Exhibition dates: 15th June – 20th July 2013

Many thankx to Tolarno Gallery for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Download the text Un/settling Aboriginality (1.1Mb pdf)

Un/settling Aboriginality

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Abstract

This text investigates the concepts of postcolonialism / neo-colonialism and argues that Australia is a neo-colonial rather than a postcolonial country. It examines the work of two Australian artists in order to understand how their work is linked to the concept of neo-colonialism and ideas of contemporary Aboriginal identity, Otherness, localism and internationalism.

Keywords

postcolonialism, postcolonial, art, neo-colonialism, Australian art, Australian artists, Aboriginal photography, hybridism, localism, internationalism, Otherness, Australian identity, Brook Andrew, Ricky Maynard, Helen Ennis.

Australia and postcolonialism / neo-colonialism

Defining the concept of postcolonialism is difficult. “To begin with, “post-colonial” is used as a temporal marker referring to the period after official decolonisation,”1 but it also refers to a general theory that Ania Loomba et al. call “the shifting and often interrelated forms of dominance and resistance; about the constitution of the colonial archive; about the interdependent play of race and class; about the significance of gender and sexuality; about the complex forms in which subjectivities are experienced and collectivities mobilized; about representation itself; and about the ethnographic translation of cultures.”2

“Postcolonial theory formulates its critique around the social histories, cultural differences and political discrimination that are practised and normalised by colonial and imperial machineries… Postcolonial critique can be defined as a dialectical discourse which broadly marks the historical facts of decolonisation. It allows people emerging from socio-political and economic domination to reclaim their sovereignty; it gives them a negotiating space for equity.”3

While colonialism and imperialism is about territory, possession, domination and power,4 postcolonialism is concerned with the history of colonialism, the psychology of racial representation and the frame of representation of the ‘Other’. It addresses the ongoing effects of colonialism and imperialism even after the colonial period has ended.

“Past and present inform each other, each implies the other and… each co-exists with the other.”5 Even after colonialism has supposedly ended there will always be remains that flow into the next period. What is important is not so much the past itself but its bearing upon cultural attitudes of the present and how the uneven relationships of the past are remembered differently.6 While the aims of postcolonialism are transformative, its objectives involve a wide-ranging political project – to reorient ethical norms, turn power structures upside down and investigate “the interrelated histories of violence, domination, inequality and injustice”7 and develop a tradition of resistance to the praxis of hegemony.

McCarthy and Dimitriadis posit three important motifs in postcolonial art.8 Briefly, they can be summarised as follows:

1/ A vigorous challenge to hegemonic forms of representation in Western models of classical realism and technologies of truth in which the eye of the Third World is turned on the West and challenges the ruling narrating subject through multiple perspectives and points of view.

2/ A rewriting of the narrative of modernity through a joining together of the binaries ‘centre’ and ‘periphery’, ‘developed’ and ‘underdeveloped’, and ‘civilised’ and ‘primitive’. “Culture, for these [postcolonial] artists, is a crucible of encounter, a crucible of hybridity in which all of cultural form is marked by twinness of subject and other.”9

3/ A critical reflexivity and thoughtfulness as elements of an artistic practice of freedom. This practice looks upon traditions with dispassion, one in which all preconceived visions and discourses are disrupted, a practice in which transformative possibilities are not given but have to worked for in often unpredictable and counter-intuitive ways.

According to Robert Young the paradigm of postcolonialism is to “locate the hidden rhizomes of colonialism’s historical reach, of what remains invisible, unseen, silent or unspoken” to examine “the continuing projection of past conflicts into the experience of the present, the insistent persistence of the afterimages of historical memory that drive the desire to transform the present.”10 This involves an investigation into a dialectic of visibility and invisibility where subjugated peoples were present but absent under the eye of the coloniser through a refusal of those in power to see who or what was there. “Postcolonialsm, in its original impulse, was concerned to make visible areas, nations, cultures of the world which were notionally acknowledged, technically there, but which in significant other senses were not there…”11 In other words, to acknowledge the idea of the ‘Other’ as a self determined entity if such an other should ever exist because, as Young affirms, “Tolerance requires that there be no “other,” that others should not be othered. We could say that there can be others, but there should be no othering of “the other.”12

The “Other” itself is a product of racial theory but Young suggests that “the question is not how to come to know “the other,” but for majority groups to stop othering minorities altogether, at which point minorities will be able to represent themselves as they are, in their specific forms of difference, rather than as they are othered.”13 Unfortunately, with regard to breaking down the divisiveness of the same-other split, “As soon as you have employed the very category of “the other” with respect to other peoples or societies, you are imprisoned in the framework of your own predetermining conceptualisation, perpetuating its form of exclusion.”14 Hence, as soon as the dominant force names the “other” as a paradigm of society, you perpetuate its existence as an object of postcolonial desire. This politics of recognition can only be validated by the other if the other choses to name him or herself in order to “describe a situation of historical discrimination which requires challenge, change and transformation… Othering was a colonial strategy of exclusion: for the postcolonial, there are only other human beings.”15

Important questions need to be asked about the contextual framework of postcolonialism as it is linked to race, culture, gender, settler and native: “When does a settler become coloniser, colonised and postcolonial? When does a race cease to be an oppressive agent and become a wealth of cultural diversities of a postcolonial setting? Or in the human history of migrations, when does the settler become native, indigenous, a primary citizen? And lastly, when does the native become truly postcolonial?”16

This last question is pertinent with regard to Australian culture and identity. It can be argued that Australia is not a postcolonial but a neo-colonial country. Imperialism as a concept and colonialism as a practice are still active in a new form. This new form is neo-colonialism. Rukundwa and van Aarde observe that, “Neo-colonialism is another form of imperialism where industrialised powers interfere politically and economically in the affairs of post-independent nations. For Cabral (in McCulloch 1983: 120-121), neo-colonialism is “an outgrowth of classical colonialism.” Young (2001: 44-52) refers to neo-colonialism as “the last stage of imperialism” in which a postcolonial country is unable to deal with the economic domination that continues after the country gained independence. Altbach (1995: 452-56) regards neo-colonialism as “partly planned policy” and a “continuation of the old practices”.”17

Australia is not a post-independent nation but an analogy can be made. The Australian government still interferes with the running of Aboriginal communities through the NT Intervention or, as it is more correctly known, Northern Territory National Emergency Response Act 2007. Under the Stronger Futures legislation that recently passed through the senate, this intervention has been extended by another 10 years. “Its flagship policies are increased government engagement, income management, stabilisation, mainstreaming, and the catch cries “closing the gap” and “real jobs”.”18 As in colonial times the government has control of a subjugated people, their lives, income, health and general wellbeing, instead of partnering and supporting Aboriginal organisations and communities to take control of their futures.19

Further, Australia is still a colony, the Queen of England is still the Queen of Australia; Britannia remains in the guise of the “Commonwealth.” Racism, an insidious element of the colonial White Australia Policy (which only ended in 1973), is ever prevalent beneath the surface of Australian society. Witness the recent racial vilification of Sydney AFL (Aussie Rules!) player Adam Goodes by a teenager20 and the inexcusable racial vilification by Collingwood president Eddie McGuire when he said that Goodes could be used to promote the musical King Kong.21

“The dialectics of liberation from colonialism, whether political, economic, or cultural, demand that both the colonizer and the colonized liberate themselves at the same time.”22 This has not happened in Australia. The West’s continuing political, economic and cultural world domination has “lead to a neo-colonial situation, mistakenly called post-coloniality, which does not recognize the liberated other as a historical subject (in sociological theory, a historical subject is someone thought capable of taking an active role in shaping events) – as part of the historical transforming processes of modernity.”23 As has been shown above, Aboriginal communities are still thought incapable of taking an active role in shaping and administering their own communities. The result of this continuation of old practices is that Australia can be seen as a neo-colonial, not postcolonial, country.

