November 2009

Sue Ford (Australian, 1943-2009)

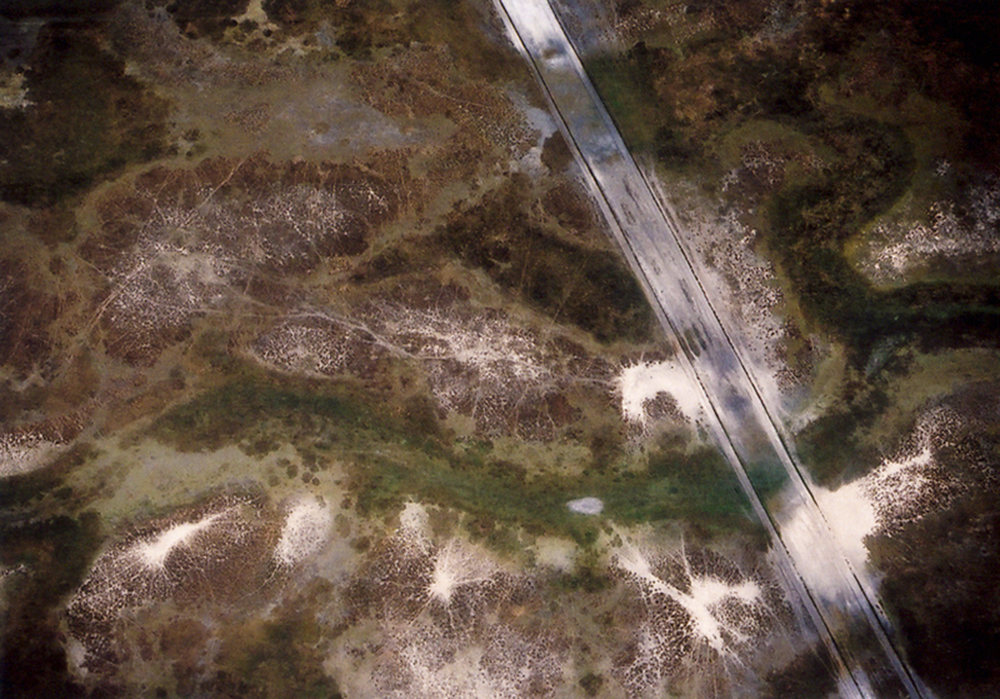

Dissolution

2006

From the Last Light series

One thing always struck me about Sue Ford’s work when I saw it. The work had integrity.

Whatever she produced it was always interesting, valid and had integrity. She followed her own path as we all do – and her voice was clear, focused and eloquent. I loved her series Shadow Portraits – an erudite investigation into the nature of Australian identity if ever there was one!

Vale Sue Ford.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Please click on some of the photographs for a larger version of the image.

See also Barbara Hal. “Australian pioneer focused on her art,” in The Age newspaper November 21, 2009 [Online] Cited 10 May 2019

