Exhibition dates: 28th June 2013 – 5th January 2014

1st floor West, American Art Museum (8th and F Streets, N.W.)

Browse the exhibition and related works on the exhibition website

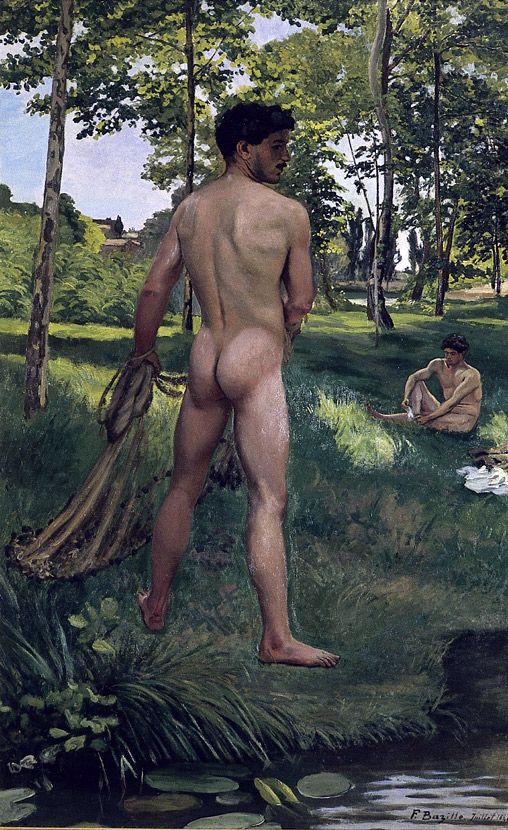

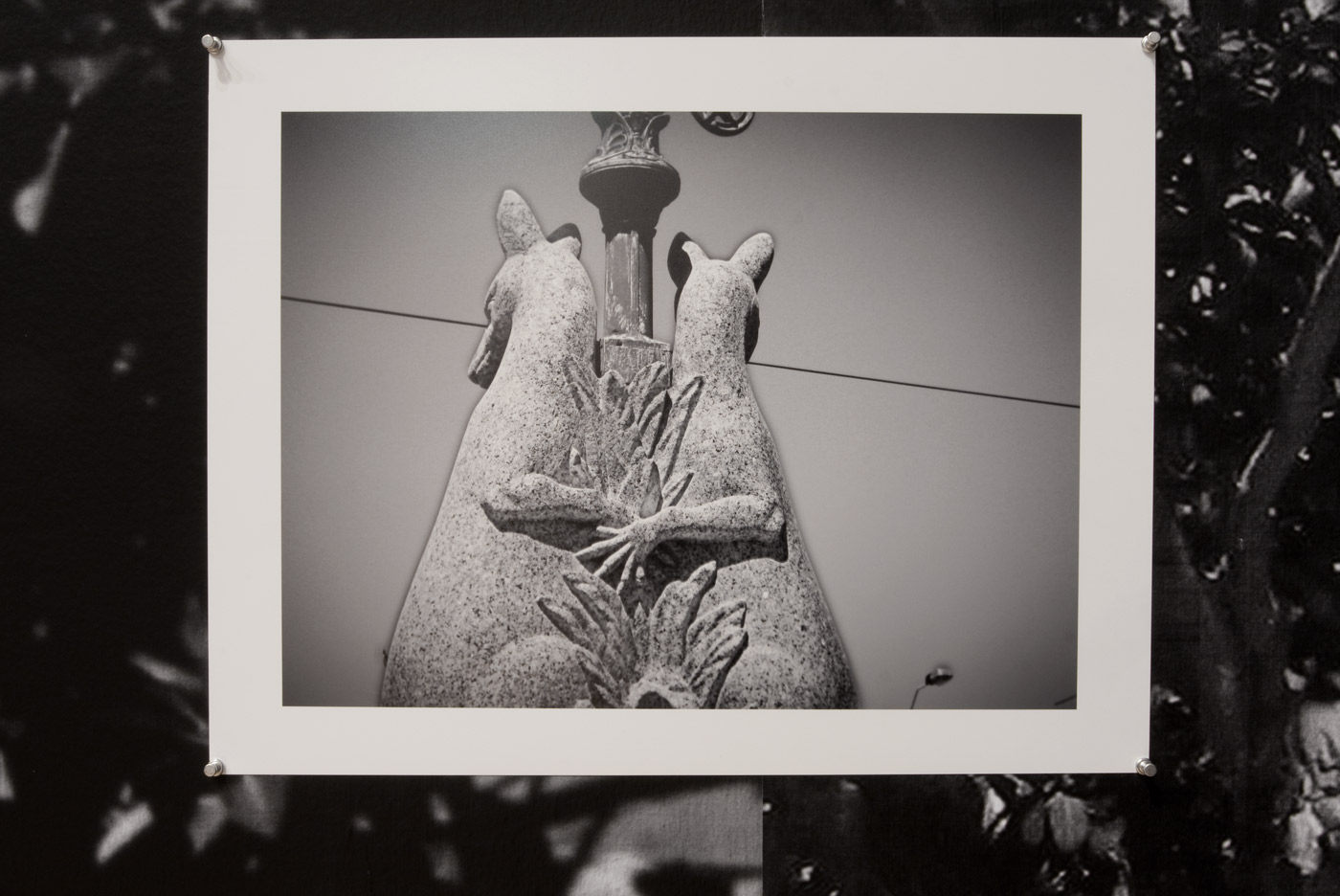

Unidentified artist

[Bird in Basin with Thread Spool and Patterned Cloth]

c. 1855

Daguerreotype

Plate: 2 3/4 x 3 1/4 in. (6.9 x 8.2cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Museum purchase from the Charles Isaacs Collection made possible in part by the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment

The next two weeks sees a lot of exhibitions finish their run on the 5th January 2014.

