Exhibition dates: 3rd October, 2021 – 23rd January, 2022

Curator: Peter Barberie, Brodsky Curator of Photographs, Alfred Stieglitz Center

Field Galleries and Honickman Galleries 154-157

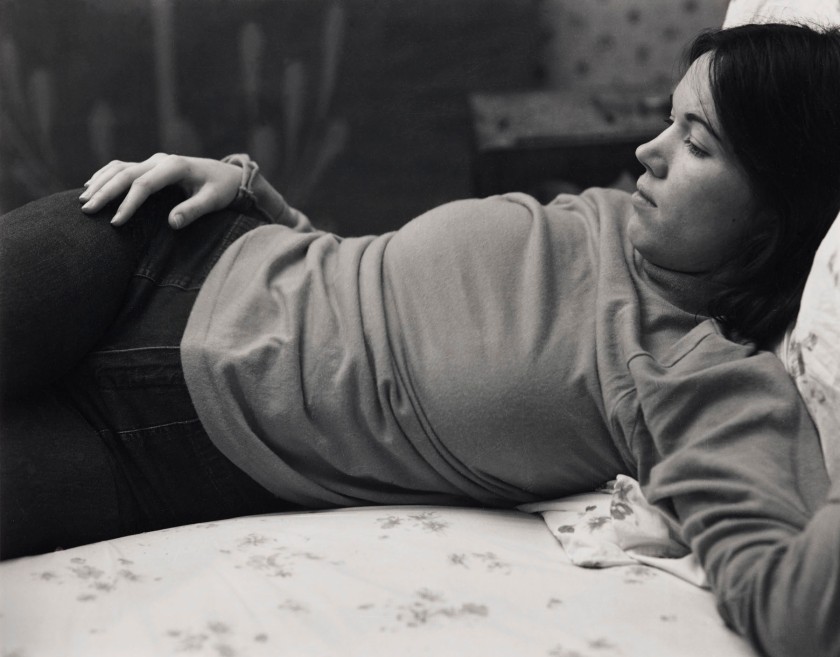

Richard Benson (American, 1943-2017)

Barbara Benson

1968

Gelatin silver print

Image and sheet: 7 1/2 × 9 1/2 inches

Mount: 9 1/8 × 11 inches

© Estate of Richard M. A. Benson. Promised gift of William M. and Elizabeth Ann Kahane

Image courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021

Welcome to the first posting on Art Blart for 2022 and a Happy New Year to you all.

We start with an exhibition by highly regarded photographic printer (including prints for Paul Strand and Walker Evans and books for Lee Friedlander and about Eugène Atget) and teacher Richard Benson. A master of the craft of photography, “Benson became devoted to the technical aspects of printing and reproducing photographs” … “thoroughly imbued with the tradition, science and artistry of photography.” Benson was also an artist and the exhibition includes prints from the late 1960s until shortly before Benson’s death in 2017, the exhibition tracing his quest for the perfect print.

And therein lies the rub. It feels to me as though Benson’s work is more about the aesthetic of the print than about a good photograph and here I am going to call it as I see it. It might be a little controversial or even sacrilegious to one held in so high esteem for his printing, but I don’t particularly like his photographic work. Why?

Benson’s subject matter (“ageing farm machinery, austerely utilitarian boats, derelict factories, and the frequent intersections of history, nature, and our built environments”) can be found throughout the history of American photography. In that sense he offers few new insights on the environment in which he operates. Further, his “unsentimental specificity” – “or what his friend and fellow photographer Garry Winogrand referred to as the mystery of “a fact clearly described” – leaves me feeling … well, nothing really. To me his photographs are emotionally dead photographic experiments become artefacts. What is the story that he is telling, what was his vision?

Benson went to extraordinary lengths to make the print look how the world looked, because he wanted things to look in a print the way things looked when he saw them. But, as Paul Turounet comments, “Craft and technical execution function to support the photographers’ vision and curiosity with visual engagement, and clarity of intention and purpose. It becomes a tremendous opportunity for the photographer to experience how all of photography’s materials and processes, analog, digital or an alternative / hybrid system, can be used to reveal a personal photographic vision and what pictures are going to be about.”1

A personal photographic vision! What was that for Benson, for he has no signature style, his photographs being a mishmash of influences. As Arthur Lubow has observed, “In some of Benson’s black-and-white photographs of building interiors, like “65 Kenyon Street, Hartford, Connecticut” (1974), I thought of Walker Evans. Edward Weston floated into my consciousness as I looked at the organic semi-abstraction of “Agave” (c. 1975-85). And it was hard to avoid recalling Eggleston in viewing the colour jolts of the vintage red truck in “Wyoming” (2008), or the lime-green rowboat in “Newfoundland” (2006-8).”2 Quite so.

So we are left with what exactly. Beautiful but emotionally stilted representations of the world that offer small insight into the condition of its becoming.

Benson’s two statements, “Go out into the world with the camera and photograph and find out that the world is smarter than you are” and “When I make the picture, I’m seeing how I could make the print” are instructive here. Firstly, the world is not smarter than you are, it’s just more confusing. Nothing is ever as neat and tidy, as perfect as Benson would have us believe in his perfect prints. This is when the mystery of the fact clearly described is just that – a description and not a feeling. Secondly, when he’s taking a photograph he thinking about the print! He’s not thinking about resonances, vibrations of energy, time and space in the place itself but only what he sees as its perfect outcome. But Richard, there are many ways to make a print! You can print a mid-grey Zone V and as near black Zone 2, or use digital manipulation to intensive the feeling of an image. There is no single way to print a photographic image that is “correct” for there are many interpretations of a constructed reality. In my humble opinion Benson has his equation arse about tit. As Minor White in one of his Three Canons (1955) would say,

When the image mirrors the man

And the man mirrors the subject

Something might take over

Minor White elaborates further,

“To get from the tangible to the intangible (which mature artists in any medium claim as part of their task) a paradox of some kind has frequently been helpful. For the photographer to free himself of the tyranny of the visual facts upon which he is utterly dependent, a paradox is the only possible tool. And the talisman paradox for unique photography is to work “the mirror with a memory” as if it were a mirage, and the camera as a metamorphosing machine, and the photograph as if it were a metaphor… Once freed of the tyranny of surfaces and textures, substance and form [the photographer] can use the same to pursue poetic truth.”3

The critical observation is that craft and technical execution function to support the photographers’ vision and curiosity with visual engagement.

My friend and mentor IL keeps saying to me, “the really good stuff is there, I KNOW its there” – but you have to dig really deep to find it. Perhaps p. 25 in the preview of Benson’s book North South East West gets as close as I have felt (a sense of mystery and subtle spirit) … but I remain a skeptic with regard not to Benson’s craft but to his artistic vision, for he seems to have never freed himself of the tyranny of visual facts bound to their reproduction in the perfect print.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Footnotes

1/ Paul Turounet. “Well-Executed, Poorly Conceived Photographs,” on A Photo Teacher website Nd [Online] Cited 18/12/2021

2/ Arthur Lubow. “When a Master Printer Picks Up the Camera,” on The New York Times website December 30, 2021 [Online] Cited 02/01/2022

3/ Minor White quoted in Beaumont Newhall (ed.,). The History of Photography. Boston: Little, Brown, and Co., 1982, p. 281

Many thankx to the Philadelphia Museum of Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

The fundamental problem any artist faces in regard to craft is that it must be largely ignored. This seems to be an extreme statement, but it is surely true. Today we are experiencing a revival of sorts of non-silver, or alternative, systems for photographic printing, and the field is littered with well-executed, poorly conceived photographs. It seems to me that this has happened because all these photographers, or printers, are more interested in how they print their pictures than in what these pictures might be about.