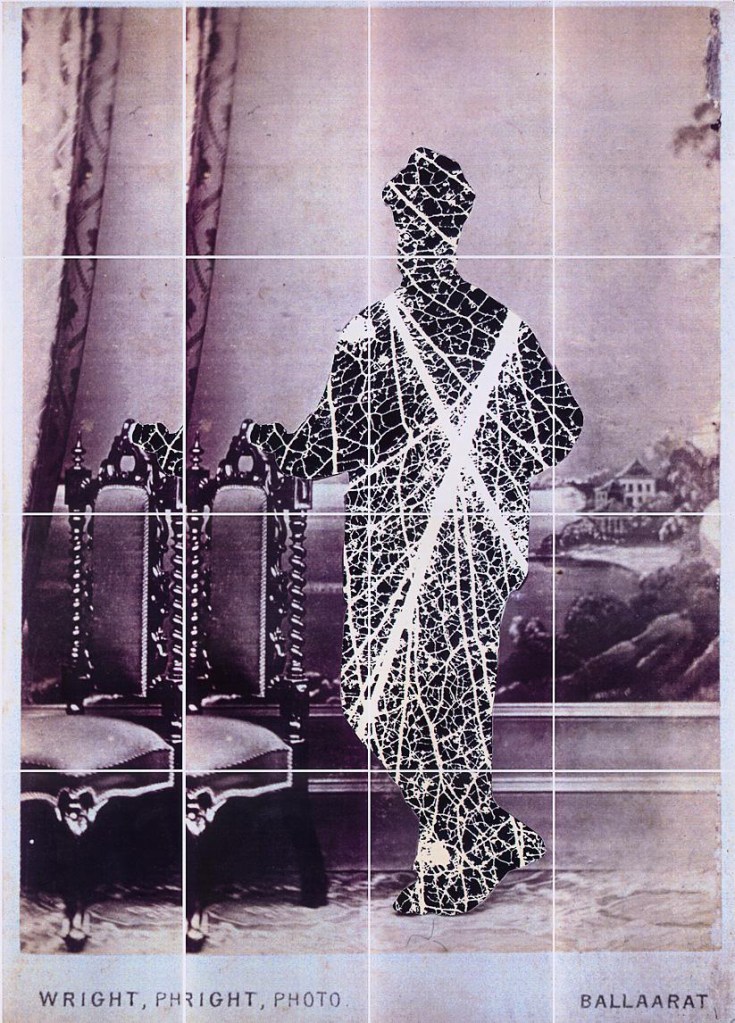

Sue Ford (Australian, 1943-2009)

