Exhibition dates: 31st October, 2021 – 30th January, 2022

Curator: The exhibition is curated by Andrea Nelson, associate curator in the department of photographs, National Gallery of Art, Washington.

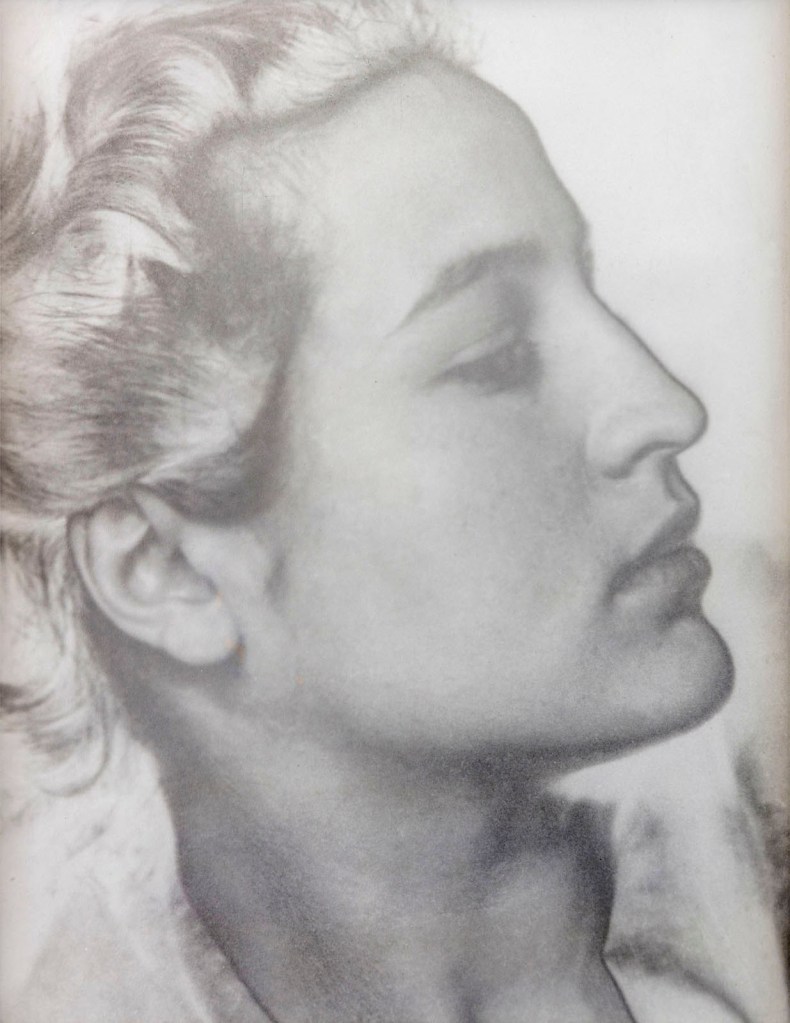

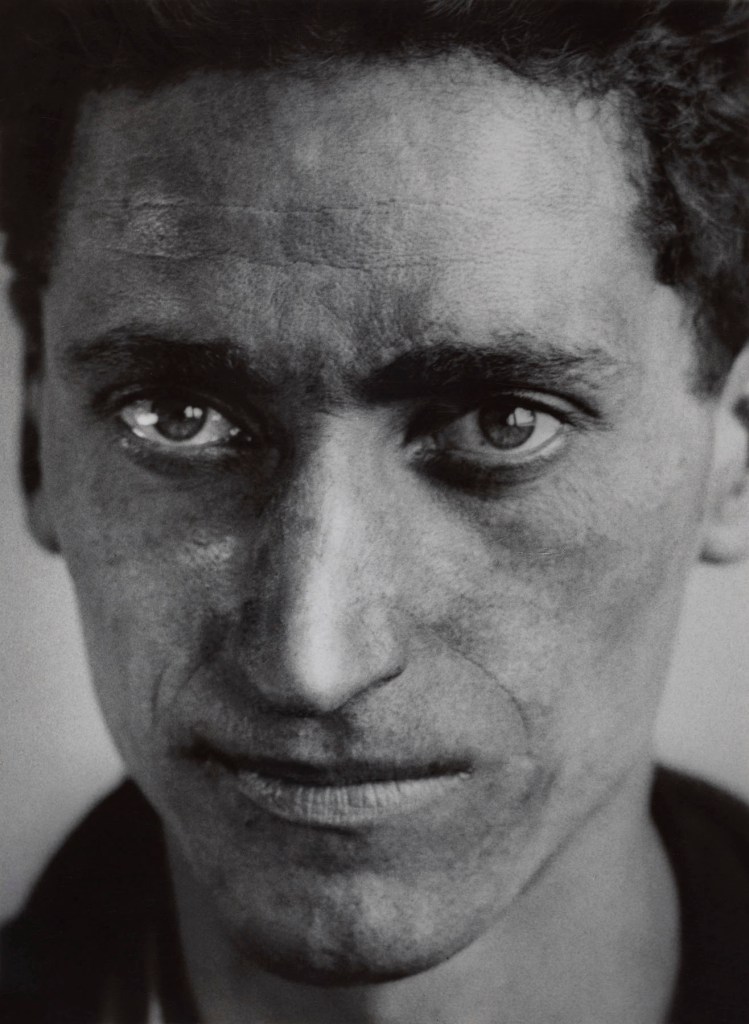

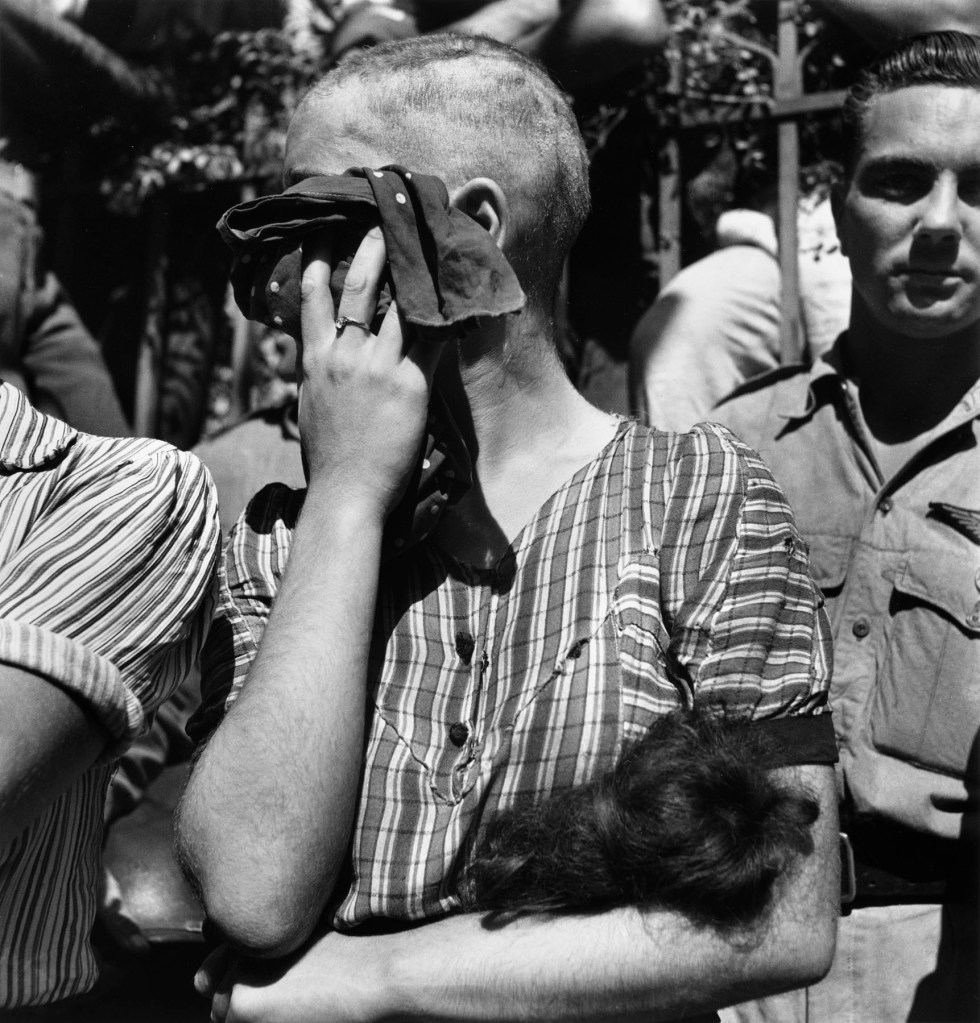

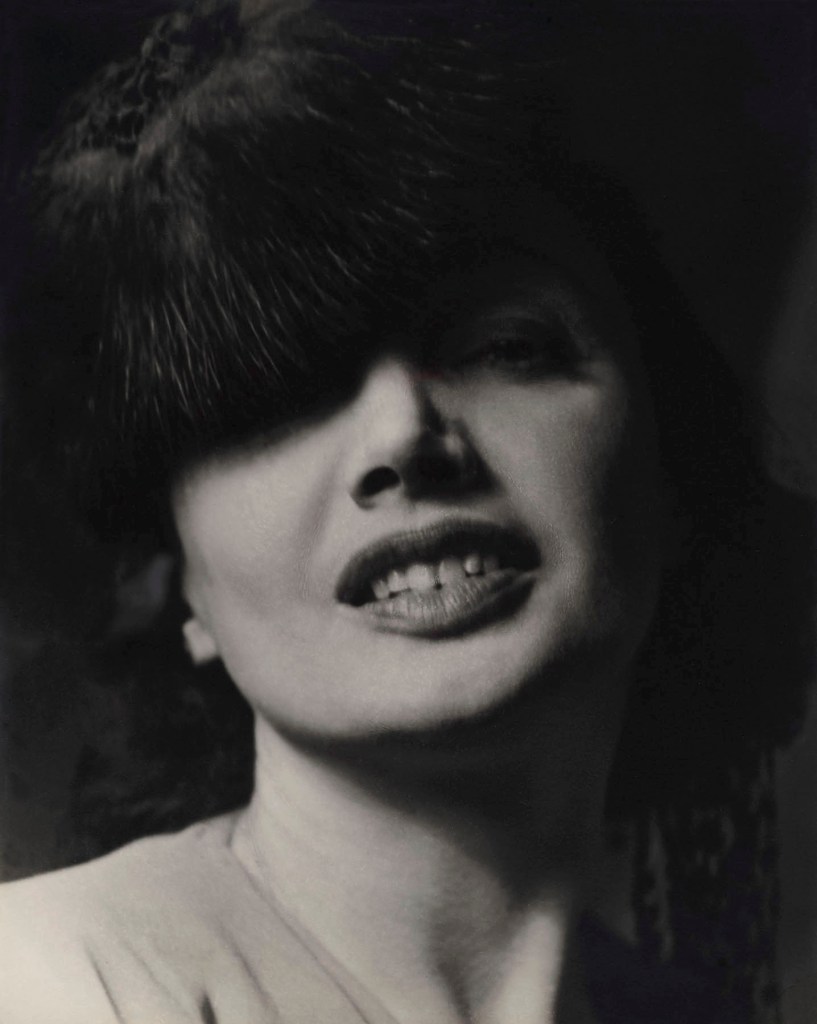

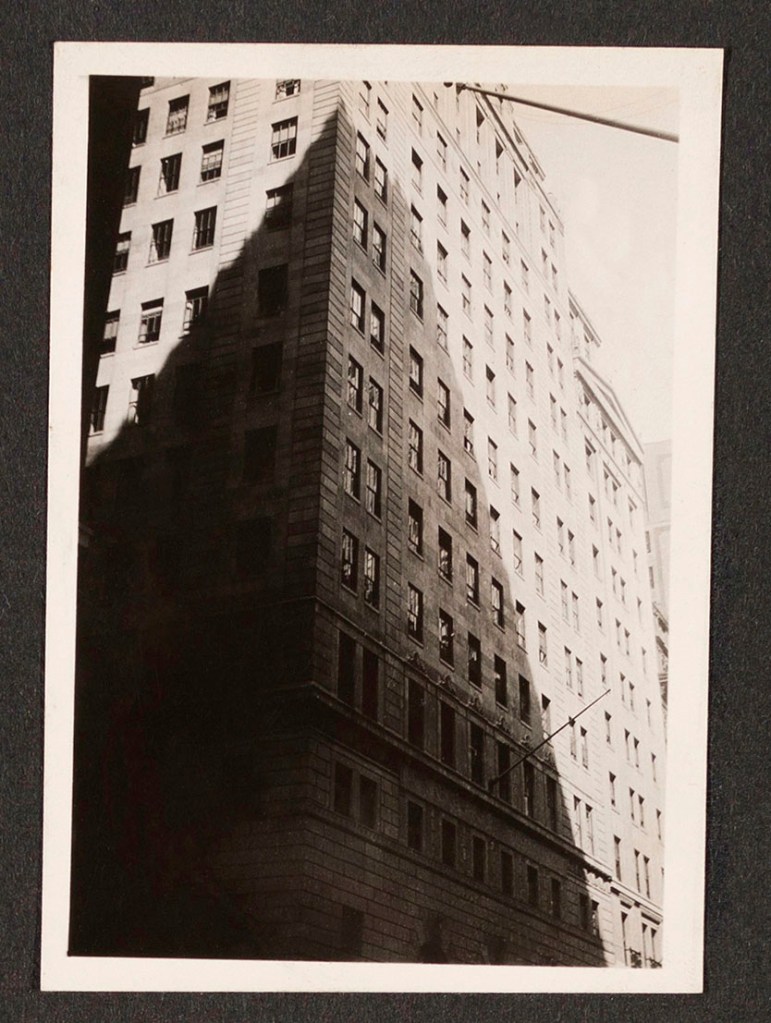

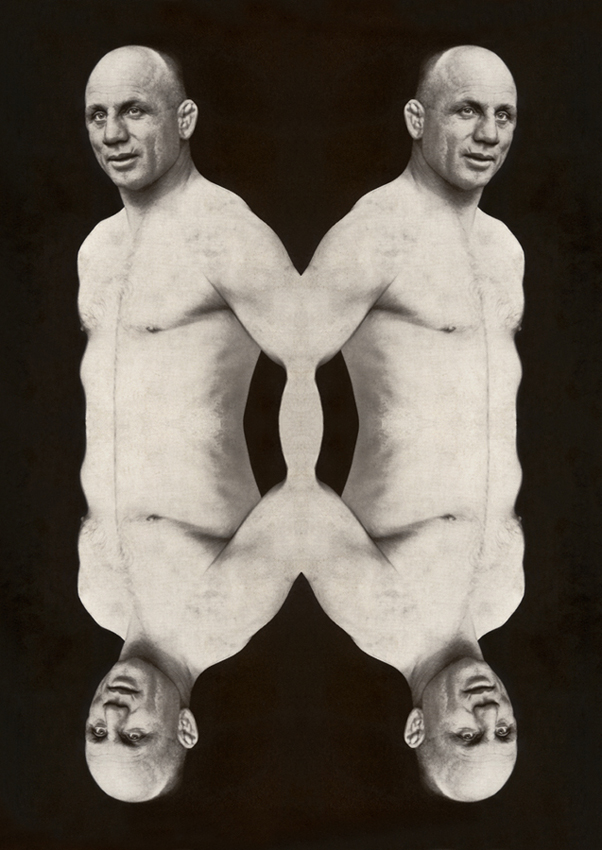

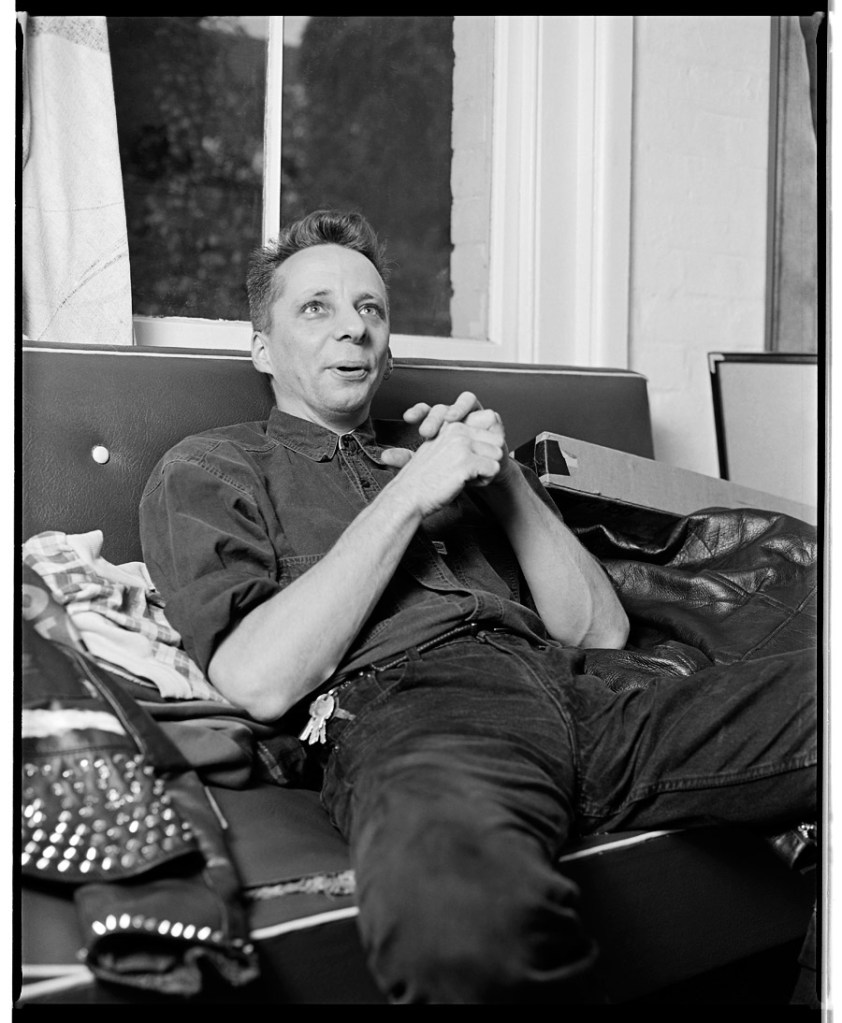

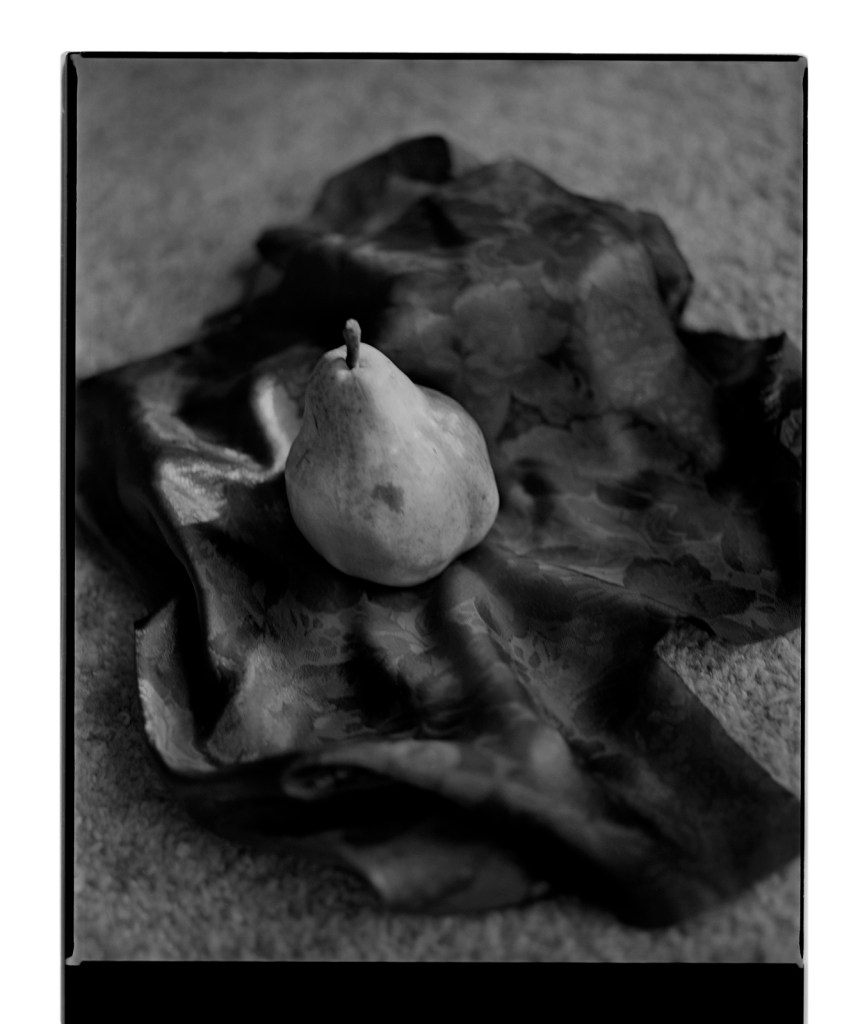

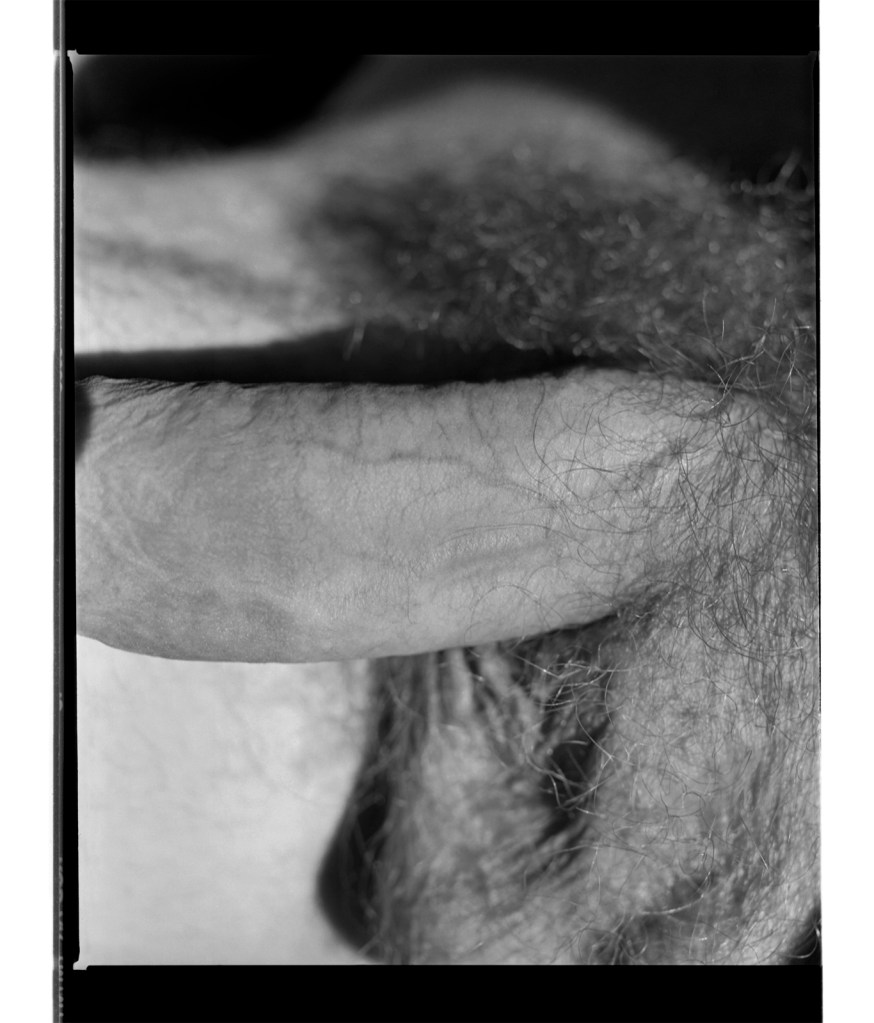

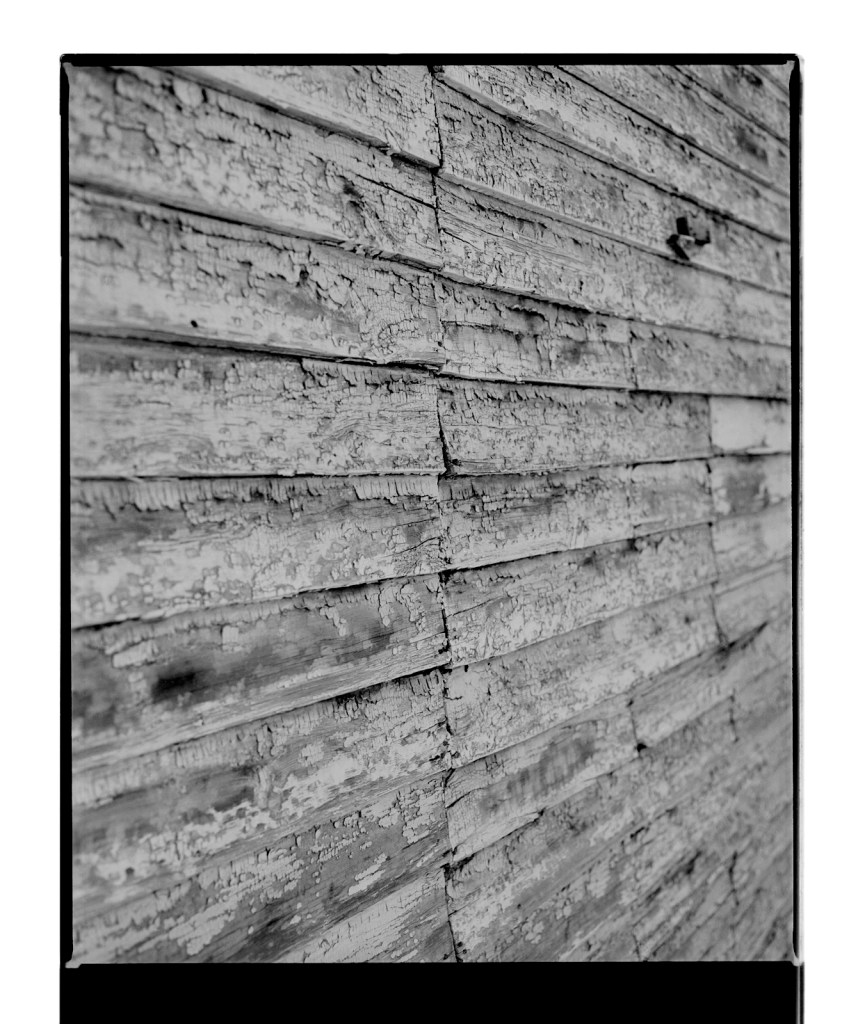

Ilse Salberg (German, 1899-1947)

Anton im Detail (Anton in Detail)

1938

Gelatin silver print

Image: 29.6 x 39.8cm (11 5/8 x 15 11/16 in.)

