Exhibition dates: 20th September – 17th December 2012

Dennis Hopper (American, 1936-2010)

Guy With 5 Hogs

1961-1967

Location: USA

6.97 x 9.85 inch

© The Dennis Hopper Trust, Courtesy of The Dennis Hopper Trust

Unlike an earlier posting of photographs by a well known film director (the underwhelming, in fact pretty awful, Wim Wenders: Places, Strange and Quiet), these “lost” photographs by Dennis Hopper are very good. I love their quiet, intimate strength, their fun, wit and vivacity; and the portraits capture the essence of the sitter with a decisive elegance and eloquence.

The photographs perfectly capture the social milieu of the time and the pervading ethos of the fracturing of the image plane, a la Gary Winogrand or Lee Friedlander. Nice to see the work full frame as well, meaning that the photographers’ previsualisation was strong in camera; that Hopper had an excellent understanding of the construction of the pictorial frame negating the necessity for cropping of the image.

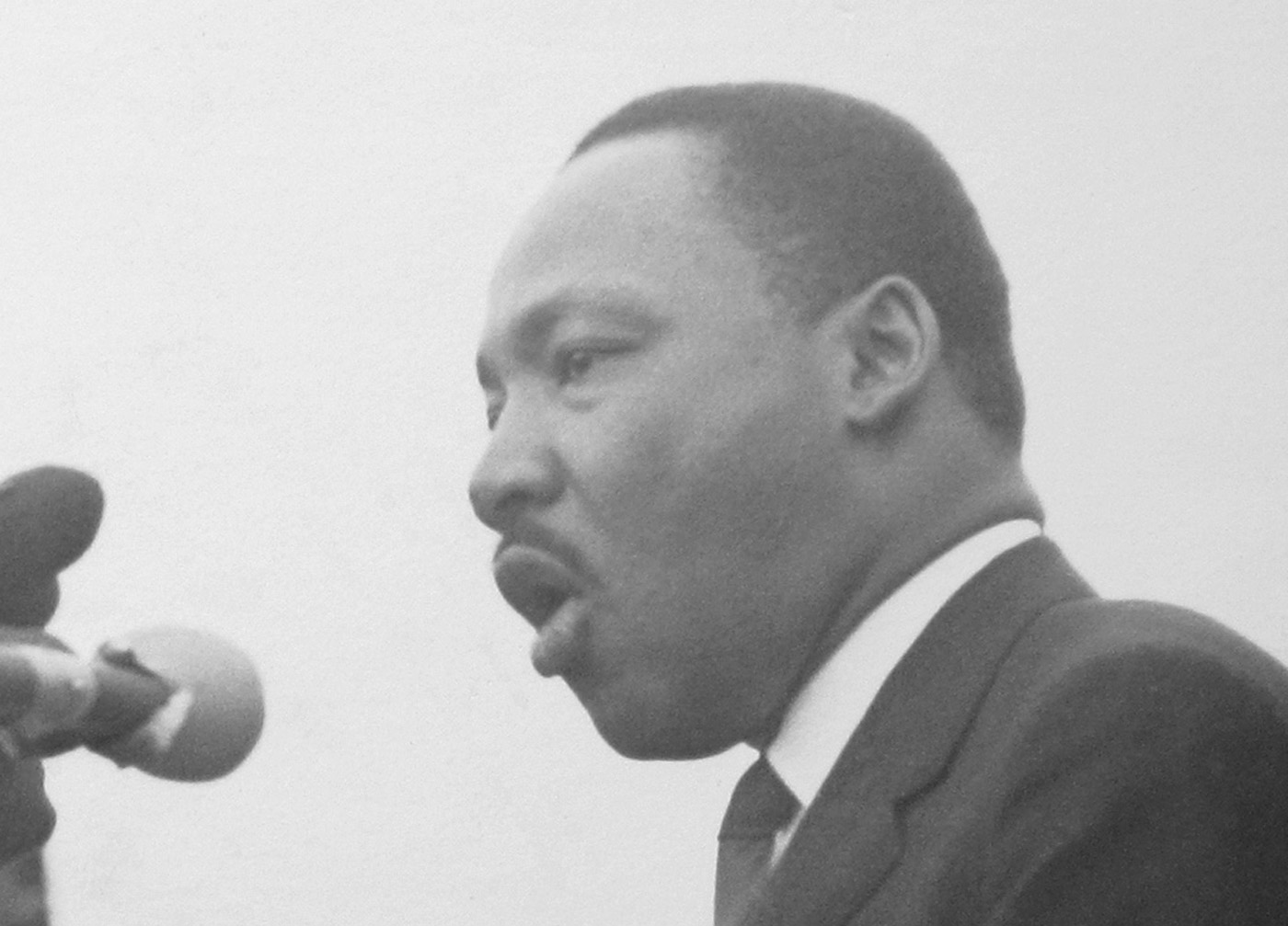

Enlarging the face of Martin Luther King Jr., (below) and then looking into his eyes, I felt I had a connection with this person. Nostalgia, longing, sadness and joy at his life and the feeling that I was looking into the eyes of one of the great human beings of the twentieth century.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to Martin-Gropius-Bau for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“I never made a cent from these photos. They cost me money but kept me alive. These are my photos. I started at eighteen taking pictures. I stopped at thirty-one. (…) These represent the years from twenty-five to thirty-one, 1961 to 1967. I didn’t crop my photos. They are full frame natural light Tri-X. I went under contract to Warner Brothers at eighteen. I directed Easy Rider at thirty-one. I married Brooke at twenty-five and got a good camera and could afford to take pictures and print them. They were the only creative outlet I had for these years until Easy Rider. I never carried a camera again.”

Dennis Hopper 1986

“The necessity to make these photos and paintings came from a real place – a place of desperation and solitude – with the hope that someday these objects, paintings, and photos would be seen filling the void I was feeling.”

