Exhibition dates: 24th November 2013 – 27th July 2014

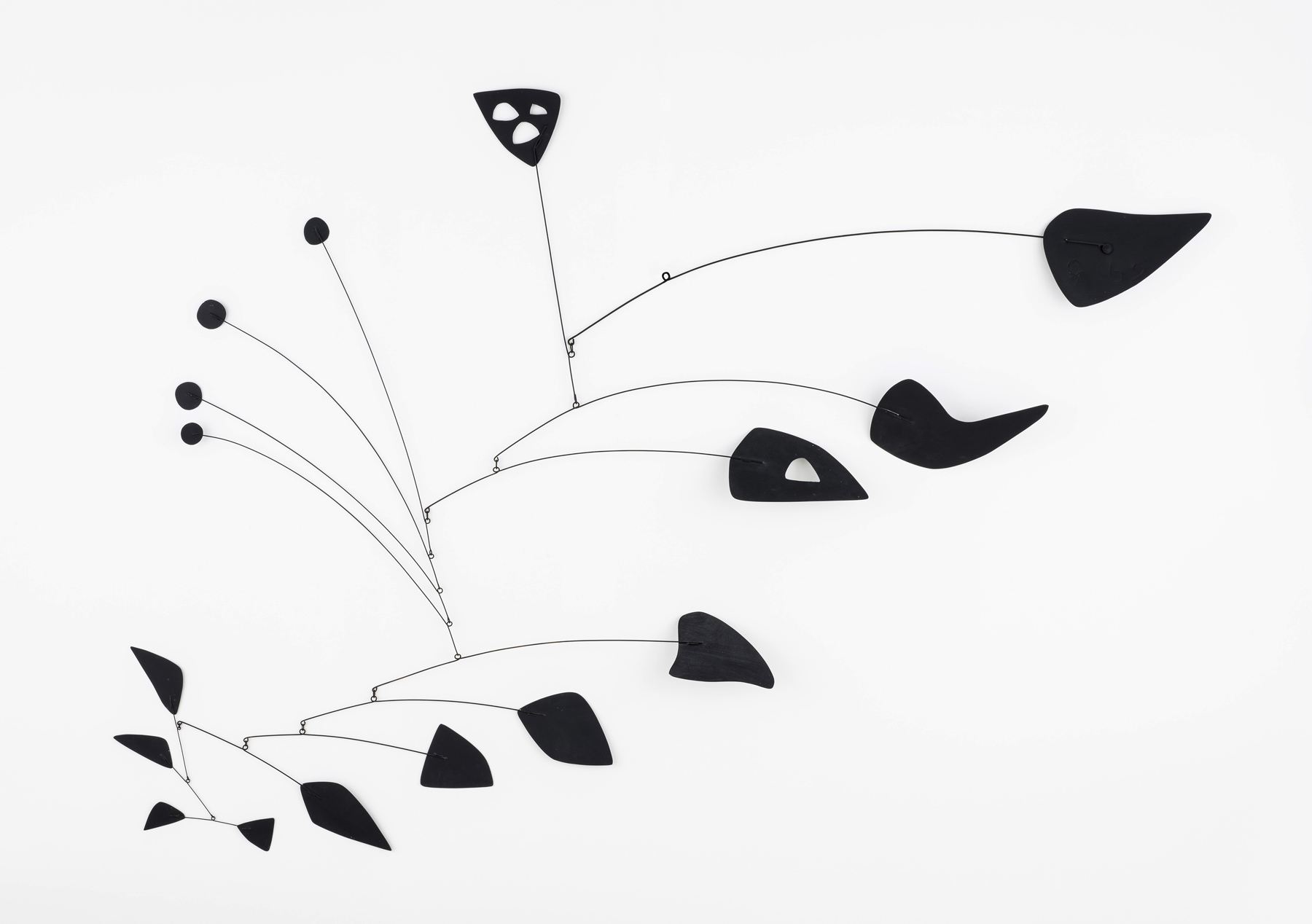

Alexander Calder (American, 1898-1976)

Blue Feather

c. 1948

Sheet metal, wire and paint

42 x 55 x 18 inches

Calder Foundation, New York

© Calder Foundation, New York/Artists Rights Society (ARS)

Photo: Calder Foundation, New York/Art Resource NY

Any of them – or just one of them. I don’t care!

