Exhibition dates: 27th April – 8th July 2017

This project has been supported by the Victorian Government through Creative Victoria

PLEASE NOTE: I am still recovering from my hand operation which is going to take longer than expected. All of the text has been constructed using a dictation programme and corrected using only my right hand – a tedious process. I have to keep my mental faculties together, otherwise this hand will drive me to distraction… Marcus

Christian Thompson (Australian, b. 1978)

Black gum 1-3

2007

From the series Australian graffiti

C-type prints

Collection of the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Photo: Andrew Curtis

Still singing, still Dreaming,

still loving… not dying.

This is a strong survey exhibition of the work of contemporary Australian Indigenous artist and Bidjara man exploring the world, Christian Thompson. As with any survey exhibition, it can only give us a glimpse into the long standing development of the artist’s work, inviting the viewer to then research more fully the themes, conceptual acts and bodies (of work) that have led the artist to this point in his artistic development. Having said that the exhibition, together with its insightful catalogue essays and additional images that do not appear in the exhibition, allow the viewer to be challenged intellectually, aesthetically and most importantly … spiritually. And to be somewhat conflicted by the art as well, it has to be said.

Thompson’s “multidisciplinary practice explores notions of cultural hybridity, along with identity and history, creating works that transcend cultural boundaries.” His self-reflexive and self-referential bodies of work, often with the artist using his body as an “armature for his characters, costumes and various props,” are intuitive and imaginative in how they relate Aboriginal and Australian/European history, taking past time into present time which influences future time. Time, memory, history, space, landscape are conflated into one point, enunciated through acts of ritual intimacy. These ritual intimacies, these performative acts, are enabled through an understanding of a regularised and constrained repetition of norms (in this case, the declarative power of colonialism), where the taking of a photograph of an Aboriginal person (for example), is “a ritual reiterated under and through constraint, under and through the force of prohibition and taboo, with the threat of ostracism and even death controlling and compelling the shape of the production…” (Judith Butler, Bodies That Matter. New York: Routledge, 1993, p. 95).

What is so heartening to see in this exhibition is a contemporary Indigenous artist not relying on re-animating colonial images of past injustices, but re-imagining these images to produce a spiritual connection to Country, to place, to people in the present moment. As Charlotte Day, Director, MUMA and Hetti Perkins, guest curator observe in the wall text at the beginning of the exhibition, “Rather than appropriating or restaging problematic ethnographic images of indigenous ancestors held in the Museum’s photographic collection, Thompson has chosen to spend significant periods of time with these images, absorbing their ‘aura’ and developing a personal artistic and deferential response that is decisively empowered.” As Marina Warner states in her excellent catalogue essay “Magical Aesthetics”, these ritual intimacies are a “magical re-animation and adopt time-honoured processes of making holy – of hallowing. Adornment is central to ritual and a prime way of glorifying and consecration.” What Thompson is doing is not quoting but translating the source-text into new material. As Mary Jacobus notes of the work of the painter Cy Twombly, “Quotation involves the repurposing of an existing text: translation requires a swerve from the source-text as it finds new directions and enters unknown terrain.” (Mary Jacobus. Reading Cy Twombly: Poetry in Paint. Princeton & Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2016, p. 7).

This auto-ethnographic exploration and adornment leads to a deterritorialisation and reterritorialisation of time in a heterotopic space, juxtaposing in a single real place several spaces, several sites of contestation – Thompson’s travels and research from around the world, the embodiment in his own culture and that of contemporary Australia, pop culture, fashion, music and language – where, as Hetti Perkins says, “the unknowable is a lovely thing” and where Thompson can affect and influence “the Zeitgeist through more subversive means.” These spaces of ritualised production overlaid with memory, imagination, desire, and nostalgia, these fragmented images, become a process and a performance in which Thompson seeks to ameliorate the objects aura through a process of ‘spiritual repatriation’. Thompson’s performativity is where the ritual of production and meaning is never fully predetermined at any stage of production and reception.

Here, in terms of ‘aura’ and ‘spirit’, I am interested in the word “repatriation”. Repatriation means to send (someone) back to their own country – from the verb repatriare, from re- ‘back’ + Latin patria ‘native land’. It has an etymological link to the word “patriot” – from late Latin patriota ‘fellow countryman’, from Greek patriōtēs, from patrios ‘of one’s fathers’, from patris ‘fatherland’ – and all the imperial connotations that are associated with the word. So, to send someone back (against their own will? by force?) or to be patriotic, as belonging to or coming from, the fatherland. A land that is father, farther away. Therefore, it is with regard to a centralised, monolithic body and its materialities (for the body is usually centrally placed in Thompson’s work) in Thompson’s instinctive works, that relations of discourse and power will always produce hierarchies and overlappings which are going to be contested. As Judith Butler notes,

“That each of those categories [body and materiality] have a history and a historicity, that each of them is constituted through the boundary lines that distinguish them and, hence, by what they exclude, that relations of discourse and power produce hierarchies and overlappings among them and challenge those boundaries, implies that these are both persistent and contested regions.” (Judith Butler. Bodies That Matter. New York: Routledge, 1993, pp. 66-67)

Thus performativity is the power of discourse, the politicisation of abjection, and the ritual of being.

