Exhibition dates: 9th April – 7th July, 2024

Curators: the exhibition is curated by Karen Hellman, former associate curator in the Department of Photographs. Carolyn Peter, assistant curator in the Department of Photographs, Getty Museum, served as organising curator with assistance from Claire L’Heureux, former Department of Photographs graduate intern and Antares Wells, curatorial assistant

At left, Julia Margaret Cameron (British born India, 1815-1879) Florence after the Manner of the Old Masters 1872; and at right, Carrie Mae Weems (American, b. 1953) After Manet 2003

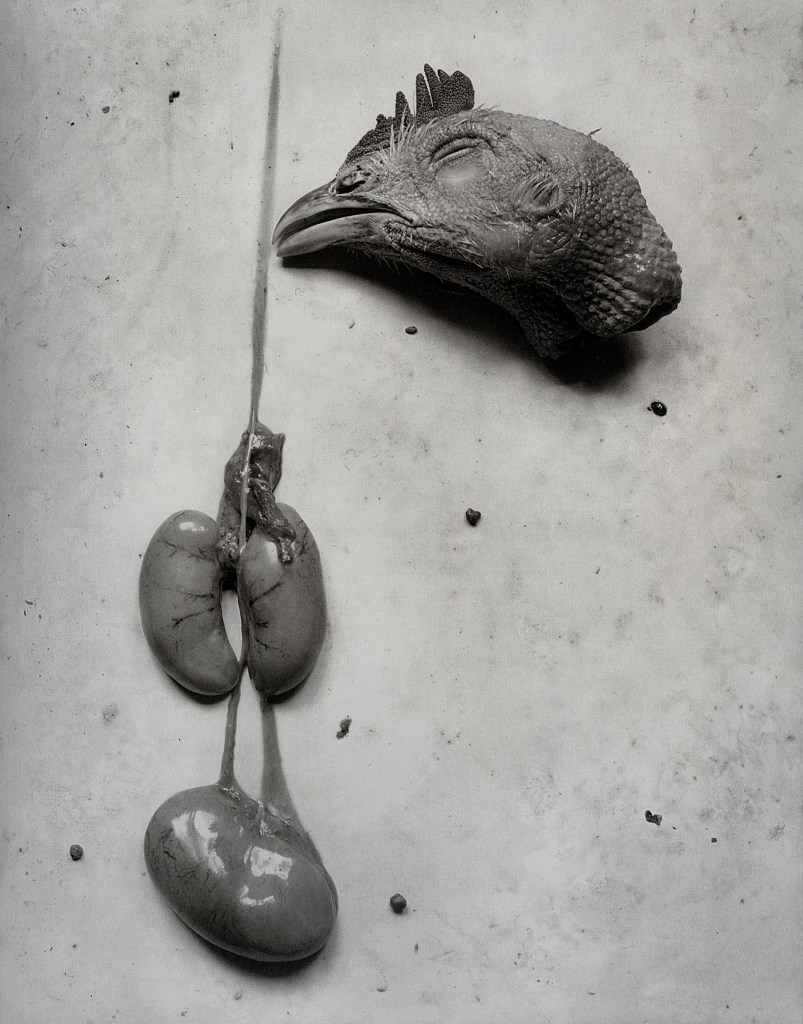

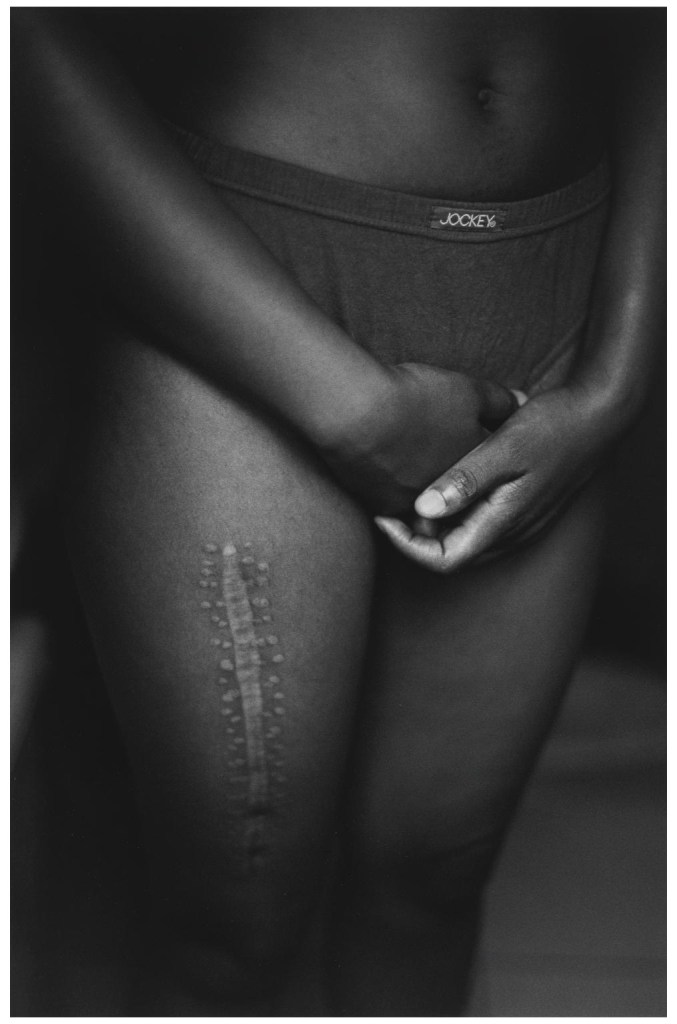

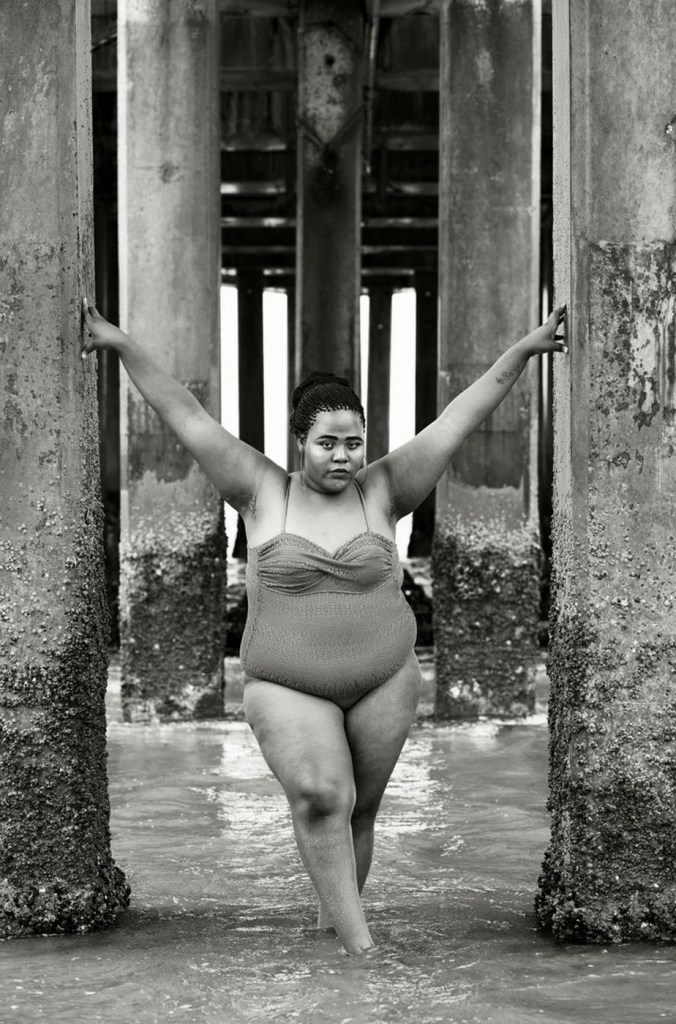

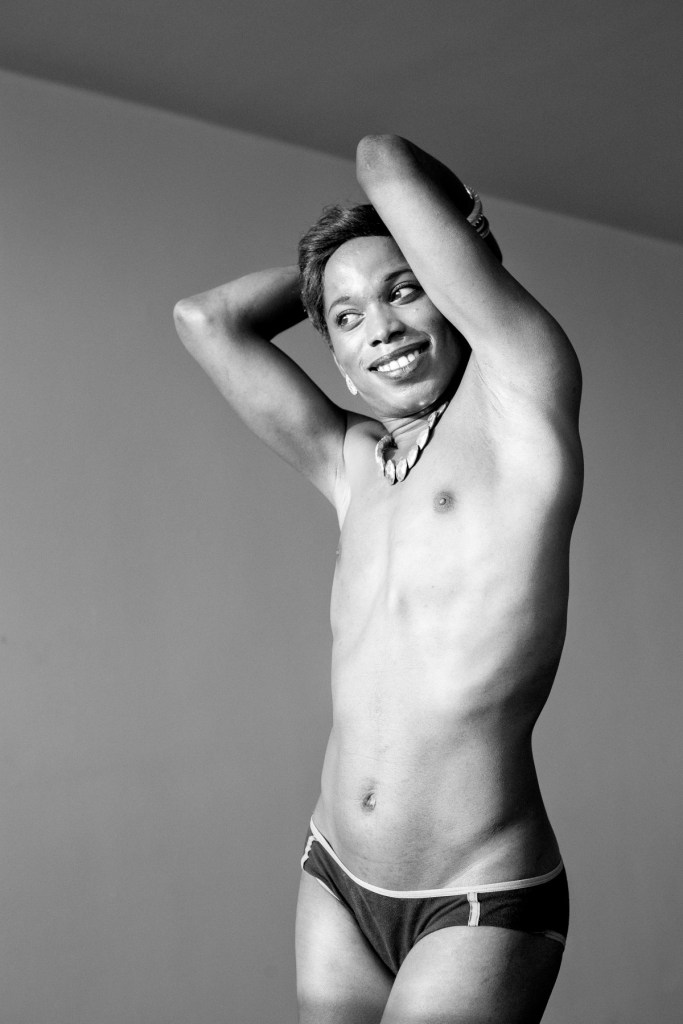

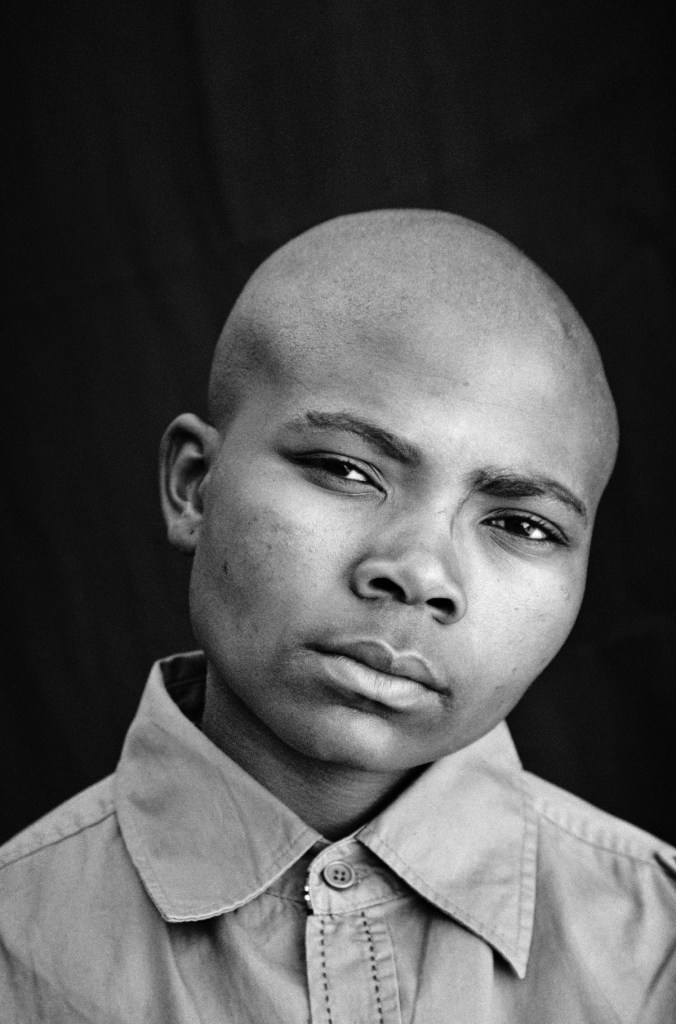

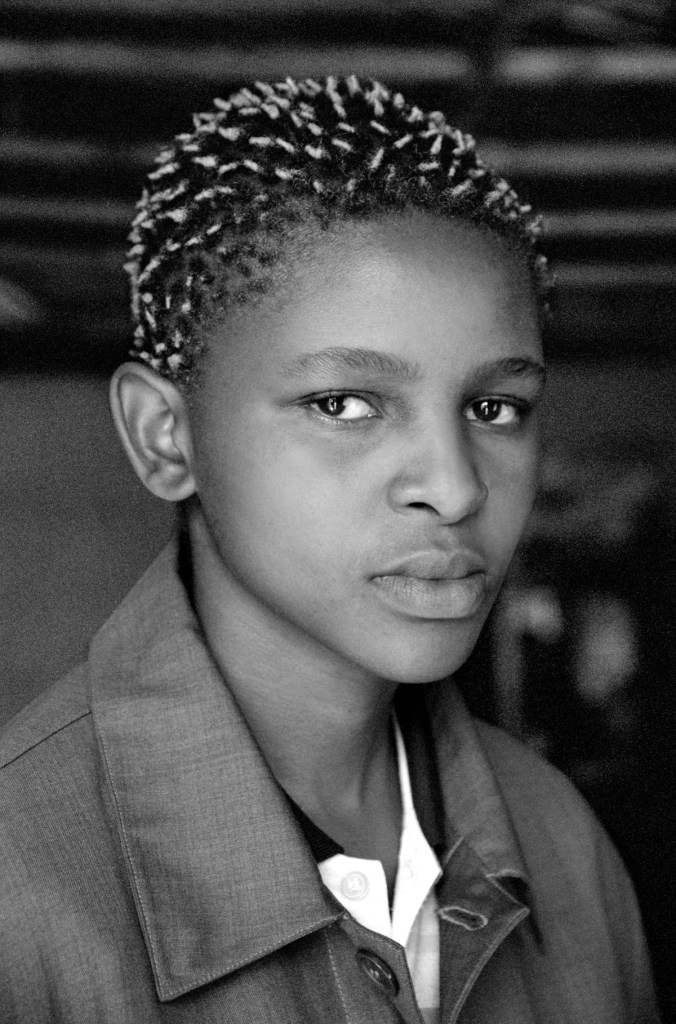

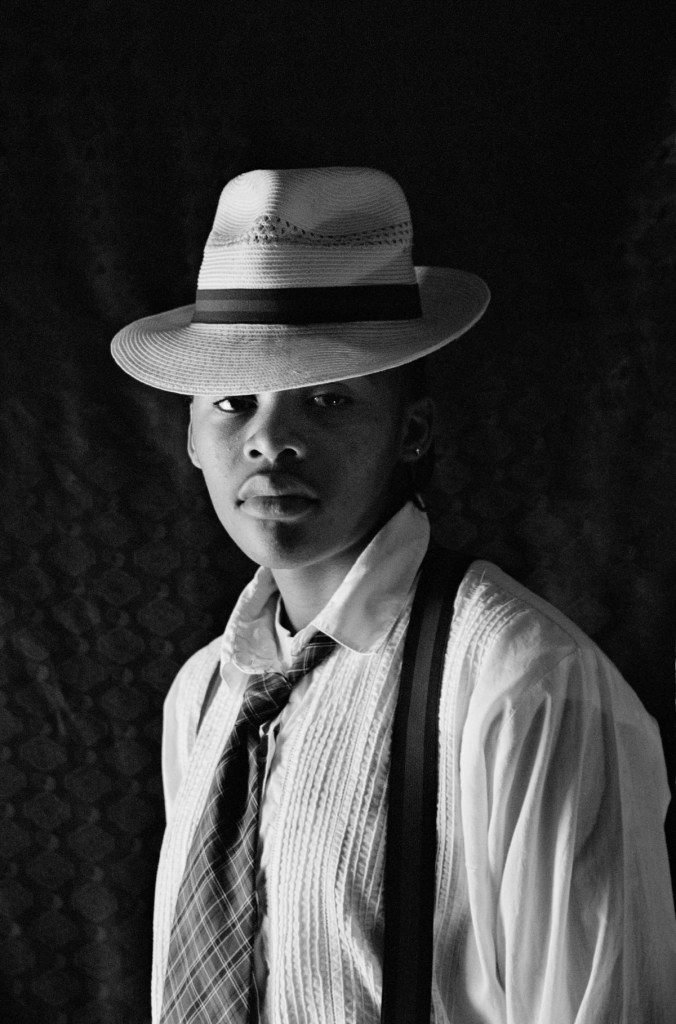

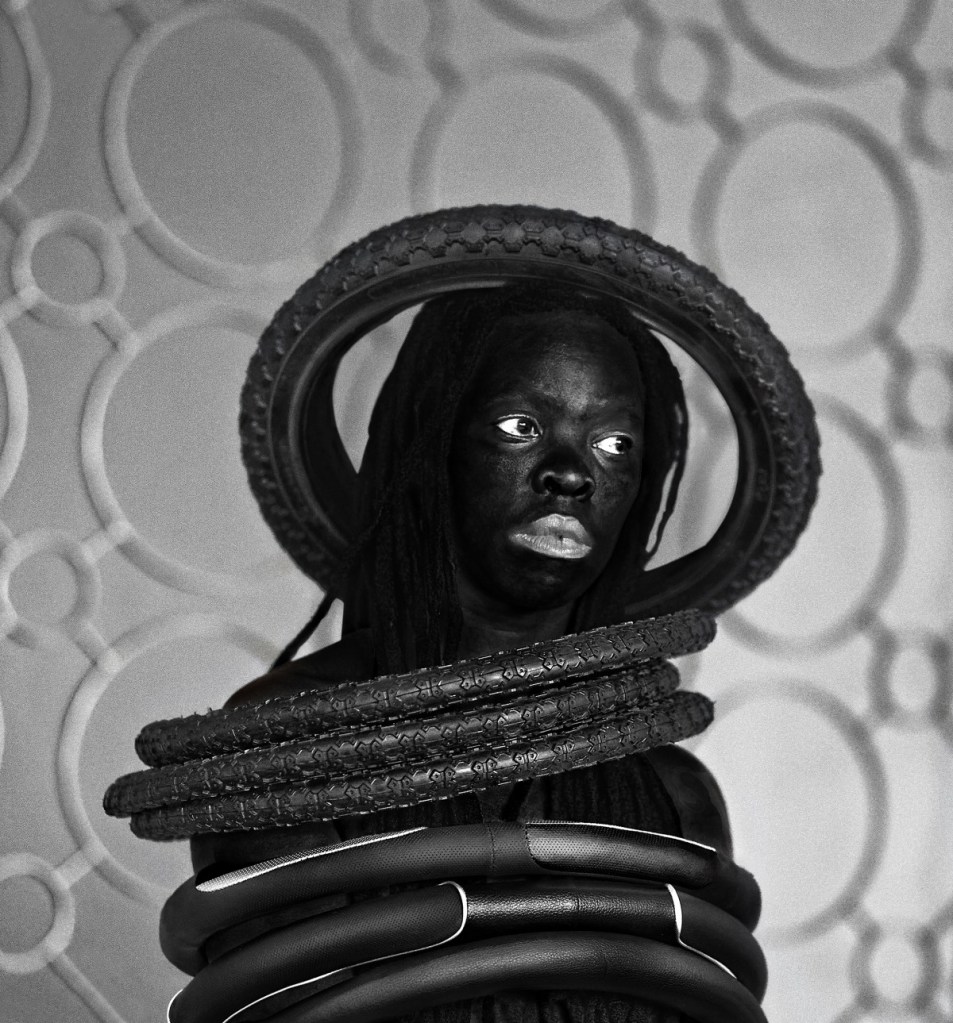

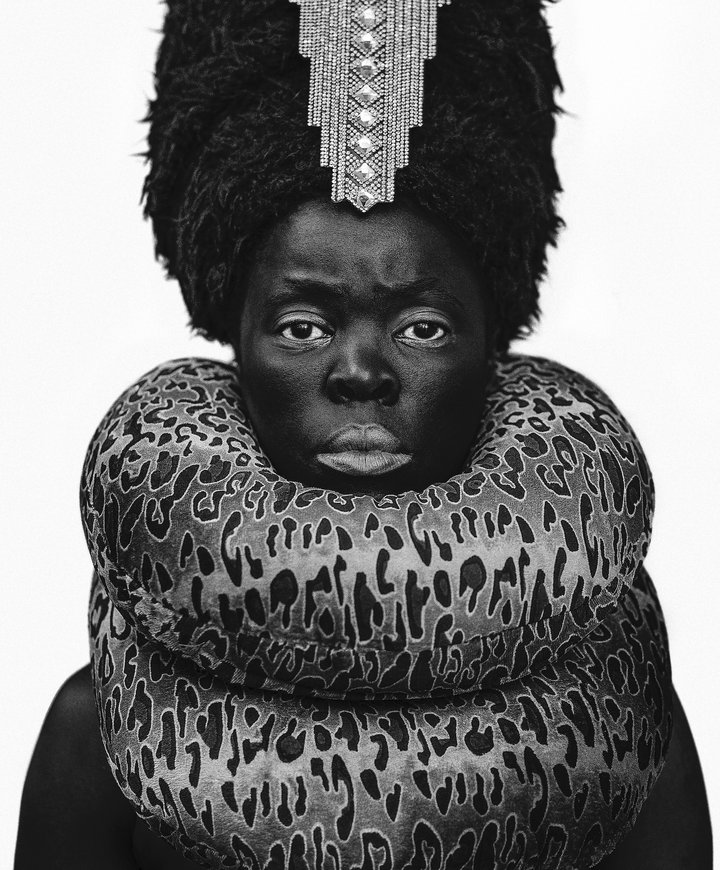

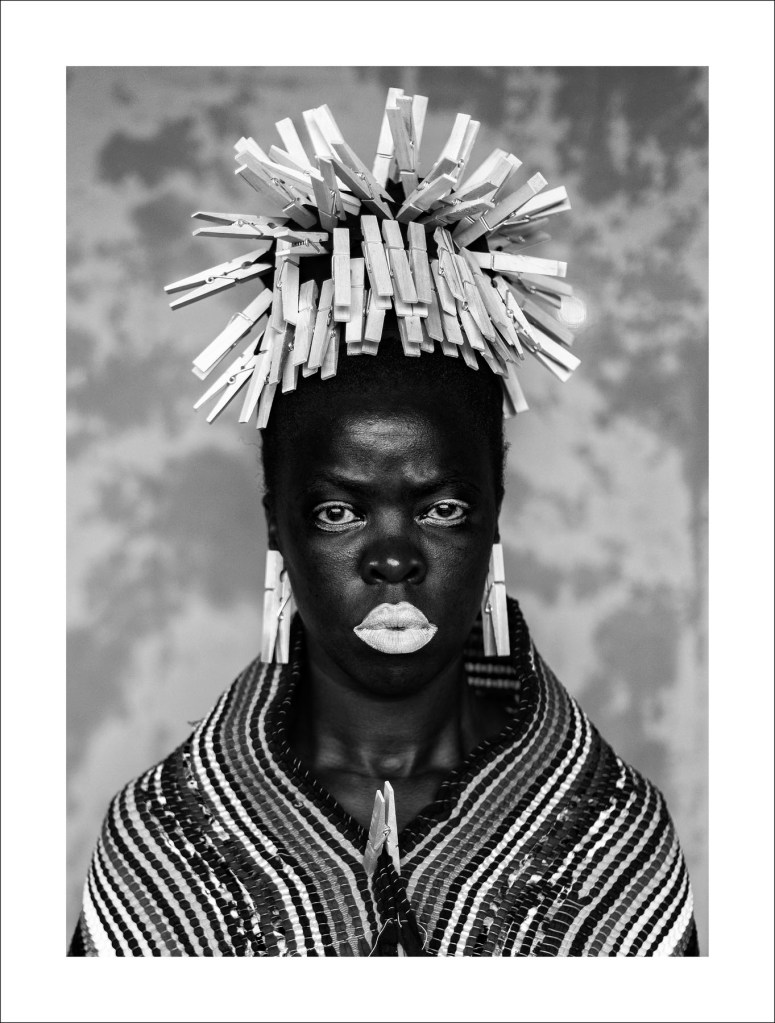

