Exhibition dates: 16th September – 23rd October 2011

Curator: Naomi Cass

Artists: ASIO de-classified photos and footage, Denis Beaubois (France/Australia), Luc Delahaye (France), Cherine Fahd (Australia), Percy Grainger (Australia/USA), Bill Henson (Australia), Sonia Leber and David Chesworth (Australia), Walid Raad (Lebanon/USA), Kohei Yoshiyuki (Japan)

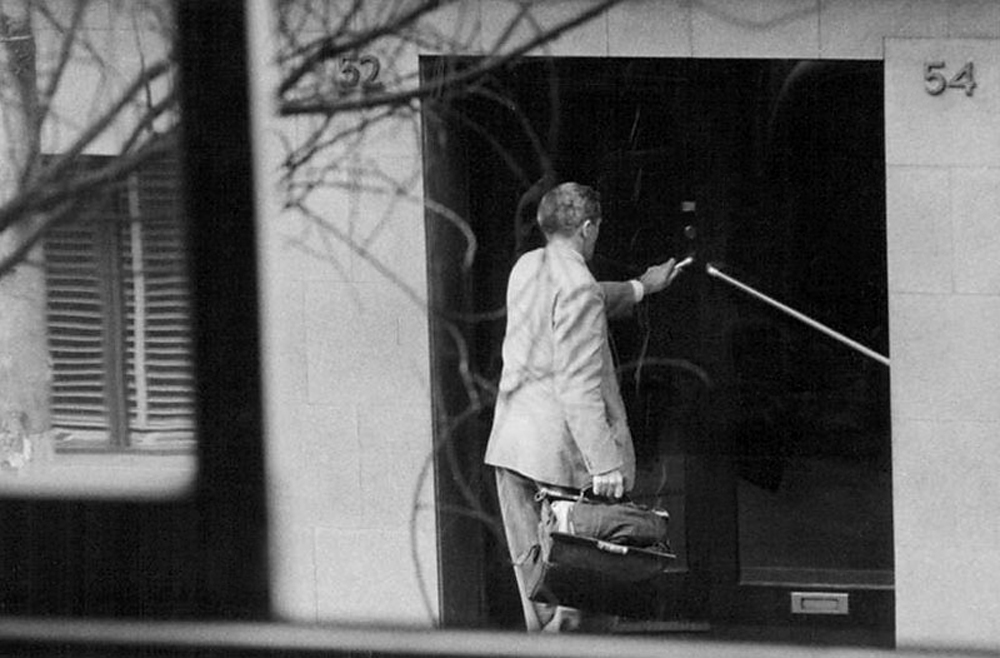

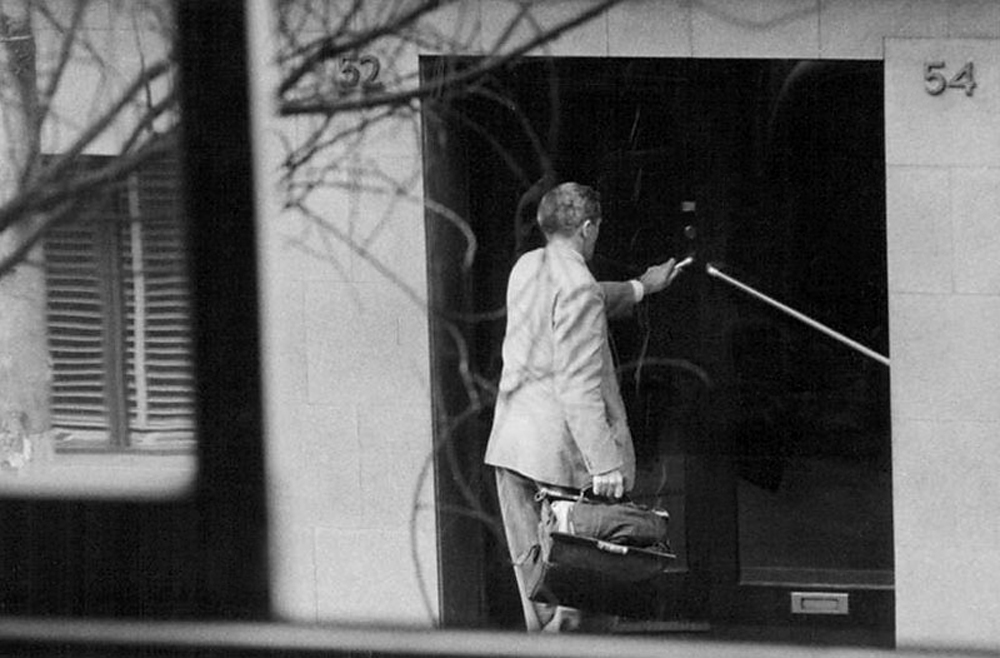

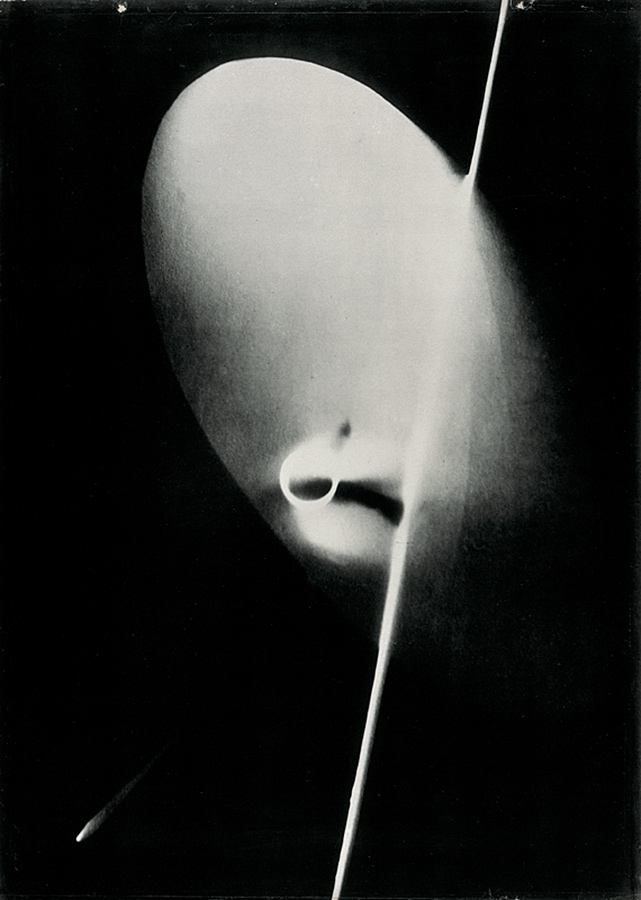

Persons Of Interest – ASIO surveillance 1949-1980

Author Frank Hardy in the doorway of the Building Workers Industrial Union, 535 George St, Sydney, August 1955

NAA A9626, 212

Un/aware and in re/pose: the self, the subject and the city

Keywords: surveillance, surveillance photography, the gaze, the camera, photography, stolen images, voyeurism, scopophilia, public/private, disciplinary systems, facework, civil inattention, portrait, social history, persons of interest, the city, the self, subject, awareness, repose, reciprocity, the spectacle, the spectator.

“The paradox is the more we seek to fix our vision of the world and to control it the less sure we are as to who we are and what our place is in the world.”

Marcus Bunyan 2011

“Stare. It is the way to educate your eye, and more. Stare, pry, listen, eavesdrop. Die knowing something. You are not here long.”

Walker Evans

“Texts that testify do not simply report facts but, in different ways, encounter – and make us encounter – strangeness.”

Shoshana Felman and Dori Laub 1

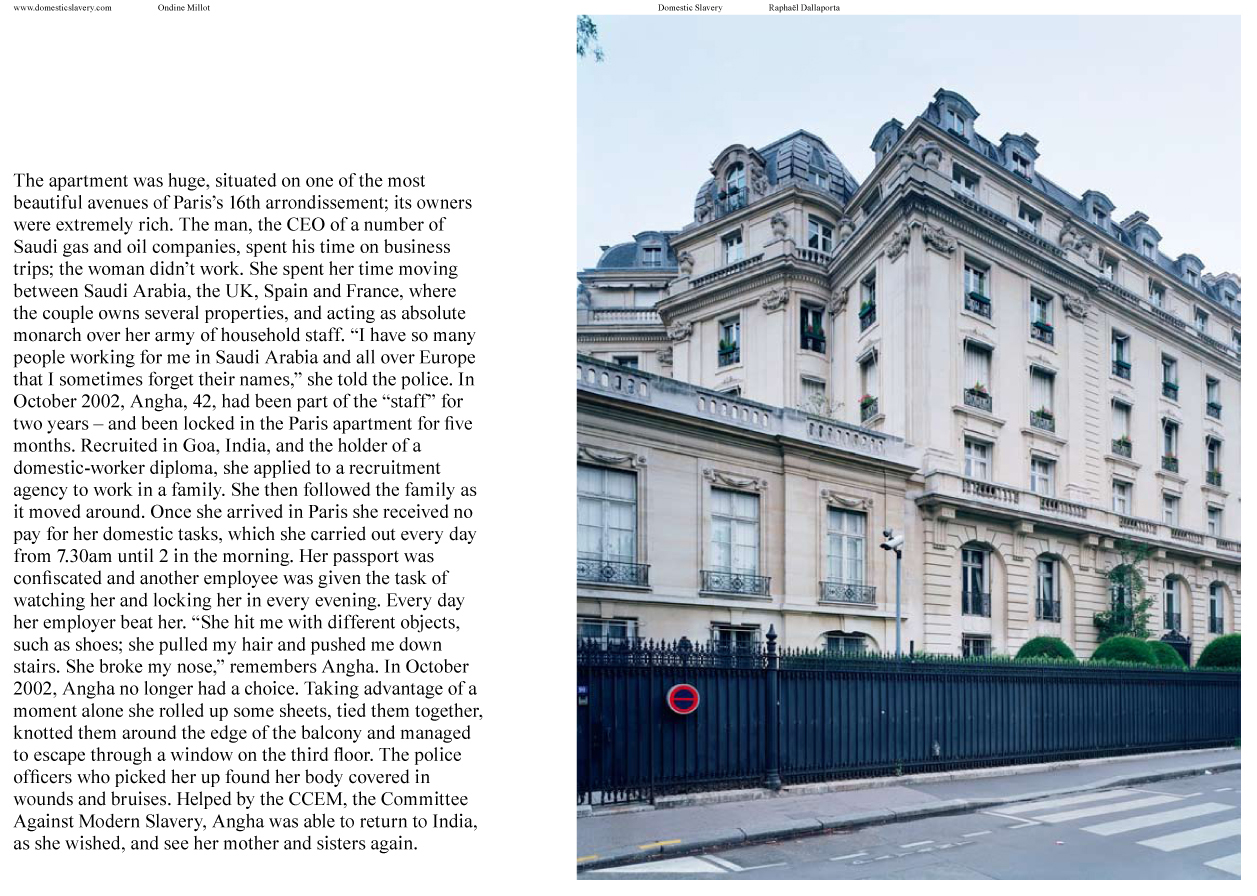

Curated by Naomi Cass as part of the Melbourne Festival, this is a brilliant exhibition at the Centre for Contemporary Photography, Melbourne. The exhibition explores, “the fraught relationship between the camera and the subject: where the image is stolen, candid or where the unspoken contract between photographer and subject is broken in some way – sometimes to make art, sometimes to do something malevolent.”2 It examines the promiscuity of gazes in public/private space specifically looking at surveillance, voyeurism, desire, scopophilia, secret photography and self-reflexivity. It investigates the camera and its moral and physical relationship to the unsuspecting subject. Does the camera see something different if the subject is unaware? Is the viewer complicit in the process as they (repeatedly) stare at the photographs? Are we all implicated in a kind of “mass social surveillance” based on Foucault’s concept of the self-regulating disciplinary society, a society that is watched from a single, panoptic vantage point (that of the omnipresent camera lens) and through the agency of the watchers watching each other?3 More on this later in the writing.