Dennis Hopper 2001

Dennis Hopper (American, 1936-2010)

Double Standard

1961

Location: Los Angeles, Ca USA

6.87 x 9.79 inch

© The Dennis Hopper Trust, Courtesy of The Dennis Hopper Trust

Dennis Hopper (American, 1936-2010)

Andy Warhol, Henry Geldzahler, David Hockney, and Jeff Goodman

1963

Location: USA

17.25 x 24.74cm

© The Dennis Hopper Trust, Courtesy of The Dennis Hopper Trust

Dennis Hopper The Lost Album – Vintage Prints From the Sixties book. Prestel, 2012, p. 78

Dennis Hopper (American, 1936-2010)

James Rosenquist

1964

Location: Billboard Factory, Los Angeles, Ca USA

6.81 x 9.68 inch

© The Dennis Hopper Trust, Courtesy of The Dennis Hopper Trust

Dennis Hopper (American, 1936-2010)

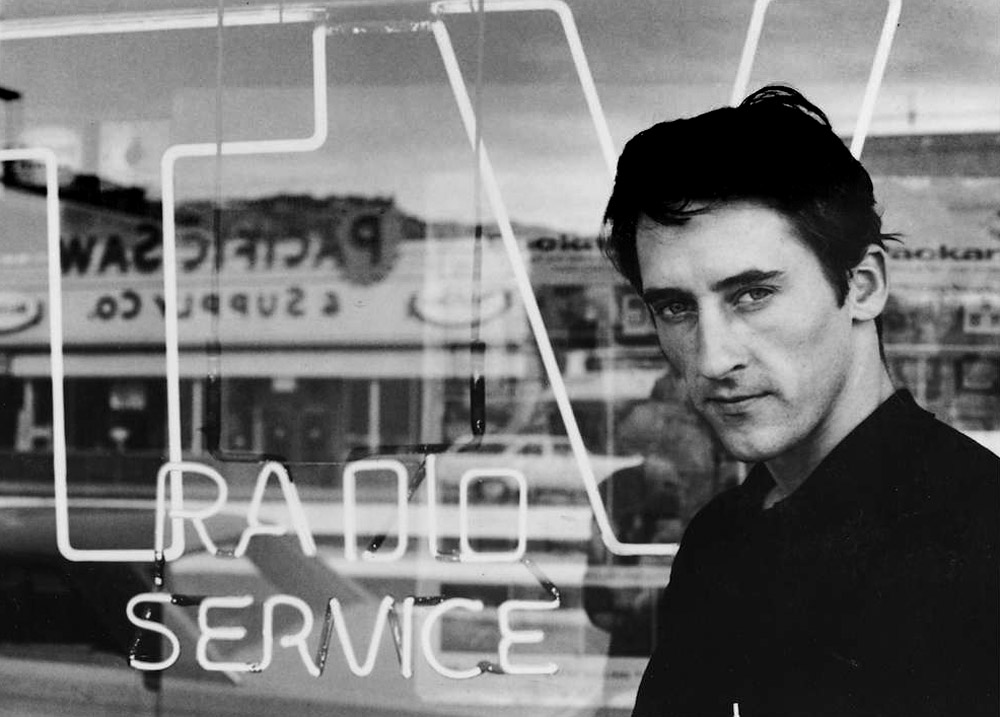

Artist Ed Ruscha

1964

© The Dennis Hopper Trust, Courtesy of The Dennis Hopper Trust

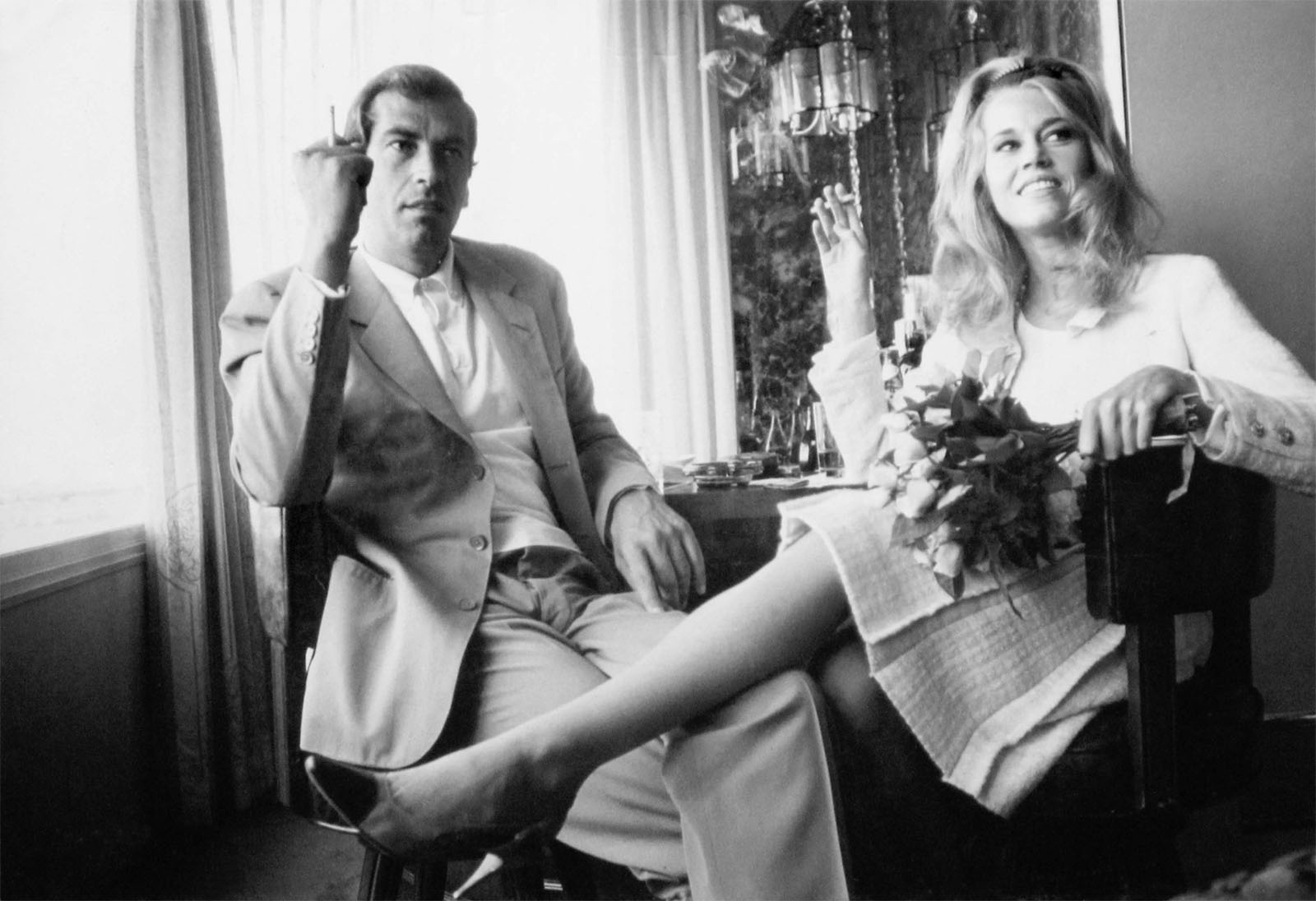

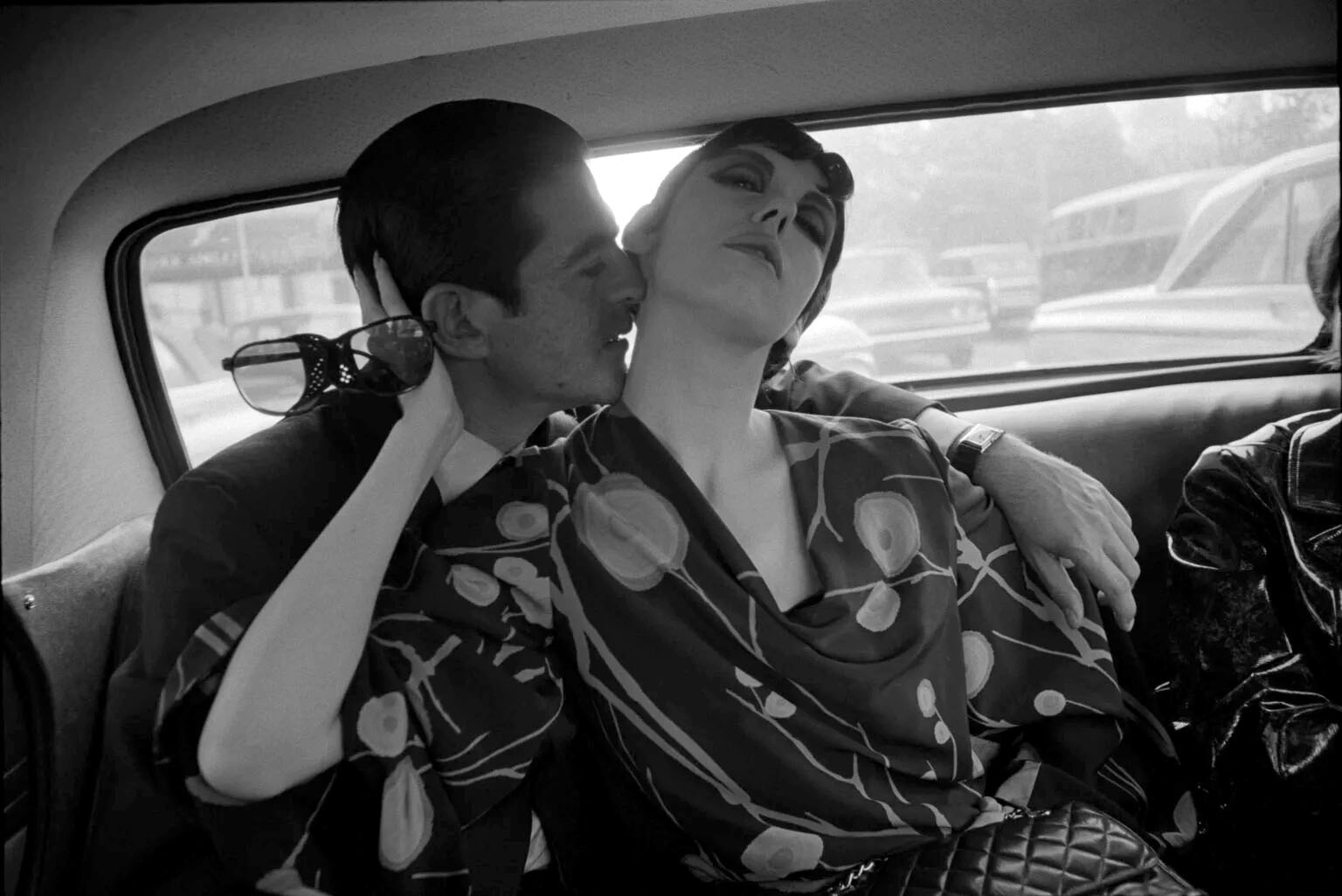

Dennis Hopper (American, 1936-2010)

Roger Vadim and Jane Fonda at their wedding, Las Vegas

1965

Location: Las Vegas, USA

© The Dennis Hopper Trust, Courtesy of The Dennis Hopper Trust

Dennis Hopper (American, 1936-2010)

Tuesday Weld

1965

© The Dennis Hopper Trust, Courtesy of The Dennis Hopper Trust

Dennis Hopper (American, 1936-2010)