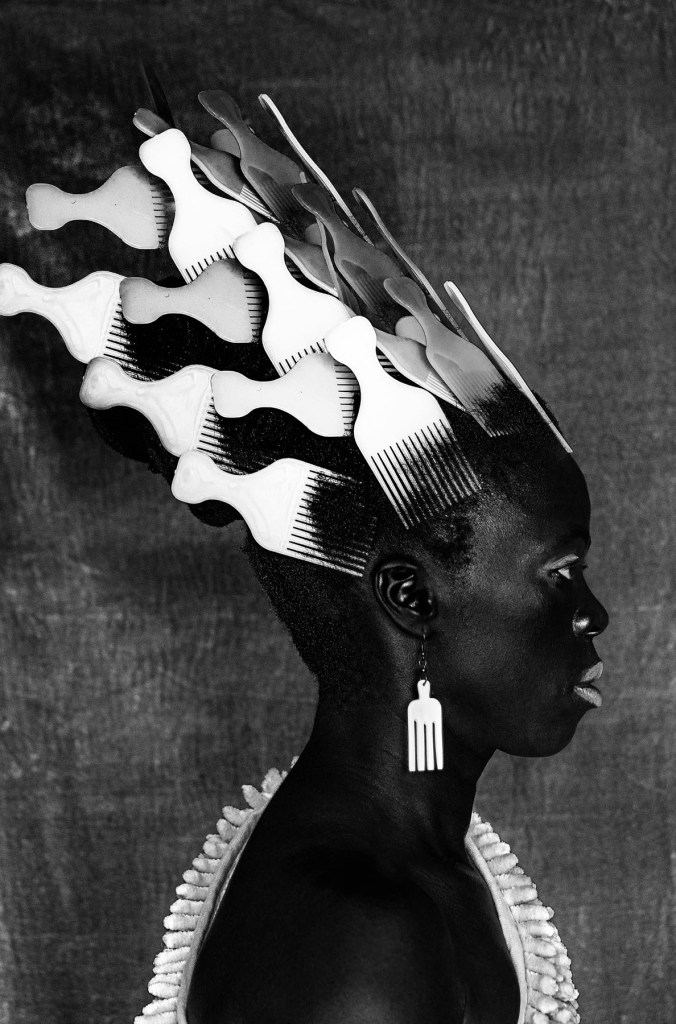

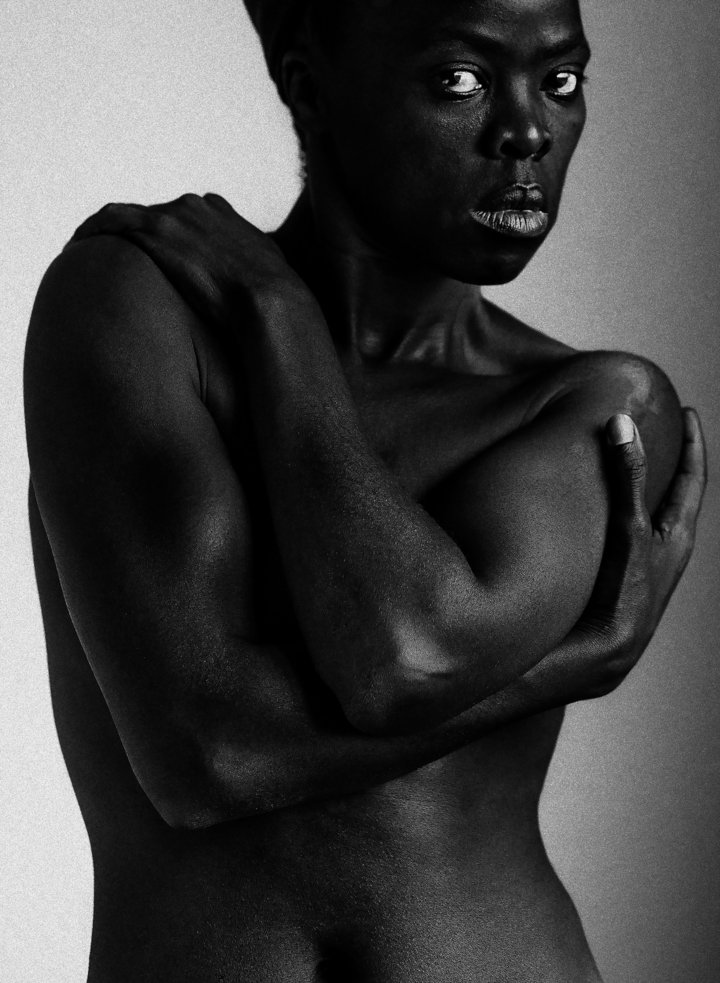

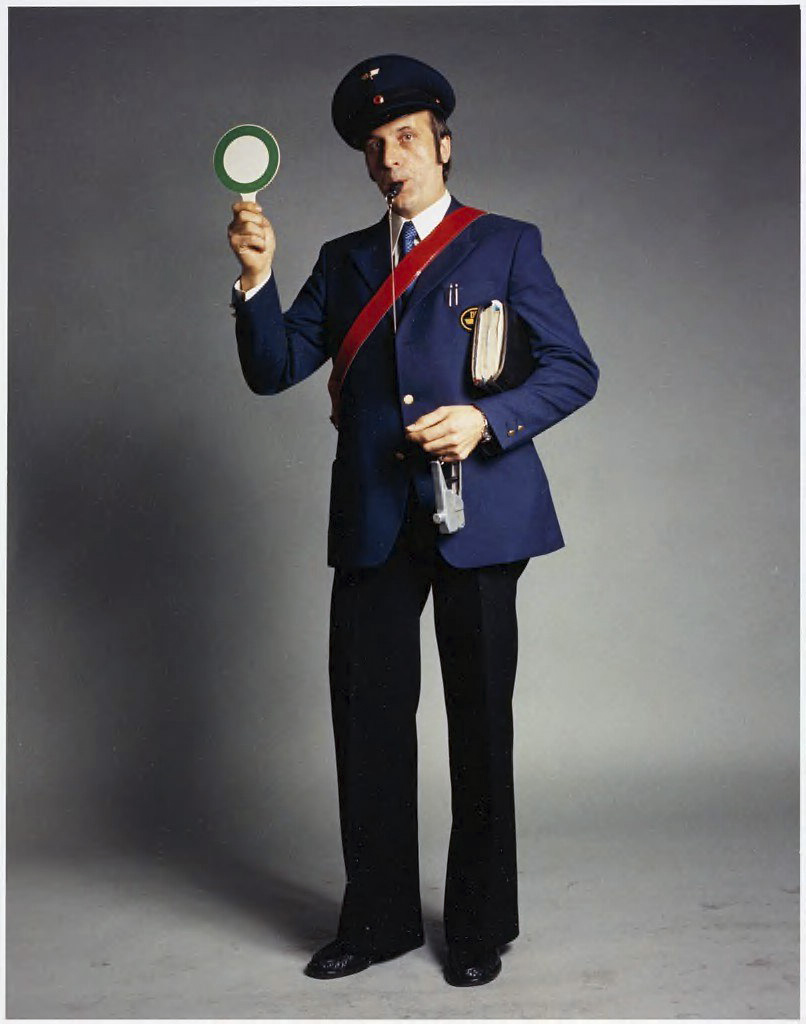

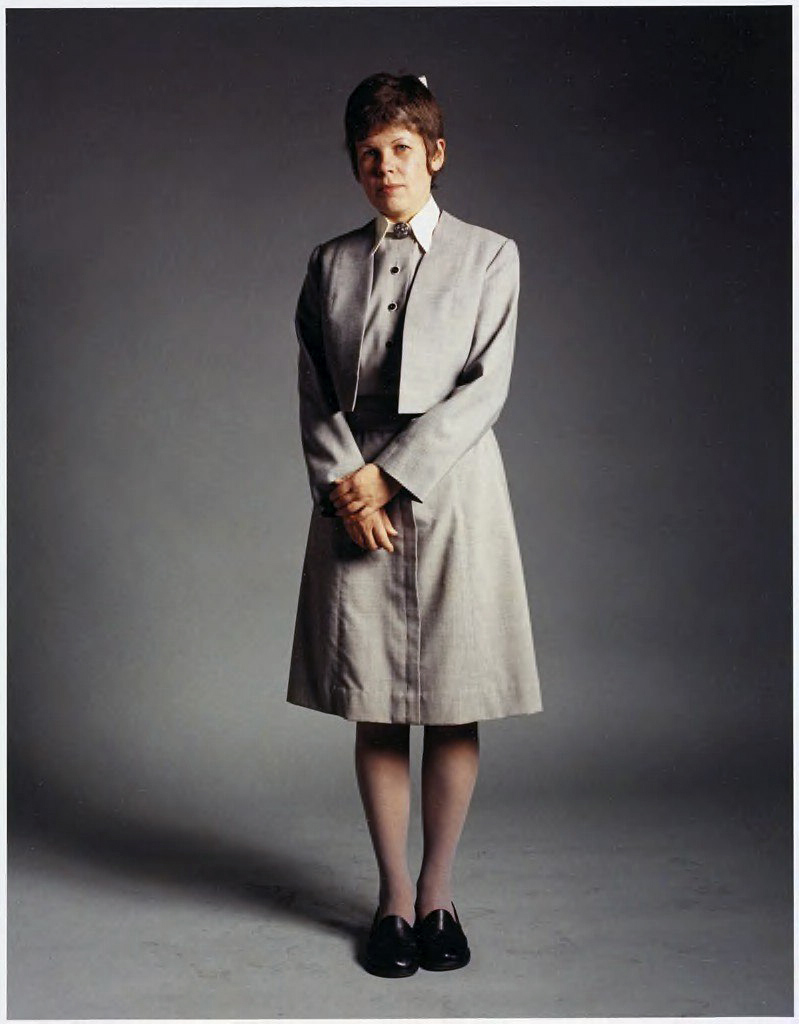

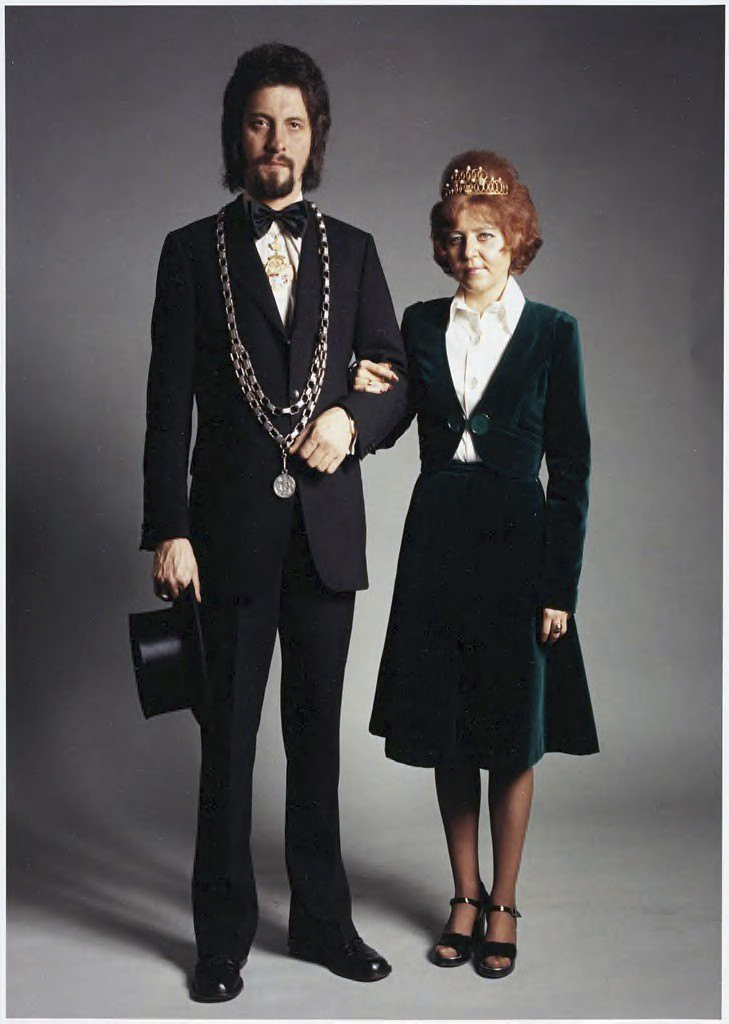

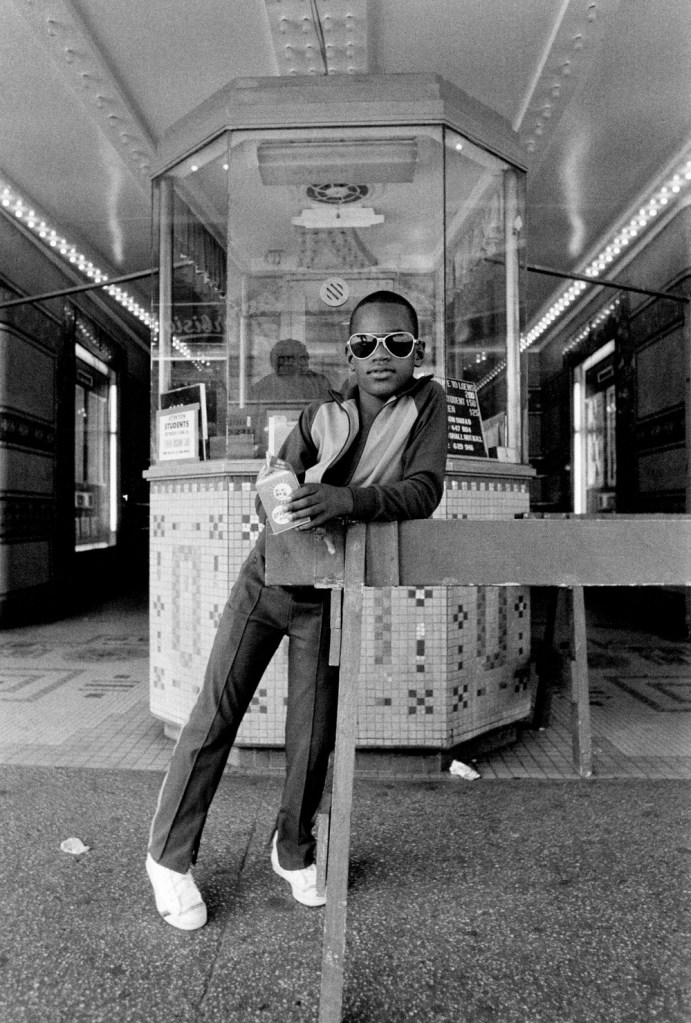

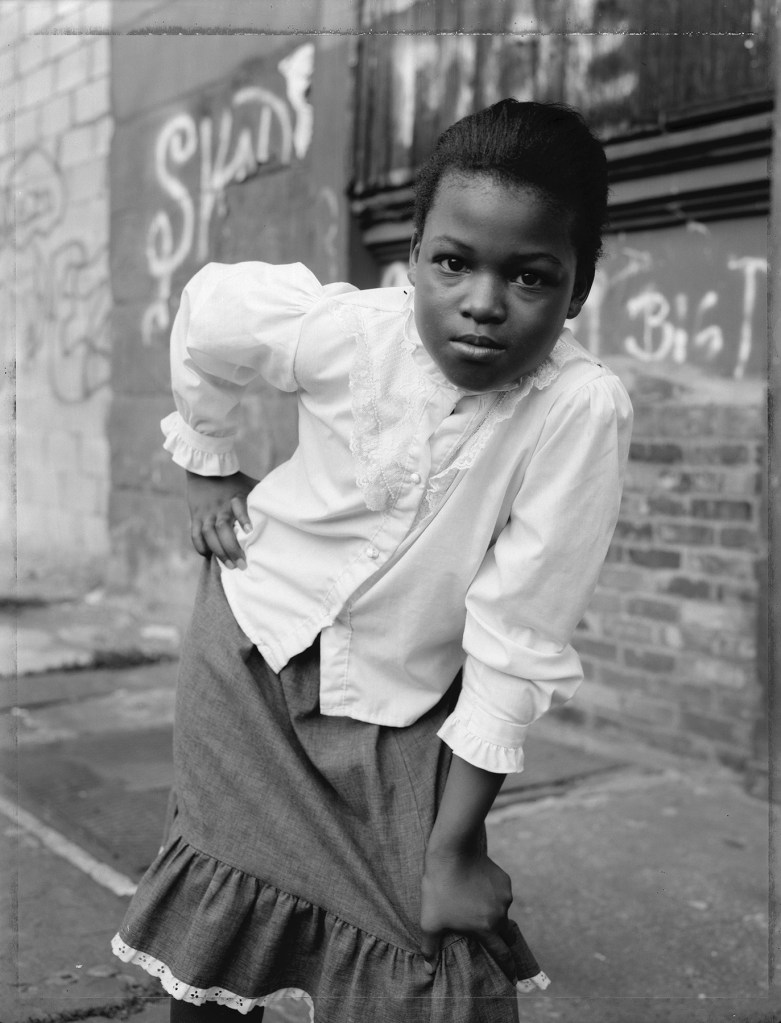

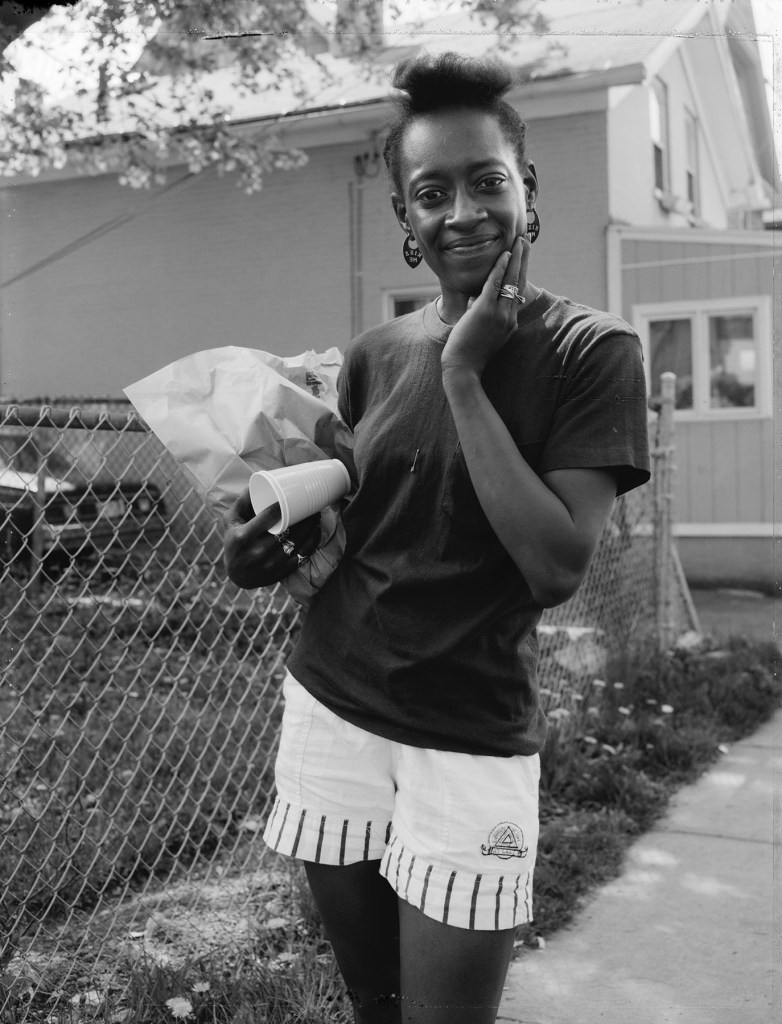

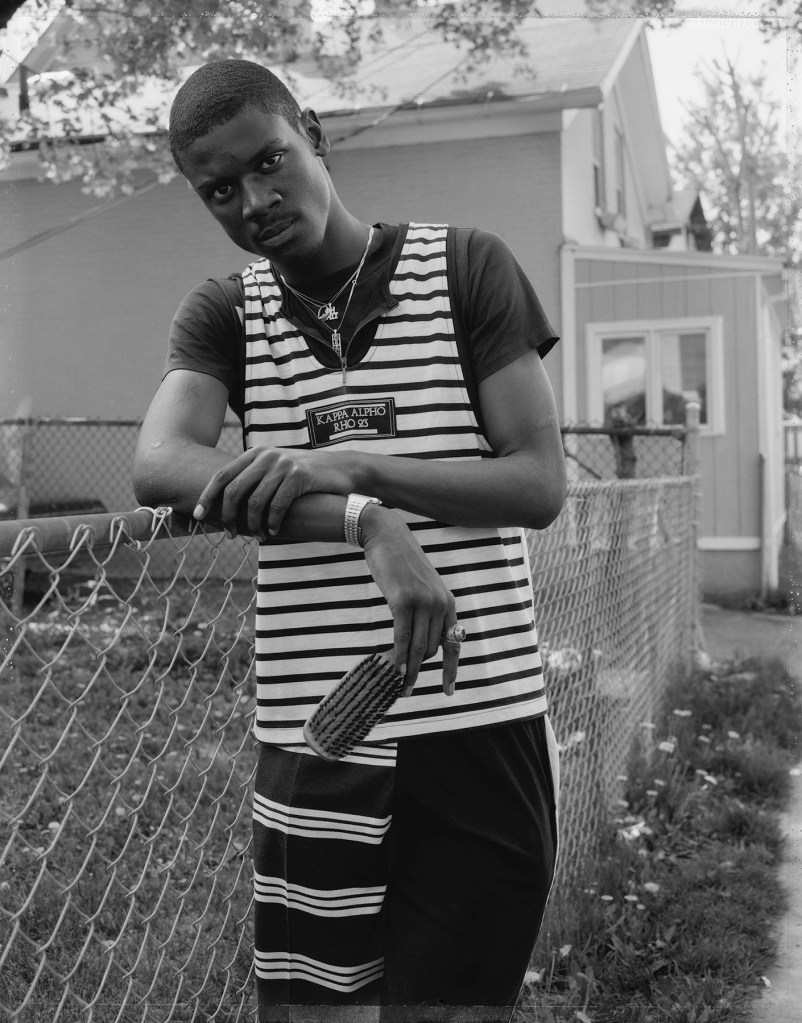

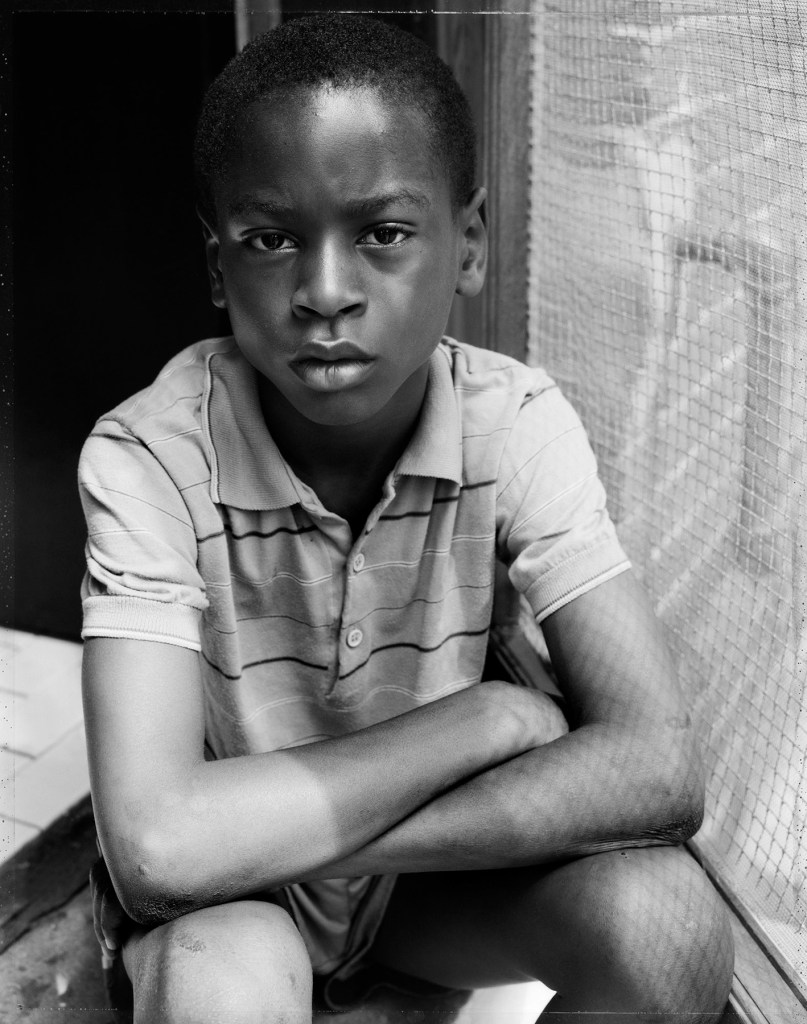

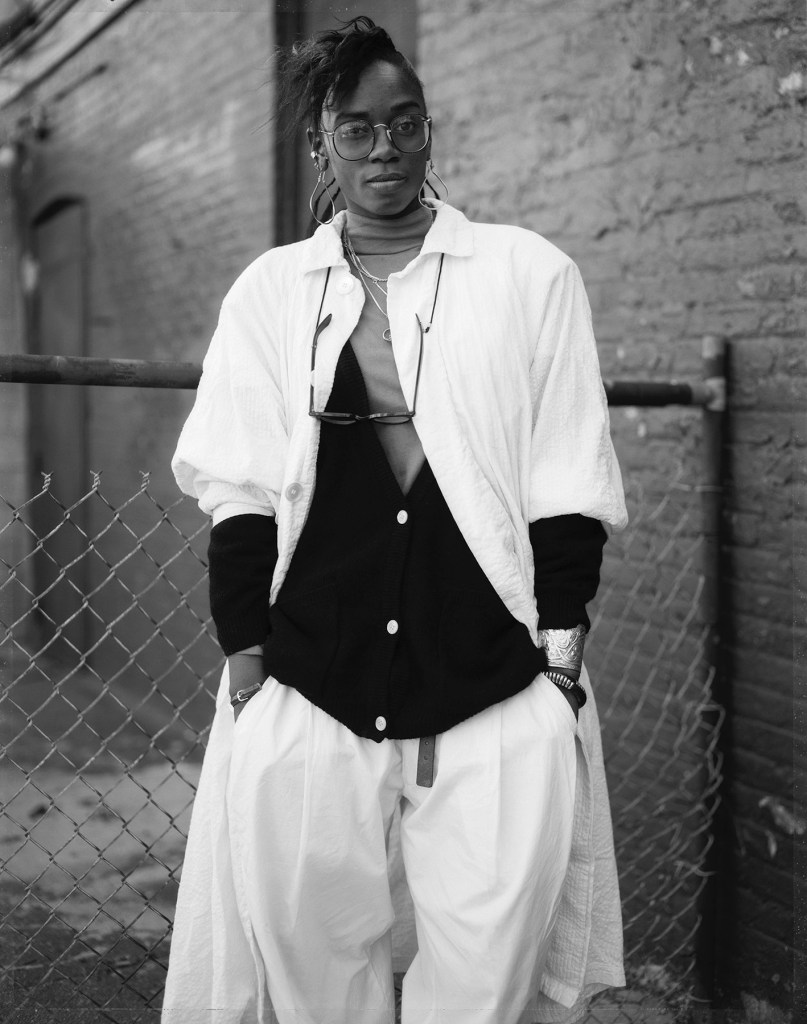

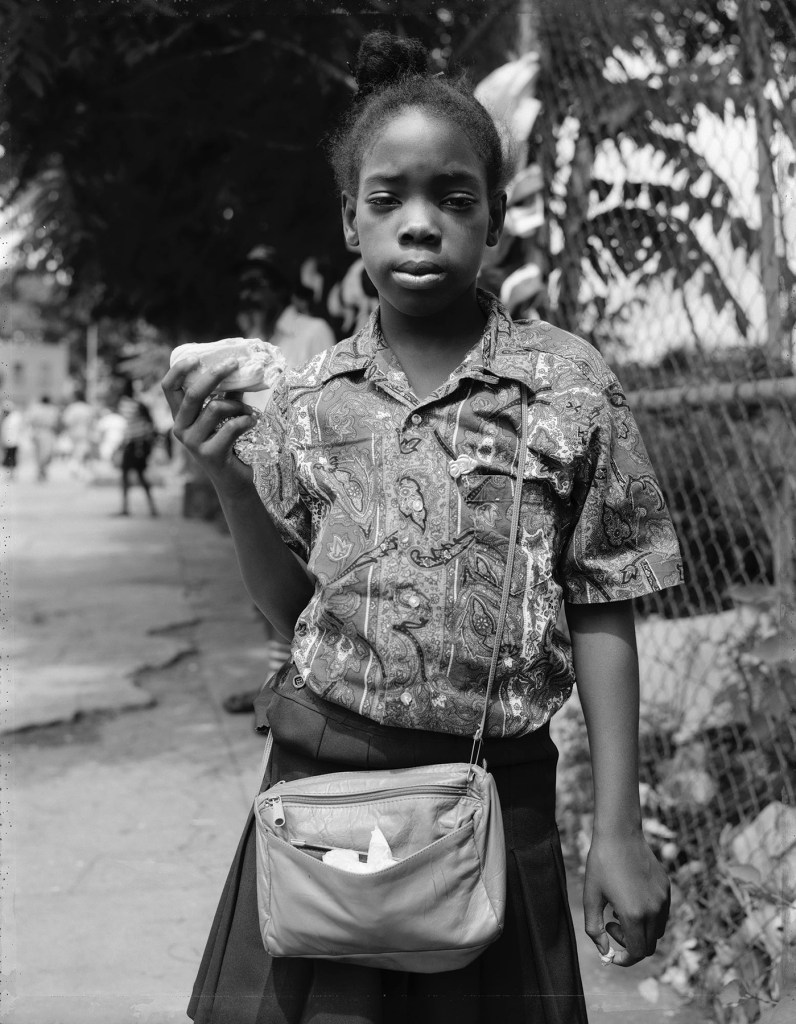

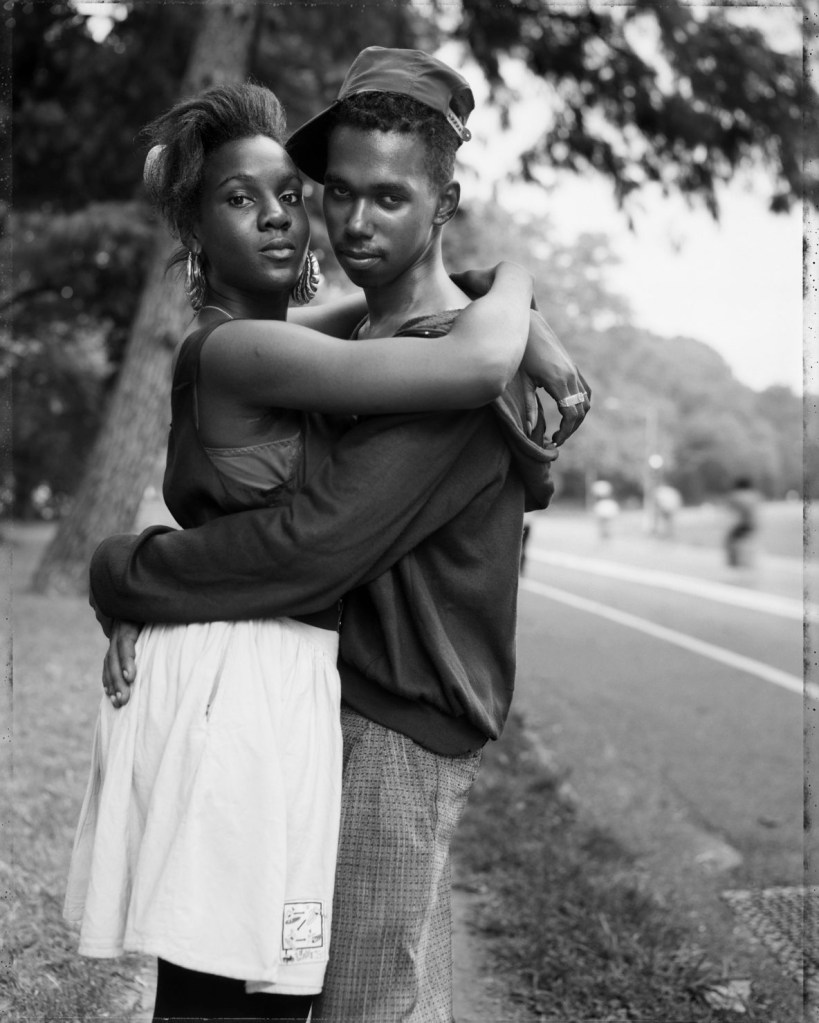

from the ‘Identity’ section of the exhibition

Magdalene Keaney, curator of the exhibition Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron: Portraits to Dream In, observes that the exhibition “poses questions about how we might think in new ways about relationships between 19th and 20th century photographic practice…”

As does this exhibition:

~ Everything emerges from something. One must be “mindful of the origins and essence of photography.” (Moriyama)