This is where I become conflicted by much of this work. Intellectually and conceptually I fully understand the instinctive, intuitive elements behind the work (crystals, flowers, maps, butterflies, dreams) but aesthetically I feel little ‘aura’ emanating from the photographs. Thompson’s “peripatetic life and your bowerbird, magpie-like fascination” (p. 107) lead to all sorts of influences emerging in the work – orange from The Netherlands, Morris dancers from England, Jewish heritage, Aboriginal and Australian heritage, fashion, pop culture, music, language – all evidenced through “acts of concealment in his self-portraits.” (p. 75). Now there’s the rub!

In Thompson’s ritual intimacies the intimacy is performed only once, for the camera. It is not didactic, but it is interior and hidden, leaving much to the feelings of the viewer, looking. The re-presentation of that intimacy is performed by the viewer every time they look at the art. I think of the work of one of my favourite performance artists, Claude Cahun, where the artist inhabits her personas, adorning her androgynous face with costume after costume to become something that she wants to become – a buddha, a double, a harpy, a lunatic or a doll with equal ease. Cahun is always and emphatically herself, undermining a certain authority… and she produces indelible images that sear the mind.

I don’t get that from Thompson. I don’t know who he really is. Does it matter? Yes it does. In supposedly his most autobiographic work (according to Hetti Perkins), the video Heat (2010, below) the work emerges out of Thompson’s memories of growing up in the desert surrounding Barcaldine in central west Queensland where “heat captures the sensation that he associates with being on his country: the dry wind blowing through his hair.” Perhaps for him or someone from the desert country like Hetti Perkins (as she states in the catalogue), but not for me. I feel no ‘heat’ from these three beautiful woman standing in a contextless background with a wind machine blowing their hair. The only ‘heat’ I felt was perhaps the metaphoric heat of colonisation, violence and abuse thrust on a vulnerable culture.

Talking of vulnerable cultures, in the work Polari (2014, below) Thompson invokes the history of languages in an intimate ritual “as he seeks to reanimate and repossess vanishing knowledge. Polari is a private language … a kind of code used by sailors, circus and fairground folk, and in gay circles. … Thompson’s Polari series warns us that the artist has a language of his own, which we can overhear but not fully understand: something is withheld, in contrast to the imposed and implacable exposure which the subjects of scientific collections were made to suffer in the past.” (Warner, p. 74) But why is he using Polari specifically, a language that is strongly associated with the libertine gay culture of the 1950s-70s? Does he have a right to use this word and its linguistic heritage because he is gay? It is never stated, again another thing left hidden, concealed and unresolved.

Although no culture can ever fully own its language (language is a construct after all) … if Thompson is not gay, then I would take exception to his invoking the Polari language, just as an Indigenous artist would take exception to me using Bidjara language in an art work of my own. I remember coming out in London in 1975 and speaking Polari myself when it was still being used in pubs and clubs such as the A + B club in Soho. It was not being used as a language of resistance, far from it, but as a language of desire. It was a language used to inculcate that desire. As a video on YouTube observes of speaking Polari, “you didn’t think, oh God I’m so oppressed I can never speak about myself, you just did it, you just slipped into it without thinking.” It was your own language, like a comfortable pair of slippers. Does Thompson understand how using that word to title a body of work could be as offensive to some people as he finds the denaturing of his own culture? For me this is where the work really becomes problematic, when an artist does not enunciate these connections, where things, like sexuality, remain hidden. Similarly, with historical photographs of Indigenous people taken for ethnographic study, Thompson fails to acknowledge the work of academics such as Jane Lydon and her important books Eye Contact: Photographing Indigenous Australians (2005) and Photography, Humanitarianism, Empire (2016) where she unpacks the historical baggage of the images and notes that the photographs were not solely a tool of colonial exploitation. Lydon articulates an understanding in Eye Contact that the residents of Coranderrk, an Aboriginal settlement near Healsville, Melbourne, “had a sophisticated understanding of how they were portrayed, and they became adept at manipulating their representations.” Again, there is more than meets the eye, more than just ‘spiritual repatriation’ of aura.

For me, the magic of this exhibition arrives when Thompson lets go all obfuscation, let’s go all actions that make something obscure, unclear, or unintelligible. Where his ritual intimacies become grounded in language, earth and spirit. This happens in the video works, Desert slippers (2006, below), Refuge (2014, below), Gamu Mambu (Blood Song) (2011) and Dhagunyilangu (Brother) (2011, below). In these videos, the Other’s gaze disintegrates and we are left with poignant, heart felt words and actions that engage history, emotion, family and Country.

