Exhibition dates: 22nd May – 23rd September 2012

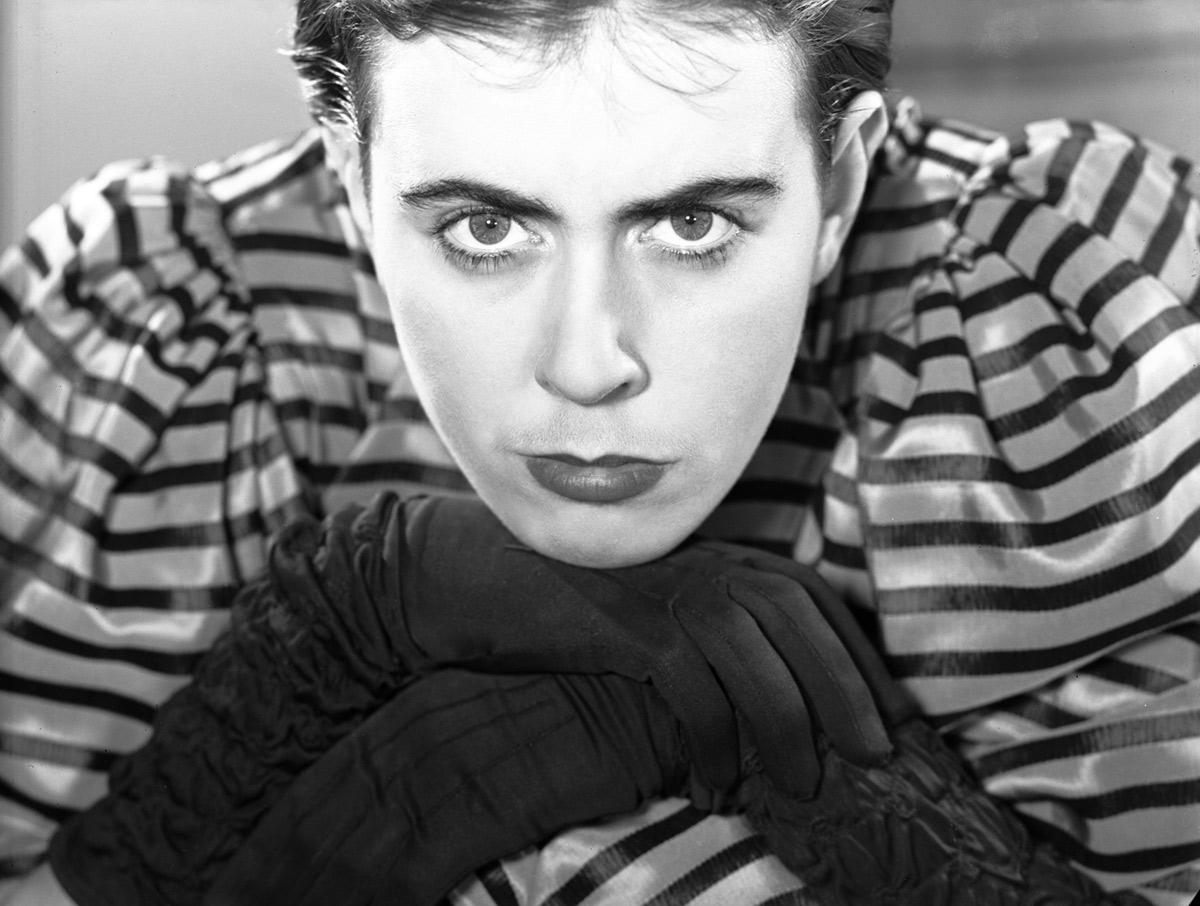

Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003)

Self Portrait

1932

Silver gelatin photograph

Private Collection, Berlin

© Eva Besnyö / Maria Austria Instituut Amsterdam

One of the purposes of this archive is to bring relatively unknown artists into the spotlight. Eva Besnyö is one such artist. Leaving the repressive atmosphere of Hungary in 1930, Besnyö joined László Moholy-Nagy, Martin Munkácsi, György Kepes and Endre Friedmann (Robert Capa) in Berlin before, sensing the danger of National Socialism, she moved to the Netherlands in 1932. After the invasion of the Netherlands by Nazi Germany in 1940 Besnyö survived four long years in hiding before obtaining false papers in 1944 that allowed her to emerge into the open. She was Jewish.

Exploring elements of the New Vision and New Objectivity in her work, Besnyö explored “the different terrains that photography was opening up” through various bodies of work: “ranging from experimental to the photojournalistic, from street scenes to portraits, and from new architecture to the aftermath of the aerial bombardment of Rotterdam.” As John Yau observes in the quote at the top of the posting, “The various bodies of work make it difficult to characterise her… she seems to have no signature body of work, which is one of her abiding strengths. Just when you think you have gotten some sense of her, she slips through your fingers.”

Continuing the conversation from my recent review of the work of Pat Brassington (where I noted that curators and collectors alike try to pigeon hole artists into one particular style, mainly so that they can compartmentalise and order the work that they produce: such and such produces this kind of work – and that the work produced in this style is not necessarily their best), Besnyö can be seen to be a transmogrifying artist, one that experimented and investigated the same themes through different subject matter – hence no signature body of work. One of my friends observed that this kind of art making could be mistaken for a strange form of nihilism (in which nothing in the world has a real existence). It could be argued that the artist keeps changing subject matter, just dabbling really, pleasing herself with the images that she took, without committing to a particular style. Without seeing the 120 vintage prints it is hard to make a judgement.

From the work posted here it would seem that for Besnyö, observation and exploration of the lines of sight of life were the most critical guide to her art. In other words her shifting viewpoints create a multi-dimensional narrative that coalesces in a holistic journey that challenges our point of view in a changing world. As Victor Burgin notes in Thinking Photography, “The structure of presentation – point-of-view and frame – is intimately implicated in the reproduction of ideology (the ‘frame of mind’ of our ‘points-of-view’)” (1982, p. 146). The frame of mind of our points of view… this is what Eva’s work challenges, the reproduction of our own ideology. Her morphology (the philosophical study of forms and structures) challenges the cameras and our own point of view. As Paul Virilio observes,

“In calling his first photographs of his surroundings ‘points of view’, around 1820, their inventor, Nicéphore Nièpce came as close as possible to Littré’s rigorous definition: ‘The point of view is a collection of objects to which the eye is directed and on which it rests within a certain distance.'” (Virilio, Paul. The Vision Machine (trans. Julie Rose). Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994, p. 19.)

Besnyö changes the collection of objects to which the eye is directed as she also changes the distance and feeling of the objects upon which the eye rests. Notice how in most of the photographs the human subjects all have their back to the camera or are looking away from the instrument of objectification (or looking down into it). Even in the two self portraits Besnyö – formal in one with bobbed hair and skirt, wild in the other with a shock of tousled hair – she avoids the gaze of the camera. Like most of her subjects she remains hard to pin down. What Besnyö does so well (and why she isn’t just pleasing herself) is to construct a mythology of the city, a mythology of life which resonates through the ages. She creates a visual acoustics (if you like), a vibration of being that is commensurate with an understanding of the vulnerability of existence.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to Jeu de Paume for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“Ranging from the experimental to the photojournalistic, from street scenes to portraits, and from new architecture to the aftermath of the aerial bombardment of Rotterdam, July 1940, Besnyö explored the different terrains that photography was opening up, while at the same time helping to define them. The various bodies of work make it difficult to characterise her… she seems to have no signature body of work, which is one of her abiding strengths. Just when you think you have gotten some sense of her, she slips through your fingers.”