~ History often repeats itself in different forms.

~ Memory often returns in fragmentary form.

~ The wisdom and spirit of the past speaks to the practitioners of the future.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

NB: Transubstantiation, an un/explainable change in form, substance, or appearance (from the Latin roots trans, “across or beyond,” and substania, “substance”)

Many thankx to the J. Paul Getty Museum for allowing me to publish the photographs in the website. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

The earliest photographs – often associated with small, faded, sepia-toned images – may seem to belong to a bygone era, but many of the conventions established during photography’s earliest years persist today. Organised around five themes dating back to the medium’s beginnings, this exhibition explores nineteenth-century photographs through the work of twenty-one contemporary artists. These interchanges between the first decades of the medium and the most recent invite us to reimagine nineteenth-century photography while exploring its complexities.

Text from the J. Paul Getty Museum website

“Ms. Hellman, a former associate curator, inspired by her work with the Bayard materials, conceived “Nineteenth-Century Photography Now” as a way to access the influence that early photographers still have. The exhibition includes work from the past by 23 named and three anonymous photographers plus an additional 16 included in an album; there are 21 present-day artists. It is organised around five themes: Identity, Time, Spirit, Landscape and Circulation. The picture that serves as an introduction to the show is “Untitled ‘point de vue'” (1827) by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, a faded heliograph on pewter, that Daido Moriyama keeps a reproduction in his studio; the wall text quotes him saying, “it serves as a gentle daily reminder to be mindful of the origins and essence of photography.” There are two photographs by Mr. Moriyama prompted by Niépce’s bit of primitive technology.”

