Exhibition dates: 31st October, 2021 – 30th January, 2022

Curator: The exhibition is curated by Andrea Nelson, associate curator in the department of photographs, National Gallery of Art, Washington.

Tsuneko Sasamoto (Japanese, b. 1914)

Ginza 4 Chome P.X.

1946, printed 1993

Gelatin silver print

Image: 29.6 x 29.6cm (11 5/8 x 11 5/8 in.)

Frame: 40.64 x 50.8cm (16 x 20 in.)

Frame (outer): 41 x 51.2 x 2.5cm (16 1/8 x 20 3/16 x 1 in.)

Collection of Tokyo Photographic Art Museum

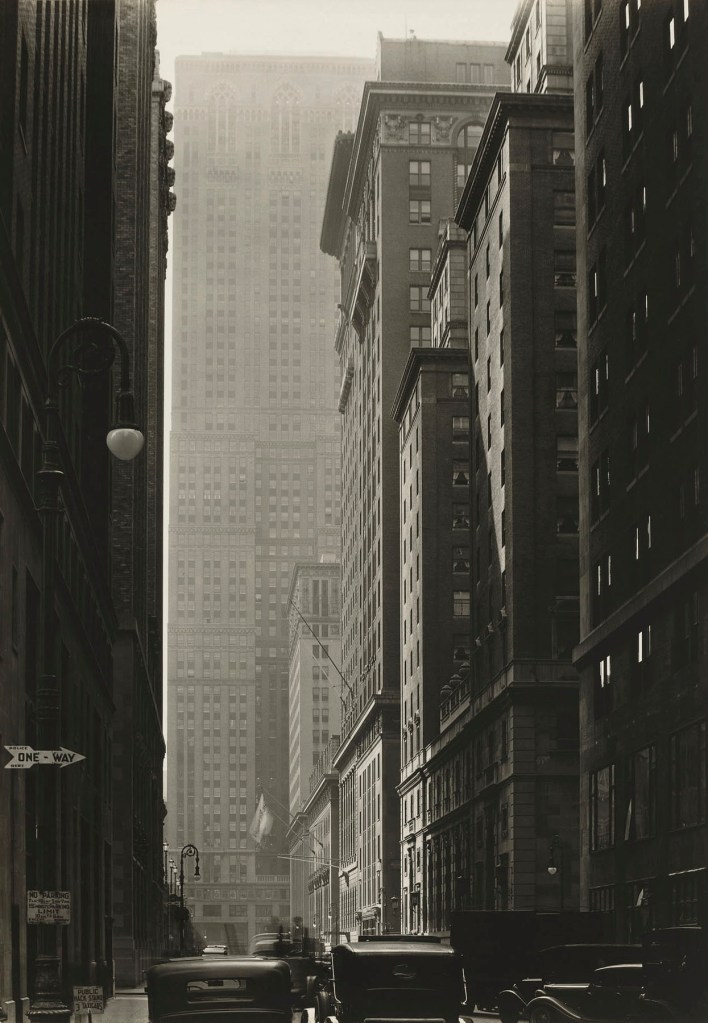

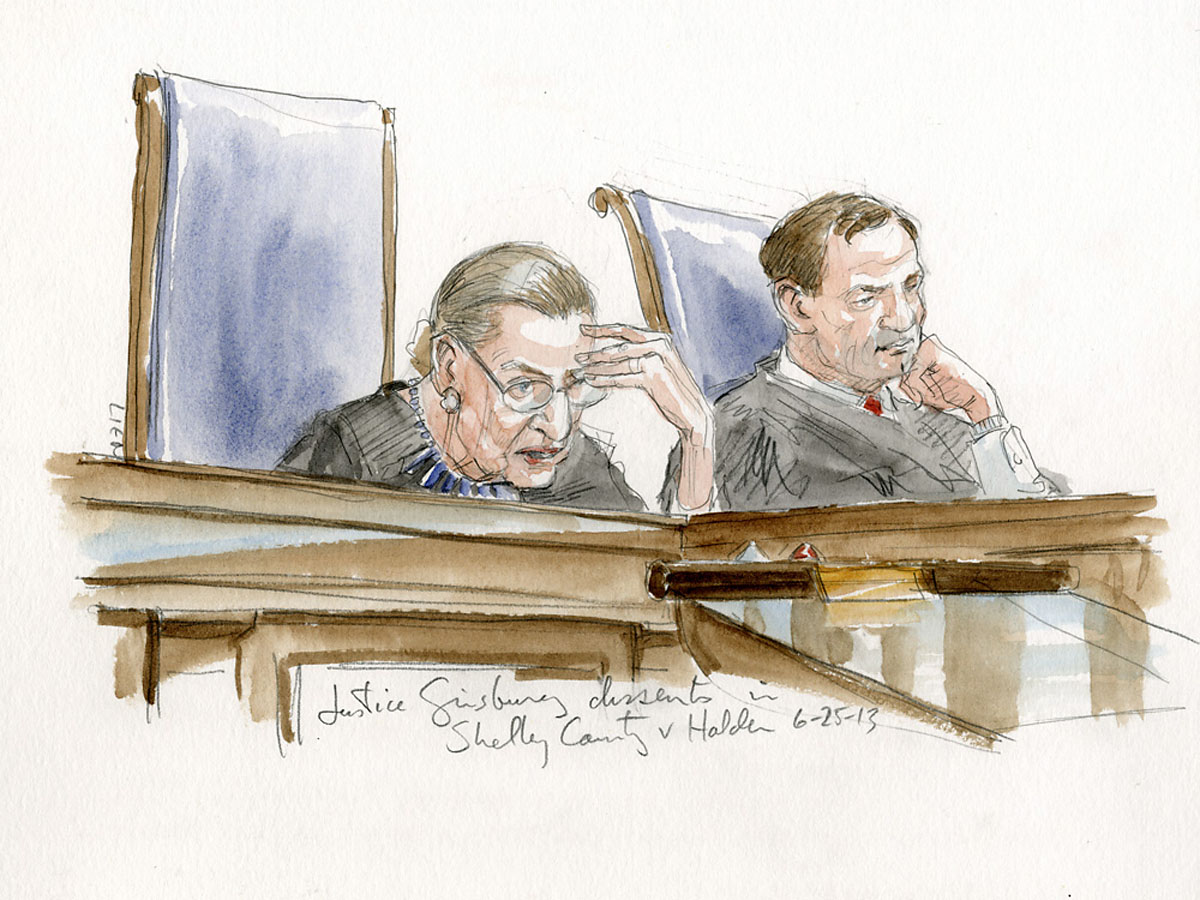

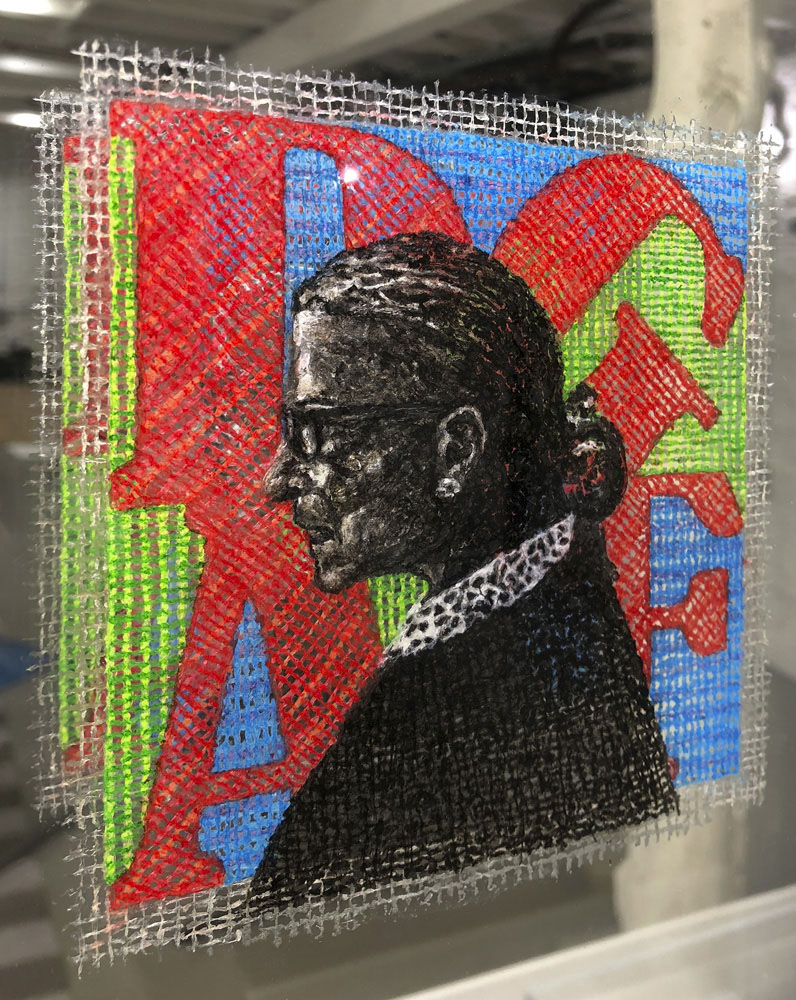

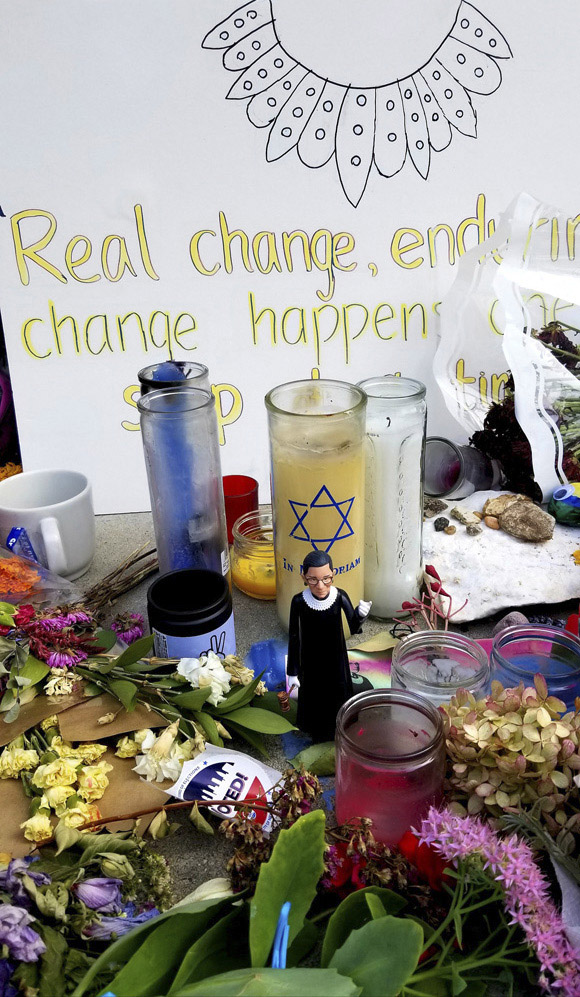

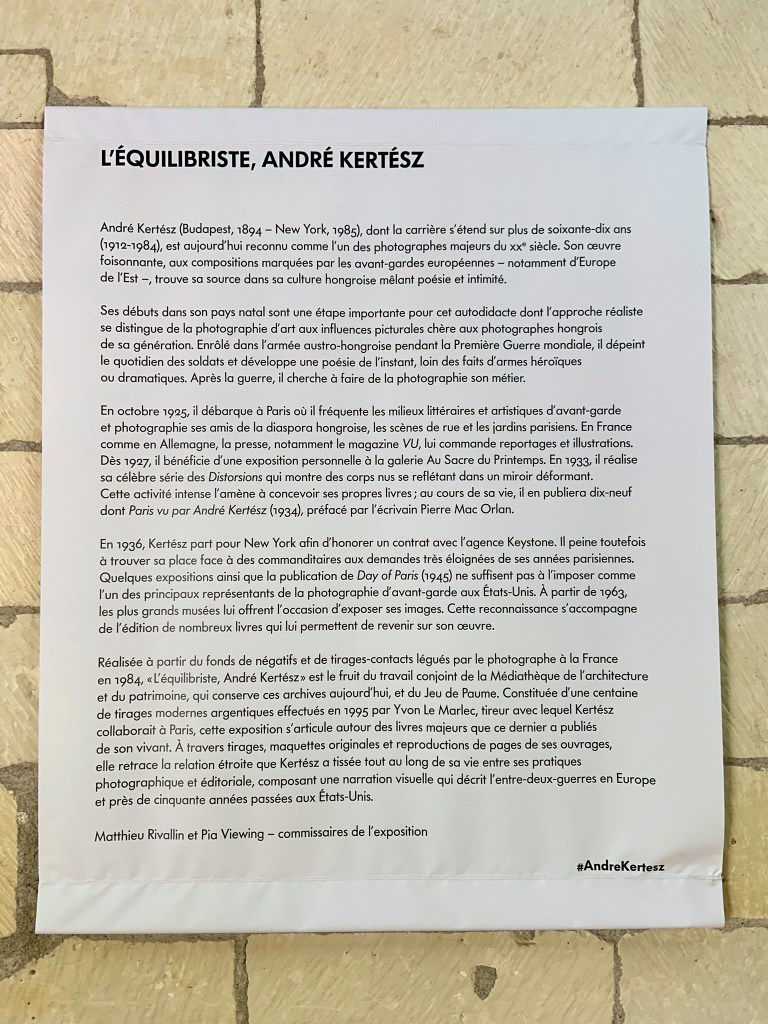

Abstract

Using the media images from the exhibition The New Woman Behind the Camera at the National Gallery of Art, Washington (31st October, 2021 – 30th January, 2022) as a starting point, this text examines the (in)visibility of the “New Woman” behind the camera. The text briefly investigates the disenfranchisement of women in 19th century through the work of George Sand and Camille Claudel; the role of the female flâneuse and the rise of the suffragettes; the relationship between two women and two men; a story; the work of two women photographers (Germaine Krull and Claude Cahun) who through photography challenged the representation of gender identity; a Zen proposition, and the particular becomes universal – in order to understand how artists, both female and male, find integrity on their chosen path.

Keywords

New Woman, photography, art, integrity, George Sand, Camille Claudel, female flâneuse, suffragette, camera, Germaine Krull, Claude Cahun, Leni Reifenstahl, Georgia O’Keeffe, Alfred Stieglitz, female emancipation, gender identity, representation, Sabine Weiss, Susan Sontag, self recognition, patriarchal society.

Download the complete text of Finding Integrity: “New Woman” artists and female emancipation in the first half of the twentieth-century (5.6Mb Word docx)

“The world doesn’t like independent women, why, I don’t know, but I don’t care.”

Berenice Abbott

Finding Integrity: “New Woman” artists and female emancipation in the first half of the twentieth-century

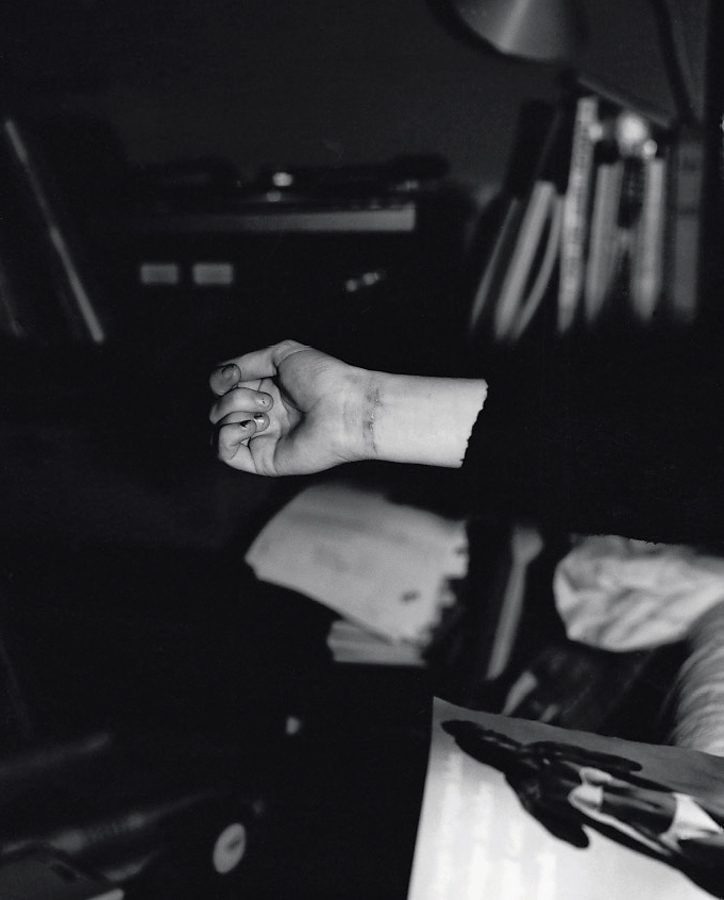

After thousands of years of human existence, woman still do not have equality. They have to fight for equal pay for the same job, they fight for equal opportunity in many jobs and top level positions, they fight for control of their body, and they fight against misogyny, discrimination and the aggression of hypermasculinity. They, and their children, fight not to be killed by jealous and enraged (x)lovers or (x)husbands – where x in mathematics is a variable number which is not yet known (in 2021 in Australia 43 women died at the hands of men) – whose ego and possessiveness cannot bear the thought of a vibrant, free thinking woman living beyond their control. I know of these things having grown in the womb, having grown up for the first 18 years of my life feeling my mother being abused, and then being abused myself trying to protect my mother.

My mother wanted to study music at Cambridge after graduating from the Royal College of Music but because she got married and had children she never had the opportunity. Her struggle, as with many women still, was to find her place in a man’s world – as a wife and mother in her case – to live within the parameters of the social construct that is a patriarchal society. At the time (in the 1960s) she said she felt less than human… for there was no help and little opportunity for women to escape their situation. Her one salvation was music and the one way she found to subvert the dominant structures was to teach piano. Now ninety years old, she has taught piano for the rest of her life. She found her voice and her independence. She found her integrity.

Earlier generations

In earlier generations, before the “New Woman”, women had to conform (to society’s expectations) and submit (to men) … unless they were notorious, celebrities or geniuses. Otherwise they were mainly disenfranchised and disempowered.

Women had to write under men’s names to be accepted, to sell and make a living. The novelist Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin initially collaborated with the male writer Jules Sandeau and they published under the name Jules Sand before Dupin took up the pen name that was to make her famous and a celebrity across Europe: George Sand (French, 1804-1876). “Sand’s writing was immensely popular during her lifetime and she was highly respected by the literary and cultural elite in France.”1 She chose to wear male attire in public without a permit (which “enabled her to circulate more freely in Paris than most of her female contemporaries, and gave her increased access to venues from which women were often barred, even women of her social standing”1), and she smoked “tobacco in public; neither peerage nor gentry had yet sanctioned the free indulgence of women in such a habit, especially in public… While there were many contemporary critics of her comportment, many people accepted her behaviour until they became shocked with the subversive tone of her novels.”1 Sand was also politically active and “sided with the poor and working class as well as women’s rights. When the 1848 Revolution began, she was an ardent republican. Sand started her own newspaper, published in a workers’ co-operative.”1

![Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'George Sand (Amandine-Aurore-Lucile Dupin), Writer' c. 1865 Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'George Sand (Amandine-Aurore-Lucile Dupin), Writer' c. 1865](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/realideal5-web.jpg?w=780)

Nadar (Gaspard Félix Tournachon) (French, 1820-1910)

George Sand (Amandine-Aurore-Lucile Dupin), Writer

c. 1865

Albumen silver print from a glass negative

24.1 x 18.3 cm (9 1/2 x 7 1/4 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Used under fair use conditions for the purposes of academic research and education

In other words because of her visibility, celebrity, social standing, writing, intellect and revolutionary fervour she was acknowledged as a great woman. Men consulted with her and took her advice. Upon her death under the heading “Emancipated Woman,” in The Saturday Review, Victor Hugo commented: “George Sand was an idea. She has a unique place in our age. Others are great men … she was a great woman.” All well and good, but then he continues, “In this country, whose law is to complete the French Revolution, and begin that of the equality of the sexes, being a part of the equality of men, a great woman was needed. It was necessary to prove that a woman could have all the manly gifts without losing any of her angelic qualities; be strong without ceasing to be tender. George Sand proved it.”2 In other words to be the equal of a man, a woman must act like a man but also keep her womanly qualities (tenderness, femininity). She couldn’t really be herself because she had to measure up to the ideals of men. What a slap in the face, a kind of pseudo-equality – if you played your cards right and obeyed the rules of the game.

An incredibly sad example of female disenfranchisement in the arts is that of August Rodin’s assistant Camille Claudel (French, 1864-1943) who became his model, his confidante, and his lover. Claudel started working in Rodin’s workshop in 1883 and became a source of inspiration for him.

César (French)

Portrait de Camille Claudel

before 1883

Musée Camille Claudel

Used under fair use conditions for the purposes of academic research and education

“The exact nature of the tasks with which she was entrusted remains uncertain, but she apparently spent most of her time on difficult pieces, such as the hands and feet of figures for monumental sculptures (notably The Gates of Hell). For Claudel, this was an intensive period of training under Rodin’s supervision: she learned about his profiles method and the importance of expression. In tandem, she pursued her own investigations, accepted her first commissions and sought recognition as an independent artist at the Salon. Between 1882 and 1889, Claudel regularly exhibited busts and portraits of people close to her at the Salon des Artistes Français. Largely thanks to Léon Gauchez, Rodin’s friend the Belgian art dealer and critic, several of her works were purchased by French museums in the 1890s.”3

But women working under the “master” were not often acknowledged.

“Le Cornec and Pollock state that after the sculptors’ physical relationship ended [with Rodin in 1892 after an abortion], she was not able to get the funding to realise many of her daring ideas – because of sex-based censorship and the sexual element of her work. Claudel thus had to either depend on Rodin, or to collaborate with him and see him get the credit as the lionised figure of French sculpture. She also depended on him financially, especially after her loving and wealthy father’s death, which allowed her mother and brother, who disapproved of her lifestyle, to maintain control of the family fortune and leave her to wander the streets dressed in beggars’ clothing.

Claudel’s reputation survived not because of her once notorious association with Rodin, but because of her work. The novelist and art critic Octave Mirbeau described her as “A revolt against nature: a woman genius.”” …

Ayral-Clause says that even though Rodin clearly signed some of her works, he was not treating her as different because of her gender; artists at this time generally signed their apprentices’ work. Others also criticise Rodin for not giving her the acknowledgment or support she deserved. …

Other authors write that it is still unclear how much Rodin influenced Claudel – and vice versa, how much credit has been taken away from her, or how much he was responsible for her woes. Most modern authors agree that she was an outstanding genius who, starting with wealth, beauty, iron will and a brilliant future even before meeting Rodin, was never rewarded and died in loneliness, poverty, and obscurity. Others like Elsen, Matthews and Flemming suggest it was not Rodin, but her brother Paul who was jealous of her genius, and that he conspired with her mother, who never forgave her for her supposed immorality, to later ruin her and keep her confined to a mental hospital.”4

This “sculptor of genius” was eventually “voluntarily” committed by her family to a psychiatric hospital in 1913 where she lived the remaining 30 years of her life, unable to practice her art. Her remains were buried in a communal grave at the asylum, her bones mixed with the bones of the most destitute. Her brother Paul Claudel could not be bothered with a grave for her, while he specified the exact place of his internment… the ultimate irony being that, Rodin had decided to include an exhibition space reserved exclusively for Camille Claudel’s works in the future museum that would house the collections he bequeathed to the French state on his death (at the Rodin Museum) – a request that could not be honoured until 1952, when Paul Claudel donated four major works by his sister to the museum.5 Bitter irony.

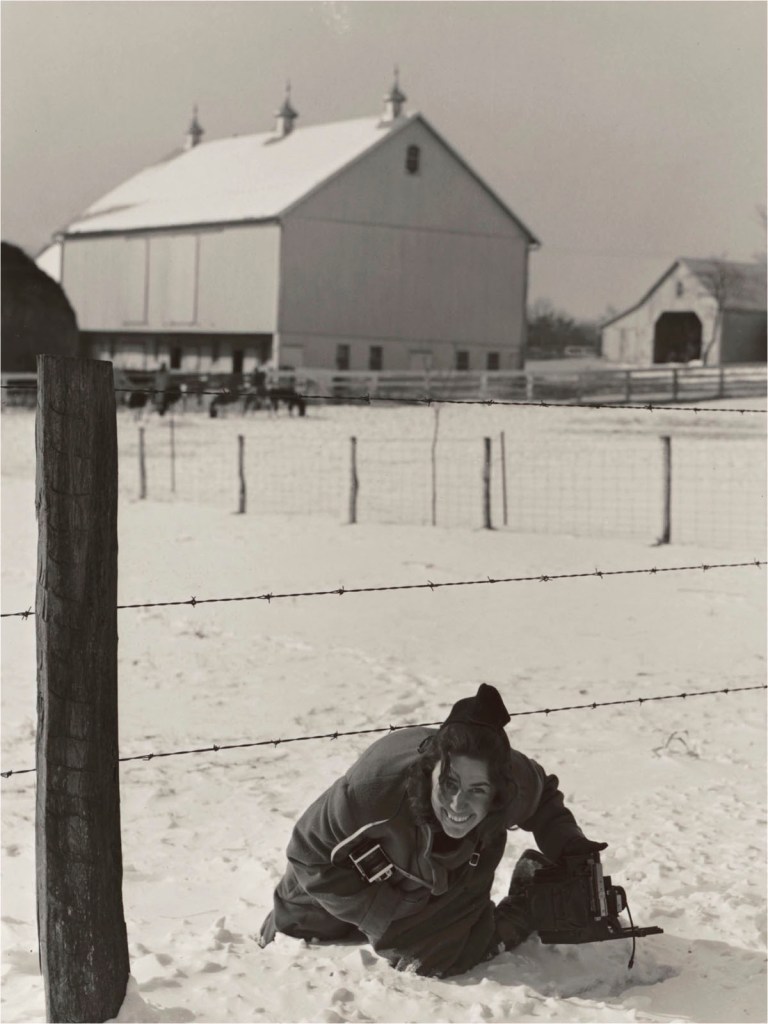

Ruth Orkin (American, 1921-1985)

American Girl in Italy

1951

Gelatin silver print

© Ruth Orkin

Courtesy of Howard Greenberg Collection

Used under fair use conditions for the purposes of academic research and education

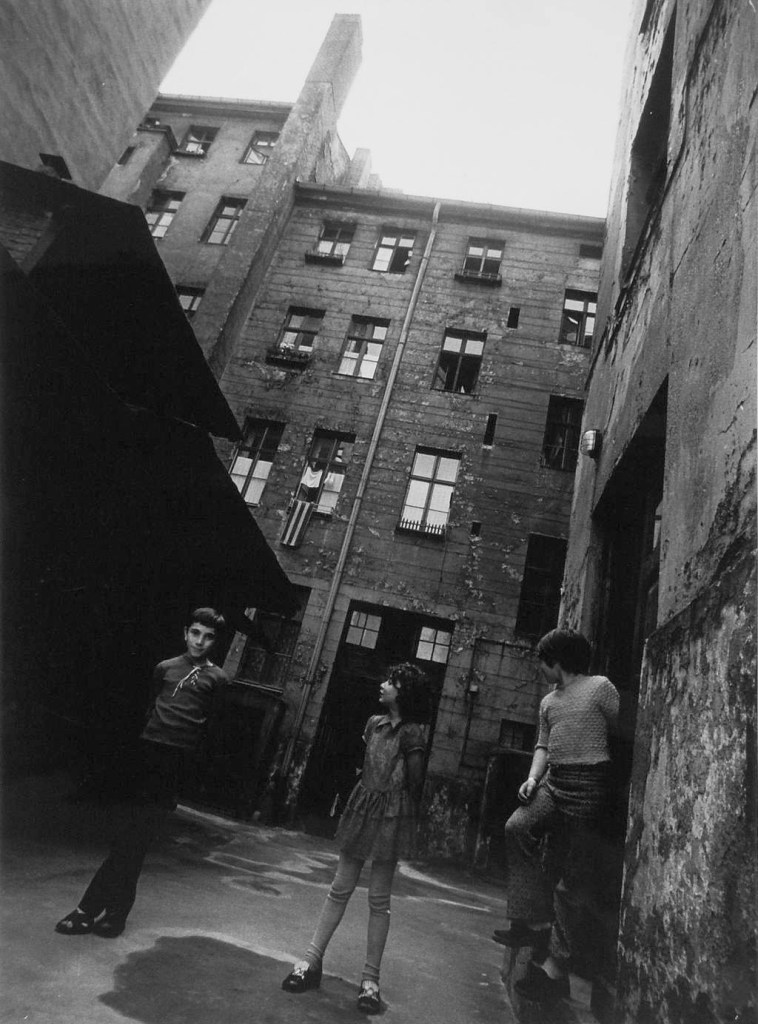

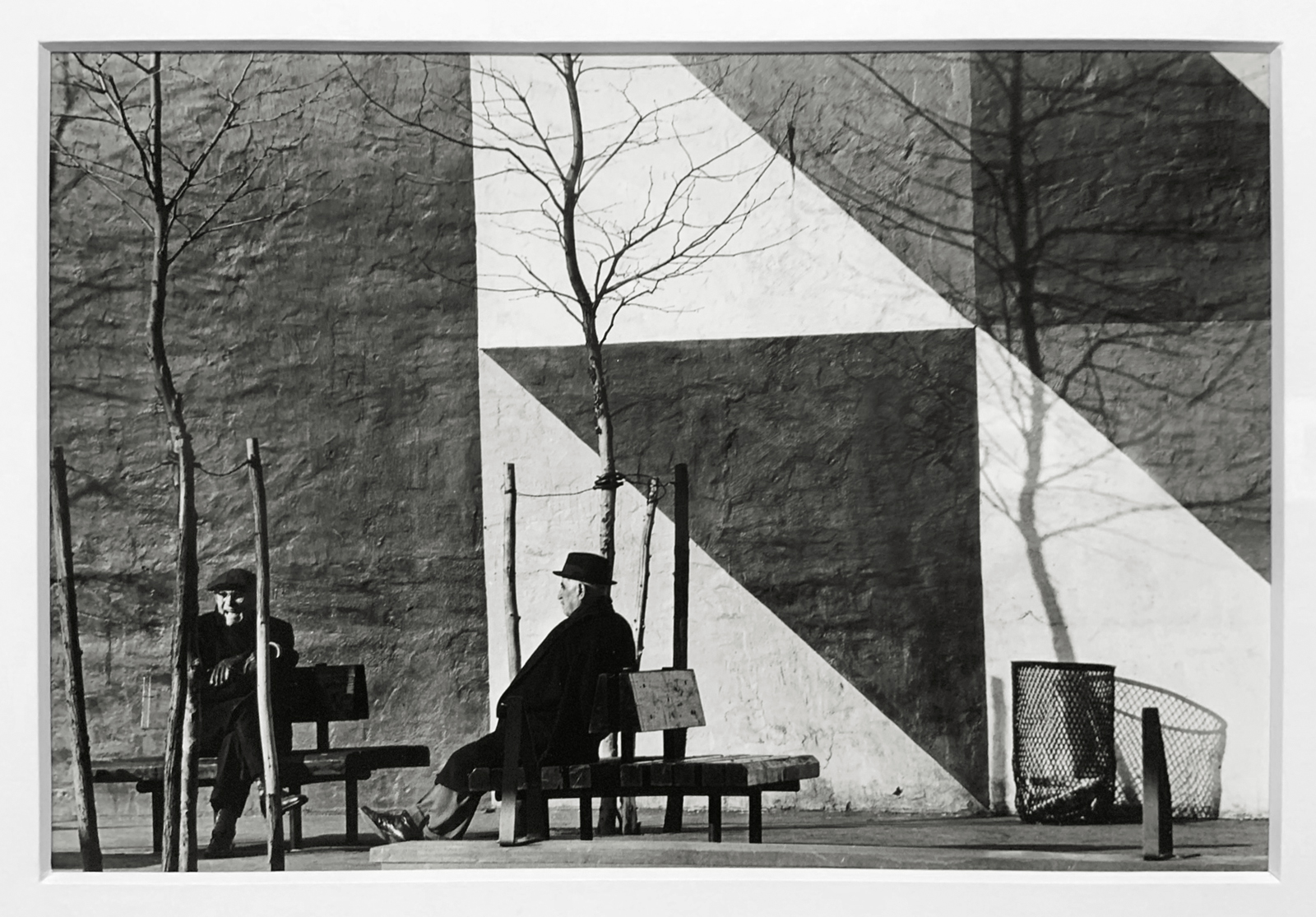

The female flâneuse and a period of transition

During the 19th century women could not stroll alone in the city.

“In Baudelaire’s essays and poems, women appear very often. Modernity breeds, or makes visible, a number of categories of female city-dwellers. Among the most prominent in these texts are: the prostitute, the widow, the old lady, the lesbian, the murder victim, and the passing unknown woman… But none of these women meet the poet as his equal. They are subjects of his gaze, objects of his ‘botanising’. The nearest he comes to a direct encounter, with a woman who is not either marginal or debased, is in the poem, À Une Passante (Even here, it is worth noting that the woman in question is in mourning – en grand deuil). The tall, majestic woman passes him in the busy street; their eyes meet for a moment before she continues her journey, and the poet remains to ask whether they will only meet again in eternity… (But if this is the rare exception of a woman sharing the urban experience, we may also ask whether a ‘respectable’ woman, in the 1850s would have met the gaze of a strange man).”6

But as Janet Wolff observes, women clearly were active and visible in other ways in the public arena, especially when it came to the construction of women’s dress as a sign of their husbands’ position: in effect, the less they worked and the more they evidenced the performance of conspicuous leisure and consumption, the more this was to the credit of their master rather than to their own credit. Wolff further notes, “The establishment of the department store in the 1850s and the 1860s provided an important new arena for the legitimate public appearance of middle-class women…” but denies this has anything to do with women being a female flâneur – a flâneuse – because the fleeting, anonymous encounters and purposeless strolling she has been considering “do not apply to shopping, or to women’s activities either as public signs of their husband’s wealth or as consumers.”7 Wolff rejects the notion of a female flâneuse as “such a character was rendered impossible by the sexual divisions of the nineteenth century.”8

Others disagree with this interpretation. In a paper titled “Gender Differences in the Urban Environment: The flâneur and flâneuse of the 21st Century”, Akkelies van Nes and Tra My Nguyen offer the following history of the flâneur9 and the flâneuse concepts (apologies for the long quotation but it necessary):

“The term flâneur originated from the 18th century. It was described by Charles Baudelaire as ‘gentleman stroller of city streets’ (van Godsendthoven, 2005). …

‘The flâneur was an idle stroller with an inquisitive mind and an aesthetic eye, a mixture of the watchful detective, the aesthetic dandy and the gaping consumer, the badaud. A solitary character, he avoided serious political, familial or sexual relationships, and was only keen on the aesthetics of city life. He read the city as a book, finding beauty in the obsolete objects of other people, but in a distanced, superior way’ (van Godsendthoven, 2005).

The flâneur is a product of modern life and the industrial revolution, parallel to the references of the tourist in contemporary times. The arrival of department stores and the ‘Haussmannization’ of Paris’ streets in the second half of the nineteenth century swept away large parts of the historical city and also the domain of the flâneur. The archetype of the flâneur disappeared with its surroundings, in favour of the women- oriented department stores. ‘The department store may have been, as Benjamin put it, the flâneur’s last coup, but it was the flâneuse’s first’ (Friedberg, 1993).

The flâneuse is not a female flâneur, but she is a version of the flâneur. She does not experience the city in the same way as he does. It is hard to define the archetype of the flâneuse, because the flâneur himself consists of paradoxes and many subcategories. Key concepts for flâneur and flâneuse are the amount of spare time, the aesthetic detachment towards objects, crowd and sceneries they see and their ambiguity about it.

The department stores were a starting point for the existence of the flâneuse, but this also marked her as a consumer, a ‘badaud’. The difference between badauds and flâneuses are the distance they create between themselves and the activities in the city. A characteristic of flânerie is an aesthetic distance between the subject and the object of attention. The badaud-flâneuse lacks this distance. The city is not being experienced, but is reduced to a place to consume.

As implied, the badaud-flâneuse did not have the full ability to flânerie. However, she has many qualities, which are at least some first initiatives to stroll around. Her domain moved from the interior of her home to the interior of the department store and sometimes even to the streets (Parsons, 2000). Shopping, art and day trips contribute to develop a certain view in that period of society, which was at the end of 19th century. Friedberg was very well aware that this new freedom was not the same as the freedom of the flâneur (Friedberg, 1993).

The flâneuse concept developed throughout the years expanded somehow further than being a badaud. She was discovering domains like art forms, like for example the cinema and the theatre at the beginning of the 20th century. But she was still objectified by men and patriarchic institutes. However, women became independent, without taking over the absent look and gaze of the flâneur. They changed their lives into art forms and had an opinion about the society they lived in. To gain respect as artists, the image of women as muses had to disappear. She had to claim an active role and to develop her own personality.

Through the literature, the life of the flâneuse and the female characters in the city, like passersby, artists, dandies and badauds [gawkers, bystanders] are often interlaced with each other, and difficulties they experienced are alike. The flâneuse often shifted between these roles, but distinguished herself by her independency and distanced. She became a symbol for post-modern urban life: a wanderer in many shapes.”10

Nes and Nguyen further argue that the emancipation of women over the last two decades “has brought the flâneuse to a more equal position with the flâneur in the invisible right to be in public urban space. However, aspects like safety and when and where women are spending time in urban space still have effect on how women use public spaces and affect the public spheres.”11 Indeed, with the despicable murder of too many women in Melbourne in recent years by predatory men (Aiia Maasarwe, Mersina Halvagis, Masa Vukotic, Eurydice Dixon, Tracey Connelly, Sarah Cafferkey, Renea Lau and Jill Meagher to name just a few…), women still fear walking the streets alone. “Even when grief enveloped his family, Bill Halvagis can recall the wider sense of public outrage that followed the murder of his older sister Mersina. The shock that someone could do such a thing in a public place was as brutal as the crime itself.”12

Unknown photographer (Australian)

People march through Brunswick in Melbourne after the murder of Jill Meagher in 2012

2012

Australian Associated Press (AAP)

Republished under Creative Commons from The Conversation website

Used under fair use conditions for the purposes of academic research and education

Looking back a century later, one of the key points of female emancipation in the early twentieth century is that women gained their independence “and had an opinion about the society they lived in… She had to claim an active role and to develop her own personality” while present and visible in the community, present in a public place. The world-wide suffragette movement was at the forefront of this early twentieth-century revolution.

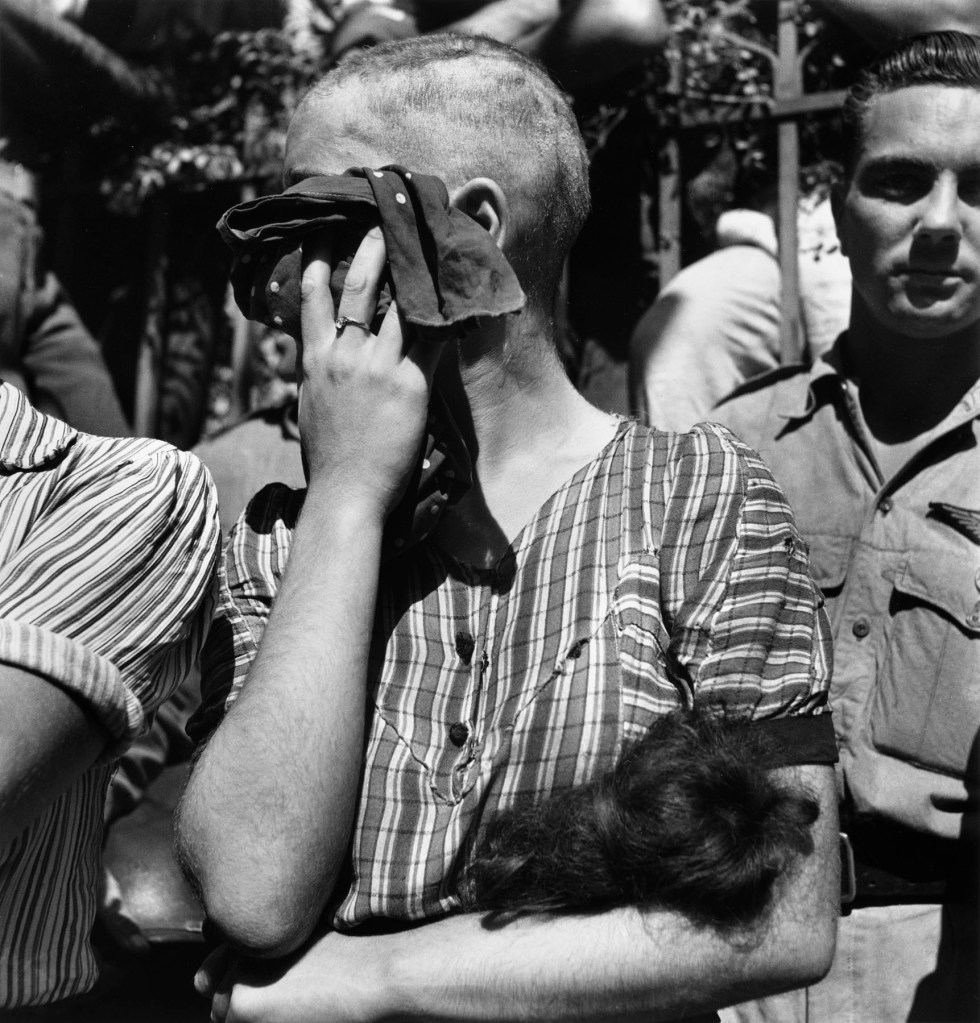

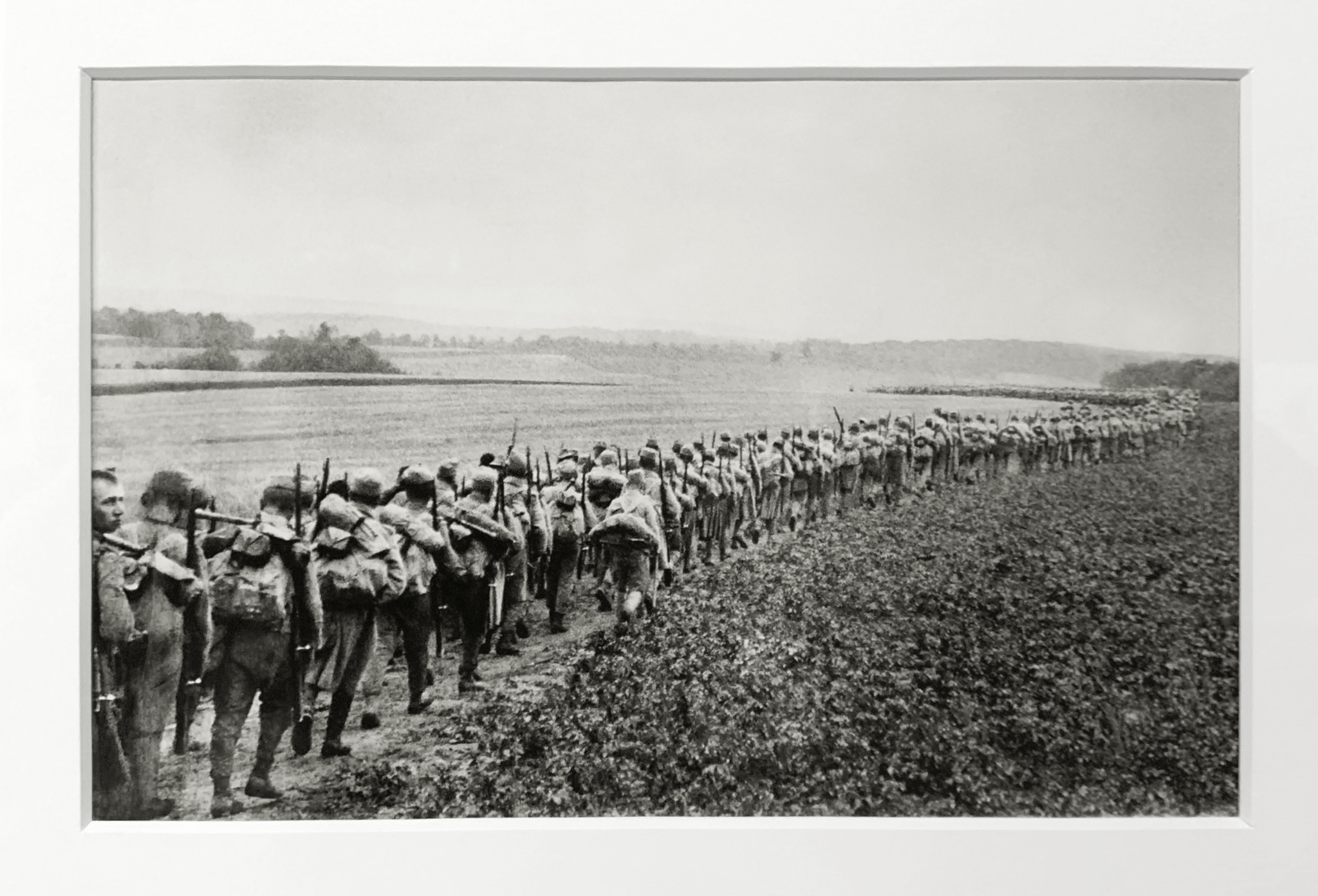

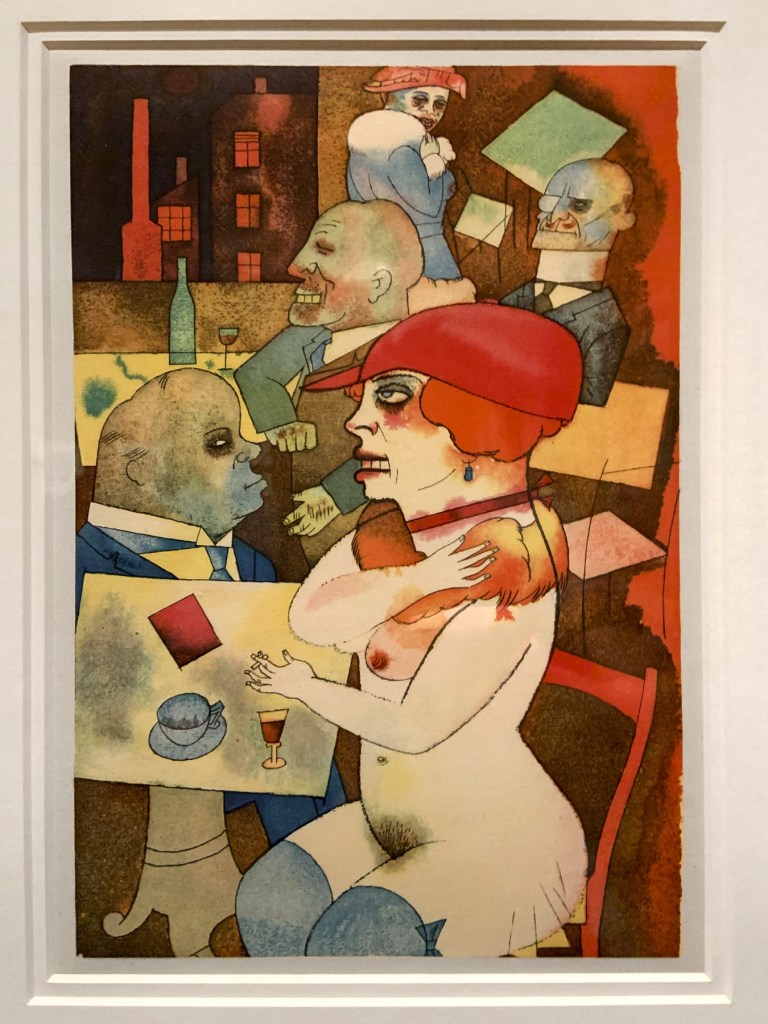

“A suffragette was a member of an activist women’s organisation in the early 20th century who, under the banner “Votes for Women”, fought for the right to vote in public elections. The term refers in particular to members of the British Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), a women-only movement founded in 1903 by Emmeline Pankhurst, which engaged in direct action and civil disobedience.” During the First World War “the suffragette movement in Britain moved away from suffrage activities and focused on the war effort… Women eagerly volunteered to take on many traditional male roles – leading to a new view of what women were capable of.”13 However, this new found capability and visibility in society “cast women as passive, erotic objects, subjecting them to a kind of voyeuristic control” by men, embodying the gaze of modernity which is both covetous and erotic – public sites (of interaction) producing “meanings and positions from which those meanings are consumed.”14 Women were “playing” in a man’s world subject to their approval, their gaze and their desire to possess and control the female both physically and sexually.

But, as Griselda Pollock observes, “modernity was not represented as taking place in exclusively masculine, because public, domains: rather, the spaces of modernity were in fact marginal spaces, those in which the city’s “new subjective experiences of exhilaration and alienation, pleasure and fear, mobility and confinement, expansiveness and fragmentation,” were most intense. These spaces of intersection happened to be sites in which bourgeois men came into contact with women…”15

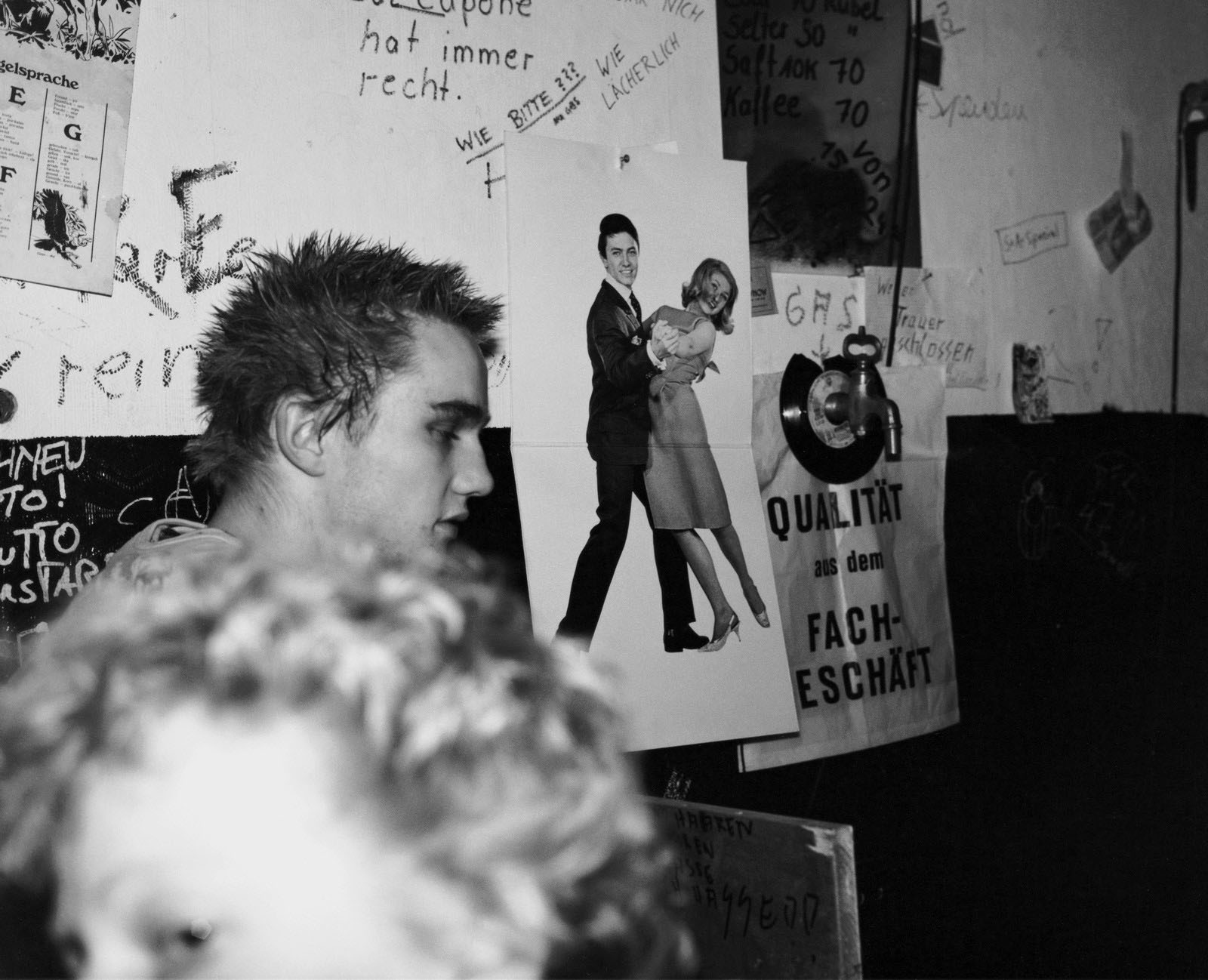

Here comes the “New Woman” taking on traditional male roles, socialising in marginalised spaces, boldly going where few women had gone before, sampling new subjective experiences, becoming who they wanted to be… all under the munificent gaze of the (bourgeois) male.

