Exhibition dates: 28th July – 1st November 2015

Curated by Jens Daehner and Kenneth Lapatin, both of the J. Paul Getty Museum

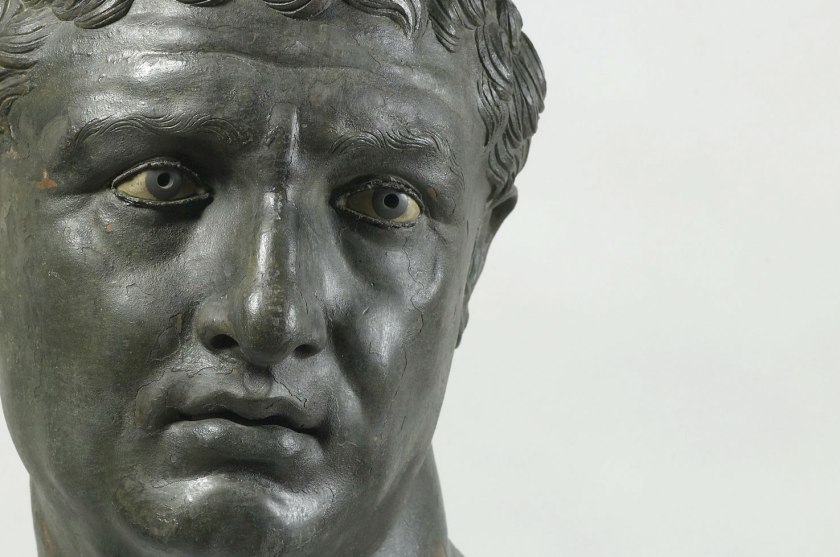

Hermes

About 150 B.C.

Bronze

H 49cm; W 20cm; D 15cm

The Trustees of the British Museum

Image © The Trustees of the British Museum

The fascination continues. All these centuries later.

Marcus

Many thankx to the J. Paul Getty Museum for allowing me to publish the art work in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“Beauty is the only thing that time cannot harm. Philosophies fall away like sand, creeds follow one another, but what is beautiful is a joy for all seasons, a possession for all eternity.”

Oscar Wilde

“Our ambition should be to rule ourselves, the true kingdom for each one of us; and true progress is to know more, and be more, and to do more.”

Oscar Wilde

During the Hellenistic period – from the death of Alexander the Great in 323 B.C. until the establishment of the Roman Empire in 31 B.C. – the medium of bronze drove artistic innovation in Greece and elsewhere across the Mediterranean. Sculptors moved beyond Classical norms, supplementing traditional subjects and idealised forms with realistic renderings of physical and emotional states. Bronze – surpassing marble with its tensile strength, reflective effects, and ability to hold the finest detail – was employed for dynamic compositions, dazzling displays of the nude body, and graphic expressions of age and character.

Cast from alloys of copper, tin, lead, and other elements, bronze statues were produced in the thousands throughout the Hellenistic world. They were concentrated in public spaces and outdoor settings: honorific portraits of rulers and citizens populated city squares, and images of gods, heroes, and mortals crowded sanctuaries. Few, however, survive, and those that do are dispersed worldwide and customarily displayed as isolated masterpieces. This exhibition unites a significant number of the large-scale bronzes preserved today so that they can be seen in context. New discoveries are presented together with works known for centuries, and several closely related statues are shown side by side for the first time.

Text from the J. Paul Getty Museum website

Pathos

Pathos is one of the three modes of persuasion in rhetoric (along with ethos and logos).

Pathos appeals to the audience’s emotions.

It is a part of Aristotle’s philosophies in rhetoric.

It is not to be confused with ‘bathos’,

which is an attempt to perform in a serious,

dramatic fashion that fails

and ends up becoming comedy.

Pathetic events in a plot are also not to be confused with tragic events.

In a tragedy, the character brings about his or her own demise, whereas

those invoking pathos often occur to innocent characters, invoking

unmerited grief.

Emotional appeal can be accomplished in a multitude of ways:

by a metaphor or story telling, common as a hook,

by a general passion in the delivery and an overall number

of emotional items in the text of the speech, or in writing.

Pathos is an appeal to the audience’s ethical judgment.

It can be in the form of metaphor, simile, a passionate delivery,

or even a simple claim that a matter is unjust.

Pathos can be particularly powerful if used well, but most speeches

do not solely rely on pathos. Pathos is most effective when the author

connects with an underlying value of the reader.

Aristotle’s Three Modes of Persuasion in Rhetoric

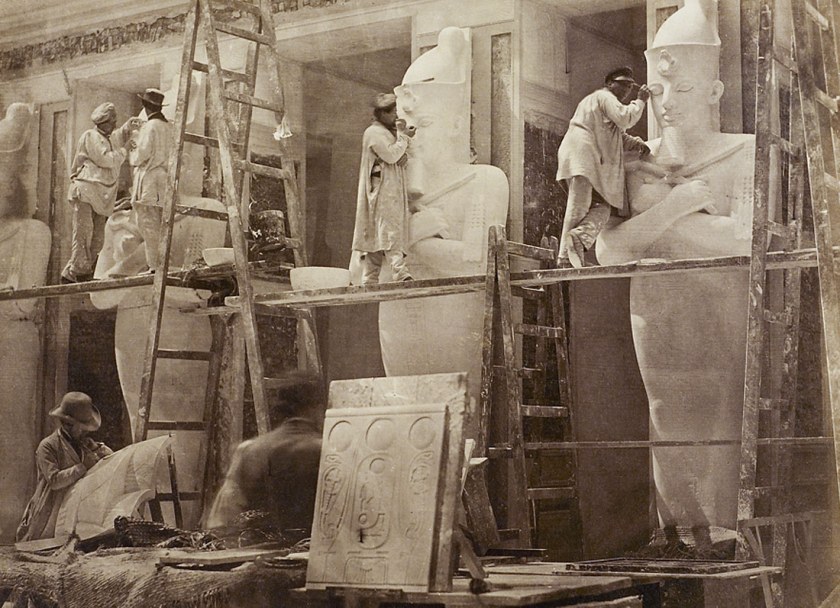

Installation views of the exhibition Power and Pathos at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

During the Hellenistic era artists around the Mediterranean created innovative, realistic sculptures of physical power and emotional intensity. Bronze – with its reflective surface, tensile strength, and ability to hold the finest details – was employed for dynamic compositions, graphic expressions of age and character, and dazzling displays of the human form. On view at the J. Paul Getty Museum from July 28 through November 1, 2015, Power and Pathos: Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World is the first major international exhibition to bring together more than 50 ancient bronzes from the Mediterranean region and beyond ranging from the 4th century B.C. to the 1st century A.D.