Kathryn Trees asks, “Does post-colonial suggest colonialism has passed? For whom is it ‘post’? Surely not for Australian Aboriginal people at least, when land rights, social justice, respect and equal opportunity for most does not exist because of the internalised racism of many Australians. In countries such as Australia where Aboriginal sovereignty, in forms appropriate to Aboriginal people, is not legally recognised, post-colonialism is not merely a fiction, but a linguistic manoeuvre on the part of some ‘white’ theorists who find this a comfortable zone that precludes the necessity for political action.”24

Two Australian artists, two different approaches

There are no dots or cross-hatching in the work of Ricky Maynard or Brook Andrew; no reference to some arcane Dreaming, for their work is contemporary art that addresses issues of identity and empowerment in different ways. Unlike remote Indigenous art that artist Richard Bell has labelled ‘Ooga Booga Art’ (arguing that it is based upon a false notion of tradition that casts Indigenous people as the exotic other, produced under the white, primitivist gaze),25 the work of these two artists is temporally complex (conflating past, present and future) and proposes that identity is created at the intersection of historically shifting subject positions, which destabilises any claim to an ‘authentic’ identity position and brings into question the very label ‘Aboriginal’ art and ‘Aboriginality’. By labelling an artist ‘Aboriginal’ or ‘gay’ for example, do you limit the subject matter that those artists can legitimately talk about, or do you just call them artists?

As Stephanie Radok has speculated, “surely as long as we call it Aboriginal art we are defining it ethnically and foregrounding its connection to a particular culture, separating it from other art and seeing it as a gift, a ‘present’ from another ethnography.”26 Be that as it may, artists can work from within a culture, a system, in order to critique the past in new ways: “The collective efforts of contemporary artists… do not reflect an escapist return to the past but a desire to think about what the past might now mean in new, creative ways.”27

Ways that un/settle Aboriginality through un/settling photography, in this case.

Since the 1980s photographers addressing Indigenous issues have posed an alternative reality or viewpoint that, “articulates the concept of time as a continuum where the past, present and future co-exist in a dynamic form. This perspective has an overtly political dimension, making the past not only visible but also unforgettable.”28 The perspective proposes different strategies to deliberately unsettle white history so that “the future is as open as the past, and both are written in tandem.”29

Artists Ricky Maynard and Brook Andrew both critique neo-colonialism from inside the Western gallery system using a relationship of interdependence (Aboriginal/colonial) to find their place in the world, to help understand who they are and, ex post facto, to make a living from their art. They both offer an examination of place, space and identity construction through what I call ‘the industry of difference’.

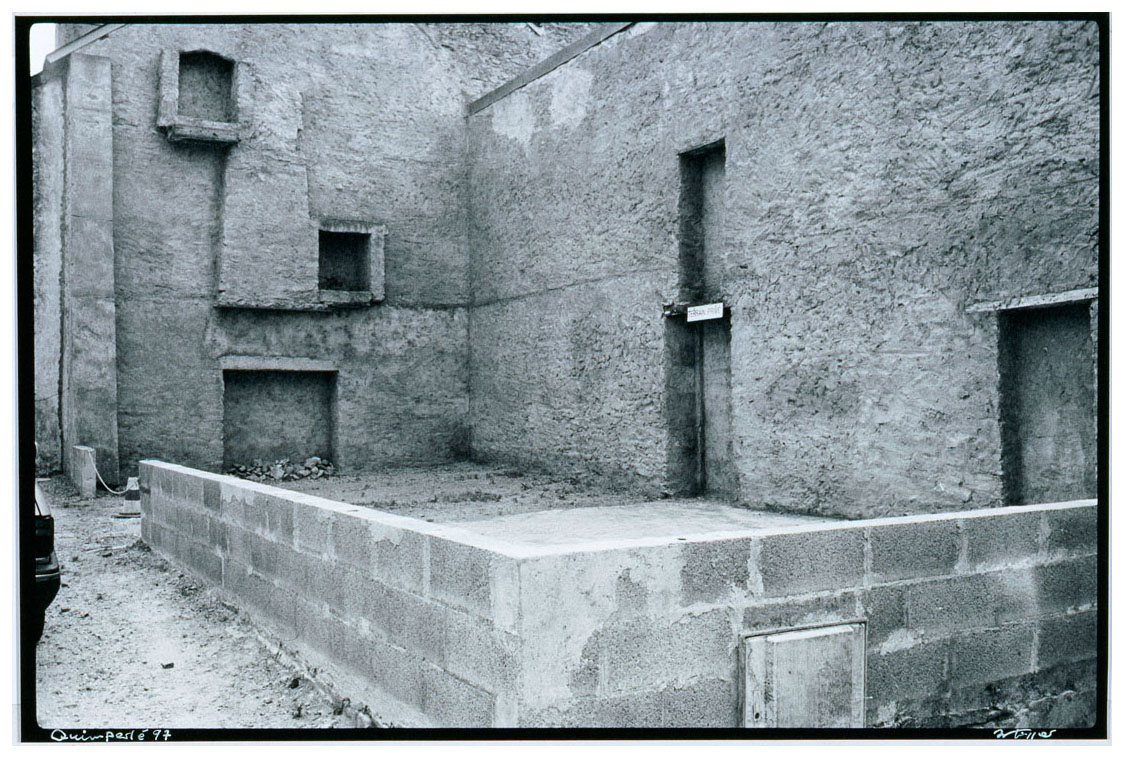

Ricky Maynard works with a large format camera and analogue, black and white photography in the Western documentary tradition to record traditional narratives of Tasmanian Aboriginal people in order to undermine the myth that they were all wiped off the face of the planet by colonisation. Through his photography he re-identifies the narratives of a subjugated and supposedly exterminated people, narratives that are thousands of years old, narratives that challenge a process of Othering or exclusion and which give voice to the oppressed.

“Portrait of a Distant Land is done through the genre of documentary in a way that offers authenticity and honest image making in the process. It has to deal with all those ethical questions of creating visual history, the tools to tell it with and how we reclaim our own identity and history from the way we tell our own stories. It comes from the extension of the way the colonial camera happened way back in the 19th century and how it misrepresented Aboriginal people. The Government anthropologists and photographers were setting up to photograph the dying race. Of course it simply wasn’t true. That was a way that colonial people wanted to record their history. You see those earlier colonial and stereotypical images of Aboriginal people in historic archives, their photographic recordings were acts of invasion and subjugation used for their own purpose.”30

Ricky Maynard (Australian, b. 1953)

Coming Home

2005

from Portrait of a Distant Land

Gelatin silver print

34 x 52cm, edition of 10 + 3 AP

“I can remember coming here as a boy in old wooden boats to be taught by my grandparents and my parents.

I’ll be 57 this year and I have missed only one year when my daughter Leanne was born. Mutton birding is my life. To me it’s a gathering of our fella’s where we sit and yarn we remember and we honour all of those birders who have gone before us. Sometimes I just stand and look out across these beautiful islands remembering my people and I know I’m home. It makes me proud to be a strong Tasmanian black man.

This is something that they can never take away from me.”