John Yau. “Something Special About Her, Eva Besnyö at the Jeu de Paume” on the Hyperallergic website, July 8th 2012

Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003)

Self Portrait

Nd

Silver gelatin photograph

© Eva Besnyö / Maria Austria Instituut Amsterdam

Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003)

Untitled [boy with a violoncello, Balaton, Hungary]

1931

Silver gelatin photograph

29.4 x 24.3cm

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

© Eva Besnyö / Maria Austria Instituut Amsterdam

Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003)

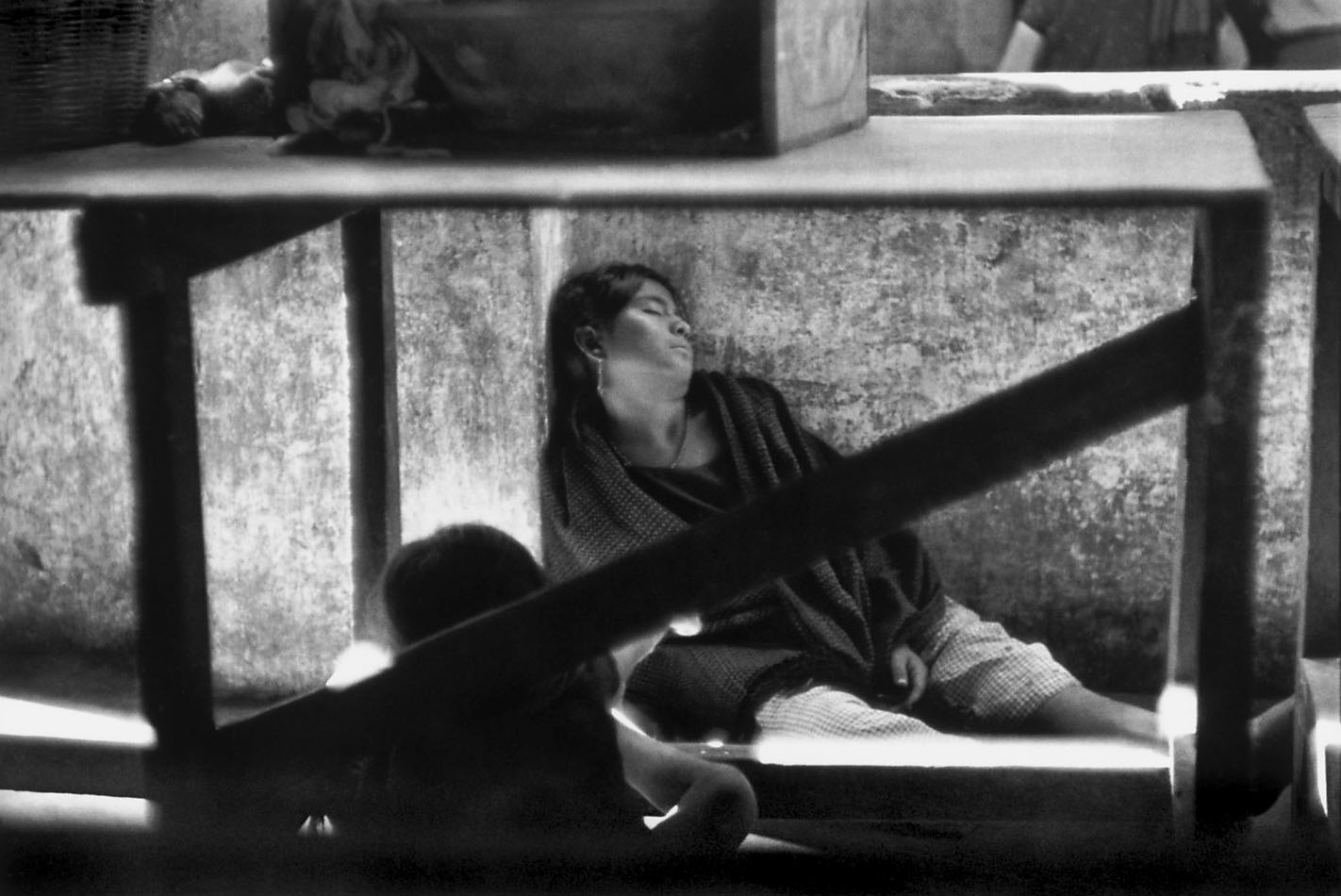

Gypsies

1931

Silver gelatin photograph

© Eva Besnyö / Maria Austria Instituut Amsterdam

Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003)

Der Monteur am Ladenfenster

Berlin, 1931

Silver gelatin photograph

20.1 x 17.7cm

Collection Iara Brusse, Amsterdam.

© Eva Besnyö / Maria Austria Instituut Amsterdam

Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003)

Starnberger Straße

Berlin, 1931

Silver gelatin photograph

© Eva Besnyö / Maria Austria Instituut Amsterdam

Renger-Patzsch was associated with the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity), an attitude towards life and art that many Germans understood as distinctly American: the cult of the objective. Along with Regner-Patzsch, August Sander is another photographer associated with this tendency. (Karl Hubbuch, Otto Dix and Christian Schad are among the painters associated with it). The difference between the two photographers is that the human being is at the center of Sander’s work, while the world of things is at the center of Renger-Patcsch’s. Besnyö situates herself between the two, finding her own way.

The other influence on Besnyö was Låslø Moholy-Nagy’s New Vision, a term he coined to define his belief that photography enabled the viewer to see the world in ways the eyes could not. In 1930, at the age of 20, she moved to Berlin, rather than to Paris, where Hungarian photographers such as Andre Kertesz and Brassaï had gone. According to Besnyö, “The whole German side interested me. Paris was the Romantic, old-fashioned trend. The second reason was Gyørgy Kepes, who was a good friend of mine and had gone to Berlin as an assistant to Moholy.”

It was Gyørgy Kepes who said to Besnyö; “If you want to be a photographer, you must go to Berlin.” It was from this relationship and the circle around Moholy-Nagy that Besnyö learned of Russian Constructivism and began incorporating the diagonal into her photographs.

John Yau. “Something Special About Her, Eva Besnyö at the Jeu de Paume” on the Hyperallergic website, July 8th 2012

