December 2023

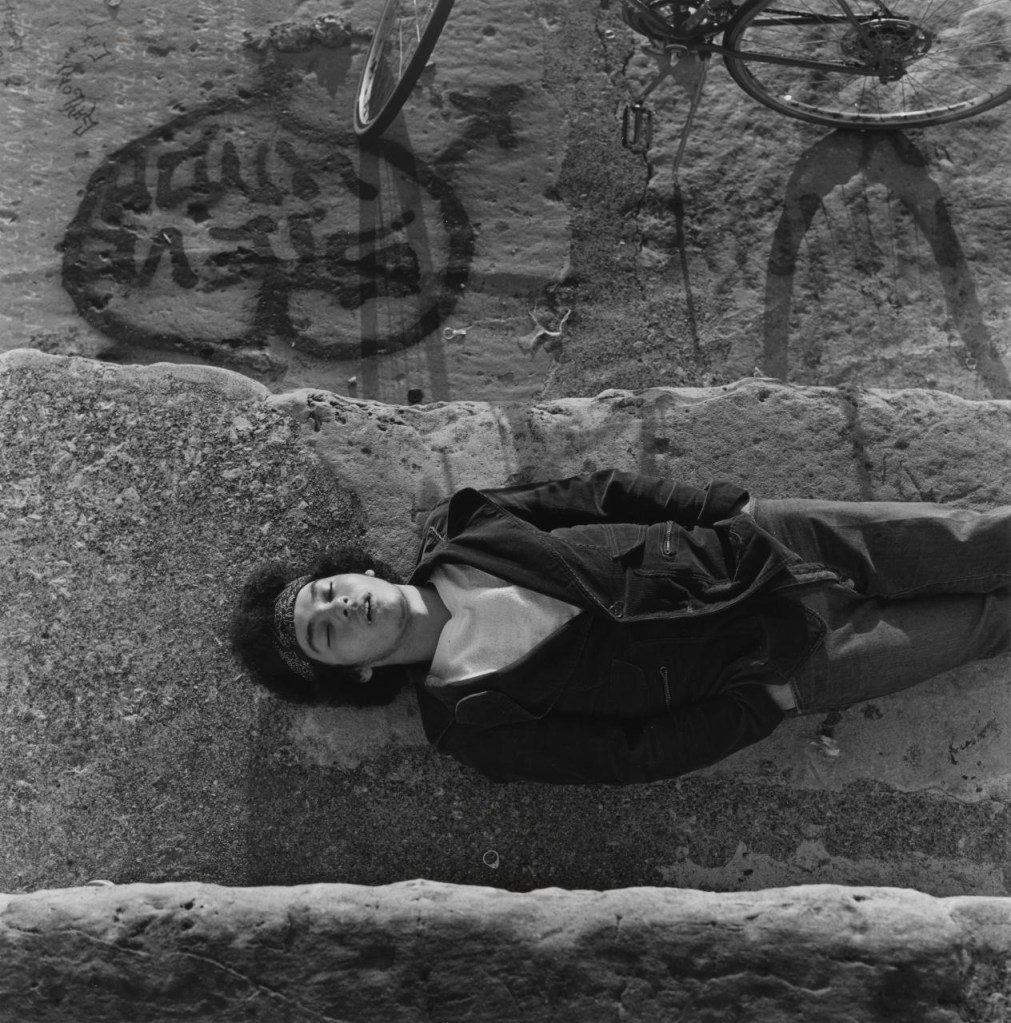

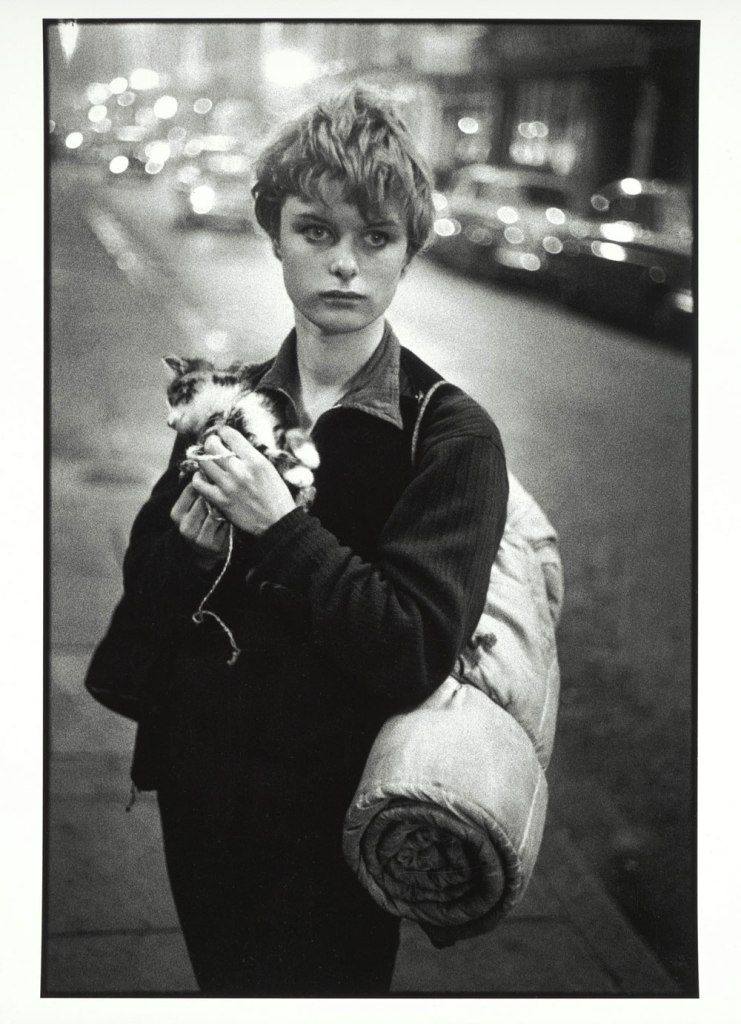

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Ian Lobb, Station Street, Fairfield

5 October 2022

The luminosity of Ian Lobb

These words are a celebration of the life of an extraordinary human, a heartfelt stream of consciousness text that touches on aspects of the life of Ian Lobb, photographer.

Ian Lobb was my friend. He was a poet, photographer, raconteur. He my first photographer lecturer at university who I could always rely on for advice on art, photography, writing and life. He was an audiophile and a lover of music, anything from classical to jazz to Nina Simone, Paul McCartney and Bob Dylan. He was a lover of women. He was dreamer and a philosopher. He adored the American artist Cy Twombly. He was a rabid Sydney Swans fan!

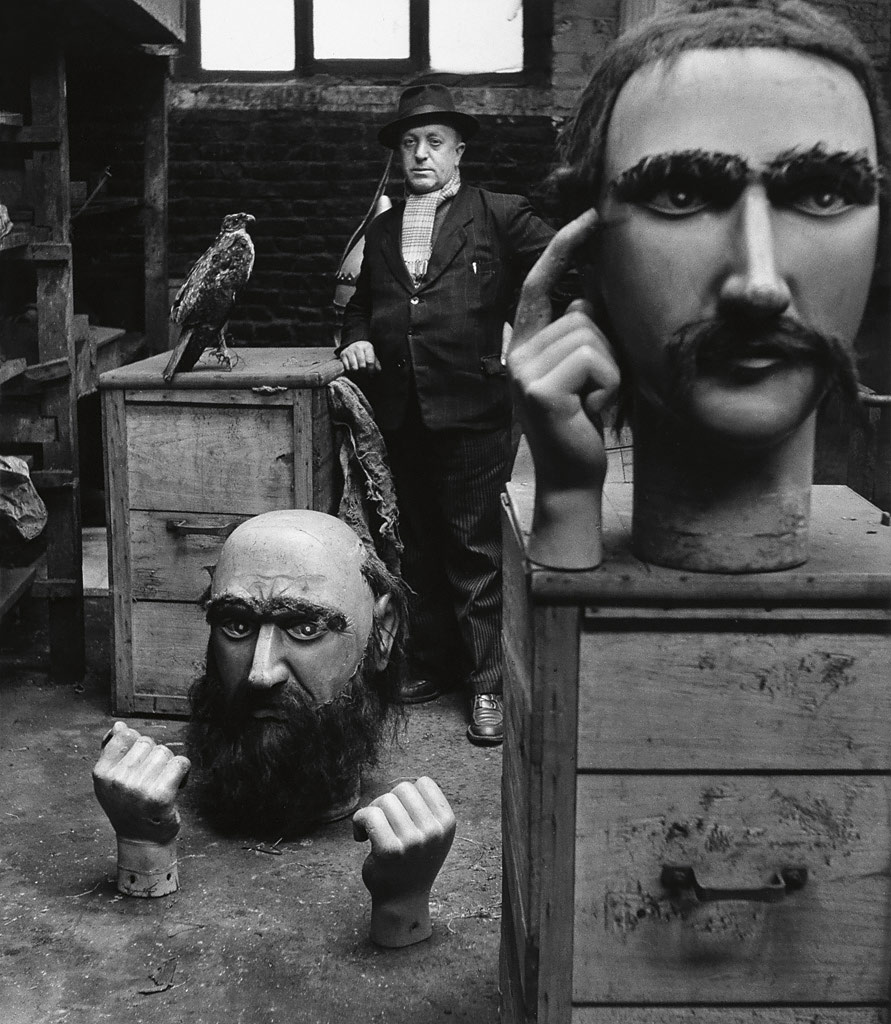

In the early 1990s monthly reviews of student photographic work at Phillip Institute of Technology (PIT, which later became part of RMIT University) with Ian and fellow lecturer Les Walkling were electric. Ideas and passion for the work abounded, discussions ran for hours on how to create work – with feeling and insight into the condition of image (and human) becoming. Here Ian introduced me to Tarkovsky, Eisenstein and Joseph Campbell, and the Marathon Monks of Mount Hiei, Kyoto, Japan. And of course he introduced me to the French photographer Eugène Atget – oh how we loved Atget, and Strand, Weston, Caponigro and Minor White. We could talk on any subject. Many years later, at our regular coffee catchups in Fairfield, I would take him new photography books that I had bought and recent object d’art purchases and, over lunch, the conversation would range far and wide about photography, art and life. He helped me sequence my work – have you thought about this pairing together, what about swapping this one over – and we drew inspiration from the sequences of Minor White and his use of “ice/fire”.

Ian was a storyteller. His photographs tell stories. From the teachings of Minor White (especially his “Three Canons”) there was an acknowledgement in his work of the spirit of the object he was photographing – a moment of revelation sought in the negative and subsequent print through a connection and circular transmission of energy between artist and object back through the camera and onto film (Zen)(for example see Eagles Nest, Cape Paterson 1975, below). A moment of revelation of spirit that was so important to Ian that this moment of “revelatio” can still be seen and felt in his recent mobile phone images.

Ian was aware, fully present. He was attuned to his surroundings like few people I have met for he was tremendously attentive, tremendously awake and sensitive to the environment and the vibrations of energy that emanated from the city, the land, the sky. Imagine travelling to a small patch of earth in the Black Ranges year after year to photograph in all seasons and in all weather something that he could see and feel in that land… something any other human would not even recognise, would walk past without a moments hesitation as though nothing was there, was of no import. But not Ian. He recognised and felt the energy of that place, space.

