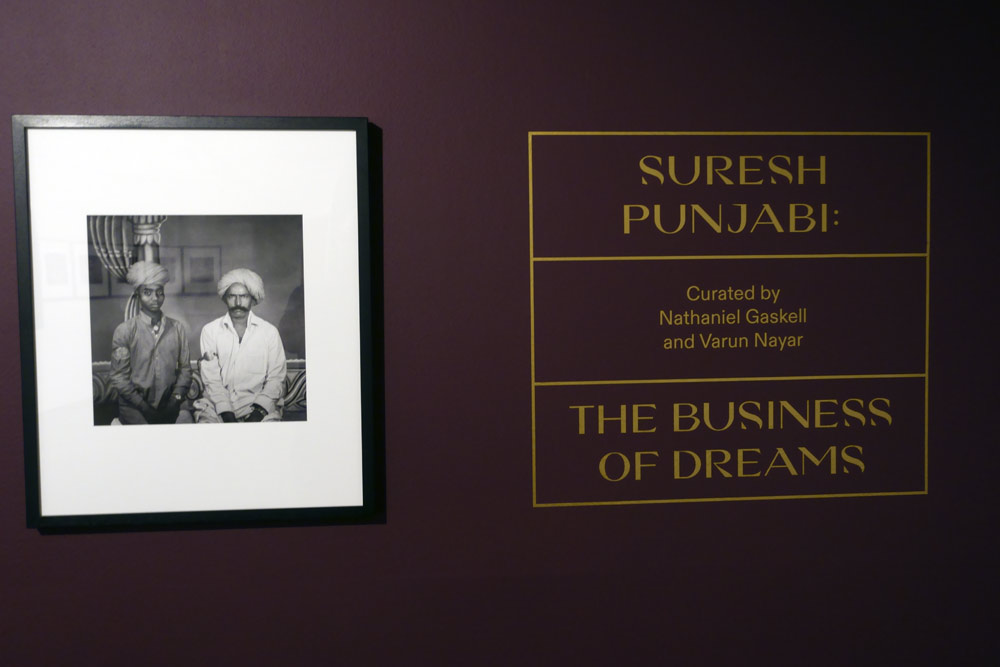

Exhibition dates: 6th November, 2021 – 6th November, 2022

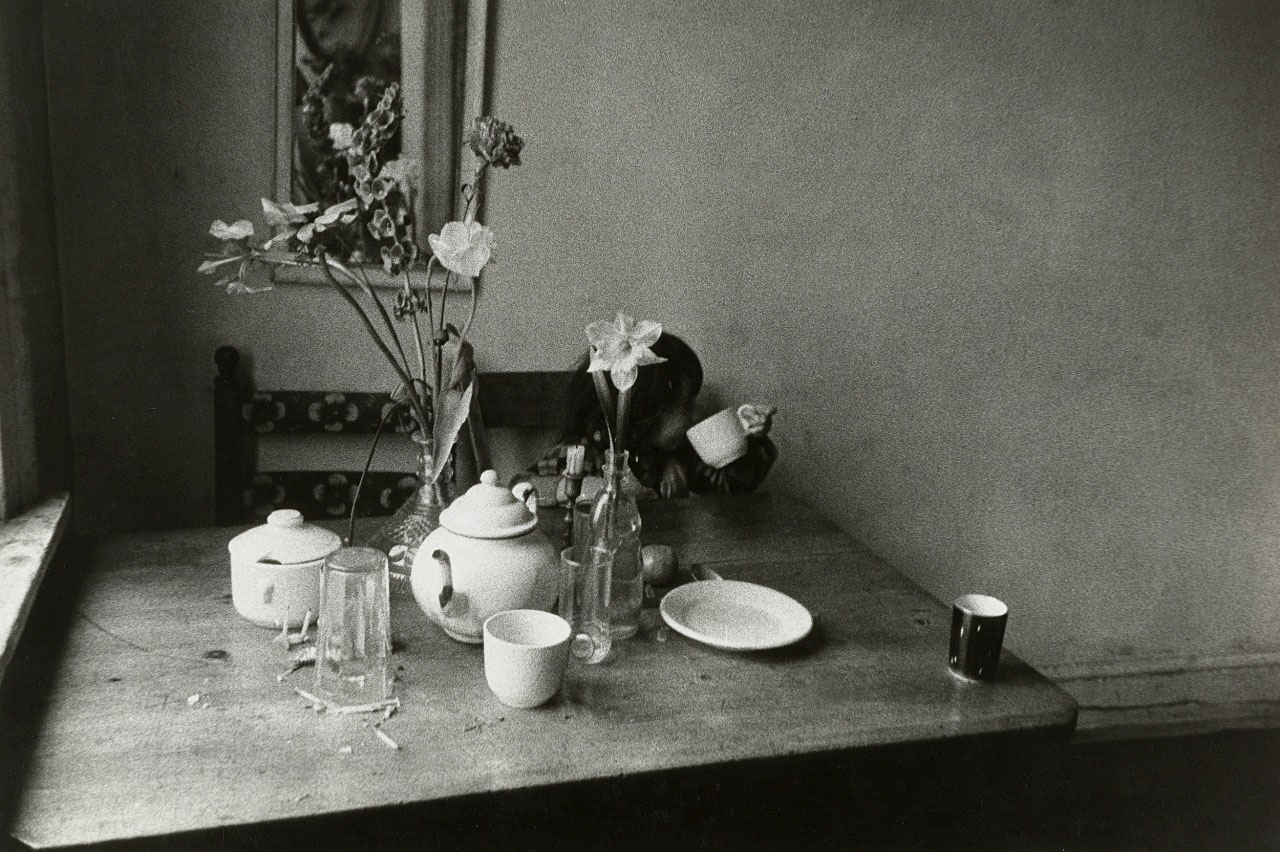

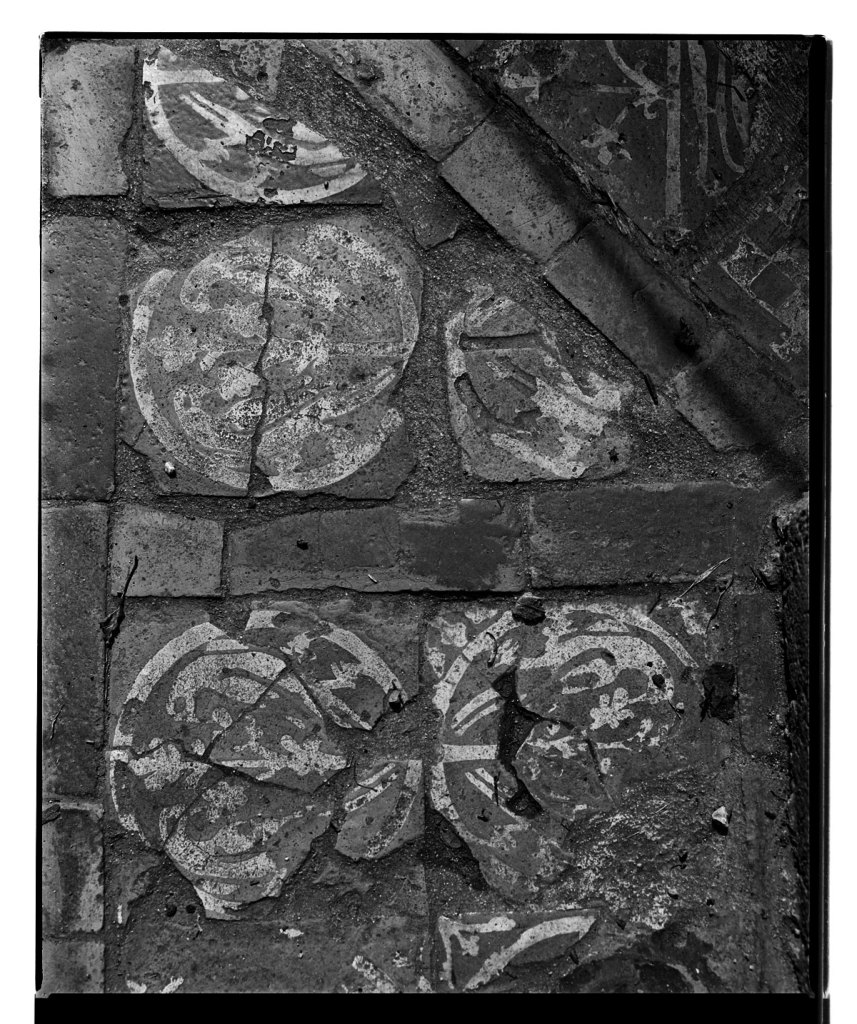

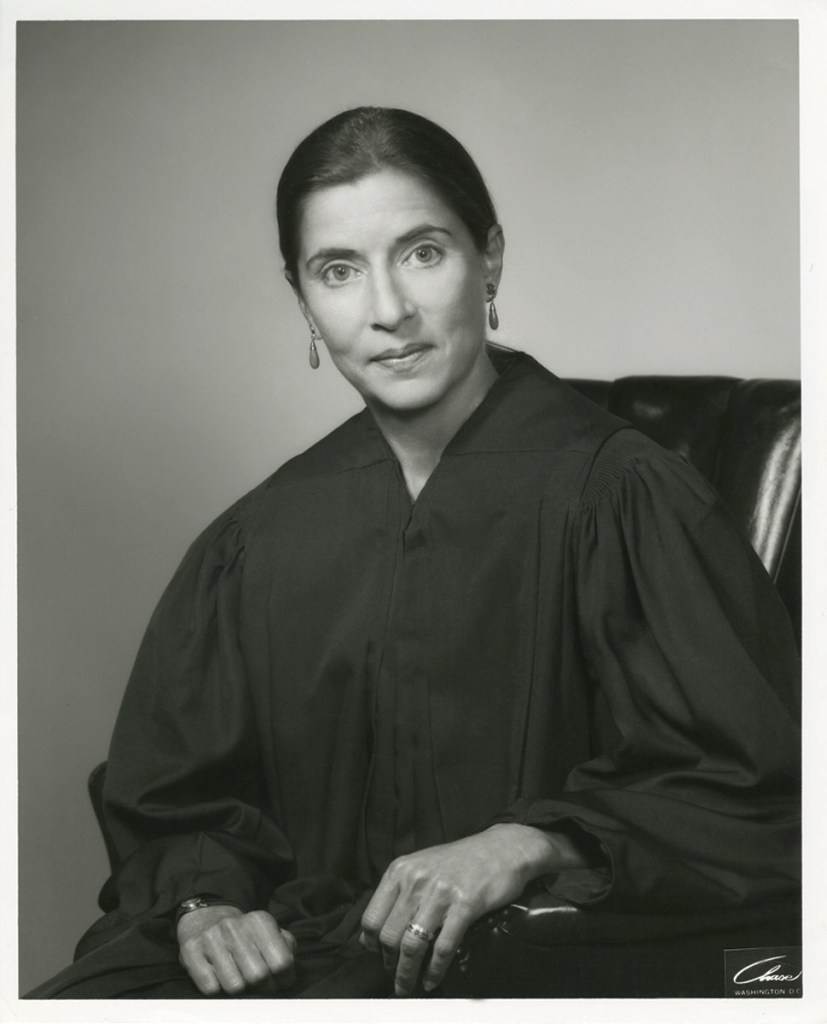

Tereza Zelenková (Czech, b. 1985)

Georges Bataille’s Grave, Vèzelay

2013

Gelatin silver print

Image: 23 x 29cm

Purchase funded by the Photographs Acquisition Group

© Tereza Zelenková

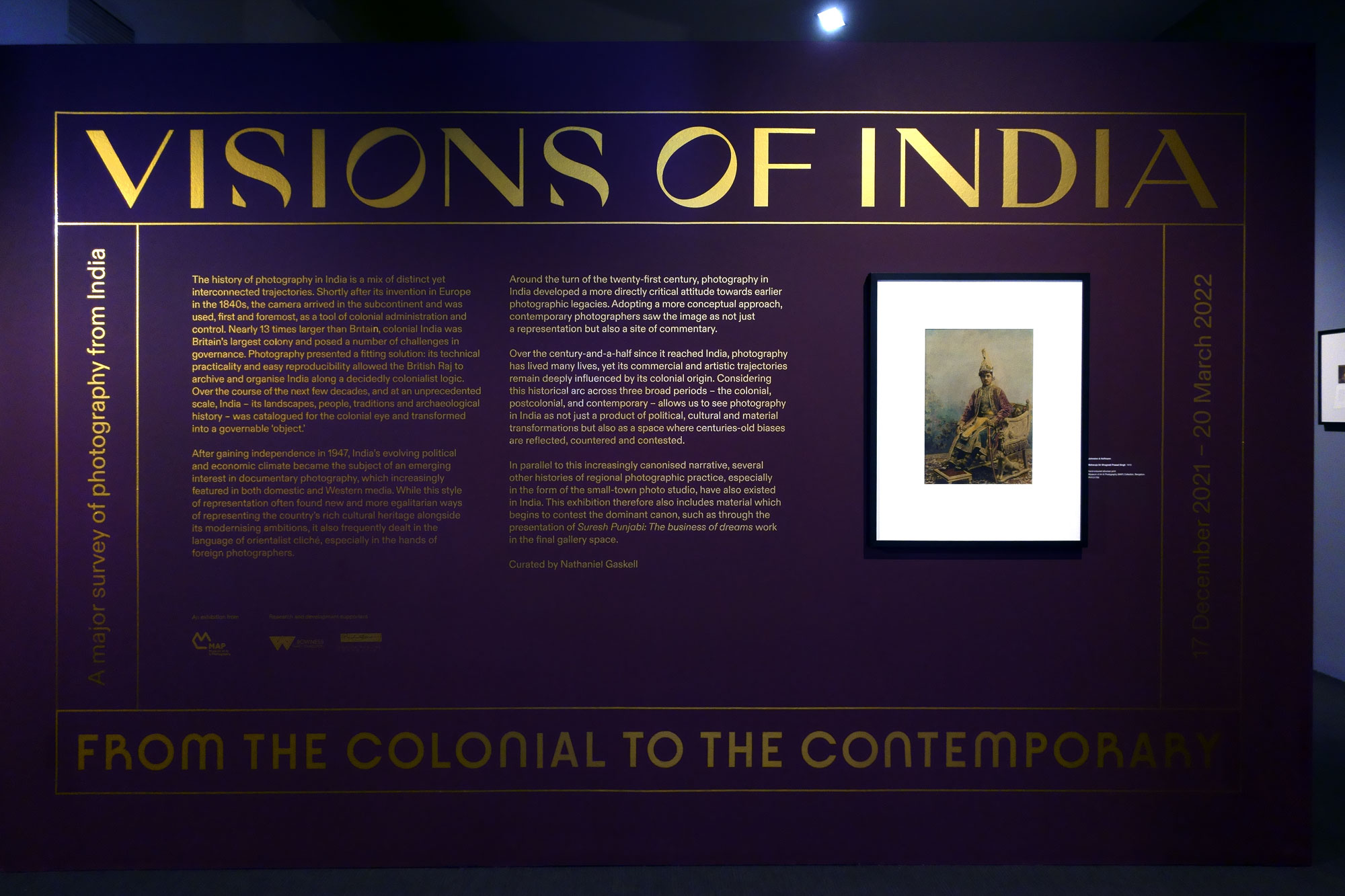

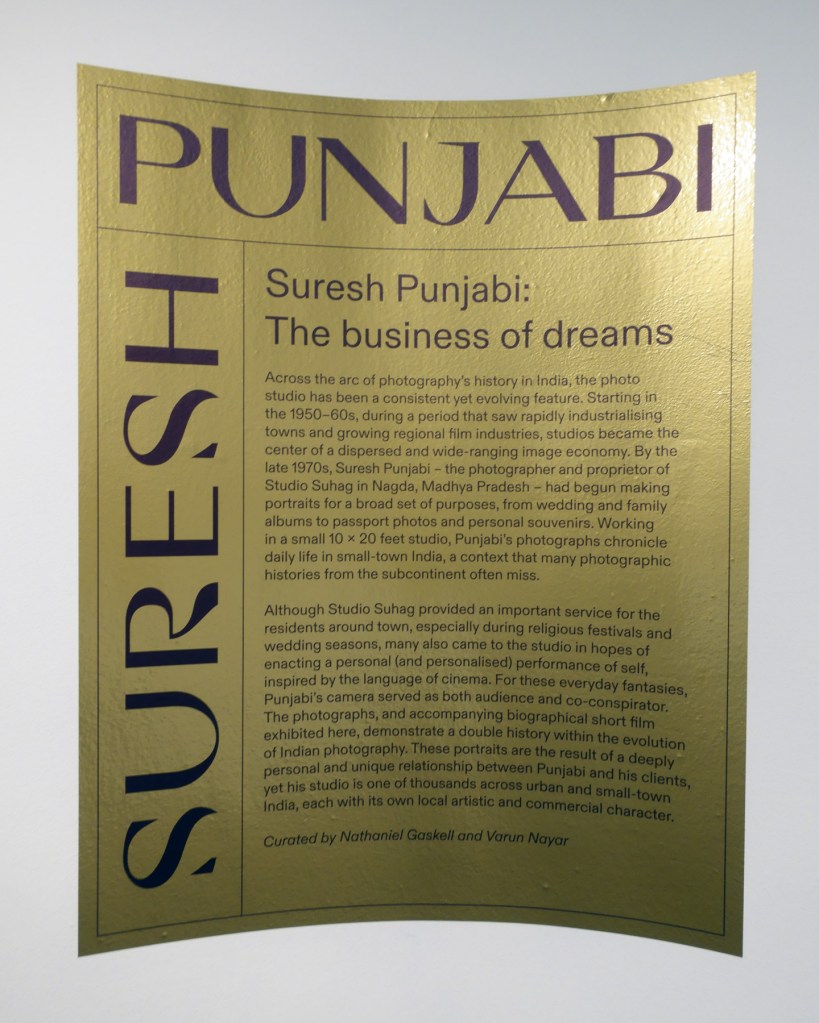

This is a fascinating and intelligent selection of photographs in the display Known and Strange: Photographs from the Collection at the V&A Photography Centre, London which highlights photography’s power to transform the familiar into the unfamiliar, and the ordinary into the extraordinary. Each series shows honesty and integrity of conceptualisation and purpose, evidenced through strong photographs that engage the viewer in the visual narrative.

The catch all ‘Known and Strange’ somehow seems inadequate to describe the myriad threads of intertextuality (the way that similar or related texts influence, reflect, or differ from each other) and intersectionality (the interconnected nature of social categorisations such as race, class, and gender as they apply to a given individual or group, regarded as creating overlapping and interdependent systems of discrimination or disadvantage) created by the nexus of this photographic display.

Of course, photographs can never been “known” in the truest sense: “A photograph, however much it may pretend to authenticity, must always in the final instance admit that it is not real, in the sense that what is in the picture is not here, but elsewhere.”1 Elsewhere, and always in the past. But if they cannot be known, this strangeness, their strangeness can open up a new language of visual literacy which offers the viewer new ways of approaching the world – by transcending past time into present future, time. By allowing the viewer the possibility of many different interpretations and points of view when looking at photographs. As Judy Weiser observes,

“Consider the situation of many people viewing the same photograph of a person very different from all of them. Each will be likely to perceive the photo’s subject a bit differently, depending on their own smaller differences from each other. Each person’s perceptions about that photo’s subject is indeed true and correct for that particular perceiver, even though possibly radically different from those of its other perceivers. If they can consciously recognise that all of them hold different truths about the photograph that are equally valid, they may begin to see that they need not feel threatened the next time they encounter a real-life person whose opinion or appearance is very different from theirs.”2

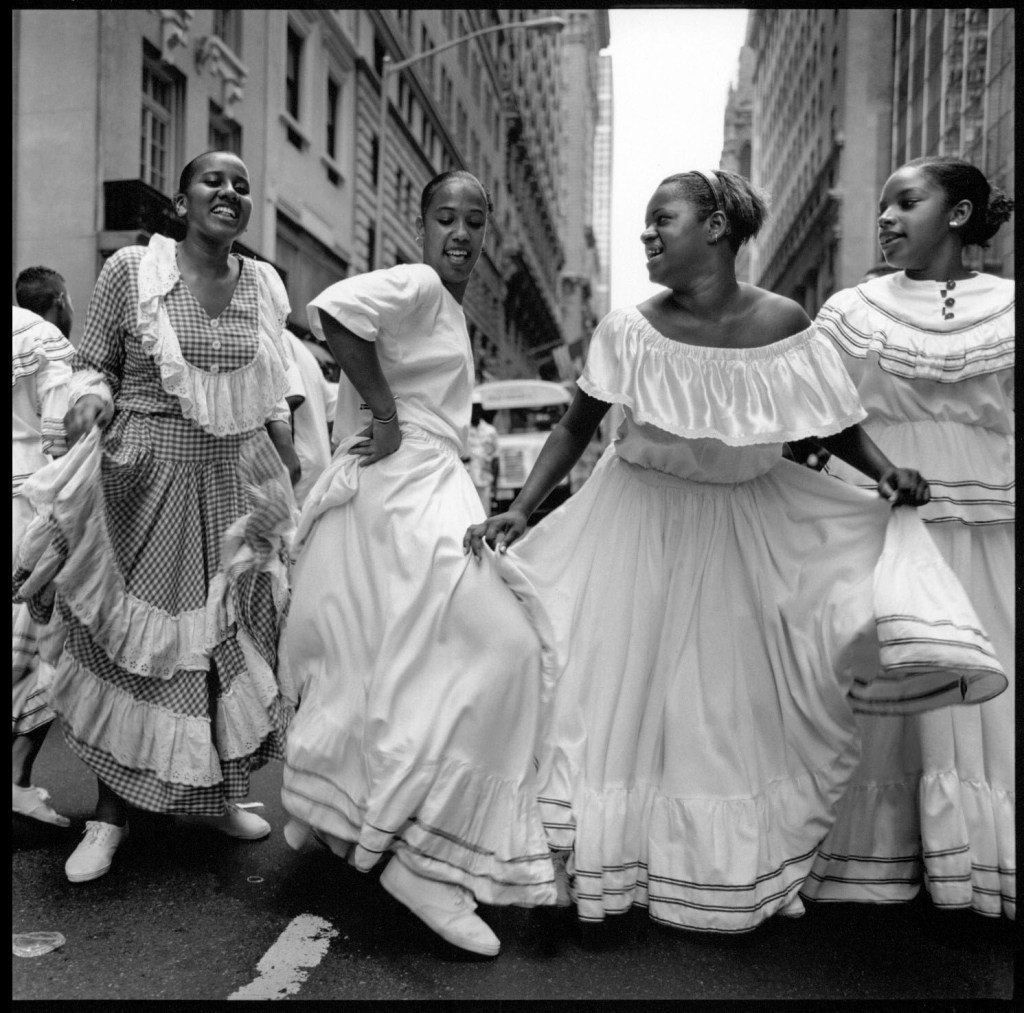

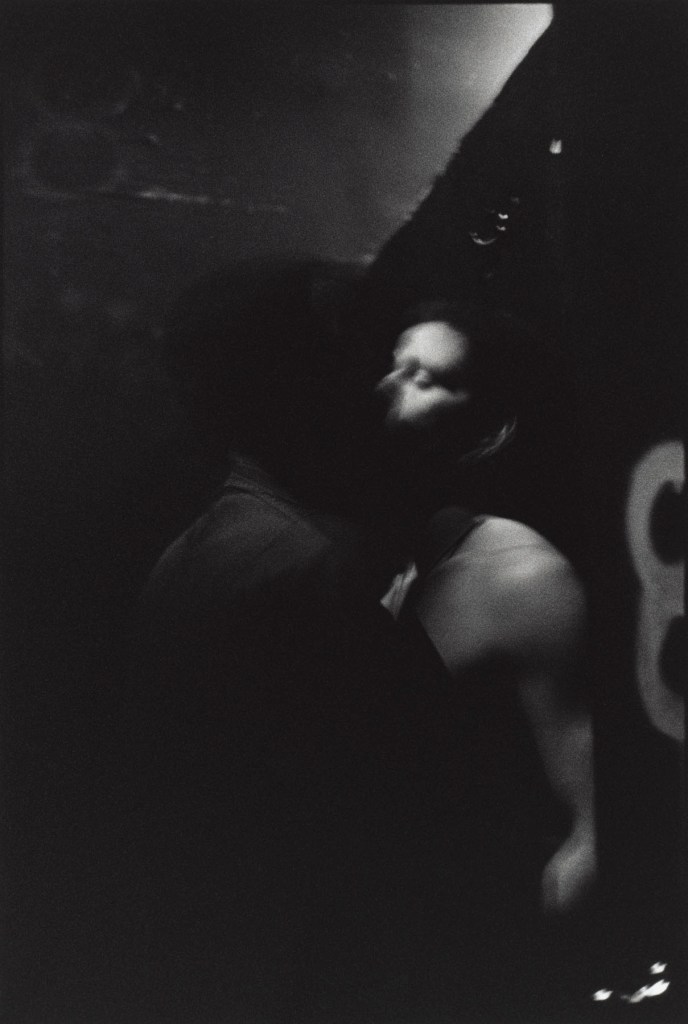

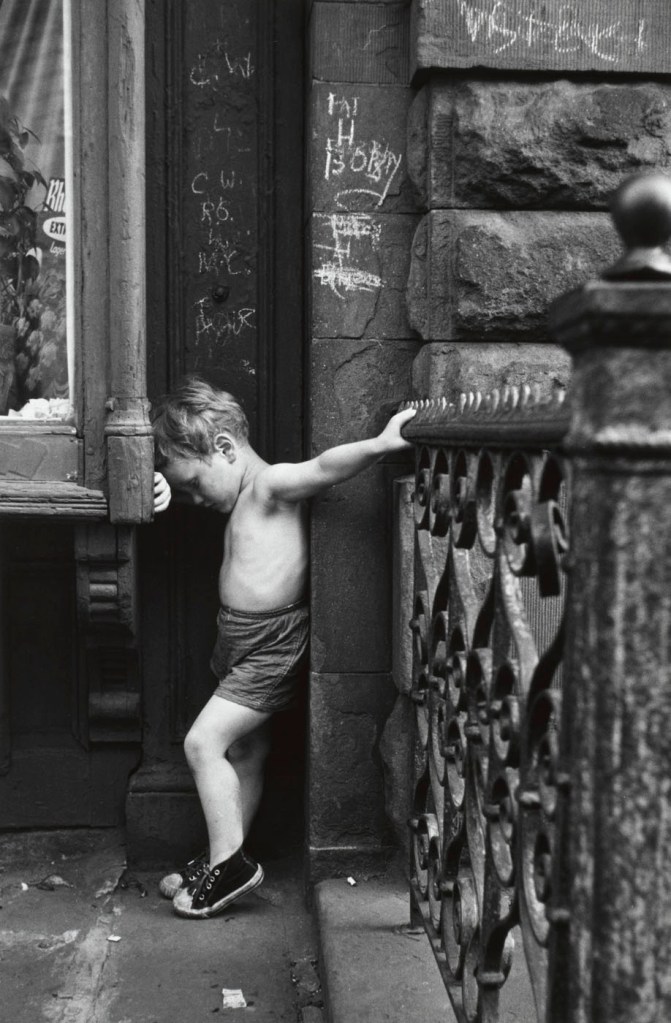

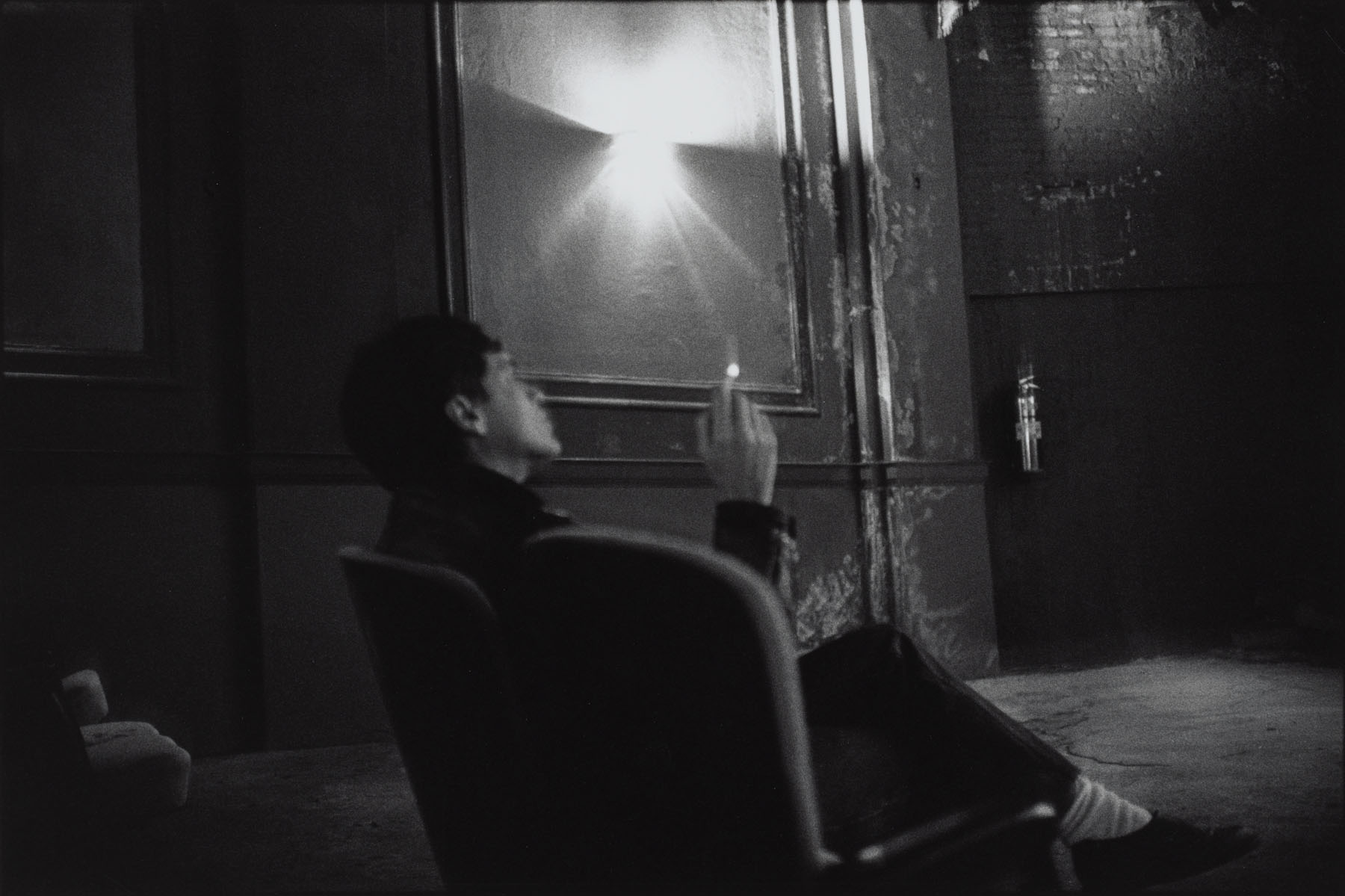

Following the last posting on Carnival attractions and circus photos where I showed photographs of burlesque and “girl revue” show fronts, the final and most essential selection in this posting – Susan Meiselas’ 1972-1975 Carnival Strippers series – goes behind the “front” to document the lives of women who performed striptease for small-town carnivals in New England, Pennsylvania and South Carolina. “Meiselas’ frank description of these women brought a hidden world to public attention, and explored the complex role the carnival played in their lives: mobility, money and liberation, but also undeniable objectification and exploitation. Produced during the early years of the women’s movement, Carnival Strippers reflects the struggle for identity and self-esteem that characterised a complex era of change.” (Booktopia)

Intense, intimate and revealing, the series proves that we can think we know something (the phenomenal) and yet photography reveals how strange and different each world is – whether that be in trying to understand the mind of the artist and what they intended in a constructed photograph or, in this case, having an impression of someone else’s life, a life we can perceive (through the “presence” of the photograph) but never truly know (the noumenal).