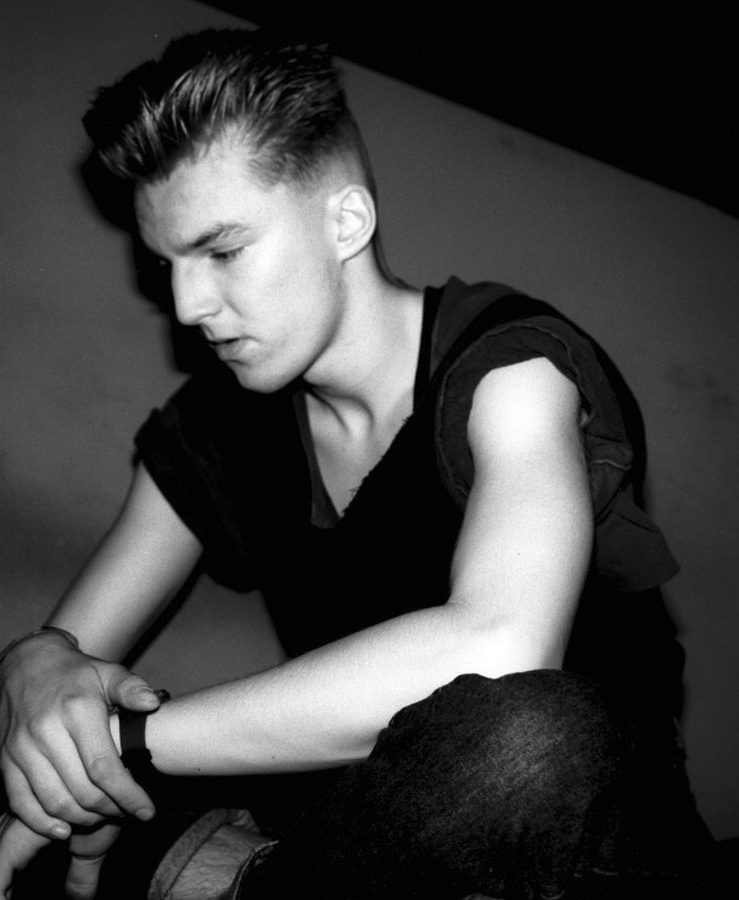

Two women and two men

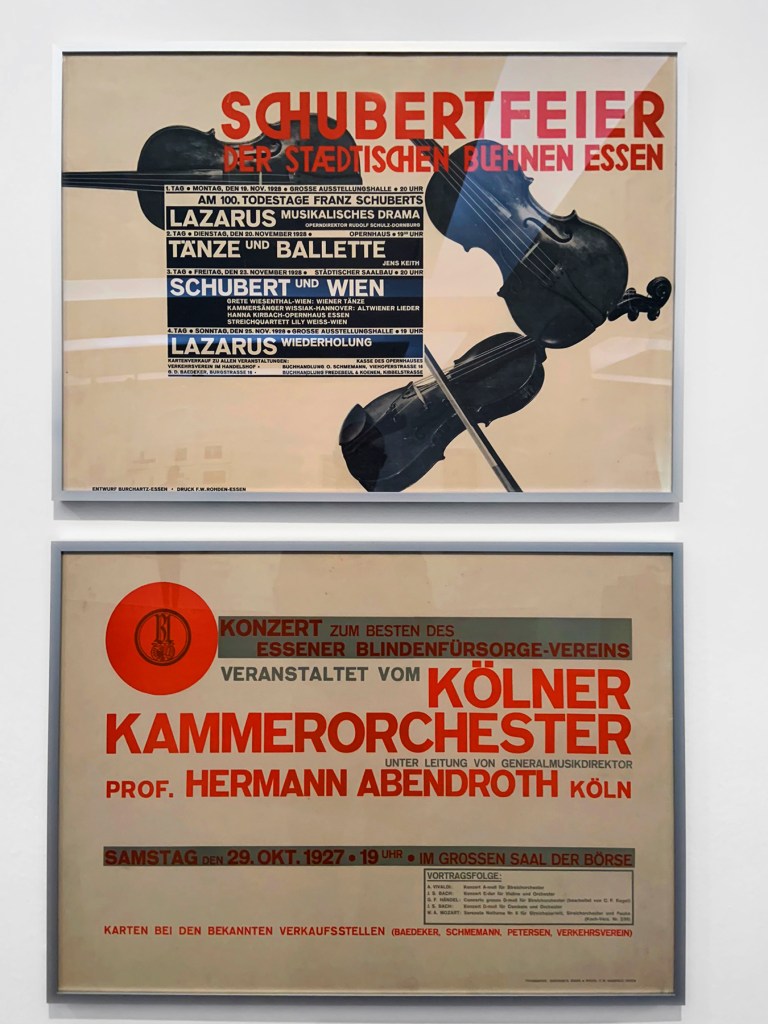

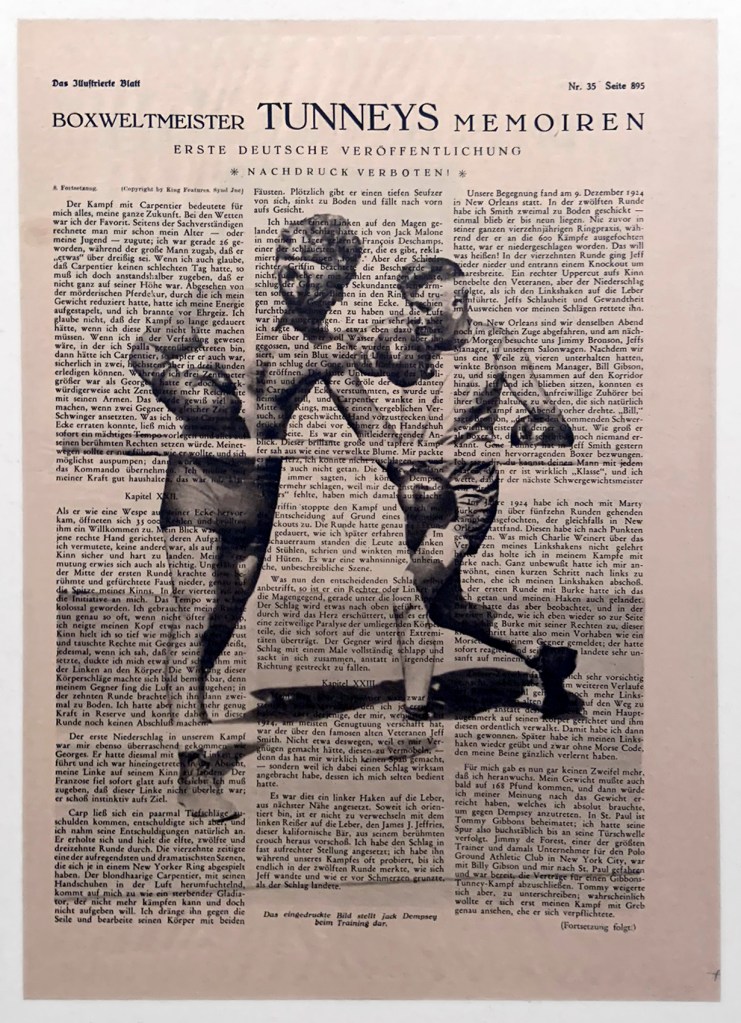

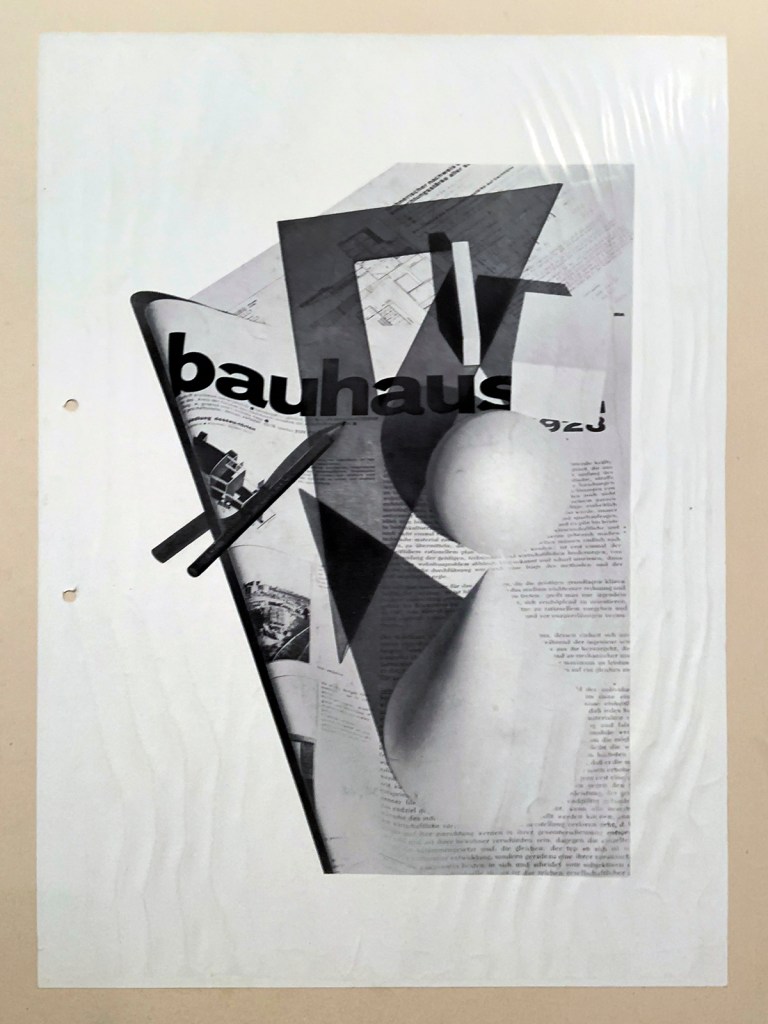

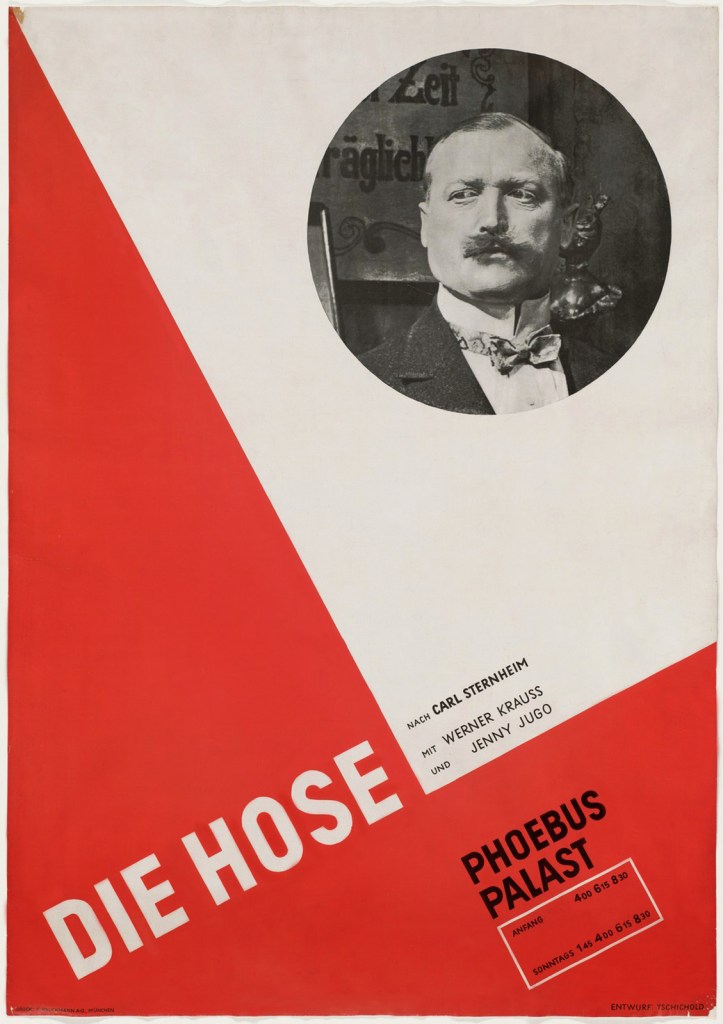

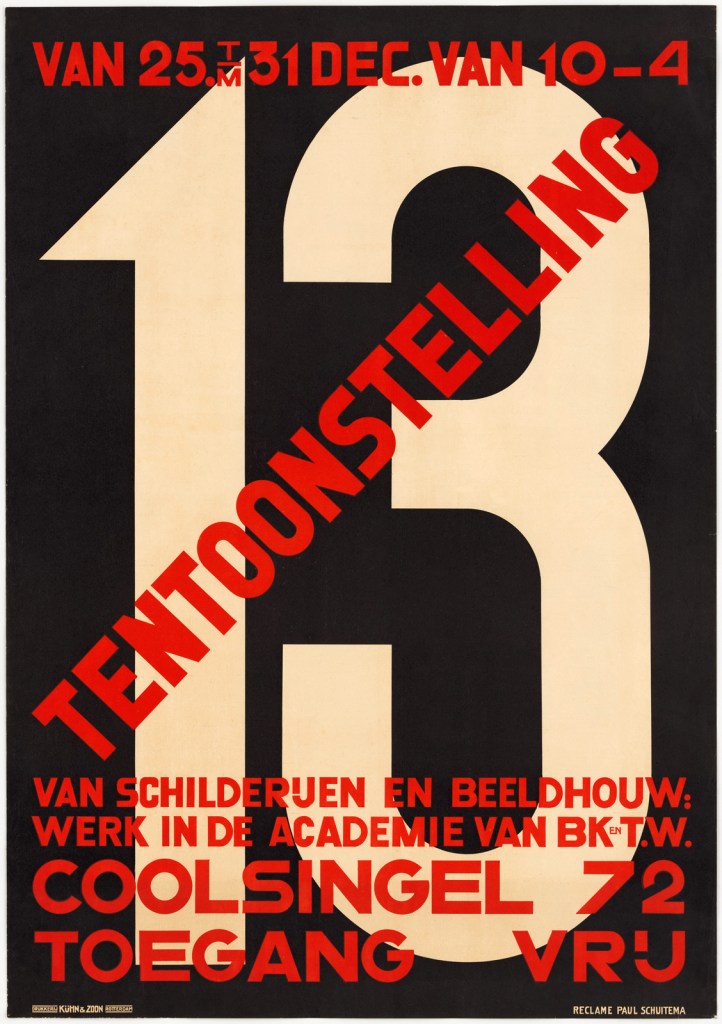

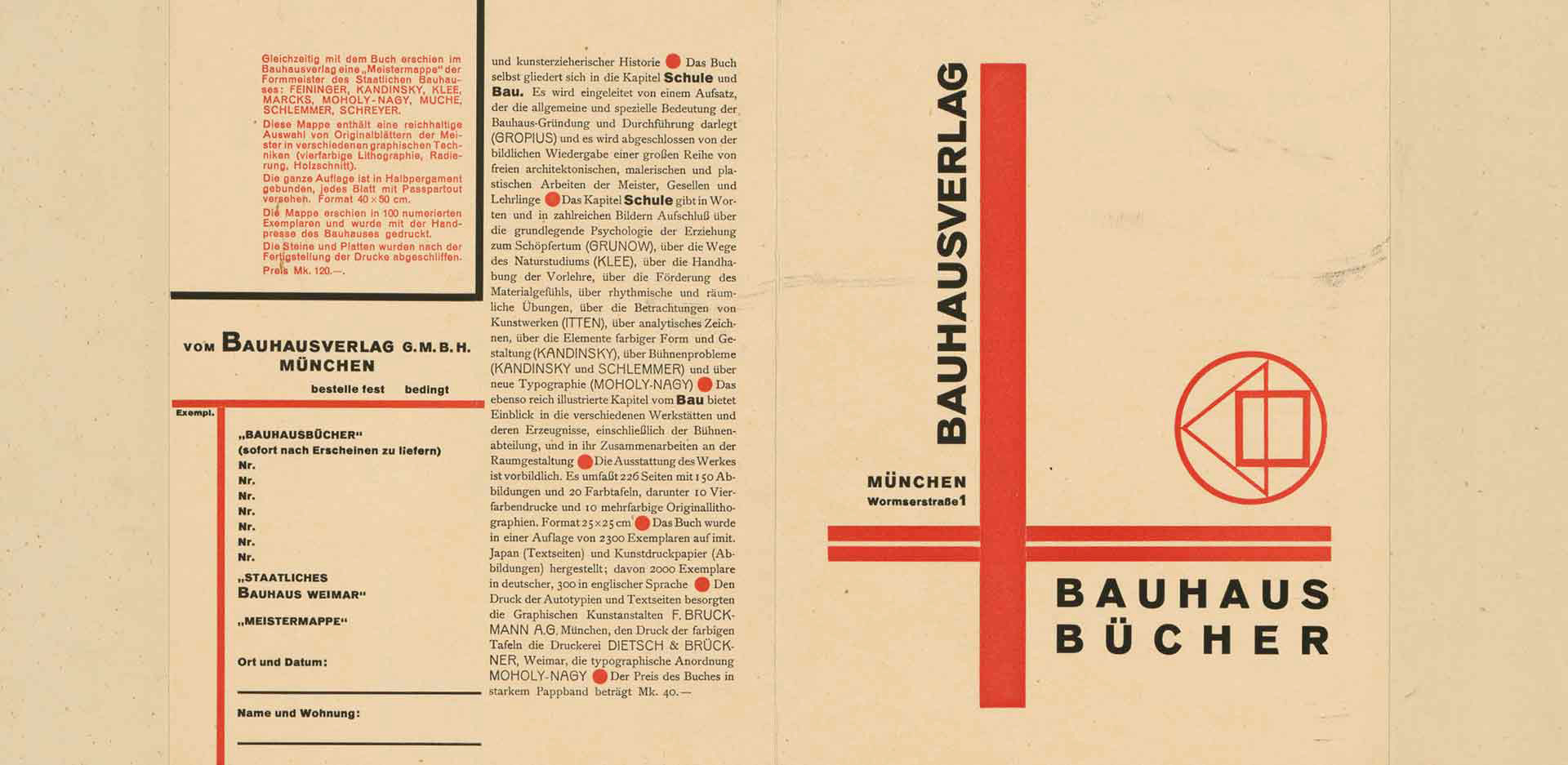

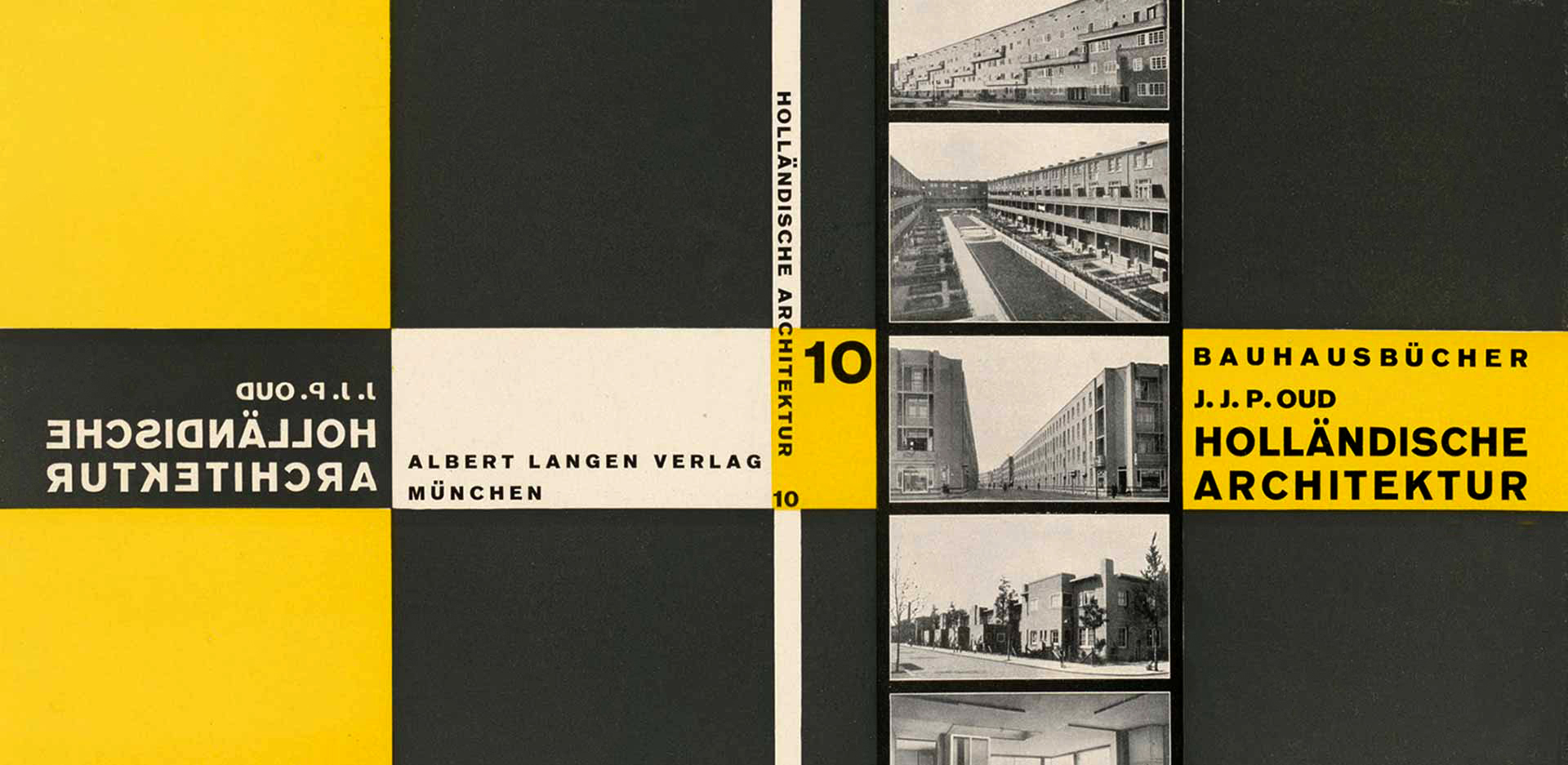

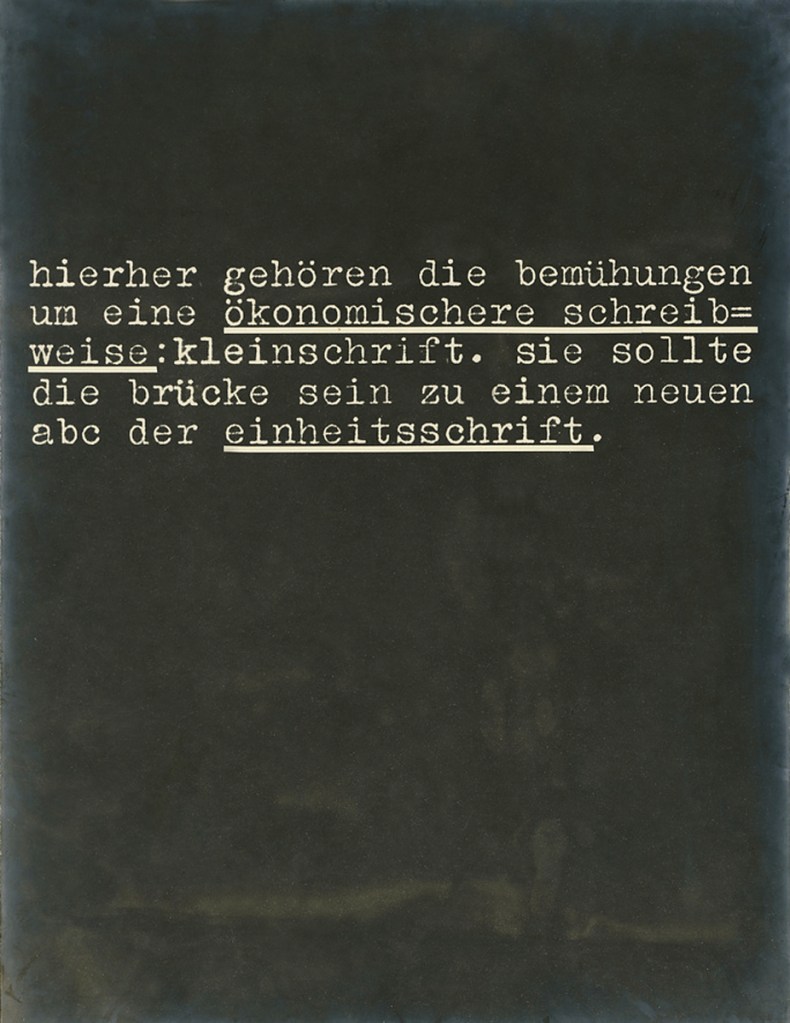

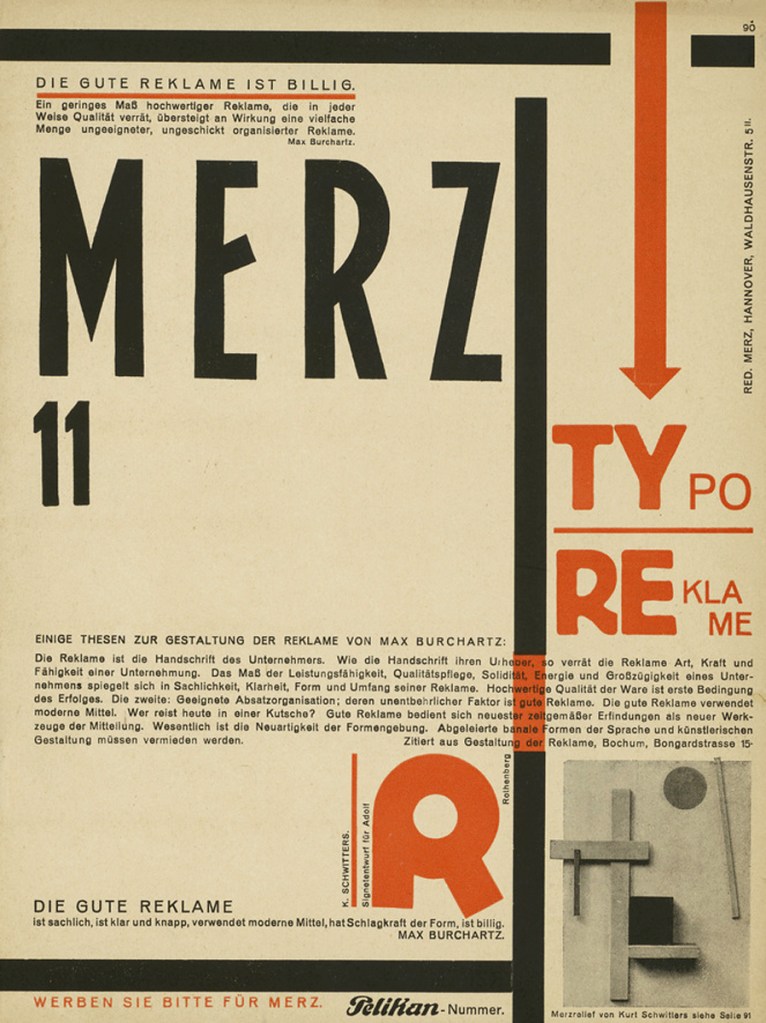

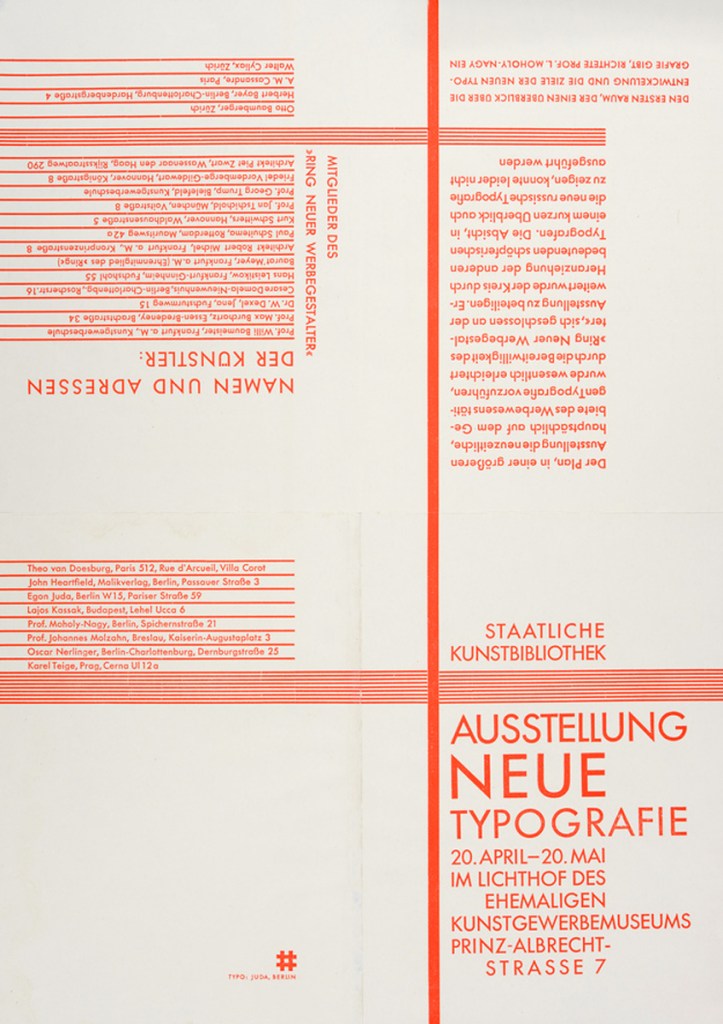

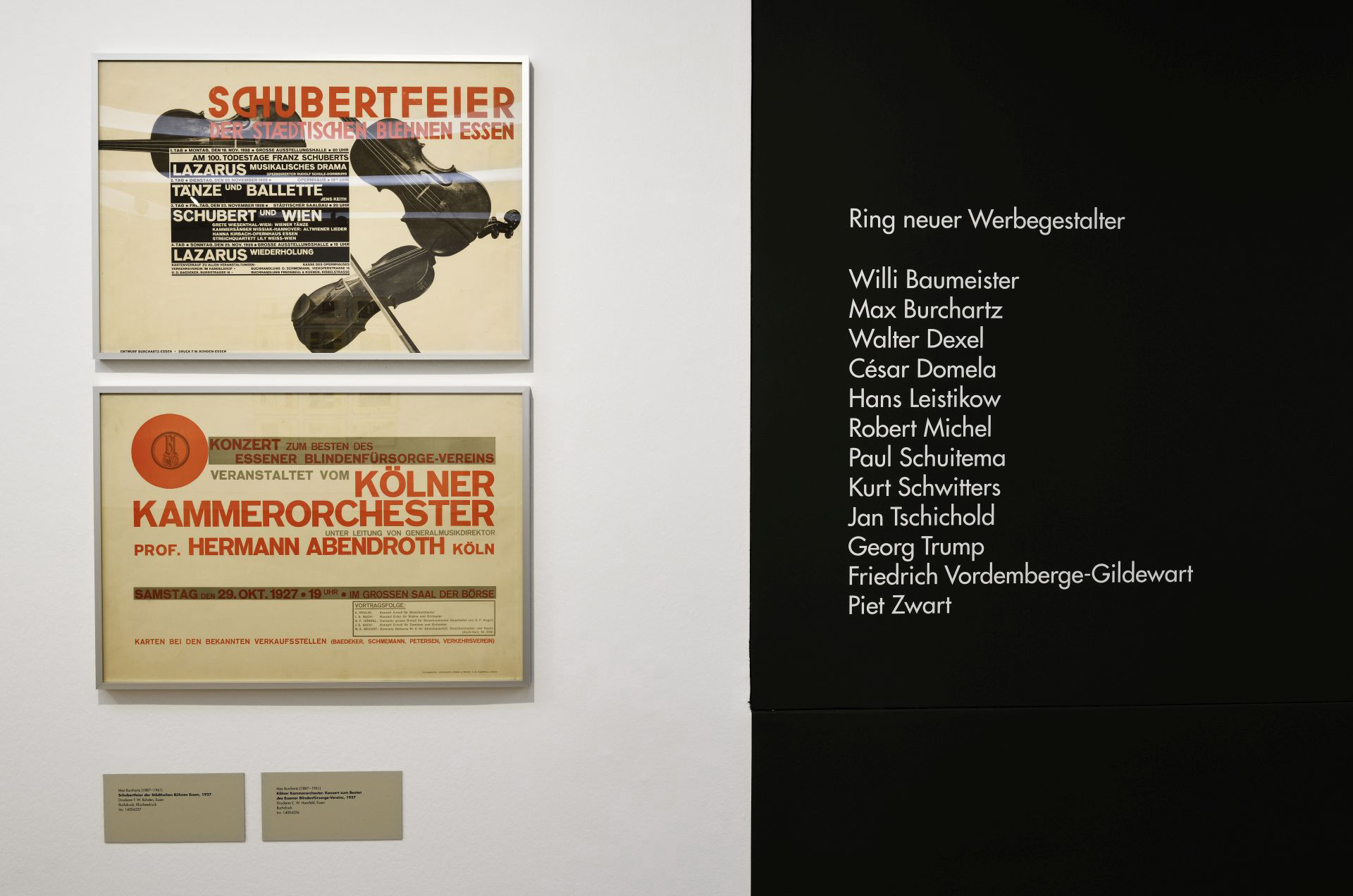

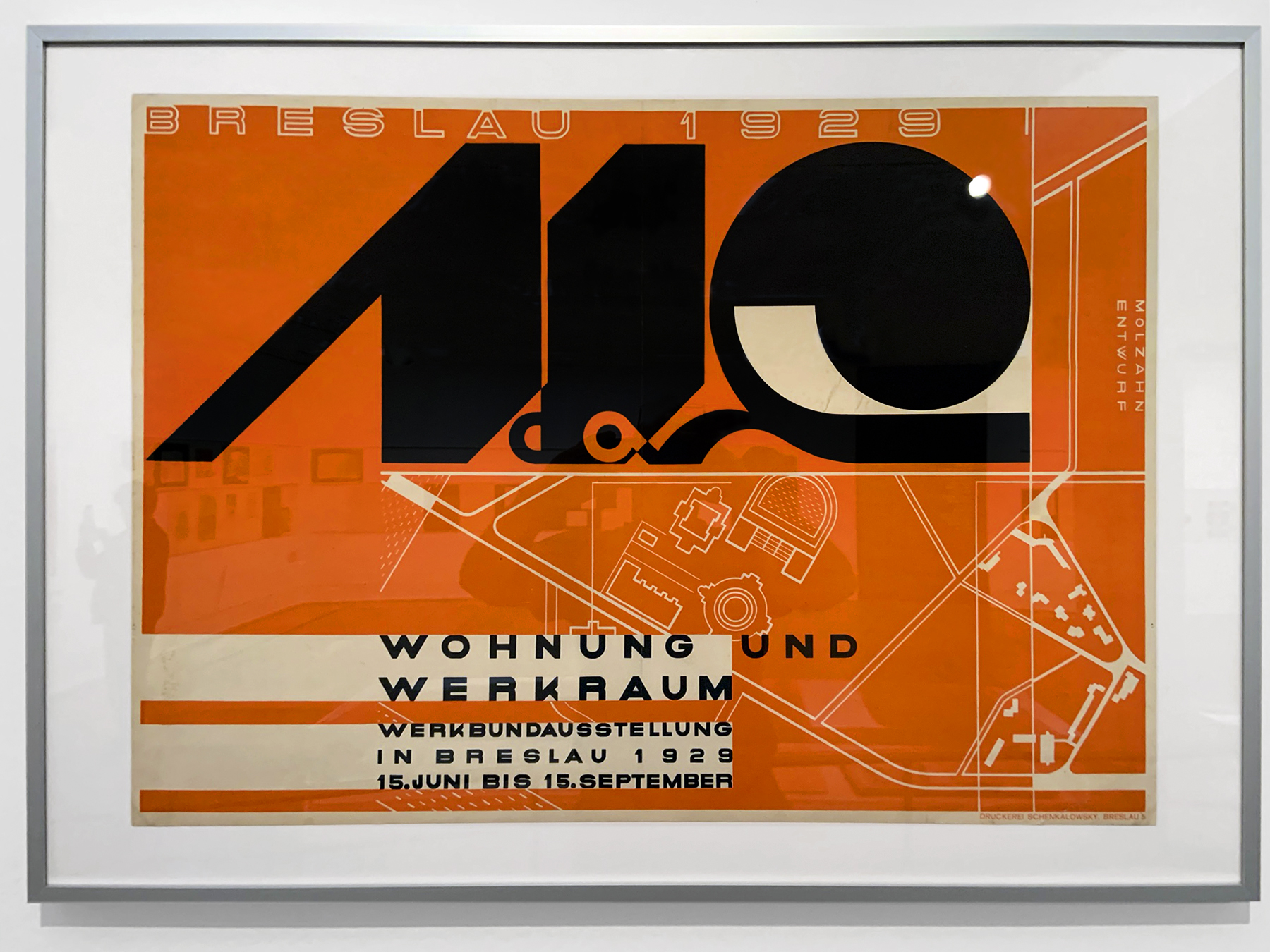

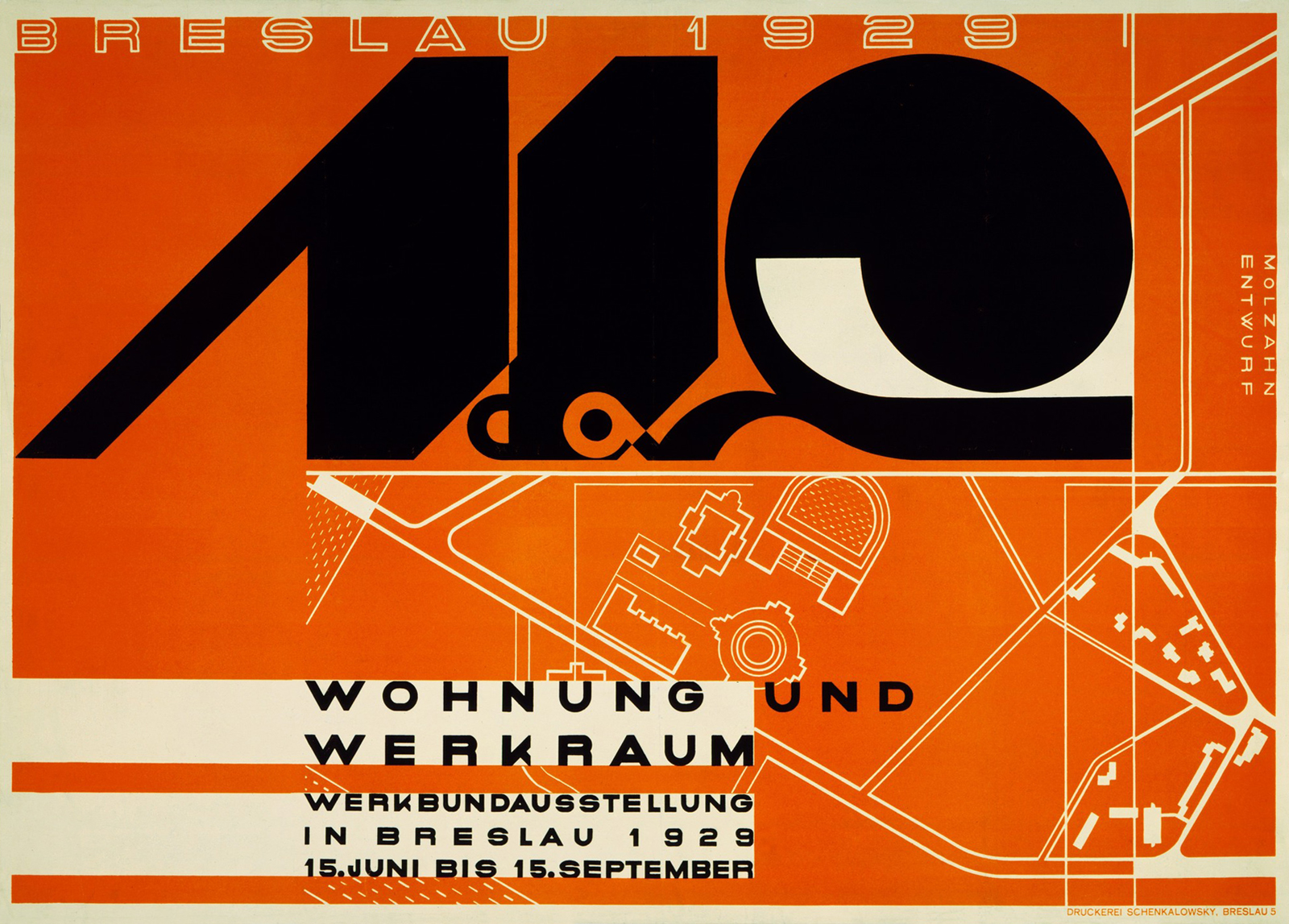

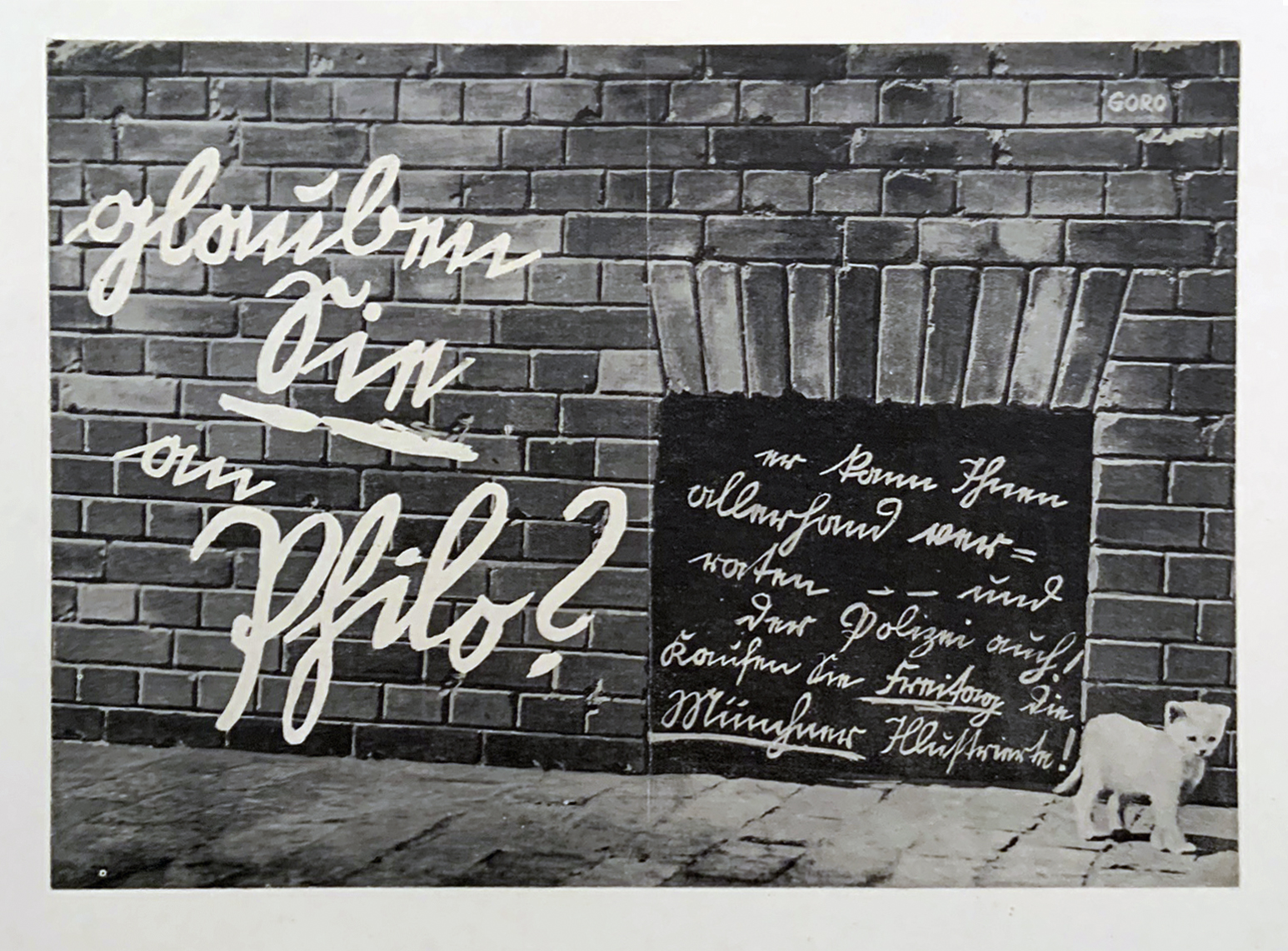

The “New Woman”, mainly middle class females, took their courage in their hands to become professional photographers and artists: photojournalists, fashion photographers, war photographers, magazine and picture photographers, working with successful men and women in fashion, interior design, news, graphics and art. At the Bauhaus female students pushed the boundaries in fields such as textiles, lighting, ceramics and costume, the “New Woman” putting her femininity under the spotlight.

By pushing boundaries, female artists and photographers broke ground becoming female in a male world… within the framework of modernity and aesthetics, to form the modern divine. In a youthful culture of commercial and technological changes they gained their independence through hard work and talent via the stereotype of the “New Woman” – a constructed image portrayed in the magazines (bobbed hair beauty, flapper, speed, fast cars, cigarette smoking) which played into the male system of the recognition of the feminine subject. By playing the system they became successful and visible, self conscious of their undeniable abilities. But at what cost? Many women, excited by the world of men, where chewed up and spat out, dumped, and sometimes met a terrible end.

Unknown photographer (German)

Leni Riefenstahl with Heinrich Himmler (left) during the 1934 Nuremberg Nazi Party Rally in the Luitpold Arena while recording her film “Triumph of the Will”

September 9, 1934

German Federal Archives / Wikipedia (public domain)

The epito/me of this new self consciousness and will to power was the Nazi film director Leni Reifenstahl (German, 1902-2003). Reifenstahl began as an interpretive dancer who often made almost 700 Reichsmarks for each performance. “Her dancing revealed her childlike quality, her surrender to the moment, and this natural, naïve quality made her the perfect heroine for his [Arnold Fanck’s] Alpine love stories. Riefenstahl was involved in a love triangle involving Fanck and her leading man [in director Fanck’s 1920s “mountain films”], Luis Trenker, demonstrating, in Mr. Bach’s words, “Leni’s skill at dominating the exclusive male society in which she found herself now and for almost all the rest of her professional life.””16 Reifenstahl used her beauty, voracious sexual prowess (with both women and men) and talent to infiltrate the world of film and learn acting and film editing techniques. Hitler saw her films and thought Riefenstahl epitomised the perfect German female.

“Riefenstahl heard Nazi Party (NSDAP) leader Adolf Hitler speak at a rally in 1932 and was mesmerised by his talent as a public speaker… Hitler was immediately captivated by Riefenstahl’s work. She is described as fitting in with Hitler’s ideal of Aryan womanhood, a feature he had noted when he saw her starring performance in Das Blaue Licht. After meeting Hitler, Riefenstahl was offered the opportunity to direct Der Sieg des Glaubens (“The Victory of Faith”), an hour-long propaganda film about the fifth Nuremberg Rally in 1933… Still impressed with Riefenstahl’s work, Hitler asked her to film Triumph des Willens (“Triumph of the Will”), a new propaganda film about the 1934 party rally in Nuremberg. More than one million Germans participated in the rally. The film is sometimes considered the greatest propaganda film ever made… In February 1937, Riefenstahl enthusiastically told a reporter for the Detroit News, “To me, Hitler is the greatest man who ever lived. He truly is without fault, so simple and at the same time possessed of masculine strength”.”17

After the Second World War Riefenstahl was tried four times by postwar authorities for denazification and eventually found to be a “fellow traveller” (Mitläufer) who sympathised with the Nazis but she won more than fifty libel cases against people accusing her of having previous knowledge regarding the Nazi party.18 Research in the first decade of the twenty-first century (Jürgen Trimborn Leni Riefenstahl: A Life Faber & Faber, 2007 and Steven Bach Leni – The Life and Work of Leni Riefenstahl Knopf, 2007) dismantle Riefenstahl’s myth that she was an artist innocent of political motivations. She hitched her wagon to National Socialism, taking money to make her film Tiefland (Lowlands) and then bringing in extras from a concentration camp, keeping them in rags and starving them. After filming some were executed in the gas chambers. “Bach shows that the contract she entered into with the camp commandant makes clear the terms on which she had access to these ‘extras’ and that she knew they were going back to (at the very least) an uncertain future ‘in the east’.”19 Riefenstahl would later claim that all of the Romani extras – 53 Roma and Sinti from Maxglan, and a further 78 from a camp in eastern Berlin – had survived the war. In fact, almost 100 of them are known or believed to have been gassed in Auschwitz.20

Riefenstahl’s image of wholesome “New Woman” – a “version of an ideal presence, a kind of imperishable beauty” – never faded and she never wavered in her belief in herself and her innocence. The hubris of her egotistical narcissism denied any other version of history was possible, jealousy protecting her self-believed legacy like a protective tigress guarding her cubs, all the while denying her servitude and slavery to Nazi propaganda. Of course, all of it is a lie. There is Riefenstahl after the invasion of Poland filming away dressed as a uniformed army war correspondent replete with revolver around her waist.

Oswald Burmeister (German)

Visit of Leni Riefenstahl with a pistol at the XIV Army Corps, conversation with soldiers, on the left a film camera

Poland, September, 1939

German Federal Archives / Wikipedia (public domain)

“Four of the six feature films she directed are documentaries, made for and financed by the Nazi government… [they] celebrate the rebirth of the body and of community, mediated through the worship of an irresistible leader.”21 Susan Sontag saw Riefenstahl’s aesthetics as entirely inseparable from Nazi ideology, “consistent with some of the larger themes of Nazi ideology: the contrast between the clean and the impure, the incorruptible and the defiled, the physical and the mental, the joyful and the critical.”22

Naturally, and I use the word advisedly, the leader was male. While Riefenstahl could wish all she liked that she had power as a “New Woman”, “dominating the exclusive male society” of Nazi Germany, she was in reality just a pawn of their largesse. Women in Nazi Germany were seen mainly as baby producing machines, representing the fundamental ideologies of the role of the mother (the role of women under National Socialism). To that end the Cross of Honour of the German Mother (Mutterkreuz – Mother’s Cross) conferred by the government of the German Reich to honour a Reichsdeutsche German mother for exceptional merit to the German nation – 1st class, Gold Cross: eligible mothers with eight or more children; 2nd class, Silver Cross: eligible mothers with six or seven children; 3rd class, Bronze Cross: eligible mothers with four or five children – reinforced traditional feminine and family values, and “traditional” lifestyle patterns.23 The New Woman in Germany thus became a pure woman of German blood-heredity and genetically fit, the mother worthy of the decoration. In Nazi Germany the New Woman became “decoration” herself, the ideal protected as Sontag puts it as, “the family of man (under the parenthood of leaders).”24