Frame (outer): 41.3 x 51.3 x 2.7cm (16 1/4 x 20 3/16 x 1 1/16 in.)

Galerie Berinson, Berlin

Ilse Salberg (1899-1947) worked in the New Vision style in Paris and Sanary-sur-Mer. Driven from Cologne, Germany by persecutions, escaping the SS in Barjols, France, she died early of cancer in Switzerland. …

For a long time, Ilse Salberg’s photographs went unnoticed by the public. Most of her photographs from exile in France were lost while fleeing. Fortunately, in 1963 Anton Räderscheidt and his new wife Giséle found paintings and negatives by Ilse Salberg in a cellar in Barjols, which she had to leave behind when she fled to Switzerland.

For more information please see the German Wikipedia website entry

The second of a humungous three-part posting on this archaeological exhibition.

Combined with the posting I did on this exhibition when it was on view at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, this three-part posting will include over 160 new images from the exhibition… meaning a combined total over the four postings of over 200 images with biographical information.

This has been a mammoth effort to construct these postings but so worthwhile!

See Part 1 of the posting. I will make comment on the exhibition in part 3 of the posting.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the National Gallery of Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“[Lee] Miller was the quintessential New Woman, as were the photographers in The New Woman Behind the Camera in New York. Andrea Nelson, who organised the show at its next destination, the National Gallery in Washington, says these new women were independent, competent, and – especially in the 1920s – found themselves in a moment when they were fighting for, then winning the right to vote, “and had really started examining their lives, their marriages and children.” They were also exploring what it meant to be professional photographers. “It was a time when photography was replacing drawings in all the magazines,” says Nelson. And women could sell their advertising and fashion pictures readily.”

Susan Stamberg. “Behind The Lens, These Women Created Photographs That Leap Over Decades,” on the NPR website July 25th, 2021 [Online] Cited 28/11/2021

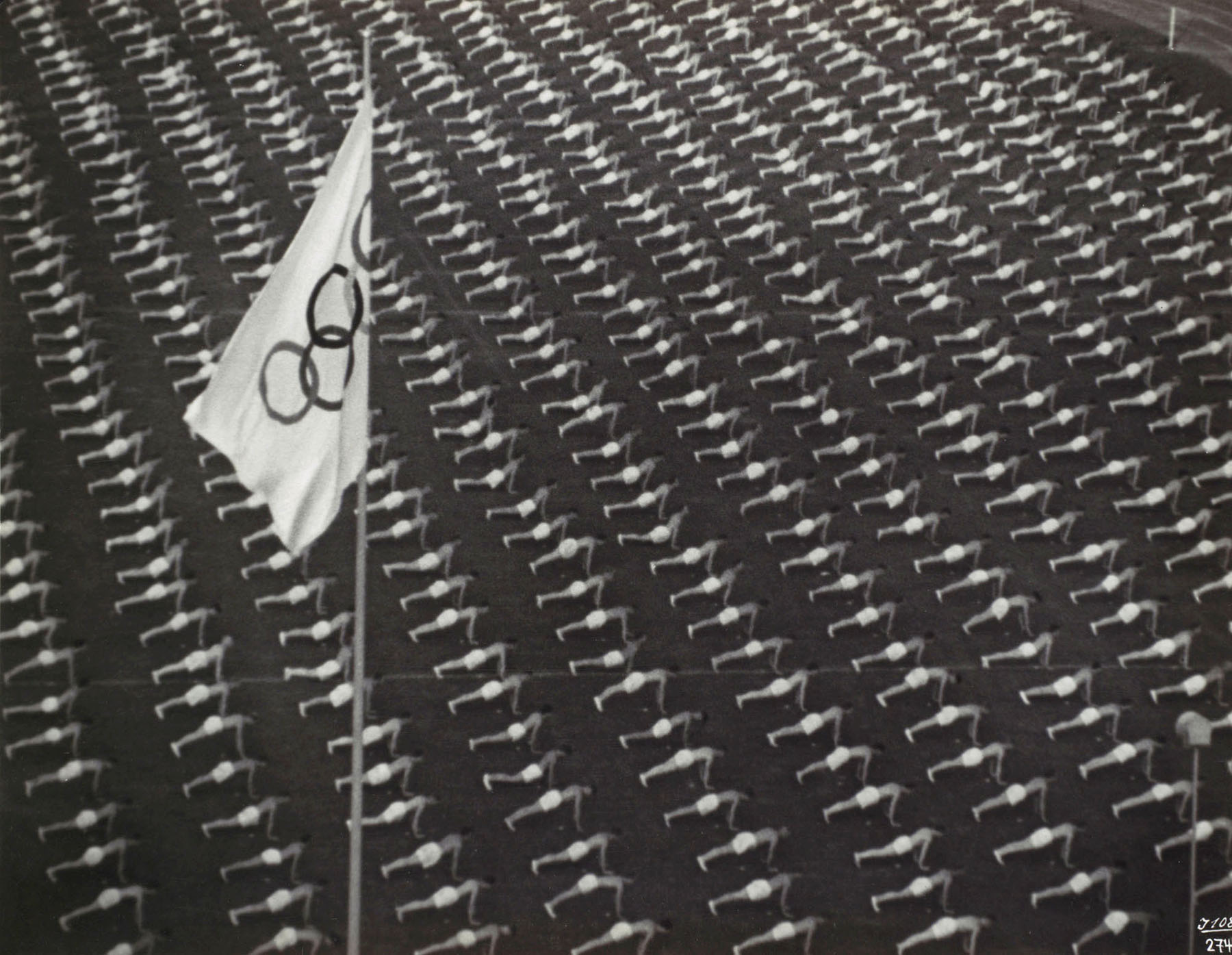

Leni Riefenstahl (German, 1902-2003)

Freiübungen im Stadion, Olympischen Kampf, Berlin (Calisthenics in the Stadium, Olympic Games, Berlin)

1936

Gelatin silver print

Image: 21.8 x 28.2cm (8 9/16 x 11 1/8 in.)

Mount: 29.9 x 36.9cm (11 3/4 x 14 1/2 in.)

Mat: 42.5 x 49.5 cm (16 3/4 x 19 1/2 in.)

Frame (outer): 47.9 x 52.7 cm (18 7/8 x 20 3/4 in.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Ford Motor Company Collection, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell, 1987 bpk / Leni Riefenstahl

Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Art Resource, NY

Helene Bertha Amalie “Leni” Riefenstahl (German, 22 August 1902 – 8 September 2003) was a German film director, photographer, and actress, known for her seminal role in producing Nazi propaganda.

Read a fuller biography on this “fellow traveller” (Mitläufer) on the Wikipedia website

The relentless pursuit of the truth about Riefenstahl. About time.

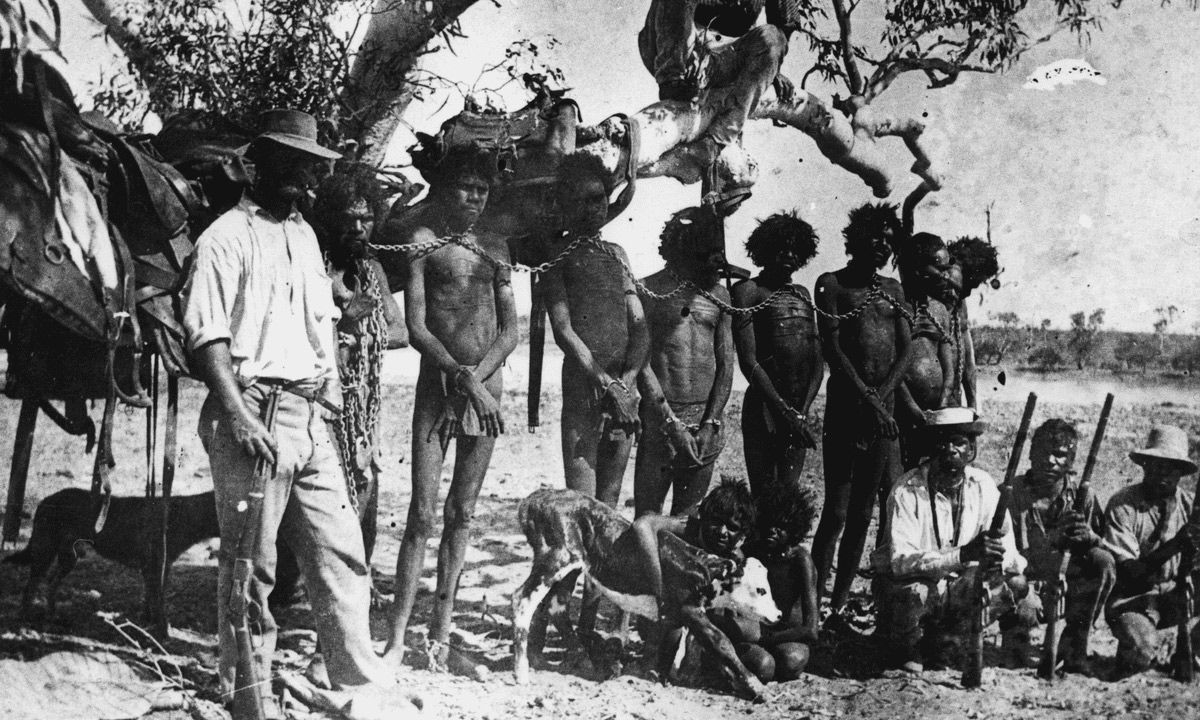

She knew what was going on and hitched her wagon to National Socialism, taking money to make her film Tiefland (Lowlands), bringing in extra from a concentration camp, keeping them in rags and starving them. After filming some were executed in the gas chambers. Her story is similar to that of Albert Speer (Hitler’s architect) who after being released from Spandau prison in 1966 rehabilitated himself by writing books and public speaking about his wartime experiences. Only recently has it come to light that Speer knew all along about the ruthlessness of the Nazi regime and – as Reich Minister of Armaments and War Production (until 2 September 1943 Reich Minister of Armaments and Munitions) – used conscripted labour and prisoners of war in appalling conditions to power the Nazi war effort. Many thousands died as a result of his zeal.

Read the excellent article on The Guardian website about Riefenstahl.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

“Riefenstahl denied that she had visited the camp to handpick the extras, denied failing to pay them and denied having promised and subsequently failed to save them from Auschwitz. She claimed that, while making the film, she had not known of the existence of the gas chambers, nor of the fate of the Roma and Sinti.”

Kate Connolly. “Burying Leni Riefenstahl: one woman’s lifelong crusade against Hitler’s favourite film-maker,” on The Guardian website Thursday 9 December 2021 [Online] Cited 11/12/2021

Vera Jackson (American, 1911-1999)

Man at Printing Press

1940s

Gelatin silver print

Image/sheet: 27.94 x 35.56cm (11 x 14 in.)

Frame: 40.64 x 50.8cm (16 x 20 in.)

Framed (outer): 43.18 x 53.34cm (17 x 21 in.)

Collection of Friends, the Foundation of the California African American Museum. Gift of the artist

Courtesy of the California African American Museum

Vera Jackson (July 21, 1911 – January 26, 1999) was a “pioneer woman photographer in the black press”. She photographed African-American social life and celebrity culture in 1930s and 1940s Los Angeles. Noted photographic subjects included major league baseball player Jackie Robinson, educator Mary McLeod Bethune, and actresses Dorothy Dandridge, Hattie McDaniel and Lena Horne.

Hildegard Rosenthal (Brazilian born Switzerland, 1913-1990)

Ponto de encontro Ladeira Porto Geral, esquina da Rua 25 de Março, São Paulo (Meeting Place Ladeira Porto Geral, Corner of 25 de Março Street, São Paulo)

c. 1940, printed later

Gelatin silver print

Image: 24 x 36cm (9 7/16 x 14 3/16 in.)

Mount: 40 x 50cm (15 3/4 x 19 11/16 in.)

Frame (outer): 42 x 52cm (16 9/16 x 20 1/2 in.)

Instituto Moreira Salles Collection Hildegard Rosenthal / Acervo Instituto Moreira Salles

Hildegard Rosenthal (Brazilian born Switzerland, 1913-1990)

Hildegard Baum Rosenthal (March 25, 1913 – September 16, 1990) was a Swiss-born Brazilian photographer, the first woman photojournalist in Brazil. She was part of the generation of European photographers who emigrated during World War II and, acting in the local press, contributed to the photographic aesthetic renovation of Brazilian newspapers.

Life and career

Rosenthal was born in Zurich, Switzerland. Until her adolescence, she lived in Frankfurt (Germany), where she studied pedagogy from 1929 until 1933. She lived in Paris between 1934 and 1935. Upon her return to Frankfurt, she studied photography for about 18 months in a program led by Paul Wolff [de]. Wolff emphasised small, portable cameras that used 35 mm film. These were a recent innovation at the time, and could be used unobtrusively for street photography. She also studied photographic laboratory techniques at the Gaedel Institute.

In this same period, she had entered a relationship with Walter Rosenthal. Rosenthal was Jewish, and Jews were increasingly persecuted in Germany in the 1930s under the National Socialist (Nazi) regime that took power in 1933. Walter Rosenthal emigrated to Brazil in 1936. Hildegard joined him in São Paulo in 1937. That same year she began working as a laboratory supervisor at the Kosmos photographic materials and services company. A few months later, the agency Press Information hired her as a photojournalist and she did news reports for national and international newspapers. During this period, she took photographs of the city of São Paulo and the state countryside of Rio de Janeiro and other cities in southern Brazil, as well as portraying several personalities from the São Paulo cultural scene, such as the painter Lasar Segall, the writers Guilherme de Almeida and Jorge Amado, the humorist Aparicio Torelly (Barão de Itararé) and the cartoonist Belmonte. Her images sought to capture the artist at his moment of creation, in obvious connection with his spirit of reporter. She interrupted her professional activity in 1948, after the birth of her first daughter. And in 1959, after her husband died, she took over the management of her family’s company.

Artistic trajectory

Her photographs remained little known until 1974, when art historian Walter Zanini held a retrospective of her work at the Museum of Contemporary Art of the University of São Paulo. The following year the Museum of Image and Sound of São Paulo (MIS) was opened with the exhibition Memória Paulistana, by Rosenthal. In 1996 the Instituto Moreira Salles acquired more than 3,000 of her negatives, in which urban scenes of São Paulo from the 1930s and 1940s stood out, during which time the city underwent a vertiginous growth, both material and cultural. Other negatives were donated by her during her life to the Lasar Segall Museum.

“Photography without people does not interest me,” she said at the Museum of Image and Sound of São Paulo in 1981.

Text from the Wikipedia website

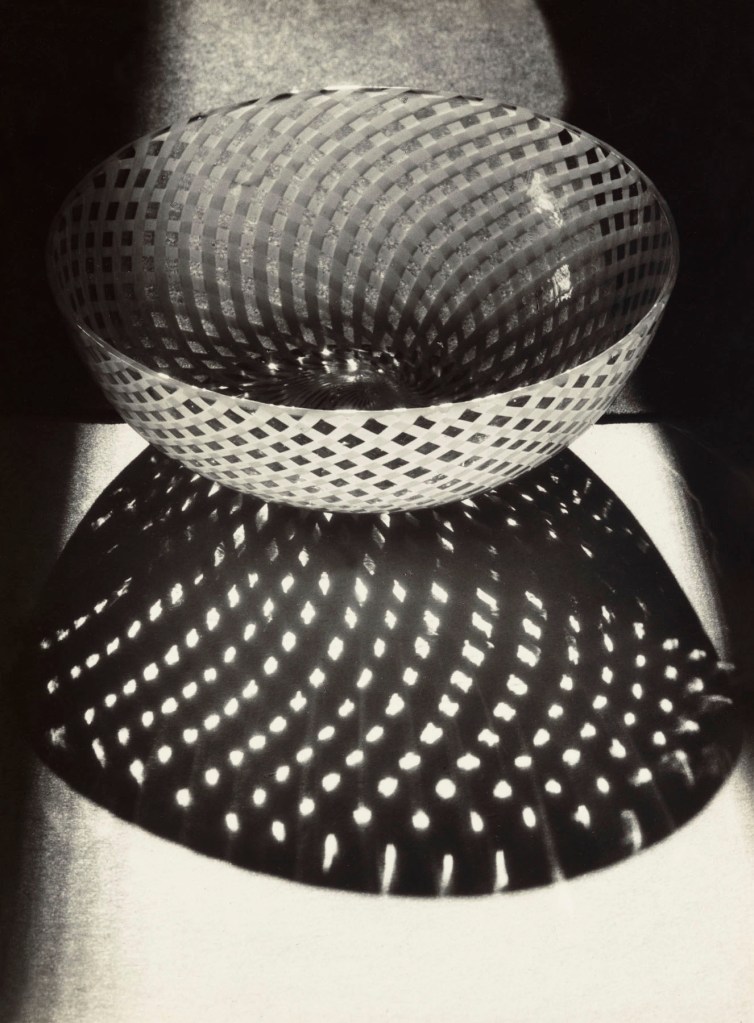

Liselotte Grschebina (Israeli born Germany, 1908-1994)

Arbeiterin, Primazon GmbH, Netanya (Worker, Primazon Ltd., Netanya)

c. 1937

Gelatin silver print

Image: 16.8 x 22.7cm (6 5/8 x 8 15/16 in.)

Frame (outer): 38.4 x 46cm (15 1/8 x 18 1/8 in.)

The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, Gift of Beni and Rina Gjebin, Shoham, Israel, with the assistance of Rachel and Dov Gottesman, Tel Aviv and London

Photo: Liselotte Grschebina

© The Israel Museum, Jerusalem

Liselotte Grschebina (Israeli born Germany, 1908-1994)

Liselotte Grschebina (or Grjebina; 1908-1994) was an Israeli photographer. …

In January 1932 Grschebina opens Bilfoto, her own studio, announcing her specialisation in child photography, and takes on students. In 1933, following the Nazis come to power and the restrictions on professional freedom for Jews, Grschebina closed her studio. Before leaving Germany, she marries Dr. Jacob (Jasha) Grschebin. …

The Grschebin couple reaches Tel Aviv in March 1934. The same year, Grschebina opens the Ishon studio on Allenby Street with her friend Ellen Rosenberg (Auerbach), previously a partner in the Berlin photographic studio ringl + pit. In 1936 the Ishon studio is closed when Rosenberg leaves the country; Grschebina continues to work from her home.

Style

Grschebina arrived in Palestine in 1934, a trained professional profoundly influenced by the revolutionary movements of the Weimar Republic: New Objectivity in painting and New Vision in photography, as well as by a number of prominent professors, including Karl Hubbuch and Wilhelm Schnarrenberger. Unlike many of her colleagues in Palestine, who sought their identities in the collective Zionist endeavour by documenting and extolling it in their work, Grschebina did not use photography as a means of forming her identity. She came with a full-fledged style and remained committed to Weimar artistic ideals and principles in her new home, where she continued to apply and develop them. … Grschebina’s artistic roots clearly lay in New Vision, which defined photography as an artistic field in its own right and called on camera artists to portray subjects in a new, different way to convey their unique qualities and their essence. She did this through striking vantage points and strong diagonals, making masterful use of mirrors, reflections, and plays of light and shadow to create geometric shapes and to endow her photographs with atmosphere, appeal, and meaning.

In Germany, most of her photographs – usually advertising commissions – were taken in the studio. In the land of Israel, she also worked outdoors, observing those around her with a clear, impartial eye. She photographed people going about their daily routine, unaffected by the presence of the camera. The viewer of her pictures feels like an outsider looking in, gaining a new, objective perspective on the subject: the “objective portrait … not encumbered with subjective intention” wherein, according to New Vision photographer László Moholy-Nagy, lies the genius of photography.

Legacy

The photographs of Liselotte Grschebina, rediscovered casually, almost miraculously, in a cupboard in Tel Aviv, reveal a talent that might otherwise have remained forgotten.

The archive of Liselotte Grschebina’s photographs were given to the Israel Museum by her son, Beni Gjebin and his wife Rina, from Shoham, with the assistance of Rachel and Dov Gottesman, the museum president between 2001 and 2011.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Liselotte Grschebina (Israeli born Germany, 1908-1994)

Hebräische Wassermelone (Hebrew Watermelon)

c. 1935

Gelatin silver print

Image: 22.7 x 29cm (8 15/16 x 11 7/16 in.)

Frame (outer): 43.5 x 53.8cm (17 1/8 x 21 3/16 in.)

The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, Gift of Beni and Rina Gjebin, Shoham, Israel, with the assistance of Rachel and Dov Gottesman, Tel Aviv and London Photo Liselotte Grschebina

© The Israel Museum, Jerusalem

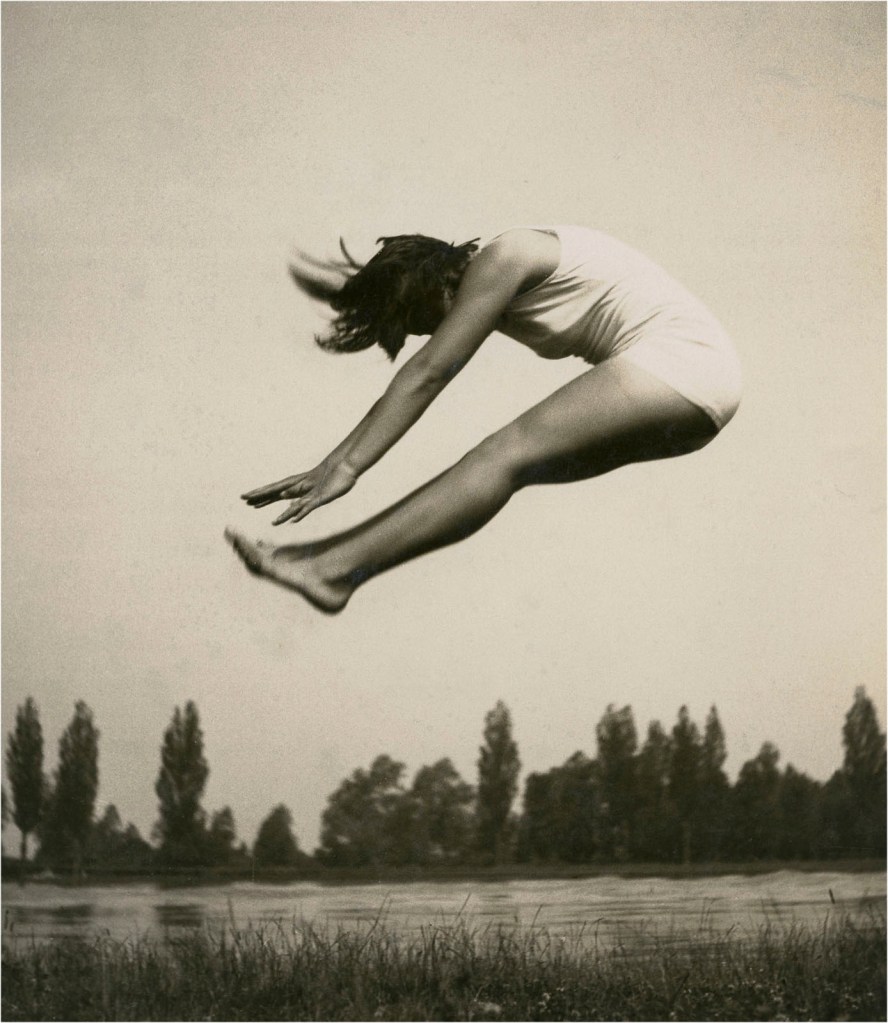

Liselotte Grschebina (Israeli born Germany, 1908-1994)

Turnerin (Gymnast)

1930

Gelatin silver print

Image: 23.5 x 17.5cm (9 1/4 x 6 7/8 in.)

Frame (outer): 46 x 38.4cm (18 1/8 x 15 1/8 in.)

