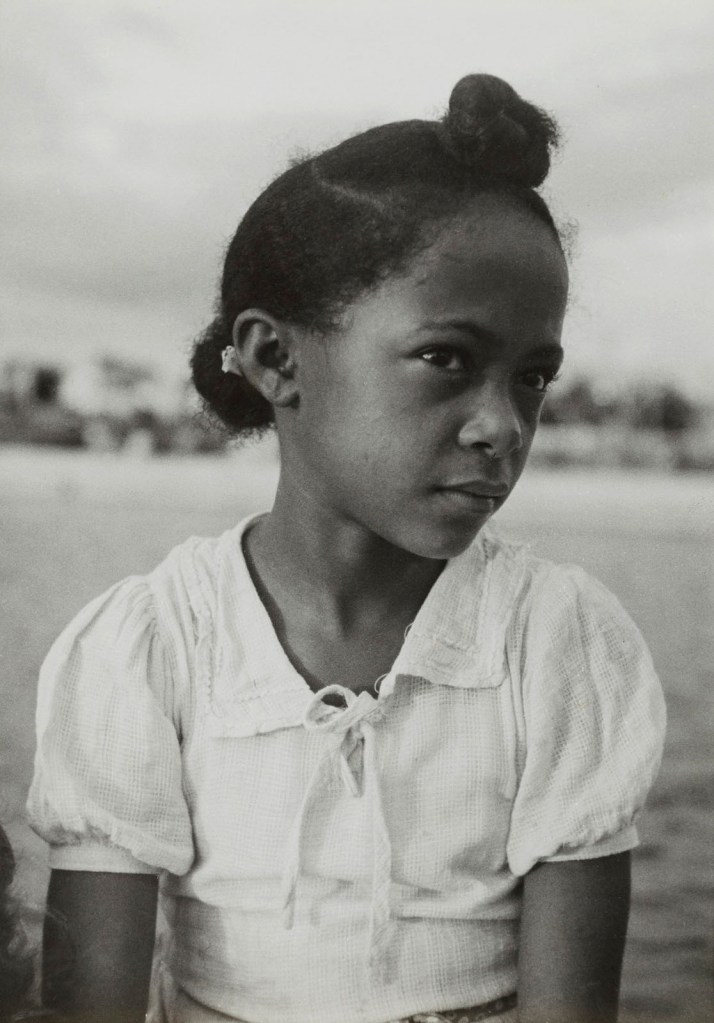

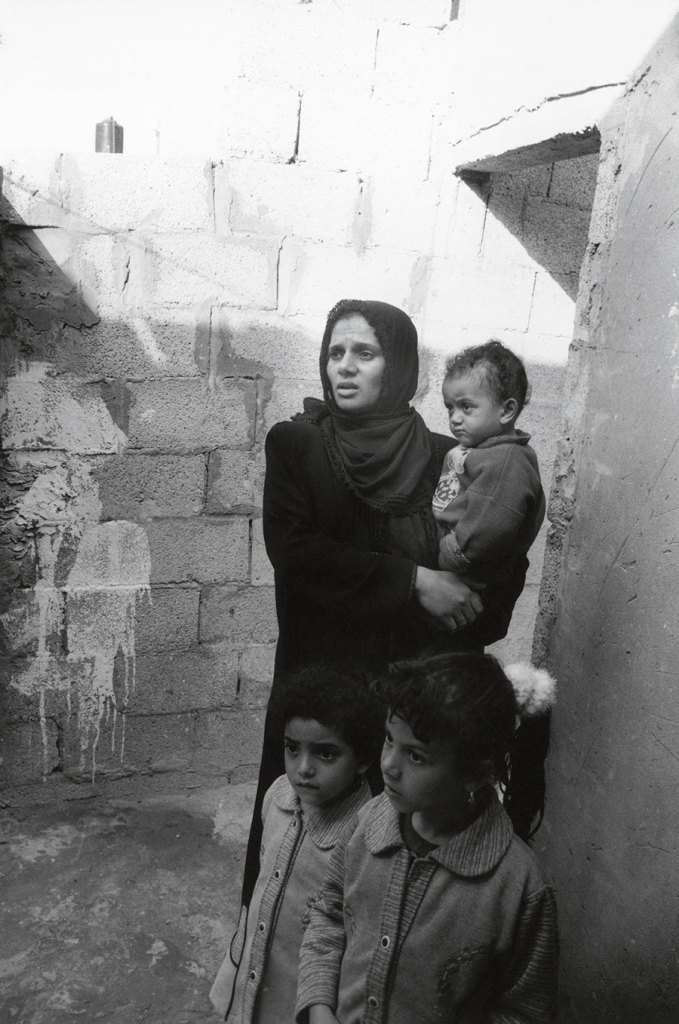

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Child of Impoverished Black Tenant Family Working on Farm, Alabama

July 1936

Gelatin silver print

Image: 20 x 19.2cm (7 7/8 x 7 9/16 in.)

Sheet: 25.4 x 20.2cm (10 x 7 15/16 in.)

Mat: 14 x 14 in.

Frame (outside): 15 x 15 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

A humungous two-part posting on the work of American photographer Dorothea Lange (1895-1965) which features over 110 of her photographs many of which were unknown to me.

Of course, the posting features the photographs for which she is rightly famous (Migrant Mother; White Angel Breadline; Nettie Featherston; Migratory cotton picker with his cotton sack slung over his shoulder rests at the scales before returning to work in the field; Once a Missouri farmer, now a Migratory Farm Laborer) but others are a surprise for the senses, especially the Irish portrait photographs.

See my comment on the photographs in Part 2 of the posting.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the National Gallery of Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

During her long, prolific, and groundbreaking career, the American photographer Dorothea Lange made some of the most iconic portraits of the 20th century. Dorothea Lange: Seeing People reframes Lange’s work through the lens of portraiture, highlighting her unique ability to discover and reveal the character and resilience of those she photographed.

Featuring some 100 photographs, the exhibition addresses her innovative approaches to picturing people, emphasising her work on social issues including economic disparity, migration, poverty, and racism.

“The portrait is made more meaningful by intimacy – an intimacy shared not only by the photographer with his subject but by the audience.”

Dorothea Lange

“The power of her pictures – their ability to speak to the character and resilience of those she photographed – lies not only in her desire to effect social change, but also in her deep humanism, her abiding interest in people, and the skills and insights she learned as a portrait photographer.”

Sarah Greenough

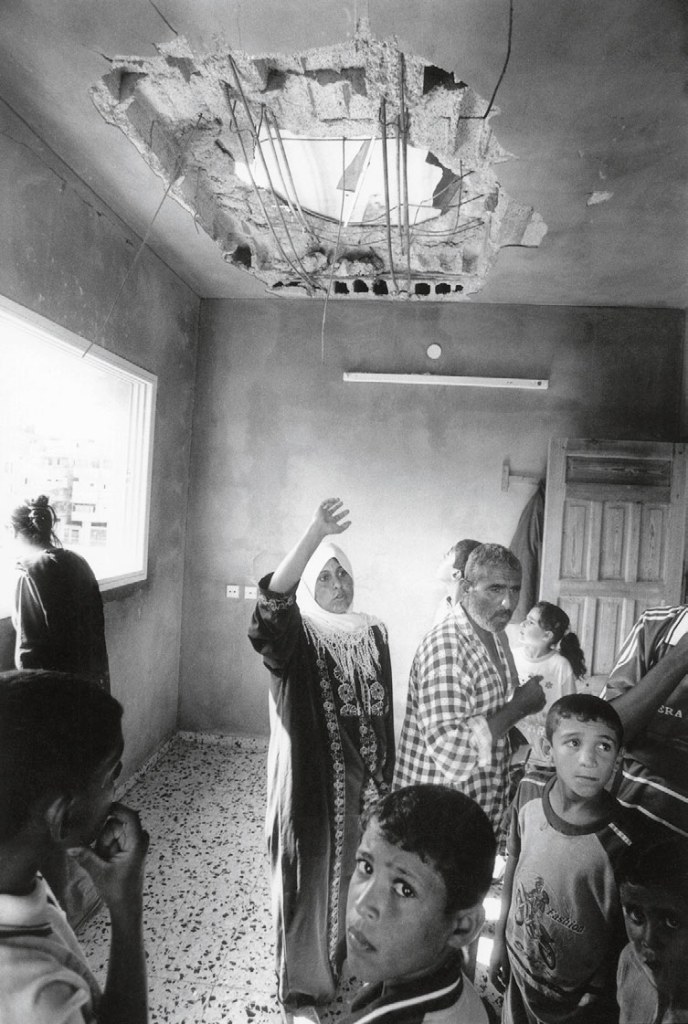

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

White Angel Breadline, San Francisco, California

1933

Gelatin silver print

Image/sheet: 34 x 26.5cm (13 3/8 x 10 7/16 in.)

Mat: 20 x 16 in.

Frame (outside): 21 x 17 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

A growing desire to capture the Depression’s impact drew Lange to the White Angel Jungle, a San Francisco soup kitchen run by Lois Jordan, the “White Angel.” There Lange photographed this downtrodden man leaning on a barricade, his jaw clenched, shoulders hunched, back to the crowd, and eyes covered by the brim of his hat. Though anonymous, he drew Lange’s sympathetic eye and became a symbol of the nameless masses who faced economic hardship as the United States plunged deep into financial crisis.

Label text from the exhibition

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Street Demonstration, San Francisco

1934

Gelatin silver print

Image: 24.4 x 19.1cm (9 5/8 x 7 1/2 in.)

Mount: 27.9 x 20.2cm (11 x 7 15/16 in.)

Mat: 20 x 16 in.

Frame (outside): 21 x 17 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Diana and Mallory Walker Fund and Robert Menschel and the Vital Projects Fund, in Honor of the 25th Anniversary of Photography at the National Gallery of Art

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

In spring and summer 1934, a longshoremen’s strike gripped San Francisco and demonstrations took place throughout the city. Protesters also advocated for Japanese unions, which were being threatened by anti-labor forces in Japan. Lange wrote in her notes, “This was just before the New Deal during a time when Communists were very active. A few blocks away … soup was being distributed daily to the unemployed.”

Lange focused on a lone policeman standing before a crowd of protesters holding placards in English and Japanese. The policeman projects authority through his firm stance, crisp uniform, and shiny badge, creating a barrier between the photographer and the crowd.

Label text from the exhibition

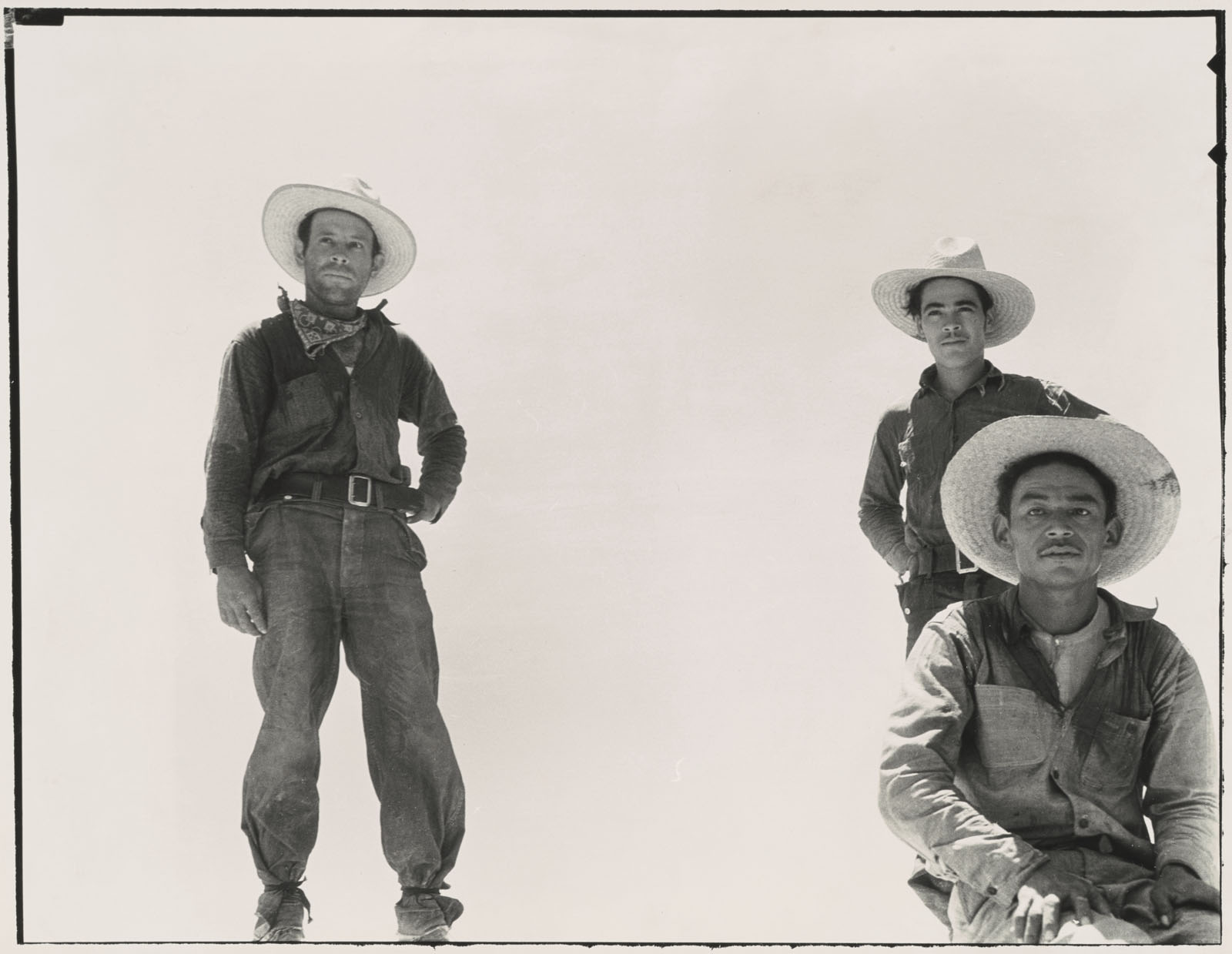

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Mexican Workers Leaving for Melon Fields, Imperial Valley, California

June 1935, printed 1940s

Gelatin silver print

Image: 45 x 58cm (17 11/16 x 22 13/16 in.)