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Annette Kuhn, The Power of the Image: Essays on Representation and Sexuality, Routledge and Kegan Paul, London, 1985, pp. 30-31.

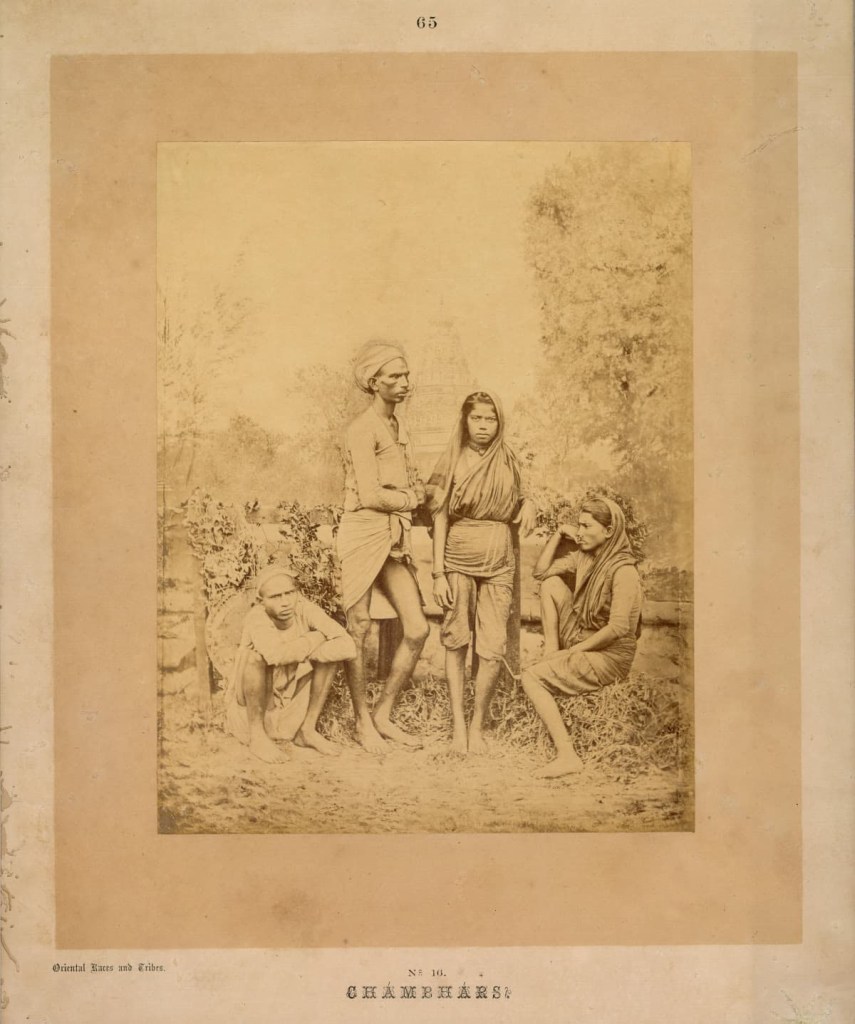

2/ Judy Weiser, PhotoTherapy Techniques, Jossey-Bass Publishers, San Francisco, 1993, p. 18.

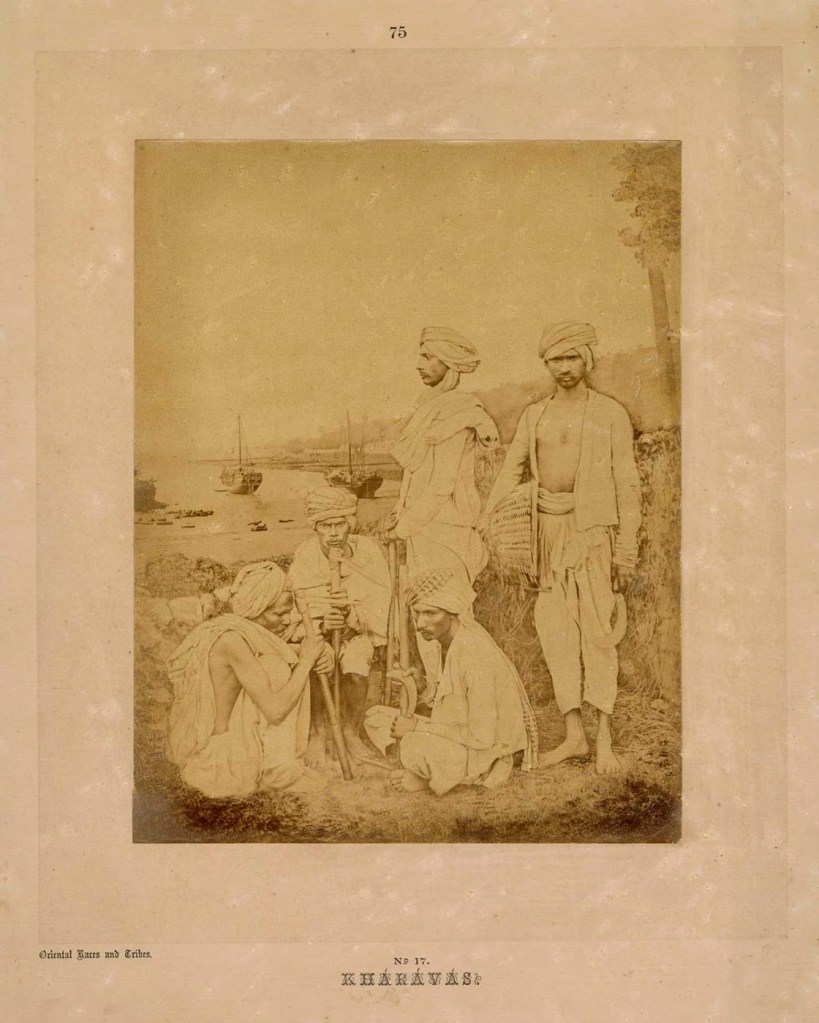

Many thankx to the V&A for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

This display highlights photography’s power to transform the familiar into the unfamiliar, and the ordinary into the extraordinary. Showcasing new acquisitions, it presents some of the most compelling achievements in contemporary art photography.

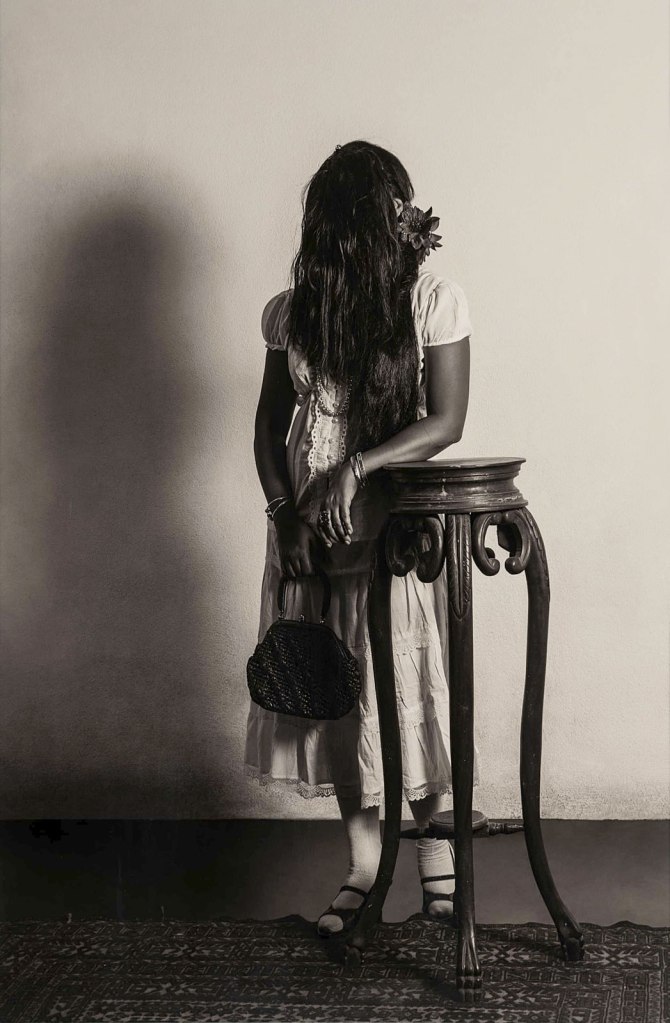

Tereza Zelenková (Czech, b. 1985)

The Unseen

2015

Gelatin silver print

Image: 100 x 125cm

Purchase funded by the Photographs Acquisition Group

© Tereza Zelenková

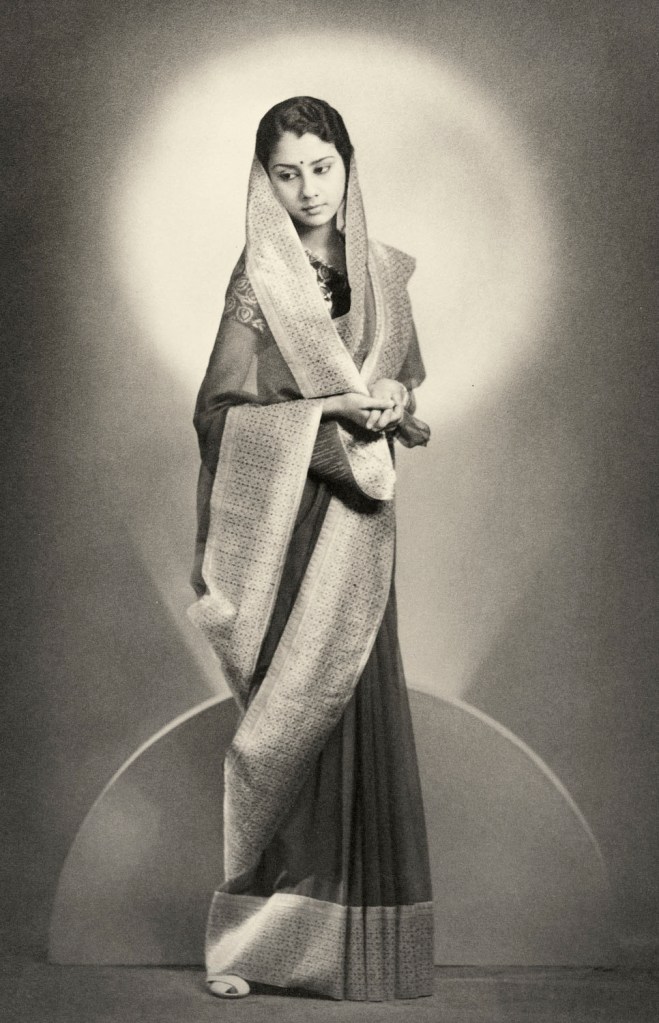

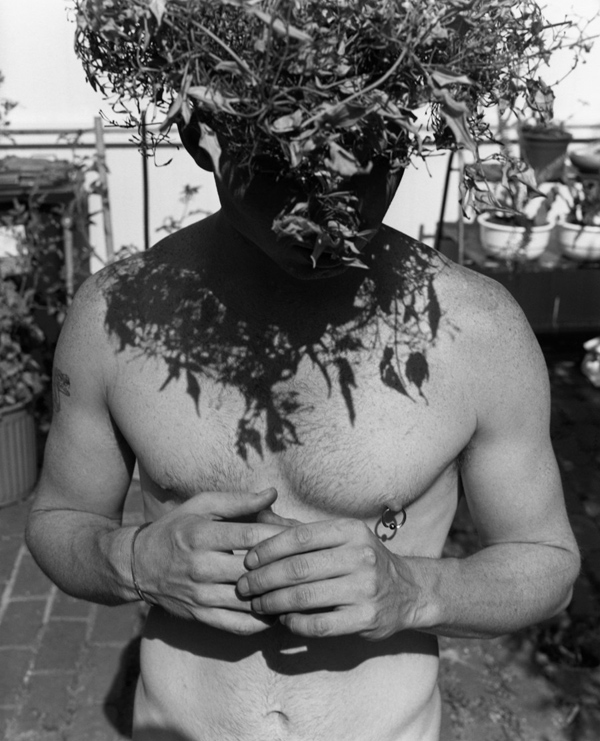

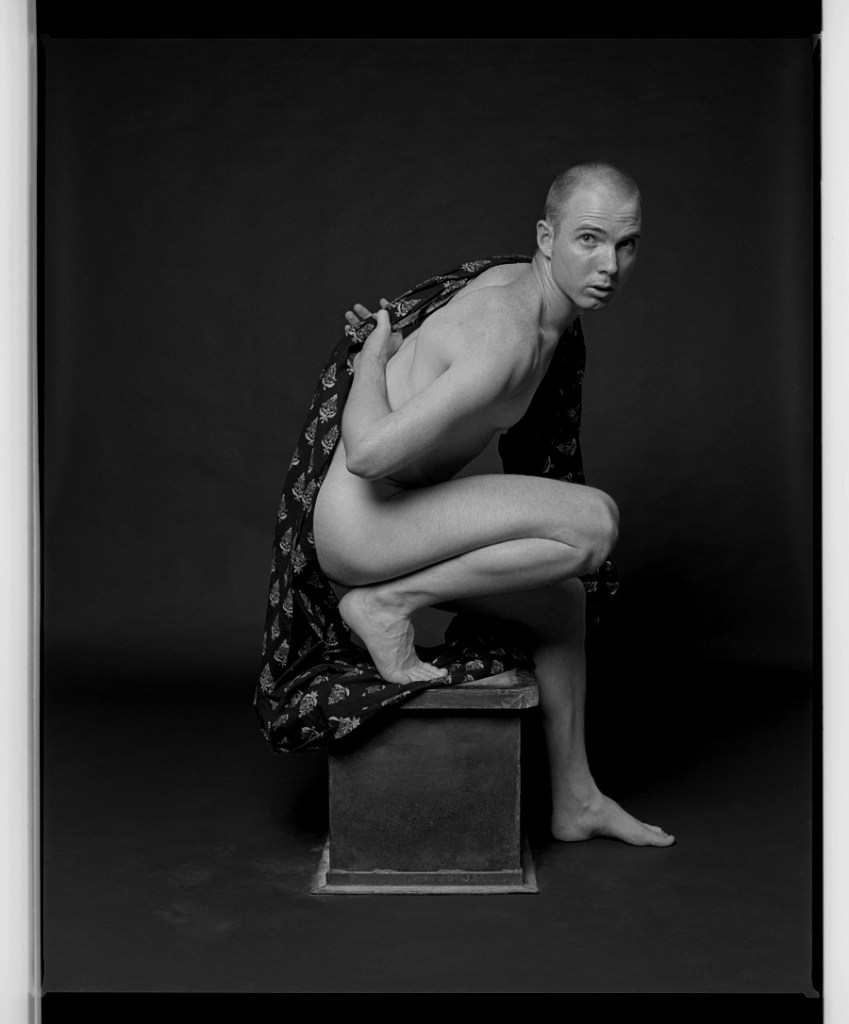

Tereza Zelenkova is a Czech-born artist known for her imaginative exploration of mysticism. She is inspired by literature and philosophy, but also values intuition and coincidence as essential guides in her creative process. Zelenkova’s work peels back the layers of myth that build up over time, interrogating the historical past of places and people, probing at folklore and imparting a modern sense of Surrealism onto familiar things, such as the grave of Georges Bataille, the Moravian cave of Byci Skala, or a statue by Michelangelo in the V&A’s cast courts.

Text from the V&A website

The first photograph I’d like to talk about is The Unseen. I get asked quite often how this sits within the series and what has been the inspiration for the image. Although I rarely stage my photographs, I had a quite clear vision of this particular photograph. It is an amalgamation of two themes that somehow merged in my mind and crystalized into this heavily distilled vision that I then went on to stage and photograph. Ever since I remember, I’ve been interested in photography’s peculiar relationship with death. It may sound like a cliché now but it can’t be denied that photography, similarly as a reflection in a mirror, offers the viewer aside of the image of his or her likeness also a glimpse of his or her mortality. Moreover, as Václav Vanek writes* when he talks about the loneliness and “deathly anxiety that we feel when, while trying to find a companion, we keep finding only a mirror image of ourselves and ultimately our death, which is always present in such mirroring”. Photography offers us both a promise of immortality alongside the reminder of our discontinuity. At the same time, due to its peculiar relationship with time, its strange stillness and minute detail it promises to reveal a bit more, something beyond the ordinary image of ourselves, or the everyday reality. It lures us to believe that it can see what’s unseen to the naked eye, that it can trespass the ordinary notion of time, and even blur the thresholds between the worlds of living and those long gone. Most of the people will be probably familiar with spirit photography, in which the 19th century society believed to find a way of communicating with their deceased loved ones. What’s interesting to note in this case is that the automatism of photographic medium was one of the key elements in this wide spread belief of photography’s ability to capture the world of spirits. Automatism of photography suggested the medium’s detachment from the cognitive processes of the human brain and its ability to tap into the unconscious, be it individual or collective. Automatism played a vital role not only in communicating with spirits, but also in early modernist art, especially in Surrealism. We have remarkable examples of automatic drawings, paintings or writings. In the Czech Republic, there’s a very special collection of such automatic drawings from the early 20th century, that however don’t come from avant-garde artists but from ordinary people found in one small region right at the foot of the tallest Czech mountain range, Krkonoše (Giant Mountains in English). From the end of the 19th century up until 1945, there seemed to be a golden age of Spiritism, that was however very unique to the region due to people’s relative isolation, living in the secluded farmhouses scattered at the foot of the mountains and meeting at each other’s houses for regular Spiritistic séances mainly held to bring back relatives who died during the war. The local people often used automatic drawing to receive hallucinatory visions from the other side and the collections of these remarkable drawings can be found in a museum in Nova Paka, but their notoriety goes well beyond the Czech borders as some of the finest examples of the so called Art Brut. So this is the first ingredient of my photograph. The second one is much more visual and comes as a snippet from a Czech fairytale Goldielocks, written by one of the most famous Czech 19th century writers, Karel Jaromír Erben. The scene that I used as a base for my photograph comes from the 1970’s version of the tale and it is a moment when the main hero needs to recognise Goldielocks, the princess with golden hair, amongst her twelve sisters, even though their hair is covered with a veil. I’ve always found the scene rather surreal and it immediately connected for me with the popular image of ghosts. There’s also something ritualistic and esoteric about the whole thing.

* In an introduction to a J.J. Kolár’s short story At The Red Dragon’s in a compilation of Czech Romantic prose.

Tereza Zelenková. “The Unseen,” on the Der Greif website July 02, 2016 [Online] Cited 22/02/2022

Tereza Zelenková (Czech, b. 1985)

Giuliano de Medici by Michelangelo

2013

Gelatin silver print

40 x 30cm

Purchase funded by the Photographs Acquisition Group

© Tereza Zelenková

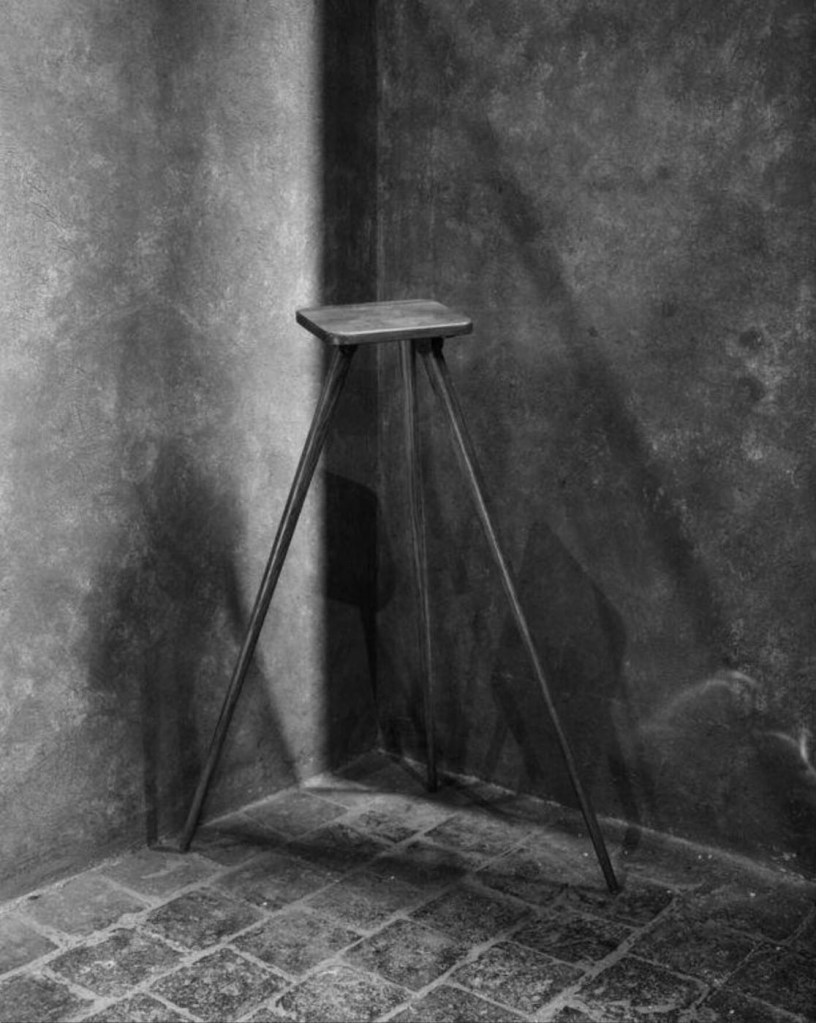

Tereza Zelenková (Czech, b. 1985)

Tripod, Meridian Hall

2016

Gelatin silver print

29 x 23cm

Purchase funded by the Photographs Acquisition Group

© Tereza Zelenková

Opening November 2021, Known and Strange: Photographs from the Collection will highlight photography’s power to transform the familiar into the unfamiliar, and the ordinary into the extraordinary.

Since its invention, photography has changed the way we see the world by inviting us to interpret reality in our own way. Known and Strange will focus on photography’s creative capacity to blur fact with fiction. The display will showcase over 50 recent contemporary acquisitions for the V&A permanent collection – created by established and emerging photographers across the globe – including Paul Graham, Susan Meiselas, Andy Sewell, Tereza Zelenková, Dafna Talmor, Zanele Muholi, Rinko Kawauchi, and Mitch Epstein. Each has expanded the ever-changing field of photography, both in terms of stylistic experimentation and intellectual inquiry, and their work represents some of today’s most compelling achievements in contemporary photography.

The display title Known and Strange, originally from a line from the poem ‘Postscript’ by Seamus Heaney, is borrowed from a series of photographs by Andy Sewell and captures the sentiment of the works that will be presented in the display. Sewell’s series was taken on both sides of the Atlantic, taking as its visual and conceptual departure point places where internet cables are routed from the land to cross the seabed. The series – which will be presented in the display – explores the idea that the internet and the ocean, human communication and its related technologies, are both vast and unknowably strange.

Known and Strange will also feature diverse and innovative works within this broader theme, from Rinko Kawauchi’s focus on simple moments of illumination in everyday life and Mitch Epstein’s search for trees in New York City, to Zanele Muholi’s powerful series that exposes the persistent violence and discrimination faced by the South African Black LGBTQIA+ community. Tereza Zelenková – known for her imaginative explorations of mysticism – peels back the layers of myth that build up over time, whilst Dafna Talmor transforms her own photographs of landscapes by cutting them up and recombining them to create new hybrid compositions. In addition, the display will include over 20 photobooks by contemporary photographers, drawn from the collection of the National Art Library, further highlighting the innovation present in photography today.

The display will highlight the diversity of a medium that, through its malleability, allows for many different perspectives to be captured. As viewers, we can challenge everyday assumptions, be reminded of the world’s wonder, and perhaps poignantly, become aware that we might not be able to witness everything we want to during our own comparatively fleeting lives.

