Exhibition dates: 8th July – 19th October 2014

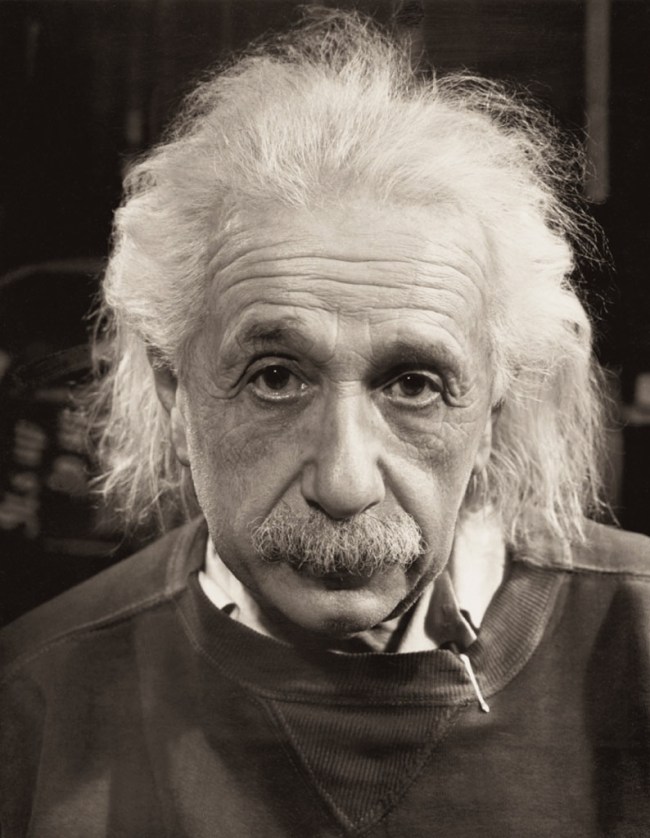

Curator: Paul Martineau is associate curator in the Department of Photographs at the J. Paul Getty Museum.

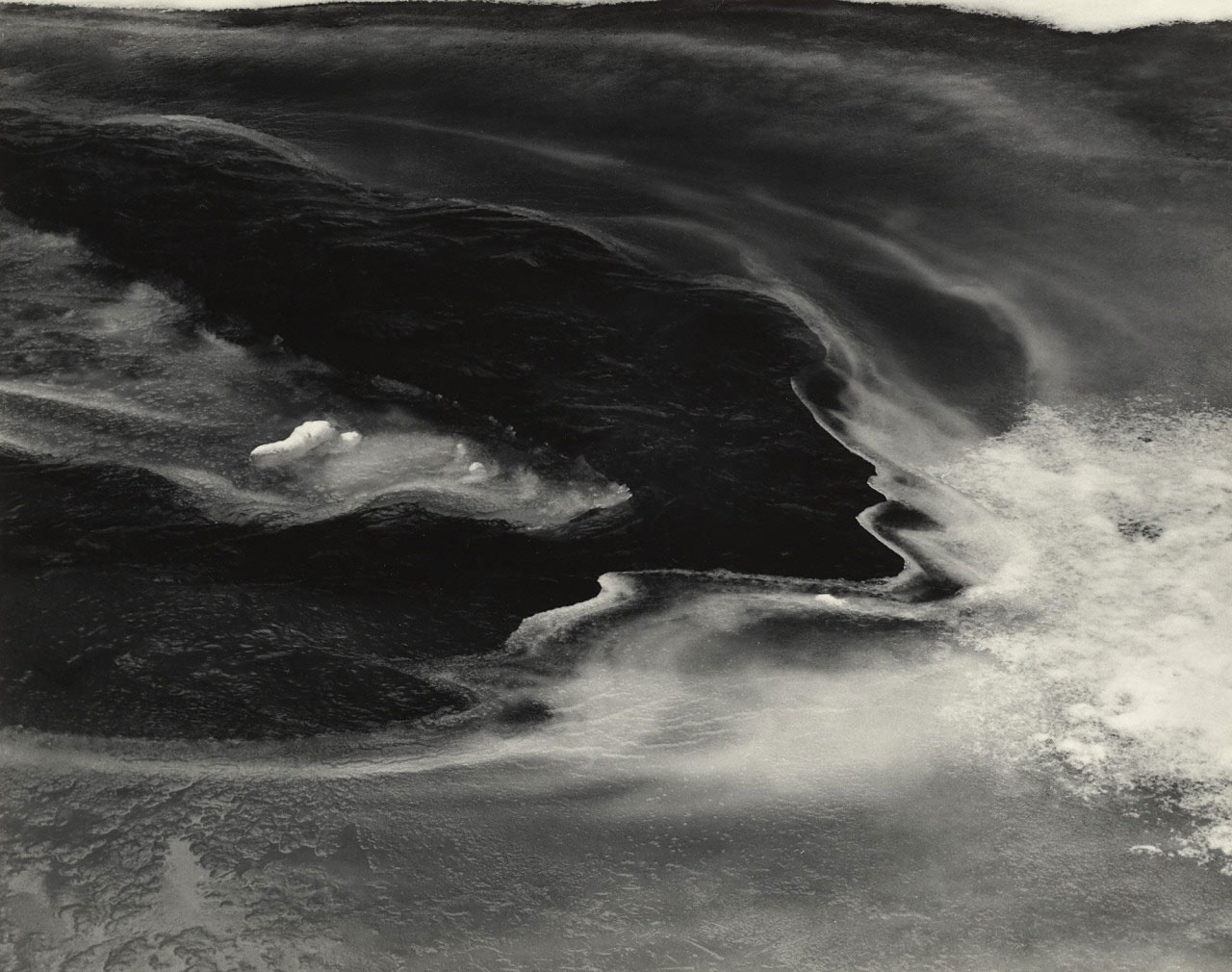

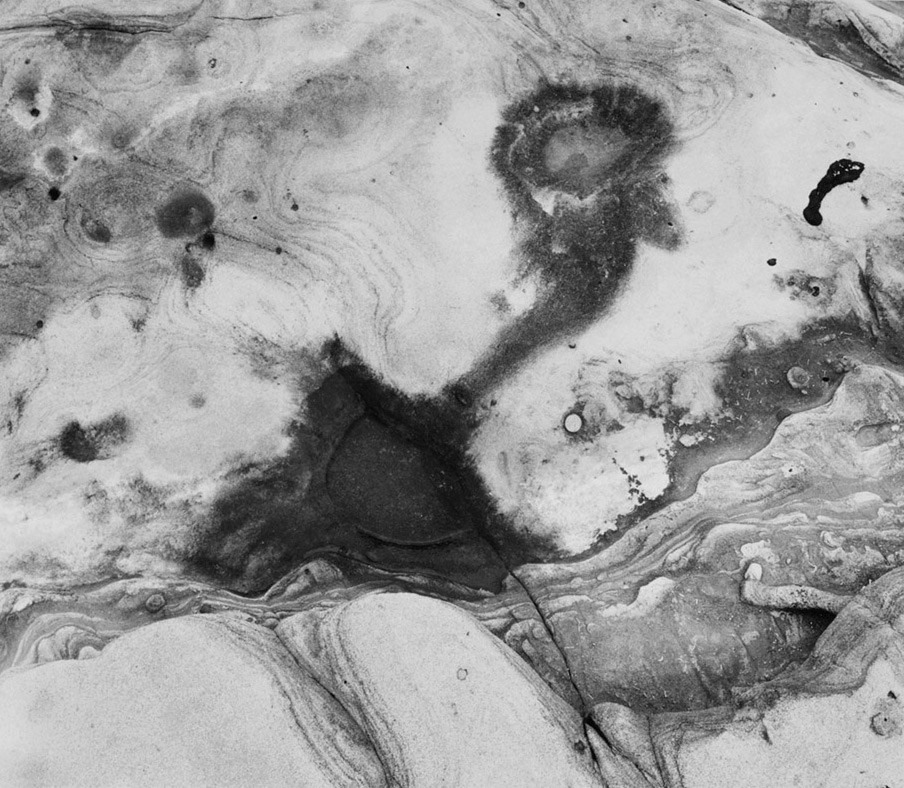

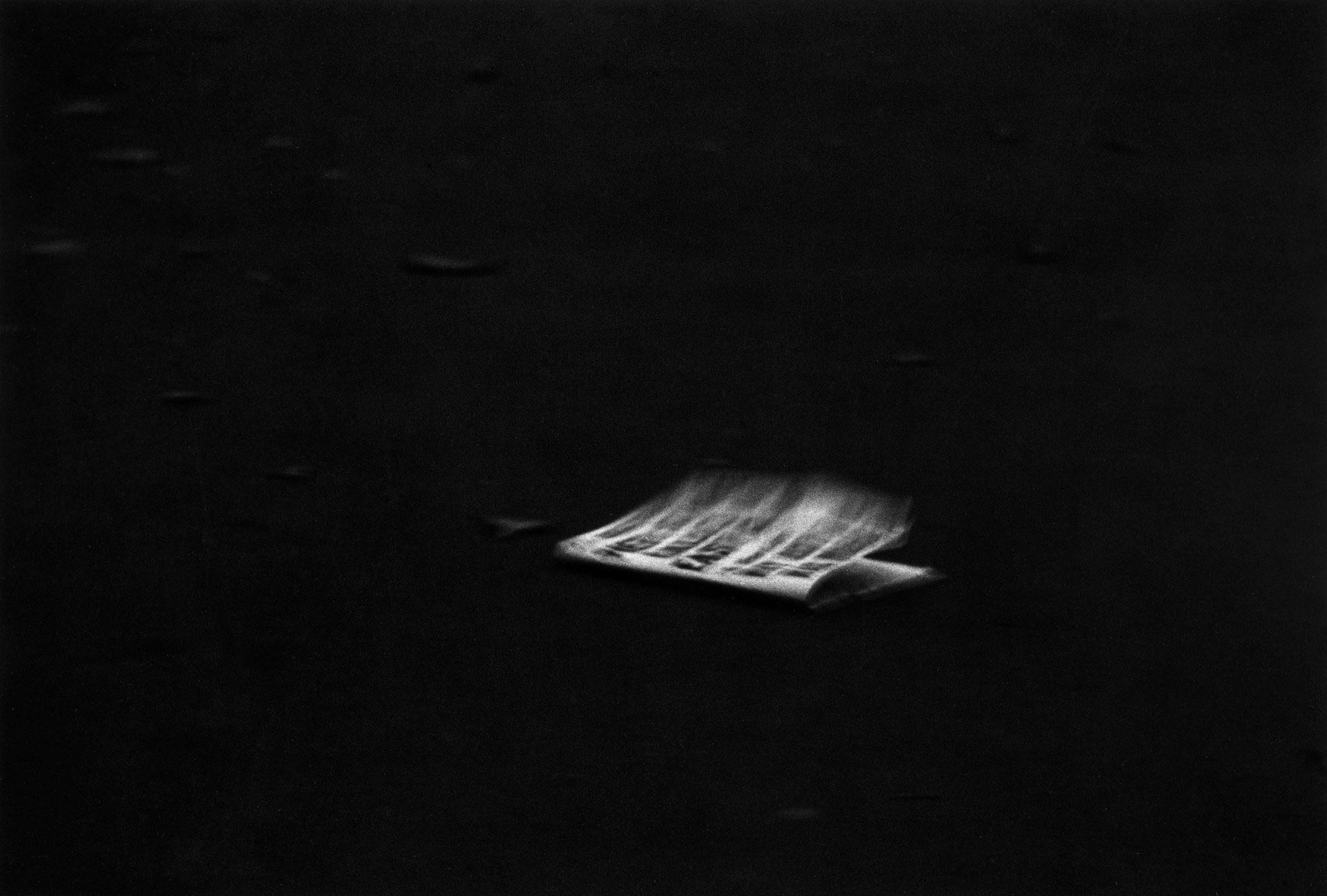

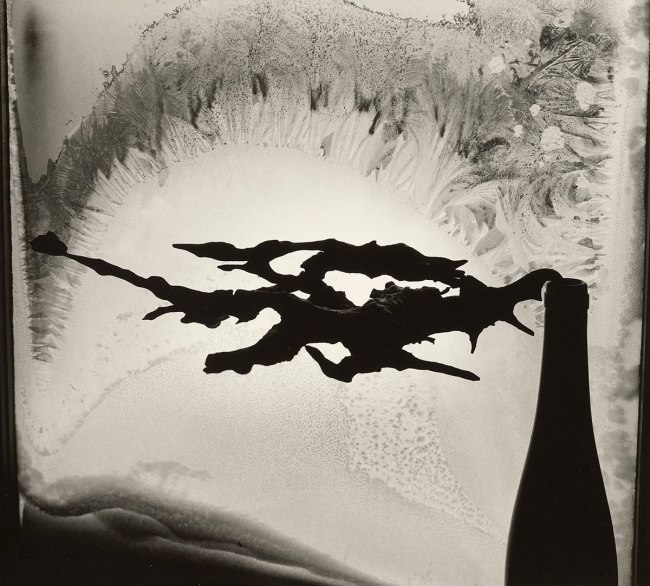

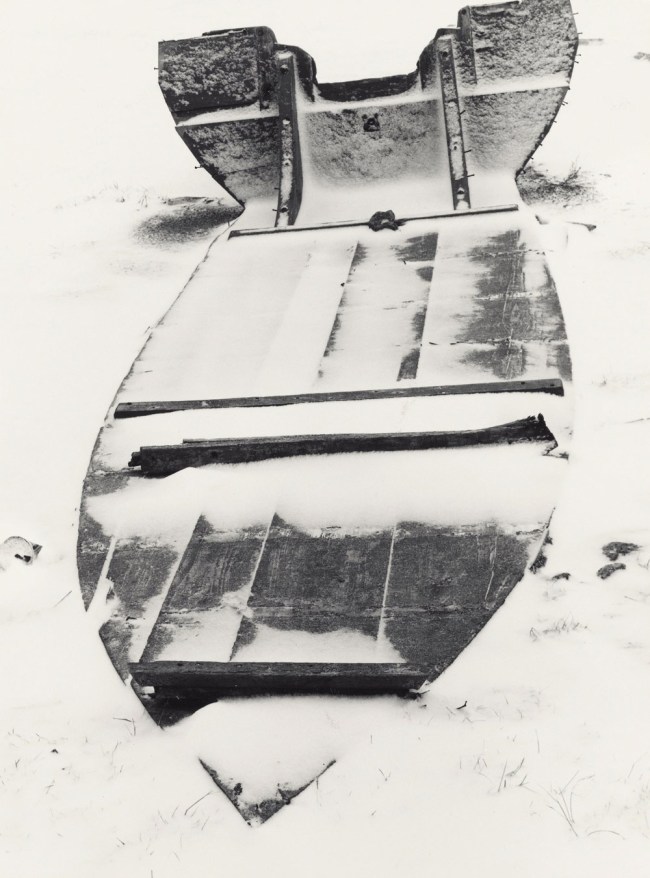

Minor White (American, 1908-1976)

Vicinity of Rochester, New York

1954

Gelatin silver print

18.4 x 23.2cm (7 1/4 x 9 1/8 in.)

Promised gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced with permission of the Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum

© Trustees of Princeton University

Never the objective camera, always a mixture of spirit and emotion

Minor White and Eugène Atget. Eugène Atget and Minor White. These two photographers were my heroes when I first started studying photography in the early 1990s. They remain so today. Nothing anyone can say can take away from the sheer simple pleasure of really looking at photographs by these two icons of the art form.

I have waited six years to do a posting on the work of Minor White, and this exhibition is the first major retrospective of White’s work since 1989. This posting contains thirty seven images, one of the biggest collections of his photographs available on the web.

What drew me to his work all those years ago? I think it was his clarity of vision that so enthralled me, that showed me what is possible – with previsualisation, clear seeing, feeling and thinking – when exposing a photograph. And that exposing is really an exposing of the Self.

Developing the concept of Steiglitz’s ‘equivalents’ (where a photograph can stand for an/other state of being), White “sought to access, and have connection to, fundamental truths… Studying Zen Buddhism, Gurdjieff and astrology, White believed in the photographs’ connection to the subject he was photographing and the subject’s connection back via the camera to the photographer forming a holistic circle. When, in meditation, this connection was open he would then expose the negative in the camera hopeful of a “revelation” of spirit in the subsequent photograph.” (MB) The capturing of these liminal moments in the flux of time and space is such a rare occurrence that one must be patient for the sublime to reveal itself, if only for a fraction of a second.

Although I cannot view this exhibition, I have seen the checklist of all the works in the exhibition. The selection is solid enough covering all the major periods in White’s long career. The book is also solid enough BUT BOTH EXHIBITION AND BOOK ARE NOT WHAT WE REALLY WANT TO SEE!

At first, Minor White photographed for the individual image – and then when he had a body of work together he would form a sequence. He seemed to be able to switch off the sequence idea until he felt “a storm was brewing” and his finished prints could be placed in another context. It was only with the later sequences that he photographed with a sequence in mind (of course there is also the glorious fold-out in The Eye That Shapes that is the Totemic sequence that is more a short session that became a sequence). In his maturity Minor White composed in sequences of images, like music, with the rise and fall of tonality and range, the juxtaposition of one image next to another, the juxtaposition of twenty or more images together to form compound meanings within a body of work. This is what we really need to see and are waiting to see: an exhibition and book titled: THE SEQUENCES OF MINOR WHITE. I hope in my lifetime! **

How can you really judge his work without understanding the very form that he wanted the work to be seen in? We can access individual images and seek to understand and feel them, but in MW their meaning remains contingent upon their relationship to the images that surround them, the ice/fire frisson of that space between images that guides the tensions and relations to each other. Using my knowledge as an artist and musician, I have sequenced the first seven images in this posting just to give you an idea of what a sequence of associations may look like using the photographs of Minor White. I hope he would be happy with my selection. I hope I have made them sing.

Other than a superb range of tones (for example, in Pavilion, New York 1957 between the flowers in shadow and sun – like an elegy to Edward Weston and the nautilus shell / pepper in the tin) the size, contrast, lighter/darker – warmer/cooler elements of MW’s photographs are all superb. These are the first things we look at when we technically critique prints from these simple criteria, and there aren’t many that pass. But these are all well made images by MW. He was never Diogenes with a camera, never the objective camera, he was always involved… and his images were printed with a mixture of spirit and emotion. Now, try and FEEL your response to the first seven images that I have put together. Don’t be too analytical, just try, with clear, peaceful mind and still body, to enter into the space of those images, to let them take you away to a place that we rarely allow ourselves to visit, a place that is is out of our normal realm of existence. It is possible, everything is possible. If photography becomes something else -then it does -then it does.