The video Desert slippers “features a Bidjara ritual in which a father and son transfer sweat. The desert slipper is a native cactus that symbolises the transferal of the spirit back to earth as the plant grows.” It is simple, eloquent, powerful, present. The other videos feature two baroque singers from Europe and Thompson singing in his native tongue Bidjara (Bidyara, Pitjara), a language that Wikipedia states “is an extinct Australian Aboriginal language. In 1980 it was spoken by twenty elders in Queensland, between Tambo and Augathella, Warrego and Langlo rivers.” Spelt out in black and white. Extinct. To hear Thompson sing a berceuse (French, from bercer ‘to rock’), or lullaby in his native language, a language taught to him by his father, is the most emotional of experiences. The work “combines evocative chanting and electronic elements to invoke the cultural experiences and narratives of his Bidjara culture,” and “is premised on the notion that if one word of Bidjara is spoken, or sung in this case, it remains a living language.” Amen to that.

This is the real hallowing, not the dress ups or the concealments. It is in these videos that the raw material of his and his cultures experience is transmuted into living, breathing stories, in an alchemical transmutation, a magical re-animation of past time into present and future time. My transfiguration into a more spiritual state was complete when listening in quiet contemplation. For I was given, if only for a very brief moment, access to the pain of our first peoples and a vision of hope for their future healing.

Still singing, still Dreaming,

still loving… and certainly not dying.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Word count: 2,053

Many thankx to MUMA for allowing me to publish the photographs and videos in the posting. All installation photographs unless otherwise noted © Marcus Bunyan, the artist and MUMA. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Christian Thompson (Australian, b. 1978)

Black gum 1 (installation view)

2007

From the series Australian graffiti

C-type print

Collection of the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Christian Thompson (Australian, b. 1978)

Black gum 2 (installation view)

C-type print

2007

From the series Australian graffiti

Collection of the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

“While I’m interested in portraiture – I don’t consider my work as portraiture because that suggests that I’m trying to portray myself, my own visage, my own image. I employ images, icons, materials, metaphors to capture and idea and moment in time. There are many different things at play; taking a picture of myself is really the last thing that’s on my mind.”

Christian Thompson in conversation with Hetti Perkins, catalogue extract

“I’m interested in simple aesthetic gestures that can say something … something quite profound about the world that we live in. I tend to build images how I create a sculpture. I borrow from the world around me.”

On being away from home: “You’re able to remove yourself from the local discourse, and romanticise home. When you’re displaced you tend to gravitate towards certain memories … But this is who I am. It would be weird not to express that somehow. I combine memories of my past with my lived experience and an idea of where I’d like to be … it’s all montaged into one.”

Christian Thompson quoted in Will Cox. “Christian Thompson’s Ritual Intimacy,” on the Broadsheet website 15 June 2017 [Online] Cited 22/12/2021

“But Thompson makes things up. His ‘We bury our own’ does not let us see the early daguerreotype but improvises a series of fugues on its spiritual essence. This is the crucial step that Thompson has taken: if you repeat the spectacle you cannot escape the past. But if you, a spiritual descendant, transmogrify yourself in keeping with the aura of the image’s subject, during the prolonged period of encounter and immersion, you can ‘repatriate’ that forebear. Or so he desires.”

“Through these conjurings of the language his people spoke before colonisation set out to strip them of their culture as well as their land, Christian Thompson performs private ceremonies – to reach beyond visual statements of personal presence and reawaken the knowledge of his forebears, and allow us, his listeners and viewers, into their living story.”

Marina Warner. “Magical Aesthetics,” extracts from the catalogue essay

“At the heart of my practice is a concern with aura: what it is, how it can be photographed and how it can be repatriated.”

