Exhibition dates: 3rd May – 26th July 2015

Curators: The curators of In Light of the Past: Celebrating 25 Years of Photography at the National Gallery of Art are Sarah Greenough, senior curator and head of the department of photographs, and Diane Waggoner, associate curator, department of photographs, National Gallery of Art.

Charles Nègre (French, 1820-1880)

Market Scene at the Port of the Hotel de Ville, Paris

before February 1852

Salted paper print

14.7 x 19.9cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Patrons’ Permanent Fund, 2003

What a great title for an exhibition. Photography always evidences light of the past, we live in light of the past (the light of the Sun takes just over 8 minutes to reach Earth) and, for whatever reason, human beings never seem to learn from mistakes, in light of the past history of the human race.

My favourites in this postings are the 19th century photographs, to which I am becoming further attuned the more I look at them. There is almost a point when you become psychologically enmeshed with their light, with the serenity of the images, a quality that most contemporary photographs seem to have lost. There is a quietness to their presence, a contemplation on the nature of the world through the pencil of nature that is captivating. You only have to look at Gustave Le Gray’s The Pont du Carrousel, Paris: View to the West from the Pont des Arts (1856-1858, below) to understand the everlasting, transcendent charisma of these images. Light, space, time, eternity.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the National Gallery of Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

The Collection of Photographs at the National Gallery of Art, Washington (110kb Word doc)

William Henry Fox Talbot (English, 1800-1877)

A Scene in York: York Minster from Lop Lane

1845

Salted paper print

16.2 x 20.4cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Edward J. Lenkin Fund, Melvin and Thelma Lenkin Fund and Stephen G. Stein Fund, 2011

A British polymath equally adept in astronomy, chemistry, Egyptology, physics, and philosophy, Talbot spent years inventing a photographic process that created paper negatives, which were then used to make positive prints – the conceptual basis of nearly all photography until the digital age. Calotypes, as he came to call them, are softer in effect than daguerreotypes, the other process announced in 1839. Though steeped in the sciences, Talbot understood the ability of his invention to make striking works of art. Here the partially obstructed view of the cathedral rising from the confines of the city gives a sense of discovery, of having just turned the corner and encountered this scene.

Carleton E. Watkins (American, 1829-1916)

Piwac, Vernal Falls, 300 feet, Yosemite

1861

Albumen print

39.9 x 52.3cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Mary and David Robinson, 1995

The westward expansion of America opened up new opportunities for photographers such as Watkins and William Bell. Joining government survey expeditions, hired by railroad companies, or catering to tourists and the growing demand for grand views of nature, they created photographic landscapes that reached a broad audience of scientists, businessmen, and engineers, as well as curious members of the middle class. Watkins’s photographs of the sublime Yosemite Valley, which often recall landscape paintings of similar majestic subjects, helped convince Congress to pass a bill in 1864 protecting the area from development and commercial exploitation.

Eugène Cuvelier (French, 1837-1900)

Belle-Croix

1860s

Albumen print

25.4 x 34.3cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gail and Benjamin Jacobs for the Millennium Fund, 2007

In the second half of the nineteenth century, some photographers in France, hired by governmental agencies to make photographic inventories or simply catering to the growing demand for pictures of Paris, drew on the medium’s documentary abilities to record the nation’s architectural patrimony and the modernisation of Paris. Others explored the camera’s artistic potential by capturing the ephemeral moods of nature in the French countryside. Though photographers faced difficulties in carting around heavy equipment and operating in the field, they learned how to master the elements that directly affected their pictures, from securing the right vantage point to dealing with movement, light, and changing atmospheric conditions during long exposure times.

Gustave Le Gray (French, 1820-1884)

The Pont du Carrousel, Paris: View to the West from the Pont des Arts

1856-1858

Albumen print

37.8 x 48.8cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Patrons’ Permanent Fund, 1995

Édouard-Denis Baldus (French, 1813-1889)

Toulon, Train Station

c. 1861

Albumen print

27.4 x 43.1cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Patrons’ Permanent Fund, 1995

In Light of the Past: Celebrating 25 Years of Photography at the National Gallery of Art, on view in the West Building from May 3 through July 26, 2015, will commemorate more than two decades of the Gallery’s robust photography program. Some 175 of the collection’s most exemplary holdings will reveal the evolution of the art of photography, from its birth in 1839 to the late 1970s. In Light of the Past is one of three stellar exhibitions that will commemorate the 25th anniversary of the National Gallery of Art’s commitment to photography acquisitions, exhibitions, scholarly catalogues, and programs.

“In Light of the Past includes some of the rarest and most compelling photographs ever created,” said Earl A. Powell III, director, National Gallery of Art, Washington. “It also honours the generous support of our donors who have enabled us to achieve this new place of prominence for photography at the Gallery.