Murray Mansell Big Dog Island, Bass Strait, 2005 31

Ricky Maynard (Australian, b. 1953)

Vansittart Island, Bass Strait, Tasmania

2005

from Portrait of a Distant Land

Gelatin silver print

34 x 52cm, edition of 10 + 3 AP

“As late as 1910 men came digging on Vansittart and Tin Kettle Islands looking for skeletons here. We moved them where none will find them, at the dead of night my people removed the bodies of our grandmothers and took them to other islands, we planted shamrocks over the disturbed earth, so the last resting place of those girls who once had slithered over the rocks for seals will remain a secret forever.”

Old George Maynard 1975 32

Ricky Maynard (Australian, b. 1953)

The Healing Garden, Wybalenna, Flinders Island, Tasmania

2005

from Portrait of a Distant Land

Gelatin silver print

34 x 52cm, edition of 10 + 3 AP

“It’s pretty important you know, the land, it doesn’t matter how small, it’s something, just a little sacred site, that’s Wybalenna. There was a massacre there, sad things there, but we try not to go over that. Where the bad was we can always make it good.”

Aunty Ida West 1995 Flinders Island, Tasmania 33

Maynard’s photographs are sites of contestation, specific, recognisable sites redolent with contested history. They are at once both local (specific) and global (addressing issues that affect all subjugated people and their stories, histories). Through his art practice Maynard journeys from the periphery to the centre to become a fully recognised historical subject, one that can take an active role in shaping events on a global platform, a human being that aims to create what he describes as “a true visual account of life now.”34 But, as Ian McLean has noted of the work of Derrida on the idea of repression, what returns in such narratives is not an authentic, original Aboriginality but the trace of an economy of repression: “Hence the return of the silenced nothing called Aboriginal as the being and truth of the place, is not the turn-around it might seem, because it does not reinstate an original Aboriginality, but reiterates the discourses of colonialism.”35

Sad and poignant soliloquies they may be, but in these ‘true’ visual accounts it is the trace of repression represented through Western technology (the camera, the photograph) and language (English is used to describe the narratives, see above) that is evidenced in these critiques of neo-colonialism (a reiteration of the discourses of colonialism) – not just an authentic lost and reclaimed Aboriginality – for these photographs are hybrid discourses that are both local/global, European/Indigenous.