Sheet: 50.2 x 67.5cm (19 3/4 x 26 9/16 in.)

Mat: 24 x 28 in.

Frame (outside): 25 x 29 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

In the summer of 1935, Lange traveled with Paul Taylor, working with his research team on a study of migrant labourers funded by California’s State Emergency Relief Administration. Mexican farm labourers, like this trio of cantaloupe harvesters, saw wages plummet during the Depression as thousands of westbound American migrants flooded the labour market. Angling her camera upward, Lange silhouetted the workers against a hazy sky, producing a striking group portrait. Working together solidified Lange and Taylor’s professional relationship, which developed into a romantic partnership and marriage later that same year.

Label text from the exhibition

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Once a Missouri farmer, now a Migratory Farm Laborer. San Joaquin Valley, California

February 1936, printed c. 1965

Gelatin silver print

Image/sheet: 44.6 x 39.5cm (17 9/16 x 15 9/16 in.)

Mat: 26 x 22 in.

Frame (outside): 27 x 23 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Although this farm labourer from Missouri seems to be alone behind the wheel of his car, he is actually seated beside his wife, in the passenger seat. Her overcoat and right arm are easily overlooked at the bottom left. By focusing only on the driver, with his gaunt features and intense gaze, Lange heightens our sense of his isolation to create an evocative portrait of a man grappling with the consequences of dislocation. The photograph also calls attention to the automobile as a means of transport and escape for some Depression-era migrants.

Label text from the exhibition

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Former Tenant Farmer on Relief Grant in the Imperial Valley, California

March 1937

Gelatin silver print

Image/sheet: 9.5 x 9cm (3 3/4 x 3 9/16 in.)

Mat: 14 x 11 in.

Frame (outside): 15 x 12 3/4 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Eighteen-Year-Old Mother from Oklahoma, now a California Migrant

March 1937

Gelatin silver print

Image: 18.9 x 24.5cm (7 7/16 x 9 5/8 in.)

Sheet: 20.6 x 25.5cm (8 1/8 x 10 1/16 in.)

Mat: 13 x 16 in.

Frame (outside): 14 x 17 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Displaced Tenant Farmers, Goodlett, Hardeman County, Texas

July 1937, printed 1950s

Gelatin silver print

Image: 19 x 24 cm (7 1/2 x 9 7/16 in.)

Sheet: 20.3 x 25.2 cm (8 x 9 15/16 in.)

Mat: 14 x 16 in.

Frame (outside): 15 x 17 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

During the 1930s, machines began to replace people in some cotton-growing regions like Hardeman County in Northeast Texas; consequently, many tenant farmers were evicted from their land. Already reckoning with severe drought and economic depression, these “tractored out” farmers were forced to seek work as day labourers, a precarious livelihood offering little security. In this picture, five displaced tenant farmers congregate outside the screened porch of a small house. Although they are united by a common plight, each man seems utterly alone, unable to find solace or support within an eroding agricultural system.

Label text from the exhibition

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Nettie Featherston, Wife of a Migratory Laborer with Three Children, near Childress, Texas, from The American Country Woman

June 1938

Gelatin silver print

Image: 34 x 26.8cm (13 3/8 x 10 9/16 in.)

Sheet: 35.2 x 28cm (13 7/8 x 11 in.)

Mount: 45.4 x 38.3cm (17 7/8 x 15 1/16 in.)

Mat: 22 x 18 in.

Frame (outside): 23 x 19 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

When Lange photographed her on a North Texas farm, 40-year-old Nettie Featherston was accustomed to a life of hard labor and poverty. She and her family had left Oklahoma seeking work in California when they ran out of money in Texas and found work picking cotton. Lange’s portrait reveals a gaunt survivor of the Dust Bowl, her right arm echoing the shape of the storm cloud behind her – a symbol of the difficult road ahead for migrant families looking for work. Reflecting on the photograph of herself years later, Featherston said, “It seems like … I have too much on my mind. I can just be burdened so bad, awful burdens they’ll be.”

Label text from the exhibition

Nettie Featherston

Lange met Nettie Featherston while working on that same FSA project. Like Turpen, Featherston’s family had been forced off their farm in Oklahoma. On their way to California to find work, they ran out of money and found themselves stranded in Childress, Texas.

The Featherstons sold their car for money to buy food. That left them with no way out of the dry and dusty landscape we seen behind Featherston. She looks desperate and distraught. “This county’s a hard county. They won’t help bury you here. If you die, you’re dead, that’s all,” she told Lange.

Decades later photographer and author Bill Ganzel tracked down Featherston. Then in her 80s, she still remembered how difficult that time had been. “Your kids would cry for something to eat, and you couldn’t give it. We cooked with black-eyed peas until I never wanted to ever see another black-eyed pea.”

Anonymous. “The Real Lives of People in Dorothea Lange’s Portraits,” on the National Gallery of Art website November 03, 2023 [Online] Cited 25/02/2024

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Arkansas mother come to California for a new start, with husband and eleven children. Now a rural rehabilitation client. Tulare County, California, from The American Country Woman

November 1938, printed 1965

Gelatin silver print

Image/sheet: 35.5 x 27.9cm (14 x 11 in.)

Mat: 20 x 16 in.

Frame (outside): 21 x 17 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

On the Plains a Hat Is More Than a Covering

1938, printed c. 1965

Gelatin silver print

Image/sheet: 32 x 26.3cm (12 5/8 x 10 3/8 in.)

Mat: 20 x 18 in.

Frame (outside): 21 x 19 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Lange wrote in her field notes that a “hat is more than a covering against sun and wind … it is a badge of service … linking past and present.” This artfully cropped photograph of James Abner Turpen, a 70-year-old Texas tenant farmer, focuses on Turpen’s hand as his fingers curl around the brim of a hat. Both hand and hat are weathered, aged by time and work, and portray Turpen without showing his face.

Label text from the exhibition

James Abner Turpen

From 1936 to 1939, Lange worked for the Resettlement Administration (which later became the Farm Security Administration). In Texas she documented the impacts of mechanisation on farmers. In the town of Goodlett she met James Abner Turpen, a 70-year-old tenant farmer who was about to be “tractored out” of his farm. Realising that agricultural machines like tractors could replace many farmers, landowners would evict their tenant farmers.

Turpen’s sons had already been tractored out. In her caption, Lange recorded his distress. “What are my boys going to do?” he asked. He believed the government was partly to blame. “They’re not any up there in Congress but what are big landowners and they’re going to see that the program is in their interest.”

Lange cropped one image to focus on Turpen’s weathered hand grasping his hat. The photograph is titled On the Plains a Hat Is More Than a Covering. But curator Philip Brookman inspected the image closely and compared it with others to confirm that Turpen is the subject.

Anonymous. “The Real Lives of People in Dorothea Lange’s Portraits,” on the National Gallery of Art website November 03, 2023 [Online] Cited 25/02/2024

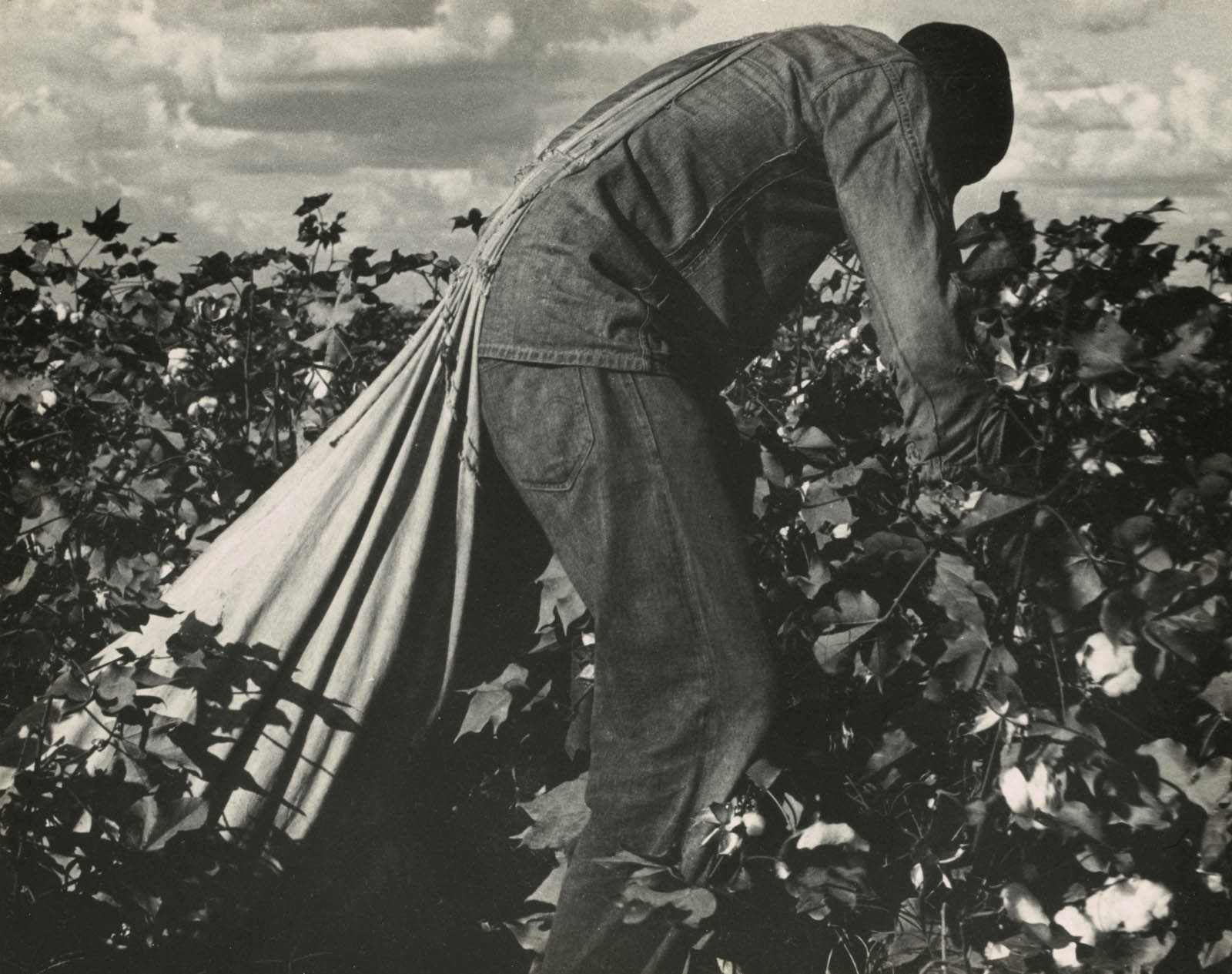

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Migratory Field Worker Picking Cotton in San Joaquin Valley, California from An American Exodus

November 1938, printed later

Gelatin silver print

Image/sheet: 19 x 24cm (7 1/2 x 9 7/16 in.)

Mat: 14 x 18 in.

Frame (outside): 15 x 19 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

This photograph of hard stoop labor appeared in Lange and Paul Taylor’s 1939 book An American Exodus. According to Taylor’s field notes, “These pickers are paid seventy-five cents per hundred pounds of picked cotton. Strikers organising under CIO union (Congress of Industrial Organizations) are demanding one dollar. A good male picker, in good cotton, under favourable weather conditions, can pick about two hundred pounds in a day’s work.”