Christian Thompson

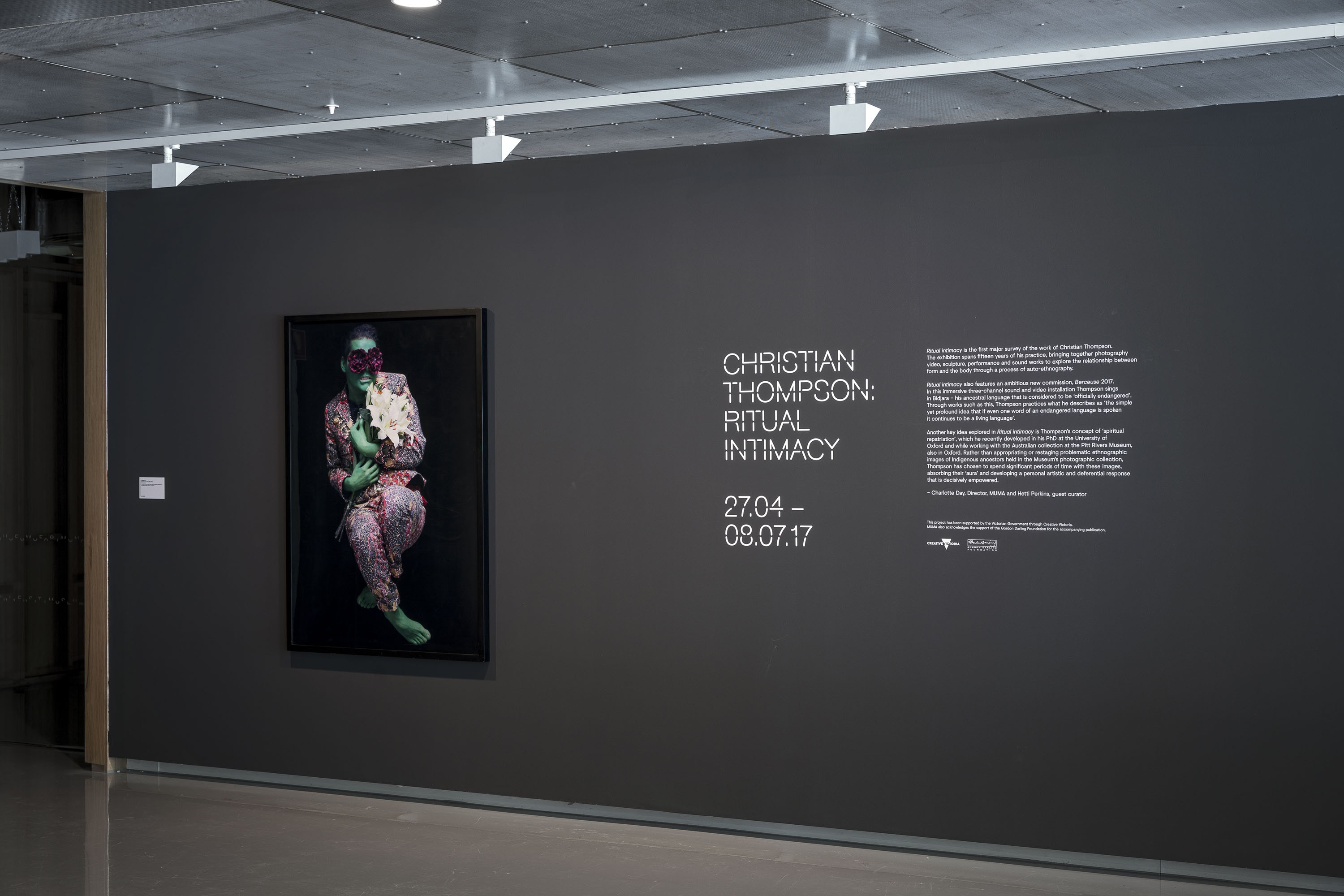

Christian Thompson: Ritual intimacy, installation view: Monash University Museum of Art, Melbourne 2017

Photo: Andrew Curtis

Christian Thompson (Australian, b. 1978)

Untitled #6

2010

From the series King Billy

C-type print

Image courtesy of the artist, Sarah Scout Presents, Melbourne, and Michael Reid, Sydney and Berlin

Christian Thompson: Ritual intimacy, installation view: Monash University Museum of Art, Melbourne 2017 featuring stills from the video Berceuse (2017)

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Christian Thompson (Australian, b. 1978)

Berceuse (extract installation view)

2017

Three-channel digital colour video, sound

5.47 minutes

Sound design: Duane Morrison

Christian Thompson (Australian, b. 1978)

Berceuse

2017

Three-channel digital colour video, sound

5.47 minutes

Sound design: Duane Morrison

In this newly commissioned work, Thompson sings a berceuse – a cradle song or lullaby – that combines evocative chanting and electronic elements to invoke the cultural experiences and narratives of his Bidjara culture. Intended as a gesture of re-imagining his traditional Bidjara language, which is been categorised as extinct, the work is premised on the notion that if one word of Bidjara is spoken, or sung in this case, it remains a living language.

Thompson makes subtle reference to his maternal Sephardic Jewish roots by ruminating in this work on the lullaby Nani Nani:

Lullaby, lullaby

The boy wants a lullaby,

The mother’s son,

Who although small will grow.

Oh, oh my lady open,

Open the door,

I come home tired,

From ploughing the fields.

Oh, I won’t open them,

You don’t come home tired,

You’ve just come back,

From seeing your new lover.

Christian Thompson: Ritual intimacy, installation view: Monash University Museum of Art, Melbourne 2017 featuring the series Museum of Others (2016)

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of Museum of Others (Othering the Ethnologist, Augustus Pitt Rivers) 2016

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Christian Thompson (Australian, b. 1978)

Museum of Others (Othering the Anthropologist, Walter Baldwin Spencer)

2016

From the series Museum of Others

C-type print

Installation view of Museum of Others (Othering the Explorer, James Cook) 2016

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Christian Thompson (Australian, b. 1978)

Museum of Others (Othering the Explorer, James Cook)

2016

From the series Museum of Others

C-type print

Christian Thompson (Australian, b. 1978)

Equilibrium

2016

From the series Museum of Others

C-type print

Museum of others is Thompson’s most recent photographic series and continues to reflect on his time at the University of Oxford. It features several ‘dead white males’ from the pantheon of British and Australian culture. The explorer, the ethnologist and the anthropologist all had roles in the process of colonisation in Australia but the art critic is particular to Thompson; Ruskin was the first Slade Professor of Fine Art at University of Oxford, just as Thompson was one of its first Australian Aboriginal students. Thompson explains his motivation for the series:

“Historically, it was the western gaze that was projected onto the ethnic other and I thought I’ll create a ‘museum of others’ and I’ll be the one othering, so to speak. ‘Equilibrium’ is based around the idea that the vessel is the equaliser. The vessel is the cradle of all civilisations. We all have that in common.”