Talking to the wonderful Australian photographer David Tatnall who was also a friend of Ian’s we reminisced the other day. Ian had won an Australia Council grant and went to America on board a cargo ship teaching yoga on the way over, first going to South America and then on to America. There he visited Barbara, Wynn Bullock’s wife, and Ralph Gibson, Brett Weston, Harry Callahan and William Clift. He attended workshops with Ansel Adams and Paul Caponigro. He visited the Museum of Modern Art’s reading room and examined box after box of iconic prints by the masters, all jumbled together as he told me in folders with little order or care for their preservation. David told me he rocked up unannounced at Eliot Porter’s and said he was a visiting photographer from Australia, and while Eliot made a pot of tea he was left to go through boxes of dye transfer prints. Back then there was a camaraderie of photography very different from the present. Can you imagine doing that today!

He conversed with the masters. Like a pebble making ripples in a pond the energy of these photographers was transferred by osmosis through Ian to a wider network of artists. David and I remembered how Ian taught us to look at the print upside down in order to understand the balance of the print and develop an appreciation of its structure and the music inherent in it. Look at the image of Caponigro’s Reflecting Stream, Redding, CT (1968, below) – one of Ian’s favourites – and you just know that water has to be “wet” in that print, that the shadows of the trees on the water have to be (Ansel Adams) Zone 2, and that the Zone 7 patch of grey under the boulder in the centre of the image is critical to its music, its balance. Ian knew these things instinctively, intuitively. Ian also taught both of us how to make Ansel Adams’ “burning in” tool… three pieces of stiff black board (with the top two pieces secured by tape to make a hinges) with gradually larger holes in each board for use under the enlarger, so that you could easily flip the boards to a larger or smaller hole for “burning in” while making a print. We both still have these indispensable tools, passed down like an oral history from the master. On reflection, learning from Ian and Les during those early days printing black and white photographs in the basement darkroom at Phillip Institute of Technology (PIT) in Bundoora, Melbourne were some of the happiest days of my life.

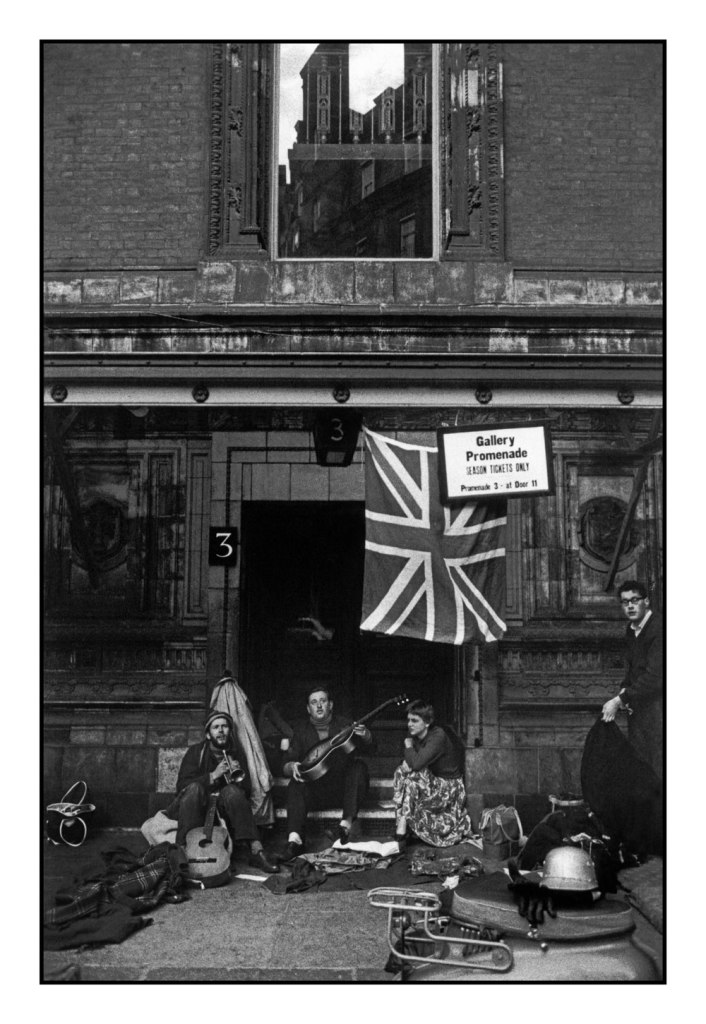

With friend and fellow director William (Bill) Heimerman (1950-2017), The Photographers’ Gallery and Workshop, Melbourne brought to Australia some of the most respected master photographers from around the world: Wynn Bullock, Emmet Gowin, Eikoh Hosoe, William Clift, Harry Callahan, Paul Caponigro, William Eggleston, Ralph Gibson, Duane Michaels, Lisette Model, August Sander, Aaron Siskind among others … and promoted local Australian photographers such as John Cato, Carol Jerrems, Christopher Koller, Jeff Busby and more. I was privileged to have several solo exhibitions in the gallery space. For the opening of Carol Jerrems exhibition at the gallery, Ian asked her who she would most like to attend – and Carol said Ron Barassi, then the most popular sporting and cultural personality in Australia. And on the day of the opening who attended – the great man himself. I don’t know how Ian did it, but he did!

David Tatnall took Ian to Cape Paterson only a couple of weeks before his passing, the first time he had been there since his father’s death many years ago (see the photographs below). Ian took some photographs with camera on tripod and on the mobile phone and then sat down, sat down and just looked at things in that self deprecating way of his. He just looked at the rocks and the form and the light and soaked in the spirit of the place. The same with his favourite tree, his beloved lemon scented gum in the garden of his church in Fairfield. Much as the Black Range series many years earlier, he took thousands of photographs on his mobile phone of this tree in all weather conditions, at all times of the day and year. He saw and felt something there that he kept coming back too, searching for the answer to that one great question that he could never answer.

David said that he believed that he was only using the mobile phone as a visual notebook before he came back to the place to photograph with an SLR – but respectfully I must disagree. Increasingly in his later years Ian surrendered the use of his bigger digital cameras to the flexibility of his mobile phone camera, trading in their heft for the felt immediacy of the mobile phone image and his ability to study the results as he pleased. While many would dismiss these phones images as preludes to the finished work, Ian recognised (as do many artists) that these impressions, these deeply felt visual sketches, had become fully rendered works of art. He moved with the times. As he observed, “For the last 18 months I’ve been spending the first few hours of the day in the local church yard where I am photographing a lemon scented gum. I’m doing this with an iPhone as a way of exploring different ways of working that facilitates.” (Email for William Clift sent to Marcus Bunyan 22 January 2023)

Ian loved telling a story. And he was passionate about the Sydney Swans. He regaled me with the story of how he was so incensed by seeing photographers inside the circle of players celebrating in the rooms after a victory that he wrote to the club to explain that this space, this inner sanctum of celebration, should be a “sacred space” as he put it just for the players… and that photographers should not be allowed in to that space, but only be able to look in from the outside. He was special like that. He understood the significance of that circle and the energy that flowed across the space as players linked arms and belted out the club song. Nothing should disturb the sanctity of that space, much as nothing should disturb the energy of a rock face.

Ian was a (com)passionate man. He was a spiritual man. Throughout his life he had a deep abiding faith in Jesus and the benevolence and goodness of the Almighty. Now he is be gone but his energy still surrounds us. In his beloved lemon scented gum and in the many memorable ideas and images he shared with us.

Ian Lobb was my friend. I will miss his wise counsel.

God bless him xx

Dr Marcus Bunyan

PS. A very interesting analysis by Gary Sauer-Thompson on Ian Lobb’s Black Range series and new concepts in contemporary landscape photography can be found in the article “Ian Lobb + contemporary landscape photography” on the Thought Factory website January 28, 2024. Recommended reading.

Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image. Many thankx to David Tatnall for allowing me to publish his images that are included in this posting.

“If you think of all the wonderful experiences of making images – and then sequencing them – really it is top of the world experience. If this then happens when society is particularly in flux – on spiritual and identity issues, and sequencing happens by someone who is sensitive to the time and the issues. And is sensitive to “image”. Then you really really hope that the book is well produced.”

Ian Lobb email to Marcus Bunyan, 29 May 2015

“In “LA Confidential” they give away their source by using the word “valediction”. A good name for a poem, maybe the best, but not an exhausted idea. Look out I have been inspired by genius. People say that they have to do something more difficult than they need. That’s ok. – there are angels to prevent that – but if you don’t want to go that way, most of them aren’t against us.”

Ian Lobb text to Marcus Bunyan, Monday 11 September 2023

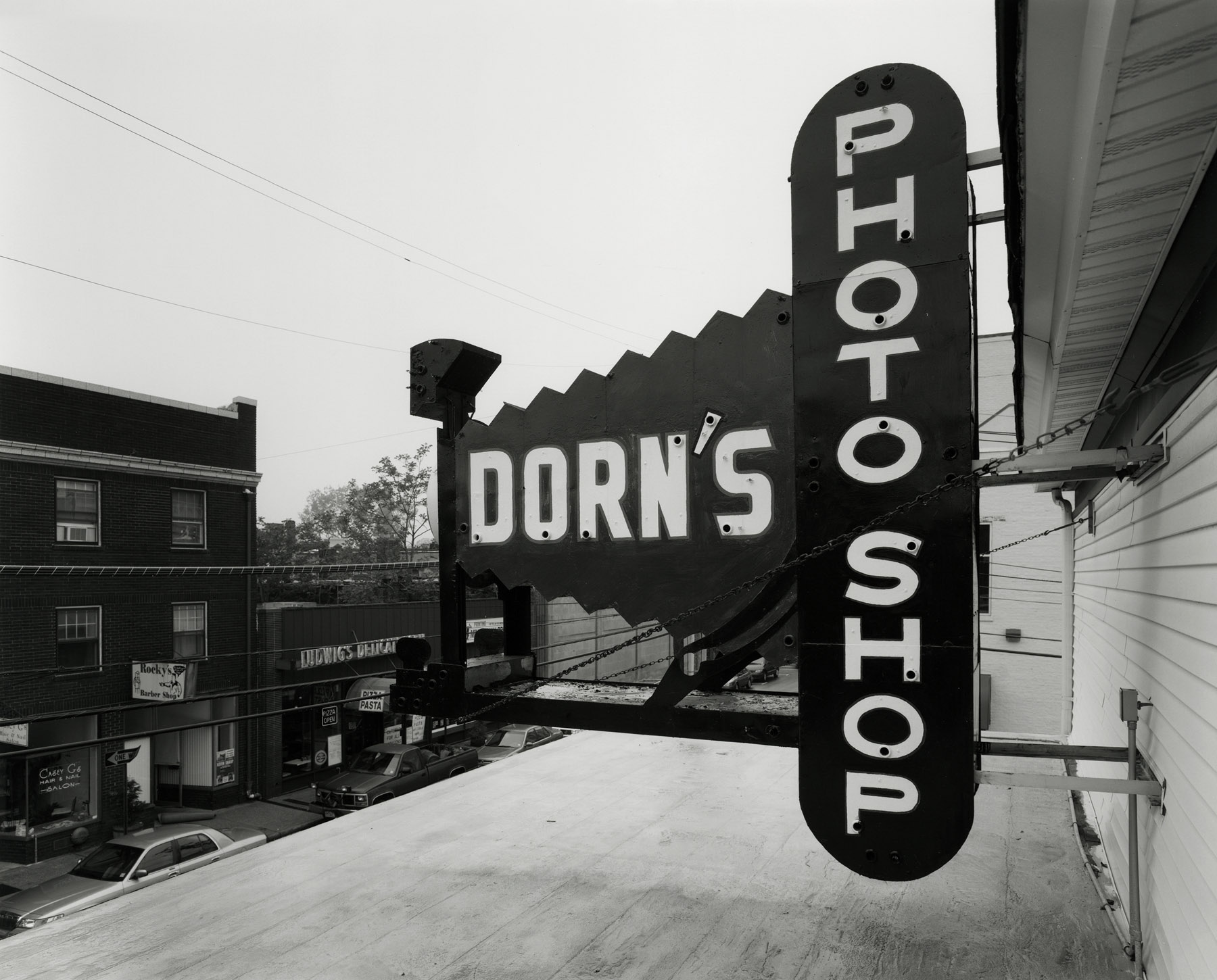

“Marcus – can we be told how to love ? The first thought is no – but I’m not going to rush into an answer. Can we be told how to love a photograph or which photographs to love? I do know that my walk this morning has been recalling which photographs I have loved – and stopping on those where I have not lately dwelt. I didn’t get past the Paul Strand of the white picket fence. Sitting now on Station st as the coffee shops carry out their tables and seeing it.”