Silhouette

2006

From the Last Light series

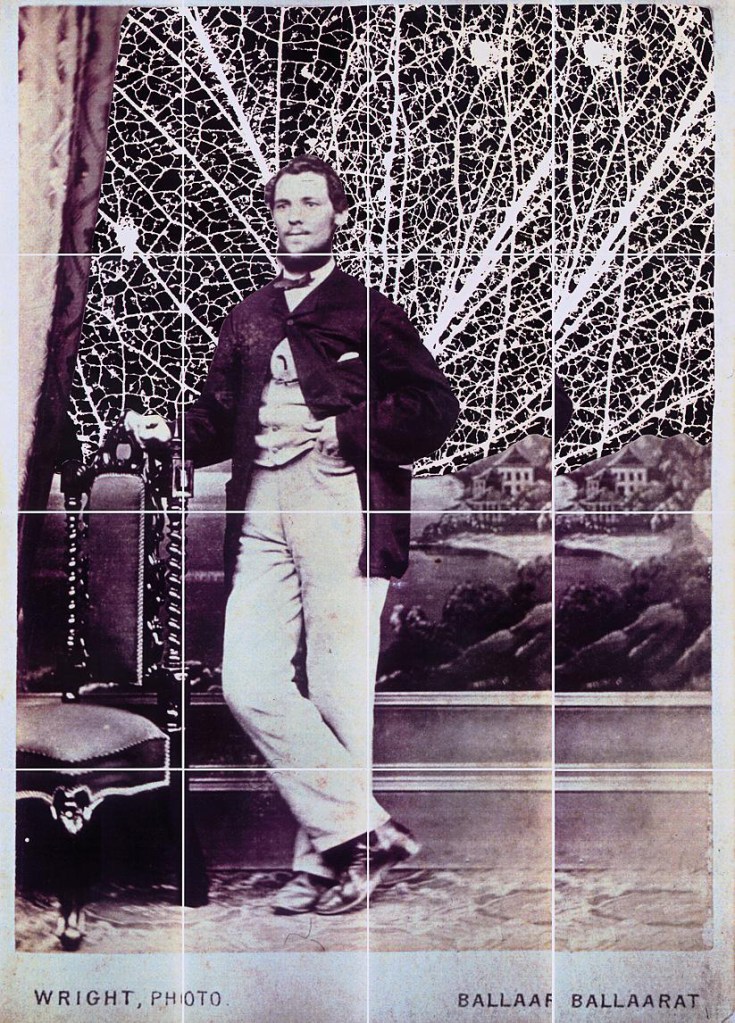

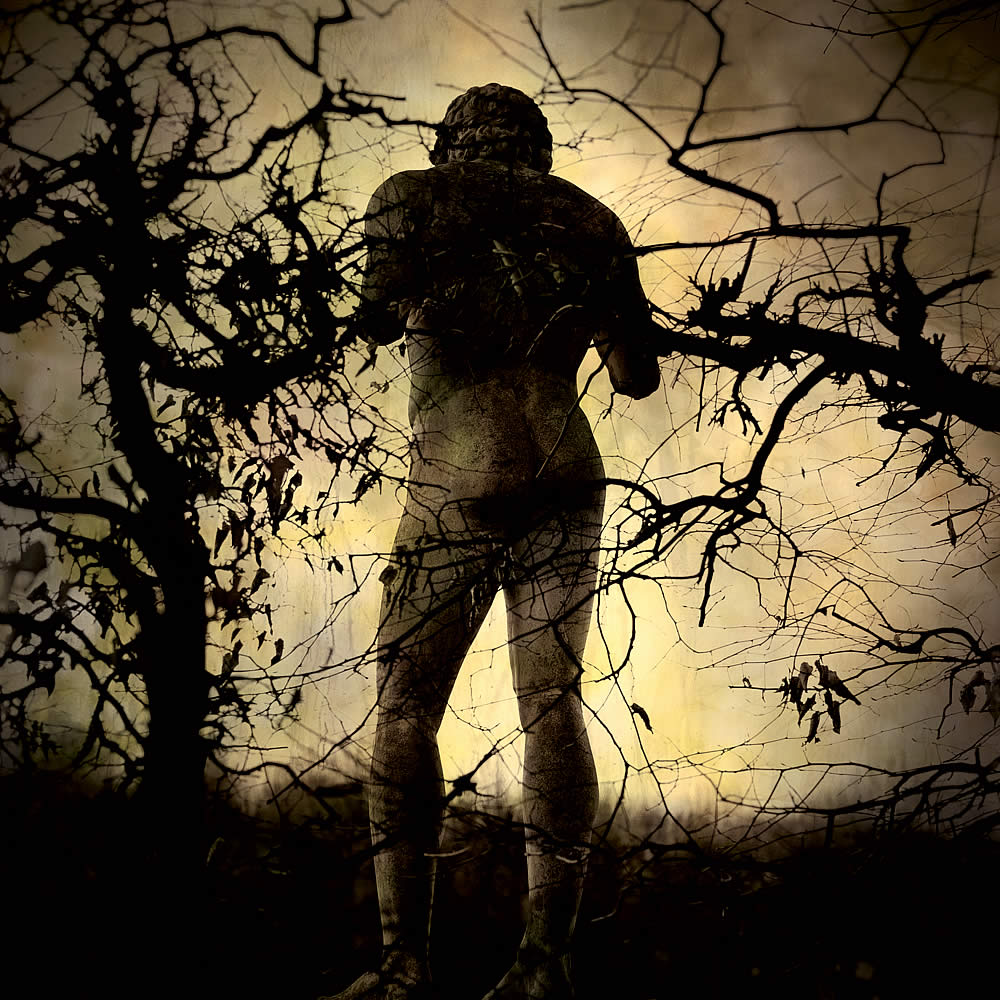

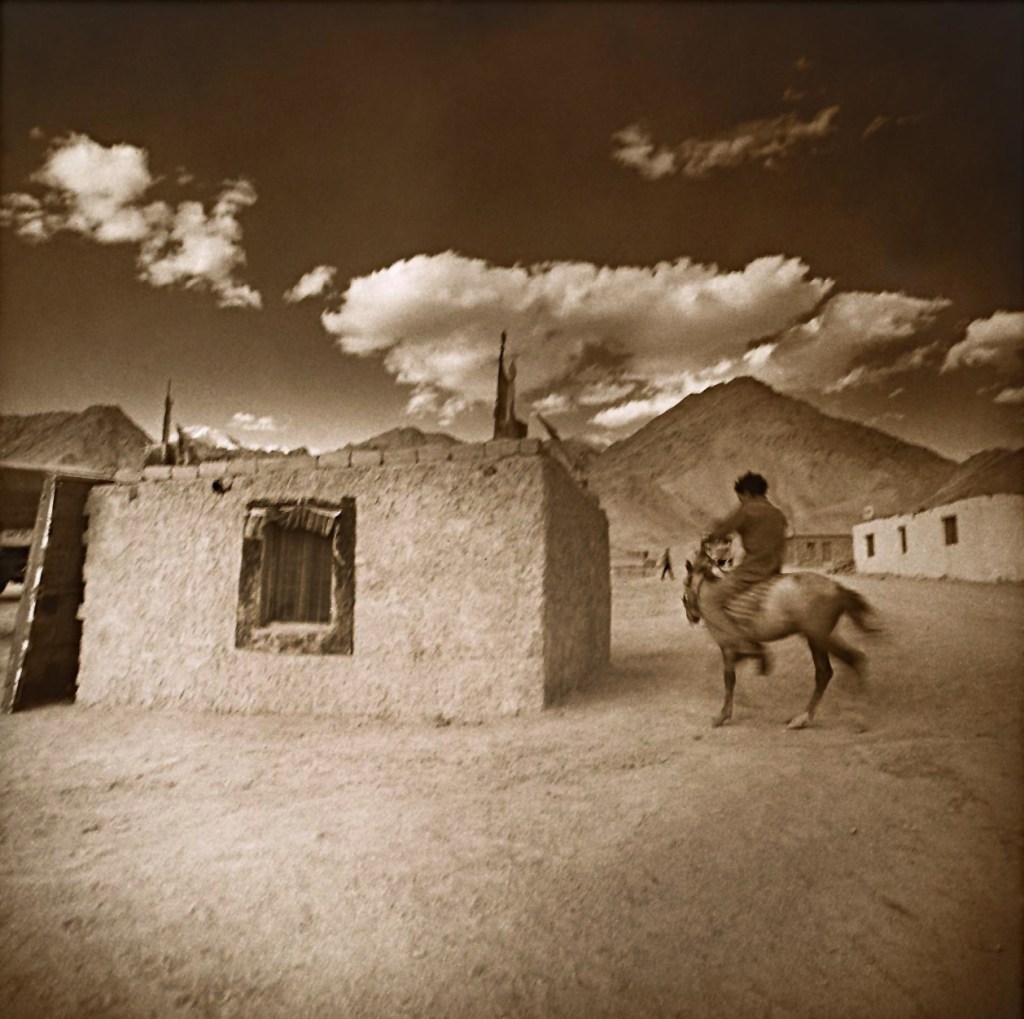