Excerpt from the essay “Print Making” by Richard Benson in the book Paul Strand: Essays on His Life and Work. Aperture, 1991

“Isn’t that what we do as artists… don’t we try to create a surrogate that gives to the viewer something that was given to us when we saw the thing.

We get an inkling that there is something extraordinary there, we’ve stumbled on something extraordinary and the picture is our mechanism for understanding it.

When I make the picture, I’m seeing how I could make the print.”

Excerpts from a conversation with Richard Benson and Jay Maisel by George Jardine for Adobe Lightroom

“In black-and-white and color, in film and digital, in platinum prints, offset lithographs and inkjet prints, Benson mastered the procedures and, when he found them inadequate, invented his own. Like those sonically stunning LPs that were recorded to demonstrate the range of the first generation of stereos, Benson’s photographs often seem designed to mark the outer limits of what photography can practically achieve. …

Walking through the show, I saw the work of someone thoroughly imbued with the tradition, science and artistry of photography. But I was also reminded of a remark by Henry James, in a letter from 1888, about John Singer Sargent, who, similarly, could achieve with a brush anything he asked of it. “Yes, I have always thought Sargent a great painter,” James remarked. “He would be greater still if he had one or two little things he hasn’t – but he will do.””

Arthur Lubow. “When a Master Printer Picks Up the Camera,” on The New York Times website December 30, 2021 [Online] Cited 02/01/2022

Curators’ Talk on Richard Benson

Curator Peter Barberie and Sarah Meister of Aperture discuss the life and work of photographer Richard Benson.

Speakers

Peter Barberie is Brodsky Curator of Photographs, Alfred Stieglitz Center, at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Sarah Meister is Executive Director of Aperture, a not-for-profit foundation, multi-platform publisher, and center for the photo community.

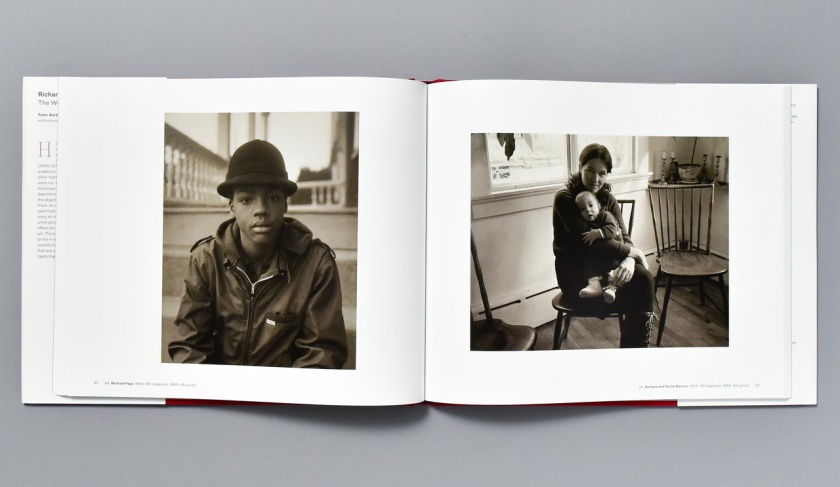

Richard Benson (American, 1943-2017)

Barbara Benson (Young, Skinny, and Pissed Off)

1970 (negative); 2005-2014 (print)

Inkjet print

Image: 17 3/16 × 13 3/8 inches (43.6 × 33.9cm)

Sheet: 19 1/16 × 15 5/16 inches (48.4 × 38.9cm)

© Estate of Richard M. A. Benson. Promised gift of William M. and Elizabeth Ann Kahane

Image courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021

Richard Benson (American, 1943-2017)

Sarah Benson

1974

Palladium print

Image: 6 1/2 × 4 5/8 inches

Sheet: 6 3/4 × 4 3/4 inches

Mount: 7 7/8 × 6 inches

© Estate of Richard M. A. Benson. Promised gift of William M. and Elizabeth Ann Kahane

Image courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021

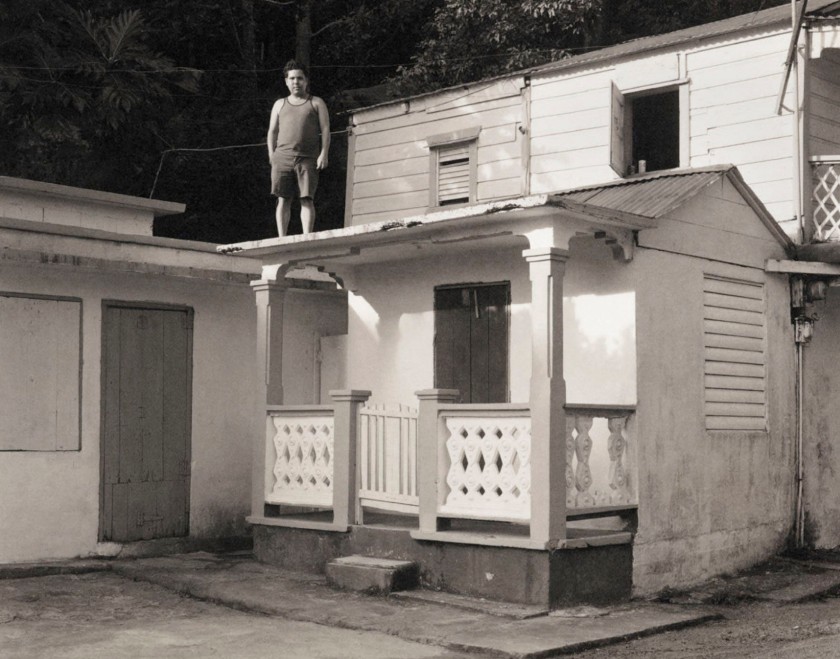

Richard Benson (American, 1943-2017)

Christopher Benson

1981-1982 (negative); 1985-1995 (print)

Offset lithograph

Image: 16 1/4 × 12 7/8 inches (41.2 × 32.7cm)

Sheet: 24 15/16 × 19 inches (63.4 × 48.2cm)

© Estate of Richard M. A. Benson. Promised gift of William M. and Elizabeth Ann Kahane

Image courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021

Richard Benson (American, 1943-2017)

Barbara and Daniel Benson

1978-79 (negative), 1985–95 (print)

© Estate of Richard M. A. Benson. Promised gift of William M. and Elizabeth Ann Kahane

Image courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021

It’s worth mentioning that this was the late 1980s, when everywhere you looked it appeared as if “art photography” needed big ideas more than it needed great photographs. Benson would shoot down our art-speak while sympathising with our ambitions and the obstacles we faced in wanting to break new ground. He reminded us that “an artist is a person who tends to be really good at one thing but spends most of their time trying to do something else.” For him, the revelations and the ideas in photographs were in the details, in the unsentimental specificity, or what his friend and fellow photographer Garry Winogrand referred to as the mystery of “a fact clearly described.”