The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, Gift of Beni and Rina Gjebin, Shoham, Israel, with the assistance of Rachel and Dov Gottesman, Tel Aviv and London

Photo: Liselotte Grschebina

© The Israel Museum, Jerusalem

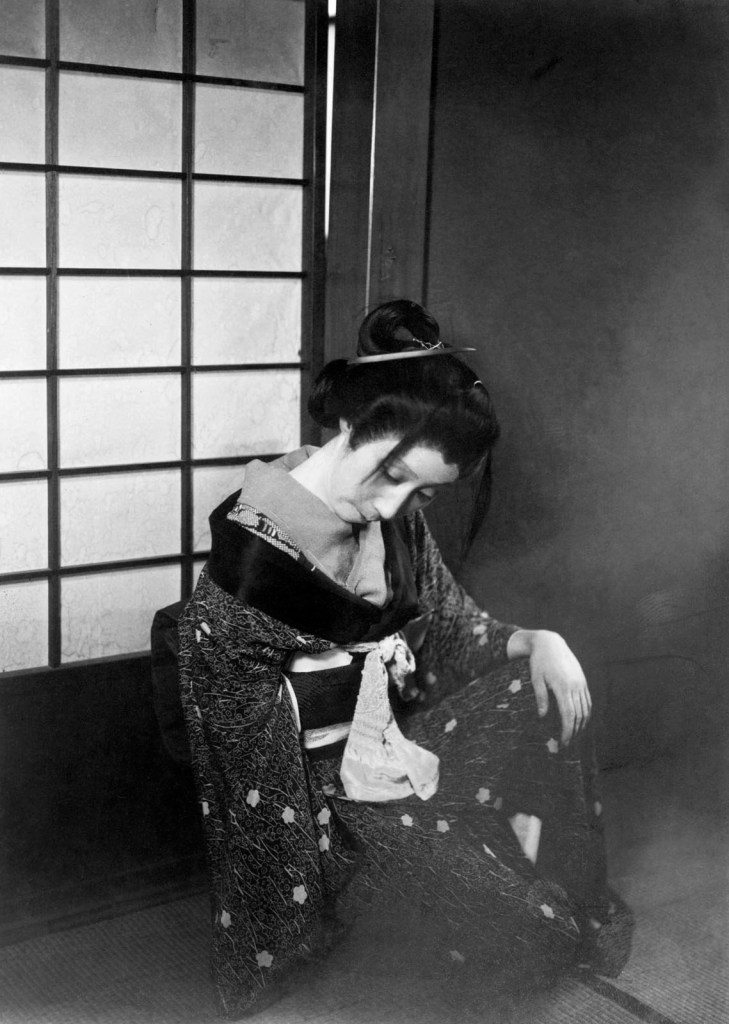

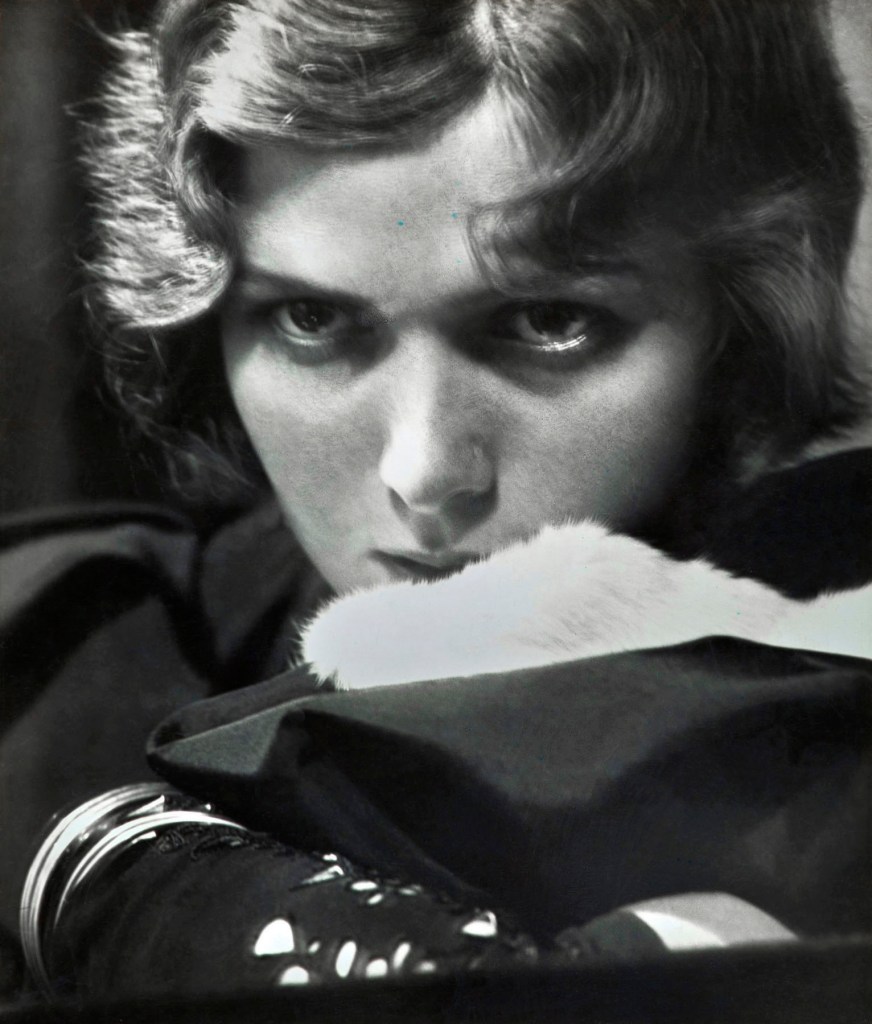

Eiko Yamazawa (Japanese, 1899-1995)

(Untitled (Yasue Yamamoto as Okichi in “Elegy for a Woman” by Yuzo Yamamoto))

c. 1943-1944, printed 1944

Gelatin silver print

Image: 15 x 10.5cm (5 7/8 x 4 1/8 in.)

Mat: 50.8 x 40.64cm (20 x 16 in.)

Frame (outer): 54.61 x 44.45cm (21 1/2 x 17 1/2 in.)

Tomoka Aya, The Third Gallery Aya

© Yamazawa Eiko

Eiko Yamazawa (Japanese, 1899-1995)

Eiko Yamazawa (山沢 栄子, Yamazawa Eiko, February 19, 1899 – July 16, 1995) was a renowned Japanese photographer. She is considered one of Japan’s earliest women photographers and is among the few women photographers in Japan who were active both before and after World War II. First trained in Nihonga, she later studied photography in the U.S. under the mentorship of Consuelo Kanaga, and also exposed to the work of Kanaga’s contemporaries such as Paul Strand and Edward Weston.

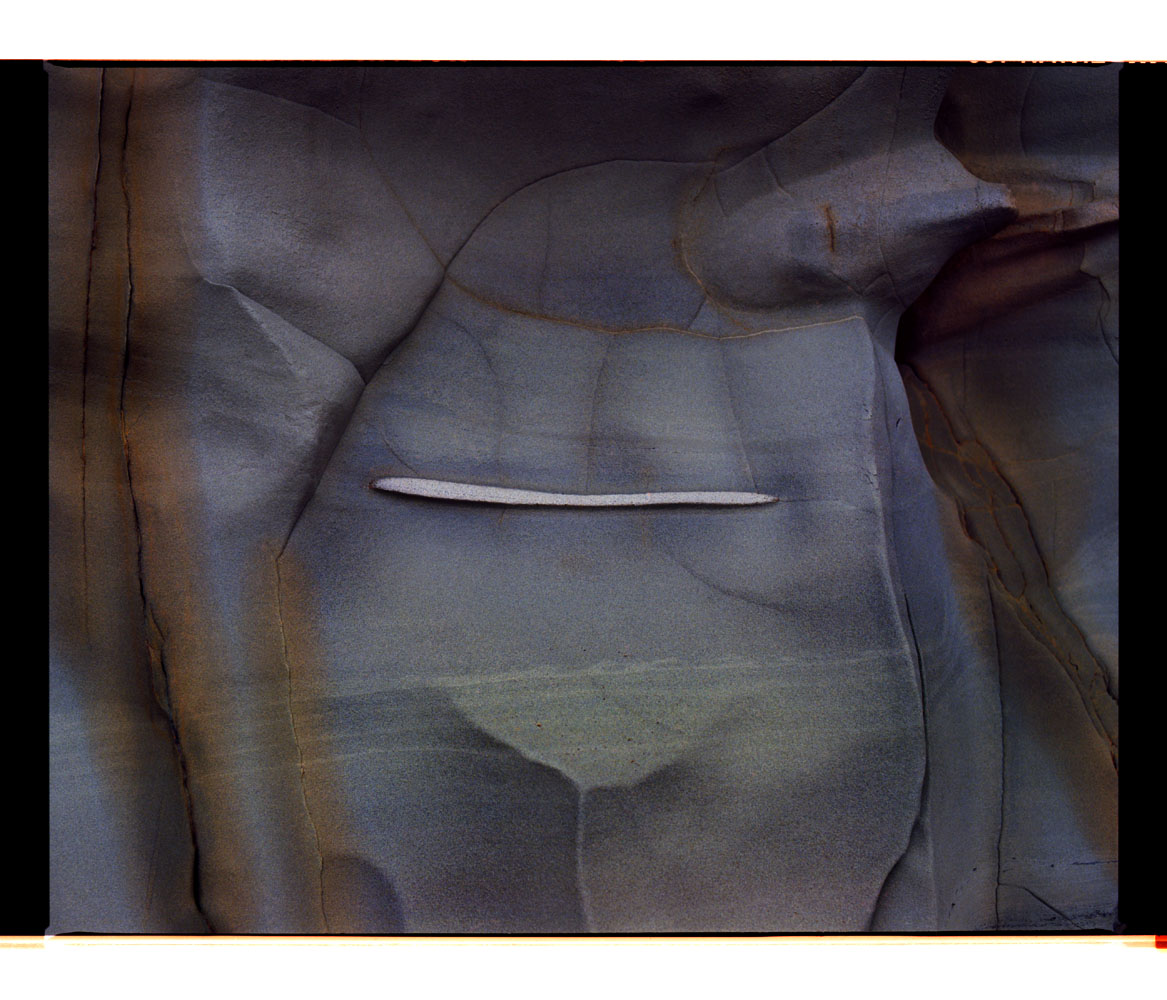

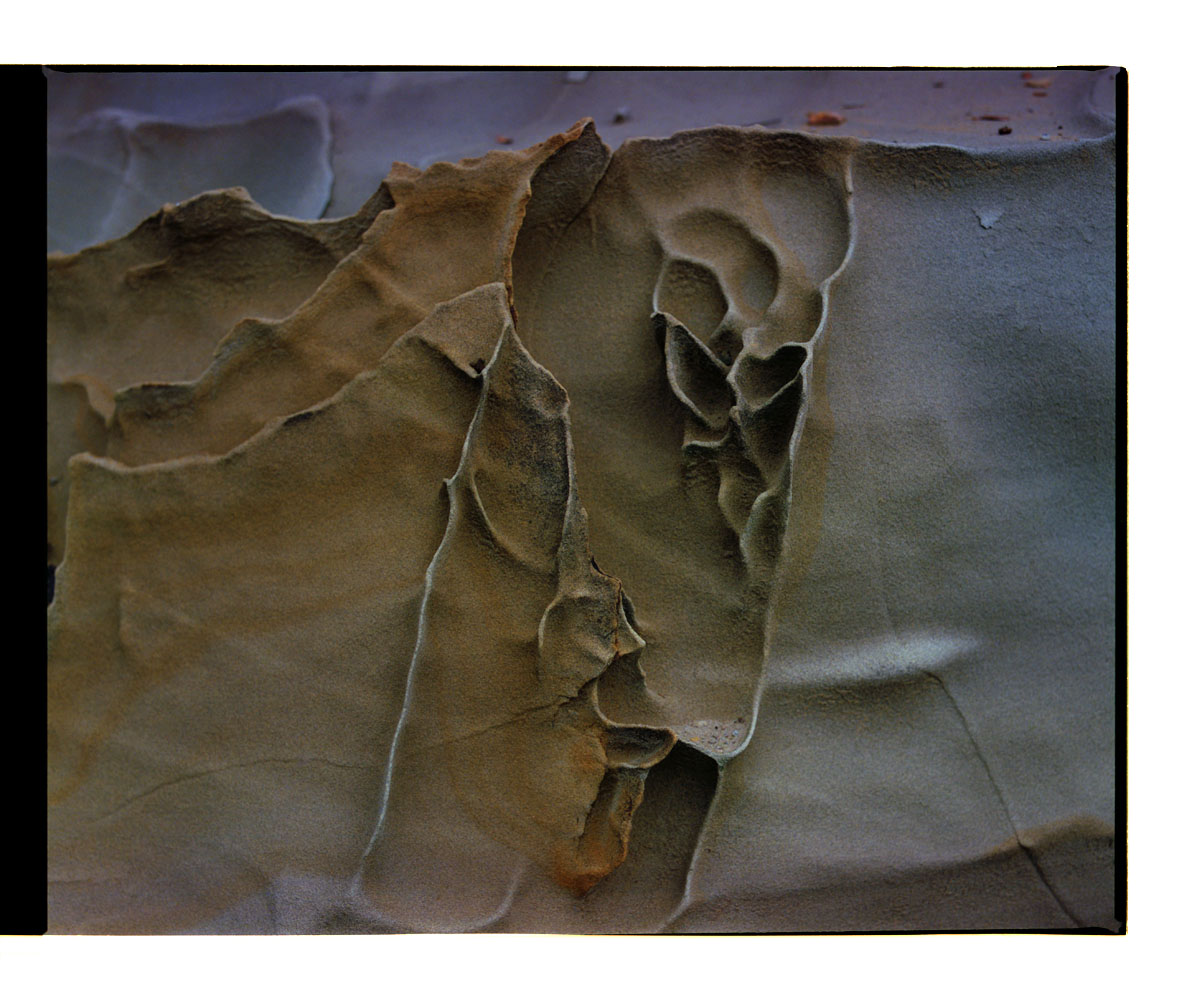

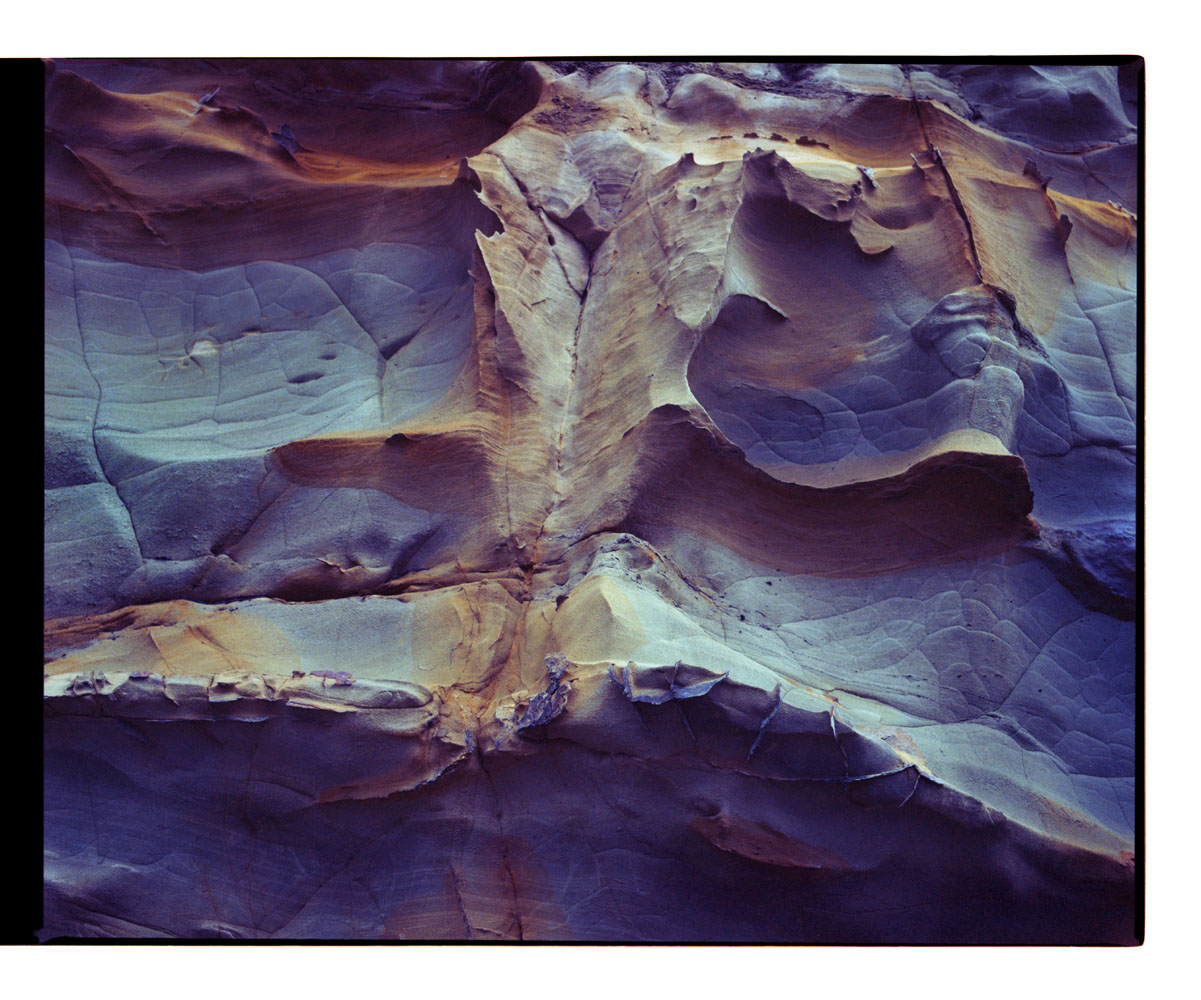

After coming back to Japan in 1929, she established herself as a professional photographer. In 1931 she opened a portrait studio in Osaka, and in 1950 she established the Yamazawa Institute of Photography also in Osaka. In the early half of her career, Yamazawa was engaged in portraiture and commercial photography, having produced work for major Osaka department stores. In 1960 she shifted abstraction away from realism. Her work in this latter half of her career is characterised by her photographing art materials in distortion and reflection. Yamazawa’s photographs were unique at the time for their use of vibrant colour, which was in stark contrast to black and white photography championed by other Japanese photographers.

Read a fuller biography on the Wikipedia website

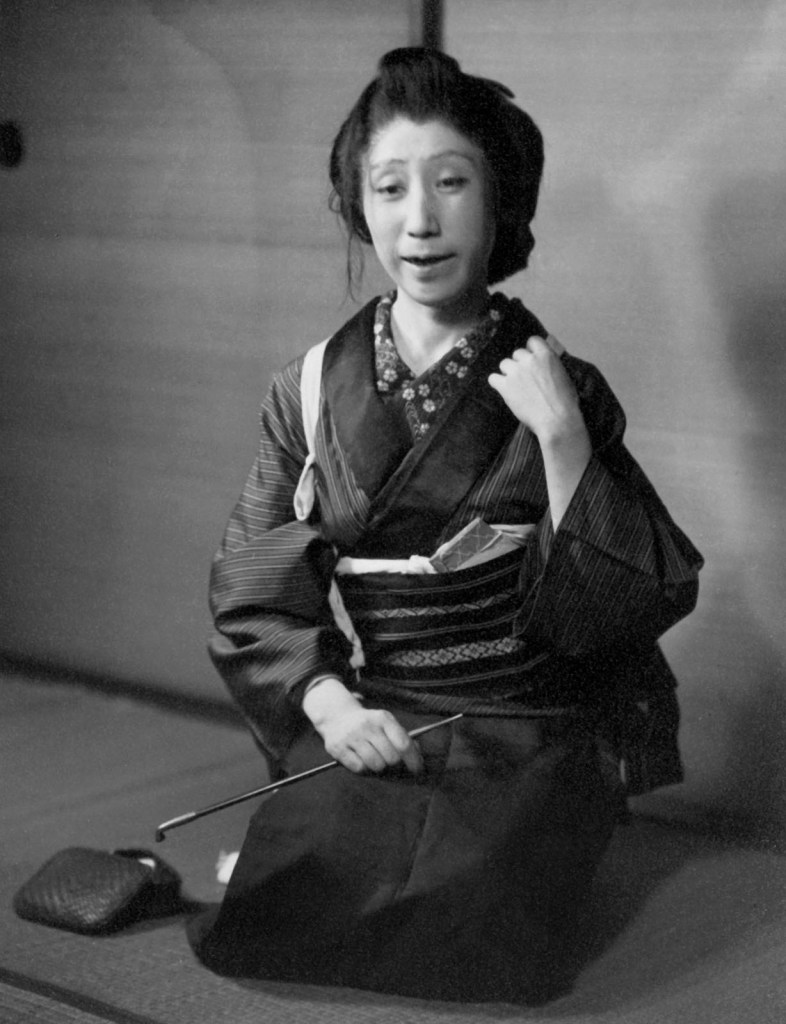

Eiko Yamazawa (Japanese, 1899-1995)

(Untitled (Yasue Yamamoto as Okichi in “Elegy for a Woman” by Yuzo Yamamoto))

c. 1943-1944, printed 1944

Gelatin silver print

Image: 15 x 10.5cm (5 7/8 x 4 1/8 in.)

Mat: 50.8 x 40.64cm (20 x 16 in.)

Frame (outer): 54.61 x 44.45cm (21 1/2 x 17 1/2 in.)

Tomoka Aya, The Third Gallery Aya

© Yamazawa Eiko

Eiko Yamazawa (Japanese, 1899-1995)

(Untitled (Yasue Yamamoto as Okichi in “Elegy for a Woman” by Yuzo Yamamoto))

c. 1943-1944, printed 1944

Gelatin silver print

Image: 15 x 10.5cm (5 7/8 x 4 1/8 in.)

Mat: 50.8 x 40.64cm (20 x 16 in.)

Frame (outer): 54.61 x 44.45cm (21 1/2 x 17 1/2 in.)

Tomoka Aya, The Third Gallery Aya

© Yamazawa Eiko

Yamamoto Yasue (Japanese 山 本 安 英, actually Yamamoto Chiyo (山 本 千代); born October 29, 1906 in Tōkyō ; died December 29, 1993 there) was a Japanese actress.

Yamamoto Yasue attended from 1921 the “School for modern theater training for women” (現代 劇 女優 養成 所, Gendaigeki joyū yōseijo), which was directed by Ichikawa Sadanji II (二世 市 川 左 団 次; 1880-1940). In 1924 she became a founding member of the “Small Theater Tsukiji” (築 地 小 劇 所) directed by Osanai Kaoru and played the leading role in 67 productions. After Osanai’s death in 1928, Yamamoto and Hijikata Yoshi (1998-1959) founded the “New Tsukiji Theater Company” (新 築 地 劇 団, Shin Tsukiji gekidan). Until the end of the Pacific War, she also took part in radio broadcasts.

In 1951 the Ministry of Culture honored Yamamoto for her role as Tsū in Kinoshita Junji’s internationally acclaimed play “Yūzuru” (夕 鶴), “Crane in the Twilight” [A1] , which had been performed since 1949. In 1966 she founded the “Yasue no kai” (安 英 の 会) to research recitation in contemporary pieces. Yamamoto had a unique presence on stage and a sophisticated way of speaking. In 1974 she was awarded the Asahi Prize and in 1984 the Mainichi Art Prize.

Eiko Yamazawa (Japanese, 1899-1995)

Yūzō Yamamoto (山本 有三, Yamamoto Yūzō, July 27, 1887 – January 11, 1974) was a Japanese novelist and playwright. His real name was written as “山本 勇造” but pronounced the same as his pen name. He was born to a family of kimono makers in Tochigi-city, Tochigi Prefecture.

He studied German literature at Tokyo Imperial University. After graduating, he gained popularity for his solidly crafted plays, some twenty in all, notably Professor Tsumura (Tsumura kyōju, 1919), The Crown of Life (生命の冠, Inochi no kanmuri, 1920), Infanticide (Eijigoroshi, 1920), and People Who Agree (同志の人々, Dōshi no hitobito, 1923). In 1926 he turned to novels, known for their clarity of expression and dramatic composition. Later, with the writers Kan Kikuchi and Ryūnosuke Akutagawa, he helped to co-found the Japanese Writer’s Association and openly criticised Japan’s wartime military government for its censorship policies.

After World War II he joined the debate on Japanese language reform, and from 1947 to 1953 he served in the National Diet as a member of the House of Councillors. He is well known for his opposition to the use of enigmatic expressions in written Japanese and his advocacy for the limited use of furigana [a Japanese reading aid]. In 1965 he was awarded the prestigious Order of Culture. He died at his summer villa in Yugawara, Kanagawa in 1974.

Yamamoto’s large European-style house in Mitaka, Tokyo, was expropriated by the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers by eminent domain during the occupation period from 1945 to 1953. The mansion was then used as an archive and research lab by non-profit organisations for years, until it was converted into the Mitaka City Yūzō Yamamoto Memorial Museum in 1996. There is also a museum dedicated to him in his hometown of Tochigi.

Text from the Wikipedia website

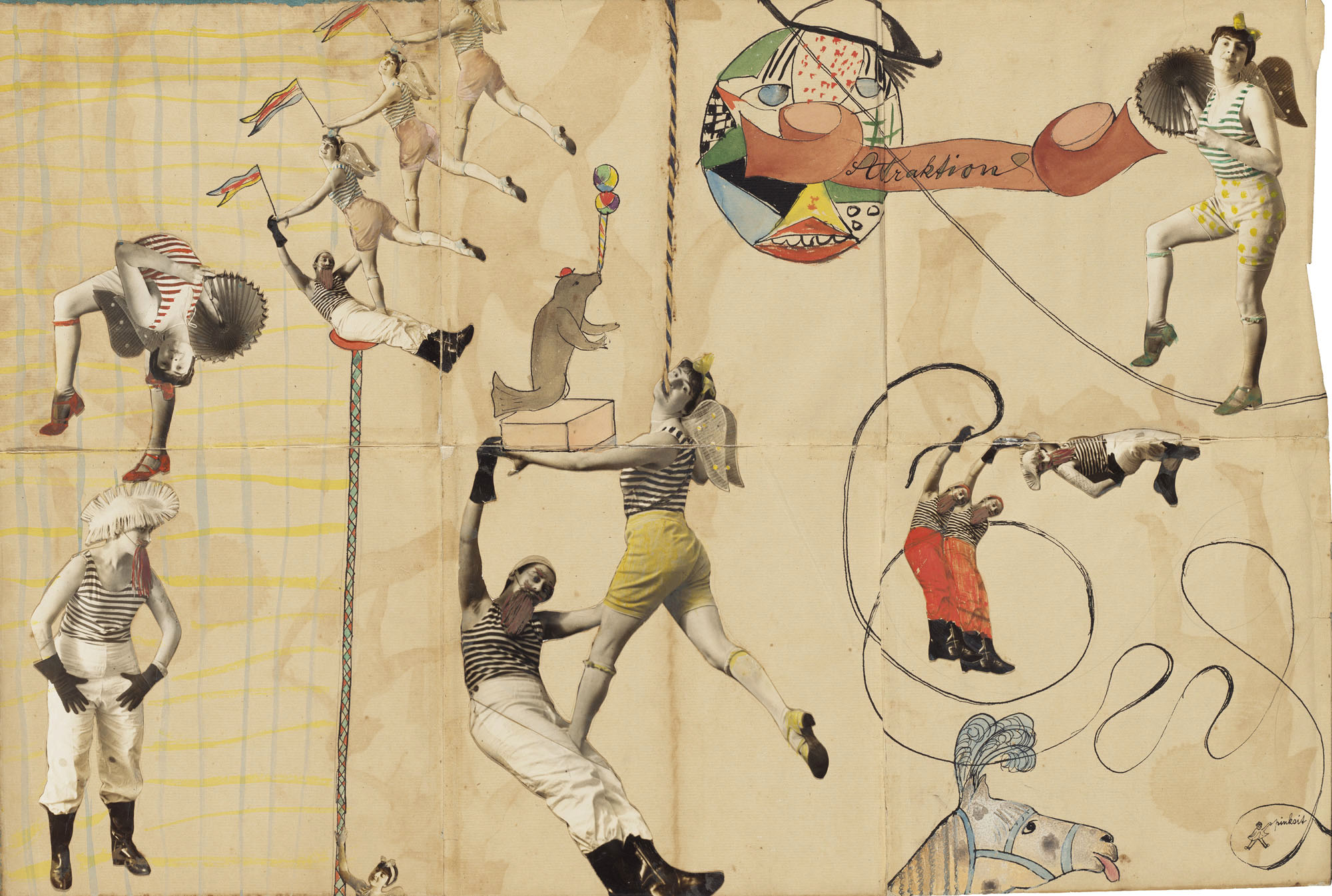

Valentina Kulagina (Russian, 1902-1987)

A. Tarasov-Rodionov’s “October”

1930

Book cover maquette with collage of cut-and-pasted gelatin silver prints, gouache, and ink on paper

Overall: 20.7 x 31.2cm (8 1/8 x 12 1/4 in.)