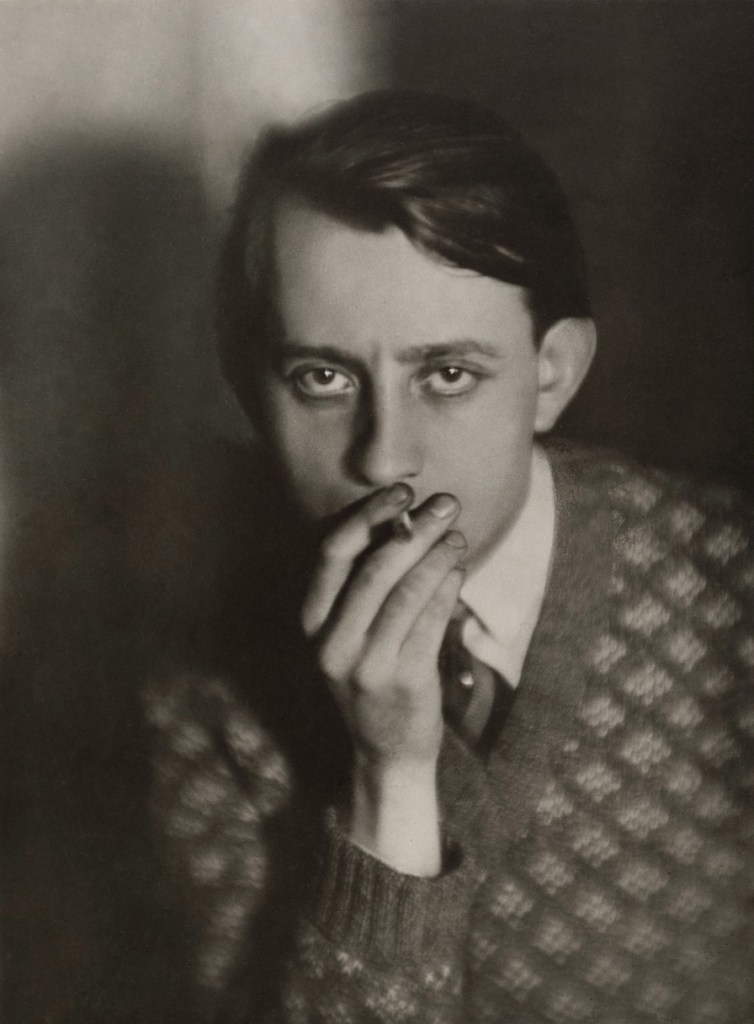

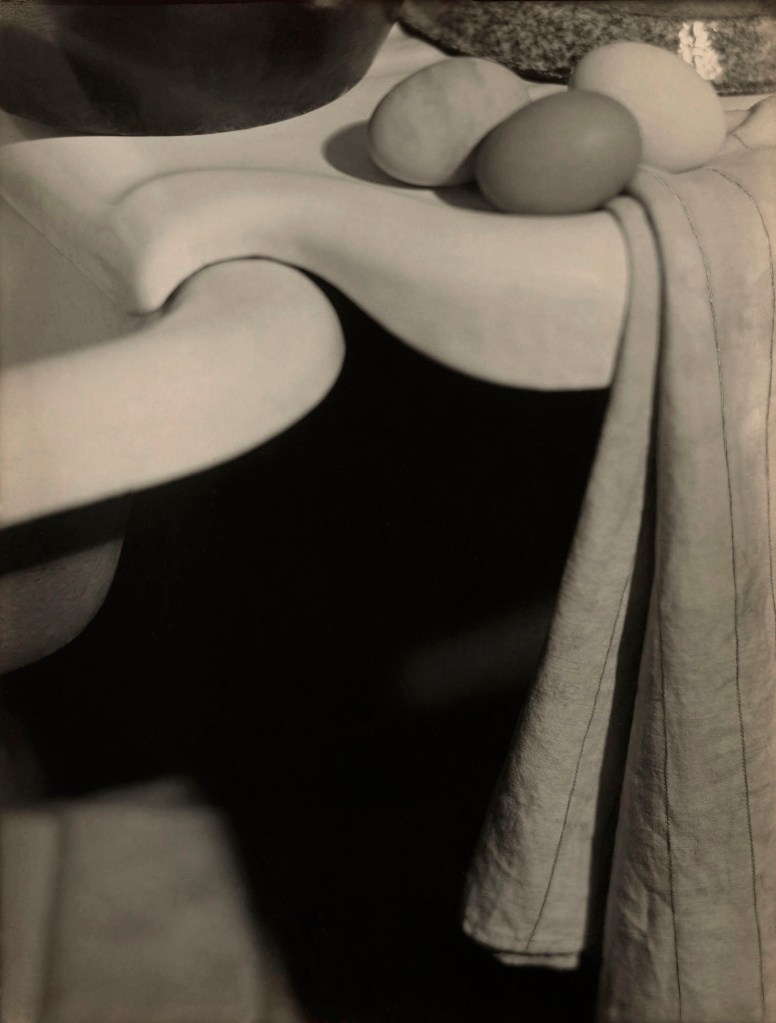

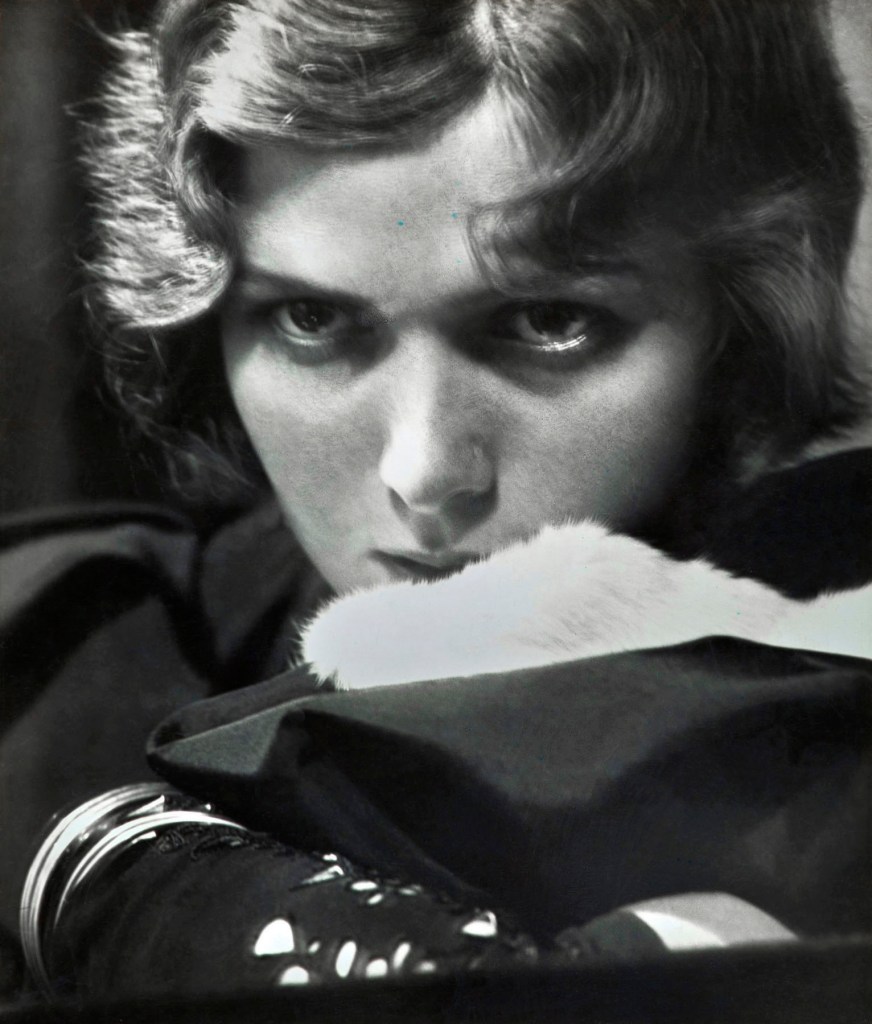

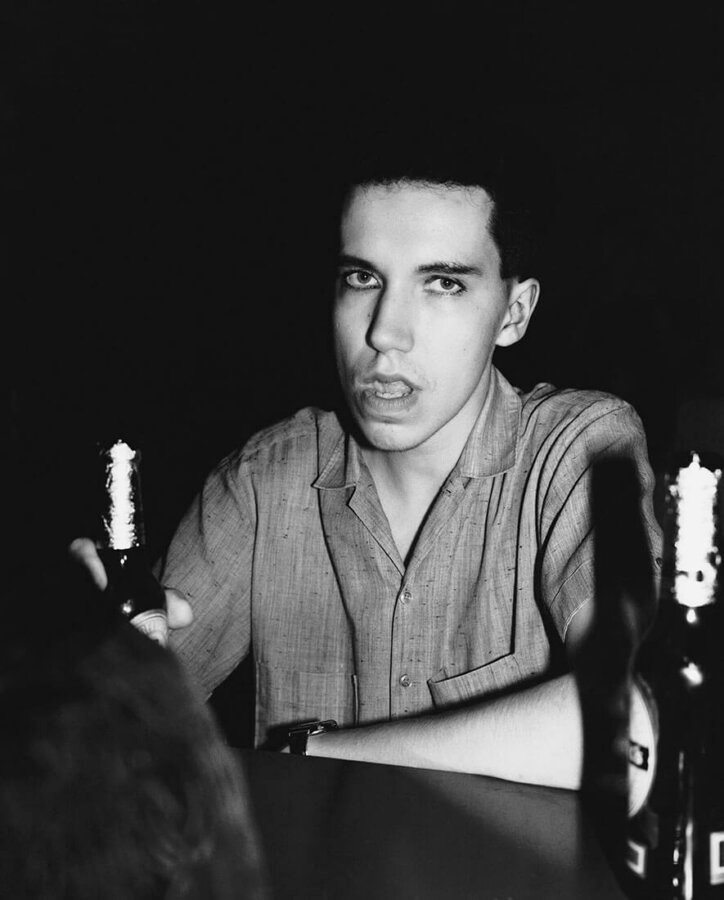

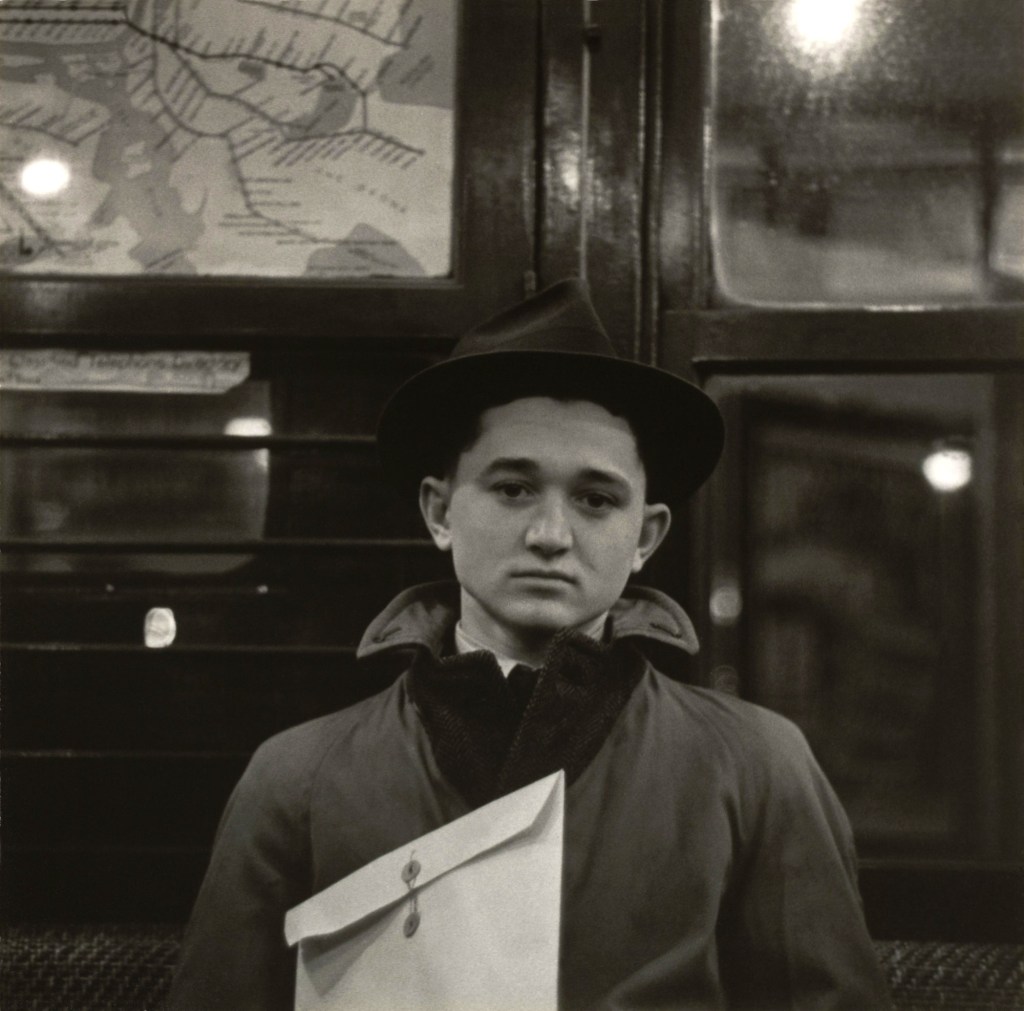

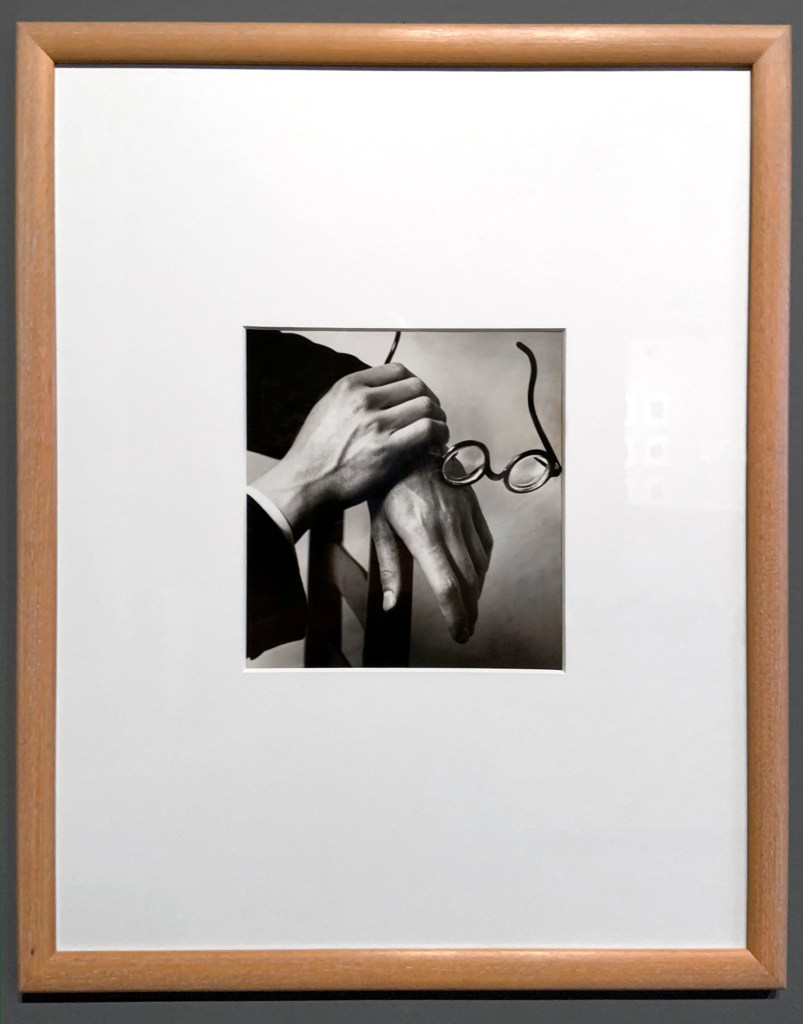

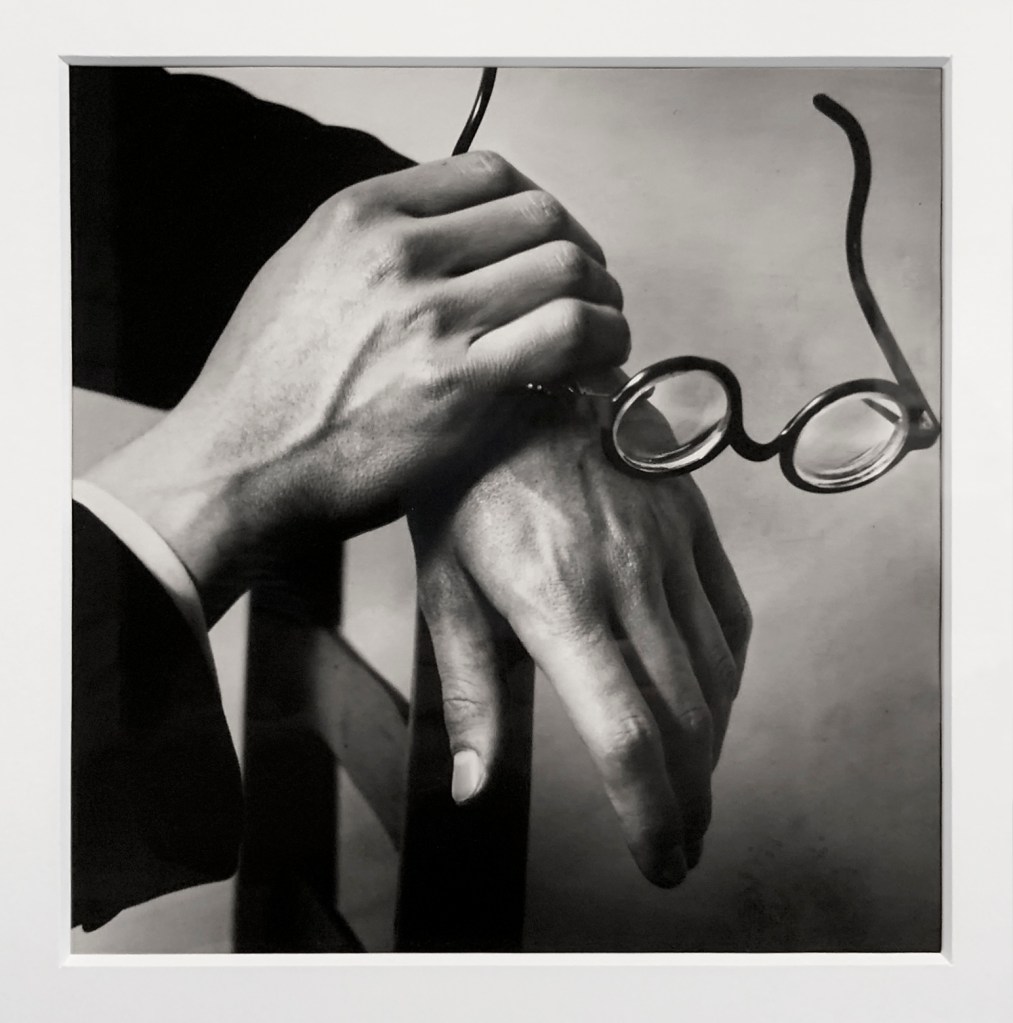

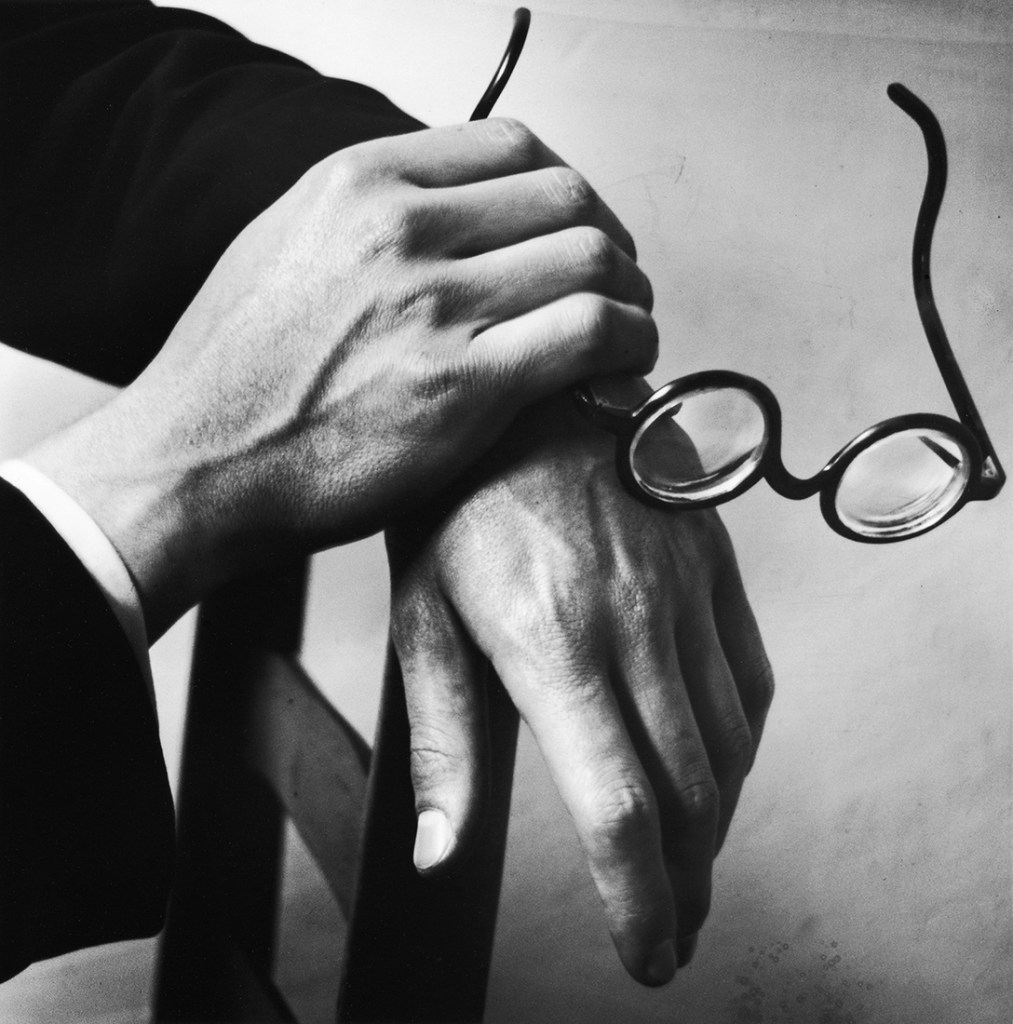

Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946)

Georgia O’Keeffe

1920

Platinum print

Wikiart (Public domain)

One of the greatest artists of the twentieth-century was the painter Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986). O’Keeffe, born in a small town named Sun Prairie in Dane County, Wisconsin grew up on the family farm south of the city. “As a child she received art lessons and her abilities were recognised and encouraged by local teaches and family throughout her school years. After O’Keeffe left Sun Prairie she pursued studies at the Art Institute of Chicago (1905-1906) and at the Arts Students League, New York (1907-9108).”25 She took a job as a commercial artist and then began teaching art, taking summer at classes at the University of Virginia for several years before becoming chair of an art department beginning the fall of 1916. A friend sent some of O’Keeffe’s charcoal drawings to the photographer, gallerist and impresario Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946) who exhibited them at his 291 gallery in April 1916. Stieglitz found them to be the “purest, finest, sincerest things that had entered 291 in a long while,” and in the spring of 1917 he sponsored her first one-artist exhibition at 291 – the last show held at the galleries before they closed in July of that year.

At this time, “O’Keeffe painted to express her most private sensations and feelings. Rather than sketching out a design before painting, she freely created designs. O’Keeffe continued to experiment until she believed she truly captured her feelings [in watercolour] … After her relationship with Alfred Stieglitz started, her watercolour paintings ended quickly. Stieglitz heavily encouraged her to quit because the use of watercolour was associated with amateur women artists. … Stieglitz, twenty-four years older than O’Keeffe, provided financial support and arranged for a residence and place for her to paint in New York in 1918. They developed a close personal relationship while he promoted her work. She came to know the many early American modernists who were part of Stieglitz’s circle of artists, including painters Charles Demuth, Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley, John Marin, and photographers Paul Strand and Edward Steichen. Strand’s photography, as well as that of Stieglitz and his many photographer friends, inspired O’Keeffe’s work.”26 Stieglitz and O’Keeffe were married in 1924. Between 1918 and 1928 O’Keeffe worked primarily in New York City and at the Stieglitz family’s summer home at Lake George.

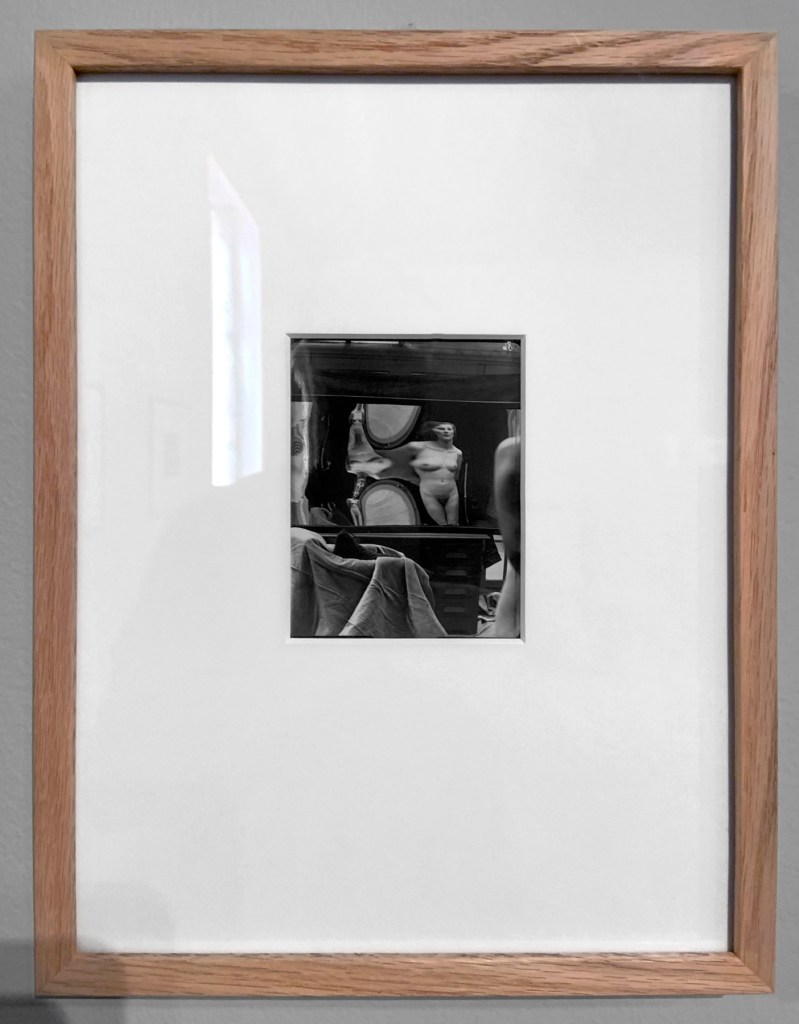

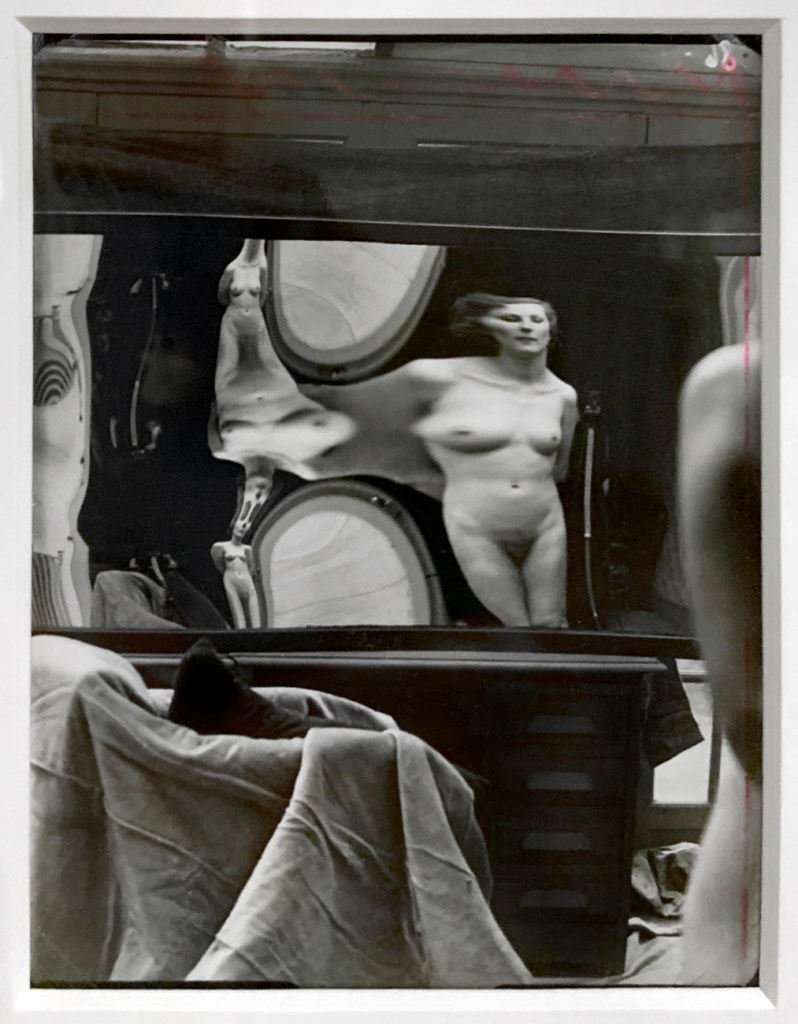

Working creatively side by side with that egotistical beomoth of American art that was Stieglitz could not have been easy. While Stieglitz promoted his wife’s art, provided financial support, directed the medium of her continued development, he also controlled her “purest” form (a symbol of the ideal) – that of her image. O’Keeffe became Stieglitz’s muse (a goddess, a person or personified force who is the source of inspiration for a creative artist), between 1918-1920 the photographer “making more than 140 photographs of O’Keeffe that, unlike his earlier analytic work, resonated with emotion and personal meaning… conjoining her art and her body, suggesting they were one.”27

“Stieglitz conceived of his portraits of O’Keeffe as a single work – a composite portrait. Each photograph stands on its own, revealing a certain innate quality at a given moment. But because change is a constant, only a series of photographs can evoke a subject’s entire being over time. To underscore the composite nature of his project, in 1921 Stieglitz exhibited more than forty photographs of O’Keeffe – many clustered by body part – under the title “Demonstration of Portraiture.”

Stieglitz and O’Keeffe married in 1924, and he continued to photograph her through the 1930s – his composite portrait eventually numbering 331 works. But his pictures of her changed markedly over the years. In 1923 when he became entranced with photographing clouds, he made smaller, more casual pictures of her at work or holding the subjects of her paintings. Many of his portraits of her from the 1930s lack the feverish intensity of those he made from 1918 to 1920 and reveal instead the distance in their relationship.”28

Stieglitz’s early photographs of O’Keeffe capture her in intimate encounters with the camera, portraying her through the gaze of male passion. “Extreme close-ups evoke an intimate sense of touch,” “different body parts were expressive of O’Keeffe’s individuality,” while in other photographs “she looks directly and longingly at the camera…”.29 O’Keeffe’s supposed independent New Woman was tied to the coat tails of an older man, her place in the cult of beauty (the ideal of life as art) an ideal eroticism. Her image was presented not as a temptation, not as a repression of the sexual impulse … but as its ultimate revelation in the seduction of the physicality of the photograph. Stieglitz’s composite “portrait in time,” “reflects his ideals of modern womanhood and is evocative of their close relationship.”30 Under the control of the man.

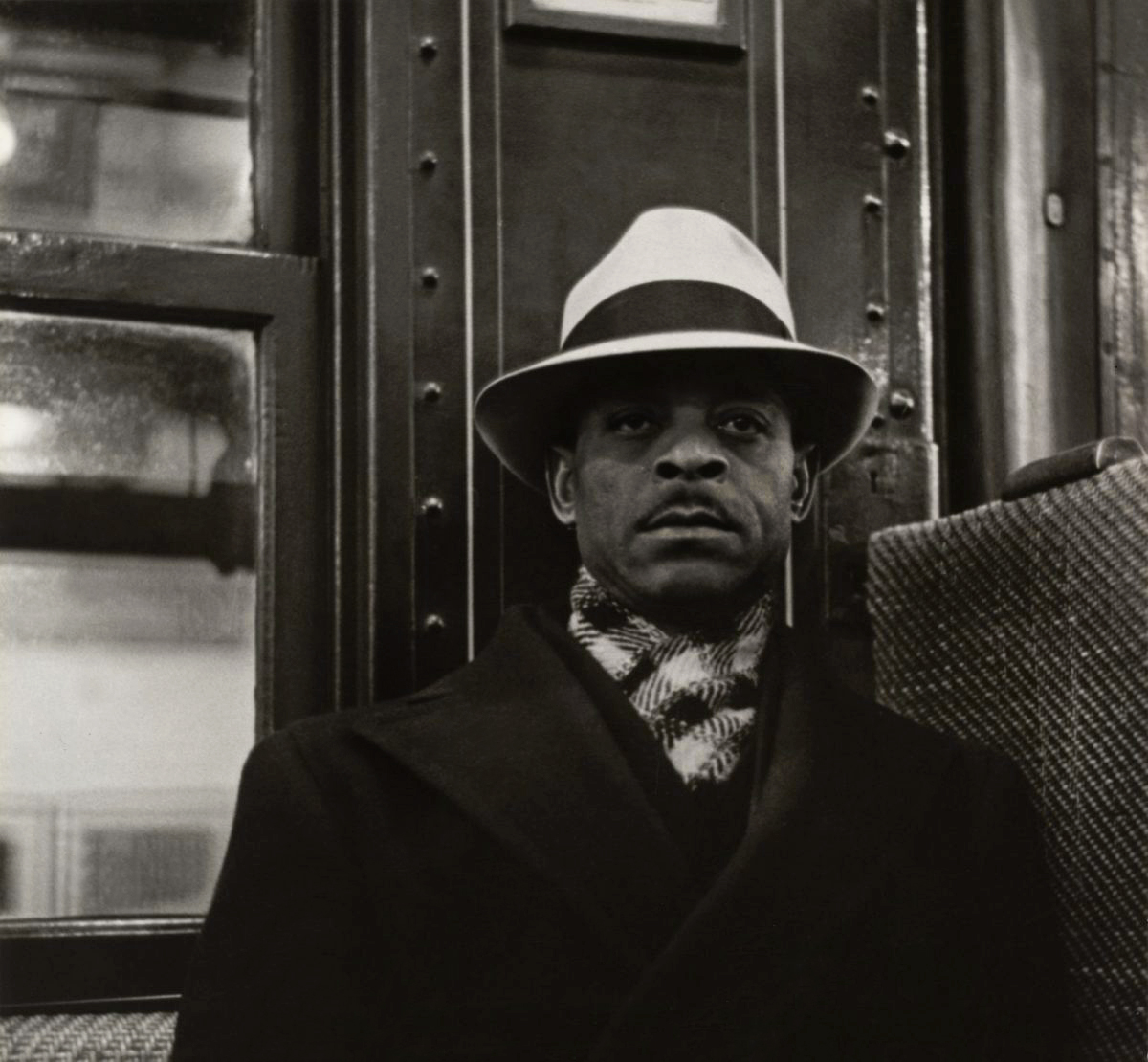

Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946)

Georgia O’Keeffe

1918

Wikipedia (Public domain)

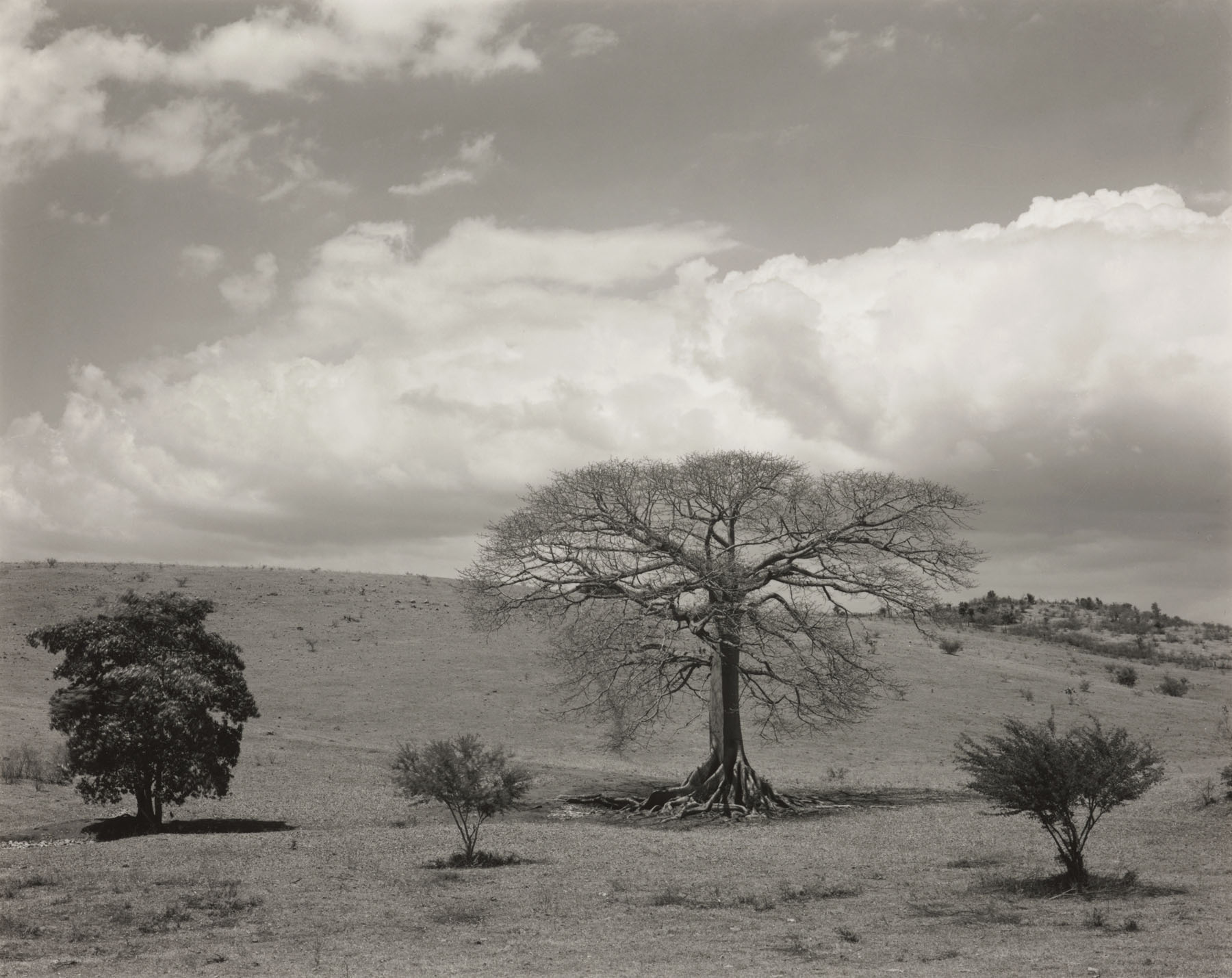

O’Keeffe of course realised the power that Stieglitz had over her and she started to remove herself from his field of vision, from his power of influence. To truly gain her independence. As Akkelies van Nes and Tra My Nguyen observed earlier, “To gain respect as artists, the image of women as muses had to disappear” as so this is what O’Keeffe did: she stopped becoming Stieglitz’s muse. After first visiting New Mexico in 1917 O’Keeffe returned to what was her spiritual home in 1929 when she travelled to Mexico with her friend Rebecca Strand and stayed in Taos with Mabel Dodge Luhan, who provided the women with studios,31 from then on spending part of nearly every year working in New Mexico. “Upon returning to the place that touched her heart so deeply, O’Keeffe’s mental health did indeed improve. Her life and her artwork would never be the same again. “I felt as if something was ending and another was beginning,” O’Keeffe once said. She began to feel more like her true self, integrated with parts of her personality that had been submerged in New York City.”32

The distance in the relationship between O’Keeffe and Stieglitz (both physical, he in New York and she in New Mexico, and spiritual with her attenuation to the Cerro Pedernal landscape) was exacerbated by his long-term relationship with Dorothy Norman which started in 1928, leading to O’Keeffe’s mental breakdown and hospitalisation in 1933. She returned to New Mexico and in August 1934 moved to Ghost Ranch, north of Abiquiú. Literally, her place in Mexico was faraway, an isolated landscape which she called the Faraway: “She often talked about her fondness for Ghost Ranch and Northern New Mexico, as in 1943, when she explained, “Such a beautiful, untouched lonely feeling place, such a fine part of what I call the ‘Faraway’. It is a place I have painted before … even now I must do it again.””33 Metaphorically, it was faraway from the life she led with Stieglitz, far away from her wifely concerns. “Shortly after O’Keeffe arrived for the summer in New Mexico in 1946, Stieglitz suffered a cerebral thrombosis. She immediately flew to New York to be with him. He died on July 13, 1946. She buried his ashes at Lake George. She spent the next three years mostly in New York settling his estate, and moved permanently to New Mexico in 1949, spending time at both Ghost Ranch and the Abiquiú house that she made into her studio.”34

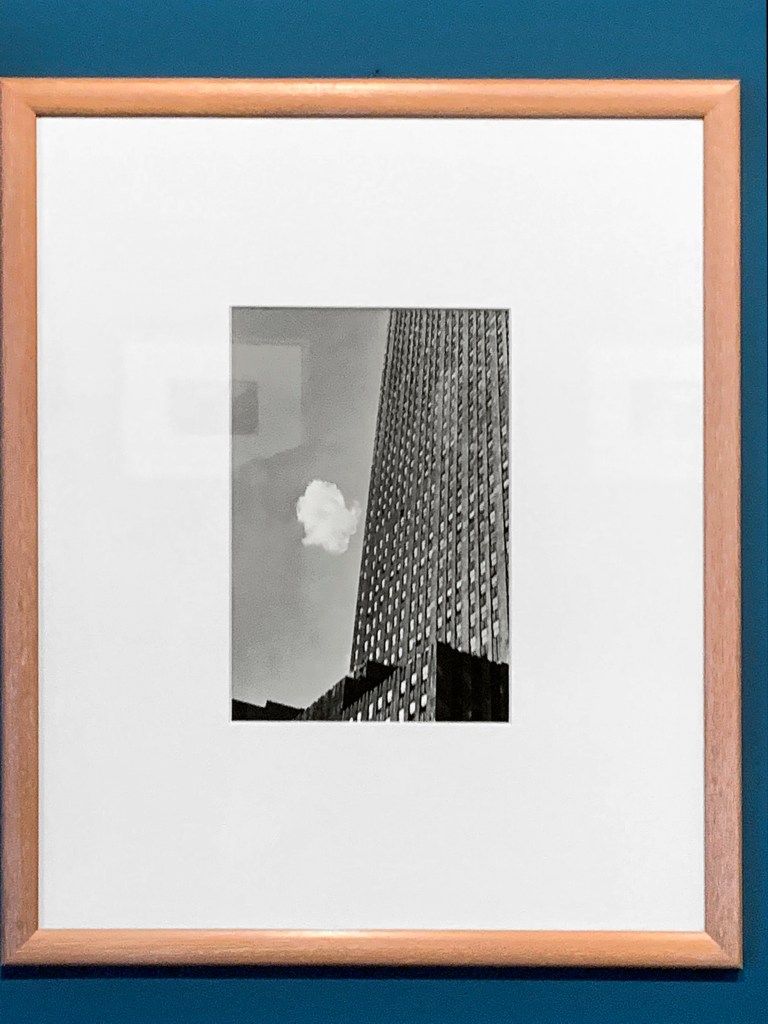

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Rams Head and White Hollyhock, New Mexico

1935

Oil on canvas

Brooklyn Museum

Used under fair use conditions for the purposes of academic research and education

Stieglitz never came to New Mexico. It was her space. Here she found her integrity, her own voice, far from the madding crowd, far from the gallery openings – a voice full of songs of the world. “She painted Taos Pueblo, San Francisco de Asís Catholic Church, a tree on the D.H. Lawrence ranch (that still stands), Mexican paper flowers, wood carvings, wild flowers, hills and sky around Taos.”35 She painted her “flowers of the desert”, bleached animal bones that were alive to her; and “she hoped people could see the music that she painted.” In New Mexico she truly became a “New Woman”: independent, intelligent, talented and famous … and her own woman – untamed by men, full of fierce self-protection and formidable work ethic, a woman adept at embracing the unknown and appreciative of the art of solitude.

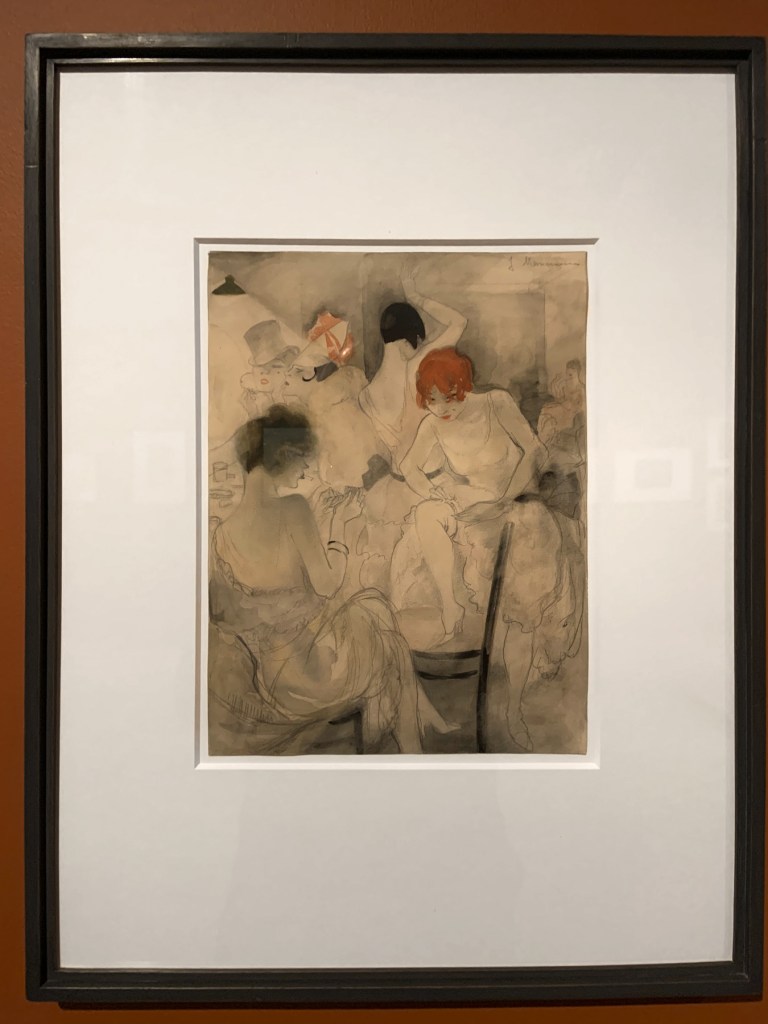

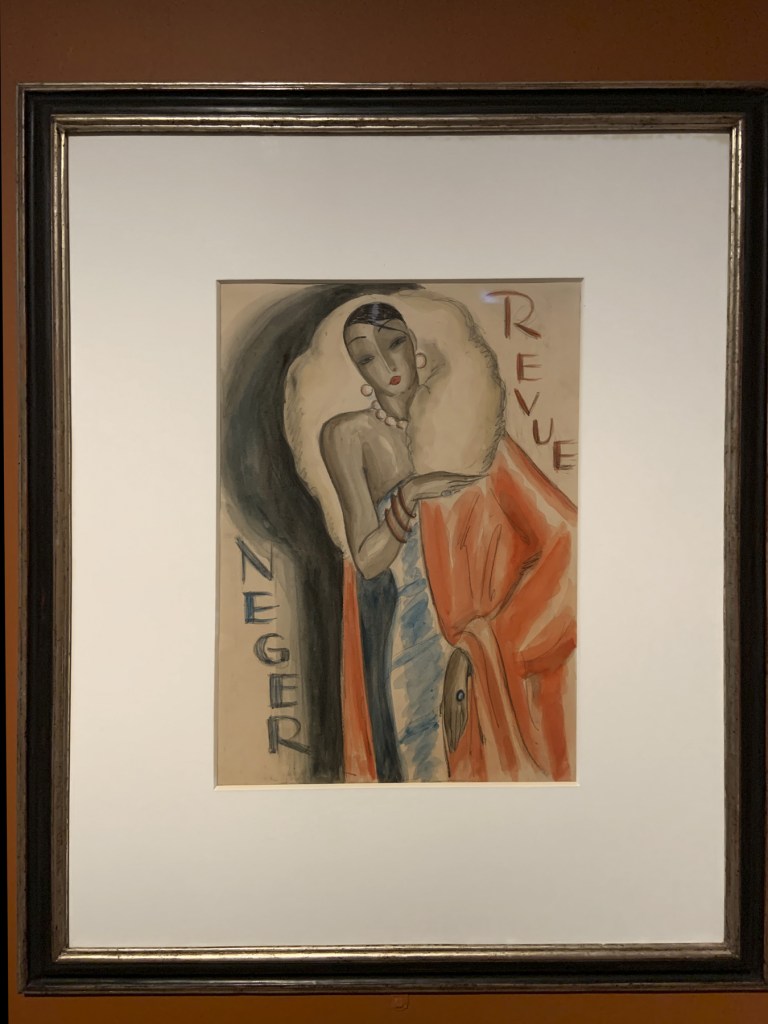

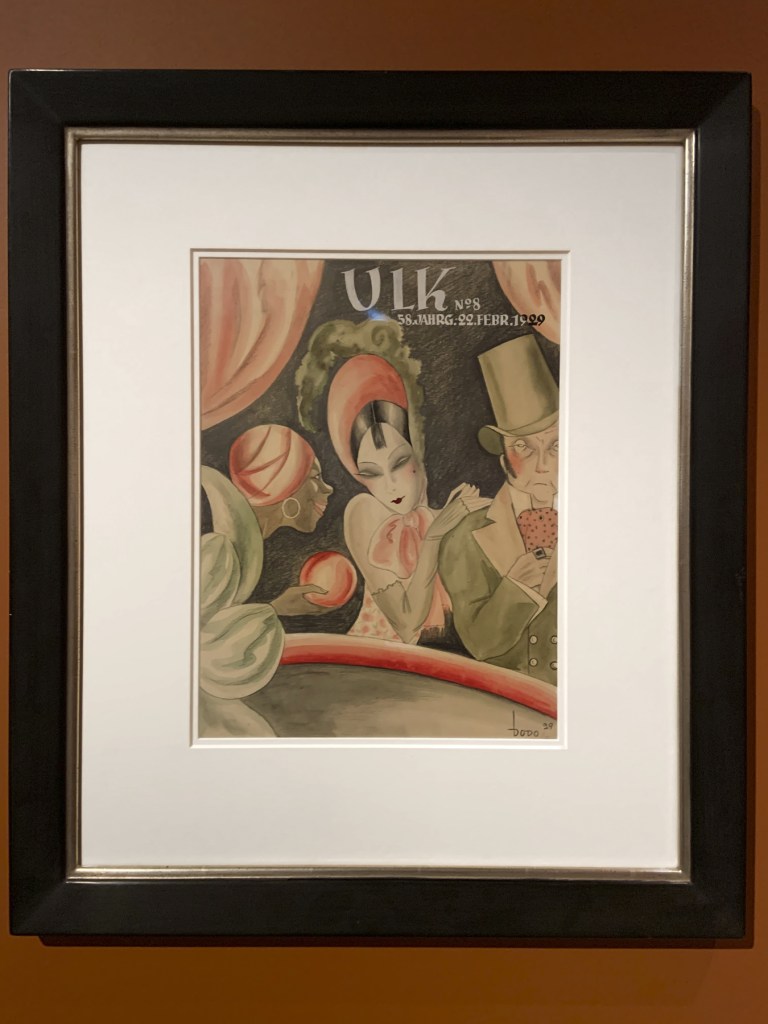

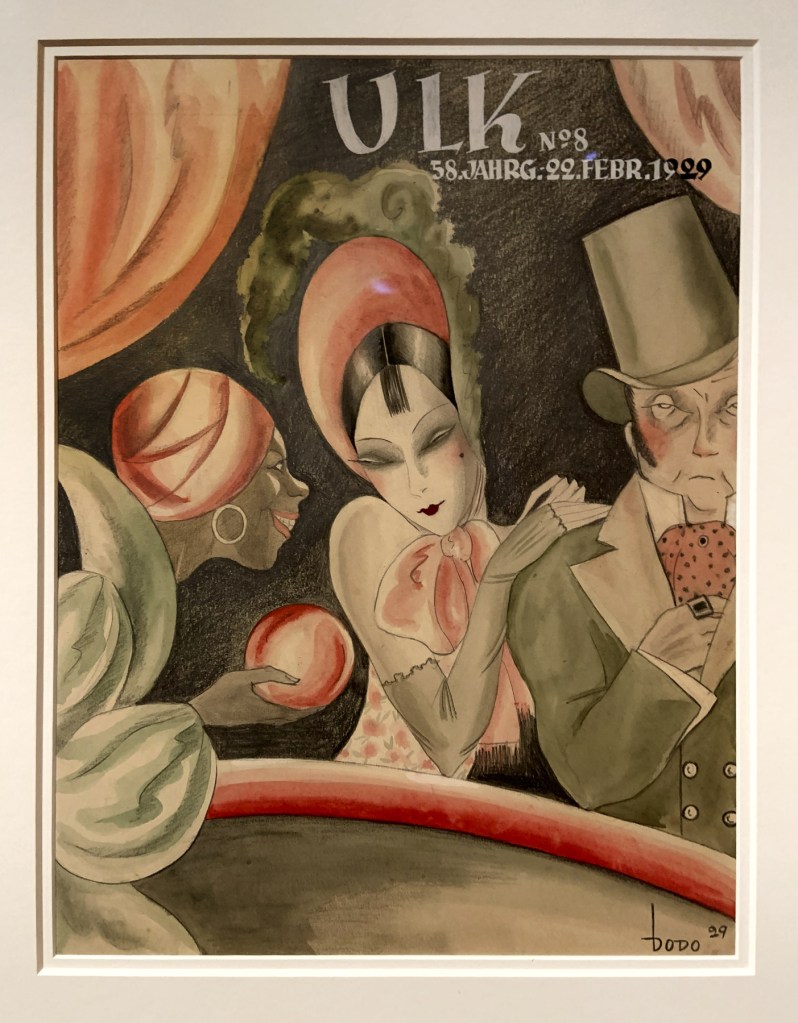

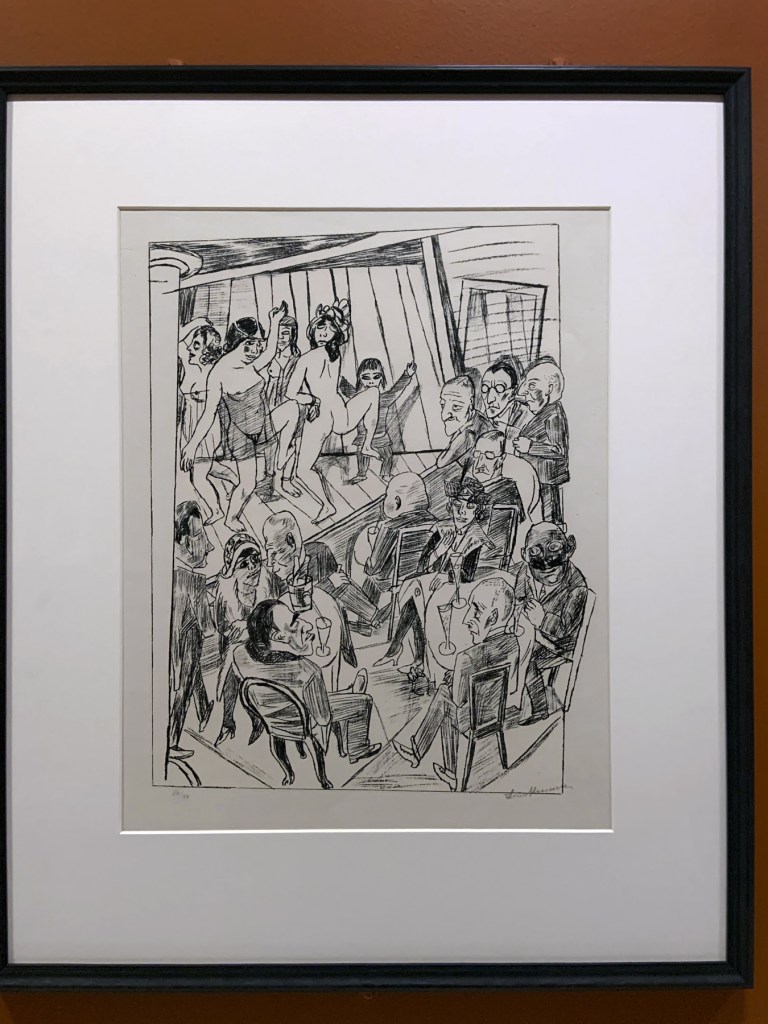

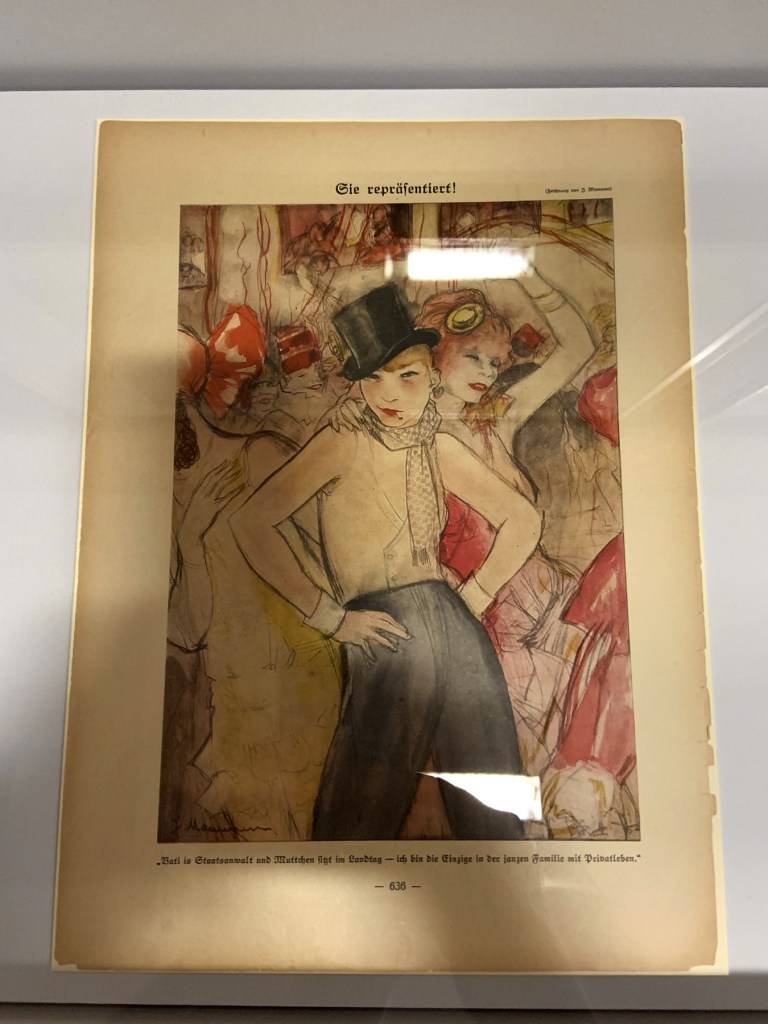

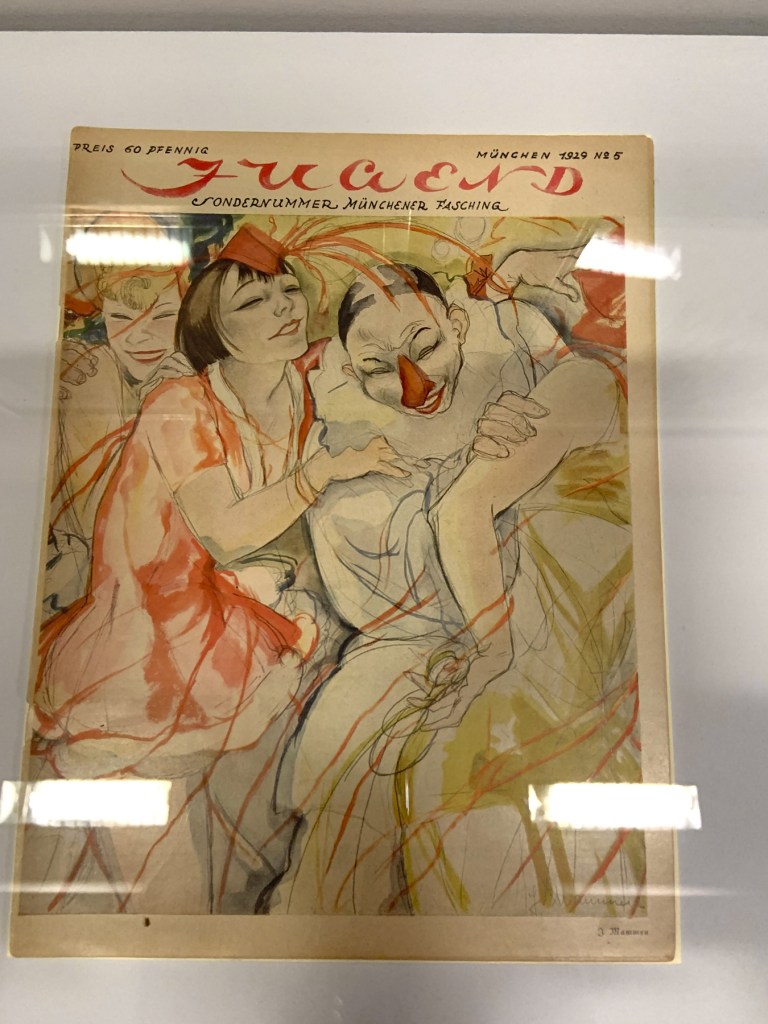

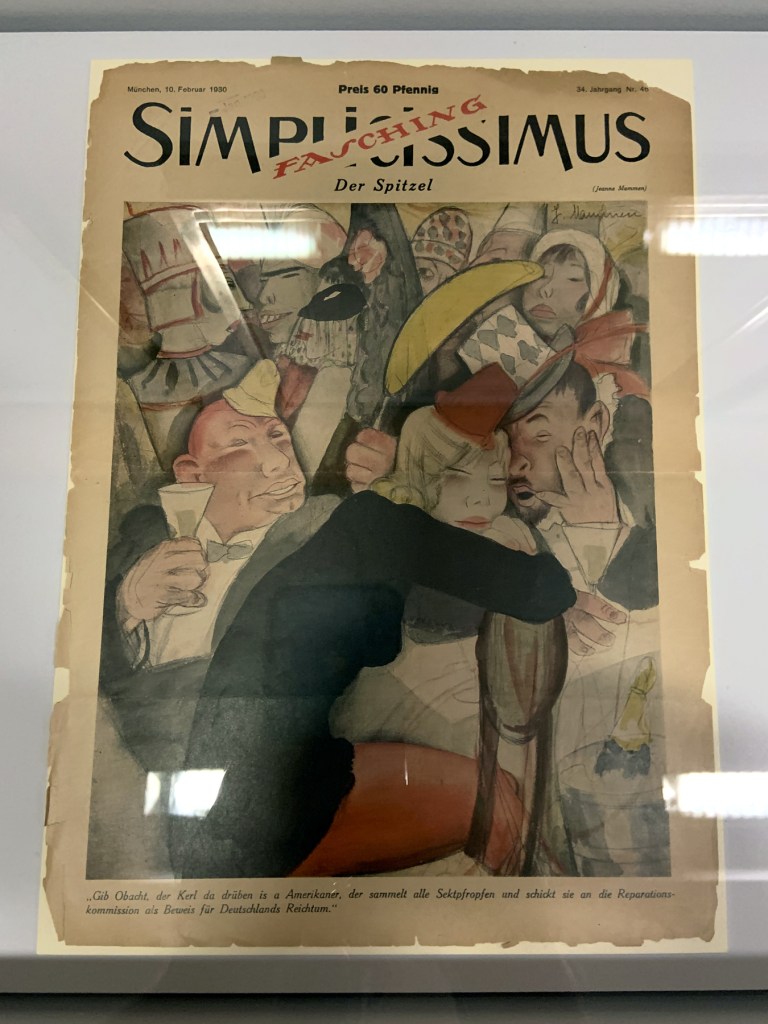

Pushing the boundaries, finding themselves

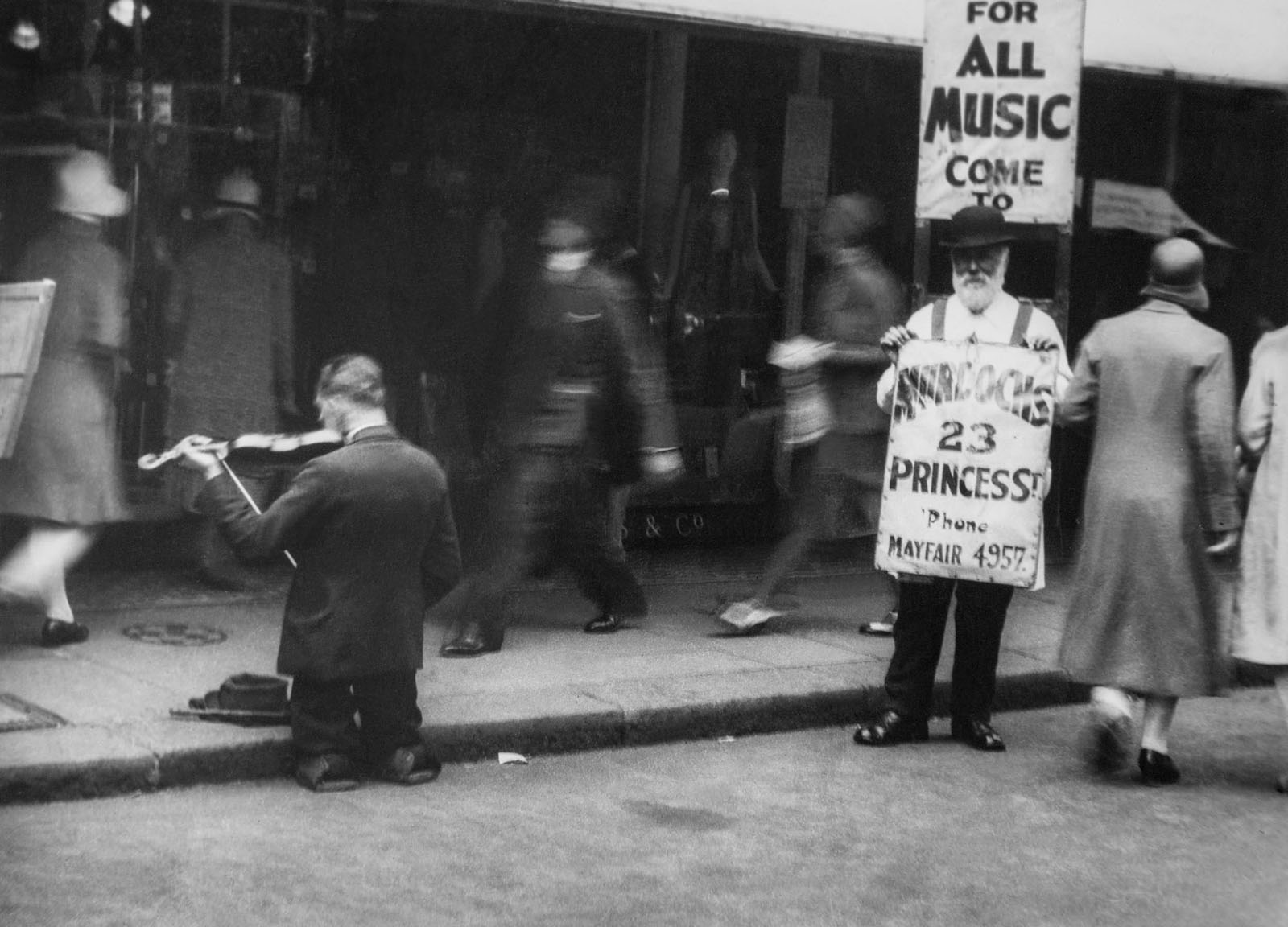

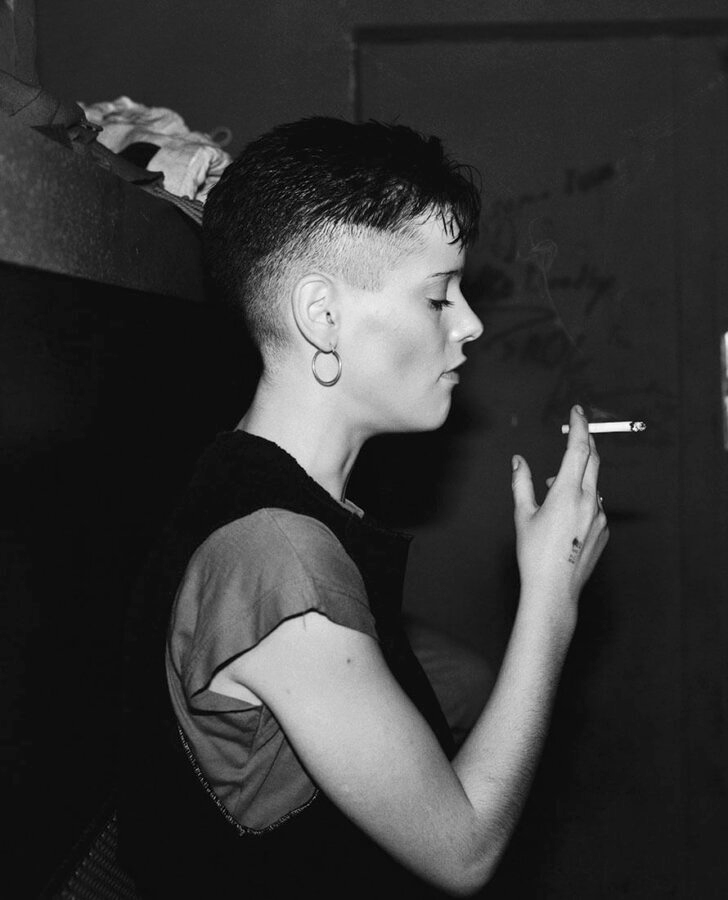

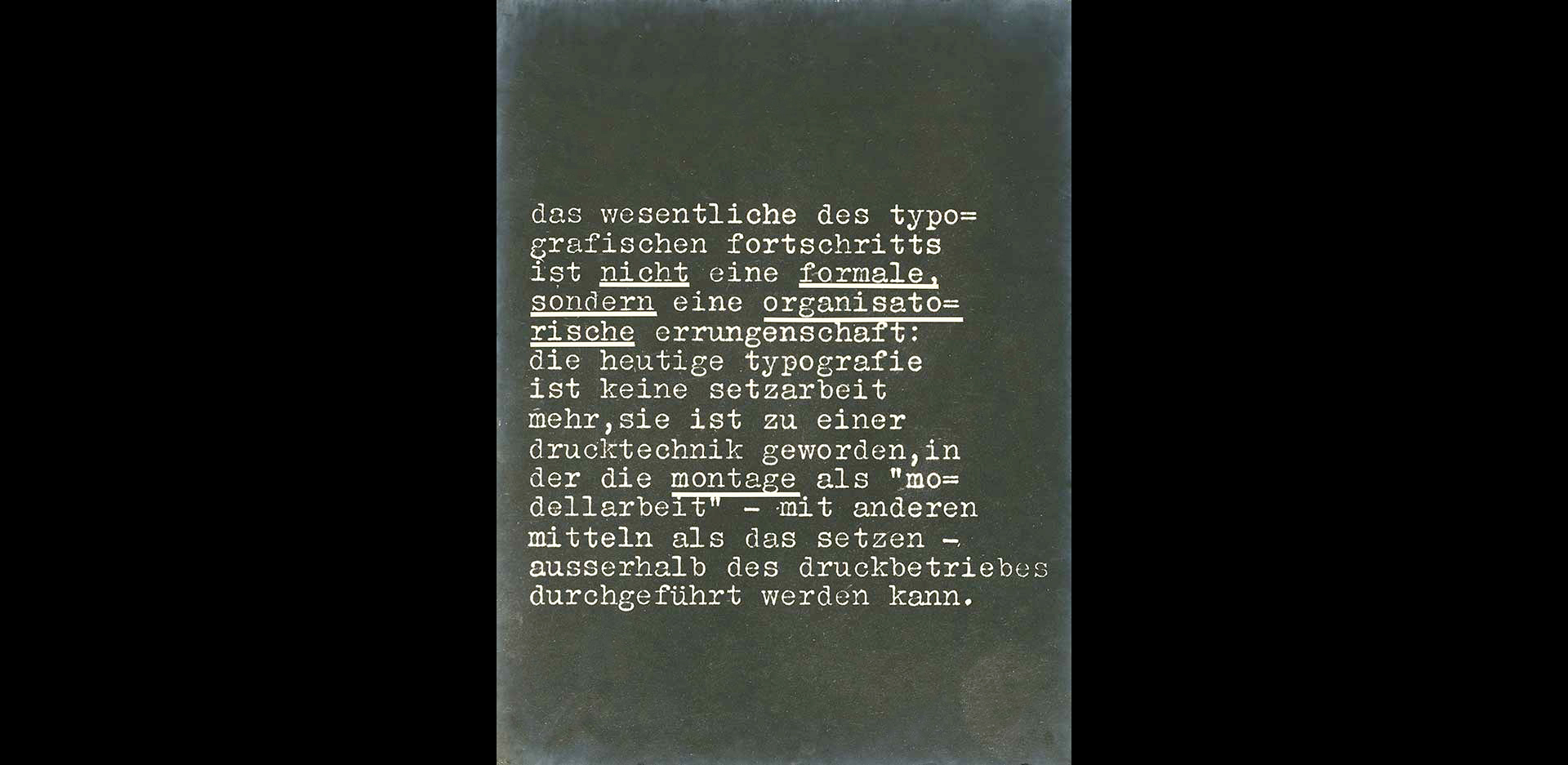

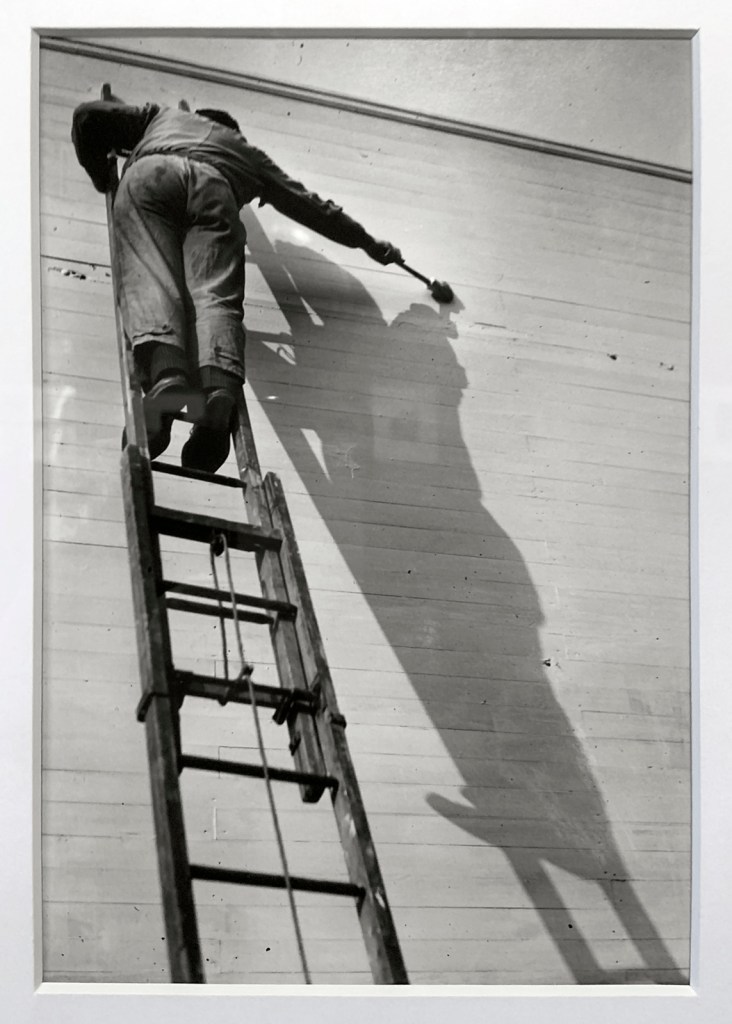

While the physical presence of women photographers and their work in the “Roaring Twenties” or “golden 1920s” – “which saw young women breaking with traditional “mores” or likewise step aside from “traditional” lifestyle patterns”36 – was apsirational for young and independent women in order to achieve social prestige and material success, for most women photographers it was all about having a job and making a living.

