Exhibition dates: 30th September 2017 – 4th February 2018

Curator: Clément Chéroux

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Self-Portrait

1927

Gelatin silver print

Collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Ford Motor Company Collection, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

I have posted on this exhibition before, when it was at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, but this iteration at SFMOMA is the exclusive United States venue for the Walker Evans retrospective exhibition – and the new posting contains fresh media images not available previously.

I can never get enough of Walker Evans. This perspicacious artist had a ready understanding of the contexts and conditions of the subject matter he was photographing. His photographs seem easy, unpretentious, and allow his sometimes “generally unaware” subjects (subway riders, labor workers) to speak for themselves. Does it matter that he was an outsider, rearranging furniture in workers homes while they were out in the fields: not at all. Photography has always falsified truth since the beginning of the medium and, in any case, there is never a singular truth but many truths told from many perspectives, many different points of view. For example, who is to say that the story of America proposed by Robert Frank in The Americans, from the point of view of an outsider, is any less valuable than that of Helen Levitt’s view of the streets of New York? For different reasons, both are as valuable as each other.

Evans’ photographs for the Farm Security Administration (FSA) documenting the effects of the Great Depression on American life are iconic because they are cracking good photographs, not because he was an insider or outsider. He was paid to document, to enquire, and that is what he did, by getting the best shot he could. It is fascinating to compare Floyd and Lucille Burroughs, Hale County, Alabama (1936, below) with Alabama Tenant Farmer Floyd Bourroughs (1936, below). In the first photograph the strong diagonal element of the composition is reinforced by the parallel placement of the three feet, the ‘Z’ shape of Lucille Burroughs leg then leading into her upright body, which is complemented by the two vertical door jams, Floyd’s head silhouetted by the darkness beyond. There is something pensive about the clasping of his hands, and something wistful and sad, an energy emanating from the eyes. If you look at the close up of his face, you can see that it is “soft” and out of focus, either because he moved and/or the low depth of field. Notice that the left door jam is also out of focus, that it is just the hands of both Floyd and Lucille and her face that are in focus. Does this low depth of field and lack of focus bother Evans? Not one bit, for he knows when he has captured something magical.

A few second later, he moves closer to Floyd Burroughs. You can almost hear him saying to Floyd, “Stop, don’t move a thing, I’m just going to move the camera closer.” And in the second photograph you notice the same wood grain to the right of Floyd as in the first photograph, but this time the head is tilted slightly more, the pensive look replaced by a steely gaze directed straight into the camera, the reflection of the photographer and the world beyond captured on the surface of the eye. Walker Evans is the master of recognising the extra/ordinary. “The street was an inexhaustible source of poetic finds,” describes Chéroux. In his creation of visual portfolios of everyday life, his “notions of realism, of the spectator’s role, and of the poetic resonance of ordinary subjects,” help Evans created a mythology of American life: a clear vision of the present as the past, walking into the future.

With the contemporary decline of small towns and blue collar communities across the globe Evans’ concerns, for the place of ordinary people and objects in the world, are all the more relevant today. As the text from the Metropolitan Museum observes, it is the individuals and social institutions that are the sites and relics that constitute the tangible expressions of American desires, despairs, and traditions. And not just of American people, of all people… for it is community that binds us together.

Marcus

Many thankx to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art for allowing me to publish the text and photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Walker Evans is one of the most influential artists of the twentieth century. His elegant, crystal-clear photographs and articulate publications have inspired several generations of artists, from Helen Levitt and Robert Frank to Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander, and Bernd and Hilla Becher. The progenitor of the documentary tradition in American photography, Evans had the extraordinary ability to see the present as if it were already the past, and to translate that knowledge and historically inflected vision into an enduring art. His principal subject was the vernacular – the indigenous expressions of a people found in roadside stands, cheap cafés, advertisements, simple bedrooms, and small-town main streets. For fifty years, from the late 1920s to the early 1970s, Evans recorded the American scene with the nuance of a poet and the precision of a surgeon, creating an encyclopaedic visual catalogue of modern America in the making. …