Frame: 40.64 x 50.8cm (16 x 20 in.)

Frame (outer): 43.18 x 53.34cm (17 x 21 in.)

Collection Merrill C. Berman

Valentina Kulagina, full name Valentina Nikiforovna Kulagina-Klutsis (Russian: Валентина Никифоровна Кулагина-Клуцис, 1902-1987) was a Russian painter and book, poster, and exhibition designer. She was a central figure in Constructivist avant-garde in the early 20th century alongside El Lissitzky, Alexander Rodchenko other and her husband Gustav Klutsis. She is known for the Soviet revolutionary and Stalinist propaganda she produced in collaboration with Klutsis.

Read a fuller biography on the Wikipedia website

Elizaveta Ignatovich (Russian, 1903-1983)

The struggle for the polytechnical school is the struggle for the five-year plan, for the communist education about class consciousness

1931

Photolithograph

Sheet: 51.4 x 72.1cm (20 1/4 x 28 3/8 in.)

Frame: 66.04 x 86.36cm (26 x 34 in.)

Collection Merrill C. Berman

Elizaveta Ignatovich (Russian, 1903-1983)

Elizaveta Ignatovich (1903-1983) was born in Moscow, and was a well-regarded photographer and photojournalist of the 1920s through 1940s. In 1929, Elizaveta joined the experimental October organisation with such artists as Alexander Rodchenko, Elizar Langman, Dmitry Debabov, and her husband Boris Ignatovich. After October disbanded, she joined the Ignatovich Brigade along with her husband; her sister-in-law, Olga; Elizar Langman; J. Brodsky and L. Bach.

Elizaveta participated in many photographic exhibitions in the 1930s both in the Soviet Union and abroad including the seminal 1937 exhibition, First all-Union Exhibition of Soviet Photographic Art. While a prolific photographer of her day, Elizaveta’s photographs are now distinguished for their rarity. Among her photographs are Family of Kolkhoz Farmer, Portrait of Pioneer Leader Galina Pogrebniak, The Worker Tatiana Surina, and At the Kokhoz’s 10 Year Anniversary. By 1940, having gained a reputation as a veteran of documentary art photography, Sovetskoe Foto (1940, no. 3, “Zhenshchiny-fotoreportery”) wrote on Elizaveta:

“She is captivated by the fast-paced developments and the colourfulness of our lives, and she knows how to present it in a new fashion with the eyes of an artist. Her work is opposed to posturing and artificiality; as well as to the flashiness in formalist scholasticism.

Overall, E. Ignatovich tends to analyse every component of the scene before taking the shot. For this reason, she is attracted to creating monumental work and to constructing the scene. And E. Ignatovich truly succeeds in creating these scenes. A rich characterisation of her subjects and an artistic integrity distinguish her work.”

The writer for Sovetskoe Foto underscores Ignatovich’s ability to breath life into her subjects by manifesting their histories and personalities on film. In Family of Kolzhoz Farmer, Ignatovich creates an elaborate scene framed compositionally by tasseled curtains. Occupied by their tasks, Ignatovich’s subjects reveal their dynamic as a tight-knit Soviet family, and suggest their own personalities and concerns.

Later in her career, Ignatovich worked creating commercial photographic albums and post cards for the art publishing house Izogiz and the art journal Iskusstvo. In 1956, she received a silver medal and diploma at the Fifth International Salon of Art Photography (see Power of Pictures, 2015, p. 223) in Paris.

In 2015, E. Ignatovich’s artwork was included in the acclaimed exhibition The Power of Pictures: Early Soviet Photography, Early Soviet Film at the Jewish Museum in New York.

Anonymous text. “Elizaveta Ignatovich,” on the Nailya Alexander Gallery website [Online] Cited 28/11/2021. No longer available online

Elizaveta Ignatovich (Russian, 1903-1983)

Family of a Kolkhoz Farmer

1930s

Gelatin silver print

Overall: 40.64 x 27.94cm (16 x 11 in.)

Frame: 60.96 x 45.72cm (24 x 18 in.)

Frame (outer): 64.77 x 49.53cm (25 1/2 x 19 1/2 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred H. Moses and Fern M. Schad Fund

© Elizaveta Ignatovich

Courtesy of Nailya Alexander Gallery, New York

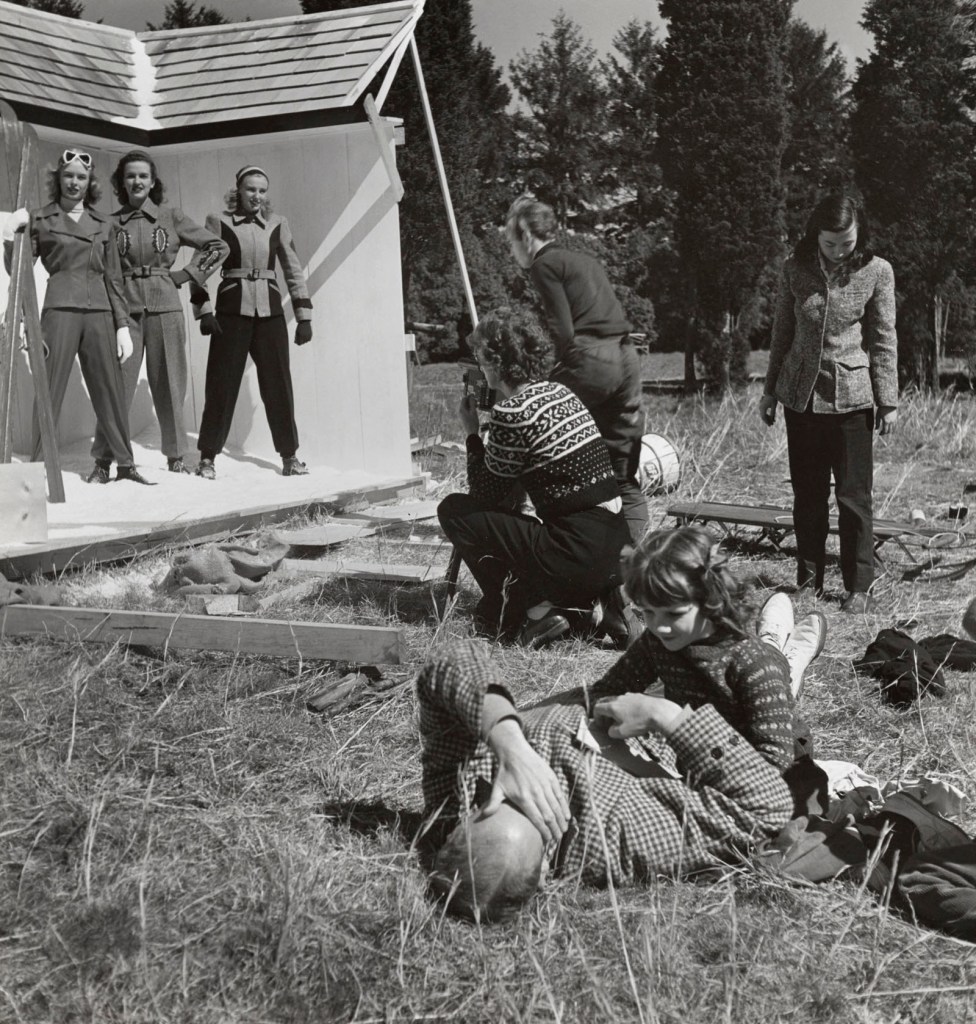

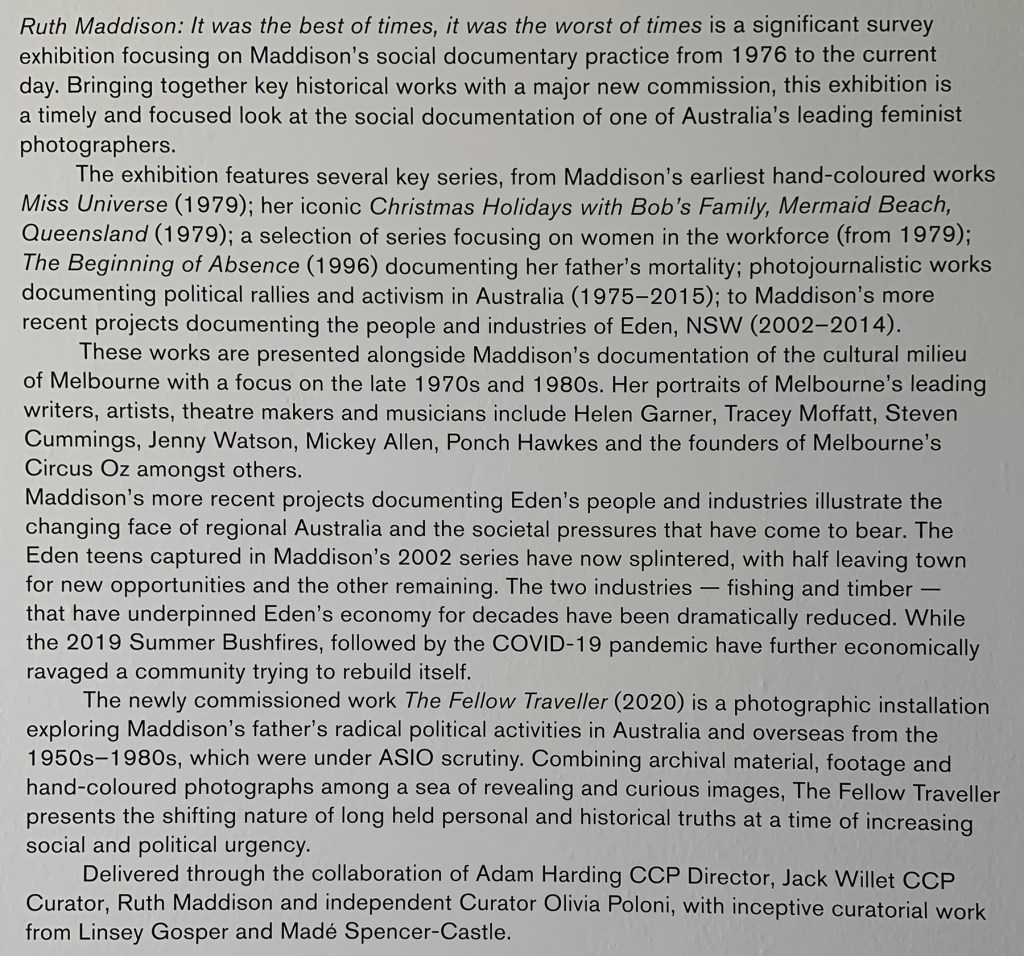

During the 1920s, the iconic New Woman was splashed across the pages of magazines and projected on the silver screen. As a global phenomenon, she embodied an ideal of female empowerment based on real women making revolutionary changes in life and art. Featuring more than 120 photographers from over 20 countries, the groundbreaking exhibition, The New Woman Behind the Camera, explores the diverse “new” women who embraced photography as a mode of professional and personal expression from the 1920s to the 1950s. The first exhibition to take an international approach to the subject, it examines how women brought their own perspectives to artistic experimentation, studio portraiture, fashion and advertising work, scenes of urban life, ethnography, and photojournalism, profoundly shaping the medium during a time of tremendous social and political change. Accompanied by a fully illustrated catalogue, this landmark exhibition will be on view from October 31, 2021 through January 30, 2022, in the West Building of the National Gallery of Art, Washington. It was previously on view at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, from July 2 through October 3, 2021.

In an era when traditional definitions of womanhood were being questioned, women’s lives were a mix of emancipating and confining experiences that varied by country. Many women around the world found the camera to be a means of independence as they sought to redefine their positions in society and expand their rights. This exhibition presents a geographically, culturally, and artistically diverse range of practitioners to advance new conversations about the history of modern photography and the continual struggle of women to gain creative agency and self-representation.

“This innovative exhibition reevaluates the history of modern photography through the lens of the New Woman, a feminist ideal that emerged at the end of the 19th century and spread globally during the first half of the 20th century,” said Kaywin Feldman, director, National Gallery of Art. “The transnational realities of modernism visualised in photography by women such as Lola Álvarez Bravo, Berenice Abbott, Claude Cahun, Germaine Krull, Dorothea Lange, Niu Weiyu, Tsuneko Sasamoto, and Homai Vyarawalla offer us an opportunity to better understand the present by becoming more fully informed of the past.”

About the exhibition

This landmark exhibition critically examines the extraordinary impact women had on the practice of photography worldwide from the 1920s to the 1950s. It presents the work of over 120 international photographers who took part in a dramatic expansion of the medium propelled by artistic creativity, technological innovation, and the rise of the printed press. Photographers such as Berenice Abbott, Ilse Bing, Lola Álvarez Bravo, Madame d’Ora, Florence Henri, Elizaveta Ignatovich, Germaine Krull, Dorothea Lange, Dora Maar, Niu Weiyu, Eslanda Goode Robeson, Tsuneko Sasamoto, Gerda Taro, and Homai Vyarawalla, among many others, emerged at a tumultuous moment in history that was profoundly shaped by two world wars, a global economic depression, struggles for decolonisation, and the rise of fascism and communism. Against the odds, these women were at the forefront of experimentation with the camera and produced invaluable visual testimony that reflects both their personal experiences and the extraordinary social and political transformations of the era.

Organised thematically in eight galleries, The New Woman Behind the Camera illustrates women’s groundbreaking work in modern photography, exploring their innovations in the fields of social documentary, avant-garde experimentation, commercial studio practice, photojournalism, ethnography, and the recording of sports, dance, and fashion. By evoking the global phenomenon of the New Woman, the exhibition seeks to reevaluate the history of photography and advance new and more inclusive conversations on the contributions of female photographers.

Known by different names, from nouvelle femme and neue Frau to modan gāru and xin nüxing, the New Woman was easy to recognise but hard to define. Fashionably dressed with her hair bobbed, the self-assured cosmopolitan New Woman was arguably more than a marketable image. She was a contested symbol of liberation from traditional gender roles. Revealing how women photographers from around the world gave rise to and embodied the quintessential New Woman even as they critiqued the popular construction of the role, the exhibition opens with a group of compelling portraits and self-portraits. In these works, women defined their positions as professionals and artists during a time when they were seeking greater personal rights and freedoms.

For many women, the camera became an effective tool for self-determination as well as a source of income. With better access to education and a newfound independence, female photographers emerged as a major force in studio photography. From running successful businesses in Berlin, Buenos Aires, London, and Vienna, to earning recognition as one of the first professional female photographers in their home country, women around the world, including Karimeh Abbud, Steffi Brandl, Trude Fleischmann, Annemarie Heinrich, Eiko Yamazawa, and Madame Yevonde, reinvigorated studio practice. A collaborative space where both sitters and photographers negotiated gender, race, and cultural difference, the portrait studio was also vitally important to African American communities which sought to represent and define themselves within a society that continued to be plagued by racism. Photography studios run by Black women, such as Florestine Perrault Collins and Winifred Hall Allen, thrived throughout the United States, and not only preserved likenesses and memories, but also constructed a counter narrative to the stereotyping images that circulated in the mass media.

With the invention of smaller lightweight cameras, a growing number of women photographers found that the camera’s portability created new avenues of discovery outside the studio. In stunning photographs of the city, photographers such as Alice Brill, Rebecca Lepkoff, Helen Levitt, Lisette Model, Genevieve Naylor, and Tazue Satō Matsunaga used their artistic vision to capture the exhilarating modern world around them. They depicted everyday life, spontaneous encounters on the street, and soaring architectural views in places like Bombay (now Mumbai), New York, Paris, São Paulo, and Tokyo, revealing the multiplicity of urban experience. Many incorporated the newest photographic techniques to convey the energy of the city, and the exhibition continues with a gallery focused on those radical formal approaches that came to define modern photography. Through techniques like photomontage, photograms, sharp contrasts of light and shadow, extreme cropping, and dizzying camera angles, women including Aenne Biermann, Imogen Cunningham, Dora Maar, Tina Modotti, Lucia Moholy, and Cami Stone pushed the boundaries of the medium.

Women also produced dynamic pictures of the modern body, including innovative nude studies as well as sport and dance photography. Around the world, participation in spectator and team sports increased along with membership in fitness and hygiene reform movements. New concepts concerning health and sexuality along with new attitudes in movement and dress emphasised the body as a central site of experiencing modernity. On view are luminous works by photographers Laure Albin Guillot, Yvonne Chevalier, Florence Henri, and Jeanne Mandello who reimagined the traditional genre of the nude. Photographs by Irene Bayer-Hecht and Liselotte Grschebina highlight joyous play and gymnastic exercise, while Charlotte Rudolph, Ilse Bing, Trude Fleischmann, and Lotte Jacobi made breathtaking images of dancers in motion, revealing the body as artistic medium.

During the modern period, a growing number of women pursued professional photographic careers and traveled widely for the first time. Many took photographs that documented their experiences abroad and interactions with other cultures as they engaged in formal and informal ethnographic projects. The exhibition continues with a selection of photographs and photobooks by women, mainly from Europe and the United States, that reveal a diversity of perspectives and approaches. Gender provided some of these photographers with unusual access and the drive to challenge discriminatory practices, while others were not exempt from portraying stereotypical views. Publications by Jette Bang, Hélène Hoppenot, Ella Maillart, Anna Riwkin, Eslanda Goode Robeson, and Ellen Thorbecke exemplify how photographically illustrated books and magazines were an influential form of communication about travel and ethnography during the modern period. Other works on display include those by Denise Bellon and Ré Soupault, who traveled to foreign countries on assignment for magazines and photo agencies seeking ethnographic and newsworthy photographs, and those by Marjorie Content and Laura Gilpin, who worked on their own in the southwestern United States.

The New Woman – both as a mass-circulating image and as a social phenomenon – was confirmed by the explosion of photographs found in popular fashion and lifestyle magazines. Fashion and advertising photography allowed many women to gain unprecedented access to the public sphere, establish relative economic independence, and attain autonomous professional success. Producing a rich visual language where events and ideas were expressed directly in pictures, illustrated fashion magazines such as Die Dame, Harper’s Bazaar, and Vogue became an important venue for photographic experimentation by women for a female readership. Photographers producing original views of women’s modernity include Lillian Bassman, Ilse Bing, Louise Dahl-Wolfe, Toni Frissell, Toni von Horn, Frances McLaughlin-Gill, ringl + pit, Margaret Watkins, Caroline Whiting Fellows, and Yva.

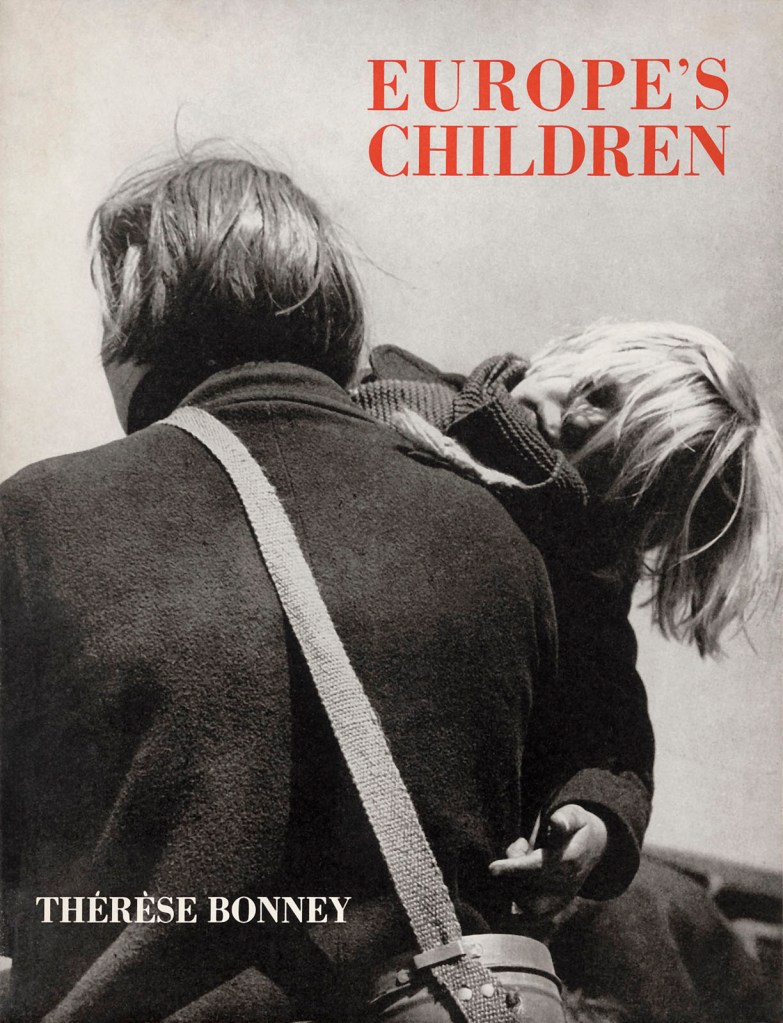

The rise of the picture press also established photojournalism and social documentary as dominant forms of visual expression during the modern period. Ignited by the effects of a global economic crisis and growing political and social unrest, numerous women photographers including Lucy Ashjian, Margaret Bourke-White, Kati Horna, Elizaveta Ignatovich, Kata Kálmán, Dorothea Lange, and Hansel Mieth engaged a wide public with gripping images. So-called soft topics such as “women and children,” “the family,” and “the home front” were more often assigned to female photojournalists than to their male counterparts. The exhibition asks viewers to question the effect of having women behind the camera in these settings. Pictures produced during the war, from combat photography by Galina Sanko and Gerda Taro to images of the Blitz in London by Thérèse Bonney and the Tuskegee airmen by Toni Frissell, are also featured. At the war’s end, haunting images by Lee Miller of the opening of Nazi concentration camps and celebratory images of the victory parade of Allied Forces in New Delhi by Homai Vyarawalla made way for the transition to the complexities of the postwar era, including images of daily life in US-occupied Japan by Tsuneko Sasamoto and the newly formed People’s Republic of China by Hou Bo and Niu Weiyu.

The New Woman Behind the Camera acknowledges that women are a diverse group whose identities are defined not exclusively by gender but rather by a host of variable factors. It contends that gender is an important aspect in understanding their lives and work and provides a useful framework for analysis to reveal how photography by women has powerfully shaped our understanding of modern life.

Exhibition catalog

Published by the National Gallery of Art, Washington and distributed by DelMonico Books | D.A.P., this groundbreaking, richly illustrated 288-page catalog examines the diverse women whose work profoundly marked the medium of photography from the 1920s to the 1950s. The book – featuring over 120 international photographers, including Lola Álvarez Bravo, Elizaveta Ignatovich, Germaine Krull, Dorothea Lange, Tsuneko Sasamoto, and Homai Vyarawalla – reevaluates the history of modern photography through the lens of the iconic New Woman. Inclusive scholarly essays introduce readers to these important photographers and question the past assumptions about gender in the history of photography. Contributors include Andrea Nelson, associate curator in the department of photographs, National Gallery of Art; Elizabeth Cronin, assistant curator of photography in the Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints, and Photographs, New York Public Library; Mia Fineman, curator in the department of photographs, Metropolitan Museum of Art; Mila Ganeva, professor of German in the department of German, Russian, Asian, and Middle Eastern languages and cultures, Miami University, Ohio; Kristen Gresh, Estrellita and Yousuf Karsh Senior Curator of Photographs, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Elizabeth Otto, professor of modern and contemporary art history, University at Buffalo (The State University of New York); and Kim Sichel, associate professor in the department of the history of art and architecture at Boston University; biographies of the photographers by Kara Felt, Andrew W. Mellon postdoctoral fellow in the department of photographs, National Gallery of Art.

Press release from the National Gallery of Art

Ella Maillart (Swiss, 1903-1997)

Turkistan Solo

1935

Bound volume

Open: 21.59 x 22.86cm (8 1/2 x 9 in.)

Cradle: 12.07 x 27.31 x 22.54cm (4 3/4 x 10 3/4 x 8 7/8 in.)