Press release from the V&A

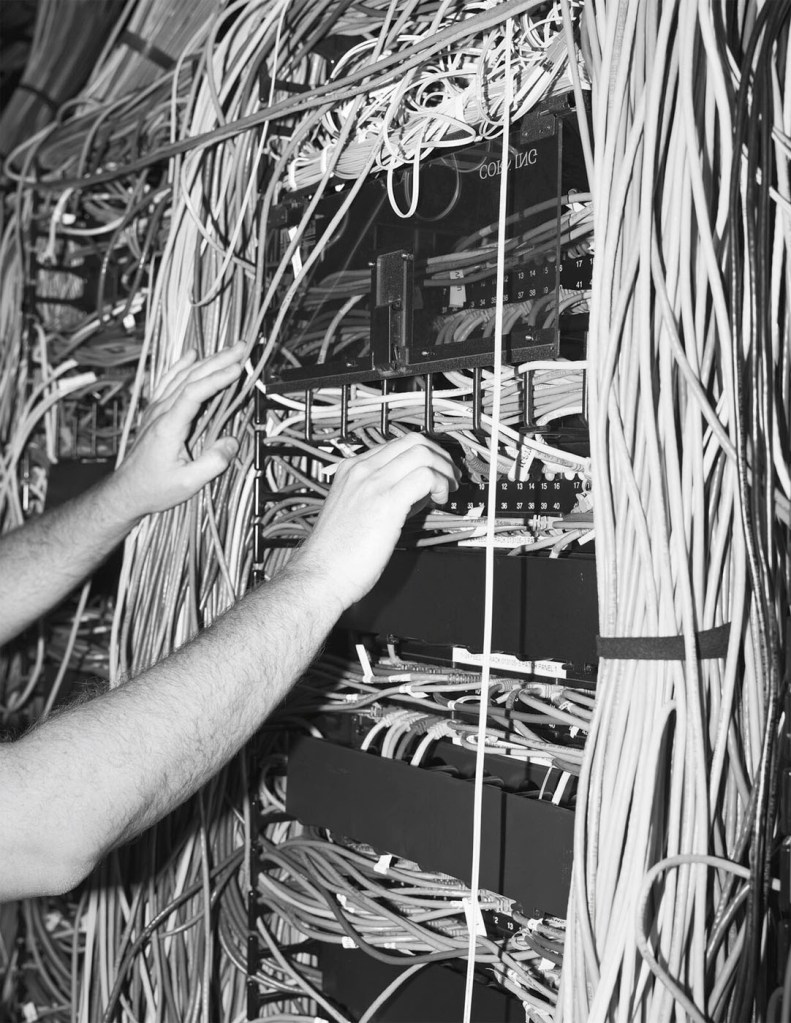

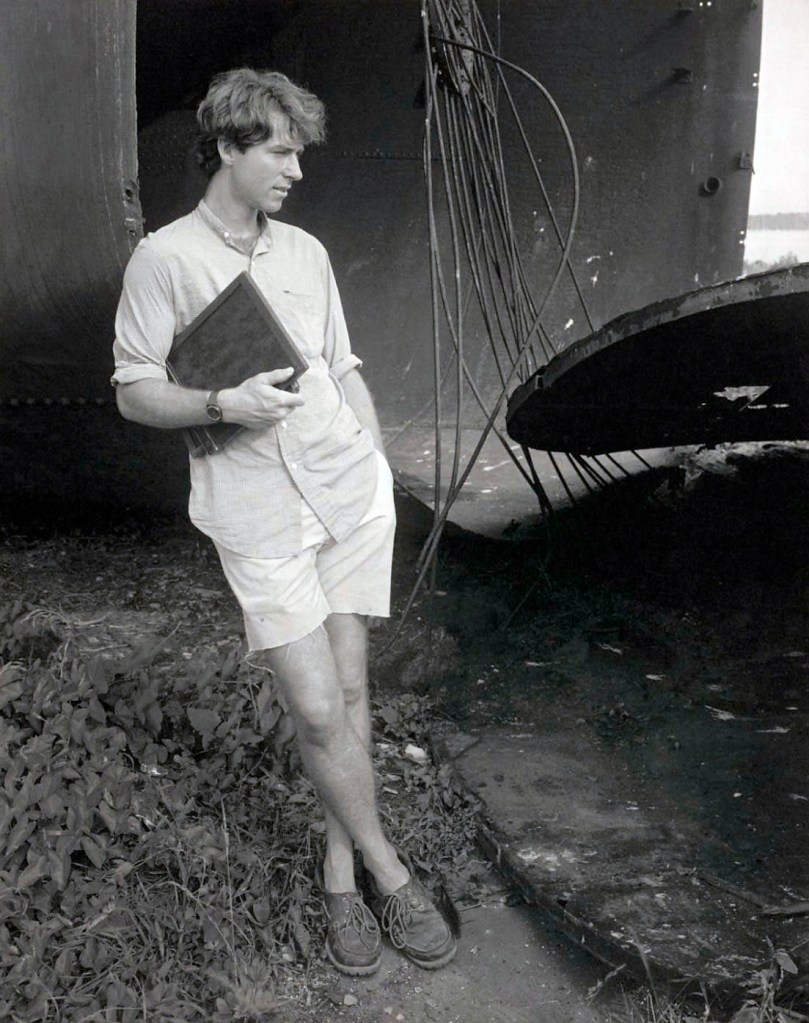

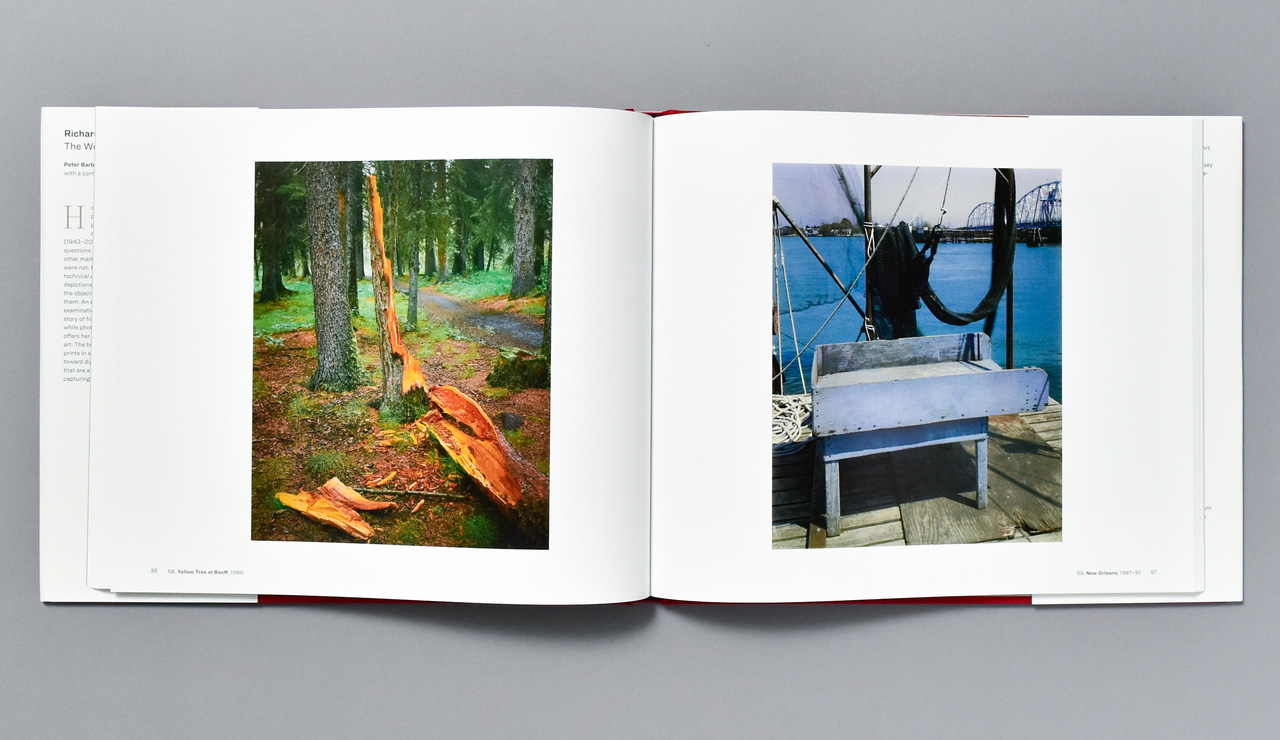

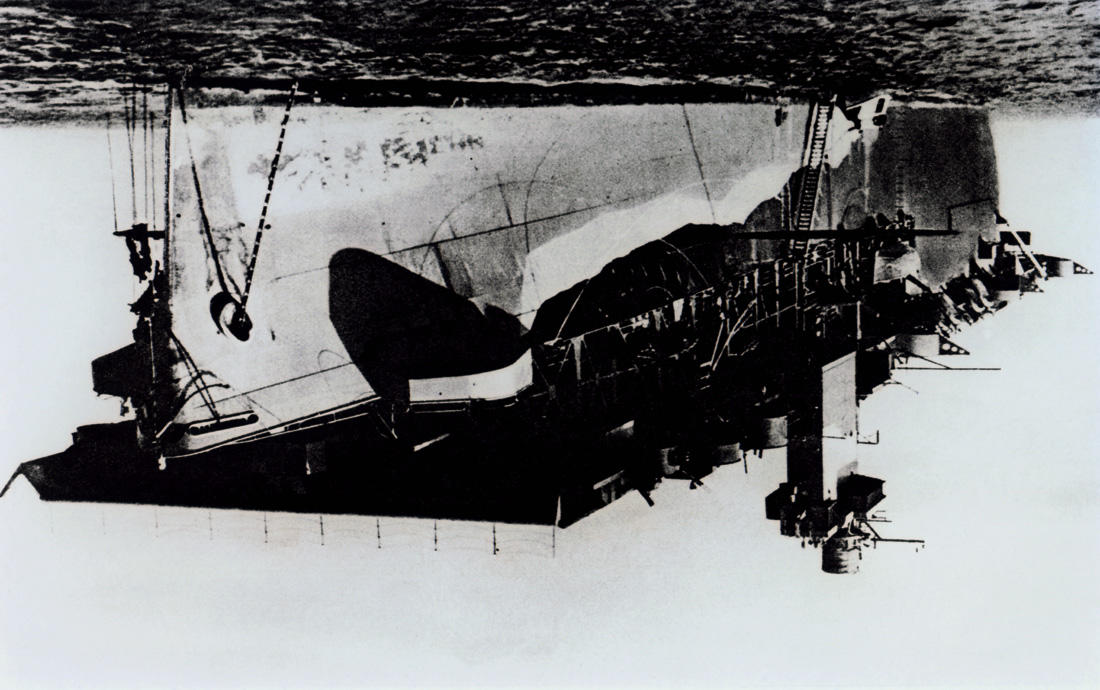

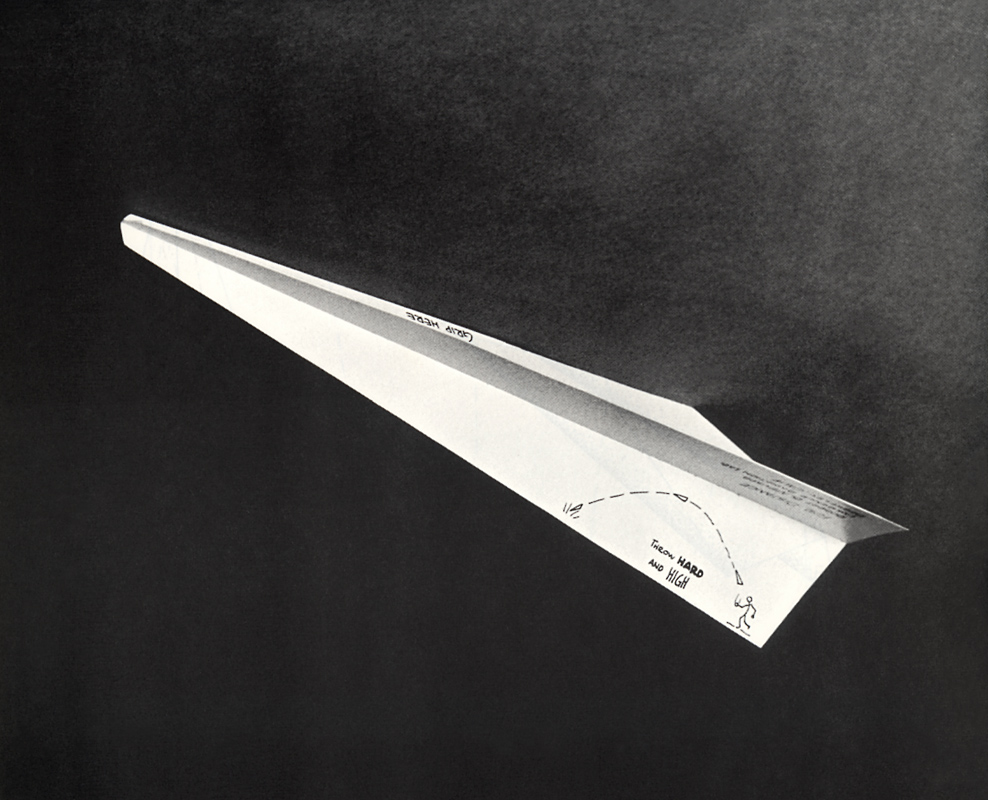

Andy Sewell (British, b. 1978)

Untitled

2020

From the series Known and Strange Things Pass

Pigment print

Purchase funded by Cecil Beaton Fund

© Andy Sewell

Andy Sewell (British, b. 1978)

Untitled

2020

From the series Known and Strange Things Pass

Pigment print

Purchase funded by Cecil Beaton Fund

© Andy Sewell

“Known and Strange Things Pass is about the deep and complex entanglement of technology with contemporary life. It’s about the immediacy of touch and the commonplace miracle of action at a distance; the porosity of the boundaries that hold things apart, and the fragility of the bonds that lock them together.”

~ Eugenie Shinkle, 1000 Words Magazine

The photographs in this work are taken on either side of the Atlantic in places where the Internet is concentrated. Where the fibres come together, and almost everything we do online passes down a few impossibly narrow tubes, stretching along the seabed, connecting one continent to another.

Looking at these vast unknowable entities – the ocean and the Internet – we sense their strangeness. We can understand each conceptually but can only ever see or bump into small bits of them. They challenge our everyday assumptions and show us that the boundaries we put between things are more permeable than we might like to think. That the objects surrounding us daily, appearing so reliable and mundane, are actually parts of much larger, more complex, bodies extended across space and time.

The work is structured through the push and pull of intermeshing sequences. Things, in different times and places, intertwine and coexist. As we look closer, worlds we think of as separate dissolve into each other – the near and the distant, the ocean and the internet, the physical and the virtual, what we think of as natural with the cultural and technological.

Text from the Andy Sewell website [Online] Cited 22/04/2022

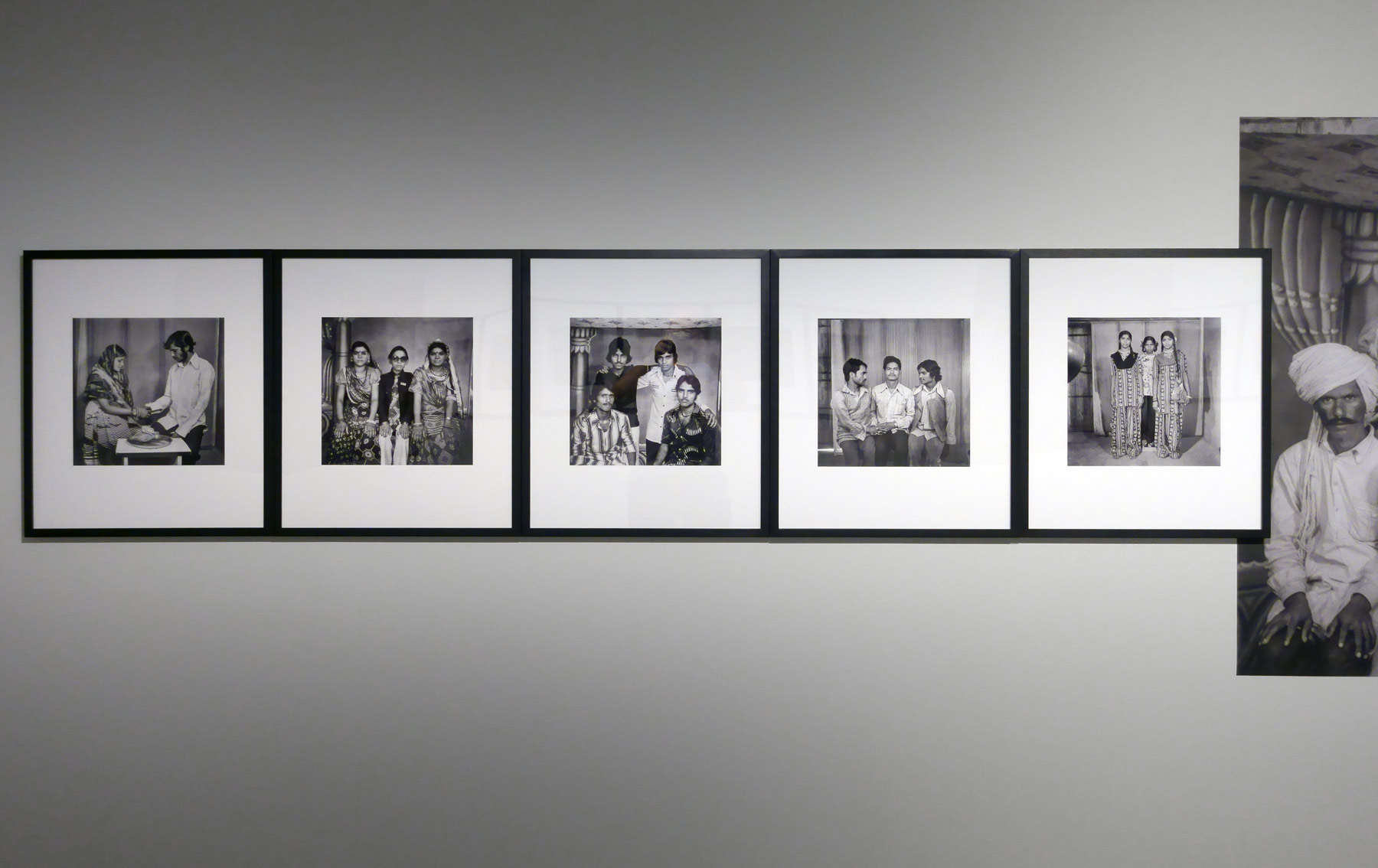

Installation view of Known and Strange: Photographs from the Collection display at V&A showing at middle left the work of Andy Sewell from the Known and Strange Things Pass series

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Installation view of Known and Strange: Photographs from the Collection display at V&A showing the work of Andy Sewell from the Known and Strange Things Pass series, installation of 20 framed prints (sizes 144 x 108cm to 28 x 21cm)

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

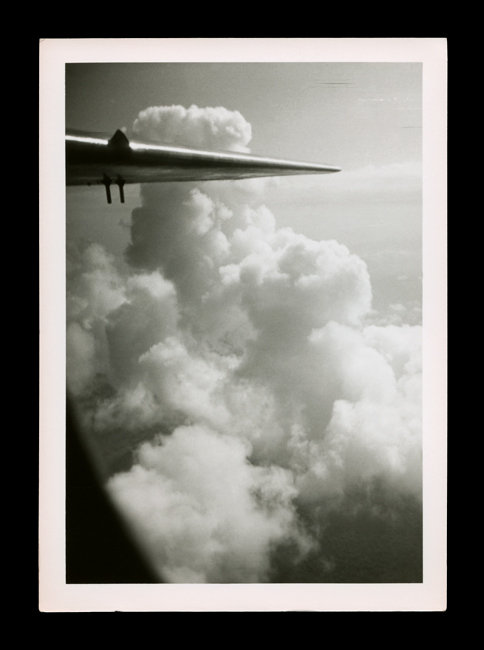

Andy Sewell (British, b. 1978)

Untitled

2020

From the series Known and Strange Things Pass

Pigment print

Purchase funded by Cecil Beaton Fund

© Andy Sewell

Andy Sewell (British, b. 1978)

Untitled

2020

From the series Known and Strange Things Pass

Pigment print

Purchase funded by Cecil Beaton Fund

© Andy Sewell

Andy Sewell (British, b. 1978)

Untitled

2020

From the series Known and Strange Things Pass

Pigment print

Purchase funded by Cecil Beaton Fund

© Andy Sewell

Andy Sewell (British, b. 1978)

Untitled

2020

From the series Known and Strange Things Pass

Pigment print

Purchase funded by Cecil Beaton Fund

© Andy Sewell

Andy Sewell (British, b. 1978)

Untitled

2020

From the series Known and Strange Things Pass

Pigment print

Purchase funded by Cecil Beaton Fund

© Andy Sewell

Andy Sewell (British, b. 1978)

Untitled

2020

From the series Known and Strange Things Pass

Pigment print

Purchase funded by Cecil Beaton Fund

© Andy Sewell

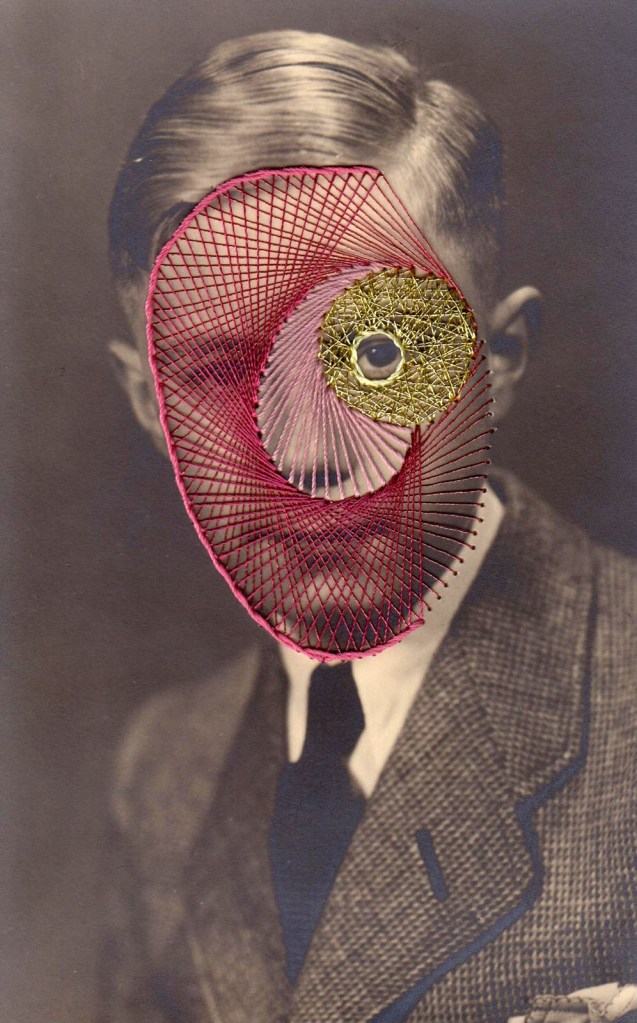

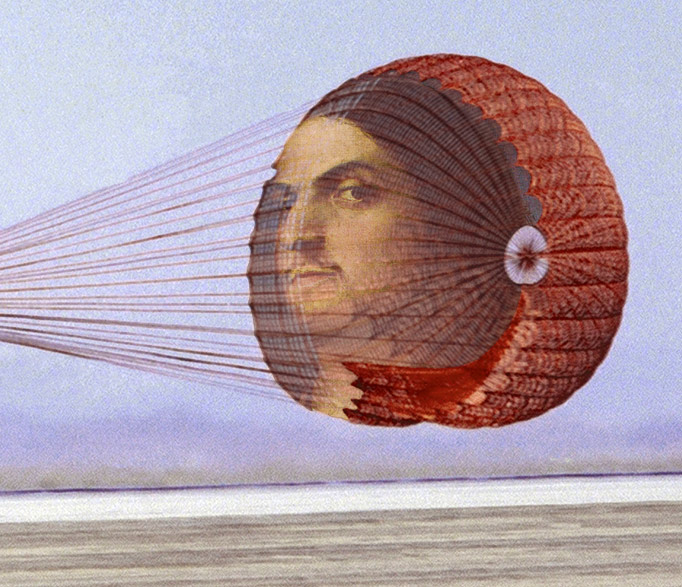

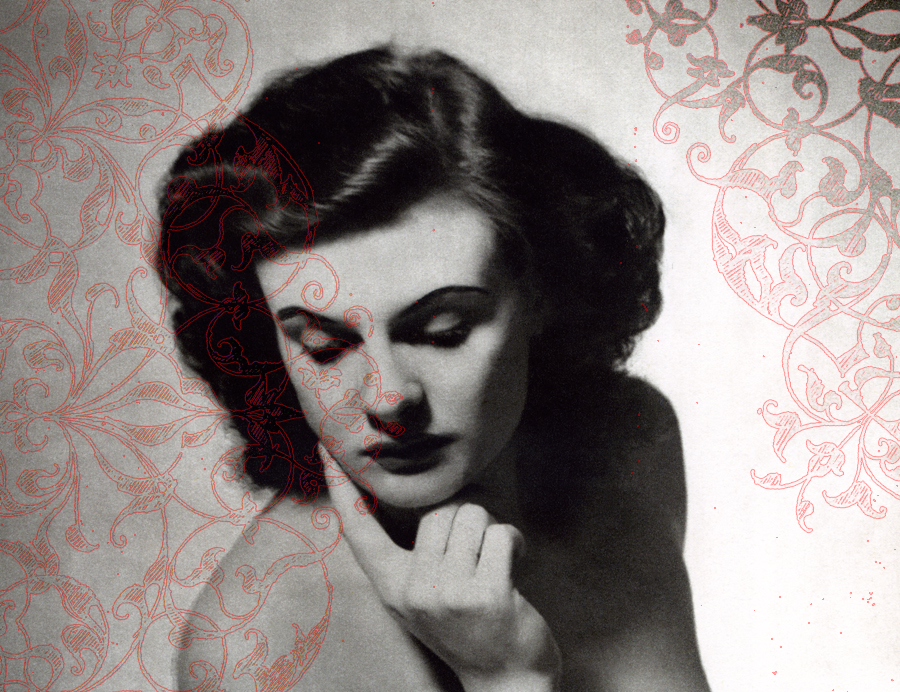

Maurizio Anzeri (Italian, b. 1969)

Lucy

2018

Embroidery on gelatin silver print

292 x 444 mm

Purchase funded by the Photographs Acquisition Group

© Maurizio Anzeri

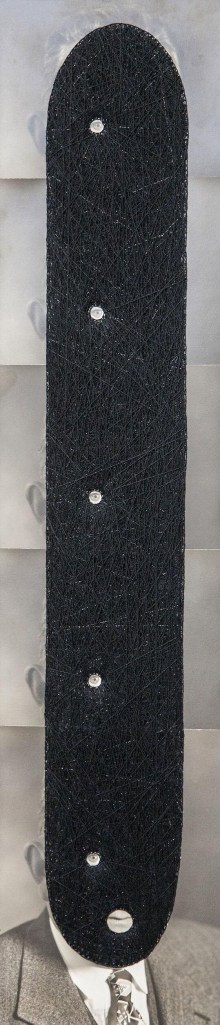

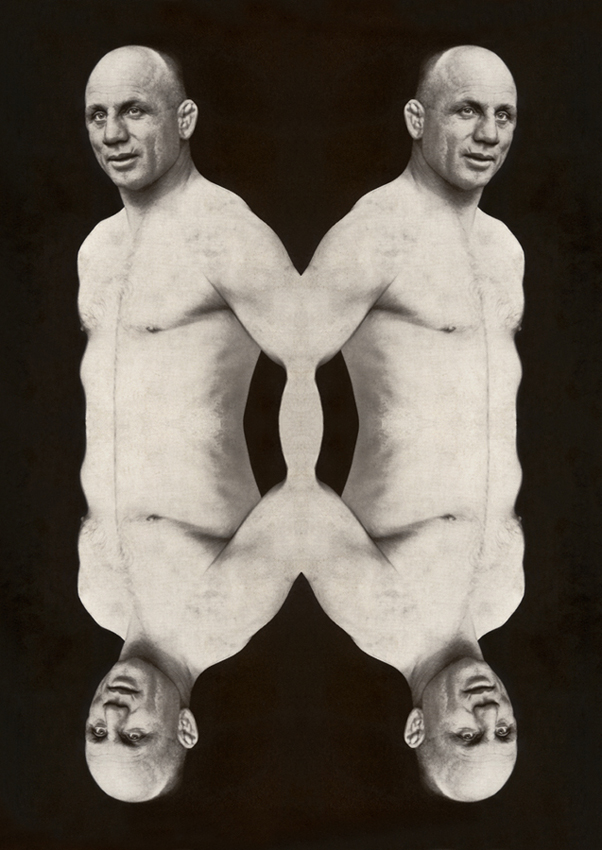

Italian artist Maurizio Anzeri lives and works in London. He uses delicate embroidery on vintage photographs that he finds at flea markets, creating otherworldly portraits and surreal landscapes. The subjects in Anzeri’s found photographs are transformed by his threadwork; the vintage photographs often appear at odds with the sharp lines and silky shimmer of the colourful threads. Through this combination of media, Anzeri’s works create a dimension where past and present converge.

Text from the V&A website

I work with sewing, embroidery and drawing to explore the essence of signs in their physical manifestation. I take inspiration from my own personal experience and observation of how, in other cultures, bodies themselves are treated as living graphic symbols. I then use sewing and embroidery in a further attempt to re-signify, and mark the space with a man-made sign, a trace. The intimate human action of embroidery is a ritual of making and reshaping stories and history of these people. I am interested in the relation between intimacy and the outer world.