About the exhibition

In Light of the Past begins with exceptional 19th-century salted paper prints, daguerreotypes, and albumen prints by acclaimed early practitioners such as William Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877), Gustave Le Gray (1820-1884), Roger Fenton (1819-1869), Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-1879), Albert Sands Southworth (1811-1894), and Josiah Johnson Hawes (1808-1901). It also displays works by American expeditionary photographers, including William Bell (1830-1910) and Carleton E. Watkins (1829-1916).

The exhibition continues with late 19th- and early 20th-century American Pictorialist photographs by Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946), Clarence H. White (1871-1925), Gertrude Käsebier (1852-1934), and Alvin Langdon Coburn (1882-1966), among others, as well as European masters such as Eugène Atget (1857-1927). The exhibition also examines the international photographic modernism of artists such as Paul Strand (1890-1976), André Kertész (1894-1985), Marianne Brandt (1893-1983), László Moholy-Nagy (1895-1946), and Ilse Bing (1899-1998) before turning to the mid-20th century, where exceptional work by Walker Evans (1903-1975), Robert Frank (b. 1924), Harry Callahan (1912-1999), Irving Penn (1917-2009), Lee Friedlander (b. 1934), and Diane Arbus (1923-1971) will be on view.

The exhibition concludes with pictures from the 1960s and 1970s, showcasing works by photographers such as Robert Adams (b. 1937), Lewis Baltz (1945-2014), and William Eggleston (b. 1939), as well as Mel Bochner (b. 1940) and Sol LeWitt (1928-2007), which demonstrate the diverse practices that invigorated photography during these decades.

Press release from the National Gallery of Art

Albert Sands Southworth (American, 1811-1894) and Josiah Johnson Hawes (American, 1808-1901)

The Letter

c. 1850

Daguerreotype

Plate: 20.3 x 15.2cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Patrons’ Permanent Fund, 1999

Working together in Boston, the portrait photographers Southworth and Hawes aimed to capture the character of their subjects using the daguerreotype process. Invented in France and one of the two photographic processes introduced to the public in early 1839, the daguerreotype is made by exposing a silver-coated copper plate to light and then treating it with chemicals to bring out the image. The heyday of the technique was the 1840s and 1850s, when it was used primarily for making portraits. The daguerreotype’s long exposure time usually resulted in frontal, frozen postures and stern facial expressions; this picture’s pyramidal composition and strong sentiments of friendship and companionship are characteristic of Southworth and Hawes’s innovative approach.

Clarence H. White (American, 1871-1925)

The Hillside

c. 1898

Gum dichromate print

20.8 x 15.88cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Patrons’ Permanent Fund, 2008

The Photo-Secession

At the turn of the century in America, Alfred Stieglitz and his colleague Edward Steichen led the movement to establish photography’s status as a fine art. In 1902 Stieglitz founded an organisation called the Photo-Secession, consisting of young artists who shared his belief in the creative potential of the medium. Many of the photographers featured here were members of the group, including Gertrude Käsebier, Clarence White, and Alvin Langdon Coburn. Through the exhibitions Stieglitz organised in his New York gallery, called 291, and the essays he published in his influential quarterly, Camera Work, he and the Photo-Secession promoted the Pictorialist aesthetic of softly textured, painterly pictures that elicit emotion and appeal to the imagination. Occasionally the photographers’ compositions refer to other works of art, such as Steichen’s portrait of his friend Auguste Rodin, whose pose recalls one of the sculptor’s most famous works, The Thinker. Influenced by the modern European and American painting, sculpture, and drawing he exhibited at 291, Stieglitz lost interest in the Photo-Secession in the early 1910s and began to explore a more straightforward expression.

Eugène Atget (French, 1857-1927)

Saint-Cloud

1926

Albumen print

22.2 x 18.1cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Mary and Dan Solomon and Patrons’ Permanent Fund, 2006

Using a cumbersome camera mounted on a tripod, Atget recorded the myriad facets of Paris and its environs at the turn of the century. Transforming ordinary scenes into poetic evocations, he created a visual compendium of the objects, architecture, and landscapes that were expressive of French culture and its history. He sold his photographs to artists, architects, and craftsmen, as well as to libraries and museums interested in the vanishing old city. Throughout his career he returned repeatedly to certain subjects and discovered that the variations caused by changing light, atmosphere, and season provided inexhaustible subjects for the perceptive photographer.