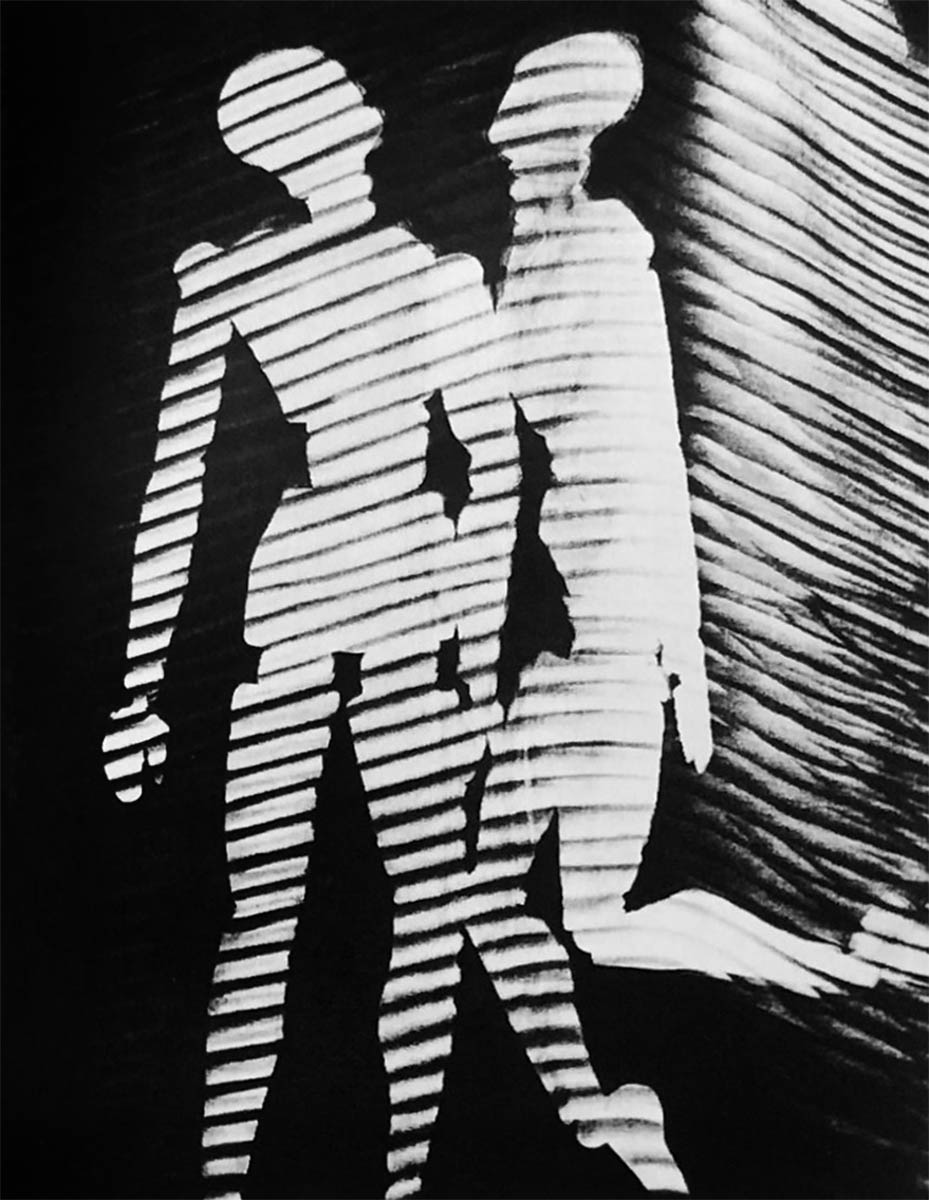

Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003)

Untitled [Shadow play]

Hungary 1931

Silver gelatin photograph

© Eva Besnyö / Maria Austria Instituut Amsterdam

Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003)

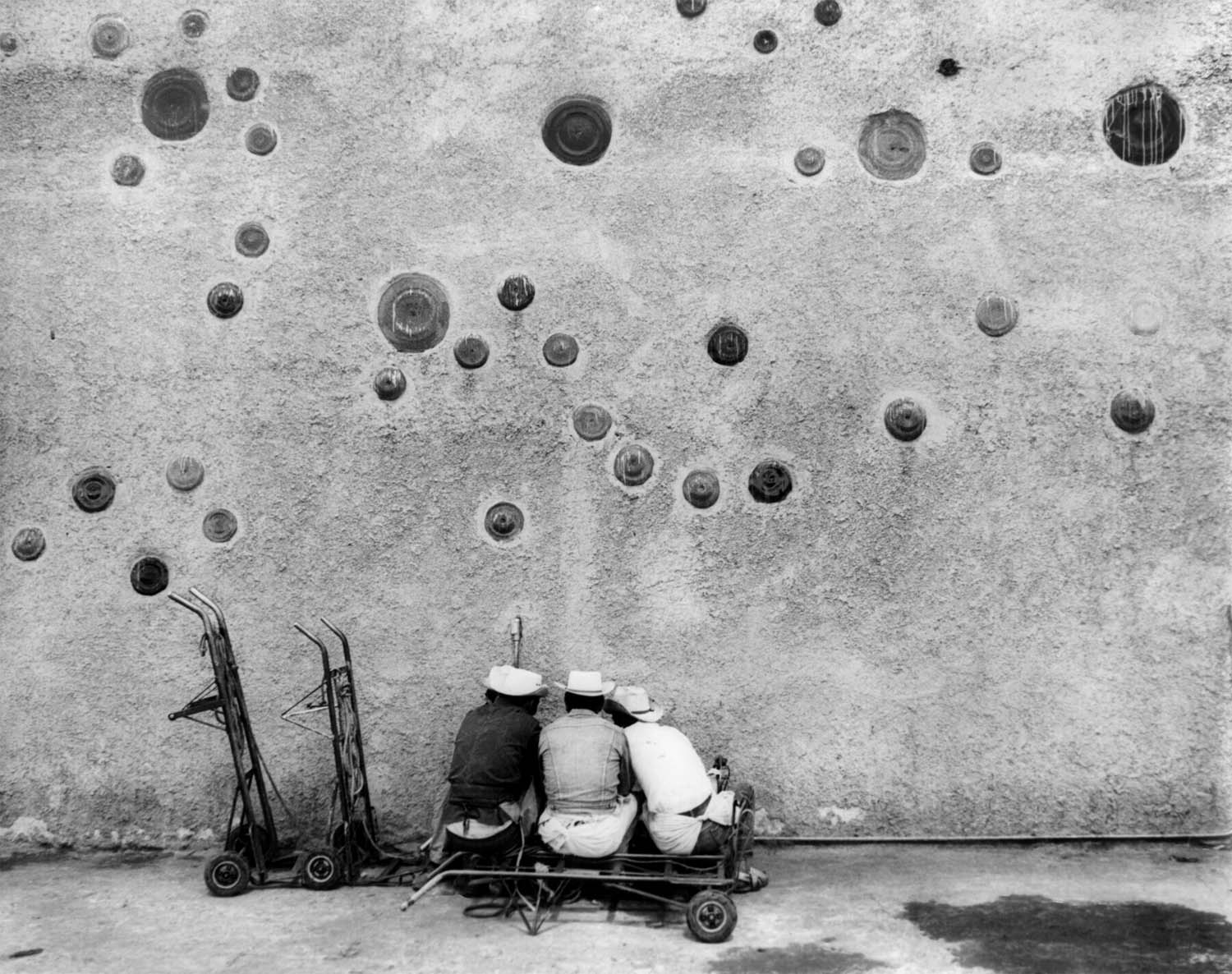

Untitled [dockers on the Spree]

Berlin, 1931

Silver gelatin photograph

© Eva Besnyö / Maria Austria Instituut Amsterdam

Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003)

Untitled [Vertigo #3]

Nd

Silver gelatin photograph

© Eva Besnyö / Maria Austria Instituut Amsterdam

Eva Besnyö (1910-2003) is one of those women who found in photography not just a profession but also a form of liberation, and of those cosmopolitan avant-garde artists who chose Europe as their playing field for both play and work. Immediately after her photographic training in the studio of József Pécsi in Budapest, Eva Besnyö left the repressive, anti-progressive environment of her native Hungary for ever. Then aged 20, she decided, like her compatriots László Moholy-Nagy, Martin Munkácsi, György Kepes and Endre Friedmann (Robert Capa), to go to Berlin. As soon as she arrived in autumn 1930, she discovered there a dynamic photographic scene, open to experimentation and placed under the double sign of the New Vision and the New Objectivity, whose modern language would allow her to develop her personal style.