“The representation of the human figure is central to the art of almost all ancient cultures, but nowhere did it have greater importance, or more influence on later art history, than in Greece,” said Timothy Potts, director of the J. Paul Getty Museum. “It was in the Hellenistic period that sculptors pushed to the limit the dramatic effects of billowing drapery, tousled hair, and the astonishingly detailed renderings of veins, wrinkles, tendons, and musculature, making the sculpture of their time the most life-like and emotionally charged ever made, and still one of the high points of European art history. At its best, Hellenistic sculpture leaves nothing to be desired or improved upon. The more than 50 works in the exhibition represent the finest of these spectacular and extremely rare works that survive, and makes this one of the most important exhibitions of ancient classical sculpture ever mounted. This is a must-see event for anyone with an interest in classical art or sculpture.”

Large-scale bronze sculptures are among the rarest survivors of antiquity; their valuable metal was typically melted and reused. Rows of empty pedestals still seen at many ancient sites are a stark testimony to the bygone ubiquity of bronze statuary in the Hellenistic era. Ironically, many bronzes known today still exist because they were once lost at sea, only to be recovered centuries later. Power and Pathos: Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World is especially remarkable for bringing together rare works of art that are usually exhibited in isolation. When viewed in proximity to one another, the variety of styles and techniques employed by ancient sculptors is emphasised to greater effect, as are the varying functions and histories of the bronze sculptures. Bronze, cast in moulds, was a material well-suited to reproduction, and the exhibition provides an unprecedented opportunity to see objects of the same type, and even from the same workshop together for the first time. For example, two herms of Dionysos – the Mahdia Herm from the Bardo National Museum, Tunisia and the Getty Herm were made in the same workshop and have not been shown together since antiquity.

“The Mahdia Herm was found off the Tunisian coast in 1907 together with the cargo of an ancient ship carrying many artworks from Greece,” said Jens Daehner, one of the curators of the exhibition. “It is the only surviving case of an ancient bronze signed by an artist (Boëthos of Kalchedon). The idea that the Getty Herm comes from the same workshop is based on the close match of the bronze – an alloy of copper, tin, lead, and other trace elements that’s like the DNA of bronze sculptures. The information that these two works yield when studied together is extraordinary. It is a perfect example of how revealing and instructive it is to contemplate Hellenistic bronzes in concert with one another.”

The exhibition is organised into six sections: Images of Rulers, Bodies Ideal and Extreme, Images of the Gods, The Art of Replication, Likeness and Expression, and Retrospective Styles.

“Our aim in bringing together this extraordinary group of the most significant ancient bronzes that have survived is to present these works, normally viewed as isolated masterpieces, in their larger contexts,” said Kenneth Lapatin, the show’s co-curator. “These stunning sculptures come together to tell a rich story, not only of artistic accomplishment, but also of the political and cultural concerns of the people who commissioned, created, and viewed them more than two thousand years ago.”

Among the many famous works is the so-called Head of a Man from Delos from the National Museum of Athens, a compellingly expressive portrait with well-preserved inlaid eyes. The dramatic image of an unknown sitter is believed to date from the end of the second or beginning of the first century BC. The iconic Terme Boxer on loan from the National Roman Museum, with its realistic scars and bruises, stands out as the epitome of the modern understanding of Hellenistic art, employing minute detail and an emphatic, arresting subject. The weary fighter, slumped and exhausted after his brutal competition, combines the power and pathos that is unique to Hellenistic sculpture.

Although rarely surviving today, multiple versions of the same work were the norm in antiquity. A good example is the figure of an athlete shown holding a strigil, a curved blade used to scrape oil and dirt off the skin, known in Greek as the apoxyomenos or “scraper”. This exhibition brings together three bronze casts – two full statues and a head – that are late Hellenistic or early Roman Imperial versions of a statue created in the 300s BC by a leading sculptor of the time. This was evidently one of the most famous works of its time and copies were made well into the Roman Imperial period.

Press release from the J. Paul Getty Museum website

Encountering Ancient Bronzes

Portrait of Aule Meteli “The Arringatore”

125-100 B.C.

Greek

Bronze and copper

H: 170 x W: 68.6 x D: 101.6cm (5 ft 6 15/16 x 27 x 40 in.)

Image courtesy of the Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici della Toscana – Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Firenze

Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Firenze (Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici della Toscana)

Discovered in the mid-1500s at Sanguineto, in the Etruscan heartland that is now the border between Tuscany and Umbria, this statue entered the Medici collection in Florence shortly thereafter. Identified as Aule Meteli in an Etruscan inscription on the lower edge of the garment, the figure raises one hand in a gesture that appears to request silence at the start of a speech – hence the modern Italian name Arringatore (Orator). He wears a striped tunic under a toga, laced sandals, and a ring on his left hand. The realism of his facial features is a Hellenistic Greek hallmark that is also seen in contemporary Italic and Roman Republican portraits. The statue was assembled from nine separately cast parts. The extended right arm demonstrates the ability of bronze – stronger and lighter than marble – to render dynamic poses without support.

The retrograde inscription is in the Etruscan alphabet reads: “auleśi meteliś ve[luś] vesial clenśi / cen flereś tece sanśl tenine / tu θineś χisvlicś” (“To (or from) Auli Meteli, the son of Vel and Vesi, Tenine (?) set up this statue as a votive offering to Sans, by deliberation of the people”)

Herm of Dionysos

200-100 B.C.