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

The Mountain Nymph, Sweet Liberty

June 1866

Albumen print

36.1 x 26.7cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, New Century Fund, 1997

Ensconced in the intellectual and artistic circles of midcentury England, Cameron manipulated focus and light to create poetic pictures rich in references to literature, mythology, and history. Her monumental views of life-sized heads were unprecedented, and with them she hoped to define a new mode of photography that would rival the expressive power of painting and sculpture. The title of this work alludes to John Milton’s mid-seventeenth-century poem L’Allegro. Describing the happy life of one who finds pleasure and beauty in the countryside, the poem includes the lines:

Come, and trip it as ye go

On the light fantastic toe;

And in thy right hand lead with thee,

The mountain nymph, sweet Liberty.

Dr Guillaume-Benjamin-Amant Duchenne (de Boulogne) (French, 1806-1875)

Figure 63, “Fright” from “Mécanisme de la physionomie humaine (Mechanism of human physiognomy)” (1862)

1854-1855

Albumen print

21.5 × 16cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Pepita Milmore Memorial Fund, 2015

A neurologist, physiologist, and photographer, Duchenne de Boulogne conducted a series of experiments in the mid-1850s in which he applied electrical currents to various facial muscles to study how they produce expressions of emotion. Convinced that these electrically-induced expressions accurately rendered internal feelings, he then photographed his subjects to establish a precise visual lexicon of human emotions, such as pain, surprise, fear, and sadness. In 1862 he included this photograph representing fright in a treatise on physiognomy (a pseudoscience that assumes a relationship between external appearance and internal character), which enjoyed broad popularity among artists and scientists.

Lewis Hine (American, 1874-1940)

An Anaemic Little Spinner in a New England Cotton Mill (North Pownal, Vermont)

1910

Gelatin silver print

24.1 × 19.2cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Pepita Milmore Memorial Fund, 2015

Trained as a sociologist and initially employed as a teacher, Hine used the camera both as a research tool and an instrument of social reform. One of the earliest and most influential social documentary photographers of his time, he made many pictures under the auspices of the National Child Labor Committee, an organisation formed in 1904 to promote better working conditions for children. Hine’s focus on the thin, frail body of this barefoot twelve-year-old spinner, who stands before rows of bobbins in the mill where she worked, was meant to illustrate the unhealthy effects of her employment. Photographs like this one were crucial to the campaign to change American child labor laws in the early twentieth century.

In Light of the Past: Twenty-Five Years of Photography at the National Gallery of Art

Georgia O’Keeffe and the Alfred Stieglitz Estate laid the foundation of the photography collection of the National Gallery of Art in 1949 with their donation of 1,650 Stieglitz photographs, an unparalleled group known as the Key Set. Yet the Gallery did not start actively acquiring photographs until 1990, when it launched an initiative to build a collection of works by European and American photographers from throughout the history of the medium and mount major exhibitions with scholarly publications. Now including nearly fifteen thousand prints, the collection encompasses the rich diversity of photographic practice from fine art to scientific and amateur photography, as well as photojournalism. It is distinguished by its large holdings of works by many of the medium’s most acclaimed masters, such as Paul Strand, Walker Evans, André Kertész, Ilse Bing, Robert Frank, Harry Callahan, Lee Friedlander, Gordon Parks, Irving Penn, and Robert Adams, among others.

In Light of the Past celebrates the twenty-fifth anniversary of the 1990 initiative by presenting some of the Gallery’s finest photographs made from the early 1840s to the late 1970s. It is divided into four sections arranged chronologically. The first traces the evolution of the art of photography during its first decades in the work of early British, French, and American practitioners. The second looks at the contributions of late nineteenth and early twentieth-century photographers, from Stieglitz and the American Pictorialists to European masters such as Eugène Atget. The third section examines the international photographic modernism of the 1920s and 1930s, and the fourth features seminal mid-twentieth-century photographers. The exhibition concludes with pictures representing the varied practices of those working in the late 1960s and 1970s.

The Nineteenth Century: The Invention of Photography

In 1839 a new means of visual representation was announced to a startled world: photography. Although the medium was immediately and enthusiastically embraced by the public at large, photographers themselves spent the ensuing decades experimenting with techniques and debating the nature of this new invention. The works in this section suggest the range of questions addressed by these earliest practitioners. Was photography best understood as an art or a science? What subjects should photographs depict, what purpose should they serve, and what should they look like? Should photographers work within the aesthetics established in other arts, such as painting, or explore characteristics that seemed unique to the medium? This first generation of photographers became part scientists as they mastered a baffling array of new processes and learned how to handle their equipment and material. Yet they also grappled with aesthetic issues, such as how to convey the tone, texture, and detail of multicoloured reality in a monochrome medium. They often explored the same subjects that had fascinated artists for centuries – portraits, landscapes, genre scenes, and still lifes – but they also discovered and exploited the distinctive ways in which the camera frames and presents the world.