Of Jewish origins, Eva Besnyö, who foresaw the threat of National Socialism, moved to the Netherlands in 1932 where she met again her companion the film director John Fernhout. There she was welcomed into the circle of international artists around the painter Charley Toorop, and rapidly became known in Amsterdam, where she had her own photographic studio. A solo exhibition at the Kunstzaal van Lier in 1933 gained the attention notably of the Dutch followers of the “Neues Bauen” (New Building), whose architecture she recorded, in a highly personal manner, over a long period. The invasion of the Netherlands by Nazi Germany in 1940 marked a dramatic turning point in Eva Besnyö’s life. If she managed to come out of hiding in 1944, thanks to an invented genealogy, the traces of this experience would remain acute throughout the postwar decades. During the 1950s and 60s, her family life led her to abandon street photography for commissions. Finally, in the twilight of her career, the photographer militated in the Dolle Mina feminist movement, whose street actions she chronicled in the 1970s.

With more than 120 vintage prints, some modern prints and numerous documents, this first French retrospective devoted to Eva Besnyö aims to show the public the different facets of her work, which is situated between New Vision, New Objectivity and social documentary, at the crossroads between poetry and political activism.

With other eyes

In 1929, during her second year of apprenticeship to József Pécsi, portrait and advertising photographer in Budapest, Eva Besnyö received the book of photographs Die Welt ist schön (The World is Beautiful), published a few months earlier in Munich. Its author, Albert Renger-Patzsch, is the precursor of New Objectivity in photography. While pictorialism reigned in Hungary, Eva Besnyö discovered the world with other eyes: from up close and under unexpected angles. With these new models in mind and her Rolleiflex in hand, she strode along the banks of the Danube in search of subjects and daring viewpoints, showing concern for a precise, close-up description of the most diverse objects, as well as a taste for fragmentation and for the repetition of the motif in the frame.

As soon as she finished her studies, Eva Besnyö went to Berlin on the advice of the painter and photographer György Kepes – and against the wishes of her father who would have preferred that she chose Paris. The Berlin years, between 1930 and 1932, were for her those of a political and aesthetic awakening. Besides the influence of the revolutionary aesthetic of Russian cinema, she came under that of the New Vision, which took off with László Moholy-Nagy and his book Painting Photography Film (1925), using a whole stylistic grammar, advocating downward perspectives or low-angle shots, a taste for the isolated object and its repetition, as well as optical manipulations revealing an unknown, but very real, world. The activity of the town or the empty crossroads of Starnberger Straße, portraits and images of summer on the banks of Lake Wannsee count among Besnyö’s most successful compositions.

Worker and social photography

At the Marxist Workers’ School in Berlin, Eva Besnyö schooled her social and political conscience. In her circle of friends gathered around fellow Hungarian György Kepes, she discussed passionately the role of the workers’ movements. In Berlin, as earlier in Budapest, Eva Besnyö took her camera to the principal sites of trade and business, where she photographed labourers hard at work: dockers on the Spree, coalmen in the street, fitters perched on ladders; in the city centre, she followed the workers at Alexanderplatz, in around 1930 the largest construction site in Europe. In Hungary, where she returned from time to time from Berlin, she carried out an extraordinary documentary project on the people of Kiserdö, in the suburbs of Budapest. Blessed with a heightened political awareness, she had already understood by 1932 that, as a Jew, her future was not in this country, and left Berlin for Amsterdam.

New Vision and New Building

In 1933, the solo show devoted by the Kunstzaal van Lier to Eva Besnyö just one year after her arrival in Amsterdam aroused the enthusiasm of numerous architects – her principal clients in the years to come. Mostly members of the group de 8 in Amsterdam and the radical abstract collective Opbouw in Rotterdam, they discerned in her images, which emphasised the functional side of objects, their structure and their texture, a suitable approach for explaining their buildings.

Equipped with a Linhof 9 x 12 cm plate camera acquired especially for the purpose, Eva Besnyö went to building sites and photographed public and private buildings, notably the studios of the Dutch radio station AVRO at Hilversum, the Cineac cinema in Amsterdam and a summer house in Groet, in the north of the country. Become, in the 1930s, the preferred photographer of Dutch New Building, Eva Besnyö made most of her income at the time from architectural photography.

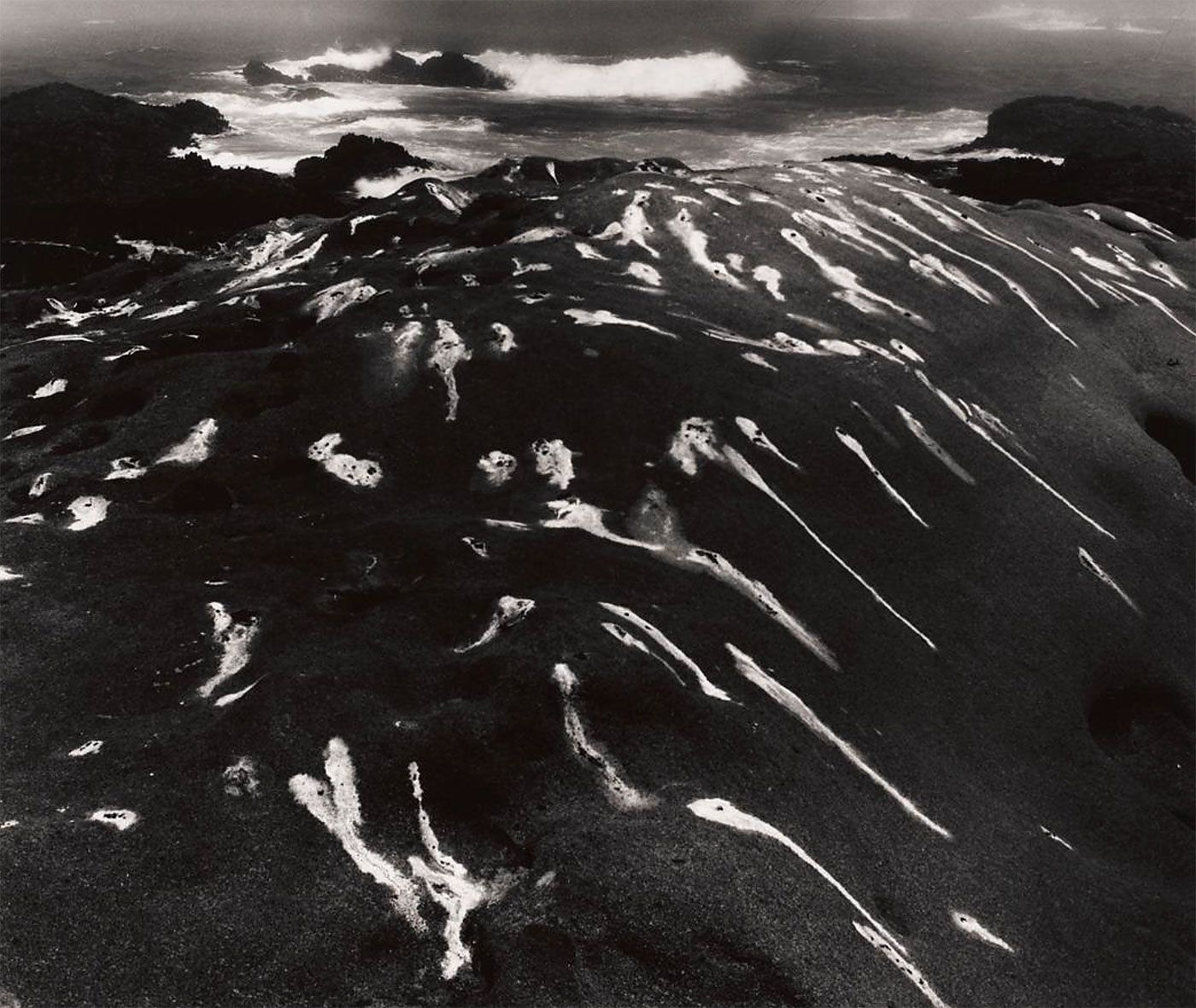

Bergen and Westkapelle

From Amsterdam, where from 1935 to 1939 she shared a studio at Keizersgracht 522 with the photographer Carel Blazer and the architect Alexander Bodon, Eva Besnyö went regularly to Bergen and Westkapelle, two villages where many artists gathered. In Bergen, north of Amsterdam, Charley Toorop, Expressionist painter and mother of the film director John Fernhout, whom Eva had married in 1933, held an artistic salon in the De Vlerken studio. It was at Westkapelle, a centuries-old village built on a polder in Zealand, that the family often spent their holidays. In this landscape shaped by the natural elements, Eva Besnyö returned to a free photographic practice, with views of vast beaches of white sand, of black silhouettes against a background of old windmills and cut-out shadows.