Bronze, copper, and stone

H 103.5cm; W 23.5cm; D 19.5cm

Attributed to the Workshop of Boëthos of Kalchedon (Greek, active about 200-100 B.C.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum

This herm is nearly identical in type and size to its “twin” from Mahdia, which is signed by the artist Boëthos of Kalchedon. Both were manufactured using the same method: hollow casting by the lost-wax process. Somewhat better preserved, this example retains one of its original stone eyes, encased in copper lashes. Its wax model, however, was less artfully prepared than that of the signed version. There are shortcuts in the looping of the ribbons, and the absence of grape leaves on the headdress is particularly noticeable. Metal analysis has established that both works were cast with a remarkably similar alloy that distinguishes them from other bronze sculptures. Thus despite differences in detail and execution, they were likely produced at the same time, in the same workshop, and using the same batch of metal.

Survival

Large-scale bronze statues have rarely survived from antiquity, as most were melted down so that their valuable metal could be reused. Rows of empty stone pedestals can still be seen at ancient sites, leaving just an impression of the ubiquity of bronze sculpture in the Hellenistic world. Ironically, many bronzes known today have been preserved because they were buried or lost at sea, only to be recovered centuries later by archaeologists, divers, and fishermen.

Cultural Geography

Hellenistic art was a widespread phenomenon, propelled by the vast expansion of the Greek world under Alexander the Great in the late fourth century B.C. The impact of Greek culture can be traced not only throughout the Mediterranean from Italy to Egypt, but also in regions beyond such as Thrace in the Balkans, Colchis (in the present-day Republic of Georgia), and the southern Arabian Peninsula. Itinerant Greek bronze workers satisfied commissions far from their homeland, while local craftsmen employed indigenous techniques to create statues in fashionable Greek styles. Through trade, migration, plunder, and emulation, bronze sculpture served as a vehicle for the transfer of culture and technology.

Reproduction

Unique as most ancient bronzes appear today, many were never intended as “originals” in the modern sense of the word. The process of casting statues in moulds not only facilitated the production of multiples but also allowed for the faithful reproduction of older works from the Archaic and Classical periods of the sixth and fifth centuries B.C. Bronze copies as well as adaptations and recombinations in a variety of styles were made well into the Roman Imperial period.

Formulas of Power: Images of Rulers

The conquests of Alexander the Great (ruled 336-323 B.C.) transformed ancient politics and culture, creating new kingdoms and diminishing the autonomy of individual city-states. Alexander’s early death left his domain in the hands of his generals, the Diadochoi (Successors). They sought to emulate his charismatic style of leadership and adopted the visual models used to portray him as a dynamic, invincible young ruler. Many of these images were fashioned by Lysippos of Sikyon, Alexander’s favorite sculptor and the most celebrated artist of the time. Lysippos seems to have worked exclusively in bronze, adapting earlier Classical formulas for athletes, heroes, and gods and turning them into vigorous depictions of powerful kings.

Ruler portraiture emerged as a distinctive genre in the Hellenistic age, and bronze was its primary medium. The Diadochoi, like Alexander, were shown in various modes – nude, in armour, and on horseback. Although they typically commissioned their own portraits, statues of them were also erected as public honors by disempowered cities seeking or acknowledging favour. Today, the fragmentary condition of most of the surviving sculptures makes identification of the individuals difficult.

Alexander the Great on Horseback

100-1 B.C.

Greek

Bronze and silver

H: 51 x W: 29 x D: 51cm (20 1/16 x 11 7/16 x 20 1/16 in.)

Su concessione Ministero dei Beni e delle Attività Culturali e del Turismo – Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici di Napoli

Photo: Giorgio Albano

Alexander the Great is recognisable by the royal diadem in his characteristic wavy hair. The Macedonian king wears a short chlamys (cloak), a cuirass, and laced military sandals. He once brandished a sword in his right hand, while his left hand grasped the reins of his rearing horse, presumably his favourite Boukephalos (Bull Head). Found in 1761 at Herculaneum in Italy, the statuette is thought to be a small-scale replica of the centrepiece of a monumental group by Lysippos. The now-lost original was set up in the Sanctuary of Zeus at Dion, in northern Greece, to commemorate Alexander’s victory over the Persians at the Granikos River in 334 B.C.; it was transferred to Rome in 146 B.C.

Horse Head “The Medici Riccardi Horse”

About 350 B.C.

Italian

Bronze and gold

H: 81.3 x W: 97 x D: 35cm (32 x 38 3/16 x 13 3/4 in.)

National Archaeological Museum of Florence (Superintendency for the Archaeological Heritage of Tuscany)

Image courtesy of the Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici della Toscana – Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Firenze

Once part of an equestrian statue, this well preserved horse head displays highly realistic anatomical features. Although the inset eyes are missing, the flaring nostrils, the folds of the neck, and the open mouth stretched by a bit serve to emphasise the dynamic posture. Traces remain of the original gilding and the now-lost bridle. The medium of bronze allowed for the fine detail of the sculpture, whose vigorous muscularity and pulsing veins are among the expressive forms developed by Hellenistic artists.

Portrait of Seuthes III

about 310-300 B.C.

Greek

Bronze, copper, calcite, alabaster, and glass

Object: H: 32 x W: 28 x D: 27.9cm (12 5/8 x 11 x 11 in.)

Image courtesy of National Institute of Archaeology with Museum, BAS

Photo: Krasimir Georgiev

The power and intensity of this man’s gaze are enhanced by the use of several kinds of materials for his eyes. With long hair and full beard, the portrait is thought to depict Seuthes III, who ruled the Odrysian kingdom of Thrace (in present day Bulgaria) from about 331 B.C. to 300 B.C. Found in 2004 at the monumental tomb of Seuthes at Šipka, the head may have been part of a full-length statue that originally stood in Seuthopolis, a city he founded in the vicinity.

Portrait of a Man

100-1 B.C.

Bronze

H 29.5cm; W 21.5cm; D 21.5cm

The J. Paul Getty Museum

Probably once part of a full-length statue, this head has roughly modelled hair that recalls portraits of Alexander the Great. The deep-set eyes were originally inlaid in another material, and the lips – with edges outlined in bronze – may have been plated with copper to achieve a more realistic polychromatic effect. Two short bronze rods inside the mouth could have been used to facilitate casting, or perhaps to attach teeth from the interior.