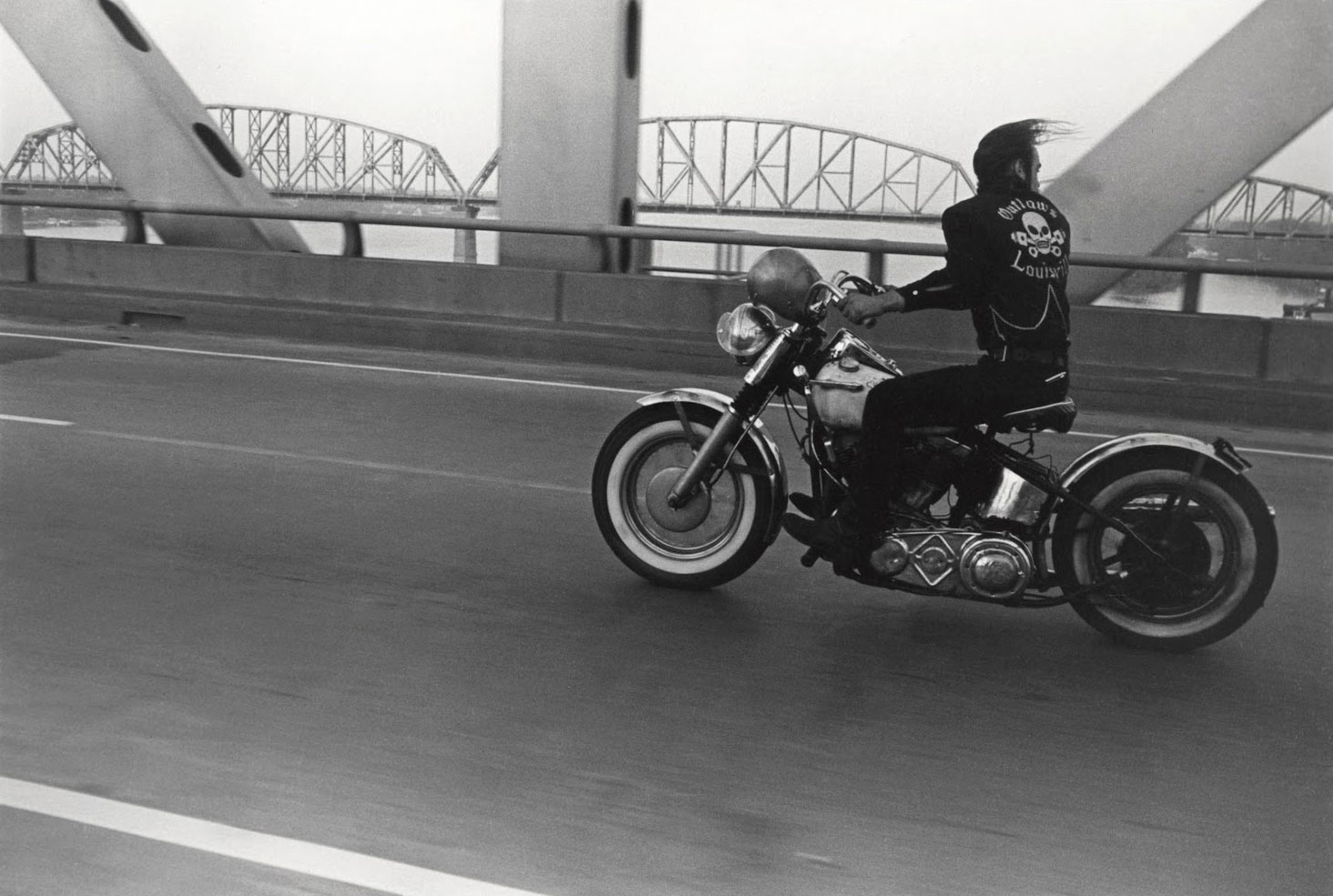

Here is a bumper posting which contains one of my favourite photographs of all time: Danny Lyon’s Crossing the Ohio River, Louisville (1966, below). From a distance, this looks to be a very interesting exhibition on a large topic, delineated for the viewer into four main sections. The task of the curator cannot have been easy, picking 113 images to represent a “democracy” of images out of a collection of over 7,000 images. Of course there can never be a true “democracy” of images as some will always be more valued within our culture than others. There is a meritocracy in this exhibition which features images by masters of the medium but this is balanced by the inclusion of images by anonymous photographers, little known photographers and vernacular and street photography.

What is most impressive is the specially developed website which includes many images from the different sections of the exhibition. These images are of good quality and, along with relevant text, help the viewer place the images in context. Related content is also suggested from the full photographic collection at The Smithsonian which has been placed online with good image quality. This is a far cry from many exhibitions at state galleries in Australia where there are hardly any dedicated exhibition websites. Most of the photographic collection from these galleries is not available online and if it has been scanned, the image quality is generally poor. How many times have I searched a state gallery or library collection and come up with the answer: “Image not available” ?

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Smithsonian American Art Museum for allowing me to publish the photographs and text in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“More often, though, the moments, places, people and views that have been collected here feel offhand and stumbled upon, telling a fragmentary, incomplete tale. Sometimes it’s literally a glance, as in “Girl Holding Popsicle,” a 1972 image by Mark Cohen, who rarely even looked through his viewfinder. Other times, it’s more like a long stare, as in William Christenberry’s 1979 “China Grove Church – Hale County, Alabama,” a locale that the Washington-based artist and Alabama native returned to again and again. These 113 pictures are, at the same time, quietly telling, revealing bits of America in oblique, prismatic ways.”

Part of Michael O’Sullivan’s review of the exhibition in The Washington Post.

American Characters

Photographers have captured the texture of everyday life since the medium’s arrival in the United States in 1839. Photographic portraits have made both the iconic and the commonplace serve as stand-ins for all of us, forging a shared language of political and social understanding. In charting the passing parade of history – the faces of the anonymous and the famous; evolving stories of immigration, disenfranchisement, and assimilation; as well as emblematic objects and celebrated landmarks lodged within our collective memory – photographs reveal the complexities of America.

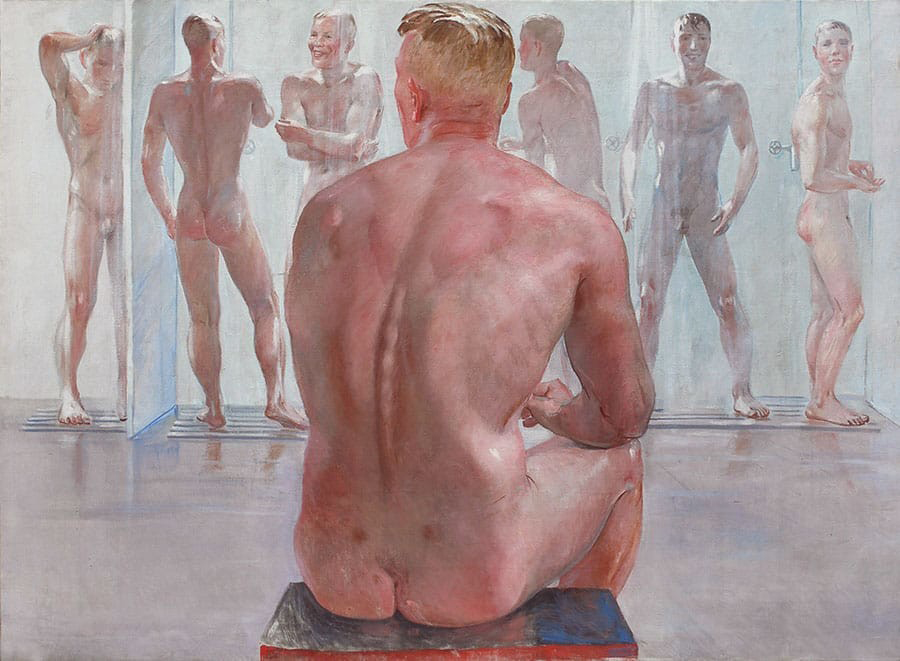

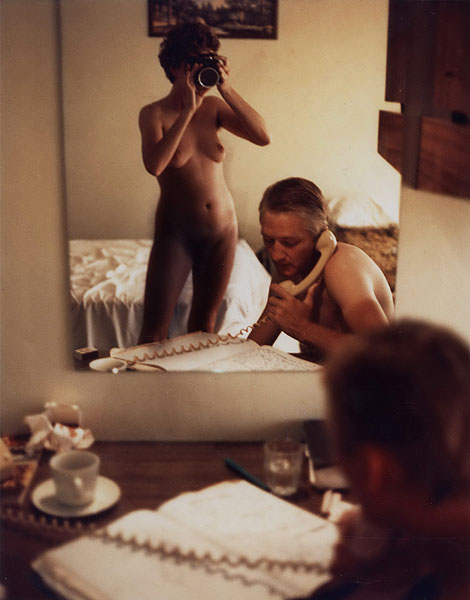

Larry Sultan (American, 1946-2009)

Portrait of My Father with Newspaper

1988

Chromogenic print

Image: 28 5/8 x 34 5/8 in. (72.7 x 87.9cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Gift of Nan Tucker McEvoy

© 1988, Larry Sultan

In Portrait of My Father with Newspaper, Irving Sultan reads the Los Angeles Times as light pours in behind him. This carefully composed portrait reveals the artist’s father almost entirely through reflections and shadows. Thin newsprint shields his body from the camera, while only a vague profile of his face is discernible on the right half of the spread. Prompted by the discovery of a box of home movies, Larry Sultan embarked on an eight-year enquiry into his parents’ lives. He stayed in their home for weeks at a time, interviewing them about their marriage and photographing their domestic activities.

Eugene Richards (American, b. 1944)

First Communion (Dorchester, Mass.)

