Exhibition dates: 5th February – 27th February 2021

Photography & Curation/Art Direction – Tom Goldner

Moving Image – Angus Scott

Sound – Sean Kenihan

Poetry – Dr Judith Crispin (publication)

Colourist – CJ Dobson (moving image)

Audio Visual – Toto Creative

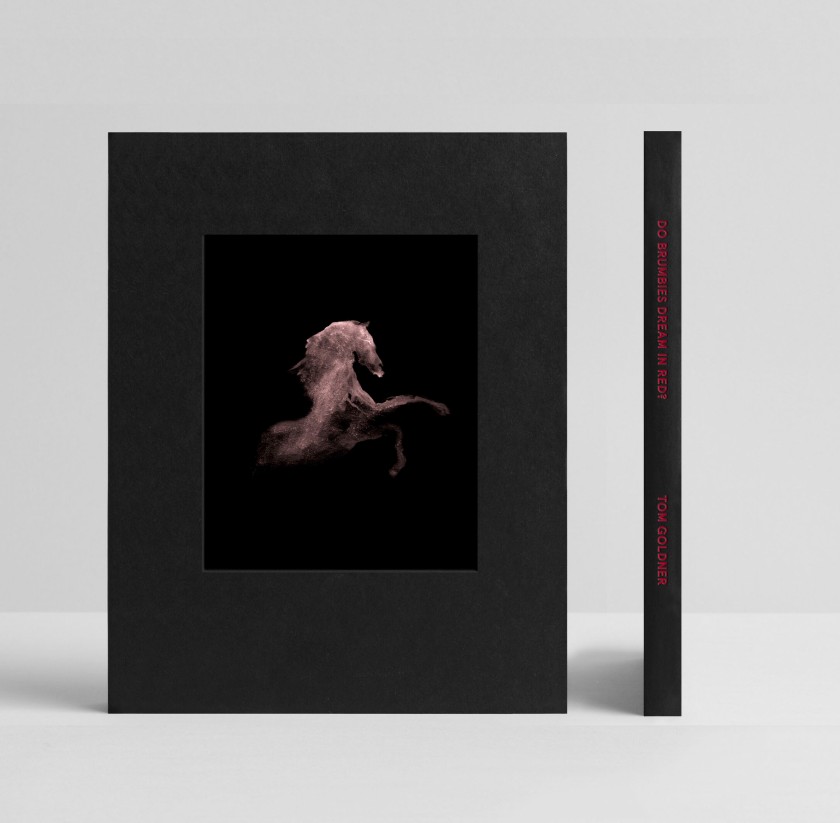

Cover Art – Katherina Rodrigues (publication)

Tom Goldner (Australian, b. 1984)

Untitled from the series Do Brumbies Dream In Red?

2020

Strange Beauty

Bloated prostrate tentacles

wither into our idea of dying

overlapping human, shit

feeding foulest vegetables,

regenerating sourly

Kingdoms of foulest water

regorging sourly

Bloated brumbies, winged coal

rejigs

Strange Beauty

Floating in our mind

In grey greasy horror water

Full of surprises –

like a holocaust holding pond

At your peril

Skull twisted,

Served on corrugated soot

Land, once precious

disguised, drained

black, gold – split

burnt to reburn

charred brumbies, flying coal

rem/embers,

Millions of worst worst

Strange Beauty

lost as sources

Boiling, bubbling – like a holocaust

At your peril

Belching wishes to reassemble

Hexing new forms

Bottom of our nightmare

Bottom of our innings

Animals worst worst

Plants unredeemable

Satan not lucifer

Sky a trap

Wings a trap

Escape a trap

Strange Beauty

beside the dead and ugly

like a holocaust

Do you want to …

(At your peril)

… Remember ?