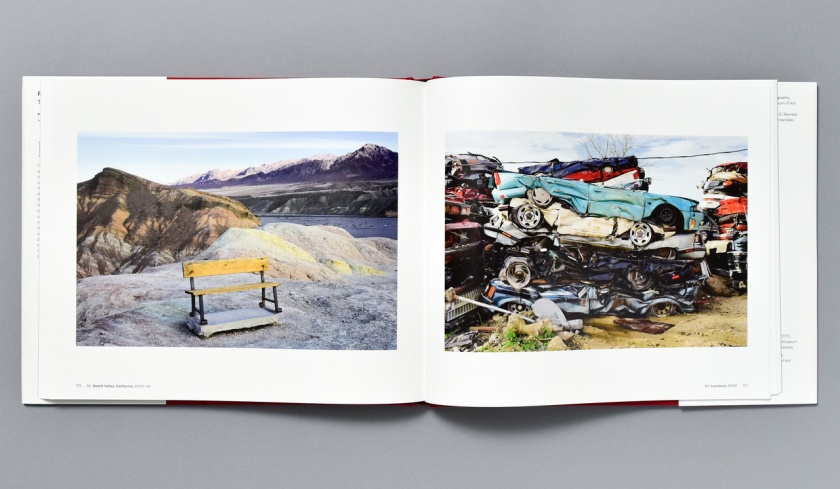

Many of the subjects Benson photographed across decades will be instantly familiar to anyone who’s ever crossed the US by car or run a few errands via bicycle in coastal New England: ageing farm machinery, austerely utilitarian boats, derelict factories, and the frequent intersections of history, nature, and our built environments. Benson’s encyclopaedic knowledge of the Industrial Revolution only partly accounts for the complete absence of nostalgia in photographs that regularly describe remnants and artefacts sharing present-tense place and time within a single frame.

At certain moments in his work, Benson chose black-and-white film and inkjet printers. In others he found it necessary – and appropriate – to hack a twenty-first-century desktop printer with nineteenth-century brass registration pins. Or, frustrated with pre-Photoshop colour gamut limitations, he needed to invent a technique combining multiple halftone separations and layers upon layers of hand-applied house paint. It was the only way to produce colour prints from his large-format colour negatives that finally met his exacting standards.

If asked why he had gone to such lengths while others remained content with the latest readymade printer options from Kodak or Epson, Richard would simply offer: “Because that’s the way the world looks … and I want things to look in a print the way things looked when I saw them.”

As fascinating and impressive as many of Benson’s technical innovations may have been, none were intended to be more interesting than the photographs they made possible.

The building blocks of the medium (optics, resolution, inherent qualities of various printing methods) often served as dowsing rods to suggest where, what, or whom to photograph. For example, many of Benson’s photographs of his family are produced with and informed by the unique properties of the 8 x 10-inch view camera and black-and-white negative film. Photographing this way requires a mixture of emphatic care and authoritarian control. But in the course of Benson’s work, photographs of family and other closest-to-home subjects are entirely natural extensions of a larger inquiry into our designs, arrangements, purpose-driven work, civic progress, and looming fragilities written across a landscape without end.

Although Richard Benson’s working life ranged across disciplines (hand-tooled mechanical clockworks, steam and combustion-engine design and restoration, hand-ground lenses, and custom-built telescopes), the exhibition at the museum limits its scope to Benson’s photographs. For Benson, neither capital-A “Art” nor rigorous craft were virtues unto themselves. Yet the world described in these photographs, with their “just-the-facts” titles – places and dates without backstory or anecdote – tell us all we need to know about Benson’s omnivorous curiosity and his belief in the nature and purpose of photographic seeing.

Extract from John Pilson. “Richard Benson’s All-Seeing Eye,” on the Philadelphia Museum of Art website November 15, 2021 [Online] Cited 18/12/2021

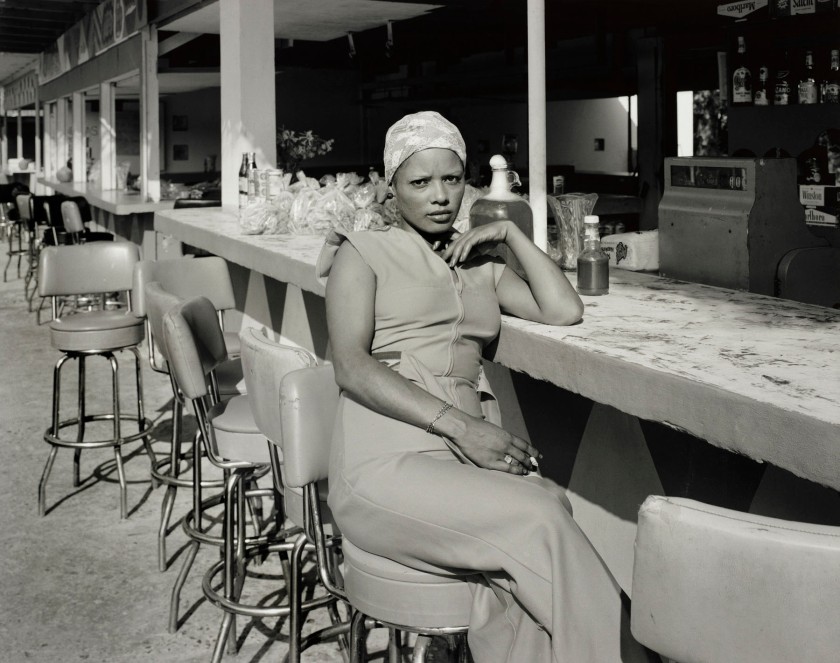

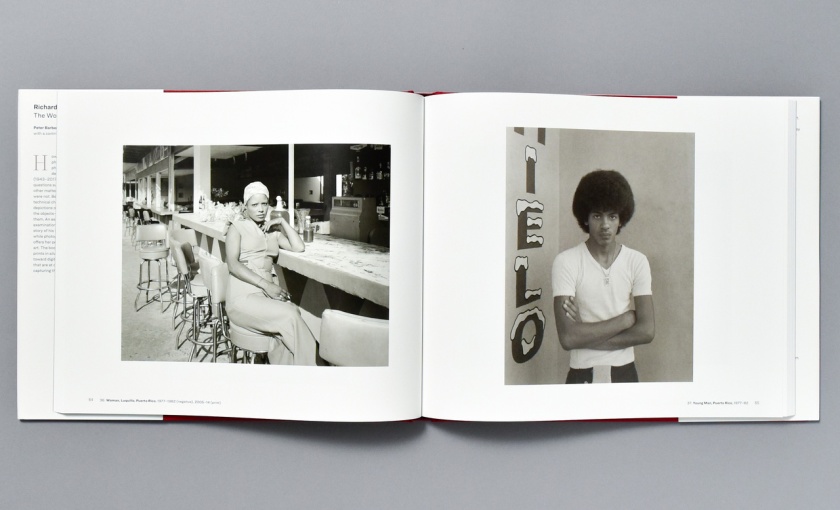

Richard Benson (American, 1943-2017)

Luquillo Woman, Puerto Rico

c. 1980

Inkjet print

Image: 13 5/8 × 17 1/8 inches

Sheet: 15 1/2 × 18 7/8 inches

© Estate of Richard M. A. Benson. Promised gift of William M. and Elizabeth Ann Kahane

Image courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021

Richard Benson (American, 1943-2017)

John Bull’s Great Stone, Common Burying Ground, Newport, Rhode Island

1973-1978

© Estate of Richard M. A. Benson. Promised gift of William M. and Elizabeth Ann Kahane

Image courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021

One of his early pictures, “John Bull’s Great Stone, Common Burying Ground, Newport, Rhode Island” (1973-78), was made with a large-format view camera and composed of two contact prints mounted side by side. It depicts a series of six headstones for babies in one family, each marker incised with the face of an angel. Benson descended from a family of Newport stone carvers that dated to Colonial times. This composition, framed with perfect symmetry and sharp as a scalpel, is almost palpable, an appreciative flourish across the centuries from one consummate craftsman to another.