Jane Fonda (with bow & arrow), Malibu

1965

© The Dennis Hopper Trust, Courtesy of The Dennis Hopper Trust

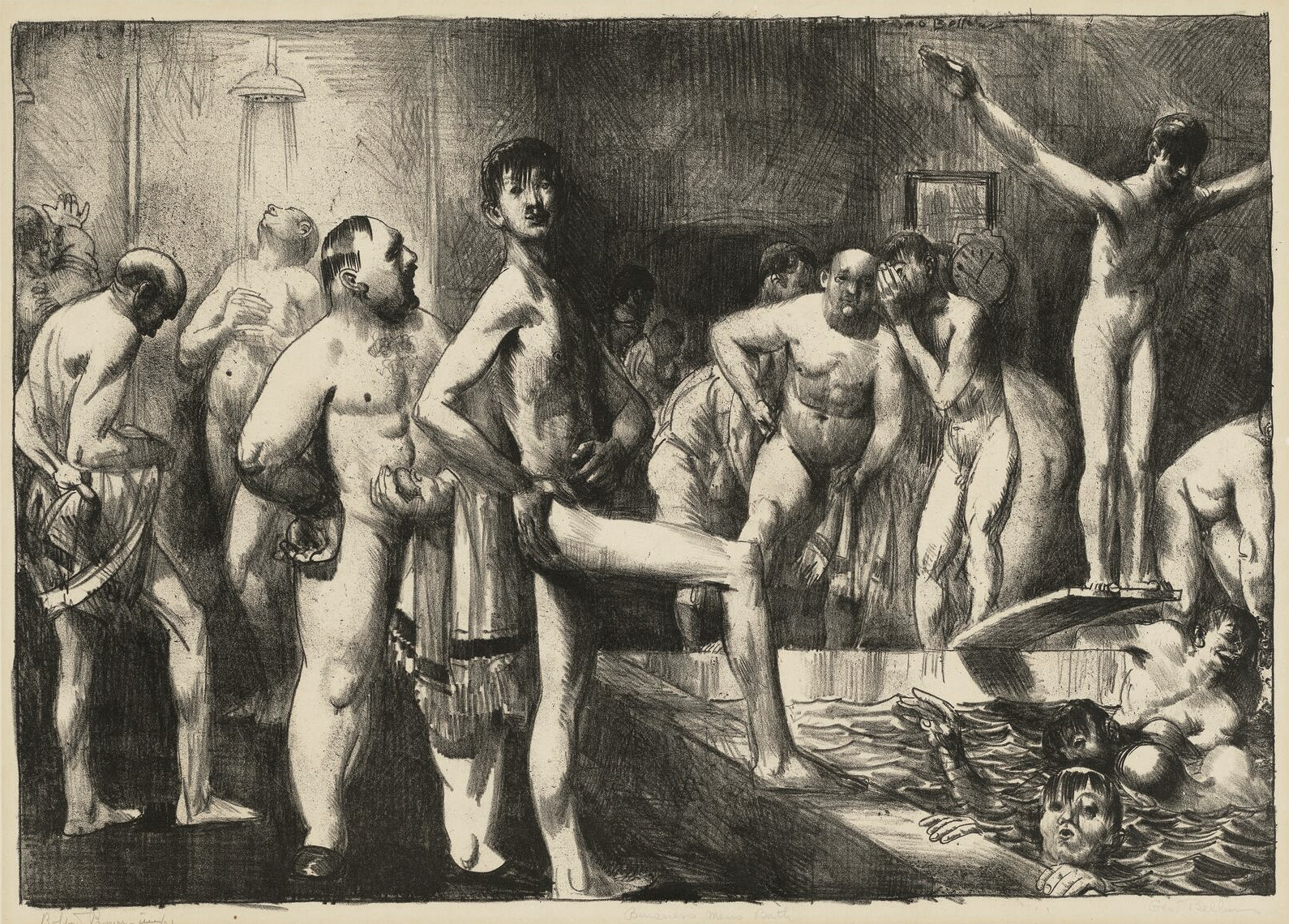

Dennis Hopper (American, 1936-2010)

Bruce Conner (in tub), Toni Basil, Teri Garr, and Ann Marshall

1965

© The Dennis Hopper Trust, Courtesy of The Dennis Hopper Trust

Dennis Hopper (American, 1936-2010)

Untitled (Blue Chips Stamps)

1961-1967

© The Dennis Hopper Trust, Courtesy of The Dennis Hopper Trust

Dennis Hopper The Lost Album – Vintage Prints From the Sixties book. Prestel, 2012, p. 154

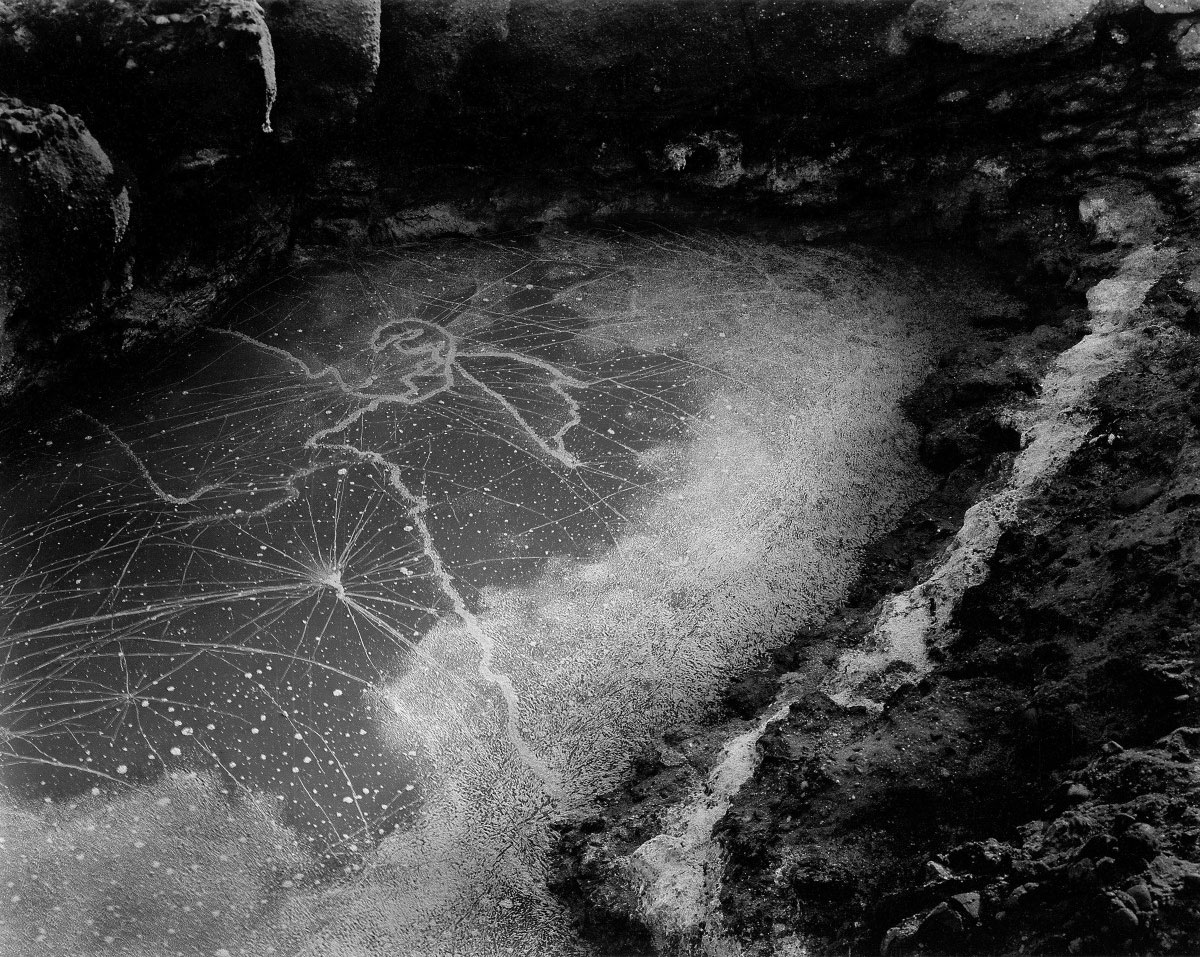

Dennis Hopper (American, 1936-2010)