Sue Ford (Australian, 1943-2009)

Apparition

2007

From the Last Light series

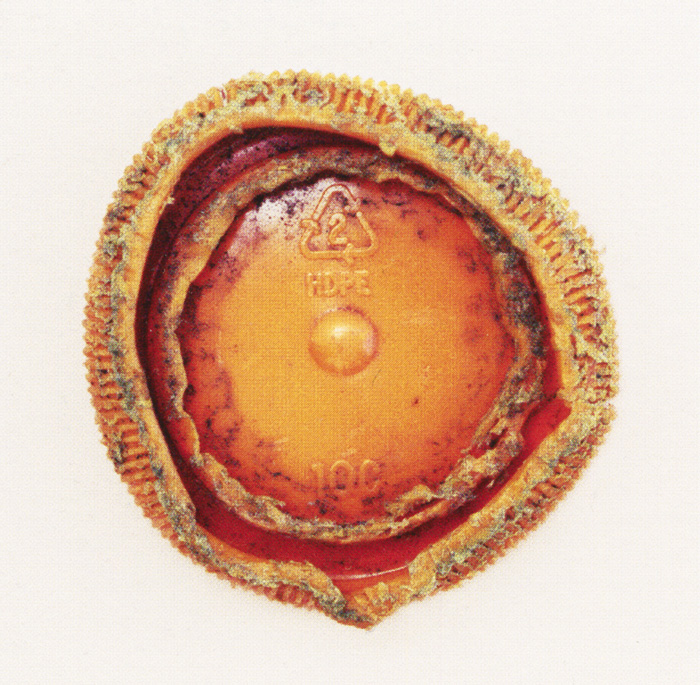

Sue Ford (Australian, 1943-2009)