Label text from the exhibition

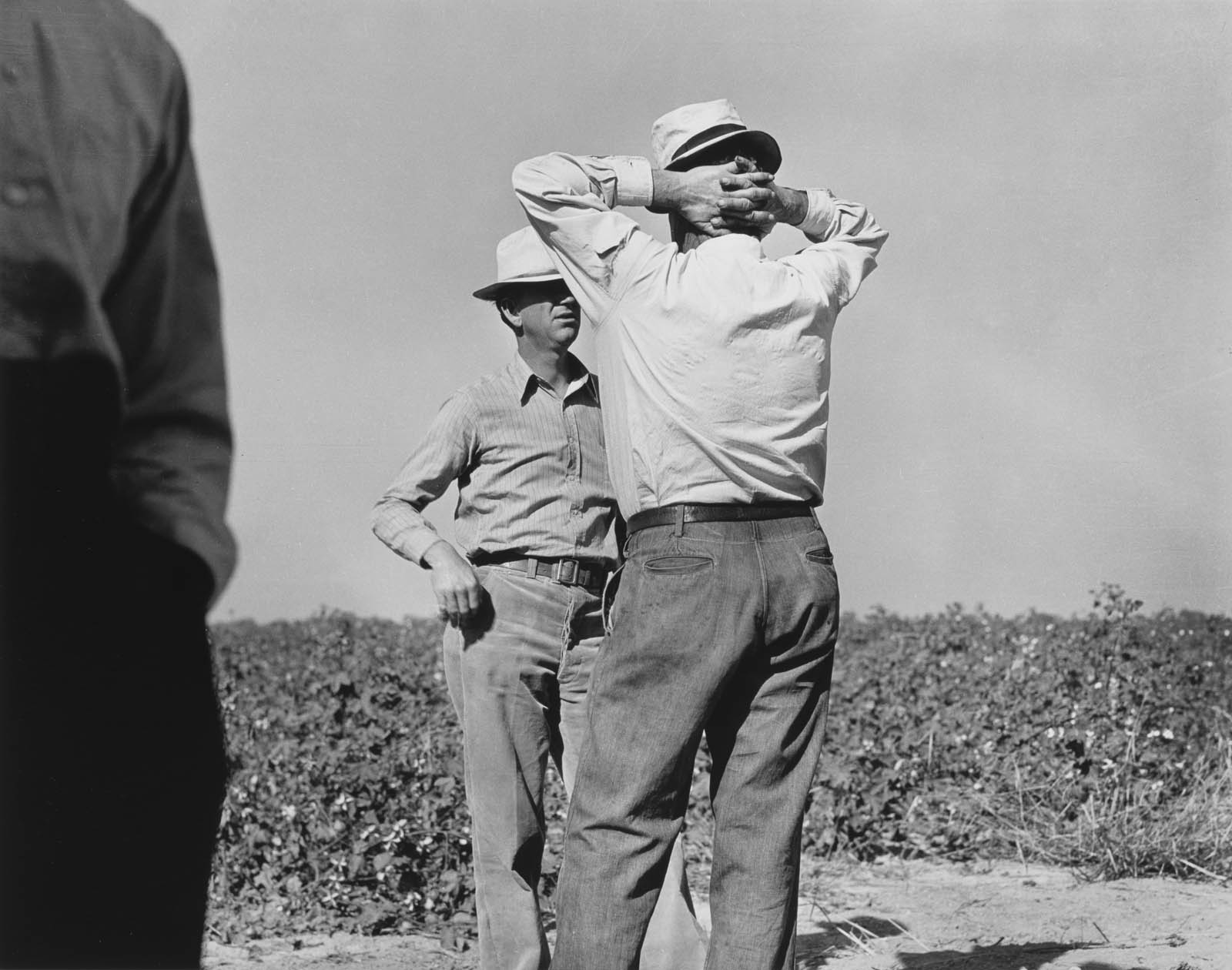

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Cotton Pickers and Farm Owners, Bakersfield, California

1938, printed c. 1950s

Gelatin silver print

Image: 19 x 24cm (7 1/2 x 9 7/16 in.)

Sheet: 20.32 x 25.4cm (8 x 10 in.)

Mat: 13 x 16 in.

Frame (outside): 14 x 17 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Yazoo Delta, Mississippi from An American Exodus

1938, printed 1965

Gelatin silver print

Image/sheet: 34.2 x 44.7cm (13 7/16 x 17 5/8 in.)

Mat: 20 x 24 in.

Frame (outside): 21 x 25 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

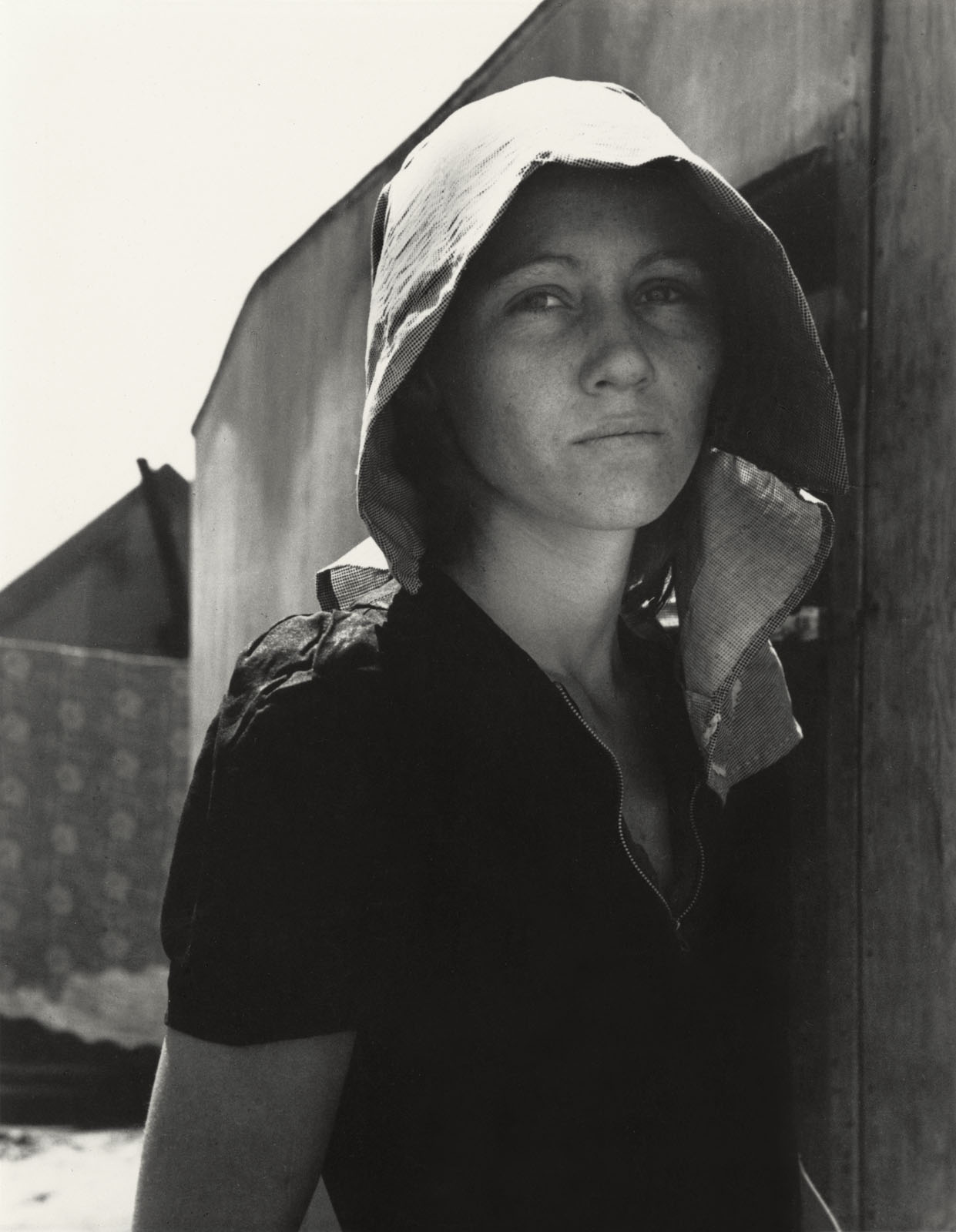

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Edison, Kern County, California. Young migratory mother, originally from Texas. On the day before the photograph was made, she and her husband traveled 35 miles each way to pick peas. They worked 5 hours each and together earned $2.25. They have two young children… Live in auto camp.

April 11, 1940, printed 1950s

Gelatin silver print

Image/sheet: 30.1 x 24cm (11 7/8 x 9 7/16 in.)

Mount: 30.8 x 24 cm (12 1/8 x 9 7/16 in.)

Mat: 20 x 16 in.

Frame (outside): 21 x 17 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Children of the Weill Public School Shown in a Flag Pledge Ceremony, San Francisco, California

April 1942, printed c. 1965

Gelatin silver print

Image: 23.5 x 17.4 cm (9 1/4 x 6 7/8 in.)

Mat: 18 x 14 in.

Frame (outside): 19 x 15 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

End of Shift, 3:30, Shipyard Construction Workers, Richmond, California

September 1943

Gelatin silver print

Image: 24 x 19 cm (9 7/16 x 7 1/2 in.)

Sheet: 25.4 x 20.32 cm (10 x 8 in.)

Mat: 18 x 14 in.

Frame (outside): 19 x 15 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

Fortune magazine commissioned Lange to document the bustling shipyards in Richmond, north of Oakland, where newly desegregated defence firms were rapidly constructing transport, cargo, and warships for the United States Navy. With its tight cropping and dynamic configuration, End of Shift focuses on the rushing legs and torsos of shipbuilders leaving a wartime facility. Lange expressed the urgency of their work in defence production without showing their individual features. The angled composition and complex interplay of light and shadow demonstrate Lange’s understanding of how modern design techniques could convey the force and energy of a group working together on a project critical to the nation’s defence.

Label text from the exhibition

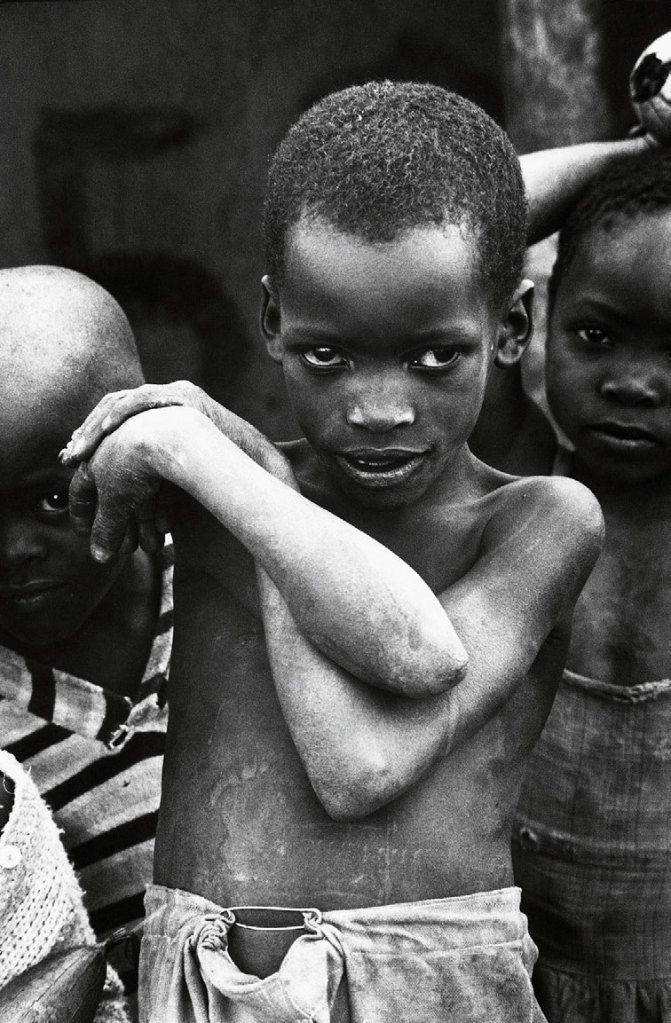

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

War Babies, Richmond, California

1944, printed c. 1965

Gelatin silver print

Image/sheet: 26.4 x 25.6cm (10 3/8 x 10 1/16 in.)

Mat: 18 x 18 in.

Frame (outside): 19 x 19 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

While in Richmond, Lange photographed not only shipyard workers but also local people on the street, such as this pair of young mothers. Cradling swaddled infants, with a knee-high toddler between them, the two women personify the prosperity and growth generated by the wartime boom, which brought renewed economic stability to many Californians. Lange’s pictures from Richmond capitalise on the symbolism presented by the backdrop of expanding production. In this photograph, for example, cruciform utility poles seem to watch over the women and children like industrial guards, symbolically guiding them away from the poverty of the Depression years.