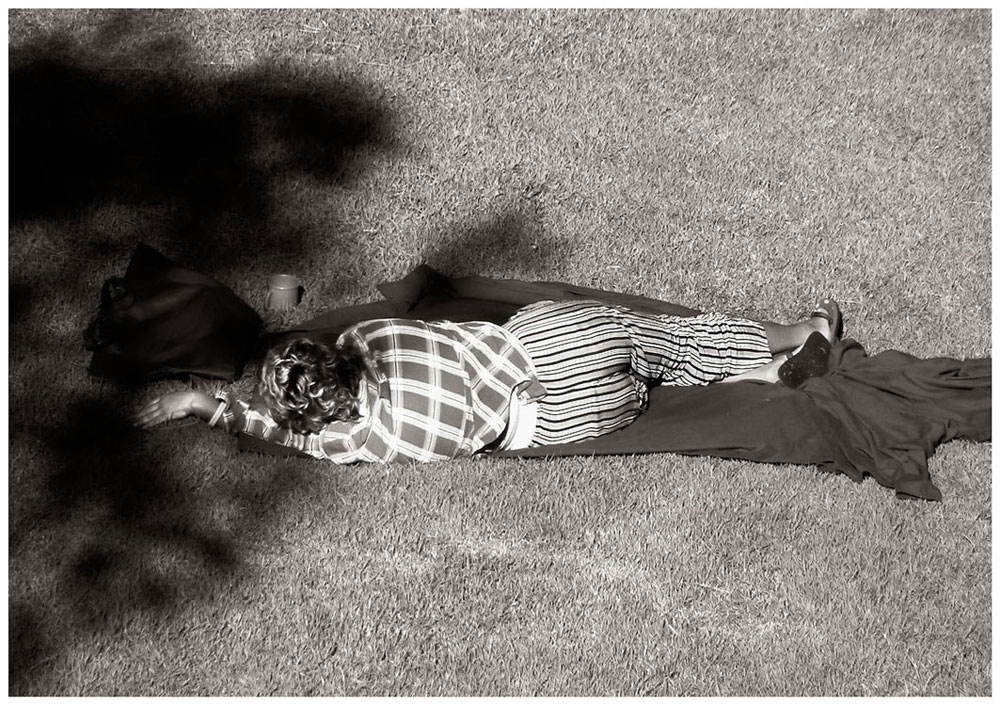

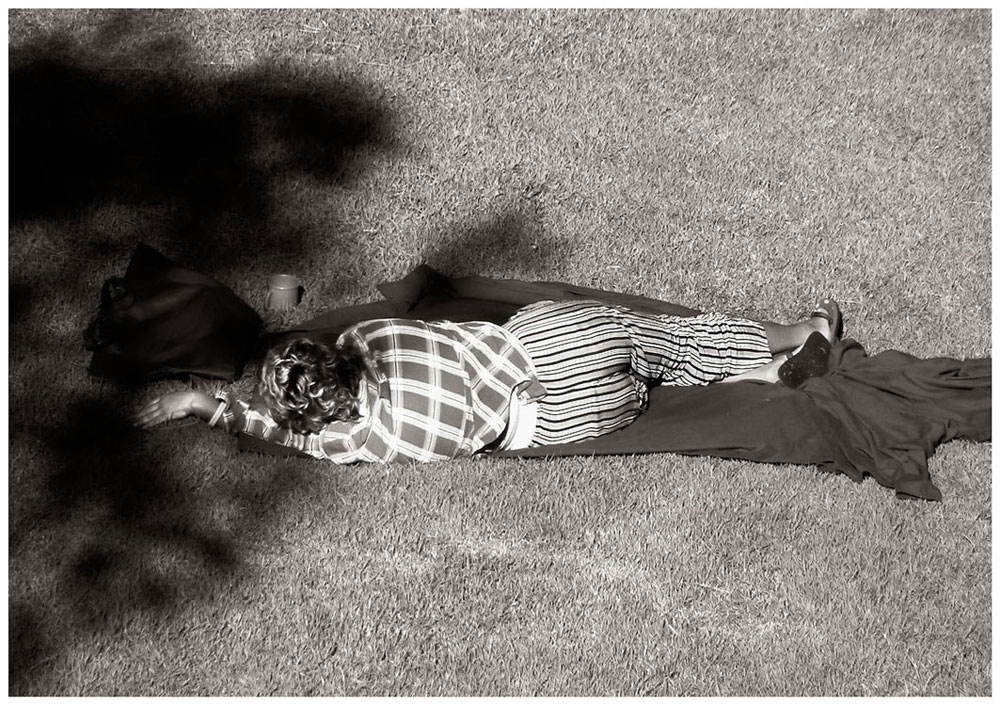

To the left

A selection of photographs from the series The Sleepers by Cherine Fahd, A4 sized black and white photographs of homeless people, asleep on the grass in a park, taken in secret from a sixth floor apartment in Kings Cross, Sydney. Fahd “went to great pains to make sure her subjects were anonymous, unidentifiable, their faces turned away”4 resulting in photographs of corpse-like bodies on contextless backgrounds – wrapped, isolated, entwined, covered in shadow, the bodies disorientated in space and consequently disorientating the gaze of the viewer.

To the right

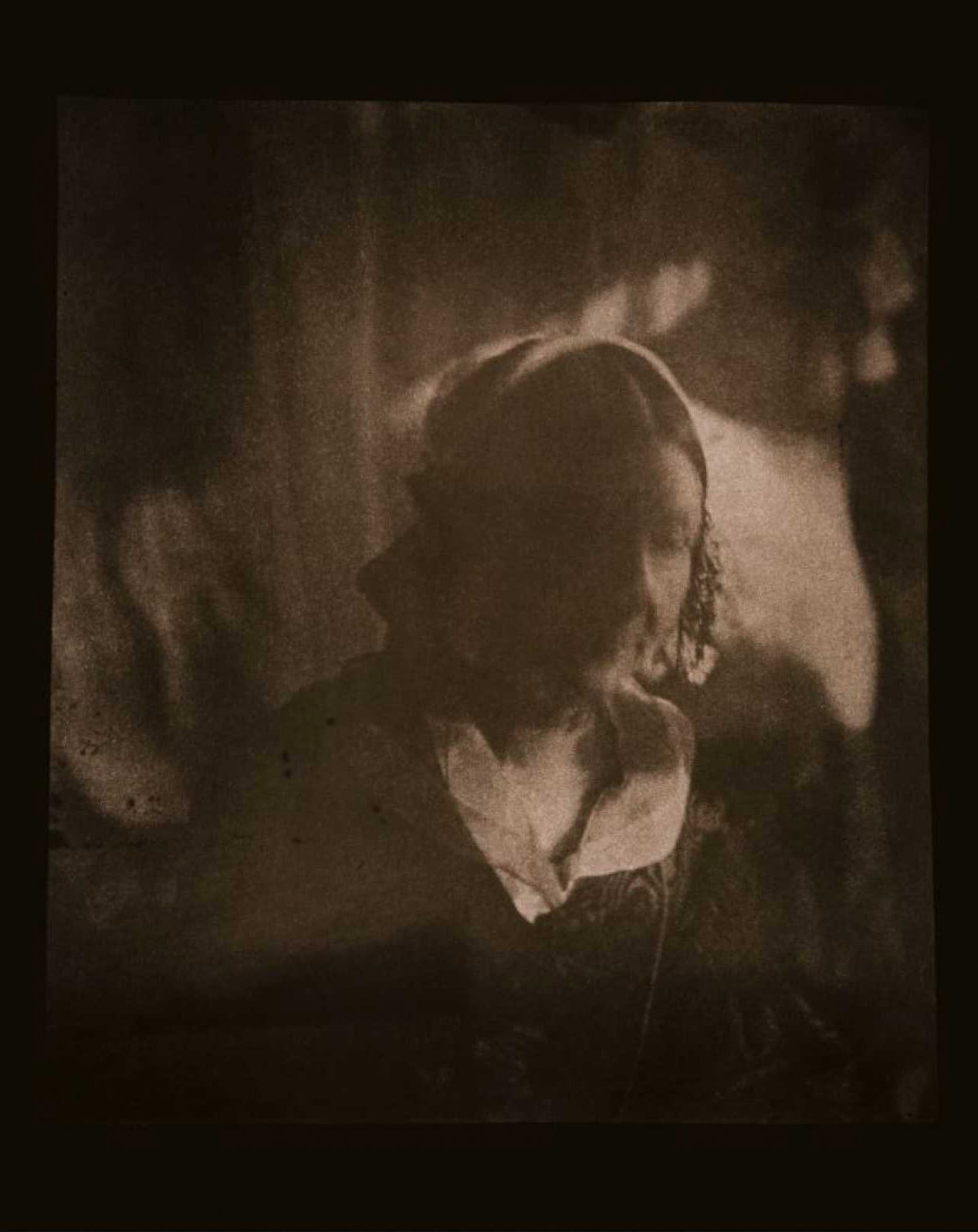

A selection of photographs from the Crowd Series (1980-82) by Bill Henson. Snapped in secret these black and white journalistic surveillance photographs (‘taken’ in an around Flinders Street railway station in Melbourne) have a brooding intensity and melancholic beauty. Henson uses a flattened perspective that is opposed to the principles of linear perspective in these photographs. Known as The Art of Describing5 and much used in Dutch still life painting of the 17th century to give equal weight to objects within the image plane, here Henson uses the technique to emphasise the mass and jostle of the crowd with their “waiting, solemn and compliant” people.

“When exhibiting the full series, Henson arranges the works into small groupings that create an overall effect of aberrant movement and fragmentation. From within these bustling clusters of images, individual faces emerge like spectres of humanity that will once again dissolve into the crowd … all apparently adrift in the flow of urban life. The people in these images have an anonymity that allows them to represent universal human experiences of alienation, mortality and fatigue.”6

Henson states, “The great beauty in the subject comes, for me, from the haunted space, that unbridgeable gap – which separates the profound intimacy and solitude of our interior world from the ‘other’… The business of how a child’s small hand appearing between two adults at a street crossing can suggest both a vulnerability, great tenderness, and yet also contain within it all of the power that beauty commands, is endlessly fascinating to me.”7 His observation is astute but for me it is the un/awareness of the people in these photographs that are their beauty, their insertion into the crowd but their isolation from the crowd and from themselves. As Maggie Finch observes, it is “that feeling of being both alone and private in a crowd, thus free but also exposed.”8

In the sociologist Erving Goffman’s terms the photographs can be seen as examples of what he calls “civil inattention”9 which is a carefully monitored demonstration of what might be called polite estrangement, the “facework” as we glance at people in the crowd, holding the gaze of the other only briefly, then looking ahead as each passes the other.

“Civil inattention is the most basic type of facework commitment involved in encounters with strangers in circumstances of modernity. It involves not just the use of the face itself, but the subtle employment of bodily posture and positioning which gives off the message “you may trust me to be without hostile intent” – in the street, public buildings, trains or buses, or at ceremonial gatherings, parties, or other assemblies. Civil inattention is TRUST as ‘background noise’ – not as a random collection of sounds, but as carefully restrained and controlled social rhythms. It is characteristic of what Goffman calls “unfocused interaction.””10

This is what I believe Henson’s photographs are about. Not so much the tenderness of the child’s hand but a fear of engagement with the ‘other’. As such they can be seen as image precursors to the absence/presence of contemporary communication and music technologies. How many times do people talk on their mobile phone or listen to iPods in crowds, on trams and trains, physically present but absenting themselves from interaction with other people. Here but not here; here and there. The body is immersed in absent presence, present and not present, conscious and not conscious, aware and yet not aware of the narratives of a ‘recipro/city failure’. A failure to engage with the light of place, the time of exposure and an attentiveness to the city.