Photography at the Turn of the Twentieth Century

In the late nineteenth century, improvements in technology and processing, along with the invention of small handheld cameras such as the Kodak, suddenly made it possible for anyone of middle-class means to take photographs. Many amateurs took up the camera to commemorate family, friends, and special events. Others, such as the sociologist Lewis Hine, used it as a tool for social and political change. Partially in response to the new ease of photography, more serious practitioners in America and Europe banded together to assert the artistic merit of the medium. Called Pictorialists, they sought to prove that photography was just as capable of poetic, subjective expression as painting. They freely manipulated their prints to reveal their authorial control, often resulting in painterly effects, and consciously separated themselves from amateur photographers and mechanised processes.

Photography Between the Wars

In the aftermath of World War I – the first modern, mechanised conflict – sweeping changes transformed photography. Avant-garde painters, graphic designers, and journalists turned to the medium, seeing it as the most effective tool to express the fractured, fast-paced nature of modernity and the new technological culture of the twentieth century. A wide variety of new approaches and techniques flourished during these years, especially in Europe. Photographers adopted radical cropping, unusual angles, disorienting vantage points, abstraction, collage, and darkroom alchemy to achieve what the influential Hungarian teacher László Moholy-Nagy celebrated as the “new vision.” Other photographers, such as the German August Sander or the Americans Alfred Stieglitz, Edward Weston, and Walker Evans, sought a more rigorous objectivity grounded in a precise examination of the world.

Postwar Photography

Photography thrived in the decades after World War II, invigorated by new ideas, practices, and expanding venues for circulating and displaying pictures. Immediately after the war, many photographers sought to publish their pictures in illustrated magazines, which prospered during these years. Some, such as Gordon Parks, made photographs highlighting racial, economic, and social disparities. Others, such as Louis Faurer, Sid Grossman, and Robert Frank, turned to the street to address the conditions of modern life in pictures that expose both its beauty and brutality. Using handheld cameras and available light, they focused on the random choreography of sidewalks, making pictures that are often blurred, out of focus, or off-kilter.

In the later 1950s and 1960s a number of photographers pushed these ideas further, mining the intricate social interactions of urban environments. Unlike photographers from the 1930s, these practitioners, such as Garry Winogrand, Lee Friedlander, and Diane Arbus, sought not to reform American society but to record it in all its complexity, absurdity, and chaos. By the late 1960s and 1970s, other photographers, such as Robert Adams and Lewis Baltz, looked beyond conventional notions of natural beauty to explore the despoliation of the urban and suburban landscape. Their pictures of tract houses, highways, and motels are stripped of any artistic frills, yet they are exquisitely rendered and replete with telling details. Also starting in the 1960s, many conceptual or performance artists working in a variety of media embraced what they perceived to be photography’s neutrality and turned to it as an essential part of their experiments to expand traditional notions of art. In the late 1960s, improvements in colour printing techniques led others, such as William Eggleston, to explore the artistic potential of colour photography.

Edward Steichen (American, 1879-1973)

An Apple, A Boulder, A Mountain

1921

Platinum print

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Patrons’ Permanent Fund, 2014

After World War I, Steichen became disillusioned with the painterly aesthetic of his earlier work and embarked on a series of experiments to study light, form, and texture. Inverting an apple, he demonstrated how a small object, when seen in a new way, can assume the monumentality and significance of a much larger one. His close-up scrutiny of a natural form closely links this photograph with works by other American modernists of the 1920s, such as Edward Weston, Paul Strand, and Georgia O’Keeffe.

Paul Strand (American, 1890-1976)

People, Streets of New York, 83rd and West End Avenue

1916

Platinum print

24.2 x 33cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Patrons’ Permanent Fund, 1990

Strand was introduced to photography in high school by his teacher Lewis Hine, who instilled in him a strong interest in social issues. In 1907, Hine took his pupil to Alfred Stieglitz’s 291 gallery in New York, which launched Strand’s desire to become a fine art photographer. By the early 1910s, influenced by Stieglitz, he began to make clearly delineated portraits, pictures of New York, and nearly abstract still lifes. Strand came to believe that photography was a gift of science to the arts, that it was an art of selection, not translation, and that objectivity was its very essence.

American 20th Century

Untitled

c. 1930

Gelatin silver print

5.7 x 10cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Robert E. Jackson, 2007

Snapshots

After World War I, a parade of technological improvements transformed the practice of photography. With smaller cameras, faster shutter speeds, and more sensitive film emulsions, both amateurs and more serious practitioners could now easily record motion, investigate unexpected angles and points of view, and work in dim light and inclement weather. The amateur’s less staid, more casual approach began to play an important role in the work of modernist photographers as they explored spontaneity and instantaneity, seeking to capture the cacophony and energy of modern life. Blurriness, distorted perspectives, and seemingly haphazard cropping-once considered typical amateur mistakes-were increasingly embraced as part of the modern, vibrant way of picturing the world.