Label text from the exhibition

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Lyde Wall, friend and neighbor, who makes “the world’s best apple pie,” and knows everything going on for miles around, Berkeley, California, from The American Country Woman

1944

Gelatin silver print

Image/sheet: 35.1 x 27.9cm (13 13/16 x 11 in.)

Mount: 35.2 x 28 cm (13 7/8 x 11 in.)

Mat: 22 x 18 in.

Frame (outside): 23 x 19 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

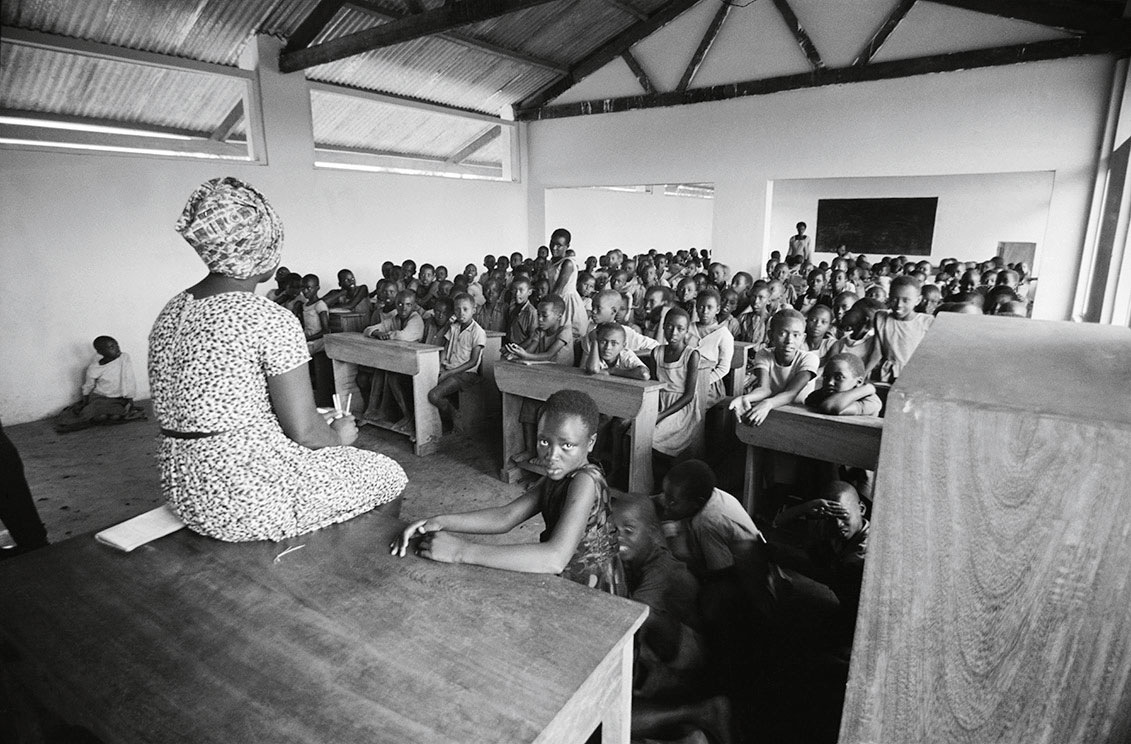

During her prolific and groundbreaking career, the American photographer Dorothea Lange (1895-1965) made some of the most iconic portraits of the 20th century. Dorothea Lange: Seeing People examines Lange’s decades-long investigation into how portrait photography could embody the humanity of the people she depicted. It demonstrates how her photographs helped shape contemporary documentary practice by connecting everyday people with moments of history – from the Great Depression through the mid-1960s – that still resonate with our lives in the 21st century. Featuring 101 photographs, the exhibition addresses her innovative approaches to picturing people, emphasising her work on various social issues including economic disparity, migration, poverty, and racism. The exhibition is on view from November 5, 2023, through March 31, 2024, in the West Building of the National Gallery of Art.

“Throughout the course of her 50-year career, Lange created an intensely humanistic body of work that sought to transform how we see and understand people,” said Kaywin Feldman, director of the National Gallery of Art. “Merging her skills as a portrait artist, a social documentary photographer, and a storyteller, she helped redefine photography through images that emphasise social issues.”

About the Exhibition

Dorothea Lange: Seeing People examines how Lange’s portraits have shaped our contemporary understanding of documentary photography as well as its importance to her vision and creative practice. Divided into six thematic sections, the exhibition features portraits ranging from her early career as a San Francisco studio photographer – the earliest work is from 1919 – and her powerful coverage of the Great Depression through expressive photographs of everyday people and communities during the 1950s and early 1960s.

Among the works on view are portraits of Indigenous people in Arizona and New Mexico from the 1920s and early 1930s; later depictions of striking labourers, migrant farmworkers, rural African Americans during the Jim Crow era, Japanese Americans denied their civil rights during World War II, and postwar baby boomers; and portraits of people in Ireland, Korea, Vietnam, Egypt, and Venezuela that Lange made in the decade before her death in 1965.

Lange began her career as a commercial studio photographer in San Francisco in 1918. Her studio became a gathering spot for artists who had serious discussions about photography and art. In 1920 she married Maynard Dixon, a painter of western subjects, who encouraged Lange to take her photography outside. She accompanied him on trips through the American Southwest, photographing rural landscapes and Dixon at work, along with the Indigenous communities he was portraying.

She started to work in the streets of San Francisco in 1933, making photographs such as White Angel Breadline, San Francisco, California (1933) that capture the effects of the Great Depression and the plight of the city’s dispossessed men and women. Lange also photographed labor organisers and protesters at May Day events around San Francisco’s Civic Center Plaza: she focused on the protesters speaking, listening, or holding signs, and vowed to produce prints within 24 hours, as in May Day, San Francisco, California (1934). She also documented ensuing strikes, creating portraits of speakers and demonstrators with placards as well as photographs of the police presence in works such as Street Demonstration, San Francisco (1934). When she met the labor economist Paul Schuster Taylor in 1934, Lange began to photograph the plight of migrant farmers who had moved to California from the South and Midwest seeking new livelihoods.

From 1935 to 1943, while working for the for the US Resettlement Administration, Farm Security Administration, and War Relocation Authority, Lange focused on the resilience of Depression-era families, farmworkers, rural cooperative communities, migrant camps, and the forced incarceration of Japanese Americans in the early days of World War II. The resulting images illustrate the human and economic impact wrought across the United States by farm tenancy, racism, the legacy of slavery, climate change, and migrations. These portraits, sometimes combined with interviews, added a personal element to Lange’s stark pictures of makeshift housing and agricultural fields and cemented her documentary style.

During World War II Lange produced one of her most powerful series for the War Relocation Authority, depicting the forced incarceration of California’s Japanese Americans at Manzanar, in works on view such as Grandfather and Grandson of Japanese Ancestry at a War Relocation Authority Center, Manzanar, California (July 1942). She also photographed the shifts in California’s social fabric as its rising economy – sparked by growing defence industries – drew African Americans from the South and women into previously male-dominated and segregated businesses such as shipbuilding. In the 1950s, Lange continued to pursue stories about people and their communities for personal projects, as well as for Life magazine, that include her first photographs from Europe. Asia, South America, and North Africa.

Exhibition Publication

Published by the National Gallery of Art and distributed by Yale University Press, this 208-page illustrated volume explores Dorothea Lange’s decades-long investigation of how photography, through articulating people’s core values and their sense of self, helped to expand our current understanding of portraiture and the meaning of documentary practice. Lange’s sensitive, humane portraits of often-marginalised people galvanised public understanding of important social problems in the 20th century.

Compassion guided Lange’s early portraits of Indigenous people in Arizona and New Mexico from the 1920s and 1930s, as well as her depictions of striking workers, migrant farmers, rural African Americans during the Jim Crow era, Japanese Americans in internment camps, and the people she met while traveling in Europe, Asia, Venezuela, and Egypt. Drawing on new research, Philip Brookman, Sarah Greenough, Andrea Nelson, and Laura Wexler, examine Lange’s roots in studio portraiture and demonstrate how her influential and widely seen photographs addressed issues of identity as well as social, economic, and racial inequalities – topics that remain as relevant for our times as they were for hers.

Press release from the National Gallery of Art

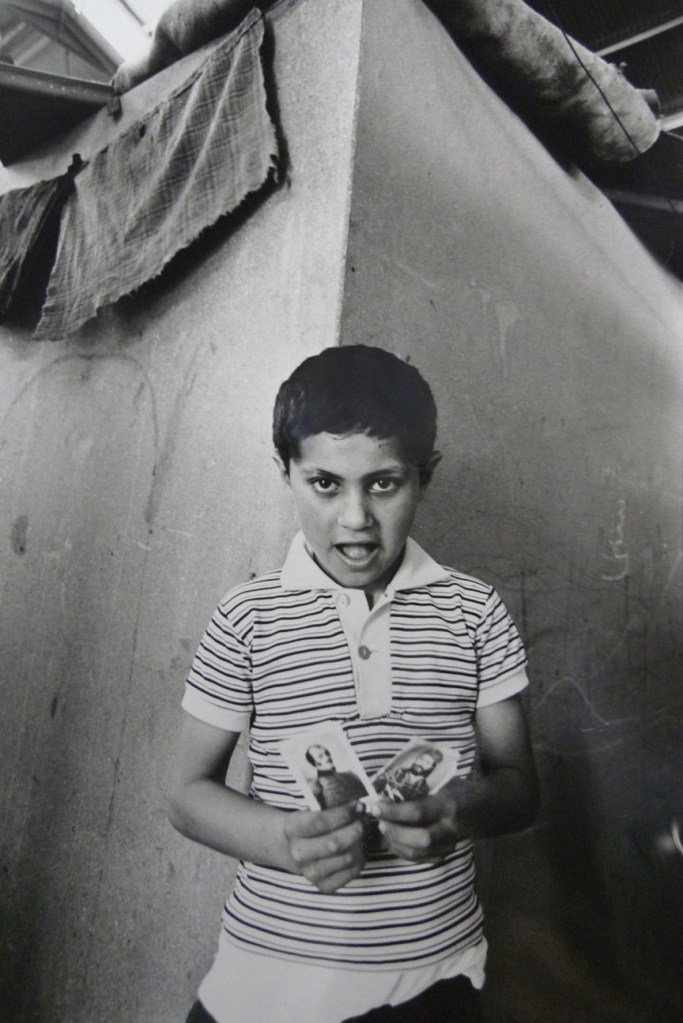

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Mexican American Child, San Francisco

1928

Gelatin silver print

Image/sheet: 34 x 29.8cm (13 3/8 x 11 3/4 in.)

Mat: 16 x 20 in.

Frame (outside): 16 1/2 x 16 1/4 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Maynard and Dan Dixon

1930, printed c. 1960s

Gelatin silver print

Image: 19 x 24cm (7 1/2 x 9 7/16 in.)

Sheet: 20.32 x 25.4 cm (8 x 10 in.)

Mat: 14 x 17 in.

Frame (outside): 15 1/4 x 18 1/4 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

In fall 1919 Lange met Maynard Dixon, a painter and illustrator of western subjects and one of the best-known artists in California. Early the following year, Lange and Dixon were married. Their first son, Daniel, was born in 1925 and their second, John, in 1928. This intimate portrait presents a close-up view of Dixon’s hands holding Dan in a gentle embrace, with the boy’s tiny fingers quietly resting on top of his father’s. Here Lange directed their pose to express both character and personal narrative, which recalls her training in New York portrait studios, as well as Alfred Stieglitz’s “portraits” of Georgia O’Keeffe that focused on her hands to convey her personality.

Label text from the exhibition

Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946)

Georgia O’Keeffe – Hands

1917

Silver-platinum print

National Gallery of Art, Alfred Stieglitz Collection

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Mary Ann Savage, a Faithful Mormon All Her Life, Toquerville, Utah

1931, printed c. 1950

Gelatin silver print

Image/sheet: 35.2 x 27.9cm (13 7/8 x 11 in.)

Mount: 38.2 x 28cm (15 1/16 x 11 in.)

Mat: 22 x 18 in.

Frame (outside): 23 x 19 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

Mary Ann Savage

was a faithful Mormon all her life.

She was a plural wife.

She was a pioneer.

She crossed the plains in 1856

with her family

when she was six years old.

Her mother

pushed her little children

across plain and desert

in a hand-cart.

A sister died along the way.

“My mother wrapped her in a blanket

and put her to one side.”

From Dorothea Lange Looks at the American Country Woman

Label text from the exhibition

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

San Francisco Waterfront

1934

Gelatin silver print

Image/sheet: 11.8 x 9.1cm (4 5/8 x 3 9/16 in.)

Mat: 14 x 11 in.

Frame (outside): 15 x 12 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

May Day, San Francisco, California

1934, printed c. 1960s

Gelatin silver print

Image: 24 x 19 cm (9 7/16 x 7 1/2 in.)