Finally, I want to address the review of the book by Blake Andrews on the photo-eye blog website (Blake Andrews. “Book Review: Manifestations of the Spirit,” on the photo-eye blog website October 6, 2014 [Online] Cited 26/06/2021). The opening statement opines: “Is photography in crisis again? Well then, it must be time for another Minor White retrospective.” What a thrown away line. As can be seen from the extract of an interview with MW (published 1977, below), White didn’t care what direction photography took because he could do nothing about it. He just accepted it for what it is and moved with it. He was not distressed at the direction of contemporary photography because it was all grist to the mill. To say that when photography is in crisis (it’s always in crisis!) you wheel out the work of Minor White to bring it back into line is just ridiculous… photography is -what it is, -what it is.

Blake continues, “Minor White was a jack-of-all-styles in the photo world, trying his hand at just about everything at one time or another. The plates in the book give a flavour of his shifting – some might say dilettantish – photo styles.” Obviously he agrees with this assessment otherwise he would not have put it in. I do not. Almost every artist in the world goes on a journey of discovery to find their voice, their metier, and that early experimentation is part of the overall journey, the personal and universal narrative that an artist pictures. Look at the early paintings of Jackson Pollock or Mark Rothko in their representational ease, or the early photographs of Aaron Siskind and how they progress from social documentary to abstract expressionism. The same with MW. In this sense every artist is a dilettante. Every photograph is part of his journey as an artist and has value in an of itself.

And I don’t believe that his mature voice was “internalised, messy, and deliberately obtuse,” – it is only so to those that do not understand what he sought to achieve through his images, those who don’t really understand his work.

Blake comments, “Twenty-five years later White’s star is rising again. One could speculate the reasons for the timing, that photography is in crisis, or at least adrift, and in need of a guru. But the truth is photography has been on the therapist’s couch since day one, going through this or that level of doubt or identity crisis. Is it an art? Science? Documentation? Can it be trusted? When Minor White came along none of these questions had been resolved, and they never will. But every quarter century or so it sure feels good to hang your philosopher’s hat on something solid. Or at least someone self-assured.”

Every quarter of a century, hang your philosophers hat on something solid? Or at least someone self-assured? The last thing that you would say about MW was that the was self-assured (his battles with depression, homosexuality, God, and the aftermath of his experiences during the Second World War); and the last thing that you would say about the philosophy and photographs of MW is that they are something solid and immovable.

For me, the man and his images are always moving, always in a constant state of flux, as avant-garde (in the sense of their accessing of the eternal) and as challenging and essential as they ever were. Through his work and writings Minor White – facilitator, enabler – allowed the viewer to become an active participant in an aesthetic experience that alters reality, creating an über reality (if you like), one whose aesthetics promotes an interrogation of both ourselves and the world in which we live.

“There are plays written on the simplest themes which in themselves are not interesting. But they are permeated by the eternal and he who feels this quality in them perceives that they are written for all eternity.” ~ Constantin Stanislavsky, (1863-1938) / My Life in Art.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

**The Minor White Archive at Princeton University Museum of Art has a project called The Minor White Archive proof cards: “The ultimate goal of this project is a stand-alone website dedicated to the Minor White Archive, and the completely scanned proof cards represent significant progress to this end. The website will be an authoritative source for the titles and dates of White’s photographs. All of the scanned proof cards will be available on the website so that users can search the primary source information as well as major published titles. Additionally, the website will include White’s major published sequences, with additional sequences uploaded gradually until the complete set is online. Eventually, the hope is to have subject-term browsing available, adding another access point to the Archive.”

Sarah Moore. “The Minor White Archive proof cards,” on the Princeton University Art Museum website 2014 [Online] Cited 26/06/2021

Many thankx to the J. Paul Getty Museum for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“Self-discovery through a camera? I am scared to look for fear of discovering how shallow my Self is! I will persist however … because the camera has its eye on the exterior world. Camera will lead my constant introspection back into the world. So camerawork will save my life.”

“When you try to photograph something for what it is, you have to go out of yourself, out of your way, to understand the object, its facts and essence. When you photograph things for what ‘Else’ they are, the object goes out of its way to understand you.”