Arthur Lubow. “When a Master Printer Picks Up the Camera,” on The New York Times website December 30, 2021 [Online] Cited 02/01/2022

Richard Benson (American, 1943-2017)

John Bull’s Great Stone, Common Burying Ground, Newport, Rhode Island (detail)

1973-1978

© Estate of Richard M. A. Benson. Promised gift of William M. and Elizabeth Ann Kahane

Image courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021

Richard Benson (American, 1943-2017)

53 Tilden Avenue Porch

Date unknown

Offset lithograph

Image: 16 3/16 × 12 13/16 inches (41.1 × 32.5cm)

Sheet: 24 15/16 × 19 inches (63.3 × 48.2cm)

© Estate of Richard M. A. Benson. Promised gift of William M. and Elizabeth Ann Kahane

Image courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021

Richard Benson (American, 1943-2017)

Harford, Connecticut

c. 1974 (negative); c. 2005-2011 (print)

Inkjet print

Image: 13 9/16 × 17 3/16 inches (34.5 × 43.6cm)

Sheet: 15 7/8 × 19 3/16 inches (40.4 × 48.8cm)

© Estate of Richard M. A. Benson. Promised gift of William M. and Elizabeth Ann Kahane

Image courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021

Richard Benson (American, 1943-2017)

65 Kenyon Street, Hartford, Connecticut

1974

© Estate of Richard M. A. Benson. Promised gift of William M. and Elizabeth Ann Kahane

Image courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021

Richard Benson (American, 1943-2017)

Billy Goode’s, Newport, Rhode Island

1976-1978

Platinum/palladium print

Image: 7 7/16 × 9 7/16 inches (18.9 × 24cm)

Sheet: 8 7/16 × 10 7/8 inches (21.4 × 27.6cm)

© Estate of Richard M. A. Benson. Promised gift of William M. and Elizabeth Ann Kahane

Image courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021

Richard Benson (American, 1943-2017)

The Dark House (49 Tilden Avenue, Newport, Rhode Island)

c. 1975-1980

Platinum/palladium print

Image: 9 7/16 × 7 7/16 inches (24 × 18.9cm)

Sheet: 9 13/16 × 7 13/16 inches (24.9 × 19.8cm)

© Estate of Richard M. A. Benson. Promised gift of William M. and Elizabeth Ann Kahane

Image courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021

Richard Benson (American, 1943-2017)

Puerto Rico

1977-1985

Platinum/palladium print

Image: 7 3/8 × 9 3/8 inches (18.7 × 23.8cm)

Sheet: 8 × 9 15/16 inches (20.3 × 25.2cm)

© Estate of Richard M. A. Benson. Promised gift of William M. and Elizabeth Ann Kahane

Image courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021

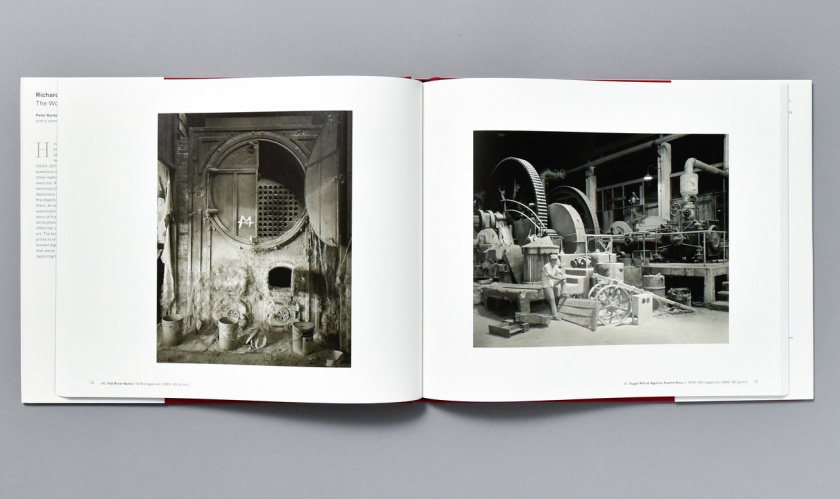

Richard Benson (American, 1943-2017)

Sugar Mill at Aguirre, Puerto Rico

c. 1978-1985 (negative); 1985-1995 (print)

Offset lithograph

Image: 12 3/16 × 15 5/16 inches (31 × 38.9cm)

Sheet: 19 1/8 × 25 inches (48.5 × 63.5cm)

© Estate of Richard M. A. Benson. Promised gift of William M. and Elizabeth Ann Kahane

Image courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021

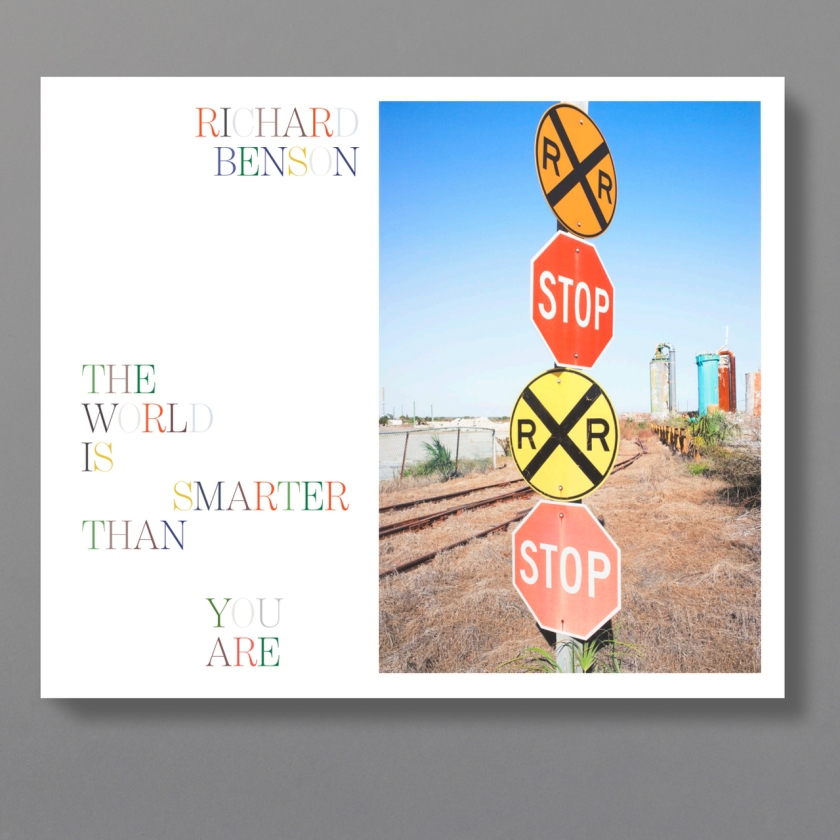

“Go out into the world with the camera and photograph and find out that the world is smarter than you are.”

With this exhortation, Richard Benson encouraged his students to explore one of photography’s core functions: recording things and events in the world. He wanted them to step out of their own mindsets and grapple with the many challenges – material, physical, and conceptual – encountered when making anything. It is precisely how Benson approached his own art. This exhibition surveys nearly fifty years of his photography, a wide-ranging body of work that reflects his humility and boundless curiosity about the world.

Renowned in photography circles for his acumen and inventiveness at printing and his far-ranging impact as a teacher and dean at the Yale University School of Art, Benson is best known today for the remarkable photography books he helped produce and the prints he made of other artists’ work. This exhibition puts his photography at the centre of these other achievements. It follows his continuous investigation of photographic processes and technologies and explores the dialogue between his pictures and other projects.