Untitled (Hippie Girl Dancing)

1967

© The Dennis Hopper Trust, Courtesy of The Dennis Hopper Trust

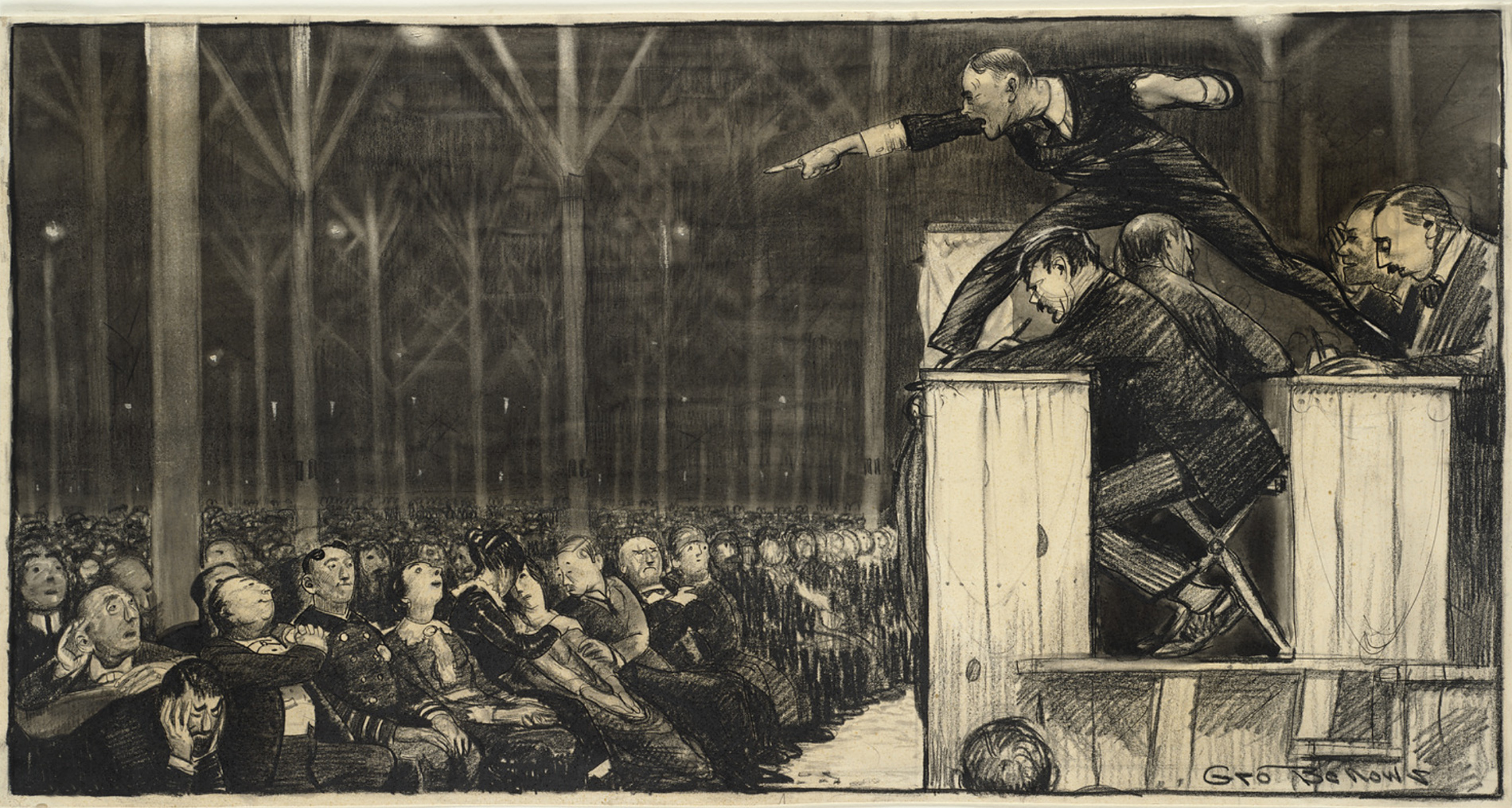

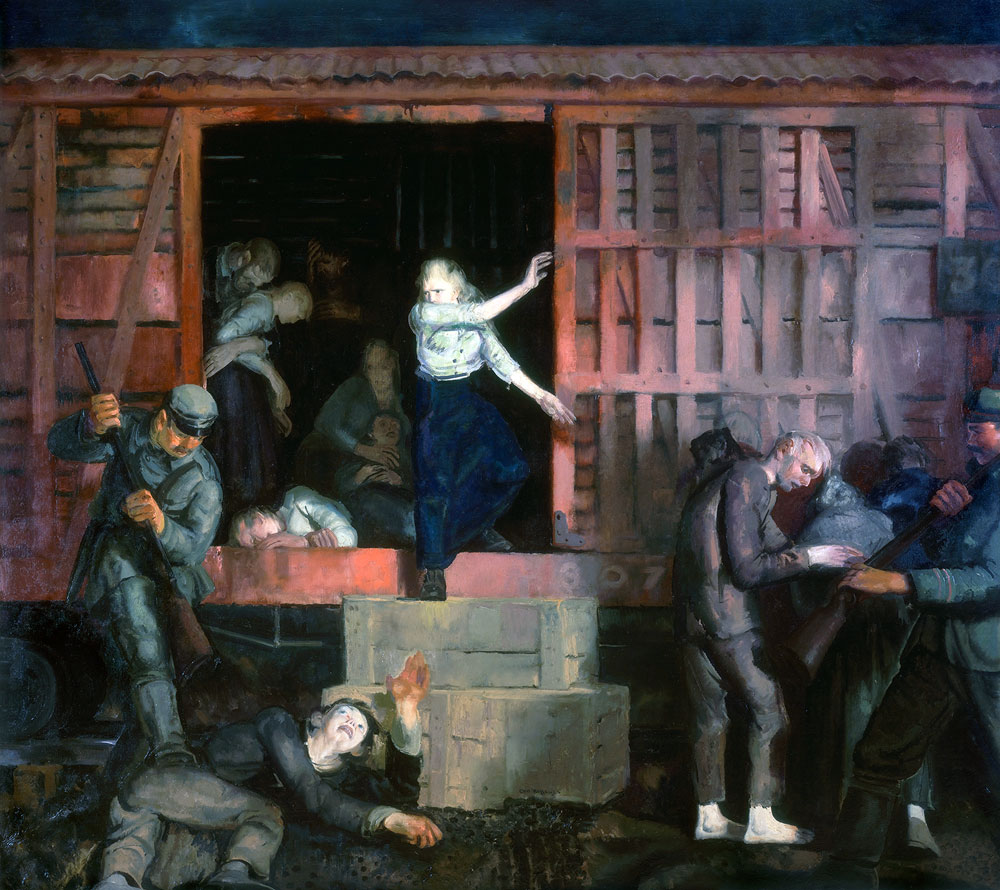

The exhibition shows a spectacular portfolio of over four hundred vintage photographs taken by Dennis Hopper in the 1960s. Tucked away in five crates and forgotten, they were discovered after his death. There can be no doubt that these works are those personally selected by Hopper from the wealth of shots he took between 1961 and 1967 for the first major exhibition of his photography. The pictures themselves document how the works were installed in the Fort Worth Art Center Museum, Texas, in 1970 by himself and Henry T. Hopkins, the museum’s director at the time. None of these works have been displayed in Europe before. The portfolio that has now come to light is a treasure. It consists of small plates, sometimes numbered on the back with brief notes in Hopper’s hand and showing traces of wear. Mounted on cardboard, without frame of glass, they were attached directly to the wall.

The images have a legendary quality. Spontaneous, intimate, poetic, unabashedly political and keenly observed, they document an exciting epoch, its protagonists and milieus. These photographs reflect the atmosphere of an era, being outstanding testimonials to America’s dynamic cultural scene in the 1960s. On the viewer they exercise an irresistible attraction, bearing him away on a journey into the past, often into his own history.

Many of these pictures are icons, such as the portraits of Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, Paul Newman and Jane Fonda. They also cover a wide range of subjects. Dennis Hopper is interested in everything. Wherever he happens to be, whether in Los Angeles, New York, London, Mexico or Peru, he takes in his surroundings with empathy, enthusiasm and intense curiosity. He seeks and savours the “essential moment”, capturing the celebrities and types of his time with the camera: actors, artists, musicians, his family, bikers