Portrait of a Man

300-200 B.C.

Greek, found in the Aegean Sea near Kalynmos

Bronze, copper, glass, and stone

Object (greatest extent): H: 32 x W: 27.9 x Diam.: 98cm (12 5/8 x 11 x 38 9/16 in.)

Image courtesy of the Hellenic Ministry of Culture, Education and Religious Affairs

The Archaeological Museum of Kalymnos

Image © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Archaeological Receipts Fund

The kausia, a brimmed hat that originated in Macedonia (northern Greece), suggests that this figure is a Macedonian general or king. The band underneath his kausia may be a royal diadem. His preserved eyes are composed of different materials, including glass paste for the whites, a metal ring outlining each iris, and dark stone for the pupils. The head was found in 1997 in the Aegean Sea off the Greek island of Kalymnos. Components of bronze sculptures depicting cuirassed horsemen were recovered nearby.

Portrait of a Ruler (Demetrios Poliorketes?)

310-290 B.C.

Bronze

H 45cm; W 35cm; D 39cm

Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

Image © 2015 Photographic Archive. Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid/Scala, Firenze

The thick, curly hair of this youthful male recalls the style popularised by Alexander the Great, while the individualised features are reminiscent of portraits of his successors in the late fourth century B.C. The head originally belonged to a full-length figure that would have stood some 3.5 meters tall. Although lacking a diadem signifying royalty, the colossal portrait may represent the Macedonian ruler Demetrios Poliorketes, who was first proclaimed king at the age of thirty in 307 B.C., along with his father, Alexander’s general, Antigonos I Monophthalmos.

Ruler in the Guise of Hermes or Perseus

100 B.C. – A.D. 100

Bronze and copper

H 71.2cm (76.5cm with base); W 30cm

Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici di Napoli

The distinctive facial features suggest that this figure is a Hellenistic ruler, and the strap under his chin indicates that he originally wore a petasos, a wide-brimmed traveler’s hat. This cap as well as the wings attached to his ankles are attributes of both the god Hermes and the hero Perseus. Hellenistic kings were often shown in the guise of deities or mythological heroes, and scholars have proposed various identities for the individual depicted here. The statuette was discovered in 1901 in a house at Pompeii.

Flesh and Bronze: Bodies Ideal and Extreme

Hellenistic sculptors exploited Classical prototypes and continued to create idealised figures, but with a new interest in realistic detail and movement. Lysistratos, the brother of Lysippos, was credited with fashioning moulds directly from living bodies, and many Hellenistic bronzes exhibit considerable anatomical subtlety. Lifelike effects were achieved through the use of alloys and inlays to convey the contrasting colours of eyes, nipples, lips, teeth, bruises, and even blood.

Expanding the repertoire of images, Hellenistic artists represented diverse body types in a variety of states – young and old, energised and exhausted, ecstatic and asleep. Looking back to their predecessors, sculptors adopted the contrapposto stance that had become the norm in the Classical period, but they also experimented with extreme poses that took greater advantage of the tensile strength of bronze. Figures were shown moving more fully in three dimensions, with limbs emphatically advanced, heads and bodies dynamically turned. Even figures at rest occupied more space, encouraging viewers to walk around them. This experience of viewer and statue sharing a common space enhanced the understanding of complex imagery and heightened empathy with the subjects depicted.

Sleeping Eros

300-100 B.C.

Greek

Bronze (with a modern marble base)

H: 41.9 x D: 35.6 x W: 85.2cm (16 1/2 x 14 x 33 9/16 in.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1943 (43.11.4)

Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Scala, Firenze

Reportedly found on the Greek island of Rhodes, this statue of Eros as a sleeping infant departs from Classical images of the deity as a graceful adolescent. For the Hellenistic sculptor, the recumbent Eros, draped limply over a rock, provided a perfect subject for the artistic exploration of a child’s body at rest. The statue may even be a playful inversion of the earlier Greek characterisation of the love god as “limb loosening.” Hellenistic images of Eros as a winged baby inspired many depictions of Cupid in Roman art and, much later, the cherubs and putti of the Renaissance.

Artisan

About 50 B.C.

Bronze and silver

H 40.3cm; W 13cm; D 10.8cm

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1972

Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Scala, Firenze

Hellenistic artists represented subjects not previously considered worthy of depiction, such as elderly individuals, dysfunctional bodies, and figures from the periphery of society. This stocky, balding old man wears an exomis (short tunic) that identifies him as an artisan. Tucked into his belt is a small notebook that suggests he may not be an ordinary day labourer. Among the identities scholars have proposed for him are the god Hephaistos, the mythical craftsman-engineer Daidalos, and the famous fifth-century B.C. sculptor Pheidias. The statuette is said to have been found at the site of Cherchel in Algeria.

Male Torso

300-200 B.C.

Bronze

H 152cm; W 52cm; D 68cm

The Hellenic Ministry of Culture, Education and Religious Affairs. The Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities, Athens

In 2004 this torso was accidentally netted by fishermen at a depth of five hundred meters near the Greek island of Kythnos in the Aegean Sea. The absence of attributes leaves the figure’s identity open: he could be an athlete, a hero, or even a god. The position of his left hand suggests that he held a flat object, perhaps a discus or a scabbard. The artist realistically rendered the body’s anatomical details as well as the texture and creases of the skin.

Victorious Athlete, “The Getty Bronze”

300-100 B.C.

Greek

Bronze and copper

H: 151.5 x W: 70 x D: 27.9cm (59 5/8 x 27 9/16 x 11 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum

Victorious Athlete, “The Getty Bronze” (detail)

300-100 B.C.

Greek

Bronze and copper

H: 151.5 x W: 70 x D: 27.9cm (59 5/8 x 27 9/16 x 11 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum

Italian fishermen recovered this bronze from the depths of the Adriatic Sea in the early 1960s. Commemorating a successful athlete, the figure stands in the conventional pose of a victor: he is about to remove his victory wreath and dedicate it to the gods in gratitude. The rendering of the nude body, with its rounded volumes and softly swelling forms, is a subtle description of male post-adolescence. The face is less idealised, seeming to convey the distinct features of a real individual.

