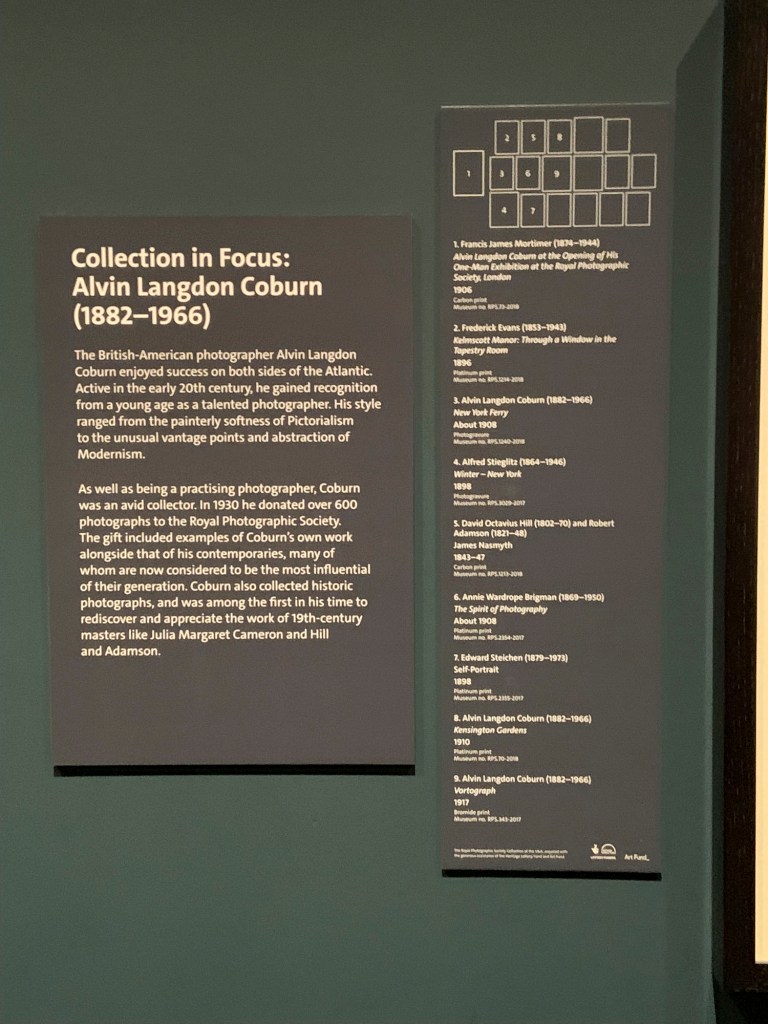

Exhibition dates: 19th June, 2021 – 9th January, 2022

Curator: Anna Tellgren

Artists represented in the exhibition: Anna Boberg, Helmer Bäckström, Julia Margaret Cameron, Uno Falkengren, Gustaf Fjæstad, Ferdinand Flodin, Henry B. Goodwin, John Hertzberg, Gösta Hübinette, Eugène Jansson, Nicola Perscheid and Ture Sellman.

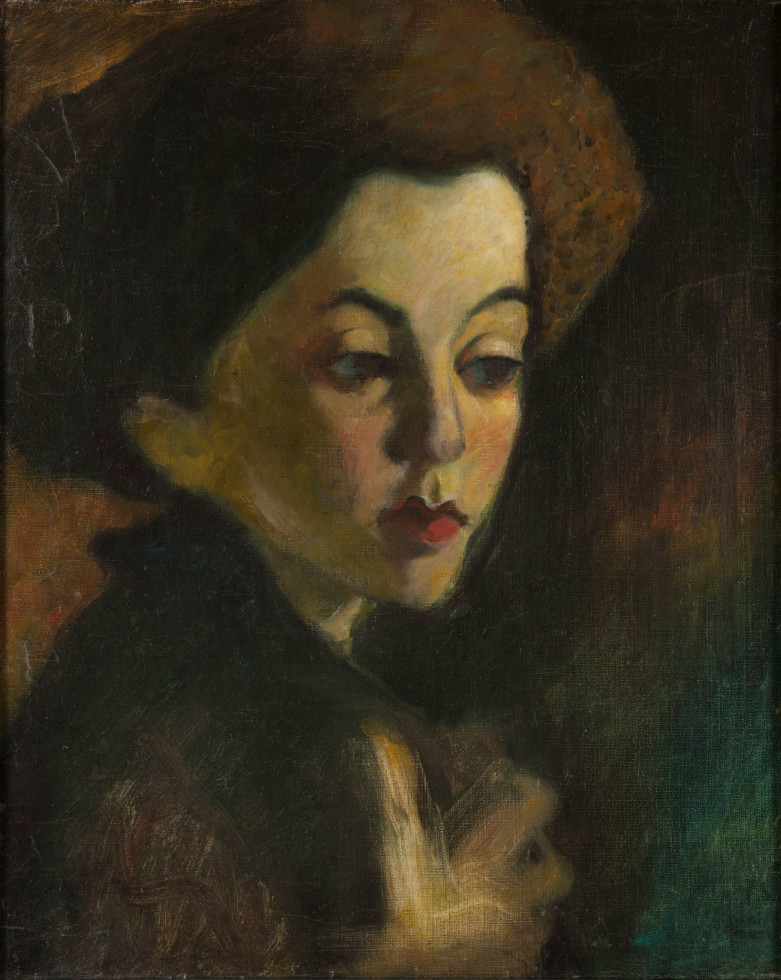

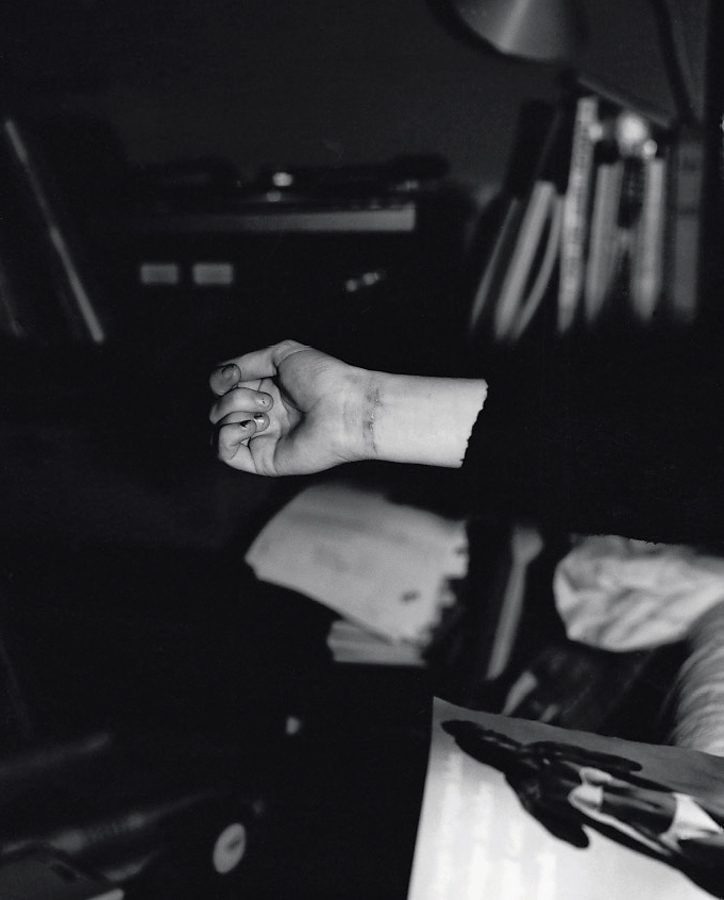

Otto

Girl in Chair

c. 1892

Reproduction photo: Prallan Allsten/Moderna Museet

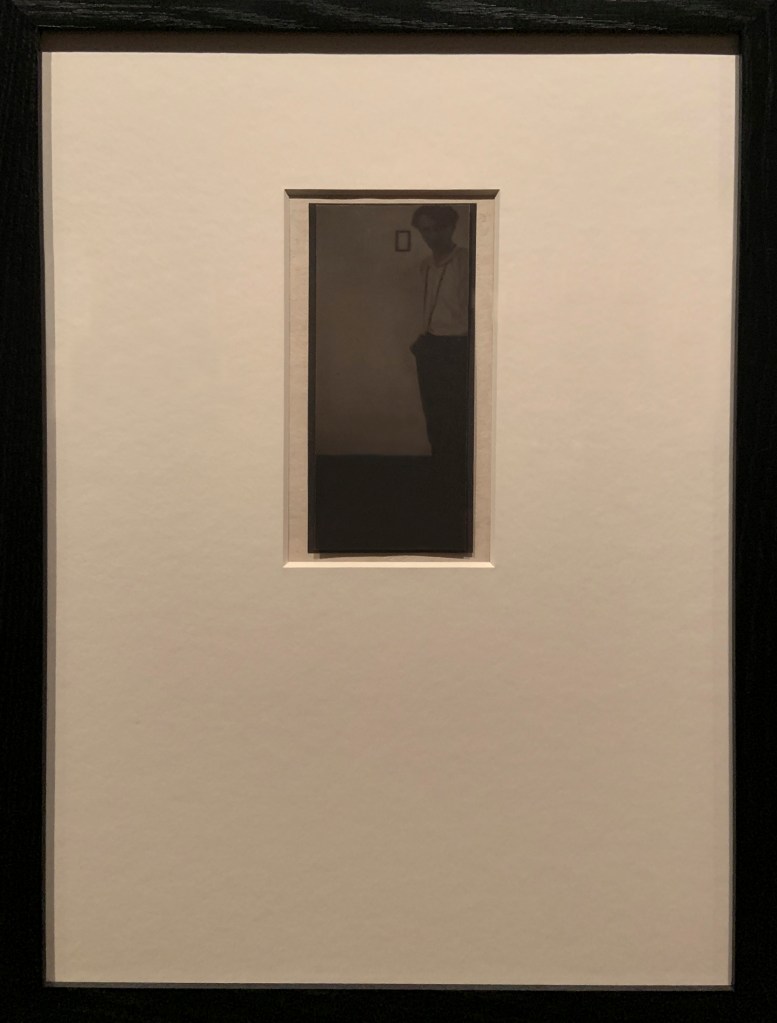

Apologies, a short text today… my lower back is not very good and I am not feeling that well.

Another “niche” exhibition that Art Blart likes to promote, one that fills a gap in our greater knowledge of world art and artists. But why the distinction in the title of the exhibition between art and photography? That old chestnut rears its ugly head again… why not just ‘art around 1900’?

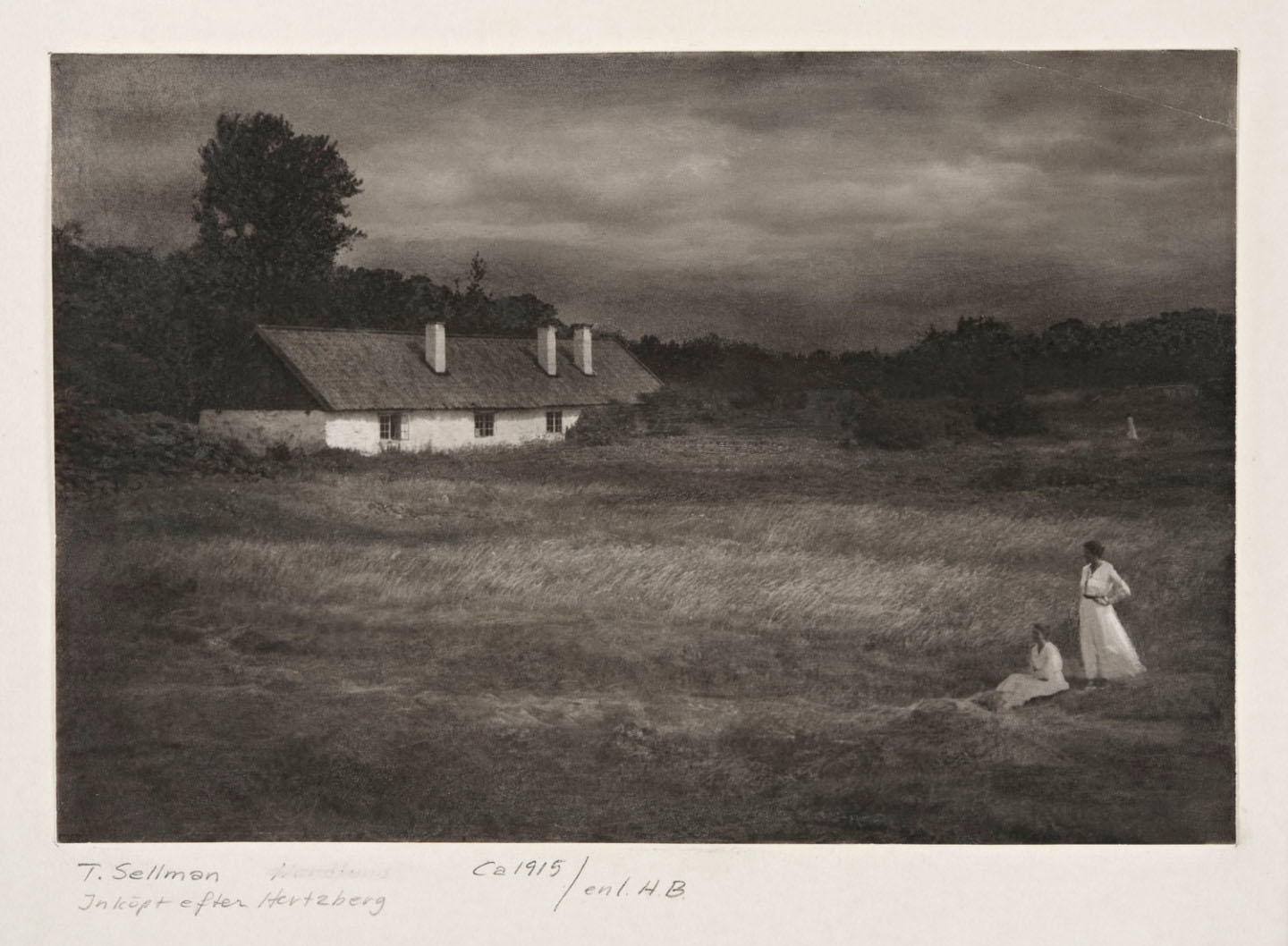

My particular favourites in the posting are the muscular yet translucent Anna Boberg painting A Quiet Evening. Study from North Norway (Nd); the gossamer wispiness and beauty of Ferdinand Flodin’s Portrait of a young lady (1922); and the velvety softness and light of Ture Sellman’s Untitled landscape (c. 1915).

I have added detail of the artists and sitters where possible and information on early photographic processes.

Enjoy!

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Moderna Museet for allowing me to publish the photographs and the text in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Moderna Museet highlights Pictorialism – a movement in photography that arose around 1900. The exhibition In Lady Barclay’s Salon – Art and Photography Around 1900 also includes paintings from the same period, treating visitors to a selection of nearly 300 works from the collections of Moderna Museet and Nationalmuseum.

This exhibition is based on the rich collections of Moderna Museet and Nationalmuseum, with art and photography dating from the late 1800s to the First World War. During this period, pictorialism was a style that many prominent photographers worked in; it was inspired by impressionism, symbolism and naturalism.

Pictorialism was the first international art photography movement, with many active practitioners throughout Europe and the USA. Sweden was on the periphery of this movement, but the style became popular here too among several influential amateur and professional photographers. This was a pivotal period in painting, where the younger artists who went abroad and were inspired by a freer approach broke with the more conservative academic painters. This exhibition will highlight works by famous photographers and painters from the years around the turn of the century.

Dark haired, almond eyed, and irresistibly charming, Lady Sarita Enriqueta Barclay was an influential figure of Stockholm’s Pictorialism movement. Captivated by the experimental nature of Swedish art during the fin de siècle, she hosted elaborate viewings and events, and was photographed often. Known for diffused light, sepia tones, and romanticism, the impressionistic photographs of the era capture a cultural moment in Swedish history.

Look into Lady Barclays Salon: Live curator talk

Look into Lady Barclay’s salon and discover Pictorialism, the first art photo stream. Many prominent photographers worked in the style that prevailed from the 1890s and a few decades onwards. Anna Tellgren, curator and Karin Malmquist, program curator, talk about Pictorialism and some of the approximately 300 paintings and photographs that you can see in the exhibition “In Lady Barclays Salon”.

August Strindberg (Swedish, 1849-1912)

Underlandet (The Wonderland)

1894

Oil on cardboard

72.5cm (28.5 in) x 52cm (20.4 in)

Nationalmuseum (Stockholm)

Johan August Strindberg

Johan August Strindberg (22 January 1849 – 14 May 1912) was a Swedish playwright, novelist, poet, essayist and painter. A prolific writer who often drew directly on his personal experience, Strindberg’s career spanned four decades, during which time he wrote more than sixty plays and more than thirty works of fiction, autobiography, history, cultural analysis, and politics. A bold experimenter and iconoclast throughout, he explored a wide range of dramatic methods and purposes, from naturalistic tragedy, monodrama, and history plays, to his anticipations of expressionist and surrealist dramatic techniques. From his earliest work, Strindberg developed innovative forms of dramatic action, language, and visual composition. He is considered the “father” of modern Swedish literature and his The Red Room (1879) has frequently been described as the first modern Swedish novel. In Sweden, Strindberg is known as an essayist, painter, poet, and especially as a novelist and playwright, but in other countries he is known mostly as a playwright. …

Strindberg, something of a polymath, was also a telegrapher, theosophist, painter, photographer and alchemist. Painting and photography offered vehicles for his belief that chance played a crucial part in the creative process.

Strindberg’s paintings were unique for their time, and went beyond those of his contemporaries for their radical lack of adherence to visual reality. The 117 paintings that are acknowledged as his were mostly painted within the span of a few years, and are now seen by some as among the most original works of 19th-century art.

Today, his best-known pieces are stormy, expressionist seascapes, selling at high prices in auction houses. Though Strindberg was friends with Edvard Munch and Paul Gauguin, and was thus familiar with modern trends, the spontaneous and subjective expressiveness of his landscapes and seascapes can be ascribed also to the fact that he painted only in periods of personal crisis.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Joseph Mallard William Turner (British, 1775-1851)

A View of Deal

Nd

Oil on paper on panel

32 x 24cm (12.6 x 9.6 inches)

Nationalmuseum (Stockholm)

The years from 1890 to the first World War were a golden era for the arts in Sweden. This exhibition presents beautiful Pictorialist photographs and selected paintings from this period. The more than 300 works from the rich collections of Moderna Museet and Nationalmuseum give us an insight into art at the time.

In Lady Barclay’s Salon, we imagine a meeting between photographers and painters, their friends and the public. Lady Sarita Enriqueta Barclay (1891-1985) was married to a British diplomat, and they both lived in Stockholm for a few years around 1921. She was portrayed several times in the studio of the photographer Henry B. Goodwin. We can assume that she was prominent in the city’s social life and went to previews, dinners and other events.

This exhibition is an opportunity to see a selection of some 300 works by famous photographers and painters in the Moderna Museet and Nationalmuseum collections, including Anna Boberg, Helmer Bäckström, Julia Margaret Cameron, Uno Falkengren, Gustaf Fjæstad, Ferdinand Flodin, Henry B. Goodwin, John Hertzberg, Gösta Hübinette, Eugène Jansson, Nicola Perscheid and Ture Sellman.