Marcus Bunyan and Ian Lobb, May 2021

Contested Ground

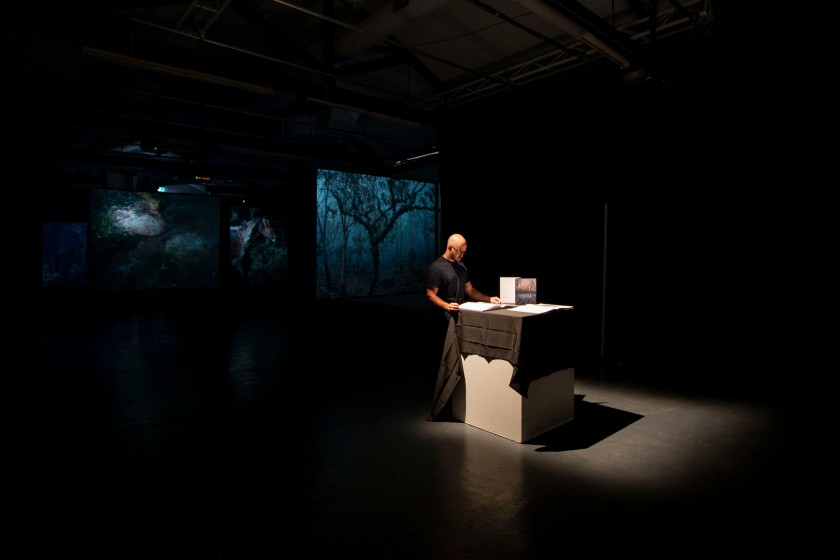

I saw this darkly mysterious, immersive exhibition by the artist Tom Goldner just after Melbourne suffered its mini-five day COVID lock down in February 2021, but I have been awaiting the installation photographs and video of the event to publish this posting.

This stimulating exhibition, with its wonderfully atmospheric sound track, was an overlapping animation of conceptual, documentary photographs that appear in Goldner’s book Do Brumbies Dream in Red? – and placed “the audience within the Snowy Mountains and Victorian Alpine regions during the period of 2019-2020 referred to as the Black Summer“, the project (both multimedia exhibition and book) considering “the systems which position the Snowy Mountain brumby and the catastrophic 2019-2020 Australian bushfires within a time of ecological uncertainty.” The starting point into Goldner’s investigation was that of the Snowy Mountain brumby, an Australian feral wild-roaming horse, an invasive, non-native species introduced during colonisation. The brumbies cannot see in red, and the artist wondered how the world must have appeared to them illuminated by the strange light of the raging bushfires. He uses this idea as a metonym throughout the project which acts as an entry point into both the human and nonhuman world, to begin to understand the human perception of this catastrophic event and the anthropogenic changes that are happening in the Australian landscape.

The research which underpins Goldner’s project is guided “by the work of English professor Timothy Morton and his theories on ‘ecological awareness’ in Dark Ecology (2016), which examine the intersection of places, scales and nonhuman interrelations. Running parallel to these ideas are those of American professor Donna Haraway’s most recent book, Staying with the Trouble (2016). Particularly her concept of the ‘Chthulucene’ that strives to capture a future in which all things in the world are connected, coexist and, in many cases, ‘collaborate’, and through this, we learn to ‘live and die well together’ and achieve a kind of ‘ongoingness’.” The artist seeks to flatten the hierarchy between human and nonhuman life by allowing us to recognise ourselves within the violence we inflict on the natural world during this human-assisted ecological disaster.

While the project professes to challenge the notion of clear and tidy boundaries in a time of ecological uncertainty, in reality it offers a particularly one-eyed perspective on the subject of anthropogenic changes to the landscape. I don’t mind this perspective at all, in fact I applaud it, for the ultimate goal of the photographs is to open our eyes to the destruction that human actions are inflicting on our environment. Through beautifully modulated photographs of great sensitivity Goldner pictures these spaces of destruction and re/generation. But is there ever an “original” landscape to which we must return?

In humans, a reduced sensitivity to red light due to missing or defective L-cones (or long wave cones) is known as protanopia or protanomaly. The derivation of the word protanopia is from the early 20th century: from proto- ‘original’ (red being regarded as the first component of colour vision) + an- ‘lacking’ + ‘opia’- (denoting a visual disorder). Protanomaly makes red look more green and less bright while protanopia makes you unable to tell the difference between red and green at all. People with protanopia are more likely to confuse black with many shades of red; dark brown with dark green, dark orange and dark red; some blues with some reds, purples and dark pinks; and mid-greens with some oranges (see image below).