William Meyers. “Photography’s Past and Present at the Getty Center,” on The Wall Street Journal website May 29, 2024 [Online] Cited 16/06/2024

Julia Margaret Cameron (British born India, 1815-1879)

Florence after the Manner of the Old Masters

1872

Albumen silver print

Image: 34 × 25.6cm (13 3/8 × 10 1/16 in.)

Mount: 43.3 × 32.4cm (17 1/16 × 12 3/4 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Portrait of Florence Fisher posing with a rose stem with the leaves attached. She holds the rose in place with one arm folded across her chest.

Carrie Mae Weems (American, b. 1953)

After Manet

2003

From the series May Days Long Forgotten

Chromogenic print

Object: 84.3cm (33 3/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© Carrie Mae Weems

The black and white photograph – one from the nine-part series May Days Long Forgotten – depicts four African American girls in summer dresses, with garlands in their hair, reclining on a lawn. The piece is mounted in a circular frame prepared by the artist, and is number five of an edition of eight.

Joseph Nicéphore Niépce (French, 1765-1833)

Untitled ‘point de vue’

1827

Heliograph on pewter

16.7 x 20.3 x .15cm

The invention of photography was announced simultaneously in France and England in 1839, dazzling the public and sending waves of excitement around the world. These astonishing breakthroughs depended upon centuries of developments in chemistry, optics, and the visual arts, accelerating in the decades after 1790. The Niépce Heliograph was made in 1827, during this period of fervent experimentation. It is the earliest photograph produced with the aid of the camera obscura known to survive today.

Text from the Harry Ransom Center website

At left, André Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri (French, 1819-1889) Uncut Sheet of Cartes-de-Visite Portraits, 1860s; and at right, Paul Mpagi Sepuya (American, b. 1982) Daylight Studio with Garden Cuttings (_DSF0340) 2022

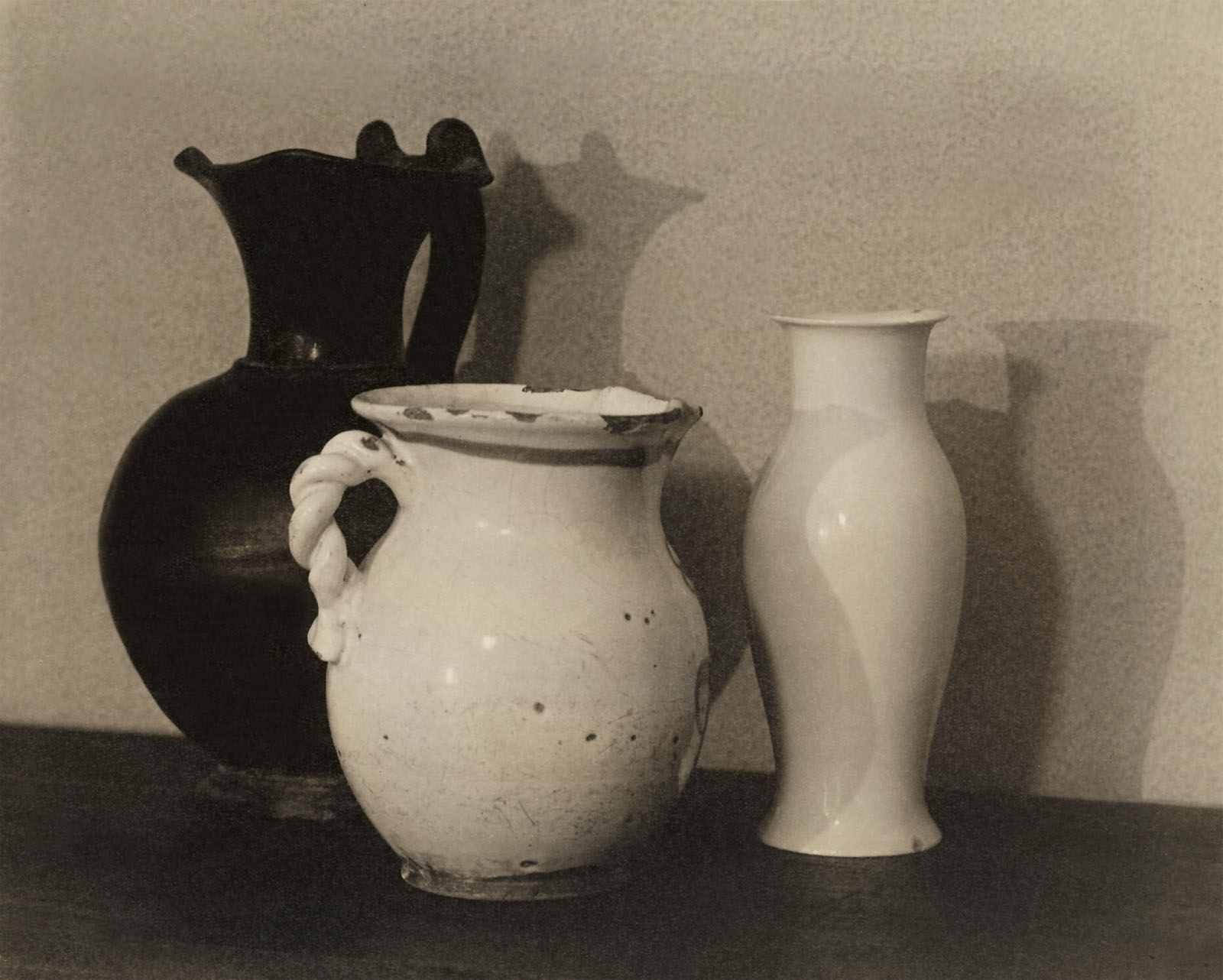

William Henry Fox Talbot (English, 1800-1877)

[A Stem of Delicate Leaves of an Umbrellifer]

probably 1843-1846

Photogenic drawing negative

Image: 18.1 × 22.1cm (7 1/8 × 8 11/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

The exceptional boldness of this image conveys a visual impression that at first may seem quite unlike other of William Henry Fox Talbot’s pictures. He made it with the same photogenic drawing process he used for much of his work by placing the stem of leaves directly on top of the prepared paper and then exposing to sunlight without the aid of a camera. Although the original plant was delicate, its sharply delineated white shadow on the rich dark brown background creates a graphic, two-tone effect. The same specimen was used in a slightly different orientation to make a negative that is preserved in one of the family albums formerly at the Fox Talbot Museum in Lacock and now at the British Library, London.

Other visually similar works in Talbot’s oeuvre help us to understand what we are seeing here. Some of them show the interior structure of the plant specimens he photographed, proving that the negatives at first had fuller details. Because the most vulnerable sections of the silver-based images are those that are light in tone, these areas will fade disproportionately faster than the darker parts. In this case, the lightest tones would have been in the interior spaces of the plant, and these at some point faded. It is unlikely that Talbot saw the same picture we see today, at least not when he first made it, but the boldness of the present state reminds us that changes over time can create as well as destroy.

Adapted from Larry Schaaf. William Henry Fox Talbot, In Focus: Photographs from the J. Paul Getty Museum (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2002), 68. © 2002 J. Paul Getty Trust

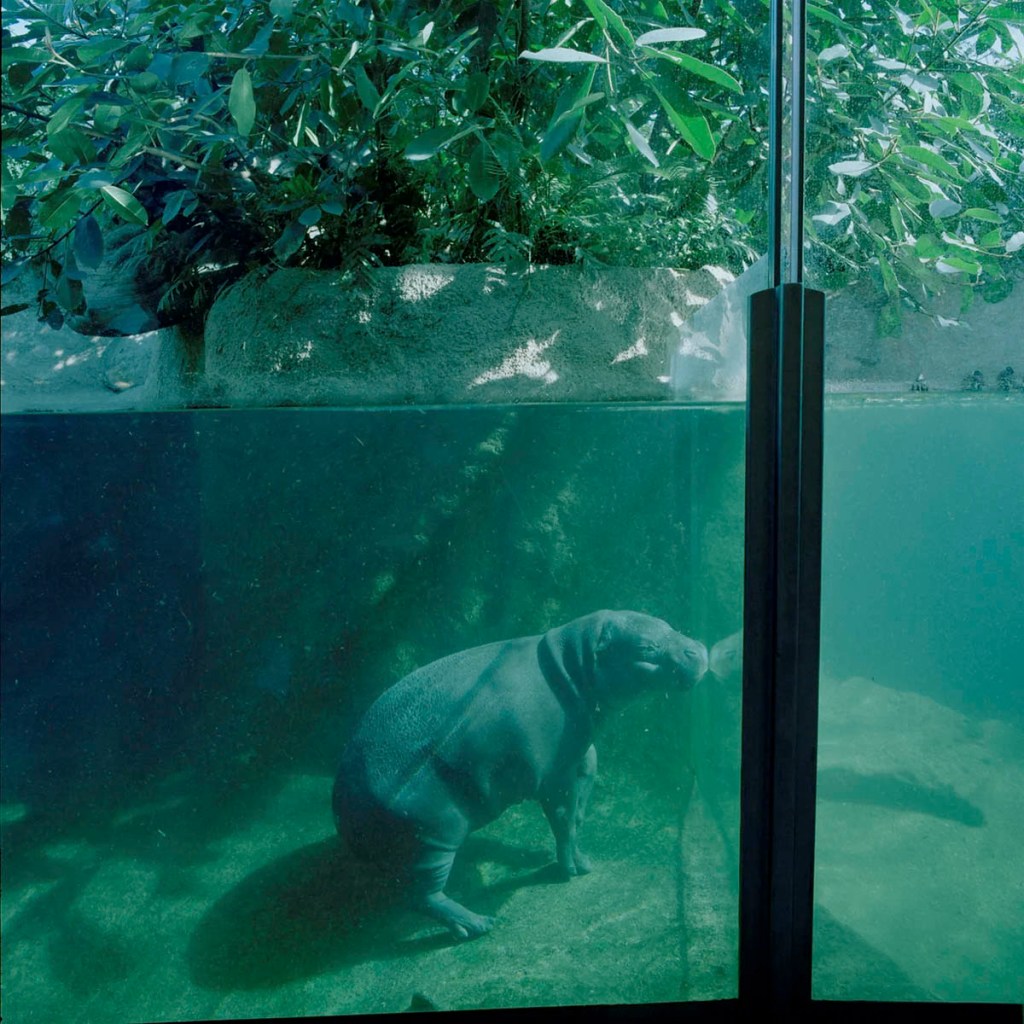

Hiroshi Sugimoto (Japanese, b. 1948)

A Stem of Delicate Leaves of an Umbrellifer, circa 1843-1846

2009

Toned gelatin silver print

Image: 93.7 × 74.9cm (36 7/8 × 29 1/2 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Gift of the artist

© Hiroshi Sugimoto

“To look at Fox Talbot’s earliest experiments, the blurred and hazy images suffuse the excited anticipation of discovering how light could transfer the shape of things onto paper. … I decided to collect Fox Talbot’s earliest negatives, from a time in photographic history very likely before positive images existed, and print the photographs that not even he saw.”

~ Hiroshi Sugimoto (p. 349, in Hiroshi Sugimoto, Ostfildern-Ruit, 2005)

Hiroshi Sugimoto visited the Getty Museum in 2007 to study the earliest photographs in the collection. After photographing some of William Henry Fox Talbot’s photogenic drawing negatives, he produced large-scale prints and coloured them with toning agents to replicate the hues of the paper negatives. The scale of the enlarged prints reveals the fibers of the original paper, which create delicate patterns embedded in the images.

At left, Herbert Bell et al, [Amateur World Tour Album, taken with early Kodak cameras, plus purchased travel photographs by various photographers] (2 page spread); and at right, Stephanie Syjuco (American born Philippines, b. 1974)

Herbaria 2021 (detail)

Herbert Bell (English, 1856-1946)

Frederick Nutt Broderick (English, about 1854-1913)

Gustave Hermans (Belgian, 1856-1934)

Anthony Horner (English, 1853-1923)

Michael Horner (English, 1843-1869)

C. W. J. Johnson (American, 1833-1903)

Léon & Lévy (French, active 1864-1913 or 1920)

Léopold Louis Mercier (French, b. 1866)

Neurdein Frères (French, founded 1860s, dissolved 1918)

Louis Parnard (French, 1840-1893)

Alfred Pettitt (English, 1820-1880)

Francis Godolphin Osborne Stuart (British born Scotland, 1843-1923)

Unknown maker

Valentine & Sons (Scottish, founded 1851, dissolved 1910)

L. P. Vallée (Canadian, 1837-1905)

York and Son

J. Kühn (French, active Paris, France 1885 – early 20th century)

[Amateur World Tour Album, taken with early Kodak cameras, plus purchased travel photographs by various photographers] (2 page spread)

Albumen silver print

Closed: 35.4 × 28 × 3.5cm (13 15/16 × 11 × 1 3/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Google Arts & Culture website

Includes amateur photographs taken with early Kodak cameras, including the original Kodak or Kodak no. 1, and Kodak no. 2 cameras, as well as commercially produced images.

Stephanie Syjuco (American born Philippines, b. 1974)

Herbaria (detail)

2021

From the series Pileups

Hand-assembled pigmented inkjet prints on Hahnemühle Baryta

Framed [Outer Dim]: 121.9 × 91.4cm (48 × 36 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© Stephanie Syjuco

A collage composed of diverse naturalist archival sources, including photographs of bones, foliage, and crystal formations.