Transparent

2007

From the Last Light series

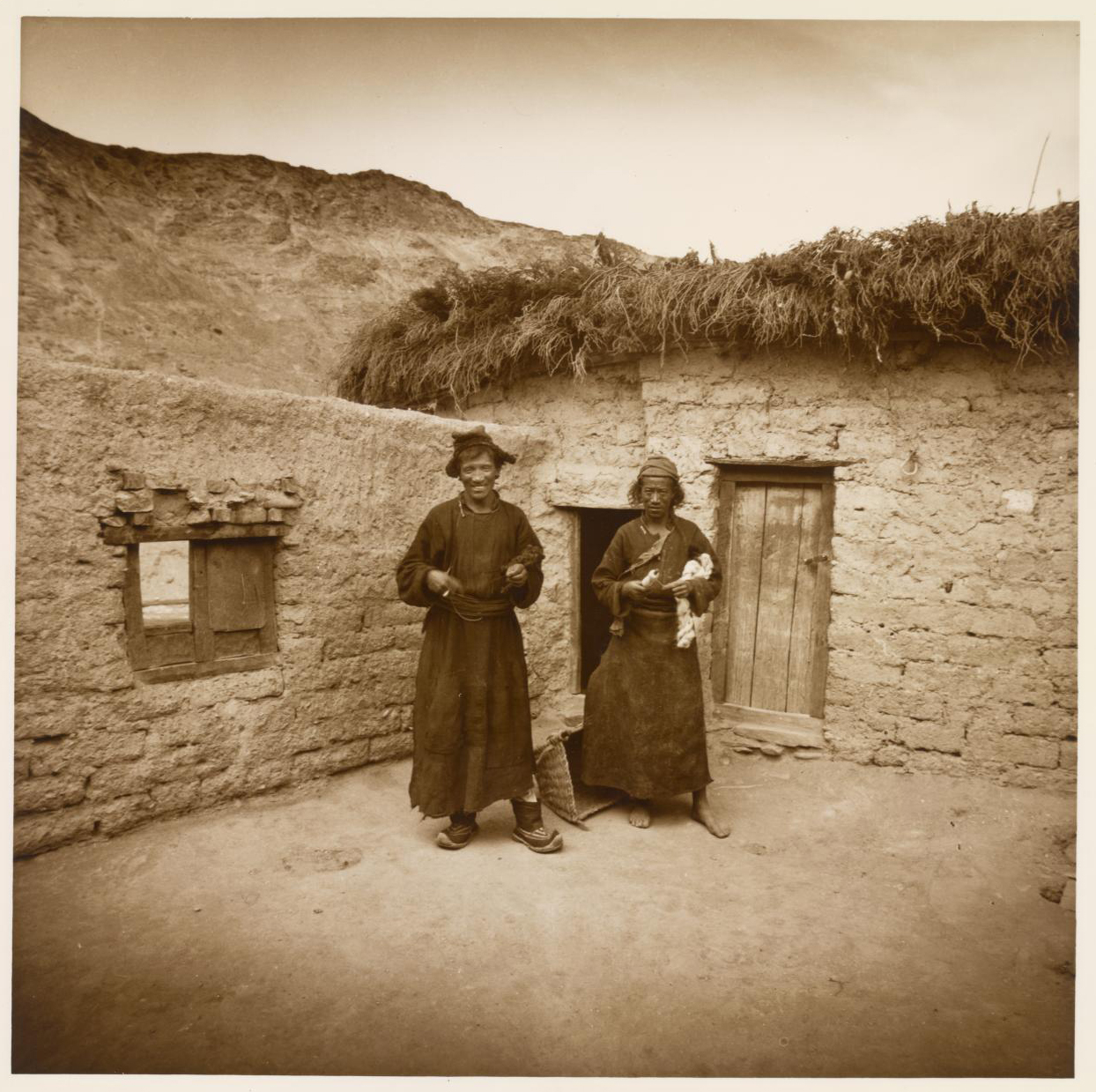

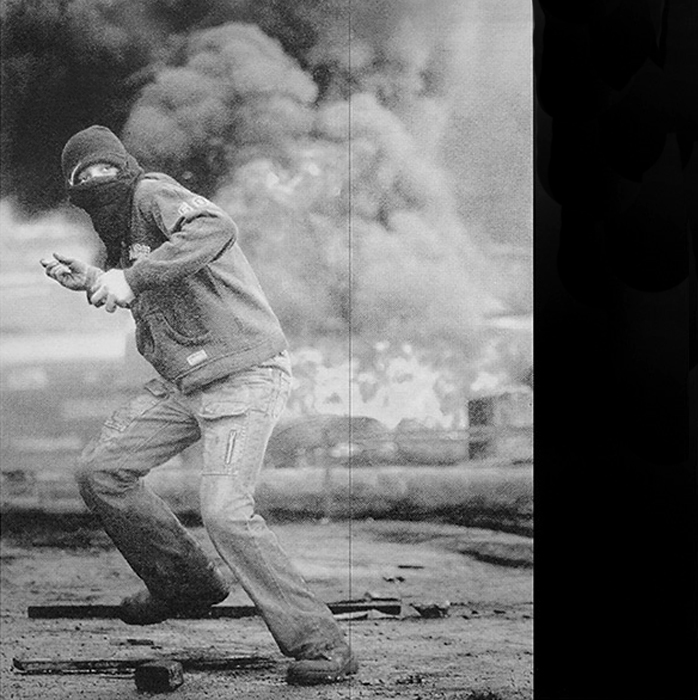