Most of Evans’ early photographs reveal the influence of European modernism, specifically its formalism and emphasis on dynamic graphic structures. But he gradually moved away from this highly aestheticised style to develop his own evocative but more reticent notions of realism, of the spectator’s role, and of the poetic resonance of ordinary subjects. …

In September 1938, the Museum of Modern Art opened American Photographs, a retrospective of Evans’ first decade of photography. The museum simultaneously published American Photographs – still for many artists the benchmark against which all photographic monographs are judged. The book begins with a portrait of American society through its individuals – cotton farmers, Appalachian miners, war veterans – and social institutions – fast food, barber shops, car culture. It closes with a survey of factory towns, hand-painted signs, country churches, and simple houses – the sites and relics that constitute the tangible expressions of American desires, despairs, and traditions.

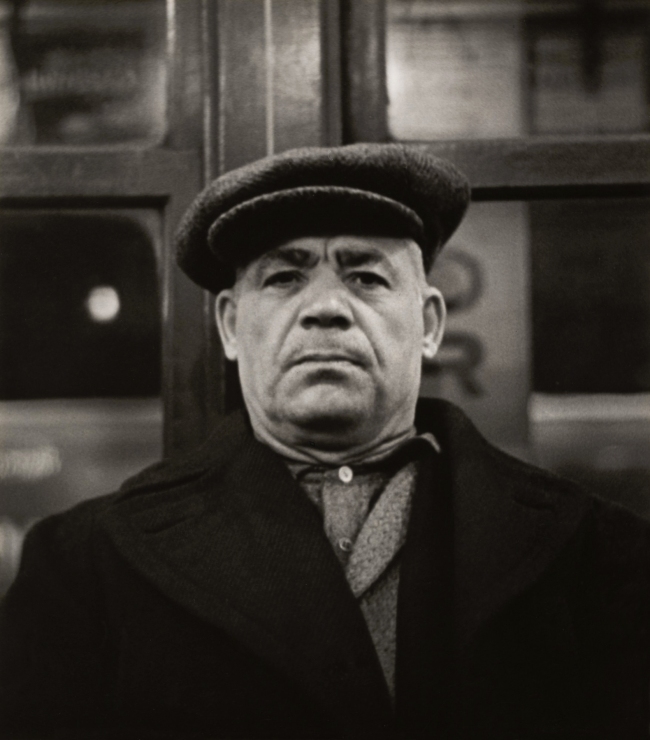

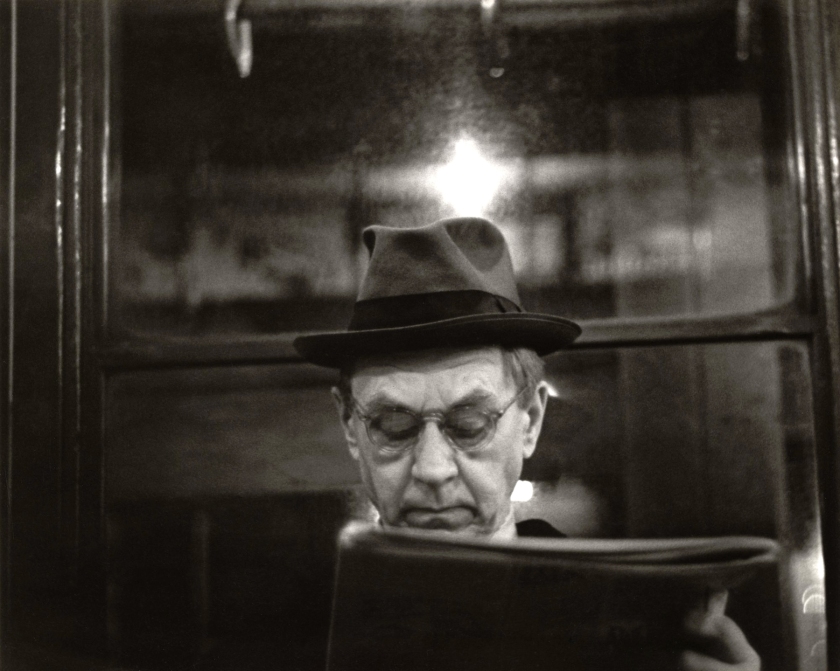

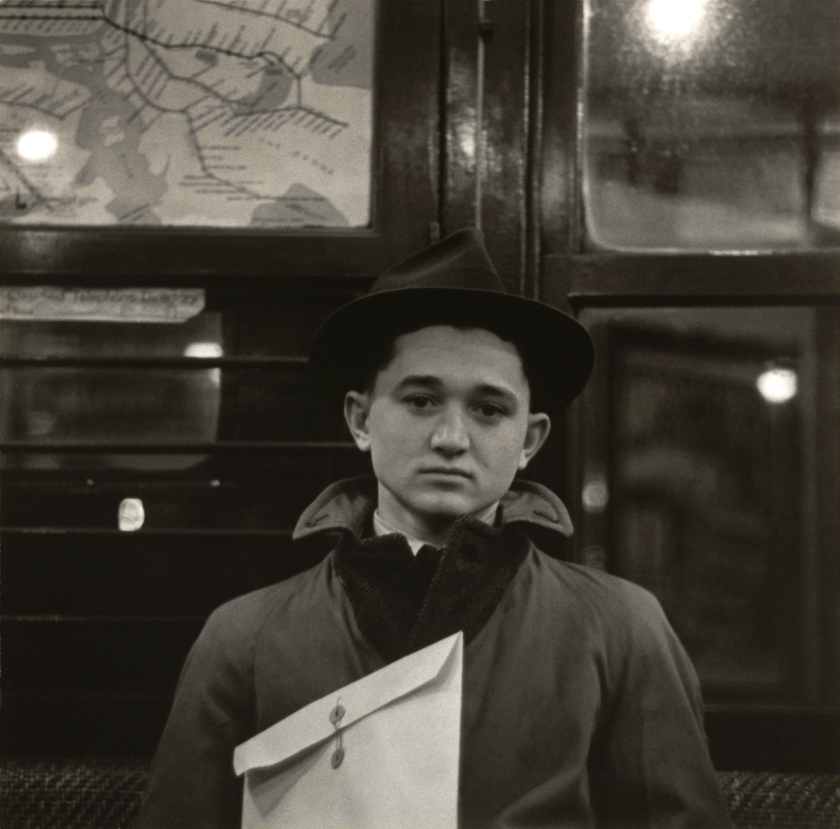

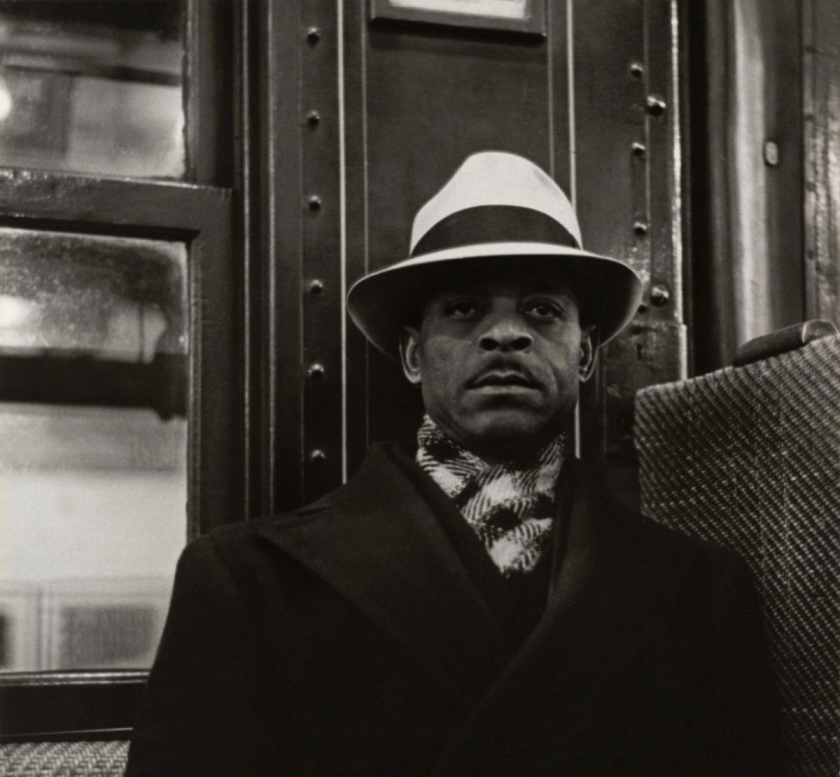

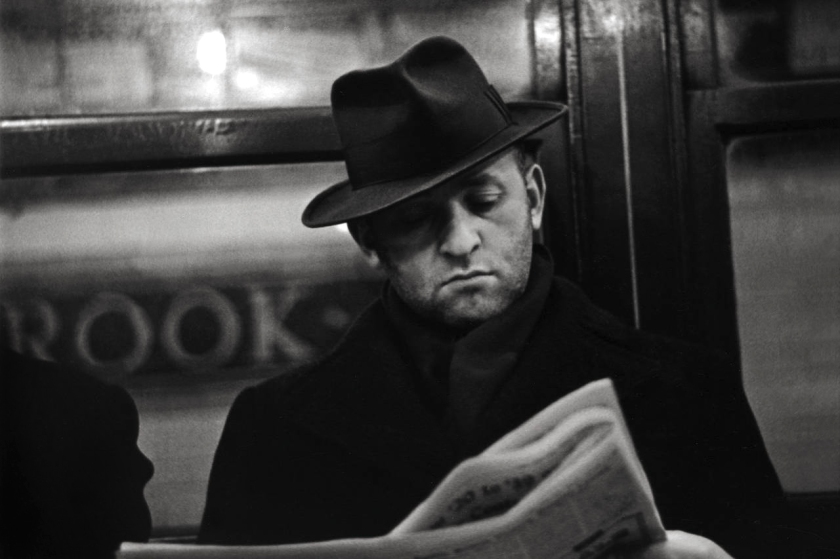

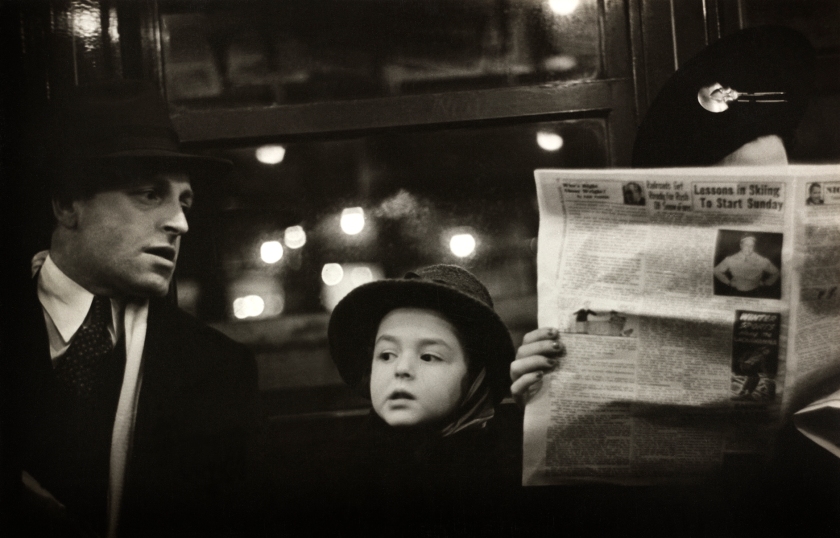

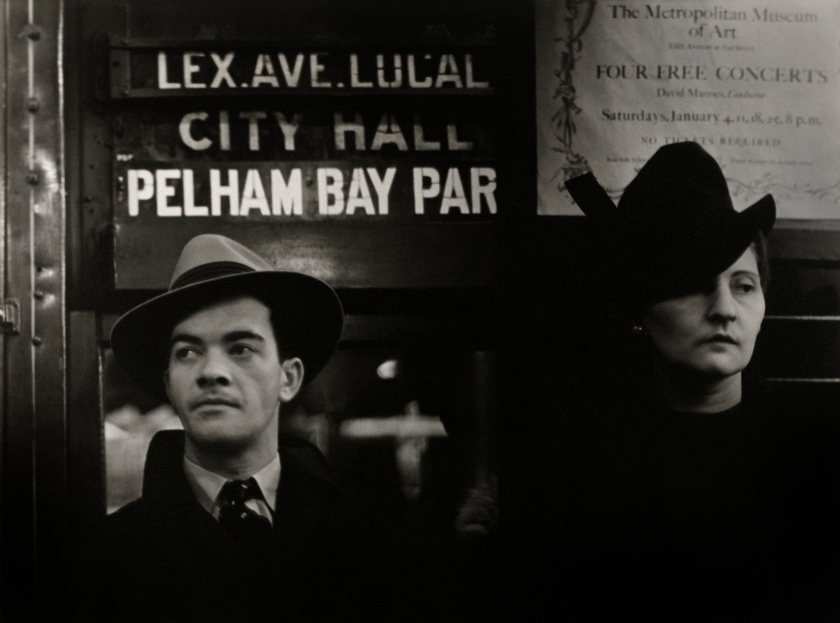

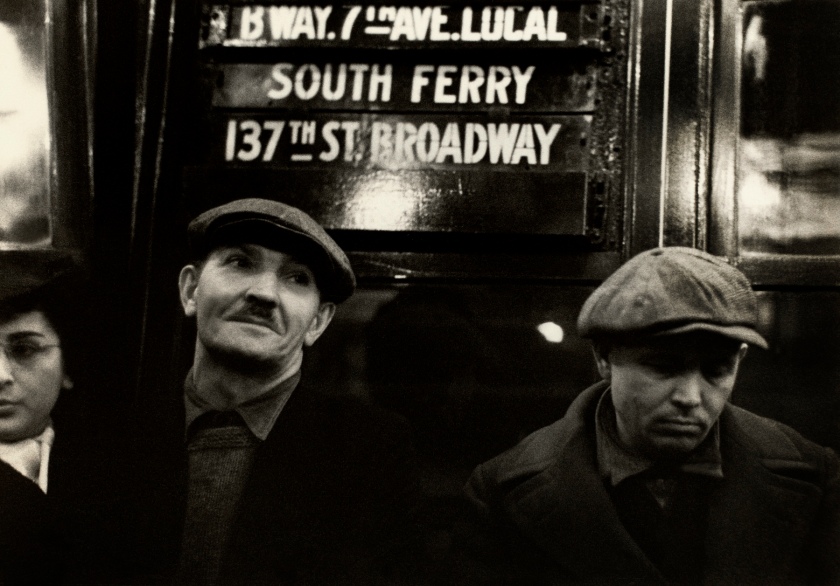

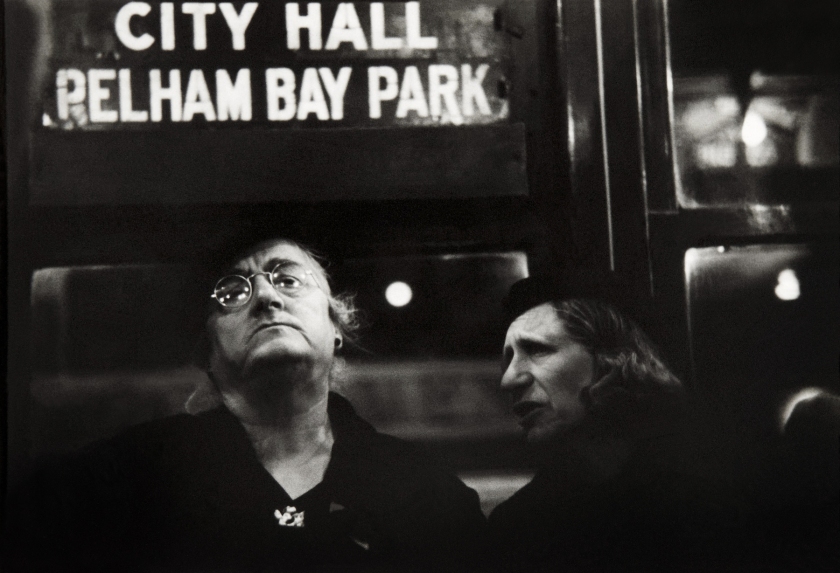

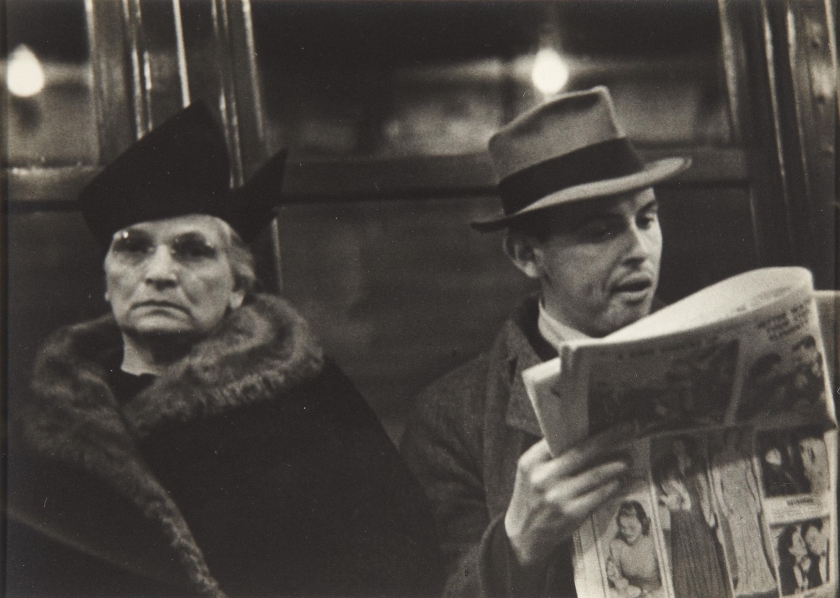

Between 1938 and 1941, Evans produced a remarkable series of portraits in the New York City subway. They remained unpublished for twenty-five years, until 1966, when Houghton Mifflin released Many Are Called, a book of eighty-nine