At left, Paul-Marie-Léon Regnard (French, 1850-1927) Passionate Ecstatic Position/Expression 1878; and at right, Laura Larson (American, b. 1965)

The Mind Is a Muscle 2019

Paul-Marie-Léon Regnard (French, 1850-1927)

Passionate Ecstatic Position/Expression

1878

Part of Iconographie Photographique de la Salpetriere (Service de M. Charcot)

Photogravure

Image: 10.3 × 7.1cm (4 1/16 × 2 13/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

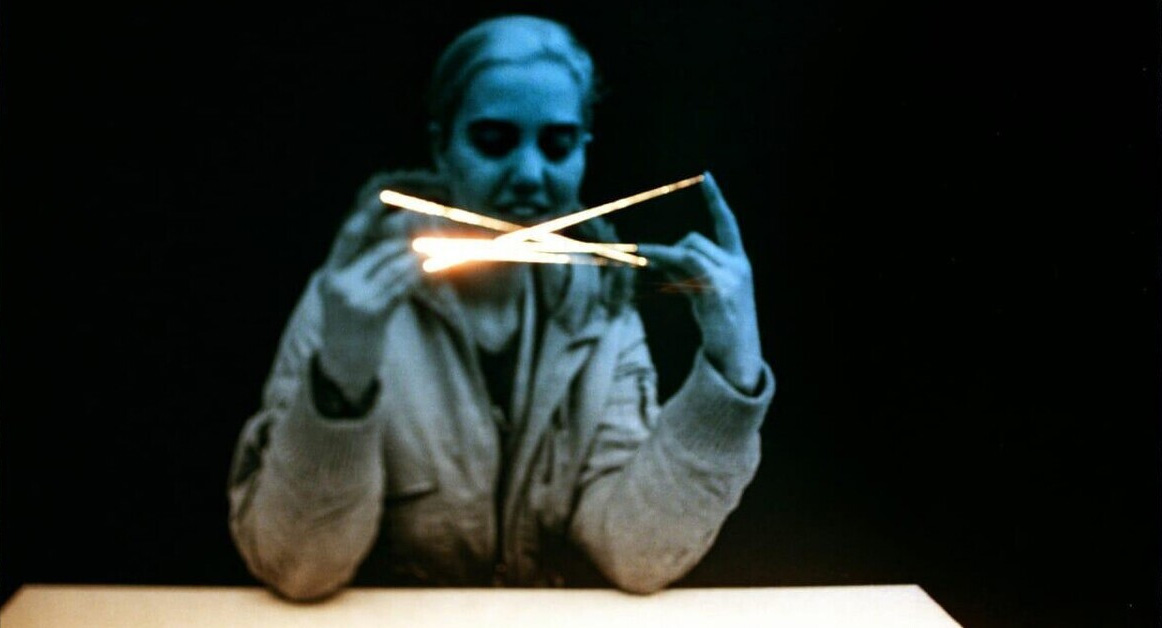

Laura Larson (American, b. 1965)

The Mind Is a Muscle

2019

from the series City of Incurable Women

Inkjet print

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Courtesy of and © Laura Larson

At first glance, photographs made in the 19th century may seem like faded relics of an increasingly distant and forgotten age, yet they persist in inspiring, challenging, and resonating with artists today.

Nineteenth-Century Photography Now, on view April 9 through July 7, 2024 at the Getty Center, offers new perspectives on early photography by looking through the lens of contemporary artists who respond directly to their historical themes and subject matter.

“This exhibition provides an opportunity to connect visitors with some of the earliest photographs in the Museum’s collection, now almost two centuries old, via the responses of contemporary makers,” says Timothy Potts, Maria Hummer-Tuttle and Robert Tuttle Director of the J. Paul Getty Museum. “The revelatory ability of early photography to capture images of the world around us still resonates with practitioners today, and bridges between past and present photography are as active and relevant as they have ever been.”

Organised around five themes, dating back to the medium’s beginnings, Identity, Time, Spirit, Landscape, and Circulation, this exhibition explores 19th-century photographs through the work of 21 contemporary artists. Reflecting the inventiveness of early practitioners as well as the more disturbing historical aspects of their era, these interchanges between the first decades of the medium and the most recent invite us to reimagine 19th century photography while exploring its complexities.

In their work, artists Daido Moriyama, Hanako Murakami, and Carrie Mae Weems look back to the invention of photography to convey a sense of how this revolutionary discovery changed people’s perceptions.

As is still the case today, the most popular subjects for the camera in the 19th century were people. In the galleries focused on Identity, Paul Mpagi Sepuya and Myra Greene respond to the complex history of photographic portraiture while Laura Larson, Stephanie Solinas, and Fiona Tan investigate the pseudosciences of the 19th century and how they reinforced stereotypes and identification systems that impact us today.

Photography and Time have been inextricably linked ever since early inventors struggled to permanently fix a fleeting moment on a sheet of paper. This section includes work by Lisa Oppenheim and Liz Deschenes exploring 19th-century photographers’ technical innovations and the ways in which the medium affects our perception of time.

The genre of Spirit photography emerged from the Victorian obsession with death in Europe and North America. Photographers exploited the ability to manipulate photographic images, employing multiple exposures and staged photography to create otherworldly scenes or to summon loved ones back from the dead. In this section, Khadija Saye and Lieko Shiga respond to the possibilities that spirit photography offers in rendering the unseen.

19th-century photographers went to great lengths to make images of remote Landscapes. Government-sponsored surveys and expeditionary programs employed the camera to justify the expansion and to record the resulting military conflicts. Mark Ruwedel, Michelle Stuart, and An-My Lê re-envision some of these same historical landscapes and offer up new ones that bring the past closer to our present.

By the middle of the 19th century, thousands of photographs were in Circulation worldwide, the result of photographers’ ability to reproduce the same image multiple times. Pictures of historical events, tourist destinations, and anthropological expeditions made the world seem more accessible, but with time and distance, they became disconnected from their original contexts. In this section, early photographs appear next to projects that make these historical absences present. Wendy Red Star, Stephanie Syjuco, Ken Gonzales-Day, and Andrea Chung recover what has been lost, calling out the residual effects of the 19th-century photograph on our present knowledge of global cultures and histories.

“Through the works of these visionary contemporary artists, 19th-century photography is not faded and dead but very much alive, an active material that enables us to rethink the medium and our relationship to it,” says Karen Hellman, curator of the exhibition.

Nineteenth-Century Photography Now is curated by Karen Hellman, former associate curator in the Department of Photographs. Carolyn Peter, assistant curator in the Department of Photographs, Getty Museum, served as organising curator with assistance from Claire L’Heureux, former Department of Photographs graduate intern and Antares Wells, curatorial assistant.

Related programming includes Who or What is Missing in Nineteenth-Century Photography?, a discussion featuring artists Laura Larson, Wendy Red Star, and Paul Mpagi Sepuya in a conversation about their artistic practices and how they are engaging with, and critiquing photography from the 19th century, and Art Break: The Precarious Nature of Photography, Society, and Life, June 6, 12pm. Artist Phil Chang talks with curator Carolyn Peter about his series “Unfixed” on view in Nineteenth-Century Photography Now and how an economic crisis and a pandemic inspired him to create photographs that will intentionally fade away to express the fragility of societal systems and life.

Press release from the J. Paul Getty Museum website

Introduction

At left, Maker unknown Kuroda Yasaburo, 50 Years Old January 6, 1882; and at right, Myra Greene (American, b. 1975) Undertone #10 2017-2018

Introduction

The earliest photographs – often associated with small, faded, sepia-toned images – may seem to belong to a bygone era, but many of the conventions established during photography’s earliest years persist today. Organised around five themes dating back to the medium’s beginnings, this exhibition explores nineteenth-century photographs through the work of twenty-one contemporary artists. Reflecting the inventiveness of early practitioners as well as the more disturbing historical aspects of their era, these interchanges between the first decades of the medium and the most recent invite us to reimagine nineteenth-century photography while exploring its complexities.

Maker unknown

Kuroda Yasaburo, 50 Years Old

January 6, 1882

Ambrotype

Closed: 11.5 × 9 × 1cm (4 1/2 × 3 9/16 × 3/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Gift of Virginia Heckert in memory of Gordon Baldwin

Myra Greene (American, b. 1975)

Undertone #10

2017-2018

Ambrotype

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© Myra Greene

__________________________________________

Identity

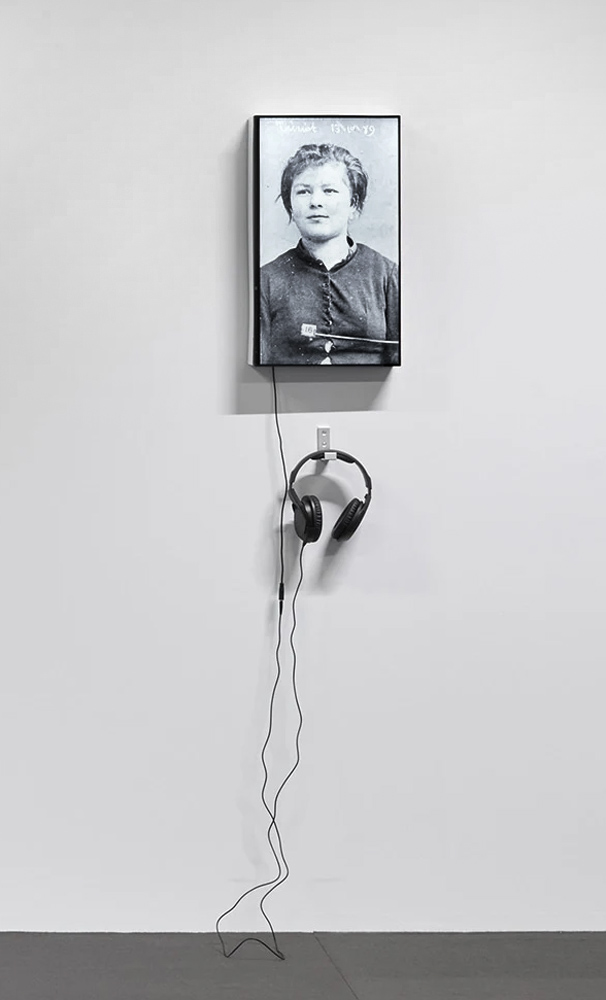

At left, Various makers Pickpockets at the Universal Exposition of 1889 1889; and at right, Fiona Tan (Indonesia, b. 1966) Marie Thiriot 2021

Fiona Tan (Indonesia, b. 1966)

Marie Thiriot

2021

From the series Pickpockets

HD video installation, stereo, flat-screen monitor

Courtesy of the artist and Frith Street Gallery, London

© Fiona Tan

Photo: Frith Street Gallery CC

‘As an artist working almost entirely with time-based and lens-based media, time is one of my major tools … time is both tool with which to shape and chisel and material to fold, distort and configure.’

Fiona Tan (b. 1966, Pekanbaru) explores history and time and our place within them, working within the contested territory of representation. Deeply embedded in all of Tan’s works is her fascination with the mutability of identity, the deceptive nature of representation and the play of memory across time and space in a world increasingly shaped by global culture. She investigates how we represent ourselves and the mechanisms that determine how we interpret the representation of others. …

A testament to Tan’s passion for archives, her video installation Pickpockets (2020) stems from an album of photographs she came across when in residence at the Getty Research Center, Los Angeles. It contained early examples of mugshots taken of pickpockets apprehended at the World’s Fair in Paris in 1889. Fascinated by the subjects of these portraits, their names and countries of origin, and their unknown stories, she invited a group of writers to devise monologues from the point of view of these individuals, which were then performed and recorded by actors.

Anonymous. “Fiona Tan,” on the Frith Street Gallery website Nd [Online] Cited 29/04/2024

[The identity section] has “Affaire Alaux, Faubourg St. Honoré – L’Assassin” (Nov. 2, 1902), a print by Alphonse Bertillon, the inventor of the mug shot, showing the mustached villain full-face and in profile; it is accompanied by over 20 pictures of sites that played a significant role in Bertillon’s life taken in 2012 by Stéphanie Solinas employing a “crime scene” approach.

William Meyers. “Photography’s Past and Present at the Getty Center,” on The Wall Street Journal website May 29, 2024 [Online] Cited 16/06/2024

At left, Attributed to Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914) Affaire Alaux, Faubourg St. Honoré – L’Assassin November 2, 1902; and at right, Stéphanie Solinas (French, b. 1978) Untitled (M. Bertillon) – Two Faces 2012

Identity

As is still the case today, the most popular subjects for the camera in the nineteenth century were people. Early commercial portrait photographers set up studios and established standards for posing and props, serving clients who eagerly shared these prized images with family and friends. Other portraits of the time, however, such as the mug shot and studies of female “hysterics,” reinforced questionable forms of objectification. Paul Mpagi Sepuya and Myra Greene respond to the complex history of photographic portraiture. Fiona Tan, Laura Larson, and Stéphanie Solinas investigate the nineteenth century pseudosciences that relied on the perceived accuracy of the new medium.

Attributed to Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853-1914)

Affaire Alaux, Faubourg St. Honoré – L’Assassin

November 2, 1902

Gelatin silver print

Image: 7.9 × 12.7cm (3 1/8 × 5 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

The mugshot of Henri-Léon Scheffer, the man who murdered Joseph Reibel.

CAUGHT BY A FINGER PRINT

A unique piece of detective work has been accomplished in Paris by a retiring scientist. A mysterious murder had been committed. The detectives arrested one wrong man dis charged him, and were preparing .to arrest another when to their chief came the quiet scientist, saying,

“The assassin’s name is Henri Léon Scheffor. Here is his photograph, his description and past record.” M. Cochefert, chief of the police hesitated. “My men know nothing of this person.” he said. “How shall we accuse him ?”

“Arrest him,” insisted the other, “and should he prove to innocent I will pay him 1,000 francs as an indemnity.”

“But what basis have you for your certainty of his guilt ?” asked M. Cochefert.

“Some finger prints he left on a piece of broken glass,” replied the man of science.

It was not necessary to pay the indemnity. He who was thus strangely accused was arrested and confessed his crime. The quiet man of science was M. Alphonse Bertillon, already celebrated as the founder and present chief of tho anthropometric service of tho Paris prefecture of police. Alphonse Bertillon has the gentle, weary smile of the over-worked and nervous student. He speaks mildly, moves softly, like one on his guard against strain and haste, until now and again, his thoughtful face will light up with enthusiasm as he lets himself go. Then his conversation becomes rapid and eloquent ; he runs through books and documents with ardour, pulls down boxes from high shelves, spreads out charts, explains them, performs experiments to illustrate his statements and darts back by a short cut to tho point where he had left off; tho whole man is transformed. Thus we heard the tale of the Accusing Finger Prints.

“A man named Joseph Reibel, porter to tho dentist Allaux, in his apartment and offices in the Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honore, was found choked to death and clumsily tied, lying in his master’s office,” began M. Bertillon. “The place had been looted hastily, closets and drawers being open and their contents tossed about. In particular a handsome cabinet holding a collection of coins was found with its glass door broken and its gold coins absent. There were- practically no clues to the identity of the assassin, the janitress at the street door, having a confused memory as to visitors, which set the detectives on more than one wrong scent. They arrested one man and the papers published his portrait. Then the newspapers at least began to suspect the innocent dentist himself.

“They had taken a flashlight photograph of the office,” continued M. Bertillon. “Looking at that photograph one day, I noticed two glittering little white marks on the edge of the broken glass of the coin cabinet. I asked my self what they could be. They might be defects in the printing ; but, on the other hand their situation suggested that they might be finger prints – and finger-prints are very much in my line ! The thought wore upon me until at last I jumped into a cab and drove to tho place. Examining the edge of the glass I found tho marks to be really finger-marks, and in spite of the thousand chances still in good condition.