1976

Gelatin silver print

Image: 8 x 12 in. (20.3 x 30.5cm)

Sheet: 11 x 14 in. (27.9 x 35.6cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the National Endowment for the Arts

© 1974, Eugene Richards

Mark Cohen (American, b. 1943)

Girl Holding Popsicle

1972, printed 1983

Gelatin silver print

Sheet: 14 x 17 in. (35.5 x 43.2cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Gift of Dene and Mel Garbow

© 1972, Mark Cohen

In Girl Holding Popsicle a young girl twists shyly as she poses before a graffiti-inscribed brick wall. Mark Cohen took this photograph spontaneously as he passed through a back alley. Cohen does not hesitate to get assertively close to the strangers he meets in his hometown of Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. Many of his photographs are made without looking through a viewfinder, and so remain a mystery even to Cohen until they are developed.

Unidentified artist

[Gold Nugget]

c. 1860s

Albumen silver print

Image: 2 1/8 x 3 5/8 in. (5.4 x 9.2cm)

Sheet: 2 3/8 x 3 7/8 in. (6.1 x 9.8cm) irregular

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Gift of Charles Isaacs and Carol Nigro

Mathew B. Brady (American, 1823-1896)

Reviewing Stand in Front of the Executive Mansion, Washington, D.C., May, 1865

1865, printed early 1880s

Albumen silver print

Sheet and image: 6 1/2 x 9 in. (16.5 x 22.9cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Museum purchase through the Julia D. Strong Endowment

Kevin Bubriski (American, b. 1954)

World Trade Center Series, New York City

2001

Gelatin silver print

Image: 18 x 18 in. (45.7 x 45.7cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Gift of the Consolidated Natural Gas Company Foundation

© 2001, Kevin Bubriski

In the weeks and months following the World Trade Center attacks on September 11, 2001, Kevin Bubriski photographed people who gathered at Ground Zero. Frozen in awe, struck with disbelief, and overcome with loss, people stood before the destroyed building site to confront the horrible tragedy. More than ten years later, Bubriski’s photographs preserve the emotional impact of this infamous day through images of those who witnessed its aftermath first-hand.

Deborah Luster (American, b. 1951)

01-26 Location. 1800 Leonidas Street (Carrollton) Date(s). July 14, 2009 7:55 a.m. Name(s). Brian Christopher Smith (22) Notes. Face up with multiple gunshot wounds

2008-2012

Gelatin silver print

55 x 55 in. (139.7 x 139.7cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Museum purchase through the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment

© 2010, Deborah Luster

This photograph, from a series that documents contemporary and historical homicide sites in New Orleans, presents Deborah Luster’s interpretation of the last view of the crime victim lying face up on the ground. The title is the entry from the New Orleans Police blotter, but the photograph is Luster’s meditation on looking, seeing, and the power of images to haunt our imagination.

Unidentified artist

[Two Workmen Polishing a Stove]

c. 1865

Albumen silver print

Sheet and image: 14 1/8 x 11 in. (35.9 x 28cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Museum purchase from the Charles Isaacs Collection made possible in part by the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment

Anthony Barboza (American, b. 1944)

“Marvelous” Marvin Hagler, boxer

1981

Gelatin silver print

Image: 13 7/8 x 13 7/8 in. (35.2 x 35.2cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Gift of Kenneth B. Pearl

© 1981, Anthony Barboza

Edward S. Curtis (American, 1868-1952)

Girl and Jar – San Ildefonso

1905

Photogravure

16 5/8 x 12 1/4 in. (12.3 x 31.1cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the United States Marshal Service of the U.S. Department of Justice

Between 1900 and 1930, Edward S. Curtis traveled across the continent photographing more than seventy Native American tribes. The photographs, compiled into twenty volumes, presented daily activities, customs, and religions of a people he called “a vanishing race.” Curtis hoped to preserve the legacy of Native peoples in lasting images. To this end, Curtis often costumed his subjects and set up scenes, mixing tribal artefacts and traditions to match his romantic vision of the people he studied. In this intimate portrait, a young Tewa woman named Povi-Tamu (“Flower Morning”) balances a large jug with help from a hidden fiber ring. She is from the San Ildefonso Pueblo of New Mexico, which is famed for its rich tradition of fine pottery. Curtis associated the serpentine design of the vessel with the serpent cult, which he noted was central to Tewa life.

Oliver H. Willard (American, active 1850s-1870s, died 1875)

Portrait of a Young Woman

c. 1857

Salted paper print

8 7/8 x 6 3/4 in. (22.5 x 17.1cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Museum purchase through the Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation, 1999.29.1

Spiritual Frontier

The earliest photographs made in America describe an awesome land blessed with such an abundance of natural beauty that it seemed heaven sent. Images of waterfalls, mountains, and vast open spaces conveyed the beauty, the grandeur, the sublimity, and dynamics of a great spiritual endeavour. In the nineteenth century photographers pictured wilderness landscapes that symbolised American greatness. More recently, photographers have described a landscape no less romantic, but now recalibrated to account for the interaction of nature and culture.

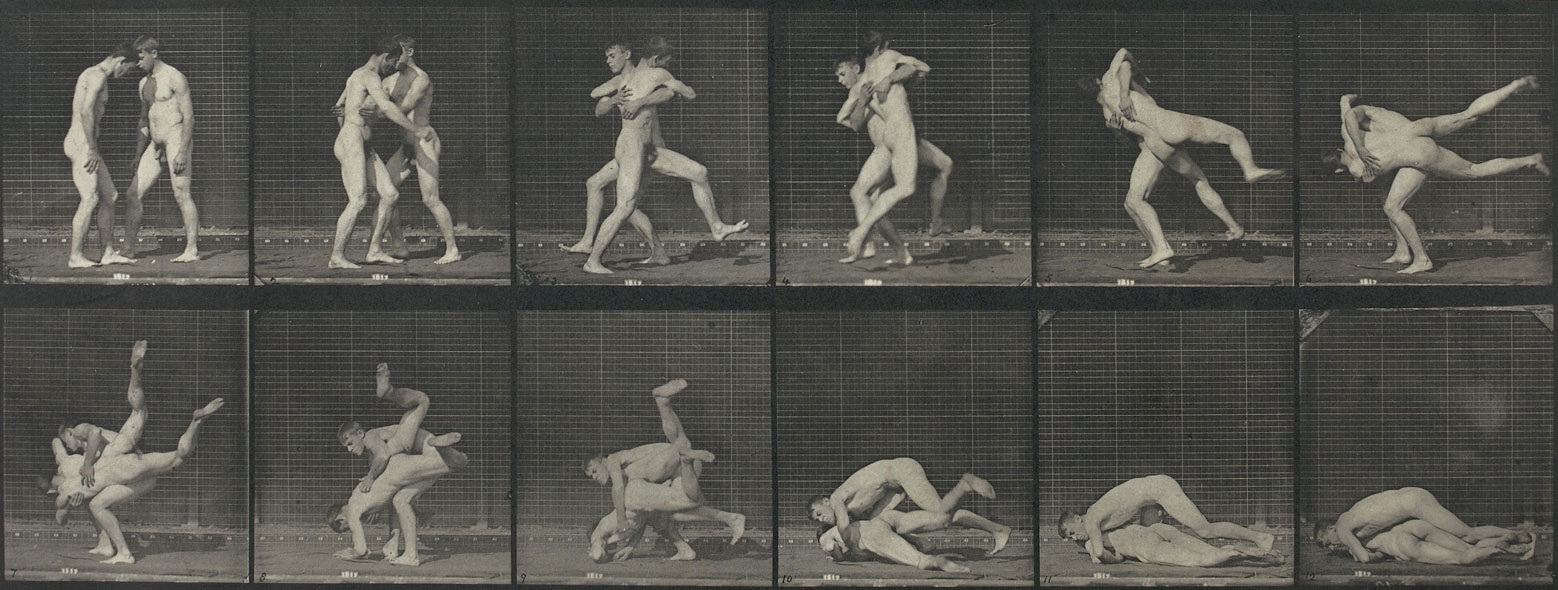

Eadweard Muybridge (English, 1830-1904)

Valley of the Yosemite from Union Point

1872

Albumen silver print

Sheet: 17 x 21 1/2 in. (43.2 x 54.6cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Charles T. Isaacs

Eadweard Muybridge went to great lengths to photograph the best possible views of the West. He chopped down trees if they obstructed his camera, and ventured to “points where his packers refused to follow him.” Muybridge was determined to produce the most comprehensive photographs ever made of Yosemite and the surrounding region. His views were sold widely in both large-format prints and stereograph cards, which are viewed through a device that creates the illusion of three-dimensional space. This allowed Muybridge to transport his audience, if just for a moment, to a faraway place caught on film.