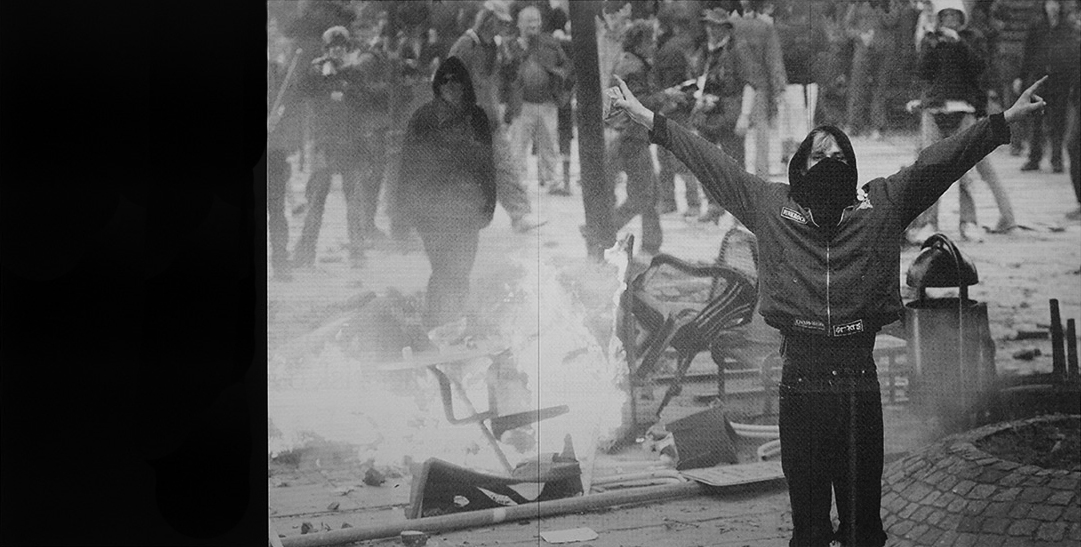

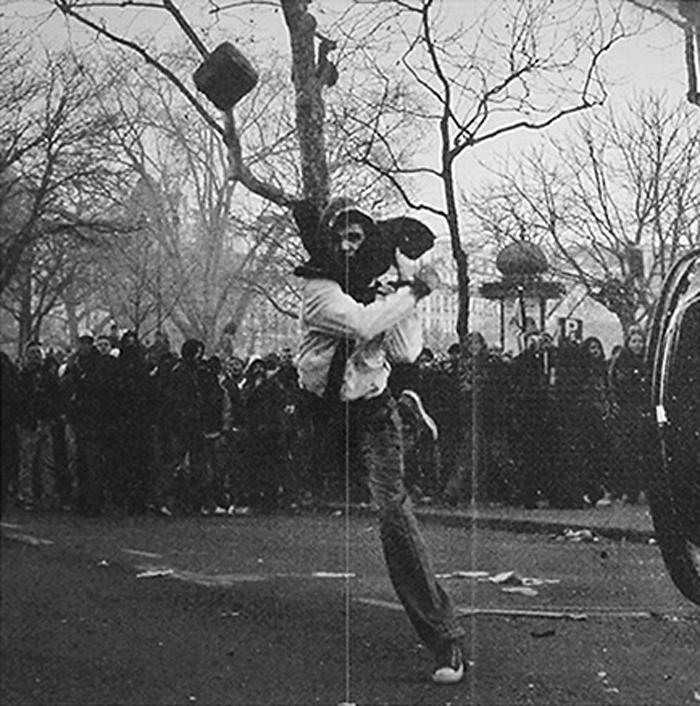

Sue Ford (Australian, 1943-2009)