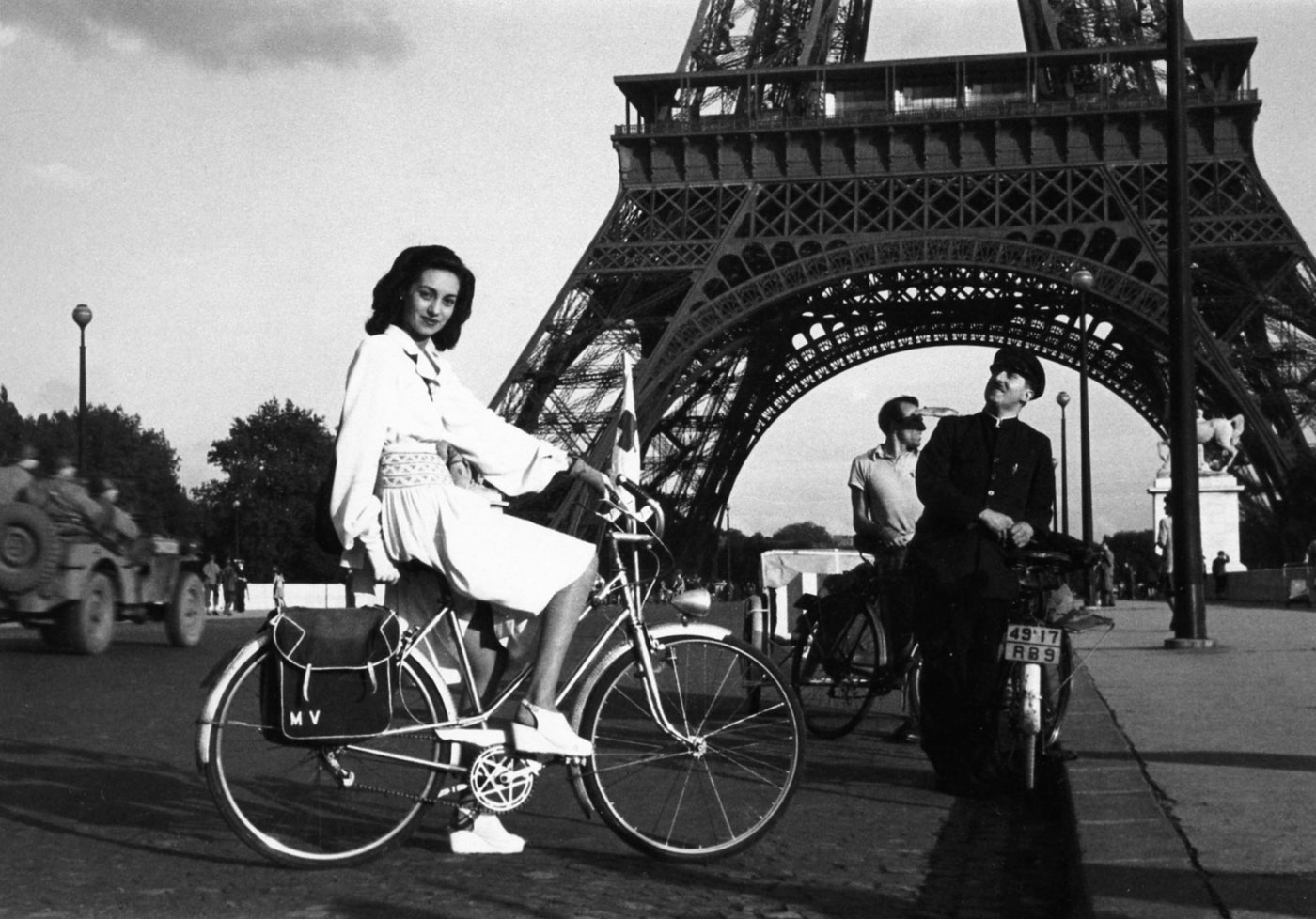

Robert Frank (Swiss, 1924-2019)

City of London

1951

Gelatin silver print

23 x 33.6cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Robert Frank Collection, Purchased as a Gift of The Howard Gilman Foundation, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National Gallery of Art, 1991