Wall text from the exhibition

Christian Thompson: Ritual intimacy, installation view: Monash University Museum of Art, Melbourne 2017 featuring photographs from the series We bury our own 2010 (C-type prints)

Photos: Andrew Curtis

We bury our own is a body of work that was developed in response to the historic collection of photography, featuring Aboriginal people from the late nineteenth century, at the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford. Thompson noted in 2012 that these early images “have permeated my work over the last year. They have remained at the forefront of every artistic experiment and they have pushed me into new territory, they have travelled with me… I was drawn to elements of opulence, ritual, homage, fragility, melancholy, strength and even a sense of play operating in the photographs…”

Each of Thompson’s lyrical photographic images from We bury our own and Pagan sun feature himself partially disguised with props and costumes. The works are virtually monochromatic with elements highlighted in full colour, and his eyes, or face, are partially concealed or painted. The use of votive objects is explained in his equally lyrical 2012 statement: “I lamented the passing of the flowers at the meadow, I lit candles and offered blood to the ancestral beings, looked into the black sparkling sea, donned the Oxford garb, visited the water by fire light and bowed at the knees of the old father ghost gum.”

Text from the Turner Galleries website [Online] Cited 22/12/2021

Christian Thompson (Australian, b. 1978)

Energy Matter

2010

From the series We bury our own

C-type print

Christian Thompson (Australian, b. 1978)

Lamenting the flowers

2010

From the series We bury our own

C-type print

Christian Thompson (Australian, b. 1978)

Forgiveness of Land

2010

From the series We bury our own

C-type print

Christian Thompson (Australian, b. 1978)

Down Under World

2010

From the series We bury our own

C-type print

I conceived the We Bury Our Own series in 2010 after curator Christopher Morton invited me to develop a body of work that would be inspired by and in dialogue with the Australian photographic collection at the Pitt Rivers Museum…

The archival images have permeated my work over the last year. They have remained at the forefront of every artistic experiment and pushed me into new territory; they have travelled with me to residencies at the Fonderie Darling in Montreal and Greene Street Studio, New York. I was drawn to elements of opulence, ritual, homage, fragility, melancholy, strength and even a sense of play operating in the photographs. The simplicity of a monochrome and sepia palette, the frayed delicate edges and the cracks on the surface like a dry desert floor that reminded me of the salt plains of my own traditional lands.

I wanted to generate an aura around this series, a meditative space that was focused on freeing oneself of hurt, employing crystals and other votive objects that emit frequencies that can heal, ward off negative energies, psychic attack, geopathic stress and electro magnetic fields, and, importantly, transmit ideas.

I lamented the passing of the flowers at the meadow, I lit candles and offered blood to the ancestral beings, looked into the black sparkling sea, donned the Oxford garb, visited the water by fire light and bowed at the knees of the old father ghost gum. I asked the photographs in the Pitt Rivers Museum to be catalysts and waited patiently to see what ideas and images would surface in the work, I think with surprising results. Perhaps this is what art is able to do, perform a ‘spiritual repatriation’ rather than a physical one, fragment the historical narrative and traverse time and place to establish a new realm in the cosmos, set something free, allow it to embody the past and be intrinsically connected to the present?

I heard a story many years ago from some old men, they told me about a ceremony where young warriors would make incisions through the flesh exposing the joints, they would insert gems between the bones to emulate the creator spirits, often enduring infection and agonising pain or resulting in death. The story has stuck with me for many years, one that suggests immense pain fused with intoxicating beauty. The idea of aspiring to embody the creators, to transgress the physical body by offering to our gods our spiritual heart, freeing ourselves of suffering by inducing a kind of excruciating decadent torture. This was something that played on my mind during the production of this series of photos and video work. The deliverance of the spirit back to land – the notion that art could be the vehicle for such a passage, the aspiration to occupy a space that belongs to something higher than one’s physical self.

Christian Thompson artist statement in “Christian Thompson: We Bury Our Own,” on the Pitt Rivers Museum website [Online] Cited 21/12/2021

Christian Thompson: Ritual intimacy, installation view: Monash University Museum of Art, Melbourne 2017 featuring Ship of dreams, Ancient bloom, Death’s second self, and Gods and kings from the series Imperial relic 2015 (C-type prints) and a still from the video dead tongue 2015

Photo: Andrew Curtis

In Dead tongue Thompson continues to interrogate the implications of England’s empirical quest on the former colonies of the British Empire through the threat to or loss of Indigenous languages. In works such as this, Thompson actively challenges the perception that Aboriginal culture has become reduced to a captured trophy of Empire.