Herakles Epitrapezios

100 B.C. – A.D. 79

Bronze and limestone

H 75cm (95cm with base); W of base 67cm; D of base 54cm

Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici di Napoli

Su concessione del Ministero dei Beni e delle Attività Culturali e del Turismo – Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici di Napoli – Foto Giorgio Albano

Excavated in 1902 in a suburban villa just outside Pompeii, this figure of Herakles seated on a rock is one of dozens of this type to survive. They range in scale from miniature to colossal, and the composition has been associated with Lysippos based on ancient descriptions. Both Martial and Statius, Roman writers of the late first century A.D., recount attending a dinner hosted by the collector Novius Vindex, who showed them a statuette of Herakles Epitrapezios (At / Upon the Table) created by Lysippos. Martial describes the “small bronze statue of a large god,” and Statius further contrasts its small size with the enormity of the subject represented: “How great was the experience of that learned artist in the details of his art, endowing him with the ingenuity to fashion a table ornament but at the same time to conceive a colossus.”

Seated Boxer, “The Terme Boxer”

300-200 B.C.

Greek, from Herculaneum

Bronze and copper

Object (with base): H: 140 x W: 64 x D: 115cm (55 1/8 x 25 3/16 x 45 1/4 in.)

Museo Nazionale Romano – Palazzo Massimo alle Terme Su concessione del Ministero dei beni e delle attività culturali e del turismo – Soprintendenza Speciale per il Colosseo, il Museo Nazionale Romano e l’area archeologica di Roma

Photo © Vanni Archive/Art Resource, NY

Seated Boxer, “The Terme Boxer” (detail)

300-200 B.C.

Greek, from Herculaneum

Bronze and copper

Object (with base): H: 140 x W: 64 x D: 115cm (55 1/8 x 25 3/16 x 45 1/4 in.)

Museo Nazionale Romano – Palazzo Massimo alle Terme Su concessione del Ministero dei beni e delle attività culturali e del turismo – Soprintendenza Speciale per il Colosseo, il Museo Nazionale Romano e l’area archeologica di Roma

Photo © Vanni Archive/Art Resource, NY

The brutal realism of this boxer – a man who has received many violent blows and is ready to deal them himself – is designed to arouse empathy in the viewer. Copper inlays line the cuts of the skin and represent dripping blood. The swollen right cheekbone was cast in a different alloy (containing less tin), imitating the discolouration of a hematoma. While the face expresses physical and mental exhaustion after a fight, the boxer’s body is toned and strong, showing few signs of age, and his hair and beard are neatly coiffed. Excavated in 1885 on the south side of the Quirinal Hill in Rome, this statue was found carefully deposited in the foundations of an ancient building. Originally, the figure would have been erected in a Greek sanctuary or displayed publicly in the hometown of the athlete it commemorated.

A New Realism: Images of the Gods

Statues of divinities, an important genre in Archaic and Classical Greek art, remained significant in the Hellenistic period, especially as new shrines were established in new cities. The expressive capabilities of bronze and the dynamic styles of Hellenistic sculpture were adapted to representations of divine beings. Indeed, it seems to have been expected that the gods be depicted in the most up-to-date manner, and thus their images, like those of mortals, sometimes became less ideal and more “realistic” or “human.” Athena, for example, was portrayed as a young maiden as well as a formidable warrior; Eros, an elegant adolescent in Classical art, was shown as a pudgy infant. Deities were now thought of and represented more as living beings – in touch with human experience and with changing physical and emotional states.

Athena “The Minerva of Arezzo”

300-270 B.C.

Bronze and copper

H 155cm; W 50cm; D 50cm

Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Firenze (Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici della Toscana)

Wearing a protective aegis with a Gorgon’s head, the goddess of war and wisdom probably held a spear in her right hand. An owl decorates her helmet; most of the serpent on top is modern restoration. Athena’s lips are plated with copper, and her eyes were originally inlaid to achieve a more lifelike appearance. This statue is a variant of a popular type invented in the fourth century B.C., but technical features – the composition of the alloy, casting process, and assembly method – suggest a date in the early third century B.C. Discovered in fragments in the remains of an ancient Roman house at Arezzo, Italy, in 1541, the sculpture was acquired by the Medici and brought to Florence. The gray epoxy-resin fills were added in a recent conservation treatment.

Head of Apollo

50 B.C. – A.D. 50

Bronze

H 51cm; W40cm; D 38cm

H of the face 23cm

Province of Salerno – Museums Sector

Image courtesy of Archivio Fotografico del Settore Musei e Biblioteche della Provincia di Salerno – Foto Gaetano Guida

Found in 1930 by Italian fishermen dragging their nets in the Gulf of Salerno, this monumental head of the god Apollo probably belonged to a statue installed in an ancient building or precinct along the coastal bluffs. While the idealised face shares much with Classical antecedents, the extreme turn of the neck and the exuberant locks of hair (many of which were individually cast and attached) are more typical of Hellenistic sculpture.

Head of a God or Poet

100-1 B.C.

Bronze

H 29cm

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Museum purchase funded by Isabel B. and Wallace S. Wilson, 2001

Cast in several pieces, this head is marked by its strong individualism, yet the identity of the figure remains uncertain. The fillet in the hair suggests a god but is also a common attribute of poets such as Homer. While the furrowed brow, sunken cheeks, and bags under the eyes characterise an older man, the luxuriant beard and full mouth, with lips parted as if to speak, convey power. Pronounced asymmetries indicate that the head was turned energetically to its left and – with the neck stretched forward – may have belonged to a seated figure. Paternal deities such as Poseidon or Asklepios were commonly depicted in a seated position, a format likewise employed for portraits of intellectuals.

Apoxyomenos and the Art of Replication

Although rarely surviving today, multiple bronze versions of the same work were the norm in antiquity. Statues honouring victorious athletes, for example, were likely commissioned in a first edition of two: one to be dedicated in the sanctuary where the competition was held, and the other for display in the winner’s proud hometown.