Around the end of the previous century

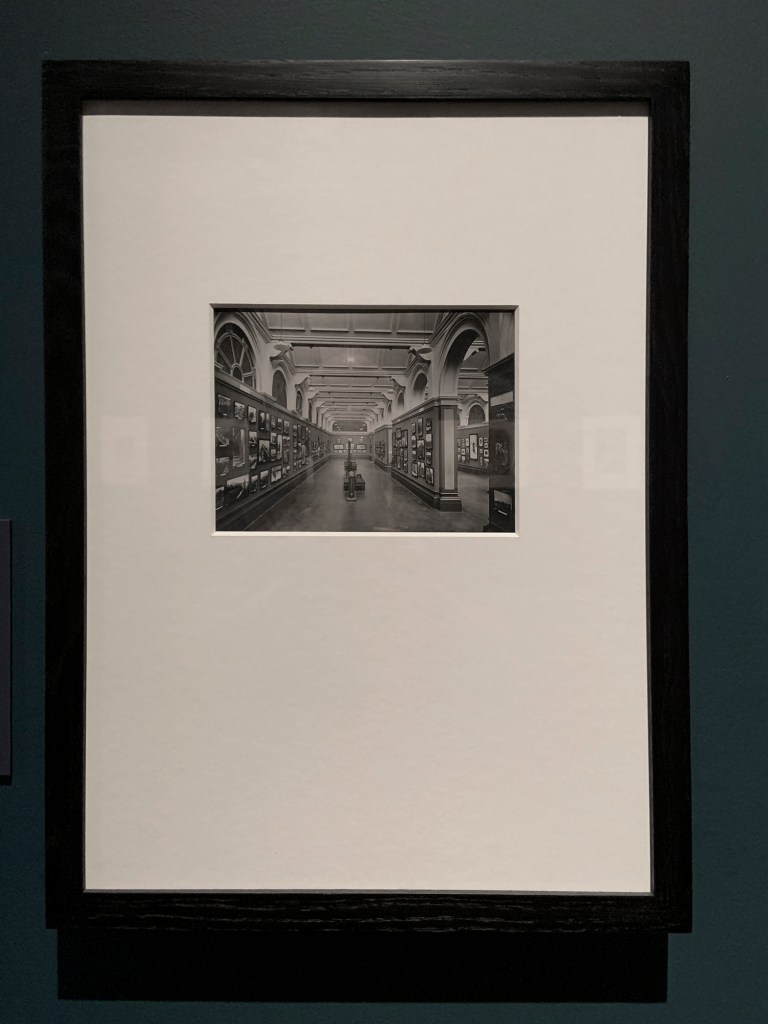

In the years around 1900, a number of colourful personalities emerged in literature, music, art and architecture, and patrons such as Prince Eugen and Ernest Thiel were building major art collections. The Art and Industry Exhibition in Stockholm in 1897 and the Baltic Exhibition in Malmö in 1914 had sections for art and photography.

The exhibition “In Lady Barclay’s Salon” gives a picture of the visual culture at the time. It features mainly Swedish material, with a few international highlights. The works date from the late-19th century to 1930, a period when Pictorialism was emerging in photography. The style was inspired by impressionism, symbolism and naturalism, and there were lively debates on how to make photography more artistic.

Unlike the increasing number of amateur and professional photographers – who had gained access to the medium thanks to technological progress – the Pictorialists emphasised craftsmanship. Their images are characterised by soft focus and with colours ranging from brown, earthy tones to strong reds and blues. They worked with a variety of processes with the purpose of creating or “painting” on light-sensitive paper. This was the first international art photography movement, and it had many prominent practitioners throughout Europe and the USA.

A pivotal time for painting

This was a pivotal period in painting, when the younger artists who travelled abroad and were inspired by a freer approach broke with the more conservative academic painters. The French painter Paul Gauguin and the Pont-Aven school had a strong influence on Swedish artists who adopted symbolist or synthetist approaches. Images were reproduced and distributed more widely in books, posters and magazines, making it easier to share ideas. No longer was it necessary to visit other countries to see the latest art, but Paris was still a mecca for art students. Towards the end of the century, however, Paris was rivalled by Berlin, Munich, Dresden and Hamburg. Copenhagen, with its international relations and exhibitions, also offered a natural meeting place for Swedes.

Text from the Moderna Museet website

Ferdinand Flodin (Swedish, 1863-1935)

View from My Window over Skeppsholmen, Stockholm

1929

Bromoil print mounted on board

Moderna Museet

Reproduction photo: Prallan Allsten/Moderna Museet

Eugène Jansson (Swedish, 1862-1915)

Hornsgatan nattetid (Hornsgatan at night)

1902

Oil on canvas

152cm (59.8 in) x 182cm (71.6 in)

National Museum (Stockholm)

Moderna Museet highlights Pictorialism – a movement in photography that arose around 1900. The exhibition In Lady Barclay’s Salon – Art and Photography Around 1900 also includes paintings from the same period, treating visitors to a selection of nearly 300 works from the collections of Moderna Museet and Nationalmuseum.

Lady Sarita Enriqueta Barclay (1891-1985) became a prominent figure on the Stockholm arts scene after her husband, a British diplomat, had been posted to Stockholm. Lady Barclay frequently hosted cultural gatherings and events in the five years following the end of the First World War when she lived here. The photographer Henry B. Goodwin (1878-1931) portrayed Lady Barclay on several occasions, and his pictures show her as a stylish woman with a cosmopolitan air – an emblem of Sweden’s flourishing arts scene at the time.

In the years around 1900, a number of colourful personalities emerged in literature, music, art and architecture, and patrons such as Prince Eugen and Ernest Thiel were building major art collections. The Art and Industry Exhibition in Stockholm in 1897, and the Baltic Exhibition in Malmö in 1914, included separate sections for art and photography.

The exhibition In Lady Barclay’s Salon gives a picture of the visual culture at the time, and consists mainly of Swedish material, with a few international highlights. The works date from the late-19th century to 1930, a period when Pictorialism was emerging in photography. The style embraced inspiration from impressionist, symbolist and naturalism, and there was a lively debate on how to make photography more artistic. Unlike the increasing number of amateur and professional photographers – who had gained access to the medium thanks to technological progress – the Pictorialists emphasised craftsmanship. Their images are characterised by soft focus and with colours ranging from brown, earthy tones to strong reds and blues. They worked with a variety of processes with the purpose of creating or “painting” on light-sensitive paper.

Painting also moved into a new phase around 1900. While the older members of the artist federation Konstnärsförbundet, founded in 1886, maintained their dominance, a younger generation was beginning to step in at the turn of the century. The French artist Paul Gauguin and the Pont-Aven school had a strong influence on Swedish artists who adopted symbolist or synthetist approaches. Ideas could be shared more easily with mass-produced images in books, posters and magazines.

In Lady Barclay’s Salon presents a fictive encounter between photographers and painters, their friends and the audience. The exhibition features some 300 works from the collections of Moderna Museet and Nationalmuseum, including works by Anna Boberg, Helmer Bäckström, Julia Margaret Cameron, Uno Falkengren, Gustaf Fjæstad, Ferdinand Flodin, Henry B. Goodwin, John Hertzberg, Gösta Hübinette, Eugène Jansson, Nicola Perscheid and Ture Sellman.

“This is an opportunity to discover a less well-known part in the history of photography, where the artistic aspects of the medium were discussed fervently, and where there are many intriguing links to painting at the time,” says the exhibition’s curator, Anna Tellgren. “The exhibition highlights both famous and unknown photographers and artists who were practising around 1900, and reveals some fantastic visual treasures from our collection.”

Press release from Moderna Museet

Prince Eugen, Duke of Närke (Swedish, 1865-1947)

Tidig vintermorgon (Early winter morning)

1906-1907

Oil on canvas

77cm (30.3 in) x 89cm (35 in)

Nationalmuseum (Stockholm)

Prince Eugen

After finishing high school, Prince Eugen studied art history at Uppsala University. Although supported by his parents, Prince Eugen did not make the decision to pursue a career in painting easily, not least because of his royal status. He was very open-minded and interested in the radical tendencies of the 1880s. The Duke became one of the era’s most prominent landscape painters. He was first trained in painting by Hans Gude and Wilhelm von Gegerfelt.

Between 1887 and 1889, he studied in Paris under Léon Bonnat, Alfred Philippe Roll, Henri Gervex and Pierre Puvis de Chavannes. Puvis de Chavannes’s classical simplicity had the greatest influence on Prince Eugen’s work. The Duke devoted himself entirely to landscape painting. He was mainly interested in the lake Mälaren, the countryside of Stockholm (such as Tyresö, where he spent his summers), Västergötland (most notably Örgården, another summer residence) and Skåne (especially Österlen).

Text from the Wikipedia website

Henry B. Goodwin (Swedish born Germany, 1878-1931)

Bragevägen Stockholm’s loveliest street

1917

Reproduction photo: Prallan Allsten/Moderna Museet

About the exhibition In Lady Barclay’s Salon

The exhibition “In Lady Barclay’s Salon – Art and Photography around 1900” highlights the period from 1890 and up to the First World War. It was a golden age for the arts in Sweden. A number of noteworthy figures appear within the fields of literature, music, art and architecture. Among them are Verner von Heidenstam, Ellen Key, Selma Lagerlöf and August Strindberg.

Art patrons Prince Eugen and Ernest Thiel acquired large art collections, that can still be admired in their respective homes: Waldermarsudde and Thielska Galleriet on Djurgården. Both buildings were designed by the architect Ferdinand Boberg, who included Renaissance, oriental and late Jugend style elements.

The renowned artist Eva Bonnier was another important figure. Better communications in the form of railways and telephone networks contributed to the development of cities, and a growing, export-oriented industry in Sweden. The 1897 Art and Industry Exposition in Stockholm and, a few years later, the 1914 Baltic Exhibition in Malmö, were manifestations of this progressive outlook. Both included sections that showed art and photography.

It was a time of Scandinavianism, and many Nordic collaborations and groups were formed. The women’s movement gained momentum, and in 1919 women were finally given the right to vote. For the first time, after a long struggle, they were able to cast their vote in the 1921 lower house election – exactly one hundred years ago.

Pictorialism developed as a photographic movement

This exhibition offers a glimpse of visual culture from this period by means of some 300 works from the rich collections of Moderna Museet and National museum. While most of these are Swedish in origin, there are some international examples.

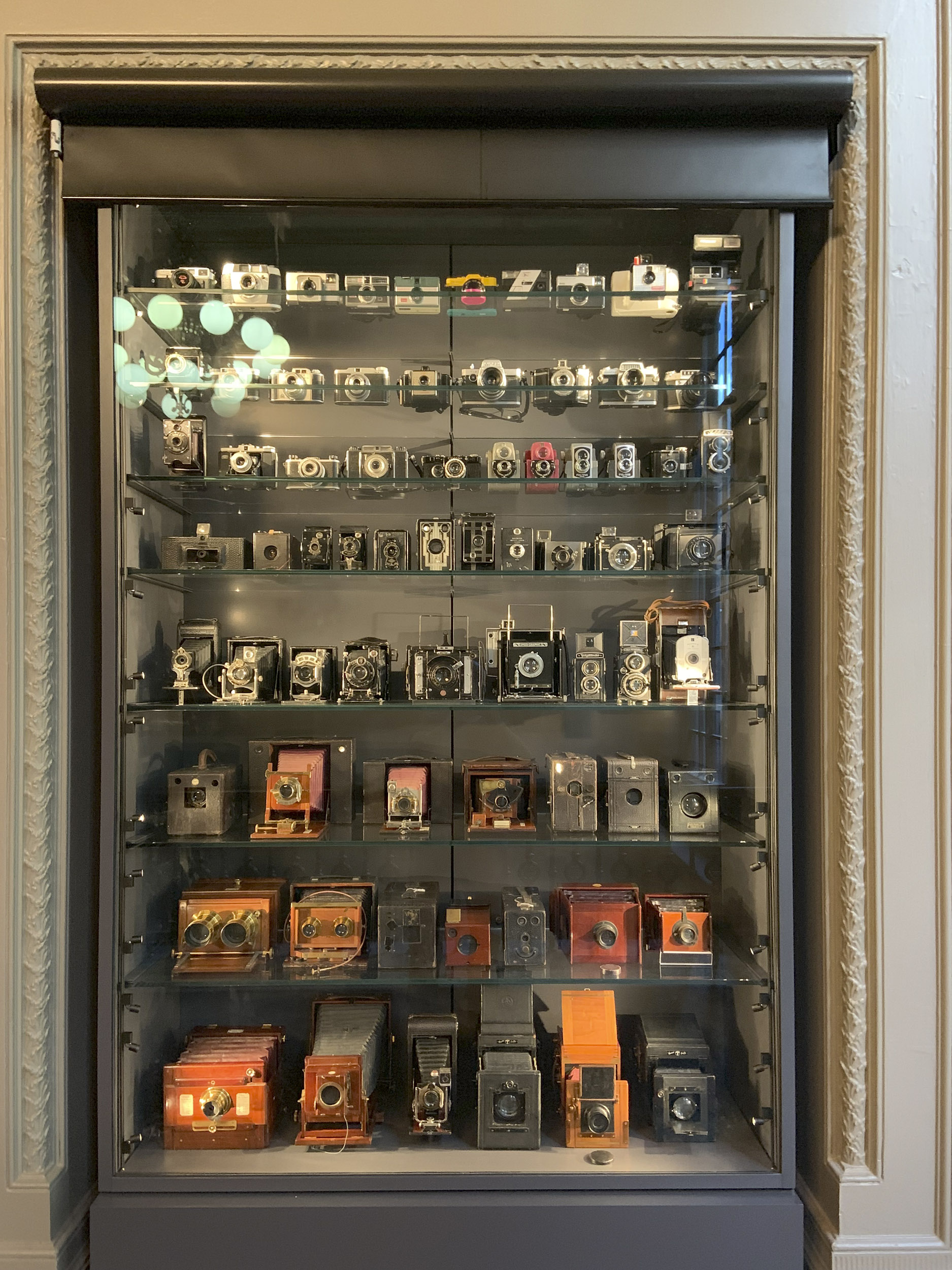

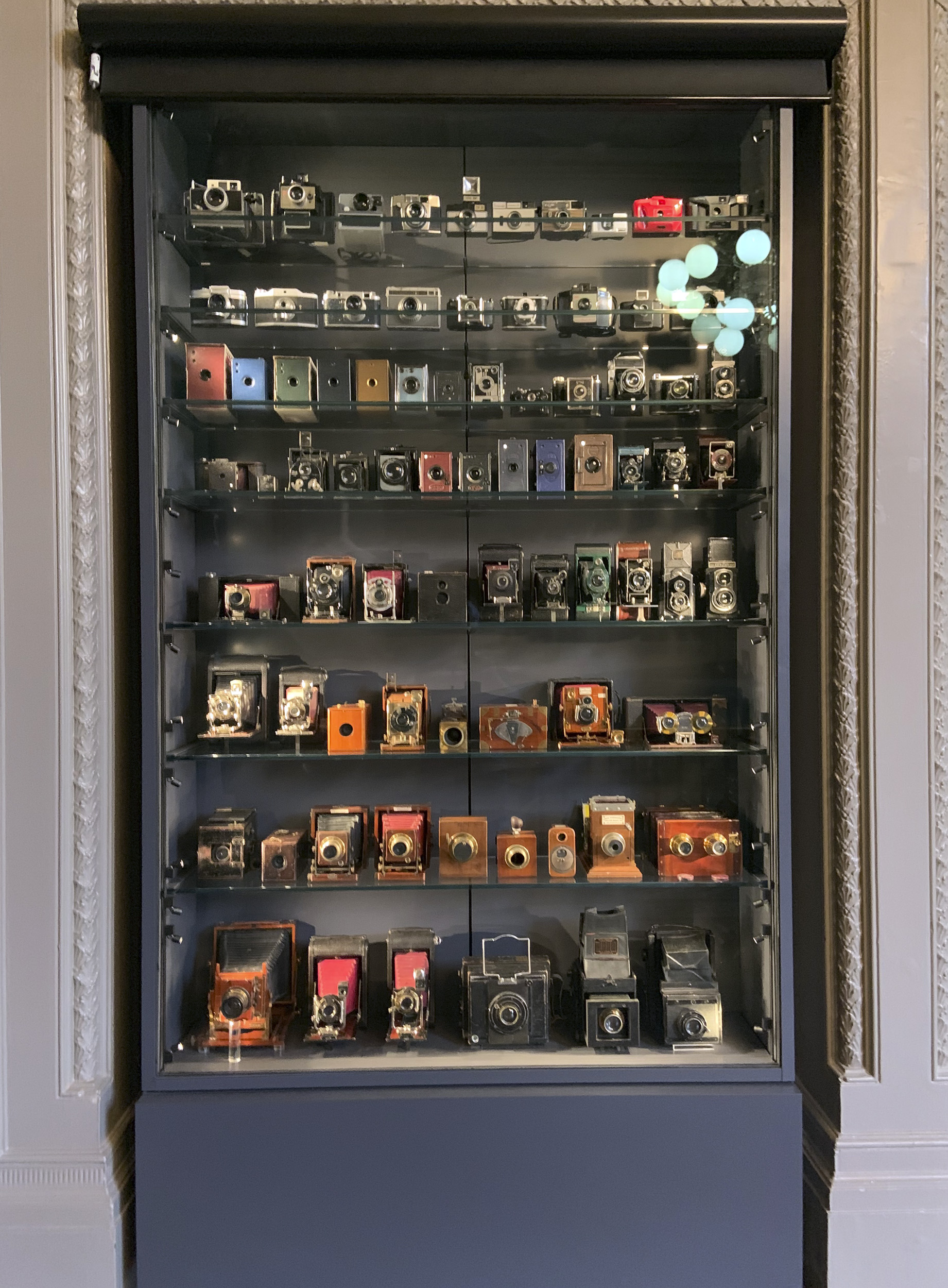

The works span a period from the late 19th century to 1930. During this period, Pictorialism developed as a distinct movement that took a different direction from amateur and professional photography. Technical advances, the arrival of roll film for example, made photography accessible to a wider circle of practitioners. The Pictorialists, however, were interested in the craft of photography.

The style was inspired by impressionism, symbolism and naturalism, and there was a heated debate on how to develop photography as an art form. The monochrome portrait paintings of the symbolist Eugène Carrière, for example, clearly influenced art photography around 1900.

The Pictorialists’ images are characterised by soft focus and a palette that ranges from brown, earthy tones to strong reds and blues. They worked with a variety of processes such as gum bichromate, platinum and bromoil printing with the purpose of creating or “painting” on light-sensitive paper.

This was the first international art photography movement to have a large number of prominent practitioners across Europe and the United States. Clubs were formed to promote this new art photography, among them were the Wiener Camera-Club, the Photo-Club de Paris and the Photo-Secession in New York, with famous members such as Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Steichen. The works were judged in competitions and shown in galleries and museums and at international salons. The style thus spread to Belgium, Holland, Italy, Poland, Russia, Spain and the Nordic countries.

The artistic period

Sweden was on the periphery of this movement, but it found a following here too, with a number of talented photographers. This period is known as the “artistic period” (konstnärstiden), a term coined in an article by the keen Pictorialist Professor Helmer Bäckström. Bäckström was also an active member of Fotografiska Föreningen (the Photographic Association), a Swedish version of the clubs abroad. The association was established in 1888. Its purpose was to organise meetings and dinners where photography was discussed.