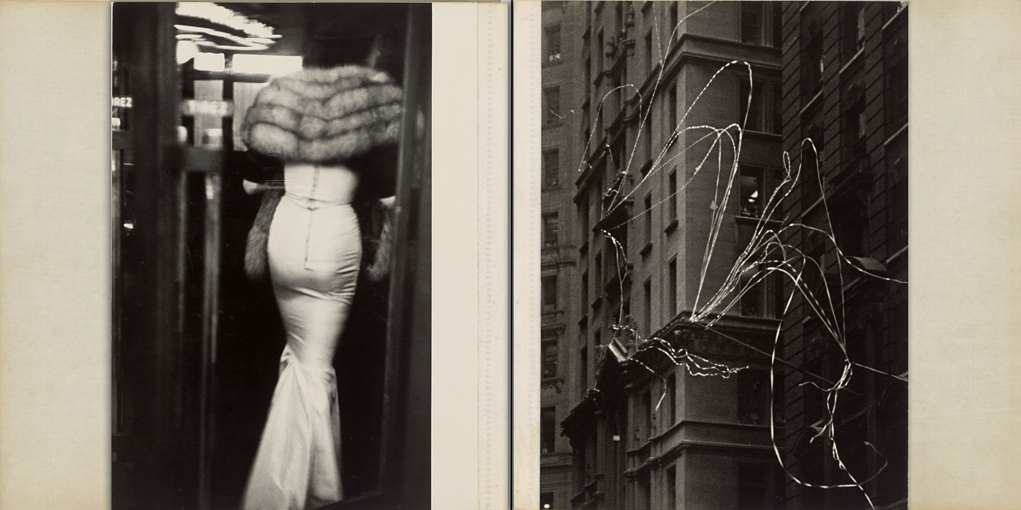

Robert Frank (Swiss, 1924-2019)

Woman/Paris

1952

Gelatin silver print in bound volume

Image: 35.1 x 25.4cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Robert Frank Collection, Gift (Partial and Promised) of Robert Frank, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National Gallery of Art, 1990

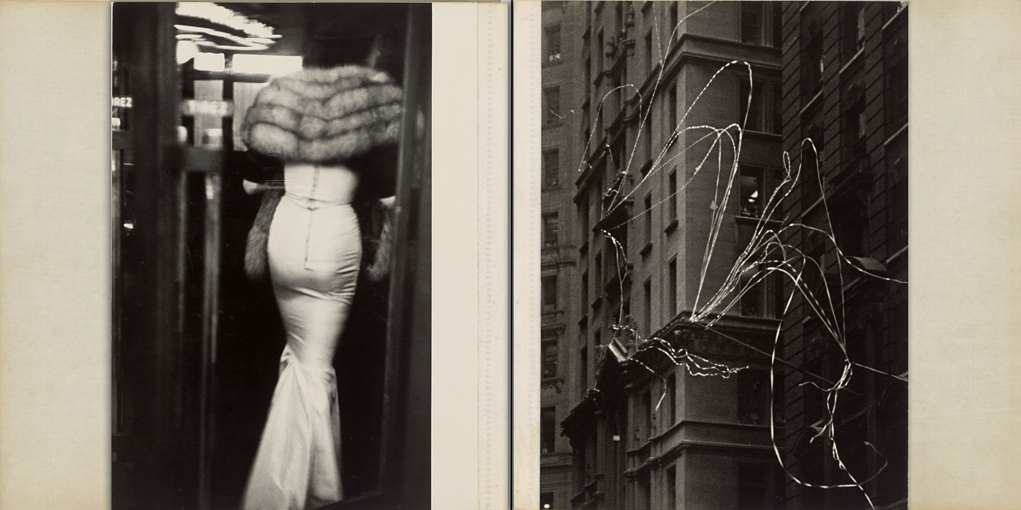

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, Frank made several handbound volumes of photographs, exploring different ways to link his pictures through non-narrative sequences. While in Zurich in October 1952, he assembled pictures taken in Europe, South America, and the United States in a book called Black White and Things. With a brief introductory quote from Antoine de Saint-Exupéry – “it is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye” – the photographs are arranged in a sophisticated sequence that uses formal repetition, conceptual contrasts, and, as here, witty juxtapositions to evoke a range of ideas …

While in Zurich in October of 1952, Frank assembled photographs taken in Europe, South America, and the United States in the preceding years into a bound book called Black White and Things. Designed by Frank’s friend Werner Zryd, and with only a brief introductory statement describing the three sections, the photographs appear in a sophisticated sequence that relies on subtle, witty juxtapositions and powerful visual formal arrangements to evoke a wide range of emotions.

Frank made three copies of this book, all identical in size, construction, and sequence. He gave one copy to his father, gave one to Edward Steichen, and kept one. The book that belonged to his father is now in a private collection; Steichen’s copy resides at the Museum of Modern Art, New York; and in 1990 Frank gave his copy to the Robert Frank Collection at the National Gallery of Art.

Robert Frank (Swiss, 1924-2019)

Trolley – New Orleans

1955

Gelatin silver print

Sheet: 21 x 31.6cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Maria and Lee Friedlander, 2001

Roy DeCarava (American, 1919-2009)

Mississippi Freedom Marcher, Washington, D.C.