Ian Lobb text to Marcus Bunyan, Saturday, 16 September 2023

Ian Lobb speaking at a celebration of the life of William (Bill) Heimerman (1950-2017)

Windsor, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, October 21, 2017.

Thank you to Peter Leiss for allowing me to publish this video.

Paul Strand (American, 1890 – 1976)

White Fence, Port Kent, New York

1916 (negative); 1945 (print)

Gelatin silver print

Paul Caponigro (American, 1932-2024)

Reflecting Stream, Redding, CT

1968

Gelatin silver print

During this particular workshop Caponigro was sometimes in a room where he could display several prints at once – he would never take them all down after talking, but move the first images away and attach new images to the right as he talked. The workshop was with the senior students of an Oregon art school, it can be dated because it was during the impeachment of Nixon.

~ Ian Lobb email to Marcus Bunyan, 6 January 2015

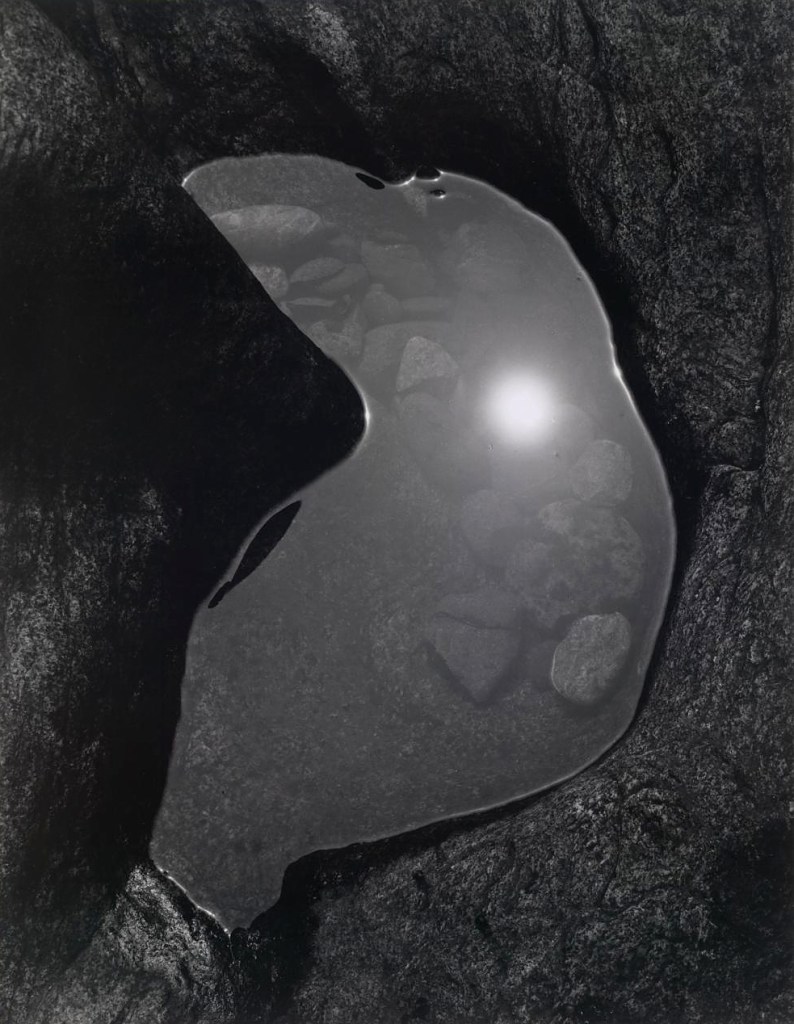

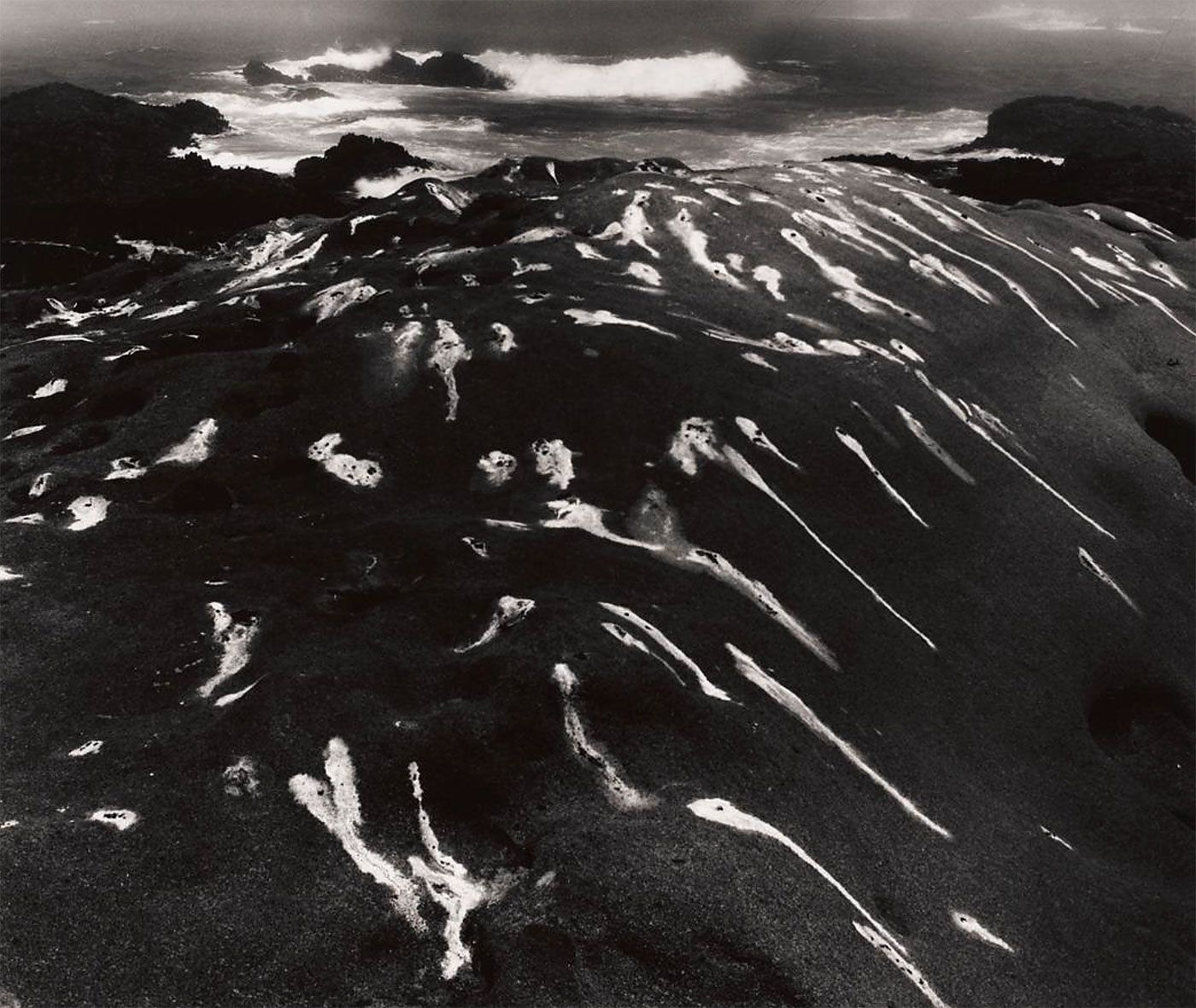

Minor White (American, 1908-1976)

Point Lobos, California

1948

Gelatin silver print

Marcus, have you been to Point Lobos? I think you would find it a big experience if you were there at a quiet time. Imagine Minor White going to visit Weston on Wildcat Hill, and then the short drive down to Point Lobos – there would be some frisson in that car!! It’s not quite Nietzsche going to visit Wagner – but it’s not bad. For a lot of the year the day starts with fog and then the fog pulls back a little offshore and then comes back again. I think Weston’s Pelican would have been photographed in fog.

~ Ian Lobb email to Marcus Bunyan, 29 May 2015

Ansel Adams (American, 1902-1984)

Merced River, Cliffs, Autumn

1939

Gelatin silver print

When talking to him [Ansel Adams] you can imagine the number of mediocre questions. While I was listening all of his answers were quotes from his books. There had to be an extraordinary move to get him to break ranks with this rule.

~ Ian Lobb text to Marcus Bunyan, Sunday, 5 March 2023

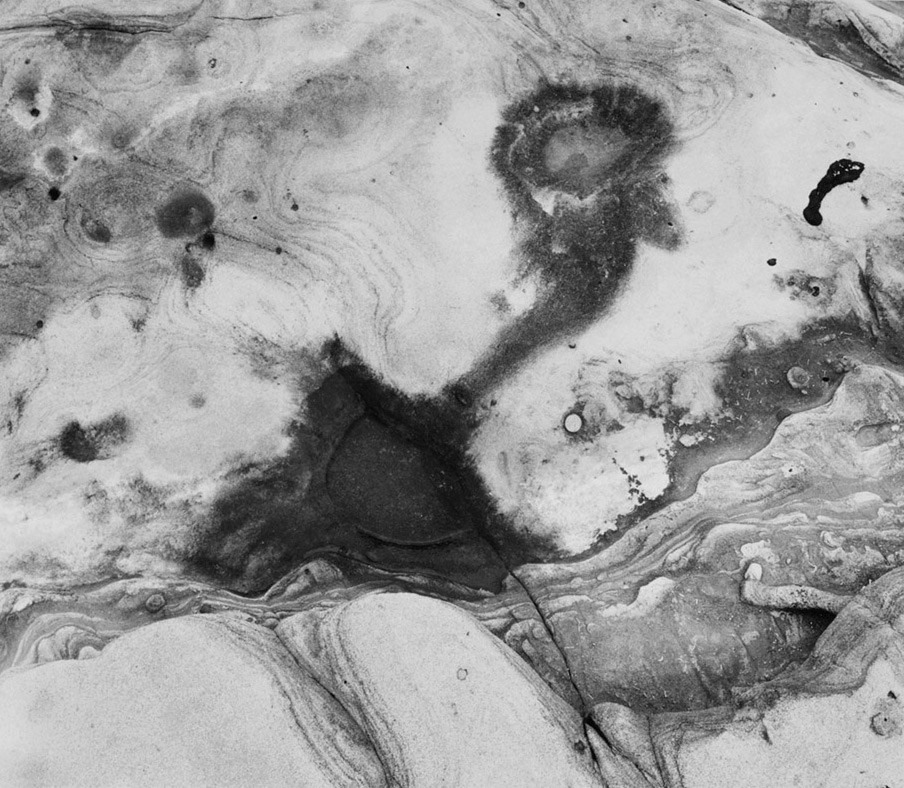

Black Range series

Ian Lobb (Australian, 1948-2023)