In the 1890s, the professional photographer Herman Hamnqvist was an important introducer of Pictorialism. He promoted artistic photography in his many articles and lectures. Other colourful representatives were Uno Falkengren, Ferdinand Flodin, John Hertzberg, Gösta Hübinette and Ture Sellman.

In Sweden, these new ideas were first picked up by the older generation. They were followed by a younger generation of photographers who introduced and disseminated Pictorialism. This second wave includes Henry B. Goodwin, a major figure in Sweden and the Nordic countries. Goodwin was renowned for his expressive, subdued portraits and his many Stockholm cityscapes.

He also kept up with what went on abroad; among his contacts was the well-known portrait photographer Nicola Persheid, who was active in Berlin for many years. Women photographers disappeared from the history of photography during this period. The networking that took place in clubs and associations seems to have excluded many women, even if they had their own successful studios.

Atmospheric style typical of the period

Around 1900, painters entered a new, exciting era. The older members of Konstnärsförbundet (the Artists’ Association), established in 1886, continued to dominate, but a new generation came to the fore around the turn of the century. The French artist Paul Gaugin and the Pont-Aven school were important influences among the Swedish artists.

Helmer Osslund was able to visit Gauguin’s studio, and he later put this experience to practice in his northern landscapes. Carl Wilhelmson was known for his many portraits with motifs from his native West Coast. He taught at the Valand art school in Gothenburg and had a major influence on many artists. Maja and Gustaf Fjæstad founded an artists’ colony by Lake Racken in Värmland where a style in line with current national romanticism tendencies developed. Several local circles or schools in a similar vein were formed across Sweden.

Other important artists at the time were Richard Bergh, Eugène Jansson, Nils Kreuger and Karl Nordström, who all represented and developed an atmospheric style typical of the period. New ideas were now rapidly disseminated via mass-produced pictures in books, volumes of prints and magazines. The artists did not always have to travel abroad in order to find inspiration. However, study trips to Paris, the current art hub, were still important, although Berlin, Munich, Dresden and Hamburg were taking over that role at the end of the 1800s. To Swedish artists, Copenhagen, with its international outlook and exhibitions, became a natural place to gather.

New ways of framing and cropping

Japanese art, especially colour woodcuts, which reached Europe via the impressionists were fashionable and encouraged painters and photographers to try new ways of cropping and framing their motifs. The ornamental details and undulating lines that are typical of the Jugend (Art Noveau) period also inspired many painters. Eccentrics such as Ivar Arosenius and Olof Sager-Nelson (see below) were renowned for their sensitive, almost fairy tale-like portraits.

The author August Strindberg (see above) experimented with both painting and photography, which has been studied closely in recent years. Around the turn of the last century, an intermediary generation were overshadowed by great national artists such as Bruno Liljefors, Carl Larsson and Anders Zorn. However, they became an important link to the emerging expressionism and other modernist movements that came to the fore in the first decades of the 20th century.

Lady Barclay’s Salon

In Lady Barclay’s Salon we have created a fictional encounter between photographers, painters, their friends and audiences. Sarita Barclay was married to a British diplomat, and the couple lived in Stockholm for a few years around 1921. During these years she attended several portrait sittings with Henry B. Goodwin. We can assume she visited exhibition openings, dinners and other society events.

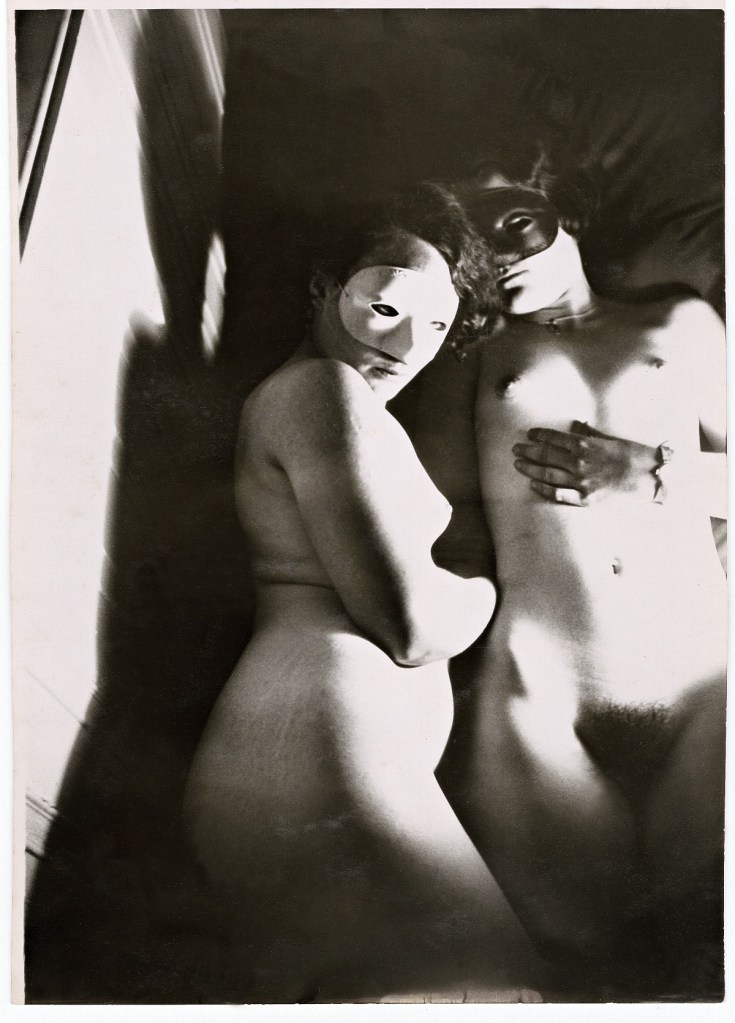

Social circles do not seem to have mixed a great deal, but there is clear evidence of links between painting and photography. Portraits are a common motif, but the many landscapes, cityscapes, dancers and nudes also offer us information about and a glimpse of the past.

Text from the Moderna Museet website

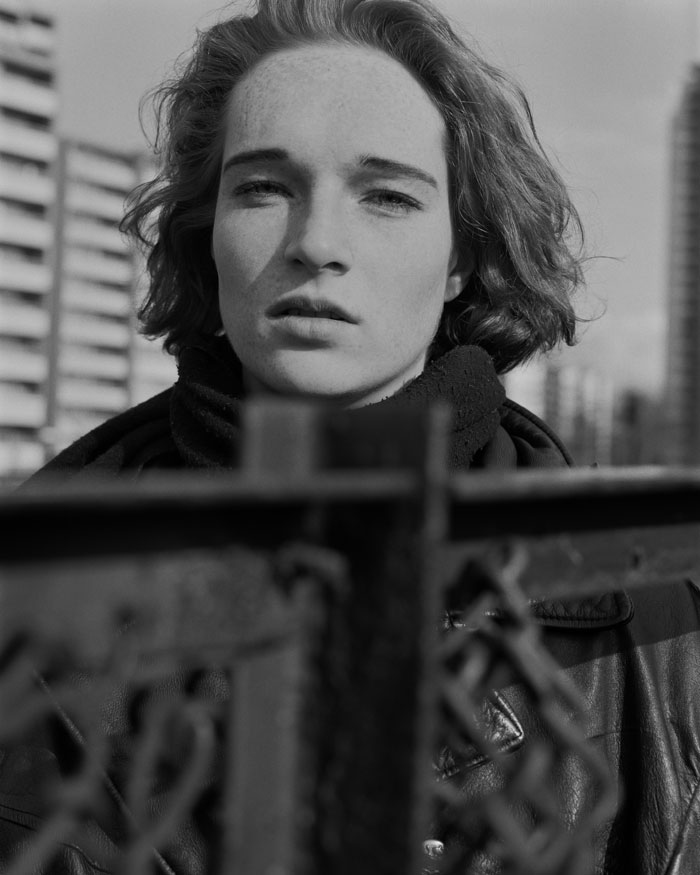

Ferdinand Flodin (Swedish, 1863-1935)

Greta Gustavsson Garbo

1923

Reproduction photo: Prallan Allsten/Moderna Museet

Greta Garbo

Greta Garbo (born Greta Lovisa Gustafsson 18 September 1905 – 15 April 1990) was a Swedish-American actress. She was known for her melancholic, somber persona due to her many portrayals of tragic characters in her films and for her subtle and understated performances. In 1999, the American Film Institute ranked Garbo fifth on its list of the greatest female stars of classic Hollywood cinema. She was nicknamed “The Divine” because of her whimsical attitude and her willingness to avoid the press. Garbo launched her career with a secondary role in the 1924 Swedish film The Saga of Gösta Berling.

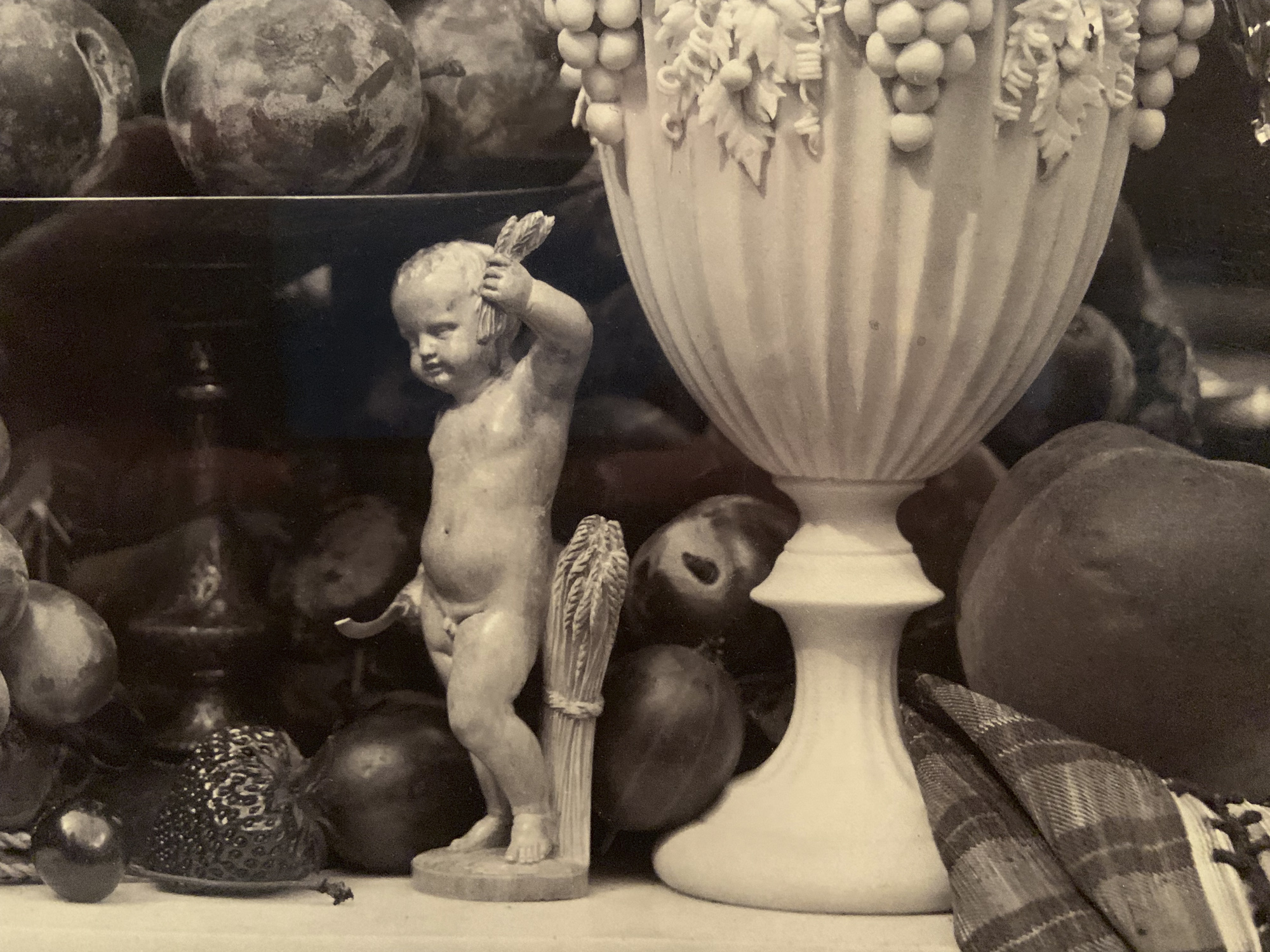

James Bourn (Swedish, Gothenburg)

No title

1905

Herrman Sylwander (Swedish, 1883-1948)

Tora Teje in ‘Inom lagens gränser’ (Tora Teje in ‘Within the Limits of the Law’)

1914

Tora Teje (17 January 1893 – 30 April 1970) was a Swedish theatre and silent film actress. She appeared in ten films between 1920 and 1939.

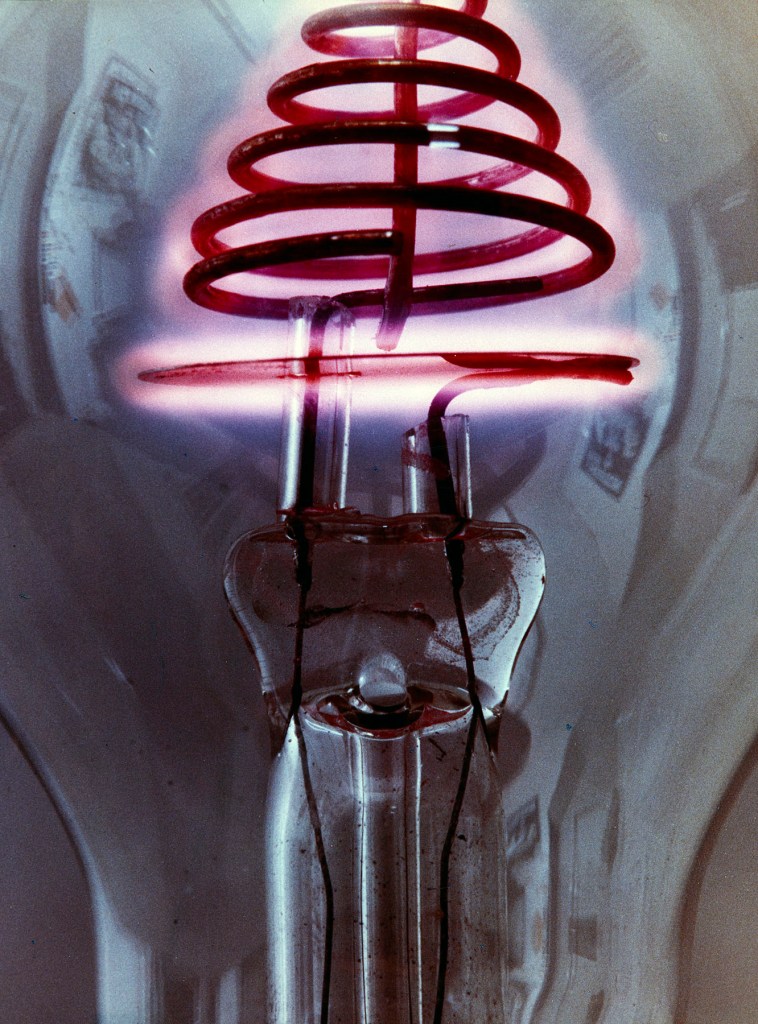

Photographic Processes and Materials around 1900

In 1888, Kodak launched the first roll-film hand camera. It revolutionised the market and turned photography into something everyone could enjoy. The specially constructed cameras were sent back to the factory where the pictures were processed. In 1900, Kodak introduced the popular Brownie, a classic box camera.

Another aspect of the increased interest in and use of photographs was that mass produced pictures were now easy to publish in books, volumes of prints and magazines. One example is photogravure, but there were many other processes. The Pictorialists used various processing methods and materials, some of which were closer to printmaking and painting, and they avoided regular photographic materials. The craft of making photographs was important, which was in line with an interest in and revival of older techniques as industrialism gained momentum during the Jugend period.

Professional photographers engaged in portrait photography and took on other commissions for their customers. Among the most prominent Pictorialists, many had second jobs. The tension between, or the different preconditions for photographers who embraced a more artistic form of expression and those who were forced to earn a living from selling their photographs is relevant to this day. There were many conflicts between members of Fotografiska Föreningen (the Photographers’ Association) – which to begin with only accepted amateurs – and the industry association Svenska Fotografers Förbund (the Association of Professional Photographers). At the same time, there are many examples of contacts and collaborations between different types of photographers around the turn of the last century.

Terminology was often translated from German and English, and in older literature you often find processes described in Swedish as gummitryck (gum print), pigmenttryck (pigment print) or oljetryck (oil print). However, the process is not strictly “printing”; the images were developed on light-sensitive paper. Instead of using the most common type of photographic paper with light-sensitive coating of silver salts in gelatine or albumin, the Pictorialists worked with other light-sensitive solutions. The image was often contact printed under a negative, which resulted in a picture with the same dimensions as the negative. The Pictorialists’ images are characterised by soft focus and often a grainy, print-like texture in hues that go from earthy browns to strong reds and blues.

Carbon print

A pigment, potassium bichromate and gelatine emulsion on thin paper is subjected to natural light in contact with a negative. The image is formed with the help of pigment in the desired colour. After exposure, the image is transferred to a new paper. This is the original. The image stands out in clear relief and is reversed, which can be corrected by repeating the transfer process onto a new paper. The tone is often dark brown or black, but it varies depending on the type of pigment used. Factory-made paper by Bühler and Höchheimer were sensitised in alcohol. This process is called carbon print, especially when it features black pigment. It was in use between 1864 until the end of the 1930s.