1963

Gelatin silver print

25.5 x 33cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation through Robert and Joyce Menschel, 1999

Lee Friedlander (American, b. 1934)

New York City

1966

Gelatin silver print

Image: 13.3 x 20.6 cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Trellis Fund, 2001

Heir to the tradition of documentary photography established by Eugène Atget, Walker Evans, and Robert Frank, Friedlander focuses on the American social landscape in photographs that can seem absurd, comical, and even bleak. In dense, complex compositions, he frequently depicts surprising juxtapositions that make the viewer look twice. He has made numerous self-portraits, yet he appears in these pictures in oblique and unexpected ways, for example reflected in a mirror or window. The startling intrusion of Friedlander’s shadow onto the back of a pedestrian’s coat, at once threatening and humorous, slyly exposes the predatory nature of street photography.

Giovanni Anselmo (Italian, 1934-2023)

Entering the Work

1971

Photographic emulsion on canvas

49 x 63.5cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Glenstone in honor of Eileen and Michael Cohen, 2008

Conceptual Photography

In the 1960s, many painters and sculptors questioned the traditional emphasis on aesthetics and turned to creating art driven by ideas. Photography’s association with mechanical reproduction appealed to them as they sought to downplay the hand of the artist while promoting his or her role as idea maker. Some conceptual artists, such as Sol Lewitt and Mel Bochner, used photographs to explore an interest in perspective, scale, and mathematics. Others turned to photography as a tool to record performances and artistic undertakings, the resulting pictures acting as an integral part of those projects.

Anselmo was a member of the Italian Arte Povera group, which sought to break down the separation of art and life through experimental performances and the use of natural materials such as trees and leaves. To make this work, Anselmo set his camera up with a timed shutter release, and raced into view so that his running figure creates a modest yet heroic impression on the landscape.

Robert Adams (American, b. 1937)

Colorado Springs, Colorado

1974

Gelatin silver print, printed 1983

15.2 x 15.2cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Mary and Dan Solomon and Patrons’ Permanent Fund, 2006

For more than forty years, Adams has recorded the changing American landscape, especially the ongoing settlement of the West. Although he has photographed roads, tract houses, and strip malls that have utterly transformed the landscape, he has also captured the beauty that remains and indeed, that refuses to die, as in his poetic picture of morning fog over California hills. He is convinced, as he wrote in 1974, that “all land, no matter what has happened to it, has over it a grace, an absolutely persistent beauty.”

Margaret Bourke-White (American, 1904-1971)

Fort Peck Dam, Montana

1936

Gelatin silver print

33.02 × 27.31cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Patrons’ Permanent Fund, 2014

One of the most iconic photographs by the pioneering photojournalist Bourke-White, Fort Peck Dam, Montana was published on the cover of the inaugural issue of Life magazine on November 23, 1936. A striking representation of the machine age, the photograph depicts the stark, massive piers for an elevated highway over the spillway near the dam. The two men at the bottom of the print indicate the piers’ massive scale while revealing the vulnerable position of the worker in the modern industrial landscape.

György Kepes (American born Hungary, 1906-2001)

Juliet with Peacock Feather and Red Leaf

1937-1938

Gelatin silver print with gouache

15.7 × 11.6cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Pepita Milmore Memorial Fund, 2014

Trained as a painter at the Academy of Fine Arts in Budapest, Kepes was an influential designer, educator, aesthetic theorist, and photographer. In 1930 he moved to Berlin, where he worked with László Moholy-Nagy, but eventually settled in Chicago and later Cambridge, Massachusetts. Created soon after his arrival in America, this startling photograph is both an intimate depiction of Kepes’s wife and a study of visual perception. Like the red leaf that seems to float above the image, the peacock feather – its eye carefully lined up with Juliet’s – obscures not only her vision but also the viewer’s ability to see her clearly.

Irving Penn (American, 1917-2009)

Woman with Roses (Lisa Fonssagrives-Penn in Lafaurie Dress), Paris

1950

Platinum/palladium print, 1977

55.1 x 37cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Irving Penn, 2002

One of the most influential fashion and portrait photographers of his time, Penn made pictures marked by refinement, elegance, and clarity. Trained as a painter and designer, he began to photograph in the early 1940s while working at Vogue; more than 150 of his photographs appeared on the cover of the magazine during his long career. A perfectionist, Penn explored earlier printing techniques, such as a late nineteenth-century process that used paper coated with solutions of platinum or palladium rather than silver, to achieve the subtle tonal range he desired.