Minor White

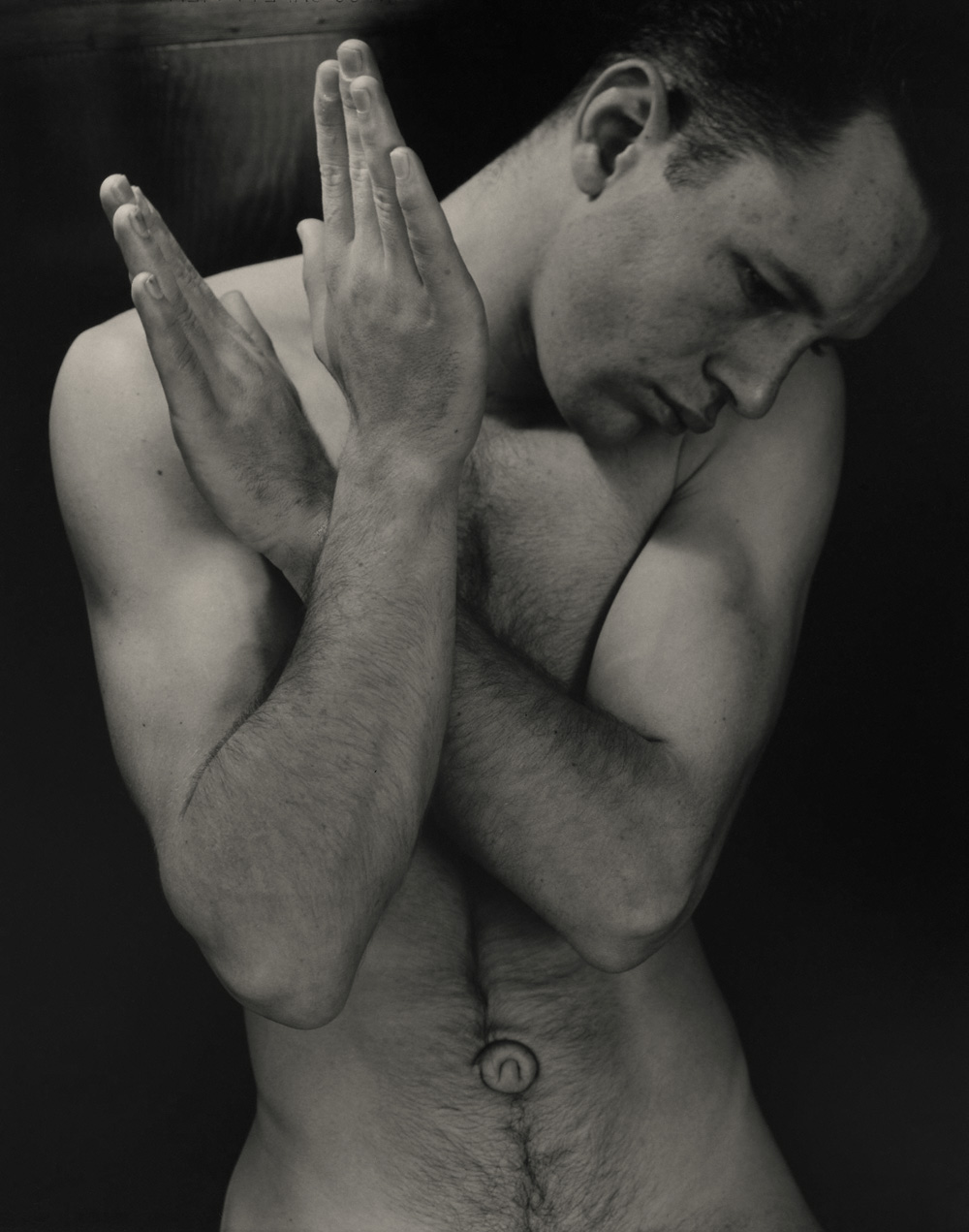

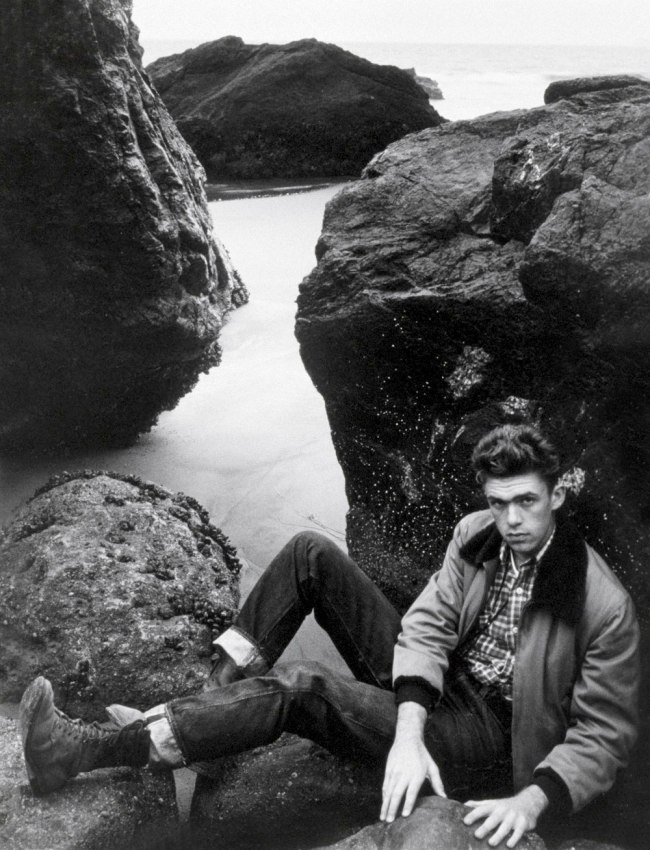

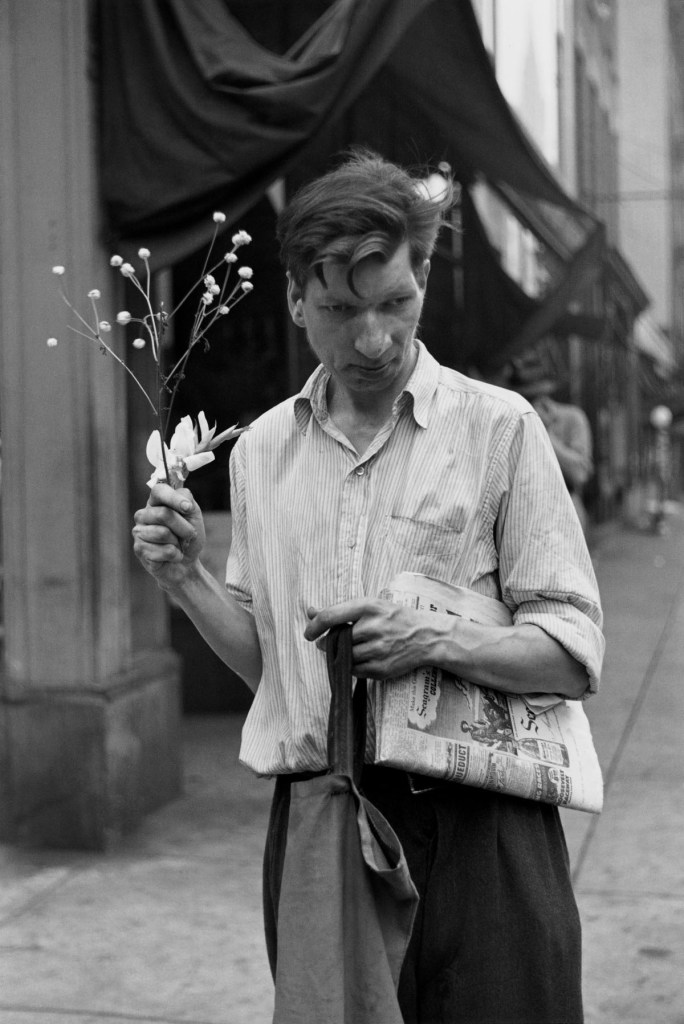

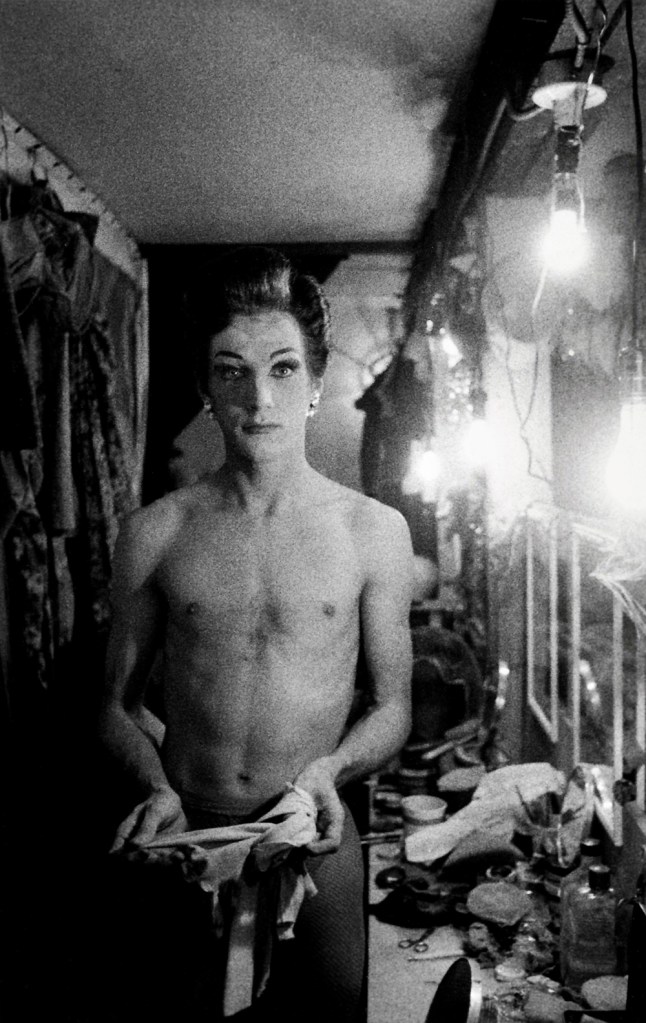

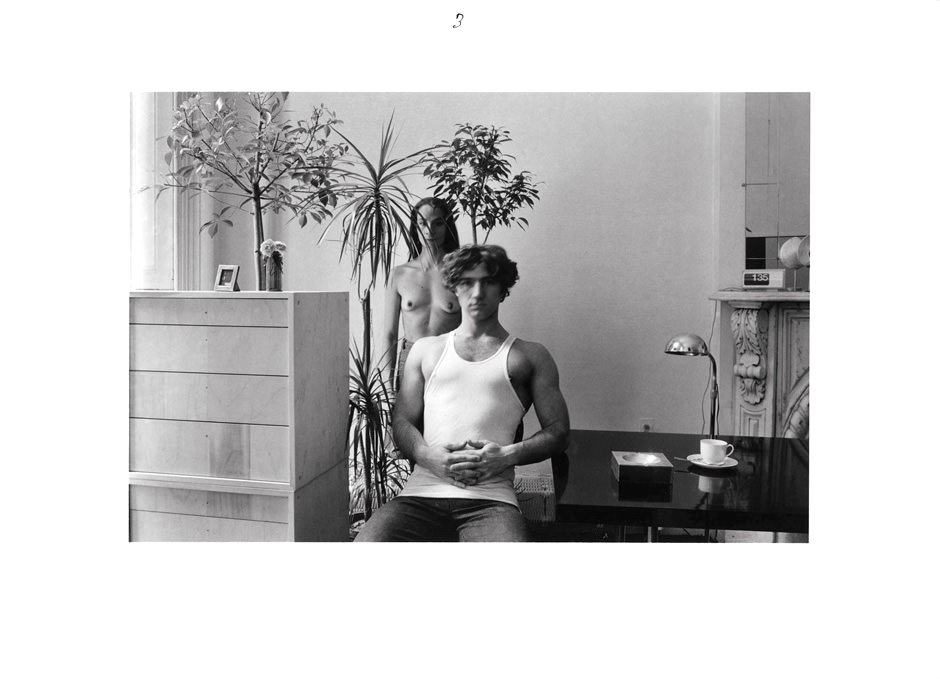

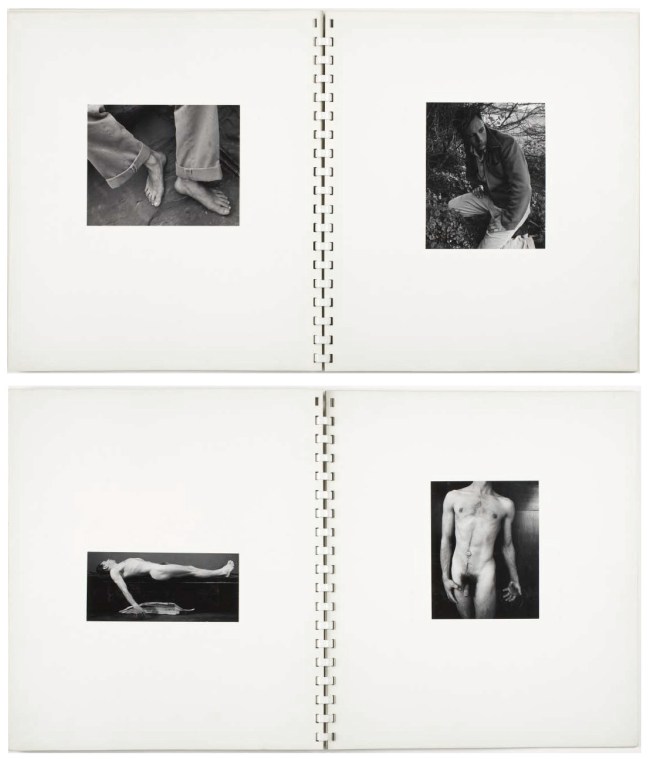

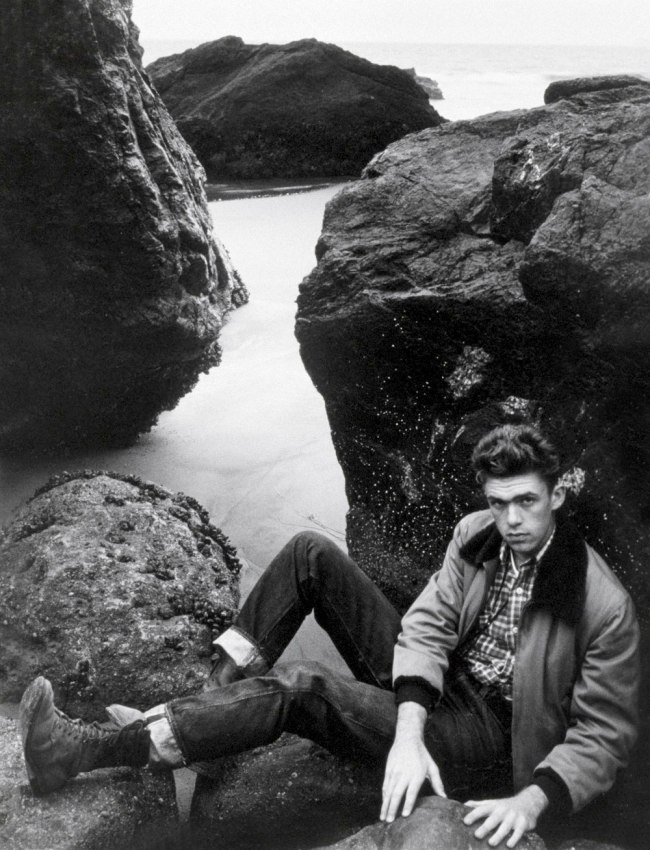

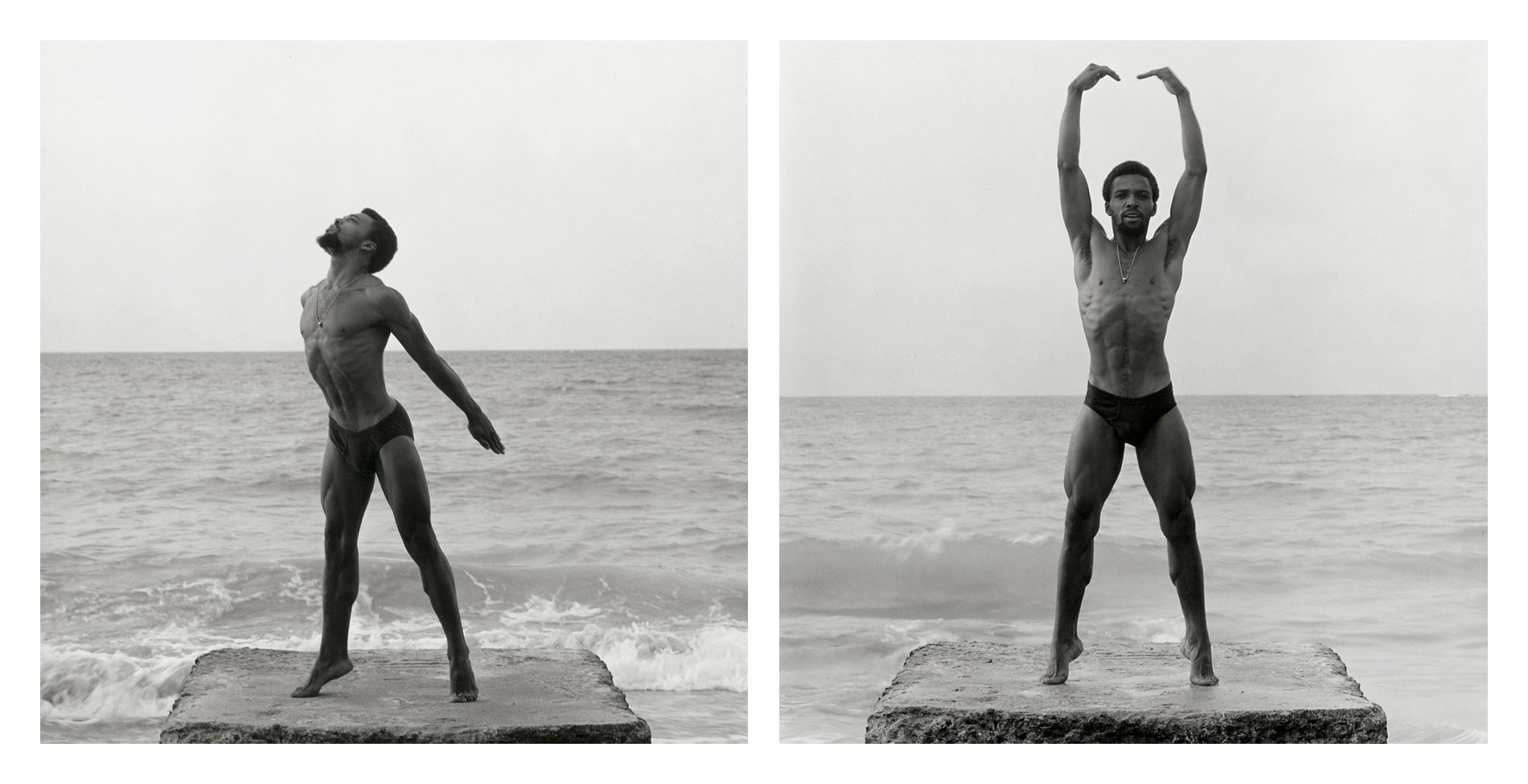

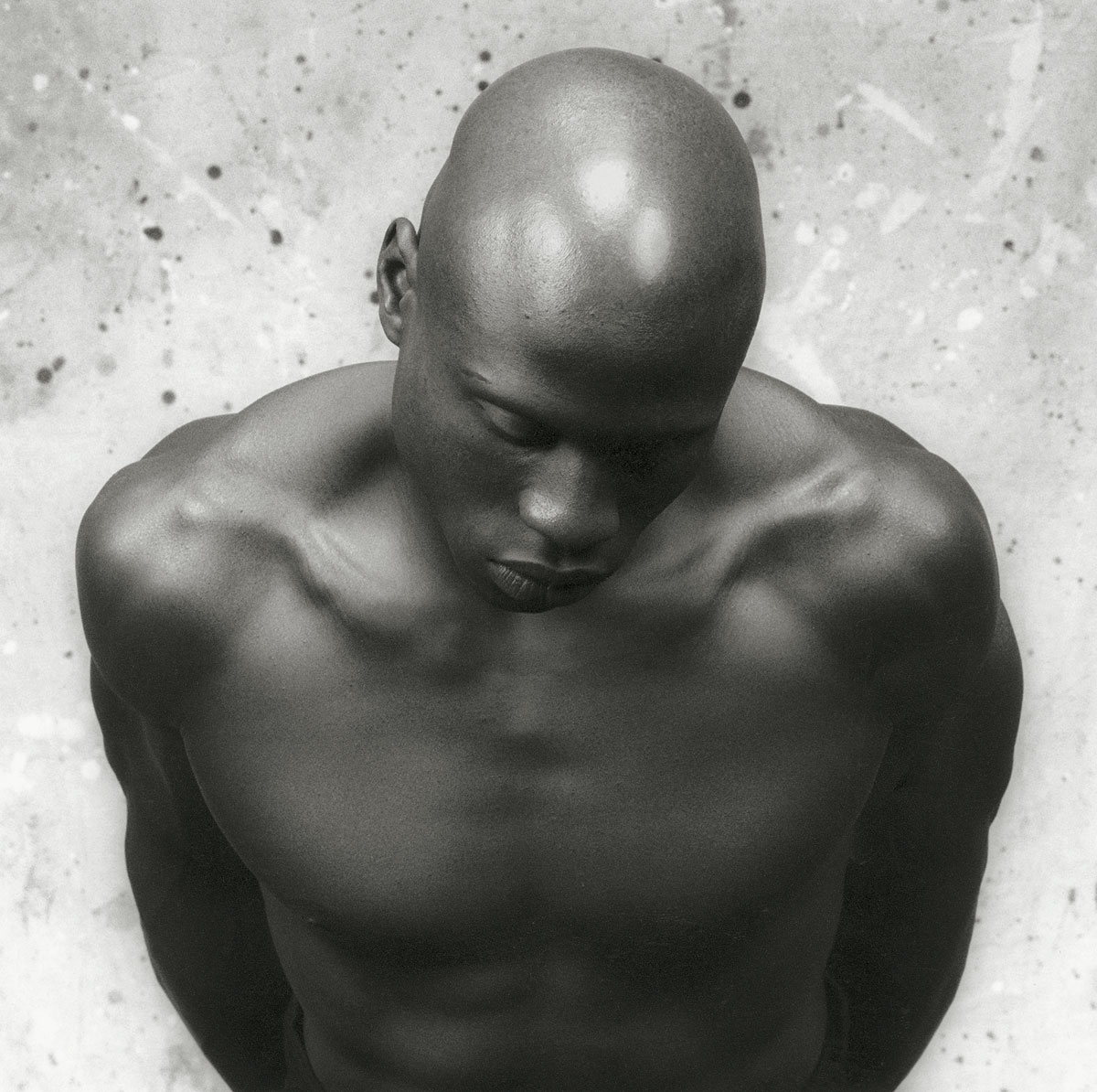

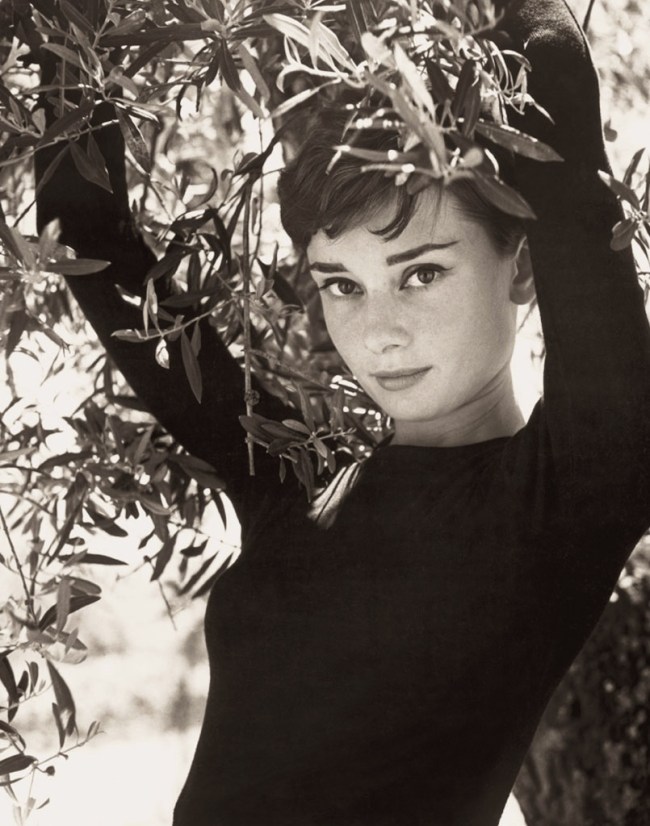

When Paul Martineau, an associate curator at the J. Paul Getty Museum, in Los Angeles, was collecting photographs for a new retrospective of Minor White’s photography, he discovered an album called The Temptation of Saint Anthony Is Mirrors. Only two copies of the volume were produced, each containing thirty-two images of Tom Murphy, Minor’s student and model. “It’s a visual love letter: he only created two, one given to Tom and one for him,” Martineau told me.

Martineau’s show, Minor White: Manifestations of the Spirit, is the first major retrospective of White’s work since 1989. White was born in Minneapolis, in 1908, took photographs for the Works Progress Administration during the nineteen-thirties, and served in the Army during the Second World War. He kept company with Ansel Adams, Alfred Steiglitz, and Edward Steichen, and, in 1952, he helped found the influential photography magazine Aperture. Martineau said that, while the Getty retrospective “comes at a time when life is rife with visual imagery, most of it designed to capture our attention momentarily and communicate a simple message,” White aimed to more durably express “our relationships with one another, with the natural world, with the infinite.” White believed that all of his photographs were self-portraits; as Martineau put it, “he pushed himself to live what he called a life in photography.”