~ Maurizio Anzeri

Maurizio Anzeri (Italian, b. 1969)

Alex

2018

Embroidery on gelatin silver print

14 x 9cm

Purchase funded by the Photographs Acquisition Group

© Maurizio Anzeri

Maurizio Anzeri (Italian, b. 1969)

Double and more, 5faces gent

2018

Embroidery on gelatin silver print

82 x 20cm

Purchase funded by the Photographs Acquisition Group

© Maurizio Anzeri

Maurizio Anzeri (Italian, b. 1969)

Double and more, 5faces gent (detail)

2018

Embroidery on gelatin silver print

82 x 20cm

Purchase funded by the Photographs Acquisition Group

© Maurizio Anzeri

Maurizio Anzeri (Italian, b. 1969)

Heavenly Sounds Mountain Pink (triptych)

2018

Embroidery on gelatin silver print

120 x 50cm (each)

Purchase funded by the Photographs Acquisition Group

© Maurizio Anzeri

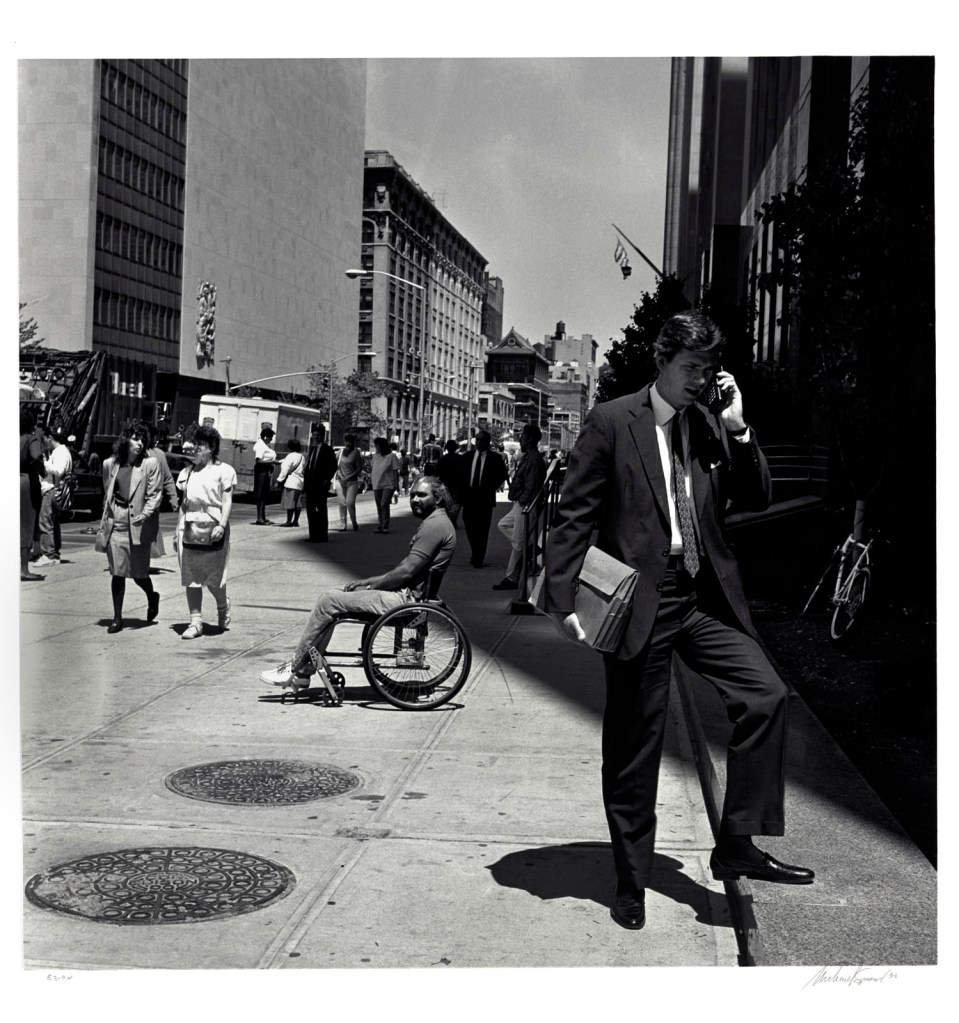

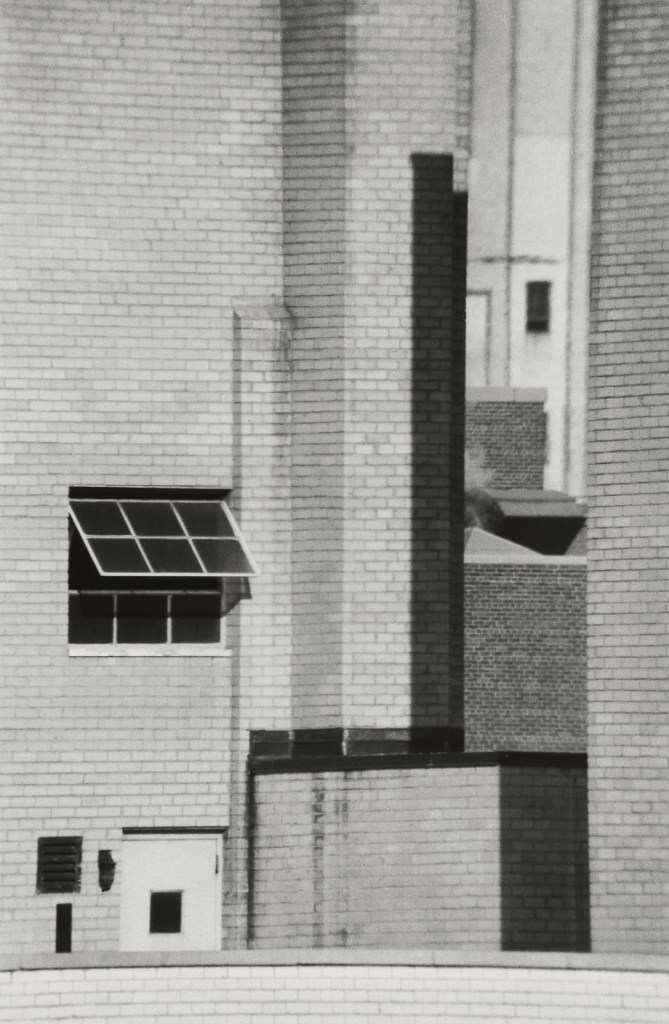

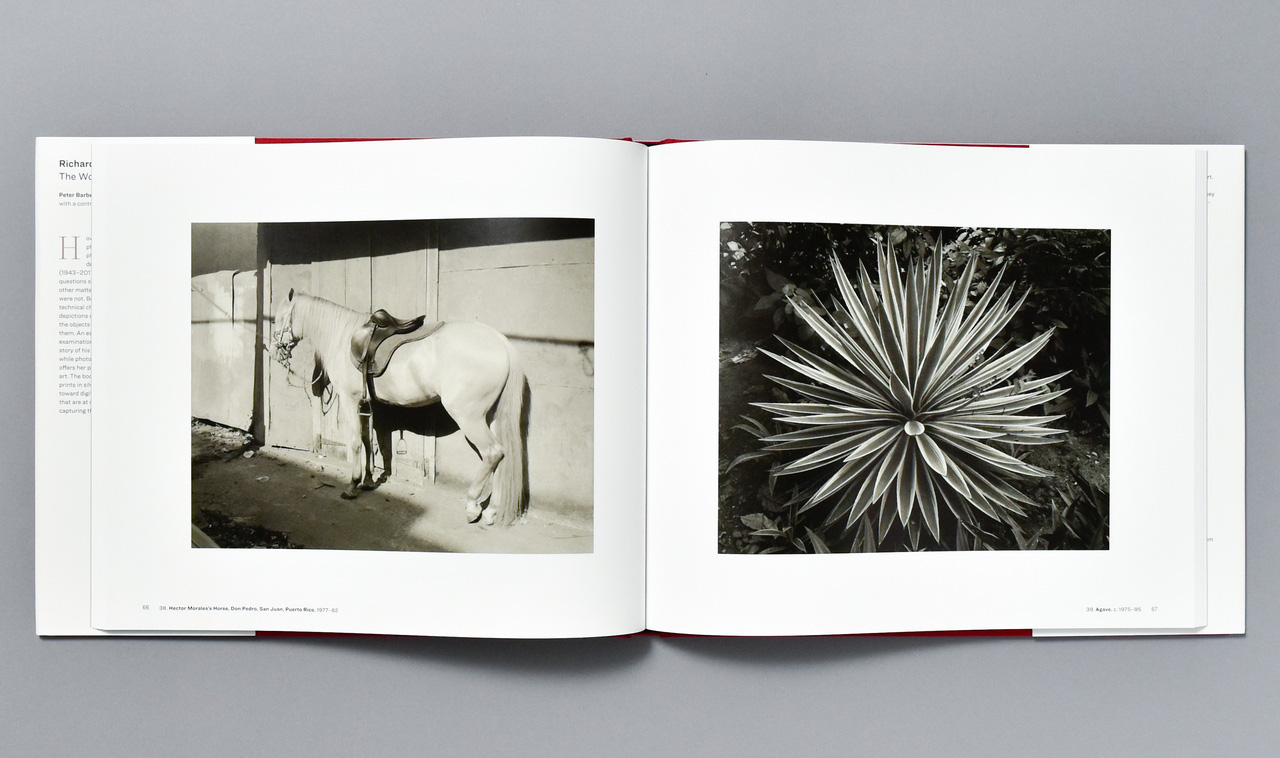

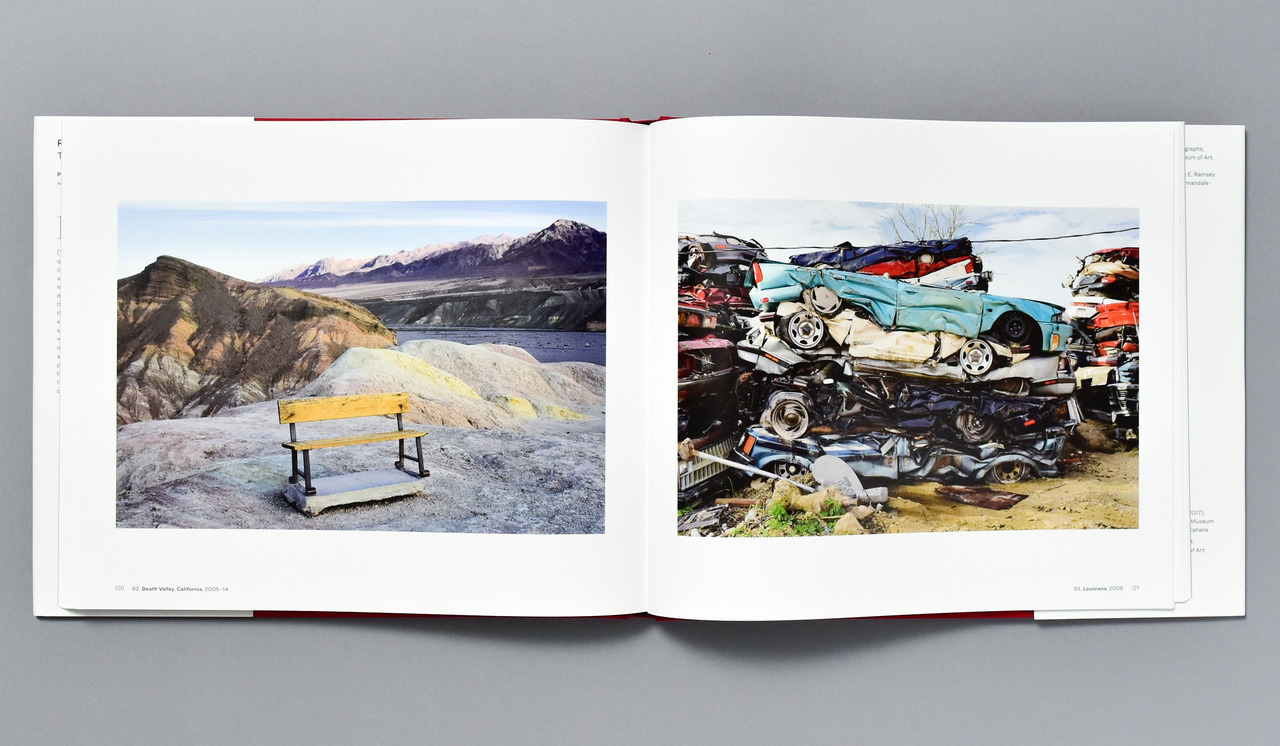

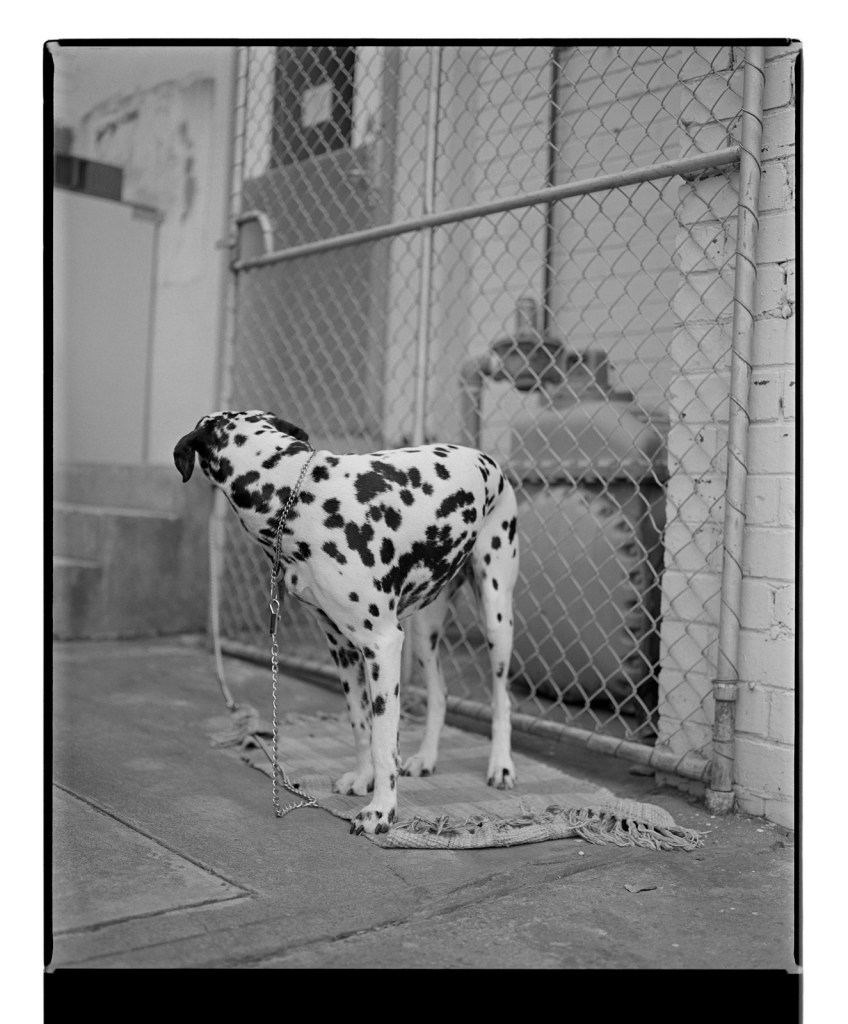

Mitch Epstein (American, b. 1952)

American Elm, Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn

2012

From the series New York Arbor

Gelatin silver print

Purchase funded by Mark Storey and Carey Adina Karmel in memory of George Sassower

© Mitch Epstein

New York Arbor is a series of photographs of idiosyncratic trees that inhabit New York City; these pictures underscore the complex relationship between trees and their human counterparts. Rooted in New York’s parks, gardens, sidewalks, and cemeteries, some trees grow wild, some are contortionists adapting to their constricted surroundings, and others are pruned into prized specimens. Many of these trees are hundreds of years old and arrived as souvenirs and diplomatic gifts from abroad. As urban development closes in on them, New York’s trees surprisingly continue to thrive. The cumulative effect of these photographs is to invert people’s usual view of their city: trees no longer function as background, but instead dominate the human life and architecture around them.

Text from the Mitch Epstein website Nd [Online] Cited 22/04/2022

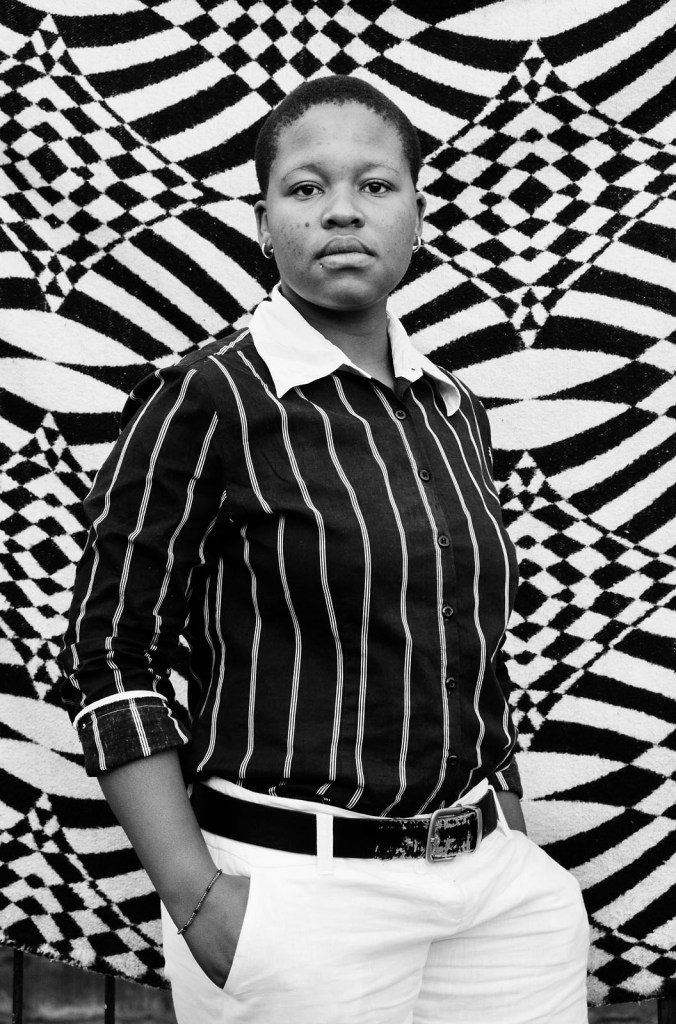

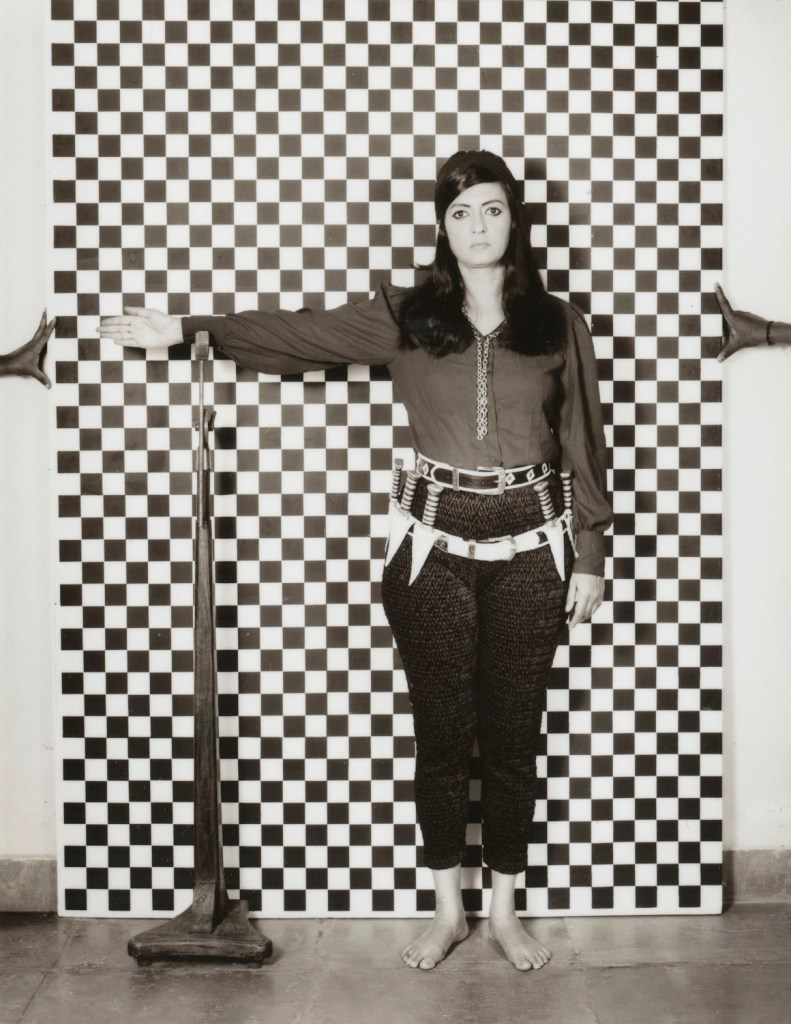

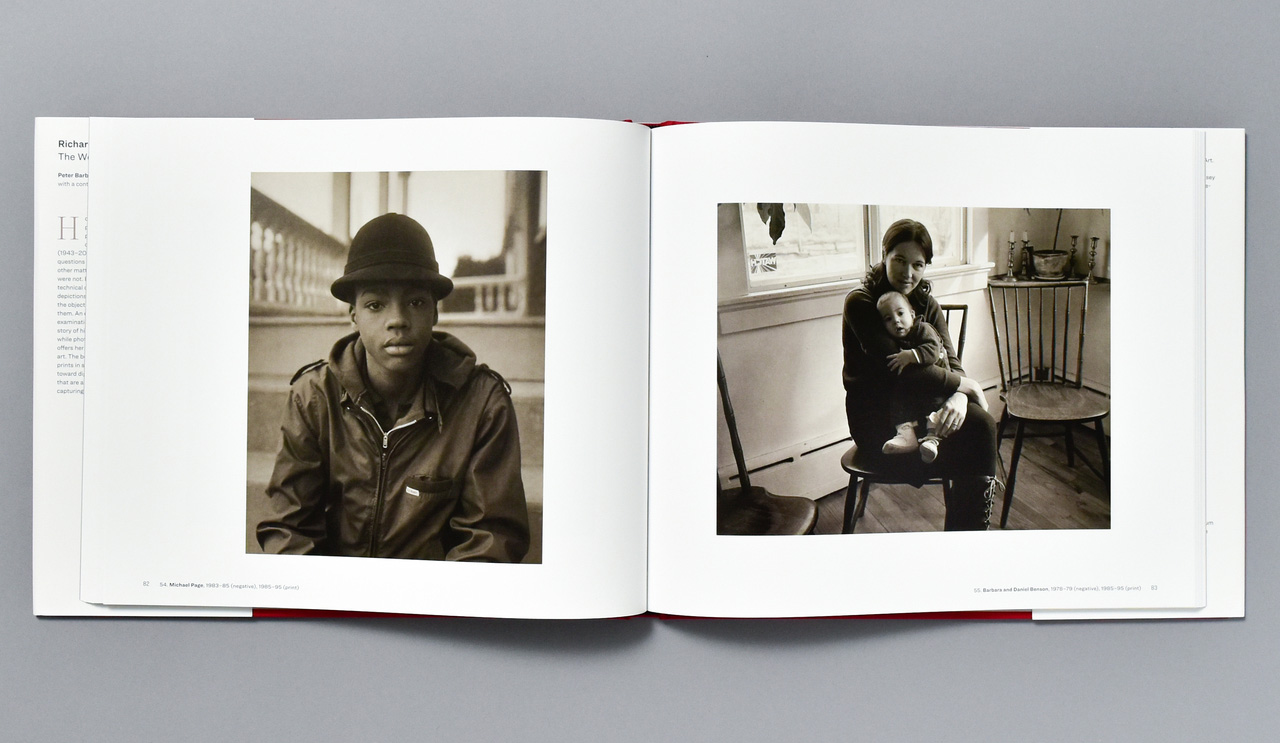

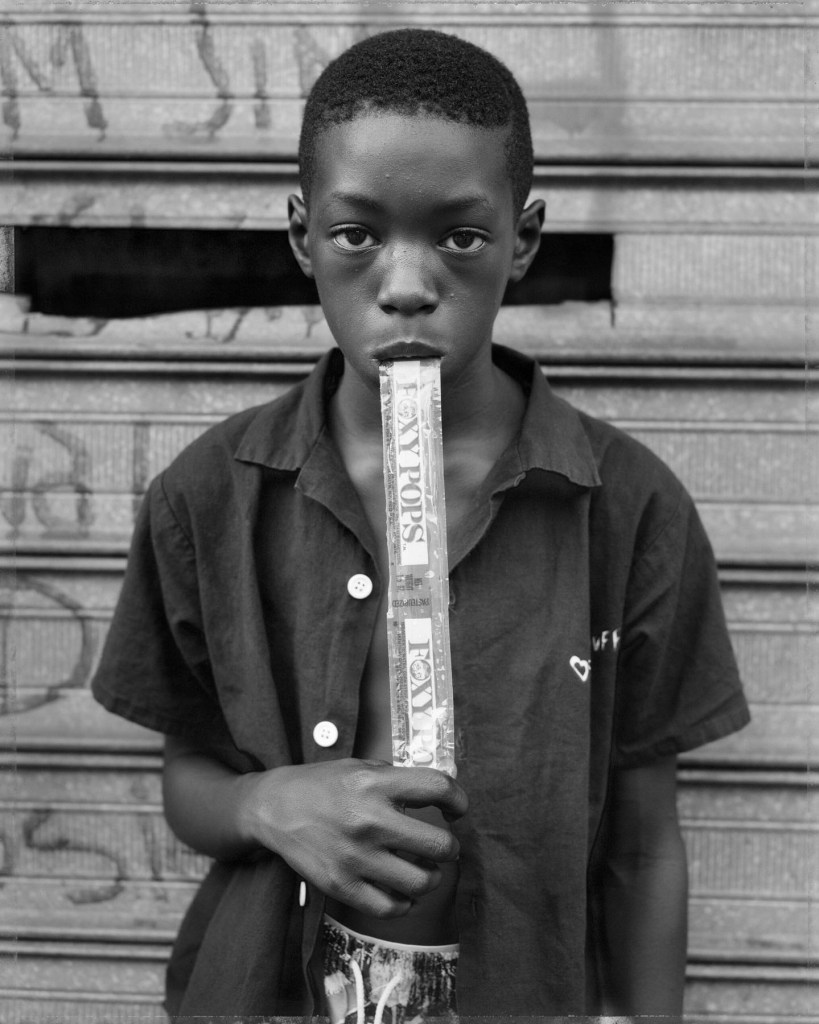

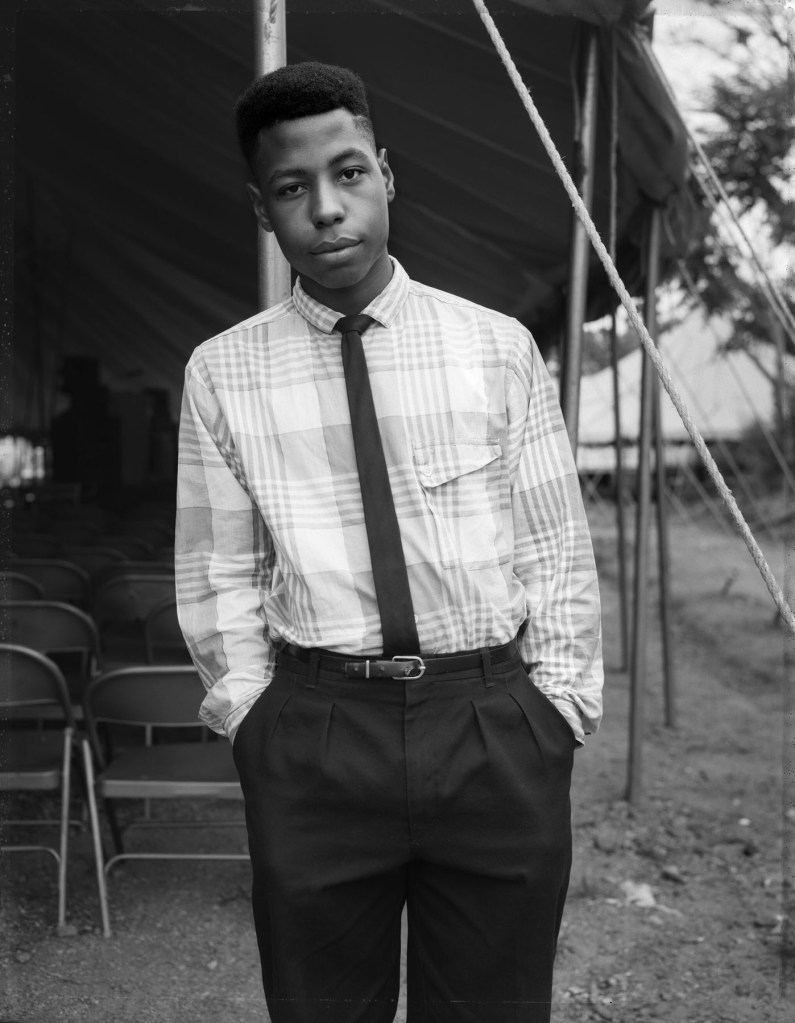

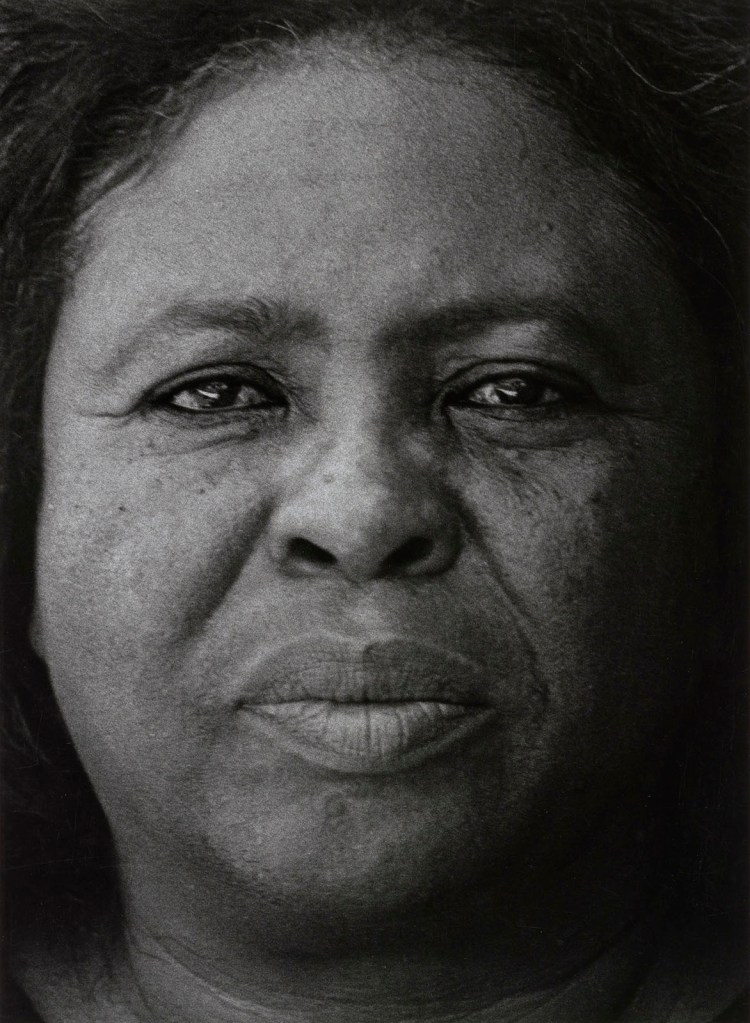

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Bakhambile Skhosana, Natalspruit