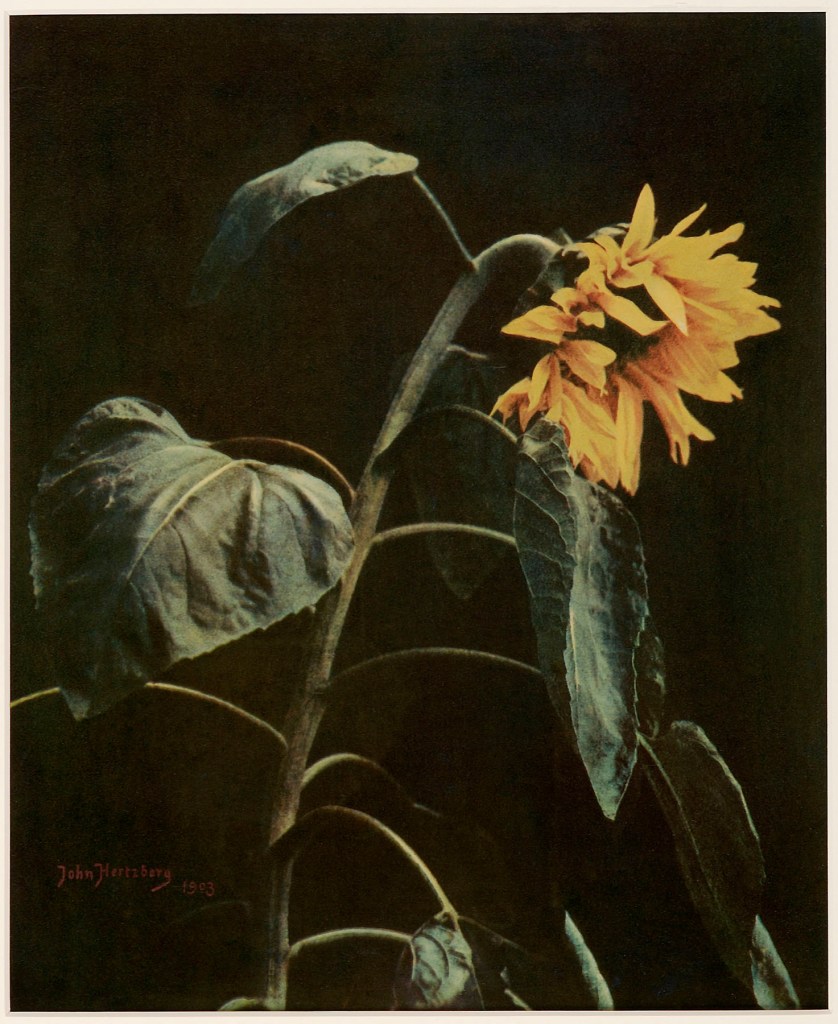

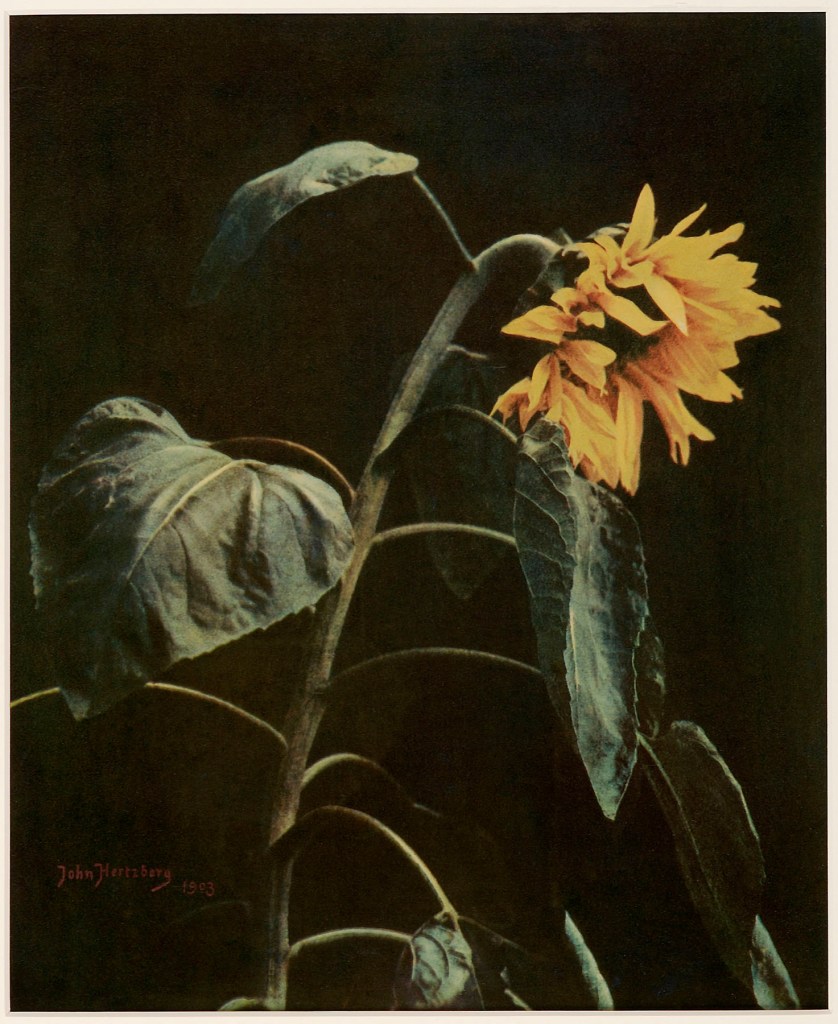

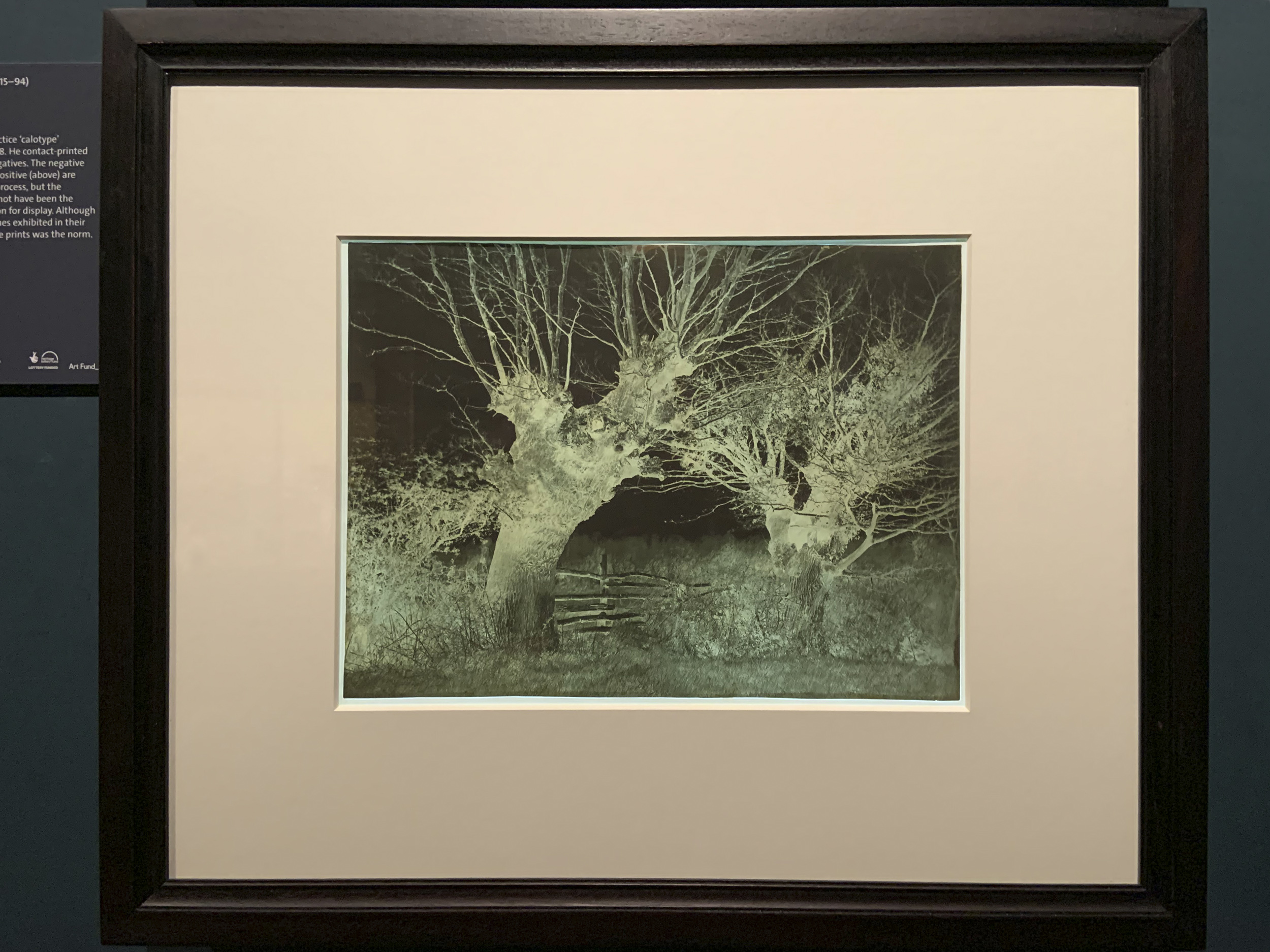

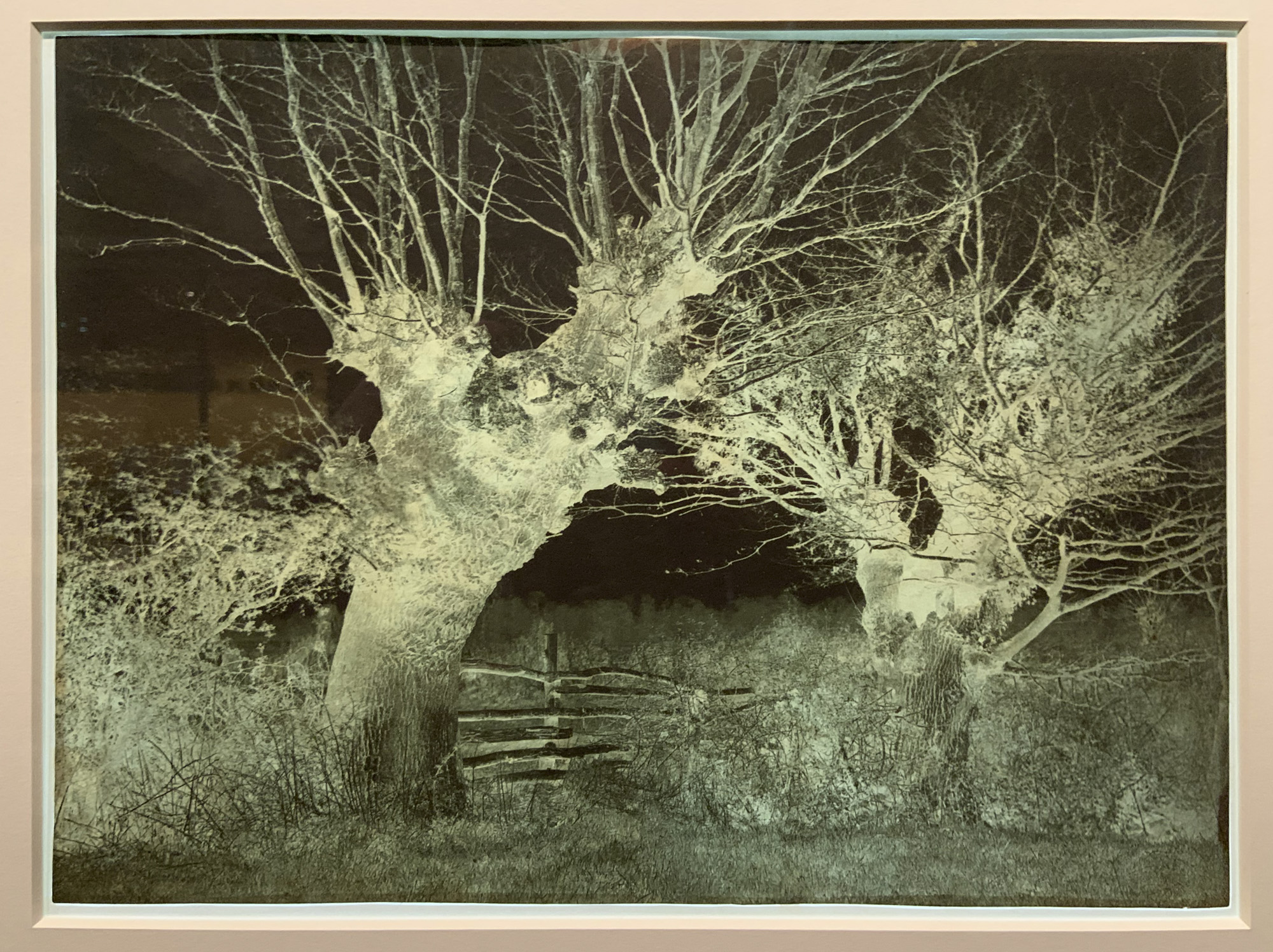

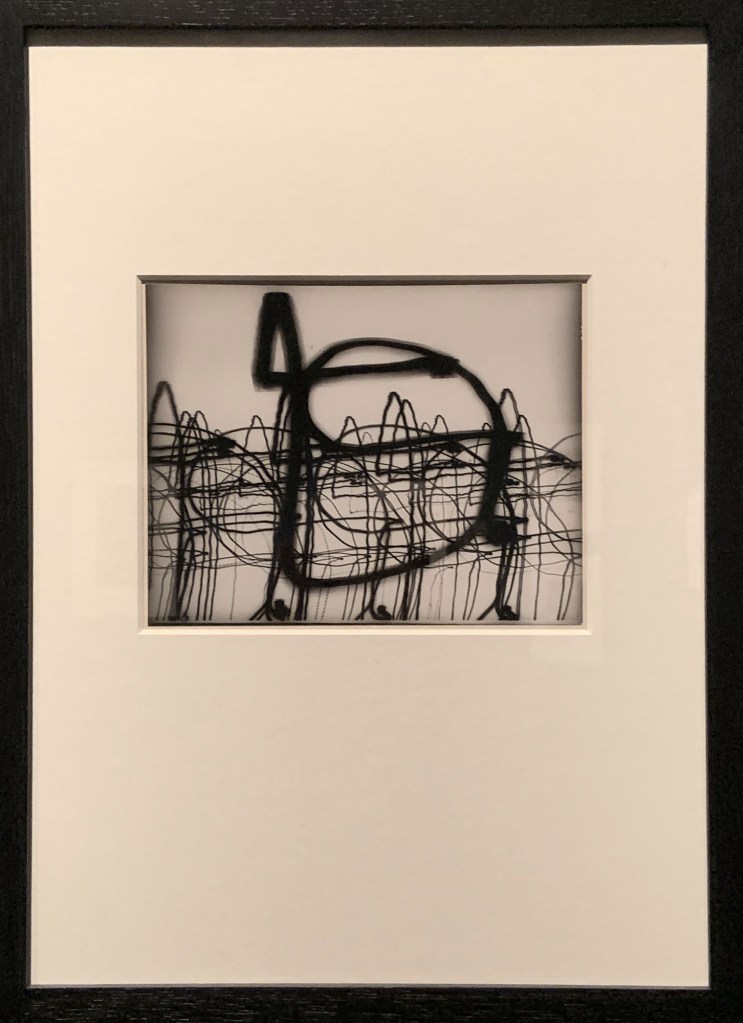

John Hertzberg (Swedish, 1871-1935)

No title

1903

Gum Bichromate Print

Gum Bichromate print

The gum bichromate process was invented in 1894. It is achieved by applying a solution of pigment, potassium bicharbonate and gum arabic to paper. The components are mixed in water and brushed on. When the coat has dried, it is light-sensitive, and the areas under the negative that are not exposed to light is stabilised. The rest is rinsed off in water. The colour range is very limited. The motif is often built up through multiple coats, erasures and applications of colour. The images are generally monochrome, reminiscent of charcoal or pastels. It is necessary to use a coarse-grained or uneven paper for the emulsion to adhere, which enhances the graphic qualities of the image. Custom-made paper for this method was marketed by Höchheimer, Bühler and Fresson.

Ture Sellman (Swedish, 1888-1969)

Landskap (Landscape)

c. 1913

Pigment print mounted on board

27.5 × 21.4cm

Oil print

An emulsion consisting of potassium bichromate and gelatine is applied to paper and exposed to light. It results in an almost invisible gelatine image in relief. The gelatine absorbs and repels greasy pigments, which can be fixed by means of a rubber roller or brush. This method gives a grainy image that resembles art prints and drawings.

Olof Sager-Nelson (Swedish, 1868–1896)

Flickhuvud II (A Girl’s Head II)

1902

Oil on canvas

41cm (16.1 in) x 33cm (12.9 in)

Nationalmuseum (Stockholm)

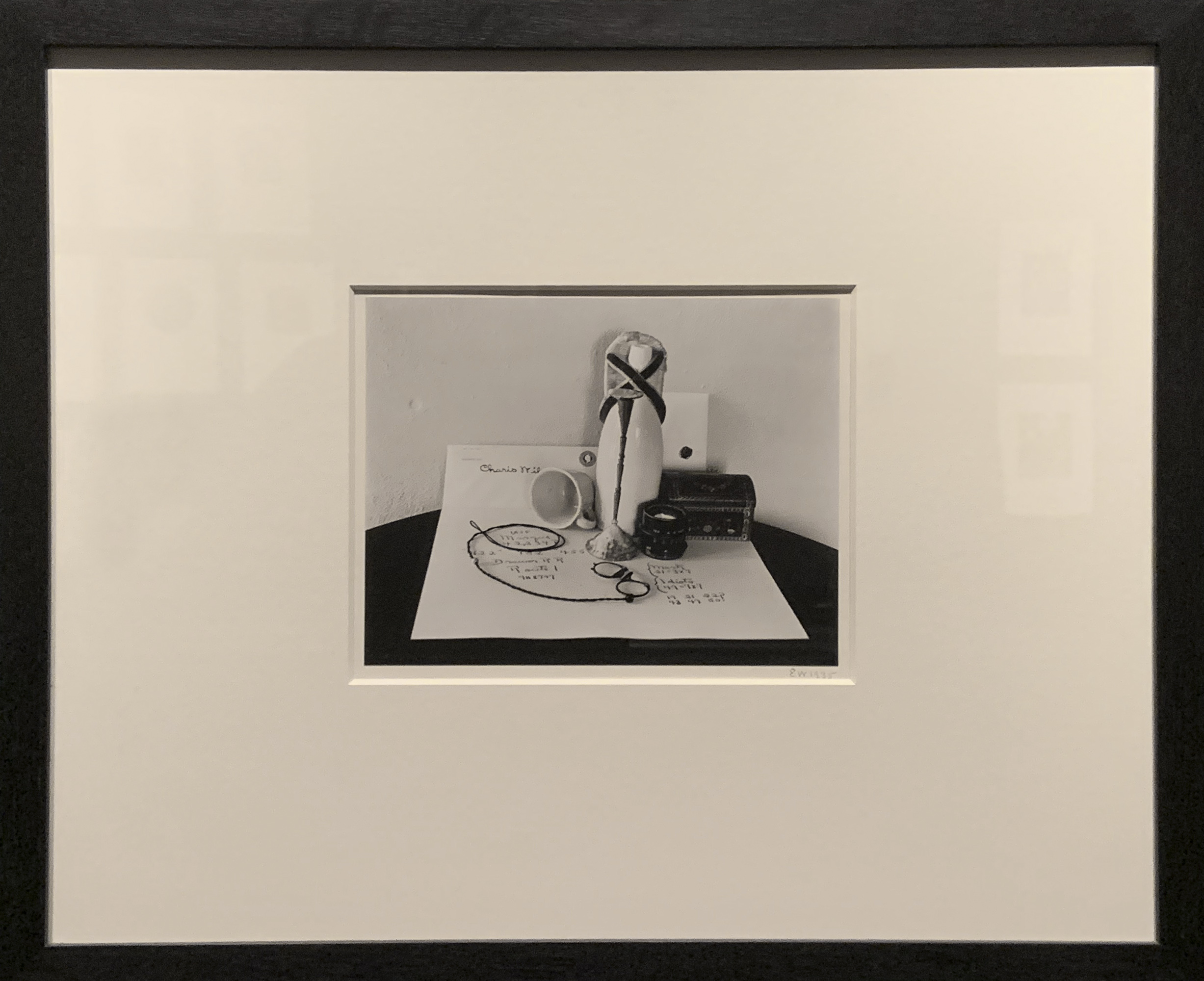

Ebba-Lisa Roberg (Swedish, 1904-1993)

No title

1927

Bromoil print

Bromoil print

Colour pigments on a silver, potassium bichromate and gelatine emulsion on paper. A silver bromide image on paper is sensitised by means of potassium bichromate with an addition of copper sulphate and potassium bromide, then fixer is added. The image is soaked in water, and a gelatine relief is produced, which can be coloured multiple times by brushing or rolling on greasy ink. The tone is determined by the pigments in the ink. A variation is achieved when the wet, tinted gelatine relief is pressed against a paper and the ink is transferred. The image is reversed with a matt finish and pressure marks from the original print. This method was used between 1907 and the 1940s.