The figure of an athlete holding a strigil (a curved blade used to scrape oil and dirt off the skin) is often referred to as an apoxyomenos (scraper). The three bronze replicas in this room – two full statues and one head – are not first editions but late Hellenistic or early Roman Imperial copies of a statue created in the 300s B.C., probably by a prominent sculptor. The original must have been so famous that it was still reproduced centuries later. An additional ten replicas in marble and dark stone further attest to its reputation. The exact relationship of the bronze copies to the original and to one another remains to be investigated by comparing their technique, metallurgy, and craftsmanship.

Athlete, “The Ephesian Apoxyomenos”

A.D. 1-90

Greek

Bronze and copper

H: 205.4 x W: 78.7 x D: 77.5cm (80 7/8 x 31 x 30 1/2 in.)

Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, Antikensammlung

Image © KHM-Museumsverband. Collection of Greek and Roman Antiquities / Ephesos Museum

Athlete, “The Ephesian Apoxyomenos” (detail)

A.D. 1-90

Greek

Bronze and copper

H: 205.4 x W: 78.7 x D: 77.5cm (80 7/8 x 31 x 30 1/2 in.)

Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, Antikensammlung

Image © KHM-Museumsverband. Collection of Greek and Roman Antiquities / Ephesos Museum

During Austrian excavations at Ephesos (in present-day Turkey) in 1896, this bronze sculpture was found broken into 234 fragments. Previously thought to be an athlete scraping his skin with a strigil – a literal apoxyomenos – the figure is better understood as cleaning the strigil by running the fingers of his left hand over the blade. The statue is widely accepted as an early Roman Imperial replica of a famed Greek work created in the late fourth century B.C., which has been variously attributed to the school of Polykleitos, to Daidalos, or to Lysippos. The circular plinth is modern but of a type used for mounting bronze sculptures in Roman times.

Athlete “The Croatian Apoxyomenos”

100-1 B.C.

Greek

Bronze and copper

H 192cm; W 50cm; D 40cm

Head H 29cm

Bronze plinth H 7.8cm

Republic of Croatia, Ministry of Culture

Athlete “The Croatian Apoxyomenos” (detail)

100-1 B.C.

Greek

Bronze and copper

H 192cm; W 50cm; D 40cm

Head H 29cm

Bronze plinth H 7.8cm

Republic of Croatia, Ministry of Culture

Head of an Athlete Ephesian Apoxyomenos type

200-1 B.C.

Greek

Bronze and copper

H 29.2cm; W 21cm; D 27.3cm

The Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas

Image courtesy of Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas/Scala, Firenze

This head of an apoxyomenos has been known since the 1700s, when it was part of a private collection in Venice. The rendering of the hair – with rows of finely delineated strands swept from the forehead in different directions – creates the realistically disheveled look of an athlete still sweating after a competition. A distinctive technique was used to attach the head to the now-missing body: the join runs beneath the chin and jaw and follows the hairline behind the ears to the base of the skull. Like the head of the Croatian Apoxyomenos, this head rested on the neck by means of an interior bronze ledge, which was practically invisible from the front.

When Pathos Became Form: Likeness and Expression

Realistic features and emotional states are hallmarks of Hellenistic sculpture. Whether depicting fresh youth or withered age, stoic calm or attention to cares, individualised portraits superseded the largely idealised types of earlier periods through details such as soft, rolling flesh, furrowed brows, and crow’s-feet. Personal traits were even given to fictive portraits of historical figures such as Homer and other significant literati of the past.

Pathos – lived experience – came to be represented physically, and naturalistic, expressive forms soon became formulas. Hellenistic conventions of balancing pathos with the ideal were borrowed by sculptors working in Italy for both Etruscan and Roman Republican patrons, spreading Greek styles to the West just as Alexander and his successors had in the East. Realism was also applied to images of foreigners and figures on the margins of society – new subjects that further broadened the sculptural genres of the period.

Portrait of a Man

about 100 B.C.

Greek, from Delos

Bronze, copper, glass, and stone

H: 32.5 x W: 22 x D: 22cm (12 13/16 x 8 11/16 x 8 11/16 in.)

Image courtesy of the Hellenic Ministry of Culture, Education and Religious Affairs. The National Archaeological Museum, Athens

Photo: Marie Mauzy/Art Resource, NY

Portrait of a Man (detail)

about 100 B.C.

Greek, from Delos

Bronze, copper, glass, and stone

H: 32.5 x W: 22 x D: 22cm (12 13/16 x 8 11/16 x 8 11/16 in.)

Image courtesy of the Hellenic Ministry of Culture, Education and Religious Affairs. The National Archaeological Museum, Athens

Photo: Marie Mauzy/Art Resource, NY

Highly individualised, this beardless male head epitomises the intense realism employed by Greek artists in the late Hellenistic period. The portrait was once part of a full-length statue, and its dynamic turn to the left would have further enhanced the pathos of the expression. Both inserted eyes are preserved, giving a vivid impression of the original appearance of portraits that have lost them. Found in 1912 at the Granite Palaistra on the Greek island of Delos, the head likely belonged to an honorific statue of a citizen displayed in or near the palaistra, a training ground for athletes.

Portrait of a Poet, “The Arundel Head”

200-1 B.C.

Greek

Bronze and copper

H: 41 x W: 21 x D: 26cm (16 1/8 x 8 1/4 x 10 1/4 in.)

Image courtesy of and © The Trustees of the British Museum

Portrait of a Poet, “The Arundel Head” (detail)

200-1 B.C.

Greek

Bronze and copper

H: 41 x W: 21 x D: 26cm (16 1/8 x 8 1/4 x 10 1/4 in.)

Image courtesy of and © The Trustees of the British Museum

Discovered in the 1620s at Smyrna (present-day Izmir, in western Turkey), this portrait originally had inset eyes, and the open mouth may have contained silvered teeth. Its copper lips are still preserved. The graphic realism of the wrinkled face, the interest in characterising old age, and the heightened emotional expression embody Hellenistic style, yet the locks of hair are neatly arranged in a Classical fashion. The full beard, long hair, and round fillet on the head are attributes of Greek poets, playwrights, and other intellectuals.

Portrait of a North African Man, from Cyrene (in present day Libya),

300-150 B.C.