Rotterdam

In July 1940, Eva Besnyö photographed the old town of Rotterdam destroyed by German airforce bombing. Far from classic photo-journalism, these images of ruins and traces of devastation – from which, in retrospect, she distanced herself – are today silent, bare statements of the wounds and scars of history.

Dolle Mina

The Dolle Mina feminist movement gathered both men and women, mainly from the student protest movement. In the 1970s, Eva Besnyö militated actively within it, alongside sympathisers of all ages. In a second phase, she focused on photographic documentation of the movement’s actions and activities, taking responsibility for sending out images daily, like a press agency.

Text by Marion Beckers and Elisabeth Moortgat, curators of the exhibition

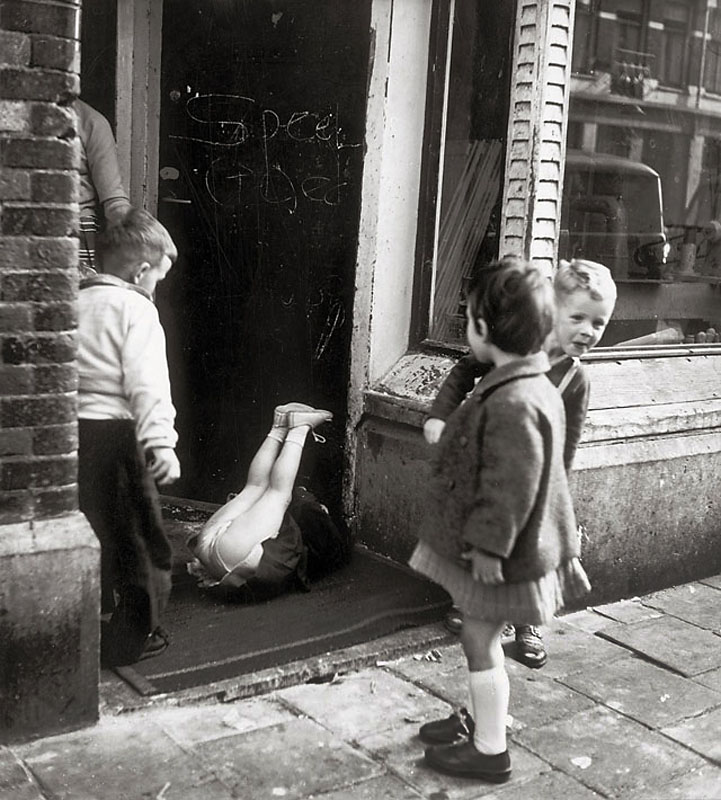

Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003)

Untitled

1934

Collection Iara Brusse, Amsterdam

© Eva Besnyö / Maria Austria Instituut Amsterdam

Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003)

Untitled [Summer house in Groet, North Holland. Architects Merkelbach & Karsten]

1934

18.2 x 24.2cm

Collection Iara Brusse, Amsterdam

© Eva Besnyö / Maria Austria Instituut Amsterdam

Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003)

Stadion, Berlin, 1931

1931

16.8 x 23.9cm

Collection Iara Brusse, Amsterdam

© Eva Besnyö / Maria Austria Instituut Amsterdam

Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003)

Untitled [Lieshout, The Netherlands]

1954

Silver gelatin photograph

25.3 x 17.7cm

Collection Iara Brusse, Amsterdam

© Eva Besnyö / Maria Austria Instituut Amsterdam

In 1930, when Eva Besnyö arrived in Berlin at the age of only twenty, a certificate of successful apprenticeship from a recognised Budapest photographic studio in her bag, she had made two momentous decisions already: to turn photography into her profession and to put fascist Hungary behind her forever.