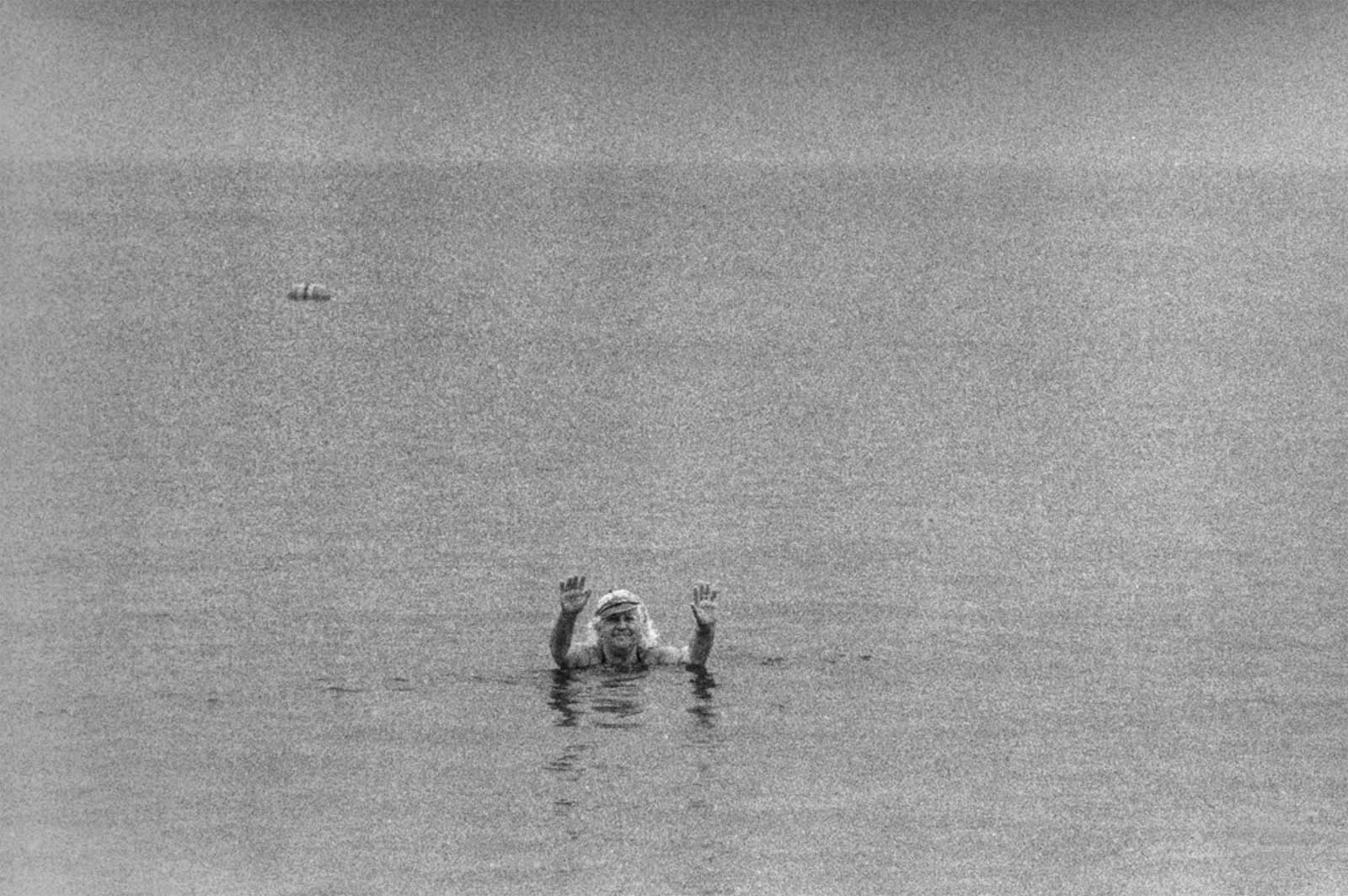

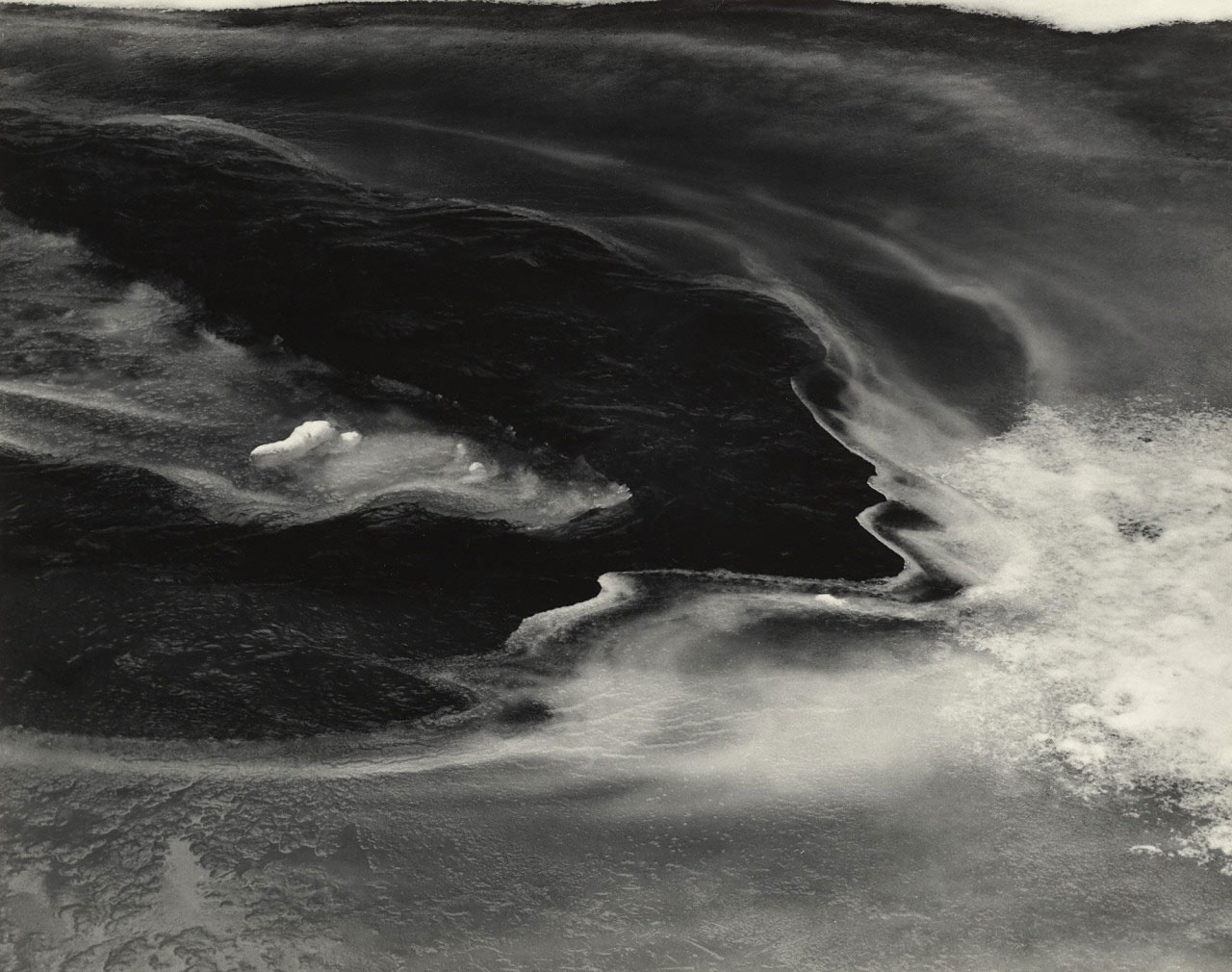

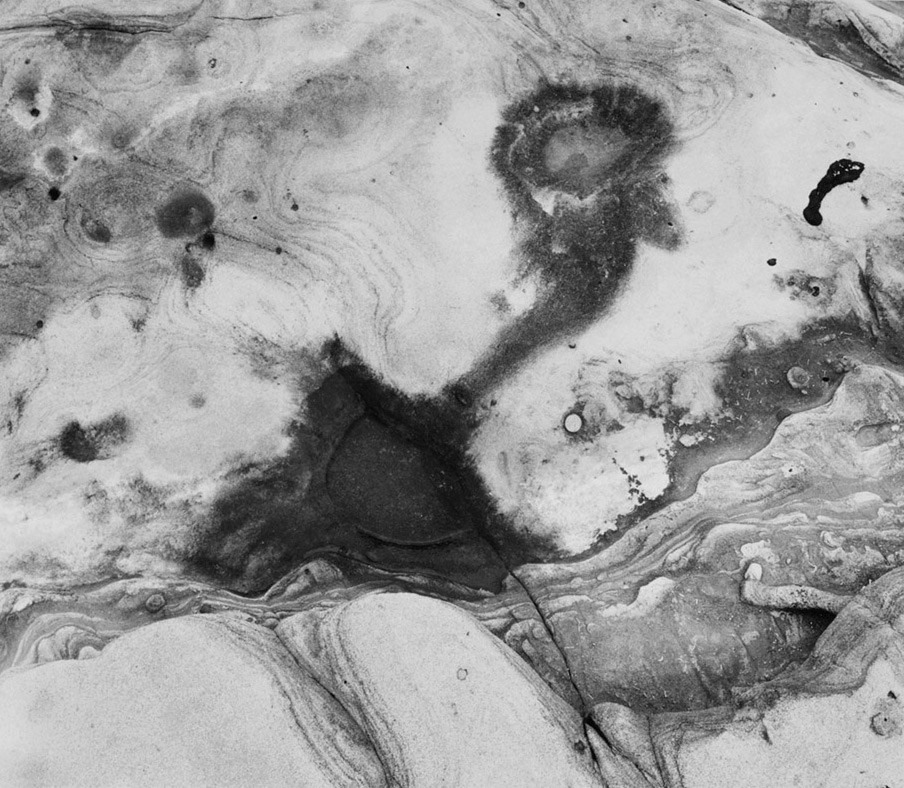

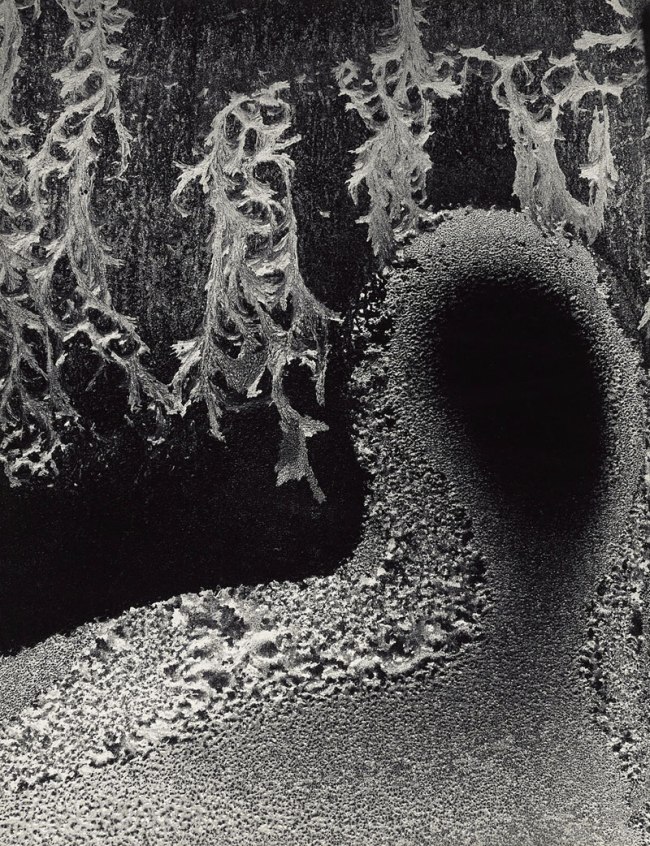

Minor White (American, 1908-1976)

Stony Brook State Park, New York

1960

Gelatin silver print

30.5 x 24.1cm (12 x 9 1/2 in.)

Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced with permission of the Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum

© Trustees of Princeton University

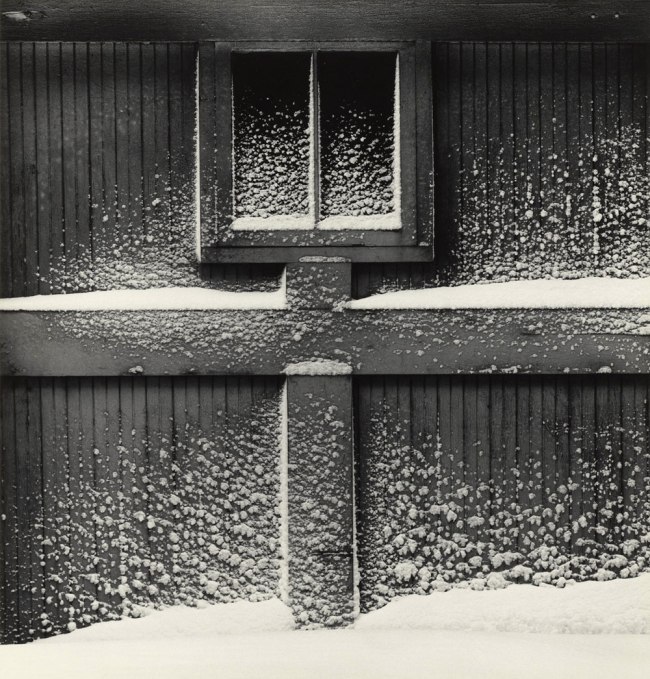

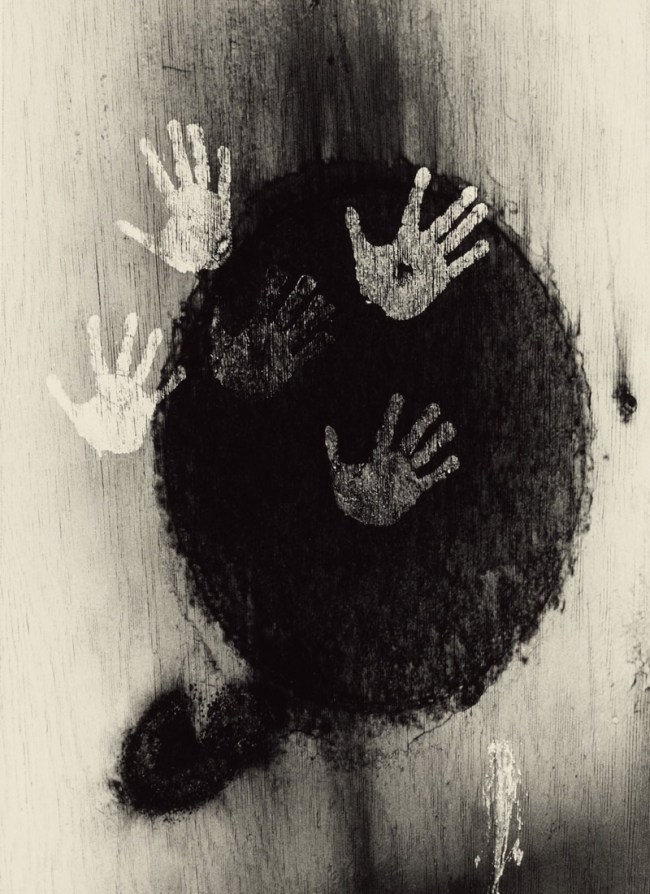

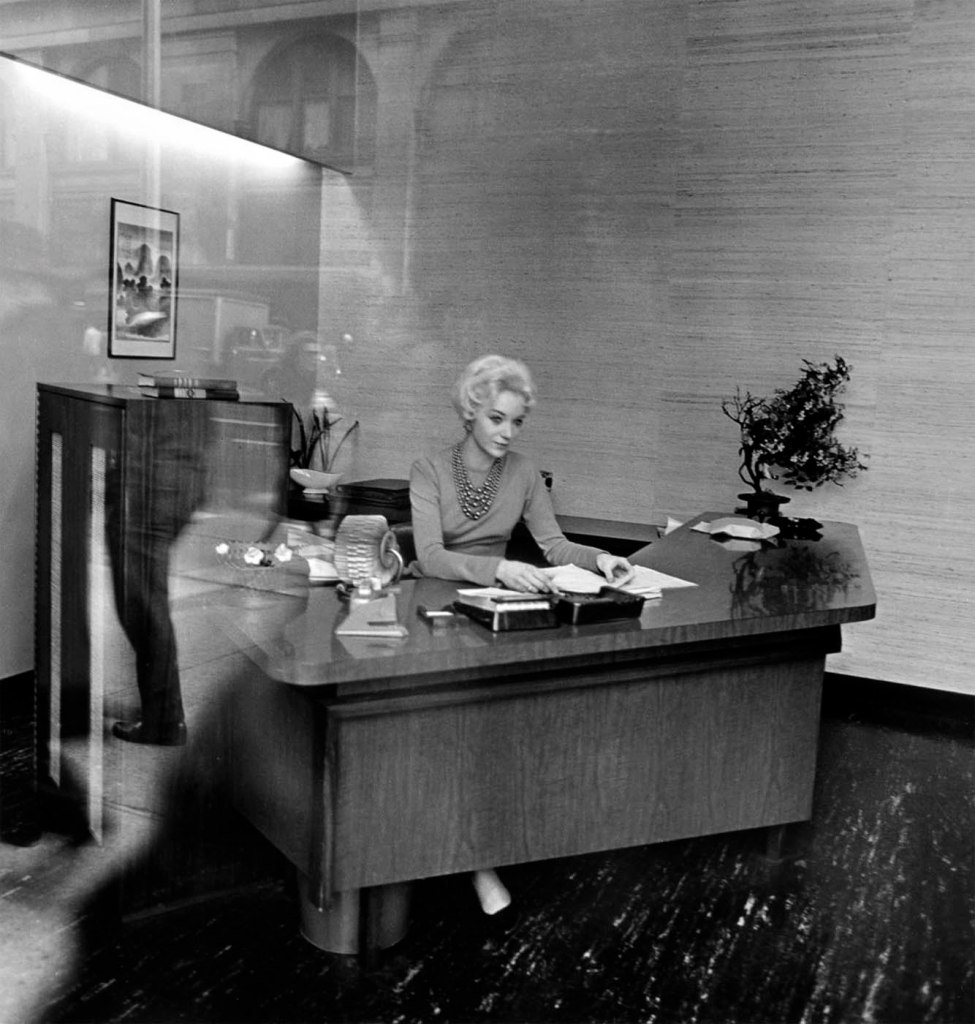

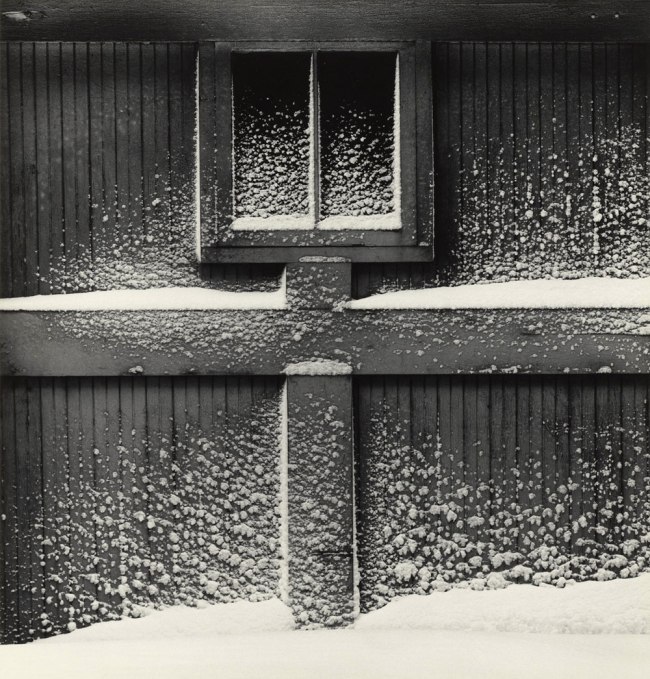

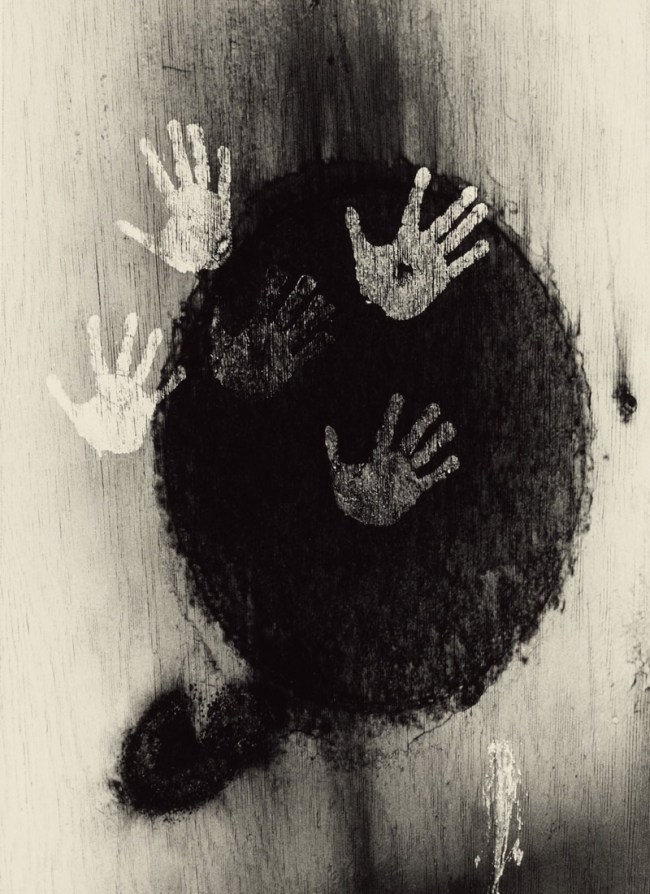

Minor White (American, 1908-1976)

72 N. Union Street, Rochester, New York

1960

Gelatin silver print

30.5 x 24.1cm (12 x 9 1/2 in.)

Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced with permission of the Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum

© Trustees of Princeton University

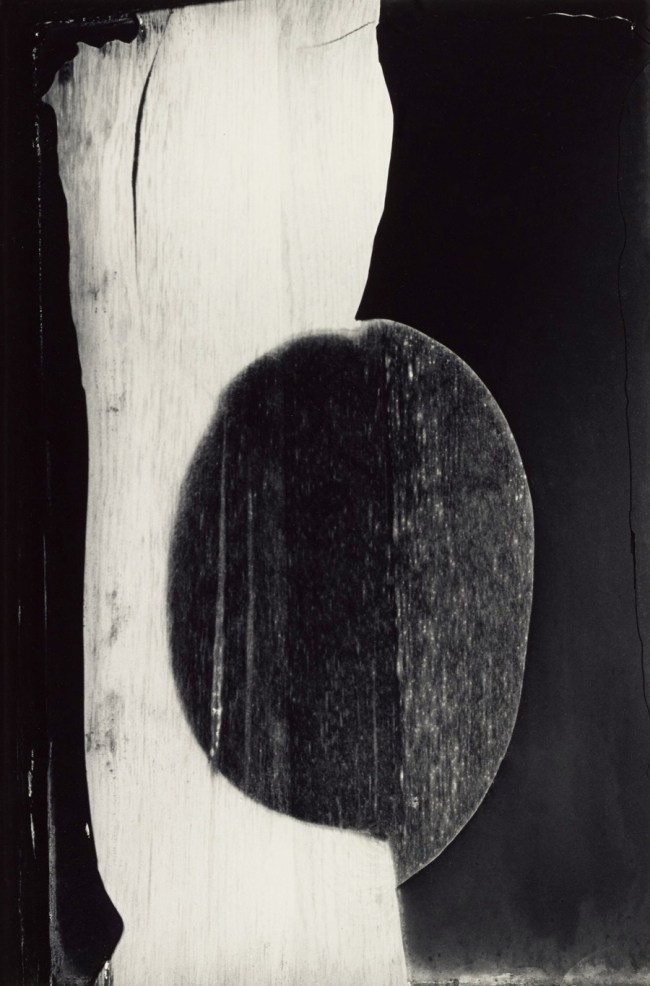

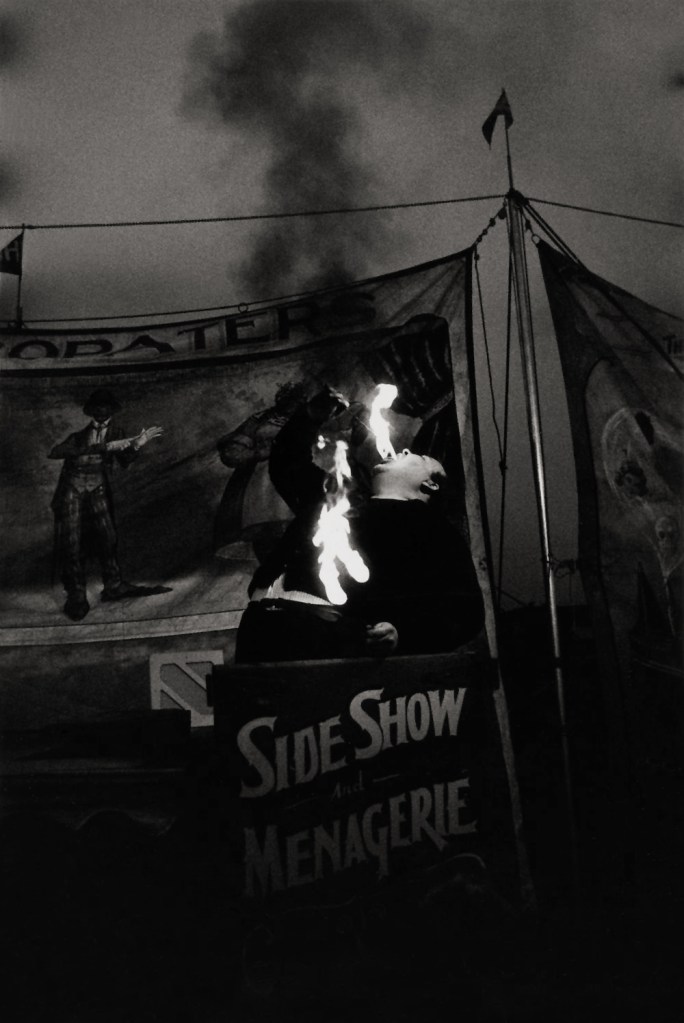

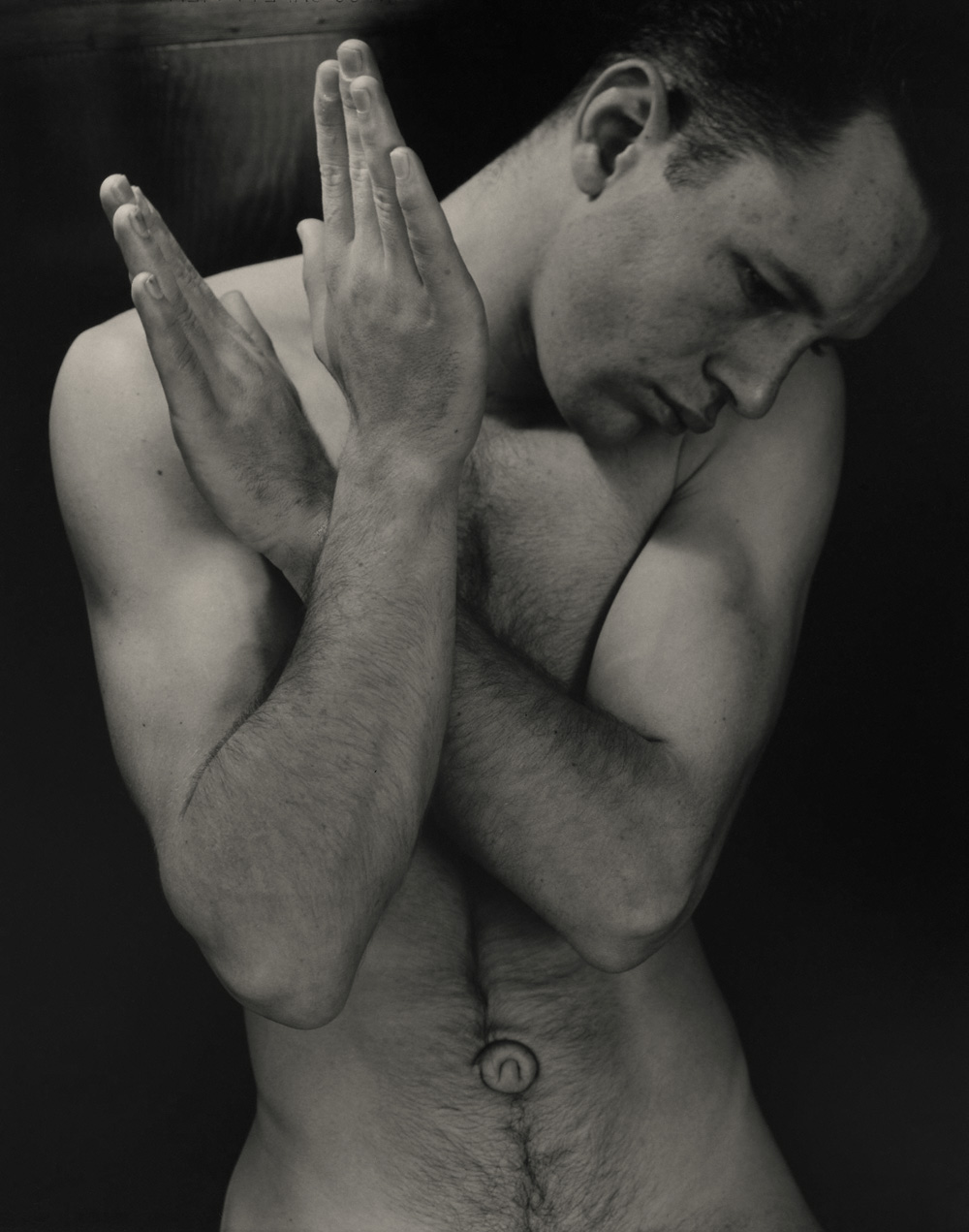

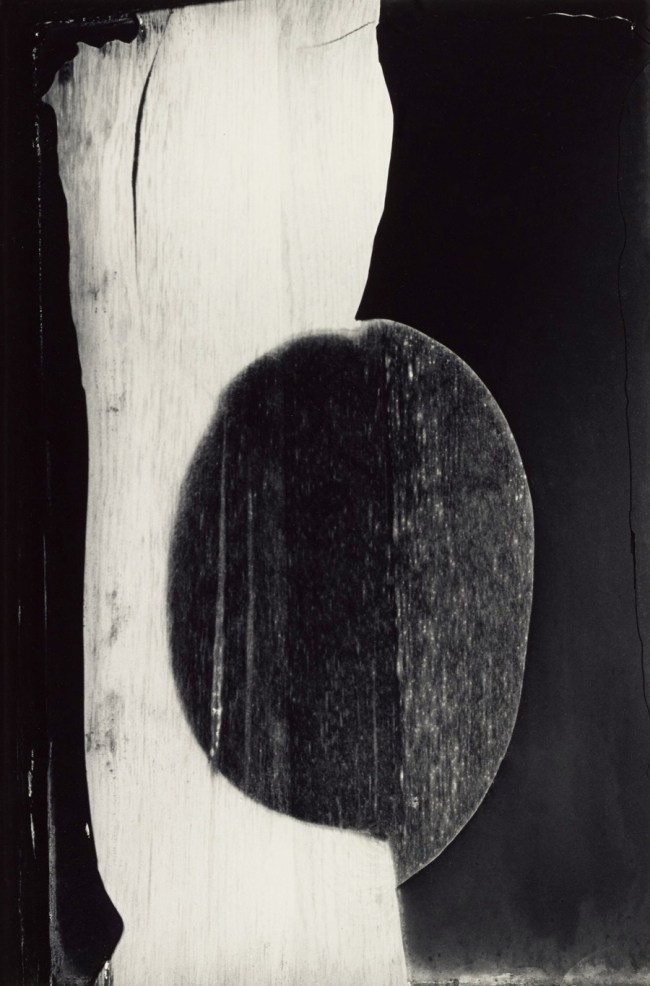

Minor White (American, 1908-1976)

The Sound of One Hand Clapping, Pultneyville, New York

1957

Gelatin silver print

24.4 x 25.1cm (9 5/8 x 9 7/8 in.)

Purchased in part with funds provided by Daniel Greenberg, Susan Steinhauser, and the Greenberg Foundation

Reproduced with permission of the Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum

© Trustees of Princeton University

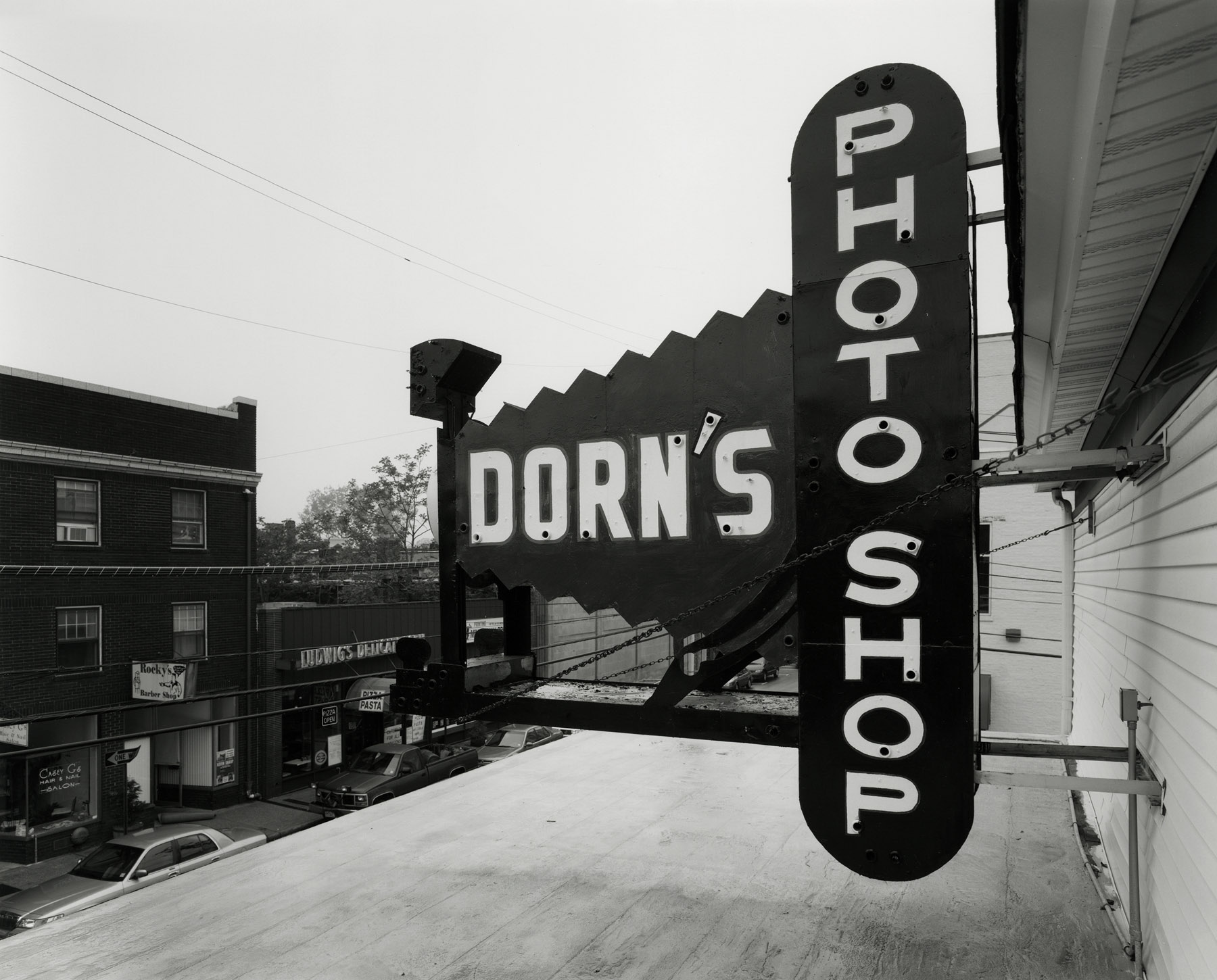

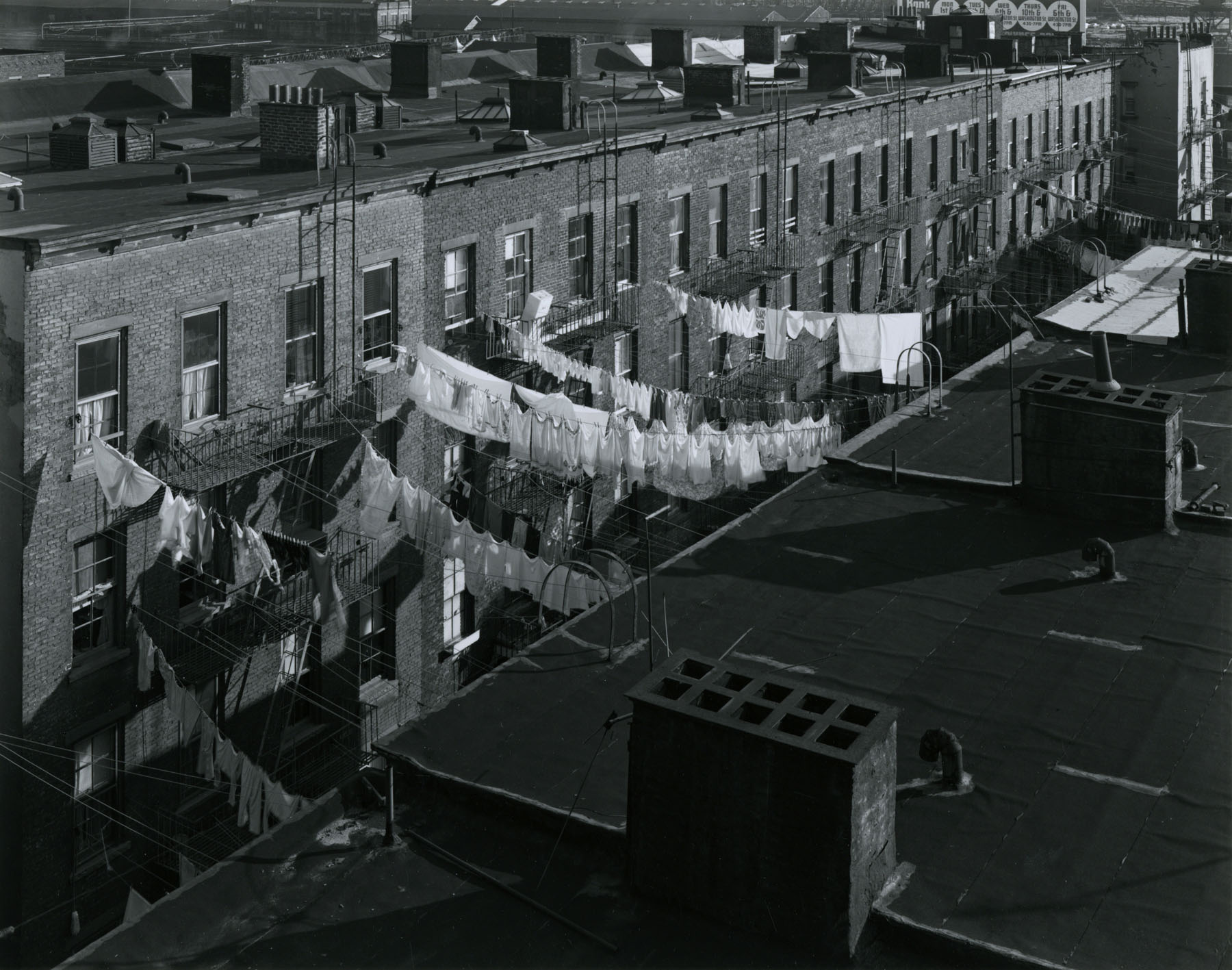

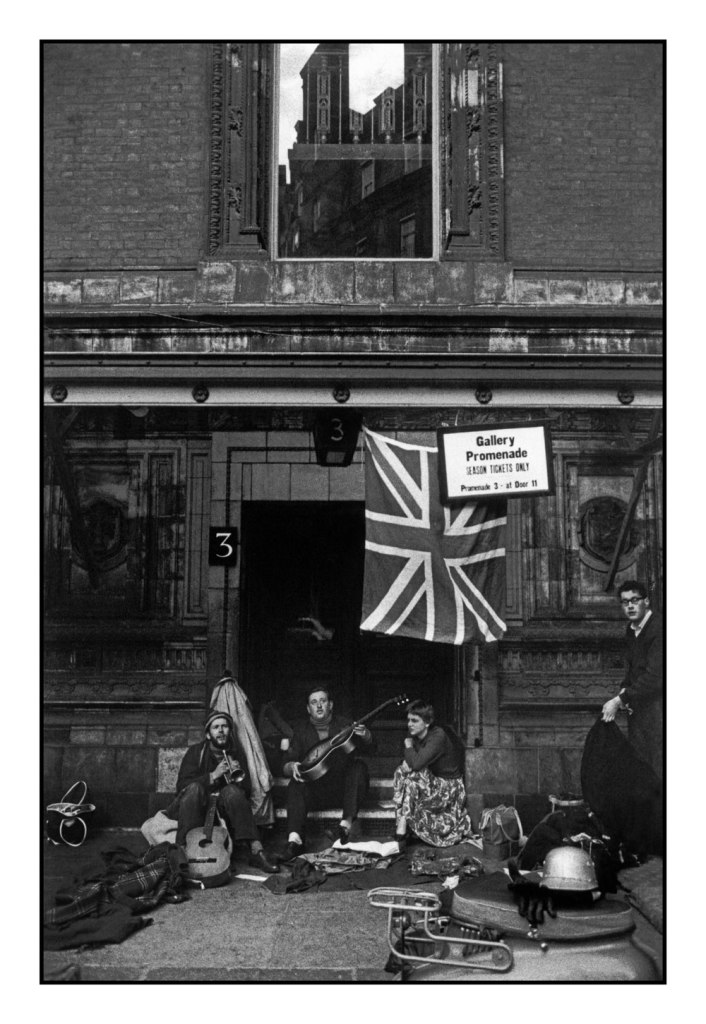

Minor White (American, 1908-1976)

Haags Alley, Rochester, New York

1960

Gelatin silver print

30.5 x 24.1cm (12 x 9 1/2 in.)

Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced with permission of the Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum

© Trustees of Princeton University

Minor White (American, 1908-1976)

Tom Murphy, San Francisco, California

1948

Gelatin silver print

12.5 x 10cm (4 15/16 x 3 15/16 in.)

The Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum, bequest of Minor White

© Trustees of Princeton University

Minor White (American, 1908-1976)

72 N. Union Street, Rochester, New York

1958

Gelatin silver print

26.7 x 29.2cm (10 1/2 x 11 1/2 in.)

Promised gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced with permission of the Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum

© Trustees of Princeton University

Controversial, misunderstood, and sometimes overlooked, Minor White (American 1908-1976) pursued a life in photography with great energy and ultimately extended the expressive possibilities of the medium. A tireless worker, White’s long career as a photographer, teacher, editor, curator, and critic was highly influential and remains central to understanding the history of photographic modernism. Minor White: Manifestations of the Spirit, on view July 8 – October 19, 2014 at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Getty Center is the first major retrospective of his work since 1989.

The exhibition includes never-before-seen photographs from the artist’s archive at Princeton University, recent Getty Museum acquisitions, a significant group of loans from the collection of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser, alongside loans from the Museum of Modern Art, New York, the Portland Art Museum, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Also featured is White’s masterly photographic sequence Sound of One Hand (1965).

“Minor White had a profound impact on his many students, colleagues, and the photographers who considered him a true innovator, making this retrospective of his work long overdue” says Timothy Potts, director of the J. Paul Getty Museum. “The exhibition brings together a number of loans from private and public collections, and offers a rare opportunity to see some of his greatest work alongside unseen photographs from his extensive archive.”