Untitled

1989

from the Black Range series 1986-1989

36.9 × 36.7cm (image)

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased with funds donated by Hallmark Cards Australia Pty Ltd, 1989

© Ian Lobb

Ian Lobb (Australian, 1948-2023)

Untitled

1989

from the Black Range series 1986-1989

35.6 × 35.6cm (image)

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased with funds donated by Hallmark Cards Australia Pty Ltd, 1989

© Ian Lobb

Ian Lobb (Australian, 1948-2023)

Untitled

1986, printed 1989

from the Black Range series 1986-1989

26.4 × 26.4cm (image)

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased with funds donated by Hallmark Cards Australia Pty Ltd, 1989

© Ian Lobb

Ian Lobb (Australian, 1948-2023)

Untitled

1989

from the Black Range series 1986-1989

36.5 × 36.5cm (image)

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased with funds donated by Hallmark Cards Australia Pty Ltd, 1989

© Ian Lobb

Ian Lobb (Australian, 1948-2023)

No title (Soft focus landscape with branch detail in foreground)

1989, printed 1998

from the Black Range series 1986-1989

38.2 × 38.4cm (image)

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Presented through The Art Foundation of Victoria by the artist, Fellow, 2000

© Ian Lobb

The Photographers’ Gallery and Workshop

Peter Leiss (Australian, b. 1951)

Untitled [Bill Heimerman and Ian Lobb at the rear of the Photographers’ Gallery]

c. 1975-1980

Gelatin silver print

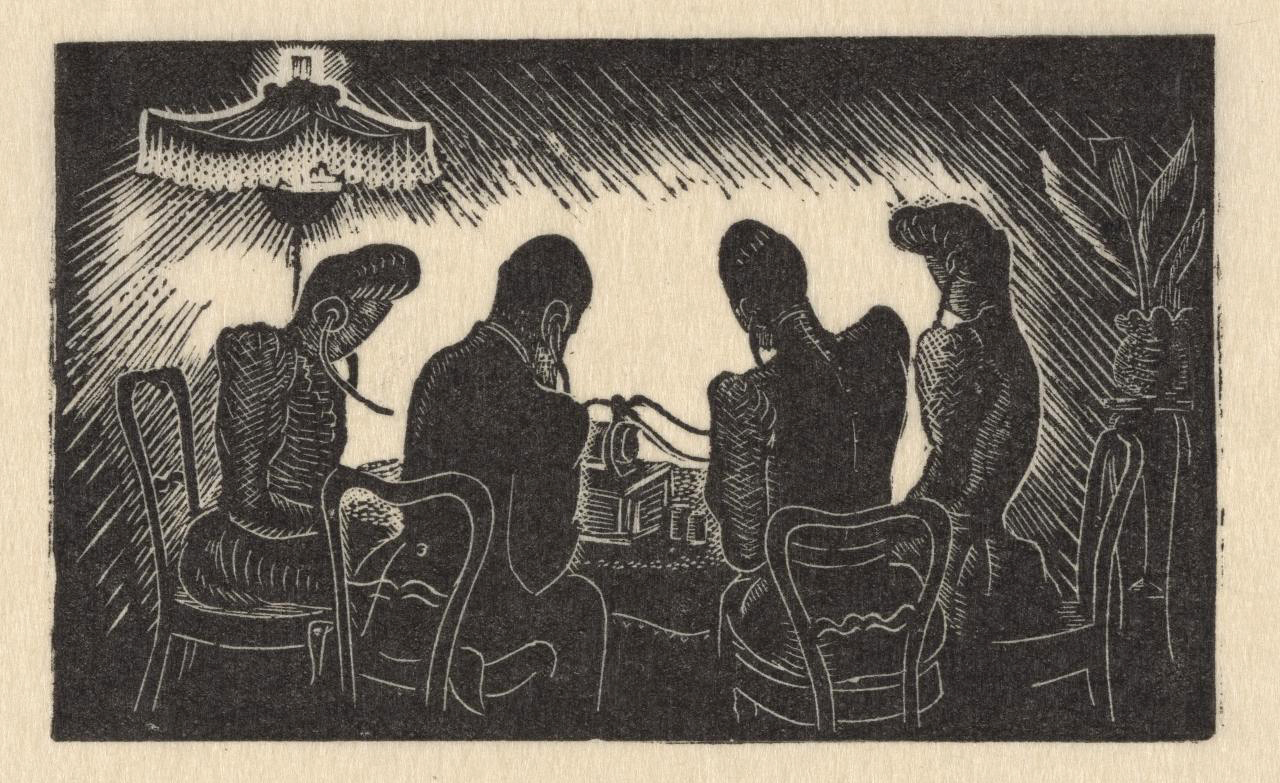

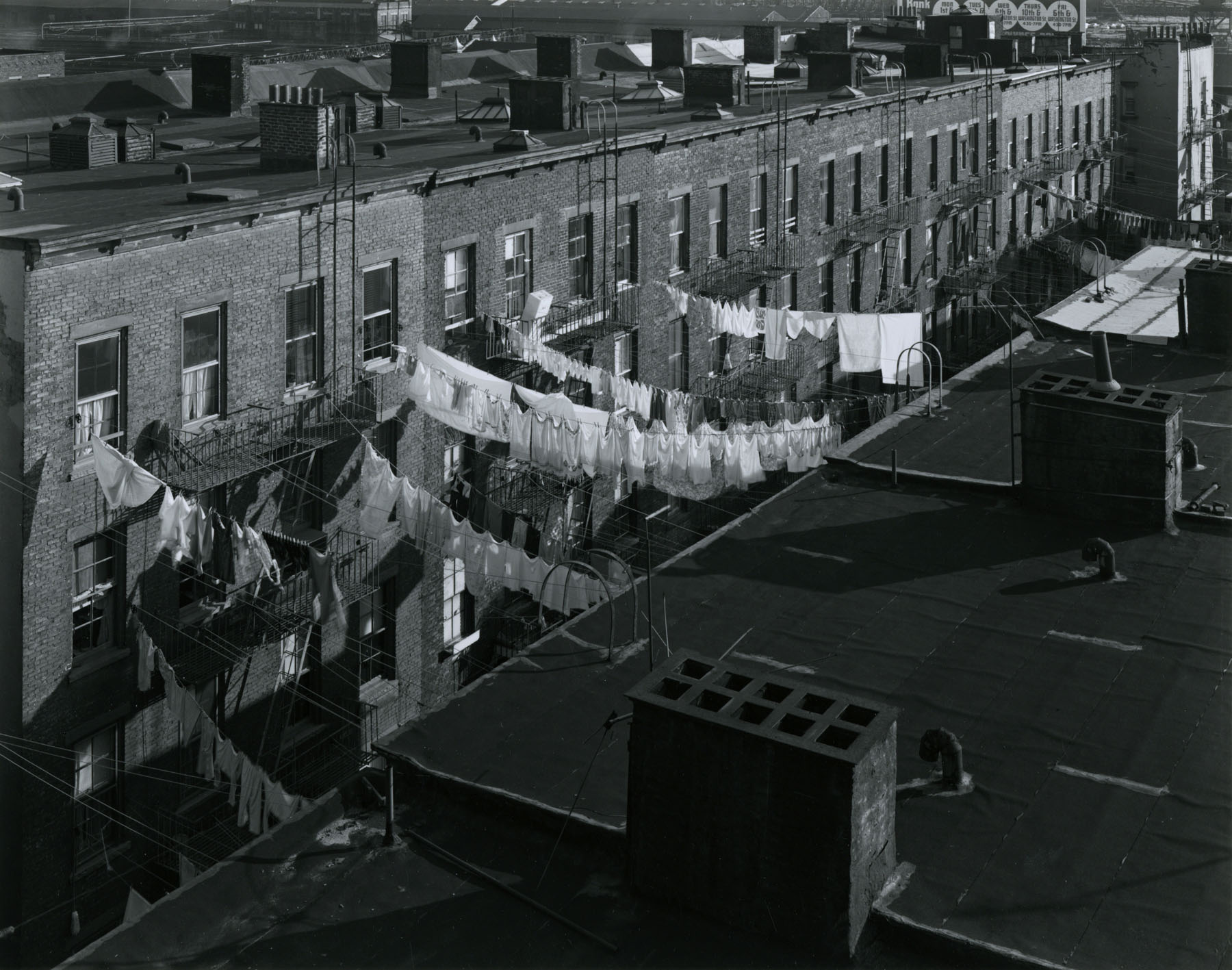

Eugène Atget (French, 1857-1927)

Untitled [Atget’s Work Room with Contact Printing Frames]

c. 1910

I am very familiar with the old suitcases under the desk – I think that only one – if any – is a suitcase.

This is typically how an exhibition would arrive at the Photographers’ Gallery – it would hold about 40 matted prints. Undo the strap and open the box to typically find 2 or 3 brown paper parcels. Maybe some archival tissue on the next layer down = sometimes not = and then about 20 mounted and matted prints sometimes face to face. This is the way Caponigro for example sent his prints – I’m trying to remember William Clift – Maybe one box like that and a handmade bigger one – or maybe 2 wooden boxes = but at least half the exhibitions arrived in boxes like that.

But have a look to the left of those boxes –what are they? They look like old fashioned double-darks – maybe for a quarter plate camera. The distance from the emulsion to the edge of the case was different for these compared to the last generation 5×4 double darks. People sometimes tried to make a way of putting the old film carriers onto 5×4″ cameras – but they would be focussing on the wrong spot by not making adjustments for the different positions of the emulsion.

To return to the boxes – they would be waiting for us at the airport, and we would have to spin a yarn to the customs agents telling them that the prints were for “educational purposes only”. It was a great educational experience to unwrap some of the prints when they came with a piece of tissue paper between the print and the mat – you could see something of the image and then get to imagine it before removing the tissue.

Re Robert Frank – also note the size of the Lupe next to his hand. Ralph Gibson had Robert Franks Leica enlarger – For some reason it was in his “living room” – I have seen it!!!