National Gallery of Art Library, Gift of the Department of Photographs

Ella Maillart (Swiss, 1903-1997)

Ella Maillart (or Ella K. Maillart; 20 February 1903, Geneva – 27 March 1997, Chandolin) was a Swiss adventurer, travel writer and photographer, as well as a sportswoman.

Career

From the 1930s onwards she spent years exploring Muslim republics of the USSR, as well as other parts of Asia, and published a rich series of books which, just as her photographs, are today considered valuable historical testimonies. Her early books were written in French but later she began to write in English. Turkestan Solo describes a journey in 1932 in Soviet Turkestan. Photos from this journey are now displayed in the Ella Maillart wing of the Karakol Historical Museum. In 1934, the French daily Le Petit Parisien sent her to Manchuria to report on the situation under the Japanese occupation. It was there that she met Peter Fleming, a well-known writer and correspondent of The Times, with whom she would team up to cross China from Peking to Srinagar (3,500 miles), much of the route being through hostile desert regions and steep Himalayan passes. The journey started in February 1935 and took seven months to complete, involving travel by train, on lorries, on foot, horse and camelback. Their objective was to ascertain what was happening in Xinjiang (then also known as Sinkiang or Chinese Turkestan) where the Kumul Rebellion had just ended. Maillart and Fleming met the Hui Muslim forces of General Ma Hushan. Ella Maillart later recorded this trek in her book Forbidden Journey, while Peter Fleming’s parallel account is found in his News from Tartary. In 1937 Maillart returned to Asia for Le Petit Parisien to report on Afghanistan, Iran and Turkey, while in 1939 she undertook a trip from Geneva to Kabul by car, in the company of the Swiss writer, Annemarie Schwarzenbach. The Cruel Way is the title of Maillart’s book about this experience, cut short by the outbreak of the second World War.

She spent the war years at Tiruvannamalai in the South of India, learning from different teachers about Advaita Vedanta, one of the schools of Hindu philosophy. On her return to Switzerland in 1945, she lived in Geneva and at Chandolin, a mountain village in the Swiss Alps. She continued to ski until late in life and last returned to Tibet in 1986.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Ellen Thorbecke (Dutch, 1902-1973)

People in China: Thirty-Two Photographic Studies from Life

1935

Bound volume

Closed: 30.48 x 22.86cm (12 x 9 in.)

Open: 29.85 x 43.18cm (11 3/4 x 17 in.)

Cradle: 13.97 x 40.64 x 30.48cm (5 1/2 x 16 x 12 in.)

National Gallery of Art Library, David K.E. Bruce Fund

Ellen Thorbecke (Dutch, 1902-1973)

(Ellen Thorbecke, born Ellen Kolban, 1902-1973) is a woman who holds a unique position in Dutch photography. Her small yet extraordinary photo archive, one of the Nederlands Fotomuseum Collection’s true gems, shows rare images of everyday life in China during that era. She photographed with an open mind and as a result Ellen Thorbecke’s images are still relevant and immensely popular in China today.

Compelling photographer

In 1931, Ellen Thorbecke left Berlin for China to be reunited with her beloved husband Willem Thorbecke, who had been appointed as an envoy in China on behalf of the Netherlands. Before she left for China, she bought her first camera, as she was planning to work in China as a correspondent for the Berlin newspapers. To illustrate her articles, she captured a series of portraits and street scenes in the Chinese countryside and in the cities of Beijing, Shanghai and Hong Kong. This was during the era when the idea of ‘East Meets West’ was gaining ground and a number of Western writers, filmmakers and artists were shining the spotlight on China.

Being a journalist from origin, Thorbecke gradually developed into a compelling photographer who infused her photographs with fully-engaged observation of the people and places she visited. The exhibition Ellen Thorbecke’s China presents photographs that capture the changing identity of the young Chinese Republic between centuries-old traditions and Western modernisation. Her images range from those that refer to traditional Chinese role patterns – such as arranged marriages at a young age – to modern portraits showing the desire for freedom and independence.

Anonymous text. “Ellen Thorbecke’s China,” on the Nederlands Fotomuseum website [Online] Cited 29/11/2021. No longer available online

Photographer and journalist Ellen Thorbecke (born Ellen Kolban, 1902-1973) occupies a unique and forgotten position in the photography world. In 1931 she left Berlin for Beijing. For this trip she bought her first camera. Thorbecke developed into a compelling photographer who provided her photos with engaged observations about the people and places she visited. She made reports in a lively candid style with an eye for the vitality of street life and has produced several photo books including Peking Studies (1934) and People in China (1935).

Her visual stories and travel guides make her oeuvre a unique time document. Her compact but special photo archive is held at the Dutch Fotomuseum in Rotterdam and consists of 638 black and white negatives, 166 of which were made in China. The photographs Thorbecke made are still relevant today because of her human, direct and unbiased way of looking.

Anonymous text. “Ellen Thorbecke,” on the Photography of China website [Online] Cited 29/11/2021

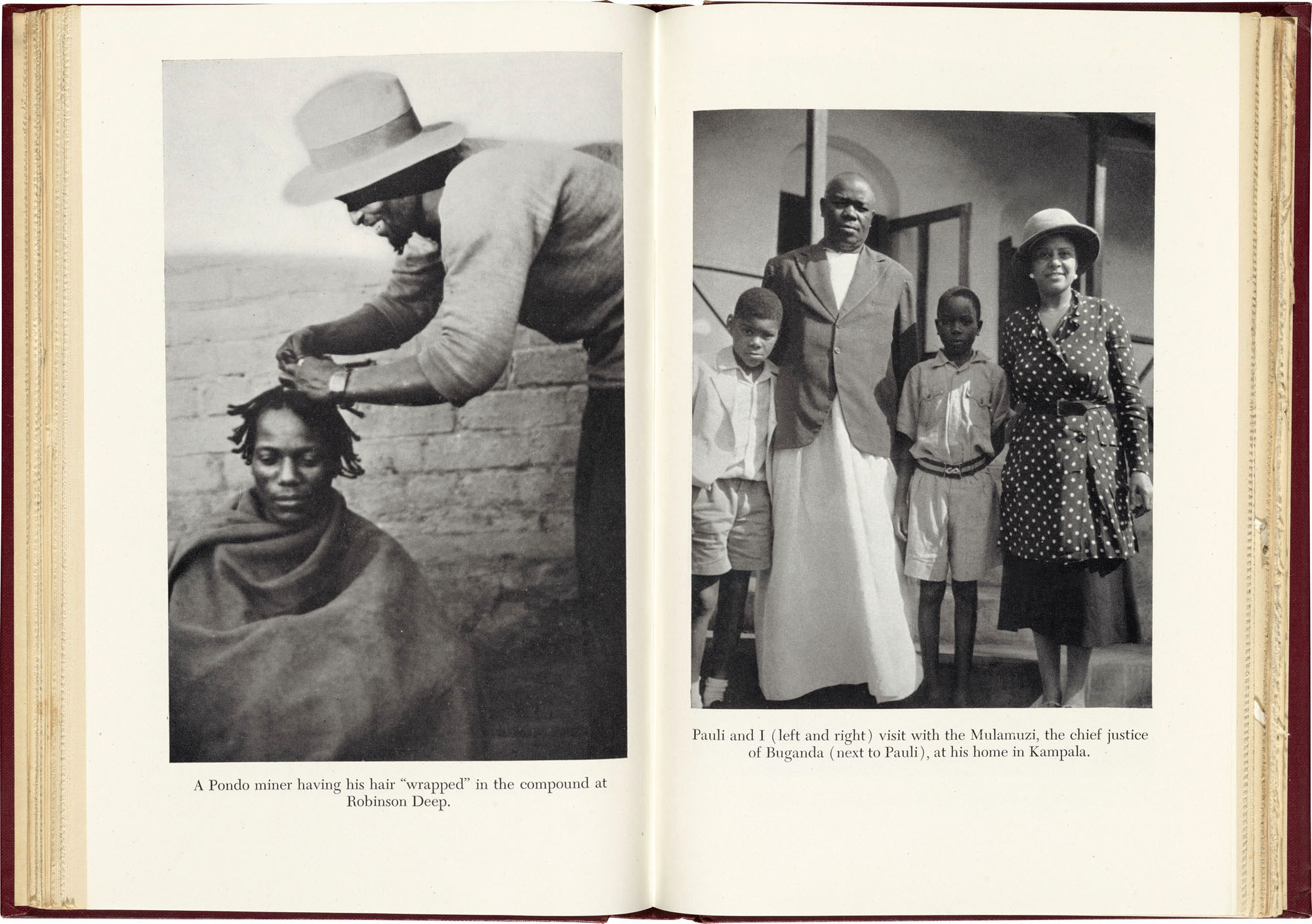

Eslanda Goode Robeson (American, 1896-1965)

African Journey

1945

Bound volume

Open: 21.59 x 31.75cm (8 1/2 x 12 1/2 in.)

Mount: 3.49 x 31.27 x 21.75cm (1 3/8 x 12 5/16 x 8 9/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art Library, Gift of the Department of Photographs

Eslanda Goode Robeson (American, 1896-1965)

Eslanda Cardozo Goode Robeson (American, 1896-1965), “Essie,” as she was called, was a photographer, actress, world traveler, author and activist

Born Eslanda Cardoza Goode in Washington, D.C., in 1896, “Essie,” as she was known by her intimates, was the wife of the dynamic performer and activist Paul Robeson. Although not as well known as her famous husband, Eslanda Robeson by no means hid in his shadow. Through her writings and actions, she advocated racial equality and withstood considerable political and social pressure in the course of her long activist career. …

The mid-1940s brought significant accolades to the Robesons as Eslanda’s book African Journey appeared in 1945 and Paul received the Spingarn Medal that same year. While a scholarly work, African Journey was not so much analytical as it was descriptive of the living habits and cultural customs of different tribes, complete with photographs taken by Eslanda. Both provocative and enlightening, it was a landmark work in the sense that it was the first by an American to show the need for reform among the colonial powers. This theme of colonialism became a focal point of Eslanda’s later writings; she strongly believed that the end of World War II hearkened a new era of freedom from European colonisers for emerging nations in Asia and Africa.

Anonymous text. “Robeson, Eslanda Goode (1896-1965),” on the Women in World History: A Biographical Encyclopedia website [Online] Cited 28/11/2021

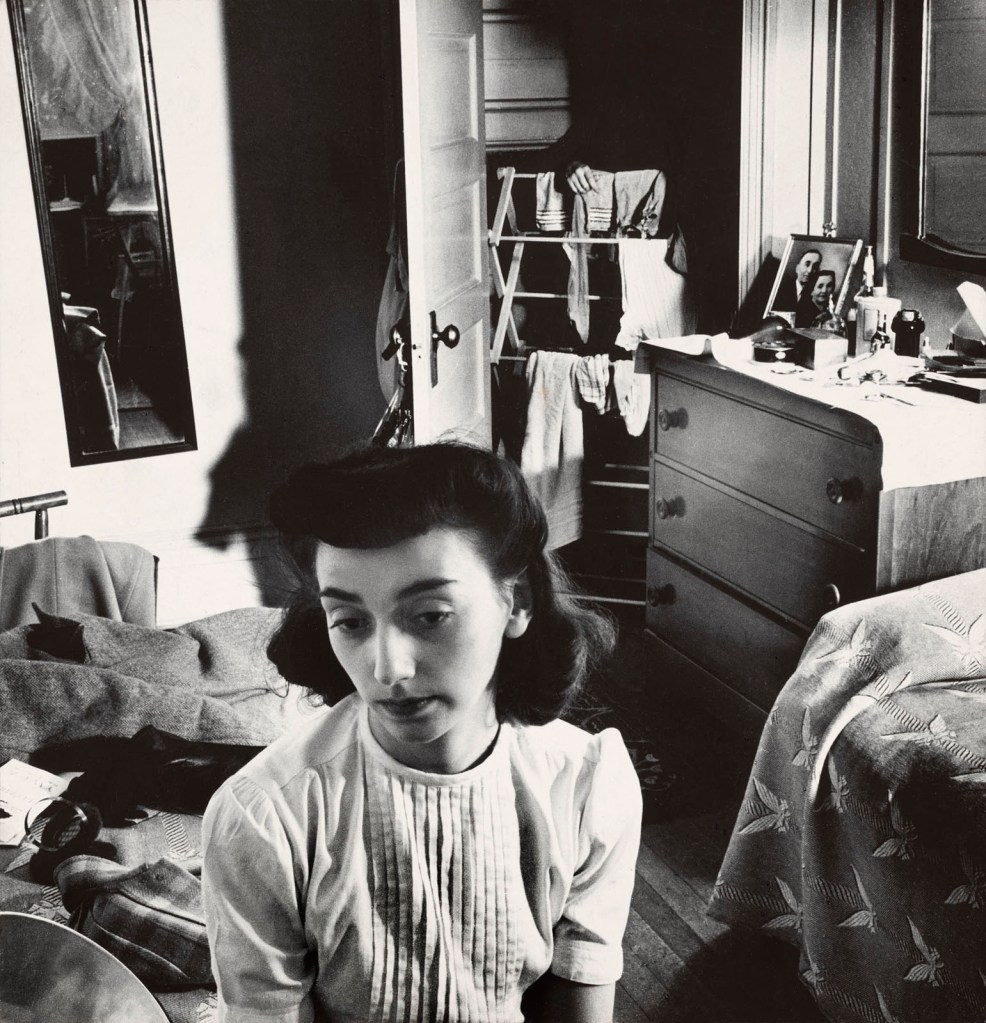

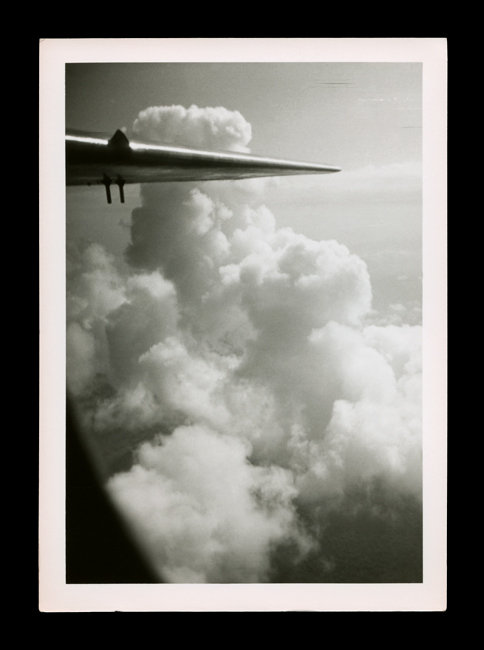

Esther Bubley (American, 1921-1998)

Young woman in the doorway of her room at a boardinghouse, Washington, DC

1943

Gelatin silver print

Image/sheet: 26.42 x 25.4cm (10 3/8 x 10 in.)

Frame: 50.8 x 40.64cm (20 x 16 in.)

Frame (outer): 53.34 x 43.18cm (21 x 17 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Kent and Marcia Minichiello

Esther Bubley (American, 1921-1998)

Esther Bubley (February 16, 1921 – March 16, 1998) was an American photographer who specialised in expressive photos of ordinary people in everyday lives. She worked for several agencies of the American government and her work also featured in several news and photographic magazines.

A protégée of Roy Stryker at the U.S. Office of War Information and subsequently at Standard Oil Company (New Jersey), Esther Bubley (1921-1998) was a preeminent freelance photographer during the “golden age” of American photojournalism, from 1945 to 1965. At a time when most post-war American women were anchored by home and family, Bubley was a thriving professional, traveling throughout the world, photographing stories for magazines such as LIFE and the Ladies’ Home Journal and for prestigious corporate clients that included Pepsi-Cola and Pan American World Airways.

“Put me down with people, and it’s just overwhelming,” Bubley exclaimed in an interview. Like most great photojournalists, she found her art in everyday life, and she successfully balanced her artistic ambitions with the demands of commercial publishing. Edward Steichen, curator of photographs at the Museum of Modern Art and the era’s arbiter of taste, was a great supporter of Bubley, whose work embodied his aesthetic ideal that photography “explain man to man and each to himself.” …

Bubley’s photographs are of cultural as well as artistic interest. Her photo-essays explore the era’s American stereotypes – the troubled child, the high school drop-out, the harried housewife, the enterprising farm family – that were elaborated in the pages of the magazines for which she worked. Her corporate assignments document the introduction of American companies into traditional cultures abroad. Bubley developed a specialty in stories about health care and mental health, documenting the era’s faith in new technologies and the growing prestige of psychology and psychiatry. She also covered her share of celebrities and popular culture topics, including children’s television and beauty contests. A cross-section of Bubley’s work provides a revealing glimpse into the post-war decades, seen not only through Bubley’s lens but through the pages of the illustrated magazines that dominated the mass media of the time.

Bonnie Yochelson. “Biography of Esther Bubley,” on the Esther Bubley website [Online] Cited 28/11/2021

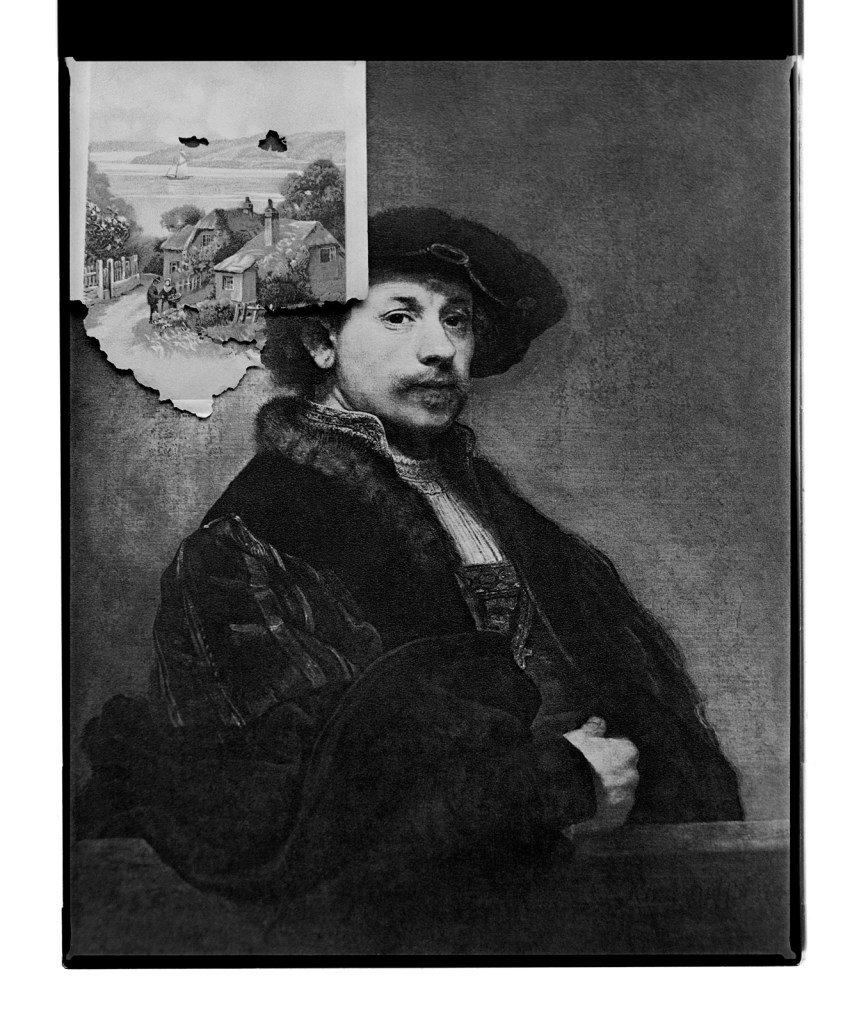

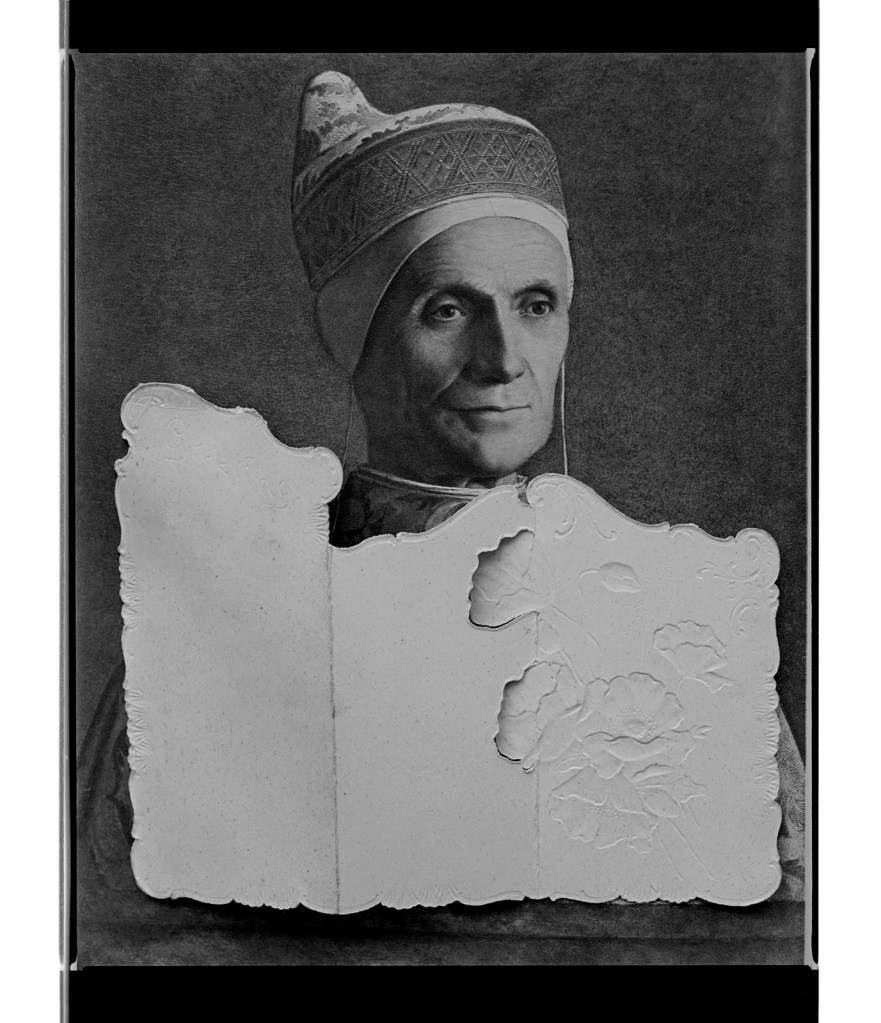

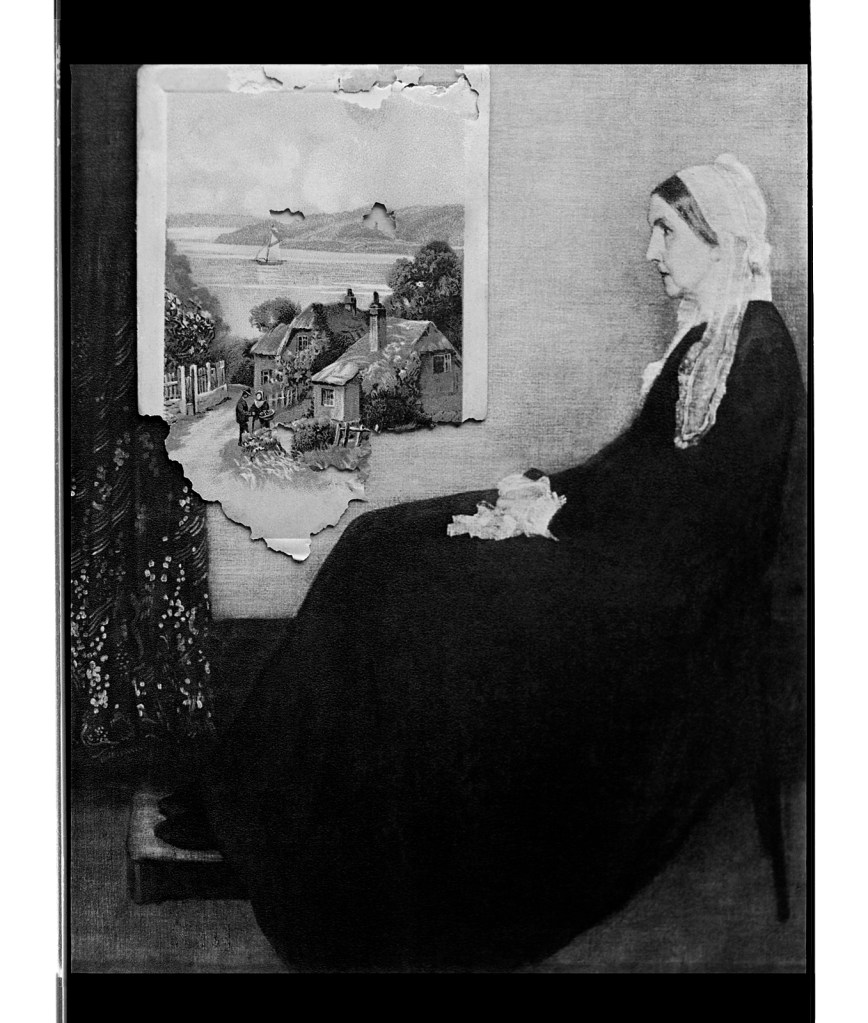

Florence Henri (European, 1893-1982)

Portrait Composition (Femme aux cartes) (Portrait Composition (Woman with Cards))

1930

Gelatin silver print

Image: 28 x 22.4cm (11 x 8 13/16 in.)

Mount: 38.1 x 33cm (15 x 13 in.)