Shadow portraits (detail)

1994

Colour photocopies

Sue Ford (Australian, 1943-2009)

Shadow portraits (detail)

1994

Colour photocopies

Sue Ford (Australian, 1943-2009)

Shadow portraits (detail)

1994

Colour photocopies

For Shadow portraits, Ford, like numerous artists in this period, mined historical archives of photographs for her source material, decontextualising and reworking it. Her starting point was nineteenth-century studio portraits of settler Australians that were popular in colonial society. She exploded her previous practice and intense focus on the faces of individuals; in most cases the subjects of the original photographs used in Shadow portraits are unrecognisable. Their faces have been emptied out and replaced by Ford’s generic images of Australian foliage, especially fern fronds. All the details that define an individual, their character and appearance, have disappeared, just like the sitters themselves who have been dead for decades and exist only in ghosted form.

Individual works in Shadow portraits (above) rely on a dynamic relationship between historical and contemporary images to create something new. The original studio portrait is not intact, having undergone an extended process of transformation; being re-photographed, cut up and photocopied to eventually take the form of a large gridded image. Use of the grid – an obvious reference to European systems of containment and control – continues the experimentation evident in Yellowcake. Overlaps, like the doubled image of a stereoscopic card, are purposefully exploited. The aim is to destabilise a once-static historic image, to turn the small into big, the tones into colour, the positive into negative and so on. Through these means the colonial past is represented as having continuing reverberations: the loss of concreteness in the images and distortions of scale parallel the incompleteness, gaps and blow-outs characteristic of any historical narrative. As Zara Stanhope writes, Ford’s Shadow portraits ‘image the ongoing processes involved in the construction of histories, and the power to know and remember, that provides the opportunity to revisit or critique such accounts’.

Associate Professor Helen Ennis. “Sue Ford’s history,” in Art Journal 50, National Gallery of Victoria, 1 Jan 2013 [Online] Cited 11/05/2019

Sue Ford (Australian, 1943-2009)

Ross, 1964; Ross, 1974

Printed 1974

From the Time series (1962-1974)

Gelatin silver print

11.1 × 20.1cm

© Sue Ford

“I have always been interested in how actions taken in the past could affect and echo in peoples’ lives in the present. Most of my work is to do with thinking about human existence from this perspective.”

Sue Ford, “Project X’, in Helen Ennis & Virginia Fraser, Sue Ford: A Survey 1960-1995. Monash University Gallery, Clayton, 1995, p. 17

Sue Ford (Australian, 1943-2009)

Big secret!