Just to have one in your home would be like wishing upon a star… to contemplate, to observe, to understand these inherently tactile sculptures. What a joy.

Marcus

Many thankx to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) for allowing me to publish the art work in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image. Download Calder and Abstraction: From Avant-Garde to Iconic Didactics (30kb pdf)

Installation views of Calder and Abstraction: From Avant-Garde to Iconic at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA)

© Calder Foundation, New York/Artists Rights Society (ARS)

Photos: Fredrik Nilsen

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) presents Calder and Abstraction: From Avant-Garde to Iconic, the first monographic presentation of Alexander Calder’s work in a Los Angeles museum. Taking as its compass the large-scale sculpture Three Quintains (Hello Girls), a site-specific fountain commissioned by LACMA’s Art Museum Council in 1964 for the opening of LACMA’s Hancock Park campus, Calder and Abstraction brings together a range of nearly fifty abstract sculptures, including mobiles, stabiles, and maquettes for larger outdoor works, that span more than four decades of the artist’s career. The exhibition at LACMA is organised by LACMA’s senior curator of modern art Stephanie Barron and designed by Gehry Partners, LLP.

Barron remarks, “Calder is recognised as one of the greatest pioneers of modernist sculpture, but his contribution to the development of abstract modern sculpture – steeped in beauty and humour – has long been underestimated by critics. Calder was considered a full-fledged member of the European avant-garde, becoming friendly with André Breton, Marcel Duchamp, Joan Miró, and Piet Mondrian, and exhibited alongside Jean Arp, Wassily Kandinsky, Fernand Léger, and many of the Surrealists. His radical inventions move easily between seeming opposites: the avant-garde and the iconic, the geometric and the organic, art and science – an anarchic upending of the sculptural paradigm.”

“Calder and Abstraction offers a window into the remarkably original thinking of this distinguished artist and elucidates his revolutionary and pivotal contribution to the development of modern sculpture,” says Michael Govan, CEO and Wallis Annenberg Director of LACMA. “Three Quintains (Hello Girls) at LACMA has for decades been seen as an emblem of the museum. Following in the footsteps of its legacy, our campus continues to be enhanced by large-scale, public art – most recently with the inclusion of Chris Burden’s Urban Light (2008) and Michael Heizer’s Levitated Mass (2012).”

Exhibition overview

Calder and Abstraction traces the evolution of abstraction in the artist’s sculptural practice. The exhibition, arranged in loose chronological order, presents highlights of Calder’s oeuvre from his earliest abstract works to the crescendo of his career in the late 1940s to his later public sculptural commissions. While he is considered one of the most popular artists of his time, his work also shares sensibilities with less immediately accessible artists, including the Surrealists and the champions of pure abstraction that made up the Abstraction-Création group, such as Robert Delaunay, Theo van Doesburg, and Kurt Schwitters, among others.

From 1926 to 1933, Pennsylvania-born Calder lived primarily in Paris and was a prevalent figure of the European avant-garde along with peers Marcel Duchamp, Joan Miró, Piet Mondrian, Jean Hélion, Wassily Kandinsky, Fernand Léger, Alberto Giacometti, fellow American Man Ray, and many of the Surrealists. At the time, Paris was the epicentre of creative production, and Surrealism was the most significant artistic movement in France. A number of his works from the 1930s referenced astronomy, a preoccupation shared by a number of avant-garde artists. In Gibraltar two off-kilter rods thrust upward from a plane encircling a wood base, suggesting a personal solar system. Calder was fascinated with representing the natural world and the cosmos as potent and brimming with energy: “When I have used spheres and discs … they should represent more than what they just are. … [T]he earth is a sphere but also has some miles of gas about it, volcanoes upon it, and the moon making circles around it. … A ball of wood or a disc of metal is rather a dull object without this sense of something emanating from it.”

A crucial encounter for Calder occurred in 1930 upon visiting artist Piet Mondrian’s studio. Calder credited Mondrian with opening his eyes to the term “abstract,” providing the catalyst to a new phase in his practice. Calder later described this visit as pivotal in his move towards abstraction: “The visit gave me a shock. … Though I had heard the word ‘modern’ before, I did not consciously know or feel the term ‘abstract.’ So now, at thirty-two, I wanted to paint and work in the abstract.”