Robert Frank (Swiss, 1924-2019)

Butte, Montana

1956, printed 1973

Gelatin silver print

Image: 8 3/4 x 13 in. (22.2 x 33cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Museum purchase

Robert Adams (American, b. 1937)

New Housing, Longmont, Colorado

1973

Gelatin silver print

Sheet: 6 x 7 5/8 in. (15.1 x 19.3cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the National Endowment for the Arts

© 1973, Robert Adams

As both a photographer and writer, Robert Adams is committed to describing the western American landscape as both awe-inspiring and scarred by man. In New Housing, Longmont Colorado, Adams contrasted the vast space of the distant landscape view with a foreground image of the wall of a newly constructed suburban tract house. Adams invites a consideration of the balance between myth and reality and the land as home as well as scenic backdrop.

Charles L. Weed (American, 1824-1903)

Mirror Lake and Reflections, Yosemite Valley, Mariposa County, California

1865

Albumen silver print

Sheet and image: 15 1/2 x 20 1/4 in. (39.4 x 51.4cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Charles T. Isaacs

Like Carleton Watkins, his better-known competitor, Charles Weed recognised the pictorial dividend to be gained by showing Yosemite’s glorious geological features in duplicate, using the valley’s lakes as reflecting ponds. Weed first traveled to what was then known as “Yo-Semite,” in 1859, but with a relatively small camera; he returned in 1865 with a larger model capable of using what were called mammoth plates. Like Watkins, he sold his prints to buyers eager to own a photograph of majestic natural beauty.

Ansel Adams (American, 1902-1984)

Monolith: The Face of Half Dome, Yosemite Valley

1926-1927, printed 1927

Gelatin silver print

Sheet: 11 7/8 x 9 7/8 in. (30.2 x 25.1cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Museum purchase

© 2013 The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

At just over 4,700 feet above the valley, Half Dome is the most iconic rock formation in Yosemite National Park. Adams squeezed the monolith into the frame to emphasise the majesty of its scale and the drama of its cliff. As it thrusts out of the brilliant white snow, Half Dome stands as a symbol of the unspoiled western landscape. Ansel Adams made his first trip to the Sierra Nevada mountain range when he was fourteen years old, and he returned every year until the end of his life, often for month-long stretches. Throughout his career Adams traveled widely – from Hawaii to Maine – to photograph the most picturesque vistas in America. After his death in 1984, a section of the Sierra Nevada was named the Ansel Adams Wilderness in his honour.

John Pfahl (American, 1939-2020)

Goodyear #5, Niagara Falls, New York

1989

Chromogenic print

Sheet: 20 x 24 in. (50.8 x 61.0cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Gift of the Consolidated Natural Gas Company Foundation

© 1989, John Pfahl

John Pfahl’s photographs embody the conflict between progress and preservation. Throughout the 1980s he focused on oil refineries and power plants. He chose the sites strategically based on their location in picturesque landscapes, where he observed a “transcendental” connection between industry and nature. In Goodyear #5 a nuclear power plant occupies the horizon. The setting sun provides a romantic colour palette as light filters through clouds of billowing steam. The landscape is reduced to an abstract composition that celebrates colour and texture. Pfahl’s intention with this series, titled Smoke, was to “make photographs whose very ambiguity provokes thought.” This photograph complicates popular notions of power plants by revealing an uncommonly beautiful view of a controversial structure.