Sheet: 25.4 x 20.32 cm (10 x 8 in.)

Mat: 16 x 14 in.

Frame (outside): 17 x 15 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Dispossessed Arkansas farmers. These people are resettling themselves on the dump outside of Bakersfield, California from An American Exodus

1935

Gelatin silver print

Image: 24.1 x 18.8cm (9 1/2 x 7 3/8 in.)

Sheet: 25.3 x 20.7cm (9 15/16 x 8 1/8 in.)

Mat: 16 x 14 in.

Frame (outside): 17 x 15 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Black Woman Working in Field near Eutaw, Alabama

1936

Gelatin silver print

Image/sheet: 20.5 x 13.8cm (8 1/16 x 5 7/16 in.)

Mount: 21.2 x 14.5 cm (8 3/8 x 5 11/16 in.)

Mat: 15 x 12 in.

Frame (outside): 16 x 13 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Calipatria (vicinity), California. Native of Indiana in a migratory labor contractor’s camp. “It’s root hog or die for us folks.”

February 1937

Gelatin silver print

Image/sheet: 24.1 x 19.1 cm (9 1/2 x 7 1/2 in.)

Mat: 16 x 14 in.

Frame (outside): 17 x 15 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Line of men inside a division office of the State Employment Service office at San Francisco, California, waiting to register for unemployment benefits

January 1938, printed c. 1960s

Gelatin silver print

Image: 19 x 24cm (7 1/2 x 9 7/16 in.)

Sheet: 25.08 x 20.32cm (9 7/8 x 8 in.)

Mat: 14 x 17 in.

Frame (outside): 15 x 18 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Funeral Cortege, San Joaquin Valley, California

1938, printed early 1950s

Gelatin silver print

Image: 20 x 19 cm (7 7/8 x 7 1/2 in.)

Sheet: 25.08 x 20.32 cm (9 7/8 x 8 in.)

Mat: 16 x 14 in.

Frame (outside): 17 x 15 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Hitch-hiking from Joplin, Missouri, to a sawmill job in Arizona. On U.S. 66 near Weatherford, western Oklahoma

August 12, 1938, printed c. 1960s

Gelatin silver print

Image: 24 x 19.5cm (9 7/16 x 7 11/16 in.)

Sheet: 25.4 x 20.32cm (10 x 8 in.)

Mat: 16 x 13 in.

Frame (outside): 17 x 14 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Formerly Enslaved Woman, Alabama from The American Country Woman

1938, printed 1950s

Gelatin silver print

Image/sheet: 20.3 x 27.9cm (8 x 11 in.)

Mat: 14 x 18 in.

Frame (outside): 15 x 19 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

This formerly enslaved woman, whom Lange does not name, would have witnessed several events that transformed the nation. She would have experienced the tragedy of chattel slavery in the United States and the victory for enslaved people in the South through Emancipation, as well as the ups and downs of Reconstruction, the passage of Jim Crow laws that permitted segregation, and the Great Depression. The dilapidated home, falling and standing simultaneously, suggests her own perseverance amid a lifetime of racial, gender, and class oppression.

Label text from the exhibition

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Formerly Enslaved Woman, Alabama from The American Country Woman

1938, printed c. 1955

Gelatin silver print

Image: 24 x 19cm (9 7/16 x 7 1/2 in.)

Sheet: 25 x 20cm (9 13/16 x 7 7/8 in.)

Mat: 16 x 13 in.

Frame (outside): 17 x 14 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Lange’s portraits of Depression-era people have inspired other artists, such as Elizabeth Catlett, to remember that time. In Survivor, Catlett translated the power of Lange’s photograph of a formerly enslaved woman into a linocut, an image cut into a linoleum block, inked, and then pressed onto paper, which prints it in reverse from the original.

Label text from the exhibition

Elizabeth Catlett (American, 1915-2012)

Survivor

1983

Linocut

National Gallery of Art

Purchased as the Gift of the Roy Lichtenstein Foundation in Honor of Mary Lee Corlett

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Member of the congregation of Wheeley’s church who is called “Queen.” She is wearing the old-fashioned type of sunbonnet. Her dress and apron were made at home. Near Gordonton, North Carolina from The American Country Woman

July 1939, printed no later than 1965

Gelatin silver print

Image: 38.7 x 31.9cm (15 1/4 x 12 9/16 in.)

Sheet: 39.5 x 34.1cm (15 9/16 x 13 7/16 in.)

Mat: 20 x 18 in.

Frame (outside): 21 x 19 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

Wheeley’s Church was a congregation of Primitive Baptists, conservative practitioners located primarily in the South. Lange had a knack for building rapport with people from various religious communities and worked to gain their trust and respect to make photographs. This portrait features one church member, “Queen” Bowes, a devout widow shaded by her elaborate sunbonnet. Lange captured her stern expression, with piercing eyes and a tightly closed mouth that hid her false teeth.

Label text from the exhibition

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Scandinavian Homesteader, Great Plains, South Dakota from The American Country Woman

1939, printed 1950s

Gelatin silver print

Image/sheet: 25.9 x 26.6cm (10 3/16 x 10 1/2 in.)

Mat: 18 x 18 in.

Frame (outside): 19 x 19 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Near Coolidge, Arizona. Migratory cotton picker with his cotton sack slung over his shoulder rests at the scales before returning to work in the field

November 1940, printed c. 1965

Gelatin silver print

Image/sheet: 31.5 x 41cm (12 3/8 x 16 1/8 in.)

Mat: 24 x 20 in.

Frame (outside): 21 x 25 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Edison, Kern County, California. Young girl looks up from her work. She picks and sacks potatoes on large-scale ranch

April 11, 1940

Gelatin silver print

Image: 18.7 x 24cm (7 3/8 x 9 7/16 in.)

Sheet: 20.2 x 25.3 cm (7 15/16 x 9 15/16 in.)

Mat: 13 x 16 in.

Frame (outside): 14 x 17 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Riley Savage, Toquerville, Utah

1953, printed c. 1965

Gelatin silver print

Image/sheet: 27.9 x 21.5cm (11 x 8 1/2 in.)

Mat: 18 x 14 in.

Frame (outside): 19 x 15 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

Riley Savage, son of Mary Ann Savage (pictured in the photograph nearby), was a third-generation Mormon settler whose grandmother had crossed the plains to the Utah Territory in 1856.

Label text from the exhibition

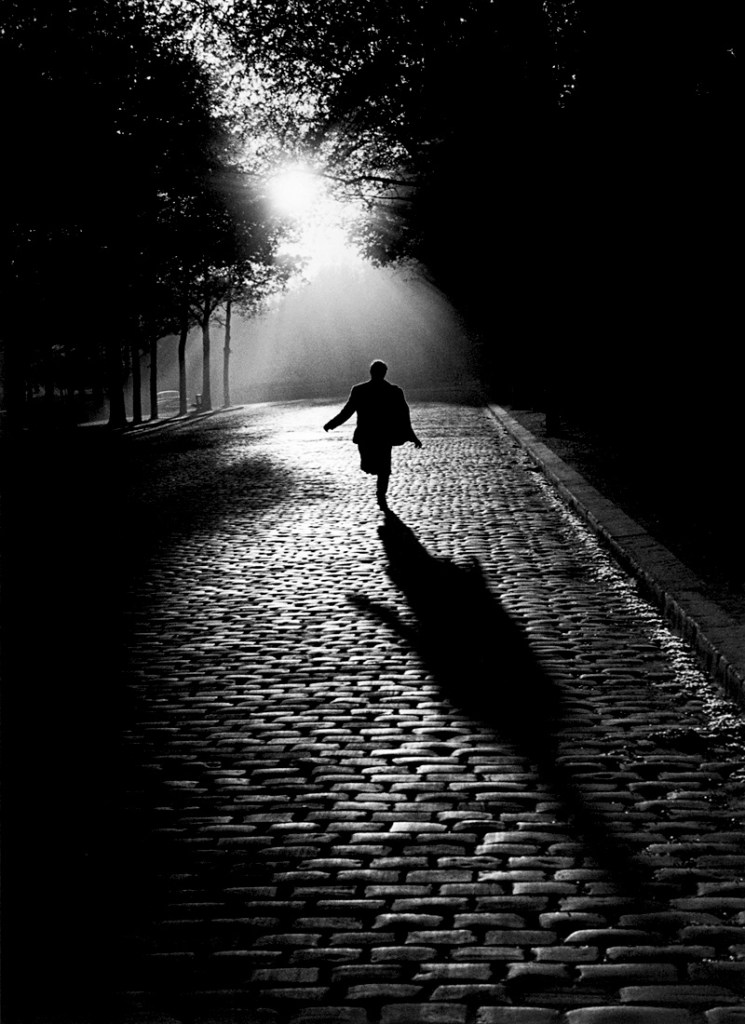

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Man Walking Down a Country Road from the Kenneally Family Farm, County Clare, Ireland from The Irish Countryman

1954

Gelatin silver print

Image/sheet: 31.2 x 26cm (12 5/16 x 10 1/4 in.)

Mat: 19 x 17 in.

Frame (outside): 20 x 18 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Man Walking Down a Country Road from the Kenneally Family Farm, County Clare, Ireland from The Irish Countryman

1954

Gelatin silver print

Image/sheet: 26.5 x 21.5cm (10 7/16 x 8 7/16 in.)

Mat: 18 x 16 in.

Frame (outside): 19 x 17 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Nora Kenneally, Widow, County Clare, Ireland from The Irish Countryman

1954

Gelatin silver print

Image/sheet: 22.6 x 28.5cm (8 7/8 x 11 1/4 in.)

Mount: 47.8 x 37.8cm (18 13/16 x 14 7/8 in.)

Mat: 22 x 18 in.

Frame (outside): 23 x 19 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Patrick Flanagan on Tubber Green, County Galway, Ireland from The Irish Countryman

1954, printed no later than 1965

Gelatin silver print

Image/sheet: 30.7 x 28.4cm (12 1/16 x 11 3/16 in.)

Mat: 19 x 18 in.

Frame (outside): 20 x 19 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Irish Child, County Clare, Ireland from The Irish Countryman

1954

Gelatin silver print

Image: 25.4 x 25.4cm (10 x 10 in.)

Sheet: 35.2 x 27.9 cm (13 7/8 x 11 in.)

Mat: 16 x 18 in.

Frame (outside): 17 x 19 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

On assignment for Life magazine in 1954, Lange spent six weeks in Ireland with her son, Dan Dixon – her first time overseas. They stayed in Ennis, a small town in County Clare, and traveled extensively; Lange took some 2,400 photographs. Twenty-two of these were featured in Life the following year. Lange enjoyed working in Ireland and was particularly fond of this portrait of a smiling girl in a rain bonnet, which she pinned to a corkboard in her home kitchen. “Isn’t that a beautiful face?” she declared. “That’s pure Ireland.”

Label text from the exhibition

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

A Young Girl in Ennis, County Clare, Ireland from The Irish Countryman

1954, printed c. 1965

Gelatin silver print

Image: 30.9 x 29cm (12 3/16 x 11 7/16 in.)

Sheet: 34.1 x 29.3cm (13 7/16 x 11 9/16 in.)

Mount: 35 x 29.7cm (13 3/4 x 11 11/16 in.)

Mat: 19 x 17 in.

Frame (outside): 20 x 18 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Rebecca Dixon Chambers, Sausalito, California from The American Country Woman

1954

Gelatin silver print

Image: 22 x 29.6cm (8 11/16 x 11 5/8 in.)

Mount: 47.7 x 37.5cm (18 3/4 x 14 3/4 in.)

Mat: 20 x 18 in.

Frame (outside): 21 x 19 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Hand of Dancer, Java, Indonesia

1958

Gelatin silver print

Image: 34 x 26.5cm (13 3/8 x 10 7/16 in.)

Sheet: 35.2 x 27.9 cm (13 7/8 x 11 in.)

Mat: 20 x 16 in.

Frame (outside): 21 x 17 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

During a 1958 trip to Indonesia with Paul Taylor, Lange observed a practice session of traditional gamelan music and Javanese dance. In this photograph, she focused on a gesture known as Ngrayung / Nangreu. Although such gestures can carry different meanings depending on the choreography, each highly controlled movement is believed to embody an expression of the soul and requires deep concentration.