Wall text from the exhibition

Christian Thompson: Ritual intimacy, installation view: Monash University Museum of Art, Melbourne 2017 featuring Ship of dreams, Ancient bloom, Death’s second self, and Gods and kings from the series Imperial relic 2015 (C-type prints)

Photo: Andrew Curtis

In … Imperial relic, he continues to use himself as the ‘armature for his characters, costumes and various props’. Drawing on his background in sculpture, he has created ‘wearable sculptures’ including a trumpet shaped shirt collar, an eruption of white flowers from a union jack hoodie, and an armature of maps. In each his face is partially or fully obscured again. “I’m interested in ideas of submission and domination,” he says. “So the trumpet headpiece is beautiful, but it also potentially muffles or silences the voice. The same thing with maps: they are purporting different kinds of historical narrative, depending who is telling the story. One is about the history of Indigenous people, one is about the history of white colonisers and then one is about the idea of charting the land and of discovery. I’m wearing it as an armature over my own body: that’s part of my own history but also of Australian history.”

Text from the Turner Galleries website [Online] Cited 22/12/2021

Christian Thompson (Australian, b. 1978)

Ancient bloom

2015

From the series Imperial relic

C-type print on fuji pearl metallic paper

100 x 100cm

Image courtesy of the artist, Sarah Scout Presents, Melbourne, and Michael Reid, Sydney and Berlin

Christian Thompson (Australian, b. 1978)

Ship of dreams

2015

From the series Imperial relic

C-type print on fuji pearl metallic paper

100 x 100 cm

Image courtesy of the artist, Sarah Scout Presents, Melbourne, and Michael Reid, Sydney and Berlin

The series title Imperial relic, summarises the fundamental philosophy underpinning the colonial occupation of Australia. Like the nearby series We bury our own, it is closely connected to Thompson’s studies in the collections of the Pitt Rivers Museum and shares with the Australian graffiti series Thomson’s physical presence is standing in for the Australian landscape.

The work Ancient bloom alludes to the phonograph horn out which might be heard the voice of Fanny Cochran Smith, who’s wax cylinder recordings of songs are the only historical audio recordings of any of the Tasmanian Aboriginal languages. Is also represents a Victorian-era shirt collar – a motif that has appeared in Thompson’s work since his Emotional striptease series of 2003 – but here is exaggerated into a soft-sculptural form that both projects and stifles the voice.

In Death’s second self the artist’s face is uncovered but distorted by make up and digital postproduction effects.The title quotes William Shakespeare’s Sonnet 73:

As after sunset fadeth in the west,

Which by and by black night doth take away,

Death’s second self, that seals up all in rest.

In God and Kings Thompson is cloaked with a map of Aboriginal language groups like a coat of armour. In the Ship of dreams he reprises the motif of Australian flora obscuring his face but here his hoodie is stitched together from several flags: the red ensign (flown by British registered ships), the RAAF flag and the Australian flag.

“I’m interested in ideas of submission and domination … So the trumpet headpiece is beautiful, but it also potentially muffles or silences the voice. The same thing with maps: they are purporting different kinds of historical narrative, depending who is telling the story. One is about the history of Indigenous people, one is about the history of white colonisers and then one is about the idea of charting the land and of discovery. I’m wearing it as an armature over my own body: that’s part of my own history but also of Australian history.”

Christian Thompson in text from the Turner Galleries website [Online] Cited 22/12/2021

Christian Thompson: Ritual intimacy, installation view: Monash University Museum of Art, Melbourne 2017 featuring Isabella kept her dignity, I’m not going anywhere without you, Dead as a door nail and Hannah’s diary from the series Lost together 2009 (C-type prints)

Photo: Andrew Curtis

On 13 February 2008 then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd made an official apology to Aboriginal Australians for the Stolen Generations – the children of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent who were removed from their families between 1910 and 1970 under the respective Federal and State government policies of assimilation. At the time, Thompson was preparing to leave Australia for further studies aboard and felt this historic gesture allowed him to proudly take his culture and history with him as he ventured into the world.

Thompson photographed the series Lost together in the Netherlands while studying at the DasArts Academy of Theatre and Dance at Amsterdam University. The theme of the orange throughout the series is a reference to the national colour of the Netherlands, while the tartan patterning refers to early clan societies in the United Kingdom. The combination of these different styles is based on counter-cultural aesthetics – particularly punk collage of 1970s London.

Christian Thompson (Australian, b. 1978)

Hannah’s Diary

2009

From the series Lost Together

C-type print

Image courtesy of the artist, Sarah Scout Presents, Melbourne, and Michael Reid, Sydney and Berlin

MUMA | Monash University Museum of Art is proud to announce the first major survey exhibition of the work of Bidjara artist, Christian Thompson, one of Australia’s leading and most intriguing contemporary artists.

Thompson works across photography, video, sculpture, performance and sound, interweaving themes of identity, race and history with his lived experience. His work is held in the collections of major state and national art museums in Australia and internationally.

Thompson made history as one of the first two Aboriginal Australians to be accepted into the University of Oxford as a Charlie Perkins Scholar, where he completed his Doctorate of Philosophy (Fine Art) in 2016. Christian Thompson: Ritual Intimacy opens as the artist looks forward to the graduation ceremony in July, when he will be conferred his degree.