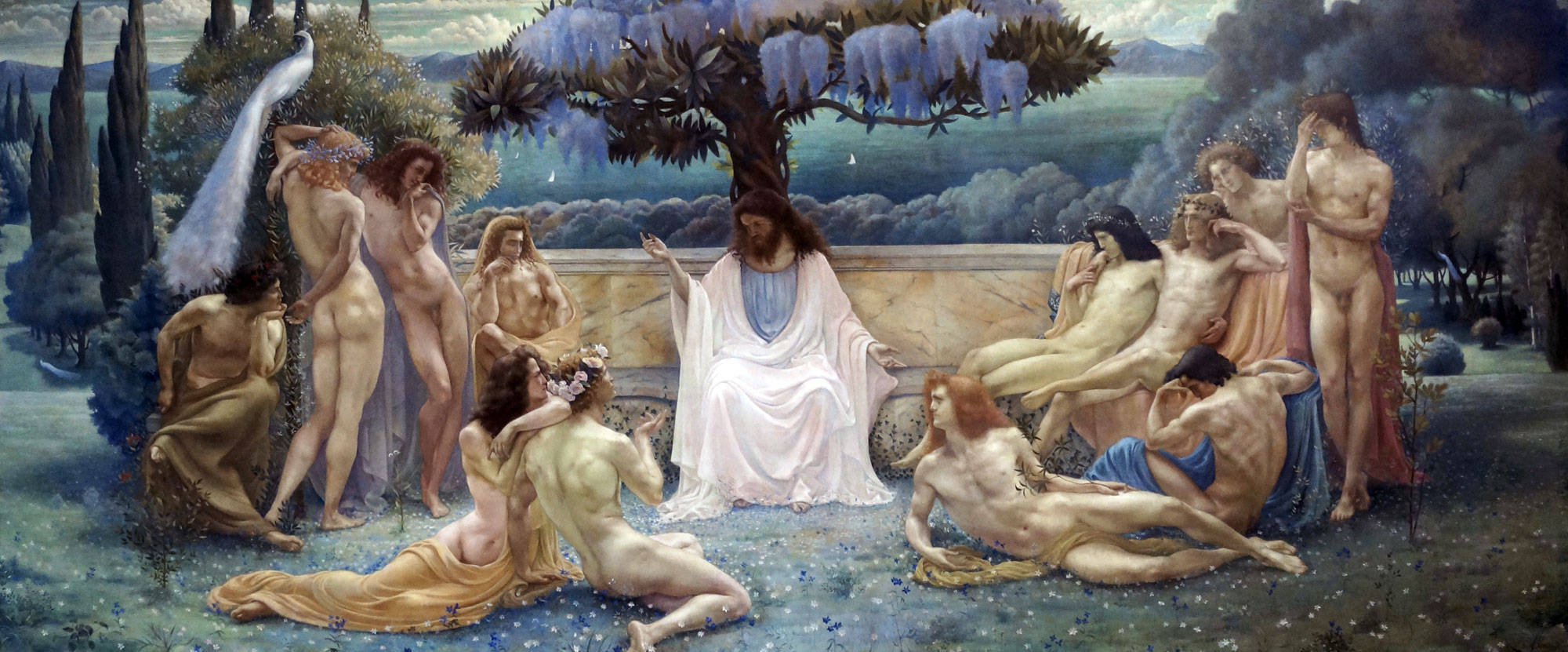

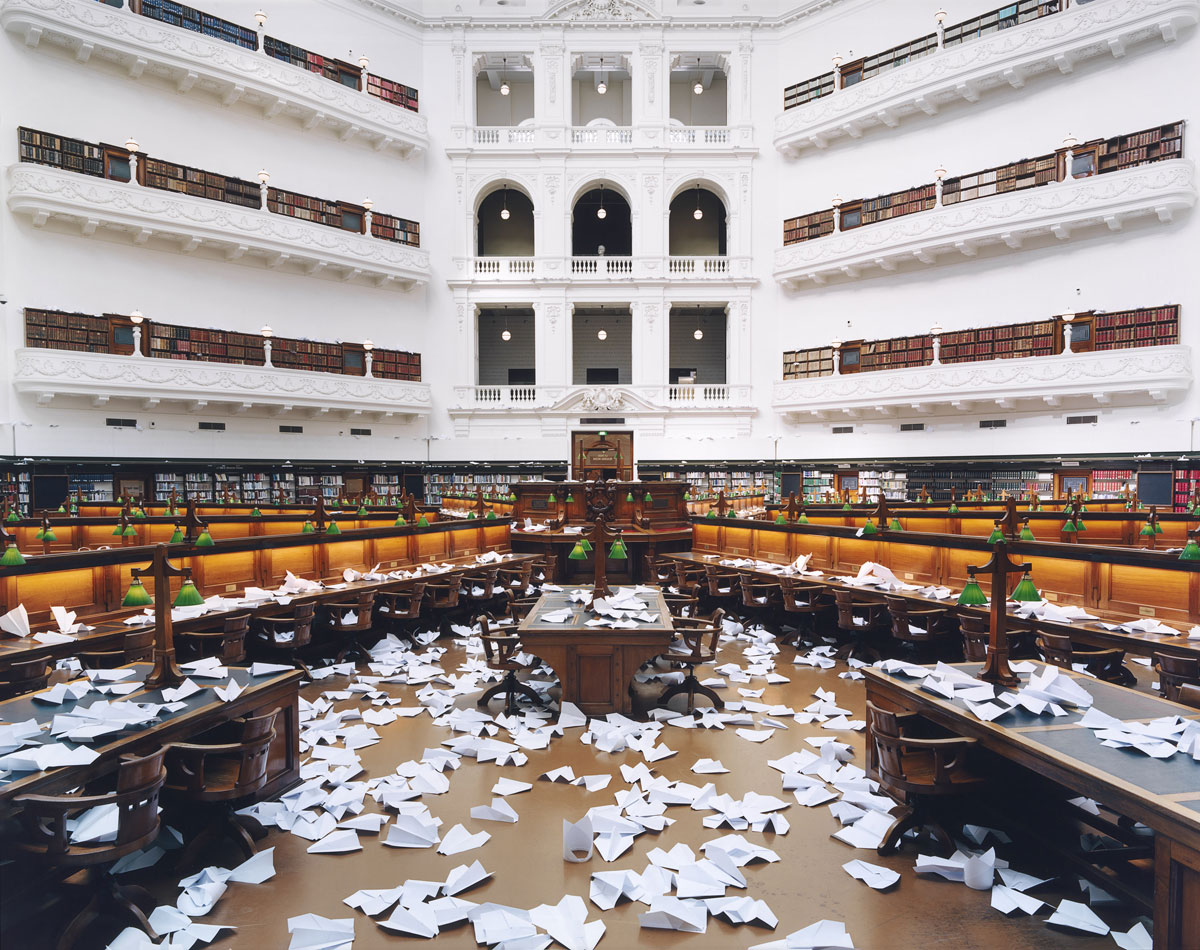

A Democracy of Images: Photographs from the Smithsonian American Art Museum celebrates the numerous ways in which photography, from early daguerreotypes to contemporary digital works, has captured the American experience. The photographs presented here are selected from the approximately 7,000 images collected since the museum’s photography program began thirty years ago, in 1983. Ranging from daguerreotype to digital, they depict the American experience and are loosely grouped around four ideas: American Characters, Spiritual Frontier, America Inhabited, and Imagination at Work.

The exhibition’s title is inspired by American poet Walt Whitman’s belief that photography provided America with a new, democratic art form that matched the spirit of the young country and his belief that photography was a quintessentially American activity, rooted in everyday people and ordinary things and presented in a straightforward way. Known as the “poet of democracy,” Whitman wrote after visiting a daguerreotype studio in 1846: “You will see more life there – more variety, more human nature, more artistic beauty… than in any spot we know.” At the time of Whitman’s death, in 1892, George Eastman had just introduced mass market photography when he put an affordable box camera into the hands of thousands of Americans. The ability to capture an instant of lasting importance and fundamental truth mesmerised Americans then and continues to inspire photographers working today. Marking the thirtieth anniversary of the establishment of the museum’s pioneering photography collection, the exhibition examines photography’s evolution in the United States from a documentary medium to a full-fledged artistic genre and showcases the numerous ways in which it has distilled our evolving idea of “America.”

The exhibition features 113 photographs selected from the museum’s permanent collection, including works by Edward S. Curtis, Timothy H. O’Sullivan, Berenice Abbott, Diane Arbus, Roy DeCarava, Walker Evans,Irving Penn, Trevor Paglen, among others, as well as vernacular works by unknown artists. A number of recent acquisitions are featured, including works by Ellen Carey, Mitch Epstein, Muriel Hasbun, Alfredo Jaar, Annie Leibovitz, Deborah Luster, and Sally Mann. Landscapes, portraits, documentary-style works from the New York Photo League and images from surveying expeditions sent westward after the Civil War are among the images on display, and explore how photographs have been used to record and catalogue, to impart knowledge, to project social commentary, and as instruments of self-expression.

Photography’s arrival in the United States in 1840 allowed ordinary people to make and own images in a way that had not been previously possible. Photographers immediately became engaged with the life of the emerging nation, the activity of new urban centers, and the possibilities of unprecedented access to the vast western frontier. From the nineteenth to the twentieth century, photography not only captured the country’s changing cultural and physical landscape, but also developed its own language and layers of meaning.

A Democracy of Images: Photographs from the Smithsonian American Art Museum is organised around four major themes that defined American photography. “American Characters” examines the ways in which photographs of individuals, places, and objects become a catalogue of our collective memory and have contributed to the ever-evolving idea of the American character. “Spiritual Frontier” investigates early ideas of a vast, inexhaustible wilderness that symbolised American greatness. “America Inhabited” traces the nation’s rapid industrialisation and urbanisation through images of speed, change, progress, immigration, and contemporary rural, urban, and suburban landscapes. “Imagination at Work” demonstrates how photography’s role of spontaneous witness gradually gave way to contrived arrangement and artistic invention. The exhibition is organised by Merry Foresta, guest curator and independent consultant for the arts. She was the museum’s curator of photography from 1983 to 1999.

Connecting online

A complementary website designed for viewing on tablets includes photographs on view in the exhibition, an expanded selection of works from the museum’s collection and a timeline of American photography. It is available through tablet stations in the exhibition galleries, online, and on mobile devices.”

Press release from the Smithsonian American Art Museum website

America Inhabited

Photography’s early presence in America coincided with the rise of an industrial economy, the growth of major urban population centers, and the fulfilling of what some saw as the Manifest Destiny of spanning the continent from sea to sea. Images of progress and industry, as well as of city and suburbs, quickly added themselves to photography’s catalogue of places and people. Some of these images reflect idealistically, and at times nostalgically, on the beauty and humanity of our own backyards. Others stand as social documents that can be seen as critical and ironic, inviting outrage as well as compassion about the way we now live our lives.

Helen Levitt (American, 1913-2009)

New York

c. 1942, printed later

Gelatin silver print

Image: 7 1/8 x 10 1/2 in. (18.1 x 26.6cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Museum purchase

© 1981, Helen Levitt

Caught before they run off into the streets, three masked youngsters pause on their front stoop. Expressive postures and mysterious disguises give this trio a theatrical quality. Helen Levitt, who found poetry in the uninhibited gestures of children, used a right-angle viewfinder to capture boys and girls roaming freely and playing with found objects. Working in New York City during the years surrounding World War II, her photographs show the drama of life that unfolded on the sidewalks of poor and working-class neighbourhoods.