c. 1960-1961

Gelatin silver print

28.9 × 23.6cm

© Sue Ford

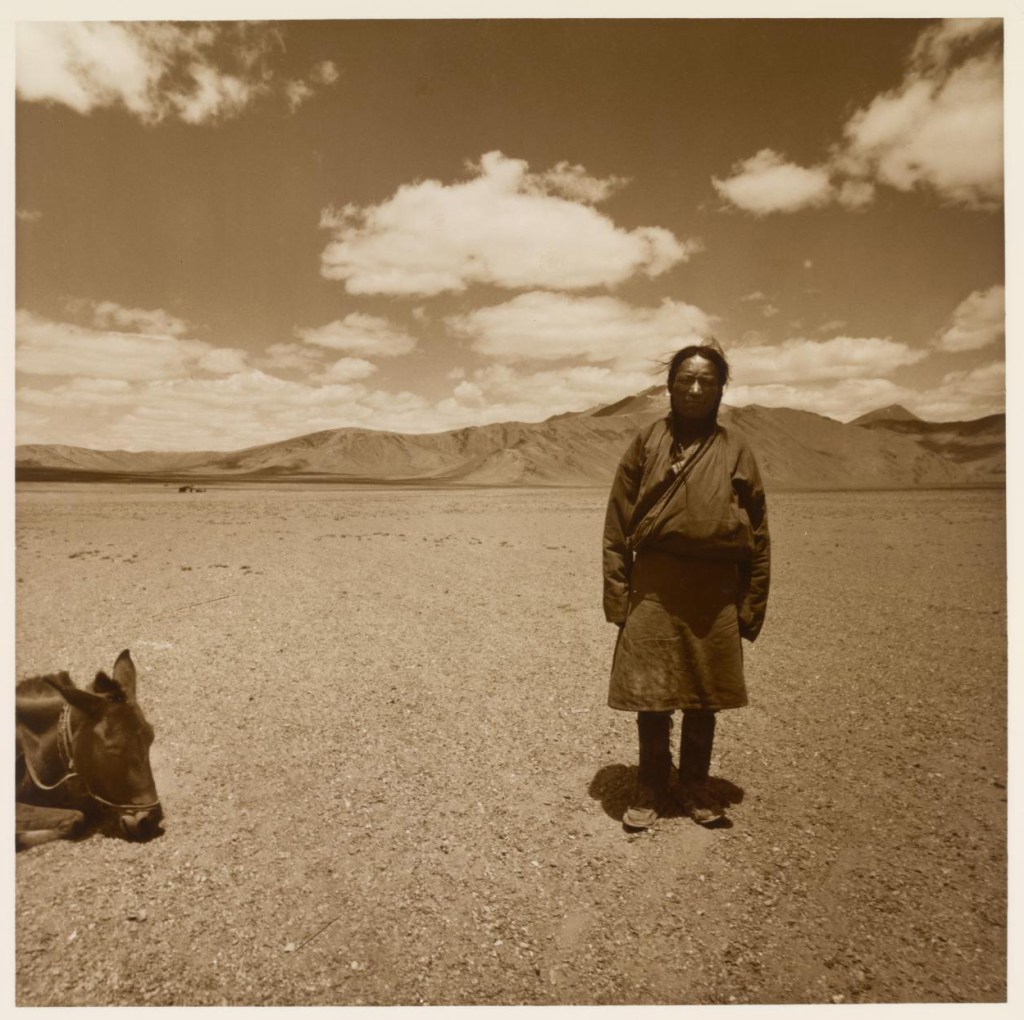

Sue Ford (Australian, 1943-2009)

Orpheus

1972

Gelatin silver print

33.8 × 33.8cm

© Sue Ford

A feminist approach

Until 1988 Ford was known principally for work that was motivated by feminist politics, that dealt with the lives of contemporary women and the politics of representation. She worked across media, using black and white photography, film and video. Her photography from the early 1960s onwards was based on what she regarded as photography’s objective capacity; in other words, she utilised the camera as a means of recording whatever she placed in front of it. This interest in ‘objectivity’ related more to the practices of conceptual art than to the heightened subjectivity, or subjective documentary that prevailed in art photography, especially during the seventies. Ford’s feminist photography can be regarded as objective but not as ‘documentary’ in the terms the latter is conventionally understood because there was nothing surreptitious or spontaneous about it. Her approach was non-exploitative and consensual in keeping with the politics of feminism and the counterculture. From the beginning of her career, her subjects were mostly friends and acquaintances; they knew they were being photographed and agreed to it. This consensual approach and its interrelated performative element were adopted by other feminist photographers, such as Carol Jerrems, Ponch Hawkes and Ruth Maddison, in their work during the 1970s.

In the 1970s and 80s Ford’s photography differed from mainstream practice in another fundamental way. It did not relate to the purist and fine art traditions that underpinned the case for photography’s acceptance as art. Her prints were grainy, rough and often very small. Ford conceived photography in radical terms, as a plastic medium that was entwined with other art practices. In an interview at the time she was awarded a scholarship to fund her studies at the Victorian College of the Arts in 1973-74, she emphasised her interest in artists’ use of photography: ‘Some artists are utilising phototechniques and are thinking in a photographic way. I want to use some of their techniques and materials to extend photography into other dimensions’.

Associate Professor Helen Ennis. “Sue Ford’s history,” in Art Journal 50, National Gallery of Victoria, 1 Jan 2013 [Online] Cited 11/05/2019

Sue Ford (Australian, 1943-2009)

No title (Photogram of two hands and garden path)

c. 1970

Gelatin silver print

27.6 × 34.7cm irreg. (image and sheet)

© Sue Ford

![E. J. Bellocq (American, 1873-1949) 'Untitled [prostitute of Storyville, New Orleans]' 1912 E. J. Bellocq (American, 1873-1949) 'Untitled [prostitute of Storyville, New Orleans]' 1912](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/09/bellocq_1912_g.jpg?w=382)

You must be logged in to post a comment.