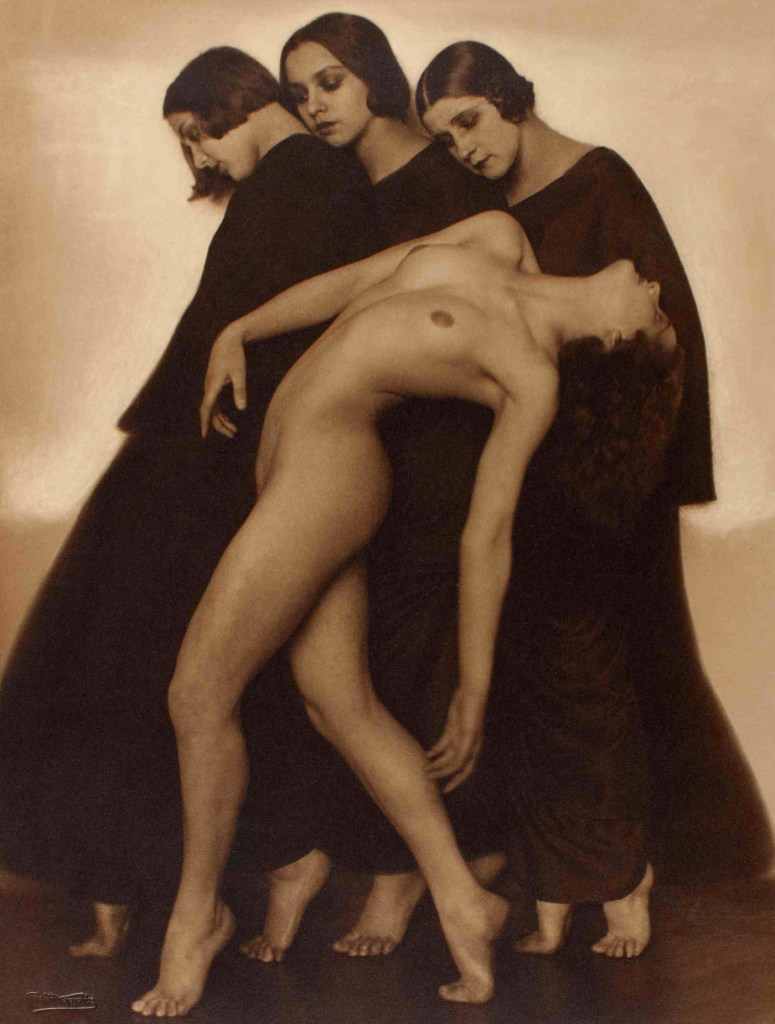

Uno Falkengren (Swedish, 1889-1964)

Nöd. Arranged dance group with Anna Behle in the middle, Stockholm

1917

Sepia platinum type mounted on paper

23.7 x 24.2cm

Platinum print

A paper is given a coat of a potassium chloropatinate and iron oxalate. It is then exposed to daylight through a negative. The image is developed as potassium oxalate dissolves the iron salts and transform the platinum salts to metallic platinum embedded in the paper fibres. This process offers few opportunities for manual manipulation. Platinum prints are characterised by a smooth, neutral greyscale. Platinum was relatively inexpensive before the First World War, and prepared papers were readily available. Today, platinum is used in combination with palladium. The method was used as far back as in 1873.

Photogravure

Colour pigment on paper. A paper base coated in potassium bichromates in gelatine are exposed to UV light in contact with a transparent positive. The gelatine coating is thereby stabilised and is then transferred face down to a copper plate. When ink is applied to the plate, it adheres to the etched areas after which the image is printed on paper in a printing press. Photogravures have a clearly defined depression from the edges of the plate, and each print is an original. Shadows are similar to charcoal pigment and highlights match the colour of the paper. This method is classified as a photomechanical print and is not in fact a true photograph. It has been used since the 1880s.

Nils Kreuger (Swedish, 1838-1930)

Vårafton (Spring evening)

1896

Oil on mahogany panel

48.5cm (19 inches) x 60.1cm (23.6 inches)

Nationalmuseum (Stockholm)

Nils Edvard Kreuger

Nils Edvard Kreuger (11 October 1858 – 11 May 1930) was a Swedish painter. He specialised in landscapes and rural scenes.

In 1874, he began his studies at the Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts, but was forced to discontinue them due to illness. In 1878, he was able to resume studying at the private painting school of Edvard Perséus. He then went to Paris, in 1881, and studied with Jean-Paul Laurens at the Académie Colarossi. Much of his time was spent painting en plein air in Grez-sur-Loing. As his style progressed, he showed a preference for painting at dawn or dusk, in haze or rain. His first exhibition at the Salon came in 1882.

After 1885, he was a supporter of the “Opponenterna [sv]”, a group that was opposed to the outmoded teaching methods at the Royal Academy. He was also active in creating the Konstnärsförbundet [sv] (Artists’ Union). At this time, he abandoned painting en plein air in favour of Romantic nationalism. In 1886, he married Bertha Elisabeth von Essen (1857-1932), the daughter of an army officer, and settled in Bourg-la-Reine.

In 1887, he returned to Sweden, looking for a quiet place to paint, and chose Varberg, where he worked with Richard Bergh and Karl Nordstrom to establish what came to be known as the Varbergsskolan [sv]; a term coined by Prince Eugen, himself an amateur artist. It was a reaction to the prevailing realistic style of landscape painting and may have been inspired by Bergh’s attraction to the works of Paul Gauguin. He was also influenced by Van Gogh, whose paintings were exhibited in Copenhagen in 1893.

In 1896, he moved to Stockholm, but visited Öland in the summers, where he painted cows and horses. After 1900, his palette lightened and he began adding dots to his work. He also did illustrations, designed furniture and produced some humorous paintings called the “historiska baksidor” (historic backs), showing famous rulers from behind. Between 1904 and 1905, he executed some large wall paintings at the Engelbrektsskolan [sv]. In his final years, he had problems with his eyesight, but was able to continue painting.

Text from the Wikipedia website

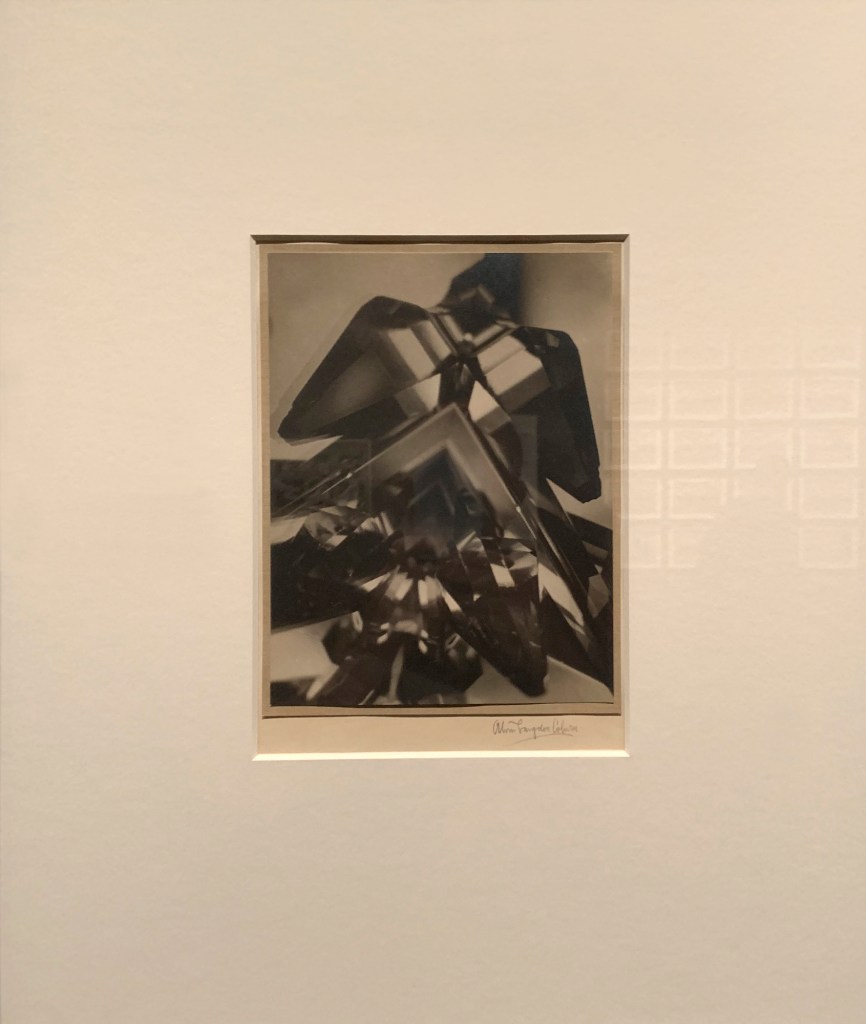

Gösta Hübinette (Swedish, 1897-1980)

Forntida (Ancient)

1928

Gelatine Silver Print

Gelatine silver print

The most common form of black and white photography in the 20th century. A photo paper with a coating of light-sensitive silver halogens in gelatine are exposed and developed. There are many varieties of this process with different texture and glossiness, dynamic range and contrast. The result depends on the types of paper, developer and additive tones that are used.

Bibliography

Håkan Petersson, “Photographic materials”, Another Story. Photography from the Moderna Museet Collection, ed. Anna Tellgren, Stockholm: Moderna Museet and Göttingen: Steidl, 2011, pp. lxi-lxiii.

Pär Rittsel and Rolf Söderberg, “Konstnärstidens metoder”, Den svenska fotografins historia 1840–1940, Stockholm: Bonnier Fakta Bokförlag AB, 1983, p. 240-241.

Lena Johannesson, Den massproducerade bilden. Ur bildindustrialismens historia, Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell Förlag AB, 1978.

Impressionist Camera. Pictorial Photography in Europe, 1889-1918, ed. Philip Prodger, London/New York: Merrell Publishers Limited, 2006, pp. 322-324.

Text from the Moderna Museet website

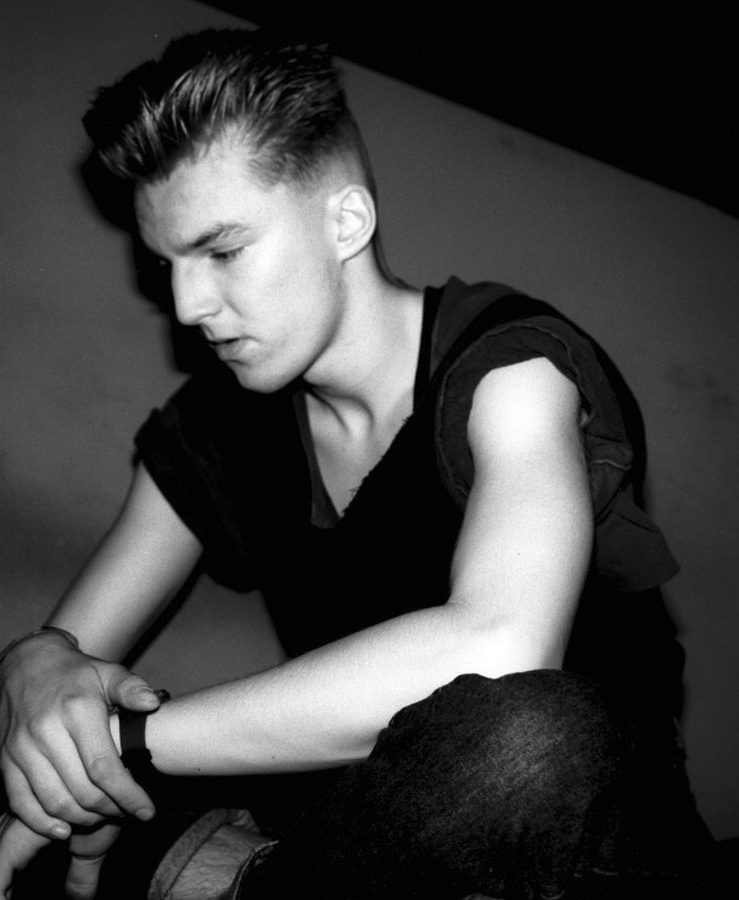

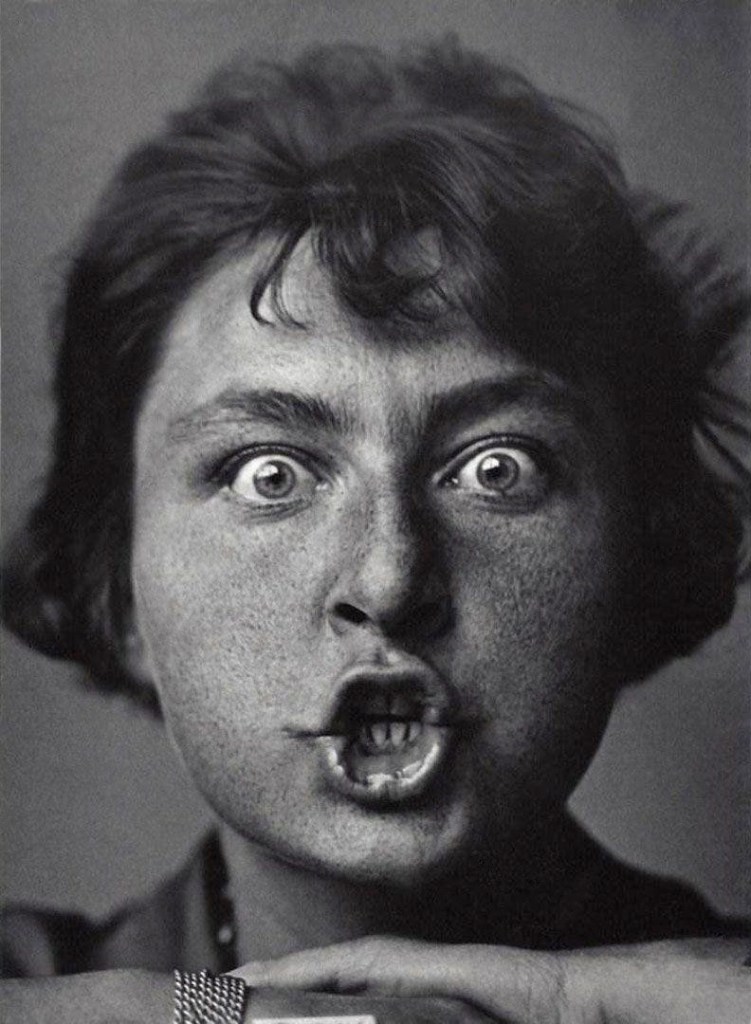

Henry B. Goodwin (Swedish born Germany, 1878-1931)

Carin

1920

Reproduction photo: Prallan Allsten/Moderna Museet

Henry B. Goodwin (Swedish born Germany, 1878-1931)

Henry B. Goodwin, born in Munich as Henry Buergel, was the most successful representative of Pictorialism. He arrived in Sweden in 1905 in order to teach German at Uppsala University. Some ten years later, in 1914, he moved to Stockholm where he opened a studio, Kamerabilder, which was popular with painters and artists.

His many superb portraits were achieved with small means: the subject is captured against a dark, neutral backdrop. His soft, smoky Stockholm cityscapes have been collected in a series of special editions, and Goodwin’s keen interest in gardening was expressed through meticulously arranged close-ups of plants.

Goodwin enjoyed a large, international network and launched the term bildmässig (pictorial) photography as an alternative to artistic photography. It was a term that came to be used frequently in the photographic debate.