photographs, with an introduction by James Agee written in 1940. With a 35mm Contax camera strapped to his chest, its lens peeking out between two buttons of his winter coat, Evans was able to photograph his fellow passengers surreptitiously, and at close range. Although the setting was public, he found that his subjects, unposed and lost in their own thoughts, displayed a constantly shifting medley of moods and expressions – by turns curious, bored, amused, despondent, dreamy, and dyspeptic. “The guard is down and the mask is off,” he remarked. “Even more than in lone bedrooms (where there are mirrors), people’s faces are in naked repose down in the subway.”

Extract from Department of Photographs. “Walker Evans (1903-1975),” in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000 on the Metropolitan Museum of Art website October 2004 [Online] Cited 08/02/2022

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Truck and Sign

1928-1930

Gelatin silver print

Private collection, San Francisco

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Floyd and Lucille Burroughs, Hale County, Alabama

1936

Gelatin silver print

Collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Floyd and Lucille Burroughs, Hale County, Alabama (detail)

1936

Gelatin silver print

Collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Alabama Tenant Farmer Floyd Bourroughs

1936

Gelatin silver print

22.9 x 18.4cm

Collection particulière, San Francisco

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Photo: © Fernando Maquieira, Cromotex

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Allie Mae Burroughs, Wife of a Cotton Sharecropper, Hale County, Alabama

1936

Gelatin silver print

Private collection

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

“These are not photographs like those of Walker Evans who in James Agee’s account in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men took his pictures of the bare floors and iron bedsteads of the American mid-western sharecroppers while they were out tending their failing crops, and who even, as the evidence of his negatives proves, rearranged the furniture for a ‘better shot’. The best shot that Heilig could take was one that showed things as they were and as they should not be. …

To call these ‘socially-conscious documentary’ photographs is to acknowledge the class from which the photographer [Heilig] comes, not to see them as the result of a benign visit by a more privileged individual [Evans], however well-intentioned.”