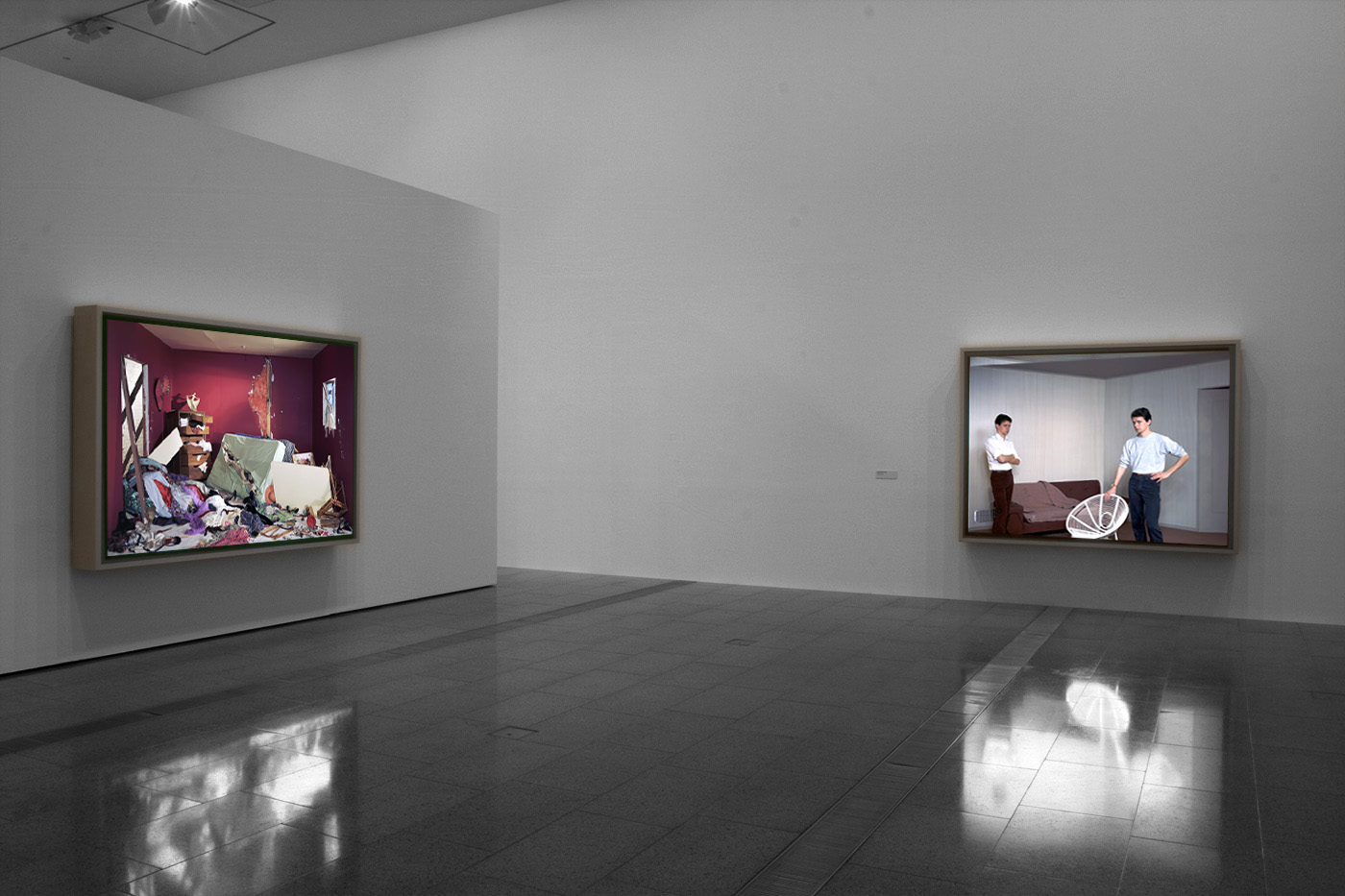

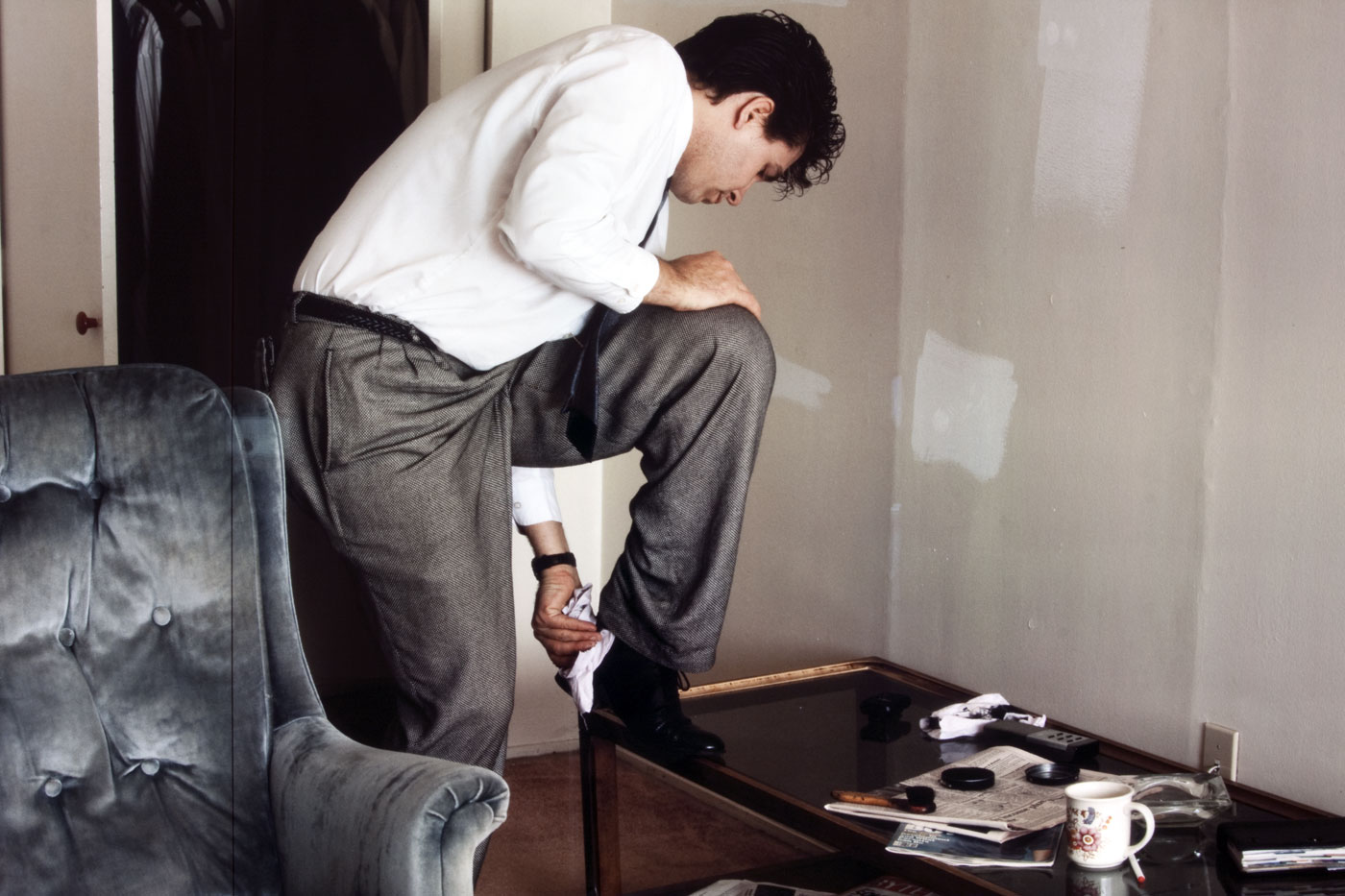

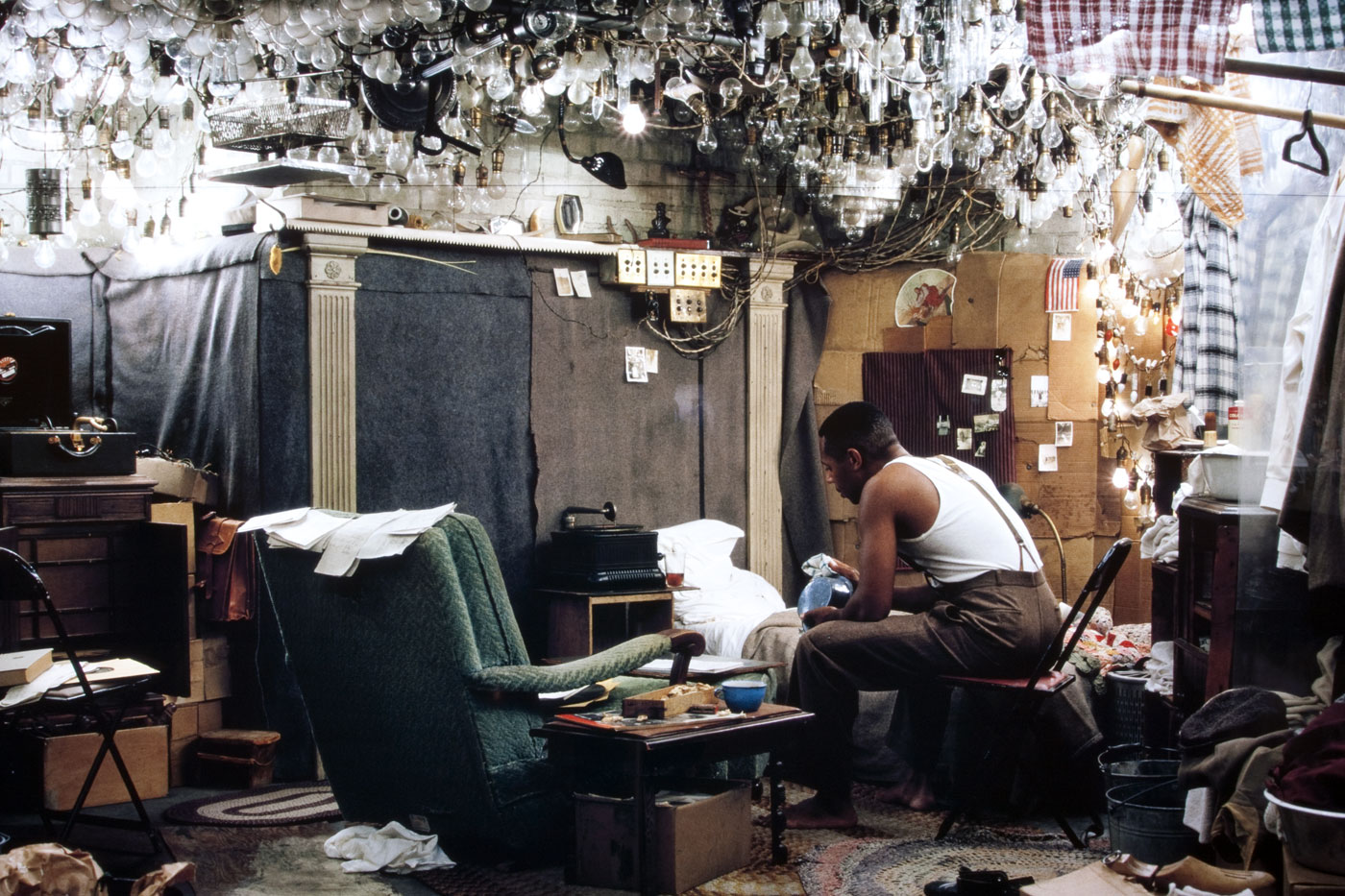

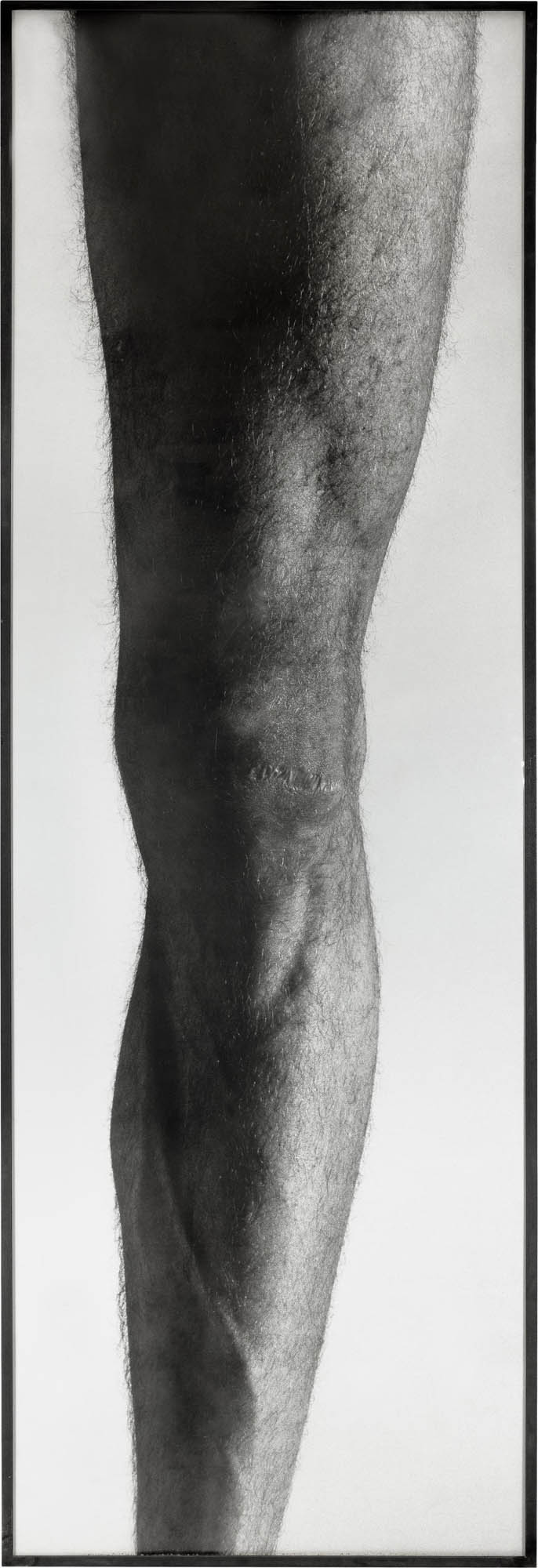

In his art practice Brook Andrew pursues a more conceptual mutli-disciplinary approach, one that successfully mines the colonial photographic archive to interrogate the colonial power narrative of subjugation, genocide, disenfranchisement through a deconstructive discourse, one that echoes with the repetitions of coloniality and evidences the fragments of racism through the status of appearances. “Through his persistent confrontation with the historical legacy of physiognomia in our public Imaginary”36 in video, neon, sculpture, craniology, old photography, old postcards, music, books, ethnography and anthropology, Andrew re-images and reconceptualises the colonial archive. His latest body of work 52 Portraits (Tolarno Galleries 15 June – 20 July 2013), is “a play on Gerhard Richter’s 48 Portraits projects, which lifted images of influential Western men from the pages of encyclopaedias, 52 Portraits shifts the gaze to the ubiquitous and exotic other.”37 The colonial portraits are screen-printed in black onto silver-coated canvases giving them an ‘other’ worldly, alien effect (as of precious metal), which disrupts the surface and identity of the original photographs. Variously, the unnamed portraits taken from his personal collection of old colonial postcards re-present unknown people from the Congo, Africa, Argentina, Ivory Coast, Brazil, Algeria, Australia, South America, etc… the images incredibly beautiful in their silvered, slivered reality (as of the time freeze of the camera), replete with fissures and fractures inherent in the printing process. Accompanying the series is an installation titled Vox: Beyond Tasmania (2013), a Wunderkammer containing a skeleton and colonial artefacts, the case with attached wooden trumpet (reminding me appropriately of His Master’s Voice) that focuses the gaze upon an anonymous skull, an unknowable life from the past. In the catalogue essay for the exhibition, Ian Anderson observes, “His view is global – and even though my response is highly local – I too see the resonances of a global cultural process that re-ordered much of humanity through the perspective of colonizing peoples.”38

While this may be true, it is only true for the limited number of people that will see the exhibition – usually white, well-educated people, “The realities of the commercial art world are such that it is chiefly the white upper crust that will see these works. Make of that what you will.”39 Through a lumping together of all minority people – as though multiple, local indigeneties can be spoken for through a single global indigeneity – Andrew seems to want to speak for all anonymous Indigenous people from around the world through his ‘industry of difference’. Like colonialism, this speaking is again for the privileged few, as only they get to see these transformed images, in which only those with money can afford to buy into his critique.

Personally, I believe that Andrew’s constant remapping and re-presentation of the colonial archive in body after body of work, this constant picking at the scab of history, offers no positive outcomes for the future. It is all too easy for an artist to be critical; it takes a lot more imagination for an artist to create positive images for a better future.

Conclusion