Frame (outer): 52.7 x 47.6cm (20 3/4 x 18 3/4 in.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Ford Motor Company Collection, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell, 1987

Florence Henri © Galleria Martini & Ronchetti, courtesy Archives Florence Henri

Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Art Resource, NY

Florence Henri (European, 1893-1982)

Florence Henri (28 June 1893 – 24 July 1982) was a surrealist artist; primarily focusing her practice on photography and painting, in addition to pianist composition. In her childhood, she traveled throughout Europe, spending portions of her youth in Paris, Vienna, and the Isle of Wight. She studied in Rome, where she would encounter the Futurists, finding inspiration in their movement. From 1910 to 1922, she studied piano in Berlin, under the instruction of Egon Petri and Ferrucio Busoni. She would find herself landlocked to Berlin during the first World War, supporting herself by composing piano tracks for silent films. She returned to Paris in 1922, to attend the Académie André Lhote, and would attend until the end of 1923. From 1924 to 1925, she would study under painters Fernand Léger and Amédée Ozenfant at the Académie Moderne. Henri’s most important artistic training would come from the Bauhaus in Dessau, in 1927, where she studied with masters Josef Albers and László Moholy-Nagy, who would introduce her to the medium of photography. She returned to Paris in 1929 where she started seriously experimenting and working with photography up until 1963. Finally, she would move to Compiègne, where she concentrated her energies on painting until the end of her life in 1982. Her work includes experimental photography, advertising, and portraits, many of which featured other artists of the time.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Florestine Perrault Collins (American, 1895-1988)

Mae Fuller Keller

Early 1920s

Gelatin silver print

Overall: 35.56 x 27.94cm (14 x 11 in.)

Frame: 35.56 x 27.94cm (14 x 11 in.)

Frame (outer): 39.37 x 31.75cm (15 1/2 x 12 1/2 in.)

Dr Arthé A. Anthony

Florestine Perrault Collins (American, 1895-1988)

Florestine Perrault Collins (1895-1988) was an American professional photographer from New Orleans. Collins is noted for having created photographs of African-American clients that “reflected pride, sophistication, and dignity,” instead of racial stereotypes.

In 1909, Collins began practicing photography at age 14. Her subjects ranged from weddings, First Communions, and graduations to personal photographs of soldiers who had returned home. At the beginning of her career, Collins had to pass as a white woman to be able to assist photographers.

Collins eventually opened her own studio, catering to African-American families. She gained a loyal following and had success, due to both her photography and marketing skills. Out of 101 African-American women who identified themselves as photographers in the 1920 U.S. Census, Collins was the only one listed in New Orleans.

She advertised in newspapers, playing up the sentimentality of a well-done photograph. Collins also included her photograph in the ads to appeal to customers who thought a female photographer might take better pictures of babies and children.

According to the Encyclopedia of Louisiana, Collins’ career “mirrored a complicated interplay of gender, racial and class expectations”.

“The history of black liberation in the United States could be characterised as a struggle over images as much as it has also been a struggle over rights,” according to Bell Hooks. Collins’ photographs are representative of that. By taking pictures of black women and children in domestic settings, she challenged the pervasive stereotypes of the time about black women.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Photographer unknown

Florestine Perrault Collins

1920s

Gelatin silver print

Overall: 35.56 x 27.94cm (14 x 11 in.)

Frame: 35.56 x 27.94cm (14 x 11 in.)

Frame (outer): 39.37 x 31.75cm (15 1/2 x 12 1/2 in.)

Dr Arthé A. Anthony

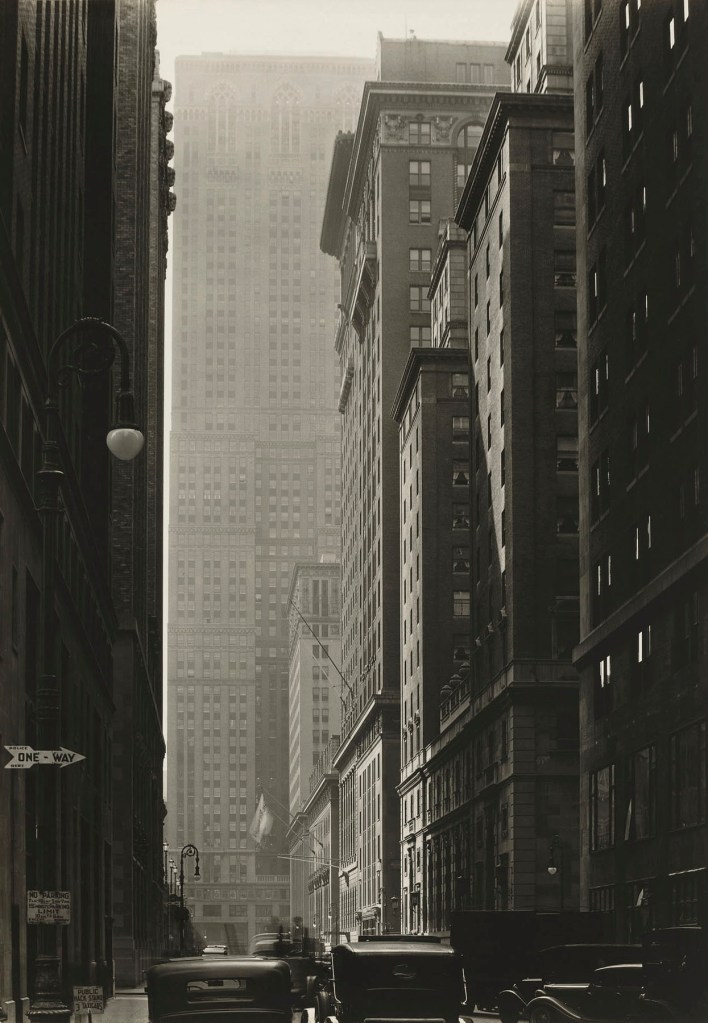

Germaine Krull (German, French, and Dutch, Brazil, Republic of the Congo, Thailand and India, 1897-1985)

Eielturm (Eifel Tower)

1928

Gelatin silver print

Image: 22.5 x 15.2cm (8 7/8 x 6 in.)

Frame: 50 x 40cm (19 11/16 x 15 3/4 in.)

Frame (outer): 52 x 42 x 2.8cm (20 1/2 x 16 9/16 x 1 1/8 in.)

Museum Folkwang, Essen © Estate Germaine Krull, Museum Folkwang, Essen

Photo © Museum Folkwang Essen – ARTOTHEK

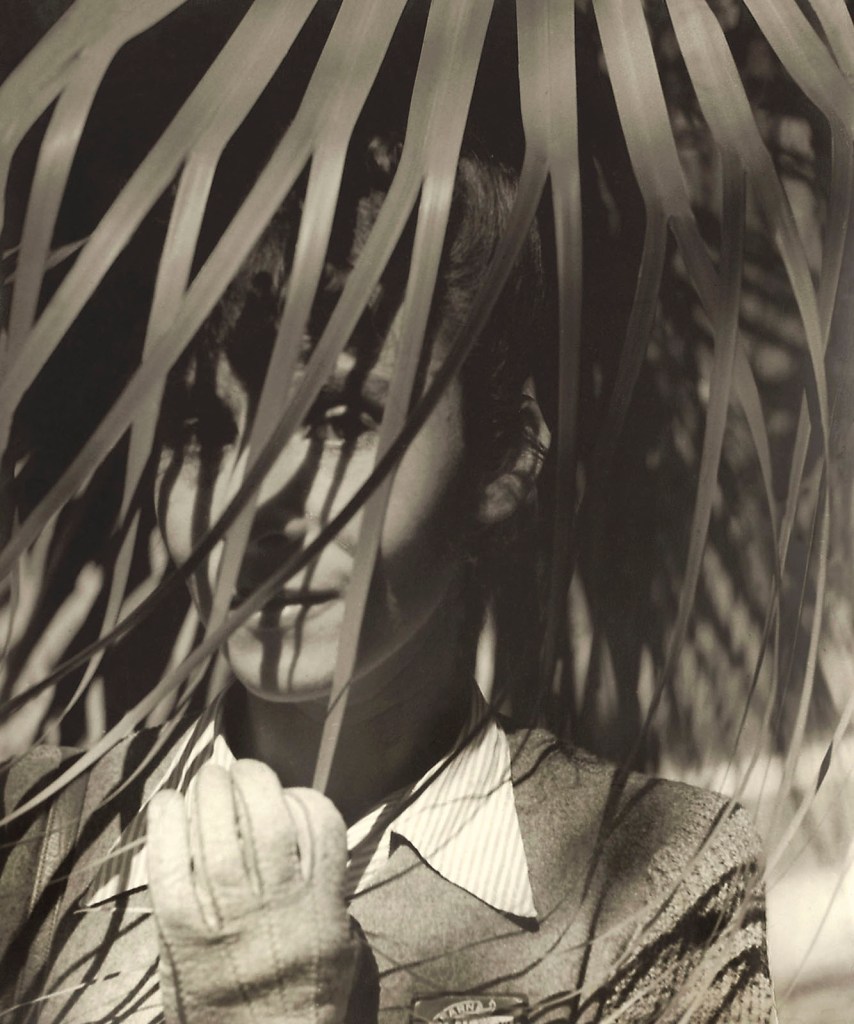

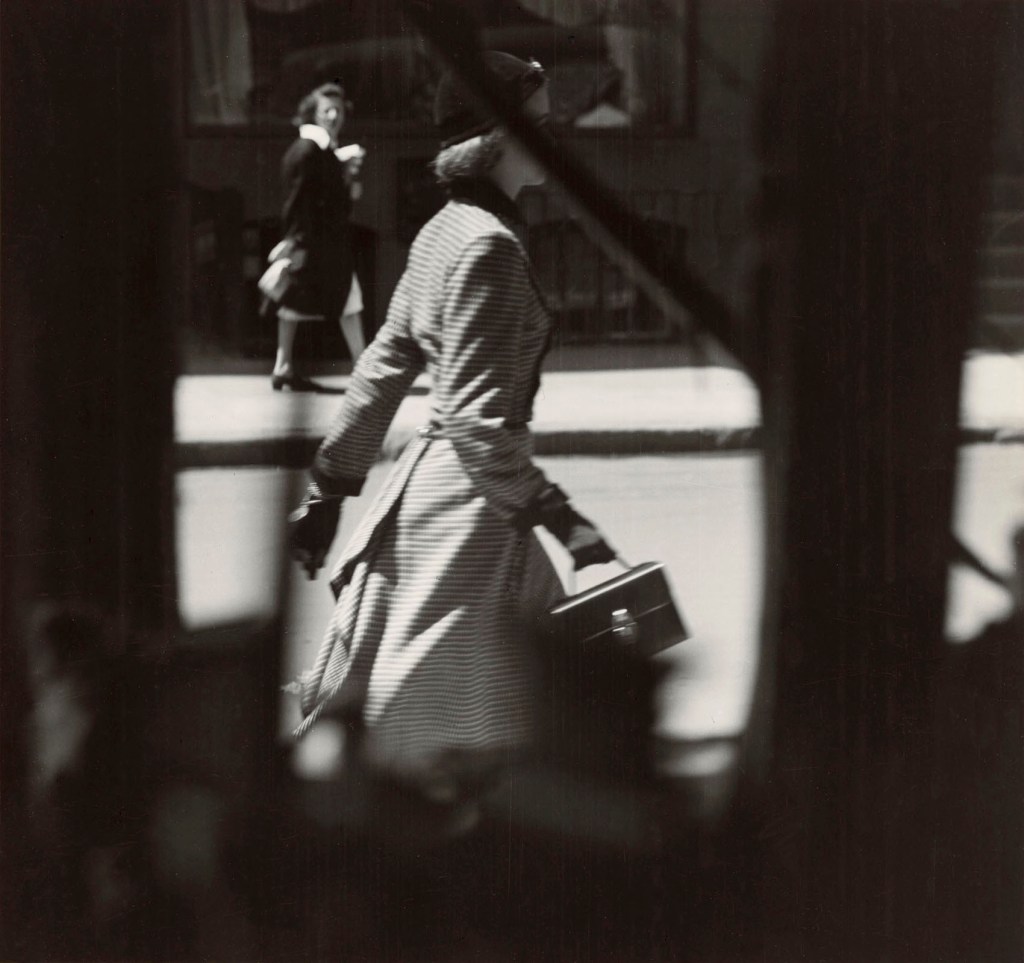

Gertrude Fehr (German, 1895-1996)

Odile

1936

Gelatin silver print

Image: 32.39 x 29.21cm (12 3/4 x 11 1/2 in.)

Frame: 60.96 x 50.8cm (24 x 20 in.)

Frame (outer): 25.75 x 21.75cm (10 1/8 x 8 9/16 in.)

Trish and Jan de Bont

Gertrude Fehr (German, 1895-1996)

Gertrude Fehr was a German photographer. She was born in Mainz on Tuesday 5 March 1895 and died in 1996 at the age of 101. She was one of the earliest professional female photographers.

Fehr studied photography at the Bavarian School of photography in Munich and undertook an apprenticeship in the Munich studio of Eduard Wasow. Shortly after finishing the apprenticeship, she set up a photographic studio dedicated fundamentally to the theatre and to the portrait technique which employed six people. In 1933, the rise of Hitler and the establishment of the Third Reich forced Fehr to close the studio and to emigrate to Paris with her future Swiss husband, the painter Jules Fehr. Installed in the French capital there she opened her own school of photography: PUBLI-phot.

In Paris she found the artistic atmosphere of the avant-garde of the time and, influenced by the movements modernism, began photographic experiments. Patent in those moments was the tremendous influence of the most transgressive photographer-painter of the moment, Man Ray, which she considered “fascinating”. Like him, she started experimenting with the solarisation process. The solarisation of Fehr (unlike Man Ray) are works that have a aesthetic which resembles an academic charcoal drawing. If it were not for the difference in procedures, Fehr’s “Odile” (1940) seems rather an image enhanced by traditional procedures rather than by the photographic avant-garde.

At the end of the 1930s she and her husband moved to Switzerland, where they opened a photography school in Lausanne.

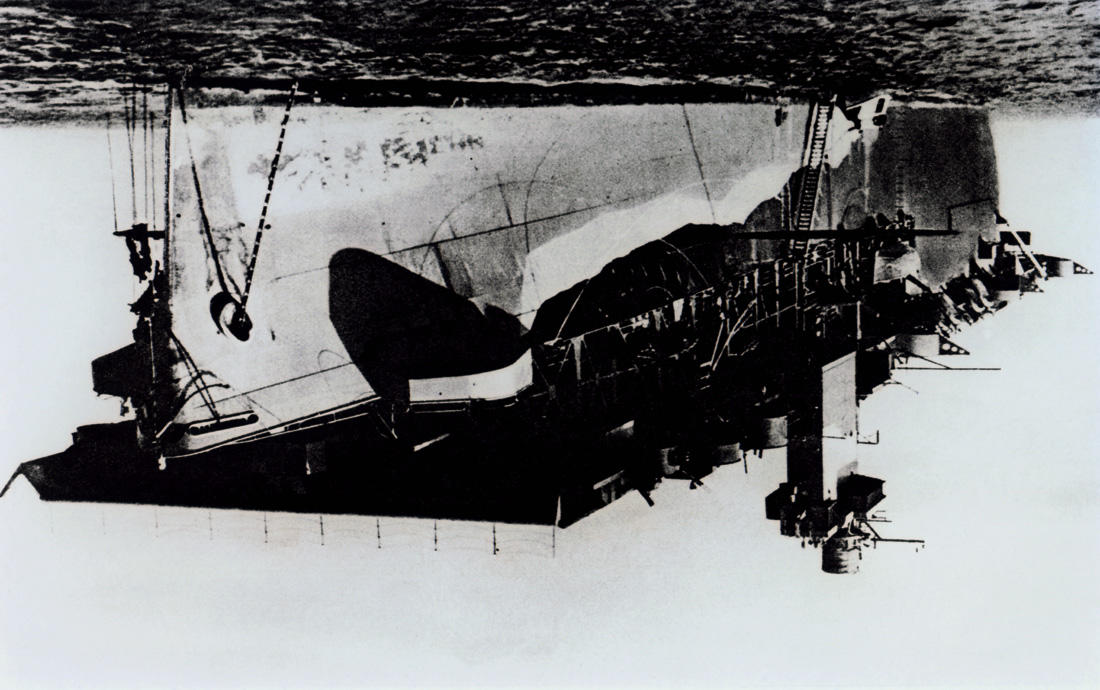

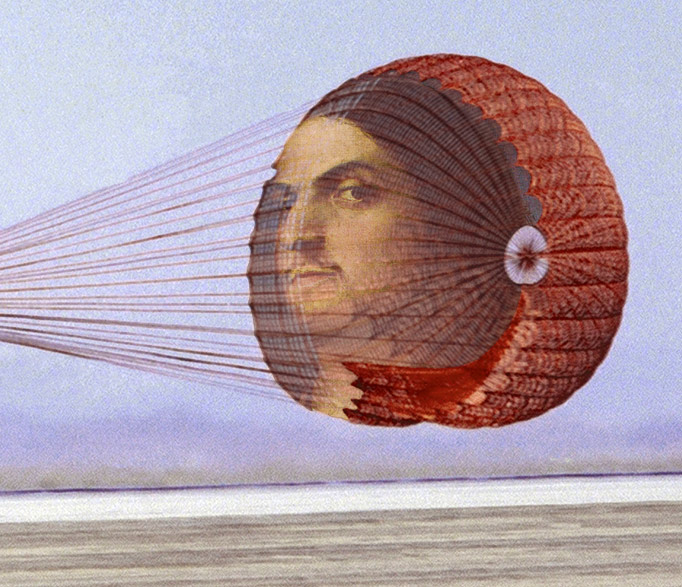

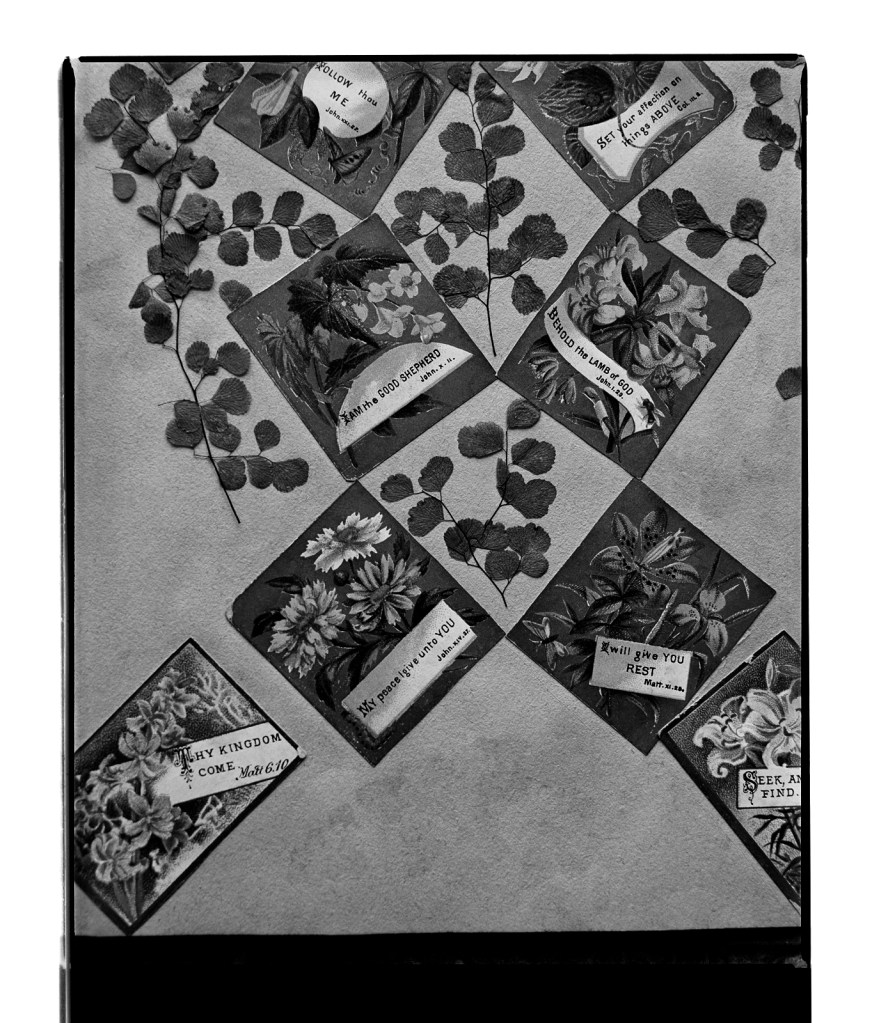

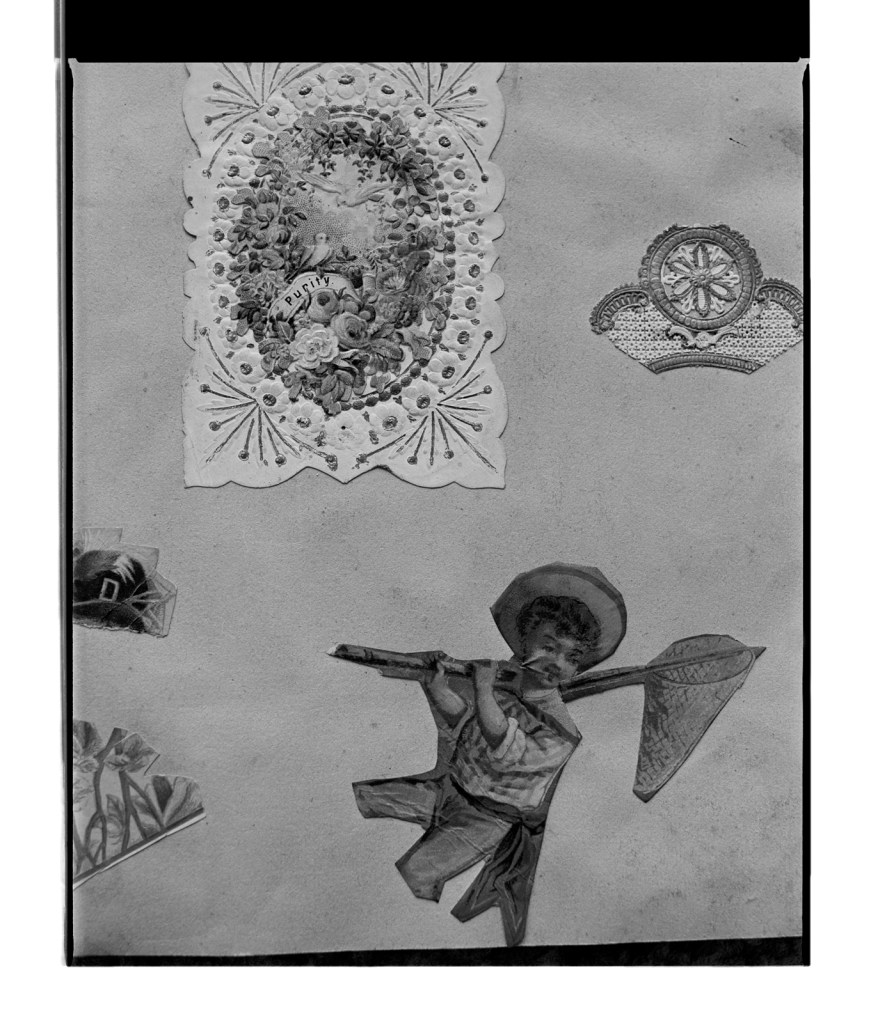

Adele Gloria (Italian, 1910-1984)

Senza titolo (Untitled)

c. 1933

Collage with gelatin silver prints

Overall: 18.2 x 21.27cm (7 3/16 x 8 3/8 in.)

Mat: 39.37 x 49.85cm (15 1/2 x 19 5/8 in.)

Frame: 40.64 x 50.8cm (16 x 20 in.)

Frame (outer): 43.18 x 53.34cm (17 x 21 in.)

Collection Merrill C. Berman

Adele Gloria was the only futurist woman in Sicily, she distinguished herself in the field of aeropainting and avant-garde, in the early 30s in Catania. She was a poet, photographer, painter, sculptor and journalist, a “total” artist according to the canons of the Futurist movement.

Adele Gloria (Italian, 1910-1984)

Senza titolo (Untitled) (detail)

c. 1933

Collage with gelatin silver prints

Overall: 18.2 x 21.27cm (7 3/16 x 8 3/8 in.)

Mat: 39.37 x 49.85cm (15 1/2 x 19 5/8 in.)

Frame: 40.64 x 50.8cm (16 x 20 in.)

Frame (outer): 43.18 x 53.34cm (17 x 21 in.)

Collection Merrill C. Berman

Adele Gloria (Italian, 1910-1984)

Senza titolo (Untitled) (detail)

c. 1933

Collage with gelatin silver prints

Overall: 18.2 x 21.27cm (7 3/16 x 8 3/8 in.)

Mat: 39.37 x 49.85cm (15 1/2 x 19 5/8 in.)

Frame: 40.64 x 50.8cm (16 x 20 in.)

Frame (outer): 43.18 x 53.34cm (17 x 21 in.)

Collection Merrill C. Berman

Hélène Hoppenot (French, 1894-1990)

Chine

1946

Bound volume

Open: 35.56 x 33.02cm (14 x 13 in.)

Cradle:11.43 x 49.85 x 36.2cm (4 1/2 x 19 5/8 x 14 1/4 in.)

National Gallery of Art Library, Gift of the Department of Photographs

Hélène Hoppenot (1894-1990) was a French amateur photographer who made thousands of snapshots using the Rolleiflex from 1933 to the 1970s.

Hoppenot made a trip to China where she photographed the everyday life and habits of Chinese people in the country and in the city. This book is her testimony of this travel. It is accompanied with a text from writer Paul Claudel who was deeply interested in Chinese culture and traveled to China as well.

Homai Vyarawalla (Indian, 1913-2012)

The Ashes of Mahatma Gandhi Being Carried in a Procession, Allahabad

February 1948

Gelatin silver print

Image/sheet: 38.1 x 38.1cm (15 x 15 in.)

Frame: 53.34 x 53.34cm (21 x 21 in.)

Frame (outer): 55.88 x 55.88cm (22 x 22 in.)