“Being composed of tiny quantities of grease and dirt they made the glass slightly opaque, so that they came out bright by contrast in the photograph. Except when looked at in a favourable light they were practically invisible to the naked eye. There were marks of a right-hand thumb in one place and of the same thumb and four fingers in another. I had the two pieces of glass cut out with a diamond. I gave one to a policeman, instructing him to hold it just so, and saw him start off to my office with it in a cab. Then I gave tho other piece to a second policeman, with the same instructions, and started him off in a second cab, so that if an accident should happen to one of the pieces the other might be spared.

“In the workrooms of the anthropometric service I had the finger-marks immediately photographed. At first I admit I did not attach overmuch importance to them. They might be the prints of one of the detectives, or of the dentist Allaux – naturally solicitous of his broken cabinet – or even the finger-prints of M. Cochefert ! One by one I took their finger-prints for comparison. One by one I found that they did not at all correspond with those on the glass. This started me in earnest,” admitted M. Bertillon. “I began to ask myself, if among the thousands of criminals, swindlers and violent and suspicious characters photo-graphed, measured, and, finger-printed yearly by the anthropometric service the author of these finger-prints might not, at some time or other, himself have passed.” Here M. Bertillon called our attention to the thumb mark (“pouce”) of Scheffer, the assassin, Just below his full-face and profile photographs. Though small it was very distinct.

“Look at the central point of that thumb-print,” he exclaimed. “Look where the innermost loop moves up and over a single diagonal. Now jumping two loops from that interior diagonal, towards tho direct left you see a plain little fork in tho third loop. It is the exact reproduction of just such another in the thumb-mark on the broken glass ! Tho next thing was to arrest Scheffer though it took a little time to find him. Here, again, the information obtainable from his ‘fiche’ in the anthropometric service rendered service. It was seen that he had been a native of Aubervilliers (the Paris suburb and had worked in the government match factory. When arrested he confessed, at the same time trying to make out a case of extenuating circumstances. According to his story, Reibel planned that they should simulate a burglary of his master’s premises. They quarrelled over the division of the spoils and Scheffer says he thought he had merely choked his friend into un-consciousness and left him tied – according to original agreement. And all discovered through an accidental finger-print which the assassin had left as an index to the crime. “Science Siftings.”

Anonymous. “Caught by a Finger Print,” in the Balmain Observer and Western Suburbs Advertiser (NSW: 1884-1907), Sat 4 Mar 1905, Page 2 on the Trove website [Online] Cited 29/04/2024

__________________________________________

Time

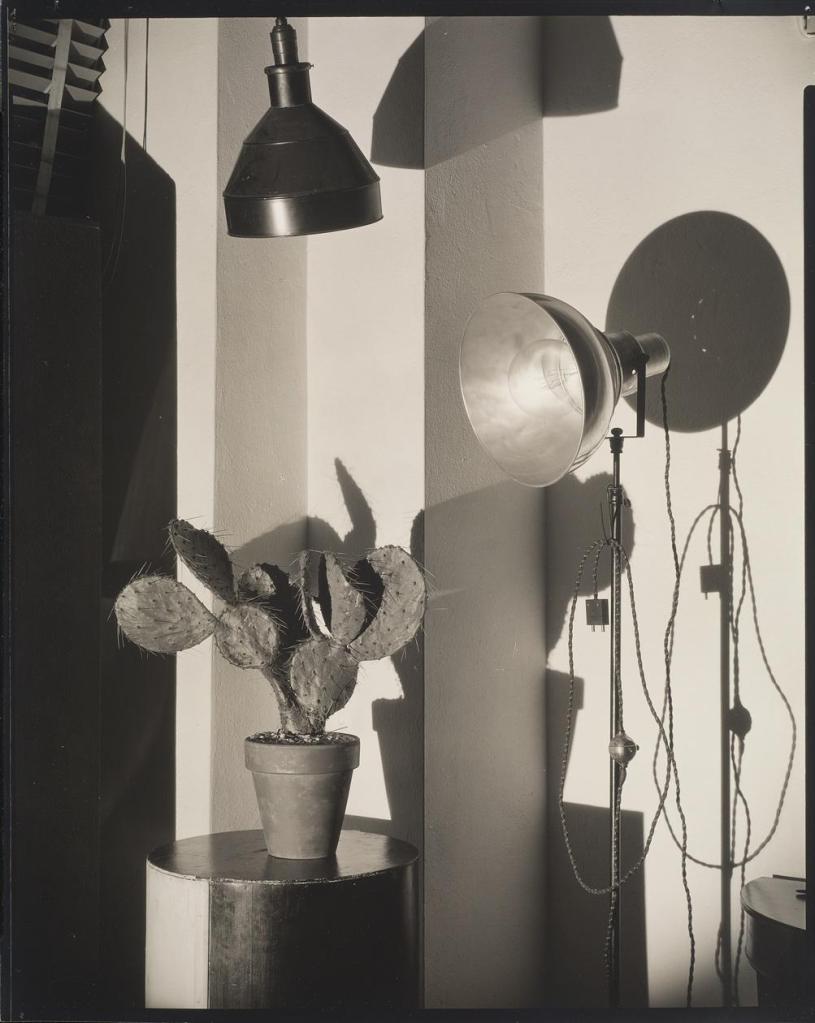

Gustave Le Gray (French, 1820-1884)

An Effect of Sunlight – Ocean No. 23

1857-1858

Albumen silver print from glass negatives

12 5/8 × 16 7/16 in.

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Lisa Oppenheim (American, b. 1975)

An Effect of Sunlight – Ocean No. 23 (1857/2019)

2019

Gelatin silver print, exposed to sunlight and toned with silver

Framed [Outer Dim]: 35.6 × 47.7 × 3.7cm (14 × 18 3/4 × 1 7/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© Lisa Oppenheim

Time

Photography and time have been inextricably linked ever since early inventors such as William Henry Fox Talbot struggled to permanently fix a fleeting moment on a sheet of paper. The development of the camera coincided with new discoveries about how we perceive an instant in time or an object in motion, and people praised photography for its ability to “stop time” and record what the unaided eye could not see. Lisa Oppenheim and Liz Deschenes respond to nineteenth century photographers’ technical innovations and the ways in which the medium affects our perception of time. Phil Chang and Hiroshi Sugimoto address the fate of photographs across minutes or even centuries.

At left, Étienne-Jules Marey (French, 1830-1904) and Michel Berthaud (French, active 1860s-1880s) Walking/Running (La Marche/La Course Rapide) about 1890, published 1893; and at right, Liz Deschenes (American, b. 1966) FPS (120) 2018-2021

Étienne-Jules Marey (French, 1830-1904) and Michel Berthaud (French, active 1860s-1880s)

Walking/Running (La Marche/La Course Rapide)

about 1890, published 1893

Collotype

Image: 11.3 × 17.6cm (4 7/16 × 6 15/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

__________________________________________

Spirit

At left, William H. Mumler (American, 1832-1884) Mrs. Swan 1869-1878; and at right, Khadija Saye (Gambian-British, b. 1992) Nak Bejjen [Cow’s Horn] 2017-2018

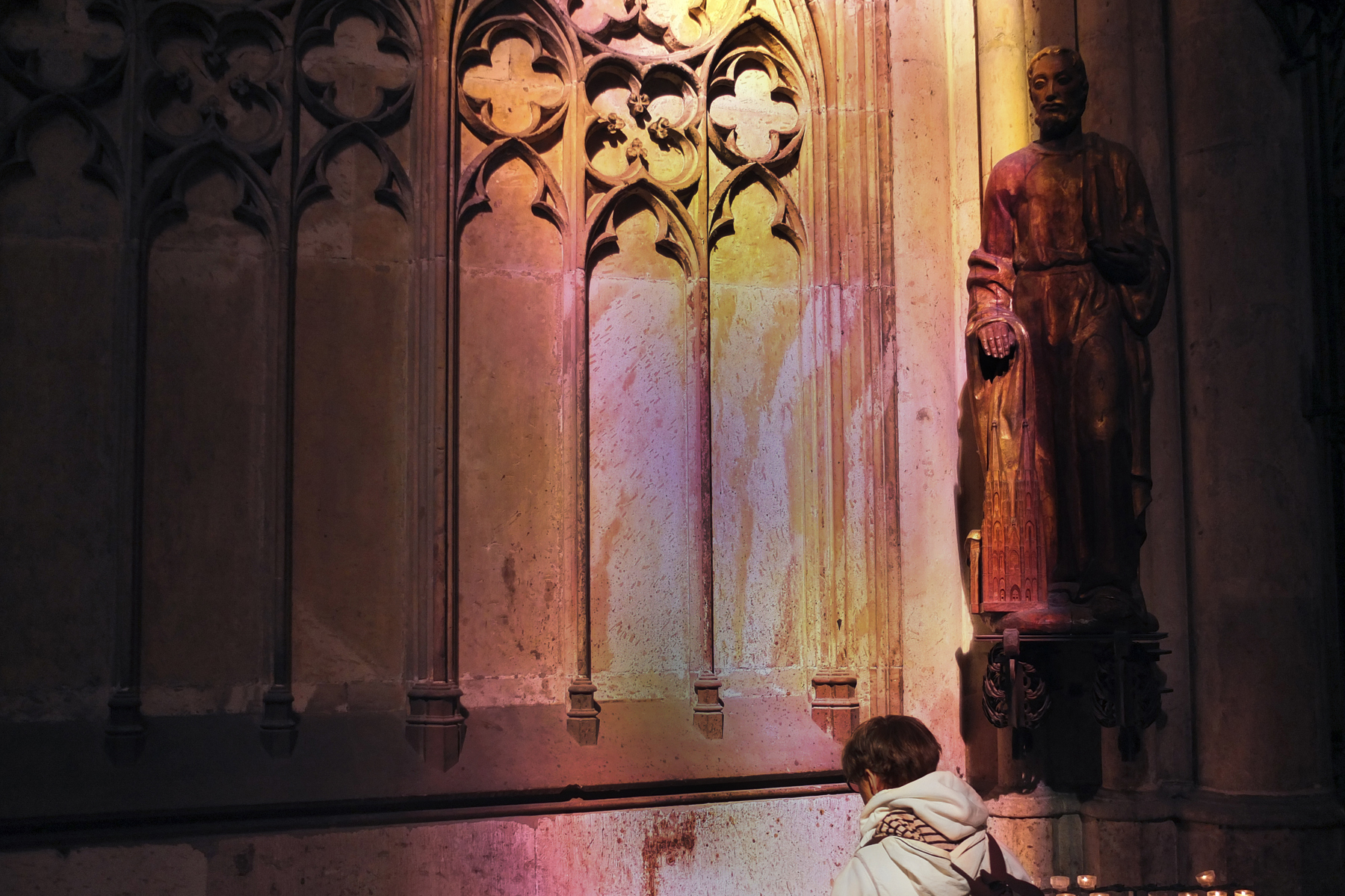

Spirit

The genre of spirit photography – which used photographic tricks to insert ghostly figures among the living – emerged during the nineteenth century from the Victorian obsession with death, séances, and mediums in Europe and North America and from the losses of the Civil War in the United States. Photographers exploited the ability to manipulate photographic images, employing multiple exposures and staged photography to create otherworldly scenes or to summon loved ones back from the dead. Khadija Saye and Lieko Shiga respond to the possibilities that spirit photography offers in rendering the unseen.

William H. Mumler (American, 1832-1884)

Mrs. Swan

1869-1878

Albumen silver print

Image: 8.9 × 5.7cm (3 1/2 × 2 1/4 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Public domain

Khadija Saye (Gambian-British, b. 1992)

Nak Bejjen [Cow’s Horn]

2017-2018

From the series in this space we breathe

Silkscreen print

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Purchased with funds provided by the Photographs Council

© Estate of Khadija Saye

At left, Unknown maker (American) [Seated Woman with “Spirit” of a Young Man] about 1865-1875; and at right, Lieko Shiga (Japanese, b. 1980) Talking with Me 2005 From the series Lilly

Unknown maker (American)

[Seated Woman with “Spirit” of a Young Man]

about 1865-1875

Tintype

Image: 8.7 × 6.4cm (3 7/16 × 2 1/2 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Lieko Shiga (Japanese, b. 1980)

Talking with Me

2005

From the series Lilly

‘Lilly’ is a photographic essay that was initiated in 2005 when Lieko Shiga was living in London. During that period she produced a series of images of her neighbours that lived alongside her in a block of East London council flats, drawing techniques and inspiration from paranormal photographs that were popular in the early days of photography. Haunting, mysterious, playful and captured in an array of muted colours, the photographs [are] grouped around different subjects…

Publisher’s Description

__________________________________________

Landscape

At left, Roger Fenton (English, 1819-1869) Plateau of Sebastopol II 1855; and at right, An-My Lê (Vietnamese American, b. 1960) Security and Stabilization Operations, Iraqi Police 2003-2004

Roger Fenton (English, 1819-1869)

Plateau of Sebastopol II

1855

Albumen silver print

Image: 22.2 × 34.4cm (8 3/4 × 13 9/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Public domain

An-My Lê (Vietnamese American, b. 1960)

Security and Stabilization Operations, Iraqi Police

2003-2004

From the series 29 Palms

Gelatin silver print

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery

© An-My Lê

Landscape

Nineteenth-century photographers went to great lengths to make images of remote landscapes, which required traveling with large format cameras, glass plates, and chemicals. Ideological forces drove many of these journeys, with the ultimate goal of imperial expansion through industrial development and war. Government sponsored surveys and expeditionary programs employed the camera to justify the expansion and to record the resulting military conflicts. Mark Ruwedel, Michelle Stuart, and An-My Lê re-envision some of these same historical landscapes and offer up new ones that bring the past closer to our present.

At left, Timothy O’Sullivan (American, about 1840-1882) Desert Sand Hills Near Sink of Carson, Nevada 1867; and at right, Michelle Stuart (American, b. 1933) Timeless Land 2021

Timothy O’Sullivan (American, about 1840-1882)

Desert Sand Hills Near Sink of Carson, Nevada

1867

Albumen silver print

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Public domain

Timothy O’Sullivan’s darkroom wagon, pulled by four mules, entered the frame at the right side of the photograph, reached the center of the image, and abruptly U-turned, heading back out of the frame. Footprints leading from the wagon toward the camera reveal the photographer’s path. Made at the Carson Sink in Nevada, this image of shifting sand dunes reveals the patterns of tracks recently reconfigured by the wind. The wagon’s striking presence in this otherwise barren scene dramatises the pioneering experience of exploration and discovery in the wide, uncharted landscapes of the American West.

O’Sullivan’s photographs from the 1867 Geological Exploration of the Fortieth Parallel expedition were intended to provide information for the purpose of expanding railroads and industry, yet they demonstrate his eye for poetic beauty.