Extract from James McCardle. “Weapon,” on the On This Day In Photography website [Online] Cited 29/01/2018

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Sidewalk and Shopfront, New Orleans

1935

Gelatin silver print

Collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York, gift of Willard Van Dyke

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Roadside Stand Near Birmingham/Roadside Store Between Tuscaloosa and Greensboro, Alabama

1936

Gelatin silver print

Collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Penny Picture Display, Savannah

1936

Gelatin silver print

Pilara Foundation Collection

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Subway Portrait

1938-1941

Gelatin silver print

Collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Subway Portrait

1938-1941

Gelatin silver print

Collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Subway Portrait

1938-1941

Gelatin silver print

Collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

![Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975) '[Subway Passengers, New York City]' 1938 Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975) '[Subway Passengers, New York City]' 1938](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2016/07/walker-evans-subway-passengers-new-york-city-web.jpg?w=840)

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Subway Portrait

1938-1941

Gelatin silver print

Collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Subway Portraits

1938-1941

Gelatin silver print

Collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Exhibition Displays Over 400 Photographs, Paintings, Graphic Ephemera and Objects from the Artist’s Personal Collection

The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) will be the exclusive United States venue for the retrospective exhibition Walker Evans, on view September 30, 2017, through February 4, 2018. As one of the preeminent photographers of the 20th century, Walker Evans’ 50-year body of work documents and distills the essence of life in America, leaving a legacy that continues to influence generations of contemporary photographers and artists. The exhibition will encompass all galleries in the museum’s Pritzker Center for Photography, the largest space dedicated to the exhibition, study and interpretation of photography at any art museum in the United States.

“Conceived as a complete retrospective of Evans’ work, this exhibition highlights the photographer’s fascination with American popular culture, or vernacular,” explains Clément Chéroux, senior curator of photography at SFMOMA. “Evans was intrigued by the vernacular as both a subject and a method. By elevating it to the rank of art, he created a unique body of work celebrating the beauty of everyday life.”

Using examples from Evans’ most notable photographs – including iconic images from his work for the Farm Security Administration (FSA) documenting the effects of the Great Depression on American life; early visits to Cuba; street photography and portraits made on the New York City subway; layouts and portfolios from his more than 20-year collaboration with Fortune magazine and 1970s Polaroids – Walker Evans explores Evans’ passionate search for the fundamental characteristics of American vernacular culture: the familiar, quotidian street language and symbols through which a society tells its own story. Decidedly popular and more linked to the masses than the cultural elite, vernacular culture is perceived as the antithesis of fine art.

While many previous exhibitions of Evans’ work have drawn from single collections, Walker Evans will feature over 300 vintage prints from the 1920s to the 1970s on loan from the important collections at major museums including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Getty Museum, the Museum of Modern Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., the National Gallery of Canada, the Musée du Quai Branly and SFMOMA’s own collection, as well as prints from private collections from around the world. More than 100 additional objects and documents, including examples of the artist’s paintings; items providing visual inspiration sourced from Evans’ personal collections of postcards, graphic arts, enamelled plates, cut images and signage; as well as his personal scrapbooks and ephemera will be on display. The exhibition is curated by the museum’s new senior curator of photography, Clément Chéroux, who joined SFMOMA in 2017 from the Musée National d’Art Moderne of the Centre Pompidou, Paris, organiser of the exhibition.

While most exhibitions devoted to Walker Evans are presented chronologically, Walker Evans‘ presentation is thematic. The show begins with an introductory gallery displaying Evans’ early modernist work whose style he quickly rejected in favour of focusing on the visual portfolio of everyday life. The exhibition then examines Evans’ captivation with the vernacular in two thematic contexts. The first half of the exhibition will focus on many of the subjects that preoccupied Evans throughout his career, including text-based images such as signage, shop windows, roadside stands, billboards and other examples of typography. Iconic images of the Great Depression, workers and stevedores, street photography made surreptitiously on New York City’s subways and avenues and classic documentary images of life in America complete this section. By presenting this work thematically, the exhibition links work separated by time and place and highlights Evans’ preoccupation with certain subjects and recurrent themes. The objects that moved him were ordinary, mass-produced and intended for everyday use. The same applied to the people he photographed – the ordinary human faces of office workers, labourers and people on the street.