By the mid-eighties black and indigenous subjectivities were no longer transgressive and the ‘black man’s’ burden’ had shifted from being a figure of oblivion to that of a minority voice.40 Black subjectivities as minority identities use the language of difference to envisage zones of liberation in which marginality is a site of transformation. But, as Ian McLean asks, “Have these post or anti-colonial identities repulsed the return of coloniality?”41 In the fight against neo-colonialism he suggests not, when the role of minority discourses “are simultaneously marginalised and occupy an important place in majority texts.”42 Periphery becomes centre becomes periphery again. “Minority artists are not left alone on the periphery of dominant discourse. Indeed, they are required to be representatives of, or speak for, a particular marginalised community; and because of this, their speech is severely circumscribed. They bear a ‘burden of representation’.”43 McLean goes on to suggest the burden of representation placed on Aboriginal artists is one that cannot be escaped. The category ‘Aboriginal’ is too over determined. Aboriginal artists, like gay artists addressing homosexuality, can only address issues of race, identity and place.44

“Aboriginal artists must address issues of race, and all on the stage of an identity politics. Black artists, it seems, can perform only if they perform blackness. Reduced to gestures of revolt, they only reinforce the scene of repression played out in majority discourses of identity and otherness. Allowed to enter the field of majority language as divergent and hence transgressive discourses which police as much as they subvert the boundaries of this field, they work to extend certain boundaries necessary to Western identity formations, but which its traditions have repressed. In other words, minority discourses are complicit with majority texts.”45

As social constructs (the heart of the political terrain of imperial worlds) have been interrogated by artists, this has led to the supposed dissolution of conceptual binaries such as European Self / Indigenous Other, superior / inferior, centre / periphery.46 The critique of neo-colonialism mobilises a new, unstable conceptual framework, one that unsettles both imperialist structures of domination and a sense of an original Aboriginality. Counter-colonial perspectives might critique neo-colonial power through disruptive inhabitations of colonialist constructs (such as the photograph and the colonial photographic archive) but they do so through a nostalgic reworking and adaptation of the past in the present (through stories that are eons old in the case of Ricky Maynard or through appropriation of the colonial photographic archive in the case of Brook Andrew). Minority discourses un/settle Aboriginality in ways not intended by either Ricky Maynard or Brook Andrew, by reinforcing the boundaries of the repressed ‘Other’ through a Western photographic interrogation of age-old stories and the colonial photographic archive.

Both Maynard and Andrew picture identities that are reductively marshalled under the sign of minority discourse, a discourse that re-presents a field of representation in a particularly singular way (addressed to a privileged few). The viewer is not caught between positions, between voices, as both artists express an Aboriginal (not Australian) subjectivity, one that reinforces a black subjectivity and oppression by naming Aboriginal as ‘Other’ (here I am not proposing “assimilation” far from it, but inclusion through difference, much as gay people are now just members of society not deviants and outsiders).

Finally, what interests me further is how minority voices can picture the future not by looking at the past or by presenting some notion of a unitary representation (local / global) of identity, but by how they can interrogate and image the subject positions, political processes, cultural articulation and critical perspectives of neo-colonialism in order that these systems become the very preconditions to decolonisation.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

July 2013

Word count: 3,453 excluding image titles and captions.