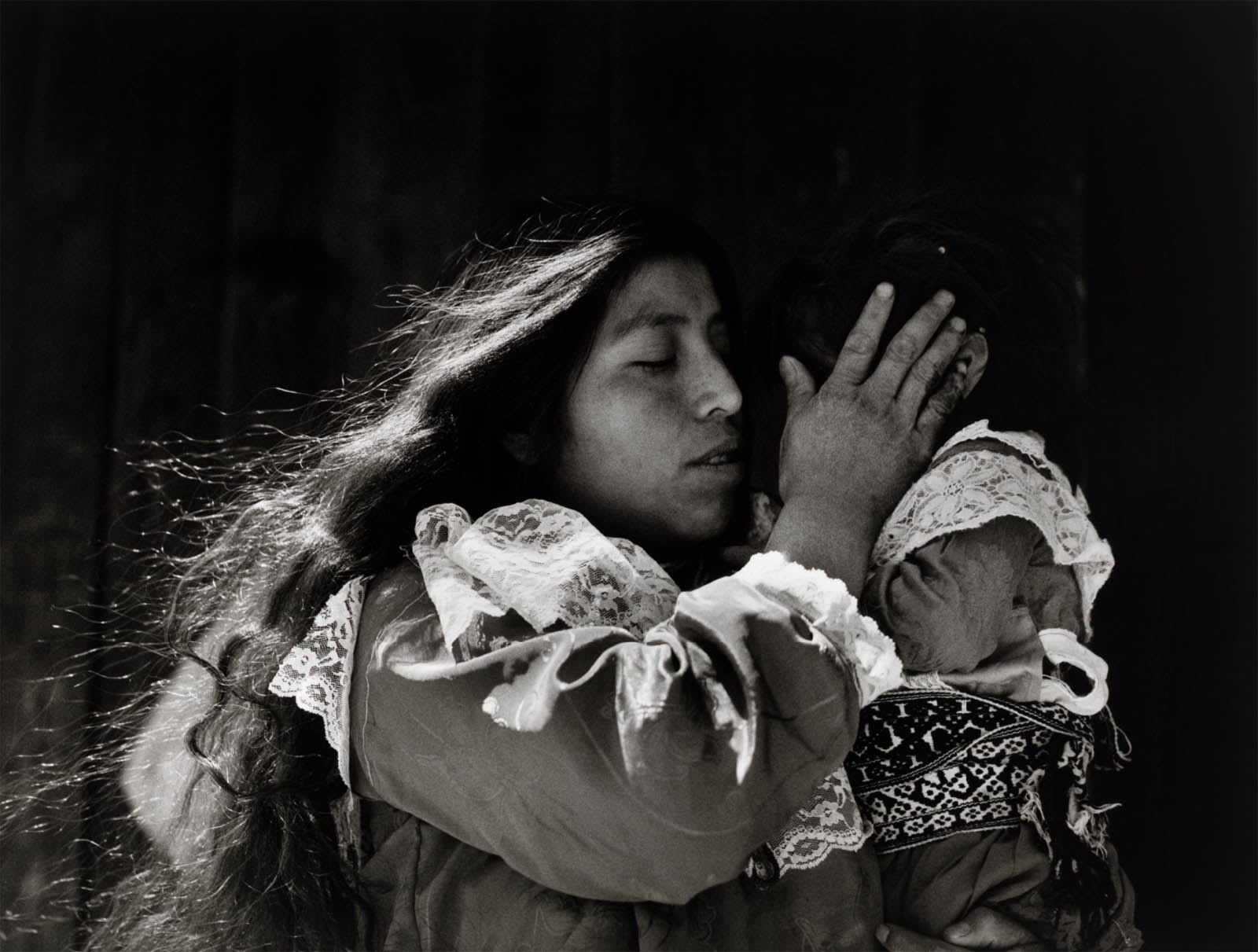

Like her Hungarian colleagues Moholy-Nagy, Kepes and Munkacsi and – a little later – Capa, Besnyö experienced Berlin as a metropolis of deeply satisfying artistic experimentation and democratic ways of life. She had found work with the press photographer Dr. Peter Weller and roamed the city with her camera during the day, searching for motifs on construction sites, by Lake Wannsee, at the zoo or in the sports stadiums, and her photographs were published – albeit, as was customary at the time, under the name of the studio. Besnyö’s best-known photo originates from those years: the gypsy boy with a cello on his back – an image of the homeless tramp that has become familiar all over the world.

Eva Besnyö had a keen political sense, evidenced by the fact that she fled in good time from anti-Semitic, National Socialist persecution, leaving Berlin for Amsterdam in autumn 1932. Supported by the circle surrounding woman painter Charley Toorop, filmmaker Joris Ivens and designer Gerrit Rietveld, Besnyö – meanwhile married to cameraman John Fernhout – soon enjoyed public recognition as a photographer. An individual exhibition in the internationally respected Van Lier art gallery in 1933 made her reputation in the Netherlands practically overnight. Besnyö experienced a further breakthrough with her architectural photography only a few years later: translating the idea of functionalist “New Building” into a “New Seeing.” In the second half of the 30s, Besnyö demonstrated an intense commitment to cultural politics, eg. at the anti-Olympiad exhibition “D-O-O-D” (De Olympiade onder Diktatuur) in 1936; in the following year, 1937, she was curator of the international exhibition “foto ’37” in the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam.

The invasion of German troops in May 1940 meant that as a Jew, Eva Besnyö was compelled to go into hiding underground. She was attracted to a world view shaped by humanism in the post-war years, and her photographs became stylistically decisive for neo-Realism and immensely suitable for the moralising exhibition, the “Family of Man” (1955). The mother of two children, she had experienced the classic female conflict between bringing up children and a profession career as a crucial and very personal test. Consequentially, Besnyö became an activist in the Dutch women’s movement “Dolle Mina” during the 70s, making a public commitment to equal rights and documenting demonstrations and street protests on camera.

This first retrospective exhibition, showing approximately 120 vintage prints, aims to introduce the public to the life and work of this emigrant and “Berliner by choice”, a convinced cosmopolitan and the “Grande Dame” of Dutch photography. “Like many other talents, that of Eva Besnyö was lost to Germany and its creative art as a direct consequence of the National Socialists’ racial mania.” (Karl Steinorth, DGPh, 1999)

Press release from the Jeu de Paume website

Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003)

Narda, Amsterdam

1937

Private collection, Berlin

40 x 50cm

© Eva Besnyö / Maria Austria Instituut Amsterdam

Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003)

Untitled

Berlin, 1931

17.4 x 17.4cm

Collection Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam

© Eva Besnyö / Maria Austria Instituut Amsterdam

Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003)

Berlin

1931

© Eva Besnyö / Maria Austria Instituut Amsterdam

Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003)

Untitled [John Fernout with Rolleiflex at the Baltic seaside]

1932

44.2 x 39.5cm

Private collection, Berlin

© Eva Besnyö / Maria Austria Instituut Amsterdam

Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003)

Untitled [Magda, Balaton, Hungary]

1932

40.5 x 30.6cm

Collection Iara Brusse, Amsterdam

© Eva Besnyö / Maria Austria Instituut Amsterdam

Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003)

Untitled [The shadow of John Fernhout, Westkapelle, Zeeland, Netherlands]

1933

25.3 x 20.4cm

Collection Iara Brusse, Amsterdam

© Eva Besnyö / Maria Austria Instituut Amsterdam

Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003)

Borgerstraat, Amsterdam

1961

Gelatin silver print

© Eva Besnyö / Maria Austria Instituut Amsterdam

Jeu de Paume

1, Place de la Concorde

75008 Paris

métro Concorde

Phone: 01 47 03 12 50

Opening hours:

Tuesday – Friday 12 – 8pm

Saturday – Sunday 11am – 7pm

Closed Monday

![Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003) 'Untitled Untitled [boy with a violoncello, Balaton, Hungary]' 1931 Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003) 'Untitled Untitled [boy with a violoncello, Balaton, Hungary]' 1931](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/eva_besnyo_gypsy_boy-web.jpg?w=655&h=644)

![Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003) 'Untitled [Shadow play]' Hungary 1931 Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003) 'Untitled [Shadow play]' Hungary 1931](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/eva_besnyo_shadow_play-web.jpg?w=650&h=651)

![Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003) 'Untitled [dockers on the Spree]' Berlin, 1931 Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003) 'Untitled [dockers on the Spree]' Berlin, 1931](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/eva_besnyo_docks-web.jpg?w=650&h=774)

![Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003) 'Untitled [Vertigo #3]' Nd Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003) 'Untitled [Vertigo #3]' Nd](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/photo_by_eva_besnyo_vertigo3-web.jpg?w=650&h=536)

![Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003) 'Untitled [Summer house in Groet, North Holland. Architects Merkelbach & Karsten]' 1934 Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003) 'Untitled [Summer house in Groet, North Holland. Architects Merkelbach & Karsten]' 1934](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/eb18-web.jpg)

![Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003) 'Untitled [Lieshout, The Netherlands]' 1954 Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003) 'Untitled [Lieshout, The Netherlands]' 1954](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/eb15-web.jpg?w=650&h=806)

![Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003) 'Untitled [John Fernout with Rolleiflex at the Baltic seaside]' 1932 Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003) 'Untitled [John Fernout with Rolleiflex at the Baltic seaside]' 1932](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/eb02-web.jpg?w=650&h=727)

![Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003) 'Untitled [Magda, Balaton, Hungary]' 1932 Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003) 'Untitled [Magda, Balaton, Hungary]' 1932](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/eb04-web.jpg?w=650&h=869)

![Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003) 'Untitled [The shadow of John Fernhout, Westkapelle, Zeeland, Netherlands]' 1933 Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003) 'Untitled [The shadow of John Fernhout, Westkapelle, Zeeland, Netherlands]' 1933](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/eb13-web.jpg?w=650&h=649)