Featuring a major new commission created for this exhibition, Christian Thompson: Ritual Intimacy will survey Thompson’s diverse practice, spanning fifteen years, and will also be accompanied by the publication of the first monograph on the artist’s career and work, including essays by Brian Catling RA and Professor Dame Marina Warner DBE, CBE, FBA, FRSL.

The specially commissioned installation will be an ambitious multichannel composition, developing the sonic experimentation that is a signature of Thompson’s work. Incorporating Bidjara language, it will invite viewers into an immersive space of wall-to-wall imagery and sound:

“Bidjara is officially an endangered language but my work is motivated by the simple yet profound idea that if even one word of an endangered language is spoken it continues to be a living language,” Thompson says.

Christian Thompson: Ritual Intimacy explores the unique perspective and breadth of Thompson’s practice from the fashioning of identity through to his ongoing interest in Indigenous language as the expression of cultural survival. The new multichannel work will develop musical ideas Thompson has previously explored.

“It will be a much more ambitious iteration of a song in Bidjara. At one stage I’m singing on one screen and then other versions of me appear singing the melodies. I really see it as an opportunity to do something that’s more complex musically, more textured sonically – I also want it to be more intricate with my use of language,” the artist says.

Ritual Intimacy is curated by MUMA director Charlotte Day and guest curator Hetti Perkins. Day explains that the exhibition is part of MUMA’s Australian artist series, which affords the opportunity to look at each artist’s practice in depth. “Christian’s exhibition traces a particularly productive period of research and development, from early well-known works such as the Australian Graffiti series to more recent experiments with language in sound and song works,” Day says.

A long-time curatorial collaborator with Thompson, Perkins is the writer and presenter of art + soul, the ABC’s acclaimed television series about contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art. Thompson was accepted to Oxford University on an inaugural Charlie Perkins Scholarship, set up to honour Hetti Perkins’s famous father – a leader, activist and the first Aboriginal Australian to graduate from university. Perkins says the MUMA exhibition is well-earned recognition for Thompson’s work, which she featured in the second series of art + soul.

“Christian has spent periods of his adult life, as a practicing artist, away from home, but there is a common thread in his work, and it’s this connection to home or Country,” Perkins says. “In terms of the rituals or rites of the exhibition title, he is constantly reiterating that connection to home – through words, through performance, through his art, through ideas and writing,” she says.

Alongside performance and ritual, Thompson’s concept of “spiritual repatriation” is central to his work. Working with the Australian collection at famed ethnographic storehouse the Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford, the artist was offered copies of colonial photographs of Aboriginal people but preferred not to work this way. Instead, he chose to spend significant periods of time with these ancestral images, absorbing their “aura” in order to then make his own artistic response that did not reproduce those original problematic images.

Dr Christian Thompson is a Bidjara contemporary artist whose work explores notions of identity, cultural hybridity, and history; often referring to the relationships between these concepts and the environment. Formally trained as a sculptor, Thompson’s multidisciplinary practice engages mediums such as photography, video, sculpture, performance, and sound. His work focuses on the exploration of identity, sexuality, gender, race, and memory. In his live performances and conceptual anti-portraits he inhabits a range of personas achieved through handcrafted sculptures and carefully orchestrated poses and backdrops.

Press release from MUMA

Christian Thompson: Ritual intimacy, installation view: Monash University Museum of Art, Melbourne 2017 featuring the series Polari (2014)

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

‘Polari’ is a form of cant or cryptic slang that evolved over several centuries from the various languages that converged in London’s theatres, circuses and fairgrounds, the merchant navy and criminal circles. It came to be associated with gay subculture, as many gay men worked in theatrical entertainment or joined ocean liners as waiters, stewards and entertainers at a time when homosexual activity was illegal. This slang rendered the speaker unintelligible to hostile outsiders, such as policeman, but fell out of use after the Sexual Offences Act (1967) effectively decriminalised homosexuality in the United Kingdom. Attracted to the theatricality and defiant nature of Polari (which he likens to the situation of Australian Indigenous languages under assimilationist policies), Thompson borrowed its name for the series which examines how subcultures express themselves.

Christian Thompson (Australian, b. 1978)

Siren

2014

From the series Polari

C-type print

Image courtesy of the artist, Sarah Scout Presents, Melbourne, and Michael Reid, Sydney and Berlin

Christian Thompson (Australian, b. 1978)

Trinity II

2014

From the series Polari

C-type print

Image courtesy of the artist, Sarah Scout Presents, Melbourne, and Michael Reid, Sydney and Berlin

Christian Thompson (Australian, b. 1978)

Trinity III

2014

From the series Polari

C-type print

Image courtesy of the artist, Sarah Scout Presents, Melbourne, and Michael Reid, Sydney and Berlin

Christian Thompson (Australian, b. 1978)

Ariel

2014

From the series Polari

C-type print

Image courtesy of the artist, Sarah Scout Presents, Melbourne, and Michael Reid, Sydney and Berlin

Christian Thompson: Ritual intimacy, installation view: Monash University Museum of Art, Melbourne 2017 showing at left, Ellipse (2014, below)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Christian Thompson (Australian, b. 1978)

Ellipse

2014

From the series Polari

C-type print

Image courtesy of the artist, Sarah Scout Presents, Melbourne, and Michael Reid, Sydney and Berlin

Putting on the Dish – A short film in Polari

Polari was a form of slang used by gay men in Britain prior to the decriminalisation of homosexuality in 1967, used primarily as a coded way for them to discuss their experiences. It quickly fell out of use in the 70s, although several words entered mainstream English and are still used today. For more about Polari see Wikipedia.