When the first component of colour vision (red) is lacking we have a visual disorder. How, then, can we see the intersection of the human and non-human world clearly if we have a visual disorder? To what are we to return, to an untouched paradisiacal landscape pre-colonisation, pre-human inhabitation – to an “original” we can no longer see – or do we acknowledge the paradoxical “nature” of our contemporary existence on this earth in a more balanced way. Nothing is ever black and white, or in this case colour(–).1

For many generations humans have lived in the Snowy Mountains and Victorian Alpine regions, singing pastorals to the gods, seeking guidance to live on the land: the mountain ranges are thought to have had Aboriginal occupation for 20,000 years and after the areas were first explored by Europeans from the 1830s-1850s, high country stockmen followed using the mountains for grazing during the summer months (Wikipedia). Over the last few years, people of Victoria’s high country and animal lovers have rallied against the proposed culling of feral brumbies in the state’s national parks. They cite that brumbies hold “heritage value, they are part of our cultural and social history. Brumbies have lived in our Heritage National Parks for two centuries; are descendants of remounts that were sent to War with our soldiers… Brumbies were immortalised by Banjo Patterson, feature in paintings by Sydney Nolan and written about in the Silvery Brumby novels by Ellyne Mitchell. Brumbies are part of the fabric of our Australian society. It is undeniable that extremist elements must not be allowed to dictate on cultural and social values.”2 Goldner states that, “Brumbies are a symbol of national consciousness. While they may be labelled as a ‘feral species’ and a threat to native ecosystems by environmentalists, they are also valued as an important part of Australia’s history as a symbol of national spirit.”

Contested ground indeed, and perhaps one that needed to be more fully investigated in Goldner’s project.

While the second sentence in the above paragraph is true I would argue that the opposite of the first sentence is at least possible – that brumbies are an anti-symbol of national consciousness, for the animals hardly ever impinge on the collective consciousness of most Australians when they think about the Australian landscape. How often would the vast bulk of the city-dwelling Australian population think about the brumby as a symbol of national consciousness? Hardly ever would be my answer. It is not an original thought about the landscape that they would have.

Walking through the darkened spaces of the exhibition, I let the phenomena of superb images and sounds wash over me. The experience was particularly moving given the strange beauty of the limited colour palette images and the atmospheric vibrations of the music. For me, the key image of the exhibition was not that of the bloated brumby lying prostrate on the blackened earth, but that of an isolated grave standing erect in the scorched landscape. With no context to allow the viewer to anchor this grave to a historical past, all we are left with are questions and metaphors. What is this grave doing seemingly in the middle of nowhere? Who is the person buried there? The metaphors are rich indeed: the erect whiteness of the white man’s grave stone isolated against the black ness of the landscape, a landscape not their own, and perhaps not of their own making. The anonymous writing on the grave stone standing as a metaphor for any human who has ever lived. The iron fence that segregates the human from the land even as they buried in it… as though they are a part of this earth but apart from it. A masterful image if ever I saw one.

In the overlapping, interstitial, spatio-temporal dimensions of the gallery I placed myself into the existence of these works, into their networks of existence. As the artist wanted, I recognised “the violence we inflict on the natural world during this human-assisted ecological disaster” but not, I insist, through the flattening of the hierarchy between human and nonhuman life but through it’s very opposite – through an acknowledgement of the multiple, fragmented, lexias of existence,2 networks that live in multiple levels of intersectionality, like a spiders web created in the dimensions of extended space. Into this geometry of space, into the spatio-temporal ‘nature’ of photography – death, power, transcendence, timelines, delay, exposure, territorialisations, assemblage, bricolage, rhizomic structures and the author – “seeing is no longer framed or presupposed through relations of distance or perspective. Rather, the eye and the visible are embodied as they struggle with positionality, in the physical, mental, and emotional conflicts that result when you have to take responsibility for what you see, instead of conferring that responsibility on an-other.”4

Goldner’s vision embodies this ongoing thickness, this ongoing responsibility.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Footnotes

1/ “Conceptually, wholes are divided up or taken apart, dis-integrated into component pieces. They may be reintegrated, but in a way that reflects the understanding of those pieces at the time of their disassembly; the way the functions of individual parts of a whole are seen depends on the way the whole is divided into parts. Different visions result in different views of the whole.”

Wolf, Mark. Abstracting Reality: Art, Communication, and Cognition in the Digital Age. Lanham: University Press of America, 2000, p. 196.

2/ Anonymous author. “Melbourne rally “Stop the bullets”,” media release on the Australian Brumby Alliance website May 1, 2021 [Online] Cited 09/05/2021.

3/ Lexia is perhaps the most widely applicable term for describing the linked pieces of information within a hypertext, referred to in various contexts as nodes, pages, frames and workspaces.

4/ Burnett, Ron. Cultures of Vision: Images, Media, & the Imaginary. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1995, pp. 137-138.

Many thankx to Tom Goldner for allowing me to publish the photographs and video in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image. The Do Brumbies Dream in Red? – Photo Book is available from Tom Goldner’s website.