National Gallery of Art

National Mall between 3rd and 7th Streets

Constitution Avenue NW, Washington

Opening hours:

Open daily 10.00 am – 5.00pm

National Gallery of Art website

LIKE ART BLART ON FACEBOOK

Back to top

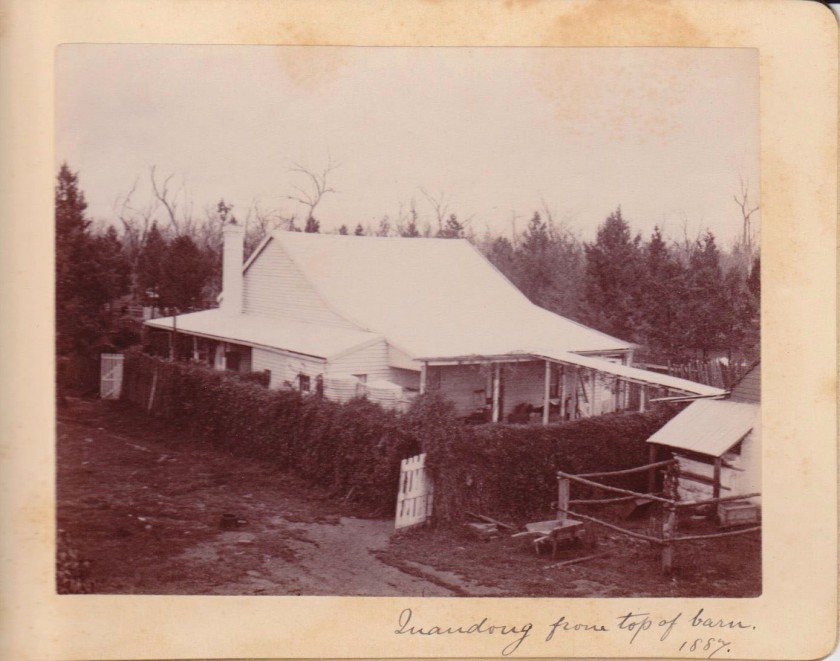

![Unknown photographer. 'Untitled [Horse and trap], Quandong' 1887 Unknown photographer. 'Untitled [Horse and trap], Quandong' 1887](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/quandong11.jpg?w=840)

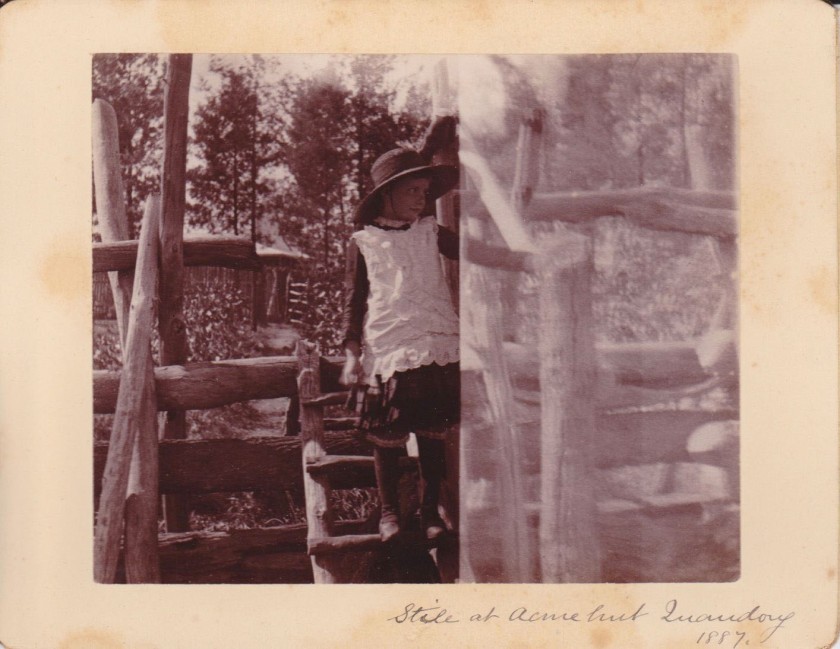

![Unknown photographer. 'At Quandong [Horse, foal and cart]' 1887 Unknown photographer. 'At Quandong [Horse, foal and cart]' 1887](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/quandong9.jpg?w=840)

![Germaine Krull (European, 1897-1985) 'Étalage: les mannequins [Display: mannequins]' 1928 Germaine Krull (European, 1897-1985) 'Étalage: les mannequins [Display: mannequins]' 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/gkrull_09-web.jpg)

![Germaine Krull (European, 1897-1985) 'Étude pour La Folle d’Itteville [Study for The Madwoman of Itteville]' 1931 Germaine Krull (European, 1897-1985) 'Étude pour La Folle d’Itteville [Study for The Madwoman of Itteville]' 1931](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/gkrull_14-web.jpg?w=650&h=868)

You must be logged in to post a comment.