Text from the Moderna Museet website

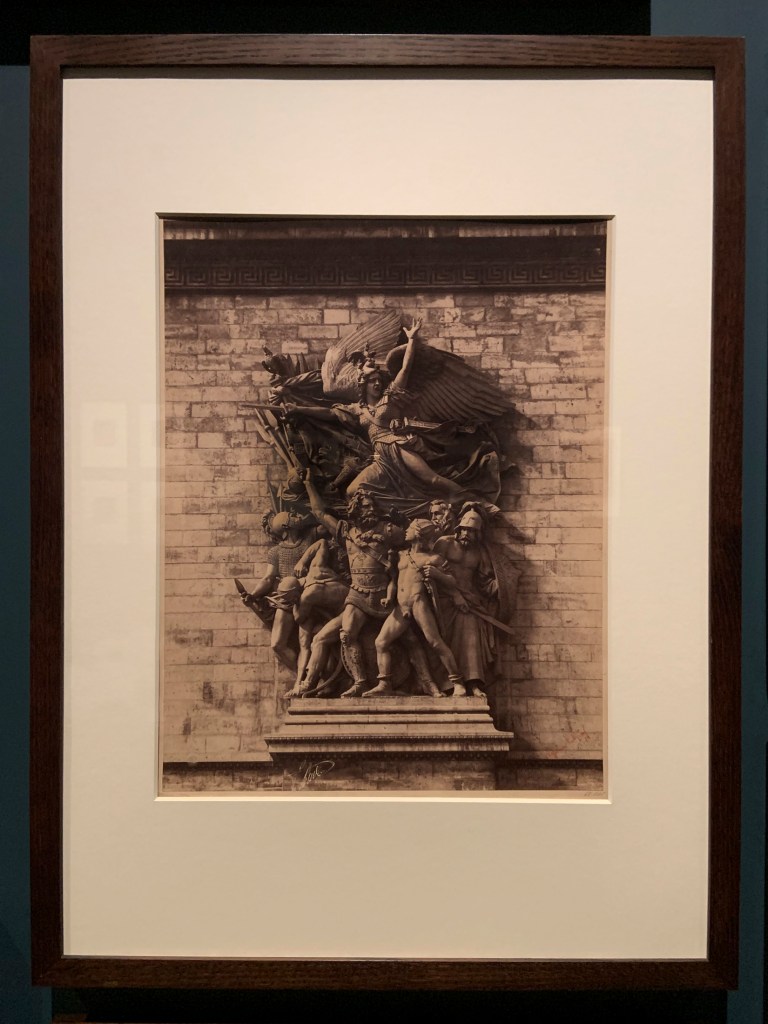

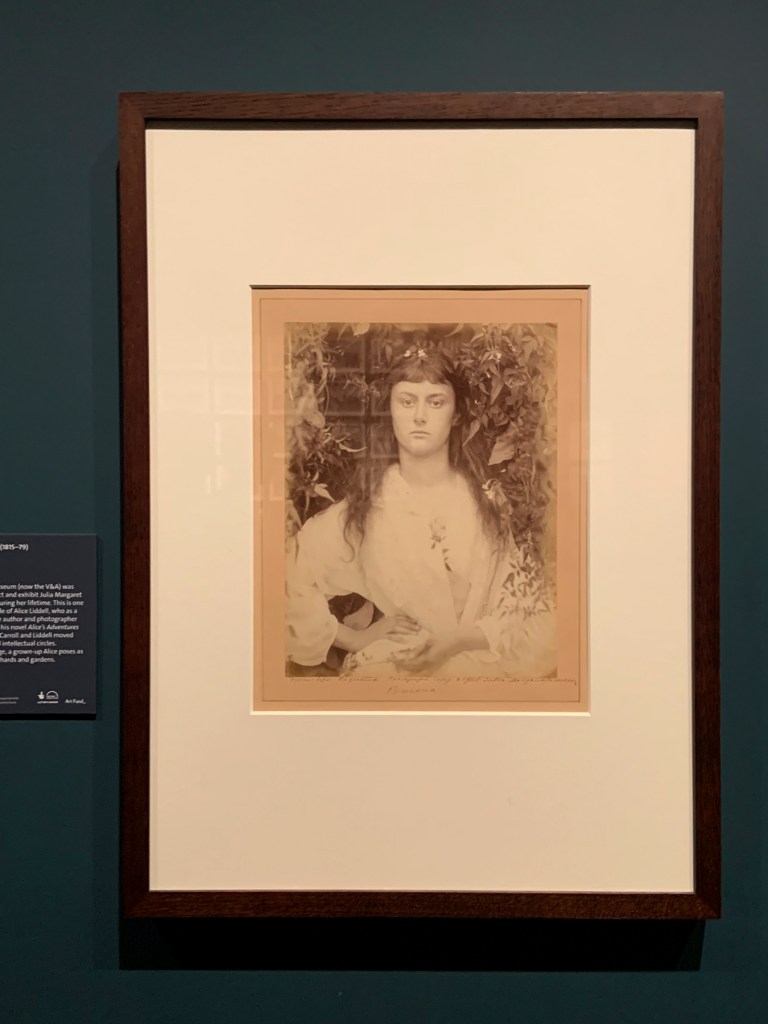

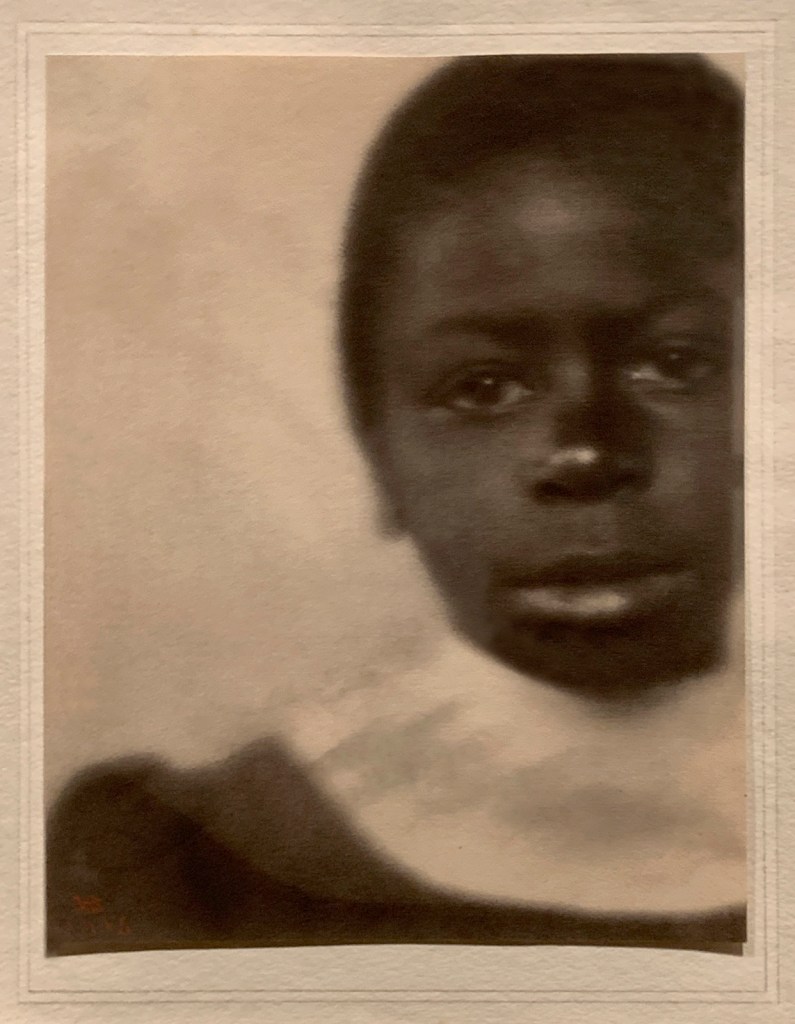

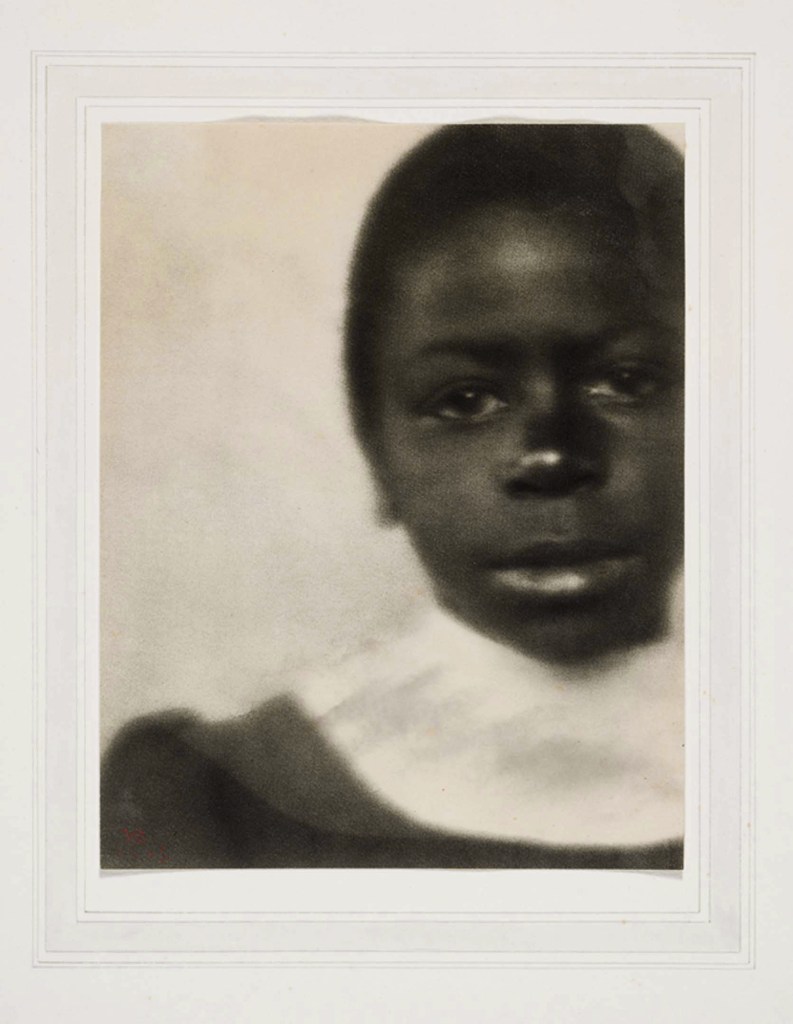

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

The Mountain Nymph, Sweet Liberty

1866

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

A small pioneering group of photographers in Victorian England were the first to experiment with, and who attempted to formulate, an aesthetic around artistic photography. Julia Margaret Cameron was part of this group. She left behind a wonderful collection of intimate portraits of members of her family and large circle of friends. She was an amateur, predominantly active during the 1860s and 1870s.

Cameron specialised in expressive soft-focus photographs of staged motifs borrowed from mythology, the Bible or English literature, as in her rendering of Alfred Tennyson’s famous poem “Maud” from 1855.

Cameron’s photographs evoke the Pre-Raphaelites with their penchant for the Middle Ages and Renaissance painting. She was a precursor of the photographers that a few decades later formed part of the pictorial movement.

Text from the Moderna Museet website

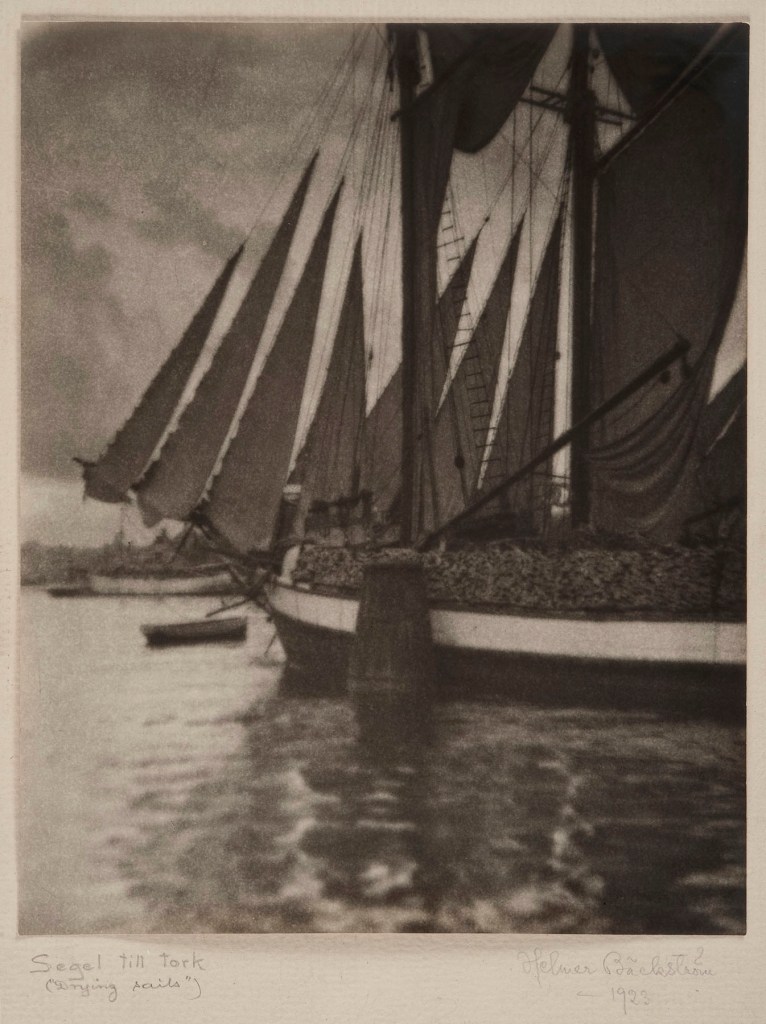

Helmer Bäckström (Swedish, 1891-1964)

Segel till tork (Drying sails)

1923

Helmer Bäckström (Swedish, 1891-1964)

Helmer Bäckström was an important member of Fotografiska Föreningen (the Photographic Association). The association, which was formed in 1888, organised meetings where photography was discussed. A library of books on photography was accumulated, but most important were the photo competitions. Bäckström was a researcher, collector, historian and photographer. In 1948, he was appointed professor of photography at the Royal Institute of Technology. Throughout his career, he wrote about early photography and technical innovations in a series of articles entitled “Samlingar till kamerans och fotografins svenska historia” (Collections of the Swedish History of Cameras and Photography). They were published in the association’s journal, “Nordisk Tidskrift för Fotografi”.

Bäckström was also a Pictorialist; studies of flora and fauna were his favourite motifs. His large collection of photographs was acquired by the Swedish state in 1965. It has been part of the Moderna Museet collection since 1971.

Text from the Moderna Museet website

Anna Boberg (Swedish, 1864-1935)

Stilla afton. Studie från Nordlandet (A Quiet Evening. Study from North Norway)

Nd

40.5 x 70.5cm

Nationalmuseum (Stockholm)

Anna Boberg (Swedish, 1864-1935)

Anna Scholander’s family was part of the Stockholm elite. She was well educated and moved with ease in the salons of Paris and other cities. In Paris she met Ferdinand Boberg, who was to become one of Sweden’s leading architects. They were married in 1888. The couple dedicated their lives to work and travel.

Anna Boberg was highly versatile. She designed textiles, glass and Jugend pottery – one example is the elegant peacock vase from around 1897 for Rörstrand. In 1901, she made a life-changing trip to northern Norway where she fell in love with the rocky landscape around Lofoten, which seemed to rise out of the sea. It woke in her an irresistible urge to paint.

Anna Boberg returned to this location over a period of thirty years. Contrary to her life as a society lady, she embarked on strenuous expeditions on foot and by sea, and she made oil sketches of what she saw which she later used as inspiration in her studio.

Text from the Moderna Museet website

Ferdinand Flodin (Swedish, 1863-1935)

Portrait of a young lady

1922

Ferdinand Flodin (Swedish, 1863-1935)

One of the foremost portrait photographers of the period was Ferdinand Flodin. During his long career he tried all the different processes that were typical of Pictorialism, and he became a highly skilled photographer. As a young man, he travelled to the United States, and for a number of years he worked in Worcester near Boston. After his return in 1889, he opened a studio in Stockholm where he received celebrities associated with the theatre, art, politics and science.

Besides portraits, his large body of work includes a number of beautiful cityscapes in different colour tones. Flodin continued to travel; he was interested in the international scene and he knew a great deal about early photography. He went on to build a collection of historical photographs, later acquired by Helmer Bäckström. Flodin was active in Svenska Fotografers Förbund (the Swedish Association of Professional Photographers) for many years, and he regularly wrote about technical and financial matters in the association’s journal.

Text from the Moderna Museet website

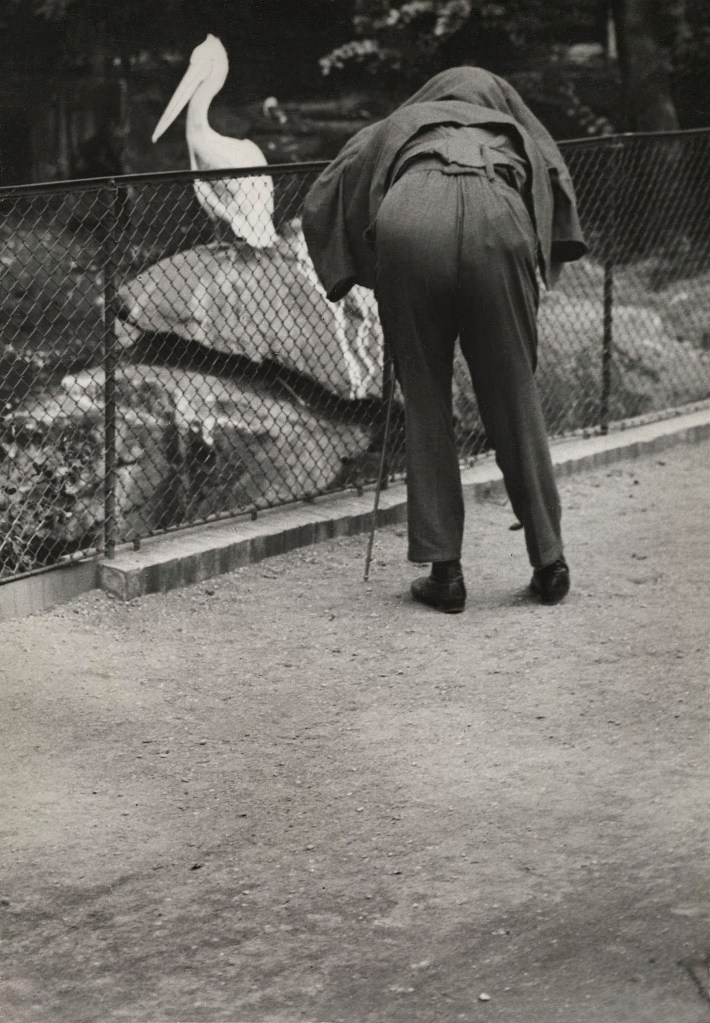

Gösta Hübinette (Swedish, 1897-1980)

Japanskt

c. 1925

Gösta Hübinette (Swedish, 1897-1980)

With their more independent position and experimental approach, amateur photographers were fundamental to the development of the pictorial movement in Sweden and internationally. Gösta Hübinette was interested in art from an early age, but on his family’s advice he studied business administration, and he worked at the carpet business, Myrstedts Matthörna, until he retired. He practiced several disciplines, including painting, but he was most successful as a photographer. Hübinette was part of the circle around Henry B. Goodwin, and in the 1920s he often took part in exhibitions and the important photo competitions.

Hübinette’s photographs are testament to his proficiency in painting, drawing and printmaking. With delicate works such as “Japanskt” (c. 1925) he is also one of the Swedish photographers for whom Japanese woodcuts served as inspiration.

Text from the Moderna Museet website

Ture Sellman (Swedish, 1888-1969)

No title

c. 1915

Ture Sellman (Swedish, 1888-1969)

As an architect, Ture Sellman had his own approach to photography. He was well acquainted with the compositional and technical aspects and was therefore an important figure who also gave lectures. He later became an astute critic. Sellman was among the most vociferous advocates of photography as an artistic medium. His early Bromoil prints are some of the most graphic examples of Swedish Pictorialism.

After having experimented with different artisan processes, Sellman did a complete U-turn in 1920 and became a supporter of the straight photography expression, but his interest in tonality and composition are still visible in his soft-focus photographs from the 1920s.

Sellman designed some seventy buildings, and many of his photographs are testament to his eye for architecture.