Greek

Bronze, copper, enamel, and bone

H: 27 x W: 20 x D: 24cm (10 5/8 x 7 7/8 x 9 7/16 in.)

Image courtesy of and © The Trustees of the British Museum

Excavated in 1861 near the Temple of Apollo at Cyrene (in present-day Libya) along with fragments of a gilt-bronze horse, this head represents an indigenous Libyan or Berber. High cheekbones, crow’s-feet at the eyes, and a short beard contribute to the image’s realism. The full lips, inset with copper, are slightly parted to reveal bone teeth, and the inlaid eyes, outlined with copper lashes, preserve traces of white enamel. The portrait’s distinctive features demonstrate the widespread popularity of Greek-style works as well as Hellenistic artists’ interest in depicting different ethnic characteristics.

Portrait of a Man

About 150 B.C.

Marble

H 40.7cm; W 25cm; D 31.7cm

The J. Paul Getty Museum

Drapery at the back of the neck suggests that this over-life-size head belonged to a full-length figure wearing a cloak – possibly a hero, a king, or a benefactor. Although carved in marble, the portrait displays traits associated with bronze sculpture: sharply outlined lips, rendered as if inset in copper, and finely incised eyebrows, moustache, and beard. The fleshy neck and highly modelled forehead and cheeks are also features of Hellenistic bronzes, and similarly derive from prototypes worked in softer materials such as clay or wax.

Head of a Votive Statue

375-350 B.C.

Bronze

H 24.3cm; W 15.5cm; D 15.5cm

The Trustees of the British Museum

Image © The Trustees of the British Museum

The idealised features of this head and the arrangement of the hair reflect pre-Hellenistic traditions of Greek sculpture. The short bangs and the large, compass-drawn pupils, however, are distinctly Etruscan, as is the beard stubble, which seems to have been employed in central Italian portraiture to express strength and wisdom. Reportedly found on an island in Lake Bolsena, Italy, in 1771, this sculpture may have been produced by a workshop in nearby Volsinii (present-day Orvieto). According to ancient sources, Roman soldiers plundered two thousand bronzes when they sacked that city in 265 B.C.

Portrait of a Man

About 300 B.C.

Bronze, copper, and glass

H 26.8cm; W 21.8cm; D 23.5cm

Bibliothèque nationale de France

Found near San Giovanni Lipioni in central Italy, this portrait has been linked with Rome’s conquest of the region of Samnium, but whether it depicts a Roman general or a local leader remains uncertain. The crown of the head, now lost, was separately cast. Glass-paste eyes are set between copper lashes, and the lips too are copper. As on the Head of a Votive Statue, a faint beard is indicated. The cubic shape of the head, the flat facial planes, and the distinctive forward comb of the hair situate this sculpture within an Etrusco-Italic artistic tradition.

Portrait of a Boy

100-50 B.C.

Bronze and copper

H 140cm; W 57.2cm; D 45.1cm

H of the head 23cm

H of the base 4.5cm

The Hellenic Ministry of Culture, Education and Religious Affairs. The Archaeological Museum of Herakleion

Image © Archaeological Museum of Heraklion, Ministry of Culture & Sports, Archaeological Receipts Fund

Wearing a long cloak that envelops both arms and hands, this figure was discovered in 1958 along the beach of Hierapetra, on the Greek island of Crete. Its original context and function remain uncertain, and the subject’s identity is unknown. Distinguished by the individualised, almost petulant face and elaborate sandals, the portrait may have been intended to honour a local youth of high status.

Portrait of a Boy

25 B.C. – A.D. 25

Bronze

H 132.4cm; W 50.8cm; D 41.9cm

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1914

Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Scala, Firenze

Said to be from Rhodes, a Greek island noted for its skilled bronze workers, this graceful figure was assembled from at least seven separately cast parts: two arms, two legs, the torso and head, and two sections of drapery. Apparently intended to be seen from below, the statue may have been erected on a tall base and set into a niche. The comma-shaped curls over the forehead echo portraits of the Roman imperial family, but the garment is Greek. The boy may have been a young member of the local aristocracy.

Portrait of a Man

100 – 1 B.C.

Bronze

H 43cm; W 26cm; D 25cm

Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici di Napoli

Su concessione del Ministero dei Beni e delle Attività Culturali e del Turismo – Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici di Napoli

Foto Giorgio Albano

This portrait of an anonymous older man is distinguished by its meticulous characterisation of the hair, eyebrows, and beard. These features were worked into the wax model before casting, using different techniques and tools including a pointed modelling knife, a multi-pronged instrument, and a pen-like device. The asymmetry of the face and neck muscles suggests that the head was originally turned further to its right. The current orientation is the creation of a Renaissance restorer, who transformed the ancient fragment into a bust.

Editions of the Past / Retrospective Styles

Retrospection, or the borrowing of earlier forms and styles, appears to have begun as early as the fifth century B.C. It continued into Hellenistic and early Roman Imperial times, when sculptors regularly employed and adapted Archaic and Classical features, sometimes eclectically, to recall the art of previous periods. Throughout the second century B.C., conquering Roman generals took original Greek art back to Rome, where it was paraded in triumphal processions, dedicated in temples, erected in civic spaces, and displayed in elite homes. To satisfy an eager market, Greek artists flocked to Rome and produced new works emulating older ones, often taking advantage of bronze as an ideal medium for replication and serial production. Statues in Archaic style were created not only to appeal to the interests of antiquarian collectors but also to evoke the religious piety of a bygone age. The Classical style came to be favoured by the emperor Augustus for much of his official art, as it conjured the golden age of Athens.

Herm Bust of the Doryphoros

50-1 B.C.

Bronze

H 58cm; W 66cm; D 27cm

Inscribed in Greek: “Apollonios, son of Archias, of Athens, made [this]”

Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici di Napoli

Su concessione del Ministero dei Beni e delle Attività Culturali e del Turismo – Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici di Napoli

Foto Luigi Spina

The Doryphoros was a famous full-length statue of a heroic spear bearer created by the fifth-century B.C. Greek sculptor Polykleitos. This herm bust, which excerpts just the head and chest of that figure, is considered one of the most accurate surviving replicas, capturing the finely incised hair and idealised facial features of the now-lost original; its eyes are eighteenth-century restorations. The bust was found amid an extensive collection of sculpture that decorated the Villa dei Papiri at Herculaneum. The artist Apollonios of Athens added his signature in Greek along the front, advertising his skill and guaranteeing the authenticity of his work for his Roman patron.