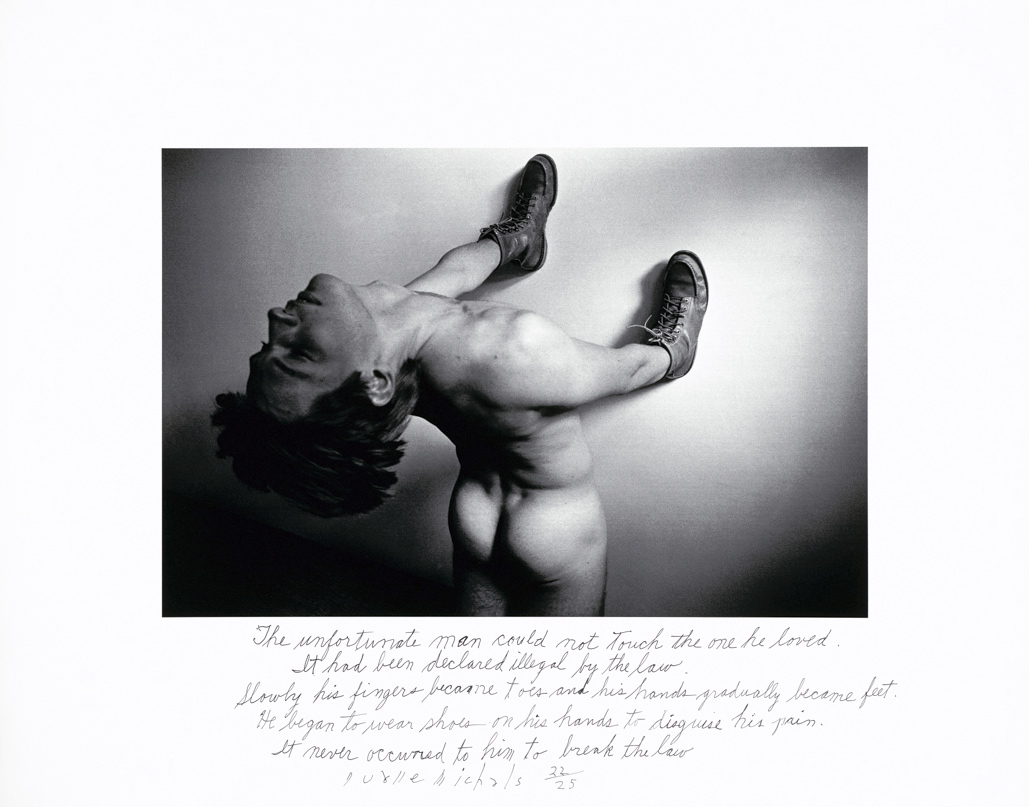

One of White’s goals was to photograph objects not only for what they are but also for what they may suggest, and his pictures teem with symbolic and metaphorical allusions. White was a closeted homosexual, and his sexual desire for men was a source of turmoil and frustration. He confided his feelings in the journal he kept throughout his life and sought comfort in a variety of Western and Eastern religious practices. This search for spiritual transcendence continually influenced his artistic philosophy.

Early Career, 1937-1945

In 1937, White relocated from Minneapolis, where he was born and educated, to Portland, Oregon. Determined to become a photographer, he read all the photography books he could get his hands on and joined the Oregon Camera Club to gain access to their darkroom. Within five years, he was offered his first solo exhibition at the Portland Art Museum (1942). White’s early work exhibits his nascent spiritual awakening while exploring the natural magnificence of Oregon. His Cabbage Hill, Oregon (Grande Ronde Valley) (1941) uses a split-rail fence and a coil of barbed wire to demonstrate the hard physical labor required to live off the land as well as the redemption of humankind through Christ’s sacrifice on the cross.

During World War II, White served in Army Intelligence in the South Pacific. Upon discharge, rather than return to Oregon, he spent the winter in New York City. There, he studied art history with Meyer Shapiro at Columbia University, museum work with Beaumont Newhall at the Museum of Modern Art, and creative thought in photography with photographer, gallerist, and critic Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946).

Midcareer, 1946-1964

In 1946, famed photographer Ansel Adams (American, 1902-1984) invited White to teach photography at the California School of Fine Arts (CSFA) in San Francisco. The following year, White established himself as head of the program and developed new methods for training students. His own work during this period began to shift toward the metaphorical with the creation of images charged with symbolism and a critical aspect known as “equivalence,” meaning an image may serve as an idea or emotional state beyond the subject pictured. In 1952, White co-founded the seminal photography journal Aperture and was its editor until 1975.

In 1953, White accepted a job as an assistant curator at the George Eastman House (GEH) in Rochester, New York, where he organised exhibitions and edited GEH’s magazine Image. Coinciding with his move east was an intensification of his study of Christian mysticism, Zen Buddhism, and the I Ching. In 1955, he began teaching a class in photojournalism at the Rochester Institute of Technology and shortly after began to accept one or two live-in students to work on a variety of projects that were alternately practical and spiritually enriching. During the late 1950s and continuing until the mid-1960s, White traveled the United States during the summers, making his own photographs and organising photographic workshops in various cities across the country.

By the late 1950s, at the height of his career, White pushed himself to do the impossible – to make the invisible world of the spirit visible through photography. White’s masterpiece – and the summation of his persistent search for a way to communicate ecstasy – is the sequence Sound of One Hand, so named after the Zen koan which asks “What is the sound of one hand clapping?”

“White’s sequences are meant to be viewed from left to right, preferably in a state of relaxation and heightened awareness,” says Paul Martineau, associate curator of photographs at the J. Paul Getty Museum and curator of the exhibition. “White called on the viewer to be an active participant in experiencing the varied moods and associations that come from moving from one photograph to the next.”

Late Career, 1965-1976

In 1965, White was appointed professor of creative photography at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where he developed an ambitious program in photographic education. As he aged, he became increasingly concerned with his legacy, and began working on his first monograph, Mirrors Messages Manifestations, which was published by Aperture in 1969. The following year, White was awarded a Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship, and he was the subject of a major traveling retrospective organised by the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1971.

Beginning in the late 1960s and continuing until the early 1970s, White organised a series of groundbreaking thematic exhibitions at MIT – the first of which served as a springboard for forming the university’s photographs collection. In 1976, White died of heart failure and bequeathed his home to the Aperture Foundation and his photographic archive of more than fifteen thousand objects to Princeton University. The exhibition also includes work by two of White’s students, each celebrated photographers in their own right, Paul Caponigro (American, 1932-2024) and Carl Chiarenza (American, born 1935).

“An important aspect of Minor White’s legacy was his influence on the next generation of photographers,” says Martineau. “Over the course of a career that lasted nearly four decades, he managed to maintain personal and professional connections with hundreds of young photographers – an impressive feat for a man dedicated to the continued exploration of photography’s possibilities.

Press release from the J. Paul Getty Museum website

Minor White (American, 1908-1976)

Navarro River, California

1947

Gelatin silver print

35.6 x 45.7cm (14 x 18 in.)

Lent by Gloria Katz and Willard Huyck

Reproduced with permission of the Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum

© Trustees of Princeton University

Minor White (American, 1908-1976)

Nude Foot, San Francisco, California

Negative, 1947; print, 1975

Gelatin silver print

22.9 x 30.5cm (9 x 12 in.)

Promised gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced with permission of the Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum

© Trustees of Princeton University

Minor White (American, 1908-1976)

Pavilion, New York

1957

Gelatin silver print

22.5 x 29.5cm (8 7/8 x 11 5/8 in.)

Purchased in part with funds provided by Daniel Greenberg, Susan Steinhauser, and the Greenberg Foundation

Reproduced with permission of the Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum

© Trustees of Princeton University

Minor White (American, 1908-1976)

Cabbage Hill, Oregon (Grande Ronde Valley)

1941

Gelatin silver print

18 x 22.9cm (7 1/16 x 9 in.)

The Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum, bequest of Minor White

© Trustees of Princeton University

Minor White (American, 1908-1976)

Self-Portrait, West Bloomfield, New York

1957

Gelatin silver print

17.8 x 20.6cm (7 x 8 1/8 in.)

The Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum, bequest of Minor White

© Trustees of Princeton University

Interview with Minor White

Q. How would you like to see photography develop?

A. It makes absolutely no difference what I want it to do. It’s going to do what it’s going to do. All I can do is stand back and observe it.

Q. What don’t you want it to do?

A. That doesn’t make any difference either, It’ll do that whether I want it to or not!

Q. Surely, you’ve got to have some feelings?

A. In one sense I don’t care what photography does at all. I can just watch it do it. I can control my photography, I can do what I want with it – a little. If I can get into contact with something much wiser than myself , and it says get out of photography, maybe I would. I hesitate to say this because I know its going to be misunderstood. I’ll put I this way – I’m trying to be in contact with my Creator when I photograph. I know perfectly well its not possible to do this all the time, but there can be moments.

Q. Do you see anything in contemporary photography that distresses you?

A. What ever they do is fine.

Q. Is there any work that you are particularly interested in?

A. What ever my students are doing.

Q. There seems to be a passing on of certain sets of ideas and understandings. Do you feel yourself to be an inheritor of a set of ideas or ideals?

A. Naturally. After all I have two parents, so I inherited some thing. I’ve had many spiritual fathers for example. The photographers who I have been influenced by for example. There have been many other external influences. Students have had an influence. In a sense that’s an inheritance. After a while we work with material that comes to us and it becomes ours, we digest it. It becomes energy and food for us, its ours. And then I can pass it on to somebody else with a sense of responsibility and validity. I am quoting it in my words, it has become mine and that person will take it from me – just as I have taken it from people who have influenced me. Take what you can use, digest it, make it yours, and then transmit it to your children or your students.

Q. It’s a cycle?

A. No, it’s a continuous line. Not a cycle at all.

Interview by Paul Hill and Thomas Cooper of Minor White, published in 3 parts in the January, February and March editions of Camera 1977.

Minor White (American, 1908-1976)

Point Lobos, California

1948

Gelatin silver print

16.8 x 19.5cm (6 5/8 x 7 11/16 in.)

The Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum, bequest of Minor White

© Trustees of Princeton University

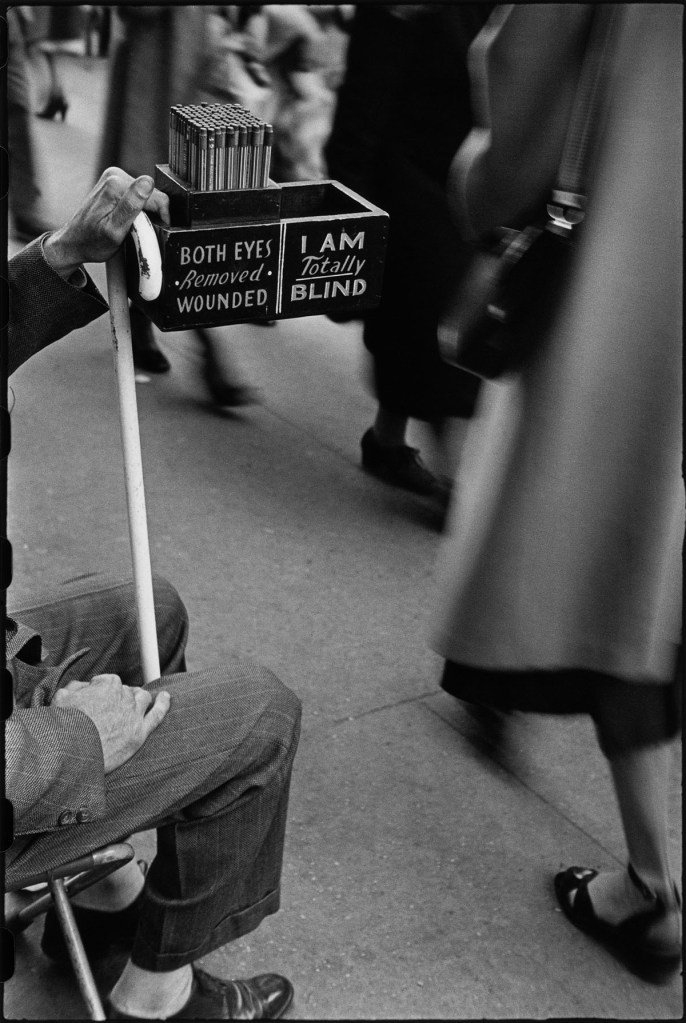

Minor White (American, 1908-1976)

San Francisco, California

1949

Gelatin silver print

18.5 x 18.7cm (7 5/16 x 7 3/8 in.)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Purchase

Reproduced with permission of the Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum

© Trustees of Princeton University

Minor White (American, 1908-1976)

Vicinity of Dansville, New York

Negative, 1955; print, 1975

Gelatin silver print

22.9 x 30.5cm (9 x 12 in.)

Promised gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced with permission of the Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum

© Trustees of Princeton University

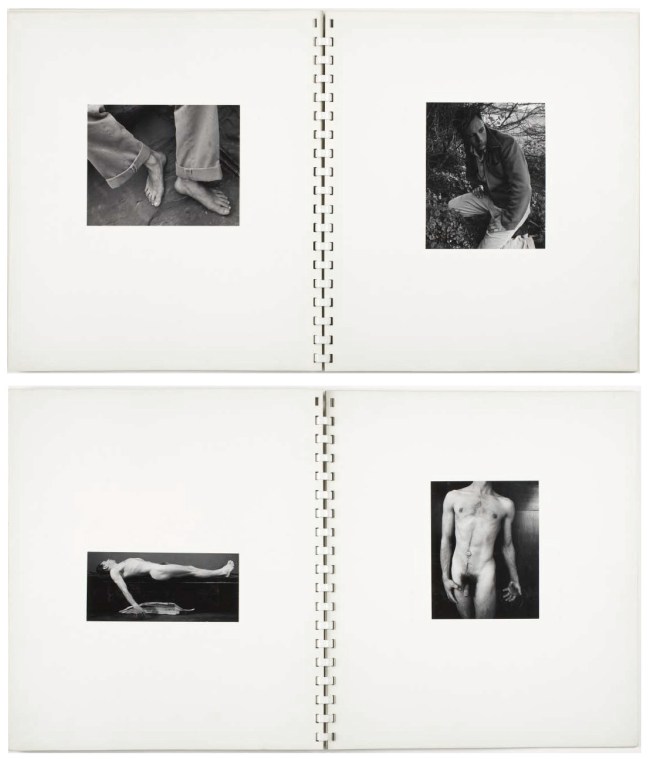

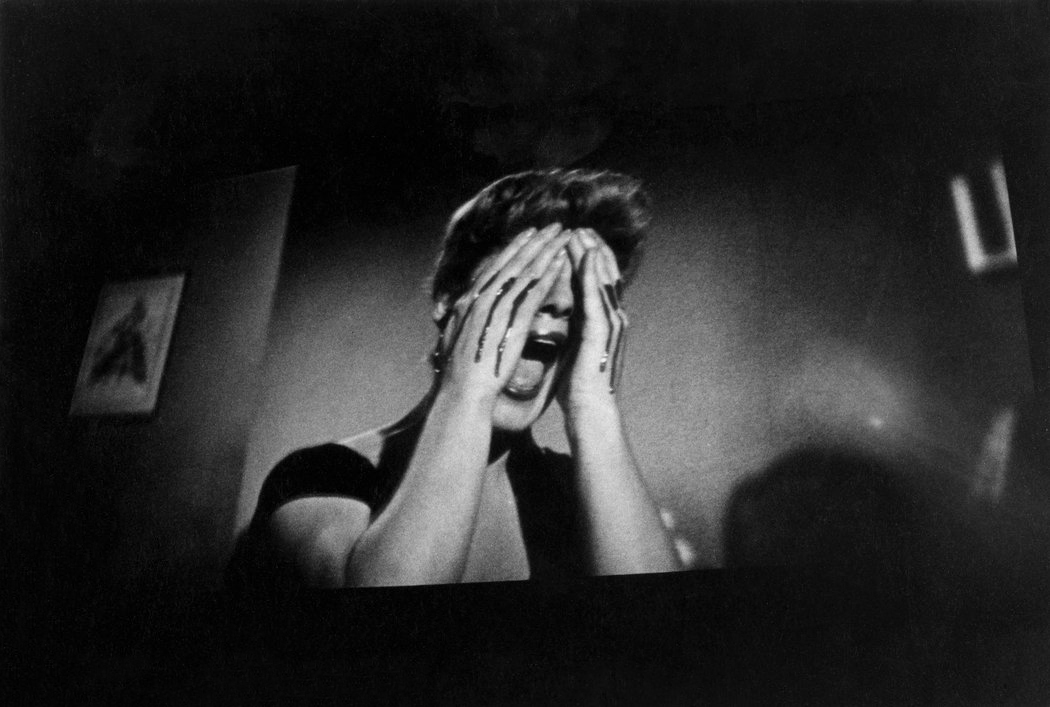

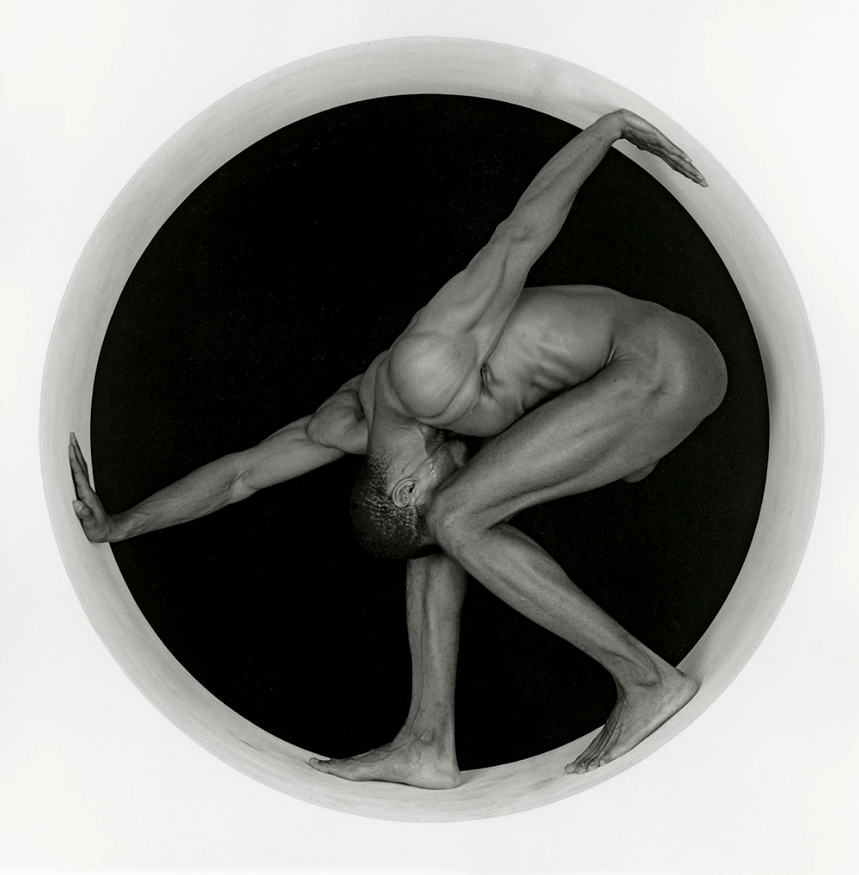

(top)

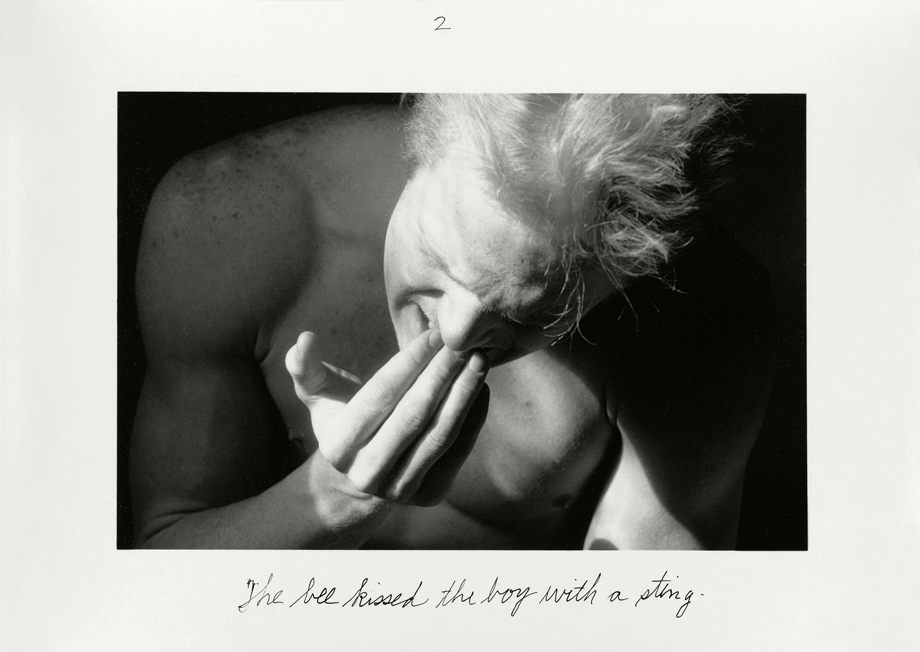

Minor White (American, 1908-1976)