~ Ian Lobb email to Marcus Bunyan 1 December, 2015

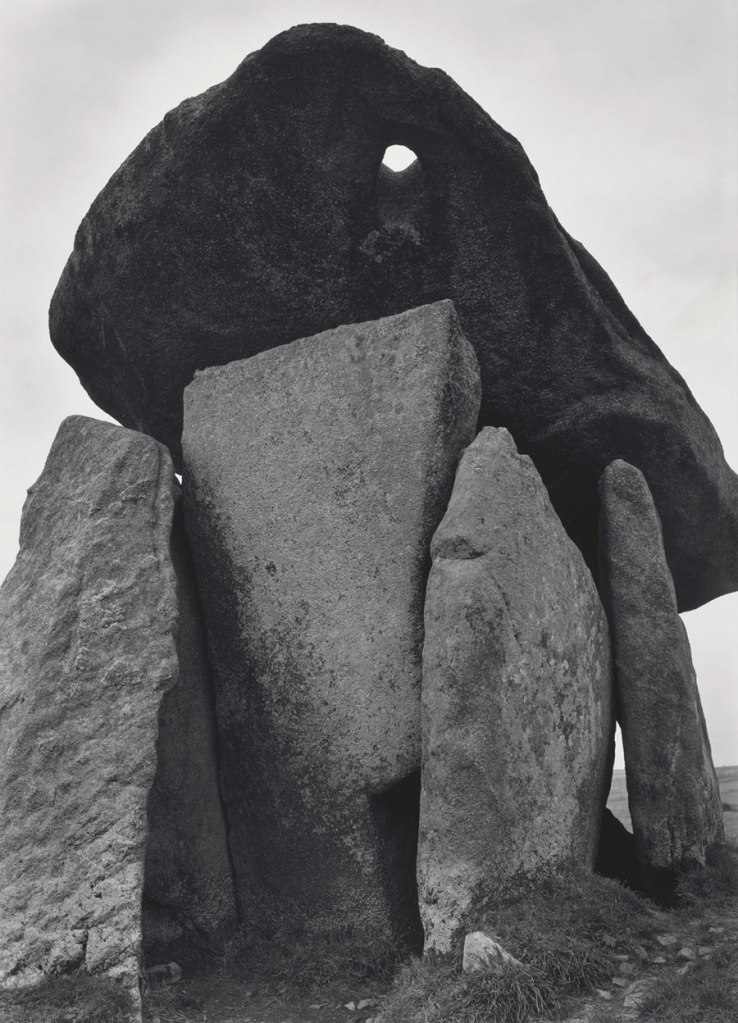

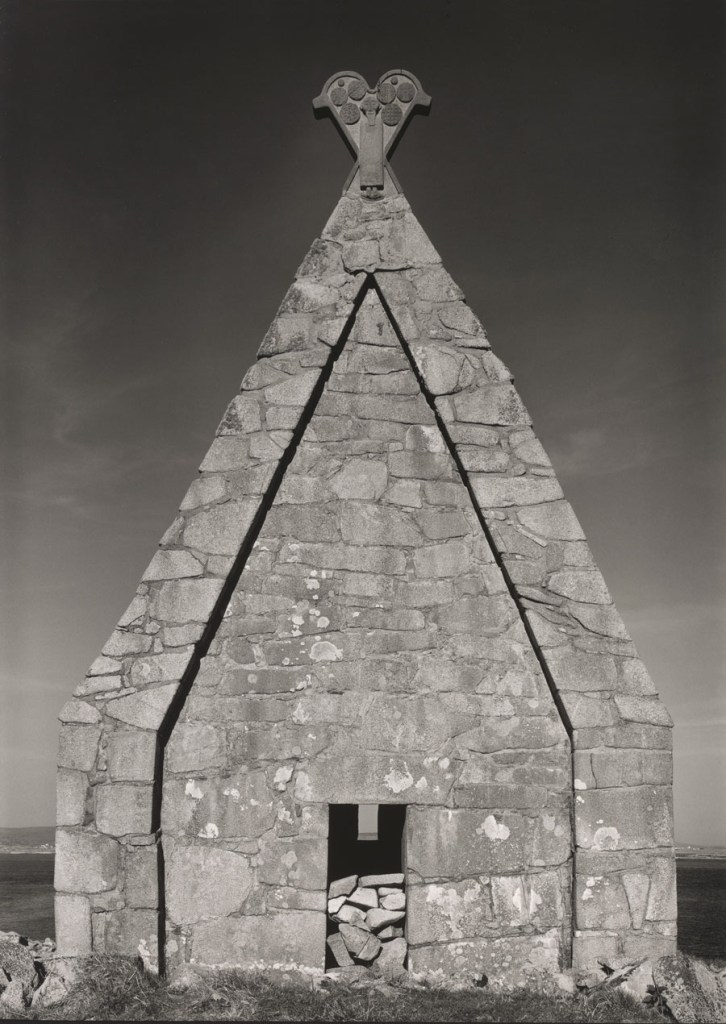

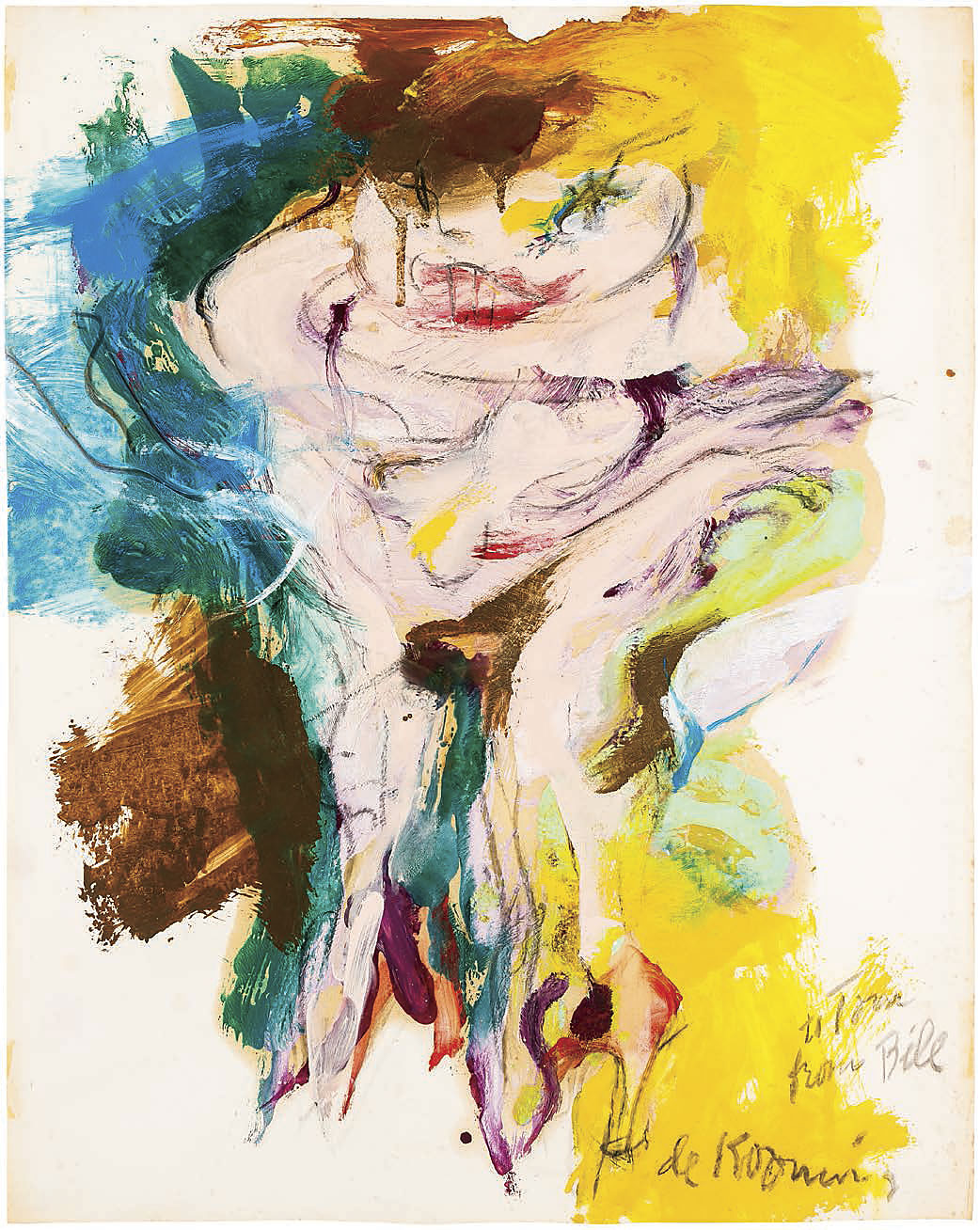

Carol Jerrems (Australian, 1949-1980)

Untitled [Bill Heimerman and Ian Lobb at the Dog Rocks near Geelong]

c. 1975-1980

Gelatin silver print

Cape Liptrap and Cape Paterson

Ian Lobb (Australian, 1948-2023)

Ocean (Cape Liptrap)

1979

Gelatin silver photograph

17.3 × 22.5cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased, 1980

© Ian Lobb

Ian Lobb (Australian, 1948-2023)

No title (Black sand and rocks)

1989; printed 1992

Gelatin silver photograph

34.3 × 34.3cm (image)

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Presented through The Art Foundation of Victoria by the artist, Fellow, 2000

© Ian Lobb

Ian Lobb (Australian, 1948-2023)

Eagles Nest, Cape Paterson

1975; printed 1979

Gelatin silver photograph

17.6 × 17.4cm (image)

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased, 1980

© Ian Lobb

David Tatnall (Australian, b. 1955)

Ian at Eagles Nest, Cape Paterson

November 2023

This was the first Ian time had returned to Cape Paterson since the death of his father many years ago.

David Tatnall (Australian, b. 1955)

Ian at Eagles Nest, Cape Paterson

November 2023

David Tatnall (Australian, b. 1955)