“The street was an inexhaustible source of poetic finds,” describes Chéroux.

The second half of the exhibition explores Evans’ fascination with the methodology of vernacular photography, or styles of applied photography that are considered useful, domestic and popular. Examples include architecture, catalog and postcard photography as well as studio portraiture, and the exhibition juxtaposes this work with key source materials from the artist’s personal collections of 10,000 postcards, hand-painted signage and graphic ephemera (tickets, flyers, logos and brochures). Here Evans elevates vernacular photography to art, despite his disinclination to create fine art photographs. Rounding out this section are three of Evans’ paintings using vernacular architecture as inspiration. The exhibition concludes with Evans’ look at photography itself, with a gallery of photographs that unite Evans’ use of the vernacular as both a subject and a method.

About Walker Evans

Born in St. Louis, Walker Evans (1903-1975) was educated at East Coast boarding schools, Williams College, the Sorbonne and College de France before landing in New York in the late 1920s. Surrounded by an influential circle of artists, poets and writers, it was there that he gradually redirected his passion for writing into a career as a photographer, publishing his first photograph in the short-lived avant-garde magazine Alhambra. The first significant exhibition of his work was in 1938, when the Museum of Modern Art, New York presented Walker Evans: American Photographs, the first major solo exhibition at the museum devoted to a photographer.

In the 50 years that followed, Evans produced some of the most iconic images of his time, contributing immensely to the visibility of American culture in the 20th century and the documentary tradition in American photography. Evans’ best known photographs arose from his work for the Farm Security Administration (FSA), in which he documented the hardships and poverty of Depression-era America using a large-format, 8 x 10-inch camera. These photographs, along with his photojournalism projects from the 1940s and 1950s, his iconic visual cataloguing of the common American and his definition of the “documentary style,” have served as a monumental influence to generations of photographers and artists.

Press release from SFMOMA

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Resort Photographer at Work

1941, printed later

Gelatin silver print

Collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

![Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975) 'Untitled [Street scene]' 1950s Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975) 'Untitled [Street scene]' 1950s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/01/walker-evans-untitled-web.jpg?w=840)

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Untitled [Street scene]

1950s

Gouache on paper

Collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Street Debris, New York City

1968

Gelatin silver print

Private collection, San Francisco

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

“Labor Anonymous,” Fortune 34, no. 5, November 1946

1946

Offset lithography

Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Paris, Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Collection of David Campany

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

“The Pitch Direct. The Sidewalk Is the Last Stand of Unsophisticated Display,” Fortune 58, no. 4, October 1958

1958

Offset lithography

Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Paris, Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Collection of David Campany

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Collage with Thirty-Six Ticket Stubs

1975

Cut and pasted photomechanical prints on paper

Collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Walker Evans Archive

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Unidentified Sign Painter

Coca-Cola Thermometer

1930-1970

Enamel on ferrous metal

Collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Walker Evans Archive

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Chain-Nose Pliers

1955

Gelatin silver print

The Bluff Collection

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

John T. Hill (American, b. 1934)

Interior of Walker Evans’s House, Fireplace with Painting of Car

1975, printed 2017

Inkjet print

Private collection

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Lenoir Book Co.,

Main Street, Showing Confederate Monument, Lenoir, North Carolina

1900-1940

Offset lithography

Collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Walker Evans Archive

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

151 Third Street

San Francisco, CA 94103

Opening hours:

Monday – Tuesday 10am – 5pm

Wednesday Closed

Thursday 1pm – 8pm

Friday – Sunday 10am – 5pm

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art website

LIKE ART BLART ON FACEBOOK

Back to top

![Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975) '[Subway Passengers, New York City]' 1938 Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975) '[Subway Passengers, New York City]' 1938](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2016/07/walker-evans-subway-passengers-new-york-city-web.jpg?w=840)

![Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975) 'Untitled [Street scene]' 1950s Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975) 'Untitled [Street scene]' 1950s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/01/walker-evans-untitled-web.jpg?w=840)

You must be logged in to post a comment.