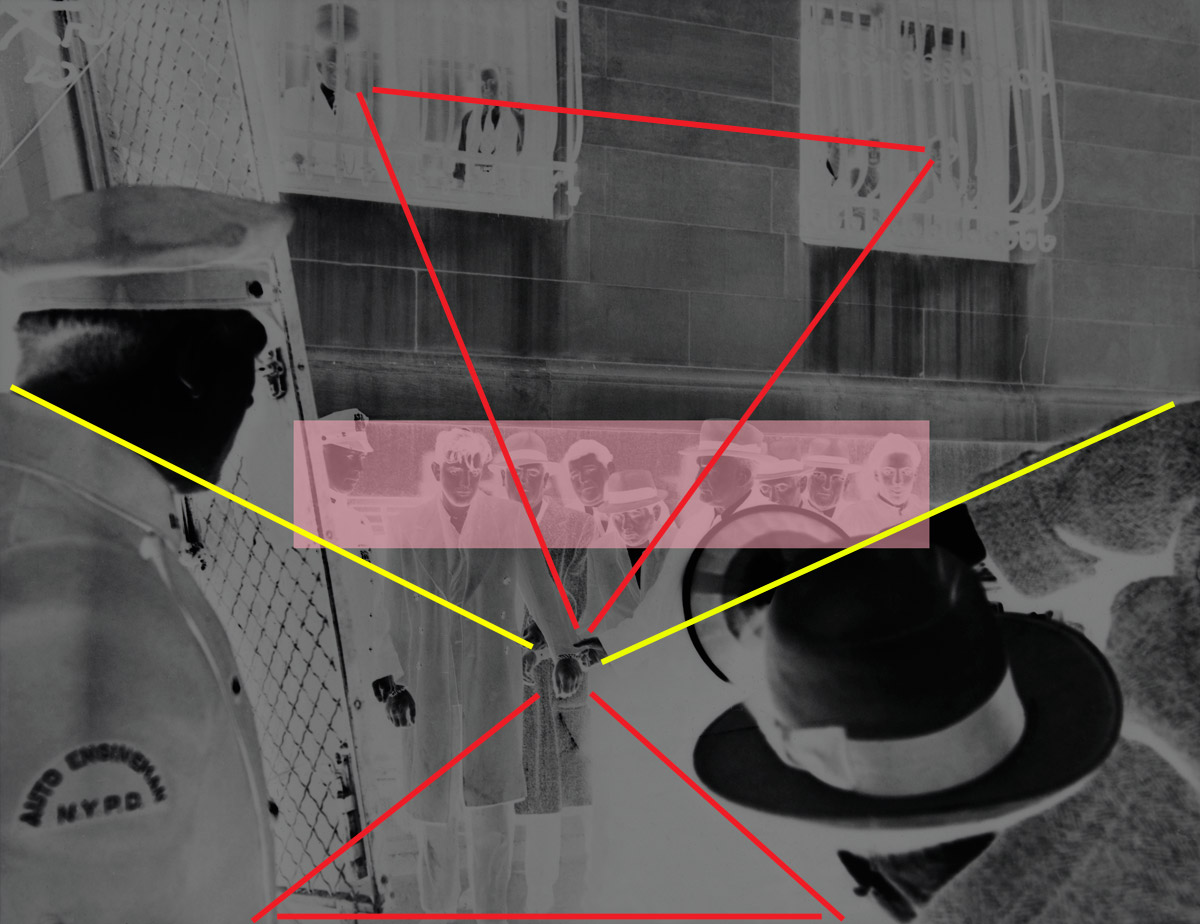

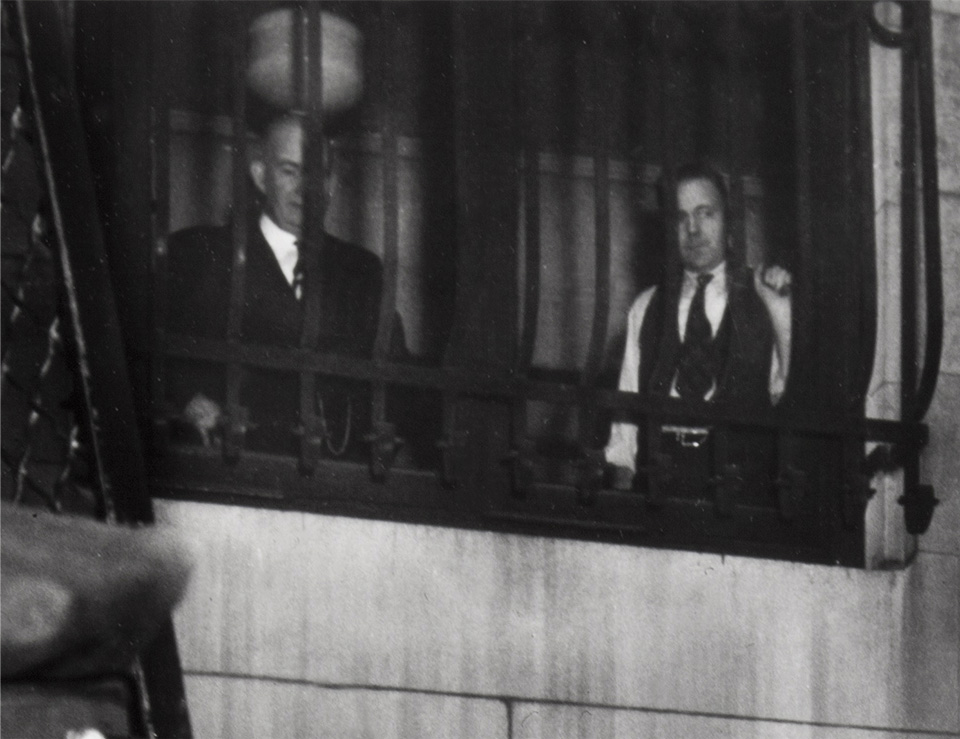

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Anthony Esposito, booked on suspicion of killing a policeman, New York]' January 16, 1941 Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Anthony Esposito, booked on suspicion of killing a policeman, New York]' January 16, 1941](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/3-weegee_anthony-esposito-web.jpg)

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Installation view of "Weegee: Murder Is My Business" at the Photo League, New York]' 1941 Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Installation view of "Weegee: Murder Is My Business" at the Photo League, New York]' 1941](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/17-weegee_19982_1993-web.jpg)

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Installation view of "Weegee: Murder Is My Business" at the Photo League, New York]' 1941 Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Installation view of "Weegee: Murder Is My Business" at the Photo League, New York]' 1941](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/6-weegee_19969_1993-web.jpg)

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Installation view of "Weegee: Murder Is My Business" at the Photo League, New York]' 1941 Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Installation view of "Weegee: Murder Is My Business" at the Photo League, New York]' 1941](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/15-weegee_19961_1993-web.jpg)

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Installation view of "Weegee: Murder Is My Business" at the Photo League, New York]' 1941 Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Installation view of "Weegee: Murder Is My Business" at the Photo League, New York]' 1941](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/16-weegee_19972_1993-web.jpg)

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled ["Ruth Snyder Murder" wax display, Eden Musée, Coney Island, New York]' c. 1941 Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled ["Ruth Snyder Murder" wax display, Eden Musée, Coney Island, New York]' c. 1941](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/5-weegee_7221_1993-web.jpg)

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Hats in a pool room, Mulberry Street, New York]' c. 1943 Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Hats in a pool room, Mulberry Street, New York]' c. 1943](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/14-weegee_15595_1993-web.jpg)