Endnotes

1/ Abraham, Susan. “What Does Mumbai Have to Do with Rome? Postcolonial Perspectives on Globalization and Theology,” in Theological Studies 69, 2008, pp. 376-93 cited in Kenzo, Mabiala Justin-Robert. What Is Postcolonialism and Why Does It Matter: An African Perspective. Nd [Online] Cited 13/06/2013. No longer available online

2/ Loomba, Ania et al. “Beyond What? An Introduction,” in Loomba, Ania et al. (ed.,). Postcolonial Studies and Beyond. Durham, N.C.: Duke University, 2005, pp. 1-38

3/ Rukundwa, Lazare S and van Aarde, Andries G. “The formation of postcolonial theory,” in HTS Teologiese Studies / Theological Studies 63(3), 2007, p. 1174

4/ “Neither imperialism nor colonialism is a simple act of accumulation and acquisition. Both are supported and perhaps even impelled by impressive ideological formations that include notions that certain territories and people require and beseech domination, as well as forms of knowledge affiliated with domination: the vocabulary of classic nineteenth-century imperial cultural is plentiful with such words and concepts as ‘inferior’ or ‘subject races’, ‘subordinate people’, ‘dependency’, ‘expansion’, and ‘authority’.”

Said, Edward. “Overlapping Territories, Intertwined Histories,” in Said, Edward. Culture and Imperialism. London: Chatto and Windus, 1993, p. 8

5/ Ibid., p. 2

6/ Ibid., p. 19

7/ Young, Robert J.C. “Postcolonial Remains,” in New Literary History Vol. 43. No. 1. Winter 2012, p. 20

8/ See McCarthy, Cameron and Dimitriadis, Greg. “The Work of Art in the Postcolonial Imagination,” in Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 21(1), 2000, p. 61

9/ Ibid., p. 61

10/ Young, Op. cit., p. 21

11/ Young, Ibid., p. 23

12/ “Critical analysis of subjection to the demeaning experience of being othered by a dominant group has been a long-standing focus for postcolonial studies, initiated by Frantz Fanon in his Black Skin, White Masks (1952).”

Young, Robert J.C. “Postcolonial Remains,” in New Literary History Vol. 43. No. 1. Winter 2012, p. 36

13/ Ibid., p. 37

14/ Ibid., p. 38

15/ Ibid., p. 39

16/ Rukundwa, Op cit., p. 1173

17/ Ibid., p. 1173

18/ Anon. “The 30-year cycle: Indigenous policy and the tide of public opinion” on The Conversation website 06/06/2012 [Online] Cited 16/06/2013

19/ Karvelas, Patricia. “Senate approves Aboriginal intervention by 10 years,” on The Australian website June 29, 2012 [Online] Cited 16/06/2013. No longer available online

20/ ABC/AAP. “AFL: Adam Goodes racially abused while leading Sydney to Indigenous Round win over Collingwood Sat May 25, 2013” on the ABC News website [Online] Cited 15/06/2013

21/ Anon. “Eddie McGuire, Adam Goodes and ‘apes’: a landmark moment in Australian race relations,” on The Conversation website, 31 May 2013 [Online] Cited 15/06/2013

22/ Araeen, Rasheed. “The artist as a post-colonial subject and this individual’s journey towards ‘the centre’,” in King, Catherine. View of Difference. Different Views of Art. Yale University Press, 1999, p. 232

23/ Ibid.,

24/ Trees, Kathryn. “Postcolonialism: Yet Another Colonial Strategy?” in Span, Vol. 1, No. 36, 1993, pp. 264-265 quoted in Heiss, Anita. “Post-Colonial-NOT!” in Dhuuluu Yala (To Talk Straight): Publishing Aboriginal Writing in Australia. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press, 2003, pp. 43-46

25/ Skerritt, Henry F. “Drawing NOW: Jus’ Drawn'” in Art Guide Australia, September/ October 2010, pp. 34-35 [Online] Cited 17/06/2013.

26/ Ibid.,

27/ Ennis, Helen. “The Presence of the Past,” in Ennis, Helen. Photography and Australia. London: Reaktion Books, 2007, p. 141

28/ Ibid., p. 135

29/ Ibid., “Black to Blak,” p. 45

30/ Maynard, Ricky quoted in Perkins, Hetti. Art + Soul. Melbourne: The Miegunyah Press, Melbourne University Publishing, 2010, p. 85

31/ Mansell, Murray quoted on the Stills Gallery website [Online] Cited 22/06/2013

32/ Maynard, George quoted on the Stills Gallery website [Online] Cited 22/06/2013

33/ West, Ida quoted on the Stills Gallery website [Online] Cited 22/06/2013

34/ Maynard, Ricky. “The Craft of Documentary Photography,” in Phillips, Sandra. Racism, Representation and Photography. Sydney, 1994, p. 115 quoted in Ennis, Helen. Photography and Australia. London: Reaktion Books, 2007, p. 106

35/ McLean, Ian. “Post colonial: return to sender” 1998 paper delivered as the Hancock lecture at the University of Sydney on 11/11/1998 as part of the annual conference of the Australian Academy of Humanities which had as its theme: ‘First Peoples Second Chance Australia In Between Cultures’

36/ Papastergiadis, Nikos. “Brook Andrew: Counterpoints and Harmonics.” Catalogue essay for Brook Andrew’s exhibition 52 Portraits at Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne, June 2013

37/ Rule, Dan. “Brook Andrew: 52 Portraits,” in Arts & Entertainment, Lifestyle, in The Saturday Age newspaper, June 29th 2013, p. 5

38/ Anderson, Pangkarner Ian. “Re-Assembling the trophies and curios of Colonialism & the Silent Terror.” Catalogue essay for Brook Andrew’s exhibition 52 Portraits at Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne, June 2013

39/ Rule, Dan. Op. cit.,

40/ McLean, Ian. “Post colonial: return to sender” 1998

41/ Ibid.,

42/ Ibid.,

43/ Ibid.,

44/ “Whether they like it or not, they [Aboriginal artists] bear a burden of representation. This burden is triply inscribed. First, they can only enter the field of representation or art as a disruptive force. Second, their speaking position is rigidly circumscribed: they are made to speak as representatives of a particular, that is, Aboriginal community. Third, this speaking is today made an essential component of the main game, the formation of Australian identity – what Philip Batty called ‘Australia’s desire to know itself through Aboriginal culture’.”

McLean, Ian. “Post colonial: return to sender” 1998

45/ Ibid.,

46/ Jacobs observes, “As the work on the nexus of power and identity within the imperial process has been elaborated, so many of the conceptual binaries that were seen as fundamental to its architecture of power have been problematised. Binary couplets like core / periphery, inside / outside. Self / Other, First World / Third World, North / South have given way to tropes such as hybridity, diaspora, creolisation, transculturation, border.”

Jacobs, J. M. “(Post)colonial spaces,” Chapter 2 in Edge of Empire. London: Routledge, 1996, p. 13

Bibliography

Anderson, Pangkarner Ian. “Re-Assembling the trophies and curios of Colonialism & the Silent Terror.” Catalogue essay for Brook Andrew’s exhibition 52 Portraits at Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne, June 2013

Araeen, Rasheed. “The artist as a post-colonial subject and this individual’s journey towards ‘the centre’,” in King, Catherine. View of Difference. Different Views of Art. Yale University Press, 1999, p. 232

ABC/AAP. “AFL: Adam Goodes racially abused while leading Sydney to Indigenous Round win over Collingwood Sat May 25, 2013” on the ABC News website [Online] Cited 15/06/2013.