Homai Vyarawalla Archive / The Alkazi Collection of Photography

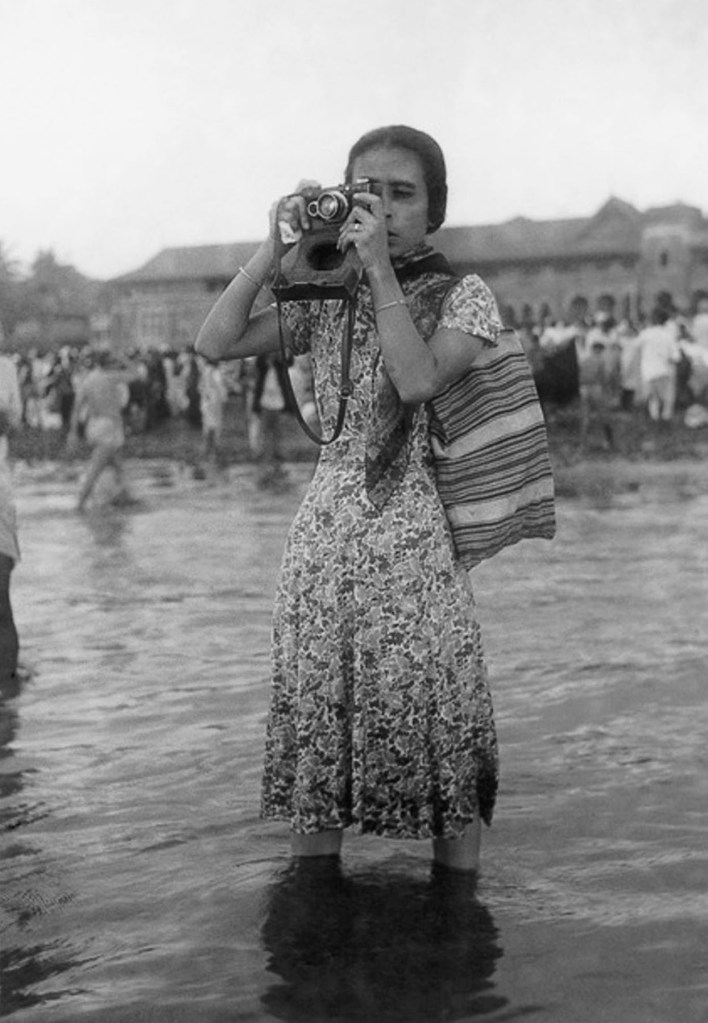

Homai Vyarawalla (Indian, 1913-2012)

Homai Vyarawalla (9 December 1913 – 15 January 2012), commonly known by her pseudonym Dalda 13, was India’s first woman photojournalist. She began work in the late 1930s and retired in the early 1970s. In 2011, she was awarded Padma Vibhushan, the second highest civilian award of the Republic of India. She was amongst the first women in India to join a mainstream publication when she joined The Illustrated Weekly of India.

Career

Vyarawalla started her career in the 1930s. At the onset of World War II, she started working on assignments for Mumbai-based The Illustrated Weekly of India magazine which published many of her most admired black-and-white images. In the early years of her career, since Vyarawalla was unknown and a woman, her photographs were published under her husband’s name. Vyarawalla stated that because women were not taken seriously as journalists she was able to take high-quality, revealing photographs of her subjects without interference:

People were rather orthodox. They didn’t want the women folk to be moving around all over the place and when they saw me in a sari with the camera, hanging around, they thought it was a very strange sight. And in the beginning they thought I was just fooling around with the camera, just showing off or something and they didn’t take me seriously. But that was to my advantage because I could go to the sensitive areas also to take pictures and nobody will stop me. So I was able to take the best of pictures and get them published. It was only when the pictures got published that people realized how seriously I was working for the place.

~ Homai Vyarawalla in Dalda 13: A Portrait of Homai Vyarawalla (1995)

Eventually her photography received notice at the national level, particularly after moving to Delhi in 1942 to join the British Information Services. As a press photographer, she recorded many political and national leaders in the period leading up to independence, including Mohandas Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Indira Gandhi and the Nehru-Gandhi family.

The Dalai Lama in ceremonial dress enters India through Nathu La in Sikkim on 24 November 1956, photographed by Homai Vyarawalla. In 1956, she photographed for Life Magazine the 14th Dalai Lama when he entered Sikkim in India for the first time via the Nathu La. Most of her photographs were published under the pseudonym “Dalda 13”. The reasons behind her choice of this name were that her birth year was 1913, she met her husband at the age of 13 and her first car’s number plate read “DLD 13”.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Photographer unknown

Homai Vyarawalla photographing Ganesh Chaturthi at Chowpatty Beach, Bombay

Late 1930s, printed later

Inkjet print

Image: 30.48 x 20.8cm (12 x 8 3/16 in.)

Frame: 45.72 x 35.56cm (18 x 14 in.)

Frame (outer): 48.26 x 38.1cm (19 x 15 in.)

Homai Vyarawalla Archive / The Alkazi Collection of Photography

Homai Vyarawalla (Indian, 1913-2012)

The Victory Parade by the Allied Forces in India Marking the End of the Second World War, Connaught Place, New Delhi

1945

Gelatin silver print

Image/sheet: 31 x 30.8cm (12 3/16 x 12 1/8 in.)

Frame: 45.72 x 45.72cm (18 x 18 in.)

Frame (outer): 48.26 x 48.26cm (19 x 19 in.)

Homai Vyarawalla Archive / The Alkazi Collection of Photography

Homai Vyarawalla (Indian, 1913-2012)

Students at the Sir Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy School of Art, Bombay

Late 1930s, printed later

Inkjet print

Image/sheet: 40.7 x 40.7cm (16 x 16 in.)

Frame: 55.88 x 55.88cm (22 x 22 in.)

Frame (outer): 58.42 x 58.42cm (23 x 23 in.)

Homai Vyarawalla Archive / The Alkazi Collection of Photography

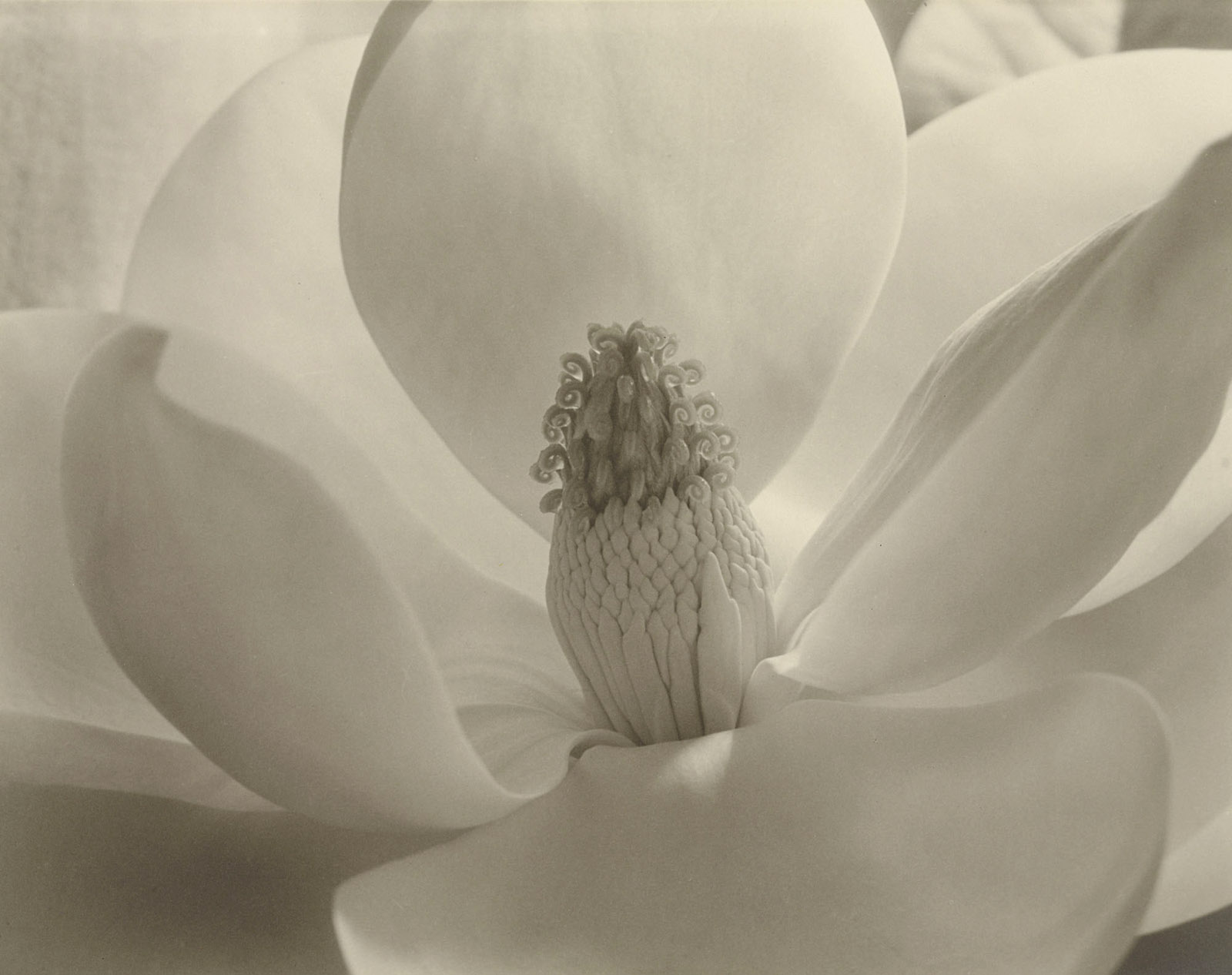

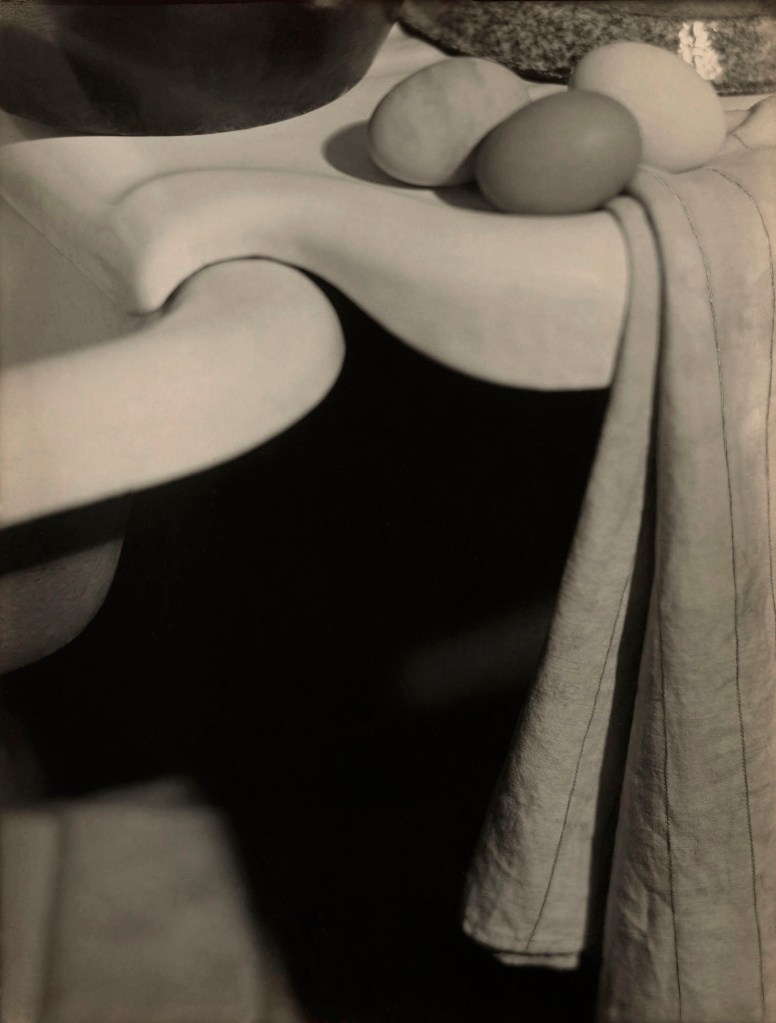

Imogen Cunningham (American, 1883-1976)

Magnolia Blossom

c. 1925

Gelatin silver print

17.1 x 21.6cm (6 3/4 x 8 1/2 in.)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Albert M. Bender

© 2020 Imogen Cunningham Trust

Judit Kárász (Hungarian, 1912-1977)

Kávészemek cukorral (Coffee Beans and Sugar)

1931

Gelatin silver print

Image: 13.02 x 20.96cm (5 1/8 x 8 1/4 in.)

Support: 13.02 x 20.96cm (5 1/8 x 8 1/4 in.)

Mat: 40.64 x 50.8cm (16 x 20 in.)

Frame: 40.64 x 50.8cm (16 x 20 in.)

Frame (outer): 41.28 x 51.44 x 3.33cm (16 1/4 x 20 1/4 x 1 5/16 in.)

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Gift of Louis Stern Digital Image

© 2019 Museum Associates / LACMA / Licensed by Art Resoure, NY

Judit Kárász (Hungarian, 1912-1977)

Judit Kárász (21 May 1912 – 30 May 1977) was a Hungarian photographer interested in the medium’s ability to reveal the hidden structures of everyday subject matter. Her photography brought together social documentary and modernist ideas such as Gestalt theory.

Bauhaus

On 21 June 1932 Kárász received her Bauhaus diploma, where she majored in photography. She was taught by Walter Peterhans, who founded the school’s photography department in 1929. Influenced by the work of artists such as fellow Hungarian László Moholy-Nagy who had previously taught at the school, Kárász began to experiment with compositional devices, such as bird’s-eye perspective, and explored modernist themes and subject matters including industrial landscapes.

Career

In 1931 Kárász became a member of Kostufa (Kommunistische Studenten Fraktion) a communist student group, and following her active role in election campaigns she was expelled from the Sachsen-Anhalt area of Germany. Between 1932-1935 Karasz worked as a laboratory technician at the Dephot in Berlin, a photographic agency that represented photojournalists, such as Robert Capa.

Karasz was involved with the Workers-Photography movement, a collective associated with communism dedicated to activating photography for social ends.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Vera Gabrielová (Czech, 1919-2002)

Bez názvu (lžíce) (Untitled (Spoons))

1935-1936

Gelatin silver print

Image: 23.8 x 17.5cm (9 3/8 x 6 7/8 in.)

Frame: 50.8 x 40.64cm (20 x 16 in.)

Frame (outer): 53.34 x 43.18cm (21 x 17 in.)

Ellen and Robert Grimes

Jaroslava Hatláková (Czech, 1904-1989)

Bez názvu (Untitled)

c. 1936

Gelatin silver print

10.8 x 8.26cm (4 1/4 x 3 1/4 in.)

Trish and Jan de Bont

Jeanne Mandello (German, 1907-2001)

Arbeiter der neuen uruguayischen Fakultät für Architektur, Montevideo (Workers on the new Uruguayan School of Architecture, Montevideo)

c. 1945, printed later

Gelatin silver print

Image: 35 x 27cm (13 3/4 x 10 5/8 in.)

Frame: 50.8 x 40.64cm (20 x 16 in.)

Frame (outer): 53.34 x 43.18cm (21 x 17 in.)

Isabel Mandello Collection

© 2020 Isabel Mandello

Jeanne Mandello (German, 1907-2001)

Jeanne Mandello (née Johanna Mandello; October 18, 1907, Frankfurt – December 17, 2001, Barcelona) was a German modern artist and experimental photographer. …

In 1926 she began studying photography at Lette-Verein. In a time when it was difficult for a woman to get attention as an artist, photography opened a way into the art world. Inspired by the spirit of freedom in Berlin in the 1920s, the women’s movement offered an opportunity to go out, attended theater performances, concerts, exhibitions and decide on the model of the “new woman”, imitating Grete Stern and Ellen Auerbach who wore pants and short hair. In 1927, she studied at the studio of Paul Wolff and Alfred Tritschler. Through Wolff, she became familiar with Leica Camera photography. Back in Berlin, she returned to Lette and finished her studies. Using a Leica film camera, she photographed portraits, landscapes and scenes of everyday life. In 1929, she taught in Frankfurt, creating a studio at her parents’ house. Here, she collaborated with the photographer Nathalie Reuter (1911-1990), a former classmate and friend. In 1932, she met Arno Grünebaum. Under Mandello’s guidance, he learned photography. In 1933, they married. Being Jewish and being aware of the coming danger, they left Germany in 1934 and began in Paris a new life.

Career

In Paris, she changed her first name Johanna into the French form, Jeanne. Like other modern photographers of the Weimar Republic, Mandello found inspiration during her exile in Paris. She was influenced by the Nouvelle Vision; by Man Ray, Brassaï and Doisneau, in redefined photography. They experimented with new techniques, unusual camera angles, picture cutouts, exposures and photomontages. Mandello and Grunbaum specialised in commercial and portrait photography and established themselves as fashion photographers. In 1937, they opened a studio in 17th Arrondissement under the name “Mandello”. “Mandello” did work for Fémina, Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue, as well as the fashion houses of Balenciaga, Guerlain, Maggy Rouff, and Creed. Occasionally, they worked with the photographer Hermann Landshoff, who had also fled Nazi Germany. After the outbreak of World War II, Mandello and her husband were considered Alien Enemies within the French Republic and were forced to leave Paris in early 1940. They had to leave everything behind: the photo studio, camera equipment, archived works and negatives. They were allowed to take only 14 kilos of luggage. They came to the village of Dognen where she helped out in the infirmary. Her German citizenship was withdrawn on 28 October 1940. With visas to Uruguay, Mandello and Grunebaum left France and started a new life in South America where she exhibited beginning in 1943. Her new work included architecture, landscapes, photograms, portraits, and solarisations. In 1952, she exhibited at Museum of Modern Art, Rio de Janeiro, and two years later, she separated from her husband, and moved to Brazil to be with the journalist, Lothar Bauer. With Bauer, she moved to Barcelona at the end of the decade where she worked the rest of her life. She married Bauer, and they adopted a daughter, Isabel, in 1970. Mandello died in Barcelona in 2001.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Jeanne Mandello was a pioneer of modern photography and a Jewish avant-garde woman artist working in Berlin, Frankfurt, Paris, Montevideo, Rio de Janeiro and Barcelona.

She belongs to the same school of modern female photographers of the early 20th century as her contemporaries Grete Stern, Ellen Auerbach, Ilse Bing, Marianne Breslauer, Gisèle Freund, or, even though some years older, Germaine Krull. …

Jeanne Mandello became a cosmopolitan artist by the force of circumstances and brought the geometry of the Bauhaus and the surrealist fantasy of pre-war Paris to her later countries of residence, Uruguay, Brazil and Spain. Her eye remained European and wherever she lived her photographs rendered homage to her new countries. No country can claim her for itself but her work is another example of the universality of art, which transcends all physical frontiers.

Forgotten for nearly 50 years because of the historical circumstances surrounding her life, she is today rediscovered and seen as she should have been: an avant-garde Jewish-German woman artist and a pioneer in the field of modern photography.

Anonymous text. “Jeanne Mandello: Photographer in Exile,” on the Jeanne Mandello website [Online] Cited 28/11/2021

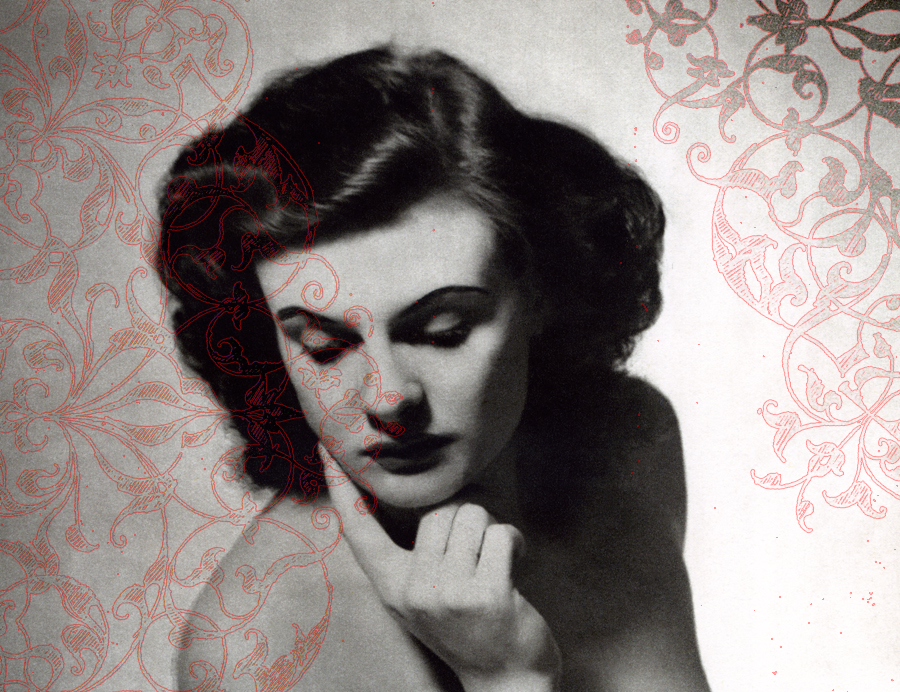

Jeanne Mandello (German, 1907-2001)

Perfume Advertisement for Maggy Rou

c. 1935-1938, printed later

Gelatin silver print

Image: 29 x 22cm (11 7/16 x 8 11/16 in.)

Frame: 50.8 x 40.64cm (20 x 16 in.)

Frame (outer): 53.34 x 43.18cm (21 x 17 in.)

Isabel Mandello Collection

© 2020 Isabel Mandello

Jeanne Mandello (German, 1907-2001)

Selbstporträt, Montevideo (Self-Portrait, Montevideo)

c. 1942-1943, printed later

Gelatin silver print

Image: 28.5 x 24cm (11 1/4 x 9 7/16 in.)

Frame: 50.8 x 40.64cm (20 x 16 in.)

Framed (outer): 53.34 x 43.18cm (21 x 17 in.)

Isabel Mandello Collection

© 2020 Isabel Mandello

Laura Gilpin (American, 1891-1979)

Untitled (Pueblo dwelling, woman holding a bowl)

c. 1930

Platinum print

Sheet: 24.7 x 19.8cm (9 3/4 x 7 13/16 in.)

Mat: 45.72 x 35.56cm (18 x 14 in.)

Frame: 45.72 x 35.56cm (18 x 14 in.)

Frame (outer): 48.26 x 38.74cm (19 x 15 in.)

Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

© 1979 Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

Laura Gilpin (April 22, 1891 – November 30, 1979) was an American photographer. Gilpin is known for her photographs of Native Americans, particularly the Navajo and Pueblo, and Southwestern landscapes. Gilpin began taking photographs as a child in Colorado and formally studied photography in New York from 1916 to 1917 before returning to her home in Colorado to begin her career as a professional photographer.

Read a fuller biography on the Wikipedia website

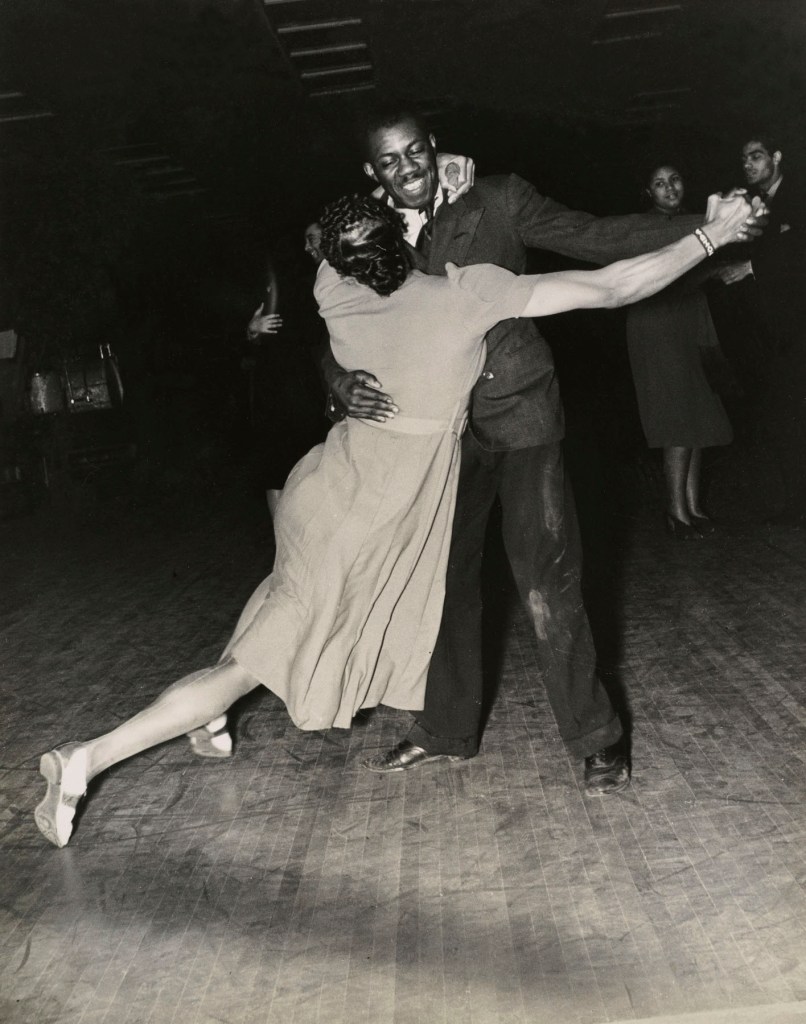

Lucy Ashjian (American, 1907-1993)

Savoy Dancers

1935-1943

Gelatin silver print

Image: 24 x 18.8cm (9 7/16 x 7 3/8 in.)

Sheet: 26.2 x 20.2cm (10 5/16 x 7 15/16 in.)

Frame (outer): 47.3 x 39.5cm (18 5/8 x 15 9/16 in.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Gregor Ashjian Preston, 2004

Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Art Resource, NY

Lucy Ashjian (1907-1993) is an American photographer best known as a member of the New York Photo League. Her work is included in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, the Center for Creative Photography in Tucson, Arizona and the Museum of the City of New York.