2010

From the series Faces and Phases, 2007-2010

Gelatin silver print

Image: 76.5 x 50.5cm

© Zanele Muholi

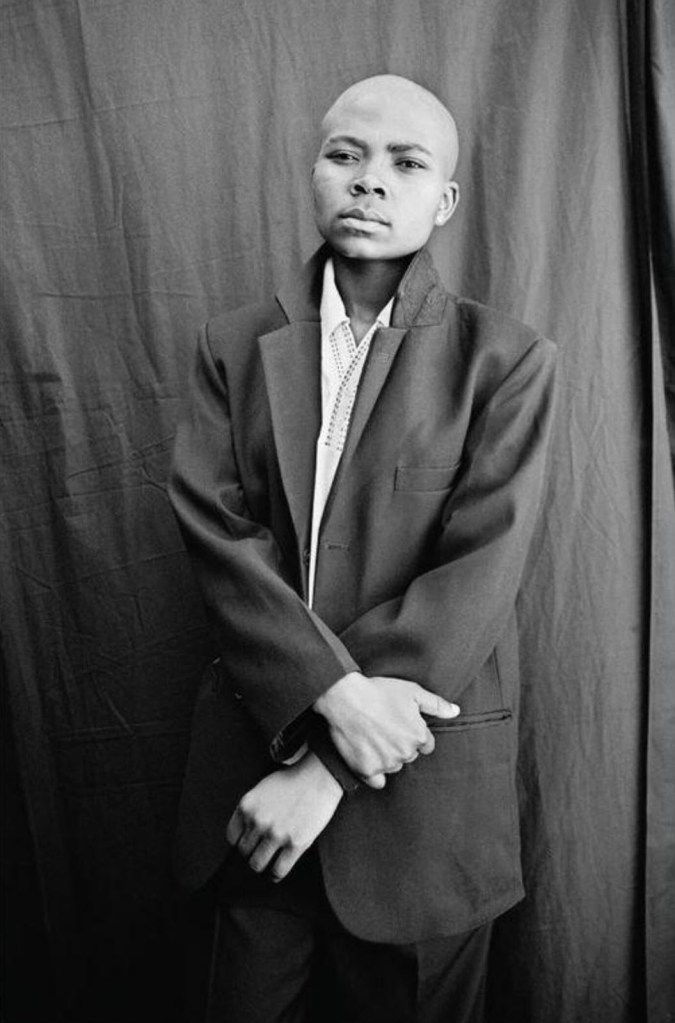

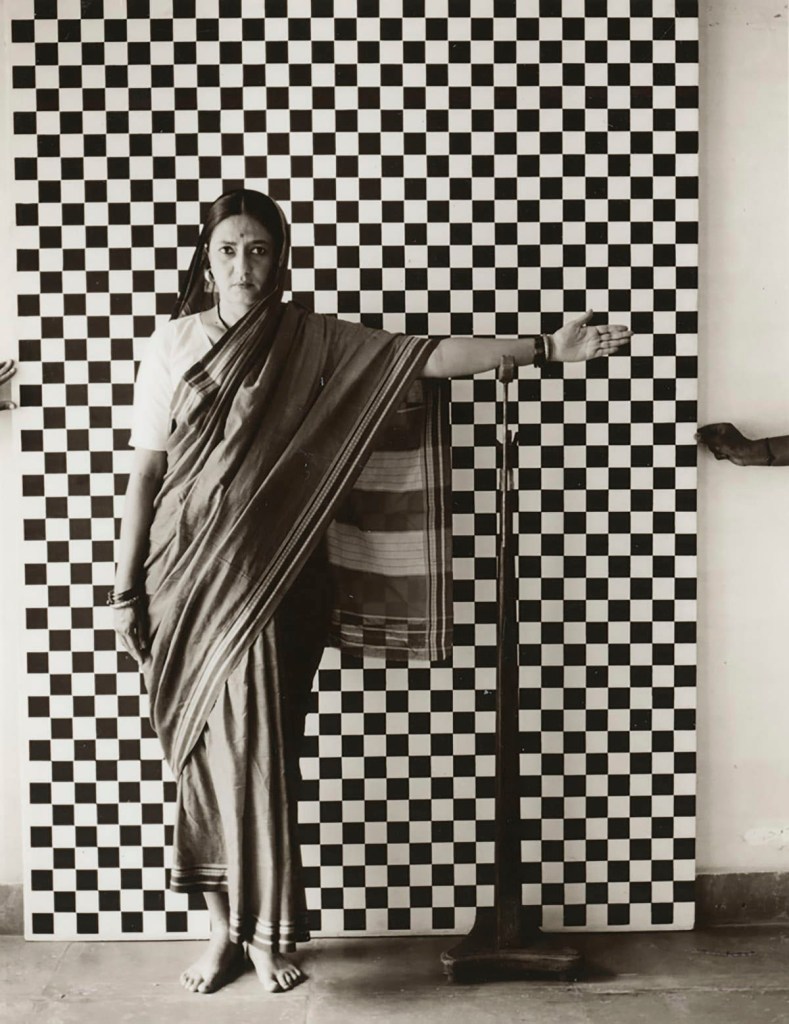

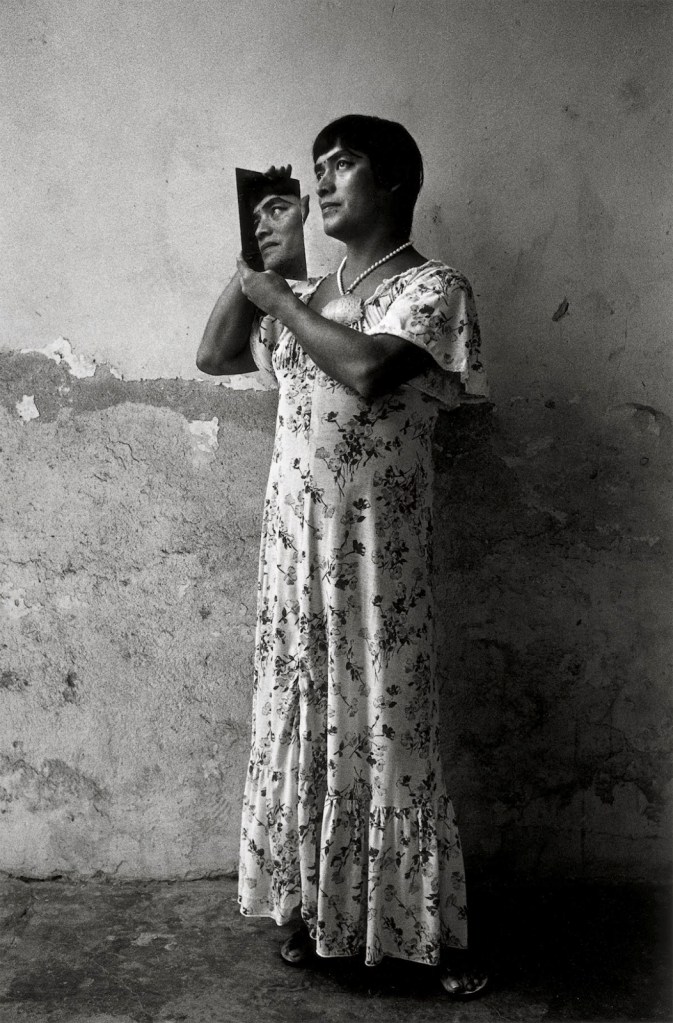

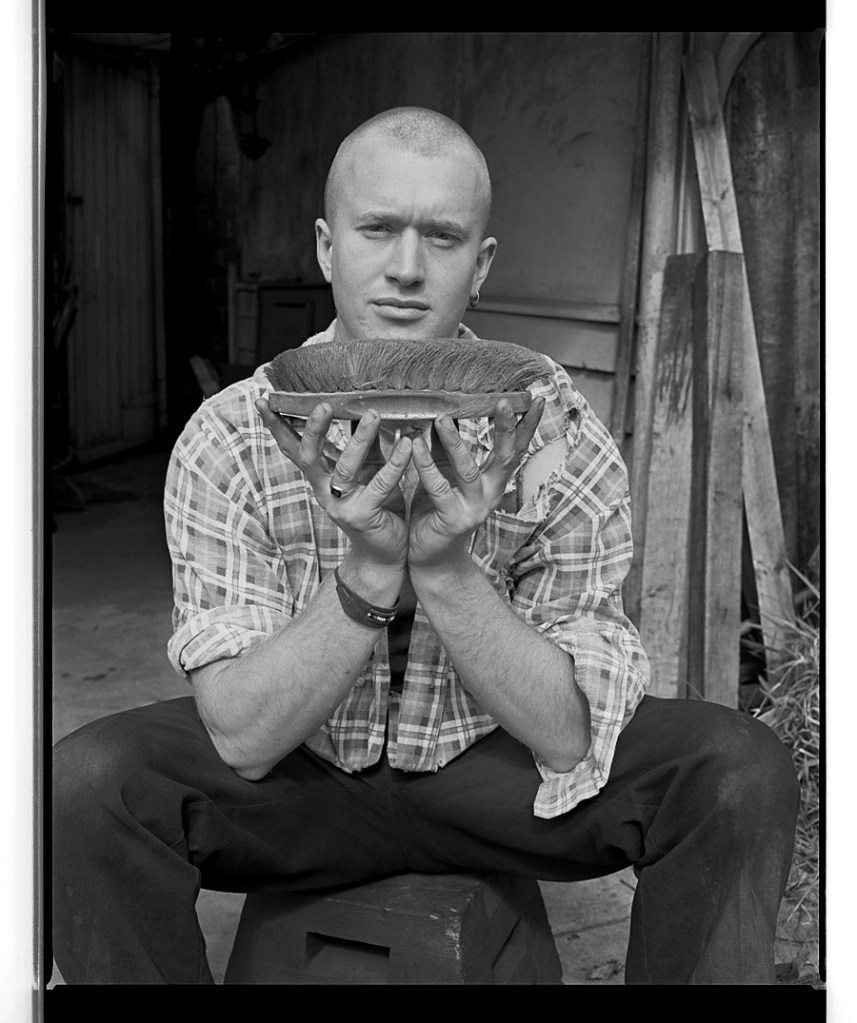

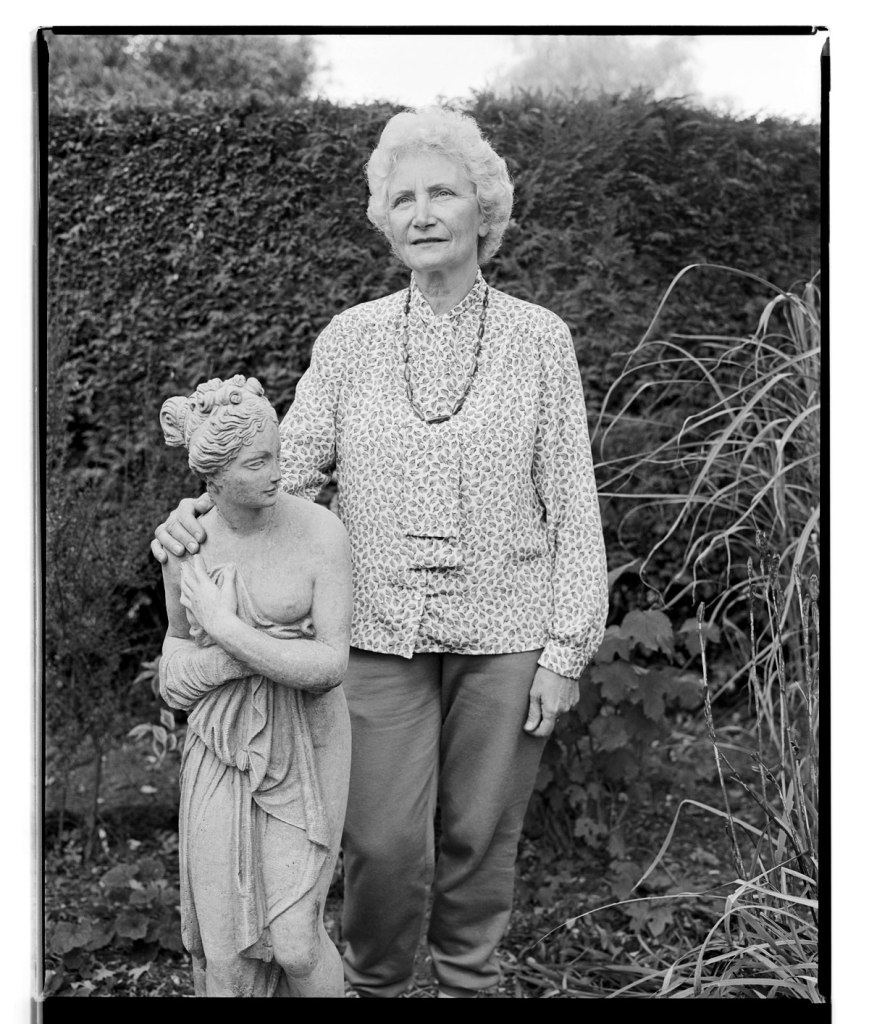

Award-winning photographer Zanele Muholi’s images offer a bold stance against the stigmatisation of lesbian and gay sexualities in Africa and beyond. The ‘Faces and Phases’ series of black and white portraits by Zanele Muholi focuses on the commemoration and celebration of black lesbians’ lives. Muholi embarked on this project in 2007, taking portraits of women from the townships in South Africa. In 2008, after the xenophobic and homophobic attacks that led to the mass displacement of people in that country, she decided to expand the ongoing series to include photographs of woman from different countries. Collectively, the portraits are an act of visual activism. Depicting women of various ages and backgrounds, this gallery of images offers a powerful statement about the similarities and diversity that exist within the human race.

“I am producing this photographic document to encourage people to be brave enough to occupy space, brave enough to create without fear of being vilified … To teach people about our history, to re-think what history is all about, to re-claim it for ourselves, to encourage people to use artistic tools such as cameras as weapons to fight back … forcing the viewer to question their desire to gaze at images of my black figure”

Faces and Phases is a commemoration and celebration of black lesbians, Transgender individuals and Gender non-conforming people from South Africa and beyond. Muholi embarked on this project in 2006. To date, more than 500 portraits are part of this series. Collectively, the portraits are an act of visual activism, depicting participants of various ages, backgrounds and at different stages of their lives. Faces and Phases started months before the Civil Union Act was passed in 2006, legalising same-sex marriage in South Africa. Muholi was aware of the absence of this community from visual history. Choosing to photograph people they know, the artist has maintained these relationships across time, producing follow-up images of some participants in different periods of their lives. The project is a living archive, and Muholi continues to introduce the audience to new participants.

“[The project] started in 2006 and I dedicated it to a good friend of mine who died from HIV complications in 2007, at the age of twenty-five. I just realized that as black South Africans, especially lesbians, we don’t have much visual history that speaks to pressing issues, both current and also in the past. South Africa has the best constitution on the African continent and, dare I say, world – when it comes to recognizing LGBTI (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Intersex) persons and other sexual minorities. It is the only country on the continent that legalised same-sex marriage in 2006. I thought to myself that if you have remarkable women in America and around the globe, you equally have remarkable lesbian women in South Africa.

We should be counted and certainly counted on to write our own history and validate our existence. We should not feel that somebody owes us these liberties. So, it’s another way in which I personally claim my full citizenship as a South African photographer, as a South African female in this space, as a South African who identifies as black, and also as a lesbian. I’m basically saying we deserve recognition, respect, validation, and to have publications that mark and trace our existence.”

Anonymous text. “Zanele Muholi’s Faces & Phases,” on the Aperture Magazine website April 21, 2015 [Online] Cited 22/04/2022

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Sosi Molotsane, Yeoville, Johannesburg

2007

From the series Faces and Phases, 2007-2010

Gelatin silver print

Image: 76.5 x 50.5cm

© Zanele Muholi

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Nosipho ‘Brown’ Solundwana, Parktown, Johnannesburg

2007

From the series Faces and Phases, 2007-2010

Gelatin silver print

Image: 76.5 x 50.5cm

© Zanele Muholi

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Amogelang Senokwane, District Six, Cape Town

2007

From the series Faces and Phases, 2007-2010

Gelatin silver print

Image: 76.5 x 50.5cm

© Zanele Muholi

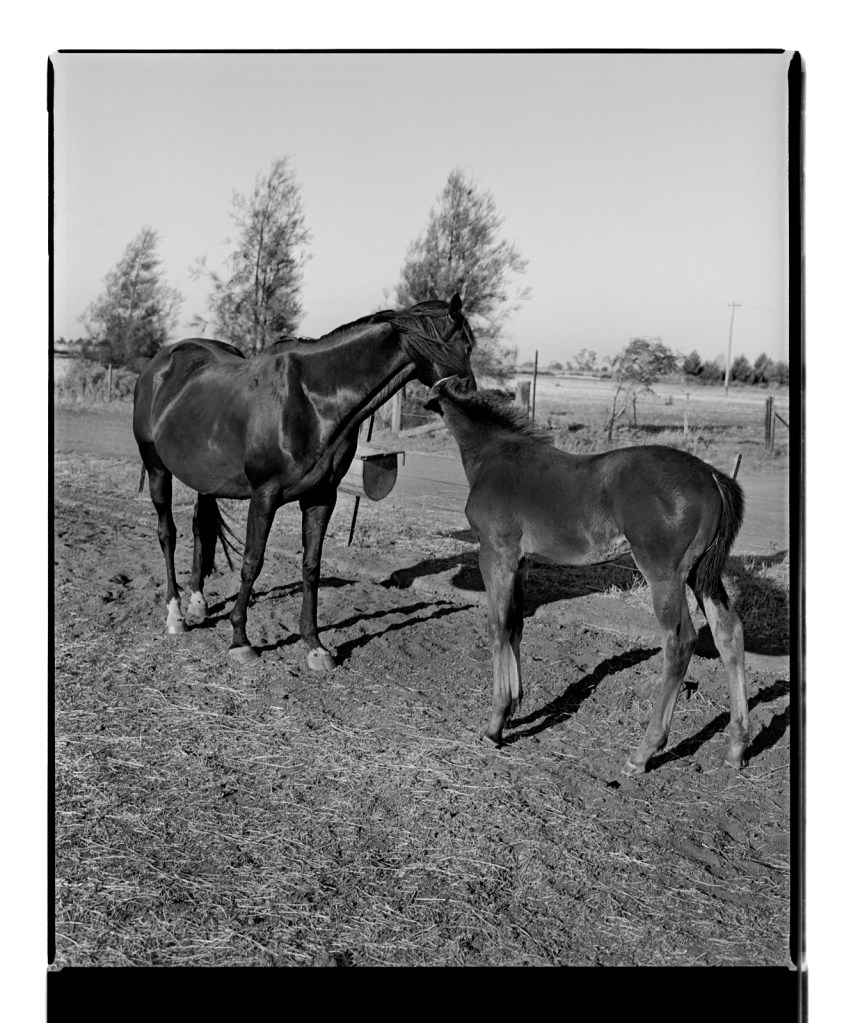

Rinko Kawauchi (Japanese, b. 1972)

Untitled

2011

From the series Illuminance

C-type print

Image: 101 x 101cm

Purchased with the support of Prix Pictet

© Rinko Kawauchi courtesy PRISKA PASQUER, Cologne

These photographs are from the series Illuminance, which was nominated for the Deutsche Börse prize in 2012. In this series, Kawauchi continues with many of the themes and techniques that informed her earlier work, such as her focus on ordinary subjects and everyday situations. Her use of cropping and offhand composition as well as the subtle use of natural light evoke a dreamlike, poetical element in her photographs. Her focus in ‘Illuminance’ is on depicting the fundamental cycles of life within a personal interpretation, as well as exploring the seemingly inadvertent patterns that can be found in the natural world.

Text from the V&A website

Ten years after her precipitous entry onto the international stage, Aperture has published Illuminance (2011), the latest volume of Kawauchi’s work and the first to be published outside of Japan. Kawauchi’s photography has frequently been lauded for its nuanced palette and offhand compositional mastery, as well as its ability to incite wonder via careful attention to tiny gestures and the incidental details of her everyday environment. As Sean O’Hagan, writing in The Guardian in 2006, noted, “there is always some glimmer of hope and humanity, some sense of wonder at work in the rendering of the intimate and fragile.” In Illuminance, Kawauchi continues her exploration of the extraordinary in the mundane, drawn to the fundamental cycles of life and the seemingly inadvertent, fractal-like organisation of the natural world into formal patterns. Gorgeously produced as a clothbound volume with Japanese binding, this impressive compilation of previously unpublished images – which garnered Kawauchi a nomination for the Deutsche Börse Prize – is proof of her unique sensibility and ongoing appeal to lovers of photography.

Text from the Amazon website

In the words of the exhibition’s curator Verena Kaspar-Eisert:

The mindful awareness of what is special in simple things – which Rinko Kawauchi dedicates herself to in her photographs – must be contemplated on the background of the aesthetic concept of wabi-sabi. This philosophy postulates reduction, modesty and a symbiotic relationship with nature and is applied to many areas of life, whether architecture, dance, tea ceremonies or haiku poetry. Wabi-sabi allows room for “mistakes.” Applied to photography, the goal is not the “perfect photograph;” rather, expressivity and depth make a picture meaningful – and therein lies its beauty.

Anonymous text. “Illuminance,” on the Lens Culture website Nd [Online] Cited 22/04/2022

Installation view of Known and Strange: Photographs from the Collection display at V&A showing at right the work of Rinko Kawauchi from the Illuminance series

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Rinko Kawauchi (Japanese, b. 1972)

Untitled

2011

From the series Illuminance

C-type print

Image: 101 x 101cm

Purchased with the support of Prix Pictet

© Rinko Kawauchi courtesy PRISKA PASQUER, Cologne

Rinko Kawauchi (Japanese, b. 1972)

Untitled

2011

From the series Illuminance

C-type print

Image: 101 x 101cm

Purchased with the support of Prix Pictet

© Rinko Kawauchi courtesy PRISKA PASQUER, Cologne

A photograph has the power to transform the familiar into the unfamiliar, and to make the ordinary extraordinary. Since its invention, photography has changed the way we see the world by inviting us to interpret reality in our own way. Its creative capacity to blur fact with fiction is the focus of Known and Strange: Photographs from the Collection .

The display showcases over 50 recent contemporary acquisitions for the V&A’s permanent collection, created by internationally well-known names and emerging talents, including Paul Graham, Susan Meiselas, Maurizio Anzeri, Tom Lovelace, Pierre Cordier, Klea McKenna, Donna Ruff and James Welling. These artists have expanded the ever-changing field of photography, both through stylistic experimentation and intellectual inquiry. Individually and collectively, their work represents some of today’s most compelling achievements in contemporary photography.

The display highlights the diversity of a medium that, through its malleability, enables many different perspectives to be captured. As viewers, we can challenge everyday assumptions, be reminded of the world’s wonders and, perhaps poignantly, become aware that we might not be able to witness everything we want to during our own comparatively fleeting lives. The title Known and Strange, originally a line from the poem ‘Postscript’ by Seamus Heaney, is borrowed from a series of photographs by Andy Sewell. It captures the sentiment of the full collection of works on display.

The internet, carried by cables along the seabed, and the ocean above them are both vast and unknowably strange. In his series of photographs taken on either side of the Atlantic, Andy Sewell explores an entwining of ‘separate’ worlds – the immediate and distant, physical and virtual, natural and technological. Sewell describes how “the boundaries we put between things are more permeable than we might like to think. The objects surrounding us, appearing so reliable and mundane, are actually parts of much larger, more complex bodies extended across space and time”.

Tereza Zelenková is known for her imaginative explorations of mysticism. She is inspired by literature and philosophy, but also values intuition and coincidence as essential guides in her creative process. Zelenková’s work peels back the layers of myth that build up over time. Her photographs demonstrate how she interrogates the past, probing at folklore and overlaying a modern sense of surrealism onto objects that are loaded with history.

Dafna Talmor transforms her own photographs of landscapes by cutting them up and recombining them to create new hybrid compositions. Her work retains ghostly traces of the original locations through multiple negatives shot from different positions and places. She says “the idea that a single image is somehow insufficient is one that is also close to my own heart – particularly when that image fails to capture whatever it was about a site that motivated us to photograph it in the first place”.

Zanele Muholi‘s work exposes the persistent violence and discrimination faced by the South African Black LGBTQIA+ community. Describing themself as a visual activist, for this ongoing series Muholi photographed over 300 Black people living in South Africa who identify as lesbian, queer, trans or gender non-conforming, ranging from a soccer player to a dancer, a scholar to an activist. The portraits and their accompanying testimonies celebrate and empower each participant and, in Muholi’s words, are “a visual statement and an archive, marking, mapping and preserving an often-invisible community for posterity”.

Rinko Kawauchi focuses on simple moments encountered in everyday life: light caught in a mirror, spiderwebs threaded across garden plants or water splashing into a metal sink. Through the unusual compositional choices and the transformative effects of natural light, the objects take on a new meaning, changed into something poetic. The studies appear intimate and instinctive, capturing Kawauchi’s personal observations and encouraging the viewer to find beauty in the ordinary.

In search of trees, Mitch Epstein wandered the streets of New York City. This leaning elm, simultaneously restricted and protected by its concrete support, is a symbol of nature in an otherwise urban landscape. Epstein opens our eyes to the trees rooted in New York and their often-hidden presence in the city. His practice deals with looking and seeing, exploring the way that nature – its adaptability and endurance – can go almost unnoticed in a big city.

Anonymous text. “About the Known & Strange display,” on the V&A website Nd [Online] Cited 22/04/2022

Dafna Talmor

Untitled (NE-04040404-1)

2015

From the series Constructed Landscapes

C-type print

30.48 x 25.4cm

Purchase funded by the Photographs Acquisition Group

© Dafna Talmor

Constructed Landscapes is an ongoing project that stems from Talmor’s personal archive of photographs initially shot as mere keepsakes across different locations that include Venezuela, Israel, the US and UK. Produced by collaging medium format colour negatives, the process relies on experimentation, involving several incisions and configurations before a right match is achieved.

Transformed through the act of slicing and splicing, the resulting images are staged landscapes, a conflation combining the ‘real’ and the imaginary. Through this work, specific places initially loaded with personal meaning and political connotations, are transformed into a space of greater universality. Blurring place, memory and time, the work alludes to idealised and utopian spaces.

In Constructed Landscapes, condensing multiple time frames by collaging negatives to construct an image transfers the notion of the ‘decisive moment’ from the photographic act to the act of assembling and printing in the darkroom. In turn, fragments of varying source images collide and collude to create an illusory landscape; gaps and voids where negatives fail to meet or overlap mimic (and form new) elements of landscape, disrupting composition and distorting perspective.

In dialogue with the history of photography, Constructed Landscapes references Pictorialist processes of combination printing as well as Modernist experiments with the materiality of film. Whilst distinctly holding historical references, the work engages with contemporary discourse on manipulation, the analogue / digital divide and its effect on photography’s status.