Text from the Moderna Museet website

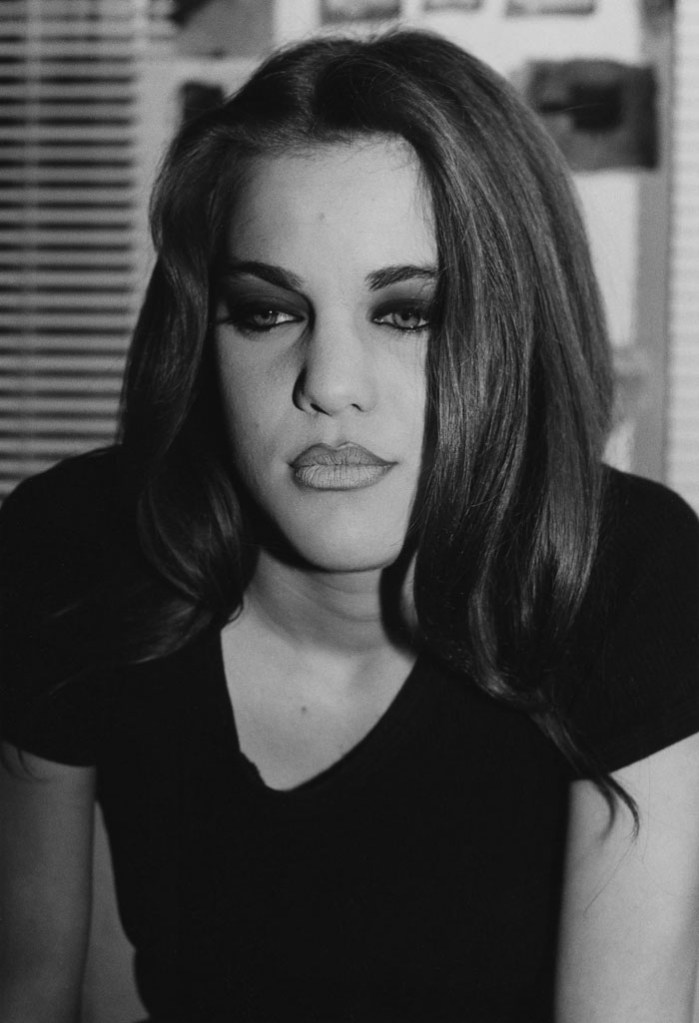

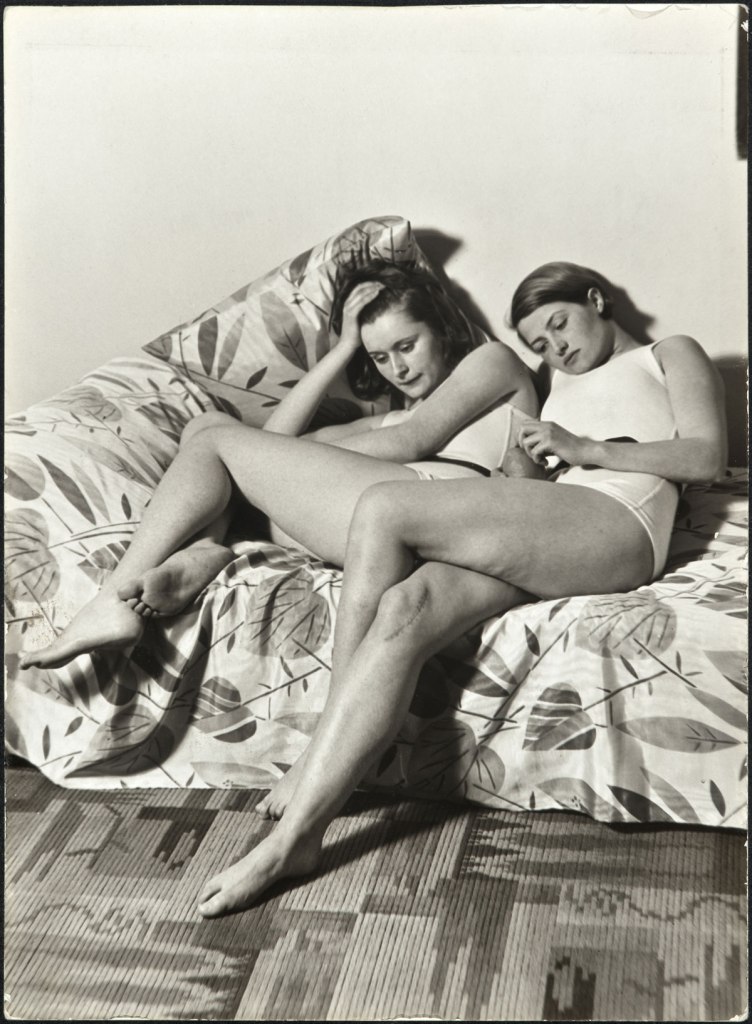

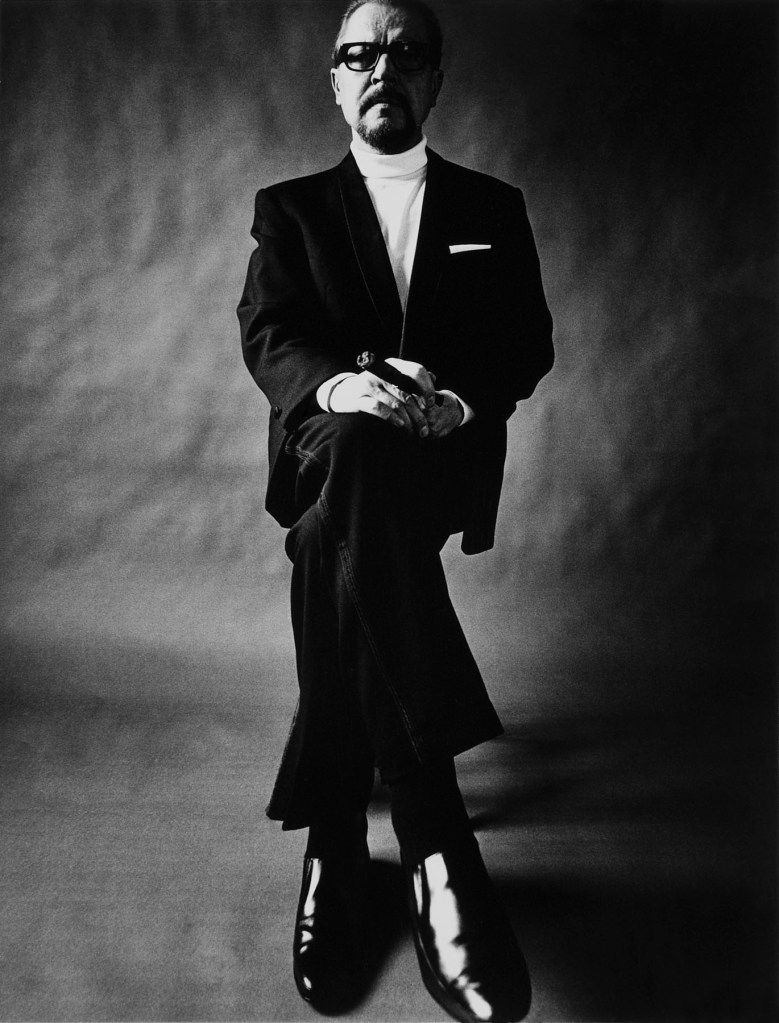

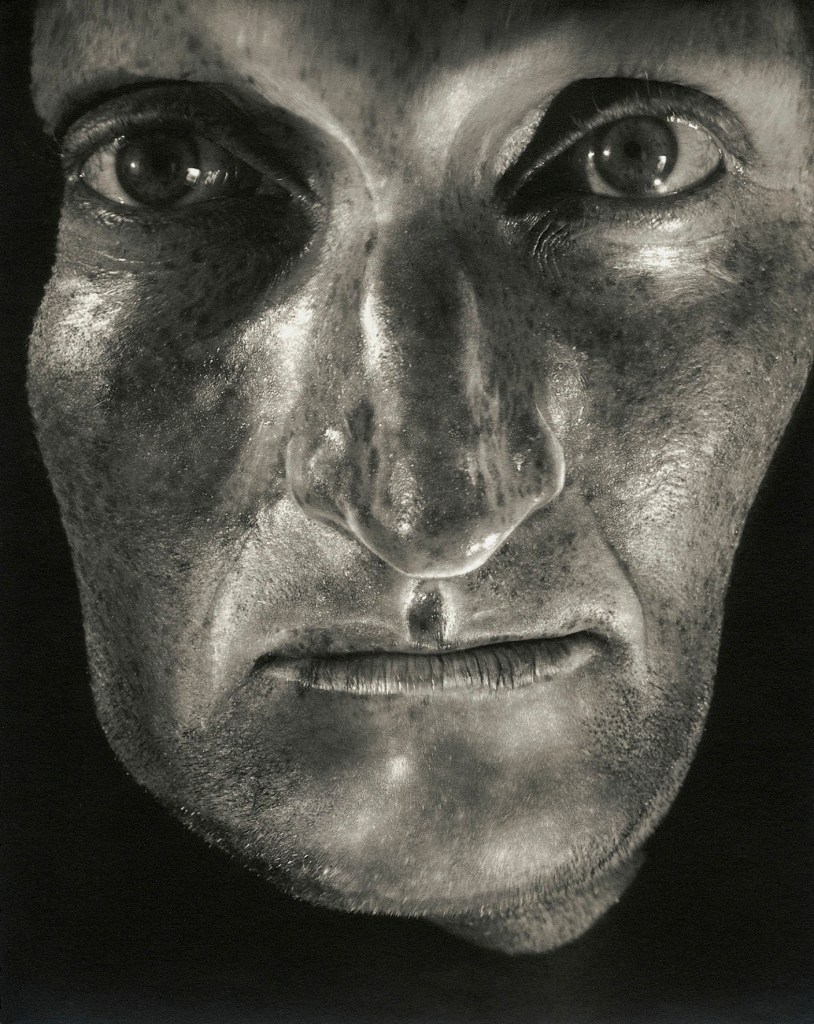

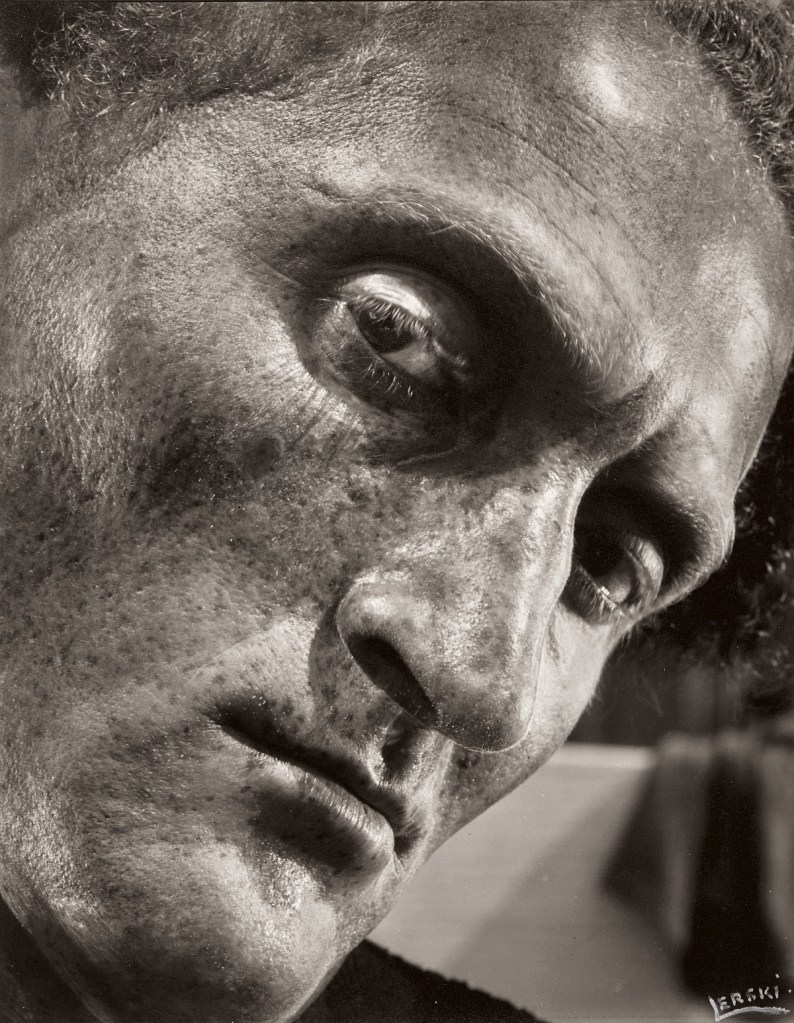

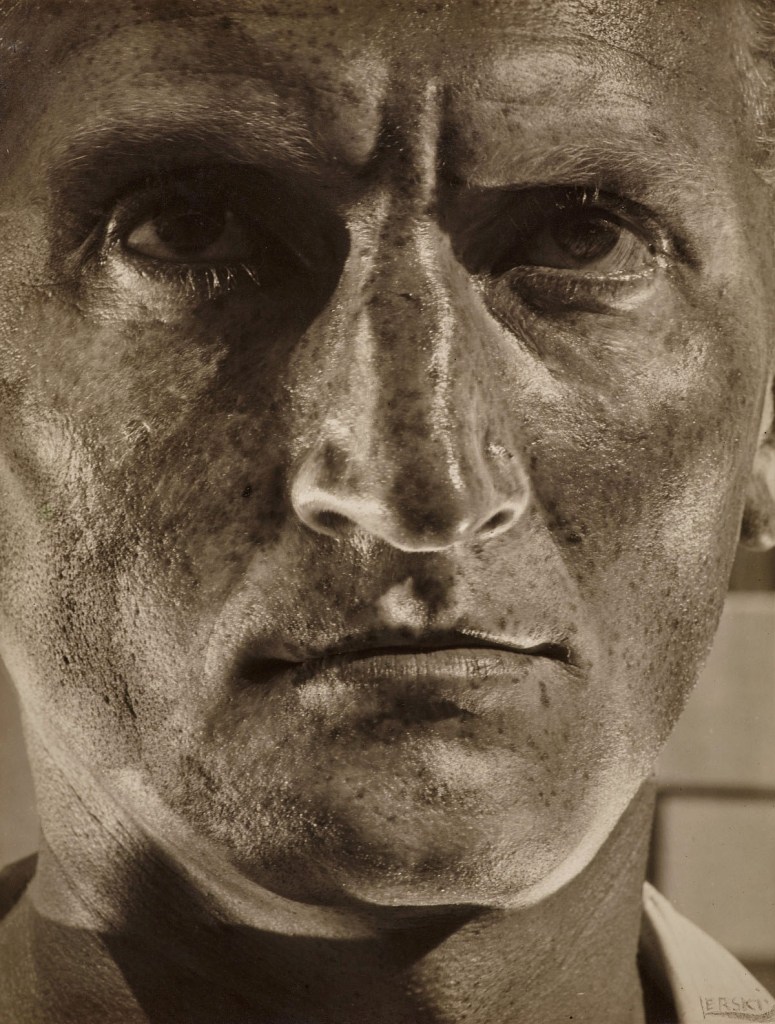

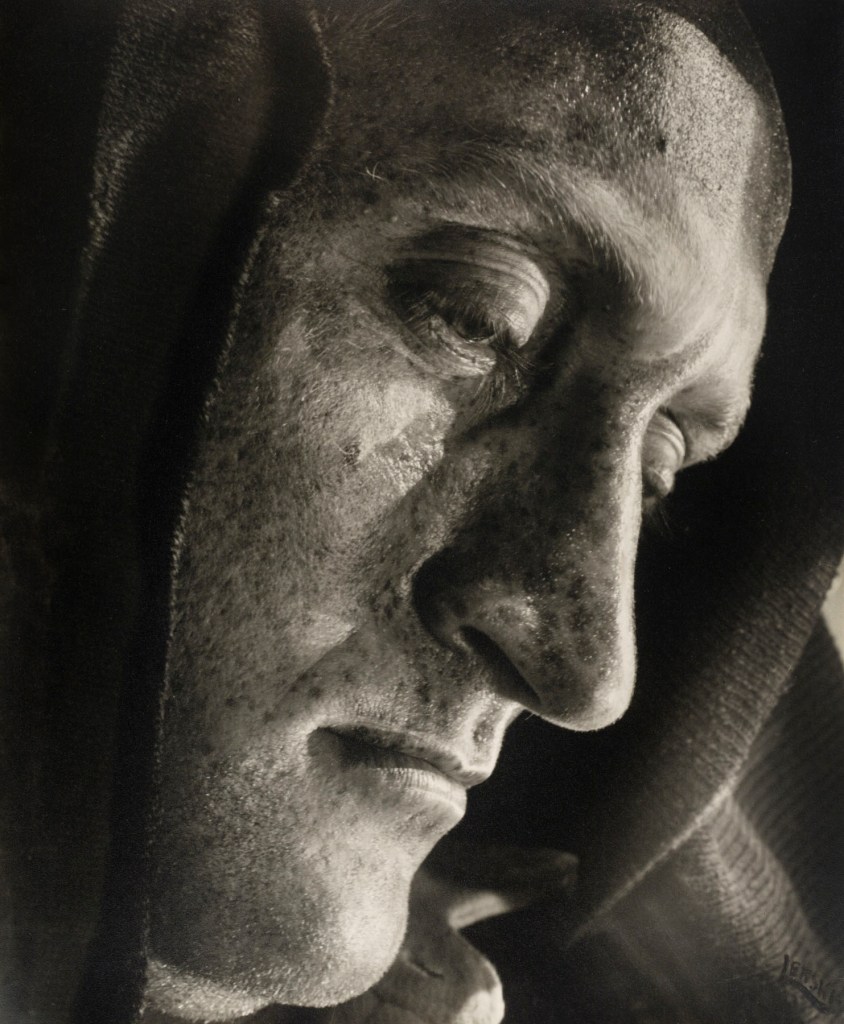

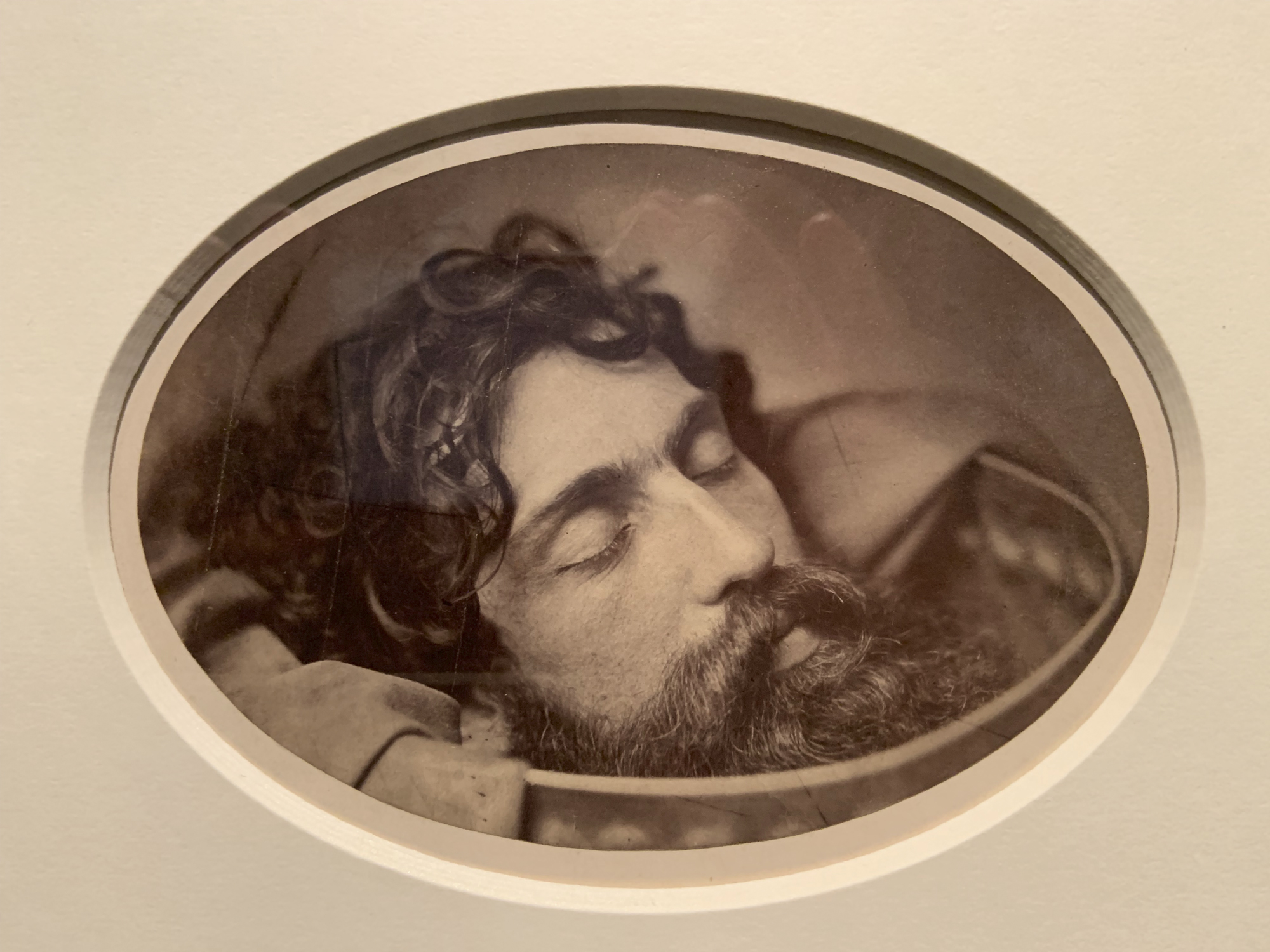

Nicola Perscheid (German, 1864-1930)

No title

c. 1920

Nicola Perscheid (German, 1864-1930)

Nicola Perscheid was one of the international figures that came to have a major influence on Pictorialism in Sweden. In the autumn of 1913, he arrived in Stockholm in order to conduct what we would today call a workshop. It was enormously popular. His fame had reached Sweden partly via his former pupil, Henry B. Goodwin.

Perscheid was against retouching, which meant he spend a great deal of time on preparations. Among his portraits are many full-length and half-length photographs of distinguished men and nameless women. Especially his expansive, pared down photographs of women with their soft lines and ornamental jewellery and flowers evoke the pictorial language of symbolism, but also older painting practices.