Louis Faurer (American, 1916-2001)

Broadway, New York, N.Y.

1949-1950, printed 1980-1981

Gelatin silver print

Image: 8 3/8 x 12 9/16 in. (21.3 x 32cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Gift of David L. Davies and John D. Weeden and museum purchase

© Estate of Louis Faurer

Danny Lyon (American, b. 1942)

Crossing the Ohio River, Louisville

1966, printed 1985

Gelatin silver print

Image: 8 3/4 x 12 7/8 in. (22.2 x 32.7cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Museum purchase made possible by Mrs. Marshall Langhorne

Photo courtesy Edwynn Houk Gallery

William Eggleston (American, b. 1939)

Tricycle (Memphis)

about 1975, printed 1980

Dye transfer print

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Amy Loeserman Klein

An ordinary tricycle is made monumental in this playful colour photograph. Taken from below, it suggests a child’s perspective – elevating this rusty tricycle to a symbol of innocence and freedom. The quiet Memphis suburb in the background typifies the safe neighbourhoods where children could spend hours playing after school. This print was made with the expensive and exacting dye imbibition process, which was typically used for fashion and advertising at the time. Eggleston began experimenting with colour photography in the mid-1960s. Inspired by trips to a commercial photography lab, he developed an approach that imitates the random, imperfect style of amateur snapshots to describe his immediate surroundings combined with a keen interest in the effects of colour.

Tina Barney (American, b. 1945)

Marina’s Room

1987

Chromogenic print

Sheet: 48 x 60 in. (121.9 x 52.3cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Museum purchase

© 1987, Tina Barney, Courtesy Janet Borden, Inc.

Aaron Siskind (American, 1903-1991)

Untitled

1937, printed later

Gelatin silver print

Sheet: 10 x 14 in. (25.4 x 35.5cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Gift of Tennyson and Fern Schad, courtesy of Light Gallery

© 1940, Aaron Siskind

In this untitled photograph Aaron Siskind focused on the regular grid of boarded-up windows on a derelict tenement building. Once portals into intimate domestic spaces, the windows represent loss in a community plagued by poverty, unemployment, and racial discrimination. Building upon the traditions of social documentary photographers before him, Siskind used his camera to raise public awareness of Harlem’s struggle, even as he created a modernist work of art.

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Kitchen Wall, Alabama Farmstead

1936, printed 1974

Gelatin silver print

Sheet and image: 9 3/8 x 12 in. (23.9 x 30.5cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Gift of Lee and Maria Friedlander

During the summer of 1936, Walker Evans joined writer James Agee in rural Alabama to work on a magazine assignment on cotton farming. Evans and Agee met with three tenant farm families and documented every detail of their experiences. The result, which the magazine declined to publish, was released as the book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men in 1941. It contains some of the most iconic and contentious photographs to document the Great Depression. Kitchen Wall, Alabama Farmstead reads like a modern novel. Every crack in the wood, every speck of paint tells part of the story. Evans drew special attention to the scarcity of cooking tools at the family’s disposal. These everyday utensils illustrate a metaphor for the struggle to meet basic needs.

Judy Fiskin (American, b. 1945)

Long Beach Pike (broken fence), from the Long Beach, California Documentary Survey Project

1980

Gelatin silver print

Image: 2 1/2 x 2 1/2 in. (6.2 x 6.2cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the National Endowment for the Arts

© 1980, Judy Fiskin

For this series, sponsored by the National Endowment of the Art’s Long Beach Documentary Survey Project, Judy Fiskin focused on the Long Beach Pike, an amusement park that was demolished soon after she made the photographs. By printing in high contrast and restricting the scale of her prints, Fiskin reduced form to its bare essentials. Devoid of superfluous detail, these photographs appear more like conjured images than documents of reality. Judy Fiskin systematically catalogues the world of architecture and design in order to study variations of historical styles. Her series carefully investigate esoteric subjects such as military base architecture, “dingbat” style houses in southern California, and the art of flower arranging.

Berenice Abbott (American, 1898-1991)

Brooklyn Bridge, Water and Dock Streets, Brooklyn

1936

Gelatin silver print

Sheet: 18 x 14 3/8 in. (45.7 x 36.6cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the Evander Childs High School, Bronx, New York through the General Services Administration

Berenice Abbott returned home in 1929 after nearly eight years abroad and found herself fascinated by the rapid growth of New York City. She saw the city as bristling with new buildings and structures which seemed to her as solid and as permanent as a mountain range. Aiming to capture “the past jostling the present,” Abbott spent the next five years on a project she called Changing New York. In Brooklyn Bridge, Water and Dock Streets, Brooklyn, Abbott presented a century of history in a single image. The Brooklyn Bridge, once a marvel of modern engineering, seems dark and heavy compared with the skeletal structure beneath it. The construction site at center suggests the never-ending cycle of death and regeneration. And the Manhattan skyline, veiled and weightless, hangs just out of reach, its shape accommodating the ambitious spirit of American modernism.

Robert Disraeli (American, 1905-1987)

Cold Day on Cherry Street

1932

Gelatin silver print

Image and sheet: 14 x 11 in. (35.5 x 28cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Museum purchase made possible by Mr. and Mrs. G. Howland Chase, Mrs. James S. Harlan (Adeline M. Noble Collection), Lucie Louise Fery, Berthe Girardet, and Mrs. George M. McClellan