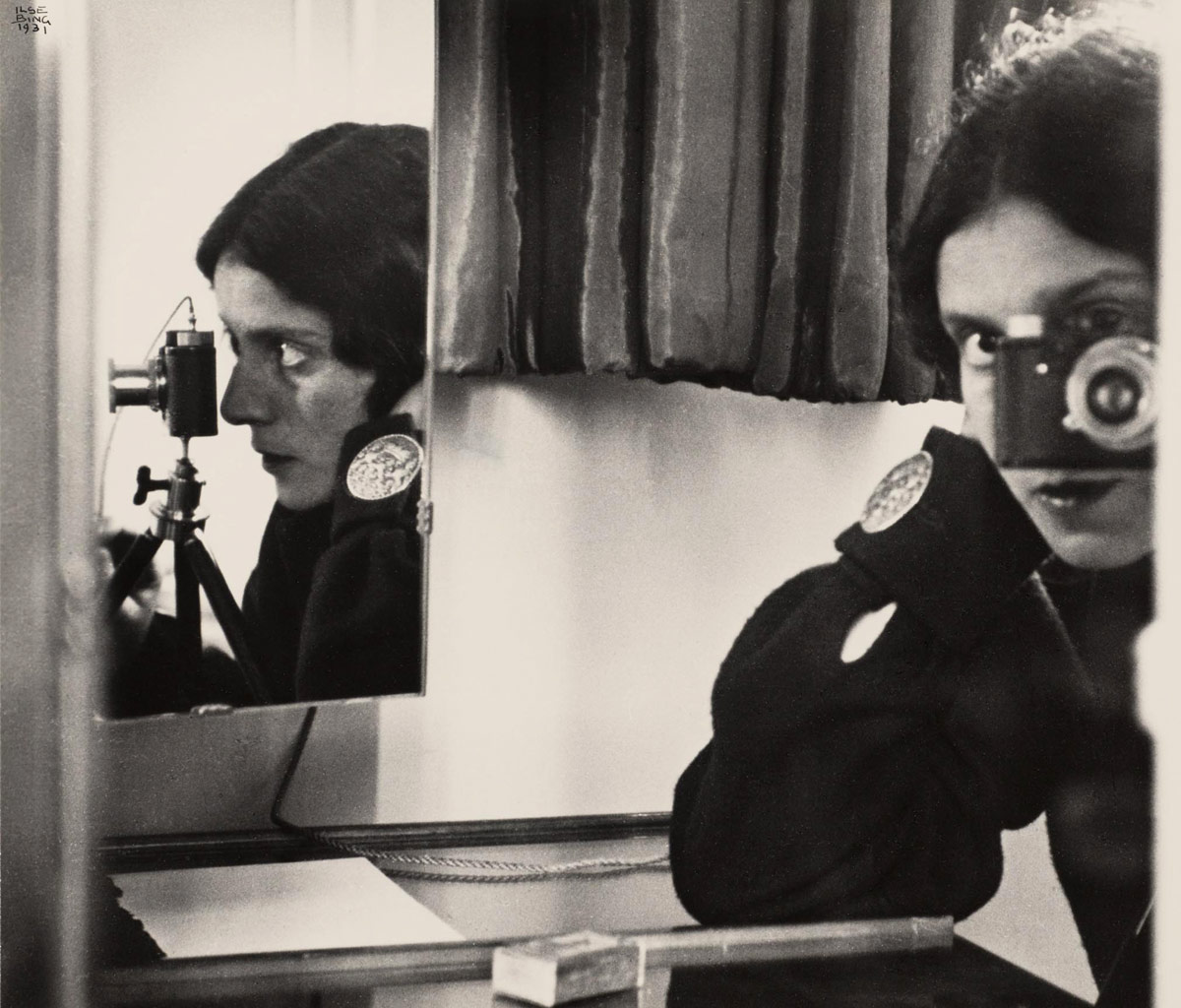

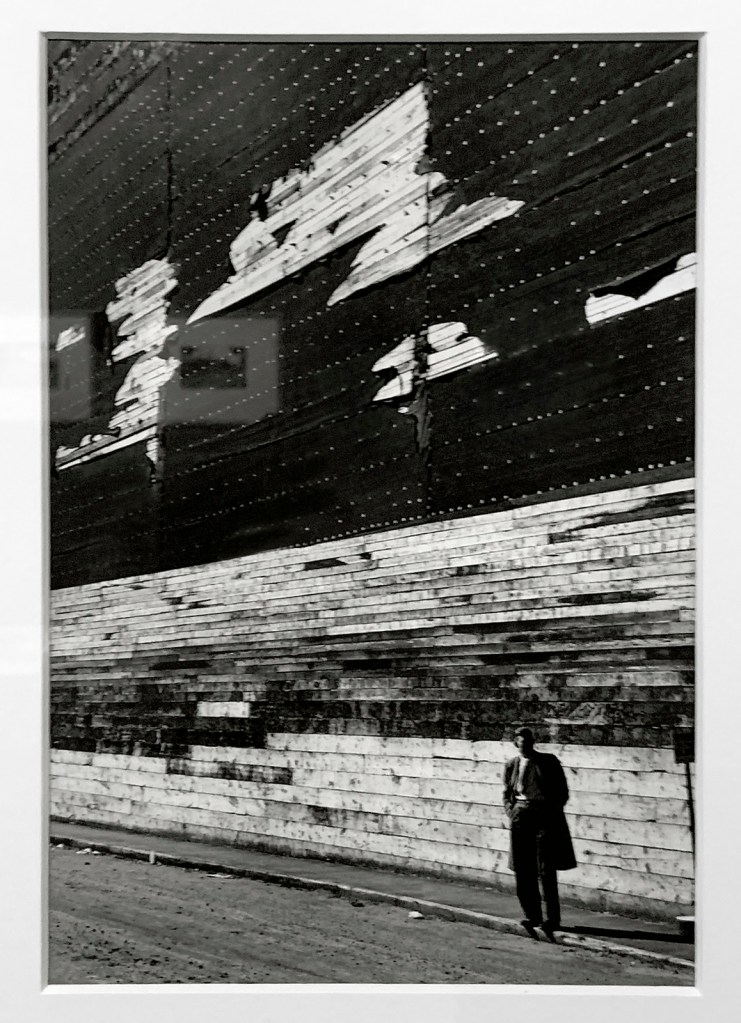

Paradoxically, while the “New Woman” behind the camera “embraced photography as a mode of professional and personal expression”, promoting female empowerment based on real women making revolutionary changes in life and art they also bought into a capitalist system of male dominance in a patriarchal society where the “feminine” – that is a feminine perspective – underwent a process of sublimation through the sequestering (hiding away) of gender. As women photographers “sought to redefine their positions in society and expand their rights”, their independence, so women were still outsiders in the male system of the recognition of the feminine subject – both of the female body as subject and that of the female photographers’ body (although the latter less so, with the numerous self-portraits of the “New Woman” and their cameras captured in mirrors). Indeed, most “New Woman” photographers never seem to have had the desire, or the eroticism, to virtually put gender in the image. They were still in servitude to the dominant status quo.

The story of the two mites is apposite here. In the story (see below) many rich people put money into the treasury, while a poor widow puts in two mites (two small coins worth a few cents) which is all she has. “The same religious leaders who would reduce widows to poverty also encourage them to make pious donations beyond their means. In [Adison] Wright’s opinion, rather than commending the widow’s generosity, Jesus is condemning both the social system that renders her poor, and “… the value system that motivates her action, and he condemns the people who conditioned her to do it.””37 In other words, the widow (in our case the New Woman) contributes her whole livelihood to maintaining the social system (patriarchal society) that oppresses her by supporting the value system that motivates her action… a system, controlled by men, that keeps her in servitude.

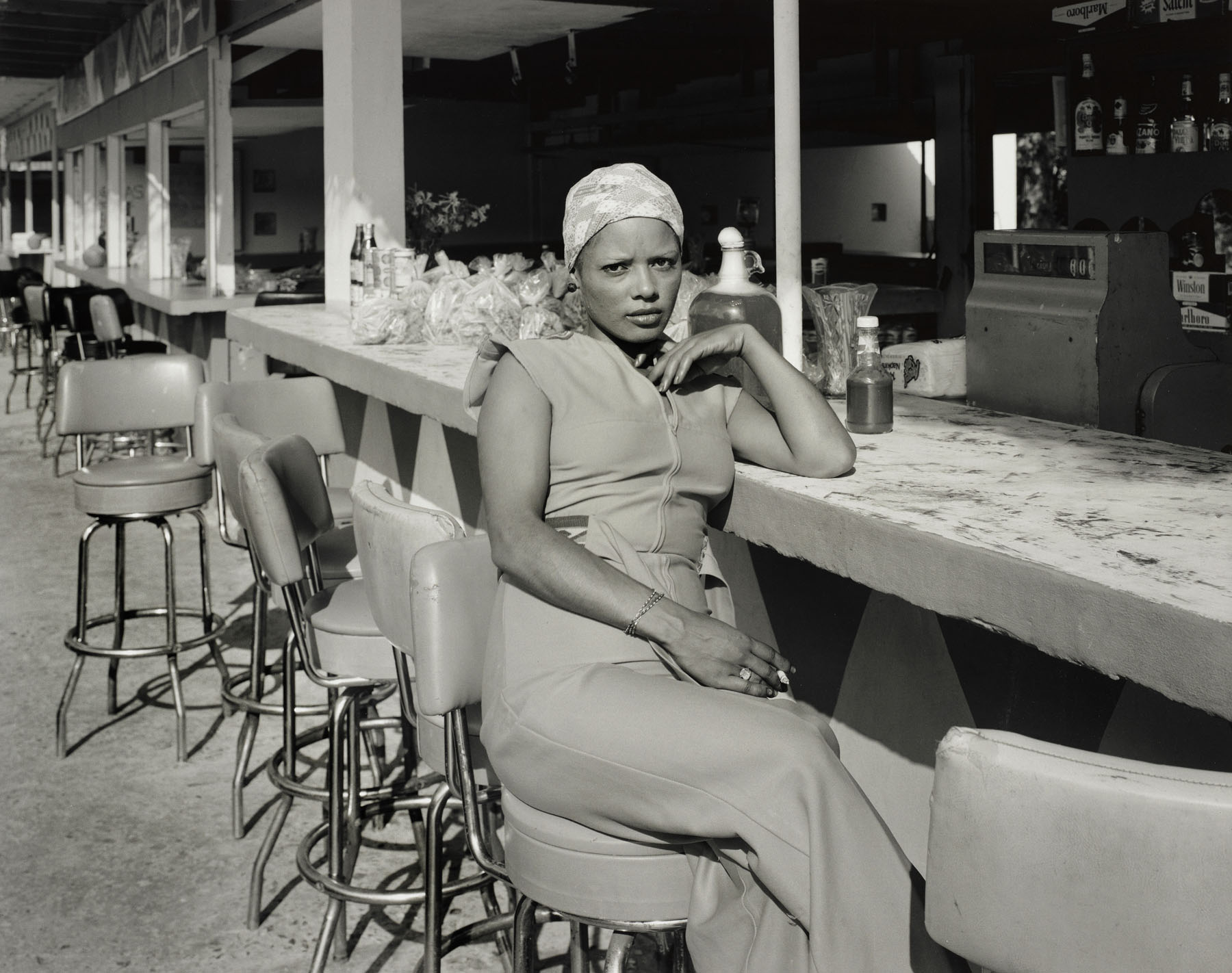

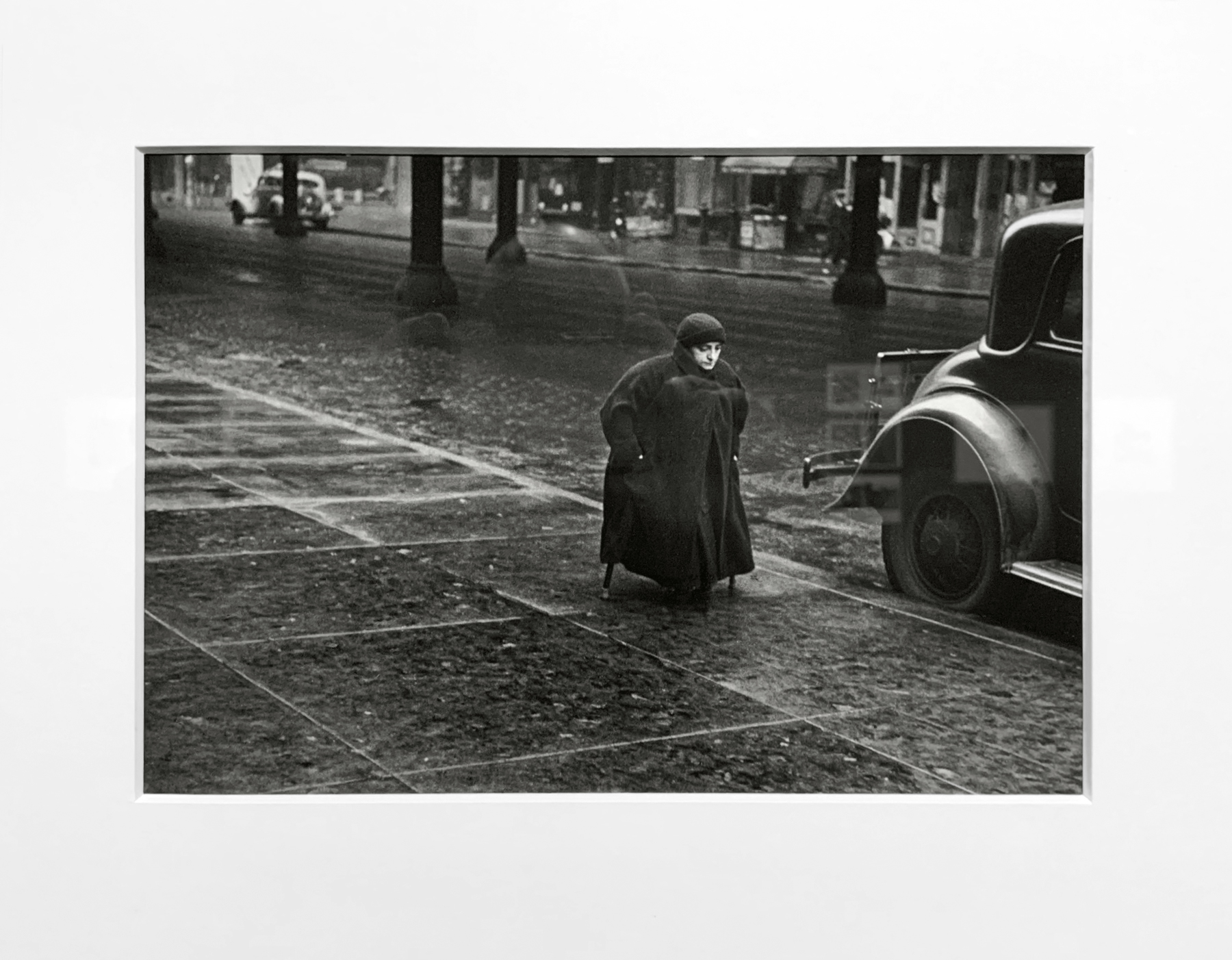

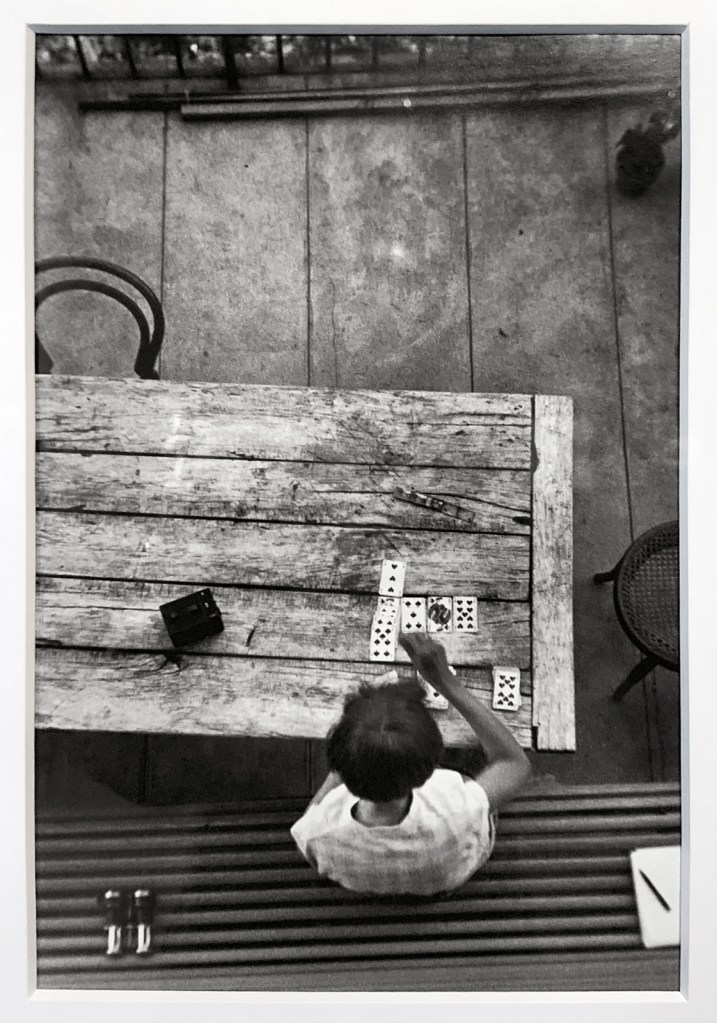

Many “New Woman” photographers behind the camera had to operate in such a value system in order have a job and make a living. Variously, they had to build a career as a fashion photographer, advertising and graphic photographer, magazine photographer, studio photographer, photojournalist, war photographer, social documentary photographer, street photographer and ethnographic photographic … and usually had be proficient at most styles of photography in order to obtain sufficient work for survive. For example, Sabine Weiss bridled at being labelled a humanist, “because she considered her street photography to be just one part of her oeuvre. Most of her career was spent as a fashion photographer and a photojournalist, shooting celebrities like Brigitte Bardot and musicians like Benjamin Britten. “From the start I had to make a living from photography; it wasn’t something artistic,” Weiss told Agence France-Presse in 2014. “It was a craft, I was a craftswoman of photography.”38

I suspect for most women photographers of the era this was the truth: taking photographs wasn’t something artistic it was a craft from which they earned a living. While part of the profound shaping of the medium during a time of tremendous social and political change they did not initiate the “modernisation” of photography but were undoubtedly an important part of that movement. But, and here is the key point, they were still producing “mainstream” images and, as Annette Kuhn notes, “‘Mainstream’ images in our culture bear the traces of the capitalist and patriarchal social relations in which they are produced, exchanged and consumed.”39 They bought into the value system.

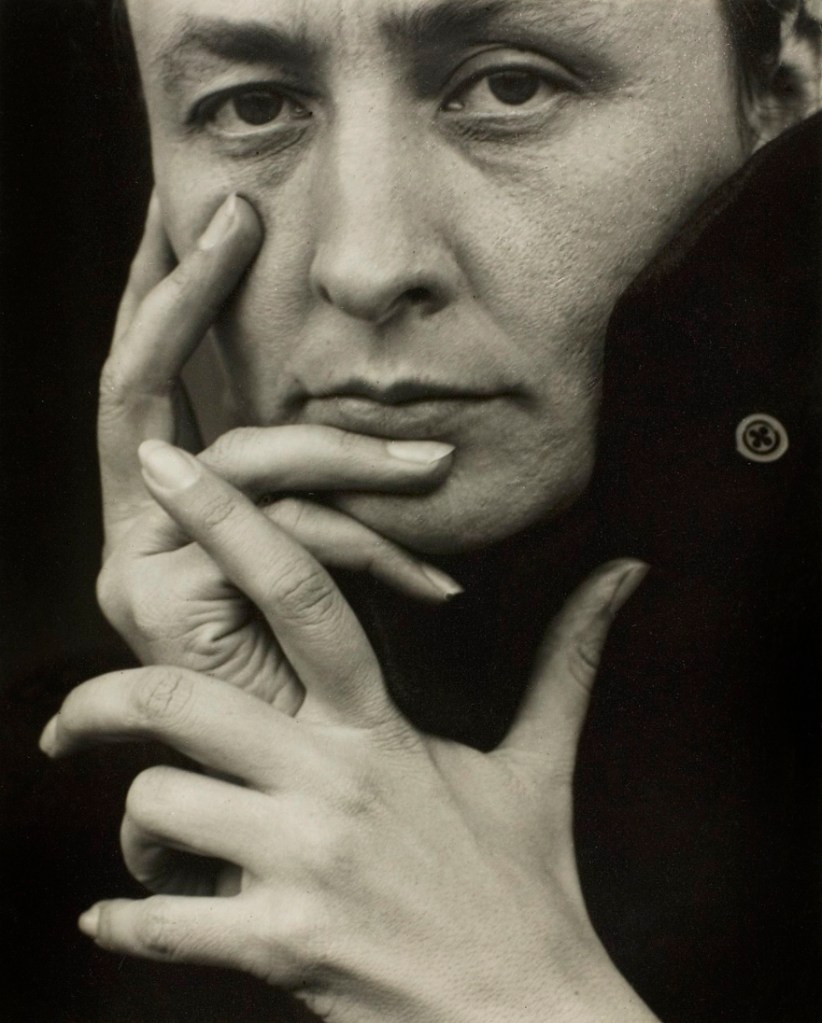

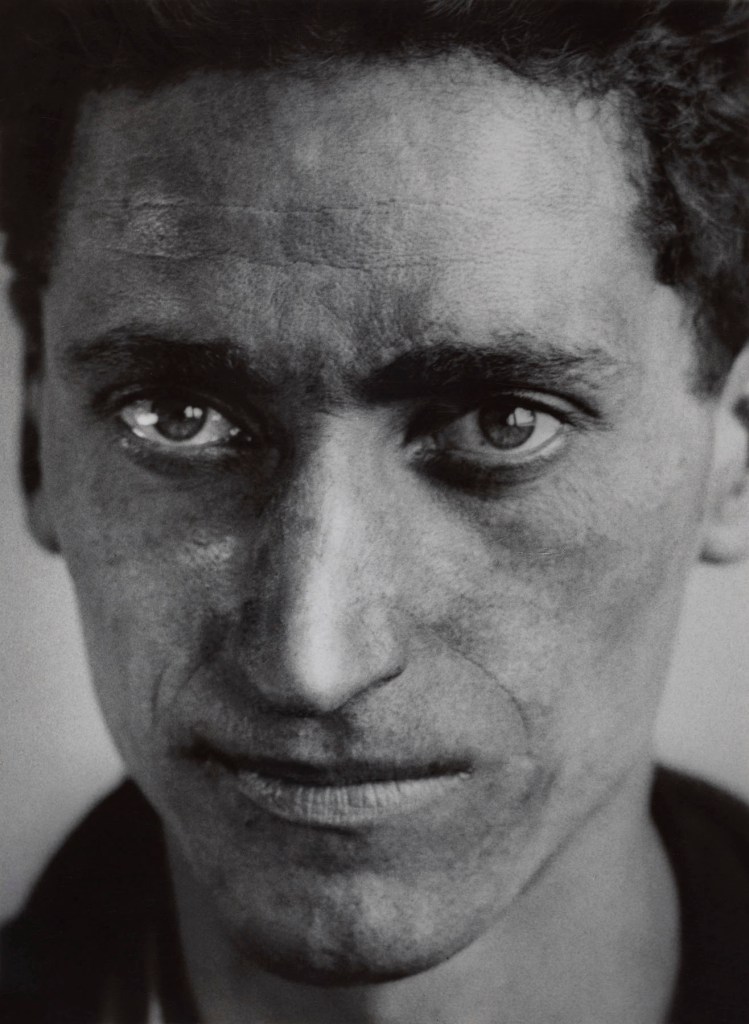

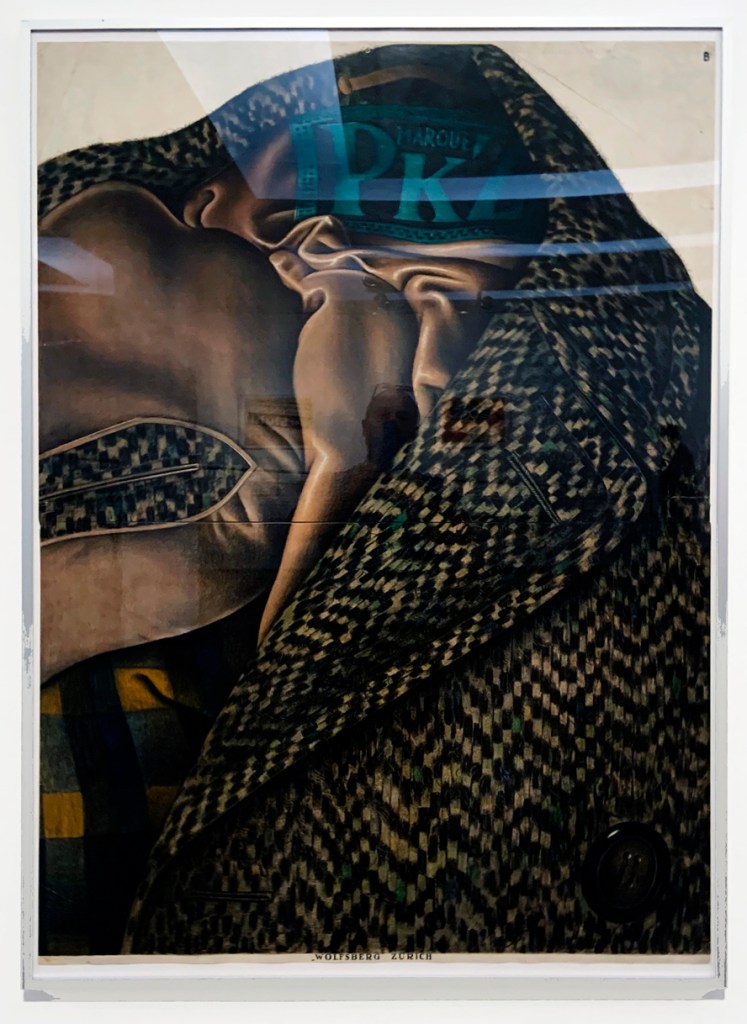

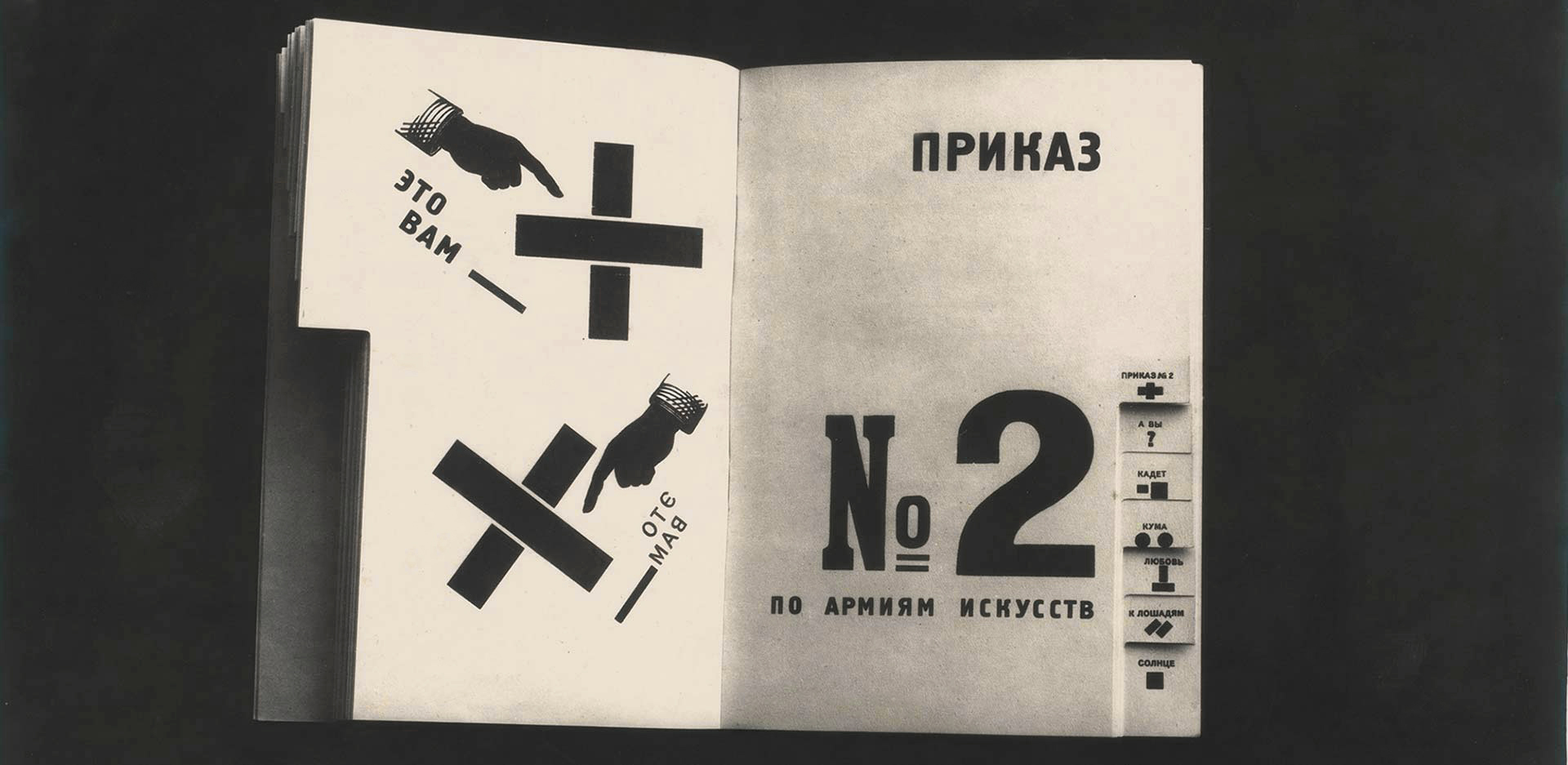

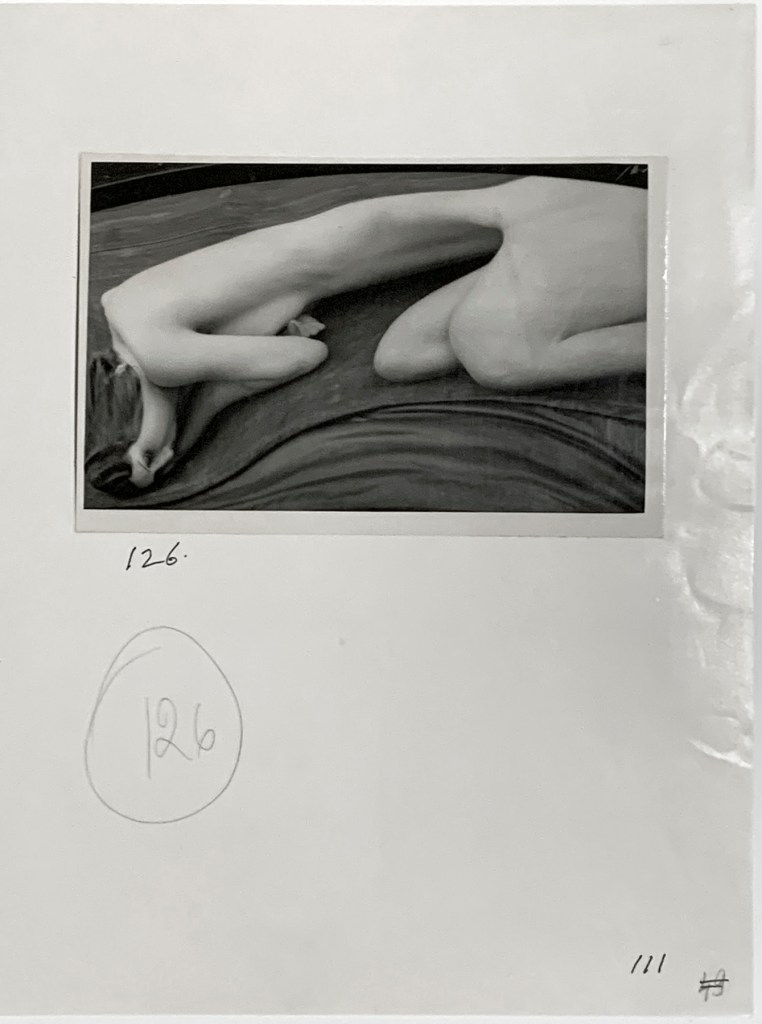

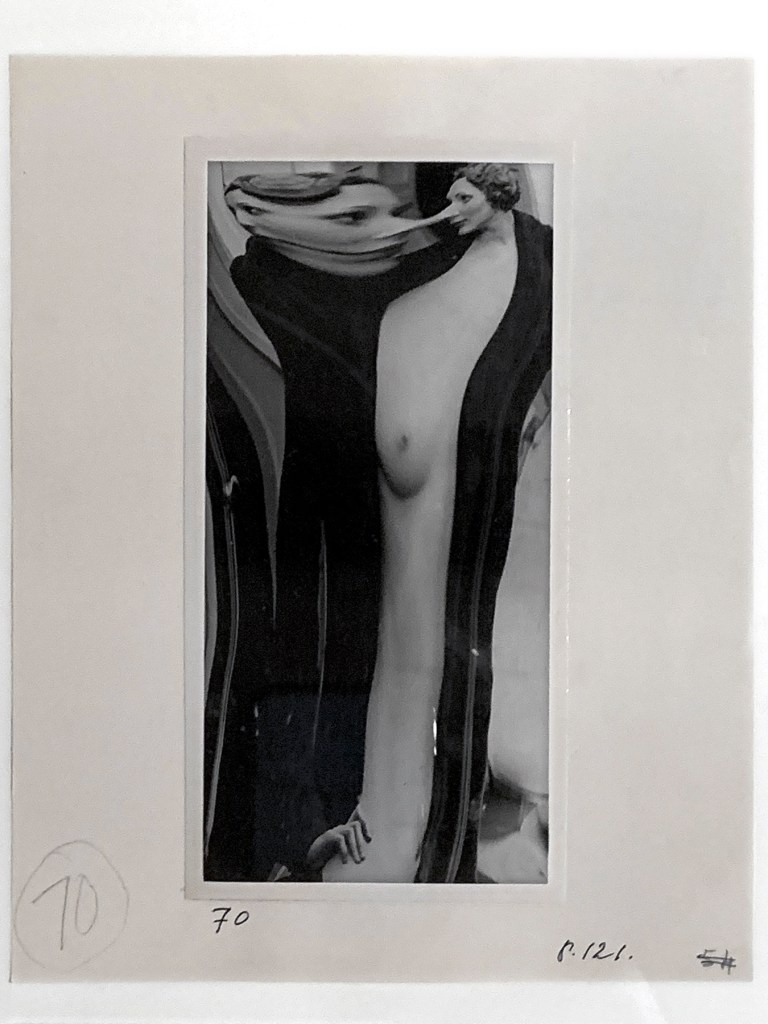

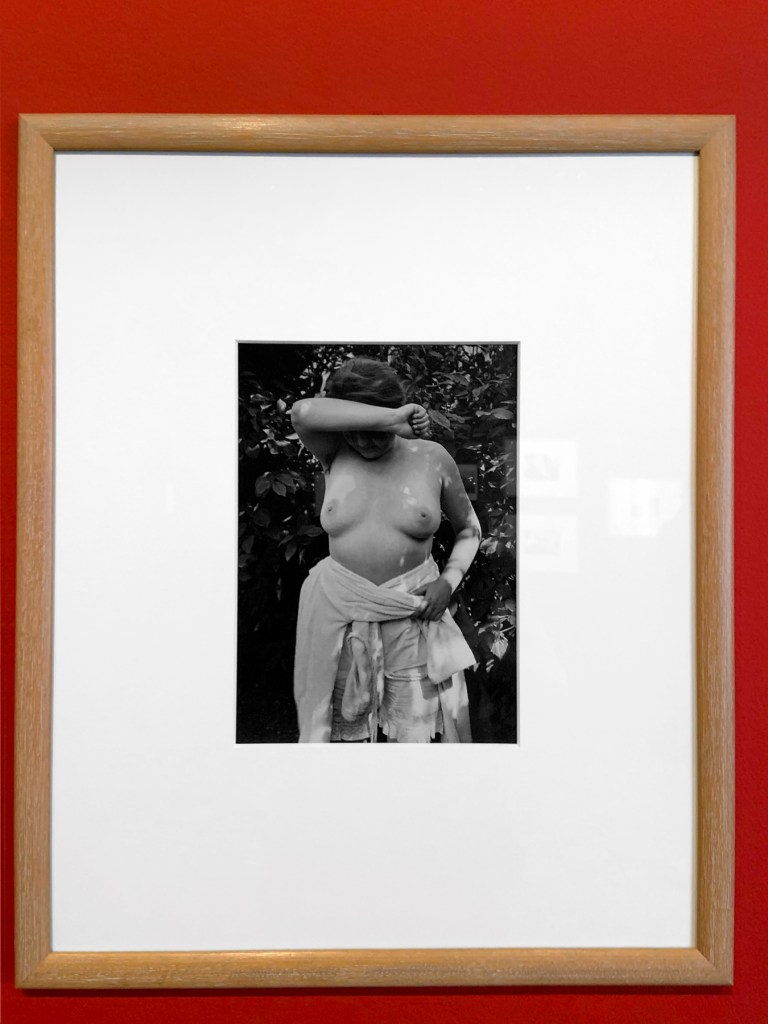

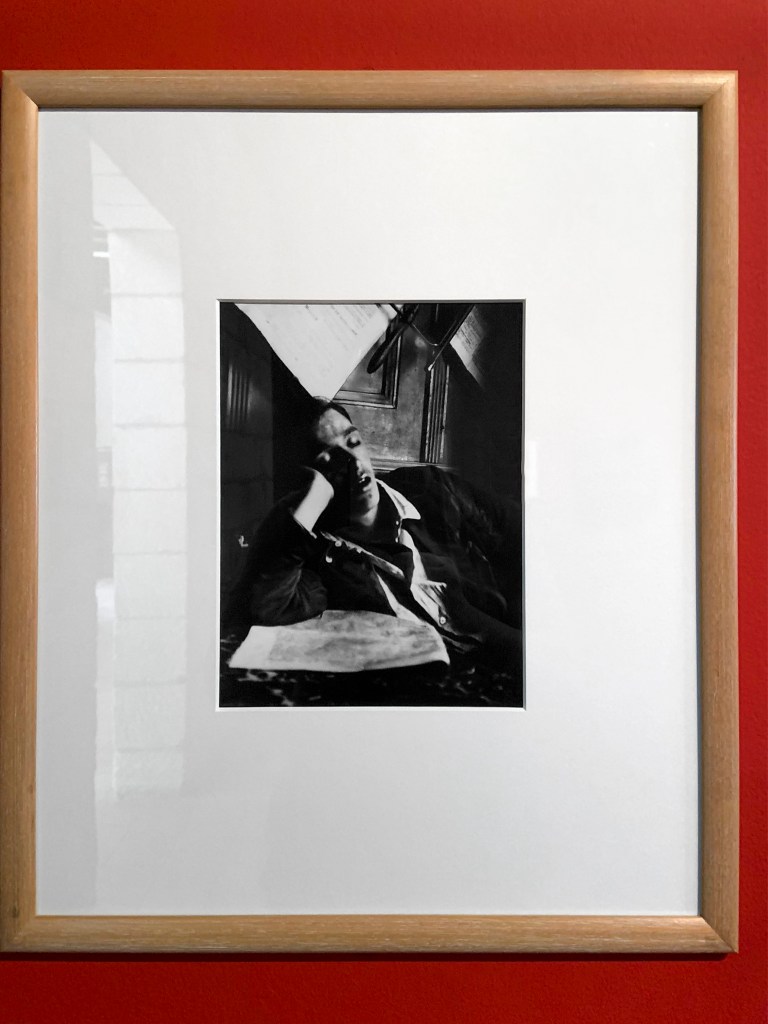

Among others (such as Dora Maar, Tina Modotti, Lucia Moholy, Aenne Biermann, Eva Besnyö and Florence Henri to name just a few of my favourites) … two women photographers who did push the boundaries of the art of photography and, in their case, what was acceptable in terms of the representation of gender identity were the temporarily bisexual, pan-world Germaine Krull (1897-1985) and the “neuter” (neither) photographer Claude Cahun (French, 1894-1954).