Abraham, Susan. “What Does Mumbai Have to Do with Rome? Postcolonial Perspectives on Globalization and Theology,” in Theological Studies 69, 2008, pp. 376-93 cited in Kenzo, Mabiala Justin-Robert. What Is Postcolonialism and Why Does It Matter: An African Perspective. Nd [Online] Cited 13/06/2013

Anon. “Eddie McGuire, Adam Goodes and ‘apes’: a landmark moment in Australian race relations,” on The Conversation website, 31 May 2013 [Online] Cited 15/06/2013

Anon. “The 30-year cycle: Indigenous policy and the tide of public opinion,” on The Conversation website 06/06/2012 [Online] Cited 16/06/2013

Ennis, Helen. “The Presence of the Past,” in Ennis, Helen. Photography and Australia. London: Reaktion Books, 2007, p. 141

Heiss, Anita. “Post-Colonial-NOT!” in Dhuuluu Yala (To Talk Straight): Publishing Aboriginal Writing in Australia. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press, 2003, pp. 43-46

Jacobs, J. M. “(Post)colonial spaces,” Chapter 2 in Edge of Empire. London: Routledge, 1996, p. 13

Karvelas, Patricia. “Senate approves Aboriginal intervention by 10 years,” on The Australian website June 29, 2012 [Online] Cited 16/06/2013

Kenzo, Mabiala Justin-Robert. What Is Postcolonialism and Why Does It Matter: An African Perspective. Nd [Online] Cited 13/06/2013.

King, Catherine. View of Difference. Different Views of Art. Yale University Press, 1999

Loomba, Ania et al. “Beyond What? An Introduction,” in Loomba, Ania et al. (ed.,). Postcolonial Studies and Beyond. Durham, N.C.: Duke University, 2005, pp. 1-38

Maynard, Ricky. “The Craft of Documentary Photography,” in Phillips, Sandra. Racism, Representation and Photography. Sydney, 1994, p.115 quoted in Ennis, Helen. Photography and Australia. London: Reaktion Books, 2007, p. 106

McCarthy, Cameron and Dimitriadis, Greg. “The Work of Art in the Postcolonial Imagination,” in Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 21(1), 2000, p. 61

McLean, Ian. “Post colonial: return to sender” 1998 paper delivered as the Hancock lecture at the University of Sydney on 11/11/1998 as part of the annual conference of the Australian Academy of Humanities which had as its theme: ‘First Peoples Second Chance Australia In Between Cultures’

Papastergiadis, Nikos. “Brook Andrew: Counterpoints and Harmonics.” Catalogue essay for Brook Andrew’s exhibition 52 Portraits at Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne, June 2013

Perkins, Hetti. Art + Soul. Melbourne: The Miegunyah Press, Melbourne University Publishing, 2010, p. 85

Phillips, Sandra. Racism, Representation and Photography. Sydney, 1994, p. 115

Rukundwa, Lazare S and van Aarde, Andries G. “The formation of postcolonial theory” in HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 63(3), 2007, p. 1174

Rule, Dan. “Brook Andrew: 52 Portraits,” in Arts & Entertainment, Lifestyle, in The Saturday Age newspaper, June 29th 2013, p. 5

Said, Edward. “Overlapping Territories, Intertwined Histories,” in Said, Edward. Culture and imperialism. London: Chatto and Windus, 1993, p. 8

Skerritt, Henry F. “Drawing NOW: Jus’ Drawn'” in Art Guide Australia, September/ October 2010, pp. 34-35 [Online] Cited 17/06/2013

Trees, Kathryn. “Postcolonialism: Yet Another Colonial Strategy?” in Span, Vol. 1, No. 36, 1993, pp. 264-265 quoted in Heiss, Anita. “Post-Colonial-NOT!” in Dhuuluu Yala (To Talk Straight): Publishing Aboriginal Writing in Australia. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press, 2003, pp. 43-46

Young, Robert J.C. “Postcolonial Remains,” in New Literary History Vol. 43. No. 1. Winter 2012, p. 20

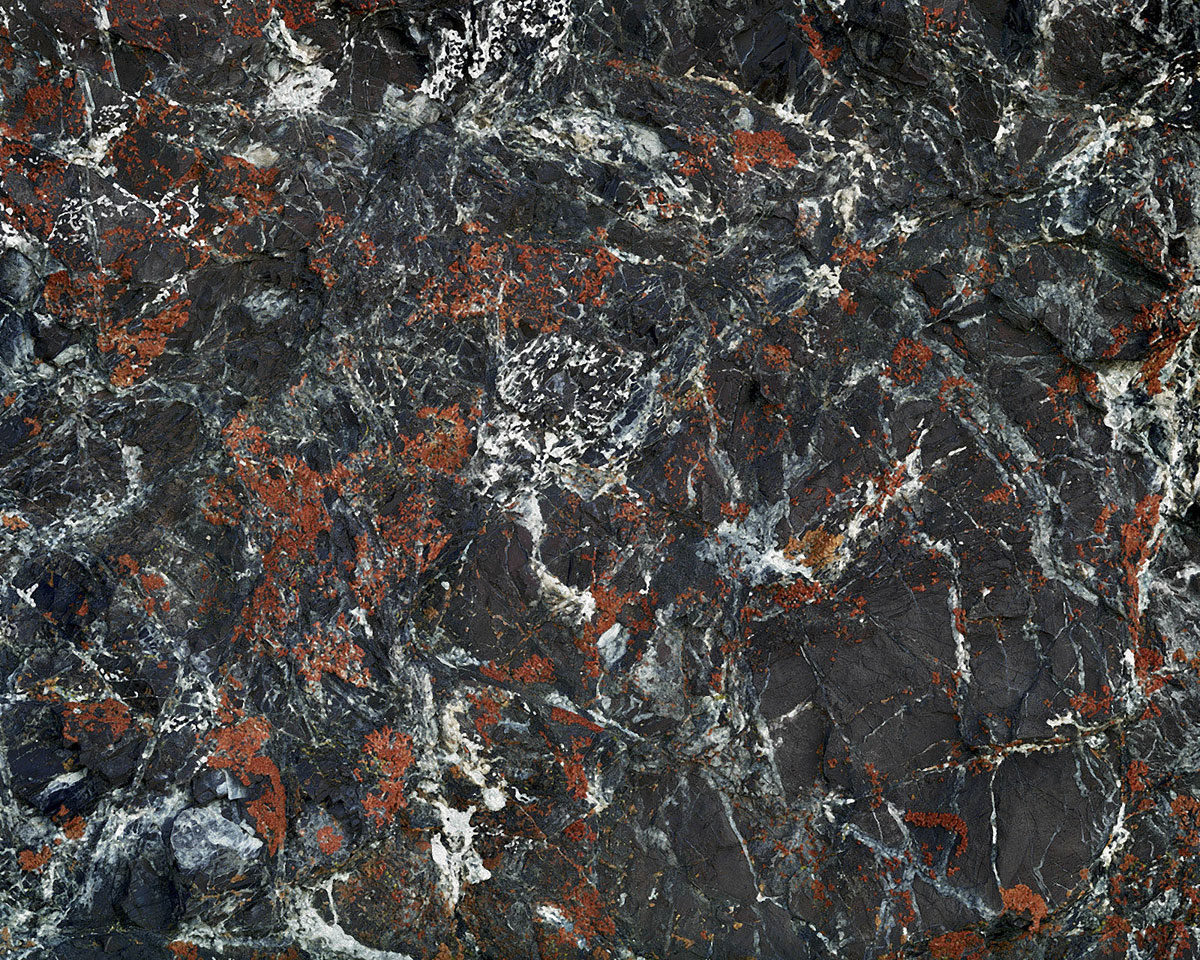

Brook Andrew (Australian, b. 1970)

Portrait 19 (Manitoba, Canada)

2013

Mixed media on Belgian linen

70 x 55 x 5cm

Edition of 3 + 2 AP

Real photo postcard

Title: An Old Savage of Manitoba

Brook Andrew (Australian, b. 1970)

Portrait 9 (Arab)

2013

Mixed media on Belgian linen

70 x 55 x 5cm

Edition of 3 + 2 AP

Real photo postcard

Title: Danseuse arabe

Publisher: Photo Garrigues Tunis – 2008

Inscribed on front: Tunis 20/8/04

Brook Andrew (Australian, b. 1970)

Portrait 7 (Australia)

2013

Mixed media on Belgian linen

70 x 55 x 5cm

Edition of 3 + 2 AP

Title: “An Australian Wild Flower”

Pub. Kerry & Co., Sydney One Penny Stamp with post mark on image side of card. No Address.