Polari – The Story of Britain’s Gay Slang

Author and academic Paul Baker of Lancaster University discusses a form of gay slang known as Polari that was spoken in Britain. It was a secret type of language used mainly by gay men and some lesbians and members of the trans, drag and other communities in the United Kingdom in the 20th century until it largely died out by the early 1970s.

Christian Thompson (Australian, b. 1978)

Refuge

2014

Video and sound

4 mins 18 secs

Refuge is a video work by contemporary Australian artist Christian Thompson. Thompson sings in the endangered Bidjara language of his heritage. A collaboration with James Young formerly of ‘Nico’ and recorded the original track in Oxford, United Kingdom.

Christian Thompson: Ritual intimacy, installation view: Monash University Museum of Art, Melbourne 2017 featuring stills from the video Heat (2010)

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Christian Thompson (Australian, b. 1978)

Heat (extract)

2010

Three-channel digital colour video, sound

5.52 minutes

Like the Australian graffiti photographs [see photographs below], Heat come out of Thompson’s memories of growing up in the desert surrounding Barcaldine in central west Queensland. Barcaldine is famous for its role in the foundation organised labor in Queensland and ultimately the formation of the Australian Labor Party. It also holds historical significance for Thompson’s family as it is where his great-great-grandfather, Charlie Thompson, surreptitiously bought a block of land before Aboriginal people could legally buy land, creating a safe haven for his family and other Aboriginal families at the time when Aboriginal people had few legal rights. For Thompson, heat captures the sensation that he associates with being on his country: the dry wind blowing through his hair. It features the three granddaughters of Aboriginal rights pioneer Charlie Perkins, who are the daughters of Thompson’s Long time collaborator Hetti Perkins.

Christian Thompson: Ritual intimacy, installation view: Monash University Museum of Art, Melbourne 2017 featuring photographs from the series Australian graffiti (2007)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Christian Thompson (Australian, b. 1978)

Untitled (blue gum)

2007

From the series Australian graffiti

C-type print

Image courtesy of the artist, Sarah Scout Presents, Melbourne, and Michael Reid, Sydney and Berlin

Christian Thompson (Australian, b. 1978)

Untitled (banksia)

2007

From the series Australian graffiti

C-type print

Monash University Collection

Australian graffiti was the last work that Thompson made before leaving Australia for Europe. It connects with his memories of growing up in the outback and its desert flowers, which he perceives to be both fragile and immensely powerful. I adorning himself with garlands of these flowers and flamboyant garments of the 1980s and 1990s – the period in which he grew up – Thompson juxtaposes these elements against his own Bidjara masculinity. By wearing native flora he also stands in for the landscape, invoking an Indigenous understanding of the landscape as a corporeal, living ancestral being.

Christian Thompson (Australian, b. 1978)

Desert slippers (extract)

2006

Single-channel digital colour video, sound

34 seconds

Desert slippers was made at the time the Northern Territory government commissioned research into allegations of the abuse of children in Aboriginal communities. When the ‘Little Children are Sacred’ report was tabled the following year, the federal government under John Howard staged the Northern Territory Emergency Response (NTER), which quickly became known as ‘the intervention’. This action was enacted without consultation with Indigenous people and ignored the substantive recommendations of the report to which it was allegedly responding.

Thompson made this video, involving his father, and the ceremonial aspects of their daily lives, during this period. Desert slippers features a Bidjara ritual in which a father and son transfer sweat. The desert slipper is a native cactus that symbolises the transferal of the spirit back to earth as the plant grows.

Christian Thompson (Australian, b. 1978)

Dhagunyilangu (Brother) (extract installation view)

2011

Single-channel digital colour video, sound, subtitled

2.19 minutes

Christian Thompson

Dhagunyilangu (Brother)

2011

Single-channel digital colour video, sound, subtitled

2.19 minutes

Gamu Mambu (Blood Song) and Dhagunyilangu (Brother) were made in England and in the Netherlands respectively. While studying at the DasArts Academy of Theatre and Dance in Amsterdam, a centre for the study of early musical styles such as the baroque, Thompson realised that his own Bidjara language could be interpreted through the matrix of another cultural context and sphere. He undertook operatic training with this in mind, choosing in the end to work with specialist singers Sonja Gruys and Jeremy Vinogradov to realise the two works.

Monash University Museum of Art (MUMA)

Ground Floor, Building F,

Monash University Caulfield campus,

900 Dandenong Road,

Caulfield East, VIC 3145

Phone: 61 3 9905 4217

Opening hours:

Tuesday – Friday 10am – 5pm

Saturday 12 – 5pm

You must be logged in to post a comment.