As Susan Stewart insightfully observes,

“To walk in the city is to experience the disjuncture of partial vision/partial consciousness … The walkers of the city travel at different speeds, their steps like handwriting of a personal mobility. In the milling of the crowd is the choking of class relations, the interruption of speed, and the machine.”11

On a pedestal

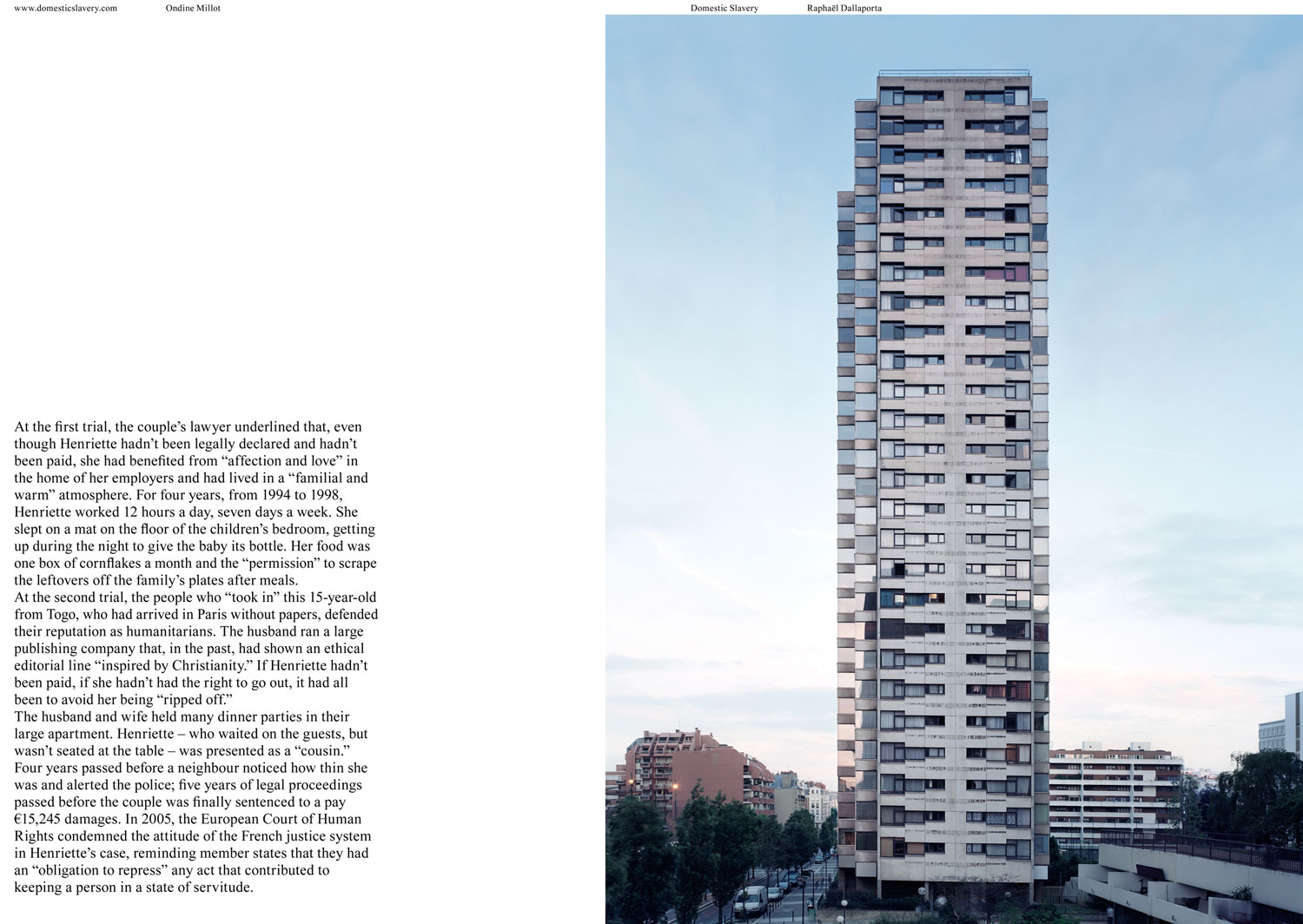

Travelling in the city, in a machine (in this case a subway train) is the subject of the next body of work in the exhibition, represented by the book L’Autre (The Other) by French artist Luc Delahaye.12 Using a hidden camera Delahaye photographs the commuters faces in repose.

“I stole these photographs between ’95 and ’97 in the Paris metro. ‘Stole’ because it is against the law to take them, it’s forbidden. The law states that everyone owns their own image. But our image, this worthless alias of ourselves, is everywhere without us knowing it. How and why can it be said to belong to us? But more importantly, there’s another rule, that non-aggression pact we all subscribe to: the prohibition against looking at others. Apart from the odd illicit glance, you keep staring at the wall. We are very much alone in these public places and there’s violence in this calm acceptance of a closed world.”13

This is another example of Goffman’s civil inattention as Delahaye stares into the distance and feigns absence long enough to get his stolen photograph (much like Walker Evans earlier photographs of people on the New York subway photographed with Evans’s camera concealed inside his overcoat).14 Here the photographs are much closer cropped than Evans’, allowing the viewer no escape from staring at the stolen faces. The faces seen in repose remind me of the composite portraits of criminals and the diseased, Specimens of Composite Portraiture c. 1883 by Sir Francis Galton, remembering that one of the earliest scientific functions of the camera was to document the likenesses of criminals, degenerates and other aberrant beings. We must also remember that, as Geoffrey Batchen suggests, “we are so used to the idea that we are always being watched that we might have turned our whole lives into “a grand, impenetrable pose” because we assume the camera eye is always present.”15

In the physiognomy of these faces the viewer is asked to assess a person’s character or personality from their outer appearance. While the viewer may be complicit in this task we must also remember that the photographer who stole these photographs has also re/posed these faces, choosing which people to secretly photograph and culling images that did not meet his conceptual project. We find no smiling or laughing faces in the book, no context is given (the photographs being tightly cropped on the body and face) and the phatic image, the one that grabs us has been manipulated, reposed and restaged for our edification. While the subject may be unaware of being photographed and their face may be in repose, this repose is as much a cultural construct as if they had known their photograph was being taken.

As John Berger and Jean Mohr write,

“The photographer choses the events he photographs. This choice can be thought of as a cultural construction. The space for this construction is, as it were, cleared by his rejection of what he did not choose to photograph.”16

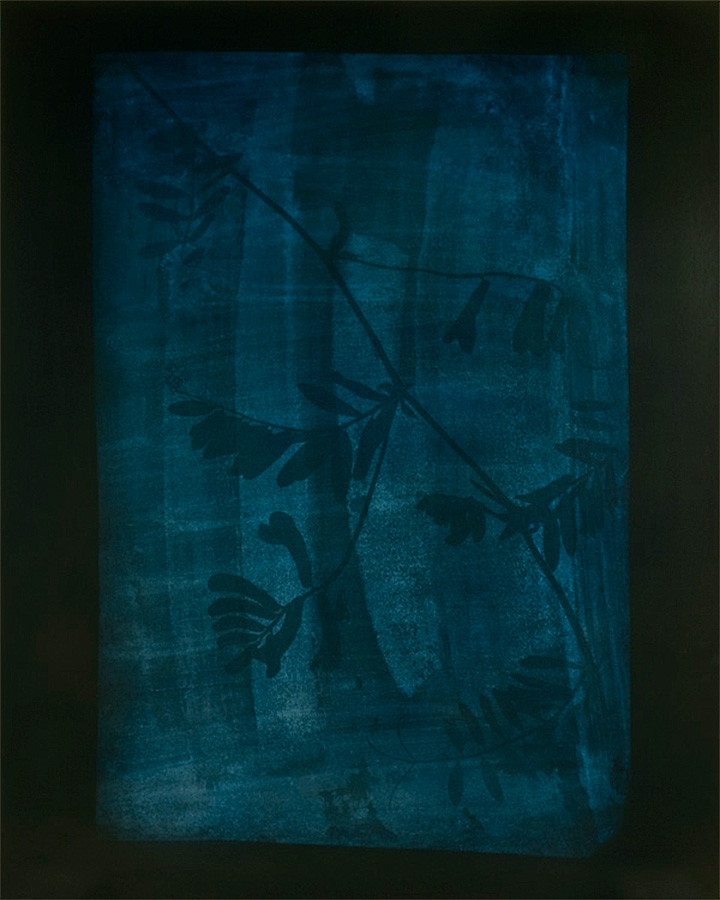

On the wall in front

Series of images from Persons of Interest: ASIO surveillance photographs 1949-1980 taken in secret to record the state’s purported enemies (ASIO is the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation, Australia’s national security service, which is responsible for the protection of the country and its citizens from espionage, sabotage, acts of foreign interference, politically-motivated violence, attacks on the Australian defence system, and terrorism). The photographs were not taken as art and served a purely utilitarian purpose, that of recording and documenting the conversations and movements of persons of interest to the powers that be. “The camera can’t change the world, but there’s an idea that it can protect us – hence surveillance, which promises to watch over us, and watch out for us, rather than merely watch.”17

According to Haydn Keenan, director of the documentary Persons of Interest “Surveillance secretly records an image of someone so that the recorder so that the recorder can have advantage over the subject. Sometimes it’s political, sometimes social, but the very essence of surveillance is the secret theft of the image.”18 Keenan goes on to identify four types of photographic surveillance:

1/ Photographs taken by ASIO agents who are known to the person of interest. These are particularly disconcerting because they are the kind of intimate photographs that you would see in a family album

2/ ASIO photographer taking photographs in public, at demos and public meetings, always happening to get the person of interest “in the frame” so to speak.

3/ Long lens photographs taken by setting up an observation post and then sitting down and waiting.

4/ Photographs taken by what was called a ‘butterbox’ – a camera concealed in another object like a briefcase.19

There are thousands of these images, photographs of people in the wrong place at the wrong time. The closely cropped black and white photographs have an intimacy and anonymity to them. They build up a mental image of the changing face of what the State saw as threat: Aboriginal land rights, gay rights, women’s liberation, anti-Vietnam demonstrations, youth culture, Communism – and now terrorism. These photographs evince an inherent suspicion about social issues and they had the power to dramatically alter lives (through the loss of work or home, through imprisonment). “Yet what ASIO didn’t realise is that they were constructing an invaluable social history of Australian dissent as they gradually confused subversion with dissent.”20 The eye of the beholder cast a dark shadow but one that would not remain private forever.