Brook Andrew (Australian, b. 1970)

Portrait 40 (Unknown)

2013

Mixed media on Belgian linen

70 x 55 x 5cm

Edition of 3 + 2 AP

Title: “Typical Ricksha Boys.”

R.111. Copyright Pub. Sapsco Real Photo, Pox 5792, Johannesburg

Pencil Mark €5

Brook Andrew (Australian, b. 1970)

Portrait 44 (Syria)

2013

Mixed media on Belgian linen

70 x 55 x 5cm Edition of 3 + 2 AP

Real photo postcard

Title: Derviches tourneurs á Damas

Printed on verso: Turquie, Union Postal Universelle, Carte postale

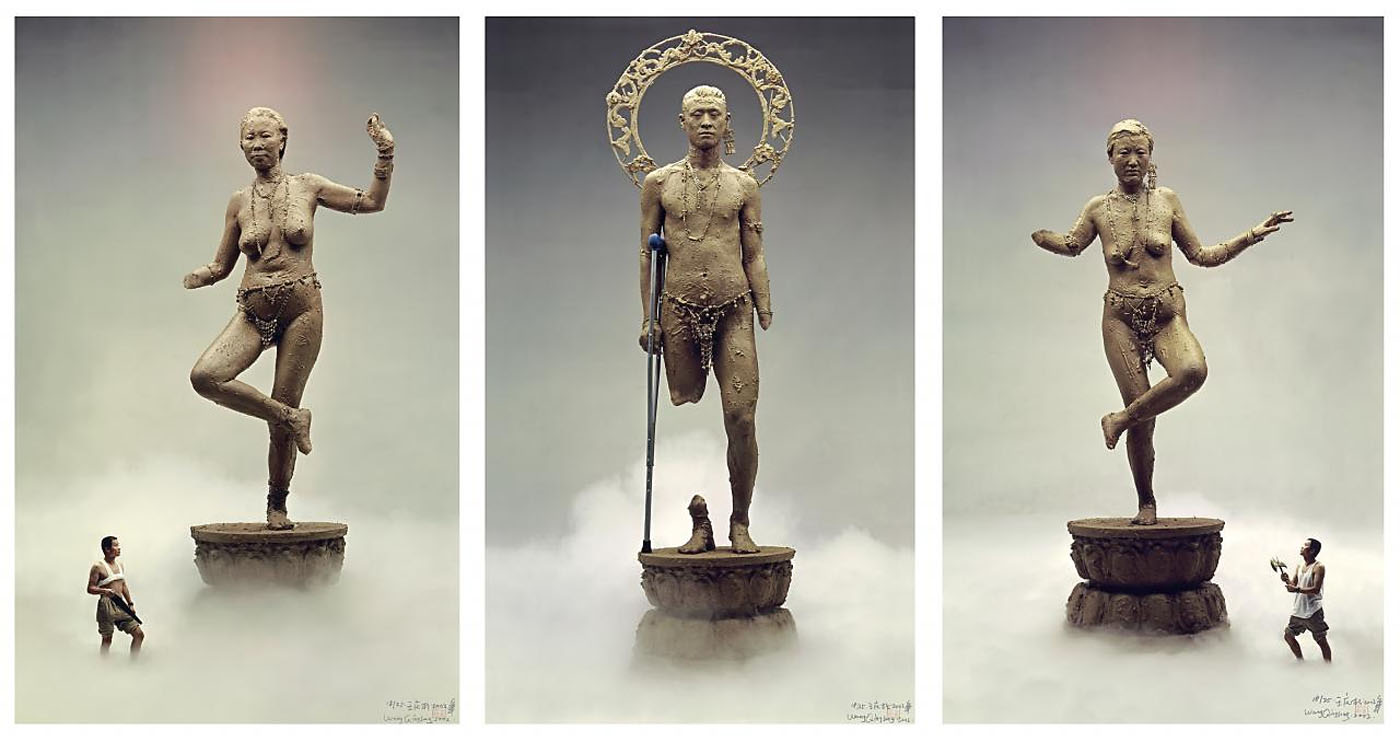

Brook Andrew (Australian, b. 1970)

Vox: Beyond Tasmania (full piece and detail shots)

2013

Timber, glass and mixed media

267 x 370 x 271cm

Brook Andrew’s newest exhibition is a blockbuster comprising 52 portraits, all mixed media and all measuring 70 x 55 x 5cm. The portraits are of unknown people from Africa, Argentina, Ivory Coast, Syria, Sudan, Japan, Australia … They are based on 19th century postcards which Brook Andrew has collected over many years. These postcards were originally made for an international market interested in travel.

‘Colonial photographers made a trade in photographic images, which were on sold as postcards and souvenirs,’ writes Professor Ian Anderson in Re-assembling the trophies and curios of Colonialism & the Silent Terror. According to Brook Andrew, ‘names were not recorded when Indigenous peoples were photographed for ethnographic and curio purposes. The history and identity of these people remain absent. In rare instances, some families might know an ancestor from a postcard.’

The exhibition takes it title from a book of drawings by Anatomist Richard Berry: TRANSACTIONS of the ROYAL SOCIETY OF VICTORIA. Published in 1909, Volume V of this rare book contains FIFTY-TWO TASMANIA CRANIA – tracings of 52 Tasmanian Aboriginal skulls that were at the time mainly in private collections.

‘These skulls,’ says Brook Andrew, ‘represented a pan-international practice of collecting Aboriginal skulls as trophies, a practice dependent on theories of Aboriginal people being part of the most primitive race of the world, hence a dying species. This theory activated many collections and grave robbing simultaneously.’

In 52 Portraits Brook Andrew delves into hidden histories such as the ‘dark art of body-snatching’ and continues his fascination with the meaning of appearances. ‘He zooms in on the head and torso of young men and women,’ says Nikos Papastergiadis. ‘Brook Andrew’s exhibition, takes us to another intersection where politics and aesthetics run in and over each other.’

The original images embody the colonial fantasies of innocence and backwardness, as well as more aggressive, but tacit expression of the wish to express uninhibited sexual availability. Brook Andrew aims to confront both the lascivious fascination that dominated the earlier consumption of these images and prudish aversions and repressive gaze that informs our more recent and much more ‘politically correct’ vision. His images make the viewer consider the meaning of these bodies and his focus also directs a critical reflection on the assumptions that frame the status of these images.

The centre piece of the exhibition is a kind of Wunderkammer containing all manner of ‘curiosities’ including a skull, drawings of skulls, a partial skeleton, photographs, diaries, glass slides, a stone axe and Wiradjuri shield. Titled Vox: Beyond Tasmania, the Wunderkammer/Gramophone plays out stories of Indigenous peoples.

In the interplay between the 52 Portraits and Vox: Beyond Tasmania, Brook Andrew aims to stir and open our hearts with his powerful 21st century ‘memorial’.

Press release from the Tolarno Galleries website

Tolarno Galleries

Level 4

104 Exhibition Street

Melbourne VIC 3000

Australia

Phone: 61 3 9654 6000

Opening hours:

Tuesday – Friday 10am – 5pm

Saturday 1pm – 4pm

You must be logged in to post a comment.