Text from the J. Paul Getty Museum website

Michelle Stuart (American, b. 1933)

Timeless Land

2021

Ambrotypes

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Purchased with funds provided by the Photographs Council

© Michelle Stuart

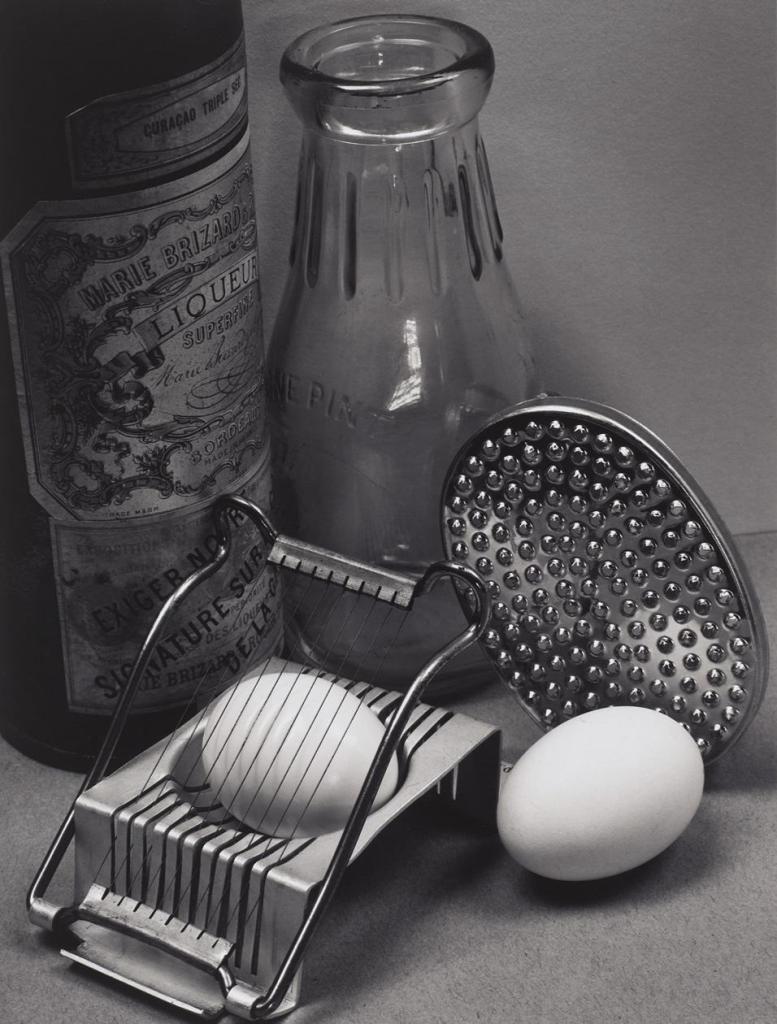

A.J. Russell (American, 1830-1902)

Embankment No. 3 West of Granite Cannon [Wyoming]

April 1868

Albumen silver print

Image: 21.9 × 29.4 cm (8 5/8 × 11 9/16 in.)

Mount: 34.1 × 43.1 cm (13 7/16 × 16 15/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Mark Ruwedel (American/Canadian, b. 1954)

Union Pacific #67 (after A.J. Russell)

1996

Gelatin silver print

Image: 18.9 × 23.9cm (7 7/16 × 9 7/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© Mark Ruwedel

Mark Ruwedel’s statement in a wall text notes that “The legacy of nineteenth-century expeditionary photography was most important to me when working on my Westward series.” He cites Timothy O’Sullivan, Alexander Gardner and A.J. Russell. The Landscape section has a print by A.J. Russell, “Embankment No. 3 West of Granite Cannon. [Wyoming]” (April 1868), and seven pictures by Mr. Ruwedel: “Union Pacific #39 (After A.J. Russell)” and “Union Pacific #67 (After A.J. Russell)” (1994 and 1996, respectively) and five others with no specific acknowledgments but clearly influenced by his 19th-century mentors.

William Meyers. “Photography’s Past and Present at the Getty Center,” on The Wall Street Journal website May 29, 2024 [Online] Cited 16/06/2024

At left, Carleton Watkins (American, 1829-1916) Cathedral Spires – Yo Semite 1861; and at right, Ken Gonzales-Day (American, b. 1964) At daylight the miserable man was carried to an oak… Negative 2002; print 2021

Carleton Watkins (American, 1829-1916)

Cathedral Spires – Yo Semite

1861

Albumen silver print

Image (Dome-Topped): 52.2 × 40.3cm (20 9/16 × 15 7/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

When Carleton Watkins photographed the remote Yosemite wilderness, America was not yet a century old. Conscious of their country’s lack of a national cultural identity, Americans adopted particularly dramatic geologic formations such as Cathedral Spires as their version of ancient ruins and soaring Gothic churches. The great pine tree in the foreground here became another form of this uniquely American history. Watkins’s images helped define America’s preference for landscape views depicting rugged wilderness and celebrating spectacular landforms on the grandest of scales.

Ken Gonzales-Day (American, b. 1964)

At daylight the miserable man was carried to an oak…

Negative 2002; print 2021

From the series Searching for California’s Hang Trees

Pigment print

Image: 92.7 × 117.5cm (36 1/2 × 46 1/4 in.)

© Ken Gonzales-Day

This print: Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase through the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment

Through meticulous research, Gonzales-Day documented approximately 350 lynching incidents that occurred in California between 1850 and 1935, most of which involved victims of Mexican descent. To create the series Searching for California Hang Trees, the artist visited many of these sites and captured the likeness of trees that may have borne witness to these events. Gonzales-Day’s landscapes unearth traces of this little-known history.

Our America: The Latino Presence in American Art, 2013

__________________________________________

Circulation

Charles M. Bell (American, 1848-1893)

Manulitó, Chief of the Navajos

1874

Albumen silver print

Image (Arched): 18.4 × 14.9cm (7 1/4 × 5 7/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Public domain

Wendy Red Star (American/Apsáalooke, b. 1981)

Peelatchiwaaxpáash / Medicine Crow (Raven)

2014

From the series Crow Peace Delegation

Inkjet print

Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University

Museum purchase with funds provided by Jennifer McCracken New and Jason G. New

© Wendy Red Star

Image courtesy of the Nasher Museum of Art

Artist-manipulated digitally reproduced photograph by C.M. (Charles Milton) Bell, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution, 24 x 16 9/20 inches

Circulation

By the middle of the nineteenth century, thousands of photographs were in circulation worldwide, the result of photographers’ ability to reproduce the same image multiple times. Pictures of historical events, tourist destinations, and anthropological expeditions made the world seem more accessible, but with time and distance, they became disconnected from their original contexts. Many eventually ended up in archives (including at Getty). Early photographs appear next to projects that make these historical absences present. Wendy Red Star, Stephanie Syjuco, Ken Gonzales-Day, and Andrea Chung recover what has been lost, calling out the residual effects of the nineteenth-century photograph on our present knowledge of global cultures and histories.

Text from the J. Paul Getty Museum

At left, Anna Atkins (British, 1799-1871) possibly with Anne Dixon (British, 1799-1877) Ceylon/Fern about 1854; and at right, Andrea Chung (American, b. 1978) Untitled 2016

Anna Atkins (British, 1799-1871) possibly with Anne Dixon (British, 1799-1877)

Ceylon/Fern

about 1854

Cyanotype

Image: 34.8 × 24.7cm (13 11/16 × 9 3/4 in.)

Sheet: 48.3 × 37.5cm (19 × 14 3/4 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Public domain

Cyanotypes of British and Foreign Flowering Plants

After completing the highly ambitious, decade-long project Photographs of Blue Algae: Cyanotype Impressions in the summer of 1853, Anna Atkins turned to new botanical subjects. She would eventually produce several unique presentation albums with cyanotypes of ferns and flowering plants. Atkins most likely collaborated on these albums with her dear friend, Anne Dixon. Dixon came to Halstead Place for an extended stay in the summer of 1852 to comfort Atkins who was deeply shaken by the death of her father and frequent scientific partner John George Children earlier that year. Photo historian Larry Schaaf suggests that it was during this stay or perhaps one the next summer that Dixon began assisting Atkins and creating her own cyanotypes. Thus, it becomes difficult to know whether surviving works from this time period were created by Atkins, Dixon, or both.1

These seven pieces in the J. Paul Getty Museum Collection (figs. 1-7) were extracted from an 1854 presentation album Cyanotypes of British and Foreign Flowering Plants given by Anna Atkins to Anne Dixon in 1854. The album remained intact until sometime around 1981, when it was broken up after being sold at auction.

Atkins and Dixon shared a deep interest in botany, a science that was considered well suited to women since it could be studied locally, even in one’s own garden. Serious “lady botanists” could join the Botanical Society in London, one of the first scientific organisations to admit women. Atkins joined in 1839. The two friends’ interest in botany is documented in a letter of 1851 from Children to Sir William Hooker in which he discussed the two women’s longtime plant collecting. Later, in a letter that Atkins wrote to Hooker in 1864, she extended an offer from Dixon to send him samples of any of the plants from her own collection.2

Carolyn Peter, J. Paul Getty Museum, Department of Photographs

2019

© J. Paul Getty Trust

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

1/ Larry Schaaf, Sun Gardens: Cyanotypes by Anna Atkins (New York: The New York Public Library, 2018), 77

2/ Ibid, 80

Andrea Chung (American, b. 1978)

Untitled

2016

From the series Anthropocene

Cyanotypes

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© Andrea Chung

Anna Atkins was a 19th-century botanist who documented plant specimens to make the world’s first photo book.

Today, artist Andrea Chung makes images of lionfish. Invasive to the Caribbean, they stand as a metaphor for the impact of colonisation in the region.

Text and photograph from the Getty Museum X web page

The J. Paul Getty Museum

1200 Getty Center Drive

Los Angeles, California 90049

Opening hours:

Daily 10am – 5pm

![William Henry Fox Talbot (English, 1800-1877) '[A Stem of Delicate Leaves of an Umbrellifer]' probably 1843-1846 William Henry Fox Talbot (English, 1800-1877) '[A Stem of Delicate Leaves of an Umbrellifer]' probably 1843-1846](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/talbot-a-stem-of-delicate-leaves-of-an-umbrellifer.jpg?w=650&h=779)

![At left, Herbert Bell et al, '[Amateur World Tour Album, taken with early Kodak cameras, plus purchased travel photographs by various photographers]' (2 page spread); and at right, Stephanie Syjuco (American born Philippines, b. 1974) 'Herbaria' 2021 (detail) At left, Herbert Bell et al, '[Amateur World Tour Album, taken with early Kodak cameras, plus purchased travel photographs by various photographers]' (2 page spread); and at right, Stephanie Syjuco (American born Philippines, b. 1974) 'Herbaria' 2021 (detail)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/bell-and-syjuco-herbaria.jpg?w=840&h=380)

![Herbert Bell (English, 1856-1946) Frederick Nutt Broderick (English, about 1854-1913) Gustave Hermans (Belgian, 1856-1934) Anthony Horner (English, 1853-1923) Michael Horner (English, 1843-1869) C. W. J. Johnson (American, 1833-1903) Léon & Lévy (French, active 1864-1913 or 1920) Léopold Louis Mercier (French, b. 1866) Neurdein Frères (French, founded 1860s, dissolved 1918) Louis Parnard (French, 1840-1893) Alfred Pettitt (English, 1820-1880) Francis Godolphin Osborne Stuart (British born Scotland, 1843-1923) Unknown maker Valentine & Sons (Scottish, founded 1851, dissolved 1910) L. P. Vallée (Canadian, 1837-1905) York and Son J. Kühn (French, active Paris, France 1885 - early 20th century) '[Amateur World Tour Album, taken with early Kodak cameras, plus purchased travel photographs by various photographers]' (2 page spread) Herbert Bell (English, 1856-1946) Frederick Nutt Broderick (English, about 1854-1913) Gustave Hermans (Belgian, 1856-1934) Anthony Horner (English, 1853-1923) Michael Horner (English, 1843-1869) C. W. J. Johnson (American, 1833-1903) Léon & Lévy (French, active 1864-1913 or 1920) Léopold Louis Mercier (French, b. 1866) Neurdein Frères (French, founded 1860s, dissolved 1918) Louis Parnard (French, 1840-1893) Alfred Pettitt (English, 1820-1880) Francis Godolphin Osborne Stuart (British born Scotland, 1843-1923) Unknown maker Valentine & Sons (Scottish, founded 1851, dissolved 1910) L. P. Vallée (Canadian, 1837-1905) York and Son J. Kühn (French, active Paris, France 1885 - early 20th century) '[Amateur World Tour Album, taken with early Kodak cameras, plus purchased travel photographs by various photographers]' (2 page spread)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/amateur-world-tour-album.jpg?w=840&h=578)

![At left, William H. Mumler (American, 1832-1884) 'Mrs. Swan' 1869-1878; and at right, Khadija Saye (Gambian-British, b. 1992) 'Nak Bejjen' [Cow's Horn] 2017-2018 At left, William H. Mumler (American, 1832-1884) 'Mrs. Swan' 1869-1878; and at right, Khadija Saye (Gambian-British, b. 1992) 'Nak Bejjen' [Cow's Horn] 2017-2018](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/mumler-mrs.-swan-and-saye-nak-bejjen.jpg)

![Khadija Saye (Gambian-British, b. 1992) 'Nak Bejjen' [Cow's Horn] 2017-2018 Khadija Saye (Gambian-British, b. 1992) 'Nak Bejjen' [Cow's Horn] 2017-2018](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/saye-nak-bejjen.jpg?w=650&h=809)

![At left, Unknown maker (American) '[Seated Woman with "Spirit" of a Young Man]' about 1865-1875; and at right, Lieko Shiga (Japanese, b. 1980) 'Talking with Me' 2005 From the series 'Lilly' At left, Unknown maker (American) '[Seated Woman with "Spirit" of a Young Man]' about 1865-1875; and at right, Lieko Shiga (Japanese, b. 1980) 'Talking with Me' 2005 From the series 'Lilly'](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/seated-woman-and-shiga-talking-with-me.jpg?w=840&h=374)

![Unknown maker (American) '[Seated Woman with "Spirit" of a Young Man]' about 1865-1875 Unknown maker (American) '[Seated Woman with "Spirit" of a Young Man]' about 1865-1875](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/seated-woman-with-spirit.jpg?w=650&h=839)

![A.J. Russell (American, 1830-1902) 'Embankment No. 3 West of Granite Cannon [Wyoming]' April 1868 A.J. Russell (American, 1830-1902) 'Embankment No. 3 West of Granite Cannon [Wyoming]' April 1868](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/russell-embankment-no.-3-west-of-granite-cannon.jpg?w=840&h=671)

You must be logged in to post a comment.