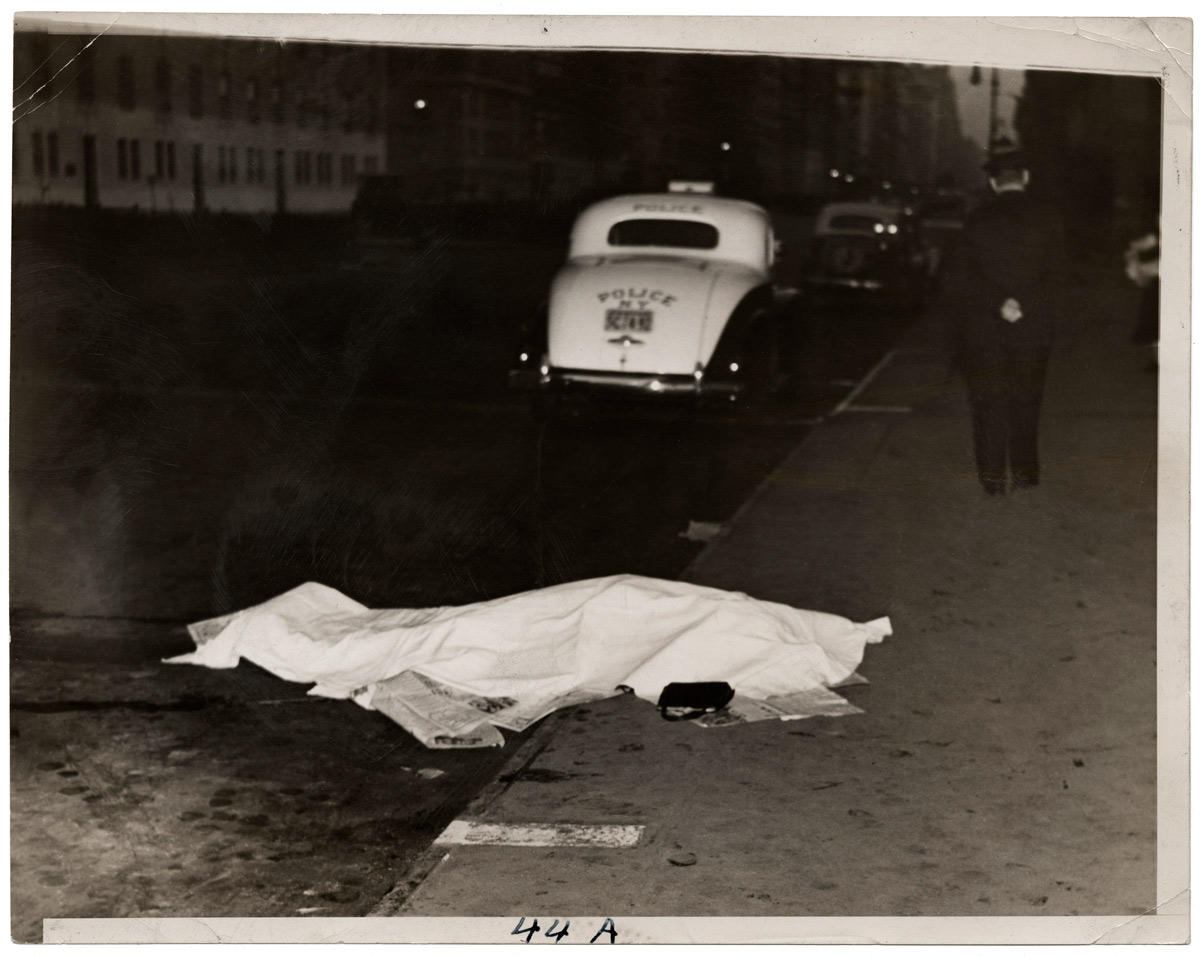

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Body of Dominick Didato, Elizabeth Street, New York]' August 7, 1936 Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Body of Dominick Didato, Elizabeth Street, New York]' August 7, 1936](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/8-weegee_2070_1993-web.jpg?w=650&h=811)

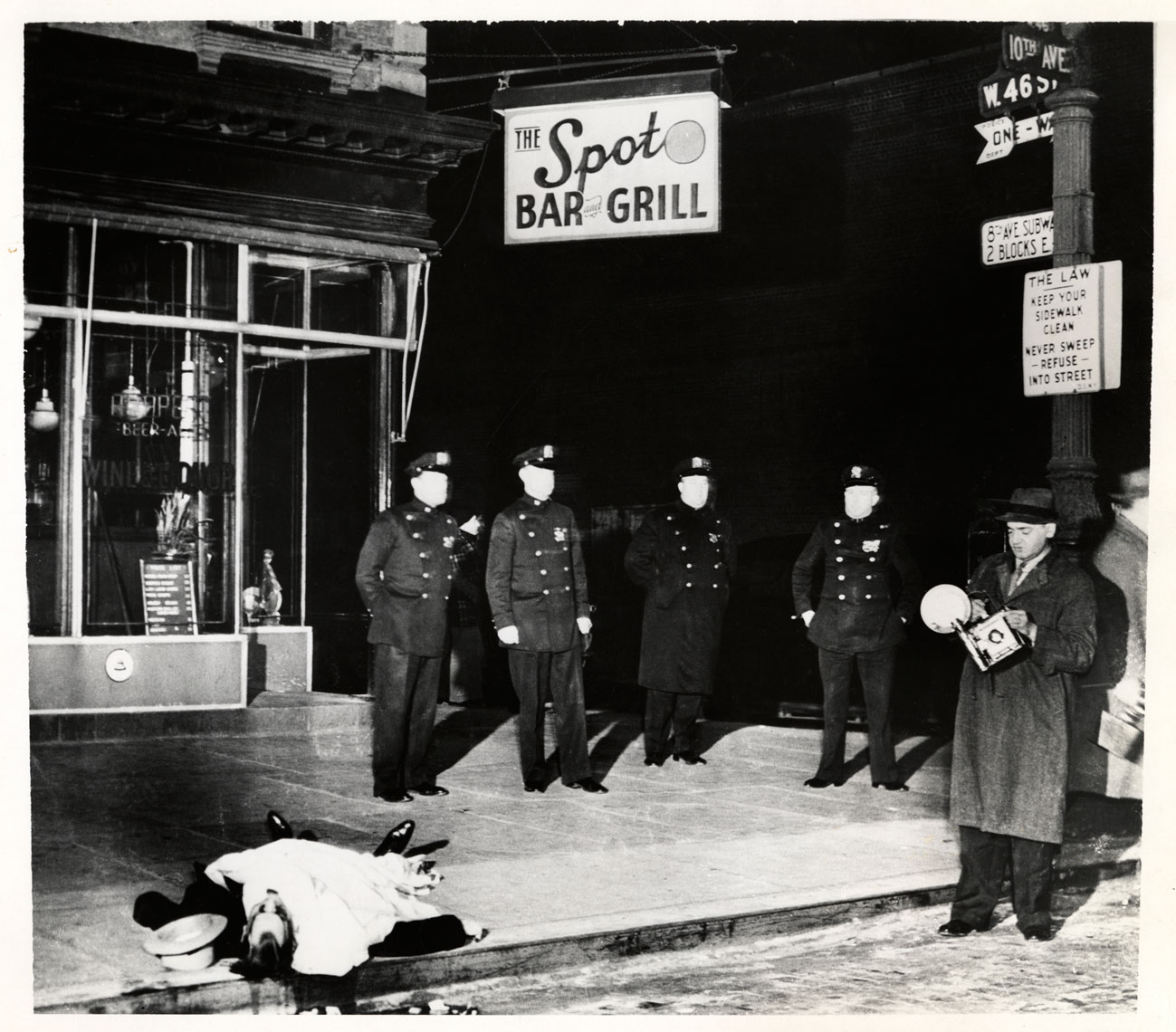

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Police officer and lodge member looking at blanket-covered body of woman trampled to death in excursion-ship stampede, New York]' August 18, 1941 Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Police officer and lodge member looking at blanket-covered body of woman trampled to death in excursion-ship stampede, New York]' August 18, 1941](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/11-weegee_1016_1993-web.jpg?w=650&h=807)

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Police officer and assistant removing body of Reception Hospital ambulance driver Morris Linker from East River, New York]' August 24, 1943 Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Police officer and assistant removing body of Reception Hospital ambulance driver Morris Linker from East River, New York]' August 24, 1943](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/9-weegee_133_1982-web.jpg?w=650&h=824)

You must be logged in to post a comment.