© 1932, Robert Disraeli

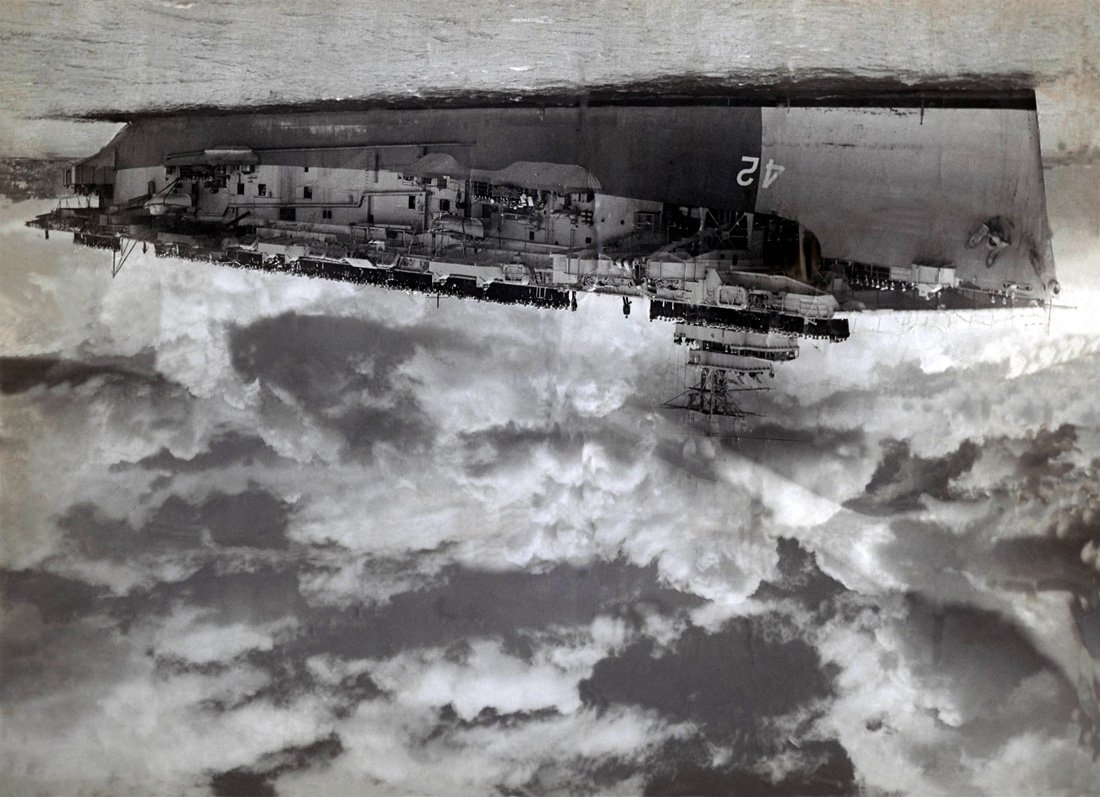

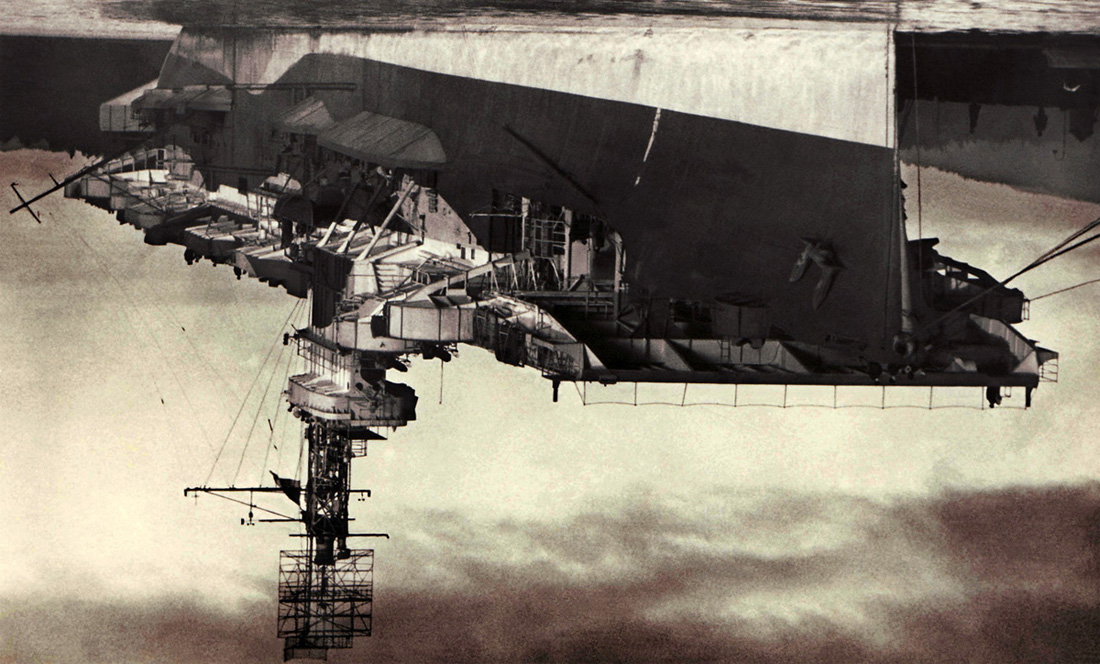

Imagination at Work

Nineteenth-century French commentator Alexis de Tocqueville observed that in America, nothing is ever quite what it seems. Yet the idea that “seeing is believing” is deeply ingrained in the American character. By yoking together style and subject under the guise of the real, today’s photographers borrow from photography’s rich past while embracing the conceptual framework of contemporary art. They read reality as something on the surface of a picture or, more complexly, as something located in the mind of its beholder.

Sonya Noskowiak (American born Germany, 1900-1975)

Calla Lily

c. 1930s

Gelatin silver print

Sheet: 7 3/8 x 9 3/4 in. (18.8 x 24.7cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Museum purchase made possible through Deaccession Funds

Ray K. Metzker (American, 1931-2014)

Composites: Philadelphia (Car and Street Lamp)

1966

Gelatin silver prints

Image: 25 3/8 x 17 3/4 in. (64.5 x 45cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Museum purchase

© 1966, Ray K. Metzker

Ray Metzker’s Composites series, begun in 1964, connected in a dramatic fashion his interests in contrasts of light and shadow, his strong sense of design, and his earlier explorations of the multiple image. Metzker studied at Chicago’s Institute of Design, where a rigorously formal, problem-solving approach to photography was taught. For this series he assembled grids of individual photographs to create complex image-fields. When viewed from a distance, this work reads as an abstract, rhythmic pattern of light and dark. On closer inspection, however, many crisply descriptive images are revealed. The Composites function somewhat like short filmstrips. The mystery of these brief narratives is exaggerated by the repetitive design and provides a unique opportunity, in Metzker’s words, “to deal with complexity of succession and simultaneity, of collected and related moments.”

Irving Penn (American, 1917-2009)

Mud Glove – New York

1975, printed 1976

Platinum-palladium print

Sheet and image: 29 3/4 x 22 1/4 in. (75.5 x 56.5cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Gift of the artist

Irving Penn was one of the most important and influential photographers of the twentieth century. In a career that spanned almost seventy years, Penn worked across multiple genres, from celebrity portraits to fashion, from still lives to images of native cultures in remote places of the world. Throughout his career Penn also worked on a series of photographs of discarded objects: things that had been lost, neglected, or misused. Printed in platinum, these detailed photographs of objects such as a lost glove found in the gutter, are Penn’s photographic memento mori, offering beauty compromised by age or disuse.

Edward Weston (American, 1886-1958)

Pepper no. 30

1930

Gelatin silver print

Sheet: 9 1/2 x 7 1/2 in. (24.3 x 19.2cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Museum purchase

Imogen Cunningham (American, 1883-1976)

Auragia

1953, printed c. 1960s

Gelatin silver print

Sheet and image: 11 1/8 x 8 3/4 in. (28.3 x 22.2cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Gift of Charles Isaacs and Carol Nigro

Ellen Carey (American, b. 1952)

Dings and Shadows

2012

Chromogenic print

Sheet and image: 40 x 30 in. (101.6 x 76.2cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Gift of Linda Cheverton Wick and Walter Wick

© 2012, Ellen Carey

Ellen Carey created the series she calls Dings and Shadows by exposing photosensitive paper to light projected through primary and complementary colour filters. The artist first folds and crushes paper; then after exposing the paper to light from a colour enlarger, flattens it out again for processing. In doing so, Carey dissects the process of developing film, and evokes the hand-crafted nature of early photographic techniques.

Some images from the Timeline on the website

1843

Daguerreotypists Albert S. Southworth and Josiah Johnson Hawes begin a partnership, establishing Southworth & Hawes as the most highly regarded portrait studio in Boston, Mass. The studio caters to the city’s elite, and is visited by Charles Dickens, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Oliver Wendell Holmes, among many other influential people of the time.

Albert Sands Southworth (American, 1811-1894) and Josiah Johnson Hawes (American, 1808-1901)

A Bride and Her Bridesmaids

1851

Daguerreotype

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Museum purchase made possible by Walter Beck

1853

The New York Daily Tribune estimates that in the United States, three million daguerreotypes are being produced annually.

Unidentified artist

Mother and Son

c. 1855

Daguerreotype with applied colour

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Museum purchase from the Charles Isaacs Collection made possible in part by the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment

1857

Julian Vannerson and Samuel Cohner make the first systematic photographs of Native American delegations to visit Washington, D.C. They photograph ninety delegates representing thirteen tribes who conduct treaty and other negotiations with government officials.

Julian Vannerson (American, 1827-1875)

Shining Metal

1858

Salted paper print

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Museum purchase from the Charles Isaacs Collection made possible in part by the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment

1861

American Civil War begins with shots fired on Fort Sumter by Confederate troops. Portrait photographer Mathew Brady is given permission by President Abraham Lincoln to photograph the First Battle of Bull Run, but comes so close to the battle that he narrowly avoids capture. Using paid assistants Alexander Gardner, Timothy O’Sullivan, George N. Barnard, and others, Brady’s studio makes thousands of photos of the sites, material, and people of the war. Civilian free-lance photographer Egbert Guy Fowx sells numerous negatives to Brady’s studio, which publishes and copyrights many of them. Many other images are credited to Fowx, including this group of Union officers.