Benson’s subjects

Benson viewed human knowledge – particularly technology – as a cumulative, almost organic process, more a matter of continual adaptation and adjustment than of individual genius. This outlook is reflected in his photographic subjects. He recorded products of human ingenuity from stone carvings to steam engines and complex constructions of every sort. He also made straightforward and sensitive portraits of people and things he loved. And his subjects include the diverse spaces people create for themselves, which Benson viewed as “living rooms” that help us recover from the continuous disruptions of our technological age.

Richard Benson (American, 1943-2017)

Fort Adams, Newport, Rhode Island

1975 (negative); 1975 (print)

Platinum/palladium print

Image: 7 7/8 × 9 5/8 inches (20 × 24.4cm)

Sheet: 8 1/16 × 10 1/8 inches (20.5 × 25.7cm)

Mount: 8 7/8 × 11 inches (22.5 × 27.9cm)

© Estate of Richard M. A. Benson. Promised gift of William M. and Elizabeth Ann Kahane

Image courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021

Richard Benson (American, 1943-2017)

Fall River Boiler

1978 (negative); 1985-1995 (print)

Offset lithograph

Image: 16 3/8 × 13 1/16 inches (41.6 × 33.1cm)

Sheet: 24 15/16 × 18 15/16 inches (63.3 × 48.1cm)

© Estate of Richard M. A. Benson. Promised gift of William M. and Elizabeth Ann Kahane

Image courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021

For reproducing photographs in a 1985 book devoted to the extraordinary Gilman Paper Company Collection (later acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art), he amplified the duotone process, where ink is passed through a fine mesh screen to impart subtle shades of black, gray and even, for older photographs, purple and sepia. The technique also allowed him to enlarge a negative without sacrificing detail. “Fall River Boiler,” a black-and-white image that he photographed in 1978 and printed a decade or so later, is a nocturne of texture and tone: feathery asbestos, gloppy encrustations, circular black holes.

Arthur Lubow. “When a Master Printer Picks Up the Camera,” on The New York Times website December 30, 2021 [Online] Cited 02/01/2022

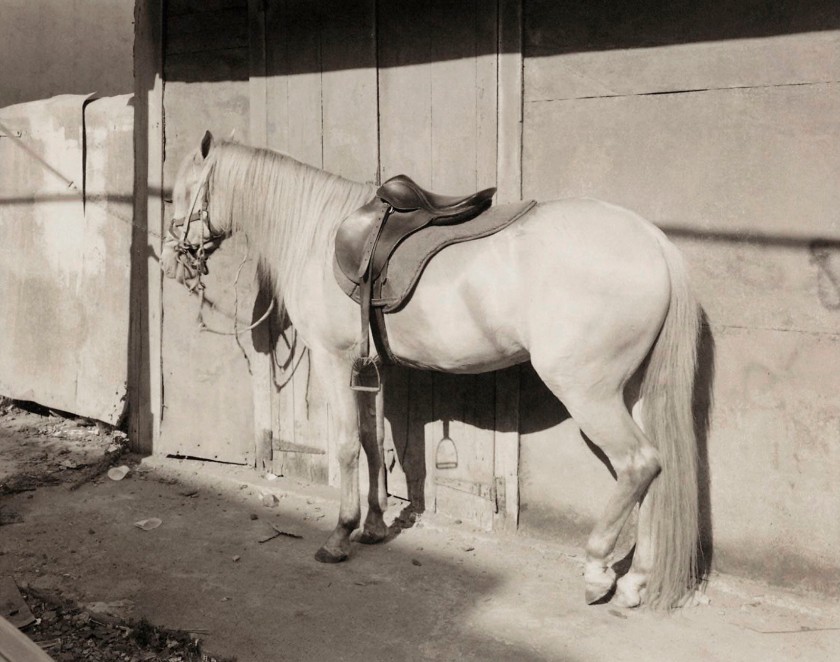

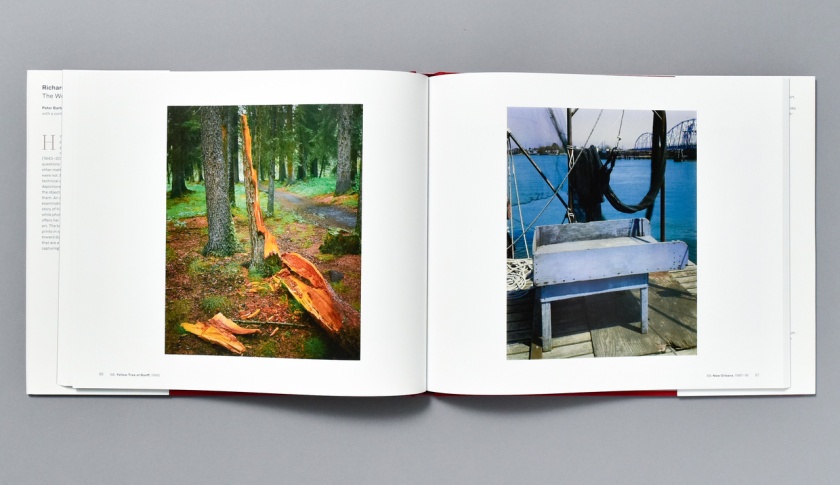

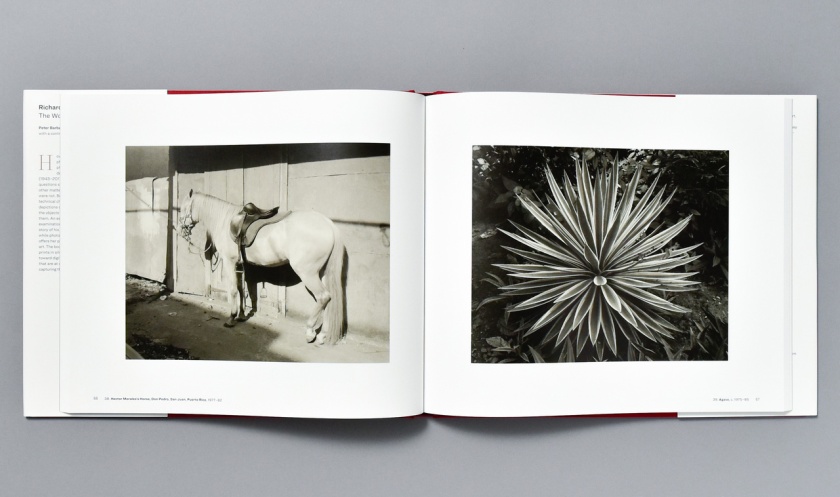

Richard Benson (American, 1943-2017)

Hector Morales’s Horse, Don Pedro, San Juan, Puerto Rico

1977-1982

Platinum/palladium print

Image: 7 5/8 × 9 1/2 inches (19.4 × 24.1cm)

Sheet: 8 × 10 1/8 inches (20.3 × 25.7cm)

© Estate of Richard M. A. Benson. Promised gift of William M. and Elizabeth Ann Kahane

Image courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021

Richard Benson (American, 1943-2017)

Poplar Street Driftway, Newport, Rhode Island

1975-1985

Gelatin silver print

Image and sheet: 7 1/2 × 9 1/2 inches (19.1 × 24.1cm)

Mount: 18 × 14 inches (45.7 × 35.6cm)

© Estate of Richard M. A. Benson. Promised gift of William M. and Elizabeth Ann Kahane

Image courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021

Richard Benson (American, 1943-2017)

Agave plant

1975-1985

Collection of Barbara Benson

Richard Benson (American, 1943-2017)

New Orleans Tugboat

Mid-1980s (negative); 1985-1995 (print)

Offset lithograph

Image: 12 15/16 × 16 1/4 inches (32.9 × 41.3cm)