Images 9 and 10 in the bound sequence The Temptation of Saint Anthony Is Mirrors

1948

Gelatin silver prints

9.3 x 11.8cm; 11.2 x 9.1cm

The Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum, bequest of Minor White

© Trustees of Princeton University

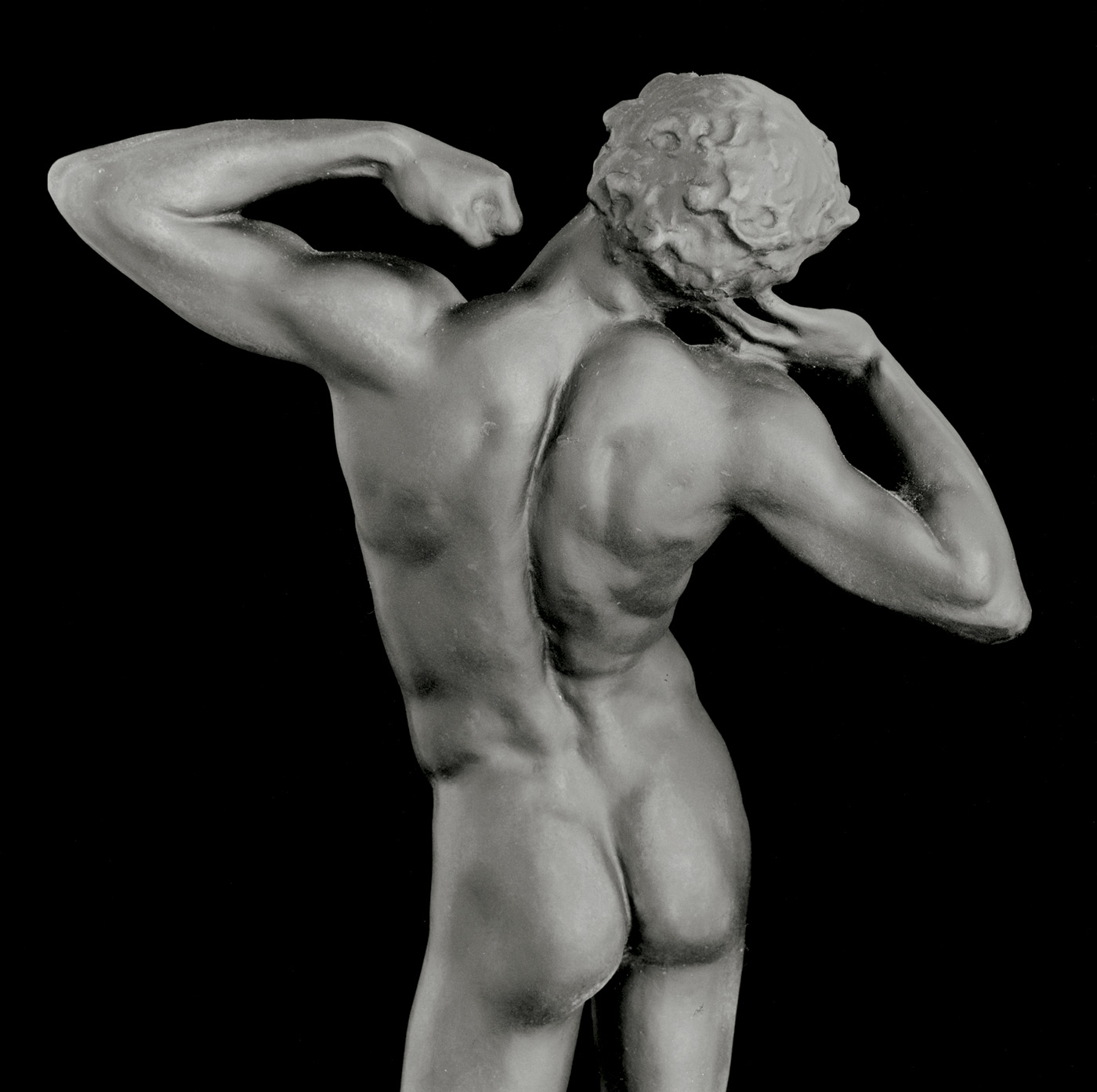

(bottom)

Minor White (American, 1908-1976)

Images 27 and 28 in the bound sequence The Temptation of Saint Anthony Is Mirrors

1948

Gelatin silver prints

5.3 x 11.6cm; 10.6 x 8.9cm

The Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum, bequest of Minor White

© Trustees of Princeton University

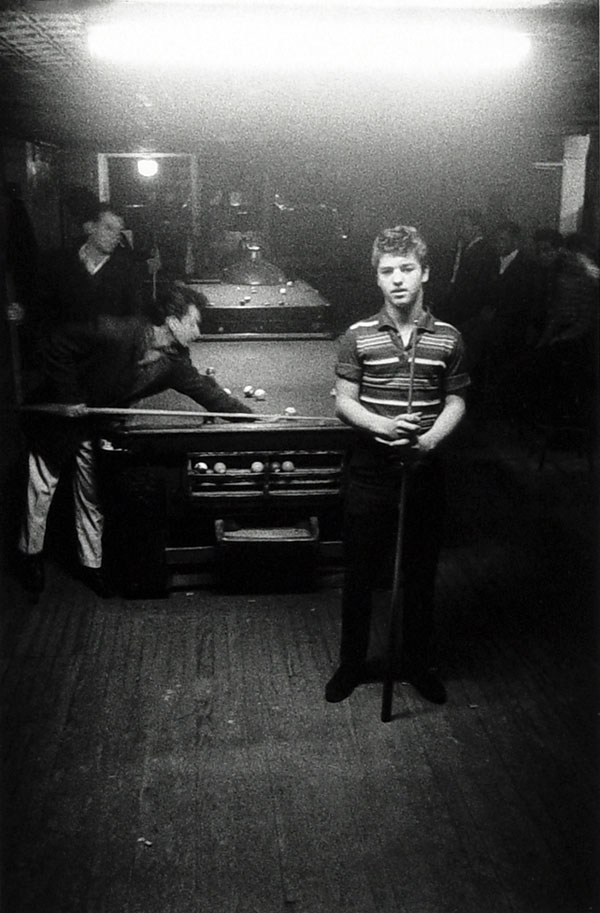

Minor White (American, 1908-1976)

Rochester, New York

1963

Gelatin silver print

9.2 x 7.3cm (3 5/8 x 2 7/8 in.)

Promised gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced with permission of the Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum

© Trustees of Princeton University

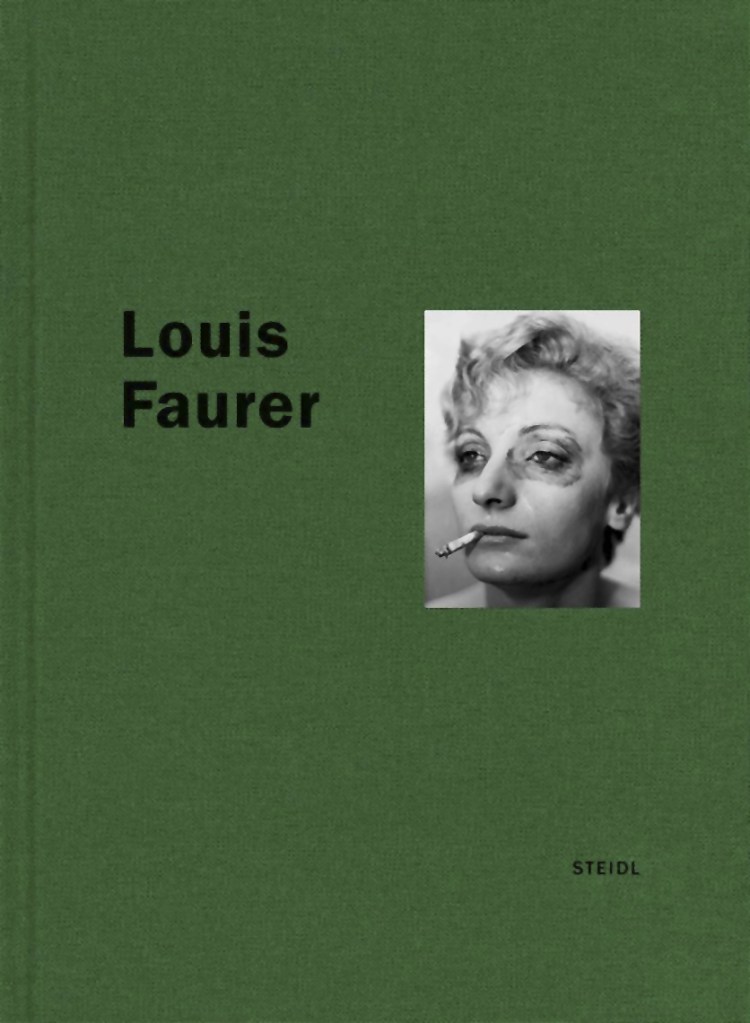

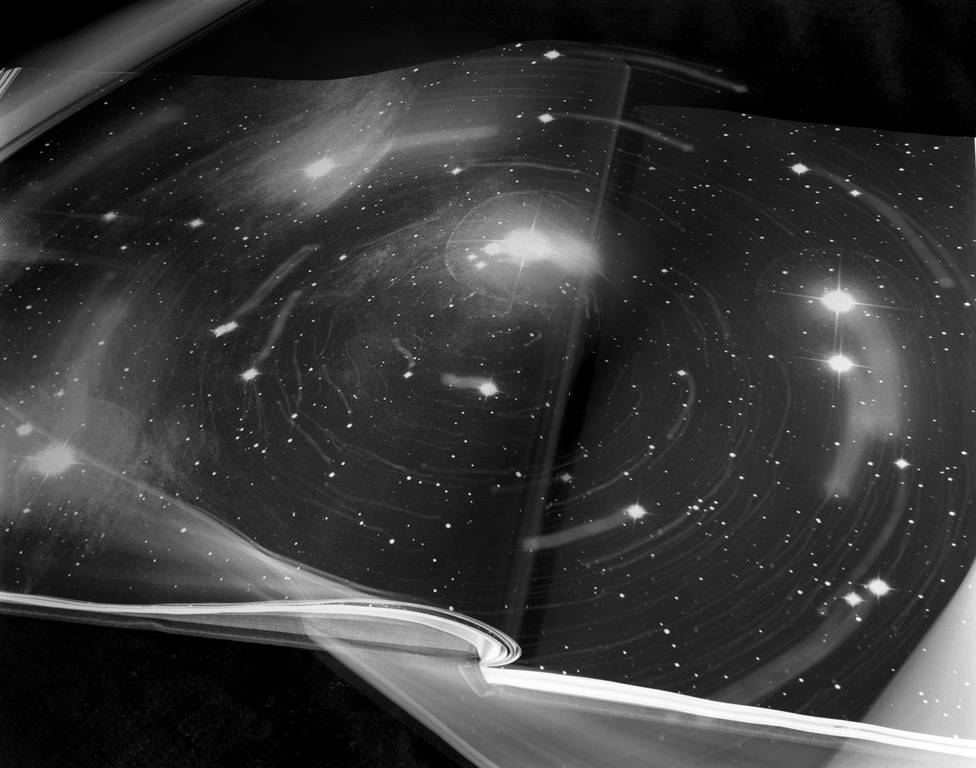

Minor White: Manifestations of the Spirit book

Controversial, eccentric, and sometimes overlooked, Minor White (1908-1976) is one of the great photographers of the twentieth century, whose ideas and philosophies about the medium of photography have exerted a powerful influence on a generation of practitioners and still resonate today. Born and raised in Minneapolis, his photographic career began in 1938 in Portland, Oregon with assignments as a “creative photographer” for the Oregon Art Project, an outgrowth of the Works Progress Administration (WPA).

After serving in World War II as a military intelligence officer, White studied art history at Columbia University in New York. It was during this period that White’s focus started to shift toward the metaphorical. He began to create images charged with symbolism and a critical aspect called “equivalency,” which referred to the invisible spiritual energy present in a photograph made visible to the viewer and was inspired by the work of Alfred Stieglitz. White’s belief in the spiritual and metaphysical qualities in photography, and in the camera as a tool for self-discovery, was crucial to his oeuvre.

Minor White: Manifestations of the Spirit (Getty Publications, 2014) gathers together for the first time a diverse selection of more than 160 images made by Minor White over five decades, including some never published before. Accompanying the photographs is an in-depth critical essay by Paul Martineau entitled “‘My Heart Laid Bare’: Photography, Transformation, and Transcendence,” which includes particularly insightful quotations from his journals, which he kept for more than forty years.

The result is an engaging narrative that weaves through the main threads of White’s work and life – his growth and tireless experimentation as an artist; his intense mentorship of his students; his relationships with Edward Weston, Alfred Stieglitz, and Ansel Adams, who had a profound influence on his work; and his labor of love as cofounder and editor of Aperture magazine from 1952 until 1976. The book also addresses White’s life-long spiritual search and ongoing struggle with his own sexuality and self-doubt, in response to which he sought comfort in a variety of religious practices that influenced his continually metamorphosing artistic philosophy.

Published here in its entirety for the first time is White’s stunning series The Temptation of Anthony Is Mirrors, consisting of 32 photographs of White’s student and model Tom Murphy made in 1947 and 1948 in San Francisco. White’s photographs of Murphy’s hands and feet are interspersed within a larger group of portraits and nude figure studies. White kept the series secret for years as at the time he made the photographs it was illegal to publish or show images with male frontal nudity. Anyone making such images would be assumed to be homosexual and outed at a time when this invariably meant losing gainful employment.

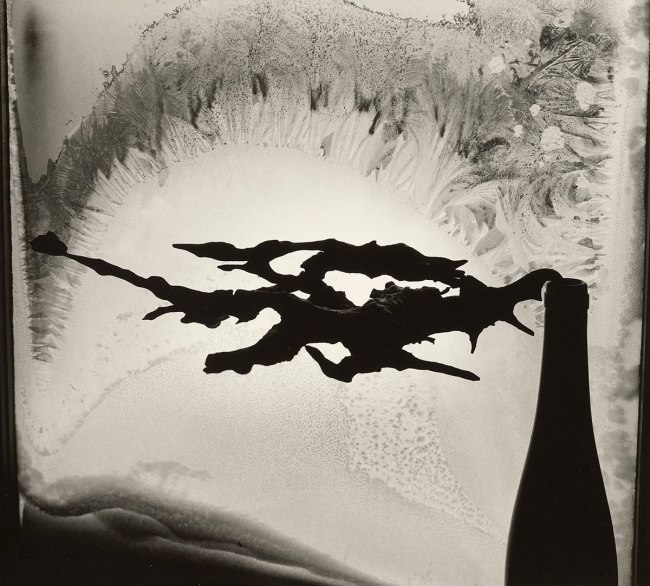

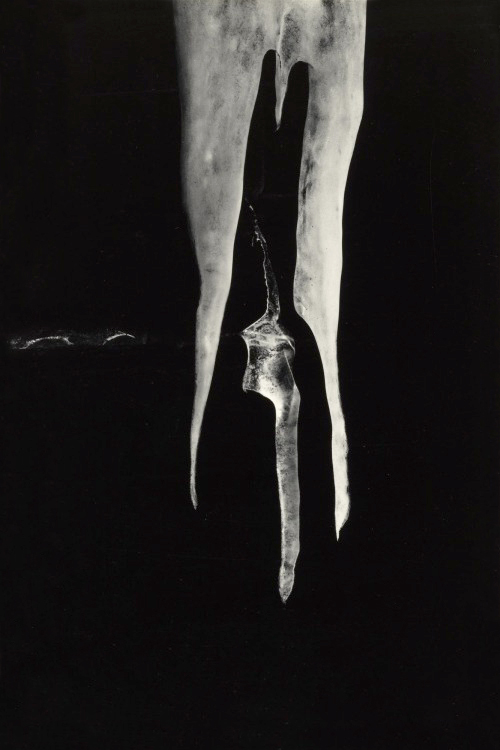

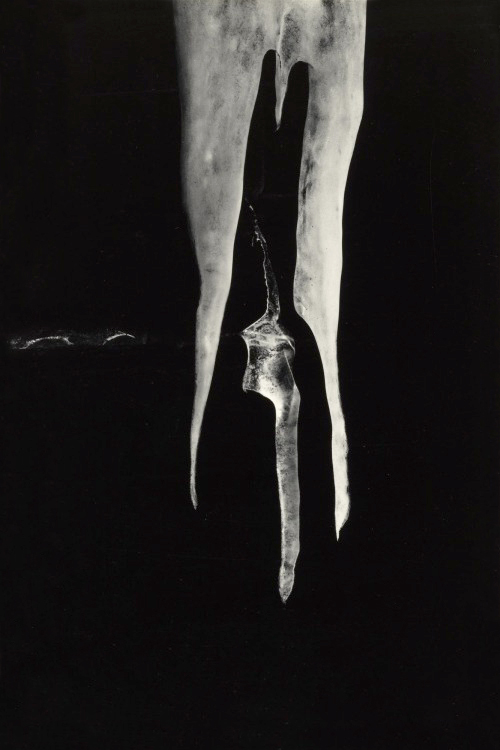

Other works shown in this rich collection are White’s early images of the city of Portland that depict his experimentations with different styles and nascent spiritual awakening; his photographs of the urban streets of San Francisco where he lived for a time; his elegant images of rocks, sandy beaches and tidal pools in Point Lobos State Park in Northern California that are an homage to Edward Weston; and the series The Sound of One Hand made in the vicinity of Rochester, New York where he also taught classes at the Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT) and curated shows at the George Eastman House (GEH). Paul Martineau describes this iconic series as “White’s chef d’oeuvre, the work that is the summation of his persistent search or a way to communicate ecstasy.” Among the eleven images in the Getty collection are Windowsill Daydreaming, Rochester, Night Icicle, 72 N. Union Street, Rochester, and Pavilion, New York.