Bust of a Youth “The Beneventum Head”

About 50 B.C.

H 33cm; W 23cm; D 20cm

Bronze and copper

Musée du Louvre, Département des antiquités grecques, étrusques et romaines, Paris

Image © RMN – Réunion des Musées Nationaux

Foto Daniel Arnaudet/Gérard Blot

The wreath of wild olive suggests that this figure is a victorious athlete, and the form of the bust indicates that it was set atop the pillar of a herm. The precise arrangement and striations of the hair are reminiscent of works by the fifth-century B.C. sculptor Polykleitos, but the melancholy expression and the delicate appearance of the face are characteristic of first-century B.C. Roman creations made in Classical Greek style. Found in Herculaneum, this bust was given by King Ferdinand II to the Pedicini family of Beneventum and subsequently sold to the emperor Napoleon III in the 1800s.

Apollo “The Piombino Apollo”

About 120-100 B.C.

Bronze, copper, and silver

H 117cm

Musée du Louvre, Département des antiquités grecques, étrusques et romaines, Paris

Image © RMN-Réunion des Musées Nationaux

Foto Stéphane Maréchalle

With its stiff posture and left foot placed forward, this figure of a nude male youth looks like an Archaic Greek kouros. Yet the smooth musculature, relatively slender limbs, and treatment of the hands and feet appear more naturalistic than original Archaic kouroi, which functioned as religious dedications and grave markers in the sixth century B.C. A pseudo-Archaic votive inscription to Athena on the left foot, now only partially legible, indicates that this statue too was intended as an offering in a sanctuary. Another inscription on a lead tablet found inside the bronze links it to the Greek island of Rhodes. The statue was eventually transported to Italy and lost when the ship carrying it foundered in port at Piombino, where the figure was discovered in 1832.

Torso of a Youth “The Vani Torso”

200 – 100 B.C.

Bronze

H 105cm; W 45cm; D 25cm

Georgian National Museum, Vani Archaeological Museum-Reserve

Photo: Rob Harrell, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Boy Removing a Thorn from His Foot “The Spinario”

About 50 B.C.

Bronze and copper

H 73cm

Musei Capitolini, Rome, 1186

Image courtesy of Archivio Fotografico dei Musei Capitolini, Palazzo dei Conservatori, Sala dei Trionfi – foto Zeno Colantoni

The lithe body and naturalistic pose of this boy contrast with the highly stylised face and hair, and the fall of the hair does not correspond to gravity given the inclination of the head. Other versions of the sculpture (no. 54) confirm that this bronze combines a Hellenistic body with an early-fifth-century B.C. head type originally intended for another figure. Such eclecticism is characteristic of late Hellenistic and early Roman Imperial sculpture. This statue seems never to have been buried underground and has been famous in Rome since medieval times, inspiring artists for centuries.

Boy with Thorn, also called Fedele (Fedelino) or Spinario, is a Greco-Roman Hellenistic bronze sculpture of a boy withdrawing a thorn from the sole of his foot, now in the Palazzo dei Conservatori, Rome. A Roman marble of this subject from the Medici collections is in a corridor of the Uffizi Gallery, Florence.

The sculpture was one of the very few Roman bronzes that was never lost to sight. It was standing outside the Lateran Palace when the Navarrese rabbi Benjamin of Tudela saw it in the 1160s and identified it as Absalom, who “was without blemish from the sole of his foot to the crown of his head.” It was noted in the late twelfth or early thirteenth century by the English visitor, Magister Gregorius, who noted in his De mirabilibus urbis Romae that it was ridiculously thought to be Priapus. It must have been one of the sculptures transferred to the Palazzo dei Conservatori by Pope Sixtus IV in the 1470s, though it is not recorded there until 1499-1500. It was celebrated in the Early Renaissance, one of the first Roman sculptures to be copied: there are bronze reductions by Severo da Ravenna and Jacopo Buonaccolsi, called “L’Antico” for his refined classicising figures: he made a copy for Isabella d’Este about 1501 and followed it with an untraced pendant that perhaps reversed the pose. For a fountain of 1500 in Messina, Antonello Gagini made a full-size variant, probably the bronze that is now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Text from the Wikipedia website

The J. Paul Getty Museum

1200 Getty Center Drive

Los Angeles, California 90049

Opening hours:

Daily 10am – 5pm

![Capt. Horatio Ross (British, 1801-1886) '[Dead stag in a sling]' c. 1850s - 1860s Capt. Horatio Ross (British, 1801-1886) '[Dead stag in a sling]' c. 1850s - 1860s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/gm_05996801-web.jpg?w=840)

![Capt. Horatio Ross (British, 1801-1886) '[Dead stag in a sling]' c. 1850s - 1860s (detail) Capt. Horatio Ross (British, 1801-1886) '[Dead stag in a sling]' c. 1850s - 1860s (detail)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/gm_05996801-detail.jpg?w=650&h=818)

![André Kertész (American born Hungary, 1894-1985) '[Wooden Mouse and Duck]' 1929 André Kertész (American born Hungary, 1894-1985) '[Wooden Mouse and Duck]' 1929](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/gm_04006701-web.jpg?w=650&h=808)

![Unknown maker (American) '[Dog sitting on a table]' c. 1854 Unknown maker (American) '[Dog sitting on a table]' c. 1854](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/gm_05620501-web.jpg?w=650&h=780)

![William Wegman (American, b. 1943) 'In the Box/Out of the Box [right]' 1971 William Wegman (American, b. 1943) 'In the Box/Out of the Box [right]' 1971](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/gm_32612201-web.jpg?w=650&h=838)

![William Wegman (American, b. 1943) 'In the Box/Out of the Box [left]' 1971 William Wegman (American, b. 1943) 'In the Box/Out of the Box [left]' 1971](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/gm_32612101-web.jpg?w=650&h=846)

You must be logged in to post a comment.