Sheet: 19 1/16 × 25 inches (48.4 × 63.5cm)

© Estate of Richard M. A. Benson. Promised gift of William M. and Elizabeth Ann Kahane

Image courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021

Richard Benson (American, 1943-2017)

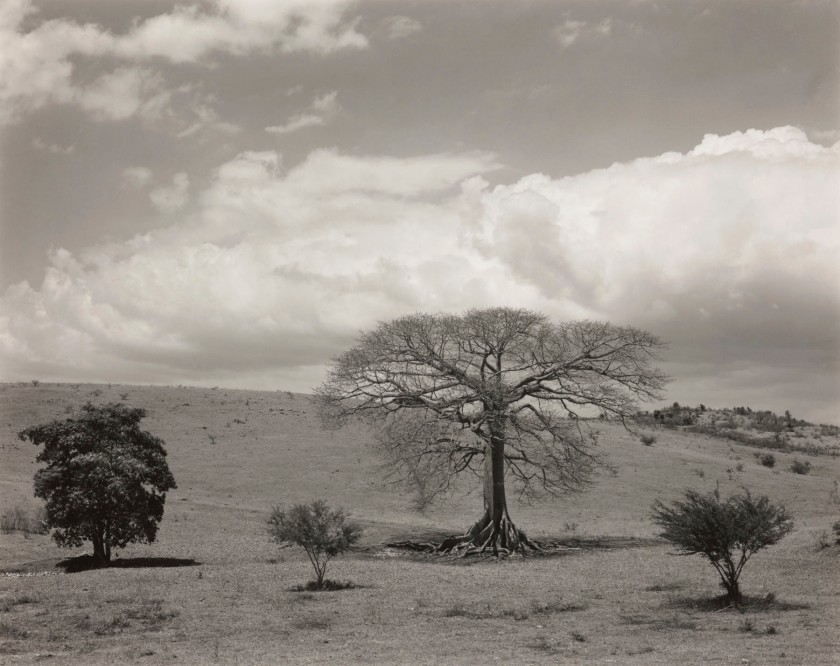

Puerto Rico Landscape

c. 1980

Gelatin silver print

Image and sheet: 7 1/2 × 9 1/2 inches

Mount: 18 × 14 inches

© Estate of Richard M. A. Benson. Promised gift of William M. and Elizabeth Ann Kahane

Image courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021

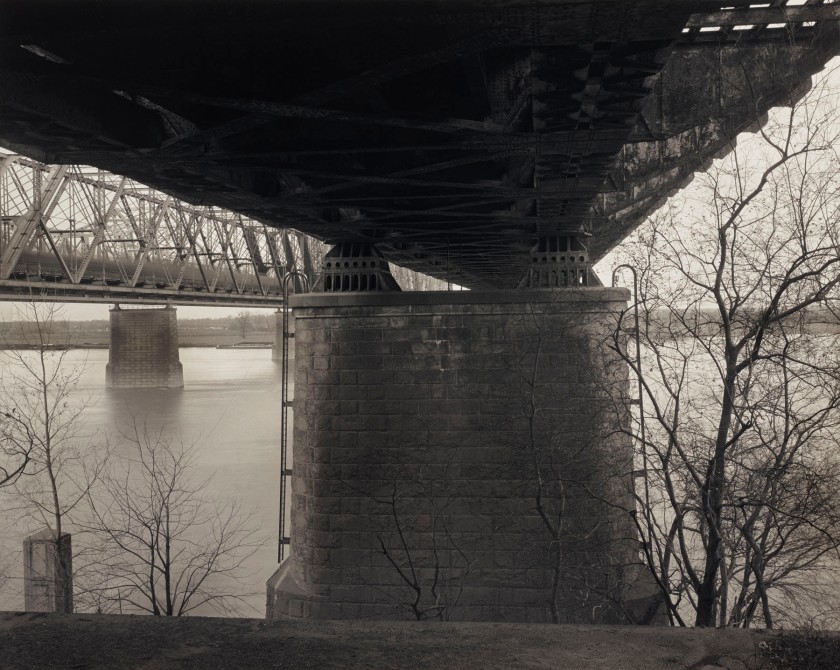

Richard Benson (American, 1943-2017)

Memphis, TN

1987

Offset lithograph

Image: 12 7/8 × 16 3/4 inches

Sheet: 16 × 19 3/8 inches

© Estate of Richard M. A. Benson. Promised gift of William M. and Elizabeth Ann Kahane

Image courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021

Richard Benson (American, 1943-2017)

Scottish Engine, Puerto Rico

c. 1980

Gelatin silver print

Image and sheet: 7 1/2 × 9 1/2 inches

Mount: 18 × 14 inches

© Estate of Richard M. A. Benson. Promised gift of William M. and Elizabeth Ann Kahane

Image courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021

Richard Benson (American, 1943-2017)

Scottish Engine, Puerto Rico

c. 1980; 2005-2014 (print)

Gelatin silver print

Image: 13 9/16 × 17 3/16 inches

Sheet: 15 7/16 × 18 7/8 inches

© Estate of Richard M. A. Benson. Promised gift of William M. and Elizabeth Ann Kahane

Image courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021

Steam engines were among Richard Benson’s many enthusiasms. He was particularly excited to come across this one in a field in Puerto Rico, recognising it as a version of the engine invented by Scottish engineer James Watt in 1776. Watt’s engine was one of the key developments of the Industrial Revolution. Benson surmised this example was a relic from one of the sugar plantations that existed on the island in the 1800s.

Richard Benson (American, 1943-2017)

The Beaubourg, Paris, France

1976

Platinum/palladium print

Image: 7 1/2 × 9 1/2 inches (19.1 × 24.1cm)

Sheet: 8 1/2 × 11 inches (21.6 × 27.9cm)

© Estate of Richard M. A. Benson. Promised gift of William M. and Elizabeth Ann Kahane

Image courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021

Richard Benson (American, 1943-2017)

Wildwood, New Jersey

Date unknown

Offset lithograph

Image: 16 3/8 × 13 1/16 inches

Sheet: 24 15/16 × 19 1/16 inches

© Estate of Richard M. A. Benson. Promised gift of William M. and Elizabeth Ann Kahane

Image courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021

In October, the Philadelphia Museum of Art will present an exhibition dedicated to the late Richard Benson, who is most often celebrated as a virtuoso printer and gifted teacher and is perhaps best known for helping produce some of the most significant photography books of the past fifty years. The World Is Smarter Than You Are is the first in-depth survey of Benson’s own photography. This exhibition includes around 100 works that convey his pathfinding exploration of photographic processes, his embrace of technologies old and new, and his deep empathy for his human subjects and the objects and environments they have built. It celebrates an important promised gift of Benson’s art, assembled by the artist and offered to the museum by his close friends, collectors William H. and Elizabeth Ann Kahane. It is accompanied by a major publication of the same title.

Including prints from the late 1960s until shortly before Benson’s death in 2017, the exhibition traces his quest for the perfect print. This reflects both his abiding interest in improving traditional photo-making methods as well as his gradual embrace of digital photography and experiments in printing that yielded new directions for his artistic craft. It also explores his philosophical musings and writings, teaching materials and work as a printer, underscoring the deep connections between his intellectual, technical, and creative pursuits.