Ian at Eagles Nest, Cape Paterson

November 2023

Lemon scented gum, Fairfield

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Ian Lobb, Fairfield

December 2021

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Ian Lobb, Fairfield

December 2021

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Ian Lobb, Fairfield

December 2021

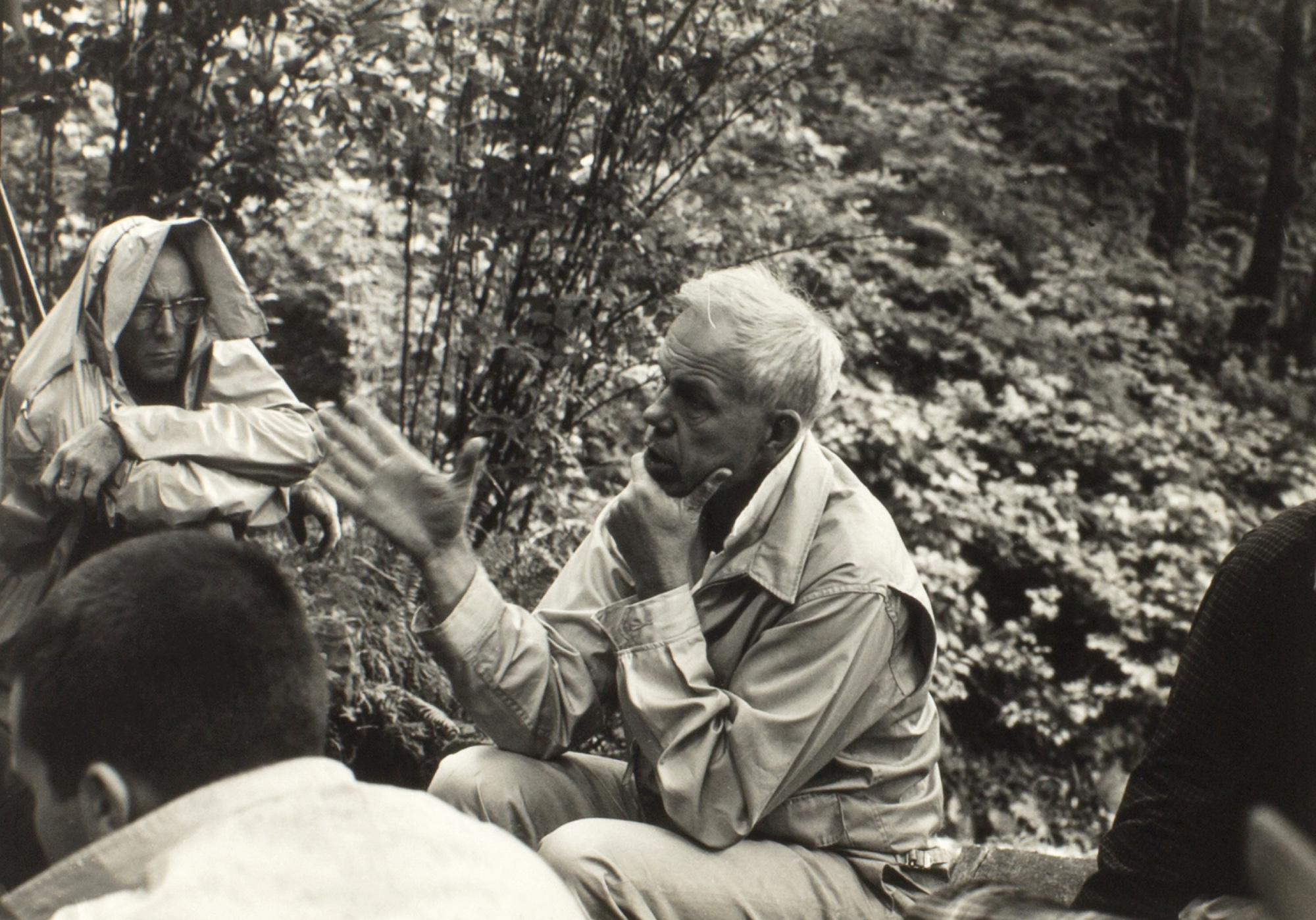

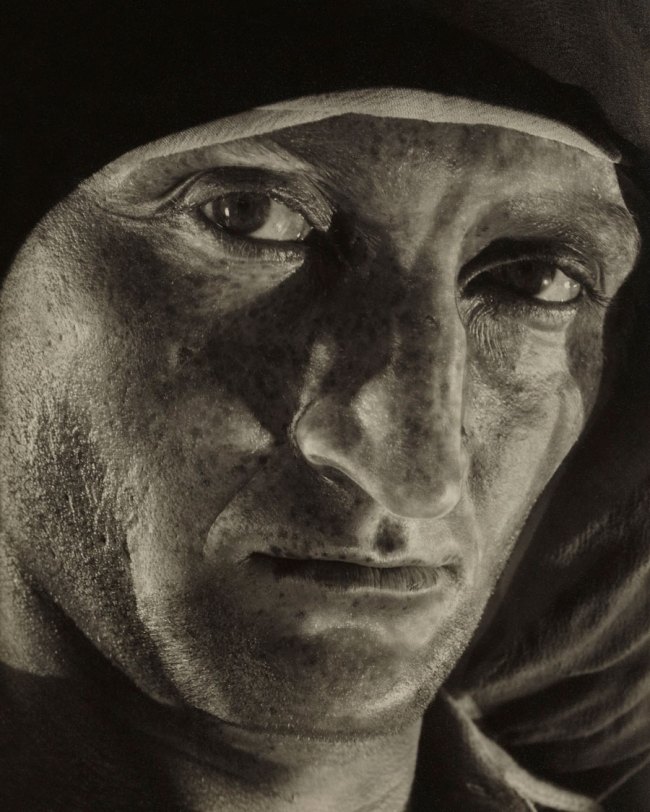

Maxwell Allara (American born Italy, 1906-1981)

Untitled (Minor White During a Workshop)

1959

Gelatin silver print

David Tatnall (Australian, b. 1955)

Ian in front of his favourite tree, Fairfield

November 2021

Minor White (American, 1908-1976)

Moencopi Strata, Capital Reef, Utah

1962

Gelatin silver print

Ian Lobb (Australian, 1948-2023)

Lemon scented gum

24 January 2023

Ian Lobb (Australian, 1948-2023)

Lemon scented gum

14 February 2023

“The light comes down the tree. But for some days it twists right to left and makes an early morning shadow.

~ Ian Lobb text to Marcus Bunyan, Monday 11 September 2023

Ian Lobb (Australian, 1948-2023)

Lemon scented gum

22 February 2023

Ian Lobb (Australian, 1948-2023)

Lemon scented gum

8 March 2023

Marcus – thanks for the mystic particles. After I have apple and rhubarb I’ll be walking to check on the tree in the church-garden. I’m interested in this, rather than my own garden. Who knows why I can’t photograph my own. Do you have a garden close by that you can walk through easily? I can’t wait for the sun to move a bit further and the light to come back on church gum. A few weeks.

~ Ian Lobb text to Marcus Bunyan, Wednesday 12 July 2023

Ian Lobb (Australian, 1948-2023)

Lemon scented gum

13 September 2023

Mobile phone photographs

Ian Lobb (Australian, 1948-2023)

Untitled (Green woman)

22 November 2022

Ian Lobb (Australian, 1948-2023)

Alex

21 December 2022

Ian Lobb (Australian, 1948-2023)

Untitled (pink and black)

31 January 2023

Ian Lobb (Australian, 1948-2023)

The path from the coffee shop

Fairfield, 4 February 2023

Ian Lobb (Australian, 1948-2023)

The path to the coffee shop

Fairfield, 4 February 2023

Ian Lobb (Australian, 1948-2023)

Building his ying, Ignoring his yang

21 February 2023

The First One

First one through the forest

First one on the beach

First one through the shallows

First one in the deep

Yes, first in the water

To swim out of reach

First one to belong

And then to be gone

First one to be gone too soon.

First foot off the platform

First step off the map

First one to learn

With nothing to teach

First one in this life

To whisper my name.

First one through my shallows

First one in my deep

First one to be gone too soon.

First winter field night

When the fires are lit

First soul at midnight

Watching burning trees twist.

At your back is the darkness

That turns you to see …

First one to the shadows

First one to the deep

First one to be gone too soon.

There’s a sound that’s so big

We can’t even hear

Not a murmur, a pulse

A note, nor a song

After midnight it wakes you

To its echoes and trace

First one to be swallowed

First one in the deep

First one to be gone too soon.

You’re the first, yes its true

On the roll call of friends

Now there’s spaces, not names

And you: you’re the worst.

You’re a very faint glow

On a very faint path

You were first through the shallows

First one in the deep

First one to be gone too soon.

Ian Lobb 28 August 2018

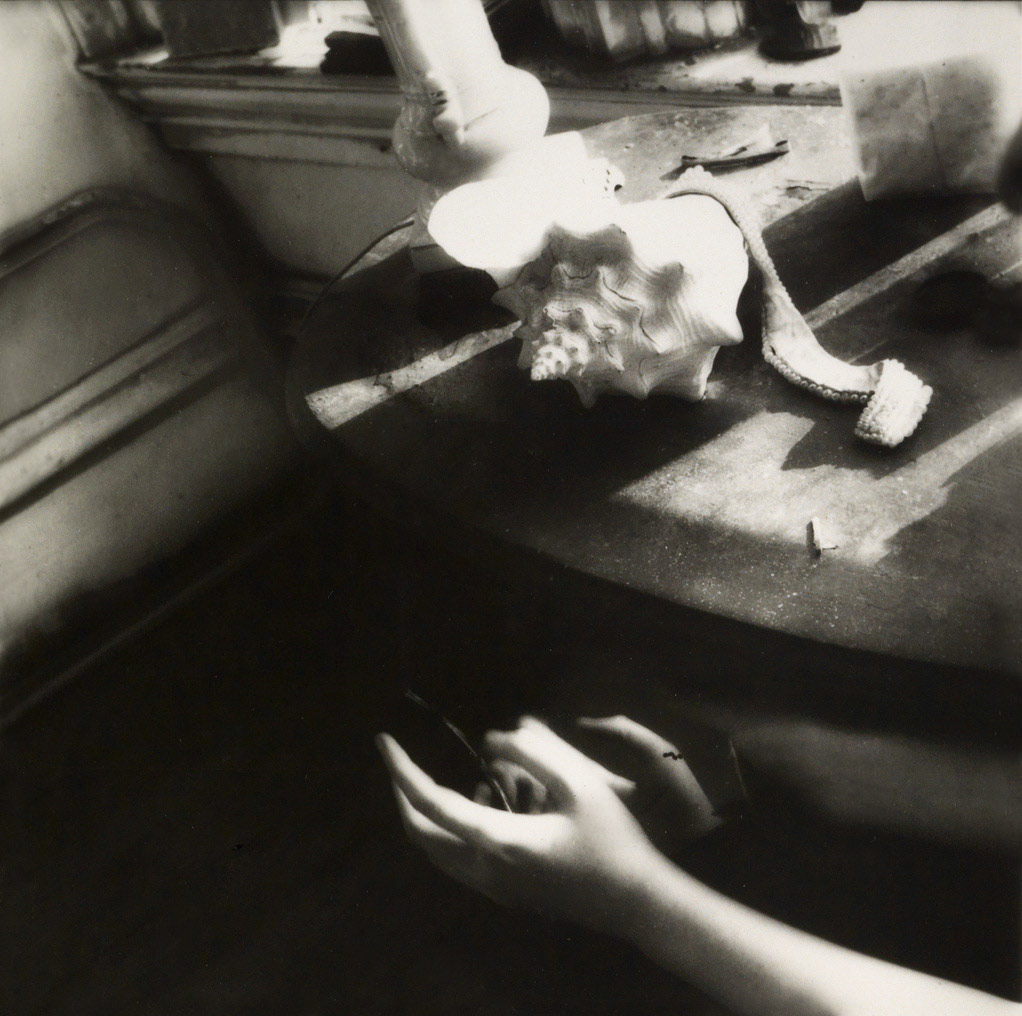

Ian Lobb (Australian, 1948-2023)

A small moment with…

25 February 2023

“If only the lens didn’t have anti flare – it would have been an Atget moment.”

~ Ian Lobb

Eugène Atget (French, 1857-1927)

Saint-Cloud

1926

Albumen print

Ian Lobb (Australian, 1948-2023)

Billiard

2 March 2023

Ian: Please see full screen for pleasing puns

Marcus: Love how the graffiti imitates the shape of the wood in the trolley and how the triangle of white dots is a metaphor for the billiard triangle used to rack up the balls

Ian: Yes. And with the billiard signage I thought it was like a players gesture – towards the corner pocket

~ Ian Lobb text to Marcus Bunyan, Friday, 3 March 2023

Ian Lobb (Australian, 1948-2023)

Untitled (Mother)

30 April 2023

Apart from the teenagers at church, the mention that you were talking to your mother, was one of the few mentions of that relationship since my mother had passed. One minute after that I took this on my way home.