Protanopia vision

Photography & Curation/Art Direction – Tom Goldner

Moving Image – Angus Scott

Photography & Curation/Art Direction – Tom Goldner

Moving Image – Angus Scott

“A large portion of the project was made in the Snowy Mountain region of New South Wales.

During the first tip to the fire grounds in early January 2020 we came across a wild horse… It had died of a lung bleed while trying to escape the bushfires. I used the brumby as an entry point into Australia’s colonial history, proposing that the brumby is a manifestation of our collective actions.

I later learn that horses only see in blues and greens, and I wondered how the world must have appeared to them illuminated by that strange red light.

The project asks, can we too see the world differently?”

Tom Goldner on the Blackriver website [Online] Cited 05/04/2021

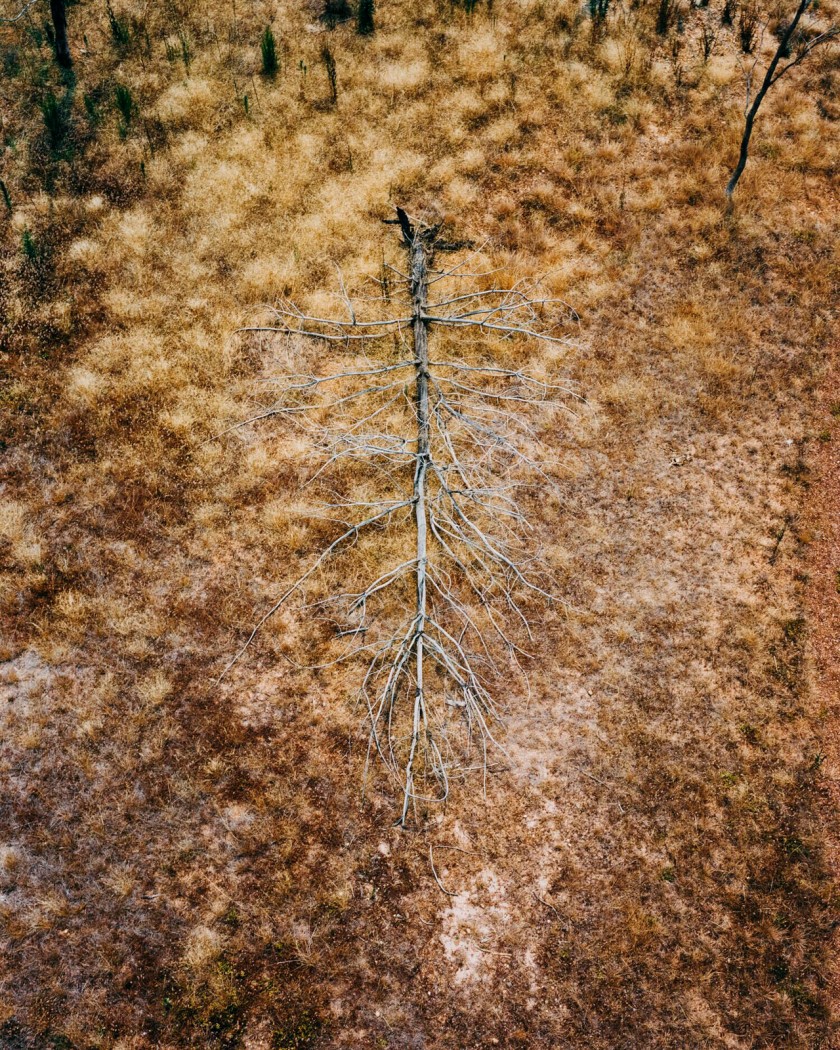

Do Brumbies Dream in Red? is a research-driven project which explores anthropogenic changes in the Australian landscape through the use of conceptual documentary photography. Presented as an immersive experience this collaborative project utilises large-scale projection to place the audience within the Snowy Mountains and Victorian Alpine regions during the period of 2019-2020 referred to as the Black Summer.

Do Brumbies Dream in Red? negotiates the human perception of this catastrophic event. This exhibition and publication reveals the bushfires and resulting damage through the eyes of another human-assisted ecological disaster, one of an invasive species: the Snowy Mountain Brumby.

The project considers the systems which position the Snowy Mountain brumby and the catastrophic 2019-2020 Australian bushfires within a time of ecological uncertainty. The Snowy Mountain brumby, an Australian feral wild-roaming horse, appears as a metonym throughout the project and acts as an entry point into both the human and nonhuman world.