and hippies. He leaves an impressive photographic record of the “street life” of Harlem, of cemeteries in Mexico, and of bullfights in Tijuana. Hopper accompanies Martin Luther King Jr. on the march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, and, in images of great beauty and serenity, he converts the every day life and the neglected into a picture of beauty and silence as if converting Abstract Expressionism from the language of painting into that of photography.

Between 1961 and 1967 Hopper applied himself intensely on photography.

Hopper’s photographs are legendary images, spontaneous, intimate, and poetic as well as decidedly political and keenly observant – documents of an exciting period, its protagonists and milieus. Many of these photos have become iconic: the portraits of Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, Paul Newman or Jane Fonda. They also cover a range of topics and motifs. Hopper was interested in everything. Wherever he was, in Los Angeles, New York, London, Mexico or Peru, he was a precise observer, full of empathy and curiosity. He captured the geniuses of his day, the actors, artists, musicians and poets, his family and friends, the “scene”, bikers and hippies. He wandered the streets of Harlem and the graveyards of Durango and watched the bullfights in Tijuana with fascination. Hopper followed Martin Luther King Jr. with his camera on the march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama. And he paid attention to things small, ordinary, and neglected, transforming the “remains of our world” into images of great beauty and tranquility, as if converting Abstract Expressionist painting into the language of photography.

Press release from the Martin-Gropius-Bau website

Dennis Hopper (American, 1936-2010)

Beverly Renee on Bed

1961

© The Dennis Hopper Trust, Courtesy of The Dennis Hopper Trust

Dennis Hopper The Lost Album – Vintage Prints From the Sixties book. Prestel, 2012, p. 62

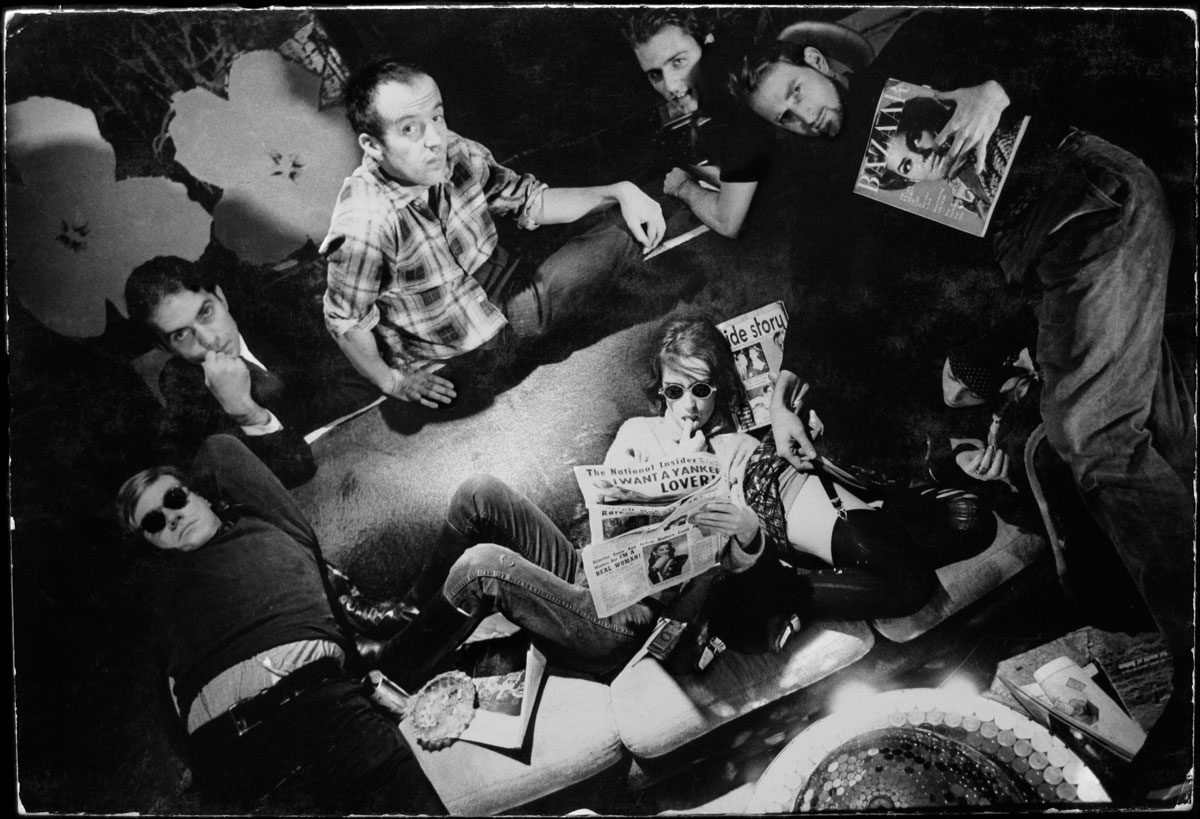

Dennis Hopper (American, 1936-2010)