~ Ian Lobb text to Marcus Bunyan, Sunday, 30 April 2023

Ian Lobb (Australian, 1948-2023)

Untitled (black oblong)

Fairfield, 8 May 2023

Ian Lobb (Australian, 1948-2023)

Untitled (My walk this morning)

Fairfield, 11 May 2023

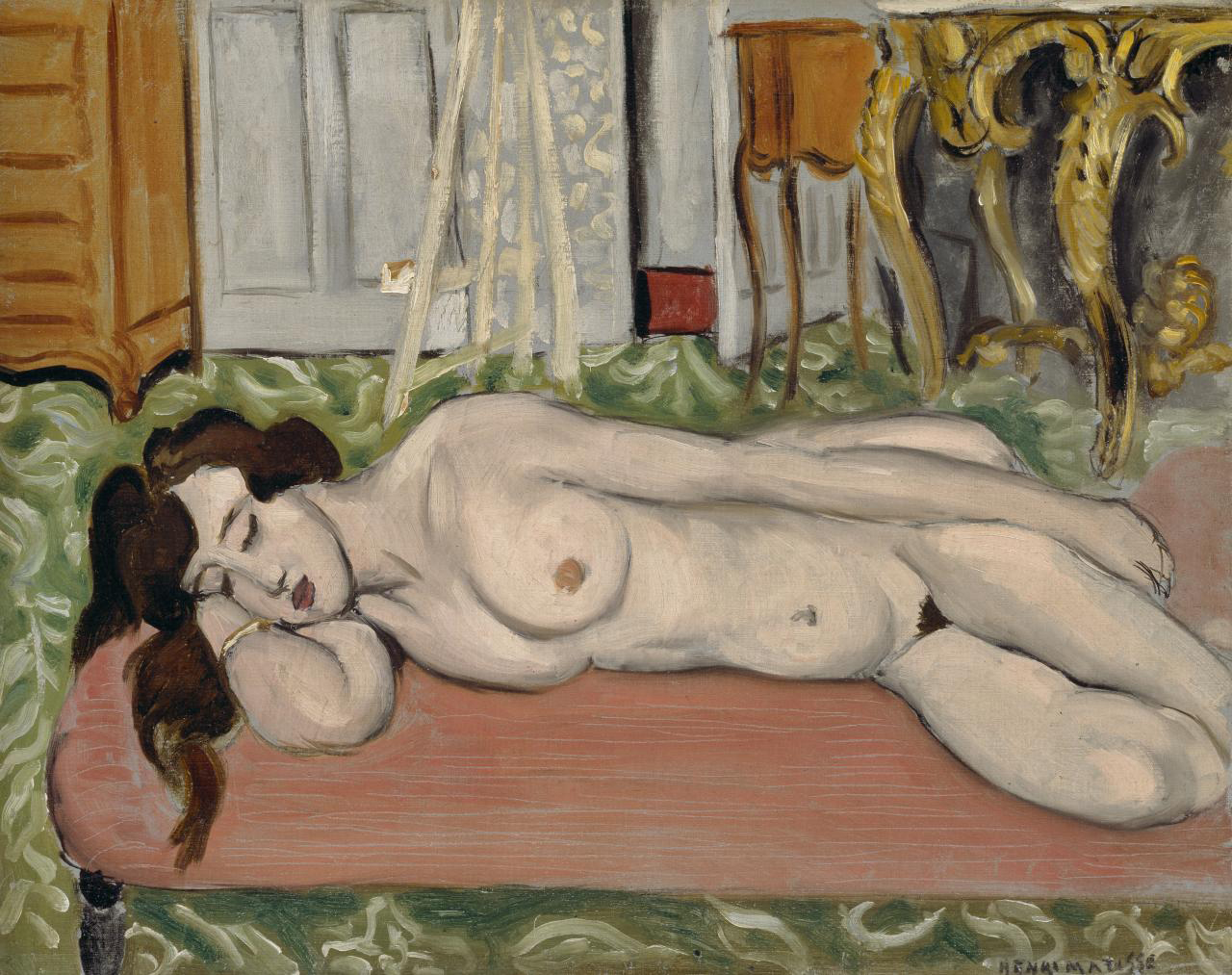

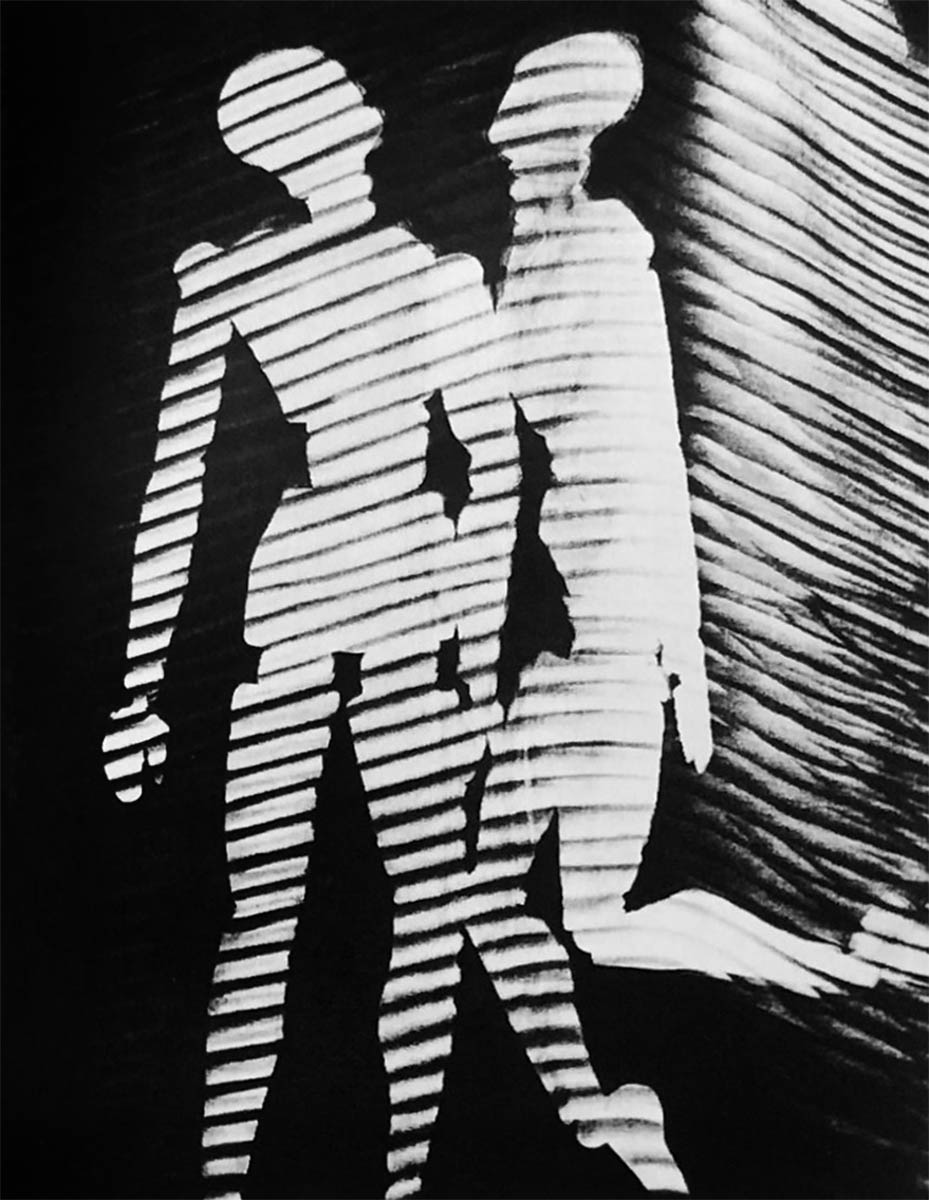

On my second roll of HP4 were pictures of a young lady lying under clear sheets of curved 2mm plastic that I had sprayed with water (1968?). The attached is from my walk this morning. The similar mood is quite scary.

~ Ian Lobb text to Marcus Bunyan, Thursday, 11 May 2023

Ian Lobb (Australian, 1948-2023)

mmmm, Pasta Poetry

Fairfield, 21 June 2023

Thinking about John Cato this morning. If you can google “the world is too much with us” – Wordsworth – and give a toast to John. Proteus!!!

~ Ian Lobb text to Marcus Bunyan, Wednesday, 5 July 2023

The world is too much with us

The world is too much with us; late and soon,

Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers;–

Little we see in Nature that is ours;

We have given our hearts away, a sordid boon!

This Sea that bares her bosom to the moon;

The winds that will be howling at all hours,

And are up-gathered now like sleeping flowers;

For this, for everything, we are out of tune;

It moves us not. Great God! I’d rather be

A Pagan suckled in a creed outworn;

So might I, standing on this pleasant lea,

Have glimpses that would make me less forlorn;

Have sight of Proteus rising from the sea;

Or hear old Triton blow his wreathèd horn.