Anonymous text. “Dafna Talmor | Constructed Landscapes,” on the Photofusion website Nd [Online] Cited 23/04/2022

Dafna Talmor

Untitled (JE-12121212-2)

2015

From the series Constructed Landscapes

C-type print

Purchase funded by the Photographs Acquisition Group

© Dafna Talmor

Installation view of Known and Strange: Photographs from the Collection display at V&A showing at second right, Klea McKenna’s Life Hours (4)

(2019, below); and at far right, Dafna Talmor’s Untitled (JE-12121212-2) (2015, above)

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

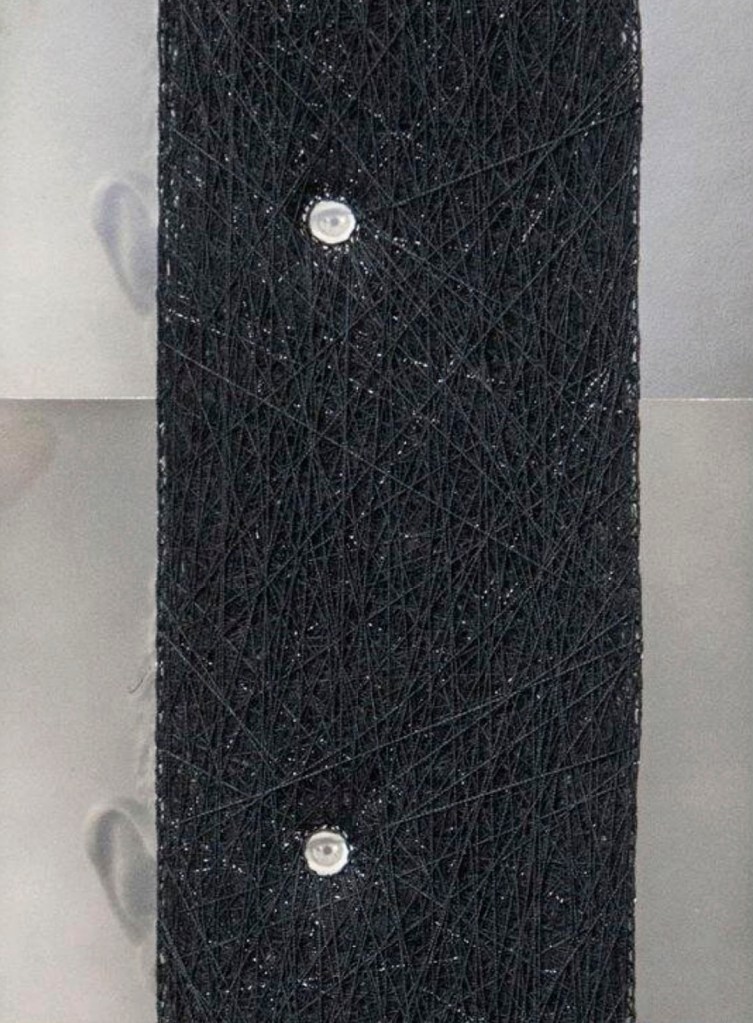

Klea McKenna (American, b. 1980)

Life Hours (4)

2019

From the series Generation

Gelatin silver photogram

Gift of Jim and Ruth Grover

© Klea McKenna

The strength of a photogram is that it physically meets its subject and records that touch, the mark of an interaction. Photography, throughout its short history, has been modelled after the vision of an eye; a lens opens to record the light reflecting off of the world around it. By subverting this intended use and making touch more primary than sight, I urge my already antiquated medium forward – asking it to transcribe texture, pressure and force – to read the surface of the world in a new way. I use simple materials – analog light-sensitive paper, my hands, a flashlight and sometimes an etching press – to make “photographic rubbings” and “photographic reliefs”. In darkness, I emboss the paper onto the surface of patterns from the landscape or artefacts of material culture and then cast light onto the resulting textures. This method of working feels simultaneously like reading braille, like prayer and like gambling. Risk, faith, and touching the unknowable are all part of my practice. This method is unruly, revealing nuance beyond what my eyes or fingertips can confirm and inventing new marks along the way: evidence of the friction and limitations of my materials. Yet, even when used in this crude and unbidden way, photography has a gift for describing the strange detail of reality.

In “Generation” I apply this method to textiles and clothing from the last two centuries, objects rich in touch, from the labor of their making to the marks of wear. With each alteration, mending, and use someone has inscribed themselves onto these textiles. Just as each garment was made through the patient labor of one woman’s body, so is it undone that way, worn-down slowly, deconstructed, or cannibalised to make something new. The history of textiles, of clothing and style is made up of a million stories of migration, cultural appropriation and women’s labor and sexuality. They each contain moments of aesthetic innovation and decades of ordinary devotion.

I begin by researching each garment’s origin, construction, intended meaning and broader representation, piecing together a possible history from the available world of text and images. This is a poetic form of research; simultaneously a inquiry into what one can learn from a physical object – history having inscribed itself on the material world – and an acknowledgement of how little I can know from this distance; how much these textures show only the surface of someone’s experience and nothing of it’s interior. My goal is to find a fracture, an insight that allows me to re-animate these objects and illuminate them. My inquiry is evidenced in “Legend”, a printed journal that is a companion piece and key to these photographic reliefs. When amassed, this deluge of reference images becomes a visual history not of the textiles themselves, but of changing notions of femininity and ornament and of the West’s relentless appropriation of traditional fashion, patterns and symbols. It is a glimpse into a chaotic flowchart of influences, trends and the migration of objects that has shaped what women make and wear. My process of applying pressure – even to the point of disintegration – is driven by a desire for haptic communication with a distant time and place.

Klea McKenna. “Generation,” on the Lens Culture website Nd [Online] Cited 24/02/2022

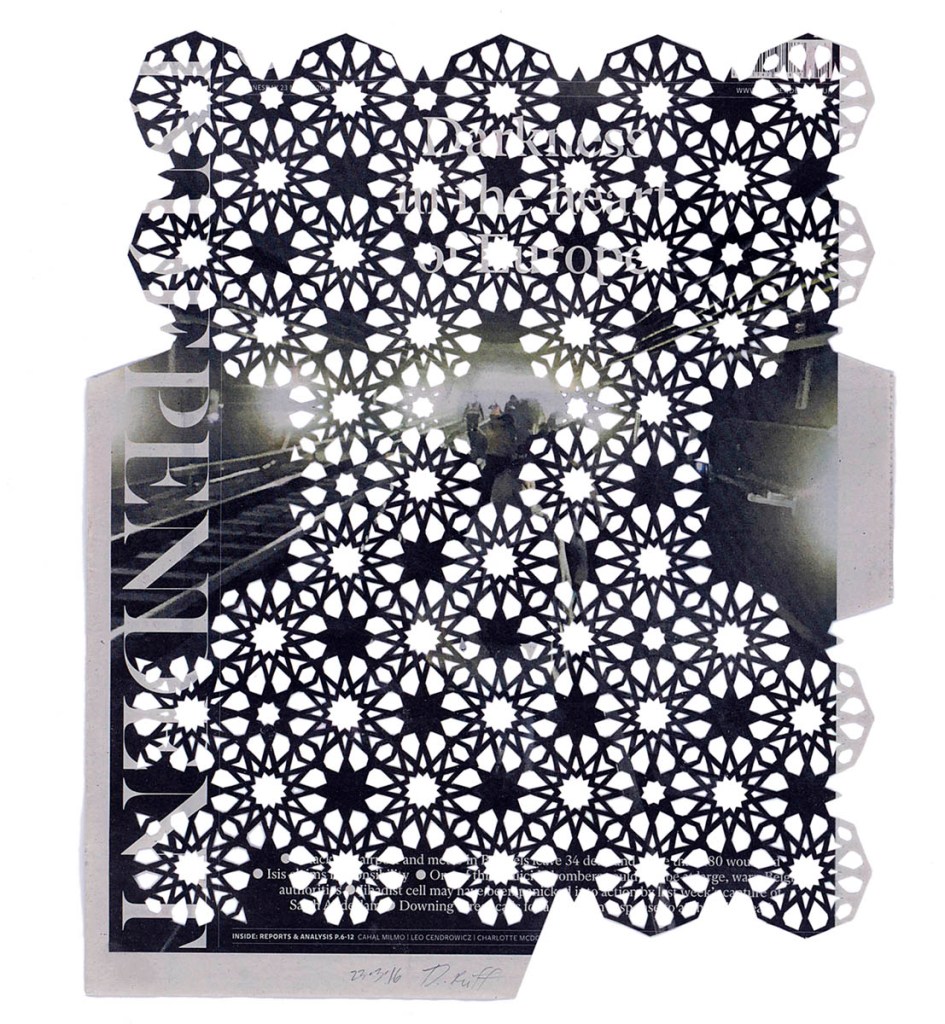

Donna Ruff (American, b. 1947)

23.3.16

2016

From the series Migrant, 2011-2016

Hand-cut pattern on deacidified newspaper

Purchase funded by the Photographs Acquisition Group

© Donna Ruff

Ruff’s Migrant Series uses cover pages from The New York Times as a point of departure; she has reshaped them with intricate cutouts that offer an alternative reading. Her hand-cut templates prioritise images over journalistic framing, and in a sense, people over politics. Her intricate patterns reflect designs found in Moorish tile work and screens found in the Middle East, Spain, and North Africa, while many of the highlighted images feature migrants, some juxtaposed with text or images specific to American culture – an image of Donald Trump or a headline referencing a Kardashian.

iana McClure. “Ima Mfon: Nigerian Identities / Donna Ruff: The Migrant Series at Rick Wester Fine Art,” on the Photograph website April 8, 2017 [Online] Cited 22/04/2022