Label text from the exhibition

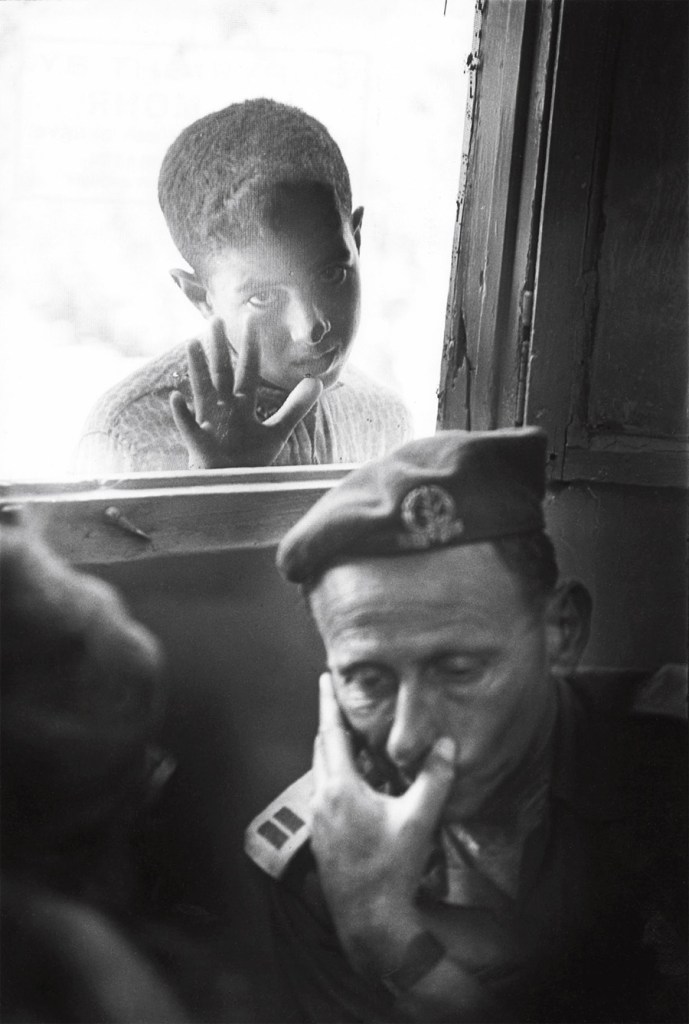

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Vietnam

1958

Gelatin silver print

Image/sheet: 26.3 x 31cm (10 3/8 x 12 3/16 in.)

Mat: 16 x 20 in.

Frame (outside): 17 x 21 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Venezuela

1960

Gelatin silver print

Image/sheet: 35.5 x 23.4cm (14 x 9 3/16 in.)

Mat: 20 x 16 in.

Frame (outside): 21 x 17 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

Lange joined Taylor on a trip to Venezuela, where he was consulting on agrarian reform. Here, she captured a man holding an axe in one hand and a machete in the other – blades used to clear corn stalks in the field. The presence of these sharp tools, along with the man’s torn clothing and bare feet, hint at the physical and economic vulnerability of farm labourers working on the land.

Label text from the exhibition

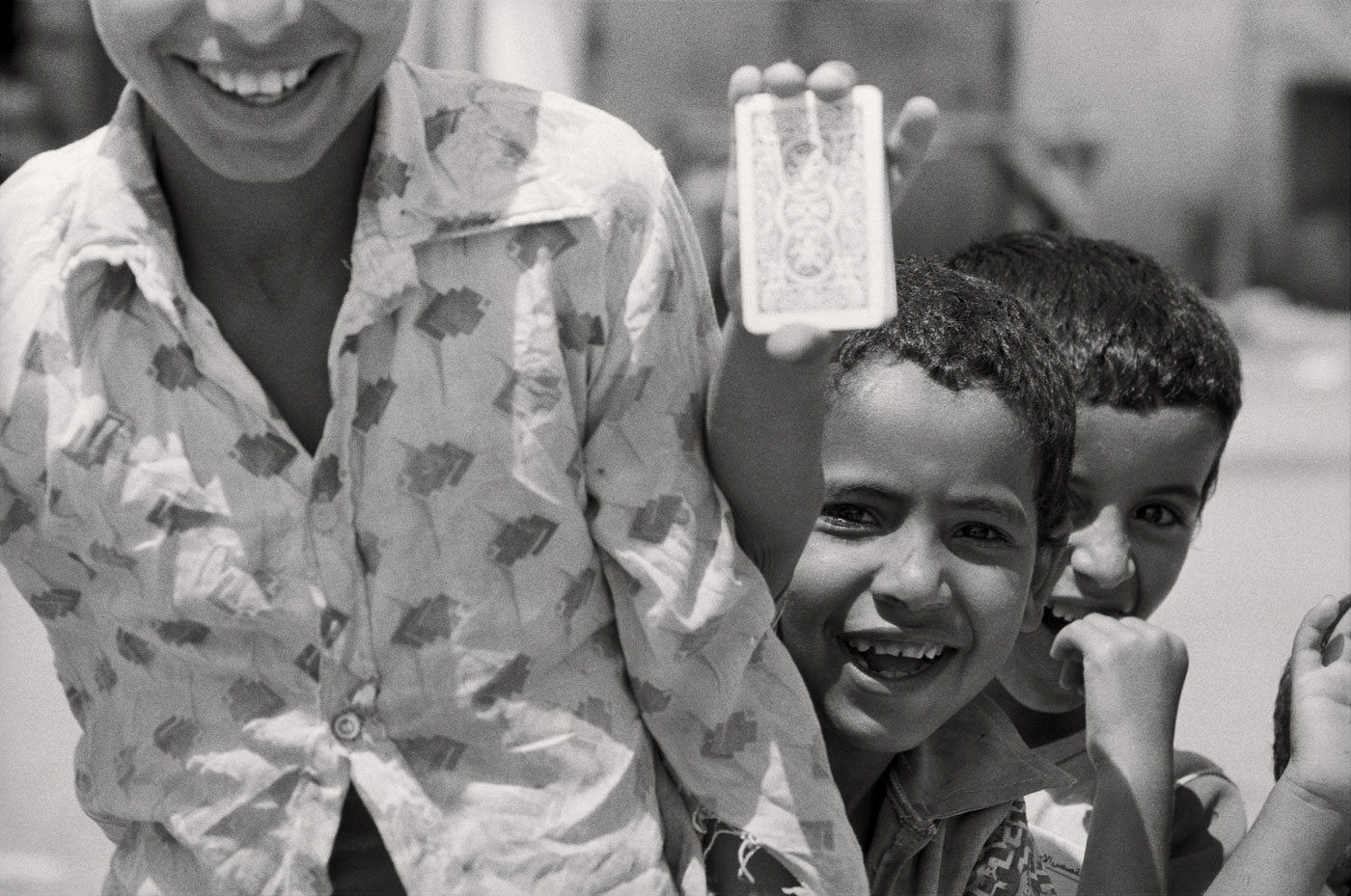

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Egypt

1963

Gelatin silver print

Image: 30.2 x 19.6cm (11 7/8 x 7 11/16 in.)

Mat: 18 x 14 in.

Frame (outside): 19 x 15 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

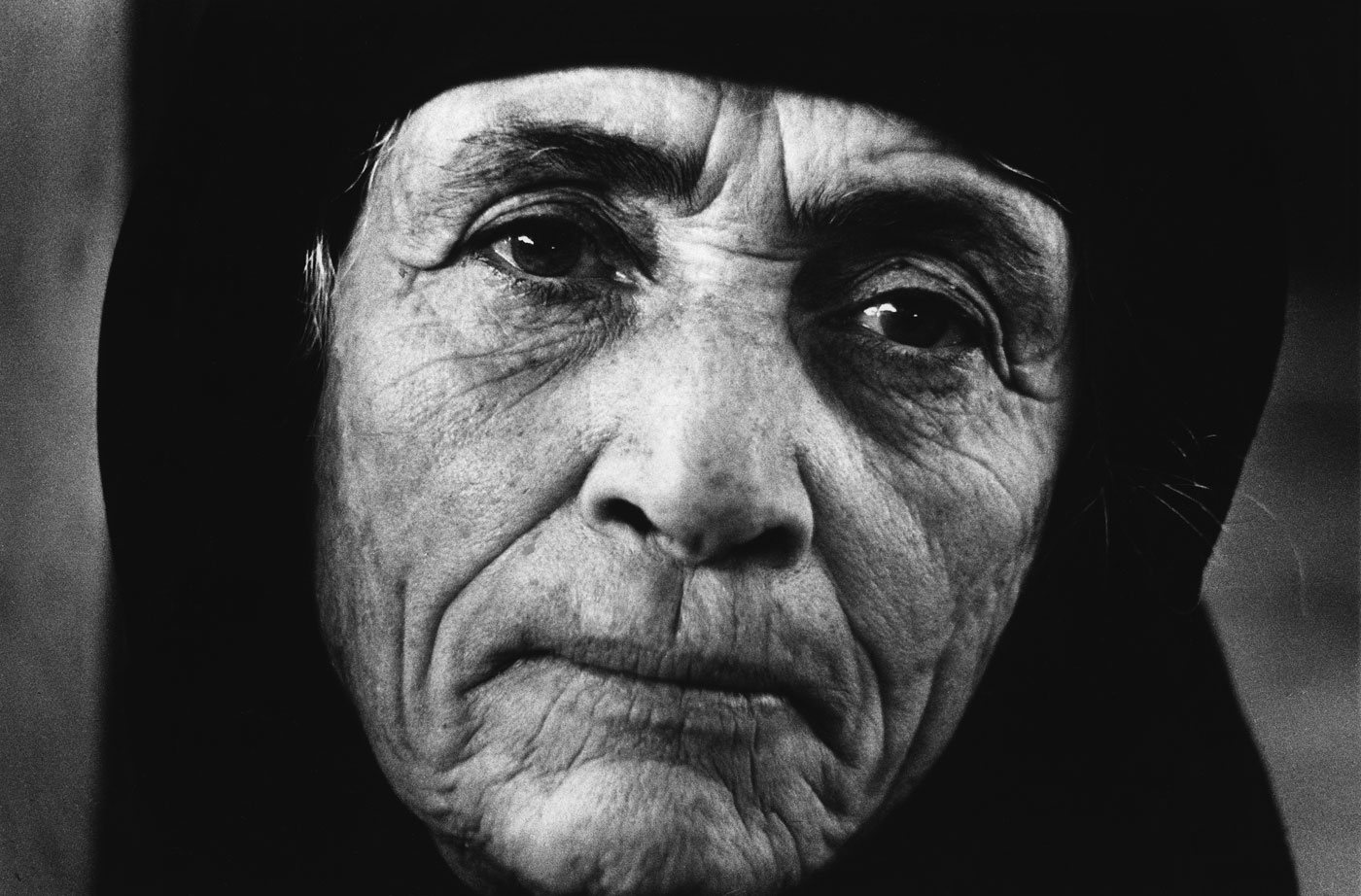

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Egypt

1963

Gelatin silver print

Image: 23.1 x 33.9cm (9 1/8 x 13 3/8 in.)

Mat: 18 x 14

Frame (outside): 19 x 15 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

National Gallery of Art

National Mall between 3rd and 7th Streets

Constitution Avenue NW, Washington

Opening hours:

Daily 10am – 5pm

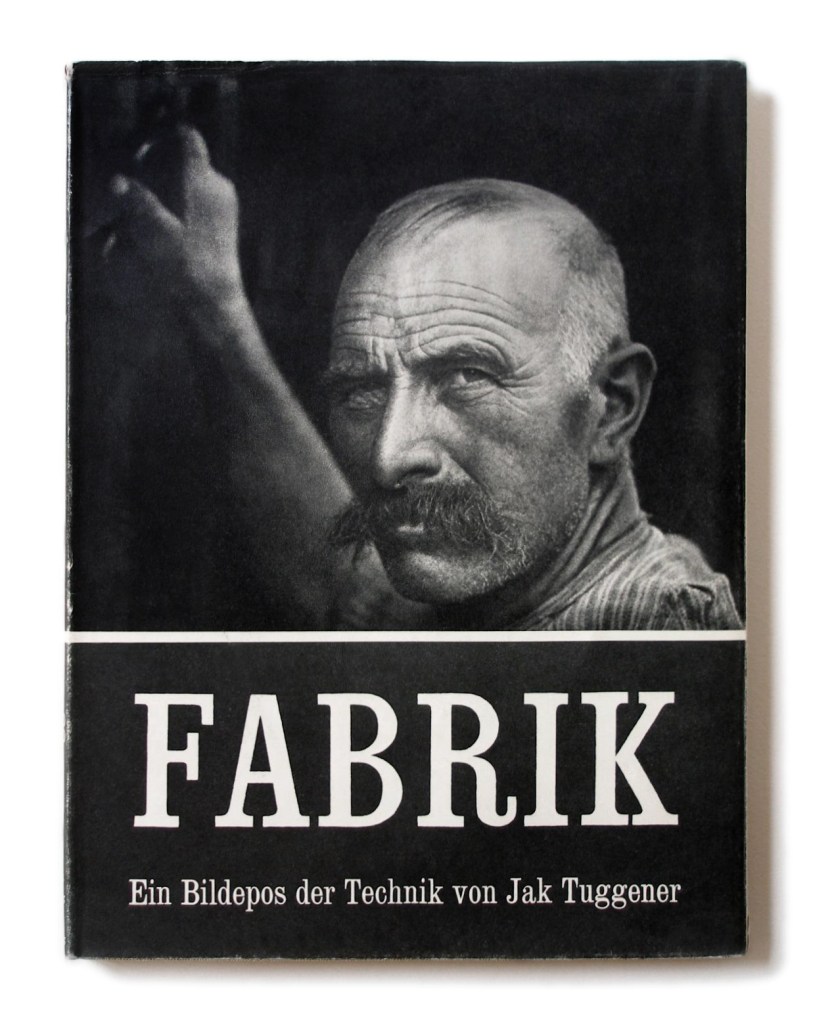

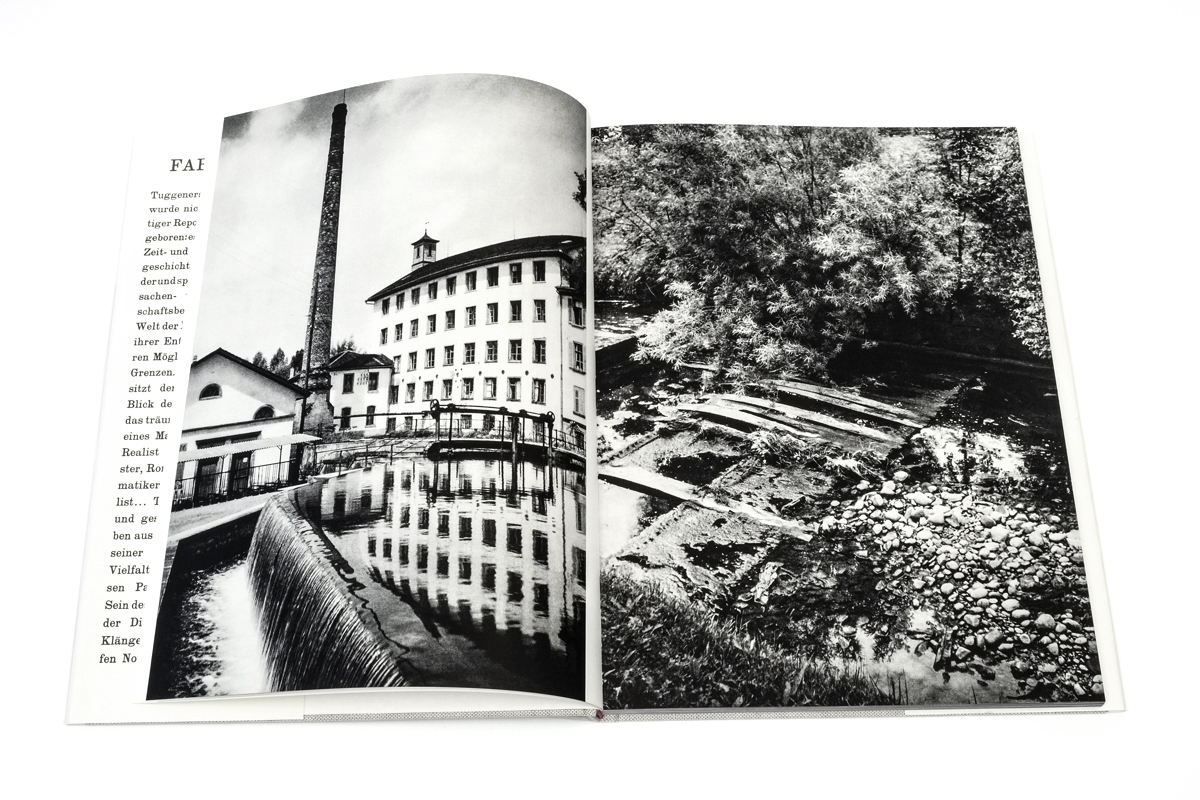

![Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Autoritratto, Zurigo [Self-portrait, Zurich]' 1927 from the exhibition Exhibition: 'Jakob Tuggener – Machine time' at Fotostiftung Schweiz, Winterthur, Zurich, Oct 2017 - Jan 2018 Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Autoritratto, Zurigo [Self-portrait, Zurich]' 1927 from the exhibition Exhibition: 'Jakob Tuggener – Machine time' at Fotostiftung Schweiz, Winterthur, Zurich, Oct 2017 - Jan 2018](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/jakob-tuggener-autoritratto-zurigo-1927-web.jpg?w=825)

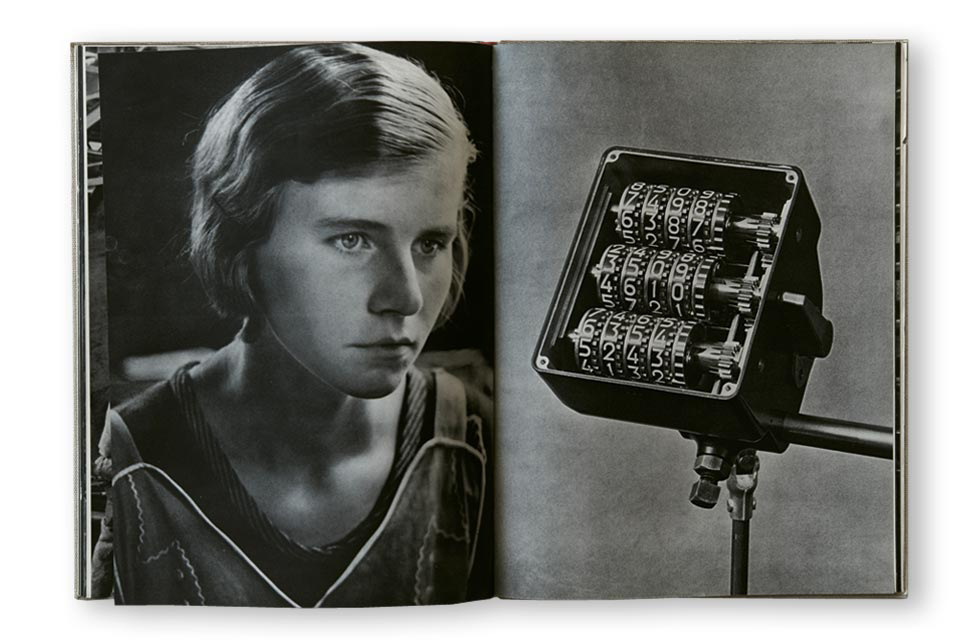

![Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Nell'ufficio della fonderia, fabbrica di costruzioni meccaniche Oerlikon' [In the foundry office, Oerlikon mechanical engineering factory] 1937 Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Nell'ufficio della fonderia, fabbrica di costruzioni meccaniche Oerlikon' [In the foundry office, Oerlikon mechanical engineering factory] 1937](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/jakob-tuggener-nellufficio-della-fonderia-web.jpg?w=766)

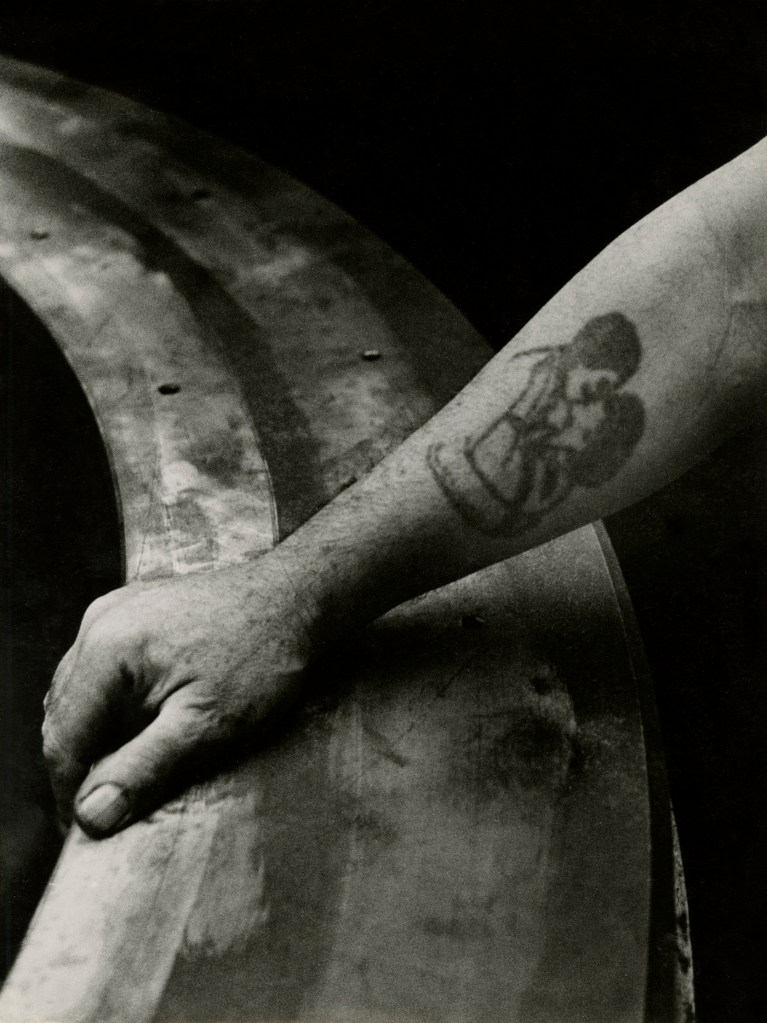

![Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Navy Cut, Ateliers de construction mécanique Oerlikon (MFO)' [Navy Cut, Machine Shops Oerlikon (MFO)] 1940 Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Navy Cut, Ateliers de construction mécanique Oerlikon (MFO)' [Navy Cut, Machine Shops Oerlikon (MFO)] 1940](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/tuggener-navy-cut-web.jpg?w=763)

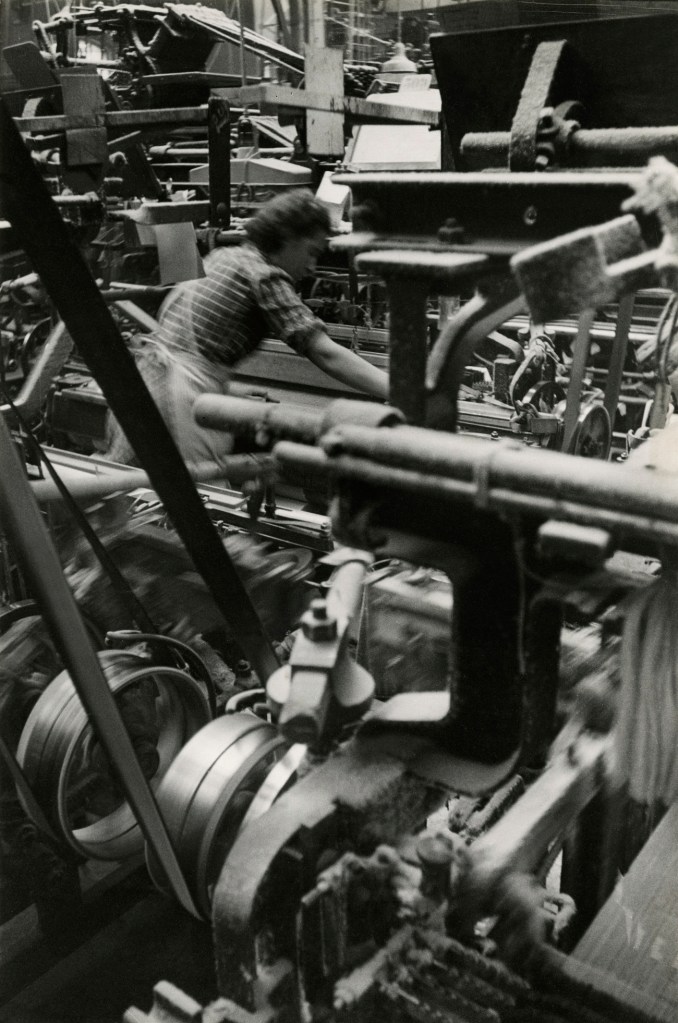

![Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Laboratorio di ricerca, fabbrica di costruzioni meccaniche Oerlikon' [Research laboratory, Oerlikon mechanical engineering factory] 1941 Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Laboratorio di ricerca, fabbrica di costruzioni meccaniche Oerlikon' [Research laboratory, Oerlikon mechanical engineering factory] 1941](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/jakob-tuggener-laboratorio-di-ricerca-web.jpg?w=709)