Benson’s interest in photography began with utilising this medium to document examples of fine craftsmanship and technological innovation, ranging from stone carving and antique buildings to machines such as steam engines or contemporary feats of engineering in steel and other modern materials. This breadth of interests can be seen in work from visits he made to France in the 1970s, when he recorded such sites as the Château de Maintenon and the recently completed Centre Pompidou. In another project of the 1970s, Benson photographed grave markers in the Common Burying Ground in his hometown of Newport, Rhode Island. He was the son and brother of celebrated stone carvers, and these pictures reflect his desire to document not only this antique art form, but also his developing ideas about the continual evolution of human technology which, in his thinking, comprised everything from language to microchips.

During this same decade Benson also made sensitive portraits of friends and family members – most notably his wife, Barbara Benson – and views of interiors and townscapes that often stand as indirect portraits of anonymous subjects. Numerous family portraits are presented throughout the exhibition and a concentrated grouping appears in the first galleries.

In the late ’70s and early ’80s, Benson made several trips to Puerto Rico. Included in the exhibition are his records of an antique steam engine he discovered on an old sugar plantation, Scottish Engine, Puerto Rico, c. 1980, and a variety of portraits and landscapes that represent the unique characteristics of the island. Luquillo Woman, Puerto Rico (c. 1980), is representative of the candid pictures he captured during these visits.

Benson embarked on his most ambitious book project in 1981, dedicated to the Gilman Paper Company Collection. It was considered to be one of the most important private photography collections ever assembled and included rare nineteenth-century prints in diverse processes as well as works by noted twentieth-century photographers such as Diane Arbus, Henri Cartier-Bresson, and Alfred Stieglitz, among others. Benson’s efforts to make the reproductions in this book by using offset lithography, printing each sheet up to six times in order to achieve specific print tonalities, remain unmatched. Spreads from the book, Photographs from the Collection of the Gilman Paper Company, will be on view in the exhibition. Displayed in cases are other notable books on which he worked including Lay This Laurel (Benson and Lincoln Kirstein); The American Monument (Lee Friedlander); The Face of Lincoln (James Mellon); O, Write My Name (a portfolio of Benson photogravures from Carl Van Vechten photographs); Paul Strand prints of Wall Street and Wild Iris, Maine; and three later Benson books, A Maritime Album, The Printed Picture, and North South East West.

As his reputation as an innovator in printing processes grew, so too did his influence. In 1986, following the success of the Gilman Paper Company Collection project, Benson was awarded both his second Guggenheim Fellowship and a MacArthur Fellowship. Seven years earlier, in 1979, Benson had begun teaching at Yale University, where he would become a professor and later Dean of the Art School. His idiosyncratic teaching style is described by the noted artist An-My Lê, who reflects in her essay: “His lectures were dazzling with information, but we were chided for taking notes. This was in line with this wanting us to think for ourselves and not passively absorb information that was thrown at us. As I have progressed in my work over the years, I have come to realise that one of Richard’s most important lessons was about humility.”

Another section of the exhibition will be devoted to his work in colour photography. Benson had avoided colour photography through much of his career, in part because of the unreliability of colour processes. But with the emergence of digital photography in the 1990s, he embraced working in colour, leading to the creation of an extraordinary body of pictures. Three works known as “photographs in paint” will be shown with two chromogenic prints from the 1990s to demonstrate his shift from offset lithography to inkjet printing. Moving into the early 2000s, Benson would fully deploy colour into his photographic practice. This shift can be seen in the examples of his pictures taken on the road in Georgia (2007), Texas (2008), Ohio (2009), and even Apples for John (2007).

The exhibition is organised by Peter Barberie, the Brodsky Curator of Photographs, Alfred Stieglitz Center, Philadelphia Museum of Art, who also edited the book that accompanies the exhibition. Barberie said: “In the photography world, Benson is highly regarded as a printer and teacher, but never before has there been an in-depth survey to explore his own photographs, which are challenging, difficult, and beautiful representations of everyday life. His free-thinking blend of traditional craftsmanship, cutting-edge technology, and human empathy resulted in a unique and powerful body of work, and I am gratified to bring his important contributions to photography to audiences in Philadelphia and beyond.”

Related publication

The first major survey of Benson’s photography, this volume features works from the gift complemented by important prints from other collections and comparative illustrations from several of the photography books Benson helped produce in his career. It includes a critical and historical essay about Benson’s photography by Peter Barberie. Artist An-My Lê has written an essay about her memories of her teacher and friend. Publication date: September 2021 (160 pages; $45.00).

About Richard Benson (1943-2017)

Richard Benson spent much of his life in Newport, Rhode Island, where he grew up. His father, John Howard Benson (1901-1956), was a noted stone carver and calligrapher who in 1927 acquired the John Stevens Shop, which had been in operation since 1705. It became under the elder Benson’s direction a nationally celebrated firm for monumental lettering. Known by his nickname “Chip,” Richard occupied a workshop at the back of their house, where he pursued his craft and tinkered with a variety of creative pursuits including antique vehicles.

In 1961 he enrolled at Brown University but left after one semester before serving for three years in the Navy, studying at its Optical Repair School. He also took courses at the Art Students League in New York City. In 1966, after marrying Barbara Murray, he obtained a job at Meriden Gravure, a printing company in Connecticut that would expose him to the highest levels of craft in printing and set the course for his career in books and photography.

Benson became devoted to the technical aspects of printing and reproducing photographs. He made fine prints for other artists, including Paul Strand and Walker Evans and helped produce many of the finest photography books of his generation, including Lee Friedlander’s American Monument (1976); The Work of Atget (4 vols., 1981-84); and Photographs from the Collection of the Gilman Paper Company (1985). During these years, he quietly pursued his own photography, working with a large camera and producing black-and-white prints in various processes.

In 1979 Benson began teaching at Yale University School of Art, where he eventually served as dean from 1996 to 2006. He mentored younger colleagues and a generation of art students, many of whom recall his teaching as a formative experience. The unique quality of his teaching is reflected in his book The Printed Picture (2008), a survey of the entire history of printing as seen in the teaching materials he assembled over forty years. …

In the 1990s Benson embraced digital photography and dove into colour. He experimented with inkjet printing and traveled broadly to make photographs, many of which were published in North South East West (2011), a collection of his pictures from the previous six years.

Benson’s work is represented in the collections of the Eakins Press Foundation, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, San Francisco Museum of Art, Whitney Museum of American Art, and Yale University Art Gallery.

About the Promised Gift

In 2015, William H. and Elizabeth Ann Kahane, collectors and close friends of Richard Benson, pledged a promised gift of 180 of Benson’s works to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, which fulfilled a commitment they had made to the artist to keep a significant body of his work intact as a single collection. The exhibition and the publication have been six years in the making.

Richard Benson (American, 1943-2017)

Manhattan Waterfront Project

c. 1992

Chromogenic print

Image: 8 3/8 × 12 5/8 inches (21.3 × 32.1cm)

Sheet: 10 7/8 × 14 inches (27.6 × 35.6cm)

© Estate of Richard M. A. Benson. Promised gift of William M. and Elizabeth Ann Kahane

Image courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021

Richard Benson (American, 1943-2017)

Manhattan Waterfront Project

c. 1992

Chromogenic print

Image: 8 3/8 × 12 5/8 inches (21.2 × 32cm)

Sheet: 10 15/16 × 13 15/16 inches (27.8 × 35.4cm)

© Estate of Richard M. A. Benson. Promised gift of William M. and Elizabeth Ann Kahane

Image courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021

Richard Benson (American, 1943-2017)

New Mexico

2006

Pigment print

Image: 13 3/8 × 20 1/16 inches (34 × 51cm)

Sheet: 16 × 21 15/16 inches (40.7 × 55.8cm)

© Estate of Richard M. A. Benson. Promised gift of William M. and Elizabeth Ann Kahane

Image courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021

Richard Benson (American, 1943-2017)