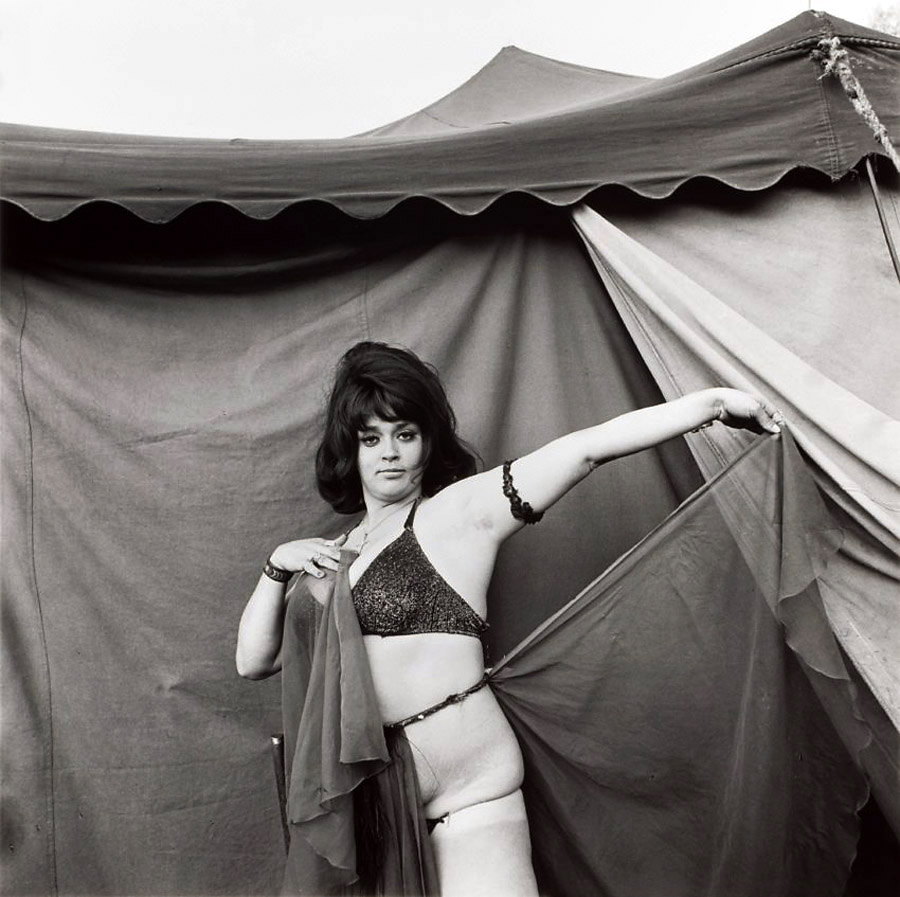

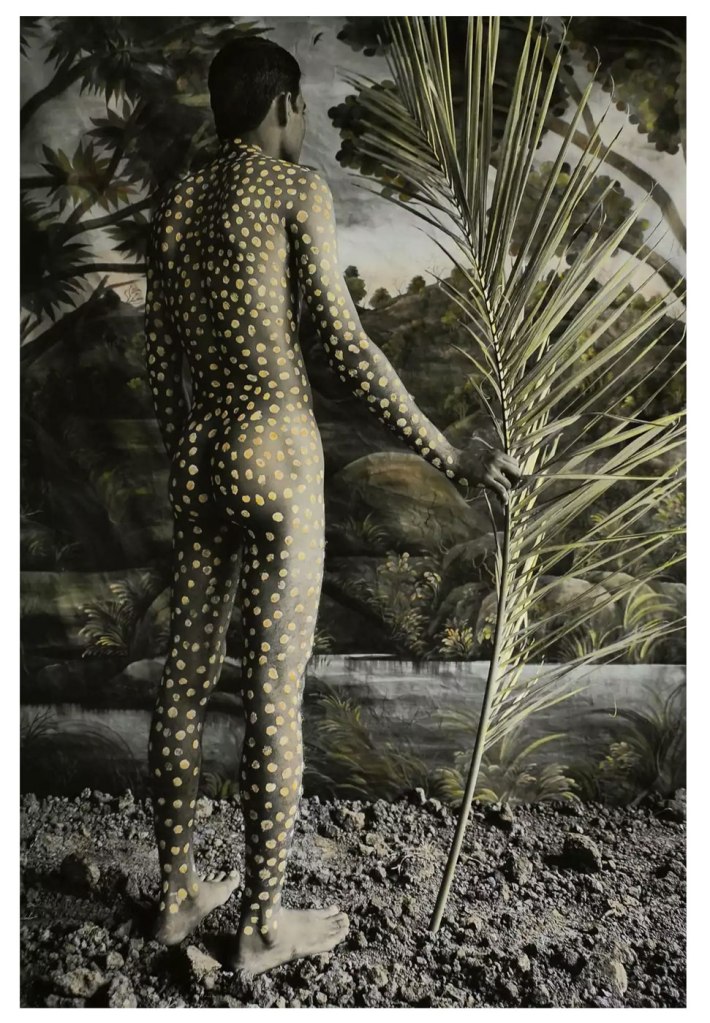

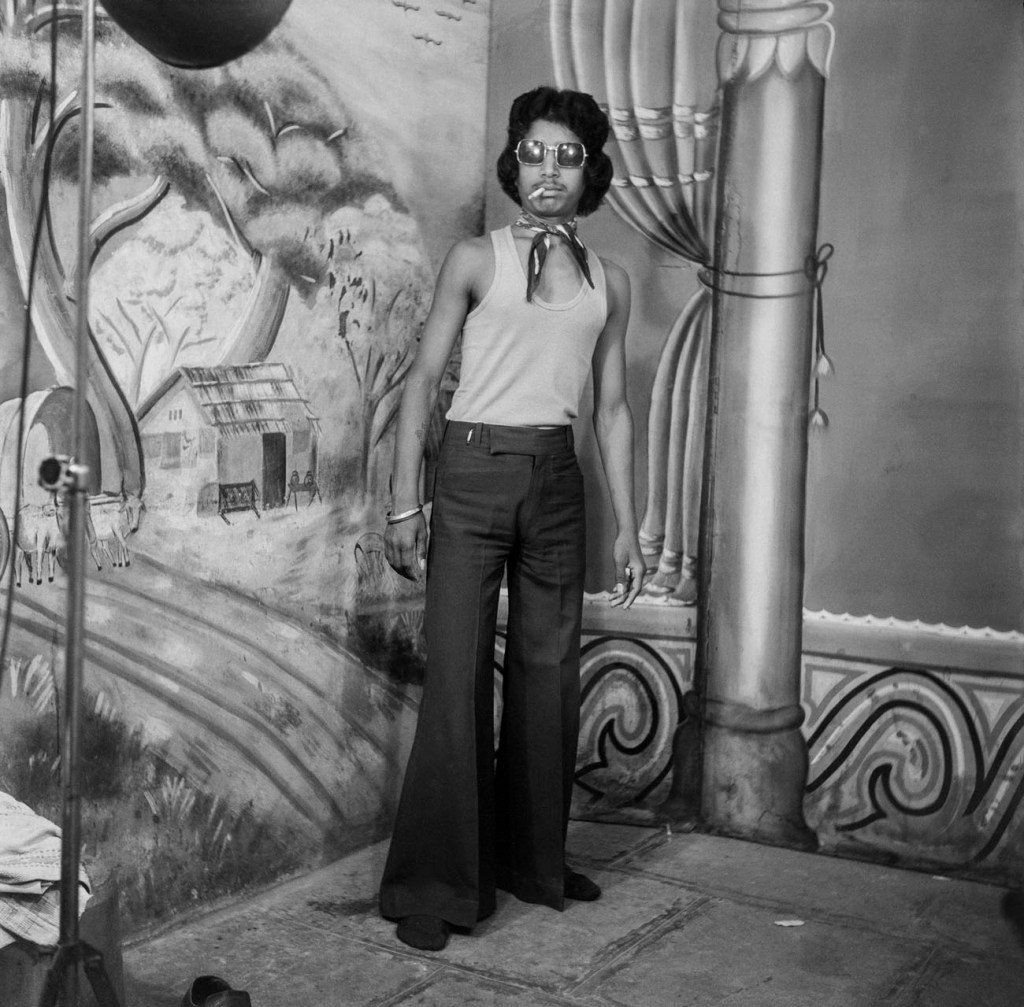

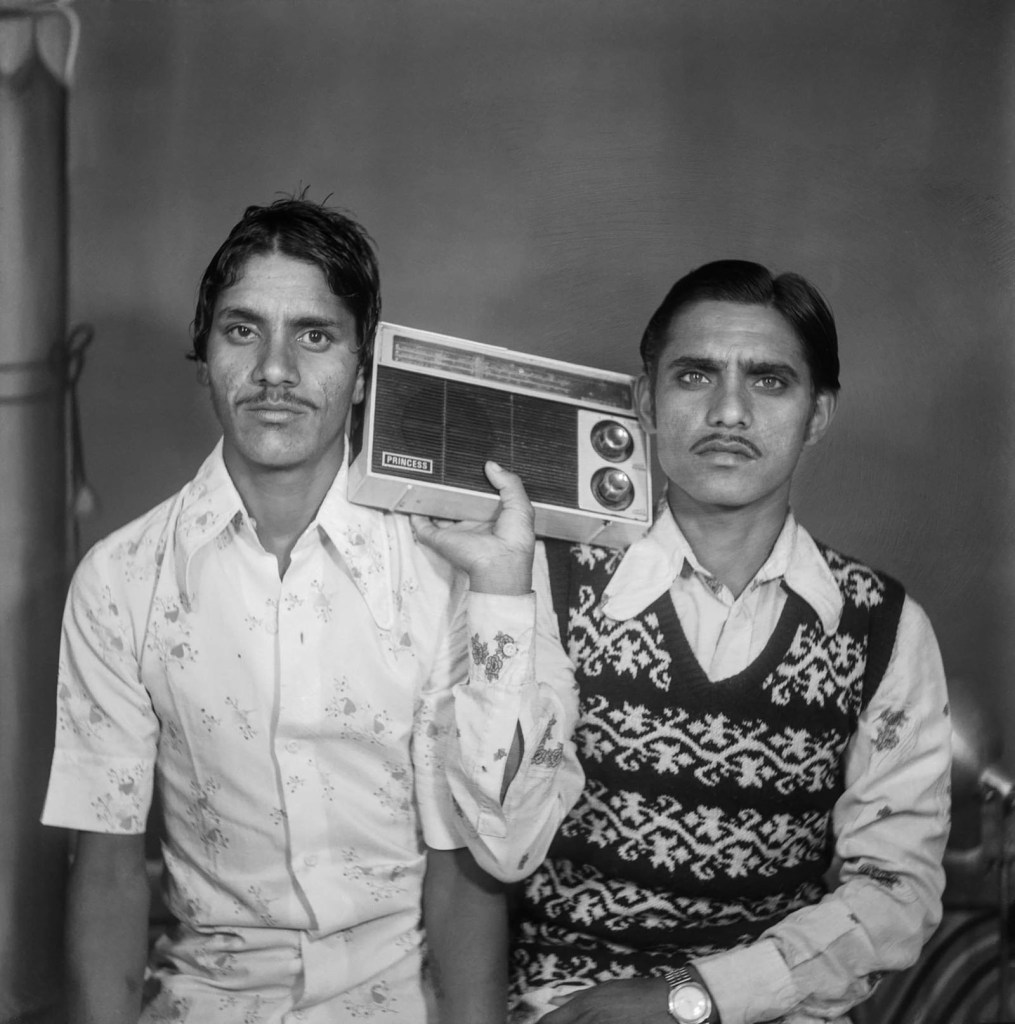

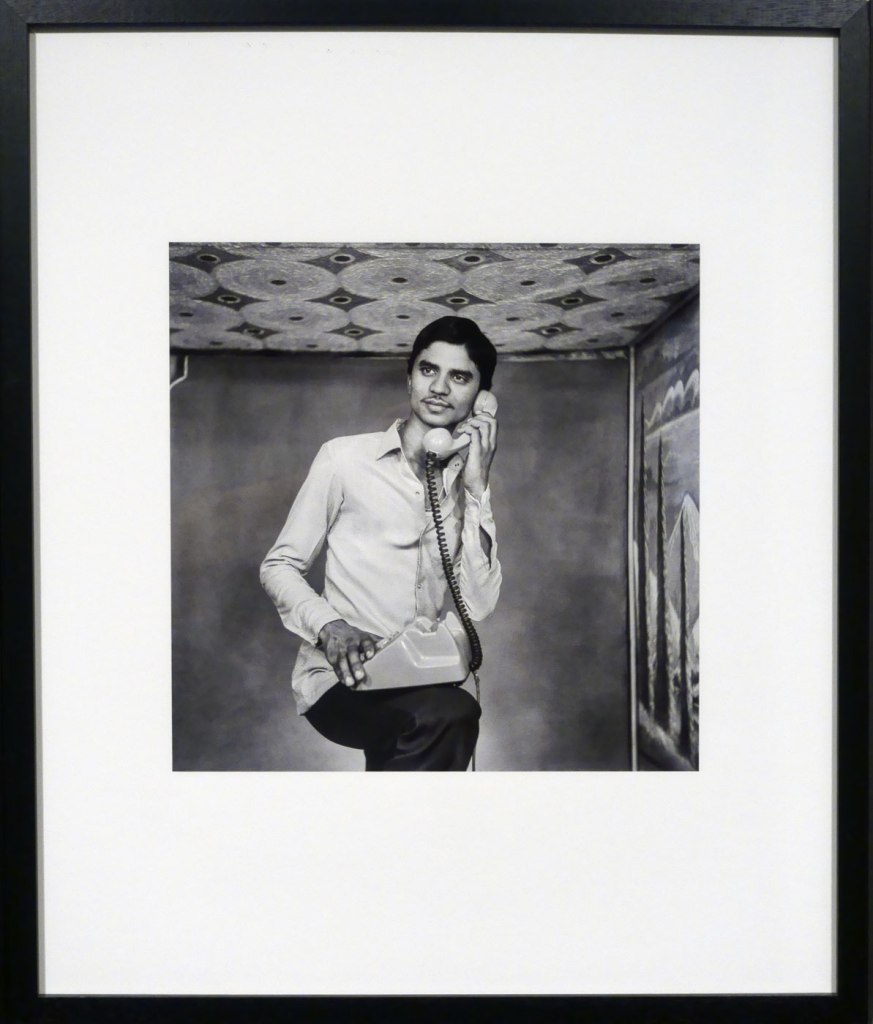

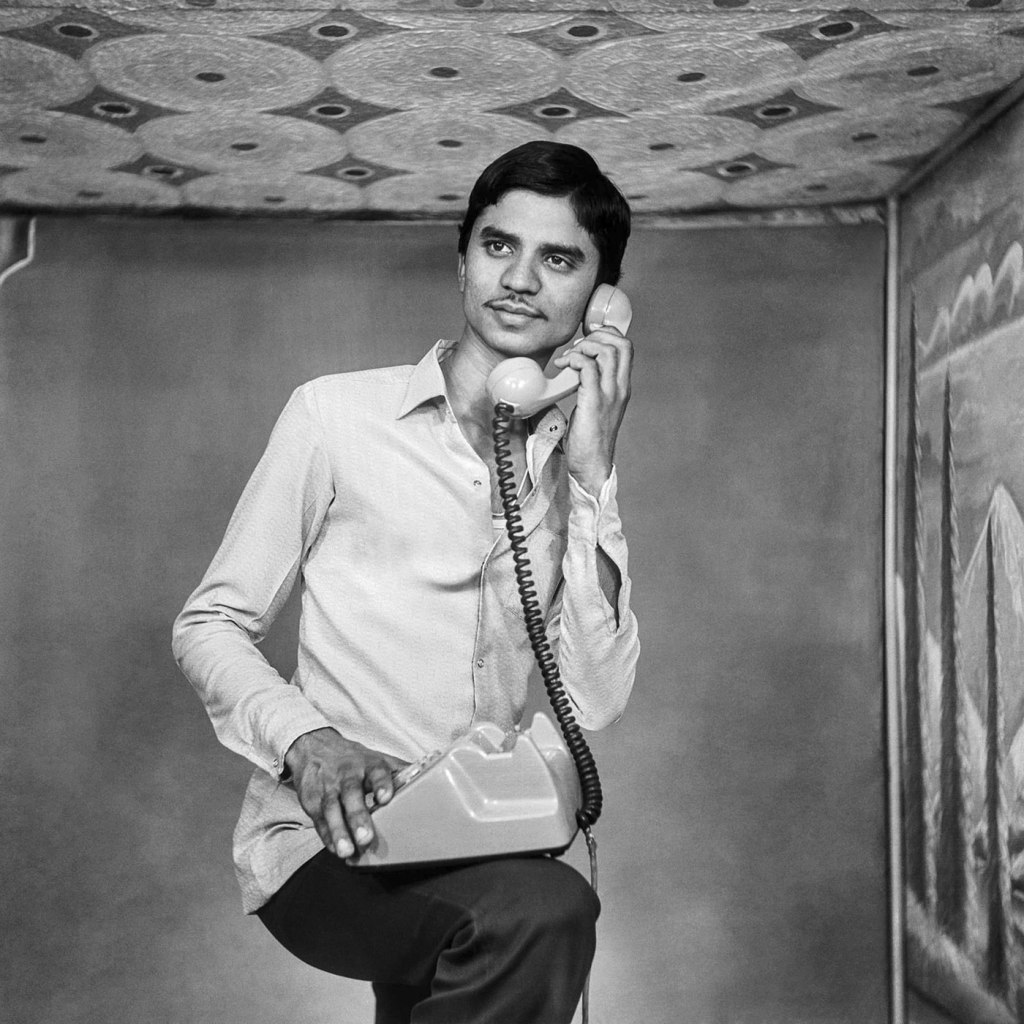

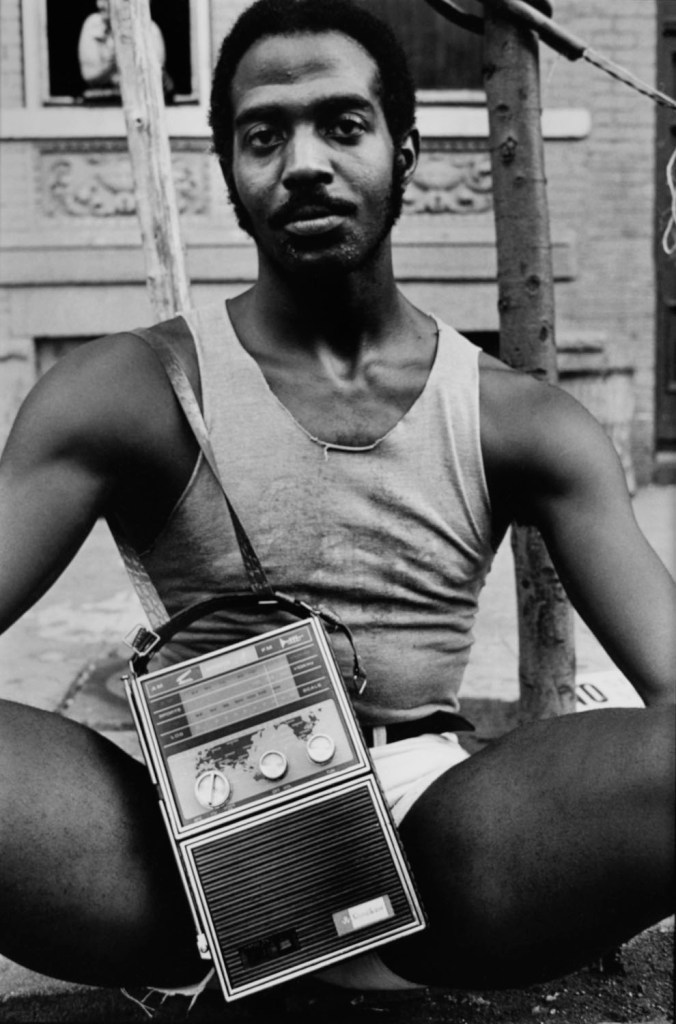

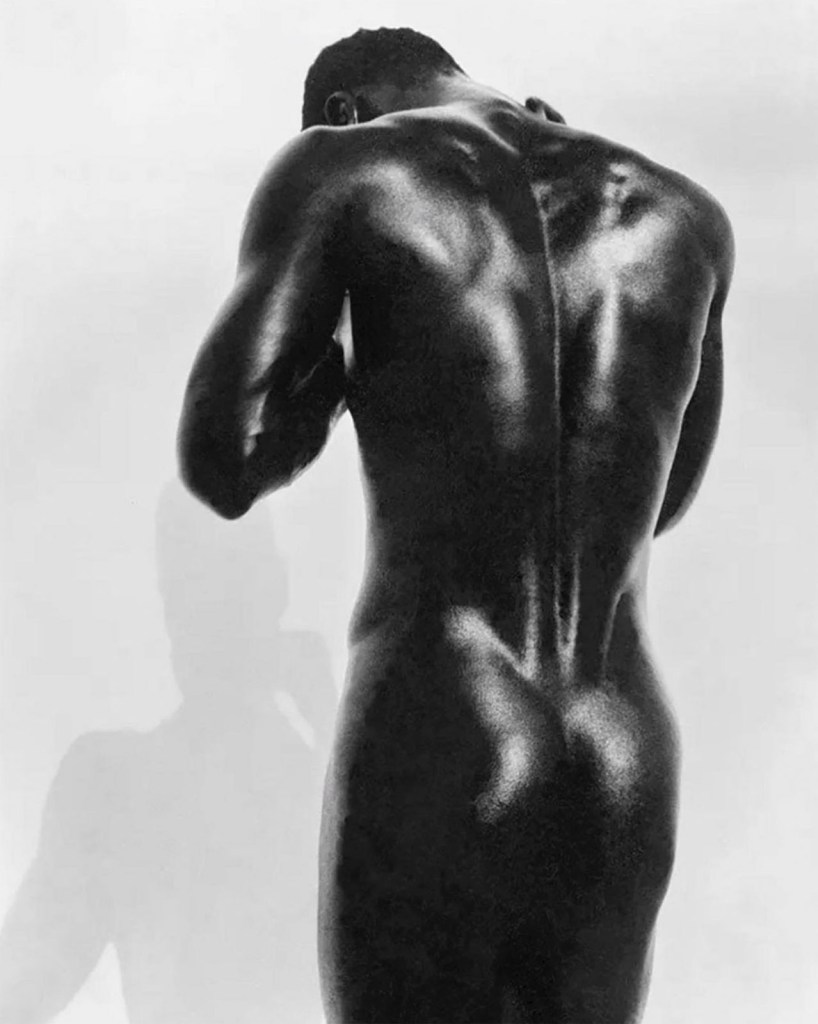

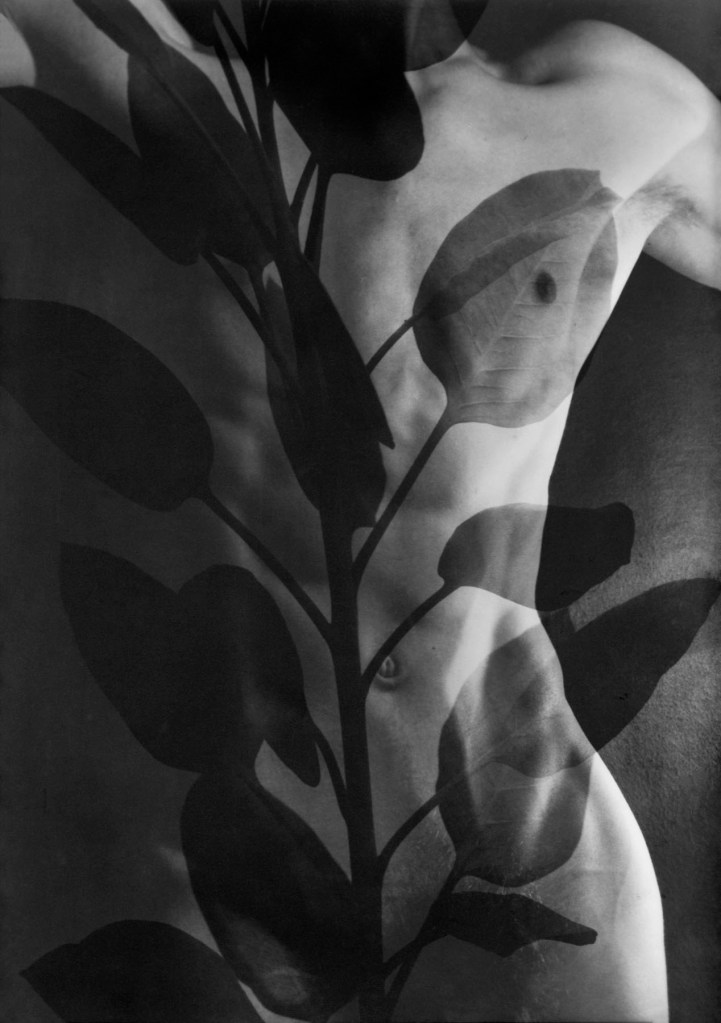

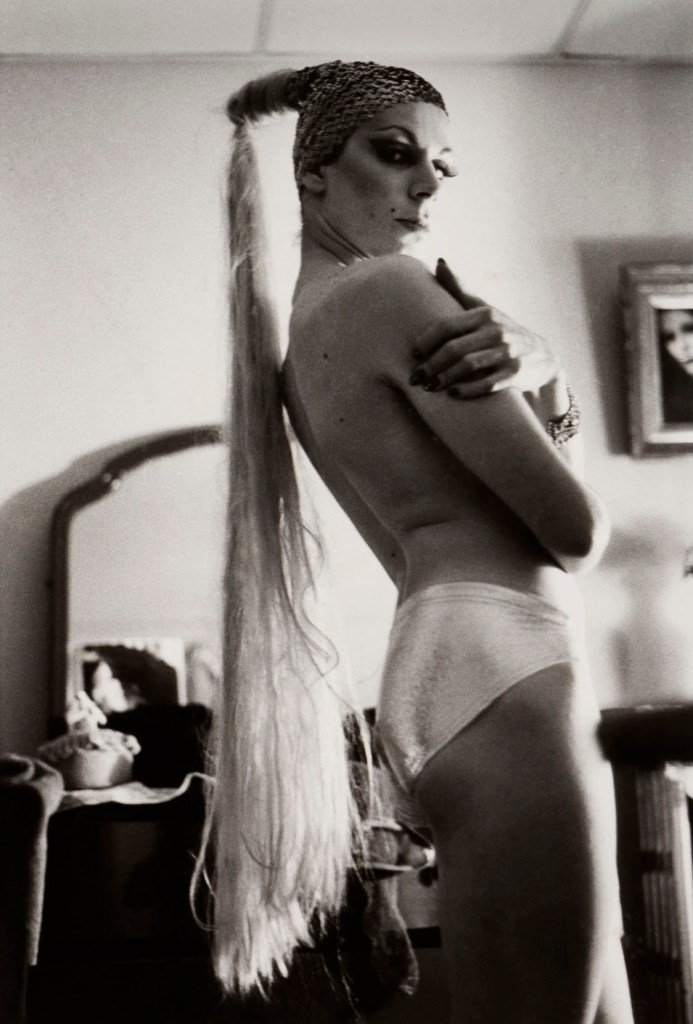

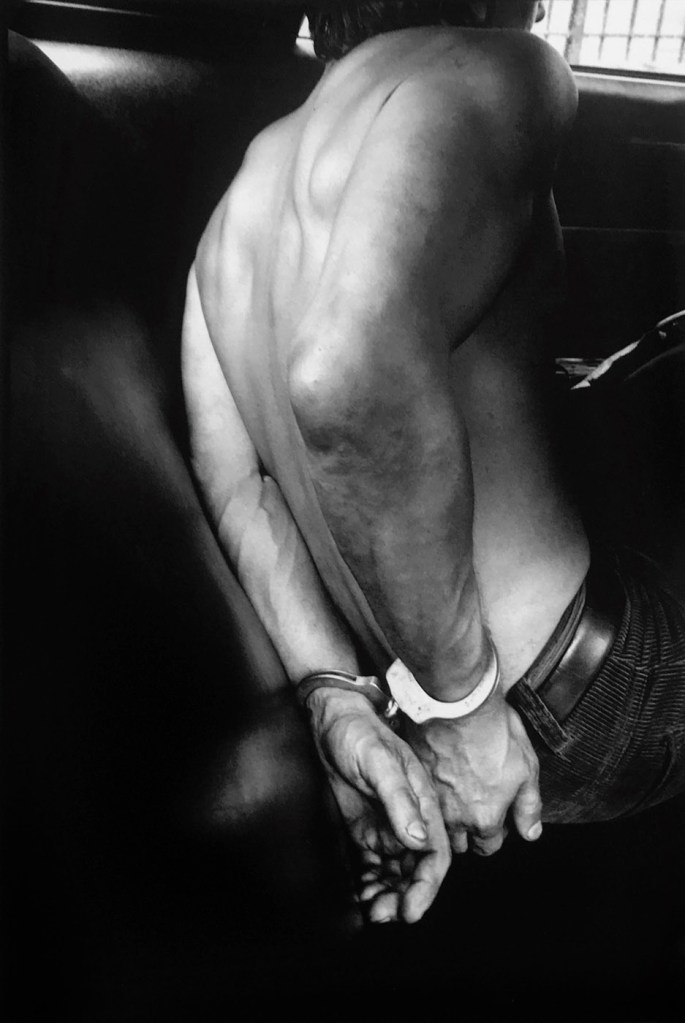

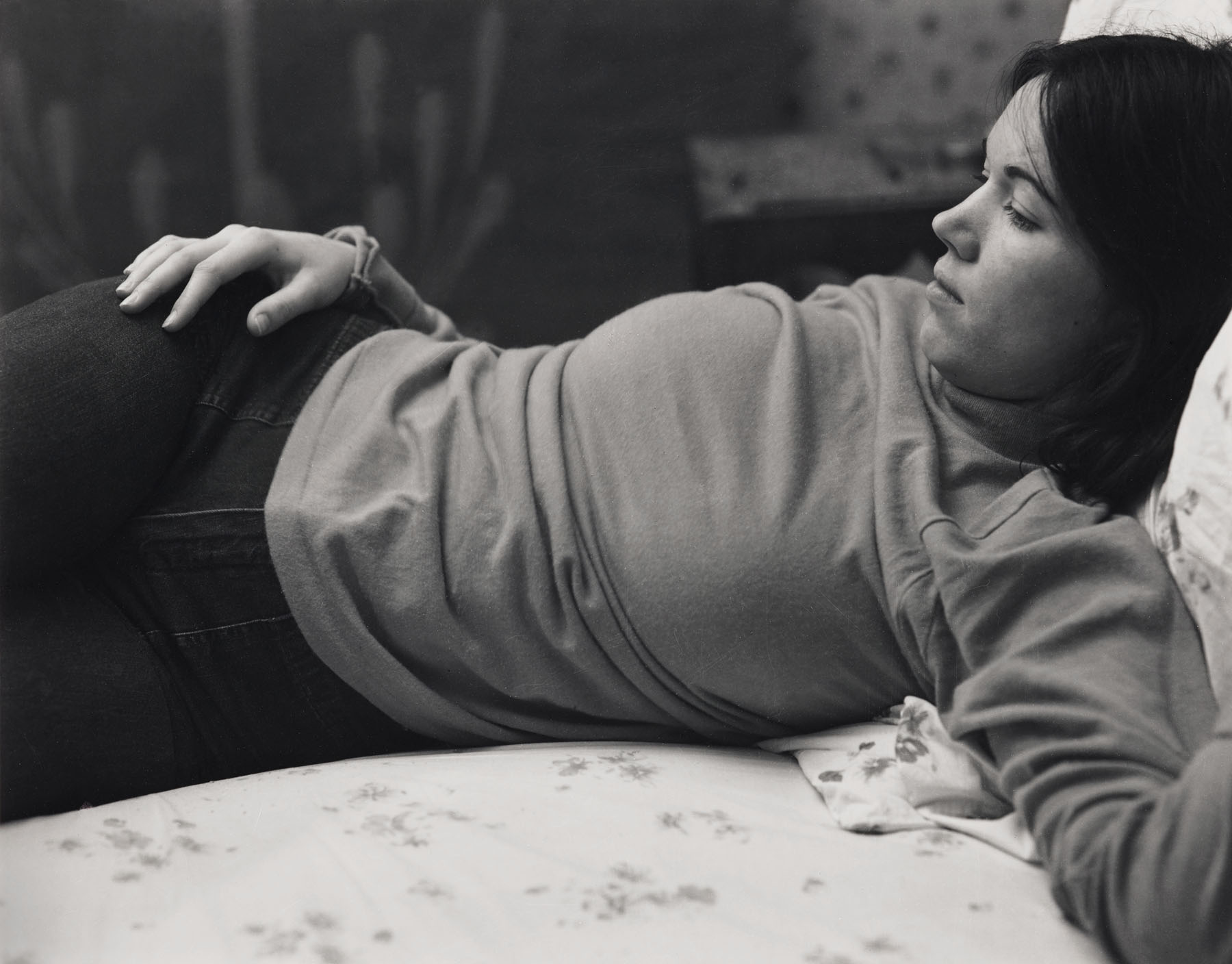

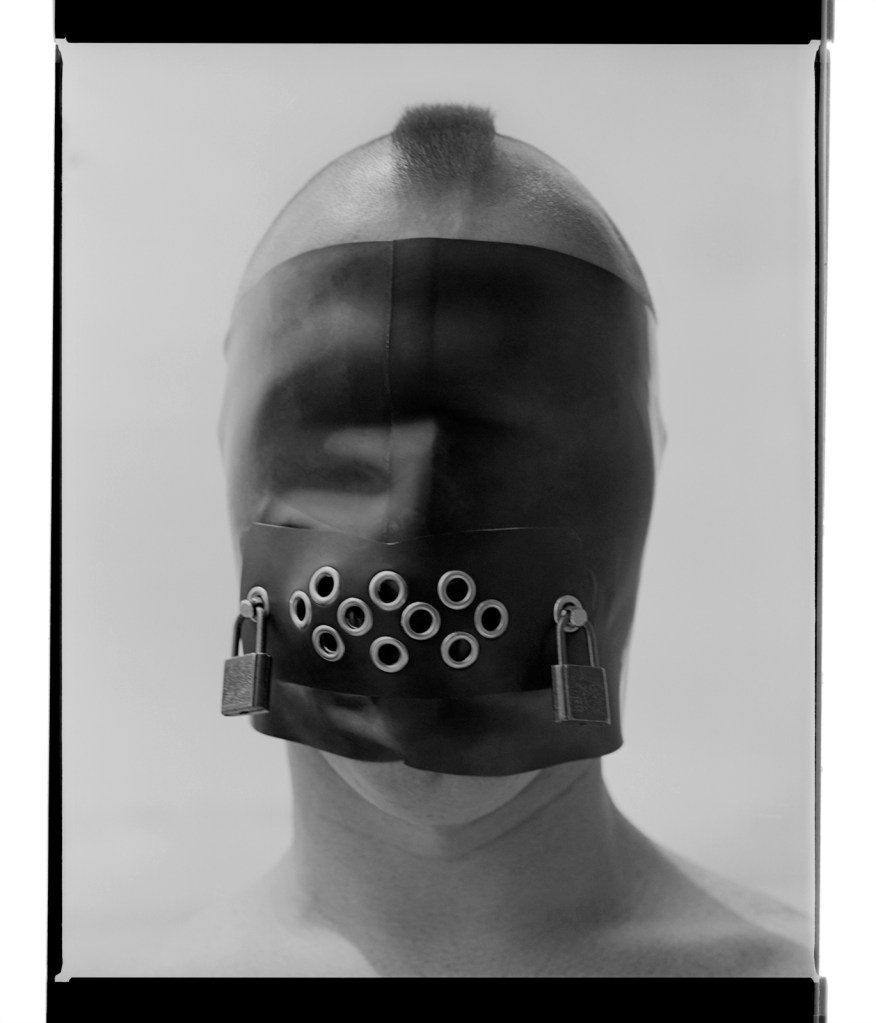

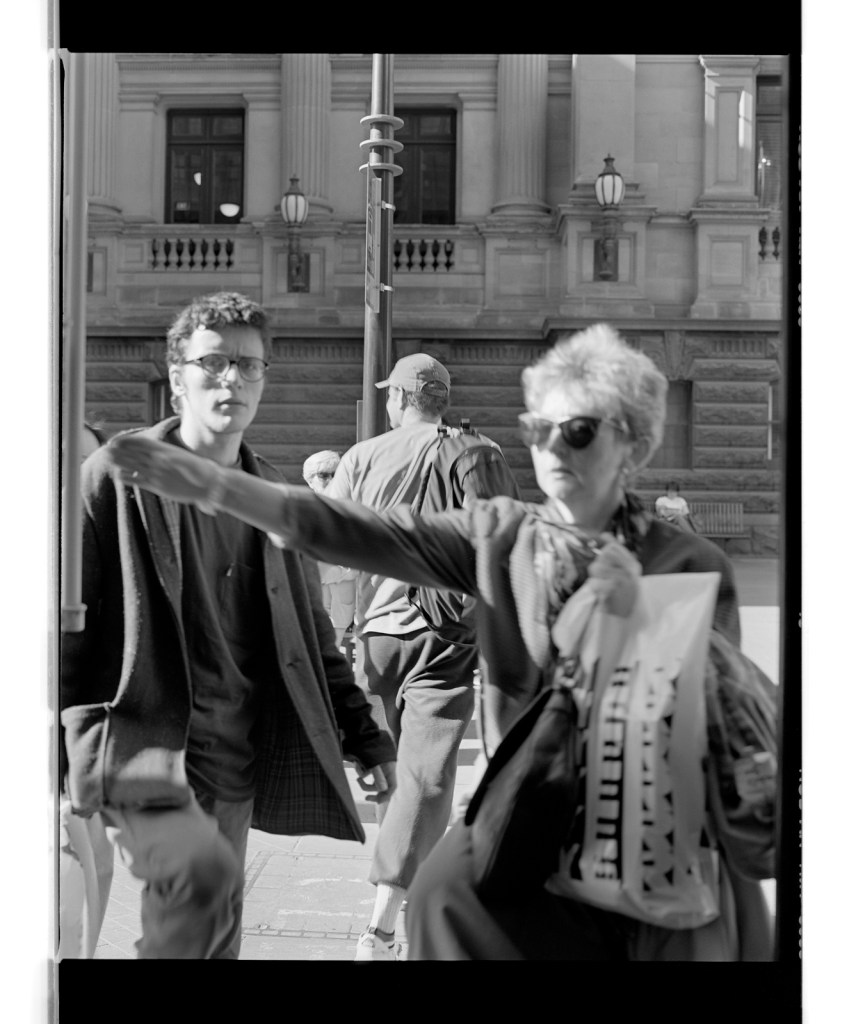

Susan Meiselas (American, b. 1948)

Carnival Strippers book cover

1975

Susan Meiselas (American, b. 1948)

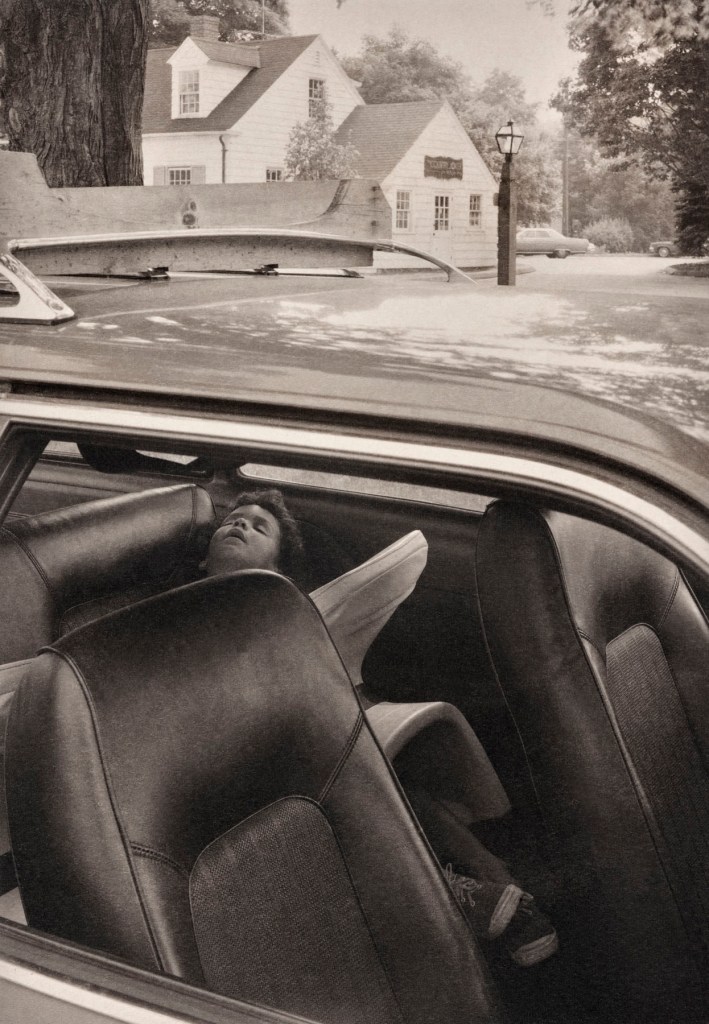

Lena’s first day, Essex Junction, VT

1973

From the series Carnival Strippers, 1972-1975, printed in 2016-2017

Gelatin silver print

292 x 444mm

Gift of Rafael Biosse Duplan

© Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos. Courtesy Danziger Gallery

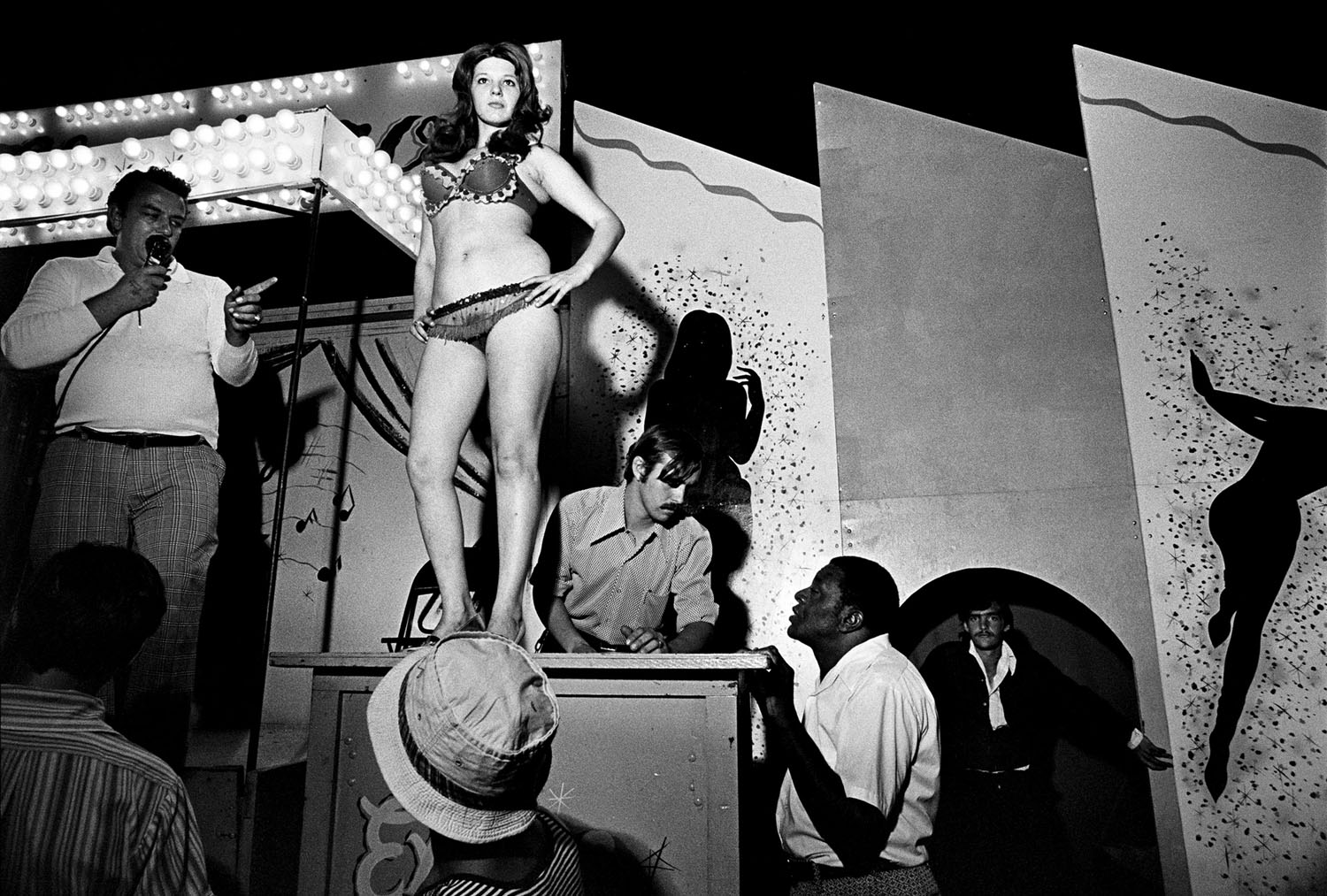

Susan Meiselas (American, b. 1948)

Lena on the Bally Box, Essex Junction, Vermont

1973

From the series Carnival Strippers, 1972-1975, printed in 2016-2017

Gelatin silver print

Gift of Rafael Biosse Duplan

© Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos. Courtesy Danziger Gallery