Text from the J. Paul Getty Museum

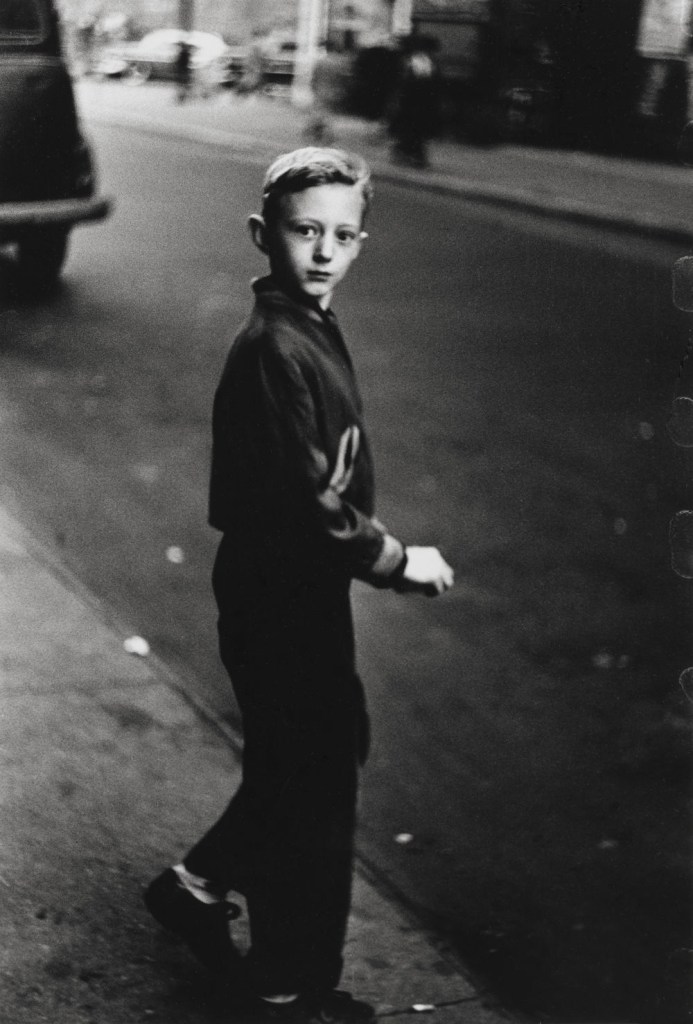

Minor White (American, 1908-1976)

“Something Died Here,” San Francisco, California

1947

Gelatin silver print

22.8 x 17.5cm (9 x 6 7/8 in.)

The Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum, bequest of Minor White

© Trustees of Princeton University

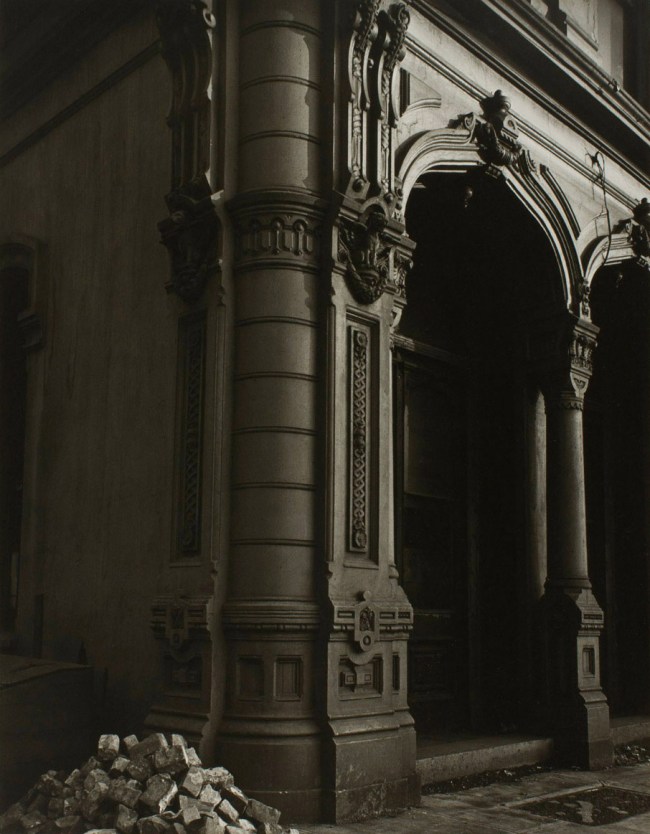

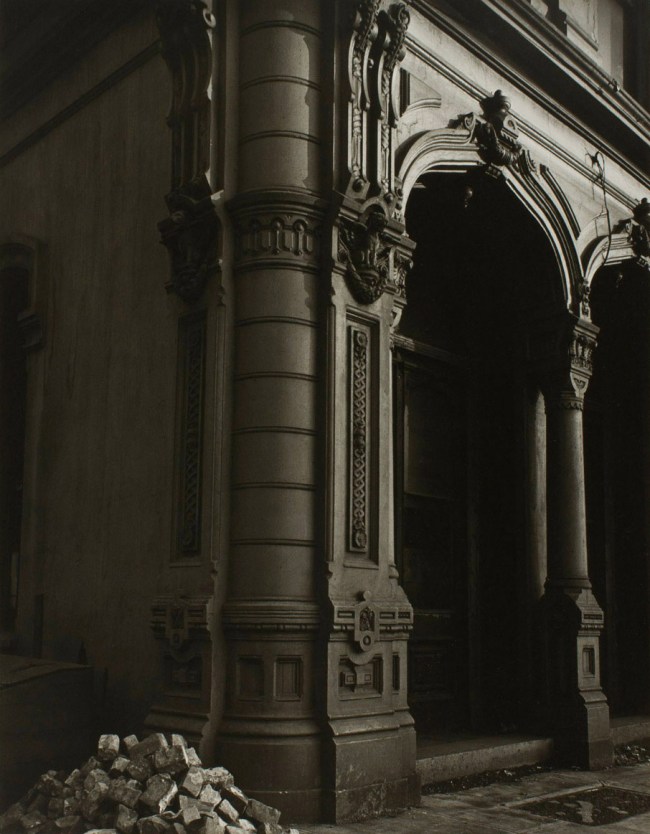

Minor White (American, 1908-1976)

Dodd Building, Portland, Oregon

c. 1939

Gelatin silver print

34.3 x 26.7cm (13 1/2 x 10 1/2 in.)

Fine Arts Program, Public Buildings Service, U.S. General Services Administration

Minor White (American, 1908-1976)

San Mateo County, California / Leonard Nelson, Vicinity of Stinson Beach, Marin County, California, November 1947

1947

Gelatin silver print

30.5 x 50.8cm (12 x 20 in.)

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Ralph M. Parsons Fund

Reproduced with permission of the Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum

© Trustees of Princeton University

Minor White (American, 1908-1976)

Lily Pads and Pike, Portland, Oregon

c. 1939

Gelatin silver print

34 x 26.8cm (13 3/8 x 10 9/16 in.)

Fine Arts Program, Public Buildings Service, U.S. General Services

Minor White (American, 1908-1976)

Design (Cable and Chain), Portland, Oregon

c. 1940

Gelatin silver print

33.8 x 25.8cm (13 5/16 x 10 3/16 in.)

Fine Arts Program, Public Buildings Service, U.S. General Services Administration

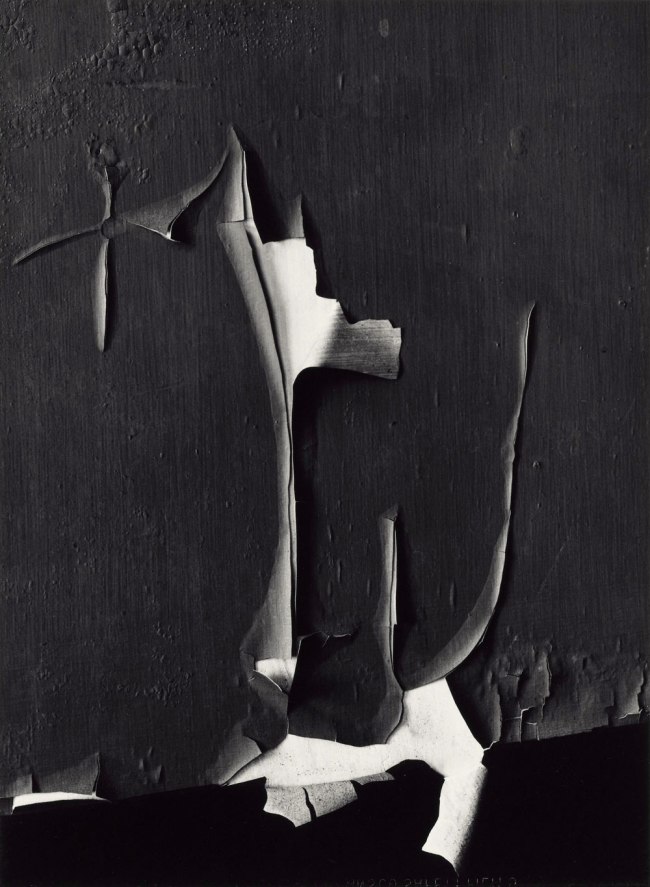

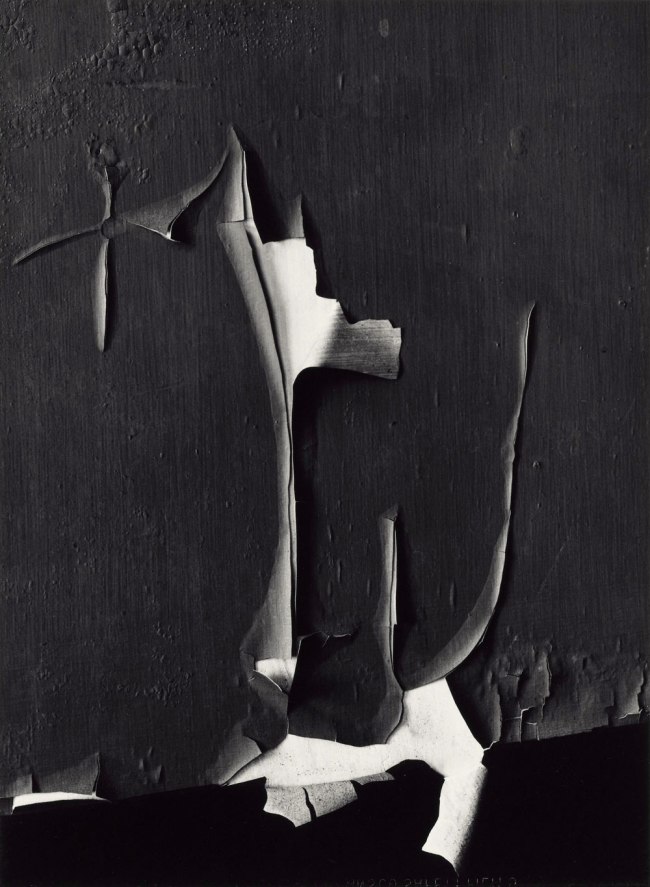

Minor White (American, 1908-1976)

Peeled Paint, Rochester, New York

1959

Gelatin silver print

31.1 x 22.9cm (12 1/4 x 9 in.)

Promised gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced with permission of the Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum

© Trustees of Princeton University

Minor White (American, 1908-1976)

Empty Head, 72 N. Union Street, Rochester, New York

1962

Gelatin silver print

30 x 23cm (11 13/16 x 9 1/16 in.)

Purchased in part with funds provided by Daniel Greenberg, Susan Steinhauser, and the Greenberg Foundation

Reproduced with permission of the Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum

© Trustees of Princeton University

Minor White (American, 1908-1976)

Burned Mirror, Rochester, New York

1959

Gelatin silver print

30.5 x 22cm (12 x 8 11/16 in.)

Purchased in part with funds provided by Daniel Greenberg, Susan Steinhauser, and the Greenberg Foundation

Reproduced with permission of the Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum

© Trustees of Princeton University

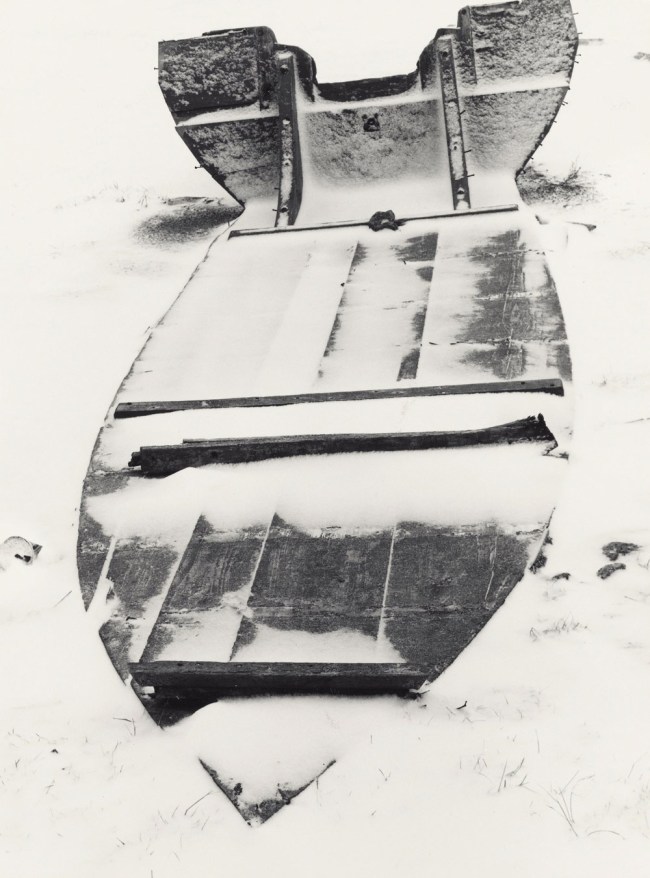

Minor White (American, 1908-1976)

Essence of Boat, Lanesville, Massachusetts

1967

Gelatin silver print

31.8 x 23.8cm (12 1/2 x 9 3/8 in.)

Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced with permission of the Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum

© Trustees of Princeton University

Minor White (American, 1908-1976)

Ivy, Portland, Oregon

Negative,1964; print, 1975

Gelatin silver print

22.9 x 30.5cm (9 x 12 in.)

Promised gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced with permission of the Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum

© Trustees of Princeton University

Minor White (American, 1908-1976)

72 N. Union Street, Rochester, New York

1960

Gelatin silver print

30.5 x 24.1cm (12 x 9 1/2 in.)

Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced with permission of the Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum

© Trustees of Princeton University

Minor White (American, 1908-1976)

Moencopi Strata, Capitol Reef National Park, Utah

1962

Gelatin silver print

32.7 x 24.1cm (12 7/8 x 9 1/2 in.)

Promised gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced with permission of the Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum

© Trustees of Princeton University

Minor White (American, 1908-1976)

Windowsill Daydreaming, Rochester, New York

1958

Gelatin silver print

24.4 x 25.1cm (9 5/8 x 9 7/8 in.)

Purchased in part with funds provided by Daniel Greenberg, Susan Steinhauser, and the Greenberg Foundation

Reproduced with permission of the Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum

© Trustees of Princeton University

Minor White (American, 1908-1976)

Notom, Utah

1963

Gelatin silver print

39.4 x 31.1cm (15 1/2 x 12 1/4 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Reproduced with permission of the Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum

© Trustees of Princeton University

Minor White (American, 1908-1976)

Gloucester, Massachusetts

1973

Gelatin silver print

21.6 x 29.2cm (8 1/2 x 11 1/2 in.)

Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced with permission of the Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum

© Trustees of Princeton University

Minor White (American, 1908-1976)

Batavia, New York

1958

Gelatin silver print

34 x 20.3cm (13 3/8 x 8 in.)

Purchased in part with funds provided by Daniel Greenberg, Susan Steinhauser, and the Greenberg Foundation

Reproduced with permission of the Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum

© Trustees of Princeton University

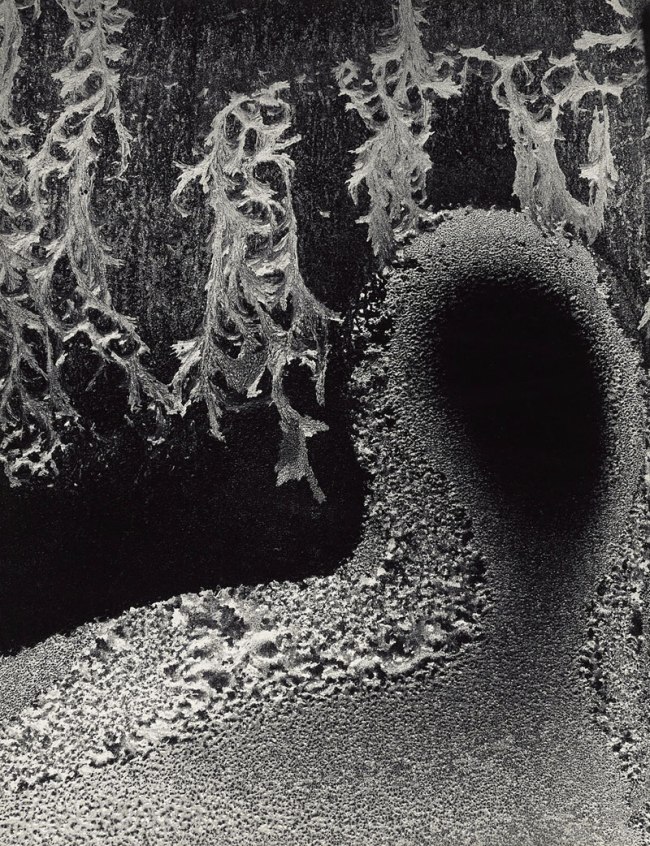

Minor White (American, 1908-1976)

Night Icicle, 72 N. Union Street, Rochester, New York

1959

Gelatin silver print

30.5 x 23cm (12 x 9 1/16 in.)

Purchased in part with funds provided by Daniel Greenberg, Susan Steinhauser, and the Greenberg Foundation

Reproduced with permission of the Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum

© Trustees of Princeton University

Minor White (American, 1908-1976)

203 Park Ave., Arlington, Massachusetts

1966

Gelatin silver print

34.3 x 12.7cm (13 1/2 x 5 in.)

Promised gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced with permission of the Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum

© Trustees of Princeton University

Minor White (American, 1908-1976)

Easter Sunday, Stony Brook State Park, New York

1963

Gelatin silver print

23.7 x 9.2cm (9 5/16 x 3 5/8 in.)

Promised gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced with permission of the Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum

© Trustees of Princeton University

Minor White (American, 1908-1976)

Mission District, San Francisco, California

1949

Gelatin silver print

33.8 x 9.5cm (13 5/16 x 3 3/4 in.)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Purchase

Reproduced with permission of the Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum. © Trustees of Princeton University

The J. Paul Getty Museum

1200 Getty Center Drive

Los Angeles, California 90049

Opening hours:

Tuesday – Friday, Sunday 10am – 5.30pm

Saturday 10am – 8pm

Monday Closed

The J. Paul Getty Museum website

LIKE ART BLART ON FACEBOOK

Back to top

You must be logged in to post a comment.