Newfoundland (Green Boat)

c. 2006

Multiple impression pigment print

Image: 11 9/16 × 17 3/8 inches

Sheet: 12 15/16 × 19 inches

© Estate of Richard M. A. Benson. Collection of Barbara Benson

Image courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021

Richard Benson (American, 1943-2017)

Georgia

2007

Pigment print

Image: 20 × 13 3/8 inches (50.8 × 34cm)

Sheet: 22 × 16 inches (55.9 × 40.6cm)

© Estate of Richard M. A. Benson. Promised gift of William M. and Elizabeth Ann Kahane

Image courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021

“Georgia” (2007), which portrays a vertical array of four signs – two red octagonal stop signs, two circular railroad crossings, in yellow and orange – makes a visual counterpoint to three storage silos in the background that are painted red, blue and yellow-embellished silver. But the most virtuosic turn is the rendition of the sky, which is bleached out to a pale blue-gray at the horizon and gradually darkens to a full-throated cerulean at the top. If, as Willem de Kooning once remarked, flesh was the reason oil paint was created, Benson in his many crepuscular photographs makes the case that twilight skies were the reason color film was invented.

Arthur Lubow. “When a Master Printer Picks Up the Camera,” on The New York Times website December 30, 2021 [Online] Cited 02/01/2022

Richard Benson (American, 1943-2017)

Apples for John

2007

Pigment print

Image: 13 3/8 × 20 inches

Sheet: 15 7/8 × 22 inches

© Estate of Richard M. A. Benson. Promised gift of William M. and Elizabeth Ann Kahane

Image courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021

Richard Benson (American, 1943-2017)

Selma, Alabama

2007

Pigment print

Image: 11 5/8 × 17 3/8 inches (29.5 × 44.1cm)

Sheet: 13 × 19 inches (33 × 48.3cm)

© Estate of Richard M. A. Benson. Promised gift of William M. and Elizabeth Ann Kahane

Image courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021

Richard Benson (American, 1943-2017)

Kentucky

2007

Pigment print

Image: 11 5/8 × 17 3/8 inches (29.5 × 44.2cm)

Sheet: 12 15/16 × 19 inches (32.8 × 48.2cm)

© Estate of Richard M. A. Benson. Promised gift of William M. and Elizabeth Ann Kahane

Image courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021

Richard Benson (American, 1943-2017)

Okeechobee, Florida

2007

Pigment print

© Estate of Richard M. A. Benson. Promised gift of William M. and Elizabeth Ann Kahane

Image courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021

Richard Benson (American, 1943-2017)

Wyoming (Reinke Sprinkler)

2008

Multiple impression pigment print

Image: 13 3/8 × 20 1/8 inches

Sheet: 16 1/8 × 22 inches

© Estate of Richard M. A. Benson. Collection of Barbara Benson

Image courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021

Richard Benson (American, 1943-2017)

Untitled (Cotton Farm)

2008

Pigment print

Image: 13 3/8 × 20 inches (34 × 50.8cm)

Sheet: 14 15/16 × 21 15/16 inches (38 × 55.8cm)

© Estate of Richard M. A. Benson. Promised gift of William M. and Elizabeth Ann Kahane

Image courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021

Richard Benson (American, 1943-2017)

Louisiana

2008

Pigment print

© Estate of Richard M. A. Benson. Promised gift of William M. and Elizabeth Ann Kahane

Image courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021

Richard Benson (American, 1943-2017)

Texas

2008

Pigment print

Image: 13 3/8 × 20 inches

Sheet: 15 9/16 × 22 inches

© Estate of Richard M. A. Benson. Promised gift of William M. and Elizabeth Ann Kahane

Image courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021

Richard Benson (American, 1943-2017)

Arizona

2008

Pigment print

Image: 13 3/8 × 20 inches (34 × 50.8cm)

Sheet: 14 15/16 × 21 15/16 inches (38 × 55.8cm)

© Estate of Richard M. A. Benson. Promised gift of William M. and Elizabeth Ann Kahane

Image courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021

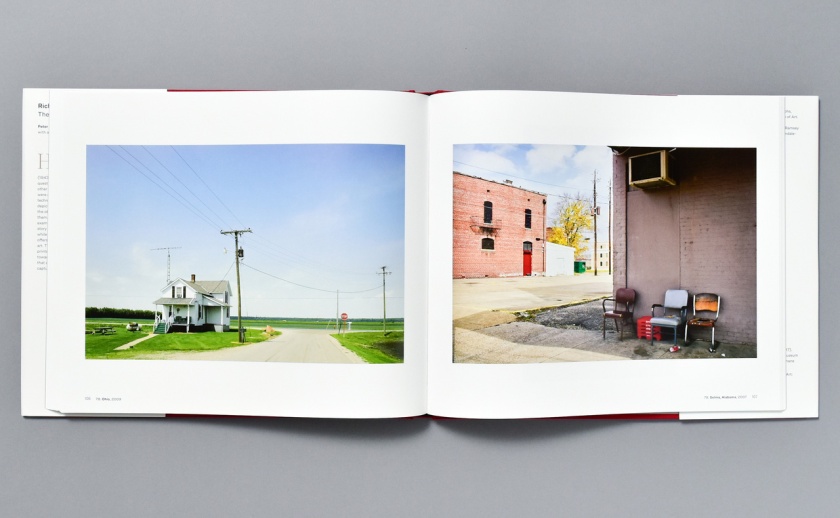

Richard Benson (American, 1943-2017)

Ohio

2009

Pigment print

Image: 13 3/8 × 20 inches (34 × 50.8cm)

Sheet: 16 × 22 inches (40.6 × 55.9cm)

© Estate of Richard M. A. Benson. Promised gift of William M. and Elizabeth Ann Kahane

Image courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021

Richard Benson (American, 1943-2017)

Untitled (Celeryville field)

2009 (negative); 2009 (print)

Pigment print

Image: 13 3/8 × 20 inches (34 × 50.8cm)

Sheet: 14 15/16 × 21 15/16 inches (38 × 55.8cm)

© Estate of Richard M. A. Benson. Promised gift of William M. and Elizabeth Ann Kahane

Image courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021

Publication

A wide-ranging retrospective that reveals a master printer’s own photographs to be technically brilliant work of remarkable breadth and complexity.

This book presents the first in-depth survey of photographs by Richard Benson (1943-2017), who approached photography as a thrilling set of technical challenges and used the medium to craft profound depictions of people, the spaces of their lives and work, and the products of their labor. An essay by curator Peter Barberie interweaves examination of Benson’s photographic practices with the story of his ideas, writing, and reproductive printing, while photographer An-My Lê, Benson’s former student, offers her perspective on his teaching, family life, and art. The book begins with his stunning darkroom prints in silver and platinum and follows his trajectory toward extraordinary digital photography, culminating in later colour prints that are at once elegant and garish, representing the contemporary world in vivid detail. Benson’s democratic eye also extended to human subjects: he photographed loved ones and strangers with extraordinary attention, and directed the same gaze to the buildings and landscapes entwined with individual lives.

Author: Peter Barberie

Hardcover

Publisher: Philadelphia Museum of Art, October 2021

152 pages, 11 3/4 x 9 3/4

134 color illustrations

ISBN: 9780876332016

Richard Benson: The World Is Smarter Than You Are publication

Philadelphia Museum of Art

26th Street and the Benjamin Franklin Parkway

Philadelphia, PA 19130

Opening hours:

Thursday – Monday: 10am – 5pm

Closed Tuesday and Wednesday

You must be logged in to post a comment.