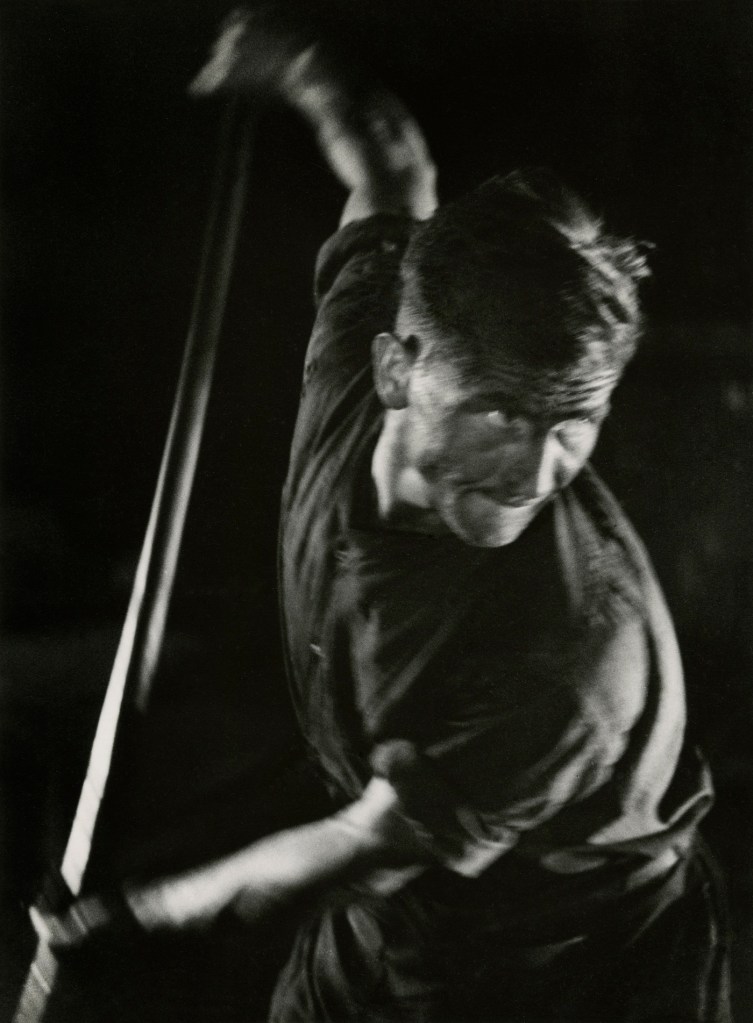

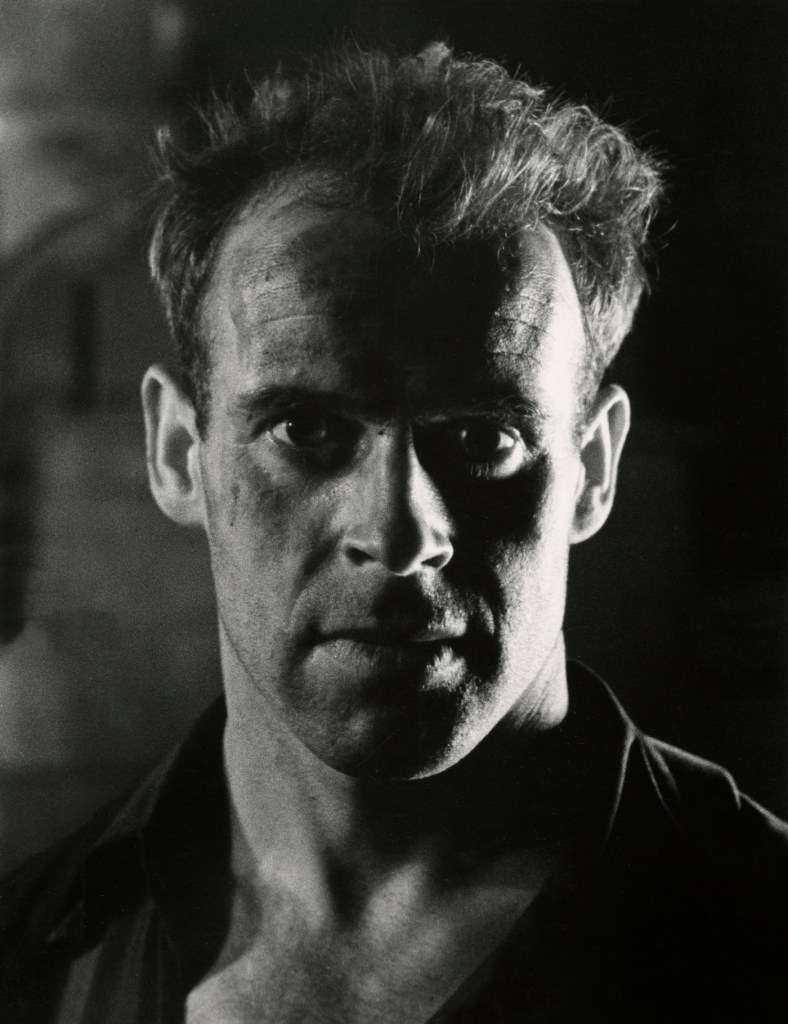

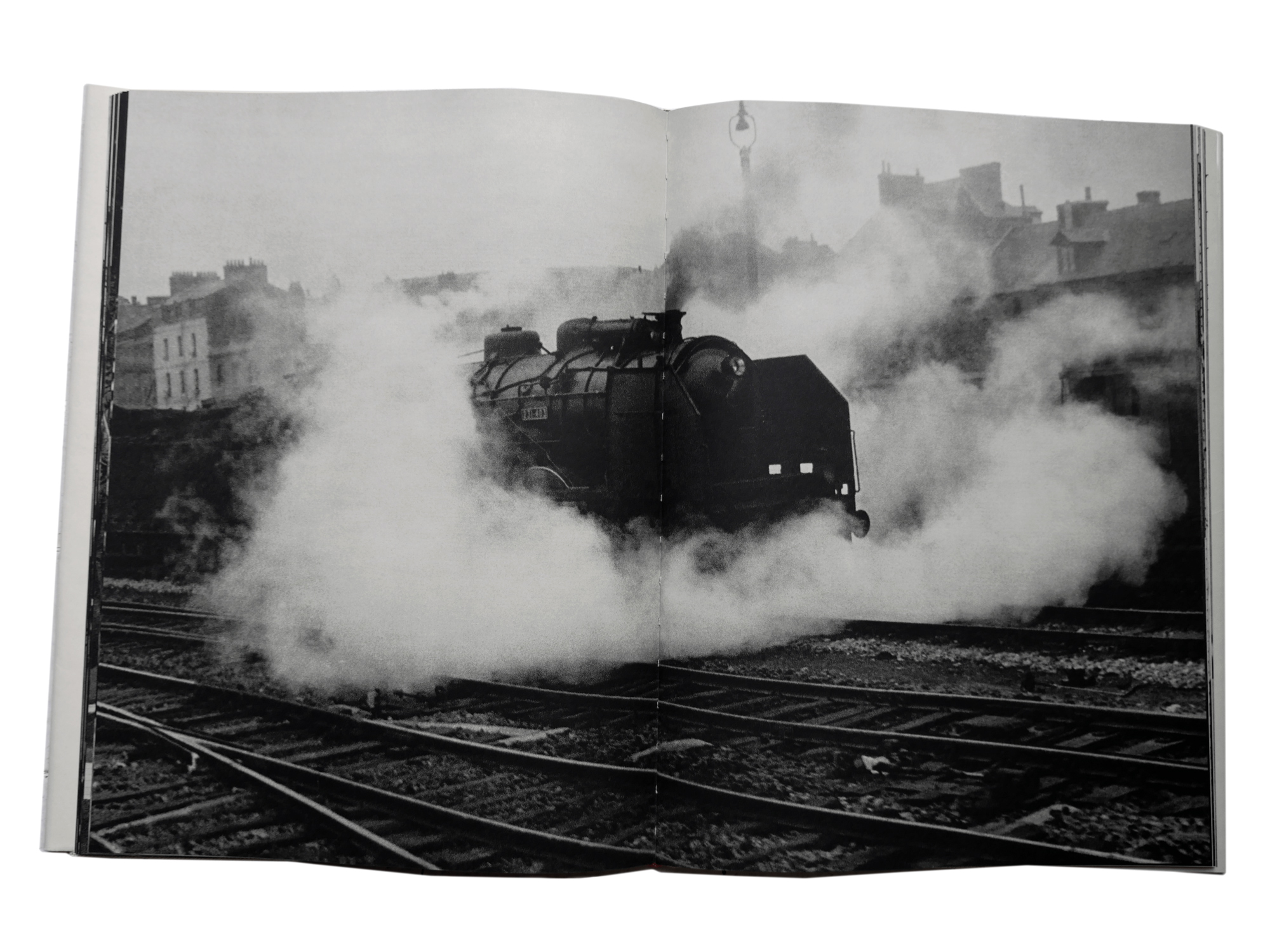

![Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Forgeron dans une fabrique de wagons de Schlieren' [Blacksmith in a Schlieren wagon factory] 1949 Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Forgeron dans une fabrique de wagons de Schlieren' [Blacksmith in a Schlieren wagon factory] 1949](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/tuggener-forgeron-dans-une-fabrique-de-wagons-web.jpg?w=741)

![Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Ballo ungherese, Grand Hotel Dolder, Zurigo, 1935' [Hungarian dance, Grand Hotel Dolder, Zurich, 1935] 1935 Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Ballo ungherese, Grand Hotel Dolder, Zurigo, 1935' [Hungarian dance, Grand Hotel Dolder, Zurich, 1935] 1935](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/tuggener-ballo-ungherese-web.jpg?w=757)

![Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Ballo ungherese, Grand Hotel Dolder, Zurigo, 1935' [Hungarian dance, Grand Hotel Dolder, Zurich, 1935] 1935 Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Ballo ungherese, Grand Hotel Dolder, Zurigo, 1935' [Hungarian dance, Grand Hotel Dolder, Zurich, 1935] 1935](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/jakob-tuggener-ballo-ungherese-web.jpg?w=698)

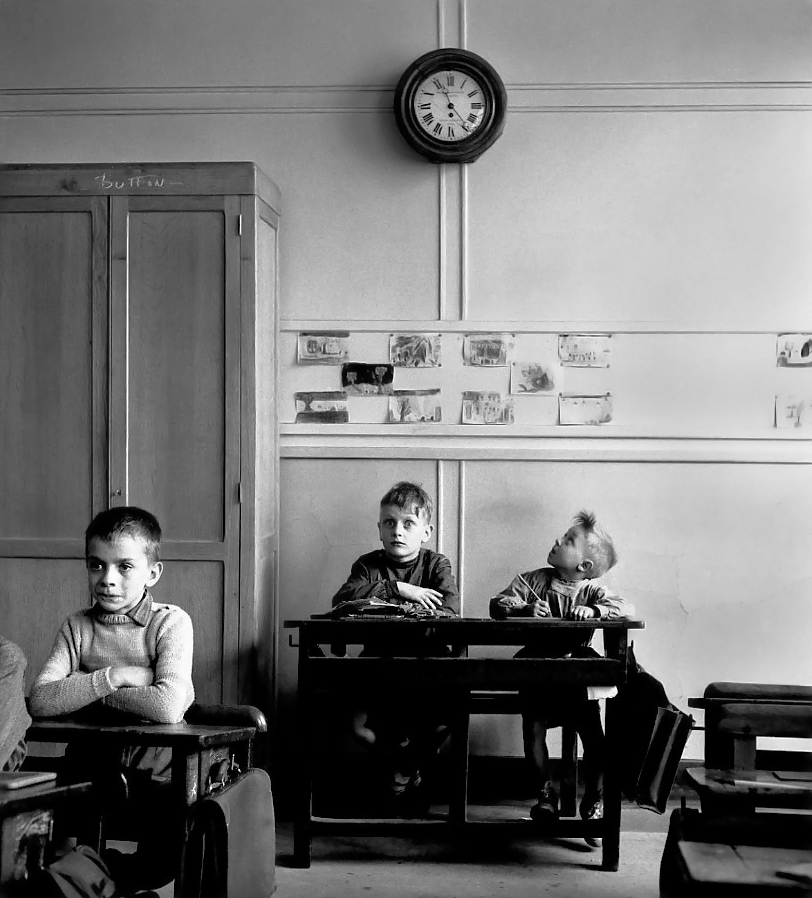

![Sabine Weiss (Swiss-French, 1924-2021) 'Enfants jouant, rue Edmond-Flamand' [Children playing, rue Edmond-Flamand] Paris, 1952 Sabine Weiss (Swiss-French, 1924-2021) 'Enfants jouant, rue Edmond-Flamand' [Children playing, rue Edmond-Flamand] Paris, 1952](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/weiss-children-playing-web.jpg?w=798)

![Sabine Weiss (Swiss-French, 1924-2021) 'Anna Karina pour la marque Korrigan' [Anna Karina for the brand Korrigan] 1958 Sabine Weiss (Swiss-French, 1924-2021) 'Anna Karina pour la marque Korrigan' [Anna Karina for the brand Korrigan] 1958](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/weiss-karina-web.jpg?w=812)

You must be logged in to post a comment.