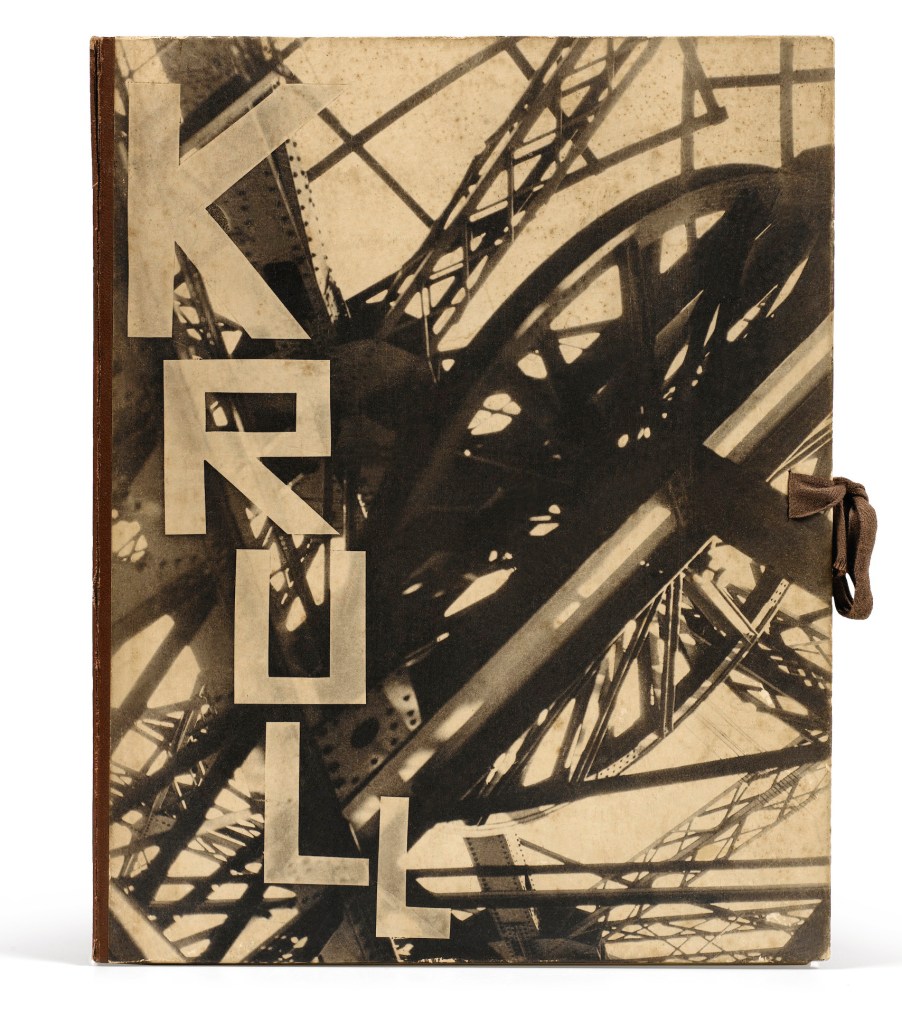

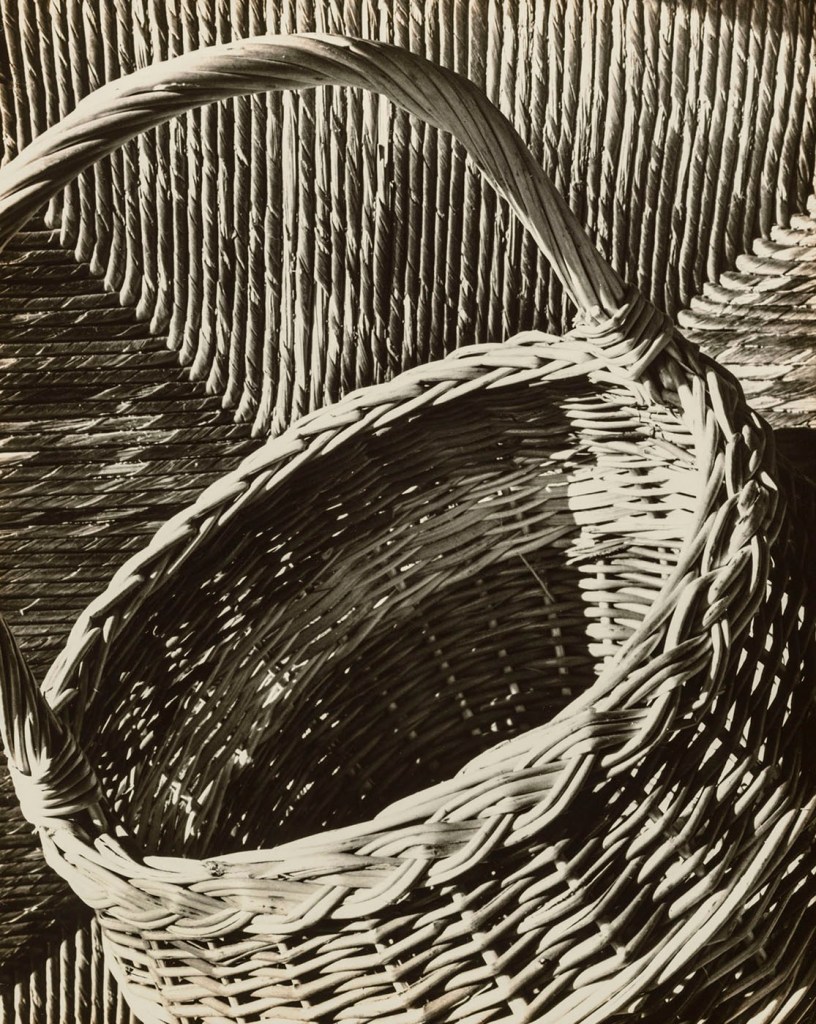

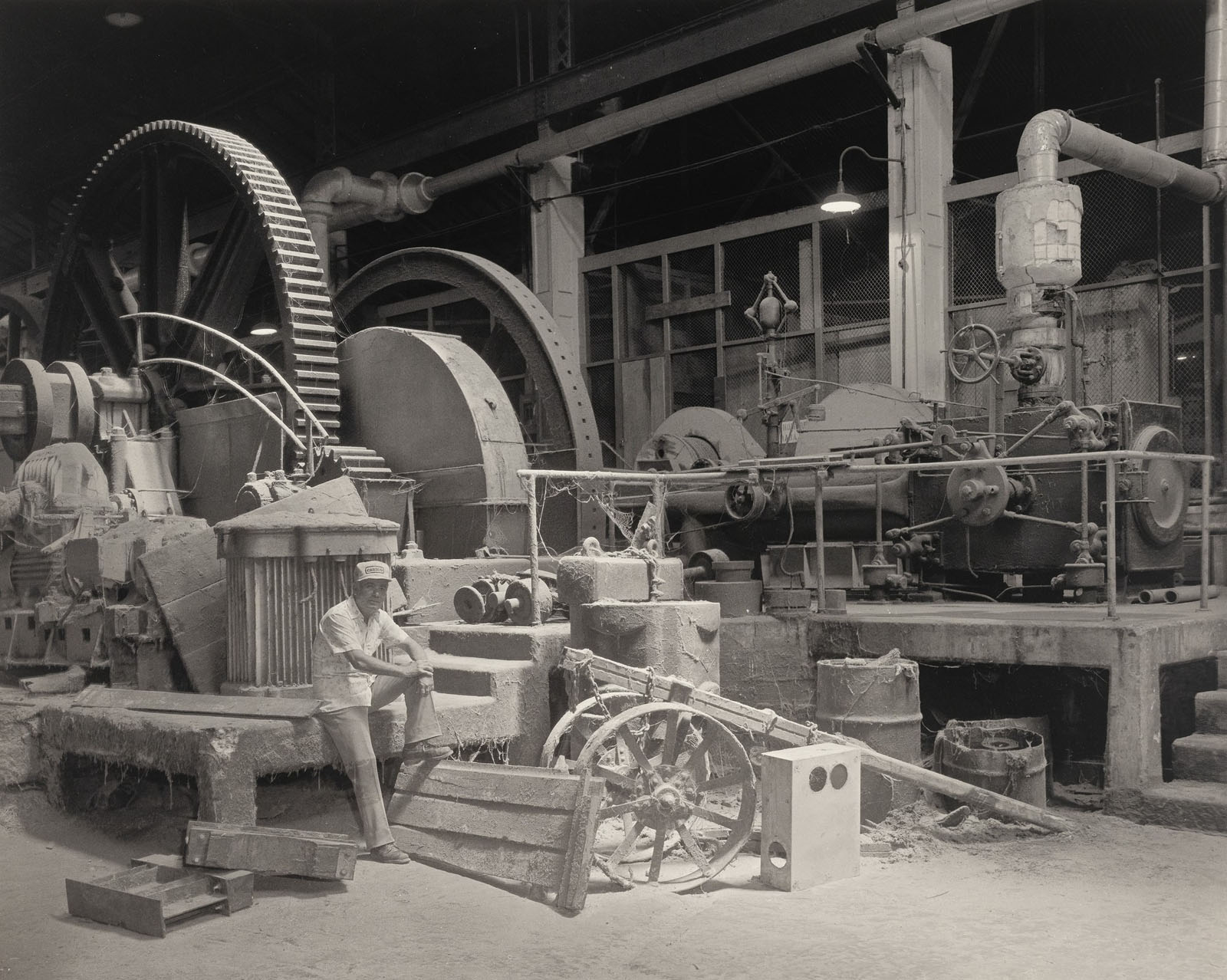

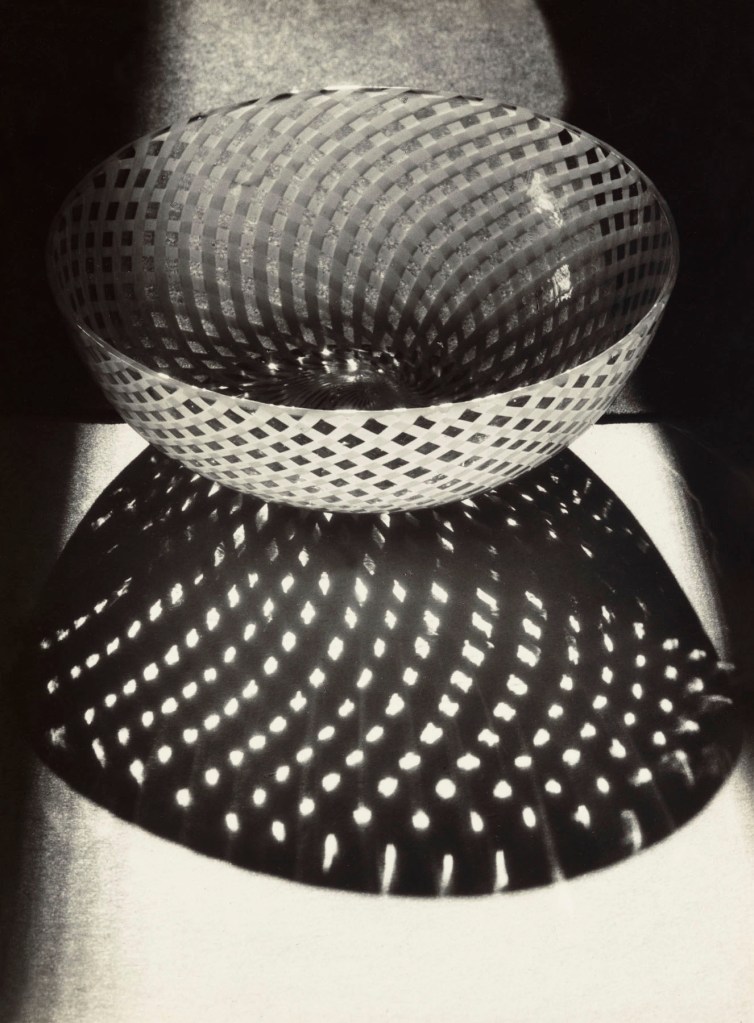

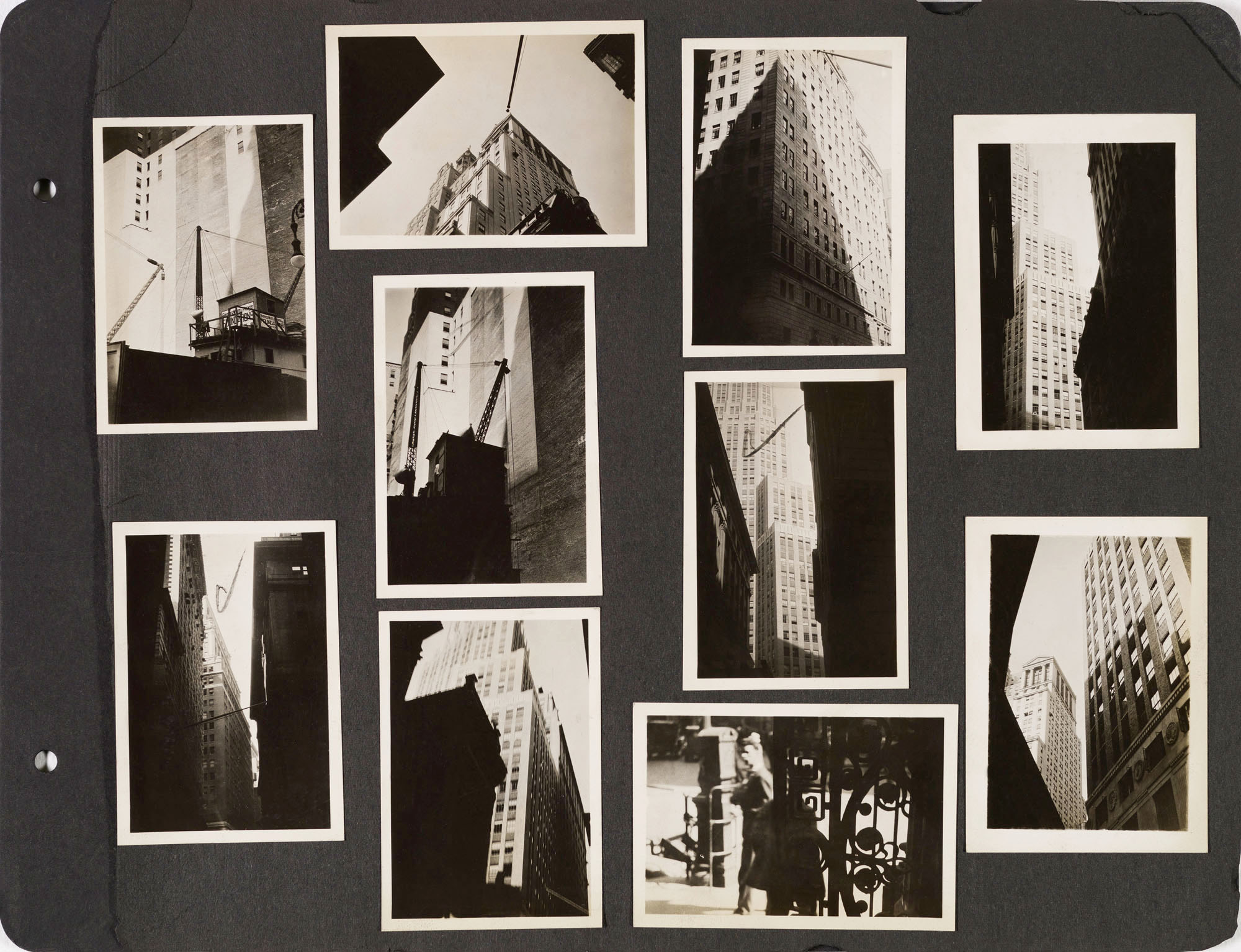

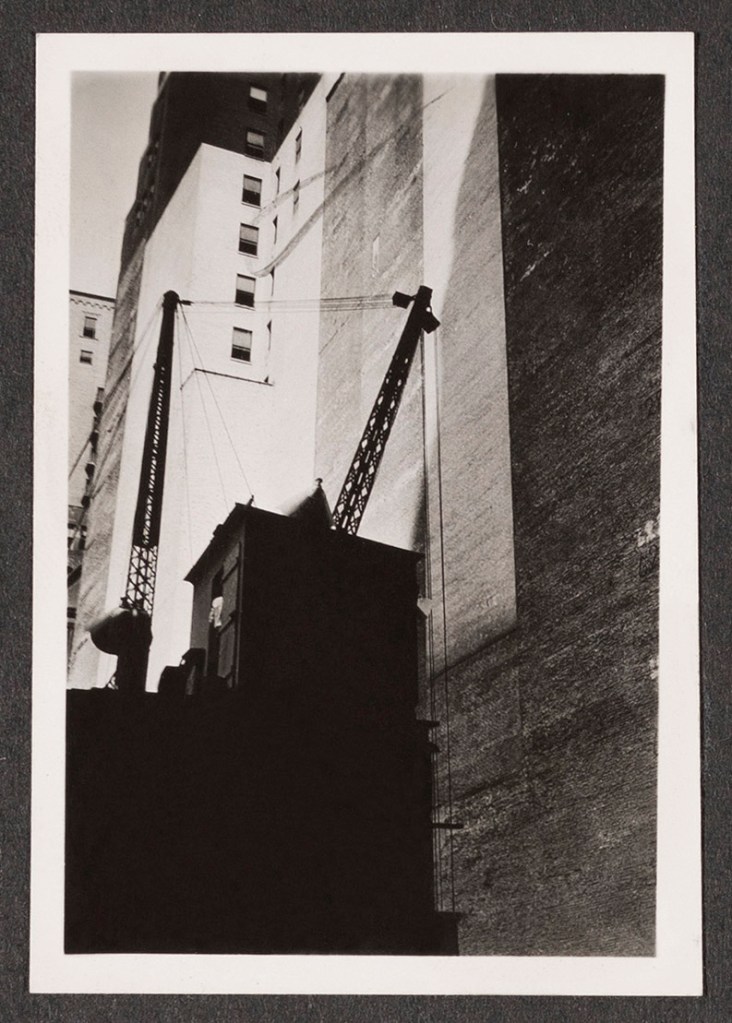

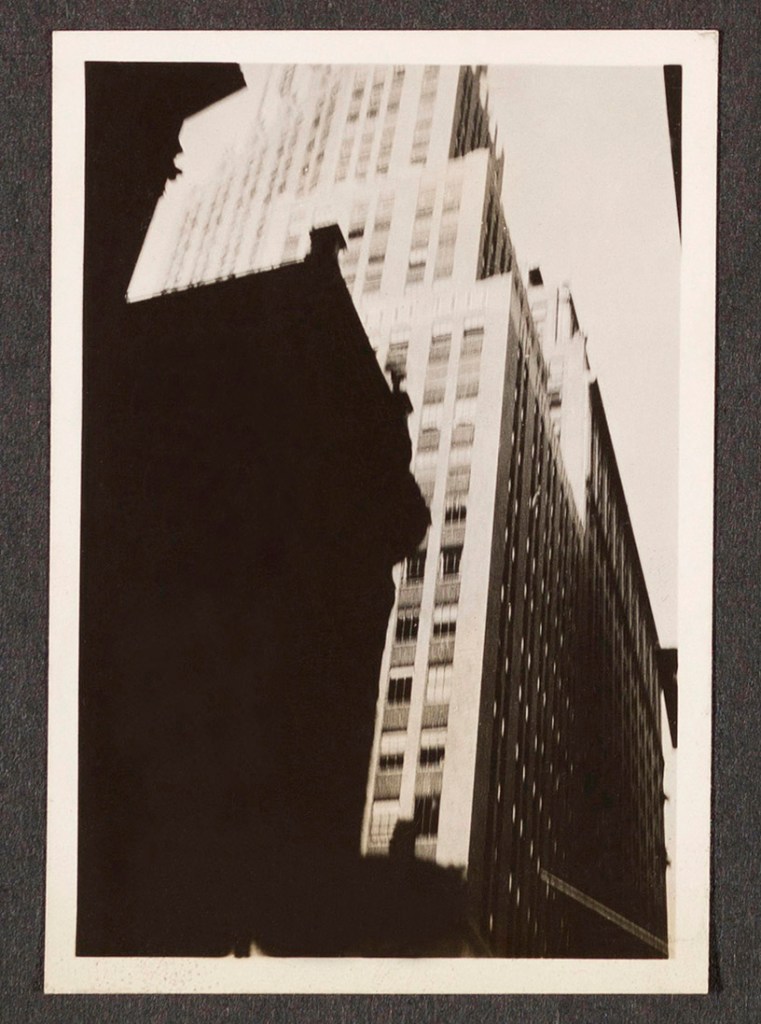

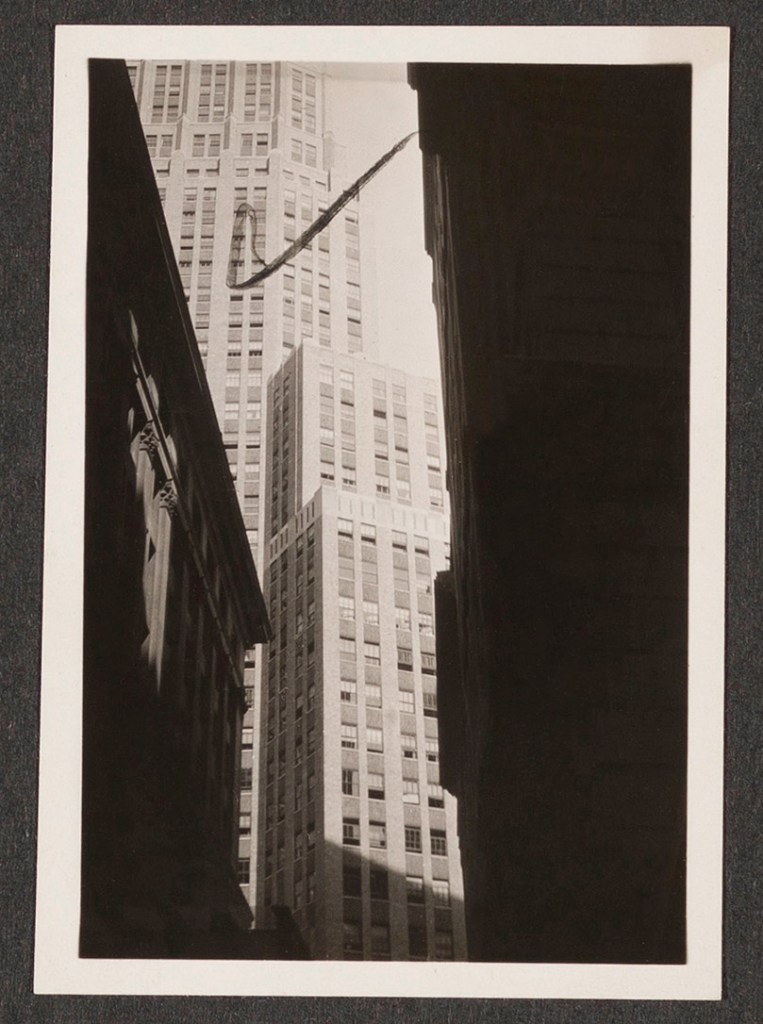

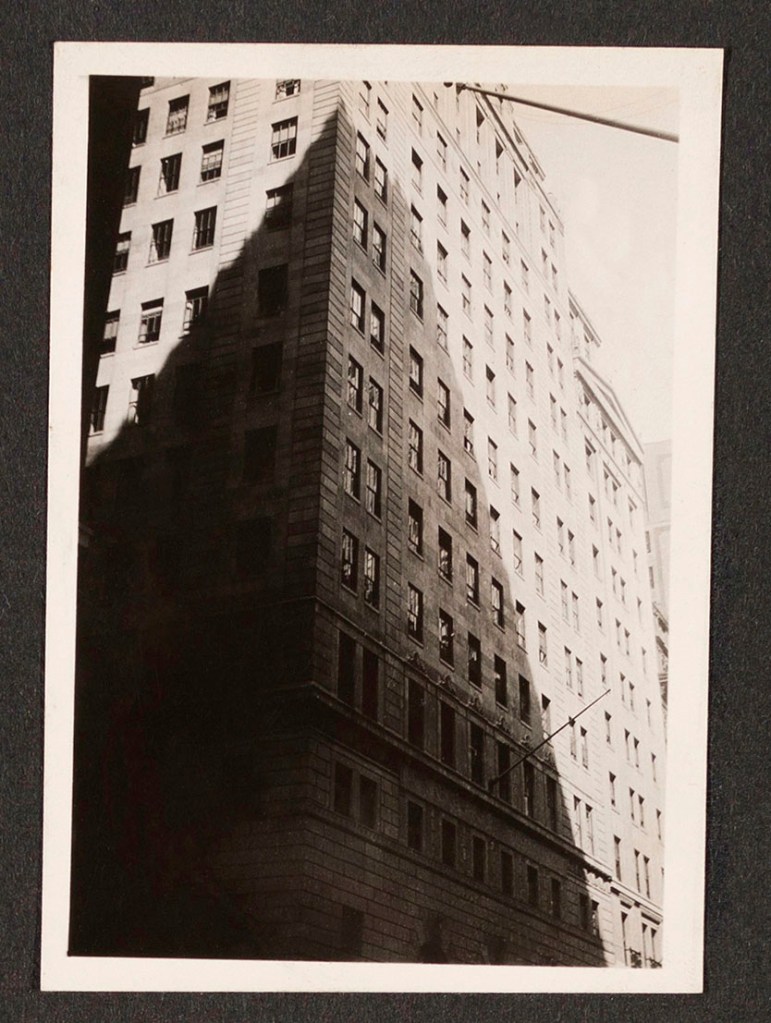

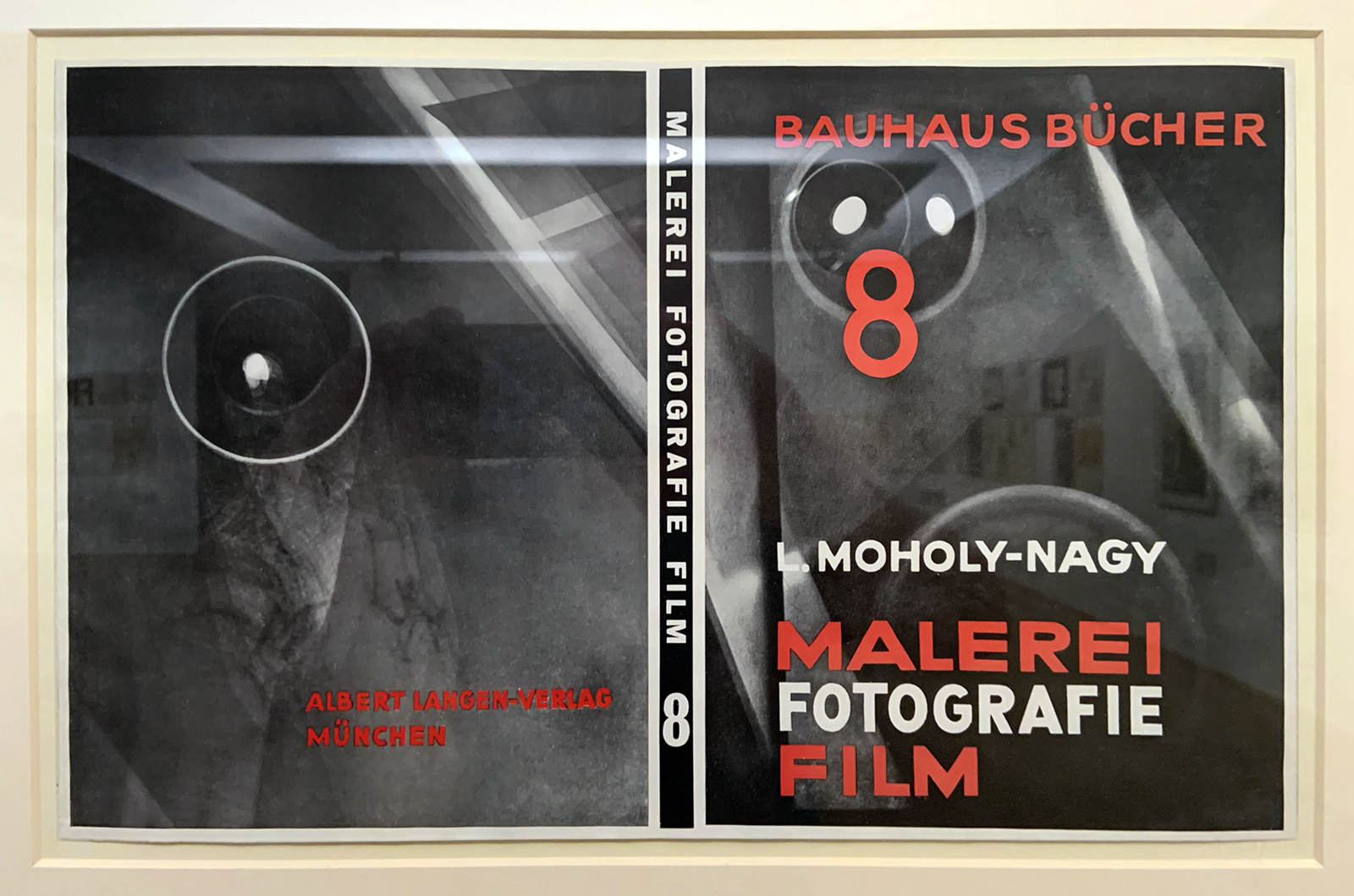

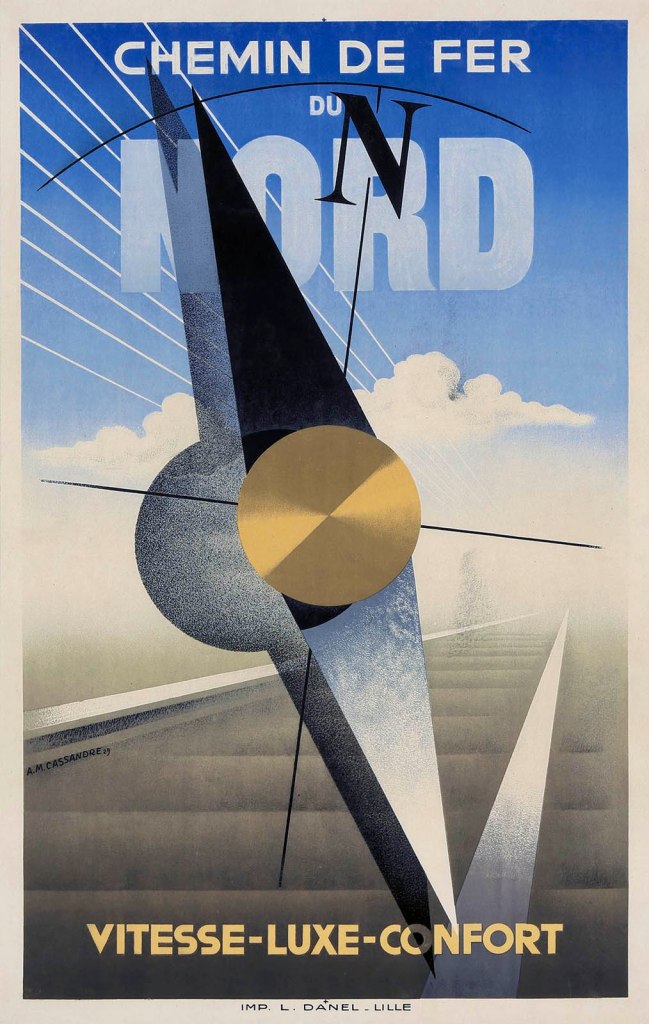

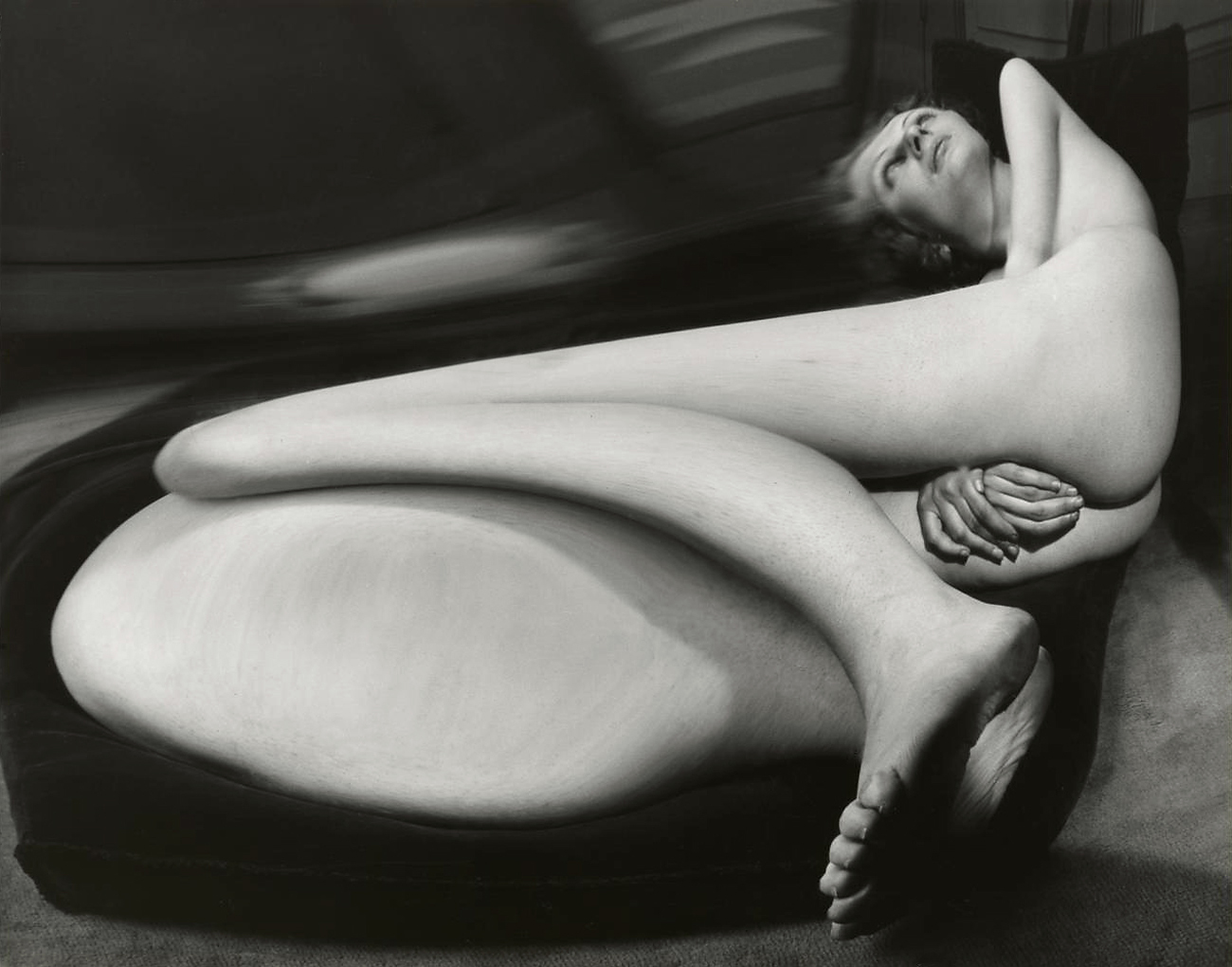

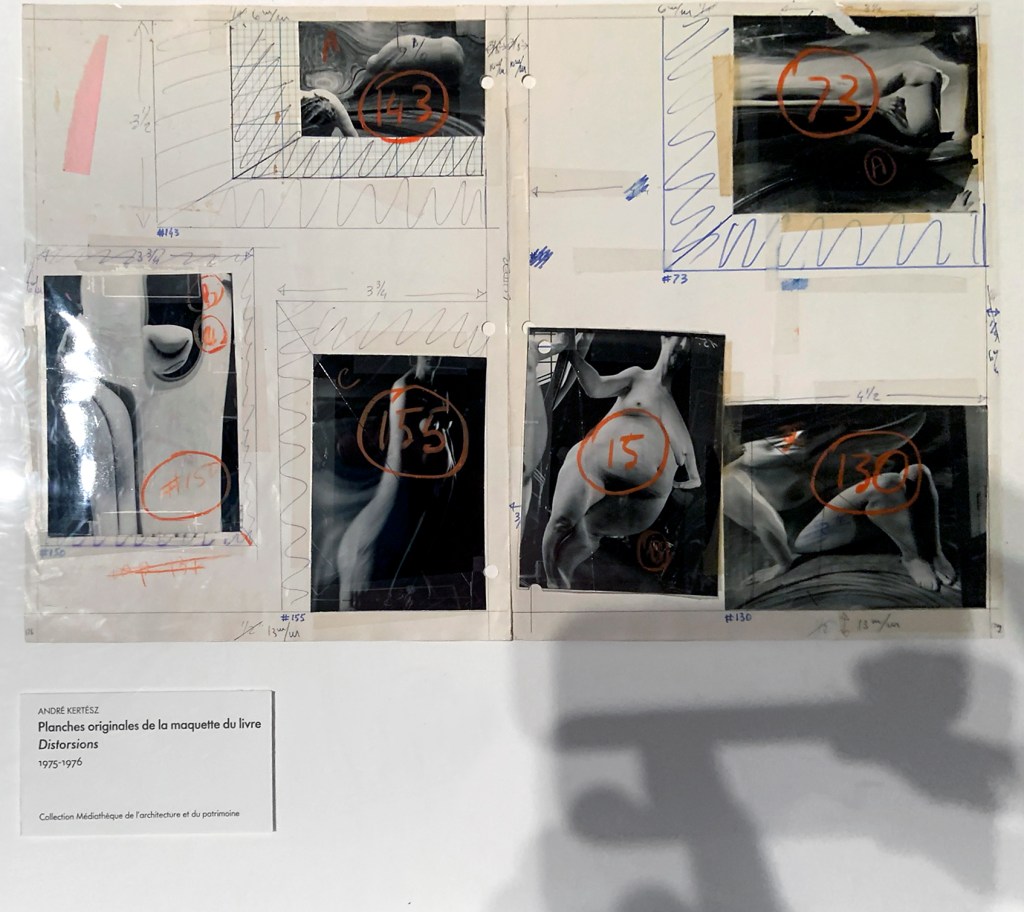

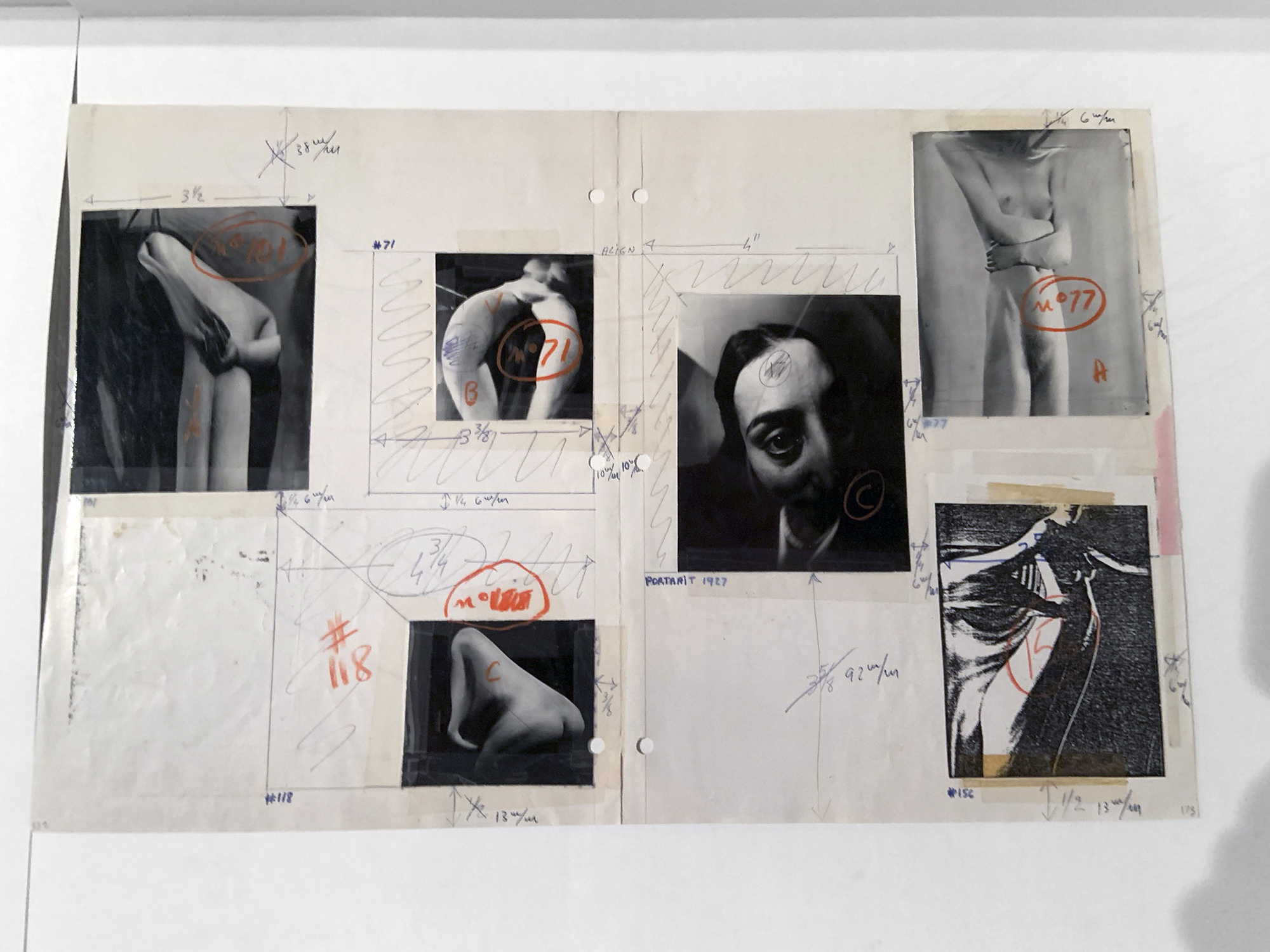

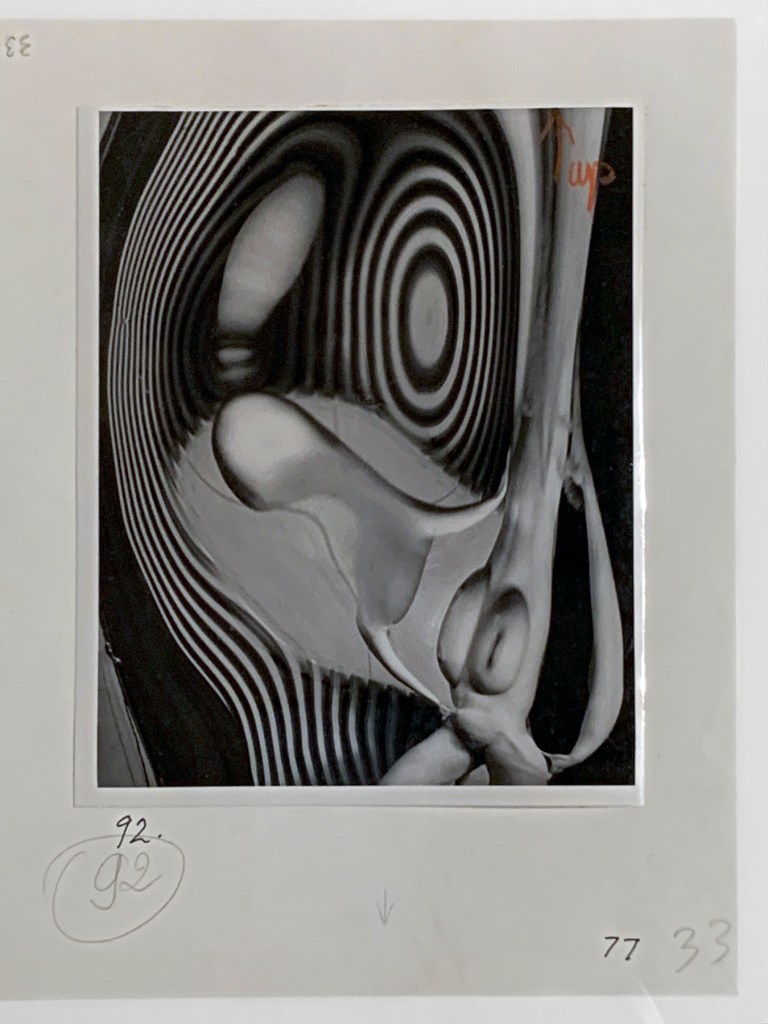

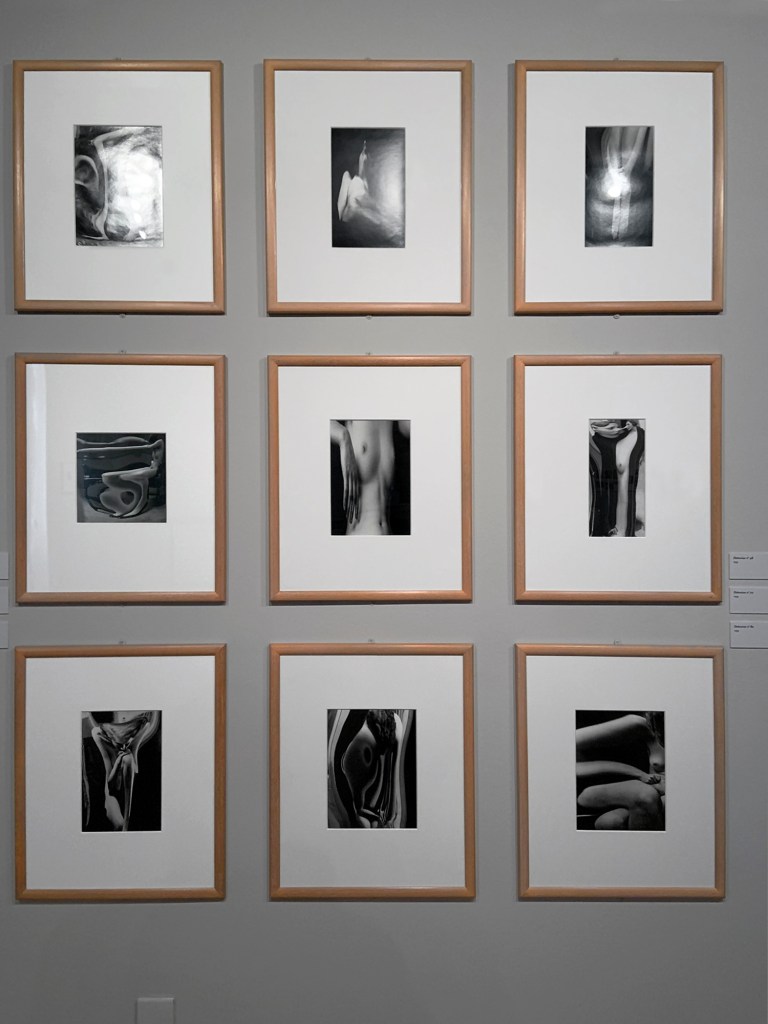

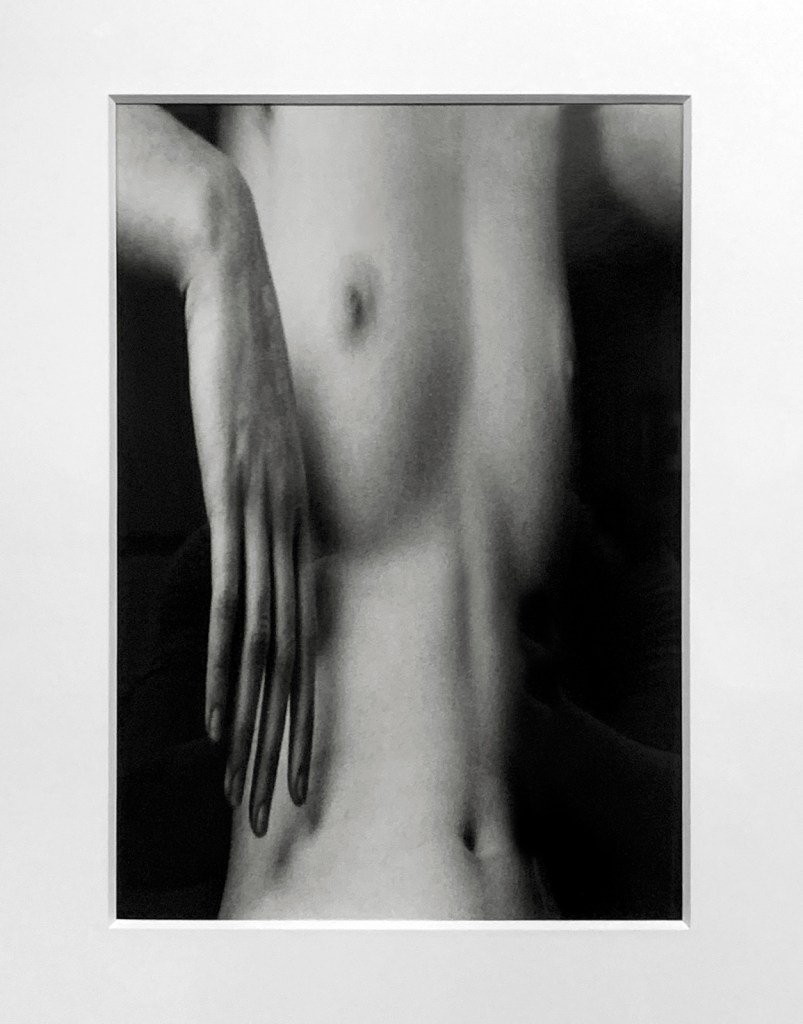

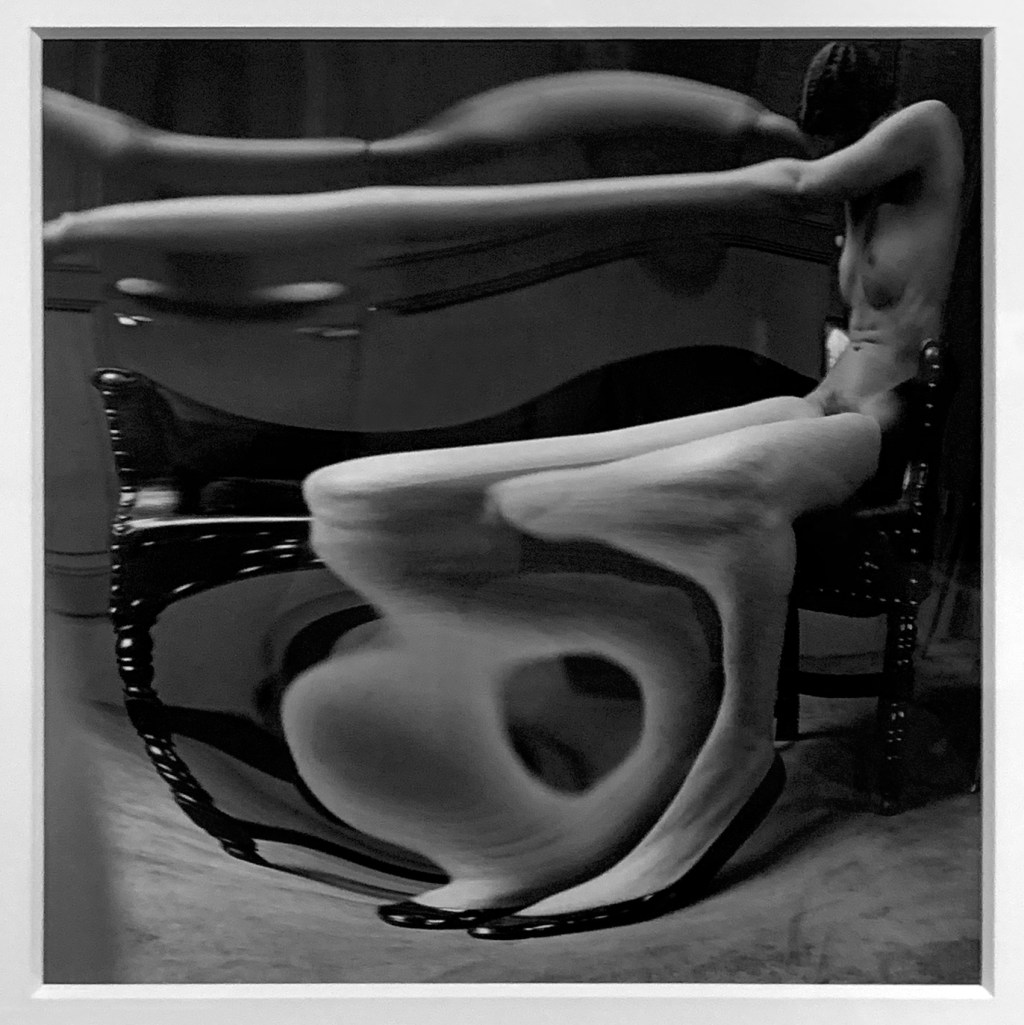

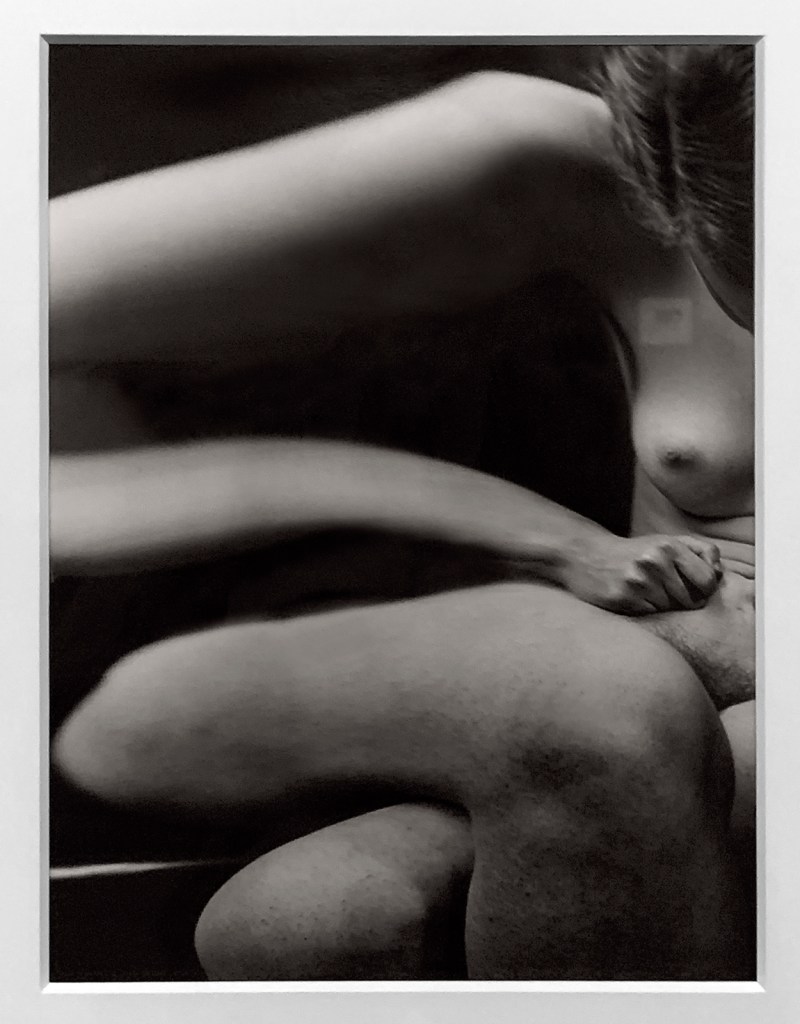

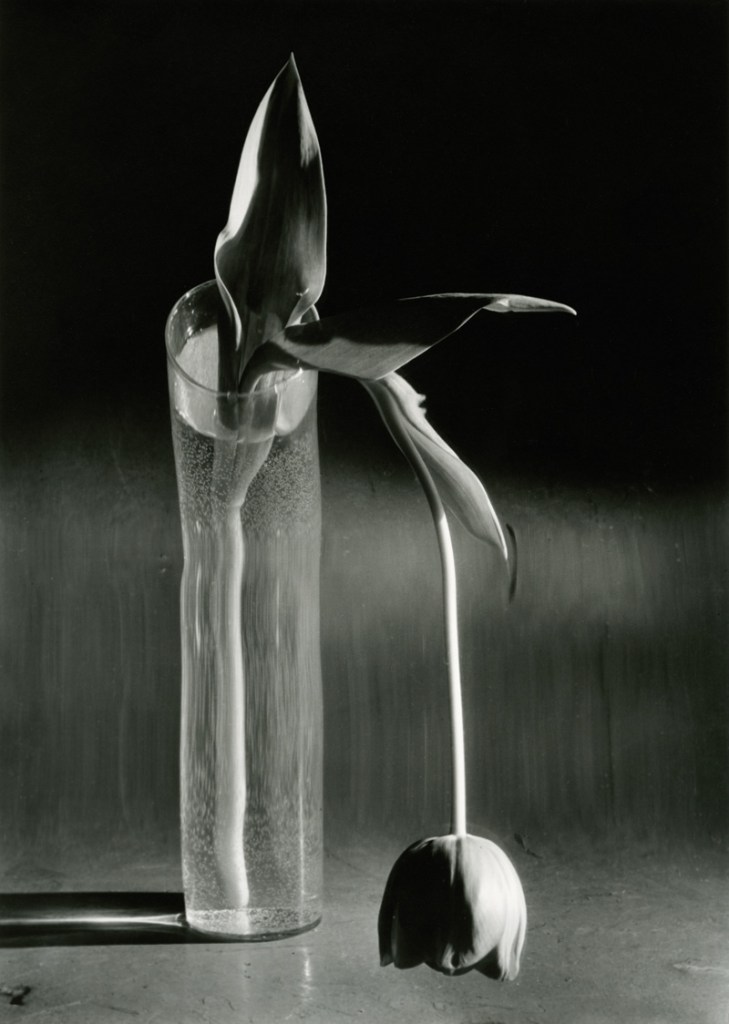

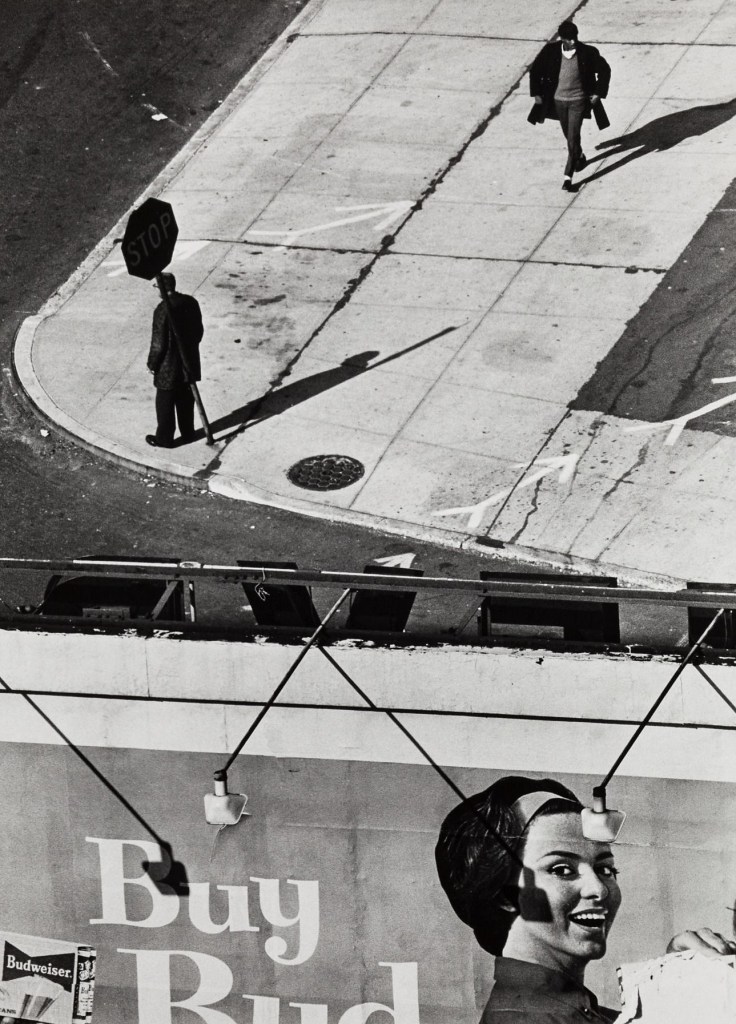

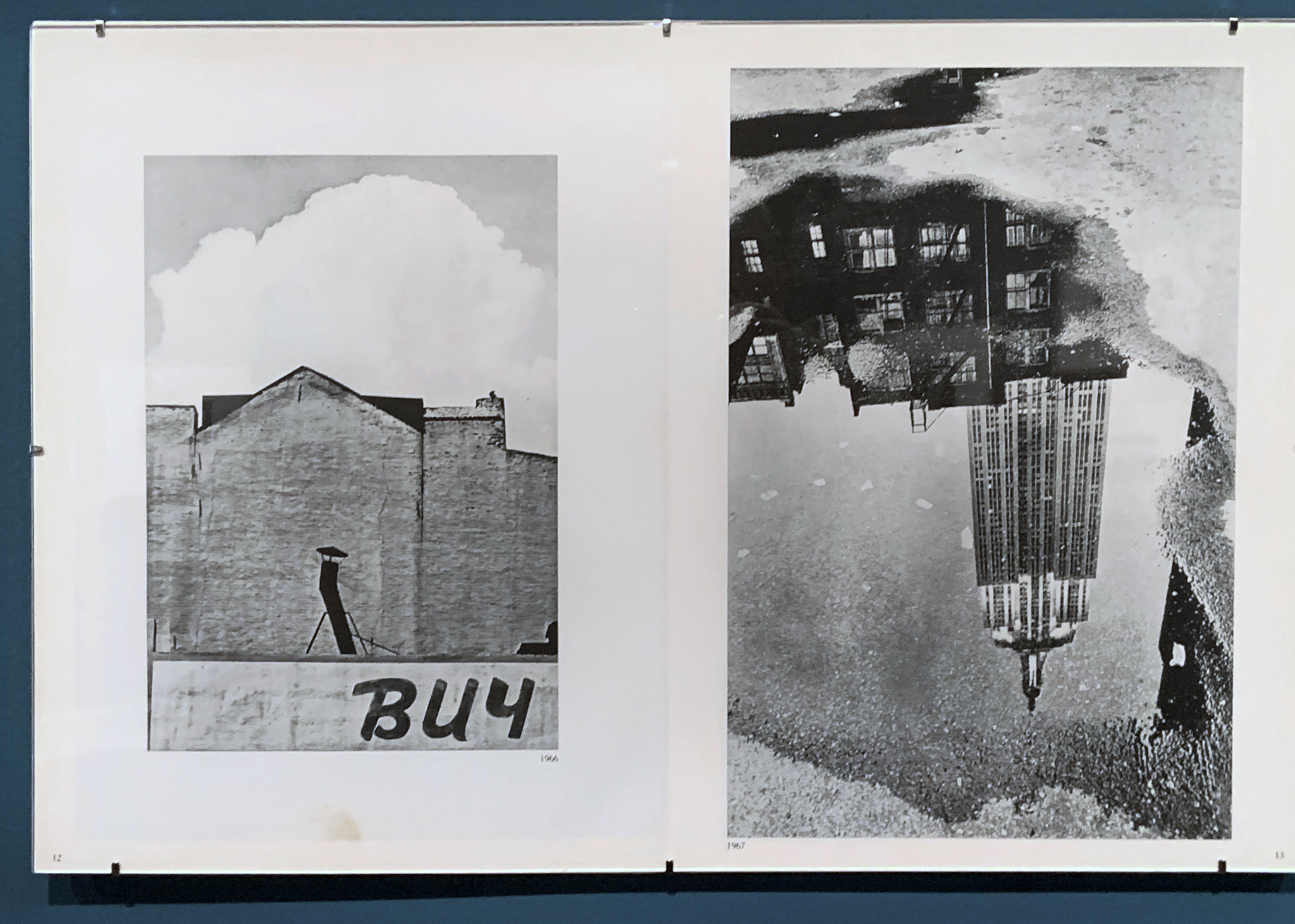

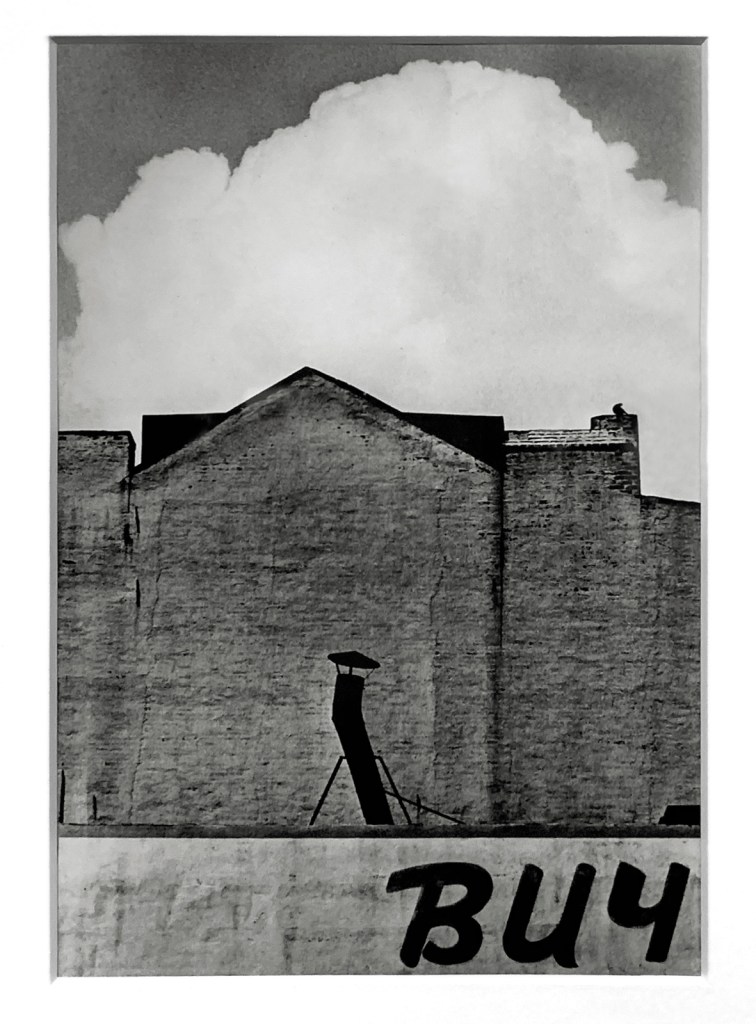

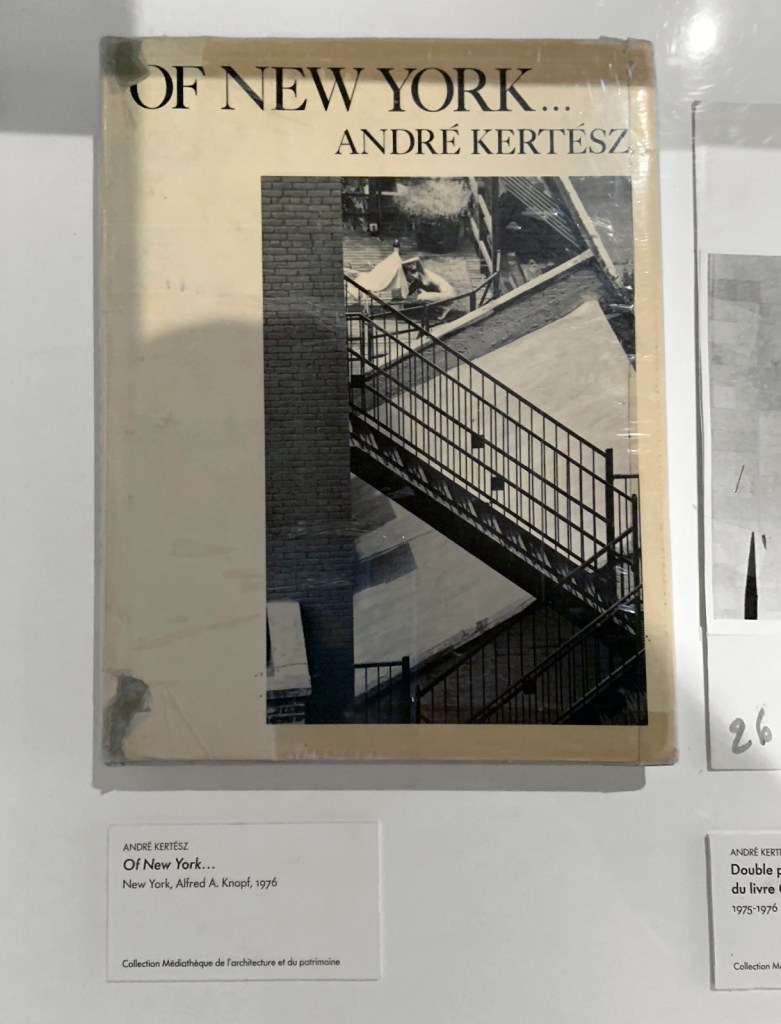

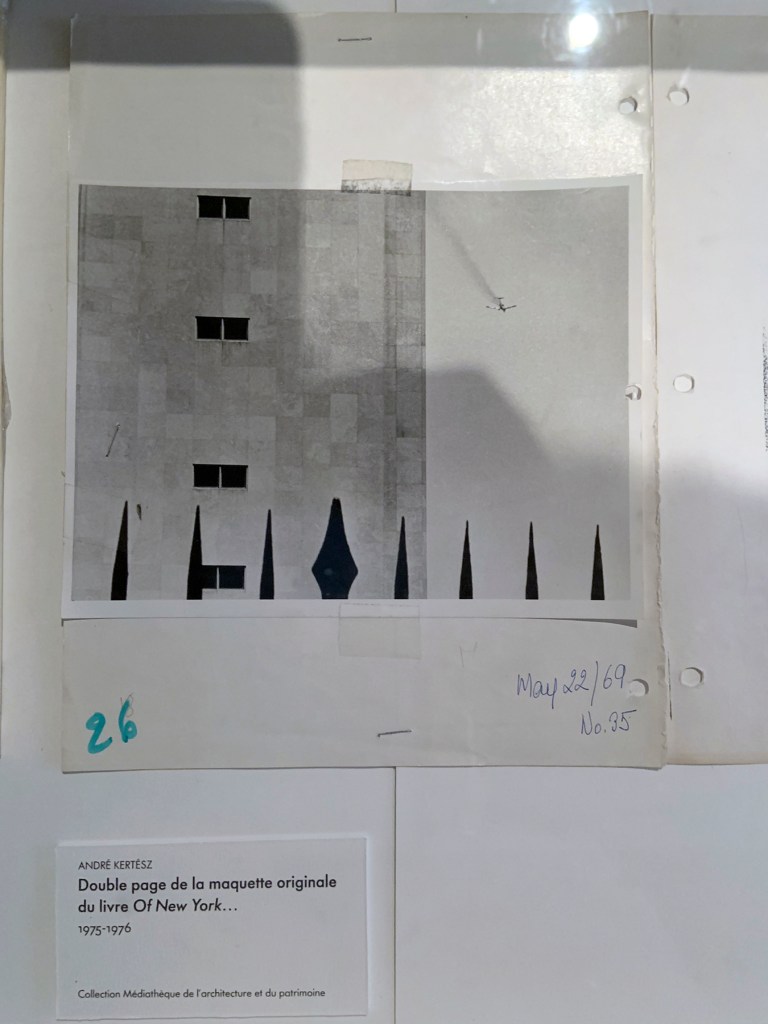

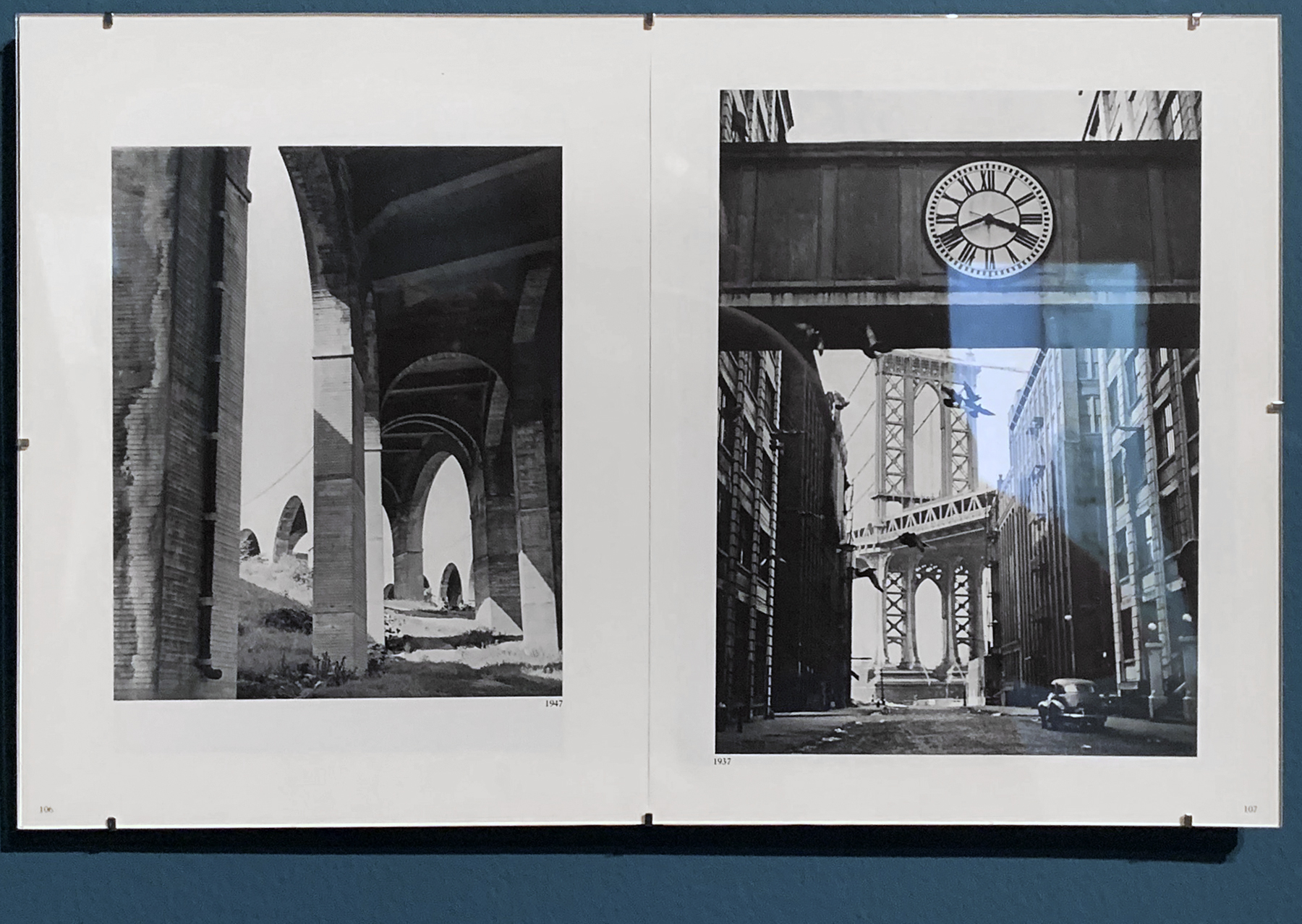

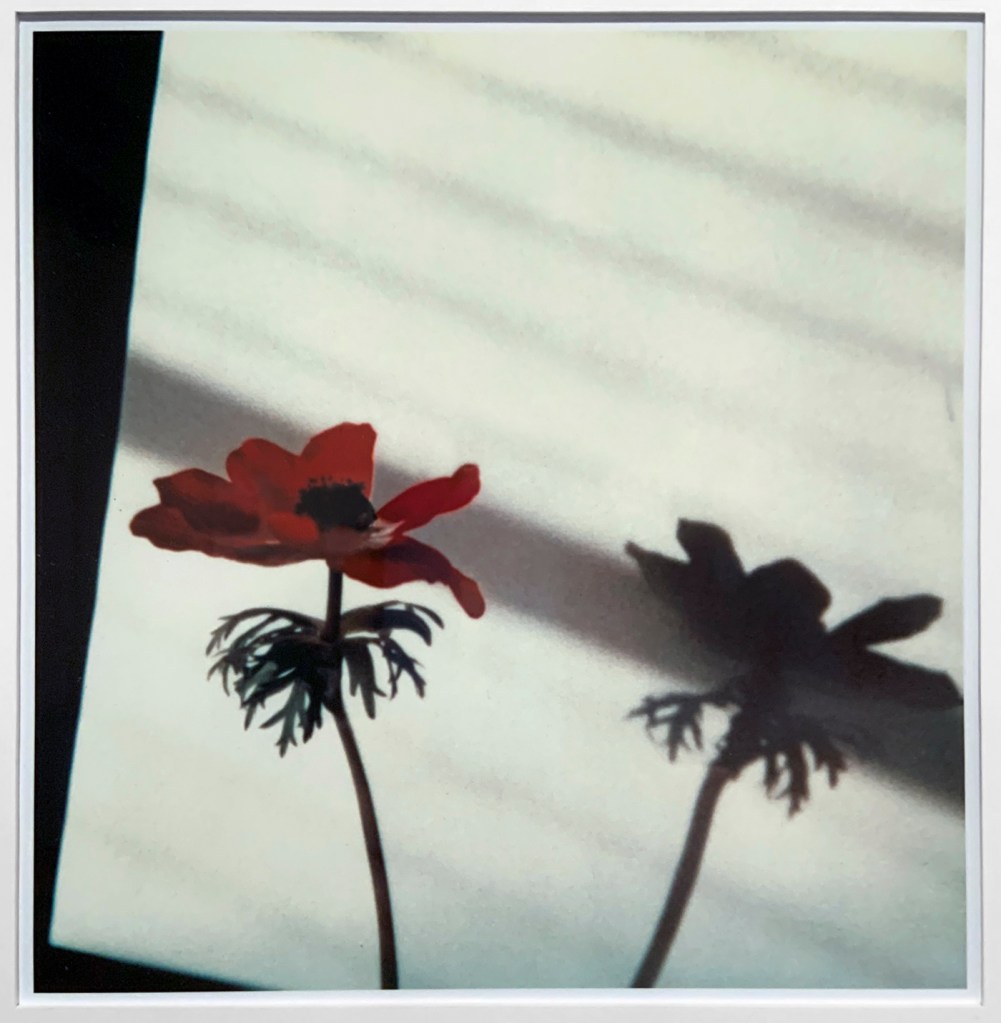

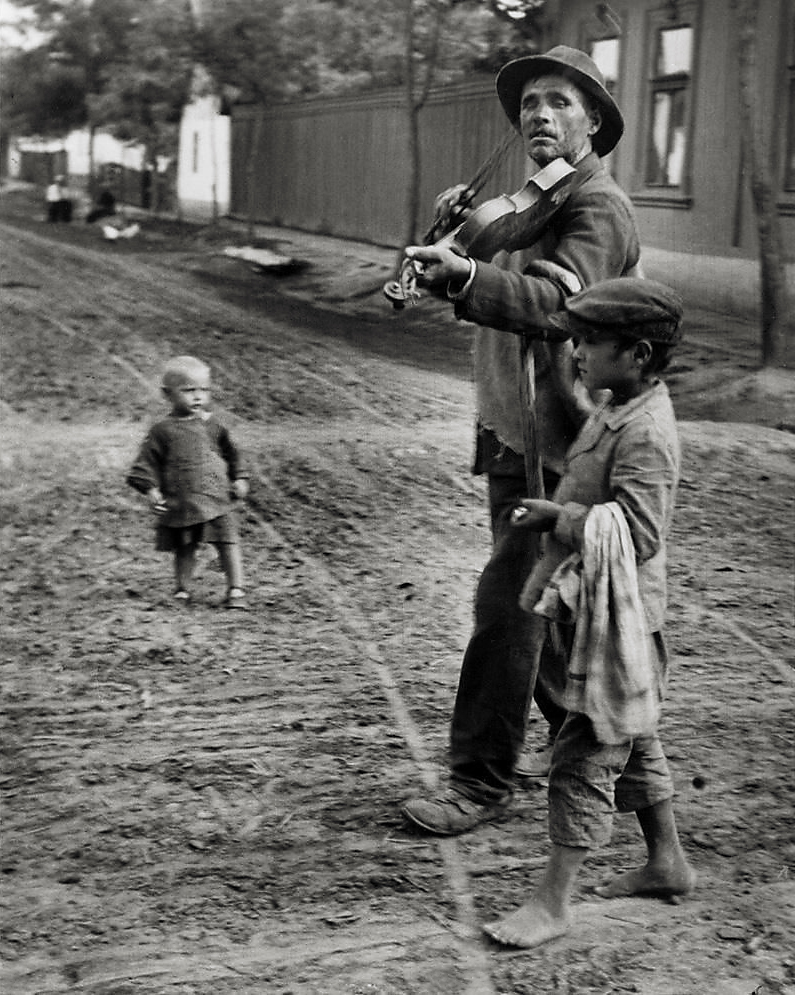

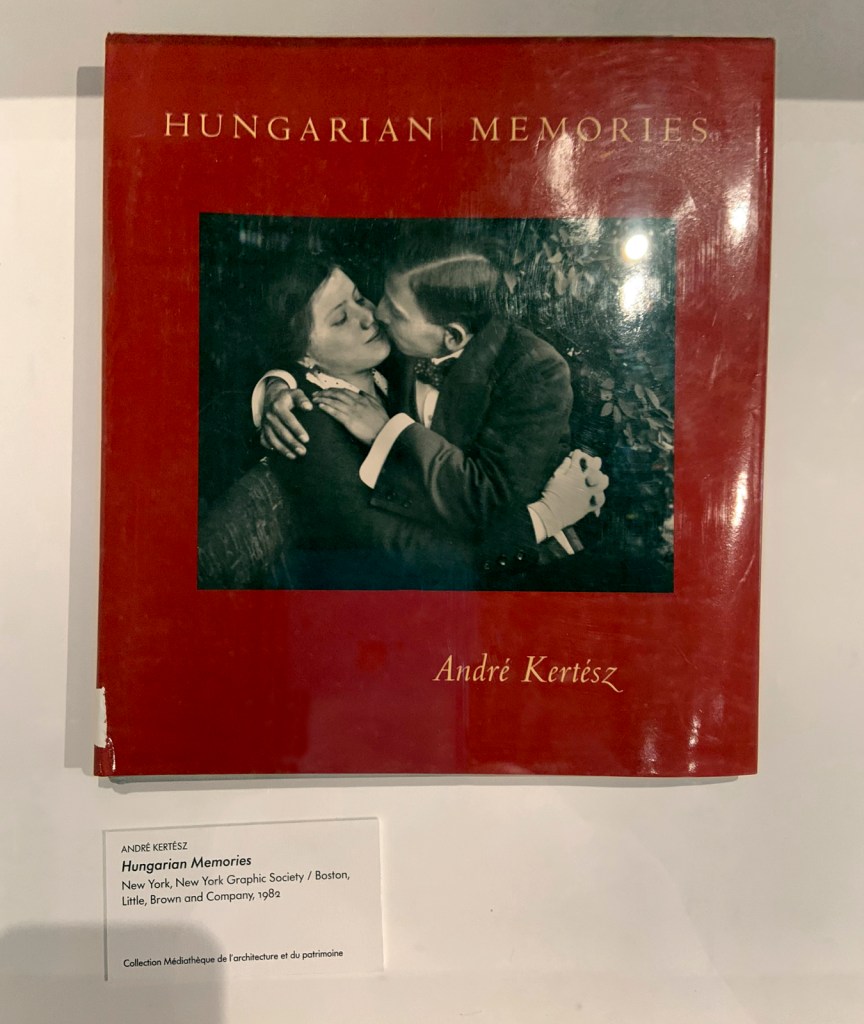

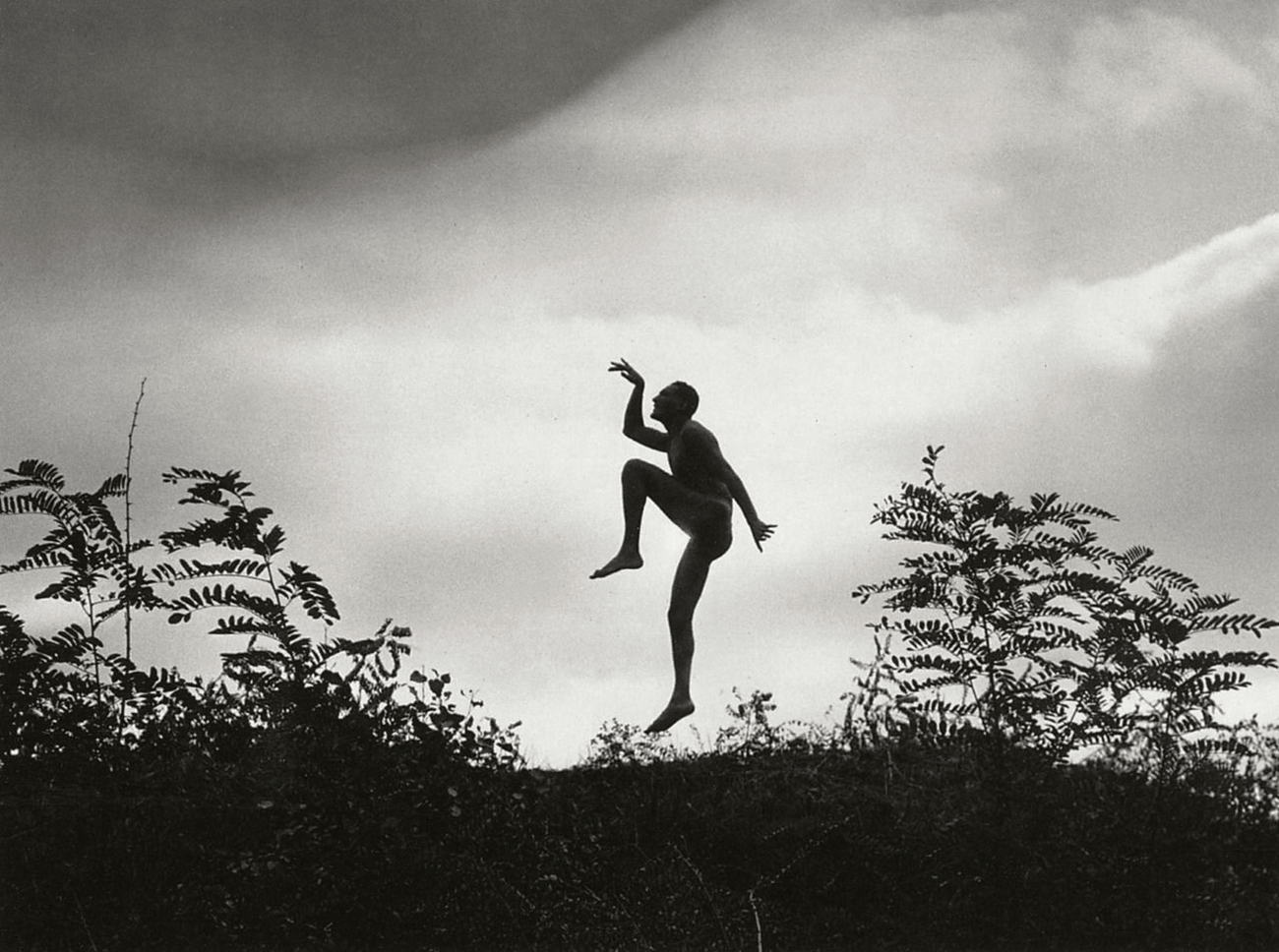

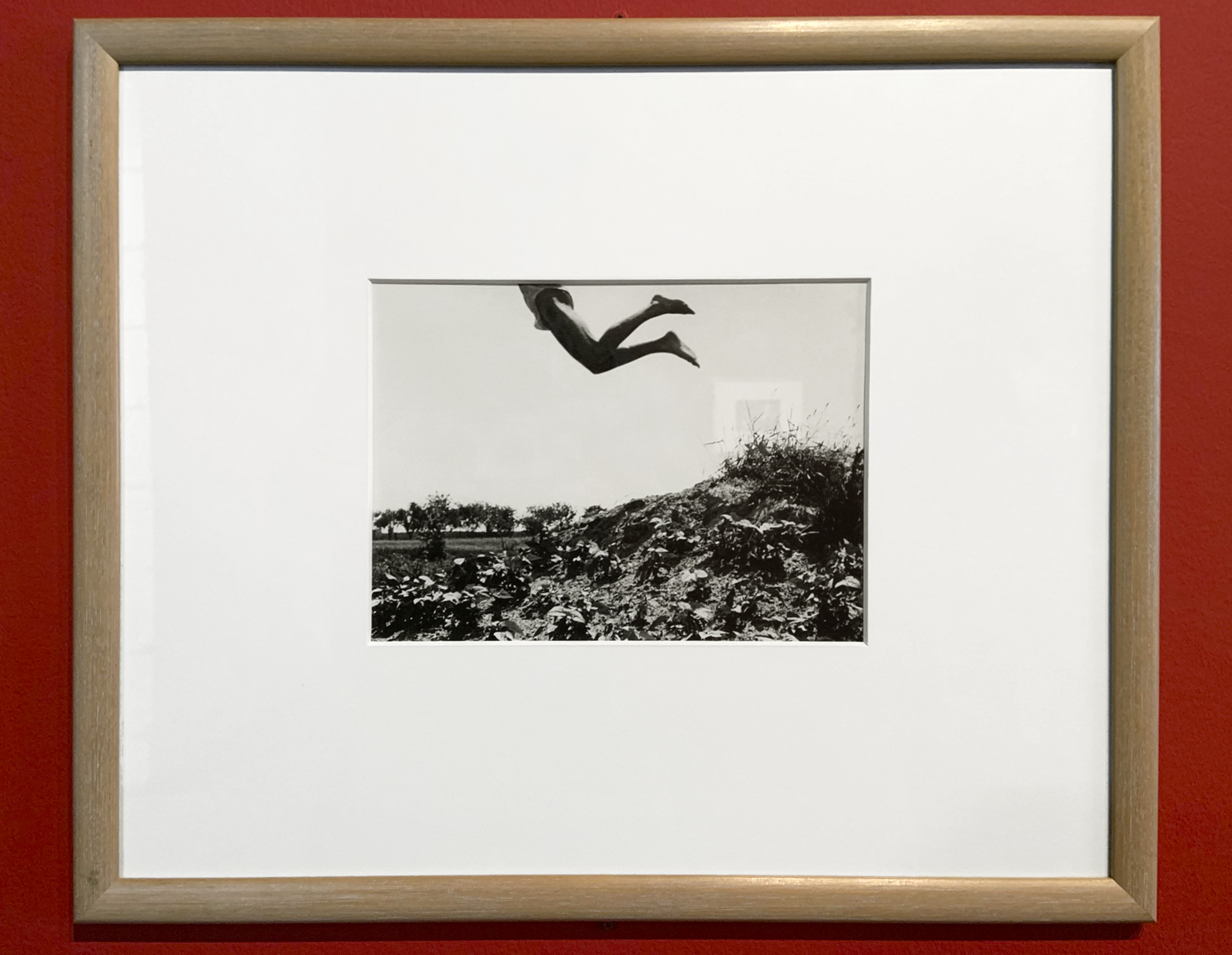

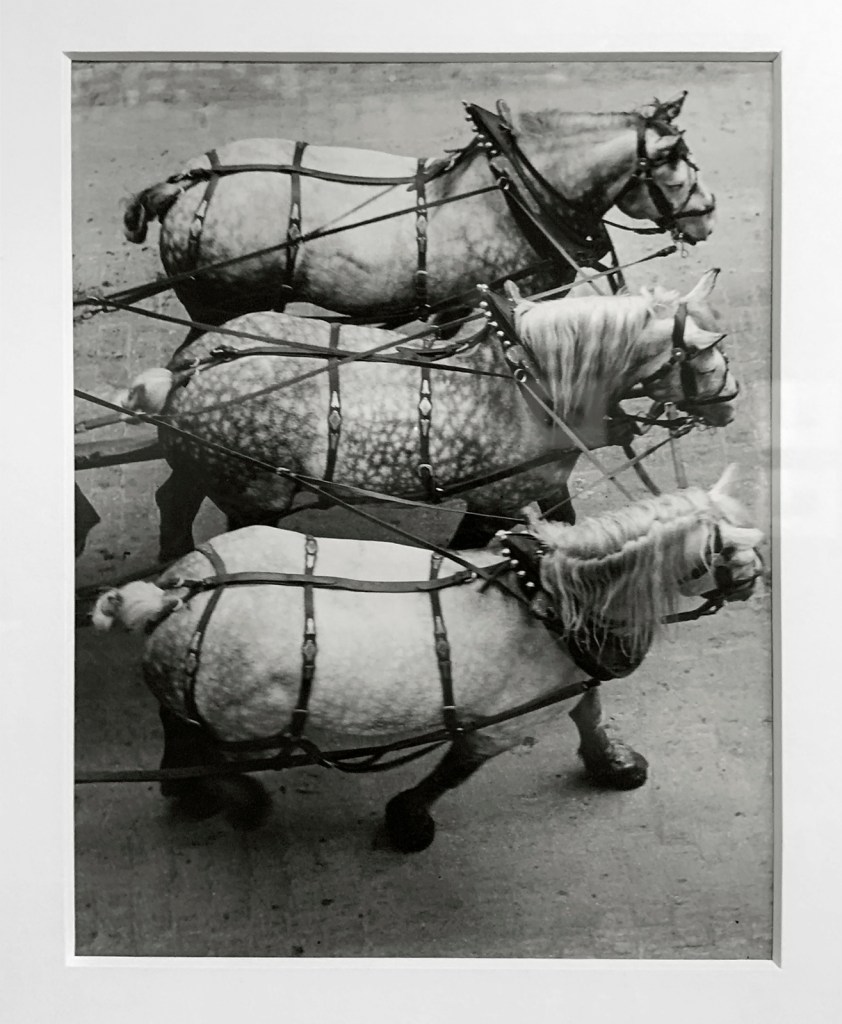

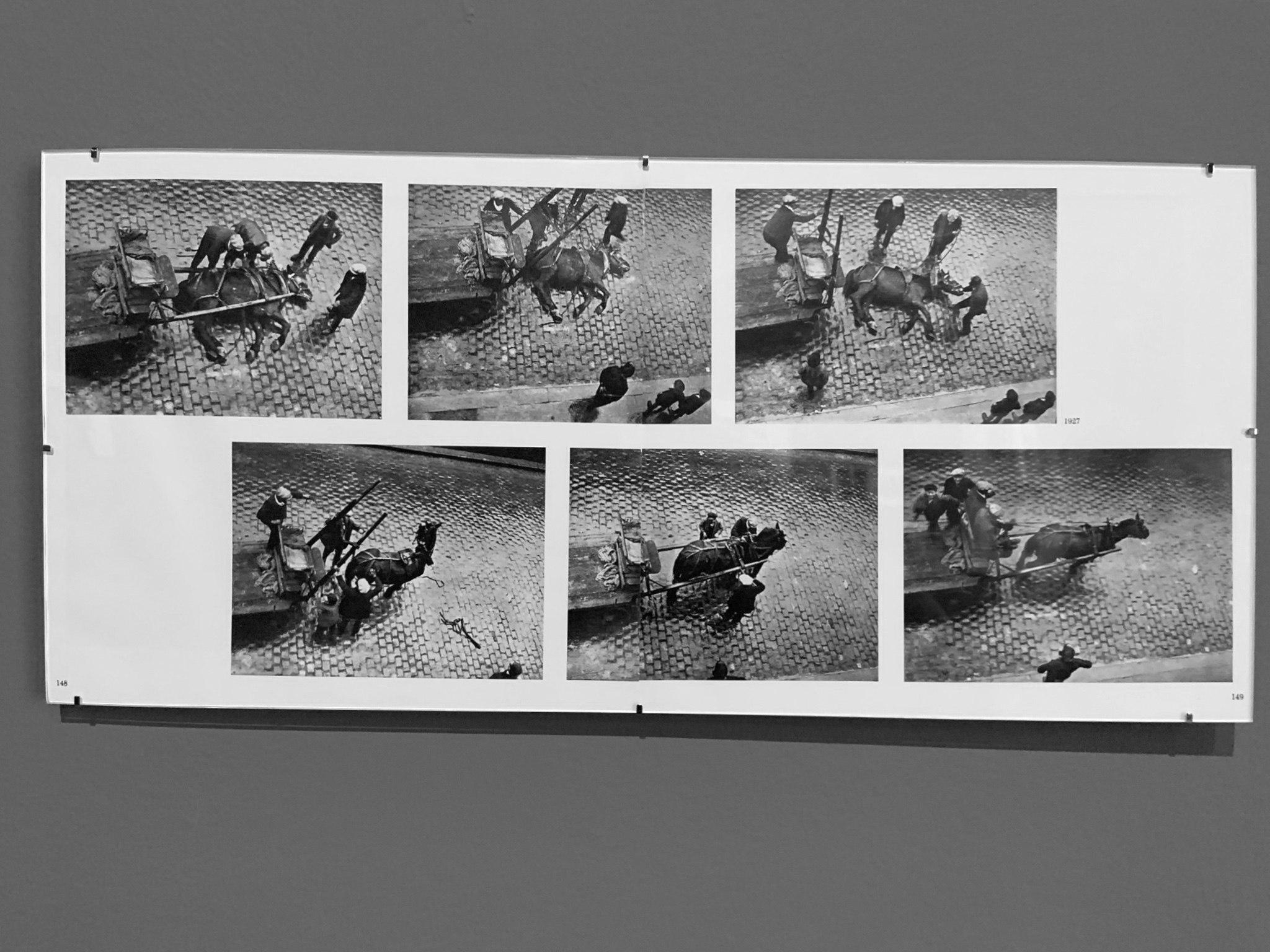

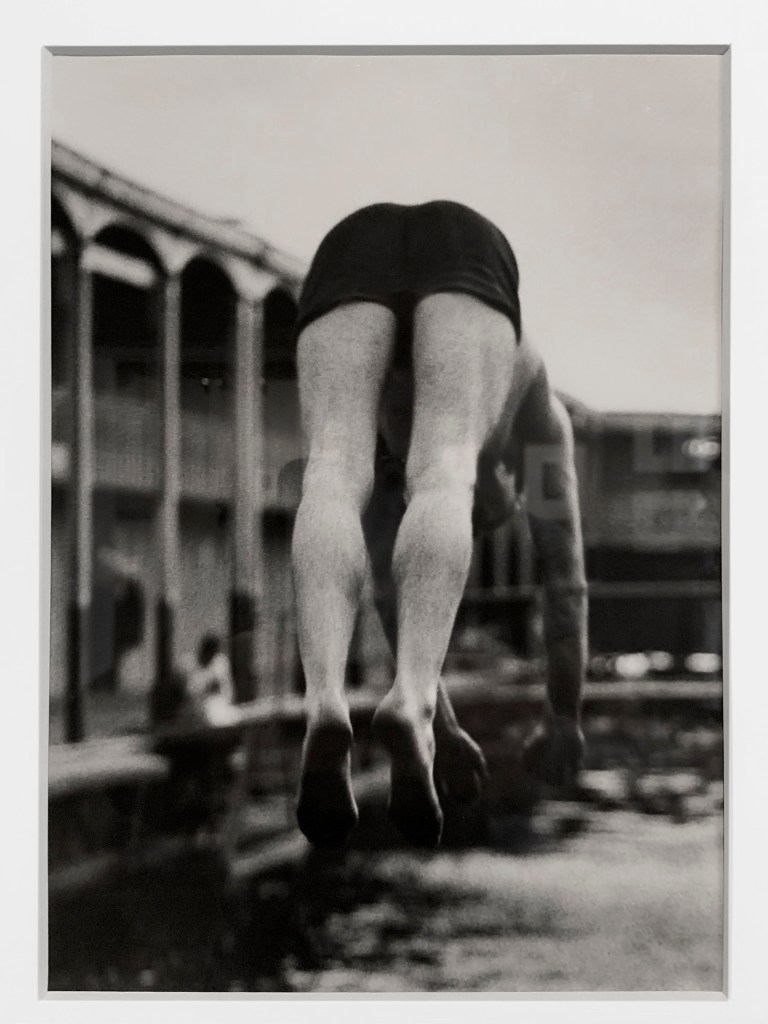

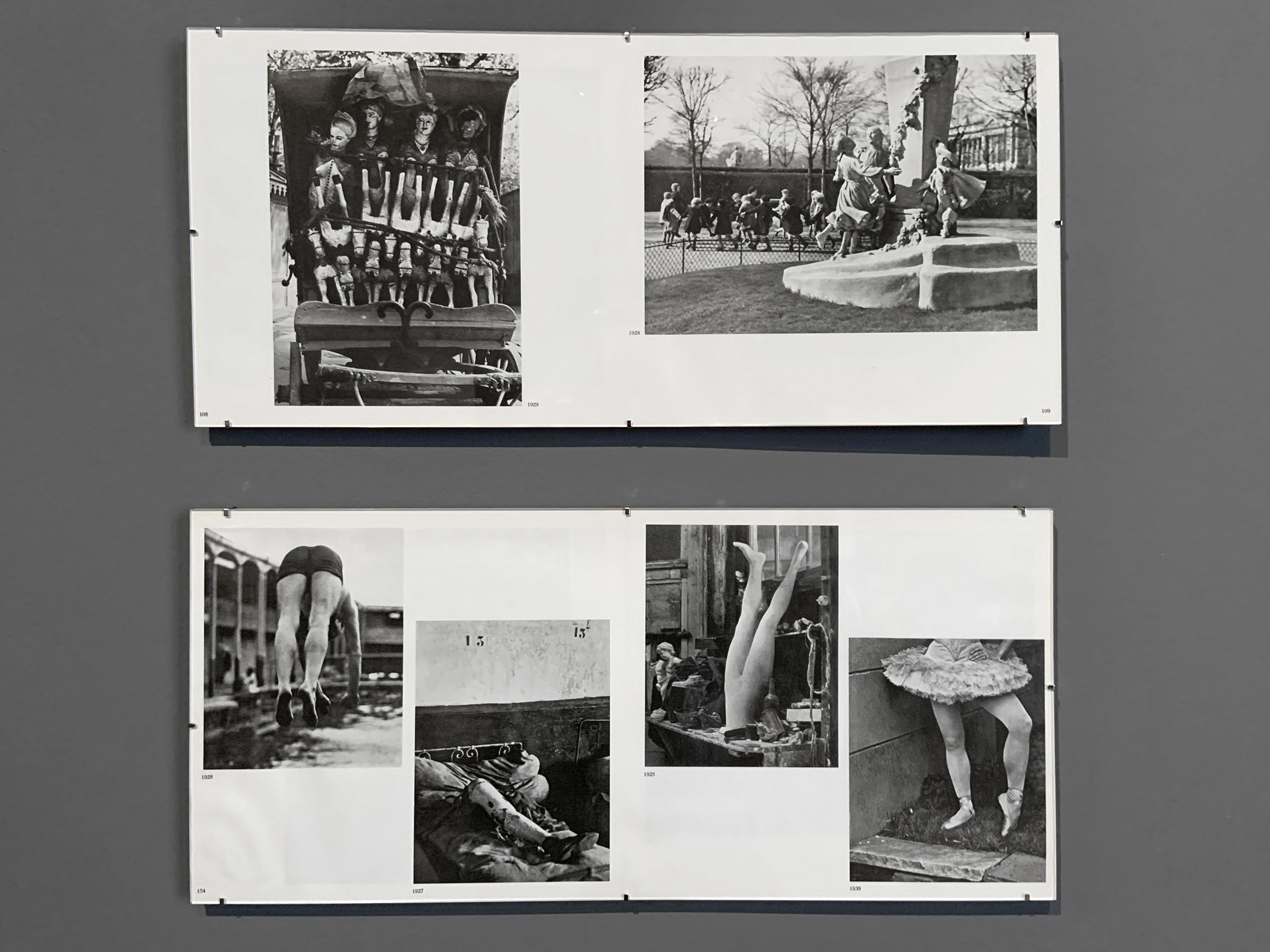

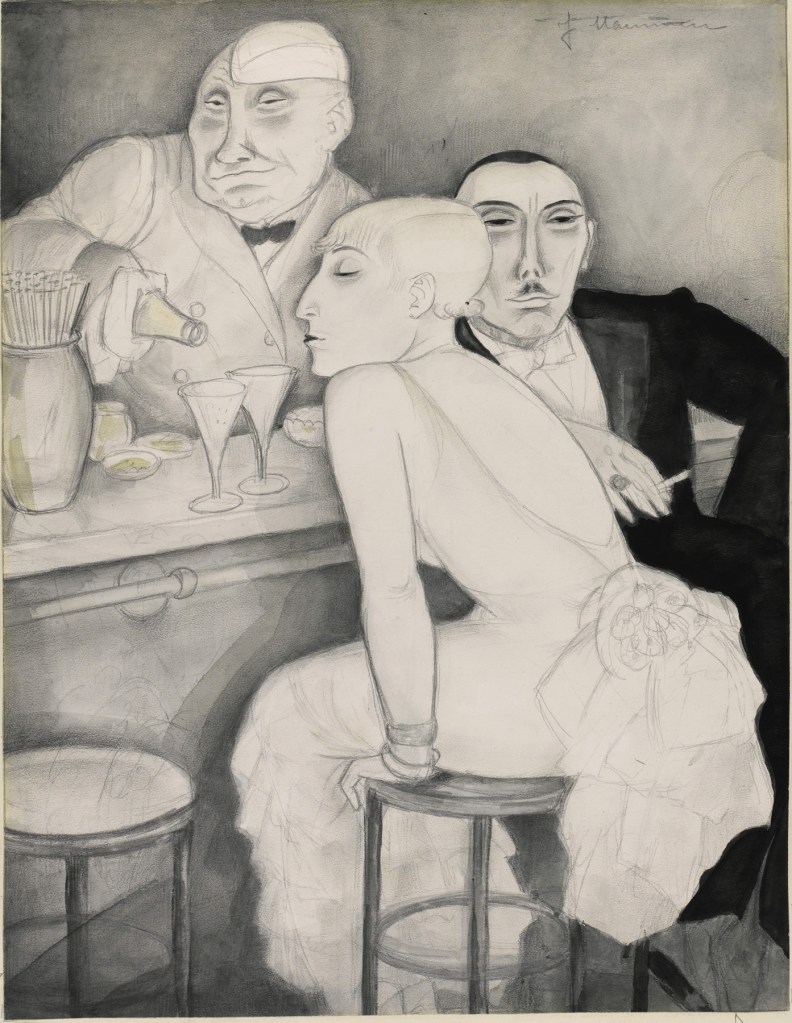

Krull published her seminal book Métal in 1928 in Paris, and began to receive attention alongside other practitioners of new, assertively modern photographic styles such as Man Ray and André Kertész.

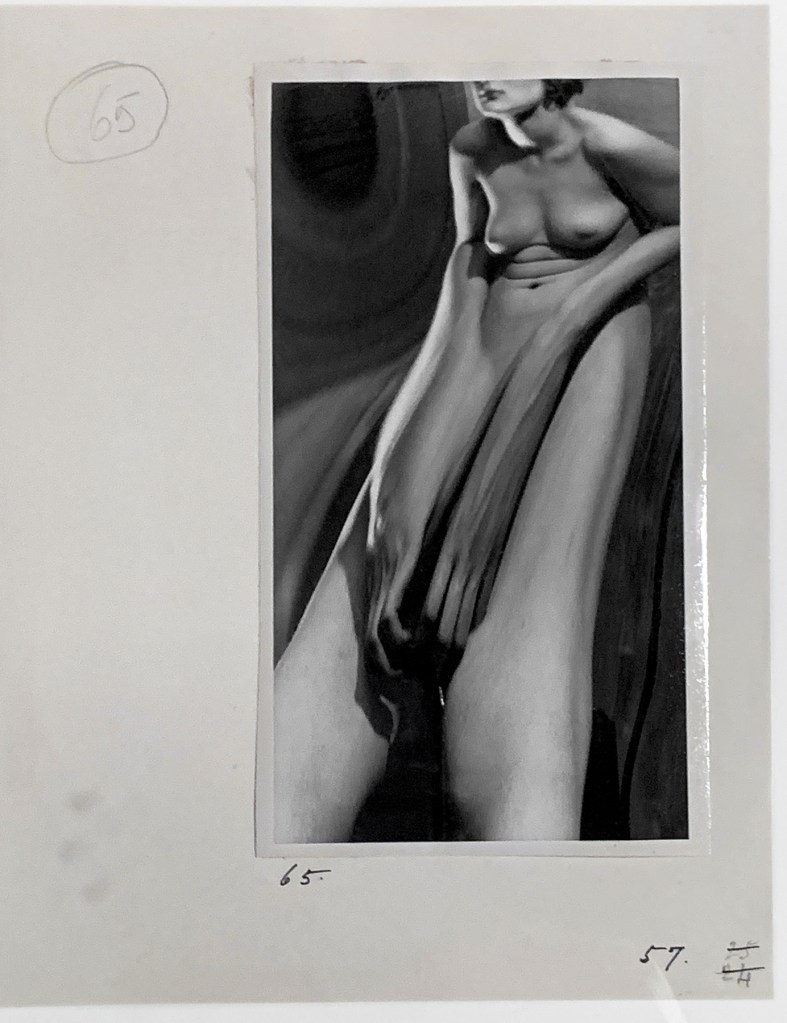