Around the corner

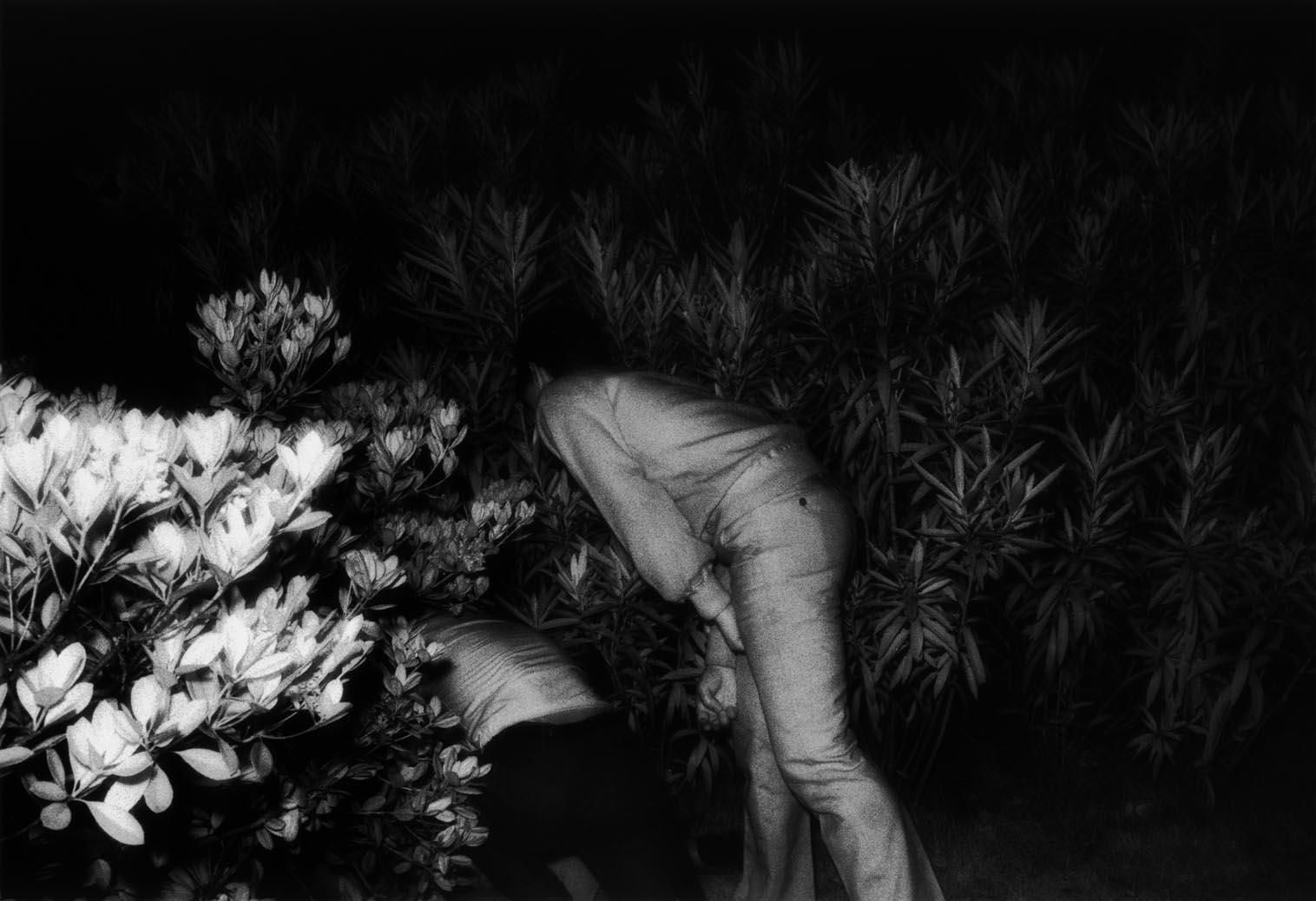

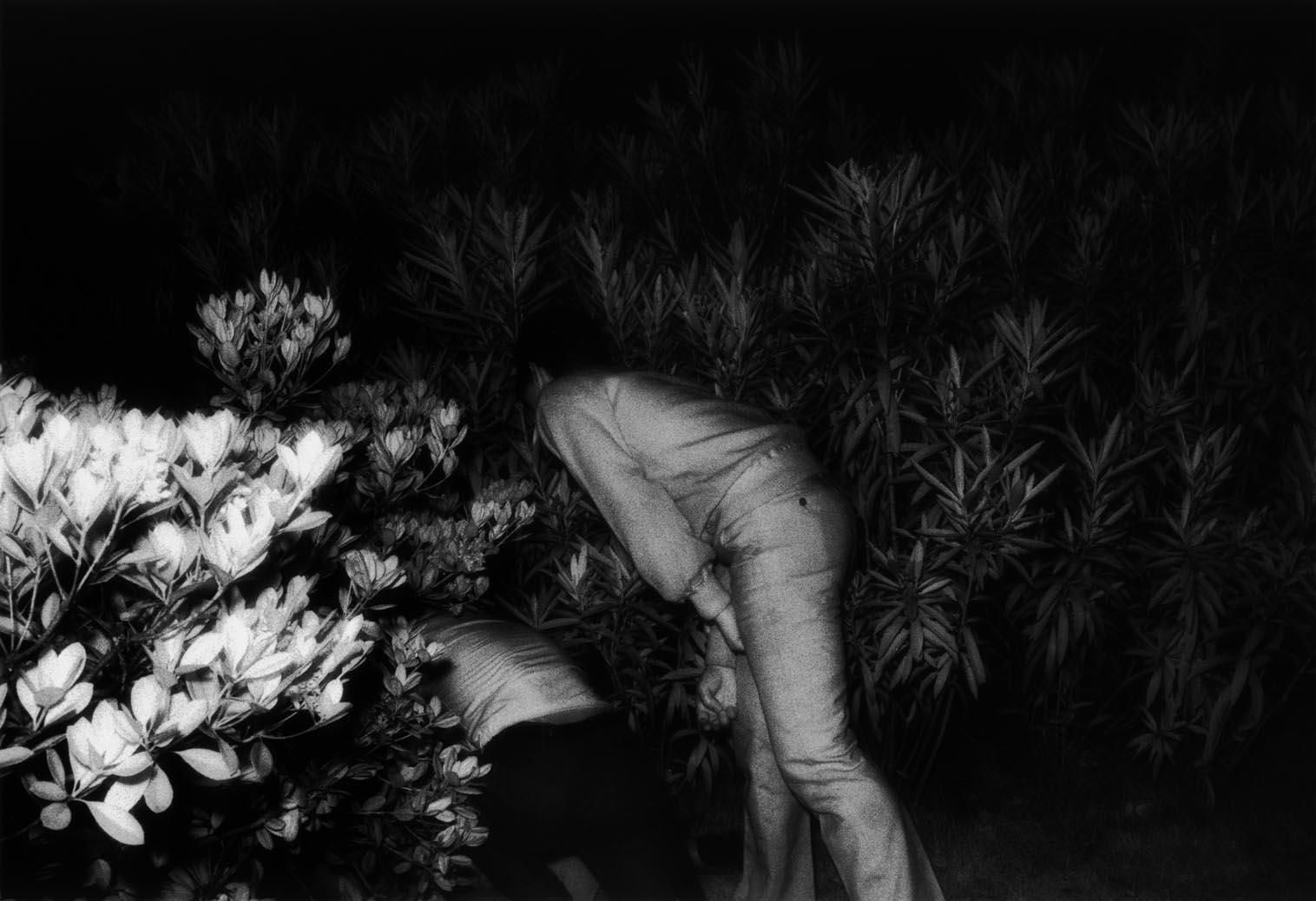

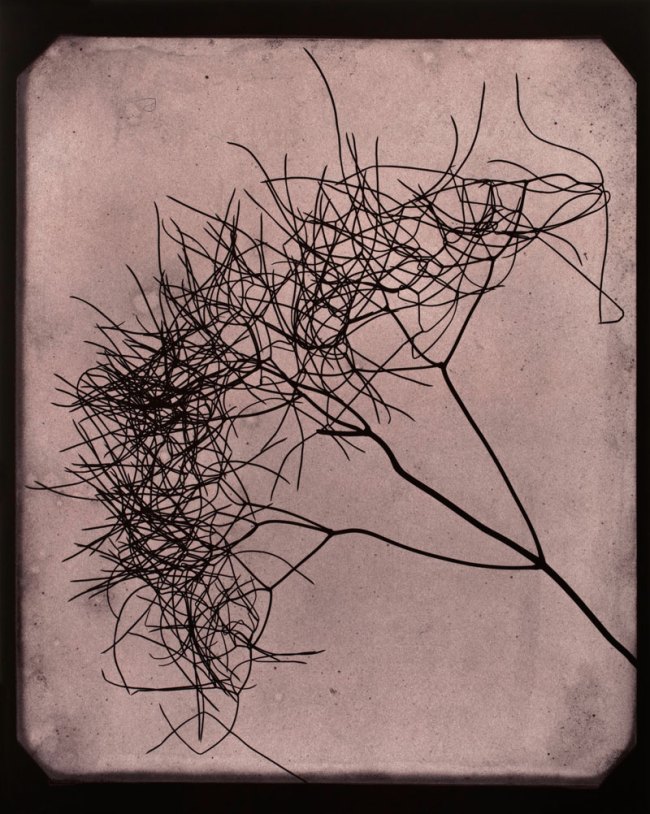

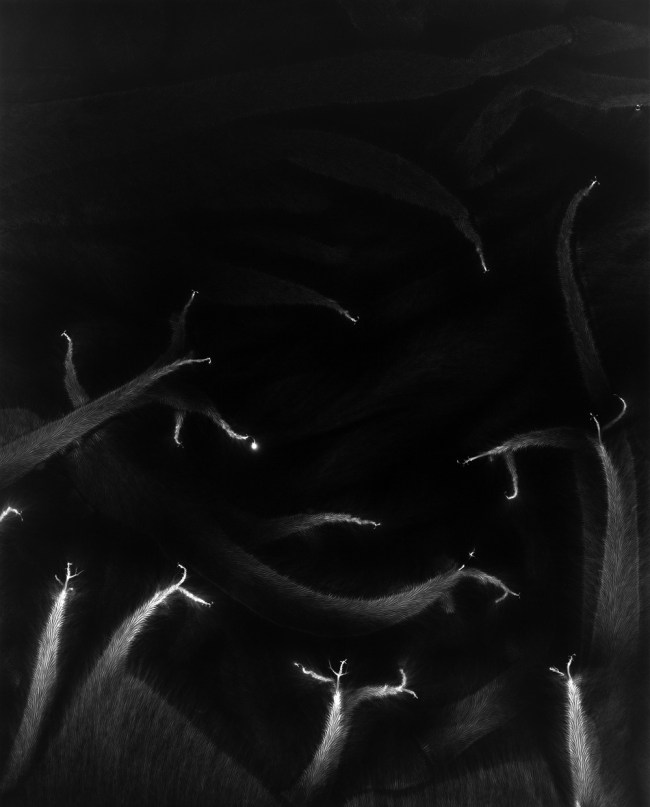

The largest series of the exhibition, The Park by Japanese photographer Kohei Yoshiyuki (1971-1979), features twenty-five luscious A3 sized black and white photographs with deep blacks, framed in thin white, wood frames. The photographs were taken in Japanese parks at night where fornicating couples use public space as private space. In most cases the couples were not aware they were being observed by voyeurs and if they were, “with exhibitionist complicity, they fornicate to an audience of peeping Toms.”21 What they were definitely not aware of was that they were being photographed. As Amelia Groom observes, “The levels of complicity, performativity and victimisation of the subjects remains ambiguous.”22

These informal, grainy, infra-red flash photographs, “were first published in 1972 in the popular ‘secret camera’ genre magazine Shukan Shincho and were not initially considered as art photography … however they also sit within a broad tradition of voyeurism in Japanese art.”23 Starting in mid-distance the photographs eventually close right in on the subject matter, tightly composed on the mass of hands going everywhere, the flash over exposing various elements of the infra-red composition. The photographs are most effective when the viewer does not see the object of desire, but is positioned behind the voyeur who is hidden behind the hedge, looking. The viewpoint of the erotic act is denied, is out of shot/sight. We are literally “lined up right behind Yoshiyuki in the chain of voyeurism”24 imbibing the camera’s active, desiring masculine gaze. “Looking at Yoshiyuki’s images induces an uneasiness that has something to do with seeing the seer looking while seeing ourselves being seen looking.”25 The photographs are multiply voyeuristic, implicating the watchers, the photographer and us.26 But they implicate us only as part of a larger cultural signification.

Penny Modra in The Sunday Age M magazine observes of these photographs that, “you are a peeping Tom peeping at peeping Toms peeping at people.”27 I believe it is more than that. The definition of “peeping” is that of stealing a quick glance; to peer through a small aperture or from behind something (peering through a small aperture number is quite an appropriate metaphor since we are dealing with the photographic lens). While this may be true of the act of photography itself it is not true of the process of photography that took place to get the photographer to the point of exposure. Yoshiyuki himself “assembled the story of his association with the park voyeurs and details how the series was shot after spending six months getting to know those observers in the shrubbery.”28 Much as Diane Arbus befriended the subjects in her photographs, Yoshiyuki, rather than having a furtive glance of desire, planned his series using the all seeing narrative eye trained on its target over several months. He positions his subject squarely in his line of sight. And while a voyeur “can be defined as a person who observes without participation, a powerless or passive spectator … a photographer, contemplating a nude or any sexual subject is also a voyeur, but someone with a camera, or the means to distribute a photograph, is not entirely passive or powerless.”29 This power can be seen in the fame that the series has bought the photographer, his infamous series now heralded around the world.