The Perscheid lens was launched in 1920. This soft-focus lens became especially popular in Europe and Japan.

Text from the Moderna Museet website

Uno Falkengren (Swedish, 1889-1964)

Nöd. Arranged dance group with Anna Behle in the middle, Stockholm

1917

Sepia platinum type mounted on paper

23.7 x 24.2cm

Uno Falkengren (Swedish, 1889-1964)

Uno Falkengren belonged to the inner circle around Henry B. Goodwin. Goodwin was also instrumental in allowing Falkengren to study under the distinguished German photographer Nicola Perscheid in Berlin. It was a formative period during which Falkengren developed a minimalistic, elegant style. Among his works are a number of interesting portraits of famous dancers in expressive scenes and groups.

In 1916, he was appointed head of the Nordiska Kompaniet studio. He then worked at his own studio for a few years until he moved to Berlin in 1924. Only a year later, he returned to Stockholm and gave up photography completely. On account of his homosexuality, Falkengren lived an itinerant, partly secret, life. There are elements of queer culture within Pictorialism, as practitioners were often attracted to alternative settings or artists’ communities.

Text from the Moderna Museet website

Anna Behle (Swedish, 1876-1966)

Anna Charlotta Behle (Stockholm, August 9, 1876 – Gothenburg, October 2, 1966) was a Swedish dancer and dance teacher. Considered a pioneer of modern dance in Sweden, she first became interested in the art after watching Isadora Duncan perform. She was born to unwed parents, and was adopted, along with her brother August, by the Granbäck family, who ensured that she had a full education. After initial studies in singing with Eugène Crosti and Emile Wartel in Paris, she studied dance with Duncan and with Emile Jacques-Dalcroze; later she would open her own school in Stockholm.

Text from the Wikipedia website

John Hertzberg (Swedish, 1871-1935)

No title

1903

Gum Bichromate Print

John Hertzberg (1871-1935)

John Hertzberg was a technically accomplished photographer. He developed colour photography in Sweden. He was educated in Vienna and was later offered to teach at the Royal Institute of Technology where he was later senior lecturer in photography. He was thereby a key figure in photographic circles.

When Nils Strindberg’s rolls of film were discovered on Kvitøya in the Svalbard archipelago thirty years after S. A. Andrée’s failed balloon Arctic Expedition in 1897, Hertzberg was given the prestigious task of developing the exposed films. He was also editor of the journal “Nordisk Tidskrift för Fotografi” for many years and chairman of Fotografiska Föreningen.

He experimented with different techniques and groups of motifs in a style typical of the time. These include pictures of Stockholm from the water as well as compositions of clouds and shadows.

Text from the Moderna Museet website

Eugène Jansson (Swedish, 1862-1915)

Hornsgatan nattetid (Hornsgatan at night)

1902

Oil on canvas

152cm (59.8 in) x 182cm (71.6 in)

National Museum (Stockholm)

Eugène Jansson (Swedish, 1862-1915)

Eugène Jansson became a member of the Konstnärsförbundet association of artists in 1886. Inspired by periods spent in France, they painted plein air, impressionist landscapes. Jansson was influenced by these movements from early on. However, he soon progressed to depicting moods rather than the concrete objects he observed.

Many know him from his blue, early evening panoramas of south Stockholm, where he moved in the mid-1890s. In “Hornsgatan nattetid” (1902), everything seems to merge into a blue vision where houses, gas lights and sky form a synthesis.

When Eugène Jansson embarked on a new phase a few years into the 20th century, his motifs were athletic, sun-lit, bathing men. Many found these paintings offensive. Eugène Jansson was a homosexual man at a time when sexual activity between men was against the law.

Text from the Moderna Museet website

Gustaf Fjæstad (Swedish, 1868-1948)

Vinterafton vid en älv (Winter evening by a river)

1907

Oil on canvas

150cm (59 in) x 185cm (72.8 in)

Nationalmuseum (Stockholm)

Gustaf Fjæstad (Swedish, 1868-1948)

After having attended art school in Stockholm, Gustaf Fjæstad settled by Lake Racken in Värmland where he founded an artists’ colony. The collective had no common programme, but they supported each other and exhibited their work together. There was also an idea of not distinguishing art from craft.

Fjæstad was not only a painter, he also designed furniture and textiles. “Vinterafton vid en älv” (Winter Evening at the River Bank, 1907) is testament to Fjæstad’s interest in Japanese woodcuts. The painting communicates a strong sense of nature and existential intensity. The surface is accentuated by fields of colour and a Jugend-inspired linear pattern. The motif is a seemingly random section of the river. The trees are cropped at the top of the canvas but touch the water where the eddies evoke the growth rings of the wood.

Text from the Moderna Museet website

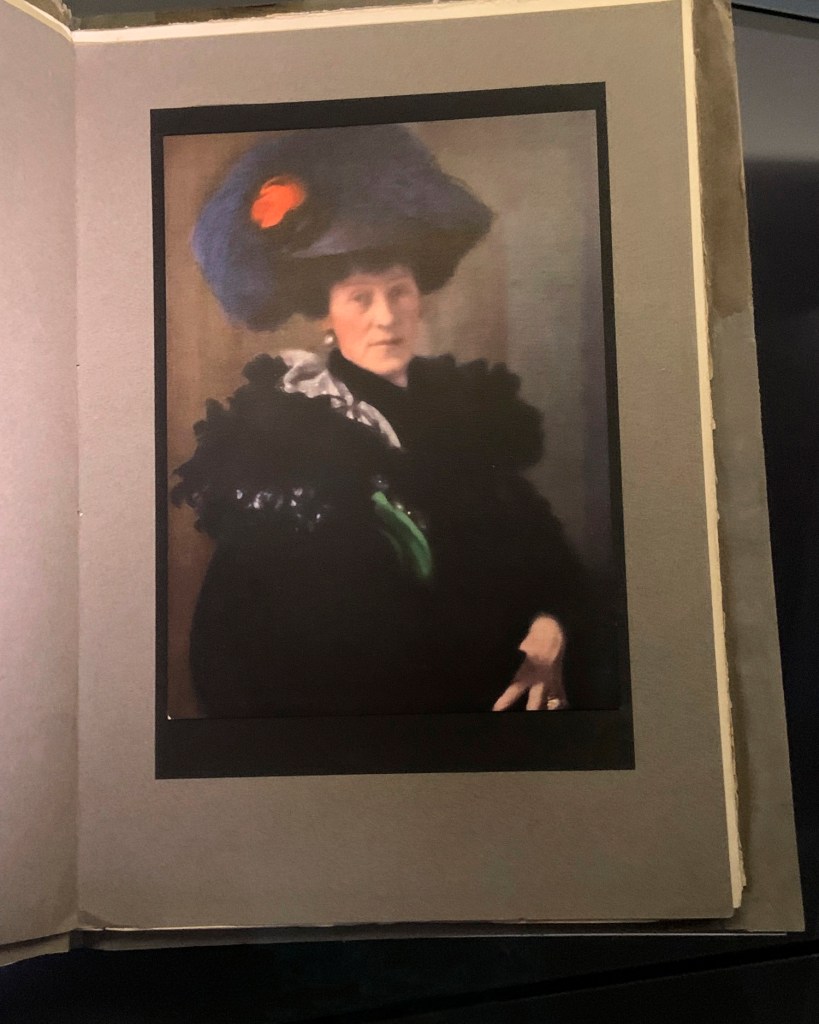

Henry B. Goodwin (Swedish born Germany, 1878-1931)

Lady Barclay

1921

Lady Sarita Enriqueta Barclay (British, 1891-1985)

The portraits that Henry B. Goodwin took of Lady Barclay between 1920 and 1922 show a fashion-conscious society woman. Sarita Barclay moved to Stockholm just after the end of the First World War with her husband, Sir Colville Barclay, and their three children. Her husband was Minister to Sweden, a high-ranking British diplomat.

During the five years that Lady Barclay lived in Stockholm she hosted various events, including a dinner in conjunction with an exhibition of French art at the Liljevalchs art gallery at the initiative of Prince Eugen in 1923. Sarita was the daughter of the British sculptor Herbert Ward.

After the death of her first husband, she married Robert Vansittart, a diplomat who spoke out against Nazism before and during the Second World War.

Text from the Moderna Museet website

Moderna Museet, Stockholm

Moderna Museet is ten minutes away from Kungsträdgården, and twenty minutes from T-Centralen or Gamla Stan. Walk past Grand Hotel and Nationalmuseum on Blasieholmen, opposite the Royal Palace. After crossing the bridge to Skeppsholmen, continue up the hill. The entrance to Moderna Museet and Arkitekturmuseet is on the left-hand side.

Opening hours:

Tuesday – Sunday 11 – 18

Monday closed

![August Sander (German, 1876-1964). 'Das Siebengebirge: Blick vom Rolandsbogen' [The Siebengebirge: view from the Rolandsbogen] 1929-30 (center) and 'Untitled [Remagen Bridge on the Rhine]' c. 1930 (right) August Sander (German, 1876-1964). 'Das Siebengebirge: Blick vom Rolandsbogen' [The Siebengebirge: view from the Rolandsbogen] 1929-30 (center) and 'Untitled [Remagen Bridge on the Rhine]' c. 1930 (right)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/sander-landscape-a.jpg)

![August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Das Siebengebirge: Blick vom Rolandsbogen' [The Siebengebirge: view from the Rolandsbogen] 1929-1930 August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Das Siebengebirge: Blick vom Rolandsbogen' [The Siebengebirge: view from the Rolandsbogen] 1929-1930](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/sander-landscape-b1.jpg)

![August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Das Siebengebirge: Blick vom Rolandsbogen' [The Siebengebirge: view from the Rolandsbogen] 1929-1930 August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Das Siebengebirge: Blick vom Rolandsbogen' [The Siebengebirge: view from the Rolandsbogen] 1929-1930](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/sander-landscape-b.jpg)

![August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Das Siebengebirge: Blick vom Rolandsbogen' [The Siebengebirge: view from the Rolandsbogen] 1929-1930 August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Das Siebengebirge: Blick vom Rolandsbogen' [The Siebengebirge: view from the Rolandsbogen] 1929-1930](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/sander-the-siebengebirge.jpg)

![August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Untitled [Remagen Bridge on the Rhine]' c. 1930 August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Untitled [Remagen Bridge on the Rhine]' c. 1930](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/sander-landscape-c.jpg)

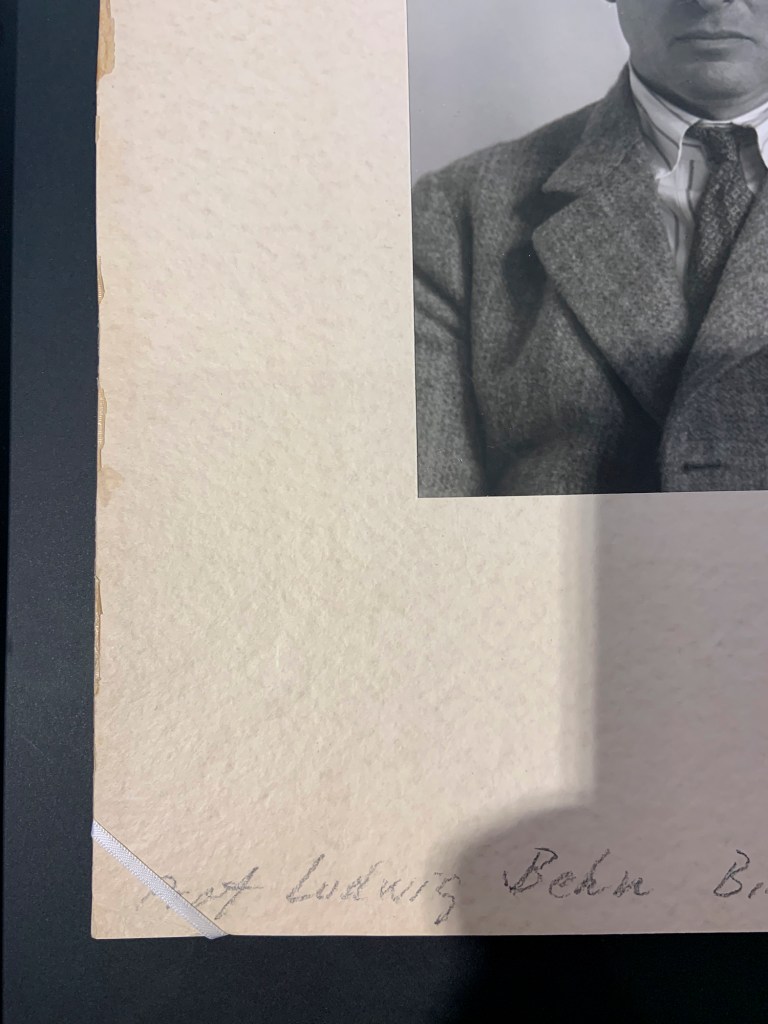

![August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Untitled [Bohemians: avant-garde of Cologne]' 1920s (left) and 'Professor Ludwig Behn' 1920s (right) August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Untitled [Bohemians: avant-garde of Cologne]' 1920s (left) and 'Professor Ludwig Behn' 1920s (right)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/sander-installation-a.jpg)

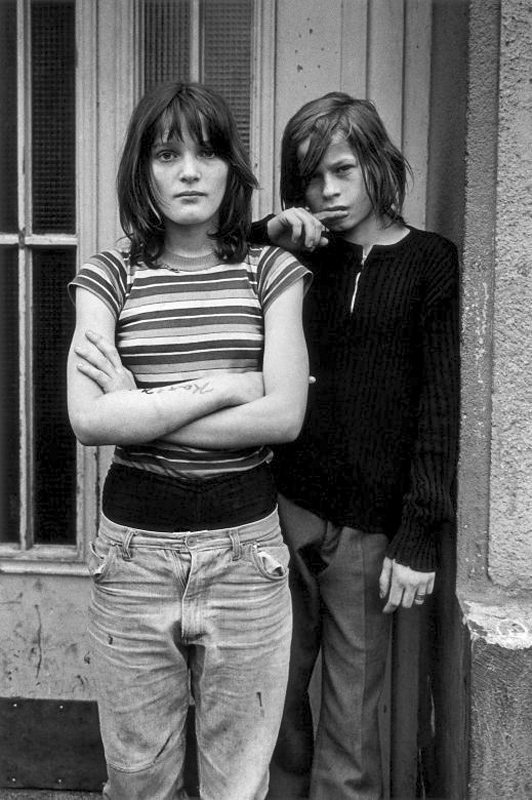

![August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Untitled [Bohemians: avant-garde of Cologne]' 1920s August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Untitled [Bohemians: avant-garde of Cologne]' 1920s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/sander-avant-garde-a.jpg?w=768)

![August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Untitled [Bohemians: avant-garde of Cologne]' 1920s August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Untitled [Bohemians: avant-garde of Cologne]' 1920s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/sander-avant-garde.jpg?w=768)

![August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Painter's Wife [Helene Abelen]' 1926 August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Painter's Wife [Helene Abelen]' 1926](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/sander-painters-wife.jpg?w=749)

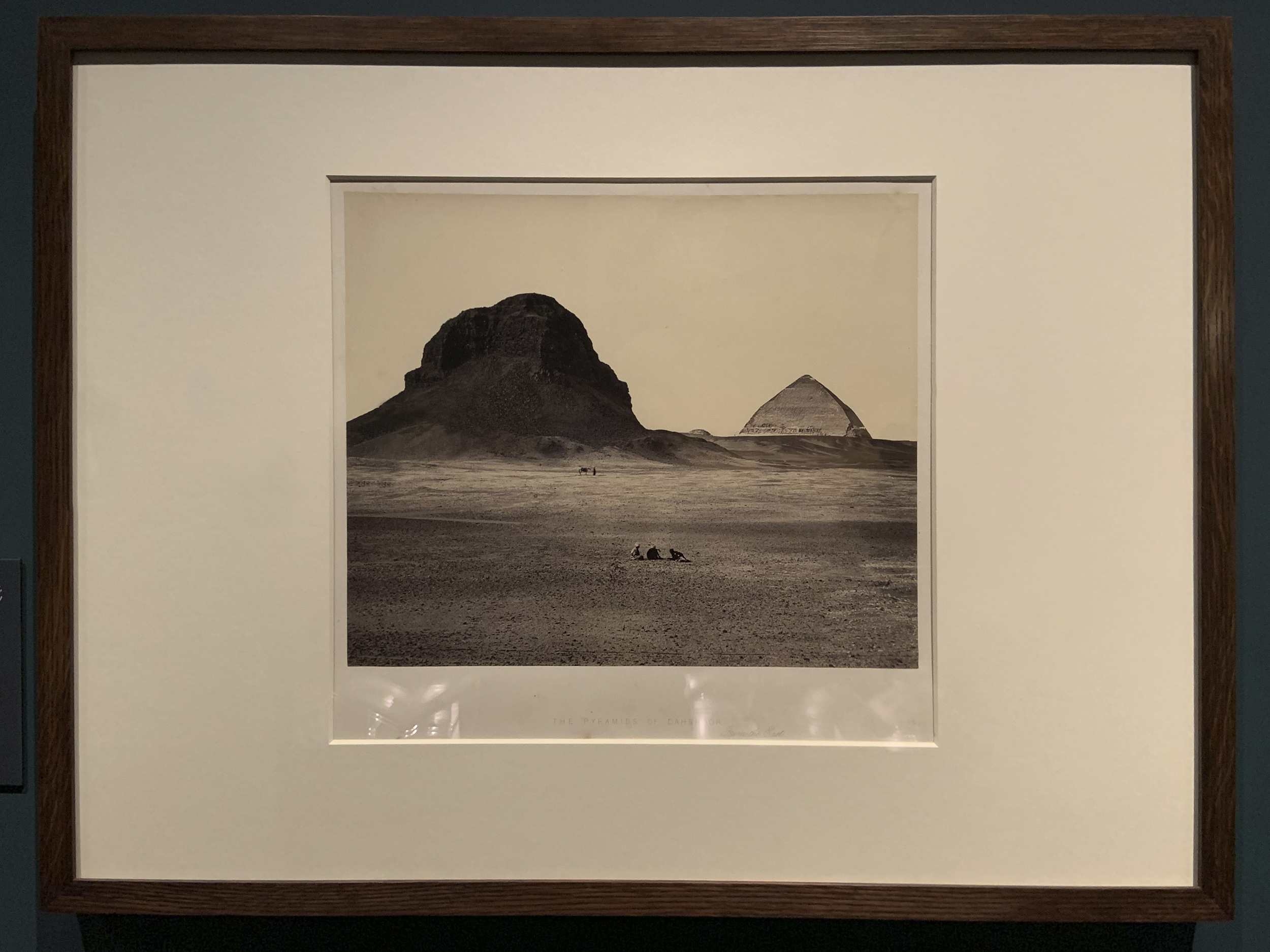

![Francis Frith (British, 1822-98) 'The Pyramids of Dahshoor [Dahshur], from the East, from Egypt, Sinai, and Jerusalem: A Series of Twenty Photographic Views by Francis Frith' 1858 (published 1860 or 1862) from the V&A Photography Centre, London 2019 Francis Frith (British, 1822-98) 'The Pyramids of Dahshoor [Dahshur], from the East, from Egypt, Sinai, and Jerusalem: A Series of Twenty Photographic Views by Francis Frith' 1858 (published 1860 or 1862) from the V&A Photography Centre, London 2019](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/frith-the-pyramids-of-dahshoor-web.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.