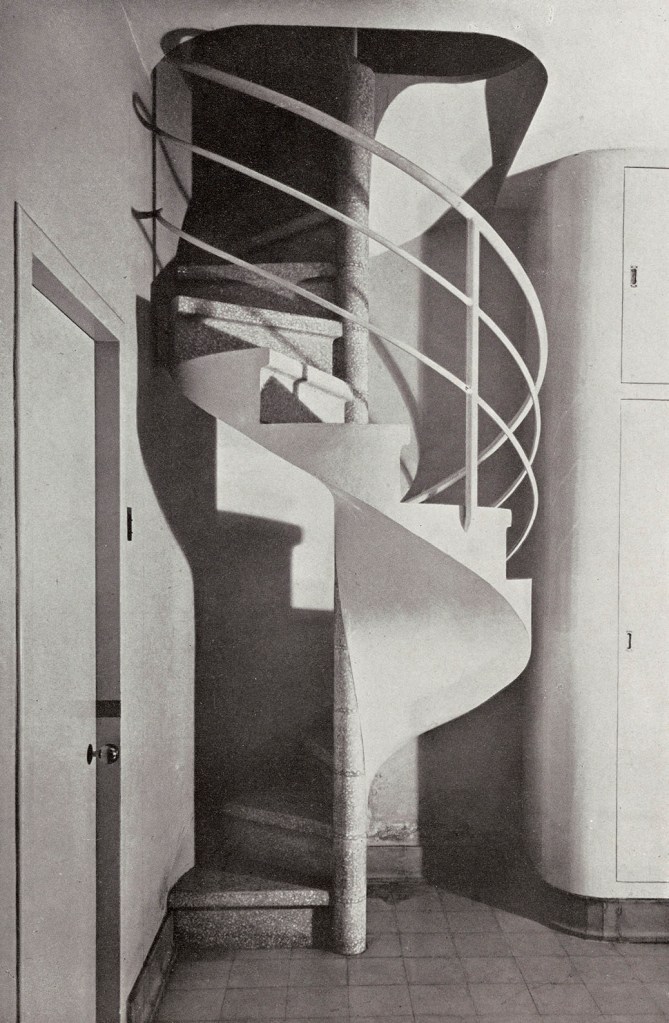

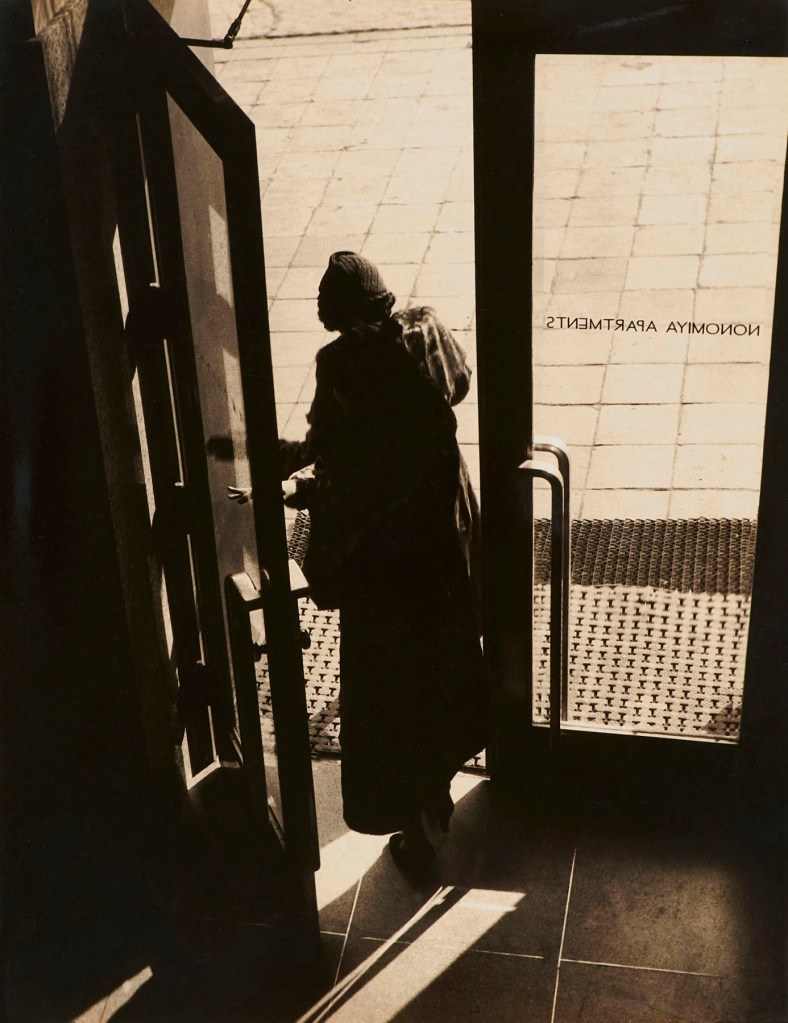

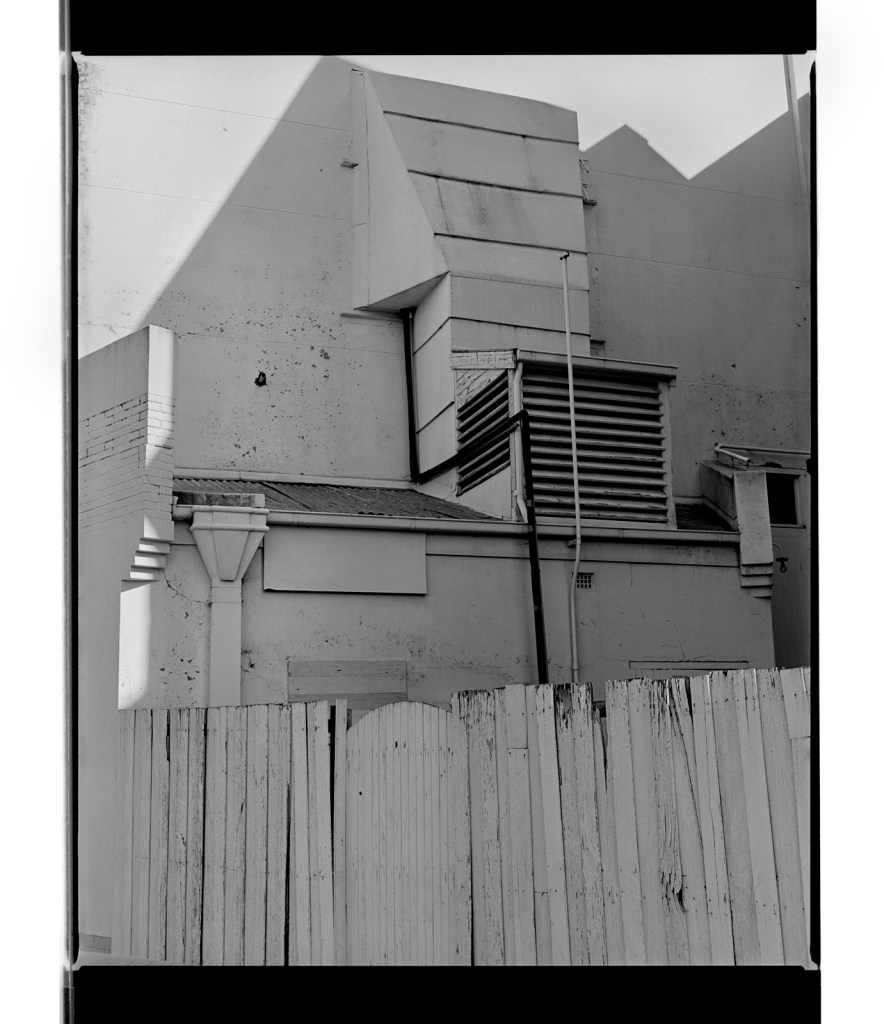

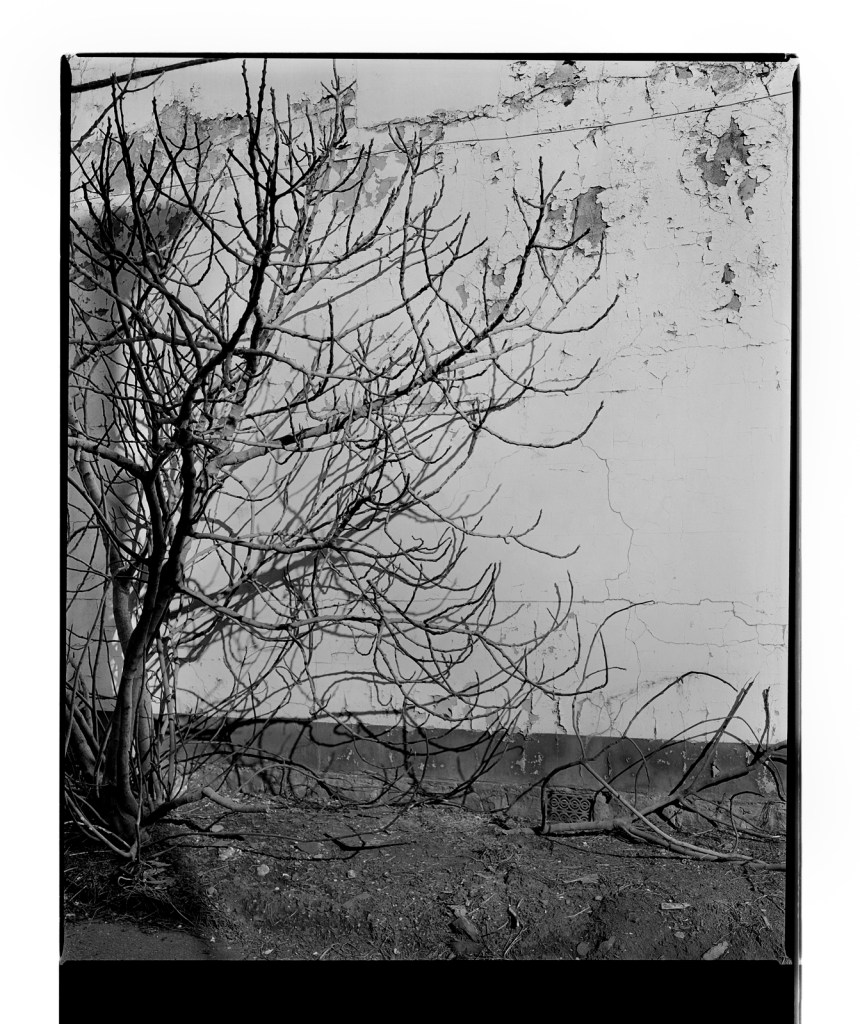

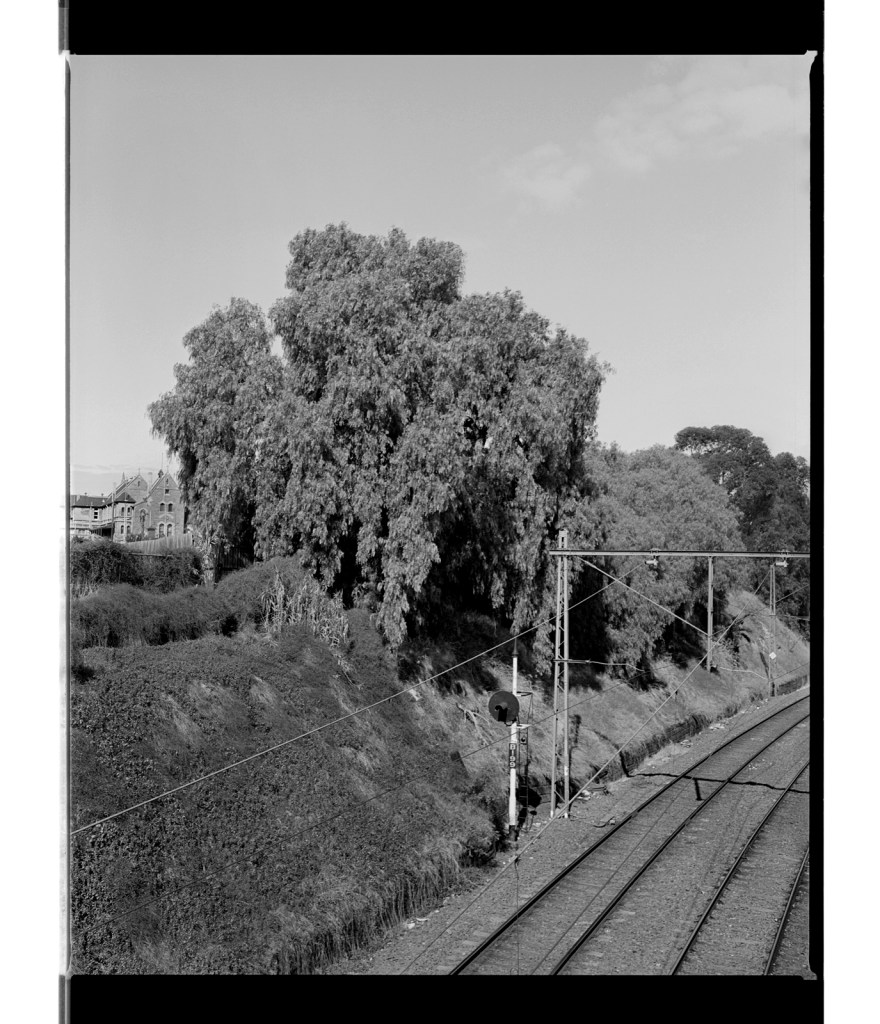

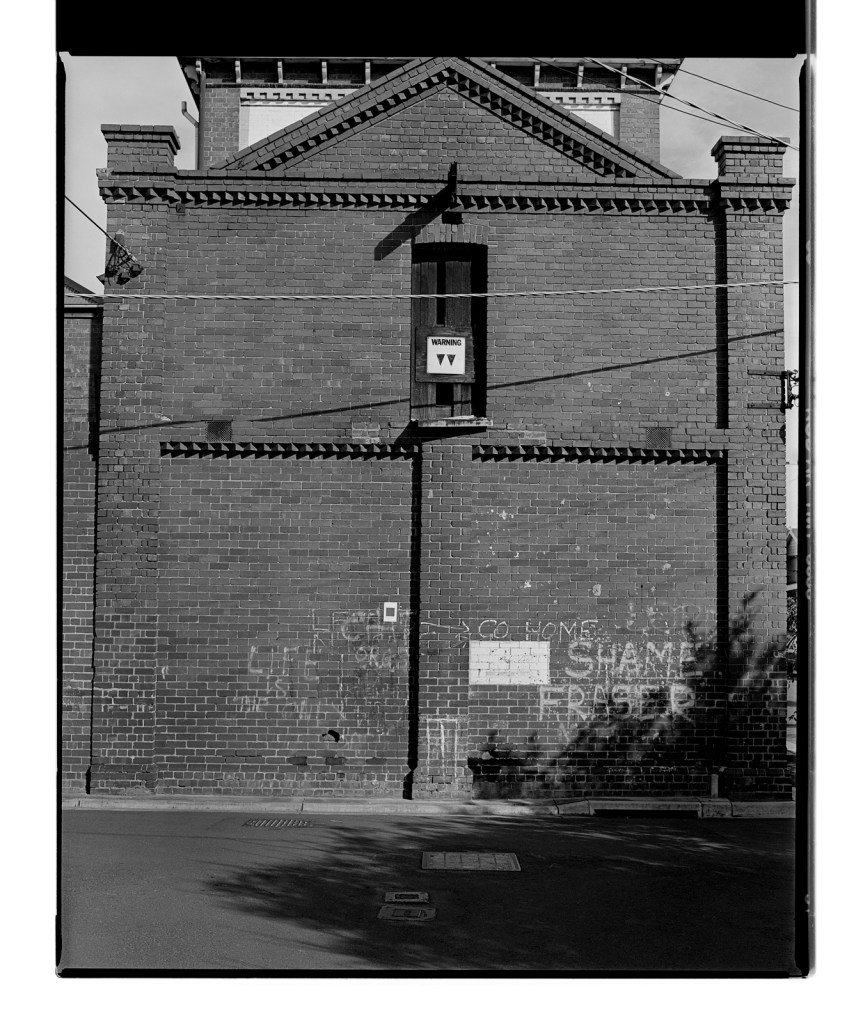

Margaret Michaelis (Austrian-Australian, 1902-1985)

“Residencia de J. M. a Barcelona,” in D’Ací i d’Allà

Spring 1936

Bound volume

Open: 32.39 x 52.07cm (12 3/4 x 20 1/2 in.)

Closed: 32.39 x 29.21cm (12 3/4 x 11 1/2 in.)

Cradle: 15.88 x 57.15 x 33.02cm (6 1/4 x 22 1/2 x 13 in.)

National Gallery of Art Library, David K.E. Bruce Fund

Margaret Michaelis (Austrian-Australian, 1902-1985)

“Residencia de J. M. a Barcelona,” in D’Ací i d’Allà (detail)

Spring 1936

Bound volume

Open: 32.39 x 52.07cm (12 3/4 x 20 1/2 in.)

Closed: 32.39 x 29.21cm (12 3/4 x 11 1/2 in.)

Cradle: 15.88 x 57.15 x 33.02cm (6 1/4 x 22 1/2 x 13 in.)

National Gallery of Art Library, David K.E. Bruce Fund

Margaret Michaelis (Austrian-Australian, 1902-1985)

Margaret (Margarethe) Michaelis-Sachs (née Gross, 1902-1985) was an Austrian-Australian photographer of Polish-Jewish origin. In addition to her many portraits, her architectural scenes of Barcelona and her images of the Jewish quarter in Kraków in the 1930s are of lasting historical interest.

Michaelis studied photography at Vienna’s Graphische Lehr-und Versuchsanstalt from 1918 to 1921.

Career

In 1922, still in Vienna, she first worked for a period at the Studio d’Ora before spending a number of years at the Atelier für Porträt Photographie. She went on to work for Binder Photographie in Berlin and Fotostyle in Prague, and finally returned to Berlin in 1929 to work intermittently for a variety of studios during the hard times of the Depression.

In October 1933, she married Rudolf Michaelis who, as an anarcho-syndicalist, was almost immediately arrested and imprisoned by the Nazis. In December 1933, after Rudolf’s release, the couple moved to Spain but they separated shortly afterwards. In Barcelona, Michaelis opened her own studio, Foto-elis. Collaborating with a group of architects, she produced documentary images of progressive architecture which were published in Catalan journals such as D’Ací i d’Allà and, after the start of the civil war, Nova Iberia.

After returning to Poland in 1937, she obtained a German passport, went to London and, in September 1939, emigrated to Australia, first working as a house maid in Sydney. In 1940, she opened her “Photo-studio”, becoming one of the few women photographers in Sydney. She specialised in portraits, especially of Europeans, Jews and people in the arts, many published in Australia and Australian Photography. A member of the photographers’ associations of New South Wales and Australia, in 1941 she was the only woman to join the Institute of Photographic Illustrators.

Margaret Michaelis’ photographic career came to an end in 1952 as a result of poor eyesight. In 1960, she married Albert George Sachs, a glass merchant. She died on 10 October 1985 in Melbourne.

Styles

In her early life, Michaelis used the sharp focus and sometimes unusual vantage points of modernist photography while her portraits sought to reveal the psychological essence of her sitters. Her portraits were primarily focused on capturing the lives of Jewish immigrants. Of particular significance is the small set of scenes from the Jewish market in Kraków taken in the 1930s. Helen Ennis of the National Gallery of Australia stated the images “carry the weight of history, offering a visual trace of a way of life that was destroyed by fascism.”

Michaelis was also fond of self-portraiture using the landscapes around Sydney and Melbourne as her backdrop.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Niu Weiyu (Chinese, b. 1927)

The Handcrafts Group Organised by Families of Shanghai Business Owners Making Chinese Dolls

1956, printed later

Gelatin silver print

Image: 43.9 x 45.8cm (17 5/16 x 18 1/16 in.)

Sheet: 60.9 x 50.8cm (24 x 20 in.)

Frame: 60.96 x 60.96 cm (24 x 24 in.)

Frame (outer): 63.5 x 63.5cm (25 x 25 in.)

Gao Fan & Niu Weiyu Foundation

Niu Weiyu (Chinese: 牛畏予; born 1927 in Tanghe, Henan) is a Chinese photojournalist whose career started in the 1940s with coverage of the Chinese Communist Party’s wartime experiences and continued after 1949. She is praised for her photographs of ordinary workers and ethnic groups, and as one of the few women in photography, she specialised in female images.

She is a member of the Chinese Communist Party and the Chinese Photographers Association. Her husband, Gao Fan (1922-2004) was also a wartime and post-1949 photographer.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Niu Weiyu 牛畏予 (1927- ) is a native of Tanghe County, Henan Province. In the spring of 1945, she joined in revolution. She studied in Chinese People’s Anti-Japanese Military and Political College. In 1947, she served as Publicity Officer of Shanxi-Hebei-Shandong-Henan Military Region Political Department. In 1948, she served as a photographer of North China Pictorial. Later, she followed the Second Field Army to advance southwards, and worked as a photographer in Southwest Pictorial. In the early 1951, she was transferred to civilian work and served as a photographer of News Photography Bureau. She was the Head of photography team in North China Branch and Beijing Branch of Xinhua News Agency. In 1955, she began to serve as the central news photojournalist of Xinhua News Agency. In 1973, she was transferred to the post of photographer of foreign affairs team of Xinhua News Agency. In 1978, she began to serve as Head of photography team of Hong Kong Branch of Xinhua News Agency. She retired as a veteran cadre in 1982.

Anonymous text. “Niu Weiyu,” on the Photography of China website [Online] Cited 29/11/2021

Niu Weiyu (Chinese, b. 1927)

Female Pilot

1952, printed 1988

Gelatin silver print

Image: 43.8 x 33cm (17 1/4 x 13 in.)

Frame: 60.96 x 50.8cm (24 x 20 in.)

Frame (outer): 63.5 x 53.34cm (25 x 21 in.)

Gao Fan & Niu Weiyu Foundation

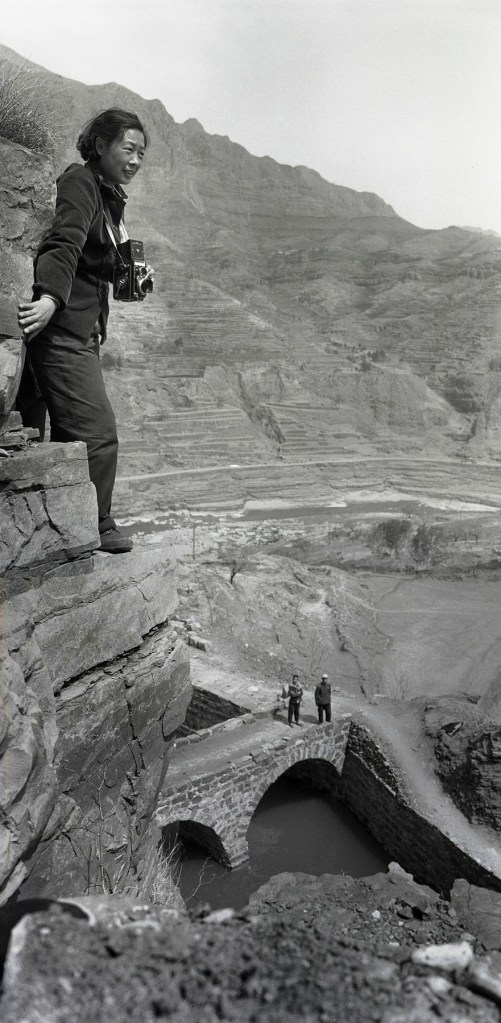

Shu Ye (Chinese)

Niu Weiyu with Camera

c. 1960

Gelatin silver print

Image: 15.4 x 7.1 cm (6 1/16 x 2 13/16 in.)

Mount: 25.4 x 12.8 cm (10 x 5 1/16 in.)

Frame: 45.72 x 35.56 cm (18 x 14 in.)

Frame (outer): 48.26 x 38.1 cm (19 x 15 in.)

Gao Fan & Niu Weiyu Foundation

Niu Weiyu (Chinese, b. 1927)

Train, Bridge, Highway, and Elephant

1950s, printed later

Gelatin silver print

Image: 38.8 x 55.9cm (15 1/4 x 22 in.)

Sheet: 50.8 x 60.9cm (20 x 24 in.)

Frame: 50.8 x 60.9cm (20 x 24 in.)

Gao Fan & Niu Weiyu Foundation

Niu Weiyu (Chinese, b. 1927)

The First Beginning of Spring After Liberation, an International Women’s Day Celebration in front of the Temple of the Forbidden City

1949, printed 2017

Gelatin and silver bromide printing

National Art Museum Collection of China

Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

Behind the Camera

Women actively participated in the development of photography soon after its inception in the 19th century. Yet it was in the 1920s, after the seismic disruptions of World War I, that women entered the field of photography in force. Aided by advances in technology and mass communications, along with growing access to training and acceptance of their presence in the workplace, women around the world made an indelible mark on the growth and diversification of the medium. They brought innovation to a range of photographic disciplines, from avant-garde experimentation and commercial studio practice to social documentary, photojournalism, ethnography, and the recording of sports, dance, and fashion.

The New Woman

A global phenomenon, the New Woman of the 1920s embodied an ideal of female empowerment based on real women making revolutionary changes in life and art. Her image – a woman with bobbed hair, stylish dress, and a confident stride – was a staple of newspapers and magazines first in Europe and the United States and soon in China, Japan, India, Australia, and elsewhere. A symbol of the pursuit of liberation from traditional gender roles, the New Woman in her many guises represented women who faced a mix of opportunities and obstacles that varied from country to country. The camera became a powerful means for female photographers to assert their self-determination and redefine their position in society. Producing compelling portraits, including self-portraits featuring the artist with her camera, they established their roles as professionals and artists.

The Studio