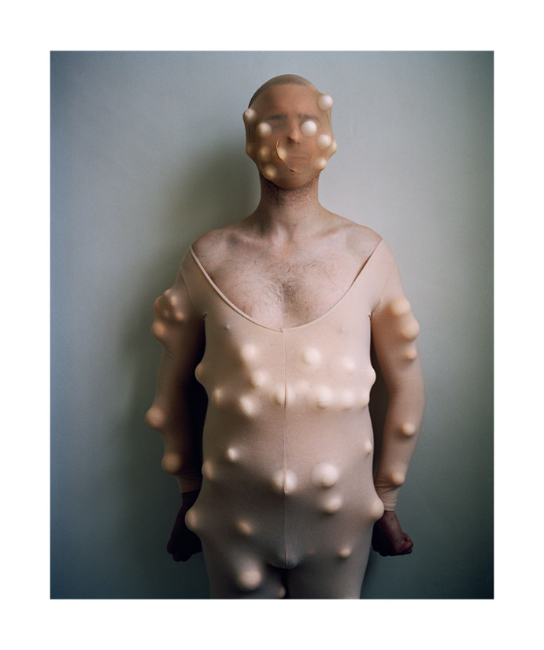

At the centre

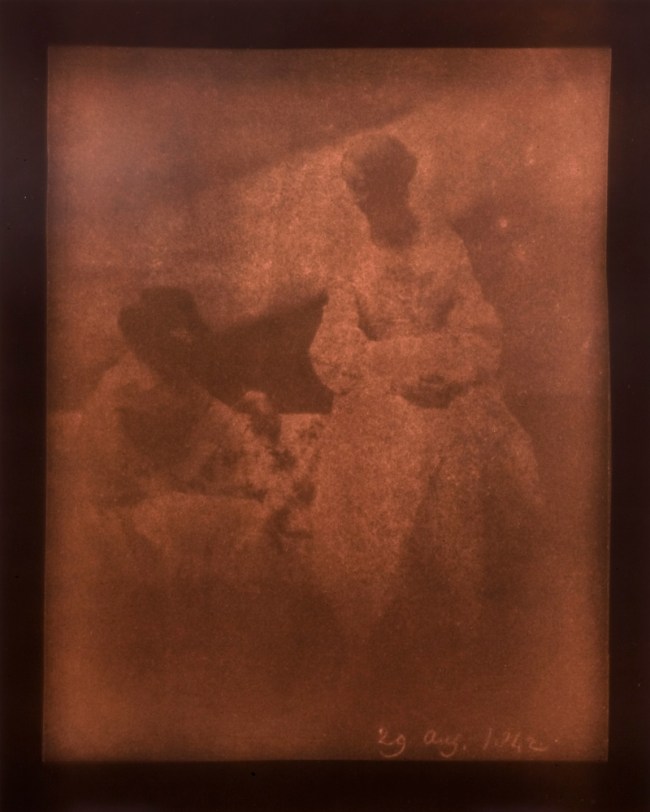

Black and white ‘snapshot’ photographs from the series Lust Branch by Percy Grainger, printed between 1933 and 1942, that document his sadomasochistic sexual practices including ‘self beating’ which he believed were intrinsic to his creativity. The envelope containing some of the photographs was marked “Private Matters: Do Not Open Until 10 (ten) Years After My Death.” The archive has the quality of forensic records as it documents, in a quasi-scientific Victorian tradition, evidence of his proclivities, his normalcy. The dark 4″ x 5″ brown-toned photographs show Grainger posing in a domestic setting (in Kansas) with a chair and also show the use of a suspended mirror to document his fustigations. Robert Nelson states that the shock of these images isn’t the flagellantism itself but that we’re looking at it. “The transgression isn’t the perversity but the breach of privacy the composer orchestrated: he lashed himself not only with a whip but a camera.”30 Personally I don’t register this shock as S/M practices have regularly been part of my life. What I find more disquieting is people who try to define what is normal and what should be recorded or not and by whom and who gets to see them.

I vividly remember going to the Minor White archive at Princeton University and seeing photographs of erect penises taken by White (who was gay) and thinking why I hadn’t seen these photographs before. The shock was not of seeing them but the fact that they were still hidden and had never been reproduced. Similarly, at The Kinsey Institute there are colour photographs of 1950s physique magazine body builders having full on sex, never to be seen in public. Also at the Kinsey are erotic photographs by the gay George Platt Lynes, taken for his own pleasure but never exhibited in public.31 Lynes had to resort to sending his erotic work to an early German pornographic magazine to get the photographs published. Taking these photographs is not a breach of privacy but an expression of normalcy, freedom and creativity.

In conclusion

“The idea of a photographic ‘gaze’ relates to a specific way of looking, and being looked at through the camera, and implies a certain psychological relationship of power and control.”32 Foucault’s analysis of the gaze as a means of surveillance, which is predatory and controlling, used to classify and discipline, allows the camera and mirror to be equated as tools of self-reflection and surveillance, where the double (created through self-reflection and surveillance) can be alienated from the self, taken away (like a photograph) for closer examination.33 Victor Burgin in his seminal 1977 essay Looking at photographs “argues that the ‘recording eye’ of the camera sets it apart from the subject at which it looks. The camera creates an ordering device which ‘depicts a scene and the gaze of the spectator, an object and a viewing subject.'”34 The camera’s gaze is not passive, it is active; it imparts its own subjectivity forming a triangular relationship between the object being photographed, camera and photographer. It has its own reality.

In a society where we are living in the age of ubiquitous networked photography35 the borders between public and private are collapsing. The idea that the gazer is able to see but not be seen; in essence, that the looking is anonymous36 is becoming a fallacy. Everything, even the watcher, becomes visible (after an ever shorter time). The separation that takes place between the looker and the looked-at is disappearing; we all know we are being watched even as we watch (and post) ourselves. “The act of seeing and the thing seen, the seer and the spectacle … are [becoming] one.”37

I would suggest that there is no fixed definition of private and public. For example even after people sign out from Facebook the sites they visit are still tracked.38 Anything that you post on Facebook, the music you like – if you just listen to it, Facebook takes it to mean that you approve of it and distributes it too your friends. Similarly with CCTV, ASIO images, mobile phone images, what is thought of as an invasion of privacy is eventually made public through FOI, leaking, teenage girls posting online (Ricky Nixon) etc … As noted earlier someone with a camera, or the means to distribute a photograph, is not entirely passive or powerless.

Even as the photographer “lifts” the object of his attention with his machine, the camera, he “takes” a picture, “and in so doing he makes a claim for that object or that composition, and a claim for his act of seeing in the first place … transposing a particular and emphatically personal point of view”39 and making a claim for the very act of seeing itself. The thing itself (the object photographed) and the way the photographer looks at it cannot be separated. In other words, in constant oscillation, we stand behind but also in front of the metaphorical camera: “I am nothing; I see all.”40

We know that we are being monitored and so we conform; even if no one is there, even if we cannot see the guard (as in Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon prison) we suspect we are being watched and so self regulate our behaviour. “And yet, our contemporary society … has ironically embraced surveillance … This is most apparent in social media where millions of people regularly upload their most intimate moments via webcam … we happily embrace the mechanisms devised to control us and turn them into a kind of freefall celebration.”41

“It is though the millions of people, artists or not, who produce and publish images of themselves, their friends, surroundings and ideas in a sort of mass social surveillance (while often being tracked by the devices they are using) are implicated … in surveillance as a source of entertainment and personal gratification.”42

Surveillance, sousveillance as the sight of (perverse) resistance.

These contradictory, constantly shifting contemporary information and image flows tends to erode the moral authority of any social order, patriarchal or otherwise, opening up an expanded and abstracted terrain of becoming. Images exceed, incorporate or reverse the values that are presumed to reside within them.43 These phatic images, for that is what they are – targeted images that force you to look and hold your attention – “produce a ‘message-intensification’ within the visual image that accentuates pictorial detail while simultaneously forcing image context and location to recede or disappear. The phatic image is at once technically-mediated, manipulable, intensified and perhaps most importantly for [Paul] Virilio de-localized.”44 This can be observed in bodies of work in this exhibition: most have no image context or defined location while intensifying their message through close-up details. All have been circulated around the world for consumption. Vision is everywhere and nowhere at one and the same time.

The person who gazes is not unfamiliar with the world upon which he looks; he understands the image as seen from without as another would see it, in the midst of the visible.45 No longer is the image seen or considered from a certain spot. That vision is decentred by the networks of signifiers that come to me from the social milieu …

“The viewing subject does not stand at the center of the perceptual horizon, and cannot command the chains and series of signifiers passing across the visual domain. Vision unfolds to the side of, in tangent to, the field of the other. And to that form of seeing Lacan gives a name: seeing on the field of the other, seeing under the Gaze.”46

While the self and environment are under constant surveillance in an attempt to resemble the truth, to re-assemble the referentiality of the image, it is not the breakdown of an already existing web of visuality (the disciplinary gaze of surveillance) but the wilful amending of its intent that opens up new terrains of becoming. In the public city it is the publicity of the image that will continue to thwart the controlling eye. We are all actors in a performative space, transforming the gaze and collapsing its vision into the tactile worlds of virtual reality (Ron Burnett), “engaging with ideas of pose, of masquerade, of performance, of witness and record as they transact across increasingly contingent boundaries of private and public, fact and artifice,”47 to question who we become in the necessarily public register of the photographic – the public register of memory and history.48

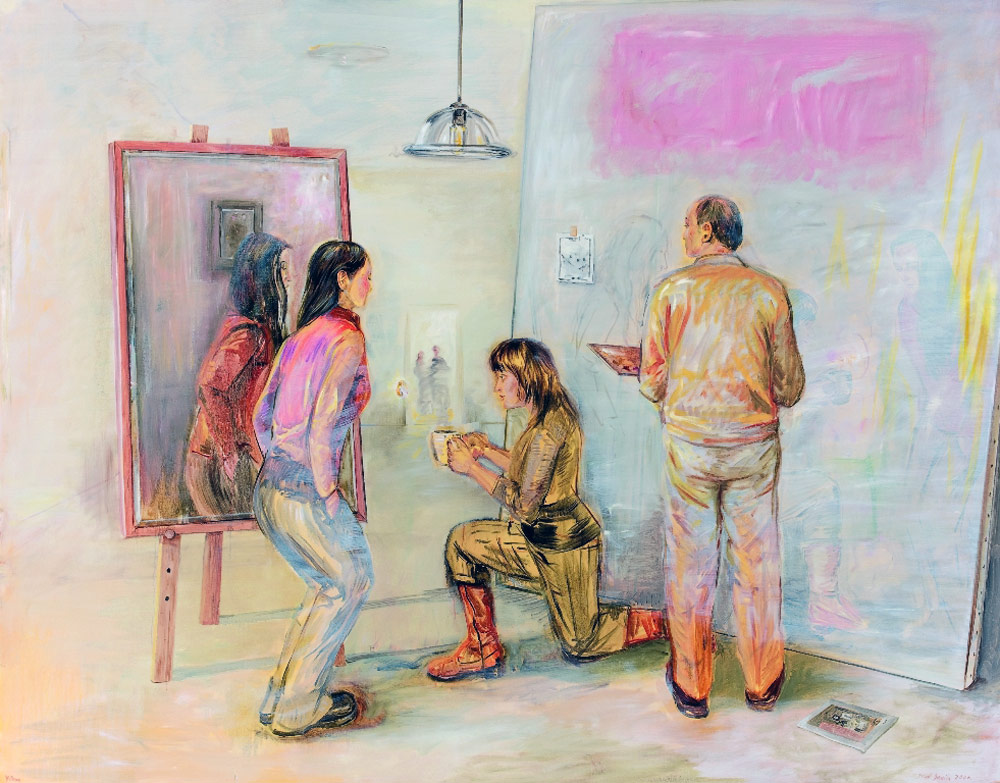

Each enframing of reality opens up the possibility of new discourses. The paradox is the more we seek to fix our vision of the world and to control it the less sure we are as to who we are and what our place is in the world. Does the painting emerge from the figure or the figure from the painting?

Does the image/reality emerge from the image …

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Word count: 3,870

Many thank to the CCP and Naomi Cass for allowing me to publish the text and photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image. Text © Centre for Contemporary Photography 2011.