“With Métal, Krull turned her lens on the soaring structures of industrial Europe: Rotterdam’s railroad bridge De Hef, Marseille’s Pont Transbordeur, a number of nameless industrial cranes, factory machinery, and, most recognizably, the Eiffel Tower. The portfolio bore the subtitle “métaux nus” (bare metals), and critics have often likened these metallic bodies to the nude photographs she made around the same time. In both cases, Krull got close to her subjects, dislocating them from their environments. In Métal, Krull rendered the familiar form of the Eiffel Tower nearly unrecognizable…

In an untitled nude photograph from 1928 or ’29, she deployed a similar approach, keeping the camera fixed on an unclothed torso twisting off toward the edge of the frame with upturned face cut off at mid-cheek. The dramatic play of shadow and light renders the figure’s gender indistinct. Whether focused on a living subject or an architectural one, Krull’s camera resists the viewer’s urge to name and categorize.”40

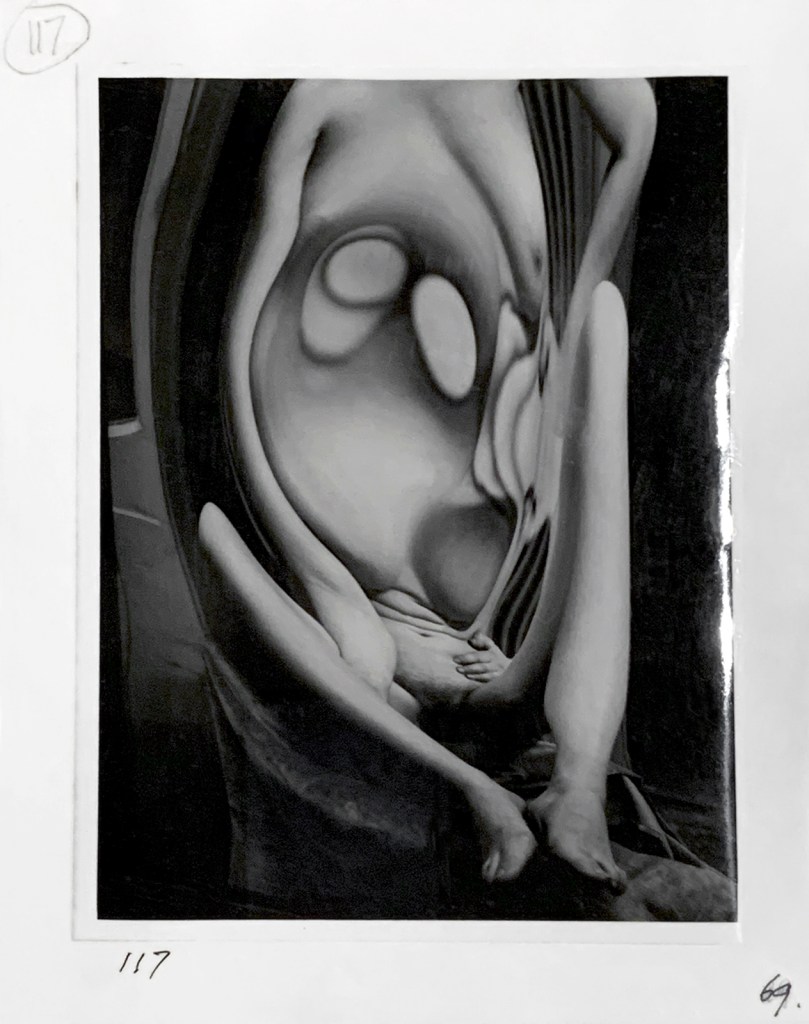

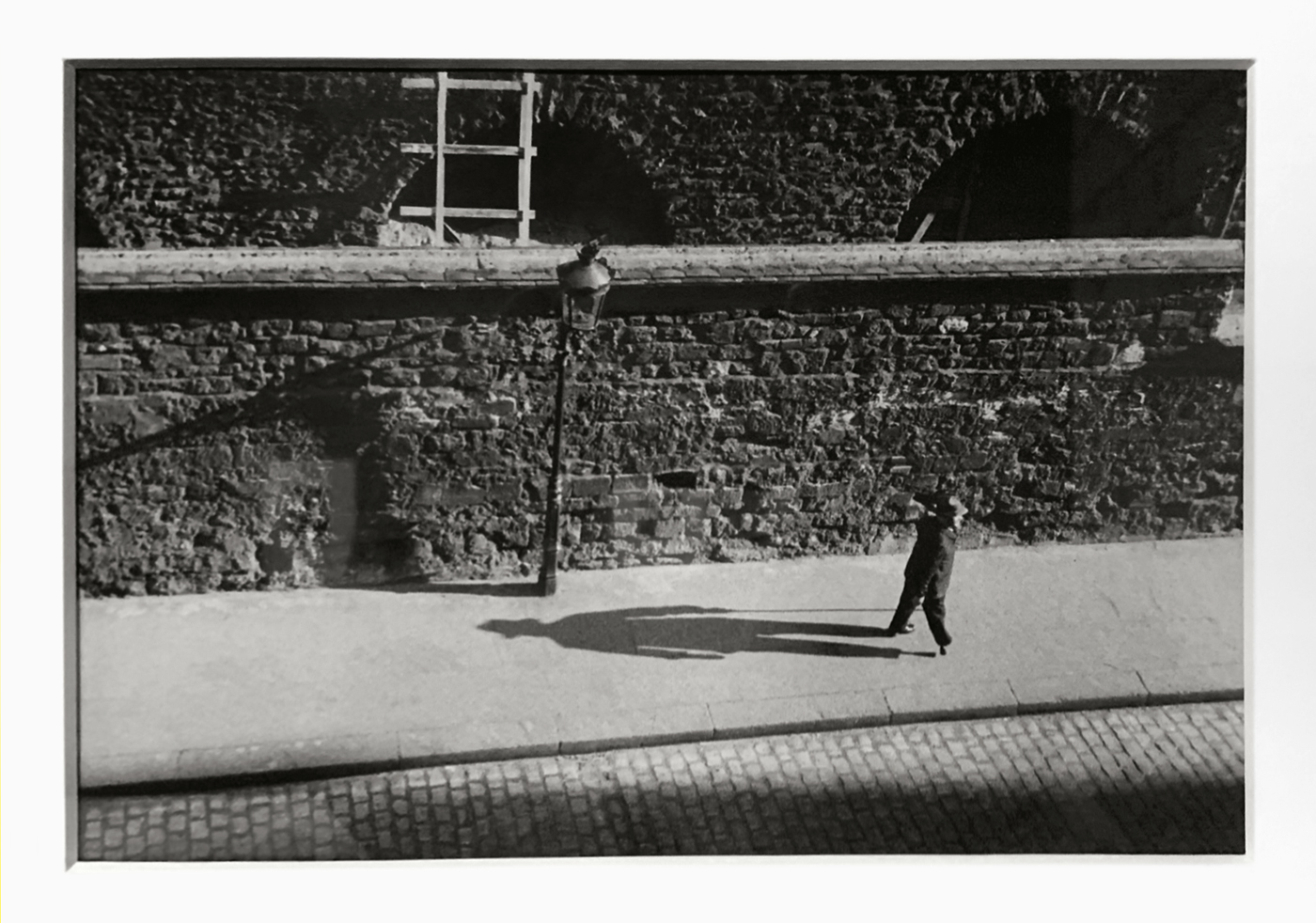

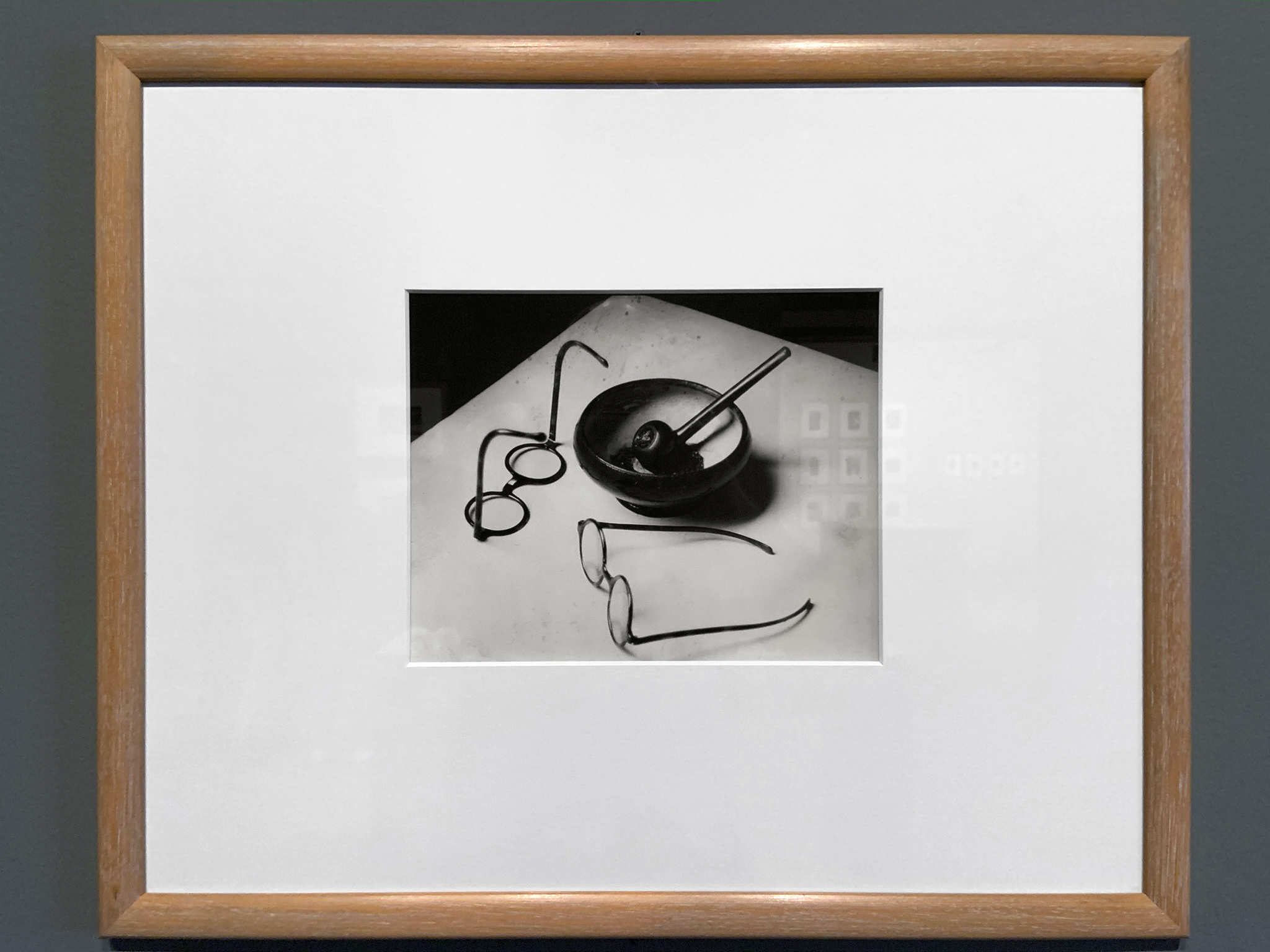

Germaine Krull (1897-1985, photographer)

Cover design by M. Tchimoukow (Louis Bonin)

MÉTAL cover

1928

Librairie des Arts décoratifs A. Calavas, Editeur.

Portfolio comprising a title page, a preface by Florent Fels and sixty four (64) loose photogravures, each mentioning the photographer’s name, titled ‘MÉTAL’, plate number and publisher’s name. Original dust jacket. Used under fair use conditions for the purposes of academic research and education

Folio 30 x 23.5cm; 11 3/4 x 9 1/4 in.

Plate 29.2 x 22.5cm; 11 1/2 x 8 3/4 in.

Image 23.6 x 17.1cm; 9 1/4 x 6 1/2 in.