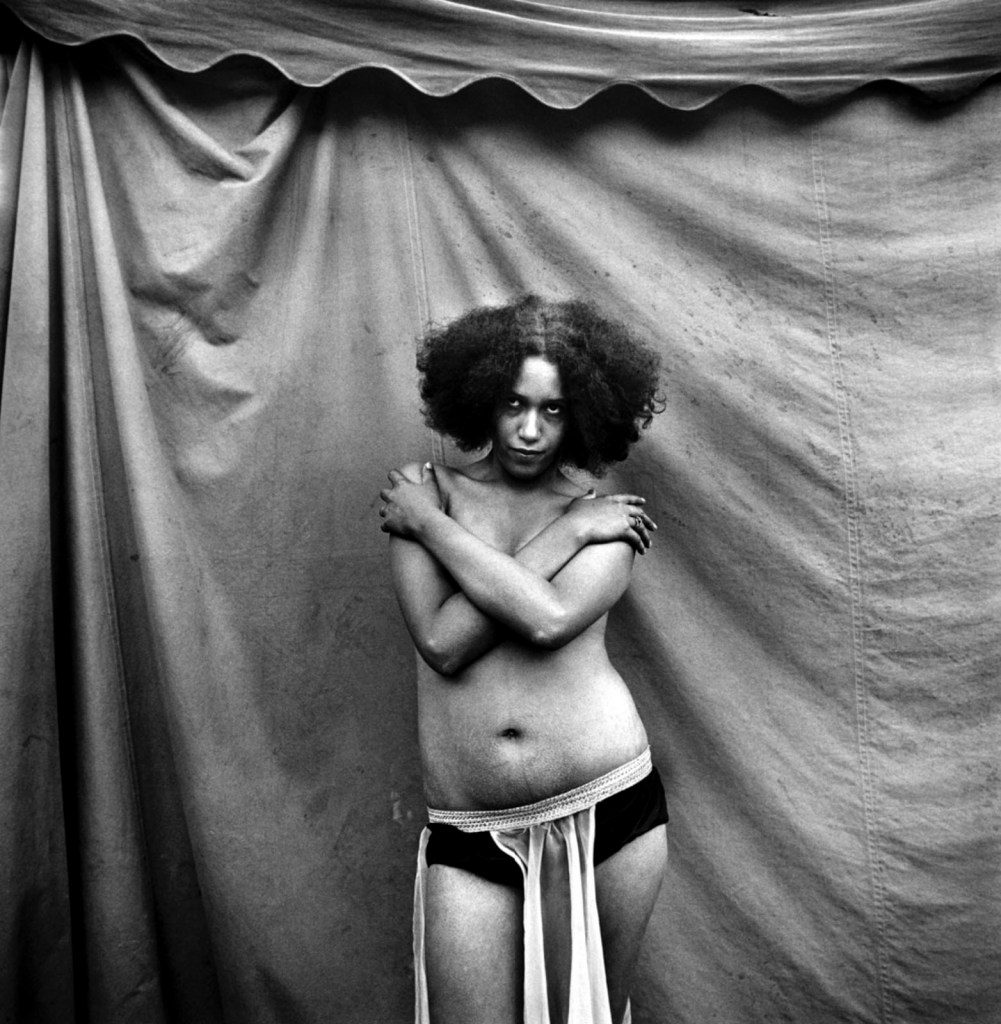

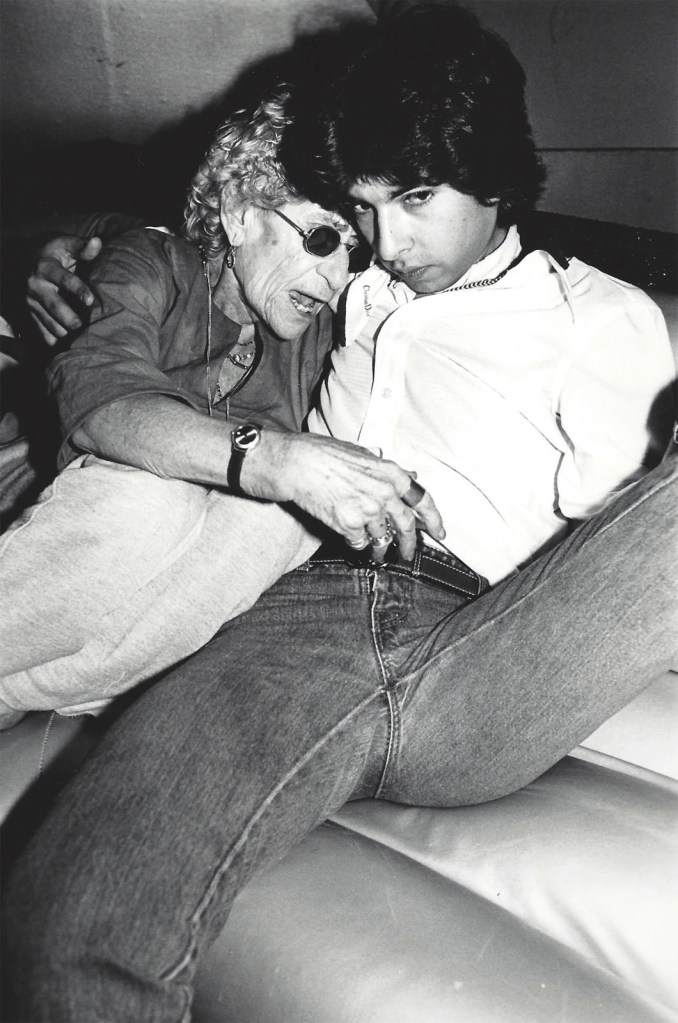

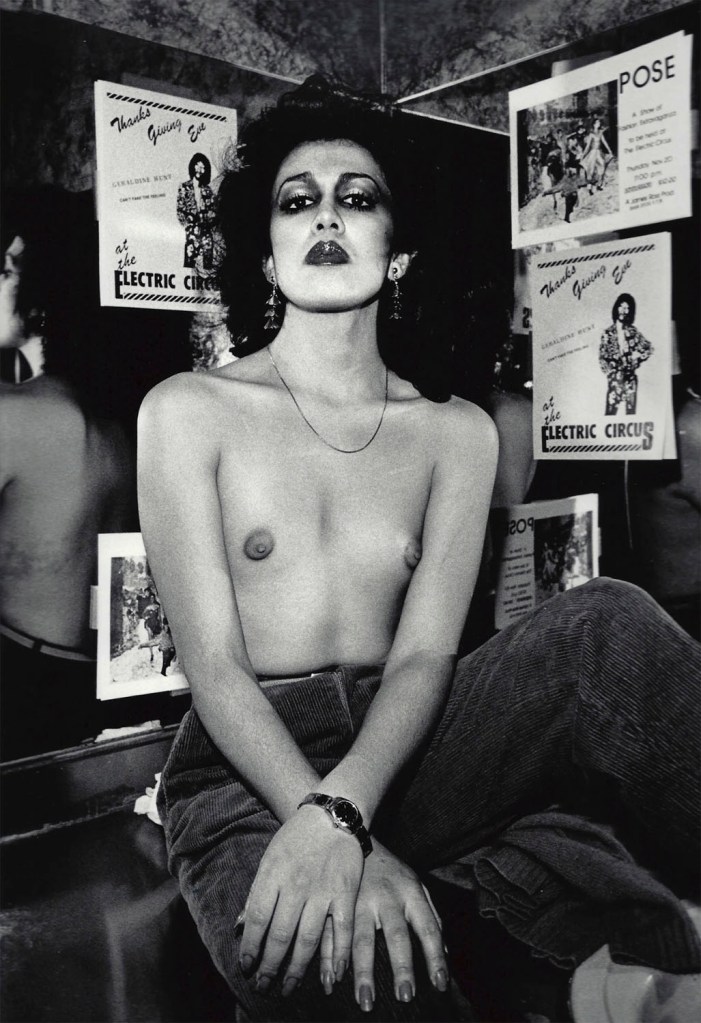

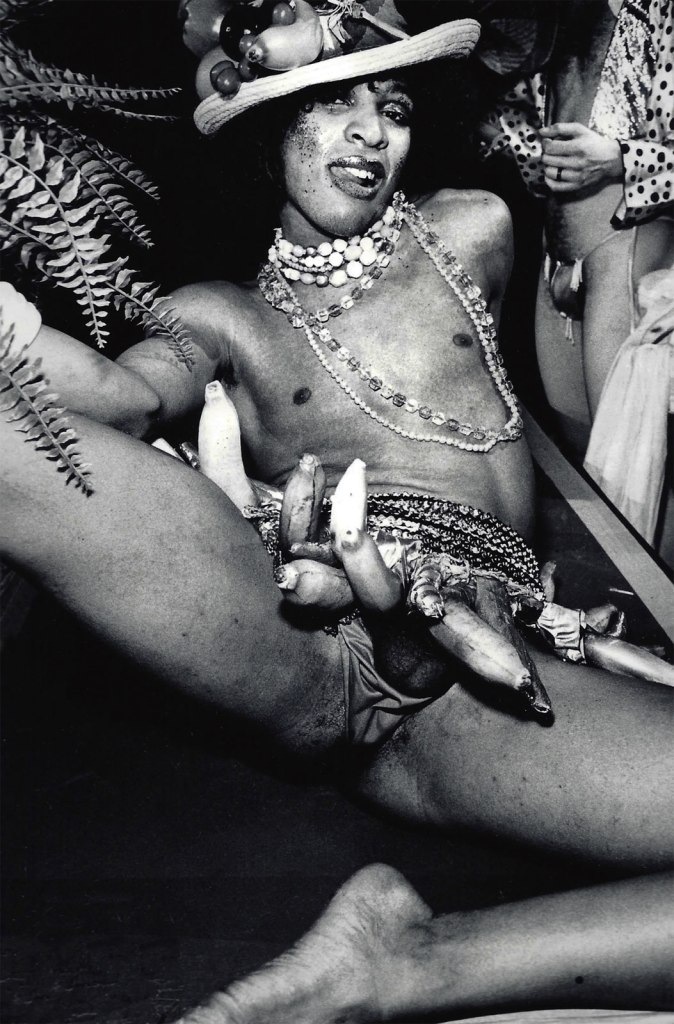

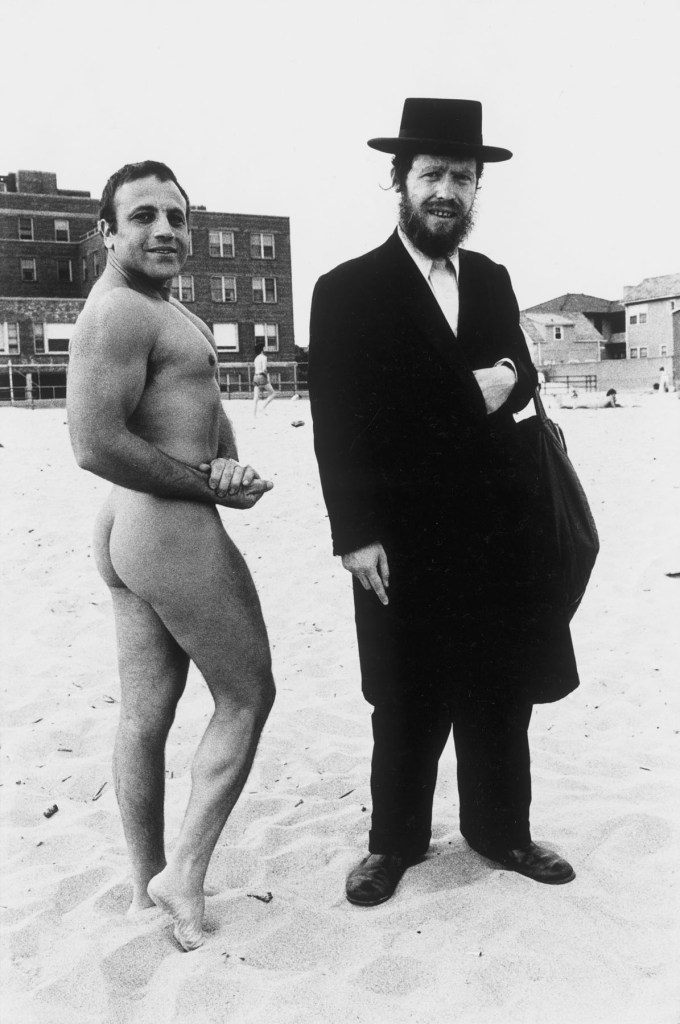

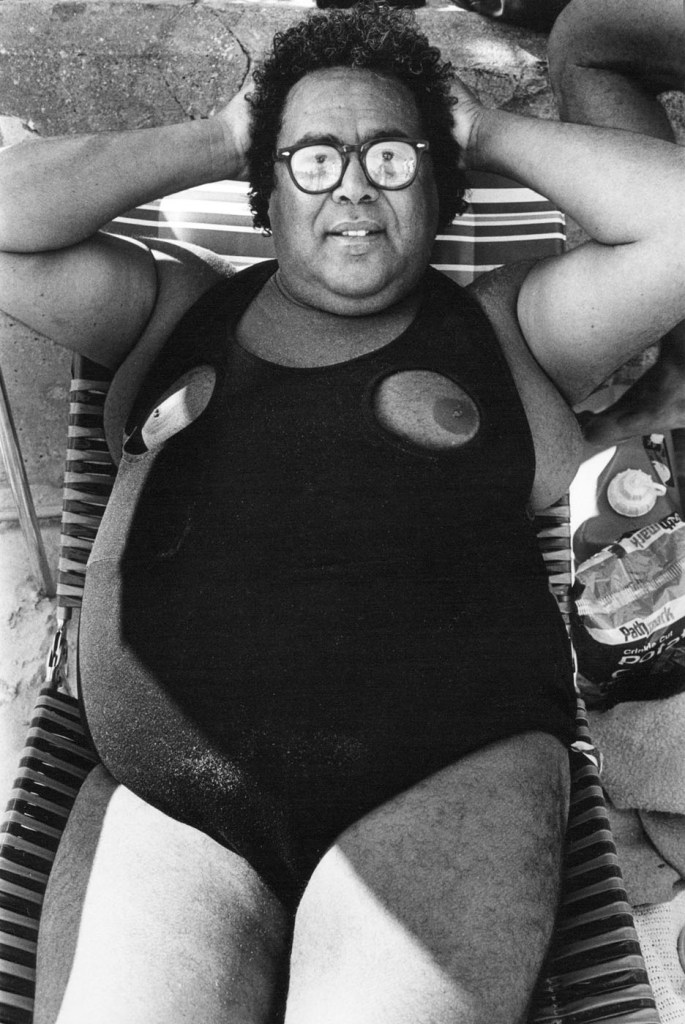

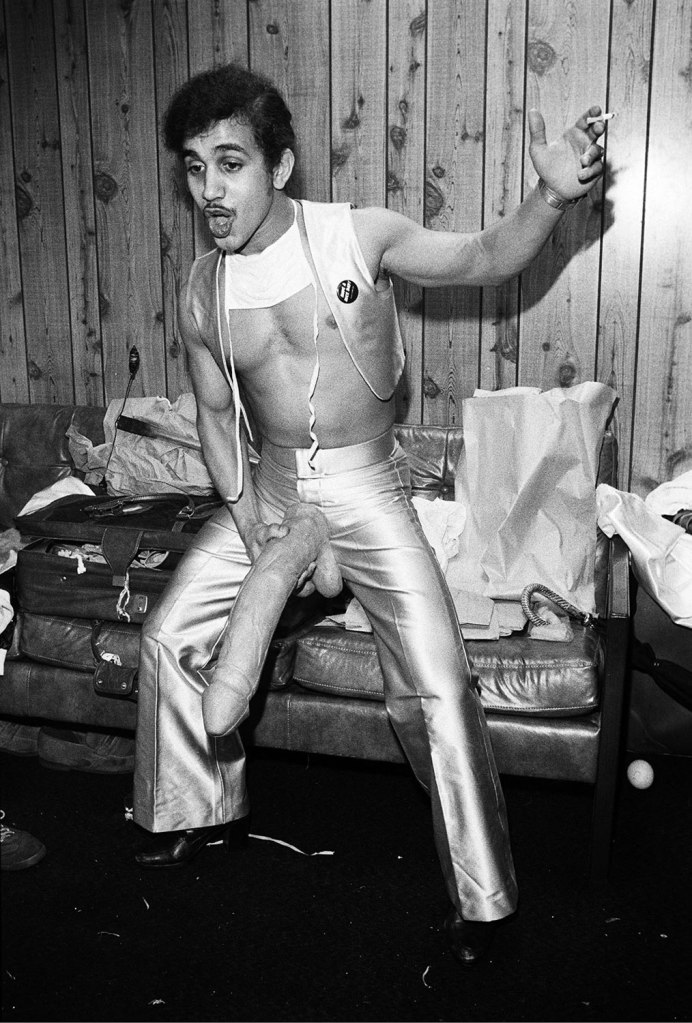

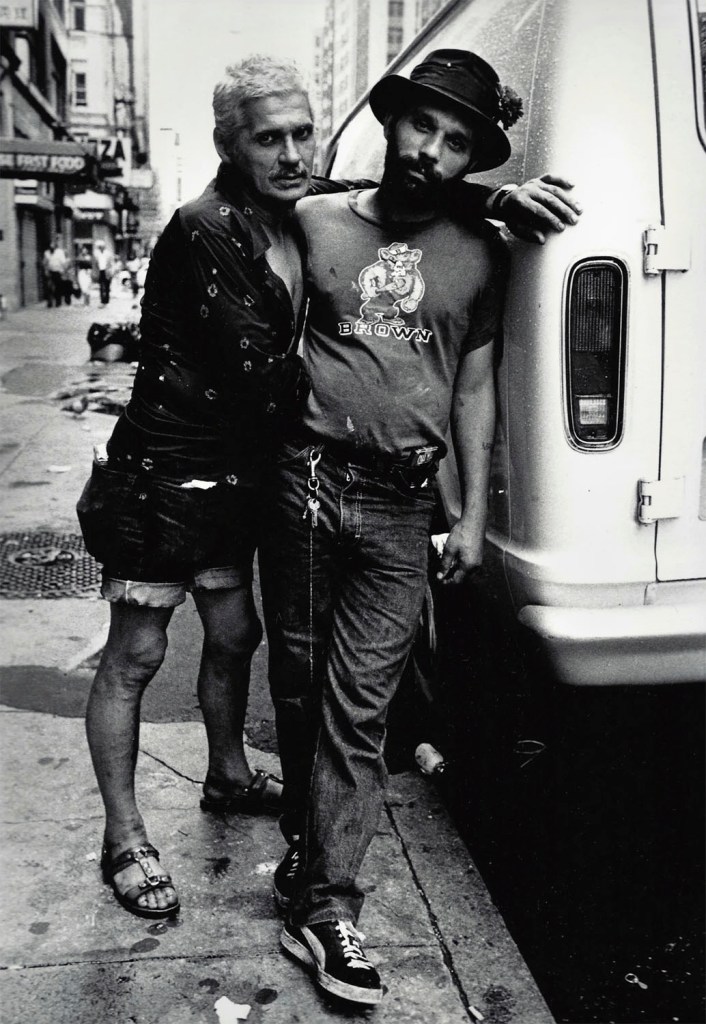

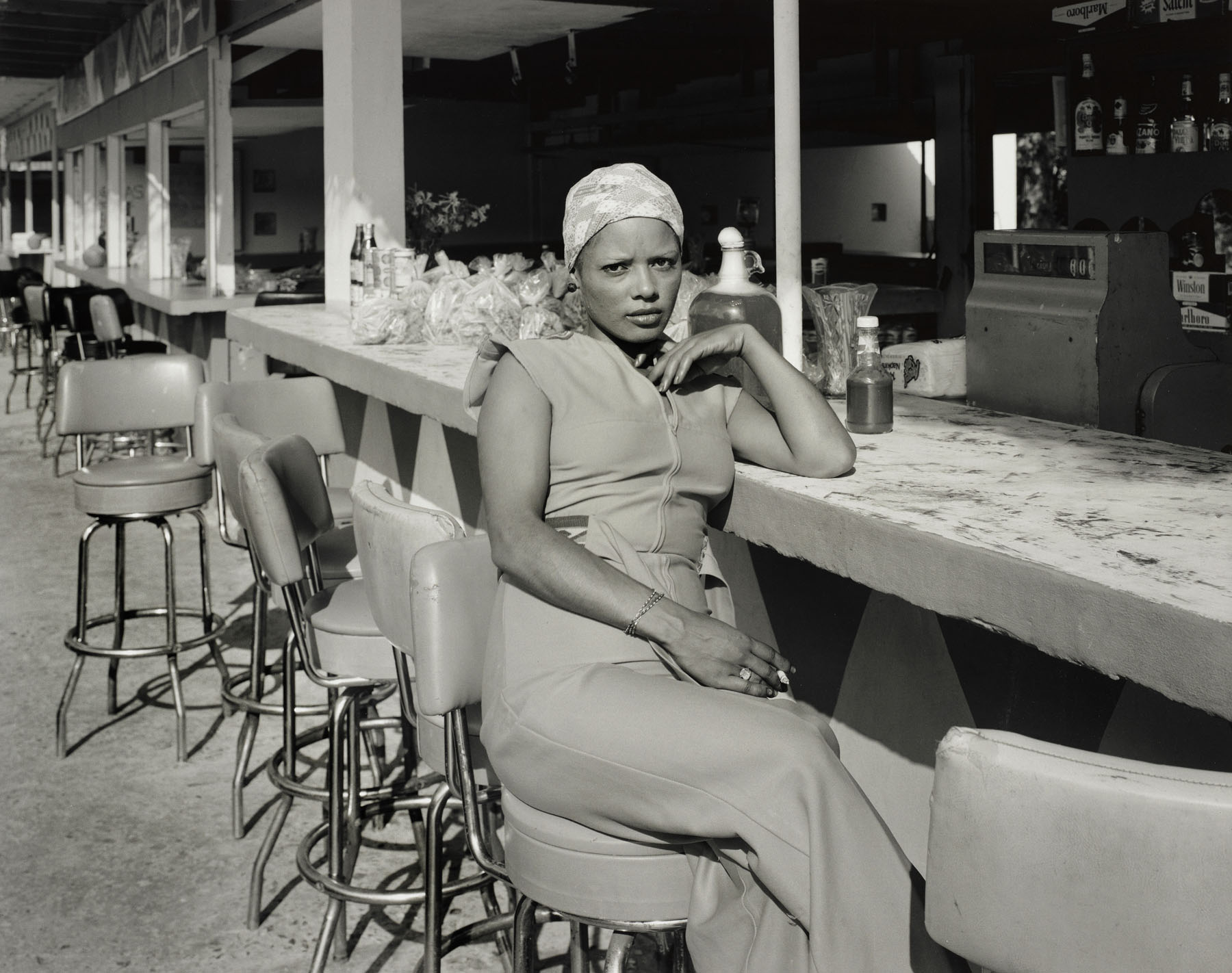

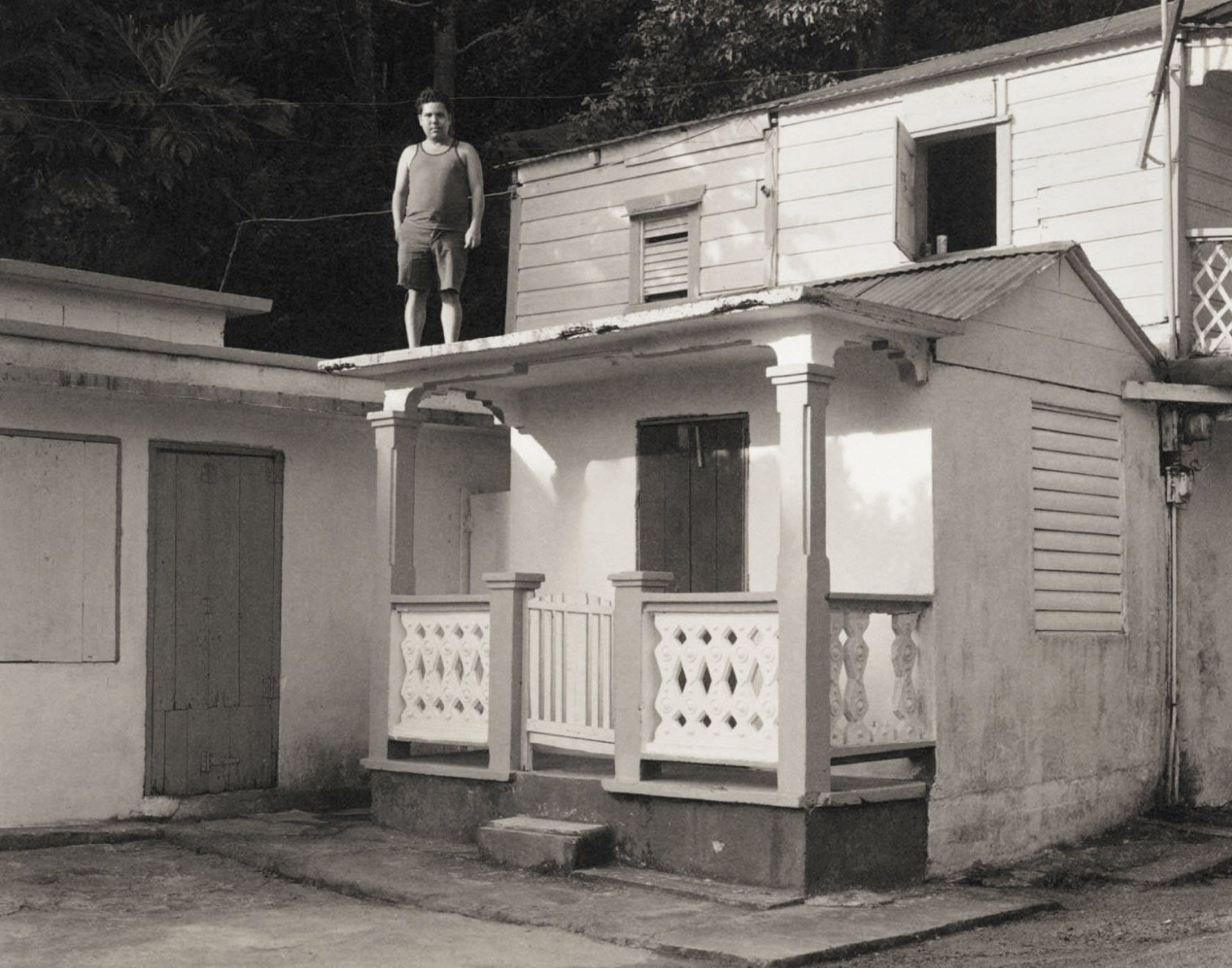

From 1972 to 1975, Susan Meiselas spent her summers photographing women who performed striptease for small-town carnivals in New England, Pennsylvania and South Carolina. As she followed the shows from town to town, she captured the dancers on stage and off, their public performances as well as their private lives, creating a portrait both documentary and empathetic: “The recognition of this world is not the invention of it. I wanted to present an account of the girl show that portrayed what I saw and revealed how the people involved felt about what they were doing.” Meiselas also taped candid interviews with the dancers, their boyfriends, the show managers and paying customers, which form a crucial part of the book.

Meiselas’ frank description of these women brought a hidden world to public attention, and explored the complex role the carnival played in their lives: mobility, money and liberation, but also undeniable objectification and exploitation. Produced during the early years of the women’s movement, Carnival Strippers reflects the struggle for identity and self-esteem that characterised a complex era of change.

Text from the Booktopia website [Online] Cited 22/04/2022

Installation view of Known and Strange: Photographs from the Collection display at V&A showing at left, the work of Susan Meiselas from the Carnival Strippers series

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Susan Meiselas (American, b. 1948)

The Star, Tunbridge, VT

1975

From the series Carnival Strippers, 1972-1975, printed in 2016-2017

Gelatin silver print

292 x 444mm

Gift of Rafael Biosse Duplan

© Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos. Courtesy Danziger Gallery

Susan Meiselas (American, b. 1948)

The Managers, Essex Junction, VT

1974

From the series Carnival Strippers, 1972-1975, printed in 2016-2017

Gelatin silver print

292 x 444mm

Gift of Rafael Biosse Duplan

© Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos. Courtesy Danziger Gallery

Susan Meiselas (American, b. 1948)

New girl, Tunbridge, VT

1975

From the series Carnival Strippers, 1972-1975, printed in 2016-2017

Gelatin silver print

292 x 444mm

Gift of Rafael Biosse Duplan

© Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos. Courtesy Danziger Gallery

Wary of photography’s power to shape our understanding of social, political and global issues and of the potentially complex ethical relationship between photographer and subject, Susan Meiselas has developed an immersive approach through which she gets to know her subjects intimately. Carnival Strippers is among her earliest projects and the first in which she became accepted by the community she was documenting. Over the summers of 1972 to 1975, she followed an itinerant, small-town carnival, photographing the women who performed in the striptease shows. She captured not only their public performances, but also their private lives. To more fully contextualise these images, Meiselas presents them with audio recordings of interviews with the dancers, giving them voice and a measure of control over the way they are presented.

Additional text from Seeing Through Photographs online course, Coursera, 2016

Text from the MoMA website [Online] Cited 23/04/2022

Susan Meiselas (American, b. 1948)

End of the lot, Essex Junction, VT

1973

From the series Carnival Strippers, 1972-1975, printed in 2016-2017

Gelatin silver print

292 x 444mm

Gift of Rafael Biosse Duplan

© Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos. Courtesy Danziger Gallery

Susan Meiselas (American, b. 1948)

Shortie on the Bally, Barton, VT

1974

From the series Carnival Strippers, 1972-1975, printed in 2016-2017

Gelatin silver print

292 x 444mm

Gift of Rafael Biosse Duplan

© Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos. Courtesy Danziger Gallery

Susan Meiselas (American, b. 1948)

Tentful of marks, Tunbridge, VT

1974

From the series Carnival Strippers, 1972-1975, printed in 2016-2017

Gelatin silver print

292 x 444mm

Gift of Rafael Biosse Duplan

© Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos. Courtesy Danziger Gallery

Susan Meiselas (American, b. 1948)

Before the show, Tunbridge, VT

1973

From the series Carnival Strippers, 1972-1975, printed in 2016-2017

Gelatin silver print

292 x 444mm

Gift of Rafael Biosse Duplan

© Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos. Courtesy Danziger Gallery

Susan Meiselas (American, b. 1948)

Curtain call, Essex Junction, VT

1973

From the series Carnival Strippers, 1972-1975, printed in 2016-2017

Gelatin silver print

292 x 444mm

Gift of Rafael Biosse Duplan

© Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos. Courtesy Danziger Gallery

Susan Meiselas (American, b. 1948)

Lena in the motel, Barton, VT

1974

From the series Carnival Strippers, 1972-1975, printed in 2016-2017

Gelatin silver print

292 x 444mm

Gift of Rafael Biosse Duplan

© Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos. Courtesy Danziger Gallery

Susan Meiselas (American, b. 1948)

Mitzi, Tunbridge, VT

1974

From the series Carnival Strippers, 1972-1975, printed in 2016-2017

Gelatin silver print

292 x 444mm

Gift of Rafael Biosse Duplan

© Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos. Courtesy Danziger Gallery

Susan Meiselas (American, b. 1948)

Playing strong, Tunbridge, VT

1975

From the series Carnival Strippers, 1972-1975, printed in 2016-2017

Gelatin silver print

292 x 444mm

Gift of Rafael Biosse Duplan

© Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos. Courtesy Danziger Gallery

Susan Meiselas (American, b. 1948)

Sammy, Essex Junction, VT

1974

From the series Carnival Strippers, 1972-1975, printed in 2016-2017

Gelatin silver print

292 x 444mm

Gift of Rafael Biosse Duplan

© Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos. Courtesy Danziger Gallery

Susan Meiselas (American, b. 1948)

Teen Dream, Woodstock, VT

1973

From the series Carnival Strippers, 1972-1975, printed in 2016-2017

Gelatin silver print

292 x 444mm

Gift of Rafael Biosse Duplan

© Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos. Courtesy Danziger Gallery

Victoria and Albert Museum

Cromwell Road

London

SW7 2RL

Phone: +44 (0)20 7942 2000

Opening hours:

Daily 10.00 – 17.30

Friday 10.00 – 21.30

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Celebrating the City: Recent Acquisitions from the Joy of Giving Something' at the Museum of the City of New York showing at right, Mitch Epstein's 'Untitled [New York #3]' 1995 Installation view of the exhibition 'Celebrating the City: Recent Acquisitions from the Joy of Giving Something' at the Museum of the City of New York showing at right, Mitch Epstein's 'Untitled [New York #3]' 1995](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/blf-2022-mcny-celebratingthecity-119.jpg?w=650)

![Ian Lobb (Australian, b. 1948) 'Marcus 31/8/92 Taken by Ian Lobb at Phillip [Institute]' 1992 Ian Lobb (Australian, b. 1948) 'Marcus 31/8/92 Taken by Ian Lobb at Phillip [Institute]' 1992](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/ian-lobb-marcus-phillip-institute-1992.jpg?w=650)

![Underwood & Underwood (American, founded 1881, dissolved 1940s) '[Women's Campaign Train for Hughes]' 1916 from the exhibition 'In Focus: Protest' at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, June - Oct, 2021 Underwood & Underwood (American, founded 1881, dissolved 1940s) '[Women's Campaign Train for Hughes]' 1916 from the exhibition 'In Focus: Protest' at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, June - Oct, 2021](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/underwood-underwood-womens-campaign-train-for-hughes.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.