Endnotes

1/ Felman, Shoshana and Laub, Dori. Testimony: Crises of Witnessing in Literature, Psychoanalysis, and History. London: Routledge, 1992, p. 5 quoted in Fisher, Jean. “Witness for the Prosecution: The Writings of Coco Fusco,” in Fusco, Coco. The Bodies That Were Not Ours. London: Routledge, 2001, pp. 227-228

2/ Stephens, Andrew. “Who’s watching you?” in The Saturday Age. 23rd September 2011 [Online] Cited 14/10/2011

3/ Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Translated from the French by Alan Sheridan. New York: Pantheon Books, 1977 cited in McDonald, Helen. “It’s Rude to Stare,” Footnote 9 in Radok, Stephanie (ed.,). Artlink: Art & Surveillance. South Australia: Artlink, Vol. 31, No. 3, 2011, p. 25

4/ Stephens, Op. cit.,

5/ See Alpers, Svetlana. The Art of Describing: Dutch Art in the Seventeenth Century. University Of Chicago Press, 1984

6/ Anon. BILL HENSON: early work from the MGA collection. Education Resource. A Monash Gallery of Art Travelling Exhibition [Online] Cited 14/10/2011. No longer available online

7/ Henson, Bill quoted in the exhibition catalogue. First published as a pdf for the exhibition In camera and in public. Curated by Naomi Cass. Centre for Contemporary Photography, 16 September – 23 October 2011

8/ Stephens, Op. cit.,

9/ See Goffman, E. Behaviour in Public Places. New York: Free Press, 1963

10/ Giddens, Anthony. The Consequences of Modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1991, pp. 82-83

11/ Stewart, Susan. On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection. Durham: Duke University Press, 1993, p. 2. Prologue

12/ Delahaye, Luc. L’Autre. Phaidon Press, 1999

13/ Delahaye, Luc quoted in the exhibition catalogue. First published as a pdf for the exhibition In camera and in public. Curated by Naomi Cass. Centre for Contemporary Photography, 16 September – 23 October 2011

14/ Morrison, Blake. “Exposed: Voyeurism, Surveillance and the Camera,” on the The Guardian website 22nd May 2011 [Online] Cited 14/10/2011

15/ Stephens, Op. cit.,

16/ Berger, John and Mohr, Jean. Another Way of Telling. New York: Pantheon Books, 1982, pp. 92-93

17/ Morrison, Op. cit.,

18/ Keenan, Haydn. “A Job for the Dogs,” in Radok, Stephanie (ed.,). Artlink: Art & Surveillance. South Australia: Artlink, Vol. 31, No. 3, 2011, p. 18

19/ Ibid.,

20/ Keenan, Haydn quoted in the exhibition catalogue. First published as a pdf for the exhibition In camera and in public. Curated by Naomi Cass. Centre for Contemporary Photography, 16 September – 23 October 2011

21/ Nelson, Robert. “Snapped in the moment – forever,” in The Age newspaper. Wednesday, October 5th 2011, p. 19

22/ Groom, Amelia. “Seeing Darkness,” in Kohei Yoshiyuki: The Park. Institute of Modern Art pamphlet for the exhibition

23/ Cass, Naomi quoted in the exhibition catalogue. First published as a pdf for the exhibition In camera and in public. Curated by Naomi Cass. Centre for Contemporary Photography, 16 September – 23 October 2011

24/ Groom, Op. cit.,

25/ Ibid.,

26/ Goldberg, Vicky. “Voyeurism Exposed,” on Artnet magazine website. 2010 [Online] Cited 14/10/2011

27/ Modra, Penny. The Sunday Age M magazine. September 25th, 2011

28/ Gefter, Philip. “Sex in the Park, and its Sneaky Spectators,” in The New York Times, 23rd September 2007 cited in Lida, Shihoko. “Gaze without Subjectivity: Kohei Yoshiyuki and Yoko Asakai,” Footnote 4 in Radok, Stephanie (ed.,). Artlink: Art & Surveillance. South Australia: Artlink, Vol. 31, No. 3, 2011, p. 28

29/ Goldberg, Op. cit.,

30/ Nelson, Op cit.,

31/ See Bunyan, Marcus, “Thesis Notes II – Research Notes and Papers: Research Notes on the Photographs from the Collection at The Minor White Archive and The Kinsey Insitute,” in Pressing the Flesh: Sex, Body Image and the Gay Male. 2001 [Online] Cited 14/10/2011. No longer available online

32/ Finch, Maggie. Looking at Looking. Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 2011, p. 2

33/ Ibid.,

34/ Burgin, Victor, “Looking at photographs,” in Burgin, Victor (ed.,). Thinking Photography. London: Macmillan Education, 1987, p. 146 quoted in Finch, Maggie. Looking at Looking. Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 2011, p. 3

35/ Palmer, Daniel and Whyte, Jessica. “‘No credible photographic interest’: photographic restrictions and surveillance in a time of terror,” in Philosophy of Photography Vol. 1, No. 2, 2010, p. 182

36/ Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Film Theory and Criticism: Introductory Readings in Braudy, Leo and Cohen, Marshall (eds.,). New York: Oxford UP, 1999, pp. 833-44 cited in Boen, Ashley. “The Male Pornographic Gaze,” on Boen, Ashley. Cultures of the Camera: The Male Gaze website [Online] Cited 15/10/2011. No longer available online

37/ Parrington, Vernon Louis. Main Currents in American Thought 1927-1930. New York: Harcourt Brace and Co., 1930 quoted in Blinder, Caroline. “”The Transparent Eyeball”: On Emerson and Walker Evans,” Footnote 11 in Mosaic: a Journal for the Interdisciplinary Study of Literature. Winnipeg: Dec 2004. Vol. 37, Iss. 4; pg. 149, 15 pgs

38/ Bloomberg. “Facebook in tracking suit,” in The Age newspaper. Monday, October 3rd 2011, p. 3

39/ Blinder, Caroline. “”The Transparent Eyeball”: On Emerson and Walker Evans,” Footnote 11 in Mosaic: a Journal for the Interdisciplinary Study of Literature. Winnipeg: Dec 2004. Vol. 37, Iss. 4; pg. 149, 15 pgs

40/ Ibid.,

41/ Marsh, Anne. “Surveillance Art: Genre and Political Action,” in Radok, Stephanie (ed.,). Artlink: Art & Surveillance. South Australia: Artlink, Vol. 31, No. 3, 2011, p. 57

42/ King, Natalie and Fraser, Virginia. “People Who Love To Watch,” in Radok, Stephanie (ed.,). Artlink: Art & Surveillance. South Australia: Artlink, Vol. 31, No. 3, 2011, p. 15

43/ Lumby, Catharine. “Nothing Personal: Sex, Gender and Identity in The Media Age,” in Matthews, Jill (ed.,). Sex in Public: Australian Sexual Cultures. St. Leonards: Allen and Unwin, 1997, pp. 14-15

44/ Virilio, Paul. “A topographical amnesia,” in The Vision Machine. London: British Film Institute, 1994 cited in Thumlert, Kurt. Intervisuality, Visual Culture, and Education. [Online] Cited 10/10/2011. No longer available online

45/ Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. Le Visible et l’invisible. Paris: 1964, p. 177 (trans. by Alphonso Lingis, Evanston, 1968, p. 134) quoted in Damisch, Hubert. The Origin of Perspective. (trans. John Goodman). Cambridge, MA.: MIT Press, 1994, pp. 34-35

46/ Foster, Hal (ed.,). Vision and Visuality. Bay Press, Seattle: Dia Art Foundation Discussions in Contemporary Culture, Number 2, 1988, p. 94

47/ French, Blair. “The Things That Bill Sees,” catalogue essay from the exhibition Perfect Strangers. Canberra: Canberra Contemporary Art Space, 2000, np.

48/ Ibid.,

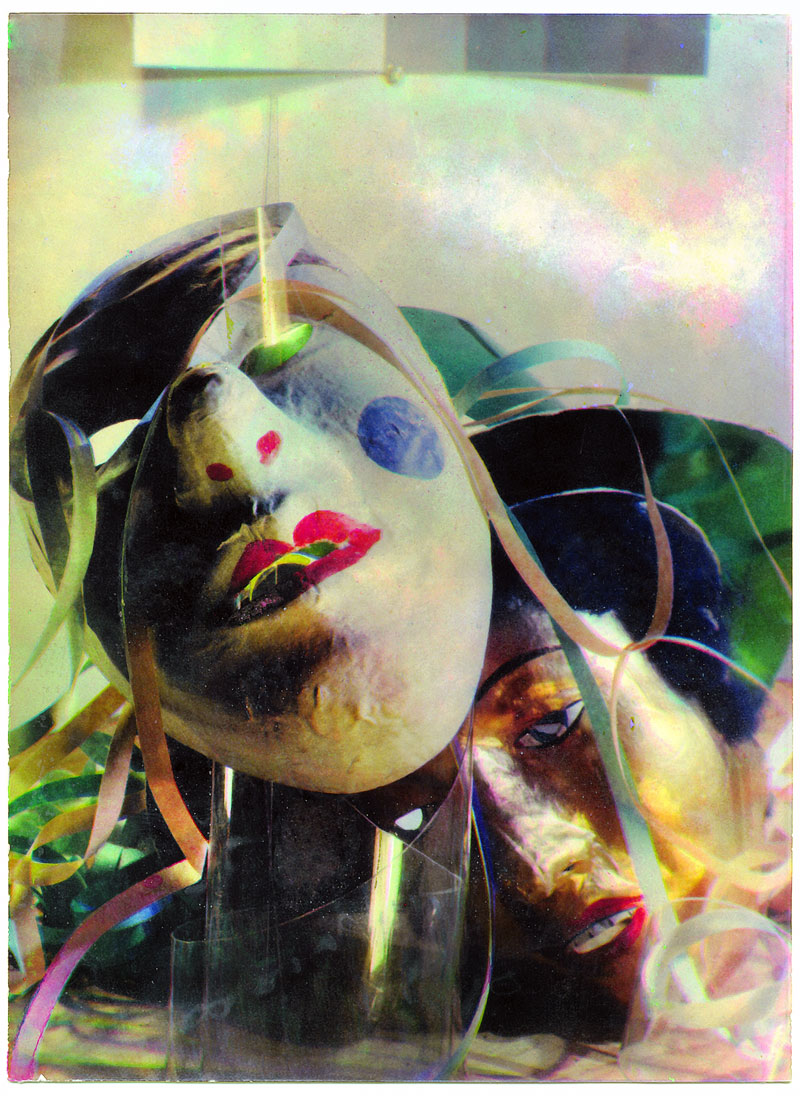

Cherine Fahd (Australian, b. 1974)

Untitled

From the series The Sleepers

2005-2008

Lightjet print

28.5 × 40.2 cm

Courtesy the artist

Cherine Fahd (Australian, b. 1974)

Untitled

From the series The Sleepers

2005-2008

Lightjet print

28.5 × 40.2 cm

Courtesy the artist

In 2003 I began photographing people I didn’t know in the streets of Paris, working in a conventional street photography style. I became a prowler searching for photographic opportunities in the faces and gestures of total strangers, fascinated with capturing private moments within the public realm.

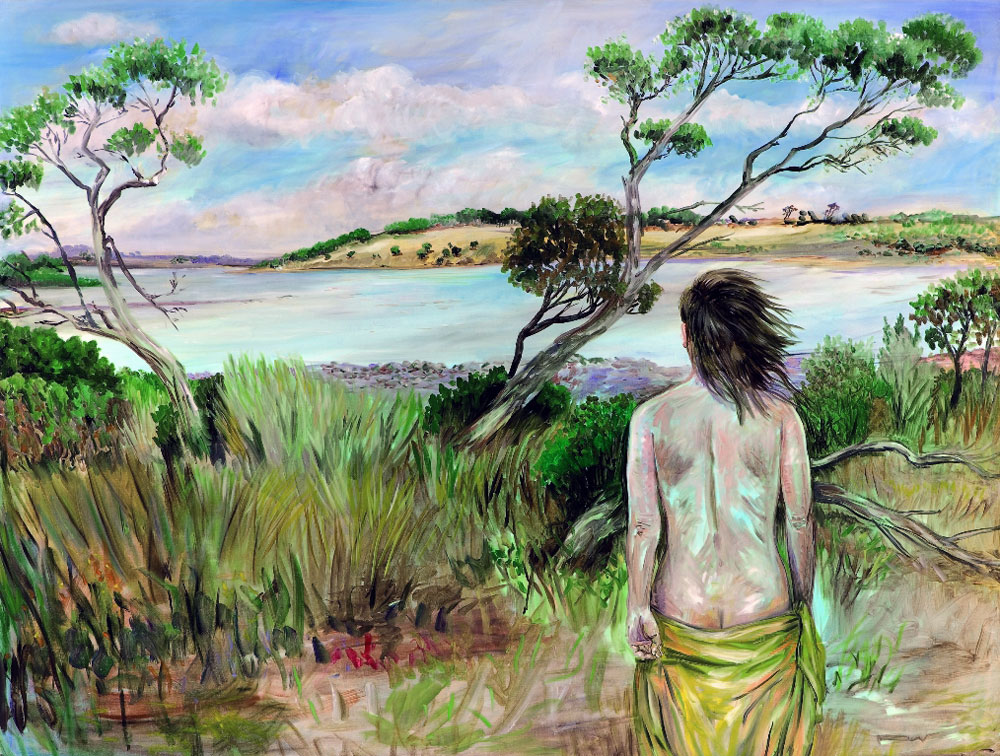

In 2005 I was living on the sixth floor of an apartment in Kings Cross, Sydney, below was a park unadorned by play equipment or even a bench. From my window I could see homeless people asleep on the grass in the middle of the day. What struck me most were their bodies resting in dappled light and gesturing in ways usually saved for private moments. The drape of their clothes and the quality of light reminded me of so many paintings I had seen.