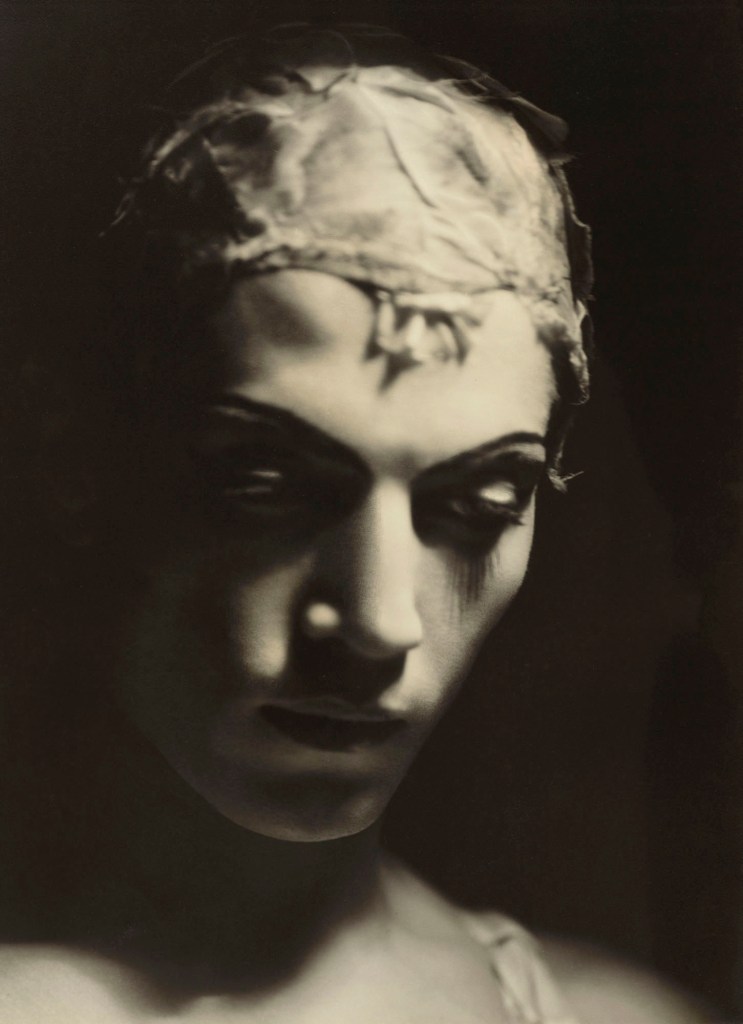

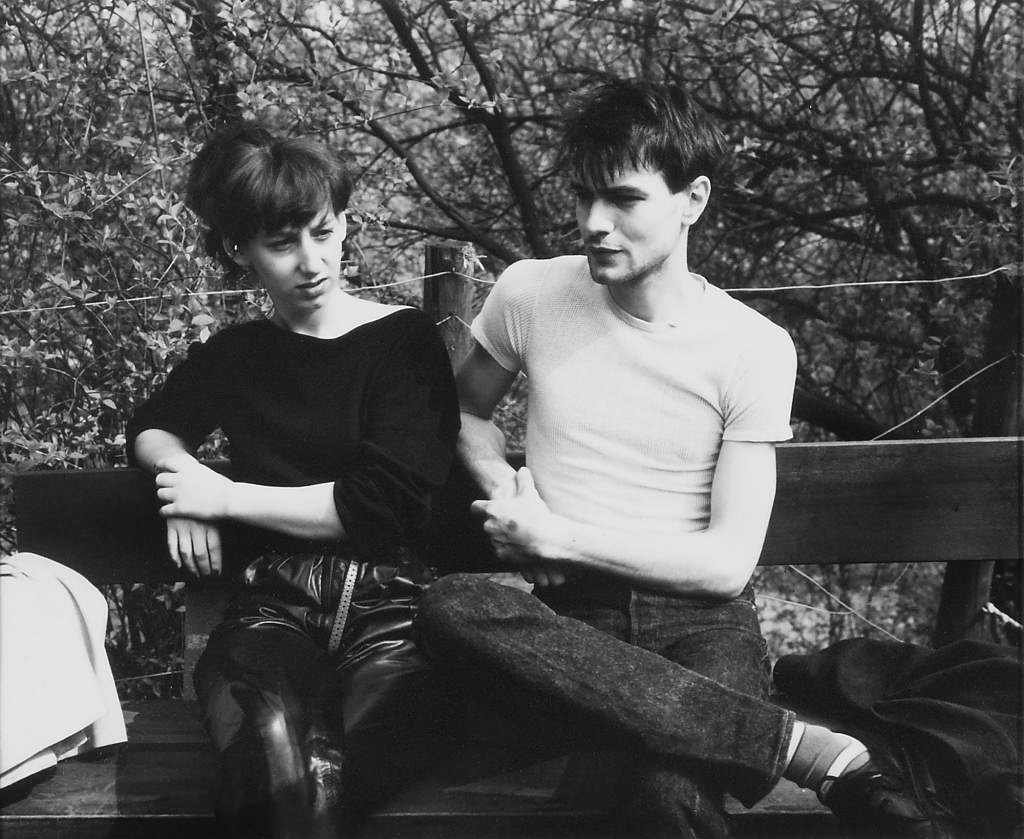

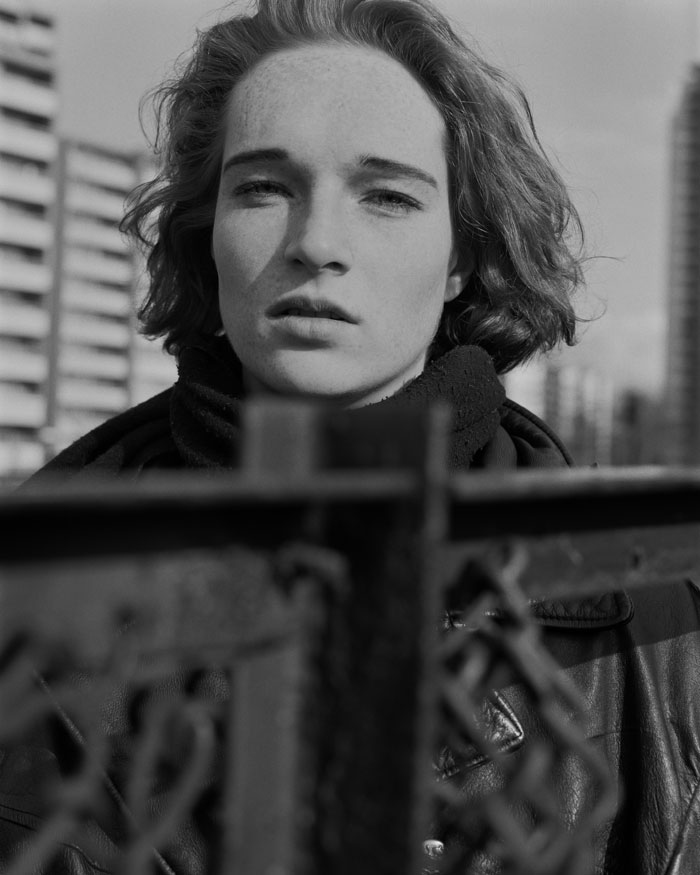

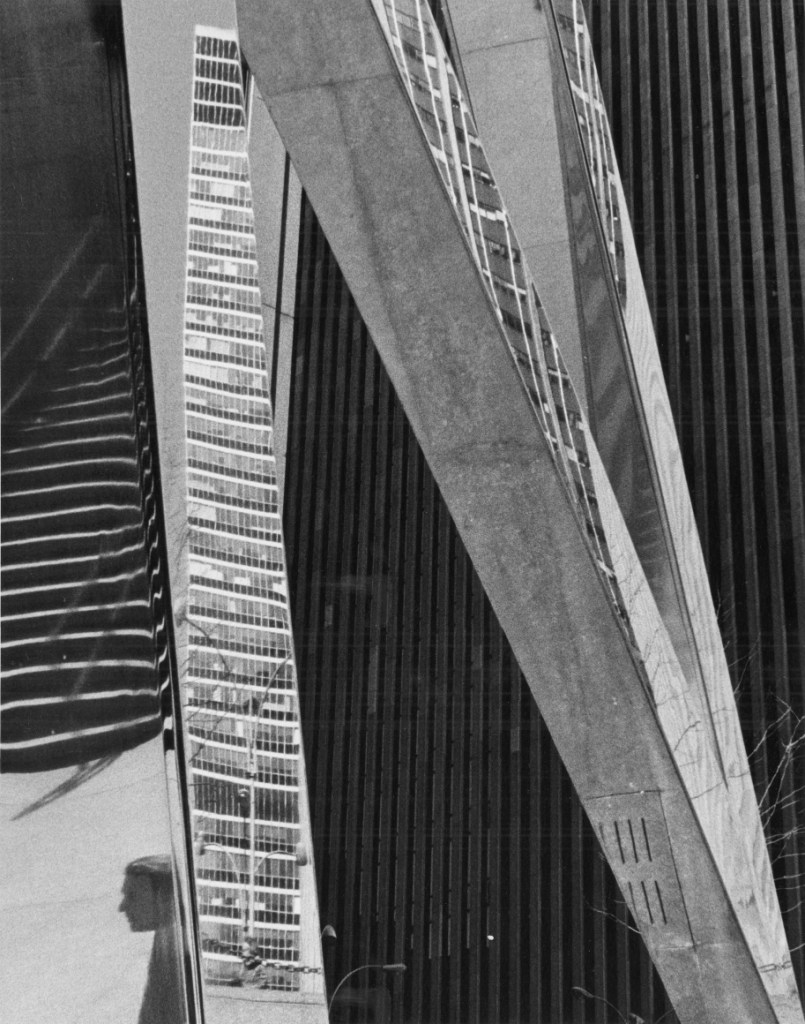

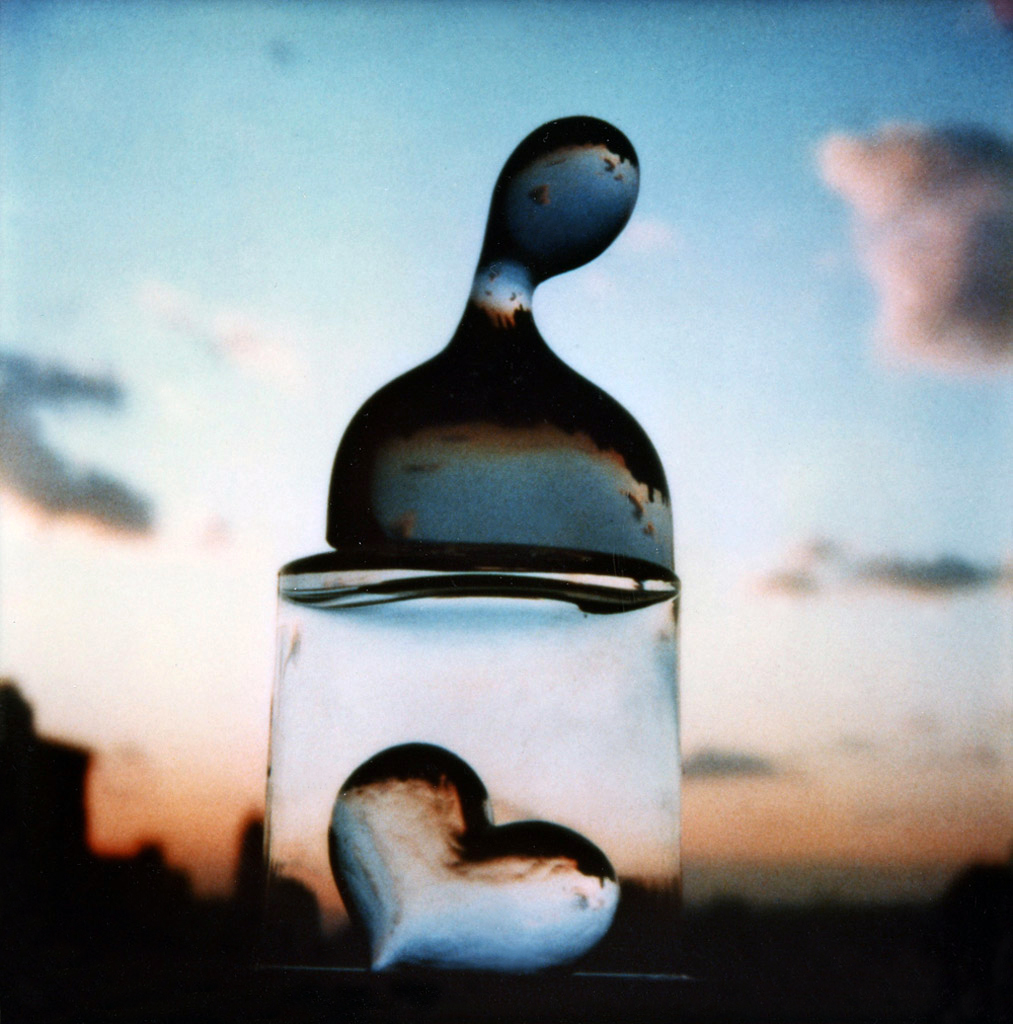

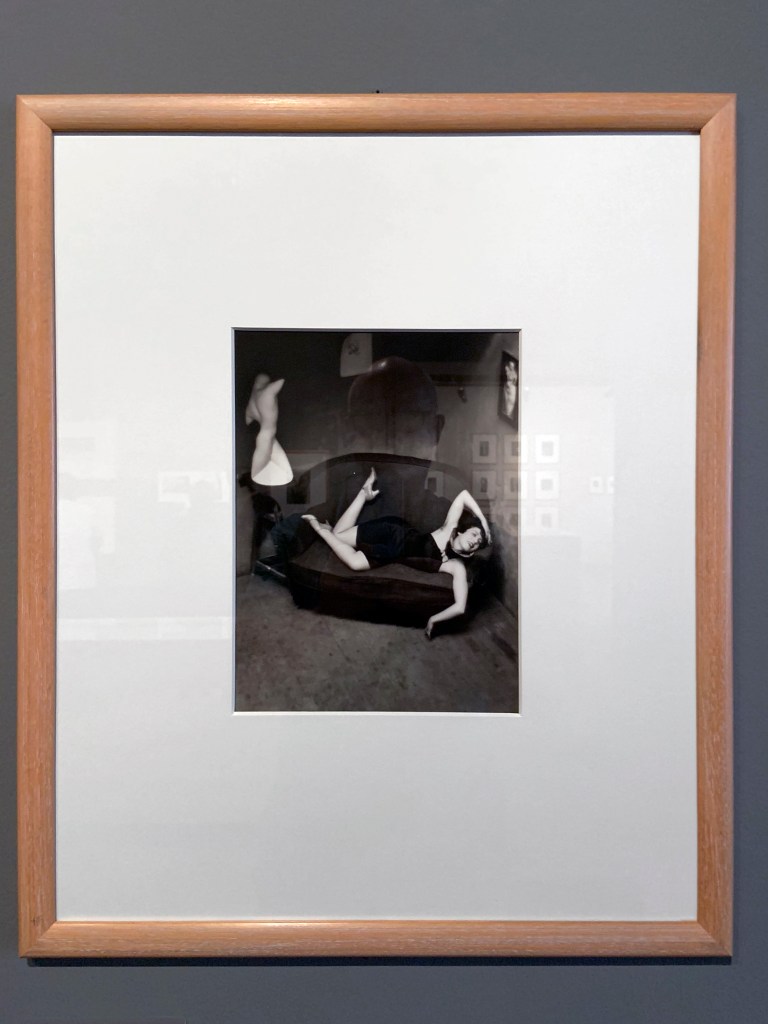

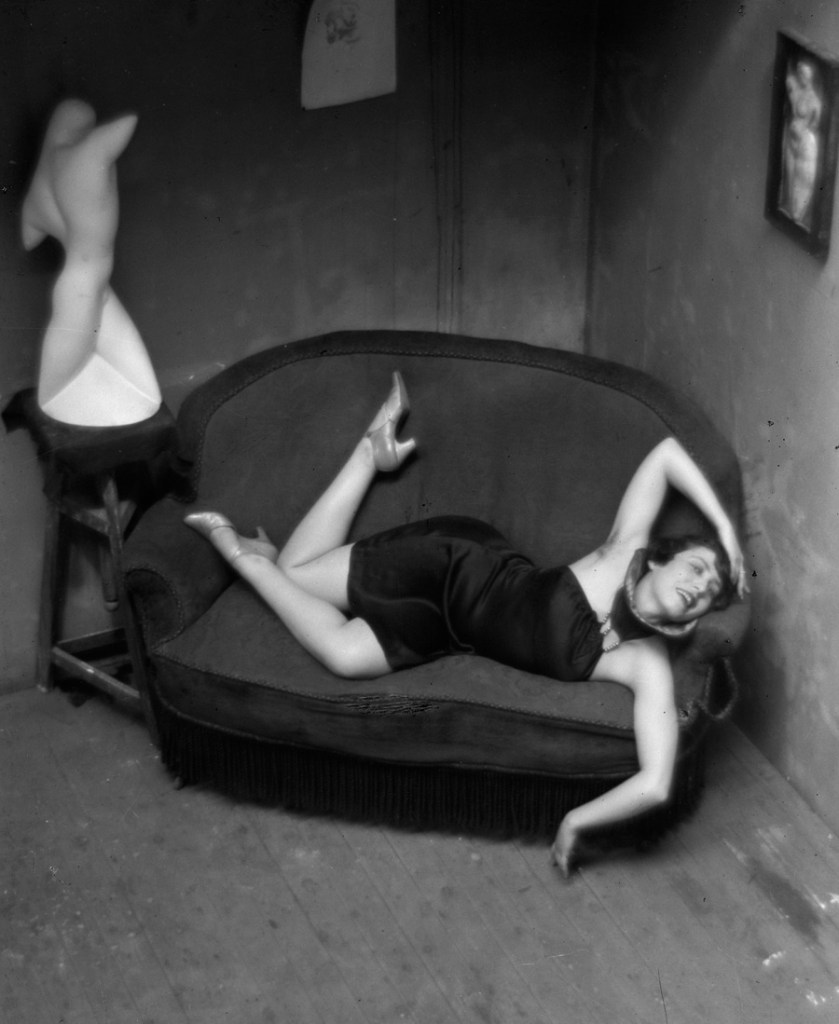

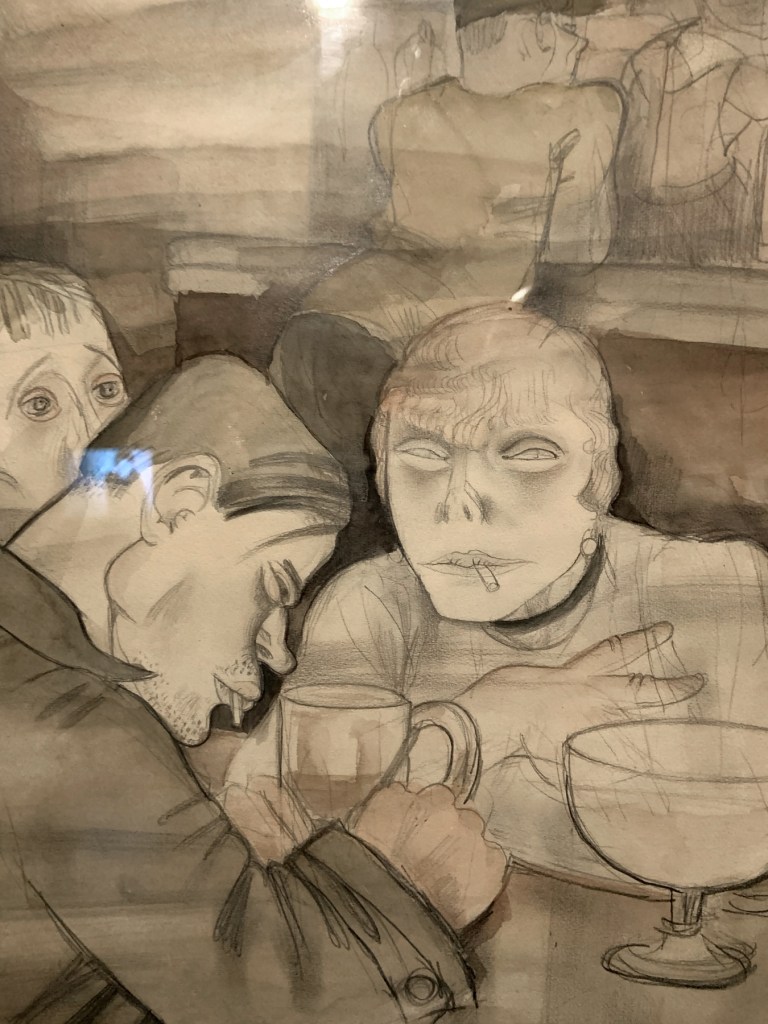

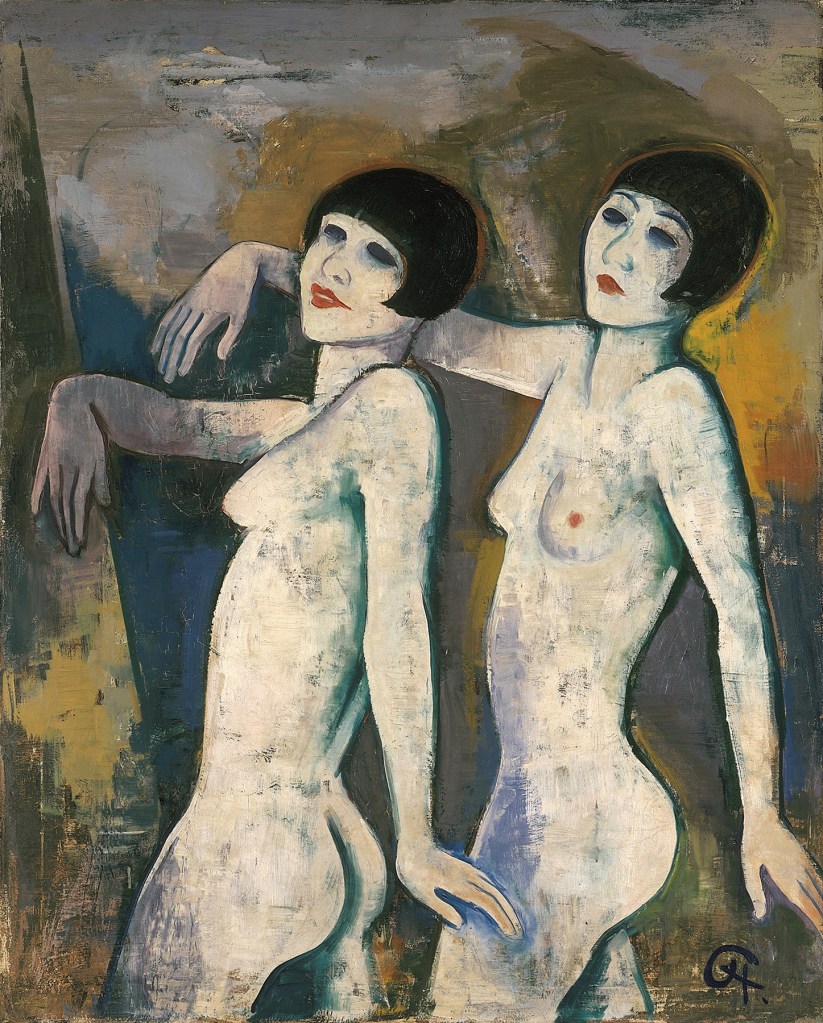

Germaine Krull (1897-1985, photographer)

From the portfolio Les amies

c. 1924

Used under fair use conditions for the purposes of academic research and education

In 1924, in an earlier portfolio of eleven photographs titled Les amies (French for “the friends,” specifically denoting female friends), Krull depicts “a pair of women in stages of gradual undress, eventually left only in their stockings, the rest of their flesh laid bare.” In a tangle of insouciant bodies that hid breasts and eyes, in which none of the models stares at the camera, Krull presents an eroticism that “is contained between the two women, with no imaginary space for a third, presumably male, viewer to enter…,” Krull dismissing “”the male gaze of Weimar culture in favor of a female gaze” and her emphasis on the gazes within the images as the female models view each other. In Les Amies, there is no space for a third party: the only possibility is to become one of the women.”41

“By photographing erotic scenes, Krull not only constructed the desiring gaze but also placed herself in the position of that gaze, taking on privileges previously permitted only to male photographers…”42 whilst at the same time transgressing the definition of middle-class respectability – all the while emphasising the fluidity of female sexual identity in the 1920s, especially for the adventurous “New Woman”.

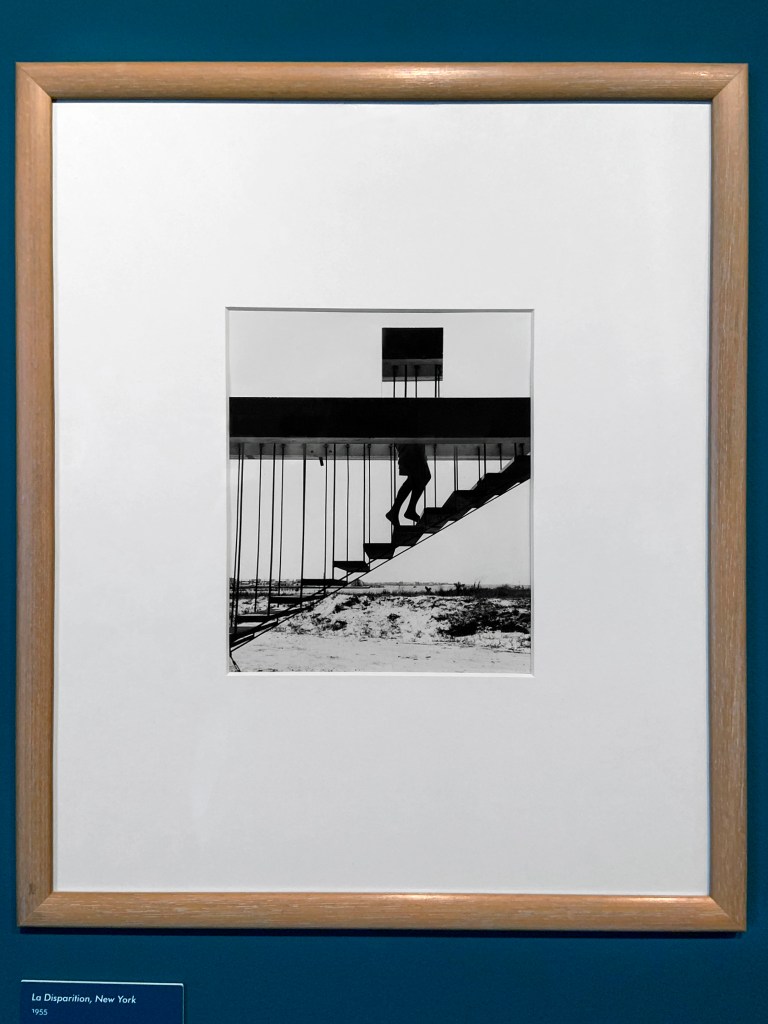

While these images received little attention during her lifetime (much like the gender bending images of Claude Cahun) they are representations of queer desire which picture the dissolution of the controlling male gaze. Using the mirror of her / Self and her camera, Krull’s staged (erotic) encounters in Les Amies and Métal undermine the male space of control through spatial disorientation – her “reforming mirror” performing a tangle of limbs, the fragmentation of the female body in which gender becomes neutral coupled with the dismantling of the phallocentrism of the (Eiffel) tower until its form becomes an unrecognisable and different “other”. “Armed with her camera, she had the power not only to depict reality but to transform it.”43

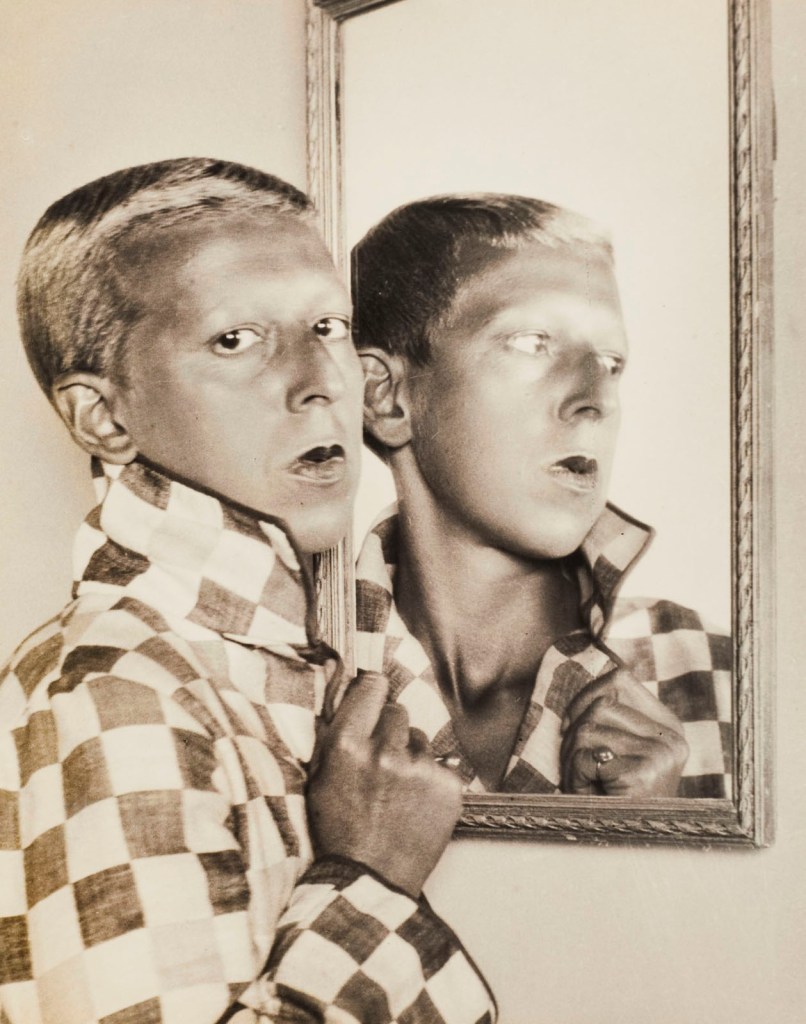

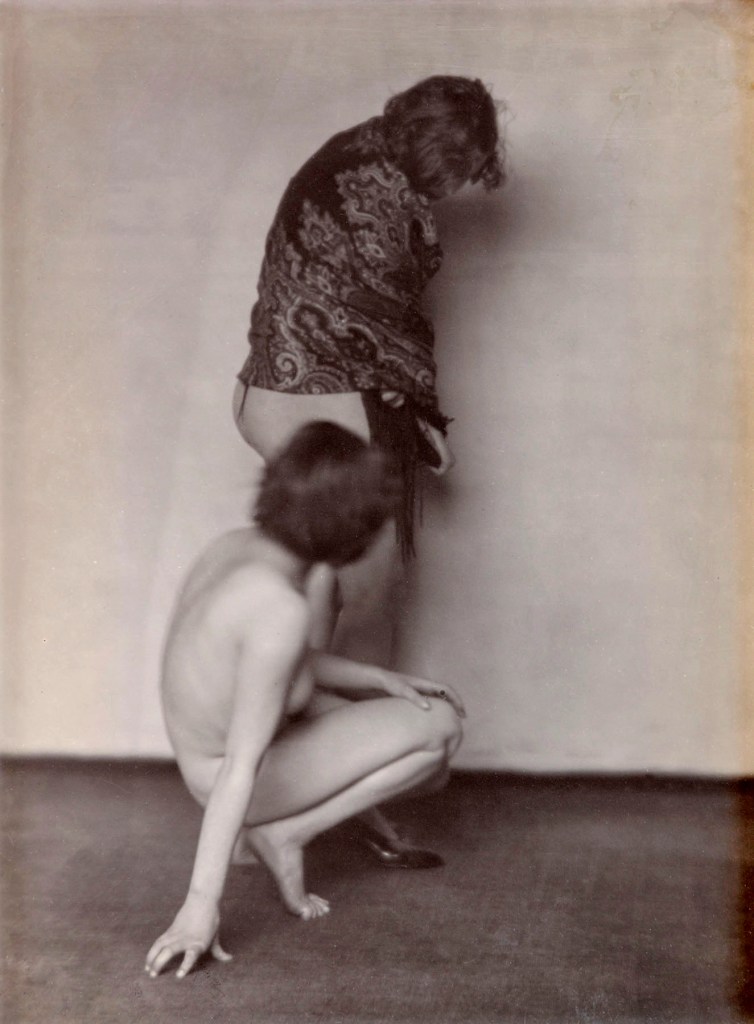

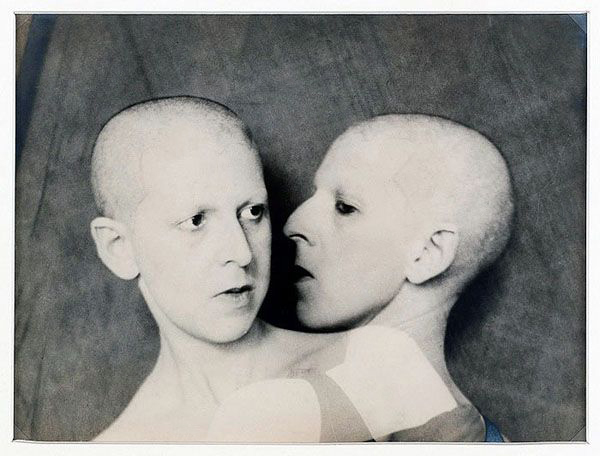

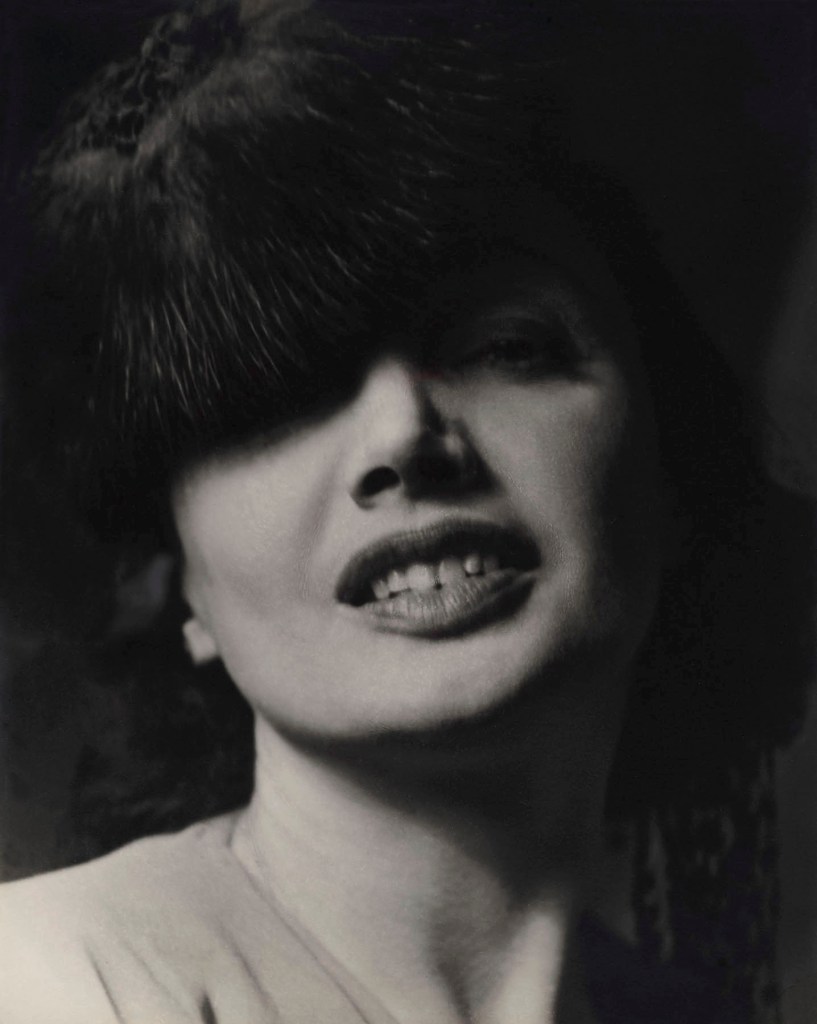

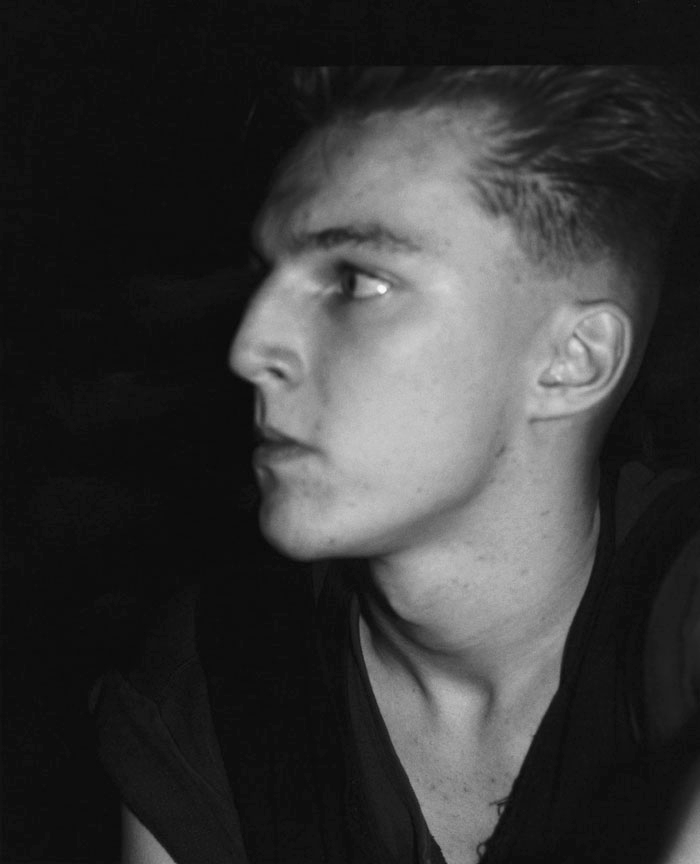

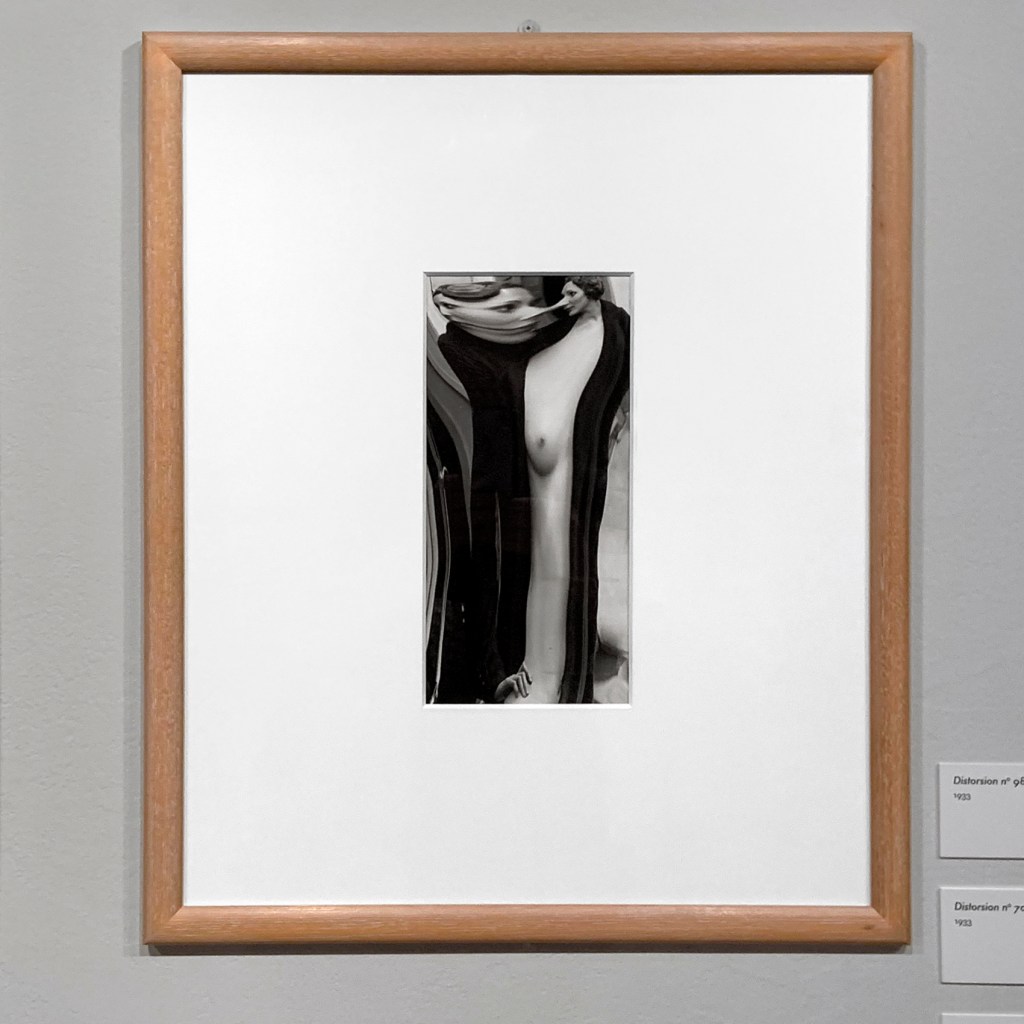

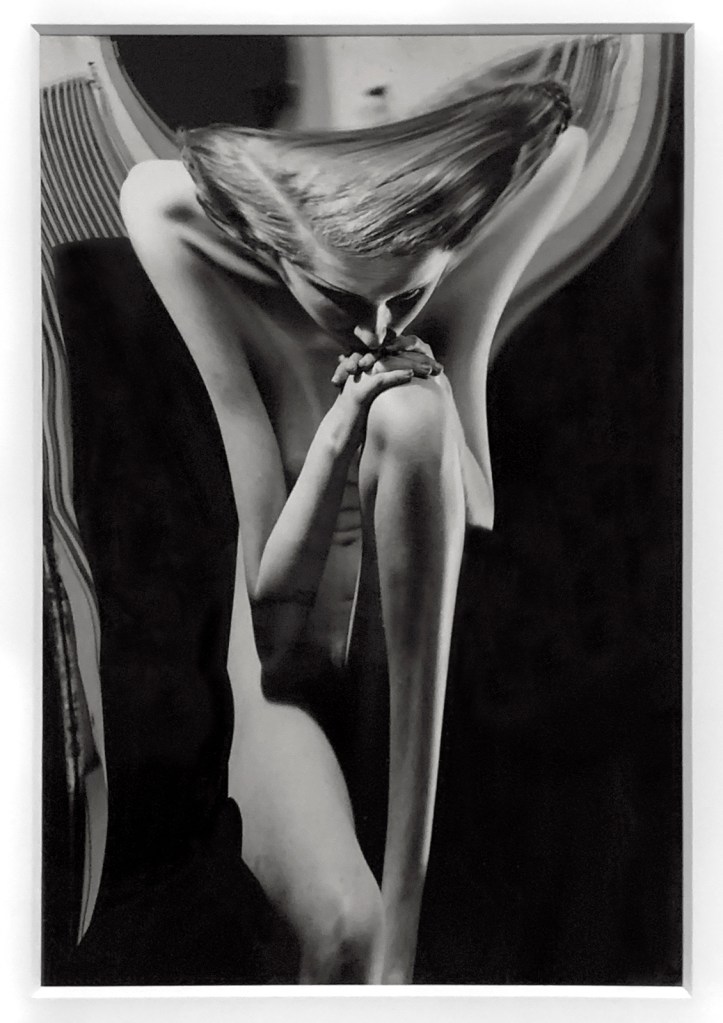

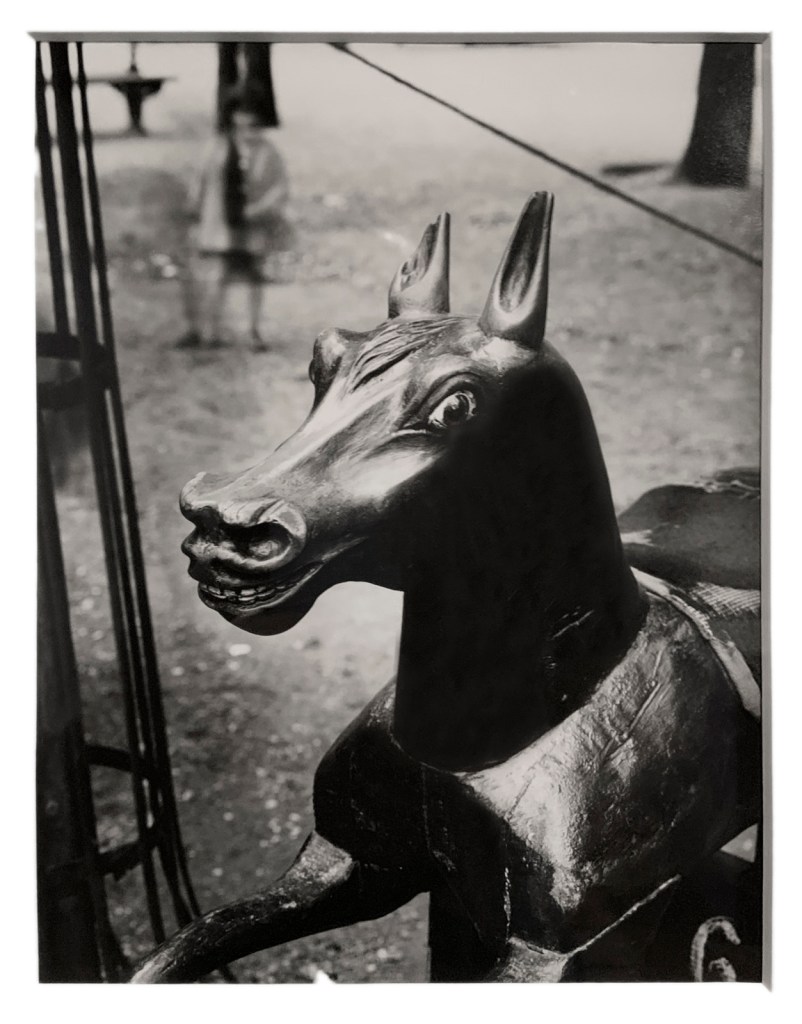

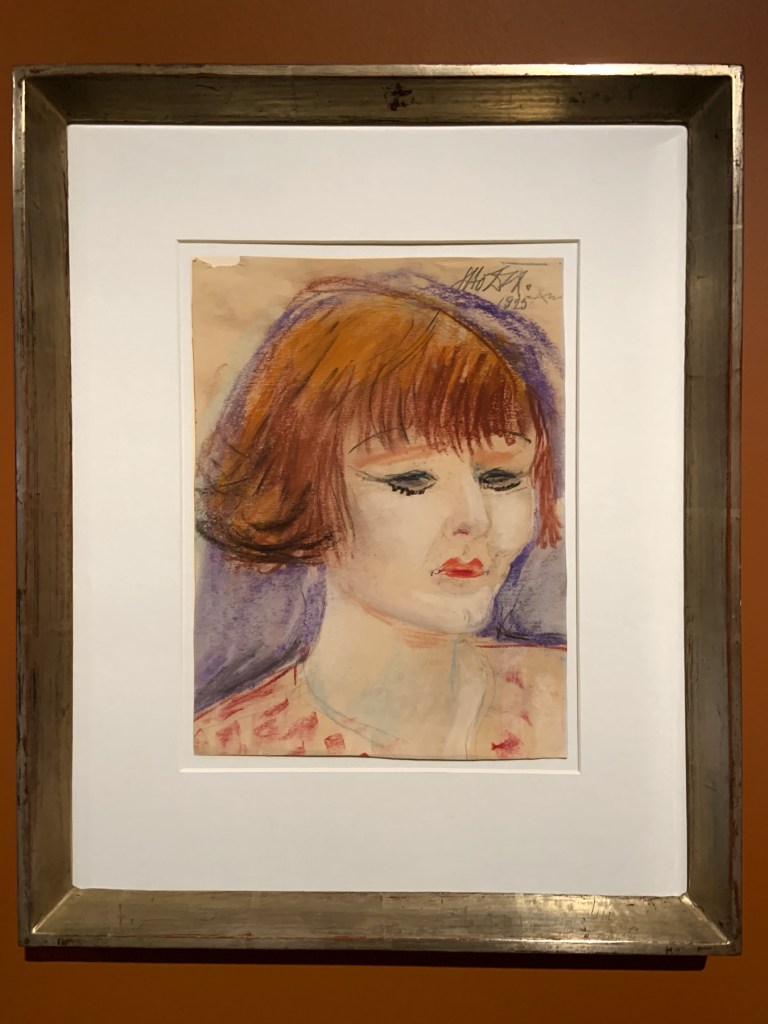

The French surrealist photographer, sculptor, and writer Lucy Renee Mathilde Schwob adopted the pseudonym Claude Cahun in 1914.

“In Disavowals, she writes: “Masculine? Feminine? It depends on the situation. Neuter is the only gender that always suits me.” … [She] is most remembered for her highly staged self-portraits and tableaux that incorporated the visual aesthetics of Surrealism. During the 1920s, Cahun produced an astonishing number of self-portraits in various guises such as aviator, dandy, doll, body builder, vamp and vampire, angel, and Japanese puppet.

Some of Cahun’s portraits feature the artist looking directly at the viewer, head shaved, often revealing only head and shoulders (eliminating body from the view), and a blurring of gender indicators and behaviours which serve to undermine the patriarchal gaze. Scholar Miranda Welby-Everard has written about the importance of theatre, performance, and costume that underlies Cahun’s work, suggesting how this may have informed the artist’s varying gender presentations.”44

Cahun’s self-portraiture over a period of 27 years (in collaboration with her lover Marcel Moore) was a unique investigation into the multiplicity of sexuality and gender identity. “By 1930, Cahun had amassed a considerable image bank of photographic self-portraits; that year, she publicly disseminated a handful of those images for the first and only time.”45 In her photographs she explored the mutable definitions of gender through multiple ‘masked’ personas – using photomontage, the doubling of the image (asserting another conception of gender identity that of a “third sex” or an “Androgyne”), the various ways photographs can be produced and viewed (meant to unsettle the audience’s understanding of photography as a documentation of reality), and the dissolution of the self in the space between the body and the mirror to aid her investigation. Self-reflection was not her objective in the use of the mirror but Cahun did use the mirror as a source of reflection in a contemplative, interrogatory mode in her photographs; and these were private photographs never intended for public display. “It has been proposed that these personal photographs allowed for Cahun to experiment with gender presentation and the role of the viewer to a greater degree.”46

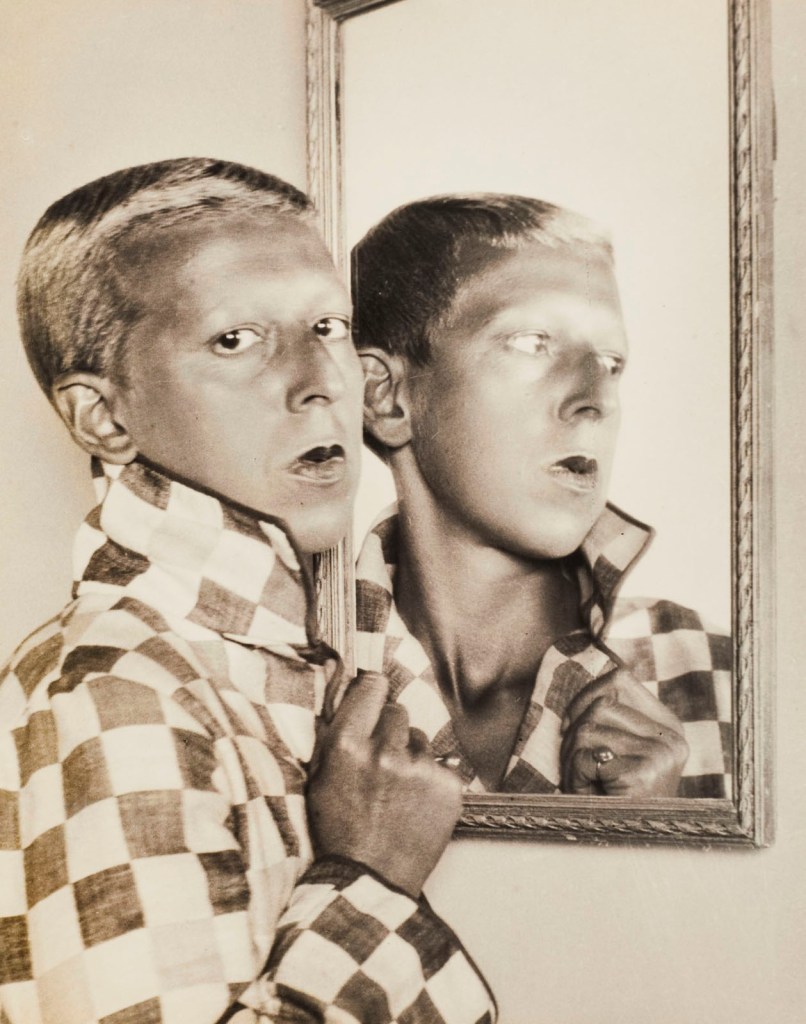

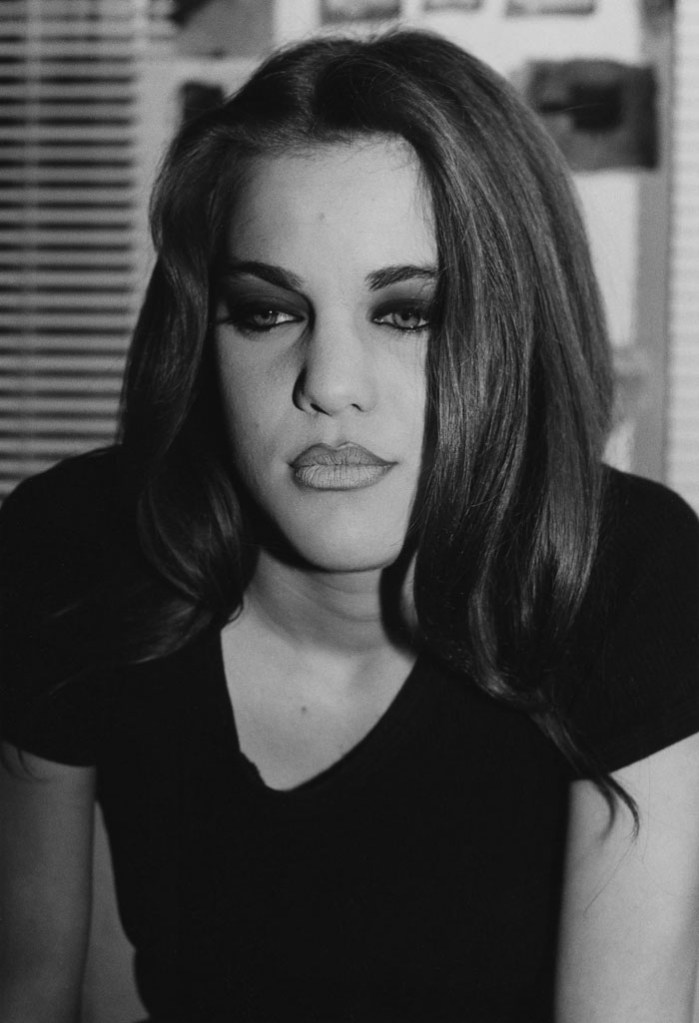

Claude Cahun (French, 1894-1954)

Autoportrait (Self-Portrait)

c. 1927

Gelatin silver print

Used under fair use conditions for the purposes of academic research and education

Claude Cahun (French, 1894-1954)

Self-Portrait

1927

Gelatin silver print

Used under fair use conditions for the purposes of academic research and education

In Cahun’s gender non-conforming self-portraits “identity and gender is played out through performance and masquerade in a constructive way, a deep, probing interrogation of the self in front of the camera. While Cahun engages with Surrealist ideas – wearing masks and costumes and changing her appearance, often challenging traditional notions of gender representation – she does so in a direct and powerful way. As Laura Cumming observes, “She is not trying to become someone else, not trying to escape. Cahun is always and emphatically herself. Dressed as a man, she never appears masculine, nor like a woman in drag. Dressed as a woman, she never looks feminine. She is what we refer to as non-binary47 these days, though Cahun called it something else: “Neuter is the only gender that always suits me.””

Cahun had a gift for the indelible image but more than that, she possesses the propensity for humility and openness in these portraits, as though she is opening her soul for interrogation, even as she explores what it is to be Cahun, what it is to be human. This is a human being in full control of the balance between the ego and the self, of dream-state and reality. The photographs, little shown in Cahun’s lifetime, are her process of coming to terms with the external world, on the one hand, and with one’s own unique psychological characteristics on the other. They are her adaption48 to the world.”49

These were private manifestations of her inner self for the benevolence of her own spirit. She made art for herself, willing enough to face uncertainty and take the untrodden path of inner discovery. She was a “New Woman” where the term “woman” is fluid and fragmentary, open to adaptation and interpretation.

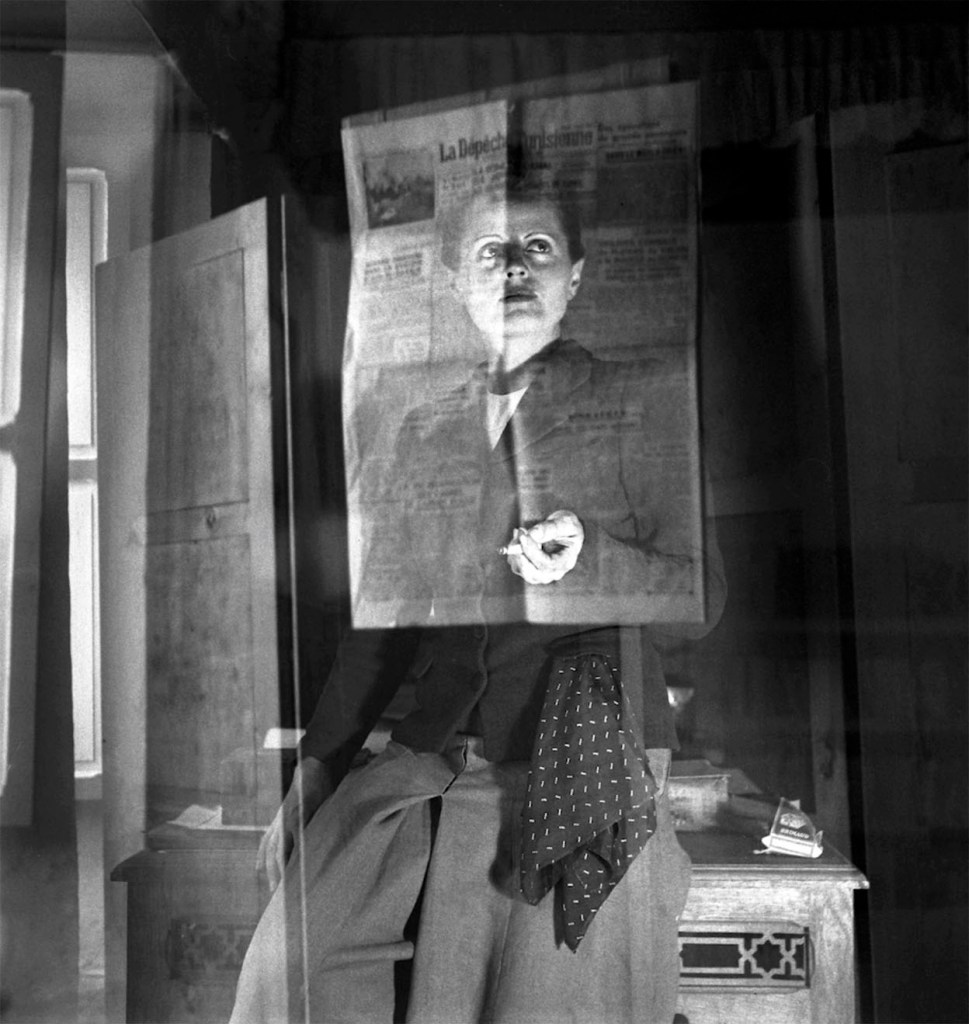

Claude Cahun (French, 1894-1954)

Que me veux tu? (What do you want from me?)

1929

Gelatin silver print

Used under fair use conditions for the purposes of academic research and education

A proposition and, the particular becomes universal

So the question becomes – when is a photographer a photographer a photographer. Does it matter who is behind the lens?