Egbert Guy Fowx (American, 1821-1889)

New York 7th Regiment Officers

c. 1863

Salted paper print

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Museum purchase from the Charles Isaacs Collection made possible in part by the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment

1867

Eadweard Muybridge begins trip to photograph in Yosemite Valley. He publishes his photographs under the name “Helios,” which is also the name of his San Francisco studio. An exhibition of more than 300 photographic portraits of Native American delegates to Washington, D.C., opens in the Smithsonian Castle. Clarence R. King begins direction of the U.S. Geological Expedition of the Fortieth Parallel, appointing Timothy O’Sullivan as the official photographer. Photographer Carleton Watkins joins the survey in 1871.

Timothy H. O’Sullivan (American born Ireland, 1840-1882)

Tufa Domes, Pyramid Lake, Nevada

1867

Albumen silver print

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Museum purchase from the Charles Isaacs Collection made possible in part by the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment

1869

Andrew J. Russell’s album, The Great West Illustrated in a Series of Photographic Views across the Continent; Taken along the Line of the Union Pacific Railroad from Omaha, Nebraska, Volume I, is published. George M. Wheeler begins direction of the United States Geological Surveys West of the 100th Meridian for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Wheeler makes fourteen trips to the West over the next eight years. Photographer Timothy O’Sullivan accompanies him in 1871, 1873, and 1874.

Andrew Joseph Russell (American, 1829-1902)

Sphinx of the Valley

1869

Albumen silver print

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Museum purchase from the Charles Isaacs Collection made possible in part by the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment

1967

The Friends of Photography is founded in Carmel, California, by Ansel Adams, Beaumont and Nancy Newhall, Brett Weston, and others, with the aim of promoting creative photography and supporting its practitioners. It remains in existence until 2001.

Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993)

Untitled (Snow Covered Mountains)

1973

Gelatin silver print

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the National Endowment for the Arts

© 1973, Brett Weston

1975

New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape opens at the International Museum of Photography in Rochester, N.Y. It includes photographs by Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, Bernd and Hilla Becher, Joe Deal, Frank Gohlke, Nicholas Nixon, John Schott, Stephen Shore, and Henry Wessel Jr.

Frank Gohlke (American, b. 1942)

Grain Elevator, Dumas, Texas, 1973

1973, printed 1994

Gelatin silver print

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase through the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment

© 1973, Frank Gohlke

Smithsonian American Art Museum

8th and F Streets, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20004

Opening hours:

11.30am – 7.00pm daily

![Unidentified artist. '[Bird in Basin with Thread Spool and Patterned Cloth]' c. 1855 Unidentified artist. '[Bird in Basin with Thread Spool and Patterned Cloth]' c. 1855](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/bird-in-basin-web.jpg)

![Unidentified artist. '[Gold Nugget]' c. 1860s Unidentified artist. '[Gold Nugget]' c. 1860s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/gold-nugget-web.jpg)

![Unidentified artist. '[Two Workmen Polishing a Stove]' c. 1865 Unidentified artist. '[Two Workmen Polishing a Stove]' c. 1865](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/two-workmen-polishing-a-stove-web.jpg?w=650&h=847)

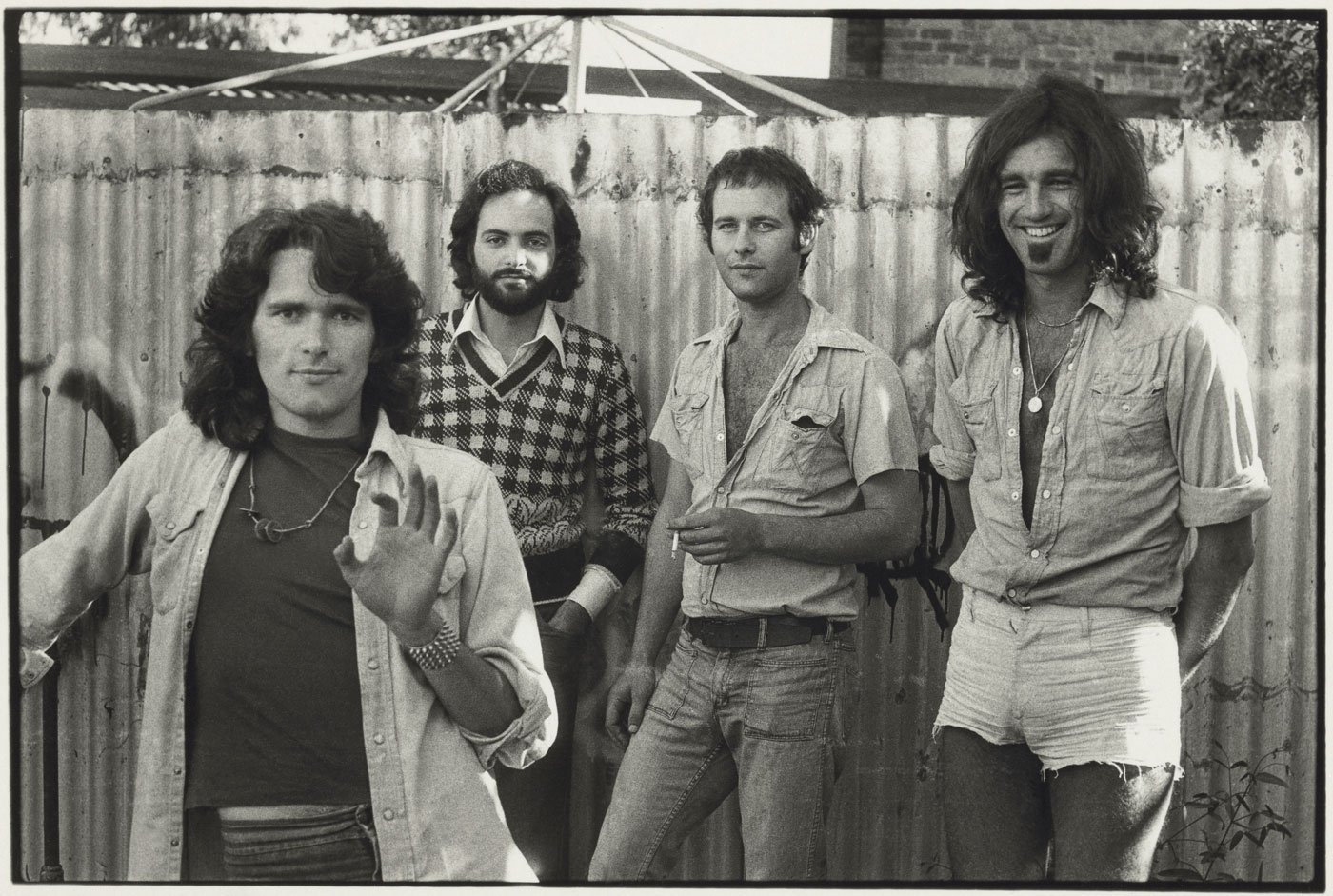

![Carol Jerrems (Australian, 1949-1980) 'Butterfly behind glass [Red Symons from Skyhooks]' 1975 Carol Jerrems (Australian, 1949-1980) 'Butterfly behind glass [Red Symons from Skyhooks]' 1975](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/butterfly_174882_web.jpg)

![Carol Jerrems (Australian, 1949-1980) 'Performers on stage,' Hair', Metro Theatre Kings Cross, Sydney, January 1970 [Jim Sharman Director cast included Reg Livermore]' 1970 Carol Jerrems (Australian, 1949-1980) 'Performers on stage,' Hair', Metro Theatre Kings Cross, Sydney, January 1970 [Jim Sharman Director cast included Reg Livermore]' 1970](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/jerrems_performers-on-stage-hair-web.jpg?w=650&h=818)

You must be logged in to post a comment.