William Wordsworth 1802

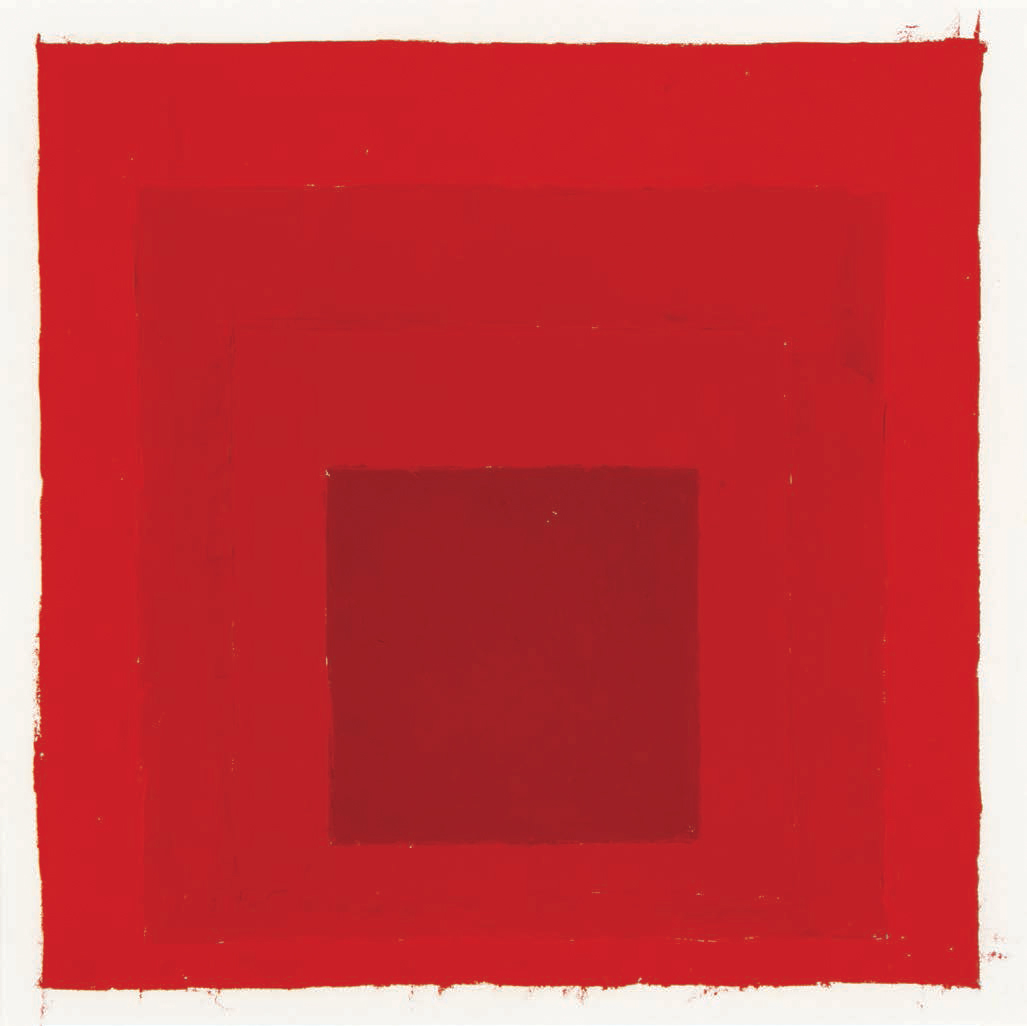

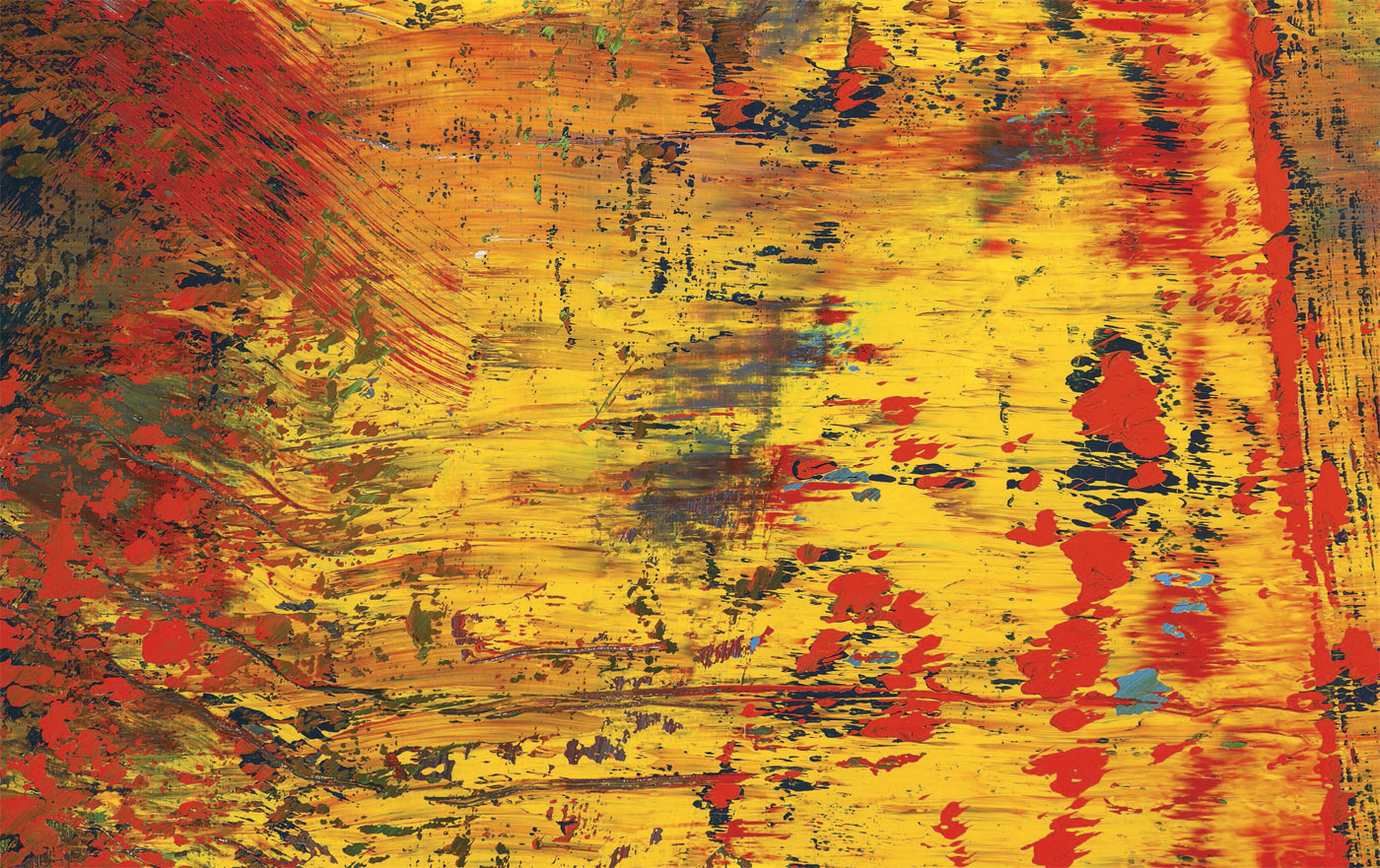

Cy Twombly (American, 1928-2011)

Coronation of Sesostris (Part III)

2000

Affirmation: When you Sing

(An affirmation from Cy Twombly’s Coronation of Sesostris)

If you sing, don’t let them hesitate

When you sing, don’t let them make signs of regret

When you sing, let them bear the loss of silence

When you sing, the lost gods are found

When you sing, the birds and trees love their shadows

Lying quietly on the ground

When you sing, the mark of nature and the mark of the mark rejoice

When you sing we trace to the source of trace – the realm.

Sing to the ghosts, sing to those to come

Flow over – into – flow over

Let the trees rise from the earth because you sing:

New sunlight on new leaves cutting into space

Write your name

with their scintilla through the air as you sing

Then each letter narrows, fades white

Still unending trace as sing and sing as a lost god.

One majesty fades to another

Sing Osiris , sing that god into Orpheus

scribes

Porous sparse voice, could have been scattered

Empty surface – instead open sky

Bell

Nothing to shatter

Sing for the old rivers,

Sailors sink into sails,

The opposite bank still opposite

Take this – sing – most important , to the next life.

Like tall trees, rising from …

Gods cannot depart while love, I mean song, remains

Gods have not departed: it would have been heeded,

Reported as a hoax,

No arc of departure divulged

song, weightless

Gods have not departed – it is a drunken hoax, rumour.

Ian Lobb 30 August 2018

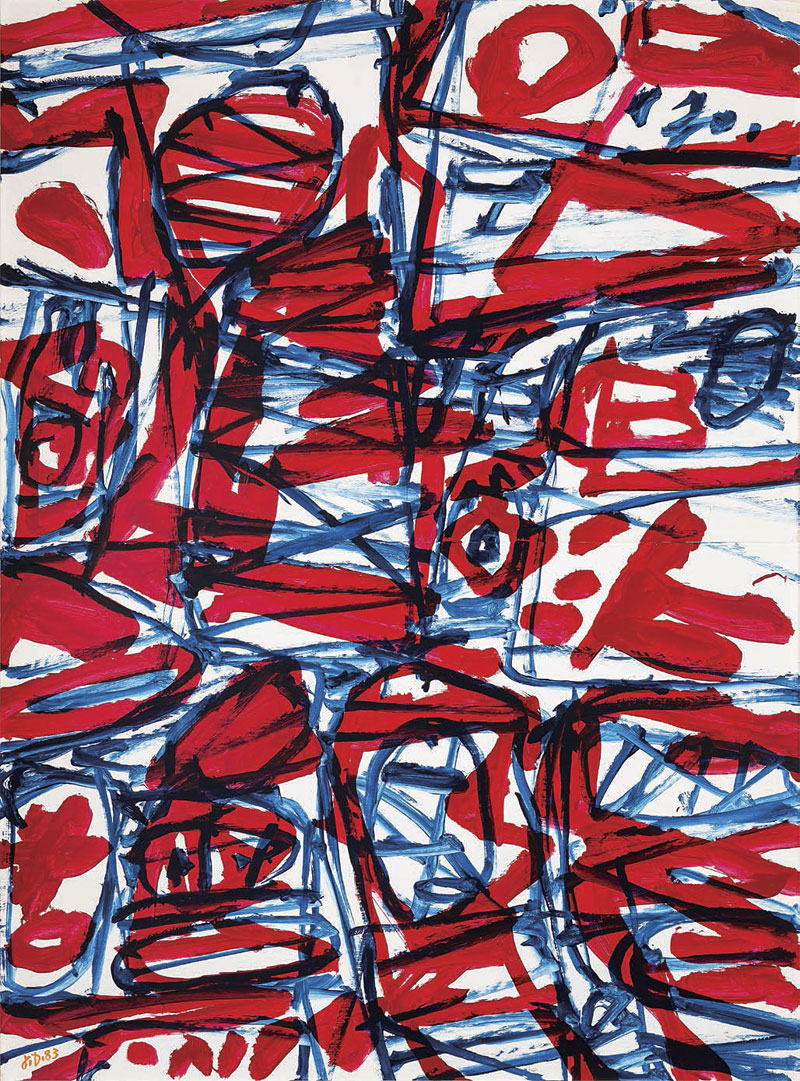

Cy Twombly (American, 1928-2011)

Coronation of Sesostris (Part V)

2000

Cy Twombly (American, 1928-2011)

Coronation of Sesostris (Part VI)

2000

Last house

Are you travelling to this very last house

On the very last street of this town?

That I built here for you,

Where I wait for you

If you go round the back you’ll find wild flowers

That you could almost touch

And you would watch the clouds come down from the hills

Long ago I promised this to you

It became my story that you’d come

To the last street

And to the last house

I watch all the doors to see you enter

So that we would almost touch

And you could watch the rain come down from the hills

Yes, it’s true, the house backs onto darkness

I swear there’s really nothing out there

Beyond this last street

Beyond this last house

Nothing you could be sure to name

Nothing we can almost touch

And at night you could keep watch, from here to the hills

You can smell salt in the air from all of the rooms

And hear the wind in the waves

But out the back you’ll only find wildflowers.

Not those grey choppy waves

That we can almost touch

On this last street

In this last house.

Ian Lobb 29 August 2018

Flickerd (Australian)

Zac Foot of Sydney during the 2019 NEAFL round 14 match between NT Thunder and Sydney at TIO Stadium on Saturday, 6 July 2019 in Darwin, Northern Territory

2019

Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International

![Peter Leiss (Australian, b. 1951) 'Untitled [Bill Heimerman and Ian Lobb at the rear of the Photographers' Gallery]' c. 1975-1980 Peter Leiss (Australian, b. 1951) 'Untitled [Bill Heimerman and Ian Lobb at the rear of the Photographers' Gallery]' c. 1975-1980](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/leiss-william-heimerman2-web.jpg)

![Eugène Atget (French, 1857-1927) 'Untitled [Atget's Work Room with Contact Printing Frames]' c. 1910 Eugène Atget (French, 1857-1927) 'Untitled [Atget's Work Room with Contact Printing Frames]' c. 1910](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/atgets-work-room-web1.jpg?w=650&h=783)

![Carol Jerrems. 'Untitled [Bill Heimerman and Ian Lobb at the Dog Rocks near Geelong]' c. 1975-1980 Carol Jerrems. 'Untitled [Bill Heimerman and Ian Lobb at the Dog Rocks near Geelong]' c. 1975-1980](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/jerrems-william-heimerman-ian-lobb-web.jpg?w=650&h=650)

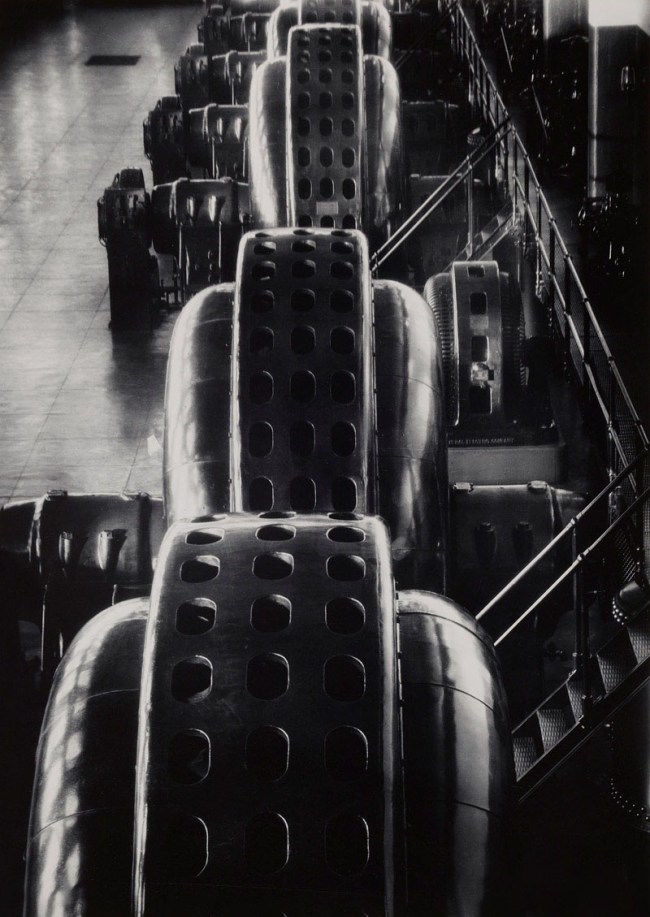

![Margaret Bourke-White (American, 1904-1971) 'Terminal Tower [Cleveland]' c. 1928 Margaret Bourke-White (American, 1904-1971) 'Terminal Tower [Cleveland]' c. 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/margaret-bourke-white-terminal-tower-cleveland-web.jpg?w=719)

You must be logged in to post a comment.