Calder appropriated Surrealism’s affinity to curvilinear, biomorphic forms into his sculptures, and when he met Miró in 1928, the two men discovered a mutual admiration for each other’s work and developed a close friendship. As Calder stated, “Well, the archaeologists will tell you there’s a little bit of Miró in Calder and a little bit of Calder in Miró.”

The decade after he met Miró and Mondrian proved to be the most radical of Calder’s career. He embraced the Surrealist notion of integrating chance into his works in addition to the Constructivist idea that painting and sculpture should be freed from their standard constraints, such as gravity and traditional sculptural mass. He consequently developed his two signature typologies: the mobile, a term coined by Marcel Duchamp after a visit to Calder’s home and studio in 1931; and the stabile, named by Jean Arp in 1932.

Calder’s mobiles are hanging, kinetic sculptures made of discrete movable parts stirred by air currents, creating sinuous and delicate drawings in space. Either suspended or freestanding, these often large constructions consist of flat pieces of painted metal connected by wire veins and stems. Eucalyptus (1940), one of Calder’s first mature mobiles, was created during World War II. The piece can be seen as a composition of violent, tortured biomorphic shapes that suggest gaping mouths, body parts, sexual organs, and sinister weapons.

Stabiles, which were developed alongside Calder’s mobiles but came to full maturity later in his career, are stationary abstract sculptures, often with mobiles attached to them (standing mobiles). In several of Calder’s works from the 1940s – the most prolific decade of his sculptural production – he effectively blended the mobile and stabile forms, as seen in Laocoön (1947), in which the stabile supports graceful, arcing branches that cut a broad swath as they rotate at an irregular rhythm.

In the mid-1950s, Calder began working with quarter-inch steel (thicker than the aluminium he had used during the 1940s), which enabled him to construct larger, more durable, and more ambitious sculptures and posed him as an ideal collaborator with architects to create works for public spaces. With commissions from the city of Spoleto, Italy (1962), Montreal’s Expo (1967) and Grand Rapids, Michigan (1969) – represented in the exhibition by La Grande vitesse (intermediate maquette) – Calder began a virtually non-stop output of public sculpture until his death in 1976.

Calder’s public sculpture evolved at a time when communities were becoming increasingly proud of public sculpture, although his resolutely bold abstract forms, though hard to imagine now, were initially met with some controversy. Today encountering Calder’s iconic sculpture in the centre of a city, in front of a courthouse, in the midst of the Senate Office Building, or in front of a museum is a hallmark of postwar public sculpture that he helped to invent.

Exhibition design and installation

Calder was constantly in conversation and collaborated with other artists and architects in his lifetime, but a major architect has not designed a Calder show since the 1980s. Frank O. Gehry’s design for LACMA’s exhibition allows for quiet areas of contemplation, unexpected juxtapositions of related works, and opportunities for both intimate and panoramic views of the works. Gehry’s gently curved walls frame the sculptures and recall the harmony between art and architecture, emphasising the organic nature of Calder’s works. Gehry’s own method of developing architectural forms is inherently tactile, sharing some of the same hands-on techniques of a sculptor.

With the assistance of technology and effective planning, Calder and Abstraction at LACMA features a selection of sculptures that are animated throughout the course of the day.

Press release from the LACMA website

Alexander Calder (American, 1898-1976)

Three Quintains (Hello Girls)

1964

Sheet metal and paint with motor

275 x 288 inches

Los Angeles County Museum of Art

© Calder Foundation, New York/Artists Rights Society (ARS)

Photo: Museum Associates/LACMA

Alexander Calder (American, 1898-1976)

Little Face

1962

Sheet metal, wire and paint

42 x 56 inches

Los Angeles County Museum of Art

© Calder Foundation, New York/Artists Rights Society (ARS)

Photo: Museum Associates/LACMA

Alexander Calder (American, 1898-1976)

Laocoön

1947

Sheet metal, wire, rod, string and paint

80 x 120 x 28 inches

The Eli and Edythe L. Broad Collection

© Calder Foundation, New York/Artists Rights Society (ARS)