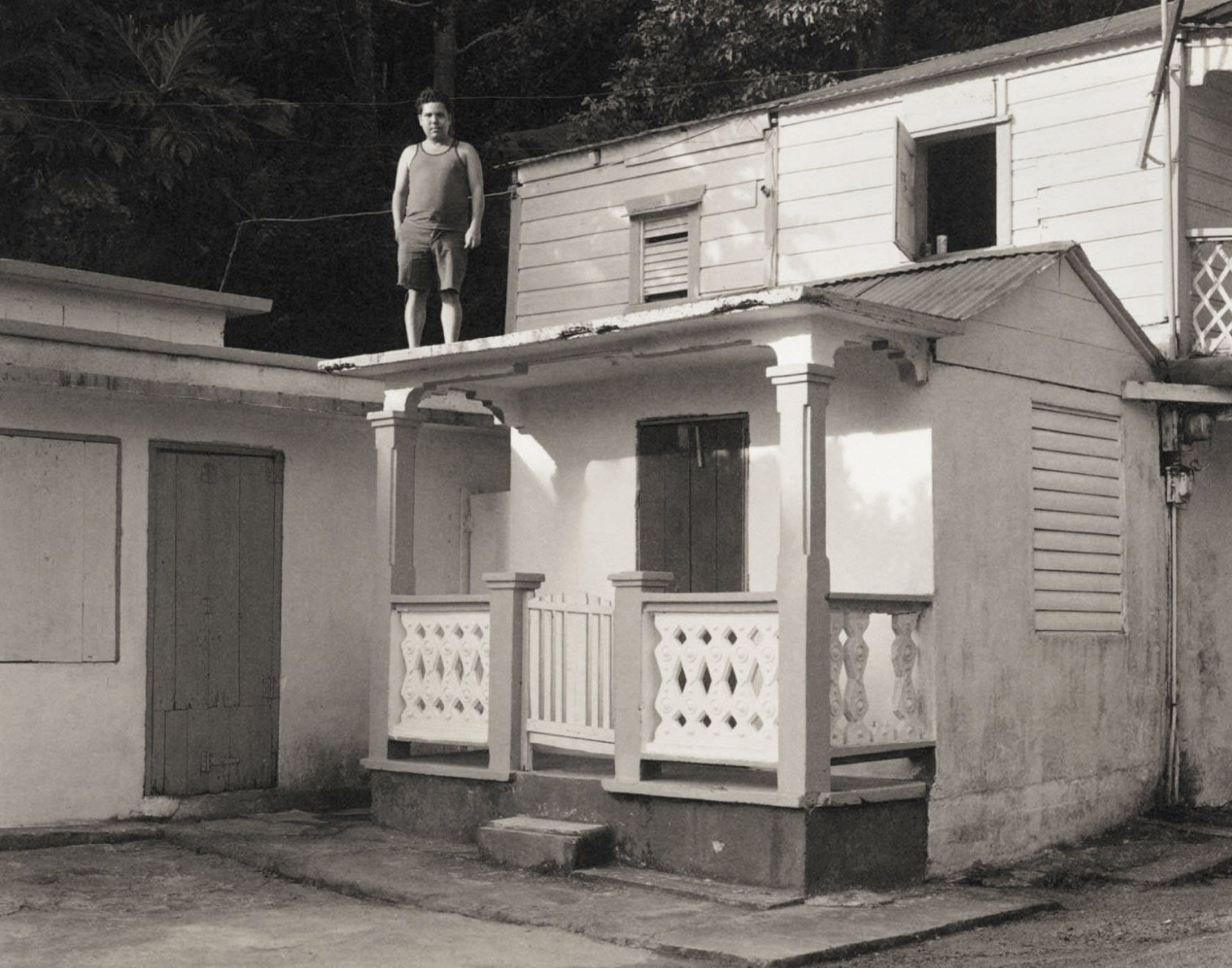

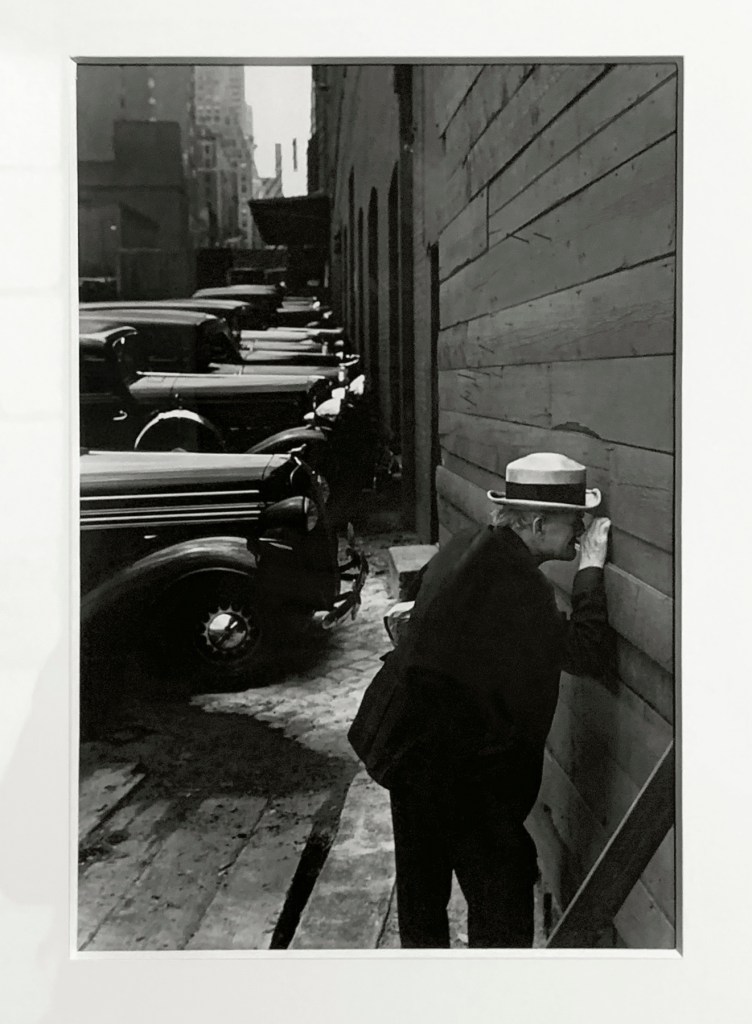

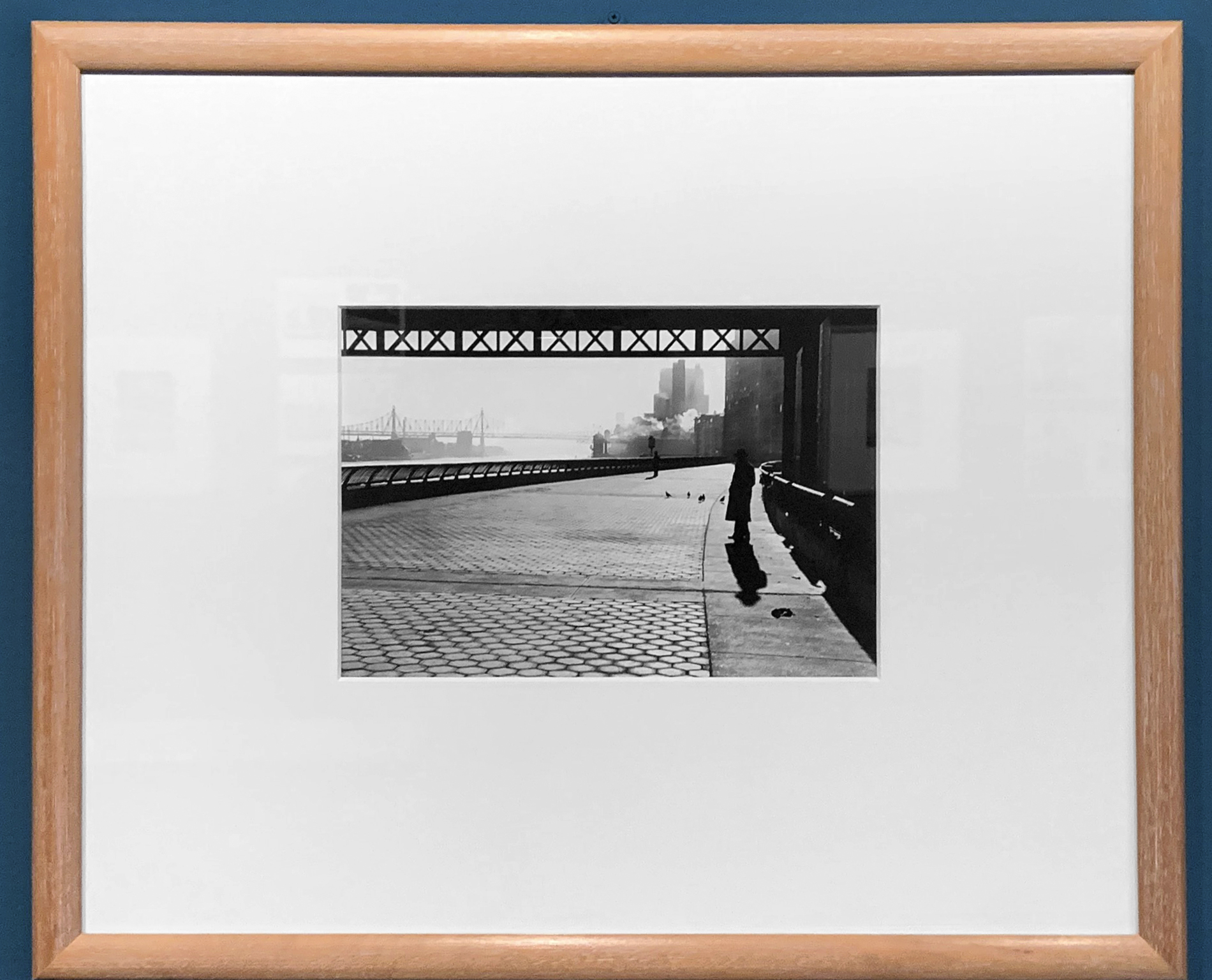

On the evidence of almost 200 photographs in the postings on this exhibition, if the photographs were labelled “unknown photographer”, many of these images could as easily have been made by men as by women. So in one sense it does not matter. What matters is the quality of the work.

But from other perspectives of course it matters, it matters a great deal. These women photographers have been whitewashed from the history of photography as though they never existed. Their challenge to the dominant narrative of male supremacy in society and the continuation of the struggle for female visibility and emancipation, requires a recognition of their courage and sacrifices. These were talented, strong and creative human beings and their work demands the recognition it deserves.

And then we ask, why has it taken a hundred years to shift the institutionally constructed history of photography, which has been perpetuated from generation to generation, where only male photographers were to be looked at, collected, admired and displayed? And the simple answer is that one word: “men”. Although things are changing slowly, too slowly, it was and still is a patriarchal society, a system of society controlled by men, and in the time period we are talking about (1920s-1950s), it was a world where institutions and their collecting practices were controlled by men; where photography was not being collected by many museums; and where the photographs of the “New Woman” behind the camera was not seen as collectible because it was what they did to make a living… it wasn’t art.

Further, we might postulate a proposition with regard to the practice of “New Woman” photographers, a form of Zen kōan if you like:

It doesn’t matter that I am a woman / I am a woman

In relation to this in/sight, I muse on a quotation about the work of Imogen Cunningham: “I keep coming back to this duality: Don’t pigeonhole her for being a woman. But don’t forget she’s a woman!” says Dunn Marsh. “She photographed flowers, which people sort of treated as a feminine subject matter. But Edward Weston was photographing peppers, and nobody considered that to be an exclusively masculine subject matter.”50

If we unpack this quotation, it reads as ‘it doesn’t matter that Cunningham was a woman… but don’t forget she’s a woman!’. Weston made images of peppers and nobody commented on his masculinity or the masculine “nature” of his subject matter and the same should go for Cunningham. Just because she is a women why comment on the femininity of flowers – but don’t forget Imogen is a women! It’s about the quality of the work, not the gender of the artist and then maybe it’s about being female but only if the artist chooses it to be … (Georgia O’Keeffe got very annoyed by the reading of her close-up flower paintings which many interpreted as representing female genitalia, insisting that the paintings has nothing to do with female sexuality).

Finally we can say, it’s doesn’t matter what gender you are when you look through the camera lens (as a machine it’s impartial), it is about the reality of yourself as a human being and your relationship to the camera. The actions of the photographer are a personal engagement with the camera (in other words, in relation to the women behind the camera, the camera in relation to her/Self) but through direct action – an engagement with time and light – their can be a shift in consciousness from the personal (the particular) to the universal.

It shouldn’t (that is the key word) matter whether you are male or female … it’s about the quality of the work and it’s about following the light. The light of self recognition of the path that you are on. As Maria Popova insightfully observes,

“And so the best we can do is walk step by next intuitively right step until one day, pausing to catch our breath, we turn around and gasp at a path. If we have been lucky enough, if we have been willing enough to face the uncertainty, it is our own singular path, unplotted by our anxious younger selves, untrodden by anyone else.”51

The “New Woman” broke new ground by challenging the (in)visibility of women in a male dominated world. She placed herself in a man’s world but she still had to fit into that man’s world and conform to his image of her. But she followed her path of uncertainty with conviction and motivation, a path until then untrodden by anyone else, until she turned around and found that she had forged her own singular path, had looked within and had found her own voice. Looking back from a contemporary perspective we can finally recognise the struggle of the “New Woman” behind the camera, we can see their singular paths and recognise their achievements. What we can learn from the “New Woman” today, is that we all have a choice… to accept the status quo or offer determined defiance to prejudiced social conventions.

All human beings have to live within the parameters of social constructs but as human beings what we can do is push against the limits society imposes on us, push against the barriers of economic, political and sexual freedom. We can transgress the taboo. We can struggle that great and mighty struggle on the path of life, to push at the boundaries of being. What we all need to do, both women and men, is to find our integrity in relation to the reality of the world and to our own spirit. Through the efforts of those that came before us, we all now have a choice as to the path we follow and how we fit into this multifarious society.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

January 2021

Word count: 8,590

Footnotes

1/ Anonymous text. “George Sand,” on the Wikipedia website [Online] Cited 14/12/2021

2/ Victor Hugo. Les funérailles de George Sand quoted “Emancipated Woman,” in the Saturday Review: Politics, Literature, Science and Art, Volume 41, June 17, 1876, pp. 771 [Online] Cited 14/12/2021

3/ Anonymous text. “Camille Claudel,” on the Musée Rodin website [Online] Cited 14/12/2021

4/ Anonymous text. “Camille Claudel,” on the Wikipedia website [Online] Cited 14/12/2021

5/ Musée Rodin op cit.,

6/ Janet Wolff. “The Invisible Flaneuse. Women and the Literature of Modernity” in Theory, Culture and Society Volume 2, Number 3, Sage, 1985, p. 42

7/ Ibid., p. 44

8/ Ibid.,

“When flanerie moves into the private realm of the department store, feminization alters this urban practice almost beyond recognition … By abolishing the distance between the individual and the commodity, the feminization of flanerie redefines it out of existence. The flaneur‘s dispassionate gaze dissipates under pressure from the shoppers’ passionate engagement in the world of things to be purchase and possessed. The flaneur ends up going shopping after all. … The department store cannot be the scene of urban strolling, not only because it is an enclosed and circumscribed space, but, more importantly, because shopping is a pre-defined and purposeful activity.”

Janet Wolff. “Gender and the haunting of cities (or, the retirement of the flâneur),” in Aruna D’Souza and Tom McDonough (eds.,) The Invisible Flâneuse? Gender, Public Space, and Visual Culture in Nineteenth-Century Paris. London, UK: Manchester UP, 2006, p. 21

9/ Flaneur – “The flaneur symbolises the privilege or freedom to move about the public arenas of the city observing but never interacting, consuming the sights through a controlling but rarely-acknowledged gaze… The flaneur embodies the gaze of modernity which is both covetous and erotic. … The site of pleasurable looking, this look actively cast women as passive, erotic objects, subjecting them to a kind of voyeuristic control; it was in this sense that the visual purview of the bourgeois stroller – now the representative of middle-class masculinity in its entirety – became thoroughly implicated in issues of gender.”

Griselda Pollock. Vision and Difference: Femininity, Feminism and the Histories of Art. London, UK: Routledge, 1988.

10/ Akkelies van Nes and Tra My Nguyen. “Gender Differences in the Urban Environment: The flâneur and flâneuse of the 21st Century,” in Daniel Koch, Lars Marcus and Jesper Steen (eds.,). Proceedings of the 7th International Space Syntax Symposium. Stockholm: KTH, 2009

11/ Ibid.,

“Prostitution was indeed the female version of flânerie, which serves only to emphasise the inequality of gender differences in this era. The male flâneur was simply a man who loitered on the streets; but women who loitered risked being seen as prostitutes, streetwalkers, or les grandes horizontales as they were known in nineteenth-century Paris.”

Bobby Seal. “From Streetwalker to Street Walker: The Rise of the Flâneuse,” on the Psychogeographic Review website 24/12/20212 [Online] Cited 20/01/2022

12/ Bianca Hall and Adam Cooper. “From Jill Meagher to Aiia Maasarwe: The murders that changed Melbourne over the past decade,” on The Age website December 30, 2019 [Online] Cited 15/12/2021.

13/ “Suffragette,” on the Wikipedia website [Online] Cited 14/12/2021

14/ Aruna D’Souza and Tom McDonough (eds.,) The Invisible Flâneuse? Gender, Public Space, and Visual Culture in Nineteenth-Century Paris. London, UK: Manchester UP, 2006, p. 8

15/ Ibid., p. 6

16/ Steven Bach quoted in Carl Rollyson. “Leni Riefenstahl on Trial,” on The New York Sun website March 7, 2007 [Online] Cited 04/01/2022

17/ Anonymous. “Leni Riefenstahl,” on the Wikipedia website [Online] Cited 02/01/2021

18/ Ibid.,

19/ Taylor Downing. “Leni: fully exposed,” on The Observer website Sun 29 April 2007 [Online] Cited 12/01/2022

20/ Kate Connolly. “Burying Leni Riefenstahl: one woman’s lifelong crusade against Hitler’s favourite film-maker,” on The Guardian website Thursday 9 December 2021 [Online] Cited 12/01/2022

21/ Susan Sontag. “Fascinating Fascism,” in The New York Review February 6, 1975 issue [Online] Cited 12/02/2022

22/ Ibid.,

23/ See “Cross of Honour of the German Mother” on the Wikipedia website [Online] Cited 12/01/2022

24/ Sontag, op. cit.,

25/ Text from a sign commemorating birth of Georgia O’Keeffe, located next to Sun Prairie City Hall, 300 E, Main Street

26/ Anonymous. “Georgia O’Keeffe,” on the Wikipedia website [Online] Cited 02/01/2022

27/ Mark Levitch. “Stieglitz Career Overview: Georgia O’Keeffe, 1918-1920,” on the National Gallery of Art website Nd [Online] Cited 12/02/2022

28/ Ibid.,

29/ Ibid.,

30/ John Black. “Alfred Stieglitz and Modern America,” on the Boston Event Guide website Wednesday, 23 August 2017 [Online] Cited 12/02/2022. No longer available online

31/ Anonymous. “Georgia O’Keeffe,” on the Wikipedia website [Online] Cited 12/02/2022

32/ Roberta Courtney Meyers. “O’Keeffe in Taos,” on the Taos News website May 21, 2019 [Online] Cited 12/02/2022

33/ Anonymous. “Georgia O’Keeffe,” on the Wikipedia website [Online] Cited 12/02/2022

34/ Ibid.,

35/ Meyers, op. cit.,

36/ Anonymous. “Cross of Honour of the German Mother” on the Wikipedia website [Online] Cited 12/01/2022

37/ Anonymous. “Lesson of the widow’s mite,” on the Wikipedia website [Online] Cited 15/02/2022

38/ Clay Risen. “Sabine Weiss, Last of the ‘Humanist’ Street Photographers, Dies at 97,” on The New York Times website Jan 4, 2022 [Online] Cited 06/01/2022

39/ Annette Kuhn. The Power of the Image: Essays on Representation and Sexuality. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1985, p. 10.

40/ Marina Molarsky-Beck. “Germaine Krull’s Queer Vision,” on The Met website August 17 2021 [Online] Cited 15/12/2021

41/ Anonymous. “Germaine Krull, From Séries les Amies, 1924,” on the La Petite Mélancolie website 19/06/2012 [Online] Cited 15/01/2022

42/ Ibid.,

43/ Ibid.,

44/ Anonymous. “Claude Cahun,” on the Wikipedia website [Online] Cited 16/01/2022

45/ Jennifer Josten. “Reconsidering Self-Portraits by Women Surrealists: A Case Study of Claude Cahun and Frida Kahlo,” in the Atlantis Journal Vol. 30, No. 2, 30/02/2006 p. 24

46/ Anonymous. “Claude Cahun,” on the Wikipedia website [Online] Cited 16/01/2022

47/ Those with non-binary genders can feel that they: Have an androgynous (both masculine and feminine) gender identity, such as androgyne. Have an identity between male and female, such as intergender. Have a neutral or unrecognised gender identity, such as agender, neutrois, or most xenogenders.

48/ “The constant flow of life again and again demands fresh adaptation. Adaptation is never achieved once and for all.” Carl Jung. “The Transcendent Function,” CW 8, par. 143.

49/ Marcus Bunyan. “Gillian Wearing and Claude Cahun: Behind the mask, another mask” on the Art Blart website 24th May 2017 [Online] Cited 16/01/2022

50/ Dunn Marsh quoted in Margo Vansynghel. “How Seattle’s Imogen Cunningham changed photography forever,” on the Crosscut website November 16, 2021 [Online] Cited 08/01/2022

51/ Maria Popova. “Carl Jung on How to Live and the Origin of “Do the Next Right Thing”,” on The Marginalian website 12th July 2021 [Online] Cited 13/12/2021

Many thankx to the National Gallery of Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Uncertainty is the price of beauty, and integrity the only compass for the territory of uncertainty that constitutes the landmass of any given life.

And so the best we can do is walk step by next intuitively right step until one day, pausing to catch our breath, we turn around and gasp at a path. If we have been lucky enough, if we have been willing enough to face the uncertainty, it is our own singular path, unplotted by our anxious younger selves, untrodden by anyone else.

Maria Popova. “Carl Jung on How to Live and the Origin of “Do the Next Right Thing”,” on The Marginalian website 12th July 2021 [Online] Cited 13/12/2021

The beautiful woman will continue to serve as a symbol of feminine mystery to the man who desires her and of potency and success to the man who can claim her. And to the women around her, she will remain a symbol of the ideal against which they will be judged. This can only change when beauty loses its distorted power in the evaluation of a “woman’s worth”; that is, when the dependent relationship between women and men has been dismantled. Thus are the politics of appearance inextricably bound up with the structures of social, political and economic inequality … Fighting pressure to conform, attempting to hold one’s own against the commercial and cultural images of the acceptable is a crucial first act of resistance. The attempt to pass and blend in actually hides us from those we most resemble. We end up robbing each other of authentic reflections of ourselves. Instead, imperfectibly visible behind a fashion of conformity, we fear to meet each others’ eyes …

Real diversity can only become a source of strength if we learn to acknowledge it rather than disguise it. Only then can we recognize each other as different and therefore exciting, imperfect and as such enough.

Wendy Chapkis. Beauty Secrets: Women and the Politics of Appearance. Boston: South End Press, 1986, p. 175.

… in practice, images are always seen in context: they always have a specific use value in the particular time and place of their consumption. This, together with their formal characteristics, conditions and limits the meanings available from them at any on moment. But if representations always have use value, then more often than not they also have exchange value: they circulate as commodities in a social / economic system. This further conditions, or overdetermines, the meanings available from representations. Meanings do not reside in images, then: they are circulated between representation, spectator and social function.

Kuhn, Annette. The Power of the Image: Essays on Representation and Sexuality. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1985, p. 6.

Meanings readable from photographs … are at all points connected with the status they occupy as products, with the contexts of reception and the discourses of authorship, aesthetics, criticism and marketing which surround them. ‘Mainstream’ images in our culture bear the traces of the capitalist and patriarchal social relations in which they are produced, exchanged and consumed.

Kuhn, Annette. The Power of the Image: Essays on Representation and Sexuality. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1985, p. 10.

Tsuneko Sasamoto (Japanese, b. 1914)

Woman Selling Her and Her Husband’s Poetry Books (Street Snapshot in Tokyo)

c. 1950-1953, printed 1993

Gelatin silver print

Image: 29.6 x 29.6cm (11 5/8 x 11 5/8 in.)

Frame: 40.64 x 50.8cm (16 x 20 in.)

Frame (outer): 41 x 51.2 x 2.5cm (16 1/8 x 20 3/16 x 1 in.)

Collection of Tokyo Photographic Art Museum

Lesson of the widow’s mite

The lesson of the widow’s mite or the widow’s offering is presented in the Synoptic Gospels (Mark 12:41-44, Luke 21:1-4), in which Jesus is teaching at the Temple in Jerusalem. The Gospel of Mark specifies that two mites (Greek lepta) are together worth a quadrans, the smallest Roman coin. A lepton was the smallest and least valuable coin in circulation in Judea, worth about six minutes of an average daily wage.

Biblical narrative

“He sat down opposite the treasury and observed how the crowd put money into the treasury. Many rich people put in large sums. A poor widow also came and put in two small coins worth a few cents. Calling his disciples to himself, he said to them, ‘Amen, I say to you, this poor widow put in more than all the other contributors to the treasury. For they have all contributed from their surplus wealth, but she, from her poverty, has contributed all she had, her whole livelihood.'”

Commentary

… In the passage immediately prior to Jesus taking a seat opposite the Temple treasury, he is portrayed as condemning religious leaders who feign piety, accept honour from people, and steal from widows. “Beware of the scribes, who like to go around in long robes and accept greetings in the marketplaces, seats of honour in synagogues, and places of honour at banquets. They devour the houses of widows and, as a pretext, recite lengthy prayers. They will receive a very severe condemnation.”

The same religious leaders who would reduce widows to poverty also encourage them to make pious donations beyond their means. In [Adison] Wright’s opinion, rather than commending the widow’s generosity, Jesus is condemning both the social system that renders her poor, and “… the value system that motivates her action, and he condemns the people who conditioned her to do it.”

Text from the Wikipedia website

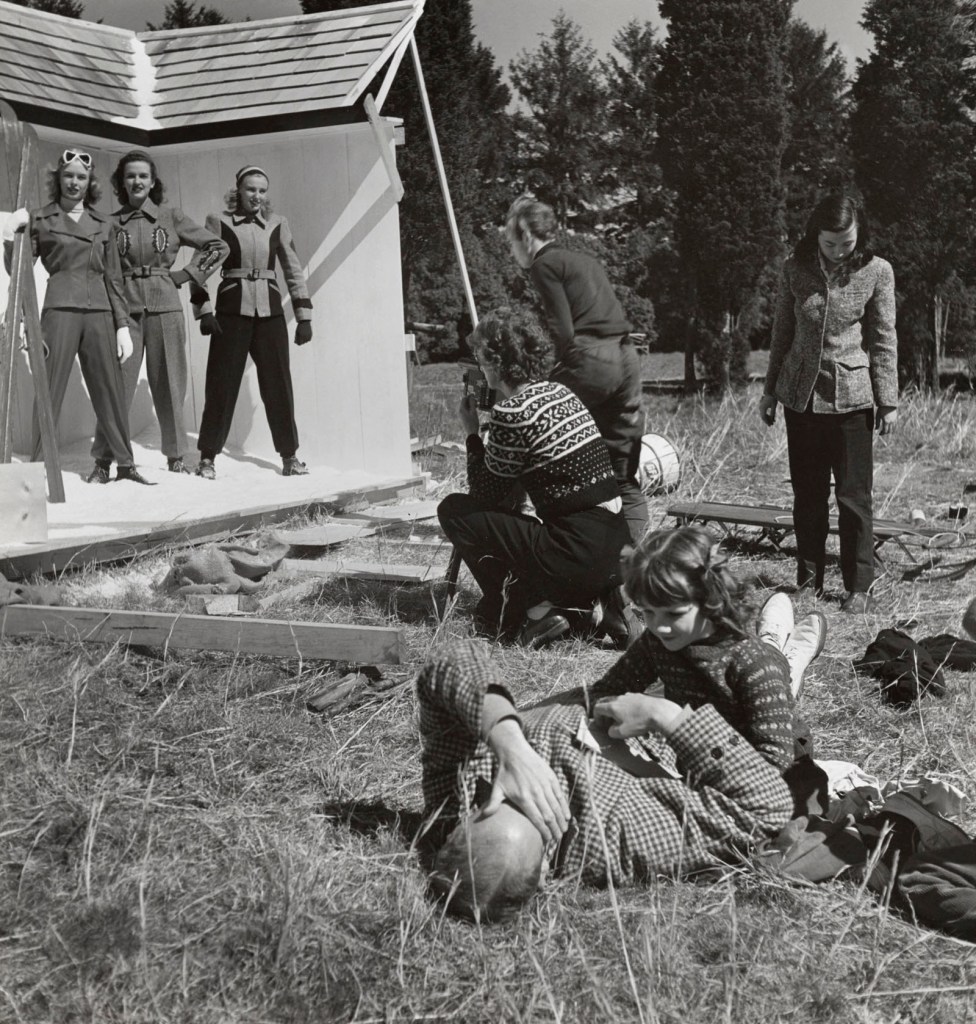

Tsuneko Sasamoto (Japanese, b. 1914)

The Labor Offensive Heats Up

1946, printed 1993

Gelatin silver print

Image: 24.9 x 37.2cm (9 13/16 x 14 5/8 in.)

Frame: 40.64 x 50.8cm (16 x 20 in.)

Frame (outer): 41 x 51.2 x 2.5cm (16 1/8 x 20 3/16 x 1 in.)

Collection of Tokyo Photographic Art Museum

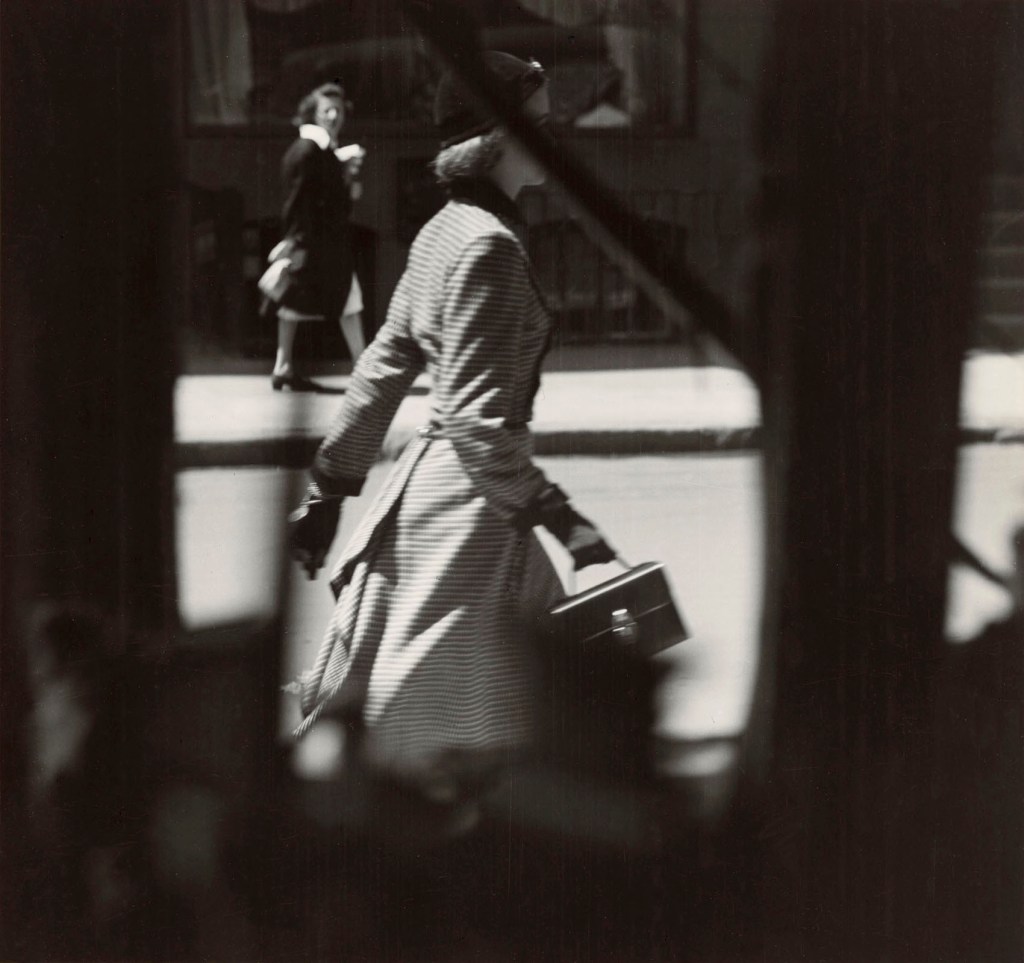

Tsuneko Sasamoto (Japanese, b. 1914)

“Living New Look” Photography Exhibitionkru

1950, printed 1993

Gelatin silver print

Image: 37.6 x 29.5cm (14 13/16 x 11 5/8 in.)

Frame: 40.64 x 50.8 cm (16 x 20 in.)

Frame (outer): 41 x 51.2 x 2.5 cm (16 1/8 x 20 3/16 x 1 in.)

Collection of Tokyo Photographic Art Museum

Photographer unknown

Tsuneko Sasamoto, Tokyo

1940, printed 2020

Inkjet print

Image: 18.2 x 18.2cm (7 3/16 x 7 3/16 in.)

Frame: 45.72 x 35.56cm (18 x 14 in.)

Frame (outer): 46.99 x 36.83cm (18 1/2 x 14 1/2 in.)

Tsuneko Sasamoto / Japan Professional Photographers Society

Tsuneko Sasamoto (Japanese, 1914-2022)

Hiroshima Peace Memorial

1953, printed 2020

Inkjet print

Image: 37.4 x 37.3cm (14 3/4 x 14 11/16 in.)

Frame: 55.88 x 50.8cm (22 x 20 in.)

Frame (outer): 57.15 x 52.07cm (22 1/2 x 20 1/2 in.)

Tsuneko Sasamoto / Japan Professional Photographers Society

Tsuneko Sasamoto (Japanese, 1914-2022)

Untitled

1940, printed 2020

Inkjet print image: 47.5 x 33.8cm (18 11/16 x 13 5/16 in.)

Frame: 60.96 x 45.72cm (24 x 18 in.)

Tsuneko Sasamoto / Japan Professional Photographers Society

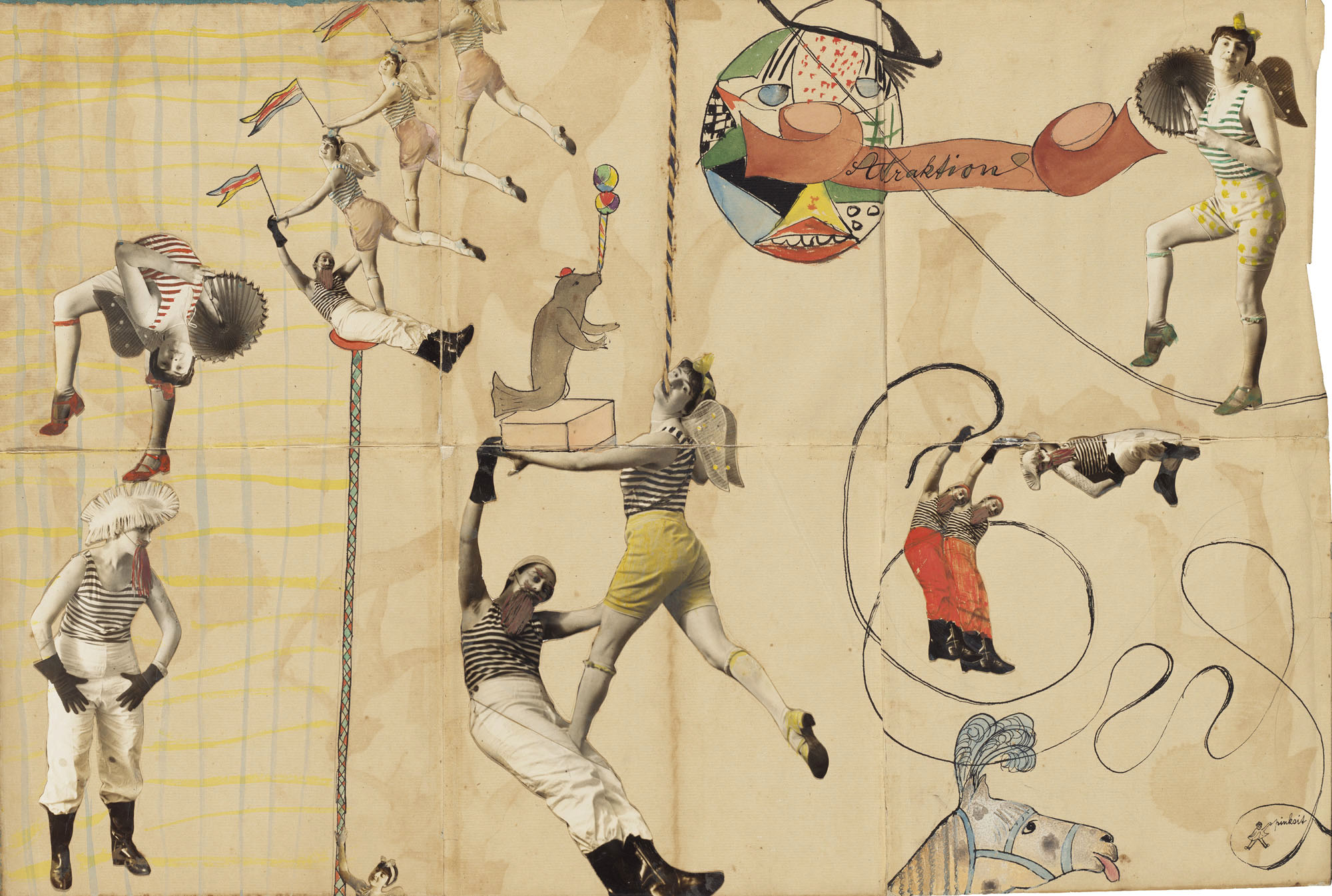

Toshiko Okanoue (Japanese, b. 1928)

Full of Life

1954

Collage on paper

Image/sheet: 23.8 x 24.9cm (9 3/8 x 9 13/16 in.)

Frame: 50.8 x 40.64cm (20 x 16 in.)

Frame (outer): 53.34 x 43.18cm (21 x 17 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred H. Moses and Fern M. Schad Fund

© Okanoue Toshiko

Toshiko Okanoue (Japanese, b. 1928)

Toshiko Okanoue (岡上 淑子, Okanoue Toshiko, born 3 January 1928) is a Japanese artist associated with the Japanese avant-garde art world of the 1950s and best known for her Surrealist photo collages. …

Early career

Born in Kochi and raised in Tokyo, Okanoue began to make photo collages while studying fashion and drawing at the Bunka Gakuin in Tokyo in the early 1950s. The young Okanoue, initially knew little of art history or the Surrealist movement.

In 1952, a classmate from Keisen Girls’ High School introduced Okanoue to poet and art critic Shuzo Takiguichi, a leading figure in the Japanese Surrealist movement, who would help introduce her to the wider art world, including the work of European Surrealists, such as German artist Max Ernst, who was an influence on her subsequent work.

Over the next six years she would produce over 100 works. She exhibited in two exhibits including, solo shows at the Takemiya Gallery in Tokyo, In the second show at Takemiya, over fifty pieces of Okanoue’s monochrome photographs were hung on display. Also exhibited at the “Abstract and Illusion” exhibition at the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo between 1 December 1953 and 20 January 1954, which attracted total of 16,657 audiences appreciating 91 artworks by 91 artists.

Artistic style

In post-war Japan, shortages of goods meant that foreign goods filled the market and fashion and lifestyle magazines such as Vogue, Harpers Bazaar and Life magazine provided the raw materials for Okanoue’s collages. Her black and white photo collages mix images of places, objects and people, often fashionable European women, in dynamic and often unsettling compositions whose subjects explored themes of war, femininity and the relations between the sexes.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Photographer unknown

Page spread featuring Eiko Yamazawa and her assistant, from the “Photo Times”

October 1940

Magazine

Open: 25.4 x 30.48cm (10 x 12 in.)

Cradle: 8.89 x 33.02 x 26.35 cm (3 1/2 x 13 x 10 3/8 in.)

National Gallery of Art Library, Gift of the Department of Photographs

American, 20th Century

“Photo-Fighter,” in “True Comics”

July 1944

Comic book

Open: 25.4 x 35.56cm (10 x 14 in.)

National Gallery of Art Library, Gift of the Department of Photographs

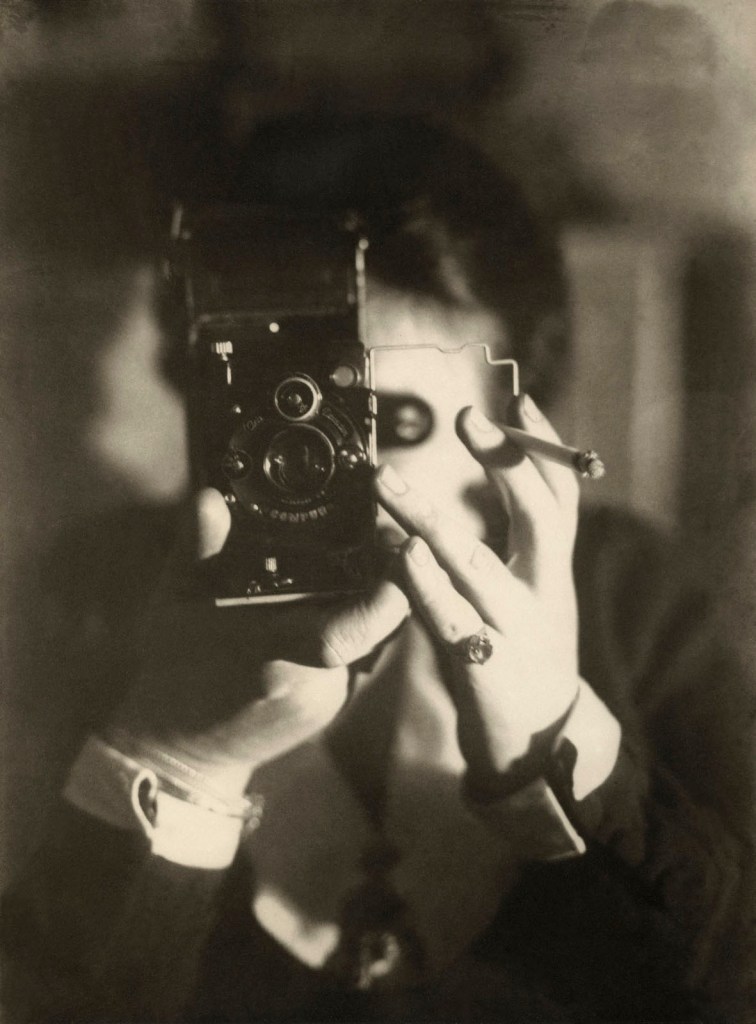

Ilse Bing (United States of America, Germany 1899-1998)

Self-Portrait With Leica

1931

Gelatin silver print

Collection of Michael Mattis and Judith Hochberg/Ilse Bing Estate

Ré Soupault (German, 1901–1996)

Self-Portrait, Tunis

1939

Gelatin silver print

Artists Rights Society, New York

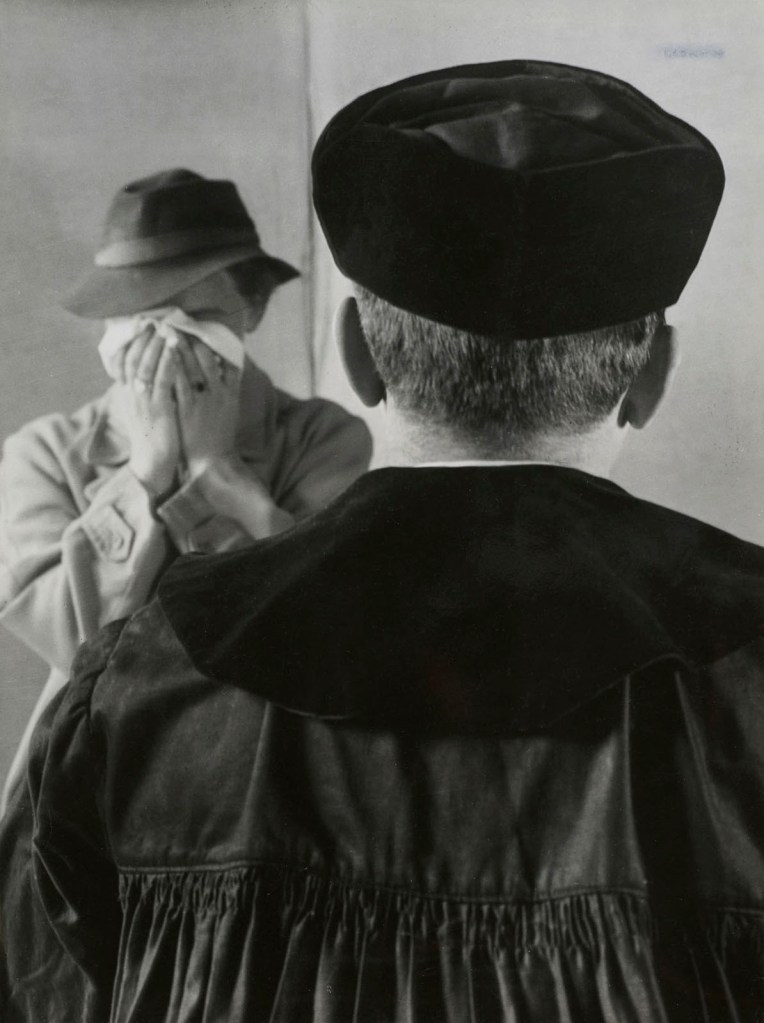

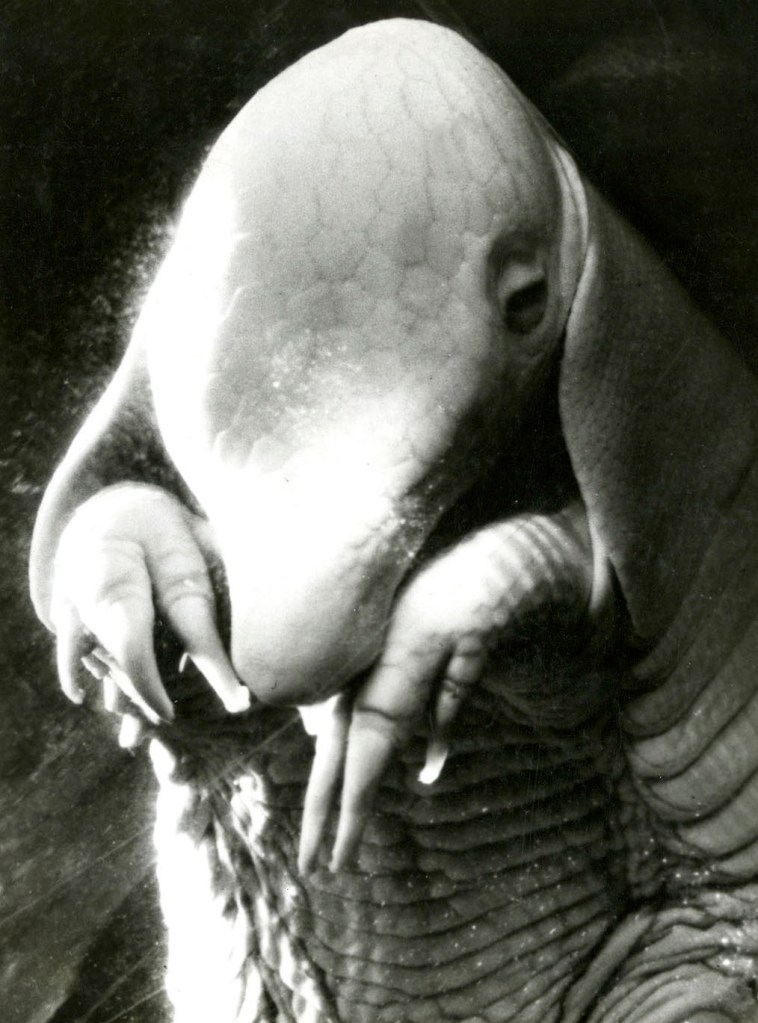

Elisabeth Hase (German, 1905-1991)

Ohne Titel (Weinende Frau) (Untitled (Crying woman))

c. 1934

Gelatin silver print

Image/sheet: 22.8 x 17.1cm (9 x 6 3/4 in.)

Frame (outer): 44.5 x 36.8cm (17 1/2 x 14 1/2 in.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Twentieth-Century Photography Fund, 2016

Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Art Resource, NY

Elisabeth Hase (German, 1905-1991)

Elisabeth Hase (December 16, 1905 – October 9, 1991) was a German commercial and documentary photographer active in Frankfurt from 1932 until her death in 1991, at the age of 85.

Hase was born in Döhlen bei Leipzig, Germany. She studied typography and commercial art from 1924 to 1929 at the School of Applied Arts, and later at the Städelschule, under, among other teachers, Paul Renner and Willi Baumeister. Hase was active as a photographer during the time of the transition from the Weimar Republic to the Third Reich and through post-WWII Germany. She was able to avoid government oversight of her work by establishing her own photographic studio in 1933.

Hase’s work included surreal photography, such as close-up photographs of dolls.

She received several awards, several for paper designs and collages. During a two-year collaboration in the studio of Paul Wolff and Alfred Tritschler, Hase took architectural photographs in New Objectivity style for the magazine Das Neue Frankfurt (The New Frankfurt) and documentary photographs of modern housing projects, including those of Ferdinand Kramer.

In 1932, Hase started her own business. It focused on timeless designs like still life, structures, plants, dolls, people, especially self-portraits. Often she used herself as a model in her photographic “picture stories.” Cooperation with agencies like Holland Press Service and the Agency Schostal enabled her to publish her photographs internationally.

Despite the bombing of Frankfurt in 1944 by the Allies, Hare’s photographic archive survived the war without major damage. Many of those works are now part of the collections held by the Folkwang Museum in Essen, Germany, in the Albertina (Vienna) in Vienna, and in the Walter Gropius estate in the Bauhaus Archive in Berlin, as well as in private collections in Germany and abroad.

Despite loss of her cameras and other technical equipment in the chaos of war, Hase was able to resume taking photographs in 1946 by the help of emigre friends who provided her with film and cameras to use. Among other subjects Hase documented was the reconstruction of St. Paul’s Church in Frankfurt.

From 1949, her work focused on advertising, consisting mostly of plant portraits.

Hase died at the age of 85 in 1991 in Frankfurt am Main.

Text from the Wikipedia website

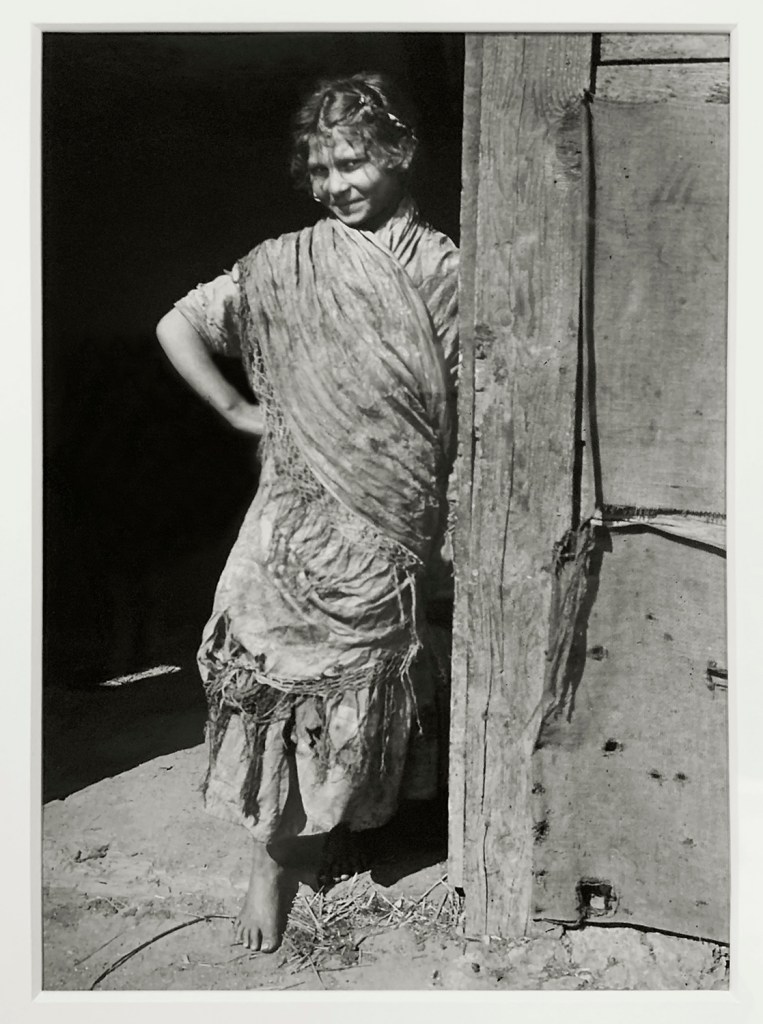

Erna Lendvai-Dircksen (German, 1883-1962)

Mädchen aus dem Guttachtal, Schwarzwald (Young Woman from the Guttach Valley, Black Forest)

Before 1934

Gelatin silver print

Image: 17.1 x 13.2cm (6 3/4 x 5 3/16 in.)

Mount: 26 x 18.4cm (10 1/4 x 7 1/4 in.)

Frame (outer): 52.07 x 39.37cm (20 1/2 x 15 1/2 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Erna Lendvai-Dircksen (German, 1883-1962)

Erna Lendvai-Dircksen (born Erna Katherina Wilhelmine Dircksen, 31 May 1883 – 8 May 1962) was a German photographer known for a series of volumes of portraits of rural individuals from throughout Germany. During the Third Reich, she also photographed for eugenicist publications and was commissioned to document the new autobahn and the workers constructing it. …

Critical reception

Lendvai-Dircksen’s portraits of farmers suited the Nazi ethos except that in her initial publication, almost all her subjects were old, and indeed she clearly portrayed the damage to their bodies as a sign of authenticity. She later widened her focus to include children. She never, however, photographed sport, whether for technical reasons or because of her personal philosophy.

Although Lendvai-Dircksen has been referred to as “brown Erna” for the promotion of Nazi ideals in her work under the Third Reich, her portrait photography can be compared to the work of Dorothea Lange or Walker Evans as documentation of impoverished people, and Margaret Bourke-White also photographed labourers in a heroic light. As pointed out by Berlin photographic curator Janos Frecot in the catalogue of an exhibition at the Albertina which included her work, her portraits and those of others at the time can be seen as applications of the same ethnographic principle as portraits of people in faraway cultures; similarly, Leesa Rittelmann has shown that the same principle of characterising a country by the physiognomies of its people, although a throwback to 19th-century theories, was shared by Weimar-era photographers such as the progressive August Sander, in his Antlitz der Zeit (Face of Our Time).

Text from the Wikipedia website

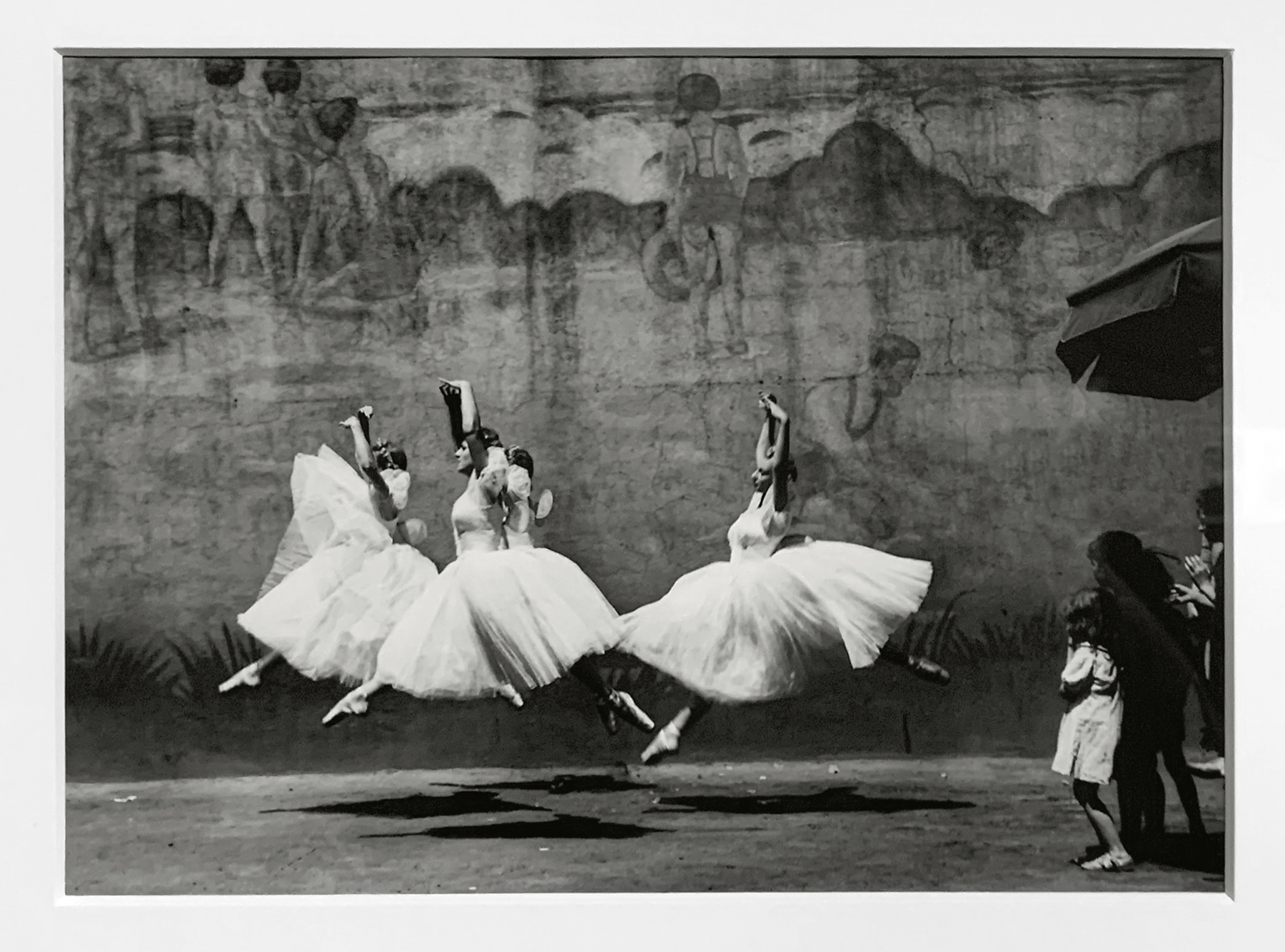

Annemarie Heinrich (Argentinian born Germany, 1912-2005)

Serge Lifar, “El espectro de la rosa” (Serge Lifar, “The Spirit of the Rose”)

1935

Gelatin silver print

Image: 28.4 x 20.7cm (11 3/16 x 8 1/8 in.)

Frame: 45.72 x 35.56cm (18 x 14 in.)

Frame (outer): 49.53 x 39.37cm (19 1/2 x 15 1/2 in.)