So The Sleepers began. I photographed people asleep in the park with my mini DV camera, which allowed me to zoom in and capture detail but also allowed for a grainy image reminiscent of surveillance footage. In the sleeping posture – curled up or lying flat – people generally covered their faces, ensuring their anonymity. I liked this aspect of the work. Although I was photographing them unawares, I wasn’t really intruding if I couldn’t see their faces. Oddly, I have stopped working in this candid way. I wasn’t sure why at the time. In retrospect I understand that it became too difficult because audiences became obsessed with whether I had permission to photograph people. I never considered asking anyone if I could take their photo. It would have defeated the whole point. People change when they know there is a camera present, better to let them be.

The moral dilemmas engulfing candid photography are not something I am interested in addressing in my work. I would much rather ponder whether their faces, or their bodies, or their gestures are cues to something more mysterious, spiritual and human.

Cherine Fahd 2011 text from the exhibition catalogue

Kohei Yoshiyuki (Japanese, b. 1946)

Untitled

1971

From the series The Park

Gelatin Silver Print

© Kohei Yoshiyuki, Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

Kohei Yoshiyuki (Japanese, b. 1946)

Untitled

1971

From the series The Park

Gelatin Silver Print

© Kohei Yoshiyuki, Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

Kohei Yoshiyuki’s now infamous documentation of voyeurism features confronting photographs of public space clandestinely used as private space at night: Japanese parks where, in the absence of privacy, young people perform intimate acts while being watched by onlookers.

During the 1970s, young commercial photographer Kohei Yoshiyuki (a pseudonym; his real name remains unknown) frequented Tokyo’s Shinjuku, Yoyogi and Aoyama parks at night with a 35mm camera, infrared film and a flash. Photographed over a decade, the series was exhibited at the Komai Gallery in Tokyo in 1979 where the images were printed life-size and exhibited in the dark while visitors used hand held torches to view the photographs. These prints were subsequently destroyed.1

Images from The Park were first published in 1972 in the popular ‘secret camera’ genre magazine Shukan Shincho and were not initially considered as art photography.2 However, Yoshiyuki’s series also sits within a broad tradition of voyeurism in Japanese art, including eighteenth and nineteenth century erotic ukiyo-e prints and in cinema.

In 1980 Yoshiyuki published a further selection and, in 1989, he wrote about the process of getting to know the park voyeurs. In 2006 Yoshiyuki was included in Martin Parr’s publication The Photobook: A History: Volume 2 as an unknown innovator, prompting Yossi Milo Gallery to track down the reclusive artist and convince him to reprint the remaining negatives for what became a highly successful exhibition in 2007.

Of the relationship between couples and voyeur Yoshiyuki wrote: ‘The couples were not aware of the voyeurs in most cases. The voyeurs try to look at the couple from a distance … then slowly approach toward the couple behind the bushes, and from the blind spots of the couple they try to come as close as possible, and finally peep from a very close distance. But sometimes there are the voyeurs who try to touch … and gradually escalating – then trouble would happen.’3

Naomi Cass text from the exhibition catalogue

1/ Amelia Groom. “Seeing Darkness,” in Kohei Yoshiyuki: The Park exhibition catalogue, IMA, Brisbane, July 2011

2/ Shihoko Iida, “Gaze without subjectivity,” in Artlink: Art and Surveillance, 31: 3, 2011, p. 28

3/ Philip Gefter, “Sex in the Park, and its Sneaky Spectators,” in The New York Times, 23 Sept 2007

Luc Delahaye (French, b. 1962)

Untitled

1995/1997

From the series L’Autre

Courtesy the artist and Galerie Nathalie Obadia

I stole these photographs between ’95 and ’97 in the Paris metro. ‘Stole’ because it is against the law to take them, it’s forbidden. The law states that everyone owns their own image. But our image, this worthless alias of ourselves, is everywhere without us knowing it. How and why can it be said to belong to us? But more importantly, there’s another rule, that non-aggression pact we all subscribe to: the prohibition against looking at others. Apart from the odd illicit glance, you keep staring at the wall. We are very much alone in these public places and there’s violence in this calm acceptance of a closed world.

I am sitting in front of someone to record his image, the form of evidence, but just like him I too stare into the distance and feign absence. I try to be like him. It’s all a sham, a necessary lie lasting long enough to take a picture. If to look is to be free, the same holds true for photographing: I hold my breath and let the shutter go.

Luc Delahaye, from L’Autre, Phaidon Press, London, 1999 text from the exhibition catalogue

Luc Delahaye (French, b. 1962)

Untitled

1995/1997

From the series L’Autre

Courtesy the artist and Galerie Nathalie Obadia

To photograph people is to violate them, by seeing them as they never see themselves, by having knowledge of them that they can never have; it turns people into objects that can be symbolically possessed. Just as a camera is a sublimation of the gun, to photograph someone is a subliminal murder – a soft murder, appropriate to a sad, frightened time.

Susan Sontag On Photography 1977

In camera and in pubic is about the relationship between camera and subject when this is fraught in some way, in particular, where the subject is not aware of being photographed, where the contract between photographer and subject has been broken.

Candid photography has been critical in the development of art and evidential photography, in revealing aspects of our history and society which have been hidden, ignored, lied about or simply abandoned. Candid photography has delivered some of the most widely regarded, potent and treasured images.

However, the camera is merely a technical device and some would even say a dumb device, which can be, and is used for contradictory and malicious ends. Candid photography has also hurt, harmed and destroyed people. There are more images in the world than ever before, and image sharing technologies in the hands of those with subversive, destructive or immature desires. Paradoxically, on one hand there is greater access to unmediated information of all genres through the internet but also a counter move of public disquiet about candid photography. Many well-regarded, indeed renowned photographers will no longer photograph at the beach, by a pubic pool, at a junior sports match, on the street. The context for photography has changed.

This exhibition looks at the physical and moral proximity of camera to subject in both historical and contemporary work by Cherine Fahd, Bill Henson, Luc Delahaye, Sonia Leber and David Chesworth, Kohei Yoshiyuki, Denis Beaubois, Percy Grainger, Walid Raad and declassified ASIO images from the late 1940s to the 1980s.

In viewing In camera… it is sobering to consider where the photographer is positioned, to viscerally experience the proximity of camera to unsuspecting subject because, importantly, the exhibition moves from candid photography taken with the sole intention of making art (Henson, Fahd, Delahaye, Leber and Chesworth, Raad and Yoshiyuki) through to the intention of surveillance. Not surprisingly, on first view, even the declassified ASIO images are compelling and beautiful.

Of the artists, the viewer might well ask, have you obtained permission to photograph? But as we all know the unprepared body and face reveals quite a different story than the figure composed for the camera. It is the non-composed figure which is the lifeblood of much art and photography.

Surveillance is in part the subject of work by Denis Beaubois, Walid Raad and to some extent in Leber and Chesworth’s multi-media work. Certainly Beaubois, Leber and Chesworth consider the role of architectural space and the all-seeing eye of the state and in the latter, the eye of god within the panopticon of the domed cathedral. Walid Raad puts the tedium of surveillance in perspective when his fictional operative repeatedly forgoes his designated work to relish the setting sun.

In camera and in public exploits the form of CCP’s nautilus galleries and reflects the progress of the camera turned towards an unsuspecting subject until Gallery 4 where, in the hand of Percy Grainger, the camera is turned towards himself, in an astonishing series of vintage photographs, possibly created for display in the Grainger Museum. ‘In camera’ and in public, indeed. In 1941 Grainger wrote, “Most museums, most cultural endeavours, suffer from being subjected to too much taste, too much elimination, too much selection, too much specialisation! What we want (in museums and cultural records) is all-sidedness, side lights, crossreferences.”

We all love to stare, to linger, to see what we might have missed, and with advancing technologies, to see what is unavailable to the naked human eye, and here lies the problem. In looking at these images, are we implicated in an act of transgression?”