Andy Warhol and Members of The Factory (Gregory Markopoulos, Taylor Mead, Gerard Malanga, Jack Smith)

1963

Location: in The Factory, NYC, NY USA

6.57 x 9.87 inch

© The Dennis Hopper Trust, Courtesy of The Dennis Hopper Trust

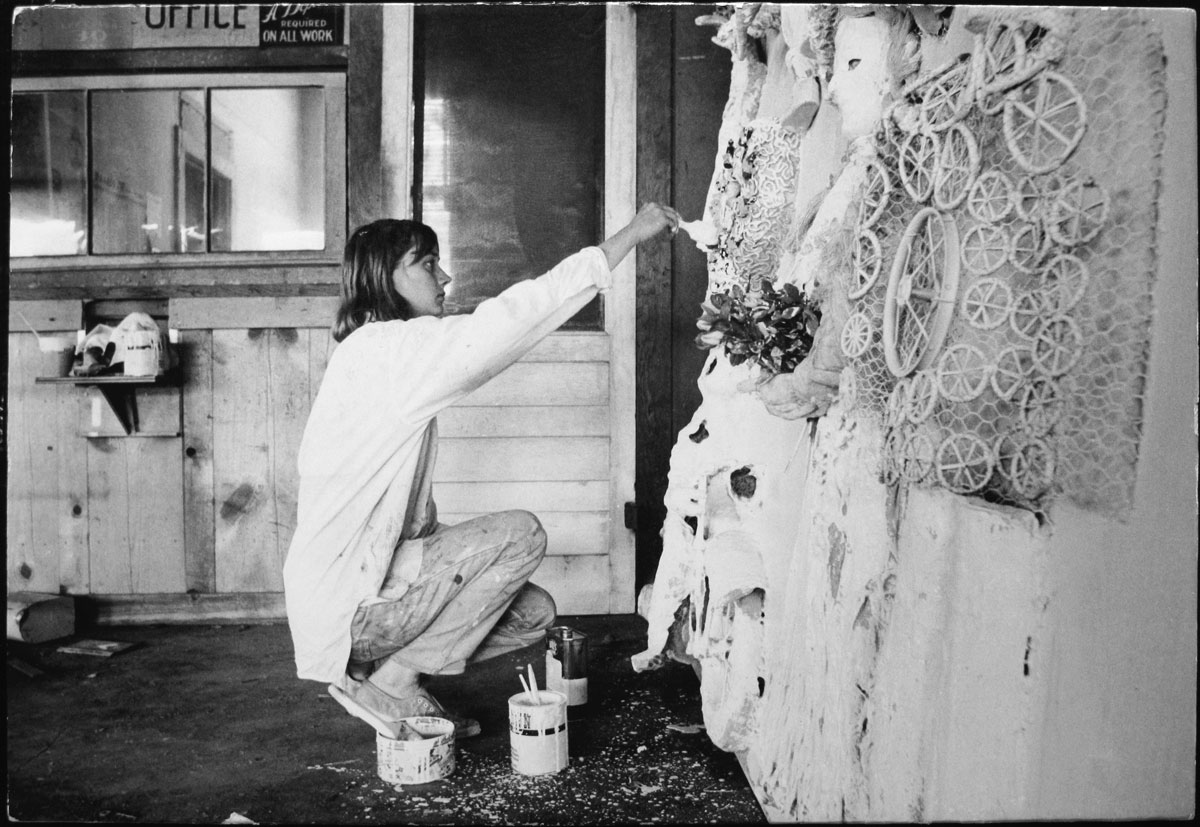

Dennis Hopper (American, 1936-2010)

Niki de Saint Phalle (kneeling)

1963

Location: USA

6.66 x 9.83 inch

© The Dennis Hopper Trust, Courtesy of The Dennis Hopper Trust

Dennis Hopper (American, 1936-2010)

Art dealer Irving Blum with model Peggy Moffitt

1964

© The Dennis Hopper Trust, Courtesy of The Dennis Hopper Trust

The Lost Album

Gelatine silver vintage prints, 1970

Collection of the Dennis Hopper Art Trust

More than four hundred photos came to light after Hopper’s death. He had selected them for his first photography exhibition in 1970 at the Fort Worth Art Center Museum. They show signs of wear: fingerprints, scratches, discolouration, a frayed corner or tiny dent. Mounted on cardboard, numbered on the back with notes in Hopper’s handwriting, they were hung directly on the wall from small wooden strips without frames or glass. The hanging in the Martin-Gropius-Bau is based on the original installation of 1970.

The vintage prints, in portrait and landscape format, are all of a similar size, c. 24 x 16cm; twenty of them are in a larger format (c. 33 x 23cm). Of the 429 Hopper chose for his first exhibition, eleven are believed lost; they are replaced here by new prints, which will be clearly indicated. In only two cases was it impossible to locate the corresponding negative, and a placeholder with the title is mounted instead. The rediscovered boxes contained an additional nineteen, unnumbered vintage prints along with the 429, which Hopper took with him to Fort Worth but probably never hung in the exhibition. They have been incorporated into the “Album” here (I-XIX).

Additional information on the photographs

1. Brooke Hayward, Marin Hopper

Brooke Hayward, born and raised in Los Angeles, was at home in the glamorous world of Hollywood through her parents, the film producer Leland Hayward and Hollywood star Margaret Sullavan, and Hopper in turn knew a lot of extraordinary people through his involvement in the acting and art worlds. Hopper and Hayward’s home became the center of an illustrious group of actors, artists, musicians, writers, and film producers. Soon after moving [into their house] they threw a “movie star party” for Andy Warhol to celebrate his second exhibition at the Ferus Gallery (1963).