Photo: Douglas M. Parker Studio, Los Angeles

Alexander Calder (American, 1898-1976)

Yucca

1941

Sheet metal, wire and paint

73 x 23 x 20 inches

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Hilla Rebey Collection, 1971

© Calder Foundation, New York/Artists Rights Society (ARS)

Photo: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York, by Kristopher McKay

Alexander Calder (American, 1898-1976)

Un effet du japonais

1941

Sheet metal, rod, wire and paint

80 x 80 x 48 inches

Calder Foundation, New York

© Calder Foundation, New York/Artists Rights Society (ARS)

Photo: Calder Foundation, New York/Art Resource NY

Alexander Calder (American, 1898-1976)

Gibraltar

1936

Lignum vitae, walnut, steel rods, and painted wood

52 x 24 x 11 inches

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of the artist.

© Calder Foundation, New York/Artists Rights Society (ARS)

Digital image: © 2013 The Museum of Modern Art/Licences by SCALA/Art Resource, NY

Alexander Calder (American, 1898-1976)

Constellation Mobile

1943

Wood, wire, string and paint

53 x 48 x 35 inches

Calder Foundation, New York

© Calder Foundation, New York/Artists Rights Society (ARS)

Photo: Calder Foundation, New York/Art Resource NY

Alexander Calder (American, 1898-1976)

Bougainvillier

1947

Sheet metal, wire, lead and paint

78 x 86 inches

Collection of John and Mary Shirley

© Calder Foundation, New York/Artists Rights Society (ARS)

Photo: Calder Foundation, New York/Art Resource NY

Alexander Calder (American, 1898-1976)

Le Demoiselle

1939

Sheet metal, wire and paint

58 x 21 x 29 inches

Glenstone

© Calder Foundation, New York/Artists Rights Society (ARS)

Alexander Calder (American, 1898-1976)

Red Disc

1947

Sheet metal, wire and paint

81 x 78 inches

Frances A. Bass

© Calder Foundation, New York/Artists Rights Society (ARS)

Alexander Calder (American, 1898-1976)

Untitled

1947

Sheet metal, wire and paint

66 x 53 inches

Private collection

© Calder Foundation, New York/Artists Rights Society (ARS)

Photo: Calder Foundation, New York/Art Resource NY

Alexander Calder (American, 1898-1976)

Trois Pics (intermediate maquette)

1967

Sheet metal, bolts, and paint

96 x 63 x 70 inches

Calder Foundation, New York

© Calder Foundation, New York/Artists Rights Society (ARS)

Photo: Calder Foundation, New York/Art Resource NY

Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA)

5905 Wilshire Boulevard (at Fairfax Avenue)

Los Angeles, CA, 90036

Phone: 323 857 6000

Opening hours:

Monday, Tuesday, Thursday: 11am – 6pm

Friday: 11am – 8pm

Saturday, Sunday: 10am – 7pm

Closed Wednesday

![Ana Mendieta (Cuban-American, 1948-1985) 'Itiba Cahubaba (Esculturas Rupestres)' [Old Mother Blood (Rupestrian Sculptures)] 1982 Ana Mendieta (Cuban-American, 1948-1985) 'Itiba Cahubaba (Esculturas Rupestres)' [Old Mother Blood (Rupestrian Sculptures)] 1982](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/ana-mendieta_itiba-cuhababa-web.jpg?w=650&h=878)

![George Platt Lynes (American, April 15, 1907 - December 6, 1955) 'Untitled' Nd [c. 1951] George Platt Lynes (American, April 15, 1907 - December 6, 1955) 'Untitled' Nd [c. 1951]](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/george-platt-lynes-untitled-1953.jpg)

![George Platt Lynes (American, April 15, 1907 - December 6, 1955) 'Untitled [Charles 'Tex' Smutney, Charles 'Buddy' Stanley, and Bradbury Ball]' c. 1942 George Platt Lynes (American, April 15, 1907 - December 6, 1955) 'Untitled [Charles 'Tex' Smutney, Charles 'Buddy' Stanley, and Bradbury Ball]' c. 1942](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/lynes-c-1942.jpg?w=840)

You must be logged in to post a comment.