Installation views of the exhibition Do Brumbies Dream In Red? – Tom Goldner 2021 at the Meat Market Stables, Melbourne

“Mixed-up times are overflowing with both pain and joy – with vastly unjust patterns of pain and joy, with unnecessary killing of ongoingness but also with necessary resurgence. The task is to make kin in lines of inventive connection as a practice of learning to live and die well with each other in a thick present. Our task is to make trouble, to stir up potent response to devastating events, as well as to settle troubled waters and rebuild quiet places.”

Donna Haraway, 2016

Do Brumbies Dream in Red? is a project driven by research which explores anthropogenic changes in the Australian landscape through the use of conceptual documentary photography, video and audio recordings.

The project considers the systems which position the Snowy Mountain brumby and the catastrophic 2019-2020 Australian bushfires within a time of ecological uncertainty. The Snowy Mountain brumby, an Australian feral wild-roaming horse, appears as a metonym throughout the project and acts as an entry point into both the human and nonhuman world.

Brumbies are a symbol of national consciousness. While they may be labelled as a ‘feral species’ and a threat to native ecosystems by environmentalists, they are also valued as an important part of Australia’s history as a symbol of national spirit. Brumbies represent wildness and the way we relate to, and attempt to control, nature.

The project challenges the notion of clear and tidy boundaries in a time of ecological uncertainty. The research is underpinned by the work of English professor Timothy Morton and his theories on ‘ecological awareness’ in Dark Ecology (2016), which examine the intersection of places, scales and nonhuman interrelations. Running parallel to these ideas are those of American professor Donna Haraway’s most recent book, Staying with the Trouble (2016). Particularly her concept of the ‘Chthulucene’ that strives to capture a future in which all things in the world are connected, coexist and, in many cases, ‘collaborate’, and through this, we learn to ‘live and die well together’ and achieve a kind of ‘ongoingness’.

Do Brumbies Dream in Red? seeks to flatten the hierarchy between human and nonhuman life by allowing us to recognise ourselves within the violence we inflict on the natural world. The visual outcomes that navigate these ideas are intertwined and are driven by a series of photographs, moving images and audio recordings. The project culminates in a photobook with an accompanying poem by Australian artist and academic Dr Judith Nangala Crispin. The publication was produced to be presented alongside a mixed-media exhibition, comprising of large-format projected still and moving imagery and a soundscape.

Text from the Tom Goldner website [Online] Cited 05/04/2021

Tom Goldner (Australian, b. 1984)

Untitled from the series Do Brumbies Dream In Red?

2020

Tom Goldner (Australian, b. 1984)

Untitled from the series Do Brumbies Dream In Red?

2020

Tom Goldner (Australian, b. 1984)

Untitled from the series Do Brumbies Dream In Red?

2020

Tom Goldner (Australian, b. 1984)

Untitled from the series Do Brumbies Dream In Red?

2020

Tom Goldner (Australian, b. 1984)

Untitled from the series Do Brumbies Dream In Red?

2020

Tom Goldner (Australian, b. 1984)

Untitled from the series Do Brumbies Dream In Red?

2020

Tom Goldner (Australian, b. 1984)

Untitled from the series Do Brumbies Dream In Red?

2020

Tom Goldner (Australian, b. 1984)

Untitled from the series Do Brumbies Dream In Red?

2020

Tom Goldner (Australian, b. 1984)

Untitled from the series Do Brumbies Dream In Red?

2020

Tom Goldner (Australian, b. 1984)

Untitled from the series Do Brumbies Dream In Red?

2020

Tom Goldner (Australian, b. 1984)

Untitled from the series Do Brumbies Dream In Red?

2020

Tom Goldner (Australian, b. 1984)

Untitled from the series Do Brumbies Dream In Red?

2020

Tom Goldner (Australian, b. 1984)

Untitled from the series Do Brumbies Dream In Red?

2020

Tom Goldner (Australian, b. 1984)

Untitled from the series Do Brumbies Dream In Red?

2020

Tom Goldner (Australian, b. 1984)

Untitled from the series Do Brumbies Dream In Red?

2020

Tom Goldner (Australian, b. 1984)

Untitled from the series Do Brumbies Dream In Red?

2020

Tom Goldner (Australian, b. 1984)

Untitled from the series Do Brumbies Dream In Red?

2020

Do Brumbies Dream in Red? – Photo Book

Meat Market Stables

2 Wreckyn St, North Melbourne

You must be logged in to post a comment.