“Since I was a small child, growing up in L.A., I remember that my dad was always capturing the scene around him through the lens of his camera. What he always described as taking the most pleasure in exploring, or focusing on, much like Marcel Duchamp signing the Hotel-Green-Sign for him on the night of his opening at the Pasadena Art Museum in 1963, and Rauschenberg’s practice, was the philosophy that an artist can point to something and claim it’s art because in that moment it is to them.” (Marin Hopper, 2012)

2. Los Angeles Art Scene

Walter Hopps and Edward Kienholz founded the Ferus Gallery at 736A North La Cienega Boulevard in March 1957. Ferus was very underground, like a crazy club with exhibitions, readings and fashion shows. “The openings were wild, everybody had a blast, and nobody made a penny.” Hopper attended every opening and went to performances and happenings, whether it was Oldenburg’s Los Angeles performance Autobodys in 1963, Robert Rauschenberg’s performance Pelican at the Culver City Ice Rink in 1966, or Allan Kaprow’s Fluids in 1967, when with the help of friends he stacked blocks of ice to form enclosures at different sites in Los Angeles.

In 1966, Claes Oldenburg made a piece of plaster wedding cake (which he stamped on the back) for each guest at the wedding party for Jim Elliot, curator at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Rauschenberg was wearing this stamp on his tongue when Hopper photographed him at the wedding.

3. New York

Hopper frequently traveled to New York, strolling through the Museum of Modern Art and the galleries, sometimes in the company of Henry Geldzahler, curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and visited Warhol, at whose Factory he encountered Gerard Malanga, Taylor Mead or David Hockney. Hopper met Robert Rauschenberg in New York and visited Roy Lichtenstein in his studio.

In London, where he exhibited his assemblages at the Robert Fraser Gallery in 1964, he made the acquaintance of Peter Blake, one of the key figures of British Pop Art, David Hemmings, the star of Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow up (1966), and Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones.

4. Civil Rights Marches

The Selma to Montgomery March: “[Marlon] Brando got me involved [in the march] … He pulled up in his car and said, ‘What are you doing day after tomorrow?’ and I said ‘Nothing’, and he said, ‘You want to go to Selma?’ And I said, ‘Sure, man. Thanks for asking me!’ [Then at the march, police] dogs were biting, and people were being bombed, and it was like, ‘Where are we?'” (Dennis Hopper)

The third march from Selma to Montgomery, the capital of Alabama, began on March 21, 1965, extended for 54 miles, took five days, and involved 4,000 marchers led by Martin Luther King Jr. and allies such as Ralph David Abernathy, Sr. It was the highpoint of the American Civil Rights Movements. Hundreds of ministers, priests, nuns, and rabbis followed King’s call to Selma. “It was like a holy crusade …” Numerous photographers, such as Spider Martin, James Karales, Steve Shapiro, and Bruce Davidson, documented the largest ever gathering of people during the civil rights movement in the South.

5. Mexico

He was completely obsessed with bullfighting and began attending fights regularly at the Tijuana arena in the 1950s. Hopper went to Mexico as an actor in 1965 when Henry Hathaway surprisingly offered him a role in his film The Sons of Katie Elder (1965).

A Western town was erected in the middle of Durango. Of course, Hopper had his camera with him. He photographed John Wayne and Dean Martin on the set and natives who were part of the crew or who just stopped by to watch, but he also roamed the area and the streets of Durango and Mexico City. In the 1920s and 1930s Mexico had held a great fascination for European as well as American avant-garde painters, photographers, and writers. Edward Weston lived in Mexico City; Henri Cartier-Bresson went there for a year in 1934, befriending the young photographer Manuel Álvarez Bravo. Their images have shaped our perception of that country, a perception that is also echoed by some of Hopper’s photographs.

Wall texts from the exhibition

Dennis Hopper (American, 1936-2010)

Paul Newman

1964

Location: Malibu, Ca USA

9.7 x 6.66 inches

© The Dennis Hopper Trust, Courtesy of The Dennis Hopper Trust

Dennis Hopper (American, 1936-2010)

Ike and Tina Turner

1965

© The Dennis Hopper Trust, Courtesy of The Dennis Hopper Trust

Dennis Hopper (American, 1936-2010)

Martin Luther King, Jr.

1965

Location: Montgomery, Alabama, USA

9.2 x 13.6 inch

© The Dennis Hopper Trust, Courtesy of The Dennis Hopper Trust

Dennis Hopper (American, 1936-2010)

Martin Luther King, Jr. (detail)

1965

Location: Montgomery, Alabama, USA

9.2 x 13.6 inch

© The Dennis Hopper Trust, Courtesy of The Dennis Hopper Trust

Dennis Hopper (American, 1936-2010)

James Brown

1966

Location: USA

9.7 x 6.77 inch

© The Dennis Hopper Trust, Courtesy of The Dennis Hopper Trust

Dennis Hopper (American, 1936-2010)

Self-portrait at porn stand

1962

© The Dennis Hopper Trust, Courtesy of The Dennis Hopper Trust

Dennis Hopper The Lost Album – Vintage Prints From the Sixties book cover

Lying hidden away in Dennis Hopper’s home until their discovery months after the artist’s death in 2010, this collection of spectacular photographs, exhibited only once in 1969-70 at the Fort Worth Art Center Museum, is a testament to Hopper’s prolific and enormous talent behind the camera. These photographs are spontaneous, intimate, poetic, observant, and decidedly political. While some are portraits of figures within Hopper’s circle of actor, artist, musician, and poet friends – including Jane Fonda, Paul Newman, and Robert Rauschenberg – they also include images from his extensive travels in Los Angeles, New York, London, Mexico, and Peru. Hopper’s abiding support of the Civil Rights movement and social justice is evident in his shots from the march on Selma and Harlem street scenes. In images of beauty and stillness he transfers Abstract Expressionism into the artistic language of photography. Throughout this stunning volume Hopper’s sensitive, keenly observant eye shines through, making it clear that he was a deeply committed chronicler of the events that were unfolding around him.

Author: Petra Giloy-Hirtz

Prestel

240 pages

25 x 2.5 x 30cm

25 September 2012

Purchase on the Amazon website

Martin-Gropius-Bau Berlin

Niederkirchnerstraße 7

Corner Stresemannstr. 110

10963 Berlin

Phone: +49 (0)30 254 86-0

Opening hours:

Wednesday – Monday 10 – 19

Tuesday closed

![Harry Callahan (American, 1912-1999) '[Detroit]' 1941 Harry Callahan (American, 1912-1999) '[Detroit]' 1941](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/harry-callahan-detroit.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.