Text Naomi Cass September 2011 from the exhibition catalogue

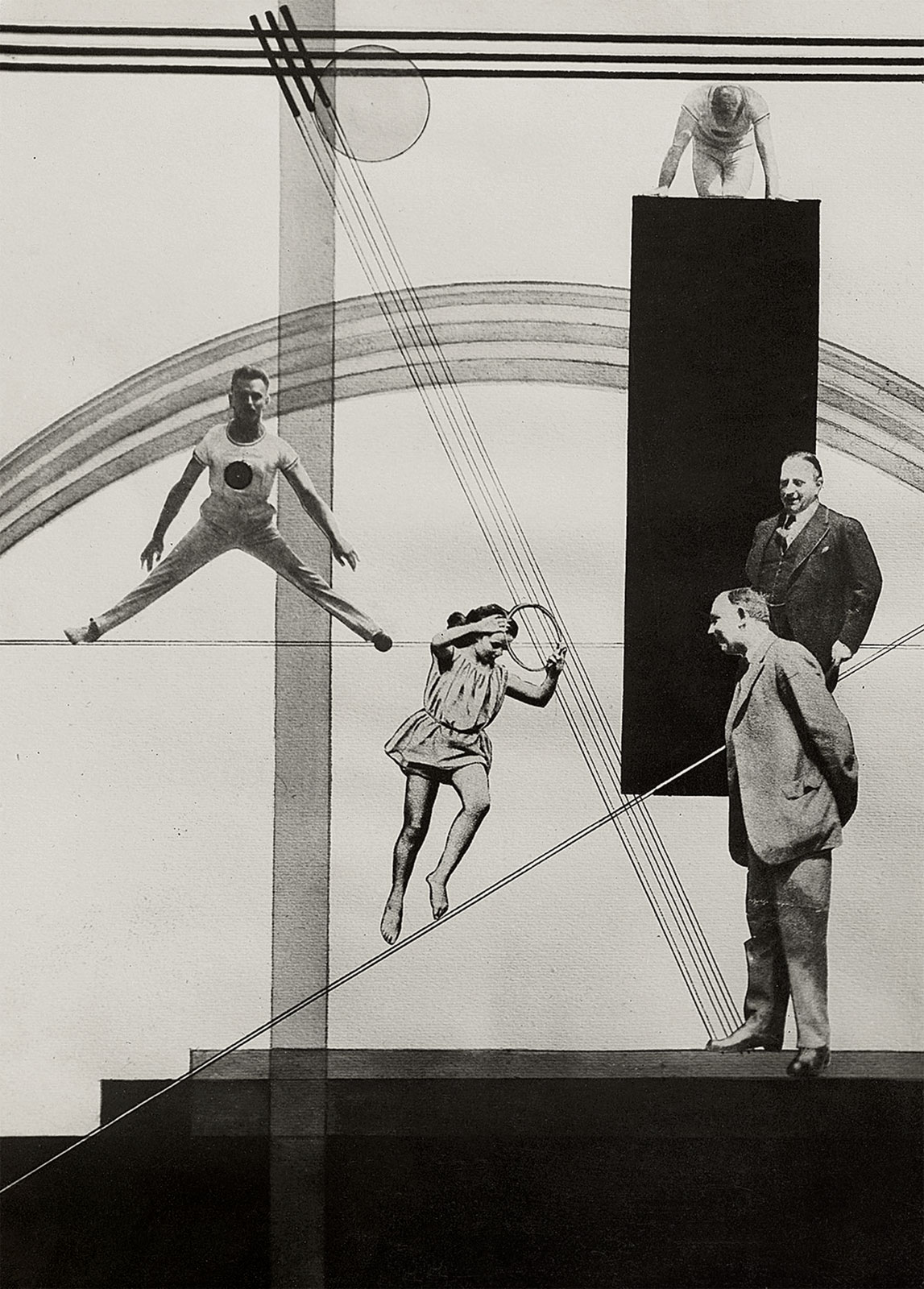

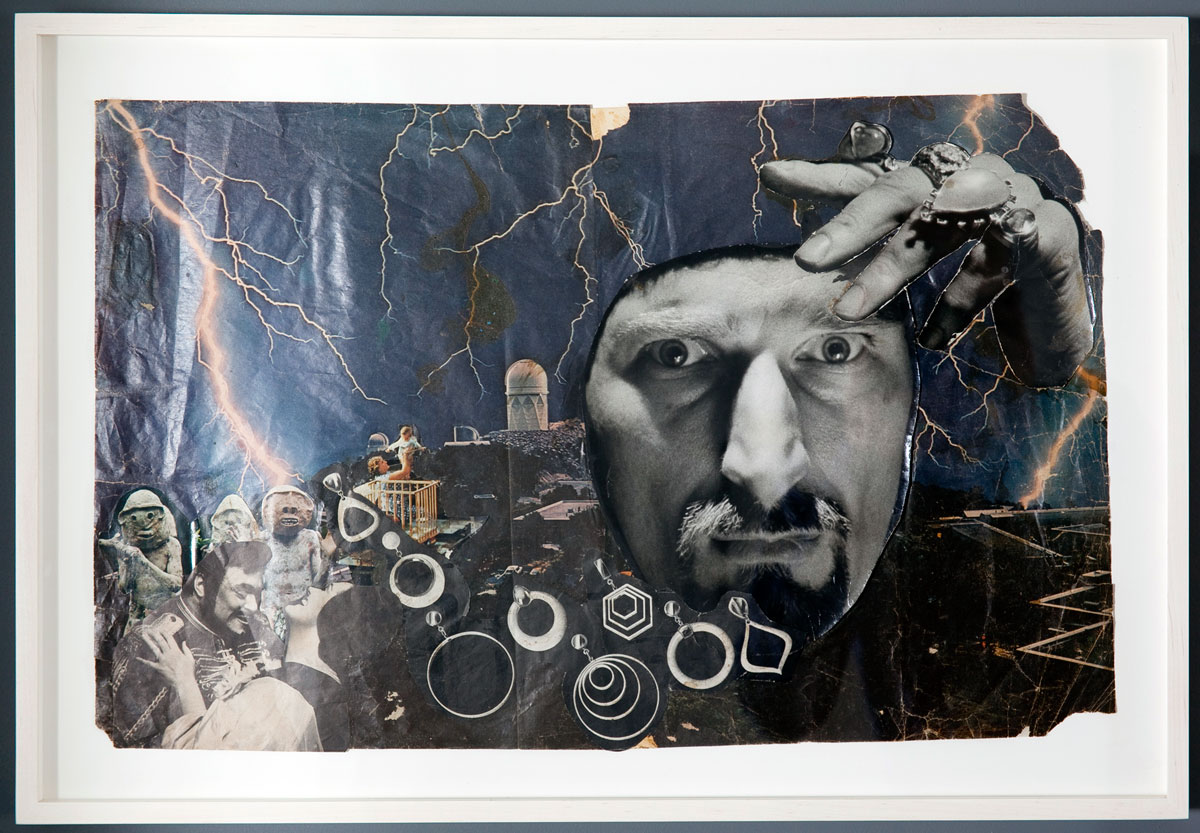

Denis Beaubois (Mauritius, b. 1970)

In the event of Amnesia the city will recall…

1996-1997

DVD

9 mins 30 secs

Courtesy the artist

This work explores the relationship between the individual and the metropolis. Twelve sites were selected around the city of Sydney where surveillance cameras are prominently placed, the locations were mapped out and the stage for this work was created. A daily pilgrimage was made to the sites for a period of three days. No permission was sought for the use of these sites. The performer arrived unannounced and carried out his actions. Upon arrival the performer attempted to engage with the electronic eye. The performer’s actions were directed to the camera, which adopted the role of audience.

The primary audience was the surveillance camera (or those who monitor them). Their willingness to observe is not based upon the longing for entertainment. It stems from a necessity to assess and monitor designated terrain. Imbued with a watchdog consciousness, the primary audience scans the field for suspects, clues and leads. Like many audiences, it assesses the scene and attempts to pre-empt the plot. However this audience is extremely discerning and, ultimately, by assessing and reacting to the event it also adopts the role of performer.

Within this metropolis the walls do not have ears but are equipped with eyes. The city must understand the movements of those who dwell within its domain. To successfully achieve this it must be capable of reading its inhabitants. What can be read can be controlled in theory. Yet the city’s eyes are not content following the narrative provided by its inhabitants. The city weaves its own text within the surface narrative. A paranoid fiction based on foresight.

Denis Beaubois 1997 text from the exhibition catalogue

Denis Beaubois (Mauritius, b. 1970)

In the event of Amnesia the city will recall…

1996-1997

DVD

9 mins 30 secs

Courtesy the artist

In camera and in public represents a very different approach to this year’s Festival theme of protest and revolution. Taking a look at society through the lens of the state, the street photographer, the artist and the eye of the voyeur, this exhibition curated by Naomi Cass examines the abandonment of the contract between photographer and subject.

Ranging from candid street photography through to surveillance photography, In camera explores the camera and its relationship to the subject, unaware of being photographed. From images taken in public spaces, including a series of striking faces taken on the Paris metro, the exhibition proceeds to the grainy anxiety of declassified ASIO photos from the 1960s.

Kohei Yoshiyuki’s now infamous documentation of voyeurism, The Park (1970-1979), features confronting photographs of public space clandestinely used as private space at night: Japanese parks where, in the absence of privacy, young people perform intimate acts while being watched by onlookers.

At the heart of CCP galleries are Percy Grainger’s extraordinary naked self-portraits from his so-called ‘lust branch’ collection, hand printed by Grainger between 1933 and 1942. Here the camera is turned on himself, in camera.

Cherine Fahd offers frank photographs of daytime sleeping bodies in a Kings Cross park taken from her 6th floor apartment, while Bill Henson captures hauntingly beautiful crowd scenes during the 1980s. Sonia Leber and David Chesworth secretly film from the dome of St Pauls Cathedral, London and Walid Raad impersonates a fictional operative who failing in his surveillance task, repeatedly films the sunset.

Finally, Denis Beaubois, with a playful and performative video, seeks a kind of revenge of the subject, through his attempts to engage with a number of surveillance cameras, inviting the camera to respond to pleas earnestly delivered on cue cards.

Press release from the CCP website

Bill Henson (Australian, b. 1955)

Untitled 1980/82

Gelatin silver chlorobromide print

From a series of 220

57.5 × 53.4cm

Courtesy the artist and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Bill Henson (Australian, b. 1955)

Untitled 1980/82

Gelatin silver chlorobromide print

from a series of 220

57.5 × 53.4cm

courtesy the artist and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

The great beauty in the subject comes, for me, from the haunted space, that unbridgeable gap – which separates the profound intimacy and solitude of our interior world from the ‘other’ and in trying to show, in this case through envisioning the crowd, how an awesome, unassailable, even monumental, beauty and grace might attend the undulating, fluid mass of a wall of people as they move toward you.

It is the contradictory nature of life and the way in which this can be suggested in art which first drew me to photograph crowds – much as this underpins my interest in any art form…

The business of how a child’s small hand appearing between two adults at a street crossing can suggest both a vulnerability, great tenderness, and yet also contain within it all of the power that beauty commands, is endlessly fascinating to me.

Bill Henson 2011 text from the exhibition catalogue

Persons Of Interest – ASIO surveillance 1949-1980

Writer Frank Hardy, St Kilda, July 1964

NAA 9626, 212

Persons Of Interest – ASIO surveillance 1949-1980

Eddie Mabo, CPA district conference, Townsville, September 1965

NAA A9626, 162

Persons Of Interest – ASIO surveillance 1949-1980

Curated by Haydn Keenan

Selected surveillance images from a forthcoming documentary series from Smart Street Films

I discovered these images as part of my research for our documentary series Persons Of Interest which will be screened on SBS early next year. They are part of a massive archive of pictures secretly recorded by the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) from 1949 onwards.

These images are not art. Unlike art these pictures have the power to alter lives dramatically. Be photographed at the wrong place and you’ll find it hard to get a job, when you do you’ll get the sack soon after. Appear in these images and your career will go nowhere without explanation. The eye of the beholder will cast a shadow you will not see until thirty years later when you get access to your file.

The photos create a strange world of frozen youth, high hopes and issues that were seen as subversive then but are now so integrated into the mainstream that they need explanation for Gen Y. ASIO was created to hunt down and eliminate a Soviet spy ring operating in Canberra in the late 1940s. Most of the members of the spy ring were connected with or were members of the Communist Party of Australia. For the next forty years ASIO followed everything the Party did.

The purpose of photographic surveillance is to identify Persons Of Interest in a definitive manner and to record their associations and contacts thereby building a network. Surveillance would occur during demonstrations, May Day marches and at political meetings. It would also occur at specific locations and everyone entering or leaving the location would be recorded. Each person in a photograph with an ASIO file would have an identifying number marked on the image next to them.

I have thousands of these images and what I have noticed is that one builds up a mental image of the changing face of what the State saw as a threat. What starts as the hunt for Communist spies gradually evolves into suspicion about social issues like Aboriginal land rights, youth culture, Women’s Liberation, anti Vietnam, Apartheid – even amateur actors at New Theatre were thoroughly photographed. There’s even a file on the Mother’s Club at Gardenvale Primary School. The absurdity is evident in hindsight. Yet what ASIO didn’t realise is that they were constructing an invaluable social history of Australian dissent as they gradually confused subversion with dissent.

They recorded many people, especially in the 1960s filled with youthful exuberance, high in hope and action. These people were questioning the central values of a society their parents had created. Here they are frozen in the malevolent eye of the security services. Whilst it’s invasive, seedy and incompetent, even they can’t diminish sunlit youth.

Haydn Keenan 2011 text from the exhibition catalogue

Percy Grainger (Australian, 1882-1961)

Private Matters: Do not open until 10 (ten) years after my death

1955-1956

Envelope

25.1 x 32cm

Courtesy the Grainger Museum, The University of Melbourne

Internationally renowned Australian pianist and composer Percy Grainger (1882-1961) built new sounds by modifying old instruments. He built electronic instruments from recycled materials; he built new words, new types of garments and previously unforged links between folk and classical music. He also built the Past-Horde-House, his term for museum, in which he curated his life.

In these photographs, hand printed between 1933 and 1942, Percy Grainer turns the camera on himself (and to a lesser degree his wife Ella) to document his sexual practices, which he believed were intrinsic to his being and his creativity. These works form part of what Grainer called the ‘lust branch’ of his Museum.

Grainger was a sadomasochist and wrote to his partners and friends quite openly about his thoughts on sex, including what he called ‘self beating’. However when in 1956 Sir Eugene Goossens, British composer and Sydney Symphony Orchestra conductor was detained for bringing pornography into the country, and was subsequently destroyed by the scandal, Grainger, like a number of prominent Australian artists, either left the country or outwardly restrained their behaviour. Consequently, Grainger sealed his ‘lust branch’ of the Museum, a selection of books, whips and photographs related to sadomasochistic behaviour in a travelling trunk, and left the instruction: Not to be opened until 10 (ten) years after my death (exhibited). Contained within the accompanying envelope is a kind of manifesto in the form of a letter, the pages of which are carefully bound together by hand, in which he writes, ‘The photographs of myself whipped by myself in Kansas City and the various photographs of my wife whipped by me show that my flagellantism was not make-believe or puerility, but had the element of drasticness in it. Nevertheless my flagellantism was never inhuman or uncontrolled.’

While Grainger was the subject of intense, international media scrutiny, marketing and photography, to document their sadomasochistic practices Grainger had to teach himself photography. The archive he left has the quality of forensic records, consistent with the quasi scientific method he practiced in other aspects of his life. Exhibited is Grainger’s self-printed, hand-made album, Photo-skills Guide in which he makes technical observations, similarly evident in and on other ‘lust branch’ photographs.

Grainger considered his sexual expression integral to all aspects of his life, indeed for Grainger sexuality was inseparable from his renowned life as a pianist and composer. It is probable that the ‘lust branch’ images were designed for display in the Museum, in a more enlightened period. In 1941 Grainger wrote, ‘I have a bottomless hunger for truth … life is innocent, yet full of meaning. Destroy nothing, forget nothing … say all. Trust life, trust mankind. As long as the picture of truth is placed in the right frame (art, science, history) it will offend none.’

Naomi Cass 2011 text from the exhibition catalogue

Centre for Contemporary Photography

Level 2, Perry St Building

Collingwood Yards, Collingwood

Victoria 3066

Opening hours:

Wednesday – Saturday 11am – 5pm

Centre for Contemporary Photography website

LIKE ART BLART ON FACEBOOK

Back to top

You must be logged in to post a comment.